Квакеры

| Религиозное общество друзей | |

|---|---|

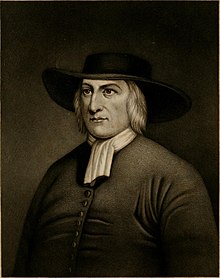

Джордж Фокс , главный ранний лидер квакеров | |

| Theology | Variable; depends on meeting |

| Polity | Congregational |

| Distinct fellowships | Friends World Committee for Consultation |

| Associations | Britain Yearly Meeting, Friends United Meeting, Evangelical Friends Church International, Central Yearly Meeting of Friends, Conservative Friends, Friends General Conference, Beanite Quakerism |

| Founder | George Fox Margaret Fell |

| Origin | Mid-17th century England |

| Separated from | Church of England |

| Separations | Shakers[1] |

| Part of a series on |

| Quakerism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Protestantism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Квакеры – это люди, принадлежащие к обществу друзей , исторически протестантской христианской конфессии Религиозному . Члены движения называют друг друга «Друзьями» после Иоанна 15:14 в Библии, а первоначально другие называли их квакерами, поскольку основатель движения Джордж Фокс велел судье трепетать «перед властью Божьей». [2] Друзей обычно объединяет вера в способность каждого человека руководствоваться внутренним светом, чтобы «сделать свидетельство Божье» известным всем. [3] [4] Квакеры традиционно исповедовали священство всех верующих, вдохновленные Первым посланием Петра . [5] [6] [7] [8] В их число входят те, кто придерживается евангелического , святого , либерального и традиционного квакерского понимания христианства, а также квакеры-нетеисты . В разной степени Друзья избегают вероисповеданий и иерархических структур . [9] In 2017, there were an estimated 377,557 adult Quakers, 49% of them in Africa.[10]

Some 89% of Quakers worldwide belong to evangelical and programmed branches that hold services with singing and a prepared Bible message coordinated by a pastor (with the largest Quaker group being the Evangelical Friends Church International).[11][12] Some 11% practice waiting worship or unprogrammed worship (commonly Meeting for Worship),[13] where the unplanned order of service is mainly silent and may include unprepared vocal ministry from those present. Some meetings of both types have Recorded Ministers present, Friends recognised for their gift of vocal ministry.[14]

The proto-evangelical Christian movement dubbed Quakerism arose in mid-17th-century England from the Legatine-Arians and other dissenting Protestant groups breaking with the established Church of England.[15] The Quakers, especially the Valiant Sixty, sought to convert others by travelling through Britain and overseas preaching the Gospel. Some early Quaker ministers were women.[16] They based their message on a belief that "Christ has come to teach his people himself", stressing direct relations with God through Jesus Christ and belief in the universal priesthood of all believers.[17] This personal religious experience of Christ was acquired by direct experience and by reading and studying the Bible.[18] Friends focused their private lives on behaviour and speech reflecting emotional purity and the light of God, with a goal of Christian perfection.[19][20] A prominent theological text of the Religious Society of Friends is A Catechism and Confession of Faith (1673), published by Quaker divine Robert Barclay.[21][22] The Richmond Declaration of Faith (1887) was adopted by many Orthodox Friends and continues to serve as a doctrinal statement of many yearly meetings.[23][24]

Quakers were known to use thee as an ordinary pronoun, refuse to participate in war, wear plain dress, refuse to swear oaths, oppose slavery, and practice teetotalism.[25] Some Quakers founded banks and financial institutions, including Barclays, Lloyds, and Friends Provident; manufacturers including the footwear firm of C. & J. Clark and the big three British confectionery makers Cadbury, Rowntree and Fry; and philanthropic efforts, including abolition of slavery, prison reform, and social justice.[26] In 1947, in recognition of their dedication to peace and the common good, Quakers represented by the British Friends Service Council and the American Friends Service Committee were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.[27][28]

History[edit]

Beginnings in England[edit]

During and after the English Civil War (1642–1651) many dissenting Christian groups emerged, including the Seekers and others. A young man, George Fox, was dissatisfied with the teachings of the Church of England and nonconformists. He claimed to have received a revelation that "there is one, even Christ Jesus, who can speak to thy condition",[29] and became convinced that it was possible to have a direct experience of Christ without the aid of ordained clergy. In 1652 he had a vision on Pendle Hill in Lancashire, England, in which he believed that "the Lord let me see in what places he had a great people to be gathered".[29] Following this he travelled around England, the Netherlands,[30] and Barbados[31] preaching and teaching with the aim of converting new adherents to his faith. The central theme of his Gospel message was that Christ has come to teach his people himself.[29] Fox considered himself to be restoring a true, "pure" Christian church.[32]

In 1650, Fox was brought before the magistrates Gervase Bennet and Nathaniel Barton, on a charge of religious blasphemy. According to Fox's autobiography, Bennet "was the first that called us Quakers, because I bade them tremble at the word of the Lord".[29]: 125 It is thought that Fox was referring to Isaiah 66:2 or Ezra 9:4. Thus the name Quaker began as a way of ridiculing Fox's admonition, but became widely accepted and used by some Quakers.[33] Quakers also described themselves using terms such as true Christianity, Saints, Children of the Light, and Friends of the Truth, reflecting terms used in the New Testament by members of the early Christian church.

Quakerism gained a considerable following in England and Wales, not least among women. An address "To the Reader" by Mary Forster accompanied a Petition to the Parliament of England presented on 20 May 1659, expressing the opposition of over 7000 women to "the oppression of Tithes".[34] The overall number of Quakers increased to a peak of 60,000 in England and Wales by 1680[35] (1.15% of the population of England and Wales).[35] But the dominant discourse of Protestantism viewed the Quakers as a blasphemous challenge to social and political order,[36] leading to official persecution in England and Wales under the Quaker Act 1662 and the Conventicle Act 1664. This persecution of Dissenters was relaxed after the Declaration of Indulgence (1687–1688) and stopped under the Act of Toleration 1689.

One modern view of Quakerism at this time was that the direct relationship with Christ was encouraged through spiritualisation of human relations, and "the redefinition of the Quakers as a holy tribe, 'the family and household of God'".[37] Together with Margaret Fell, the wife of Thomas Fell, who was the vice-chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and an eminent judge, Fox developed new conceptions of family and community that emphasised "holy conversation": speech and behaviour that reflected piety, faith, and love.[38] With the restructuring of the family and household came new roles for women; Fox and Fell viewed the Quaker mother as essential to developing "holy conversation" in her children and husband.[37] Quaker women were also responsible for the spirituality of the larger community, coming together in "meetings" that regulated marriage and domestic behaviour.[39]

Migration to North America[edit]

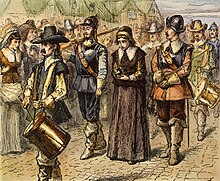

The persecution of Quakers in North America began in July 1656 when English Quaker missionaries Mary Fisher and Ann Austin began preaching in Boston.[40] They were considered heretics because of their insistence on individual obedience to the Inward light. They were imprisoned for five weeks and banished[40] by the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Their books were burned,[40] and most of their property confiscated. They were imprisoned in terrible conditions, then deported.[41]

In 1660, English Quaker Mary Dyer was hanged near[42] Boston Common for repeatedly defying a Puritan law banning Quakers from the colony.[43] She was one of the four executed Quakers known as the Boston martyrs. In 1661, King Charles II forbade Massachusetts from executing anyone for professing Quakerism.[44] In 1684, England revoked the Massachusetts charter, sent over a royal governor to enforce English laws in 1686 and, in 1689, passed a broad Toleration Act.[44]

Some Friends migrated to what is now the north-eastern region of the United States in the 1660s in search of economic opportunities and a more tolerant environment in which to build communities of "holy conversation".[45] In 1665 Quakers established a meeting in Shrewsbury, New Jersey (now Monmouth County), and built a meeting house in 1672 that was visited by George Fox in the same year.[46] They were able to establish thriving communities in the Delaware Valley, although they continued to experience persecution in some areas, such as New England. The three colonies that tolerated Quakers at this time were West Jersey, Rhode Island, and Pennsylvania, where Quakers established themselves politically. In Rhode Island, 36 governors in the first 100 years were Quakers. West Jersey and Pennsylvania were established by affluent Quaker William Penn in 1676 and 1682 respectively, with Pennsylvania as an American commonwealth run under Quaker principles. William Penn signed a peace treaty with Tammany, leader of the Delaware tribe,[47] and other treaties followed between Quakers and Native Americans.[32] This peace endured almost a century, until the Penn's Creek Massacre of 1755.[48] Early colonial Quakers also established communities and meeting houses in North Carolina and Maryland, after fleeing persecution by the Anglican Church in Virginia.[49]

