Азербайджан

Азербайджанская Республика Азербайджанская Республика ( азербайджанский ) | |

|---|---|

| Гимн: Гимн Азербайджана «Марш Азербайджана» | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Baku 40°23′43″N 49°52′56″E / 40.39528°N 49.88222°E |

| Official languages | Azerbaijani[1] |

| Minority languages | See full list |

| Ethnic groups (2019[2]) |

|

| Religion | Islam 97% Christianity 3% |

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic[3] under a hereditary dictatorship |

| Ilham Aliyev | |

| Mehriban Aliyeva | |

| Ali Asadov | |

| Sahiba Gafarova | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Formation | |

| 28 May 1918 | |

| 28 April 1920 | |

• Independence from Soviet Union |

|

• Constitution adopted | 12 November 1995 |

| Area | |

• Total | 86,600 km2 (33,400 sq mi) (112th) |

• Water (%) | 1.6 |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 10,353,296[4] (90th) |

• Density | 117/km2 (303.0/sq mi) (99th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2008) | medium |

| HDI (2022) | high (89th) |

| Currency | Manat (₼) (AZN) |

| Time zone | UTC+4 (AZT) |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy (CE) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +994 |

| ISO 3166 code | AZ |

| Internet TLD | .az |

Азербайджан , [а] официально Азербайджанская Республика , [б] — трансконтинентальная страна, расположенная на границе Восточной Европы и Западной Азии . [9] Он является частью региона Южного Кавказа и граничит с Каспийским морем на востоке, Российской Республикой Дагестан на севере, Грузией на северо-западе, Арменией и Турцией на западе и Ираном на юге. Баку – столица и крупнейший город.

Территория нынешнего Азербайджана сначала находилась под властью Кавказской Албании , а затем различных персидских империй. До 19 века она оставалась частью Каджарского Ирана , но русско-персидские войны 1804–1813 и 1826–1828 годов вынудили Каджарскую империю уступить свои кавказские территории Российской империи ; договор Гюлистанский 1813 г. и Туркменчайский договор 1828 г. определили границу между Россией и Ираном. [10] [11] Регион к северу от Аракса был частью Ирана, пока не был завоеван Россией в 19 веке. [12] [13] где оно управлялось в составе Кавказского наместничества .

By the late 19th century, an Azerbaijani national identity emerged when the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic proclaimed its independence from the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic in 1918, a year after the Russian Empire collapsed, and became the first secular democratic Muslim-majority state. In 1920, the country was conquered and incorporated into the Soviet Union as the Azerbaijan SSR.[12][14] The modern Republic of Azerbaijan proclaimed its independence on 30 August 1991,[15][16] shortly before the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the same year. In September 1991, the ethnic Armenian majority of the Nagorno-Karabakh region formed the self-proclaimed Republic of Artsakh,[17] which became de facto independent with the end of the First Nagorno-Karabakh War in 1994, although the region and seven surrounding districts remained internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan.[18][19][20][21] Following the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War in 2020, the seven districts and parts of Nagorno-Karabakh were returned to Azerbaijani control.[22] An Azerbaijani offensive in 2023 ended the Republic of Artsakh and resulted in the flight of Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians.[23]

Azerbaijan is a unitary semi-presidential republic.[3] It is one of six independent Turkic states and an active member of the Organization of Turkic States and the TÜRKSOY community. Azerbaijan has diplomatic relations with 182 countries and holds membership in 38 international organizations,[24] including the United Nations, the Council of Europe, the Non-Aligned Movement, the OSCE, and the NATO PfP program. It is one of the founding members of GUAM, the CIS,[25] and the OPCW. Azerbaijan is also an observer state of the WTO.

The vast majority of the country's population (97%) is nominally[26] Muslim,[27] but the constitution does not declare an official religion and all major political forces in the country are secular. Azerbaijan is a developing country and ranks 91st on the Human Development Index. The ruling New Azerbaijan Party, in power since 1993, has been accused of authoritarianism under president Heydar Aliyev and his son Ilham Aliyev, and deteriorating the country's human rights record, including increasing restrictions on civil liberties, particularly on press freedom and political repression.[28]

Etymology

According to a modern etymology, the term Azerbaijan derives from that of Atropates,[29][30] a Persian[31][32] satrap under the Achaemenid Empire, who was later reinstated as the satrap of Media under Alexander the Great.[33][34] The original etymology of this name is thought to have its roots in the once-dominant Zoroastrianism. In the Avesta's Frawardin Yasht ("Hymn to the Guardian Angels"), there is a mention of âterepâtahe ashaonô fravashîm ýazamaide, which literally translates from Avestan as "we worship the fravashi of the holy Atropatene".[35] The name "Atropates" itself is the Greek transliteration of an Old Iranian, probably Median, compounded name with the meaning "Protected by the (Holy) Fire" or "The Land of the (Holy) Fire".[36] The Greek name was mentioned by Diodorus Siculus and Strabo. Over the span of millennia, the name evolved to Āturpātākān (Middle Persian), then to Ādharbādhagān, Ādhorbāygān, Āzarbāydjān (New Persian) and present-day Azerbaijan.[37]

The name Azerbaijan was first adopted for the area of the present-day Republic of Azerbaijan by the government of Musavat in 1918,[38] after the collapse of the Russian Empire, when the independent Azerbaijan Democratic Republic was established. Until then, the designation had been used exclusively to identify the adjacent region of contemporary northwestern Iran,[39][40][41][42] while the area of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic was formerly referred to as Arran and Shirvan.[43] On that basis Iran protested the newly adopted country name.[44]

During Soviet rule, the country was also spelled in Latin from the Russian transliteration as Azerbaydzhan (Russian: Азербайджа́н).[45] The country's name was also spelled in Cyrillic script from 1940 to 1991 as Азәрбајҹан.

History

Antiquity

The earliest evidence of human settlement in the territory of Azerbaijan dates back to the late Stone Age and is related to the Guruchay culture of Azykh Cave.[46]

Early settlements included the Scythians during the 9th century BC.[36] Following the Scythians, Iranian Medes came to dominate the area to the south of the Aras river.[34] The Medes forged a vast empire between 900 and 700 BC, which was integrated into the Achaemenid Empire around 550 BC.[47] The area was conquered by the Achaemenids leading to the spread of Zoroastrianism.[48]

From the Sasanid period to the Safavid period

The Sasanian Empire turned Caucasian Albania into a vassal state in 252, while King Urnayr officially adopted Christianity as the state religion in the 4th century.[49] Despite Sassanid rule, Caucasian Albania remained an entity in the region until the 9th century, while fully subordinate to Sassanid Iran, and retained its monarchy. Despite being one of the chief vassals of the Sasanian emperor, the Albanian king had only a semblance of authority, and the Sasanian marzban (military governor) held most civil, religious, and military authority.[50]

In the first half of the 7th century, Caucasian Albania, as a vassal of the Sasanians, came under nominal Muslim rule due to the Muslim conquest of Persia. The Umayyad Caliphate repulsed both the Sasanians and Byzantines from the South Caucasus and turned Caucasian Albania into a vassal state after Christian resistance led by King Juansher was suppressed in 667. The power vacuum left by the decline of the Abbasid Caliphate was filled by numerous local dynasties such as the Sallarids, Sajids, and Shaddadids. At the beginning of the 11th century, the territory was gradually seized by the waves of migrating Oghuz Turks from Central Asia, who adopted a Turkoman ethnonym at the time.[51] The first of these Turkic dynasties established was the Seljuk Empire, which entered the area now known as Azerbaijan by 1067.[52]

The pre-Turkic population that lived on the territory of modern Azerbaijan spoke several Indo-European and Caucasian languages, among them Armenian[53][54][55][56][57] and an Iranian language, Old Azeri, which was gradually replaced by a Turkic language, the early precursor of the Azerbaijani language of today.[58] Some linguists have also stated that the Tati dialects of Iranian Azerbaijan and the Republic of Azerbaijan, like those spoken by the Tats, are descended from Old Azeri.[59][60]Locally, the possessions of the subsequent Seljuk Empire were ruled by Eldiguzids, technically vassals of the Seljuk sultans, but sometimes de facto rulers themselves. Under the Seljuks, local poets such as Nizami Ganjavi and Khaqani gave rise to a blossoming of Persian literature on the territory of present-day Azerbaijan.[61][62]

