Бостон

Бостон | |

|---|---|

Желудь-стрит на Бикон-Хилл Фенуэй Парк во время Бостон Ред Сокс игры Back Bay from the Charles River | |

| Nickname(s): Bean Town, Title Town, others | |

| Motto(s): Sicut patribus sit Deus nobis (Latin) 'As God was with our fathers, so may He be with us' | |

| Coordinates: 42°21′37″N 71°3′28″W / 42.36028°N 71.05778°W | |

| Country | United States |

| Region | New England |

| State | Massachusetts |

| County | Suffolk[1] |

| Historic countries | Kingdom of England Commonwealth of England Kingdom of Great Britain |

| Historic colonies | Massachusetts Bay Colony, Dominion of New England, Province of Massachusetts Bay |

| Settled | 1625 |

| Incorporated (town) | September 7, 1630 (date of naming, Old Style) September 17, 1630 (date of naming, New Style) |

| Incorporated (city) | March 19, 1822 |

| Named for | Boston, Lincolnshire |

| Government | |

| • Type | Strong mayor / Council |

| • Mayor | Michelle Wu (D) |

| • Council | Boston City Council |

| • Council President | Ruthzee Louijeune (D) |

| Area | |

| • State capital city | 89.61 sq mi (232.10 km2) |

| • Land | 48.34 sq mi (125.20 km2) |

| • Water | 41.27 sq mi (106.90 km2) |

| • Urban | 1,655.9 sq mi (4,288.7 km2) |

| • Metro | 4,500 sq mi (11,700 km2) |

| • CSA | 10,600 sq mi (27,600 km2) |

| Elevation | 46 ft (14 m) |

| Population | |

| • State capital city | 675,647 |

| • Estimate (2021)[4] | 654,776 |

| • Rank | 66th in North America 24th in the United States 1st in Massachusetts |

| • Density | 13,976.98/sq mi (5,396.51/km2) |

| • Urban | 4,382,009 (US: 10th) |

| • Urban density | 2,646.3/sq mi (1,021.8/km2) |

| • Metro | 4,941,632 (US: 10th) |

| Demonym | Bostonian |

| GDP | |

| • Boston (MSA) | $571.6 billion (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 53 ZIP Codes[8] |

| Area codes | 617 and 857 |

| FIPS code | 25-07000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 617565 |

| Website | boston |

Бостон ( США : / ˈ b ɔː s t ə n / [9] ), официально Бостон , является столицей и самым густонаселенным городом Содружества Массачусетс в город Соединенных Штатах. Город служит культурным и финансовым центром региона Новая Англия на северо-востоке США . Его площадь составляет 48,4 квадратных миль (125 км²). 2 ) [10] а население составляет 675 647 человек по данным переписи 2020 года , что делает его третьим по величине городом на северо-востоке после Нью-Йорка и Филадельфии . [4] Большого Бостона Статистический район , включая город и его окрестности, является крупнейшим в Новой Англии и одиннадцатым по величине в стране. [11] [12] [13]

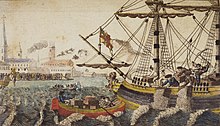

Бостон был основан на полуострове Шаумут в 1630 году поселенцами -пуританами . Город был назван в честь Бостона, Линкольншир , Англия. [14] [15] Во время американской революции Бостон был домом для нескольких событий, которые оказались центральными для революции и последующей войны за независимость , включая Бостонскую резню (1770 г.), Бостонское чаепитие (1773 г.), Полуночную поездку Пола Ревера (1775 г.), битву при Бункере. Хилл (1775 г.) и Осада Бостона (1775–1776 гг.). После обретения Америкой независимости от Великобритании город продолжал играть важную роль порта, производственного центра и центра образования и культуры. [16][17]

The city expanded significantly beyond the original peninsula by filling in land and annexing neighboring towns. It now attracts many tourists, with Faneuil Hall alone drawing more than 20 million visitors per year.[18] Boston's many firsts include the United States' first public park (Boston Common, 1634),[19] the first public school (Boston Latin School, 1635),[20] and the first subway system (Tremont Street subway, 1897).[21]

Since the nation's founding, Boston has been a national leader in higher education and research. Boston University and Northeastern University are both located within the city, with Boston College located in nearby Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. Two of the world's most prestigious and consistently highly ranked universities, Harvard University (the nation's oldest university) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, are both located in neighboring Cambridge, Massachusetts.[22]

Boston has emerged as the largest biotechnology hub in the world.[23] The city is also a national leader in scientific research, law, medicine, engineering, and business. With nearly 5,000 startup companies, the city is considered a global pioneer in innovation and entrepreneurship,[24][25][26] and more recently in artificial intelligence.[27] Boston's economy also includes finance,[28] professional and business services, information technology, and government activities.[29] Households in the city claim the highest average rate of philanthropy in the United States.[30] Furthermore, Boston's businesses and institutions rank among the top in the country overall for environmental sustainability and new investment.[31]

History[edit]

Indigenous era[edit]

Prior to European colonization, the region surrounding present-day Boston was inhabited by the Massachusett people who had small, seasonal communities.[32][33] When a group of settlers led by John Winthrop arrived in 1630, the Shawmut Peninsula was nearly empty of the Native people, as many had died of European diseases brought by early settlers and traders.[34][35] Archaeological excavations unearthed one of the oldest fishweirs in New England on Boylston Street, which Native people constructed as early as 7,000 years before European arrival in the Western Hemisphere.[33][32][36]

Settlement by Europeans[edit]

The first European to live in what would become Boston was a Cambridge-educated Anglican cleric named William Blaxton. He was the person most directly responsible for the foundation of Boston by Puritan colonists in 1630. This occurred after Blaxton invited one of their leaders, Isaac Johnson, to cross Back Bay from the failing colony of Charlestown and share the peninsula. The Puritans made the crossing in September 1630.[37][38][39]

The name "Boston"[edit]

Before Johnson died on September 30, 1630, he named their then-new settlement across the river "Boston". (This was one of his last official acts as the leader of the Charlestown community.) The settlement's name came from Johnson's hometown of Boston, Lincolnshire, from which he, his wife (namesake of the Arbella) and John Cotton (grandfather of Cotton Mather) had emigrated to New England. The name of the English town ultimately derives from its patron saint, St. Botolph, in whose church John Cotton served as the rector until his emigration with Johnson. In early sources, Lincolnshire's Boston was known as "St. Botolph's town", later contracted to "Boston". Before this renaming, the settlement on the peninsula had been known as "Shawmut" by Blaxton and "Tremontaine"[40] by the Puritan settlers he had invited.[41][42][43][44][45]

Puritan occupation[edit]

Puritan influence on Boston began even before the settlement was founded with the 1629 Cambridge Agreement. This document created the Massachusetts Bay Colony and was signed by its first governor John Winthrop. Puritan ethics and their focus on education also influenced the early history of the city. America's first public school, Boston Latin School, was founded in Boston in 1635.[20][46]

Boston was the largest town in the Thirteen Colonies until Philadelphia outgrew it in the mid-18th century.[47] Boston's oceanfront location made it a lively port, and the then-town primarily engaged in shipping and fishing during its colonial days. Boston was a primary stop on a Caribbean trade route and imported large amounts of molasses, which led to the creation of Boston baked beans.[48]

Boston's economy stagnated in the decades prior to the Revolution. By the mid-18th century, New York City and Philadelphia had surpassed Boston in wealth. During this period, Boston encountered financial difficulties even as other cities in New England grew rapidly.[49][50]

Revolution and the siege of Boston[edit]

The weather continuing boisterous the next day and night, giving the enemy time to improve their works, to bring up their cannon, and to put themselves in such a state of defence, that I could promise myself little success in attacking them under all the disadvantages I had to encounter.

