Итальянская диаспора

Итальянская эмиграция ( итал .) | |

|---|---|

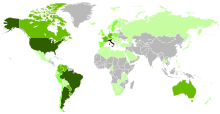

Карта итальянской диаспоры в мире | |

| Общая численность населения | |

| в. 80 миллионов по всему миру [1] | |

| Регионы со значительной численностью населения | |

| Бразилия , Аргентина , США , Франция , Колумбия , Канада , Перу , Уругвай , Австралия , Венесуэла , Германия , Швейцария , Великобритания , Бельгия , Чили и Парагвай. | |

| Языки | |

| Итальянский , другие языки Италии , английский , французский , испанский , португальский и немецкий. | |

| Религия | |

| Христианство (преимущественно католицизм ) [2] | |

| Родственные этнические группы | |

| Европейская диаспора , итальянцы |

Итальянская диаспора ( итал . emigrazione italiana , произносится [emiɡratˈtsjoːne itaˈljaːna] ) — масштабная эмиграция итальянцев из Италии . существовало две основные итальянские диаспоры В истории Италии . Первая диаспора возникла примерно в 1880 году, через два десятилетия после объединения Италии , и закончилась в 1920-х - начале 1940-х годов с подъемом фашистской Италии . [3] Бедность была основной причиной эмиграции, особенно нехватка земли, поскольку меццадрии в Италии, особенно на Юге, процветало издольство , и собственность делилась из поколения в поколение. особенно в Южной Италии . Условия были суровыми, [3] С 1860-х по 1950-е годы Италия все еще была в основном сельским обществом со многими небольшими городами и поселками, почти не имевшими современной промышленности, и в которой методы управления земельными ресурсами, особенно на юге и северо-востоке , нелегко убедить фермеров оставаться на земле. и обрабатывать почву. [4]

Другой фактор был связан с перенаселением Италии в результате улучшения социально-экономических условий после Объединения . [5] Это вызвало демографический бум и вынудило новые поколения массово эмигрировать в конце 19-го и начале 20-го веков, в основном в Америку . [6] Новая миграция капитала создала миллионы неквалифицированных рабочих мест по всему миру и стала причиной одновременной массовой миграции итальянцев в поисках «хлеба и работы» ( итальянский : pane e lavoro , произносится [ˈpaːne e llaˈvoːro] ). [7]

Вторая диаспора возникла после окончания Второй мировой войны и завершилась примерно в 1970-х годах. Между 1880 и 1980 годами страну навсегда покинули около 15 миллионов итальянцев. [8] К 1980 году было подсчитано, что около 25 миллионов итальянцев проживали за пределами Италии. [9] Между 1861 и 1985 годами 29 036 000 итальянцев эмигрировали в другие страны; из них 16 000 000 (55%) прибыли до начала Первой мировой войны . Около 10 275 000 вернулись в Италию (35%), а 18 761 000 постоянно поселились за границей (65%). [10]

Предполагается , что третья волна, затрагивающая в первую очередь молодых людей, широко называемая в итальянских СМИ «fuga di cervelli» ( утечка мозгов ), возникает из-за социально-экономических проблем, вызванных финансовым кризисом начала 21 века. По данным Публичного реестра итальянцев, проживающих за рубежом (AIRE), число итальянцев за рубежом выросло с 3 106 251 в 2006 году до 4 636 647 в 2015 году и таким образом выросло на 49% всего за 10 лет. [11] За пределами Италии проживает более 5 миллионов итальянских граждан. [12] и в. 80 миллионов человек во всем мире заявляют о своем полном или частичном итальянском происхождении. [1]

Внутренняя миграция в пределах географических границ Италии также происходила по тем же причинам; [13] самая большая волна состояла из 4 миллионов человек, переехавших из Южной Италии в Северную Италию (и в основном в промышленные города Северной или Центральной Италии, такие как Рим или Милан и т. д.) в период с 1950-х по 1970-е годы. [14] Сегодня здесь находится Национальный музей итальянской эмиграции ( итал . Museo Nazionale dell'Emigrazione Italiana , «MEI»), расположенный в Генуе , Италия. [15] Выставочное пространство, занимающее три этажа и 16 тематических зон, описывает феномен итальянской эмиграции, существовавший до объединения Италии и до настоящего времени. [15] Музей описывает итальянскую эмиграцию через автобиографии, дневники, письма, фотографии и газетные статьи того времени, посвященные теме итальянской эмиграции. [15]

древних Предыстория миграций итальянских

Итальянские левантийцы — это люди, живущие в основном в Турции и являющиеся потомками генуэзских и венецианских колонистов в Леванте в средние века. [16] Итальянские левантийцы имеют корни даже на восточном побережье Средиземного моря (Левант, особенно в современном Ливане и Израиле ) со времен крестовых походов и Византийской империи. Небольшая группа прибыла из Крыма и генуэзских колоний на Черном море после падения Константинополя Большинство итальянских левантийцев в современной Турции являются потомками торговцев и колонистов из морских республик Средиземноморья в 1453 году . (таких как Республика Венеции , Генуэзской республики и Пизанской республики или жителей государств крестоносцев ). Есть две большие общины итальянских левантийцев: одна в Стамбуле, а другая в Измире . В конце XIX века в Измире проживало около 6000 левантийцев итальянского происхождения. [17] Они прибыли в основном с генуэзского острова Хиос . [18] община насчитывала более 15 000 членов Во времена Ататюрка , но сейчас, по словам итальянского левантийского писателя Джованни Сконьямилло, она сократилась до нескольких сотен. [19]

Итальянцы в Ливане (или итальянские ливанцы) — это община в Ливане. Между 12 и 15 веками Итальянская Генуэзская республика имела несколько генуэзских колоний в Бейруте , Триполи и Библосе . В более поздние времена итальянцы приезжали в Ливан небольшими группами во время Первой и Второй мировых войн , пытаясь избежать войн того времени в Европе. Одними из первых итальянцев, выбравших Ливан в качестве места для поселения и поиска убежища, были итальянские солдаты, участвовавшие в итало-турецкой войне 1911–1912 годов. Большинство итальянцев предпочли поселиться в Бейруте из-за его европейского образа жизни. После обретения независимости немногие итальянцы уехали из Ливана во Францию . Итальянская община в Ливане очень мала (около 4300 человек) и в основном ассимилирована ливанской католической общиной. Растет интерес к экономическим отношениям между Италией и Ливаном (как в случае с «Винифестом 2011»). [20]

Итальянцы Одессы впервые упоминаются в документах XIII века, когда на территории будущей Одессы, города на юге Украины на Черном море , была поставлена якорная стоянка генуэзских торговых судов, получившая название «Одесса». Гинестра", возможно, от названия метельчатого растения , очень распространенного в степях Причерноморья. Приток итальянцев на юг Украины особенно усилился с основанием Одессы, состоявшимся в 1794 году. Всему этому способствовало то, что во главе вновь основанной столицы Черноморского бассейна стоял неаполитанец испанского происхождения. , Джузеппе Де Рибас , на посту до 1797 года. В 1797 году в Одессе проживало около 800 итальянцев, что составляло 10% от общей численности населения: в основном это были торговцы и неаполитанские, генуэзские и ливорнские моряки, к которым позже присоединились художники, техники. , ремесленники, фармацевты и учителя. [21] Революция 1917 года отправила многих из них в Италию или в другие города Европы. В советские времена в Одессе осталось всего несколько десятков итальянцев, большинство из которых уже не знали родного языка. Со временем они слились с местным населением, потеряв этническую окраску происхождения.