Shirvanshahs, the local dynasty of Arabic origin that was later Persianized, became a vassal state of Timurid Empire of Timur and assisted him in his war with the ruler of the Golden Horde Tokhtamysh. Following Timur's death, two independent and rival Turkoman states emerged: Qara Qoyunlu and Aq Qoyunlu. The Shirvanshahs returned, maintaining for numerous centuries to come a high degree of autonomy as local rulers and vassals as they had done since 861. In 1501, the Safavid dynasty of Iran subdued the Shirvanshahs and gained its possessions. In the course of the next century, the Safavids converted the formerly Sunni population to Shia Islam,[63][64][65] as they did with the population in what is modern-day Iran.[66] The Safavids allowed the Shirvanshahs to remain in power, under Safavid suzerainty, until 1538, when Safavid king Tahmasp I (r. 1524–1576) completely deposed them, and made the area into the Safavid province of Shirvan. The Sunni Ottomans briefly managed to occupy present-day Azerbaijan as a result of the Ottoman–Safavid War of 1578–1590; by the early 17th century, they were ousted by Safavid Iranian ruler Abbas I (r. 1588–1629). In the wake of the demise of the Safavid Empire, Baku and its environs were briefly occupied by the Russians as a consequence of the Russo-Persian War of 1722–1723. Remainder of present Azerbaijan was occupied by the Ottomans from 1722 to 1736.[67] Despite brief intermissions such as these by Safavid Iran's neighboring rivals, the land of what is today Azerbaijan remained under Iranian rule from the earliest advent of the Safavids up to the course of the 19th century.[68][69]

Modern history

After the Safavids, the area was ruled by the Iranian Afsharid dynasty. After the death of Nader Shah (r. 1736–1747), many of his former subjects capitalized on the eruption of instability. Numerous self-ruling khanates with various forms of autonomy[70][71][72][73][74] emerged in the area. The rulers of these khanates were directly related to the ruling dynasties of Iran and were vassals and subjects of the Iranian shah.[75] The khanates exercised control over their affairs via international trade routes between Central Asia and the West.[76]

Thereafter, the area was under the successive rule of the Iranian Zands and Qajars.[77] From the late 18th century, Imperial Russia switched to a more aggressive geo-political stance towards its two neighbors and rivals to the south, namely Iran and the Ottoman Empire.[78] Russia now actively tried to gain possession of the Caucasus region which was, for the most part, in the hands of Iran.[79] In 1804, the Russians invaded and sacked the Iranian town of Ganja, sparking the Russo-Persian War of 1804–1813.[80] The militarily superior Russians ended the Russo-Persian War of 1804–1813 with a victory.[81]

Following Qajar Iran's loss in the 1804–1813 war, it was forced to concede suzerainty over most of the khanates, along with Georgia and Dagestan to the Russian Empire, per the Treaty of Gulistan.[82]

The area to the north of the Aras River, amongst which territory lies the contemporary Republic of Azerbaijan, was Iranian territory until Russia occupied it in the 19th century.[12][83][84][85][86][87] About a decade later, in violation of the Gulistan treaty, the Russians invaded Iran's Erivan Khanate.[88][89] This sparked the final bout of hostilities between the two, the Russo-Persian War of 1826–1828. The resulting Treaty of Turkmenchay, forced Qajar Iran to cede sovereignty over the Erivan Khanate, the Nakhchivan Khanate and the remainder of the Talysh Khanate,[82] comprising the last parts of the soil of the contemporary Azerbaijani Republic that were still in Iranian hands. After the incorporation of all Caucasian territories from Iran into Russia, the new border between the two was set at the Aras River, which, upon the Soviet Union's disintegration, subsequently became part of the border between Iran and the Azerbaijan Republic.[90]

Qajar Iran was forced to cede its Caucasian territories to Russia in the 19th century, which thus included the territory of the modern-day Azerbaijan Republic, while as a result of that cession, the Azerbaijani ethnic group is nowadays parted between two nations: Iran and Azerbaijan.[91]

Despite the Russian conquest, throughout the entire 19th century, preoccupation with Iranian culture, literature, and language remained widespread amongst Shia and Sunni intellectuals in the Russian-held cities of Baku, Ganja and Tiflis (Tbilisi, now Georgia).[92] Within the same century, in post-Iranian Russian-held East Caucasia, an Azerbaijani national identity emerged at the end of the 19th century.[93]

After the collapse of the Russian Empire during World War I, the short-lived Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic was declared, constituting the present-day republics of Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Armenia.It was followed by the March Days massacres[94][95] that took place between 30 March and 2 April 1918 in the city of Baku and adjacent areas of the Baku Governorate of the Russian Empire.[96] When the republic dissolved in May 1918, the leading Musavat party declared independence as the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (ADR), adopting the name of "Azerbaijan" for the new republic; a name that prior to the proclamation of the ADR was solely used to refer to the adjacent northwestern region of contemporary Iran.[39][40][41] The ADR was the first modern parliamentary republic in the Muslim world.[12][97][98] Among the important accomplishments of the Parliament was the extension of suffrage to women, making Azerbaijan the first Muslim nation to grant women equal political rights with men.[97] Another important accomplishment of ADR was the establishment of Baku State University, which was the first modern-type university founded in the Muslim East.[97]

Independent Azerbaijan lasted only 23 months until the Bolshevik 11th Soviet Red Army invaded it, establishing the Azerbaijan SSR on 28 April 1920. Although the bulk of the newly formed Azerbaijani army was engaged in putting down an Armenian revolt that had just broken out in Karabakh, Azerbaijanis did not surrender their brief independence of 1918–20 quickly or easily. As many as 20,000 Azerbaijani soldiers died resisting what was effectively a Russian reconquest.[99] Within the ensuing early Soviet period, the Azerbaijani national identity was finally forged.[93]

On 13 October 1921, the Soviet republics of Russia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia signed an agreement with Turkey known as the Treaty of Kars. The previously independent Republic of Aras would also become the Nakhchivan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic within the Azerbaijan SSR by the treaty of Kars. On the other hand, Armenia was awarded the region of Zangezur and Turkey agreed to return Gyumri (then known as Alexandropol).[100]

During World War II, Azerbaijan played a crucial role in the strategic energy policy of the Soviet Union, with 80 percent of the Soviet Union's oil on the Eastern Front being supplied by Baku. By the Decree of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR in February 1942, the commitment of more than 500 workers and employees of the oil industry of Azerbaijan were awarded orders and medals. Operation Edelweiss carried out by the German Wehrmacht targeted Baku because of its importance as the energy (petroleum) dynamo of the USSR.[12] A fifth of all Azerbaijanis fought in the Second World War from 1941 to 1945. Approximately 681,000 people with over 100,000 of them women, went to the front, while the total population of Azerbaijan was 3.4 million at the time.[101] Some 250,000 people from Azerbaijan were killed on the front. More than 130 Azerbaijanis were named Heroes of the Soviet Union. Azerbaijani Major-General Azi Aslanov was twice awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union.[102]

Independence

Following the politics of glasnost, initiated by Mikhail Gorbachev, civil unrest and ethnic strife grew in various regions of the Soviet Union, including Nagorno-Karabakh,[103] an autonomous region of the Azerbaijan SSR. The disturbances in Azerbaijan, in response to Moscow's indifference to an already heated conflict, resulted in calls for independence and secession, which culminated in the Black January events in Baku.[104] Later in 1990, the Supreme Council of the Azerbaijan SSR dropped the words "Soviet Socialist" from the title, adopted the "Declaration of Sovereignty of the Azerbaijan Republic" and restored the flag of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic as the state flag.[105] As a consequence of the failed 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt in Moscow, the Supreme Council of Azerbaijan adopted a Declaration of Independence on 18 October 1991, which was affirmed by a nationwide referendum in December 1991, while the Soviet Union officially ceased to exist on 26 December 1991.[105] The country now celebrates its Day of Restoration of Independence on 18 October.[106]

The early years of independence were overshadowed by the First Nagorno-Karabakh war with the ethnic Armenian majority of Nagorno-Karabakh backed by Armenia.[107] By the end of the hostilities in 1994, Armenians controlled up to 14–16 percent of Azerbaijani territory, including Nagorno-Karabakh itself.[26][108] During the war many atrocities and pogroms by both sides were committed including the massacres at Malibeyli, Gushchular and Garadaghly and the Khojaly massacre, along with the Baku pogrom, the Maraga massacre and the Kirovabad pogrom.[109][110] Furthermore, an estimated 30,000 people have been killed and more than a million people have been displaced, more than 800,000 Azerbaijanis and 300,000 Armenians.[111] Four United Nations Security Council Resolutions (822, 853, 874, and 884) demand for "the immediate withdrawal of all Armenian forces from all occupied territories of Azerbaijan."[112] Many Russians and Armenians left and fled Azerbaijan as refugees during the 1990s.[113] According to the 1970 census, there were 510,000 ethnic Russians and 484,000 Armenians in Azerbaijan.[114]

Aliyev family rule, 1993–present

In 1993, democratically elected president Abulfaz Elchibey was overthrown by a military insurrection led by Colonel Surat Huseynov, which resulted in the rise to power of the former leader of Soviet Azerbaijan, Heydar Aliyev. In 1994, Surat Huseynov, by that time the prime minister, attempted another military coup against Heydar Aliyev, but he was arrested and charged with treason.[115] A year later, in 1995, another coup was attempted against Aliyev, this time by the commander of the OMON special unit, Rovshan Javadov. The coup was averted, resulting in the killing of the latter and disbanding of Azerbaijan's OMON units.[116][117] At the same time, the country was tainted by rampant corruption in the governing bureaucracy.[118] In October 1998, Aliyev was reelected for a second term.

