Иммиграция

| Правовой лиц статус |

|---|

|

| Birthright |

| Nationality |

| Immigration |

Иммиграция – это международное перемещение людей в страну которой они не имеют, назначения, в которой они не являются обычными жителями или гражданства с целью обосноваться в качестве постоянных жителей . [1] [2] [3] [4] Пассажиры , туристы и другие лица, краткосрочно пребывающие в стране назначения, не подпадают под определение иммиграции или миграции; Однако иногда сюда включают сезонную трудовую иммиграцию.

Что касается экономических последствий, исследования показывают, что миграция выгодна как принимающим, так и отправляющим странам. [5] [6] [7] Исследования, за некоторыми исключениями, показывают, что иммиграция в среднем оказывает положительное экономическое воздействие на коренное население, но неоднозначно влияет ли иммиграция с низкой квалификацией на малообеспеченных коренных жителей. [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] Исследования показывают, что устранение барьеров для миграции будет иметь глубокие последствия для мирового ВВП : оценки прироста варьируются от 67 до 147 процентов для сценариев, при которых от 37 до 53 процентов рабочих развивающихся стран мигрируют в развитые страны. [13][14][15][16] Development economists argue that reducing barriers to labor mobility between developing countries and developed countries would be one of the most efficient tools of poverty reduction.[17][18][19][20] Positive net immigration can soften the demographic dilemma in the aging global North.[21][22]

The academic literature provides mixed findings for the relationship between immigration and crime worldwide, but finds for the United States that immigration either has no impact on the crime rate or that it reduces the crime rate.[23][24] Research shows that country of origin matters for speed and depth of immigrant assimilation, but that there is considerable assimilation overall for both first- and second-generation immigrants.[25][26]

Research has found extensive evidence of discrimination against foreign-born and minority populations in criminal justice, business, the economy, housing, health care, media, and politics in the United States and Europe.[27][28][29][30]

History

The term immigration was coined in the 17th century, referring to non-warlike population movements between the emerging nation states. When people cross national borders during their migration, they are called migrants or immigrants (from Latin: migrare, 'wanderer') from the perspective of the destination country. In contrast, from the perspective of the country from which they leave, they are called emigrants or outmigrants.[31]

Human migration is the movement by people from one place to another, particularly different countries, with the intention of settling temporarily or permanently in the new location. It typically involves movements over long distances and from one country or region to another. The number of people involved in every wave of immigration differs depending on the specific circumstances.

Historically, early human migration includes the peopling of the world, i.e. migration to world regions where there was previously no human habitation, during the Upper Paleolithic. Since the Neolithic, most migrations (except for the peopling of remote regions such as the Arctic or the Pacific), were predominantly warlike, consisting of conquest or Landnahme on the part of expanding populations.[citation needed] Colonialism involves expansion of sedentary populations into previously only sparsely settled territories or territories with no permanent settlements. In the modern period, human migration has primarily taken the form of migration within and between existing sovereign states, either controlled (legal immigration) or uncontrolled and in violation of immigration laws (illegal immigration).

Migration can be voluntary or involuntary. Involuntary migration includes forced displacement (in various forms such as deportation, the slave trade, flight (war refugees and ethnic cleansing), all of which could result in the creation of diasporas.Statistics

As of 2015[update], the number of international migrants has reached 244 million worldwide, which reflects a 41% increase since 2000. The largest number of international migrants live in the United States, with 19% of the world's total. One third of the world's international migrants are living in just 20 countries. Germany and Russia host 12 million migrants each, taking the second and third place in countries with the most migrants worldwide. Saudi Arabia hosts 10 million migrants, followed by the United Kingdom (9 million) and the United Arab Emirates (8 million).[33]In most parts of the world, migration occurs between countries that are located within the same major area. Between 2000 and 2015, Asia added more international migrants than any other major area in the world, gaining 26 million. Europe added the second largest with about 20 million.[33]

In 2015, the number of international migrants below the age of 20 reached 37 million, while 177 million are between the ages of 20 and 64. International migrants living in Africa were the youngest, with a median age of 29, followed by Asia (35 years), and Latin America/Caribbean (36 years), while migrants were older in Northern America (42 years), Europe (43 years), and Oceania (44 years).[33]

Nearly half (43%) of all international migrants originate in Asia, and Europe was the birthplace of the second largest number of migrants (25%), followed by Latin America (15%). India has the largest diaspora in the world (16 million people), followed by Mexico (12 million) and Russia (11 million).[33]

2012 survey

A 2012 survey by Gallup found that given the opportunity, 640 million adults would migrate to another country, with 23% of these would-be immigrant choosing the United States as their desired future residence, while 7% of respondents, representing 45 million people, would choose the United Kingdom. Canada, France, Saudi Arabia, Australia, Germany, Spain, Italy, and the United Arab Emirates made up the rest of the top ten desired destination countries.[34]

Current

In USA there were in 2023 1,197,254 immigration applications initial receipts, 523,477 immigration cases completed, and 2,464,021 immigration cases pending according to the U.S. Department of Justice.[35]

Push and pull factors of immigration

One theory of immigration distinguishes between push and pull factors, referring to the economic, political, and social influences by which people migrate from or to specific countries.[39] Immigrants are motivated to leave their former countries of citizenship, or habitual residence, for a variety of reasons, including: a lack of local access to resources, a desire for economic prosperity, to find or engage in paid work, to better their standard of living, family reunification, retirement, climate or environmentally induced migration, exile, escape from prejudice, conflict or natural disaster, or simply the wish to change one's quality of life. Commuters, tourists, and other short-term stays in a destination country do not fall under the definition of immigration or migration; seasonal labour immigration is sometimes included, however.

Push factors (or determinant factors) refer primarily to the motive for leaving one's country of origin (either voluntarily or involuntarily), whereas pull factors (or attraction factors) refer to one's motivations behind or the encouragement towards immigrating to a particular country.

In the case of economic migration (usually labor migration), differentials in wage rates are common. If the value of wages in the new country surpasses the value of wages in one's native country, he or she may choose to migrate, as long as the costs are not too high. Particularly in the 19th century, economic expansion of the US increased immigrant flow, and nearly 15% of the population was foreign-born,[40] thus making up a significant amount of the labor force.

As transportation technology improved, travel time, and costs decreased dramatically between the 18th and early 20th century. Travel across the Atlantic used to take up to 5 weeks in the 18th century, but around the time of the 20th century it took a mere 8 days.[41] When the opportunity cost is lower, the immigration rates tend to be higher.[41] Escape from poverty (personal or for relatives staying behind) is a traditional push factor, and the availability of jobs is the related pull factor. Natural disasters can amplify poverty-driven migration flows. Research shows that for middle-income countries, higher temperatures increase emigration rates to urban areas and to other countries. For low-income countries, higher temperatures reduce emigration.[42]

Emigration and immigration are sometimes mandatory in a contract of employment: religious missionaries and employees of transnational corporations, international non-governmental organizations, and the diplomatic service expect, by definition, to work "overseas". They are often referred to as "expatriates", and their conditions of employment are typically equal to or better than those applying in the host country (for similar work).[citation needed]

Non-economic push factors include persecution (religious and otherwise), frequent abuse, bullying, oppression, ethnic cleansing, genocide, risks to civilians during war, and social marginalization.[43] Political motives traditionally motivate refugee flows; for instance, people may emigrate in order to escape a dictatorship.[44]

