Культура США

В этой статье есть несколько проблем. Пожалуйста, помогите улучшить его или обсудите эти проблемы на странице обсуждения . ( Узнайте, как и когда удалять эти шаблонные сообщения )

|

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Culture of the United States |

|---|

|

| Society |

| Arts and literature |

| Other |

| Symbols |

United States portal |

Культура Соединенных Штатов Америки , также называемая американской культурой , охватывает различные формы социального поведения, институты и нормы в Соединенных Штатах , включая формы речи , литературы , музыки , изобразительного искусства , исполнительского искусства , еды , спорта , религии. , право , технологии , а также другие обычаи, верования и формы знаний. Американская культура сформировалась под влиянием истории Соединенных Штатов , их географии , а также различных внутренних и внешних сил и миграций. [1]

Its Western foundations are primarily English-influenced, with prominent French, German, Greek, Irish, Italian, Jewish, Polish, Scandinavian, and Spanish regional influences. Other non-Western influences include Asian, African, and Indigenous cultures. Since the United States was established in 1776, its culture has been influenced by successive waves of immigrants, and the resulting "melting pot" of cultures has been a distinguishing feature of its society. Americans pioneered or made great strides in musical genres such as heavy metal, rhythm and blues, jazz, gospel, country, hip hop, and rock 'n' roll. The "big four sports" are American football, baseball, basketball, and ice hockey. In terms of religion, the vast majority of Americans are Protestant, Catholic, or irreligious. American cuisine includes popular tastes such as hot dogs, milkshakes, and barbecue, as well as many other class and regional preferences. The most commonly used language is English, though the United States does not have an official language.[2] Distinct cultural regions include New England, Mid-Atlantic, the South, Midwest, Southwest, Mountain West, and Pacific Northwest.[3]

Politically, the country takes its values from the American Revolution and American Enlightenment, with an emphasis on liberty, individualism, and limited government, as well as the Bill of Rights and Reconstruction Amendments. Under the First Amendment, the United States has the strongest protections of free speech of any country.[4][5][6][7] American popular opinion is also the most supportive of free expression and the right to use the Internet.[8][9] The large majority of the United States has a legal system that is based upon English common law.[10] According to the Inglehart–Welzel cultural map, it leans greatly towards "self-expression values", while also uniquely blending aspects of "secular-rational" (with a strong emphasis on human rights, the individual, and anti-authoritarianism) and "traditional" (with high fertility rates, religiosity, and patriotism) values together.[11][12][13] Its culture can vary by factors such as region, race and ethnicity, age, religion, socio-economic status, or population density, among others. Different aspects of American culture can be thought of as low culture or high culture, or belonging to any of a variety of subcultures. The United States exerts major cultural influence on a global scale and is considered a cultural superpower.[14][15]

History

Origins, development, and spread

The European roots of the United States originate with the English and Spanish settlers of colonial North America during British and Spanish rule. The varieties of English people, as opposed to the other peoples on the British Isles, were the overwhelming majority ethnic group in the 17th century (the population of the colonies in 1700 was 250,000) and were 47.9% of percent of the total population of 3.9 million. They constituted 60% of the whites at the first census in 1790 (%: 3.5 Welsh, 8.5 Scotch Irish, 4.3 Scots, 4.7 Irish, 7.2 German, 2.7 Dutch, 1.7 French, and 2 Swedish).[16] [citation needed]The English ethnic group contributed to the major cultural and social mindset and attitudes that evolved into the American character. Of the total population in each colony, they numbered from 30% in Pennsylvania to 85% in Massachusetts.[17] Large non-English immigrant populations from the 1720s to 1775, such as the Germans (100,000 or more), Scotch Irish (250,000), added enriched and modified the English cultural substrate.[18] The religious outlook was some versions of Protestantism (1.6% of the population comprised English, German, and Irish Catholics).[citation needed]

Jeffersonian democracy was a foundational American cultural innovation, which is still a core part of the country's identity.[19] Thomas Jefferson's Notes on the State of Virginia was perhaps the first influential domestic cultural critique by an American and was written in reaction to the views of some influential Europeans that America's native flora and fauna (including humans) were degenerate.[19]

Major cultural influences have been brought by historical immigration, especially from Germany in much of the country,[20] Ireland and Italy in the Northeast, Japan in Hawaii. Latin American culture is especially pronounced in former Spanish areas but has also been introduced by immigration, as have Asian American cultures (especially in the Northeast and West Coast regions). Caribbean culture has been increasingly introduced by immigration and is pronounced in many urban areas. Since the abolition of slavery, the Caribbean has been the source of the earliest and largest Black immigrant group, a significant source of growth of the Black population in the U.S. and has made major cultural impacts in education, music, sports and entertainment.[21]

Native culture remains strong in areas with large undisturbed or relocated populations, including traditional government and communal organization of property now legally managed by Indian reservations (large reservations are mostly in the West, especially Arizona and South Dakota). The fate of native culture after contact with Europeans is quite varied. For example, Taíno culture in U.S. Caribbean territories is nearly extinct and like most Native American languages, the Taíno language is no longer spoken. By contrast, the Hawaiian language and culture of the Native Hawaiians has survived in Hawaii and mixed with that of immigrants from the mainland U.S. (starting before the 1898 annexation) and to some degree Japanese immigrants. It occasionally influences mainstream American culture with notable exports like surfing and Hawaiian shirts. Most languages native to what is now U.S. territory have gone extinct,[22] and the economic and mainstream cultural dominance of the English language threatens the surviving ones in most places. Some of the most common native languages include Samoan, Hawaiian, Navajo, Cherokee, Sioux, and a spectrum of Inuit languages. (See Indigenous languages of the Americas for a fuller listing, plus Chamorro, and Carolinian in the Pacific territories.)[23][better source needed] Ethnic Samoans are a majority in American Samoa; Chamorro are still the largest ethnic group in Guam (though a minority), and along with Refaluwasch are smaller minorities in the Northern Mariana Islands.[citation needed]

American culture includes both conservative and liberal elements, scientific and religious competitiveness, political structures, risk taking and free expression, materialist and moral elements. Despite certain consistent ideological principles (e.g. individualism, egalitarianism, and faith in freedom and republicanism), American culture has a variety of expressions due to its geographical scale and demographics.[24]

As a melting pot of cultures and ethnicities, the U.S. has been shaped by the world's largest immigrant population. The country is home to a wide variety of ethnic groups, traditions, and values,[25][26] and exerts major cultural influence on a global scale, with the phenomenon being termed Americanization.[27][28][14][15]

Regional variations

Semi-distinct cultural regions of the United States include New England, the Mid-Atlantic, the South, the Midwest, the Southwest, and the West—an area that can be further subdivided into the Pacific States and the Mountain States.[citation needed]

According to cultural geographer Colin Woodward there are as many as eleven cultural areas of the United States, which spring from their settlement history. In the east from North to South: there are Puritan areas ("Yankeedom") of New England which spread across the northern Great Lakes to the northern reaches of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers; the New Netherlands area in the densely populated New York Metropolitan Area; the Midland area which spread from Pennsylvania to the lower Great Lakes and the trans-Mississippi upper midwest; Greater Appalachia which angles from West Virginia through the lower midwest and upper-south to trans-Mississippi Arkansas, and southern Oklahoma; the Deep South from the Carolinas to Florida and west to Texas. In the west, there is the southwestern "El Norte" areas originally colonized by Spain, the "Left Coast" colonized quickly on the 19th century by a mix of Yankees and upper Appalachians, and the large but sparsely populated interior West.[29][30]

The west coast of the continental United States, consisting of California, Oregon, and Washington state, is also sometimes referred to as the Left Coast, indicating its left-leaning political orientation and tendency towards social liberalism.[citation needed]

