Нью-Джерси

Нью-Джерси | |

|---|---|

| Штат Нью-Джерси | |

| Прозвище : Штат садов [1] | |

| Девиз(ы) : Свобода и процветание | |

Map of the United States with New Jersey highlighted | |

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Province of New Jersey |

| Admitted to the Union | December 18, 1787 (3rd) |

| Capital | Trenton |

| Largest city | Newark |

| Largest county or equivalent | Bergen |

| Largest metro and urban areas | New York |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Phil Murphy (D) |

| • Lieutenant Governor | Tahesha Way (D) |

| Legislature | New Jersey Legislature |

| • Upper house | Senate |

| • Lower house | General Assembly |

| Judiciary | Supreme Court of New Jersey |

| U.S. senators | Bob Menendez (I) Cory Booker (D) |

| U.S. House delegation | 8 Democrats 3 Republicans 1 vacant (list) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 8,722.58 sq mi (22,591.38 km2) |

| • Land | 7,354.22[2] sq mi (19,047.34 km2) |

| • Water | 1,368.36 sq mi (3,544.04 km2) 15.7% |

| • Rank | 47th |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 170 mi (273 km) |

| • Width | 70 mi (112 km) |

| Elevation | 250 ft (80 m) |

| Highest elevation | 1,803 ft (549.6 m) |

| Lowest elevation (Atlantic Ocean[3]) | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 9,288,994 |

| • Rank | 11th |

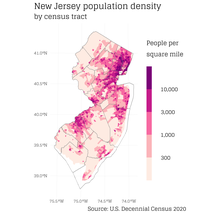

| • Density | 1,263.0/sq mi (487.6/km2) |

| • Rank | 1st |

| • Median household income | $97,126 in 2,022[4] |

| • Income rank | 3rd |

| Demonym(s) | New Jerseyan (official),[7] New Jerseyite[8][9] |

| Language | |

| • Official language | None |

| • Spoken language | |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) |

| USPS abbreviation | NJ |

| ISO 3166 code | US-NJ |

| Traditional abbreviation | N.J. |

| Latitude | 38°56′ N to 41°21′ N |

| Longitude | 73°54′ W to 75°34′ W |

| Website | nj |

Нью-Джерси — штат, расположенный как в Среднеатлантическом , так и в Северо-восточном регионах США. Это самый густонаселенный из всех 50 штатов США , расположенный в центре северо-восточного мегаполиса . Нью-Джерси граничит на севере и востоке со штатом Нью-Йорк ; на востоке, юго-востоке и юге омывается Атлантическим океаном ; на западе - у реки Делавэр и Пенсильвании ; и на юго-западе от залива Делавэр и штата Делавэр . На площади 7 354 квадратных миль (19 050 км²) 2 ), Нью-Джерси является пятым по величине штатом по площади , но с населением около 9,3 миллиона человек по данным переписи населения США 2020 года , самого высокого показателя за десятилетие, он занимает 11-е место по численности населения . Столица штата — Трентон , а самый густонаселенный город штата — Ньюарк . Нью-Джерси - единственный штат США, в котором каждый округ считается городским Бюро переписи населения США, при этом 13 округов входят в агломерацию Нью-Йорка , семь округов в агломерацию Филадельфии и округ Уоррен , являющийся частью промышленно развитой долины Лихай агломерации . .

New Jersey was first inhabited by Paleo-Indians as early as 13,000 B.C.E., with the Lenape being the dominant Indigenous group when Europeans arrived in the early 17th century. Dutch and Swedish colonists founded the first European settlements in the state,[10] with the British later seizing control of the region and establishing the Province of New Jersey, named after the largest of the Channel Islands.[11][12] The colony's fertile lands and relative religious tolerance drew a large and diverse population. New Jersey was among the Thirteen Colonies that supported the American Revolution, hosting several pivotal battles and military commands in the American Revolutionary War. On December 18, 1787, New Jersey became the third state to ratify the United States Constitution, which granted it admission to the Union, and it was the first state to ratify the U.S. Bill of Rights on November 20, 1789.

New Jersey remained in the Union during the American Civil War and provided troops, resources, and military leaders in support of the Union Army. After the war, the state emerged as a major manufacturing center and a leading destination for immigrants, helping drive the Industrial Revolution in the U.S. New Jersey was the site of many industrial, technological, and commercial innovations,[13] including the first town (Roselle) to be illuminated by electricity, the first incandescent light bulb, and the first steam locomotive.[14] Many prominent Americans associated with New Jersey have proven influential nationally and globally, including in academia, advocacy, business, entertainment, government, military, non-profit leadership, and other fields.

New Jersey's central location in the Northeast megalopolis helped fuel its rapid growth and suburbanization in the second half of the 20th century. Since the beginning of the 21st century, the state's economy has become highly diversified, with major sectors including biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, information technology, finance, and tourism, and it has become an Atlantic seaboard epicenter for logistics and distribution. New Jersey remains a major destination for immigrants and is home to one of the world's most ethnically diverse and multicultural populations.[15][16] Echoing historical trends, the state has increasingly re-urbanized, with growth in cities outpacing suburbs since 2008.[17]

As of 2022, New Jersey had the highest annual median household income, at $96,346, of all 50 states.[18] Almost one-tenth of all households in the state, or over 323,000, are millionaires, the highest representation of millionaires among all states.[19] New Jersey's public school system consistently ranks at or among the top of all U.S. states.[20][21][22][23] According to climatology research by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, New Jersey has been the fastest-warming state by average air temperature over a 100-year period beginning in the early 20th century, which has been attributed to warming of the North Atlantic Ocean.[24]

History

Around 180 million years ago, during the Jurassic Period, New Jersey bordered North Africa. The pressure of collision between North America and Africa gave rise to the Appalachian Mountains. Around 18,000 years ago, the Ice Age resulted in glaciers that reached New Jersey. As glaciers retreated, they left behind Lake Passaic along with rivers, meadows, swamps, and gorges.[25]

Since the 6th millennium BC, Native American people have inhabited New Jersey, beginning with the Lenape tribe. Scheyichbi is the Lenape name for the land that represents present-day New Jersey.[26] The Lenape were several autonomous groups that practiced maize agriculture in order to supplement their hunting and gathering in the region surrounding the Delaware River, the lower Hudson River, and western Long Island Sound. The Lenape were divided into matrilineal clans that were based upon common female ancestors. Clans were organized into three distinct phratries identified by their animal sign: Turtle, Turkey, and Wolf. They first encountered the Dutch in the early 17th century, and their primary relationship with the Dutch and later European settlers was through fur trade.

Colonial era

The Dutch were the first Europeans to lay claim to lands in New Jersey. The Dutch colony of New Netherland consisted of parts of the modern Mid-Atlantic states. Although the European principle of land ownership was not recognized by the Lenape, Dutch West India Company policy required its colonists to purchase land that they settled. The first to do so was Michiel Pauw, who established a patron ship called Pavonia in 1630 along North River, that eventually became Bergen. Peter Minuit's purchase of lands along the Delaware River established the colony of New Sweden, that lasted until the Dutch conquered it in 1655. Then the entire region became a territory of England on June 24, 1664, after an English fleet under command of Colonel Richard Nicolls sailed into what is now New York Harbor and took control of Fort Amsterdam, annexing the entire province.

During the English Civil War, the Channel Island of Jersey remained loyal to the British Crown and gave sanctuary to the King. In the Royal Square in St Helier, Charles II of England was proclaimed King in 1649, following the execution of his father, Charles I. North American lands were divided by Charles II, who gave his brother, the Duke of York (later King James II), the region between New England and Maryland as a proprietary colony (as opposed to a royal colony). James then granted land between the Hudson River and the Delaware River (the land that would become New Jersey) to two friends who had remained loyal through the English Civil War: Sir George Carteret and Lord Berkeley of Stratton.[27] The area was named the Province of New Jersey.

Since its inception, New Jersey has been characterized by ethnic and religious diversity. New England Congregationalists settled alongside Scots Presbyterians and Dutch Reformed migrants. While the majority of residents lived in towns with individual landholdings of 100 acres (40 ha), a few rich proprietors owned vast estates. English Quakers and Anglicans owned large landholdings. Unlike Plymouth Colony, Jamestown and other colonies, New Jersey was populated by a secondary wave of immigrants who came from other colonies instead of those who migrated directly from Europe. New Jersey remained agrarian and rural throughout the colonial era, and commercial farming developed sporadically. Some townships, such as Burlington on the Delaware River and Perth Amboy, emerged as important ports for shipping to New York City and Philadelphia. The colony's fertile lands and tolerant religious policy drew more settlers, and New Jersey's population had increased to 120,000 by 1775.

