Викка

| Часть серии о |

| Викка |

|---|

|

Викка ( Английский: / ˈ w ɪ k ə / ), также известный как « Ремесло », [1] Это современная языческая , синкретическая , земная религия . Считающийся новым религиозным движением религиоведами представлен , этот путь развился из западного эзотеризма , развитого в Англии в первой половине 20-го века, и был публике в 1954 году Джеральдом Гарднером , отставным британским государственным служащим . Викка опирается на древние языческие и 20-го века герметические мотивы для богословских и ритуальных целей. Дорин Валиенте присоединилась к Гарднеру в 1950-х годах, продолжая развивать литургическую традицию верований, принципов и практик Викки, распространяемую через опубликованные книги, а также секретные письменные и устные учения, передаваемые посвященным .

Многие вариации религии росли и развивались с течением времени, связанные с рядом различных линий передачи, сект и конфессий , называемых традициями , каждая из которых имела свою собственную организационную структуру и уровень централизации . Учитывая его широко децентрализованный характер, возникают разногласия по поводу границ, определяющих Викку. Некоторые традиции, вместе называемые Британской традиционной Виккой (BTW), строго следуют инициатической линии Гарднера и считают Викку специфичной для аналогичных традиций, исключая более новые, эклектичные традиции. Другие традиции, а также исследователи религии применяют Викку как широкий термин для обозначения религии с конфессиями, которые различаются по некоторым ключевым моментам, но разделяют основные убеждения и практики.

Wicca is typically duotheistic, venerating both a Goddess and a God, traditionally conceived as the Triple Goddess and the Horned God, respectively. These deities may be regarded in a henotheistic way, as having many different divine aspects which can be identified with various pagan deities from different historical pantheons. For this reason, they are sometimes referred to as the "Great Goddess" and the "Great Horned God", with the honorific "great" connoting a personification containing many other deities within their own nature. Some Wiccans refer to the goddess as "Lady" and the god as "Lord" to invoke their divinity. These two deities are sometimes viewed as facets of a universal pantheistic divinity, regarded as an impersonal force rather than a personal deity. Other traditions of Wicca embrace polytheism, pantheism, monism, and Goddess monotheism.

Wiccan celebrations encompass both the cycles of the Moon, known as Esbats and commonly associated with the Triple Goddess, alongside the cycles of the Sun, seasonally based festivals known as Sabbats and commonly associated with the Horned God. The Wiccan Rede is a popular expression of Wiccan morality, often with respect to the ritual practice of magic.

Definition and terminology[edit]

Scholars of religious studies classify Wicca as a new religious movement,[2] and more specifically as a form of modern Paganism.[3] Wicca has been cited as the largest,[4] best known,[5] most influential,[6] and most academically studied form of modern Paganism.[7] Within the movement it has been identified as sitting on the eclectic end of the eclectic to reconstructionist spectrum.[8]Several academics have also categorised Wicca as a form of nature religion, a term that is also embraced by many of its practitioners,[9] and as a mystery religion.[10] However, given that Wicca also incorporates the practice of magic, several scholars have referred to it as a "magico-religion".[11] Wicca is also a form of Western esotericism, and more specifically a part of the esoteric current known as occultism.[12] Academics like Wouter Hanegraaff and Tanya Luhrmann have categorised Wicca as part of the New Age, although other academics, and many Wiccans themselves, dispute this categorisation.[13]

Although recognised as a religion by academics, some evangelical Christians have attempted to deny it legal recognition as such, while some Wiccan practitioners themselves eschew the term "religion" – associating the latter purely with organised religion – instead favouring "spirituality" or "way of life".[14] Although Wicca as a religion is distinct from other forms of contemporary Paganism, there has been much "cross-fertilization" between these different Pagan faiths; accordingly, Wicca has both influenced and been influenced by other Pagan religions, thus making clear-cut distinctions between them more difficult for religious studies scholars to make.[15]The terms wizard and warlock are generally discouraged in the community.[16]In Wicca, denominations are referred to as traditions,[14] while non-Wiccans are often termed cowans.[17]

Wiccan definition of "Witchcraft"[edit]

When the religion first came to public attention, its followers commonly called it "Witchcraft".[18][a] Gerald Gardner—the man regarded as the "Father of Wicca"—referred to it as the "Craft of the Wise", "Witchcraft", and "the Witch-cult" during the 1950s.[21] Gardner believed in the theory that persecuted witches had actually been followers of a surviving pagan religion, but this theory has now been proven wrong.[22] There is no evidence that he ever called it "Wicca", although he did refer to its community of followers as "the Wica" (with one c).[21] As a name for the religion, "Wicca" developed in Britain during the 1960s.[14] It is not known who first used this name for the religion, although one possibility is that it might have been Gardner's rival Charles Cardell, who was calling it the "Craft of the Wiccens" by 1958.[23] The first recorded use of the name "Wicca" was in 1962,[24] and it had been popularised to the extent that several British practitioners founded a newsletter called The Wiccan in 1968.[25]

Although pronounced differently, the Modern English term "Wicca" is derived from the Old English wicca [ˈwittʃɑ] and wicce [ˈwittʃe], the masculine and feminine term for witch, respectively, that was used in Anglo-Saxon England.[26] By adopting it for modern usage, Wiccans were both symbolically linking themselves to the ancient, pre-Christian past,[27] and adopting a self-designation that would be less controversial than "Witchcraft".[28] The scholar of religion and Wiccan priestess Joanne Pearson noted that while "the words 'witch' and 'wicca' are therefore linked etymologically, […] they are used to emphasize different things today".[29]

In early sources "Wicca" referred to the whole of the religion rather than to a specific tradition.[30] In following decades, members of certain traditions – those known as British Traditional Wicca – began claiming that only they should be called "Wiccan", and that other traditions must not use it.[31] From the late 1980s onwards, various books propagating Wicca were published that again used the former, broader definition of the word.[32] Thus, by the 1980s, there were two competing definitions of the word "Wicca" in use among the Pagan and esoteric communities, one broad and inclusive, the other narrow and exclusionary.[14] Among scholars of Pagan studies it is the older, broader, inclusive meaning which is preferred.[14]

Alongside "Wicca", some practitioners still call the religion "Witchcraft" or "the Craft".[33] Using the word "Witchcraft" in this context can result in confusion with other, non-religious meanings of "witchcraft" as well as other religions—such as Satanism and Luciferianism—whose practitioners also sometimes describe themselves as "Witches".[18] Another term sometimes used as a synonym for "Wicca" is "Pagan witchcraft",[18] although there are also other forms of modern Paganism—such as types of Heathenry—which also use the term "Pagan witchcraft".[34] From the 1990s onward, various Wiccans began describing themselves as "Traditional Witches", although this term was also employed by practitioners of other magico-religious traditions like Luciferianism.[35] In some popular culture, such as television programs Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Charmed, the word "Wicca" has been used as a synonym for witchcraft more generally, including in non-religious and non-Pagan forms.[36]

Beliefs[edit]

Theology[edit]

Theological views within Wicca are diverse.[37] The religion encompasses theists, atheists, and agnostics, with some viewing the religion's deities as entities with a literal existence and others viewing them as Jungian archetypes or symbols.[38] Even among theistic Wiccans, there are divergent beliefs, and Wicca includes pantheists, monotheists, duotheists, and polytheists.[39] Common to these divergent perspectives, however, is that Wicca's deities are viewed as forms of ancient, pre-Christian divinities by its practitioners.[40]

Duotheism[edit]

Most early Wiccan groups adhered to the duotheistic worship of a Horned God and a Mother Goddess, with practitioners typically believing that these had been the ancient deities worshipped by the hunter-gatherers of the Old Stone Age, whose veneration had been passed down in secret right to the present.[38] This theology derived from Egyptologist Margaret Murray's claims about the witch-cult in her book The Witch-Cult in Western Europe published by Oxford University Press in 1921;[41] she claimed that this cult had venerated a Horned God at the time of the Early Modern witch trials, but centuries before it had also worshipped a Mother Goddess.[40] This duotheistic Horned God/Mother Goddess structure was embraced by Gardner – who claimed that it had Stone Age roots – and remains the underlying theological basis to his Gardnerian tradition.[42] Gardner claimed that the names of these deities were to be kept secret within the tradition, although in 1964 they were publicly revealed to be Cernunnos and Aradia; the secret Gardnerian deity names were subsequently changed.[43]

Although different Wiccans attribute different traits to the Horned God, he is most often associated with animals and the natural world, but also with the afterlife, and he is furthermore often viewed as an ideal role model for men.[44] The Mother Goddess has been associated with life, fertility, and the springtime, and has been described as an ideal role model for women.[45] Wicca's duotheism has been compared to the Taoist system of yin and yang.[40]

