История евреев в России.

Еврейский музей и центр толерантности в Москве, крупнейший еврейский музей в России. | |

| Регионы со значительной численностью населения | |

| Израиль | 1,200,000 [1] |

| Соединенные Штаты | 350,000 [2] |

| Германия | 178,500 [3] |

| Россия | 83 896 по переписи 2021 года. [4] |

| Австралия | 10,000–11,000 [5] |

| Языки | |

| Hebrew, Russian, Yiddish | |

| Religion | |

| Judaism (31%), Jewish atheism (27%),[6] Non-religious (25%), Christianity (17%)[7][8] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Ashkenazi Jews, Sephardi Jews, Ukrainian Jews, Belarusian Jews, Lithuanian Jews, Latvian Jews, Czech Jews, Hungarian Jews, Polish Jews, Slovak Jews, Jews in Siberia, Serbian Jews, Romanian Jews, Turkish Jews, Crimean Karaites, Krymchaks, Georgian Jews, Mountain Jews, Bukharan Jews, American Jews | |

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

История евреев в России и исторически связанных с ней областях насчитывает не менее 1500 лет. Евреи в России исторически составляли большую религиозную и этническую диаспору; Российская империя когда-то принимала самое большое население евреев в мире . [9] На этих территориях преимущественно ашкеназские еврейские общины во многих различных областях процветали и развивали многие из наиболее характерных богословских и культурных традиций современного иудаизма , а также сталкивались с периодами антисемитской дискриминационной политики и преследований , включая жестокие погромы . Некоторые описывают «ренессанс» еврейской общины внутри России с начала XXI века; [10] еврейское население России резко сократилось, однако после распада СССР что продолжается и по сей день, хотя оно по-прежнему остается одним из крупнейших в Европе . [11]

Обзор и предыстория [ править ]

Самой большой группой среди российских евреев являются евреи-ашкенази, но община также включает значительную часть других неашкенази из других еврейских диаспор, включая горских евреев , евреев-сефардов , грузинских евреев , крымских караимов , крымчаков и бухарских евреев .

The presence of Jewish people in the European part of Russia can be traced to the 7th–14th centuries CE. In the 11th and 12th centuries, the Jewish population in Kiev, in present-day Ukraine, was restricted to a separate quarter. Evidence of the presence of Jewish people in Muscovite Russia is first documented in the chronicles of 1471. During the reign of Catherine II in the 18th century, Jewish people were restricted to the Pale of Settlement (1791–1917) within Russia, the territory where they could live or to which they could immigrate. The three partitions of Poland brought much additional territory to Russia, along with the Jews who were long settled in those lands. Alexander III of Russia escalated anti-Jewish policies. Beginning in the 1880s, waves of anti-Jewish pogroms swept across different regions of the empire for several decades. More than two million Jews fled Russia between 1880 and 1920, mostly to the United States and Palestine. The Pale of Settlement took away many of the rights that the Jewish people of the late 17th century Russia had enjoyed. At this time, the Jewish people were restricted to an area of what is current day Belarus, Lithuania, eastern Poland and Ukraine.[12] Where Western Europe was experiencing emancipation at this time, in Russia the laws for the Jewish people were getting more strict. They were allowed to move further east, towards a less crowded region, though it was only a minority of Jews who took to this migration option.[12] The sporadic and often impoverished communities formed were known as Shtetls.[12]

Before 1917 there were 300,000 Zionists in Russia, while the main Jewish socialist organization, the Bund, had 33,000 members. Only 958 Jews had joined the Bolshevik Party before 1917; thousands joined after the Revolution.[13]: 565 The chaotic years of World War I, the February and October Revolutions, and the Russian Civil War had created social disruption that led to antisemitism. Some 150,000 Jews were killed in the pogroms of 1918–1922, 125,000 of them in Ukraine, 25,000 in Belarus.[14] The pogroms were mostly perpetrated by anti-communist forces; sometimes, Red Army units engaged in pogroms as well.[15] Anton Denikin's White Army was a bastion of antisemitism, using "Strike at the Jews and save Russia!" as its motto.[16] The Bolshevik Red Army, although individual soldiers committed antisemitic abuses, had a policy of opposing antisemitism, and as a result, it won the support of much of the Jewish population. After a short period of confusion, the Soviets started executing guilty individuals and even disbanding the army units whose men had attacked Jews. Although pogroms were still perpetrated after this, in general the Jews regarded the Red Army as the only force which was able and willing to defend them. The Russian Civil War pogroms shocked world Jewry and rallied many Jews to the Red Army and the Soviet regime, strengthening the desire for the creation of a homeland for the Jewish people.[15] In August 1919 the Soviet government arrested many rabbis, seized Jewish properties, including synagogues, and dissolved many Jewish communities.[17] The Jewish section of the Communist Party labeled the use of the Hebrew language "reactionary" and "elitist" and the teaching of Hebrew was banned.[18] Zionists were persecuted harshly, with Jewish communists leading the attacks.[13]: 567

Following the civil war, however, the new Bolshevik government's policies produced a flourishing of secular Jewish culture in Belarus and western Ukraine in the 1920s. The Soviet government outlawed all expressions of antisemitism, with the public use of the ethnic slur жид ("Yid") being punished by up to one year of imprisonment,[19] and tried to modernize the Jewish community by establishing 1,100 Yiddish-language schools, 40 Yiddish-language daily newspapers and by settling Jews on farms in Ukraine and Crimea; the number of Jews working in the industry had more than doubled between 1926 and 1931.[13]: 567 At the beginning of the 1930s, the Jews were 1.8 percent of the Soviet population but 12–15 percent of all university students.[20] In 1934 the Soviet state established the Jewish Autonomous Oblast in the Russian Far East. This region never came to have a majority Jewish population.[21] The JAO is Russia's only autonomous oblast[22] and, outside of Israel, the world's only Jewish territory with an official status.[23] The observance of the Sabbath was banned in 1929,[13]: 567 foreshadowing the dissolution of the Communist Party's Yiddish-language Yevsektsia in 1930 and worse repression to come. Numerous Jews were victimized in Stalin's purges as "counterrevolutionaries" and "reactionary nationalists", although in the 1930s the Jews were underrepresented in the Gulag population.[13]: 567 [24] The share of Jews in the Soviet ruling elite declined during the 1930s, but was still more than double their proportion in the general Soviet population. According to Israeli historian Benjamin Pinkus, "We can say that the Jews in the Soviet Union took over the privileged position, previously held by the Germans in tsarist Russia".[25]: 83

In the 1930s, many Jews held high rank in the Red Army High Command: Generals Iona Yakir, Yan Gamarnik, Yakov Smushkevich (Commander of the Soviet Air Forces) and Grigori Shtern (Commander-in-Chief in the war against Japan and Commander at the front in the Winter War).[25]: 84 During World War Two, an estimated 500,000 soldiers in the Red Army were Jewish; about 200,000 were killed in battle. About 160,000 were decorated, and more than a hundred achieved the rank of Red Army general.[26] Over 150 were designated Heroes of the Soviet Union, the highest award in the country.[27] More than two million Soviet Jews are believed to have died during the Holocaust in warfare and in Nazi-occupied territories. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, many Soviet Jews took the opportunity of liberalized emigration policies, with more than half of the population leaving, most for Israel and the West: Germany, the United States, Canada and Australia. For many years during this period, Russia had a higher rate of immigration to Israel than any other country.[28] Russia's Jewish population is still the third biggest in Europe, after France and United Kingdom.[29] In November 2012, the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center, one of the world's biggest museums of Jewish history, opened in Moscow.[30]

Early history[edit]

Jews have been present in contemporary Armenia and Georgia since the Babylonian captivity. Records exist from the 4th century showing that there were Armenian cities possessing Jewish populations ranging from 10,000 to 30,000 along with substantial Jewish settlements in the Crimea.[31] The presence of Jewish people in the territories corresponding to modern Belarus, Ukraine, and the European part of Russia can be traced back to the 7th–14th centuries CE.[32][33]

Kievan Rus'[edit]

In the 11th and 12th centuries, the Jewish population may have been restricted to a separate quarter in Kiev, known as the Jewish Town (Old East Slav: Жидове, Zhidovye, i.e. "The Jews"), the gates probably leading to which were known as the Jewish Gates (Old East Slavic: Жидовская ворота, Zhidovskaya vorota). The Kievan community was oriented towards Byzantium (the Romaniotes), Babylonia and Palestine in the 10th and 11th centuries, but appears to have been increasingly open to the Ashkenazim from the 12th century on. Few products of Kievan Jewish intellectual activity exist, however.[34] Other communities, or groups of individuals, are known from Chernigov and, probably, Volodymyr-Volynskyi. At that time, Jews were probably found also in northeastern Russia, in the domains of Prince Andrei Bogolyubsky (1169–1174), although it is uncertain to which degree they would have been living there permanently.[34]

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth[edit]

Although northeastern Russia had a low Jewish population, countries just to its west had rapidly growing Jewish populations, as waves of anti-Jewish pogroms and expulsions from the countries of Western Europe marked the last centuries of the Middle Ages, a sizable portion of the Jewish populations there moved to the more tolerant countries of Central and Eastern Europe, as well as the Middle East.

