Индийский океан

| Индийский океан | |

|---|---|

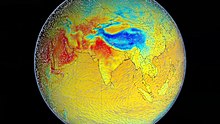

Протяженность Индийского океана по данным Международной гидрографической организации. | |

Топографическая/батиметрическая карта региона Индийского океана. | |

| Координаты | 20 ° ю.ш. , 80 ° в.д. / 20 ° ю.ш., 80 ° в.д. |

| Тип | Океан |

| Первичные притоки | Замбези , Ганг - Брахмапутра , Инд , Джубба и Мюррей (5 крупнейших) |

| Зона водосбора | 21 100 000 км 2 (8 100 000 квадратных миль) |

| бассейна Страны | Южная и Юго-Восточная Азия , Западная Азия , Северо-Восточная , Восточная и Южная Африка и Австралия. |

| Макс. длина | 9600 км (6000 миль) (от Антарктиды до Бенгальского залива) [1] |

| Макс. ширина | 7600 км (4700 миль) (от Африки до Австралии) [1] |

| Площадь поверхности | 70 560 000 км 2 (27 240 000 квадратных миль) |

| Средняя глубина | 3741 м (12274 футов) |

| Макс. глубина | 7290 м (23920 футов) ( Зондский желоб ) |

| Длина берега 1 | 66 526 км (41 337 миль) [2] |

| Острова | Мадагаскар , Шри-Ланка , Мальдивы , Реюньон , Сейшельские острова , Маврикий |

| Поселения | Список городов, портов и гаваней |

| Ссылки | [3] |

| 1 Длина берега не является четко определенной мерой . | |

Индийский океан подразделений мира является третьим по величине из пяти океанических , его площадь составляет 70 560 000 км. 2 (27 240 000 квадратных миль) или ок. 20% воды на поверхности Земли . [4] Он ограничен Азией на севере, Африкой на западе и Австралией на востоке. На юге он ограничен Южным океаном или Антарктидой , в зависимости от используемого определения. [5] Вдоль своего ядра Индийский океан имеет большие окраинные или региональные моря, такие как Андаманское море , Аравийское море , Бенгальский залив и Лаккадивское море .

Он назван в честь вдающейся в него Индии и известен под своим нынешним названием по крайней мере с 1515 года. Это единственный океан, названный в честь страны. Раньше его называли Восточным океаном. Его средняя глубина составляет 3741 м. Весь Индийский океан находится в Восточном полушарии . В отличие от Атлантического и Тихого океана, Индийский океан с трех сторон граничит с сушей и архипелагом, что делает его больше похожим на заливной океан с центром на Индийском полуострове. Его побережья и шельфы отличаются от других океанов отличительными особенностями, такими как более узкий континентальный шельф . С точки зрения геологии Индийский океан является самым молодым из крупных океанов, с активными спрединговыми хребтами и такими особенностями, как подводные горы и хребты, образованные горячими точками .

Климат Индийского океана характеризуется муссонами . Это самый теплый океан, оказывающий значительное влияние на глобальный климат из-за взаимодействия с атмосферой. На его воды влияет циркуляция Уокера в Индийском океане , что приводит к возникновению уникальных океанических течений и апвеллингов. Индийский океан экологически разнообразен, с важными морскими обитателями и экосистемами, такими как коралловые рифы, мангровые заросли и заросли морской травы. Здесь находится значительная часть мирового улова тунца, и он является домом для морских видов, находящихся под угрозой исчезновения. Он сталкивается с такими проблемами, как чрезмерный вылов рыбы и загрязнение окружающей среды , включая значительное количество мусора .

Исторически Индийский океан с древних времен был центром культурного и коммерческого обмена. Он сыграл ключевую роль в ранних миграциях людей и распространении цивилизаций. В наше время он остается решающим для мировой торговли, особенно нефтью и углеводородами. Экологические и геополитические проблемы в регионе включают последствия изменения климата , пиратства и стратегические споры по поводу островных территорий.

Этимология

[ редактировать ]Индийский океан известен под своим нынешним названием по крайней мере с 1515 года, когда латинская форма Oceanus Orientalis Indicus засвидетельствована («Индийский Восточный океан»), названная в честь Индии, выступающей в него. Ранее он был известен как Восточный океан , термин, который все еще использовался в середине 18 века, в отличие от Западного океана ( Атлантического ) до того, как было предположено о Тихом океане . [6] В наше время иногда используется название Афро-Азиатский океан. [7]

Название хинди океана на — हिंद महासागर ( Hind Mahāsāgar ; букв. перевод « Океан Индии» ). И наоборот, китайские исследователи (например, Чжэн Хэ во времена династии Мин ), путешествовавшие по Индийскому океану в 15 веке, называли его Западными океанами. [8] В древнегреческой географии известная грекам область Индийского океана называлась Эритрейским морем . [9]

География

[ редактировать ]Объем и данные

[ редактировать ]Границы Индийского океана , очерченные Международной гидрографической организацией в 1953 году, включали Южный океан , но не окраинные моря вдоль северного края, но в 2002 году МГО разделила Южный океан отдельно, что отодвинуло воды к югу от 60° ю.ш. Индийский океан, но включал северные окраинные моря. [10] [11] В меридианном направлении Индийский океан отграничен от Атлантического океана меридианом 20° восточной долготы , идущим на юг от мыса Игольный в Южной Африке, и от Тихого океана меридианом 146°49’ восточной долготы, идущим на юг от юго-восточного мыса на остров Тасмания в Австралии. Самая северная протяженность Индийского океана (включая окраинные моря) находится примерно на 30° северной широты в Персидском заливе . [11]

Индийский океан занимает 70 560 000 км. 2 (27 240 000 квадратных миль), включая Красное море и Персидский залив, но исключая Южный океан, или 19,5% мирового океана; его объем составляет 264 000 000 км. 3 (63 000 000 кубических миль) или 19,8% объема мирового океана; его средняя глубина составляет 3741 м (12 274 футов), а максимальная глубина - 7 290 м (23 920 футов). [4]

Весь Индийский океан находится в Восточном полушарии , а центр Восточного полушария, 90-й меридиан восточной долготы , проходит через хребет Девяносто Восточного .

Берега и шельфы

[ редактировать ]В отличие от Атлантического и Тихого океана, Индийский океан с трех сторон окружен крупными массивами суши и архипелагом и не простирается от полюса до полюса, его можно сравнить с заливным океаном. Его центр находится на Индийском полуострове. Хотя этот субконтинент сыграл значительную роль в своей истории, Индийский океан, прежде всего, был космополитической ареной, связывающей различные регионы посредством инноваций, торговли и религии с самого начала истории человечества. [12]

Активные окраины Индийского океана имеют среднюю ширину (расстояние по горизонтали от суши до края шельфа). [13] ) 19 ± 0,61 км (11,81 ± 0,38 миль) с максимальной шириной 175 км (109 миль). Пассивные окраины имеют среднюю ширину 47,6 ± 0,8 км (29,58 ± 0,50 миль). [14] Средняя ширина склонов ( горизонтальное расстояние от разлома шельфа до подножия склона) континентальных шельфов составляет 50,4–52,4 км (31,3–32,6 миль) для активных и пассивных окраин соответственно, с максимальной шириной 205,3–255,2 км (127,6 миль). –158,6 миль). [15]

В соответствии с разломом шельфа , также известным как шарнирная зона, сила тяжести Бугера колеблется от 0 до 30 мГал , что необычно для континентального региона с толщиной отложений около 16 км. Была выдвинута гипотеза, что «шарнирная зона может представлять собой реликт границы континентальной и протоокеанической коры, образовавшейся во время рифтогенеза Индии от Антарктиды ». [16]

Австралия, Индонезия и Индия — три страны с самой длинной береговой линией и исключительными экономическими зонами . Континентальный шельф занимает 15% территории Индийского океана.Более двух миллиардов человек живут в странах, граничащих с Индийским океаном, по сравнению с 1,7 миллиарда в Атлантическом и 2,7 миллиарда в Тихом океане (некоторые страны граничат более чем с одним океаном). [2]

Реки

[ редактировать ]Индийского океана Водосборный бассейн занимает 21 100 000 км. 2 (8 100 000 квадратных миль), что практически идентично площади Тихого океана и составляет половину площади Атлантического бассейна, или 30% поверхности его океана (по сравнению с 15% для Тихого океана). Водосборный бассейн Индийского океана разделен примерно на 800 отдельных бассейнов, половина из которых состоит из Тихого океана, из которых 50% расположены в Азии, 30% в Африке и 20% в Австралазии. Реки Индийского океана в среднем короче (740 км (460 миль)) чем реки других крупных океанов. Крупнейшие реки — ( 5-й порядок ) Замбези , Ганг - Брахмапутра , Инд , Джубба и Мюррей и (4-й порядок) Шатт-эль-Араб , Вади Ад-Давасир (высохшая речная система на Аравийском полуострове) и Лимпопо. реки. [17] После распада Восточной Гондваны и образования Гималаев реки Ганг-Брахмапутра впадают в крупнейшую в мире дельту, известную как дельта Бенгалии или Сундербанс . [16]

Окраинные моря

[ редактировать ]К окраинным морям , заливам, заливам и проливам Индийского океана относятся: [11]

Вдоль восточного побережья Африки Мозамбикский пролив отделяет Мадагаскар от материковой Африки, а море Зандж расположено к северу от Мадагаскара.

На северном побережье моря Аравийского Аденский залив соединяется с Красным морем проливом Баб-эль-Мандебским . В Аденском заливе залив Таджура находится в Джибути, а пролив Гуардафуи отделяет остров Сокотра от Африканского Рога. Северная оконечность Красного моря заканчивается в заливе Акаба и Суэцком заливе . Индийский океан искусственно соединен со Средиземным морем без шлюза для судов через Суэцкий канал , доступ к которому осуществляется через Красное море. Аравийское море соединено с Персидским заливом и Оманским заливом Ормузским проливом . В Персидском заливе Бахрейнский залив отделяет Катар от Аравийского полуострова.

