Католическая церковь

Католическая церковь | |

|---|---|

| Католическая церковь | |

Базилика Святого Петра в Ватикане, крупнейшее здание католической церкви в мире. | |

| Классификация | Католик |

| Писание | Католическая Библия |

| Theology | Catholic theology |

| Polity | Episcopal[1] |

| Governance | Holy See and Roman Curia |

| Pope | Francis |

| Particular churches sui iuris | Latin Church and 23 Eastern Catholic Churches |

| Dioceses | |

| Parishes | 221,700 approx. |

| Region | Worldwide |

| Language | Ecclesiastical Latin and native languages |

| Liturgy | Western and Eastern |

| Headquarters | Vatican City |

| Founder |

|

| Origin | 1st century Judaea, Roman Empire[2][3] |

| Separations | Protestantism |

| Members | 1.28 billion according to World Christian Database (2024)[4] 1.39 billion according to Annuario Pontificio (2022)[5][6] |

| Clergy | |

| Hospitals | 5,500[7] |

| Primary schools | 95,200[8] |

| Secondary schools | 43,800 |

| Official website | vatican |

| Part of a series on the |

| Catholic Church |

|---|

|

| Overview |

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Католическая церковь , также известная как Римско-католическая церковь , является крупнейшей христианской церковью в ней насчитывалось от 1,28 до 1,39 миллиарда крещеных католиков по всему миру . : по состоянию на 2024 год [4] [5] [9] Это одно из старейших и крупнейших международных учреждений в мире, сыгравшее заметную роль в истории и развитии западной цивилизации . [10] [11] [12] [13] Церковь состоит из 24 sui iuris церквей , включая Латинскую церковь и 23 восточно-католические церкви , которые насчитывают почти 3500 человек. [14] епархии и епархии, расположенные по всему миру . Папа Римский , епископ Рима, является главным пастором церкви. [15] , Римская епархия известная как Святой Престол , является центральным руководящим органом церкви. Административный орган Святого Престола, Римская курия , имеет свои главные офисы в Ватикане , небольшом независимом городе-государстве и анклаве в итальянской столице Риме которого является Папа Римский , главой государства .

The core beliefs of Catholicism are found in the Nicene Creed. The Catholic Church teaches that it is the one, holy, catholic and apostolic church founded by Jesus Christ in his Great Commission,[16][17][note 1] that its bishops are the successors of Christ's apostles, and that the pope is the successor to Saint Peter, upon whom primacy was conferred by Jesus Christ.[20] It maintains that it practises the original Christian faith taught by the apostles, preserving the faith infallibly through scripture and sacred tradition as authentically interpreted through the magisterium of the church.[21] The Roman Rite and others of the Latin Church, the Eastern Catholic liturgies, and institutes such as mendicant orders, enclosed monastic orders and third orders reflect a variety of theological and spiritual emphases in the church.[22][23]

Of its seven sacraments, the Eucharist is the principal one, celebrated liturgically in the Mass.[24] The church teaches that through consecration by a priest, the sacrificial bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ. The Virgin Mary is venerated as the Perpetual Virgin, Mother of God, and Queen of Heaven; she is honoured in dogmas and devotions.[25] Catholic social teaching emphasizes voluntary support for the sick, the poor, and the afflicted through the corporal and spiritual works of mercy. The Catholic Church operates tens of thousands of Catholic schools, universities and colleges, hospitals, and orphanages around the world, and is the largest non-government provider of education and health care in the world.[26] Among its other social services are numerous charitable and humanitarian organizations.

The Catholic Church has profoundly influenced Western philosophy, culture, art, literature, music, law,[27] and science.[13] Catholics live all over the world through missions, immigration, diaspora, and conversions. Since the 20th century, the majority have resided in the Southern Hemisphere, partially due to secularization in Europe. The Catholic Church shared communion with the Eastern Orthodox Church until the East–West Schism in 1054, disputing particularly the authority of the pope. Before the Council of Ephesus in AD 431, the Church of the East also shared in this communion, as did the Oriental Orthodox Churches before the Council of Chalcedon in AD 451; all separated primarily over differences in Christology. The Eastern Catholic Churches, who have a combined membership of approximately 18 million, represent a body of Eastern Christians who returned or remained in communion with the pope during or following these schisms for a variety of historical circumstances. In the 16th century, the Reformation led to the formation of separate, Protestant groups. From the late 20th century, the Catholic Church has been criticized for its teachings on sexuality, its doctrine against ordaining women, and its handling of sexual abuse cases involving clergy.

Name

Catholic (from Greek: καθολικός, romanized: katholikos, lit. 'universal') was first used to describe the church in the early 2nd century.[30] The first known use of the phrase "the catholic church" (Greek: καθολικὴ ἐκκλησία, romanized: katholikḕ ekklēsía) occurred in the letter written about 110 AD from Saint Ignatius of Antioch to the Smyrnaeans,[note 2] which read: "Wheresoever the bishop shall appear, there let the people be, even as where Jesus may be, there is the universal [katholike] Church."[31] In the Catechetical Lectures (c. 350) of Saint Cyril of Jerusalem, the name "Catholic Church" was used to distinguish it from other groups that also called themselves "the church".[31][32] The "Catholic" notion was further stressed in the edict De fide Catolica issued 380 by Theodosius I, the last emperor to rule over both the eastern and the western halves of the Roman Empire, when establishing the state church of the Roman Empire.[33]

Since the East–West Schism of 1054, the Eastern Orthodox Church has taken the adjective Orthodox as its distinctive epithet; its official name continues to be the Orthodox Catholic Church.[34] The Latin Church was described as Catholic, with that description also denominating those in communion with the Holy See after the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century, when those who ceased to be in communion became known as Protestants.[35][36]

While the Roman Church has been used to describe the pope's Diocese of Rome since the Fall of the Western Roman Empire and into the Early Middle Ages (6th–10th century), Roman Catholic Church has been applied to the whole church in the English language since the Protestant Reformation in the late 16th century.[37] Further, some will refer to the Latin Church as Roman Catholic in distinction from the Eastern Catholic churches.[38] "Roman Catholic" has occasionally appeared also in documents produced both by the Holy See,[note 3] and notably used by certain national episcopal conferences and local dioceses.[note 4]

The name Catholic Church for the whole church is used in the Catechism of the Catholic Church (1990) and the Code of Canon Law (1983). "Catholic Church" is also used in the documents of the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965),[39] the First Vatican Council (1869–1870),[40] the Council of Trent (1545–1563),[41] and numerous other official documents.[42][43]

History

Apostolic era and papacy

The New Testament, in particular the Gospels, records Jesus' activities and teaching, his appointment of the Twelve Apostles and his Great Commission of the apostles, instructing them to continue his work.[44][45] The book Acts of Apostles, tells of the founding of the Christian church and the spread of its message to the Roman Empire.[46] The Catholic Church teaches that its public ministry began on Pentecost, occurring fifty days following the date Christ is believed to have resurrected.[47] At Pentecost, the apostles are believed to have received the Holy Spirit, preparing them for their mission in leading the church.[48][49] The Catholic Church teaches that the college of bishops, led by the bishop of Rome are the successors to the Apostles.[50]

In the account of the Confession of Peter found in the Gospel of Matthew, Christ designates Peter as the "rock" upon which Christ's church will be built.[51][52] The Catholic Church considers the bishop of Rome, the pope, to be the successor to Saint Peter.[53] Some scholars state Peter was the first bishop of Rome.[54] Others say that the institution of the papacy is not dependent on the idea that Peter was bishop of Rome or even on his ever having been in Rome.[55] Many scholars hold that a church structure of plural presbyters/bishops persisted in Rome until the mid-2nd century, when the structure of a single bishop and plural presbyters was adopted,[56] and that later writers retrospectively applied the term "bishop of Rome" to the most prominent members of the clergy in the earlier period and also to Peter himself.[56] On this basis, Oscar Cullmann,[57] Henry Chadwick,[58] and Bart D. Ehrman[59] question whether there was a formal link between Peter and the modern papacy. Raymond E. Brown also says that it is anachronistic to speak of Peter in terms of local bishop of Rome, but that Christians of that period would have looked on Peter as having "roles that would contribute in an essential way to the development of the role of the papacy in the subsequent church". These roles, Brown says, "contributed enormously to seeing the bishop of Rome, the bishop of the city where Peter died and where Paul witnessed the truth of Christ, as the successor of Peter in care for the church universal".[56]

