Квебек

Эта статья может оказаться слишком длинной для удобного чтения и навигации . Когда этот тег был добавлен, его читаемый размер составлял 14 769 слов. ( июнь 2024 г. ) |

Квебек Квебек ( французский ) | |

|---|---|

| Девиз(ы): | |

| Coordinates: 52°N 72°W / 52°N 72°W[1] | |

| Country | Canada |

| Before confederation | Canada East |

| Confederation | July 1, 1867 (1st, with New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Ontario) |

| Capital | Quebec City |

| Largest city | Montreal |

| Largest metro | Greater Montreal |

| Government | |

| • Type | Parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

| • Lieutenant Governor | Manon Jeannotte |

| • Premier | François Legault |

| Legislature | National Assembly of Quebec |

| Federal representation | Parliament of Canada |

| House seats | 78 of 338 (23.1%) |

| Senate seats | 24 of 105 (22.9%) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,542,056 km2 (595,391 sq mi) |

| • Land | 1,365,128 km2 (527,079 sq mi) |

| • Water | 176,928 km2 (68,312 sq mi) 11.5% |

| • Rank | 2nd |

| 15.4% of Canada | |

| Population (2021) | |

| • Total | 8,501,833[2] |

| • Estimate (Q1 2024) | 8,984,918[3] |

| • Rank | 2nd |

| • Density | 6.23/km2 (16.1/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | in English: Quebecer, Quebecker, Québécois in French: Québécois (m),[4] Québécoise (f)[4] |

| Official languages | French[5] |

| GDP | |

| • Rank | 2nd |

| • Total (2022) | C$552.737 billion[6] |

| • Per capita | C$63,651 (9th) |

| HDI | |

| • HDI (2019) | 0.916[7]—Very high (9th) |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern Time Zone for most of the province[8]) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 |

| Canadian postal abbr. | QC[9] |

| Rankings include all provinces and territories | |

Квебек [а] ( Французский : Квебек [kebɛk] ) [12] — одна из тринадцати провинций и территорий Канады . Это самая большая по площади провинция. [б] и второй по величине по численности населения . Большая часть населения проживает в городских районах вдоль реки Святого Лаврентия . [13] между самым густонаселенным городом Монреалем и столицей провинции Квебеком . Расположенная в Центральной Канаде , провинция граничит по суше с Онтарио на западе, с Ньюфаундлендом и Лабрадором на северо-востоке, с Нью-Брансуиком на юго-востоке и прибрежной границей с Нунавутом ; на юге граничит с Соединенными Штатами . [с]

нынешнего Квебека была французской колонией Канады Между 1534 и 1763 годами территория и самой развитой колонией Новой Франции . После Семилетней войны Канада стала британской колонией , сначала как провинция Квебек (1763–1791), затем Нижняя Канада (1791–1841) и, наконец, как часть провинции Канада (1841–1867). в восстания Нижней Канаде . В 1867 году он был объединен с Онтарио, Новой Шотландией и Нью-Брансуиком. До начала 1960-х годов католическая церковь играла большую роль в социальных и культурных учреждениях Квебека. Однако Тихая революция 1960-1980-х годов увеличила роль правительства Квебека в l'État Québécois (государственной власти Квебека).

The Government of Quebec functions within the context of a Westminster system and is both a liberal democracy and a constitutional monarchy. The Premier of Quebec acts as head of government. Independence debates have played a large role in Quebec politics. Quebec society's cohesion and specificity is based on three of its unique statutory documents: the Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms, the Charter of the French Language, and the Civil Code of Quebec. Furthermore, unlike elsewhere in Canada, law in Quebec is mixed: private law is exercised under a civil-law system, while public law is exercised under a common-law system.

Quebec's official language is French; Québécois French is the regional variety. Quebec is the only Francophone-majority province. The economy of Quebec is mainly supported by its large service sector and varied industrial sector. For exports, it leans on the key industries of aeronautics, where it is the 6th largest worldwide seller,[14] hydroelectricity, mining, pharmaceuticals, aluminum, wood, and paper. Quebec is well known for producing maple syrup, for its comedy, and for making hockey one of the most popular sports in Canada. It is also renowned for its culture; the province produces literature, music, films, TV shows, festivals, and more.

Etymology

The name Québec comes from an Algonquin word meaning 'narrow passage' or 'strait'.[15] The name originally referred to the area around Quebec City where the Saint Lawrence River narrows to a cliff-lined gap. Early variations in the spelling included Québecq and Kébec.[16] French explorer Samuel de Champlain chose the name Québec in 1608 for the colonial outpost he would use as the administrative seat for New France.[17]

History

Indigenous peoples and European expeditions (pre-1608)

The Paleo-Indians, theorized to have migrated from Asia to America between 20,000 and 14,000 years ago, were the first people to establish themselves on the lands of Quebec, arriving after the Laurentide Ice Sheet melted roughly 11,000 years ago.[18][19] From them, many ethnocultural groups emerged. By the European explorations of the 1500s, there were eleven Indigenous peoples: the Inuit and ten First Nations – the Abenakis, Algonquins (or Anichinabés), Atikamekw, Cree, Huron-Wyandot, Maliseet, Miꞌkmaqs, Iroquois, Innu and Naskapis.[20] Algonquians organized into seven political entities and lived nomadic lives based on hunting, gathering, and fishing.[21] Inuit fished and hunted whales and seals along the coasts of Hudson and Ungava Bays.[22]

In the 15th century, the Byzantine Empire fell, prompting Western Europeans to search for new sea routes to the Far East.[23] Around 1522–23, Giovanni da Verrazzano persuaded King Francis I of France to commission an expedition to find a western route to Cathay (China) via a Northwest Passage. Though this expedition was unsuccessful, it established the name New France for northeast North America.[24] In his first expedition ordered from the Kingdom of France, Jacques Cartier became the first European explorer to discover and map Quebec when he landed in Gaspé on July 24, 1534.[25] In the second expedition, in 1535, Cartier explored the lands of Stadacona and named the village and its surrounding territories Canada (from kanata, 'village' in Iroquois). Cartier returned to France with about 10 St. Lawrence Iroquoians, including Chief Donnacona. In 1540, Donnacona told the legend of the Kingdom of Saguenay to the King, inspiring him to order a third expedition, this time led by Jean-François de La Rocque de Roberval; it was unsuccessful in its goal of finding the kingdom.[26]

After these expeditions, France mostly abandoned North America for 50 years because of its financial crisis; France was involved in the Italian Wars and religious wars.[27] Around 1580, the rise of the fur trade reignited French interest; New France became a colonial trading post.[28] In 1603, Samuel de Champlain travelled to the Saint Lawrence River and, on Pointe Saint-Mathieu, established a defence pact with the Innu, Maliseet and Micmacs, that would be "a decisive factor in the maintenance of a French colonial enterprise in America despite an enormous numerical disadvantage vis-à-vis the British".[29] Thus also began French military support to the Algonquian and Huron peoples against Iroquois attacks; these became known as the Iroquois Wars and lasted from the early 1600s to the early 1700s.[30]

New France (1608–1763)

In 1608, Samuel de Champlain[31] returned to the region as head of an exploration party. On July 3, 1608, with the support of King Henry IV, he founded the Habitation de Québec (now Quebec City) and made it the capital of New France and its regions.[28] The settlement was built as a permanent fur trading outpost, where First Nations traded furs for French goods, such as metal objects, guns, alcohol, and clothing.[32] Missionary groups arrived in New France after the founding of Quebec City. Coureurs des bois and Catholic missionaries used river canoes to explore the interior and establish fur trading forts.[33][34]

The Compagnie des Cent-Associés, which had been granted a royal mandate to manage New France in 1627, introduced the Custom of Paris and the seigneurial system, and forbade settlement by anyone other than Catholics.[35] In 1629, Quebec City surrendered, without battle, to English privateers during the Anglo-French War; in 1632, the English king agreed to return it with the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Trois-Rivières was founded at de Champlain's request in 1634.[36] Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve founded Ville-Marie (now Montreal) in 1642.

