Еврейская диаспора

Эта статья нуждается в дополнительных цитатах для проверки . ( январь 2023 г. ) |

| Часть серии о |

| Евреи и иудаизм |

|---|

Еврейская (Hebrew: תְּפוּצָה, romanized: təfūṣā) or exile (Hebrew: גָּלוּת gālūṯ; Yiddish: golusдиаспора [а] Это рассеяние израильтян или евреев за пределы их древней прародины ( Земли Израиля ) и их последующее расселение в других частях земного шара. [3] [4]

С точки зрения еврейской Библии , термин «Изгнание» обозначает судьбу израильтян, которые были уведены в изгнание из Израильского царства в 8 веке до нашей эры , и иудеев из Иудейского царства, которые были взяты в изгнание в 6 веке до нашей эры. век до нашей эры. Находясь в изгнании, иудеи стали известны как «евреи» ( יְהוּדִים , или Йехудим ), [ сомнительно – обсудить ] « Мордехай Иудей» из Книги Эстер является первым библейским упоминанием этого термина. [ нужна ссылка ]

Первым изгнанием было ассирийское изгнание , изгнание из Израильского царства (Самарии), начатое Тиглатпаласаром III Ассирии в 733 году до нашей эры. Этот процесс был завершен Саргоном II разрушением царства в 722 г. до н.э., завершив трехлетнюю осаду Самарии начатую Салманасаром V. , Следующим опытом изгнания было вавилонское пленение , во время которого часть населения Иудейского царства была депортирована в 597 г. до н. э. и снова в 586 г. до н. э. Нововавилонской империей под властью Навуходоносора II .

A Jewish diaspora existed for several centuries before the fall of the Second Temple, and their dwelling in other countries for the most part was not a result of compulsory dislocation.[5] Before the middle of the first century CE, in addition to Judea, Syria and Babylonia, large Jewish communities existed in the Roman provinces of Egypt, Crete and Cyrenaica, and in Rome itself;[6] after the siege of Jerusalem in 63 BCE, when the Hasmonean kingdom became a protectorate of Rome, emigration intensified.[citation needed] In 6 CE the region was organized as the Roman province of Judea. The Judean population revolted against the Roman Empire in 66 CE in the First Jewish–Roman War, which culminated in the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE. During the siege, the Romans destroyed the Second Temple and most of Jerusalem. This watershed moment, the elimination of the symbolic centre of Judaism and Jewish identity motivated many Jews to formulate a new self-definition and adjust their existence to the prospect of an indefinite period of displacement.[7]

In 132 CE, Bar Kokhba led a rebellion against Hadrian, a revolt connected with the renaming of Jerusalem as Aelia Capitolina. After four years of devastating warfare, the uprising was suppressed, and Jews were forbidden access to Jerusalem.

During the Middle Ages, due to increasing migration and resettlement, Jews divided into distinct regional groups that today are generally addressed according to two primary geographical groupings: the Ashkenazi of Northern and Eastern Europe, and the Sephardic Jews of Iberia (Spain and Portugal), North Africa and the Middle East. These groups have parallel histories sharing many cultural similarities as well as a series of massacres, persecutions and expulsions, such as the expulsion from England in 1290, the expulsion from Spain in 1492, and the expulsion from Arab countries in 1948–1973. Although the two branches comprise many unique ethno-cultural practices and have links to their local host populations (such as Central Europeans for the Ashkenazim and Hispanics and Arabs for the Sephardim), their shared religion and ancestry, as well as their continuous communication and population transfers, has been responsible for a unified sense of cultural and religious Jewish identity between Sephardim and Ashkenazim from the late Roman period to the present.

Origins and uses of the terms

Diaspora has been a common phenomenon for many peoples since antiquity, but what is particular about the Jewish instance is the pronounced negative, religious, indeed metaphysical connotations traditionally attached to dispersion and exile (galut), two conditions which were conflated.[8] The English term diaspora, which entered usage as late as 1876, and the Hebrew word galut though covering a similar semantic range, bear some distinct differences in connotation. The former has no traditional equivalent in Hebrew usage.[9]

Steven Bowman argues that diaspora in antiquity connoted emigration from an ancestral mother city, with the emigrant community maintaining its cultural ties with the place of origin. Just as the Greek city exported its surplus population, so did Jerusalem, while remaining the cultural and religious centre or metropolis (ir-va-em be-yisrael) for the outlying communities. It could have two senses in Biblical terms, the idea of becoming a 'guiding light unto the nations' by dwelling in the midst of gentiles, or of enduring the pain of exile from one's homeland. The conditions of diaspora in the former case were premised on the free exercise of citizenship or resident alien status. Galut implies by comparison living as a denigrated minority, stripped of such rights, in the host society.[10] Sometimes diaspora and galut are defined as 'voluntary' as opposed to 'involuntary' exile.[11] Diaspora, it has been argued, has a political edge, referring to geopolitical dispersion, which may be involuntary, but which can assume, under different conditions, a positive nuance. Galut is more teleological, and connotes a sense of uprootedness.[12] Daniel Boyarin defines diaspora as a state where people have a dual cultural allegiance, productive of a double consciousness, and in this sense a cultural condition not premised on any particular history, as opposed to galut, which is more descriptive of an existential situation, that properly of exile, conveying a particular psychological outlook.[13]

The Greek word διασπορά (dispersion) first appears as a neologism in the translation of the Old Testament known as the Septuagint, where it occurs 14 times,[14] starting with a passage reading: ἔση διασπορὰ ἐν πάσαις βασιλείαις τῆς γῆς (‘thou shalt be a diaspora (or dispersion) in all kingdoms of the earth’, Deuteronomy 28:25), translating 'ləza‘ăwāh', whose root suggests 'trouble, terror'. In these contexts it never translated any term in the original Tanakh drawn from the Hebrew root glt (גלה), which lies behind galah, and golah, nor even galuth.[15] Golah appears 42 times, and galuth in 15 passages, and first occurs in the 2 Kings 17:23's reference to the deportation of the Judean elite to Babylonia.[16] Stéphane Dufoix, in surveying the textual evidence, draws the following conclusion:

galuth and diaspora are drawn from two completely different lexicons. The first refers to episodes, precise and datable, in the history of the people of Israel, when the latter was subjected to a foreign occupation, such as that of Babylon, in which most of the occurrences are found. The second, perhaps with a single exception that remains debatable, is never used to speak of the past and does not concern Babylon; the instrument of dispersion is never the historical sovereign of another country. Diaspora is the word for chastisement, but the dispersion in question has not occurred yet: it is potential, conditional on the Jews not respecting the law of God. . . It follows that diaspora belongs, not to the domain of history, but of theology.'[17]

In Talmudic and post-Talmudic Rabbinic literature, this phenomenon was referred to as galut (exile), a term with strongly negative connotations, often contrasted with geula (redemption).[18] Eugene Borowitz describes Galut as "fundamentally a theological category[19] The modern Hebrew concept of Tefutzot תפוצות, "scattered", was introduced in the 1930s by the Jewish-American Zionist academic Simon Rawidowicz,[20] who to some degree argued for the acceptance of the Jewish presence outside the Land of Israel as a modern reality and an inevitability. The Greek term for diaspora (διασπορά) also appears three times in the New Testament, where it refers to the scattering of Israel, i.e., the Ten Northern Tribes of Israel as opposed to the Southern Kingdom of Judah, although James (1:1) refers to the scattering of all twelve tribes.

In modern times, the contrasting meanings of diaspora/galut have given rise to controversy among Jews. Bowman states this in the following terms,

(Diaspora) follows the Greek usage and is considered a positive phenomenon that continues the prophetic call of Israel to be a 'light unto the nations' and establish homes and families among the gentiles. The prophet Jeremiah issues this call to the preexilic emigrants in Egypt. . . Galut is a religious–nationalist term, which implies exile from the homeland as a result of collective sins, an exile that will be redeemed at YHWH’s pleasure. Jewish messianism is closely connected with the concept of galut.’[10]

In Zionist debates a distinction was made between galut and golus/gola. The latter denoted social and political exile, whereas the former, while consequential on the latter, was a psycho-spiritual framework that was not wholly dependent on the conditions of life in diasporic exile, since one could technically remain in galut even in Eretz Israel.[21][22] Whereas Theodor Herzl and his follows thought that the establishment of a Jewish state would put an end to the diasporic exile, Ahad Ha-am thought to the contrary that such a state's function would be to 'sustain Jewish nationhood' in the diaspora.[21]

Pre-Roman diaspora

In 722 BCE, the Assyrians, under Sargon II, successor to Shalmaneser V, conquered the Kingdom of Israel, and many Israelites were deported to Mesopotamia.[23] The Jewish proper diaspora began with the Babylonian exile in the 6th century BCE.[24]

After the overthrow of the Kingdom of Judah in 586 BCE by Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon (see Babylonian captivity) and the deportation of a considerable portion of its inhabitants to Mesopotamia, the Jews had two principal cultural centers: Babylonia and the land of Israel.[25][26]

