Лига Плюща

| |

| Ассоциация | NCAA |

|---|---|

| Основан | 1954 |

| комиссар | Робин Харрис [1] (с 2009 г.) |

| Спортивные поля |

|

| Разделение | Дивизион I |

| Подразделение | ФТС |

| Кол-во команд | 8 |

| Штаб-квартира | Принстон, Нью-Джерси , США |

| Область | Северо-восток |

| Official website | ivyleague |

| Locations | |

Location of the eight Ivy League universities | |

Лига плюща — это американская студенческая спортивная конференция восьми частных исследовательских университетов на северо-востоке США . Он участвует в Национальной студенческой спортивной ассоциации (NCAA) I дивизионе , а в футболе - в подразделении чемпионата по футболу (FCS). Термин «Лига плюща» используется в более широком смысле для обозначения восьми школ, входящих в лигу, которые всемирно известны как элитные колледжи, отличающиеся академическими успехами , очень избирательным приемом и социальной элитарностью . [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] Этот термин использовался еще в 1933 году, а официальным он стал в 1954 году после образования спортивной конференции Лиги плюща. [7]

Восемь членов Лиги Плюща — это Университет Брауна , Колумбийский университет , Корнеллский университет , Дартмутский колледж , Гарвардский университет , Пенсильванский университет , Принстонский университет и Йельский университет . Штаб-квартира конференции находится в Принстоне, штат Нью-Джерси . Все «Плющи», за исключением Корнелла, были основаны в колониальный период и, следовательно, составляют семь из девяти колониальных колледжей . Два других колониальных колледжа, Куинс-колледж (ныне Рутгерский университет ) и Колледж Уильяма и Мэри , стали государственными учреждениями.

Overview[edit]

Ivy League schools are some of the most prestigious universities in the world.[8] All eight universities place in the top 18 of the 2024 U.S. News & World Report National Universities ranking.[9] U.S. News has named a member of the Ivy League as the best national university[a] every year since 2001: as of 2020[update], Princeton eleven times, Harvard twice, and the two schools tied for first five times.[10] In the 2022–2023 U.S. News & World Report Best Global University Ranking, five Ivies rank in the top 20: Harvard (#1), Columbia (#7), Yale (#11), Penn (#15), and Princeton (#16)—ranks that U.S. News says are based on "indicators that measure their academic research performance and their global and regional reputations."[11] All eight Ivy League schools are members of the Association of American Universities, the most prestigious alliance of American research universities.[12]

Undergraduate enrollments range from about 4,500 to about 15,000,[13] larger than most liberal arts colleges and smaller than most state university systems. Total enrollment, which includes graduate students, ranges from approximately 6,600 at Dartmouth to over 20,000 at Columbia, Cornell, Harvard, and Penn. Ivy League financial endowments range from Brown's $6.9 billion[14] to Harvard's $53.2 billion,[15] the largest financial endowment of any academic institution in the world.[16]

The Ivy League is similar to other groups of universities in other countries, such as Oxbridge[17] in England, the C9 League[18] in China, and the Imperial Universities[19] in Japan.

Members[edit]

Ivy League universities have some of the largest university financial endowments in the world, allowing the universities to provide abundant resources for their academic programs, financial aid, and research endeavors. As of 2021, Harvard University had an endowment of $53.2 billion, the largest of any educational institution.[15] Each university attracts millions of dollars in annual research funding from both the federal government and private sources.

Current schools[edit]

| Institution | Location | Undergraduates | Postgraduates | Endowment[20] | Academic staff | Year founded | Team name | Colors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown University | Providence, Rhode Island | 7,349 | 3,347 | $6.20 billion | 736[21] | 1764 | Bears | |

| Columbia University | New York, New York | 8,148[b] | 21,987 | $13.64 billion | 4,370[24] | 1754 | Lions | |

| Cornell University | Ithaca, New York | 15,503 | 10,097 | $10.04 billion | 2,908 | 1865 | Big Red | |

| Dartmouth College | Hanover, New Hampshire | 4,556 | 2,205 | $7.93 billion | 943 | 1769 | Big Green | |

| Harvard University | Cambridge, Massachusetts[c] | 7,153 | 14,495 | $49.50 billion | 4,671[25] | 1636 | Crimson | |

| University of Pennsylvania | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | 9,962 | 13,469 | $20.96 billion | 4,464[26] | 1740 | Quakers | |

| Princeton University | Princeton, New Jersey | 5,321 | 3,157 | $34.06 billion | 1,172 | 1746 | Tigers | |

| Yale University | New Haven, Connecticut | 6,536 | 8,031 | $40.75 billion | 4,140 | 1701 | Bulldogs |

Former affiliate members[edit]

Before the 2000s, many of the Ivy League championships for men's and women's cross country, indoor and outdoor track & field, and swimming & diving were formatted as invitationals that many schools across the eastern United States would attend. In other sports such as fencing, wrestling, men's and women's ice hockey, and men's and women's rowing, all of the Ivy League schools were members of other single-sport conferences and the top performing Ivy League team would be crowned the champion.

The United States Military Academy and the United States Naval Academy were members of the Ivy League in many sports and were crowned as Ivy League champions while competing with Ivy League teams. Both schools ended up departing from the conference in the early 2000s to align with their current conference, the Patriot League.

History[edit]

Year founded[edit]

| Institution | Founded as | Founded | Chartered | First instruction | Founding affiliation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harvard University | New College | 1636 | 1650 | 1642 | Nonsectarian, founded by Calvinist Congregationalists |

| Yale University | Collegiate School | 1701 | 1701[27] | 1702 | Calvinist (Congregationalist) |

| Princeton University | College of New Jersey | 1746 | 1746[28] | 1747 | Nonsectarian,[29] founded by Calvinist Presbyterians[29] |

| Columbia University | King's College | 1754 | 1754[30] | 1754 | Church of England |

| University of Pennsylvania | College of Philadelphia[31] | 1740 or 1749 or 1755[d] | 1755 | 1755 | Nonsectarian,[36] founded by Church of England/Methodist members[37][38] |

| Brown University | College in the English Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations | 1764 | 1764 | 1765[39] | Baptist, founding charter promises "no religious tests" and "full liberty of conscience"[40] |

| Dartmouth College | 1769 | 1769[41] | 1769 | Calvinist (Congregationalist) | |

| Cornell University | 1865 | 1865 | 1868[42] | Nonsectarian |

- Note: Six of the eight Ivy League universities consider their founding dates to be simply the date that they received their charters and thus became legal corporations with the authority to grant academic degrees. Harvard University uses the date that the legislature of the Massachusetts Bay Colony formally allocated funds for the creation of a college. Harvard was chartered in 1650, although classes had been conducted for approximately a decade by then. The University of Pennsylvania initially considered its founding date to be 1750; this is the year which appears on the first iteration of the university seal.[43] Later in Penn's early history, the university changed its officially recognized founding date to 1749, which was used for all of the nineteenth century, including a centennial celebration in 1849. In 1899, Penn's board of trustees formally adopted a third founding date of 1740, in response to a petition from Penn's General Alumni Society. Penn was chartered in 1755, the same year collegiate classes began. "Religious affiliation" refers to financial sponsorship, formal association with, and promotion by, a religious denomination. All of the schools in the Ivy League are private and not currently associated with any religion.

Origin of the name[edit]

"Planting the ivy" was a customary class day ceremony at many colleges in the 1800s. In 1893, an alumnus told The Harvard Crimson, "In 1850, class day was placed upon the University Calendar ... the custom of planting the ivy, while the ivy oration was delivered, arose about this time."[44] At Penn, graduating seniors started the custom of planting ivy at a university building each spring in 1873 and that practice was formally designated as "Ivy Day" in 1874.[45] Ivy planting ceremonies are recorded at Yale, Simmons College, and Bryn Mawr College among other schools.[46][47][48] Princeton's "Ivy Club" was founded in 1879.[49]

The first usage of Ivy in reference to a group of colleges is from sportswriter Stanley Woodward (1895–1965).

A proportion of our eastern ivy colleges are meeting little fellows another Saturday before plunging into the strife and the turmoil.