In 1663, the Company of New France ceded Canada to King Louis XIV, who made New France into a royal province of France.[37] New France was now a true colony administered by the Sovereign Council of New France from Quebec City. A governor-general, governed Canada and its administrative dependencies: Acadia, Louisiana and Plaisance.[38] The French settlers were mostly farmers and known as "Canadiens" or "Habitants". Though there was little immigration,[39] the colony grew because of the Habitants' high birth rates.[40][41] In 1665, the Carignan-Salières regiment developed the string of fortifications known as the "Valley of Forts" to protect against Iroquois invasions and brought with them 1,200 new men.[42] To redress the gender imbalance and boost population growth, King Louis XIV sponsored the passage of approximately 800 young French women (King's Daughters) to the colony.[37] In 1666, intendant Jean Talon organized the first census and counted 3,215 Habitants. Talon enacted policies to diversify agriculture and encourage births, which, in 1672, had increased the population to 6,700.[43]

New France's territory grew to extend from Hudson Bay to the Gulf of Mexico, and would encompass the Great Lakes.[44] In the early 1700s, Governor Callières concluded the Great Peace of Montreal, which not only confirmed the alliance between the Algonquian and New France, but definitively ended the Iroquois Wars.[45] From 1688 onwards, the fierce competition between the French and British to control North America's interior and monopolize fur trade pitted New France and its Indigenous allies against the Iroquois and English in four successive wars called the French and Indian Wars by Americans, and the Intercolonial Wars in Quebec.[46] The first three were King William's War (1688–1697), Queen Anne's War (1702–1713), and King George's War (1744–1748). In 1713, following the Peace of Utrecht, the Duke of Orléans ceded Acadia and Plaisance Bay to Great Britain, but retained Île Saint-Jean, and Île-Royale where the Fortress of Louisbourg was subsequently erected. These losses were significant since Plaisance Bay was the primary communication route between New France and France, and Acadia contained 5,000 Acadians.[47][48] In the siege of Louisbourg (1745), the British were victorious, but returned the city to France after war concessions.[49]

The last of the four French and Indian Wars was the Seven Years' War ("The War of the Conquest" in Quebec) and lasted from 1754 to 1763.[50][51] In 1754, tensions escalated for control of the Ohio Valley, as authorities in New France became more aggressive in efforts to expel British traders and colonists.[52] In 1754, George Washington launched a surprise attack on a group of sleeping Canadien soldiers, known as the Battle of Jumonville Glen, the first battle of the war. In 1755, Governor Charles Lawrence and Officer Robert Monckton ordered the forceful explusion of the Acadians. In 1758, on Île-Royale, British General James Wolfe besieged and captured the Fortress of Louisbourg.[53] This allowed him to control access to the Gulf of St. Lawrence through the Cabot Strait. In 1759, he besieged Quebec for three months from Île d'Orléans.[54] Then, Wolfe stormed Quebec and fought against Montcalm for control of the city in the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. After a British victory, the king's lieutenant and Lord of Ramezay concluded the Articles of Capitulation of Quebec. During the spring of 1760, the Chevalier de Lévis besieged Quebec City and forced the British to entrench themselves during the Battle of Sainte-Foy. However, loss of French vessels sent to resupply New France after the fall of Quebec City during the Battle of Restigouche marked the end of France's efforts to retake the colony. Governor Pierre de Rigaud, marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnial signed the Articles of Capitulation of Montreal on September 8, 1760.

While awaiting the results of the Seven Years' War in Europe, New France was put under a British military regime led by Governor James Murray.[55] In 1762, Commander Jeffery Amherst ended the French presence in Newfoundland at the Battle of Signal Hill. France secretly ceded the western part of Louisiana and the Mississippi River Delta to Spain via the Treaty of Fontainebleau. On February 10, 1763, the Treaty of Paris concluded the war. France ceded its North American possessions to Great Britain.[56] Thus, France had put an end to New France and abandoned the remaining 60,000 Canadiens, who sided with the Catholic clergy in refusing to take an oath to the British Crown.[57] The rupture from France would provoke a transformation within the descendants of the Canadiens that would eventually result in the birth of a new nation.[58]

British North America (1763–1867)

After the British acquired Canada in 1763, the British government established a constitution for the newly acquired territory, under the Royal Proclamation.[59] The Canadiens were subordinated to the government of the British Empire and circumscribed to a region of the St. Lawrence Valley and Anticosti Island called the Province of Quebec. With unrest growing in their southern colonies, the British were worried that the Canadiens might support what would become the American Revolution. To secure allegiance to the British crown, Governor James Murray and later Governor Guy Carleton promoted the need for accommodations, resulting in the enactment of the Quebec Act[60] of 1774. This act allowed Canadiens to regain their civil customs, return to the seigneural system, regain certain rights including use of French, and reappropriate their old territories: Labrador, the Great Lakes, the Ohio Valley, Illinois Country and the Indian Territory.[61]

As early as 1774, the Continental Congress of the separatist Thirteen Colonies attempted to rally the Canadiens to its cause. However, its military troops failed to defeat the British counteroffensive during its Invasion of Quebec in 1775. Most Canadiens remained neutral, though some regiments allied themselves with the Americans in the Saratoga campaign of 1777. When the British recognized the independence of the rebel colonies at the signing of the Treaty of Paris of 1783, it conceded Illinois and the Ohio Valley to the newly formed United States and denoted the 45th parallel as its border, drastically reducing Quebec's size.

Some United Empire Loyalists from the US migrated to Quebec and populated various regions.[62] Dissatisfied with the legal rights under the French seigneurial régime which applied in Quebec, and wanting to use the British legal system to which they were accustomed, the Loyalists protested to British authorities until the Constitutional Act of 1791 was enacted, dividing the Province of Quebec into two distinct colonies starting from the Ottawa River: Upper Canada to the west (predominantly Anglo-Protestant) and Lower Canada to the east (Franco-Catholic). Lower Canada's lands consisted of the coasts of the Saint Lawrence River, Labrador and Anticosti Island, with the territory extending north to Rupert's Land, and south, east and west to the borders with the US, New Brunswick, and Upper Canada. The creation of Upper and Lower Canada allowed Loyalists to live under British laws and institutions, while Canadiens could maintain their French civil law and Catholic religion. Governor Haldimand drew Loyalists away from Quebec City and Montreal by offering free land on the north shore of Lake Ontario to anyone willing to swear allegiance to George III. During the War of 1812, Charles-Michel de Salaberry became a hero by leading the Canadian troops to victory at the Battle of the Chateauguay. This loss caused the Americans to abandon the Saint Lawrence Campaign, their major strategic effort to conquer Canada.

Gradually, the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada, who represented the people, came into conflict with the superior authority of the Crown and its appointed representatives. Starting in 1791, the government of Lower Canada was criticized and contested by the Parti canadien. In 1834, the Parti canadien presented its 92 resolutions, political demands which expressed loss of confidence in the British monarchy. Discontentment intensified throughout the public meetings of 1837, and the Lower Canada Rebellion began in 1837.[64] In 1837, Louis-Joseph Papineau and Robert Nelson led residents of Lower Canada to form an armed group called the Patriotes. They made a Declaration of Independence in 1838, guaranteeing rights and equality for all citizens without discrimination.[65] Their actions resulted in rebellions in both Lower and Upper Canada. The Patriotes were victorious in their first battle, the Battle of Saint-Denis. However, they were unorganized and badly equipped, leading to their loss against the British army in the Battle of Saint-Charles, and defeat in the Battle of Saint-Eustache.[63]

In response to the rebellions, Lord Durham was asked to undertake a study and prepare a report offering a solution to the British Parliament.[66] Durham recommended that Canadiens be culturally assimilated, with English as their only official language. To do this, the British passed the Act of Union 1840, which merged Upper Canada and Lower Canada into a single colony: the Province of Canada. Lower Canada became the francophone and densely populated Canada East, and Upper Canada became the anglophone and sparsely populated Canada West. This union, unsurprisingly, was the main source of political instability until 1867. Despite their population gap, Canada East and Canada West obtained an identical number of seats in the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada, which created representation problems. In the beginning, Canada East was underrepresented because of its superior population size. Over time, however, massive immigration from the British Isles to Canada West occurred. Since the two regions continued to have equal representation, this meant it was now Canada West that was under-represented. The representation issues were called into question by debates on "Representation by Population". The British population began to use the term "Canadian", referring to Canada, their place of residence. The French population, who had thus far identified as "Canadiens", began to be identified with their ethnic community under the name "French Canadian" as they were a "French of Canada".[67]

As access to new lands remained problematic because they were still monopolized by the Clique du Château, an exodus of Canadiens towards New England began and went on for the next hundred years. This phenomenon is known as the Grande Hémorragie and threatened the survival of the Canadien nation. The massive British immigration ordered from London that followed the failed rebellion, compounded this. To combat it, the Church adopted the revenge of the cradle policy. In 1844, the capital of the Province of Canada was moved from Kingston to Montreal.[68]

Political unrest came to a head in 1849, when English Canadian rioters set fire to the Parliament Building in Montreal following the enactment of the Rebellion Losses Bill, a law that compensated French Canadians whose properties were destroyed during the rebellions of 1837–1838.[69] This bill, resulting from the Baldwin-La Fontaine coalition and Lord Elgin's advice, was important as it established the notion of responsible government.[70] In 1854, the seigneurial system was abolished, the Grand Trunk Railway was built and the Canadian–American Reciprocity Treaty was implemented. In 1866, the Civil Code of Lower Canada was adopted.[71][72][73]

Canadian province (1867–present)

In 1864, negotiations began for Canadian Confederation between the Province of Canada, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia at the Charlottetown Conference and Quebec Conference.

