Операция Барбаросса

| Операция Барбаросса | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Часть Восточного фронта . Второй мировой войны | |||||||||

По часовой стрелке сверху слева :

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

Axis armies: | Soviet armies: | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

Frontline strength (22 June 1941) | Frontline strength (22 June 1941) | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

Total military casualties: Breakdown | Total military casualties: Breakdown | ||||||||

Операция Барбаросса (нем. Unternehmen Barbarossa ; русский: Операция Барбаросса , латинизированная: Операция Барбаросса ) — вторжение в Советский Союз нацистской Германии и многих ее союзников по Оси , начавшееся в воскресенье, 22 июня 1941 года, во время Второй мировой войны . Это было самое крупное и дорогостоящее наземное наступление в истории человечества, в котором приняли участие около 10 миллионов бойцов. [26] и более 8 миллионов жертв к концу операции. [27] [28]

Операция, получившая кодовое название в честь Фридриха Барбароссы XII века («красная борода»), императора Священной Римской империи и крестоносца , привела в действие идеологические цели нацистской Германии по искоренению коммунизма и завоеванию западной части Советского Союза с целью заселения ее немцами . Немецкий генеральный план «Ост» был направлен на использование некоторых завоеванных людей в качестве принудительного труда для военных действий Оси при приобретении нефтяных запасов Кавказа, а также сельскохозяйственных ресурсов различных советских территорий, включая Украину и Белоруссию . Их конечной целью было создание большего Lebensraum (жизненного пространства) для Германии и, в конечном итоге, истребление коренных славянских народов путем массовой депортации в Сибирь , германизации , порабощения и геноцида . [29] [30]

За два года до вторжения нацистская Германия и Советский Союз подписали политические и экономические пакты в стратегических целях. После советской оккупации Бессарабии и Северной Буковины немецкое командование начало планировать вторжение в Советский Союз в июле 1940 года (под кодовым названием «Операция Отто» ). В ходе операции более 3,8 миллиона военнослужащих держав Оси — крупнейшие силы вторжения в истории войн — вторглись на западную часть Советского Союза вдоль фронта протяженностью 2900 километров (1800 миль), используя 600 000 автомобилей и более 600 000 человек. лошадей для небоевых операций. Наступление ознаменовало масштабную эскалацию Второй мировой войны, как географически, так и благодаря англо-советскому соглашению , которое привело СССР в коалицию союзников .

The operation opened up the Eastern Front, in which more forces were committed than in any other theatre of war in human history. The area saw some of history's largest battles, most horrific atrocities, and highest casualties (for Soviet and Axis forces alike), all of which influenced the course of World War II and the subsequent history of the 20th century. The German armies eventually captured some five million Soviet Red Army troops[31] and deliberately starved to death or otherwise killed 3.3 million Soviet prisoners of war, and millions of civilians, as the "Hunger Plan" worked to solve German food shortages and exterminate the Slavic population through starvation.[32] Mass shootings and gassing operations, carried out by German death squads or willing collaborators,[f] murdered over a million Soviet Jews as part of the Holocaust.[34]

The failure of Operation Barbarossa reversed the fortunes of Nazi Germany.[35] Operationally, German forces achieved significant victories and occupied some of the most important economic areas of the Soviet Union (mainly in Ukraine) and inflicted, as well as sustained, heavy casualties. Despite these early successes, the German offensive came to an end during the Battle of Moscow near the end of 1941,[36][37] and the subsequent Soviet winter counteroffensive pushed the Germans about 250 km (160 mi) back. German high command anticipated a quick collapse of Soviet resistance as in Poland, analogous to the reaction Russia had during World War I.[38] However, no such collapse occurred; instead the Red Army absorbed the German Wehrmacht's strongest blows and bogged it down in a war of attrition for which the Germans were unprepared. Following the heavy losses and logistical strain of Barbarossa, the Wehrmacht's diminished forces could no longer attack along the entire Eastern Front, and subsequent operations to retake the initiative and drive deep into Soviet territory—such as Case Blue in 1942 and Operation Citadel in 1943—were weaker and eventually failed, which resulted in the Wehrmacht's defeat. These Soviet victories ended Germany's territorial expansion and presaged the eventual defeat and collapse of Nazi Germany in 1945.

Background[edit]

Naming[edit]

The theme of Barbarossa had long been used by the Nazi Party as part of their political imagery, though this was really a continuation of the glorification of the famous Crusader king by German nationalists since the 19th century. According to a Germanic medieval legend, revived in the 19th century by the nationalistic tropes of German Romanticism, the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa—who drowned in Asia Minor while leading the Third Crusade—was not dead but asleep, along with his knights, in a cave in the Kyffhäuser mountains in Thuringia and would awaken in the hour of Germany's greatest need and restore the nation to its former glory.[39] Originally, the invasion of the Soviet Union was codenamed Operation Otto (alluding to Holy Roman Emperor Otto the Great's expansive campaigns in Eastern Europe),[40] but Hitler had the name changed to Operation Barbarossa in December 1940.[41] Hitler had in July 1937 praised Barbarossa as the emperor who first expressed Germanic cultural ideas and carried them to the outside world through his imperial mission.[42] For Hitler, the name Barbarossa signified his belief that the conquest of the Soviet Union would usher in the Nazi "Thousand-Year Reich".[42]

Racial policies of Nazi Germany[edit]

As early as 1925, Adolf Hitler vaguely declared in his political manifesto and autobiography Mein Kampf that he would invade the Soviet Union, asserting that the German people needed to secure Lebensraum ('living space') to ensure the survival of Germany for generations to come.[43] On 10 February 1939, Hitler told his army commanders that the next war would be "purely a war of Weltanschauungen ['worldviews']... totally a people's war, a racial war". On 23 November, once World War II had already started, Hitler declared that "racial war has broken out and this war shall determine who shall govern Europe, and with it, the world".[44] The racial policy of Nazi Germany portrayed the Soviet Union (and all of Eastern Europe) as populated by non-Aryan Untermenschen ('sub-humans'), ruled by Jewish Bolshevik conspirators.[45] Hitler claimed in Mein Kampf that Germany's destiny was to Drang nach Osten ('turn to the East') as it did "600 years ago" (see Ostsiedlung).[46] Accordingly, it was a partially secret but well-documented Nazi policy to kill, deport, or enslave the majority of Russian and other Slavic populations and repopulate the land west of the Urals with Germanic peoples, under Generalplan Ost (General Plan for the East).[47] The Nazis' belief in their ethnic superiority pervades official records and pseudoscientific articles in German periodicals, on topics such as "how to deal with alien populations."[48]

While older histories tended to emphasize the myth of the "clean Wehrmacht," upholding its honor in the face of Hitler's fanaticism, the historian Jürgen Förster notes that "In fact, the military commanders were caught up in the ideological character of the conflict, and involved in its implementation as willing participants".[44] Before and during the invasion of the Soviet Union, German troops were indoctrinated with anti-Bolshevik, anti-Semitic and anti-Slavic ideology via movies, radio, lectures, books, and leaflets.[49] Likening the Soviets to the forces of Genghis Khan, Hitler told the Croatian military leader Slavko Kvaternik that the "Mongolian race" threatened Europe.[50] Following the invasion, many Wehrmacht officers told their soldiers to target people who were described as "Jewish Bolshevik subhumans," the "Mongol hordes," the "Asiatic flood" and the "Red beast."[51] Nazi propaganda portrayed the war against the Soviet Union as an ideological war between German National Socialism and Jewish Bolshevism and a racial war between the disciplined Germans and the Jewish, Romani and Slavic Untermenschen.[52] An 'order from the Führer' stated that the paramilitary SS Einsatzgruppen, which closely followed the Wehrmacht's advance, were to execute all Soviet functionaries who were "less valuable Asiatics, Gypsies and Jews."[53] Six months into the invasion of the Soviet Union, the Einsatzgruppen had murdered more than 500,000 Soviet Jews, a figure greater than the number of Red Army soldiers killed in battle by then.[54] German army commanders cast Jews as the major cause behind the "partisan struggle."[55] The main guideline for German troops was "Where there's a partisan, there's a Jew, and where there's a Jew, there's a partisan" or "The partisan is where the Jew is."[56][57] Many German troops viewed the war in Nazi terms and regarded their Soviet enemies as sub-human.[58]

After the war began, the Nazis issued a ban on sexual relations between Germans and foreign slaves.[59] There were regulations enacted against the Ost-Arbeiter ('Eastern workers') that included the death penalty for sexual relations with a German.[60] Heinrich Himmler, in his secret memorandum, Reflections on the Treatment of Peoples of Alien Races in the East (dated 25 May 1940), outlined the Nazi plans for the non-German populations in the East.[61] Himmler believed the Germanisation process in Eastern Europe would be complete when "in the East dwell only men with truly German, Germanic blood."[62]

