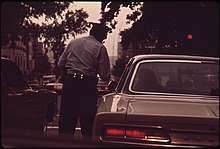

Полиция

Полиция обеспечения соблюдения представляет собой организованный орган лиц, наделенных государством полномочиями с целью закона и защиты общественного порядка , а также самой общественности . [1] Обычно это включает в себя обеспечение безопасности , здоровья и имущества граждан, а также предотвращение преступности и гражданских беспорядков . [2] [3] Их законные полномочия включают в себя арест и применение силы, узаконенные государством посредством монополии на насилие . Этот термин чаще всего ассоциируется с полицейскими силами суверенного государства , которые уполномочены осуществлять полицейскую власть этого государства в пределах определенной юридической или территориальной зоны ответственности. Полицию часто определяют как нечто отдельное от вооруженных сил и других организаций, участвующих в защите государства от иностранных агрессоров; однако жандармерия - это воинские подразделения, отвечающие за гражданскую полицию. [4] Полиция обычно представляет собой службу государственного сектора, финансируемую за счет налогов.

Правоохранительные органы – это лишь часть полицейской деятельности. [5] Полицейская деятельность включает в себя целый ряд действий в различных ситуациях, но преобладающие из них связаны с сохранением порядка. [6] In some societies, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, these developed within the context of maintaining the class system and the protection of private property.[7] Полицейские силы стали повсеместными и стали необходимостью в сложных современных обществах. Однако их роль иногда может быть противоречивой, поскольку они могут быть в той или иной степени вовлечены в коррупцию , жестокость и насаждение авторитарного правления .

A police force may also be referred to as a police department, police service, constabulary, gendarmerie, crime prevention, protective services, law enforcement agency, civil guard, or civic guard. Members may be referred to as police officers, troopers, sheriffs, constables, rangers, peace officers or civic/civil guards. Ireland differs from other English-speaking countries by using the Irish language terms Garda (singular) and Gardaí (plural), for both the national police force and its members. The word police is the most universal and similar terms can be seen in many non-English speaking countries.[8]

Numerous slang terms exist for the police. Many slang terms for police officers are decades or centuries old with lost etymologies. One of the oldest, cop, has largely lost its slang connotations and become a common colloquial term used both by the public and police officers to refer to their profession.[9]

Etymology

First attested in English in the early 15th century, originally in a range of senses encompassing '(public) policy; state; public order', the word police comes from Middle French police ('public order, administration, government'),[10] in turn from Latin politia,[11] which is the romanization of the Ancient Greek πολιτεία (politeia) 'citizenship, administration, civil polity'.[12] This is derived from πόλις (polis) 'city'.[13]

History

Ancient

China

Law enforcement in ancient China was carried out by "prefects" for thousands of years since it developed in both the Chu and Jin kingdoms of the Spring and Autumn period. In Jin, dozens of prefects were spread across the state, each having limited authority and employment period. They were appointed by local magistrates, who reported to higher authorities such as governors, who in turn were appointed by the emperor, and they oversaw the civil administration of their "prefecture", or jurisdiction. Under each prefect were "subprefects" who helped collectively with law enforcement in the area. Some prefects were responsible for handling investigations, much like modern police detectives. Prefects could also be women.[14] Local citizens could report minor judicial offenses against them such as robberies at a local prefectural office. The concept of the "prefecture system" spread to other cultures such as Korea and Japan.

Babylonia

In Babylonia, law enforcement tasks were initially entrusted to individuals with military backgrounds or imperial magnates during the Old Babylonian period, but eventually, law enforcement was delegated to officers known as paqūdus, who were present in both cities and rural settlements. A paqūdu was responsible for investigating petty crimes and carrying out arrests.[15][16]

Egypt

In ancient Egypt evidence of law enforcement exists as far back as the Old Kingdom period. There are records of an office known as "Judge Commandant of the Police" dating to the fourth dynasty.[17] During the fifth dynasty at the end of the Old Kingdom period, warriors armed with wooden sticks were tasked with guarding public places such as markets, temples, and parks, and apprehending criminals. They are known to have made use of trained monkeys, baboons, and dogs in guard duties and catching criminals. After the Old Kingdom collapsed, ushering in the First Intermediate Period, it is thought that the same model applied. During this period, Bedouins were hired to guard the borders and protect trade caravans. During the Middle Kingdom period, a professional police force was created with a specific focus on enforcing the law, as opposed to the previous informal arrangement of using warriors as police. The police force was further reformed during the New Kingdom period. Police officers served as interrogators, prosecutors, and court bailiffs, and were responsible for administering punishments handed down by judges. In addition, there were special units of police officers trained as priests who were responsible for guarding temples and tombs and preventing inappropriate behavior at festivals or improper observation of religious rites during services. Other police units were tasked with guarding caravans, guarding border crossings, protecting royal necropolises, guarding slaves at work or during transport, patrolling the Nile River, and guarding administrative buildings. By the Eighteenth Dynasty of the New Kingdom period, an elite desert-ranger police force called the Medjay was used to protect valuable areas, especially areas of pharaonic interest like capital cities, royal cemeteries, and the borders of Egypt. Though they are best known for their protection of the royal palaces and tombs in Thebes and the surrounding areas, the Medjay were used throughout Upper and Lower Egypt. Each regional unit had its own captain. The police forces of ancient Egypt did not guard rural communities, which often took care of their own judicial problems by appealing to village elders, but many of them had a constable to enforce state laws.[18][19]

Greece

In ancient Greece, publicly owned slaves were used by magistrates as police. In Athens, the Scythian Archers (the ῥαβδοῦχοι 'rod-bearers'), a group of about 300 Scythian slaves, was used to guard public meetings to keep order and for crowd control, and also assisted with dealing with criminals, handling prisoners, and making arrests. Other duties associated with modern policing, such as investigating crimes, were left to the citizens themselves.[20] Athenian police forces were supervised by the Areopagus. In Sparta, the Ephors were in charge of maintaining public order as judges, and they used Sparta's Hippeis, a 300-member Royal guard of honor, as their enforcers. There were separate authorities supervising women, children, and agricultural issues. Sparta also had a secret police force called the crypteia to watch the large population of helots, or slaves.[21][22]

Rome

In the Roman Empire, the army played a major role in providing security. Roman soldiers detached from their legions and posted among civilians carried out law enforcement tasks.[23] The Praetorian Guard, an elite army unit which was primarily an Imperial bodyguard and intelligence-gathering unit, could also act as a riot police force if required. Local watchmen were hired by cities to provide some extra security. Lictors, civil servants whose primary duty was to act as bodyguards to magistrates who held imperium, could carry out arrests and inflict punishments at their magistrate's command. Magistrates such as tresviri capitales, procurators fiscal and quaestors investigated crimes. There was no concept of public prosecution, so victims of crime or their families had to organize and manage the prosecution themselves. Under the reign of Augustus, when the capital had grown to almost one million inhabitants, 14 wards were created; the wards were protected by seven squads of 1,000 men called vigiles, who acted as night watchmen and firemen. In addition to firefighting, their duties included apprehending petty criminals, capturing runaway slaves, guarding the baths at night, and stopping disturbances of the peace. As well as the city of Rome, vigiles were also stationed in the harbor cities of Ostia and Portus. Augustus also formed the Urban Cohorts to deal with gangs and civil disturbances in the city of Rome, and as a counterbalance to the Praetorian Guard's enormous power in the city. They were led by the urban prefect. Urban Cohort units were later formed in Roman Carthage and Lugdunum.