Settlement for the first ten years of English rule took place along the Hackensack River and Arthur Kill. Settlers came primarily from New York and New England. On March 18, 1673, Berkeley sold his half of the colony to Quakers in England, who settled the Delaware Valley region as a Quaker colony, with William Penn acting as trustee for the lands for a time. New Jersey was governed as two distinct provinces, East and West Jersey, for 28 years between 1674 and 1702, which were part of the Dominion of New England from 1686 to 1689.

In 1702, the two provinces were reunited under a royal governor rather than a proprietary one. Edward Hyde, titled Lord Cornbury, became the first governor of the royal colony. Britain believed that he was an ineffective and corrupt ruler, taking bribes and speculating on land. In 1708, he was recalled to England. New Jersey was then ruled by the governors of New York, but this infuriated the settlers of New Jersey, who accused these governors of favoritism to New York. Judge Lewis Morris led the case for a separate governor, and was appointed governor by King George II in 1738.[28]

Revolutionary War era

New Jersey was one of the Thirteen Colonies that revolted against British rule in the American Revolution. The New Jersey Constitution of 1776 was passed July 2, 1776, just two days before the Second Continental Congress declared American Independence from Great Britain. It was an act of the Provincial Congress, which made itself into the State Legislature. To reassure neutrals, it provided that it would become the legislature would disband if New Jersey reached reconciliation with Great Britain. Among the 56 Founding Fathers who signed the Declaration of Independence, five were New Jersey representatives: Richard Stockton, John Witherspoon, Francis Hopkinson, John Hart, and Abraham Clark.

During the American Revolutionary War, British and American armies crossed New Jersey numerous times, and several pivotal battles took place in the state. Because of this, New Jersey today is sometimes referred to as "The Crossroads of the American Revolution".[29] The winter quarters of the Continental Army were established in New Jersey twice by General George Washington in Morristown, which has been called "The Military Capital of the American Revolution."[30]

On the night of December 25–26, 1776, the Continental Army under George Washington crossed the Delaware River. After the crossing, they surprised and defeated the Hessian troops in the Battle of Trenton. Slightly more than a week after victory at Trenton, Continental Army forces gained an important victory by stopping General Cornwallis's charges at the Second Battle of Trenton. By evading Cornwallis's army, the Continental Army was able to make a surprise attack on Princeton and successfully defeated the British forces there on January 3, 1777. Emanuel Leutze's painting of Washington Crossing the Delaware became an icon of the Revolution.

Continental Army forces under Washington's command met British forces under General Henry Clinton at the Battle of Monmouth in an indecisive engagement in June 1778. Washington's forces attempted to take the British column by surprise. When the British army attempted to flank the Americans, the Continental Army retreated in disorder. Their ranks were later reorganized and withstood British charges.[31]

In the summer of 1783, the Continental Congress met in Nassau Hall at Princeton University, making Princeton the nation's capital for four months. It was there that the Continental Congress learned of the signing of the Treaty of Paris, which ended the war.

On December 18, 1787, New Jersey became the third state to ratify the United States Constitution, which was overwhelmingly popular in New Jersey since it prevented New York and Pennsylvania from charging tariffs on goods imported from Europe. On November 20, 1789, New Jersey became the first in the newly formed Union to ratify the Bill of Rights.[32]

The 1776 New Jersey State Constitution gave the vote to all inhabitants who had a certain level of wealth. This included women and Black people, but not married women because they were not legally permitted to own property separately from their husbands. Both sides, in several elections, claimed that the other side had had unqualified women vote and mocked them for use of petticoat electors, whether entitled to vote or not; on the other hand, both parties passed Voting Rights Acts. In 1807, legislature passed a bill interpreting the constitution to mean universal white male suffrage, excluding paupers; the constitution was itself an act of the legislature and not enshrined as the modern constitution.[33]

19th century

On February 15, 1804, New Jersey became the last northern state to abolish new slavery and enacted legislation that slowly phased out existing slavery. This led to a gradual decrease of the slave population. By the American Civil War's end, about a dozen African Americans in New Jersey were still held in bondage.[34] New Jersey voters eventually ratified the constitutional amendments banning slavery and granting rights to the United States' black population.

Industrialization accelerated in the northern part of the state following completion of the Morris Canal in 1831. The canal allowed for coal to be brought from eastern Pennsylvania's Lehigh Valley to northern New Jersey's growing industries in Paterson, Newark, and Jersey City.

In 1844, the second state constitution was ratified and brought into effect. Counties thereby became districts for the state senate, and some realignment of boundaries (including the creation of Mercer County) immediately followed. This provision was retained in the 1947 Constitution, but was overturned by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1962, by the decision Baker v. Carr. While the Governorship was stronger than under the 1776 constitution, the constitution of 1844 created many offices that were not responsible to him, or to the people, and it gave him a three-year term, but he could not succeed himself.

New Jersey was one of the few Union states (the others being Delaware and Kentucky) to select a candidate other than Abraham Lincoln twice in national elections, and sided with Stephen Douglas (1860) and George B. McClellan (1864) during their campaigns. McClellan, a native Philadelphian, had New Jersey ties and formally resided in New Jersey at the time; he later became Governor of New Jersey (1878–81). (In New Jersey, the factions of the Democratic party managed an effective coalition in 1860.) During the American Civil War, the state was led first by Republican governor Charles Smith Olden, then by Democrat Joel Parker. During the course of the war, between 65,000 and 80,000 soldiers from the state enlisted in the Union army; unlike many states, including some Northern ones, no battle was fought there.[35]

In the Industrial Revolution, cities like Paterson grew and prospered. Previously, the economy had been largely agrarian, which was problematically subject to crop failures and poor soil. This caused a shift to a more industrialized economy, one based on manufactured commodities such as textiles and silk. Inventor Thomas Edison also became an important figure of the Industrial Revolution, having been granted 1,093 patents, many of which for inventions he developed while working in New Jersey. Edison's facilities, first at Menlo Park and then in West Orange, are considered perhaps the first research centers in the United States. Christie Street in Menlo Park was the first thoroughfare in the world to have electric lighting. Transportation was greatly improved as locomotion and steamboats were introduced to New Jersey.

Iron mining was also a leading industry during the middle to late 19th century. Bog iron pits in the New Jersey Pine Barrens were among the first sources of iron for the new nation.[36] Mines such as Mt. Hope, Mine Hill, and the Rockaway Valley Mines created a thriving industry. Mining generated the impetus for new towns and was one of the driving forces behind the need for the Morris Canal. Zinc mines were also a major industry, especially the Sterling Hill Mine.

20th century

New Jersey prospered through the Roaring Twenties. The first Miss America Pageant was held in 1921 in Atlantic City; the Holland Tunnel connecting Jersey City to Manhattan opened in 1927; and the first drive-in movie was shown in 1933 in Camden. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, the state offered begging licenses to unemployed residents,[37] the zeppelin airship Hindenburg crashed in flames over Lakehurst, and the SS Morro Castle beached itself near Asbury Park after going up in flames while at sea.

Through both World Wars, New Jersey was a center for war production, especially naval construction. The Federal Shipbuilding and Drydock Company yards in Kearny and Newark and the New York Shipbuilding Corporation yard in Camden produced aircraft carriers, battleships, cruisers, and destroyers.[38] New Jersey manufactured 6.8 percent of total United States military armaments produced during World War II, ranking fifth among the 48 states.[39] In addition, Fort Dix (1917) (originally called "Camp Dix"),[40] Camp Merritt (1917),[41] and Camp Kilmer (1941)[citation needed] were all constructed to house and train American soldiers through both World Wars. New Jersey also became a principal location for defense in the Cold War. Fourteen Nike missile stations were constructed for the defense of the New York City and Philadelphia areas. PT-109, a motor torpedo boat commanded by Lt. (j.g.) John F. Kennedy in World War II, was built at the Elco Boatworks in Bayonne. The aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) was briefly docked at the Military Ocean Terminal in Bayonne in the 1950s before she was sent to Kearney to be scrapped.[42] In 1962, the world's first nuclear-powered cargo ship, the NS Savannah, was launched at Camden.