The Nazi secret plan Generalplan Ost, prepared in 1941 and confirmed in 1942, called for a "new order of ethnographical relations" in the territories occupied by Nazi Germany in Eastern Europe. It envisaged ethnic cleansing, executions and enslavement of the populations of conquered countries, with very small percentages undergoing Germanisation, expulsion into the depths of Russia or other fates, while the conquered territories would be Germanised. The plan had two parts, the Kleine Planung ('small plan'), which covered actions to be taken during the war and the Große Planung ('large plan'), which covered policies after the war was won, to be implemented gradually over 25 to 30 years.[63]

A speech given by General Erich Hoepner demonstrates the dissemination of the Nazi racial plan, as he informed the 4th Panzer Group that the war against the Soviet Union was "an essential part of the German people's struggle for existence" (Daseinskampf), also referring to the imminent battle as the "old struggle of Germans against Slavs" and even stated, "the struggle must aim at the annihilation of today's Russia and must, therefore, be waged with unparalleled harshness."[64] Hoepner also added that the Germans were fighting for "the defence of European culture against Moscovite–Asiatic inundation, and the repulse of Jewish Bolshevism ... No adherents of the present Russian-Bolshevik system are to be spared." Walther von Brauchitsch also told his subordinates that troops should view the war as a "struggle between two different races and [should] act with the necessary severity."[65] Racial motivations were central to Nazi ideology and played a key role in planning for Operation Barbarossa since both Jews and communists were considered equivalent enemies of the Nazi state. Nazi imperialist ambitions rejected the common humanity of both groups, declaring the supreme struggle for Lebensraum to be a Vernichtungskrieg ('war of annihilation').[66][44]

German-Soviet relations of 1939–40[edit]

On August 23, 1939, Germany and the Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact in Moscow known as the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.[67] A secret protocol to the pact outlined an agreement between Germany and the Soviet Union on the division of the eastern European border states between their respective "spheres of influence," Soviet Union and Germany would partition Poland in the event of an invasion by Germany, and the Soviets would be allowed to overrun Finland, Estonia, Latvia and the region of Bessarabia.[68] On 23 August 1939 the rest of the world learned of this pact but were unaware of the provisions to partition Poland.[69] The pact stunned the world because of the parties' earlier mutual hostility and their conflicting ideologies.[70] The conclusion of this pact was followed by the German invasion of Poland on 1 September that triggered the outbreak of World War II in Europe, then the Soviet invasion of Poland that led to the annexation of the eastern part of the country.[71] As a result of the pact, Germany and the Soviet Union maintained reasonably strong diplomatic relations for two years and fostered an important economic relationship. The countries entered a trade pact in 1940 by which the Soviets received German military equipment and trade goods in exchange for raw materials, such as oil and wheat, to help the German war effort by circumventing the British blockade of Germany.[72]

Despite the parties' ostensibly cordial relations, each side was highly suspicious of the other's intentions. For instance, the Soviet invasion of Bukovina in June 1940 went beyond their sphere of influence as agreed with Germany.[73] After Germany entered the Axis Pact with Japan and Italy, it began negotiations about a potential Soviet entry into the pact.[74] After two days of negotiations in Berlin from 12 to 14 November 1940, Germany presented a written proposal for a Soviet entry into the Axis. On 25 November 1940, the Soviet Union offered a written counter-proposal to join the Axis if Germany would agree to refrain from interference in the Soviet Union's sphere of influence, but Germany did not respond.[74] As both sides began colliding with each other in Eastern Europe, conflict appeared more likely, although they did sign a border and commercial agreement addressing several open issues in January 1941. According to historian Robert Service, Joseph Stalin was convinced that the overall military strength of the Soviet Union was such that he had nothing to fear and anticipated an easy victory should Germany attack; moreover, Stalin believed that since the Germans were still fighting the British in the west, Hitler would be unlikely to open up a two-front war and subsequently delayed the reconstruction of defensive fortifications in the border regions.[75] When German soldiers swam across the Bug River to warn the Red Army of an impending attack, they were shot as enemy agents.[76] Some historians believe that Stalin, despite providing an amicable front to Hitler, did not wish to remain allies with Germany. Rather, Stalin might have had intentions to break off from Germany and proceed with his own campaign against Germany to be followed by one against the rest of Europe.[77] Other historians contend that Stalin did not plan for such an attack in June 1941, given the parlous state of the Red Army at the time of the invasion.[78]

Axis invasion plans[edit]

Stalin's reputation as a brutal dictator contributed both to the Nazis' justification of their assault and to their expectations of success, as Stalin's Great Purge of the 1930s had executed many competent and experienced military officers, leaving Red Army leadership weaker than their German adversary. The Nazis often emphasized the Soviet regime's brutality when targeting the Slavs with propaganda.[79] They also claimed that the Red Army was preparing to attack the Germans, and their own invasion was thus presented as a pre-emptive strike.[79]

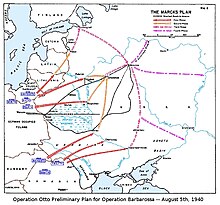

Hitler also utilised the rising tension between the Soviet Union and Germany over territories in the Balkans as one of the pretexts for the invasion.[80] While no concrete plans had yet been made, Hitler told one of his generals in June 1940 that the victories in Western Europe finally freed his hands for a "final showdown" with Bolshevism.[81] With the successful end to the campaign in France, General Erich Marcks was assigned the task of drawing up the initial invasion plans of the Soviet Union. The first battle plans were entitled Operation Draft East (colloquially known as the Marcks Plan).[82] His report advocated the A-A line as the operational objective of any invasion of the Soviet Union. This assault would extend from the northern city of Arkhangelsk on the Arctic Sea through Gorky and Rostov to the port city of Astrakhan at the mouth of the Volga on the Caspian Sea. The report concluded that—once established—this military border would reduce the threat to Germany from attacks by enemy bombers.[82]

Although Hitler was warned by many high-ranking military officers, such as Friedrich Paulus, that occupying Western Russia would create "more of a drain than a relief for Germany's economic situation," he anticipated compensatory benefits such as the demobilisation of entire divisions to relieve the acute labour shortage in German industry, the exploitation of Ukraine as a reliable and immense source of agricultural products, the use of forced labour to stimulate Germany's overall economy and the expansion of territory to improve Germany's efforts to isolate the United Kingdom.[83] Hitler was further convinced that Britain would sue for peace once the Germans triumphed in the Soviet Union,[84] and if they did not, he would use the resources gained in the East to defeat the British Empire.[85]

"We only have to kick in the door and the whole rotten structure will come crashing down."[86]

—Adolf Hitler

Hitler received the final military plans for the invasion on 5 December 1940, which the German High Command had been working on since July 1940, under the codename "Operation Otto." Upon reviewing the plans, Hitler formally committed Germany to the invasion when he issued Führer Directive 21 on 18 December 1940, where he outlined the precise manner in which the operation was to be carried out.[87] Hitler also renamed the operation to Barbarossa in honor of medieval Emperor Friedrich I of the Holy Roman Empire, a leader of the Third Crusade in the 12th century.[88] The Barbarossa Decree, issued by Hitler on 30 March 1941, supplemented the Directive by decreeing that the war against the Soviet Union would be one of annihilation and legally sanctioned the eradication of all Communist political leaders and intellectual elites in Eastern Europe.[89] The invasion was tentatively set for May 1941, but it was delayed for over a month to allow for further preparations and possibly better weather.[90]

"the purpose of the Russian campaign [is] the decimation of the Slavic population by thirty million."

