Ютуб

Логотип используется с 2017 года. | |

Скриншот видеоплеера от 13 сентября 2023 г. | |

| Тип бизнеса | Дочерняя компания |

|---|---|

Тип сайта | Онлайн-видео платформа |

| Основан | 14 февраля 2005 г |

| Headquarters | 901 Cherry Avenue San Bruno, California, United States |

| Area served | Worldwide (excluding blocked countries) |

| Owner | Google LLC |

| Founder(s) | |

| Key people |

|

| Industry | |

| Products | |

| Revenue | |

| Parent | Google LLC (2006–present) |

| URL | youtube (see list of localized domain names) |

| Advertising | Google AdSense |

| Registration | Optional |

| Users | |

| Launched | February 14, 2005 |

| Current status | Active |

Content license | Uploader holds copyright (standard license); Creative Commons can be selected. |

| Written in | Python (core/API),[3] C (through CPython), C++, Java (through Guice platform),[4][5] Go,[6] JavaScript (UI) |

YouTube — американская онлайн-платформа для обмена видео, принадлежащая Google . Доступен по всему миру, [примечание 1] YouTube был запущен 14 февраля 2005 года Стивом Ченом , Чадом Херли и Джаведом Каримом , тремя бывшими сотрудниками PayPal . Штаб-квартира находится в Сан-Бруно, штат Калифорния , США. Это второй по посещаемости веб-сайт в мире после Google Search . YouTube имеет более 2,5 миллиардов пользователей в месяц. [2] которые в совокупности смотрят более миллиарда часов видео каждый день. [7] По состоянию на май 2019 г. [update]видео загружались на платформу со скоростью более 500 часов контента в минуту, [8] [9] а по состоянию на 2021 год всего было около 14 миллиардов видео. [9]

В октябре 2006 года YouTube был куплен Google за 1,65 миллиарда долларов (что эквивалентно 2,31 миллиарду долларов в 2023 году). [10] Google расширил бизнес-модель YouTube, предусматривающую получение дохода только от рекламы , до предложения платного контента, такого как фильмы и эксклюзивный контент , созданный YouTube и для него. Он также предлагает YouTube Premium — платную подписку для просмотра контента без рекламы. YouTube внедрил программу Google AdSense , что принесло больший доход как YouTube, так и одобренным создателям контента. В 2022 году годовой доход YouTube от рекламы увеличился до $29,2 млрд, что более чем на $9 млрд выше, чем в 2020 году. [1] [11]

С момента покупки Google YouTube расширился за пределы основного веб-сайта и стал включать в себя мобильные приложения , сетевое телевидение и возможность связываться с другими платформами. Категории видео на YouTube включают музыкальные клипы , видеоклипы , новости , короткометражные и художественные фильмы , песни , документальные фильмы , трейлеры к фильмам , тизеры и телеролики , прямые трансляции , видеоблоги и многое другое. Большая часть контента создается отдельными людьми , в том числе в результате сотрудничества между « Ютуберами » и корпоративными спонсорами. Известные корпорации средств массовой информации, новостей и развлечений также создали и расширили свою видимость каналов YouTube, чтобы охватить более широкую аудиторию.

YouTube has had unprecedented social impact, influencing popular culture, internet trends, and creating multimillionaire celebrities. Despite its growth and success, the platform is sometimes criticized for allegedly facilitating the spread of misinformation, the sharing of copyrighted content, routinely violating its users' privacy, enabling censorship, endangering child safety and wellbeing, and for its inconsistent or incorrect implementation of platform guidelines.

History

Founding and initial growth (2005–2006)

YouTube was founded by Steve Chen, Chad Hurley, and Jawed Karim. The trio were early employees of PayPal, which left them enriched after the company was bought by eBay.[12] Hurley had studied design at the Indiana University of Pennsylvania, and Chen and Karim studied computer science together at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.[13]

According to a story that has often been repeated in the media, Hurley and Chen developed the idea for YouTube during the early months of 2005, after they had experienced difficulty sharing videos that had been shot at a dinner party at Chen's apartment in San Francisco. Karim did not attend the party and denied that it had occurred, but Chen remarked that the idea that YouTube was founded after a dinner party "was probably very strengthened by marketing ideas around creating a story that was very digestible".[14]

Karim said the inspiration for YouTube came from the Super Bowl XXXVIII halftime show controversy, when Janet Jackson's breast was briefly exposed by Justin Timberlake during the halftime show. Karim could not easily find video clips of the incident and the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami online, which led to the idea of a video-sharing site.[15][16] Hurley and Chen said that the original idea for YouTube was a video version of an online dating service and had been influenced by the website Hot or Not.[14][17] They created posts on Craigslist asking attractive women to upload videos of themselves to YouTube in exchange for a $100 reward.[18] Difficulty in finding enough dating videos led to a change of plans, with the site's founders deciding to accept uploads of any video.[19]

YouTube began as a venture capital–funded technology startup. Between November 2005 and April 2006, the company raised money from various investors, with Sequoia Capital and Artis Capital Management being the largest two.[12][20] YouTube's early headquarters were situated above a pizzeria and a Japanese restaurant in San Mateo, California.[21] In February 2005, the company activated www.youtube.com.[22] The first video was uploaded on April 23, 2005. Titled "Me at the zoo", it shows co-founder Jawed Karim at the San Diego Zoo and can still be viewed on the site.[23][24] In May, the company launched a public beta and by November, a Nike ad featuring Ronaldinho became the first video to reach one million total views.[25][26] The site launched officially on December 15, 2005, by which time the site was receiving 8 million views a day.[27][28] Clips at the time were limited to 100 megabytes, as little as 30 seconds of footage.[29]

YouTube was not the first video-sharing site on the Internet; Vimeo was launched in November 2004, though that site remained a side project of its developers from CollegeHumor.[30] The week of YouTube's launch, NBC-Universal's Saturday Night Live ran a skit "Lazy Sunday" by The Lonely Island. Besides helping to bolster ratings and long-term viewership for Saturday Night Live, "Lazy Sunday"'s status as an early viral video helped establish YouTube as an important website.[31] Unofficial uploads of the skit to YouTube drew in more than five million collective views by February 2006 before they were removed when NBCUniversal requested it two months later based on copyright concerns.[32] Despite eventually being taken down, these duplicate uploads of the skit helped popularize YouTube's reach and led to the upload of more third-party content.[33][34] The site grew rapidly; in July 2006, the company announced that more than 65,000 new videos were being uploaded every day and that the site was receiving 100 million video views per day.[35]

The choice of the name www.youtube.com led to problems for a similarly named website, www.utube.com. That site's owner, Universal Tube & Rollform Equipment, filed a lawsuit against YouTube in November 2006, after being regularly overloaded by people looking for YouTube. Universal Tube subsequently changed its website to www.utubeonline.com.[36][37]

"Broadcast Yourself" era (2006–2013)

On October 9, 2006, Google announced that they had acquired YouTube for $1.65 billion in Google stock.[38][39] The deal was finalized on November 13, 2006.[40][41] Google's acquisition launched newfound interest in video-sharing sites; IAC, which now owned Vimeo, focused on supporting the content creators to distinguish itself from YouTube.[30] It is at this time YouTube issued the slogan "Broadcast Yourself".The company experienced rapid growth. The Daily Telegraph wrote that in 2007, YouTube consumed as much bandwidth as the entire Internet in 2000.[42] By 2010, the company had reached a market share of around 43% and more than 14 billion views of videos, according to comScore.[43] That year, the company simplified its interface to increase the time users would spend on the site.[44] In 2011, more than three billion videos were being watched each day with 48 hours of new videos uploaded every minute.[45][46][47] However, most of these views came from a relatively small number of videos; according to a software engineer at that time, 30% of videos accounted for 99% of views on the site.[48] That year, the company again changed its interface and at the same time, introduced a new logo with a darker shade of red.[49][50] A subsequent interface change, designed to unify the experience across desktop, TV, and mobile, was rolled out in 2013.[51] By that point, more than 100 hours were being uploaded every minute, increasing to 300 hours by November 2014.[52][53]

