Загреб

Загреб | |

|---|---|

| Город Загреб Город Загреб | |

| |

The city of Zagreb in Croatia | |

| Coordinates: 45°48′47″N 15°58′39″E / 45.81306°N 15.97750°E | |

| Country | |

| County | City of Zagreb |

| RC diocese | 1094 |

| Free royal city | 1242 |

| Unified | 1850 |

| Subdivisions | 17 city districts 218 local committees 70 settlements |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-Council |

| • Mayor | Tomislav Tomašević (Možemo!) |

| • City Assembly | 48 members |

| Area | |

| • City | 641.2 km2 (247.6 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 305.8 km2 (118.1 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 158 m (518 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 1,035 m (3,396 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 122 m (400 ft) |

| Population (2021)[3] | |

| • City | 767,131 |

| • Density | 1,200/km2 (3,100/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 663,592 |

| • Urban density | 2,200/km2 (5,600/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,217,150 |

| Demonym(s) | Zagreber (en) Zagrepčanin (hr, male) Zagrepčanka (hr, female) Purger (informal, jargon) |

| GDP | |

| • City | €20.284 billion |

| • Per capita | €25,100 |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | HR-10 000, HR-10 010, HR-10 020, HR-10 040, HR-10 090 |

| Area code | +385 1 |

| Vehicle registration | ZG |

| HDI (2021) | 0.916[6] – very high |

| Website | zagreb |

Загреб ( / ˈ z ɑː ɡ r ɛ b / ZAH захват [7] Хорватский: [zώːɡreb] [а] ) [9] столица и город Хорватии крупнейший . [10] Он находится на севере страны , вдоль реки Савы , на южных склонах горы Медведница . Загреб расположен недалеко от международной границы между Хорватией и Словенией на высоте примерно 158 м (518 футов) над уровнем моря . [11] По переписи 2021 года население самого города составляло 767 131 человек. [3] в то время как население городской агломерации Загреба составляет чуть более миллиона человек.

Загреб – город с богатой историей, берущей начало еще со времен Римской империи . Самым старым поселением в окрестностях города была римская Андаутония , на территории сегодняшнего Щитарьево . [12] Историческая запись названия «Загреб» датируется 1134 годом и относится к основанию поселения Каптол в 1094 году. Загреб стал свободным королевским городом в 1242 году. [13] В 1851 году Янко Камауф Загреба стал первым мэром . [14] Загреб имеет особый статус как административное деление Хорватии — он включает в себя консолидированный город-уезд (но отдельный от Загребского округа ), [15] and is administratively subdivided into 17 city districts.[16] Most of the city districts lie at a low elevation along the valley of the river Sava, but northern and northeastern city districts, such as Podsljeme[17] and Sesvete[18] districts are situated in the foothills of the Medvednica mountain,[19] making the city's geographical image quite diverse. The city extends over 30 km (19 mi) east-west and around 20 km (12 mi) north-south.[20][21] Zagreb ranks as a global city, with a 'Beta-' rating from the Globalization and World Cities Research Network.[22]

The transport connections, the concentration of industry, scientific, and research institutions and industrial tradition underlie its leading economic position in Croatia.[23][24][25] Zagreb is the seat of the central government, administrative bodies, and almost all government ministries.[26][27][28] Almost all of the largest Croatian companies, media, and scientific institutions have their headquarters in the city. Zagreb is the most important transport hub in Croatia: here Central Europe, the Mediterranean and Southeast Europe meet, making the Zagreb area the centre of the road, rail and air networks of Croatia. It is a city known for its diverse economy, high quality of living, museums, sporting, and entertainment events. Major branches of Zagreb's economy include high-tech industries and the service sector.

Name[edit]

The etymology of the name Zagreb is unclear. It was used for the united city only from 1852, but it had been in use as the name of the Zagreb Diocese since the 12th century and was increasingly used for the city in the 17th century.[29]The name is first recorded in a charter by Felician, Archbishop of Esztergom, dated 1134, mentioned as Zagrabiensem episcopatum.[30]

The name is probably derived from Proto-Slavic word *grębъ which means "hill" or "uplift". An Old Croatian reconstructed name *Zagrębъ is manifested through the city's former German name, Agram.[31] Some linguists (e.g. Nada Klaić, Miroslav Kravar) propose a metathesis of *Zabreg, which would originate from Old Slavic breg (see Proto-Slavic *bergъ) in the sense of "riverbank", referring to River Sava. This metathesis has been attested in Kajkavian,[32] but the meaning of "riverbank" is lost in modern Croatian and folk etymology associates it instead with breg "hill", ostensibly referring to Medvednica. Hungarian linguist Gyula Décsy similarly uses metathesis to construct *Chaprakov(o), a putative Slavicisation of a Hungarian hypocorism for "Cyprian", similar to the etymology of Csepreg, Hungary.[33] The most likely derivation is *Zagrębъ in the sense of "embankment" or "rampart", i.e. remains of the 1st millennium fortifications on Grič.[32][31]

In Middle Latin and Modern Latin, Zagreb is known as Agranum (the name of an unrelated Arabian city in Strabo),[citation needed] Zagrabia or Mons Graecensis (also Mons Crecensis, in reference to Grič (Gradec)).

The most common folk etymology derives the name of the city has been from the verb stem za-grab-, meaning "to scoop" or "to dig". A folk legend illustrating this derivation, attested but discarded as a serious etymology by Ivan Tkalčić,ties the name to a drought of the early 14th century, during which Augustin Kažotić (c. 1260–1323) is said to have dug a well which miraculously produced water.[34]In another legend,[35][36][37][38][39] a city governor is thirsty and orders a girl named Manda to "scoop" water from the Manduševac well (nowadays a fountain in Ban Jelačić Square), using the imperative: Zagrabi, Mando! ("Scoop, Manda!").[40]

History[edit]

The oldest known settlement located near present-day Zagreb, the Roman town of Andautonia, now Ščitarjevo, existed between the 1st and the 5th centuries AD.[41]

The first recorded appearance of the name "Zagreb" dates from 1094, at which time the city existed as two different city centers: the smaller, eastern Kaptol, inhabited mainly by clergy and housing Zagreb Cathedral, and the larger, western Gradec, inhabited mainly by craftsmen and merchants. In 1851 the Ban of Croatia, Josip Jelačić, united Gradec and Kaptol; the name of the main city square, Ban Jelačić Square honors him.[42]

While Croatia formed part of Yugoslavia (1918 to 1991), Zagreb remained an important economic centre of that country, and was the second largest city. After Croatia declared independence from Yugoslavia in 1991, the Parliament of the Republic of Croatia (Croatian: Sabor Republike Hrvatske) proclaimed Zagreb as the capital of the Republic of Croatia.[43]

Early Zagreb[edit]

The history of Zagreb dates as far back as 1094 A.D. when the Hungarian King Ladislaus, returning from his campaign against the Kingdom of Croatia, founded a diocese. Alongside the bishop's see, the canonical settlement Kaptol developed north of Zagreb Cathedral, as did the fortified settlement Gradec on the neighbouring hill, with the border between the two formed by the Medveščak stream.[44] Today the latter is Zagreb's Upper Town (Gornji Grad) and is one of the best-preserved urban nuclei in Croatia. Both settlements came under Tatar attack in 1242.[45] As a sign of gratitude for offering him a safe haven from the Tatars, the Croatian and Hungarian King Béla IV granted Gradec the Golden Bull of 1242, which gave its citizens exemption from county rule and autonomy, as well as their own judicial system.[46][47]

The relationship between Kaptol and Gradec throughout history[edit]

The development of Kaptol began in 1094 after the foundation of the diocese, while the growth of Gradec began after the Golden Bull was issued in 1242. In the history of the city of Zagreb, there have been numerous conflicts between Gradec and Kaptol, mainly due to disputed issues of rent collection and due to disputed properties.

The first known conflicts took place in the middle of the 13th century and continued with interruptions until 1667. Because of the conflict, it was recorded that the Bishop of Kaptol excommunicated the residents of Gradec twice.

In the conflicts between Gradec and Kaptol, there were several massacres of the citizens, destruction of houses and looting of citizens. In 1850, Gradec and Kaptol, with surrounding settlements, were united into a single settlement, today's city of Zagreb.[48][49][50][51][52]

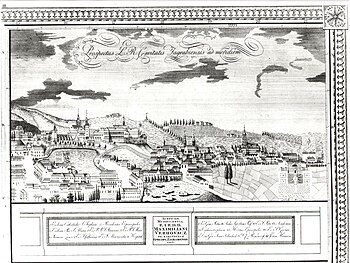

16th to 18th centuries[edit]

There were numerous connections between the Kaptol diocese and the free sovereign town of Gradec for both economic and political reasons, but they were not known as an integrated city, even as Zagreb became the political center, and the regional Sabor (Latin: Congregatio Regnorum Croatiae, Dalmatiae et Slavoniae) representing Croatia, Slavonia and Dalmatia, first convened at Gradec. Zagreb became the Croatian capital in 1557, with city also being chosen as the seat of the Ban of Croatia in 1621 under ban Nikola IX Frankopan.[53]

At the invitation of the Croatian Parliament, the Jesuits came to Zagreb and built the first grammar school,[54]the St. Catherine's Church (built 1620-1632[55])and monastery. In 1669, they founded an academy where philosophy, theology, and law were taught, the forerunner of today's University of Zagreb.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, Zagreb was badly devastated by fire and by the plague. In 1776, the royal council (government) moved from Varaždin to Zagreb and during the reign of the Emperor Joseph II Zagreb became the headquarters of the Varaždin and Karlovac general command.[56]

19th to mid-20th century[edit]

- Ban Jelačić Square in Zagreb under the Habsburgs, before the 1880 Zagreb earthquake

- The Zagreb Cathedral renovated according to designs of Hermann Bollé, between 1902 and 1906

- Zagreb 1930s

- Starčević square, first half of the 20th century

- Bronze map of the historic center of Zagreb

In the 19th century, Zagreb was the center of the Croatian National Revival and saw the foundation of important cultural and historic institutions.In 1850, the town was united under its first mayor – Janko Kamauf.[56]

The first railway line to connect Zagreb with Zidani Most and Sisak opened in 1862 and in 1863 Zagreb received a gasworks. The Zagreb waterworks opened in 1878.