In 1951, the New Jersey Turnpike opened, facilitating efficient travel by car and truck between North Jersey and metropolitan New York, and South Jersey and metropolitan Philadelphia.[43] Subsequently, in 1957, the Garden State Parkway was completed, serving as a diagonal counterpart to the Turnpike, and opening up highway travel along New Jersey's coastal flank between Bergen County in the northeast and the Cape May County peninsula at the southeastern tip of New Jersey; in doing so, the Jersey Shore became readily accessible to millions of residents in the New York metropolitan area. In 1959, Air Defense Command deployed the CIM-10 Bomarc surface-to-air missile to McGuire Air Force Base. On June 7, 1960, an explosion in a CIM-10 Bomarc missile fuel tank caused an accident and subsequent plutonium contamination.[44]

In the 1960s, race riots erupted in many of the industrial cities of North Jersey. The first race riots in New Jersey occurred in Jersey City on August 2, 1964. Several others ensued in 1967, in Newark and Plainfield. Other riots followed the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in April 1968, just as in the rest of the country. A riot occurred in Camden in 1971. As a result of an order from the New Jersey Supreme Court to fund schools equitably, the New Jersey legislature passed an income tax bill in 1976. Prior to this bill, the state had no income tax.[45]

21st century

In the early part of the 2000s, two light rail systems were opened: the Hudson–Bergen Light Rail in Hudson County and the River Line between Camden and Trenton. The intent of these projects was to encourage transit-oriented development in North Jersey and South Jersey, respectively. The HBLR was credited with a revitalization of Hudson County and Jersey City.[46][47][48][49] Urban revitalization has continued in North Jersey in the 21st century. In 2014, Jersey City's Census-estimated population was 262,146,[50] with the largest population increase of any municipality in New Jersey since 2010,[51] representing an increase of 5.9% from the 2010 U.S. census, when the city's population was enumerated at 247,597.[52][53] Between 2000 and 2010 Newark experienced its first population increase since the 1950s, and by 2020 had rebounded to 311,549.

| List of state symbols | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Living insignia | |

| Bird | Eastern goldfinch[55] |

| Fish | Brook trout[56] |

| Flower | Viola sororia[57] |

| Insect | Western honey bee[58] |

| Mammal | Horse[54] |

| Tree | Quercus rubra (northern red oak),[59] dogwood (memorial tree)[59] |

| Inanimate insignia | |

| Color(s) | Buff and blue |

| Folk dance | Square dance[60] |

| Food | Northern highbush blueberry (state fruit)[61] |

| Fossil | Hadrosaurus foulkii[62] |

| Soil | Downer[63] |

| State route marker | |

| |

| State quarter | |

Released in 1999 | |

| Lists of United States state symbols | |

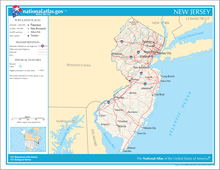

Geography

New Jersey is located at the center of the Northeast megalopolis, the most populated American urban agglomeration. It is bordered on the north and northeast by New York (parts of which are across the Hudson River, Upper New York Bay, the Kill Van Kull, Newark Bay, and the Arthur Kill); on the east by the Atlantic Ocean; on the southwest by Delaware across Delaware Bay; and on the west by Pennsylvania across the Delaware River.

New Jersey is broadly divided into the North, Central, and South Jersey geographic regions, although some residents do not consider Central Jersey a region in its own right. Across the regions are five distinct areas divided by natural geography and population concentration. Northeastern New Jersey, often referred to as the Gateway Region, lies closest to Manhattan in New York City, and up to a million residents commute daily into the city for work, many via public transportation.[64] The Jersey Shore, along the Atlantic Coast in Central and South Jersey, has its own unique natural, residential, and cultural characteristics owing to its location by the ocean. South Jersey represents the southernmost geographical region of the northeastern United States. The Delaware Valley includes the southwestern counties of the state, which reside within the Delaware Valley surrounding Philadelphia.

Despite its heavily urban character and a long history of industrialization, forests cover roughly 45 percent of New Jersey's land area, or approximately 2.1 million acres, ranking 31st among the 50 U.S. states and six territories.[65] Northwestern New Jersey, often referred to as the Skylands Region, is more wooded, rural, and mountainous. The chief tree of the northern forests is the oak. The New Jersey Pine Barrens is situated in the southern interior of New Jersey and covered extensively by mixed pine and oak forest; its population density is lower than most of the state.

High Point in Montague Township, Sussex County is the state's highest elevation at 1,803 feet (550 m) above sea level. The state's highest prominence is Kitty Ann Mountain in Morris County, rising 892 feet (272 m). The Palisades are a line of steep cliffs on the west side of the Hudson River in Bergen and Hudson Counties. Major New Jersey rivers include the Hudson, Delaware, Raritan, Passaic, Hackensack, Rahway, Musconetcong, Mullica, Rancocas, Manasquan, Maurice, and Toms rivers. Due to New Jersey's peninsular geography, both sunrise and sunset are visible over water from different points on the Jersey Shore.

Prominent geographic features

- Meadowlands

- New Jersey Pine Barrens

- Delaware Water Gap

- Great Bay

- Great Swamp National Wildlife Refuge

- Highlands

- Hudson Palisades

- Jersey Shore

- On the shore, New Jersey hosts the highest concentration of oceanside boardwalks in the world.

- Ramapo Mountain

- South Mountain

Climate

The state consists of two climate zones; the southernmost edges of the state have a humid subtropical climate, while the rest has a humid continental climate.[66] New Jersey receives between 2,400 and 2,800 hours of sunshine annually.[67]

Summers are typically hot and humid, with statewide average high temperatures of 82–87 °F (28–31 °C) and lows of 60–69 °F (16–21 °C); however, temperatures exceed 90 °F (32 °C) on average 25 days each summer, exceeding 100 °F (38 °C) in some years. Winters are usually cold, with average high temperatures of 34–43 °F (1–6 °C) and lows of 16 to 28 °F (−9 to −2 °C) for most of the state, but temperatures can, for brief periods, fall below 10 °F (−12 °C) and sometimes rise above 50 °F (10 °C). Northwestern parts of the state have significantly colder winters with sub-0 °F (−18 °C) being an almost annual occurrence. Spring and autumn may feature wide temperature variations, with lower humidity than summer. The USDA Plant Hardiness Zone classification ranges from 6 in the northwest of the state, to 7B near Cape May.[68] All-time temperature extremes recorded in New Jersey include 110 °F (43 °C) on July 10, 1936, in Runyon, Middlesex County and −34 °F (−37 °C) on January 5, 1904, in River Vale, Bergen County.[69]

Average annual precipitation ranges from 43 to 51 inches (1,100 to 1,300 mm), spread uniformly throughout the year. Average snowfall per winter season ranges from 10–15 inches (25–38 cm) in the south and near the seacoast, 15–30 inches (38–76 cm) in the northeast and central part of the state, to about 40–50 inches (1.0–1.3 m) in the northwestern highlands, but this often varies considerably from year to year. Precipitation falls on an average of 120 days a year, with 25 to 30 thunderstorms, most of which occur during the summer.

During winter and early spring, New Jersey can experience nor'easters, which are capable of causing blizzards or flooding throughout the northeastern United States. Hurricanes and tropical storms, tornadoes, and earthquakes are rare; the state was impacted by a hurricane in 1903, Tropical Storm Floyd in 1999,[70] and Hurricane Sandy in 2012, which made landfall in the state with top winds of 90 mph (145 km/h).

Climate change

Climate change is affecting New Jersey faster than much of the rest of the United States. Climatologists at the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration have concluded that New Jersey has been the fastest-warming state by average air temperature over a 100-year period beginning in the early 20th century.[24]

| Average high and low temperatures in various cities of New Jersey °C (°F)[1] [2] [3] | ||||||||||||

| City | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

| Sussex | 1/−9 (34/16) | 3/−8 (38/18) | 8/−4 (47/26) | 15/2 (59/36) | 21/7 (70/45) | 25/12 (78/55) | 28/16 (82/60) | 27/14 (81/58) | 23/10 (73/50) | 17/4 (62/38) | 11/−1 (51/31) | 4/−6 (39/22) |

| Newark | 4/−4 (39/24) | 6/−3 (42/27) | 10/1 (51/34) | 17/7 (62/44) | 22/12 (72/53) | 28/17 (82/63) | 30/20 (86/69) | 29/20 (84/68) | 25/15 (77/60) | 18/9 (65/48) | 13/4 (55/39) | 6/−1 (44/30) |

| Atlantic City | 5/−2 (42/29) | 6/−1 (44/31) | 10/3 (50/37) | 14/8 (58/46) | 19/13 (67/55) | 24/18 (76/64) | 27/21 (81/70) | 27/21 (80/70) | 24/18 (75/64) | 18/11 (65/53) | 13/6 (56/43) | 8/1 (46/34) |

| Cape May | 6/−2 (42/28) | 7/−2 (44/29) | 11/2 (51/35) | 16/7 (61/44) | 21/12 (70/53) | 26/17 (79/63) | 29/20 (85/68) | 29/19 (83/67) | 25/16 (78/61) | 19/9 (67/50) | 14/4 (57/41) | 8/0 (47/32) |

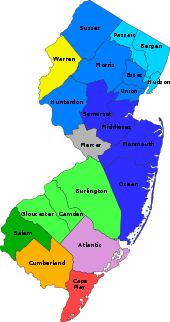

Administrative divisions

The U.S. Census Bureau divides New Jersey's 21 counties into seven metropolitan statistical areas, with 20 counties included in either the New York City or Philadelphia combined statistical area. Warren County is part of the Pennsylvania-based Lehigh Valley metro area.