— Heinrich Himmler's statement to SS officers at Wewelsburg castle, June 1941[91][92]

According to a 1978 essay by German historian Andreas Hillgruber, the invasion plans drawn up by the German military elite were substantially coloured by hubris, stemming from the rapid defeat of France at the hands of the "invincible" Wehrmacht and by traditional German stereotypes of Russia as a primitive, backward "Asiatic" country.[g] Red Army soldiers were considered brave and tough, but the officer corps was held in contempt. The leadership of the Wehrmacht paid little attention to politics, culture, and the considerable industrial capacity of the Soviet Union, in favour of a very narrow military view.[94] Hillgruber argued that because these assumptions were shared by the entire military elite, Hitler was able to push through with a "war of annihilation" that would be waged in the most inhumane fashion possible with the complicity of "several military leaders," even though it was quite clear that this would be in violation of all accepted norms of warfare.[94]

Even so, in autumn 1940, some high-ranking German military officials drafted a memorandum to Hitler on the dangers of an invasion of the Soviet Union. They argued that the eastern territories (Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic, the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic, and the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic) would only end up as a further economic burden for Germany.[95] It was further argued that the Soviets, in their current bureaucratic form, were harmless and that the occupation would not benefit Germany politically either.[95] Hitler, solely focused on his ultimate ideological goal of eliminating the Soviet Union and Communism, disagreed with economists about the risks and told his right-hand man Hermann Göring, the chief of the Luftwaffe, that he would no longer listen to misgivings about the economic dangers of a war with the USSR.[96] It is speculated that this was passed on to General Georg Thomas, who had produced reports that predicted a net economic drain for Germany in the event of an invasion of the Soviet Union unless its economy was captured intact and the Caucasus oilfields seized in the first blow; Thomas revised his future report to fit Hitler's wishes.[96] The Red Army's ineptitude in the Winter War against Finland in 1939–40 also convinced Hitler of a quick victory within a few months. Neither Hitler nor the General Staff anticipated a long campaign lasting into the winter and therefore, adequate preparations such as the distribution of warm clothing and winterisation of important military equipment like tanks and artillery, were not made.[97]

Further to Hitler's Directive, Göring's Green Folder, issued in March 1941, laid out the agenda for the next step after the anticipated quick conquest of the Soviet Union. The Hunger Plan outlined how entire urban populations of conquered territories were to be starved to death, thus creating an agricultural surplus to feed Germany and urban space for the German upper class.[98] Nazi policy aimed to destroy the Soviet Union as a political entity in accordance with the geopolitical Lebensraum ideals for the benefit of future generations of the "Nordic master race".[79] In 1941, Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg—later appointed Reich Minister of the Occupied Eastern Territories—suggested that conquered Soviet territory should be administered in the following Reichskommissariate ('Reich Commissionerships'):

| Name | Note | Map |

|---|---|---|

| Baltic countries and Belarus | ||

| Ukraine, enlarged eastwards to the Volga | ||

| Southern Russia and the Caucasus region | Unrealised | |

| Moscow metropolitan area and remaining European Russia; originally called Reichskommissariat Russland, later renamed | Unrealised | |

| Central Asian republics and territories | Unrealised |

German military planners also researched Napoleon's failed invasion of Russia. In their calculations, they concluded that there was little danger of a large-scale retreat of the Red Army into the Russian interior, as it could not afford to give up the Baltic countries, Ukraine, or the Moscow and Leningrad regions, all of which were vital to the Red Army for supply reasons and would thus, have to be defended.[101] Hitler and his generals disagreed on where Germany should focus its energy.[102][103] Hitler, in many discussions with his generals, repeated his order of "Leningrad first, the Donbas second, Moscow third;"[104] but he consistently emphasized the destruction of the Red Army over the achievement of specific terrain objectives.[105] Hitler believed Moscow to be of "no great importance" in the defeat of the Soviet Union[h] and instead believed victory would come with the destruction of the Red Army west of the capital, especially west of the Western Dvina and Dnieper rivers, and this pervaded the plan for Barbarossa.[107][108] This belief later led to disputes between Hitler and several German senior officers, including Heinz Guderian, Gerhard Engel, Fedor von Bock and Franz Halder, who believed the decisive victory could only be delivered at Moscow.[109] They were unable to sway Hitler, who had grown overconfident in his own military judgment as a result of the rapid successes in Western Europe.[110]

German preparations[edit]

The Germans had begun massing troops near the Soviet border even before the campaign in the Balkans had finished. By the third week of February 1941, 680,000 German soldiers were gathered in assembly areas on the Romanian-Soviet border.[111] In preparation for the attack, Hitler had secretly moved upwards of 3 million German troops and approximately 690,000 Axis soldiers to the Soviet border regions.[112] Additional Luftwaffe operations included numerous aerial surveillance missions over Soviet territory many months before the attack.[113]

Although the Soviet High Command was alarmed by this, Stalin's belief that Nazi Germany was unlikely to attack only two years after signing the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact resulted in slow Soviet preparation.[114] This fact aside, the Soviets did not entirely overlook the threat of their German neighbor. Well before the German invasion, Marshal Semyon Timoshenko referred to the Germans as the Soviet Union's "most important and strongest enemy," and as early as July 1940, the Red Army Chief of Staff, Boris Shaposhnikov, produced a preliminary three-pronged plan of attack for what a German invasion might look like, remarkably similar to the actual attack.[115] Since April 1941, the Germans had begun setting up Operation Haifisch and Operation Harpune to substantiate their claims that Britain was the real target. These simulated preparations in Norway and the English Channel coast included activities such as ship concentrations, reconnaissance flights and training exercises.[116]

The reasons for the postponement of Barbarossa from the initially planned date of 15 May to the actual invasion date of 22 June 1941 (a 38-day delay) are debated. The reason most commonly cited is the unforeseen contingency of invading Yugoslavia and Greece on 6 April 1941 until June 1941.[117] Historian Thomas B. Buell indicates that Finland and Romania, which weren't involved in initial German planning, needed additional time to prepare to participate in the invasion. Buell adds that an unusually wet winter kept rivers at full flood until late spring.[118][i] The floods may have discouraged an earlier attack, even if they occurred before the end of the Balkans Campaign.[120][j]

The importance of the delay is still debated. William Shirer argued that Hitler's Balkan Campaign had delayed the commencement of Barbarossa by several weeks and thereby jeopardised it.[122] Many later historians argue that the 22 June start date was sufficient for the German offensive to reach Moscow by September.[123][124][125][126] Antony Beevor wrote in 2012 about the delay caused by German attacks in the Balkans that "most [historians] accept that it made little difference" to the eventual outcome of Barbarossa.[127]

The Germans deployed one independent regiment, one separate motorised training brigade and 153 divisions for Barbarossa, which included 104 infantry, 19 panzer and 15 motorised infantry divisions in three army groups, nine security divisions to operate in conquered territories, four divisions in Finland[k] and two divisions as reserve under the direct control of OKH.[129] These were equipped with 6,867 armoured vehicles, of which 3,350–3,795 were tanks, 2,770–4,389 aircraft (that amounted to 65 percent of the Luftwaffe), 7,200–23,435 artillery pieces, 17,081 mortars, about 600,000 motor vehicles and 625,000–700,000 horses.[130][131][4][7][5] Finland slated 14 divisions for the invasion, and Romania offered 13 divisions and eight brigades over the course of Barbarossa.[3] The entire Axis forces, 3.8 million personnel,[2] deployed across a front extending from the Arctic Ocean southward to the Black Sea,[105] were all controlled by the OKH and organised into Army Norway, Army Group North, Army Group Centre and Army Group South, alongside three Luftflotten (air fleets, the air force equivalent of army groups) that supported the army groups: Luftflotte 1 for North, Luftflotte 2 for Centre and Luftflotte 4 for South.[3]

Army Norway was to operate in far northern Scandinavia and bordering Soviet territories.[3] Army Group North was to march through Latvia and Estonia into northern Russia, then either take or destroy the city of Leningrad, and link up with Finnish forces.[132][104] Army Group Centre, the army group equipped with the most armour and air power,[133] was to strike from Poland into Belorussia and the west-central regions of Russia proper, and advance to Smolensk and then Moscow.[104] Army Group South was to strike the heavily populated and agricultural heartland of Ukraine, taking Kiev before continuing eastward over the steppes of southern USSR to the Volga with the aim of controlling the oil-rich Caucasus.[104] Army Group South was deployed in two sections separated by a 198-mile (319 km) gap. The northern section, which contained the army group's only panzer group, was in southern Poland right next to Army Group Centre, and the southern section was in Romania.[134]

The German forces in the rear (mostly Waffen-SS and Einsatzgruppen units) were to operate in conquered territories to counter any partisan activity in areas they controlled, as well as to execute captured Soviet political commissars and Jews.[79] On 17 June, Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) chief Reinhard Heydrich briefed around thirty to fifty Einsatzgruppen commanders on "the policy of eliminating Jews in Soviet territories, at least in general terms".[135] While the Einsatzgruppen were assigned to the Wehrmacht's units, which provided them with supplies such as gasoline and food, they were controlled by the RSHA.[136] The official plan for Barbarossa assumed that the army groups would be able to advance freely to their primary objectives simultaneously, without spreading thin, once they had won the border battles and destroyed the Red Army's forces in the border area.[137]

Soviet preparations[edit]