Some migration is for personal reasons, based on a relationship (e.g. to be with family or a partner), such as in family reunification or transnational marriage (especially in the instance of a gender imbalance). Recent research has found gender, age, and cross-cultural differences in the ownership of the idea to immigrate.[45] In a few cases, an individual may wish to immigrate to a new country in a form of transferred patriotism. Evasion of criminal justice (e.g., avoiding arrest) is a personal motivation. This type of emigration and immigration is not normally legal, if a crime is internationally recognized, although criminals may disguise their identities or find other loopholes to evade detection. For example, there have been reports of war criminals disguising themselves as victims of war or conflict and then pursuing asylum in a different country.[46][47][48]

Barriers to immigration come not only in legal form or political form; natural and social barriers to immigration can also be very powerful. Immigrants when leaving their country also leave everything familiar: their family, friends, support network, and culture. They also need to liquidate their assets, and they incur the expense of moving. When they arrive in a new country, this is often with many uncertainties including finding work,[49] where to live, new laws, new cultural norms, language or accent issues, possible racism, and other exclusionary behavior towards them and their family.[50][51][52]

The politics of immigration have become increasingly associated with other issues, such as national security and terrorism, especially in western Europe, with the presence of Islam as a new major religion. Those with security concerns cite the 2005 French riots and point to the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy as examples of the value conflicts arising from immigration of Muslims in Western Europe. Because of all these associations, immigration has become an emotional political issue in many European nations.[54][55]

Studies have suggested that some special interest groups lobby for less immigration for their own group and more immigration for other groups since they see effects of immigration, such as increased labor competition, as detrimental when affecting their own group but beneficial when impacting other groups. A 2010 European study suggested that "employers are more likely to be pro-immigration than employees, provided that immigrants are thought to compete with employees who are already in the country. Or else, when immigrants are thought to compete with employers rather than employees, employers are more likely to be anti-immigration than employees."[56] A 2011 study examining the voting of US representatives on migration policy suggests that "representatives from more skilled labor abundant districts are more likely to support an open immigration policy towards the unskilled, whereas the opposite is true for representatives from more unskilled labor abundant districts."[57]

Another contributing factor may be lobbying by earlier immigrants. The chairman for the US Irish Lobby for Immigration Reform—which lobby for more permissive rules for immigrants, as well as special arrangements just for Irish people—has stated that "the Irish Lobby will push for any special arrangement it can get—'as will every other ethnic group in the country.'"[58][59]

Foreign involvement

Several countries have been accused of encouraging immigration to other countries in order to create divisions.[60]

Economic migrant

The term economic migrant refers to someone who has travelled from one region to another region for the purposes of seeking employment and an improvement in quality of life and access to resources. An economic migrant is distinct from someone who is a refugee fleeing persecution.

Many countries have immigration and visa restrictions that prohibit a person entering the country for the purposes of gaining work without a valid work visa. As a violation of a State's immigration laws a person who is declared to be an economic migrant can be refused entry into a country.

The World Bank estimates that remittances totaled $420 billion in 2009, of which $317 billion went to developing countries.[61]

Laws and ethics

Legislation regarding the protection of rights of immigrants and equal access to justice differs per nation. International law – the product of the United Nations and other multinational organizations – creates protocols governing immigrant rights. International law and the European Convention of Human Rights state that immigrants can only be detained for ‘legitimate aims’ of the state. It also notes that vulnerable people should be protected from unreasonable punishment and lengthy detention. International law outlines requirements for due process and suitable conditions. However, nations are sovereign, and the protocols of international law cannot be enforced upon them. Nations have the freedom to handle immigrants as they choose, and to structure how any legal aid is distributed. Human rights organizations strongly criticize individual nation-states for the limitations of their immigration policies and practices.[62]

Treatment of migrants in host countries, both by governments, employers, and original population, is a topic of continual debate and criticism, and the violation of migrant human rights is an ongoing crisis.[63] The United Nations Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families, has been ratified by 48 states, most of which are heavy exporters of cheap labor. Major migrant-receiving countries and regions—including Western Europe, North America, Pacific Asia, Australia, and the Gulf States—have not ratified the convention, even though they are host to the majority of international migrant workers.[64][65] Although freedom of movement is often recognized as a civil right in many documents such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966), the freedom only applies to movement within national borders and the ability to return to one's home state.[66][67]

Some proponents of immigration argue that the freedom of movement both within and between countries is a basic human right, and that the restrictive immigration policies, typical of nation-states, violate this human right of freedom of movement.[68] Such arguments are common among ideologies like anarchism and libertarianism.[69][70] As philosopher and open borders activist Jacob Appel has written, "Treating human beings differently, simply because they were born on the opposite side of a national boundary, is hard to justify under any mainstream philosophical, religious or ethical theory."[citation needed]

Where immigration is permitted, it is typically selective. As of 2003[update], family reunification accounted for approximately two-thirds of legal immigration to the US every year.[71] Ethnic selection, such as the White Australia policy, has generally disappeared, but priority is usually given to the educated, skilled, and wealthy. Less privileged individuals, including the mass of poor people in low-income countries, cannot avail themselves of the legal and protected immigration opportunities offered by wealthy states. This inequality has also been criticized as conflicting with the principle of equal opportunities. The fact that the door is closed for the unskilled, while at the same time many developed countries have a huge demand for unskilled labor, is a major factor in illegal immigration. The contradictory nature of this policy—which specifically disadvantages the unskilled immigrants while exploiting their labor—has also been criticized on ethical grounds.[citation needed]

Immigration policies which selectively grant freedom of movement to targeted individuals are intended to produce a net economic gain for the host country. They can also mean net loss for a poor donor country through the loss of the educated minority—a "brain drain". This can exacerbate the global inequality in standards of living that provided the motivation for the individual to migrate in the first place. One example of competition for skilled labour is active recruitment of health workers from developing countries by developed countries.[72][73] There may however also be a "brain gain" to emigration, as migration opportunities lead to greater investments in education in developing countries.[74][75][76][77] Overall, research suggests that migration is beneficial both to the receiving and sending countries.[6]

Economic effects

Overall national impact

A survey of European economists shows a consensus that freer movement of people to live and work across borders within Europe makes the average European better off, and strong support behind the notion that it has not made low-skilled Europeans worse off.[10] According to David Card, Christian Dustmann, and Ian Preston, "most existing studies of the economic impacts of immigration suggest these impacts are small, and on average benefit the native population".[8] In a survey of the existing literature, Örn B Bodvarsson and Hendrik Van den Berg write, "a comparison of the evidence from all the studies... makes it clear that, with very few exceptions, there is no strong statistical support for the view held by many members of the public, mainly that immigration has an adverse effect on native-born workers in the destination country."[78]Research also suggests that diversity and immigration have a net positive effect on productivity[79][80][81][82][83][84] and economic prosperity.[85][86][87][88][89] Immigration has also been associated with reductions in offshoring.[84] A study found that the Age of Mass Migration (1850–1920) contributed to "higher incomes, higher productivity, more innovation, and more industrialization" in the short-run and "higher incomes, less poverty, less unemployment, higher rates of urbanization, and greater educational attainment" in the long-run for the United States.[90] Research also shows that migration to Latin America during the Age of Mass Migration had a positive impact on long-run economic development.[91] A 2016 paper by University of Southern Denmark and University of Copenhagen economists found that the 1924 immigration restrictions enacted in the United States impaired the economy.[92][93]

The view that economic impact on the average native tends to be only small and positive is disputed by some studies, such as a 2023 statistical analysis of historical immigration data in Netherlands which found economic effects with both larger positive and negative net contributions per capita depending on different factors including previous education and income of the immigrant.[94] Effects may vary due to factors like the migrants' age, education, reason for migration,[95] the strength of the economy, and how long ago the migration took place.[96]