Counties

The 21 counties in New Jersey, listed in order by population (as of the 2020 census) are:[71]

- Bergen County: 955,732

- Essex County: 863,728

- Middlesex County: 863,162

- Hudson County: 724,854

- Monmouth County: 643,615

- Ocean County: 637,229

- Union County: 575,345

- Passaic County: 524,118

- Camden County: 523,485

- Morris County: 509,285

- Burlington County: 461,860

- Mercer County: 387,340

- Somerset County: 345,361

- Gloucester County: 302,294

- Atlantic County: 274,534

- Cumberland County: 154,152

- Sussex County: 144,221

- Hunterdon County: 128,947

- Warren County: 109,632

- Cape May County: 95,263

- Salem County: 64,837

Municipalities

For its overall population and nation-leading population density, New Jersey has a relative paucity of classic large cities. This paradox is most pronounced in Bergen County, the state's most populous county, whose 955,732 residents at the 2020 census inhabited 70 municipalities, of which the most populous is Hackensack, with 46,030 residents. Many urban areas extend far beyond the limits of a single large city, as New Jersey municipalities tend to be geographically small; three of the four largest cities in New Jersey by population have under 20 square miles (52 km2) of land area, and eight of the top ten, including all the top five, have a land area under 30 square miles (78 km2). As of the 2010 United States census[update], only four municipalities had over 100,000 residents (although Edison and Woodbridge Township came very close); this number increased to seven by the 2020 census.

| Rank | Name | County | Municipal pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Newark  Jersey City | 1 | Newark | Essex | 311,549 |  Paterson  Elizabeth | ||||

| 2 | Jersey City | Hudson | 292,449 | ||||||

| 3 | Paterson | Passaic | 159,732 | ||||||

| 4 | Elizabeth | Union | 137,298 | ||||||

| 5 | Lakewood Township | Ocean | 135,158 | ||||||

| 6 | Edison | Middlesex | 107,588 | ||||||

| 7 | Woodbridge Township | Middlesex | 103,639 | ||||||

| 8 | Toms River | Ocean | 95,438 | ||||||

| 9 | Hamilton Township | Mercer | 92,297 | ||||||

| 10 | Clifton | Passaic | 90,296 | ||||||

Demographics

Population

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 184,139 | — | |

| 1800 | 211,149 | 14.7% | |

| 1810 | 245,562 | 16.3% | |

| 1820 | 277,575 | 13.0% | |

| 1830 | 320,823 | 15.6% | |

| 1840 | 373,306 | 16.4% | |

| 1850 | 489,555 | 31.1% | |

| 1860 | 672,035 | 37.3% | |

| 1870 | 906,096 | 34.8% | |

| 1880 | 1,131,116 | 24.8% | |

| 1890 | 1,444,933 | 27.7% | |

| 1900 | 1,883,669 | 30.4% | |

| 1910 | 2,537,167 | 34.7% | |

| 1920 | 3,155,900 | 24.4% | |

| 1930 | 4,041,334 | 28.1% | |

| 1940 | 4,160,165 | 2.9% | |

| 1950 | 4,835,329 | 16.2% | |

| 1960 | 6,066,782 | 25.5% | |

| 1970 | 7,168,164 | 18.2% | |

| 1980 | 7,364,823 | 2.7% | |

| 1990 | 7,730,188 | 5.0% | |

| 2000 | 8,414,350 | 8.9% | |

| 2010 | 8,791,894 | 4.5% | |

| 2020 | 9,288,994 | 5.7% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 9,290,841 | [73] | 0.0% |

| Sources:[5][74] | |||

Residents of New Jersey are most commonly referred to as New Jerseyans or, less commonly, as New Jerseyites. According to the 2020 U.S. census, the state had a population of 9,288,994, a 5.7% increase since the 2010 U.S. census, which counted 8,791,894 residents.[6] The state ranked eleventh in the country by total population and first in population density, with 1,185 residents per square mile (458 per km2). Historically, New Jersey has experienced one of the fastest growth rates in the country, with its population increasing by double digits almost every decade until 1980; growth has since slowed but remained relatively robust until recently. In 2022, the Census Bureau estimated there were 6,262 fewer residents than in 2020, a decline of 0.3% from 2020, related to the COVID-19 pandemic.[75]

New Jersey is the only state where every county is deemed urban as defined by the Census Bureau.[76] Most residents live in the counties surrounding New York City, the nation's largest city, Philadelphia, the nation's sixth-largest city, or along the eastern Jersey Shore; the extreme southern and northwestern counties are relatively less dense overall. Since the 2000 census, the United States Census Bureau calculated that New Jersey's center of population was located in East Brunswick.[77][78][79] The state is located in the middle of the Northeast megalopolis, which has more than 50 million residents.

As of 2019, New Jersey was the third highest U.S. state measured by median household income, behind Maryland and Massachusetts;[80] the state's median household income was over $85,000 compared to the national average of roughly $65,000.[81] Conversely, New Jersey's poverty rate of 9.4% was slightly lower than the national average of 11.4%,[81] and the sixth lowest of the fifty states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico. This is attributed to several factors, including the state's proximity to the major economic centers of New York City and Philadelphia, its hosting the highest number of millionaires both per capita and per square mile in the U.S., and the fact that it has the most scientists and engineers per square mile in the world.[82][83][84]

According to HUD's 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 8,752 homeless people in New Jersey.[85][86]

The top countries of origin for New Jersey's immigrants in 2018 were India, Dominican Republic, Mexico, Ecuador and the Philippines.[87]

Race and ethnicity

New Jersey is one of the most ethnically diverse states in the nation: as of 2022, over one-fifth of its residents are Hispanic (21.5%) of its residents are Hispanic or Latino, 15.3% are Black, and one-tenth are Asian. One in four New Jerseyans were born abroad and more than one million (12.1%) are not fully fluent in English. Compared to the U.S. as a whole, the state is more racially and ethnically diverse and has a higher proportion of immigrants.[88]

| Race and Ethnicity[89] | Alone | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 51.9% | 54.5% | ||

| Hispanic or Latino[b] | — | 21.6% | ||

| African American (non-Hispanic) | 12.4% | 13.6% | ||

| Asian | 10.2% | 11.0% | ||

| Native American | 0.1% | 0.7% | ||

| Pacific Islander | 0.02% | 0.1% | ||

| Other | 0.8% | 1.8% | ||

| Racial composition | 1970[90] | 1990[90] | 2000[91] | 2010[92] | 2020[93] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 88.6% | 79.3% | 72.5% | 68.6% | 55.0% |

| Black | 10.7% | 13.4% | 13.6% | 13.7% | 13.1% |

| Asian | 0.3% | 3.5% | 5.7% | 8.3% | 10.2% |

| Native | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.6% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander | – | – | – | – | – |

| Other race | 0.3% | 3.6% | 5.4% | 6.4% | 11.3% |

| Two or more races | – | – | 2.5% | 2.7% | 9.7% |

New Jersey is home to roughly half a million unauthorized immigrants,[95][96] comprising an estimated 6.2% of the population, which in 2018 was the fifth-highest percentage of any U.S. state.[97] The municipalities of Camden, Jersey City, and Newark are considered sanctuary cities for illegal immigrants.[98]

For further information on various ethnoracial groups and neighborhoods prominently featured within New Jersey, see the following articles:

- History of the Jews in New Jersey

- Hispanics and Latinos in New Jersey

- Indians in the New York City metropolitan region

- Chinese in the New York City metropolitan region

- List of U.S. cities with significant Korean American populations

- Filipinos in the New York City metropolitan region

- Filipinos in New Jersey

- Russians in the New York City metropolitan region

- Bergen County

- Jersey City

- India Square in Jersey City, home to the highest concentration of Asian Indians in the Western Hemisphere

- Ironbound, a Portuguese and Brazilian enclave in Newark

- Five Corners, a Filipino enclave in Jersey City

- Havana on the Hudson, a Cuban enclave in Hudson County

- Koreatown, Fort Lee, a Korean enclave in southeast Bergen County

- Koreatown, Palisades Park, also a Korean enclave in southeast Bergen County

- Little Bangladesh, a Bangladeshi enclave in Paterson

- Little India (Edison/Iselin), the largest and most diverse South Asian hub in the United States

- Little Istanbul, also known as Little Ramallah, a Middle Eastern enclave in Paterson