In 1930, Mikhail Tukhachevsky, a prominent military theorist in tank warfare in the interwar period and later Marshal of the Soviet Union, forwarded a memo to the Kremlin that lobbied for colossal investment in the resources required for the mass production of weapons, pressing the case for "40,000 aircraft and 50,000 tanks."[138] In the early 1930s, a modern operational doctrine for the Red Army was developed and promulgated in the 1936 Field Regulations in the form of the Deep Battle Concept. Defence expenditure also grew rapidly from just 12 percent of the gross national product in 1933 to 18 percent by 1940.[139]

During Joseph Stalin's Great Purge in the late 1930s, which had not ended by the time of the German invasion on 22 June 1941, much of the officer corps of the Red Army was executed or imprisoned. Many of their replacements, appointed by Stalin for political reasons, lacked military competence.[140][141][142] Of the five Marshals of the Soviet Union appointed in 1935, only Kliment Voroshilov and Semyon Budyonny survived Stalin's purge. Tukhachevsky was killed in 1937. Fifteen of 16 army commanders, 50 of the 57 corps commanders, 154 of the 186 divisional commanders, and 401 of 456 colonels were killed, and many other officers were dismissed.[142] In total, about 30,000 Red Army personnel were executed.[143] Stalin further underscored his control by reasserting the role of political commissars at the divisional level and below to oversee the political loyalty of the army to the regime. The commissars held a position equal to that of the commander of the unit they were overseeing.[142] But in spite of efforts to ensure the political subservience of the armed forces, in the wake of Red Army's poor performance in Poland and in the Winter War, about 80 percent of the officers dismissed during the Great Purge were reinstated by 1941. Also, between January 1939 and May 1941, 161 new divisions were activated.[144][145] Therefore, although about 75 percent of all the officers had been in their position for less than one year at the start of the German invasion of 1941, many of the short tenures can be attributed not only to the purge but also to the rapid increase in the creation of military units.[145]

Beginning in July 1940, the Red Army General Staff developed war plans that identified the Wehrmacht as the most dangerous threat to the Soviet Union, and that in the case of a war with Germany, the Wehrmacht's main attack would come through the region north of the Pripyat Marshes into Belorussia,[146][137] which later proved to be correct.[146] Stalin disagreed, and in October, he authorised the development of new plans that assumed a German attack would focus on the region south of Pripyat Marshes towards the economically vital regions in Ukraine. This became the basis for all subsequent Soviet war plans and the deployment of their armed forces in preparation for the German invasion.[146][147]

In the Soviet Union, speaking to his generals in December 1940, Stalin mentioned Hitler's references to an attack on the Soviet Union in Mein Kampf and Hitler's belief that the Red Army would need four years to ready itself. Stalin declared "we must be ready much earlier" and "we will try to delay the war for another two years".[148] As early as August 1940, British intelligence had received hints of German plans to attack the Soviets a week after Hitler informally approved the plans for Barbarossa and warned the Soviet Union accordingly.[149] Some of this intelligence was based on Ultra information obtained from broken Enigma traffic.[150] But Stalin's distrust of the British led him to ignore their warnings in the belief that they were a trick designed to bring the Soviet Union into the war on their side.[149][151] Soviet intelligence also received word of an invasion around 20 June from Mao Zedong whose spy, Yan Baohang, had overheard talk of the plans at a dinner with a German military attaché and sent word to Zhou Enlai.[152] The Chinese maintain the tipoff helped Stalin make preparations, though little exists to confirm the Soviets made any real changes upon receiving the intelligence.[152] In early 1941, Stalin's own intelligence services and American intelligence gave regular and repeated warnings of an impending German attack.[153] Soviet spy Richard Sorge also gave Stalin the exact German launch date, but Sorge and other informers had previously given different invasion dates that passed peacefully before the actual invasion.[154][155] Stalin acknowledged the possibility of an attack in general and therefore made significant preparations, but decided not to run the risk of provoking Hitler.[156]

In early 1941, Stalin authorised the State Defence Plan 1941 (DP-41), which along with the Mobilisation Plan 1941 (MP-41), called for the deployment of 186 divisions, as the first strategic echelon, in the four military districts[l] of the western Soviet Union that faced the Axis territories; and the deployment of another 51 divisions along the Dvina and Dnieper Rivers as the second strategic echelon under Stavka control, which in the case of a German invasion was tasked to spearhead a Soviet counteroffensive along with the remaining forces of the first echelon.[147] But on 22 June 1941 the first echelon contained 171 divisions,[157] numbering 2.6–2.9 million;[2][158] and the second strategic echelon contained 57 divisions that were still mobilising, most of which were still understrength.[159] The second echelon was undetected by German intelligence until days after the invasion commenced, in most cases only when German ground forces encountered them.[159]

At the start of the invasion, the manpower of the Soviet military force that had been mobilised was 5.3–5.5 million,[2][160] and it was still increasing as the Soviet reserve force of 14 million, with at least basic military training, continued to mobilise.[161][162] The Red Army was dispersed and still preparing when the invasion commenced.[163] Their units were often separated and lacked adequate transportation. While transportation remained insufficient for Red Army forces, when Operation Barbarossa kicked off, they possessed some 33,000 pieces of artillery, a number far greater than the Germans had at their disposal.[164][m]

The Soviet Union had around 23,000 tanks available of which 14,700 were combat-ready.[166] Around 11,000 tanks were in the western military districts that faced the German invasion force.[11] Hitler later declared to some of his generals, "If I had known about the Russian tank strength in 1941 I would not have attacked".[167] However, maintenance and readiness standards were very poor; ammunition and radios were in short supply, and many armoured units lacked the trucks for supplies.[168][169] The most advanced Soviet tank models—the KV-1 and T-34—which were superior to all current German tanks, as well as all designs still in development as of the summer 1941,[170] were not available in large numbers at the time the invasion commenced.[171] Furthermore, in the autumn of 1939, the Soviets disbanded their mechanised corps and partly dispersed their tanks to infantry divisions;[172] but following their observation of the German campaign in France, in late 1940 they began to reorganise most of their armoured assets back into mechanised corps with a target strength of 1,031 tanks each.[144] But these large armoured formations were unwieldy, and moreover they were spread out in scattered garrisons, with their subordinate divisions up to 100 kilometres (62 miles) apart.[144] The reorganisation was still in progress and incomplete when Barbarossa commenced.[173][172] Soviet tank units were rarely well equipped, and they lacked training and logistical support. Units were sent into combat with no arrangements in place for refuelling, ammunition resupply, or personnel replacement. Often, after a single engagement, units were destroyed or rendered ineffective.[163] The Soviet numerical advantage in heavy equipment was thoroughly offset by the superior training and organisation of the Wehrmacht.[143]

The Soviet Air Force (VVS) held the numerical advantage with a total of approximately 19,533 aircraft, which made it the largest air force in the world in the summer of 1941.[174] About 7,133–9,100 of these were deployed in the five western military districts,[l][174][11][12] and an additional 1,445 were under naval control.[175]

| 1 January 1939 | 22 June 1941 | Increase | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Divisions calculated | 131.5 | 316.5 | 140.7% |

| Personnel | 2,485,000 | 5,774,000 | 132.4% |

| Guns and mortars | 55,800 | 117,600 | 110.7% |

| Tanks | 21,100 | 25,700 | 21.8% |

| Aircraft | 7,700 | 18,700 | 142.8% |

Historians have debated whether Stalin was planning an invasion of German territory in the summer of 1941. The debate began in the late 1980s when Viktor Suvorov published a journal article and later the book Icebreaker in which he claimed that Stalin had seen the outbreak of war in Western Europe as an opportunity to spread communist revolutions throughout the continent, and that the Soviet military was being deployed for an imminent attack at the time of the German invasion.[177] This view had also been advanced by former German generals following the war.[178] Suvorov's thesis was fully or partially accepted by a limited number of historians, including Valeri Danilov, Joachim Hoffmann, Mikhail Meltyukhov, and Vladimir Nevezhin, and attracted public attention in Germany, Israel, and Russia.[179][180] It has been strongly rejected by most historians,[181][182] and Icebreaker is generally considered to be an "anti-Soviet tract" in Western countries.[183] David Glantz and Gabriel Gorodetsky wrote books to rebut Suvorov's arguments.[184] The majority of historians believe that Stalin was seeking to avoid war in 1941, as he believed that his military was not ready to fight the German forces.[185] The debate on whether Stalin intended to launch an offensive against Germany in 1941 remains inconclusive but has produced an abundance of scholarly literature and helped to expand the understanding of larger themes in Soviet and world history during the interwar period.[186]

Order of battle[edit]

| Axis forces | Soviet forces[l] |

|---|---|

Stavka Reserve Armies (second strategic echelon)[195] | |

| Total number of divisions (22 June) | |

German : 152[196] Romanian : 14[197] | Soviet : 220[196] |

Invasion[edit]

