Декларация независимости США

| Соединенные Штаты Декларация независимости | |

|---|---|

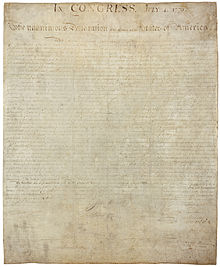

Факсимиле 1823 года погруженной копии Декларации независимости. | |

| Созданный | Июнь – июль 1776 г. |

| Ратифицирован | 4 июля 1776 г |

| Расположение | Загруженная копия: Здание Национального архива. Черновой вариант: Библиотека Конгресса США. |

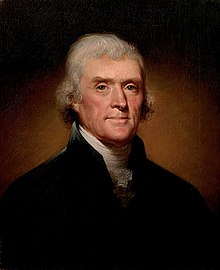

| Author(s) | Thomas Jefferson, Committee of Five |

| Signatories | 56 delegates to the Second Continental Congress |

| Purpose | To announce and explain separation from Great Britain[1]: 5 |

| Part of a series on the |

| American Revolution |

|---|

|

Декларация независимости , официально озаглавленная «Единогласная декларация тринадцати Соединенных Штатов Америки» (в расширенной версии, а также в оригинальной печати), является основополагающим документом Соединенных Штатов . 4 июля 1776 года он был единогласно принят 56 делегатами Второго Континентального конгресса , собравшихся в Доме штата Пенсильвания, позже переименованном в Индепенденс-холл , в колониальной эпохи столице Филадельфии . Декларация объясняет миру, почему Тринадцать колоний считали себя независимыми суверенными государствами, больше не подчиняющимися британскому колониальному правлению.

нации 56 делегатов, подписавших Декларацию независимости, стали известны как отцы-основатели , и Декларация стала одним из наиболее распространенных, переиздаваемых и влиятельных документов в мировой истории.

Второй Континентальный Конгресс поручил Комитету пяти , в том числе Джону Адамсу , Бенджамину Франклину , Томасу Джефферсону , Роберту Р. Ливингстону и Роджеру Шерману , написать Декларацию. Адамс, ведущий сторонник независимости, убедил Комитет пяти поручить Джефферсону написать первоначальный проект документа, который затем отредактировал Второй Континентальный Конгресс. Джефферсон в основном писал Декларацию в изоляции между 11 и 28 июня 1776 года, на втором этаже трехэтажного дома, который он снимал на Маркет-стрит, 700 в Филадельфии.

The Declaration was a formal explanation of why the Continental Congress voted to declare American independence from the Kingdom of Great Britain, a year after the American Revolutionary War began in April 1775. Two days prior to the Declaration's unanimous adoption, the Second Continental Congress unanimously passed the Lee Resolution, which established the consensus of the Congress that the British had no governing authority over the Thirteen Colonies.

After ratifying the text on July 4, Congress issued the Declaration of Independence in several forms. It was published as the printed Dunlap broadside that was widely distributed. The Declaration was first read to the public simultaneously at noon on July 8, 1776, in three exclusively designated locations: Easton, Pennsylvania; Philadelphia; and Trenton, New Jersey.[2]

What Jefferson called his "original Rough draft", one of several revisions,[3] is currently preserved at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., complete with changes made by Adams and Benjamin Franklin, and Jefferson's notes of changes made by Congress. The best-known version of the Declaration is the signed copy now displayed at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., which is popularly regarded as the official document; this copy, engrossed by Timothy Matlack, was ordered by Congress on July 19 and signed primarily on August 2, 1776.[4][5]

The Declaration justified the independence of the United States by listing 27 colonial grievances against King George III and by asserting certain natural and legal rights, including a right of revolution. Its original purpose was to announce independence, and references to the text of the declaration were few in the following years. On November 19, 1863, following the Battle of Gettysburg, the bloodiest battle of the American Civil War, Abraham Lincoln made the Declaration the centerpiece of his Gettysburg Address, a brief but powerful and enduring 271-word statement dedicating what is now Gettysburg National Cemetery.[6]

The Declaration of Independence has proven an influential and globally impactful statement on human rights, particularly its second sentence: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness." Stephen Lucas called the Declaration of Independence "one of the best-known sentences in the English language."[7] Historian Joseph Ellis has written that the document contains "the most potent and consequential words in American history".[8] The passage came to represent a moral standard to which the United States should strive. This view was notably promoted by Lincoln, who considered the Declaration to be the foundation of his political philosophy and argued that it is a statement of principles through which the United States Constitution should be interpreted.[9]: 126

The 56 delegates who signed the declaration represented each of the Thirteen Colonies: New Hampshire, Massachusetts Bay, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia.

The Declaration of Independence inspired many similar documents in other countries, the first being the 1789 Declaration of United Belgian States issued during the Brabant Revolution in the Austrian Netherlands. It also served as the primary model for numerous declarations of independence in Europe, Latin America, Africa, and Oceania following its adoption.[10]: 113

Background

Believe me, dear Sir: there is not in the British empire a man who more cordially loves a union with Great Britain than I do. But, by the God that made me, I will cease to exist before I yield to a connection on such terms as the British Parliament propose; and in this, I think I speak the sentiments of America.

— Thomas Jefferson, November 29, 1775[11]

By the time the Declaration of Independence was adopted in July 1776, the Thirteen Colonies and Great Britain had been at war for more than a year. Relations had been deteriorating between the colonies and the mother country since 1763. Parliament enacted a series of measures to increase revenue from the colonies, such as the Stamp Act of 1765 and the Townshend Acts of 1767. Parliament believed that these acts were a legitimate means of having the colonies pay their fair share of the costs to keep them in the British Empire.[12]

Many colonists, however, had developed a different perspective of the empire. The colonies were not directly represented in Parliament, and colonists argued that Parliament had no right to levy taxes upon them. This tax dispute was part of a larger divergence between British and American interpretations of the British Constitution and the extent of Parliament's authority in the colonies.[13]: 162 The orthodox British view, dating from the Glorious Revolution of 1688, was that Parliament was the supreme authority throughout the empire, and anything that Parliament did was constitutional.[13]: 200–202 In the colonies, however, the idea had developed that the British Constitution recognized certain fundamental rights that no government could violate, including Parliament.[13]: 180–182 After the Townshend Acts, some essayists questioned whether Parliament had any legitimate jurisdiction in the colonies.[14]

Anticipating the arrangement of the British Commonwealth, by 1774 American writers such as Samuel Adams, James Wilson, and Thomas Jefferson argued that Parliament was the legislature of Great Britain only, and that the colonies, which had their own legislatures, were connected to the rest of the empire only through their allegiance to the Crown.[13]: 224–225 [15]

Continental Congress convenes

In 1774, Parliament passed the Coercive Acts, known as the Intolerable Acts in the colonies. This was intended to punish the colonists for the Gaspee Affair of 1772 and the Boston Tea Party of 1773. Many colonists considered the Coercive Acts to be in violation of the British Constitution and a threat to the liberties of all of British America. In September 1774, the First Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia to coordinate a formal response. Congress organized a boycott of British goods and petitioned the king for repeal of the acts. These measures were unsuccessful, however, since King George and the Prime Minister, Lord North, were determined to enforce parliamentary supremacy over the Thirteen Colonies. In November 1774, King George, in a letter to North, wrote, "blows must decide whether they are to be subject to this country or independent".[16][17]