During this time, the company also went through some organizational changes. In October 2006, YouTube moved to a new office in San Bruno, California.[54] Hurley announced that he would be stepping down as chief executive officer of YouTube to take an advisory role and that Salar Kamangar would take over as head of the company in October 2010.[55]

In December 2009, YouTube partnered with Vevo.[56] In April 2010, Lady Gaga's "Bad Romance" became the most viewed video, becoming the first video to reach 200 million views on May 9, 2010.[57]

YouTube faced a major lawsuit by Viacom International in 2011 that nearly resulted in the discontinuation of the website. The lawsuit was filed as a result of alleged copyright infringement of Viacom's material by YouTube. However, the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ruled that YouTube was not liable, and thus YouTube won the case in 2012.[58]

Susan Wojcicki and going mainstream (2014–2018)

Susan Wojcicki was appointed CEO of YouTube in February 2014.[59] In January 2016, YouTube expanded its headquarters in San Bruno by purchasing an office park for $215 million. The complex has 51,468 square metres (554,000 square feet) of space and can house up to 2,800 employees.[60] YouTube officially launched the "polymer" redesign of its user interfaces based on Material Design language as its default, as well a redesigned logo that is built around the service's play button emblem in August 2017.[61]

Through this period, YouTube tried several new ways to generate revenue beyond advertisements. In 2013, YouTube launched a pilot program for content providers to offer premium, subscription-based channels.[62][63] This effort was discontinued in January 2018 and relaunched in June, with US$4.99 channel subscriptions.[64][65] These channel subscriptions complemented the existing Super Chat ability, launched in 2017, which allows viewers to donate between $1 and $500 to have their comment highlighted.[66] In 2014, YouTube announced a subscription service known as "Music Key", which bundled ad-free streaming of music content on YouTube with the existing Google Play Music service.[67] The service continued to evolve in 2015 when YouTube announced YouTube Red, a new premium service that would offer ad-free access to all content on the platform (succeeding the Music Key service released the previous year), premium original series, and films produced by YouTube personalities, as well as background playback of content on mobile devices. YouTube also released YouTube Music, a third app oriented towards streaming and discovering the music content hosted on the YouTube platform.[68][69][70]

The company also attempted to create products appealing to specific viewers. YouTube released a mobile app known as YouTube Kids in 2015, designed to provide an experience optimized for children. It features a simplified user interface, curated selections of channels featuring age-appropriate content, and parental control features.[71] Also in 2015, YouTube launched YouTube Gaming—a video gaming-oriented vertical and app for videos and live streaming, intended to compete with the Amazon.com-owned Twitch.[72]

The company was attacked on April 3, 2018, when a shooting occurred at YouTube's headquarters in San Bruno, California, which wounded four and resulted in the death of the shooter.[73]

Recent history (2019–present)

By February 2017, one billion hours of YouTube videos were being watched every day, and 400 hours worth of videos were uploaded every minute.[7][74] Two years later, the uploads had risen to more than 500 hours per minute.[8] During the COVID-19 pandemic, when most of the world was under stay-at-home orders, usage of services like YouTube significantly increased. One data firm[which?] estimated that YouTube was accounting for 15% of all internet traffic, twice its pre-pandemic level.[75] In response to EU officials requesting that such services reduce bandwidth as to make sure medical entities had sufficient bandwidth to share information, YouTube and Netflix stated they would reduce streaming quality for at least thirty days as to cut bandwidth use of their services by 25% to comply with the EU's request.[76] YouTube later announced that they would continue with this move worldwide: "We continue to work closely with governments and network operators around the globe to do our part to minimize stress on the system during this unprecedented situation."[77]

Following a 2018 complaint alleging violations of the Children's Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA),[78] the company was fined $170 million by the FTC for collecting personal information from minors under the age of 13.[79] YouTube was also ordered to create systems to increase children's privacy.[80][81] Following criticisms of its implementation of those systems, YouTube started treating all videos designated as "made for kids" as liable under COPPA on January 6, 2020.[82][83] Joining the YouTube Kids app, the company created a supervised mode, designed more for tweens, in 2021.[84] Additionally, to compete with TikTok, YouTube released YouTube Shorts, a short-form video platform.

During this period, YouTube entered disputes with other tech companies. For over a year, in 2018 and 2019, no YouTube app was available for Amazon Fire products.[85] In 2020, Roku removed the YouTube TV app from its streaming store after the two companies were unable to reach an agreement.[86]

After testing earlier in 2021, YouTube removed public display of dislike counts on videos in November 2021, claiming the reason for the removal was, based on its internal research, that users often used the dislike feature as a form of cyberbullying and brigading.[87] While some users praised the move as a way to discourage trolls, others felt that hiding dislikes would make it harder for viewers to recognize clickbait or unhelpful videos and that other features already existed for creators to limit bullying. YouTube co-founder Jawed Karim referred to the update as "a stupid idea", and that the real reason behind the change was "not a good one, and not one that will be publicly disclosed." He felt that users' ability on a social platform to identify harmful content was essential, saying, "The process works, and there's a name for it: the wisdom of the crowds. The process breaks when the platform interferes with it. Then, the platform invariably declines."[88][89][90] Shortly after the announcement, software developer Dmitry Selivanov created Return YouTube Dislike, an open-source, third-party browser extension for Chrome and Firefox that allows users to see a video's number of dislikes.[91] In a letter published on January 25, 2022, by then YouTube CEO Susan Wojcicki, acknowledged that removing public dislike counts was a controversial decision, but reiterated that she stands by this decision, claiming that "it reduced dislike attacks."[92]

In 2022, YouTube launched an experiment where the company would show users who watched longer videos on TVs a long chain of short un-skippable adverts, intending to consolidate all ads into the beginning of a video. Following public outrage over the unprecedented amount of un-skippable ads, YouTube "ended" the experiment on September 19 of that year.[93] In October, YouTube announced that they would be rolling out customizable user handles (e.g. @MrBeast6000) in addition to channel names, which would also become channel URLs.[94]

On February 16, 2023, Wojcicki announced that she would step down as CEO, with Neal Mohan named as her successor. Wojcicki will take on an advisory role for Google and parent company Alphabet.[95]

In late October 2023, YouTube began cracking down on the use of ad blockers on the platform. Users of ad blockers may be given a pop-up warning saying "Video player will be blocked after 3 videos". Users of ad blockers are shown a message asking them to allow ads or inviting them to subscribe to the ad-free YouTube Premium subscription plan. YouTube says that the use of ad blockers violates its terms of service.[96][97]

In April 2024, YouTube announced it would be "strengthening our enforcement on third-party apps that violate YouTube's Terms of Service, specifically ad-blocking apps". The change affects apps such as NewPipe.[98]

Senior leadership

YouTube has been led by a CEO since its founding in 2005, beginning with Chad Hurley, who led the company until 2010. After Google's acquisition of YouTube, the CEO role was retained. Salar Kamangar took over Hurley's position and held the job until 2014. He was replaced by Susan Wojcicki, who later resigned in 2023.[95] The current CEO is Neal Mohan, who was appointed on February 16, 2023.[95]

Features

Video technology

YouTube primarily uses the VP9 and H.264/MPEG-4 AVC video codecs, and the Dynamic Adaptive Streaming over HTTP protocol.[99] MPEG-4 Part 2 streams contained within 3GP containers are also provided for low bandwidth connections.[100] By January 2019, YouTube had begun rolling out videos in AV1 format.[101] In 2021 it was reported that the company was considering requiring AV1 in streaming hardware in order to decrease bandwidth and increase quality.[102] Video is usually streamed alongside the Opus and AAC audio codecs.[100]