The South is sometimes informally called the "Bible Belt" due to socially conservative evangelical Protestantism, which is a significant part of the region's culture. Christian church attendance across all denominations is generally higher there than the national average. This region is usually contrasted with the mainline Protestantism and Catholicism of the Northeast, the religiously diverse Midwest and Great Lakes, the Mormon Corridor in Utah and southern Idaho, and the relatively secular West. The percentage of non-religious people is the highest in the northeastern and New England state of Vermont at 34%, compared to 6% in the Bible Belt state of Alabama.[31]

Strong cultural differences have a long history in the U.S., with the southern slave society in the antebellum period serving as a prime example. Social and economic tensions between the Northern and Southern states were so severe that they eventually caused the South to declare itself an independent nation, the Confederate States of America; thus initiating the American Civil War.[32]

Cultures of regions in the United States

- Culture of New England

- Culture of the Southern United States

- Culture of the Midwest

- Culture of Western United States

- Appalachian Culture

Language

Although the United States has no official language at the federal level, 28 states have passed legislation making English the official language, and it is considered to be the de facto national language. According to the 2000 U.S. Census, more than 97% of Americans can speak English well, and for 81%, it is the only language spoken at home. The national dialect is known as American English, which itself consists of numerous regional dialects, but has some shared unifying features that distinguish it from British English and other varieties of English. There are four large dialect regions in the United States—the North, the Midland, the South, and the West—and several dialects more focused within metropolitan areas such as those of New York City, Philadelphia, and Boston. A standard dialect called "General American" (analogous in some respects to the received pronunciation elsewhere in the English-speaking world), lacking the distinctive noticeable features of any particular region, is believed by some to exist as well; it is sometimes regionally associated with the Midwest. American Sign Language, used mainly by the deaf, is also native to the United States.[citation needed]

More than 300 languages nationwide, and up to 800 languages in New York City, besides English, have native speakers in the United States—some are spoken by indigenous peoples (about 150 living languages) and others imported by immigrants. English is not the first language of most immigrants in the US, though many do arrive knowing how to speak it, especially from countries where English is broadly used.[33] This not only includes immigrants from countries such as Canada, Jamaica, and the UK, where English is the primary language, but also countries where English is an official language, such as India, Nigeria, and the Philippines.[33]

According to the 2000 census, there are nearly 30 million native speakers of Spanish in the United States. Spanish has official status in the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, where it is the primary language spoken, and the state of New Mexico; various smaller Spanish enclaves exist around the country as well.[34] Bilingual speakers may use both English and Spanish reasonably well and may code-switch according to their dialog partner or context, a phenomenon known as Spanglish.[citation needed]

Indigenous languages of the United States include the Native-American languages (including Navajo, Yupik, Dakota, and Apache), which are spoken on the country's numerous Indian reservations and at cultural events such as pow wows; Hawaiian, which has official status in the state of Hawaii; Chamorro, which has official status in the commonwealths of Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands; Carolinian, which has official status in the commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands; and Samoan, which has official status in the commonwealth of American Samoa.

| Language | Percentage of the total population |

|---|---|

| English only | 78.2% |

| Spanish | 13.4% |

| Chinese | 1.1% |

| Other | 7.3% |

Customs and traditions

Cuisine

The cuisine of the United States is extremely diverse, owing to the vastness of the country, the relatively large population (1⁄3 of a billion people) and the number of native and immigrant influences. Mainstream American culinary arts are similar to those in other Western countries. Wheat and corn are the primary cereal grains.[citation needed] Traditional American cuisine uses ingredients such as turkey, potatoes, sweet potatoes, corn (maize), squash, and maple syrup, as well as indigenous foods employed by American Indians and early European settlers, African slaves, and their descendants.[citation needed]

Iconic American dishes such as apple pie, donuts, fried chicken, pizza, hamburgers, and hot dogs derive from the recipes of various immigrants and domestic innovations.[36][37] French fries, Mexican dishes such as burritos and tacos, and pasta dishes freely adapted from Italian sources are consumed.[38]

The types of food served at home vary greatly and depend upon the region of the country and the family's own cultural heritage. Recent immigrants tend to eat food similar to that of their country of origin, and Americanized versions of these cultural foods, such as Chinese American cuisine or Italian American cuisine often eventually appear. Vietnamese cuisine, Korean cuisine, and Thai cuisine in authentic forms are often readily available in large cities. German cuisine has a profound impact on American cuisine, especially Midwestern cuisine; potatoes, noodles, roasts, stews, cakes, and other pastries are the most iconic ingredients in both cuisines.[39] Dishes such as the hamburger, pot roast, baked ham, and hot dogs are examples of American dishes derived from German cuisine.[40][41]

Different regions of the United States have their own cuisine and styles of cooking. The states of Louisiana and Mississippi, for example, are known for their Cajun and Creole cooking. Cajun and Creole cooking are influenced by French, Acadian, and Haitian cooking, although the dishes themselves are original and unique. Examples include Crawfish Étouffée, Red beans and rice, seafood or chicken gumbo, jambalaya, and boudin. Italian, German, Hungarian, and Chinese influences, traditional Native American, Caribbean, Mexican, and Greek dishes have also diffused into the general American repertoire. It is not uncommon for a middle-class family from Middle America to eat, for example, restaurant pizza, home-made pizza, enchiladas con carne, chicken paprikash, beef stroganoff, and bratwurst with sauerkraut for dinner throughout a single week.[citation needed]

Soul food, mostly the same as food eaten by white southerners, developed by southern African slaves, and their free descendants, is popular around the South and among many African Americans elsewhere. Syncretic cuisines such as Louisiana Creole, Cajun, Pennsylvania Dutch, and Tex-Mex are regionally important.

Americans generally prefer coffee to tea, and more than half the adult population drinks at least one cup a day.[42] Marketing by U.S. industries is largely responsible for making orange juice and milk (now often fat-reduced) ubiquitous breakfast beverages.[43] During the 1980s and 1990s, the caloric intake of Americans rose by 24%;[38] and frequent dining at fast food outlets is associated with what health officials call the American "obesity epidemic." Highly sweetened soft drinks are popular; sugared beverages account for 9% of the average American's daily caloric intake.[44]

The American fast food industry, the world's first and largest, is also often viewed as being a symbol of U.S. marketing dominance. Companies such as McDonald's,[45] Burger King, Pizza Hut, Kentucky Fried Chicken, and Domino's Pizza among others, have numerous outlets around the world,[46] and pioneered the drive-through format in the 1940s.[47]

- Some representative American foods

- Traditional Thanksgiving dinner with turkey, dressing, sweet potatoes, and cranberry sauce

- A cream-based New England chowder, traditionally made with clams and potatoes

- Fried chicken, a southern dish consisting of chicken pieces that have been coated with seasoned flour or batter and deep fried

- Creole Jambalaya with shrimp, ham, tomato, and Andouille sausage

- Chicken-fried steak (or Country Fried Steak)

- A submarine sandwich, which includes a variety of Italian luncheon meats

- American style breakfast with pancakes, maple syrup, sausage links, bacon strips, and fried eggs

- A hot dog sausage topped with beef chili, white onions and mustard

- An apple cobbler dessert

Sports

In the 1800s, colleges were encouraged to focus on intramural sports, particularly track and field, and, in the late 1800s, American football. Physical education was incorporated into primary school curriculums in the 20th century.[48]

Baseball is the oldest of the major American team sports. Professional baseball dates from 1869 and had no close rivals in popularity until the 1960s. Though baseball is no longer the most popular sport,[49] it is still referred to as "the national pastime." Also unlike the professional levels of the other popular spectator sports in the U.S., Major League Baseball teams play almost every day. The Major League Baseball regular season consists of each of the 30 teams playing 162 games from late March to early October. The season ends with the postseason and World Series in October. Unlike most other major sports in the country, professional baseball draws most of its players from a "minor league" system, rather than from university athletics.