Most colonists still hoped for reconciliation with Great Britain, even after fighting began in the American Revolutionary War at Lexington and Concord in April 1775.[18][19] The Second Continental Congress convened at Pennsylvania State House, later renamed Independence Hall, in Philadelphia in May 1775. Some delegates supported eventual independence for the colonies, but none had yet declared it publicly, which was an act of treason punishable by death under the laws of the British monarchy at the time.[19]

Many colonists believed that Parliament no longer had sovereignty over them, but they were still loyal to King George, thinking he would intercede on their behalf. They were disabused of that notion in late 1775, when the king rejected Congress's second petition, issued a Proclamation of Rebellion, and announced before Parliament on October 26 that he was considering "friendly offers of foreign assistance" to suppress the rebellion.[20]: 25 [21] A pro-American minority in Parliament warned that the government was driving the colonists toward independence.[20]: 25

Growing support for independence

Despite this growing popular support for independence, the Second Continental Congress initially lacked the clear authority to declare it. Delegates had been elected to Congress by 13 different governments, which included extralegal conventions, ad hoc committees, and elected assemblies, and they were bound by the instructions given to them. Regardless of their personal opinions, delegates could not vote to declare independence unless their instructions permitted such an action.[22] Several colonies, in fact, expressly prohibited their delegates from taking any steps toward separation from Great Britain, while other delegations had instructions that were ambiguous on the issue;[20]: 30 consequently, advocates of independence sought to have the Congressional instructions revised. For Congress to declare independence, a majority of delegations would need authorization to vote for it, and at least one colonial government would need to specifically instruct its delegation to propose a declaration of independence in Congress.

Between April and July 1776, a "complex political war"[20]: 59 was waged to bring this about.[23]: 671 [24]

In January 1776, Thomas Paine's pamphlet Common Sense, which described the uphill battle against the British for independence as a challenging but achievable and necessary objective, was published Philadelphia.[25] In Common Sense, Paine wrote the famed phrase:

These are the times that try men's souls; the summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.[26][20]: 31–32

Common Sense made a persuasive, impassioned case for independence, which had not been given serious consideration in the colonies. Paine linked independence with Protestant beliefs, as a means to present a distinctly American political identity, and he initiated open debate on a topic few had dared to discuss.[27][20]: 33

As Common Sense was circulated throughout the Thirteen Colonies, public support for independence from Great Britain steadily increased. After reading it, Washington ordered that it be read by his Continental Army troops, who were demoralized following recent military defeats. A week later, Washington led the crossing of the Delaware in one of the Revolutionary War's most complex and daring military campaigns, resulting in a much-needed military victory in the Battle of Trenton against a Hessian military garrison at Trenton.[20]: 33–34 Common Sense was sold and distributed widely and read aloud at taverns and meeting places. In proportion to the population of the colonies at that time (2.5 million), it had the largest sale and circulation of any book published in American history.[28] As of 2006, it remains the all-time best-selling American title and is still in print today.[29]

While some colonists still hoped for reconciliation, public support for independence strengthened considerably in early 1776. In February 1776, colonists learned of Parliament's passage of the Prohibitory Act, which established a blockade of American ports and declared American ships to be enemy vessels. John Adams, a strong supporter of independence, believed that Parliament had effectively declared American independence before Congress had been able to. Adams labeled the Prohibitory Act the "Act of Independency", calling it "a compleat Dismemberment of the British Empire".[30][20]: 25–27 Support for declaring independence grew even more when it was confirmed that King George had hired German mercenaries to use against his American subjects.[31]

Revising instructions

In the campaign to revise Congressional instructions, many Americans formally expressed their support for separation from Great Britain in what were effectively state and local declarations of independence. Historian Pauline Maier identifies more than ninety such declarations that were issued throughout the Thirteen Colonies from April to July 1776.[20]: 48, Appendix A These "declarations" took a variety of forms. Some were formal written instructions for Congressional delegations, such as the Halifax Resolves of April 12, with which North Carolina became the first colony to explicitly authorize its delegates to vote for independence.[23]: 678–679 Others were legislative acts that officially ended British rule in individual colonies, such as the Rhode Island legislature renouncing its allegiance to Great Britain on May 4—the first colony to do so.[23]: 679 [32][33] Many declarations were resolutions adopted at town or county meetings that offered support for independence. A few came in the form of jury instructions, such as the statement issued on April 23, 1776, by Chief Justice William Henry Drayton of South Carolina: "the law of the land authorizes me to declare ... that George the Third, King of Great Britain ... has no authority over us, and we owe no obedience to him."[20]: 69–72 Most of these declarations are now obscure, having been overshadowed by the resolution for independence, approved by Congress on July 2, and the declaration of independence, approved and printed on July 4 and signed in August.[20]: 48 The modern scholarly consensus is that the best-known and earliest of the local declarations is most likely inauthentic, the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence, allegedly adopted in May 1775 (a full year before other local declarations).[20]: 174

Some colonies held back from endorsing independence. Resistance was centered in the middle colonies of New York, New Jersey, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. Advocates of independence saw Pennsylvania as the key; if that colony could be converted to the pro-independence cause, it was believed that the others would follow.[23]: 682 On May 1, however, opponents of independence retained control of the Pennsylvania Assembly in a special election that had focused on the question of independence.[23]: 683 In response, Congress passed a resolution on May 10 which had been promoted by John Adams and Richard Henry Lee, calling on colonies without a "government sufficient to the exigencies of their affairs" to adopt new governments.[23]: 684 [20]: 37 [34] The resolution passed unanimously, and was even supported by Pennsylvania's John Dickinson, the leader of the anti-independence faction in Congress, who believed that it did not apply to his colony.[23]: 684

May 15 preamble

This Day the Congress has passed the most important Resolution, that ever was taken in America.

—John Adams, May 15, 1776[35]

As was the custom, Congress appointed a committee to draft a preamble to explain the purpose of the resolution. John Adams wrote the preamble, which stated that because King George had rejected reconciliation and was hiring foreign mercenaries to use against the colonies, "it is necessary that the exercise of every kind of authority under the said crown should be totally suppressed".[20]: 37 [23]: 684 [36] Adams' preamble was meant to encourage the overthrow of the governments of Pennsylvania and Maryland, which were still under proprietary governance.[37][23]: 684 [38] Congress passed the preamble on May 15 after several days of debate, but four of the middle colonies voted against it, and the Maryland delegation walked out in protest.[39][23]: 685 Adams regarded his May 15 preamble effectively as an American declaration of independence, although a formal declaration would still have to be made.[20]: 38

Lee's resolution

On the same day that Congress passed Adams' preamble, the Virginia Convention set the stage for a formal Congressional declaration of independence. On May 15, the Convention instructed Virginia's congressional delegation "to propose to that respectable body to declare the United Colonies free and independent States, absolved from all allegiance to, or dependence upon, the Crown or Parliament of Great Britain".[40][20]: 63 [41] In accordance with those instructions, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia presented a three-part resolution to Congress on June 7.[42] The motion was seconded by John Adams, calling on Congress to declare independence, form foreign alliances, and prepare a plan of colonial confederation. The part of the resolution relating to declaring independence read: "Resolved, that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved."[20]: 41 [43]

Lee's resolution met with resistance in the ensuing debate. Opponents of the resolution conceded that reconciliation was unlikely with Great Britain, while arguing that declaring independence was premature, and that securing foreign aid should take priority.[23]: 689–690 [20]: 42 Advocates of the resolution countered that foreign governments would not intervene in an internal British struggle, and so a formal declaration of independence was needed before foreign aid was possible. All Congress needed to do, they insisted, was to "declare a fact which already exists".[23]: 689 [10]: 33–34 [44] Delegates from Pennsylvania, Delaware, New Jersey, Maryland, and New York were still not yet authorized to vote for independence, however, and some of them threatened to leave Congress if the resolution were adopted. Congress, therefore, voted on June 10 to postpone further discussion of Lee's resolution for three weeks.[20]: 42–43 [45] Until then, Congress decided that a committee should prepare a document announcing and explaining independence in case Lee's resolution was approved when it was brought up again in July.