At launch in 2005, viewing YouTube videos on a personal computer required the Adobe Flash Player plug-in to be installed in the browser.[103] In January 2010, YouTube launched an experimental version of the site that used the built-in multimedia capabilities of Web browsers supporting HTML video.[104] This allowed videos to be viewed without requiring Adobe Flash Player or any other plug-in to be installed.[105] On January 27, 2015, YouTube announced that HTML video would be the default playback method on supported browsers.[104] HTML video streams use Dynamic Adaptive Streaming over HTTP (MPEG-DASH), an HTTP-based adaptive bit-rate streaming solution optimizes the bitrate and quality for the available network.[106]

The platform can serve videos at optionally lower resolution levels starting at 144p for smoother playback in areas and countries with limited Internet speeds, improving compatibility, as well as for the preservation of limited cellular data plans. The resolution can be adjusted automatically based on detected connection speed or set manually.[107][108]

From 2008 to 2017, users could add "annotations" to their videos, such as pop-up text messages and hyperlinks, which allowed for interactive videos. By 2019, all annotations had been removed from videos, breaking some videos that depended on the feature. YouTube introduced standardized widgets intended to replace annotations in a cross-platform manner, including "end screens" (a customizable array of thumbnails for specified videos displayed near the end of the video).[109][110][111]

In 2018, YouTube became an International Standard Name Identifier (ISNI) registry, and announced its intention to begin creating ISNI identifiers to uniquely identify the musicians whose videos it features.[112]

Users can verify their account, normally through a mobile phone, to gain the ability to upload videos up to 12 hours in length, as well as produce live streams.[113][114] Users who have built sufficient channel history and have a good track record of complying with the site's Community Guidelines will also gain access to these aforementioned features as well.[115] When YouTube was launched in 2005, it was possible to upload longer videos, but a 10-minute limit was introduced in March 2006 after YouTube found that the majority of videos exceeding this length were unauthorized uploads of television shows and films.[116] The 10-minute limit was increased to 15 minutes in July 2010.[117] Videos can be at most 256 GB in size or 12 hours, whichever is less.[113] As of 2021[update], automatic closed captions using speech recognition technology when a video is uploaded are available in 13 languages, and can be machine-translated during playback.[118]

YouTube also offers manual closed captioning as part of its creator studio.[119] YouTube formerly offered a 'Community Captions' feature, where viewers could write and submit captions for public display upon approval by the video uploader, but this was deprecated in September 2020.[120]

YouTube accepts the most common container formats, including MP4, Matroska, FLV, AVI, WebM, 3GP, MPEG-PS, and the QuickTime File Format. Some intermediate video formats (i.e., primarily used for professional video editing, not for final delivery or storage) are also accepted, such as ProRes.[121] YouTube provides recommended encoding settings.[122]

Each video is identified by an eleven-character case-sensitive alphanumerical Base64 string in the Uniform Resource Locator (URL) which can contain letters, digits, an underscore (_), and a dash (-).[123]

In 2018, YouTube added a feature called Premiere which displays a notification to the user mentioning when the video will be available for the first time, like for a live stream but with a prerecorded video. When the scheduled time arrives, the video is aired as a live broadcast with a two-minute countdown. Optionally, a premiere can be initiated immediately.[124]

Quality and formats

YouTube originally offered videos at only one quality level, displayed at a resolution of 320×240 pixels using the Sorenson Spark codec (a variant of H.263),[125][126] with mono MP3 audio.[127] In June 2007, YouTube added an option to watch videos in 3GP format on mobile phones.[128] In March 2008, a high-quality mode was added, which increased the resolution to 480×360 pixels.[129] In December 2008, 720p HD support was added. At the time of the 720p launch, the YouTube player was changed from a 4:3 aspect ratio to a widescreen 16:9.[130] With this new feature, YouTube began a switchover to H.264/MPEG-4 AVC as its default video compression format. In November 2009, 1080p HD support was added. In July 2010, YouTube announced that it had launched a range of videos in 4K format, which allows a resolution of up to 4096×3072 pixels.[131][132] In July 2010, support for 2160p UHD was added, with the videos playing at 3840 × 2160 pixels.[133] In June 2014, YouTube began to deploy support for high frame rate videos up to 60 frames per second (as opposed to 30 before), becoming available for user uploads in October. YouTube stated that this would enhance "motion-intensive" videos, such as video game footage.[134][135][136][137] In June 2015, support for 8K resolution was added, with the videos playing at 7680×4320 pixels.[138] In November 2016, support for HDR video was added which can be encoded with hybrid log–gamma (HLG) or perceptual quantizer (PQ).[139] HDR video can be encoded with the Rec. 2020 color space.[140]

YouTube videos are available in a range of quality levels. Viewers only indirectly influence the video quality. In the mobile apps, users choose between "Auto", which adjusts resolution based on the internet connection, "High Picture Quality" which will prioritize playing high-quality video, "Data saver" which will sacrifice video quality in favor of low data usage and "Advanced" which lets the user choose a stream resolution.[141] On desktop, users choose between "Auto" and a specific resolution.[142] It is not possible for the viewer to directly choose a higher bitrate (quality) for any selected resolution.

Since 2009, viewers have had the ability to watch 3D videos.[143] In 2015, YouTube began natively supporting 360-degree video. Since April 2016, it allowed live streaming 360° video, and both normal and 360° video at up to 1440p, and since November 2016 both at up to 4K (2160p) resolution.[144][145][146] Citing the limited number of users who watched more than 90-degrees, it began supporting an alternative stereoscopic video format known as VR180 which it said was easier to produce,[147] which allows users to watch any video using virtual reality headsets.[148]

In response to increased viewership during the COVID-19 pandemic, YouTube temporarily downgraded the quality of its videos.[149][150] YouTube developed its own chip, called "Argos", to help with encoding higher resolution videos in 2021.[151]

In April 2023, YouTube began offering some videos in an enhanced bitrate "1080p Premium" option for YouTube Premium subscribers on iOS.[152] In August 2023, the feature became available to subscribers on desktop platforms.[153]

In certain cases, YouTube allows the uploader to upgrade the quality of videos uploaded a long time ago in poor quality. One such partnership with Universal Music Group included remasters of 1,000 music videos.[154]

Live streaming

YouTube carried out early experiments with live streaming, including its YouTube Live event in 2008,[155] a concert by U2 in 2009, and a question-and-answer session with US President Barack Obama in February 2010.[156] These tests had relied on technology from 3rd-party partners, but in September 2010, YouTube began testing its own live streaming infrastructure.[157] In April 2011, YouTube announced the rollout of YouTube Live. The creation of live streams was initially limited to select partners.[158] It was used for real-time broadcasting of events such as the 2012 Olympics in London.[159] In October 2012, more than 8 million people watched Felix Baumgartner's jump from the edge of space as a live stream on YouTube.[160]

In May 2013, creation of live streams was opened to verified users with at least 1,000 subscribers; in August of the same year the number was reduced to 100 subscribers,[161] and in December the limit was removed.[162] In February 2017, live streaming was introduced to the official YouTube mobile app. Live streaming via mobile was initially restricted to users with at least 10,000 subscribers,[163] but as of mid-2017 it has been reduced to 100 subscribers.[164] Live streams support HDR, can be up to 4K resolution at 60 fps, and also support 360° video.[145][165]

User features

Comment system

Most videos enable users to leave comments, which have attracted attention for the negative aspects of their form and content.[specify] In 2006, Time praised Web 2.0 for enabling "community and collaboration on a scale never seen before", and added that YouTube "harnesses the stupidity of crowds as well as its wisdom. Some of the comments on YouTube make you weep for the future of humanity just for the spelling alone, never mind the obscenity and the naked hatred".[166] The Guardian in 2009 described users' comments on YouTube as:[167]

Juvenile, aggressive, misspelt, sexist, homophobic, swinging from raging at the contents of a video to providing a pointlessly detailed description followed by a LOL, YouTube comments are a hotbed of infantile debate and unashamed ignorance—with the occasional burst of wit shining through.