Antiquity and Roman Empire

Conditions in the Roman Empire facilitated the spread of new ideas. The empire's network of roads and waterways facilitated travel, and the Pax Romana made travelling safe. The empire encouraged the spread of a common culture with Greek roots, which allowed ideas to be more easily expressed and understood.[60]

Unlike most religions in the Roman Empire, however, Christianity required its adherents to renounce all other gods, a practice adopted from Judaism (see Idolatry). The Christians' refusal to join pagan celebrations meant they were unable to participate in much of public life, which caused non-Christians—including government authorities—to fear that the Christians were angering the gods and thereby threatening the peace and prosperity of the Empire. The resulting persecutions were a defining feature of Christian self-understanding until Christianity was legalized in the 4th century.[61]

In 313, Emperor Constantine I's Edict of Milan legalized Christianity, and in 330 Constantine moved the imperial capital to Constantinople, modern Istanbul, Turkey. In 380 the Edict of Thessalonica made Nicene Christianity the state church of the Roman Empire, a position that within the diminishing territory of the Byzantine Empire would persist until the empire itself ended in the fall of Constantinople in 1453, while elsewhere the church was independent of the empire, as became particularly clear with the East–West Schism. During the period of the Seven Ecumenical Councils, five primary sees emerged, an arrangement formalized in the mid-6th century by Emperor Justinian I as the pentarchy of Rome, Constantinople, Antioch, Jerusalem and Alexandria.[62][63] In 451 the Council of Chalcedon, in a canon of disputed validity,[64] elevated the see of Constantinople to a position "second in eminence and power to the bishop of Rome".[65] From c. 350 – c. 500, the bishops, or popes, of Rome, steadily increased in authority through their consistent intervening in support of orthodox leaders in theological disputes, which encouraged appeals to them.[66] Emperor Justinian, who in the areas under his control definitively established a form of caesaropapism,[67] in which "he had the right and duty of regulating by his laws the minutest details of worship and discipline, and also of dictating the theological opinions to be held in the Church",[68] re-established imperial power over Rome and other parts of the West, initiating the period termed the Byzantine Papacy (537–752), during which the bishops of Rome, or popes, required approval from the emperor in Constantinople or from his representative in Ravenna for consecration, and most were selected by the emperor from his Greek-speaking subjects,[69] resulting in a "melting pot" of Western and Eastern Christian traditions in art as well as liturgy.[70]

Most of the Germanic tribes who in the following centuries invaded the Roman Empire had adopted Christianity in its Arian form, which the Council of Nicea declared heretical.[71] The resulting religious discord between Germanic rulers and Catholic subjects[72] was avoided when, in 497, Clovis I, the Frankish ruler, converted to orthodox Catholicism, allying himself with the papacy and the monasteries.[73] The Visigoths in Spain followed his lead in 589,[74] and the Lombards in Italy in the course of the 7th century.[75]

Western Christianity, particularly through its monasteries, was a major factor in preserving classical civilization, with its art (see Illuminated manuscript) and literacy.[76] Through his Rule, Benedict of Nursia (c. 480–543), one of the founders of Western monasticism, exerted an enormous influence on European culture through the appropriation of the monastic spiritual heritage of the early Catholic Church and, with the spread of the Benedictine tradition, through the preservation and transmission of ancient culture. During this period, monastic Ireland became a centre of learning and early Irish missionaries such as Columbanus and Columba spread Christianity and established monasteries across continental Europe.[76]

Middle Ages and Renaissance

The Catholic Church was the dominant influence on Western civilization from Late Antiquity to the dawn of the modern age.[13] It was the primary sponsor of Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, Mannerist and Baroque styles in art, architecture and music.[77] Renaissance figures such as Raphael, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Botticelli, Fra Angelico, Tintoretto, Titian, Bernini and Caravaggio are examples of the numerous visual artists sponsored by the church.[78] Historian Paul Legutko of Stanford University said the Catholic Church is "at the center of the development of the values, ideas, science, laws, and institutions which constitute what we call Western civilization".[79]

In Western Christendom, the first universities in Europe were established by monks.[80][81][82] Beginning in the 11th century, several older cathedral schools became universities, such as the University of Oxford, University of Paris, and University of Bologna. Higher education before then had been the domain of Christian cathedral schools or monastic schools, led by monks and nuns. Evidence of such schools dates back to the 6th century CE.[83] These new universities expanded the curriculum to include academic programs for clerics, lawyers, civil servants, and physicians.[84] The university is generally regarded as an institution that has its origin in the Medieval Christian setting.[85][86][87]

The massive Islamic invasions of the mid-7th century began a long struggle between Christianity and Islam throughout the Mediterranean Basin. The Byzantine Empire soon lost the lands of the eastern patriarchates of Jerusalem, Alexandria and Antioch and was reduced to that of Constantinople, the empire's capital. As a result of Islamic domination of the Mediterranean, the Frankish state, centred away from that sea, was able to evolve as the dominant power that shaped the Western Europe of the Middle Ages.[88] The battles of Toulouse and Poitiers halted the Islamic advance in the West and the failed siege of Constantinople halted it in the East. Two or three decades later, in 751, the Byzantine Empire lost to the Lombards the city of Ravenna from which it governed the small fragments of Italy, including Rome, that acknowledged its sovereignty. The fall of Ravenna meant that confirmation by a no longer existent exarch was not asked for during the election in 752 of Pope Stephen II and that the papacy was forced to look elsewhere for a civil power to protect it.[89] In 754, at the urgent request of Pope Stephen, the Frankish king Pepin the Short conquered the Lombards. He then gifted the lands of the former exarchate to the pope, thus initiating the Papal States. Rome and the Byzantine East would delve into further conflict during the Photian schism of the 860s, when Photius criticized the Latin west of adding of the filioque clause after being excommunicated by Nicholas I. Though the schism was reconciled, unresolved issues would lead to further division.[90]

In the 11th century, the efforts of Hildebrand of Sovana led to the creation of the College of Cardinals to elect new popes, starting with Pope Alexander II in the papal election of 1061. When Alexander II died, Hildebrand was elected to succeed him, as Pope Gregory VII. The basic election system of the College of Cardinals which Gregory VII helped establish has continued to function into the 21st century. Pope Gregory VII further initiated the Gregorian Reforms regarding the independence of the clergy from secular authority. This led to the Investiture Controversy between the church and the Holy Roman Emperors, over which had the authority to appoint bishops and popes.[91][92]

In 1095, Byzantine emperor Alexius I appealed to Pope Urban II for help against renewed Muslim invasions in the Byzantine–Seljuk Wars,[93] which caused Urban to launch the First Crusade aimed at aiding the Byzantine Empire and returning the Holy Land to Christian control.[94] In the 11th century, strained relations between the primarily Greek church and the Latin Church separated them in the East–West Schism, partially due to conflicts over papal authority. The Fourth Crusade and the sacking of Constantinople by renegade crusaders proved the final breach.[95] In this age great gothic cathedrals in France were an expression of popular pride in the Christian faith.