— Stanley Woodward, New-York Tribune, October 14, 1933, describing the football season[50]

The first known instance of the term Ivy League appeared in The Christian Science Monitor on February 7, 1935.[7][51][52] Several sportswriters and other journalists used the term shortly later to refer to the older colleges, those along the northeastern seaboard of the United States, chiefly the nine institutions with origins dating from the colonial era, together with the United States Military Academy (West Point), the United States Naval Academy, and a few others. These schools were known for their long-standing traditions in intercollegiate athletics, often being the first schools to participate in such activities. At this time, however, none of these institutions made efforts to form an athletic league.

A common folk etymology attributes the name to the Roman numeral for four (IV), asserting that there was such a sports league originally with four members. The Morris Dictionary of Word and Phrase Origins helped to perpetuate this belief. The supposed "IV League" was formed over a century ago and consisted of Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and a fourth school that varies depending on who is telling the story.[53][54][55] However, it is clear that Harvard, Princeton, Columbia, and Yale met on November 23, 1876, at the so-called Massasoit Convention to decide on uniform rules for the emerging game of American football, which rapidly spread.[56]

Pre-Ivy League[edit]

Seven out of the eight Ivy League schools are Colonial Colleges: institutions of higher education founded prior to the American Revolution. Cornell, the exception to this commonality, was founded immediately after the American Civil War. These seven colleges served as the primary institutions of higher learning in British America's Northern and Middle Colonies. During the colonial era, the schools' faculties and founding boards were largely drawn from other Ivy League institutions. Also represented were British graduates from the University of Cambridge, the University of Oxford, the University of St. Andrews, and the University of Edinburgh.

The influence of these institutions on the founding of other colleges and universities is notable. This included the Southern public college movement which blossomed in the decades surrounding the turn of the 19th century when Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina and Virginia established what became the flagship universities of their respective states. In 1801, a majority of the first board of trustees for what became the University of South Carolina were Princeton alumni. They appointed Jonathan Maxcy, a Brown graduate, as the university's first president. Thomas Cooper, an Oxford alumnus and University of Pennsylvania faculty member, became the second president of the South Carolina college. The founders of the University of California came from Yale, hence Berkeley's colors are Yale Blue and California Gold.[57] Stanford University has, since its earliest days, been nicknamed the "Cornell of the West": more than half of Stanford's initial faculty, as well as its first two presidents, had connections to Cornell as alumni or faculty.[58]

A plurality of the Ivy League schools have identifiable Protestant roots. Harvard, Yale, and Dartmouth all held early associations with the Congregationalists. Princeton was financed by New Light Presbyterians, though originally led by a Congregationalist. Brown was founded by Baptists, though the university's charter stipulated that students should enjoy "full liberty of conscience." Columbia was founded by Anglicans, who composed 10 of the college's first 15 presidents. Penn and Cornell were officially nonsectarian, though Protestants were well represented in their respective founding. In the early nineteenth century, the specific purpose of training Calvinist ministers was handed off to theological seminaries, but a denominational tone and religious traditions including compulsory chapel often lasted well into the twentieth century.

"Ivy League" is sometimes used as a way of referring to an elite class, even though institutions such as Cornell University were among the first in the United States to reject racial and gender discrimination in their admissions policies. This dates back to at least 1935.[59] Novels and memoirs attest this sense, as a social elite; to some degree independent of the actual schools.[60][61]

History of the athletic league[edit]

19th century[edit]

In 1870, the nation's first formal athletic league was created in 1870 with the formation of the Rowing Association of American Colleges (RAAC), composed exclusively of Ivy League universities. RAAC hosted a national championship in rowing from 1870 to 1894.

The first Harvard vs Yale rugby football contest was held in 1875, two years after the inaugural Princeton–Yale rugby football contest. Harvard athlete Nathaniel Curtis challenged Yale's captain, William Arnold to a rugby-style game.[62][63]Program for the "Foot Ball Match", Harvard v Yale, the first intercollegiate game. It is considered the first rugby game between Ivy League teams. The game was played at Hamilton Park, a venue in New Haven, Connecticut (located at the intersection of Whalley Avenue and West Park Avenue[64]). The two teams played with 15 players (rugby) on a side instead of 11 (soccer) as Yale would have preferred.

In 1881, Penn, Harvard College, Haverford College, Princeton University (then known as College of New Jersey), and Columbia University (then known as Columbia College) formed The Intercollegiate Cricket Association,[65] which Cornell University later joined.[66] Penn won The Intercollegiate Cricket Association championship 23 times, including 18 solo victories and three shared with Haverford and Harvard, one shared with Haverford and Cornell, and one shared with just Haverford, during the 44 years that the Intercollegiate Cricket Association existed from 1881 through 1924.[67]

In 1895, Cornell, Columbia, and Penn founded the Intercollegiate Rowing Association, which remains the oldest collegiate athletic organizing body in the US. To this day, the IRA Championship Regatta determines the national champion in rowing and all of the Ivies are regularly invited to compete.

A basketball league was later created in 1902, when Columbia, Cornell, Harvard, Yale, and Princeton formed the Eastern Intercollegiate Basketball League; they were later joined by Penn and Dartmouth.

20th century[edit]

In 1906, the organization that eventually became the National Collegiate Athletic Association was formed, primarily to formalize rules for the emerging sport of football. But of the 39 original member colleges in the NCAA, only two of them (Dartmouth and Penn) later became Ivies. In February 1903, intercollegiate wrestling began when Yale accepted a challenge from Columbia, published in the Yale News. The dual meet took place prior to a basketball game hosted by Columbia and resulted in a tie.

Two years later, Penn and Princeton also added wrestling teams, leading to the formation of the student-run Intercollegiate Wrestling Association, now the Eastern Intercollegiate Wrestling Association (EIWA), the first and oldest collegiate wrestling league in the US.[68]

Though schools now in Ivy League (such as Yale and Columbia) played against each other in the 1880s, it was not until 1930 that Columbia, Cornell, Dartmouth, Penn, Princeton and Yale formed the Eastern Intercollegiate Baseball League; they were later joined by Harvard, Brown, Army and Navy. Before the formal establishment of the Ivy League, there was an "unwritten and unspoken agreement among certain Eastern colleges on athletic relations". The earliest reference to the "Ivy colleges" came in 1933, when Stanley Woodward of the New York Herald Tribune used it to refer to the eight current members plus Army.[7] In 1935, the Associated Press reported on an example of collaboration between the schools:

The athletic authorities of the so-called "Ivy League" are considering drastic measures to curb the increasing tendency toward riotous attacks on goal posts and other encroachments by spectators on playing fields.

— The Associated Press, The New York Times[69]

Despite such collaboration, the universities did not seem to consider the formation of the league as imminent. Romeyn Berry, Cornell's manager of athletics, reported the situation in January 1936 as follows:

I can say with certainty that in the last five years—and markedly in the last three months—there has been a strong drift among the eight or ten universities of the East which see a good deal of one another in sport toward a closer bond of confidence and cooperation and toward the formation of a common front against the threat of a breakdown in the ideals of amateur sport in the interests of supposed expediency.Please do not regard that statement as implying the organization of an Eastern conference or even a poetic "Ivy League". That sort of thing does not seem to be in the cards at the moment.[70]

Within a year of this statement and having held month-long discussions about the proposal, on December 3, 1936, the idea of "the formation of an Ivy League" gained enough traction among the undergraduate bodies of the universities that the Columbia Daily Spectator, The Cornell Daily Sun, The Dartmouth, The Harvard Crimson, The Daily Pennsylvanian, The Daily Princetonian and the Yale Daily News would simultaneously run an editorial entitled "Now Is the Time", encouraging the seven universities to form the league in an effort to preserve the ideals of athletics.[71] Part of the editorial read as follows:

The Ivy League exists already in the minds of a good many of those connected with football, and we fail to see why the seven schools concerned should be satisfied to let it exist as a purely nebulous entity where there are so many practical benefits which would be possible under definite organized association. The seven colleges involved fall naturally together by reason of their common interests and similar general standards and by dint of their established national reputation they are in a particularly advantageous position to assume leadership for the preservation of the ideals of intercollegiate athletics.[72]

The Ivies have been competing in sports as long as intercollegiate sports have existed in the United States. Rowing teams from Harvard and Yale met in the first sporting event held between students of two U.S. colleges on Lake Winnipesaukee, New Hampshire, on August 3, 1852. Harvard's team, "The Oneida", won the race and was presented with trophy black walnut oars from then-presidential nominee General Franklin Pierce. The proposal to create an athletic league did not succeed. On January 11, 1937, the athletic authorities at the schools rejected the "possibility of a heptagonal league in football such as these institutions maintain in basketball, baseball and track." However, they noted that the league "has such promising possibilities that it may not be dismissed and must be the subject of further consideration."[73]

Integration of athletic competition in the Ivy League[edit]

The integration of athletics followed a similar pattern to the overall integration of the Ivy League's in the 19th and early 20th century. There was no active policy that would discriminate against incorporating Black student athletes into the athletic coalition. Harvard has the earliest record of breaking the color barrier in athletics after recruiting William Henry Lewis to their football team in 1892.[75] Dartmouth followed suit, with Black athletes integrating onto their football teams in 1904.[76] Brown integrated their football team shortly after, in 1916.[77] Cornell would follow suit in 1937.