India

Law enforcement systems existed in the various kingdoms and empires of ancient India. The Apastamba Dharmasutra prescribes that kings should appoint officers and subordinates in the towns and villages to protect their subjects from crime. Various inscriptions and literature from ancient India suggest that a variety of roles existed for law enforcement officials such as those of a constable, thief catcher, watchman, and detective.[24] In ancient India up to medieval and early modern times, kotwals were in charge of local law enforcement.[25]

Achaemenid (First Persian) Empire

The Achaemenid Empire had well-organized police forces. A police force existed in every place of importance. In the cities, each ward was under the command of a Superintendent of Police, known as a Kuipan. Police officers also acted as prosecutors and carried out punishments imposed by the courts. They were required to know the court procedure for prosecuting cases and advancing accusations.[26]

Israel

In ancient Israel and Judah, officials with the responsibility of making declarations to the people, guarding the king's person, supervising public works, and executing the orders of the courts existed in the urban areas. They are repeatedly mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, and this system lasted into the period of Roman rule. The first century Jewish historian Josephus related that every judge had two such officers under his command. Levites were preferred for this role. Cities and towns also had night watchmen. Besides officers of the town, there were officers for every tribe. The temple in Jerusalem had special temple police to guard it. The Talmud mentions various local police officials in the Jewish communities of the Land of Israel and Babylon who supervised economic activity. Their Greek-sounding titles suggest that the roles were introduced under Hellenic influence. Most of these officials received their authority from local courts and their salaries were drawn from the town treasury. The Talmud also mentions city watchmen and mounted and armed watchmen in the suburbs.[27]

Africa

In many regions of pre-colonial Africa, particularly West and Central Africa, guild-like secret societies emerged as law enforcement. In the absence of a court system or written legal code, they carried out police-like activities, employing varying degrees of coercion to enforce conformity and deter antisocial behavior.[28] In ancient Ethiopia, armed retainers of the nobility enforced law in the countryside according to the will of their leaders. The Songhai Empire had officials known as assara-munidios, or "enforcers", acting as police.[29]

The Americas

Pre-Columbian civilizations in the Americas also had organized law enforcement. The city-states of the Maya civilization had constables known as tupils.[30] In the Aztec Empire, judges had officers serving under them who were empowered to perform arrests, even of dignitaries.[31] In the Inca Empire, officials called curaca enforced the law among the households they were assigned to oversee, with inspectors known as tokoyrikoq (lit. 'he who sees all') also stationed throughout the provinces to keep order.[32][33]

Post-classical

In medieval Spain, Santas Hermandades, or 'holy brotherhoods', peacekeeping associations of armed individuals, were a characteristic of municipal life, especially in Castile. As medieval Spanish kings often could not offer adequate protection, protective municipal leagues began to emerge in the twelfth century against banditry and other rural criminals, and against the lawless nobility or to support one or another claimant to a crown.

These organizations were intended to be temporary, but became a long-standing fixture of Spain. The first recorded case of the formation of an hermandad occurred when the towns and the peasantry of the north united to police the pilgrim road to Santiago de Compostela in Galicia, and protect the pilgrims against robber knights.

Throughout the Middle Ages such alliances were frequently formed by combinations of towns to protect the roads connecting them, and were occasionally extended to political purposes. Among the most powerful was the league of North Castilian and Basque ports, the Hermandad de las marismas: Toledo, Talavera, and Villarreal.

As one of their first acts after end of the War of the Castilian Succession in 1479, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile established the centrally-organized and efficient Holy Brotherhood as a national police force. They adapted an existing brotherhood to the purpose of a general police acting under officials appointed by themselves, and endowed with great powers of summary jurisdiction even in capital cases. The original brotherhoods continued to serve as modest local police-units until their final suppression in 1835.

The Vehmic courts of Germany provided some policing in the absence of strong state institutions. Such courts had a chairman who presided over a session and lay judges who passed judgement and carried out law enforcement tasks. Among the responsibilities that lay judges had were giving formal warnings to known troublemakers, issuing warrants, and carrying out executions.

In the medieval Islamic Caliphates, police were known as Shurta. Bodies termed Shurta existed perhaps as early as the Caliphate of Uthman. The Shurta is known to have existed in the Abbasid and Umayyad Caliphates. Their primary roles were to act as police and internal security forces but they could also be used for other duties such as customs and tax enforcement, rubbish collection, and acting as bodyguards for governors. From the 10th century, the importance of the Shurta declined as the army assumed internal security tasks while cities became more autonomous and handled their own policing needs locally, such as by hiring watchmen. In addition, officials called muhtasibs were responsible for supervising bazaars and economic activity in general in the medieval Islamic world.

In France during the Middle Ages, there were two Great Officers of the Crown of France with police responsibilities: The Marshal of France and the Grand Constable of France. The military policing responsibilities of the Marshal of France were delegated to the Marshal's provost, whose force was known as the Marshalcy because its authority ultimately derived from the Marshal. The marshalcy dates back to the Hundred Years' War, and some historians trace it back to the early 12th century. Another organisation, the Constabulary (Old French: Connétablie), was under the command of the Constable of France. The constabulary was regularised as a military body in 1337. Under Francis I (reigned 1515–1547), the Maréchaussée was merged with the constabulary. The resulting force was also known as the Maréchaussée, or, formally, the Constabulary and Marshalcy of France.

In late medieval Italian cities, police forces were known as berovierri. Individually, their members were known as birri. Subordinate to the city's podestà, the berovierri were responsible for guarding the cities and their suburbs, patrolling, and the pursuit and arrest of criminals. They were typically hired on short-term contracts, usually six months. Detailed records from medieval Bologna show that birri had a chain of command, with constables and sergeants managing lower-ranking birri, that they wore uniforms, that they were housed together with other employees of the podestà together with a number of servants including cooks and stable-keepers, that their parentage and places of origin were meticulously recorded, and that most were not native to Bologna, with many coming from outside Italy.[34][35]

The English system of maintaining public order since the Norman conquest was a private system of tithings known as the mutual pledge system. This system was introduced under Alfred the Great. Communities were divided into groups of ten families called tithings, each of which was overseen by a chief tithingman. Every household head was responsible for the good behavior of his own family and the good behavior of other members of his tithing. Every male aged 12 and over was required to participate in a tithing. Members of tithings were responsible for raising "hue and cry" upon witnessing or learning of a crime, and the men of his tithing were responsible for capturing the criminal. The person the tithing captured would then be brought before the chief tithingman, who would determine guilt or innocence and punishment. All members of the criminal's tithing would be responsible for paying the fine. A group of ten tithings was known as a "hundred" and every hundred was overseen by an official known as a reeve. Hundreds ensured that if a criminal escaped to a neighboring village, he could be captured and returned to his village. If a criminal was not apprehended, then the entire hundred could be fined. The hundreds were governed by administrative divisions known as shires, the rough equivalent of a modern county, which were overseen by an official known as a shire-reeve, from which the term sheriff evolved. The shire-reeve had the power of posse comitatus, meaning he could gather the men of his shire to pursue a criminal.[36] Following the Norman conquest of England in 1066, the tithing system was tightened with the frankpledge system. By the end of the 13th century, the office of constable developed. Constables had the same responsibilities as chief tithingmen and additionally as royal officers. The constable was elected by his parish every year. Eventually, constables became the first 'police' official to be tax-supported. In urban areas, watchmen were tasked with keeping order and enforcing nighttime curfew. Watchmen guarded the town gates at night, patrolled the streets, arrested those on the streets at night without good reason, and also acted as firefighters. Eventually the office of justice of the peace was established, with a justice of the peace overseeing constables.[37][38] There was also a system of investigative "juries".