In a 2007 interview, author David Yount (How the Quakers Invented America) said that Quakers first introduced many ideas that later became mainstream, such as democracy in the Pennsylvania legislature, the Bill of Rights to the U.S. Constitution from Rhode Island Quakers, trial by jury, equal rights for men and women, and public education. The Liberty Bell was cast by Quakers in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[50]

Quietism[edit]

Early Quakerism tolerated boisterous behaviour that challenged conventional etiquette, but by 1700, its adherents no longer supported disruptive and unruly behaviour.[51] During the 18th century, Quakers entered the Quietist period in the history of their church, becoming more inward-looking spiritually and less active in converting others. Marrying outside the Society was cause for having one's membership revoked. Numbers dwindled, dropping to 19,800 in England and Wales by 1800 (0.21% of the population),[35] and 13,859 by 1860 (0.07% of population).[35] The formal name "Religious Society of Friends" dates from this period and was probably derived from the appellations "Friends of the Light" and "Friends of the Truth".[52]

| Divisions of the Religious Society of Friends | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Showing the divisions of Quakers occurring in the 19th and 20th centuries |

Splits[edit]

Around the time of the American Revolutionary War, some American Quakers split from the main Society of Friends over issues such as support for the war, forming groups such as the Free Quakers and the Universal Friends.[53] Later, in the 19th century, there was a diversification of theological beliefs in the Religious Society of Friends, and this led to several larger splits within the movement.

Hicksite–Orthodox split[edit]

The Hicksite–Orthodox split arose out of both ideological and socioeconomic tensions. Philadelphia Yearly Meeting Hicksites tended to be agrarian and poorer than the more urban, wealthier, Orthodox Quakers. With increasing financial success, Orthodox Quakers wanted to "make the Society a more respectable body – to transform their sect into a church – by adopting mainstream Protestant orthodoxy".[54] Hicksites, though they held a variety of views, generally saw the market economy as corrupting, and believed Orthodox Quakers had sacrificed their orthodox Christian spirituality for material success. Hicksites viewed the Bible as secondary to the individual cultivation of God's light within.[55]

With Gurneyite Quakers' shift toward Protestant principles and away from the spiritualisation of human relations, women's role as promoters of "holy conversation" started to decrease. Conversely, within the Hicksite movement the rejection of the market economy and the continuing focus on community and family bonds tended to encourage women to retain their role as powerful arbiters.

Elias Hicks's religious views were claimed to be universalist and to contradict Quakers' historical orthodox Christian beliefs and practices. Hicks' Gospel preaching and teaching precipitated the Great Separation of 1827, which resulted in a parallel system of Yearly Meetings in America, joined by Friends from Philadelphia, New York, Ohio, Indiana, and Baltimore. They were referred to by opponents as Hicksites and by others and sometimes themselves as Orthodox. Quakers in Britain recognised only the Orthodox Quakers and refused to correspond with the Hicksites.

Beaconite controversy[edit]

Isaac Crewdson was a Recorded Minister in Manchester. His 1835 book A Beacon to the Society of Friends insisted that the inner light was at odds with a religious belief in salvation by the atonement of Christ.[56]: 155 This Christian controversy led to Crewdson's resignation from the Religious Society of Friends, along with 48 fellow members of Manchester Meeting and about 250 other British Quakers in 1836–1837. Some of these joined the Plymouth Brethren.

Rise of Gurneyite Quakerism, and the Gurneyite–Conservative split[edit]

Orthodox Friends became more evangelical during the 19th century[57] and were influenced by the Second Great Awakening. This movement was led by British Quaker Joseph John Gurney. Christian Friends held Revival meetings in America and became involved in the Holiness movement of churches. Quakers such as Hannah Whitall Smith and Robert Pearsall Smith became speakers in the religious movement and introduced Quaker phrases and practices to it.[56]: 157 British Friends became involved with the Higher Life movement, with Robert Wilson from the Cockermouth meeting founding the Keswick Convention.[56]: 157 From the 1870s it became common in Britain to have "home mission meetings" on Sunday evening with Christian hymns and a Bible-based sermon, alongside the silent meetings for worship on Sunday morning.[56]: 155

The Quaker Yearly Meetings supporting the religious beliefs of Joseph John Gurney were known as Gurneyite yearly meetings. Many eventually collectively became the Five Years Meeting (FYM) and then the Friends United Meeting, although London Yearly Meeting, which had been strongly Gurneyite in the 19th century, did not join either of these. In 1924, the Central Yearly Meeting of Friends, a Gurneyite yearly meeting, was started by some Friends who left the Five Years Meeting due to a concern of what they saw as the allowance of modernism in the FYM.[58]

Some Orthodox Quakers in America disliked the move towards evangelical Christianity and saw it as a dilution of Friends' traditional orthodox Christian belief in being inwardly led by the Holy Spirit. These Friends were headed by John Wilbur, who was expelled from his yearly meeting in 1842. He and his supporters formed their own Conservative Friends Yearly Meeting. Some UK Friends broke away from the London Yearly Meeting for the same reason in 1865. They formed a separate body of Friends called Fritchley General Meeting, which remained distinct and separate from London Yearly Meeting until 1968. Similar splits took place in Canada. The Yearly Meetings that supported John Wilbur's religious beliefs became known as Conservative Friends.

Richmond Declaration[edit]

In 1887, a Gurneyite Quaker of British descent, Joseph Bevan Braithwaite, proposed to Friends a statement of faith known as the Richmond Declaration. This statement of faith was agreed to by 95 of the representatives at a meeting of Five Years Meeting Friends, but unexpectedly the Richmond Declaration was not adopted by London Yearly Meeting because a vocal minority, including Edward Grubb, opposed it.[59]

Missions to Asia and Africa[edit]

Following the Christian revivals in the mid-19th century, Friends in Great Britain sought also to start missionary activity overseas. The first missionaries were sent to Benares (Varanasi), in India, in 1866. The Friends Foreign Mission Association was formed in 1868 and sent missionaries to Madhya Pradesh, India, forming what is now the Mid-India Yearly Meeting. Later it spread to Madagascar from 1867, China from 1896, Sri Lanka from 1896, and Pemba Island from 1897.[60]

The Friends Syrian Mission was established in 1874, which among other institutions ran the Ramallah Friends Schools, which still exist today. The Swiss missionary Theophilus Waldmeier founded Brummana High School in Lebanon in 1873,[60] Evangelical Friends Churches from Ohio Yearly Meeting sent missionaries to India in 1896,[61] forming what is now Bundelkhand Yearly Meeting. Cleveland Friends went to Mombasa, Kenya, and started what became the most successful Friends' mission. Their Quakerism spread within Kenya and to Uganda, Tanzania, Burundi, and Rwanda.

Theory of evolution[edit]

The theory of evolution as described in Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species (1859) was opposed by many Quakers in the 19th century,[62] particularly by older evangelical Quakers who dominated the Religious Society of Friends in Great Britain. These older Quakers were suspicious of Darwin's theory and believed that natural selection could not explain life on its own.[63] The influential Quaker scientist Edward Newman[64] said that the theory was "not compatible with our notions of creation as delivered from the hands of a Creator".

However, some young Friends such as John Wilhelm Rowntree and Edward Grubb supported Darwin's theories, using the doctrine of progressive revelation.[63] In the United States, Joseph Moore taught the theory of evolution at the Quaker Earlham College as early as 1861.[65] This made him one of the first teachers to do so in the Midwest.[66] Acceptance of the theory of evolution became more widespread in Yearly Meetings who moved toward liberal Christianity in the 19th and 20th centuries.[67] However, creationism predominates within evangelical Friends Churches, particularly in East Africa and parts of the United States.

Quaker Renaissance[edit]

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, the so-called Quaker Renaissance movement began within London Yearly Meeting. Young Friends in London Yearly Meeting at this time moved away from evangelicalism and towards liberal Christianity.[68] This movement was particularly influenced by Rowntree, Grubb, and Rufus Jones. Such Liberal Friends promoted the theory of evolution, modern biblical criticism, and the social meaning of Christ's teaching – encouraging Friends to follow the New Testament example of Christ by performing good works. These men downplayed the evangelical Quaker belief in the atonement of Christ on the Cross at Calvary.[68] After the Manchester Conference in England in 1895, one thousand British Friends met to consider the future of British Quakerism, and as a result, Liberal Quaker thought gradually increased within the London Yearly Meeting.[69]

Conscientious objection[edit]

During World War I and World War II, Friends' opposition to war was put to the test. Many Friends became conscientious objectors and some formed the Friends Ambulance Unit, aiming at "co-operating with others to build up a new world rather than fighting to destroy the old", as did the American Friends Service Committee. Birmingham in England had a strong Quaker community during the war.[70] Many British Quakers were conscripted into the Non-Combatant Corps during both world wars.