American football, known in the United States as simply "football", now attracts more television viewers than any other sport and is considered to be the most popular sport in the United States.[50] The 32-team National Football League (NFL) is the most popular professional American football league.The National Football League differs from the other three major pro sports leagues in that each of its 32 teams plays one game a week over 18 weeks, for a total of 17 games with one bye week for each team. The NFL season lasts from September to December, ending with the playoffs and Super Bowl in January and February.Its championship game, the Super Bowl, has often been the highest rated television show, and it has an audience of over 100 million viewers annually.[citation needed]

College football also attracts audiences of millions. Some communities, particularly in rural areas, place great emphasis on their local high school football team. American football games usually include cheerleaders and marching bands, which aim to raise school spirit and entertain the crowd at halftime.

Basketball is another major sport, represented professionally by the National Basketball Association. It was invented in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1891, by Canadian-born physical education teacher James Naismith. College basketball is also popular, due in large part to the NCAA men's Division I basketball tournament in March, colloquially known as "March Madness".

Ice hockey is the fourth-leading professional team sport. Always a mainstay of Great Lakes and New England-area culture, the sport gained tenuous footholds in regions like the American South since the early 1990s, as the National Hockey League pursued a policy of expansion.[51]

Lacrosse is a team sport of American and Canadian Native American origin and is most popular on the East Coast. NLL and MLL are the national box and outdoor lacrosse leagues. Many of the top Division I college lacrosse teams draw upwards of 7–10,000 for a game, especially in the Mid-Atlantic and New England areas.

Soccer is very popular as a participation sport, particularly among youth, and the US national teams are competitive internationally. A twenty-six-team (with four more confirmed to be added within the next few years) professional league, Major League Soccer, plays from March to October, but its television audience and overall popularity lag behind other American professional sports.[53]

Other popular sports are tennis, softball, rodeo, swimming, water polo, fencing, shooting sports, hunting, volleyball, skiing, snowboarding, skateboarding, ultimate, disc golf, cycling, MMA, roller derby, wrestling, weightlifting, and rugby.

Relative to other parts of the world, the United States is unusually competitive in women's sports, a fact usually attributed to the Title IX anti-discrimination law, which requires most American colleges to give equal funding to men's and women's sports.[54] Despite that, however, women's sports are not nearly as popular among spectators as men's sports.

The United States enjoys a great deal of success both in the Summer Olympics and Winter Olympics, constantly finishing among the top medal winners.

Sports and community culture

Homecoming is an annual tradition in the United States. People, towns, high schools and colleges come together, usually in late September or early October, to welcome back former residents and alumni. It is built around a central event, such as a banquet, a parade, and most often, a game of American football, or, on occasion, basketball, wrestling or ice hockey. When celebrated by schools, the activities vary. However, they usually consist of a football game, played on the school's home football field, activities for students and alumni, a parade featuring the school's marching band and sports teams, and the coronation of a Homecoming Queen.

American high schools commonly field football, basketball, baseball, softball, volleyball, soccer, golf, swimming, track and field, and cross-country teams as well.

Public holidays

The United States observes holidays derived from events in American history, Christian traditions, and national patriarchs.

Thanksgiving is the principal traditionally-American holiday, evolving from the English Pilgrim's custom of giving thanks for one's welfare. Thanksgiving is generally celebrated as a family reunion with a large afternoon feast. Independence Day (or the Fourth of July) celebrates the anniversary of the country's Declaration of Independence from Great Britain, and is generally observed by parades throughout the day and the shooting of fireworks at night.

Christmas Day, celebrating the birth of Jesus Christ, is widely celebrated and a federal holiday, though a fair amount of its current cultural importance is due to secular reasons. European colonization has led to some other Christian holidays such as Easter and St. Patrick's Day to be observed, though with varying degrees of religious fidelity.

Halloween is thought to have evolved from the ancient Celtic/Gaelic festival of Samhain, which was introduced in the American colonies by Irish settlers. It has become a holiday that is celebrated by children and teens who traditionally dress up in costumes and go door to door trick-or-treating for candy. It also brings about an emphasis on eerie and frightening urban legends and movies. Mardi Gras, which evolved from the Catholic tradition of Carnival, is observed in the state of Louisiana.

| Date | Official name | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| January 1 | New Year's Day | Celebrates beginning of the Gregorian calendar year. Festivities include counting down to midnight (12:00 am) on a preceding night, New Year's Eve. The traditional end of the holiday season. |

| Third Monday of January | Birthday of Martin Luther King Jr., or Martin Luther King Jr. Day | Honors Martin Luther King Jr., Civil Rights leader, who was actually born on January 15, 1929; combined with other holidays in several states. |

| Third Monday of February | Washington's Birthday | Washington's Birthday was first declared a federal holiday by an 1879 act of Congress. The Uniform Holidays Act, 1968, shifted the date of the commemoration of Washington's Birthday from February 22 to the third Monday in February. Though its formal name was never changed, many call it "Presidents' Day" and consider it a day honoring all American presidents.[56] |

| Last Monday of May | Memorial Day | Honors the nation's war dead from the Civil War onwards; marks the unofficial beginning of the summer season. (Previously May 30, shifted by the Uniform Holidays Act.) |

| June 19 | Juneteenth | Juneteenth honors the emancipation of enslaved African Americans in the United States. The word comes from "June" and "nineteenth"[57] |

| July 4 | Independence Day | Celebrates Declaration of Independence, also called the Fourth of July. |

| First Monday of September | Labor Day | Celebrates the achievements of workers and the labor movement; marks the unofficial end of the summer season. |

| Second Monday of October | Columbus Day | Honors Christopher Columbus, traditional discoverer of the Americas. In some areas it is also a celebration of Italian culture and heritage. It is celebrated as American Indian Heritage Day and Fraternal Day in Alabama;[58] celebrated as Native American Day in South Dakota.[59] In Hawaii, it is celebrated as Discoverer's Day, though is not an official state holiday.[60] |

| November 11 | Veterans Day | Honors all veterans of the United States armed forces. A traditional observation is a moment of silence at 11:00 am remembering those killed in WWI. (Commemorates the 1918 armistice, which began at "the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month.") |

| Fourth Thursday of November | Thanksgiving Day | Traditionally celebrates the giving of thanks for the autumn harvest. Traditionally includes the consumption of a turkey dinner, and starts the holiday season. |

| December 25 | Christmas | Celebrates the Nativity of Jesus. |

Names

The United States has few laws governing given names. Traditionally, the right to name your child or yourself as you choose has been upheld by court rulings and is rooted in the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution and the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment. This freedom, along with the cultural diversity within the United States has given rise to a wide variety of names and naming trends.

Creativity has also long been a part of American naming traditions and names have been used to express personality, cultural identity, and values.[61][62] Naming trends vary by race, geographic area, and socioeconomic status. African Americans, for instance, have developed a very distinct naming culture.[62] Both religious names and those inspired by popular culture are common.[63]

A few restrictions do exist, varying by state, mostly for the sake of practicality (e.g., limiting the number of characters due to limitations in record-keeping software).