Вдоль западного побережья Индии заливы Кач и Хамбат расположены в Гуджарате на северной оконечности, а Лаккадивское море отделяет Мальдивы от южной оконечности Индии. находится Бенгальский залив у восточного побережья Индии. и Маннарский залив Полкский пролив отделяют Шри-Ланку от Индии, а мост Адама разделяет их. Андаманское море расположено между Бенгальским заливом и Андаманскими островами.

В Индонезии так называемый Индонезийский морской путь состоит из Малаккского , Зондского и Торресова проливов .Залив Карпентария расположен на северном побережье Австралии, а Большой Австралийский залив составляет большую часть южного побережья. [18] [19] [20]

- Аравийское море – 3,862 млн км. 2

- Бенгальский залив - 2,172 млн км 2

- Андаманское море - 797 700 км. 2

- Лаккадивское море - 786 000 км. 2

- Мозамбикский канал – 700 000 км. 2

- Тиморское море – 610 000 км. 2

- Красное море – 438 000 км. 2

- Аденский залив – 410 000 км. 2

- Персидский залив – 251 000 км. 2

- Море Флорес - 240 000 км. 2

- Молуккское море - 200 000 км. 2

- Оманское море - 181 000 км. 2

- Большой Австралийский залив - 45 926 км. 2

- Залив Акаба - 239 км 2

- Хамбхатский залив

- Качский залив

- Суэцкий залив

Климат

[ редактировать ]

Несколько особенностей делают Индийский океан уникальным. Он представляет собой ядро крупномасштабного Тропического теплого бассейна , который при взаимодействии с атмосферой влияет на климат как на региональном, так и на глобальном уровне. Азия блокирует экспорт тепла и предотвращает вентиляцию термоклина Индийского океана . в Индийском океане Этот континент также вызывает муссоны , самые сильные на Земле, которые вызывают крупномасштабные сезонные колебания океанских течений, включая изменение направления Сомалийского течения и Индийского муссонного течения . в Индийском океане Из-за циркуляции Уокера непрерывных экваториальных восточных ветров нет. Апвеллинг происходит вблизи Африканского Рога и Аравийского полуострова в Северном полушарии и к северу от пассатов в Южном полушарии. Индонезийский проток — уникальное экваториальное соединение с Тихим океаном. [21]

На климат к северу от экватора влияет муссонный климат. С октября по апрель дуют сильные северо-восточные ветры; с мая по октябрь преобладают южные и западные ветры. В Аравийском море сильный муссон приносит дожди на Индийский субконтинент. В южном полушарии ветры, как правило, мягче, но летние штормы возле Маврикия могут быть сильными. При смене муссонных ветров циклоны иногда обрушиваются на берега Аравийского моря и Бенгальского залива . [22] Около 80% общего годового количества осадков в Индии выпадает летом, и регион настолько зависит от этих осадков, что многие цивилизации погибли из-за отсутствия муссонов в прошлом. Огромная изменчивость бабьего летнего муссона также наблюдалась в доисторические времена, с сильной влажной фазой 33 500–32 500 лет назад; слабая сухая фаза 26 000–23 500 до н. э.; и очень слабая фаза 17 000–15 000 л.н.,соответствует серии драматических глобальных событий: потеплению Бёллинга-Аллерёда , Генриху и Младшему Дриасу . [23]

Индийский океан – самый теплый океан в мире. [24] Долгосрочные записи температуры океана показывают быстрое и непрерывное потепление в Индийском океане примерно на 1,2 ° C (34,2 ° F) (по сравнению с 0,7 ° C (33,3 ° F) для теплого региона бассейна) в течение 1901–2012 годов. [25] Исследования показывают, что вызванное деятельностью человека парниковое потепление , а также изменения в частоте и величине явлений Эль-Ниньо (или диполя Индийского океана ) являются триггером этого сильного потепления в Индийском океане. [25] В то время как Индийский океан нагревался со скоростью 1,2 °C за столетие в течение 1950–2020 годов, климатические модели предсказывают ускоренное потепление со скоростью 1,7–3,8 °C в столетие в 2020–2100 годах. [26] [27] Хотя потепление происходит во всем бассейне, максимальное потепление наблюдается в северо-западной части Индийского океана, включая Аравийское море, а пониженное потепление наблюдается у берегов Суматры и Явы в юго-восточной части Индийского океана. По прогнозам, к концу XXI века глобальное потепление приведет к тому, что тропическая часть Индийского океана перейдет в почти постоянное состояние волны тепла по всему бассейну, при этом морские волны тепла, по прогнозам, увеличатся с 20 дней в году (в течение 1970–2000 гг.) до 220–250 дней в году. дней в году. [26] [27]

К югу от экватора (20–5° ю.ш.) Индийский океан набирает тепло с июня по октябрь во время южной зимы и теряет тепло с ноября по март во время южного лета. [28]

В 1999 году эксперимент в Индийском океане показал, что сжигание ископаемого топлива и биомассы в Южной и Юго-Восточной Азии вызывает загрязнение воздуха (также известное как азиатское коричневое облако ), которое достигает даже внутритропической зоны конвергенции . Это загрязнение имеет последствия как в местном, так и в глобальном масштабе. [29]

Океанография

[ редактировать ]Сорок процентов осадков Индийского океана находится в веерах Инда и Ганга. Океанические котловины, прилегающие к континентальным склонам, содержат преимущественно терригенные отложения. Океан к югу от полярного фронта (примерно 50° южной широты ) отличается высокой биологической продуктивностью и в нем преобладают нестратифицированные отложения, состоящие в основном из кремнистых илов . Вблизи трех основных срединно-океанических хребтов дно океана относительно молодо и поэтому лишено отложений, за исключением Юго-Западного Индийского хребта из-за его сверхмедленной скорости расширения. [30]

Океанские течения в основном контролируются муссонами. Два больших круговорота , один в северном полушарии, текущий по часовой стрелке, а другой к югу от экватора, движущийся против часовой стрелки (включая течение Агульяс и возвратное течение Агульяс ), составляют доминирующую структуру потока. Однако во время зимнего муссона (ноябрь – февраль) циркуляция меняется на противоположную к северу от 30 ° ю.ш., и ветры ослабевают зимой и в переходные периоды между муссонами. [31]

В Индийском океане находятся крупнейшие подводные конусы в мире — Бенгальский веер и Индский веер , а также крупнейшие площади склоновых террас и рифтовых долин . [32]

Приток глубинных вод в Индийский океан составляет 11 Св , большая часть которых приходится на Циркумполярные глубокие воды (ЦГВ). ВДВ входит в Индийский океан через бассейны Крозе и Мадагаскар и пересекает Юго-Западный Индийский хребет на 30° ю.ш. В Маскаренском бассейне CDW становится глубоким западным пограничным течением, прежде чем он встретится с рециркулирующей ветвью самого себя, Глубоководными водами Северной Индии. Эта смешанная вода частично течет на север, в Сомалийский бассейн , тогда как большая часть ее течет по часовой стрелке в Маскаренский бассейн, где колеблющийся поток создается волнами Россби . [33]

В циркуляции вод Индийского океана преобладает субтропический антициклонический круговорот, восточное продолжение которого блокируется Юго-Восточным Индийским хребтом и хребтом 90° в.д. Мадагаскар и Юго-Западный Индийский хребет разделяют три ячейки к югу от Мадагаскара и у берегов Южной Африки. Глубокие воды Северной Атлантики достигают Индийского океана к югу от Африки на глубине 2 000–3 000 м (6 600–9 800 футов) и течет на север вдоль восточного континентального склона Африки. Глубже, чем NADW, придонная вода Антарктики течет из бассейна Эндерби в бассейн Агульяс по глубоким каналам (<4000 м (13 000 футов)) на юго-западе Индийского хребта, откуда она продолжается в Мозамбикский пролив и зону разлома Принца Эдуарда . [34]

К северу от 20 ° южной широты минимальная температура поверхности составляет 22 ° C (72 ° F), а к востоку превышает 28 ° C (82 ° F). К югу от 40° южной широты температура быстро падает. [22]

приходится На долю Бенгальского залива более половины (2950 км2). 3 или 710 кубических миль) сточных вод в Индийский океан. В основном летом этот сток течет в Аравийское море, но также и на юг, через экватор, где он смешивается с более пресной морской водой из Индонезийского протока . Эта смешанная пресная вода присоединяется к Южному экваториальному течению в южной тропической части Индийского океана. [35] Соленость поверхности моря самая высокая (более 36 PSU ) в Аравийском море, поскольку там испарение превышает количество осадков. В юго-восточной части Аравийского моря соленость падает до менее 34 ЕПС. Это самый низкий показатель (около 33 PSU) в Бенгальском заливе из-за речного стока и осадков. Индонезийский сток и осадки приводят к снижению солености (34 PSU) вдоль западного побережья Суматры. Муссонные изменения приводят к переносу более соленой воды на восток из Аравийского моря в Бенгальский залив с июня по сентябрь и к переносу на запад Ост-Индским прибрежным течением в Аравийское море с января по апрель. [36]

В 2010 году в Индийском океане было обнаружено мусорное пятно площадью не менее 5 миллионов квадратных километров (1,9 миллиона квадратных миль). Направляясь по южному круговороту Индийского океана , этот вихрь пластикового мусора постоянно циркулирует по океану от Австралии до Африки, вниз по Мозамбикскому проливу и обратно в Австралию в течение шести лет, за исключением мусора, который застревает на неопределенный срок в центре круговорота. . [37] Согласно исследованию 2012 года, мусорное пятно в Индийском океане через несколько десятилетий уменьшится в размерах и полностью исчезнет в течение столетий. Однако через несколько тысячелетий глобальная система мусорных пятен скопится в северной части Тихого океана. [38]

В Индийском океане имеются два амфидрома противоположного вращения, вероятно, вызванные распространением волн Россби . [39]

Айсберги дрейфуют на север до 55° южной широты , подобно Тихому океану, но меньше, чем в Атлантике, где айсберги достигают 45° южной широты. Объем потерь айсбергов в Индийском океане с 2004 по 2012 год составил 24 Гт . [40]