The Daily Telegraph commented in September 2008, that YouTube was "notorious" for "some of the most confrontational and ill-formed comment exchanges on the internet", and reported on YouTube Comment Snob, "a new piece of software that blocks rude and illiterate posts".[168] The Huffington Post noted in April 2012 that finding comments on YouTube that appear "offensive, stupid and crass" to the "vast majority" of the people is hardly difficult.[169]

Google subsequently implemented a comment system oriented on Google+ on November 6, 2013, that required all YouTube users to use a Google+ account to comment on videos. The stated motivation for the change was giving creators more power to moderate and block comments, thereby addressing frequent criticisms of their quality and tone.[170] The new system restored the ability to include URLs in comments, which had previously been removed due to problems with abuse.[171][172] In response, YouTube co-founder Jawed Karim posted the question "why the fuck do I need a google+ account to comment on a video?" on his YouTube channel to express his negative opinion of the change.[173] The official YouTube announcement[174] received 20,097 "thumbs down" votes and generated more than 32,000 comments in two days.[175] Writing in the Newsday blog Silicon Island, Chase Melvin noted that "Google+ is nowhere near as popular a social media network like Facebook, but it's essentially being forced upon millions of YouTube users who don't want to lose their ability to comment on videos" and added that "Discussion forums across the Internet are already bursting with the outcry against the new comment system". In the same article Melvin goes on to say:[176]

Perhaps user complaints are justified, but the idea of revamping the old system isn't so bad.Think of the crude, misogynistic and racially-charged mudslinging that has transpired over the last eight years on YouTube without any discernible moderation. Isn't any attempt to curb unidentified libelers worth a shot? The system is far from perfect, but Google should be lauded for trying to alleviate some of the damage caused by irate YouTubers hiding behind animosity and anonymity.

Later, on July 27, 2015, Google announced in a blog post that it would be removing the requirement to sign up to a Google+ account to post comments to YouTube.[177] On November 3, 2016, YouTube announced a trial scheme which allows the creators of videos to decide whether to approve, hide or report the comments posted on videos based on an algorithm that detects potentially offensive comments.[178] Creators may also choose to keep or delete comments with links or hashtags in order to combat spam. They can also allow other users to moderate their comments.[179]

In December 2020, it was reported that YouTube would launch a new feature that will warn users who post a comment that "may be offensive to others."[180][181]

Community

On September 13, 2016, YouTube launched a public beta of Community, a social media-based feature that allows users to post text, images (including GIFs), live videos and others in a separate "Community" tab on their channel.[182] Prior to the release, several creators had been consulted to suggest tools Community could incorporate that they would find useful; these YouTubers included Vlogbrothers, AsapScience, Lilly Singh, The Game Theorists, Karmin, The Key of Awesome, The Kloons, Peter Hollens, Rosianna Halse Rojas, Sam Tsui, Threadbanger and Vsauce3.[183][non-primary source needed]

After the feature has been officially released, the community post feature gets activated automatically for every channel that passes a specific threshold of subscriber counts or already has more subscribers. This threshold was lowered over time,[when?] from 10,000 subscribers to 1500 subscribers, to 1000 subscribers,[184][non-primary source needed] to 500 subscribers.[185]

Channels that the community tab becomes enabled for, get their channel discussions (previously known as channel comments) permanently erased, instead of co-existing or migrating.[186][non-primary source needed]

TestTube

Experimental features of YouTube could be accessed in an area of the site formerly named TestTube.[187][188]For example, in October 2009, a comment search feature accessible under /comment_search was implemented as part of this program. The feature was removed later.[189] Later the same year, YouTube Feather was introduced as a "lightweight" alternative website for countries with limited internet speeds.[190] Following the transition to the Polymer layout, TestTube was disabled, and the URL redirects to video playback settings. TestTube was replaced by a new system that requires users to be premium members to enable or disable experiments.

Content accessibility

YouTube offers users the ability to view its videos on web pages outside their website. Each YouTube video is accompanied by a piece of HTML that can be used to embed it on any page on the Web.[191] This functionality is often used to embed YouTube videos in social networking pages and blogs. Users wishing to post a video discussing, inspired by, or related to another user's video can make a "video response". The eleven character YouTube video identifier (64 possible characters used in each position), allows for a theoretical maximum of 6411 or around 73.8 quintillion (73.8 billion billion) unique ids.

YouTube announced that it would remove video responses for being an underused feature on August 27, 2013.[192] Embedding, rating, commenting and response posting can be disabled by the video owner.[193] YouTube does not usually offer a download link for its videos, and intends for them to be viewed through its website interface.[194] A small number of videos can be downloaded as MP4 files.[195] Numerous third-party web sites, applications and browser plug-ins allow users to download YouTube videos.[196]

In February 2009, YouTube announced a test service, allowing some partners to offer video downloads for free or for a fee paid through Google Checkout.[197] In June 2012, Google sent cease and desist letters threatening legal action against several websites offering online download and conversion of YouTube videos.[198] In response, Zamzar removed the ability to download YouTube videos from its site.[199] Users retain copyright of their own work under the default Standard YouTube License,[200] but have the option to grant certain usage rights under any public copyright license they choose.

Since July 2012, it has been possible to select a Creative Commons attribution license as the default, allowing other users to reuse and remix the material.[201]

Platforms

Most modern smartphones are capable of accessing YouTube videos, either within an application or through an optimized website. YouTube Mobile was launched in June 2007, using RTSP streaming for the video.[202] Not all of YouTube's videos are available on the mobile version of the site.[203]

Since June 2007, YouTube's videos have been available for viewing on a range of Apple products. This required YouTube's content to be transcoded into Apple's preferred video standard, H.264, a process that took several months. YouTube videos can be viewed on devices including Apple TV, iPod Touch and the iPhone.[204]

The mobile version of the site was relaunched based on HTML video in July 2010, avoiding the need to use Adobe Flash Player and optimized for use with touch screen controls.[205] The mobile version is also available as an app for the Android platform.[206][207]

In September 2012, YouTube launched its first app for the iPhone, following the decision to drop YouTube as one of the preloaded apps in the iPhone 5 and iOS 6 operating system.[208] According to GlobalWebIndex, YouTube was used by 35% of smartphone users between April and June 2013, making it the third-most used app.[209]

A TiVo service update in July 2008 allowed the system to search and play YouTube videos.[210]

In January 2009, YouTube launched "YouTube for TV", a version of the website tailored for set-top boxes and other TV-based media devices with web browsers, initially allowing its videos to be viewed on the PlayStation 3 and Wii video game consoles.[211][212]

During the month of June that same year, YouTube XL was introduced, which has a simplified interface designed for viewing on a standard television screen.[213] YouTube is also available as an app on Xbox Live.[214]

On November 15, 2012, Google launched an official app for the Wii, allowing users to watch YouTube videos from the Wii channel.[215] An app was available for Wii U and Nintendo 3DS, but was discontinued in August 2019.[216] Videos can also be viewed on the Wii U Internet Browser using HTML video.[217][non-primary source needed] Google made YouTube available on the Roku player on December 17, 2013,[218] and, in October 2014, the Sony PlayStation 4.[219]

YouTube launched as a downloadable app for the Nintendo Switch in November 2018.[220]

International and localization

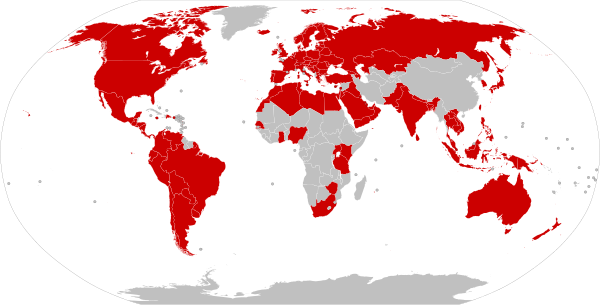

In early years of operation, Google faced some criticism for 'encouraging the dominance of US values', by prioritising English over other languages. On June 19, 2007, at a conference in Paris, Google CEO Eric Schmidt launched YouTube localization, with stated aims including customizing the YouTube experience by country, including country-specific comments, metrics, and video rankings. From 2007, YouTube's localization was rolled out.[221][222]