The Assize of Arms of 1252, which required the appointment of constables to summon men to arms, quell breaches of the peace, and to deliver offenders to the sheriff or reeve, is cited as one of the earliest antecedents of the English police.[39] The Statute of Winchester of 1285 is also cited as the primary legislation regulating the policing of the country between the Norman Conquest and the Metropolitan Police Act 1829.[39][40]

From about 1500, private watchmen were funded by private individuals and organisations to carry out police functions. They were later nicknamed 'Charlies', probably after the reigning monarch King Charles II. Thief-takers were also rewarded for catching thieves and returning the stolen property. They were private individuals usually hired by crime victims.

The earliest English use of the word police seems to have been the term Polles mentioned in the book The Second Part of the Institutes of the Lawes of England published in 1642.[41]

Early modern

The first example of a statutory police force in the world was probably the High Constables of Edinburgh, formed in 1611 to police the streets of Edinburgh, then part of the Kingdom of Scotland. The constables, of whom half were merchants and half were craftsmen, were charged with enforcing 16 regulations relating to curfews, weapons, and theft.[42] At that time, maintenance of public order in Scotland was mainly done by clan chiefs and feudal lords. The first centrally organised and uniformed police force was created by the government of King Louis XIV in 1667 to police the city of Paris, then the largest city in Europe. The royal edict, registered by the Parlement of Paris on March 15, 1667, created the office of lieutenant général de police ("lieutenant general of police"), who was to be the head of the new Paris police force, and defined the task of the police as "ensuring the peace and quiet of the public and of private individuals, purging the city of what may cause disturbances, procuring abundance, and having each and everyone live according to their station and their duties".

This office was first held by Gabriel Nicolas de la Reynie, who had 44 commissaires de police ('police commissioners') under his authority. In 1709, these commissioners were assisted by inspecteurs de police ('police inspectors'). The city of Paris was divided into 16 districts policed by the commissaires, each assigned to a particular district and assisted by a growing bureaucracy. The scheme of the Paris police force was extended to the rest of France by a royal edict of October 1699, resulting in the creation of lieutenants general of police in all large French cities and towns.

After the French Revolution, Napoléon I reorganized the police in Paris and other cities with more than 5,000 inhabitants on February 17, 1800, as the Prefecture of Police. On March 12, 1829, a government decree created the first uniformed police in France, known as sergents de ville ('city sergeants'), which the Paris Prefecture of Police's website claims were the first uniformed policemen in the world.[43]

In feudal Japan, samurai warriors were charged with enforcing the law among commoners. Some Samurai acted as magistrates called Machi-bugyō, who acted as judges, prosecutors, and as chief of police. Beneath them were other Samurai serving as yoriki, or assistant magistrates, who conducted criminal investigations, and beneath them were Samurai serving as dōshin, who were responsible for patrolling the streets, keeping the peace, and making arrests when necessary. The yoriki were responsible for managing the dōshin. Yoriki and dōshin were typically drawn from low-ranking samurai families. Assisting the dōshin were the komono, non-Samurai chōnin who went on patrol with them and provided assistance, the okappiki, non-Samurai from the lowest outcast class, often former criminals, who worked for them as informers and spies, and gōyokiki or meakashi, chōnin, often former criminals, who were hired by local residents and merchants to work as police assistants in a particular neighborhood. This system typically did not apply to the Samurai themselves. Samurai clans were expected to resolve disputes among each other through negotiation, or when that failed through duels. Only rarely did Samurai bring their disputes to a magistrate or answer to police.[44][45][46]

In Joseon-era Korea, the Podocheong emerged as a police force with the power to arrest and punish criminals. Established in 1469 as a temporary organization, its role solidified into a permanent one.

In Sweden, local governments were responsible for law and order by way of a royal decree issued by Magnus III in the 13th century. The cities financed and organized groups of watchmen who patrolled the streets. In the late 1500s in Stockholm, patrol duties were in large part taken over by a special corps of salaried city guards. The city guard was organized, uniformed and armed like a military unit and was responsible for interventions against various crimes and the arrest of suspected criminals. These guards were assisted by the military, fire patrolmen, and a civilian unit that did not wear a uniform, but instead wore a small badge around the neck. The civilian unit monitored compliance with city ordinances relating to e.g. sanitation issues, traffic and taxes. In rural areas, the King's bailiffs were responsible for law and order until the establishment of counties in the 1630s.[47][48]

Up to the early 18th century, the level of state involvement in law enforcement in Britain was low. Although some law enforcement officials existed in the form of constables and watchmen, there was no organized police force. A professional police force like the one already present in France would have been ill-suited to Britain, which saw examples such as the French one as a threat to the people's liberty and balanced constitution in favor of an arbitrary and tyrannical government. Law enforcement was mostly up to the private citizens, who had the right and duty to prosecute crimes in which they were involved or in which they were not. At the cry of 'murder!' or 'stop thief!' everyone was entitled and obliged to join the pursuit. Once the criminal had been apprehended, the parish constables and night watchmen, who were the only public figures provided by the state and who were typically part-time and local, would make the arrest.[49] As a result, the state set a reward to encourage citizens to arrest and prosecute offenders. The first of such rewards was established in 1692 of the amount of £40 for the conviction of a highwayman and in the following years it was extended to burglars, coiners and other forms of offense. The reward was to be increased in 1720 when, after the end of the War of the Spanish Succession and the consequent rise of criminal offenses, the government offered £100 for the conviction of a highwayman. Although the offer of such a reward was conceived as an incentive for the victims of an offense to proceed to the prosecution and to bring criminals to justice, the efforts of the government also increased the number of private thief-takers. Thief-takers became infamously known not so much for what they were supposed to do, catching real criminals and prosecuting them, as for "setting themselves up as intermediaries between victims and their attackers, extracting payments for the return of stolen goods and using the threat of prosecution to keep offenders in thrall". Some of them, such as Jonathan Wild, became infamous at the time for staging robberies in order to receive the reward.[50][51]

In 1737, George II began paying some London and Middlesex watchmen with tax monies, beginning the shift to government control. In 1749, Judge Henry Fielding began organizing a force of quasi-professional constables known as the Bow Street Runners. The Bow Street Runners are considered to have been Britain's first dedicated police force. They represented a formalization and regularization of existing policing methods, similar to the unofficial 'thief-takers'. What made them different was their formal attachment to the Bow Street magistrates' office, and payment by the magistrate with funds from the central government. They worked out of Fielding's office and court at No. 4 Bow Street, and did not patrol but served writs and arrested offenders on the authority of the magistrates, travelling nationwide to apprehend criminals. Fielding wanted to regulate and legalize law enforcement activities due to the high rate of corruption and mistaken or malicious arrests seen with the system that depended mainly on private citizens and state rewards for law enforcement. Henry Fielding's work was carried on by his brother, Justice John Fielding, who succeeded him as magistrate in the Bow Street office. Under John Fielding, the institution of the Bow Street Runners gained more and more recognition from the government, although the force was only funded intermittently in the years that followed. In 1763, the Bow Street Horse Patrol was established to combat highway robbery, funded by a government grant. The Bow Street Runners served as the guiding principle for the way that policing developed over the next 80 years. Bow Street was a manifestation of the move towards increasing professionalisation and state control of street life, beginning in London.

The Macdaniel affair, a 1754 British political scandal in which a group of thief-takers was found to be falsely prosecuting innocent men in order to collect reward money from bounties,[52] added further impetus for a publicly salaried police force that did not depend on rewards. Nonetheless, In 1828, there were privately financed police units in no fewer than 45 parishes within a 10-mile radius of London.

The word police was borrowed from French into the English language in the 18th century, but for a long time it applied only to French and continental European police forces. The word, and the concept of police itself, were "disliked as a symbol of foreign oppression".[53] Before the 19th century, the first use of the word police recorded in government documents in the United Kingdom was the appointment of Commissioners of Police for Scotland in 1714 and the creation of the Marine Police in 1798.