At around 01:00 on 22 June 1941, the Soviet military districts in the border area[l] were alerted by NKO Directive No. 1, issued late on the night of 21 June.[198] It called on them to "bring all forces to combat readiness", but to "avoid provocative actions of any kind".[199] It took up to two hours for several of the units subordinate to the Fronts to receive the order of the directive,[199] and the majority did not receive it before the invasion commenced.[198] A German communist deserter, Alfred Liskow, had crossed the lines at 21:00 on 21 June[n] and informed the Soviets that an attack was coming at 04:00. Stalin was informed, but apparently regarded it as disinformation. Liskow was still being interrogated when the attack began.[201]

On 21 June, at 13:00 Army Group North received the codeword "Düsseldorf", indicating Barbarossa would commence the next morning, and passed down its own codeword, "Dortmund".[202] At around 03:15 on 22 June 1941, the Axis Powers commenced the invasion of the Soviet Union with the bombing of major cities in Soviet-occupied Poland[203] and an artillery barrage on Red Army defences on the entire front.[198] Air-raids were conducted as far as Kronstadt near Leningrad, Ismail in Bessarabia, and Sevastopol in the Crimea. At the same time the German declaration of war was presented by Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop. Meanwhile, ground troops crossed the border, accompanied in some locales by Lithuanian and Ukrainian partisans.[204] Roughly three million soldiers of the Wehrmacht went into action and faced slightly fewer Soviet troops at the border.[203] Accompanying the German forces during the initial invasion were Finnish and Romanian units as well.[205]

At around noon, the news of the invasion was broadcast to the population by Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov: "... Without a declaration of war, German forces fell on our country, attacked our frontiers in many places ... The Red Army and the whole nation will wage a victorious Patriotic War for our beloved country, for honour, for liberty ... Our cause is just. The enemy will be beaten. Victory will be ours!"[206][207] By calling upon the population's devotion to their nation rather than the Party, Molotov struck a patriotic chord that helped a stunned people absorb the shattering news.[206] Within the first few days of the invasion, the Soviet High Command and Red Army were extensively reorganised so as to place them on the necessary war footing.[208] Stalin did not address the nation about the German invasion until 3 July, when he also called for a "Patriotic War... of the entire Soviet people".[209]

In Germany, on the morning of 22 June, Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels announced the invasion to the waking nation in a radio broadcast with Hitler's words: "At this moment a march is taking place that, for its extent, compares with the greatest the world has ever seen. I have decided today to place the fate and future of the Reich and our people in the hands of our soldiers. May God aid us, especially in this fight!"[210] Later the same morning, Hitler proclaimed to his colleagues, "Before three months have passed, we shall witness a collapse of Russia, the like of which has never been seen in history".[210] Hitler also addressed the German people via the radio, presenting himself as a man of peace, who reluctantly had to attack the Soviet Union.[211] Following the invasion, Goebbels instructed that Nazi propaganda use the slogan "European crusade against Bolshevism" to describe the war; subsequently thousands of volunteers and conscripts joined the Waffen-SS.[212]

Initial attacks[edit]

The initial momentum of the German ground and air attack completely destroyed the Soviet organisational command and control within the first few hours, paralyzing every level of command from the infantry platoon to the Soviet High Command in Moscow.[213] Moscow failed to grasp the magnitude of the catastrophe that confronted the Soviet forces in the border area, and Stalin's first reaction was disbelief.[214] At around 07:15, Stalin issued NKO Directive No. 2, which announced the invasion to the Soviet Armed Forces, and called on them to attack Axis forces wherever they had violated the borders and launch air strikes into the border regions of German territory.[215] At around 09:15, Stalin issued NKO Directive No. 3, signed by Timoshenko, which now called for a general counteroffensive on the entire front "without any regards for borders" that both men hoped would sweep the enemy from Soviet territory.[216][199] Stalin's order, which Timoshenko authorised, was not based on a realistic appraisal of the military situation at hand, but commanders passed it along for fear of retribution if they failed to obey; several days passed before the Soviet leadership became aware of the enormity of the opening defeat.[216]

Air war[edit]

Luftwaffe reconnaissance units plotted Soviet troop concentrations, supply dumps and airfields, and marked them down for destruction.[217] Additional Luftwaffe attacks were carried out against Soviet command and control centres to disrupt the mobilisation and organisation of Soviet forces.[218][219] In contrast, Soviet artillery observers based at the border area had been under the strictest instructions not to open fire on German aircraft prior to the invasion.[114] One plausible reason given for the Soviet hesitation to return fire was Stalin's initial belief that the assault was launched without Hitler's authorisation. Significant amounts of Soviet territory were lost along with Red Army forces as a result; it took several days before Stalin comprehended the magnitude of the calamity.[220] The Luftwaffe reportedly destroyed 1,489 aircraft on the first day of the invasion[221] and over 3,100 during the first three days.[222] Hermann Göring, Minister of Aviation and Commander-in-Chief of the Luftwaffe, distrusted the reports and ordered the figure checked. Luftwaffe staffs surveyed the wreckage on Soviet airfields, and their original figure proved conservative, as over 2,000 Soviet aircraft were estimated to have been destroyed on the first day of the invasion.[221] In reality, Soviet losses were likely higher; a Soviet archival document recorded the loss of 3,922 Soviet aircraft in the first three days against an estimated loss of 78 German aircraft.[222][223] The Luftwaffe reported the loss of only 35 aircraft on the first day of combat.[222] A document from the German Federal Archives puts the Luftwaffe's loss at 63 aircraft for the first day.[224]

By the end of the first week, the Luftwaffe had achieved air supremacy over the battlefields of all the army groups,[223] but was unable to extend this air dominance over the vast expanse of the western Soviet Union.[225][226] According to the war diaries of the German High Command, the Luftwaffe by 5 July had lost 491 aircraft with 316 more damaged, leaving it with only about 70 percent of the strength it had at the start of the invasion.[227]

Baltic countries[edit]

On 22 June, Army Group North attacked the Soviet Northwestern Front and broke through its 8th and 11th Armies.[228] The Soviets immediately launched a powerful counterattack against the German 4th Panzer Group with the Soviet 3rd and 12th Mechanised Corps, but the Soviet attack was defeated.[228] On 25 June, the 8th and 11th Armies were ordered to withdraw to the Western Dvina River, where it was planned to meet up with the 21st Mechanised Corps and the 22nd and 27th Armies. However, on 26 June, Erich von Manstein's LVI Panzer Corps reached the river first and secured a bridgehead across it.[229] The Northwestern Front was forced to abandon the river defences, and on 29 June Stavka ordered the Front to withdraw to the Stalin Line on the approaches to Leningrad.[229] On 2 July, Army Group North began its attack on the Stalin Line with its 4th Panzer Group, and on 8 July captured Pskov, devastating the defences of the Stalin Line and reaching Leningrad oblast.[229] The 4th Panzer Group had advanced about 450 kilometres (280 mi) since the start of the invasion and was now only about 250 kilometres (160 mi) from its primary objective Leningrad. On 9 July it began its attack towards the Soviet defences along the Luga River in Leningrad oblast.[230]

Ukraine and Moldavia[edit]

The northern section of Army Group South faced the Southwestern Front, which had the largest concentration of Soviet forces, and the southern section faced the Southern Front. In addition, the Pripyat Marshes and the Carpathian Mountains posed a serious challenge to the army group's northern and southern sections respectively.[231] On 22 June, only the northern section of Army Group South attacked, but the terrain impeded their assault, giving the Soviet defenders ample time to react.[231] The German 1st Panzer Group and 6th Army attacked and broke through the Soviet 5th Army.[232] Starting on the night of 23 June, the Soviet 22nd and 15th Mechanised Corps attacked the flanks of the 1st Panzer Group from north and south respectively. Although intended to be concerted, Soviet tank units were sent in piecemeal due to poor coordination. The 22nd Mechanised Corps ran into the 1st Panzer Army's III Motorised Corps and was decimated, and its commander killed. The 1st Panzer Group bypassed much of the 15th Mechanised Corps, which engaged the German 6th Army's 297th Infantry Division, where it was defeated by antitank fire and Luftwaffe attacks.[233] On 26 June, the Soviets launched another counterattack on the 1st Panzer Group from north and south simultaneously with the 9th, 19th and 8th Mechanised Corps, which altogether fielded 1649 tanks, and supported by the remnants of the 15th Mechanised Corps. The battle lasted for four days, ending in the defeat of the Soviet tank units.[234] On 30 June Stavka ordered the remaining forces of the Southwestern Front to withdraw to the Stalin Line, where it would defend the approaches to Kiev.[235]