In the early 13th century mendicant orders were founded by Francis of Assisi and Dominic de Guzmán. The studia conventualia and studia generalia of the mendicant orders played a large role in the transformation of church-sponsored cathedral schools and palace schools, such as that of Charlemagne at Aachen, into the prominent universities of Europe.[96] Scholastic theologians and philosophers such as the Dominican priest Thomas Aquinas studied and taught at these studia. Aquinas' Summa Theologica was an intellectual milestone in its synthesis of the legacy of ancient Greek philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle with the content of Christian revelation.[97]

A growing sense of church-state conflicts marked the 14th century. To escape instability in Rome, Clement V in 1309 became the first of seven popes to reside in the fortified city of Avignon in southern France[98] during a period known as the Avignon Papacy. The Avignon Papacy ended in 1376 when the pope returned to Rome,[99] but was followed in 1378 by the 38-year-long Western schism, with claimants to the papacy in Rome, Avignon and (after 1409) Pisa.[99] The matter was largely resolved in 1415–17 at the Council of Constance, with the claimants in Rome and Pisa agreeing to resign and the third claimant excommunicated by the cardinals, who held a new election naming Martin V pope.[100]

In 1438, the Council of Florence convened, which featured a strong dialogue focussed on understanding the theological differences between the East and West, with the hope of reuniting the Catholic and Orthodox churches.[101] Several eastern churches reunited, forming the majority of the Eastern Catholic Churches.[102]

Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery beginning in the 15th century saw the expansion of Western Europe's political and cultural influence worldwide. Because of the prominent role the strongly Catholic nations of Spain and Portugal played in Western colonialism, Catholicism was spread to the Americas, Asia and Oceania by explorers, conquistadors, and missionaries, as well as by the transformation of societies through the socio-political mechanisms of colonial rule. Pope Alexander VI had awarded colonial rights over most of the newly discovered lands to Spain and Portugal[103] and the ensuing patronato system allowed state authorities, not the Vatican, to control all clerical appointments in the new colonies.[104] In 1521 the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan made the first Catholic converts in the Philippines.[105] Elsewhere, Portuguese missionaries under the Spanish Jesuit Francis Xavier evangelized in India, China, and Japan.[106] The French colonization of the Americas beginning in the 16th century established a Catholic francophone population and forbade non-Catholics to settle in Quebec.[107]

Protestant Reformation and Counter-Reformation

In 1415, Jan Hus was burned at the stake for heresy, but his reform efforts encouraged Martin Luther, an Augustinian friar in modern-day Germany, who sent his Ninety-five Theses to several bishops in 1517.[108] His theses protested key points of Catholic doctrine as well as the sale of indulgences, and along with the Leipzig Debate this led to his excommunication in 1521.[108][109] In Switzerland, Huldrych Zwingli, John Calvin and other Protestant Reformers further criticized Catholic teachings. These challenges developed into the Reformation, which gave birth to the great majority of Protestant denominations[110] and also crypto-Protestantism within the Catholic Church.[111] Meanwhile, Henry VIII petitioned Pope Clement VII for a declaration of nullity concerning his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. When this was denied, he had the Acts of Supremacy passed to make himself Supreme Head of the Church of England, spurring the English Reformation and the eventual development of Anglicanism.[112]

The Reformation contributed to clashes between the Protestant Schmalkaldic League and the Catholic Emperor Charles V and his allies. The first nine-year war ended in 1555 with the Peace of Augsburg but continued tensions produced a far graver conflict—the Thirty Years' War—which broke out in 1618.[113] In France, a series of conflicts termed the French Wars of Religion was fought from 1562 to 1598 between the Huguenots (French Calvinists) and the forces of the French Catholic League, which were backed and funded by a series of popes.[114] This ended under Pope Clement VIII, who hesitantly accepted King Henry IV's 1598 Edict of Nantes granting civil and religious toleration to French Protestants.[113][114]

The Council of Trent (1545–1563) became the driving force behind the Counter-Reformation in response to the Protestant movement. Doctrinally, it reaffirmed central Catholic teachings such as transubstantiation and the requirement for love and hope as well as faith to attain salvation.[115] In subsequent centuries, Catholicism spread widely across the world, in part through missionaries and imperialism, although its hold on European populations declined due to the growth of religious scepticism during and after the Enlightenment.[116]

Enlightenment and modern period

| Part of a series on |

| Persecutions of the Catholic Church |

|---|

From the 17th century onward, the Enlightenment questioned the power and influence of the Catholic Church over Western society.[117] In the 18th century, writers such as Voltaire and the Encyclopédistes wrote biting critiques of both religion and the Catholic Church. One target of their criticism was the 1685 revocation of the Edict of Nantes by King Louis XIV of France, which ended a century-long policy of religious toleration of Protestant Huguenots. As the papacy resisted pushes for Gallicanism, the French Revolution of 1789 shifted power to the state, caused the destruction of churches, the establishment of a Cult of Reason,[118] and the martyrdom of nuns during the Reign of Terror.[119] In 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte's General Louis-Alexandre Berthier invaded the Italian Peninsula, imprisoning Pope Pius VI, who died in captivity. Napoleon later re-established the Catholic Church in France through the Concordat of 1801.[120] The end of the Napoleonic Wars brought Catholic revival and the return of the Papal States.[121]

In 1854, Pope Pius IX, with the support of the overwhelming majority of Catholic bishops, whom he had consulted from 1851 to 1853, proclaimed the Immaculate Conception as a dogma in the Catholic Church.[122] In 1870, the First Vatican Council affirmed the doctrine of papal infallibility when exercised in specifically defined pronouncements,[123][124] striking a blow to the rival position of conciliarism. Controversy over this and other issues resulted in a breakaway movement called the Old Catholic Church,[125]

The Italian unification of the 1860s incorporated the Papal States, including Rome itself from 1870, into the Kingdom of Italy, thus ending the papacy's temporal power. In response, Pope Pius IX excommunicated King Victor Emmanuel II, refused payment for the land, and rejected the Italian Law of Guarantees, which granted him special privileges. To avoid placing himself in visible subjection to the Italian authorities, he remained a "prisoner in the Vatican".[126] This stand-off, which was spoken of as the Roman Question, was resolved by the 1929 Lateran Treaties, whereby the Holy See acknowledged Italian sovereignty over the former Papal States in return for payment and Italy's recognition of papal sovereignty over Vatican City as a new sovereign and independent state.[127]

Catholic missionaries generally supported, and sought to facilitate, the European imperial powers' conquest of Africa during the late nineteenth century. According to the historian of religion Adrian Hastings, Catholic missionaries were generally unwilling to defend African rights or encourage Africans to see themselves as equals to Europeans, in contrast to Protestant missionaries, who were more willing to oppose colonial injustices.[128]

20th century

During the 20th century, the church's global reach continued to grow, despite the rise of anti-Catholic authoritarian regimes and the collapse of European Empires, accompanied by a general decline in religious observance in the West. Under Popes Benedict XV, and Pius XII, the Holy See sought to maintain public neutrality through the World Wars, acting as peace broker and delivering aid to the victims of the conflicts. In the 1960s, Pope John XXIII convened the Second Vatican Council, which ushered in radical change to church ritual and practice, and in the later 20th century, the long reign of Pope John Paul II contributed to the fall of communism in Europe, and a new public and international role for the papacy.[129][130]From the late 20th century, the Catholic Church has been criticized for its doctrines on sexuality, its inability to ordain women, and its handling of sexual abuse cases.

Pope Pius X (1903–1914) renewed the independence of papal office by abolishing the veto of Catholic powers in papal elections, and his successors Benedict XV (1914–1922) and Pius XI (1922–1939) concluded the modern independence of the Vatican State within Italy.[131] Benedict XV was elected at the outbreak of the First World War. He attempted to mediate between the powers and established a Vatican relief office, to assist victims of the war and reunite families.[132] The interwar Pope Pius XI modernized the papacy, appointing 40 indigenous bishops and concluding fifteen concordats, including the Lateran Treaty with Italy which founded the Vatican City State.[133]

His successor Pope Pius XII led the Catholic Church through the Second World War and early Cold War. Like his predecessors, Pius XII sought to publicly maintain Vatican neutrality in the War, and established aid networks to help victims, but he secretly assisted the anti-Hitler resistance and shared intelligence with the Allies.[132] His first encyclical Summi Pontificatus (1939) expressed dismay at the 1939 Invasion of Poland and reiterated Catholic teaching against racism.[134] He expressed concern against race killings on Vatican Radio, and intervened diplomatically to attempt to block Nazi deportations of Jews in various countries from 1942 to 1944. But the Pope's insistence on public neutrality and diplomatic language has become a source of much criticism and debate.[135] Nevertheless, in every country under German occupation, priests played a major part in rescuing Jews.[136] Israeli historian Pinchas Lapide estimated that Catholic rescue of Jews amounted to somewhere between 700,000 and 860,000 people.[137]