Fashion and dress

Fashion in the United States is eclectic and predominantly informal. While the diverse cultural roots of Americans are reflected in their clothing, particularly those of recent immigrants, cowboy hats and boots, and leather motorcycle jackets are emblematic of specifically-American styles.[citation needed]

Blue jeans were popularized as work clothes in the 1850s by merchant Levi Strauss, a German-Jewish immigrant in San Francisco, and adopted by many American teenagers a century later. They are worn in every state by people of all ages and social classes. Along with mass-marketed informal wear in general, blue jeans are arguably one of US culture's primary contributions to global fashion.[64]

Though the informal dress is more common, certain professionals, such as bankers and lawyers, traditionally dress formally for work, and some occasions, such as weddings, funerals, dances, and some parties, typically call for formal wear.[citation needed]

Some cities and regions have specialties in certain areas. For example, Miami for swimwear, Boston and the general New England area for formal menswear, Los Angeles for casual attire and womenswear, and cities like Seattle and Portland for eco-conscious fashion. Chicago is known for its sportswear, and is the premier fashion destination in the middle American market. Dallas, Houston, Austin, Nashville, and Atlanta are big markets for the fast fashion and cosmetics industries, alongside having their own distinct fashion sense that mainly incorporates cowboy boots and workwear, greater usage of makeup, lighter colors and pastels, "college prep" style, sandals, bigger hairstyles, and thinner, airier fabrics due to the heat and humidity of the region.

The nuclear family and family structure

Family arrangements in the United States reflect the nature of contemporary American society. The classic nuclear family is a man and a woman, united in marriage, with one or more biological children.[65] Today, a person may grow up in a single-parent family, go on to marry and live in a childfree couple arrangement, then get divorced, live as a single for a couple of years, remarry, have children and live in a nuclear family arrangement.[26][66]

| Year | Families (69.7%) | Non-families (31.2%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Married couples (52.5%) | Single parents | Other blood relatives | Singles (25.5%) | Other non-family | |||

| Nuclear family | Without children | Male | Female | ||||

| 2000 | 24.1% | 28.7% | 9.9% | 7% | 10.7% | 14.8% | 5.7% |

| 1970 | 40.3% | 30.3% | 5.2% | 5.5% | 5.6% | 11.5% | 1.7% |

Youth dependence

Exceptions to the custom of leaving home when one reaches legal adulthood at age eighteen can occur especially among Italian and Hispanic Americans, and in expensive urban real estate markets such as New York City,[67] California,[68] and Honolulu,[69] where monthly rents commonly exceed $1,000 a month.

Marriage and divorce

Marriage laws are established by individual states. The typical wedding involves a couple proclaiming their commitment to one another in front of their close relatives and friends, often presided over by a religious figure such as a minister, priest, or rabbi, depending upon the faith of the couple. In traditional Christian ceremonies, the bride's father will "give away" (handoff) the bride to the groom. Secular weddings are also common, often presided over by a judge, Justice of the Peace, or other municipal officials. Same-sex marriage is legal in all states since June 26, 2015.[citation needed]

Divorce is the province of state governments, so divorce law varies from state to state. Prior to the 1970s, divorcing spouses had to allege that the other spouse was guilty of a crime or sin like abandonment or adultery; when spouses simply could not get along, lawyers were forced to manufacture "uncontested" divorces. The no-fault divorce revolution began in 1969 in California; New York and South Dakota were the last states to begin allowing no-fault divorce. No-fault divorce on the grounds of "irreconcilable differences" is now available in all states. However, many states have recently required separation periods prior to a formal divorce decree.

State law provides for child support where children are involved, and sometimes for alimony. "Married adults now divorce two-and-a-half times as often as adults did 20 years ago and four times as often as they did 50 years ago... between 40% and 60% of new marriages will eventually end in divorce. The probability within... the first five years is 20%, and the probability of its ending within the first 10 years is 33%... Perhaps 25% of children (ages 16 and under) live with a stepparent."[70] The median length for a marriage in the U.S. today is 11 years with 90% of all divorces being settled out of court.[citation needed]

Housing

Historically, Americans mainly lived in a rural environment, with a few important cities of moderate size. The Industrial Revolution brought a period of urbanization accelerated by the GI Bill that incentivized soldiers returning from WWII to purchase a house in the suburbs.

American cities with housing prices near the national median have also been losing the middle income neighborhoods, those with median income between 80% and 120% of the metropolitan area's median household income. Here, the more affluent members of the middle-class, who are also often referred to as being professional or upper-middle-class, have left in search of larger homes in more exclusive suburbs. This trend is largely attributed to the middle-class squeeze, which has caused a starker distinction between the statistical middle class and the more privileged members of the middle class.[71] In more expensive areas such as California, however, another trend has been taking place where an influx of more affluent middle-class households has displaced those in the actual middle of society and converted former American middle-middle-class neighborhoods into upper-middle-class neighborhoods.[72]

Volunteerism

Alexis de Tocqueville first noted, in 1835, the American attitude towards helping others in need. A 2011 Charities Aid Foundation study found that Americans were the first most willing to help a stranger and donate time and money in the world at 60%. Many low-level crimes are punished by assigning hours of "community service", a requirement that the offender perform volunteer work;[73] some high schools also require community service to graduate. Since US citizens are required to attend jury duty, they can be jurors in legal proceedings.

Drugs and alcohol

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2012) |

American attitudes towards drugs and alcoholic beverages have evolved considerably throughout the country's history. In the 19th century, alcohol was readily available and consumed, and no laws restricted the use of other drugs. Attitudes on drug addiction started to change, resulting in the Harrison Act, which eventually became proscriptive.

A movement to ban alcoholic beverages called the Temperance movement, emerged in the late 19th century. Several American Protestant religious groups and women's groups, such as the Women's Christian Temperance Union, supported the movement. In 1919, Prohibitionists succeeded in amending the Constitution to prohibit the sale of alcohol. Although the Prohibition period did result in a 50% decrease in alcohol consumption,[74] banning alcohol outright proved to be unworkable, as the previously legitimate distillery industry was replaced by criminal gangs that trafficked in alcohol. Prohibition was repealed in 1933. States and localities retained the right to remain "dry", and to this day, a handful still do.

During the Vietnam War era, attitudes swung well away from prohibition.[clarification needed] Commentators noted that an 18-year-old could be drafted to war but could not buy a beer.[citation needed]

Since 1980, the trend has been toward greater restrictions on alcohol and drug use. The focus this time, however, has been to criminalize behaviors associated with alcohol, rather than attempt to prohibit consumption outright. New York was the first state to enact tough drunk-driving laws in 1980; since then all other states have followed suit. All states have also banned the purchase of alcoholic beverages by individuals under 21.

A "Just Say No to Drugs" movement replaced the more liberal ethos of the 1960s. This led to stricter drug laws and greater police latitude in drug cases. Drugs are, however, widely available, and 16% of Americans 12 and older used an illicit drug in 2012.[75]

Since the 1990s, marijuana use has become increasingly tolerated in America, and a number of states allow the use of marijuana for medical purposes. In most states marijuana is still illegal without a medical prescription. Since the 2012 general election, voters in the District of Columbia and the states of Alaska, California, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington approved the legalization of marijuana for recreational use. Marijuana is illegal under federal law.

Death and funerals

This section may contain material not related to the topic of the article. (January 2013) |

It is customary for Americans to hold a wake in a funeral home within a couple of days of the death of a loved one. The body of the deceased may be embalmed and dressed in fine clothing if there will be an open-casket viewing. Traditional Jewish and Muslim practices include a ritual bath and no embalming. Friends, relatives and acquaintances gather, often from distant parts of the country, to "pay their last respects" to the deceased. Flowers are brought to the coffin and sometimes eulogies, elegies, personal anecdotes or group prayers are recited. Otherwise, the attendees sit, stand or kneel in quiet contemplation or prayer. Kissing the corpse on the forehead is typical among Italian Americans[76] and others. Condolences are also offered to the widow or widower and other close relatives.

A funeral may be held immediately afterward or the next day. The funeral ceremony varies according to religion and culture. American Catholics typically hold a funeral mass in a church, which sometimes takes the form of a Requiem mass. Jewish Americans may hold a service in a synagogue or temple. Pallbearers carry the coffin of the deceased to the hearse, which then proceeds in a procession to the place of final repose, usually a cemetery. The unique Jazz funeral of New Orleans features joyous and raucous music and dancing during the procession.