Expelled en masse from England, France, Spain and most other Western European countries at various times, and persecuted in Germany in the 14th century, many Western European Jews migrated to Poland upon the invitation of Polish ruler Casimir III the Great to settle in Polish-controlled areas of Eastern Europe as a third estate, although restricted to commercial, middleman services in an agricultural society for the Polish king and nobility between 1330 and 1370, during the reign of Casimir the Great.

After settling in Poland (later Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth) and Hungary (later Austria-Hungary), the population expanded into the lightly populated areas of Ukraine and Lithuania, which were to become part of the expanding Russian Empire. In 1495, Alexander the Jagiellonian expelled Jewish residents from Grand Duchy of Lithuania, but reversed his decision in 1503.

In the shtetls populated almost entirely by Jews, or in the middle-sized town where Jews constituted a significant part of population, Jewish communities traditionally ruled themselves according to halakha, and were limited by the privileges granted them by local rulers. (See also Shtadlan). These Jews were not assimilated into the larger eastern European societies, and identified as an ethnic group with a unique set of religious beliefs and practices, as well as an ethnically unique economic role.

Tsardom of Russia[edit]

Documentary evidence as to the presence of Jews in Muscovite Russia is first found in the chronicles of 1471. The relatively small population of them were subject to discriminatory laws, but these laws do not appear to have been enforced at all times. Jews residing in Russian and Ukrainian towns suffered numerous religious persecutions. Converted Jews occasionally rose to important positions in the Russian State, for example Peter Shafirov, vice-chancellor under Peter the Great. Shafirov came, as most Russian Jews after the fall of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1795, from a Jewish family of Polish origin. He had extraordinary knowledge of foreign languages and served as the chief translator in the Russian Foreign Office, subsequently he began to accompany Tsar Peter on his international travels. Following this, he was raised to the rank of vice-chancellor because of his many diplomatic talents and skills, but was later imprisoned, sentenced to death, and eventually banished.

Russian Empire[edit]

Their situation changed radically during the reign of Catherine II, when the Russian Empire acquired large Lithuanian and Polish territories which historically included a high proportion of Jewish residents, especially during the second (1793) and the third (1795) Partitions of Poland. Under the Commonwealth's legal system, Jews endured economic restrictions euphemised as "disabilities", which also continued following the Russian occupation. Catherine established the Pale of Settlement, which included Congress Poland, Lithuania, Ukraine, and the Crimea (the latter was later excluded). Jews were required to live within the Pale and could not migrate elsewhere in Russia without special permission. Within the Pale, the Jewish residents were permitted to vote in municipal elections, but their vote was limited to one third of the total number of voters, even though their proportion in many areas was much higher, even a majority. This served to provide an aura of democracy, while institutionalizing local inter-ethnic conflict.

Jewish communities in Russia were governed internally by local administrative bodies, called the Councils of Elders (Qahal, Kehilla), constituted in every town or hamlet possessing a Jewish population. These councils had jurisdiction over Jews in matters of internal litigation, as well as fiscal transactions relating to the collection and payment of taxes (poll tax, land tax, etc.). Later, this right of collecting taxes was much abused, and the councils lost civil authority in 1844.[35]

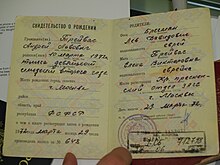

Under Alexander I and Nicholas I, decrees were put forth requiring a Russian-speaking member of a Jewish community to be named to act as an intermediary between his community and the Imperial government to perform certain civil duties, such as registering births, marriages, and divorces. This position came to be known as the crown rabbi although they were not always rabbis and often were not respected by members of their own communities because their main job qualification was fluency in Russian, and they often had no education in, or knowledge of Jewish law.[36][37][38]The beginning of the 19th century was marked by intensive movement of Jews to Novorossiya, where towns, villages and agricultural colonies rapidly sprang up.

In 19th century, legally the Jews were a subcategory of the inorodtsy category, special ethnicity-based category of non-Slavic population that received a special treatment under the law.

Forcible conscription of Jewish cantonists[edit]

The 'decree of August 26, 1827' made Jews liable for military service, and allowed their conscription between the ages of twelve and twenty-five. Each year, the Jewish community had to supply four recruits per thousand of the population. However, in practice, Jewish children were often conscripted as young as eight or nine years old.[42] At the age of twelve, they would be placed for their six-year military education in cantonist schools. They were then required to serve in the Imperial Russian army for 25 years after the completion of their studies, often never seeing their families again. Strict quotas were imposed on all communities and the qahals were given the unpleasant task of implementing conscription within the Jewish communities. Since the merchant-guild members, agricultural colonists, factory mechanics, clergy, and all Jews with secondary education were exempt, and the wealthy bribed their way out of having their children conscripted, fewer potential conscripts were available; the adopted policy deeply sharpened internal Jewish social tensions. Seeking to protect the socio-economic and religious integrity of Jewish society, the qahals did their best to include “non-useful Jews” in the draft lists so that the heads of tax-paying middle-class families were predominantly exempt from conscription, whereas single Jews, as well as "heretics" (Haskalah influenced individuals), paupers, outcasts, and orphaned children were drafted. They used their power to suppress protests and intimidate potential informers who sought to expose the arbitrariness of the qahal to the Russian government. In some cases, communal elders had the most threatening informers murdered (such as the Ushitsa case, 1836).

The zoning rule was suspended during the Crimean War, when conscription became annual. During this period the qahals leaders would employ informers and kidnappers (Russian: "ловчики", lovchiki, Yiddish: khappers), as many potential conscripts preferred to run away rather than voluntarily submit. In the case of unfulfilled quotas, younger Jewish boys of eight and even younger were frequently taken. The official Russian policy was to encourage the conversion of Jewish cantonists to the state religion of Orthodox Christianity and Jewish boys were coerced to baptism. As kosher food was unavailable, they were faced with the necessity of abandoning of Jewish dietary laws. Polish Catholic boys were subject to similar pressure to convert and assimilate as the Russian Empire was hostile to Catholicism and Polish nationalism.

Haskalah in the Russian Empire[edit]

The cultural and habitual isolation of the Jews gradually began eroding. An ever-increasing number of Jewish people adopted Russian customs and the Russian language. Russian education was spread among the Jewish population. A number of Jewish-Russian periodicals appeared.

Alexander II was known as the "Tsar liberator" for the 1861 abolition of serfdom in Russia. Under his rule Jewish people could not hire Christian servants, could not own land, and were restricted in travel.[43]

Alexander III was a staunch reactionary and an antisemite[44] (influenced by Pobedonostsev[45]) who strictly adhered to the old doctrine of Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality. His escalation of anti-Jewish policies sought to ignite "popular antisemitism", which portrayed the Jews as "Christ-killers" and the oppressors of the Slavic, Christian victims.

A large-scale wave of anti-Jewish pogroms swept Ukraine in 1881, after Jews were scapegoated for the assassination of Alexander II. In the 1881 outbreak, there were pogroms in 166 Ukrainian towns, thousands of Jewish homes were destroyed, many families reduced to extremes of poverty;[citation needed] large numbers of men, women, and children were injured and some killed. Disorders in the south once again recalled the government attention to the Jewish question. A conference was convened at the Ministry of Interior and on May 15, 1882, so-called Temporary Regulations were introduced that stayed in effect for more than thirty years and came to be known as the May Laws.

The repressive legislation was repeatedly revised. Many historians noted the concurrence of these state-enforced antisemitic policies with waves of pogroms[46] that continued until 1884, with at least tacit government knowledge and in some cases policemen were seen inciting or joining the mob. The systematic policy of discrimination banned Jewish people from rural areas and towns of fewer than ten thousand people, even within the Pale, assuring the slow death of many shtetls. In 1887, the quotas placed on the number of Jews allowed into secondary and higher education were tightened down to 10% within the Pale, 5% outside the Pale, except Moscow and Saint Petersburg, held at 3%, even though the Jewish population was a majority or plurality in many communities. It was possible to evade these restrictions upon secondary education by combining private tuition with examination as an "outside student". Accordingly, within the Pale such outside pupils were almost entirely young Jews. The restrictions placed on education, traditionally highly valued in Jewish communities, resulted in ambition to excel over the peers and increased emigration rates. Special quotas restricted Jews from entering profession of law, limiting number of Jews admitted to the bar.

In 1886, an Edict of Expulsion was enforced on the historic Jewish population of Kiev. Most Jews were expelled from Moscow in 1891 (except few deemed useful) and a newly built synagogue was closed by the city's authorities headed by the Tsar's brother. Tsar Alexander III refused to curtail repressive practices and reportedly noted: "But we must never forget that the Jews have crucified our Master and have shed his precious blood."[47]

In 1892, new measures banned Jewish participation in local elections despite their large numbers in many towns of the Pale. The Town Regulations prohibited Jews from the right to elect or be elected to town Dumas. Only a small number of Jews were allowed to be members of a town Duma, through appointment by special committees.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Russian Empire had not only the largest Jewish population in the world, but actually a majority of the world's Jews living within its borders.[48] In 1897, according to Russian census of 1897, the total Jewish population of Russia was 5,189,401 persons of both sexes (4.13% of total population). Of this total, 93.9% lived in the 25 provinces of the Pale of Settlement. The total population of the Pale of Settlement amounted to 42,338,367—of these, 4,805,354 (11.5%) were Jews.