Итальянцы Крыма — небольшое этническое меньшинство, проживающее в Крыму. Итальянцы заселили некоторые районы Крыма еще со времен Генуэзской и Венецианской республик. был В 1783 году 25 000 итальянцев иммигрировали в Крым, который недавно аннексирован Российской империей . [22] В 1830 и 1870 годах в Керчь прибыли две отдельные миграции из городов Трани , Бишелье и Мольфетта . Этими мигрантами были крестьяне и моряки, привлеченные возможностями трудоустройства в местных крымских морских портах и возможностью обрабатывать почти неиспользуемые и плодородные крымские земли. После Октябрьской революции многие итальянцы считались иностранцами и рассматривались как враги. Поэтому они столкнулись с серьезными репрессиями. [22] Между 1936 и 1938 годами, во время сталинской Великой чистки , многие итальянцы были обвинены в шпионаже и были арестованы, подвергнуты пыткам, депортированы или казнены. [23] Немногим выжившим было разрешено вернуться в Керчь под Никиты Хрущева регентством . Некоторые семьи разошлись по другим территориям Советского Союза, в основном в Казахстане и Узбекистане . Потомки итальянцев Крыма насчитывают сегодня 3000 человек, преимущественно проживающих в Керчи. [24] [25]

Генуэзская община существовала в Гибралтаре с 16 века и позднее стала важной частью населения. Существует много свидетельств существования сообщества эмигрантов из Генуи, переселившихся в Гибралтар в 16 веке. [26] и это составляло более трети населения Гибралтара в первой половине 18 века. Хотя их называли «генуэзцами», они были не только выходцами из города Генуя, но и со всей Лигурии , региона в Северной Италии , который был центром морской Генуэзской республики. Согласно переписи 1725 года, при общей численности гражданского населения в 1113 человек было 414 генуэзцев, 400 испанцев, 137 евреев, 113 британцев и 49 других (в основном португальцев и голландцев). [27] По переписи 1753 года генуэзцы составляли самую большую группу (почти 34%) гражданских жителей Гибралтара, и вплоть до 1830 года на итальянском языке говорили вместе с английским и испанским языками и использовали в официальных объявлениях. [28] После наполеоновских времен многие сицилийцы и некоторые тосканцы мигрировали в Гибралтар, но генуэзцы и лигурийцы оставались большинством итальянской группы. Действительно, на генуэзском диалекте говорили в Каталонском заливе еще в 20 веке и вымерли в 1970-х годах. [29] Сегодня потомки генуэзской общины Гибралтара считают себя гибралтарцами и большинство из них выступают за автономию Гибралтара. [30] Генуэзское наследие очевидно по всему Гибралтару, но особенно в архитектуре старых зданий города, на которые повлиял традиционный стиль генуэзского жилищного строительства с внутренними дворами (также известными как «патио»).

Корфиотские итальянцы (или «корфиотские итальянцы») — население греческого острова Корфу (Керкира), имеющее этнические и языковые связи с Венецианской республикой. Истоки корфиотской итальянской общины можно найти в расширении итальянских государств на Балканы во время и после крестовых походов . В 12 веке Неаполитанское королевство отправило на Корфу несколько итальянских семей, чтобы они управляли островом. Начиная с Четвертого крестового похода 1204 года, Венецианская республика отправила на Корфу множество итальянских семей. итальянский язык Средневековья . Эти семьи принесли на остров [31] Когда Венеция правила Корфу и Ионическими островами , что продолжалось в эпоху Возрождения и до конца 18 века, большая часть высших классов Корфиота говорила по-итальянски (или во многих случаях конкретно по-венециански ), но масса людей оставалась греческой этнически, лингвистически и религиозно до и после османской осады 16 века. Корфиотские итальянцы были в основном сконцентрированы в городе Корфу, который венецианцы называли «Читта-ди-Корфу». Более половины населения города Корфу в 18 веке говорило на венецианском языке. [32] Возрождение греческого национализма после наполеоновской эпохи способствовало постепенному исчезновению корфиотских итальянцев. В конечном итоге Корфу был включен в состав Королевства Греции в 1864 году. Греческое правительство отменило все итальянские школы на Ионических островах в 1870 году, и, как следствие, к 1940-м годам на острове осталось всего 400 итальянцев-корфиотов. [33] Архитектура города Корфу по-прежнему отражает его давнее венецианское наследие с его многоэтажными зданиями, просторными площадями, такими как популярная «Спианада», и узкими мощеными улочками, известными как «Кантуния».

всегда существовала миграция, с древних времен Между нынешней Италией и Францией . С 16 века Флоренция и ее жители долгое время поддерживали очень тесные отношения с Францией. [35] В 1533 году в возрасте четырнадцати лет Екатерина Медичи вышла замуж за Генриха , второго сына короля Франциска I и королевы Франции Клод. Под галлицизированной версией своего имени, Екатерина Медичи, она стала королевой-консортом Франции , когда Генрих взошел на престол в 1547 году. Позже, после смерти Генриха, она стала регентшей от имени своего десятилетнего сына короля Карла IX. и получил широкие полномочия. После смерти Карла в 1574 году Екатерина сыграла ключевую роль в правлении своего третьего сына Генриха III . Другие известные примеры итальянцев, сыгравших важную роль в истории Франции, включают кардинала Мазарини , родившегося в Пешине, который был кардиналом, дипломатом и политиком, который занимал пост главного министра Франции с 1642 года до своей смерти в 1661 году. Что касается личностей, В современную эпоху Наполеон Бонапарт , французский император и генерал, был этническим итальянцем корсиканского происхождения, чья семья имела генуэзские и тосканские корни. [34]

После завоевания англосаксонской Англии в 1066 году первые зафиксированные итальянские общины в Англии начались из купцов и моряков, живших в Саутгемптоне . Знаменитая « Ломбард-стрит » в Лондоне получила свое название от небольшой, но влиятельной общины из северной Италии, жившей там в качестве банкиров и торговцев после 1000 года . [36] Перестройка Вестминстерского аббатства продемонстрировала значительное итальянское художественное влияние в строительстве так называемого тротуара Космати , завершенного в 1245 году, и являющегося уникальным примером стиля, неизвестного за пределами Италии, работы высококвалифицированной команды итальянских мастеров под руководством римлянина. по имени Ордорикус. [37] В 1303 году Эдуард I заключил соглашение с торговым сообществом Ломбардии, которое закрепляло таможенные пошлины, а также определенные права и привилегии. [38] Доходами от таможенных пошлин распоряжалась Риккарди , группа банкиров из Лукки в Италии. [39] Это было в обмен на их службу в качестве ростовщиков короне, которая помогла финансировать валлийские войны. Когда разразилась война с Францией, французский король конфисковал активы Риккарди, и банк обанкротился. [40] После этого Фрескобальди из Флоренции взял на себя роль ростовщиков английской короны. [41]

Большое количество итальянцев проживало в Германии с раннего средневековья , особенно архитекторы, ремесленники и торговцы. В период позднего средневековья и раннего Нового времени многие итальянцы приезжали в Германию по делам, и отношения между двумя странами процветали. Политические границы также были несколько переплетены из-за попыток немецких князей распространить контроль на всю Священную Римскую империю , которая простиралась от северной Германии до Северной Италии. В эпоху Возрождения многие итальянские банкиры, архитекторы и художники переехали в Германию и успешно интегрировались в немецкое общество.

Первые итальянцы приехали в Польшу в средние века, однако значительная миграция итальянцев в Польшу началась в 16 веке (см. раздел «Польша» ниже). [42]

История [ править ]

войны Италии до Первой мировой От объединения

Объединение Италии разрушило феодальную земельную систему, которая сохранилась на юге со времен средневековья, особенно там, где земля была неотъемлемой собственностью аристократов, религиозных организаций или короля. Однако распад феодализма и перераспределение земли не обязательно привели к тому, что мелкие фермеры на юге получили собственную землю или землю, на которой они могли работать и получать прибыль. Многие оставались безземельными, а участки становились все меньше и меньше и, следовательно, все менее и менее продуктивными, поскольку земля делилась между наследниками. [4]

Between 1860 and World War I, 9 million Italians left permanently of a total of 16 million who emigrated, most travelling to North or South America.[43] The numbers may have even been higher; 14 million from 1876 to 1914, according to another study. Annual emigration averaged almost 220,000 in the period 1876 to 1900, and almost 650,000 from 1901 through 1915. Prior to 1900 the majority of Italian immigrants were from northern and central Italy. Two-thirds of the migrants who left Italy between 1870 and 1914 were men with traditional skills. Peasants were half of all migrants before 1896.[6]

As the number of Italian emigrants abroad increased, so did their remittances, which encouraged further emigration, even in the face of factors that might logically be thought to decrease the need to leave, such as increased salaries at home. It has been termed "persistent and path-dependent emigration flow".[43] Friends and relatives who left first sent back money for tickets and helped relatives as they arrived. That tended to support an emigration flow since even improving conditions in the original country took time to trickle down to potential emigrants to convince them not to leave. The emigrant flow was stemmed only by dramatic events, such as the outbreak of World War I, which greatly disrupted the flow of people trying to leave Europe, and the restrictions on immigration that were put in place by receiving countries. Examples of such restrictions in the United States were the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the Immigration Act of 1924. Restrictive legislation to limit emigration from Italy was introduced by the fascist government of the 1920s and 1930s.[44]