Ilham Aliyev, Heydar Aliyev's son, became chairman of the New Azerbaijan Party as well as President of Azerbaijan when his father died in 2003. He was reelected to a third term as president in October 2013.[119] In April 2018, President Ilham Aliyev secured his fourth consecutive term in the election that was boycotted by the main opposition parties as fraudulent.[120] On 27 September 2020, new clashes in the unresolved Nagorno-Karabakh conflict resumed along the Nagorno-Karabakh Line of Contact. Both the armed forces of Azerbaijan and Armenia reported military and civilian casualties.[121] The Nagorno-Karabakh ceasefire agreement and the end of the six-week war between Azerbaijan and Armenia was widely celebrated in Azerbaijan, as they made significant territorial gains.[122] Despite the much improved economy,[123] particularly with the exploitation of the Azeri–Chirag–Guneshli oil field and Shah Deniz gas field, the Aliyev family rule has been criticized due to election fraud,[124] high levels of economic inequality[125] and domestic corruption.[126] In September 2023, Azerbaijan launched an offensive against the breakaway Republic of Artsakh in Nagorno-Karabakh that resulted in the dissolution and reintegration of Artsakh on 1 January 2024 and the flight of nearly all ethnic Armenians from the region.[127]

Geography

Geographically, Azerbaijan is located in the South Caucasus region of Eurasia, straddling Western Asia and Eastern Europe. It lies between latitudes 38° and 42° N, and longitudes 44° and 51° E. The total length of Azerbaijan's land borders is 2,648 km (1,645 mi), of which 1,007 km (626 mi) are with Armenia, 756 km (470 mi) with Iran, 480 kilometers with Georgia, 390 km (242 mi) with Russia and 15 km (9 mi) with Turkey.[129] The coastline stretches for 800 km (497 mi), and the length of the widest area of the Azerbaijani section of the Caspian Sea is 456 km (283 mi).[129] The country has a landlocked exclave, the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic.[130]

Three physical features dominate Azerbaijan: the Caspian Sea, whose shoreline forms a natural boundary to the east; the Greater Caucasus mountain range to the north; and the extensive flatlands at the country's center. There are also three mountain ranges, the Greater and Lesser Caucasus, and the Talysh Mountains, together covering approximately 40% of the country.[131] The highest peak of Azerbaijan is Mount Bazardüzü 4,466 m (14,652 ft), while the lowest point lies in the Caspian Sea −28 m (−92 ft) . Nearly half of all the mud volcanoes on Earth are concentrated in Azerbaijan, these volcanoes were also among nominees for the New 7 Wonders of Nature.[132]

The main water sources are surface waters. Only 24 of the 8,350 rivers are greater than 100 km (62 mi) in length.[131] All the rivers drain into the Caspian Sea in the east of the country.[131] The largest lake is Sarysu 67 km2 (26 sq mi), and the longest river is Kur 1,515 km (941 mi), which is transboundary with Armenia. Azerbaijan has several islands along the Caspian sea, mostly located in the Baku Archipelago.

Since the independence of Azerbaijan in 1991, the Azerbaijani government has taken measures to preserve the environment of Azerbaijan. National protection of the environment accelerated after 2001 when the state budget increased due to new revenues provided by the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipeline. Within four years, protected areas doubled and now make up eight percent of the country's territory. Since 2001 the government has set up seven large reserves and almost doubled the sector of the budget earmarked for environmental protection.[133]

Landscape

Azerbaijan is home to a wide variety of landscapes. Over half of Azerbaijan's landmass consists of mountain ridges, crests, highlands, and plateaus which rise up to hypsometric levels of 400–1000 meters (including the Middle and Lower lowlands), in some places (Talis, Jeyranchol-Ajinohur and Langabiz-Alat foreranges) up to 100–120 meters, and others from 0–50 meters and up (Qobustan, Absheron). The rest of Azerbaijan's terrain consists of plains and lowlands. Hypsometric marks within the Caucasus region vary from about −28 meters at the Caspian Sea shoreline up to 4,466 meters (Bazardüzü peak).[134]

The formation of climate in Azerbaijan is influenced particularly by cold arctic air masses of Scandinavian anticyclone, temperate air masses of Siberian anticyclone, and Central Asian anticyclone.[135] Azerbaijan's diverse landscape affects the ways air masses enter the country.[135] The Greater Caucasus protects the country from direct influences of cold air masses coming from the north. That leads to the formation of subtropical climate on most foothills and plains of the country. Meanwhile, plains and foothills are characterized by high solar radiation rates.[136]

Nine out of eleven existing climate zones are present in Azerbaijan.[137] Both the absolute minimum temperature (−33 °C or −27.4 °F ) and the absolute maximum temperature[quantify] were observed in Julfa and Ordubad – regions of Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic.[137] The maximum annual precipitation falls in Lankaran (1,600 to 1,800 mm or 63 to 71 in) and the minimum in Absheron (200 to 350 mm or 7.9 to 13.8 in).[137]

Rivers and lakes form the principal part of the water systems of Azerbaijan, they were formed over a long geological timeframe and changed significantly throughout that period. This is particularly evidenced by remnants of ancient rivers found throughout the country. The country's water systems are continually changing under the influence of natural forces and human-introduced industrial activities. Artificial rivers (canals) and ponds are a part of Azerbaijan's water systems. In terms of water supply, Azerbaijan is below the average in the world with approximately 100,000 cubic metres (3,531,467 cubic feet) per year of water per square kilometer.[137] All big water reservoirs are built on Kur. The hydrography of Azerbaijan basically belongs to the Caspian Sea basin.

The Kura and Aras are the major rivers in Azerbaijan. They run through the Kura-Aras Lowland. The rivers that directly flow into the Caspian Sea, originate mainly from the north-eastern slope of the Major Caucasus and Talysh Mountains and run along the Samur–Devechi and Lankaran lowlands.[138]

Yanar Dag, translated as "burning mountain", is a natural gas fire which blazes continuously on a hillside on the Absheron Peninsula on the Caspian Sea near Baku, which itself is known as the "land of fire." Flames jet out into the air from a thin, porous sandstone layer. It is a tourist attraction to visitors to the Baku area.[139]

Biodiversity

The first reports on the richness and diversity of animal life in Azerbaijan can be found in travel notes of Eastern travelers. Animal carvings on architectural monuments, ancient rocks, and stones survived up to the present times. The first information on flora and fauna of Azerbaijan was collected during the visits of naturalists to Azerbaijan in the 17th century.[131]

There are 106 species of mammals, 97 species of fish, 363 species of birds, 10 species of amphibians, and 52 species of reptiles which have been recorded and classified in Azerbaijan.[131] The national animal of Azerbaijan is the Karabakh horse, a mountain-steppe racing and riding horse endemic to Azerbaijan. The Karabakh horse has a reputation for its good temper, speed, elegance, and intelligence. It is one of the oldest breeds, with ancestry dating to the ancient world, but today the horse is an endangered species.[140]

Azerbaijan's flora consists of more than 4,500 species of higher plants. Due to the unique climate in Azerbaijan, the flora is much richer in the number of species than the flora of the other republics of the South Caucasus. 66 percent of the species growing in the whole Caucasus can be found in Azerbaijan.[141] The country lies within four ecoregions: Caspian Hyrcanian mixed forests, Caucasus mixed forests, Eastern Anatolian montane steppe, and Azerbaijan shrub desert and steppe.[142] Azerbaijan had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 6.55/10, ranking it 72nd globally out of 172 countries.[143]

Government and politics

Azerbaijan's government functions as an authoritarian regime in practice;[144][145][146][147] although it regularly holds elections, these are marred by electoral fraud and other unfair election practices.[148][149][150][151][152][153][154] Azerbaijan has been ruled by the Aliyev political family and the New Azerbaijan Party (Yeni Azərbaycan Partiyası, YAP) established by Heydar Aliyev continuously since 1993.[155] It is categorised as "not free" by Freedom House,[156][157] who ranked it 7/100 on Global Freedom Score in 2024, calling its regime authoritarian.[158]

The structural formation of Azerbaijan's political system was completed by the adoption of the new Constitution on 12 November 1995. According to Article 23 of the Constitution, the state symbols of the Azerbaijan Republic are the flag, the coat of arms, and the national anthem. The state power in Azerbaijan is limited only by law for internal issues, but international affairs are also limited by international agreements' provisions.[159][better source needed]

