индонезийский язык

| индонезийский | |

|---|---|

| индонезийский | |

| Произношение | [baha.sa in.doˈne.si.ja] |

| Родной для | Индонезия |

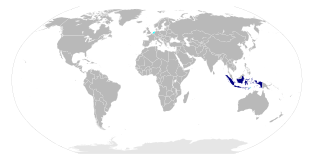

| Область | Индонезия (как официальный язык) Значимые носители языка: Восточный Тимор , Малайзия , Сингапур , Саудовская Аравия , Австралия , Тайвань , Нидерланды , Япония , Южная Корея , Объединенные Арабские Эмираты , США и другие. |

| Этническая принадлежность | Более 1300 индонезийских этнических групп |

Носители языка | Носители L1 : 43 миллиона (перепись 2010 г.) [1] L2 speakers: 156 million (2010 census)[1] Total speakers: 300 million (2022)[2] |

Early forms | |

Standard forms | |

| Dialects |

|

| Latin (Indonesian alphabet) Indonesian Braille | |

| SIBI (Manually Coded Indonesian) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Language Development and Fostering Agency (Badan Pengembangan dan Pembinaan Bahasa) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | id |

| ISO 639-2 | ind |

| ISO 639-3 | ind |

| Glottolog | indo1316 |

| Linguasphere | 33-AFA-ac |

Countries of the world where Indonesian is a majority native language Countries where Indonesian is a minority language | |

Индонезийский ( Bahasa Indonesia [ baˈhasa indoˈnesija] ) — официальный и национальный язык Индонезии ; . [8] Это стандартизированная разновидность языка малайского . [9] австронезийский язык , который на протяжении веков использовался в качестве лингва-франка на многоязычном индонезийском архипелаге. Индонезия является четвертой по численности населения страной в мире, с населением более 279 миллионов человек, большинство из которых говорит на индонезийском языке, что делает его одним из наиболее распространенных языков в мире. [10] На индонезийский словарный запас повлияли различные региональные языки, такие как яванский , сунданский , минангкабау , балийский , банджарский , бугийский и т. д., а также иностранные языки, такие как арабский , голландский , португальский и английский . Многие заимствованные слова были адаптированы в соответствии с фонетическими и грамматическими правилами индонезийского языка.

Most Indonesians, aside from speaking the national language, are fluent in at least one of the more than 700 indigenous local languages; examples include Javanese and Sundanese, which are commonly used at home and within the local community.[11][12] However, most formal education and nearly all national mass media, governance, administration, and judiciary and other forms of communication are conducted in Indonesian.[13]

Under Indonesian rule from 1976 to 1999, Indonesian was designated as the official language of Timor Leste. It has the status of a working language under the country's constitution along with English.[7][14]: 3 [15] In November 2023, the Indonesian language was recognized as one of the official languages of the UNESCO General Conference.

The term Indonesian is primarily associated with the national standard dialect (bahasa baku).[16] However, in a looser sense, it also encompasses the various local varieties spoken throughout the Indonesian archipelago.[9][17] Standard Indonesian is confined mostly to formal situations, existing in a diglossic relationship with vernacular Malay varieties, which are commonly used for daily communication, coexisting with the aforementioned regional languages and with Malay creoles;[16][11] standard Indonesian is spoken in informal speech as a lingua franca between vernacular Malay dialects, Malay creoles, and regional languages.

The Indonesian name for the language (bahasa Indonesia) is also occasionally used in English and other languages. Bahasa Indonesia is sometimes improperly reduced to Bahasa, which refers to the Indonesian subject (Bahasa Indonesia) taught in schools, on the assumption that this is the name of the language. But the word bahasa only means language. For example, French language is translated as bahasa Prancis, and the same applies to other languages, such as bahasa Inggris (English), bahasa Jepang (Japanese), bahasa Arab (Arabic), bahasa Italia (Italian), and so on. Indonesians generally may not recognize the name Bahasa alone when it refers to their national language.[18]

History[edit]

Early kingdoms era[edit]

Standard Indonesian is a standard language of "Riau Malay",[4][5] which despite its common name is not based on the vernacular Malay dialects of the Riau Islands, but rather represents a form of Classical Malay as used in the 19th and early 20th centuries in the Riau-Lingga Sultanate. Classical Malay had emerged as a literary language in the royal courts along both shores of the Strait of Malacca, including the Johor Sultanate and Malacca Sultanate.[19][20][21] Originally spoken in Northeast Sumatra,[22] Malay has been used as a lingua franca in the Indonesian archipelago for half a millennium. It might be attributed to its ancestor, the Old Malay language (which can be traced back to the 7th century). The Kedukan Bukit Inscription is the oldest surviving specimen of Old Malay, the language used by Srivijayan empire.[23] Since the 7th century, the Old Malay language has been used in Nusantara (archipelago) (Indonesian archipelago), evidenced by Srivijaya inscriptions and by other inscriptions from coastal areas of the archipelago, such as Sojomerto inscription.[23]

Old Malay as lingua franca[edit]

Trade contacts carried on by various ethnic peoples at the time were the main vehicle for spreading the Old Malay language, which was the main communications medium among the traders. Ultimately, the Old Malay language became a lingua franca and was spoken widely by most people in the archipelago.[25][26]

Indonesian (in its standard form) has essentially the same material basis as the Malaysian standard of Malay and is therefore considered to be a variety of the pluricentric Malay language. However, it does differ from Malaysian Malay in several respects, with differences in pronunciation and vocabulary. These differences are due mainly to the Dutch and Javanese influences on Indonesian. Indonesian was also influenced by the Melayu pasar (lit. 'market Malay'), which was the lingua franca of the archipelago in colonial times, and thus indirectly by other spoken languages of the islands.

Malaysian Malay claims to be closer to the classical Malay of earlier centuries, even though modern Malaysian has been heavily influenced, in lexicon as well as in syntax, by English. The question of whether High Malay (Court Malay) or Low Malay (Bazaar Malay) was the true parent of the Indonesian language is still in debate. High Malay was the official language used in the court of the Johor Sultanate and continued by the Dutch-administered territory of Riau-Lingga, while Low Malay was commonly used in marketplaces and ports of the archipelago. Some linguists have argued that it was the more common Low Malay that formed the base of the Indonesian language.[27]

Colonial era and the birth of Indonesian[edit]

When the Dutch East India Company (VOC) first arrived in the archipelago at the start of the 1600s, the Malay language was a significant trading and political language due to the influence of the Malaccan Sultanate and later the Portuguese. However, the language had never been dominant among the population of the Indonesian archipelago as it was limited to mercantile activity. The VOC adopted the Malay language as the administrative language of their trading outpost in the east. Following the bankruptcy of the VOC, the Batavian Republic took control of the colony in 1799, and it was only then that education in and promotion of Dutch began in the colony. Even then, Dutch administrators were remarkably reluctant to promote the use of Dutch compared to other colonial regimes. Dutch thus remained the language of a small elite: in 1940, only 2% of the total population could speak Dutch. Nevertheless, it did have a significant influence on the development of Malay in the colony: during the colonial era, the language that would be standardized as Indonesian absorbed a large amount of Dutch vocabulary in the form of loanwords.

The nationalist movement that ultimately brought Indonesian to its national language status rejected Dutch from the outset. However, the rapid disappearance of Dutch was a very unusual case compared with other colonized countries, where the colonial language generally has continued to function as the language of politics, bureaucracy, education, technology, and other fields of importance for a significant time after independence.[28] The Indonesian scholar Soenjono Dardjowidjojo even goes so far as to say that when compared to the situation in other Asian countries such as India, Malaysia, Singapore and the Philippines, "Indonesian is perhaps the only language that has achieved the status of a national language in its true sense" since it truly dominates in all spheres of Indonesian society.[29] The ease with which Indonesia eliminated the language of its former colonial power can perhaps be explained as much by Dutch policy as by Indonesian nationalism. In marked contrast to the French, Spanish and Portuguese, who pursued an assimilation colonial policy, or even the British, the Dutch did not attempt to spread their language among the indigenous population. In fact, they consciously prevented the language from being spread by refusing to provide education, especially in Dutch, to the native Indonesians so they would not come to see themselves as equals.[28] Moreover, the Dutch wished to prevent the Indonesians from elevating their perceived social status by taking on elements of Dutch culture. Thus, until the 1930s, they maintained a minimalist regime and allowed Malay to spread quickly throughout the archipelago.