The Italian diaspora did not affect all regions of the nation equally. In the second phase of emigration (1900 to World War I), slightly less than half of emigrants were from the south and most of them were from rural areas, as they were driven off the land by inefficient land management, lawlessness and sickness (pellagra and cholera). Robert Foerster, in Italian Emigration of our Times (1919) says, "[Emigration has been]… well nigh expulsion; it has been exodus, in the sense of depopulation; it has been characteristically permanent".[45] The very large number of emigrants from Friuli-Venezia Giulia, a region with a population of only 509,000 in 1870 until 1914 is due to the fact that many of those counted among the 1.407 million emigrants actually lived in the Austrian Littoral which had a larger polyglot population of Croats, Friulians, Italians and Slovenes than in the Italian Friuli.[46]

Mezzadria, a form of sharefarming where tenant families obtained a plot to work on from an owner and kept a reasonable share of the profits, was more prevalent in central Italy, and is one of the reasons that there was less emigration from that part of Italy. The south lacked entrepreneurs, and absentee landlords were common. Although owning land was the basic yardstick of wealth, farming there was socially despised. People invested not in agricultural equipment, but in such things as low-risk state bonds.[4]

The rule that emigration from cities was negligible has an important exception, in Naples.[4] The city went from being the capital of its own kingdom in 1860 to being just another large city in Italy. The loss of bureaucratical jobs and the subsequently declining financial situation led to high unemployment in the area. In the early-1880s, epidemics of cholera also struck the city, causing many people to leave. The epidemics were the driving force behind the decision to rebuild entire sections of the city, an undertaking known as the "risanamento" (literally "making healthy again"), a pursuit that lasted until the start of World War I.

During the first few years before the unification of Italy, emigration was not particularly controlled by the state. Emigrants were often in the hands of emigration agents whose job was to make money for themselves by moving emigrants. Such labor agents and recruiters were called padroni, translating to patron or boss.[6] Abuses led to the first migration law in Italy, passed in 1888, to bring the many emigration agencies under state control.[47] On 31 January 1901, the Commissariat of Emigration was created, granting licenses to carriers, enforcing fixed ticket costs, keeping order at ports of embarkation, providing health inspection for those leaving, setting up hostels and care facilities and arranging agreements with receiving countries to help care for those arriving. The Commissariat tried to take care of emigrants before they left and after they arrived, such as dealing with the American laws that discriminated against alien workers (like the Alien Contract Labor Law) and even suspending, for some time, emigration to Brazil, where many migrants had wound up as quasi-slaves on large coffee plantations.[47] The Commissariat also helped to set up remittances sent by emigrants from the United States back to their homeland, which turned into a constant flow of money amounting, by some accounts, to about 5% of the Italian GNP.[48] In 1903, the Commissariat also set the available ports of embarkation as Palermo, Naples and Genoa, excluding the port of Venice, which had previously also been used.[49]

Interwar period[edit]

Although the physical perils involved with transatlantic ship traffic during World War I disrupted emigration from all parts of Europe, including Italy, the condition of various national economies in the immediate post-war period was so bad that immigration picked up almost immediately. Foreign newspapers ran scare stories similar to those published 40 years earlier (when, for example, on December 18, 1880, The New York Times ran an editorial, "Undesirable Emigrants", full of typical invective of the day against the "promiscuous immigration… [of]…the filthy, wretched, lazy, criminal dregs of the meanest sections of Italy"). An article written during the interwar period on April 17, 1921, in the same newspaper, used the headlines "Italians Coming in Great Numbers" and "Number of Immigrants Will Be Limited Only By Capacity of Liners" (there was now a limited number of ships available because of recent wartime losses) and that potential immigrants were thronging the quays in the cities of Genoa. This article continues: ... the foreigner who walks through a city like Naples can easily realize the problem the government is dealing with: the back streets are literally teeming with children running around the streets and on the dirty and happy sidewalks. ... The suburbs of Naples ... teem with children who, in number, can only be compared to those found in Delhi, Agra and other cities of the East Indies ...".[50]

The extreme economic difficulties of post-war Italy and the severe internal tensions within the country, which led to the rise of fascism, led 614,000 immigrants away in 1920, half of them going to the United States. When the fascists came to power in 1922, there was a gradual slowdown in the flow of emigrants from Italy. However, during the first five years of fascist rule, 1,500,000 people left Italy.[51] By then, the nature of the emigrants had changed; there was, for example, a marked increase in the rise of relatives outside the working age moving to be with their families, who had already left Italy.

The bond of the emigrants with their mother country continued to be very strong even after their departure. Many Italian emigrants made donations to the construction of the Altare della Patria (1885–1935), a part of the monument dedicated to King Victor Emmanuel II of Italy, and in memory of that, the inscription of the plaque on the two burning braziers perpetually at the Altare della Patria next to the tomb of the Italian Unknown Soldier, reads "Gli italiani all'estero alla Madre Patria" ("Italians abroad to the Motherland").[52] The allegorical meaning of the flames that burn perpetually is linked to their symbolism, which is centuries old, since it has its origins in classical antiquity, especially in the cult of the dead.[53] A fire that burns eternally symbolizes that the memory, in this case of the sacrifice of the Unknown Soldier and the bond of the country of origin, is perpetually alive in Italians, even in those who are far from their country, and will never fade.[53]

After World War II[edit]

Following the defeat of Italy in World War II and the Paris Treaties of 1947, Istria, Kvarner and most of Julian March, with the cities of Pola, Fiume and Zara, passed from Italy to Yugoslavia, causing the Istrian-Dalmatian exodus, which led to the emigration of between 230,000 and 350,000 of local ethnic Italians (Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians), towards Italy, and in smaller numbers, towards the Americas, Australia and South Africa.[54][55]

The Italian emigration of the second half of the 20th century, on the other hand, was mostly to European nations experiencing economic growth. From the 1940s onwards, Italian emigration flow headed mainly to Switzerland and Belgium, while from the following decade, France and Germany were added among the top destinations.[56][57][58] These countries were considered by many, at the time of departure, as a temporary destination—often only for a few months—in which to work and earn money in order to build a better future in Italy. This phenomenon took place the most in the 1970s, a period that was marked by the return to their homeland of many Italian emigrants.

The Italian state signed an emigration pact with Germany in 1955 which guaranteed mutual commitment in the matter of migratory movements and which led almost three million Italians to cross the border in search of work. As of 2017, there are approximately 700,000 Italians in Germany, while in Switzerland this number reaches approximately 500,000. They are mainly of Sicilian, Calabrian, Abruzzese and Apulian origin, but also Venetian and Emilian, many of whom have dual citizenship and therefore the ability to vote in both countries. In Belgium and Switzerland, the Italian communities remain the most numerous foreign representations, and although many return to Italy after retirement, often the children and grandchildren remain in the countries of birth, where they have now taken root.

An important phenomenon of aggregation that is found in Europe, as well as in other countries and continents that have been the destination of migratory flows of Italians, is that of emigration associations. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs estimates that over 10,000 associations set up by Italian emigrants over the course of over a century are present abroad. Benefit, cultural, assistance and service associations that have constituted a fundamental point of reference for emigrants. The major associative networks of various ideal inspirations are now gathered in the National Council of Emigration. One of the largest associative networks in the world, together with those of the Catholic world, is that of the Italian Federation of migrant workers and families.

"New emigration" of the 21st century[edit]

Between the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the next, the flow of Italian emigrants around the world greatly attenuated. Nevertheless, migration from certain regions never stopped, such as in Sicily.[59] However, following the effects of the Great Recession, a continuous flow of expatriates has spread since the end of the 2010s. Although numerically lower than the previous two, this period mainly affects young people who are often graduates, so much so that is defined as a "brain drain".

In particular, this flow is mainly directed towards Germany, where over 35,000 Italians arrived in 2012 alone, but also towards other countries such as the United Kingdom, France, Switzerland, Canada, Australia, the United States and the South American countries. This is an annual flow which, according to the 2012 data from the registry office of Italians residing abroad (AIRE), is around 78,000 people with an increase of about 20,000 compared to 2011, even if it is estimated that the actual number of people who have emigrated is considerably higher (between two and three times), as many compatriots cancel their residence in Italy with much delay compared to their actual departure.

The phenomenon of the so-called "new emigration"[60] caused by the serious economic crisis also affects all of southern Europe such as countries like Spain, Portugal and Greece (as well as Ireland and France) which record similar, if not greater, emigration trends. It is widely believed that the places where there are no structural changes in economic and social policies are those most subject to the increase in this emigration flow. Regarding Italy, it is also significant that these flows no longer concern only the regions of southern Italy, but also those of the north, such as Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna.