A 2015 report on YouTube's localization showed it to be continuing, and expanding.[223] In February 2023, YouTube made it possible to upload a single video in multiple languages. Prior to 2023, the only option for YouTubers to broaden their content's reach to audiences speaking different languages was to launch an entirely separate secondary channel for each language and upload dubbed versions of their videos across all those channels. MrBeast called multi-language dub tracks a “giant win” for creators. With the introduction of the dubbing localization option, many creators switched from uploading to separate channels to uploading to their main channel with dubbed versions.[224]

YouTube localization by country

As of 2024, the interface of YouTube is available with localized versions in 104 countries, one territory (Hong Kong) and a worldwide version[225] and continues to extend the availability of its localized version to additional countries and regions.[226]

If YouTube is unable to identify a specific country or region according to the IP address, the default location is the United States. However, YouTube offers language and content preferences for all accessible countries, regions, and languages.[227]

Click at right to show/hide list of countries with YouTube launch dates |

|---|

The YouTube interface suggests which local version should be chosen based on the IP address of the user. In some cases, the message "This video is not available in your country" may appear because of copyright restrictions or inappropriate content.[276] The interface of the YouTube website is available in 76 language versions, including Amharic, Albanian, Armenian, Burmese, Haitian Creole, Kyrgyz, Malagasy, Mongolian, Persian, Samoan, Somali and Uzbek, which do not have local channel versions. Access to YouTube was blocked in Turkey between 2008 and 2010, following controversy over the posting of videos deemed insulting to Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and some material offensive to Muslims.[277][278] In October 2012, a local version of YouTube was launched in Turkey, with the domain youtube.com.tr. The local version is subject to the content regulations found in Turkish law.[279] In March 2009, a dispute between YouTube and the British royalty collection agency PRS for Music led to premium music videos being blocked for YouTube users in the United Kingdom. The removal of videos posted by the major record companies occurred after failure to reach an agreement on a licensing deal. The dispute was resolved in September 2009.[280] In April 2009, a similar dispute led to the removal of premium music videos for users in Germany.[281]

Videos

In January 2012, it was estimated that visitors to YouTube spent an average of 15 minutes a day on the site, in contrast to the four or five hours a day spent by a typical US citizen watching television.[282] In 2017, viewers on average watched YouTube on mobile devices for more than an hour every day.[283]

In December 2012, two billion views were removed from the view counts of Universal and Sony music videos on YouTube, prompting a claim by The Daily Dot that the views had been deleted due to a violation of the site's terms of service, which ban the use of automated processes to inflate view counts. This was disputed by Billboard, which said that the two billion views had been moved to Vevo, since the videos were no longer active on YouTube.[284][285] On August 5, 2015, YouTube patched the formerly notorious behavior which caused a video's view count to freeze at "301" (later "301+") until the actual count was verified to prevent view count fraud.[286] YouTube view counts once again updated in real time.[287]

Since September 2019, subscriber counts are abbreviated. Only three leading digits of channels' subscriber counts are indicated publicly, compromising the function of third-party real-time indicators such as that of Social Blade. Exact counts remain available to channel operators inside YouTube Studio.[288]

On November 11, 2021, after testing out this change in March of the same year, YouTube announced it would start hiding dislike counts on videos, making them invisible to viewers. The company stated the decision was in response to experiments which confirmed that smaller YouTube creators were more likely to be targeted in dislike brigading and harassment. Creators will still be able to see the number of likes and dislikes in the YouTube Studio dashboard tool, according to YouTube.[289][290][291]

Copyright issues

YouTube has faced numerous challenges and criticisms in its attempts to deal with copyright, including the site's first viral video, Lazy Sunday, which had to be taken down, due to copyright concerns.[31] At the time of uploading a video, YouTube users are shown a message asking them not to violate copyright laws.[292] Despite this advice, many unauthorized clips of copyrighted material remain on YouTube. YouTube does not view videos before they are posted online, and it is left to copyright holders to issue a DMCA takedown notice pursuant to the terms of the Online Copyright Infringement Liability Limitation Act. Any successful complaint about copyright infringement results in a YouTube copyright strike. Three successful complaints for copyright infringement against a user account will result in the account and all of its uploaded videos being deleted.[293][294] From 2007 to 2009 organizations including Viacom, Mediaset, and the English Premier League have filed lawsuits against YouTube, claiming that it has done too little to prevent the uploading of copyrighted material.[295][296][297]

In August 2008, a US court ruled in Lenz v. Universal Music Corp. that copyright holders cannot order the removal of an online file without first determining whether the posting reflected fair use of the material.[298] YouTube's owner Google announced in November 2015 that they would help cover the legal cost in select cases where they believe fair use defenses apply.[299]

In the 2011 case of Smith v. Summit Entertainment LLC, professional singer Matt Smith sued Summit Entertainment for the wrongful use of copyright takedown notices on YouTube.[300] He asserted seven causes of action, and four were ruled in Smith's favor.[301] In April 2012, a court in Hamburg ruled that YouTube could be held responsible for copyrighted material posted by its users.[302] On November 1, 2016, the dispute with GEMA was resolved, with Google content ID being used to allow advertisements to be added to videos with content protected by GEMA.[303]

In April 2013, it was reported that Universal Music Group and YouTube have a contractual agreement that prevents content blocked on YouTube by a request from UMG from being restored, even if the uploader of the video files a DMCA counter-notice.[304][305] As part of YouTube Music, Universal and YouTube signed an agreement in 2017, which was followed by separate agreements other major labels, which gave the company the right to advertising revenue when its music was played on YouTube.[306] By 2019, creators were having videos taken down or demonetized when Content ID identified even short segments of copyrighted music within a much longer video, with different levels of enforcement depending on the record label.[307] Experts noted that some of these clips said qualified for fair use.[307]

Content ID

In June 2007, YouTube began trials of a system for automatic detection of uploaded videos that infringe copyright. Google CEO Eric Schmidt regarded this system as necessary for resolving lawsuits such as the one from Viacom, which alleged that YouTube profited from content that it did not have the right to distribute.[308] The system, which was initially called "Video Identification"[309][310] and later became known as Content ID,[311] creates an ID File for copyrighted audio and video material, and stores it in a database. When a video is uploaded, it is checked against the database, and flags the video as a copyright violation if a match is found.[312] When this occurs, the content owner has the choice of blocking the video to make it unviewable, tracking the viewing statistics of the video, or adding advertisements to the video.

An independent test in 2009 uploaded multiple versions of the same song to YouTube and concluded that while the system was "surprisingly resilient" in finding copyright violations in the audio tracks of videos, it was not infallible.[313] The use of Content ID to remove material automatically has led to controversy in some cases, as the videos have not been checked by a human for fair use.[314] If a YouTube user disagrees with a decision by Content ID, it is possible to fill in a form disputing the decision.[315]

Before 2016, videos were not monetized until the dispute was resolved. Since April 2016, videos continue to be monetized while the dispute is in progress, and the money goes to whoever won the dispute.[316] Should the uploader want to monetize the video again, they may remove the disputed audio in the "Video Manager".[317] YouTube has cited the effectiveness of Content ID as one of the reasons why the site's rules were modified in December 2010 to allow some users to upload videos of unlimited length.[318]

Moderation and offensive content

This section may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (January 2024) |

YouTube has a set of community guidelines aimed to reduce abuse of the site's features. The uploading of videos containing defamation, pornography, and material encouraging criminal conduct is forbidden by YouTube's "Community Guidelines".[319][better source needed] Generally prohibited material includes sexually explicit content, videos of animal abuse, shock videos, content uploaded without the copyright holder's consent, hate speech, spam, and predatory behavior.[319] YouTube relies on its users to flag the content of videos as inappropriate, and a YouTube employee will view a flagged video to determine whether it violates the site's guidelines.[319] Despite the guidelines, YouTube has faced criticism over aspects of its operations,[320] its recommendation algorithms perpetuating videos that promote conspiracy theories and falsehoods,[321] hosting videos ostensibly targeting children but containing violent or sexually suggestive content involving popular characters,[322] videos of minors attracting pedophilic activities in their comment sections,[323] and fluctuating policies on the types of content that is eligible to be monetized with advertising.[320]