Dutch dominance at that time covered nearly all aspects, with official forums requiring the use of Dutch, although since the Second Youth Congress (1928) the use of Indonesian as the national language was agreed on as one of the tools in the independence struggle. As of it, Mohammad Hoesni Thamrin inveighed actions underestimating Indonesian. After some criticism and protests, the use of Indonesian was allowed since the Volksraad sessions held in July 1938.[30] By the time they tried to counter the spread of Malay by teaching Dutch to the natives, it was too late, and in 1942, the Japanese conquered Indonesia. The Japanese mandated that all official business be conducted in Indonesian and quickly outlawed the use of the Dutch language.[31] Three years later, the Indonesians themselves formally abolished the language and established bahasa Indonesia as the national language of the new nation.[32] The term bahasa Indonesia itself had been proposed by Mohammad Tabrani in 1926,[33] and Tabrani had further proposed the term over calling the language Malay language during the First Youth Congress in 1926.[3]

Indonesian language (old VOS spelling):

Jang dinamakan 'Bahasa Indonesia' jaitoe bahasa Melajoe jang soenggoehpoen pokoknja berasal dari 'Melajoe Riaoe' akan tetapi jang soedah ditambah, dioebah ataoe dikoerangi menoeroet keperloean zaman dan alam baharoe, hingga bahasa itoe laloe moedah dipakai oleh rakjat diseloeroeh Indonesia; pembaharoean bahasa Melajoe hingga menjadi bahasa Indonesia itoe haroes dilakoekan oleh kaoem ahli jang beralam baharoe, ialah alam kebangsaan Indonesia

Indonesian (modern EYD spelling):

Yang dinamakan 'Bahasa Indonesia' yaitu bahasa Melayu yang sungguhpun pokoknya berasal dari 'Melayu Riau' akan tetapi yang sudah ditambah, diubah atau dikurangi menurut keperluan zaman dan alam baru, hingga bahasa itu lalu mudah dipakai oleh rakyat di seluruh Indonesia; pembaharuan bahasa Melayu hingga menjadi bahasa Indonesia itu harus dilakukan oleh kaum ahli yang beralam baru, ialah alam kebangsaan Indonesia

English:

"What is named as 'Indonesian language' is a true Malay language derived from 'Riau Malay' but which had been added, modified or subscribed according to the requirements of the new age and nature, until it was then used easily by people across Indonesia; the renewal of Malay language until it became Indonesian it had to be done by the experts of the new nature, the national nature of Indonesia"

— Ki Hajar Dewantara in the Congress of Indonesian Language I 1938, Solo[34][35]

Several years prior to the congress, Swiss linguist, Renward Brandstetter wrote An Introduction to Indonesian Linguistics in 4 essays from 1910 to 1915. The essays were translated into English in 1916. By "Indonesia", he meant the name of the geographical region, and by "Indonesian languages" he meant Malayo-Polynesian languages west of New Guinea, because by that time there was still no notion of Indonesian language.

Sutan Takdir Alisjahbana was a great promoter of the use and development of Indonesian and he was greatly exaggerating the decline of Dutch. Higher education was still in Dutch and many educated Indonesians were writing and speaking in Dutch in many situations (and were still doing so well after independence was achieved). He believed passionately in the need to develop Indonesian so that it could take its place as a fully adequate national language, able to replace Dutch as a means of entry into modern international culture. In 1933, he began the magazine Pujangga Baru (New Writer — Poedjangga Baroe in the original spelling) with co-editors Amir Hamzah and Armijn Pane. The language of Pujangga Baru came in for criticism from those associated with the more classical School Malay and it was accused of publishing Dutch written with an Indonesian vocabulary. Alisjahbana would no doubt have taken the criticism as a demonstration of his success. To him the language of Pujangga Baru pointed the way to the future, to an elaborated, Westernised language able to express all the concepts of the modern world. As an example, among the many innovations they condemned was use of the word bisa instead of dapat for 'can'. In Malay bisa meant only 'poison from an animal's bite' and the increasing use of Javanese bisa in the new meaning they regarded as one of the many threats to the language's purity. Unlike more traditional intellectuals, he did not look to Classical Malay and the past. For him, Indonesian was a new concept; a new beginning was needed and he looked to Western civilisation, with its dynamic society of individuals freed from traditional fetters, as his inspiration.[10]

The prohibition on use of Dutch led to an expansion of Indonesian language newspapers and pressure on them to increase the language's wordstock. The Japanese agreed to the establishment of the Komisi Bahasa (Language Commission) in October 1942, formally headed by three Japanese but with a number of prominent Indonesian intellectuals playing the major part in its activities. Soewandi, later to be Minister of Education and Culture, was appointed secretary, Alisjahbana was appointed an 'expert secretary' and other members included the future president and vice-president, Sukarno and Hatta. Journalists, beginning a practice that has continued to the present, did not wait for the Komisi Bahasa to provide new words, but actively participated themselves in coining terms. Many of the Komisi Bahasa's terms never found public acceptance and after the Japanese period were replaced by the original Dutch forms, including jantera (Sanskrit for 'wheel'), which temporarily replaced mesin (machine), ketua negara (literally 'chairman of state'), which had replaced presiden (president) and kilang (meaning 'mill'), which had replaced pabrik (factory). In a few cases, however, coinings permanently replaced earlier Dutch terms, including pajak (earlier meaning 'monopoly') instead of belasting (tax) and senam (meaning 'exercise') instead of gimnastik (gymnastics). The Komisi Bahasa is said to have coined more than 7000 terms, although few of these gained common acceptance.[10]

Adoption as the national language[edit]

The adoption of Indonesian as the country's national language was in contrast to most other post-colonial states. Neither the language with the most native speakers (Javanese) nor the language of the former European colonial power (Dutch) was to be adopted. Instead, a local language with far fewer native speakers than the most widely spoken local language was chosen (nevertheless, Malay was the second most widely spoken language in the colony after Javanese, and had many L2 speakers using it for trade, administration, and education).

In 1945, when Indonesia declared its independence, Indonesian was formally declared the national language,[8] despite being the native language of only about 5% of the population. In contrast, Javanese and Sundanese were the mother tongues of 42–48% and 15% respectively.[36] The combination of nationalistic, political, and practical concerns ultimately led to the successful adoption of Indonesian as a national language.In 1945, Javanese was easily the most prominent language in Indonesia. It was the native language of nearly half the population, the primary language of politics and economics, and the language of courtly, religious, and literary tradition.[28] What it lacked, however, was the ability to unite the diverse Indonesian population as a whole. With thousands of islands and hundreds of different languages, the newly independent country of Indonesia had to find a national language that could realistically be spoken by the majority of the population and that would not divide the nation by favouring one ethnic group, namely the Javanese, over the others. In 1945, Indonesian was already in widespread use;[36] in fact, it had been for roughly a thousand years. Over that long period, Malay, which would later become standardized as Indonesian, was the primary language of commerce and travel. It was also the language used for the propagation of Islam in the 13th to 17th centuries, as well as the language of instruction used by Portuguese and Dutch missionaries attempting to convert the indigenous people to Christianity.[28] The combination of these factors meant that the language was already known to some degree by most of the population, and it could be more easily adopted as the national language than perhaps any other. Moreover, it was the language of the sultanate of Brunei and of future Malaysia, on which some Indonesian nationalists had claims.

Over the first 53 years of Indonesian independence, the country's first two presidents, Sukarno and Suharto constantly nurtured the sense of national unity embodied by Indonesian, and the language remains an essential component of Indonesian identity. Through a language planning program that made Indonesian the language of politics, education, and nation-building in general, Indonesian became one of the few success stories of an indigenous language effectively overtaking that of a country's colonisers to become the de jure and de facto official language.[32] Today, Indonesian continues to function as the language of national identity as the Congress of Indonesian Youth envisioned, and also serves as the language of education, literacy, modernization, and social mobility.[32] Despite still being a second language to most Indonesians, it is unquestionably the language of the Indonesian nation as a whole, as it has had unrivalled success as a factor in nation-building and the strengthening of Indonesian identity.

Modern and colloquial Indonesian[edit]

Indonesian is spoken as a mother tongue and national language. Over 200 million people regularly make use of the national language, with varying degrees of proficiency. In a nation that is home to more than 700 native languages and a vast array of ethnic groups, it plays an important unifying and cross-archipelagic role for the country. Use of the national language is abundant in the media, government bodies, schools, universities, workplaces, among members of the upper-class or nobility and also in formal situations, despite the 2010 census showing only 19.94% of over-five-year-olds speak mainly Indonesian at home.[37]

Standard Indonesian is used in books and newspapers and on television/radio news broadcasts. The standard dialect, however, is rarely used in daily conversations, being confined mostly to formal settings. While this is a phenomenon common to most languages in the world (for example, spoken English does not always correspond to its written standards), the proximity of spoken Indonesian (in terms of grammar and vocabulary) to its normative form is noticeably low. This is mostly due to Indonesians combining aspects of their own local languages (e.g., Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese) with Indonesian. This results in various vernacular varieties of Indonesian, the very types that a foreigner is most likely to hear upon arriving in any Indonesian city or town.[38] This phenomenon is amplified by the use of Indonesian slang, particularly in the cities. Unlike the relatively uniform standard variety, Vernacular Indonesian exhibits a high degree of geographical variation, though Colloquial Jakartan Indonesian functions as the de facto norm of informal language and is a popular source of influence throughout the archipelago.[16] There is language shift of first language among Indonesian into Indonesian from other language in Indonesia caused by ethnic diversity than urbanicity.[39]

The most common and widely used colloquial Indonesian is heavily influenced by the Betawi language, a Malay-based creole of Jakarta, amplified by its popularity in Indonesian popular culture in mass media and Jakarta's status as the national capital. In informal spoken Indonesian, various words are replaced with those of a less formal nature. For example, tidak (no) is often replaced with the Betawi form nggak or the even simpler gak/ga, while seperti (like, similar to) is often replaced with kayak [kajaʔ]. Sangat or amat (very), the term to express intensity, is often replaced with the Javanese-influenced banget. As for pronunciation, the diphthongs ai and au on the end of base words are typically pronounced as /e/ and /o/. In informal writing, the spelling of words is modified to reflect the actual pronunciation in a way that can be produced with less effort. For example, capai becomes cape or capek, pakai becomes pake, kalau becomes kalo. In verbs, the prefix me- is often dropped, although an initial nasal consonant is often retained, as when mengangkat becomes ngangkat (the basic word is angkat). The suffixes -kan and -i are often replaced by -in. For example, mencarikan becomes nyariin, menuruti becomes nurutin. The latter grammatical aspect is one often closely related to the Indonesian spoken in Jakarta and its surrounding areas.