According to the available statistics, the community of Italian citizens residing abroad amounts to 4,600,000 people (2015 data). It is therefore greatly reduced, from a percentage point of view, from 9,200,000 in the early 1920s (when it was about one fifth of the entire Italian population).[61]

The "Report of Italians in the World 2011" produced by the Migrantes Foundation, which is part of the CEI, specified that:

Italians residing abroad as of 31 December 2010 were 4,115,235 (47.8% are women).[62] The Italian emigrant community continues to increase both for new departures, and for internal growth (enlargement of families or people who acquire citizenship by descent). Italian emigration is concentrated mainly between Europe (55.8%) and America (38.8%). Followed by Oceania (3.2%), Africa (1.3%) and Asia with 0.8%. The country with the most Italians is Argentina (648,333), followed by Germany (631,243), then Switzerland (520,713). Furthermore, 54.8% of Italian emigrants are of southern origin (over 1,400,000 from the South and almost 800,000 from the Islands); 30.1% comes from the northern regions (almost 600,000 from the Northeast and 580,000 from the Northwest); finally, 15% (588,717) comes from the central regions. Central-southern emigrants are the overwhelming majority in Europe (62.1%) and Oceania (65%). In Asia and Africa, however, half of the Italians come from the North. The region with the most emigrants is Sicily (646,993), followed by Campania (411,512), Lazio (346,067), Calabria (343,010), Apulia (309,964) and Lombardy (291,476). The province with the most emigrants is Rome (263,210), followed by Agrigento (138,517), Cosenza (138,152), Salerno (108,588) and Naples (104,495).[63]

— CEI report on "new emigration"

In 2008, about 60,000 Italians changed citizenship; they mostly come from Northern Italy (74%) and have preferred Germany as their adopted country (12% of the total emigrants).[64] The number of Italian citizens residing abroad according to those registered in the AIRE registry:

| Year | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 2,352,965 | 2,536,643 | 2,751,593 | 3,045,064 | 3,316,635 | 3,520,809 | 3,547,808 | 3,649,377 | 3,853,614 |

| Year | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2014 | 2016 | 2018 | 2020 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 3,995,732 | 4,115,235 | 4,208,877 | 4,341,156 | 4,521,000 | 4,973,940 | 5,134,000 | 5,652,080 | 5,806,068 |

By continent[edit]

Africa[edit]

Although Italians did not emigrate to South Africa in large numbers, those who arrived there have nevertheless made an impact on the country. Before World War II, relatively few Italian immigrants arrived, though there were some prominent exceptions such as the Cape's first Prime Minister John Molteno. South African Italians made big headlines during World War II, when Italians were captured in Italian East Africa, they needed to be sent to a safe stronghold to be detained as prisoners of war (POWs). South Africa was the perfect destination, and the first POWs arrived in Durban, in 1941.[65][66] In the early 1970s, there were over 40,000 Italians in South Africa, scattered throughout the provinces but concentrated in the main cities. Some of these Italians had taken refuge in South Africa, escaping the decolonization of Rhodesia and other African states. In the 1990s, a period of crisis began for Italian South Africans and many returned to Europe; however, the majority successfully integrated into the multiracial society of contemporary South Africa. The Italian community consists of over 77,400 people (0.1–2% of South Africa's population),[67] half of whom have Italian citizenship. Those of Venetian origin number about 5,000, mainly residing in Johannesburg,[68] while the most numerous Italian regional communities are the southern ones. The official Italian registry records 28,059 Italians residing in South Africa in 2007, excluding South Africans with dual citizenship.[69]

Very numerous was the presence of Italian emigrants in African territories that were Italian colonies, namely in Eritrea, Ethiopia, Libya and Somalia.

In 1911, the Kingdom of Italy waged war on the Ottoman Empire and captured Libya as a colony. Italians settlers were encouraged to come to Libya and did so from 1911 until the outbreak of World War II. In less than thirty years (1911–1940), the Italians in Libya built a significant amount of public works (roads, railways, buildings, ports, etc.) and the Libyan economy flourished. They even created the Tripoli Grand Prix, an international motor racing event first held in 1925 on a racing circuit outside Tripoli (it lasted until 1940).[70] Italian farmers cultivated lands that had returned to native desert for many centuries, and improved Italian Libya's agriculture to international standards (even with the creation of new farm villages).[71] Libya had some 150,000 Italians settlers when Italy entered World War II in 1940, constituting about 18% of the total population in Italian Libya.[72][73] The Italians in Libya resided (and many still do) in most major cities like Tripoli (37% of the city was Italian), Benghazi (31%), and Hun (3%). Their numbers decreased after 1946. France and the UK took over the spoils of war that included Italian discovery and technical expertise in the extraction and production of crude oil, superhighways, irrigation, electricity. Most of Libya's Italian residents were expelled from the country in 1970, a year after Muammar Gaddafi seized power in a coup d'état on October 7, 1970,[74] but a few hundred Italian settlers returned to Libya in the 2000s (decade).

| Year | Italians | Percentage | Total Libya | Source for data on population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1936 | 112,600 | 13.26% | 848,600 | Enciclopedia Geografica Mondiale K-Z, De Agostini, 1996 |

| 1939 | 108,419 | 12.37% | 876,563 | Guida Breve d'Italia Vol.III, C.T.I., 1939 (Censimento Ufficiale) |

| 1962 | 35,000 | 2.1% | 1,681,739 | Enciclopedia Motta, Vol.VIII, Motta Editore, 1969 |

| 1982 | 1,500 | 0.05% | 2,856,000 | Atlante Geografico Universale, Fabbri Editori, 1988 |

| 2004 | 22,530 | 0.4% | 5,631,585 | L'Aménagement Linguistique dans le Monde Archived 26 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine |

Somalia had some 50,000 Italian Somali settlers during World War II, constituting about 5% of the total population in Italian Somaliland.[75][76] The Italians resided in most major cities in the central and southern parts of the territory, with around 10,000 living in the capital Mogadishu. Other major areas of settlement included Jowhar, which was founded by the Italian prince Luigi Amedeo, Duke of the Abruzzi. Italian used to be a major language, but its influence significantly diminished following independence. It is now most frequently heard among older generations.[77]

Former Italian communities also once thrived in the Horn of Africa, with about 50,000 Italian settlers living in Eritrea in 1935.[78] The Italian Eritrean population grew from 4,000 during World War I, to nearly 100,000 at the beginning of World War II.[79] Their ancestry dates back from the beginning of the Italian colonization of Eritrea at the end of the 19th century, but only during 1930s they settled in large numbers.[80] In the 1939 census of Eritrea there were more than 76,000 Eritrean Italians, most of them living in Asmara (53,000 out of the city's total of 93,000).[81][82] Many Italian settlers got out of their colony after its conquest by the Allies in November 1941 and they were reduced to only 38,000 by 1946.[83] This also includes a population of mixed Italian and Eritrean descent; most Italian Eritreans still living in Eritrea are from this mixed group. Although many of the remaining Italians stayed during the decolonization process after World War II and are actually assimilated to the Eritrean society, a few are stateless today, as none of them were given citizenship unless through marriage or, more rarely, by having it conferred upon them by the State.

Italians of Ethiopia are immigrants who moved from Italy to Ethiopia starting in the 19th century, as well as their descendants. Most of the Italians moved to Ethiopia after the Italian conquest of Abyssinia in 1936. Italian Ethiopia was made of Harrar, Galla-Sidamo, Amhara and Scioa Governorates in summer 1936 and became a part of the Italian colony Italian East Africa, with capital Addis Abeba and with Victor Emmanuel III proclaiming himself Emperor of Ethiopia. During the Italian occupation of Ethiopia, roughly 300,000 Italians settled in the Italian East Africa (1936–1941). Over 49,000 lived in Asmara in 1939 (around 10% of the city's population), and over 38,000 resided in Addis Abeba. After independence, some Italians remained for decades after receiving full pardon by Emperor Selassie,[84] but eventually nearly 22,000 Italo-Ethiopians left the country due to the Ethiopian Civil War in 1974.[84] 80 original Italian colonists remain alive in 2007, and nearly 2000 mixed descendants of Italians and Ethiopians. In the 2000s, some Italian companies returned to operate in Ethiopia, and a large number of Italian technicians and managers arrived with their families, residing mainly in the metropolitan area of the capital.[85]

Conspicuous was the presence of Italian emigrants even in territories that have never been Italian colonies, such as Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, Zimbabwe and Algeria.