After the 1880 Zagreb earthquake, up to the 1914 outbreak of World War I, development flourished and the town received the characteristic layout which it has today.The first horse-drawn tram dated from 1891. The construction of railway lines enabled the old suburbs to merge gradually into Donji Grad, characterized by a regular block pattern that prevails in Central European cities. This bustling core includes many imposing buildings, monuments, and parks as well as a multitude of museums, theatres, and cinemas. An electric-power plant was built in 1907.

Since 1 January 1877, the Grič cannon fires daily from the Lotrščak Tower on Grič to mark midday.

The first half of the 20th century saw a considerable expansion of Zagreb. Before World War I, the city expanded and neighborhoods like Stara Peščenica in the east and Črnomerec in the west grew up. The Rokov perivoj neighbourhood, noted for its Art Nouveau features, was established at the start of the century.[57]

After the war, working-class districts such as Trnje emerged between the railway and the Sava, whereas the construction of residential districts on the hills of the southern slopes of Medvednica was completed between the two World Wars.

In the 1920s, the population of Zagreb increased by 70 percent – the largest demographic boom in the history of the town. In 1926, the first radio station in the region began broadcasting from Zagreb, and in 1947 the Zagreb Fair opened.[56]

During World War II, Zagreb became the capital of the Independent State of Croatia (1941–1945), which was backed by Nazi Germany and by the Italians. The history of Zagreb in World War II became rife with incidents of régime terror and resistance sabotage - the Ustaša régime had thousands of people executed during the war in and near the city. Partisans took the city at the end of the war. From 1945 until 1990, Zagreb functioned as the capital of the Socialist Republic of Croatia, one of the six constituent socialist republics of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

Contemporary era[edit]

The area between the railway and the Sava river witnessed a new construction-boom after World War II. After the mid-1950s, construction of new residential areas south of the Sava river began, resulting in Novi Zagreb (Croatian for New Zagreb), originally called "Južni Zagreb" (Southern Zagreb).[58]From 1999 Novi Zagreb has comprised two city districts: Novi Zagreb – zapad (New Zagreb – West) and Novi Zagreb – istok (New Zagreb – East)

The city also expanded westward and eastward, incorporating Dubrava, Podsused, Jarun, Blato, and other settlements.

The cargo railway hub and the international airport (Pleso) were built south of the Sava river. The largest industrial zone (Žitnjak) in the south-eastern part of the city, represents an extension of the industrial zones on the eastern outskirts of the city, between the Sava and the Prigorje region. Zagreb hosted the Summer Universiade in 1987.[56] This event initiated the creation of pedestrian-only zones in the city centre and extensive new sport infrastructure, lacking until then, all around the city.[citation needed]

During the 1991–1995 Croatian War of Independence, the city saw some sporadic fighting around its JNA army barracks, but escaped major damage. In May 1995, it was targeted by Serb rocket artillery in two rocket attacks which killed seven civilians and wounded many.

An urbanized area connects Zagreb with the surrounding towns of Zaprešić, Samobor, Dugo Selo, and Velika Gorica. Sesvete was the first and the closest area to become a part of the agglomeration and is already included in the City of Zagreb for administrative purposes and now forms the easternmost city district.[59]

In 2020 the city experienced a 5.5 magnitude earthquake, which damaged various buildings in the historic downtown area. The city's iconic cathedral lost the cross off of one of its towers. This earthquake was the strongest one to affect the city since the destructive 1880 Zagreb earthquake.

Geography[edit]

Climate[edit]

The climate of Zagreb is classified as an oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb), bordering a humid continental climate (Dfb).

Zagreb has four separate seasons. Summers are generally warm, sometimes hot. In late May it gets significantly warmer, temperatures start rising and it often becomes very warm or even hot with occasional afternoon and evening thunderstorms. Heatwaves can occur but are short-lived. Temperatures rise above 30 °C (86 °F) on average 14.6 days each summer. During summertime, rainfall is abundant and it mainly falls during thunderstorms. With 840 mm of precipitation per year, Zagreb is Europe's ninth wettest capital, receiving less precipitation than Luxembourg but more than Brussels, Paris or London. Compared to these cities, however, Zagreb has fewer rainy days, but the annual rainfall is higher due to heavier showers occurring mainly in late spring and summer. Autumn in its early stage often brings pleasant and sunny weather with occasional episodes of rain later in the season. Late autumn is characterized by a mild increase in the number of rainy days and a gradual decrease in daily temperature averages. Morning fog is common from mid-October to January, with northern city districts at the foothills of the Medvednica mountain as well as south-central districts along the Sava river being more prone to longer fog accumulation.

Winters are relatively cold, bringing overcast skies and a precipitation decrease pattern. February is the driest month, averaging 39 mm of precipitation. On average there are 29 days with snowfall, with the first snow usually falling in early December. However, in recent years, the number of days with snowfall in wintertime has decreased considerably. Spring is characterized by often pleasant but changeable weather. As the season progresses, sunny days become more frequent, bringing higher temperatures. Sometimes cold spells can occur as well, mostly in the season's early stages. The average daily mean temperature in the winter is around 1 °C (34 °F) (from December to February) and the average temperature in the summer is 20 °C (68.0 °F).[60]The highest recorded temperature at the Maksimir weather station was 40.4 °C (104.7 °F) in July 1950, and lowest was −27.3 °C (−17.1 °F) in February 1956.[61] A temperature of −30.5 °C (−22.9 °F) was recorded on the since defunct Borongaj Airfield in February 1940.[62]

| Climate data for Zagreb Maksimir (1971–2000, extremes 1949–2019) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.4 (66.9) | 22.6 (72.7) | 26.0 (78.8) | 30.5 (86.9) | 33.7 (92.7) | 37.6 (99.7) | 40.4 (104.7) | 39.8 (103.6) | 34.0 (93.2) | 28.3 (82.9) | 25.4 (77.7) | 22.5 (72.5) | 40.4 (104.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.7 (38.7) | 6.8 (44.2) | 11.9 (53.4) | 16.3 (61.3) | 21.5 (70.7) | 24.5 (76.1) | 26.7 (80.1) | 26.3 (79.3) | 22.1 (71.8) | 15.8 (60.4) | 8.9 (48.0) | 4.6 (40.3) | 15.8 (60.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.3 (32.5) | 2.3 (36.1) | 6.4 (43.5) | 10.7 (51.3) | 15.8 (60.4) | 18.8 (65.8) | 20.6 (69.1) | 20.1 (68.2) | 15.9 (60.6) | 10.5 (50.9) | 5.0 (41.0) | 1.4 (34.5) | 10.7 (51.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −3.0 (26.6) | −1.8 (28.8) | 1.6 (34.9) | 5.2 (41.4) | 9.8 (49.6) | 13.0 (55.4) | 14.7 (58.5) | 14.4 (57.9) | 10.8 (51.4) | 6.2 (43.2) | 1.4 (34.5) | −1.7 (28.9) | 5.9 (42.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −24.3 (−11.7) | −27.3 (−17.1) | −18.3 (−0.9) | −4.4 (24.1) | −1.8 (28.8) | 2.5 (36.5) | 5.4 (41.7) | 3.7 (38.7) | −0.6 (30.9) | −5.6 (21.9) | −13.5 (7.7) | −19.8 (−3.6) | −27.5 (−17.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 43.2 (1.70) | 38.9 (1.53) | 52.6 (2.07) | 59.3 (2.33) | 72.6 (2.86) | 95.3 (3.75) | 77.4 (3.05) | 92.3 (3.63) | 85.8 (3.38) | 82.9 (3.26) | 80.1 (3.15) | 59.6 (2.35) | 840.1 (33.07) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 9.8 | 9.4 | 11.0 | 13.0 | 13.5 | 13.7 | 11.2 | 10.4 | 10.4 | 10.9 | 11.3 | 11.0 | 135.6 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 1.0 cm) | 10.3 | 7.1 | 1.8 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 6.7 | 29.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 82.5 | 76.4 | 70.3 | 67.5 | 68.3 | 69.7 | 69.1 | 72.1 | 77.7 | 81.3 | 83.6 | 84.8 | 75.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 55.8 | 98.9 | 142.6 | 168.0 | 229.4 | 234.0 | 275.9 | 257.3 | 189.0 | 124.0 | 63.0 | 49.6 | 1,887.5 |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 9.2 | 10.4 | 11.9 | 13.6 | 15 | 15.7 | 15.3 | 14.1 | 12.5 | 10.9 | 9.5 | 8.7 | 12.2 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 23 | 39 | 43 | 45 | 54 | 55 | 63 | 63 | 54 | 41 | 26 | 23 | 47 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Source 1: Croatian Meteorological and Hydrological Service[60][61] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas[63] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape[edit]

The most important historical high-rise constructions are Neboder (1958) on Ban Jelačić Square, Cibona Tower (1987), and Zagrepčanka (1976) on Savska Street, Mamutica in Travno (Novi Zagreb – istok district, built in 1974) and Zagreb TV Tower on Sljeme (built in 1973).[64]

In the 2000s, the City Assembly approved a new plan that allowed for the many recent high-rise buildings in Zagreb, such as the Almeria Tower, Eurotower, HOTO Tower, Zagrebtower, Sky Office Tower and the tallest high-rise building in Zagreb Strojarska Business Center.[65][66]

In Novi Zagreb, the neighbourhoods of Blato and Lanište expanded significantly, including the Zagreb Arena and the adjoining business centre.[67]

Due to a long-standing restriction that forbade the construction of 10-story or higher buildings, most of Zagreb's high-rise buildings date from the 1970s and 1980s and new apartment buildings on the outskirts of the city are usually 4–8 floors tall. Exceptions to the restriction have been made in recent years, such as permitting the construction of high-rise buildings in Lanište or Kajzerica.[68]

Surroundings[edit]

The wider Zagreb area has been continuously inhabited since the prehistoric period, as witnessed by archaeological findings in the Veternica cave from the Paleolithic and excavation of the remains of the Roman Andautonia near the present village of Šćitarjevo.