After having fought as a Patriote, George-Étienne Cartier entered politics in the Province of Canada, becoming one of the co-premiers and advocate for the union of the British North American provinces. He became a leading figure at the Quebec Conference, which produced the Quebec Resolutions, the foundation for Canadian Confederation.[74] Recognized as a Father of Confederation, he successfully argued for the establishment of the province of Quebec, initially composed of the historic heart of the territory of the French Canadian nation and where French Canadians would most likely retain majority status.

Following the London Conference of 1866, the Quebec Resolutions were implemented as the British North America Act, 1867 and brought into force on July 1, 1867, creating Canada. Canada was composed of four founding provinces: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Ontario and Quebec. These last two came from splitting the Province of Canada, and used the old borders of Lower Canada for Quebec, and Upper Canada for Ontario. On July 15, 1867, Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau became Quebec's first premier.

From Confederation until World War I, the Catholic Church was at its peak. The objective of clerico-nationalists was promoting the values of traditional society: family, French, the Catholic Church and rural life. Events such as the North-West Rebellion, the Manitoba Schools Question and Ontario's Regulation 17 turned the promotion and defence of the rights of French Canadians into an important concern.[75] Under the aegis of the Catholic Church and the political action of Henri Bourassa, symbols of national pride were developed, like the Flag of Carillon, and "O Canada" – a patriotic song composed for Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day. Many organizations went on to consecrate the affirmation of the French-Canadian people, including the caisses populaires Desjardins in 1900, the Club de hockey Canadien in 1909, Le Devoir in 1910, the Congress on the French language in Canada in 1912, and L'Action nationale in 1917. In 1885, liberal and conservative MPs formed the Parti national out of anger with the previous government for not having interceded in the execution of Louis Riel.[76]

In 1898, the Canadian Parliament enacted the Quebec Boundary Extension Act, 1898, which gave Quebec part of Rupert's Land, which Canada had bought from the Hudson's Bay Company in 1870.[77] This act expanded the boundaries of Quebec northward. In 1909, the government passed a law obligating wood and pulp to be transformed in Quebec, which helped slow the Grande Hémorragie by allowing Quebec to export its finished products to the US instead of its labour force.[78] In 1910, Armand Lavergne passed the Lavergne Law, the first language legislation in Quebec. It required use of French alongside English on tickets, documents, bills and contracts issued by transportation and public utility companies. At this time, companies rarely recognized the majority language of Quebec.[79] Clerico-nationalists eventually started to fall out of favour in the federal elections of 1911. In 1912, the Canadian Parliament enacted the Quebec Boundaries Extension Act, 1912, which gave Quebec another part of Rupert's Land: the District of Ungava.[80] This extended the borders of Quebec northward to the Hudson Strait.

When World War I broke out, Canada was automatically involved and many English Canadians volunteered. However, because they did not feel the same connection to the British Empire and there was no direct threat to Canada, French Canadians saw no reason to fight. By late 1916, casualties were beginning to cause reinforcement problems. After enormous difficulty in the federal government, because almost every French-speaking MP opposed conscription while almost all English-speaking MPs supported it, the Military Service Act became law on August 29, 1917.[81] French Canadians protested in what is now called the Conscription Crisis of 1917, which led to the Quebec riot.[82]

In 1919, the prohibition of spirits was enacted following a provincial referendum.[83] But, prohibition was abolished in 1921 due to the Alcoholic Beverages Act which created the Commission des liqueurs du Québec.[84] In 1927, the British Judicial Committee of the Privy Council drew a clear border between northeast Quebec and south Labrador. However, the Quebec government did not recognize the ruling of the Judicial Committee, resulting in a boundary dispute which remains ongoing. The Statute of Westminster 1931 was enacted, and confirmed the autonomy of the Dominions – including Canada and its provinces – from the UK, as well as their free association in the Commonwealth.[85] In the 1930s, Quebec's economy was affected by the Great Depression because it greatly reduced US demand for Quebec exports. Between 1929-32 the unemployment rate increased from 8% to 26%. In an attempt to remedy this, the Quebec government enacted infrastructure projects, campaigns to colonize distant regions, financial assistance to farmers, and the secours directs – the ancestor to Canada's Employment Insurance.[86]

French Canadians remained opposed to conscription during the Second World War. When Canada declared war in September 1939, the federal government pledged not to conscript soldiers for overseas service. As the war went on, more and more English Canadians voiced support for conscription, despite firm opposition from French Canada. Following a 1942 poll that showed 73% of Quebec's residents were against conscription, while 80% or more were for conscription in every other province, the federal government passed Bill 80 for overseas service. Protests exploded and the Bloc Populaire emerged to fight conscription.[81] The stark differences between the values of French and English Canada popularized the expression the "Two Solitudes".

In the wake of the conscription crisis, Maurice Duplessis of the Union Nationale ascended to power and implemented conservative policies known as the Grande Noirceur. He focused on defending provincial autonomy, Quebec's Catholic and francophone heritage, and laissez-faire liberalism instead of the emerging welfare state.[87] However, as early as 1948, French Canadian society began to develop new ideologies and desires in response to societal changes such as the television, the baby boom, workers' conflicts, electrification of the countryside, emergence of a middle class, the rural exodus and urbanization, expansion of universities and bureaucracies, creation of motorways, renaissance of literature and poetry, and others.

Modern Quebec (1960–present)

The Quiet Revolution was a period of modernization, secularization and social reform, where French Canadians expressed their concern and dissatisfaction with their inferior socioeconomic position, and the cultural assimilation of francophone minorities in the English-majority provinces. It resulted in the formation of the modern Québécois identity and Quebec nationalism.[88][89] In 1960, the Liberal Party of Quebec was brought to power with a two-seat majority, having campaigned with the slogan "It's time for things to change". This government made reforms in social policy, education, health and economic development. It created the Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec, Labour Code, Ministry of Social Affairs, Ministry of Education, Office québécois de la langue française, Régie des rentes and Société générale de financement. In 1962, the government of Quebec dismantled the financial syndicates of Saint Jacques Street. Quebec began to nationalize its electricity. In order to buy out all the private electric companies and build new Hydro-Québec dams, Quebec was lent $300 million by the US in 1962,[90] and $100 million by British Columbia in 1964.[91]

The Quiet Revolution was particularly characterized by the 1962 Liberal Party's slogan "Masters in our own house", which, to the Anglo-American conglomerates that dominated the economy and natural resources, announced a collective will for freedom of the French-Canadian people.[92] As a result of confrontations between the lower clergy and the laity, state institutions began to deliver services without the assistance of the church, and many parts of civil society began to be more secular. In 1965, the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism[93] wrote a preliminary report underlining Quebec's distinct character, and promoted open federalism, a political attitude guaranteeing Quebec a minimum amount of consideration.[94][95] To favour Quebec during its Quiet Revolution, Lester B. Pearson adopted a policy of open federalism.[96][97] In 1966, the Union Nationale was re-elected and continued on with major reforms.[98]

In 1967, President of France Charles de Gaulle visited Quebec, to attend Expo 67. There, he addressed a crowd of more than 100,000, making a speech ending with the exclamation: "Long live free Quebec". This declaration had a profound effect on Quebec by bolstering the burgeoning modern Quebec sovereignty movement and resulting in a political crisis between France and Canada. Following this, various civilian groups developed, sometimes confronting public authority, for example in the October Crisis of 1970.[99] The meetings of the Estates General of French Canada in 1967 marked a tipping point where relations between francophones of America, and especially francophones of Canada, ruptured. This breakdown affected Quebec society's evolution.[100]

In 1968, class conflicts and changes in mentalities intensified.[101] Option Quebec sparked a constitutional debate on the political future of the province by pitting federalist and sovereignist doctrines against each other. In 1969, the federal Official Languages Act was passed to introduce a linguistic context conducive to Quebec's development.[102][103] In 1973, the liberal government of Robert Bourassa initiated the James Bay Project on La Grande River. In 1974, it enacted the Official Language Act, which made French the official language of Quebec. In 1975, it established the Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms and the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement.