Final push

Support for a Congressional declaration of independence was consolidated in the final weeks of June 1776. On June 14, the Connecticut Assembly instructed its delegates to propose independence and, the following day, the legislatures of New Hampshire and Delaware authorized their delegates to declare independence.[23]: 691–692 In Pennsylvania, political struggles ended with the dissolution of the colonial assembly, and a new Conference of Committees under Thomas McKean authorized Pennsylvania's delegates to declare independence on June 18.[47][23]: 691 The Provincial Congress of New Jersey had been governing the province since January 1776; they resolved on June 15 that Royal Governor William Franklin was "an enemy to the liberties of this country" and had him arrested.[23]: 692 On June 21, they chose new delegates to Congress and empowered them to join in a declaration of independence.[23]: 693

As of the end of June, only two of the thirteen colonies had yet to authorize independence, Maryland and New York. Maryland's delegates previously walked out when the Continental Congress adopted Adams' May 15 preamble, and had sent to the Annapolis Convention for instructions.[23]: 694 On May 20, the Annapolis Convention rejected Adams' preamble, instructing its delegates to remain against independence. But Samuel Chase went to Maryland and, thanks to local resolutions in favor of independence, was able to get the Annapolis Convention to change its mind on June 28.[23]: 694–696 [48][20]: 68 Only the New York delegates were unable to get revised instructions. When Congress had been considering the resolution of independence on June 8, the New York Provincial Congress told the delegates to wait.[49][23]: 698 But on June 30, the Provincial Congress evacuated New York as British forces approached, and would not convene again until July 10. This meant that New York's delegates would not be authorized to declare independence until after Congress had made its decision.[50]

Draft and adoption

Political maneuvering was setting the stage for an official declaration of independence even while a document was being written to explain the decision. On June 11, 1776, Congress appointed the Committee of Five to draft a declaration, including John Adams of Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, Robert R. Livingston of New York, and Roger Sherman of Connecticut.

The committee took no minutes, so there is some uncertainty about how the drafting process proceeded; contradictory accounts were written many years later by Jefferson and Adams, too many years to be regarded as entirely reliable, although their accounts are frequently cited.[20]: 97–105 [51] What is certain is that the committee discussed the general outline which the document should follow and decided that Jefferson would write the first draft.[52] The committee in general, and Jefferson in particular, thought that Adams should write the document, but Adams persuaded them to choose Jefferson and promised to consult with him personally.[53]

Jefferson largely wrote the Declaration of Independence in isolation between June 11, 1776, and June 28, 1776, from the second floor of a three-story home he was renting at 700 Market Street in Philadelphia, now called the Declaration House and within walking distance of Independence Hall.[54] Considering Congress's busy schedule, Jefferson probably had limited time for writing over these 17 days, and he likely wrote his first draft quickly.[20]: 104

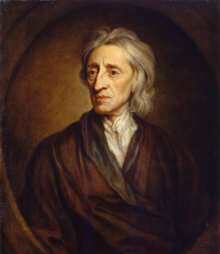

Examination of the text of the early Declaration drafts reflects the influence that John Locke and Thomas Paine, author of Common Sense had on Jefferson. He then consulted the other members of the Committee of Five who offered minor changes, and then produced another copy incorporating these alterations. The committee presented this copy to the Congress on June 28, 1776. The title of the document was "A Declaration by the Representatives of the United States of America, in General Congress assembled."[1]: 4

Congress ordered that the draft "lie on the table"[23]: 701 and then methodically edited Jefferson's primary document for the next two days, shortening it by a fourth, removing unnecessary wording, and improving sentence structure.[55] They removed Jefferson's assertion that King George III had forced slavery onto the colonies,[56] in order to moderate the document and appease those in South Carolina and Georgia, both states which had significant involvement in the slave trade.

Jefferson later wrote in his autobiography that Northern states were also supportive towards the clauses removal, "for though their people had very few slaves themselves, yet they had been pretty considerable carriers of them to others."[57] Jefferson wrote that Congress had "mangled" his draft version, but the Declaration that was finally produced was "the majestic document that inspired both contemporaries and posterity", in the words of his biographer John Ferling.[55]

Congress tabled the draft of the declaration on Monday, July 1 and resolved itself into a committee of the whole, with Benjamin Harrison of Virginia presiding, and they resumed debate on Lee's resolution of independence.[58] John Dickinson made one last effort to delay the decision, arguing that Congress should not declare independence without first securing a foreign alliance and finalizing the Articles of Confederation.[23]: 699 John Adams gave a speech in reply to Dickinson, restating the case for an immediate declaration.

A vote was taken after a long day of speeches, each colony casting a single vote, as always. The delegation for each colony numbered from two to seven members, and each delegation voted among themselves to determine the colony's vote. Pennsylvania and South Carolina voted against declaring independence. The New York delegation abstained, lacking permission to vote for independence. Delaware cast no vote because the delegation was split between Thomas McKean, who voted yes, and George Read, who voted no. The remaining nine delegations voted in favor of independence, which meant that the resolution had been approved by the committee of the whole. The next step was for the resolution to be voted upon by Congress itself. Edward Rutledge of South Carolina was opposed to Lee's resolution but desirous of unanimity, and he moved that the vote be postponed until the following day.[59][23]: 700

On July 2, South Carolina reversed its position and voted for independence. In the Pennsylvania delegation, Dickinson and Robert Morris abstained, allowing the delegation to vote three-to-two in favor of independence. The tie in the Delaware delegation was broken by the timely arrival of Caesar Rodney, who voted for independence. The New York delegation abstained once again since they were still not authorized to vote for independence, although they were allowed to do so a week later by the New York Provincial Congress.[20]: 45 The resolution of independence was adopted with twelve affirmative votes and one abstention, and the colonies formally severed political ties with Great Britain.[43] John Adams wrote to his wife on the following day and predicted that July 2 would become a great American holiday[23]: 703–704 He thought that the vote for independence would be commemorated; he did not foresee that Americans would instead celebrate Independence Day on the date when the announcement of that act was finalized.[20]: 160–161

I am apt to believe that [Independence Day] will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.[60]

Congress next turned its attention to the committee's draft of the declaration. They made a few changes in wording during several days of debate and deleted nearly a fourth of the text. The wording of the Declaration of Independence was approved on July 4, 1776, and sent to the printer for publication.