World Committee for Consultation[edit]

After the two world wars had brought the different Quaker strands closer together, Friends from different yearly meetings – many having served together in the Friends Ambulance Unit or the American Friends Service Committee, or in other relief work – later held several Quaker World Conferences. This brought about a standing body of Friends: the Friends World Committee for Consultation.

Evangelical Friends[edit]

A growing desire for a more fundamentalist approach among some Friends after the First World War began a split among Five Years Meetings. In 1924, the Central Yearly Meeting of Friends was started by some Friends who left the Five Years Meeting.[58] In 1926, Oregon Yearly Meeting seceded from the Five Years Meeting, bringing together several other yearly meetings and scattered monthly meetings.

In 1947, the Association of Evangelical Friends was formed, with triennial meetings until 1970. In 1965, this was replaced by the Evangelical Friends Alliance, which in 1989 became Evangelical Friends Church International.[71]

Role of women[edit]

In the 1650s, individual Quaker women prophesied and preached publicly, developing charismatic personae and spreading the sect. This practice was bolstered by the movement's firm concept of spiritual equality for men and women.[72] Moreover, Quakerism initially was propelled by the nonconformist behaviours of its followers, especially women who broke from social norms.[73] By the 1660s, the movement had gained a more structured organisation, which led to separate women's meetings.[74] Through the women's meetings, women oversaw domestic and community life, including marriage.[39] From the beginning, Quaker women, notably Margaret Fell, played an important role in defining Quakerism.[75][76] Others active in proselytising included Mary Penington, Mary Mollineux and Barbara Blaugdone.[77] Quaker women published at least 220 texts during the 17th century.[78] However, some Quakers resented the power of women in the community.

In the early years of Quakerism, George Fox faced resistance in developing and establishing women's meetings. As controversy increased, Fox did not fully adhere to his agenda. For example, he established the London Six Weeks Meeting in 1671 as a regulatory body, led by 35 women and 49 men.[79] Even so, conflict culminated in the Wilkinson–Story split, in which a portion of the Quaker community left to worship independently in protest at women's meetings.[80] After several years, this schism became largely resolved, testifying to the resistance of some within the Quaker community and to the spiritual role of women that Fox and Margaret Fell had encouraged. Particularly within the relatively prosperous Quaker communities of the eastern United States, the focus on the child and "holy conversation" gave women unusual community power, although they were largely excluded from the market economy. With the Hicksite–Orthodox split of 1827–1828, Orthodox women found their spiritual role decreased, while Hicksite women retained greater influence.

Friends in business and education[edit]

Described as "natural capitalists" by the BBC, many Quakers were successful in a variety of industries.[26][81] Two notable examples were Abraham Darby I and Edward Pease. Darby and his family played an important role in the British Industrial Revolution with their innovations in ironmaking.[82][83] Pease, a Darlington manufacturer, was the main promoter of the Stockton and Darlington Railway, which was the world's first public railway to use steam locomotives.[81] Other industries with prominent Quaker businesses included banking (Lloyds Banking Group and Barclays PLC), pharmaceuticals (Allen & Hanburys), chocolate (Cadbury and Fry's), confectionery (Rowntree), shoe manufacturing (Clarks), and biscuit manufacturing (Huntley & Palmers).[26][83][84]

Quakers have a long history of establishing educational institutions. Initially, Quakers had no ordained clergy, and therefore needed no seminaries for theological training. In England, Quaker schools sprang up soon after the movement emerged, with Friends School Saffron Walden being the most prominent.[85] Quaker schools in the UK and Ireland are supported by The Friends' Schools' Council.[86] In Australia, Friends' School, Hobart, founded in 1887, has grown into the largest Quaker school in the world. In Britain and the United States, friends have established a variety of institutions at a variety of educational levels. In Kenya, Quakers founded several primary and secondary schools in the first half of the 20th century before the country's independence in 1963.[87]

International development[edit]

International volunteering organisations such as Service Civil International and International Voluntary Service were founded by leading Quakers. Eric Baker, a prominent Quaker, was one of the founders of Amnesty International and of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.[88]

The Quaker Edith Pye established a national Famine Relief Committee in May 1942, encouraging a network of local famine relief committees, among the most energetic of which was the Oxford Committee for Famine Relief, Oxfam.[89] Irving and Dorothy Stowe co-founded Greenpeace with many other environmental activists in 1971, shortly after becoming Quakers.[90]

Friends and slavery[edit]

Some Quakers in America and Britain became known for their involvement in the abolitionist movement. In the early history of Colonial America, it was fairly common for Friends to own slaves, e.g. in Pennsylvania. During the early to mid-1700s, disquiet about this practice arose among Friends, best exemplified by the testimonies of Benjamin Lay, Anthony Benezet and John Woolman, and this resulted in an abolition movement among Friends.

Nine of the twelve founding members of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, or The Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, were Quakers:[91] John Barton (1755–1789); William Dillwyn (1743–1824); George Harrison (1747–1827); Samuel Hoare Jr (1751–1825); Joseph Hooper (1732–1789); John Lloyd; Joseph Woods Sr (1738–1812); James Phillips (1745–1799); and Richard Phillips.[92] Five of the Quakers had been amongst the informal group of six Quakers who had pioneered the movement in 1783, when the first petition against the slave trade was presented to Parliament. As Quakers could not serve as Members of Parliament, they relied on the help of Anglican men who could, such as William Wilberforce and his brother-in-law James Stephen.

By the beginning of the American Revolutionary War, few Friends owned slaves. At the war's end in 1783, Yarnall family members along with fellow Meeting House Friends made a failed petition to the Continental Congress to abolish slavery in the United States. In 1790, the Society of Friends petitioned the United States Congress to abolish slavery.[93]

One example of a reversal in sentiment about slavery took place in the life of Moses Brown, one of four Rhode Island brothers who, in 1764, organized and funded the tragic and fateful voyage of the slave ship Sally.[94] Brown broke away from his three brothers, became an abolitionist, and converted to Christian Quakerism. During the 19th century, Quakers such as Levi Coffin and Isaac Hopper played a major role in helping enslaved people escape through the Underground Railroad.[95] Black Quaker Paul Cuffe, a sea captain and businessman, was active in the abolitionist and resettlement movement in the early part of that century.[96] Quaker Laura Smith Haviland, with her husband, established the first station on the Underground Railroad in Michigan. Later, Haviland befriended Sojourner Truth, who called her the Superintendent of the Underground Railroad.[97]

However, in the 1830s, the abolitionist Grimké sisters dissociated themselves from the Quakers "when they saw that Negro Quakers were segregated in separate pews in the Philadelphia meeting house".[98]

Theology[edit]

Quakers' theological beliefs vary considerably. Tolerance of dissent widely varies among yearly meetings.[99] Most Friends believe in continuing revelation: that God continuously reveals truth directly to individuals. George Fox, an "early Friend", said, "Christ has come to teach His people Himself".[29] Friends often focus on trying to feel the presence of God. As Isaac Penington wrote in 1670, "It is not enough to hear of Christ, or read of Christ, but this is the thing – to feel him to be my root, my life, and my foundation..."[100] Quakers reject the idea of priests, believing in the priesthood of all believers. Some express their concept of God using phrases such as "the inner light", "inward light of Christ", or "Holy Spirit".[101]

Diverse theological beliefs, understandings of the "leading of the Holy Spirit" and statements of "faith and practice" have always existed among Friends.[102] Due in part to the emphasis on immediate guidance of the Holy Spirit, Quaker doctrines have only at times been codified as statements of faith, confessions or theological texts. Those that exist include the Letter to the Governor of Barbados (Fox, 1671),[103] An Apology for the True Christian Divinity (Barclay, 1678),[104] A Catechism and Confession of Faith (Barclay, 1690),[105] The Testimony of the Society of Friends on the Continent of America (adopted jointly by all Orthodox yearly meetings in the United States, 1830),[106] the Richmond Declaration of Faith (adopted by Five Years Meeting, 1887),[107] and Essential Truths (Jones and Wood, adopted by Five Years Meeting, 1922).[108] Most yearly meetings make a public statement of faith in their own Book of Discipline, expressing Christian discipleship within the experience of Friends in that yearly meeting.