The Nazi persecution of the Catholic Church was at its most intense in Poland, and Catholic resistance to Nazism took various forms. Some 2,579 Catholic clergy were sent to the Priest Barracks of Dachau Concentration Camp, including 400 Germans.[138][139] Thousands of priests, nuns and brothers were imprisoned, taken to a concentration camp, tortured and murdered, including Saints Maximilian Kolbe and Edith Stein.[140][141] Catholics fought on both sides in the conflict. Catholic clergy played a leading role in the government of the fascist Slovak State, which collaborated with the Nazis, copied their anti-Semitic policies, and helped them carry out the Holocaust in Slovakia. Jozef Tiso, the President of the Slovak State and a Catholic priest, supported his government's deportation of Slovakian Jews to extermination camps.[142] The Vatican protested against these Jewish deportations in Slovakia and in other Nazi puppet regimes including Vichy France, Croatia, Bulgaria, Italy and Hungary.[143][144]

Around 1943, Adolf Hitler planned the kidnapping of the Pope and his internment in Germany. He gave SS General Wolff a corresponding order to prepare for the action.[145][146] While Pope Pius XII has been credited with helping to save hundreds of thousands of Jews during the Holocaust,[147][148] the church has also been accused of having encouraged centuries of antisemitism by its teachings[149] and not doing enough to stop Nazi atrocities.[150] Many Nazi criminals escaped overseas after the Second World War, also because they had powerful supporters from the Vatican.[151][152][153] The judgment of Pius XII is made more difficult by the sources, because the church archives for his tenure as nuncio, cardinal secretary of state and pope are in part closed or not yet processed.[154]

The Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) introduced the most significant changes to Catholic practices since the Council of Trent, four centuries before.[155] Initiated by Pope John XXIII, this ecumenical council modernized the practices of the Catholic Church, allowing the Mass to be said in the vernacular (local language) and encouraging "fully conscious, and active participation in liturgical celebrations".[156] It intended to engage the church more closely with the present world (aggiornamento), which was described by its advocates as an "opening of the windows".[157] In addition to changes in the liturgy, it led to changes to the church's approach to ecumenism,[158] and a call to improved relations with non-Christian religions, especially Judaism, in its document Nostra aetate.[159]

The council, however, generated significant controversy in implementing its reforms: proponents of the "Spirit of Vatican II" such as Swiss theologian Hans Küng said that Vatican II had "not gone far enough" to change church policies.[160] Traditionalist Catholics, such as Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, however, strongly criticized the council, arguing that its liturgical reforms led "to the destruction of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass and the sacraments", among other issues.[161] The teaching on the morality of contraception also came under scrutiny; after a series of disagreements, Humanae vitae upheld the church's prohibition of all forms of contraception.[162][163][note 5][164]

In 1978, Pope John Paul II, formerly Archbishop of Kraków in the Polish People's Republic, became the first non-Italian pope in 455 years. His 26 1/2-year pontificate was one of the longest in history, and was credited with hastening the fall of communism in Europe.[165][166] John Paul II sought to evangelize an increasingly secular world. He travelled more than any other pope, visiting 129 countries,[167] and used television and radio as means of spreading the church's teachings. He also emphasized the dignity of work and natural rights of labourers to have fair wages and safe conditions in Laborem exercens.[168] He emphasized several church teachings, including moral exhortations against abortion, euthanasia, and against widespread use of the death penalty, in Evangelium Vitae.[169]

21st century

Pope Benedict XVI, elected in 2005, was known for upholding traditional Christian values against secularization,[170] and for increasing use of the Tridentine Mass as found in the Roman Missal of 1962, which he titled the "Extraordinary Form".[171] Citing the frailties of advanced age, Benedict resigned in 2013, becoming the first pope to do so in nearly 600 years.[172]

Pope Francis, the current pope of the Catholic Church, became in 2013 the first pope from the Americas, the first from the Southern Hemisphere, and the first Pope from outside Europe since the eighth-century Gregory III.[173][174] Francis has made efforts to further close Catholicism's estrangement with the Orthodox Churches.[175] His installation was attended by Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople of the Eastern Orthodox Church,[176] the first time since the Great Schism of 1054 that the Eastern Orthodox Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople has attended a papal installation,[177] while he also met Patriarch Kirill of Moscow, head of the largest Eastern Orthodox church, in 2016; this was reported as the first such high-level meeting between the two churches since the Great Schism of 1054.[178] In 2017 during a visit in Egypt, Pope Francis reestablished mutual recognition of baptism with the Coptic Orthodox Church.[179]

Organization

The Catholic Church follows an episcopal polity, led by bishops who have received the sacrament of Holy Orders who are given formal jurisdictions of governance within the church.[180][181] There are three levels of clergy: the episcopate, composed of bishops who hold jurisdiction over a geographic area called a diocese or eparchy; the presbyterate, composed of priests ordained by bishops and who work in local dioceses or religious orders; and the diaconate, composed of deacons who assist bishops and priests in a variety of ministerial roles. Ultimately leading the entire Catholic Church is the bishop of Rome, known as the pope (Latin: papa, lit. 'father'), whose jurisdiction is called the Holy See (Sancta Sedes in Latin).[182] In parallel to the diocesan structure are a variety of religious institutes that function autonomously, often subject only to the authority of the pope, though sometimes subject to the local bishop. Most religious institutes only have male or female members but some have both. Additionally, lay members aid many liturgical functions during worship services. The Catholic Church has been described as the oldest multinational organization in the world.[183][184][185]

Holy See, papacy, Roman Curia, and College of Cardinals

The hierarchy of the Catholic Church is headed[note 6] by the pope, currently Pope Francis, who was elected on 13 March 2013 by a papal conclave.[191] The office of the pope is known as the papacy. The Catholic Church holds that Christ instituted the papacy upon giving the keys of Heaven to Saint Peter. His ecclesiastical jurisdiction is called the Holy See, or the Apostolic See (meaning the see of the apostle Peter).[192][193] Directly serving the pope is the Roman Curia, the central governing body that administers the day-to-day business of the Catholic Church.

The pope is also sovereign of Vatican City,[194] a small city-state entirely enclaved within the city of Rome, which is an entity distinct from the Holy See. It is as head of the Holy See, not as head of Vatican City State, that the pope receives ambassadors of states and sends them his own diplomatic representatives.[195] The Holy See also confers orders, decorations and medals, such as the orders of chivalry originating from the Middle Ages.

While the famous Saint Peter's Basilica is located in Vatican City, above the traditional site of Saint Peter's tomb, the papal cathedral for the Diocese of Rome is the Archbasilica of Saint John Lateran, located within the city of Rome, though enjoying extraterritorial privileges accredited to the Holy See.

The position of cardinal is a rank of honour bestowed by popes on certain clerics, such as leaders within the Roman Curia, bishops serving in major cities and distinguished theologians. For advice and assistance in governing, the pope may turn to the College of Cardinals.[196]

Following the death or resignation of a pope,[note 7] members of the College of Cardinals who are under age 80 act as an electoral college, meeting in a papal conclave to elect a successor.[198] Although the conclave may elect any male Catholic as pope, since 1389 only cardinals have been elected.[199]

Canon law

Catholic canon law (Latin: jus canonicum)[200] is the system of laws and legal principles made and enforced by the hierarchical authorities of the Catholic Church to regulate its external organization and government and to order and direct the activities of Catholics toward the mission of the church.[201] The canon law of the Latin Church was the first modern Western legal system,[202] and is the oldest continuously functioning legal system in the West,[203][204] while the distinctive traditions of Eastern Catholic canon law govern the 23 Eastern Catholic particular churches sui iuris.