Overall immigration was found to account for a relatively small share of the rise of native wage inequality,[97][98] but low-skill immigration has been linked to greater income inequality in the native population.[99][100]

Measuring the national impact of immigration on the change of total GDP or on the change of GDP per capita can have distinct results.[101]

Study methodologies

David Card's 1990 work[102] is considered a landmark study in the topic. It followed the Mariel boatlift, a natural experiment when 125,000 Cubans (Marielitos) came to Miami after a sudden relaxation in emigration rules. It lacked the limitations of previous studies, including that migrants often choose high-wage cities, so increases in wages could simply be a result of the economic success of the city rather than the migrants. But the Marielitos chose Miami simply because it was near Cuba rather than for lucrative wages. Preceding studies were also limited in that firms and natives may respond to migration and its effects by moving to more lucrative areas. However, the six-month period of this migration was too brief for most firms or individuals to leave Miami.[103][104]Another natural experiment followed a group of Czech workers who, shortly after the fall of the Berlin wall, were suddenly able to work in Germany though they continued to live in Czechia. It found significant declines in native wages and employment as a result.[105] It is argued migrants must also spend their wages in the employing country in order to stimulate the economy and offset their impacts.[103]

Global impact

According to economists Michael Clemens and Lant Pritchett, "permitting people to move from low-productivity places to high-productivity places appears to be by far the most efficient generalized policy tool, at the margin, for poverty reduction".[19] A successful two-year in situ anti-poverty program, for instance, helps poor people make in a year what is the equivalent of working one day in the developed world.[19] A slight reduction in the barriers to labor mobility between the developing and developed world could do more to reduce poverty in the developing world than any remaining trade liberalization.[106] Studies show that the elimination of barriers to migration could have profound effects on world GDP, with estimates of gains ranging between 67 and 147.3%.[13][14][15][107][108][109] Research also finds that migration leads to greater trade in goods and services,[110][111][112][113][114] and increases in financial flows between the sending and receiving countries.[115][116]

Greater openness to low-skilled immigration in wealthy countries could drastically reduce global income inequality.[100][117] According to Branko Milanović, country of residency is by far the most important determinant of global income inequality, which suggests that the reduction in labor barriers could significantly reduce global income inequality.[17][118]

Impact on immigrants

Research on a migration lottery allowing Tongans to move to New Zealand found that the lottery winners saw a 263% increase in income from migrating (after only one year in New Zealand) relative to the unsuccessful lottery entrants.[119] A longer-term study on the Tongan lottery winners finds that they "continue to earn almost 300 percent more than non-migrants, have better mental health, live in households with more than 250 percent higher expenditure, own more vehicles, and have more durable assets".[120] A conservative estimate of their lifetime gain to migration is NZ$315,000 in net present value terms (approximately US$237,000).[120]

A 2017 study of Mexican immigrant households in the United States found that by virtue of moving to the United States, the households increase their incomes more than fivefold immediately.[121] The study also found that the "average gains accruing to migrants surpass those of even the most successful current programs of economic development."[121]

A 2017 study of European migrant workers in the UK shows that upon accession to the EU, the migrant workers see a substantial positive impact on their earnings. The data indicate that acquiring EU status raises earnings for the workers by giving them the right to freely change jobs.[122]

A 2017 study in the Quarterly Journal of Economics found that immigrants from middle- and low-income countries to the United States increased their wages by a factor of two to three upon migration.[123]

For individual groups

A survey of leading economists shows a consensus behind the view that high-skilled immigration makes the average American better off.[124] A survey of the same economists also shows support behind the notion that low-skilled immigration makes the average American better off and makes many low-skilled American workers substantially worse off unless they are compensated by others.[125]

Studies show more mixed results for low-skilled natives, but whether the effects are positive or negative, they tend to be small either way.[126][127][128][129][130][131] Research indicates immigrants are more likely to work in risky jobs than U.S.-born workers, partly due to differences in average characteristics, such as immigrants' lower English language ability and educational attainment.[132] According to a 2017 survey of the existing economic literature, studies on high-skilled migrants "rarely find adverse wage and employment consequences, and longer time horizons tend to show greater gains".[133]

Competition from immigrants in a particular profession may aggravate underemployment in that profession,[134] but increase wages for other natives;[133] for instance, a 2017 study in Science found that "the influx of foreign-born computer scientists since the early 1990s... increased the size of the US IT sector... benefited consumers via lower prices and more efficient products... raised overall worker incomes by 0.2 to 0.3% but decreased wages of U.S. computer scientists by 2.6 to 5.1%."[135] A 2019 study found that foreign college workers in STEM occupations did not displace native college workers in STEM occupations, but instead had a positive impact on the latter group's wages.[136] A 2021 study similarly found that highly educated immigrants to Switzerland caused wages to increase for highly educated Swiss natives.[137] A 2019 study found that greater immigration led to less off-shoring by firms.[138]

By increasing overall demand, immigrants could push natives out of low-skilled manual labor into better paying occupations.[139][140] A 2018 study in the American Economic Review found that the Bracero program (which allowed almost half a million Mexican workers to do seasonal farm labor in the United States) did not have any adverse impact on the labor market outcomes of American-born farm workers.[141] A 2019 study by economic historians found that immigration restrictions implemented in the 1920s had an adverse impact on US-born workers' earnings.[142]

Fiscal effects

A 2011 literature review of the economic impacts of immigration found that the net fiscal impact of migrants varies across studies but that the most credible analyses typically find small and positive fiscal effects on average.[143] According to the authors, "the net social impact of an immigrant over his or her lifetime depends substantially and in predictable ways on the immigrant's age at arrival, education, reason for migration, and similar".[143] According to a 2007 literature review by the Congressional Budget Office, "Over the past two decades, most efforts to estimate the fiscal impact of immigration in the United States have concluded that, in aggregate and over the long term, tax revenues of all types generated by immigrants—both legal and unauthorized—exceed the cost of the services they use."[144] A 2022 study found that the sharp reduction in refugee admissions adversely affected public coffers at all levels of government in the United States.[145]

A 2018 study found that inflows of asylum seekers into Western Europe from 1985 to 2015 had a net positive fiscal impact.[146][147] Research has shown that EU immigrants made a net positive fiscal contribution to Denmark[148] and the United Kingdom.[149][150] A 2017 study found that when Romanian and Bulgarian immigrants to the United Kingdom gained permission to acquire welfare benefits in 2014 that it had no discernible impact on the immigrants' use of welfare benefits.[151] A paper by a group of French economists found that over the period 1980–2015, "international migration had a positive impact on the economic and fiscal performance of OECD countries."[152] A 2023 study in the Netherlands found both large positive and large negative fiscal impact depending on previous education and income of immigrant.[94]

Impact of refugees

A 2017 survey of leading economists found that 34% of economists agreed with the statement "The influx of refugees into Germany beginning in the summer of 2015 will generate net economic benefits for German citizens over the succeeding decade", whereas 38% were uncertain and 6% disagreed.[153] Studies of refugees' impact on native welfare are scant but the existing literature shows mixed results (negative, positive and no significant effects).[154][155][156][157][158][159][160][161][162][163][164] According to economist Michael Clemens, "when economists have studied past influxes of refugees and migrants they have found the labor market effects, while varied, are very limited, and can in fact be positive."[165] A 2018 study in the Economic Journal found that Vietnamese refugees to the United States had a positive impact on American exports, as exports to Vietnam grew most in US states with larger Vietnamese populations.[114] A 2018 study in the journal Science Advances found that asylum seekers entering Western Europe in the period 1985–2015 had a positive macroeconomic and fiscal impact.[146][147] A 2019 study found that the mass influx of 1.3 million Syrian refugees to Jordan (total population: 6.6 million) did not have harm the labor market outcomes of native Jordanians.[156] A 2020 study found that Syrian refugees to Turkey improved the productivity of Turkish firms.[166]