The first Italians in Tunisia at the beginning of the 19th century were mainly traders and professionals in search of new opportunities, coming from Liguria and the other regions of northern Italy. At the end of the 19th century, Tunisia received the immigration of tens of thousands of Italians, mainly from Sicily and also Sardinia.[86] As a consequence, in the first years of the 20th century there were more than 100,000 Italian residents in Tunisia.[87] In 1926, there were 100,000 Italians in Tunisia, compared to 70,000 Frenchmen (unusual since Tunisia was a French protectorate).[88] In the 1946 census, the Italians in Tunisia were 84,935, but in 1959 (3 years after many Italian settlers left to Italy or France after independence from France) there were only 51,702, and in 1969 there were less than 10,000. As of 2005, there are only 900, mainly concentrated in the metropolitan area of Tunis. Another 2,000 Italians, according to the Italian Embassy in Tunis, are "temporary" residents, working as professionals and technicians for Italian companies in different areas of Tunisia.

During the Middle Ages Italian communities from the "Maritime Republics" of Italy (mainly Pisa, Genoa and Amalfi) were present in Egypt as merchants. Since the Renaissance the Republic of Venice has always been present in the history and commerce of Egypt: there was even a Venetian Quarter in Cairo. From the time of Napoleon I, Italian Egyptians started to grow in a huge way: the size of the community had reached around 55,000 just before World War II, forming the second largest immigrant community in Egypt. After World War II, like many other foreign communities in Egypt, migration back to Italy and the West reduced the size of the community greatly due to wartime internment and the rise of Nasserist nationalism against Westerners. After the war many members of the Italian community related to the defeated Italian expansion in Egypt were forced to move away, starting a process of reduction and disappearance of the Italian Egyptians. After 1952 the Italian Egyptians were reduced – from the nearly 60,000 of 1940 – to just a few thousands. Most Italian Egyptians returned to Italy during the 1950s and 1960s, although a few Italians continue to live in Alexandria and Cairo. Officially the Italians in Egypt at the end of 2007 were 3,374 (1,980 families).[90]

The oldest area of Italian settlement in Zimbabwe was established as Sinoia - today's Chinhoyi - in 1906, as a group settlement scheme by a wealthy Italian lieutenant, Margherito Guidotti, who encouraged several Italian families to settle in the area. The name Sinoria derives from Tjinoyi, a Lozwi/Rozwi Chief who is believed to have been a son of Lukuluba who was the third son of Emperor Netjasike. The Kalanga (Lozwi/Rozwi name) was changed to Sinoia by the white settlers and later Chinhoyi by the Zezuru.[91] Along with other Zimbabweans, a disproportionate number of people of Italian descent now reside abroad, many of whom hold dual Italian or British citizenship. Regardless of the country's economic challenges, there is still a sizable Italian population in Zimbabwe. Though never comprising more than a fraction of the white Zimbabwean population, Italo-Zimbabweans are well represented in the hospitality, real estate, tourism and food and beverage industries. The majority live in Harare, with over 9,000 in 2012, (less than one percent of the city's population), while over 30,000 live abroad mostly in the UK, South Africa, Canada, Italy and Australia.[92][93]

The first Italian presence in Morocco dates back to the times of the Italian maritime republics, when many merchants of the Republic of Venice and of the Republic of Genoa settled on the Maghreb coast.[95] This presence lasted until the 19th century.[95] he Italian community had a notable development in French Morocco; already in the 1913 census about 3,500 Italians were registered, almost all concentrated in Casablanca, and mostly employed as excavators and construction workers.[95][94] The Italian presence in the Rif, included in Spanish Morocco, was minimal, except in Tangier, an international city, where there was an important community, as evidenced by the presence of the Italian School.[96] A further increase of Italian immigrants in Morocco was recorded after World War I, reaching 12,000 people, who were employed among the workers and as farmers, unskilled workers, bricklayers and operators.[95][94] In the 1930s, Italian-Moroccans, almost all of Sicilian origin, numbered over 15,600 and lived mainly in the Maarif district of Casablanca.[95] With decolonization, most Italian Moroccans left Morocco for France and Spain.[95] The community has started to grow again since the 1970s and 1980s with the arrival of industrial technicians, tourism and international cooperation managers, but remains very limited.

The first Italian presence in Algeria dates back to the times of the Italian maritime republics, when some merchants of the Republic of Venice settled on the central Maghreb coast. The first Italians took root in Algiers and in eastern Algeria, especially in Annaba and Constantine. A small minority went to Oran, where the Spanish community had been substantial for many centuries. These first Italians (estimated at 1,000) were traders and artisans, with a small presence of peasants. When France occupied Algeria in 1830, it counted over 1,100 Italians in its first census (done in 1833),[95] concentrated in Algiers and in Annaba. With the arrival of the French, the migratory flow from Italy grew considerably: in 1836 the Italians had grown to 1,800, to 8,100 in 1846, to 9,000 in 1855, to 12,000 in 1864 and to 16,500 in 1866.[95] Italians were an important community among foreigners in Algeria.[95] In 1889, French citizenship was granted to foreign residents, mostly settlers from Spain or Italy, so as to unify all European settlers (pieds-noirs) in the political consensus for an "Algérie française". The French wanted to increase the European numerical presence in the recently conquered Algeria,[97] and at the same time limit and prevent the aspirations of Italian colonialism in neighboring Tunisia and possibly also in Algeria.[98] As a consequence, the Italian community in Algeria began to decline, going from 44,000 in 1886, to 39,000 in 1891 and to 35,000 in 1896.[95] In the 1906 census, 12,000 Italians in Algeria were registered as naturalized Frenchmen,[99] demonstrating a very different attitude from that of the Italian Tunisians, much more sensitive to the irredentist bond with the motherland.[98] After World War II, Italian Algerians followed the fate of the French pieds-noirs, especially in the years of the Algerian War, repatriating massively to Italy.[95] Still in the 1960s, immediately after Algeria's independence from France, the Italian community had a consistency of about 18,000 people, almost all residing in the capital, a number that dropped to 500-600 people in a short time.[95]

Italian settlers also stayed in Portuguese colonies in Africa (Angola and Mozambique) after World War II. As the Portuguese government had sought to enlarge the small Portuguese population settled there through emigration from Europe,[100] the Italian migrants gradually assimilated into the Angolan and Mozambican Portuguese community.

Americas[edit]

Italian[102] navigators and explorers played a key role in the exploration and settlement of the Americas by Europeans. Genoese explorer Christopher Columbus (Italian: Cristoforo Colombo [kriˈstɔːforo koˈlombo]) completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean for the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, opening the way for the widespread European exploration and colonization of the Americas. Another Italian, John Cabot (Italian: Giovanni Caboto [dʒoˈvanni kaˈbɔːto]), together with his son Sebastian, explored the eastern seaboard of North America for Henry VII in the early 16th century. Amerigo Vespucci, sailing for Portugal, who first demonstrated in about 1501 that the New World (in particular Brazil) was not Asia as initially conjectured, but a fourth continent previously unknown to people of the Old World: America is named after him.[103] In 1524 the Florentine explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano was the first European to map the Atlantic coast of today's United States, and to enter New York Bay.[104] A number of Italian navigators and explorers in the employ of Spain and France were involved in exploring and mapping their territories, and in establishing settlements; but this did not lead to the permanent presence of Italians in America.

The first Italians that headed to the Americas settled in the territories of the Spanish Empire as early as the 16th century. They were mainly Ligurians from the Republic of Genoa, who worked in activities and businesses related to transoceanic maritime navigation. The flow in the Río de la Plata region grew in the 1830s, when substantial Italian colonies arose in the cities of Buenos Aires and Montevideo. After the unification of Italy in 1861, there was a notable emigration from Italy to Uruguay that peaked in the last decades of the 19th century, when over 110,000 Italian emigrants arrived. In 1976, Uruguayans with Italian descent amounted to over 1.5 million (about 44% of the total population).[105]

The symbolic starting date of Italian emigration to the Americas is considered to be 28 June 1854 when, after a twenty-six day journey from Palermo, the steamship Sicilia arrived in the port of New York City. For the first time, a steamship flying the flag of a state on the Italian peninsula, in this case the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, reached the US coasts.[106] Two years earlier, the Transatlantic Steam Navigation Company with the New World had been founded in Genoa, the main shareholder of which was King Victor Emmanuel II of Piedmont-Sardinia. The aforementioned association commissioned the large twin steamships Genova and Torino to the Blackwall shipyards, launched respectively on April 12 and May 21, 1856, both destined for the maritime connection between Italy and the Americas.[107] Emigration to the Americas was of considerable size from the second half of the 19th century to the first decades of the 20th century. It nearly ran out during Fascism, but had a small revival soon after the end of World War II. Mass Italian emigration to the Americas ended in the 1960s, after the Italian economic miracle, although it continued until the 1980s in Canada and the United States.