Quebec's first modern sovereignist government, led by René Lévesque, materialized when the Parti Québécois was brought to power in the 1976 Quebec general election.[104] The Charter of the French Language came into force the following year, which increased the use of French. Between 1966-69, the Estates General of French Canada confirmed the state of Quebec to be the nation's fundamental political milieu and for it to have the right to self-determination.[105][106] In the 1980 referendum on sovereignty, 60% were against.[107] After the referendum, Lévesque went back to Ottawa to start negotiating constitutional changes. On November 4, 1981, the Kitchen Accord took place. Delegations from the other nine provinces and the federal government reached an agreement in the absence of Quebec's delegation, which had left for the night.[108] Because of this, the National Assembly refused to recognize the new Constitution Act, 1982, which patriated the Canadian constitution and made modifications to it.[109] The 1982 amendments apply to Quebec despite Quebec never having consented to it.[110]

Between 1982-92, the Quebec government's attitude changed to prioritize reforming the federation. Attempts at constitutional amendments by the Mulroney and Bourassa governments ended in failure with the Meech Lake Accord of 1987 and the Charlottetown Accord of 1992, resulting in the creation of the Bloc Québécois.[111][112] In 1995, Jacques Parizeau called a referendum on Quebec's independence from Canada. This consultation ended in failure for sovereignists, though the outcome was very close: 50.6% "no" and 49.4% "yes".[113][114][115]

In 1998, following the Supreme Court of Canada's decision on the Reference Re Secession of Quebec, the Parliaments of Canada and Quebec defined the legal frameworks within which their respective governments would act in another referendum. On October 30, 2003, the National Assembly voted unanimously to affirm "that the people of Québec form a nation".[116] On November 27, 2006, the House of Commons passed a symbolic motion declaring "that this House recognize that the Québécois form a nation within a united Canada."[117] In 2007, the Parti Québécois was pushed back to official opposition in the National Assembly, with the Liberal party leading. During the 2011 Canadian federal elections, Quebec voters rejected the Bloc Québécois in favour of the previously minor New Democratic Party (NDP). As the NDP's logo is orange, this was called the "orange wave".[118] After three subsequent Liberal governments, the Parti Québécois regained power in 2012 and its leader, Pauline Marois, became the first female premier of Quebec.[119] The Liberal Party of Quebec then returned to power in 2014.[120] In 2018, the Coalition Avenir Québec won the provincial general elections.[121] Between 2020-21, Quebec took measures against the COVID-19 pandemic.[122] In 2022, Coalition Avenir Québec, led by Quebec's premier François Legault, increased its parliamentary majority in the provincial general elections.[123]

- Territorial evolution of Quebec

- Canada in the 18th century.

- The Province of Quebec from 1763 to 1783.

- Quebec from 1867 to 1927.

- Quebec today. Quebec (in blue) has a border dispute with Labrador (in red).

Geography

Located in the eastern part of Canada, Quebec occupies a territory nearly three times the size of France or Texas. Most of Quebec is very sparsely populated.[124] The most populous physiographic region is the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence Lowlands. The combination of rich soils and the lowlands' relatively warm climate makes this valley the most prolific agricultural area of Quebec. The rural part of the landscape is divided into narrow rectangular tracts of land that extend from the river and date back to the seigneurial system.

Quebec's topography is very different from one region to another due to the varying composition of the ground, the climate, and the proximity to water. More than 95% of Quebec's territory, including the Labrador Peninsula, lies within the Canadian Shield.[125] It is generally a quite flat and exposed mountainous terrain interspersed with higher points such as the Laurentian Mountains in southern Quebec, the Otish Mountains in central Quebec and the Torngat Mountains near Ungava Bay. While low and medium altitude peaks extend from western Quebec to the far north, high altitudes mountains emerge in the Capitale-Nationale region to the extreme east. Quebec's highest point at 1,652 metres (5,420 ft) is Mont d'Iberville, known in English as Mount Caubvick.[126] In the Labrador Peninsula portion of the Shield, the far northern region of Nunavik includes the Ungava Peninsula and consists of flat Arctic tundra inhabited mostly by the Inuit. Further south is the Eastern Canadian Shield taiga ecoregion and the Central Canadian Shield forests. The Appalachian region has a narrow strip of ancient mountains along the southeastern border of Quebec.

Quebec has one of the world's largest reserves of fresh water,[127] occupying 12% of its surface[128] and representing 3% of the world's renewable fresh water.[129] More than half a million lakes and 4,500 rivers[127] empty into the Atlantic Ocean, through the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the Arctic Ocean, by James, Hudson, and Ungava bays. The largest inland body of water is the Caniapiscau Reservoir; Lake Mistassini is the largest natural lake.[130] The Saint Lawrence River has some of the world's largest sustaining inland Atlantic ports. Since 1959, the Saint Lawrence Seaway has provided a navigable link between the Atlantic Ocean and the Great Lakes.

The public lands of Quebec cover approximately 92% of its territory, including almost all of the bodies of water. Protected areas can be classified into about twenty different legal designations (ex. exceptional forest ecosystem, protected marine environment, national park, biodiversity reserve, wildlife reserve, zone d'exploitation contrôlée (ZEC), etc.).[131] More than 2,500 sites in Quebec today are protected areas.[132] As of 2013, protected areas comprise 9.14% of Quebec's territory.[133]

Climate

In general, the climate of Quebec is cold and humid, with variations determined by latitude, maritime and elevation influences.[134] Because of the influence of both storm systems from the core of North America and the Atlantic Ocean, precipitation is abundant throughout the year, with most areas receiving more than 1,000 mm (39 in) of precipitation, including over 300 cm (120 in) of snow in many areas.[135] During the summer, severe weather patterns (such as tornadoes and severe thunderstorms) occur occasionally.[136]

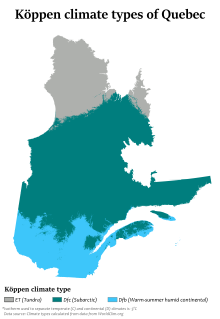

Quebec is divided into four climatic zones: arctic, subarctic, humid continental and East maritime. From south to north, average temperatures range in summer between 25 and 5 °C (77 and 41 °F) and, in winter, between −10 and −25 °C (14 and −13 °F).[137][138] In periods of intense heat and cold, temperatures can reach 35 °C (95 °F) in the summer[139] and −40 °C (−40 °F) during the Quebec winter,[139] Most of central Quebec, ranging from 51 to 58 degrees North has a subarctic climate (Köppen Dfc).[134] Winters are long, very cold, and snowy, and among the coldest in eastern Canada, while summers are warm but very short due to the higher latitude and the greater influence of Arctic air masses. Precipitation is also somewhat less than farther south, except at some of the higher elevations. The northern regions of Quebec have an arctic climate (Köppen ET), with very cold winters and short, much cooler summers.[134] The primary influences in this region are the Arctic Ocean currents (such as the Labrador Current) and continental air masses from the High Arctic.

The all-time record high temperature was 40.0 °C (104.0 °F) and the all-time record low was −51.0 °C (−59.8 °F).[140] The all-time record of the greatest precipitation in winter was established in winter 2007–2008, with more than five metres[141] of snow in the area of Quebec City.[142] March 1971, however, saw the "Century's Snowstorm" with more than 40 cm (16 in) in Montreal to 80 cm (31 in) in Mont Apica of snow within 24 hours in many regions of southern Quebec. The winter of 2010 was the warmest and driest recorded in more than 60 years.[143]

Flora and fauna

Given the geology of the province and its different climates, there are a number of large areas of vegetation in Quebec. These areas, listed in order from the northernmost to the southernmost are: the tundra, the taiga, the Canadian boreal forest (coniferous), mixed forest and deciduous forest.[125] On the edge of Ungava Bay and Hudson Strait is the tundra, whose flora is limited to lichen with less than 50 growing days per year. Further south, the climate is conducive to the growth of the Canadian boreal forest, bounded on the north by the taiga. Not as arid as the tundra, the taiga is associated with the subarctic regions of the Canadian Shield[144] and is characterized by a greater number of both plant (600) and animal (206) species. The taiga covers about 20% of the total area of Quebec.[125] The Canadian boreal forest is the northernmost and most abundant of the three forest areas in Quebec that straddle the Canadian Shield and the upper lowlands of the province. Given a warmer climate, the diversity of organisms is also higher: there are about 850 plant species and 280 vertebrate species. The mixed forest is a transition zone between the Canadian boreal forest and deciduous forest. This area contains a diversity of plant (1000) and vertebrates (350) species, despite relatively cool temperatures. The ecozone mixed forest is characteristic of the Laurentians, the Appalachians and the eastern lowland forests.[144] The third most northern forest area is characterized by deciduous forests. Because of its climate, this area has the greatest diversity of species, including more than 1600 vascular plants and 440 vertebrates.