The Constitution of Azerbaijan states that it is a presidential republic with three branches of power – Executive, Legislative, and Judicial. The legislative power is held by the unicameral National Assembly and the Supreme National Assembly in the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic. The Parliament of Azerbaijan, called Milli Majlis, consists of 125 deputies elected based on majority vote, with a term of five years for each elected member. The elections are held every five years, on the first Sunday of November. The Parliament is not responsible for the formation of the government, but the Constitution requires the approval of the Cabinet of Ministers by Milli Majlis.[160] The New Azerbaijan Party, and independents loyal to the ruling government, currently hold almost all of the Parliament's 125 seats. During the 2010 Parliamentary election, the opposition parties, Musavat and Azerbaijani Popular Front Party, failed to win a single seat. European observers found numerous irregularities in the run-up to the election and on election day.[161]

The executive power is held by the President, who is elected for a seven-year term by direct elections, and the Prime Minister. The president is authorized to form the Cabinet, a collective executive body accountable to both the President and the National Assembly.[3] The Cabinet of Azerbaijan consists primarily of the prime minister, his deputies, and ministers. The 8th Government of Azerbaijan is the administration in its current formation. The president does not have the right to dissolve the National Assembly but has the right to veto its decisions. To override the presidential veto, the parliament must have a majority of 95 votes. The judicial power is vested in the Constitutional Court, Supreme Court, and the Economic Court. The president nominates the judges in these courts.[citation needed]

Azerbaijan's system of governance nominally can be called two-tiered. The top or highest tier of the government is the Executive Power headed by President. The President appoints the Cabinet of Ministers and other high-ranking officials. The Local Executive Authority is merely a continuation of Executive Power. The Provision determines the legal status of local state administration in Azerbaijan on Local Executive Authority (Yerli Icra Hakimiyati), adopted 16 June 1999. In June 2012, the President approved the new Regulation, which granted additional powers to Local Executive Authorities, strengthening their dominant position in Azerbaijan's local affairs[162] The Security Council is the deliberative body under the president, and he organizes it according to the Constitution. It was established on 10 April 1997. The administrative department is not a part of the president's office but manages the financial, technical and pecuniary activities of both the president and his office.[163]

Foreign relations

The short-lived Azerbaijan Democratic Republic succeeded in establishing diplomatic relations with six countries, sending diplomatic representatives to Germany and Finland.[164] The process of international recognition of Azerbaijan's independence from the collapsing Soviet Union lasted roughly one year. The most recent country to recognize Azerbaijan was Bahrain, on 6 November 1996.[165] Full diplomatic relations, including mutual exchanges of missions, were first established with Turkey, Pakistan, the United States, Iran[164] and Israel.[166] Azerbaijan has placed a particular emphasis on its "special relationship" with Turkey.[167][168]

Azerbaijan has diplomatic relations with 158 countries so far and holds membership in 38 international organizations.[24] It holds observer status in the Non-Aligned Movement and World Trade Organization and is a correspondent at the International Telecommunication Union.[24]

On 9 May 2006 Azerbaijan was elected to membership in the newly established Human Rights Council by the United Nations General Assembly. The term of office began on 19 June 2006.[169] Azerbaijan was first elected as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council in 2011 with the support of 155 countries.

Foreign policy priorities of Azerbaijan include, first of all, the restoration of its territorial integrity; elimination of the consequences of occupation of Nagorno-Karabakh and seven other regions of Azerbaijan surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh;[170][171] integration into European and Euro-Atlantic structure; contribution to international security; cooperation with international organizations; regional cooperation and bilateral relations; strengthening of defense capability; promotion of security by domestic policy means; strengthening of democracy; preservation of ethnic and religious tolerance; scientific, educational, and cultural policy and preservation of moral values; economic and social development; enhancing internal and border security; and migration, energy, and transportation security policy.[170]

Azerbaijan is an active member of international coalitions fighting international terrorism, and was one of the first countries to offer support after the September 11 attacks.[172] The country is an active member of NATO's Partnership for Peace program, contributing to peacekeeping efforts in Kosovo, Afghanistan and Iraq.[citation needed] Azerbaijan is also a member of the Council of Europe since 2001 and maintains good relations with the European Union. The country may eventually apply for EU membership.[170]

On 1 July 2021, the US Congress advanced legislation that will have an impact on the military aid that Washington has sent to Azerbaijan since 2012. This was due to the fact that the packages to Armenia, instead, are significantly smaller.[173]

Azerbaijan has been harshly criticized for bribing foreign officials and diplomats to promote its causes abroad and legitimize its elections at home, a practice termed caviar diplomacy.[174][175][176][177] The Azerbaijani laundromat money laundering operation involved the bribery of foreign politicians and journalists to serve the Azerbaijani government's public relations interests.[178]

Military

The history of the modern Azerbaijan army dates back to Azerbaijan Democratic Republic in 1918 when the National Army of the newly formed Azerbaijan Democratic Republic was created on 26 June 1918.[179][180] When Azerbaijan gained independence after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the Armed Forces of the Republic of Azerbaijan were created according to the Law on the Armed Forces of 9 October 1991.[181] The original date of the establishment of the short-lived National Army is celebrated as Army Day (26 June) in today's Azerbaijan.[182]As of 2021, Azerbaijan had 126,000 active personnel in its armed forces. There are also 17,000 paramilitary troops and 330,00 reserve personnel.[183] The armed forces have three branches: the Land Forces, the Air Forces and the Navy. Additionally the armed forces embrace several military sub-groups that can be involved in state defense when needed. These are the Internal Troops of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the State Border Service, which includes the Coast Guard as well.[26] The Azerbaijan National Guard is a further paramilitary force. It operates as a semi-independent entity of the Special State Protection Service, an agency subordinate to the President.[184]

Azerbaijan adheres to the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe and has signed all major international arms and weapons treaties. Azerbaijan closely cooperates with NATO in programs such as Partnership for Peace and Individual Partnership Action Plan/pfp and ipa. Azerbaijan has deployed 151 of its Peacekeeping Forces in Iraq and another 184 in Afghanistan.[185]

Azerbaijan spent $2.24 billion on its defence budget as of 2020[update],[186] which amounted to 5.4% of its total GDP,[187] and some 12.7% of general government expenditure.[188] Azerbaijani defense industry manufactures small arms, artillery systems, tanks, armors and night vision devices, aviation bombs, UAV'S/unmanned aerial vehicle, various military vehicles and military planes and helicopters.[189][190][191][192]

Human rights and freedom

The Constitution of Azerbaijan claims to guarantee freedom of speech, but this is denied in practice. After several years of decline in press and media freedom, in 2014, the media environment in Azerbaijan deteriorated rapidly under a governmental campaign to silence any opposition and criticism, even while the country led the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe (May–November 2014). Spurious legal charges and impunity in violence against journalists have remained the norm.[193] All foreign broadcasts are banned in the country.[194]

According to the 2013 Freedom House Freedom of the Press report, Azerbaijan's press freedom status is "not free", and Azerbaijan ranks 177th out of 196 countries.[195]

Christianity is officially recognized. All religious communities are required to register to be allowed to meet, under the risk of imprisonment. This registration is often denied. "Racial discrimination contributes to the country's lack of religious freedom, since many of the Christians are ethnic Armenian or Russian, rather than Azeri Muslim".[196][197]

Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and Voice of America are banned in Azerbaijan.[198] Discrimination against LGBT people in Azerbaijan is widespread.[199][200]

During the last few years,[when?] three journalists were killed and several prosecuted in trials described as unfair by international human rights organizations. Azerbaijan had the biggest number of journalists imprisoned in Europe in 2015, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists, and is the 5th most censored country in the world, ahead of Iran and China.[201] Some critical journalists have been arrested for their coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic in Azerbaijan.[202][203]

A report by an Amnesty International researcher in October 2015 points to "...the severe deterioration of human rights in Azerbaijan over the past few years. Sadly Azerbaijan has been allowed to get away with unprecedented levels of repression and in the process almost wipe out its civil society."[204] Amnesty's 2015/16 annual report[205] on the country stated "... persecution of political dissent continued. Human rights organizations remained unable to resume their work. At least 18 prisoners of conscience remained in detention at the end of the year. Reprisals against independent journalists and activists persisted both in the country and abroad, while their family members also faced harassment and arrests. International human rights monitors were barred and expelled from the country. Reports of torture and other ill-treatment persisted."[206]

The Guardian reported in April 2017 that "Azerbaijan's ruling elite operated a secret $2.9bn (£2.2bn) scheme to pay prominent Europeans, buy luxury goods and launder money through a network of opaque British companies .... Leaked data shows that the Azerbaijani leadership, accused of serial human rights abuses, systemic corruption and rigging elections, made more than 16,000 covert payments from 2012 to 2014. Some of this money went to politicians and journalists, as part of an international lobbying operation to deflect criticism of Azerbaijan's president, Ilham Aliyev, and to promote a positive image of his oil-rich country." There was no suggestion that all recipients were aware of the source of the money as it arrived via a disguised route.[207]

Administrative divisions

Azerbaijan is administratively divided into 14 economic regions; 66 rayons (rayonlar, singular rayon) and 11 cities (şəhərlər, singular şəhər) under the direct authority of the republic.[208] Moreover, Azerbaijan includes the Autonomous Republic (muxtar respublika) of Nakhchivan.[26] The President of Azerbaijan appoints the governors of these units, while the government of Nakhchivan is elected and approved by the parliament of Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic.