William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe, in a letter to William Legge, 2nd Earl of Dartmouth, about the British army's decision to leave Boston, dated March 21, 1776.[51]

Many crucial events of the American Revolution[52] occurred in or near Boston. The then-town's mob presence, along with the colonists' growing lack of faith in either Britain or its Parliament, fostered a revolutionary spirit there.[49] When the British parliament passed the Stamp Act in 1765, a Boston mob ravaged the homes of Andrew Oliver, the official tasked with enforcing the Act, and Thomas Hutchinson, then the Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts.[49][53] The British sent two regiments to Boston in 1768 in an attempt to quell the angry colonists. This did not sit well with the colonists, however. In 1770, during the Boston Massacre, British troops shot into a crowd that had started to violently harass them. The colonists compelled the British to withdraw their troops. The event was widely publicized and fueled a revolutionary movement in America.[50]

In 1773, Parliament passed the Tea Act. Many of the colonists saw the act as an attempt to force them to accept the taxes established by the Townshend Acts. The act prompted the Boston Tea Party, where a group of angered Bostonians threw an entire shipment of tea sent by the East India Company into Boston Harbor. The Boston Tea Party was a key event leading up to the revolution, as the British government responded furiously with the Coercive Acts, demanding compensation for the destroyed tea from the Bostonians.[49] This angered the colonists further and led to the American Revolutionary War. The war began in the area surrounding Boston with the Battles of Lexington and Concord.[49][54]

Boston itself was besieged for almost a year during the siege of Boston, which began on April 19, 1775. The New England militia impeded the movement of the British Army. Sir William Howe, then the commander-in-chief of the British forces in North America, led the British army in the siege. On June 17, the British captured Charlestown (now part of Boston) during the Battle of Bunker Hill. The British army outnumbered the militia stationed there, but it was a pyrrhic victory for the British because their army suffered irreplaceable casualties. It was also a testament to the skill and training of the militia, as their stubborn defense made it difficult for the British to capture Charlestown without suffering further irreplaceable casualties.[55][56]

Several weeks later, George Washington took over the militia after the Continental Congress established the Continental Army to unify the revolutionary effort. Both sides faced difficulties and supply shortages in the siege, and the fighting was limited to small-scale raids and skirmishes. The narrow Boston Neck, which at that time was only about a hundred feet wide, impeded Washington's ability to invade Boston, and a long stalemate ensued. A young officer, Rufus Putnam, came up with a plan to make portable fortifications out of wood that could be erected on the frozen ground under cover of darkness. Putnam supervised this effort, which successfully installed both the fortifications and dozens of cannons on Dorchester Heights that Henry Knox had laboriously brought through the snow from Fort Ticonderoga. The astonished British awoke the next morning to see a large array of cannons bearing down on them. General Howe is believed to have said that the Americans had done more in one night than his army could have done in six months. The British Army attempted a cannon barrage for two hours, but their shot could not reach the colonists' cannons at such a height. The British gave up, boarded their ships, and sailed away. This has become known as "Evacuation Day", which Boston still celebrates each year on March 17. After this, Washington was so impressed that he made Rufus Putnam his chief engineer.[54][55][57]

Post-revolution and the War of 1812[edit]

After the Revolution, Boston's long seafaring tradition helped make it one of the nation's busiest ports for both domestic and international trade. Boston's harbor activity was significantly curtailed by the Embargo Act of 1807 (adopted during the Napoleonic Wars) and the War of 1812. Foreign trade returned after these hostilities, but Boston's merchants had found alternatives for their capital investments in the meantime. Manufacturing became an important component of the city's economy, and the city's industrial manufacturing overtook international trade in economic importance by the mid-19th century. The small rivers bordering the city and connecting it to the surrounding region facilitated shipment of goods and led to a proliferation of mills and factories. Later, a dense network of railroads furthered the region's industry and commerce.[58]

During this period, Boston flourished culturally as well. It was admired for its rarefied literary life and generous artistic patronage.[59][60] Members of old Boston families—eventually dubbed the Boston Brahmins—came to be regarded as the nation's social and cultural elites.[61] They are often associated with the American upper class, Harvard University,[62] and the Episcopal Church.[63][64]

Boston was an early port of the Atlantic triangular slave trade in the New England colonies, but was soon overtaken by Salem, Massachusetts and Newport, Rhode Island.[65] Boston eventually became a center of the abolitionist movement.[66] The city reacted strongly to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850,[67] contributing to President Franklin Pierce's attempt to make an example of Boston after the Anthony Burns Fugitive Slave Case.[68][69]

In 1822,[16] the citizens of Boston voted to change the official name from the "Town of Boston" to the "City of Boston", and on March 19, 1822, the people of Boston accepted the charter incorporating the city.[70] At the time Boston was chartered as a city, the population was about 46,226, while the area of the city was only 4.8 sq mi (12 km2).[70]

19th century[edit]

In the 1820s, Boston's population grew rapidly, and the city's ethnic composition changed dramatically with the first wave of European immigrants. Irish immigrants dominated the first wave of newcomers during this period, especially following the Great Famine; by 1850, about 35,000 Irish lived in Boston.[71] In the latter half of the 19th century, the city saw increasing numbers of Irish, Germans, Lebanese, Syrians,[72] French Canadians, and Russian and Polish Jews settling there. By the end of the 19th century, Boston's core neighborhoods had become enclaves of ethnically distinct immigrants with their residence yielding lasting cultural change. Italians became the largest inhabitants of the North End,[73] Irish dominated South Boston and Charlestown, and Russian Jews lived in the West End. Irish and Italian immigrants brought with them Roman Catholicism. Currently, Catholics make up Boston's largest religious community,[74] and the Irish have played a major role in Boston politics since the early 20th century; prominent figures include the Kennedys, Tip O'Neill, and John F. Fitzgerald.[75]

Between 1631 and 1890, the city tripled its area through land reclamation by filling in marshes, mud flats, and gaps between wharves along the waterfront. Reclamation projects in the middle of the century created significant parts of the South End, the West End, the Financial District, and Chinatown.[76]

After the Great Boston fire of 1872, workers used building rubble as landfill along the downtown waterfront. During the mid-to-late 19th century, workers filled almost 600 acres (240 ha) of brackish Charles River marshlands west of Boston Common with gravel brought by rail from the hills of Needham Heights. The city annexed the adjacent towns of South Boston (1804), East Boston (1836), Roxbury (1868), Dorchester (including present-day Mattapan and a portion of South Boston) (1870), Brighton (including present-day Allston) (1874), West Roxbury (including present-day Jamaica Plain and Roslindale) (1874), Charlestown (1874), and Hyde Park (1912).[77][78] Other proposals were unsuccessful for the annexation of Brookline, Cambridge,[79] and Chelsea.[80][81]

- Downtown Boston from Dorchester Heights in 1841

- Tremont Street in 1843

- The Old City Hall was home to the Boston city council from 1865 to 1969.

- View of Boston by J. J. Hawes, c. 1860s–1880s

- Haymarket Square in 1909

20th century[edit]

Fenway Park, home of the Boston Red Sox, opened in 1912.[82]

Many architecturally significant buildings were built during these early years of the 20th century: Horticultural Hall,[83] the Tennis and Racquet Club,[84] Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum,[85] Fenway Studios,[86] Jordan Hall,[87] and the Boston Opera House. The Longfellow Bridge,[88] built in 1906, was mentioned by Robert McCloskey in Make Way for Ducklings, describing its "salt and pepper shakers" feature.[89]

Logan International Airport opened on September 8, 1923.[90] The Boston Bruins were founded in 1924 and played their first game at Boston Garden in November 1928.[91]

Boston went into decline by the early to mid-20th century, as factories became old and obsolete and businesses moved out of the region for cheaper labor elsewhere.[92] Boston responded by initiating various urban renewal projects, under the direction of the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) established in 1957. In 1958, BRA initiated a project to improve the historic West End neighborhood. Extensive demolition was met with strong public opposition, and thousands of families were displaced.[93]

The BRA continued implementing eminent domain projects, including the clearance of the vibrant Scollay Square area for construction of the modernist style Government Center. In 1965, the Columbia Point Health Center opened in the Dorchester neighborhood, the first Community Health Center in the United States. It mostly served the massive Columbia Point public housing complex adjoining it, which was built in 1953. The health center is still in operation and was rededicated in 1990 as the Geiger-Gibson Community Health Center.[94] The Columbia Point complex itself was redeveloped and revitalized from 1984 to 1990 into a mixed-income residential development called Harbor Point Apartments.[95]

By the 1970s, the city's economy had begun to recover after 30 years of economic downturn. A large number of high-rises were constructed in the Financial District and in Boston's Back Bay during this period.[96] This boom continued into the mid-1980s and resumed after a few pauses. Hospitals such as Massachusetts General Hospital, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and Brigham and Women's Hospital lead the nation in medical innovation and patient care. Schools such as the Boston Architectural College, Boston College, Boston University, the Harvard Medical School, Tufts University School of Medicine, Northeastern University, Massachusetts College of Art and Design, Wentworth Institute of Technology, Berklee College of Music, the Boston Conservatory, and many others attract students to the area. Nevertheless, the city experienced conflict starting in 1974 over desegregation busing, which resulted in unrest and violence around public schools throughout the mid-1970s.[97]

21st century[edit]

Boston is an intellectual, technological, and political center. However, it has lost some important regional institutions,[98] including the loss to mergers and acquisitions of local financial institutions such as FleetBoston Financial, which was acquired by Charlotte-based Bank of America in 2004.[99] Boston-based department stores Jordan Marsh and Filene's have both merged into the New York City–based Macy's.[100]The 1993 acquisition of The Boston Globe by The New York Times[101] was reversed in 2013 when it was re-sold to Boston businessman John W. Henry. In 2016, it was announced General Electric would be moving its corporate headquarters from Connecticut to the Seaport District in Boston, joining many other companies in this rapidly developing neighborhood.