Positive ecclesiastical laws, based directly or indirectly upon immutable divine law or natural law, derive formal authority in the case of universal laws from promulgation by the supreme legislator—the Supreme Pontiff—who possesses the totality of legislative, executive and judicial power in his person,[205] while particular laws derive formal authority from promulgation by a legislator inferior to the supreme legislator, whether an ordinary or a delegated legislator. The actual subject material of the canons is not just doctrinal or moral in nature, but all-encompassing of the human condition. It has all the ordinary elements of a mature legal system:[206] laws, courts, lawyers, judges,[206] a fully articulated legal code for the Latin Church[207] as well as a code for the Eastern Catholic Churches,[207] principles of legal interpretation,[208] and coercive penalties.[209][210]

Canon law concerns the Catholic Church's life and organization and is distinct from civil law. In its own field it gives force to civil law only by specific enactment in matters such as the guardianship of minors.[211] Similarly, civil law may give force in its field to canon law, but only by specific enactment, as with regard to canonical marriages.[212] Currently, the 1983 Code of Canon Law is in effect for the Latin Church.[213] The distinct 1990 Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches (CCEO, after the Latin initials) applies to the autonomous Eastern Catholic Churches.[214]

Latin and Eastern churches

In the first thousand years of Catholic history, different varieties of Christianity developed in the Western and Eastern Christian areas of Europe, Asia and Africa. Though most Eastern-tradition churches are no longer in communion with the Catholic Church after the Great Schism of 1054 (as well as the earlier Nestorian Schism and Chalcedonian Schism), 23 autonomous particular churches of eastern traditions participate in the Catholic communion, also known as "churches sui iuris" (Latin: "of one's own right"). The largest and most well known is the Latin Church, the only Western-tradition church, with more than 1 billion members worldwide. Relatively small in terms of adherents compared to the Latin Church, are the 23 self-governing Eastern Catholic Churches with a combined membership of 17.3 million as of 2010[update].[215][216][217][218]

The Latin Church is governed by the pope and diocesan bishops directly appointed by him. The pope exercises a direct patriarchal role over the Latin Church, which is considered to form the original and still major part of Western Christianity, a heritage of certain beliefs and customs originating in Europe and northwestern Africa, some of which are inherited by many Christian denominations that trace their origins to the Protestant Reformation.[219]

The Eastern Catholic Churches follow the traditions and spirituality of Eastern Christianity and are churches that have always remained in full communion with the Catholic Church or who have chosen to re-enter full communion in the centuries following the East–West Schism or earlier divisions. These churches are communities of Catholic Christians whose forms of worship reflect distinct historical and cultural influences rather than differences in doctrine. The pope's recognition of Eastern Catholic Churches, though, has caused controversy in ecumenical relations with the Eastern Orthodox and other eastern churches. Historically, pressure to conform to the norms of the Western Christianity practised by the majority Latin Church led to a degree of encroachment (Liturgical Latinisation) on some of the Eastern Catholic traditions. The Second Vatican Council document, Orientalium Ecclesiarum, built on previous reforms to reaffirm the right of Eastern Catholics to maintain their distinct liturgical practices.[220]

A church sui iuris is defined in the Code of Canons for the Eastern Churches as a "group of Christian faithful united by a hierarchy" that is recognized by the pope in his capacity as the supreme authority on matters of doctrine within the church.[221] The Eastern Catholic Churches are in full communion with the pope, but have governance structures and liturgical traditions separate from that of the Latin Church.[216] While the Latin Church's canons do not explicitly use the term, it is tacitly recognized as equivalent.

Some Eastern Catholic churches are governed by a patriarch who is elected by the synod of the bishops of that church,[222] others are headed by a major archbishop,[223] others are under a metropolitan,[224] and others are organized as individual eparchies.[225] Each church has authority over the particulars of its internal organization, liturgical rites, liturgical calendar and other aspects of its spirituality, subject only to the authority of the pope.[226] The Roman Curia has a specific department, the Congregation for the Oriental Churches, to maintain relations with them.[227] The pope does not generally appoint bishops or clergy in the Eastern Catholic Churches, deferring to their internal governance structures, but may intervene if he feels it necessary.

Dioceses, parishes, organizations, and institutes

Individual countries, regions, and major cities are served by particular churches known as dioceses in the Latin Church, or eparchies in the Eastern Catholic Churches, each of which are overseen by a bishop. As of 2021[update], the Catholic Church has 3,171 dioceses globally.[229] The bishops in a particular country are members of a national or regional episcopal conference.[230]

Dioceses are divided into parishes, each with one or more priests, deacons, or lay ecclesial ministers.[231] Parishes are responsible for the day to day celebration of the sacraments and pastoral care of the laity.[232] As of 2016[update], there are 221,700 parishes worldwide.[8]

In the Latin Church, Catholic men may serve as deacons or priests by receiving sacramental ordination. Men and women may serve as extraordinary ministers of Holy Communion, as readers (lectors), or as altar servers. Historically, boys and men have only been permitted to serve as altar servers; however, since the 1990s, girls and women have also been permitted.[233][note 8]

Ordained Catholics, as well as members of the laity, may enter into consecrated life either on an individual basis, as a hermit or consecrated virgin, or by joining an institute of consecrated life (a religious institute or a secular institute) in which to take vows confirming their desire to follow the three evangelical counsels of chastity, poverty and obedience.[234] Examples of institutes of consecrated life are the Benedictines, the Carmelites, the Dominicans, the Franciscans, the Missionaries of Charity, the Legionaries of Christ and the Sisters of Mercy.[234]

"Religious institutes" is a modern term encompassing both "religious orders" and "religious congregations", which were once distinguished in canon law.[235] The terms "religious order" and "religious institute" tend to be used as synonyms colloquially.[236]

By means of Catholic charities and beyond, the Catholic Church is the largest non-government provider of education and health care in the world.[26]

Membership

As of 2020, Catholicism is the second-largest religious body in the world after Sunni Islam.[237] According to World Christian Database, there are 1.278 billion Catholics globally, as of 2024.[4] According to Annuario Pontificio, church membership, defined as baptized Catholics, was 1.378 billion at the end of 2021, which is 17.67% of the world population.[5] Brazil has the largest Catholic population in the world, followed by Mexico, the Philippines, and the United States.[238] Catholics represent about half of all Christians.[239]

Geographic distribution of Catholics worldwide continues to shift, with 19.3% in Africa, 48.0% in the Americas, 11.0% in Asia, 20.9% in Europe, and 0.8% in Oceania.[5]

Catholic ministers include ordained clergy, lay ecclesial ministers, missionaries, and catechists. Also as of the end of 2021, there were 462,388 ordained clergy, including 5,353 bishops, 407,730 priests (diocesan and religious), and 50,150 deacons (permanent).[5] Non-ordained ministers included 3,157,568 catechists, 367,679 lay missionaries, and 39,951 lay ecclesial ministers.[240]

Catholics who have committed to religious or consecrated life instead of marriage or single celibacy, as a state of life or relational vocation, include 49,414 male religious and 599,228 women religious. These are not ordained, nor generally considered ministers unless also engaged in one of the lay minister categories above.[5]

Doctrine

Catholic doctrine has developed over the centuries, reflecting direct teachings of early Christians, formal definitions of heretical and orthodox beliefs by ecumenical councils and in papal bulls, and theological debate by scholars. The church believes that it is continually guided by the Holy Spirit as it discerns new theological issues and is protected infallibly from falling into doctrinal error when a firm decision on an issue is reached.[241][242]

It teaches that revelation has one common source, God, and two distinct modes of transmission: Sacred Scripture and Sacred Tradition,[243][244] and that these are authentically interpreted by the Magisterium.[245][246] Sacred Scripture consists of the 73 books of the Catholic Bible, consisting of 46 Old Testament and 27 New Testament writings. Sacred Tradition consists of those teachings believed by the church to have been handed down since the time of the Apostles.[247] Sacred Scripture and Sacred Tradition are collectively known as the "deposit of faith" (depositum fidei in Latin). These are in turn interpreted by the Magisterium (from magister, Latin for "teacher"), the church's teaching authority, which is exercised by the pope and the College of Bishops in union with the pope, the Bishop of Rome.[248] Catholic doctrine is authoritatively summarized in the Catechism of the Catholic Church, published by the Holy See.[249][250]

Nature of God

The Catholic Church holds that there is one eternal God, who exists as a perichoresis ("mutual indwelling") of three hypostases, or "persons": God the Father; God the Son; and God the Holy Spirit, which together are called the "Holy Trinity".[251]