Mount Auburn Cemetery (founded in 1831) is known as "America's first garden cemetery."[77] American cemeteries created since are distinctive for their park-like setting. Rows of graves are covered by lawns and are interspersed with trees and flowers. Headstones, mausoleums, statuary or simple plaques typically mark off the individual graves. Cremation is another common practice in the United States, though it is frowned upon by various religions. The ashes of the deceased are usually placed in an urn, which may be kept in a private house, or they are interred. Sometimes the ashes are released into the atmosphere. The "sprinkling" or "scattering" of the ashes may be part of an informal ceremony, often taking place at a scenic natural feature (a cliff, lake or mountain) that was favored by the deceased.

Arts

Architecture

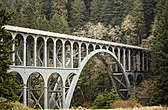

Architecture in the United States is regionally diverse and has been shaped by many external forces. U.S. architecture can therefore be said to be eclectic.[78] Traditionally American architecture has influences from English architecture[79] to Greco Roman architecture.[80] The overriding theme of city American Architecture is modernity, as manifest in the skyscrapers of the 20th century, with domestic and residential architecture greatly varying according to local tastes and climate, rural American and suburban architecture tends to be more traditional.

Visual arts

In the late-18th and early-19th centuries, American artists primarily painted landscapes and portraits in a realistic style or that which looked to Europe for answers on technique: for example, John Singleton Copley was born in Boston, but most of his portraiture for which he is famous follow the trends of British painters like Thomas Gainsborough and the transitional period between Rococo and Neoclassicism. The later 18th century was a time when the United States was just an infant as a nation and as far away from the phenomenon where artists would receive training as craftsmen by apprenticeship and later seeking a fortune as a professional, ideally getting a patron: Many artists benefited from the patronage of Grand Tourists eager to procure mementos of their travels. There were no temples of Rome or grand nobility to be found in the Thirteen Colonies. Later developments of the 19th century brought America one of its earliest native homegrown movements, like the Hudson River School and portrait artists with a uniquely American flavor like Winslow Homer.

A parallel development taking shape in rural America was the American craft movement, which began as a reaction to the Industrial Revolution. As the nation grew wealthier, it had patrons able to buy the works of European painters and attract foreign talent willing to teach methods and techniques from Europe to willing students as well as artists themselves; photography became a very popular medium for both journalism and in time as a medium in its own right with America having plenty of open spaces of natural beauty and growing cities in the East teeming with new arrivals and new buildings. Museums in New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C. began to have a booming business in acquisitions, competing for works as diverse as the then more recent work of the Impressionists to pieces from ancient Egypt, all of which captured the public imaginations and further influenced fashion and architecture. Developments in modern art in Europe came to America from exhibitions in New York City such as the Armory Show in 1913. After World War II, New York emerged as a center of the art world. Painting in the United States today covers a vast range of styles. American painting includes works by Jackson Pollock, John Singer Sargent, Georgia O'Keeffe, and Norman Rockwell, among many others.

Literature

Theater and performing arts

Theater of the United States is based in the Western tradition. The United States originated stand-up comedy and modern improvisational theatre, which involves taking suggestions from the audience.

Minstrel show

The minstrel show, though now widely recognized as racist and offensive, is also recognized as the first uniquely American theatrical art form. Minstrel shows were developed in the 19th century and they were typically performed by white actors wearing blackface makeup for the purpose of imitating and caricaturing the speech and music of African Americans. Stephen Foster was a famous composer for minstrel shows. Many of his songs such as "Camptown Races", "Oh Susanna", and "My Old Kentucky Home" became popular American folk songs. Tap dancing and stand-up comedy have origins in minstrel shows.[81]

Banjos, originally hand-made by slaves for entertainment on plantations, began to be mass-produced in the United States in the 1840s as a result of their extensive use on the minstrel stage.[82]

Drama

American theater did not take on a unique dramatic identity until the emergence of Eugene O'Neill in the early 20th century, now considered by many to be the father of American drama.[citation needed] O'Neill is a four-time winner of the Pulitzer Prize for drama and the only American playwright to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. After O'Neill, American drama came of age and flourished with the likes of Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams, Lillian Hellman, William Inge, and Clifford Odets during the first half of the 20th century. After this fertile period, American theater broke new ground, artistically, with the absurdist forms of Edward Albee in the 1960s.

Social commentary has also been a preoccupation of American theater, often addressing issues not discussed in the mainstream. Writers such as Lorraine Hansbury, August Wilson, David Mamet and Tony Kushner have all won Pulitzer Prizes for their polemical plays on American society.[83]

Musical theater

The United States is also the home and largest exporter of modern musical theater, producing such musical talents as Rodgers and Hammerstein, Lerner and Loewe, Cole Porter, Irving Berlin, Leonard Bernstein, George and Ira Gershwin, Kander and Ebb, and Stephen Sondheim. Broadway is one of the largest theater communities in the world and is the epicenter of American commercial theater.

Music

American music styles and influences (such as country, jazz, blues, rock, pop, techno, soul, and hip hop) and music based on them can be heard all over the world. Music in the U.S. is very diverse, and the country has the world's largest music market with a total retail value of $4.9 billion in 2014.[84]

The rhythmic and lyrical styles of African-American music have significantly influenced American music at large, distinguishing it from European and African traditions. The Smithsonian Institution states, "African-American influences are so fundamental to American music that there would be no American music without them."[85] Country music developed in the 1920s, and rhythm and blues in the 1940s. Elements from folk idioms such as the blues and what is known as old-time music were adopted and transformed into popular genres with global audiences. Jazz was developed by innovators such as Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington early in the 20th century.[86] Known for singing in a wide variety of genres, Aretha Franklin is considered one of the all-time greatest American singers.[87]

Elvis Presley and Chuck Berry were among the pioneers of rock and roll in the mid-1950s. Rock bands such as Metallica, the Eagles, and Aerosmith are among the highest grossing in worldwide sales.[88][89][90] In the 1960s, Bob Dylan emerged from the folk revival to become one of America's most celebrated songwriters.[91] Mid-20th-century American pop stars such as Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra,[92] and Elvis Presley became global celebrities,[86] as have artists of the late 20th century such as Prince, Michael Jackson, Madonna, Whitney Houston, and Mariah Carey.[93][94] American professional opera singers have reached the highest level of success in that form, including Renée Fleming, Leontyne Price, Beverly Sills, Nelson Eddy, and many others.

American popular music, as part of the wider U.S. pop culture, has a worldwide influence and following.[95] As of 2022[update], Taylor Swift, Miley Cyrus, Ariana Grande, Eminem, Lady Gaga, Katy Perry, and many others contemporary artists dominate global streaming rankings.[96]

The annual Coachella music festival in California is one of the largest, most famous, and most profitable music festivals in the United States and the world.[97][98]

Cinema

The United States movie industry has a worldwide influence and following. Hollywood, a northern district of Los Angeles, California, is the leader in motion picture production and the most recognizable movie industry in the world.[99][100][101] The major film studios of the United States are the primary source of the most commercially successful and most ticket selling movies in the world.[102][103]

The dominant style of American cinema is classical Hollywood cinema, which developed from 1913 to 1969 and is still typical of most films made there to this day. While Frenchmen Auguste and Louis Lumière are generally credited with the birth of modern cinema,[104] American cinema soon came to be a dominant force in the emerging industry. The world's first sync-sound musical film, The Jazz Singer, was released in 1927,[105] and was at the forefront of sound-film development in the following decades. Orson Welles's Citizen Kane (1941) is frequently cited in critics' polls as the greatest film of all time.[106]

Broadcasting

This article needs to be updated. (March 2023) |

Television constitutes a significant part of the traditional media of the United States. Household ownership of television sets in the country is 96.7%,[107] and the majority of households have more than one set. The peak ownership percentage of households with at least one television set occurred during the 1996–97 season, with 98.4% ownership.[108] As a whole, the television networks of the United States is the largest and most syndicated in the world.[109]

As of August 2013, approximately 114,200,000 American households own at least one television set.[110]

In 2014, due to a recent surge in the number and popularity of critically acclaimed television series, many critics have said that American television is currently enjoying a golden age.[111][112]

Philosophy

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2023) |

Early American philosophy was heavily shaped by the European Age of Enlightenment, which promoted ideals such as reason and individual liberty.[113] Enlightenment ideals influenced the American Revolution and the Constitution of the United States. Major figures in the American Enlightenment included Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Paine.