- Little Lima, a Peruvian enclave in Paterson

New Jersey is one of the most ethnically and religiously diverse states in the United States. Nearly one-fourth of New Jerseyans (22.7%) were foreign born, compared to the national average of 13.5%.[81] As of 2011, 56.4% of New Jersey's children under the age of one belonged to racial or ethnic minority groups, meaning that they had at least one parent who was not non-Hispanic white.[99] The 2019 Vintage Year Census estimated that the state's ethnic makeup was as follows: 71.9% White alone, 15.1% Black or African American alone, 10.0% Asian alone, 0.6% American Indian and Alaska Native alone, 0.1% Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander alone, and 2.3% Two or more races. Hispanic or Latino accounted for 20.9%, while White alone (non-Hispanic or Latino) accounted for 54.6% of the population.[100] Many of the municipalities in Bergen County, New Jersey, the state's largest county, have a sizeable minority population of Hispanics and Asians.[101]

New Jersey hosts some of the nation's largest communities of religious and ethnic minorities in proportional or absolute terms. It has the second-largest Jewish population by percentage (after New York);[102] the largest Muslim population by percentage;[103] the largest population of Peruvians in the U.S.; the largest population of Cubans outside Florida; the third-highest Asian population by percentage; and the second highest Italian population,[104] according to the 2000 Census. African Americans, Hispanics (Puerto Ricans and Dominicans), West Indians, Arabs, and Brazilian and Portuguese Americans are also high in number. Overall, New Jersey has the third-largest Korean population, with Bergen County home to the highest Korean concentration per capita of any U.S. county[105] (6.9% in 2011). New Jersey also has the fourth-largest Filipino population, and fourth-largest Chinese population, per the 2010 U.S. Census.

New Jersey has the-third highest Indian population of any state by absolute numbers and the highest by percentage,[106][107][108][109] with India Square in Jersey City, Hudson County[94] hosting the highest concentration of Asian Indians in the Western Hemisphere.[110] A study by the Pew Research Center found that in 2013, New Jersey was the only U.S. state in which immigrants born in India constituted the largest foreign-born nationality, representing roughly 10% of all foreign-born residents in the state.[111] Central New Jersey, particularly Edison and surrounding Middlesex County, has the highest concentration of Indians, at nearly 20% in 2020; Little India is the largest and most diverse South Asian cultural hub in the United States.[112][113][114][115][116] The area includes a sprawling Chinatown and Koreatown running along New Jersey Route 27.[117] Monroe Township in Middlesex County has experienced a particularly rapid growth rate in its Indian American population with an estimated 5,943 (13.6%) as of 2017,[118] which was 23 times the 256 (0.9%) counted at the 2000 Census; Diwali is celebrated by the township as a Hindu holiday. In Middlesex County, election ballots are printed in English, Spanish, Gujarati, Hindi, and Punjabi.[119] Robbinsville, in neighboring Mercer County, hosts the world's largest Hindu temple outside Asia.[120] Carteret's Punjabi Sikh community, variously estimated at upwards of 3,000, is the largest concentration of Sikhs in the state.[121] Bergen County is home to America's largest Malayali community.[122] from New York City (뉴욕), is a growing hub and home to all of the nation's top ten municipalities by percentage of Korean population,[123] led (above) by Palisades Park (벼랑 공원),[124] the municipality with the highest density of ethnic Koreans in the Western Hemisphere. Displaying ubiquitous Hangul (한글) signage and known as the Korean village,[125] Palisades Park uniquely comprises a Korean majority (52% in 2010) of its population,[126][127] with both the highest Korean-American density and percentage of any municipality in the United States.

Birth data

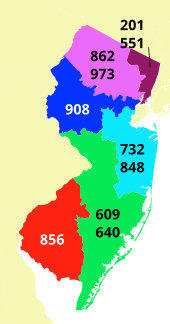

Languages

| Language | Percentage of population (as of 2010)[137] |

|---|---|

| Spanish | 14.59% |

| Chinese (including Cantonese and Mandarin) | 1.23% |

| Italian | 1.06% |

| Portuguese | 1.06% |

| Filipino | 0.96% |

| Korean | 0.89% |

| Gujarati | 0.83% |

| Polish | 0.79% |

| Hindi | 0.71% |

| Arabic | 0.62% |

| Russian | 0.56% |

As of 2010, 71.31% (5,830,812) of New Jersey residents age 5 and older spoke English at home as a primary language, while 14.59% (1,193,261) spoke Spanish, 1.23% (100,217) Chinese (which includes Cantonese and Mandarin), 1.06% (86,849) Italian, 1.06% (86,486) Portuguese, 0.96% (78,627) Tagalog, and Korean was spoken as a main language by 0.89% (73,057) of the population over the age of five. In total, 28.69% (2,345,644) of New Jersey's population age 5 and older spoke a mother language other than English.[137]

A diverse collection of languages has since evolved amongst the state's population, given that New Jersey has become cosmopolitan and is home to ethnic enclaves of non-English-speaking communities:[138][139][140][141]

- Albanian – Paterson, Garfield

- Arabic – Bayonne, Paterson, Jersey City

- Armenian – Bergen County

- Bengali – Paterson

- Gujarati and Hindi – Jersey City, all of Middlesex County, Cherry Hill, Parsippany, Princeton

- Indonesian – Gloucester City, Middlesex, Somerset, and Union counties

- Japanese – Edgewater and Fort Lee boroughs in Bergen County

- Korean – Bergen County (numerous municipalities); Edison; and Cherry Hill

- Macedonian – Bergen County

- Malayalam – Bergen County

- Polish – Bergen County (Garfield, Wallington); Mercer County (Top Road, Lawrence Township, Hopewell); Linden

- Portuguese – Ironbound section of Newark; Elizabeth

- Russian – Fair Lawn borough of Bergen County, Princeton area and Mercer County

- Tamil and Telugu – Edison, Monroe Township (Edison-South), and all of Middlesex County; Fair Lawn, Parsippany

- Turkish – Little Istanbul section of Paterson, Mount Ephraim (which has a large, vibrant and growing Turkish Community), Delran, Cherry Hill

- Urdu – Mount Ephraim has a significant number of residents of Pakistani origin.

- Vietnamese – Atlantic City,[142] Camden/Cherry Hill, Edison Township, Jersey City, Woodlynne[143]

- Yiddish – Lakewood Township, Ocean County, Jackson

- High-rise residential complexes in the borough of Fort Lee

- Federal Courthouse in Camden, which is connected to Philadelphia via the Benjamin Franklin Bridge in the background

Sexual orientation and gender identity

New Jersey is an LGBTQ+ friendly state and is now home to more gay villages per square mile than any other U.S. state. Same-sex marriage in New Jersey has been legally recognized since October 21, 2013, the effective date of a trial court ruling invalidating New Jersey's restriction of marriage to persons of different sexes at the time. In September 2013, Mary C. Jacobson, Assignment Judge of the Mercer Vicinage of the Superior Court, ruled that as a result of the U.S. Supreme Court's June 2013 decision in United States v. Windsor, the Constitution of New Jersey requires the state to recognize same-sex marriages.[150]

Numerous gayborhoods have emerged in New Jersey, most prominently in Jersey City,[151] Asbury Park, Maplewood,[152] Montclair, and Lambertville.[153] Trenton, the state capital of New Jersey, elected Reed Gusciora, its first openly gay mayor, in 2018,[154] and Jennifer Williams, New Jersey's first openly transgender city councilmember, in 2022.[155] In June 2018, Maplewood, Essex County unveiled permanent rainbow-colored crosswalks to celebrate LGBTQ pride, a feature displayed by only a few other towns in the world,[156] including Rahway, Union County, which unveiled its own rainbow-colored crosswalks in June 2019.[157] In January 2019, New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy signed legislation mandating LGBTQ+ inclusive educational curriculum in schools.[158] In February 2019, New Jersey began allowing a neutral or non-binary gender choice on birth certificates.[159]

Religion

By number of adherents, the largest religious traditions in New Jersey, according to the 2010 Association of Religion Data Archives, were the Roman Catholic Church with 3,235,290; Islam with 160,666; and the United Methodist Church with 138,052.[161] The world's largest Hindu temple outside Asia is in Robbinsville, Mercer County.[120] In September 2021, the State of New Jersey aligned with the World Hindu Council to declare October Hindu Heritage Month. In January 2018, Gurbir Grewal became the first Sikh American to serve as state attorney general in the United States.[162] In January 2019, Sadaf Jaffer of Montgomery became the first female Muslim American mayor, first female South Asian mayor, and first female Pakistani-American mayor in the U.S.[163] Large numbers of Orthodox Jews are now migrating to New Jersey from New York, due to the latter's higher cost of living.[164]

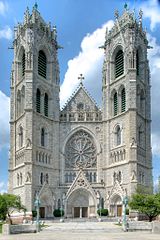

- Cathedral Basilica of the Sacred Heart in Newark, the fifth-largest cathedral in North America, is the seat of the city's Roman Catholic Archdiocese.