On 2 July, the southern section of Army Group South—the Romanian 3rd and 4th Armies, alongside the German 11th Army—invaded Soviet Moldavia, which was defended by the Southern Front.[236] Counterattacks by the Front's 2nd Mechanised Corps and 9th Army were defeated, but on 9 July the Axis advance stalled along the defences of the Soviet 18th Army between the Prut and Dniester Rivers.[237]

Belorussia[edit]

In the opening hours of the invasion, the Luftwaffe destroyed the Western Front's air force on the ground, and with the aid of Abwehr and their supporting anti-communist fifth columns operating in the Soviet rear paralyzed the Front's communication lines, which particularly cut off the Soviet 4th Army headquarters from headquarters above and below it.[238] On the same day, the 2nd Panzer Group crossed the Bug River, broke through the 4th Army, bypassed Brest Fortress, and pressed on towards Minsk, while the 3rd Panzer Group bypassed most of the 3rd Army and pressed on towards Vilnius.[238] Simultaneously, the German 4th and 9th Armies engaged the Western Front forces in the environs of Białystok.[239] On the order of the Western Front commander, Dmitry Pavlov, the 6th and 11th Mechanised Corps and the 6th Cavalry Corps launched a strong counterstrike towards Grodno on 24–25 June in hopes of destroying the 3rd Panzer Group. However, the 3rd Panzer Group had already moved on, with its forward units reaching Vilnius on the evening of 23 June, and the Western Front's armoured counterattack instead ran into infantry and antitank fire from the V Army Corps of the German 9th Army, supported by Luftwaffe air attacks.[238] By the night of 25 June, the Soviet counterattack was defeated, and the commander of the 6th Cavalry Corps was captured. The same night, Pavlov ordered all the remnants of the Western Front to withdraw to Slonim towards Minsk.[238] Subsequent counterattacks to buy time for the withdrawal were launched against the German forces, but all of them failed.[238] On 27 June, the 2nd and 3rd Panzer Groups met near Minsk and captured the city the next day, completing the encirclement of almost all of the Western Front in two pockets: one around Białystok and another west of Minsk.[240] The Germans destroyed the Soviet 3rd and 10th Armies while inflicting serious losses on the 4th, 11th and 13th Armies, and reported to have captured 324,000 Soviet troops, 3,300 tanks, 1,800 artillery pieces.[241][242]

A Soviet directive was issued on 29 June to combat the mass panic rampant among the civilians and the armed forces personnel. The order stipulated swift, severe measures against anyone inciting panic or displaying cowardice. The NKVD worked with commissars and military commanders to scour possible withdrawal routes of soldiers retreating without military authorisation. Field expedient general courts were established to deal with civilians spreading rumours and military deserters.[243] On 30 June, Stalin relieved Pavlov of his command, and on 22 July tried and executed him along with many members of his staff on charges of "cowardice" and "criminal incompetence".[244][245]

On 29 June, Hitler, through Brauchitsch, instructed Bock to halt the advance of the panzers of Army Group Centre until the infantry formations liquidating the pockets caught up.[246] But Guderian, with the tacit support of Bock and Halder, ignored the instruction and attacked on eastward towards Bobruisk, albeit reporting the advance as a reconnaissance-in-force. He also personally conducted an aerial inspection of the Minsk-Białystok pocket on 30 June and concluded that his panzer group was not needed to contain it, since Hermann Hoth's 3rd Panzer Group was already involved in the Minsk pocket.[247] On the same day, some of the infantry corps of the 9th and 4th Armies, having sufficiently liquidated the Białystok pocket, resumed their march eastward to catch up with the panzer groups.[247] On 1 July, Bock ordered the panzer groups to resume their full offensive eastward on the morning of 3 July. But Brauchitsch, upholding Hitler's instruction, and Halder, unwillingly going along with it, opposed Bock's order. However, Bock insisted on the order by stating that it would be irresponsible to reverse orders already issued. The panzer groups resumed their offensive on 2 July before the infantry formations had sufficiently caught up.[247]

Northeast Finland[edit]

During German-Finnish negotiations, Finland had demanded to remain neutral unless the Soviet Union attacked them first. Germany therefore sought to provoke the Soviet Union into an attack on Finland. After Germany launched Barbarossa on 22 June, German aircraft used Finnish air bases to attack Soviet positions. The same day the Germans launched Operation Rentier and occupied the Petsamo Province at the Finnish-Soviet border. Simultaneously Finland proceeded to remilitarise the neutral Åland Islands. Despite these actions the Finnish government insisted via diplomatic channels that they remained a neutral party, but the Soviet leadership already viewed Finland as an ally of Germany. Subsequently, the Soviets proceeded to launch a massive bombing attack on 25 June against all major Finnish cities and industrial centres, including Helsinki, Turku and Lahti. During a night session on the same day the Finnish parliament decided to go to war against the Soviet Union.[248][249]

Finland was divided into two operational zones. Northern Finland was the staging area for Army Norway. Its goal was to execute a two-pronged pincer movement on the strategic port of Murmansk, named Operation Silver Fox. Southern Finland was still under the responsibility of the Finnish Army. The goal of the Finnish forces was, at first, to recapture Finnish Karelia at Lake Ladoga as well as the Karelian Isthmus, which included Finland's second largest city Viipuri.[250][251]

Further German advances[edit]

On 2 July and through the next six days, a rainstorm typical of Belarusian summers slowed the progress of the panzers of Army Group Centre, and Soviet defences stiffened.[252] The delays gave the Soviets time to organise a massive counterattack against Army Group Centre. The army group's ultimate objective was Smolensk, which commanded the road to Moscow. Facing the Germans was an old Soviet defensive line held by six armies. On 6 July, the Soviets launched a massive counter-attack using the V and VII Mechanised Corps of the 20th Army,[253] which collided with the German 39th and 47th Panzer Corps in a battle where the Red Army lost 832 tanks of the 2,000 employed during five days of ferocious fighting.[254] The Germans defeated this counterattack thanks largely to the coincidental presence of the Luftwaffe's only squadron of tank-busting aircraft.[254] The 2nd Panzer Group crossed the Dnieper River and closed in on Smolensk from the south while the 3rd Panzer Group, after defeating the Soviet counterattack, closed on Smolensk from the north. Trapped between their pincers were three Soviet armies. The 29th Motorised Division captured Smolensk on 16 July yet a gap remained between Army Group Centre. On 18 July, the panzer groups came to within ten kilometres (6.2 mi) of closing the gap but the trap did not finally close until 5 August, when upwards of 300,000 Red Army soldiers had been captured and 3,205 Soviet tanks were destroyed. Large numbers of Red Army soldiers escaped to stand between the Germans and Moscow as resistance continued.[255]

Four weeks into the campaign, the Germans realised they had grossly underestimated Soviet strength.[256] The German troops had used their initial supplies, and General Bock quickly came to the conclusion that not only had the Red Army offered stiff opposition, but German difficulties were also due to the logistical problems with reinforcements and provisions.[257] Operations were now slowed down to allow for resupply; the delay was to be used to adapt strategy to the new situation.[258] In addition to strained logistics, poor roads made it difficult for wheeled vehicles and foot infantry to keep up with the faster armoured spearheads, and shortages in boots and winter uniforms were becoming apparent. Furthermore, all three army groups had suffered 179,500 casualties by 2 August, and had only received 47,000 replacements.[259]

Hitler by now had lost faith in battles of encirclement as large numbers of Soviet soldiers had escaped the pincers.[258] He now believed he could defeat the Soviet state by economic means, depriving them of the industrial capacity to continue the war. That meant seizing the industrial centre of Kharkov, the Donbas and the oil fields of the Caucasus in the south and the speedy capture of Leningrad, a major centre of military production, in the north.[260]

Halder, Bock, and almost all the German generals involved in Operation Barbarossa argued vehemently in favour of continuing the all-out drive toward Moscow.[261][262] Besides the psychological importance of capturing the Soviet capital, the generals pointed out that Moscow was a major centre of arms production, the centre of the Soviet communications system and an important transport hub. Intelligence reports indicated that the bulk of the Red Army was deployed near Moscow under Timoshenko for the defence of the capital.[258] Guderian was sent to Hitler by Bock and Halder to argue their case for continuing the assault against Moscow, but Hitler issued an order through Guderian (bypassing Bock and Halder) to send Army Group Centre's tanks to the north and south, temporarily halting the drive to Moscow.[263] Convinced by Hitler's argument, Guderian returned to his commanding officers as a convert to the Führer's plan, which earned him their disdain.[264]

Northern Finland[edit]