[edit]

Malay historical linguists agree on the likelihood of the Malay homeland being in western Borneo stretching to the Bruneian coast.[40] A form known as Proto-Malay language was spoken in Borneo at least by 1000 BCE and was, it has been argued, the ancestral language of all subsequent Malayan languages. Its ancestor, Proto-Malayo-Polynesian, a descendant of the Proto-Austronesian language, began to break up by at least 2000 BCE, possibly as a result of the southward expansion of Austronesian peoples into Maritime Southeast Asia from the island of Taiwan.[41] Indonesian, which originated from Malay, is a member of the Austronesian family of languages, which includes languages from Southeast Asia, the Pacific Ocean and Madagascar, with a smaller number in continental Asia. It has a degree of mutual intelligibility with the Malaysian standard of Malay, which is officially known there as bahasa Malaysia, despite the numerous lexical differences.[42] However, vernacular varieties spoken in Indonesia and Malaysia share limited intelligibility, which is evidenced by the fact that Malaysians have difficulties understanding Indonesian sinetron (soap opera) aired on Malaysia TV stations, and vice versa.[43]

Malagasy, a geographic outlier spoken in Madagascar in the Indian Ocean; the Philippines national language, Filipino; Formosan in Taiwan's aboriginal population; and the native Māori language of New Zealand are also members of this language family. Although each language of the family is mutually unintelligible, their similarities are rather striking. Many roots have come virtually unchanged from their common ancestor, Proto-Austronesian language. There are many cognates found in the languages' words for kinship, health, body parts and common animals. Numbers, especially, show remarkable similarities.

| Language | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAN, c. 4000 BCE | *isa | *DuSa | *telu | *Sepat | *lima | *enem | *pitu | *walu | *Siwa | *puluq |

| Malay/Indonesian | satu | dua | tiga | empat | lima | enam | tujuh | lapan/delapan | sembilan | sepuluh |

| Amis | cecay | tusa | tulu | sepat | lima | enem | pitu | falu | siwa | pulu' |

| Sundanese | hiji | dua | tilu | opat | lima | genep | tujuh | dalapan | salapan | sapuluh |

| Tsou | coni | yuso | tuyu | sʉptʉ | eimo | nomʉ | pitu | voyu | sio | maskʉ |

| Tagalog | isá | dalawá | tatló | ápat | limá | ánim | pitó | waló | siyám | sampu |

| Ilocano | maysá | dua | talló | uppát | limá | inném | pitó | waló | siam | sangapúlo |

| Cebuano | usá | duhá | tuló | upat | limá | unom | pitó | waló | siyám | napulu |

| Hiligaynon | isá | duwá | tatló | apat | limá | anom | pitó | waló | siyám | pulo |

| Chamorro | maisa/håcha | hugua | tulu | fatfat | lima | gunum | fiti | guålu | sigua | månot/fulu |

| Malagasy | iray/isa | roa | telo | efatra | dimy | enina | fito | valo | sivy | folo |

| Cham | sa | dua | klau | pak | limâ | nam | tajuh | dalipan | thalipan | pluh |

| Toba Batak | sada | dua | tolu | opat | lima | onom | pitu | ualu | sia | sampulu |

| Minangkabau | ciek | duo | tigo | ampek | limo | anam | tujuah | salapan | sambilan | sapuluah |

| Rejang[44] | do | duai | tlau | pat | lêmo | num | tujuak | dêlapên | sêmbilan | sêpuluak |

| Javanese | siji | loro | telu | papat | lima | nem | pitu | wolu | sanga | sepuluh |

| Tetun | ida | rua | tolu | hat | lima | nen | hitu | ualu | sia | sanulu |

| Biak | eser/oser | suru | kyor | fyak | rim | wonem | fik | war | siw | samfur |

| Fijian | dua | rua | tolu | vā | lima | ono | vitu | walu | ciwa | tini |

| Kiribati | teuana | uoua | teniua | aua | nimaua | onoua | itiua | waniua | ruaiua | tebuina |

| Samoan | tasi | lua | tolu | fā | lima | ono | fitu | valu | iva | sefulu |

| Hawaiian | kahi | lua | kolu | hā | lima | ono | hiku | walu | iwa | -'umi |

There are more than 700 local languages in Indonesian islands, such as Javanese, Sundanese, etc. While Malay as the source of Indonesian is the mother tongue of ethnic Malay who lives along the east coast of Sumatra, in the Riau Archipelago, and on the south and west coast of Kalimantan (Borneo). There are several areas, such as Jakarta, Manado, Lesser Sunda islands, and Mollucas which has Malay-based trade languages. Thus, a large proportion of Indonesian, at least, use two language daily, those are Indonesian and local languages. When two languages are used by the same people in this way, they are likely to influence each other.[45]

Aside from local languages, Dutch made the highest contribution to the Indonesian vocabulary, due to the Dutch colonization over three centuries, from the 16th century until the mid-20th century.[46][47][45] Asian languages also influenced the language, with Chinese influencing Indonesian during the 15th and 16th centuries due to the spice trade; Sanskrit, Tamil, Prakrit and Hindi contributing during the flourishing of Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms from the 2nd to the 14th century; followed by Arabic after the spread of Islam in the archipelago in the 13th century.[48] Loanwords from Portuguese were mainly connected with articles that the early European traders and explorers brought to Southeast Asia. Indonesian also receives many English words as a result of globalization and modernization, especially since the 1990s, as far as the Internet's emergence and development until the present day.[49] Some Indonesian words correspond to Malay loanwords in English, among them the common words orangutan, gong, bamboo, rattan, sarong, and the less common words such as paddy, sago and kapok, all of which were inherited in Indonesian from Malay but borrowed from Malay in English. The phrase "to run amok" comes from the Malay verb amuk (to run out of control, to rage).[50][51][52][53]

Indonesian is neither a pidgin nor a creole since its characteristics do not meet any of the criteria for either. It is believed that the Indonesian language was one of the means to achieve independence, but it is opened to receive vocabulary from other foreign languages aside from Malay that it has made contact with since the colonialism era, such as Dutch, English and Arabic among others, as the loan words keep increasing each year.[54]

Geographical distribution[edit]

In 2010, Indonesian had 42.8 million native speakers and 154.9 million second-language speakers,[1] who speak it alongside their local mother tongue, giving a total number of speakers in Indonesia of 197.7 million.[1] It is common as a first language in urban areas, and as a second language by those residing in more rural parts of Indonesia.

The VOA and BBC use Indonesian as their standard for broadcasting in Malay.[55][56] In Australia, Indonesian is one of three Asian target languages, together with Japanese and Mandarin, taught in some schools as part of the Languages Other Than English programme.[57] Indonesian has been taught in Australian schools and universities since the 1950s.[58]

In East Timor, which was occupied by Indonesia between 1975 and 1999, Indonesian is recognized by the constitution as one of the two working languages (the other being English), alongside the official languages of Tetum and Portuguese.[7] It is understood by the Malay people of Australia's Cocos Keeling Islands in the Indian Ocean, also in some parts of the Sulu area of the southern Philippines and traces of it are to be found among people of Malay descent in Sri Lanka, South Africa, and other places.[13]

Indonesian as a foreign language[edit]

Indonesian is taught as a foreign language in schools, universities and institutions around the world, especially in Australia, the Netherlands, Japan, South Korea, Timor-Leste, Vietnam, Taiwan, the United States, and England.[59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68][non-primary source needed]

Official status[edit]

Indonesian is the official language of Indonesia, and its use is encouraged throughout the Indonesian archipelago. It is regulated in Chapter XV, 1945 Constitution of Indonesia about the flag, official language, coat of arms, and national anthem of Indonesia.[8] Also, in Chapter III, Section 25 to 45, Government regulation No. 24/ 2009 mentions explicitly the status of the Indonesian language.[69]

The national language is Indonesian.