Penn had black students on their track and field team as early as 1903 (John Baxter Taylor, Jr., the first black athlete in the U.S. to win a gold medal in the Olympics) and a black student was named captain of the track team in 1918.[79] Columbia's track and field team would be integrated in 1934.[80] Basketball would become integrated at Yale in 1926,[81] at Princeton in 1947.[82]

Post-World War II[edit]

In 1945 the presidents of the eight schools signed the first Ivy Group Agreement, which set academic, financial, and athletic standards for the football teams.[83] The principles established reiterated those put forward in the Harvard-Yale-Princeton presidents' Agreement of 1916. The Ivy Group Agreement established the core tenet that an applicant's ability to play on a team would not influence admissions decisions:

The members of the Group reaffirm their prohibition of athletic scholarships. Athletes shall be admitted as students and awarded financial aid only on the basis of the same academic standards and economic need as are applied to all other students.[84]

In 1954, the presidents extended the Ivy Group Agreement to all intercollegiate sports, effective with the 1955–56 basketball season. This is generally reckoned as the formal formation of the Ivy League. As part of the transition, Brown, the only Ivy that had not joined the EIBL, did so for the 1954–55 season. A year later, the Ivy League absorbed the EIBL. The Ivy League claims the EIBL's history as its own. Through the EIBL, it is the oldest basketball conference in Division I.[85][86]

As late as the 1960s many of the Ivy League universities' undergraduate programs remained open only to men, with Cornell the only one to have been coeducational from its founding (1865) and Columbia being the last (1983) to become coeducational. Before they became coeducational, many of the Ivy schools maintained extensive social ties with nearby Seven Sisters women's colleges, including weekend visits, dances and parties inviting Ivy and Seven Sisters students to mingle. This was the case not only at Barnard College and Radcliffe College, which are adjacent to Columbia and Harvard, but at more distant institutions as well. The movie Animal House includes a satiric version of the formerly common visits by Dartmouth men to Massachusetts to meet Smith and Mount Holyoke women, a drive of more than two hours. As noted by Irene Harwarth, Mindi Maline, and Elizabeth DeBra, "The 'Seven Sisters' was the name given to Barnard, Smith, Mount Holyoke, Vassar, Bryn Mawr, Wellesley, and Radcliffe, because of their parallel to the Ivy League men's colleges."[87]

In 1982 the Ivy League considered adding two members, with Army, Navy, and Northwestern as the most likely candidates; if it had done so, the league could probably have avoided being moved into the recently created Division I-AA (now Division I FCS) for football.[88] In 1983, following the admission of women to Columbia College, Columbia University and Barnard College entered into an athletic consortium agreement by which students from both schools compete together on Columbia University women's athletic teams, which replaced the women's teams previously sponsored by Barnard.

When Army and Navy departed the Eastern Intercollegiate Baseball League in 1992, nearly all intercollegiate competition involving the eight schools became united under the Ivy League banner. The two major exceptions are wrestling, with the Ivies that sponsor wrestling—all except Dartmouth and Yale—members of the EIWA and hockey, with the Ivies that sponsor hockey—all except Penn and Columbia—members of ECAC Hockey.

The Ivy League was the first athletic conference to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic by shutting down all athletic competition in March 2020, leaving many Spring schedules unfinished.[89] The Fall 2020 schedule was canceled in July, and winter sports were canceled before Thanksgiving.[89] Of the 357 men's basketball teams in Division I, only ten did not play; the Ivy League made up eight of those ten.[89] By giving up its automatic qualifying bid to March Madness, the Ivy League forfeited at least $280,000 in NCAA basketball funds.[89] As a consequence of the pandemic, an unprecedented number of student athletes in the Ivy League either transferred to other schools, or temporarily unenrolled in hopes of maintaining their eligibility to play post-pandemic.[89] Some Ivy alumni expressed displeasure with the League's position.[89] In February 2021 it was reported that Yale declined a multi-million dollar offer from alum Joseph Tsai to create a sequestered "bubble" for the lacrosse team.[89] The league announced in a May 2021 joint statement that "regular athletic competition" would resume "across all sports" in fall 2021.[90]

Following the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, the Ivy League Conference committed itself to uphold "diversity, equity, and inclusion," to combat racism and homophobia. At Brown, Columbia, Cornell, Dartmouth, Harvard, and Princeton there are Black Student Athlete groups and other affinity groups that are dedicated to ensuring their organizations are committed to anti-racism and anti-homophobia.[91] In 2023, two former Brown University basketball players sued the Ivy League alleging that by denying athletic scholarships, the 1954 "Ivy League Agreement" is anticompetititive and violates antitrust laws.[92][93] The lawsuit claims that the agreement constitutes price-fixing in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, and in effect raises the cost of Ivy League education for student athletes.[92][93]

Academics[edit]

Admissions[edit]

| Applicants | Admission rates | |

|---|---|---|

| Brown | 46,568 | 5.4%[94] |

| Columbia | 60,551 | 3.7%[94] |

| Cornell | 67,380 | 8.7%[95] |

| Dartmouth | 28,357 | 6.2%[94] |

| Harvard | 57,435 | 3.4%[94] |

| Penn | 56,333 | 5.7%[94] |

| Princeton | 37,601 | 4.0%[94] |

| Yale | 46,905 | 4.6%[94] |

The Ivy League schools are highly selective, with all schools reporting acceptance rates at or below approximately 10% at all of the universities. For the class of 2025, six of the eight schools reported acceptance rates below 6%.[96][97][98][99][100][101] Admitted students come from around the world, although those from the Northeastern United States make up a significant proportion of students.[102][103][104]

In 2021, all eight Ivy League schools recorded record high numbers of applications and record low acceptance rates.[96][105][97][98][99][106] Year over year increases in the number of applicants ranged from a 14.5% increase at Princeton to a 51% increase at Columbia.[100][101]

There have been arguments that Ivy League schools discriminate against Asian-American candidates. For example, in August 2020, the US Justice Department argued that Yale University discriminated against Asian-American candidates on the basis of their race, a charge the university denied.[107] Harvard was subject to a similar challenge in 2019 from an Asian American student group, with regard to which a federal judge found Harvard to be in compliance with constitutional requirements. The student group has since appealed that decision, and the appeal is still pending as of August 2020.[107]

Prestige[edit]

Members of the League have been highly ranked by various university rankings. All of the Ivy League schools are consistently ranked within the top 20 national universities by the U.S. News & World Report Best Colleges Ranking.[9]

|

|

Collaboration[edit]

Collaboration between the member schools is illustrated by the student-led Ivy Council that meets in the fall and spring of each year, with representatives from every Ivy League school. The governing body of the Ivy League is the Council of Ivy Group presidents, composed of each university president. During meetings, the presidents discuss common procedures and initiatives for their universities.