There is a distinct change in wording from this original broadside printing of the Declaration and the final official engrossed copy. The word "unanimous" was inserted as a result of a Congressional resolution passed on July 19, 1776: "Resolved, That the Declaration passed on the 4th, be fairly engrossed on parchment, with the title and stile of 'The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America,' and that the same, when engrossed, be signed by every member of Congress."[61] Historian George Athan Billias says: "Independence amounted to a new status of interdependence: the United States was now a sovereign nation entitled to the privileges and responsibilities that came with that status. America thus became a member of the international community, which meant becoming a maker of treaties and alliances, a military ally in diplomacy, and a partner in foreign trade on a more equal basis."[62]

Annotated text of the engrossed declaration

The declaration is not divided into formal sections; but it is often discussed as consisting of five parts: introduction, preamble, indictment of King George III, denunciation of the British people, and conclusion.[63]

| Introduction Asserts as a matter of Natural Law the ability of a people to assume political independence; acknowledges that the grounds for such independence must be reasonable, and therefore explicable, and ought to be explained. | In CONGRESS, July 4, 1776. The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America, "When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation."[64] |

| Preamble Outlines a general philosophy of government that justifies revolution when government harms natural rights.[63] | "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.—That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed,—That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security." |

| Indictment A bill of grievances documenting the king's "repeated injuries and usurpations" of the Americans' rights and liberties.[63] | "Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world. "He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good. "He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them. "He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only. "He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their Public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures. "He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness of his invasions on the rights of the people. "He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected, whereby the Legislative Powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the meantime exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within. "He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands. "He has obstructed the Administration of Justice by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary Powers. "He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries. "He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harass our people and eat out their substance. "He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures. "He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil Power. "He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation: "For quartering large bodies of armed troops among us: "For protecting them, by a mock Trial from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States: "For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world: "For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent: "For depriving us in many cases, of the benefit of Trial by Jury: "For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences: "For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies: "For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments: "For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever. "He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us. "He has plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people. "He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation, and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & Perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation. "He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands. "He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions. "In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince, whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people." |

| Failed warnings Describes the colonists' attempts to inform and warn the British people of the king's injustice, and the British people's failure to act. Even so, it affirms the colonists' ties to the British as "brethren."[63] | "Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our British brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity." |

| Denunciation This section essentially finishes the case for independence. The conditions that justified revolution have been shown.[63] | "We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends." |

| Conclusion The signers assert that there exist conditions under which people must change their government, thatthe British have produced such conditions and, by necessity, the colonies must throw off political ties with the British Crown and become independent states.The conclusion contains, at its core, the Lee Resolution that had been passed on July 2. | "We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these united Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor." |

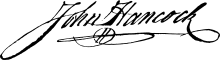

| Signatures The first and most famous signature on the engrossed copy was that of John Hancock, President of the Continental Congress. Two future presidents (Thomas Jefferson and John Adams) and a father and great-grandfather of two other presidents (Benjamin Harrison V) were among the signatories. Edward Rutledge (age 26) was the youngest signer, and Benjamin Franklin (age 70) was the oldest signer. The fifty-six signers of the Declaration represented the new states as follows (from north to south):[65] |

|

Influences and legal status

Historians have often sought to identify the sources that most influenced the words and political philosophy of the Declaration of Independence. By Jefferson's own admission, the Declaration contained no original ideas, but was instead a statement of sentiments widely shared by supporters of the American Revolution. As he explained in 1825:

Neither aiming at originality of principle or sentiment, nor yet copied from any particular and previous writing, it was intended to be an expression of the American mind, and to give to that expression the proper tone and spirit called for by the occasion.[66]

Jefferson's most immediate sources were two documents written in June 1776: his own draft of the preamble of the Constitution of Virginia, and George Mason's draft of the Virginia Declaration of Rights. Ideas and phrases from both of these documents appear in the Declaration of Independence.[67][20]: 125–126 Mason's opening was:

Section 1. That all men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.[68]

Mason was, in turn, directly influenced by the 1689 English Declaration of Rights, which formally ended the reign of King James II.[20]: 126–128 During the American Revolution, Jefferson and other Americans looked to the English Declaration of Rights as a model of how to end the reign of an unjust king.[20]: 53–57 The Scottish Declaration of Arbroath (1320) and the Dutch Act of Abjuration (1581) have also been offered as models for Jefferson's Declaration, but these models are now accepted by few scholars. Maier found no evidence that the Dutch Act of Abjuration served as a model for the Declaration, and considers the argument "unpersuasive".[20]: 264 Armitage discounts the influence of the Scottish and Dutch acts, and writes that neither was called "declarations of independence" until fairly recently.[10]: 42–44 Stephen E. Lucas argued in favor of the influence of the Dutch act.[69][70]

Jefferson wrote that a number of authors exerted a general influence on the words of the Declaration.[71] English political theorist John Locke is usually cited as one of the primary influences, a man whom Jefferson called one of "the three greatest men that have ever lived".[72]

In 1922, historian Carl L. Becker wrote, "Most Americans had absorbed Locke's works as a kind of political gospel; and the Declaration, in its form, in its phraseology, follows closely certain sentences in Locke's second treatise on government."[1]: 27 The extent of Locke's influence on the American Revolution has been questioned by some subsequent scholars, however. Historian Ray Forrest Harvey argued in 1937 for the dominant influence of Swiss jurist Jean Jacques Burlamaqui, declaring that Jefferson and Locke were at "two opposite poles" in their political philosophy, as evidenced by Jefferson's use in the Declaration of Independence of the phrase "pursuit of happiness" instead of "property".[73] Other scholars emphasized the influence of republicanism rather than Locke's classical liberalism.[74]

Historian Garry Wills argued that Jefferson was influenced by the Scottish Enlightenment, particularly Francis Hutcheson, rather than Locke,[75] an interpretation that has been strongly criticized.[76]

Legal historian John Phillip Reid has written that the emphasis on the political philosophy of the Declaration has been misplaced. The Declaration is not a philosophical tract about natural rights, argues Reid, but is instead a legal document—an indictment against King George for violating the constitutional rights of the colonists.[77] As such, it follows the process of the 1550 Magdeburg Confession, which legitimized resistance against Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in a multi-step legal formula now known as the doctrine of the lesser magistrate.[78]

Historian David Armitage has argued that the Declaration was strongly influenced by de Vattel's The Law of Nations, the dominant international law treatise of the period, and a book that Benjamin Franklin said was "continually in the hands of the members of our Congress".[79] Armitage writes, "Vattel made independence fundamental to his definition of statehood"; therefore, the primary purpose of the Declaration was "to express the international legal sovereignty of the United States". If the United States were to have any hope of being recognized by the European powers, the American revolutionaries first had to make it clear that they were no longer dependent on Great Britain.[10]: 21, 38–40 The Declaration of Independence does not have the force of law domestically, but nevertheless it may help to provide historical and legal clarity about the Constitution and other laws.[80][81][82][83]

Signing

The Declaration became official when Congress recorded its vote adopting the document on July 4; it was transposed on paper and signed by John Hancock, President of the Congress, on that day. Signatures of the other delegates were not needed to further authenticate it.[84] The signatures of fifty-six delegates are affixed to the Declaration, though the exact date when each person signed became debatable.[84] Jefferson, Franklin, and Adams all wrote that the Declaration was signed by Congress on July 4.[85] But in 1796, signer Thomas McKean disputed that, because some signers were not then present, including several who were not even elected to Congress until after that date.[84][86] Historians have generally accepted McKean's version of events.[87][88][89] History particularly shows most delegates signed on August 2, 1776, and those who were not then present added their names later.[90]

In an 1811 letter to Adams, Benjamin Rush recounted the signing on August 2 in stark fashion, describing it as a scene of "pensive and awful silence". Rush said the delegates were called up, one after another, and then filed forward somberly to subscribe what each thought was their ensuing death warrant.[91] He related that the "gloom of the morning" was briefly interrupted when the rotund Benjamin Harrison of Virginia said to a diminutive Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts, at the signing table, "I shall have a great advantage over you, Mr. Gerry, when we are all hung for what we are now doing. From the size and weight of my body I shall die in a few minutes and be with the Angels, but from the lightness of your body you will dance in the air an hour or two before you are dead."[91] According to Rush, Harrison's remark "procured a transient smile, but it was soon succeeded by the Solemnity with which the whole business was conducted."[91]

The signatories include then future presidents John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, though the most legendary signature is John Hancock's.[92] His large, flamboyant signature became iconic, and the term John Hancock emerged in the United States as a metaphor of "signature".[93] A commonly circulated but apocryphal account claims that, after Hancock signed, the delegate from Massachusetts commented, "The British ministry can read that name without spectacles." Another report indicates that Hancock proudly declared, "There! I guess King George will be able to read that!"[94]

A legend emerged years later about the signing of the Declaration, after the document had become an important national symbol. John Hancock is supposed to have said that Congress, having signed the Declaration, must now "all hang together", and Benjamin Franklin replied: "Yes, we must indeed all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately." That quotation first appeared in print in an 1837 London humor magazine.[95]

The Syng inkstand used at the signing was also used at the signing of the United States Constitution in 1787.