— Article 36, Chapter XV, Constitution of Indonesia[8]

Indonesian functions as a symbol of national identity and pride, and is a lingua franca among the diverse ethnic groups in Indonesia and the speakers of vernacular Malay dialects and Malay creoles. The Indonesian language serves as the national and official language, the language of education, communication, transaction and trade documentation, the development of national culture, science, technology, and mass media. It also serves as a vehicle of communication among the provinces and different regional cultures in the country.[69]

According to Indonesian law, the Indonesian language was proclaimed as the unifying language during the Youth Pledge on 28 October 1928 and developed further to accommodate the dynamics of Indonesian civilization.[69] As mentioned previously, the language was based on Riau Malay,[4][70] though linguists note that this is not the local dialect of Riau, but the Malaccan dialect that was used in the Riau court.[20] Since its conception in 1928 and its official recognition in the 1945 Constitution, the Indonesian language has been loaded with a nationalist political agenda to unify Indonesia (former Dutch East Indies). This status has made it relatively open to accommodate influences from other Indonesian ethnic languages, most notably Javanese as the majority ethnic group, and Dutch as the previous coloniser. Compared to the indigenous dialects of Malay spoken in Sumatra and Malay peninsula or the normative Malaysian standard, the Indonesian language differs profoundly by a large amount of Javanese loanwords incorporated into its already-rich vocabulary. As a result, Indonesian has more extensive sources of loanwords, compared to Malaysian Malay.

The disparate evolution of Indonesian and Malaysian has led to a rift between the two standardized varieties. This has been based more upon political nuance and the history of their standardization than cultural reasons, and as a result, there are asymmetrical views regarding each other's variety among Malaysians and Indonesians. Malaysians tend to assert that Malaysian and Indonesian are merely different normative varieties of the same language, while Indonesians tend to treat them as separate, albeit closely related, languages. Consequently, Indonesians feel little need to harmonise their language with Malaysia and Brunei, whereas Malaysians are keener to coordinate the evolution of the language with Indonesians,[71] although the 1972 Indonesian alphabet reform was seen mainly as a concession of Dutch-based Indonesian to the English-based spelling of Malaysian.

In November 2023, the Indonesian language was recognised as one of the official languages of the UNESCO General Conference. Currently there are 10 official languages of the UNESCO General Conference, consisting of the six United Nations languages, namely English, French, Arabic, Chinese, Russian, and Spanish, as well as four other languages of UNESCO member countries, namely Hindi, Italian, Portuguese, and Indonesian.[72][73]

Official policy[edit]

As regulated by Indonesian state law UU No 24/2009, other than state official speeches and documents between or issued to Indonesian government, Indonesian language is required by law to be used in:[74]

- Official speeches by the president, vice president, and other state officials delivered within or outside Indonesia

- Agreements involving either government, private institutions, or individuals

- National or international forums held in Indonesia

- Scientific papers and publications in Indonesia

- Geographical names in Indonesia (name of buildings, roads, offices, complexes, institutions)

- Public signs, road signs, public facilities, banners, and other information of public services in public area.

- Information through mass media

However, other languages may be used in dual-language setting to accompany but not to replace Indonesian language in: agreements, information regarding goods / services, scientific papers, information through mass media, geographical names, public signs, road signs, public facilities, banners, and other information of public services in public area.[74]

While there are no sanctions of the uses of other languages,[74] in Indonesian court's point of view, any agreements made in Indonesia but not drafted in Indonesian language, is null and void.[75] In any different interpretations in dual-language agreements setting, Indonesian language shall prevail.[76]

Phonology[edit]

Vowels[edit]

Indonesian has six vowel phonemes as shown in the table below.[77][78]

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | /i/ | /u/ | |

| Close-Mid | /e/ | /ə/ | /o/ |

| Open | /a/ |

In standard Indonesian orthography, the Latin alphabet is used, and five vowels are distinguished: a, i, u, e, o. In materials for learners, the mid-front vowel /e/ is sometimes represented with a diacritic as ⟨é⟩ to distinguish it from the mid-central vowel ⟨ê⟩ /ə/. Since 2015, the auxiliary graphemes ⟨é⟩ and ⟨è⟩ are used respectively for phonetic [e] and [ɛ] in Indonesian, while Standard Malay has rendered both of them as ⟨é⟩.[79]

The phonetic realization of the mid vowels /e/ and /o/ ranges from close-mid ([e]/[o]) to open-mid ([ɛ]/[ɔ]) allophones. Some analyses set up a system which treats the open-mid vowels /ɛ/ and /ɔ/ as distinct phonemes.[80] Poedjosoedarmo argued the split of the front mid vowels in Indonesian is due to Javanese influence which exhibits a difference between ⟨i⟩ [i], ⟨é⟩ [e] and è [ɛ]. Another example of Javanese influence in Indonesian is the split of back mid vowels into two allophones of [o] and [ɔ]. These splits (and loanwords) increase instances of doublets in Indonesian, such as ⟨satai⟩ and ⟨saté⟩. Javanese words adopted into Indonesian have greatly increased the frequency of Indonesian ⟨é⟩ and ⟨o⟩.[45]

High vowels (⟨i⟩, ⟨u⟩) could not appear in a final syllable in traditional Malay if a mid-vowel (⟨e⟩, ⟨o⟩) happened in the previous syllable, and mid-vowels could not occur in the final syllable if a high vowel was present in the second-to-last syllable.[10]

Traditional Malay does not allow the mid-central schwa vowel to occur in consonant open or closed word-final syllables. The schwa vowel was introduced in closed syllables under the influence of Javanese and Jakarta Malay, but Dutch borrowings made it more acceptable. Although Alisjahbana argued against it, insisting on writing ⟨a⟩ instead of an ⟨ê⟩ in final syllables such as koda (vs kodə 'code') and nasionalisma (vs nasionalismə 'nationalism'), he was unsuccessful.[10] This spelling convention was instead survived in Balinese orthography.

Diphthongs[edit]

Indonesian has four diphthong phonemes only in open syllables.[81] They are:

- /ai̯/: kedai ('shop'), pandai ('clever')

- /au̯/: kerbau ('buffalo'), limau ('lime')

- /oi̯/ (or /ʊi̯/ in Indonesian): amboi ('wow'), toilet ('toilet')

- /ei̯/: survei ('survey'), geiser ('geyser')

Some analyses assume that these diphthongs are actually a monophthong followed by an approximant, so ⟨ai⟩ represents /aj/, ⟨au⟩ represents /aw/, and ⟨oi⟩ represents /oj/. On this basis, there are no phonological diphthongs in Indonesian.[82]

Diphthongs are differentiated from two vowels in two syllables, such as:

- /a.i/: e.g. lain ('other') [la.in], air ('water') [a.ir]

- /a.u/: bau ('smell') [ba.u], laut ('sea') [la.ut]

Consonants[edit]

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||

| Plosive/ Affricate | voiceless | p | t̪ | t͡ʃ | k | (ʔ) |

| voiced | b | d | d͡ʒ | ɡ | ||

| Fricative | voiceless | (f) | s | (ʃ) | (x) | h |

| voiced | (v) | (z) | ||||

| Approximant | w | l | j | |||

| Trill | r | |||||

The consonants of Indonesian are shown above.[77][83] Non-native consonants that only occur in borrowed words, principally from Arabic and English, are shown in parentheses. Some analyses list 19 "primary consonants" for Indonesian as the 18 symbols that are not in parentheses in the table as well as the glottal stop [ʔ]. The secondary consonants /f/, /v/, /z/, /ʃ/ and /x/ only appear in loanwords. Some speakers pronounce /v/ in loanwords as [v], otherwise it is [f]. Likewise, /x/ may be replaced with [h] or [k] by some speakers. /ʃ/ is sometimes replaced with /s/, which was traditionally used as a substitute for /ʃ/ in older borrowings from Sanskrit, and /f/ is rarely replaced, though /p/ was substituted for /f/ in older borrowings such as kopi "coffee" from Dutch koffie. /z/ may occasionally be replaced with /s/ or /d͡ʒ/. [z] can also be an allophone of /s/ before voiced consonants.[84][85] According to some analyses, postalveolar affricates /tʃ/ and /dʒ/ are instead palatals [c] and [ɟ] in Indonesian.[86]

The consonants in Indonesian are influenced by other important languages in Indonesian history. The influences included schwa in final closed syllable (e.g. Indonesian pəcəl vs Malay pəcal), initial homorganic nasal stop clusters of ⟨mb⟩, ⟨nd⟩, and ⟨nj⟩ (e.g. Indonesian mbolos 'to malinger'), the consonant-semivowel clusters (e.g. Indonesian pria vs Malay pəria 'male'),[clarification needed] introduction of consonant clusters ⟨-ry-⟩ and ⟨-ly-⟩ (e.g. Indonesian gərilya vs Malay gərila 'guerrilla'), increased usage of initial ⟨w-⟩ (e.g. warta and bərita 'news') and intervocalic ⟨w-⟩, and increase of initial and post-consonant ⟨y⟩ [j]. These changes resulted from influences of local languages in Indonesia, such as Balinese, Madurese, Sundanese and especially Javanese, and foreign languages such as Arabic and Dutch.[45]

Orthographic note:

The sounds are represented orthographically by their symbols as above, except:

- /ɲ/ is written ⟨ny⟩.