С 1960-х годов антропогенное потепление мирового океана в сочетании с поступлением пресной воды из отступающего материкового льда вызывает глобальное повышение уровня моря. Уровень моря также повышается в Индийском океане, за исключением южной тропической части Индийского океана, где он снижается, что, скорее всего, вызвано повышением уровня парниковых газов . [41]

Морская жизнь

[ редактировать ]Среди тропических океанов западная часть Индийского океана является местом одной из крупнейших концентраций цветения фитопланктона летом из-за сильных муссонных ветров. Воздействие муссонного ветра приводит к сильному апвеллингу в прибрежных районах и открытом океане , который переносит питательные вещества в верхние зоны, где достаточно света для фотосинтеза и производства фитопланктона. Цветение фитопланктона поддерживает морскую экосистему как основу морской пищевой сети и, в конечном итоге, более крупные виды рыб. На Индийский океан приходится вторая по величине доля наиболее экономически ценного улова тунца . [42] Ее рыба имеет огромное и растущее значение для соседних стран для внутреннего потребления и экспорта. Рыболовные флоты России, Японии, Южной Кореи и Тайваня также эксплуатируют Индийский океан, в основном для добычи креветок и тунца. [3]

Исследования показывают, что повышение температуры океана наносит ущерб морской экосистеме. Исследование изменений фитопланктона в Индийском океане указывает на сокращение численности морского планктона в Индийском океане на 20% за последние шесть десятилетий. Коэффициенты вылова тунца также снизились на 50–90% за последние полвека, в основном из-за увеличения промышленного рыболовства, а потепление океана усиливает стресс для видов рыб. [43]

Endangered and vulnerable marine mammals and turtles:[44]

| Name | Distribution | Trend |

|---|---|---|

| Endangered | ||

| Australian sea lion (Neophoca cinerea) | Southwest Australia | Decreasing |

| Blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) | Global | Increasing |

| Sei whale (Balaenoptera borealis) | Global | Increasing |

| Irrawaddy dolphin (Orcaella brevirostris) | Southeast Asia | Decreasing |

| Indian Ocean humpback dolphin (Sousa plumbea) | Western Indian Ocean | Decreasing |

| Green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) | Global | Decreasing |

| Vulnerable | ||

| Dugong (Dugong dugon) | Equatorial Indian Ocean and Pacific | Decreasing |

| Sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) | Global | Unknown |

| Fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) | Global | Increasing |

| Australian snubfin dolphin (Orcaella heinsohni) | Northern Australia, New Guinea | Decreasing |

| Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis) | Southeast Asia | Decreasing |

| Indo-Pacific finless porpoise (Neophocaena phocaenoides) | Northern Indian Ocean, Southeast Asia | Decreasing |

| Australian humpback dolphin (Sousa sahulensis) | Northern Australia, New Guinea | Decreasing |

| Leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea) | Global | Decreasing |

| Olive ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) | Global | Decreasing |

| Loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) | Global | Decreasing |

80% of the Indian Ocean is open ocean and includes nine large marine ecosystems: the Agulhas Current, Somali Coastal Current, Red Sea, Arabian Sea, Bay of Bengal, Gulf of Thailand, West Central Australian Shelf, Northwest Australian Shelf and Southwest Australian Shelf. Coral reefs cover c. 200,000 km2 (77,000 sq mi). The coasts of the Indian Ocean includes beaches and intertidal zones covering 3,000 km2 (1,200 sq mi) and 246 larger estuaries. Upwelling areas are small but important. The hypersaline salterns in India covers between 5,000–10,000 km2 (1,900–3,900 sq mi) and species adapted for this environment, such as Artemia salina and Dunaliella salina, are important to bird life.[45]

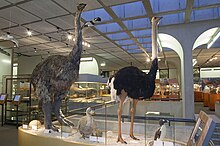

Right: The coelacanth (here a model from Oxford), thought extinct for millions of years, was rediscovered in the 20th century. The Indian Ocean species is blue whereas the Indonesian species is brown.

Coral reefs, sea grass beds, and mangrove forests are the most productive ecosystems of the Indian Ocean — coastal areas produce 20 tones of fish per square kilometre. These areas, however, are also being urbanised with populations often exceeding several thousand people per square kilometre and fishing techniques become more effective and often destructive beyond sustainable levels while the increase in sea surface temperature spreads coral bleaching.[46]

Mangroves covers 80,984 km2 (31,268 sq mi) in the Indian Ocean region, or almost half of the world's mangrove habitat, of which 42,500 km2 (16,400 sq mi) is located in Indonesia, or 50% of mangroves in the Indian Ocean. Mangroves originated in the Indian Ocean region and have adapted to a wide range of its habitats but it is also where it suffers its biggest loss of habitat.[47]

In 2016, six new animal species were identified at hydrothermal vents in the Southwest Indian Ridge: a "Hoff" crab, a "giant peltospirid" snail, a whelk-like snail, a limpet, a scaleworm and a polychaete worm.[48]

The West Indian Ocean coelacanth was discovered in the Indian Ocean off South Africa in the 1930s and in the late 1990s another species, the Indonesian coelacanth, was discovered off Sulawesi Island, Indonesia. Most extant coelacanths have been found in the Comoros. Although both species represent an order of lobe-finned fishes known from the Early Devonian (410 mya) and though extinct 66 mya, they are morphologically distinct from their Devonian ancestors. Over millions of years, coelacanths evolved to inhabit different environments — lungs adapted for shallow, brackish waters evolved into gills adapted for deep marine waters.[49]

Biodiversity

[edit]Of Earth's 36 biodiversity hotspots nine (or 25%) are located on the margins of the Indian Ocean.

- Madagascar and the islands of the western Indian Ocean (Comoros, Réunion, Mauritius, Rodrigues, the Seychelles, and Socotra), includes 13,000 (11,600 endemic) species of plants; 313 (183) birds; reptiles 381 (367); 164 (97) freshwater fishes; 250 (249) amphibians; and 200 (192) mammals.[50]

The origin of this diversity is debated; the break-up of Gondwana can explain vicariance older than 100 mya, but the diversity on the younger, smaller islands must have required a Cenozoic dispersal from the rims of the Indian Ocean to the islands. A "reverse colonisation", from islands to continents, apparently occurred more recently; the chameleons, for example, first diversified on Madagascar and then colonised Africa. Several species on the islands of the Indian Ocean are textbook cases of evolutionary processes; the dung beetles,[51][52] day geckos,[53][54] and lemurs are all examples of adaptive radiation.[55]Many bones (250 bones per square metre) of recently extinct vertebrates have been found in the Mare aux Songes swamp in Mauritius, including bones of the Dodo bird (Raphus cucullatus) and Cylindraspis giant tortoise. An analysis of these remains suggests a process of aridification began in the southwest Indian Ocean began around 4,000 years ago.[56]

- Maputaland-Pondoland-Albany (MPA); 8,100 (1,900 endemic) species of plants; 541 (0) birds; 205 (36) reptiles; 73 (20) freshwater fishes; 73 (11) amphibians; and 197 (3) mammals.[50]

Mammalian megafauna once widespread in the MPA was driven to near extinction in the early 20th century. Some species have been successfully recovered since then — the population of white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum simum) increased from less than 20 individuals in 1895 to more than 17,000 as of 2013. Other species still depend on fenced areas and management programs, including black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis minor), African wild dog (Lycaon pictus), cheetah (Acynonix jubatus), elephant (Loxodonta africana), and lion (Panthera leo).[57]

- Coastal forests of eastern Africa; 4,000 (1,750 endemic) species of plants; 636 (12) birds; 250 (54) reptiles; 219 (32) freshwater fishes; 95 (10) amphibians; and 236 (7) mammals.[50]

This biodiversity hotspot (and namesake ecoregion and "Endemic Bird Area") is a patchwork of small forested areas, often with a unique assemblage of species within each, located within 200 km (120 mi) from the coast and covering a total area of c. 6,200 km2 (2,400 sq mi). It also encompasses coastal islands, including Zanzibar and Pemba, and Mafia.[58]

- Horn of Africa; 5,000 (2,750 endemic) species of plants; 704 (25) birds; 284 (93) reptiles; 100 (10) freshwater fishes; 30 (6) amphibians; and 189 (18) mammals.[50]

Coral reefs of the Maldives

This area, one of the only two hotspots that are entirely arid, includes the Ethiopian Highlands, the East African Rift valley, the Socotra islands, as well as some small islands in the Red Sea and areas on the southern Arabic Peninsula. Endemic and threatened mammals include the dibatag (Ammodorcas clarkei) and Speke's gazelle (Gazella spekei); the Somali wild ass (Equus africanus somaliensis) and hamadryas baboon (Papio hamadryas). It also contains many reptiles.[59]In Somalia, the centre of the 1,500,000 km2 (580,000 sq mi) hotspot, the landscape is dominated by Acacia-Commiphora deciduous bushland, but also includes the Yeheb nut (Cordeauxia edulus) and species discovered more recently such as the Somali cyclamen (Cyclamen somalense), the only cyclamen outside the Mediterranean. Warsangli linnet (Carduelis johannis) is an endemic bird found only in northern Somalia. An unstable political situation and mismanagement has resulted in overgrazing which has produced one of the most degraded hotspots where only c. 5 % of the original habitat remains.[60]

- The Western Ghats–Sri Lanka; 5,916 (3,049 endemic) species of plants; 457 (35) birds; 265 (176) reptiles; 191 (139) freshwater fishes; 204 (156) amphibians; and 143 (27) mammals.[50]

Encompassing the west coast of India and Sri Lanka, until c. 10,000 years ago a landbridge connected Sri Lanka to the Indian Subcontinent, hence this region shares a common community of species.[61]

- Indo-Burma; 13.500 (7,000 endemic) species of plants; 1,277 (73) birds; 518 (204) reptiles; 1,262 (553) freshwater fishes; 328 (193) amphibians; and 401 (100) mammals.[50]