Deportees returned to the Samaria after the Neo-Babylonian Empire was in turn conquered by Cyrus the Great. The biblical book of Ezra includes two texts said to be decrees allowing the deported Jews to return to their homeland after decades and ordering the Temple rebuilt. The differences in content and tone of the two decrees, one in Hebrew and one in Aramaic, have caused some scholars to question their authenticity.[27] The Cyrus Cylinder, an ancient tablet on which is written a declaration in the name of Cyrus referring to restoration of temples and repatriation of exiled peoples, has often been taken as corroboration of the authenticity of the biblical decrees attributed to Cyrus,[28] but other scholars point out that the cylinder's text is specific to Babylon and Mesopotamia and makes no mention of Judah or Jerusalem.[28] Lester L. Grabbe asserted that the "alleged decree of Cyrus"[29] regarding Judah, "cannot be considered authentic", but that there was a "general policy of allowing deportees to return and to re-establish cult sites". He also stated that archaeology suggests that the return was a "trickle" taking place over decades, rather than a single event. There is no sudden expansion of the population base of 30,000 and no credible indication of any special interest in Yehud.[30]

Although most of the Jewish people during this period, especially the wealthy families, were to be found in Babylonia, the existence they led there, under the successive rulers of the Achaemenids, the Seleucids, the Parthians, and the Sassanians, was obscure and devoid of political influence. The poorest but most fervent of the exiles returned to Judah / the Land of Israel during the reign of the Achaemenids (c. 550–330 BCE). There, with the reconstructed Temple in Jerusalem as their center, they organized themselves into a community, animated by a remarkable religious ardor and a tenacious attachment to the Torah as the focus of their identity. As this little nucleus increased in numbers with the accession of recruits from various quarters, it awoke to a consciousness of itself, and strove once again for national independence and political enfranchisement and sovereignty.[citation needed]

The first Jewish diaspora in Egypt arose in the last century of pharaonic rule, apparently with the settlement there, either under Ashurbanipal or during the reign of Psammeticus of a colony of Jewish mercenaries, a military class that successively served the Persian, the Ptolemaic and Roman governments down to the early decades of the second century CE, when the revolt against Trajan destroyed them. Their presence was buttressed by numerous Jewish administrators who joined them in Egypt's military and urban centres.[31] According to Josephus, when Ptolemy I took Judea, he led 120,000 Jewish captives to Egypt, and many other Jews, attracted by Ptolemy's liberal and tolerant policies and Egypt's fertile soil, emigrated from Judea to Egypt of their own free will.[32] Ptolemy settled the Jews in Egypt to employ them as mercenaries. Philadelphus subsequently emancipated the Jews taken to Egypt as captives and settled them in cleruchs, or specialized colonies, as Jewish military units.[33][better source needed]

While communities in Alexandria and Rome dated back to before the Maccabean Revolt, the population in the Jewish diaspora expanded after the Pompey's campaign in 62 BCE. Under the Hasmonean princes, who were at first high priests and then kings, the Jewish state displayed even a certain luster[clarification needed] and annexed several territories. Soon, however, discord within the royal family and the growing disaffection of the pious towards rulers who no longer evinced any appreciation of the real aspirations of their subjects made the Jewish nation easy prey for the ambitions of the now increasingly autocratic and imperial Romans, the successors of the Seleucids. In 63 BCE Pompey invaded Jerusalem, the Jewish people lost their political sovereignty and independence, and Gabinius subjected the Jewish people to tribute.[citation needed]

Early diaspora populations

As early as the third century BCE Jewish communities sprang up in the Aegean islands, Greece, Asia Minor, Cyrenaica, Italy and Egypt.[34]: 8–11 In Palestine, under the favourable auspices of the long period of peace—almost a whole century—which followed the advent of the Ptolemies, the new ways were to flourish. By means of all kinds of contacts, and particularly thanks to the development of commerce, Hellenism infiltrated on all sides in varying degrees. The ports of the Mediterranean coast were indispensable to commerce and, from the very beginning of the Hellenistic period, underwent great development. In the Western diaspora Greek quickly became dominant in Jewish life and little sign remains of profound contact with Hebrew or Aramaic, the latter probably being the more prevalent. Jews migrated to new Greek settlements that arose in the Eastern Mediterranean and former subject areas of the Persian Empire on the heels of Alexander the Great's conquests, spurred on by the opportunities they expected to find.[35] The proportion of Jews in the diaspora in relation to the size of the nation as a whole increased steadily throughout the Hellenistic era and reached astonishing dimensions in the early Roman period, particularly in Alexandria. It was not least for this reason that the Jewish people became a major political factor, especially since the Jews in the diaspora, notwithstanding strong cultural, social and religious tensions, remained firmly united with their homeland.[36] Smallwood writes that, 'It is reasonable to conjecture that many, such as the settlement in Puteoli attested in 4 BCE went back to the late (pre-Roman Empire) Roman Republic or early Empire and originated in voluntary emigration and the lure of trade and commerce."[37] Many Jews migrated to Rome from Alexandria due to flourishing trade relations between the cities.[38] Dating the numerous settlements is difficult. Some settlements may have resulted from Jewish emigration following the defeat of Jewish revolts. Others, such as the Jewish community in Rome, were far older, dating back to at least the mid second century BCE, although it expanded greatly following Pompey’s campaign in 62 BCE. In 6 CE the Romans annexed Judaea. Only the Jews in Babylonia remained outside of Roman rule.[39]: 168 Unlike the Greek speaking Hellenized Jews in the west the Jewish communities in Babylonian and Judea continued the use of Aramaic as a primary language.[24]

As early as the middle of the 2nd century BCE the Jewish author of the third book of the Oracula Sibyllina addressed the "chosen people," saying: "Every land is full of thee and every sea." The most diverse witnesses, such as Strabo, Philo, Seneca, Luke (the author of the Acts of the Apostles), Cicero, and Josephus, all mention Jewish populations in the cities of the Mediterranean basin. See also History of the Jews in India and History of the Jews in China for pre-Roman (and post-) diasporic populations.

King Agrippa I, in a letter to Caligula, enumerated among the provinces of the Jewish diaspora almost all the Hellenized and non-Hellenized countries of the Orient. This enumeration was far from complete as Italy and Cyrene were not included. The epigraphic discoveries from year to year augment the number of known Jewish communities but must be viewed with caution due to the lack of precise evidence of their numbers. According to the ancient Jewish historian Josephus, the next most dense Jewish population after the Land of Israel and Babylonia was in Syria, particularly in Antioch, and Damascus, where 10,000 to 18,000 Jews were massacred during the great insurrection. The ancient Jewish philosopher Philo gives the number of Jewish inhabitants in Egypt as one million, one-eighth of the population. Alexandria was by far the most important of the Egyptian Jewish communities. The Jews in the Egyptian diaspora were on a par with their Ptolemaic counterparts and close ties existed for them with Jerusalem. As in other Hellenistic diasporas, the Egyptian diaspora was one of choice not of imposition.[36]

To judge by the later accounts of wholesale massacres in 115 CE, the number of Jewish residents in Cyrenaica, Cyprus, and Mesopotamia must also have been large. At the commencement of the reign of Caesar Augustus, there were over 7,000 Jews in Rome (though this is only the number that is said to have escorted the envoys who came to demand the deposition of Archelaus; compare: Bringmann: Klaus: Geschichte der Juden im Altertum, Stuttgart 2005, S. 202. Bringmann talks about 8,000 Jews who lived in the city of Rome.). Many sources say that the Jews constituted a full one-tenth (10%) of the population of the ancient city of Rome itself. Finally, if the sums confiscated by the governor Lucius Valerius Flaccus in the year 62/61 BCE represented the tax of a didrachma per head for a single year, it would imply that the Jewish population of Asia Minor numbered 45,000 adult males, for a total of at least 180,000 persons.[citation needed]

Under the Roman Empire

The 13th-century author Bar Hebraeus gave a figure of 6,944,000 Jews in the Roman world. Salo Wittmayer Baron considered the figure convincing.[40] The figure of seven million within and one million outside the Roman world in the mid-first century became widely accepted, including by Louis Feldman. However, contemporary scholars now accept that Bar Hebraeus based his figure on a census of total Roman citizens and thus, included non-Jews. The figure of 6,944,000 being recorded in Eusebius' Chronicon.[41]: 90, 94, 104–05 [42] Louis Feldman, previously an active supporter of the figure, now states that he and Baron were mistaken.[43]: 185 Philo gives a figure of one million Jews living in Egypt. John R. Bartlett rejects Baron's figures entirely, arguing that we have no clue as to the size of the Jewish demographic in the ancient world.[41]: 97–103 The Romans did not distinguish between Jews inside and outside of the Land of Israel/Judaea. They collected an annual temple tax from Jews both in and outside of Israel. The revolts in and suppression of diaspora communities in Egypt, Libya and Crete in 115–117 CE had a severe impact on the Jewish diaspora.