About 450,000 Jewish soldiers served in the Russian Army during World War I,[49] and fought side by side with their Slavic fellows. When hundreds of thousands of refugees from Poland and Lithuania, among them innumerable Jews, fled in terror before enemy invasion[citation needed], the Pale of Settlement de facto ceased to exist. Most of the education restrictions on the Jews were removed with the appointment of count Pavel Ignatiev as Minister of Education.

Mass emigration[edit]

Even though the persecutions provided the impetus for mass emigration, there were other relevant factors that can account for the Jews' migration. After the first years of large emigration from Russia, positive feedback from the emigrants in the U.S. encouraged further emigration. Indeed, more than two million[50] Jews fled Russia between 1880 and 1920. While a large majority emigrated to the United States, some turned to Zionism. In 1882, members of Bilu and Hovevei Zion made what came to be known the First Aliyah to Palestine, then a part of the Ottoman Empire.

The Tsarist government sporadically encouraged Jewish emigration. In 1890, it approved the establishment of "The Society for the Support of Jewish Farmers and Artisans in Syria and Palestine"[51] (known as the "Odessa Committee" headed by Leon Pinsker) dedicated to practical aspects in establishing agricultural Jewish settlements in Palestine.

| Destination | Number |

|---|---|

| Australia | 5,000 |

| Canada | 70,000 |

| Europe | 240,000 |

| Palestine (modern day Israel) | 45,000 |

| South Africa | 45,000 |

| South America | 111,000 |

| United States | 1,749,000 |

Jewish members of the Duma[edit]

In total, there were at least twelve Jewish deputies in the First Duma (1906–1907), falling to three or four in the Second Duma (February 1907 to June 1907), two in the Third Duma (1907–1912) and again three in the fourth, elected in 1912. Converts to Christianity like Mikhail Herzenstein and Ossip Pergament were still considered as Jews by the public (and antisemitic) opinion and are most of the time included in these figures.

At the 1906 elections, the Jewish Labour Bund had made an electoral agreement with the Lithuanian Labourers' Party (Trudoviks), which resulted in the election to the Duma of two (non-Bundist) candidates in the Lithuanian provinces: Dr. Shmaryahu Levin for the Vilnius province and Leon Bramson for the Kaunas province.[53]

Among the other Jewish deputies were Maxim Vinaver, chairman of the League for the Attainment of Equal Rights for the Jewish People in Russia (Folksgrupe) and cofounder of the Constitutional Democratic Party (Kadets), Dr. Nissan Katzenelson (Courland province, Zionist, Kadet), Dr. Moisei Yakovlevich Ostrogorsky (Grodno province), attorney Simon Yakovlevich Rosenbaum (Minsk province, Zionist, Kadet), Mikhail Isaakovich Sheftel (Ekaterinoslav province, Kadet), Dr. Grigory Bruk, Dr. Benyamin Yakubson, Zakhar Frenkel, Solomon Frenkel, Meilakh Chervonenkis.[54] There was also a Crimean Karaim deputy, Salomon Krym.[55]

Three of the Jewish deputies, Bramson, Chervonenkis and Yakubson, joined the Labour faction; nine others joined the Kadet fraction.[54] According to Rufus Learsi, five of them were Zionists, including Dr. Shmaryahu Levin, Dr. Victor Jacobson and Simon Yakovlevich Rosenbaum.[56]

Two of them, Grigori Borisovich Iollos (Poltava province) and Mikhail Herzenstein (b. 1859, d. 1906 in Terijoki), both from the Constitutional Democratic Party, were assassinated by the Black Hundreds antisemite terrorist group. "The Russkoye Znamya declares openly that 'Real Russians' assassinated Herzenstein and Iollos with knowledge of officials, and expresses regret that only two Jews perished in crusade against revolutionaries.[57]

The Second Duma included seven Jewish deputies: Shakho Abramson, Iosif Gessen, Vladimir Matveevich Gessen, Lazar Rabinovich, Yakov Shapiro (all of them Kadets) and Avigdor Mandelberg (Siberia Social Democrat),[58] plus a convert to Christianity, the attorney Ossip Pergament (Odessa).[59]

The two Jewish members of the Third Duma were the Judge Leopold Nikolayevich (or Lazar) Nisselovich (Courland province, Kadet) and Naftali Markovich Friedman (Kaunas province, Kadet). Ossip Pergament was reelected and died before the end of his mandate.[60]

Friedman was the only one reelected to the Fourth Duma in 1912, joined by two new deputies, Meer Bomash, and Dr. Ezekiel Gurevich.[58]

Jews in the revolutionary movement[edit]

Many Jews were prominent in Russian revolutionary parties. The idea of overthrowing the Tsarist regime was attractive to many members of the Jewish intelligentsia because of the oppression of non-Russian nations and non-Orthodox Christians within the Russian Empire. For much the same reason, many non-Russians, notably Latvians or Poles, were disproportionately represented in the party leaderships.

In 1897 General Jewish Labour Bund (The Bund), was formed. Many Jews joined the ranks of two principal revolutionary parties: Socialist-Revolutionary Party and Russian Social Democratic Labour Party—both Bolshevik and Menshevik factions. A notable number of Bolshevik party members were ethnically Jewish, especially in the leadership of the party, and the percentage of Jewish party members among the rival Mensheviks was even higher. Both the founders and leaders of Menshevik faction, Julius Martov and Pavel Axelrod, were Jewish.

Because some of the leading Bolsheviks were Ethnic Jews, and Bolshevism supports a policy of promoting international proletarian revolution—most notably in the case of Leon Trotsky—many enemies of Bolshevism, as well as contemporary antisemites, draw a picture of Communism as a political slur at Jews and accuse Jews of pursuing Bolshevism to benefit Jewish interests, reflected in the terms Jewish Bolshevism or Judeo-Bolshevism.[citation needed] The original atheistic and internationalistic ideology of the Bolsheviks (See proletarian internationalism, bourgeois nationalism) was incompatible with Jewish traditionalism. Bolsheviks such as Trotsky echoed sentiments dismissing Jewish heritage in place of "internationalism".

Soon after seizing power, the Bolsheviks established the Yevsektsiya, the Jewish section of the Communist party in order to destroy the rival Bund and Zionist parties, suppress Judaism and replace traditional Jewish culture with "proletarian culture".[61]

In March 1919, Vladimir Lenin delivered a speech "On Anti-Jewish Pogroms"[62] on a gramophone disc. Lenin sought to explain the phenomenon of antisemitism in Marxist terms. According to Lenin, antisemitism was an "attempt to divert the hatred of the workers and peasants from the exploiters toward the Jews". Linking antisemitism to class struggle, he argued that it was merely a political technique used by the tsar to exploit religious fanaticism, popularize the despotic, unpopular regime, and divert popular anger toward a scapegoat. The Soviet Union also officially maintained this Marxist-Leninist interpretation under Joseph Stalin, who expounded Lenin's critique of antisemitism. However, this did not prevent the widely publicized repressions of Jewish intellectuals during 1948–1953 when Stalin increasingly associated Jews with "cosmopolitanism" and pro-Americanism.

Jews were prominent in the Russian Constitutional Democrat Party, Russian Social Democratic Party (Mensheviks) and Socialist-Revolutionary Party. The Russian Anarchist movement also included many prominent Jewish revolutionaries. In Ukraine, Makhnovist anarchist leaders also included several Jews.[63]

Dissolution and seizure of Jewish properties and institutions[edit]

In August 1919 Jewish properties, including synagogues, were seized and many Jewish communities were dissolved. New laws against all expressions of religion and religious education were imposed upon Jews and other religious groups. Many Rabbis and other religious officials were forced to resign from their posts under the threat of violent persecution. This type of persecution continued into the 1920s.[64]

In 1921, a large number of Jews opted for Poland, as the Peace of Riga entitled them to choose the country they preferred. Several hundred thousand joined the already numerous Jewish population of Poland.

The chaotic years of World War I, the February and October Revolutions, and the Civil War were fertile ground for the antisemitism that was endemic to tsarist Russia. During the World War, Jews were often accused of sympathizing with Germany and often persecuted.