Aldabra giant tortoise from the islands of the Aldabra Atoll in the Seychelles

Indo-Burma encompasses a series of mountain ranges, five of Asia's largest river systems, and a wide range of habitats. The region has a long and complex geological history, and long periods rising sea levels and glaciations have isolated ecosystems and thus promoted a high degree of endemism and speciation. The region includes two centres of endemism: the Annamite Mountains and the northern highlands on the China-Vietnam border.[62]Several distinct floristic regions, the Indian, Malesian, Sino-Himalayan, and Indochinese regions, meet in a unique way in Indo-Burma and the hotspot contains an estimated 15,000–25,000 species of vascular plants, many of them endemic.[63]

- Sundaland; 25,000 (15,000 endemic) species of plants; 771 (146) birds; 449 (244) reptiles; 950 (350) freshwater fishes; 258 (210) amphibians; and 397 (219) mammals.[50]

Sundaland encompasses 17,000 islands of which Borneo and Sumatra are the largest. Endangered mammals include the Bornean and Sumatran orangutans, the proboscis monkey, and the Javan and Sumatran rhinoceroses.[64]

- Wallacea; 10,000 (1,500 endemic) species of plants; 650 (265) birds; 222 (99) reptiles; 250 (50) freshwater fishes; 49 (33) amphibians; and 244 (144) mammals.[50]

- Southwest Australia; 5,571 (2,948 endemic) species of plants; 285 (10) birds; 177 (27) reptiles; 20 (10) freshwater fishes; 32 (22) amphibians; and 55 (13) mammals.[50]

Stretching from Shark Bay to Israelite Bay and isolated by the arid Nullarbor Plain, the southwestern corner of Australia is a floristic region with a stable climate in which one of the world's largest floral biodiversity and an 80% endemism has evolved. From June to September it is an explosion of colours and the Wildflower Festival in Perth in September attracts more than half a million visitors.[65]

Geology

[edit]As the youngest of the major oceans,[66] the Indian Ocean has active spreading ridges that are part of the worldwide system of mid-ocean ridges. In the Indian Ocean these spreading ridges meet at the Rodrigues Triple Point with the Central Indian Ridge, including the Carlsberg Ridge, separating the African Plate from the Indian Plate; the Southwest Indian Ridge separating the African Plate from the Antarctic Plate; and the Southeast Indian Ridge separating the Australian Plate from the Antarctic Plate. The Central Indian Ridge is intercepted by the Owen Fracture Zone.[67]Since the late 1990s, however, it has become clear that this traditional definition of the Indo-Australian Plate cannot be correct; it consists of three plates — the Indian Plate, the Capricorn Plate, and Australian Plate — separated by diffuse boundary zones.[68]Since 20 Ma the African Plate is being divided by the East African Rift System into the Nubian and Somalia plates.[69]

There are only two trenches in the Indian Ocean: the 6,000 km (3,700 mi)-long Java Trench between Java and the Sunda Trench and the 900 km (560 mi)-long Makran Trench south of Iran and Pakistan.[67]

A series of ridges and seamount chains produced by hotspots pass over the Indian Ocean. The Réunion hotspot (active 70–40 million years ago) connects Réunion and the Mascarene Plateau to the Chagos-Laccadive Ridge and the Deccan Traps in north-western India; the Kerguelen hotspot (100–35 million years ago) connects the Kerguelen Islands and Kerguelen Plateau to the Ninety East Ridge and the Rajmahal Traps in north-eastern India; the Marion hotspot (100–70 million years ago) possibly connects Prince Edward Islands to the Eighty Five East Ridge.[70] These hotspot tracks have been broken by the still active spreading ridges mentioned above.[67]

There are fewer seamounts in the Indian Ocean than in the Atlantic and Pacific. These are typically deeper than 3,000 m (9,800 ft) and located north of 55°S and west of 80°E. Most originated at spreading ridges but some are now located in basins far away from these ridges. The ridges of the Indian Ocean form ranges of seamounts, sometimes very long, including the Carlsberg Ridge, Madagascar Ridge, Central Indian Ridge, Southwest Indian Ridge, Chagos-Laccadive Ridge, 85°E Ridge, 90°E Ridge, Southeast Indian Ridge, Broken Ridge, and East Indiaman Ridge. The Agulhas Plateau and Mascarene Plateau are the two major shallow areas.[34]

The opening of the Indian Ocean began c. 156 Ma when Africa separated from East Gondwana. The Indian Subcontinent began to separate from Australia-Antarctica 135–125 Ma and as the Tethys Ocean north of India began to close 118–84 Ma the Indian Ocean opened behind it.[67]

History

[edit]The Indian Ocean, together with the Mediterranean, has connected people since ancient times, whereas the Atlantic and Pacific have had the roles of barriers or mare incognitum. The written history of the Indian Ocean, however, has been Eurocentric and largely dependent on the availability of written sources from the European colonial era. This history is often divided into an ancient period followed by an Islamic period; the subsequent colonial-era periods are often subdivided into Portuguese, Dutch, and British periods.[71] Milo Kearney argues that the postwar time period can also be split into a period of competition for oil during the Cold War followed by American dominance.[72]

A concept of an "Indian Ocean World" (IOW), similar to that of the "Atlantic World", exists but emerged much more recently and is not well established. The IOW is, nevertheless, sometimes referred to as the "first global economy" and was based on the monsoon which linked Asia, China, India, and Mesopotamia. It developed independently from the European global trade in the Mediterranean and Atlantic and remained largely independent from them until European 19th-century colonial dominance.[73]

The diverse history of the Indian Ocean is a unique mix of cultures, ethnic groups, natural resources, and shipping routes. It grew in importance beginning in the 1960s and 1970s and, after the Cold War, it has undergone periods of political instability, most recently with the emergence of India and China as regional powers.[74]

First settlements

[edit]

Pleistocene fossils of Homo erectus and other pre–H. sapiens hominid fossils, similar to H. heidelbergensis in Europe, have been found in India. According to the Toba catastrophe theory, a supereruption c. 74,000 years ago at Lake Toba, Sumatra, covered India with volcanic ashes and wiped out one or more lineages of such archaic humans in India and Southeast Asia.[75]

The Out of Africa theory states that Homo sapiens spread from Africa into mainland Eurasia. The more recent Southern Dispersal or Coastal hypothesis instead advocates that modern humans spread along the coasts of the Arabic Peninsula and southern Asia. This hypothesis is supported by mtDNA research which reveals a rapid dispersal event during the Late Pleistocene (11,000 years ago). This coastal dispersal, however, began in East Africa 75,000 years ago and occurred intermittently from estuary to estuary along the northern perimeter of the Indian Ocean at a rate of 0.7–4.0 km (0.43–2.49 mi) per year. It eventually resulted in modern humans migrating from Sunda over Wallacea to Sahul (Southeast Asia to Australia).[76] Since then, waves of migration have resettled people and, clearly, the Indian Ocean littoral had been inhabited long before the first civilisations emerged. 5000–6000 years ago six distinct cultural centres had evolved around the Indian Ocean: East Africa, the Middle East, the Indian Subcontinent, South East Asia, the Malay World and Australia; each interlinked to its neighbours.[77]

Food globalisation began on the Indian Ocean littoral c. 4.000 years ago. Five African crops — sorghum, pearl millet, finger millet, cowpea and hyacinth bean — somehow found their way to Gujarat in India during the Late Harappan (2000–1700 BCE). Gujarati merchants evolved into the first explorers of the Indian Ocean as they traded African goods such as ivory, tortoise shells, and slaves. Broomcorn millet found its way from Central Asia to Africa, together with chicken and zebu cattle, although the exact timing is disputed. Around 2000 BCE black pepper and sesame, both native to Asia, appear in Egypt, albeit in small quantities. Around the same time the black rat and the house mouse emigrate from Asia to Egypt. Banana reached Africa around 3000 years ago.[78]

At least eleven prehistoric tsunamis have struck the Indian Ocean coast of Indonesia between 7400 and 2900 years ago. Analysing sand beds in caves in the Aceh region, scientists concluded that the intervals between these tsunamis have varied from series of minor tsunamis over a century to dormant periods of more than 2000 years preceding megathrusts in the Sunda Trench. Although the risk for future tsunamis is high, a major megathrust such as the one in 2004 is likely to be followed by a long dormant period.[79]

A group of scientists have argued that two large-scale impact events have occurred in the Indian Ocean: the Burckle Crater in the southern Indian Ocean in 2800 BCE and the Kanmare and Tabban craters in the Gulf of Carpentaria in northern Australia in 536 CE. Evidences for these impacts, the team argue, are micro-ejecta and Chevron dunes in southern Madagascar and in the Australian gulf. Geological evidences suggest the tsunamis caused by these impacts reached 205 m (673 ft) above sea level and 45 km (28 mi) inland. The impact events must have disrupted human settlements and perhaps even contributed to major climate changes.[80]

Antiquity

[edit]The history of the Indian Ocean is marked by maritime trade; cultural and commercial exchange probably date back at least seven thousand years.[81] Human culture spread early on the shores of the Indian Ocean and was always linked to the cultures of the Mediterranean and the Persian Gulf. Before c. 2000 BCE, however, cultures on its shores were only loosely tied to each other; bronze, for example, was developed in Mesopotamia c. 3000 BCE but remained uncommon in Egypt before 1800 BCE.[82]During this period, independent, short-distance oversea communications along its littoral margins evolved into an all-embracing network. The début of this network was not the achievement of a centralised or advanced civilisation but of local and regional exchange in the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, and the Arabian Sea. Sherds of Ubaid (2500–500 BCE) pottery have been found in the western Gulf at Dilmun, present-day Bahrain; traces of exchange between this trading centre and Mesopotamia. The Sumerians traded grain, pottery, and bitumen (used for reed boats) for copper, stone, timber, tin, dates, onions, and pearls.[83]Coast-bound vessels transported goods between the Indus Valley civilisation (2600–1900 BCE) in the Indian subcontinent (modern-day Pakistan and Northwest India) and the Persian Gulf and Egypt.[81]