- Baku Economic Region

- Absheron-Khizi Economic Region

- Central Aran Economic Region

- Mil-Mughan Economic Region

- Shirvan-Salyan Economic Region

- Mountainous Shirvan Economic Region

- Ganja-Dashkasan Economic Region

- Gazakh-Tovuz Economic Region

- Guba-Khachmaz Economic Region

- East Zangezur Economic Region

- Lankaran-Astara Economic Region

- Nakhchivan Economic Region

- Shaki-Zagatala Economic Region

- Karabakh Economic Region

Economy

After gaining independence in 1991, Azerbaijan became a member of the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the Islamic Development Bank, and the Asian Development Bank.[209] The banking system of Azerbaijan consists of the Central Bank of Azerbaijan, commercial banks, and non-banking credit organizations. The National (now Central) Bank was created in 1992 based on the Azerbaijan State Savings Bank, an affiliate of the former State Savings Bank of the USSR. The Central Bank serves as Azerbaijan's central bank, empowered to issue the national currency, the Azerbaijani manat, and to supervise all commercial banks. Two major commercial banks are UniBank and the state-owned International Bank of Azerbaijan, run by Abbas Ibrahimov.[210]

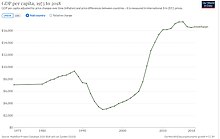

Pushed up by spending and demand growth, the 2007 Q1 inflation rate reached 16.6%.[211] Nominal incomes and monthly wages climbed 29% and 25% respectively against this figure, but price increases in the non-oil industry encouraged inflation.[211] Azerbaijan shows some signs of the so-called "Dutch disease" because of its fast-growing energy sector, which causes inflation and makes non-energy exports more expensive.[212]In the early 2000s, chronically high inflation was brought under control. This led to the launch of a new currency, the new Azerbaijani manat, on 1 January 2006, to cement the economic reforms and erase the vestiges of an unstable economy.[213][214]Azerbaijan is also ranked 57th in the Global Competitiveness Report for 2010–2011, above other CIS countries.[215] By 2012 the GDP of Azerbaijan had increased 20-fold from its 1995 level.[216]

Energy and natural resources

This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: some future tense sentences have years in the past. (December 2023) |

Two-thirds of Azerbaijan is rich in oil and natural gas.[217]The history of the oil industry of Azerbaijan dates back to the ancient period. Arabian historian and traveler Ahmad Al-Baladhuri discussed the economy of the Absheron peninsula in antiquity, mentioning its oil in particular.[218] There are many pipelines in Azerbaijan. The goal of the Southern Gas Corridor, which connects the giant Shah Deniz gas field in Azerbaijan to Europe,[219] is to reduce European Union's dependency on Russian gas.[220]

The region of the Lesser Caucasus accounts for most of the country's gold, silver, iron, copper, titanium, chromium, manganese, cobalt, molybdenum, complex ore and antimony.[217] In September 1994, a 30-year contract was signed between the State Oil Company of Azerbaijan Republic (SOCAR) and 13 oil companies, among them Amoco, BP, ExxonMobil, Lukoil and Equinor.[209] As Western oil companies are able to tap deepwater oilfields untouched by the Soviet exploitation, Azerbaijan is considered one of the most important spots in the world for oil exploration and development.[221] Meanwhile, the State Oil Fund of Azerbaijan was established as an extra-budgetary fund to ensure macroeconomic stability, transparency in the management of oil revenue, and safeguarding of resources for future generations.

Access to biocapacity in Azerbaijan is less than world average. In 2016, Azerbaijan had 0.8 global hectares[222] of biocapacity per person within its territory, half the world average of 1.6 global hectares per person.[223] In 2016 Azerbaijan used 2.1 global hectares of biocapacity per person – their ecological footprint of consumption. This means they use more biocapacity than Azerbaijan contains. As a result, Azerbaijan is running a biocapacity deficit.[222]

Azeriqaz, a sub-company of SOCAR, intends to ensure full gasification of the country by 2021.[224]Azerbaijan is one of the sponsors of the east–west and north–south energy transport corridors. Baku–Tbilisi–Kars railway line will connect the Caspian region with Turkey, which is expected to be completed in July 2017. The Trans-Anatolian gas pipeline (TANAP) and Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) will deliver natural gas from Azerbaijan's Shah Deniz gas to Turkey and Europe.[219]

Azerbaijan extended the agreement on development of ACG until 2050 according to the amended PSA signed on 14 September 2017 by SOCAR and co-ventures (BP, Chevron, Inpex, Equinor, ExxonMobil, TP, ITOCHU and ONGC Videsh).[225]

Agriculture

Azerbaijan has the largest agricultural basin in the region. About 54.9 percent of Azerbaijan is agricultural land.[129] At the beginning of 2007 there were 4,755,100 hectares of utilized agricultural area.[226] In the same year the total wood resources counted 136 million m3.[226] Azerbaijan's agricultural scientific research institutes are focused on meadows and pastures, horticulture and subtropical crops, green vegetables, viticulture and wine-making, cotton growing and medicinal plants.[227] In some areas it is profitable to grow grain, potatoes, sugar beets, cotton[228] and tobacco. Livestock, dairy products, and wine and spirits are also important farm products. The Caspian fishing industry concentrates on the dwindling stocks of sturgeon and beluga. In 2002 the Azerbaijani merchant marine had 54 ships.

Some products previously imported from abroad have begun to be produced locally. Among them are Coca-Cola by Coca-Cola Bottlers LTD., beer by Baki-Kastel, parquet by Nehir and oil pipes by EUPEC Pipe Coating Azerbaijan.[229]

Tourism

Tourism is an important part of the economy of Azerbaijan.[citation needed] The country was a well-known tourist spot in the 1980s. The fall of the Soviet Union, and the First Nagorno-Karabakh War during the 1990s, damaged the tourist industry and the image of Azerbaijan as a tourist destination.[230]

It was not until the 2000s that the tourism industry began to recover, and the country has since experienced a high rate of growth in the number of tourist visits and overnight stays.[231]

In recent years, Azerbaijan has also become a popular destination for religious, spa, and health care tourism.[232] During winter, the Shahdag Mountain Resort offers skiing with state of the art facilities.[233]

The government of Azerbaijan has set the development of Azerbaijan as an elite tourist destination as a top priority. It is a national strategy to make tourism a major, if not the single largest, contributor to the Azerbaijani economy.[234] These activities are regulated by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of Azerbaijan.

There are 63 countries which have a visa-free score.[235]E-visa[236] – for a visit of foreigners of visa-required countries to the Republic of Azerbaijan.

According to the Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report 2015 of the World Economic Forum, Azerbaijan holds 84th place.[237]

According to a report by the World Travel and Tourism Council, Azerbaijan was among the top ten countries showing the strongest growth in visitor exports between 2010 and 2016,[238] In addition, Azerbaijan placed first (46.1%) among countries with the fastest-developing travel and tourism economies, with strong indicators for inbound international visitor spending last year.[239]

Transportation

The convenient location of Azerbaijan on the crossroad of major international traffic arteries, such as the Silk Road and the south–north corridor, highlights the strategic importance of the transportation sector for the country's economy.[240] The transport sector in the country includes roads, railways, aviation, and maritime transport.