The total forest area of Quebec is estimated at 750,300 km2 (289,700 sq mi).[145] From the Abitibi-Témiscamingue to the North Shore, the forest is composed primarily of conifers such as the Abies balsamea, the jack pine, the white spruce, the black spruce and the tamarack. The deciduous forest of the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence Lowlands is mostly composed of deciduous species such as the sugar maple, the red maple, the white ash, the American beech, the butternut (white walnut), the American elm, the basswood, the bitternut hickory and the northern red oak as well as some conifers such as the eastern white pine and the northern whitecedar. The distribution areas of the paper birch, the trembling aspen and the mountain ash cover more than half of Quebec's territory.[146]

Biodiversity of the estuary and gulf of Saint Lawrence River[147] includes aquatic mammal wildlife, such as the blue whale, the beluga, the minke whale and the harp seal (earless seal). The Nordic marine animals include the walrus and the narwhal.[148] Inland waters are populated by small to large freshwater fish, such as the largemouth bass, the American pickerel, the walleye, the Acipenser oxyrinchus, the muskellunge, the Atlantic cod, the Arctic char, the brook trout, the Microgadus tomcod (tomcod), the Atlantic salmon, and the rainbow trout.[149]

Among the birds commonly seen in the southern part of Quebec are the American robin, the house sparrow, the red-winged blackbird, the mallard, the common grackle, the blue jay, the American crow, the black-capped chickadee, some warblers and swallows, the starling and the rock pigeon.[150] Avian fauna includes birds of prey like the golden eagle, the peregrine falcon, the snowy owl and the bald eagle. Sea and semi-aquatic birds seen in Quebec are mostly the Canada goose, the double-crested cormorant, the northern gannet, the European herring gull, the great blue heron, the sandhill crane, the Atlantic puffin and the common loon.[151]

The large land wildlife includes the white-tailed deer, the moose, the muskox, the caribou (reindeer), the American black bear and the polar bear. The medium-sized land wildlife includes the cougar, the coyote, the eastern wolf, the bobcat, the Arctic fox, the fox, etc. The small animals seen most commonly include the eastern grey squirrel, the snowshoe hare, the groundhog, the skunk, the raccoon, the chipmunk and the Canadian beaver.

Government and politics

Quebec is founded on the Westminster system, and is both a liberal democracy and a constitutional monarchy with parliamentary regime. The head of government in Quebec is the premier (called premier ministre in French), who leads the largest party in the unicameral National Assembly (Assemblée Nationale) from which the Executive Council of Quebec is appointed. The Conseil du trésor supports the ministers of the Executive Council in their function of stewardship of the state. The lieutenant governor represents the King of Canada and acts as the province's head of state.[152][153]

Quebec has 78 members of Parliament (MPs) in the House of Commons of Canada.[154] They are elected in federal elections. At the level of the Senate of Canada, Quebec is represented by 24 senators, which are appointed on the advice of the prime minister of Canada.[155]

The Quebec government holds administrative and police authority in its areas of exclusive jurisdiction. The Parliament of the 43rd legislature is made up of the following parties: Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ), Parti libéral du Québec (PLQ), Québec solidaire (QS) and Parti Québécois (PQ), as well as an independent member. There are 25 official political parties in Quebec.[156]

Quebec has a network of three offices for representing itself and defending its interests within Canada: one in Moncton for all provinces east, one in Toronto for all provinces west, and one in Ottawa for the federal government. These offices' mandate is to ensure an institutional presence of the Government of Quebec near other Canadian governments.[157][158]

Subdivisions

Quebec's territory is divided into 17 administrative regions as follows:[159][160]

The province also has the following divisions:

- 4 territories (Abitibi, Ashuanipi, Mistassini and Nunavik) which group together the lands that once formed the District of Ungava

- 36 judicial districts

- 73 circonscriptions foncières

- 125 electoral districts[161]

For municipal purposes, Quebec is composed of:

- 1,117 local municipalities of various types:

- 11 agglomerations (agglomérations) grouping 42 of these local municipalities

- 45 boroughs (arrondissements) within 8 of these local municipalities

- 89 regional county municipalities or RCMs (municipalités régionales de comté, MRC)

- 2 metropolitan communities (communautés métropolitaines)

- the regional Kativik administration

- the unorganised territories[162]

Ministries and policies

Quebec's constitution is enshrined in a series of social and cultural traditions that are defined in a set of judicial judgments and legislative documents, including the Loi sur l'Assemblée Nationale ("Law on the National Assembly"), the Loi sur l'éxecutif ("Law on the Executive"), and the Loi électorale du Québec ("Electoral Law of Quebec").[163] Other notable examples include the Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms, the Charter of the French language, and the Civil Code of Quebec.[164]

Quebec's international policy is founded upon the Gérin-Lajoie doctrine,[165] formulated in 1965. While Quebec's Ministry of International Relations coordinates international policy, Quebec's general delegations are the main interlocutors in foreign countries. Quebec is the only Canadian province that has set up a ministry to exclusively embody the state's powers for international relations.[166]

Since 2006, Quebec has adopted a green plan to meet the objectives of the Kyoto Protocol regarding climate change.[167] The Ministry of Sustainable Development, Environment, and Fight Against Climate Change (MELCC) is the primary entity responsible for the application of environmental policy. The Société des établissements de plein air du Québec (SEPAQ) is the main body responsible for the management of national parks and wildlife reserves.[168] Nearly 500,000 people took part in a climate protest on the streets of Montreal in 2019.[169]

Agriculture in Quebec has been subject to agricultural zoning regulations since 1978.[170] Faced with the problem of expanding urban sprawl, agricultural zones were created to ensure the protection of fertile land, which make up 2% of Quebec's total area. Quebec's forests are essentially public property. The calculation of annual cutting possibilities is the responsibility of the Bureau du forestier en chef.[171] The Union des producteurs agricoles (UPA) seeks to protect the interests of its members, including forestry workers, and works jointly with the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAPAQ) and the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources.

The Ministère de l'Emploi et de la Solidarité sociale du Québec has the mandate to oversee social and workforce developments through Emploi-Québec and its local employment centres (CLE).[172] This ministry is also responsible for managing the Régime québécois d'assurance parentale (QPIP) as well as last-resort financial support for people in need. The Commission des normes, de l'équité, de la santé et de la sécurité du travail (CNESST) is the main body responsible for labour laws in Quebec[173] and for enforcing agreements concluded between unions of employees and their employers.[174]

Revenu Québec is the body responsible for collecting taxes. It takes its revenue through a progressive income tax, a 9.975% sales tax,[175] various other provincial taxes (ex. carbon, corporate and capital gains taxes), equalization payments, transfer payments from other provinces, and direct payments.[176] By some measures Quebec residents are the most taxed;[177] a 2012 study indicated that "Quebec companies pay 26 per cent more in taxes than the Canadian average".[178]

Quebec's immigration philosophy is based on the principles of pluralism and interculturalism.The Ministère de l'Immigration et des Communautés culturelles du Québec is responsible for the selection and integration of immigrants.[179] Programs favour immigrants who know French, have a low risk of becoming criminals and have in-demand skills.