Destruction of Judea

Roman rule in Judea began in 63 BCE with the capture of Jerusalem by Pompey. After the city fell to Pompey's forces, thousands of Jewish prisoners of war were brought from Judea to Rome and sold into slavery. After these Jewish slaves were manumitted, they settled permanently in Rome on the right bank of the Tiber as traders.[45][38] In 37 BCE, the forces of the Jewish client king Herod the Great captured Jerusalem with Roman assistance, and there was likely an influx of Jewish slaves taken into the diaspora by Roman forces. In 53 BCE, a minor Jewish revolt was suppressed and the Romans subsequently sold Jewish war captives into slavery.[46] Roman rule continued until the First Jewish-Roman War, or the Great Revolt, a Jewish uprising to fight for independence, which began in 66 CE and was eventually crushed in 73 CE, culminating in the Siege of Jerusalem and the burning and destruction of the Temple, the centre of the national and religious life of the Jews throughout the world. The Jewish diaspora at the time of the Temple's destruction, according to Josephus, was in Parthia (Persia), Babylonia (Iraq), Arabia, as well as some Jews beyond the Euphrates and in Adiabene (Kurdistan). In Josephus' own words, he had informed "the remotest Arabians" about the destruction.[47] Jewish communities also existed in southern Europe, Anatolia, Syria, and North Africa. Jewish pilgrims from the diaspora, undeterred by the rebellion, had actually come to Jerusalem for Passover prior to the arrival of the Roman army, and many became trapped in the city and died during the siege.[48] According to Josephus, about 97,000 Jewish captives from Judea were sold into slavery by the Romans during the revolt.[49] Many other Jews fled from Judea to other areas around the Mediterranean. Josephus wrote that 30,000 Jews were deported from Judea to Carthage by the Romans.[50]

Exactly when Roman Anti-Judaism began is a question of scholarly debate, however historian Hayim Hillel Ben-Sasson has proposed that the "Crisis under Caligula" (37–41) was the "first open break between Rome and the Jews".[51] Meanwhile, the Kitos War, a rebellion by Jewish diaspora communities in Roman territories in the Eastern Mediterranean and Mesopotamia, led to the destruction of Jewish communities in Crete, Cyprus, and North Africa in 117 CE, and consequently the dispersal of Jews already living outside of Judea to further reaches of the Empire.[52]

Jerusalem had been left in ruins from the time of Vespasian. Sixty years later, Hadrian, who had been instrumental in the expulsion from Palestine of Marcius Turbo after his bloody repression of Jews in the diaspora in 117 CE,[53] on visiting the area of Iudaea, decided to rebuild the city in 130 CE, and settle it, circumstantial evidence suggesting it was he who renamed it[54][55] Ælia Capitolina, with a Roman colonia and foreign cults. It is commonly held that this was done as an insult to the Jews and as a means of erasing the land's Jewish identity,[56][57][58][59] Others argued that this project was expressive of an intention of establishing administratively and culturally a firm Roman imperial presence, and thus incorporating the province, now called Syro-Palaestina, into the Roman world system. These political measures were, according to Menachem Mor, devoid of any intention to eliminate Judaism,[60] indeed, the pagan reframing of Jerusalem may have been a strategic move designed to challenge, rather, the growing threat, pretensions and influence of converts to Christianity, for whom Jerusalem was likewise a crucial symbol of their faith.[61] Implementation of these plans led to violent opposition, and triggered a full-scale insurrection with the Bar Kokhba revolt (132–136 CE),[62] assisted, according to Dio Cassius, by some other peoples, perhaps Arabs who had recently been subjected by Trajan.[63] The revolt was crushed, with the Jewish population of Judea devastated. Jewish war captives were again captured and sold into slavery by the Romans. According to Jewish tradition, the Romans deported twelve boatloads of Jews to Cyrenaica.[64] Voluntary Jewish emigration from Judea in the aftermath of the Bar-Kokhba revolt also expanded Jewish communities in the diaspora.[65] Jews were forbidden entrance to Jerusalem on pain of death, except for the day of Tisha B'Av. There was a further shift of the center of religious authority from Yavne, as rabbis regrouped in Usha in the western Galilee, where the Mishnah was composed. This ban struck a blow at Jewish national identity within Palestine, while the Romans however continued to allow Jews in the diaspora their distinct national and religious identity throughout the Empire.[66]

The military defeats of the Jews in Judaea in 70 CE and again in 135 CE, with large numbers of Jewish captives from Judea sold into slavery and an increase in voluntary Jewish emigration from Judea as a result of the wars, meant a drop in Palestine's Jewish population was balanced by a rise in diaspora numbers. Jewish prisoners sold as slaves in the diaspora and their children were eventually manumitted and joined local free communities.[67] It has been argued that the archaeological evidence is suggestive of a Roman genocide taking place during the Second revolt.[68] A significant movement of gentiles and Samaritans into villages formerly with a Jewish majority appears to have taken place thereafter.[69] During the Crisis of the Third Century, civil wars in the Roman Empire caused great economic disruption, and taxes imposed to finance these wars impacted the Jewish population of Palestine heavily. As a result, many Jews emigrated to Babylon under the more tolerant Sassanid Empire, where autonomous Jewish communities continued to flourish, lured by the promise of economic prosperity and the ability to lead a full Jewish life there.[70]

Palestine and Babylon were both great centers of Jewish scholarship during this time, but tensions between scholars in these two communities grew as many Jewish scholars in Palestine feared that the centrality of the land to the Jewish religion would be lost with continuing Jewish emigration. Many Palestinian sages refused to consider Babylonian scholars their equals and would not ordain Babylonian students in their academies, fearing they would return to Babylon as rabbis. Significant Jewish emigration to Babylon adversely affected the Jewish academies of Palestine, and by the end of the third century they were reliant on donations from Babylon.[70]

It is commonly claimed that the diaspora began with Rome's twofold crushing of Jewish national aspirations. David Aberbach, for one, has argued that much of the European Jewish diaspora, by which he means exile or voluntary migration, originated with the Jewish wars which occurred between 66 and 135 CE.[71]: 224 Martin Goodman states that it is only after the destruction of Jerusalem that Jews are found in northern Europe and along the western Mediterranean coast.[72] This widespread popular belief holds that there was a sudden expulsion of Jews from Judea/Syria Palaestina and that this was crucial for the establishment of the diaspora.[73] Israel Bartal contends that Shlomo Sand is incorrect in ascribing this view to most Jewish study scholars,[74] instead arguing that this view is negligible among serious Jewish study scholars.[75] These scholars argue that the growth of diaspora Jewish communities was a gradual process that occurred over the centuries, starting with the Assyrian destruction of Israel, the Babylonian destruction of Judah, the Roman destruction of Judea, and the subsequent rule of Christians and Muslims. After the revolt, the Jewish religious and cultural center shifted to the Babylonian Jewish community and its scholars. For the generations that followed, the destruction of the Second Temple event came to represent a fundamental insight about the Jews who had become a dispossessed and persecuted people for much of their history.[76]

Erich S. Gruen maintains that focusing on the destruction of the Temple misses the point that already before this, the diaspora was well established. Compulsory dislocation of people cannot explain more than a fraction of the eventual diaspora.[77] Avrum Ehrlich also states that already well before the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE, more Jews lived in the Diaspora than in Israel.[78] Jonathan Adelman estimated that around 60% of Jews lived in the diaspora during the Second Temple period.[79] According to Gruen:

Perhaps three to five million Jews dwelled outside Palestine in the roughly four centuries that stretched from Alexander to Titus. The era of the Second Temple brought the issue into sharp focus, inescapably so. The Temple still stood, a reminder of the hallowed past, and, through most of the era, a Jewish regime existed in Palestine. Yet the Jews of the diaspora, from Italy to Iran, far outnumbered those in the homeland. Although Jerusalem loomed large in their self-perception as a nation, few of them had seen it, and few were likely to.[80]

Israel Yuval claimed the Babylonian captivity created a promise of return in the Jewish consciousness which had the effect of enhancing the Jewish self-perception of Exile after the destruction of the Second Temple, albeit their dispersion was due to an array of non-exilic factors.[81]

Byzantine, Islamic, and Crusader periods

In the 4th century, the Roman Empire split and Palestine came under the control of the Byzantine Empire. There was still a significant Jewish population there, and Jews probably constituted a majority of the population until some time after Constantine converted to Christianity in the 4th century.[82] The ban on Jewish settlement in Jerusalem was maintained. There was a minor Jewish rebellion against a corrupt governor from 351 to 352 which was put down. In the 5th century, the collapse of the Western Roman Empire resulted in Christian migration into Palestine and the development of a firm Christian majority. Judaism was the only non-Christian religion tolerated, but the Jews were discriminated against in various ways. They were prohibited from building new houses of worship, holding public office, or owning slaves.[83] The 7th century saw the Jewish revolt against Heraclius, which broke out in 614 during the Byzantine–Sasanian War. It was the last serious attempt by Jews to gain autonomy in the Land of Israel prior to modern times. Jewish rebels aided the Persians in capturing Jerusalem, where the Jews were permitted autonomous rule until 617, when the Persians reneged on their alliance. After Byzantine Emperor Heraclius promised to restore Jewish rights, the Jews aided him in ousting the Persians. Heraclius subsequently went back on his word and ordered a general massacre of the Jewish population, devastating the Jewish communities of Jerusalem and the Galilee. As a result, many Jews fled to Egypt.[84][85]