A 2017 paper by Evans and Fitzgerald found that refugees to the United States pay "$21,000 more in taxes than they receive in benefits over their first 20 years in the U.S."[163] An internal study by the Department of Health and Human Services under the Trump administration, which was suppressed and not shown to the public, found that refugees to the United States brought in $63 billion more in government revenues than they cost the government.[167] According to University of California, Davis, labor economist Giovanni Peri, the existing literature suggests that there are no economic reasons why the American labor market could not easily absorb 100,000 Syrian refugees in a year.[citation needed] A 2017 paper looking at the long-term impact of refugees on the American labor market over the period 1980–2010 found "that there is no adverse long-run impact of refugees on the U.S. labor market."[168] A 2022 study by economist Michael Clemens found that the sharp reduction in refugee admissions in the United States since 2017 had cost the U.S. economy over $9.1 billion per year and cost public coffers over $2 billion per year.[145]

Refugees integrate more slowly into host countries' labor markets than labor migrants, in part due to the loss and depreciation of human capital and credentials during the asylum procedure.[169] Refugees tend to do worse in economic terms than natives, even when they have the same skills and language proficiencies of natives. For instance, a 2013 study of Germans in West-Germany who had been displaced from Eastern Europe during and after World War II showed that the forced German migrants did far worse economically than their native West-German counterparts decades later.[170] Second-generation forced German migrants also did worse in economic terms than their native counterparts.[170] A study of refugees to the United States found that "refugees that enter the U.S. before age 14 graduate high school and enter college at the same rate as natives. Refugees that enter as older teenagers have lower attainment with much of the difference attributable to language barriers and because many in this group are not accompanied by a parent to the U.S."[163] Refugees that entered the U.S. at ages 18–45, have "much lower levels of education and poorer language skills than natives and outcomes are initially poor with low employment, high welfare use and low earnings."[163] But the authors of the study find that "outcomes improve considerably as refugees age."[163]

A 2017 study found that the 0.5 million Portuguese who returned to Portugal from Mozambique and Angola in the mid-1970s lowered labor productivity and wages.[171] A 2018 paper found that the areas in Greece that took on a larger share of Greek Orthodox refugees from the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922 "have today higher earnings, higher levels of household wealth, greater educational attainment, as well as larger financial and manufacturing sectors."[172]

Impact of undocumented immigrants

Research on the economic effects of undocumented immigrants is scant but existing studies suggests that the effects are positive for the native population,[173][174] and public coffers.[144][175] A 2015 study shows that "increasing deportation rates and tightening border control weakens low-skilled labor markets, increasing unemployment of native low-skilled workers. Legalization, instead, decreases the unemployment rate of low-skilled natives and increases income per native."[176] Studies show that legalization of undocumented immigrants could boost the U.S. economy; a 2013 study found that granting legal status to undocumented immigrants could raise their incomes by a quarter (increasing U.S. GDP by approximately $1.4 trillion over a ten-year period),[177] and a 2016 study found that "legalization would increase the economic contribution of the unauthorized population by about 20%, to 3.6% of private-sector GDP."[178] A 2018 National Bureau of Economic Research paper found that undocumented immigrants to the United States "generate higher surplus for US firms relative to natives, hence restricting their entry has a depressing effect on job creation and, in turn, on native labor markets."[179]

In the US the Immigration Reform and Control Act was passed to help remove the illegal aliens. They were trying to do this by granting legal status or by imposing penalties against the employers who would knowingly work illegal immigrants. However, IRCA did not address the reality or price which caused an issue in the accomplishing of the objectives.[180]

A 2017 study in the Journal of Public Economics found that more intense immigration enforcement increased the likelihood that US-born children with undocumented immigrant parents would live in poverty.[181]

A paper by Spanish economists found that upon legalizing the undocumented immigrant population in Spain, the fiscal revenues increased by around €4,189 per newly legalized immigrant.[175] The paper found that the wages of the newly legalized immigrants increased after legalization, some low-skilled natives had worse labor market outcomes and high-skilled natives had improved labor market outcomes.[175]

A 2018 study found no evidence that apprehensions of undocumented immigrants in districts in the United States improved the labor market outcomes for American natives.[182] A 2020 study found that immigration enforcement in the US leads to declining production in the US dairy industry and that dairy operators respond to immigration enforcement by automating their operations (rather than hire new labor).[183]

A 2021 study in the American Economic Journal found that undocumented immigrants had beneficial effects on the employment and wages of American natives. Stricter immigration enforcement adversely affected employment and wages of American natives.[184]

Impact on the sending countries

Research suggests that migration is beneficial both to the receiving and sending countries.[6][7] According to one study, welfare increases in both types of countries: "welfare impact of observed levels of migration is substantial, at about 5% to 10% for the main receiving countries and about 10% in countries with large incoming remittances".[6] A study of equivalent workers in the United States and 42 developing countries found that "median wage gap for a male, unskilled (9 years of schooling), 35-year-old, urban formal sector worker born and educated in a developing country is P$15,400 per year at purchasing power parity".[185] A 2014 survey of the existing literature on emigration finds that a 10 percent emigrant supply shock would increase wages in the sending country by 2–5.5%.[18]

Remittances increase living standards in the country of origin. Remittances are a large share of the GDP of many developing countries.[186] A study on remittances to Mexico found that remittances lead to a substantial increase in the availability of public services in Mexico, surpassing government spending in some localities.[187]

Research finds that emigration and low migration barriers has net positive effects on human capital formation in the sending countries.[74][75][76][77] This means that there is a "brain gain" instead of a "brain drain" to emigration. Emigration has also been linked to innovation in cases where the migrants return to their home country after developing skills abroad.[188][189]

One study finds that sending countries benefit indirectly in the long-run on the emigration of skilled workers because those skilled workers are able to innovate more in developed countries, which the sending countries are able to benefit on as a positive externality. Greater emigration of skilled workers consequently leads to greater economic growth and welfare improvements in the long-run.[190] The negative effects of high-skill emigration remain largely unfounded. According to economist Michael Clemens, it has not been shown that restrictions on high-skill emigration reduce shortages in the countries of origin.[191]

Research also suggests that emigration, remittances and return migration can have a positive impact on political institutions and democratization in the country of origin.[192][193][194][195][196][197][198][199][200][201][202] According to Abel Escribà-Folch, Joseph Wright, and Covadonga Meseguer, remittances "provide resources that make political opposition possible, and they decrease government dependency, undermining the patronage strategies underpinning authoritarianism."[192] Research also shows that remittances can lower the risk of civil war in the country of origin.[203]

Research suggests that emigration causes an increase in the wages of those who remain in the country of origin. A 2014 survey of the existing literature on emigration finds that a 10 percent emigrant supply shock would increase wages in the sending country by 2–5.5%.[18] A study of emigration from Poland shows that it led to a slight increase in wages for high- and medium-skilled workers for remaining Poles.[204] A 2013 study finds that emigration from Eastern Europe after the 2004 EU enlargement increased the wages of remaining young workers in the country of origin by 6%, while it had no effect on the wages of old workers.[205] The wages of Lithuanian men increased as a result of post-EU enlargement emigration.[206] Return migration is associated with greater household firm revenues.[207] Emigration leads to boosts in foreign direct investment to their home country.[208]