- /ŋ/ is written ⟨ng⟩.

- The glottal stop [ʔ] is written as a final ⟨k⟩, an apostrophe ⟨'⟩ (the use ⟨k⟩ from its being an allophone of /k/ or /ɡ/ in the syllable coda), or it can be unwritten.

- /tʃ/ is written ⟨c⟩.

- /dʒ/ is written ⟨j⟩.

- /ʃ/ is written ⟨sy⟩.

- /x/ is written ⟨kh⟩.

- /j/ is written ⟨y⟩.

Stress[edit]

Indonesian has light stress that falls on either the final or penultimate syllable, depending on regional variations as well as the presence of the schwa (/ə/) in a word. It is generally the penultimate syllable that is stressed, unless its vowel is a schwa /ə/. If the penult has a schwa, then stress usually moves to the final syllable.[87]

However, there is some disagreement among linguists over whether stress is phonemic (unpredictable), with some analyses suggesting that there is no underlying stress in Indonesian.[83][88][89]

Rhythm[edit]

The classification of languages based on rhythm can be problematic.[90] Nevertheless, acoustic measurements suggest that Indonesian has more syllable-based rhythm than British English,[91] even though doubts remain about whether the syllable is the appropriate unit for the study of Malay prosody.[88]

Grammar[edit]

Word order in Indonesian is generally subject-verb-object (SVO), similar to that of most modern European languages as well as English. However, considerable flexibility in word ordering exists, in contrast with languages such as Japanese or Korean, for instance, which always end clauses with verbs. Indonesian, while allowing for relatively flexible word orderings, does not mark for grammatical case, nor does it make use of grammatical gender.

Affixes[edit]

Indonesian words are composed of a root or a root plus derivational affixes. The root is the primary lexical unit of a word and is usually bisyllabic, of the shape CV(C)CV(C). Affixes are "glued" onto roots (which are either nouns or verbs) to alter or expand the primary meaning associated with a given root, effectively generating new words, for example, masak (to cook) may become memasak (cooking), memasakkan (cook for), dimasak (be cooked), pemasak (a cook), masakan (a meal, cookery), termasak (accidentally cooked). There are four types of affixes: prefixes (awalan), suffixes (akhiran), circumfixes (apitan) and infixes (sisipan). Affixes are categorized into noun, verb, and adjective affixes. Many initial consonants alternate in the presence of prefixes: sapu (to sweep) becomes menyapu (sweeps/sweeping); panggil (to call) becomes memanggil (calls/calling), tapis (to sieve) becomes menapis (sieves).

Other examples of the use of affixes to change the meaning of a word can be seen with the word ajar (to teach):

- ajar = to teach

- ajari = to teach (imperative, locative)

- ajarilah = to teach (jussive, locative)

- ajarkan = to teach (imperative, causative/applicative)

- ajarkanlah = to teach (jussive, causative/applicative)

- ajarlah = to teach (jussive, active)

- ajaran = teachings

- belajar = to learn (intransitive, active)

- diajar = to be taught (intransitive)

- diajari = to be taught (transitive, locative)

- diajarkan = to be taught (transitive, causative/applicative)

- dipelajari = to be studied (locative)

- dipelajarkan = to be studied (causative/applicative)

- mempelajari = to study (locative)

- mempelajarkan = to study (causative/applicative)

- mengajar = to teach (intransitive, active)

- mengajarkan = to teach (transitive, casuative/applicative)

- mengajari = to teach (transitive, locative)

- pelajar = student

- pelajari = to study (imperative, locative)

- pelajarilah = to study (jussive, locative)

- pelajarkan = to study (imperative, causative/applicative)

- pelajarkanlah = to study (jussive, causative/applicative)

- pengajar = teacher, someone who teaches

- pelajaran = subject, education

- pelajari = to study (jussive, locative)

- pelajarkan = to study (jussive, causative/applicative)

- pengajaran = lesson

- pembelajaran = learning

- terajar = to be taught (accidentally)

- terajari = to be taught (accidentally, locative)

- terajarkan = to be taught (accidentally, causative/applicative)

- terpelajar = well-educated, literally "been taught"

- terpelajari = been taught (locative)

- terpelajarkan = been taught (causative/applicative)

- berpelajaran = is educated, literally "has education"

Noun affixes[edit]

Noun affixes are affixes that form nouns upon addition to root words. The following are examples of noun affixes:

| Type of noun affixes | Affix | Example of root word | Example of derived word |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prefix | pə(r)- ~ pəng- | duduk (sit) | penduduk (population) |

| kə- | hendak (want) | kehendak (desire) | |

| Infix | ⟨əl⟩ | tunjuk (point) | telunjuk (index finger, command) |

| ⟨əm⟩ | kelut (dishevelled) | kemelut (chaos, crisis) | |

| ⟨ər⟩ | gigi (teeth) | gerigi (toothed blade) | |

| Suffix | -an | bangun (wake up, raise) | bangunan (building) |

| Circumfix | kə-...-an | raja (king) | kerajaan (kingdom) |

| pə(r)-...-an pəng-...-an | kerja (work) | pekerjaan (occupation) |

The prefix per- drops its r before r, l and frequently before p, t, k. In some words it is peng-; though formally distinct, these are treated as variants of the same prefix in Indonesian grammar books.

Verb affixes[edit]

Similarly, verb affixes in Indonesian are attached to root words to form verbs. In Indonesian, there are:

| Type of verb affixes | Affix | Example of root word | Example of derived word |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prefix | bər- | ajar (teach) | belajar (to study)[92] |

| məng- | tolong (help) | menolong (to help) | |

| di- | ambil (take) | diambil (be taken) | |

| məmpər- | panjang (length) | memperpanjang (to lengthen) | |

| dipər- | dalam (deep) | diperdalam (be deepened) | |

| tər- | makan (eat) | termakan (to have accidentally eaten) | |

| Suffix | -kan | letak (place, keep) | letakkan (keep, put) |

| -i | jauh (far) | jauhi (avoid) | |

| Circumfix | bər-...-an | pasang (pair) | berpasangan (in pairs) |

| bər-...-kan | dasar (base) | berdasarkan (based on) | |

| məng-...-kan | pasti (sure) | memastikan (to make sure) | |

| məng-...-i | teman (company) | menemani (to accompany) | |

| məmpər-...-kan | guna (use) | mempergunakan (to utilise, to exploit) | |

| məmpər-...-i | ajar (teach) | mempelajari (to study) | |

| kə-...-an | hilang (disappear) | kehilangan (to lose) | |

| di-...-i | sakit (pain) | disakiti (to be hurt by) | |

| di-...-kan | benar (right) | dibenarkan (is allowed to) | |

| dipər-...-kan | kenal (know, recognise) | diperkenalkan (is being introduced) |

Adjective affixes[edit]

Adjective affixes are attached to root words to form adjectives:

| Type of adjective affixes | Affix | Example of root word | Example of derived word |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prefix | tər- | panas (hot) | terpanas (hottest) |

| sə- | baik (good) | sebaik (as good as) | |

| Infix | ⟨əl⟩ | serak (disperse) | selerak (messy) |

| ⟨əm⟩ | cerlang (radiant bright) | cemerlang (bright, excellent) | |

| ⟨ər⟩ | sabut (husk) | serabut (dishevelled) | |

| Circumfix | kə-...-an | barat (west) | kebaratan (westernized) |

In addition to these affixes, Indonesian also has a lot of borrowed affixes from other languages such as Sanskrit, Arabic and English. For example, maha-, pasca-, eka-, bi-, anti-, pro- etc.

Nouns[edit]

Common derivational affixes for nouns are peng-/per-/juru- (actor, instrument, or someone characterized by the root), -an (collectivity, similarity, object, place, instrument), ke-...-an (abstractions and qualities, collectivities), per-/peng-...-an (abstraction, place, goal or result).

Gender[edit]

Indonesian does not make use of grammatical gender, and there are only selected words that use natural gender. For instance, the same word is used for he/him and she/her (dia or ia) or for his and her (dia, ia or -nya). No real distinction is made between "girlfriend" and "boyfriend", both of which can be referred to as pacar (although more colloquial terms as cewek girl/girlfriend and cowok boy/boyfriend can also be found). A majority of Indonesian words that refer to people generally have a form that does not distinguish between the sexes. However, unlike English, distinction is made between older or younger.