Quebec's health and social services network is administered by the Ministry of Health and Social Services. It is composed of 95 réseaux locaux de services (RLS; 'local service networks') and 18 agences de la santé et des services sociaux (ASSS; 'health and social services agencies'). Quebec's health system is supported by the Régie de l'assurance maladie du Québec (RAMQ) which works to maintain the accessibility of services for all citizens of Quebec.[180]

The Ministère de la Famille et des Aînés du Québec operate centres de la petite enfance (CPEs; 'centres for young children'). Quebec's education system is administered by the Ministry of Education and Higher Education (primary and secondary schools), the Ministère de l'Enseignement supérieur (CEGEP) and the Conseil supérieure de l'Education du Québec (universities and colleges).[181] In 2012, the annual cost for postsecondary tuition was CA$2,168 (€1,700)—less than half of Canada's average tuition. Part of the reason for this is that tuition fees were frozen to a relatively low level when CEGEPS were created during the Quiet Revolution. When Jean Charest's government decided in 2012 to sharply increase university fees, students protests erupted.[182] Because of these protests, Quebec's tuition fees remain relatively low.

External relationships

Quebec's closest international partner is the United States, with which it shares a long and positive history. Products of American culture like songs, movies, fashion and food strongly affect Québécois culture.

Quebec has a historied relationship with France, as Quebec was a part of the French Empire and both regions share a language. The Fédération France-Québec and the Francophonie are a few of the tools used for relations between Quebec and France. In Paris, a place du Québec was inaugurated in 1980.[183] Quebec also has a historied relationship with the United Kingdom, having been a part of the British Empire. Quebec and the UK share the same head of state, King Charles III.

Quebec has a network of 32 offices in 18 countries. These offices serve the purpose of representing Quebec in foreign countries and are overseen by Quebec's Ministry of International Relations. Quebec, like other Canadian provinces, also maintains representatives in some Canadian embassies and consulates general. As of 2019[update], the Government of Quebec had delegates-general (agents-general) in Brussels, London, Mexico City, Munich, New York City, Paris and Tokyo; delegates to Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Houston, Los Angeles, and Rome; and offices headed by directors offering more limited services in Barcelona, Beijing, Dakar, Hong Kong, Mumbai, São Paulo, Shanghai, Stockholm, and Washington. In addition, there are the equivalent of honorary consuls, titled antennes, in Berlin, Philadelphia, Qingdao, Seoul, and Silicon Valley.

Quebec also has a representative to UNESCO and participates in the Organization of American States.[184] Quebec is a member of the Assemblée parlementaire de la Francophonie and of the Organisation internationale de la francophonie.

Law

Quebec law is the shared responsibility of the federal and provincial government. The federal government is responsible for criminal law, foreign affairs and laws relating to the regulation of Canadian commerce, interprovincial transportation, and telecommunications.[185] The provincial government is responsible for private law, the administration of justice, and several social domains, such as social assistance, healthcare, education, and natural resources.[185]

Quebec law is influenced by two judicial traditions (civil law and common law) and four classic sources of law (legislation, case law, doctrine and customary law).[186] Private law in Quebec affects all relationships between individuals (natural or juridical persons) and is largely under the jurisdiction of the Parliament of Quebec. The Parliament of Canada also influences Quebec private law, in particular through its power over banks, bankruptcy, marriage, divorce and maritime law.[187] The Droit civil du Québec is the primary component of Quebec's private law and is codified in the Civil Code of Quebec.[188] Public law in Quebec is largely derived from the common law tradition.[189] Quebec constitutional law governs the rules surrounding the Quebec government, the Parliament of Quebec and Quebec's courts. Quebec administrative law governs relations between individuals and the Quebec public administration. Quebec also has some limited jurisdiction over criminal law. Finally, Quebec, like the federal government, has tax law power.[190] Certain portions of Quebec law are considered mixed. This is the case, for example, with human rights and freedoms which are governed by the Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms, a Charter which applies to both government and citizens.[191][192]

English is not an official language in Quebec law.[193] However, both English and French are required by the Constitution Act, 1867 for the enactment of laws and regulations, and any person may use English or French in the National Assembly and the courts. The books and records of the National Assembly must also be kept in both languages.[194][195]

Courts

Although Quebec is a civil law jurisdiction, it does not follow the pattern of other civil law systems which have court systems divided by subject matter. Instead, the court system follows the English model of unitary courts of general jurisdiction. The provincial courts have jurisdiction to decide matters under provincial law as well as federal law, including civil, criminal and constitutional matters.[196] The major exception to the principle of general jurisdiction is that the Federal Court and Federal Court of Appeal have exclusive jurisdiction over some areas of federal law, such as review of federal administrative bodies, federal taxes, and matters relating to national security.[197]

The Quebec courts are organized in a pyramid. At the bottom, there are the municipal courts, the Professions Tribunal, the Human Rights Tribunal, and administrative tribunals. Decisions of those bodies can be reviewed by the two trial courts, the Court of Quebec the Superior Court of Quebec. The Court of Quebec is the main criminal trial court, and also a court for small civil claims. The Superior Court is a trial court of general jurisdiction, in both criminal and civil matters. The decisions of those courts can be appealed to the Quebec Court of Appeal. Finally, if the case is of great importance, it may be appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada.

The Court of Appeal serves two purposes. First, it is the general court of appeal for all legal issues from the lower courts. It hears appeals from the trial decisions of the Superior Court and the Quebec Court. It also can hear appeals from decisions rendered by those two courts on appeals or judicial review matters relating to the municipal courts and administrative tribunals.[198] Second, but much more rarely, the Court of Appeal possesses the power to respond to reference questions posed to it by the Quebec Cabinet. The Court of Appeal renders more than 1,500 judgments per year.[199]

Law enforcement

The Sûreté du Québec is the main police force of Quebec. The Sûreté du Québec can also serve a support and coordination role with other police forces, such as with municipal police forces or with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP).[200][201] The RCMP has the power to enforce certain federal laws in Quebec. However, given the existence of the Sûreté du Québec, its role is more limited than in the other provinces.[202]

Municipal police, such as the Service de police de la Ville de Montréal and the Service de police de la Ville de Québec, are responsible for law enforcement in their municipalities. The Sûreté du Québec fulfils the role of municipal police in the 1038 municipalities that do not have a municipal police force.[203] The Indigenous communities of Quebec have their own police forces.[204]

For offences against provincial or federal laws in Quebec (including the Criminal Code), the Director of Criminal and Penal Prosecutions is responsible for prosecuting offenders in court through Crown attorneys. The Department of Justice of Canada also has the power to prosecute offenders, but only for offences against specific federal laws (ex. selling narcotics). Quebec is responsible for operating the prison system for sentences of less than two years, and the federal government operates penitentiaries for sentences of two years or more.[205]

Demographics

In the 2016 census, Quebec had a population of 8,164,361, a 3.3% increase from its 2011 population of 7,903,001. With a land area of 1,356,625.27 km2 (523,795.95 sq mi), it had a population density of 6.0/km2 (15.6/sq mi) in 2016. Quebec accounts for a little under 23% of the Canadian population. The most populated cities in Quebec are Montreal (1,762,976), Quebec City (538,738), Laval (431,208), and Gatineau (281,501).[206]

In 2016, Quebec's median age was 41.2 years. As of 2020, 20.8% of the population were younger than 20, 59.5% were aged between 20 and 64, and 19.7% were 65 or older. In 2019, Quebec witnessed an increase in the number of births compared to the year before (84,200 vs 83,840) and had a total fertility rate of about 1.6 children born per woman. As of 2020, the average life expectancy was 82.3 years. Quebec in 2019 registered the highest rate of population growth since 1972, with an increase of 110,000 people, mostly because of the arrival of a high number of immigrants. As of 2019, most international immigrants came from China, India or France.[207] In 2016, 30% of the population possessed a postsecondary degree or diploma. Most residents, particularly couples, are property owners. In 2016, 80% of both property owners and renters considered their housing to be "unaffordable".[208] In the 2021 Canadian census, 29.3% of Quebec's population stated their ancestry was of Canadian origin and 21.1% stated their ancestry was of French origin.[209] As of 2021, 18% of Quebec's population were visible minorities.[210]

Religion

According to the 2021 census, the most commonly cited religions in Quebec were:[211]

- Christianity (5,385,240 residents, or 64.8%)

- Irreligion (2,267,720 or 27.3%)

- Islam (421,710 or 5.1%)

- Judaism (84,530 or 1.0%)

- Buddhism (48,365 or 0.6%)

- Hinduism (47,390 or 0.6%)

- Sikhism (23,345 or 0.3%)

- Indigenous spirituality (3,790 or <0.1%)

- Other (26,385 or 0.3%)

The Roman Catholic Church has long occupied a central and integral place in Quebec society since the foundation of Quebec City in 1608. However, since the Quiet Revolution, which secularized Quebec, irreligion has been growing significantly.[212]