On 29 June, Germany launched its effort to capture Murmansk in a pincer attack. The northern pincer, conducted by Mountain Corps Norway, approached Murmansk directly by crossing the border at Petsamo. However, in mid-July after securing the neck of the Rybachy Peninsula and advancing to the Litsa River the German advance was stopped by heavy resistance from the Soviet 14th Army. Renewed attacks led to nothing, and this front became a stalemate for the remainder of Barbarossa.[265][266]

Вторая атака в клещи началась 1 июля, когда немецкий XXXVI корпус и финский III корпус должны были отбить район Саллы для Финляндии, а затем двинуться на восток, чтобы перерезать Мурманскую железную дорогу возле Кандалакши . Немецким частям было очень трудно справиться с арктическими условиями. После тяжелых боев 8 июля была взята Салла. у города Кайралы Чтобы сохранить набранный темп, немецко-финские войска продвигались на восток, пока не были остановлены советским сопротивлением . Южнее III финский корпус предпринял самостоятельную попытку достичь Мурманской железной дороги через арктическую местность. Столкнувшись лишь с одной дивизией советской 7-й армии, она смогла быстро продвинуться вперед. 7 августа, выходя к окраине Ухты, она захватила Кестенгу . Большие подкрепления Красной Армии помешали дальнейшим успехам на обоих фронтах, и немецко-финским войскам пришлось перейти к обороне. [267] [268]

Карелия [ править ]

План финнов на юге Карелии заключался в том, чтобы как можно быстрее продвинуться к Ладожскому озеру, сократив советские силы вдвое. Затем необходимо было отбить финские территории к востоку от Ладожского озера до того, как начнется наступление вдоль Карельского перешейка, включая возвращение Выборга. Финская атака началась 10 июля. Армия Карелии имела численное преимущество над советскими защитниками 7-й и 23-й армий , поэтому могла быстро наступать. Важный транспортный узел в Лоймоле был захвачен 14 июля. К 16 июля первые финские части достигли Ладожского озера у Койринои, добившись цели расколоть советские войска. В течение оставшейся части июля Армия Карелии продвинулась дальше на юго-восток в Карелию, остановившись на бывшей финско-советской границе в Мансиле. [269] [270]

Когда советские войска будут сокращены вдвое, можно будет начать наступление на Карельский перешеек. Финская армия попыталась окружить крупные советские соединения в Сортавале и Хиитоле , продвинувшись к западному берегу Ладожского озера. К середине августа окружение удалось, и оба города были взяты, но многие советские соединения смогли эвакуироваться морем. Дальше на запад началась атака на Выборг. Когда советское сопротивление было сломлено, финны смогли окружить Выборг, продвинувшись к реке Вуокса . Сам город был взят 29 августа. [271] наряду с широким наступлением на остальную часть Карельского перешейка. К началу сентября Финляндия восстановила свои границы, существовавшие до Зимней войны. [272] [270]

Наступление на центральную Россию [ править ]

К середине июля немецкие войска продвинулись на несколько километров от Киева ниже Припятских болот. Затем 1-я танковая группа двинулась на юг, а 17-я армия нанесла удар на восток и захватила три советские армии под Уманью . [273] Когда немцы ликвидировали котел, танки повернули на север и форсировали Днепр. Тем временем 2-я танковая группа, отвлеченная от группы армий «Центр», форсировала реку Десна, а 2-я армия находилась на ее правом фланге. Две танковые армии теперь захватили в ловушку четыре советские армии и части двух других. [274]

К августу, когда работоспособность и количество Люфтваффе арсенала неуклонно снижались из-за боевых действий, потребность в поддержке с воздуха только увеличивалась по мере восстановления ВВС. Люфтваффе изо всех сил пытались сохранить местное превосходство в воздухе. [275] С наступлением непогоды в октябре Люфтваффе несколько раз были вынуждены прекратить почти все воздушные операции. ВВС, хотя и столкнулись с теми же погодными трудностями, имели явное преимущество благодаря довоенному опыту полетов в холодную погоду и тому факту, что они действовали с неповрежденных авиабаз и аэропортов. [276] К декабрю ВВС сравнялись с Люфтваффе и даже стремились добиться превосходства в воздухе на полях сражений. [277]

Ленинград [ править ]

Для последнего наступления на Ленинград 4-я танковая группа была усилена танками группы армий «Центр». 8 августа танки прорвали советскую оборону. К концу августа 4-я танковая группа продвинулась к Ленинграду на расстояние 48 километров (30 миль). Финны [the] двинулись на юго-восток по обе стороны Ладожского озера, чтобы достичь старой финско-советской границы. [279]

Немцы напали на Ленинград в августе 1941 года; В следующие три «черных месяца» 1941 года 400 000 жителей города работали над строительством городских укреплений, пока продолжались боевые действия, а еще 160 000 вступили в ряды Красной Армии. Нигде советский дух массового сопротивления не был сильнее в сопротивлении немцам, чем в Ленинграде, где резервные войска и недавно импровизированные отряды Народного ополчения , состоящие из рабочих батальонов и даже школьных формирований, вместе рыли траншеи, готовясь защищать город. [280] 7 сентября немецкая 20-я моторизованная дивизия захватила Шлиссельбург , отрезав все сухопутные пути на Ленинград. Немцы перерезали железную дорогу, ведущую к Москве, и захватили железную дорогу, ведущую к Мурманску, с помощью Финляндии, положив начало осаде, которая продлилась более двух лет. [281] [282]

На этом этапе Гитлер приказал окончательно разрушить Ленинград без взятия пленных, и 9 сентября группа армий «Север» начала последний натиск. За десять дней он продвинулся на расстояние 11 километров (6,8 миль) от города. [283] Однако продвижение на последних 10 км (6,2 мили) оказалось очень медленным. и жертвы растут. Терпение Гитлера закончилось, и он приказал не штурмовать Ленинград, а заморить его голодом, чтобы заставить его подчиниться. В соответствии с этим 22 сентября 1941 года ОКХ издало директиву № ла 1601/41, которая соответствовала планам Гитлера. [284] Лишенная своих танковых сил, группа армий «Центр» оставалась неподвижной и подвергалась многочисленным советским контратакам, в частности наступлению на Ельню , в котором немцы потерпели первое крупное тактическое поражение с момента начала вторжения; эта победа Красной Армии также дала важный импульс моральному духу Советского Союза. [285] Эти атаки побудили Гитлера снова сосредоточить свое внимание на группе армий «Центр» и ее наступлении на Москву. Немцы приказали 3-й и 4-й танковым армиям прорвать блокаду Ленинграда и поддержать группу армий «Центр» в ее наступлении на Москву. [286] [287]

Киев [ править ]

Прежде чем начать наступление на Москву, необходимо было завершить операцию в Киеве. Половина группы армий «Центр» отошла на юг, в тыл киевской позиции, а группа армий «Юг» двинулась на север со своего плацдарма на Днепре . [288] Окружение советских войск в Киеве было достигнуто 16 сентября. Завязалась битва, в которой Советы были поражены танками, артиллерией и бомбардировками с воздуха. После десяти дней жестоких боев немцы заявили, что взяли в плен 665 000 советских солдат, хотя реальная цифра, вероятно, составляет около 220 000. [289] Советские потери составили 452720 человек, 3867 артиллерийских орудий и минометов из 43 дивизий 5-й, 21-й, 26-й и 37-й советских армий. [288] Несмотря на истощение и потери, понесенные некоторыми немецкими частями (более 75 процентов их личного состава) в результате интенсивных боев, массовое поражение Советов под Киевом и потери Красной Армии в течение первых трех месяцев наступления способствовали предположению немцев, что Операция «Тайфун» (нападение на Москву) еще могла увенчаться успехом. [290]

Азовское море [ править ]

После успешного завершения операции под Киевом группа армий «Юг» двинулась на восток и юг, чтобы захватить промышленный регион Донбасса и Крым . 26 сентября советский Южный фронт начал наступление двумя армиями на северном берегу Азовского моря против частей 11-й немецкой армии , которая одновременно наступала в Крым. 1 октября 1-я танковая армия под командованием Эвальда фон Клейста двинулась на юг, чтобы окружить две атакующие советские армии. К 7 октября советские 9-я и 18-я армии были изолированы, а четыре дня спустя они были уничтожены. Советское поражение было полным; В плену взято 106 332 человека, 212 танков только в котле уничтожено или захвачено , а также 766 артиллерийских орудий всех типов. [291] Гибель или пленение двух третей всех войск Южного фронта за четыре дня расшатали левый фланг фронта, позволив немцам захватить Харьков 24 октября. В том же месяце 1-я танковая армия Клейста захватила Донбасс. [291]

Центральная и северная Финляндия [ править ]