YouTube contracts companies to hire content moderators, who view content flagged as potentially violating YouTube's content policies and determines if they should be removed. In September 2020, a class-action suit was filed by a former content moderator who reported developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after an 18-month period on the job. The former content moderator said that she was regularly made to exceed YouTube's stated limit of four hours per day of viewing graphic content. The lawsuit alleges that YouTube's contractors gave little to no training or support for its moderators' mental health, made prospective employees sign NDAs before showing them any examples of content they would see while reviewing, and censored all mention of trauma from its internal forums. It also purports that requests for extremely graphic content to be blurred, reduced in size or made monochrome, per recommendations from the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, were rejected by YouTube as not a high priority for the company.[324][325][326]

To limit the spread of misinformation and fake news via YouTube, it has rolled out a comprehensive policy regarding how it plans to deal with technically manipulated videos.[327]

Controversial content has included material relating to Holocaust denial and the Hillsborough disaster, in which 96 football fans from Liverpool were crushed to death in 1989.[328][329] In July 2008, the Culture and Media Committee of the House of Commons of the United Kingdom stated that it was "unimpressed" with YouTube's system for policing its videos, and argued that "proactive review of content should be standard practice for sites hosting user-generated content". YouTube responded by stating:

We have strict rules on what's allowed, and a system that enables anyone who sees inappropriate content to report it to our 24/7 review team and have it dealt with promptly. We educate our community on the rules and include a direct link from every YouTube page to make this process as easy as possible for our users. Given the volume of content uploaded on our site, we think this is by far the most effective way to make sure that the tiny minority of videos that break the rules come down quickly.[330] (July 2008)

In October 2010, U.S. Congressman Anthony Weiner urged YouTube to remove from its website videos of imam Anwar al-Awlaki.[331] YouTube pulled some of the videos in November 2010, stating they violated the site's guidelines.[332] In December 2010, YouTube added the ability to flag videos for containing terrorism content.[333]

In 2018, YouTube introduced a system that would automatically add information boxes to videos that its algorithms determined may present conspiracy theories and other fake news, filling the infobox with content from Encyclopædia Britannica and Wikipedia as a means to inform users to minimize misinformation propagation without impacting freedom of speech.[334][335] In the wake of the Notre-Dame fire on April 15, 2019, several user-uploaded videos of the landmark fire were flagged by YouTube' system automatically with an Encyclopædia Britannica article on the false conspiracy theories around the September 11 attacks. Several users complained to YouTube about this inappropriate connection. YouTube officials apologized for this, stating that their algorithms had misidentified the fire videos and added the information block automatically, and were taking steps to remedy this.[336]

On April 18, 2023, YouTube revealed its changes in handling content associated with eating disorders. This social media platform's Community Guidelines now prohibit content that could encourage emulation from at-risk users. This content includes behavior that shows severe calorie tracking and purging after eating. However, videos featuring positive behavior such as in the context of recovery will be permitted on the platform under two conditions—the user must have a registered (logged-in) account and must be older than 18.This policy was created in collaboration with nonprofit organizations as well as the National Eating Disorder Association. Garth Graham, YouTube's Global Head of Healthcare revealed in an interview with CNN that this policy change was geared at ensuring that this video-sharing platform provides an avenue for "community recovery and resources" while ensuring continued viewer protection.[337]

Homophobia and transphobia

Five leading content creators whose channels were based on LGBTQ+ materials filed a federal lawsuit against YouTube in August 2019, alleging that YouTube's algorithms divert discovery away from their channels, impacting their revenue. The plaintiffs claimed that the algorithms discourage content with words like "lesbian" or "gay", which would be predominant in their channels' content, and because of YouTube's near-monopolization of online video services, they are abusing that position.[338]

In June 2022, Media Matters, a media watchdog group, reported that homophobic and transphobic content calling LGBT people "predators" and "groomers" was becoming more common on YouTube.[339] The report also referred to common accusations in YouTube videos that LGBT people are mentally ill.[339] The report stated the content appeared to be in violation of YouTube's hate speech policy.[339]

Animal torture

From 2020 on, the issue of videos featuring animal cruelty on YouTube has started to attract increasing attention in the media. In late 2020, animal welfare charity Lady Freethinker identified 2,053 videos on YouTube in which they stated animals were "deliberately harmed for entertainment or were shown to be under severe psychological distress, physical pain or dead."[340]

In 2021, Lady Freethinker filed a lawsuit accusing YouTube of a breach of contract in allowing a large number of videos on its site showing animal abuse and failing to remove them when notified. YouTube responded by stating that they had "expanded its policy on animal abuse videos" in 2021, and since the introduction of the new policy "removed hundreds of thousands of videos and terminated thousands of channels for violations."[341]

In 2022, Google defeated the Lady Freethinker lawsuit, with a judge ruling that YouTube was protected by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, that shields internet platforms from lawsuits based on content posted by their users.[342]

In 2023, YouTube stated that animal abuse "has no place on their platforms, and they are working to remove content (of that nature)".[343][344][345][346][347][348]

YouTube as a tool to promote conspiracy theories and far-right content

YouTube has been criticized for using an algorithm that gives great prominence to videos that promote conspiracy theories, falsehoods and incendiary fringe discourse.[349][350][351] According to an investigation by The Wall Street Journal, "YouTube's recommendations often lead users to channels that feature conspiracy theories, partisan viewpoints and misleading videos, even when those users haven't shown interest in such content. When users show a political bias in what they choose to view, YouTube typically recommends videos that echo those biases, often with more-extreme viewpoints."[349][352] When users search for political or scientific terms, YouTube's search algorithms often give prominence to hoaxes and conspiracy theories.[351][353] After YouTube drew controversy for giving top billing to videos promoting falsehoods and conspiracy when people made breaking-news queries during the 2017 Las Vegas shooting, YouTube changed its algorithm to give greater prominence to mainstream media sources.[349][354][355][356] In 2018, it was reported that YouTube was again promoting fringe content about breaking news, giving great prominence to conspiracy videos about Anthony Bourdain's death.[357]

In 2017, it was revealed that advertisements were being placed on extremist videos, including videos by rape apologists, anti-Semites, and hate preachers who received ad payouts.[358] After firms started to stop advertising on YouTube in the wake of this reporting, YouTube apologized and said that it would give firms greater control over where ads got placed.[358]

Alex Jones, known for far-right conspiracy theories, had built a massive audience on YouTube.[359] YouTube drew criticism in 2018 when it removed a video from Media Matters compiling offensive statements made by Jones, stating that it violated its policies on "harassment and bullying".[360] On August 6, 2018, however, YouTube removed Alex Jones' YouTube page following a content violation.[361]

University of North Carolina professor Zeynep Tufekci has referred to YouTube as "The Great Radicalizer", saying "YouTube may be one of the most powerful radicalizing instruments of the 21st century."[362] Jonathan Albright of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University described YouTube as a "conspiracy ecosystem".[351][363]

In January 2019, YouTube said that it had introduced a new policy starting in the United States intended to stop recommending videos containing "content that could misinform users in harmful ways." YouTube gave flat earth theories, miracle cures, and 9/11 truther-isms as examples.[364] Efforts within YouTube engineering to stop recommending borderline extremist videos falling just short of forbidden hate speech, and track their popularity were originally rejected because they could interfere with viewer engagement.[365]

In January 2019, the site announced it would be implementing measures directed towards "raising authoritative content and reducing borderline content and harmful misinformation."[366] That June, YouTube announced it would be banning Holocaust denial and neo-Nazi content.[366] YouTube has blocked the neo-Nazi propaganda film Europa: The Last Battle from being uploaded.[367]