The universities collaborate academically through the IvyPlus Exchange Scholar Program, which allows students to cross-register at one of the Ivies or another eligible school such as Berkeley, Chicago, MIT, and Stanford.[110][111]

History of diversity[edit]

Racial segregation and integration[edit]

Ivy League institutions have a complex history of racial segregation, and, eventually, integration. All of the universities in the Ivy League besides Cornell University were chartered during the American era of slavery.[112] In 2003, Brown University was the first of the Ivies to take accountability for their historic ties to slavery and the transatlantic slave trade.[113][114] Following Brown, other Ivy League universities formed committees to examine their ties to slavery, and found various institutional relationships to slavery. Yale University, for example, used profits from slave traders and owners to fund its first scholarships, libraries, and faculty positions.[115][116] To date, some of Yale's residential colleges are named after slave traders and supporters.[117] The investigations at Harvard, Princeton, Columbia, and the University of Pennsylvania all found that, in the century following their charters, enslaved Black people lived on campus to care for students, professors, or the universities' presidents.[118][119][120][121] Notably, Princeton's first nine presidents were slave owners, and in 1766, a slave auction reportedly took place on Princeton's campus.[119]

A small number of Black people did attend Ivy League institutions as students during their early years. These early students, however, were not always granted degrees. For example, some Black students were recorded studying privately with the Princeton University president as early as 1774, but no Black students received Princeton degrees until the middle of the twentieth century.[122] Jonathan and Philip Gayienquitioga, two brothers of the Mohawk People,[123] were the first people of color to enroll at Penn in 1755 after being recruited by Benjamin Franklin to attend the Academy of Philadelphia (then part of Penn),[124] but there is no evidence that either earned a degree[124] as the first native American to graduate Penn did not occur until 1847, when Robert Daniel Ross (a member of the Cherokee Nation) graduated with a degree from Penn's medical school.[124]

19th and early 20th centuries[edit]

In 1900, W. E. B. Du Bois oversaw and edited The College-bred Negro.[125] a study on Black integration in colleges and universities that found a combined total of 52 Black students had graduated from Ivy League schools in their collective histories. Since no official policies prohibited schools in the Ivy League from admitting students of color[112] each university in the League had different policies regarding the admission of Black students. Dartmouth's first Black student graduated in 1828, while Princeton would only admit their first Black student under the V-12 Navy College Training Program in the 1940s.[112][126]

Early Black student admits to Ivy League universities were controversial and often faced backlash. Dartmouth initially denied its first Black graduate, Edward Mitchell, supposedly to avoid "offend[ing] students". Dartmouth students protested this decision, leading to Mitchell's admission in 1824.[126] Richard Henry Green was awarded an MD degree by Dartmouth College in 1864.[127]

Harvard admitted its first Black student, Beverly Garnett Williams, in 1847. News of his admission incited protests by Harvard students and faculty.[128] Williams died before the academic year began, however, and never matriculated.[129] Richard Theodore Greener was the first African American to receive a Harvard degree in 1870.[130] Between 1890 and 1940, an average of three Black men enrolled at Harvard per year.[122] In 1923, Harvard's Board of Overseers overruled University President Abbot Lawrence's ban on Black students living in dorms, announcing that all freshmen would be permitted to live in dorms regardless of race, but upheld that “men of the white and colored races shall not be compelled to live and eat together."[131] Brown seems to have refused admission to Black students outright prior to the Civil War. Abolitionist Elizabeth Buffum Chase wrote in her book Anti Slavery Reminiscences about "a lad of rare excellence and attainments [who] was refused an examination for admission by the authorities of Brown University on account of the color of his skin." Inman Page was the first Black student to graduate from Brown in 1877, and was class speaker.[132]

William Adger, James Brister, and Nathan Francis Mossell were the first Black students enrolled at Penn in 1879.[133] Brister graduated from the School of Dental Medicine (Penn Dental) in 1881 as the first African American to earn a degree from Penn, while Adger was the first African American to graduate from the college in 1883.[134]

Columbia University has claimed that four Black students earned University degrees between 1875 and 1900,[129] though their names are apparently unknown.

Yale's Edward Bouchet, was the first Black person (a) elected to Phi Beta Kappa in the US in 1874 and (b) to earn a Ph.D. from any American university, completing his dissertation in physics in 1876.[135][136] Bouchet was thought to have been the first African-American graduate of Yale, but research publicized in 2014 reported that Yale awarded a Black man, Richard Henry Green, a bachelor of arts degree in 1857.[127][137]

Cornell seemed the most inclusive of the Ivy Leagues at its inception, with admission open to any race and gender.[138] University co-founder Andrew Dickson White wrote in 1874 that the school had "no colored students...at present but shall be very glad to receive any who are prepared to enter...if even one offered himself and passed the examinations, we should receive him even if all our five hundred white students were to ask for dismissal on that account."[139] In 1890, Charles Chauveau Cook and Jane Eleanor Datcher were the first Black students awarded four-year undergraduate Cornell degrees.[140] Despite this, Black students faced legal and social segregation in the town of Ithaca, New York. In 1905, Black students reported being denied housing while attending Cornell.[112]

Princeton University, sometimes referred to as the "Southern-most Ivy", was the last to integrate. In Du Bois' The College-bred Negro (1900), a Princeton representative is quoted: "We have never had any colored students here, though there is nothing in the University statutes to prevent their admission. It is possible, however, in view of our proximity to the South and the large number of southern students here, that Negro students would find Princeton less comfortable than some other institutions."[141] Notably, in 1939, Princeton revoked admittance to Black student Bruce Wright upon his arrival on campus, when Director of Admission Radcliffe Heermance noticed Wright's race.[142] When a disappointed Wright wrote Heermance requesting an explanation, Heermance responded:

"I cannot conscientiously advise a colored student to apply for admission to Princeton simply because I do not think that he would be happy in this environment. There are no colored students in the University and a member of your race might feel very much alone...My personal experience would enforce my advice to any colored student that he would be happier in an environment of others of his race, and that he would adjust himself far more easily to the life of a New England college or university, or one of the large state universities than he would to a residential college of this particular type."[143]

The few early Black students admitted to Ivy League universities were often from wealthy Caribbean families.[112] Barriers preventing African American students from attending Ivy League universities included the universities' policies, poor recruitment, tuition costs, and the lack of secondary education opportunities in a racially segregated country.[112][144] More Black students attended Ivy League graduate and professional schools than their undergraduate programs.[112] By the middle of the 20th century, only 54 Black men and women had graduated with a Bachelor degree from Ivy League universities.[112]

Late 20th century[edit]

By the middle of the 20th century, some Ivy League students and alumni were advocating for increased racial integration efforts.[145][146][147][148] These efforts were met with mixed reactions from the schools themselves.[149] Without a goal for integration shared by the institutions as a collective, each school increased racial diversity at different rates, with Dartmouth having 120 Black undergraduates in the class of 1945 and Princeton having a cumulative total of fewer than 100 Black undergraduates by 1967.[112]

The V-12 Navy College Training Program in 1942 effectively forced all eight Ivy institutions to increase Black student enrollment.[112] At Princeton University, the Black students in this program were the first ever granted bachelor's degrees by the University.[150]

The 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education did not require private universities like those in the Ivy League to abide by the ruling.[151] It wasn't until the Court's 1976 decision in Runyon v. McCrary that private institutions became legally prohibited from discriminating on the basis of race.[152] By the early 1960s, however, some admissions offices in the Ivy League began to make concerted efforts to increase their number of Black applicants, rolling out initiatives that actively sought Black talent from high schools.[153] Efforts for racial integration at Ivy League institutions relied on the support of student organizations, faculty-led initiatives, and third-party organizations like the National Scholarship Service and Fund for Negro Students[146] to seek prospective Black applicants.[153] These efforts also prompted internal University action, such as the creation of Cornell's Committee on Special Educational Projects (COSEP), an organization aimed to recruit and support Black students.[154] By 1965, however, Black students still were only 2% of admitted students across all the Ivies.[112]

Prior to the 1960s, the majority of Ivy League universities explicitly prohibited the admission of women, instead forming partnerships with nearby women's colleges.[155] As such, Black women were not able to attend Ivy League universities until they changed their policies. Lillian Lincoln Lambert was the first Black woman to receive a degree from Harvard University after graduating with a master's degree from Harvard Business School in 1969.[155] Lincoln Lambert was also a founding member of Harvard's African American Student Union, which according to her, actively recruited Black students and created "a space where Black students could find not only support but resources for everything from barber shops that cut Black hair to churches."[156]

As Black student populations grew at Ivy League schools, on-campus activism saw an increase during the civil rights movement. In 1969, students in Cornell's Afro-American Society led an armed occupation of Willard Straight Hall to protest the university's racist policies and “its slow progress in establishing a Black studies program.”[157][112] In the same year, students associated with Yale's New Left organization, Students for a Democratic Society, worked closely with the New Haven Black Panthers to lead sit-ins and protests that advocated for the admission of more students of color and the establishment of an African American studies department.[158][112] At Brown University, identity-based student organizations such as the United African People and the African American Society called for an increase to the number of Black faculty and increased attention to the needs of Black students.[113] Demonstrations at Harvard and Columbia took the form of occupations and non-violent sit-ins that were often subject to forceful removal by local police called by University administrators.[159][112] Activism at Dartmouth took a different shape during this time period, as students would use demonstrations that were happening at other Ivies and colleges around the country, to effectively position their demands for progress within the prospect of taking actions similar to those happening elsewhere.