Other Wiccans have adopted the original Gardnerian God/Goddess duotheistic structure but have adopted deity forms other than that of the Horned God and Mother Goddess.[46] For instance, the God has been interpreted as the Oak King and the Holly King, as well as the Sun God, Son/Lover God, and Vegetation God.[47] He has also been seen in the roles of the Leader of the Wild Hunt and the Lord of Death.[48] The Goddess is often portrayed as a Triple Goddess, thereby being a triadic deity comprising a Maiden goddess, a Mother goddess, and a Crone goddess, each of whom has different associations, namely virginity, fertility, and wisdom.[47][49] Other Wiccan conceptualisations have portrayed her as a Moon Goddess and as a Menstruating Goddess.[47] According to the anthropologist Susan Greenwood, in Wicca the Goddess is "a symbol of self-transformation - she is seen to be constantly changing and a force for change for those who open themselves up to her".[50]

Monotheism and polytheism[edit]

Gardner stated that beyond Wicca's two deities was the "Supreme Deity" or "Prime Mover", an entity that was too complex for humans to understand.[51] This belief has been endorsed by other practitioners, who have referred to it as "the Cosmic Logos", "Supreme Cosmic Power", or "Godhead".[51] Gardner envisioned this Supreme Deity as a deist entity who had created the "Under-Gods", among them the God and Goddess, but who was not otherwise involved in the world; alternately, other Wiccans have interpreted such an entity as a pantheistic being, of whom the God and Goddess are facets.[52]

Although Gardner criticised monotheism, citing the Problem of Evil,[51] explicitly monotheistic forms of Wicca developed in the 1960s, when the U.S.-based Church of Wicca developed a theology rooted in the worship of what they described as "one deity, without gender".[53] In the 1970s, Dianic Wiccan groups developed which were devoted to a singular, monotheistic Goddess; this approach was often criticised by members of British Traditional Wiccan groups, who lambasted such Goddess monotheism as an inverted imitation of Christian theology.[54] As in other forms of Wicca, some Goddess monotheists have expressed the view that the Goddess is not an entity with a literal existence, but rather a Jungian archetype.[55]

As well as pantheism and duotheism, many Wiccans accept the concept of polytheism, thereby believing that there are many different deities. Some accept the view espoused by the occultist Dion Fortune that "all gods are one god, and all goddesses are one goddess" – that is that the gods and goddesses of all cultures are, respectively, aspects of one supernal God and Goddess. With this mindset, a Wiccan may regard the Germanic Ēostre, Hindu Kali, and Catholic Virgin Mary each as manifestations of one supreme Goddess and likewise, the Celtic Cernunnos, the ancient Greek Dionysus and the Judeo-Christian Yahweh as aspects of a single, archetypal god. A more strictly polytheistic approach holds the various goddesses and gods to be separate and distinct entities in their own right. The Wiccan writers Janet Farrar and Gavin Bone have postulated that Wicca is becoming more polytheistic as it matures, tending to embrace a more traditionally Pagan worldview.[56] Some Wiccans conceive of deities not as literal personalities but as metaphorical archetypes or thoughtforms, thereby technically allowing them to be atheists.[57] Such a view was purported by the High Priestess Vivianne Crowley, herself a psychologist, who considered the Wiccan deities to be Jungian archetypes that existed within the subconscious that could be evoked in ritual. It was for this reason, she said "The Goddess and God manifest to us in dream and vision".[58]Wiccans often believe that the gods are not perfect and can be argued with.[59]

Many Wiccans also adopt a more explicitly polytheistic or animistic world-view of the universe as being replete with spirit-beings.[60] In many cases these spirits are associated with the natural world, for instance as genius loci, fairies, and elementals.[61] In other cases, such beliefs are more idiosyncratic and atypical; Wiccan Sybil Leek for instance endorsed a belief in angels.[61]

Afterlife[edit]

Belief in the afterlife varies among Wiccans and does not occupy a central place within the religion.[62] As the historian Ronald Hutton remarked, "the instinctual position of most [Wiccans] ... seems to be that if one makes the most of the present life, in all respects, then the next life is more or less certainly going to benefit from the process, and so one may as well concentrate on the present".[63] It is nevertheless a common belief among Wiccans that human beings have a spirit or soul that survives bodily death.[62] Understandings of what this soul constitutes vary among different traditions, with the Feri tradition of witchcraft, for instance, having adopted a belief from the Theosophy-inspired Huna movement, Kabbalah, and other sources, that the human being has three souls.[62]

Although not accepted by all Wiccans, a belief in reincarnation is the dominant afterlife belief within Wicca, having been originally espoused by Gardner.[62] Understandings of how the cycle of reincarnation operates differ among practitioners; Wiccan Raymond Buckland for instance insisted that human souls would only incarnate into human bodies, whereas other Wiccans believe that a human soul can incarnate into any life form.[64] There is also a common Wiccan belief that any Wiccans will come to be reincarnated as future Wiccans, an idea originally expressed by Gardner.[64] Gardner also articulated the view that the human soul rested for a period between bodily death and its incarnation, with this resting place commonly being referred to as "The Summerland" among the Wiccan community.[62] This allows many Wiccans to believe that mediums can contact the spirits of the deceased, a belief adopted from Spiritualism.[62]

Magic and spellcraft[edit]

Many Wiccans believe in magic, a manipulative force exercised through the practice of "spellcraft".[65] Many Wiccans agree with the definition of magic offered by ceremonial magicians,[66] such as Aleister Crowley, who declared that magic was "the science and art of causing change to occur in conformity with will", while another ceremonial magician, MacGregor Mathers stated that it was "the science of the control of the secret forces of nature".[66] Many Wiccans believe magic to be a law of nature, as yet misunderstood or disregarded by contemporary science,[66] and as such they do not view it as being supernatural, but a part of what Leo Martello calls the "super powers that reside in the natural".[67] Some Wiccans believe that magic is simply making full use of the five senses to achieve surprising results,[67] whilst other Wiccans do not claim to know how magic works, merely believing that it does because they have observed it to be so.[68]

During ritual practices, which are often staged in a sacred circle, Wiccans cast spells or "workings" intended to bring about real changes in the physical world. Common Wiccan spells include those used for healing, for protection, fertility, or to banish negative influences.[69] Many early Wiccans, such as Alex Sanders, Sybil Leek and Alex Winfield, referred to their own magic as "white magic", which contrasted with "black magic", which they associated with evil and Satanism. Sanders also used the similar terminology of "left-hand path" to describe malevolent magic, and "right-hand path" to describe magic performed with good intentions;[70] terminology that had originated with the occultist Helena Blavatsky in the 19th century. Some modern Wiccans, however, have stopped using the white/black magic and left/right-hand-path dichotomies, arguing for instance that the colour black should not necessarily have any associations with evil.[71]

Scholars of religion Rodney Stark and William Bainbridge claimed in 1985 that Wicca had "reacted to secularisation by a headlong plunge back into magic" and that it was a reactionary religion which would soon die out. This view was heavily criticised in 1999 by the historian Ronald Hutton who claimed that the evidence displayed the very opposite: that "a large number [of Wiccans] were in jobs at the cutting edge [of scientific culture], such as computer technology".[72]

Witchcraft[edit]

Identification as a witch can[…] provide a link to those persecuted and executed in the Great Witch Hunt, which can then be remembered as a holocaust against women, a repackaging of history that implies conscious victimization and the appropriation of 'holocaust' as a badge of honour — 'gendercide rather than genocide'. An elective identification with the image of the witch during the time of the persecutions is commonly regarded as part of the reclamation of female power, a myth that is used by modern feminist witches as an aid in their struggle for freedom from patriarchal oppression.

— Religious studies scholar Joanne Pearson[73]

Historian Wouter Hanegraaff noted that the Wiccan view of witchcraft was "an outgrowth of Romantic (semi)scholarship", especially the 'witch cult' theory.[74] It proposed that historical alleged witches were actually followers of a surviving pagan religion, and that accusations of infanticide, cannibalism, Satanism etc were either made up by the Inquisition or were misunderstandings of pagan rites.[75] This theory that accused witches were actually pagans has now been disproven using archive records of witch trials.[22] Nevertheless, Gardner and other founders of Wicca believed the theory was true, and saw the witch as a "positive antitype which derives much of its symbolic force from its implicit criticism of dominant Judaeo-Christian and Enlightenment values".[75]

Pearson suggested that Wiccans "identify with the witch because she is imagined as powerful - she can make people sleep for one hundred years, she can see the future, she can curse and kill as well as heal[…] and of course, she can turn people into frogs!"[76] Pearson says that Wicca "provides a framework in which the image of oneself as a witch can be explored and brought into a modern context".[77]Identifying as a witch also enables Wiccans to link themselves with those persecuted in the witch trials of the Early Modern period, often referred to by Wiccans as "the Burning Times".[78] Various practitioners have claimed that as many as nine million people were executed as witches in the Early Modern period, thus drawing comparisons with the killing of six million Jews in the Holocaust and presenting themselves, as modern witches, as "persecuted minorities".[76]

Morality[edit]

Bide the Wiccan laws ye must, in perfect love and perfect trust ...Mind the Threefold Law ye should – three times bad and three times good ...Eight words the Wiccan Rede fulfill – an it harm none, do what ye will.

Wicca has been characterised as a life-affirming religion.[80] Practitioners typically present themselves as "a positive force against the powers of destruction which threaten the world".[81]There exists no dogmatic moral or ethical code followed universally by Wiccans of all traditions, however a majority follow a code known as the Wiccan Rede, which states "an it harm none, do what ye will". This is usually interpreted as a declaration of the freedom to act, along with the necessity of taking responsibility for what follows from one's actions and minimising harm to oneself and others.[82]

Another common element of Wiccan morality is the Law of Threefold Return which holds that whatever benevolent or malevolent actions a person performs will return to that person with triple force, or with equal force on each of the three levels of body, mind, and spirit,[83] similar to the eastern idea of karma. The Wiccan Rede was most likely introduced into Wicca by Gerald Gardner and formalised publicly by Doreen Valiente, one of his High Priestesses. The Threefold Law was an interpretation of Wiccan ideas and ritual, made by Monique Wilson[84] and further popularized by Raymond Buckland, in his books on Wicca.[85]

There is some disagreement among Wiccans as to what the Law of Threefold Return (or Law of Three) actually means, or even whether such a law exists at all. As just one example, McKenzie Sage Wright discusses this in her HubPages artlcle, Ethics in Wicca: The Threefold Law.

Many Wiccans also seek to cultivate a set of eight virtues mentioned in Doreen Valiente's Charge of the Goddess,[86] these being mirth, reverence, honour, humility, strength, beauty, power, and compassion. In Valiente's poem, they are ordered in pairs of complementary opposites, reflecting a dualism that is common throughout Wiccan philosophy. Some lineaged Wiccans also observe a set of Wiccan Laws, commonly called the Craft Laws or Ardanes, 30 of which exist in the Gardnerian tradition and 161 of which are in the Alexandrian tradition. Valiente, one of Gardner's original High Priestesses, argued that the first thirty of these rules were most likely invented by Gerald Gardner himself in mock-archaic language as the by-product of inner conflict within his Bricket Wood coven.[87][72]

In British Traditional Wicca, "sex complementarity is a basic and fundamental working principle", with men and women being seen as a necessary presence to balance each other out.[88] This may have derived from Gardner's interpretation of Murray's claim that the ancient witch-cult was a fertility religion.[88] Thus, many practitioners of British Traditional Wicca have argued that gay men and women are not capable of correctly working magic without mixed-sex pairings.[89]

Although Gerald Gardner initially demonstrated an aversion to homosexuality, claiming that it brought down "the curse of the goddess",[90] it is now generally accepted in all traditions of Wicca, with groups such as the Minoan Brotherhood openly basing their philosophy upon it.[91] Nonetheless, a variety of viewpoints exist in Wicca around this point, with some covens adhering to a hetero-normative viewpoint. Carly B. Floyd of Illinois Wesleyan University has published an informative white paper on this subject: Mother Goddesses and Subversive Witches: Competing Narratives of Gender Essentialism, Heteronormativity, Feminism, and Queerness in Wiccan Theology and Ritual.

The scholar of religion Joanne Pearson noted that in her experience, most Wiccans take a "realistic view of living in the real world" replete with its many problems and do not claim that the gods "have all the answers" to these.[92] She suggested that Wiccans do not claim to seek perfection but instead "wholeness" or "completeness", which includes an acceptance of traits like anger, weakness, and pain.[93] She contrasted the Wiccan acceptance of an "interplay between light and dark" against the New Age focus on "white light".[94] Similarly, the scholar of religion Geoffrey Samuel noted that Wiccans devote "a perhaps surprising amount of attention to darkness and death".[80]

Many Wiccans are involved in environmentalist campaigns.[95]

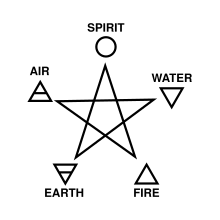

Five elements[edit]

Many traditions hold a belief in the five classical elements, although they are seen as symbolic representations of the phases of matter. These five elements are invoked during many magical rituals, notably when consecrating a magic circle. The five elements are air, fire, water, earth, and aether (or spirit), where aether unites the other four elements.[96] Various analogies have been devised to explain the concept of the five elements; for instance, the Wiccan Ann-Marie Gallagher used that of a tree, which is composed of earth (with the soil and plant matter), water (sap and moisture), fire (through photosynthesis) and air (the formation of oxygen from carbon dioxide), all of which are believed to be united through spirit.[97]

Traditionally in the Gardnerian Craft, each element has been associated with a cardinal point of the compass; air with east, fire with south, water with west, earth with north, and the spirit with centre.[98] However, some Wiccans, such as Frederic Lamond, have claimed that the set cardinal points are only those applicable to the geography of southern England, where Wicca evolved, and that Wiccans should determine which directions best suit each element in their region. For instance, those living on the east coast of North America should invoke water in the east and not the west because the colossal body of water, the Atlantic Ocean, is to their east.[99] Other Craft groups have associated the elements with different cardinal points, for instance Robert Cochrane's Clan of Tubal Cain associated earth with south, fire with east, water with west and air with north,[100] and each of which were controlled over by a different deity who were seen as children of the primary Horned God and Goddess. The five elements are symbolised by the five points of the pentagram, the most-used symbol of Wicca.[101]

Practices[edit]

The Wiccan high priestess and journalist Margot Adler stated that Wiccan rituals were not "dry, formalised, repetitive experiences", but performed with the intent of inducing a religious experience in the participants, thereby altering their consciousness.[102] She noted that many Wiccans remain skeptical about the existence of the supernatural but remain involved in Wicca because of its ritual experiences: she quoted one as saying that "I love myth, dream, visionary art. The Craft is a place where all of these things fit together – beauty, pageantry, music, dance, song, dream".[103] The Wiccan practitioner and historian Aidan Kelly wrote that the practices and experiences within Wicca were more important than the beliefs, stating: "it's a religion of ritual rather than theology. The ritual is first; the myth is second".[104] Similarly, Adler stated that Wicca permits "total skepticism about even its own methods, myths and rituals".[105]

The anthropologist Susan Greenwood characterised Wiccan rituals as "a form of resistance to mainstream culture".[89] She saw these rituals as "a healing space away from the ills of the wider culture", one in which female practitioners can "redefine and empower themselves".[106]

Wiccan rituals usually take place in private.[107] The Reclaiming tradition has utilised its rituals for political purposes.[81]

Practice in Wicca (including, as an example, matters such as the varying attributions of the elements to different directions discussed in the preceding section) varies widely due to the Craft's emphasis on individual expression in one's spiritual/magical path.[108]

Ritual practices[edit]

Many rituals within Wicca are used when celebrating the Sabbats, worshipping the deities, and working magic. Often these take place on a full moon, or in some cases a new moon, which is known as an Esbat. In typical rites, the coven or solitary assembles inside a ritually cast and purified magic circle. Casting the circle may involve the invocation of the "Guardians" of the cardinal points, alongside their respective classical elements; air, fire, water, and earth. Once the circle is cast, a seasonal ritual may be performed, prayers to the God and Goddess are said, and spells are sometimes worked; these may include various forms of 'raising energy', including raising a cone of power to send healing or other magic to persons outside of the sacred space.[citation needed]

In constructing his ritual system, Gardner drew upon older forms of ceremonial magic, in particular, those found in the writings of Aleister Crowley.[109]

The classical ritual scheme in British Traditional Wicca traditions is:[110]

- Purification of the sacred space and the participants

- Casting the circle

- Calling of the elemental quarters

- Cone of power

- Drawing down the Gods

- Spellcasting

- Great Rite

- Wine, cakes, chanting, dancing, games

- Farewell to the quarters and participants

These rites often include a special set of magical tools. These usually include a knife called an athame, a wand, a pentacle and a chalice, but other tools include a broomstick known as a besom, a cauldron, candles, incense and a curved blade known as a boline. An altar is usually present in the circle, on which ritual tools are placed and representations of the God and the Goddess may be displayed.[111] Before entering the circle, some traditions fast for the day, and/or ritually bathe. After a ritual has finished, the God, Goddess, and Guardians are thanked, the directions are dismissed and the circle is closed.[112]

A central aspect of Wicca (particularly in Gardnerian and Alexandrian Wicca), often sensationalised by the media is the traditional practice of working in the nude, also known as skyclad. Although no longer widely used, this practice seemingly derives from a line in Aradia, Charles Leland's supposed record of Italian witchcraft.[113] Many Wiccans believe that performing rituals skyclad allows "power" to flow from the body in a manner unimpeded by clothes.[114] Some also note that it removes signs of social rank and differentiation and thus encourages unity among the practitioners.[114] Some Wiccans seek legitimacy for the practice by stating that various ancient societies performed their rituals while nude.[114]

One of Wicca's best known liturgical texts is "The Charge of the Goddess".[48] The most commonly used version used by Wiccans today is the rescension of Doreen Valiente,[48] who developed it from Gardner's version. Gardner's wording of the original "Charge" added extracts from Aleister Crowley's work, including The Book of the Law, (especially from Ch 1, spoken by Nuit, the Star Goddess) thus linking modern Wicca irrevocably to the principles of Thelema. Valiente rewrote Gardner's version in verse, keeping the material derived from Aradia, but removing the material from Crowley.[115]

Sex magic[edit]

Other traditions wear robes with cords tied around the waist or even normal street clothes. In certain traditions, ritualised sex magic is performed in the form of the Great Rite, whereby a High Priest and High Priestess invoke the God and Goddess to possess them before performing sexual intercourse to raise magical energy for use in spellwork. In nearly all cases it is instead performed "in token", thereby merely symbolically, using the athame to symbolise the penis and the chalice to symbolise the womb.[116]

Gerald Gardner, the man many consider the father of Wicca, believed strongly in sex magic. Much of Gardner's witch practice centered around the power of sex and its liberation, and that one of the most important aspects of the neo-Pagan revival has been its ties, not just to sexual liberation, but also to feminism and women's liberation.[117]

For some Wiccans, the ritual space is a "space of resistance, in which the sexual morals of Christianity and patriarchy can be subverted", and for this reason they have adopted techniques from the BDSM subculture into their rituals.[118]

Publicly, many Wiccan groups have tended to excise the role of sex magic from their image.[119] This has served both to escape the tabloid sensationalism that has targeted the religion since the 1950s and the concerns surrounding the Satanic ritual abuse hysteria in the 1980s and 1990s.[119]

Some Wiccan Traditions substitute a Communion style rite in honor of the God and Goddess rather than the symbolic Great Rite in their Esbat ritual.

Wheel of the Year[edit]

Wiccans celebrate several seasonal festivals of the year, commonly known as Sabbats. Collectively, these occasions are termed the Wheel of the Year.[86] Most Wiccans celebrate a set of eight of these Sabbats; however, other groups such as those associated with the Clan of Tubal Cain only follow four. In the rare case of the Ros an Bucca group from Cornwall, only six are adhered to.[120] The four Sabbats that are common to all British derived groups are the cross-quarter days, sometimes referred to as Greater Sabbats. The names of these festivals are in some cases taken from the Old Irish fire festivals and the Welsh God Mabon,[121] though in most traditional Wiccan covens the only commonality with the Celtic festival is the name. Gardner himself made use of the English names of these holidays, stating that "the four great Sabbats are Candlemas [sic], May Eve, Lammas, and Halloween; the equinoxes and solstices are celebrated also".[122] In the Egyptologist Margaret Murray's The Witch-Cult in Western Europe (1921) and The God of the Witches (1933), in which she dealt with what she believed had been a historical Witch-Cult, she stated that the four main festivals had survived Christianisation and had been celebrated in the Pagan Witchcraft religion. Subsequently, when Wicca was first developing in the 1930s through to the 1960s, many of the early groups, such as Robert Cochrane's Clan of Tubal Cain and Gerald Gardner's Bricket Wood coven adopted the commemoration of these four Sabbats as described by Murray.[citation needed]

The other four festivals commemorated by many Wiccans are known as Lesser Sabbats. They are the solstices and the equinoxes, and they were only adopted in 1958 by members of the Bricket Wood coven,[123] before they were subsequently adopted by other followers of the Gardnerian tradition. They were eventually adopted by followers of other traditions like Alexandrian Wicca and the Dianic tradition. The names of these holidays that are commonly used today are often taken from Germanic pagan holidays. However, the festivals are not reconstructive in nature nor do they often resemble their historical counterparts, instead, they exhibit a form of universalism. The rituals that are observed may display cultural influences from the holidays from which they take their names as well as influences from other unrelated cultures.[124]

| Sabbat | Northern Hemisphere | Southern Hemisphere | Origin of Name | Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samhain | 31 October to 1 November | 30 April to 1 May | Celtic polytheism | Death and the ancestors |

| Yuletide | 21 or 22 December | 21 June | Germanic paganism | Winter solstice and the rebirth of the Sun |

| Imbolc, a.k.a. Candlemas | 1 or 2 February | 1 August | Celtic polytheism | First signs of spring |

| Ostara | 21 or 22 March | 21 or 22 September | Germanic paganism | Vernal equinox and the beginning of spring |

| Beltane, a.k.a. May Eve or May Day | 30 April to 1 May | 31 October to 1 November | Celtic polytheism | The full flowering of spring; fairy folk[125] |

| Litha | 21 or 22 June | 21 December | Early Germanic calendar | Summer solstice |

| Lughnasadh, a.k.a. Lammas | 31 July or 1 August | 1 February | Celtic polytheism | First fruits |

| Mabon, a.k.a. Modron[126] | 21 or 22 September | 21 March | No historical pagan equivalent. | Autumnal equinox; the harvest of grain |

Rites of passage[edit]

Various rites of passage can be found within Wicca. Perhaps the most significant of these is an initiation ritual, through which somebody joins the Craft and becomes a Wiccan. In British Traditional Wiccan (BTW) traditions, there is a line of initiatory descent that goes back to Gerald Gardner, and from him is said to go back to the New Forest coven; however, the existence of this coven remains unproven.[127] Gardner himself said that there was a traditional length of "a year and a day" between when a person began studying the Craft and when they were initiated, although he frequently broke this rule with initiates.[citation needed]

In BTW, initiation only accepts someone into the first degree. To proceed to the second degree, an initiate has to go through another ceremony, in which they name and describe the uses of the ritual tools and implements. It is also at this ceremony that they are given their craft name. By holding the rank of second degree, a BTW is considered capable of initiating others into the Craft, or founding their own semi-autonomous covens. The third degree is the highest in BTW, and it involves the participation of the Great Rite, either actual or symbolically, and in some cases ritual flagellation, which is a rite often dispensed with due to its sado-masochistic overtones. By holding this rank, an initiate is considered capable of forming covens that are entirely autonomous of their parent coven.[128][129]

According to new-age religious scholar James R. Lewis, in his book Witchcraft Today: An Encyclopaedia of Wiccan and Neopagan Traditions, a high priestess becomes a queen when she has successfully hived off her first new coven under a new third-degree high priestess (in the orthodox Gardnerian system). She then becomes eligible to wear the "moon crown". The sequence of high priestess and queens traced back to Gerald Gardner is known as a lineage, and every orthodox Gardnerian High Priestess has a set of "lineage papers" proving the authenticity of her status.[130]

This three-tier degree system following initiation is largely unique to BTW, and traditions heavily based upon it. The Cochranian tradition, which is not BTW, but based upon the teachings of Robert Cochrane, does not have the three degrees of initiation, merely having the stages of novice and initiate.

Some solitary Wiccans also perform self-initiation rituals, to dedicate themselves to becoming a Wiccan. The first of these to be published was in Paul Huson's Mastering Witchcraft (1970), and unusually involved recitation of the Lord's Prayer backwards as a symbol of defiance against the historical Witch Hunt.[131] Subsequent, more overtly pagan self-initiation rituals have since been published in books designed for solitary Wiccans by authors like Doreen Valiente, Scott Cunningham and Silver RavenWolf.

Handfasting is another celebration held by Wiccans, and is the commonly used term for their weddings. Some Wiccans observe the practice of a trial marriage for a year and a day, which some traditions hold should be contracted on the Sabbat of Lughnasadh, as this was the traditional time for trial, "Telltown marriages" among the Irish. A common marriage vow in Wicca is "for as long as love lasts" instead of the traditional Christian "till death do us part".[132] The first known Wiccan wedding ceremony took part in 1960 amongst the Bricket Wood coven, between Frederic Lamond and his first wife, Gillian.[72]

Infants in Wiccan families may be involved in a ritual called a Wiccaning, which is analogous to a Christening. The purpose of this is to present the infant to the God and Goddess for protection. Parents are advised to "give [their] children the gift of Wicca" in a manner suitable to their age. In accordance with the importance put on free will in Wicca, the child is not expected or required to adhere to Wicca or other forms of paganism should they not wish to do so when they reach adulthood.[133]

Book of Shadows[edit]

In Wicca, there is no set sacred text such as the Christian Bible, Jewish Tanakh, or Islamic Quran, although there are certain scriptures and texts that various traditions hold to be important and influence their beliefs and practices. Gerald Gardner used a book containing many different texts in his covens, known as the Book of Shadows (among other names), which he would frequently add to and adapt. In his Book of Shadows, there are texts taken from various sources, including Charles Godfrey Leland's Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches (1899) and the works of 19th–20th century occultist Aleister Crowley, whom Gardner knew personally. Also in the Book are examples of poetry largely composed by Gardner and his High Priestess Doreen Valiente, the most notable of which is the Charge of the Goddess.

The Book of Shadows is not a Bible or Quran. It is a personal cookbook of spells that have worked for the owner. I am giving you mine to copy to get you started: as you gain experience discard those spells that don't work for you and substitute those that you have thought of yourselves.

Gerald Gardner to his followers[134]

Similar in use to the grimoires of ceremonial magicians,[135] the Book contained instructions for how to perform rituals and spells, as well as religious poetry and chants like Eko Eko Azarak to use in those rituals. Gardner's original intention was that every copy of the book would be different because a student would copy from their initiators, but changing things which they felt to be personally ineffective, however amongst many Gardnerian Witches today, particularly in the United States, all copies of the Book are kept identical to the version that the High Priestess Monique Wilson copied from Gardner, with nothing being altered. The Book of Shadows was originally meant to be kept a secret from non-initiates into BTW, but parts of the Book have been published by authors including Charles Cardell, Lady Sheba, Janet Farrar and Stewart Farrar.[110][136]

Symbolism[edit]

The pentacle is a symbol commonly used by Wiccans.[93] Wiccans often understand the pentacle's five points as representing each of the five elements: earth, air, fire, water, and aether/spirit.[93] It is also regarded as a symbol of the human, with the five points representing the head, arms, and legs.[93]

Structure[edit]

There is no overarching organisational structure to Wicca.[137] In Wicca, all practitioners are considered to be priests and priestesses.[59]Wicca generally requires a ritual of initiation.[138]

Traditions[edit]

In the 1950s through to the 1970s, when the Wiccan movement was largely confined to lineaged groups such as Gardnerian Wicca and Alexandrian Wicca, a "tradition" usually implied the transfer of a lineage by initiation. However, with the rise of more and more such groups, often being founded by those with no previous initiatory lineage, the term came to be a synonym for a religious denomination within Wicca. Scholars of religion tend to treat Wicca as a religion with denominations that differ on some important points but share core beliefs, much like Christianity and its many denominations.[139] There are many such traditions[140][141] and there are also many solitary practitioners who do not align themselves with any particular lineage, working alone. Some covens have formed but who do not follow any particular tradition, instead choosing their influences and practices eclectically.

Those traditions which trace a line of initiatory descent back to Gerald Gardner include Gardnerian Wicca, Alexandrian Wicca and the Algard tradition; because of their joint history, they are often referred to as British Traditional Wicca, particularly in North America. Other traditions trace their origins to different figures, even if their beliefs and practices have been influenced to a greater or lesser extent by Gardner. These include Cochrane's Craft and the 1734 Tradition, both of which trace their origins to Robert Cochrane; Feri, which traces itself back to Victor Anderson and Gwydion Pendderwen; and Dianic Wicca, whose followers often trace their influences back to Zsuzsanna Budapest. Some of these groups prefer to refer to themselves as Witches, thereby distinguishing themselves from the BTW traditions, who more typically use the term Wiccan (see Etymology).[citation needed] During the 1980s, Viviane Crowley, an initiate of both the Gardnerian and Alexandrian traditions, merged the two.[142]

Pearson noted that "Wicca has evolved and, at times, mutated quite dramatically into completely different forms".[143] Wicca has also been "customized" to the various national contexts into which it has been introduced; for instance, in Ireland, the veneration of ancient Irish deities has been incorporated into Wicca.[144]

Covens[edit]

Lineaged Wicca is organised into covens of initiated priests and priestesses. Covens are autonomous and are generally headed by a High Priest and a High Priestess working in partnership, being a couple who have each been through their first, second, and third degrees of initiation. Occasionally the leaders of a coven are only second-degree initiates, in which case they come under the rule of the parent coven. Initiation and training of new priesthood is most often performed within a coven environment, but this is not a necessity, and a few initiated Wiccans are unaffiliated with any coven.[145] Most covens would not admit members under the age of 18.[146] They often do not advertise their existence, and when they do, do so through pagan magazines.[147] Some organise courses and workshops through which prospective members can come along and be assessed.[148]

A commonly quoted Wiccan tradition holds that the ideal number of members for a coven is thirteen, though this is not held as a hard-and-fast rule.[145] Indeed, many U.S. covens are far smaller, though the membership may be augmented by unaffiliated Wiccans at "open" rituals.[149] Pearson noted that covens typically contained between five and ten initiates.[150] They generally avoid mass recruitment due to the feasibility of finding spaces large enough to bring together greater numbers for rituals and because larger numbers inhibit the sense of intimacy and trust that covens utilise.[150]

Some covens are short-lived, but others have survived for many years.[150] Covens in the Reclaiming tradition are often single-sex and non-hierarchical in structure.[151] Coven members who leave their original group to form another, separate coven are described as having "hived off" in Wicca.[150]

Initiation into a coven is traditionally preceded by an apprenticeship period of a year and a day.[152] A course of study may be set during this period. In some covens a "dedication" ceremony may be performed during this period, some time before the initiation proper, allowing the person to attend certain rituals on a probationary basis. Some solitary Wiccans also choose to study for a year and a day before their self-dedication to the religion.[153]

Various high priestesses and high priests have reported being "put on a pedestal" by new initiates, only to have those students later "kick away" the pedestal as they develop their own knowledge and experience of Wicca.[154] Within a coven, different members may be respected for having particular knowledge of specific areas, such as the Qabalah, astrology, or the Tarot.[59]

Based on her experience among British Traditional Wiccans in the UK, Pearson stated that the length of time between becoming a first-degree initiate and a second was "typically two to five years".[138] Some practitioners nevertheless chose to remain as first-degree initiates rather than proceed to the higher degrees.[138]

Eclectic Wicca[edit]

Большое количество виккан не следуют исключительно какой-либо одной традиции и даже не являются посвященными. Каждый из этих эклектичных виккан создает свои собственные синкретические духовные пути, перенимая и заново изобретая верования и ритуалы различных религиозных традиций, связанных с Виккой и более широким язычеством .

В то время как истоки современной викканской практики лежат в заветной деятельности нескольких избранных посвященных в устоявшихся линиях передачи, эклектичные виккане чаще всего являются практикующими-одиночками, не посвященными ни в одну традицию. Растущий общественный интерес, особенно в Соединенных Штатах , сделал традиционное посвящение неспособным удовлетворить спрос на участие в Викке. С 1970-х годов начали создаваться более крупные, более неформальные, часто публично рекламируемые лагеря и семинары. [155] Эта менее формальная, но более доступная форма Викки оказалась успешной. Эклектическая Викка — самая популярная разновидность Викки в Америке. [156] и эклектиков сейчас значительно больше, чем виккан, принадлежащих к родословной.

Эклектика Викка не обязательно означает полный отказ от традиции. Эклектичные практикующие могут следовать своим собственным идеям и ритуальным практикам, при этом опираясь на один или несколько религиозных или философских путей. Эклектичные подходы к Викке часто опираются на религию Земли и древнеегипетские , греческие , саксонские , англосаксонские , кельтские , азиатские , еврейские и полинезийские традиции. [157]

В отличие от британских традиционных виккан, виккан-восстановителей и различных эклектичных виккан, социолог Дуглас Эззи утверждал, что существует «популярное колдовство», которое «двигалось в первую очередь потребительским маркетингом и представлено фильмами, телешоу, коммерческими журналами и потребительские товары». [158] Книги и журналы этого типа были ориентированы в основном на молодых девушек и включали заклинания для привлечения или отпугивания парней, денежные заклинания и заклинания для защиты дома. [159] Он назвал это «Колдовством Нью Эйдж». [160] и сравнил вовлеченных в это людей с участниками Нового Века. [158]

История [ править ]

Истоки, гг 1921–1935 .

Викка зародилась в первые десятилетия двадцатого века среди тех эзотерически настроенных британцев, которые хотели возродить веру своих древних предков, и привлекла внимание общественности в 1950-х и 1960-х годах, во многом благодаря небольшой группе преданных последователей, которые настаивали на представляя свою веру миру, который порой был очень враждебным. Из этого скромного начала эта радикальная религия распространилась в Соединенные Штаты, где она нашла удобного партнера в форме контркультуры 1960-х годов и стала защищаться теми секторами женских и гей -освободительных движений, которые искали духовного спасения. от христианской гегемонии.

- Религиовед Итан Дойл Уайт [161]

Викка была основана в Англии между 1921 и 1950 годами. [162] представляющий то, что историк Рональд Хаттон назвал «единственной полноценной религией, которую, можно сказать, Англия дала миру». [163] как « изобретенная традиция », Охарактеризованная учеными [164] Викка была создана путем лоскутного заимствования различных старых элементов, многие из которых были взяты из ранее существовавших религиозных и эзотерических движений. [165] Пирсон охарактеризовал его как возникший «из культурных импульсов конца века ». [166]

Викка взяла за основу гипотезу культа ведьм . Это была идея о том, что те, кого преследовали как ведьм в Европе раннего Нового времени, на самом деле были последователями сохранившейся языческой религии; не сатанисты , как утверждали преследователи, и не невиновные люди, признавшиеся под угрозой пыток, как это давно сложилось по историческому консенсусу. [162] [167] «Отец Викки» Джеральд Гарднер утверждал, что его религия является пережитком европейского «культа ведьм». [168] Теория «культа ведьм» была впервые высказана немецким профессором Карлом Эрнестом Ярке в 1828 году, а затем была поддержана немцем Францем Йозефом Моне , а затем французским историком Жюлем Мишле . [169] В конце 19-го века его переняли двое американцев, Матильда Джослин Гейдж и Чарльз Лиланд , последний из которых продвигал его вариант в своей книге 1899 года «Арадия, или Евангелие ведьм» . [170] Самым известным сторонником этой теории была английский египтолог Маргарет Мюррей , которая продвигала ее в серии книг, в первую очередь в «Культе ведьм в Западной Европе» 1933 года 1921 года и «Бог ведьм» . [171] [167]

Почти все сверстники Мюррея считали теорию культа ведьм неверной и основанной на плохой учености. Однако Мюррея пригласили написать статью о «колдовстве» для издания Британской энциклопедии 1929 года , которая переиздавалась десятилетиями и стала настолько влиятельной, что, по словам фольклористки Жаклин Симпсон , идеи Мюррея «настолько укоренились в популярной культуре, что вероятно, никогда не будет искоренен». [172] Симпсон отметил, что единственным современным членом Фольклорного общества, который серьезно воспринял теорию Мюррея, был Джеральд Гарднер, который использовал ее как основу для Викки. [172] Книги Мюррея были источником многих известных мотивов, которые часто включались в Викку. Идея о том, что в ковенах должно быть 13 членов, была развита Мюррей на основе показаний единственного свидетеля на одном из процессов над ведьмами, а также на ее утверждении, что ковены собирались в течение четырех дней между кварталами. [172] Мюррей был очень заинтересован в том, чтобы приписать натуралистические или религиозные церемониальные объяснения некоторым из наиболее фантастических описаний, встречающихся в показаниях на суде над ведьмами. Например, во многих исповеданиях содержалась идея о том, что сатана лично присутствовал на собраниях ковена. Мюррей интерпретировал это как жреца-ведьмы, носящего рога и шкуры животных, а также пару раздвоенных ботинок, символизирующих его авторитет или звание. С другой стороны, большинство основных фольклористов утверждали, что весь сценарий всегда был вымышленным и не требует натуралистического объяснения, но Гарднер с энтузиазмом перенял многие объяснения Мюррея в свою собственную традицию. [172] Теория культа ведьм была «историческим повествованием, вокруг которого построила себя Викка», причем ранние виккане утверждали, что они пережили эту древнюю языческую религию. [173]

Теория «культа ведьм» с тех пор была опровергнута дальнейшими историческими исследованиями. [22] но виккане по-прежнему часто заявляют о своей солидарности с жертвами судов над ведьмами. [174] Представление о том, что викканские традиции и ритуалы сохранились с древних времен, оспаривается новейшими исследователями, которые утверждают, что Викка — это творение 20-го века, сочетающее в себе элементы масонства и оккультизма 19-го века. [175] В своей книге 1999 года «Триумф Луны » английский историк Рональд Хаттон исследовал утверждение виккан о том, что древние языческие обычаи сохранились до наших дней после того, как в средневековые времена они были христианизированы как народные обычаи. Хаттон обнаружил, что большинство народных обычаев, которые, как утверждается, имеют языческие корни (например, танец с майским шестом ), на самом деле восходят к средневековью . Он пришел к выводу, что идея о том, что средневековые пиры имели языческое происхождение, является наследием протестантской Реформации . [72] [176] Хаттон отметил, что Викка предшествует современному движению Нью Эйдж , а также заметно отличается по своей общей философии. [72]

Другие влияния на раннюю Викку включали различные западные эзотерические традиции и практики, в том числе церемониальную магию , Алистера Кроули и его религию Телемы , масонство , спиритуализм и теософию . [177] В меньшей степени Викка также опиралась на народную магию и методы хитрого народа . [178] В дальнейшем на него повлияли как научные работы по фольклористике, особенно Джеймса Фрейзера » «Золотая ветвь , так и романтические сочинения, такие как Роберта Грейвса » «Белая богиня , и ранее существовавшие современные языческие группы, такие как Орден рыцарства по дереву и друидизм . [179]

Раннее развитие, . 1936–1959 гг

Именно в 1930-е годы появляются первые свидетельства практики неоязыческой религии «колдовства». [180] [181] (то, что сейчас можно было бы назвать Виккой) в Англии. Похоже, что несколько групп по всей стране, в таких местах, как Норфолк , [182] Чешир [183] и Нью-Форест основался после того, как его вдохновили сочинения Мюррея о «культе ведьм».

История Викки начинается с Джеральда Гарднера («Отца Викки») в середине 20 века. Гарднер был британским государственным служащим на пенсии и антропологом- любителем , хорошо знакомым с язычеством и оккультизмом . Он утверждал, что был посвящен в шабаш ведьм в Нью-Форесте , Хэмпшир , в конце 1930-х годов. Намереваясь увековечить это ремесло, Гарднер основал ковен Брикет Вуд вместе со своей женой Донной в 1940-х годах , после покупки загородного клуба натуристов Fiveacres. [184] Большая часть первых членов ковена была набрана из членов клуба. [185] и его заседания проводились на территории клуба. [186] [187] Многие известные деятели ранней Викки были непосредственными посвященными этого ковена, в том числе Дафо , Дорин Валиенте , Джек Брейселин , Фредерик Ламонд , Дайонис , Элеонора Боун и Лоис Борн .

Религия колдовства начала расти в 1951 году, с отменой Закона о колдовстве 1735 года , после чего Джеральд Гарднер , а затем другие, такие как Чарльз Карделл и Сесил Уильямсон, начали публиковать свои собственные версии колдовства. Гарднер и другие никогда не использовали термин «Викка» в качестве религиозного идентификатора, просто имея в виду «культ ведьмы», «колдовство» и «старую религию». Однако Гарднер называл ведьм «Вика». [188] В 1960-е годы название религии превратилось в «Викка». [189] Традиция Гарднера, позже названная гарднерианством , вскоре стала доминирующей формой в Англии и распространилась на другие части Британских островов .

Адаптация и распространение, 1960 время настоящее –

После смерти Гарднера в 1964 году Ремесло продолжало неустанно развиваться, несмотря на сенсационность и негативные изображения в британских таблоидах, а новые традиции пропагандировались такими фигурами, как Роберт Кокрейн , Сибил Лик и, что наиболее важно, Алекс Сандерс , чья Александрийская Викка , которая была преимущественно основана на Гарднерианская Викка, хотя и с упором на церемониальную магию , быстро распространилась и привлекла большое внимание средств массовой информации. Примерно в это же время термин «Викка» стал широко использоваться вместо «Колдовства», и вера стала экспортироваться в такие страны, как Австралия и Соединенные Штаты . [ нужна ссылка ]

В 1970-е годы к Викке присоединилось новое поколение, находившееся под влиянием контркультуры 1960-х годов . [190] Многие привнесли экологические в движение идеи, о чем свидетельствует создание таких групп, как базирующаяся в Великобритании группа Pagans Against Nukes . [190] В США Виктор Андерсон , Кора Андерсон и Гвидион Пендервен основали Традицию Фери . [191]

Именно в Соединенных Штатах и Австралии начали развиваться новые, доморощенные традиции, иногда основанные на более ранних региональных народно-магических традициях и часто смешанные с базовой структурой гарднерианской Викки, в том числе « » Виктора Андерсона Традиция Фери , Джозефа Уилсона Традиция 1734 года , Эйдана Келли Новый реформатский ортодоксальный Орден Золотой Зари и, в конечном итоге, Жужанны Будапешт , Дианическая Викка каждая из которых подчеркивала различные аспекты веры. [192] Примерно в это же время начали появляться книги, обучающие людей тому, как самим стать ведьмами без формального посвящения или обучения, среди них Пола Хьюсона ( «Освоение колдовства» 1970) и «Книга теней леди Шебы» (1971). Подобные книги продолжали публиковаться на протяжении 1980-х и 1990-х годов, чему способствовали работы таких авторов, как Дорин Валиенте , Джанет Фаррар , Стюарт Фаррар и Скотт Каннингем , которые популяризировали идею самостоятельного посвящения в Ремесло. Среди ведьм в Канаде антрополог Хизер Боттинг (урожденная Харден) из Университета Виктории была первым признанным викканским капелланом государственного университета. [193] Она первая верховная жрица Ковена Селесты . [194]

В 1990-х годах, на фоне постоянно растущего числа самозванцев, популярные средства массовой информации начали исследовать «колдовство» в художественных фильмах, таких как «Ремесло» (1996) и телесериалах, таких как «Зачарованные» (1998–2006), знакомя большое количество молодых людей с идея религиозного колдовства. Эта растущая аудитория вскоре стала обслуживаться через Интернет и такими авторами, как Сильвер РэйвенВульф , что вызвало большую критику со стороны традиционных викканских групп и отдельных лиц. В ответ на то, что Викка все чаще изображалась как модная, эклектичная и находящаяся под влиянием движения Нью-Эйдж , многие ведьмы обратились к догарднерианским истокам Ремесла и к традициям его соперников, таких как Карделл и Кокрейн, называя себя как продолжение « традиционного колдовства ». Группы возрождения традиционного колдовства включали Cultus Sabbati Эндрю Чамбли и ковен Корнуолла Рос ан Букка. [ нужна ссылка ]

Демография [ править ]

Зародившись в Великобритании, Викка затем распространилась на Северную Америку, Австралазию , континентальную Европу и Южную Африку. [143]

Фактическое количество виккан во всем мире неизвестно, и было отмечено, что установить численность представителей неоязыческих религий труднее, чем во многих других религиях, из-за их дезорганизованной структуры. [195] Однако Adherents.com, независимый веб-сайт, специализирующийся на сборе оценок мировых религий, цитирует более тридцати источников с оценками количества виккан (в основном из США и Великобритании). Исходя из этого, они получили среднюю оценку в 800 000 членов. [196] По состоянию на 2016 год Дойл Уайт предположил, что по всему миру существуют «сотни тысяч практикующих виккан». [161]

В 1998 году верховная жрица Викки и академический психолог Вивиан Кроули предположила, что Викка была менее успешной в распространении в странах, население которых в основном было католиком. Она предположила, что это может быть связано с тем, что акцент Викки на женском божестве был более новым для людей, выросших в среде с преобладанием протестантизма. [20] Основываясь на своем опыте, Пирсон согласилась, что в целом это правда. [197]

Викку называют религией, не прозелитизирующей. [198] В 1998 году Пирсон отметил, что очень немногие люди выросли викканами, хотя все большее число взрослых виккан сами были родителями. [199] Многие родители-виккане не называли своих детей также викканами, считая важным, чтобы последним было разрешено делать собственный выбор в отношении своей религиозной идентичности, когда они станут достаточно взрослыми. [199] В результате своих полевых исследований среди членов традиции Возрождения в Калифорнии в 1980-90 годах антрополог Джон Саломонсен обнаружила, что многие описывают присоединение к движению после «необычайного опыта откровения». [200]

Основываясь на своем анализе интернет-тенденций, социологи религии Дуглас Эззи и Хелен Бергер заявили, что к 2009 году «феноменальный рост», который наблюдался в Викке в предыдущие годы, замедлился. [201]

Европа [ править ]

[Средний викканец — это] мужчина лет сорока или женщина лет тридцати, европеоидной расы , достаточно хорошо образованный, мало зарабатывающий, но, вероятно, не слишком озабоченный материальными благами, человек, которого демографы назвали бы низшим средним классом .

Лео Рюикби (2004) [202]

Из своего опроса британских виккан, проведенного в 1996 году, Пирсон обнаружила, что большинство виккан были в возрасте от 25 до 45 лет, при этом средний возраст составлял около 35 лет. [146] Она отметила, что по мере старения викканского сообщества доля пожилых практикующих будет увеличиваться. [146] Она обнаружила примерно равные пропорции мужчин и женщин. [203] и обнаружил, что 62% были протестантами, что соответствовало доминированию протестантизма в Великобритании в целом. [204] Опрос Пирсона также показал, что половина представленных британских виккан имела университетское образование и, как правило, работали в «целительских профессиях», таких как медицина или консультирование, образование, информатика и управление. [205] Она отметила, что, таким образом, существует «определенная однородность происхождения» британских виккан. [205]

В Соединенном Королевстве данные переписи населения по религии были впервые собраны в 2001 году ; никакой подробной статистики за пределами шести основных религий не сообщалось. [206] В ходе переписи 2011 года была представлена более подробная разбивка ответов: 56 620 человек назвали себя язычниками, 11 766 - викканами и еще 1 276 назвали свою религию «колдовством». [207]

Северная Америка [ править ]

В Соединенных Штатах Американское исследование религиозной идентификации показало значительный рост числа самоидентифицированных виккан: с 8 000 в 1990 году до 134 000 в 2001 году и 342 000 в 2008 году. [208] Виккане также составляют значительную часть различных групп внутри этой страны; например, Викка является крупнейшей нехристианской религией, исповедуемой в ВВС США : 1434 летчика идентифицируют себя как таковые. [209] В 2014 году Исследовательский центр Pew подсчитал, что 0,3% населения США (около 950 000 человек) идентифицированы как викканцы или язычники, исходя из размера выборки в 35 000 человек. [210]

В 2018 году исследование Pew Research Center оценило количество виккан в Соединенных Штатах как минимум в 1,5 миллиона человек. [211]

Принятие [ править ]

Викка возникла в преимущественно христианской Англии, и с самого начала религия столкнулась с противодействием со стороны определенных христианских групп, а также популярных таблоидов, таких как News of the World . Некоторые христиане до сих пор верят, что Викка — это форма сатанизма , несмотря на важные различия между этими двумя религиями. [212] Недоброжелатели обычно изображают Викку как форму злонамеренного сатанизма . [17] характеристика, которую виккане отвергают. [213] Из-за негативного подтекста, связанного с колдовством, многие виккане продолжают традиционную практику секретности, скрывая свою веру из страха преследований. Раскрытие себя как викканца семье, друзьям или коллегам часто называют «выходом из чулана для метел». [214] Отношение к христианству внутри викканского движения варьируется от прямого неприятия до готовности работать вместе с христианами в межконфессиональных усилиях. [215]

Ученый-религиовед Грэм Харви писал, что «популярный и распространенный образ [Викки] в средствах массовой информации по большей части неточен». [216] Пирсон также отметил, что «восприятие Викки в обществе и средствах массовой информации часто вводит в заблуждение». [138]

В Соединенных Штатах ряд юридических решений улучшили и подтвердили статус виккан, особенно дело Деттмер против Лэндона в 1986 году. Однако виккане столкнулись с противодействием со стороны некоторых политиков и христианских организаций. [217] [218] включая бывшего президента США Джорджа Буша , который заявил, что не считает Викку религией. [219] [220]

В 2007 году Министерство по делам ветеранов США после многих лет споров добавило Пентакль в список эмблем веры, которые могут быть включены в выпущенные правительством маркеры, надгробия и мемориальные доски в честь умерших ветеранов. [221] В Канаде Хизер Боттинг («Леди Аврора») и Гэри Боттинг («Пан»), первоначальная верховная жрица и первосвященник Ковена Селесты и старейшины-основатели Скинии Водолея , успешно агитировали правительство Британской Колумбии и федеральное правительство в Канаде. В 1995 году они получили возможность проводить признанные викканские свадьбы, стать тюремными и больничными капелланами и (в случае Хизер Боттинг) стать первым официально признанным викканским капелланом в государственном университете. [222] [223]

Система многих викканских традиций, основанная на клятве, затрудняет их изучение «посторонними» учеными. [224] Например, после того, как антрополог Таня Лурман в своем академическом исследовании раскрыла информацию о том, что она узнала, будучи посвященной викканского ковена, многие виккане были расстроены, полагая, что она нарушила клятву хранить тайну, данную при посвящении. [225]

Ссылки [ править ]

Примечания [ править ]

Сноски [ править ]

- ^ Адлер 2005 , с. 10.

- ^ Ханеграаф 1996 , с. 87; Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 5.

- ^ Кроули 1998 , с. 170; Пирсон 2002 , с. 44; Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 2.

- ^ Стрмиска 2005 , с. 47; Дойл Уайт 2010 , с. 185.

- ^ Стрмиска 2005 , с. 2; Раунтри 2015 , с. 4.

- ^ Дойл Уайт 2010 , с. 185.

- ^ Стрмиска 2005 , с. 2.

- ^ Стрмиска 2005 , с. 21; Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 7.

- ^ Гринвуд 1998 , стр. 101, 102; Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 8.

- ^ Эззи 2002 , с. 117; Хаттон 2002 , с. 172.

- ^ Орион 1994 , с. 6; Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 5.

- ^ Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 8.

- ^ Пирсон 1998 , с. 45; Эззи 2003 , стр. 49–50.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с д и Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 5.

- ^ Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 7.

- ^ Харви 2007 , с. 36.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 1.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 4.

- ^ Раунтри 2015 , с. 19.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Кроули 1998 , с. 171.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Дойл Уайт 2010 , с. 188.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с Хаттон 2017 , с. 121.

- ^ Дойл Уайт 2010 , с. 190.

- ^ Дойл Уайт 2010 , стр. 191–192.

- ^ Дойл Уайт 2010 , с. 193.

- ^ Моррис 1969 , с. 1548; Дойл Уайт 2010 , с. 187; Дойл Уайт, 2016 , стр. 4–5.

- ^ Дойл Уайт 2010 , с. 187.

- ^ Дойл Уайт 2010 , с. 195.

- ^ Пирсон 2002b , с. 146.

- ^ Дойл Уайт 2010 , с. 194.

- ^ Дойл Уайт 2010 , стр. 196–197; Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 5.

- ^ Дойл Уайт 2010 , стр. 197–198.

- ^ Пирсон 2001 , с. 52; Дойл Уайт, 2016 , стр. 1–2.

- ^ Дойл Уайт 2016 , стр. 4, 198.

- ^ Дойл Уайт 2010 , стр. 199–201.

- ^ Дойл Уайт 2010 , с. 199.

- ^ Пирсон 1998 , с. 49; Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 86.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 86.

- ^ Дойл Уайт 2016 , стр. 86–87.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 87.

- ^ Мюррей 1921 .

- ^ Дойл Уайт, 2016 , стр. 87–88.

- ^ Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 91.

- ^ Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 88.

- ^ Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 89.

- ^ Дойл Уайт, 2016 , стр. 89–90.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 90.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с Пирсон 2005 .

- ^ Фаррар и Фаррар 1987 , стр. 29–37.

- ^ Гринвуд 1998 , с. 103.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 92.

- ^ Дойл Уайт, 2016 , стр. 92–93.

- ^ Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 93.

- ^ Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 94.

- ^ Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 95.

- ^ Фаррар и Боун 2004 .

- ^ Адлер 1979 , стр. 25, 34–35.

- ^ Кроули, Вивианна (1996). Викка: старая религия в новом тысячелетии . Лондон: Торсонс. п. 129. ИСБН 0-7225-3271-7 . ОСЛК 34190941 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с Пирсон 1998 , с. 52.

- ^ Дойл Уайт, 2016 , стр. 95–96.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 96.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 146.

- ^ Хаттон 1999 , с. 393.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 147.

- ^ Данвич, Герина (1998). А-Я Викки . Самшит. п. 120.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с Храбрый 1973 , с. 231.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Адлер 1979 , стр. 158–159.

- ^ Хаттон 1999 , стр. 394–395.

- ^ Галлахер 2005 , стр. 250–265.

- ^ Сандерс, Алекс (1984). Лекции Алекса Сандерса . Волшебный Чайлд. ISBN 0-939708-05-1 .

- ^ Галлахер 2005 , с. 321.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с д и Хаттон 1999 .

- ^ Пирсон 2002b , с. 164.

- ^ Ханеграаф 2002 , с. 303.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Ханеграаф 2002 , с. 304.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Пирсон 2002b , с. 163.

- ^ Пирсон 2002b , с. 167.

- ^ Пирсон 2002b , стр. 163–164.

- ^ Матьезен, Роберт; Теитик (2005). Совет Викки . Провиденс: Олимпийская пресса. стр. 60–61. ISBN 0-9709013-1-3 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Сэмюэл 1998 , с. 128.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Ханеграаф 2002 , с. 306.

- ^ Харроу, Джуди (1985). «Эксегеза о Совете » . Урожай . 5 (3). Архивировано из оригинала 14 мая 2007 года.

- ^ Лембке, Карл (2002) Тройной закон .

- ^ Адамс, Лутанил (2011). Книга Зеркал . Великобритания: Кэпалл Банн. п. 218. ИСБН 978-1-86163-325-5 .

- ^ Бакленд 1986 , Предисловие ко второму изданию .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Фаррар и Фаррар 1992 .

- ^ Храбрый 1989 , стр. 70–71.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Гринвуд 1998 , с. 105.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Гринвуд 1998 , с. 106.

- ^ Гарднер 2004 , стр. 69, 75.

- ^ Адлер 1979 , стр. 130–131.

- ^ Пирсон 1998 , с. 47.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с д Пирсон 1998 , с. 49.

- ^ Пирсон 1998 , с. 48.

- ^ Кроули 1998 , с. 178.

- ^ Зелл-Рэйвенхарт, Оберон; Зелл-Рэйвенхарт, «Утренняя слава» (2006). Создание кружков и церемоний . Франклин Лейкс : Новые страницы книг. п. 42. ИСБН 1-56414-864-5 .

- ^ Галлахер 2005 , стр. 77, 78.

- ^ Галлахер 2005 .

- ^ Ламонд 2004 , с. 88–89.

- ^ Храбрый 1989 , с. 124.

- ^ Храбрый 1973 , с. 264.

- ^ Адлер 2005 , с. 164.

- ^ Адлер 2005 , с. 172.

- ^ Адлер 2005 , с. 173.

- ^ Адлер 2005 , с. 174.

- ^ Гринвуд 1998 , стр. 101–102.

- ^ Ханеграаф 2002 , с. 305.

- ^ Макдермотт, Мэтт (2023). Сотворение собственного заклинания: роль индивидуализма в викканских верованиях . Материалы ежегодного собрания Южного антропологического общества. Том. 47.

- ^ Пирсон 2007 , с. 5.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Фаррар и Фаррар 1981 .

- ^ Кроули 1989 .

- ^ Бадо-Фралик, Никки (1998). «Поворот колеса жизни: викканские обряды смерти» . Фольклорный форум . 29:22 – через IUScholarWorks.

- ^ Лиланд, Чарльз (1899). Арадия, или Евангелие ведьм . Дэвид Натт. п. 7.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с Пирсон 2002b , с. 157.

- ^ Гайли 1999 , с. 52 .

- ^ Фаррар и Фаррар 1984 , стр. 156–174.

- ^ Урбан, Хью Б. (4 октября 2006 г.). «Богиня и Великий Ритуал, сексуальная магия и феминизм в эпоху неоязыческого возрождения» . Богиня и великий обряд: сексуальная магия и феминизм в эпоху неоязыческого возрождения . стр. 162–190. дои : 10.1525/Калифорния/9780520247765.003.0008 . ISBN 9780520247765 .

- ^ Пирсон 2005a , с. 36.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Пирсон 2005а , с. 32.

- ^ Гэри, Джемма (2008). Традиционное колдовство: книга путей Корнуолла . Трой Книги. п. 147. OCLC 935742668 .

- ^ Эванс, Эмрис (1992). «Кельты». В Кавендише, Ричард; Линг, Тревор О. (ред.). Мифология . Нью-Йорк: Литтл Браун и компания. п. 170. ИСБН 0-316-84763-1 .

- ^ Гарднер 2004 , с. 10.

- ^ Ламонд 2004 , с. 16–17.

- ^ Кроули 1989 , с. 23.

- ^ Галлахер 2005 , с. 67.

- ^ Галлахер 2005 , с. 72.

- ^ Симпсон, Жаклин (2005). «Ведьминская культура: фольклор и неоязычество в Америке». Фольклор . 116 .

- ^ Фаррар и Фаррар 1984 , Глава II – Посвящение второй степени.

- ^ Фаррар и Фаррар 1984 , Глава III – Посвящение третьей степени.

- ^ Льюис 1999 , с. 238 .

- ^ Хьюсон, Пол (1970). Освоение колдовства: Практическое руководство для ведьм, колдунов и шабашов . Нью-Йорк: Путнум. стр. 22–23. ISBN 0-595-42006-0 . OCLC 79263 .

- ^ Галлахер 2005 , с. 370.

- ^ К., Эмбер (1998). Coven Craft: Колдовство для троих и более . Ллевеллин. п. 280. ИСБН 1-56718-018-3 .

- ^ Ламонд 2004 , с. 14.

- ^ Кроули 1989 , стр. 14–15.

- ^ Гарднер, Джеральд (2004a). Нейлор, Арканзас (ред.). Колдовство и Книга Теней . Теме: Книги IHO. ISBN 1-872189-52-0 .

- ^ Пирсон 2002b , с. 135.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с д Пирсон 1998 , с. 54.

- ^ Дойл Уайт, Итан (2015). Викка: история, вера и сообщество в современном языческом колдовстве . Издательство Ливерпульского университета. стр. 160–162.

- ^ «Индекс английского традиционного колдовства Бофорта» . Ассоциация домов Бофорта . 15 января 1999 года. Архивировано из оригинала 8 июля 2011 года . Проверено 2 апреля 2007 г.

- ^ «Различные виды колдовства» . Шестнадцатеричный архив . Архивировано из оригинала 18 июня 2007 года . Проверено 2 апреля 2007 г.

- ^ Пирсон 2007 , с. 2.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Пирсон 2007 , с. 3.

- ^ Раунтри 2015 , с. 16.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Бакленд 1986 , стр. 17, 18, 53.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с Пирсон 2002b , с. 142.

- ^ Пирсон 2002b , с. 138.

- ^ Пирсон 2002b , с. 139.

- ^ К., Эмбер (1998). Covencraft: Колдовство для троих и более . Ллевеллин. п. 228. ИСБН 1-56718-018-3 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с д Пирсон 2002b , с. 136.

- ^ Саломонсен 1998 , с. 143.

- ^ Гайли 1999 , с. 169 .

- ^ Родерик, Тимоти (2005). Викка: Год и день (1-е изд.). Сент-Пол, Миннесота: Публикации Ллевеллина. ISBN 0-7387-0621-3 . ОСЛК 57010157 .

- ^ Пирсон 1998 , с. 51.

- ^ Ховард, Майкл (2010). Современная Викка . Вудбери, Миннесота: Публикации Ллевеллина. стр. 299–301. ISBN 978-0-7387-1588-9 . OCLC 706883219 .

- ^ Смит, Дайан (2005). Викка и колдовство для чайников . Индианаполис, Индиана: Уайли. п. 125. ИСБН 0-7645-7834-0 . OCLC 61395185 .

- ^ Хаттон 1991 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Эззи 2002 , с. 117.

- ^ Ezzy 2003 , стр. 48–49.

- ^ Эззи 2003 , с. 50.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 2.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 14.

- ^ Хаттон 2003 , стр. 279–230; Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 14.

- ^ Бейкер 1996 , с. 187; Мальокко 1996 , с. 94; Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 14.

- ^ Дойл Уайт 2016 , с. 13.

- ^ Пирсон 2002 , с. 32.