Publication and reaction

After Congress approved the final wording of the Declaration on July 4, a handwritten copy was sent a few blocks away to the printing shop of John Dunlap. Through the night, Dunlap printed about 200 broadsides for distribution. The source copy used for this printing has been lost and may have been a copy in Thomas Jefferson's hand.[96] It was read to audiences and reprinted in newspapers throughout the 13 states. The first formal public readings of the document took place on July 8, in Philadelphia (by John Nixon in the yard of Independence Hall), Trenton, New Jersey, and Easton, Pennsylvania; the first newspaper to publish it was The Pennsylvania Evening Post on July 6.[20]: 156 A German translation of the Declaration was published in Philadelphia by July 9.[10]: 72

President of Congress John Hancock sent a broadside to General George Washington, instructing him to have it proclaimed "at the Head of the Army in the way you shall think it most proper".[20]: 155 Washington had the Declaration read to his troops in New York City on July 9, with thousands of British troops on ships in the harbor. Washington and Congress hoped that the Declaration would inspire the soldiers, and encourage others to join the army.[20]: 156 After hearing the Declaration, crowds in many cities tore down and destroyed signs or statues representing royal authority. An equestrian statue of King George in New York City was pulled down and the lead used to make musket balls.[20]: 156–157

One of the first readings of the Declaration by the British is believed to have taken place at the Rose and Crown Tavern on Staten Island, New York in the presence of General Howe.[97] British officials in North America sent copies of the Declaration to Great Britain.[10]: 73 It was published in British newspapers beginning in mid-August, it had reached Florence and Warsaw by mid-September, and a German translation appeared in Switzerland by October. The first copy of the Declaration sent to France got lost, and the second copy arrived only in November 1776.[98] News of the Declaration managed to reach Russia on August 13 via a dispatch from the Russian chargé d'affaires in London, Nikita Panin.[99] It reached Portuguese America by Brazilian medical student "Vendek" José Joaquim Maia e Barbalho, who had met with Thomas Jefferson in Nîmes.

The Spanish-American authorities banned the circulation of the Declaration, but it was widely transmitted and translated: by Venezuelan Manuel García de Sena, by Colombian Miguel de Pombo, by Ecuadorian Vicente Rocafuerte, and by New Englanders Richard Cleveland and William Shaler, who distributed the Declaration and the United States Constitution among Creoles in Chile and Indians in Mexico in 1821.[100] The North Ministry did not give an official answer to the Declaration, but instead secretly commissioned pamphleteer John Lind to publish a response entitled Answer to the Declaration of the American Congress.[10]: 75 British Tories denounced the signers of the Declaration for not applying the same principles of "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" to African Americans.[101] Thomas Hutchinson, the former royal governor of Massachusetts, also published a rebuttal.[102][10]: 74 These pamphlets challenged various aspects of the Declaration. Hutchinson argued that the American Revolution was the work of a few conspirators who wanted independence from the outset, and who had finally achieved it by inducing otherwise loyal colonists to rebel.[13]: 155–156 Lind's pamphlet had an anonymous attack on the concept of natural rights written by Jeremy Bentham, an argument that he repeated during the French Revolution.[10]: 79–80 Both pamphlets questioned how the American slaveholders in Congress could proclaim that "all men are created equal" without freeing their own slaves.[10]: 76–77

William Whipple, a signer of the Declaration of Independence who had fought in the war, freed his slave Prince Whipple because of his revolutionary ideals. In the postwar decades, other slaveholders also freed their slaves; from 1790 to 1810, the percentage of free blacks in the Upper South increased to 8.3 percent from less than one percent of the black population.[103] Northern states began abolishing slavery shortly after the war for Independence began, and all had abolished slavery by 1804.

Later in late November 1776, a group of 547 Loyalists, largely from New York, signed a Declaration of Dependence in New York City at Fraunces Tavern in Manhattan pledging their loyalty to the Crown.[104]

History of the documents

The official copy of the Declaration of Independence was the one printed on July 4, 1776, under Jefferson's supervision. It was sent to the states and to the Army and was widely reprinted in newspapers. The slightly different "engrossed copy" (shown at the top of this article) was made later for members to sign. The engrossed version is the one widely distributed in the 21st century. Note that the opening lines differ between the two versions.[3]

The copy of the Declaration that was signed by Congress is known as the engrossed or parchment copy. It was probably engrossed (that is, carefully handwritten) by clerk Timothy Matlack.[105] A facsimile made in 1823 has become the basis of most modern reproductions rather than the original because of poor conservation of the engrossed copy through the 19th century.[105] In 1921, custody of the engrossed copy of the Declaration was transferred from the State Department to the Library of Congress, along with the United States Constitution.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the documents were moved for safekeeping to the United States Bullion Depository at Fort Knox in Kentucky, where they were kept until 1944.[106] In 1952, the engrossed Declaration was transferred to the National Archives and is now on permanent display at the National Archives in the "Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom".[107]

The document signed by Congress and enshrined in the National Archives is usually regarded as the Declaration of Independence, but historian Julian P. Boyd argued that the Declaration, like Magna Carta, is not a single document. Boyd considered the printed broadsides ordered by Congress to be official texts, as well. The Declaration was first published as a broadside that was printed the night of July 4 by John Dunlap of Philadelphia. Dunlap printed about 200 broadsides, of which 26 are known to survive. The 26th copy was discovered in The National Archives in England in 2009.[108]

In 1777, Congress commissioned Mary Katherine Goddard to print a new broadside that listed the signers of the Declaration, unlike the Dunlap broadside.[105][109] Nine copies of the Goddard broadside are known to still exist.[109] A variety of broadsides printed by the states are also extant, including seven copies of the Solomon Southwick broadside, one of which was acquired by Washington University in St. Louis in 2015.[109][110]

Several early handwritten copies and drafts of the Declaration have also been preserved. Jefferson kept a four-page draft that late in life he called the "original Rough draught".[111] Historians now understand that Jefferson's Rough draft was one in a series of drafts used by the Committee of Five before being submitted to Congress for deliberation. According to Boyd, the first, "original" handwritten draft of the Declaration of Independence that predated Jefferson's Rough draft, was lost or destroyed during the drafting process.[112] It is not known how many drafts Jefferson wrote prior to this one, and how much of the text was contributed by other committee members.