Conservatives[edit]

Conservative Friends (also known as "Wilburites" after their founder, John Wilbur), share some of the beliefs of Fox and the Early Friends. Many Wilburites see themselves as the Quakers whose beliefs are truest to original Quaker doctrine, arguing that the majority of Friends "broke away" from the Wilburites in the 19th and 20th centuries (rather than vice versa). Conservative Friends place their trust in the immediate guidance of God.[109] They reject all forms of religious symbolism and outward sacraments, such as the Eucharist and water baptism. Conservative Friends do not believe in relying upon the practice of outward rites and sacraments in their living relationship with God through Christ, believing that holiness can exist in all of the activities of one's daily life – and that all of life is sacred in God. Many believe that a meal held with others can become a form of communion with God and with one another.

Conservative Friends in the United States are part of three small Quaker Yearly Meetings in Ohio, North Carolina and Iowa. Ohio Yearly Meeting (Conservative) is generally considered the most Bible-centred of the three, retaining Christian Quakers who use plain language, wear plain dress, and are more likely to live in villages or rural areas than the Conservative Friends from their other two Yearly Meetings.[110]

In 2007, total membership of such Yearly Meetings was around 1,642,[111] making them around 0.4% of the world family of Quakers.

Evangelical[edit]

Evangelical Friends regard Jesus Christ as their personal Lord and Saviour,[109] and have similar religious beliefs to other evangelical Christians. They believe in and hold a high regard for penal substitution of the atonement of Christ on the Cross at Calvary, biblical infallibility, and the need for all to experience a relationship with God personally.[112] They believe that the Evangelical Friends Church is intended to evangelise the unsaved of the world, to transform them spiritually through God's love and through social service to others.[112] They regard the Bible as the infallible, self-authenticating Word of God. The statement of faith of Evangelical Friends International is comparable to that of other Evangelical churches. Those who are members of Evangelical Friends International are mainly located in the United States, Central America and Asia.

Beginning in the 1880s, some Friends began using outward sacraments in their Sunday services, first in Evangelical Friends Church–Eastern Region (then known as Ohio Yearly Meeting [Damascus]). Friends Church–Southwest Region also approved such a practice. In places where Evangelical Friends engage in missionary work, such as Africa, Latin America and Asia, adult baptism by immersion in water occurs. In this they differ from most other branches of the Religious Society of Friends. EFCI in 2014 was claiming to represent more than 140,000 Friends,[113] some 39% of the total number of Friends worldwide.

Gurneyites[edit]

Gurneyite Friends (also known as Friends United Meeting Friends) are modern followers of the Evangelical Quaker theology specified by Joseph John Gurney, a 19th-century British Friend. They make up 49% of the total number of Quakers worldwide.[99] They see Jesus Christ as their Teacher and Lord[109] and favour close work with other Protestant Christian churches. Gurneyite Friends balance the Bible's authority as inspired words of God with personal, direct experience of God in their lives. Both children and adults take part in religious education, which emphasises orthodox Christian teaching from the Bible, in relation to both orthodox Christian Quaker history and Quaker testimonies. Gurneyite Friends subscribe to a set of orthodox Christian doctrines, such as those found in the Richmond Declaration of faith. In later years conflict arose among Gurneyite Friends over the Richmond Declaration of faith, but after a while, it was adopted by nearly all of Gurneyite yearly meetings. The Five Years Meeting of Friends reaffirmed its loyalty to the Richmond Declaration of faith in 1912, but specified that it was not to constitute a Christian creed. Although Gurneyism was the main form of Quakerism in 19th-century Britain, Gurneyite Friends today are found also in America, Ireland, Africa and India. Many Gurneyite Friends combine "waiting" (unprogrammed) worship with practices commonly found in other Protestant Christian churches, such as readings from the Bible and singing hymns. A small minority of Gurneyite Friends practice wholly unprogrammed worship.[114]

Holiness[edit]

Holiness Friends are Quakers of the Gurneyite branch who are heavily influenced by the Holiness movement, in particular the doctrine of Christian perfection, also called "entire sanctification". This states that loving God and humanity totally, as exemplified by Christ, enables believers to rid themselves of voluntary sin. This was a dominant view within Quakerism in the United Kingdom and United States in the 19th century, and influenced other branches of Quakerism. Holiness Friends argue, leaning on writings that include George Fox's message of perfection, that the early Friends had this understanding of holiness.[115]

Today, many Friends hold holiness beliefs within most yearly meetings, but it is the predominant theological view of Central Yearly Meeting of Friends, (founded in 1926 specifically to promote holiness theology) and the Holiness Mission of the Bolivian Evangelical Friends Church (founded by missionaries from that meeting in 1919, the largest group of Friends in Bolivia).[116]

Liberal[edit]

Liberal Quakerism generally refers to Friends who take ideas from liberal Christianity, often sharing a similar mix of ideas, such as more critical Biblical hermeneutics, often with a focus on the social gospel. The ideas of that of God in everyone and the inner light were popularised by the American Friend Rufus Jones in the early 20th century, he and John Wilhelm Rowntree originating the movement. Liberal Friends predominated in Britain in the 20th century, among US meetings affiliated to Friends General Conference, and some meetings in Canada, Europe, Australia, New Zealand and Southern Africa.

These ideas remain important in Liberal Friends' understanding of God. They highlight the importance of good works, particularly living a life that upholds the virtues preached by Jesus. They often emphasise pacifism, treating others equally, living simply, and telling the truth.[99]

Like Conservative Friends, Liberal Friends reject religious symbolism and sacraments such as water baptism and the Eucharist. While Liberal Friends recognise the potential of these outward forms for awakening experiences of the Inward Light of Christ, they are not part of their worship and are thought unnecessary to authentic Christian spirituality.

The Bible remains central to most Liberal Friends' worship. Almost all meetings make it available in the meeting house, often on a table in the centre of the room, which attendees may read privately or publicly during worship. But Liberal Friends decided that the Scriptures should give way to God's lead, if God leads them in a way contrary to the Bible. Many Friends are also influenced by liberal Christian theologians and modern Biblical criticism. They often adopt non-propositional Biblical hermeneutics, such as believing that the Bible is an anthology of human authors' beliefs and feelings about God, rather than Holy Writ, and that multiple interpretations of the Scriptures are acceptable.

Liberal Friends believe that a corporate confession of faith would be an obstacle – both to authentic listening and to new insight. As a non-creed form of Christianity, Liberal Quakerism is receptive to a wide range of understandings of religion. Most Liberal Quaker Yearly Meetings publish a Faith and Practice containing a range of religious experiences of what it means to be a Friend in that Yearly Meeting.

Universalist[edit]

Universalist Friends affirm religious pluralism: there are many different paths to God and understandings of the divine reached through non-Christian religious experiences, which are as valid as Christian understandings. The group was founded in the late 1970s by John Linton, who had worshipped with the Delhi Worship Group in India (an independent meeting unaffiliated to any yearly meeting or wider Quaker group) with Christians, Muslims and Hindus worshipping together.[117]

After moving to Britain, Linton founded the Quaker Universalist Fellowship in 1978. Later his views spread to the United States, where the Quaker Universalist Fellowship was founded in 1983.[117] Most of the Friends who joined these two fellowships were Liberal Friends from the Britain Yearly Meeting in the United Kingdom and from Friends General Conference in the United States. Interest in Quaker Universalism is low among Friends from other Yearly meetings. The views of the Universalists provoked controversy in the 1980s[citation needed] among themselves and Christian Quakers within the Britain Yearly Meeting, and within Friends General Conference. Despite the label, Quaker Universalists are not necessarily Christian Universalists, embracing the doctrine of universal reconciliation.

Non-theists[edit]

A minority of Friends have views similar to post-Christian non-theists in other churches such as the Sea of Faith, which emerged from the Anglican church. They are predominantly atheists, agnostics and humanists who still value membership in a religious organization. The first organisation for non-theist Friends was the Humanistic Society of Friends, founded in Los Angeles in 1939. This remained small and was absorbed into the American Humanist Association.[118] More recently, interest in non-theism resurfaced, particularly under the British Friend David Boulton, who founded the 40-member Nontheist Friends Network in 2011.[119] Non-theism is controversial, leading some Christian Quakers from within Britain Yearly Meeting to call for non-theists to be denied membership.[120]

In one study of Friends in the Britain Yearly Meeting, some 30% of Quakers had views described as non-theistic, agnostic, or atheist.[121][122] Another study found that 75.1% of the 727 members of the Religious Society of Friends who completed the survey said that they consider themselves to be Christian and 17.6% that they did not, while 7.3% either did not answer or circled both answers.[123]: p.41 A further 22% of Quakers did not consider themselves Christian, but fulfilled a definition of being a Christian in that they said that they devoutly followed the teachings and example of Jesus Christ.[123]: p.52 In the same survey, 86.9% said they believed in God.[123]

Practical theology[edit]

Quakers bear witness or testify to their religious beliefs in their spiritual lives,[124] drawing on the Epistle of James exhortation that "faith by itself, if it is not accompanied by action, is dead".[125] This religious witness is rooted in their immediate experience of God and verified by the Bible, especially in Jesus Christ's life and teachings. They may bear witness in many ways, according to how they believe God is leading them. Although Quakers share how they relate to God and the world, mirroring Christian ethical codes, for example the Sermon on the Mount or the Sermon on the Plain, Friends argue that they feel personally moved by God rather than following an ethical code.