21st century[edit]

Continuing the trajectory of the late 20th century, the number of Black students on Ivy League campuses has continued to increase in the 21st century. From 2006 to 2018, there was an approximated 50% increase in the admission of Black students into entering classes, growing from 1,110 to 1,663.[160] As of 2018, the Ivy League universities unanimously supported Harvard University's “race-conscious admissions” model.[161] Harvard University representatives credited this form of affirmative action as one of the factors increasing campus diversity.[161]

In 2014 case Schuette v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action, 572 U.S. 291 (2014) — the Supreme Court upheld Michigan's ban on affirmative action for public institutions and in 2016 inFisher v. University of Texas II, No. 14-981, 579 U.S. ___ (2016) the court upheld the university's limited use of race in admissions decisions because the university showed it had a clear goal of limited scope without other workable race-neutral means to achieve it.However, in 2023 — Students for Fair Admissions v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, No. 20-1199, 600 U.S. ___ (2023) the United States Supreme Court overruled the decades old decisionsRegents of University of California v. Bakke and Grutter v. Bollinger and other cases mentioned above in this paragraph but disallowing non-individualized racial preferences in admissions for civilian universities. In essence, the court interpreted the Fourteenth Amendment as not permitting Harvard's “race-conscious admissions” as the court decision now forbids the consideration of race in higher education admissions.

Institutions in favor of Harvard's model argue that in addition to academic excellence they also aim to form a diverse student body, while individuals that argue against the model state that it is discriminatory against certain applicants.[162]

The growing Black student population in Ivy League universities in the early 2000s was accompanied by an increase in the number of Black faculty at these institutions, though rates of change among faculty have been slower and inconsistent. In 2005, 588– or about 3.9%– of the Ivies' 14,831 full-time faculty members were Black.[163] This proportion decreased to 3.4% in 2015.[164] Notably, in 2001, Ruth J. Simmons became the president of Brown University, making her the first and only Black president of an Ivy League institution.[165]

The 21st century saw the continuation of demonstrations by Ivy League students revolving around race. Many of these demonstrations have sought to continue the work of their 20th century predecessors by advocating for increased admission and support of Black students. In light of the Students for Fair Admissions v. President and Fellows of Harvard College Supreme Court case, students from Yale and Harvard joined other universities in protesting in defense of race-conscious admissions policies.[166][167]

Likewise, Black students from Ivy League institutions continue to protest for the betterment of Black students' lives on campus and beyond. Following Michael Brown's death in 2014, students across the Ivies formed the Black Ivy Coalition, which included members from all eight institutions and aimed to combat anti-Black racism.[168] Individual Ivy League universities also formed their own advocacy organizations and movements as a direct response to instances of anti-Black violence. After the murder of Michael Brown, Princeton University students formed the Black Justice League, which in 2015, occupied Nassau Hall and presented a list of demands to university administrators.[169] Similarly, in 2017, Cornell students made demands to their administration protesting the assault of a Black student. Led by Black Students United, the demands included banning the Psi Upsilon fraternity for hate crimes, implementing implicit bias training, and introducing policies to increase the number of Black students at the university.[170]

Student demonstrations have also focused on sparking change beyond Ivy League campuses. Following the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, Harvard's Black Law Students Association, beyond calling for more Black faculty, critical race theory curriculum, and protection for student protestors, also called on the university to divest from prisons and denounce state-sanctioned violence.[171]

In response to racially charged incidents across the country and prompting from student activists, Ivy League universities have removed and renamed campus landmarks. In response to the 2016 Black Lives Matter protests, Cornell renamed their botanical gardens, previously called the "Cornell Plantations," to the "Cornell Botanical Gardens."[172] In 2018, Brown renamed one of its largest academic and administrative buildings after its first black graduates, Inman E. Page and Ethel Tremaine Robinson.[173] In response to the murder of George Floyd in 2020, Princeton University removed Woodrow Wilson's name from a residential college and the School of Public and International Affairs because of his “racist thinking and policies.”[174]

Fashion and lifestyle[edit]

Different fashion trends and styles have emerged from Ivy League campuses over time, and fashion trends such as Ivy League and preppy are styles often associated with the Ivy League and its culture.

Ivy League style is a style of men's dress, popular during the late 1950s, believed to have originated on Ivy League campuses. The clothing stores J. Press and Brooks Brothers represent perhaps the quintessential Ivy League dress manner. The Ivy League style is said to be the predecessor to the preppy style of dress.

Preppy fashion started around 1912 to the late 1940s and 1950s as the Ivy League style of dress.[175] J. Press represents the quintessential preppy clothing brand, stemming from the collegiate traditions that shaped the preppy subculture. In the mid-twentieth century J. Press and Brooks Brothers, both being pioneers in preppy fashion, had stores on Ivy League school campuses, including Harvard, Yale, and Princeton.

Some typical preppy styles also reflect traditional upper class New England leisure activities, such as equestrian, sailing or yachting, hunting, fencing, rowing, lacrosse, tennis, golf, and rugby. Longtime New England outdoor outfitters, such as L.L. Bean, became part of conventional preppy style.[176] This can be seen in sport stripes and colors, equestrian clothing, plaid shirts, field jackets and nautical-themed accessories. Vacationing in Palm Beach, Florida, long popular with the East Coast upper class, led to the emergence of bright colors combinations in leisure wear seen in some brands such as Lilly Pulitzer.[176] By the 1980s, other brands such as Lacoste, Izod and Dooney & Bourke became associated with preppy style.[177]

Though the Ivy League style is most commonly associated with the white, male elites that historically made up Ivy League campuses, the style was quickly popularized among Black communities during the civil rights era. Reinterpretations of this style by African-American men in the 1950s and 1960s combined the preppy Ivy League style with other popular Black styles of dress. This led to the emergence of a new style of dress, the Black Ivy style.[178]

Today, Ivy League styles continue to be popular on Ivy League campuses, throughout the U.S., and abroad, and are oftentimes labeled as "Classic American style" or "Traditional American style".[179][180]

Social elitism[edit]

The Ivy League is often associated with the upper class White Anglo-Saxon Protestant community of the Northeast, Old money, or more generally, the American upper middle and upper classes.[181][182][183][184] Although most Ivy League students come from upper-middle and upper-class families, the student body has become increasingly more economically and ethnically diverse. The universities provide significant financial aid to help increase the enrollment of lower income and middle class students.[185] Several reports suggest, however, that the proportion of students from less-affluent families remains low.[186][187]

Phrases such as "Ivy League snobbery"[188] are ubiquitous in nonfiction and fiction writing of the early and mid-twentieth century. A Louis Auchincloss character dreads "the aridity of snobbery which he knew infected the Ivy League colleges".[60] A business writer, warning in 2001 against discriminatory hiring, presented a cautionary example of an attitude to avoid (the bracketed phrase is his):

We Ivy Leaguers [read: mostly white and Anglo] know that an Ivy League degree is a mark of the kind of person who is likely to succeed in this organization.[189]

The phrase Ivy League historically has been perceived as connected not only with academic excellence but also with social elitism. In 1936, sportswriter John Kieran noted that student editors at Harvard, Yale, Columbia, Princeton, Cornell, Dartmouth, and Penn were advocating the formation of an athletic association. In urging them to consider "Army and Navy and Georgetown and Fordham and Syracuse and Brown and Pitt" as candidates for membership, he exhorted:

It would be well for the proponents of the Ivy League to make it clear (to themselves especially) that the proposed group would be inclusive but not "exclusive" as this term is used with a slight up-tilting of the tip of the nose.[190]

Aspects of Ivy stereotyping were illustrated during the 1988 presidential election, when George H. W. Bush (Yale '48) derided Michael Dukakis (graduate of Harvard Law School) for having "foreign-policy views born in Harvard Yard's boutique."[191] New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd asked "Wasn't this a case of the pot calling the kettle elite?" Bush explained, however, that, unlike Harvard, Yale's reputation was "so diffuse, there isn't a symbol, I don't think, in the Yale situation, any symbolism in it. ... Harvard boutique to me has the connotation of liberalism and elitism" and said Harvard in his remark was intended to represent "a philosophical enclave" and not a statement about class.[192] Columnist Russell Baker opined that "Voters inclined to loathe and fear elite Ivy League schools rarely make fine distinctions between Yale and Harvard. All they know is that both are full of rich, fancy, stuck-up and possibly dangerous intellectuals who never sit down to supper in their undershirt no matter how hot the weather gets."[193] Still, the next five consecutive presidents all attended Ivy League schools for at least part of their education—George H. W. Bush (Yale undergrad), Bill Clinton (Yale Law School), George W. Bush (Yale undergrad, Harvard Business School), Barack Obama (Columbia undergrad, Harvard Law School), and Donald Trump (Penn undergrad).