Azerbaijan is also an important economic hub in the transportation of raw materials. The Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipeline (BTC) became operational in May 2006 and extends more than 1,774 km (1,102 mi) through the territories of Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey. The BTC is designed to transport up to 50 million tons of crude oil annually and carries oil from the Caspian Sea oilfields to global markets.[241] The South Caucasus Pipeline, also stretching through the territory of Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey, became operational at the end of 2006 and offers additional gas supplies to the European market from the Shah Deniz gas field. Shah Deniz is expected to produce up to 296 billion cubic meters of natural gas per year.[242] Azerbaijan also plays a major role in the EU-sponsored Silk Road Project.[243]

In 2002, the Azerbaijani government established the Ministry of Transport with a broad range of policy and regulatory functions. In the same year, the country became a member of the Vienna Convention on Road Traffic.[244] Priorities are upgrading the transport network and improving transportation services to better facilitate the development of other sectors of the economy.[citation needed]

The 2012 construction of Kars–Tbilisi–Baku railway was meant to improve transportation between Asia and Europe by connecting the railways of China and Kazakhstan in the east to the European railway system in the west via Turkey. In 2010 Broad-gauge railways and electrified railways stretched for 2,918 km (1,813 mi) and 1,278 km (794 mi) respectively. By 2010, there were 35 airports and one heliport.[26]

Science and technology

In the 21st century, a new oil and gas boom helped improve the situation in Azerbaijan's science and technology sectors. The government launched a campaign aimed at modernization and innovation. The government estimates that profits from the information technology and communication industry will grow and become comparable to those from oil production.[245]

Azerbaijan has a large and steadily growing Internet sector, mostly uninfluenced by the financial crisis of 2007–2008; rapid growth is forecast for at least five more years.[246] Azerbaijan was ranked 89th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.[247][248]

The country has also been making progress in developing its telecoms sector. The Ministry of Communications & Information Technologies (MCIT) and an operator through its role in Aztelekom are both policy-makers and regulators. Public payphones are available for local calls and require the purchase of a token from the telephone exchange or some shops and kiosks. Tokens allow a call of indefinite duration. As of 2009[update], there were 1,397,000 main telephone lines[249] and 1,485,000 internet users.[250] There are four GSM providers: Azercell, Bakcell [az], Azerfon (Nar Mobile), Nakhtel mobile network operators and one CDMA.

In the 21st century a number of prominent Azerbaijani geodynamics and geotectonics scientists, inspired by the fundamental works of Elchin Khalilov and others, designed hundreds of earthquake prediction stations and earthquake-resistant buildings that now constitute the bulk of The Republican Center of Seismic Service.[251][252][253]

The Azerbaijan National Aerospace Agency launched its first satellite AzerSat 1 into orbit on 7 February 2013 from Guiana Space Centre in French Guiana at orbital positions 46° East.[254][255][256] The satellite covers Europe and a significant part of Asia and Africa and serves the transmission of TV and radio broadcasting as well as the Internet.[257] The launching of a satellite into orbit is Azerbaijan's first step in realizing its goal of becoming a nation with its own space industry, capable of successfully implementing more projects in the future.[258][259]

Demographics

As of March 2022, 52.9% of Azerbaijan's total population of 10,164,464 is urban, with the remaining 47.1% being rural.[260] In January 2019, the 50.1% of the total population was female. The sex ratio in the same year was 0.99 males per female.[261]

The 2011 population growth-rate was 0.85%, compared to 1.09% worldwide.[26] A significant factor restricting population growth is a high level of migration. In 2011 Azerbaijan saw a migration of −1.14/1,000 people.[26]

The Azerbaijani diaspora is found in 42 countries[262] and in turn there are many centers for ethnic minorities inside Azerbaijan, including the German cultural society "Karelhaus", Slavic cultural center, Azerbaijani-Israeli community, Kurdish cultural center, International Talysh Association, Lezgin national center "Samur", Azerbaijani-Tatar community, Crimean Tatars society, etc.[263]

In total, Azerbaijan has 78 cities, 63 city districts, and one special legal status city. 261 urban-type settlements and 4248 villages follow these.[264]

Largest cities or towns in Azerbaijan | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Economic regions | Municipal pop. | Rank | Name | Economic regions | Municipal pop. | ||

Baku  Sumgait | 1 | Baku | Absheron | 2,150,800 | 11 | Khachmaz | Guba-Khachmaz | 64,800 |  Ganja  Mingachevir |

| 2 | Sumgait | Absheron | 325,200 | 12 | Aghdam | Upper Karabakh | 59,800 | ||

| 3 | Ganja | Ganja-Qazakh | 323,000 | 13 | Jalilabad | Lankaran | 56,400 | ||

| 4 | Mingachevir | Aran | 99,700 | 14 | Khankandi | Upper Karabakh | 55,100 | ||

| 5 | Lankaran | Lankaran | 85,300 | 15 | Agjabadi | Aran | 46,900 | ||

| 6 | Shirvan | Aran | 80,900 | 16 | Shamakhi | Daglig-Shirvan | 43,700 | ||

| 7 | Nakhchivan | Nakhchivan | 78,300 | 17 | Fuzuli | Upper Karabakh | 42,000 | ||

| 8 | Shamkir | Ganja-Qazakh | 69,600 | 18 | Salyan | Aran | 37,000 | ||

| 9 | Shaki | Shaki-Zaqatala | 66,400 | 19 | Barda | Aran | 38,600 | ||

| 10 | Yevlakh | Aran | 66,300 | 20 | Neftchala | Aran | 38,200 | ||

Ethnicity

The ethnic composition of the population according to the 2009 population census: 91.6% Azerbaijanis, 2.0% Lezgins, 1.4% Armenians (almost all Armenians live in the break-away region of Nagorno-Karabakh), 1.3% Russians, 1.3% Talysh, 0.6% Avars, 0.4% Turks, 0.3% Tatars, 0.3% Tats, 0.2% Ukrainians, 0.1% Tsakhurs, 0.1% Georgians, 0.1% Jews, 0.1% Kurds, other 0.2%.[265]

Languages

The official language of Azerbaijan is Azerbaijani, a Turkic language. Approximately 92% of the national population speak it as their mother tongue.[266]

Russian and Armenian (only in Nagorno-Karabakh) are still spoken in Azerbaijan. Each is the mother tongue of around 1.5% of the national population.[266] In 1989, Armenian was the majority language in the region of Nagorno-Karabakh, spoken by about 76% of the regional population.[267] After the first Nagorno-Karabakh war, native speakers of Armenian composed around 95% of the regional population.[268]

A dozen other minority languages are spoken natively in Azerbaijan,[269] including Avar, Budukh,[270] Georgian, Juhuri,[270] Khinalug,[270] Kryts,[270] Lezgin, Rutul,[270] Talysh, Tat,[270] Tsakhur,[270] and Udi.[270] All these are spoken only by small minority populations, some of which are tiny and decreasing.[271]

Religion

Azerbaijan is considered the most secular Muslim-majority country.[273] Around 97% of the population are Muslims.[274] Around 55–65% of Muslims are estimated to be Shia, while 35–45% of Muslims are Sunnis.[275][276][277][278] Other faiths are practised by the country's various ethnic groups. Under article 48 of its Constitution, Azerbaijan is a secular state and ensures religious freedom. In a 2006–2008 Gallup poll, only 21% of respondents from Azerbaijan stated that religion is an important part of their daily lives.[279]

Of the nation's religious minorities, the estimated 280,000 Christians (3.1%)[280] are mostly Russian and Georgian Orthodox and Armenian Apostolic (almost all Armenians live in the break-away region of Nagorno-Karabakh).[26] In 2003, there were 250 Roman Catholics.[281] Other Christian denominations as of 2002 include Lutherans, Baptists and Molokans.[282] There is also a small Protestant community.[283][284] Azerbaijan also has an ancient Jewish population with a 2,000-year history; Jewish organizations[who?] estimate that 12,000 Jews remain in Azerbaijan, which is home to the only Jewish-majority town outside of Israel and the United States.[285][286][287][288] Azerbaijan also is home to members of the Baháʼí, Hare Krishna and Jehovah's Witnesses communities, as well as adherents of the other religious communities.[282] Some religious communities have been unofficially restricted from religious freedom. A U.S. State Department report on the matter mentions detention of members of certain Muslim and Christian groups, and many groups have difficulty registering with the agency who regulates religion, The State Committee on Religious Associations of the Republic of Azerbaijan (SCWRA).[289]

Education

A relatively high percentage of Azerbaijanis have obtained some form of higher education, most notably in scientific and technical subjects.[290] In the Soviet era, literacy and average education levels rose dramatically from their very low starting point, despite two changes in the standard alphabet, from Perso-Arabic script to Latin in the 1920s and from Roman to Cyrillic in the 1930s. According to Soviet data, 100 percent of males and females (ages nine to forty-nine) were literate in 1970.[290] According to the United Nations Development Program Report 2009, the literacy rate in Azerbaijan is 99.5 percent.[291]

Since independence, one of the first laws that Azerbaijan's Parliament passed to disassociate itself from the Soviet Union was to adopt a modified-Latin alphabet to replace Cyrillic.[292] Other than that the Azerbaijani system has undergone little structural change. Initial alterations have included the reestablishment of religious education (banned during the Soviet period) and curriculum changes that have reemphasized the use of the Azerbaijani language and have eliminated ideological content. In addition to elementary schools, the education institutions include thousands of preschools, general secondary schools, and vocational schools, including specialized secondary schools and technical schools. Education through the ninth grade is compulsory.[293]

Culture

The culture of Azerbaijan has developed as a result of many influences; that is why Azerbaijanis are, in many ways, bi-cultural. Today, national traditions are well preserved in the country despite Western influences, including globalized consumer culture. Some of the main elements of the Azerbaijani culture are: music, literature, folk dances and art, cuisine, architecture, cinematography and Novruz Bayram. The latter is derived from the traditional celebration of the New Year in the ancient Iranian religion of Zoroastrianism. Novruz is a family holiday.[294]