Some theologians classify Friends' religious witness into categories, known by some Friends as Testimonies. These Friends believe these principles and practices testify to, witness to, or provide evidence for God's truth. No categorisation is universally accepted.[126]

In the United Kingdom, the acronym STEPS is sometimes used (Simplicity, Truth, Equality, Peace, and Sustainability) to help remember the Testimonies, although most Quakers just use the full words. In his book Quaker Speak, British Friend Alastair Heron, lists the following ways in which British Friends have historically applied the Testimonies to their lives:[127] Opposition to betting and gambling, capital punishment, conscription, hat honour (the largely historical practice of dipping one's hat toward social superiors), oaths, slavery, times and seasons, and tithing. Promotion of integrity (or truth), peace, penal reform, plain language, relief of suffering, simplicity, social order, Sunday observance, sustainability, temperance and moderation.

In East Africa, Friends teach peace and non-violence, simplicity, honesty, equality, humility, marriage and sexual ethics (defining marriage as lifelong between one man and one woman), sanctity of life (opposition to abortion), cultural conflicts and Christian life.[128]

In the United States, the acronym SPICES is often used by many Yearly Meetings (Simplicity, Peace, Integrity, Community, Equality and Stewardship). Stewardship is not recognised as a Testimony by all Yearly Meetings. Rocky Mountain Yearly Meeting Friends put their faith in action through living their lives by the following principles: prayer, personal integrity, stewardship (which includes giving away minimum of 10% income and refraining from lotteries), marriage and family (lifelong commitment), regard for mind and body (refraining from certain amusements, propriety and modesty of dress, abstinence from alcohol, tobacco and drugs), peace and non-violence (including refusing to participate in war), abortion (opposition to abortion, practical ministry to women with unwanted pregnancy and promotion of adoption), human sexuality, the Christian and state (look to God for authority, not the government), capital punishment (find alternatives), human equality, women in ministry (recognising women and men have an equal part to play in ministry).[129] The Southern Appalachian Yearly Meeting and Association lists as testimonies: Integrity, Peace, Simplicity, Equality and Community; areas of witness lists Children, Education, Government, Sexuality and Harmony with Nature.[130]

Calendar and church holidays[edit]

Quakers traditionally use numbers for referencing the months and days of the week, something they call the plain calendar. This does not use names of calendar units derived from the names of pagan deities. The week begins with First Day (Sunday) and ends with Seventh Day (Saturday).[131] Months run from First (January) to Twelfth (December). This rests on the terms used in the Bible, e.g. that Jesus Christ's followers went to the tomb early on the First Day.[132] The plain calendar emerged in the 17th century in England in the Puritan movement, but became closely identified with Friends by the end of the 1650s, and was commonly employed into the 20th century. It is less commonly found today. The term First Day School is commonly used for what is referred to by other churches as Sunday School.

From 1155 to 1751, the English calendar (and that of Wales, Ireland and the British colonies overseas) marked March 25 as the first day of the year. For this reason, Quaker records of the 17th and early 18th centuries usually referred to March as First Month and February as Twelfth Month.[133]

Like other Christian denominations derived from 16th-century Puritanism, many Friends eschew religious festivals (e.g. Christmas, Lent, or Easter), and believe that Christ's birth, crucifixion and resurrection, should be marked every day of the year. For example, many Quakers feel that fasting in Lent, but then eating in excess at other times of the year is hypocrisy. Many Quakers, rather than observing Lent, live a simple lifestyle all the year round (see Testimony of simplicity). Such practices are called the testimony against times and seasons.[citation needed]

Some Friends are non-Sabbatarians, holding that "every day is the Lord's day", and that what should be done on a First Day should be done every day of the week, although Meeting for Worship is usually held on a First Day, after the advice first issued by the elders of Balby in 1656.[134]

Worship[edit]

Most groups of Quakers meet for regular worship. There are two main types of worship worldwide: programmed worship and waiting worship.

Programmed worship[edit]

In programmed worship there is often a prepared Biblical message, which may be delivered by an individual with theological training from a Bible College. There may be hymns, a sermon, Bible readings, joint prayers and a period of silent worship. The worship resembles the church services of other Protestant denominations, although in most cases does not include the Eucharist. A paid pastor may be responsible for pastoral care. Worship of this kind is celebrated by about 89% of Friends worldwide.[99]: 5–6 It is found in many Yearly Meetings in Africa, Asia and parts of the US (central and southern), and is common in programmed meetings affiliated to Friends United Meeting, (who make up around 49% of worldwide membership[99]: 5 ), and evangelical meetings, including those affiliated to Evangelical Friends International, (who make up at least 40% of Friends worldwide.[99]: 5–6 ) The religious event is sometimes called a Quaker meeting for worship or sometimes a Friends church service. This tradition arose among Friends in the United States in the 19th century, and in response to many converts to Christian Quakerism during the national spiritual revival of the time. Friends meetings in Africa and Latin America were generally started by Orthodox Friends from programmed elements of the Society, so that most African and Latin American Friends worship in a programmed style.

Some Friends hold Semi-Programmed Worship, which brings programmed elements such as hymns and readings into an otherwise unprogrammed service of worship.

Unprogrammed worship[edit]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

Unprogrammed worship (also known as waiting worship, silent worship, or holy communion in the manner of Friends) rests on the practices of George Fox and early Friends, who based their beliefs and practices on their interpretation of how early Christians worshipped God their Heavenly Father. Friends gather together in "expectant waiting upon God" to experience his still small voice leading them from within. There is no plan on how the meeting will proceed, and practice varies widely between Meetings and individual worship services. Friends believe that God plans what will happen, with his spirit leading people to speak. A participant who feels led to speak will stand and share a spoken ministry in front of others. When this happens, Quakers believe that the spirit of God is speaking through the speaker. After someone has spoken, it is customary to allow a few minutes to pass in silence for reflection on what was said, before further vocal ministry is given. Sometimes a meeting is quite silent, sometimes many speak. These meetings lasted for several hours in George Fox's day.

Modern meetings are often limited to an hour, ending when two people (usually the elders) exchange the sign of peace by a handshake. This handshake is often shared by the others. This style of worship is the norm in Britain, Ireland, the continent of Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Southern Africa, Canada, and parts of the United States (particularly yearly meetings associated with Friends General Conference and Beanite Quakerism)—constituting about 11%[99]: 5 of Quakers. Those who worship in this way hold each person to be equal before God and capable of knowing the light of God directly. Anyone present may speak if feeling led to do so. Traditionally, Recorded Ministers were recognised for their particular gift in vocal ministry. This practice continues among Conservative Friends and Liberal Friends (e.g. New York Yearly Meeting,[136]), but many meetings where Liberal Friends predominate abolished this practice. London Yearly Meeting of Friends abolished the acknowledging and recording of Recorded Ministers in 1924.

Governance and organisation[edit]

Organisational government and polity[edit]

Governance and decision-making are conducted at a special meeting for worship – often called a meeting for worship with a concern for business or meeting for worship for church affairs, where all members can attend, as in a Congregational church. Quakers consider this a form of worship, conducted in the manner of meeting for worship. They believe it is a gathering of believers who wait upon the Lord to discover God's will, believing they are not making their own decisions. They seek to understand God's will for the religious community, via the actions of the Holy Spirit within the meeting.[137]

As in a meeting for worship, each member is expected to listen to God, and if led by Him, stand up and contribute. In some business meetings, Friends wait for the clerk to acknowledge them before speaking. Direct replies to someone's contribution are not permitted, with an aim of seeking truth rather than debate. A decision is reached when the meeting as a whole feels that the "way forward" has been discerned (also called "coming to unity"). There is no voting. On some occasions Friends may delay a decision because they feel the meeting is not following God's will. Others (especially non-Friends) may describe this as consensus decision-making; however, Friends in general continue to seek God's will. It is assumed that if everyone is attuned to God's spirit, the way forward becomes clear.