Pogroms were unleashed throughout the Russian Civil War, perpetrated by virtually every competing faction, from Polish and Ukrainian nationalists to the Red and White Armies.[65] 31,071 civilian Jews were killed during documented pogroms throughout the former Russian Empire; the number of Jewish orphans exceeded 300,000. A majority of pogroms in Ukraine during 1918–1920 were perpetrated by the Ukrainian nationalists, miscellaneous bands and anti-Communist forces.[66]

| Perpetrator | Number of pogroms or excesses | Number murdered[66] |

|---|---|---|

| Hryhoriv's bands | 52 | 3,471 |

| Directory of the Ukrainian National Republic | 493 | 16,706 |

| White army | 213 | 5,235 |

| Miscellaneous bands | 307 | 4,615 |

| Red Army | 106 | 725 |

| Others | 33 | 185 |

| Polish army | 32 | 134 |

| Total | 1,236 | 31,071 |

Soviet Union[edit]

Before World War II[edit]

Continuing the policy of the Bolsheviks before the Revolution, Lenin and the Bolshevik Party strongly condemned the pogroms, including official denunciations in 1918 by the Council of People's Commissars. Opposition to the pogroms and to manifestations of Russian antisemitism in this era were complicated by both the official Bolshevik policy of assimilationism towards all national and religious minorities, and concerns about overemphasizing Jewish concerns for fear of exacerbating popular antisemitism, as the White forces were openly identifying the Bolshevik regime with Jews.[67][68][69]

Lenin recorded eight of his speeches on gramophone records in 1919. Only seven of these were later re-recorded and put on sale. The one suppressed in the Nikita Khrushchev era recorded Lenin's feelings on antisemitism:[70]

The Tsarist police, in alliance with the landowners and the capitalists, organized pogroms against the Jews. The landowners and capitalists tried to divert the hatred of the workers and peasants who were tortured by want against the Jews. ... Only the most ignorant and downtrodden people can believe the lies and slander that are spread about the Jews. ... It is not the Jews who are the enemies of the working people. The enemies of the workers are the capitalists of all countries. Among the Jews there are working people, and they form the majority. They are our brothers, who, like us, are oppressed by capital; they are our comrades in the struggle for socialism. Among the Jews there are kulaks, exploiters and capitalists, just as there are among the Russians, and among people of all nations... Rich Jews, like rich Russians, and the rich in all countries, are in alliance to oppress, crush, rob and disunite the workers... Shame on accursed Tsarism, which tortured and persecuted the Jews. Shame on those who foment hatred towards the Jews, who foment hatred towards other nations.[71]

Despite the Soviet state's official opposition to antisemitism, the spring of 1918 saw widespread anti-Jewish violence perpetrated by members of the Red Guard in the former Pale of Settlement. In February 1918, as Russian forces advanced on the capital of Petrograd, the Soviet government signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which stipulated that Russia would withdraw from World War I and cede large swaths of territory in eastern Russia to the German Empire. Even after the signing of the treaty, however, the Germans continued to advance and seize territory, as the Soviets had no choice but to retreat across Ukraine. At this point in the war, the Red Guard comprised mostly untrained workers and peasants with no overarching command structure, leaving the state with virtually no control over the volunteer forces.[72] Between March and May 1918, various Red Guard squadrons, embittered by their military defeat and animated by revolutionary sentiment, attacked Jews in cities and towns across the Chernihiv region of Ukraine. One of the most brutal instances of this violence occurred in the city of Novhorod-Siverskyi, where it was reported that 88 Jews were killed and 11 injured in a pogrom incited by Red Guard soldiers.[73] Similarly, after the successful capture of the city of Hlukhiv, the Red Guard murdered at least 100 Jews, whom the soldiers accused of being 'exploiters of the proletariat.'[74] In all, Jewish activist Nahum Gergel estimated that the Red forces were responsible for about 8.6% of pogroms during the years 1918–1922, while Ukrainian and White Army forces were responsible for 40% and 17.2%, respectively.[75]

Lenin was supported by the Labor Zionist (Poale Zion) movement, then under the leadership of Marxist theorist Ber Borochov, which was fighting for the creation of a Jewish workers' state in Palestine and also participated in the October Revolution (and in the Soviet political scene afterwards until being banned by Stalin in 1928). While Lenin remained opposed to outward forms of antisemitism (and all forms of racism), allowing Jewish people to rise to the highest offices in both party and state, certain historians such as Dmitri Volkogonov argue that the record of his government in this regard was highly uneven. A former official Soviet historian (turned staunch anti-communist), Volkogonov claims that Lenin was aware of pogroms carried out by units of the Red Army during the war with Poland, particularly those carried out by Semyon Budyonny's troops,[76] though the whole issue was effectively ignored. Volkogonov writes that "While condemning antisemitism in general, Lenin was unable to analyze, let alone eradicate, its prevalence in Soviet society".[77] Likewise, the hostility of the Soviet regime towards all religion made no exception for Judaism, and the 1921 campaign against religion saw the seizure of many synagogues (whether this should be regarded as antisemitism is a matter of definition—since Orthodox Christian churches received the same treatment). In any event, there was still a fair degree of tolerance for Jewish religious practice in the 1920s: in the Belarusian capital Minsk, for example, of the 657 synagogues existing in 1917, 547 were still functioning in 1930.[78]

According to Zvi Gitelman: "Never before in Russian history—and never subsequently has a government made such an effort to uproot and stamp out antisemitism."[79]

According to the census of 1926, the total number of Jews in the USSR was 2,672,398—of whom 59% lived in Ukrainian SSR, 15.2% in Byelorussian SSR, 22% in Russian SFSR and 3.8% in other Soviet republics.

Russian Jews were long considered to be a non-native ethnic group among the Slavic Russians, and such categorization was solidified when ethnic minorities in the Soviet Union were categorized according to ethnicity (национальность). In his 1913 theoretical work Marxism and the National Question, Stalin described Jews as "not a living and active nation, but something mystical, intangible and supernatural. For, I repeat, what sort of nation, for instance, is a Jewish nation which consists of Georgian, Daghestanian, Russian, American and other Jews, the members of which do not understand each other (since they speak different languages), inhabit different parts of the globe, will never see each other, and will never act together, whether in time of peace or in time of war?!"[80] According to Stalin, who became the People's Commissar for Nationalities Affairs after the revolution, to qualify as a nation, a minority was required to have a culture, a language, and a homeland.

Yiddish, rather than Hebrew, would be the national language, and proletarian socialist literature and arts would replace Judaism as the quintessence of culture. The use of Yiddish was strongly encouraged in the 1920s in areas of the USSR with substantial Jewish populations, especially in the Ukrainian and Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republics. Yiddish was one of the Belarusian SSR's four official languages, alongside Belarusian, Russian, and Polish. The equality of the official languages was taken seriously. A visitor arriving at main train station of the Belarusian capital Minsk saw the city's name written in all four languages above the main station entrance. Yiddish was a language of newspapers, magazines, book publishing, theater, radio, film, the post office, official correspondence, election materials, and even a Central Jewish Court. Yiddish writers like Sholem Aleichem and Mendele Mocher Seforim were celebrated in the 1920s as Soviet Jewish heroes.

Minsk had a public, state-supported Yiddish-language school system, extending from kindergarten to the Yiddish-language section of the Belarusian State University. Although Jewish students tended to switch to studying in Russian as they moved on to secondary and higher education, 55.3 percent of the city's Jewish primary school students attended Yiddish-language schools in 1927.[81] At its peak, the Soviet Yiddish-language school system had 160,000 students in it.[82] Such was the prestige of Minsk's Yiddish scholarship that researchers trained in Warsaw and Berlin applied for faculty positions at the university. All this leads historian Elissa Bemporad to conclude that this “very ordinary Jewish city” was in the 1920s “one of the world capitals of Yiddish language and culture."[83]

Jews also played a disproportionate role in Belarusian politics through the Bolshevik Party's Yiddish-language branch, the Yevsekstsia. Because there were few Jewish Bolsheviks before 1917 (with a few prominent exceptions like Zinoviev and Kamenev), the Yevsekstia's leaders in the 1920s were largely former Bundists, who pursued as Bolsheviks their campaign for secular Jewish education and culture. Although for example only a bit over 40 percent of Minsk's population was Jewish at the time, 19 of its 25 Communist Party cell secretaries were Jewish in 1924.[84] Jewish predominance in the party cells was such that several cell meetings were held in Yiddish. In fact, Yiddish was spoken at citywide party meetings in Minsk into the late 1930s.

To offset the growing Jewish national and religious aspirations of Zionism and to successfully categorize Soviet Jews under Stalin's definition of nationality, an alternative to the Land of Israel was established with the help of Komzet and OZET in 1928. The Jewish Autonomous Oblast with its center in Birobidzhan in the Russian Far East was to become a "Soviet Zion".[85] Despite a massive domestic and international state propaganda campaign, however, the Jewish population in the Jewish Autonomous Oblast never reached 30% (in 2003 it was only about 1.2%[86]). The experiment ground to a halt in the mid-1930s, during Stalin's first campaign of purges.

In fact the Bolshevik Party's Yiddish-language Yevsekstia was dissolved in 1930, as part of the regime's overall turn away from encouraging minority languages and cultures and towards Russification. Many Jewish leaders, especially those with Bundist backgrounds, were arrested and executed in the purges later in the 1930s, [citation needed] and Yiddish schools were shut down. The Belasusian SSR shut down its entire network of Yiddish-language schools in 1938.