- Beth Medrash Govoha (Hebrew: בית מדרש גבוה), in Lakewood, Ocean County, the world's largest Jewish yeshiva outside Israel. New Jersey is home to the second-highest Jewish American population per capita, after New York, and the fastest-growing Orthodox Jewish population.[165][166]

- Swaminarayan Akshardham in Robbinsville, Mercer County, the world's largest Hindu temple outside Asia.[120] New Jersey is home to the highest concentration of Hindus (3%) in the U.S.

- Islamic Center of Passaic County, Paterson, Passaic County, was founded in 1990. New Jersey is home to one of the highest Muslim population concentrations in the Western hemisphere (3.5%), and Paterson, which houses the Islamic Center of Passaic County, is the epicenter of New Jersey's Muslim community, leading South Paterson to be nicknamed Little Istanbul and Little Ramallah.[167]

Economy

The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis estimates that New Jersey's gross state product in the third quarter of 2022 was $753 billion.[168]

Affluence

New Jersey's per capita gross state product routinely ranks as one of the highest in the United States. In 2020, New Jersey had the highest number of millionaires both per capita and per square mile in the United States, approximately 9.76% of households.[19]

The state is ranked second in the nation by the number of places with per capita incomes above national average with 76.4%. Nine of New Jersey's counties are among the 100 highest-income U.S. counties.[citation needed]

Fiscal policy

New Jersey has seven tax brackets that determine state income tax rates, which range from 1.4% (for income below $20,000) to 8.97% (for income above $500,000).[169]

The standard sales tax rate as of January 1, 2018, is 6.625%, applicable to all retail sales unless specifically exempt by law. This rate, which is comparably lower than that of New York City, often attracts numerous shoppers from New York City, often to suburban Paramus, New Jersey, which has five malls, one of which (the Garden State Plaza) has over 2 million square feet (200,000 m2) of retail space. Tax exemptions include most food items for at-home preparation, medications, most clothing, footwear and disposable paper products for use in the home.[170] There are 27 Urban Enterprise Zone statewide, including sections of Paterson, Elizabeth, and Jersey City. In addition to other benefits to encourage employment within the zone, shoppers can take advantage of a reduced 3.3125% sales tax rate (half the rate charged statewide) at eligible merchants.[171][172][173]

New Jersey has the highest cumulative tax rate of all 50 states with residents paying a total of $68 billion in state and local taxes annually with a per capita burden of $7,816 at a rate of 12.9% of income.[174] All real property located in the state is subject to property tax unless specifically exempted by statute. New Jersey does not assess an intangible personal property tax or an estate tax, but it does impose an inheritance tax (which is levied only on heirs who are not direct descendants).[175] In 2023, Governor Phil Murphy signed into law a new tax-relief program known as StayNJ that will provide for an annual property-tax cut of 50% for those aged 65 and over with incomes below $500,000; the cut will go into effect in January 2026 and be capped at $6,500, but with this cap rising as indexed to the increase in New Jersey's overall property taxes.[176][177]

Federal taxation disparity

New Jersey consistently ranks as having one of the highest proportional levels of disparity of any state in the United States, based upon what it receives from the federal government relative to what it gives. In 2015, WalletHub ranked New Jersey the state least dependent upon federal government aid overall and having the fourth lowest return on taxpayer investment from the federal government, at 48 cents per dollar.[178]

New Jersey has one of the highest tax burdens in the nation.[179] Factors for this include the large federal tax liability which is not adjusted for New Jersey's higher cost of living and Medicaid funding formulas.

Industries

New Jersey's economy is multifaceted, featuring high levels of both productivity and retail consumption; the Garden State's economy comprises the pharmaceutical industry, biotechnology, information technology, the financial industry, tourism, filmmaking, telecommunications, gambling, food processing, electrical equipment manufacturing, printing, and publishing. New Jersey's agricultural outputs are nursery stock, horses, vegetables, fruits and nuts, seafood, and dairy products.[180] New Jersey ranks second among states in blueberry production, third in cranberries and spinach, and fourth in bell peppers, peaches, and head lettuce.[181] The state harvests the fourth-largest number of acres planted with asparagus.[182] South Jersey has become an East Coast epicenter for logistics and warehouse construction.[183]

Scientific economy

New Jersey has a strong scientific economy and is home to major pharmaceutical and telecommunications firms, drawing on the state's large and well-educated labor pool, including one of the highest concentrations of engineers and other scientists in the world. There is also a robust service economy in retail sales, education, and real estate, serving residents who work in New York City or Philadelphia. Thomas Edison invented the first electric light bulb at his home in Menlo Park, Edison in 1879. New Jersey is also a key participant in the renewable wind industry. New Jersey has more scientists and engineers per square mile than anywhere in the world,[184] and is a global leader in pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, life sciences, and technology.[185][186]

Corporate and retail

New Jersey hosts numerous business headquarters, including twenty-four Fortune 500 companies.[187] Paramus in Bergen County has become the top retail ZIP code (07652) in the United States, with the municipality generating over US$6 billion in annual retail sales.[188] Several New Jersey counties, including Somerset (7), Morris (10), Hunterdon (13), Bergen (21), and Monmouth (42), have been ranked among the highest-income counties in the United States.

Shipping, manufacturing, and logistics

Shipping is a key industry in New Jersey because of the state's strategic geographic location, the Port of New York and New Jersey being the busiest port on the East Coast. The Port Newark-Elizabeth Marine Terminal was the world's first container port and today is one of the world's largest. New Jersey's location at the center of the Eastern North American population belt has made the state a prime hub for the logistics, warehousing, and supply chain management industries. The manufacturing economy in New Jersey had declined for several decades in the post-Industrial Revolution era but has since resumed growth.

Tourism

New Jersey's location at the center of the Northeast megalopolis and its extensive transportation system have put over one-third of all United States residents and many Canadian residents within overnight distance by land. This accessibility to consumer revenue has enabled seaside resorts such as Atlantic City and the remainder of the Jersey Shore, as well as the state's other natural and cultural attractions, to contribute significantly to the record 111 million tourist visits to New Jersey in 2018, providing US$44.7 billion in tourism revenue, directly supporting 333,860 jobs, sustaining more than 531,000 jobs overall including peripheral impacts, and generating US$5 billion in state and local tax revenue.[189]

Gambling

In 1976, a referendum by Jersey voters approved casino gambling in Atlantic City, where the first legalized casino opened in 1978.[190] At that time, Las Vegas was the only other casino resort in the country.[191] Today, several casinos lie along the Atlantic City Boardwalk, the oldest and longest boardwalk in the world, at 5+1⁄2 miles (8.9 km) in length.[192] Atlantic City experienced a dramatic contraction in its stature as a gambling destination after 2010, including the closure of multiple casinos since 2014, spurred by competition from the advent of legalized gambling in other northeastern U.S. states.[193][194]

On February 26, 2013, Governor Chris Christie signed online gambling into law.[195] Sports betting has become a growing source of gambling revenue in New Jersey, with sportsbooks bringing in almost $12 billion in bets, making over $1 billion in revenue in 2023.[196] Since being legalized across the nation by the U.S. Supreme Court on May 14, 2018, New Jersey led all states in sports betting handle until New York passed them.[197][198] In September 2022, the lifetime revenue from online casinos operating in New Jersey for the nine years since the industry's launch had surpassed $5 billion.[199]

Media

Television and film production

New Jersey is a growing center for filmmaking and television production,[200] with media companies, enticed by its proximity to Manhattan, in conjunction with tax incentives, collectively spending billions of dollars to develop large new studio facilities and sound stage complexes.[201] Motion picture technology was developed by Thomas Edison, with much of his early work done at his West Orange laboratory. Edison's Black Maria was the first motion picture studio. America's first motion picture industry started in 1907 in Fort Lee and the first studio was constructed there in 1909.[202] DuMont Laboratories in Passaic developed early sets and made the first broadcast to the private home.