International organization[edit]

Friends World Committee for Consultation (FWCC) is the international Quaker organization that loosely unifies the different religious traditions of Quakers; FWCC brings together the largest variety of Friends in the world. Friends World Committee for Consultation is divided into four sections to represent different regions of the world: Africa, Asia West Pacific, Europe and Middle East, and the Americas.[138]

Various organizations associated with Friends include a United States' lobbying organization based in Washington, D.C. called the Friends Committee on National Legislation (FCNL); service organizations such as the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), the Quaker United Nations Offices, Quaker Peace and Social Witness, Friends Committee on Scouting, the Quaker Peace Centre in Cape Town, South Africa, and the Alternatives to Violence Project.

Yearly meetings[edit]

Quakers today are organised into independent and regional, national bodies called Yearly Meetings, which have often split from one another over doctrinal differences. Several of such unite Quakers who share similar religious beliefs – for example Evangelical Friends Church International unites evangelical Christian Friends;[139] Friends United Meeting unites Friends into "fellowships where Jesus Christ is known, loved and obeyed as Teacher and Lord;"[140] and Friends General Conference links Quakers with non-creed, liberal religious beliefs. Many Quaker Yearly Meetings also belong to the Friends World Committee for Consultation, an international fellowship of Yearly Meetings from different Quaker traditions.

Membership[edit]

A Friend is a member of a Yearly Meeting, usually beginning with membership in a local monthly meeting. Means of acquiring membership vary. For example, in most Kenyan yearly meetings, attenders who wish to become members must take part in some two years' adult education, memorising key Bible passages, and learning about the history of orthodox Christianity and of Christian Quakerism. Within the Britain Yearly Meeting, membership is acquired through a process of peer review, where a potential member is visited by several members, who report to the other members before a decision is reached.

Within some Friends Churches in the Evangelical Friends Church – in particular in Rwanda, Burundi, and parts of the United States – an adult believer's baptism by immersion in water is optional. Within Liberal Friends, Conservative Friends, and Pastoral Friends Churches, Friends do not practise water baptism, Christening, or other initiation ceremonies to admit a new member or a newborn baby. Children are often welcomed into the meeting at their first attendance. Formerly, children born to Quaker parents automatically became members (sometimes called birthright membership), but this no longer applies in many areas. Some parents apply for membership on behalf of their children, while others allow children to decide whether to be a member when they are ready and older in age. Some meetings adopt a policy that children, some time after becoming young adults, must apply independently for membership.

Worship for specific tasks[edit]

Memorial services[edit]

Traditional Quaker memorial services are held as a form of worship and known as memorial meetings. Friends gather for worship and offer remembrances of the deceased. In some Quaker traditions, the coffin or ashes are not present. Memorial meetings may be held many weeks after the death, which can enable wider attendance, replacement of grief with spiritual reflection, and celebration of life to dominate. Memorial meetings can last over an hour, particularly if many people attend. Memorial services give all a chance to remember the lost individual in their own way, comforting those present and re-affirming the love of the people in the wider community.[citation needed]

Marriage[edit]

A meeting for worship for the solemnisation of marriage in an unprogrammed Friends meeting is similar to any other unprogrammed meeting for worship.[141] The pair exchange promises before God and gathered witnesses, and the meeting returns to open worship. At the rise of meeting, the witnesses, including the youngest children, are asked to sign the wedding certificate as a record. In Britain, Quakers keep a separate record of the union and notify the General Register Office.[142]

In the early days of the United States, there was doubt whether a marriage solemnised in that way was entitled to legal recognition. Over the years, each state has set rules for the procedure. Most states expect the marriage document to be signed by a single officiant (a priest, rabbi, minister, Justice of the Peace, etc.) Quakers routinely modify the document to allow three or four Friends to sign as officiant. Often these are the members of a committee of ministry and oversight, who have helped the couple to plan their marriage. Usually, a separate document containing the vows and signatures of all present is kept by the couple and often displayed prominently in their home.

In many Friends meetings, the couple meet with a clearness committee before the wedding. Its purpose is to discuss with the couple the many aspects of marriage and life as a couple. If the couple seem ready, the marriage is recommended to the meeting.

As in wider society, there is a diversity of views among Friends on the issue of same-sex marriage. Various Friends meetings around the world have voiced support for and recognised same-sex marriages. In 1986, Hartford Friends Meeting in Connecticut reached a decision that "the Meeting recognised a committed union in a celebration of marriage, under the care of the Meeting. The same loving care and consideration should be given to both homosexual and heterosexual applicants as outlined in Faith and Practice."[143] Since then, other meetings of liberal and progressive Friends from Australia, Britain, New Zealand, parts of North America, and other countries have recognised marriage between partners of the same sex. In jurisdictions where same-sex marriage is not recognised by civil authorities, some meetings follow the practice of early Quakers in overseeing the union without reference to the state. There are also Friends who do not support same-sex marriage. Some Evangelical and Pastoral yearly meetings in the United States have issued public statements stating that homosexuality is a sin.[143]

National and international divisions and organisation[edit]

By country[edit]

Like many religious movements, the Religious Society of Friends has evolved, changed, and split into sub-groups.

Quakerism started in England and Wales, and quickly spread to Ireland, the Netherlands,[30] Barbados[31] and North America. In 2012, there were 146,300 Quakers in Kenya, 76,360 in the United States, 35,000 in Burundi and 22,300 in Bolivia. Other countries with over 5,000 Quakers were Guatemala, the United Kingdom, Nepal, Taiwan and Uganda.[144] Although the total number of Quakers is around 377,000 worldwide,[144] Quaker influence is concentrated in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Kaimosi, Kenya; Newberg, Oregon; Greenleaf, Idaho; Whittier, California; Richmond, Indiana; Friendswood, Texas; Birmingham, England; Ramallah, Palestine, and Greensboro, North Carolina.

Africa[edit]

The highest concentration of Quakers is in Africa.[145] The Friends of East Africa were at one time part of a single East Africa Yearly Meeting, then the world's largest. Today, the region is served by several distinct yearly meetings. Most are affiliated with the Friends United Meeting, practise programmed worship and employ pastors. Friends meet in Rwanda and Burundi; new work is beginning in North Africa. Small unprogrammed meetings exist also in Botswana, Ghana, Lesotho, Namibia, Nigeria, South Africa and Zimbabwe.

In 2012, there were 196,800 adult Quakers in Africa.[144]

Australia and New Zealand[edit]

Друзья в Австралии и Новой Зеландии следуют незапрограммированной традиции, подобной традиции Британского Годового Собрания .Значительные расстояния между колониями и небольшое количество квакеров означали, что «Австралийские друзья» зависели от Лондона до 20 века. Общество осталось незапрограммированным и называется «Австралийское годовое собрание», а местные организации располагаются вокруг семи региональных собраний: Канберра (которая простирается на юг Нового Южного Уэльса), Новый Южный Уэльс, Квинсленд, Южная Австралия (которая простирается на Северную территорию), Тасмания, Виктория, и Западная Австралия. [146] Школа друзей находится в Хобарте . Ежегодное собрание проводится каждый январь на другом региональном совещании в течение семилетнего цикла, а Постоянный комитет создается каждый июль или август. Годовое собрание Австралии опубликовало книгу «Это мы можем сказать: жизнь, вера и мысль австралийских квакеров» в 2003 году.

Богослужения в Новой Зеландии начались в Нельсоне в 1842 году и в Окленде в 1885 году. По оценкам 1889 года, в Окленде проживало около 30 квакеров. [147] Ежегодное собрание Новой Зеландии сегодня состоит из девяти ежемесячных собраний. [148] Годовое собрание опубликовало книгу «Вера и практика квакеров в Аотеароа, Новая Зеландия» в 2003 году.

Азия [ править ]

Встречи квакеров происходят в Индии, Гонконге, Корее, Филиппинах, Японии и Непале.

В Индии проводятся четыре ежегодных собрания – незапланированное Годовое собрание Средней Индии , запланированное Годовое собрание в Бхопале и Годовое собрание Махобы. Ежегодное собрание Бунделькханда — это евангелистская церковь друзей, входящая в Международную организацию евангелических друзей. Другие запланированные и незапрограммированные группы прославления не участвуют ни в одном ежегодном собрании.

Церкви друзей-евангелистов существуют на Филиппинах и в Непале и входят в Международную организацию друзей-евангелистов.