Multiple research studies have investigated cases of misinformation in YouTube. In a July 2019 study based on ten YouTube searches using the Tor Browser related to climate and climate change, the majority of videos were videos that communicated views contrary to the scientific consensus on climate change.[368] A May 2023 study found that YouTube was monetizing and profiting from videos that included misinformation about climate change.[369] A 2019 BBC investigation of YouTube searches in ten different languages found that YouTube's algorithm promoted health misinformation, including fake cancer cures.[370] In Brazil, YouTube has been linked to pushing pseudoscientific misinformation on health matters, as well as elevated far-right fringe discourse and conspiracy theories.[371] In the Philippines, numerous channels disseminated misinformation related to the 2022 Philippine elections.[372] Additionally, research on the dissemination of Flat Earth beliefs in social media, has shown that networks of YouTube channels form an echo chamber that polarizes audiences by appearing to confirm preexisting beliefs.[373]

Use among white supremacists

Before 2019, YouTube took steps to remove specific videos or channels related to supremacist content that had violated its acceptable use policies but otherwise did not have site-wide policies against hate speech.[374]

In the wake of the March 2019 Christchurch mosque attacks, YouTube and other sites like Facebook and Twitter that allowed user-submitted content drew criticism for doing little to moderate and control the spread of hate speech, which was considered to be a factor in the rationale for the attacks.[375][376] These platforms were pressured to remove such content, but in an interview with The New York Times, YouTube's chief product officer Neal Mohan said that unlike content such as ISIS videos which take a particular format and thus easy to detect through computer-aided algorithms, general hate speech was more difficult to recognize and handle, and thus could not readily take action to remove without human interaction.[377]

In May 2019, YouTube joined an initiative led by France and New Zealand with other countries and tech companies to develop tools to be used to block online hate speech and to develop regulations, to be implemented at the national level, to be levied against technology firms that failed to take steps to remove such speech, though the United States declined to participate.[378][379] Subsequently, on June 5, 2019, YouTube announced a major change to its terms of service, "specifically prohibiting videos alleging that a group is superior in order to justify discrimination, segregation or exclusion based on qualities like age, gender, race, caste, religion, sexual orientation or veteran status." YouTube identified specific examples of such videos as those that "promote or glorify Nazi ideology, which is inherently discriminatory". YouTube further stated it would "remove content denying that well-documented violent events, like the Holocaust or the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary, took place."[374][380]

In October 2019, YouTube banned the main channel of Red Ice, a white supremacist multimedia company, for hate speech violations. The channel had about 330,000 subscribers. Lana Lokteff and Red Ice promoted a backup channel in an attempt to circumvent the ban.[381][382] A week later, the backup channel was also removed by YouTube.[383][384]

In June 2020, YouTube was criticized for allowing white supremacist content on its platform for years after it announced it would be pledging $1 million to fight racial injustice.[385] Later that month, it banned several channels associated with white supremacy, including those of Stefan Molyneux, David Duke, and Richard B. Spencer, asserting these channels violated their policies on hate speech. The ban occurred the same day that Reddit announced the ban on several hate speech sub-forums including r/The Donald.[386]

Handling of COVID-19 pandemic and other misinformation

Following the dissemination via YouTube of misinformation related to the COVID-19 pandemic that 5G communications technology was responsible for the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 which led to multiple 5G towers in the United Kingdom being attacked by arsonists, YouTube removed all such videos linking 5G and the coronavirus in this manner.[387]

In September 2021, YouTube extended this policy to cover videos disseminating misinformation related to any vaccine, including those long approved against measles or Hepatitis B, that had received approval from local health authorities or the World Health Organization.[388][389] The platform proceeded to remove the accounts of anti-vaccine campaigners such as Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Joseph Mercola.[389]

YouTube had extended this moderation to non-medical areas. In the weeks following the 2020 United States presidential election, the site added policies to remove or label videos promoting election fraud claims;[390][391] however, it reversed this policy in June 2023, citing that the removal was necessary to "openly debate political ideas, even those that are controversial or based on disproven assumptions".[392][393]

Google and YouTube implemented policies in October 2021 to deny monetization or revenue to advertisers or content creators that promoted climate change denial, which "includes content referring to climate change as a hoax or a scam, claims denying that long-term trends show the global climate is warming, and claims denying that greenhouse gas emissions or human activity contribute to climate change."[394] In January 2024, the Center for Countering Digital Hate reported that climate change deniers were instead pushing other forms of climate change denial that have not yet been banned by YouTube, including false claims that global warming is "beneficial or harmless", and which undermined climate solutions and climate science.[395][396]

In July 2022, YouTube announced policies to combat misinformation surrounding abortion, such as videos with instructions to perform abortion methods that are considered unsafe and videos that contain misinformation about the safety of abortion.[397]

Child safety and wellbeing

Leading into 2017, there was a significant increase in the number of videos related to children, coupled between the popularity of parents vlogging their family's activities, and previous content creators moving away from content that often was criticized or demonetized into family-friendly material. In 2017, YouTube reported that time watching family vloggers had increased by 90%.[398][399] However, with the increase in videos featuring children, the site began to face several controversies related to child safety. During Q2 2017, the owners of popular channel FamilyOFive, which featured themselves playing "pranks" on their children, were accused of child abuse. Their videos were eventually deleted, and two of their children were removed from their custody.[400][401][402][403] A similar case happened in 2019 when the owner of the channel Fantastic Adventures was accused of abusing her adopted children. Her videos would later be deleted.[404]

Later that year, YouTube came under criticism for showing inappropriate videos targeted at children and often featuring popular characters in violent, sexual or otherwise disturbing situations, many of which appeared on YouTube Kids and attracted millions of views. The term "Elsagate" was coined on the Internet and then used by various news outlets to refer to this controversy.[405][406][407][408] On November 11, 2017, YouTube announced it was strengthening site security to protect children from unsuitable content. Later that month, the company started to mass delete videos and channels that made improper use of family-friendly characters. As part of a broader concern regarding child safety on YouTube, the wave of deletions also targeted channels that showed children taking part in inappropriate or dangerous activities under the guidance of adults. Most notably, the company removed Toy Freaks, a channel with over 8.5 million subscribers, that featured a father and his two daughters in odd and upsetting situations.[409][410][411][412][413] According to analytics specialist SocialBlade, it earned up to $11.2 million annually prior to its deletion in November 2017.[414]

Even for content that appears to be aimed at children and appears to contain only child-friendly content, YouTube's system allows for anonymity of who uploads these videos. These questions have been raised in the past, as YouTube has had to remove channels with children's content which, after becoming popular, then suddenly include inappropriate content masked as children's content.[415] Alternative, some of the most-watched children's programming on YouTube comes from channels that have no identifiable owners, raising concerns of intent and purpose. One channel that had been of concern was "Cocomelon" which provided numerous mass-produced animated videos aimed at children. Up through 2019, it had drawn up to US$10 million a month in ad revenue and was one of the largest kid-friendly channels on YouTube before 2020. Ownership of Cocomelon was unclear outside of its ties to "Treasure Studio", itself an unknown entity, raising questions as to the channel's purpose,[415][416][417] but Bloomberg News had been able to confirm and interview the small team of American owners in February 2020 regarding "Cocomelon", who stated their goal for the channel was to simply entertain children, wanting to keep to themselves to avoid attention from outside investors.[418] The anonymity of such channel raise concerns because of the lack of knowledge of what purpose they are trying to serve.[419] The difficulty to identify who operates these channels "adds to the lack of accountability", according to Josh Golin of the Campaign for a Commercial-Free Childhood, and educational consultant Renée Chernow-O'Leary found the videos were designed to entertain with no intent to educate, all leading to critics and parents to be concerned for their children becoming too enraptured by the content from these channels.[415] Content creators that earnestly make child-friendly videos have found it difficult to compete with larger channels, unable to produce content at the same rate as them, and lacking the same means of being promoted through YouTube's recommendation algorithms that the larger animated channel networks have shared.[419]