Pragmatism and transcendentalism are uniquely American philosophical traditions founded in the 19th century by William James and Ralph Waldo Emerson respectively. Objectivism is a philosophical system founded by Ayn Rand which influenced libertarianism. John Rawls presented the theory of "justice as fairness" in A Theory of Justice (1971).

Willard Van Orman Quine, Saul Kripke, and David Lewis helped advance logic and analytic philosophy in the 20th century. Thomas Kuhn revolutionized the philosophy of science with his book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), one of the most cited academic works of all time, and he coined the term paradigm shift.

Artificial intelligence and the philosophy of mind have been heavily influenced by American philosophers such as Daniel Dennett,[114] Noam Chomsky,[115] Hilary Putnam,[116] Jerry Fodor, and John Searle, who contributed to cognitivism, the hard problem of consciousness, and the mind-body problem. The Libet experiment created by American neuroscientist Benjamin Libet raised philosophical debate regarding the neuroscience of free will. The Chinese room thought experiment presented by John Searle questions the nature of intelligence in machines, and it has been influential in cognitive science and the philosophy of artificial intelligence.

Politics

LGBT rights in the United States are comparatively advanced by world standards.[117][118][119]

Government

Law enforcement and crime

There are about 18,000 U.S. police agencies from local to federal level in the United States.[120] Law in the United States is mainly enforced by local police departments and sheriff's offices. The state police provides broader services, and federal agencies such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the U.S. Marshals Service have specialized duties, such as protecting civil rights, national security and enforcing U.S. federal courts' rulings and federal laws.[121] State courts conduct most civil and criminal trials,[122] and federal courts handle designated crimes and appeals from the state criminal courts.[123]

As of 2023[update], the United States has the sixth-highest documented incarceration rate and second-largest prison population in the world.[124] In 2019, the total prison population for those sentenced to more than a year was 1,430,800, corresponding to a ratio of 419 per 100,000 residents and the lowest since 1995.[125] Various states have attempted to reduce their prison populations via government policies and grassroots initiatives.[126]

U.S. police are comparatively violent, with deaths in custody and fatal shootings being higher than in other developed countries.[127][128]

Military culture

From the time of its inception, the military played a decisive role in the history of the United States. A sense of national unity and identity was forged out of the victorious First Barbary War, Second Barbary War, and the War of 1812. Even so, the Founders were suspicious of a permanent military force and not until the outbreak of World War II did a large standing army become officially established.[129] The National Security Act of 1947, adopted following World War II and during the onset of the Cold War, created the modern U.S. military framework;[130] the Act merged previously Cabinet-level Department of War and the Department of the Navy into the National Military Establishment (renamed the Department of Defense in 1949), headed by the Secretary of Defense; and created the Department of the Air Force and National Security Council.[131]

Military service in the United States is voluntary, although conscription may occur in wartime through the Selective Service System.[132] The United States has the third-largest combined armed forces in the world, behind the Chinese People's Liberation Army and Indian Armed Forces.[133] The U.S. military operates about 800 bases and facilities abroad,[134] maintainaining deployments greater than 100 active duty personnel in 25 foreign countries,[135] and possesses significant capabilities in both defense and power projection.[136][137]

Gun culture

In sharp contrast to most other nations, firearms laws in the United States are permissive, and private gun ownership is common; almost half of American households contain at least one firearm.[139] The Supreme Court has ruled that the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution protects an individual right to possess modern firearms, subject to reasonable regulation,[140] a view shared by the majority of Americans.

There are more privately owned firearms in the United States than in any other country, both per capita and in total.[141] Civilians in the United States possess about 42% of the global inventory of privately owned firearms.[142] Rates of gun ownership vary significantly by region and by state; gun ownership is most common in Alaska, the Mountain States, and the South, and least prevalent in Hawaii, the island territories, California, and New England. Across the board, gun ownership tends to be more common in rural than in urban areas.[143]

Hunting, plinking, and target shooting are popular pastimes, although ownership of firearms for purely utilitarian purposes such as personal protection is common as well. "Personal protection" was the most common reason given for gun ownership in a 2013 Gallup poll of gun owners, at 60%.[144] Ownership of handguns, while not uncommon, is less common than ownership of long guns. Gun ownership is much more prevalent among men than among women, with men being approximately four times more likely than women to report owning guns.[145]

Society

Science and technology

There is a regard for scientific advancement and technological innovation in American culture, resulting in the creation of many modern innovations. The great American inventors include Robert Fulton (the steamboat); Samuel Morse (the telegraph); Eli Whitney (the cotton gin, interchangeable parts); Cyrus McCormick (the reaper); and Thomas Edison (with more than a thousand inventions credited to his name). Most of the new technological innovations over the 20th and 21st centuries were either first invented in the United States, first widely adopted by Americans, or both. Examples include the lightbulb, the airplane, the transistor, the atomic bomb, nuclear power, the personal computer, the iPod, video games, online shopping, and the development of the Internet.[146] The United States also developed the Global Positioning System, which is the world's pre-eminent satellite navigation system.[147]

The United States has been a leader in technological innovation since the late 19th century and scientific research since the mid-20th century. Methods for producing interchangeable parts and the establishment of a machine tool industry enabled the U.S. to have large-scale manufacturing of sewing machines, bicycles, and other items in the late 19th century. In the early 20th century, factory electrification, the introduction of the assembly line, and other labor-saving techniques created the system of mass production. This propensity for application of scientific ideas continued throughout the 20th century with innovations that held strong international benefits. The 20th century saw the arrival of the Space Age, the Information Age, and a renaissance in the health sciences. This culminated in cultural milestones such as the Apollo Moon landings, the creation of the personal computer, and the sequencing effort called the Human Genome Project. In the 21st century, approximately two-thirds of research and development funding comes from the private sector.[148] The U.S. had 2,944 active satellites in space in December 2021, the highest number of any country.[149]

Throughout its history, American culture has made significant gains through the open immigration of accomplished scientists. Accomplished scientists include Scottish American scientist Alexander Graham Bell, who developed and patented the telephone and other devices; German scientist Charles Steinmetz, who developed new alternating-current electrical systems in 1889; Russian scientist Vladimir Zworykin, who invented the motion camera in 1919; Serb scientist Nikola Tesla who patented a brushless electrical induction motor based on rotating magnetic fields in 1888. The rise of fascism and Nazism in the 1920s and 30s led many European scientists, such as Albert Einstein, Enrico Fermi, and John von Neumann, to immigrate to the United States.[150]

Thomas Edison's research laboratory developed the phonograph, the first long-lasting light bulb, and the first viable movie camera.[151] The Wright brothers in 1903 made the first sustained and controlled heavier-than-air powered flight, and the automobile companies of Ransom E. Olds and Henry Ford popularized the assembly line in the early 20th century.[152]

Education

Education in the United States is and has historically been provided mainly by the government. Control and funding come from three levels: federal, state, and local. School attendance is mandatory and nearly universal at the elementary and high school levels (often known outside the United States as the primary and secondary levels).[citation needed]