Some research shows that the remittance effect is not strong enough to make the remaining natives in countries with high emigration flows better off.[6]

Innovation and entrepreneurship

A 2017 survey of the existing economic literature found that "high-skilled migrants boost innovation and productivity outcomes."[133] According to a 2013 survey of the existing economic literature, "much of the existing research points towards positive net contributions by immigrant entrepreneurs."[209] Areas where immigrant are more prevalent in the United States have substantially more innovation (as measured by patenting and citations).[210] Immigrants to the United States create businesses at higher rates than natives.[211] A 2010 study showed "that a 1 percentage point increase in immigrant college graduates' population share increases patents per capita by 9–18 percent."[212] Mass migration can also boost innovation and growth, as shown by the Jewish, Huguenot and Bohemian diasporas in Berlin and Prussia,[213][214][215] German Jewish Émigrés in the US,[216] the Mariel boatlift,[217] the exodus of Soviet Jews to Israel in the 1990s,[83] European migration to Argentina during the Age of Mass Migration (1850–1914),[218] west-east migration in the wake of German reunification,[219] German migration to Russian Empire,[220] and Polish immigration to Germany after joining the EU.[221] A 2018 study in the Economic Journal found that "a 10% increase in immigration from exporters of a given product is associated with a 2% increase in the likelihood that the host country starts exporting that good 'from scratch' in the next decade."[222]

Immigrants have been linked to greater invention and innovation.[223][224][225][226][227][228] According to one report, "immigrants have started more than half (44 of 87) of America's startup companies valued at $1 billion dollars or more and are key members of management or product development teams in over 70 percent (62 of 87) of these companies."[229] One analysis found that immigrant-owned firms had a higher innovation rate (on most measures of innovation) than firms owned by U.S.-born entrepreneurs.[230] Research also shows that labor migration increases human capital.[76][74][75][77][231] Foreign doctoral students are a major source of innovation in the American economy.[232] In the United States, immigrant workers hold a disproportionate share of jobs in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM): "In 2013, foreign-born workers accounted for 19.2 percent of STEM workers with a bachelor's degree, 40.7 percent of those with a master's degree, and more than half—54.5 percent—of those with a PhD"[233]

A number of countries across the globe offer Economic Citizenship Programs where in return for investing into the local economy, foreign investors are awarded citizenship. Such programs encourage innovation and entrepreneurship from foreign investors and high net worth individuals who as new citizens in the country can offer unique perspectives. St. Kitts and Nevis was the first country to offer economic citizenship back in 1984 creating a new market for citizenship and by the early 2000s other Caribbean countries joined them.[234]

Using 130 years of data on historical migrations to the United States, one study finds "that a doubling of the number of residents with ancestry from a given foreign country relative to the mean increases by 4.2 percentage points the probability that at least one local firm invests in that country, and increases by 31% the number of employees at domestic recipients of FDI from that country. The size of these effects increases with the ethnic diversity of the local population, the geographic distance to the origin country, and the ethno-linguistic fractionalization of the origin country."[235] A 2017 study found that "immigrants' genetic diversity is significantly positively correlated with measures of U.S. counties' economic development [during the Age of Mass Migration]. There exists also a significant positive relationship between immigrants' genetic diversity in 1870 and contemporaneous measures of U.S. counties' average income."[236]

Some research suggests that immigration can offset some of the adverse effects of automation on native labor outcomes.[139][140]

Quality of institutions

A 2015 study finds "some evidence that larger immigrant population shares (or inflows) yield positive impacts on institutional quality. At a minimum, our results indicate that no negative impact on economic freedom is associated with more immigration."[237] Another study, looking at the increase in Israel's population in the 1990s due to the unrestricted immigration of Jews from the Soviet Union, finds that the mass immigration did not undermine political institutions, and substantially increased the quality of economic institutions.[238] A 2017 study in the British Journal of Political Science argued that the British American colonies without slavery adopted better democratic institutions in order to attract migrant workers to their colonies.[239][240] A 2018 study fails to find evidence that immigration to the United States weakens economic freedom.[241] A 2019 study of Jordan found that the massive influx of refugees into Jordan during the Gulf War had long-lasting positive effects on Jordanian economic institutions.[242]

Welfare

Some research has found that as immigration and ethnic heterogeneity increase, government funding of welfare and public support for welfare decrease.[243][244][245][246][247][248] Ethnic nepotism may be an explanation for this phenomenon. Other possible explanations include theories regarding in-group and out-group effects and reciprocal altruism.[249]

Research however also challenges the notion that ethnic heterogeneity reduces public goods provision.[250][251][252][253] Studies that find a negative relationship between ethnic diversity and public goods provision often fail to take into account that strong states were better at assimilating minorities, thus decreasing diversity in the long run.[250][251] Ethnically diverse states today consequently tend to be weaker states.[250] Because most of the evidence on fractionalization comes from sub-Saharan Africa and the United States, the generalizability of the findings is questionable.[252] A 2018 study in the American Political Science Review cast doubts on findings that ethnoracial homogeneity led to greater public goods provision.[254]

Research finds that Americans' attitudes towards immigration influence their attitudes towards welfare spending.[255]

Education

A 2016 study found that immigration in the period 1940–2010 in the United States increased the high school completion of natives: "An increase of one percentage point in the share of immigrants in the population aged 11–64 increases the probability that natives aged 11–17 eventually complete 12 years of schooling by 0.3 percentage point."[256] A 2019 NBER paper found little evidence that exposure to foreign-born students had an impact on US-born students.[257]

Studies have found that non-native speakers of English in the UK have no causal impact on the performance of other pupils,[258] immigrant children have no significant impact on the test scores of Dutch children,[259] no effect on grade repetition among native students exposed to migrant students in Austrian schools,[260] that the presence of Latin American children in schools had no significant negative effects on peers, but that students with limited English skills had slight negative effects on peers,[261] and that the influx of Haitians to Florida public schools after the 2010 Haiti earthquake had no effects on the educational outcomes of incumbent students.[262]

A 2018 study found that the "presence of immigrant students who have been in the country for some time is found to have no effect on natives. However, a small negative effect of recent immigrants on natives' language scores is reported."[263] Another 2018 study found that the presence of immigrant students to Italy was associated with "small negative average effects on maths test scores that are larger for low ability native students, strongly non-linear and only observable in classes with a high (top 20%) immigrant concentration. These outcomes are driven by classes with a high average linguistic distance between immigrants and natives, with no apparent additional role played by ethnic diversity."[264]

After immigrant children's scores were included in Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) 15-year-old school pupils' educational evaluations in Sweden the Swedish PISA scores significantly decreased.[265]

Social capital

There is some research that suggests that immigration adversely affects social capital.[266] One study, for instance, found that "larger increases in US states' Mexican population shares correspond to larger decreases in social capital over the period" 1986–2004.[267] A 2017 study in the Journal of Comparative Economics found that "individuals whose ancestors migrated from countries with higher autocracy levels are less likely to trust others and to vote in presidential elections in the U.S. The impact of autocratic culture on trust can last for at least three generations while the impact on voting disappears after one generation. These impacts on trust and voting are also significant across Europe."[268] A 2019 study found that "humans are inclined to react negatively to threats to homogeneity... in the short term. However, these negative outcomes are compensated in the long term by the beneficial influence of intergroup contact, which alleviates initial negative influences."[269]

Health

Research suggests that immigration has positive effects on native workers' health.[270][271] As immigration rises, native workers are pushed into less demanding jobs, which improves native workers' health outcomes.[270][271]