Boston has experienced gentrification in the latter half of the 20th century,[102] with housing prices increasing sharply since the 1990s when the city's rent control regime was struck down by statewide ballot proposition.[103]

On April 15, 2013, two Chechen Islamist brothers detonated a pair of bombs near the finish line of the Boston Marathon, killing three people and injuring roughly 264.[104]

In 2016, Boston briefly shouldered a bid as the U.S. applicant for the 2024 Summer Olympics. The bid was supported by the mayor and a coalition of business leaders and local philanthropists, but was eventually dropped due to public opposition.[105] The USOC then selected Los Angeles to be the American candidate with Los Angeles ultimately securing the right to host the 2028 Summer Olympics.[106]

Geography[edit]

Boston has an area of 89.63 sq mi (232.1 km2). Of this area, 48.4 sq mi (125.4 km2), or 54%, of it is land and 41.2 sq mi (106.7 km2), or 46%, of it is water. The city's official elevation, as measured at Logan International Airport, is 19 ft (5.8 m) above sea level.[107] The highest point in Boston is Bellevue Hill at 330 ft (100 m) above sea level, and the lowest point is at sea level.[108] Boston is situated next to Boston Harbor, an arm of Massachusetts Bay, itself an arm of the Atlantic Ocean.

The geographical center of Boston is in Roxbury. Due north of the center we find the South End. This is not to be confused with South Boston which lies directly east from the South End. North of South Boston is East Boston and southwest of East Boston is the North End.[This quote needs a citation]

— author, Unknown – A local colloquialism

Boston is surrounded by the Greater Boston metropolitan region. It is bordered to the east by the town of Winthrop and the Boston Harbor Islands, to the northeast by the cities of Revere, Chelsea and Everett, to the north by the cities of Somerville and Cambridge, to the northwest by Watertown, to the west by the city of Newton and town of Brookline, to the southwest by the town of Dedham and small portions of Needham and Canton, and to the southeast by the town of Milton, and the city of Quincy.

The Charles River separates Boston's Allston-Brighton, Fenway-Kenmore and Back Bay neighborhoods from Watertown and Cambridge, and most of Boston from its own Charlestown neighborhood. The Neponset River forms the boundary between Boston's southern neighborhoods and Quincy and Milton. The Mystic River separates Charlestown from Chelsea and Everett, and Chelsea Creek and Boston Harbor separate East Boston from Downtown, the North End, and the Seaport.[109]

Neighborhoods[edit]

Boston is sometimes called a "city of neighborhoods" because of the profusion of diverse subsections.[110][111] The city government's Office of Neighborhood Services has officially designated 23 neighborhoods:[112]

More than two-thirds of inner Boston's modern land area did not exist when the city was founded. Instead, it was created via the gradual filling in of the surrounding tidal areas over the centuries.[76] This was accomplished using earth from the leveling or lowering of Boston's three original hills (the "Trimountain", after which Tremont Street is named), as well as with gravel brought by train from Needham to fill the Back Bay.[17]

Downtown and its immediate surroundings (including the Financial District, Government Center, and South Boston) consist largely of low-rise masonry buildings – often federal style and Greek revival – interspersed with modern high-rises.[113] Back Bay includes many prominent landmarks, such as the Boston Public Library, Christian Science Center, Copley Square, Newbury Street, and New England's two tallest buildings: the John Hancock Tower and the Prudential Center.[114] Near the John Hancock Tower is the old John Hancock Building with its prominent illuminated beacon, the color of which forecasts the weather.[115] Smaller commercial areas are interspersed among areas of single-family homes and wooden/brick multi-family row houses. The South End Historic District is the largest surviving contiguous Victorian-era neighborhood in the US.[116]

The geography of downtown and South Boston was particularly affected by the Central Artery/Tunnel Project (which ran from 1991 to 2007, and was known unofficially as the "Big Dig"). That project removed the elevated Central Artery and incorporated new green spaces and open areas.[117]

Climate[edit]

- Boston's skyline in the background with fall foliage in the foreground

- A graph of cumulative winter snowfall at Logan International Airport from 1938 to 2015. The four winters with the most snowfall are highlighted. The snowfall data, which was collected by NOAA, is from the weather station at the airport.

Under the Köppen climate classification, Boston has either a hot-summer humid continental climate (Köppen Dfa) under the 0 °C (32.0 °F) isotherm or a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa) under the −3 °C (26.6 °F) isotherm.[118] Summers are warm to hot and humid, while winters are cold and stormy, with occasional periods of heavy snow. Spring and fall are usually cool and mild, with varying conditions dependent on wind direction and the position of the jet stream. Prevailing wind patterns that blow offshore minimize the influence of the Atlantic Ocean. However, in winter, areas near the immediate coast often see more rain than snow, as warm air is sometimes drawn off the Atlantic.[119] The city lies at the border between USDA plant hardiness zones 6b (away from the coastline) and 7a (close to the coastline).[120]

The hottest month is July, with a mean temperature of 74.1 °F (23.4 °C). The coldest month is January, with a mean temperature of 29.9 °F (−1.2 °C). Periods exceeding 90 °F (32 °C) in summer and below freezing in winter are not uncommon but tend to be fairly short, with about 13 and 25 days per year seeing each, respectively.[121]

Sub- 0 °F (−18 °C) readings usually occur every 3 to 5 years.[122] The most recent sub- 0 °F (−18 °C) reading occurred on February 4, 2023, when the temperature dipped down to −10 °F (−23 °C); this was the lowest temperature reading in the city since 1957.[121] In addition, several decades may pass between 100 °F (38 °C) readings; the last such reading occurred on July 24, 2022.[121] The city's average window for freezing temperatures is November 9 through April 5.[121][a] Official temperature records have ranged from −18 °F (−28 °C) on February 9, 1934, up to 104 °F (40 °C) on July 4, 1911. The record cold daily maximum is 2 °F (−17 °C) on December 30, 1917, while the record warm daily minimum is 83 °F (28 °C) on both August 2, 1975 and July 21, 2019.[123][121]

Boston averages 43.6 in (1,110 mm) of precipitation a year, with 49.2 in (125 cm) of snowfall per season.[121] Most snowfall occurs from mid-November through early April, and snow is rare in May and October.[124][125] There is also high year-to-year variability in snowfall; for instance, the winter of 2011–12 saw only 9.3 in (23.6 cm) of accumulating snow, but the previous winter, the corresponding figure was 81.0 in (2.06 m).[121][b] The city's coastal location on the North Atlantic makes the city very prone to nor'easters, which can produce large amounts of snow and rain.[119]

Fog is fairly common, particularly in spring and early summer. Due to its coastal location, the city often receives sea breezes, especially in the late spring, when water temperatures are still quite cold and temperatures at the coast can be more than 20 °F (11 °C) colder than a few miles inland, sometimes dropping by that amount near midday.[126][127] Thunderstorms typically occur from May to September; occasionally, they can become severe, with large hail, damaging winds, and heavy downpours.[119] Although downtown Boston has never been struck by a violent tornado, the city itself has experienced many tornado warnings. Damaging storms are more common to areas north, west, and northwest of the city.[128] Boston has a relatively sunny climate for a coastal city at its latitude, averaging over 2,600 hours of sunshine a year.