The Red Sea, one of the main trade routes in Antiquity, was explored by Egyptians and Phoenicians during the last two millennia BCE. In the 6th century, BCE Greek explorer Scylax of Caryanda made a journey to India, working for the Persian king Darius, and his now-lost account put the Indian Ocean on the maps of Greek geographers. The Greeks began to explore the Indian Ocean following the conquests of Alexander the Great, who ordered a circumnavigation of the Arabian Peninsula in 323 BCE. During the two centuries that followed the reports of the explorers of Ptolemaic Egypt resulted in the best maps of the region until the Portuguese era many centuries later. The main interest in the region for the Ptolemies was not commercial but military; they explored Africa to hunt for war elephants.[84]

The Rub' al Khali desert isolates the southern parts of the Arabic Peninsula and the Indian Ocean from the Arabic world. This encouraged the development of maritime trade in the region linking the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf to East Africa and India. The monsoon (from mawsim, the Arabic word for season), however, was used by sailors long before being "discovered" by Hippalus in the 1st century. Indian wood have been found in Sumerian cities, there is evidence of Akkad coastal trade in the region, and contacts between India and the Red Sea dates back to 2300 B.C. The archipelagoes of the central Indian Ocean, the Laccadive and Maldive islands, were probably populated during the 2nd century B.C. from the Indian mainland. They appear in written history in the account of merchant Sulaiman al-Tajir in the 9th century but the treacherous reefs of the islands were most likely cursed by the sailors of Aden long before the islands were even settled.[85]

Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, an Alexandrian guide to the world beyond the Red Sea — including Africa and India — from the first century CE, not only gives insights into trade in the region but also shows that Roman and Greek sailors had already gained knowledge about the monsoon winds.[81] The contemporaneous settlement of Madagascar by Austronesian sailors shows that the littoral margins of the Indian Ocean were being both well-populated and regularly traversed at least by this time. Albeit the monsoon must have been common knowledge in the Indian Ocean for centuries.[81]

The Indian Ocean's relatively calmer waters opened the areas bordering it to trade earlier than the Atlantic or Pacific oceans. The powerful monsoons also meant ships could easily sail west early in the season, then wait a few months and return eastwards. This allowed ancient Indonesian peoples to cross the Indian Ocean to settle in Madagascar around 1 CE.[86]

In the 2nd or 1st century BCE, Eudoxus of Cyzicus was the first Greek to cross the Indian Ocean. The probably fictitious sailor Hippalus is said to have learnt the direct route from Arabia to India around this time.[87] During the 1st and 2nd centuries AD intensive trade relations developed between Roman Egypt and the Tamil kingdoms of the Cheras, Cholas and Pandyas in Southern India. Like the Indonesian people above, the western sailors used the monsoon to cross the ocean. The unknown author of the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea describes this route, as well as the commodities that were traded along various commercial ports on the coasts of the Horn of Africa and India circa 1 CE. Among these trading settlements were Mosylon and Opone on the Red Sea littoral.[9]

Age of Discovery

[edit]

Unlike the Pacific Ocean where the civilization of the Polynesians reached most of the far-flung islands and atolls and populated them, almost all the islands, archipelagos and atolls of the Indian Ocean were uninhabited until colonial times. Although there were numerous ancient civilizations in the coastal states of Asia and parts of Africa, the Maldives were the only island group in the Central Indian Ocean region where an ancient civilization flourished.[88] Maldivians, on their annual trade trip, took their oceangoing trade ships to Sri Lanka rather than mainland India, which is much closer, because their ships were dependent of the Indian Monsoon Current.[89]

Arabic missionaries and merchants began to spread Islam along the western shores of the Indian Ocean from the 8th century, if not earlier. A Swahili stone mosque dating to the 8th–15th centuries has been found in Shanga, Kenya. Trade across the Indian Ocean gradually introduced Arabic script and rice as a staple in Eastern Africa.[90]Muslim merchants traded an estimated 1000 African slaves annually between 800 and 1700, a number that grew to c. 4000 during the 18th century, and 3700 during the period 1800–1870. Slave trade also occurred in the eastern Indian Ocean before the Dutch settled there around 1600 but the volume of this trade is unknown.[91]

From 1405 to 1433 admiral Zheng He said to have led large fleets of the Ming dynasty on several treasure voyages through the Indian Ocean, ultimately reaching the coastal countries of East Africa.[92]

The Portuguese navigator Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope during his first voyage in 1497 and became the first European to sail to India. The Swahili people he encountered along the African east coast lived in a series of cities and had established trade routes to India and to China. Among them, the Portuguese kidnapped most of their pilots in coastal raids and on board ships. A few of the pilots, however, were gifts by local Swahili rulers, including the sailor from Gujarat, a gift by a Malindi ruler in Kenya, who helped the Portuguese to reach India. In expeditions after 1500, the Portuguese attacked and colonised cities along the African coast.[93]European slave trade in the Indian Ocean began when Portugal established Estado da Índia in the early 16th century. From then until the 1830s, c. 200 slaves were exported from Mozambique annually and similar figures has been estimated for slaves brought from Asia to the Philippines during the Iberian Union (1580–1640).[91]

The Ottoman Empire began its expansion into the Indian Ocean in 1517 with the conquest of Egypt under Sultan Selim I. Although the Ottomans shared the same religion as the trading communities in the Indian Ocean the region was unexplored by them. Maps that included the Indian Ocean had been produced by Muslim geographers centuries before the Ottoman conquests; Muslim scholars, such as Ibn Battuta in the 14th century, had visited most parts of the known world; contemporarily with Vasco da Gama, Arab navigator Ahmad ibn Mājid had compiled a guide to navigation in the Indian Ocean; the Ottomans, nevertheless, began their own parallel era of discovery which rivalled the European expansion.[94]

The establishment of the Dutch East India Company in the early 17th century lead to a quick increase in the volume of the slave trade in the region; there were perhaps up to 500,000 slaves in various Dutch colonies during the 17th and 18th centuries in the Indian Ocean. For example, some 4000 African slaves were used to build the Colombo fortress in Dutch Ceylon. Bali and neighbouring islands supplied regional networks with c. 100,000–150,000 slaves 1620–1830. Indian and Chinese slave traders supplied Dutch Indonesia with perhaps 250,000 slaves during the 17th and 18th centuries.[91]

The East India Company (EIC) was established during the same period and in 1622 one of its ships carried slaves from the Coromandel Coast to Dutch East Indies. The EIC mostly traded in African slaves but also some Asian slaves purchased from Indian, Indonesian and Chinese slave traders. The French established colonies on the islands of Réunion and Mauritius in 1721; by 1735 some 7,200 slaves populated the Mascarene Islands, a number which had reached 133,000 in 1807. The British captured the islands in 1810, however, and because the British had prohibited the slave trade in 1807 a system of clandestine slave trade developed to bring slaves to French planters on the islands; in all 336,000–388,000 slaves were exported to the Mascarene Islands from 1670 until 1848.[91]

In all, European traders exported 567,900–733,200 slaves within the Indian Ocean between 1500 and 1850, and almost that same number were exported from the Indian Ocean to the Americas during the same period. Slave trade in the Indian Ocean was, nevertheless, very limited compared to c. 12,000,000 slaves exported across the Atlantic.[91] The island of Zanzibar was the center of the Indian Ocean slave trade in the 19th century. In the mid-19th century, as many as 50,000 slaves passed annually through the port.[95]

Late modern era

[edit]

Scientifically, the Indian Ocean remained poorly explored before the International Indian Ocean Expedition in the early 1960s. However, the Challenger expedition 1872–1876 only reported from south of the polar front. The Valdivia expedition 1898–1899 made deep samples in the Indian Ocean. In the 1930s, the John Murray Expedition mainly studied shallow-water habitats. The Swedish Deep Sea Expedition 1947–1948 also sampled the Indian Ocean on its global tour and the Danish Galathea sampled deep-water fauna from Sri Lanka to South Africa on its second expedition 1950–1952. The Soviet research vessel Vityaz also did research in the Indian Ocean.[1]

The Suez Canal opened in 1869 when the Industrial Revolution dramatically changed global shipping – the sailing ship declined in importance as did the importance of European trade in favour of trade in East Asia and Australia.[96]The construction of the canal introduced many non-indigenous species into the Mediterranean. For example, the goldband goatfish (Upeneus moluccensis) has replaced the red mullet (Mullus barbatus); since the 1980s huge swarms of scyphozoan jellyfish (Rhopilema nomadica) have affected tourism and fisheries along the Levantian coast and clogged power and desalination plants. Plans announced in 2014 to build a new, much larger Suez Canal parallel to the 19th-century canal will most likely boost the economy in the region but also cause ecological damage in a much wider area.[97]

Throughout the colonial era, islands such as Mauritius were important shipping nodes for the Dutch, French, and British. Mauritius, an inhabited island, became populated by slaves from Africa and indenture labour from India. The end of World War II marked the end of the colonial era. The British left Mauritius in 1974 and with 70% of the population of Indian descent, Mauritius became a close ally of India. In the 1980s, during the Cold War, the South African regime acted to destabilise several island nations in the Indian Ocean, including the Seychelles, Comoros, and Madagascar. India intervened in Mauritius to prevent a coup d'état, backed up by the United States who feared the Soviet Union could gain access to Port Louis and threaten the U.S. base on Diego Garcia.[98]Iranrud was an unrealised plan by Iran and the Soviet Union to build a canal between the Caspian Sea and the Persian Gulf.