Catholics believe that Jesus Christ is the "Second Person" of the Trinity, God the Son. In an event known as the Incarnation, through the power of the Holy Spirit, God became united with human nature through the conception of Christ in the womb of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Christ, therefore, is understood as being both fully divine and fully human, including possessing a human soul. It is taught that Christ's mission on earth included giving people his teachings and providing his example for them to follow as recorded in the four Gospels.[252] Jesus is believed to have remained sinless while on earth, and to have allowed himself to be unjustly executed by crucifixion, as a sacrifice of himself to reconcile humanity to God; this reconciliation is known as the Paschal Mystery.[253] The Greek term "Christ" and the Hebrew "Messiah" both mean "anointed one", referring to the Christian belief that Jesus' death and resurrection are the fulfilment of the Old Testament's messianic prophecies.[254]

The Catholic Church teaches dogmatically that "the Holy Spirit proceeds eternally from the Father and the Son, not as from two principles but as from one single principle".[255] It holds that the Father, as the "principle without principle", is the first origin of the Spirit, but also that he, as Father of the only Son, is with the Son the single principle from which the Spirit proceeds.[256] This belief is expressed in the Filioque clause which was added to the Latin version of the Nicene Creed of 381 but not included in the Greek versions of the creed used in Eastern Christianity.[257]

Nature of the church

The Catholic Church teaches that it is the "one true church",[16][258] "the universal sacrament of salvation for the human race",[259][260] and "the one true religion".[261] According to the Catechism, the Catholic Church is further described in the Nicene Creed as the "one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church".[262] These are collectively known as the Four Marks of the Church. The church teaches that its founder is Jesus Christ.[263][44] The New Testament records several events considered integral to the establishment of the Catholic Church, including Jesus' activities and teaching and his appointment of the apostles as witnesses to his ministry, suffering, and resurrection. The Great Commission, after his resurrection, instructed the apostles to continue his work. The coming of the Holy Spirit upon the apostles, in an event known as Pentecost, is seen as the beginning of the public ministry of the Catholic Church.[47] The church teaches that all duly consecrated bishops have a lineal succession from the apostles of Christ, known as apostolic succession.[264] In particular, the Bishop of Rome (the pope) is considered the successor to the apostle Simon Peter, a position from which he derives his supremacy over the church.[265]

Catholic belief holds that the church "is the continuing presence of Jesus on earth"[266] and that it alone possesses the full means of salvation.[267] Through the passion (suffering) of Christ leading to his crucifixion as described in the Gospels, it is said Christ made himself an oblation to God the Father to reconcile humanity to God;[268] the Resurrection of Jesus makes him the firstborn from the dead, the first among many brethren.[269] By reconciling with God and following Christ's words and deeds, an individual can enter the Kingdom of God.[270] The church sees its liturgy and sacraments as perpetuating the graces achieved through Christ's sacrifice to strengthen a person's relationship with Christ and aid in overcoming sin.[271]

Final judgement

The Catholic Church teaches that, immediately after death, the soul of each person will receive a particular judgement from God, based on their sins and their relationship to Christ.[272][273] This teaching also attests to another day when Christ will sit in universal judgement of all mankind. This final judgement, according to the church's teaching, will bring an end to human history and mark the beginning of both a new and better heaven and earth ruled by God in righteousness.[274]

Depending on the judgement rendered following death, it is believed that a soul may enter one of three states of the afterlife:

- Heaven is a state of unending union with the divine nature of God, not ontologically, but by grace. It is an eternal life, in which the soul contemplates God in ceaseless beatitude.[275]

- Purgatory is a temporary condition for the purification of souls who, although destined for Heaven, are not fully detached from sin and thus cannot enter Heaven immediately.[276] In Purgatory, the soul suffers, and is purged and perfected. Souls in purgatory may be aided in reaching heaven by the prayers of the faithful on earth and by the intercession of saints.[277]

- Final Damnation: Finally, those who persist in living in a state of mortal sin and do not repent before death subject themselves to hell, an everlasting separation from God.[278] The church teaches that no one is condemned to hell without having freely decided to reject God.[279] No one is predestined to hell and no one can determine with absolute certainty who has been condemned to hell.[280] Catholicism teaches that through God's mercy a person can repent at any point before death, be illuminated with the truth of the Catholic faith, and thus obtain salvation.[281] Some Catholic theologians have speculated that the souls of unbaptized infants and non-Christians without mortal sin but who die in original sin are assigned to limbo, although this is not an official dogma of the church.[282]

While the Catholic Church teaches that it alone possesses the full means of salvation,[267] it also acknowledges that the Holy Spirit can make use of Christian communities separated from itself to "impel towards Catholic unity"[283] and "tend and lead toward the Catholic Church",[283] and thus bring people to salvation, because these separated communities contain some elements of proper doctrine, albeit admixed with errors. It teaches that anyone who is saved is saved through the Catholic Church but that people can be saved outside of the ordinary means known as baptism of desire, and by pre-baptismal martyrdom, known as baptism of blood, as well as when conditions of invincible ignorance are present, although invincible ignorance in itself is not a means of salvation.[284]

Saints and devotions

A saint (also historically known as a hallow) is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of holiness or likeness or closeness to God, while canonization is the act by which a Christian church declares that a person who has died was a saint, upon which declaration the person is included in the "canon", or list, of recognized saints.[285][286] The first persons honoured as saints were the martyrs. Pious legends of their deaths were considered affirmations of the truth of their faith in Christ. By the fourth century, however, "confessors"—people who had confessed their faith not by dying but by word and life—began to be venerated publicly.

In the Catholic Church, both in Latin and Eastern Catholic churches, the act of canonization is reserved to the Apostolic See and occurs at the conclusion of a long process requiring extensive proof that the candidate for canonization lived and died in such an exemplary and holy way that he is worthy to be recognized as a saint. The church's official recognition of sanctity implies that the person is now in Heaven and that he may be publicly invoked and mentioned officially in the liturgy of the church, including in the Litany of the Saints. Canonization allows universal veneration of the saint in the liturgy of the Roman Rite; for permission to venerate merely locally, only beatification is needed.[287]

Devotions are "external practices of piety" which are not part of the official liturgy of the Catholic Church but are part of the popular spiritual practices of Catholics.[288] These include various practices regarding the veneration of the saints, especially veneration of the Virgin Mary. Other devotional practices include the Stations of the Cross, the Sacred Heart of Jesus, the Holy Face of Jesus,[289] the various scapulars, novenas to various saints,[290] pilgrimages[291] and devotions to the Blessed Sacrament,[290] and the veneration of saintly images such as the santos.[292] The bishops at the Second Vatican Council reminded Catholics that "devotions should be so drawn up that they harmonize with the liturgical seasons, accord with the sacred liturgy, are in some fashion derived from it, and lead the people to it, since, in fact, the liturgy by its very nature far surpasses any of them."[293]

Virgin Mary

| Part of a series on the |

| Mariology of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

Catholic Mariology deals with the dogmas and teachings concerning the life of Mary, mother of Jesus, as well as the veneration of Mary by the faithful. Mary is held in special regard, declared the Mother of God (Greek: Θεοτόκος, romanized: Theotokos, lit. 'God-bearer'), and believed as dogma to have remained a virgin throughout her life.[294] Further teachings include the doctrines of the Immaculate Conception (her own conception without the stain of original sin) and the Assumption of Mary (that her body was assumed directly into heaven at the end of her life). Both of these doctrines were defined as infallible dogma, by Pope Pius IX in 1854 and Pope Pius XII in 1950 respectively,[295] but only after consulting with the Catholic bishops throughout the world to ascertain that this is a Catholic belief.[296] In the Eastern Catholic churches, however, they continue to celebrate the feast of the Assumption under the name of the Dormition of the Mother of God on the same date.[297] The teaching that Mary died before being assumed significantly precedes the idea that she did not. St John Damascene wrote that "St Juvenal, Bishop of Jerusalem, at the Council of Chalcedon (451), made known to the Emperor Marcian and Pulcheria, who wished to possess the body of the Mother of God, that Mary died in the presence of all the Apostles, but that her tomb, when opened, upon the request of St Thomas, was found empty; wherefrom the Apostles concluded that the body was taken up to Heaven."[298]