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °F (°C) | 74 (23) | 73 (23) | 89 (32) | 94 (34) | 97 (36) | 100 (38) | 104 (40) | 102 (39) | 102 (39) | 90 (32) | 83 (28) | 76 (24) | 104 (40) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 58.3 (14.6) | 57.9 (14.4) | 67.0 (19.4) | 79.9 (26.6) | 88.1 (31.2) | 92.2 (33.4) | 95.0 (35.0) | 93.7 (34.3) | 88.9 (31.6) | 79.6 (26.4) | 70.2 (21.2) | 61.2 (16.2) | 96.4 (35.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 36.8 (2.7) | 39.0 (3.9) | 45.5 (7.5) | 56.4 (13.6) | 66.5 (19.2) | 76.2 (24.6) | 82.1 (27.8) | 80.4 (26.9) | 73.1 (22.8) | 62.1 (16.7) | 51.6 (10.9) | 42.2 (5.7) | 59.3 (15.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 29.9 (−1.2) | 31.8 (−0.1) | 38.3 (3.5) | 48.6 (9.2) | 58.4 (14.7) | 68.0 (20.0) | 74.1 (23.4) | 72.7 (22.6) | 65.6 (18.7) | 54.8 (12.7) | 44.7 (7.1) | 35.7 (2.1) | 51.9 (11.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 23.1 (−4.9) | 24.6 (−4.1) | 31.1 (−0.5) | 40.8 (4.9) | 50.3 (10.2) | 59.7 (15.4) | 66.0 (18.9) | 65.1 (18.4) | 58.2 (14.6) | 47.5 (8.6) | 37.9 (3.3) | 29.2 (−1.6) | 44.5 (6.9) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 4.8 (−15.1) | 8.3 (−13.2) | 15.6 (−9.1) | 31.0 (−0.6) | 41.2 (5.1) | 49.7 (9.8) | 58.6 (14.8) | 57.7 (14.3) | 46.7 (8.2) | 35.1 (1.7) | 24.4 (−4.2) | 13.1 (−10.5) | 2.6 (−16.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −13 (−25) | −18 (−28) | −8 (−22) | 11 (−12) | 31 (−1) | 41 (5) | 50 (10) | 46 (8) | 34 (1) | 25 (−4) | −2 (−19) | −17 (−27) | −18 (−28) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.39 (86) | 3.21 (82) | 4.17 (106) | 3.63 (92) | 3.25 (83) | 3.89 (99) | 3.27 (83) | 3.23 (82) | 3.56 (90) | 4.03 (102) | 3.66 (93) | 4.30 (109) | 43.59 (1,107) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 14.3 (36) | 14.4 (37) | 9.0 (23) | 1.6 (4.1) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.2 (0.51) | 0.7 (1.8) | 9.0 (23) | 49.2 (125) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.8 | 10.6 | 11.6 | 11.6 | 11.8 | 10.9 | 9.4 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 10.5 | 10.3 | 11.9 | 128.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 6.6 | 6.2 | 4.4 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 4.2 | 23.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 62.3 | 62.0 | 63.1 | 63.0 | 66.7 | 68.5 | 68.4 | 70.8 | 71.8 | 68.5 | 67.5 | 65.4 | 66.5 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 16.5 (−8.6) | 17.6 (−8.0) | 25.2 (−3.8) | 33.6 (0.9) | 45.0 (7.2) | 55.2 (12.9) | 61.0 (16.1) | 60.4 (15.8) | 53.8 (12.1) | 42.8 (6.0) | 33.4 (0.8) | 22.1 (−5.5) | 38.9 (3.8) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 163.4 | 168.4 | 213.7 | 227.2 | 267.3 | 286.5 | 300.9 | 277.3 | 237.1 | 206.3 | 143.2 | 142.3 | 2,633.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 56 | 57 | 58 | 57 | 59 | 63 | 65 | 64 | 63 | 60 | 49 | 50 | 59 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Source 1: NOAA (relative humidity, dew point and sun 1961−1990)[130][121][131] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (UV)[132] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Boston, Massachusetts |

|---|

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

See or edit raw graph data.

Cityscapes[edit]

Demographics[edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1680 | 4,500 | — |

| 1690 | 7,000 | +55.6% |

| 1700 | 6,700 | −4.3% |

| 1710 | 9,000 | +34.3% |

| 1722 | 10,567 | +17.4% |

| 1742 | 16,382 | +55.0% |

| 1765 | 15,520 | −5.3% |

| 1790 | 18,320 | +18.0% |

| 1800 | 24,937 | +36.1% |

| 1810 | 33,787 | +35.5% |

| 1820 | 43,298 | +28.1% |

| 1830 | 61,392 | +41.8% |

| 1840 | 93,383 | +52.1% |

| 1850 | 136,881 | +46.6% |

| 1860 | 177,840 | +29.9% |

| 1870 | 250,526 | +40.9% |

| 1880 | 362,839 | +44.8% |

| 1890 | 448,477 | +23.6% |

| 1900 | 560,892 | +25.1% |

| 1910 | 670,585 | +19.6% |

| 1920 | 748,060 | +11.6% |

| 1930 | 781,188 | +4.4% |

| 1940 | 770,816 | −1.3% |

| 1950 | 801,444 | +4.0% |

| 1960 | 697,197 | −13.0% |

| 1970 | 641,071 | −8.1% |

| 1980 | 562,994 | −12.2% |

| 1990 | 574,283 | +2.0% |

| 2000 | 589,141 | +2.6% |

| 2010 | 617,594 | +4.8% |

| 2020 | 675,647 | +9.4% |

| 2022* | 650,706 | −3.7% |

| *=population estimate. Source: United States census records and Population Estimates Program data.[133][134][135][136][137][138][139][140][141][142][143][144][145] 2010–2020[4] Source: U.S. Decennial Census[146] | ||

| Race/ethnicity | 2020[147] | 2010[148] | 1990[149] | 1970[149] | 1940[149] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic White | 44.7% | 47.0% | 59.0% | 79.5%[e] | 96.6% |

| Black | 22.0% | 24.4% | 23.8% | 16.3% | 3.1% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 19.5% | 17.5% | 10.8% | 2.8%[e] | 0.1% |

| Asian | 9.7% | 8.9% | 5.3% | 1.3% | 0.2% |

| Two or more races | 3.2% | 3.9% | – | – | – |

| Native American | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.2% | – |

In 2020, Boston was estimated to have 691,531 residents living in 266,724 households[4]—a 12% population increase over 2010. The city is the third-most densely populated large U.S. city of over half a million residents, and the most densely populated state capital. Some 1.2 million persons may be within Boston's boundaries during work hours, and as many as 2 million during special events. This fluctuation of people is caused by hundreds of thousands of suburban residents who travel to the city for work, education, health care, and special events.[150]

In the city, 21.9% of the population was aged 19 and under, 14.3% was from 20 to 24, 33.2% from 25 to 44, 20.4% from 45 to 64, and 10.1% was 65 years of age or older. The median age was 30.8 years. For every 100 females, there were 92.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 89.9 males.[151] There were 252,699 households, of which 20.4% had children under the age of 18 living in them, 25.5% were married couples living together, 16.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 54.0% were non-families. 37.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.26 and the average family size was 3.08.[151]

The median household income in Boston was $51,739, while the median income for a family was $61,035. Full-time year-round male workers had a median income of $52,544 versus $46,540 for full-time year-round female workers. The per capita income for the city was $33,158. 21.4% of the population and 16.0% of families were below the poverty line. Of the total population, 28.8% of those under the age of 18 and 20.4% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line.[152] Boston has a significant racial wealth gap with White Bostonians having an median net worth of $247,500 compared to an $8 median net worth for non-immigrant Black residents and $0 for Dominican immigrant residents.[153]

From the 1950s to the end of the 20th century, the proportion of non-Hispanic Whites in the city declined. In 2000, non-Hispanic Whites made up 49.5% of the city's population, making the city majority minority for the first time. However, in the 21st century, the city has experienced significant gentrification, during which affluent Whites have moved into formerly non-White areas. In 2006, the U.S. Census Bureau estimated non-Hispanic Whites again formed a slight majority but as of 2010[update], in part due to the housing crash, as well as increased efforts to make more affordable housing more available, the non-White population has rebounded. This may also have to do with increased Latin American and Asian populations and more clarity surrounding U.S. Census statistics, which indicate a non-Hispanic White population of 47% (some reports give slightly lower figures).[154][155][156]

Ethnicity[edit]

African-Americans comprise 22% of the city's population. People of Irish descent form the second-largest single ethnic group in the city, making up 15.8% of the population, followed by Italians, accounting for 8.3% of the population. People of West Indian and Caribbean ancestry are another sizable group, collectively at over 15%.[157] Boston has the second-biggest congestion of Irish Americans in the United States, trailing Butte, Montana.

In Greater Boston, these numbers grew significantly, with 150,000 Dominicans according to 2018 estimates, 134,000 Puerto Ricans, 57,500 Salvadorans, 39,000 Guatemalans, 36,000 Mexicans, and over 35,000 Colombians.[158] East Boston has a diverse Hispanic/Latino population of Salvadorans, Colombians, Guatemalans, Mexicans, Dominicans and Puerto Ricans. Hispanic populations in southwest Boston neighborhoods are mainly made up of Dominicans and Puerto Ricans, usually sharing neighborhoods in this section with African Americans and Blacks with origins from the Caribbean and Africa especially Cape Verdeans and Haitians. Neighborhoods such as Jamaica Plain and Roslindale have experienced a growing number of Dominican Americans.[159]