Picturesque former villages on the slopes of Medvednica, Šestine, Gračani, and Remete, maintain their rich traditions, including folk costumes, Šestine umbrellas, and gingerbread products.

To the north is the Medvednica Mountain (Croatian: Zagrebačka gora), with its highest peak Sljeme(1,035 m), where one of the tallest structures in Croatia, Zagreb TV Tower is located. The Sava and the Kupa valleys are to the south of Zagreb, and the region of Hrvatsko Zagorje is located on the other (northern) side of the Medvednica hill. In mid-January 2005, Sljeme held its first World Ski Championship tournament.

From the summit, weather permitting, the vista reaches as far as Velebit Range along Croatia's rocky northern coast, as well as the snow-capped peaks of the towering Julian Alps in neighboring Slovenia. There are several lodging villages, offering accommodation and restaurants for hikers. Skiers visit Sljeme, which has four ski-runs, three ski-lifts, and a chairlift.

The old Medvedgrad, a recently restored medieval burg was built in the 13th century on Medvednica hill. It overlooks the western part of the city and also hosts the Shrine of the Homeland, a memorial with an eternal flame, where Croatia pays reverence to all its heroes fallen for homeland in its history, customarily on national holidays. The ruined medieval fortress Susedgrad is located on the far-western side of Medvednica hill. It has been abandoned since the early 17th century, but it is visited during the year.

Zagreb occasionally experiences earthquakes, due to the proximity of Žumberak-Medvednica fault zone.[69] It's classified as an area of high seismic activity.[70] The area around Medvednica was the epicentre of the 1880 Zagreb earthquake (magnitude 6.3), and the area is known for occasional landslide threatening houses in the area.[71] The proximity of strong seismic sources presents a real danger of strong earthquakes.[71] Croatian Chief of Office of Emergency Management Pavle Kalinić stated Zagreb experiences around 400 earthquakes a year, most of them being imperceptible. However, in case of a strong earthquake, it's expected that 3,000 people would die and up to 15,000 would be wounded.[72]

Demographics[edit]

Zagreb is by far the largest city in Croatia in terms of population, which was 767,131 in 2021.[3]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1857 | 48,266 | — |

| 1869 | 54,761 | +13.5% |

| 1880 | 67,188 | +22.7% |

| 1890 | 82,848 | +23.3% |

| 1900 | 111,565 | +34.7% |

| 1910 | 136,351 | +22.2% |

| 1921 | 167,765 | +23.0% |

| 1931 | 258,024 | +53.8% |

| 1948 | 356,529 | +38.2% |

| 1953 | 393,919 | +10.5% |

| 1961 | 478,076 | +21.4% |

| 1971 | 629,896 | +31.8% |

| 1981 | 723,065 | +14.8% |

| 1991 | 777,826 | +7.6% |

| 2001 | 779,145 | +0.2% |

| 2011 | 790,017 | +1.4% |

| 2021 | 767,131 | −2.9% |

| Source: Croatian Bureau of Statistics publications | ||

Zagreb metropolitan area population is slightly above 1.0 million inhabitants,[73] as it includes the Zagreb County.[74] Zagreb metropolitan area makes approximately a quarter of a total population of Croatia.In 1997, the City of Zagreb itself was given special County status, separating it from Zagreb County,[75] although it remains the administrative centre of both.

The majority of its citizens are Croats making up 93.53% of the city's population (2021 census). The same census records around 49,605 residents belonging to ethnic minorities: 12,035 Serbs (1.57%), 6,566 Bosniaks (0.86%), 3,475 Albanians (0.45%), 2,167 Romani (0.28%), 1,312 Slovenes (0.17%), 1,036 Macedonians (0.15%), 865 Montenegrins (0.11%), and a number of other smaller communities.[76]

After the easing of COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, thousands of foreign workers immigrated to Zagreb due to the shortage of labor force in Croatia. These workers primarily come from countries such as Nepal, the Philippines, India, and Bangladesh, as well as some European countries including Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Kosovo and North Macedonia.[77]

| population | 48266 | 54761 | 67188 | 82848 | 111565 | 136351 | 167765 | 258024 | 356529 | 393919 | 478076 | 629896 | 723065 | 777826 | 779145 | 790017 | 767131 |

| 1857 | 1869 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 | 1910 | 1921 | 1931 | 1948 | 1953 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 | 2011 | 2021 |

City districts[edit]

List of districts by area and population in 2021.[78]

Since 14 December 1999 City of Zagreb is divided into 17 city districts (gradska četvrt, pl. gradske četvrti):

| # | District | Area (km2) | Population (2001)[79] | Population (2011)[80] | Population density (2011) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Donji Grad | 3.01 | 45,108 | 37,024 | 12,333 |

| 2. | Gornji Grad–Medveščak | 10.12 | 36,384 | 30,962 | 3,091 |

| 3. | Trnje | 7.37 | 45,267 | 42,282 | 5,716 |

| 4. | Maksimir | 14.35 | 49,750 | 48,902 | 3,446 |

| 5. | Peščenica – Žitnjak | 35.30 | 58,283 | 56,487 | 1,599 |

| 6. | Novi Zagreb – istok | 16.54 | 65,301 | 59,055 | 3,581 |

| 7. | Novi Zagreb – zapad | 62.59 | 48,981 | 58,103 | 927 |

| 8. | Trešnjevka – sjever | 5.83 | 55,358 | 55,425 | 9,493 |

| 9. | Trešnjevka – jug | 9.84 | 67,162 | 66,674 | 6,768 |

| 10. | Črnomerec | 24.33 | 38,762 | 38,546 | 1,605 |

| 11. | Gornja Dubrava | 40.28 | 61,388 | 61,841 | 1,545 |

| 12. | Donja Dubrava | 10.82 | 35,944 | 36,363 | 3,370 |

| 13. | Stenjevec | 12.18 | 41,257 | 51,390 | 4,257 |

| 14. | Podsused – Vrapče | 36.05 | 42,360 | 45,759 | 1,270 |

| 15. | Podsljeme | 60.11 | 17,744 | 19,165 | 320 |

| 16. | Sesvete | 165.26 | 59,212 | 70,009 | 427 |

| 17. | Brezovica | 127.45 | 10,884 | 12,030 | 94 |

| TOTAL | 641.43 | 779,145 | 790,017 | 1,236 |

City districts are subdivided in 218 local committees as primary units of local self-government.[81]

Settlements[edit]

| Year | Area (km2) | Population (within city limits at that time) | Population (within today's city limits) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1368 | 2,810[nb 1] | |||

| 1742 | 3.33 | 5,600[nb 1] | ||

| 1805 | 3.33 | 7,706[nb 2](≈11 000 in total) | ||

| 1817 | 10.0 | 9,055 | ||

| 1837 | 25.4 | 15,155 | ||

| 1842 | 25.4 | 15,952 | ||

| 1848 | 25.4 | 15,978 | ||

| 1850 | 25.4 | 16,036 | ||

| 1857 | 25.4 | 16,657 | 48,266 | |

| 1869 | 25.4 | 19,857 | 54,761 | |

| 1880 | 25.4 | 30,830 | 67,188 | |

| 1890 | 25.4 | 40,268 | 82,848 | |

| 1900 | 64.37 | 61,002 | 111,565 | |

| 1910 | 64.37 | 79,038 | 136,351 | |

| 1921 | 64.37 | 108,674 | 167,765 | |

| 1931 | 64.37 | 185,581 | 258,024 | |

| 1948 | 74.99 | 279,623 | 356,529 | |

| 1953 | 235.74 | 350,829 | 393,919 | |

| 1961 | 495.60 | 430,802 | 478,076 | |

| 1971 | 497.95 | 602,205 | 629,896 | |

| 1981 | 1,261.54 | 768,700 | 723,065 | |

| 1991 | 1,715.55 | 933,914 | 777,826 | |

| 2001 | 641.36 | 779,145 | 779,145 | |

| 2011 | 641.36 | 790,017 | 790,017 | |

| 2019 | 641.36 | 806,341 | 806,341 | |

| The data in column 3 refers to the population in the city borders as of the census in question. Column 4 is calculated for the territory now defined as the City of Zagreb ( Narodne Novine 97/10).[82] | ||||