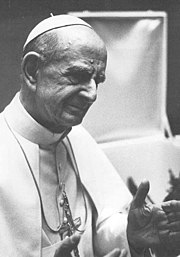

Devotions to Mary are part of Catholic piety but are distinct from the worship of God.[299] Practices include prayers and Marian art, music, and architecture. Several liturgical Marian feasts are celebrated throughout the Church Year and she is honoured with many titles such as Queen of Heaven. Pope Paul VI called her Mother of the Church because, by giving birth to Christ, she is considered to be the spiritual mother to each member of the Body of Christ.[295] Because of her influential role in the life of Jesus, prayers and devotions such as the Hail Mary, the Rosary, the Salve Regina and the Memorare are common Catholic practices.[300] Pilgrimage to the sites of several Marian apparitions affirmed by the church, such as Lourdes, Fátima, and Guadalupe,[301] are also popular Catholic devotions.[302]

Sacraments

The Catholic Church teaches that it was entrusted with seven sacraments that were instituted by Christ. The number and nature of the sacraments were defined by several ecumenical councils, most recently the Council of Trent.[303][note 9] These are Baptism, Confirmation, the Eucharist, Penance, Anointing of the Sick (formerly called Extreme Unction, one of the "Last Rites"), Holy Orders and Holy Matrimony. Sacraments are visible rituals that Catholics see as signs of God's presence and effective channels of God's grace to all those who receive them with the proper disposition (ex opere operato).[304] The Catechism of the Catholic Church categorizes the sacraments into three groups, the "sacraments of Christian initiation", "sacraments of healing" and "sacraments at the service of communion and the mission of the faithful". These groups broadly reflect the stages of people's natural and spiritual lives which each sacrament is intended to serve.[305]

The liturgies of the sacraments are central to the church's mission. According to the Catechism:

In the liturgy of the New Covenant every liturgical action, especially the celebration of the Eucharist and the sacraments, is an encounter between Christ and the Church. The liturgical assembly derives its unity from the "communion of the Holy Spirit" who gathers the children of God into the one Body of Christ. This assembly transcends racial, cultural, social—indeed, all human affinities.[306]

According to church doctrine, the sacraments of the church require the proper form, matter, and intent to be validly celebrated.[307] In addition, the Canon Laws for both the Latin Church and the Eastern Catholic Churches govern who may licitly celebrate certain sacraments, as well as strict rules about who may receive the sacraments.[308] Notably, because the church teaches that Christ is present in the Eucharist,[309] those who are conscious of being in a state of mortal sin are forbidden to receive the sacrament until they have received absolution through the sacrament of Reconciliation (Penance).[310] Catholics are normally obliged to abstain from eating for at least an hour before receiving the sacrament.[310] Non-Catholics are ordinarily prohibited from receiving the Eucharist as well.[308][311]

Catholics, even if they were in danger of death and unable to approach a Catholic minister, may not ask for the sacraments of the Eucharist, penance or anointing of the sick from someone, such as a Protestant minister, who is not known to be validly ordained in line with Catholic teaching on ordination.[312][313] Likewise, even in grave and pressing need, Catholic ministers may not administer these sacraments to those who do not manifest Catholic faith in the sacrament. In relation to the churches of Eastern Christianity not in communion with the Holy See, the Catholic Church is less restrictive, declaring that "a certain communion in sacris, and so in the Eucharist, given suitable circumstances and the approval of Church authority, is not merely possible but is encouraged."[314]

Sacraments of initiation

Baptism

As viewed by the Catholic Church, Baptism is the first of three sacraments of initiation as a Christian.[315] It washes away all sins, both original sin and personal actual sins.[316] It makes a person a member of the church.[317] As a gratuitous gift of God that requires no merit on the part of the person who is baptized, it is conferred even on children,[318] who, though they have no personal sins, need it on account of original sin.[319] If a new-born child is in a danger of death, anyone—be it a doctor, a nurse, or a parent—may baptize the child.[320] Baptism marks a person permanently and cannot be repeated.[321] The Catholic Church recognizes as valid baptisms conferred even by people who are not Catholics or Christians, provided that they intend to baptize ("to do what the Church does when she baptizes") and that they use the Trinitarian baptismal formula.[322]

Confirmation

The Catholic Church sees the sacrament of confirmation as required to complete the grace given in baptism.[323] When adults are baptized, confirmation is normally given immediately afterwards,[324] a practice followed even with newly baptized infants in the Eastern Catholic Churches.[325] In the West confirmation of children is delayed until they are old enough to understand or at the bishop's discretion.[326] In Western Christianity, particularly Catholicism, the sacrament is called confirmation, because it confirms and strengthens the grace of baptism; in the Eastern Churches, it is called chrismation, because the essential rite is the anointing of the person with chrism,[327] a mixture of olive oil and some perfumed substance, usually balsam, blessed by a bishop.[327][328] Those who receive confirmation must be in a state of grace, which for those who have reached the age of reason means that they should first be cleansed spiritually by the sacrament of Penance; they should also have the intention of receiving the sacrament, and be prepared to show in their lives that they are Christians.[329]

Eucharist

For Catholics, the Eucharist is the sacrament which completes Christian initiation. It is described as "the source and summit of the Christian life".[330] The ceremony in which a Catholic first receives the Eucharist is known as First Communion.[331]

The Eucharistic celebration, also called the Mass or Divine liturgy, includes prayers and scriptural readings, as well as an offering of bread and wine, which are brought to the altar and consecrated by the priest to become the body and the blood of Jesus Christ, a change called transubstantiation.[332][note 10] The words of consecration reflect the words spoken by Jesus during the Last Supper, where Christ offered his body and blood to his Apostles the night before his crucifixion. The sacrament re-presents (makes present) the sacrifice of Jesus on the cross,[333] and perpetuates it. Christ's death and resurrection give grace through the sacrament that unites the faithful with Christ and one another, remits venial sin, and aids against committing moral sin (though mortal sin itself is forgiven through the sacrament of penance).[334]

Sacraments of healing

The two sacraments of healing are the Sacrament of Penance and Anointing of the Sick.

Penance

The Sacrament of Penance (also called Reconciliation, Forgiveness, Confession, and Conversion[335]) exists for the conversion of those who, after baptism, separate themselves from Christ by sin.[336] Essential to this sacrament are acts both by the sinner (examination of conscience, contrition with a determination not to sin again, confession to a priest, and performance of some act to repair the damage caused by sin) and by the priest (determination of the act of reparation to be performed and absolution).[337] Serious sins (mortal sins) should be confessed at least once a year and always before receiving Holy Communion, while confession of venial sins also is recommended.[338] The priest is bound under the severest penalties to maintain the "seal of confession", absolute secrecy about any sins revealed to him in confession.[339]

Anointing of the sick

While chrism is used only for the three sacraments that cannot be repeated, a different oil is used by a priest or bishop to bless a Catholic who, because of illness or old age, has begun to be in danger of death.[340] This sacrament, known as Anointing of the Sick, is believed to give comfort, peace, courage and, if the sick person is unable to make a confession, even forgiveness of sins.[341]

The sacrament is also referred to as Unction, and in the past as Extreme Unction, and it is one of the three sacraments that constitute the last rites, together with Penance and Viaticum (Eucharist).[342]

Sacraments at the service of communion

According to the Catechism, there are two sacraments of communion directed towards the salvation of others: priesthood and marriage.[343] Within the general vocation to be a Christian, these two sacraments "consecrate to specific mission or vocation among the people of God. Men receive the holy orders to feed the Church by the word and grace. Spouses marry so that their love may be fortified to fulfil duties of their state".[344]

Holy Orders

The sacrament of Holy Orders consecrates and deputes some Christians to serve the whole body as members of three degrees or orders: episcopate (bishops), presbyterate (priests) and diaconate (deacons).[345][346] The church has defined rules on who may be ordained into the clergy. In the Latin Church, the priesthood is generally restricted to celibate men, and the episcopate is always restricted to celibate men.[347] Men who are already married may be ordained in certain Eastern Catholic churches in most countries,[348] and the personal ordinariates and may become deacons even in the Latin Church[349][350] (see Clerical marriage). But after becoming a Catholic priest, a man may not marry (see Clerical celibacy) unless he is formally laicized.