There is a large and historical Armenian community in Boston,[160] and the city is home to the Armenian Heritage Park.[161] Additionally, over 27,000 Chinese Americans made their home in Boston city proper in 2013.[162] Overall, according to the 2012–2016 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, the largest ancestry groups in Boston are:[163][164]

| Ancestry | Percentage of Boston population | Percentage of Massachusetts population | Percentage of United States population | City-to-state difference | City-to-USA difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black | 22% | 8.2% | 14-15% | 13.8% | 7% |

| Irish | 14.06% | 21.16% | 10.39% | −7.10% | 3.67% |

| Italian | 8.13% | 13.19% | 5.39% | −5.05% | 2.74% |

| other West Indian | 6.92% | 1.96% | 0.90% | 4.97% | 6.02% |

| Dominican | 5.45% | 2.60% | 0.68% | 2.65% | 4.57% |

| Puerto Rican | 5.27% | 4.52% | 1.66% | 0.75% | 3.61% |

| Chinese | 4.57% | 2.28% | 1.24% | 2.29% | 3.33% |

| German | 4.57% | 6.00% | 14.40% | −1.43% | −9.83% |

| English | 4.54% | 9.77% | 7.67% | −5.23% | −3.13% |

| American | 4.13% | 4.26% | 6.89% | −0.13% | −2.76% |

| Sub-Saharan African | 4.09% | 2.00% | 1.01% | 2.09% | 3.08% |

| Haitian | 3.58% | 1.15% | 0.31% | 2.43% | 3.27% |

| Polish | 2.48% | 4.67% | 2.93% | −2.19% | −0.45% |

| Cape Verdean | 2.21% | 0.97% | 0.03% | 1.24% | 2.18% |

| French | 1.93% | 6.82% | 2.56% | −4.89% | −0.63% |

| Vietnamese | 1.76% | 0.69% | 0.54% | 1.07% | 1.22% |

| Jamaican | 1.70% | 0.44% | 0.34% | 1.26% | 1.36% |

| Russian | 1.62% | 1.65% | 0.88% | −0.03% | 0.74% |

| Asian Indian | 1.31% | 1.39% | 1.09% | −0.08% | 0.22% |

| Scottish | 1.30% | 2.28% | 1.71% | −0.98% | −0.41% |

| French Canadian | 1.19% | 3.91% | 0.65% | −2.71% | 0.54% |

| Mexican | 1.12% | 0.67% | 11.96% | 0.45% | −10.84% |

| Arab | 1.10% | 1.10% | 0.59% | 0.00% | 0.50% |

Demographic breakdown by ZIP Code[edit]

Income[edit]

Data is from the 2008–2012 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates.[165][166][167]

| Rank | ZIP Code (ZCTA) | Per capita income | Median household income | Median family income | Population | Number of households |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 02110 (Financial District) | $152,007 | $123,795 | $196,518 | 1,486 | 981 |

| 2 | 02199 (Prudential Center) | $151,060 | $107,159 | $146,786 | 1,290 | 823 |

| 3 | 02210 (Fort Point) | $93,078 | $111,061 | $223,411 | 1,905 | 1,088 |

| 4 | 02109 (North End) | $88,921 | $128,022 | $162,045 | 4,277 | 2,190 |

| 5 | 02116 (Back Bay/Bay Village) | $81,458 | $87,630 | $134,875 | 21,318 | 10,938 |

| 6 | 02108 (Beacon Hill/Financial District) | $78,569 | $95,753 | $153,618 | 4,155 | 2,337 |

| 7 | 02114 (Beacon Hill/West End) | $65,865 | $79,734 | $169,107 | 11,933 | 6,752 |

| 8 | 02111 (Chinatown/Financial District/Leather District) | $56,716 | $44,758 | $88,333 | 7,616 | 3,390 |

| 9 | 02129 (Charlestown) | $56,267 | $89,105 | $98,445 | 17,052 | 8,083 |

| 10 | 02467 (Chestnut Hill) | $53,382 | $113,952 | $148,396 | 22,796 | 6,351 |

| 11 | 02113 (North End) | $52,905 | $64,413 | $112,589 | 7,276 | 4,329 |

| 12 | 02132 (West Roxbury) | $44,306 | $82,421 | $110,219 | 27,163 | 11,013 |

| 13 | 02118 (South End) | $43,887 | $50,000 | $49,090 | 26,779 | 12,512 |

| 14 | 02130 (Jamaica Plain) | $42,916 | $74,198 | $95,426 | 36,866 | 15,306 |

| 15 | 02127 (South Boston) | $42,854 | $67,012 | $68,110 | 32,547 | 14,994 |

| Massachusetts | $35,485 | $66,658 | $84,380 | 6,560,595 | 2,525,694 | |

| Boston | $33,589 | $53,136 | $63,230 | 619,662 | 248,704 | |

| Suffolk County | $32,429 | $52,700 | $61,796 | 724,502 | 287,442 | |

| 16 | 02135 (Brighton) | $31,773 | $50,291 | $62,602 | 38,839 | 18,336 |

| 17 | 02131 (Roslindale) | $29,486 | $61,099 | $70,598 | 30,370 | 11,282 |

| United States | $28,051 | $53,046 | $64,585 | 309,138,711 | 115,226,802 | |

| 18 | 02136 (Hyde Park) | $28,009 | $57,080 | $74,734 | 29,219 | 10,650 |

| 19 | 02134 (Allston) | $25,319 | $37,638 | $49,355 | 20,478 | 8,916 |

| 20 | 02128 (East Boston) | $23,450 | $49,549 | $49,470 | 41,680 | 14,965 |

| 21 | 02122 (Dorchester-Fields Corner) | $23,432 | $51,798 | $50,246 | 25,437 | 8,216 |

| 22 | 02124 (Dorchester-Codman Square-Ashmont) | $23,115 | $48,329 | $55,031 | 49,867 | 17,275 |

| 23 | 02125 (Dorchester-Uphams Corner-Savin Hill) | $22,158 | $42,298 | $44,397 | 31,996 | 11,481 |

| 24 | 02163 (Allston-Harvard Business School) | $21,915 | $43,889 | $91,190 | 1,842 | 562 |

| 25 | 02115 (Back Bay, Longwood, Museum of Fine Arts/Symphony Hall area) | $21,654 | $23,677 | $50,303 | 29,178 | 9,958 |

| 26 | 02126 (Mattapan) | $20,649 | $43,532 | $52,774 | 27,335 | 9,510 |

| 27 | 02215 (Fenway-Kenmore) | $19,082 | $30,823 | $72,583 | 23,719 | 7,995 |

| 28 | 02119 (Roxbury) | $18,998 | $27,051 | $35,311 | 24,237 | 9,769 |

| 29 | 02121 (Dorchester-Mount Bowdoin) | $18,226 | $30,419 | $35,439 | 26,801 | 9,739 |

| 30 | 02120 (Mission Hill) | $17,390 | $32,367 | $29,583 | 13,217 | 4,509 |

Religion[edit]

According to a 2014 study by the Pew Research Center, 57% of the population of the city identified themselves as Christians, with 25% attending a variety of Protestant churches and 29% professing Roman Catholic beliefs;[168][169] 33% claim no religious affiliation, while the remaining 10% are composed of adherents of Judaism, Buddhism, Islam, Hinduism, Baháʼí and other faiths.

As of 2010[update], the Catholic Church had the highest number of adherents as a single denomination in the Greater Boston area, with more than two million members and 339 churches, followed by the Episcopal Church with 58,000 adherents in 160 churches. The United Church of Christ had 55,000 members and 213 churches.[170]

The Boston metro area contained a Jewish population of approximately 248,000 as of 2015.[171] More than half the Jewish households in the Greater Boston area reside in the city itself, Brookline, Newton, Cambridge, Somerville, or adjacent towns.[171]

A small minority practices Confucianism, and some practice Boston Confucianism, an American evolution of Confucianism adapted for Boston intellectuals.

Economy[edit]

| Bos. | Corporation | US | Revenue (in millions) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | General Electric | 18 | $122,274 |

| 2 | Liberty Mutual | 68 | $42,687 |

| 3 | State Street | 259 | $11,774 |

| 4 | American Tower | 419 | $6,663.9 |

A global city, Boston is placed among the top 30 most economically powerful cities in the world.[174] Encompassing $363 billion, the Greater Boston metropolitan area has the sixth-largest economy in the country and 12th-largest in the world.[175]

Boston's colleges and universities exert a significant impact on the regional economy. Boston attracts more than 350,000 college students from around the world, who contribute more than US$4.8 billion annually to the city's economy.[176][177] The area's schools are major employers and attract industries to the city and surrounding region. The city is home to a number of technology companies and is a hub for biotechnology, with the Milken Institute rating Boston as the top life sciences cluster in the country.[178] Boston receives the highest absolute amount of annual funding from the National Institutes of Health of all cities in the United States.[179]

The city is considered highly innovative for a variety of reasons, including the presence of academia, access to venture capital, and the presence of many high-tech companies.[25][180] The Route 128 corridor and Greater Boston continue to be a major center for venture capital investment,[181] and high technology remains an important sector.