В центральной Финляндии немецко-финское наступление по Мурманской железной дороге возобновилось у Кайралы. Крупное окружение с севера и юга захватило обороняющийся советский корпус и позволило XXXVI корпусу продвинуться дальше на восток. [292] В начале сентября он достиг старых советских пограничных укреплений 1939 года. 6 сентября была прорвана первая линия обороны на реке Войта, но дальнейшие атаки на главную линию на реке Верман не увенчались успехом. [293] Поскольку армия Норвегии перенесла свои основные усилия дальше на юг, фронт на этом участке зашел в тупик. Южнее 30 октября 3-й финский корпус начал новое наступление в направлении Мурманской железной дороги, подкрепленный свежими подкреплениями из армии Норвегии. Несмотря на советское сопротивление, он смог подойти на расстояние 30 км (19 миль) от железной дороги, когда 17 ноября финское верховное командование приказало прекратить все наступательные операции на этом участке. Соединенные Штаты Америки оказали дипломатическое давление на Финляндию, чтобы она не препятствовала поставкам помощи союзников в Советский Союз, что заставило финское правительство остановить наступление на Мурманской железной дороге. Из-за отказа Финляндии проводить дальнейшие наступательные операции и неспособности Германии сделать это в одиночку немецко-финские усилия в центральной и северной Финляндии подошли к концу. [294] [295]

Карелия [ править ]

Германия оказала давление на Финляндию, чтобы она расширила свои наступательные действия в Карелии, чтобы помочь немцам в их Ленинградской операции. Нападения финнов на сам Ленинград оставались ограниченными. Финляндия остановила наступление недалеко от Ленинграда и не собиралась нападать на город. Иная ситуация была в восточной Карелии. Финское правительство согласилось возобновить наступление на Советскую Карелию, чтобы достичь Онежского озера и реки Свирь . 4 сентября эта новая кампания была начата широким фронтом. Хотя советские защитники 7-й армии были усилены свежими резервными частями, тяжелые потери на других участках фронта означали, что советские защитники 7-й армии не смогли противостоять наступлению финнов. Олонец был взят 5 сентября. 7 сентября финские передовые части вышли к реке Свирь. [296] Петрозаводск , столица Карело-Финской ССР , пал 1 октября. Отсюда Армия Карелии двинулась на север вдоль берегов Онежского озера, чтобы обезопасить оставшуюся территорию к западу от Онежского озера, одновременно создавая оборонительную позицию вдоль реки Свирь. Замедленные с наступлением зимы, они, тем не менее, продолжали медленно продвигаться в течение следующих недель. Медвежьегорск 5 декабря был взят Повенец , на следующий день пал . 7 декабря Финляндия прекратила все наступательные операции и перешла к обороне. [297] [298]

Битва за Москву [ править ]

После Киева Красная Армия больше не превосходила немцев по численности, и непосредственно подготовленных резервов больше не было. Для защиты Москвы Сталин мог выставить 800 000 человек в 83 дивизиях, но не более 25 дивизий были полностью боеспособны. Операция «Тайфун» — наступление на Москву — началась 30 сентября 1941 года. [299] [300] Перед группой армий «Центр» располагался ряд сложных линий обороны, первая из которых располагалась на Вязьме , а вторая — на Можайске . [274] Русские крестьяне начали бежать впереди наступающих немецких частей, сжигая собранный урожай, угоняя скот и разрушая постройки в своих деревнях в рамках политики выжженной земли, призванной лишить нацистскую военную машину необходимых припасов и продуктов питания. [301]

Первый удар застал Советы врасплох, когда 2-я танковая группа, возвращаясь с юга, взяла Орел , всего в 121 км (75 миль) к югу от первой советской главной линии обороны. [274] Через три дня танки продвинулись к Брянску , а 2-я армия атаковала с запада. [302] Советские 3-я и 13-я армии оказались в окружении. Севернее 3-я и 4-я танковые армии атаковали Вязьму, захватив в ловушку 19-ю, 20-ю, 24-ю и 32-ю армии. [274] Первая линия обороны Москвы была прорвана. В конечном итоге в кармане оказалось более 500 000 советских пленных, в результате чего общее число с начала вторжения достигло трех миллионов. Теперь у Советов осталось всего 90 000 человек и 150 танков для защиты Москвы. [303]

Правительство Германии теперь публично предсказало неминуемый захват Москвы и убедило иностранных корреспондентов в неизбежном крахе Советского Союза. [304] 13 октября 3-я танковая группа продвинулась на расстояние 140 км (87 миль) от столицы. [274] военное положение В Москве было объявлено . Однако почти с самого начала операции «Тайфун» погода ухудшилась. Температура упала, хотя дожди продолжались. Это превратило грунтовую сеть дорог в грязь и замедлило наступление немцев на Москву. [305] Выпал дополнительный снег, за которым последовал еще больший дождь, образовав липкую грязь, по которой немецким танкам было трудно пройти, и по которой советский Т-34 с его более широкой гусеницей лучше подходил для навигации. [306] В то же время ситуация со снабжением немцев резко ухудшилась. [307] 31 октября Верховное командование немецкой армии приказало остановить операцию «Тайфун» на время реорганизации армий. Пауза дала Советам, у которых было гораздо больше снабжения, время укрепить свои позиции и организовать формирования вновь задействованных резервистов. [308] [309] Чуть более чем за месяц Советы сформировали одиннадцать новых армий, включавших 30 дивизий сибирских войск. Они были освобождены с советского Дальнего Востока после того, как советская разведка заверила Сталина, что угрозы со стороны японцев больше нет. [310] В октябре и ноябре 1941 года вместе с сибирскими войсками прибыло более 1000 танков и 1000 самолетов для оказания помощи в обороне города. [311]

Земля затвердела из-за холодов, [п] 15 ноября немцы возобновили наступление на Москву. [313] Хотя сами войска теперь могли снова наступать, ситуация со снабжением не улучшилась; только 135 000 из 600 000 грузовиков, имевшихся в наличии на 22 июня 1941 года, были доступны к 15 ноября 1941 года. Запасы боеприпасов и топлива имели приоритет над едой и зимней одеждой, поэтому многие немецкие войска грабили припасы у местного населения, но не могли удовлетворить свои потребности. [314]

Противостояли немцам 5-я, 16-я, 30-я, 43-я, 49-я и 50-я советские армии. Немцы намеревались перебросить 3-ю и 4-ю танковые армии через канал имени Москвы и окружить Москву с северо-востока. 2-я танковая группа должна была атаковать Тулу , а затем приблизиться к Москве с юга. [315] Когда Советы отреагируют на их фланги, 4-я армия атакует центр. За две недели боев, не имея достаточного количества топлива и боеприпасов, немцы медленно поползли к Москве. На юге блокировалась 2-я танковая группа. 22 ноября советские сибирские части, усиленные 49-й и 50-й советскими армиями, атаковали 2-ю танковую группу и нанесли немцам поражение. Однако 4-я танковая группа отбросила советскую 16-ю армию и сумела форсировать канал имени Москвы в попытке окружить Москву. [316]

2 декабря части 258-й стрелковой дивизии продвинулись на расстояние 24 км (15 миль) от Москвы. Они были так близко, что немецкие офицеры утверждали, что видели шпили Кремля . [317] но к тому времени уже начались первые метели. [318] Разведывательному батальону удалось добраться до города Химки , расположенного всего в 8 км (5,0 миль) от советской столицы. Он захватил мост через канал Москва-Волга, а также железнодорожную станцию, что ознаменовало самое восточное продвижение немецких войск. [319] Несмотря на достигнутый прогресс, Вермахт не был подготовлен к такой суровой зимней войне. [320] Советская армия была лучше приспособлена к боевым действиям в зимних условиях, но столкнулась с нехваткой производства зимней одежды. Немецким войскам пришлось хуже: глубокий снег еще больше затруднял технику и мобильность. [321] [322] Погодные условия в значительной степени остановили действия Люфтваффе , что помешало крупномасштабным воздушным операциям. [323] Вновь созданные советские части под Москвой теперь насчитывали более 500 000 человек, которые, несмотря на свою неопытность, смогли остановить немецкое наступление к 5 декабря благодаря превосходным оборонительным укреплениям , наличию квалифицированного и опытного руководства, такого как Жуков , и плохой ситуации в Германии. [324] 5 декабря советские защитники начали массированную контратаку в рамках советского зимнего контрнаступления . Наступление остановилось 7 января 1942 года после того, как немецкие армии были отброшены на 100–250 км (62–155 миль) от Москвы. [325] Вермахт проиграл битву за Москву, и вторжение стоило немецкой армии более 830 000 человек. [326]

Последствия [ править ]