In 1947, Boyd discovered a fragment of an earlier draft in Jefferson's handwriting that predates Jefferson's Rough draft.[113] In 2018, the Thomas Paine National Historical Association published findings on an additional early handwritten draft of the Declaration, referred to as the "Sherman Copy", that John Adams copied from the lost original draft for Committee of Five members Roger Sherman and Benjamin Franklin's initial review. An inscription on the document noting "A beginning perhaps...", the early state of the text, and the manner in which this document was hastily taken, appears to chronologically place this draft earlier than both the fair Adams copy held in the Massachusetts Historical Society collection and the Jefferson "rough draft".[114] After the text was finalized by Congress as a whole, Jefferson and Adams sent copies of the rough draft to friends, with variations noted from the original drafts.

During the writing process, Jefferson showed the rough draft to Adams and Franklin, and perhaps to other members of the drafting committee,[111] who made a few more changes. Franklin, for example, may have been responsible for changing Jefferson's original phrase "We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable" to "We hold these truths to be self-evident".[1]: 1:427–28 Jefferson incorporated these changes into a copy that was submitted to Congress in the name of the committee.[111] The copy that was submitted to Congress on June 28 has been lost and was perhaps destroyed in the printing process,[115] or destroyed during the debates in accordance with Congress's secrecy rule.[116]

On April 21, 2017, it was announced that a second engrossed copy had been discovered in the archives at West Sussex County Council in Chichester, England.[117] Named by its finders the "Sussex Declaration", it differs from the National Archives copy (which the finders refer to as the "Matlack Declaration") in that the signatures on it are not grouped by States. How it came to be in England is not yet known, but the finders believe that the randomness of the signatures points to an origin with signatory James Wilson, who had argued strongly that the Declaration was made not by the States but by the whole people.[118][119]

Years of exposure to damaging lighting resulted in the original Declaration of Independence document having much of its ink fade by 1876.[120][121]

Legacy

The Declaration was given little attention in the years immediately following the American Revolution, having served its original purpose in announcing the independence of the United States.[10]: 87–88 [20]: 162, 168, 169 Early celebrations of Independence Day largely ignored the Declaration, as did early histories of the Revolution. The act of declaring independence was considered important, whereas the text announcing that act attracted little attention.[122][20]: 160 The Declaration was rarely mentioned during the debates about the United States Constitution, and its language was not incorporated into that document.[10]: 92 George Mason's draft of the Virginia Declaration of Rights was more influential, and its language was echoed in state constitutions and state bills of rights more often than Jefferson's words.[10]: 90 [20]: 165–167 "In none of these documents", wrote Pauline Maier, "is there any evidence whatsoever that the Declaration of Independence lived in men's minds as a classic statement of American political principles."[20]: 167

Global influence

Many leaders of the French Revolution admired the Declaration of Independence[20]: 167 but were also interested in the new American state constitutions.[10]: 82 The inspiration and content of the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789) emerged largely from the ideals of the American Revolution.[123] Lafayette prepared its key drafts, working closely in Paris with his friend Thomas Jefferson. It also borrowed language from George Mason's Virginia Declaration of Rights.[124][125] The declaration also influenced the Russian Empire, and it had a particular impact on the Decembrist revolt and other Russian thinkers.

According to historian David Armitage, the Declaration of Independence did prove to be internationally influential, but not as a statement of human rights. Armitage argues that the Declaration was the first in a new genre of declarations of independence which announced the creation of new states. Other French leaders were directly influenced by the text of the Declaration of Independence itself. The Manifesto of the Province of Flanders (1790) was the first foreign derivation of the Declaration;[10]: 113 others include the Venezuelan Declaration of Independence (1811), the Liberian Declaration of Independence (1847), the declarations of secession by the Confederate States of America (1860–61), and the Vietnamese Proclamation of Independence (1945).[10]: 120–135 These declarations echoed the United States Declaration of Independence in announcing the independence of a new state, without necessarily endorsing the political philosophy of the original.[10]: 104, 113

Other countries have used the Declaration as inspiration or have directly copied sections from it. These include the Haitian declaration of January 1, 1804, during the Haitian Revolution, the United Provinces of New Granada in 1811, the Argentine Declaration of Independence in 1816, the Chilean Declaration of Independence in 1818, Costa Rica in 1821, El Salvador in 1821, Guatemala in 1821, Honduras in 1821, Mexico in 1821, Nicaragua in 1821, Peru in 1821, Bolivian War of Independence in 1825, Uruguay in 1825, Ecuador in 1830, Colombia in 1831, Paraguay in 1842, Dominican Republic in 1844, Texas Declaration of Independence in March 1836, California Republic in November 1836, Hungarian Declaration of Independence in 1849, Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand in 1835, and the Czechoslovak declaration of independence from 1918 drafted in Washington, D.C., with Gutzon Borglum among the drafters. The Rhodesian declaration of independence is based on the American one, as well, ratified in November 1965, although it omits the phrases "all men are created equal" and "the consent of the governed".[100][126][127][128] The South Carolina declaration of secession from December 1860 also mentions the U.S. Declaration of Independence, though it omits references to "all men are created equal" and "consent of the governed".

Revival of interest

Interest in the Declaration was revived in the 1790s with the emergence of the United States's first political parties.[129] Throughout the 1780s, few Americans knew or cared who wrote the Declaration.[130] But in the next decade, Jeffersonian Republicans sought political advantage over their rival Federalists by promoting both the importance of the Declaration and Jefferson as its author.[131][20]: 168–171 Federalists responded by casting doubt on Jefferson's authorship or originality, and by emphasizing that independence was declared by the whole Congress, with Jefferson as just one member of the drafting committee. Federalists insisted that Congress's act of declaring independence, in which Federalist John Adams had played a major role, was more important than the document announcing it.[132][20]: 171 But this view faded away, like the Federalist Party itself, and, before long, the act of declaring independence became synonymous with the document.

A less partisan appreciation for the Declaration emerged in the years following the War of 1812, thanks to a growing American nationalism and a renewed interest in the history of the Revolution.[133]: 571–572 [20]: 175–178 In 1817, Congress commissioned John Trumbull's famous painting of the signers, which was exhibited to large crowds before being installed in the Capitol.[133]: 572 [20]: 175 The earliest commemorative printings of the Declaration also appeared at this time, offering many Americans their first view of the signed document.[133]: 572 [20]: 175–176 [134][135] Collective biographies of the signers were first published in the 1820s,[20]: 176 giving birth to what Garry Wills called the "cult of the signers".[136] In the years that followed, many stories about the writing and signing of the document were published for the first time.

Когда интерес к Декларации возродился, те разделы, которые были наиболее важными в 1776 году, уже не были актуальными: объявление независимости Соединенных Штатов и претензии к королю Георгу. Но второй параграф был применим еще долго после окончания войны с ее разговорами о самоочевидных истинах и неотъемлемых правах. [10] : 93 Идентичность естественного права с 18 века привела к все большему преобладанию политических и моральных норм по сравнению с законом природы, Бога или человеческой природы, как это наблюдалось в прошлом. [137] В Конституции и Билле о правах не хватало радикальных заявлений о правах и равенстве, и защитники групп, выражающих недовольство, обратились к Декларации за поддержкой. [20] : 196–197 Начиная с 1820-х годов выпускались варианты Декларации, провозглашающие права рабочих, фермеров, женщин и других лиц. [20] : 197 [138] В 1848 году, например, в Сенека-Фолс Конвенция защитников прав женщин провозгласила , что «все мужчины и женщины созданы равными». [20] : 197 [10] : 95

Джона Трамбулла Декларация независимости (1817–1826 гг.)