The city itself is not the only standalone settlement in the City of Zagreb administrative area – there are a number of larger urban settlements like Sesvete and Lučko and a number of smaller villages attached to it whose population is tracked separately.[83]

There are 70 settlements in the City of Zagreb administrative area:

- Adamovec, population 975

- Belovar, population 378

- Blaguša, population 594

- Botinec, population 9

- Brebernica, population 49

- Brezovica, population 594

- Budenec, population 323

- Buzin, population 1,055

- Cerje, population 398

- Demerje, population 721

- Desprim, population 377

- Dobrodol, population 1,203

- Donji Čehi, population 232

- Donji Dragonožec, population 577

- Donji Trpuci, population 428

- Drenčec, population 131

- Drežnik Brezovički, population 656

- Dumovec, population 903

- Đurđekovec, population 778

- Gajec, population 311

- Glavnica Donja, population 544

- Glavnica Gornja, population 226

- Glavničica, population 229

- Goli Breg, population 406

- Goranec, population 449

- Gornji Čehi, population 363

- Gornji Dragonožec, population 295

- Gornji Trpuci, population 87

- Grančari, population 221

- Havidić Selo, population 53

- Horvati, population 1,490

- Hrašće Turopoljsko, population 1,202

- Hrvatski Leskovac, population 2,687

- Hudi Bitek, population 441

- Ivanja Reka, population 1,800

- Jesenovec, population 460

- Ježdovec, population 1,728

- Kašina, population 1,548

- Kašinska Sopnica, population 245

- Kučilovina, population 219

- Kućanec, population 228

- Kupinečki Kraljevec, population 1,957

- Lipnica, population 207

- Lučko, population 3,010

- Lužan, population 719

- Mala Mlaka, population 636

- Markovo Polje, population 425

- Moravče, population 663

- Odra, population 1,866

- Odranski Obrež, population 1,578

- Paruževina, population 632

- Planina Donja, population 554

- Planina Gornja, population 247

- Popovec, population 937

- Prekvršje, population 809

- Prepuštovec, population 332

- Sesvete, population 54,085

- Soblinec, population 978

- Starjak, population 227

- Strmec, population 645

- Šašinovec, population 678

- Šimunčevec, population 271

- Veliko Polje, population 1,668

- Vuger Selo, population 273

- Vugrovec Donji, population 442

- Vugrovec Gornji, population 357

- Vurnovec, population 201

- Zadvorsko, population 1,288

- Zagreb, population 688,163

- Žerjavinec, population 556

Politics and government[edit]

Zagreb is the capital of the Republic of Croatia, its political center and the center of various state institutions.

On the St. Mark's Square are the seats of the Government of the Republic of Croatia in the Banski Dvori complex, the Croatian Parliament (Sabor), as well as the Constitutional Court of the Republic of Croatia. Various ministries and state agencies are located in the wider area of the City of Zagreb.

City governance[edit]

The current mayor of Zagreb is Tomislav Tomašević ('We can!'), elected in the 2021 Zagreb local elections, the second round of which was held on 30 May 2021. There are two deputy mayors elected from the same list, Danijela Dolenec and Luka Korlaet.[84]

The Zagreb Assembly is composed of 51 representatives, elected in the 2021 Zagreb local elections.

The political groups represented in the Assembly (as of June 2021):[85]

| Groups | No. of members per group | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Green–Left | 23 / 47 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| HDZ | 6 / 47 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DP | 5 / 47 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| BM365 | 5 / 47 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SDP | 5 / 47 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Most | 3 / 47 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source:[86][87] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Zagreb Assembly is composed of 51 representatives, elected in the 2021 Zagreb local elections.

According to the Constitution, the city of Zagreb, as the capital of Croatia, has a special status. As such, Zagreb performs self-governing public affairs of both city and county. It is also the seat of the Zagreb County which encircles Zagreb.

The city administration bodies are the Zagreb City Assembly (Gradska skupština Grada Zagreba) as the representative body and the mayor of Zagreb (Gradonačelnik Grada Zagreba) who is the executive head of the city.

The City Assembly is the representative body of the citizens of the City of Zagreb elected for a four-year term on the basis of universal suffrage in direct elections by secret ballot using proportional system with d'Hondt method in a manner specified by law. There are 51 representatives in the City Assembly, among them the president and vice-presidents of the assembly are elected by the representatives.

Before 2009, the mayor was elected by the City Assembly. It was changed to direct elections by majoritarian vote (two-round system) in 2009. The mayor is the head of the city administration and has two deputies (directly elected together with him/her).

The term of office of the mayor (and his/her deputies) is four years. The mayor (with the deputies) may be recalled by a referendum according to the law (not less than 20% of all electors in the City of Zagreb or not less than two-thirds of the Zagreb Assembly city deputies have the right to initiate a city referendum regarding recalling of the mayor; when a majority of voters taking part in the referendum vote in favor of the recall, provided that majority includes not less than one-third of all persons entitled to vote in the City of Zagreb, i.e. 1⁄3 of persons in the City of Zagreb electoral register, the mayor's mandate shall be deemed revoked and special mayoral by-elections shall be held).

In the City of Zagreb, the mayor is also responsible for the state administration (due to the special status of Zagreb as a "city with county rights", there isn't a State Administration Office which in all counties performs tasks of the central government).City administration offices, institutions and services (18 city offices, 1 public institute or bureau and 2 city services) have been founded for performing activities within the self-administrative sphere and activities entrusted by the state administration.The city administrative bodies are managed by the principals (appointed by the mayor for a four-year term of office, may be appointed again to the same duty). The City Assembly Professional Service is managed by the secretary of the City Assembly (appointed by the Assembly).

Local government is organised in 17 city districts represented by City District Councils. Residents of districts elect members of councils.[88]

Minority councils and representatives[edit]

Directly elected minority councils and representatives are tasked with consulting tasks for the local or regional authorities in which they are advocating for minority rights and interests, integration into public life and participation in the management of local affairs.[89] At the 2023 Croatian national minorities councils and representatives elections Albanians, Bosniaks, Czechs, Hungarians, Macedonians, Montenegrins, Roma, Slovenes and Serbs of Croatia each fulfilled legal requirements to elect 25 members minority councils of the City of Zagreb while Bulgarians, Poles, Pannonian Rusyns, Russians, Slovaks, Italians, Turks, Ukrainians and Jews of Croatia elected individual representatives with representative of the Germans of Croatia remaining unelected due to the lack of candidates.[90]

International relations[edit]

Twin towns – sister cities[edit]

Zagreb is twinned with the following towns and cities:[91][92][93]

Bologna, Italy (since 1963)

Bologna, Italy (since 1963) Mainz, Germany (since 1967)

Mainz, Germany (since 1967) Saint Petersburg, Russia (since 1968)[94]

Saint Petersburg, Russia (since 1968)[94] Tromsø, Norway (since 1971)

Tromsø, Norway (since 1971) Buenos Aires, Argentina (since 1972)

Buenos Aires, Argentina (since 1972) Kyoto, Japan (since 1972)[95]

Kyoto, Japan (since 1972)[95] Lisbon, Portugal (since 1977)[96][97]

Lisbon, Portugal (since 1977)[96][97] Pittsburgh, United States (since 1980)

Pittsburgh, United States (since 1980) Shanghai, China (since 1980)

Shanghai, China (since 1980) Budapest, Hungary (since 1994)[98]

Budapest, Hungary (since 1994)[98] La Paz, Bolivia (since 2000)

La Paz, Bolivia (since 2000) Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina (since 2001)[99]

Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina (since 2001)[99] Ljubljana, Slovenia (since 2001)[100]

Ljubljana, Slovenia (since 2001)[100] Podgorica, Montenegro (since 2006)

Podgorica, Montenegro (since 2006) Tabriz, Iran (since 2006)[101]

Tabriz, Iran (since 2006)[101] Ankara, Turkey (since 2008)[102]

Ankara, Turkey (since 2008)[102] London, United Kingdom (since 2009)

London, United Kingdom (since 2009) Skopje, Macedonia (since 2011)

Skopje, Macedonia (since 2011) Warsaw, Poland (since 2011)[103]

Warsaw, Poland (since 2011)[103] Pristina, Kosovo (since 2012)

Pristina, Kosovo (since 2012) Astana, Kazakhstan (since 2014)[104]

Astana, Kazakhstan (since 2014)[104] Rome, Italy (since 2014)[93]

Rome, Italy (since 2014)[93] Vienna, Austria (since 2014)[93]

Vienna, Austria (since 2014)[93] Petrinja, Croatia (since 2015)[105]

Petrinja, Croatia (since 2015)[105] Vukovar, Croatia (since 2016)[106]

Vukovar, Croatia (since 2016)[106] Xiangyang, China (since 2017)[107]

Xiangyang, China (since 2017)[107]

Partner cities[edit]

The city has partnership arrangements with:

Kraków, Poland (since 1975)[108]

Kraków, Poland (since 1975)[108] Tirana, Albania[109][110]

Tirana, Albania[109][110] Pécs, Hungary[111]

Pécs, Hungary[111] Kyiv, Ukraine (since 2024)[112]

Kyiv, Ukraine (since 2024)[112]

Culture[edit]

Tourism[edit]

Zagreb is an important tourist center, not only in terms of passengers traveling from the rest of Europe to the Adriatic Sea but also as a travel destination itself. Since the end of the war, it has attracted close to a million visitors annually, mainly from Austria, Germany, and Italy, and in recent years many tourists from far east (South Korea, Japan, China, and last two years, from India). It has become an important tourist destination, not only in Croatia, but considering the whole region of southeastern Europe.There are many interesting sights and happenings for tourists to attend in Zagreb, for example, the two statues of Saint George, one at the Republic of Croatia Square, the other at the Stone Gate, where the image of Virgin Mary is said to be the only thing that did not burn in the 17th-century fire. Also, there is an art installation starting in the Bogovićeva Street, called Nine Views.Zagreb is also famous for its award-winning Christmas market that had been named the one in Europe for three years in a row (2015, 2016, 2017) by European Best Destinations.[113][114]

The capital is also known for its top Restaurants in Zagreb[115] that offer more than traditional Croatian food and classic dishes. In addition to that, a lot of international hotel chains are offering their accommodations in Zagreb, including: Best Western, Hilton Worldwide: (DoubleTree by Hilton, Hilton Garden Inn & Canopy by Hilton), Marriott International: (Sheraton Hotels & Westin Hotels), Radisson Hotel Group, Mövenpick Hotels & Resorts and a former Regent Hotels & Resorts which is now Esplanade Zagreb Hotel.