Testimonies from the colonial era are stories of African slaves, Indian indentured labourers and white settlers. But, while there was a clear racial line between free men and slaves in the Atlantic World, this delineation is less distinct in the Indian Ocean — there were Indian slaves and settlers as well as black indentured labourers. There were also a string of prison camps across the Indian Ocean, such as Cellular Jail in the Andamans, in which prisoners, exiles, POWs, forced labourers, merchants and people of different faiths were forcefully united. On the islands of the Indian Ocean, therefore, a trend of creolisation emerged.[99]

On 26 December 2004, fourteen countries around the Indian Ocean were hit by a wave of tsunamis caused by the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake. The waves radiated across the ocean at speeds exceeding 500 km/h (310 mph), reached up to 20 m (66 ft) in height, and resulted in an estimated 236,000 deaths.[100]

In the late 2000s, the ocean evolved into a hub of pirate activity. By 2013, attacks off the Horn region's coast had steadily declined due to active private security and international navy patrols, especially by the Indian Navy.[101]

Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, a Boeing 777 airliner with 239 persons on board, disappeared on 8 March 2014 and is alleged to have crashed into the southern Indian Ocean about 2,500 km (1,600 mi) from the coast of southwest Western Australia. Despite an extensive search, the whereabouts of the remains of the aircraft is unknown.[102]

The Sentinelese people of North Sentinel Island, which lies near South Andaman Island in the Bay of Bengal, have been called by experts the most isolated people in the world.[103]

The sovereignty of the Chagos Archipelago in the Indian Ocean is disputed between the United Kingdom and Mauritius.[104] In February 2019, the International Court of Justice in The Hague issued an advisory opinion stating that the UK must transfer the Chagos Archipelago to Mauritius.[105]

Trade

[edit]

The sea lanes in the Indian Ocean are considered among the most strategically important in the world with more than 80 percent of the world's seaborne trade in oil transits through the Indian Ocean and its vital chokepoints, with 40 percent passing through the Strait of Hormuz, 35 percent through the Strait of Malacca and 8 percent through the Bab el-Mandab Strait.[106]

The Indian Ocean provides major sea routes connecting the Middle East, Africa, and East Asia with Europe and the Americas. It carries a particularly heavy traffic of petroleum and petroleum products from the oil fields of the Persian Gulf and Indonesia. Large reserves of hydrocarbons are being tapped in the offshore areas of Saudi Arabia, Iran, India, and Western Australia. An estimated 40% of the world's offshore oil production comes from the Indian Ocean.[3] Beach sands rich in heavy minerals, and offshore placer deposits are actively exploited by bordering countries, particularly India, Pakistan, South Africa, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Thailand.

In particular, the maritime part of the Silk Road leads through the Indian Ocean on which a large part of the global container trade is carried out. The Silk Road runs with its connections from the Chinese coast and its large container ports to the south via Hanoi to Jakarta, Singapore and Kuala Lumpur through the Strait of Malacca via the Sri Lankan Colombo opposite the southern tip of India via Malé, the capital of the Maldives, to the East African Mombasa, from there to Djibouti, then through the Red Sea over the Suez Canal into the Mediterranean, there via Haifa, Istanbul and Athens to the Upper Adriatic to the northern Italian junction of Trieste with its international free port and its rail connections to Central and Eastern Europe.[107][108][109][110]

The Silk Road has become internationally important again on the one hand through European integration, the end of the Cold War and free world trade and on the other hand through Chinese initiatives. Chinese companies have made investments in several Indian Ocean ports, including Gwadar, Hambantota, Colombo and Sonadia. This has sparked a debate about the strategic implications of these investments.[111] There are also Chinese investments and related efforts to intensify trade in East Africa and in European ports such as Piraeus and Trieste.[112][113][114]

See also

[edit]- Connected bodies of water:

- Indian Ocean Geoid Low

- Indian Ocean in World War II

- Indian Ocean literature

- Indian Ocean Naval Symposium

- Indian Ocean Research Group

- List of islands in the Indian Ocean

- List of sovereign states and dependent territories in the Indian Ocean

- Indian Ocean Rim Association

- Maritime Silk Road

- Territorial claims in Antarctica

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c Demopoulos, Smith & Tyler 2003, Introduction, p. 219

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b Keesing & Irvine 2005, Introduction, p. 11–12; Table 1, p.12

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c CIA World Fact Book 2018

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b Eakins & Sharman 2010

- ^ "'Indian Ocean' — Merriam-Webster Dictionary Online". Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

ocean E of Africa, S of Asia, W of Australia, & N of Antarctica area ab 73,427,795 square kilometres (28,350,630 sq mi)

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Indian Ocean". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 14 January 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

first attested 1515 in Modern Latin (Oceanus Orientalis Indicus), named for India, which projects into it; earlier it was the Eastern Ocean, as opposed to the Western Ocean (Atlantic) before the Pacific was surmised.

- ^ Braun, Dieter (1972). "The Indian Ocean in Afro-Asian Perspective". The World Today. 28 (6): 249–256. JSTOR 40394632.

- ^ Hui 2010, Abstract

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b Anonymous (1912). . Translated by Schoff, Wilfred Harvey.

- ^ IHO 1953

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с ВНИЗ 2002

- ^ Прейндж 2008 , Жидкие границы: охватывая океан, стр. 1382–1385.

- ^ «Континентальный шельф» . Национальное географическое общество . 4 марта 2011 г. Архивировано из оригинала 5 октября 2021 г. Проверено 5 октября 2021 г.

- ^ Харрис и др. 2014 г. , Таблица 2, с. 11

- ^ Харрис и др. 2014 г. , Таблица 3, с. 11

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Дамодара, Н.; Рао, В. Виджая; Саин, Калачанд; Прасад, АССРС; Мурти, ASN (март 2017 г.). «Конфигурация фундамента осадочного бассейна Западной Бенгалии в Индии, выявленная с помощью сейсмической рефракционной томографии: ее тектонические последствия». Международный геофизический журнал . 208 (3): 1490–1507. дои : 10.1093/gji/ggw461 .

- ^ Вёрёсмарти и др. 2000 , Площадь водосборного бассейна каждого океана, стр. 609–616; Табл. 5, стр. 614; Примирение континентальных и океанических перспектив, стр. 616–617.

- ^ «Самые большие океаны и моря мира» . Живая наука . 4 июня 2010 г. Архивировано из оригинала 15 сентября 2020 г. . Проверено 9 сентября 2020 г.

- ^ «Карта мира / Атлас мира / Атлас мира, включая географические факты и флаги - WorldAtlas.com» . Архивировано из оригинала 27 апреля 2019 года . Проверено 28 апреля 2019 г.

- ^ «Список морей» . Архивировано из оригинала 8 ноября 2020 года . Проверено 9 сентября 2020 г.

- ^ Шотт, Се и МакКрири, 2009 г. , Введение, стр. 1–2.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б «Океанограф ВМС США» . Архивировано из оригинала 2 августа 2001 года . Проверено 4 августа 2001 г.

- ^ Датт и др. 2015 , Аннотация; Введение, стр. 5526–5527.

- ^ «Какой океан самый теплый?» . Мировой атлас. 17 сентября 2018 года. Архивировано из оригинала 28 апреля 2019 года . Проверено 28 апреля 2019 г.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Рокси и др. 2014 , Аннотация

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Рокси, МК; Саранья, Дж.С.; Моди, Адити; Анусри, А.; Цай, Вэньцзюй; Респланди, Лора; Виалар, Жером; Фрелихер, Томас Л. (2024). «Прогнозы на будущее для тропической части Индийского океана». Индийский океан и его роль в глобальной климатической системе . стр. 469–482. дои : 10.1016/b978-0-12-822698-8.00004-4 . ISBN 978-0-12-822698-8 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б «Будущий Индийский океан» . Лаборатория климатических исследований @ IITM . Проверено 1 июля 2024 г.

- ^ Картон, Чепурин и Цао 2000 , с. 321

- ^ Лелиевельд и др. 2001 , Аннотация.

- ^ Юинг и др. 1969 , Аннотация

- ^ Шанкар, Винаячандран и Унникришнан, 2002 , Введение, стр. 64–66

- ^ Харрис и др. 2014 , Геоморфическая характеристика океанических регионов, стр. 17–18.

- ^ Wilson et al. 2012, Regional setting and hydrography, pp. 4–5; Fig. 1, p. 22

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b Rogers 2012, The Southern Indian Ocean and its Seamounts, pp. 5–6

- ^ Sengupta, Bharath Raj & Shenoi 2006, Abstract; p. 4

- ^ Felton 2014, Results, pp. 47–48; Average for Table 3.1, p. 55

- ^ Parker, Laura (4 April 2014). "Plane Search Shows World's Oceans Are Full of Trash". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ Van Sebille, England & Froyland 2012

- ^ Chen & Quartly 2005, pp. 5–6

- ^ Matsumoto et al. 2014, pp. 3454–3455

- ^ Han et al. 2010, Abstract

- ^ FAO 2016

- ^ Roxy 2016, Discussion, pp. 831–832

- ^ "IUCN Red List". IUCN. Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.. Search parametres: Mammalia/Testudines, EN/VU, Indian Ocean Antarctic/Eastern/Western

- ^ Wafar et al. 2011, Marine ecosystems of the IO

- ^ Souter & Lindén 2005, Foreword, pp. 5–6

- ^ Kathiresan & Rajendran 2005, Introduction; Mangrove habitat, pp. 104–105

- ^ «Новая морская жизнь обнаружена в глубоководных жерлах» . Новости Би-би-си . 15 декабря 2016 года. Архивировано из оригинала 15 декабря 2016 года . Проверено 15 декабря 2016 г.

- ^ Купелло и др. 2019 , Введение, с. 29

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я Миттермайер и др. 2011 г. , Таблица 1.2, стр. 12–13.

- ^ Миральдо, Андрея; Вирта, Хелена; Хански, Илкка (20 апреля 2011 г.). «Происхождение и разнообразие навозных жуков на Мадагаскаре» . Насекомые . 2 (2): 112–127. дои : 10.3390/insects2020112 . ПМЦ 4553453 . ПМИД 26467617 .

- ^ Вирта, Хелена; Орсини, Луиза; Хански, Илкка (июнь 2008 г.). «Старая адаптивная радиация лесных навозных жуков на Мадагаскаре». Молекулярная филогенетика и эволюция . 47 (3): 1076–1089. Бибкод : 2008MolPE..47.1076W . дои : 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.03.010 . ПМИД 18424187 . S2CID 7509190 .

- ^ Радтки, Рэй Р. (апрель 1996 г.). «Адаптивная радиация дневных гекконов ( Phelsuma ) на Сейшельском архипелаге: филогенетический анализ». Эволюция . 50 (2): 604–623. дои : 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1996.tb03872.x . ПМИД 28568942 .

- ^ Осень, Келлар; Невяровский, Питер Х.; Путхофф, Джонатан Б. (23 ноября 2014 г.). «Адгезия гекконов как модельная система для интегративной биологии, междисциплинарной науки и биоинженерии». Ежегодный обзор экологии, эволюции и систематики . 45 (1): 445–470. doi : 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-120213-091839 .