There are some words that have gender: for instance, putri means "daughter" while putra means "son"; pramugara means "male flight attendant" while pramugari means "female flight attendant". Another example is olahragawan, which means "sportsman", versus olahragawati, meaning "sportswoman". Often, words like these (or certain suffixes such as "-a" and "-i" or "-wan" and "wati") are absorbed from other languages (in these cases, from Sanskrit).In some regions of Indonesia such as Sumatra and Jakarta, abang (a gender-specific term meaning "older brother") is commonly used as a form of address for older siblings/males, while kakak (a non-gender specific term meaning "older sibling") is often used to mean "older sister". Similarly, more direct influences from other languages, such as Javanese and Chinese, have also seen further use of other gendered words in Indonesian. For example: Mas ("older brother"), Mbak ("older sister"), Koko ("older brother") and Cici ("older sister").

Number[edit]

Indonesian grammar does not regularly mark plurals. In Indonesian, to change a singular into a plural one either repeats the word or adds para before it (the latter for living things only); for example, "students" can be either murid-murid or para murid. Plurals are rarely used in Indonesian, especially in informal parlance. Reduplication is often mentioned as the formal way to express the plural form of nouns in Indonesian; however, in informal daily discourse, speakers of Indonesian usually use other methods to indicate the concept of something being "more than one". Reduplication may also indicate the conditions of variety and diversity as well, and not simply plurality.

Reduplication is commonly used to emphasise plurality; however, reduplication has many other functions. For example, orang-orang means "(all the) people", but orang-orangan means "scarecrow". Similarly, while hati means "heart" or "liver", hati-hati is a verb meaning "to be careful". Also, not all reduplicated words are inherently plural, such as orang-orangan "scarecrow/scarecrows", biri-biri "a/some sheep" and kupu-kupu "butterfly/butterflies". Some reduplication is rhyming rather than exact, as in sayur-mayur "(all sorts of) vegetables".

Distributive affixes derive mass nouns that are effectively plural: pohon "tree", pepohonan "flora, trees"; rumah "house", perumahan "housing, houses"; gunung "mountain", pegunungan "mountain range, mountains".

Quantity words come before the noun: seribu orang "a thousand people", beberapa pegunungan "a series of mountain ranges", beberapa kupu-kupu "some butterflies".

Plural in Indonesian serves just to explicitly mention the number of objects in sentence. For example, Ani membeli satu kilo mangga (Ani buys one kilogram of mangoes). In this case, "mangoes", which is plural, is not said as mangga-mangga because the plurality is implicit: the amount a kilogram means more than one mango rather than one giant mango. So, as it is logically, one does not change the singular into the plural form, because it is not necessary and considered a pleonasm (in Indonesian often called pemborosan kata).

Pronouns[edit]

Personal pronouns are not a separate part of speech, but a subset of nouns. They are frequently omitted, and there are numerous ways to say "you". Commonly the person's name, title, title with name, or occupation is used ("does Johnny want to go?", "would Madam like to go?"); kin terms, including fictive kinship, are extremely common. However, there are also dedicated personal pronouns, as well as the demonstrative pronouns ini "this, the" and itu "that, the".

Personal pronouns[edit]

From the perspective of a European language, Indonesian boasts a wide range of different pronouns, especially to refer to the addressee (the so-called second person pronouns). These are used to differentiate several parameters of the person they are referred to, such as the social rank and the relationship between the addressee and the speaker. Indonesian also exhibits pronoun avoidance, often preferring kinship terms and titles over pronouns, particularly for respectful forms of address.

The table below provides an overview of the most commonly and widely used pronouns in the Indonesian language:

| Person | Respect | Singular | Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person exclusive | Informal, Familiar | aku | I | kami | we (s/he,they, not you) |

| Standard, Polite | saya | ||||

| 1st person inclusive | All | kita | we (s/he,they, and you) | ||

| 2nd person | Familiar | kamu, engkau, kau | you | kalian | you all |

| Polite | Anda | Anda sekalian | |||

| 3rd person | Familiar | dia, ia | s/he, it | mereka | they |

| Polite | beliau | s/he | |||

- First person pronouns

Notable among the personal-pronoun system is a distinction between two forms of "we": kita (you and me, you and us) and kami (us, but not you). The distinction is not always followed in colloquial Indonesian.

Saya and aku are the two major forms of "I". Saya is the more formal form, whereas aku is used with family, friends, and between lovers. Sahaya is an old or literary form of saya. Sa(ha)ya may also be used for "we", but in such cases it is usually used with sekalian or semua "all"; this form is ambiguous as to whether it corresponds with inclusive kami or exclusive kita. Less common are hamba "slave", hamba tuan, hamba datuk (all extremely humble), beta (a royal addressing oneselves), patik (a commoner addressing a royal), kami (royal or editorial "we"), kita, təman, and kawan.

- Second person pronouns

There are three common forms of "you", Anda (polite), kamu (familiar), and kalian "all" (commonly used as a plural form of you, slightly informal). Anda is used with strangers, recent acquaintances, in advertisements, in business, and when you wish to show distance, while kamu is used in situations where the speaker would use aku for "I". Anda sekalian is polite plural. Particularly in conversation, respectful titles like Bapak/Pak "father" (used for any older male), Ibu/Bu "mother" (any older woman), and tuan "sir" are often used instead of pronouns.[93][better source needed]

Engkau (əngkau), commonly shortened to kau.

- Third person pronouns

The common word for "s/he" and "they" is ia, which has the object and emphatic/focused form dia. Bəliau "his/her Honour" is respectful. As with "you", names and kin terms are extremely common. Mereka "someone", mereka itu, or orang itu "those people" are used for "they".

- Regional varieties

There are a large number of other words for "I" and "you", many regional, dialectical, or borrowed from local languages. Saudara "you" (male) and saudari (female) (plural saudara-saudara or saudari-saudari) show utmost respect. Daku "I" and dikau "you" are poetic or romantic. Indonesian gua "I" (from Hokkien Chinese: 我; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: góa) and lu "you" (Chinese: 汝; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: lú) are slang and extremely informal.

The pronouns aku, kamu, engkau, ia, kami, and kita are indigenous to Indonesian.

Possessive pronouns[edit]

Aku, kamu, engkau, and ia have short possessive enclitic forms. All others retain their full forms like other nouns, as does emphatic dia: meja saya, meja kita, meja anda, meja dia "my table, our table, your table, his/her table".

| Pronoun | Enclitic | Possessed form |

|---|---|---|

| aku | -ku | mejaku (my table) |

| kamu | -mu | mejamu (your table) |

| ia | -nya | mejanya (his, her, their table) |

There are also proclitic forms of aku, ku- and kau-. These are used when there is no emphasis on the pronoun:

- Ku-dengar raja itu menderita penyakit kulit. Aku mengetahui ilmu kedokteran. Aku-lah yang akan mengobati dia.

- "It has come to my attention that the King has a skin disease. I am skilled in medicine. I will cure him."

Here ku-verb is used for a general report, aku verb is used for a factual statement, and emphatic aku-lah meng-verb (≈ "I am the one who...") for focus on the pronoun.[94]

Demonstrative pronouns[edit]

There are two demonstrative pronouns in Indonesian. Ini "this, these" is used for a noun which is generally near to the speaker. Itu "that, those" is used for a noun which is generally far from the speaker. Either may sometimes be equivalent to English "the". There is no difference between singular and plural. However, plural can be indicated through duplication of a noun followed by a ini or itu. The word yang "which" is often placed before demonstrative pronouns to give emphasis and a sense of certainty, particularly when making references or enquiries about something/ someone, like English "this one" or "that one".

| Pronoun | Indonesian | English |

|---|---|---|

| ini | buku ini | This book, these books, the book(s) |

| buku-buku ini | These books, (all) the books | |

| itu | kucing itu | That cat, those cats, the cat(s) |

| kucing-kucing itu | Those cats, the (various) cats |

| Pronoun + yang | Example sentence | English meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Yang ini | Q: Anda mau membeli buku yang mana? A: Saya mau yang ini. | Q: Which book do you wish to purchase? A: I would like this one. |

| Yang itu | Q: Kucing mana yang memakan tikusmu? A: Yang itu! | Q: Which cat ate your mouse? A: That one! |

Verbs[edit]

Verbs are not inflected for person or number, and they are not marked for tense; tense is instead denoted by time adverbs (such as "yesterday") or by other tense indicators, such as sudah "already" and belum "not yet". On the other hand, there is a complex system of verb affixes to render nuances of meaning and to denote voice or intentional and accidental moods. Some of these affixes are ignored in colloquial speech.

Examples of these are the prefixes di- (patient focus, traditionally called "passive voice", with OVA word order in the third person, and OAV in the first or second persons), meng- (agent focus, traditionally called "active voice", with AVO word order), memper- and diper- (causative, agent and patient focus), ber- (stative or habitual; intransitive VS order), and ter- (agentless actions, such as those which are involuntary, sudden, stative or accidental, for VA = VO order); the suffixes -kan (causative or benefactive) and -i (locative, repetitive, or exhaustive); and the circumfixes ber-...-an (plural subject, diffuse action) and ke-...-an (unintentional or potential action or state).