Italian immigration to Argentina, along with Spanish, formed the backbone of Argentine society. Minor groups of Italians started to emigrate to Argentina as early as the second half of the 17th century.[108] However, the stream of Italian immigration to Argentina became a mass phenomenon between 1880 and 1920 when Italy was facing social and economic disturbances. Platinean culture has significant connections to Italian culture in terms of language, customs and traditions.[109] It is estimated that up to 62.5% of the population, or 25 million Argentines, have full or partial Italian ancestry.[110][111] Italian is the largest single ethnic origin of modern Argentines,[112] surpassing even the descendants of Spanish immigrants.[113][114] According to the Ministry of the Interior of Italy, there are 527,570 Italian citizens living in the Argentine Republic, including Argentines with dual citizenship.[115]

Italian Brazilians are the largest number of people with full or partial Italian ancestry outside Italy, with São Paulo as the most populous city with Italian ancestry in the world. Nowadays, it is possible to find millions of descendants of Italians, from the southeastern state of Minas Gerais to the southernmost state of Rio Grande do Sul, with the majority living in São Paulo state[117] and the highest percentage in the southeastern state of Espírito Santo (60-75%).[118][119] Small southern Brazilian towns, such as Nova Veneza, have as much as 95% of their population as people with Italian descent.[120]

A substantial influx of Italian immigrants to Canada began in the early 20th century when over 60,000 Italians moved to Canada between 1900 and 1913.[121] Approximately 40,000 Italians came to Canada during the interwar period between 1914 and 1918, predominantly from southern Italy where an economic depression and overpopulation had left many families in poverty.[121] Between the early-1950s and the mid-1960s, approximately 20,000 to 30,000 Italians emigrated to Canada each year.[121] Pier 21 in Halifax, Nova Scotia, was an influential port of Italian immigration between 1928 until it ceased operations in 1971, where 471,940 individuals came to Canada from Italy making them the third-largest ethnic group to emigrate to Canada during that time period.[122] Almost 1,000,000 Italians reside in the Province of Ontario, making it a strong global representation of the Italian diaspora.[123] For example, Hamilton, Ontario, has around 24,000 residents with ties to its sister city Racalmuto in Sicily.[124] The city of Vaughan, just north of Toronto, and the town of King, just north of Vaughan, have the two largest concentrations of Italians in Canada at 26.5% and 35.1% of the total population of each community respectively.[125][126]

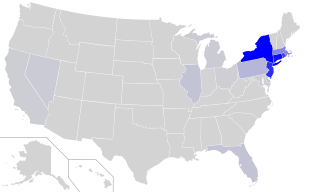

From the late 19th century until the 1930s, the United States was a main destination for Italian immigrants, with most first settling in the New York metropolitan area, but with other major Italian American communities developing in Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, Baltimore, San Francisco, Providence, and New Orleans. Most Italian immigrants to the United States came from the Southern regions of Italy, namely Campania, Apulia, Basilicata, Calabria, and Sicily. Many of them coming to the United States were also small landowners.[6] Between 1880 and 1914, more than 4 million Italians immigrated to the United States.[127] Italian Americans are known for their tight-knit communities and ethnic pride, and have been highly influential in the development of modern U.S. culture, particularly in the Northeastern region of the country. Italian American communities have often been depicted in U.S. film and television, with distinct Italian-influenced dialects of English prominently spoken by many characters. Although many do not speak Italian fluently, over a million still speak Italian at home, according to the 2000 US Census.[128] According to the Italian American Studies Association, the population of the Italian Americans is about 18 million, corresponding to about 5.4% of the total population of the United States.[129]

Another very conspicuous Italian community is in Venezuela, which developed especially after World War II. There are about 5 million Venezuelans with at least one Italian ancestor, corresponding to more than 6% of the total population.[130] Italo-Venezuelans have achieved significant results in modern Venezuelan society. The Italian embassy estimates that a quarter of Venezuelan industries not related to the oil sector are directly or indirectly owned and/or operated by Italo-Venezuelans.

After the unification of Italy there was a considerable emigration from Italy to Uruguay, which reached its peak in the last decades of the 19th century, when over 110,000 Italian emigrants arrived. In the early 20th century the migratory flow began to run out. In 1976, Uruguayans of Italian ancestry numbered over 1,300,000.[131] The maximum concentration is found, as well as in Montevideo, in the city of Paysandú (where almost 65% of the inhabitants are of Italian origin).

Many Italian-Mexicans live in cities founded by their ancestors in the states of Veracruz (Huatusco) and San Luis Potosí. Smaller numbers of Italian-Mexicans live in Guanajuato and the State of Mexico, and the former haciendas (now cities) of Nueva Italia, Michoacán and Lombardia, Michoacán, both founded by Dante Cusi from Gambar in Brescia.[132] Playa del Carmen, Mahahual and Cancun in the state of Quintana Roo have also received a significant number of immigrants from Italy. Several families of Italian-Mexican descent were granted citizenship in the United States under the Bracero program to address a labor shortage of labor. Italian companies have invested in Mexico, primarily in the tourism and hospitality industries. These ventures have sometimes resulted in settlements, but residents primarily live in the resort areas of the Riviera Maya, Baja California, Puerto Vallarta and Cancun.

In the mid-19th century, many Italians arrived in Colombia from South Italy (especially from the province of Salerno, and the areas of Basilicata and Calabria), arrived on the north coast of Colombia: Barranquilla was the first center affected by this mass migration.[133] One of the first complete maps of Colombia, adopted today with some modifications, was prepared earlier by another Italian, Agustino Codazzi, who arrived in Bogota in 1849. The Colonel Agustin Codazzi also proposed the establishment of an agricultural colony of Italians, on model of what was done with the Colonia Tovar in Venezuela, but some factors prevented it.[134]

Italian immigration to Paraguay has been one of the largest migration flows this South American country has received.[135] Italians in Paraguay are the second-largest immigrant group in the country after the Spaniards. The Italian embassy calculates that nearly 40% of the Paraguayans have recent and distant Italian roots: about 2,500,000 Paraguayans are descendants of Italian emigrants to Paraguay.[136][137][138] Over the years, many descendants of Italian immigrants came to occupy important positions in the public life of the country, such as the presidency of the republic, the vice-presidency, local administrations and congress.[139]

Most of Italian Costa Ricans reside in San Vito, the capital city of the Coto Brus Canton. Both Italians and their descendants are referred to in the country as tútiles.[140][141] In the 1920s and 1930s, the Italian community grew in importance, even because some Italo-Costa Ricans reached top levels in the political arena. Julio Acosta García, a descendant from a Genoese family in San Jose since colonial times, served as President of Costa Rica from 1920 to 1924.

Among European Peruvians, Italian Peruvians were the second largest group of immigrants to settle in the country.[142] The first wave of Italian immigration to an independent Peru occurred during the period 1840–1866 (the "Guano" Era): not less than 15,000 Italians arrived to Peru during this period (without counting the non-registered Italians) and established mainly in the coastal cities, especially, in Lima and Callao. They came, mostly, from the northern states (Liguria, Piedmont, Tuscany and Lombardy). Giuseppe Garibaldi arrived to Peru in 1851, as well as other Italians who participated in the Milan rebellion like Giuseppe Eboli, Steban Siccoli, Antonio Raimondi, Arrigoni, etc.

Italian immigrants to Chile settled especially in Capitán Pastene, Angol, Lumaco, and Temuco but also in Valparaiso, Concepción, Chillán, Valdivia, and Osorno. One of the notable Italian influences in Chile is, for example, the sizable number of Italian surnames of a proportion of Chilean politicians, businessmen, and intellectuals, many of whom intermarried into the Castilian-Basque elites. Italian Chileans contributed to the development, cultivation and ownership of the world-famous Chilean wines from haciendas in the Central Valley, since the first wave of Italians arrived in colonial Chile in the early 19th century.

The Italian immigration in Guatemala began in a consistent way only in the early Republican era. One of the first Italians to come to Guatemala was Geronimo Mancinelli, an Italian coffee farmer who lived in San Marcos (Guatemala) in 1847.[143] However, the first wave of Italian immigrants came in 1873, under the government of Justo Rufino Barrios, these immigrants were mostly farmers attracted by the wealth of natural and spacious highlands of Guatemala. Most of them settled in Quetzaltenango and Guatemala City.[144]

Italian emigration into Cuba was minor (a few thousand emigrates) in comparison with other waves of Italian emigration to the Americas (millions went to Argentina, Venezuela, Brazil and the United States). Only in the mid-19th century did there develop a small Italian community in Cuba: they were mostly people of culture, architects, engineers, painters and artists and their families.