The oldest parish church in North America is the Cathedral-Basilica of Notre-Dame de Québec. Its construction began in 1647, when it was known under the name Notre-Dame-de-la-Paix, and it was finished in 1664.[213] The most frequented place of worship in Quebec is the Basilica of Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré. This basilica welcomes millions of visitors each year. Saint Joseph's Oratory is the largest place of worship in the world dedicated to Saint Joseph. Many pilgrimages include places such as Saint Benedict Abbey, Sanctuaire Notre-Dame-du-Cap, Notre-Dame de Montréal Basilica, Marie-Reine-du-Monde de Montréal Basilica-Cathedral, Saint-Michel Basilica-Cathedral, and Saint-Patrick's Basilica. Another important place of worship in Quebec is the Anglican Holy Trinity Cathedral, which was erected between 1800 and 1804. It was the first Anglican cathedral built outside the British Isles.[214]

Language

Linguistic map of the province of Quebec (source: Statistics Canada, 2006 census) Francophone majority, less than 33% Anglophone Francophone majority, more than 33% Anglophone Anglophone majority, more than 33% Francophone Anglophone majority, less than 33% Francophone Data not available |

Quebec differs from other Canadian provinces in that French is the only official and preponderant language, while English predominates in the rest of Canada.[215] French is the common language, understood and spoken by 94.4% of the population.[216][217] Québécois French is the local variant of the language. Canada is estimated to be home to roughly 30 regional French accents,[218][219] 17 of which can be found in Quebec.[220] The Office québécois de la langue française oversees the application of linguistic policies respecting French on the territory, jointly with the Superior Council of the French Language and the Commission de toponymie du Québec. The foundation for these linguistic policies was created in 1968 by the Gendron Commission and they have been accompanied the Charter of the French language ("Bill 101") since 1977. The policies are in effect to protect Quebec from being assimilated by its English-speaking neighbours (the rest of Canada and the United States)[221][222] and were also created to rectify historical injustice between the Francophone majority and Anglophone minority, the latter of which were favoured since Quebec was a colony of the British Empire.[223]

Quebec is the only Canadian province whose population is mainly Francophone, meaning that French is their native language. In the 2011 Census, 6,102,210 people (78.1% of the population) recorded French as their sole native language and 6,249,085 (80.0%) recorded that they spoke French most often at home.[224]

People with English as their native language, called Anglo-Quebecers, constitute the second largest linguistic group in Quebec. In 2011, English was the mother tongue of nearly 650,000 Quebecers (8% of the population).[225] Anglo-Quebecers reside mainly in the west of the island of Montreal (West Island), downtown Montreal and the Pontiac.

Three families of Indigenous languages encompassing eleven languages exist in Quebec: the Algonquian language family (Abenaki, Algonquin, Maliseet-passamaquoddy, Mi'kmaq, and the linguistic continuum of Atikamekw, Cree, Innu-aimun, and Naskapi), the Inuit–Aleut language family (Nunavimmiutitut, an Inuktitut dialect spoken by the Inuit of Nord-du-Québec), and the Iroquoian language family (Mohawk and Wendat). In the 2016 census, 50,895 people said they knew at least one Indigenous language[226] and 45,570 people declared having an Indigenous language as their mother tongue.[227] In Quebec, most Indigenous languages are transmitted quite well from one generation to the next with a mother tongue retention rate of 92%.[228]

As of the 2016 census, the most common immigrant languages claimed as a native language were Arabic (2.5% of the total population), Spanish (1.9%), Italian (1.4%), Creole languages (mainly Haitian Creole) (0.8%), and Mandarin (0.6%).[229]

As of the 2021 Canadian Census, the ten most spoken languages in the province were French (spoken by 7,786,735 people, or 93.72% of the population), English (4,317,180 or 51.96%), Spanish (453,905 or 5.46%), Arabic (343,675 or 4.14%), Italian (168,040 or 2.02%), Haitian Creole (118,010 or 1.42%), Mandarin (80,520 or 0.97%), Portuguese (65,605 or 0.8%), Russian (55,485 or 0.7%), and Greek (50,375 or 0.6%).[230] The question on knowledge of languages allows for multiple responses.

Indigenous peoples

In 2021, the Indigenous population of Quebec numbered 205,010 (2.5% of the population), including 15,800 Inuit, 116,550 First Nations people, and 61,010 Métis.[231] There is an undercount, as some Indian bands regularly refuse to participate in Canadian censuses. In 2016, the Mohawk reserves of Kahnawake and Doncaster 17 along with the Indian settlement of Kanesatake and Lac-Rapide, a reserve of the Algonquins of Barriere Lake, were not counted.[232]

The Inuit of Quebec live mainly in Nunavik in Nord-du-Québec. They make up the majority of the population living north of the 55th parallel. There are ten First Nations ethnic groups in Quebec: the Abenaki, the Algonquin, the Attikamek, the Cree, the Wolastoqiyik, the Mi'kmaq, the Innu, the Naskapis, the Huron-Wendat and the Mohawks. The Mohawks were once part of the Iroquois Confederacy.Aboriginal rights were enunciated in the Indian Act and adopted at the end of the 19th century. This act confines First Nations within the reserves created for them. The Indian Act is still in effect today.[233] In 1975, the Cree, Inuit and the Quebec government agreed to an agreement called the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement that would extended indigenous rights beyond reserves, and to over two-thirds of Quebec's territory. Because this extension was enacted without the participation of the federal government, the extended indigenous rights only exist in Quebec. In 1978, the Naskapis joined the agreement when the Northeastern Quebec Agreement was signed. Discussions have been underway with the Montagnais of the Côte-Nord and Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean for the potential creation of a similar autonomy in two new distinct territories that would be called Innu Assi and Nitassinan.[234]

A few political institutions have also been created over time:

- The Assembly of First Nations Quebec-Labrador[235]

- The Grand Council of the Crees[236]

- The Makivik Corporation[237]

Acadians

The subject of Acadians in Quebec is an important one as more than a million people in Quebec are of Acadian descent, with roughly 4.8 million people possessing one or multiple Acadian ancestors in their genealogy tree, because a large number of Acadians had fled Acadia to take refuge in Quebec during the Great Upheaval. Furthermore, more than a million people have a patronym of Acadian origin.[238][239][240][241]

Quebec houses Acadian communities. Acadians mainly live on the Magdalen Islands and in Gaspesia, but about thirty other communities are present elsewhere in Quebec, mostly in the Côte-Nord and Centre-du-Québec regions. An Acadian community in Quebec can be called a "Cadie", "Petite Cadie" or "Cadien".[242]

Economy

This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: Economic data is out-of-date, most is from 2011. (June 2019) |

Quebec has an advanced, market-based, and open economy. In 2022, its gross domestic product (GDP) was US$50,000 per person at purchasing power parity.[243] The economy of Quebec is the 46th largest in the world behind Chile and 29th for GDP per person.[244][245] Quebec represents 19% of the GDP of Canada. The provincial debt-to-GDP ratio peaked at 51% in 2012–2013, and declined to 43% in 2021.[246]

Like most industrialized countries, the economy is based mainly on the services sector. Quebec's economy has traditionally been fuelled by abundant natural resources and a well-developed infrastructure, but has undergone significant change over the past decade.[247] Firmly grounded in the knowledge economy, Quebec has one of the highest growth rates of GDP in Canada. The knowledge sector represents about 31% of Quebec's GDP.[248] In 2011, Quebec experienced faster growth of its research-and-development (R&D) spending than other Canadian provinces.[249] Quebec's spending in R&D in 2011 was equal to 2.63% of GDP, above the European Union average of 1.8%.[250] The percentage spent on research and technology is the highest in Canada and higher than the averages for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the G7 countries.[251]

Some of the most important companies from Quebec are: Bombardier, Desjardins, the National Bank of Canada, the Jean Coutu Group, Transcontinental média, Quebecor, the Métro Inc. food retailers, Hydro-Québec, the Société des alcools du Québec, the Bank of Montreal, Saputo, the Cirque du Soleil, the Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec, the Normandin restaurants, and Vidéotron.

Exports and imports

Thanks to the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), Quebec had, as of 2009[update], experienced an increase in its exports and in its ability to compete on the international market. International exchanges contribute to the strength of the Quebec economy.[252] NAFTA is especially advantageous as it gives Quebec, among other things, access to a market of 130 million consumers within a radius of 1,000 kilometres.