U.S. presidents in the Ivy League[edit]

Of the 45[e] persons who have served as President of the United States, 16 have graduated from an Ivy League university. Of them, eight have degrees from Harvard, five from Yale, three from Columbia, two from Princeton and one from Penn. Twelve presidents have earned Ivy undergraduate degrees. Four of these were transfer students: Woodrow Wilson transferred from Davidson College, Barack Obama transferred from Occidental College, Donald Trump transferred from Fordham University, and John F. Kennedy transferred from Princeton to Harvard. John Adams was the first president to graduate from college, graduating from Harvard in 1755.

| President | School(s) | Graduation year |

|---|---|---|

| John Adams | Harvard University | 1755 |

| James Madison | Princeton University | 1771 |

| John Quincy Adams | Harvard University | 1787 |

| William Henry Harrison | University of Pennsylvania | (withdrew, class of 1793) |

| Rutherford B. Hayes | Harvard Law School | 1845 |

| Theodore Roosevelt | Harvard University Columbia Law School | 1880 (withdrew, class of 1882)[194] |

| William Howard Taft | Yale University | 1878 |

| Woodrow Wilson | Princeton University | 1879 |

| Franklin D. Roosevelt | Harvard University Columbia Law School | 1903 (withdrew, class of 1907)[195] |

| John F. Kennedy | Princeton University Harvard University | (withdrew) 1940 |

| Gerald Ford | Yale Law School | 1941 |

| George H. W. Bush | Yale University | 1948 |

| Bill Clinton | Yale Law School | 1973 |

| George W. Bush | Yale University Harvard Business School | 1968 1975 |

| Barack Obama | Columbia University Harvard Law School | 1983 1991 |

| Donald Trump | University of Pennsylvania | 1968 |

Student demographics[edit]

Race and ethnicity[edit]

| College | Asian | Black | Hispanic (of any race) | Non-Hispanic White | Other/ International | Two or more races | Unknown |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown | 16% | 7% | 10% | 39% | 18% | 5% | 4% |

| Columbia | 13% | 5% | 8% | 31% | 35% | 3% | 4% |

| Cornell | 17% | 6% | 11% | 34% | 22% | 4% | 6% |

| Dartmouth | 14% | 5% | 9% | 48% | 17% | 5% | 3% |

| Harvard | 14% | 7% | 9% | 40% | 23% | 4% | 3% |

| Penn | 18% | 7% | 8% | 40% | 20% | 4% | 3% |

| Princeton | 19% | 6% | 9% | 35% | 23% | 5% | 3% |

| Yale | 16% | 7% | 11% | 39% | 21% | 5% | 1% |

| United States[197] | 6% | 14% | 19% | 59% | 2% | 3% | — |

Geographic distribution[edit]

Students of the Ivy League largely hail from the Northeast, largely from the New York City, Boston, and Philadelphia areas. As all eight Ivy League universities are within the Northeast, most graduates end up working and residing in the Northeast after graduation. An unscientific survey of Harvard seniors from the Class of 2013 found that 42% hailed from the Northeast and 55% overall were planning on working and residing in the Northeast.[198] Boston and New York City are traditionally where many Ivy League graduates end up living.[199][200]

Socioeconomics and social class[edit]

| College | Median | Top 1% | Top 10% | Top 20% | Bottom 20% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown | $204,200 | 19% | 60% | 70% | 4.1% |

| Columbia | $150,900 | 13% | 48% | 62% | 5.1% |

| Cornell | $151,600 | 10% | 48% | 64% | 3.8% |

| Dartmouth | $200,400 | 21% | 58% | 69% | 2.6% |

| Harvard | $168,800 | 15% | 53% | 67% | 4.5% |

| Penn | $195,500 | 19% | 45% | 58% | 3.3% |

| Princeton | $186,100 | 17% | 58% | 72% | 2.2% |

| Yale | $192,600 | 19% | 57% | 69% | 2.1% |

Students of the Ivy League, both graduate and undergraduate, come primarily from upper middle and upper class families. In recent years, however, the universities have looked towards increasing socioeconomic and class diversity, by providing greater financial aid packages to applicants from lower, working, and lower middle class American families.[185][202]

In 2013, a Harvard Crimson writer estimated that 46% of Harvard undergraduate students came from families in the top 3.8% of all American households (i.e., over $200,000 annual income).[202] In 2012, the bottom 25% of the American income distribution accounted for only 3–4% of students at Brown, a figure that had remained unchanged since 1992.[203] In 2014, 69% of incoming freshmen students at Yale College came from families with annual incomes of over $120,000, putting most Yale College students in the upper-middle and upper classes. (The median household income in the U.S. in 2013 was $52,700.)[204]

In the 2011–2012 academic year, students qualifying for Pell Grants (federally funded scholarships on the basis of need) constituted 20% at Harvard, 18% at Cornell, 17% at Penn, 16% at Columbia, 15% at Dartmouth and Brown, 14% at Yale, and 12% at Princeton. Nationally, 35% of American university students qualify for a Pell Grant.[205]

Graduation rates[edit]

| College | American Indian or Alaska Native | Asian | Black | Hispanic (of any race ) | Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | Non-Hispanic White | Two or more races | Unknown |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown | 57% | 96% | 95% | 95% | - | 97% | 98% | 96% |

| Columbia | 83% | 98% | 95% | 98% | 50% | 98% | 95% | 100% |

| Cornell | 73% | 96% | 90% | 90% | 75% | 95% | 95% | 94% |

| Dartmouth | 96% | 96% | 82% | 93% | 100% | 95% | 93% | 83% |

| Harvard | 75% | 98% | 96% | 97% | - | 97% | 98% | 100% |

| Penn | 100% | 97% | 96% | 95% | - | 96% | 99% | 98% |

| Princeton | 100% | 99% | 95% | 99% | 100% | 99% | 96% | 94% |

| Yale | 100% | 99% | 95% | 95% | - | 97% | 97% | 100% |

Faculty demographics[edit]

Race and ethnicity[edit]

| College | Asian | Black | Hispanic (of any race) | Non-Hispanic White | Native American, Native Alaskan or Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | Two or more races | Unknown | "Under Represented Minorities" & "Historically Underrepresented Groups" |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown[207] | - | - | - | 86% | - | - | 13% | |

| Columbia[208] | 19% | - | - | 63% | - | - | 3% | 12% |

| Cornell[209] | 12% | 8% | (Combined with Black) | 72% | - | - | 7% | - |

| Dartmouth[210] | 9% | 4% | 6% | 80% | 1% | 2% | - | - |

| Harvard[211] | 12% | 4% | 3% | 79% | .1% | 1% | - | - |

| Penn[212] | 17% | 4% | 5% | 71% | (Combined with Asian) | 1% | .7% | - |

| Princeton[213] | 11% | 4% | 3% | 78% | 0% | 0% | 4% | - |

| Yale[214] | 21% | 5% | 5% | 62% | - | 1% | 6% | - |

Competition and athletics[edit]

Ivy champions are recognized in sixteen men's and sixteen women's sports. In some sports, Ivy teams actually compete as members of another league, the Ivy championship being decided by isolating the members' records in play against each other; for example, the six league members who participate in ice hockey do so as members of ECAC Hockey, but an Ivy champion is extrapolated each year. In one sport, rowing, the Ivies recognize team champions for each sex in both heavyweight and lightweight divisions. While the Intercollegiate Rowing Association governs all four sex- and bodyweight-based divisions of rowing, the only one that is sanctioned by the NCAA is women's heavyweight. The Ivy League was the last Division I basketball conference to institute a conference postseason tournament; the first tournaments for men and women were held at the end of the 2016–17 season. The tournaments only award the Ivy League automatic bids for the NCAA Division I Men's and Women's Basketball Tournaments; the official conference championships continue to be awarded based solely on regular-season results.[215] Before the 2016–17 season, the automatic bids were based solely on regular-season record, with a one-game playoff (or series of one-game playoffs if more than two teams were tied) held to determine the automatic bid.[216] The Ivy League is one of only two Division I conferences which award their official basketball championships solely on regular-season results; the other is the Southeastern Conference.[217][218] Since its inception, an Ivy League school has yet to win either the men's or women's Division I NCAA basketball tournament.