Italian Dominicans have left its mark on the history of the Caribbean country. The foundation of the oldest Dominican newspaper in 1889 was the work of an Italian, while the establishment of the Navy of the Dominican Republic was the work of the Genoese merchant Giovanni Battista Cambiaso.[145] Finally, the design of the Palace of the President of the Dominican Republic, both aesthetically and structurally, was the work of an Italian engineer, Guido D'Alessandro.[145] In 2010, Dominicans of Italian descent numbered around 300,000 (corresponding to about 3% of the total population of the Dominican Republic), while Italian citizens residing in the Caribbean nation numbered around 50,000, mainly concentrated in Boca Chica, Santiago de los Caballeros, La Romana and in the capital Santo Domingo.[146][147] The Italian community in the Dominican Republic, considering both people of Italian ancestry and Italian birth, is the largest in the Caribbean region.[146]

Italian Salvadorans are one of the largest European communities in El Salvador, and one of the largest in Central America and the Caribbean, as well as one of those with the greatest social and cultural weight of America.[148] Italians have strongly influenced Salvadoran society and participated in the construction of the country's identity. Italian culture is distinguished by infrastructure, gastronomy, education, dance, and other distinctions, there being several notable Salvadorans of Italian descent.[148][149][150][151] As of 2009, the Italian community in El Salvador is officially made up of 2,300 Italian citizens, while Salvadoran citizens with Italian descent exceed 200,000.[152][153]

Italian Panamanians are mainly descendant of Italians attracted by the construction of the Panama Canal, between the 19th and 20th century. The wave of Italian immigration occurred around 1880. With the construction of the Canal by the Universal Panama Canal Company came the arrival of up to 2,000 Italians. Actually there it is an agreement/treaty between the Italian and Panamanian governments, that facilitates since 1966 the Italian immigration to Panama for investments[154]

In 2010, there were over 15,000 Bolivians of Italian descent, while there were around 2,700 Italian citizens.[155] One of the most famous Italian Bolivian is the writer and poet Óscar Cerruto, considered one of the great authors of Bolivian literature.[156] There are currently almost 56,000 descendants of Italians in Ecuador, being one of the lowest rates of migrant ancestry in Ecuador, where Arabs and Spaniards play a more prominent role.[157] However, Argentine and Colombian immigrants who have entered the country since the end of the last century (80% and 50% respectively were made up of Italian descendants).[157]

The business sector of Haiti, was controlled by German and Italian immigrants in the mid-19th century.[158] In 1908 there were 160 Italians residing in Haiti, according to the Italian consul De Matteis, of whom 128 lived in the capital Port-au-Prince.[159] In 2011, according to the Italian census, there were 134 Italians who were resident in Haiti, nearly all of them living in the capital. However, there were nearly 5,000 Haitians with recent & distant Italians roots (according to the Italian embassy). In 2010, Puerto Ricans of Italian descent numbered around 10,000, while Italian citizens residing in Puerto Rico are 344, concentrated in Ponce and San Juan.[160] In addition, there is also an Italian Honorary Consulate in San Juan.[161]

The influx of Italian citizens to settle in the Republic of Honduras became evident within the first three decades of the 20th century. Among them stood out businessmen, architects, aviators, engineers, artists in various fields, etc. In 1911 the participation of immigrants in the development of the country began to be evident, especially families from Europe (Germany, Italy, France). The main marketing items were coffee, bananas, precious woods, gold and silver.[162] In 2014, there were about 14,000 Hondurans of Italian descent, while there were around 400 Italian citizens.[163]

Italian emigration to Nicaragua occurred from the 1880s until World War II.[164] Emigration was not consistent as there were only several hundred Italians who emigrated to Nicaragua, therefore with much lower numbers than the Italian emigration to other countries.[164] However, Italian emigration to Nicaragua was substantial if the other ethnic groups who emigrated to the South American country is considered, as well as the direct migratory flow to other Central American countries.[164] Another aspect to consider was the density of the Nicaraguan population of the time with respect to its territory, which was not very high, thus making the Italian presence, and more generally the presence of foreign citizens in Nicaragua, more significant.[164]

Asia[edit]

There is a small Italian community in India consisting mainly of Indian citizens of Italian heritage as well with expatriates and migrants from Italy who reside in India. Since the 16th century, many of these Italian Jesuits came to South India, mainly Goa, Kerala and Tamil Nadu. Some of the most well known Jesuits in India include Antonio Moscheni, Constanzo Beschi, Roberto de Nobili and Rodolfo Acquaviva. In the 1940s, during World War II, the British brought Italian prisoners of war, who were captured in either Europe or North Africa, to Bangalore and Madras. They were put up at the Garrison Grounds, today's Parade Grounds-Cubbon Road area.[165] In February 1941, about 2,200 Italian prisoners of war arrived in Bangalore by a special train and marched to internment camps at Byramangala, 20 miles from Bangalore.[166] In recent years, many Italians have been coming to India for business purposes. Today, Italy is India's fifth largest trading partner in the European Union. There are currently between 15,000 and 20,000 Italian nationals in India[167] based mostly in South India.[168] The city of Mumbai itself has a sizeable number of Italians and some in Chennai.[169]

Italians in Lebanon (or Italian Lebanese) are a community in Lebanon with a history that goes back to Roman times. In more recent times the Italians came to Lebanon in small groups during the World War I and World War II, trying to escape the wars at that time in Europe.Some of the first Italians who choose Lebanon as a place to settle and find a refuge were Italian soldiers from the Italo-Turkish War in 1911 to 1912. Also most of the Italians chose to settle in Beirut, because of its European style of life. Only a few Italians left Lebanon for France after independence. The Italian community in Lebanon is very small (about 4,300 people) and it is mostly assimilated into the Lebanese Catholic community.

There are up to 10,000 Italians in the United Arab Emirates, approximately two-thirds of whom are in Dubai, and the rest in Abu Dhabi.[170][171] The UAE in recent years has attained the status of a favourite destination for Italian immigrants, with the rate of Italians moving into the country having increased by forty percent between 2005 and 2007.[171] Italians make up one of the largest European groups in the UAE. The community is structured through numerous social circles and organisations such as the Italian Cultural and Recreational Circle (now known as "Cicer"),[171] the Italian Industry and Commerce Office (UAE) and the Italian Business Council Dubai. Social activities like outdoor excursions, gastronomy evenings, language courses, activities for children, exhibitions and concerts are frequent; there have been talks of setting up a permanent Italian cultural centre in Abu Dhabi which would act as a venue for activities.[171] Italian cuisine, culture, and fashion are widespread throughout Dubai and Abu Dhabi, with a large number of native Italians running restaurants.

Europe[edit]

The Italian colonists in Albania were Italians who, between the two World Wars, moved to Albania to colonize the Balkan country for the Kingdom of Italy. When Benito Mussolini took power in Italy, he turned with renewed interest to Albania. Italy began penetrating Albania's economy in 1925, when Albania agreed to allow it to exploit its mineral resources.[172] That was followed by the First Treaty of Tirana in 1926 and the Second Treaty of Tirana in 1927, whereby Italy and Albania entered into a defensive alliance.[172] Italian loans subsidized the Albanian government and economy, and Italian military instructors trained the Albanian army. Italian colonial settlement was encouraged and the first 300 Italian colonists settled in Albania.[173] Fascist Italy increased pressure on Albania in the 1930s and, on 7 April 1939, invaded Albania,[174] five months before the start of the World War II. After the occupation of Albania in April 1939, Mussolini sent nearly 11,000 Italian colonists to Albania. Most of them were from the Veneto region and Sicily. They settled primarily in the areas of Durrës, Vlorë, Shkodër, Porto Palermo, Elbasan, and Sarandë. They were the first settlers of a huge group of Italians to be moved to Albania.[175] In addition to these colonists, 22,000 Italian casual laborers went to Albania in April 1940 to construct roads, railways and infrastructure.[176] After the World War II, no Italian colonists remain in Albania. The few who remained under the communist regime of Enver Hoxha fled (with their descendants) to Italy in 1992,[177] and actually are represented by the association "ANCIFRA".[178]