In his January 12, 1931, letter "Antisemitism: Reply to an Inquiry of the Jewish News Agency in the United States" (published domestically by Pravda in 1936), Stalin officially condemned antisemitism:

In answer to your inquiry: National and racial chauvinism is a vestige of the misanthropic customs characteristic of the period of cannibalism. Antisemitism, as an extreme form of racial chauvinism, is the most dangerous vestige of cannibalism.

Antisemitism is of advantage to the exploiters as a lightning conductor that deflects the blows aimed by the working people at capitalism. Antisemitism is dangerous for the working people as being a false path that leads them off the right road and lands them in the jungle. Hence Communists, as consistent internationalists, cannot but be irreconcilable, sworn enemies of antisemitism.

In the U.S.S.R. antisemitism is punishable with the utmost severity of the law as a phenomenon deeply hostile to the Soviet system. Under U.S.S.R. law active antisemites are liable to the death penalty.[87]

The Molotov–Ribbentrop pact—the 1939 non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany—created further suspicion regarding the Soviet Union's position toward Jews. According to the pact, Poland, the nation with the world's largest Jewish population, was divided between Germany and the Soviet Union in September 1939. While the pact had no basis in ideological sympathy (as evidenced by Nazi propaganda about "Jewish Bolshevism"), Germany's occupation of Western Poland was a disaster for Eastern European Jews. Evidence suggests that some, at least, of the Jews in the eastern Soviet zone of occupation welcomed the Russians as having a more liberated policy towards their civil rights than the preceding antisemitic Polish regime.[88] Jews in areas annexed by the Soviet Union were deported eastward in great waves;[citation needed] as these areas would soon be invaded by Nazi Germany, this forced migration, deplored by many of its victims, paradoxically also saved the lives of several hundred thousand Jewish deportees.

Jews who escaped the purges include Lazar Kaganovich, who came to Stalin's attention in the 1920s as a successful bureaucrat in Tashkent and participated in the purges of the 1930s. Kaganovich's loyalty endured even after Stalin's death, when he and Molotov were expelled from the party ranks in 1957 due to their opposition to destalinization.

Beyond longstanding controversies, ranging from the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact to anti-Zionism, the Soviet Union did grant official "equality of all citizens regardless of status, sex, race, religion, and nationality". The years before the Holocaust were an era of rapid change for Soviet Jews, leaving behind the dreadful poverty of the Pale of Settlement. Forty percent of the population in the former Pale left for large cities within the USSR.

Emphasis on education and movement from countryside shtetls to newly industrialized cities allowed many Soviet Jews to enjoy overall advances under Stalin and to become one of the most educated population groups in the world.

Because of Stalinist emphasis on its urban population, interwar migration inadvertently rescued countless Soviet Jews; Nazi Germany penetrated the entire former Jewish Pale—but were kilometers short of Leningrad and Moscow. The migration of many Jews farther East from the Jewish Pale, which would become occupied by Nazi Germany, saved at least 40 percent of the Pale's original Jewish population.

By 1941, it was estimated that the Soviet Union was home to 4.855 million Jews, around 30% of all Jews worldwide. However, the majority of these were residents of rural western Belarus and Ukraine—populations that suffered greatly due to the German occupation and the Holocaust. Only around 800,000 Jews lived outside the occupied territory, and 1,200,000 to 1,400,000 Jews were eventually evacuated eastwards.[89] Of the three million left in occupied areas, the vast majority is thought to have perished in German extermination camps.

World War II and the Holocaust[edit]

Over two million Soviet Jews are believed to have died during the Holocaust, second only to the number of Polish Jews who fell victim to Hitler (see The Holocaust in Poland). Among some of the larger massacres which were committed in 1941 were: 33,771 Jews of Kiev shot in ditches at Babi Yar; 100,000 Jews and Poles of Vilnius killed in the forests of Ponary, 20,000 Jews killed in Kharkiv at Drobnitzky Yar, 36,000 Jews machine-gunned in Odessa, 25,000 Jews of Riga killed in the woods at Rumbula, and 10,000 Jews slaughtered in Simferopol in the Crimea.[citation needed] Although mass shootings continued through 1942, most notably 16,000 Jews shot at Pinsk, Jews were increasingly shipped to concentration camps in German Nazi-occupied Poland.

Local residents of German-occupied areas, especially Ukrainians, Lithuanians, and Latvians, sometimes played key roles in the genocide of other Latvians, Lithuanians, Ukrainians, Slavs, Romani, homosexuals and Jews alike. Under the Nazi occupation, some members of the Ukrainian and Latvian Nazi police carried out deportations in the Warsaw Ghetto, and Lithuanians marched Jews to their death at Ponary. Even as some assisted the Germans, a significant number of individuals in the territories under German control also helped Jews escape death (see Righteous Among the Nations). In Latvia, particularly, the number of Nazi-collaborators was only slightly more than that of Jewish saviours. It is estimated that up to 1.4 million Jews fought in Allied armies; 40% of them in the Red Army.[90] In total, at least 142,500 Soviet soldiers of Jewish nationality lost their lives fighting against the German invaders and their allies[91]

The typical Soviet policy regarding the Holocaust was to present it as atrocities against Soviet citizens, not emphasizing the genocide of the Jews. For example, after the liberation of Kiev from the Nazi occupation, the Extraordinary State Commission (Чрезвычайная Государственная Комиссия; Chrezv'chaynaya Gosudarstvennaya Komissiya) was set out to investigate Nazi crimes. The description of the Babi Yar massacre was officially censored as follows:[92]

| Draft report (December 25, 1943) | Censored version (February 1944) |

|---|---|

|

|

Stalinist antisemitic campaigns[edit]

The revival of Jewish identity after the war, stimulated by the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, was cautiously welcomed by Stalin as a means to put pressure on Western imperialism in the Middle East, but when it became evident that many Soviet Jews expected the revival of Zionism to enhance their own aspirations for separate cultural and religious development in the Soviet Union, a wave of repression was unleashed.[93]

In January 1948 Solomon Mikhoels, a popular actor-director of the Moscow State Jewish Theater and the chairman of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, was killed in a suspicious car accident.[94] Mass arrests of prominent Jewish intellectuals and suppression of Jewish culture followed under the banners of campaign against "rootless cosmopolitans" and anti-Zionism. On August 12, 1952, in the event known as the Night of the Murdered Poets, thirteen of the most prominent Yiddish writers, poets, actors and other intellectuals were executed on the orders of Joseph Stalin, among them Peretz Markish, Leib Kvitko, David Hofstein, Itzik Feffer and David Bergelson.[95] In the 1955 United Nations General Assembly's session a high Soviet official still denied the "rumors" about their disappearance.

The Doctors' Plot allegation in 1953 was a deliberately antisemitic policy: Stalin targeted "corrupt Jewish bourgeois nationalists", eschewing the usual code words like "rootless cosmopolitans" or "cosmopolitans". Stalin died, however, before this next wave of arrests and executions could be launched in earnest. A number of historians claim that the Doctors' Plot was intended as the opening of a campaign that would have resulted in the mass deportation of Soviet Jews had Stalin not died on March 5, 1953. Days after Stalin's death the plot was declared a hoax by the Soviet government.

These cases may have reflected Stalin's paranoia, rather than state ideology—a distinction that made no practical difference as long as Stalin was alive, but which became salient on his death.

In April 1956, the Warsaw Yiddish language Jewish newspaper Folkshtimme published sensational long lists of Soviet Jews who had perished before and after the Holocaust. The world press began demanding answers from Soviet leaders, as well as inquiring about the current condition of the Jewish education system and culture. The same autumn, a group of leading Jewish world figures publicly requested the heads of Soviet state to clarify the situation. Since no cohesive answer was received, their concern was only heightened. The fate of Soviet Jews emerged as a major human rights issue in the West.

The Soviet Union and Zionism[edit]

Marxist anti-nationalism[vague] and anti-clericalism had a mixed effect on Soviet Jews. Jews were the immediate benefactors, but they were also long-term victims, of the Marxist notion that any manifestation of nationalism is "socially retrogressive". On one hand, Jews were liberated from the religious persecution of the Tsarist years of "Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality". On the other, this notion was threatening to Jewish cultural institutions, the Bund, Jewish autonomy, Judaism and Zionism.

Political Zionism was officially stamped out as a form of bourgeois nationalism during the entire history of the Soviet Union. Although Leninism emphasizes the belief in "self-determination", this fact did not make the Soviet state more accepting of Zionism. Leninism defines self-determination by territory or culture, rather than by religion, which allowed Soviet minorities to have separate oblasts, autonomous regions, or republics, which were nonetheless symbolic until its later years. Jews, however, did not fit such a theoretical model; Jews in the Diaspora did not even have an agricultural base, as Stalin often asserted when he attempted to deny the existence of a Jewish nation, and they certainly did not have a territorial unit. Marxist notions even denied the existence of a Jewish identity beyond the existence of a religion and caste; Marx defined Jews as a "chimerical nation".