On average, each Ivy school has more than 35 varsity teams. All eight are in the top 20 for number of sports offered for both men and women among Division I schools. Unlike most Division I athletic conferences, the Ivy League prohibits the granting of athletic scholarships; all scholarships awarded are need-based (financial aid).[219] In addition, the Ivies have a rigid policy against redshirting, even for medical reasons; an athlete loses a year of eligibility for every year enrolled at an Ivy institution.[220] Additionally, the Ivies prohibit graduate students from participating in intercollegiate athletics, even if they have remaining athletic eligibility.[221] The only exception to the ban on graduate students was that seniors graduating in 2021 were allowed to play at their current institutions as graduate students in 2021–22. This was a one-time-only response to the Ivies shutting down most intercollegiate athletics in 2020–21 due to COVID-19.[222] Ivy League teams' non-league games are often against the members of the Patriot League, which have similar academic standards and athletic scholarship policies (although unlike the Ivies, the Patriot League allows both redshirting and play by eligible graduate students).

In the time before recruiting for college sports became dominated by those offering athletic scholarships and lowered academic standards for athletes, the Ivy League was successful in many sports relative to other universities in the country. In particular, Princeton won 26 recognized national championships in college football (last in 1935), and Yale won 18 (last in 1927).[223] Both of these totals are considerably higher than those of other historically strong programs such as Alabama, which has won 15, Notre Dame, which claims 11 but is credited by many sources with 13, and USC, which has won 11. Yale, whose coach Walter Camp was the "Father of American Football," held on to its place as the all-time wins leader in college football throughout the entire 20th century, but was finally passed by Michigan on November 10, 2001. Harvard, Yale, Princeton and Penn each have over a dozen former scholar-athletes enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame. Currently Dartmouth holds the record for most Ivy League football titles, with 18, followed closely by Harvard and Penn, each with 17 titles. In addition, the Ivy League has produced Super Bowl winners Kevin Boothe (Cornell), two-time Pro Bowler Zak DeOssie (Brown), Sean Morey (Brown), All-Pro selection Matt Birk (Harvard), Calvin Hill (Yale), Derrick Harmon (Cornell) and 1999 "Mr. Irrelevant" Jim Finn (Penn).

Beginning with the 1982 football season, the Ivy League has competed in Division I-AA (renamed FCS in 2006).[224][225] The Ivy League teams are eligible for the FCS tournament held to determine the national champion, and the league champion is eligible for an automatic bid (and any other team may qualify for an at-large selection) from the NCAA. However, since its inception in 1956, the Ivy League has not played any postseason games due to concerns about the extended December schedule's effects on academics. (The last postseason game for a member was 90 years ago, the 1934 Rose Bowl, won by Columbia.)[226][227] For this reason, any Ivy League team invited to the FCS playoffs turns down the bid. The Ivy League plays a strict 10-game schedule, compared to other FCS members' schedules of 11 (or, in some seasons, 12) regular season games, plus post-season, which expanded in 2013 to five rounds with 24 teams, with a bye week for the top eight teams. Football is the only sport in which the Ivy League declines to compete for a national title.

In addition to varsity football, Penn and Cornell also field teams in the 9-team Collegiate Sprint Football League, in which all players must weigh 178 pounds or less. With Princeton canceling its program in 2016,[228] Penn is the last remaining founding members of the league from its 1934 debut, and Cornell is the next-oldest, joining in 1937. Yale and Columbia previously fielded teams in the league but no longer do so.

Teams[edit]

| Sport | Men's | Women's |

|---|---|---|

| Baseball | 8 | - |

| Basketball | 8 | 8 |

| Cross-country | 8 | 8 |

| Fencing | 6 | 7 |

| Field hockey | - | 8 |

| Football | 8 | - |

| Golf | 8 | 7 |

| Ice hockey | 6 | 6 |

| Lacrosse | 7 | 8 |

| Rowing | 7 | 7 |

| Soccer | 8 | 8 |

| Softball | - | 8 |

| Squash | 8 | 8 |

| Swimming and diving | 8 | 8 |

| Tennis | 8 | 8 |

| Track and field (indoor) | 8 | 8 |

| Track and field (outdoor) | 8 | 8 |

| Volleyball | - | 8 |

| Wrestling | 6 | - |

Men's sponsored sports by school[edit]

| School | Baseball | Basketball | Cross Country | Fencing | Football | Golf | Lacrosse | Rowing | Soccer | Squash | Swimming & Diving | Tennis | Track & Field (Indoor) | Track & Field (Outdoor) | Total Ivy League Sports |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 10 |

| Columbia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 13 |

| Cornell | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 13 |

| Dartmouth | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 13 |

| Harvard | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 14 |

| Penn | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 14 |

| Princeton | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 14 |

| Yale | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 13 |

| Totals | 8 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 104 |

Men's varsity sports not sponsored by the Ivy League[edit]

| School | Crew | Ice Hockey1 | Polo | Sailing | Skiing | Volleyball | Water Polo | Wrestling2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown | Independent | ECAC Hockey | No | Independent | No | No | CWPA | EIWA |

| Columbia | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | EIWA |

| Cornell | No | ECAC Hockey | Independent | No | No | No | No | EIWA |

| Dartmouth | No | ECAC Hockey | No | Independent | Independent | No | No | No |

| Harvard | No | ECAC Hockey | No | Independent | Independent | EIVA | CWPA | EIWA |

| Penn | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | EIWA |

| Princeton | No | ECAC Hockey | No | No | No | EIVA | CWPA | EIWA |

| Yale | Independent | ECAC Hockey | No | Independent | No | No | No | No |

Notes:

1: Though the Ivy League lists ice hockey as a sponsored sport, all six ice hockey playing Ivy League schools participate as members of ECAC Hockey.

2: Though the Ivy League lists wrestling as a sponsored sport, all six Ivy League schools with wrestling teams currently participate as members of the Eastern Intercollegiate Wrestling Association. On December 19, 2023, the Ivy League announced that the inaugural Ivy League Tournament will be instituted for the 2024-25 season, ending over a century of affiliation with EIWA. The winner of the ILT will receive Automatic Qualification to the NCAA tournament.[230]

Women's sponsored sports by school[edit]

| School | Basketball | Cross Country | Fencing | Field Hockey | Golf | Lacrosse | Rowing | Soccer | Softball | Squash | Swimming & Diving | Tennis | Track & Field (Indoor) | Track & Field (Outdoor) | Volleyball | Total Ivy League Sports |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 12 |

| Columbia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 15 |

| Cornell | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 14 |

| Dartmouth | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 14 |

| Harvard | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 15 |

| Penn | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 15 |

| Princeton | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 15 |

| Yale | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 15 |

| Totals | 8 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 115 |

Women's varsity sports not sponsored by the Ivy League[edit]

| School | Archery | Crew | Equestrian | Gymnastics | Ice Hockey1 | Polo | Rugby2 | Sailing | Skiing | Water Polo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown | No | Independent | Independent | Independent | ECAC Hockey | No | Independent | Independent | No | CWPA |

| Columbia | Independent | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Cornell | No | No | Independent | Independent | ECAC Hockey | Independent | No | Independent | No | No |

| Dartmouth | No | No | Independent | No | ECAC Hockey | No | Independent | Independent | Independent | No |

| Harvard | No | No | No | No | ECAC Hockey | No | Independent | Independent | Independent | CWPA |

| Penn | No | No | No | Independent | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Princeton | No | No | No | No | ECAC Hockey | No | Independent[231] | No | No | CWPA |

| Yale | No | No | No | Independent | ECAC Hockey | No | No | Independent | No | No |

Notes:

1: Though the Ivy League lists ice hockey as a sponsored sport, all six ice hockey playing Ivy League schools participate as members of ECAC Hockey.