A number of television shows and films have been filmed in New Jersey. Since 1978, the state has maintained a Motion Picture and Television Commission to encourage filming in-state.[203] New Jersey has long offered tax credits to television producers. Governor Chris Christie suspended the credits in 2010, but the New Jersey State Legislature in 2011 approved the restoration and expansion of the tax credit program. Under bills passed by both the state Senate and Assembly, the program offers 20 percent tax credits (22% in urban enterprise zones) to television and film productions that shoot in the state and meet set standards for hiring and local spending.[204] When Governor Phil Murphy took office, he instated the New Jersey Film & Digital Media Tax Credit Program in 2018 and expanded it in 2020. The benefits include a 30% tax credit on film projects and a 40% subsidy for studio developments.[205]

Newspapers

- Asbury Park Press

- Burlington County Times

- Courier News

- Courier-Post

- Daily Record (Morristown)[206]

- The Express-Times

- Gloucester County Times

- Herald News

- Home News Tribune

- Hunterdon County Democrat

- Jersey Journal

- New Jersey Herald[207]

- The News of Cumberland County

- The Press of Atlantic City

- The Record[208]

- South Jersey Times

- The Star-Ledger

- The Times (Trenton)

- Today's Sunbeam

- Trentonian (Mercer)

Radio stations

Television stations

New Jersey has several PBS affiliates: WNET (13) in Newark, WNJN (50) in Montclair, WNJB (58) in New Brunswick, WNJS (23) in Camden and WNJT (52) in Trenton.

There are no standard commercial network affiliates in the state. WMGM-TV (Wildwood) lost its affiliation with NBC in 2014. Viewers in northern New Jersey receive New York City market stations over cable or over the air; southern New Jersey viewers receive Philadelphia market stations over cable or over the air.

WMGM now affiliates with the True Crime Network. WJLP (Middletown) affiliates with the retro network MeTV. There are Telemundo affiliates in Fort Lee, Linden and Mount Laurel, and Univision affiliates in Paterson and Vineland.

Finance as Wall Street West

Jersey City's Hudson River waterfront, from Exchange Place to Newport, is known as Wall Street West[209] and has over 13 million square feet of Class A office space. One third of the private sector jobs in the city are in the financial services sector: more than 60% are in the securities industry, 20% are in banking and 8% in insurance.[210] Jersey City is home to the headquarters of Verisk Analytics and Lord Abbett,[211] a privately held money management firm.[212] Companies such as Computershare, ADP, IPC Systems, and Fidelity Investments also conduct operations in the city.[213] In 2014, Forbes magazine moved its headquarters to the district, having been awarded a $27 million tax grant in exchange for bringing 350 jobs to the city over a ten-year period.[214] By the early 2020s, the construction of residential skyscrapers Downtown made median rental rates in Jersey City amongst the highest of any city in the United States.[215]

Natural resources and energy

Limited mining activity of zinc, iron, and manganese still takes place in the area in and around the Franklin Furnace in Sussex County.

Although New Jersey is home to many energy-intensive industries, its energy consumption is only 2.7% of the U.S. total, and its carbon dioxide emissions are 0.8% of the U.S. total. New Jersey's electricity comes primarily from natural gas and nuclear power.[216] New Jersey is seventh in the nation in solar power installations,[217] enabled by one of the country's most favorable net metering policies and renewable portfolio standard. The state has more than 140,000 solar installations.[218]

Education

As of the 2020–2021 school year, there were 686 operating districts in the state. Of these, 599 were traditional public school districts and 87 were charter school districts.[219][220] The NJDOE reported a total district enrollment of 1,362,400 students, the lowest total enrollment since the early 2000s, though these figures do not consider homeschooled students or those attending out-of-state schools.[221] New Jersey public schools emphasize STEM subjects, and New Jersey is home to more scientists and engineers per square mile than anywhere else in the world.[82][222]

Secretary of Education Rick Rosenberg, appointed by Governor Jon Corzine, created the Education Advancement Initiative (EAI) to increase college admission rates by 10% for New Jersey's high school students, decrease dropout rates by 15%, and increase the amount of money devoted to schools by 10%. Rosenberg retracted this plan when criticized for taking the money out of healthcare to fund this initiative.

Educational standards

New Jersey is known for the quality of its education. In 2015, the state spent more per each public school student than any other U.S. state except New York, Alaska, and Connecticut, amounting to $18,235 spent per pupil; over 50% of the expenditure was allocated to student instruction.[223]

According to 2011 Newsweek statistics, students of High Technology High School in Lincroft, Monmouth County and Bergen County Academies in Hackensack, Bergen County registered average SAT scores of 2145 and 2100, respectively,[224] representing the second- and fourth-highest scores, respectively, of all listed U.S. high schools.[224]

The state includes private universities such as Princeton University in Princeton, Mercer County, one of the world's most prominent research universities featured often at or near the top of U.S. News & World Report's national university rankings,[225] and public universities such as Rutgers University, headquartered in New Brunswick, Middlesex County, the state's flagship institution of higher education.[226]

In 2014, New Jersey's school systems were ranked at the top of all fifty U.S. states by financial website Wallethub.com.[227] In 2018, New Jersey's overall educational system was ranked second among all states to Massachusetts by U.S. News & World Report.[23] In both 2019 and 2020, Education Week also ranked New Jersey public schools the best of all U.S. states.[20][21]

Nine New Jersey high schools were ranked among the top 25 in the U.S. on the Newsweek "America's Top High Schools 2016" list, more than from any other state.[228] A 2017 UCLA Civil Rights project found that New Jersey has the sixth-most segregated classrooms in the United States.[229]

In November 2023, Governor Phil Murphy signed into law legislation eliminating testing for prospective teachers in reading, writing, and math, replacing it with an alternative certification process.[230]

Environment

Due to past industrial activity, New Jersey has more Superfund toxic waste sites than any other state in the union despite its small geographic size. By 2024, only 35 of New Jersey's Superfund sites (out of about 150 that have been on the EPA's list since the Superfund law was passed in 1980) have actually been cleaned up.[231]

Transportation

New Jersey's population density and location at the geographic center of the Northeast Megalopolis have rendered it a vital transportation for hub for both passengers and industry.

Roadways

The New Jersey Turnpike is one of the most prominent and heavily trafficked roadways in the United States. This toll road, which overlaps with Interstate 95 for much of its length, carries traffic between Delaware and New York, and up and down the East Coast in general. Commonly referred to as simply "the Turnpike", it is known for its numerous rest areas named after prominent New Jerseyans.

The Garden State Parkway, or simply "the Parkway", carries relatively more in-state traffic than interstate traffic and runs from New Jersey's northern border to its southernmost tip at Cape May. It is the main route that connects the New York metropolitan area to the Jersey Shore. With a total of fifteen travel and six shoulder lanes, the Driscoll Bridge on the Parkway, spanning the Raritan River in Middlesex County, is the widest motor vehicle bridge in the world by number of lanes as well as one of the busiest.[234]

New Jersey is connected to New York City via various key bridges and tunnels. The double-decked George Washington Bridge carries the heaviest load of motor vehicle traffic of any bridge in the world, at 102 million vehicles per year, across fourteen lanes.[232][233] It connects Fort Lee, New Jersey to the Washington Heights neighborhood of Upper Manhattan, and carries Interstate 95 and U.S. Route 1/9 across the Hudson River. The Lincoln Tunnel connects to Midtown Manhattan carrying New Jersey Route 495, and the Holland Tunnel connects to Lower Manhattan carrying Interstate 78. New Jersey is also connected to Staten Island by three bridges—from north to south, the Bayonne Bridge, the Goethals Bridge, and the Outerbridge Crossing.

New Jersey has interstate compacts with all three of its neighboring states. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, the Delaware River Port Authority (with Pennsylvania), the Delaware River Joint Toll Bridge Commission (with Pennsylvania), and the Delaware River and Bay Authority (with Delaware) operate most of the major transportation routes in and out of the state. Bridge tolls are collected only from traffic exiting the state, with the exception of the private Dingman's Ferry Bridge over the Delaware River, which charges a toll in both directions.

It is unlawful for a customer to serve themselves gasoline in New Jersey. It became the last remaining U.S. state where all gas stations are required to sell full-service gasoline to customers at all times in 2016, after Oregon's introduction of restricted self-service gasoline availability took effect.[235]

Airports

Newark Liberty International Airport (EWR) is one of the busiest airports in the United States. Operated by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, it is one of the three main airports serving the New York metropolitan area, along with John F. Kennedy International Airport and LaGuardia Airport, which are both in Queens, New York. United Airlines is the airport's largest tenant, operating an entire terminal (Terminal C) there, which it uses as one of its primary hubs. FedEx Express operates a large cargo terminal at EWR as well. The adjacent Newark Airport railroad station provides access to Amtrak and NJ Transit trains along the Northeast Corridor Line.

Two smaller commercial airports, Atlantic City International Airport and rapidly growing Trenton-Mercer Airport, also operate in other parts of the state. Teterboro Airport in Bergen County and Millville Municipal Airport in Cumberland County are general aviation airports popular with private and corporate aircraft due to their proximity to New York City and the Jersey Shore, respectively.