In 638, Palestine came under Muslim rule with the Muslim conquest of the Levant. One estimate placed the Jewish population of Palestine at between 300,000 and 400,000 at the time.[86] However, this is contrary to other estimates which place it at 150,000 to 200,000 at the time of the revolt against Heraclius.[87][88] According to historian Moshe Gil, the majority of the population was Jewish or Samaritan.[89] The land gradually came to have an Arab majority as Arab tribes migrated there. Jewish communities initially grew and flourished. Umar allowed and encouraged Jews to settle in Jerusalem. It was the first time in about 500 years that Jews were allowed to freely enter and worship in their holiest city. In 717, new restrictions were imposed against non-Muslims that negatively affected the Jews. Heavy taxes on agricultural land forced many Jews to migrate from rural areas to towns. Social and economic discrimination caused significant Jewish emigration from Palestine, and Muslim civil wars in the 8th and 9th centuries pushed many Jews out of the country. By the end of the 11th century the Jewish population of Palestine had declined substantially.[90][91]

During the First Crusade, Jews in Palestine, along with Muslims, were indiscriminately massacred and sold into slavery by the Crusaders. The majority of Jerusalem's Jewish population was killed during the Crusader Siege of Jerusalem and the few thousand survivors were sold into slavery. Some of the Jews sold into slavery later had their freedom bought by Jewish communities in Italy and Egypt, and the redeemed slaves were taken to Egypt. Some Jewish prisoners of war were also deported to Apulia in southern Italy.[92][93][94]

Relief for the Jewish population of Palestine came when the Ayyubid dynasty defeated the Crusaders and conquered Palestine (see 1187 Battle of Hattin). Some Jewish immigration from the diaspora subsequently took place, but this came to an end when Mamluks took over Palestine (see 1291 Fall of Acre). The Mamluks severely oppressed the Jews and greatly mismanaged the economy, resulting in a period of great social and economic decline. The result was large-scale migration from Palestine, and the population declined. The Jewish population shrunk especially heavily, as did the Christian population. Though some Jewish immigration from Europe, North Africa, and Syria also occurred in this period, which potentially saved the collapsing Jewish community of Palestine from disappearing altogether, Jews were reduced to an even smaller minority of the population.[95]

The result of these waves of emigration and expulsion was that the Jewish population of Palestine was reduced to a few thousand by the time the Ottoman Empire conquered Palestine, after which the region entered a period of relative stability. At the start of Ottoman rule in 1517, the estimated Jewish population was 5,000, composed of both descendants of Jews who had never left the land and migrants from the diaspora.[96][97][better source needed]

Post-Roman period Jewish diaspora populations

During the Middle Ages, due to increasing geographical dispersion and re-settlement, Jews divided into distinct regional groups which today are generally addressed according to two primary geographical groupings: the Ashkenazi of Northern and Eastern Europe, and the Sephardic Jews of Iberia (Spain and Portugal), North Africa and the Middle East. These groups have parallel histories sharing many cultural similarities as well as a series of massacres, persecutions and expulsions, such as the expulsion from England in 1290, the expulsion from Spain in 1492, and the expulsion from Arab countries in 1948–1973. Although the two branches comprise many unique ethno-cultural practices and have links to their local host populations (such as Central Europeans for the Ashkenazim and Hispanics and Arabs for the Sephardim), their shared religion and ancestry, as well as their continuous communication and population transfers, has been responsible for a unified sense of cultural and religious Jewish identity between Sephardim and Ashkenazim from the late Roman period to the present.

By 1764 there were about 750,000 Jews in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The worldwide Jewish population (comprising the Middle East and the rest of Europe) was estimated at 1.2 million.[98]

Classical period

After the Persian conquest of Babylon in 539 BCE, Judah (יְהוּדָה Yehuda) became a province of the Persian empire. This status continued into the following Hellenistic period, when Yehud became a disputed province of Ptolemaic Egypt and Seleucid Syria. In the early part of the 2nd century BCE, a revolt against the Seleucids led to the establishment of an independent Jewish kingdom under the Hasmonean dynasty. The Hasmoneans adopted a deliberate policy of imitating and reconstituting the Davidic kingdom, and as part of this forcibly converted to Judaism their neighbours in the Land of Israel. The conversions included Nabateans (Zabadeans) and Itureans, the peoples of the former Philistine cities, the Moabites, Ammonites and Edomites. Attempts were also made to incorporate the Samaritans, following takeover of Samaria. The success of mass-conversions is however questionable, as most groups retained their tribal separations and mostly turned Hellenistic or Christian, with Edomites perhaps being the only exception to merge into the Jewish society under Herodian dynasty and in the following period of Jewish–Roman Wars.[99]

Middle Ages

Ashkenazi Jews

Ashkenazi Jews is a general category of Jewish populations who immigrated to what is now Germany and northeastern France during the Middle Ages and until modern times used to adhere to the Yiddish culture and the Ashkenazi prayer style. There is evidence that groups of Jews had immigrated to Germania during the Roman Era; they were probably merchants who followed the Roman Legions during their conquests. However, for the most part, modern Ashkenazi Jews originated with Jews who migrated or were forcibly taken from the Middle East to southern Europe in antiquity, where they established Jewish communities before moving into northern France and lower Germany during the High and Late Middle Ages. They also descend to a lesser degree from Jewish immigrants from Babylon, Persia, and North Africa who migrated to Europe in the Middle Ages. The Ashkenazi Jews later migrated from Germany (and elsewhere in Central Europe) into Eastern Europe as a result of persecution.[100][101][102][103] Some Ashkenazi Jews also have minor ancestry from Sephardi Jews exiled from Spain, first during Islamic persecutions (11th–12th centuries) and later during Christian reconquests (13th–15th centuries) and the Spanish Inquisition (15th–16th centuries). Ashkenazi Jews are of mixed Middle Eastern and European ancestry, as they derive part of their ancestry from non-Jewish Europeans who intermixed with Jews of migrant Middle Eastern origin.

In 2006, a study by Doron Behar and Karl Skorecki of the Technion and Ramban Medical Center in Haifa, Israel demonstrated that the vast majority of Ashkenazi Jews, both men and women, have Middle Eastern ancestry.[104] According to Nicholas Wades' 2010 Autosomal study Ashkenazi Jews share a common ancestry with other Jewish groups and Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews have roughly 30% European ancestry with the rest being Middle Eastern.[105] According to Hammer, the Ashkenazi population expanded through a series of bottlenecks—events that squeeze a population down to small numbers—perhaps as it migrated from the Middle East after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, to Italy, reaching the Rhine Valley in the 10th century.

David Goldstein, a Duke University geneticist and director of the Duke Center for Human Genome Variation, has said that the work of the Technion and Ramban team served only to confirm that genetic drift played a major role in shaping Ashkenazi mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which is inherited in a matrilineal manner. Goldstein argues that the Technion and Ramban mtDNA studies fail to actually establish a statistically significant maternal link between modern Jews and historic Middle Eastern populations. This differs from the patrilineal case, where Goldstein said there is no doubt of a Middle Eastern origin.[104]

In June 2010, Behar et al. "shows that most Jewish samples form a remarkably tight subcluster with common genetic origin, that overlies Druze and Cypriot samples but not samples from other Levantine populations or paired diaspora host populations. In contrast, Ethiopian Jews (Beta Israel) and Indian Jews (Bene Israel and Cochini) cluster with neighboring autochthonous populations in Ethiopia and western India, respectively, despite a clear paternal link between the Bene Israel and the Levant."[105][106] "The most parsimonious explanation for these observations is a common genetic origin, which is consistent with an historical formulation of the Jewish people as descending from ancient Hebrew and Israelite residents of the Levant." In conclusion the authors are stating that the genetic results are concordant "with the dispersion of the people of ancient Israel throughout the Old World". Regarding the samples he used Behar points out that "Our conclusion favoring common ancestry (of Jewish people) over recent admixture is further supported by the fact that our sample contains individuals that are known not to be admixed in the most recent one or two generations."

A 2013 study of Ashkenazi mitochondrial DNA by Costa et al., reached the conclusion that the four major female founders and most of the minor female founders had ancestry in prehistoric Europe, rather than the Near East or Caucasus. According to the study these findings 'point to a significant role for the conversion of women in the formation of Ashkenazi communities" and their intermarriage with Jewish men of Middle Eastern origin.[107]

A study by Haber, et al., (2013) noted that while previous studies of the Levant, which had focused mainly on diaspora Jewish populations, showed that the "Jews form a distinctive cluster in the Middle East", these studies did not make clear "whether the factors driving this structure would also involve other groups in the Levant". The authors found strong evidence that modern Levant populations descend from two major apparent ancestral populations. One set of genetic characteristics which is shared with modern-day Europeans and Central Asians is most prominent in the Levant amongst "Lebanese, Armenians, Cypriots, Druze and Jews, as well as Turks, Iranians and Caucasian populations". The second set of inherited genetic characteristics is shared with populations in other parts of the Middle East as well as some African populations. Levant populations in this category today include "Palestinians, Jordanians, Syrians, as well as North Africans, Ethiopians, Saudis, and Bedouins". Concerning this second component of ancestry, the authors remark that while it correlates with "the pattern of the Islamic expansion", and that "a pre-Islamic expansion Levant was more genetically similar to Europeans than to Middle Easterners," they also say that "its presence in Lebanese Christians, Sephardi and Ashkenazi Jews, Cypriots and Armenians might suggest that its spread to the Levant could also represent an earlier event". The authors also found a strong correlation between religion and apparent ancestry in the Levant:

all Jews (Sephardi and Ashkenazi) cluster in one branch; Druze from Mount Lebanon and Druze from Mount Carmel are depicted on a private branch; and Lebanese Christians form a private branch with the Christian populations of Armenia and Cyprus placing the Lebanese Muslims as an outer group. The predominantly Muslim populations of Syrians, Palestinians and Jordanians cluster on branches with other Muslim populations as distant as Morocco and Yemen.[108]