Modern

Scotland and Ireland

Following early police forces established in 1779 and 1788 in Glasgow, Scotland, the Glasgow authorities successfully petitioned the government to pass the Glasgow Police Act establishing the City of Glasgow Police in 1800.[54] Other Scottish towns soon followed suit and set up their own police forces through acts of parliament.[55] In Ireland, the Irish Constabulary Act of 1822 marked the beginning of the Royal Irish Constabulary. The Act established a force in each barony with chief constables and inspectors general under the control of the civil administration at Dublin Castle. By 1841 this force numbered over 8,600 men.

London

In 1797, Patrick Colquhoun was able to persuade the West Indies merchants who operated at the Pool of London on the River Thames to establish a police force at the docks to prevent rampant theft that was causing annual estimated losses of £500,000 worth of cargo in imports alone.[56] The idea of a police, as it then existed in France, was considered as a potentially undesirable foreign import. In building the case for the police in the face of England's firm anti-police sentiment, Colquhoun framed the political rationale on economic indicators to show that a police dedicated to crime prevention was "perfectly congenial to the principle of the British constitution". Moreover, he went so far as to praise the French system, which had reached "the greatest degree of perfection" in his estimation.[57]

With the initial investment of £4,200, the new force the Marine Police began with about 50 men charged with policing 33,000 workers in the river trades, of whom Colquhoun claimed 11,000 were known criminals and "on the game". The force was part funded by the London Society of West India Planters and Merchants. The force was a success after its first year, and his men had "established their worth by saving £122,000 worth of cargo and by the rescuing of several lives". Word of this success spread quickly, and the government passed the Depredations on the Thames Act 1800 on 28 July 1800, establishing a fully funded police force the Thames River Police together with new laws including police powers; now the oldest police force in the world. Colquhoun published a book on the experiment, The Commerce and Policing of the River Thames. It found receptive audiences far outside London, and inspired similar forces in other cities, notably, New York City, Dublin, and Sydney.[56]

Colquhoun's utilitarian approach to the problem – using a cost-benefit argument to obtain support from businesses standing to benefit – allowed him to achieve what Henry and John Fielding failed for their Bow Street detectives. Unlike the stipendiary system at Bow Street, the river police were full-time, salaried officers prohibited from taking private fees.[58] His other contribution was the concept of preventive policing; his police were to act as a highly visible deterrent to crime by their permanent presence on the Thames.[57]

Metropolitan

London was fast reaching a size unprecedented in world history, due to the onset of the Industrial Revolution.[59] It became clear that the locally maintained system of volunteer constables and "watchmen" was ineffective, both in detecting and preventing crime. A parliamentary committee was appointed to investigate the system of policing in London. Upon Sir Robert Peel being appointed as Home Secretary in 1822, he established a second and more effective committee, and acted upon its findings.

Royal assent to the Metropolitan Police Act 1829 was given[60] and the Metropolitan Police Service was established on September 29, 1829, in London.[61][62] Peel, widely regarded as the father of modern policing,[63] was heavily influenced by the social and legal philosophy of Jeremy Bentham, who called for a strong and centralised, but politically neutral, police force for the maintenance of social order, for the protection of people from crime and to act as a visible deterrent to urban crime and disorder.[64] Peel decided to standardise the police force as an official paid profession, to organise it in a civilian fashion, and to make it answerable to the public.[65]

Due to public fears concerning the deployment of the military in domestic matters, Peel organised the force along civilian lines, rather than paramilitary. To appear neutral, the uniform was deliberately manufactured in blue, rather than red which was then a military colour, along with the officers being armed only with a wooden truncheon and a rattle[66] to signal the need for assistance. Along with this, police ranks did not include military titles, with the exception of Sergeant.

To distance the new police force from the initial public view of it as a new tool of government repression, Peel publicised the so-called Peelian principles, which set down basic guidelines for ethical policing:[67][68]

- Whether the police are effective is not measured on the number of arrests but on the deterrence of crime.

- Above all else, an effective authority figure knows trust and accountability are paramount. Hence, Peel's most often quoted principle that "The police are the public and the public are the police."

The Metropolitan Police Act 1829 created a modern police force by limiting the purview of the force and its powers and envisioning it as merely an organ of the judicial system. Their job was apolitical; to maintain the peace and apprehend criminals for the courts to process according to the law.[70] This was very different from the "continental model" of the police force that had been developed in France, where the police force worked within the parameters of the absolutist state as an extension of the authority of the monarch and functioned as part of the governing state.

In 1863, the Metropolitan Police were issued with the distinctive custodian helmet, and in 1884 they switched to the use of whistles that could be heard from much further away.[71][72] The Metropolitan Police became a model for the police forces in many countries, including the United States and most of the British Empire.[73][74] Bobbies can still be found in many parts of the Commonwealth of Nations.

Australia

In Australia, organized law enforcement emerged soon after British colonization began in 1788. The first law enforcement organizations were the Night Watch and Row Boat Guard, which were formed in 1789 to police Sydney. Their ranks were drawn from well-behaved convicts deported to Australia. The Night Watch was replaced by the Sydney Foot Police in 1790. In New South Wales, rural law enforcement officials were appointed by local justices of the peace during the early to mid-19th century and were referred to as "bench police" or "benchers". A mounted police force was formed in 1825.[75]

The first police force having centralised command as well as jurisdiction over an entire colony was the South Australia Police, formed in 1838 under Henry Inman. However, whilst the New South Wales Police Force was established in 1862, it was made up from a large number of policing and military units operating within the then Colony of New South Wales and traces its links back to the Royal Marines. The passing of the Police Regulation Act of 1862 essentially tightly regulated and centralised all of the police forces operating throughout the Colony of New South Wales.

Each Australian state and territory maintain its own police force, while the Australian Federal Police enforces laws at the federal level. The New South Wales Police Force remains the largest police force in Australia in terms of personnel and physical resources. It is also the only police force that requires its recruits to undertake university studies at the recruit level and has the recruit pay for their own education.

Brazil

In 1566, the first police investigator of Rio de Janeiro was recruited. By the 17th century, most captaincies already had local units with law enforcement functions. On July 9, 1775, a Cavalry Regiment was created in the state of Minas Gerais for maintaining law and order. In 1808, the Portuguese royal family relocated to Brazil, because of the French invasion of Portugal. King João VI established the Intendência Geral de Polícia ('General Police Intendancy') for investigations. He also created a Royal Police Guard for Rio de Janeiro in 1809. In 1831, after independence, each province started organizing its local "military police", with order maintenance tasks. The Federal Railroad Police was created in 1852, Federal Highway Police, was established in 1928, and Federal Police in 1967.

Canada

During the early days of English and French colonization, municipalities hired watchmen and constables to provide security.[76] Established in 1729, the Royal Newfoundland Constabulary (RNC) was the first policing service founded in Canada. The establishment of modern policing services in the Canadas occurred during the 1830s, modelling their services after the London Metropolitan Police, and adopting the ideas of the Peelian principles.[77] The Toronto Police Service was established in 1834 as the first municipal police service in Canada. Prior to that, local able-bodied male citizens had been required to report for night watch duty as special constables for a fixed number of nights a year on penalty of a fine or imprisonment in a system known as "watch and ward."[78] The Quebec City Police Service was established in 1840.[77]

A national police service, the Dominion Police, was founded in 1868. Initially the Dominion Police provided security for parliament, but its responsibilities quickly grew. In 1870, Rupert's Land and the North-Western Territory were incorporated into the country. In an effort to police its newly acquired territory, the Canadian government established the North-West Mounted Police in 1873 (renamed Royal North-West Mounted Police in 1904).[77] In 1920, the Dominion Police, and the Royal Northwest Mounted Police were amalgamated into the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP).[77]

The RCMP provides federal law enforcement; and law enforcement in eight provinces, and all three territories. The provinces of Ontario, and Quebec maintain their own provincial police forces, the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP), and the Sûreté du Québec (SQ). Policing in Newfoundland and Labrador is provided by the RCMP, and the RNC. The aforementioned services also provide municipal policing, although larger Canadian municipalities may establish their own police service.