Европа [ править ]

В Соединенном Королевстве преимущественно либеральное и незапрограммированное Ежегодное собрание Религиозного общества друзей (квакеров) в Британии имеет 478 местных собраний. [149] и 14 260 взрослых участников, [149] и еще 8560 взрослых, не являющихся членами организации, которые посещают богослужения [149] и 2251 ребенок. [149] С середины 20 века их число неуклонно снижалось. [149] Запланированные встречи происходят, в том числе в Wem. [150] и Лондон . [151] Небольшие группы консервативных друзей встречаются в Рипли и Гринвиче в Англии, а также в Арброте в Шотландии. [152] которые следуют Огайо Годового собрания Книге дисциплины . [153]

Ежегодное собрание Евангелических друзей Центральной Европы насчитывает 4306 членов. [144] в шести странах, [154] включая Албанию, Венгрию и Румынию. [144]

Годовое собрание Ирландии не имеет программы и более консервативно, чем Годовое собрание Великобритании. В нем 1591 член [144] в 28 встречах [155] по всей Ирландии и в Северной Ирландии.

Немецкое Годовое собрание не имеет программы и либерально и насчитывает 340 членов. [144] поклонение на 31 собрании в Германии и Австрии.

Небольшие группы Друзей из Чехии, Эстонии, Греции, Латвии, Литвы, Мальты, Польши, Португалии и Украины посещают там богослужения. [144]

Ближний Восток [ править ]

Ежегодное собрание Ближнего Востока проводит встречи в Ливане и Палестине .

существует активная и энергичная община палестинских квакеров в Рамалле С конца 1800-х годов . В 1910 году эта община построила Дом собраний друзей Рамаллаха, а позже добавила еще одно здание, которое использовалось для работы с населением. Встреча друзей Рамаллаха всегда играла жизненно важную роль в жизни общества. В 1948 году здания и территория стали домом для многих палестинских беженцев. На протяжении многих лет члены «Собрания друзей Рамаллаха» организовывали многочисленные общественные программы, такие как Детский игровой центр, Первая дневная школа и женские мероприятия.

К началу 1990-х годов Дом собраний и пристройка, в которых располагались конференц-залы и ванные комнаты, пришли в упадок в результате повреждений, нанесенных временем и последствиями конфликта. Разрушение молитвенного дома было настолько серьезным, что к середине 1990-х годов здание вообще невозможно было использовать. Еще одним ударом по «Друзьям» и всему палестинскому сообществу в целом стал высокий уровень эмиграции, вызванный экономической ситуацией и трудностями, возникшими в результате продолжающейся израильской военной оккупации. Дом собраний, который служил местом поклонения Друзей в Рамалле, больше не мог использоваться как таковой, а пристройка больше не могла использоваться для работы с населением.

В 2002 году комитет, состоящий из членов Религиозного общества друзей в США и секретаря Собрания в Рамалле, начал сбор средств на ремонт зданий и территории Дома собраний. К ноябрю 2004 года ремонт был завершен, и 6 марта 2005 года, ровно через 95 лет со дня открытия, Дом собраний и пристройка были вновь посвящены квакерам и общественным ресурсам. Друзья собираются каждое воскресенье утром в 10:30 на незапланированное богослужение. Приглашаются все желающие.

Северная и Южная Америка [ править ]

Квакеров можно найти по всей Америке. Друзья в Соединенных Штатах, в частности, имеют разные стили поклонения и различия в богословии, словарном запасе и практике.

Местное собрание в незапрограммированной традиции называется собранием или ежемесячным собранием (например, Smalltown Meeting или Smalltown Monthly Meeting ). Слово «ежемесячно» используется потому, что собрание собирается ежемесячно для ведения дел группы. Большинство «ежемесячных собраний» собираются для поклонения не реже одного раза в неделю; на некоторых собраниях в течение недели проводится несколько богослужений. В программных традициях местные общины часто называют «Церквями друзей» или «Встречами».

Ежемесячные собрания часто являются частью региональной группы, называемой ежеквартальными собраниями , которая обычно является частью еще большей группы, называемой ежегодными собраниями; прилагательные «ежеквартально» и «ежегодно» относятся конкретно к частоте богослужений с заботой о бизнесе .

Некоторые ежегодные собрания, такие как Ежегодное собрание в Филадельфии, принадлежат более крупным организациям и помогают поддерживать порядок и общение внутри Общества. Тремя главными из них являются Генеральная конференция друзей (FGC), Объединенное собрание друзей (FUM) и Международная церковь евангелических друзей (EFCI). Во всех трех группах большинство членских организаций, хотя и не обязательно членов, представляют Соединенные Штаты. FGC теологически является самой либеральной из трех групп, а EFCI - самой евангелистской. ФУМ – самый крупный. Встреча «Объединенных друзей » изначально называлась «Встреча пяти лет». Некоторые ежемесячные собрания принадлежат более чем одной более крупной организации, тогда как другие полностью независимы.

Сервисные организации [ править ]

Существует множество квакерских сервисных организаций, занимающихся вопросами мира и гуманитарной деятельности за рубежом. Первый, Британский совет службы друзей (FSC), был основан в Великобритании в 1927 году и разделил Нобелевскую премию мира 1947 года с Комитетом службы американских друзей (AFSC). [156]

Звезда квакеров используется многими квакерскими сервисными организациями, такими как Комитет службы американских друзей, Комитет службы канадских друзей и Quaker Peace and Social Witness (ранее - Совет службы друзей). Первоначально он использовался британскими квакерами, оказывавшими помощь во время франко-прусской войны, чтобы отличиться от Красного Креста . [157] Сегодня звезда используется многими квакерскими организациями в качестве своего символа, символизирующего «общую приверженность служению и дух, в котором оно предоставляется». [158]

Отношения с другими церквями и конфессиями [ править ]

Экуменические отношения [ править ]

Квакеры до 20-го века считали Религиозное общество друзей христианским движением, но многие не чувствовали, что их религиозная вера вписывается в категории католиков , православных или протестантов . [32] Многие консервативные друзья, хотя и считают себя ортодоксальными христианами, предпочитают оставаться отдельно от других христианских групп.

Многие Друзья на собраниях Либеральных Друзей активно участвуют в экуменическом движении , часто тесно сотрудничая с другими основными протестантскими и либеральными христианскими церквями, с которыми они разделяют общие религиозные взгляды. Забота о мире и социальной справедливости часто объединяет Друзей с другими христианскими церквями и другими христианскими группами. Некоторые ежегодные собрания либеральных квакеров являются членами экуменических панхристианских организаций, в которые входят протестантские и православные церкви - например, Годовое собрание Филадельфии является членом Национального совета церквей . [159] Британское Годовое собрание является членом организации «Совместные церкви» в Великобритании и Ирландии , а Генеральная конференция Друзей является членом Всемирного совета церквей . [160]

Гернитские друзья обычно считают себя частью ортодоксального христианского движения и тесно сотрудничают с другими христианскими конфессиями. Friends United Meeting (международная организация ежегодных собраний гурнейцев) является членом Национального совета церквей. [159] и Всемирный совет церквей , [160] которые являются панхристианскими организациями, включающими, среди прочего, лютеранскую, православную, реформатскую, англиканскую и баптистскую церкви. [161] [162]

Друзья-евангелисты тесно сотрудничают с другими евангелическими церквями других христианских традиций. Североамериканское отделение Международной церкви друзей-евангелистов является членом Национальной ассоциации евангелистов . Друзья-евангелисты, как правило, меньше связаны с неевангелическими церквями и не являются членами Всемирного совета церквей или Национального совета церквей .

Большинство других христианских групп признают Друзей среди своих собратьев-христиан. [32] Некоторые люди, посещающие собрания квакеров, предполагают, что квакеры не христиане, когда они не слышат откровенно христианской речи во время собрания богослужения. [163]

Отношения с другими конфессиями [ править ]

Отношения между квакерами и нехристианами значительно различаются в зависимости от секты, географии и истории.

Ранние квакеры дистанцировались от практик, которые они считали языческими . Например, они отказывались использовать обычные названия дней недели, поскольку они произошли от имен языческих божеств. [164] Они отказывались праздновать Рождество , поскольку считали, что оно основано на языческих праздниках. [165]

Ранние Друзья призывали приверженцев других мировых религий обратиться к «Свету Христа внутри», который, по их мнению, присутствовал во всех людях, рожденных в мире. [166] Например, Джордж Фокс написал ряд открытых писем евреям и мусульманам , в которых призывал их обратиться к Иисусу Христу как к единственному пути к спасению (например, «Посещение евреев» , [167] Великому турку и королю Алжира в Алжире и всем, кто находится под его властью, прочитать это, что касается их спасения. [168] [169] и Великому турку и королю Алжира в Алжире ). [170] В письмах к читателям-мусульманам Фокс отличается исключительным для своего времени сочувствием и широким использованием Корана , а также своей верой в то, что его содержание соответствует христианским писаниям. [171] [172]

Мэри Фишер, вероятно, проповедовала то же самое, когда предстала перед мусульманином Мехмедом IV (султаном Османской империи ) в 1658 году. [173]

В 1870 году Ричард Прайс Хэллоуэлл утверждал, что логическим продолжением христианского квакерства является универсальная церковь, которая «требует религии, охватывающей иудеев, язычников и христиан, и которая не может быть ограничена догмами того или другого». [174]

С конца 20-го века некоторые посетители либеральных квакерских собраний активно отождествляли себя с мировыми конфессиями, отличными от христианства, такими как иудаизм , ислам , [175] буддизм [176] и язычество .