- duduk to sit down

- mendudukkan to sit someone down, give someone a seat, to appoint

- menduduki to sit on, to occupy

- didudukkan to be given a seat, to be appointed

- diduduki to be sat on, to be occupied

- terduduk to sink down, to come to sit

- kedudukan to be situated

Forms in ter- and ke-...-an are often equivalent to adjectives in English.

Negation[edit]

Four words are used for negation in Indonesian, namely tidak, bukan, jangan, and belum.

- Tidak (not), often shortened to tak, is used for the negation of verbs and "adjectives".

- Bukan (be-not) is used in the negation of a noun.

For example:

| Indonesian | Gloss | English |

|---|---|---|

| Saya tidak tahu (Saya gak/nga tahu(informal) | I not know | I do not know |

| Ibu saya tidak senang (Ibu saya gak/nga senang(informal)) | mother I not be-happy | My mother is not happy |

| Itu bukan anjing saya | that be-not dog I | That is not my dog |

Prohibition[edit]

For negating imperatives or advising against certain actions in Indonesian, the word jangan (do not) is used before the verb. For example,

- Jangan tinggalkan saya di sini!

- Don't leave me here!

- Jangan lakukan itu!

- Don't do that!

- Jangan! Itu tidak bagus untukmu.

- Don't! That's not good for you.

Adjectives[edit]

There are grammatical adjectives in Indonesian. Stative verbs are often used for this purpose as well. Adjectives are always placed after the noun that they modify.

| Indonesian | Gloss | English |

|---|---|---|

| Hutan hijau | forest green | (The) green forest |

| Hutan itu hijau | forest that green | That/the forest is green |

| Kereta yang merah | carriage which red | (The) carriage which is red = the red carriage |

| Kereta merah | carriage red | Red carriage |

| Dia orang yang terkenal sekali | he/she person which famous very | He/she is a very famous person |

| Orang terkenal | person famous | Famous person |

| Orang ini terkenal sekali | person this famous very | This person is very famous |

To say that something "is" an adjective, the determiners "itu" and "ini" ("that" and "this") are often used. For example, in the sentence "anjing itu galak", the use of "itu" gives a meaning of "the/that dog is ferocious", while "anjing ini galak", gives a meaning of "this dog is ferocious". However, if "itu" or "ini" were not to be used, then "anjing galak" would only mean "ferocious dog", a plain adjective without any stative implications. The all-purpose determiner, "yang", is also often used before adjectives, hence "anjing yang galak" also means "ferocious dog" or more literally "dog which is ferocious"; "yang" will often be used for clarity. Hence, in a sentence such as "saya didekati oleh anjing galak" which means "I was approached by a ferocious dog", the use of the adjective "galak" is not stative at all.

Often the "ber-" intransitive verb prefix, or the "ter-" stative prefix is used to express the meaning of "to be...". For example, "beda" means "different", hence "berbeda" means "to be different"; "awan" means "cloud", hence "berawan" means "cloudy". Using the "ter-" prefix, implies a state of being. For example, "buka" means "open", hence "terbuka" means "is opened"; "tutup" means "closed/shut", hence "tertutup" means "is closed/shut".

Word order[edit]

Adjectives, demonstrative determiners, and possessive determiners follow the noun they modify.

Indonesian does not have a grammatical subject in the sense that English does. In intransitive clauses, the noun comes before the verb. When there is both an agent and an object, these are separated by the verb (OVA or AVO), with the difference encoded in the voice of the verb. OVA, commonly but inaccurately called "passive", is the basic and most common word order.

Either the agent or object or both may be omitted. This is commonly done to accomplish one of two things:

- 1) Adding a sense of politeness and respect to a statement or question

For example, a polite shop assistant in a store may avoid the use of pronouns altogether and ask:

| Ellipses of pronoun (agent & object) | Literal English | Idiomatic English |

|---|---|---|

| Bisa dibantu? | Can + to be helped? | Can (I) help (you)? |

- 2) Agent or object is unknown, not important, or understood from context

For example, a friend may enquire as to when you bought your property, to which you may respond:

| Ellipses of pronoun (understood agent) | Literal English | Idiomatic English |

|---|---|---|

| Rumah ini dibeli lima tahun yang lalu | House this + be purchased five-year(s) ago | The house 'was purchased' five years ago |

Ultimately, the choice of voice and therefore word order is a choice between actor and patient and depends quite heavily on the language style and context.

Emphasis[edit]

Word order is frequently modified for focus or emphasis, with the focused word usually placed at the beginning of the clause and followed by a slight pause (a break in intonation):

- Saya pergi ke pasar kemarin "I went to the market yesterday" – neutral, or with focus on the subject.

- Kemarin, saya pergi ke pasar "Yesterday I went to the market" – emphasis on yesterday.

- Ke pasar, saya pergi kemarin "To the market I went yesterday" – emphasis on where I went yesterday.

- Pergi ke pasar, saya, kemarin "To the market went I yesterday" – emphasis on the process of going to the market.

The last two are more likely to be encountered in speech than in writing.

Measure words[edit]

Another distinguishing feature of Indonesian is its use of measure words, also called classifiers (kata penggolong). In this way, it is similar to many other languages of Asia, including Chinese, Japanese, Vietnamese, Thai, Burmese, and Bengali.

Measure words are also found in English such as two head of cattle or a loaf of bread, where *two cattle and a bread[a] would be ungrammatical. The word satu reduces to se- /sə/, as it does in other compounds:

| Measure word | Used for measuring | Literal translation | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| buah | things (in general), large things, abstract nouns houses, cars, ships, mountains; books, rivers, chairs, some fruits, thoughts, etc. | 'fruit' | dua buah meja (two tables), lima buah rumah (five houses) |

| ekor | animals | 'tail' | seekor ayam (a chicken), tiga ekor kambing (three goats) |

| orang | human beings | 'person' | seorang laki-laki (a man), enam orang petani (six farmers), seratus orang murid (a hundred students) |

| biji | smaller rounded objects most fruits, cups, nuts | 'grain' | sebiji/ sebutir telur (an egg), sebutir/ butiran-butiran beras (rice or rices) |

| batang | long stiff things trees, walking sticks, pencils | 'trunk, rod' | sebatang tongkat (a stick) |

| həlai | things in thin layers or sheets paper, cloth, feathers, hair | 'leaf' | sepuluh helai pakaian (ten cloths) |

| kəping keping | flat fragments, slabs of stone, pieces of wood, pieces of bread, land, coins, paper | 'chip' | sekeping uang logam (a coin) |

| pucuk | letters, firearms, needles | 'sprout' | sepucuk senjata (a weapon) |

| bilah | things which cut lengthwise and thicker | 'blade' | sebilah kayu (a piece of wood) |

| bidanɡ | things shaped square or which can be measured with number | 'field' | sebidang tanah/lahan (an area) |

| potong | things that are cut bread | 'cut' | sepotong roti (slices of bread) |

| utas | nets, cords, ribbons | 'thread' | seutas tali (a rope) |

| carik | things easily torn, like paper | 'shred' | secarik kertas (a piece of paper) |

Example:Measure words are not necessary just to say "a": burung "a bird, birds". Using se- plus a measure word is closer to English "one" or "a certain":

- Ada seekor burung yang bisa berbicara

- "There was a (certain) bird that could talk"

Writing system[edit]

Indonesian is written with the Latin script. It was originally based on the Dutch spelling and still bears some similarities to it. Consonants are represented in a way similar to Italian, although ⟨c⟩ is always /tʃ/ (like English ⟨ch⟩), ⟨g⟩ is always /ɡ/ ("hard") and ⟨j⟩ represents /dʒ/ as it does in English. In addition, ⟨ny⟩ represents the palatal nasal /ɲ/, ⟨ng⟩ is used for the velar nasal /ŋ/ (which can occur word-initially), ⟨sy⟩ for /ʃ/ (English ⟨sh⟩) and ⟨kh⟩ for the voiceless velar fricative /x/. Both /e/ and /ə/ are represented with ⟨e⟩.