Another 2013 study, made by Doron M. Behar of the Rambam Health Care Campus in Israel and others, suggests that: "Cumulatively, our analyses point strongly to ancestry of Ashkenazi Jews primarily from European and Middle Eastern populations and not from populations in or near the Caucasus region. The combined set of approaches suggests that the observations of Ashkenazi proximity to European and Middle Eastern populations in population structure analyses reflect actual genetic proximity of Ashkenazi Jews to populations with predominantly European and Middle Eastern ancestry components, and lack of visible introgression from the region of the Khazar Khaganate—particularly among the northern Volga and North Caucasus populations—into the Ashkenazi community."[109]

A 2014 study by Fernández et al. found that Ashkenazi Jews display a frequency of haplogroup K in their maternal (mitochondrial) DNA, suggesting an ancient Near Eastern matrilineal origin, similar to the results of the Behar study in 2006. Fernández noted that this observation clearly contradicts the results of the 2013 study led by Costa, Richards et al. that suggested a European source for 3 exclusively Ashkenazi K lineages.[110]

Sephardic Jews

Sephardi Jews are Jews whose ancestors lived in Spain or Portugal. Some 300,000 Jews resided in Spain before the Spanish Inquisition in the 15th century, when the Reyes Católicos reconquered Spain from the Arabs and ordered the Jews to convert to Catholicism, leave the country or face execution without trial. Those who chose not to convert, between 40,000 and 100,000, were expelled from Spain in 1492 in the wake of the Alhambra decree.[111] Sephardic Jews subsequently migrated to North Africa (Maghreb), Christian Europe (Netherlands, Britain, France and Poland), throughout the Ottoman Empire and even the newly discovered Latin America. In the Ottoman Empire, the Sephardim mostly settled in the European portion of the Empire, and mainly in the major cities such as: Istanbul, Selânik and Bursa. Selânik, which is today known as Thessaloniki and found in modern-day Greece, had a large and flourishing Sephardic community as was the community of Maltese Jews in Malta.

A small number of Sephardic refugees who fled via the Netherlands as Marranos settled in Hamburg and Altona Germany in the early 16th century, eventually appropriating Ashkenazic Jewish rituals into their religious practice. One famous figure from the Sephardic Ashkenazic population is Glückel of Hameln. Some relocated to the United States, establishing the country's first organized community of Jews and erecting the United States' first synagogue. Nevertheless, the majority of Sephardim remained in Spain and Portugal as Conversos, which would also be the fate for those who had migrated to Spanish and Portuguese ruled Latin America. Sephardic Jews evolved to form most of North Africa's Jewish communities of the modern era, as well as the bulk of the Turkish, Syrian, Galilean and Jerusalemite Jews of the Ottoman period.

Mizrahi Jews

Mizrahi Jews are Jews descended from the Jewish communities of the Middle East, Central Asia and the Caucasus, largely originating from the Babylonian Jewry of the classic period. The term Mizrahi is used in Israel in the language of politics, media and some social scientists for Jews from the Arab world and adjacent, primarily Muslim-majority countries. The definition of Mizrahi includes the modern Iraqi Jews, Syrian Jews, Lebanese Jews, Persian Jews, Afghan Jews, Bukharian Jews, Kurdish Jews, Mountain Jews, Georgian Jews. Some also include the North-African Sephardic communities and Yemenite Jews under the definition of Mizrahi, but do that from rather political generalization than ancestral reasons.

Yemenite Jews

Temanim are Jews who were living in Yemen prior to immigrating to Ottoman Palestine and Israel. Their geographic and social isolation from the rest of the Jewish community over the course of many centuries allowed them to develop a liturgy and set of practices that are significantly distinct from those of other Oriental Jewish groups; they themselves comprise three distinctly different groups, though the distinction is one of religious law and liturgy rather than of ethnicity. Traditionally the genesis of the Yemenite Jewish community came after the Babylonian exile, though the community most probably emerged during Roman times, and it was significantly reinforced during the reign of Dhu Nuwas in the 6th century CE and during later Muslim conquests in the 7th century CE, which drove the Arab Jewish tribes out of central Arabia.

Karaite Jews

Karaim are Jews who used to live mostly in Egypt, Iraq, and Crimea during the Middle Ages. They are distinguished by the form of Judaism which they observe. Rabbinic Jews of varying communities have affiliated with the Karaite community throughout the millennia. As such, Karaite Jews are less an ethnic division, than they are members of a particular branch of Judaism. Karaite Judaism recognizes the Tanakh as the single religious authority for the Jewish people. Linguistic principles and contextual exegesis are used in arriving at the correct meaning of the Torah. Karaite Jews strive to adhere to the plain or most obvious understanding of the text when interpreting the Tanakh. By contrast, Rabbinical Judaism regards an Oral Law (codified and recorded in the Mishnah and the Talmud) as being equally binding on Jews, and mandated by God. In Rabbinical Judaism, the Oral Law forms the basis of religion, morality, and Jewish life. Karaite Jews rely on the use of sound reasoning and the application of linguistic tools to determine the correct meaning of the Tanakh; while Rabbinical Judaism looks towards the Oral law codified in the Talmud, to provide the Jewish community with an accurate understanding of the Hebrew Scriptures.

The differences between Karaite and Rabbinic Judaism go back more than a thousand years. Rabbinical Judaism originates from the Pharisees of the Second Temple period. Karaite Judaism may have its origins among the Sadducees of the same era. Karaite Jews hold the entire Hebrew Bible to be a religious authority. As such, the vast majority of Karaites believe in the resurrection of the dead.[112] Karaite Jews are widely regarded as being halachically Jewish by the Orthodox Rabbinate. Similarly, members of the rabbinic community are considered Jews by the Moetzet Hakhamim, if they are patrilineally Jewish.[citation needed]

Modern era

Israeli Jews

Jews of Israel comprise an increasingly mixed wide range of Jewish communities making aliyah from Europe, North Africa, and elsewhere in the Middle East. While a significant portion of Israeli Jews still retain memories of their Sephardic, Ashkenazi and Mizrahi origins, mixed Jewish marriages among the communities are very common. There are also smaller groups of Yemenite Jews, Indian Jews and others, who still retain a semi-separate communal life. There are also approximately 50,000 adherents of Karaite Judaism, most of whom live in Israel, but their exact numbers are not known, because most Karaites have not participated in any religious censuses. The Beta Israel, though somewhat disputed as the descendants of the ancient Israelites, are widely recognized in Israel as Ethiopian Jews.

American Jews

The ancestry of most American Jews goes back to Ashkenazi Jewish communities that immigrated to the US in the course of the 19th and 20th centuries, as well as more recent influxes of Persian and other Mizrahi Jewish immigrants. The American Jewish community is considered to contain the highest percentage of mixed marriages between Jews and non-Jews, resulting in both increased assimilation and a significant influx of non-Jews becoming identified as Jews. The most widespread practice in the U.S is Reform Judaism, which doesn't require or see the Jews as direct descendants of the ethnic Jews or Biblical Israelites, but rather adherents of the Jewish faith in its Reformist version, in contrast to Orthodox Judaism, the mainstream practice in Israel, which considers the Jews as a closed ethnoreligious community with very strict procedures for conversion.

French Jews

The Jews of modern France number around 400,000 persons, largely descendants of North African communities, some of which were Sephardic communities that had come from Spain and Portugal—others were Arab and Berber Jews from Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia, who were already living in North Africa before the Jewish exodus from the Iberian Peninsula—and to a smaller degree members of the Ashkenazi Jewish communities, who survived WWII and the Holocaust.

Mountain Jews

Mountain Jews are Jews from the eastern and northern slopes of the Caucasus, mainly Azerbaijan, Chechnya and Dagestan. They are the descendants of Persian Jews from Iran.[113]

Bukharan Jews

Bukharan Jews are an ethnic group from Central Asia who historically practised Judaism and spoke Bukhori, a dialect of the Tajik-Persian language.

Kaifeng Jews

The Kaifeng Jews are members of a small Jewish community in Kaifeng, in the Henan province of China who have assimilated into Chinese society while preserving some Jewish traditions and customs.

Cochin Jews

Cochin Jews, also called Malabar Jews, are the oldest group of Jews in India, with possible roots that are claimed to date back to the time of King Solomon.[114][115] The Cochin Jews settled in the Kingdom of Cochin in South India,[116] now part of the state of Kerala.[117][118] As early as the 12th century, mention is made of the Black Jews in southern India. The Jewish traveler, Benjamin of Tudela, speaking of Kollam (Quilon) on the Malabar Coast, writes in his Itinerary: "...throughout the island, including all the towns thereof, live several thousand Israelites. The inhabitants are all black, and the Jews also. The latter are good and benevolent. They know the law of Moses and the prophets, and to a small extent the Talmud and Halacha."[119] These people later became known as the Malabari Jews. They built synagogues in Kerala beginning in the 12th and 13th centuries.[120][121] They are known to have developed Judeo-Malayalam, a dialect of the Malayalam language.