Students have the option of having their education held in public schools, private schools, or home school. In most public and private schools, education is divided into three levels: elementary school, junior high school (also often called middle school), and high school. In almost all schools at these levels, children are divided by age groups into grades. Post-secondary education, better known as "college" in the United States, is generally governed separately from the elementary and high school systems.[citation needed]

In the year 2000, there were 76.6 million students enrolled in schools from kindergarten through graduate schools. Of these, 72 percent aged 12 to 17 were judged academically "on track" for their age (enrolled in school at or above grade level). Of those enrolled in compulsory education, 5.2 million (10.4 percent) were attending private schools. Among the country's adult population, over 85 percent have completed high school and 27 percent have received a bachelor's degree or higher.[153]

The large majority of the world's top universities, as listed by various ranking organizations, are in the United States, including 19 of the top 25, and the most prestigious – Harvard University.[155][156][157][158] The country also has by far the most Nobel Prize winners in history, with 403 (having won 406 awards).[159]

Religion

Self-identified religious affiliation in the United States (2023 The Wall Street Journal-NORC poll)[160]

Among developed countries, the U.S. is one of the most religious in terms of its demographics. According to a 2002 study by the Pew Global Attitudes Project, the U.S. was the only developed nation in the survey where a majority of citizens reported that religion played a "very important" role in their lives, an opinion similar to that found in Latin America.[161] Today, governments at the national, state, and local levels are secular institutions, with what is often called the "separation of church and state". The most popular religion in the U.S. is Christianity, comprising the majority of the population (73.7% of adults in 2016).[162][163]

Although participation in organized religion has been diminishing, the public life and popular culture of the United States incorporates many Christian ideals specifically about redemption, salvation, conscience, and morality. Examples are popular culture obsessions with confession and forgiveness, which extends from reality television to twelve-step meetings.[164]

Self-identified religiosity (2023 The Wall Street Journal-NORC poll)[165]

Most of the British Thirteen Colonies were generally not tolerant of dissident forms of worship. Civil and religious restrictions were most strictly applied by the Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Colony which saw various banishments applied to enforce conformity, including the branding iron, the whipping post, the bilboes and the hangman's noose.[166] The persecuting spirit was shared by Plymouth Colony and the colonies along the Connecticut river.[167] Mary Dyer was one of the four executed Quakers known as the Boston martyrs, and her death on the Boston gallows marked the beginning of the end of Puritan theocracy and New England independence from English rule; in 1661 Massachusetts was forbidden from executing anyone for professing Quakerism.[168] Anti-Catholic sentiment appeared in New England with the first Pilgrim and Puritan settlers.[169] The Pilgrims of New England held radical Protestant disapproval of Christmas.[170] Christmas observance was outlawed in Boston in 1659.[171] The ban by the Puritans was revoked in 1681 by an English appointed governor; however, it was not until the mid-19th century that celebrating Christmas became common in the Boston region.[172]

The colony of Maryland, founded by the Catholic Lord Baltimore in 1634, came closest to applying freedom of religion.[173] Fifteen years later (1649), the Maryland Toleration Act, drafted by Lord Baltimore, provided: "No person or persons...shall from henceforth be any waies troubled, molested or discountenanced for or in respect of his or her religion nor in the free exercise thereof." The Act allowed freedom of worship for all Trinitarian Christians in Maryland, but sentenced to death anyone who denied the divinity of Jesus.

Modeling the provisions concerning religion within the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, the framers of the United States Constitution rejected any religious test for office, and the First Amendment specifically denied the central government any power to enact any law respecting either an establishment of religion or prohibiting its free exercise. In the following decades, the animating spirit behind the constitution's Establishment Clause led to the disestablishment of the official religions within the member states. The framers were mainly influenced by secular, Enlightenment ideals, but they also considered the pragmatic concerns of minority religious groups who did not want to be under the power or influence of a state religion that did not represent them.[174] Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence said: "The priest has been hostile to liberty. He is always in alliance with the despot."[175]

Gallup polls during the early 2020s found that about 81% of Americans believe in some conception of a God and 45% report praying on a daily basis.[176][177][178] According to their poll in December 2022, "31% report attending a church, synagogue, mosque or temple weekly or nearly weekly today."[178] In the "Bible Belt", which is located primarily within the Southern United States, socially conservative evangelical Protestantism plays a significant role culturally. New England and the Western United States tend to be less religious.[179] Around 6% of Americans claim a non-Christian faith;[180] the largest of which are Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism.[181] The United States either has the first or second-largest Jewish population in the world, and the largest outside of Israel.[182] "Ceremonial deism" is common in American culture.[183][184]

Around 30% of Americans describe themselves as having no religion.[180] Membership in a house of worship fell from 70% in 1999 to 47% in 2020, much of the decline related to the number of Americans expressing no religious preference. Membership also fell among those who identified with a specific religious group.[185][186] According to Gallup, trust in "the church or organized religion" has declined significantly since the 1970s.[187] According to the 2022 Cooperative Election Study, younger Americans are significantly less religious. Among Generation Z, a near-majority consider themselves atheist, agnostic, or nothing in particular.[188]

Social class and work

Though most Americans in the 21st century identify themselves as middle class, American society, and its culture are considerably fragmented.[26][189][190] Social class, generally described as a combination of educational attainment, income and occupational prestige, is one of the greatest cultural influences in America.[26] Nearly all cultural aspects of mundane interactions and consumer behavior in the U.S. are guided by a person's location within the country's social structure.

Distinct lifestyles, consumption patterns and values are associated with different classes. Early sociologist-economist Thorstein Veblen, for example, said that those at the top of the societal hierarchy engage in conspicuous leisure and conspicuous consumption. Upper class Americans commonly have elite Ivy League educations and are traditionally members of exclusive clubs and fraternities with connections to high society, distinguished by their enormous incomes derived from their wealth in assets. The upper-class lifestyle and values often overlap with that of the upper middle class, but with more emphasis on security and privacy in home life and for philanthropy (i.e. the "Donor Class") and the arts. Due to their large wealth (inherited or accrued over a lifetime of investments) and lavish, leisurely lifestyles, the upper class are more prone to idleness. The upper middle class, or the "working rich",[191] commonly identify education and being cultured as prime values, similar to the upper class. Persons in this particular social class tend to speak in a more direct manner that projects authority, knowledge and thus credibility. They often tend to engage in the consumption of so-called mass luxuries, such as designer label clothing. A strong preference for natural materials, organic foods, and a strong health consciousness tend to be prominent features of the upper middle class. American middle-class individuals in general value expanding one's horizon, partially because they are more educated and can afford greater leisure and travel. Working-class individuals take great pride in doing what they consider to be "real work" and keep very close-knit kin networks that serve as a safeguard against frequent economic instability.[26][192][193]

Working-class Americans and many of those in the middle class may also face occupation alienation. In contrast to upper-middle-class professionals who are mostly hired to conceptualize, supervise, and share their thoughts, many Americans have little autonomy or creative latitude in the workplace.[194] As a result, white collar professionals tend to be significantly more satisfied with their work.[195][196] In 2006, Elizabeth Warren presented her article entitled "The Middle Class on the Precipice", stating that individuals in the center of the income strata, who may still identify as middle class, have faced increasing economic insecurity,[197] supporting the idea of a working-class majority.[198] Additionally, working-class Americans who work in the public sector, excluding politicians, are respected and generally respected in the culture, notably postal workers.[199][200]

Political behavior is affected by class; more affluent individuals are more likely to vote, and education and income affect whether individuals tend to vote for the Democratic or Republican party. Income also had a significant impact on health as those with higher incomes had better access to health care facilities, higher life expectancy, lower infant mortality rate and increased health consciousness.[201][202][203] This is particularly noticeable with black voters who are often socially conservative, yet overwhelmingly vote Democratic.[204][205]