Spelling changes in the language that have occurred since Indonesian independence include:

| Phoneme | Obsolete spelling | Modern spelling |

|---|---|---|

| /u/ | oe | u |

| /tʃ/ | tj | c |

| /dʒ/ | dj | j |

| /j/ | j | y |

| /ɲ/ | nj | ny |

| /ʃ/ | sj | sy |

| /x/ | ch | kh |

Introduced in 1901, the van Ophuijsen system (named from the advisor of the system, Charles Adriaan van Ophuijsen) was the first standardization of romanized spelling. It was most influenced by the then current Dutch spelling system and based on the dialect of Malay spoken in Johor.[95] In 1947, the spelling was changed into Republican Spelling or Soewandi Spelling (named by at the time Minister of Education, Soewandi). This spelling changed formerly spelled oe into u (however, the spelling influenced other aspects in orthography, for example writing reduplicated words). All of the other changes were a part of the Perfected Spelling System, an officially mandated spelling reform in 1972. Some of the old spellings (which were derived from Dutch orthography) do survive in proper names; for example, the name of a former president of Indonesia is still sometimes written Soeharto, and the central Java city of Yogyakarta is sometimes written Jogjakarta. In time, the spelling system is further updated and the latest update of Indonesian spelling system issued on 16 August 2022 by Head of Language Development and Fostering Agency decree No 0424/I/BS.00.01/2022.[81]

Letter names and pronunciations[edit]

The Indonesian alphabet is exactly the same as in ISO basic Latin alphabet.

| Majuscule Forms | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z |

| Minuscule Forms | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | t | u | v | w | x | y | z |

Indonesian follows the letter names of the Dutch alphabet. Indonesian alphabet has a phonemic orthography; words are spelled the way they are pronounced, with few exceptions. The letters Q, V and X are rarely encountered, being chiefly used for writing loanwords.

| Letter | Name (in IPA) | Sound (in IPA) | English equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aa | a (/a/) | /a/ | a as in father |

| Bb | be (/be/) | /b/ | b as in bed |

| Cc | ce (/t͡ʃe/) | /t͡ʃ/ | ch as in check |

| Dd | de (/de/) | /d/ | d as in day |

| Ee | e (/e/) | /e/ | e as in red |

| Ff | ef (/ef/) | /f/ | f as in effort |

| Gg | ge (/ge/) | /ɡ/ | g as in gain |

| Hh | ha (/ha/) | /h/ | h as in harm |

| Ii | i (/i/) | /i/ | ee as in see |

| Jj | je (/d͡ʒe/) | /d͡ʒ/ | j as in jam |

| Kk | ka (/ka/) | /k/ | k as in karma |

| Ll | el (/el/) | /l/ | l as in else |

| Mm | em (/em/) | /m/ | m as in empty |

| Nn | en (/en/) | /n/ | n as in energy |

| Oo | o (/o/) | /o/ | o as in owe |

| Pp | pe (/pe/) | /p/ | p as in pet |

| qi or qiu (/ki/ or /kiu̯/) | /k/ | q as in queue | |

| Rr | er (/er/) | /r/ | Spanish rr as in perro |

| Ss | es (/es/) | /s/ | s as in establish |

| Tt | te (/te/) | /t/ | t as in text |

| Uu | u (/u/) | /u/ | oo as in pool |

| Vv | ve (/ve/ or /fe/) | /v/ or /f/ | v as in vest |

| Ww | we (/we/) | /w/ | w as in wet |

| Xx | ex (/eks/) | /ks/ or /s/ | x as in ex |

| Yy | ye (/je/) | /j/ | y as in yes |

| Zz | zet (/zet/) | /z/ | z as in zebra |

In addition, there are digraphs that are not considered separate letters of the alphabet:[96]

| Digraph | Sound | English equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| ai | /aɪ/ | uy as in buy |

| au | /aʊ/ | ou as in ouch |

| oi | /oɪ/ | oy as in boy |

| ei | /eɪ/ | ey as in survey |

| gh | /ɣ/ or /x/ | similar to Dutch and German ch, but voiced |

| kh | /x/ | ch as in loch |

| ng | /ŋ/ | ng as in sing |

| ny | /ɲ/ | Spanish ñ; similar to ny as in canyon with a nasal sound |

| sy | /ʃ/ | sh as in shoe |

Vocabulary[edit]

Pie chart showing percentage of other languages contribute on loan words of Indonesian language

As a modern variety of Malay, Indonesian has been influenced by other languages, including Dutch, English, Greek (where the name of the country, Indonesia, comes from), Arabic, Chinese, Portuguese, Sanskrit, Tamil, Hindi, and Persian. The vast majority of Indonesian words, however, come from the root lexical stock of Austronesian (including Old Malay).[32]

The study of Indonesian etymology and loan words reveals both its historical and social contexts. Examples are the early Sanskrit borrowings from the 7th century during the trading era, the borrowings from Arabic and Persian during the time of the establishment of Islam in particular, and those from Dutch during the colonial period. Linguistic history and cultural history are clearly linked.[97]

List of loan words of Indonesian language published by the Badan Pengembangan Bahasa dan Perbukuan (The Language Center) under the Ministry of Education and Culture:[98]

| Language origin | Number of words |

|---|---|

| Dutch | 3280 |

| English | 1610 |

| Arabic | 1495 |

| Sanskrit | 677 |

| Chinese | 290 |

| Portuguese | 131 |

| Tamil | 131 |

| Persian | 63 |

| Hindi | 7 |

Note: This list only lists foreign languages, thus omitting numerous local languages of Indonesia that have also been major lexical donors, such as Javanese, Sundanese, Betawi, etc.

Loan words of Sanskrit origin[edit]

Влияние санскрита пришло из контактов с Индией с древних времен. Слова были либо заимствованы непосредственно из Индии, либо при посредничестве древнеяванского языка . Хотя индуизм и буддизм больше не являются основными религиями Индонезии, санскрит , который был языковым средством этих религий, по-прежнему пользуется большим уважением и сравним со статусом латыни в английском и других западноевропейских языках. Санскрит также является основным источником неологизмов , которые обычно образуются от санскритских корней. Заимствования из санскрита охватывают многие аспекты религии , искусства и повседневной жизни.

Из санскрита пришли такие слова, как сварг сурга (небеса), язык языка , стекло , зеркало, царь - царь , человечество , любовь , земля , бхуван буана (мир), агама (религия), стри истри (жена/женщина), джай джайя. (победоносный/победоносный), пур Пура (город/храм/место), ракшаса Ракшаса (гигант/монстр), дхарма ( правило)/правила), Мантра Мантра ( слова/поэт/духовные молитвы), Кшатрия Сатрия (воин/храбрый/солдат) ), Виджай Виджая (большая победа/великая победа) и т. д. Санскритские слова и предложения также используются в именах, титулах и девизах Индонезийской национальной полиции и индонезийских вооруженных сил, таких как: Бхаянкара , Лакшамана , Джатаю , Гаруда , Дхармакерта Марга Рекшьяка , Джалесвева Джаямахе , Картика Эка Пакси , Сва Бхувана , Ракша Севакоттама. , Юдха Сиага и др.

Поскольку санскрит уже давно известен на Индонезийском архипелаге , санскритские заимствованные слова, в отличие от слов из других языков, вошли в основной словарный запас индонезийского языка до такой степени, что для многих они больше не воспринимаются как иностранные. Таким образом, можно написать небольшой рассказ, используя в основном слова санскритского происхождения. Приведенный ниже рассказ состоит примерно из 80 слов на индонезийском языке, все они заимствованы из санскрита, а также нескольких местных служебных слов и аффиксов.

- Потому все было оплачено использованием с из фондов государственных миллионов рупий кави преподавателя литературы языке на , студентов обучения послов . частного swasta , их стран duta negeri партнеров и мужей / жен , министра культуры туризма и , работников - что деловых , и - рабочая сила , а также члены немедленно некоммерческих отправились на экскурсию в на местность сельскую севере города , и Проболинго между в район древними со организаций на храмами статуями , ослах в катались в повозке сумерках , затем вместе с главой деревни я стал свидетелем святого фермеры того , как что и пастухи смиренные духом , добродетельные и , и совершают радостно Готовы , церемонии , Пертиви распевая им . звуки мантр Земли , является средством прославления благословения имени Богини дать дары , тела защитите души и от опасностей , бедствий бедствий и свои .

китайского Заимствованные слова происхождения

Отношения с Китаем начались в VII веке, когда китайские купцы торговали в некоторых районах архипелага, таких как Риау , Западное Борнео , Восточный Калимантан и Северное Малуку . По мере появления и процветания королевства Шривиджая Китай открыл дипломатические отношения с королевством, чтобы обеспечить торговлю и мореплавание. В 922 году китайские путешественники посетили Кахурипан на Восточной Яве . Начиная с XI века, сотни тысяч китайских мигрантов покинули материковый Китай и поселились во многих частях Нусантары (ныне Индонезия).

Китайские . заимствования обычно связаны с кухней, торговлей или часто просто с вещами, исключительно китайскими Слова китайского происхождения (представленные здесь с сопровождающими производными от хоккиенского /мандаринского произношения, а также традиционными и упрощенными иероглифами ) включают лотэн , (樓/層 = lóu/céng – [верхний] этаж/уровень), миэ (麵 > 面 хоккиен ми – лапша), лумпия (潤餅 (Hokkien = lūn-piáⁿ) – блинчики с начинкой), каван (茶碗 cháwǎn – чашка), теко (茶壺 > 茶壶 = cháhú [мандарин], teh-ko [Hokkien] = чайник), 苦力 кули ( = 苦 khu (твердый) и 力 li (энергия) – кули) и даже широко используемые жаргонные термины gua и lu (от хоккиенского «гоа» 我 и «lu/li» 汝 – означающие «я/мне» и «ты»). ').

арабского Заимствованные слова происхождения