Tourism also composes a large part of Boston's economy, with 21.2 million domestic and international visitors spending $8.3 billion in 2011.[182] Excluding visitors from Canada and Mexico, over 1.4 million international tourists visited Boston in 2014, with those from China and the United Kingdom leading the list.[183] Boston's status as a state capital as well as the regional home of federal agencies has rendered law and government to be another major component of the city's economy.[184] The city is a major seaport along the East Coast of the United States and the oldest continuously operated industrial and fishing port in the Western Hemisphere.[185]

In the 2018 Global Financial Centres Index, Boston was ranked as having the thirteenth most competitive financial services center in the world and the second most competitive in the United States.[186] Boston-based Fidelity Investments helped popularize the mutual fund in the 1980s and has made Boston one of the top financial centers in the United States.[187] The city is home to the headquarters of Santander Bank, and Boston is a center for venture capital firms. State Street Corporation, which specializes in asset management and custody services, is based in the city. Boston is a printing and publishing center[188]—Houghton Mifflin Harcourt is headquartered within the city, along with Bedford-St. Martin's Press and Beacon Press. Pearson PLC publishing units also employ several hundred people in Boston. The city is home to three major convention centers—the Hynes Convention Center in the Back Bay, and the Seaport World Trade Center and Boston Convention and Exhibition Center on the South Boston waterfront.[189] The General Electric Corporation announced in January 2016 its decision to move the company's global headquarters to the Seaport District in Boston, from Fairfield, Connecticut, citing factors including Boston's preeminence in the realm of higher education.[190] Boston is home to the headquarters of several major athletic and footwear companies including Converse, New Balance, and Reebok. Rockport, Puma and Wolverine World Wide, Inc. headquarters or regional offices[191] are just outside the city.[192]

In 2019, a yearly ranking of time wasted in traffic listed Boston area drivers lost approximately 164 hours a year in lost productivity due to the area's traffic congestion. This amounted to $2,300 a year per driver in costs.[193]

Education[edit]

Primary and secondary education[edit]

The Boston Public Schools enroll 57,000 students attending 145 schools, including Boston Latin Academy, John D. O'Bryant School of Math & Science, and the renowned Boston Latin School. The Boston Latin School was established in 1635 and is the oldest public high school in the US. Boston also operates the United States' second-oldest public high school and its oldest public elementary school.[20] The system's students are 40% Hispanic or Latino, 35% Black or African American, 13% White, and 9% Asian.[194] There are private, parochial, and charter schools as well, and approximately 3,300 minority students attend participating suburban schools through the Metropolitan Educational Opportunity Council.[195] In September 2019, the city formally inaugurated Boston Saves, a program that provides every child enrolled in the city's kindergarten system a savings account containing $50 to be used toward college or career training.[196]

Higher education[edit]

Several of the most renowned and highly ranked universities in the world are near Boston.[198] Three universities with a major presence in the city, Harvard, MIT, and Tufts, are just outside of Boston in the cities of Cambridge and Somerville, known as the Brainpower Triangle.[199] Harvard is the nation's oldest institute of higher education and is centered across the Charles River in Cambridge, though the majority of its land holdings and a substantial amount of its educational activities are in Boston. Its business school and athletics facilities are in Boston's Allston neighborhood, and its medical, dental, and public health schools are located in the Longwood area.[200]

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) originated in Boston and was long known as "Boston Tech"; it moved across the river to Cambridge in 1916.[201] Tufts University's main campus is north of the city in Somerville and Medford, though it locates its medical and dental schools in Boston's Chinatown at Tufts Medical Center.[202]

Five members of the Association of American Universities are in Greater Boston (more than any other metropolitan area): Harvard University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Tufts University, Boston University, and Brandeis University.[203] Furthermore, Greater Boston contains seven Highest Research Activity (R1) Universities as per the Carnegie Classification. This includes, in addition to the aforementioned five, Boston College, and Northeastern University. This is, by a large margin, the highest concentration of such institutions in a single metropolitan area. Hospitals, universities, and research institutions in Greater Boston received more than $1.77 billion in National Institutes of Health grants in 2013, more money than any other American metropolitan area.[204] This high density of research institutes also contributes to Boston's high density of early career researchers, which, due to high housing costs in the region, have been shown to face housing stress.[205][206]

Greater Boston has more than 50 colleges and universities, with 250,000 students enrolled in Boston and Cambridge alone.[207] The city's largest private universities include Boston University (also the city's fourth-largest employer),[208] with its main campus along Commonwealth Avenue and a medical campus in the South End, Northeastern University in the Fenway area,[209] Suffolk University near Beacon Hill, which includes law school and business school,[210] and Boston College, which straddles the Boston (Brighton)–Newton border.[211] Boston's only public university is the University of Massachusetts Boston on Columbia Point in Dorchester. Roxbury Community College and Bunker Hill Community College are the city's two public community colleges. Altogether, Boston's colleges and universities employ more than 42,600 people, accounting for nearly seven percent of the city's workforce.[212]

Smaller private colleges include Babson College, Bentley University, Boston Architectural College, Emmanuel College, Fisher College, MGH Institute of Health Professions, Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, Simmons University, Wellesley College, Wheelock College, Wentworth Institute of Technology, New England School of Law (originally established as America's first all female law school),[213] and Emerson College.[214]

Metropolitan Boston is home to several conservatories and art schools, including Lesley University College of Art and Design, Massachusetts College of Art, the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, New England Institute of Art, New England School of Art and Design (Suffolk University), Longy School of Music of Bard College, and the New England Conservatory (the oldest independent conservatory in the United States).[215] Other conservatories include the Boston Conservatory and Berklee College of Music, which has made Boston an important city for jazz music.[216]

Many trade schools also exist in the city, such as the Boston Career Institute, the North Bennet Street School, the Madison Park technical School, JATC of Greater Boston, and many others.

Healthcare[edit]

Many of Boston's medical facilities are associated with universities. The Longwood Medical and Academic Area, adjacent to the Fenway, district, is home to a large number of medical and research facilities, including Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston Children's Hospital, Dana–Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Harvard School of Dental Medicine, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Joslin Diabetes Center, and the Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences.[217]Prominent medical facilities, including Massachusetts General Hospital, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary and Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital are in the Beacon Hill area. Many of the facilities in Longwood and near Massachusetts General Hospital are affiliated with Harvard Medical School.[218] Tufts Medical Center (formerly Tufts-New England Medical Center), in the southern portion of the Chinatown neighborhood, is affiliated with Tufts University School of Medicine. Boston Medical Center, in the South End neighborhood, is the region's largest safety-net hospital and trauma center. Formed by the merger of Boston City Hospital, the first municipal hospital in the United States, and Boston University Hospital, Boston Medical Center now serves as the primary teaching facility for the Boston University School of Medicine.[219][220] St. Elizabeth's Medical Center is in Brighton Center of the city's Brighton neighborhood. New England Baptist Hospital is in Mission Hill. The city has Veterans Affairs medical centers in the Jamaica Plain and West Roxbury neighborhoods.[221] The Boston Public Health Commission, an agency of the Massachusetts government, oversees health concerns for city residents.[222] Boston EMS provides pre-hospital emergency medical services to residents and visitors.

Public safety[edit]

Boston included $414 million in spending on the Boston Police Department in the fiscal 2021 budget. This is the second largest allocation of funding by the city after the allocation to Boston Public Schools.[223]

Like many major American cities, Boston has experienced a great reduction in violent crime since the early 1990s. Boston's low crime rate since the 1990s has been credited to the Boston Police Department's collaboration with neighborhood groups and church parishes to prevent youths from joining gangs, as well as involvement from the United States Attorney and District Attorney's offices. This helped lead in part to what has been touted as the "Boston Miracle". Murders in the city dropped from 152 in 1990 (for a murder rate of 26.5 per 100,000 people) to just 31—not one of them a juvenile—in 1999 (for a murder rate of 5.26 per 100,000).[224]

In 2008, there were 62 reported homicides.[225] Through December 30, 2016, major crime was down seven percent and there were 46 homicides compared to 40 in 2015.[226]

Culture[edit]

Boston shares many cultural roots with greater New England, including a dialect of the non-rhotic Eastern New England accent known as the Boston accent[227] and a regional cuisine with a large emphasis on seafood, salt, and dairy products.[228] Boston also has its own collection of neologisms known as Boston slang and sardonic humor.[229]

In the early 1800s, William Tudor wrote that Boston was "'perhaps the most perfect and certainly the best-regulated democracy that ever existed. There is something so impossible in the immortal fame of Athens, that the very name makes everything modern shrink from comparison; but since the days of that glorious city I know of none that has approached so near in some points, distant as it may still be from that illustrious model.'[230] From this, Boston has been called the "Athens of America" (also a nickname of Philadelphia)[231] for its literary culture, earning a reputation as "the intellectual capital of the United States".[232]

In the nineteenth century, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Margaret Fuller, James Russell Lowell, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote in Boston. Some consider the Old Corner Bookstore to be the "cradle of American literature", the place where these writers met and where The Atlantic Monthly was first published.[233] In 1852, the Boston Public Library was founded as the first free library in the United States.[232] Boston's literary culture continues today thanks to the city's many universities and the Boston Book Festival.