A 2018 study found that immigration to the United Kingdom "reduced waiting times for outpatient referrals and did not have significant effects on waiting times in accident and emergency departments (A&E) and elective care."[272] The study also found "evidence that immigration increased waiting times for outpatient referrals in more deprived areas outside of London" but that this increase disappears after 3 to 4 years.[272]

A 2018 systemic review and meta-analysis in The Lancet found that migrants generally have better health than the general population.[273]

In the EU, the use of personal health records for migrants is being tested in the new REHEALTH 2 project.[274]

High immigration can cause higher stress on highly regulated sectors such as healthcare, education, and housing, leading to negative effects.[275]

Housing

Immigration tends to increase both local rents and house prices,[276] but this dependency varies depending on factors including price elasticity of new housing supply,[277] socioeconomics of immigrants, and internal migration of natives.[276]

Crime

Immigration and crime refers to the relationship between criminal activity and the phenomenon of immigration. The academic literature and official statistics provide mixed findings for the relationship between immigration and crime. Research in the United States tends to suggest that immigration either has no impact on the crime rate or even that immigrants are less prone to crime.[278][279][280] A meta-analysis of 51 studies from 1994–2014 on the relationship between immigration and crime in the United States found that, overall, the immigration-crime association is negative, but the relationship is very weak and there is significant variation in findings across studies.[281] This is in line with a 2009 review of high-quality studies conducted in the United States that also found a negative relationship.[282]

Research and statistics in some other, mainly European countries suggest a positive link between immigration and crime: immigrants from particular countries are often overrepresented in crime figures.[283][284][285] The over-representation of immigrants in the criminal justice systems of several countries may be due to socioeconomic factors, imprisonment for migration offenses, and racial and ethnic discrimination by police and the judicial system.[286][287][288] The relationship between immigration and terrorism is understudied, but existing research is inconclusive.[289][290][291] Research on the relationship between refugee migration and crime is scarce and existing empirical evidence is often contradictory.[292][293] According to statistics from some countries, asylum seekers are overrepresented in crime figures.[294][295][296][failed verification]Bogus recruitment agencies and rogue recruitment agencies make fake promises of better opportunities, education, income, some of the abuses and crimes experienced by immigrants are the followed:

- Employees are forced to work in activities that were not included in their contracts, where workplace harassment is openly allowed, tolerated and even promoted.

- Workers are forced to work more than 20 hours a day with low wages or no payment,

- Slavery,

- human trafficking,

- Sexual harassment, sexual abuse, sexual assault, sexual exploitation.

- Offering fake immigrant visas in order to make it impossible for employees to return to their countries.

In many countries there is a lack of prosecution of this crimes, since these countries obtain benefits and taxes paid by these companies that benefit the economies and also because of the current shortage of workers.[297][298][299][300]

Impact on demographic tension

Assimilation

A 2019 review of existing research in the Annual Review of Sociology on immigrant assimilation in the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Sweden, Norway, Belgium, the Netherlands and Spain concluded "we find an overall pattern of intergenerational assimilation in terms of socioeconomic attainment, social relations, and cultural beliefs."[301]

Country of origin

Return migration from countries with liberal gender norms has been associated with the transfer of liberal gender norms to the home country.[302]

United States

A 2018 study in the American Sociological Review found that within racial groups, most immigrants to the United States had fully assimilated within a span of 20 years.[25] Immigrants arriving in the United States after 1994 assimilate more rapidly than immigrants who arrived in previous periods.[25] Measuring assimilation can be difficult due to "ethnic attrition", which refers to when descendants of migrants cease to self-identify with the nationality or ethnicity of their ancestors. This means that successful cases of assimilation will be underestimated. Research shows that ethnic attrition is sizable in Hispanic and Asian immigrant groups in the United States.[303][304] By taking account of ethnic attrition, the assimilation rate of Hispanics in the United States improves significantly.[303][305] A 2016 paper challenges the view that cultural differences are necessarily an obstacle to long-run economic performance of migrants. It finds that "first generation migrants seem to be less likely to success the more culturally distant they are, but this effect vanishes as time spent in the US increases."[306]

A 2018 study found that Chinese nationals in the United States who received permanent residency permits from the US government amid the Tiananmen Square protests (and subsequent Chinese government clampdown) experienced significant employment and earnings gains relative to similar immigrant groups who did not have the same residency rights.[307]

During the Age of Mass Migration, infant arrivals to the United States had greater economic success over their lifetime than teenage arrivals.[308]

Europe

A 2015 report by the National Institute of Demographic Studies finds that an overwhelming majority of second-generation immigrants of all origins in France feel French, despite the persistent discrimination in education, housing and employment that many of the minorities face.[309]

Research shows that country of origin matters for speed and depth of immigrant assimilation but that there is considerable assimilation overall.[26] Research finds that first generation immigrants from countries with less egalitarian gender cultures adopt gender values more similar to natives over time.[310][311] According to one study, "this acculturation process is almost completed within one generational succession: The gender attitudes of second generation immigrants are difficult to distinguish from the attitudes of members of mainstream society. This holds also for children born to immigrants from very gender traditional cultures and for children born to less well integrated immigrant families."[310] Similar results are found on a study of Turkish migrants to Western Europe.[311] The assimilation on gender attitudes has been observed in education, as one study finds "that the female advantage in education observed among the majority population is usually present among second-generation immigrants."[312]

A 2017 study of Switzerland found that naturalization strongly improves long-term social integration of immigrants: "The integration returns to naturalization are larger for more marginalized immigrant groups and when naturalization occurs earlier, rather than later in the residency period."[313] A separate study of Switzerland found that naturalization improved the economic integration of immigrants: "winning Swiss citizenship in the referendum increased annual earnings by an average of approximately 5,000 U.S. dollars over the subsequent 15 years. This effect is concentrated among more marginalized immigrants."[314]

First-generation immigrants tend to hold less accepting views of homosexuality but opposition weakens with longer stays.[315] Second-generation immigrants are overall more accepting of homosexuality, but the acculturation effect is weaker for Muslims and to some extent, Eastern Orthodox migrants.[315]

A study of Bangladeshi migrants in East London found they shifted towards the thinking styles of the wider non-migrant population in just a single generation.[316]

A study on Germany found that foreign-born parents are more likely to integrate if their children are entitled to German citizenship at birth.[317] A 2017 study found that "faster access to citizenship improves the economic situation of immigrant women, especially their labour market attachment with higher employment rates, longer working hours and more stable jobs. Immigrants also invest more in host country-specific skills like language and vocational training. Faster access to citizenship seems a powerful policy instrument to boost economic integration in countries with traditionally restrictive citizenship policies."[318] Naturalization is associated with large and persistent wage gains for the naturalized citizens in most countries.[319] One study of Denmark found that providing immigrants with voting rights reduced their crime rate.[320]

Studies on programs that randomly allocate refugee immigrants across municipalities find that the assignment of neighborhood impacts immigrant crime propensity, education and earnings.[321][322][323][324][325][326] A 2019 study found that refugees who resettled in areas with many conationals were more likely to be economically integrated.[327]

Research suggests that bilingual schooling reduces barriers between speakers from two different communities.[328]

Research suggests that a vicious cycle of bigotry and isolation could reduce assimilation and increase bigotry towards immigrants in the long-term. For instance, University of California, San Diego political scientist Claire Adida, Stanford University political scientist David Laitin and Sorbonne University economist Marie-Anne Valfort argue "fear-based policies that target groups of people according to their religion or region of origin are counter-productive. Our own research, which explains the failed integration of Muslim immigrants in France, suggests that such policies can feed into a vicious cycle that damages national security. French Islamophobia—a response to cultural difference—has encouraged Muslim immigrants to withdraw from French society, which then feeds back into French Islamophobia, thus further exacerbating Muslims' alienation, and so on. Indeed, the failure of French security in 2015 was likely due to police tactics that intimidated rather than welcomed the children of immigrants—an approach that makes it hard to obtain crucial information from community members about potential threats."[329][330]