Lenin, who claimed to be deeply committed to egalitarian ideals and the universality of all humanity, rejected Zionism as a reactionary movement, "bourgeois nationalism", "socially retrogressive", and a backward force that deprecates class divisions among Jews. Moreover, Zionism entailed contact between Soviet citizens and westerners, which was dangerous in a closed society. Soviet authorities were likewise fearful of any mass-movement which was independent of the monopolistic Communist Party, and not tied to the state or the ideology of Marxism-Leninism.

Without changing his official anti-Zionist stance, from late 1944 until 1948 Joseph Stalin adopted a de facto pro-Zionist foreign policy, apparently believing that the new country would be socialist and hasten the decline of British influence in the Middle East.[96]

In a May 14, 1947 speech during the UN Partition Plan debate, published in Izvestiya two days later, the Soviet ambassador Andrei Gromyko announced:

As we know, the aspirations of a considerable part of the Jewish people are linked with the problem of Palestine and of its future administration. This fact scarcely requires proof... During the last war, the Jewish people underwent exceptional sorrow and suffering...

The United Nations cannot and must not regard this situation with indifference, since this would be incompatible with the high principles proclaimed in its Charter...

The fact that no Western European State has been able to ensure the defence of the elementary rights of the Jewish people and to safeguard it against the violence of the fascist executioners explains the aspirations of the Jews to establish their own State. It would be unjust not to take this into consideration and to deny the right of the Jewish people to realize this aspiration.[97]

Soviet approval in the United Nations Security Council was critical to the UN partitioning of the British Mandate of Palestine, which led to the founding of the State of Israel.Three days after Israel declared its independence, the Soviet Union legally recognized it de jure. In addition, the USSR allowed Czechoslovakia to continue supplying arms to the Jewish forces during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, even though this conflict took place after the Soviet-supported Czechoslovak coup d'état of 1948. At the time, the U.S. maintained an arms embargo on both sides in the conflict. See Arms shipments from Czechoslovakia to Israel 1947–1949.

By the end of 1957 the USSR switched sides in the Arab–Israeli conflict and throughout the course of the Cold War unequivocally supported various Arab regimes against Israel. The official position of the Soviet Union and its satellite states and agencies was that Zionism was a tool used by the Jews and Americans for "racist imperialism".

As Israel was emerging as a close Western ally, the specter of Zionism raised fears of internal dissent and opposition. During the later parts of the Cold War, Soviet Jews were suspected of being possible traitors, Western sympathisers, or a security liability. The Communist leadership closed down various Jewish organizations and declared Zionism an ideological enemy. Synagogues were often placed under police surveillance, both openly and through the use of informers.[citation needed]

As a result of the persecution, both state-sponsored and unofficial, antisemitism was ingrained in the society and remained for years: ordinary Soviet Jews often suffered hardships, epitomized by often not being allowed to enlist in universities, work in certain professions, or participate in government. However, it should be mentioned that this was not always the case and this kind of persecution varied depending on the region. Still many Jews felt compelled to hide their identities by changing their names.

The word "Jew" was also avoided in the media when criticising undertakings by Israel, which the Soviets often accused of racism, chauvinism etc. Instead of Jew, the word Israeli was used almost exclusively, so as to paint its harsh criticism not as antisemitism but anti-Zionism. More controversially, the Soviet media, when depicting political events, sometimes used the term 'fascism' to characterise Israeli nationalism (e.g. calling Jabotinsky a 'fascist', and claiming 'new fascist organisations were emerging in Israel in the 1970s' etc.).

1967–1985[edit]

According to the census of 1959 the Jewish population of the city of Leningrad numbered 169,000 and the Great Choral synagogue was open in the 1960s with some 1,200 seats. The rabbi was Avraham Lubanov. This synagogue has never been closed. The great majority of the Leningrad Jews were not religious, but several thousand used to visit the synagogue on great holidays, mostly on Simchat Torah.[99]

A mass emigration was politically undesirable for the Soviet regime. As increasing numbers of Soviet Jews applied to emigrate to Israel in the period following the 1967 Six-Day War, many were formally refused permission to leave. A typical excuse given by the OVIR (ОВиР), the MVD department responsible for the provisioning of exit visas, was that persons who had been given access at some point in their careers to information vital to Soviet national security could not be allowed to leave the country.

After the Dymshits–Kuznetsov hijacking affair in 1970 and the crackdown that followed, strong international condemnations caused the Soviet authorities to increase the emigration quota. From 1960 to 1970, only 4,000 people left the USSR; in the following decade, the number rose to 250,000.[100]

In 1972, the USSR imposed the so-called "diploma tax" on would-be emigrants who received higher education in the USSR.[101] In some cases, the fee was as high as twenty annual salaries. This measure was possibly designed to combat the brain drain caused by the growing emigration of Soviet Jews and other members of the intelligentsia to the West. Although Jews now made up less than 1% of the population, some surveys have suggested that around one-third of the emigrating Jews had achieved some form of higher education. Furthermore, Jews holding positions requiring specialized training tended to be highly concentrated in a small set of specialties, including medicine, mathematics, biology and music.[102] Following international protests, the Kremlin soon revoked the tax, but continued to sporadically impose various limitations. Besides, an unofficial Jewish quota was introduced in the leading institutions of higher education by subjecting Jewish applicants to harsher entrance examinations.[103][104][105][106]

At first almost all of those who managed to get exit visas to Israel actually made aliyah, but after the mid-1970s, most of those allowed to leave for Israel actually chose other destinations, most notably the United States.

Glasnost and end of the USSR[edit]

In 1989 a record 71,000 Soviet Jews were granted exodus from the USSR, of whom only 12,117 immigrated to Israel. At first, American policy treated Soviet Jews as refugees and allowed unlimited numbers to emigrate, but this policy eventually came to an end. As a result, more Jews began moving to Israel, as it was the only country willing to take them unconditionally.

In the 1980s, the liberal government of Mikhail Gorbachev allowed unlimited Jewish emigration, and the Soviet Union itself collapsed in 1991. As a result, a mass emigration of Jews from the former Soviet Union took place. Since the 1970s, over 1.1 million Russians of Jewish origin immigrated to Israel, of whom 100,000 emigrated to third countries such as the United States and Canada soon afterward and 240,000 were not considered Jewish under Halakha, but were eligible under the Law of Return due to Jewish ancestry or marriage. Since the adoption of the Jackson–Vanik amendment, over 600,000 Soviet Jews have emigrated.

Modern-day Russia[edit]

Judaism today is officially designated as one of Russia's four "traditional religions", alongside Orthodox Christianity, Islam and Buddhism.[107] However, the Jewish community continues to decrease rapidly, going from 232,267 people in the 2002 census to 83,896 in 2021, not counting 500 Crimean Karaites, of which 28,119 lived in Moscow and 5,111 lived in the surrounding Moscow Oblast for a total of 33,230, or 39.61% of the entire Russian Jewish population. A further 9,215 lived in Saint-Petersburg with 851 in the surrounding Leningrad Oblast for a total of 10,066, or 12.00% of the entire Russian Jewish population; thus, Russia's two largest cities and surrounding areas hosted 51.61% of the total Russian Jewish population.

The third most populous community was Crimea, which had a population of 2,522 (of which 864 Krymchaks) in the Autonomous Republic in addition to 517 (including 35 Krymchaks) in Sevastopol, for a total of 3,039 (of which 29.58% Krymchaks), not counting 215 Crimean Karaites. This amounts to 3.62% of the total Russian Jewish population.

After Crimea, the most numerically significant populations were Sverdlovsk with 2,354 (2.81%) and Samara, with 2,266 (2.70%), followed by Tatarstan with 1,792 (2.14%), Rostov Oblast with 1,690 (2.01%), Chelyabinsk with 1,677 (2.00%), Krasnodar Krai with 1,620 (1.93%), Stavropol with 1,614 (1.92%), Nizhny Novgorod with 1,473 (1.76%), Bashkortostan with 1,209 (1.44%), Saratov with 1,151 (1.37%) and Novosibirsk with 1,150 (1.37%). The remaining 20,565 (24.52%) of Russian Jews lived in regions with communities numbering fewer than 1,000 Jews.

Despite being designated as a Jewish oblast, the Jewish Autonomous Oblast has only 837 self-identifying Jews, or 0.56% of the total population of the Autonomous Oblast. This is down 64.03% from the 2,327 recorded in the 2002 census, or 1.22% of the Oblast's population at the time.

As of the 2021 census, most Russian Jews are Ashkenazi (82,644 of the 83,896 total, or 98.51%). The second largest community are the Krymchaks, who numbered 954, or 1.14% of the Jewish population. There were 266 Mountain Jews (0.32%) and only remnants of the formerly significant Bukharan and Georgian communities, who numbered 18 (0.02%) and 14 (0.02%) respectively. In addition to this, there were 500 Crimean Karaites, who have historically not identified as Jews.