Lebanon

In Lebanon, the current police force was established in 1861, with creation of the Gendarmerie.[79]

India

Under the Mughal Empire, provincial governors called subahdars (or nazims), as well as officials known as faujdars and thanadars were tasked with keeping law and order. Kotwals were responsible for public order in urban areas. In addition, officials called amils, whose primary duties were tax collection, occasionally dealt with rebels. The system evolved under growing British influence that eventually culminated in the establishment of the British Raj. In 1770, the offices of faujdar and amil were abolished. They were brought back in 1774 by Warren Hastings, the first Governor of the Presidency of Fort William (Bengal). In 1791, the first permanent police force was established by Charles Cornwallis, the Commander-in-Chief of British India and Governor of the Presidency of Fort William.[80]

A single police force was established after the formation of the British Raj with the Government of India Act 1858. A uniform police bureaucracy was formed under the Police Act 1861, which established the Superior Police Services. This later evolved into the Indian Imperial Police, which kept order until the Partition of India and independence in 1947. In 1948, the Indian Imperial Police was replaced by the Indian Police Service.

In modern India, the police are under the control of respective States and union territories and are known to be under State Police Services (SPS). The candidates selected for the SPS are usually posted as Deputy Superintendent of Police or Assistant Commissioner of Police once their probationary period ends. On prescribed satisfactory service in the SPS, the officers are nominated to the Indian Police Service.[81] The service color is usually dark blue and red, while the uniform color is Khaki.[82]

United States

In Colonial America, the county sheriff was the most important law enforcement official. For instance, the New York Sheriff's Office was founded in 1626, and the Albany County Sheriff's Department in the 1660s. The county sheriff, who was an elected official, was responsible for enforcing laws, collecting taxes, supervising elections, and handling the legal business of the county government. Sheriffs would investigate crimes and make arrests after citizens filed complaints or provided information about a crime but did not carry out patrols or otherwise take preventive action. Villages and cities typically hired constables and marshals, who were empowered to make arrests and serve warrants. Many municipalities also formed a night watch, a group of citizen volunteers who would patrol the streets at night looking for crime and fires. Typically, constables and marshals were the main law enforcement officials available during the day while the night watch would serve during the night. Eventually, municipalities formed day watch groups. Rioting was handled by local militias.[83][84]

In the 1700s, the Province of Carolina (later North- and South Carolina) established slave patrols in order to prevent slave rebellions and enslaved people from escaping.[85][86] By 1785 the Charleston Guard and Watch had "a distinct chain of command, uniforms, sole responsibility for policing, salary, authorized use of force, and a focus on preventing crime."[87]

In 1789 the United States Marshals Service was established, followed by other federal services such as the U.S. Parks Police (1791)[88] and U.S. Mint Police (1792).[89] In 1751 moves towards a municipal police service in Philadelphia were made when the city's night watchmen and constables began receiving wages and a Board of Wardens was created to oversee the night watch.[90][91] Municipal police services were createed in Richmond, Virginia in 1807,[92] Boston in 1838,[93] and New York City in 1845.[94] The United States Secret Service was founded in 1865 and was for some time the main investigative body for the federal government.[95]

Modern policing influenced by the British model of policing established in 1829 based on the Peelian principles began emerging in the United States in the mid-19th century, replacing previous law enforcement systems based primarily on night watch organizations.[96] Cities began establishing organized, publicly funded, full-time professional police services. In Boston, a day police consisting of six officers under the command of the city marshal was established in 1838 to supplement the city's night watch. This paved the way for the establishment of the Boston Police Department in 1854.[97][98] In New York City, law enforcement up to the 1840s was handled by a night watch as well as 100 city marshals, 51 municipal police officers, and 31 constables. In 1845, the New York City Police Department was established.[99] In Philadelphia, the first police officers to patrol the city in daytime were employed in 1833 as a supplement to the night watch system, leading to the establishment of the Philadelphia Police Department in 1854.[100]

In the American Old West, law enforcement was carried out by local sheriffs, rangers, constables, and federal marshals. There were also town marshals responsible for serving civil and criminal warrants, maintaining the jails, and carrying out arrests for petty crime.[101][102]

In addition to federal, state, and local forces, some special districts have been formed to provide extra police protection in designated areas. These districts may be known as neighborhood improvement districts, crime prevention districts, or security districts.[103]

In 2022, San Francisco supervisors approved a policy allowing municipal police (San Francisco Police Department) to use robots for various law enforcement and emergency operations, permitting their employment as a deadly force option in cases where the "risk of life to members of the public or officers is imminent and outweighs any other force option available to SFPD."[104] This policy has been criticized by groups such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the ACLU, who have argued that "killer robots will not make San Francisco better" and "police might even bring armed robots to a protest."[105][106]

Development of theory

Michel Foucault wrote that the contemporary concept of police as a paid and funded functionary of the state was developed by German and French legal scholars and practitioners in public administration and statistics in the 17th and early 18th centuries, most notably with Nicolas Delamare's Traité de la Police ("Treatise on the Police"), first published in 1705. The German Polizeiwissenschaft (Science of Police) first theorized by Philipp von Hörnigk, a 17th-century Austrian political economist and civil servant, and much more famously by Johann Heinrich Gottlob Justi, who produced an important theoretical work known as Cameral science on the formulation of police.[107] Foucault cites Magdalene Humpert author of Bibliographie der Kameralwissenschaften (1937) in which the author makes note of a substantial bibliography was produced of over 4,000 pieces of the practice of Polizeiwissenschaft. However, this may be a mistranslation of Foucault's own work since the actual source of Magdalene Humpert states over 14,000 items were produced from the 16th century dates ranging from 1520 to 1850.[108][109]

As conceptualized by the Polizeiwissenschaft, according to Foucault the police had an administrative, economic and social duty ("procuring abundance"). It was in charge of demographic concerns[vague] and needed to be incorporated within the western political philosophy system of raison d'état and therefore giving the superficial appearance of empowering the population (and unwittingly supervising the population), which, according to mercantilist theory, was to be the main strength of the state. Thus, its functions largely overreached simple law enforcement activities and included public health concerns, urban planning (which was important because of the miasma theory of disease; thus, cemeteries were moved out of town, etc.), and surveillance of prices.[110]

The concept of preventive policing, or policing to deter crime from taking place, gained influence in the late 18th century. Police Magistrate John Fielding, head of the Bow Street Runners, argued that "...it is much better to prevent even one man from being a rogue than apprehending and bringing forty to justice."[111]

The Utilitarian philosopher, Jeremy Bentham, promoted the views of Italian Marquis Cesare Beccaria, and disseminated a translated version of "Essay on Crime in Punishment". Bentham espoused the guiding principle of "the greatest good for the greatest number":

It is better to prevent crimes than to punish them. This is the chief aim of every good system of legislation, which is the art of leading men to the greatest possible happiness or to the least possible misery, according to calculation of all the goods and evils of life.[111]

Patrick Colquhoun's influential work, A Treatise on the Police of the Metropolis (1797) was heavily influenced by Benthamite thought. Colquhoun's Thames River Police was founded on these principles, and in contrast to the Bow Street Runners, acted as a deterrent by their continual presence on the riverfront, in addition to being able to intervene if they spotted a crime in progress.[112]