All clergy, whether deacons, priests or bishops, may preach, teach, baptize, witness marriages and conduct funeral liturgies.[351] Only bishops and priests can administer the sacraments of the Eucharist, Reconciliation (Penance) and Anointing of the Sick.[352][353] Only bishops can administer the sacrament of Holy Orders, which ordains someone into the clergy.[354]

Matrimony

The Catholic Church teaches that marriage is a social and spiritual bond between a man and a woman, ordered towards the good of the spouses and procreation of children; according to Catholic teachings on sexual morality, it is the only appropriate context for sexual activity. A Catholic marriage, or any marriage between baptized individuals of any Christian denomination, is viewed as a sacrament. A sacramental marriage, once consummated, cannot be dissolved except by death.[355][note 11] The church recognizes certain conditions, such as freedom of consent, as required for any marriage to be valid; In addition, the church sets specific rules and norms, known as canonical form, that Catholics must follow.[358]

The church does not recognize divorce as ending a valid marriage and allows state-recognized divorce only as a means of protecting the property and well-being of the spouses and any children. However, consideration of particular cases by the competent ecclesiastical tribunal can lead to declaration of the invalidity of a marriage, a declaration usually referred to as an annulment. Remarriage following a divorce is not permitted unless the prior marriage was declared invalid.[359]

Liturgy

Among the 24 autonomous (sui iuris) churches, numerous liturgical and other traditions exist, called rites, which reflect historical and cultural diversity rather than differences in belief.[360] In the definition of the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches, "a rite is the liturgical, theological, spiritual, and disciplinary patrimony, culture and circumstances of history of a distinct people, by which its own manner of living the faith is manifested in each Church sui iuris".[361]

The liturgy of the sacrament of the Eucharist, called the Mass in the West and Divine Liturgy or other names in the East, is the principal liturgy of the Catholic Church.[362] This is because it is considered the propitiatory sacrifice of Christ himself.[363] Its most widely used form is that of the Roman Rite as promulgated by Paul VI in 1969 (see Missale Romanum) and revised by Pope John Paul II in 2002 (see Liturgiam Authenticam). In certain circumstances, the 1962 form of the Roman Rite remains authorized in the Latin Church. Eastern Catholic Churches have their own rites. The liturgies of the Eucharist and the other sacraments vary from rite to rite, reflecting different theological emphases.

Western rites

Part of a series on |

| Roman Rite Mass of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

| A. Introductory rites |

|

| B. Liturgy of the Word |

| C. Liturgy of the Eucharist |

|

| D. Concluding rites |

| Ite, missa est |

The Roman Rite is the most common rite of worship used by the Catholic Church, with the Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite form of the Mass. Its use is found worldwide, originating in Rome and spreading throughout Europe, influencing and eventually supplanting local rites.[364] The present ordinary form of Mass in the Roman Rite, found in the post-1969 editions of the Roman Missal, is usually celebrated in the local vernacular language, using an officially approved translation from the original text in Latin. An outline of its major liturgical elements can be found in the sidebar.

In 2007, Pope Benedict XVI affirmed the licitness of continued use of the 1962 Roman Missal as an "extraordinary form" (forma extraordinaria) of the Roman Rite, speaking of it also as an usus antiquior ("older use"), and issuing new more permissive norms for its employment.[365] An instruction issued four years later spoke of the two forms or usages of the Roman Rite approved by the pope as the ordinary form and the extraordinary form ("the forma ordinaria" and "the forma extraordinaria").[366]

The 1962 edition of the Roman Missal, published a few months before the Second Vatican Council opened, was the last that presented the Mass as standardized in 1570 by Pope Pius V at the request of the Council of Trent and that is therefore known as the Tridentine Mass.[309] Pope Pius V's Roman Missal was subjected to minor revisions by Pope Clement VIII in 1604, Pope Urban VIII in 1634, Pope Pius X in 1911, Pope Pius XII in 1955, and Pope John XXIII in 1962. Each successive edition was the ordinary form of the Roman Rite Mass until superseded by a later edition. When the 1962 edition was superseded by that of Paul VI, promulgated in 1969, its continued use at first required permission from bishops;[367] but Pope Benedict XVI's 2007 motu proprio Summorum Pontificum allowed free use of it for Mass celebrated without a congregation and authorized parish priests to permit, under certain conditions, its use even at public Masses. Except for the scriptural readings, which Pope Benedict allowed to be proclaimed in the vernacular language, it is celebrated exclusively in liturgical Latin.[368] These permissions were largely removed by Pope Francis in 2021, who issued the motu proprio Traditionis custodes to emphasize the Ordinary Form as promulgated by Popes Paul VI and John Paul II.[369]

Since 2014, clergy in the small personal ordinariates set up for groups of former Anglicans under the terms of the 2009 document Anglicanorum Coetibus[370] are permitted to use a variation of the Roman Rite called "Divine Worship" or, less formally, "Ordinariate Use",[371] which incorporates elements of the Anglican liturgy and traditions,[note 12] an accommodation protested by Anglican leaders.

In the Archdiocese of Milan, with around five million Catholics the largest in Europe,[372] Mass is celebrated according to the Ambrosian Rite. Other Latin Church rites include the Mozarabic[373] and those of some religious institutes.[374] These liturgical rites have an antiquity of at least 200 years before 1570, the date of Pope Pius V's Quo primum, and were thus allowed to continue.[375]

Eastern rites

The Eastern Catholic Churches share common patrimony and liturgical rites as their counterparts, including Eastern Orthodox and other Eastern Christian churches who are no longer in communion with the Holy See. These include churches that historically developed in Russia, Caucasus, the Balkans, North Eastern Africa, India and the Middle East. The Eastern Catholic Churches are groups of faithful who have either never been out of communion with the Holy See or who have restored communion with it at the cost of breaking communion with their associates of the same tradition.[376]

The liturgical rites of the Eastern Catholic Churches include the Byzantine Rite (in its Antiochian, Greek and Slavonic recensions), the Alexandrian Rite, the West Syrian Rite, the Armenian Rite, and the East Syriac Rite. Eastern Catholic Churches have the autonomy to set the particulars of their liturgical forms and worship, within certain limits to protect the "accurate observance" of their liturgical tradition.[377] In the past some of the rites used by the Eastern Catholic Churches were subject to a degree of liturgical Latinization. However, in recent years Eastern Catholic Churches have returned to traditional Eastern practices in accord with the Vatican II decree Orientalium Ecclesiarum.[378] Each church has its own liturgical calendar.[379]

Social and cultural issues

Catholic social teaching

Catholic social teaching, reflecting the concern Jesus showed for the impoverished, places a heavy emphasis on the corporal works of mercy and the spiritual works of mercy, namely the support and concern for the sick, the poor and the afflicted.[380][381] Church teaching calls for a preferential option for the poor while canon law prescribes that "The Christian faithful are also obliged to promote social justice and, mindful of the precept of the Lord, to assist the poor."[382] Its foundations are widely considered to have been laid by Pope Leo XIII's 1891 encyclical letter Rerum novarum which upholds the rights and dignity of labour and the right of workers to form unions.

Catholic teaching regarding sexuality calls for a practice of chastity, with a focus on maintaining the spiritual and bodily integrity of the human person. Marriage is considered the only appropriate context for sexual activity.[383] Church teachings about sexuality have become an issue of increasing controversy, especially after the close of the Second Vatican Council, due to changing cultural attitudes in the Western world described as the sexual revolution.

The church has also addressed stewardship of the natural environment, and its relationship to other social and theological teachings. In the document Laudato si', dated 24 May 2015, Pope Francis critiques consumerism and irresponsible development, and laments environmental degradation and global warming.[384] The pope expressed concern that the warming of the planet is a symptom of a greater problem: the developed world's indifference to the destruction of the planet as humans pursue short-term economic gains.[385]

Social services

The Catholic Church is the largest non-government provider of education and medical services in the world.[26] In 2010, the Catholic Church's Pontifical Council for Pastoral Assistance to Health Care Workers said that the church manages 26% of health care facilities in the world, including hospitals, clinics, orphanages, pharmacies and centres for those with leprosy.[386]

The church has always been involved in education, since the founding of the first universities of Europe.[83] It runs and sponsors thousands of primary and secondary schools, colleges and universities throughout the world[387][8] and operates the world's largest non-governmental school system.[388]