Rail and bus

NJ Transit operates extensive rail and bus service throughout the state. A state-run corporation, it began with the consolidation of several private bus companies in North Jersey in 1979. In the early 1980s, it acquired Conrail's commuter train operations that connected suburban towns to New York City. NJ Transit has 12 rail lines that run through different parts of the state and 165 stations statewide.[236] Most of the lines end at either Penn Station in New York City or Hoboken Terminal in Hoboken, although some lines serve service to both terminal stations. One line provides service between Atlantic City and Philadelphia.

NJ Transit also operates three light rail systems in the state. The Hudson-Bergen Light Rail connects Bayonne to North Bergen, through Hoboken and Jersey City. The Newark Light Rail is partially underground, and connects downtown Newark with other parts of the city and its suburbs, Belleville and Bloomfield. The River Line connects Trenton, and Camden.

The PATH is a rapid transit system consisting of four lines operated by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. It links Hoboken, Jersey City, Harrison, and Newark with New York City. The PATCO Speedline is a rapid transit system that links Camden County to Philadelphia. Both the PATCO and the PATH are two of only five rapid transit systems in the United States to operate 24 hours a day.

Amtrak operates numerous long-distance passenger trains in New Jersey, both to and from neighboring states and around the country. In addition to the Newark Airport connection, other major Amtrak railway stations include Trenton Transit Center, Metropark, and the historic Newark Penn Station.

The Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority, or SEPTA, has two commuter rail lines that operate into New Jersey. The Trenton Line terminates at the Trenton Transit Center, and the West Trenton Line terminates at the West Trenton Rail Station in Ewing.

AirTrain Newark is a monorail connecting the Amtrak/NJ Transit station on the Northeast Corridor to the airport's terminals and parking lots.

Some private bus carriers still remain in New Jersey. Most of these carriers operate with state funding to offset losses and state owned buses are provided to these carriers, of which Coach USA companies make up the bulk. Other carriers include private charter and tour bus operators that take gamblers from other parts of New Jersey, New York City, Philadelphia, and Delaware to the casino resorts of Atlantic City.

Ferries

New York Waterway has ferry terminals at Belford, Jersey City, Hoboken, Weehawken, and Edgewater, with service to different parts of Manhattan. Liberty Water Taxi in Jersey City has ferries from Paulus Hook and Liberty State Park to Battery Park City in Manhattan. Statue Cruises offers service from Liberty State Park to the Statue of Liberty National Monument, including Ellis Island. SeaStreak offers services from the Raritan Bayshore to Manhattan, Martha's Vineyard, and Nantucket.

The Delaware River and Bay Authority operates the Cape May–Lewes Ferry on Delaware Bay, carrying both passengers and vehicles between New Jersey and Delaware as part of US 9. The agency also operates the Forts Ferry Crossing for passengers across the Delaware River. The Delaware River Port Authority operates the RiverLink Ferry between the Camden waterfront and Penn's Landing in Philadelphia.

Culture

General

New Jersey has continued to play a prominent role as a U.S. cultural nexus. Like every state, New Jersey has its own cuisine, religious communities, museums, and halls of fame.

New Jersey is the birthplace of many modern inventions, including FM radio, the motion picture camera, the lithium battery, the light bulb, transistors, and the electric train. Other New Jersey creations include: the drive-in movie, the cultivated blueberry, cranberry sauce, the boardwalk, the zipper, the phonograph, saltwater taffy, the dirigible, the seedless watermelon,[237] the first use of a submarine in warfare, and the ice cream cone.[238]

Diners are iconic to New Jersey. The state is home to many diner manufacturers and has over 600 diners, more than any other place in the world.[239]

New Jersey is the only state to have never had a state song;[240] as of 2021, it is one of only two states (the other being Maryland[241]) that are currently without a state song. "I'm From New Jersey" is incorrectly listed on many websites as being the New Jersey state song, but it was not even a contender when the New Jersey Arts Council submitted state song suggestions to the New Jersey Legislature in 1996.[242]

New Jersey is frequently the target of jokes in American culture,[243] especially from New York City-based television shows, such as Saturday Night Live.[244] Academic Michael Aaron Rockland attributes this to New Yorkers' view that New Jersey is the beginning of Middle America. The New Jersey Turnpike, which runs between two major East Coast cities, New York City and Philadelphia, is also cited as a reason, as people who traverse through the state may only see its industrial zones.[245] Reality television shows like Jersey Shore and The Real Housewives of New Jersey have reinforced stereotypical views of New Jersey culture,[246] but Rockland cited The Sopranos and the music of Bruce Springsteen as exporting a more positive image.[245]

The "New" in "New Jersey" is often omitted in casual conversation.[247]

Cuisine

New Jersey is known for several foods developed within the region, including Taylor Ham (also known as pork roll), sloppy joe sandwiches, tomato pies, salt water taffy, and Texas wieners. Just as New York City's cuisine has an influence on North Jersey, Philadelphia's cuisine influences South Jersey.

New Jersey third-largest industry is food and agriculture just behind pharmaceuticals and tourism. New Jersey is one of the top 10 producers of blueberries, cranberries, peaches, tomatoes, bell peppers, eggplant, cucumbers, apples, spinach, squash, and asparagus in the United States. Many restaurants in the state offer locally grown ingredients because of this.[248]

Campbell's Soup Company has been headquartered in Camden since 1869.[249] Goya Foods, the largest Hispanic-owned food company in the United States, operates a corporate headquarters in Jersey City.[250] Mars Wrigley Confectionery's US headquarters has been based in Hackettstown and Newark since 2007.[251]

Several states with substantial Italian American populations take credit for the development of submarine sandwiches, including New Jersey.[252]

Music

New Jersey has long been an important origin for both rock and rap music. Prominent musicians from or with significant connections to New Jersey include:

- Singer Frank Sinatra was born in Hoboken. He sang with a neighborhood vocal group, the Hoboken Four, and appeared in neighborhood theater amateur shows before he became an Academy Award-winning actor.

- Bruce Springsteen, who has sung of New Jersey life on most of his albums, is from Freehold. Some of his songs that represent New Jersey life are "Born to Run", "Spirit in the Night", "Rosalita (Come Out Tonight)", "Thunder Road", "Atlantic City", and "Jungleland".

- Irvington's Queen Latifah was one of the first female rappers to succeed in music, film, and television.[253]

- Southside Johnny, eponymous leader of Southside Johnny and the Asbury Jukes was raised in Ocean Grove. He is considered the "Grandfather of the New Jersey Sound"[254] and is cited by Jersey-born Jon Bon Jovi as his reason for singing.[255]

- Jon Bon Jovi, from Sayreville, reached fame in the 1980s with hard rock outfit Bon Jovi. The band has also written many songs about life in New Jersey, including "Livin' On A Prayer",[256] and named one of their albums after the state.

- Grammy-winning jazz vocalist Sarah Vaughn was born and raised in Newark. After singing in her church's choir as a child, she was sneaking into Newark nightclubs to sing and play piano by the time she was a teenager.[257]

- In 1964, the Isley Brothers founded the record label T-Neck Records, named after Teaneck, their home at the time.[258]

- The Broadway musical Jersey Boys is based on the lives of the members of the Four Seasons, three of whose members were born in New Jersey (Tommy DeVito, Frankie Valli, and Nick Massi) while a fourth, Bob Gaudio, was born in the Bronx but raised in Bergenfield.[259]

Sports

New Jersey currently has six teams from major professional sports leagues playing in the state, although one Major League Soccer team and two National Football League teams identify themselves as being from the New York metropolitan area.

Professional sports

The National Hockey League's New Jersey Devils, based in Newark at the Prudential Center, is the only major league sports franchise to bear the state's name. Founded in 1974 in Kansas City, Missouri, as the Kansas City Scouts, the team played in Denver, Colorado, as the Colorado Rockies from 1976 until the spring of 1982 when naval architect, businessman, and Jersey City native John J. McMullen purchased, renamed, and moved the franchise to Brendan Byrne Arena in East Rutherford's Meadowlands Sports Complex. While the team was poor to mediocre in Kansas City, Denver, and its first years in New Jersey, qualifying for the playoffs once in the 13 seasons from 1974 to 1987, the Devils ultimately established themselves in late 1980s and early 1990s during the tenure of Hall of Fame president and general manager Lou Lamoriello. As of 2023, the Devils have appeared in 23 postseasons in 40 seasons in New Jersey, reaching five Stanley Cup Finals (most recently in 2012) and winning it in 1995, 2000, and 2003. The organization is the youngest of the nine "Big Four" major league teams based in New York metropolitan area, ultimately establishing its core following throughout the northern and central portions of the state and carving a place in a media market once dominated by the New York Rangers and Islanders which has the distinction of being the only metropolitan area in the country with three major league professional sports teams participating in the same sport.

In 2018, the Philadelphia Flyers renovated and expanded their training facility, the Virtua Center Flyers Skate Zone, in Voorhees Township in the southern portion of the state.[260]