Джона Трамбалла Картина «Декларация независимости» сыграла значительную роль в популярных концепциях Декларации независимости. Картина размером 12 на 18 футов (3,7 на 5,5 м) была заказана Конгрессом США в 1817 году; он висит в ротонде Капитолия Соединенных Штатов с 1826 года. Иногда его называют подписанием Декларации независимости, но на самом деле на нем изображен Комитет пяти, представляющий свой проект Декларации Второму Континентальному Конгрессу 28 июня 1776 года. а не подписание документа, которое произошло позже. [140]

Трамбалл рисовал фигуры с натуры, когда это было возможно, но некоторые умерли, и изображения невозможно было найти; следовательно, на картине не изображены все подписавшие Декларацию. Один человек участвовал в разработке, но не подписал окончательный документ; другой отказался подписать. Фактически, состав Второго Континентального Конгресса со временем менялся, и фигуры на картине никогда не находились в одной комнате одновременно. Однако это точное изображение комнаты в Индепенденс-холле , центральной части Национального исторического парка Независимости в Филадельфии, штат Пенсильвания .

Картина Трамбулла неоднократно изображалась на валюте и почтовых марках США. Впервые его использовали на обратной стороне банкноты Национального банка стоимостью 100 долларов , выпущенной в 1863 году. Несколько лет спустя гравировка на стали, использованная при печати банкнот, была использована для изготовления марки номиналом 24 цента, выпущенной в рамках иллюстрированного выпуска 1869 года. . присутствует гравюра со сценой подписания контракта С 1976 года на обратной стороне двухдолларовой купюры США .

Рабство и Декларация

Очевидное противоречие между утверждением о том, что «все люди созданы равными» и существованием рабства в Соединенных Штатах, вызвало комментарии, когда Декларация была впервые опубликована. Многие из основателей понимали несовместимость утверждения о естественном равенстве с институтом рабства, но продолжали пользоваться «правами человека». [141] Джефферсон включил в свой первоначальный черновой проект Декларации независимости параграф, решительно осуждающий зло работорговли и осуждающий короля Георга III за навязывание ее колониям, но он был удален из окончательной версии. [20] : 146–150 [56]

Он вел жестокую войну против самой человеческой природы, нарушая ее священнейшие права на жизнь и свободу в людях далекого народа, никогда его не обижавшего, пленяя и уводя их в рабство в другом полушарии, или навлекая на себя несчастную смерть при их транспортировке сюда. . эта пиратская война, позор неверных держав, является войной христианского короля Великобритании. Будучи преисполнен решимости сохранить открытым рынок, на котором МУЖЧИНЫ должны покупаться и продаваться , он проституировал свой негатив за подавление каждой законодательной попытки запретить или ограничить эту отвратительную торговлю: и чтобы это сборище ужасов не нуждалось ни в одном факте выдающейся смерти, он теперь побуждая эти самые люди восстать среди нас с оружием в руках и купить ту свободу, которой он их лишил, убивая людей, которым он также навязывал их: расплачиваясь таким образом за прежние преступления, совершенные против свобод одного народа, преступлениями, которые он призывает их совершить действия против жизни другого человека.

Сам Джефферсон был известным рабовладельцем в Вирджинии , владевшим шестьюстами порабощенных африканцев на своей в Монтичелло плантации . [142] Ссылаясь на это противоречие, английский аболиционист Томас Дэй писал в письме 1776 года: «Если и существует предмет по-настоящему смешной по своей природе, так это американский патриот, одной рукой подписывающий резолюции о независимости, а другой размахивающий кнутом над своим испуганные рабы». [10] [143] Афро-американский писатель Лемюэль Хейнс выразил аналогичные точки зрения в своем эссе «Расширенная свобода», где он написал, что «Свобода одинаково ценна для чернокожего человека, как и для белого». [144]

В XIX веке Декларация приобрела особое значение для аболиционистского движения. Историк Бертрам Вятт-Браун писал, что «аболиционисты склонны интерпретировать Декларацию независимости как теологический, так и политический документ». [145] Лидеры аболиционистов Бенджамин Ланди и Уильям Ллойд Гаррисон приняли «камни-близнецы» «Библии и Декларации независимости» в качестве основы своей философии. Он написал: «Пока на нашей земле останется хотя бы один экземпляр Декларации независимости или Библии, мы не будем отчаиваться». [146] Для радикальных аболиционистов, таких как Гаррисон, самой важной частью Декларации было утверждение права на революцию . Гаррисон призвал к разрушению правительства, основанного на Конституции, и созданию нового государства, приверженного принципам Декларации. [20] : 198–199

5 июля 1852 года Фредерик Дуглас произнес речь, задав вопрос: « Что для раба четвертое июля? ».

Спорный вопрос о том, следует ли допускать в состав Соединенных Штатов дополнительные рабовладельческие штаты , совпал с растущим авторитетом Декларации. Первые крупные публичные дебаты о рабстве и Декларации произошли во время споров в Миссури 1819–1821 годов. [147] Конгрессмены, выступающие против рабства, утверждали, что формулировка Декларации указывает на то, что отцы-основатели Соединенных Штатов были против рабства в принципе, и поэтому к стране не следует добавлять новые рабовладельческие штаты. [147] : 604 Конгрессмены, выступающие за рабство, во главе с сенатором от Северной Каролины Натаниэлем Мейконом утверждали, что Декларация не является частью Конституции и, следовательно, не имеет отношения к данному вопросу. [147] : 605

Поскольку аболиционистское движение набирало обороты, защитники рабства, такие как Джон Рэндольф и Джон К. Кэлхун, сочли необходимым доказать, что утверждение Декларации о том, что «все люди созданы равными», было ложным или, по крайней мере, что оно не распространялось на чернокожих людей. . [20] : 199 [13] : 246 во время дебатов по Закону Канзаса-Небраски Например, в 1853 году сенатор Джон Петтит от Индианы утверждал, что утверждение «все люди созданы равными» было не «самоочевидной истиной», а «самоочевидной ложью». [20] : 200 Противники Закона Канзаса-Небраски, в том числе Сэлмон П. Чейз и Бенджамин Уэйд , защищали Декларацию и то, что они считали ее антирабовладельческими принципами. [20] : 200–201

Декларация свободы Джона Брауна

Готовясь к набегу на Харперс-Ферри , который, по словам Фредерика Дугласа, стал началом конца рабства в Соединённых Штатах , [148] : 27–28 аболиционист Джон Браун напечатал много экземпляров Временной конституции . Когда 16 месяцев спустя отделившиеся штаты создали Конфедеративные Штаты Америки , они более года действовали в соответствии с Временной конституцией . В нем очерчены три ветви власти в квази-стране, которую он надеялся создать в Аппалачах . Оно было широко воспроизведено в прессе и полностью в отчете Специального комитета Сената о восстании Джона Брауна (« Отчет Мейсона» ). [149]

Браун не напечатал ее, а его Декларация свободы, датированная 4 июля 1859 года, была найдена среди его бумаг на ферме Кеннеди . [150] : 330–331 Его записывали на листах бумаги, прикрепленных к ткани, чтобы его можно было свернуть, и сворачивали, когда находили. Рука принадлежит Оуэну Брауну своего отца , который часто был секретарем . [151]

Имитируя словарный запас, пунктуацию и использование заглавных букв Декларации США 73-летней давности, документ из 2000 слов начинается так:

4 июля 1859 г.