The historical part of the city to the north of Ban Jelačić Square is composed of the Gornji Grad and Kaptol, a medieval urban complex of churches, palaces, museums, galleries and government buildings that are popular with tourists on sightseeing tours. The historic district can be reached on foot, starting from the Ban Jelačić Square, the center of Zagreb, or by a funicular on nearby Tomićeva Street. Each Saturday, (from April until the end of September), on St. Mark's Square in the Upper town, tourists can meet members of the Order of The Silver Dragon (Red Srebrnog Zmaja), who reenact famous historical conflicts between Gradec and Kaptol.

In 2010 more than 600,000[116] tourists visited the city, with a 10%[117] increase seen in 2011. In 2012 a total of 675 707 tourists[118] visited the city. A record number of tourists visited Zagreb in 2017. – 1.286.087, up 16% compared to the year before, which generated 2.263.758 overnight stays, up 14,8%.

Souvenirs and gastronomy[edit]

Numerous shops, boutiques, store houses and shopping centers offer a variety of quality clothing. There are about fourteen big shopping centers in Zagreb. Zagreb's offerings include crystal, china and ceramics, wicker or straw baskets, and top-quality Croatian wines and gastronomic products.

Notable Zagreb souvenirs are the tie or cravat, an accessory named after Croats who wore characteristic scarves around their necks in the Thirty Years' War in the 17th century and the ball-point pen, a tool developed from the inventions by Slavoljub Eduard Penkala, an inventor and a citizen of Zagreb.

Many Zagreb restaurants offer various specialties of national and international cuisine. Domestic products which deserve to be tasted include turkey, duck or goose with mlinci (flat pasta, soaked in roast juices), a famous Zagrebački odrezak (type of cordon bleu), Štrukli (cottage cheese strudel), sir i vrhnje (cottage cheese with cream), kremšnite (custard slices in flaky pastry), orehnjača (traditional walnut roll), and sarma (Sauerkraut rolls filed with minced pork meat and rice, served with mashed potato).

Cultural institutions[edit]

Zagreb's museums reflect the history, art, and culture not only of Zagreb and Croatia, but also of Europe and the world. Around thirty collections in museums and galleries comprise more than 3.6 million various exhibits, excluding church and private collections.

The Archaeological Museum collections, today consisting of nearly 450,000 varied archaeological artefacts and monuments, have been gathered over the years from many different sources. These holdings include evidence of Croatian presence in the area.[119] The most famous are the Egyptian collection, the Zagreb mummy and bandages with the oldest Etruscan inscription in the world (Liber Linteus Zagrabiensis), as well as the numismatic collection.

Modern Gallery (Croatian: Moderna galerija) holds the most important and comprehensive collection of paintings, sculptures and drawings by 19th- and 20th-century Croatian artists. The collection numbers more than 10,000 works of art, housed since 1934 in the historic Vranyczany Palace in the center of Zagreb, overlooking the Zrinjevac Park. A secondary gallery is the Josip Račić Studio.[120]

Croatian Natural History Museum holds one of the world's most important collections of Neanderthal remains found at one site.[121] These are the remains, stone weapons, and tools of prehistoric Krapina man. The holdings of the Croatian Natural History Museum comprise more than 250,000 specimens distributed among various collections.

Technical Museum was founded in 1954 and it maintains the oldest preserved machine in the area, dating from 1830, which is still operational. The museum exhibits numerous historic aircraft, cars, machinery and equipment. There are some distinct sections in the museum: the Planetarium, the Apisarium, the Mine (model of mines for coal, iron and non-ferrous metals, about 300 m (980 ft) long), and the Nikola Tesla study.[122][123]

Museum of the City of Zagreb was established in 1907 by the Association of the Braća Hrvatskog Zmaja. It is located in a restored monumental complex (Popov toranj, the Observatory, Zakmardi Granary) of the former Convent of the Poor Clares, of 1650.[124] The Museum deals with topics from the cultural, artistic, economic and political history of the city spanning from Roman finds to the modern period. The holdings comprise over 80,000 items arranged systematically into collections of artistic and mundane objects characteristic of the city and its history.

Arts and Crafts Museum was founded in 1880 with the intention of preserving the works of art and craft against the new predominance of industrial products. With its 160,000 exhibits, the Arts and Crafts Museum is a national-level museum for artistic production and the history of material culture in Croatia.[125]

Ethnographic Museum was founded in 1919. It lies in the fine Secession building of the one-time Trades Hall of 1903. The ample holdings of about 80,000 items cover the ethnographic heritage of Croatia, classified in three cultural zones: the Pannonian, Dinaric and Adriatic.[126]

Mimara Museum an art museum, that was founded with a donation from Ante Topić Mimara and opened to the public in 1987. It is located in a late 19th-century neo-Renaissance palace.[127] The holdings comprise 3,750 works of art of various techniques and materials, and different cultures and civilizations, including paintings from great European masters like: Caravaggio, Raphael, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Rembrandt, Hieronymus Bosch, Francisco Goya, Diego Velázquez and many others.

Croatian Museum of Naïve Art is one of the first museums of naïve art in the world. The museum holds works of Croatian naïve expression of the 20th century. It is located in the 18th-century Raffay Palace in the Gornji Grad. The museum holdings consist of almost 2000 works of art – paintings, sculptures, drawings, and prints, mainly by Croatians but also by other well-known world artists.[128] From time to time, the museum organizes topics and retrospective exhibitions by naïve artists, expert meetings and educational workshops and playrooms.

The Museum of Contemporary Art was founded in 1954. Its new building hosts a rich collection of Croatian and international contemporary visual art which has been collected throughout the decades from the nineteen-fifties until today. The museum is located in the center of Novi Zagreb, opened in 2009. The old location is now part of the Kulmer Palace in the Gornji Grad.[129]

The Institute for Contemporary Art (Institut za suvremenu umjetnost), successor to the Soros Center for Contemporary Art – Zagreb (SCCA – Zagreb), was founded in 1993, and registered as an independent nonprofit organization in 1998. It was founded and run by art historians, curators, artists, photographers, designers, publishers, academics, and journalists, and initially located at the Museum of Contemporary Art. After moving a number of times, the institute has a gallery at the Academia Moderna. Its aims are to promote contemporary Croatian artists and the visual and other creative arts; to start documenting contemporary artists; and to build a body of contemporary art. It established the Radoslav Putar Award in 2002.[130]

The Strossmayer Gallery of Old Masters offers permanent holdings presenting European paintings from the 14th to 19th centuries,[131] and the Ivan Meštrović Studio, with sculptures, drawings, lithography portfolios and other items, was a donation of this great artist to his homeland The Museum and Gallery Center introduces on various occasions the Croatian and foreign cultural and artistic heritage. The Art Pavilion by Viennese architects Hellmer and Fellmer who were the most famous designers of theatres in Central Europe is a neo-classical exhibition complex and one of the landmarks of the downtown. The exhibitions are also held in the Meštrović building on the Square of the Victims of Fascism – the Home of Croatian Fine Artists. The World Center "Wonder of Croatian Naïve Art" exhibits masterpieces of Croatian naïve art as well as the works of a new generation of artists. The Modern Gallery comprises all relevant fine artists of the 19th and 20th centuries. The Museum of Broken Relationships at 2 Ćirilometodska holds people's mementos of past relationships.[132][133][134] It is the first private museum in the country.[135] Lauba House (23a Baruna Filipovića) presents works from Filip Trade Collection, a large private collection of modern and contemporary Croatian art and current artistic production.[136][137]

Other museums and galleries are also found in the Croatian School Museum, the Croatian Hunting Museum, the Croatian Sports Museum, the Croatian Post and Telecommunications Museum, the HAZU (Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts) Glyptotheque (collection of monuments), and the HAZU Graphics Cabinet.

There are five castles in Zagreb: Dvorac Brezovica, Kašina (Castrum antiquum Paganorum), Medvedgrad, Susedgrad and Kulmerovi dvori.[138]

Events[edit]

Zagreb has been, and is, hosting some of the most popular mainstream artists, in the past few years their concerts held the Queen, Rolling Stones, U2, Guns N' Roses, Eric Clapton, Deep Purple, Bob Dylan, David Bowie, Elton John, Roger Waters, Depeche Mode, Prodigy, Beyoncé, Lady Gaga, Britney Spears, Justin Bieber, Shakira, Nick Cave, Jamiroquai, George Michael, Sade, Sting, Rod Stewart, Eros Ramazzotti, Manu Chao, Massive Attack, Andrea Bocelli, Metallica, 50 Cent, Snoop Dogg, Duran Duran as well as some of world most recognised underground artists such as Dimmu Borgir, Sepultura, Melvins, Mastodon and many more.