In the United States, occupation is one of the prime factors of social class and is closely linked to an individual's identity. The average workweek in the U.S. for those employed full-time was 42.9 hours long with 30% of the population working more than 40 hours a week.[206] The Average American worker earned $16.64 an hour in the first two quarters of 2006.[207] Overall Americans worked more than their counterparts in other developed post-industrial nations. While the average worker in Denmark enjoyed 30 days of vacation annually, the average American had 16 annual vacation days.[208]

In 2000, the average American worked 1,978 hours per year, 500 hours more than the average German, yet 100 hours less than the average Czech. Overall, the U.S. labor force is one of the most productive in the world, largely due to its workers working more than those in any other post-industrial country, except for South Korea.[209] Americans generally hold working and being productive in high regard.[193] Individualism,[210] having a strong work ethic,[211] competitiveness,[212] and altruism[213][214][215] are among the most cited American values. According to a 2016 study by the Charities Aid Foundation, Americans donated 1.44% of total GDP to charity, the highest in the world by a large margin.[216]

Race, ancestry, and immigration

The United States has a diverse population; 37 ancestry groups have more than one million members.[218] White Americans with ancestry from Europe, the Middle East or North Africa, form the largest racial and ethnic group at 57.8% of the U.S. population.[219][220] Hispanic and Latino Americans form the second-largest group and are 18.7% of the U.S. population. African Americans constitute the nation's third-largest ancestry group and are 12.1% of the total U.S. population.[218] Asian Americans are the country's fourth-largest group, composing 5.9% of the U.S. population, while the country's 3.7 million Native Americans account for about 1%.[218] In 2020, the median age of the U.S. population was 38.5 years.[221]

According to the United Nations, the U.S. has the highest number of immigrant population in the world, with 50,661,149 people.[222][223] In 2018, there were almost 90 million immigrants and U.S.-born children of immigrants in the U.S., accounting for 28% of the overall U.S. population.[224] In 2017, out of the U.S. foreign-born population, some 45% (20.7 million) were naturalized citizens, 27% (12.3 million) were lawful permanent residents, 6% (2.2 million) were temporary lawful residents, and 23% (10.5 million) were unauthorized immigrants.[225] The U.S. led the world in refugee resettlement for decades, admitting more refugees than the rest of the world combined.[226]

Race in the U.S. is based on physical characteristics, such as skin color, and has played an essential part in shaping American society even before the nation's conception.[26] Until the civil rights movement of the 1960s, racial minorities in the U.S. faced institutional discrimination and both social and economic marginalization.[227] The U.S. Census Bureau currently recognizes five racial groupings: White, African, Native, Asian, and Pacific Islander. According to the U.S. government, Hispanic Americans do not constitute a race, but rather an ethnic group. During the 2000 U.S. census, Whites made up 75.1% of the population; those who are Hispanic or Latino constituted the nation's prevalent minority with 12.5% of the population. African Americans made up 12.3% of the total population, 3.6% were Asian American, and 0.7% were Native American.[228]

With its ratification on December 6, 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution abolished slavery in the U.S. The Northern states had outlawed slavery in their territory in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, though their industrial economies relied on raw materials produced by slaves in the South. Following the Reconstruction period in the 1870s, racist legislation emerged in the Southern states named the Jim Crow laws that provided for legal segregation. Lynching was practiced throughout the U.S., including in the Northern states, until the 1930s, while continuing well into the civil rights movement in the South.[227]

Chinese Americans were earlier marginalized as well during a significant proportion of U.S. history. Between 1882 and 1943, the U.S. instituted the Chinese Exclusion Act barring all Chinese immigrants from entering the U.S. During the Second World War against the Empire of Japan, roughly 120,000 Japanese Americans, 62% of whom were U.S. citizens,[229] were imprisoned in Japanese internment camps by the U.S. government following the attack on Pearl Harbor, an American military base, by Japanese forces in December 1941.

Из-за исключения или маргинализации со стороны более раннего основного общества среди расовых меньшинств в США возникла уникальная субкультура. В 1920-х годах Гарлем , Нью-Йорк, стал домом для Гарлемского Возрождения . Музыкальные стили, такие как джаз , блюз , рэп , рок-н-ролл и многочисленные народные песни, такие как Blue Tail Fly (Jimmy Crack Corn), зародились в сфере афроамериканской культуры и позже были приняты мейнстримом. [227] Чайнатауны можно найти во многих городах по всей стране, а азиатская кухня стала основным продуктом питания в основной Америке. Латиноамериканское сообщество также оказало огромное влияние на американскую культуру. Сегодня католики являются крупнейшей религиозной конфессией в США и превосходят по численности протестантов на Юго-Западе и в Калифорнии. [230] Музыка мариачи и мексиканская кухня широко распространены на Юго-Западе, а некоторые латинские блюда, такие как буррито и тако, можно найти практически повсюду в стране.

У американцев азиатского происхождения средний доход семьи и уровень образования превышают показатели представителей других рас. Афроамериканцы, латиноамериканцы и коренные американцы имеют значительно более низкие доходы и образование, чем белые американцы или американцы азиатского происхождения. [231] [232]

Расовые отношения

Белые американцы ( неиспаноязычные/латиноамериканцы и латиноамериканцы/латиноамериканцы ) составляют расовое большинство и составляют 72% населения США, согласно переписи населения США 2010 года. [233] Латиноамериканцы и латиноамериканцы составляют 15% населения, составляя крупнейшее этническое меньшинство. [234] Чернокожие американцы являются крупнейшим расовым меньшинством, составляющим почти 13% населения. [233] [234] Белое , неиспаноязычное или латиноамериканское население составляет 63% от общей численности населения страны. [234]

На протяжении большей части истории страны до и после обретения независимости расовое большинство в Соединенных Штатах составляли представители европеоидной расы, чему способствовали исторические ограничения на гражданство и иммиграцию, а крупнейшее расовое меньшинство составляли афроамериканцы, большинство из которых произошли от контрабандно ввезенных рабов. в Америку европейскими колониальными державами . Эти отношения исторически были самыми важными с момента основания Соединенных Штатов. Рабство существовало в США на момент образования страны в 1770-х годах. Компромисс Миссури провозгласил политику запрета рабства на оставшихся землях Луизианы к северу от 36 ° 30 'параллели . Де-факто он разделил страну на две фракции: свободные государства, запрещающие институт рабства; и рабовладельческие государства, которые защищали этот институт. Компромисс Миссури вызвал споры, поскольку считался законным разделом страны по сектантскому признаку. Хотя федеральное правительство поставило вне закона участие Америки в Работорговля в Атлантике резко возросло выращивание высокодоходного урожая хлопка в 1807 году, после 1820 года, на Глубоком Юге , а вместе с ним и использование рабского труда. [235] [236] [237] Второе великое пробуждение , особенно в период 1800–1840 годов, обратило миллионы людей в евангелический протестантизм. На Севере это дало импульс многочисленным движениям за социальные реформы, включая аболиционизм ; [238] на Юге методисты и баптисты занимались прозелитизмом среди рабов. [239]

Рабство было частично отменено Прокламацией об освобождении изданной президентом Авраамом Линкольном рабов на юго-востоке США во время Гражданской войны, в 1862 году . После победы и сохранения Соединенных Штатов рабство было отменено на национальном уровне Тринадцатой поправкой . Законы Джима Кроу препятствовали полному использованию афроамериканского гражданства до движения за гражданские права в 1960-х годах, а Закон о гражданских правах 1964 года поставил вне закона официальную или юридическую сегрегацию на любом уровне и запретил налагать ограничения на доступ меньшинств в общественные места.