A study which examined Catalan nationalism examined the Catalan Government's policy towards the integration of immigrants during the start of the 1990s. At this time the Spanish region of Catalonia was experiencing a large influx in the number of immigrants from Northern Africa, Latin America and Asia. The Spanish government paid little attention to this influx of immigrants. However, Catalan politicians began discussing how the increase in immigrants would effect Catalan identity. Members of the Catalan parliament petitioned for a plan to integrate these immigrants into Catalan society. Crucially, the plan did not include policies regarding naturalisation, which were key immigration policies of the Spanish government. The plan of the Catalan parliament aimed to create a shared Catalan identity which included both the native Catalan population and immigrant communities. This meant that immigrants were encouraged to relate as part of the Catalan community but also encouraged to retain their own culture and traditions. In this way assimilation of immigrant cultures in Catalonia was avoided.[331]

A 2018 study in the British Journal of Political Science found that immigrants in Norway became more politically engaged the earlier that they were given voting rights.[332]

A 2019 study in the European Economic Review found that language training improved the economic assimilation of immigrants in France.[333]

A 2020 study using data from large-scale comparative surveys in Germany, France, and United Kingdom found that sampled households with a language barrier tend to have poor living conditions and are migrants. Inferences about their demographic, attitudinal, or behavioral traits cannot be made because the ability to speak the official language(s) of the country is one of the criteria for survey participation.[334]

A 2020 paper on reforms of refugee policy in Denmark found that language training boosted the economic and social integration of refugees, whereas cuts to refugees' welfare benefits had no impact, except to temporarily increase property crimes.[335]

Discrimination

Europe

Research suggests that police practices, such as racial profiling, over-policing in areas populated by minorities and in-group bias may result in disproportionately high numbers of racial minorities among crime suspects in Sweden, Italy, and England and Wales.[336][337][338][339][340] Research also suggests that there may be possible discrimination by the judicial system, which contributes to a higher number of convictions for racial minorities in Sweden, the Netherlands, Italy, Germany, Denmark and France.[336][338][339][341][342][343][344] A 2018 study found that the Dutch are less likely to reciprocate in games played with immigrants than the native Dutch.[345]

Several meta-analyses find extensive evidence of ethnic and racial discrimination in hiring in the North-American and European labor markets.[28][27][346] A 2016 meta-analysis of 738 correspondence tests in 43 separate studies conducted in OECD countries between 1990 and 2015 finds that there is extensive racial discrimination in hiring decisions in Europe and North-America.[27] Equivalent minority candidates need to send around 50% more applications to be invited for an interview than majority candidates.[27]

A 2014 meta-analysis found extensive evidence of racial and ethnic discrimination in the housing market of several European countries.[28]

United Kingdom

Since 2010, the United Kingdom's policies surrounding immigrant detention have come under fire for insufficiently protecting vulnerable groups. In the early 2000s, the United Kingdom adopted the Detention Duty Advice (DDA) scheme in order to provide free, government-funded, legal aid to immigrants. The DDA scheme at face value granted liberty on administrative grounds by considering immigrant merits, nature of their work, their financial means, and other factors that would then determine how much free legal aid detainees were granted. Recent research by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), demonstrates that marginalized groups have been barred from legal assistance in detention centers. The barriers immigrants face in order to access justice through the DDA disproportionately impacted underrepresented groups of immigrants, and the language barrier and lack of interpreters led to further hurdles that detainees were unable to jump through.[62]

Canada

In Canada immigrant detainees face barriers to justice due to a lack of international enforcement. Canada's immigration detention system has significant legal and normative problems, and the rubric of ‘access to justice’ that is presented by international law fails to identify these faults. There is a lack of access to legal aid for immigrants in detention, as well as inhumane treatment in detention centers. Research has demonstrated irreparable psychological, physical, and social damage to immigrants, and the international community ignores these injustices.[347]

United States

Business

A 2014 meta-analysis of racial discrimination in product markets found extensive evidence of minority applicants being quoted higher prices for products.[28] A 1995 study found that car dealers "quoted significantly lower prices to white males than to black or female test buyers using identical, scripted bargaining strategies."[348] A 2013 study found that eBay sellers of iPods received 21 percent more offers if a white hand held the iPod in the photo than a black hand.[349]

Criminal justice system

Research suggests that police practices, such as racial profiling, over-policing in areas populated by minorities and in-group bias may result in disproportionately high numbers of racial minorities among crime suspects.[350][351][352][353] Research also suggests that there may be possible discrimination by the judicial system, which contributes to a higher number of convictions for racial minorities.[354][355][356][357][358] A 2012 study found that "(i) juries formed from all-white jury pools convict black defendants significantly (16 percentage points) more often than white defendants, and (ii) this gap in conviction rates is entirely eliminated when the jury pool includes at least one black member."[356] Research has found evidence of in-group bias, where "black (white) juveniles who are randomly assigned to black (white) judges are more likely to get incarcerated (as opposed to being placed on probation), and they receive longer sentences."[358] In-group bias has also been observed when it comes to traffic citations, as black and white cops are more likely to cite out-groups.[352]

Education

A 2015 study using correspondence tests "found that when considering requests from prospective students seeking mentoring in the future, faculty were significantly more responsive to White males than to all other categories of students, collectively, particularly in higher-paying disciplines and private institutions."[359]

According to an analysis of the National Study of College Experience, elite colleges may favor minority applicants due to affirmative action policies.[360]

A 2018 National Bureau of Economic Research paper found that math teachers discriminate against the children of immigrants. When the teachers were informed about negative stereotypes towards the children of immigrants, they gave higher grades to the children of immigrants.[361]

As of 2020, 2 percent of all students enrolled in U.S. higher education. That comes out to about 454,000 students. Fewer than half of the undocumented are eligible for the DACA program. DACA is formally known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals.[362]

Housing

A 2014 meta-analysis found extensive evidence of racial discrimination in the American housing market.[28] Minority applicants for housing needed to make many more enquiries to view properties.[28] Geographical steering of African-Americans in US housing remained significant.[28] A 2003 study finds "evidence that agents interpret an initial housing request as an indication of a customer's preferences, but also are more likely to withhold a house from all customers when it is in an integrated suburban neighborhood (redlining). Moreover, agents' marketing efforts increase with asking price for white, but not for black, customers; blacks are more likely than whites to see houses in suburban, integrated areas (steering); and the houses agents show are more likely to deviate from the initial request when the customer is black than when the customer is white. These three findings are consistent with the possibility that agents act upon the belief that some types of transactions are relatively unlikely for black customers (statistical discrimination)."[363]

A report by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development where the department sent African-Americans and whites to look at apartments found that African-Americans were shown fewer apartments to rent and houses for sale.[364]

Labor market

Several meta-analyses find extensive evidence of ethnic and racial discrimination in hiring in the American labor market.[28][346][27] A 2016 meta-analysis of 738 correspondence tests—tests where identical CVs for stereotypically black and white names were sent to employers—in 43 separate studies conducted in OECD countries between 1990 and 2015 finds that there is extensive racial discrimination in hiring decisions in Europe and North-America.[27] These correspondence tests showed that equivalent minority candidates need to send around 50% more applications to be invited for an interview than majority candidates.[27][365] A study that examine the job applications of actual people provided with identical résumés and similar interview training showed that African-American applicants with no criminal record were offered jobs at a rate as low as white applicants who had criminal records.[366]