Zagreb is also the home of the INmusic festival, one of the biggest open-air festivals in Croatia which is held every year, usually at the end of June. There is also the Zagreb Jazz Festival which has featured popular jazz artists like Pat Metheny or Sonny Rollins. Many others festivals occur in Zagreb like Žedno uho featuring indie, rock, metal and electronica artists such as Animal Collective, Melvins, Butthole Surfers, Crippled Black Phoenix, NoMeansNo, The National, Mark Lanegan, Swans, Mudhoney around the clubs and concert halls of Zagreb.

Performing arts[edit]

There are about 20 permanent or seasonal theatres and stages. The Croatian National Theater in Zagreb was built in 1895 and opened by emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria. The most renowned concert hall named "Vatroslav Lisinski", after the composer of the first Croatian opera, was built in 1973.

The World Theatre Festival and International Puppet Festival both take place in Zagreb in September and October.[139]

Animafest, the World Festival of Animated Films, takes place every even-numbered year, and the Music Biennale, the international festival of avant-garde music, every odd-numbered year. It also hosts the annual ZagrebDox documentary film festival. The Festival of the Zagreb Philharmonic and the flowers exhibition Floraart (end of May or beginning of June), the Old-timer Rally annual events. In the summer, theatre performances and concerts, mostly in the Upper Town, are organized either indoors or outdoors. The stage on Opatovina hosts the Zagreb Histrionic Summer theatre events.

Zagreb is also the host of Zagrebfest, the oldest Croatian pop-music festival, as well as of several traditional international sports events and tournaments. The Day of the City of Zagreb on 16 November is celebrated every year with special festivities, especially on the Jarun lake in the southwestern part of the city.

Recreation and sports[edit]

Zagreb is home to numerous sports and recreational centers. Recreational Sports Center Jarun, situated on Jarun Lake in the southwest of the city, has fine shingle beaches, a world-class regatta course, a jogging lane around the lake, several restaurants, many night clubs and a discothèque. Its sports and recreation opportunities include swimming, sunbathing, waterskiing, angling, and other water sports, but also beach volleyball, football, basketball, handball, table tennis, and mini-golf.

Dom Sportova, a sport centre in northern Trešnjevka features six halls. The largest two have seating capacity of 5,000 and 3,100 people, respectively.[140] This centre is used for basketball, handball, volleyball, hockey, gymnastics, tennis, etc. It also hosts music events.

Arena Zagreb was finished in 2008. The 16,500-seat arena[141] hosted the 2009 World Men's Handball Championship. The Dražen Petrović Basketball Hall seats 5,400 people. Alongside the hall is the 94 m (308 ft) high glass Cibona Tower. Sports Park Mladost, situated on the embankment of the Sava river, has an Olympic-size swimming pool, smaller indoor and outdoor swimming pools, a sunbathing terrace, 16 tennis courts as well as basketball, volleyball, handball, football and field hockey courts. A volleyball sports hall is within the park. Sports and Recreational Center Šalata, located in Šalata, only a couple hundred meters from the Jelačić Square, is most attractive for tennis players. It comprises a big tennis court and eight smaller ones, two of which are covered by the so-called "balloon", and another two equipped with lights. The center also has swimming pools, basketball courts, football fields, a gym, and fitness center, and a four-lane bowling alley. Outdoor ice skating is a popular winter recreation. There are also several fine restaurants within and near the center.

Maksimir Tennis Center, located in Ravnice east of downtown, consists of two sports blocks. The first comprises a tennis center situated in a large tennis hall with four courts. There are 22 outdoor tennis courts with lights. The other block offers multipurpose sports facilities: apart from tennis courts, there are handball, basketball and indoor football grounds, as well as track and field facilities, a bocci ball alley and table tennis opportunities.

Recreational swimmers can enjoy a smaller-size indoor swimming pool in Daničićeva Street, and a newly opened indoor Olympic-size pool at Utrine sports center in Novi Zagreb. Skaters can skate in the skating rink on Trg Sportova (Sports Square) and on the lake Jarun Skaters' park. Hippodrome Zagreb offers recreational horseback riding opportunities, while horse races are held every weekend during the warmer part of the year.

The 38,923[142]-seat Maksimir Stadium, last 10 years under renovation, is located in Maksimir in the northeastern part of the city. The stadium is part of the immense Svetice recreational and sports complex (ŠRC Svetice), south of the Maksimir Park. The complex covers an area of 276,440 m2 (68 acres). It is part of a significant green zone, which passes from Medvednica in the north toward the south. ŠRC Svetice, together with Maksimir Park, creates an ideal connection of areas which are assigned to sport, recreation, and leisure.

The latest larger recreational facility is Bundek, a group of two small lakes near the Sava in Novi Zagreb, surrounded by a partly forested park. The location had been used prior to the 1970s, but then went to neglect until 2006 when it was renovated.

In year 2021 Zagreb was the host city of Croatia Rally, round three of 2021 World Rally Championship. The Rally was won by Sébastien Ogier and Julien Ingrassia, Toyota Gazoo Racing WRT crew. Service parc, Overnight parc ferme and Shakedown Medvedgrad took place in Zagreb placing him as a lone capital in the championship. 2021 Croatia Rally became third tightest WRC event up to date, with only 0,6 seconds dividing the winning crew and second placed Elfyn Evans and Scott Martin (co-driver) in Toyota Yaris WRC. The Croatian round of WRC was praised by becoming the part of 2022 World Rally Championship.

Some of the most notable sport clubs in Zagreb are: GNK Dinamo Zagreb, KHL Medveščak Zagreb, RK Zagreb, KK Cibona, KK Zagreb, KK Cedevita, NK Zagreb, HAVK Mladost and others. The city hosted the 2016 Davis Cup World Group final between Croatia and Argentina.

Religion[edit]

The Archdiocese of Zagreb is a metropolitan see of the Catholic Church in Croatia, serving as its religious center. The Archbishop is Dražen Kutleša. The Catholic Church is the largest religious organisation in Zagreb, Catholicism being the predominant religion of Croatia, with over 1.1 million adherents.[143] Zagreb is also the Episcopal see of the Metropolitanate of Zagreb and Ljubljana of the Serbian Orthodox Church. Islamic religious organization of Croatia has the see in Zagreb. President is Mufti Aziz Hasanović. There used to be a mosque in the Meštrović Pavilion during World War II[144] at the Square of the Victims of Fascism, but it was relocated to the neighborhood of Borovje in Peščenica. Mainstream Protestant churches have also been present in Zagreb – Evangelical (Lutheran) Church and Reformed Christian (Calvinist) Church. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) is also present in the Zagreb neighborhood of Jarun whereas Jehovah's Witnesses have their headquarters in Central Zagreb.[145] In total there are around 40 non-Catholic religious organizations and denominations in Zagreb with their headquarters and places of worship across the city making it a large and diverse multicultural community. There is also significant Jewish history through the Holocaust.

Economy[edit]

Important branches of industry are: production of electrical machines and devices, chemical, pharmaceutical, textile, food and drink processing. Zagreb is an international trade and business centre, as well as an essential transport hub placed at the crossroads of Central Europe, the Mediterranean and the Southeast Europe.[146] Almost all of the largest Croatian as well as Central European companies and conglomerates such as Agrokor, INA, Hrvatski Telekom have their headquarters in the city.

The only Croatian stock exchange is the Zagreb Stock Exchange (Croatian: Zagrebačka burza), which is located in Eurotower, one of the tallest Croatian skyscrapers.

According to 2008 data, the city of Zagreb has the highest PPP and nominal gross domestic product per capita in Croatia at $32,185 and $27,271 respectively, compared to the Croatian averages of US$18,686 and $15,758.[147]

As of May 2015, the average monthly net salary in Zagreb was 6,669 kuna, about €870 (Croatian average is 5,679 kuna, about €740).[148][149] At the end of 2012, the average unemployment rate in Zagreb was around 9.5%.[150]34% of companies in Croatia have headquarters in Zagreb, and 38.4% of the Croatian workforce works in Zagreb, including almost all banks, utility and public transport companies.[151][152][153]

Companies in Zagreb create 52% of the total turnover and 60% of the total profit of Croatia in 2006 as well as 35% of Croatian export and 57% of Croatian import.[154][155]The following table includes some of the main economic indicators for the period 2011–2019, based on the data by the Croatian Bureau of Statistics.[156][157] A linear interpolation was used for the population data between 2011 and 2021. While data on the yearly averaged conversion rates between HRK, EUR and USD is provided by the Croatian National Bank.[158]

| Year | Population | Exchange rate (EUR : USD) | GDP (nominal in mil. EUR) | GDP (nominal in mil. USD) | GDP per capita (nominal in EUR) | GDP per capita (nominal in USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 790,017 | 1.3913 | 15,513 | 21,583 | 19,636 | 27,319 |

| 2012 | 788,010 | 1.2848 | 15,188 | 19,514 | 19,274 | 24,763 |

| 2013 | 786,002 | 1.3281 | 15,029 | 19,960 | 19,121 | 25,394 |

| 2014 | 783,995 | 1.3285 | 15,004 | 19,933 | 19,121 | 25,394 |

| 2015 | 781,988 | 1.1095 | 15,457 | 17,161 | 19,779 | 21,945 |

| 2016 | 779,981 | 1.1069 | 16,114 | 17,837 | 20,659 | 22,868 |

| 2017 | 777,973 | 1.1297 | 17,097 | 19,314 | 21,976 | 24,827 |

| 2018 | 775,966 | 1.1810 | 18,155 | 21,441 | 23,397 | 27,631 |

| 2019 | 773,959 | 1.1195 | 19,264 | 21,566 | 24,890 | 27,865 |

| 2020 | 771,951 | 1.1422 | 17,699 | 20,216 | 22,928 | 26,188 |

| 2021 | 767,131 | 1.1827 | 20,053 | 23,717 | 26,140 | 30,916 |

Transport[edit]

Highways[edit]

Zagreb is the hub of five major Croatian highways.