The profile of Azerbaijan's population consists, as stated above, of Azerbaijanis, as well as other nationalities or ethnic groups, compactly living in various areas of the country. Azerbaijani national and traditional dresses are the Chokha and Papakhi. There are radio broadcasts in Russian, Georgian, Kurdish, Lezgian and Talysh languages, which are financed from the state budget.[263] Some local radio stations in Balakan and Khachmaz organize broadcasts in Avar and Tat.[263] In Baku several newspapers are published in Russian, Kurdish (Dengi Kurd), Lezgian (Samur) and Talysh languages.[263] Jewish society "Sokhnut" publishes the newspaper Aziz.[263]

Architecture

Azerbaijani architecture typically combines elements of East and West.[295] Azerbaijani architecture has heavy influences from Persian architecture. Many ancient architectural treasures such as the Maiden Tower and Palace of the Shirvanshahs in the Walled City of Baku survive in modern Azerbaijan. Entries submitted on the UNESCO World Heritage tentative list include the Ateshgah of Baku, Momine Khatun Mausoleum, Hirkan National Park, Binagadi asphalt lake, Lökbatan Mud Volcano, Shusha State Historical and Architectural Reserve, Baku Stage Mountain, Caspian Shore Defensive Constructions, Ordubad National Reserve and the Palace of Shaki Khans.[296][297]

Among other architectural treasures are Quadrangular Castle in Mardakan, Parigala in Yukhary Chardaglar, a number of bridges spanning the Aras River, and several mausoleums. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, little monumental architecture was created, but distinctive residences were built in Baku and elsewhere. Among the most recent architectural monuments, the Baku subways are noted for their lavish decor.[298]

The task for modern Azerbaijani architecture is diverse application of modern aesthetics, the search for an architect's own artistic style and inclusion of the existing historico-cultural environment. Major projects such as Heydar Aliyev Cultural Center, Flame Towers, Baku Crystal Hall, Baku White City and SOCAR Tower have transformed the country's skyline and promotes its contemporary identity.[299][300]

Music and dance

Music of Azerbaijan builds on folk traditions that reach back nearly a thousand years.[301] For centuries Azerbaijani music has evolved under the badge of monody, producing rhythmically diverse melodies.[302] Azerbaijani music has a branchy mode system, where chromatization of major and minor scales is of great importance.[302] Among national musical instruments there are 14 string instruments, eight percussion instruments and six wind instruments.[303] According to The Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, "in terms of ethnicity, culture and religion the Azerbaijani are musically much closer to Iran than Turkey."[304]

Mugham, meykhana and ashiq art are among the many musical traditions of Azerbaijan. Mugham is usually a suite with poetry and instrumental interludes. When performing mugham, the singers have to transform their emotions into singing and music. In contrast to the mugham traditions of Central Asian countries, Azerbaijani mugham is more free-form and less rigid; it is often compared to the improvised field of jazz.[305] UNESCO proclaimed the Azerbaijani mugham tradition a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity on 7 November 2003. Meykhana is a kind of traditional Azerbaijani distinctive folk unaccompanied song, usually performed by several people improvising on a particular subject.[306]

Ashiq combines poetry, storytelling, dance, and vocal and instrumental music into a traditional performance art that stands as a symbol of Azerbaijani culture. It is a mystic troubadour or traveling bard who sings and plays the saz. This tradition has its origin in the Shamanistic beliefs of ancient Turkic peoples.[307] Ashiqs' songs are semi-improvised around common bases. Azerbaijan's ashiq art was included in the list of Intangible Cultural Heritage by the UNESCO on 30 September 2009.[308]

Since the mid-1960s, Western-influenced Azerbaijani pop music, in its various forms, that has been growing in popularity in Azerbaijan, while genres such as rock and hip hop are widely produced and enjoyed. Azerbaijani pop and Azerbaijani folk music arose with the international popularity of performers like Alim Qasimov, Rashid Behbudov, Vagif Mustafazadeh, Muslim Magomayev, Shovkat Alakbarova and Rubaba Muradova.[309] Azerbaijan is an enthusiastic participant in the Eurovision Song Contest. Azerbaijan made its debut appearance at the 2008 Eurovision Song Contest. The country's entry gained third place in 2009 and fifth the following year.[310] Ell and Nikki won the first place at the Eurovision Song Contest 2011 with the song "Running Scared", entitling Azerbaijan to host the contest in 2012, in Baku.[311][312] They have qualified for every Grand Final up until the 2018 edition of the contest, entering with X My Heart by singer Aisel.[313]

There are dozens of Azerbaijani folk dances. They are performed at formal celebrations and the dancers wear national clothes like the Chokha, which is well-preserved within the national dances. Most dances have a very fast rhythm.[314]

Art

- Folk art

Azerbaijanis have a rich and distinctive culture, a major part of which is decorative and applied art. This art form is represented by a wide range of handicrafts, such as chasing, jeweling, engraving in metal, carving in wood, stone, bone, carpet-making, lasing, pattern weaving and printing, and knitting and embroidery. Each of these types of decorative art, evidence of the endowments of the Azerbaijan nation, is very much in favor here. Many interesting facts pertaining to the development of arts and crafts in Azerbaijan were reported by numerous merchants, travelers, and diplomats who had visited these places at different times.[315]

The Azerbaijani carpet is a traditional handmade textile of various sizes, with a dense texture and a pile or pile-less surface, whose patterns are characteristic of Azerbaijan's many carpet-making regions. In November 2010 the Azerbaijani carpet was proclaimed a Masterpiece of Intangible Heritage by UNESCO.[316][317]

Azerbaijan has been since ancient times known as a center of a large variety of crafts. The archeological dig on the territory of Azerbaijan testifies to the well-developed agriculture, stock raising, metalworking, pottery, ceramics, and carpet-weaving that date as far back as to the 2nd millennium BC. Archeological sites in Dashbulaq, Hasansu, Zayamchai, and Tovuzchai uncovered from the BTC pipeline have revealed early Iron Age artifacts.[318]

Azerbaijani carpets can be categorized under several large groups and a multitude of subgroups. Scientific research of the Azerbaijani carpet is connected with the name of Latif Karimov, a prominent Soviet-era scientist and artist.[319]

- Visual art

The Gamigaya Petroglyphs, which date back to the 1st to 4th millennium BC, are located in Azerbaijan's Ordubad District. They consist of some 1500 dislodged and carved rock paintings with images of deer, goats, bulls, dogs, snakes, birds, fantastic beings, and people, carriages, and various symbols were found on basalt rocks.[320] Norwegian ethnographer and adventurer Thor Heyerdahl was convinced that people from the area went to Scandinavia in about 100 AD, took their boat building skills with them, and transmuted them into the Viking boats in Northern Europe.[321][322]

Over the centuries, Azerbaijani art has gone through many stylistic changes. Azerbaijani painting is traditionally characterized by a warmth of colour and light, as exemplified in the works of Azim Azimzade and Bahruz Kangarli, and a preoccupation with religious figures and cultural motifs.[323] Azerbaijani painting enjoyed preeminence in Caucasus for hundreds of years, from the Romanesque and Ottoman periods, and through the Soviet and Baroque periods, the latter two of which saw fruition in Azerbaijan. Other notable artists who fall within these periods include Sattar Bahlulzade, Togrul Narimanbekov, Tahir Salahov, Alakbar Rezaguliyev, Mirza Gadim Iravani, Mikayil Abdullayev and Boyukagha Mirzazade.[324]

Literature

Among the medieval authors born within the territorial limits of modern Azerbaijani Republic was Persian poet and philosopher Nizami, called Ganjavi after his place of birth, Ganja, who was the author of the Khamsa ("The Quintuplet"), composed of five romantic poems, including "The Treasure of Mysteries", "Khosrow and Shīrīn", and "Leyli and Mejnūn".[325]

The earliest known figure in written Azerbaijani literature was Izzeddin Hasanoghlu, who composed a divan consisting of Persian and Azerbaijani ghazals.[326][327] In Persian ghazals he used his pen-name, while his Azerbaijani ghazals were composed under his own name of Hasanoghlu.[326]

Classical literature in Azerbaijani was formed in the 14th century based on the various Early Middle Ages dialects of Tabriz and Shirvan. Among the poets of this period were Gazi Burhanaddin, Haqiqi (pen-name of Jahan Shah Qara Qoyunlu), and Habibi.[328] The end of the 14th century was also the period of starting literary activity of Imadaddin Nasimi,[329] one of the greatest Azerbaijani[330][331][332] Hurufi mystical poets of the late 14th and early 15th centuries[333] and one of the most prominent early divan masters in Turkic literary history,[333] who also composed poetry in Persian[331][334] and Arabic.[333] The divan and ghazal styles were further developed by poets Qasem-e Anvar, Fuzuli and Khatai (pen-name of Safavid Shah Ismail I).