Most Crimean Karaites lived in Crimea (215, or 43.00%) or Moscow (60); most Krymchaks lived in Crimea (864, or 90.57% of the total) or Sebastopol (35, or 3.68%) meaning 899, or 94.23% of the Russian Krymchak population, still lives on the Crimean peninsula, largely rurally. The Crimean Karaite population in Crimea has declined by well over 50% since the Ukrainian census of 2001. Conversely, most Juhurim have left the Caucasus region, and the largest single community still in Russia (84, 31.58%) is found in Moscow. Of the Jewish populations remaining in the northern Caucasus, most are now Ashkenazi, with only a few being Mountain Jews. There are still 145 Mountain Jews scattered throughout the northern Caucasus, of which 60 are in Dagestan (amounting to 6.49% of the republic's Jewish population), 47 are in Kabardino-Balkaria (6.02%), 29 are in Stavropol (1.80%), 6 are in Krasnodar (0.37%) and 3 are in Adygea (2.24%). There are no Mountain Jews remaining in Chechnya, Ingushetia, North Ossetia-Alania or Karachay-Cherkessia.

Apart from the Krymchaks, all Jewish communities were heavily urbanised - 100% of Bukharan and Georgian Jew, 95.39% of Ashkenazim, 94.74% of Mountain Jews and 91.00% of Crimean Karaites lived in urban areas, whereas only 34.91% of Krymchaks did.

Most Russian Jews are secular and identify themselves as Jews via ethnicity rather than religion, although interest about Jewish identity as well as practice of Jewish tradition amongst Russian Jews is growing.[citation needed] The Lubavitcher Jewish Movement has been active in this sector, setting up synagogues and Jewish kindergartens in Russian cities with Jewish populations. In addition, most Russian Jews have relatives who live in Israel.

There are several major Jewish organizations in the territories of the former USSR. The central Jewish organization is the Federation of Jewish Communities of the CIS under the leadership of Chief Rabbi Berel Lazar.[108]

A linguistic distinction remains to this day in the Russian language where there are two distinct terms that correspond to the word Jew in English. The word еврей ("yevrey" – Hebrew) typically denotes a Jewish ethnicity, as "Hebrew" did in English up until the early 20th century. The word иудей ("iudey" – Judean, etymologically related to the English Jew) is reserved for denoting a follower of the Jewish religion, whether he or she is ethnically Jewish or ethnically Gentile; this term has largely fallen out of use in favor of the equivalent term иудаист ("iudaist"-Judaist). For example, according to a 2012 Russian survey, евреи account for only 32.2% of иудаисты in Russia, with nearly half (49.8%) being Ethnic Russians (русские),.[109] An ethnic slur, жид (borrowed from the Polish Żyd, Jew), also remains in widespread use in Russia.

Antisemitism is one of the most common expressions of xenophobia in post-Soviet Russia, even among some groups of politicians,[110] despite laws against fomenting hatred based on ethnic or religious grounds (Article 282 of Russian Federation Penal Code).[111] In 2002, the number of antisemitic neo-Nazi groups in the republics of the former Soviet Union, led Pravda to declare in 2002 that "Anti-Semitism is booming in Russia".[112] In January 2005, a group of 15 Duma members demanded that Judaism and Jewish organizations be banned from Russia.[113] In 2005, 500 prominent Russians, including some 20 members of the nationalist Rodina party, demanded that the state prosecutor investigate ancient Jewish texts as "anti-Russian" and ban Judaism. An investigation was in fact launched, but halted after an international outcry.[114][115]

Overall, in recent years, particularly since the early 2000s, levels of antisemitism in Russia have been reportedly low, and steadily decreasing.[116][117] In 2019, Ilya Yablogov wrote that many Russians were keen on antisemitic conspiracy theories in 1990s but it declined after 2000 and many high-ranking officials were forced to apologize for the antisemitic behavior.[118]

In Russia, both historical and contemporary antisemitic materials are frequently published. For example, a set (called Library of a Russian Patriot) consisting of twenty five antisemitic titles was recently published, including Mein Kampf translated to Russian (2002), which although was banned in 2010,[119] The Myth of Holocaust by Jürgen Graf, a title by Douglas Reed, Protocols of the Elders of Zion, and others.

Antisemitic incidents are mostly conducted by extremist, nationalist, and Islamist groups. Most of the antisemitic incidents are against Jewish cemeteries and building (community centers and synagogues) such as the assault against the Jewish community's center in Perm in March 2013[120] and the attack on Jewish nursery school in Volgograd in August 2013.[121] Nevertheless, there were several violent attacks against Jews in Moscow in 2006 when a neo-Nazi stabbed 9 people at the Bolshaya Bronnaya Synagogue,[122] the failed bomb attack on the same synagogue in 1999.[123]

Attacks against Jews made by extremist Islamic groups are rare in Russia although there has been increase in the scope of the attacks mainly in Muslim populated areas. On July 25, 2013, the rabbi of Derbent was attacked and badly injured by an unknown person near his home, most likely by a terrorist. The incident sparked concerns among the local Jews of further acts against the Jewish community.[124]

After the passage of some anti-gay laws in Russia in 2013 and the incident with the "Pussy-riot" band in 2012 causing a growing criticism on the subject inside and outside Russia a number of verbal antisemitic attacks were made against Russian gay activists by extremist activists and antisemitic writers such as Israel Shamir who viewed the "Pussy-riot" incident as the war of Judaism on the Christian Orthodox church.[125][126][127]

Today, the Jewish population of Russia is shrinking due to small family sizes, and high rates of assimilation and intermarriage. This shrinkage has been slowed by some Russian-Jewish emigrants having returned from abroad, especially from Germany. The great majority of up to 90% of children born to a Jewish parent are the offspring of mixed marriages, and most Jews have only one or two children.[128]

The EuroStars young adults program provides Jewish learning and social activities in 32 cities across Russia.[129][130][131] Some have described a 'renaissance' in the Jewish community inside Russia since the beginning of the 21st century.[10]

The Chief Rabbi of Russia, Rabbi Berel Lazar, spoke out against the Russian invasion of Ukraine, called Russia to withdraw and for an end to the war, and offered to mediate.[132] The Chief Rabbi of Moscow, Pinchas Goldschmidt, left Russia after he refused a request from state officials to publicly support the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[133] On 30 June 2023, Goldschmidt was designated in Russia as a foreign agent.[134]

Historical demographics[edit]

- Jewish % of the population in each SSR

- 1939

- 1959

- 1989

| Год | Еврейское население (в том числе горские евреи ) | Примечания |

|---|---|---|

| 1914 | Более 5 250 000 | Российская Империя |

| 1926 [135] | 2,672,499 | Первая Всесоюзная перепись населения Советского Союза. Результат изменения границ (отделение Польши и объединение Бессарабии с Румынией), эмиграции и ассимиляции. |

| 1939 [136] | 3,028,538 | Результат естественного прироста, эмиграции, ассимиляции и репрессий. |

| Начало 1941 года | 5,400,000 | Результат аннексии Западной Украины и Белоруссии, прибалтийских республик и притока еврейских беженцев из Польши. |

| 1959 | 2,279,277 | См. Холокост и иммиграцию в Израиль . |

| 1970 | 2,166,026 | Результат естественной убыли населения (уровень смертности превышает рождаемость), эмиграции и ассимиляции (например, смешанных браков). |

| 1979 | 1,830,317 | Снижение по той же причине, что и в 1970 году. |

| 1989 | 1,479,732 | Советская перепись . Итоговая перепись населения во всем Советском Союзе. Спад по той же причине, что и в 1970 году. |

| 2002 | 233,439 | Результат изменения границ (а именно, распад Советского Союза, когда в переписи 2002 года учитывалась только Россия, а не весь СССР) массовая эмиграция, естественная убыль населения и ассимиляция. |

| 2010 | 159,348 | Дальнейшая массовая эмиграция, естественная убыль населения и ассимиляция. |

| 2021 | 83,896 | Снижение по той же причине, что и в 2010 году. Однако в эту перепись был включен Крым, в котором, включая Севастополь, проживало 3039 евреев; это означает, что население увеличилось в одном отношении из-за изменения границ. Таким образом, население по сравнению с 2010 годом составило всего 80 857 человек, что составляет снижение примерно на 50%. |

| ССР | 1897 | 1926 | 1939 | 1959 | 1970 | 1979 | 1989 | 1999-2001 | 2009-2011 | 2019-2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Российская СФСР /Россия | 250,000 [138] | 539,037 | 891,147 | 880,443 | 816,668 | 713,399 | 570,467 | 233,439 | 159,348 | 83,896 |

| Украинская ССР / Украина | 2,680,000 [139] | 2,720,000 [140] | 2,700,000 [141] [142] [с] | 840,446 | 777,406 | 634,420 | 487,555 | 106,600 | 71,500 | 45,000 [143] |

| Белорусская ССР / Беларусь | 690,000 [144] [с] | 150,090 | 148,027 | 135,539 | 112,031 | 24,300 | 12,926 | 13,705 [145] | ||

| Узбекская ССР / Узбекистан | 37,896 | 50,676 | 94,488 | 103,058 | 100,067 | 95,104 | 40,000 | 15,000 | 9,865 [146] | |