The highway A6 was upgraded in October 2008 and leads from Zagreb to Rijeka, and forming a part of the Pan-European Corridor Vb. The upgrade coincided with the opening of the bridge over the Mura river on the A4 and the completion of the Hungarian M7, which marked the opening of the first freeway corridor between Rijeka and Budapest.[159] The A1 starts at the Lučko interchange and concurs with the A6 up to the Bosiljevo 2 interchange, connecting Zagreb and Split (As of October 2008[update] Vrgorac). A further extension of the A1 up to Dubrovnik is under construction[needs update]. Both highways are tolled by the Croatian highway authorities Hrvatske autoceste and Autocesta Rijeka - Zagreb.[citation needed]

Highway A3 (formerly named Bratstvo i jedinstvo) was the showpiece of Croatia in the SFRY. It is the oldest Croatian highway.[160][161]A3 forms a part of the Pan-European Corridor X. The highway starts at the Bregana border crossing, bypasses Zagreb forming the southern arch of the Zagreb bypass, and ends at Lipovac near the Bajakovo border crossing. It continues in Southeast Europe in the direction of Near East. This highway is tolled except for the stretch between Bobovica and Ivanja Reka interchanges.[162]

Highway A2 is a part of the Corridor Xa.[163] It connects Zagreb and the frequently congested Macelj border crossing, forming a near-continuous motorway-level link between Zagreb and Western Europe.[164] Forming a part of the Corridor Vb, highway A4 starts in Zagreb forming the northeastern wing of the Zagreb bypass and leads to Hungary until the Goričan border crossing. It is often used highway around Zagreb.[165]

The railway and the highway A3 along the Sava river that extend to Slavonia (towards Slavonski Brod, Vinkovci, Osijek and Vukovar) are some of the busiest traffic corridors in the country.[166] The railway running along the Sutla river and the A2 highway (Zagreb-Macelj) running through Zagorje, as well as traffic connections with the Pannonian region and Hungary (the Zagorje railroad, the roads and railway to Varaždin – Čakovec and Koprivnica) are linked with truck routes.[167] The southern railway connection to Split operates on a high-speed tilting trains line via the Lika region (renovated in 2004 to allow for a five-hour journey); a faster line along the Una river valley is in use only up to the border between Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina.[167][168]

Roads[edit]

The city has an extensive avenue network with numerous main arteries up to ten lanes wide and Zagreb bypass, a congested four-lane highway encircling most of the city. Finding a parking space is supposed to be made somewhat easier by the construction of new underground multi-story parking lots (Importanne Center, Importanne Gallery, Lang Square, Tuškanac, Kvaternik Square, Klaić Street, etc.). The busiest roads are the main east–west arteries, former Highway "Brotherhood and Unity", consisting of Ljubljanska Avenue, Zagrebačka Avenue and Slavonska Avenue; and the Vukovarska Avenue, the closest bypass of the city center. The avenues were supposed to alleviate the traffic problem, but most of them are nowadays gridlocked during rush hour and others, like Branimirova Avenue and Dubrovnik Avenue which are gridlocked for the whole day.[169][170][171] European routes E59, E65 and E70 serve Zagreb.

Bridges[edit]

Zagreb has seven road traffic bridges across the river Sava, and they all span both the river and the levees, making them all by and large longer than 200 m (660 ft). In downstream order, these are:

| Name (English) | Name (Croatian) | Year Finished | Type of bridge | Road that goes over | Other Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Podsused Bridge | Podsusedski most | 1982 | Two-lane road bridge with a commuter train line (not yet completed) | Samoborska Road | Connects Zagreb to its close suburbs by a road to Samobor, the fastest route to Bestovje, Sveta Nedelja, and Strmec. |

| Jankomir Bridge | Jankomirski most | 1958, 2006 (upgrade) | Four lane road bridge | Ljubljanska Avenue | Connects Ljubljanska Avenue to the Jankomir interchange and Zagreb bypass. |

| Adriatic Bridge | Jadranski most | 1981 | Six lane road bridge (also carries tram tracks) | Adriatic Avenue | The most famous bridge in Zagreb. The bridge spans from Savska Street in the north to the Remetinec Roundabout in the south. |

| Sava Bridge | Savski most | 1938 | Pedestrian since the construction of the Adriatic Bridge | Savska Road | The official name at the time of building was New Sava bridge, but it is the oldest still standing bridge over Sava. The bridge is known among experts due to some construction details.[172] |

| Liberty Bridge | Most slobode | 1959 | Four lane road bridge | Većeslav Holjevac Avenue | It used to hold a pair of bus lanes, but due to the increasing individual traffic and better tram connections across the river, those were converted to normal lanes. |

| Youth Bridge | Most mladosti | 1974 | Six lane road bridge (also carries tram tracks) | Marin Držić Avenue | Connects eastern Novi Zagreb to the districts of Trnje, Peščenica, Donja Dubrava and Maksimir. |

| Homeland Bridge | Domovinski most | 2007 | Four-lane road bridge (also carries two bicycle and two pedestrian lanes; has space reserved for light railroad tracks) | Radnička (Workers') Road | This bridge is the last bridge built on the Sava river to date; it links Peščenica via Radnička street to the Zagreb bypass at Kosnica. It is planned to continue towards Zagreb Airport at Pleso and Velika Gorica, and on to state road D31 going to the south. |

Есть также два железнодорожных моста через Саву, один возле моста Сава и один возле Мичевца , а также два моста, которые являются частью обходной дороги Загреба , один возле Запрешича (запад), а другой возле Иванья Река (восток). .

два дополнительных моста через реку Сава Предлагаются : мост Ярун и мост Бундек.

Общественный транспорт [ править ]

Общественный транспорт в городе организован в несколько уровней: внутренние части города в основном охвачены трамваями , внешние районы города и ближайшие пригороды связаны автобусами и скоростными пригородными поездами .

Компания общественного транспорта ZET ( Zagrebački električni tromvaj , Загребский электрический трамвай) управляет трамваями, всеми внутренними автобусными линиями и большинством пригородных автобусных линий и субсидируется городским советом.

Национальный железнодорожный оператор «Хорватские железные дороги» ( Hrvatske željeznice , HŽ) управляет сетью городских и пригородных железнодорожных линий в столичном районе Загреба и является государственной корпорацией .

Фуникулер успиньяча ( ) в исторической части города является туристической достопримечательностью .

Рынок такси был либерализован в начале 2018 года [173] и многочисленным транспортным компаниям было разрешено выйти на рынок; следовательно, цены значительно упали, а обслуживание значительно улучшилось, поэтому с тех пор популярность такси в Загребе растет.

Трамвайная сеть [ править ]

Загреб имеет разветвленную трамвайную сеть с 15 дневными и 4 ночными линиями, охватывающую большую часть внутренних и средних пригородов города. Первая трамвайная линия была открыта 5 сентября 1891 года, и с тех пор трамваи служат жизненно важным компонентом общественного транспорта Загреба. Трамваи обычно движутся со скоростью 30–50 км/ч (19–31 миль в час), но в час пик значительно замедляются . На более узких улицах пути либо используются совместно с автомобильным движением, либо разделены окрашенной желтой линией, по которой по-прежнему могут ездить такси, автобусы и машины скорой помощи, тогда как на более крупных проспектах пути расположены внутри зеленых поясов .

амбициозная программа, которая предусматривала замену старых трамваев на новые и современные, построенные в основном в Загребе компаниями Končar elektroindustrija и, в меньшей степени, TŽV Gredelj Недавно завершилась . Новые трамваи ТМК 2200 к концу 2012 года составили около 95% парка. [174]

Сеть пригородных железных дорог [ править ]

Сеть пригородных железных дорог в Загребе существует с 1992 года. В 2005 году частота движения пригородных поездов была увеличена до 15 минут, обслуживающих средние и внешние пригороды Загреба, прежде всего в направлении восток-запад и южные районы. Это расширило возможности передвижения по городу. [175]

новом сообщении с близлежащим городом Самобор Было объявлено о , строительство которого должно начаться в 2014 году. Это сообщение будет стандартной колеи и будет связано с обычной деятельностью Хорватских железных дорог . Предыдущая узкоколейная линия на Самобор под названием Самоборчек была закрыта в 1970-х годах. [176]

Воздушное сообщение [ править ]

Аэропорт Загреба ( IATA : ZAG , ICAO : LDZA ) — главный международный аэропорт Хорватии, расположенный в 17 км (11 милях) к юго-востоку от Загреба в городе Велика Горица . Аэропорт также является главной хорватской авиабазой, располагающей истребительной эскадрильей, вертолетами, а также военными и грузовыми транспортными самолетами . [177] В 2019 году аэропорт принял 3,45 миллиона пассажиров, а в конце марта 2017 года был открыт новый пассажирский терминал, способный принять до 5,5 миллионов пассажиров.