In 2008, Quebec's exports to other provinces in Canada and abroad totalled 157.3 billion CND$, or 51.8% of Quebec's gross domestic product (GDP). Of this total, 60.4% were international exports, and 39.6% were interprovincial exports. The breakdown by destination of international merchandise exports is: United States (72.2%), Europe (14.4%), Asia (5.1%), Middle East (2.7%), Central America (2.3%), South America (1.9%), Africa (0.8%) and Oceania (0.7%).[252]

In 2008, Quebec imported $178 billion worth of goods and services, or 58.6% of its GDP. Of this total, 62.9% of goods were imported from international markets, while 37.1% of goods were interprovincial imports. The breakdown by origin of international merchandise imports is as follows: United States (31.1%), Europe (28.7%), Asia (17.1%), Africa (11.7%), South America (4.5%), Central America (3.7%), Middle East (1.3%) and Oceania (0.7%).[252]

Primary sector

Quebec produces most of Canada's hydroelectricity and is the second biggest hydroelectricity producer in the world (2019).[253] Because of this, Quebec has been described as a potential clean energy superpower.[254] In 2019, Quebec's electricity production amounted to 214 terawatt-hours (TWh), 95% of which comes from hydroelectric power stations, and 4.7% of which come from wind energy. The public company Hydro-Québec occupies a dominant position in the production, transmission and distribution of electricity in Quebec. Hydro-Québec operates 63 hydroelectric power stations and 28 large reservoirs.[255] Because of the remoteness of Hydro-Québec's TransÉnergie division, it operates the largest electricity transmission network in North America. Quebec stands out for its use of renewable energy. In 2008, electricity ranked as the main form of energy used in Quebec (41.6%), followed by oil (38.2%) and natural gas (10.7%).[256] In 2017, 47% of all energy came from renewable sources.[257] The Quebec government's energy policy seeks to build, by 2030, a low carbon economy.

Quebec ranks among the top ten areas to do business in mining in the world.[258] In 2011, the mining industry accounted for 6.3% of Quebec's GDP[259] and it employed about 50,000 people in 158 companies.[260] It has around 30 mines, 158 exploration companies and 15 primary processing industries. While many metallic and industrial minerals are exploited, the main ones are gold, iron, copper and zinc. Others include: titanium, asbestos, silver, magnesium and nickel, among many others.[261] Quebec is also as a major source of diamonds.[262] Since 2002, Quebec has seen an increase in its mineral explorations. In 2003, the value of mineral exploitation reached $3.7 billion.[263]

The agri-food industry plays an important role in the economy of Quebec, with meat and dairy products being the two main sectors. It accounts for 8% of the Quebec's GDP and generate $19.2 billion. In 2010, this industry generated 487,000 jobs in agriculture, fisheries, manufacturing of food, beverages and tobacco and food distribution.[264]

Secondary sector

In 2021, Quebec's aerospace industry employed 35,000 people and its sales totalled C$15.2 billion. Many aerospace companies are active here, including CMC Electronics, Bombardier, Pratt & Whitney Canada, Héroux-Devtek, Rolls-Royce, General Electric, Bell Textron, L3Harris, Safran, SONACA, CAE Inc., and Airbus, among others. Montreal is globally considered one of the aerospace industry's great centres, and several international aviation organisations seat here.[265] Both Aéro Montréal and the CRIAQ were created to assist aerospace companies.[266][267]

The pulp and paper industry accounted for 3.1% of Quebec's GDP in 2007 [268] and generated annual shipments valued at more than $14 billion.[269] This industry employs 68,000 people in several regions of Quebec.[270] It is also the main -and in some circumstances only- source of manufacturing activity in more than 250 municipalities in the province. The forest industry has slowed in recent years because of the softwood lumber dispute.[271] In 2020, this industry represented 8% of Quebec's exports.[272]

As Quebec has few significant deposits of fossil fuels,[273] all hydrocarbons are imported. Refiners' sourcing strategies have varied over time and have depended on market conditions. In the 1990s, Quebec purchased much of its oil from the North Sea. Since 2015, it now consumes almost exclusively the crude produced in western Canada and the United States.[274] Quebec's two active refineries have a total capacity of 402,000 barrels per day, greater than local needs which stood at 365,000 barrels per day in 2018.[273]

Thanks to hydroelectricity, Quebec is the world's fourth largest aluminum producer and creates 90% of Canadian aluminum. Three companies make aluminum here: Rio Tinto, Alcoa and Aluminium Alouette. Their 9 alumineries produce 2,9 million tons of aluminum annually and employ 30,000 workers.[275]

Tertiary sector

The finance and insurance sector employs more than 168,000 people. Of this number, 78,000 are employed by the banking sector, 53,000 by the insurance sector and 20,000 by the securities and investment sector.[276] The Bank of Montreal, founded in 1817 in Montreal, was Quebec's first bank but, like many other large banks, its central branch is now in Toronto. Several banks remain based in Quebec National Bank of Canada, the Desjardins Group and the Laurentian Bank.

The tourism industry is a major sector in Quebec. The Ministry of Tourism ensures the development of this industry under the commercial name "Bonjour Québec".[277] Quebec is the second most important province for tourism in Canada, receiving 21.5% of tourists' spending (2021).[278] The industry provides employment to over 400,000 people.[279] These employees work in the more than 29,000 tourism-related businesses in Quebec, most of which are restaurants or hotels. 70% of tourism-related businesses are located in or close to Montreal or Quebec City. It is estimated that, in 2010, Quebec welcomed 25.8 million tourists. Of these, 76.1% came from Quebec, 12.2% from the rest of Canada, 7.7% from the United States and 4.1% from other countries. Annually, tourists spend more than $6.7 billion in Quebec's tourism industry.[280]

Quebec's IT sector has 7,600 businesses and employs 140,000 people.[281][282][283] Its most developed sectors are telecommunications, multimedia and video game software, computer services, microelectronics, and the components sector. There are currently 115 telecommunications companies established in the province, including Motorola, Ericsson and Mitec.[284] The multimedia and video game sector has been growing fast since the early 2000s. The Digital Alliance, which claims 191 active members in video games, online education, mobility and Internet services, estimates the annual revenue of the sector at $827 million in 2014.[285] The microelectronics sector is made up of more than 100 companies employing 13,000 people. Computer services, software development, and consulting engineering employ 60,000 skilled workers. While the largest IT employers are CMC Electronics, IBM, and Matrox, many other tech companies are present here, including Ubisoft, Electronic Arts, Microids, Strategy First, Eidos, Activision, A2M, Frima Studio, etc.[286]

Approximately 1.1 million Quebecers work in the field of science and technology.[287] In 2007, the Government of Quebec launched the Stratégie québécoise de la recherche et de l'innovation (SQRI) aiming to promote development through research, science and technology. The government hoped to create a strong culture of innovation in Quebec for the next decades and to create a sustainable economy.[288]

Quebec is considered one of world leaders in fundamental scientific research, having produced ten Nobel laureates in either physics, chemistry, or medicine.[289] It is also considered one of the world leaders in sectors such as aerospace, information technology, biotechnology and pharmaceuticals, and therefore plays a significant role in the world's scientific and technological communities.[290] Between 2000 and 2011, Quebec had over 9,469 scientific publications in biomedical research and engineering.[291] The contribution of Quebec in science and technology represented approximately 1% of the research worldwide between the 1980s and 2009.[292]

The province is one of the world leaders in the field of space science and contributed to important discoveries in this field.[293] One of the most recent is the discovery of the complex extrasolar planets system HR 8799. HR 8799 is the first direct observation of an exoplanet in history.[294][295] The Canadian Space Agency was established in Quebec due to its major role in this research field. A total of four Quebecers have been in space since the creation of the CSA: Marc Garneau, Julie Payette, and David Saint-Jacques as CSA astronauts, plus Guy Laliberté as a private citizen who paid for his trip. Quebec has also contributed to the creation of some Canadian artificial satellites including SCISAT-1, ISIS, Radarsat-1 and Radarsat-2.[296][297][298]

Quebec ranks among the world leaders in the field of life science.[299] William Osler, Wilder Penfield, Donald Hebb, Brenda Milner, and others made significant discoveries in medicine, neuroscience and psychology while working at McGill University in Montreal. Quebec has more than 450 biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies which together employ more than 25,000 people and 10,000 highly qualified researchers.[299] Montreal is ranked fourth in North America for the number of jobs in the pharmaceutical sector.[299][300]

Education