| Азербайджанская ССР / Азербайджан | 59,768 | 41,245 | 46,091 | 49,057 | 44,345 | 41,072 | 8,916 | 9,084 [147] | 9,500 | |

| Латвийская ССР / Латвия | 95,675 [148] [б] | 95,600 [149] | 36,604 | 36,686 | 28,338 | 22,925 | 9,600 | 6,454 | 8,094 [150] | |

| Казахская ССР / Казахстан | 3,548 | 19,240 | 28,085 | 27,676 | 23,601 | 20,104 | 6,823 | 3,578 [151] | 2,500 [143] | |

| Литовская ССР / Литва | 263,000 [149] | 24,683 | 23,566 | 14,703 | 12,398 | 4,007 | 3,050 | 2,256 [152] [и] | ||

| Эстонская ССР / Эстония | 4,309 [149] | 5,439 | 5,290 | 4,993 | 4,653 | 2,003 | 1,738 | 1,852 [153] | ||

| Молдавская ССР / Молдова | 250,000 [154] | 95,107 | 98,072 | 80,124 | 65,836 | 5,500 | 3,628 | 1,597 [155] [д] | ||

| Грузинская ССР / Грузия | 30,389 | 42,300 | 51,582 | 55,382 | 28,298 | 24,795 | 2,333 | 2,000 | 1,405 [156] [ф] | |

| Киргизская ССР / Киргизия | 318 | 1,895 | 8,607 | 7,677 | 6,836 | 6,005 | 1,571 | 604 | 433 [157] | |

| Туркменская ССР / Туркменистан | 2,045 | 3,037 | 4,102 | 3,530 | 2,866 | 2,509 | 1,000 [158] | 700 [159] | 200 | |

| Армянская ССР / Армения | 335 | 512 | 1,042 | 1,049 | 962 | 747 | 109 | 127 | 150 | |

| Таджикская ССР / Таджикистан | 275 | 5,166 | 12,435 | 14,627 | 14,697 | 14,580 | 197 | 36 [160] | 25 | |

| Советский Союз / Бывший Советский Союз | 5,250,000 | 2,672,499 | 3,028,538 | 2,279,277 | 2,166,026 | 1,830,317 | 1,479,732 | 460,000 | 280,678 | 180,478 |

| Год | Поп. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1897 | 250,000 | — |

| 1926 | 539,037 | +115.6% |

| 1939 | 891,147 | +65.3% |

| 1959 | 880,443 | −1.2% |

| 1970 | 816,668 | −7.2% |

| 1979 | 713,399 | −12.6% |

| 1989 | 570,467 | −20.0% |

| 2002 | 233,439 | −59.1% |

| 2010 | 159,348 | −31.7% |

| 2021 | 83,896 | −47.4% |

| Источник: [137] [161] [162] [138] Данные о еврейском населении включают горских евреев , грузинских евреев , бухарских евреев (или среднеазиатских евреев), крымчаков (все по советской переписи 1959 года) и татов . [163] | ||

| ССР | % 1926 | % 1939 | % 1959 | % 1970 | % 1979 | % 1989 | % 2002 [161] | % 2010 [162] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Российская СФСР /Россия | 0.58% | 0.81% | 0.75% | 0.63% | 0.52% | 0.39% | 0.18% | 0.11% |

| Украинская ССР / Украина | 6.55% [164] [с] | 2.01% | 1.65% | 1.28% | 0.95% | 0.20% | 0.16% | |

| Белорусская ССР / Беларусь | 6.55% [165] [с] | 1.86% | 1.64% | 1.42% | 1.10% | 0.24% | 0.14% [166] | |

| Молдавская ССР / Молдова | 3.30% | 2.75% | 2.03% | 1.52% | 0.13% | 0.11% | 0.06% | |

| Эстонская ССР / Эстония | 0.38% [149] | 0.45% | 0.39% | 0.34% | 0.30% | 0.14% | 0.13% | |

| Латвийская ССР / Латвия | 5.19% [148] [б] | 4.79% [149] | 1.75% | 1.55% | 1.13% | 0.86% | 0.40% | 0.31% [167] |

| Литовская ССР / Литва | 9.13% [149] | 0.91% | 0.75% | 0.43% | 0.34% | 0.10% | 0.10% [168] | |

| Грузинская ССР / Грузия | 1.15% | 1.19% | 1.28% | 1.18% | 0.57% | 0.46% | 0.10% | 0.08% |

| Армянская ССР / Армения | 0.04% | 0.04% | 0.06% | 0.04% | 0.03% | 0.02% | <0,01% | <0,01% |

| Азербайджанская ССР / Азербайджан | 2.58% | 1.29% | 1.25% | 0.96% | 0.74% | 0.58% | 0.10% | 0.10% [147] |

| Туркменская ССР / Туркменистан | 0.20% | 0.24% | 0.27% | 0.16% | 0.10% | 0.07% | 0.01% | <0,01% |

| Узбекская ССР / Узбекистан | 0.80% | 0.81% | 1.17% | 0.86% | 0.65% | 0.48% | 0.02% | 0.02% |

| Таджикская ССР / Таджикистан | 0.03% | 0.35% | 0.63% | 0.50% | 0.39% | 0.29% | <0,01% | <0,01% |

| Киргизская ССР / Киргизия | 0.03% | 0.13% | 0.42% | 0.26% | 0.20% | 0.14% | 0.02% | 0.01% |

| Казахская ССР / Казахстан | 0.06% | 0.31% | 0.30% | 0.22% | 0.16% | 0.12% | 0.03% | 0.02% |

| Советский Союз / Бывший Советский Союз | 1.80% | 1.80% | 1.09% | 0.90% | 0.70% | 0.52% | 0.16% | 0.10% |

а ^ Данные о еврейском населении за все годы включают горских евреев , грузинских евреев , бухарских евреев (или среднеазиатских евреев), крымчаков (все согласно советской переписи 1959 года) и татов . [169]

б ^ Данные за 1925 год.

с ^ Данные за 1941 год.

д ^ Данные за 2014 год.

и ^ Не включает 192 караима.

алия и иммиграция в страны за Израиля пределами Русско- еврейская

Израиль [ править ]

| Год | СКР |

|---|---|

| 2000 | 1.544 |

| 1999 | 1.612 |

| 1998 | 1.632 |

| 1997 | 1.723 |

| 1996 | 1.743 |

| 1995 | 1.731 |

| 1994 | 1.756 |

| 1993 | 1.707 |

| 1992 | 1.604 |

| 1991 | 1.398 |

| 1990 | 1.390 |

В настоящее время наибольшее количество русских евреев составляют олимы (עוֹלים) и сабры . В 2011 году русские составляли около 15% 7,7-миллионного населения Израиля (включая галахалльских неевреев, которые составляли около 30% иммигрантов из бывшего Советского Союза). [170] Алия в 1990-е годы охватила 85–90% этого населения.Темпы прироста населения родившихся в бывшем Советском Союзе (БСС), олимов, были одними из самых низких среди всех израильских групп: коэффициент рождаемости составлял 1,70, а естественный прирост составлял всего +0,5% в год. [171] Увеличение рождаемости среди евреев в Израиле в период 2000–2007 годов было частично связано с ростом рождаемости среди олимов бывшего СССР , которые сейчас составляют 20% еврейского населения Израиля. [172] [173] 96,5% увеличившегося российского еврейского населения в Израиле либо принадлежат к иудаизму , либо нерелигиозны, в то время как 3,5% (35 000) принадлежат к другим религиям (в основном христианству), и около 10 000 идентифицируют себя как мессианские евреи , отдельные от евреев-христиан . [174]

Общий коэффициент рождаемости для олимов , родившихся в странах бывшего СССР , в Израиле приведен в таблице ниже. СКР со временем увеличивался, достигнув пика в 1997 году, затем немного снизился, а затем снова увеличился после 2000 года. [171]

В 1999 году в Израиле проживало около 1 037 000 олимов , родившихся в странах бывшего Советского Союза , из которых около 738 900 совершили алию после 1989 года. [175] [176] Вторая по величине группа оле (עוֹלֶה) ( марокканские евреи ) насчитывала всего 1 000 000 человек. С 2000 по 2006 год 142 638 олимов , родившихся в странах бывшего СССР , переехали в Израиль, а 70 000 из них эмигрировали из Израиля в такие страны, как США и Канада, в результате чего общая численность населения достигла 1 150 000 человек.Январь 2007 года. [1] В конце 1990-х годов естественный прирост составлял около 0,3%. Например, 2456 в 1996 г. (7463 рождения на 5007 смертей), 2819 в 1997 г. (8214–5395), 2959 в 1998 г. (8926–5967) и 2970 в 1999 г. (9282–6312). В 1999 году естественный прирост составил +0,385%. (Цифры только для олимов, родившихся в странах бывшего Советского Союза , приехавших сюда после 1989 года). [177]

По оценкам, в конце 2010 года в Израиле проживало около 45 000 нелегальных иммигрантов из бывшего Советского Союза, но неясно, сколько из них на самом деле являются евреями. [178]