The most important migratory flows of Italians to Austria began after 1870, when the Austro-Hungarian Empire was still in existence. Between 1876 and 1900, Austria-Hungary was the second European country after France to absorb the largest number of Italian emigrants.[179] These migratory phenomena were of an economic nature, mainly of a temporary nature, and involved agricultural labourers, workers and bricklayers. After 1907, due to the decline in requests for Italian labor by the Austro-Hungarian authorities, the rise of inter-ethnic clashes between the Italian ethnic community and the Slavic ethnic community present in the Habsburg empire (moreover fomented by the Vienna government),[180] there was a drop in migratory flows of Italians to the country, going from over 50,000 annual entries recorded in 1901 to around 35,000 in 1912.[181] The phenomenon of Italian emigration to Austria ended after 1918, with the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. According to official AIRE data for 2007, there were 15,765 Italian citizens residing in Austria.[182]

The Italian community in Belgium is very well integrated into Belgian society. The Italo-Belgians occupy roles of the utmost importance; the Queen of Belgium Paola Ruffo di Calabria or the former Prime Minister Elio Di Rupo are examples. According to official statistics from AIRE (Register of Italians residing abroad), in 2012 there were approximately 255,000 Italian citizens residing in Belgium (including Belgians with dual citizenship).[183] According to data from the Italian consular registers, it appears that almost 50,000 Italians in Belgium (i.e. more than 25%) come from Sicily, followed by Apulia (9.5%), Abruzzo (7%), Campania (6.5%), and Veneto (6%).[184] There are about 450,000 (about 4% of the total Belgian population) people of Italian origin in Belgium.[185] The community of Belgians of Italian descent is said to be 85% concentrated in Wallonia and in Brussels. More precisely, 65% of Belgians of Italian descent live in Wallonia, 20% in Brussels and 15% in the Flemish Region.[186]

Štivor, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, is almost exclusively inhabited by descendants of Italian emigrants, which are about 92% of the total population of the village.[187] Their number amounts to 270 people, all of Trentino origin.[187] The Italian language is also taught in the village schools, and the 270 Italian Bosnians of Štivor have Italian passports, read Italian newspapers and live on Italian pensions.[187] Three quarters of them still speak the Trentino dialect.[187] The presence of Italian-Bosnians in Štivor can be explained by a flood caused by the Brenta river which hit the Valsugana in 1882.[187] Trentino at the time was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which had recently annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina. In order to help the people of Trentino devastated by the flood, and to repopulate Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Austrian authorities encouraged the emigration of Trentino people to the Balkan country.[187] The Trentino immigrants were distributed throughout the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina, but mainly only those in Štivor kept their identity, while the others were absorbed by the local population.[187] The Trentino immigrants brought an important tradition to Bosnia and Herzegovina, the cultivation of grapevines and the production of wine, a tradition that is still practiced in the Balkan country.[187]

Italian migration to France has occurred, in different migrating cycles since the end of the 19th century to the present day.[188] In addition, Corsica passed from the Republic of Genoa to France in 1770, and the area around Nice and Savoy from the Kingdom of Sardinia to France in 1860. Initially, Italian immigration to modern France (late 18th to the early 20th centuries) came predominantly from northern Italy (Piedmont, Veneto), then from central Italy (Marche, Umbria), mostly to the bordering southeastern region of Provence.[188] It was not until after World War II that large numbers of immigrants from southern Italy emigrated to France, usually settling in industrialized areas of France such as Lorraine, Paris and Lyon.[188] Today, it is estimated that as many as 5,000,000 French nationals have Italian ancestry going as far back as three generations.[188]

Italian colonists were settled in the Dodecanese Islands of the Aegean Sea in the 1930s by the Fascist Italian government of Benito Mussolini, Italy having been in occupation of the Islands since the Italian-Turkish War of 1911. By 1940, the number of Italians settled in the Dodecanese was almost 8,000, concentrated mainly in Rhodes. In 1947, after the Second World War, the islands came into the possession of Greece: as a consequence most of the Italians were forced to emigrate and all of the Italian schools were closed. Some of the Italian colonists remained in Rhodes and were quickly assimilated. Currently, only a few dozen old colonists remain, but the influence of their legacy is evident in the relative diffusion of the Italian language mainly in Rhodes and Leros. However, their architectural legacy is still evident, especially in Rhodes and Leros. The citadel of Rhodes city is a UNESCO World Heritage Site thanks in great part to the large-scale restoration work carried out by the Italian authorities.[189]

In the 1890s, Germany transformed from a country of emigration to a country of immigration. Starting from this period the migratory flows from Italy expanded (mostly coming from Friuli, Lombardy, Veneto and Emilia-Romagna), and with them the numerical consistency of the Italian communities increased. In fact, it went from 4,000 Italians in 1871 to over 120,000 registered in 1910. Italian immigration to Germany resumed after the rise to power of Nazism in 1933. This time, however, it was not a voluntary migration, but a forced recruitment of Italian workers, based on an agreement stipulated in 1937 between Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini, to satisfy the need to find cheap labor for German factories in exchange for the supply of coal to Italy. On December 20, 1955, a bilateral agreement was signed between Italy and West Germany for the recruitment and placement of Italian labor in German companies. From that date there was a boom in migratory flows towards West Germany, which were much more conspicuous than those that had occurred between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. It is estimated that from 1956 to 1976 over 4 million Italians entered West Germany, 3.5 million of whom later returned to Italy.[190]

The first Italians in Luxembourg arrived in 1892, and at the end of the 19th century the Italian community numbered only 439 people, but already in 1900 the Italian community rose to 7,000 people and then to 10,000 only ten years later. The Italian emigrants worked above all in the mines and in the steel industry of the country (as in neighboring Belgium) until their closure, while today the Italian community is employed in the tertiary sector, especially banks.[191] In 1960, Italians constituted 37.8% of all foreign residents in Luxembourg (against only 8.2% in 2011).[192] The historical peak of the Italian community was in 1970, when the Italians in Luxembourg numbered 23,490, or as much as 6.9% of the entire population of the Grand Duchy.[192] The most important Italian-Luxembourg was the politician and trade unionist Luigi Reich who, from 1985 to 1993, was mayor of Dudelange and national vice-president of the Confédération générale du travail luxembourgeoise (CGT-L).[193] On 1 January 2011, according to AIRE, there were 22,965 Italians in Luxembourg (equal to 4.8% of the Luxembourg population) and almost a quarter of the emigrants are of Apulian origin.[194]

The first Italians came to Poland in the Middle Ages, however, substantial migration of Italians to Poland began in the 16th century.[42] Those included merchants, craftsmen, architects, artists, physicians, inventors, engineers, diplomats, chefs.[195] Famous Italians in Poland included inventors Tito Livio Burattini, Paolo del Buono, architects Bartolommeo Berrecci, Bernardo Morando, painters Tommaso Dolabella, Bernardo Bellotto, Marcello Bacciarelli, scholar Filippo Buonaccorsi, and religious reformer Fausto Sozzini.[196] The largest number of Italians lived in Kraków, while other significant concentrations were in Gdańsk, Lwów, Poznań, Warsaw and Wilno.[197] According to the 1921 Polish census, the largest Italian populations lived in the cities of Warsaw and Lwów with 100 and 22 people, respectively.[198][199] In the 2011 Polish census, 8,641 people declared Italian nationality, of which 7,548 declared both Polish and Italian nationality.[200]

In recent years a growing Italian community has also emerged in Portugal. Now the country hosts more than 34,000 Italian nationals[201][202] and almost 400 Italians have acquires the Portuguese citizenship since 2008.[203] Many of the Italians living in Portugal are Italian-Brazilians who have taken advantage of their EU citizenship and subsequently settled in a country where they already spoke the language.[204][205]

Italians in Romania are people of Italian descent who reside, or have moved to Romania. During the 19th and 20th centuries, many Italians from Western Austria-Hungary settled in Transylvania. During the interwar period, some Italians settled in Dobruja. After 1880, Italians from Friuli and Veneto settled in Greci, Cataloi and Măcin in Northern Dobruja. Most of them worked in the granite quarries in the Măcin Mountains, some became farmers[206] and others worked in road building.[207] As an officially recognised ethnic minority, Italians have one seat reserved in the Romanian Chamber of Deputies.

Italians in Spain are one of the largest communities of immigrant groups in Spain, with 257.256 Italian citizens in the country;[208] conversely, 142,401 residents in Spain were born in Italy.[209] A significant part of the Italian citizens in Spain are not born in Italy but emigrate from Argentina or Uruguay.[210][211]

Swedish Italians are Swedish citizens or residents of Italian ethnic, cultural and linguistic heritage or identity. There are approximately 8,126 people born in Italy living in Sweden today, as well as 10,961 people born in Sweden with at least one parent born in Italy.[212]