Paradesi Jews

Paradesi Jews are mainly the descendants of Sephardic Jews who originally immigrated to India from Sepharad (Spain and Portugal) during the 15th and 16th centuries in order to flee forced conversion or persecution in the wake of the Alhambra Decree which expelled the Jews from Spain. They are sometimes referred to as White Jews, although that usage is generally considered pejorative or discriminatory and it is instead used to refer to relatively recent Jewish immigrants (end of the 15th century onwards), who are predominantly Sephardim.[122]

The Paradesi Jews of Cochin are a community of Sephardic Jews whose ancestors settled among the larger Cochin Jewish community located in Kerala, a coastal southern state of India.[122]

The Paradesi Jews of Madras traded in diamonds, precious stones and corals, they had very good relations with the rulers of Golkonda, they maintained trade connections with Europe, and their language skills were useful. Although the Sephardim spoke Ladino (i.e. Spanish or Judeo-Spanish), in India they learned to speak Tamil and Judeo-Malayalam from the Malabar Jews.[123][full citation needed]

Georgian Jews

The Georgian Jews are considered ethnically and culturally distinct from neighboring Mountain Jews. They were also traditionally a highly separate group from the Ashkenazi Jews in Georgia.

Krymchaks

The Krymchaks are Jewish ethno-religious communities of Crimea derived from Turkic-speaking adherents of Orthodox Judaism.

Anusim

During the history of the Jewish diaspora, Jews who lived in Christian Europe were often attacked by the local Christian population, and they were often forced to convert to Christianity. Many, known as "Anusim" ('forced-ones'), continued practicing Judaism in secret while living outwardly as ordinary Christians. The best known Anusim communities were the Jews of Spain and the Jews of Portugal, although they existed throughout Europe. In the centuries since the rise of Islam, many Jews living in the Muslim world were forced to convert to Islam,[citation needed] such as the Mashhadi Jews of Persia, who continued to practice Judaism in secret and eventually moved to Israel. Many of the Anusim's descendants left Judaism over the years. The results of a genetic study of the population of the Iberian Peninsula released in December 2008 "attest to a high level of religious conversion (whether voluntary or enforced) driven by historical episodes of religious intolerance, which ultimately led to the integration of the Anusim's descendants.[124]

Modern Samaritans

The Samaritans, who comprised a comparatively large group in classical times, now number 745 people, and today they live in two communities in Israel and the West Bank, and they still regard themselves as descendants of the tribes of Ephraim (named by them as Aphrime) and Manasseh (named by them as Manatch). Samaritans adhere to a version of the Torah known as the Samaritan Pentateuch, which differs in some respects from the Masoretic text, sometimes in important ways, and less so from the Septuagint.

The Samaritans consider themselves Bnei Yisrael ("Children of Israel" or "Israelites"), but they do not regard themselves as Yehudim (Jews). They view the term "Jews" as a designation for followers of Judaism, which they assert is a related but an altered and amended religion which was brought back by the exiled Israelite returnees, and is therefore not the true religion of the ancient Israelites, which according to them is Samaritanism.

Genetic studies

Y DNA studies tend to imply a small number of founders in an old population whose members parted and followed different migration paths.[125] В большинстве еврейских популяций эти предки по мужской линии, по-видимому, были в основном выходцами с Ближнего Востока . Например, евреи-ашкенази имеют больше общих отцовских линий с другими еврейскими и ближневосточными группами, чем с нееврейским населением в районах, где евреи жили в Восточной Европе , Германии и французской долине Рейна . Это соответствует еврейским традициям, согласно которым большинство евреев по отцовской линии происходят из региона Ближнего Востока. [126] [127] И наоборот, материнские линии еврейского населения, изученные на основе митохондриальной ДНК , в целом более гетерогенны. [128] Такие ученые, как Гарри Острер и Рафаэль Фальк, считают, что это указывает на то, что многие еврейские мужчины нашли новых партнеров из европейских и других общин в тех местах, куда они мигрировали в диаспоре после бегства из древнего Израиля. [129] Напротив, Бехар обнаружил доказательства того, что около 40% евреев-ашкенази происходят по материнской линии всего от четырех женщин-основателей, которые были ближневосточного происхождения. Население еврейских общин сефардов и мизрахи «не продемонстрировало никаких доказательств узкого эффекта основателя». [128] Последующие исследования, проведенные Feder et al. подтвердили значительную часть неместного материнского происхождения среди евреев-ашкенази. Размышляя о своих выводах, касающихся материнского происхождения евреев-ашкенази, авторы заключают: «Очевидно, что различия между евреями и неевреями гораздо больше, чем те, которые наблюдаются среди еврейских общин. -Евреи включены в сравнения». [130] [131] [132]

Исследования аутосомной ДНК , изучающие всю смесь ДНК, становятся все более важными по мере развития технологии. Они показывают, что еврейское население имеет тенденцию образовывать относительно тесно связанные группы в независимых общинах, при этом большинство людей в общине имеют значительное общее происхождение. [133] Что касается еврейского населения диаспоры, генетический состав еврейского населения ашкенази , сефардов и мизрахи демонстрирует преобладающее количество общего ближневосточного происхождения. По словам Бехара, наиболее скудное объяснение этого общего ближневосточного происхождения состоит в том, что оно «согласуется с историческим представлением о еврейском народе как потомке древних евреев и израильтян , жителей Леванта » и «рассредоточение народа древнего Израиля». по всему Старому Свету ». [106] Североафриканцы , итальянцы и другие представители иберийского происхождения демонстрируют различную частоту примеси с нееврейскими историческими популяциями хозяев по материнской линии. В случае евреев-ашкенази и сефардов (в частности, марокканских евреев ), которые тесно связаны между собой, источником нееврейской примеси является главным образом южная Европа , в то время как евреи-мизрахи демонстрируют признаки примеси с другими популяциями Ближнего Востока и африканцами к югу от Сахары . Бехар и др. отметили особенно тесную связь евреев-ашкенази и современных итальянцев . [106] [134] [135] Было обнаружено, что евреи более тесно связаны с группами на севере Плодородного полумесяца (курды, турки и армяне), чем с арабами. [136]

Исследования также показывают, что лица сефардского происхождения Бней-Анусим (те, кто являются потомками « анусимов », которые были вынуждены обратиться в католицизм ) на территории сегодняшней Иберии ( Испания и Португалия ) и Иберо-Америки ( латиноамериканская Америка и Бразилия ), по оценкам, до 19,8% современного населения Иберии и по крайней мере 10% современного населения Иберо-Америки имеют сефардское еврейское происхождение в течение последних нескольких столетий. Между тем, бене -исраэль и кочинские евреи в Индии , бета-исраэль в Эфиопии и часть народа лемба в южной Африке , несмотря на то, что они более похожи на местное население своих родных стран, также имеют более отдаленное древнее еврейское происхождение. [137] [138] [139] [132]

Сионистское «отрицание диаспоры»

| Часть серии о |

| Алия |

|---|

|

| Концепции |

| Досовременная алия |

| Алия в наше время |

| Поглощение |

| Организации |

| Связанные темы |

По мнению Элиэзера Швайда , неприятие жизни в диаспоре является центральным допущением всех течений сионизма . [140] В основе такого отношения лежало ощущение, что диаспора ограничивает полный рост еврейской национальной жизни. Например, поэт Хаим Нахман Бялик писал:

И сердце мое плачет о моих несчастных людях...

Как сожжена, как проклята должна быть наша доля,

Если такое семя засохнет в своей почве. ...

По словам Швайда, Бялик имел в виду, что «семя» — это потенциал еврейского народа. Сохранившееся в диаспоре это семя могло дать лишь деформированные результаты; однако, как только условия изменятся, семена все равно смогут дать обильный урожай. [141]

В этом вопросе Стернхелл различает две школы мысли в сионизме. Одной из них была либеральная или утилитарная школа Теодора Герцля и Макса Нордау . Особенно после дела Дрейфуса они считали, что антисемитизм никогда не исчезнет, и видели в сионизме рациональное решение для евреев.

Другой была органическая националистическая школа. Оно было распространено среди сионистских олимов , и они рассматривали это движение как проект по спасению еврейской нации, а не как проект только по спасению евреев. Для них сионизм был «Возрождением нации». [142]

В книге 2008 года «Изобретение еврейского народа » Шломо Санд утверждал, что формирование «еврейско-израильской коллективной памяти » положило начало «периоду молчания» в еврейской истории , особенно в отношении формирования Хазарского царства из обращенные языческие племена. Исраэль Барталь , тогдашний декан гуманитарного факультета Еврейского университета , возразил, что «ни один историк еврейского национального движения никогда по-настоящему не верил, что происхождение евреев этнически и биологически «чисто». [...] Никаких «националистов». «Еврейский историк всегда пытался скрыть тот общеизвестный факт, что обращение в иудаизм оказало большое влияние на еврейскую историю в древний период и в раннем средневековье. Хотя миф об изгнании с еврейской родины (Палестины) действительно существует. в популярной израильской культуре он незначителен в серьезных еврейских исторических дискуссиях. [75]

Мистическое объяснение

Раввин Цви Элимелех из Динова (Бней Иссашар, Ходеш Кислев, 2:25) объясняет, что каждое изгнание характеризовалось своим негативным аспектом: [143]

- Вавилонское изгнание характеризовалось физическими страданиями и угнетением. Вавилоняне были однобокими в отношении сфиры Гвура . , силы и телесной мощи

- Персидское изгнание было периодом эмоционального искушения. Персы были гедонистами и заявляли, что цель жизни — потакать потворству и похотям: «Давайте есть и пить, ибо завтра мы можем умереть». Они были однобокими по отношению к качеству Хесед , привлекательности и доброте (хотя и к себе).