Iran

Iranian companies faced a mass exodus of youth and skilled labor out of the country in recent years.[367] In June 2023 Iranian parliament illegalized immigration ads online.[368][369][370][371][372]

See also

- Criticism of multiculturalism

- Immigration law

- Immigration reform

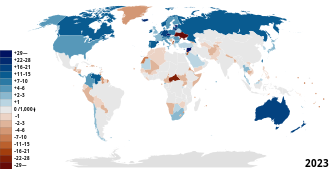

- List of sovereign states by net migration rate

- List of countries and dependencies by population density

- Multiculturalism

- Opposition to immigration

- People smuggling

- Repatriation

- Replacement migration

- Non-citizen suffrage

- White genocide conspiracy theory

- Women migrant workers from developing countries

- Xenophobia

References

- ^ "immigration". OxfordDictionaries.com. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ "immigrate". Merriam-Webster.com. Merriam-Webster, In. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ "Who's who: Definitions". London, England: Refugee Council. 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- ^ "International Migration Law No. 34 – Glossary on Migration". International Organization for Migration. 19 June 2019. ISSN 1813-2278.

- ^ Koczan, Zsoka; Peri, Giovanni; Pinat, Magali; Rozhkov, Dmitriy (2021), "Migration", in Valerie Cerra; Barry Eichengreen; Asmaa El-Ganainy; Martin Schindler (eds.), How to Achieve Inclusive Growth, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/oso/9780192846938.003.0009, ISBN 978-0-19-284693-8

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c d e di Giovanni, Julian; Levchenko, Andrei A.; Ortega, Francesc (1 February 2015). "A Global View of Cross-Border Migration" (PDF). Journal of the European Economic Association. 13 (1): 168–202. doi:10.1111/jeea.12110. hdl:10230/22196. ISSN 1542-4774. S2CID 3465938.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b Andreas, Willenbockel, Dirk; Sia, Go, Delfin; Amer, Ahmed, S. (11 April 2016). "Global migration revisited: short-term pains, long-term gains, and the potential of south-south migration". The World Bank.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b Card, David; Dustmann, Christian; Preston, Ian (1 February 2012). "Immigration, Wages, and Compositional Amenities" (PDF). Journal of the European Economic Association. 10 (1): 78–119. doi:10.1111/j.1542-4774.2011.01051.x. ISSN 1542-4774. S2CID 154303869.

- ^ Bodvarsson, Örn B; Van den Berg, Hendrik (2013). The economics of immigration: theory and policy. New York; Heidelberg [u.a.]: Springer. p. 157. ISBN 978-1-4614-2115-3. OCLC 852632755.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b "Migration Within Europe | IGM Forum". www.igmchicago.org. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ "Poll Results | IGM Forum". www.igmchicago.org. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ^ "Poll Results | IGM Forum". www.igmchicago.org. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b Iregui, Ana Maria (1 January 2003). "Efficiency Gains from the Elimination of Global Restrictions on Labour Mobility: An Analysis using a Multiregional CGE Model". Wider Working Paper Series.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b Clemens, Michael A (1 August 2011). "Economics and Emigration: Trillion-Dollar Bills on the Sidewalk?". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 25 (3): 83–106. doi:10.1257/jep.25.3.83. ISSN 0895-3309. S2CID 59507836.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b Hamilton, B.; Whalley, J. (1 February 1984). "Efficiency and distributional implications of global restrictions on labour mobility: calculations and policy implications". Journal of Development Economics. 14 (1–2): 61–75. doi:10.1016/0304-3878(84)90043-9. ISSN 0304-3878. PMID 12266702.

- ^ Dustmann, Christian; Preston, Ian P. (2 August 2019). "Free Movement, Open Borders, and the Global Gains from Labor Mobility". Annual Review of Economics. 11 (1): 783–808. doi:10.1146/annurev-economics-080218-025843. ISSN 1941-1383.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b Milanovic, Branko (7 January 2014). "Global Inequality of Opportunity: How Much of Our Income Is Determined by Where We Live?". Review of Economics and Statistics. 97 (2): 452–460. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00432. hdl:10986/21484. ISSN 0034-6535. S2CID 11046799.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c Mishra, Prachi (2014). "Emigration and wages in source countries: A survey of the empirical literature". International Handbook on Migration and Economic Development. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 241–266. doi:10.4337/9781782548072.00013. ISBN 978-1-78254-807-2. S2CID 143429722.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c Clemens, Michael A.; Pritchett, Lant (2019). "The New Economic Case for Migration Restrictions: An Assessment". Journal of Development Economics. 138 (9730): 153–164. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2018.12.003. S2CID 204418677.

- ^ Pritchett, Lant; Hani, Farah (30 July 2020). The Economics of International Wage Differentials and Migration. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190625979.013.353. ISBN 978-0-19-062597-9. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Peri, Giovanni. "Can Immigration Solve the Demographic Dilemma?". www.imf.org. IMF. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ Harvey, Fiona (15 July 2020). "World population in 2100 could be 2 billion below UN forecasts, study suggests". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ The Integration of Immigrants into American Society. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2015. doi:10.17226/21746. ISBN 978-0-309-37398-2.

Americans have long believed that immigrants are more likely than natives to commit crimes and that rising immigration leads to rising crime... This belief is remarkably resilient to the contrary evidence that immigrants are in fact much less likely than natives to commit crimes.

- ^ Lee, Matthew T.; Martinez Jr., Ramiro (2009). "Immigration reduces crime: an emerging scholarly consensus". Immigration, Crime and Justice. Emerald Group Publishing. pp. 3–16. ISBN 978-1-84855-438-2.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c Villarreal, Andrés; Tamborini, Christopher R. (2018). "Immigrants' Economic Assimilation: Evidence from Longitudinal Earnings Records". American Sociological Review. 83 (4): 686–715. doi:10.1177/0003122418780366. PMC 6290669. PMID 30555169.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b Blau, Francine D. (2015). "Immigrants and Gender Roles: Assimilation vs. Culture" (PDF). IZA Journal of Migration. 4 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1186/s40176-015-0048-5. S2CID 53414354. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c d e f g Zschirnt, Eva; Ruedin, Didier (27 May 2016). "Ethnic discrimination in hiring decisions: a meta-analysis of correspondence tests 1990–2015". Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 42 (7): 1115–1134. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2015.1133279. hdl:10419/142176. ISSN 1369-183X. S2CID 10261744.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Rich, Judy (October 2014). "What Do Field Experiments of Discrimination in Markets Tell Us? A Meta Analysis of Studies Conducted since 2000". IZA Discussion Papers (8584). SSRN 2517887. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ Rehavi, M. Marit; Starr, Sonja B. (2014). "Racial Disparity in Federal Criminal Sentences". Journal of Political Economy. 122 (6): 1320–1354. doi:10.1086/677255. ISSN 0022-3808. S2CID 3348344.

- ^ Enos, Ryan D. (1 January 2016). "What the Demolition of Public Housing Teaches Us about the Impact of Racial Threat on Political Behavior". American Journal of Political Science. 60 (1): 123–142. doi:10.1111/ajps.12156. S2CID 51895998.

- ^ "outmigrant". OxfordDictionaries.com. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ "United Nations Population Division | Department of Economic and Social Affairs". www.un.org. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c d "Trends in international migration, 2015" (PDF). UN.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. December 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ "150 Million Adults Worldwide Would Migrate to the U.S". Gallup.com. 20 April 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2014.