Edwin Chadwick's 1829 article, "Preventive police" in the London Review,[113] argued that prevention ought to be the primary concern of a police body, which was not the case in practice. The reason, argued Chadwick, was that "A preventive police would act more immediately by placing difficulties in obtaining the objects of temptation." In contrast to a deterrent of punishment, a preventive police force would deter criminality by making crime cost-ineffective – "crime doesn't pay". In the second draft of his 1829 Police Act, the "object" of the new Metropolitan Police, was changed by Robert Peel to the "principal object," which was the "prevention of crime."[114] Later historians would attribute the perception of England's "appearance of orderliness and love of public order" to the preventive principle entrenched in Peel's police system.[115]

Development of modern police forces around the world was contemporary to the formation of the state, later defined by sociologist Max Weber as achieving a "monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force" and which was primarily exercised by the police and the military. Marxist theory situates the development of the modern state as part of the rise of capitalism, in which the police are one component of the bourgeoisie's repressive apparatus for subjugating the working class. By contrast, the Peelian principles argue that "the power of the police ... is dependent on public approval of their existence, actions and behavior", a philosophy known as policing by consent.

Personnel and organization

Police forces include both preventive (uniformed) police and detectives. Terminology varies from country to country. Police functions include protecting life and property, enforcing criminal law, criminal investigations, regulating traffic, crowd control, public safety duties, civil defense, emergency management, searching for missing persons, lost property and other duties concerned with public order. Regardless of size, police forces are generally organized as a hierarchy with multiple ranks. The exact structures and the names of rank vary considerably by country.

Uniformed

The police who wear uniforms make up the majority of a police service's personnel. Their main duty is to respond to calls for service. When not responding to these calls, they do work aimed at preventing crime, such as patrols. The uniformed police are known by varying names such as preventive police, the uniform branch/division, administrative police, order police, the patrol bureau/division, or patrol. In Australia and the United Kingdom, patrol personnel are also known as "general duties" officers.[116] Atypically, Brazil's preventive police are known as Military Police.[117]

As stated by the name, uniformed police wear uniforms. They perform functions that require an immediate recognition of an officer's legal authority and a potential need for force. Most commonly this means intervening to stop a crime in progress and securing the scene of a crime that has already happened. Besides dealing with crime, these officers may also manage and monitor traffic, carry out community policing duties, maintain order at public events or carry out searches for missing people (in 2012, the latter accounted for 14% of police time in the United Kingdom).[118] As most of these duties must be available as a 24/7 service, uniformed police are required to do shift work.

Detectives

Police detectives are responsible for investigations and detective work. Detectives may be called Investigations Police, Judiciary/Judicial Police, or Criminal Police. In the United Kingdom, they are often referred to by the name of their department, the Criminal Investigation Department. Detectives typically make up roughly 15–25% of a police service's personnel.

Detectives, in contrast to uniformed police, typically wear business-styled attire in bureaucratic and investigative functions, where a uniformed presence would be either a distraction or intimidating but a need to establish police authority still exists. "Plainclothes" officers dress in attire consistent with that worn by the general public for purposes of blending in.

In some cases, police are assigned to work "undercover", where they conceal their police identity to investigate crimes, such as organized crime or narcotics crime, that are unsolvable by other means. In some cases, this type of policing shares aspects with espionage.

The relationship between detective and uniformed branches varies by country. In the United States, there is high variation within the country itself. Many American police departments require detectives to spend some time on temporary assignments in the patrol division.[citation needed][119] The argument is that rotating officers helps the detectives to better understand the uniformed officers' work, to promote cross-training in a wider variety of skills, and prevent "cliques" that can contribute to corruption or other unethical behavior.[citation needed] Conversely, some countries regard detective work as being an entirely separate profession, with detectives working in separate agencies and recruited without having to serve in uniform. A common compromise in English-speaking countries is that most detectives are recruited from the uniformed branch, but once qualified they tend to spend the rest of their careers in the detective branch.

Another point of variation is whether detectives have extra status. In some forces, such as the New York Police Department and Philadelphia Police Department, a regular detective holds a higher rank than a regular police officer. In others, such as British police and Canadian police, a regular detective has equal status with regular uniformed officers. Officers still have to take exams to move to the detective branch, but the move is regarded as being a specialization, rather than a promotion.

Volunteers and auxiliary

Police services often include part-time or volunteer officers, some of whom have other jobs outside policing. These may be paid positions or entirely volunteer. These are known by a variety of names, such as reserves, auxiliary police or special constables.

Other volunteer organizations work with the police and perform some of their duties. Groups in the U.S. including the Retired and Senior Volunteer Program, Community Emergency Response Team, and the Boy Scouts Police Explorers provide training, traffic and crowd control, disaster response, and other policing duties. In the U.S., the Volunteers in Police Service program assists over 200,000 volunteers in almost 2,000 programs.[120] Volunteers may also work on the support staff. Examples of these schemes are Volunteers in Police Service in the US, Police Support Volunteers in the UK and Volunteers in Policing in New South Wales.

Specialized

Specialized preventive and detective groups, or Specialist Investigation Departments, exist within many law enforcement organizations either for dealing with particular types of crime, such as traffic law enforcement, K9/use of police dogs, crash investigation, homicide, or fraud; or for situations requiring specialized skills, such as underwater search, aviation, explosive disposal ("bomb squad"), and computer crime.

Most larger jurisdictions employ police tactical units, specially selected and trained paramilitary units with specialized equipment, weapons, and training, for the purposes of dealing with particularly violent situations beyond the capability of a patrol officer response, including standoffs, counterterrorism, and rescue operations.

In counterinsurgency-type campaigns, select and specially trained units of police armed and equipped as light infantry have been designated as police field forces who perform paramilitary-type patrols and ambushes whilst retaining their police powers in areas that were highly dangerous.[121]

Because their situational mandate typically focuses on removing innocent bystanders from dangerous people and dangerous situations, not violent resolution, they are often equipped with non-lethal tactical tools like chemical agents, stun grenades, and rubber bullets. The Specialist Firearms Command (MO19)[122] of the Metropolitan Police in London is a group of armed police used in dangerous situations including hostage taking, armed robbery/assault and terrorism.

Administrative duties

Police may have administrative duties that are not directly related to enforcing the law, such as issuing firearms licenses. The extent that police have these functions varies among countries, with police in France, Germany, and other continental European countries handling such tasks to a greater extent than British counterparts.[116]

Military

Military police may refer to:

- a section of the military solely responsible for policing the armed forces, referred to as provosts (e.g., United States Air Force Security Forces)

- a section of the military responsible for policing in both the armed forces and in the civilian population (e.g., most gendarmeries, such as the French Gendarmerie, the Italian Carabinieri, the Spanish Guardia Civil, and the Portuguese National Republican Guard)

- a section of the military solely responsible for policing the civilian population (e.g., Romanian Gendarmerie)

- the civilian preventive police of a Brazilian state (e.g., Policia Militar)

- a special military law enforcement service (e.g., Russian Military Police)

Religious

Some jurisdictions with religious laws may have dedicated religious police to enforce said laws. These religious police forces, which may operate either as a unit of a wider police force or as an independent agency, may only have jurisdiction over members of said religion, or they may have the ability to enforce religious customs nationwide regardless of individual religious beliefs.