Декларация свободы

Представители рабского населения [ sic ] Соединенных Штатов АмерикиКогда в ходе человеческих событий становится необходимым, чтобы угнетенный народ восстал и отстоял свои естественные права как человеческие существа, как коренные и общие граждане свободной республики, и сломал это одиозное иго угнетения, которое так несправедливо возложенные на них их соотечественниками, и принять среди сил Земли те же равные привилегии, которые им дают Законы Природы и природы Бога; Умеренное уважение к мнению Человечества требует, чтобы оно заявляло о причинах, побуждающих его к этому справедливому и достойному действию.

Мы считаем эти истины самоочевидными; Что все люди созданы равными; Что их Создатель наделил их определенными неотъемлемыми правами. Среди них — Жизнь, Свобода; и стремление к счастью. Природа щедро дала всем людям полный запас воздуха. Вода и Земля; для их существования и взаимного счастья ни один человек не имеет права лишать своего ближнего этих неотъемлемых прав, кроме как в наказание за преступление. Что для обеспечения этих прав среди людей учреждаются правительства, черпающие свою справедливую власть из согласия управляемых. Что, когда какая-либо форма правления становится разрушительной для этих целей, народ имеет право изменять, дополнять или переделывать ее, закладывая ее основу на таких принципах и организуя свою власть в такой форме, которая, по его мнению, будет наиболее вероятно, повлияет на безопасность и счастье человеческой расы. [152]

Документ, очевидно, предназначался для чтения вслух, но, насколько известно, Браун так и не сделал этого, хотя он прочитал Временную конституцию вслух в день начала рейда на Харперс-Ферри. [153] : 74 Прекрасно зная историю Американской революции , он прочитал бы Декларацию вслух после начала восстания. Документ не был опубликован до 1894 года, причем кем-то, кто не осознавал его важности и похоронил его в приложении к документам. [150] : 637–643 Он отсутствует в большинстве, но не во всех исследованиях Джона Брауна. [154] [153] : 69–73

Линкольн и Декларация

Связь Декларации с рабством была поднята в 1854 году Авраамом Линкольном , малоизвестным бывшим конгрессменом, боготворившим отцов-основателей. [20] : 201–202 Линкольн считал, что Декларация независимости отражает высшие принципы Американской революции и что отцы-основатели терпели рабство, ожидая, что оно в конечном итоге исчезнет. [9] : 126 По мнению Линкольна, для Соединенных Штатов узаконить расширение рабства в Законе Канзаса-Небраски означало бы отказаться от принципов Революции. В своей речи в Пеории в октябре 1854 года Линкольн сказал:

Почти восемьдесят лет назад мы начали с заявления, что все люди созданы равными; но теперь, начиная с этого начала, мы перешли к другому заявлению, что для одних людей порабощение других является «священным правом самоуправления». ... Наше республиканское платье запачкано и в пыли. ... Давайте заново очистим его. Давайте вновь примем Декларацию независимости, а вместе с ней и практику и политику, которые с ней гармонируют. ... Если мы сделаем это, мы не только спасем Союз, но и спасем его, чтобы сделать и сохранить его навсегда достойным спасения. [9] : 126–127

Смысл Декларации был постоянной темой в знаменитых дебатах между Линкольном и Стивеном Дугласом в 1858 году. Дуглас утверждал, что фраза «все люди созданы равными» в Декларации относится только к белым мужчинам. Целью Декларации, по его словам, было просто оправдать независимость Соединенных Штатов, а не провозгласить равенство какой-либо «неполноценной или деградировавшей расы». [20] : 204 Линкольн, однако, считал, что язык Декларации был намеренно универсальным, устанавливающим высокие моральные стандарты, к которым должна стремиться американская республика. «Я думал, что Декларация предусматривает постепенное улучшение условий жизни всех людей во всем мире», - сказал он. [20] : 204–205 Во время седьмых и последних совместных дебатов со Стивеном Дугласом в Олтоне, штат Иллинойс, 15 октября 1858 года Линкольн сказал о декларации:

Я думаю, что авторы этого замечательного документа намеревались включить в него всех людей, но они не имели в виду объявить всех людей равными во всех отношениях. Они не имели в виду, что все люди равны по цвету кожи, размеру, интеллекту, моральному развитию или социальным способностям. Они с терпимой четкостью определили, что, по их мнению, все люди созданы равными — равными в «определенных неотъемлемых правах, среди которых жизнь, свобода и стремление к счастью». Это они сказали, и это они имели в виду. Они не имели в виду очевидную неправду о том, что все тогда действительно наслаждались этим равенством, или что они собирались немедленно им его предоставить. На самом деле у них не было власти даровать такое благо. Они имели в виду просто провозгласить это право, чтобы обеспечить его соблюдение настолько быстро, насколько позволят обстоятельства. Они намеревались установить стандартную максиму свободного общества, которая должна была быть знакома всем, на которую постоянно смотрели, постоянно трудились и даже, хотя никогда и не достигали ее в совершенстве, постоянно приближались к ней и тем самым постоянно распространяли и углубляли ее влияние и увеличивали счастье. и ценность жизни для всех людей, любого цвета кожи, повсюду. [155]

По словам Полины Майер, интерпретация Дугласа была более исторически точной, но в конечном итоге точка зрения Линкольна возобладала. «В руках Линкольна, — писал Майер, — Декларация независимости стала прежде всего живым документом» с «набором целей, которые необходимо было реализовать с течением времени». [20] : 207

[T] В мире нет причины, по которой негр не имел бы права на все естественные права, перечисленные в Декларации независимости, право на жизнь, свободу и стремление к счастью. Я считаю, что он имеет на это такое же право, как и белый человек.

—Авраам Линкольн, 1858 г. [156] : 100

Подобно Дэниелу Вебстеру , Джеймсу Уилсону и Джозефу Стори до него, Линкольн утверждал, что Декларация независимости была основополагающим документом Соединенных Штатов и что это имело важные последствия для толкования Конституции, которая была ратифицирована более чем через десять лет после Декларация. [156] : 129–131 В Конституции не использовалось слово «равенство», однако Линкольн считал, что концепция «все люди созданы равными» остается частью основополагающих принципов нации. [156] : 145 Он, как известно, выразил это убеждение, ссылаясь на 1776 год, в первом предложении своей Геттисбергской речи 1863 года : «Четыре двадцати и семь лет назад наши отцы создали на этом континенте новую нацию, зачатую в Свободе и посвятившую себя идее, что все люди созданы равными».

Взгляд Линкольна на Декларацию стал влиятельным, поскольку он рассматривал ее как моральное руководство по толкованию Конституции. «Сейчас для большинства людей, — писал Гарри Уиллс в 1992 году, — Декларация означает то, что нам сказал Линкольн, — как способ исправить саму Конституцию, не отменяя ее». [156] : 147 Поклонники Линкольна, такие как Гарри В. Яффо, высоко оценили это развитие. Критики Линкольна, особенно Уиллмур Кендалл и Мел Брэдфорд , утверждали, что Линкольн опасно расширил сферу деятельности национального правительства и нарушил права штатов, включив Декларацию в Конституцию. [156] : 39, 145, 146 [157] [158] [159] [160]

Избирательное право женщин и Декларация

В июле 1848 года в Сенека , штат Нью-Йорк, состоялся -Фолс первый съезд по правам женщин. Его организовали Элизабет Кэди Стэнтон , Лукреция Мотт , Мэри Энн МакКлинток и Джейн Хант. Они создали свою « Декларацию чувств » по образцу Декларации независимости, в которой они требовали социального и политического равенства для женщин. Их девизом было: «Все мужчины и женщины созданы равными», и они требовали права голоса. [161] [162] Отрывок из «Декларации чувств»: