Древнескандинавская религия

| Part of a series on the |

| Norsemen |

|---|

|

| WikiProject Norse history and culture |

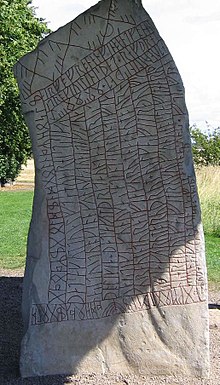

Древнескандинавская религия , также известная как скандинавское язычество , — это ветвь германской религии , которая развилась в прото-норвежский период, когда северогерманские народы выделились в отдельную ветвь германских народов . Оно было заменено христианством и забыто во время христианизации Скандинавии . Ученые реконструируют аспекты северогерманской религии с помощью исторической лингвистики , археологии , топонимики и записей, оставленных северогерманскими народами, таких как рунические надписи в Младшем Футарке , явно северогерманском расширении рунического алфавита. Многочисленные древнескандинавские XIII века произведения относятся к скандинавской мифологии , составной части северогерманской религии.

Древнескандинавская религия была политеистической , предполагавшей веру в различных богов и богинь . Эти божества в скандинавской мифологии были разделены на две группы: асов и ванов , которые, как сообщается в некоторых источниках, участвовали в древней войне, пока не осознали, что они одинаково могущественны. Среди наиболее распространенных божеств были боги Один и Тор . Этот мир также был населен различными другими мифологическими расами, в том числе йотнарами , гномами , эльфами и сухопутными духами . Скандинавская космология вращалась вокруг мирового дерева, известного как Иггдрасиль , с различными царствами, существующими наряду с человеческими, под названием Мидгард . К ним относятся несколько миров загробной жизни, некоторые из которых контролируются определенным божеством.

Transmitted through oral culture rather than through codified texts, Old Norse religion focused heavily on ritual practice, with kings and chiefs playing a central role in carrying out public acts of sacrifice. Various cultic spaces were used; initially, outdoor spaces such as groves and lakes were typically selected, but after the third century CE cult houses seem to also have been purposely built for ritual activity, although they were never widespread. Norse society also contained practitioners of Seiðr, a form of sorcery that some scholars describe as shamanistic. Various forms of burial were conducted, including both inhumation and cremation, typically accompanied by a variety of grave goods.

Throughout its history, varying levels of trans-cultural diffusion occurred among neighbouring peoples, such as the Sami and Finns. By the 12th century, Old Norse religion had been replaced by Christianity, with elements continuing into Scandinavian folklore. A revival of interest in Old Norse religion occurred amid the romanticist movement of the 19th century, during which it inspired a range of artworks. Academic research into the subject began in the early 19th century, initially influenced by the pervasive romanticist sentiment.

Terminology[edit]

The archaeologist Anders Andrén noted that "Old Norse religion" is "the conventional name" applied to the pre-Christian religions of Scandinavia.[1] See for instance[2] other terms used by scholarly sources include "pre-Christian Norse religion",[3] "Norse religion",[4] "Norse paganism",[5] "Nordic paganism",[6] "Scandinavian paganism",[7] "Scandinavian heathenism",[8] "Scandinavian religion",[9] "Northern paganism",[10] "Northern heathenism",[11] "North Germanic religion",[a][b] or "North Germanic paganism".[c][d] This Old Norse religion can be seen as part of a broader Germanic religion found across linguistically Germanic Europe; of the different forms of this Germanic religion, that of the Old Norse is the best-documented.[12]

Rooted in ritual practice and oral tradition,[12] Old Norse religion was fully integrated with other aspects of Norse life, including subsistence, warfare, and social interactions.[13] Open codifications of Old Norse beliefs were either rare or non-existent.[14] The practitioners of this belief system themselves had no term meaning "religion", which was only introduced with Christianity.[15] Following Christianity's arrival, Old Norse terms that were used for the pre-Christian systems were forn sið ("old custom") or heiðinn sið ("heathen custom"),[15] terms which suggest an emphasis on rituals, actions, and behaviours rather than belief itself.[16] The earliest known usage of the Old Norse term heiðinn is in the poem Hákonarmál; its uses here indicates that the arrival of Christianity has generated consciousness of Old Norse religion as a distinct religion.[17]

Old Norse religion has been classed as an ethnic religion,[18] and as a "non-doctrinal community religion".[13] It varied across time, in different regions and locales, and according to social differences.[19] This variation is partly due to its transmission through oral culture rather than codified texts.[20] For this reason, the archaeologists Andrén, Kristina Jennbert, and Catharina Raudvere stated that "pre-Christian Norse religion is not a uniform or stable category",[21] while the scholar Karen Bek-Pedersen noted that the "Old Norse belief system should probably be conceived of in the plural, as several systems".[22] The historian of religion Hilda Ellis Davidson stated that it would have ranged from manifestations of "complex symbolism" to "the simple folk-beliefs of the less sophisticated".[23]

During the Viking Age, the Norse likely regarded themselves as a more or less unified entity through their shared Germanic language, Old Norse.[24] The scholar of Scandinavian studies Thomas A. DuBois said Old Norse religion and other pre-Christian belief systems in Northern Europe must be viewed as "not as isolated, mutually exclusive language-bound entities, but as broad concepts shared across cultural and linguistic lines, conditioned by similar ecological factors and protracted economic and cultural ties".[25] During this period, the Norse interacted closely with other ethnocultural and linguistic groups, such as the Sámi, Balto-Finns, Anglo-Saxons, Greenlandic Inuit, and various speakers of Celtic and Slavic languages.[26] Economic, marital, and religious exchange occurred between the Norse and many of these other groups.[26] Enslaved individuals from the British Isles were common throughout the Nordic world during the Viking Age.[27] Different elements of Old Norse religion had different origins and histories; some aspects may derive from deep into prehistory, others only emerging following the encounter with Christianity.[28]

Sources[edit]

In Hilda Ellis Davidson's words, present-day knowledge of Old Norse religion contains "vast gaps", and we must be cautious and avoid "bas[ing] wild assumptions on isolated details".[29]

[edit]

A few runic inscriptions with religious content survive from Scandinavia, particularly asking Thor to hallow or protect a memorial stone;[30] carving his hammer on the stone also served this function.[31]

In contrast to the few runic fragments, a considerable body of literary and historical sources survive in Old Norse manuscripts using the Latin script, all of which were created after the Christianisation of Scandinavia, the majority in Iceland. The first extensive Nordic textual source for the Old Norse Religion was the Poetic Edda. Some of the poetic sources, in particular, the Poetic Edda and skaldic poetry, may have been originally composed by heathens, and Hávamál contains both information on heathen mysticism[32] and what Ursula Dronke referred to as "a round-up of ritual obligations".[33] In addition there is information about pagan beliefs and practices in the sagas, which include both historical sagas such as Snorri Sturluson's Heimskringla and the Landnámabók, recounting the settlement and early history of Iceland, and the so-called sagas of Icelanders concerning Icelandic individuals and groups; there are also more or less fantastical legendary sagas. Many skaldic verses are preserved in sagas. Of the originally heathen works, we cannot know what changes took place either during oral transmission or as a result of their being recorded by Christians;[34][35] the sagas of Icelanders, in particular, are now regarded by most scholars as more or less historical fiction rather than as detailed historical records.[36] A large amount of mythological poetry has undoubtedly been lost.[37]

One important written source is Snorri's Prose Edda, which incorporates a manual of Norse mythology for the use of poets in constructing kennings; it also includes numerous citations, some of them the only record of lost poems,[38] such as Þjóðólfr of Hvinir's Haustlöng. Snorri's Prologue eumerises the Æsir as Trojans, deriving Æsir from Asia, and some scholars have suspected that many of the stories that we only have from him are also derived from Christian medieval culture.[39]

[edit]

Additional sources remain by non-Scandinavians writing in languages other than Old Norse. The first non-Scandinavian textual source for the Old Norse Religion was Tacitus' book, the Germania, which dates back to around 100 CE[40] and describes religious practices of several Germanic peoples, but has little coverage of Scandinavia. In the Middle Ages, several Christian commentators also wrote about Scandinavian paganism, mostly from a hostile perspective.[40] The best known of these are Adam of Bremen's Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum (History of the Bishops of Hamburg), written between 1066 and 1072, which includes an account of the temple at Uppsala,[41][42] and Saxo Grammaticus' 12th-century Gesta Danorum (History of the Danes), which includes versions of Norse myths and some material on pagan religious practices.[43][44] In addition, Muslim Arabs wrote accounts of Norse people they encountered, the best known of which is Ibn Fadlan's 10th-century Risala, an account of Volga Viking traders that includes a detailed description of a ship burial.[45]

Archaeological and toponymic evidence[edit]

Since the literary evidence that represents Old Norse sources were recorded by Christians, archaeological evidence, especially of religious sites and burials is of great importance, particularly as a source of information on Norse religion before the conversion.[46][47] Many aspects of material culture—including settlement locations, artefacts and buildings—may cast light on beliefs, and archaeological evidence regarding religious practices indicates chronological, geographic and class differences far greater than are suggested by the surviving texts.[21]

Place names are an additional source of evidence. Theophoric place names, including instances where a pair of deity names occur near, provide an indication of the importance of the religion of those deities in different areas, dating back to before our earliest written sources. The toponymic evidence shows considerable regional variation,[48][49] and some deities, such as Ullr and Hǫrn, occur more frequently,[48] than Odin place-names occur, in other locations.[50][49]

Some place-names contain elements indicating that they were sites of religious activity: those formed with -vé, -hörgr, and -hof, words for religious sites of various kinds,[51] and also likely those formed with -akr or -vin, words for "field", when coupled with the name of a deity. Magnus Olsen developed a typology of such place names in Norway, from which he posited a development in pagan worship from groves and fields toward the use of temple buildings.[52]

Personal names are also a source of information on the popularity of certain deities; for example, Thor's name was an element in the names of both men and women, particularly in Iceland.[53]

Historical development[edit]

Iron Age origins[edit]

Andrén described Old Norse religion as a "cultural patchwork" which emerged under a wide range of influences from earlier Scandinavian religions. It may have had links to Nordic Bronze Age: while the putatively solar-oriented belief system of Bronze Age Scandinavia is believed to have died out around 500 BCE, several Bronze Age motifs—such as the wheel cross—reappear in later Iron Age contexts.[10] It is often regarded as having developed from earlier religious belief systems found among the Germanic Iron Age peoples.[54] The Germanic languages likely emerged in the first millennium BCE in present-day Denmark or northern Germany, after which they spread; several of the deities in Old Norse religion have parallels among other Germanic societies.[55] The Scandinavian Iron Age began around 500 to 400 BCE.[56]

Archaeological evidence is particularly important for understanding these early periods.[57] Accounts from this time were produced by Tacitus; according to the scholar Gabriel Turville-Petre, Tacitus' observations "help to explain" later Old Norse religion.[58] Tacitus described the Germanic peoples as having priests, open-air sacred sites, and seasonal sacrifices and feasts.[59] Tacitus notes that the Germanic peoples were polytheistic and mentions some of their deities trying to perceive them through Roman equivalents, so Romans could try to understand.[60]

Viking Age expansion[edit]

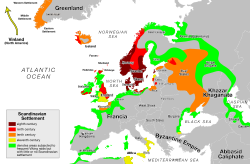

During the Viking Age, Norse people left Scandinavia and settled elsewhere throughout Northwestern Europe. Some of these areas, such as Iceland, the Orkney and Shetland Islands, and the Faroe Islands, were hardly populated, whereas other areas, such as England, Southwest Wales, Scotland, the Western Isles, Isle of Man, and Ireland, were already heavily populated.[61]

In the 870s, Norwegian settlers left their homeland and colonized Iceland, bringing their belief system with them.[62] Place-name evidence suggests that Thor was the most popular god on the island,[63] although there are also saga accounts of devotés of Freyr in Iceland,[64] including a "priest of Freyr" in the later Hrafnkels saga.[65] There are no place-names connected to Odin on the island.[66] Unlike other Nordic societies, Iceland lacked a monarchy and thus a centralising authority which could enforce religious adherence;[67] there were both Old Norse and Christian communities from the time of its first settlement.[68]

Scandinavian settlers brought Old Norse religion to Britain in the latter decades of the ninth century.[69] Several British place-names indicate possible religious sites;[70] for instance, Roseberry Topping in North Yorkshire was known as Othensberg in the twelfth century, a name deriving from the Old Norse Óðinsberg ("Hill of Óðin").[71] Several place-names also contain Old Norse references to religious entities, such as alfr, skratii, and troll.[72] The English church found itself in need of conducting a new conversion process to Christianise this incoming population.[73]

Christianisation and decline[edit]

The Nordic world first encountered Christianity through its settlements in the already Christian British Isles and through trade contacts with the eastern Christians in Novgorod and Byzantium.[74] By the time Christianity arrived in Scandinavia it was already the accepted religion across most of Europe.[75] It is not well understood how the Christian institutions converted these Scandinavian settlers, in part due to a lack of textual descriptions of this conversion process equivalent to Bede's description of the earlier Anglo-Saxon conversion.[76] However, it appears that the Scandinavian migrants had converted to Christianity within the first few decades of their arrival.[further explanation needed][77] After Christian missionaries from the British Isles—including figures like St Willibrord, St Boniface, and Willehad—had travelled to parts of northern Europe in the eighth century,[78] Charlemagne pushed for Christianisation in Denmark, with Ebbo of Rheims, Halitgar of Cambrai, and Willeric of Bremen proselytizing in the kingdom during the ninth century.[79] The Danish king Harald Klak converted (826), likely to secure his political alliance with Louis the Pious against his rivals for the throne.[80] The Danish monarchy reverted to Old Norse religion under Horik II (854 – c. 867).[81]

The Norwegian king Hákon the Good had converted to Christianity while in England. On returning to Norway, he kept his faith largely private but encouraged Christian priests to preach among the population; some pagans were angered and—according to Heimskringla—three churches built near Trondheim were burned down.[82] His successor, Harald Greycloak, was also a Christian but similarly had little success in converting the Norwegian population to his religion.[83] Haakon Sigurdsson later became the de facto ruler of Norway, and although he agreed to be baptised under pressure from the Danish king and allowed Christians to preach in the kingdom, he enthusiastically supported pagan sacrificial customs, asserting the superiority of the traditional deities and encouraging Christians to return to their veneration.[84] His reign (975–995) saw the emergence of a "state paganism", an official ideology which bound together Norwegian identity with pagan identity and rallied support behind Haakon's leadership.[85] Haakon was killed in 995 and Olaf Tryggvason, the next king, took power and enthusiastically promoted Christianity; he forced high-status Norwegians to convert, destroyed temples, and killed those he called 'sorcerers'.[86] Sweden was the last Scandinavian country to officially convert;[75] although little is known about the process of Christianisation, it is known that the Swedish kings had converted by the early 11th century and that the country was fully Christian by the early 12th.[87]

Olaf Tryggvason sent a Saxon missionary, Þangbrandr, to Iceland. Many Icelanders were angered by Þangbrandr's proselytising, and he was outlawed after killing several poets who insulted him.[88] Animosity between Christians and pagans on the island grew, and at the Althing in 998 both sides blasphemed each other's gods.[89] In an attempt to preserve unity, at the Althing in 999, an agreement was reached that the Icelandic law would be based on Christian principles, albeit with concessions to the pagan community. Private, albeit not public, pagan sacrifices and rites were to remain legal.[90]

Across Germanic Europe, conversion to Christianity was closely connected to social ties; mass conversion was the norm, rather than individual conversion.[91] A primary motivation for kings converting was the desire for support from Christian rulers, whether as money, imperial sanction, or military support.[91]Christian missionaries found it difficult convincing Norse people that the two belief systems were mutually exclusive;[92] the polytheistic nature of Old Norse religion allowed its practitioners to accept Jesus Christ as one god among many.[93]The encounter with Christianity could also stimulate new and innovative expressions of pagan culture, for instance through influencing various pagan myths.[94] As with other Germanic societies, syncretisation between incoming and traditional belief systems took place.[95] For those living in isolated areas, pre-Christian beliefs likely survived longer,[96] while others continued as survivals in folklore.[96]

Post-Christian survivals[edit]

By the 12th century, Christianity was firmly established across Northwestern Europe.[97] For two centuries, Scandinavian ecclesiastics continued to condemn paganism, although it is unclear whether it still constituted a viable alternative to Christian dominance.[98] These writers often presented paganism as being based on deceit or delusion;[99] some stated that the Old Norse gods had been humans falsely euhemerised as deities.[100]

Old Norse mythological stories survived in oral culture for at least two centuries, being recorded in the 13th century.[101] How this mythology was passed down is unclear; it is possible that pockets of pagans retained their belief system throughout the 11th and 12th centuries, or that it had survived as a cultural artefact passed down by Christians who retained the stories while rejecting any literal belief in them.[101] The historian Judith Jesch suggested that following Christianisation, there remained a "cultural paganism", the re-use of pre-Christian myth "in certain cultural and social contexts" that are officially Christian.[102] For instance, Old Norse mythological themes and motifs appear in poetry composed for the court of Cnut the Great, an eleventh-century Christian Anglo-Scandinavian king.[103]Saxo is the earliest medieval figure to take a revived interest in the pre-Christian beliefs of his ancestors, doing so not out of a desire to revive their faith but out of historical interest.[104] Snorri was also part of this revived interest, examining pagan myths from his perspective as a cultural historian and mythographer.[105] As a result, Norse mythology "long outlasted any worship of or belief in the gods it depicts".[106] There remained, however, remnants of Norse pagan rituals for centuries after Christianity became the dominant religion in Scandinavia (see Trollkyrka). Old Norse gods continued to appear in Swedish folklore up until the early 20th century. There are documented accounts of encounters with both Thor and Odin, along with a belief in Freja's power over fertility.[107]

Beliefs[edit]

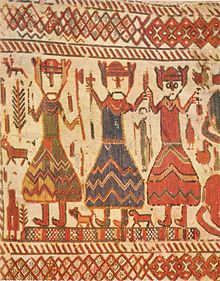

Norse mythology, stories of the Norse deities, is preserved in Eddic poetry and in Snorri Sturluson's guide for skalds, the Poetic Edda. Depictions of some of these stories can be found on picture stones in Gotland and in other visual records including some early Christian crosses, which attests to how widely known they were.[108] The myths were transmitted purely orally until the end of the period, and were subject to variation; one key poem, "Vǫluspá", is preserved in two variant versions in different manuscripts,[e] and Snorri's retelling of the myths sometimes varies from the other textual sources that are preserved.[109] There was no single authoritative version of a particular myth, and variation over time and from place to place is presumed, rather than "a single unified body of thought".[110][104] In particular, there may have been influences from interactions with other peoples, including northern Slavs, Finns, and Anglo-Saxons,[111] and Christian mythology exerted an increasing influence.[110][112]

Deities[edit]

Old Norse religion was polytheistic, with many anthropomorphic gods and goddesses, who express human emotions and in some cases are married and have children.[113][114] One god, Baldr, is said in the myths to have died. Archaeological evidence on the worship of particular gods is sparse, although placenames may also indicate locations where they were venerated. For some gods, particularly Loki,[115][116][117] there is no evidence of worship; however, this may be changed by new archaeological discoveries. Regions, communities, and social classes likely varied in the gods they venerated more or at all.[118][119] There are also accounts in sagas of individuals who devoted themselves to a single deity,[120] described as a fulltrúi or vinr (confidant, friend) as seen in Egill Skallagrímsson's reference to his relationship with Odin in his "Sonatorrek", a tenth-century skaldic poem for example.[121] This practice has been interpreted as heathen past influenced by the Christian cult of the saints. Although our literary sources are all relatively late, there are also indications of change over time.

Norse mythological sources, particularly Snorri and "Vǫluspá", differentiate between two groups of deities, the Æsir and the Vanir, who fought a war during which the Vanir broke down the walls of the Æsir's stronghold, Asgard, and eventually made peace utilizing a truce and the exchange of hostages. Some mythographers have suggested that this myth was based on recollection of a conflict in Scandinavia between adherents of different belief systems.[further explanation needed][122][123]

Major deities among the Æsir include Thor (who is often referred to in literary texts as Asa-Thor), Odin and Týr. Very few Vanir are named in the sources: Njǫrðr, his son Freyr, and his daughter Freyja; according to Snorri all of these could be called Vanaguð (Vanir-god), and Freyja also Vanadís (Vanir-dís).[124] The status of Loki within the pantheon is problematic, and according to "Lokasenna" and "Vǫluspá" and Snorri's explanation, he is imprisoned beneath the earth until Ragnarok, when he will fight against the gods. As far back as 1889 Sophus Bugge suggested this was the inspiration for the myth of Lucifer.[125]

Some of the goddesses—Skaði, Rindr, Gerðr are jötnar origins.

The general Old Norse word for the goddesses is Ásynjur, which is properly the feminine of Æsir. An old word for goddess may be dís, which is preserved as the name of a group of female supernatural beings.[126]

Localised and ancestral deities[edit]

Ancestral deities were common among Finno-Ugric peoples and remained a strong presence among the Finns and Sámi after Christianisation.[127] Ancestor veneration may have played a part in the private religious practices of Norse people in their farmsteads and villages;[128][129] in the 10th century, Norwegian pagans attempted to encourage the Christian king Haakon to take part in an offering to the gods by inviting him to drink a toast to the ancestors alongside several named deities.[128]

Þorgerðr Hölgabrúðr and Irpa appear to have been personal or family goddesses venerated by Haakon Sigurdsson, a late pagan ruler of Norway.[130]

There are also likely to have been local and family fertility cults; there is one reported example from pagan Norway in the family cult of Vǫlsi, where a deity called Mǫrnir is invoked.[131][132]

Other beings[edit]

The Norns are female figures who determine individuals' fate. Snorri describes them as a group of three, but he and other sources also allude to larger groups of Norns who decide the fate of newborns.[133] It is uncertain whether they were worshipped.[134]The landvættir, spirits of the land, were thought to inhabit certain rocks, waterfalls, mountains, and trees, and offerings were made to them.[135] For many, they may have been more important in daily life than the gods.[136] Texts also mention various kinds of elves and dwarfs. Fylgjur, guardian spirits, generally female, were associated with individuals and families. Hamingjur, dísir and swanmaidens are female supernatural figures of uncertain stature within the belief system; the dísir may have functioned as tutelary goddesses.[137] Valkyries were associated with the myths concerning Odin, and also occur in heroic poetry such as the Helgi lays, where they are depicted as princesses who assist and marry heroes.[138][139]

Conflict with the jötnar and gýgjar (often glossed as giants and giantesses respectively) is a frequent motif in the mythology.[140] They are described as both the ancestors and enemies of the gods.[141] Gods marry gýgjar but jötnar's attempts to couple with goddesses are repulsed.[142] Most scholars believe the jötnar were not worshipped, although this has been questioned.[143] The Eddic jötnar have parallels with their later folkloric counterparts, although unlike them they have much wisdom.[144]

Cosmology[edit]

Several accounts of the Old Norse cosmogony, or creation myth, appear in surviving textual sources, but there is no evidence that these were certainly produced in the pre-Christian period.[145] It is possible that they were developed during the encounter with Christianity, as pagans sought to establish a creation myth complex enough to rival that of Christianity;[further explanation needed][146] these accounts could also be the result of Christian missionaries interpreting certain elements and tales found in the Old Norse culture and presenting them to be creation myths and a cosmogony, parallel to that of the Bible, in part to aid the Old Norse in the understanding of the new Christian religion through the use of native elements as a means to facilitate conversion (a common practice employed by missionaries to ease the conversion of people from different cultures across the globe. See Syncretism). According to the account in Völuspá, the universe was initially a void known as Ginnungagap. There then appeared a jötunn, Ymir, and after him the gods, who lifted the earth out of the sea.[147] A different account is provided in Vafþrúðnismál, which describes that the world is made from the components of Ymir's body: the earth from his flesh, the mountains from his bones, the sky from his skull, and the sea from his blood.[147] Grímnismál also describes the world being fashioned from Ymir's corpse, although adds the detail that the jötnar emerged from a spring known as Élivágar.[148]

In Snorri's Gylfaginning, it is again stated that the Old Norse cosmogony began with a belief in Ginnungagap, the void. From this emerged two realms, the icy, misty Niflheim and the fire-filled Muspell, the latter ruled over by fire-jötunn, Surtr.[149] A river produced by these realms coagulated to form Ymir, while a cow known as Audumbla then appeared to provide him with milk.[150] Audumbla licked a block of ice to free Buri, whose son Bor married a gýgr named Bestla.[146] Some of the features of this myth, such as the cow Audumbla, are of unclear provenance; Snorri does not specify where he obtained these details as he did for other parts of the myths, and it may be that these were his inventions.[146]

Völuspá portrays Yggdrasil as a giant ash tree.[151] Grímnismál claims that the deities meet beneath Yggdrasil daily to pass judgement.[152] It also claims that a serpent gnaws at its roots while a deer grazes from its higher branches; a squirrel runs between the two animals, exchanging messages.[152] Grímnismál also claims that Yggdrasil has three roots; under one resides the goddess Hel, under another the frost-þursar, and under the third humanity.[152] Snorri also relates that Hel and the frost-þursar live under two of the roots but places the gods, rather than humanity, under the third root.[152]The term Yggr means "the terrifier" and is a synonym for Oðinn, while drasill was a poetic word for a horse; "Yggdrasil" thereby means "Oðinn's Steed".[153] This idea of a cosmic tree has parallels with those from various other societies, and may reflect part of a common Indo-European heritage.[154]

The Ragnarok story survives in its fullest exposition in Völuspá, although elements can also be seen in earlier poetry.[155] The Ragnarok story suggests that the idea of an inescapable fate pervaded Norse worldviews.[156] There is much evidence that Völuspá was influenced by Christian belief,[157] and it is also possible that the theme of conflict being followed by a better future—as reflected in the Ragnarok story—perhaps reflected the period of conflict between paganism and Christianity.[158]

Afterlife[edit]

Old Nordic religion had several fully developed ideas about death and the afterlife.[159] Snorri refers to multiple realms which welcome the dead;[160] although his descriptions reflect a likely Christian influence, the idea of a plurality of other worlds is likely pre-Christian.[161] Unlike Christianity, Old Norse religion does not appear to have adhered to the belief that moral concerns impacted an individual's afterlife destination.[162]

Warriors who died in battle became the Einherjar and were taken to Oðinn's hall, Valhalla. There they waited until Ragnarok when they would fight alongside the Æsir.[163] According to the poem Grímnismál, Valhalla had 540 doors and a wolf stood outside its western door, while an eagle flew overhead.[164] In that poem, it is also claimed that a boar named Sæhrímnir is eaten every day and that a goat named Heiðrún stands atop the hall's roof producing an endless supply of mead.[164] It is unclear how widespread a belief in Valhalla was in Norse society; it may have been a literary creation designed to meet the ruling class' aspirations since the idea of deceased warriors owing military service to Oðinn parallels the social structure between warriors and their lord.[165] There is no archaeological evidence clearly alluding to a belief in Valhalla.[166]

According to Snorri, while one-half of the slain go to Valhalla, the others go to Frejya's hall, Fólkvangr, and those who die from disease or old age go to a realm known as Hel;[167] it was here that Baldr went after his death.[160] The concept of Hel as an afterlife location never appears in pagan-era skaldic poetry, where "Hel" always references the eponymous goddess.[168] Snorri also mentions the possibility of the dead reaching the hall of Brimir in Gimlé, or the hall of Sindri in the Niðafjöll Mountains.[169]

Various sagas and the Eddic poem Helgakviða Hundingsbana II refer to the dead residing in their graves, where they remain conscious.[170] In these thirteenth century sources, ghosts (Draugr) are capable of haunting the living.[171] In both Laxdæla Saga and Eyrbyggja Saga, connections are drawn between pagan burials and hauntings.[172]

In mythological accounts, the deity most closely associated with death is Oðinn. In particular, he is connected with death by hanging; this is apparent in Hávamál, a poem found in the Poetic Edda.[173] In stanza 138 of Hávamál, Oðinn describes his self-sacrifice, in which he hangs himself on Yggdrasill, the world tree, for nine nights, to attain wisdom and magical powers.[174] In the late Gautreks Saga, King Víkarr is hanged and then punctured by a spear; his executioner says "Now I give you to Oðinn".[174]

Cultic practice[edit]

Textual accounts suggest a spectrum of rituals, from large public events to more frequent private and family rites, which would have been interwoven with daily life.[175][176] However, written sources are vague about Norse rituals, and many are invisible to us now even with the assistance of archaeology.[177][178] Sources mention some rituals addressed to particular deities, but the understanding of the relationship between Old Norse ritual and myth remains speculative.[179]

Religious rituals[edit]

Sacrifice[edit]

The primary religious ritual in Norse religion appears to have been sacrifice, or blót.[180] Many texts, both Old Norse and others refer to sacrifices. The Saga of Hákon the Good in Heimskringla states that there were obligatory blóts, at which animals were slaughtered and their blood, called hlaut, sprinkled on the altars and the inside and outside walls of the temple, and ritual toasts were drunk during the ensuing sacrificial feast; the cups were passed over the fire and they and the food were consecrated with a ritual gesture by the chieftain; King Hákon, a Christian, was forced to participate but made the sign of the cross.[181] The description of the temple at Uppsala in Adam of Bremen's History includes an account of a festival every nine years at which nine males of every kind of animal were sacrificed and the bodies hung in the temple grove.[182] There may have been many methods of sacrifice: several textual accounts refer to the body or head of the slaughtered animal being hung on a pole or tree.[183] In addition to seasonal festivals, an animal blót could take place, for example, before duels, after the conclusion of business between traders, before sailing to ensure favourable winds, and at funerals.[184] Remains of animals from many species have been found in graves from the Old Norse period,[185][186] and Ibn Fadlan's account of a ship burial includes the sacrifice of a dog, draft animals, cows, a rooster and a hen as well as that of a servant girl.[187]

In the Eddic poem "Hyndluljóð", Freyja expresses appreciation for the many sacrifices of oxen made to her by her acolyte, Óttar.[188] In Hrafnkels saga, Hrafnkell is called Freysgoði for his many sacrifices to Freyr.[189][64] There may also be markers by which we can distinguish sacrifices to Odin,[190] who was associated with hanging,[191] and some texts particularly associate the ritual killing of a boar with sacrifices to Freyr;[191] but in general, archaeology is unable to identify the deity to whom a sacrifice was made.[190]

The texts frequently allude to human sacrifice. Temple wells in which people were sacrificially drowned are mentioned in Adam of Bremen's account of Uppsala[192] and in Icelandic sagas, where they are called blótkelda or blótgrǫf,[193] and Adam of Bremen also states that human victims were included among those hanging in the trees at Uppsala.[194] In Gautreks saga, people sacrifice themselves during a famine by jumping off cliffs,[195] and both the Historia Norwegiæ and Heimskringla refer to the willing death of King Dómaldi as a sacrifice after bad harvests.[196] Mentions of people being "sentenced to sacrifice" and of the "wrath of the gods" against criminals suggest a sacral meaning for the death penalty;[197] in Landnamabók the method of execution is given as having the back broken on a rock.[195] It is possible that some of the bog bodies recovered from peat bogs in northern Germany and Denmark and dated to the Iron Age were human sacrifices.[198] Such a practice may have been connected to the execution of criminals or of prisoners of war,[199] and Tacitus also states that such type of execution was used as a punishment for "the coward, the unwarlike and the man stained with abominable vices" for the reason that these were considered "infamies that ought to be buried out of sight";[f] on the other hand, some textual mentions of a person being "offered" to a deity, such as a king offering his son, may refer to a non-sacrificial "dedication".[200]

Archaeological evidence supports Ibn Fadlan's report of funerary human sacrifice: in various cases, the burial of someone who died of natural causes is accompanied by another who died a violent death.[190][201] For example, at Birka a decapitated young man was placed atop an older man buried with weapons, and at Gerdrup, near Roskilde, a woman was buried alongside a man whose neck had been broken.[202] Many of the details of Ibn Fadlan's account are born out by archaeology;[203][204][115] and it is possible that those elements which are not visible in the archaeological evidence—such as the sexual encounters—are also accurate.[204]

Deposition[edit]

Deposition of artefacts in wetlands was a practice in Scandinavia during many periods of prehistory.[205][206][207] In the early centuries of the Common Era, huge numbers of destroyed weapons were placed in wetlands: mostly spears and swords, but also shields, tools, and other equipment. Beginning in the 5th century, the nature of the wetland deposits changed; in Scandinavia, fibulae and bracteates were placed in or beside wetlands from the 5th to the mid-6th centuries, and again beginning in the late 8th century,[208] when weapons, as well as jewellery, coins and tools, again began to be deposited, the practice lasting until the early 11th century.[208] This practice extended to non-Scandinavian areas inhabited by Norse people; for example in Britain, a sword, tools, and the bones of cattle, horses and dogs were deposited under a jetty or bridge over the River Hull.[209] The precise purposes of such depositions are unclear.[citation needed]

It is harder to find ritualised deposits on dry land. However, at Lunda (meaning "grove") near Strängnäs in Södermanland, archaeological evidence has been found at a hill of presumably ritual activity from the 2nd century BCE until the 10th century CE, including deposition of unburnt beads, knives and arrowheads from the 7th to the 9th century.[210][207] Also during excavations at the church in Frösö, bones of bear, elk, red deer, pigs, cattle, and either sheep or goats were found surrounding a birch tree, having been deposited in the 9th or 10th century; the tree likely had sacrificial associations and perhaps represented Yggdrasill.[210][211]

Rites of passage[edit]

A child was accepted into the family via a ritual of sprinkling with water (Old Norse ausa vatni) which is mentioned in two Eddic poems, "Rígsþula" and "Hávamál", and was afterwards given a name.[212] The child was frequently named after a dead relative, since there was a traditional belief in rebirth, particularly in the family.[213]

Old Norse sources also describe rituals for adoption (the Norwegian Gulaþing Law directs the adoptive father, followed by the adoptive child, then all other relatives, to step in turn into a specially made leather shoe) and blood brotherhood (a ritual standing on the bare earth under a specially cut strip of grass, called a jarðarmen).[214]

Weddings occur in Icelandic family sagas. The Old Norse word brúðhlaup has cognates in many other Germanic languages and means "bride run"; it has been suggested that this indicates a tradition of bride-stealing, but other scholars including Jan de Vries interpreted it as indicating a rite of passage conveying the bride from her birth family to that of her new husband.[215] The bride wore a linen veil or headdress; this is mentioned in the Eddic poem "Rígsþula".[216] Freyr and Thor are each associated with weddings in some literary sources.[217] In Adam of Bremen's account of the pagan temple at Uppsala, offerings are said to be made to Fricco (presumably Freyr) on the occasion of marriages,[182] and in the Eddic poem "Þrymskviða", Thor recovers his hammer when it is laid in his disguised lap in a ritual consecration of the marriage.[218][219] "Þrymskviða" also mentions the goddess Vár as consecrating marriages; Snorri Sturluson states in Gylfaginning that she hears the vows men and women make to each other, but her name probably means "beloved" rather than being etymologically connected to Old Norse várar, "vows".[220]

Burial of the dead is the Norse rite of passage about which we have most archaeological evidence.[221] There is considerable variation in burial practices, both spatially and chronologically, which suggests a lack of dogma about funerary rites.[221][222] Both cremations and inhumations are found throughout Scandinavia,[221][223] but in Viking Age Iceland there were inhumations but, with one possible exception, no cremations.[223] The dead are found buried in pits, wooden coffins or chambers, boats, or stone cists; cremated remains have been found next to the funeral pyre, buried in a pit, in a pot or keg, and scattered across the ground.[221] Most burials have been found in cemeteries, but solitary graves are not unknown.[221] Some grave sites were left unmarked, others memorialised with standing stones or burial mounds.[221]

Grave goods feature in both inhumation and cremation burials.[224] These often consist of animal remains; for instance, in Icelandic pagan graves, the remains of dogs and horses are the most common grave goods.[225] In many cases, the grave goods and other features of the grave reflect social stratification, particularly in the cemeteries at market towns such as Hedeby and Kaupang.[224] In other cases, such as in Iceland, cemeteries show very little evidence of it.[223]

Ship burial is a form of elite inhumation attested both in the archaeological record and in Ibn Fadlan's written account. Excavated examples include the Oseberg ship burial near Tønsberg in Norway, another at Klinta on Öland,[226] and the Sutton Hoo ship burial in England.[227] A boat burial at Kaupang in Norway contained a man, woman, and baby lying adjacent to each other alongside the remains of a horse and dismembered dog. The body of a second woman in the stern was adorned with weapons, jewellery, a bronze cauldron, and a metal staff; archaeologists have suggested that she may have been a sorceress.[226] In certain areas of the Nordic world, namely coastal Norway and the Atlantic colonies, smaller boat burials are sufficiently common to indicate it was no longer only an elite custom.[227]

Ship burial is also mentioned twice in the Old Norse literary-mythic corpus. A passage in Snorri Sturluson's Ynglinga Saga states that Odin—whom he presents as a human king later mistaken for a deity—instituted laws that the dead would be burned on a pyre with their possessions, and burial mounds or memorial stones erected for the most notable men.[228][229] Also in his Prose Edda, the god Baldr is burned on a pyre on his ship, Hringhorni, which is launched out to sea with the aid of the gýgr Hyrrokkin; Snorri wrote after the Christianisation of Iceland, but drew on Úlfr Uggason's skaldic poem "Húsdrápa".[230]

Mysticism, magic, animism and shamanism[edit]

The myth preserved in the Eddic poem "Hávamál" of Odin hanging for nine nights on Yggdrasill, sacrificing himself to secure knowledge of the runes and other wisdom in what resembles an initiatory rite,[231][232] is evidence of mysticism in Old Norse religion.[233]

The gods were associated with two distinct forms of magic. In "Hávamál" and elsewhere, Odin is particularly associated with the runes and with galdr.[234][235] Charms, often associated with the runes, were a central part of the treatment of disease in both humans and livestock in Old Norse society.[236] In contrast seiðr and the related spæ, which could involve both magic and divination,[237] were practised mostly by women, known as vǫlur and spæ-wives, often in a communal gathering at a client's request.[237] 9th- and 10th-century female graves containing iron staffs and grave goods have been identified on this basis as those of seiðr practitioners.[238] Seiðr was associated with the Vanic goddess Freyja; according to a euhemerized account in Ynglinga saga, she taught seiðr to the Æsir,[239] but it involved so much ergi ("unmanliness, effeminacy") that other than Odin himself, its use was reserved for priestesses.[240][241][242] There are, however, mentions of male seiðr workers, including elsewhere in Heimskringla, where they are condemned for their perversion.[243]

In Old Norse literature, practitioners of seiðr are sometimes described as foreigners, particularly Sami or Finns or in rarer cases from the British Isles.[244] Practitioners such as Þorbjörg Lítilvölva in the Saga of Erik the Red appealed to spirit helpers for assistance.[237] Many scholars have pointed to this and other similarities between what is reported of seiðr and spæ ceremonies and shamanism.[245] The historian of religion Dag Strömbäck regarded it as a borrowing from Sami or Balto-Finnic shamanic traditions,[246][247] but there are also differences from the recorded practices of Sami noaidi.[248] Since the 19th century, some scholars have sought to interpret other aspects of Old Norse religion itself by comparison with shamanism;[249] for example, Odin's self-sacrifice on the World Tree has been compared to Finno-Ugric shamanic practices.[250] However, the scholar Jan de Vries regarded seiðr as an indigenous shamanic development among the Norse,[251][252] and the applicability of shamanism as a framework for interpreting Old Norse practices, even seiðr, is disputed by some scholars.[199][253]

Religious sites[edit]

Выездные обряды [ править ]

Религиозные обряды часто проводились на открытом воздухе. Например, в Хове в Трёнделаге , Норвегия, подношения размещались возле столбов с изображениями богов. [254] Термины, особенно связанные с богослужением на открытом воздухе, — это ве (святилище) и хёргр (каир или каменный алтарь ). Многие топонимы содержат эти элементы в связи с именем божества, и, например, в Лилле Уллеви (составленном с именем бога Улля ) в приходе Бро, Уппланд , Швеция, археологи обнаружили покрытую камнями ритуальную зону, на которой были сданы подношения, в том числе серебряные предметы, кольца и вилка для мяса. [255] Данные по географическим названиям позволяют предположить, что культовые практики могли также иметь место на самых разных местах, включая поля и луга ( вангр , вин ), реки, озера и болота , рощи ( лундр ), отдельные деревья и скалы. [176] [256]

В некоторых исландских сагах упоминаются священные места. И в «Саге о Ланднамабоке» , и в «Саге об Эйрбюггья» говорится, что члены семьи, которые особенно поклонялись Тору, после смерти перешли на гору Хельгафелл (святая гора), которую нельзя было осквернять кровопролитием или экскрементами или даже смотреть на нее без предварительного мытья. . [257] [258] Поклонение горам также упоминается в Ланднамабоке как старая норвежская традиция, к которой Ауд Глубокомыслящей семья вернулась после ее смерти; Ученый Хильда Эллис Дэвидсон считала, что это связано, в частности, с поклонением Тору. [257] [259] В саге о Вига-Глумсе поле Витацгьяфи (определенный дающий) связано с Фрейром и также не должно быть осквернено. [260] [261] Ученый Стефан Бринк утверждал, что в дохристианской Скандинавии можно говорить о «мифической и сакральной географии». [262]

Храмы [ править ]

В некоторых сагах говорится о культовых домах или храмах, обычно называемых на древнескандинавском языке термином hof . Подробные описания больших храмов, включая отдельную область с изображениями богов и окроплением жертвенной кровью с помощью веток, подобно христианскому использованию аспергиллума , есть в «Саге о Кьялнесинге» и «Саге об Эйрбиггье» ; , сделанное Снорри Описание блота в Хеймскрингле, добавляет больше подробностей о окроплении кровью. [263] В латинской истории Адама Бременского XI века подробно описывается великий храм в Уппсале , в котором регулярно приносились человеческие жертвоприношения и содержащий статуи Тора, Вотана и Фрикко (предположительно Фрейра ); схолион . добавляет деталь: с карниза свисала золотая цепь [264] [265]

Эти детали кажутся преувеличенными и, вероятно, обязаны христианским церквям, а в случае Упсалы — библейскому описанию храма Соломона . [263] [264] [265] Основываясь на нехватке археологических свидетельств о посвященных культовых домах, особенно под ранними церковными зданиями в Скандинавии, где их ожидали найти, а также на Тацита заявлении в Германии о том, что германские племена не ограничивали своих божеств зданиями, [266] многие ученые считают, что хофс - это в значительной степени христианская идея дохристианской практики. В 1966 году, основываясь на результатах комплексного археологического исследования большей части Скандинавии, датский археолог Олаф Олсен предложил модель «храмовой фермы»: вместо того, чтобы хоф представлял собой специальное здание, а был большой длинный дом , особенно дом Самый известный фермер округа, при необходимости служил местом проведения общественных культовых торжеств. [267] [268]

Однако после исследования Олсена в Скандинавии были обнаружены археологические свидетельства храмовых построек. Хотя интерпретация Суне Линдквиста ям для столбов, которые он нашел под церковью в Гамла Упсале, как остатков почти квадратного здания с высокой крышей, была принятием желаемого за действительное, [269] раскопки неподалеку в 1990-х годах обнаружили как поселение, так и длинное здание, которое могло быть либо длинным домом, сезонно используемым как культовый дом, либо специальным хофом. [270] Строительная площадка в Хофстадире, недалеко от Миватна в Исландии, которая была предметом особого внимания в работе Ольсена, с тех пор была повторно раскопана, а планировка здания и дальнейшие открытия останков ритуально забитых животных теперь позволяют предположить, что это был культовый дом. пока не был ритуально оставлен. [271] Другие здания, которые были интерпретированы как культовые дома, были найдены в Борге в Эстергётланде , Лунде в Седерманланде , [180] и Уппакра в Скании , [272] [273] Остатки одного языческого храма были найдены под средневековой церковью в Мэре в Норд-Трёнделаге , Норвегия. [254] [274]

В Норвегии слово hof , похоже, заменило старые термины, относящиеся к культовым местам на открытом воздухе в эпоху викингов ; [275] Было высказано предположение, что использование культовых зданий было введено в Скандинавию, начиная с III века, на основе христианских церквей, которые тогда распространялись в Римской империи, как часть ряда политических и религиозных изменений, которые тогда переживало скандинавское общество. [238] Некоторые из обнаруженных культовых домов расположены в так называемых археологами «центральных местах»: поселениях с различными религиозными, политическими, судебными и торговыми функциями. [276] [272] Некоторые из этих центральных мест имеют топонимы с культовыми ассоциациями, такие как Гудме (дом богов), Ва ( ви ) и Хельго (священный остров). [272] Некоторые археологи утверждают, что они были созданы, чтобы отразить древнескандинавскую космологию, таким образом соединяя ритуальные практики с более широкими мировоззрениями. [272] [277]

Священники и цари [ править ]

Нет никаких свидетельств профессионального жречества у норвежцев, а скорее культовая деятельность осуществлялась членами общины, которые имели и другие социальные функции и положения. [278] В древнескандинавском обществе религиозная власть была привязана к светской власти; не было разделения между экономическими, политическими и символическими институтами. [279] И саги о норвежских королях, и рассказ Адама Бременского утверждают, что короли и вожди играли заметную роль в культовых жертвоприношениях. [278] В средневековой Исландии годи играла социальную роль, сочетавшую в себе религиозные, политические и судебные функции. [278] отвечал за служение вождем округа, ведение юридических споров и поддержание порядка среди своих тингменов. [280] Большинство данных свидетельствуют о том, что публичная культовая деятельность была в основном прерогативой мужчин с высоким статусом в древнескандинавском обществе. [281] Однако есть исключения. В «Ланднамабуке» говорится о двух женщинах, занимавших должность гыджи , обе из которых были членами местных вождей. [280] В рассказе Ибн Фадлана о русах он описывает пожилую женщину, известную как «Ангел смерти», которая руководила погребальным ритуалом. [226]

Среди ученых было много споров о том, практиковалось ли сакральное царствование среди древнескандинавских общин, в которых монарх был наделен божественным статусом и, таким образом, отвечал за обеспечение удовлетворения потребностей сообщества сверхъестественными средствами. [282] Доказательством этого является поэма Инглингатала , в которой шведы убивают своего короля Домальде после голода. [283] Однако возможны и другие интерпретации этого события, помимо сакрального царствования; например, Домальде мог быть убит в результате политического переворота. [283]

Иконография и образы [ править ]

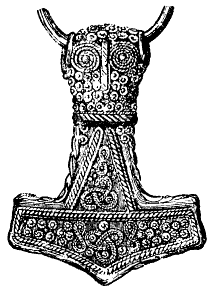

Самым распространенным религиозным символом в древнескандинавской религии эпохи викингов был Мьёлльнир, молот Тора. [284] Этот символ впервые появляется в девятом веке и может быть сознательным ответом на символику христианского креста. [28] Хотя подвески Мьёльнир встречаются по всему миру викингов, чаще всего их можно найти в могилах современной Дании, юго-восточной Швеции и южной Норвегии; их широкое распространение говорит об особой популярности Тора. [285] Подвески Мьёльнир, обнаруженные в могилах погребений, чаще встречаются в женских могилах, чем в мужских. [286] Раньше образцы делались из железа, бронзы или янтаря. [284] хотя серебряные подвески вошли в моду еще в десятом веке. [284] Возможно, это было ответом на растущую популярность христианских крестов-амулетов. [287]

Два религиозных символа, возможно, тесно сосуществовали; Одним из археологических свидетельств, подтверждающих это, является форма из мыльного камня для отливки подвесок, обнаруженная в Тренгордене в Дании. В этой форме было место для Мьёлльнира и подвески с распятием рядом, что позволяет предположить, что ремесленник, производивший эти подвески, обслуживал обе религиозные общины. [288] Обычно их интерпретировали как защитный символ, хотя они также могли быть связаны с плодородием, их носили в качестве амулетов, талисманов на удачу или источников защиты. [289] Однако около 10 процентов из тех, что были обнаружены во время раскопок, были помещены на урны для кремации, что позволяет предположить, что они имели место в определенных погребальных ритуалах. [286]

Боги и богини изображались в фигурках, подвесках, фибулах, а также в виде изображений на оружии. [290] Тора обычно узнают на изображениях по тому, как он несет Мьёлльнир. [290] Иконографический материал, предполагающий, что другие божества встречаются реже, чем те, которые связаны с Тором. [286] Некоторые графические свидетельства, в первую очередь изображения камней, пересекаются с мифологией, записанной в более поздних текстах. [159] Эти камни с изображениями, изготовленные в материковой Скандинавии в эпоху викингов, являются самыми ранними известными визуальными изображениями скандинавских мифологических сцен. [30] Тем не менее неясно, какую функцию имели эти изображения-камни и что они значили для сообществ, которые их производили. [30]

Один был идентифицирован на различных золотых брактеатах, изготовленных в пятом и шестом веках. [290] Некоторые фигурки интерпретировались как изображения божеств. Изображение Линдби из Сконе, Швеция, часто интерпретируется как Один из-за отсутствия глаза; [291] бронзовая статуэтка из Эйрарланда в Исландии в образе Тора, потому что держит молот. [292] Бронзовую статуэтку из Ряллинге в Седерманланде приписывают Фрейру, потому что у нее большой фаллос, а серебряный кулон из Аски в Эстергётланде считают Фрейей, потому что она носит ожерелье, которое может быть Брисингаменом. [290]

Еще один образ, который часто встречается в скандинавских произведениях искусства этого периода, — это валкнут (этот термин современный, а не древнескандинавский). [293] Эти символы могут иметь определенную ассоциацию с Одином, поскольку они часто сопровождают изображения воинов на каменных изображениях. [294]

Влияние [ править ]

и эстетика политика Романтизм ,

Во время романтического движения XIX века различные северные европейцы проявляли растущий интерес к древнескандинавской религии, видя в ней древнюю дохристианскую мифологию, которая представляла собой альтернативу доминирующей классической мифологии . В результате художники изображали скандинавских богов и богинь в своих картинах и скульптурах, а их имена наносились на улицы, площади, журналы и компании по всей Северной Европе. [295]

Мифологические истории, заимствованные из древнескандинавских и других германских источников, вдохновили различных художников, в том числе Рихарда Вагнера , который использовал эти повествования в качестве основы для своего «Кольца Нибелунгов» . [295] Этими древнескандинавскими и германскими сказками также вдохновился Дж. Р. Р. Толкин , который использовал их при создании своего легендариума , вымышленной вселенной, в которой он разворачивал действие таких романов, как «Властелин колец» . [295] В 1930-х и 1940-х годах элементы древнескандинавской и других германских религий были приняты нацистской Германией . [295] После падения нацистов различные правые группы продолжают использовать элементы древнескандинавской и германской религии в своих символах, названиях и упоминаниях; [295] некоторые неонацистские группы, например, используют Мьёльнир в качестве символа. [296]

Теории о шаманском компоненте древнескандинавской религии были приняты формами нордического неошаманизма ; группы, практикующие то, что они называли сейдр, были созданы в Европе и США к 1990-м годам. [297]

Научное исследование [ править ]

Исследования древнескандинавской религии носили междисциплинарный характер, в них участвовали историки, археологи, филологи, исследователи географических названий, литературоведы и историки религии. [295] Ученые разных дисциплин склонны использовать разные подходы к материалу; например, многие литературоведы весьма скептически относились к тому, насколько точно древнескандинавские тексты изображают дохристианскую религию, тогда как историки религии склонны считать эти изображения очень точными. [298]

Интерес к скандинавской мифологии возродился в восемнадцатом веке. [299] и ученые обратили на это внимание в начале 19 века. [295] Поскольку это исследование возникло на фоне европейского романтизма, многие ученые, работавшие в XIX и XX веках, основывали свой подход на основе национализма и находились под сильным влиянием своих интерпретаций романтических представлений о государственности , завоеваниях и религии. [300] Их понимание культурного взаимодействия также было окрашено европейским колониализмом и империализмом XIX века. [301] Многие считали дохристианскую религию единственной и неизменной, напрямую приравнивали религию к нации и проецировали современные национальные границы на прошлое эпохи викингов. [301]

Из-за использования нацистами древнескандинавской и германской иконографии после Второй мировой войны академические исследования древнескандинавской религии сильно сократились . [295] Научный интерес к этой теме возобновился в конце 20 века. [295] К 21 веку древнескандинавская религия считалась одной из самых известных нехристианских религий Европы, наряду с религиями Греции и Рима . [302]

См. также [ править ]

Примечания [ править ]

- ^ «Поскольку религии и языки часто распространяются с разной скоростью и охватывают разные территории, вопрос о древности религиозных структур и основных элементов северогерманской религии рассматривается отдельно от вопроса о возрасте языка» ( Вальтер де Грюйтер 2002 :390)

- ^ «Умирающий бог северогерманской религии - Бальдр, финикийский - Баал» ( Веннеманн 2012 :390)

- ^ « Аргументы Куна восходят, по крайней мере, к его эссе о северогерманском язычестве в раннехристианскую эпоху» ( Найлс и Амодио 1989 :25)

- ^ «Подлинные источники со времен северогерманского язычества (рунические надписи, древняя поэзия и т. д.)» ( Lönnroth 1965 :25)

- ^ Кроме стихов, приведенных в « Прозаической Эдде» , которые по большей части близки к одному из двух. Дронке, Поэтическая Эдда , Том 2: Мифологические стихи , Оксфорд: Оксфордский университет, 1997, респ. 2001, ISBN 978-0-19-811181-8 , стр. 61–62, 68–79.

- ^ «Предателей и дезертиров вешают на деревьях; труса, невоинственного, человека, запятнанного отвратительными пороками, погружают в трясину трясины, над ним ставят преграду. Это различие в наказании означает, что преступление, по их мнению, будучи наказанным, должно быть разоблачено, а позор должен быть спрятан от посторонних глаз». ( Германия , глава XII)

Ссылки [ править ]

- ^ Андрен 2011 , стр. 846; Андрен 2014 , стр. 14.

- ^ Нордланд 1969 , стр. 66; Турвиль-Петре 1975 , стр. 3; Нэсстрем 1999 , стр. 12; Нэсстрем 2003 , стр. 1; Хедеагер 2011 , стр. 104; Дженнберт 2011 , стр. 12.

- ^ Андрен 2005 , стр. 106; Андрен, Дженнберт и Раудвере 2006 , стр. 12.

- ^ Турвиль-Петре 1975 , стр. 1; Стейнсланд 1986 , стр. 212.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 16.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , с. 8.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , с. 52; Джеш 2004 , с. 55; О'Донохью 2008 , с. 8.

- ^ Симпсон 1967 , с. 190.

- ^ Клунис Росс 1994 , с. 41; Хултгард 2008 , с. 212.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Андрен 2011 , стр. 856.

- ^ Дэвидсон 1990 , с. 14.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Андрен 2011 , стр. 846.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Хултгард 2008 , стр. 212.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , с. 42.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Андрен, Дженнберт и Раудвере 2006 , стр. 12.

- ^ Андрен, Дженнберт и Раудвере 2006 , стр. 12; Андрен 2011 , стр. 853.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 105.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , с. 41; Бринк 2001 , с. 88.

- ^ Дэвидсон 1990 , с. 14: Дюбуа 1999 , стр. 44, 206; Андрен, Дженнберт и Раудвере, 2006 , с. 13.

- ^ Андрен 2014 , стр. 16.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Андрен, Дженнберт и Раудвере 2006 , стр. 13.

- ^ Бек-Педерсен 2011 , с. 10.

- ^ Дэвидсон 1990 , с. 16.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , с. 18.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , с. 7.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Дюбуа 1999 , с. 10.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , с. 22.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Андрен, Дженнберт и Раудвере 2006 , стр. 14.

- ^ Дэвидсон, Утраченные убеждения , стр. 1, 18.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Абрам 2011 , с. 9.

- ^ Турвиль-Петре 1975 , стр. 82–83.

- ^ Турвиль-Петре 1975 , с. 11.

- ^ Урсула Дронке , изд. и пер., Поэтическая Эдда , Том 3: Мифологические стихи II , Оксфорд: Оксфордский университет, 2011, ISBN 978-0-19-811182-5 , с. 63, примечание к « Хавамалу », стих 144.

- ^ Нэсстрем, «Фрагменты», стр. 12.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 10.

- ^ Дэвидсон, Боги и мифы , с. 15.

- ^ Турвиль Петре, с. 13.

- ^ Турвиль-Петре 1975 , стр. 22–23.

- ^ Турвиль-Петре 1975 , с. 24.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Абрам 2011 , с. 27.

- ^ Дэвидсон, «Человеческие жертвоприношения», с. 337.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 28.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , стр. 28–29.

- ^ Андрен, Религия , стр. 846; Космология , с. 14.

- ^ Турвиль-Петре 1975 , с. 8.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , стр. 2, 4.

- ^ Андрен, «За язычеством», с. 106.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Турвиль-Петре 1975 , стр. 2–3.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Абрам 2011 , с. 61.

- ^ Де Врис 1970 , Том 1, с. 46.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 60.

- ^ Де Врис 1970 , Том 1, с. 60.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , с. 5.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , стр. 53, 79.

- ^ Турвиль-Петре 1975 , с. 6.

- ^ Линдоу 2002 , с. 3.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 54.

- ^ Турвиль-Петре 1975 , с. 7.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 58.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , стр. 54–55.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , стр. 20–21.

- ^ Кьюсак 1998 , с. 160; Абрам 2011 , с. 108.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 108.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Сундквист, Арена для высших сил , стр. 87–88.

- ^ О'Донохью 2008 , стр. 60–61; Абрам 2011 , с. 108.

- ^ Кьюсак 1998 , с. 161; О'Донохью 2008 , с. 64.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 182.

- ^ Кьюсак 1998 , с. 161; О'Донохью 2008 , с. 4; Абрам 2011 , с. 182.

- ^ Веселый 1996 , с. 36; Плюсковский 2011 , с. 774.

- ^ Джеш 2011 , стр. 19–20.

- ^ Геллинг 1961 , с. 13; Мини 1970 , с. 120; Джеш 2011 , с. 15.

- ^ Мини 1970 , с. 120.

- ^ Веселый 1996 , с. 36.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , с. 154.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Кьюсак 1998 , с. 151.

- ^ Веселый 1996 , стр. 41–43; Джеш 2004 , с. 56.

- ^ Плюсковски 2011 , с. 774.

- ^ Кьюсак 1998 , стр. 119–27; Дюбуа 1999 , с. 154.

- ^ Кьюсак 1998 , с. 135.

- ^ Кьюсак 1998 , стр. 135–36.

- ^ Кьюсак 1998 , с. 140.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , стр. 99–100.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , стр. 123–24.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , стр. 128–30.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 141.

- ^ Дэвидсон 1990 , с. 12; Кьюсак 1998 , стр. 146–47; Абрам 2011 , стр. 172–74.

- ^ Линдоу 2002 , стр. 7, 9.

- ^ Кьюсак 1998 , с. 163; Абрам 2011 , с. 187.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 188.

- ^ Кьюсак 1998 , стр. 164–68; Абрам 2011 , стр. 189–90.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Кьюсак 1998 , с. 176.

- ^ Кьюсак 1998 , с. 145; Абрам 2011 , с. 176.

- ^ Дэвидсон 1990 , стр. 219–20; Абрам 2011 , с. 156.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , стр. 171; Андрен 2011 , стр. 856.

- ^ Кьюсак 1998 , с. 168.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Кьюсак 1998 , с. 179.

- ^ Дэвидсон 1990 , с. 23.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 193.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 178.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , стр. 201, 208.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Абрам 2011 , с. 191.

- ^ Джеш 2004 , с. 57.

- ^ Джеш 2004 , стр. 57–59.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Абрам 2011 , с. 207.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , стр. 208, 219.

- ^ О'Донохью 2008 , с. 6.

- ^ Шён 2004 , стр. 169–179.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 81.

- ^ Турвиль-Петре, стр. 24–25; п. 79 относительно его изменений в истории в « Торсдрапе » о путешествии Тора в дом йотуна Гейррёда .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б О'Донохью 2008 , с. 19.

- ^ О'Донохью 2008 , с. 8.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 171.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , стр. 79, 228.

- ^ О'Донохью 2008 , стр. 23–24.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б О'Донохью 2008 , с. 67.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 151.

- ^ Де Врис 1970 , Том 1, с. 265.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , стр. 62–63.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , с. 59.

- ^ Дэвидсон, Боги и мифы , с. 219.

- ^ Сундквист, Арена для высших сил , стр. 87–90 .

- ^ О'Донохью 2008 , с. 27.

- ^ Нордланд 1969 , стр. 67.

- ^ Поэзия , гл. 14, 15, 29; Эдда Снорри Стурлусона: опубликовано по рукописям , изд. Финнур Йонссон , Копенгаген: Гильдендал, 1931, стр. 97–98, 110.

- ^ Анна Биргитта Рут , Локи в скандинавской мифологии , Труды Королевского гуманитарного общества Лунда 61, Лунд: Глируп, 1961, OCLC 902409942 , стр. 162–65.

- ^ Лотте Моц , «Сестра в пещере; рост и функции женских фигур Эдд » , Arkiv for nordisk filologi 95 (1980) 168–82.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , с. 46.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Дюбуа 1999 , с. 47.

- ^ Йонас Гисласон «Принятие христианства в Исландии в 1000 (999) году», в: Древнескандинавские и финские религии и культовые топонимы , изд. Торе Альбек, Турку: Институт исследований религии и культуры Доннера, 1991, OCLC 474369969 , стр. 223–55.

- ^ Симек, "Þorgerðr H?lgabrúðr", стр. 326–27.

- ^ Де Врис 1970 , Том 2, с. 284.

- ^ Турвиль-Петре 1975 , стр. 256–57.

- ^ Линдоу, «Норны», стр. 244–45.

- ^ Де Врис 1970 , с. 272.

- ^ Дюбуа, с. 50

- ^ Дэвидсон, Боги и мифы , с. 214.

- ^ Турвиль-Петре, с. 221. Архивировано 23 апреля 2023 года в Wayback Machine .

- ^ Дэвидсон, Боги и мифы , с. 61.

- ^ Де Врис 1970 , Том 1, стр. 273–74.

- ^ Симек, «Гиганты», с. 107.

- ^ Моц, «Гиганты в фольклоре и мифологии: новый подход», Фольклор (1982) 70–84, стр. 70.

- ^ О'Донохью 2008 , с. 232.

- ^ Steinsland 1986 , стр. 212–13.

- ^ Моц, «Гиганты», с. 72.

- ^ О'Донохью 2008 , с. 116.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с О'Донохью 2008 , с. 16.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б О'Донохью 2008 , с. 13.

- ^ О'Донохью 2008 , с. 14.

- ^ О'Донохью 2008 , стр. 114–15.

- ^ О'Донохью 2008 , с. 15.

- ^ О'Донохью 2008 , стр. 17–18.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д О'Донохью 2008 , с. 18.

- ^ О'Донохью 2008 , с. 17.

- ^ Хултгард 2008 , стр. 215.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , стр. 157–58.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 163.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 165.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 164.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Абрам 2011 , с. 4.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Дюбуа 1999 , с. 79.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , с. 81.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 212.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , с. 89.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Абрам 2011 , с. 107.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , стр. 105–06.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 78.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , с. 79 Абрам 2011 , с. 116

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 119.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 80.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , с. 77.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , с. 85.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , стр. 87–88.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 75.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Абрам 2011 , с. 76.

- ^ Андрен, «Древнескандинавская и германская религия», стр. 848–49.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Андрен, «За язычеством», с. 108.

- ^ Жаклин Симпсон , «Некоторые скандинавские жертвоприношения», Folklore 78.3 (1967) 190–202, стр. 190.

- ^ Андрен, «Древнескандинавская и германская религия», стр. 853, 855.

- ^ Клунис Росс 1994 , с. 13.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Абрам 2011 , с. 70.

- ^ Турвиль-Петре 1975 , с. 251.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Турвиль-Петре 1975 , с. 244.

- ^ Симпсон 1967 , с. 193.

- ^ Магнелл 2012 , стр. 195.

- ^ Магнелл 2012 , стр. 196.

- ^ Дэвидсон, «Человеческие жертвоприношения».

- ^ Турвиль-Петре 1975 , с. 273.

- ^ Турвиль-Петре 1975 , с. 239.

- ^ "Сага о Храфнкеле", тр. Герман Палссон, в «Саге о Храфнкеле и других исландских историях» , Хармондсворт, Миддлсекс: Пингвин, 1985, ISBN 9780140442380 , гл. 1. Архивировано 23 апреля 2023 года в Wayback Machine : «Он любил Фрея больше всех других богов и дал ему половину всех своих лучших сокровищ. ... Он стал их жрецом и вождем, поэтому ему дали прозвище Фрейров- Священник."

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Абрам 2011 , с. 71.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Турвиль-Петре 1975 , с. 255.

- ^ Турвиль-Петре 1975 , стр. 245–46.

- ^ Сага о Кьялнесинге , Сага о Ватнсдале ; Де Врис Том 1, с. 410, Тюрвиль-Петре, с. 254.

- ^ Дэвидсон, «Человеческие жертвоприношения», с. 337.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Турвиль-Петре 1975 , с. 254.

- ^ Турвиль-Петре 1975 , с. 253.

- ^ Де Врис 1970 , Том 1, с. 414.

- ^ Дэвидсон, «Человеческие жертвоприношения», с. 333.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Андрен, «Древнескандинавская и германская религия», с. 849.

- ^ Де Врис 1970 , Том 1, с. 415.

- ^ Дэвидсон, «Человеческие жертвоприношения», с. 334.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 72.

- ^ Эллис Дэвидсон, «Человеческие жертвоприношения», с. 336.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Абрам 2011 , с. 73.

- ^ Бринк 2001 , с. 96.

- ^ Андрен, «За язычеством», стр. 108–09.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Андрен, «Древнескандинавская и германская религия», с. 853.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Джули Лунд (2010). «У кромки воды», в книге Мартина Карвера, Алекса Санмарка и Сары Семпл, ред., « Сигналы веры в ранней Англии: возвращение к англосаксонскому язычеству» , ISBN 978-1-84217-395-4 , Оксфорд: Oxbow, стр. 49–66. п. 51.

- ^ Хаттон 2013 , с. 328.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Андрен, «За язычеством», с. 110.

- ^ Андрен, «Древнескандинавская и германская религия», стр. 853–54.

- ^ Де Врис, Том 1, стр. 178–80. Перед водным обрядом ребенка могли отвергнуть; детоубийство все еще разрешалось согласно самым ранним христианским законам Норвегии, с. 179.

- ^ Де Врис 1970 , Том 1, стр. 181–83.

- ^ Де Врис, Том 1, стр. 184, 208, 294–95; Де Врис предполагает, что ритуал жардармен — это символическая смерть и возрождение.

- ^ Де Врис, Том 1, стр. 185–86. Brúðkaup , «покупка невесты», также встречается в древнескандинавском языке, но, по мнению де Фриза, вероятно, относится к выкупу за невесту и, следовательно, к вручению подарков, а не к «покупке» в современном смысле.

- ^ она шла и лини ; Де Врис, Том 1, с. 187.

- ^ Де Врис 1970 , Том 1, с. 187.

- ^ Турвиль-Петре 1975 , с. 81.

- ^ Маргарет Клунис Росс , «Чтение Þrymskviða », в «Поэтической Эдде: Очерки древнескандинавской мифологии », изд. Пол Акер и Кэролайн Ларрингтон, средневековые журналы дел Рутледжа, Нью-Йорк / Лондон: Рутледж, 2002, ISBN 9780815316602 , стр. 177–94, стр. 177–94. 181 .

- ^ Де Врис 1970 , Том 2, с. 327.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Андрен, «Древнескандинавская и германская религия», с. 855.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , с. 71.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Рунар Лейфссон (2012). «Развивающиеся традиции: забой лошадей как часть погребальных обычаев викингов в Исландии», в книге «Ритуальное убийство и погребение животных: европейские перспективы» , под ред. Александр Плюсковский, Оксфорд: Oxbow, 2012, ISBN 978-1-84217-444-9 , стр. 184–94, стр. 185.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Дюбуа 1999 , с. 72.

- ^ Рунар Лейфссон, с. 184.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Абрам 2011 , с. 74.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Дюбуа 1999 , с. 73.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , с. 80.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , стр. 74–75.

- ^ Gylfaginning , гл. 48; Симек, «Кольцорог», с. 159–60; «Хиррокин», с. 170.

- ^ Дэвидсон, Боги и мифы , стр. 143–44.

- ^ Симек, «(Само)пожертвование Одина», с. 249.

- ^ Турвиль-Петре 1975 , стр. 11, 48–50.

- ^ Симек, «Руны», с. 269: «Один — бог рунических знаний и рунической магии».

- ^ Турвиль-Петре 1975 , стр. 64–65.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , с. 104.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Дюбуа 1999 , с. 123.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Андрен, «Древнескандинавская и германская религия», с. 855.

- ^ Дэвидсон, Боги и мифы , с. 117.

- ^ Турвиль-Петре 1975 , с. 65.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , с. 136.

- ^ Де Врис 1970 , Том 1, с. 332.

- ^ Дэвидсон, Боги и мифы , с. 121.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , с. 128.

- ^ Дэвидсон, «Боги и мифы», с. 119.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , с. 129.

- ^ Шнурбейн 2003 , стр. 117–18.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , с. 130.

- ^ Шнурбейн 2003 , с. 117.

- ^ Турвиль-Петре 1975 , с. 50.

- ^ Шнурбейн 2003 , с. 119.

- ^ Де Врис 1970 , Том 1, стр. 330–33.

- ^ Шнурбейн 2003 , с. 123.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Беренд 2007 , с. 124 .

- ^ Сундквист, Арена для высших сил , стр. 131, 394.

- ^ Турвиль-Петре 1975 , стр. 237–38.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Дюбуа 1999 , с. 76.

- ^ Бринк 2001 , с. 100.

- ^ Эллис , Дорога в Хель , с. 90.

- ^ Турвиль-Петре 1975 , стр. 69, 165–66.

- ^ Эллис Дэвидсон, Боги и мифы , стр. 101–02.

- ^ Бринк 2001 , с. 77.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Де Врис 1970 , Том 1, стр. 382, 389, 409–10.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Турвиль-Петре 1975 , стр. 244–45.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Симек, «Храм Упсалы», стр. 341–42.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 69.

- ^ Олсен, краткое содержание на английском языке, стр. 285: «[Я] предполагаю, что здание языческого хофа в Исландии на самом деле было идентично veizluskáli [ праздничному залу] большой фермы: зданию повседневного использования, которое в особых случаях становилось местом проведения ритуальных собраний большое количество людей».

- ^ Дэвидсон, Мифы и символы в языческой Европе , с. 32: «зал фермерского дома, используемый для общественных религиозных праздников, возможно, зал годи или ведущего человека района, который председательствовал на таких собраниях».

- ^ Олсен 1966 , стр. 127–42; Краткое изложение на английском языке находится в Olsen 1966 , стр. 282–83.

- ^ Ричард Брэдли, Ритуал и домашняя жизнь в доисторической Европе , Лондон/Нью-Йорк: Routledge, 2005, ISBN 0-415-34550-2 , стр. 43–44, со ссылкой на Нила С. Прайса, Путь викингов: религия и война в Скандинавии позднего железного века , докторская диссертация, Aun 31, Упсала: Департамент археологии и древней истории, 2002 г. , ISBN 9789150616262 , с. 61.

- ^ Лукас и Макговерн, 2007 , стр. 7–30.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д Андрен, «Древнескандинавская и германская религия», с. 854.

- ^ Магнелл 2012 , стр. 199.

- ^ Дэвидсон, Мифы и символы в языческой Европе , стр. 31–32.

- ^ Турвиль-Петре 1975 , с. 243.

- ^ Хедеагер, «Скандинавские «центральные места»», стр. 7.

- ^ Хедеагер, «Скандинавские «центральные места»», стр. 5, 11–12.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Хултгард 2008 , стр. 217.

- ^ Хедеагер 2002 , стр. 5 Абрам 2011 , стр. 100.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Дюбуа 1999 , с. 66.

- ^ Дюбуа 1999 , с. 66; Абрам 2011 , с. 74.

- ^ Абрам 2011 , с. 92 Прайс и Мортимер, 2014 г. , стр. 517–18.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Абрам 2011 , с. 92.