В Загребе также есть второй, меньший аэропорт, Лучко ( ИКАО : LDZL ). Здесь расположены спортивные самолеты и хорватское специальное полицейское подразделение, а также авиабаза военных вертолетов. Лучко был главным аэропортом Загреба с 1947 по 1959 год. [178]

Третий, небольшой травяной аэродром, Бушевец, расположен недалеко от Великой Горицы . В основном используется в спортивных целях. [179]

Образование [ править ]

В Загребе 136 начальных школ и 100 средних школ, в том числе 30 гимназий . [180] [181] Есть 5 государственных высших учебных заведений и 9 частных профессиональных высших учебных заведений. [182]

В Загребе вы также найдете 4 международные школы: [183]

- Американская международная школа Загреба (AISZ)

- Международный детский сад The Learning Tree (TLT)

- Французская школа в Загребе

- Немецкая школа в Загребе. [184]

Загребский университет [ править ]

Загребский университет, основанный в 1669 году, является старейшим постоянно действующим университетом Хорватии и одним из крупнейших [185] [186] [187] [188] [189] [190] и старейшие университеты Юго-Восточной Европы. С момента своего основания университет постоянно рос и развивался и сейчас состоит из 29 факультетов, трех художественных академий и Центра хорватских исследований. Более 200 000 студентов получили степень бакалавра в университете, а также присвоили 18 000 степеней магистра и 8 000 докторов . [191] По состоянию на 2011 год [update] , Загребский университет входит в число 500 лучших университетов мира Согласно Шанхайскому академическому рейтингу университетов мира .

Загреб также является местом расположения двух частных университетов: Католического университета Хорватии и Международного университета Либертас; а также многочисленные государственные и частные политехнические институты, колледжи и высшие профессиональные школы. [ который? ]

Известные люди [ править ]

Художники

- Кристина Крепела (1979 г.р.), актриса

- Саня Ивекович (1949 г.р.), фотограф, перформер, скульптор и художник-инсталлятор.

- Ягода Калопер (1947–2016), художник и актриса.

- Игорь Кордей (1957 г.р.), художник комиксов

- Дарко Макан (1966 г.р.), писатель и иллюстратор

- Иван Мештрович (1983–1962), скульптор, архитектор и писатель.

- Велимир Нейдхардт (1942 г.р.), архитектор

- Вера Николич Подринска (1886–1972), художница и баронесса.

- Сречко Пунтарич (1952 г.р.), карикатурист

- Йосип Рачич (1885–1908), художник

- Эсад Рибич (1972 г.р.), художник комиксов

- Горан Суджука (1969 г.р.), художник комиксов

- Марино Тарталья (1894–1984), художник

- Владимир Варлай (1895–1962), художник.

- Здравко Жупан (1950–2015), создатель комиксов и историк.

Футболисты

- Милан Бадель (1989 г.р.), футболист

- Йосип Брекало (1998 г.р.), футболист

- Марсело Брозович (1992 г.р.), футболист

- Томислав Бутина (1974 г.р.), футболист

- Иван Чунчич (1985 г.р.), футболист

- Йошко Гвардиол (2002 г.р.), футболист

- Тин Джедвай (1995 г.р.), футболист

- Йосип Юранович (1995 г.р.), футболист

- Андрей Крамарич (1991 г.р.), футболист

- Нико Кранчар (1984 г.р.), футболист

- Джерко Леко (1980 г.р.), футболист

- Ловро Майер (1998 г.р.), футболист

- Ясмин Муйджа (1974 г.р.), футболист

- Менсур Муйджа (1984 г.р.), футболист

- Мислав Оршич (1992 г.р.), футболист

- Дубравко Павличич (1967–2012), футболист

- Йосип Пиварич (1989 г.р.), футболист

- Марко Пьяча (1995 г.р.), футболист

- Дарио Шимич (1975 г.р.), футболист

- Звонимир Сольдо (1967 г.р.), футболист

- Бернард Вукас (1927–1983), футболист

Военный

- Хаим Бар-Лев (1924–1994), израильский генерал и политик.

Музыка

- Златко Балокович (1895–1965), скрипач

- Йосипа Лисак (1950 г.р.), хорватский певец

- Тайчи (1970 г.р.), хорватский певец, ведущий телешоу

- Мильенко Матиевич (1964 г.р.), певец и автор песен; ведущий вокалист рок-группы Steelheart

- Зинка Миланова (1906–1906), оперное сопрано.

- Нина Бадрич (1972 г.р.), поп-певица и автор песен

- Лана Юрчевич (1984 г.р.), поп-певица

- Антония Шола (1979 г.р.), музыкант, певица и автор песен, автор текстов, актриса и музыкальный продюсер

- Саня Долежал (1963 г.р.), эстрадная певица и телеведущая, участница поп-группы Novi fosili

- Ана Руцнер (1983 г.р.), хорватская виолончелистка

Другие спортсмены

- Василие Каласан (1981 г.р.), французский автогонщик

- Марин Чолак (1984 г.р.), автогонщик

- Борна Корич (1996 г.р.), теннисист

- Крешимир Чосич (1948–1995), баскетболист

- Данко Цветичанин (1963 г.р.), баскетболист

- Йосип Гласнович (1983 г.р.), спортивный стрелок, олимпийской медали обладатель золотой

- Златко Хорват (1984 г.р.), гандболист

- Филип Хргович (1992 г.р.), профессиональный боксер

- Иво Карлович (1979 г.р.), теннисист

- Ненад Кляич (1966 г.р.), гандболист

- Вьекослав Кобешчак (1974 г.р.), игрок в водное поло и тренер

- Ивица Костелич (1979 г.р.), горнолыжник

- Яница Костелич (1982 г.р.), горнолыжница, четырехкратная олимпийская чемпионка

- Лука Лончар (1987 г.р.), игрок в водное поло

- Ива Майоли (1977 г.р.), теннисистка

- Никола Мектич (1988 г.р.), теннисист, олимпийской медали обладатель золотой

- Ника Мюль (2001 г.р.), баскетболист

- Мирко Новосел (1938 г.р.), баскетболист

- Томислав Пашквалин (1961 г.р.), игрок в водное поло

- Сандра Перкович (1990 г.р.), метательница диска, выиграла две золотые медали на летних Олимпийских играх.

- Дубравко Шименц (1966 г.р.), игрок в водное поло

- Мартин Синкович (1989 г.р.), гребец, олимпийской медали обладатель золотой

- Валент Синкович (1988 г.р.), гребец, олимпийской медали обладатель золотой

- Тин Србич (1996 г.р.), спортивная гимнастка

- Мануэль Штрлек (1988 г.р.), гандболист

- Игорь Вори (1980 г.р.), гандболист

- Ведран Зрнич (1979 г.р.), гандболист

Религия

- Михаль Шилобод Большич (1724–1787) - римско-католический священник, математик, писатель и теоретик музыки, прежде всего известный как автор первого хорватского учебника по арифметике Arithmatika Horvatzka (опубликовано в Загребе, 1758 г.)

- Иосип Юрай Штроссмайер (1815–1905), политик, римско-католический епископ и благотворитель.

Наука и гуманитарные науки

- Иван Джикич (1966 г.р.), молекулярный биолог, директор Института биохимии II Франкфуртского университета Гете

- Марио Юрич (1979 г.р.), астроном

- Весна Жирарди-Юркич (1944–2012), археолог и музеолог.

- Драгутин Горьянович-Крамбергер (1856–1936), геолог, палеонтолог и археолог.

- Милан Канрга (1923–2008), философ

- Радослав Катич (1930–2019), лингвист, филолог-классик.

- Нада Клаич (1920–1988), историк

- Иво Колин (1924–2007), изобретатель

- Здравко Лоркович (1900–1998), биолог, энтомолог и генетик.

- Ранко Матасович (1968 г.р.), лингвист

- Иво Пилар (1874–1933), историк, политик, публицист и юрист.

- Мартин Превишич (1984 г.р.), историк

- Весна Пусич (1953 г.р.), социолог и политик

- Марин Солячич (1974 г.р.), физик и инженер-электрик

- Руди Супек (1913–1993), социолог и философ.

- Горан Швоб (1947–2013), философ и логик.

- Иосип Торбар (1824–1900), естествоиспытатель.

- Хрвое Туркович (1943 г.р.), теоретик кино

- Людевит Вукотинович (1813–1893), политик, писатель и натуралист.

- Милена Жиц-Фукс (1954 г.р.), лингвист

Писатели

- Титус Брезовацкий (1757–1805), драматург, сатирик и поэт.

- Август Чезарек (1893–1941), писатель.

- Бора Чосич (1932 г.р.), писатель

- Димитрия Деметра (1811–1872), писатель.

- Даша Дрндич (1946–2018), писатель

- Зоран Ферич (1961 г.р.), писатель

- Бранко Гавелла (1885–1962), театральный режиссер и публицист.

- Мирослав Крлежа (1893–1981), писатель, считается величайшим хорватским писателем 20 века.

- Антун Миханович (1796–1861), поэт и автор текстов, написал государственный гимн Хорватии.

- Август Шеноа (1838–1881), писатель

- Сунчана Шкриньярич (1931–2004), писатель, поэт и журналист.

- Давор Сламниг (1956 г.р.), писатель и музыкант

- Слободан Шнайдер (1948 г.р.), писатель и публицист

Примечания [ править ]

- ^ Jump up to: а б Из переписи домохозяйств

- ^ Перепись населения без духовенства и дворянства

- ^ Кайкавское произношение: [ˈzaɡrep] [8]

Ссылки [ править ]

- ^ Реестр пространственных единиц Государственного геодезического управления Республики Хорватия . Викиданные Q119585703 .