- Эллинистическая цивилизация была высококультурной и сложной. Хотя у греков было сильное чувство эстетики, они были очень напыщенными и рассматривали эстетику как самоцель. Они были чрезмерно привязаны к качеству Тиферет , красоте. Это также было связано с признанием превосходства интеллекта над телом, которое раскрывает красоту духа.

- Изгнание Эдома началось с Рима , в культуре которого не было какой-либо четко определенной философии. Скорее, он перенял философию всех предшествующих культур, в результате чего римская культура находилась в постоянном изменении. Хотя Римская империя пала, евреи все еще находятся в изгнании в Эдоме, и действительно, можно обнаружить этот феномен постоянно меняющихся тенденций, доминирующих в современном западном обществе . Римляне и различные народы, унаследовавшие их правление (например, Священная Римская империя , европейцы , американцы ), однобоки по отношению к Малхут , суверенитету, низшей сфире, которую можно получить от любой другой и которая может действовать как для них средний.

Еврейский день поста Тиша бе-Ав отмечает разрушение Первого и Второго Храмов в Иерусалиме и последующее изгнание евреев из Земли Израиля . Еврейская традиция утверждает, что римское изгнание будет последним и что после того, как народ Израиля вернется на свою землю, он никогда больше не будет изгнан. Это утверждение основано на стихе: «(Вы платите за) грех ваш над дочерью Сиона , он не изгонит вас (больше)» [" תם עוונך בת ציון, לא יוסף להגלותך "]. [144]

В христианском богословии

Этот раздел нуждается в дополнении : Требуются цитаты раннехристианских богословов. Вы можете помочь, добавив к нему . ( июнь 2017 г. ) |

По мнению Аарона Оппенгеймера , концепция изгнания, начавшегося после разрушения Второго еврейского Храма, была разработана ранними христианами, которые рассматривали разрушение Храма как наказание за еврейское богоубийство и, как следствие, как утверждение христиан как Божьих божеств. новый избранный народ , или «Новый Израиль». На самом деле в период, последовавший за разрушением Храма, евреи имели много свобод. Народ Израиля имел религиозную, экономическую и культурную автономию, а восстание Бар-Кохбы продемонстрировало единство Израиля и его военно-политическую мощь в то время. Таким образом, по мнению Аарона Оппенгеймера , еврейское изгнание началось только после восстания Бар-Кохбы , опустошившего еврейскую общину Иудеи. Несмотря на распространенное мнение, евреи постоянно присутствовали в Земле Израиля, несмотря на изгнание большинства иудеев. Иерусалимский Талмуд был подписан в четвертом веке, спустя сотни лет после восстания. Более того, многие евреи остались в Израиле даже столетия спустя, в том числе и в византийский период (найдено множество остатков синагог этого периода). [145] [ нужен лучший источник ] Евреи составляли большинство или значительное большинство в Иерусалиме на протяжении тысячелетий после их изгнания, за некоторыми исключениями (включая период после осады Иерусалима (1099 г.) крестоносцами и 18 лет иорданского правления восточным Иерусалимом, в течение которых исторический Иерусалим Еврейский квартал был изгнан).

Историческое сравнение еврейского населения

| Область | Евреи, № (1900) [146] | Евреи, % (1900) [146] | Евреи, № (1942) [147] | Евреи, % (1942) [147] | Евреи, № (1970) [148] | Евреи, % (1970) [148] | Евреи, № (2010) [149] | Евреи, % (2010) [149] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Европа | 8,977,581 | 2.20% | 9,237,314 | 3,228,000 | 0.50% | 1,455,900 | 0.18% | |

| Австрия [а] | 1,224,899 | 4.68% | 13,000 | 0.06% | ||||

| Бельгия | 12,000 | 0.18% | 30,300 | 0.28% | ||||

| Босния и Герцеговина | 8,213 | 0.58% | 500 | 0.01% | ||||

| Болгария / Турция / Османская империя [б] | 390,018 | 1.62% | 24,300 | 0.02% | ||||

| Дания | 5,000 | 0.20% | 6,400 | 0.12% | ||||

| Франция | 86,885 | 0.22% | 530,000 | 1.02% | 483,500 | 0.77% | ||

| Германия | 586,948 | 1.04% | 30,000 | 0.04% | 119,000 | 0.15% | ||

| Венгрия [с] | 851,378 | 4.43% | 70,000 | 0.68% | 52,900 | 0.27% | ||

| Италия | 34,653 | 0.10% | 28,400 | 0.05% | ||||

| Люксембург | 1,200 | 0.50% | 600 | 0.12% | ||||

| Нидерланды | 103,988 | 2.00% | 30,000 | 0.18% | ||||

| Норвегия / Швеция | 5,000 | 0.07% | 16,200 | 0.11% | ||||

| Польша | 1,316,776 | 16.25% | 3,200 | 0.01% | ||||

| Португалия | 1,200 | 0.02% | 500 | 0.00% | ||||

| Румыния | 269,015 | 4.99% | 9,700 | 0.05% | ||||

| Российская Империя (Европа) [д] | 3,907,102 | 3.17% | 1,897,000 | 0.96% | 311,400 | 0.15% | ||

| Сербия | 5,102 | 0.20% | 1,400 | 0.02% | ||||

| Испания | 5,000 | 0.02% | 12,000 | 0.03% | ||||

| Швейцария | 12,551 | 0.38% | 17,600 | 0.23% | ||||

| Великобритания / Ирландия | 250,000 | 0.57% | 390,000 | 0.70% | 293,200 | 0.44% | ||

| Азия | 352,340 | 0.04% | 774,049 | 2,940,000 | 0.14% | 5,741,500 | 0.14% | |

| Аравия / Йемен | 30,000 | 0.42% | 200 | 0.00% | ||||

| Китай / Тайвань / Япония | 2,000 | 0.00% | 2,600 | 0.00% | ||||

| Индия | 18,228 | 0.0067% | 5,000 | 0.00% | ||||

| Иран | 35,000 | 0.39% | 10,400 | 0.01% | ||||

| Израиль | 2,582,000 | 86.82% | 5,413,800 | 74.62% | ||||

| Российская Империя (Азия) [и] | 89,635 | 0.38% | 254,000 | 0.57% | 18,600 | 0.02% | ||

| Африка | 372,659 | 0.28% | 593,736 | 195,000 | 0.05% | 76,200 | 0.01% | |

| Алжир | 51,044 | 1.07% | ||||||

| Египет | 30,678 | 0.31% | 100 | 0.00% | ||||

| Эфиопия | 50,000 | 1.00% | 100 | 0.00% | ||||

| Ливия | 18,680 | 2.33% | ||||||

| Марокко | 109,712 | 2.11% | 2,700 | 0.01% | ||||

| ЮАР | 50,000 | 4.54% | 118,000 | 0.53% | 70,800 | 0.14% | ||

| Тунис | 62,545 | 4.16% | 1,000 | 0.01% | ||||

| Америка | 1,553,656 | 1.00% | 4,739,769 | 6,200,000 | 1.20% | 6,039,600 | 0.64% | |

| Аргентина | 20,000 | 0.42% | 282,000 | 1.18% | 182,300 | 0.45% | ||

| Боливия / Чили / Эквадор / Перу / Уругвай | 1,000 | 0.01% | 41,400 | 0.06% | ||||

| Бразилия | 2,000 | 0.01% | 90,000 | 0.09% | 107,329 [150] | 0.05% | ||

| Канада | 22,500 | 0.42% | 286,000 | 1.34% | 375,000 | 1.11% | ||

| Центральная Америка | 4,035 | 0.12% | 54,500 | 0.03% | ||||

| Колумбия / Гвиана / Венесуэла | 2,000 | 0.03% | 14,700 | 0.02% | ||||

| Мексика | 1,000 | 0.01% | 35,000 | 0.07% | 39,400 | 0.04% | ||

| Суринам | 1,121 | 1.97% | 200 | 0.04% | ||||

| Соединенные Штаты | 1,500,000 | 1.97% | 4,975,000 | 3.00% | 5,400,000 | 2.63% | 5,275,000 | 1.71% |

| Океания | 16,840 | 0.28% | 26,954 | 70,000 | 0.36% | 115,100 | 0.32% | |

| Австралия | 15,122 | 0.49% | 65,000 | 0.52% | 107,500 | 0.50% | ||

| Новая Зеландия | 1,611 | 0.20% | 7,500 | 0.17% | ||||

| Общий | 11,273,076 | 0.68% | 15,371,822 | 12,633,000 | 0.4% | 13,428,300 | 0.19% |

а. ^ Австрия , Чехия , Словения

б. ^ Албания , Ирак , Иордания , Ливан , Македония , Сирия , Турция

в. ^ Хорватия , Венгрия , Словакия

д. ^ Страны Балтии ( Эстония , Латвия , Литва ), Белоруссия , Молдавия , Россия (включая Сибирь ), Украина .