Religious police may enforce social norms, gender roles, dress codes, and dietary laws per religious doctrine and laws, and may also prohibit practices that run contrary to said doctrine, such as atheism, proselytism, homosexuality, socialization between different genders, business operations during religious periods or events such as salah or the Sabbath, or the sale and possession of "offending material" ranging from pornography to foreign media.[123][124]

Forms of religious law enforcement were relatively common in historical religious civilizations, but eventually declined in favor of religious tolerance and pluralism. One of the most common forms of religious police in the modern world are Islamic religious police, which enforce the application of Sharia (Islamic religious law). As of 2018, there are eight Islamic countries that maintain Islamic religious police: Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Mauritania, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, and Yemen.[125]

Some forms of religious police may not enforce religious law, but rather suppress religion or religious extremism. This is often done for ideological reasons; for example, communist states such as China and Vietnam have historically suppressed and tightly controlled religions such as Christianity.

Secret

Secret police organizations are typically used to suppress dissidents for engaging in non-politically correct communications and activities, which are deemed counter-productive to what the state and related establishment promote. Secret police interventions to stop such activities are often illegal, and are designed to debilitate, in various ways, the people targeted in order to limit or stop outright their ability to act in a non-politically correct manner.[126] The methods employed may involve spying, various acts of deception, intimidation, framing, false imprisonment, false incarceration under mental health legislation, and physical violence.[127] Countries widely reported to use secret police organizations include China[128] (The Ministry of State Security) and North Korea (The Ministry of State Security).[129]

By country

Police forces are usually organized and funded by some level of government. The level of government responsible for policing varies from place to place, and may be at the national, regional or local level. Some countries have police forces that serve the same territory, with their jurisdiction depending on the type of crime or other circumstances. Other countries, such as Austria, Chile, Israel, New Zealand, the Philippines, South Africa and Sweden, have a single national police force.[130]

In some places with multiple national police forces, one common arrangement is to have a civilian police force and a paramilitary gendarmerie, such as the Police Nationale and National Gendarmerie in France.[116] The French policing system spread to other countries through the Napoleonic Wars[131] and the French colonial empire.[132][133] Another example is the Policía Nacional and Guardia Civil in Spain. In both France and Spain, the civilian force polices urban areas and the paramilitary force polices rural areas. Italy has a similar arrangement with the Polizia di Stato and Carabinieri, though their jurisdictions overlap more. Some countries have separate agencies for uniformed police and detectives, such as the Military Police and Civil Police in Brazil and the Carabineros and Investigations Police in Chile.

Other countries have sub-national police forces, but for the most part their jurisdictions do not overlap. In many countries, especially federations, there may be two or more tiers of police force, each serving different levels of government and enforcing different subsets of the law. In Australia and Germany, the majority of policing is carried out by state (i.e. provincial) police forces, which are supplemented by a federal police force. Though not a federation, the United Kingdom has a similar arrangement, where policing is primarily the responsibility of a regional police force and specialist units exist at the national level. In Canada, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) are the federal police, while municipalities can decide whether to run a local police service or to contract local policing duties to a larger one. Most urban areas have a local police service, while most rural areas contract it to the RCMP, or to the provincial police in Ontario and Quebec.

The United States has a highly decentralized and fragmented system of law enforcement, with over 17,000 state and local law enforcement agencies.[134] These agencies include local police, county law enforcement (often in the form of a sheriff's office, or county police), state police and federal law enforcement agencies. Federal agencies, such as the FBI, only have jurisdiction over federal crimes or those that involve more than one state. Other federal agencies have jurisdiction over a specific type of crime. Examples include the Federal Protective Service, which patrols and protects government buildings; the Postal Inspection Service, which protect United States Postal Service facilities, vehicles and items; the Park Police, which protect national parks; and Amtrak Police, which patrol Amtrak stations and trains. There are also some government agencies and uniformed services that perform police functions in addition to other duties, such as the Coast Guard.

International

Most countries are members of the International Criminal Police Organization (Interpol), established to detect and fight transnational crime and provide for international co-operation and co-ordination of other police activities, such as notifying relatives of the death of foreign nationals. Interpol does not conduct investigations or arrests by itself, but only serves as a central point for information on crime, suspects and criminals. Political crimes are excluded from its competencies.

The terms international policing, transnational policing, and/or global policing began to be used from the early 1990s onwards to describe forms of policing that transcended the boundaries of the sovereign nation-state.[135][136] These terms refer in variable ways to practices and forms for policing that, in some sense, transcend national borders. This includes a variety of practices, but international police cooperation, criminal intelligence exchange between police agencies working in different nation-states, and police development-aid to weak, failed or failing states are the three types that have received the most scholarly attention.

Исторические исследования показывают, что агенты полиции на протяжении многих лет выполняли различные трансграничные полицейские миссии. [137] For example, in the 19th century a number of European policing agencies undertook cross-border surveillance because of concerns about anarchist agitators and other political radicals. A notable example of this was the occasional surveillance by Prussian police of Karl Marx during the years he remained resident in London. The interests of public police agencies in cross-border co-operation in the control of political radicalism and ordinary law crime were primarily initiated in Europe, which eventually led to the establishment of Interpol before World War II. There are also many interesting examples of cross-border policing under private auspices and by municipal police forces that date back to the 19th century.[135] Установлено, что современная полицейская деятельность время от времени преступала национальные границы практически с момента своего создания. Также общепризнано, что в эпоху после окончания холодной войны практика такого типа стала более значимой и распространенной. [138]

Было проведено мало эмпирических работ по практике межнационального/транснационального обмена информацией и разведывательными данными. Заметным исключением является исследование Джеймса Шептицки о сотрудничестве полиции в районе Ла-Манша. [139] который обеспечивает систематический контент-анализ файлов обмена информацией и описание того, как этот транснациональный обмен информацией и разведывательными данными преобразуется в работу полиции. Исследование показало, что транснациональный обмен информацией между полицией стал обычным явлением в регионе, расположенном через Ла-Манш, с 1968 года на основе соглашений непосредственно между полицейскими ведомствами и без какого-либо официального соглашения между заинтересованными странами. К 1992 году, с подписанием Шенгенского договора , который официально закрепил аспекты обмена полицейской информацией на территории Европейского Союза , возникли опасения, что большая часть, если не вся, часть этого обмена разведданными была непрозрачной, что поднимало вопросы об эффективности механизмы подотчетности, регулирующие обмен информацией между полицией в Европе. [140]

Исследования такого рода за пределами Европы проводятся еще реже, поэтому трудно делать обобщения, но одно небольшое исследование, в котором сравнивались транснациональные полицейские практики обмена информацией и разведывательными данными в конкретных трансграничных точках Северной Америки и Европы, подтвердило, что низкая заметность Обмен полицейской информацией и разведданными был общей чертой. [141] Полицейская деятельность, основанная на разведке, теперь стала обычной практикой в большинстве развитых стран. [142] и вполне вероятно, что обмен полицейскими разведывательными данными и информацией имеет общую морфологию во всем мире. [142] Джеймс Шептицки проанализировал влияние новых информационных технологий на организацию полицейской разведки и предположил, что возник ряд «организационных патологий», которые делают функционирование процессов безопасности и разведки в транснациональной полиции глубоко проблематичным. Он утверждает, что транснациональные полицейские информационные сети помогают «создавать панические сцены в обществе, контролирующем безопасность». [143] Парадоксальный эффект заключается в том, что чем усерднее полицейские органы работают над обеспечением безопасности, тем сильнее чувство незащищенности.