2. The Ivy League is home to some of the oldest college rugby teams in the United States. Although none of the men's teams and half of the women's teams are not "varsity" sports, they all compete against each other as part of the Ivy Rugby Conference[232] in addition to their own local conferences. Four of the women's teams (Brown, Dartmouth, Harvard, and Princeton) play as part of the NCAA emerging sport category.[233]

Historical results[edit]

| Institution | Ivy League championships | NCAA team championships |

|---|---|---|

| Princeton Tigers | 476 | 12 |

| Harvard Crimson | 415 | 4 |

| Cornell Big Red | 231 | 5 |

| Pennsylvania Quakers | 210 | 3 |

| Yale Bulldogs | 202 | 3 |

| Dartmouth Big Green | 140 | 3 |

| Brown Bears | 123 | 7 |

| Columbia Lions | 105 | 11 |

The table above includes the number of team championships won from the beginning of official Ivy League competition (1956–57 academic year) through 2016–17. Princeton and Harvard have on occasion won ten or more Ivy League titles in a year, an achievement accomplished 10 times by Harvard and 24 times by Princeton, including a conference-record 15 championships in 2010–11. Only once has one of the other six schools earned more than eight titles in a single academic year (Cornell with nine in 2005–06). In the 38 academic years beginning 1979–80, Princeton has averaged 10 championships per year, one-third of the conference total of 33 sponsored sports.[234]

In the 12 academic years beginning 2005–06 Princeton has won championships in 31 different sports, all except wrestling and men's tennis.[235]

Rivalries[edit]

Rivalries run deep in the Ivy League. For instance, Princeton and Penn are longstanding men's basketball rivals;[236] "Puck Frinceton" T-shirts are worn by Quaker fans at games.[237] In only 11 instances in the history of Ivy League basketball, and in only seven seasons since Yale's 1962 title, has neither Penn nor Princeton won at least a share of the Ivy League title in basketball,[238] with Princeton champion or co-champion 26 times and Penn 25 times. Penn has won 21 outright, Princeton 19 outright. Princeton has been a co-champion 7 times, sharing 4 of those titles with Penn (these 4 seasons represent the only times Penn has been co-champion). In addition to their athletic rivalry, both Princeton and UPenn also have a connection to the Ivy Day tradition. Ivy Day is a traditional ceremony that takes place in the spring, where seniors don caps and gowns and march through campus carrying ivy chains, which are symbolic of the ivy-covered walls of their schools. While Ivy Day is not unique to Princeton and Penn, the two schools do have a particularly strong connection to the tradition.Harvard won its first title of either variety in 2011, losing a dramatic play-off game to Princeton for the NCAA tournament bid, then rebounded to win outright championships in 2012, 2013, and 2014. Harvard also won the 2013 Great Alaska Shootout, defeating TCU to become the only Ivy League school to win the now-defunct tournament.

Rivalries exist between other Ivy league teams in other sports, including Cornell and Harvard in hockey, Harvard and Princeton in swimming, and Harvard and Penn in football (Penn and Harvard have won 28 Ivy League Football Championships since 1982, Penn-16; Harvard-12). During that time Penn has had 8 undefeated Ivy League Football Championships and Harvard has had 6 undefeated Ivy League Football Championships.[239] In men's lacrosse, Cornell and Princeton are perennial rivals, and they are two of three Ivy League teams to have won the NCAA tournament.[240] In 2009, the Big Red and Tigers met for their 70th game in the NCAA tournament.[241] No team other than Harvard or Princeton has won the men's swimming conference title outright since 1972, although Yale, Columbia, and Cornell have shared the title with Harvard and Princeton during this time. Similarly, no program other than Princeton and Harvard has won the women's swimming championship since Brown's 1999 title. Princeton or Cornell has won every indoor and outdoor track and field championship, both men's and women's, every year since 2002–03, with one exception (Columbia women won the indoor championship in 2012). Harvard and Yale are football and crew rivals although the competition has become unbalanced; Harvard has won all but one of the last 15 football games and all but one of the last 13 crew races.

Intra-conference football rivalries[edit]

| Teams | Name | Trophy | First met | Games played | Series record |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Columbia–Cornell | Empire State Bowl | Empire Cup | 1889 | 103 games | 36–64–3 |

| Cornell–Dartmouth | None | None | 1900 | 103 games | 41–61–1 |

| Cornell–Penn | None | Trustee's Cup | 1893 | 122 games | 46–71–5 |

| Dartmouth–Harvard | None | None | 1882 | 123 games | 47–71–5 |

| Dartmouth–Princeton | None | Sawhorse Dollar | 1897 | 100 games | 50–46–4 |

| Harvard–Penn | None | None | 1881 | 90 games | 49–39–2 |

| Harvard–Princeton | None | None | 1877 | 112 games | 57–48–7 |

| Harvard–Yale | The Game | None | 1875 | 132 games | 59–65–8 |

| Penn–Princeton | None | None | 1876 | 111 games | 67–43–1 |

| Princeton–Yale | None | None | 1873 | 138 games | 52–76–10 |

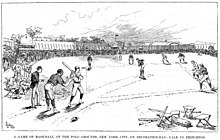

The Yale–Princeton series is the nation's second-longest by games played, exceeded only by "The Rivalry" between Lehigh and Lafayette, which began later in 1884 but included two or three games in each of 17 early seasons.[242] For the first three decades of the Yale-Princeton rivalry, the two played their season-ending game at a neutral site, usually New York City, and with one exception (1890: Harvard), the winner of the game also won at least a share of the national championship that year, covering the period 1869 through 1903.[243][244] This phenomenon of a finale contest at a neutral site for the national title created a social occasion for the society elite of the metropolitan area akin to a Super Bowl in the era prior to the establishment of the NFL in 1920.[245][246] These football games were also financially profitable for the two universities, so much that they began to play baseball games in New York City as well, drawing record crowds for that sport also, largely from the same social demographic.[247] In a period when the only professional team sports were fledgling baseball leagues, these high-profile early contests between Princeton and Yale played a role in popularizing spectator sports, demonstrating their financial potential and raising public awareness of Ivy universities at a time when few people attended college.

Extra-conference football rivalries[edit]

| Teams | Name | Trophy | First met | Games played | Series record |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown–Rhode Island | None | Governor's Cup | 1909 | 107 games | 73–32–2 |

| Columbia–Fordham | None | Liberty Cup | 1890 | 24 games | 12–12–0 |

| Cornell–Colgate | None | None | 1896 | 95 games | 48–44–3 |

| Dartmouth–New Hampshire | Granite Bowl | Granite Bowl Trophy | 1901 | 42 games | 21–19–2 |

| Harvard–Holy Cross | None | None | 1904 | 67 games | 41–24–2 |

| Penn–Lafayette | None | None | 1882 | 90 games | 63–23–4 |

| Penn–Lehigh | None | None | 1885 | 56 games | 43–13 |

| Princeton–Rutgers | None | None | 1869 | 71 games | 53–17–1 |

| Yale–Army | None | None | 1893 | 45 games | 22–16–8 |

| Yale–Connecticut | None | None | 1948 | 49 games | 32–17 |

Championships[edit]

NCAA team championships[edit]

This list, which is current through January 8, 2018,[248] includes NCAA championships and women's AIAW championships (one each for Yale and Dartmouth and five for Cornell). Excluded from this list are all other national championships earned outside the scope of NCAA competition, including football titles and retroactive Helms Foundation titles.

| School | Total | Men | Women | Co-ed | Nickname |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yale University | 29[f] | 26 | 3 | 0 | Bulldogs |

| Princeton University | 24[f] | 19 | 4 | 1 | Tigers |

| Columbia University | 14 | 11 | 0 | 3 | Lions |

| Harvard University | 10[f] | 7 | 2 | 1 | Crimson |

| Brown University | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0 | Bears |

| Cornell University | 10 | 5 | 5 | 0 | Big Red |

| Dartmouth College | 5[f] | 1 | 1 | 3 | Big Green |

| University of Pennsylvania | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | Quakers |

Athletic facilities[edit]

Other ivies[edit]