Music is afforded a high degree of civic support in Boston. The Boston Symphony Orchestra is one of the "Big Five", a group of the greatest American orchestras, and the classical music magazine Gramophone called it one of the "world's best" orchestras.[234] Symphony Hall (west of Back Bay) is home to the Boston Symphony Orchestra and the related Boston Youth Symphony Orchestra, which is the largest youth orchestra in the nation, and to the Boston Pops Orchestra. The British newspaper The Guardian called Boston Symphony Hall "one of the top venues for classical music in the world", adding "Symphony Hall in Boston was where science became an essential part of concert hall design".[235] Other concerts are held at the New England Conservatory's Jordan Hall. The Boston Ballet performs at the Boston Opera House. Other performing-arts organizations in the city include the Boston Lyric Opera Company, Opera Boston, Boston Baroque (the first permanent Baroque orchestra in the US),[236] and the Handel and Haydn Society (one of the oldest choral companies in the United States).[237] The city is a center for contemporary classical music with a number of performing groups, several of which are associated with the city's conservatories and universities. These include the Boston Modern Orchestra Project and Boston Musica Viva.[236] Several theaters are in or near the Theater District south of Boston Common, including the Cutler Majestic Theatre, Citi Performing Arts Center, the Colonial Theater, and the Orpheum Theatre.[238]

There are several major annual events, such as First Night which occurs on New Year's Eve, the Boston Early Music Festival, the annual Boston Arts Festival at Christopher Columbus Waterfront Park, the annual Boston gay pride parade and festival held in June, and Italian summer feasts in the North End honoring Catholic saints.[239] The city is the site of several events during the Fourth of July period. They include the week-long Harborfest festivities[240] and a Boston Pops concert accompanied by fireworks on the banks of the Charles River.[241]

Several historic sites relating to the American Revolution period are preserved as part of the Boston National Historical Park because of the city's prominent role. Many are found along the Freedom Trail,[242] which is marked by a red line of bricks embedded in the ground.

The city is also home to several art museums and galleries, including the Museum of Fine Arts and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.[243] The Institute of Contemporary Art is housed in a contemporary building designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro in the Seaport District.[244] Boston's South End Art and Design District (SoWa) and Newbury St. are both art gallery destinations.[245][246] Columbia Point is the location of the University of Massachusetts Boston, the Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the United States Senate, the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, and the Massachusetts Archives and Commonwealth Museum. The Boston Athenæum (one of the oldest independent libraries in the United States),[247] Boston Children's Museum, Bull & Finch Pub (whose building is known from the television show Cheers),[248] Museum of Science, and the New England Aquarium are within the city.

Boston has been a noted religious center from its earliest days. The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Boston serves nearly 300 parishes and is based in the Cathedral of the Holy Cross (1875) in the South End, while the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts serves just under 200 congregations, with the Cathedral Church of St. Paul (1819) as its episcopal seat. Unitarian Universalism has its headquarters in the Fort Point neighborhood. The Christian Scientists are headquartered in Back Bay at the Mother Church (1894). The oldest church in Boston is First Church in Boston, founded in 1630.[249] King's Chapel was the city's first Anglican church, founded in 1686 and converted to Unitarianism in 1785. Other churches include Old South Church (1669), Christ Church (better known as Old North Church, 1723), the oldest church building in the city, Trinity Church (1733), Park Street Church (1809), and Basilica and Shrine of Our Lady of Perpetual Help on Mission Hill (1878).[250]

Environment[edit]

Pollution control[edit]

Air quality in Boston is generally very good. Between 2004 and 2013, there were only four days in which the air was unhealthy for the general public, according to the EPA.[251]

Some of the cleaner energy facilities in Boston include the Allston green district, with three ecologically compatible housing facilities.[252] Boston is also breaking ground on multiple green affordable housing facilities to help reduce the carbon impact of the city while simultaneously making these initiatives financially available to a greater population. Boston's climate plan is updated every three years and was most recently modified in 2019.[253] This legislature includes the Building Energy Reporting and Disclosure Ordinance, which requires the city's larger buildings to disclose their yearly energy and water use statistics and to partake in an energy assessment every five years. These statistics are made public by the city, thereby increasing incentives for buildings to be more environmentally conscious.[254]

Mayor Thomas Menino introduced the Renew Boston Whole Building Incentive which reduces the cost of living in buildings that are deemed energy efficient. This gives people an opportunity to find housing in neighborhoods that support the environment. The ultimate goal of this initiative is to enlist 500 Bostonians to participate in a free, in-home energy assessment.[254]

Water purity and availability[edit]

Many older buildings in certain areas of Boston are supported by wooden piles driven into the area's fill; these piles remain sound if submerged in water, but are subject to dry rot if exposed to air for long periods.[255]Ground water levels have been dropping in many areas of the city, due in part to an increase in the amount of rainwater discharged directly into sewers rather than absorbed by the ground. The Boston Groundwater Trust coordinates monitoring ground water levels throughout the city via a network of public and private monitoring wells.[256] However, Boston's drinking water supply from the Quabbin and Wachusett Reservoirs[257] is one of the very few in the country so pure as to satisfy the Federal Clean Water Act without filtration.[258]

Climate change and sea level rise[edit]

The City of Boston has developed a climate action plan covering carbon reduction in buildings, transportation, and energy use.[259] Mayor Thomas Menino commissioned the city's first Climate Action Plan in 2007, with an update released in 2011.[260] Since then, Mayor Marty Walsh has built upon these plans with further updates released in 2014 and 2019. As a coastal city built largely on fill, sea-level rise is of major concern to the city government. The latest version of the climate action plan anticipates between two and seven feet of sea-level rise in Boston by the end of the century. A separate initiative, Resilient Boston Harbor, lays out neighborhood-specific recommendations for coastal resilience.[261]

Sports[edit]

Boston has teams in the four major North American men's professional sports leagues plus Major League Soccer, and, as of 2019, has won 39 championships in these leagues. It is one of nine cities, along with Chicago, Dallas, Detroit, Los Angeles, New York City, Philadelphia, St. Louis, and Washington, D.C., to have won championships in all four major North American sports leagues. During a 17-year stretch from 2001 to 2018, the city's professional sports teams won twelve championships: Patriots (2001, 2003, 2004, 2014, 2016 and 2018), Red Sox (2004, 2007, 2013, and 2018), Celtics (2008), and Bruins (2011). The Celtics and Bruins remain competitive for titles in the century's third decade, though the Patriots and Red Sox have fallen off from these recent glory days. This love of sports made Boston the United States Olympic Committee's choice to bid to hold the 2024 Summer Olympic Games, but the city cited financial concerns when it withdrew its bid on July 27, 2015.[262]

The Boston Red Sox, a founding member of the American League of Major League Baseball in 1901, play their home games at Fenway Park, near Kenmore Square, in the city's Fenway section. Built in 1912, it is the oldest sports arena or stadium in active use in the United States among the four major professional American sports leagues, Major League Baseball, the National Football League, National Basketball Association, and the National Hockey League.[263] Boston was the site of the first game of the first modern World Series, in 1903. The series was played between the AL Champion Boston Americans and the NL champion Pittsburgh Pirates.[264][265] Persistent reports that the team was known in 1903 as the "Boston Pilgrims" appear to be unfounded.[266] Boston's first professional baseball team was the Red Stockings, one of the charter members of the National Association in 1871, and of the National League in 1876. The team played under that name until 1883, under the name Beaneaters until 1911, and under the name Braves from 1912 until they moved to Milwaukee after the 1952 season. Since 1966 they have played in Atlanta as the Atlanta Braves.[267]

The TD Garden, formerly called the FleetCenter and built to replace the old, since-demolished Boston Garden, is above North Station and is the home of two major league teams: the Boston Bruins of the National Hockey League and the Boston Celtics of the National Basketball Association. The arena seats 18,624 for basketball games and 17,565 for ice hockey games. The Bruins were the first American member of the National Hockey League and an Original Six franchise.[268] The Boston Celtics were founding members of the Basketball Association of America, one of the two leagues that merged to form the NBA.[269] The Celtics, along with the Los Angeles Lakers, have the distinction of having won more championships than any other NBA team, both with seventeen.[270] The venue also hosted the 2021 Laver Cup, an international men's tennis tournament consisting of two teams: Team Europe and Team World.

While they have played in suburban Foxborough since 1971, the New England Patriots of the National Football League were founded in 1960 as the Boston Patriots, changing their name after relocating. The team won the Super Bowl after the 2001, 2003, 2004, 2014, 2016 and 2018 seasons.[271] They share Gillette Stadium with the New England Revolution of Major League Soccer. The Boston Breakers of Women's Professional Soccer, which formed in 2009, played their home games at Dilboy Stadium in Somerville.[272][needs update] The Boston Storm of the United Women's Lacrosse League was formed in 2015.[273][needs update]

The area's many colleges and universities are active in college athletics. Four NCAA Division I members play in the area—Boston College, Boston University, Harvard University, and Northeastern University. Of the four, only Boston College participates in college football at the highest level, the Football Bowl Subdivision. Harvard participates in the second-highest level, the Football Championship Subdivision.