и. ^ Кавказ ( Армения , Азербайджан , Грузия ), Средняя Азия ( Казахстан , Киргизия , Таджикистан , Туркменистан , Узбекистан ).

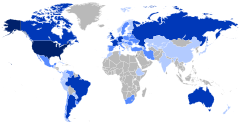

Сегодня

По состоянию на 2023 год около 8,5 миллионов евреев проживают за пределами Израиля , где проживает самое большое еврейское население в мире — 7,2 миллиона человек. За Израилем следуют Соединенные Штаты с примерно 6,3 миллионами. Другие страны со значительным еврейским населением включают Францию (440 000), Канаду (398 000), Великобританию (312 000), Аргентину (171 000), Россию (132 000), Германию (125 000), Австралию (117 200), Бразилию (90 000) и Южная Африка (50 000). Эти цифры отражают «ядро» еврейского населения, [151] [152] определяется как «не включая нееврейских членов еврейских семей, лиц еврейского происхождения, исповедующих другую монотеистическую религию, других неевреев еврейского происхождения и других неевреев, которые могут интересоваться еврейскими вопросами». [ нужна ссылка ] Еврейское население также остается в странах Ближнего Востока и Северной Африки за пределами Израиля, особенно в Турции , Иране , Марокко , Тунисе и Эмиратах . [152] В целом, это население сокращается из-за низких темпов роста и высоких темпов эмиграции (особенно с 1960-х годов). [ нужна ссылка ]

Еврейская автономная область продолжает оставаться автономной областью России . [153] Главный раввин Биробиджана , что говорит Мордехай Шайнер в столице проживают 4000 евреев. [154] Губернатор Николай Михайлович Волков заявил, что намерен «поддерживать все ценные инициативы наших местных еврейских организаций». [155] Биробиджанская синагога открылась в 2004 году, к 70-летию основания области в 1934 году. [156] По оценкам, в Сибири проживает 75 000 евреев . [157]

мегаполисы с наибольшим еврейским населением по одному из источников на сайте jewishtemples.org. Ниже перечислены [158] заявляет, что «трудно получить точные данные о численности населения по странам, не говоря уже о городах по всему миру. Цифры по России и другим странам СНГ являются всего лишь обоснованными предположениями». Цитируемый здесь источник, Всемирное обследование еврейского населения 2010 года , также отмечает, что «В отличие от наших оценок еврейского населения в отдельных странах, представленные здесь данные о городском еврейском населении не полностью учитывают возможный двойной учет из-за нескольких мест проживания. Соединенные Штаты могут быть весьма значительными, в пределах десятков тысяч, включая как крупные, так и мелкие мегаполисы». [159]

Гуш Дан (Тель-Авив) – 2 980 000

Гуш Дан (Тель-Авив) – 2 980 000  Нью-Йорк - 2 008 000

Нью-Йорк - 2 008 000  Иерусалим – 705 000

Иерусалим – 705 000  Лос-Анджелес – 685 000

Лос-Анджелес – 685 000  Хайфа - 671 000

Хайфа - 671 000  Майами – 486 000

Майами – 486 000  Беэр-Шева – 368 000

Беэр-Шева – 368 000  San Francisco – 346,000

San Francisco – 346,000  Чикаго - 319 600 [160]

Чикаго - 319 600 [160]  Париж – 284 000

Париж – 284 000  Филадельфия - 264 000

Филадельфия - 264 000  Бостон – 229 000

Бостон – 229 000  Вашингтон, округ Колумбия – 216 000

Вашингтон, округ Колумбия – 216 000  Лондон – 195 000

Лондон – 195 000  Торонто – 180 000

Торонто – 180 000  Атланта – 120 000

Атланта – 120 000  Москва – 95 000

Москва – 95 000  Сан-Диего – 89 000

Сан-Диего – 89 000  Кливленд – 87 000 [161]

Кливленд – 87 000 [161]  Финикс – 83 000

Финикс – 83 000  Монреаль – 80 000

Монреаль – 80 000  Сан-Паулу - 75 000 [162] [ нужен лучший источник ]

Сан-Паулу - 75 000 [162] [ нужен лучший источник ]

См. также

Примечания

- ^ Другие варианты на основе ашкенази или идиша включают галус , голес и голус . [1] Вариант написания на иврите — галут . [2]

Ссылки

Цитаты

- ^ «голюс» . Еврейский английский лексикон .

- ^ «галут» . Словарь Merriam-Webster.com . : «Этимология: еврейский галут ».

- ^ «Диаспора | Иудаизм» . Британская энциклопедия . Проверено 12 июля 2018 г.

- ^ Бен-Сассон, Хаим Гилель. «Галут». Энциклопедия иудаики под редакцией Майкла Беренбаума и Фреда Скольника, 2-е изд., том. 7, Macmillan Reference (США), 2007 г., стр. 352–63. Виртуальная справочная библиотека Гейла

- ^ Эрих С. Грюн , Диаспора: евреи среди греков и римлян, издательство Гарвардского университета , 2009, стр. 3–4, 233–34: «Принудительное перемещение… не могло составлять более чем часть диаспоры. … Подавляющее большинство евреев, проживавших за границей в период Второго Храма, делали это добровольно». (2)». Диаспора не ждала падения Иерусалима под властью и разрушительными действиями Рима. Рассеяние евреев началось задолго до этого — иногда путем принудительного изгнания, гораздо чаще — путем добровольной миграции».

- ^ Э. Мэри Смоллвуд (1984). «Диаспора в римский период до 70 г. н. э.» . У Уильяма Дэвида Дэвиса; Луи Финкельштейн; Уильям Хорбери (ред.). Кембриджская история иудаизма: раннеримский период, Том 3 . Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-0521243773 .

- ^ Грюн, Диаспора: евреи среди греков и римлян, Harvard University Press , 2009, стр. 233–34:

- ^ Шмуэль Ной Эйзенштадт «Исследования еврейского исторического опыта: цивилизационный аспект», BRILL , 2004, стр. 60-61: «Уникальной была тенденция объединять рассеяние с изгнанием и наделять объединенный опыт рассеяния и изгнания сильным метафизическим и религиозная негативная оценка галута . . В большинстве случаев галут рассматривался как нечто в основном негативное, объясняемое с точки зрения греха и наказания. Жизнь в галуте определялась как частичное, приостановленное существование, но в то же время ее необходимо было поддерживать, чтобы гарантировать выживание еврейского народа до Искупления».

- ^ «Диаспора» — относительно новое английское слово, не имеющее традиционного еврейского эквивалента.¹. Говард Веттштейн, «Примирившись с изгнанием». в Говарде Веттштейне (ред.) Диаспоры и изгнанники: разновидности еврейской идентичности, University of California Press , 2002 (стр. 47-59, стр. 47).

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Стивен Боуман, «Еврейская диаспора в греческом мире: принципы аккультурации», в книге Мелвина Эмбера, Кэрол Р. Эмбер, Яна Скоггарда (ред.) Энциклопедия диаспор: культуры иммигрантов и беженцев во всем мире. Том I: Обзоры и темы; Том II: Сообщества диаспоры, Springer Science & Business Media , 2004, стр. 192 и далее. стр.193

- ^ Джеффри М. Пек, Быть евреем в Новой Германии, Rutgers University Press , 2006, стр. 154.

- ^ Ховард К. Веттштейн, «Диаспора, изгнание и еврейская идентичность», в книге М. Аврума Эрлиха (редактор), Энциклопедия еврейской диаспоры: происхождение, опыт и культура, том 1, ABC-CLIO , 2009, стр.61 -63, с.61: «Диаспора – понятие политическое; это предполагает геополитическое рассеяние, возможно, непроизвольное. Однако с изменившимися обстоятельствами население может увидеть добродетель в жизни диаспоры. Таким образом, диаспора, в отличие от галута, может приобрести положительный заряд. Галут звучит как телеология, а не политика. Это предполагает вывих, ощущение того, что тебя вырвали из неправильного места. Возможно, сообщество было наказано; возможно, в нашем мире происходят ужасные вещи

- ^ Дэниел Боярин в книге Илана Гур-Зеева (ред.), «Диаспорическая философия и контробразование», Springer Science & Business Media, 2011, стр. 127

- ^ Стефан Дюфуа, Рассеяние: история мировой диаспоры, BRILL , 2016, стр. 28 и далее, 40.

- ^ Дюфуа, стр. 41,46.

- ^ Дюфуа стр.47.

- ^ Стефан Дюфуа, стр.49

- ^ См., например, Кидушин ( тосафот ) 41а, исх. «Ассур лядам...»

- ^ Юджин Б. Боровиц, Исследование еврейской этики: статьи об ответственности по Завету, издательство Wayne State University Press , 1990, стр. 129: «Галут - это, по сути, богословская категория».

- ^ Саймон Равидович , «О концепции галута» , в своей книге «Государство Израиль, диаспора и еврейская преемственность: очерки о «вечно умирающих людях», UPNE , 1998, стр. 96 и далее, стр. 80