The Book of Dede Korkut consists of two manuscripts copied in the 16th century,[335] and was not written earlier than the 15th century.[336][337] It is a collection of 12 stories reflecting the oral tradition of Oghuz nomads.[337] The 16th-century poet, Muhammed Fuzuli produced his timeless philosophical and lyrical Qazals in Arabic, Persian, and Azerbaijani. Benefiting immensely from the fine literary traditions of his environment, and building upon the legacy of his predecessors, Fuzuli was destined to become the leading literary figure of his society. His major works include The Divan of Ghazals and The Qasidas. In the same century, Azerbaijani literature further flourished with the development of Ashik (Azerbaijani: Aşıq) poetic genre of bards. During the same period, under the pen-name of Khatāī (Arabic: خطائی for sinner) Shah Ismail I wrote about 1400 verses in Azerbaijani,[338] which were later published as his Divan. A unique literary style known as qoshma (Azerbaijani: qoşma for improvisation) was introduced in this period, and developed by Shah Ismail and later by his son and successor, Shah Tahmasp I.[339]

In the span of the 17th and 18th centuries, Fuzuli's unique genres as well Ashik poetry were taken up by prominent poets and writers such as Qovsi of Tabriz, Shah Abbas Sani, Agha Mesih Shirvani [ru], Nishat, Molla Vali Vidadi, Molla Panah Vagif, Amani, Zafar and others. Along with Turks, Turkmens and Uzbeks, Azerbaijanis also celebrate the Epic of Koroglu (from Azerbaijani: kor oğlu for blind man's son), a legendary folk hero.[340] Several documented versions of Koroglu epic remain at the Institute for Manuscripts of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan.[327]

Modern Azerbaijani literature in Azerbaijan is based on the Shirvani dialect mainly, while in Iran it is based on the Tabrizi one. The first newspaper in Azerbaijani, Akinchi was published in 1875.[341] In the mid-19th century, it was taught in the schools of Baku, Ganja, Shaki, Tbilisi, and Yerevan. Since 1845, it was also taught in the University of Saint Petersburg in Russia.[citation needed]

Media

There are three state-owned television channels: AzTV, Idman TV and Medeniyyet TV. There is one public channel and 6 private channels: İctimai Television, Space TV, Lider TV, Azad Azerbaijan TV, Xazar TV [az], Real TV [az] and ARB.[342]

Cinema

The film industry in Azerbaijan dates back to 1898. Azerbaijan was among the first countries involved in cinematography,[343] with the apparatus first showing up in Baku.[344] In 1919, during the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, a documentary The Celebration of the Anniversary of Azerbaijani Independence was filmed on the first anniversary of Azerbaijan's independence from Russia, 27 May, and premiered in June 1919 at several theatres in Baku.[345] After the Soviet power was established in 1920, Nariman Narimanov, Chairman of the Revolutionary Committee of Azerbaijan, signed a decree nationalizing Azerbaijan's cinema. This also influenced the creation of Azerbaijani animation.[345]

In 1991, after Azerbaijan gained its independence from the Soviet Union, the first Baku International Film Festival East-West was held in Baku. In December 2000, the former President of Azerbaijan, Heydar Aliyev, signed a decree proclaiming 2 August to be the professional holiday of filmmakers of Azerbaijan. Today Azerbaijani filmmakers are again dealing with issues similar to those faced by cinematographers prior to the establishment of the Soviet Union in 1920. Once again, both choices of content and sponsorship of films are largely left up to the initiative of the filmmaker.[343]

Cuisine

The traditional cuisine is famous for an abundance of vegetables and greens used seasonally in the dishes. Fresh herbs, including mint, cilantro (coriander), dill, basil, parsley, tarragon, leeks, chives, thyme, marjoram, green onion, and watercress, are very popular and often accompany main dishes on the table. Climatic diversity and fertility of the land are reflected in the national dishes, which are based on fish from the Caspian Sea, local meat (mainly mutton and beef), and an abundance of seasonal vegetables and greens. Saffron-rice plov is the flagship food in Azerbaijan and black tea is the national beverage.[346] Azerbaijanis often use traditional armudu (pear-shaped) glass as they have very strong tea culture.[347][348] Popular traditional dishes include bozbash (lamb soup that exists in several regional varieties with the addition of different vegetables), qutab (fried turnover with a filling of greens or minced meat) and dushbara (sort of dumplings of dough filled with ground meat and flavor).

Sport

Freestyle wrestling has been traditionally regarded as Azerbaijan's national sport, in which Azerbaijan won up to fourteen medals, including four golds since joining the International Olympic Committee. Currently, the most popular sports include football and wrestling.[349]

Football is the most popular sport in Azerbaijan, and the Association of Football Federations of Azerbaijan with 9,122 registered players, is the largest sporting association in the country.[350][351] The national football team of Azerbaijan demonstrates relatively low performance in the international arena compared to the nation football clubs. The most successful Azerbaijani football clubs are Neftçi, Qarabağ, and Gabala. In 2012, Neftchi Baku became the first Azerbaijani team to advance to the group stage of a European competition, beating APOEL of Cyprus 4–2 on aggregate in the play-off round of the 2012–13 UEFA Europa League.[352][353] In 2014, Qarabağ became the second Azerbaijani club advancing to the group stage of UEFA Europa League. In 2017, after beating Copenhagen 2–2 (a) in the play-off round of the UEFA Champions League, Qarabağ became the first Azerbaijani club to reach the Group stage.[354] Futsal is another popular sport in Azerbaijan. The Azerbaijan national futsal team reached fourth place in the 2010 UEFA Futsal Championship, while domestic club Araz Naxçivan clinched bronze medals at the 2009–10 UEFA Futsal Cup and 2013–14 UEFA Futsal Cup.[355] Azerbaijan was the main sponsor of Spanish football club Atlético de Madrid during seasons 2013/2014 and 2014/2015, a partnership that the club described should 'promote the image of Azerbaijan in the world'.[356]

Azerbaijan is one of the traditional powerhouses of world chess,[357] having hosted many international chess tournaments and competitions and became European Team Chess Championship winners in 2009, 2013 and 2017.[358][359][360] Notable chess players from the country's chess schools that have made a great impact on the game include Teimour Radjabov, Shahriyar Mammadyarov, Vladimir Makogonov, Vugar Gashimov and former World Chess Champion Garry Kasparov. As of 2014[update], country's home of Shamkir Chess a category 22 event and one of the highest rated tournaments of all time.[361] Backgammon also plays a major role in Azerbaijani culture.[362] The game is very popular in Azerbaijan and is widely played among the local public.[363] There are also different variations of backgammon developed and analyzed by Azerbaijani experts.[364]

Azerbaijan Women's Volleyball Super League is one of the strongest women leagues in the world. Its women's national team came fourth at the 2005 European Championship.[365] Over the last years, clubs like Rabita Baku and Azerrail Baku achieved great success at European cups.[366] Azerbaijani volleyball players include likes of Valeriya Korotenko, Oksana Parkhomenko, Inessa Korkmaz, Natalya Mammadova, and Alla Hasanova.

Other Azerbaijani athletes are Namig Abdullayev, Toghrul Asgarov, Rovshan Bayramov, Sharif Sharifov, Mariya Stadnik and Farid Mansurov in wrestling, Nazim Huseynov, Elnur Mammadli, Elkhan Mammadov and Rustam Orujov in judo, Rafael Aghayev in karate, Magomedrasul Majidov and Aghasi Mammadov in boxing, Nizami Pashayev in Olympic weightlifting, Azad Asgarov in pankration, Eduard Mammadov in kickboxing, and K-1 fighter Zabit Samedov.

Azerbaijan has a Formula One race-track, made in June 2012,[367] and the country hosted its first Formula One Grand Prix on 19 June 2016[368] and the Azerbaijan Grand Prix since 2017. Other annual sporting events held in the country are the Baku Cup tennis tournament and the Tour d'Azerbaïdjan cycling race.

Azerbaijan hosted several major sport competitions since the late 2000s, including the 2013 F1 Powerboat World Championship, 2012 FIFA U-17 Women's World Cup, 2011 AIBA World Boxing Championships, 2010 European Wrestling Championships, 2009 Rhythmic Gymnastics European Championships, 2014 European Taekwondo Championships, 2014 Rhythmic Gymnastics European Championships, and 2016 World Chess Olympiad.[369] On 8 December 2012, Baku was selected to host the 2015 European Games, the first to be held in the competition's history.[370] Baku also hosted the fourth Islamic Solidarity Games in 2017[371] and the 2019 European Youth Summer Olympic Festival,[372] and it is also one of the hosts of UEFA Euro 2020, which because of Covid-19 is being held in 2021.[373]

See also