Boston has Esports teams as well, such as the Overwatch League (OWL)'s Boston Uprising. Established in 2017,[274] they were the first team to complete a perfect stage with 0 losses.[275] The Boston Breach is another esports team in the Call of Duty League (CDL).[276]

One of the best known sporting events in the city is the Boston Marathon, the 26.2 mi (42.2 km) race which is the world's oldest annual marathon,[277] run on Patriots' Day in April. On April 15, 2013, two explosions killed three people and injured hundreds at the marathon.[104]Another major annual event is the Head of the Charles Regatta, held in October.[278]

Boston is one of eleven U.S. cities which will host matches during the 2026 FIFA World Cup, with games taking place at Gillette Stadium.[279]

| Team | League | Sport | Venue | Capacity | Founded | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boston Red Sox | MLB | Baseball | Fenway Park | 37,755 | 1903 | 1912, 1915, 1916, 1918, 2004, 2007, 2013, 2018 |

| Boston Bruins | NHL | Ice hockey | TD Garden | 17,850 | 1924 | 1928–29, 1938–39, 1940–41, 1969–70, 1971–72, 2010–11 |

| Boston Celtics | NBA | Basketball | TD Garden | 19,156 | 1946 | 1956–57, 1958–59, 1959–60, 1960–61, 1961–62, 1962–63, 1963–64, 1964–65, 1965–66, 1967–68, 1968–69, 1973–74, 1975–76, 1980–81, 1983–84, 1985–86, 2007–08 |

| New England Patriots | NFL | American football | Gillette Stadium | 65,878 | 1960 | 2001, 2003, 2004, 2014, 2016, 2018 |

| New England Revolution | MLS | Soccer | Gillette Stadium | 20,000 | 1996 | None |

Parks and recreation[edit]

Boston Common, near the Financial District and Beacon Hill, is the oldest public park in the United States.[280] Along with the adjacent Boston Public Garden, it is part of the Emerald Necklace, a string of parks designed by Frederick Law Olmsted to run through the city. The Emerald Necklace includes the Back Bay Fens, Arnold Arboretum, Jamaica Pond, Boston's largest body of freshwater, and Franklin Park, the city's largest park and home of the Franklin Park Zoo.[281] Another major park is the Esplanade, along the banks of the Charles River. The Hatch Shell, an outdoor concert venue, is adjacent to the Charles River Esplanade. Other parks are scattered throughout the city, with major parks and beaches near Castle Island and the south end, in Charlestown and along the Dorchester, South Boston, and East Boston shorelines.[282]

Boston's park system is well-reputed nationally. In its 2013 ParkScore ranking, The Trust for Public Land reported Boston was tied with Sacramento and San Francisco for having the third-best park system among the 50 most populous U.S. cities.[283] ParkScore ranks city park systems by a formula that analyzes the city's median park size, park acres as percent of city area, the percent of residents within a half-mile of a park, spending of park services per resident, and the number of playgrounds per 10,000 residents.

Government and politics[edit]

Boston has a strong mayor–council government system in which the mayor (elected every fourth year) has extensive executive power. Michelle Wu, a city councilor, became mayor in November 2021, succeeding Kim Janey, a former City Council President, who became the Acting Mayor in March 2021 following Marty Walsh's confirmation to the position of Secretary of Labor in the Biden/Harris Administration. Walsh's predecessor Thomas Menino's twenty-year tenure was the longest in the city's history.[284]The Boston City Council is elected every two years; there are nine district seats, and four citywide "at-large" seats.[285] The School Committee, which oversees the Boston Public Schools, is appointed by the mayor.[286]

In addition to city government, numerous commissions and state authorities, including the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation, the Boston Public Health Commission, the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA), and the Massachusetts Port Authority (Massport), play a role in the life of Bostonians. As the capital of Massachusetts, Boston plays a major role in state politics.

The city has several federal facilities, including the John F. Kennedy Federal Office Building, the Thomas P. O'Neill Jr. Federal Building,[287] the John W. McCormack Post Office and Courthouse, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit, and the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts. Both courts are housed in the John Joseph Moakley United States Courthouse.

Federally, Boston is split between two congressional districts. Three-fourths of the city is in the 7th district and is represented by Ayanna Pressley while the remaining southern fourth is in the 8th district and is represented by Stephen Lynch,[288] both of whom are Democrats; a Republican has not represented a significant portion of Boston in over a century. The state's senior member of the United States Senate is Democrat Elizabeth Warren, first elected in 2012. The state's junior member of the United States Senate is Democrat Ed Markey, who was elected in 2013 to succeed John Kerry after Kerry's appointment and confirmation as the United States Secretary of State.

The city uses an algorithm created by the Walsh administration, called CityScore, to measure the effectiveness of various city services. This score is available on a public online dashboard and allows city managers in police, fire, schools, emergency management services, and 3-1-1 to take action and make adjustments in areas of concern.[289]

Media[edit]

The city of Boston has been featured in multiple forms of media and fiction due to its status as the capital of Massachusetts.

Newspapers[edit]

The Boston Globe is the oldest and largest daily newspaper in the city[290] and is generally acknowledged as its paper of record.[291] The city is also served by other publications such as the Boston Herald, Boston magazine, DigBoston, and the Boston edition of Metro. The Christian Science Monitor, headquartered in Boston, was formerly a worldwide daily newspaper but ended publication of daily print editions in 2009, switching to continuous online and weekly magazine format publications.[292] The Boston Globe also releases a teen publication to the city's public high schools, called Teens in Print or T.i.P., which is written by the city's teens and delivered quarterly within the school year.[293] The Improper Bostonian, a glossy lifestyle magazine, was published from 1991 through April 2019.

The city's growing Latino population has given rise to a number of local and regional Spanish-language newspapers. These include El Planeta (owned by the former publisher of the Boston Phoenix), El Mundo, and La Semana. Siglo21, with its main offices in nearby Lawrence, is also widely distributed.[294]

Various LGBT publications serve the city's large LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) population such as The Rainbow Times, the only minority and lesbian-owned LGBT news magazine. Founded in 2006, The Rainbow Times is now based out of Boston, but serves all of New England.[295]

Radio and television[edit]

Boston is the largest broadcasting market in New England, with the radio market being the ninth largest in the United States.[296] Several major AM stations include talk radio WRKO, sports/talk station WEEI, and iHeartMedia WBZ.[297] WBZ (AM) broadcasts a news radio format and is a 50,000 watt "clear channel" station, whose nighttime broadcasts are heard hundreds of miles from Boston. A variety of commercial FM radio formats serve the area, as do NPR stations WBUR and WGBH. College and university radio stations include WERS (Emerson), WHRB (Harvard), WUMB (UMass Boston), WMBR (MIT), WZBC (Boston College), WMFO (Tufts University), WBRS (Brandeis University), WTBU (Boston University, campus and web only), WRBB (Northeastern University) and WMLN-FM (Curry College).

The Boston television DMA, which also includes Manchester, New Hampshire, is the eighth largest in the United States.[298] The city is served by stations representing every major American network, including WBZ-TV 4 and its sister station WSBK-TV 38 (the former a CBS O&O, the latter an independent station), WCVB-TV 5 and its sister station WMUR-TV 9 (both ABC), WHDH 7 and its sister station WLVI 56 (the former an independent station, the latter a CW affiliate), WBTS-CD 15 (an NBC O&O), and WFXT 25 (Fox). The city is also home to PBS member station WGBH-TV 2, a major producer of PBS programs,[299] which also operates WGBX 44. Spanish-language television networks, including UniMás (WUTF-TV 27), Telemundo (WNEU 60, a sister station to WBTS-CD), and Univisión (WUNI 66), have a presence in the region, with WNEU serving as network owned-and-operated station. Most of the area's television stations have their transmitters in nearby Needham and Newton along the Route 128 corridor.[300] Six Boston television stations are carried by Canadian satellite television provider Bell TV and by cable television providers in Canada.

Film[edit]

Films have been made in Boston since as early as 1903, and it continues to be both a popular setting and a popular filming location.[301][302] Notable movies like The Departed, Good Will Hunting[303] The Fighter and The Town were filmed in Boston.[304] Notable movies set in Boston include Good Will Hunting and The Social Network.[305]

Video games[edit]

Video games have used Boston as a backdrop and setting, such as Assassin's Creed III published in 2012 and Fallout 4 in 2015.[306][307] Some characters from video games are from Boston, such as the Scout from Team Fortress 2.[308] The gaming convention PAX East is held in Boston, which many gaming companies like Microsoft, Ubisoft, and Wizards of the Coast have previously attended.[309]

Infrastructure[edit]

Transportation[edit]