См. также [ править ]

- Дэвид Купер и Энтони Бенезет - квакеры, участвовавшие в аболиционистском движении 18 века.

- «Свет на подсвечнике» - трактат 17 века, популярный среди английских квакеров.

- Список христианских конфессий

- Quaker oats Company – американский пищевой конгломерат

- Свидетельство мира - действия по укреплению мира и противодействию войне, предпринимаемые членами Религиозного общества друзей.

- Свидетельство равенства

- Свидетельство честности – Поведенческий кодекс квакеров

- Свидетельство простоты – Поведенческая практика квакеров

Ссылки [ править ]

- ^ Михаэль Бьеркнес Ауне; Валери М. ДеМаринис (1996). Религиозный и социальный ритуал: междисциплинарные исследования . СУНИ Пресс. п. 105. ИСБН 978-0-7914-2825-2 .

- ^ «Откуда произошли названия «квакер» и «друзья»?» . Церковь друзей Уолнат-Крик . Проверено 21 июня 2024 г.

Они называли себя «Друзьями» из-за слов Иисуса, записанных в Иоанна 15:14: «Вы Мои друзья, если будете делать то, что Я вам повелеваю». Первые Друзья были христианами, которые верили, что могут жить как Иисус, потому что Иисус жил в них. Название «квакер» было применено к первым Друзьям их критиками. Первые Друзья настолько осознавали присутствие Бога среди них, что иногда дрожали от волнения. Когда судья пригрозил ему «дрожать» перед властью своего суда, Джордж Фокс сказал ему трепетать перед властью Бога.

- ^ Фокс, Джордж (1903). Журнал Джорджа Фокса . Исбистер энд Компани Лимитед. стр. 215–216.

Это слово Господа Бога ко всем вам и поручение всем вам пред лицом Бога живого; будьте образцом, будьте примером во всех ваших странах, местах, островах, нациях, куда бы вы ни приехали; чтобы твое поведение и жизнь могли проповедовать среди всякого рода людей и им: тогда ты придешь радостно ходить по миру, отвечая Богу в каждом; чрез них вы можете быть благословением и явите в них свидетельство Божие, чтобы благословить вас: тогда Господу Богу вы будете приятным благоуханием и благословением.

- ^ Ходж, Чарльз (12 марта 2015 г.). Систематическое богословие . Delmarva Publications, Inc. с. 137.

Это духовное просветление свойственно истинному народу Божию; внутренний свет, в который верят квакеры, присущ всем людям. Целью и действием «внутреннего света» являются сообщение новой истины или истины, объективно не открытой, а также духовное распознавание истин Священного Писания. Целью и эффектом духовного просветления являются правильное постижение истины, уже умозрительно известной. Во-вторых. Под внутренним светом ортодоксальные квакеры понимают сверхъестественное влияние Святого Духа, о котором они учат: (1) Что оно дано всем людям. (2) Что оно не только обличает во грехе и позволяет душе правильно постичь истины Писания, но также сообщает познание «тайн спасения». ... Ортодоксальные Друзья учат относительно этого внутреннего света, как уже было показано, что он подчинен Священному Писанию, поскольку Священное Писание является непогрешимым правилом веры и практики, и все, что противоречит ему, должно быть отвергнуто как ложное. и разрушительный.

- ^ «Членство | Квакерская вера и практика» . qfp.quaker.org.uk . Проверено 9 января 2018 г.

- ^ «Балтиморское ежегодное собрание «Вера и практика»» . Август 2011 г. Архивировано из оригинала 13 апреля 2012 г.

- ^ 1 Петра 2:9.

- ^ « Божественное в каждом человеке» . Квакеры в Бельгии и Люксембурге.

- ^ Фагер, Чак. «Проблема с министрами » . Quakertheology.org . Проверено 9 января 2018 г.

- ^ «В поисках квакеров по всему миру» (PDF) . Всемирный консультативный комитет друзей. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 10 октября 2021 года . Проверено 14 марта 2019 г.

- ^ Ежегодное собрание Религиозного общества друзей (квакеров) в Великобритании (2012 г.). Послания и свидетельства (PDF) . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 15 января 2016 года.

- ^ Энджелл, Стивен Уорд; Одуванчик, Розовый (19 апреля 2018 г.). Кембриджский спутник квакерства . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 290. ИСБН 978-1-107-13660-1 .

Современные квакеры во всем мире преимущественно евангелисты, и их часто называют Церковью друзей.

- ^ Ежегодное собрание Религиозного общества друзей (квакеров) в Великобритании (2012 г.). Послания и свидетельства (PDF) . п. 7. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 19 ноября 2015 года. [ мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ Дрейтон, Брайан (23 декабря 1994 г.). «Библиотека FGC: зарегистрированные служители Общества друзей тогда и сейчас» . Архивировано из оригинала 14 апреля 2012 года . Проверено 9 января 2018 г.

- ^ Обзор христианского ученого, том 27 . Колледж Надежды . 1997. с. 205.

Это особенно справедливо в отношении протоевангелических движений, таких как квакеры, организованные Джорджем Фоксом в 1668 году как Религиозное общество друзей как группа христиан, отвергавших клерикальную власть и учивших, что Святой Дух направляет их.

- ^ Бэкон, Маргарет (1986). Матери феминизма: история женщин-квакеров в Америке . Сан-Франциско: Харпер и Роу. п. 24.

- ^ Фокс, Джордж (1803). Армистед, Уилсон (ред.). Журнал Джорджа Фокса . Том. 2 (7-е изд.). п. 186.

- ^ Всемирный совет церквей. «Друзья (квакеры)» . Церковные семьи . Архивировано из оригинала 11 августа 2011 года.

- ^ Стюарт, Кэтлин Энн (1992). Йоркский ретрит в свете квакерского пути: теория морального обращения: гуманная терапия или контроль над разумом? . Уильям Сешнс. ISBN 9781850720898 .

С другой стороны, Фокс считал, что в этом мире возможны перфекционизм и свобода от греха.

- ^ Леви, Барри (30 июня 1988 г.). Квакеры и американская семья: британское поселение в долине Делавэр . Издательство Оксфордского университета, США. стр. 128 . ISBN 9780198021674 .

- ^ Коффи, Джон (29 мая 2020 г.). Оксфордская история протестантских инакомыслящих традиций, Том I: Эпоха после Реформации, 1559–1689 гг . Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 399. ИСБН 978-0-19-252098-2 .

- ^ Краткий отчет о жизни и сочинениях Роберта Барклая . Трактат Ассоциации Общества Друзей. 1827. с. 22.

- ^ Уильямс, Уолтер Р. (13 января 2019 г.). Богатое наследие квакерства . Издательство Pickle Partners. ISBN 978-1-78912-341-8 .

Время от времени, на протяжении трех столетий своей истории, Друзья выступали с более длинными или короткими заявлениями о убеждениях. Они искренне стремятся обосновать эти декларации основных истин христианства ясным учением Священного Писания. Наиболее подробное из этих утверждений, которого обычно придерживаются ортодоксальные Друзья, известно как Ричмондская декларация веры. Этот документ был составлен девяносто девятью представителями десяти американских ежегодных собраний, а также ежегодных собраний в Лондоне и Дублине, собравшихся в Ричмонде, штат Индиана, в 1887 году.

- ^ «Декларация веры, изданная Ричмондской конференцией в 1887 году» . 23 июля 2008 года . Проверено 30 мая 2024 г.

Конференция из 95 делегатов, назначенных 12 ежегодными собраниями Друзей (квакеров), представляющих православную ветвь Друзей по всему миру, собралась в Ричмонде, штат Индиана, в сентябре 1887 года. На этой конференции была принята Декларация веры, которая с тех пор широко используется православными Друзьями. .

- ^ «Общество Друзей | Религия» . Британская энциклопедия . Проверено 13 июня 2017 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Джексон, Питер (20 января 2010 г.). «Как квакеры завоевали британскую кондитерскую?» . Новости Би-би-си . Проверено 9 января 2018 г.