- ^ Эррера, Джеймс П. (31 января 2017 г.). «Проверка гипотезы адаптивной радиации для лемуров Мадагаскара» . Королевское общество открытой науки . 4 (1): 161014. Цифровой код : 2017RSOS....461014H . дои : 10.1098/rsos.161014 . ПМЦ 5319363 . ПМИД 28280597 .

- ^ Рейсдейк и др. 2009 , Аннотация.

- ^ Ди Минин и др. 2013 г .: «Горячая точка биоразнообразия Мапуталенд-Пондоленд-Олбани признана на международном уровне...»»

- ^ WWF-EARPO 2006 , Уникальные прибрежные леса Восточной Африки, стр. 3

- ^ «Африканский Рог» . CEPF . Проверено 18 августа 2019 г.

- ^ Улла и Гадайн, 2016 , Важность биоразнообразия, стр. 17–19; Биоразнообразие Сомали, стр. 25–26.

- ^ Боссайт и др. 2004 г.

- ^ CEPF 2012: Индо-Бирма , география, климат и история, стр. 30

- ^ CEPF 2012: Индо-Бирма , Видовое разнообразие и эндемизм, стр. 36

- ^ «Сандаленд: Об этой горячей точке» . CEPF . Архивировано из оригинала 6 октября 2022 года . Проверено 1 сентября 2019 г.

- ^ Райан 2009

- ^ Стоу 2006 г.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с д Чаттерджи, Госвами и Скотезе, 2013 г. , Тектоническая обстановка Индийского океана, стр. 246

- ^ Ройер и Гордон 1997 , Аннотация

- ^ Bird 2003, Somalia Plate (SO), pp. 39–40

- ^ Müller, Royer & Lawver 1993, Fig. 1, p. 275

- ^ Parthasarathi & Riello 2014, Time and the Indian Ocean, pp. 2–3

- ^ Kearney, Milo (2004). The Indian Ocean in World History. doi:10.4324/9780203493274. ISBN 978-1-134-38175-3.[page needed]

- ^ Campbell 2017, The Concept of the Indian Ocean World (IOW), pp. 25–26

- ^ Bouchard & Crumplin 2010, Abstract

- ^ Patnaik & Chauhan 2009, Abstract

- ^ Bulbeck 2007, p. 315

- ^ McPherson 1984, History and Patterns, pp. 5–6

- ^ Boivin et al. 2014, The Earliest Evidence, pp. 4–7

- ^ Rubin et al. 2017, Abstract

- ^ Gusiakov et al. 2009, Abstract

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c d Alpers 2013, Chapter 1. Imagining the Indian Ocean, pp. 1–2

- ^ Beaujard & Fee 2005, p. 417

- ^ Alpers 2013, Chapter 2. The Ancient Indian Ocean, pp. 19–22

- ^ Burstein 1996, pp. 799–801

- ^ Forbes 1981 , Южная Аравия и центральная часть Индийского океана: доисламские контакты, стр. 62–66.

- ^ Фитцпатрик и Каллаган 2009 , Колонизация Мадагаскара, стр. 47–48.

- ^ Эль-Аббади 2000

- ^ Кабреро 2004 , с. 32

- ^ Ромеро-Фриас 2016 , Аннотация; п. 3

- ^ LaViolette 2008 , Обращение в ислам и исламская практика, стр. 39–40.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с д и Аллен, 2017 г. , Работорговля в Индийском океане: обзор, стр. 295–299.

- ^ Дрейер 2007 , с. 1

- ^ Фелбер Селигман, 2006 , Восточноафриканское побережье, стр. 90–95.

- ^ Казале 2003

- ^ «Побережье Суахили: древний перекресток Восточной Африки». Архивировано 19 января 2018 года в Wayback Machine . Знаете ли вы? боковая панель Кристи Ульрих, National Geographic .

- ^ Флетчер 1958 , Аннотация

- ^ Галил и др. 2015 , стр. 973–974

- ^ Брюстер 2014b , Отрывок.

- ^ Хофмейр 2012 , Сквозные диаспоры, стр. 587–588

- ^ Телфорд и Косгрейв 2006 , Непосредственные последствия катастрофы, стр. 33–35.

- ^ Арнсдорф 2013

- ^ МакЛауд, Зима и Серый, 2014 г.

- ^ Нувер, Рэйчел (4 августа 2014 г.). «Антропология: печальная правда о неконтактируемых племенах» . Би-би-си . Архивировано из оригинала 30 августа 2019 года . Проверено 15 мая 2021 г.

- ^ «Спор об островах Чагос: Великобритания «угрожала» Маврикию» . Новости Би-би-си . 27 августа 2018 г. Архивировано из оригинала 23 марта 2021 г. Проверено 15 мая 2021 г.

- ^ «Министерство иностранных дел тихо отвергает решение Международного суда о возвращении островов Чагос» . inews.co.uk . 18 июня 2020 года. Архивировано из оригинала 30 января 2021 года . Проверено 15 мая 2021 г.

- ^ ДеСильва-Ранасингхе, Сергей (2 марта 2011 г.). «Почему Индийский океан имеет значение» . Дипломат .

- ^ Бернхард Саймон: Может ли новый Шелковый путь конкурировать с морским Шелковым путем? в The Maritime Executive, 1 января 2020 г.

- ^ Маркус Херниг: Возрождение Шелкового пути (2018), стр. 112.

- ^ Вольф Д. Хартманн, Вольфганг Менниг, Ран Ван: Новый Шелковый путь Китая. (2017), стр. 59.

- ^ Маттео Брессан: Возможности и проблемы BRI в Европе в глобальном времени, 2 апреля 2019 г.

- ^ Brewster 2014a

- ^ Гарри Г. Бродман «Шелковый путь Африки» (2007), стр. 59.

- ↑ Андреас Эккерт: С Мао в Дар-эс-Салам, В: Die Zeit, 28 марта 2019 г., стр. 17.

- ^ Гвидо Сантевекки: Ди Майо и Шелковый путь: «Мы займемся математикой в 2020 году», соглашение, подписанное в Триесте в Corriere della Sera, 5 ноября 2019 г.

Источники

[ редактировать ]- Аллен, Ричард Б. (май 2017 г.). «Конец истории молчания: реконструкция европейской работорговли в Индийском океане» . Темп . 23 (2): 294–313. дои : 10.1590/tem-1980-542x2017v230206 .

- Альперс, Э.А. (2013). Индийский океан в мировой истории . Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 978-0-19-533787-7 .

- Арнсдорф, Исаак (22 июля 2013 г.). «Пираты Западной Африки угрожают нефти и судоходству» . Блумберг . Проверено 23 июля 2013 г.

- Божар, Филипп (декабрь 2005 г.). «Индийский океан в евразийских и африканских мир-системах до шестнадцатого века». Журнал всемирной истории . 16 (4): 411–465. дои : 10.1353/jwh.2006.0014 . S2CID 145387071 .

- Берд, П. (2003). «Обновленная цифровая модель границ плит». Геохимия, геофизика, геосистемы . 4 (3): 1027. Бибкод : 2003GGG.....4.1027B . дои : 10.1029/2001GC000252 . S2CID 9127133 .

- Бойвен, Николь; Кроутер, Элисон; Прендергаст, Мэри; Фуллер, Дориан К. (декабрь 2014 г.). «Глобализация продуктов питания в Индийском океане и Африка». Африканский археологический обзор . 31 (4): 547–581. дои : 10.1007/s10437-014-9173-4 . S2CID 59384628 .

- Боссайт, Фрэнки; Меэгаскумбура, Мадхава; Бенартс, Натали; Гауэр, Дэвид Дж.; Петиягода, Рохан; Ролантс, Ким; Маннарт, Ан; Уилкинсон, Марк; Бахир, Мохомед М.; Манамендра-Араччи, Клум; Нг, Питер К.Л.; Шнайдер, Кристофер Дж.; Ооммен, Ооммен В.; Милинкович, Мишель К. (15 октября 2004 г.). «Местный эндемизм в горячей точке биоразнообразия Западных Гат и Шри-Ланки». Наука . 306 (5695): 479–481. Бибкод : 2004Sci...306..479B . дои : 10.1126/science.1100167 . ПМИД 15486298 . S2CID 41762434 .

- Бушар, К.; Крамплин, В. (2010). «Больше не игнорируется: Индийский океан на переднем крае мировой геополитики и глобальной геостратегии». Журнал региона Индийского океана . 6 (1): 26–51. дои : 10.1080/19480881.2010.489668 . S2CID 154426445 .

- Брюстер, Дэвид (3 июля 2014 г.). «За пределами «Жемчужной нити»: действительно ли существует китайско-индийская дилемма безопасности в Индийском океане?». Журнал региона Индийского океана . 10 (2): 133–149. дои : 10.1080/19480881.2014.922350 . hdl : 1885/13060 . S2CID 153404767 .

- Брюстер, Д. (2014b). Индийский океан: история заявки Индии на региональное лидерство . Лондон: Рутледж. дои : 10.4324/9781315815244 . ISBN 978-1-315-81524-4 .

- Бульбек, Д. (2007). «Там, где река встречается с морем: экономная модель колонизации Homo sapiens побережья Индийского океана и Сахула». Современная антропология . 48 (2): 315–321. дои : 10.1086/512988 . S2CID 84420169 .

- Бурштейн, Стэнли М. (1996). «Исследование Красного моря слоновой костью и Птолемеями. Недостающий фактор». Топои . 6 (2): 799–807. дои : 10.3406/topoi.1996.1696 .

- Кабреро, Ферран (2004). «Культуры мира: проблема разнообразия» (PDF) (на каталанском языке). ЮНЕСКО. стр. 32–38 (Мальдивцы: легендарные моряки). Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 26 декабря 2016 года . Проверено 25 июля 2015 г.

- Кэмпбелл, Г. (2017). «Африка, мир Индийского океана и« раннее Новое время »: историографические конвенции и проблемы» . Журнал мировых исследований Индийского океана . 1 (1): 24–37. дои : 10.26443/jiows.v1i1.25 .