Помощь развитию полиции слабым, несостоятельным или несостоятельным государствам – это еще одна форма транснациональной полицейской деятельности, привлекшая внимание. Эта форма транснациональной полицейской деятельности играет все более важную роль в Организации Объединенных Наций миротворческой деятельности , и, похоже, в предстоящие годы она будет возрастать, особенно в связи с тем, что международное сообщество стремится развивать верховенство закона и реформировать институты безопасности в государствах, восстанавливающихся после конфликта. [144] В условиях транснациональной помощи на развитие полиции дисбаланс сил между донорами и получателями становится резким, и возникают вопросы о применимости и переносимости моделей полицейской деятельности между юрисдикциями. [145]

Одна из тем касается демократической подотчетности транснациональных полицейских институтов. [146] Согласно Глобальному отчету о подотчетности за 2007 год, Интерпол имел самые низкие оценки в своей категории (МПО), заняв десятое место с оценкой 22% по общим возможностям подотчетности. [147]

Оборудование

Оружие

Во многих юрисдикциях полицейские носят огнестрельное оружие , в основном пистолеты , при исполнении своих служебных обязанностей. В Великобритании (кроме Северной Ирландии ), Исландии, Ирландии, Норвегии, Новой Зеландии, [148] и на Мальте, за исключением специализированных подразделений, офицеры, естественно, не носят огнестрельного оружия. Норвежская полиция носит огнестрельное оружие в своих автомобилях, но не на служебных ремнях, и должна получить разрешение, прежде чем оружие можно будет вынуть из автомобиля.

В полиции часто имеются специализированные подразделения для борьбы с вооруженными правонарушителями или в опасных ситуациях, когда вероятны боевые действия, например тактические подразделения полиции или уполномоченные офицеры по огнестрельному оружию . В некоторых юрисдикциях, в зависимости от обстоятельств, полиция может обратиться за помощью к военным , поскольку военная помощь гражданским властям является одним из аспектов деятельности многих вооруженных сил. Возможно, самый громкий пример этого произошел в 1980 году, когда британской армии была Специальная воздушная служба задействована для ликвидации осады иранского посольства от имени столичной полиции .

Они также могут быть вооружены «несмертельными» (точнее, «менее смертоносными» или «менее смертоносными», учитывая, что они все еще могут быть смертоносными). [149] ) оружие, особенно для борьбы с беспорядками , или для причинения боли сопротивляющемуся подозреваемому, чтобы заставить его сдаться, не причинив ему смертельного ранения. К нелетальному оружию относятся дубинки , слезоточивый газ , средства борьбы с беспорядками , резиновые пули , щиты , водометы и электрошоковое оружие . Полицейские обычно носят наручники, чтобы удерживать подозреваемых.

Использование огнестрельного оружия или смертоносной силы обычно является последним средством, которое следует использовать только в случае необходимости для спасения жизни других или самих себя, хотя в некоторых юрисдикциях (например, в Бразилии) разрешено его использование против бегущих преступников и сбежавших осужденных. Полицейским в Соединенных Штатах обычно разрешается применять смертоносную силу, если они считают, что их жизнь находится в опасности, и эту политику критиковали за ее расплывчатость. [150] Южноафриканская полиция придерживается политики «стрелять на поражение», которая позволяет офицерам применять смертоносную силу против любого человека, который представляет для них значительную угрозу. [151] Поскольку в стране один из самых высоких уровней насильственных преступлений, президент Джейкоб Зума заявил, что Южная Африка должна бороться с преступностью иначе, чем другие страны. [152]

Коммуникации

Современные полицейские силы широко используют оборудование двусторонней радиосвязи , носимое как на человеке, так и установленное в транспортных средствах, для координации своей работы, обмена информацией и быстрого получения помощи. установленные в транспортных средствах, Мобильные терминалы передачи данных, расширяют возможности полицейской связи, упрощая отправку вызовов, проверку криминального прошлого интересующих лиц, которая выполняется за считанные секунды, а также обновление ежедневного журнала активности офицеров и других необходимых отчетов в реальном времени. -временная основа. Другие распространенные предметы полицейского снаряжения включают фонарики , свистки , полицейские блокноты и «билетные книжки» или цитаты . Некоторые полицейские управления разработали передовые компьютеризированные системы отображения и связи данных для предоставления офицерам данных в реальном времени, одним из примеров является система информирования о доменах полиции Нью-Йорка .

Транспортные средства

Полицейские машины используются для задержания, патрулирования и перевозки на обширных территориях, которые иначе офицер не смог бы эффективно охватить. Средняя полицейская машина, используемая для стандартного патрулирования, представляет собой четырехдверный седан , внедорожник или кроссовер , часто модифицированный производителем или службами автопарка полиции для обеспечения лучших характеристик. Пикапы , внедорожники и фургоны часто используются в коммунальных целях, хотя в некоторых юрисдикциях или ситуациях (например, там, где грунтовые дороги являются обычным явлением, требуется бездорожье или характер задания офицера требует этого), их можно использовать как стандартные патрульные машины. Спортивные автомобили, как правило, не используются полицией из-за проблем со стоимостью и техническим обслуживанием, хотя те, которые используются, обычно назначаются только сотрудникам дорожной полиции или общественной полиции и редко, если вообще когда-либо, назначаются для стандартного патрулирования или уполномочены реагировать на опасные вызовы ( например, вооруженные вызовы или преследования), когда вероятность повреждения или уничтожения транспортного средства высока. Полицейские машины обычно отмечены соответствующими символами и оснащены сиренами и мигающими аварийными огнями, чтобы другие знали о присутствии полиции или действиях полиции; в большинстве юрисдикций полицейские машины с включенными сиренами и аварийными огнями имеют право проезда при движении, в то время как в других юрисдикциях аварийные огни могут быть включены во время патрулирования, чтобы обеспечить видимость. Полицейские машины без опознавательных знаков или под прикрытием используются в основном для обеспечения соблюдения правил дорожного движения или задержания преступников без предупреждения их о своем присутствии. Использование полицейских машин без опознавательных знаков для обеспечения соблюдения правил дорожного движения вызывает споры: штат Нью-Йорк запретил эту практику в 1996 году на том основании, что она подвергает опасности автомобилистов, которых могут остановить имитаторы полиции . [153]

Мотоциклы , которые исторически были основой полицейских автопарков, обычно используются, особенно в местах, куда автомобиль не может добраться, для контроля потенциальных ситуаций общественного порядка, связанных со встречами мотоциклистов, и часто в полицейском сопровождении , где сотрудники полиции на мотоциклах могут быстро расчистить путь для сопровождаемых транспортных средств. Велосипедные патрули используются в некоторых районах, часто в центре города или в парках, поскольку они позволяют охватить более широкую и быструю территорию, чем пешие патрули. Велосипеды также часто используются полицией по охране общественного порядка для создания временных баррикад против протестующих. [154]

Полицейская авиация состоит из вертолетов и самолетов , а полицейская водная техника, как правило, состоит из надувных надувных лодок , моторных лодок и патрульных катеров . Автомобили спецназа используются тактическими подразделениями полиции и часто состоят из четырехколесных бронетранспортеров, используемых для перевозки тактических групп, обеспечивая при этом броневое прикрытие, место для хранения оборудования или импровизированные тарана возможности ; эти машины обычно не вооружены, не патрулируют и используются только для перевозки. Мобильные командные пункты также могут использоваться некоторыми полицейскими силами для создания идентифицируемых командных пунктов на месте серьезных ситуаций.

Полицейские машины могут содержать выданное длинноствольное оружие , боеприпасы к выданному оружию, менее летальное оружие, оборудование для борьбы с беспорядками, дорожные конусы , дорожные сигнальные огни , физические баррикады или баррикадные ленты , огнетушители , [155] аптечки первой помощи или дефибрилляторы . [156]

Стратегии

Появление полицейской машины, двусторонней радиосвязи и телефона в начале 20-го века превратило работу полиции в стратегию реагирования, которая была сосредоточена на реагировании на вызовы в службу вдали от их ритма . [157] Благодаря этой трансформации командование и контроль полиции стали более централизованными.