- Картон, Дж.А.; Чепурин Г.; Цао, X. (2000). «Простой анализ ассимиляции океанических данных верхних слоев океана в 1950–95 годах. Часть II: Результаты». Журнал физической океанографии . 30 (2): 311–326. Бибкод : 2000JPO....30..311C . doi : 10.1175/1520-0485(2000)030<0311:ASODAA>2.0.CO;2 .

- Казале, Г. (2003). Османское «Открытие» Индийского океана в шестнадцатом веке: эпоха исследований с исламской точки зрения . Морской пейзаж: морские истории, прибрежные культуры и трансокеанские обмены. Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: Библиотека Конгресса. стр. 87–104 . Проверено 21 апреля 2019 г.

- Профиль экосистемы: «Горячая точка» биоразнообразия Индо-Бирмы, обновление 2011 г. (PDF) (отчет). CEPF . 2012 . Проверено 1 сентября 2019 г.

- Чаттерджи, С.; Госвами, А.; Скотезе, ЧР (2013). «Самое длинное путешествие: тектоническая, магматическая и палеоклиматическая эволюция Индийской плиты во время ее полета на север из Гондваны в Азию». Исследования Гондваны . 23 (1): 238–267. Бибкод : 2013GondR..23..238C . дои : 10.1016/j.gr.2012.07.001 .

- Чен, Г.; Ежеквартально, ГД (2005). «Ежегодные амфидромы: обычная особенность океана?». Письма IEEE по геонаукам и дистанционному зондированию . 2 (4): 423–427. Бибкод : 2005IGRSL...2..423C . дои : 10.1109/LGRS.2005.854205 . S2CID 34522950 .

- «Океаны: Индийский океан» . ЦРУ – Всемирная книга фактов. 2015 . Проверено 25 июля 2015 г.

- Купелло, К.; Клеман, Г.; Менье, Ф.Дж.; Хербин, М.; Ябумото, Ю.; Брито, премьер-министр (2019). «Длительная адаптация целакантов к умеренной глубокой воде: обзор доказательств» (PDF) . Бюллетень Музея естественной истории и истории человечества Китакюсю, серия А (Естественная история) . 17 :29–35 . Проверено 5 июля 2019 г.

- Демопулос, AW; Смит, ЧР; Тайлер, Пенсильвания (2003). «Глубоководное дно Индийского океана – Экосистемы глубоких океанов» . В Тайлере, Пенсильвания (ред.). Экосистемы мира . Том. 28. Амстердам, Нидерланды: Эльзевир. стр. 219–237. ISBN 978-0-444-82619-0 . Проверено 11 мая 2019 г.

- Ди Минин, Э.; Хантер, ЛТБ; Бальм, Джорджия; Смит, Р.Дж.; Гудман, PS; Слотоу, Р. (2013). «Создание более крупных и лучше связанных между собой охраняемых территорий повышает устойчивость видов крупной дичи в горячей точке биоразнообразия Мапуталенд-Пондоленд-Олбани» . ПЛОС ОДИН . 8 (8): е71788. Бибкод : 2013PLoSO...871788D . дои : 10.1371/journal.pone.0071788 . ПМЦ 3743761 . ПМИД 23977144 .

- Дрейер, Э.Л. (2007). Чжэн Хэ: Китай и океаны в эпоху ранней династии Мин, 1405–1433 гг . Нью-Йорк: Пирсон Лонгман. ISBN 978-0-321-08443-9 . OCLC 64592164 .

- Датт, С.; Гупта, АК; Клеменс, Южная Каролина; Ченг, Х.; Сингх, РК; Катаят, Г.; Эдвардс, Р.Л. (2015). «Резкие изменения силы муссонов бабьего лета в период от 33 800 до 5 500 лет назад» . Письма о геофизических исследованиях . 42 (13): 5526–5532. Бибкод : 2015GeoRL..42.5526D . дои : 10.1002/2015GL064015 .

- Икинс, Б.В.; Шарман, Г.Ф. (2010). «Объемы Мирового океана по данным ETOPO1» . Боулдер, Колорадо: NOAA Национальный центр геофизических данных . Проверено 25 июля 2015 г.

- Эль-Аббади, М. (2000). «Величайший торговый центр обитаемого мира» . Справочники по управлению прибрежными зонами 2 . Париж: ЮНЕСКО. Архивировано из оригинала 31 января 2012 года.

- Юинг, М.; Эйттрейм, С.; Тручан, М.; Юинг, Дж.И. (1969). «Распространение отложений в Индийском океане». Глубоководные исследования и океанографические обзоры . 16 (3): 231–248. Бибкод : 1969DSRA...16..231E . дои : 10.1016/0011-7471(69)90016-3 .

- Фелбер Селигман, А. (2006). Послы, исследователи и союзники: исследование афро-европейских отношений, 1400–1600 гг. (PDF) (Диссертация). Пенсильванский университет . Проверено 21 июля 2019 г.

- Фелтон, CS (2014). Исследование атмосферных и океанических процессов в северной части Индийского океана (PDF) (Диссертация). Университет Южной Каролины . Проверено 23 июля 2019 г.

- Фитцпатрик, С.; Каллаган, Р. (2009). «Моделирование мореплавания и происхождение доисторических поселенцев на Мадагаскаре» (PDF) . В Кларке, Греция; О'Коннор, С.; Лич, Б.Ф. (ред.). Острова исследования: колонизация, мореплавание и археология морских ландшафтов . АНУ Э Пресс. стр. 47–58. ISBN 978-1-921313-90-5 . Проверено 25 июля 2015 г.

- Флетчер, Мэн (1958). «Суэцкий канал и мировое судоходство, 1869–1914». Журнал экономической истории . 18 (4): 556–573. дои : 10.1017/S0022050700107740 . S2CID 153427820 .

- «Промысел и использование тунца» . Продовольственная и сельскохозяйственная организация Объединенных Наций. 2016 . Проверено 29 января 2016 г.

- Форбс, Эндрю Д.В. (1981). «Южная Аравия и исламизация архипелагов центральной части Индийского океана». Архипел . 21 (1): 55–92. дои : 10.3406/arch.1981.1638 .

- Галил, Б.С.; Боэро, Ф.; Кэмпбелл, МЛ; Карлтон, Джей Ти; Кук, Э.; Фраскетти, С.; Голлаш, С.; Хьюитт, CL; Джельмерт, А.; Макферсон, Э.; Марчини, А.; Маккензи, К.; Минчин, Д.; Окчипинти-Амброджи, А.; Оджавир, Х.; Оленин С.; Пираино, С.; Руис, генеральный менеджер (2015). « Двойная беда»: расширение Суэцкого канала и морские биоинвазии в Средиземное море». Биологические инвазии . 17 (4): 973–976. Бибкод : 2015BiInv..17..973G . дои : 10.1007/s10530-014-0778-y . S2CID 10633560 .

- Гусяков Вячеслав; Эбботт, Даллас Х.; Брайант, Эдвард А.; Масс, В. Брюс; Брегер, Ди (2009). «Мегацунами Мирового океана: образование дюн Шеврон, микровыбросы и быстрое изменение климата как свидетельство недавних ударов океанических болидов». Геофизические опасности . стр. 197–227. дои : 10.1007/978-90-481-3236-2_13 . ISBN 978-90-481-3235-5 .

- Хан, Вэйцин; Мил, Джеральд А.; Раджагопалан, Баладжи; Фасулло, Джон Т.; Ху, Эксюэ; Линь, Цзялин; Лардж, Уильям Г.; Ван, Цзи-ван; Цюань, Сяо-Вэй; Тренари, Лори Л.; Уоллкрафт, Алан; Шинода, Тошиаки; Йегер, Стивен (август 2010 г.). «Схемы изменения уровня моря в Индийском океане в условиях потепления климата». Природа Геонауки . 3 (8): 546–550. Бибкод : 2010NatGe...3..546H . дои : 10.1038/NGEO901 .

- Харрис, ПТ; Макмиллан-Лоулер, М.; Рупп, Дж.; Бейкер, ЕК (июнь 2014 г.). «Геоморфология океанов». Морская геология . 352 : 4–24. Бибкод : 2014МГеол.352....4Н . дои : 10.1016/j.margeo.2014.01.011 .

- Хофмейр, Изабель (декабрь 2012 г.). «Сложное море: Индийский океан как метод». Сравнительные исследования Южной Азии, Африки и Ближнего Востока . 32 (3): 584–590. дои : 10.1215/1089201X-1891579 . S2CID 145735928 .

- Хуэй, Швейцария (2010). «Путешествие Хуанмина Цзусюня и Чжэн Хэ в Западные океаны». Журнал китайских исследований . 51 : 67–85. hdl : 10722/138150 .

- «Границы океанов и морей» . Природа . 172 (4376). Международная гидрографическая организация : 484. 1953. Бибкод : 1953Natur.172R.484. . дои : 10.1038/172484b0 . S2CID 36029611 .

- «Индийский океан и его подразделения» . Международная гидрографическая организация, Специальная публикация № 23. 2002. Архивировано из оригинала 25 июля 2015 года . Проверено 25 июля 2015 г.

- Катиресан, К.; Раджендран, Н. (2005). «Мангровые экосистемы региона Индийского океана» (PDF) . Индийский журнал морских наук . 34 (1): 104–113 . Проверено 25 мая 2019 г.

- Кизинг, Дж.; Ирвин, Т. (2005). «Прибрежное биоразнообразие Индийского океана: известное, неизвестное» (PDF) . Индийский журнал морских наук . 34 (1): 11–26 . Проверено 25 мая 2019 г.

- ЛаВиолетт, Адриа (апрель 2008 г.). «Суахилиский космополитизм в Африке и мире Индийского океана, 600–1500 гг. Н.э.». Археологии . 4 (1): 24–49. дои : 10.1007/s11759-008-9064-x . S2CID 128591857 .

- Маклауд, Калум; Зима, Майкл; Грей, Эллисон (8 марта 2014 г.). «Рейс, направлявшийся в Пекин из Малайзии, пропал» . США сегодня . Проверено 31 декабря 2018 г.