In January 2019, YouTube officially banned videos containing "challenges that encourage acts that have an inherent risk of severe physical harm" (such as the Tide Pod Challenge) and videos featuring pranks that "make victims believe they're in physical danger" or cause emotional distress in children.[420]

Sexualization of children and pedophilia

Also in November 2017, it was revealed in the media that many videos featuring children—often uploaded by the minors themselves, and showing innocent content such as the children playing with toys or performing gymnastics—were attracting comments from pedophiles[421][422] with predators finding the videos through private YouTube playlists or typing in certain keywords in Russian.[422] Other child-centric videos originally uploaded to YouTube began propagating on the dark web, and uploaded or embedded onto forums known to be used by pedophiles.[423]

As a result of the controversy, which added to the concern about "Elsagate", several major advertisers whose ads had been running against such videos froze spending on YouTube.[408][424] In December 2018, The Times found more than 100 grooming cases in which children were manipulated into sexually implicit behavior (such as taking off clothes, adopting overtly sexual poses and touching other children inappropriately) by strangers.[425] After a reporter flagged the videos in question, half of them were removed, and the rest were removed after The Times contacted YouTube's PR department.[425]

In February 2019, YouTube vlogger Matt Watson identified a "wormhole" that would cause the YouTube recommendation algorithm to draw users into this type of video content, and make all of that user's recommended content feature only these types of videos.[426] Most of these videos had comments from sexual predators commenting with timestamps of when the children were shown in compromising positions or otherwise making indecent remarks. In some cases, other users had re-uploaded the video in unlisted form but with incoming links from other videos, and then monetized these, propagating this network.[427] In the wake of the controversy, the service reported that they had deleted over 400 channels and tens of millions of comments, and reported the offending users to law enforcement and the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. A spokesperson explained that "any content—including comments—that endangers minors is abhorrent and we have clear policies prohibiting this on YouTube. There's more to be done, and we continue to work to improve and catch abuse more quickly."[428][429] Despite these measures, AT&T, Disney, Dr. Oetker, Epic Games, and Nestlé all pulled their advertising from YouTube.[427][430]

Subsequently, YouTube began to demonetize and block advertising on the types of videos that have drawn these predatory comments. The service explained that this was a temporary measure while they explore other methods to eliminate the problem.[431] YouTube also began to flag channels that predominantly feature children, and preemptively disable their comments sections. "Trusted partners" can request that comments be re-enabled, but the channel will then become responsible for moderating comments. These actions mainly target videos of toddlers, but videos of older children and teenagers may be protected as well if they contain actions that can be interpreted as sexual, such as gymnastics. YouTube stated it was also working on a better system to remove comments on other channels that matched the style of child predators.[432][433]

A related attempt to algorithmically flag videos containing references to the string "CP" (an abbreviation of child pornography) resulted in some prominent false positives involving unrelated topics using the same abbreviation, including videos related to the mobile video game Pokémon Go (which uses "CP" as an abbreviation of the statistic "Combat Power"), and Club Penguin. YouTube apologized for the errors and reinstated the affected videos.[434] Separately, online trolls have attempted to have videos flagged for takedown or removal by commenting with statements similar to what the child predators had said; this activity became an issue during the PewDiePie vs T-Series rivalry in early 2019. YouTube stated they do not take action on any video with these comments but those that they have flagged that are likely to draw child predator activity.[435]

In June 2019, The New York Times cited researchers who found that users who watched erotic videos could be recommended seemingly innocuous videos of children.[436] As a result, Senator Josh Hawley stated plans to introduce federal legislation that would ban YouTube and other video sharing sites from including videos that predominantly feature minors as "recommended" videos, excluding those that were "professionally produced", such as videos of televised talent shows.[437] YouTube has suggested potential plans to remove all videos featuring children from the main YouTube site and transferring them to the YouTube Kids site where they would have stronger controls over the recommendation system, as well as other major changes on the main YouTube site to the recommended feature and auto-play system.[438]

Misogyny

An August 2022 report by the Center for Countering Digital Hate, a British think tank, found that harassment against women was flourishing on YouTube. It noted that channels espousing a similar ideology to that of men's rights influencer Andrew Tate were using YouTube to grow their audience, despite Tate being banned from the platform.[439] In his 2022 book Like, Comment, Subscribe: Inside YouTube's Chaotic Rise to World Domination, Bloomberg reporter Mark Bergen said that many female content creators were dealing with harassment, bullying, and stalking.[439]

Russia

In 2021, two accounts linked to RT Deutsch, the German channel of the Russian RT network were removed as well for breaching YouTube's policies relating to COVID-19.[388] Russia threatened to ban YouTube after the platform deleted two German RT channels in September 2021.[440]

Shortly after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, YouTube removed all channels funded by the Russian state.[441] YouTube expanded the removal of Russian content from its site to include channels described as 'pro-Russian'. In June 2022, the War Gonzo channel run by Russian military blogger and journalist Semyon Pegov was deleted.[442] In July 2023, YouTube removed the channel of British journalist Graham Phillips, active in covering the War in Donbas from 2014.[443]

In August 2023, a Moscow court fined Google 3 million rubles, around $35,000, for not deleting what it said was "fake news about the war in Ukraine".[444]

April Fools gags

YouTube featured an April Fools prank on the site on April 1 of every year from 2008 to 2016. In 2008, all links to videos on the main page were redirected to Rick Astley's music video "Never Gonna Give You Up", a prank known as "rickrolling".[445][446] The next year, when clicking on a video on the main page, the whole page turned upside down, which YouTube claimed was a "new layout".[447] In 2010, YouTube temporarily released a "TEXTp" mode which rendered video imagery into ASCII art letters "in order to reduce bandwidth costs by $1 per second."[448]

The next year, the site celebrated its "100th anniversary" with a range of sepia-toned silent, early 1900s-style films, including a parody of Keyboard Cat.[449] In 2012, clicking on the image of a DVD next to the site logo led to a video about a purported option to order every YouTube video for home delivery on DVD.[450]

In 2013, YouTube teamed up with satirical newspaper company The Onion to claim in an uploaded video that the video-sharing website was launched as a contest which had finally come to an end, and would shut down for ten years before being re-launched in 2023, featuring only the winning video. The video starred several YouTube celebrities, including Antoine Dodson. A video of two presenters announcing the nominated videos streamed live for 12 hours.[451][452]

In 2014, YouTube announced that it was responsible for the creation of all viral video trends, and revealed previews of upcoming trends, such as "Clocking", "Kissing Dad", and "Glub Glub Water Dance".[453] The next year, YouTube added a music button to the video bar that played samples from "Sandstorm" by Darude.[454] In 2016, YouTube introduced an option to watch every video on the platform in 360-degree mode with Snoop Dogg.[455]

Services

YouTube Premium

YouTube Premium (formerly YouTube Red) is YouTube's premium subscription service. It offers advertising-free streaming, access to original programming, and background and offline video playback on mobile devices.[456] YouTube Premium was originally announced on November 12, 2014, as "Music Key", a subscription music streaming service, and was intended to integrate with and replace the existing Google Play Music "All Access" service.[457][458][459] On October 28, 2015, the service was relaunched as YouTube Red, offering ad-free streaming of all videos and access to exclusive original content.[460][461][462] As of November 2016[update], the service has 1.5 million subscribers, with a further million on a free-trial basis.[463] As of June 2017[update], the first season of YouTube Originals had received 250 million views in total.[464]

YouTube Kids

YouTube Kids is an American children's video app developed by YouTube, a subsidiary of Google. The app was developed in response to parental and government scrutiny on the content available to children. The app provides a version of the service-oriented towards children, with curated selections of content, parental control features, and filtering of videos deemed inappropriate viewing for children aged under 13, 8 or 5 depending on the age grouping chosen. First released on February 15, 2015, as an Android and iOS mobile app, the app has since been released for LG, Samsung, and Sony smart TVs, as well as for Android TV. On May 27, 2020, it became available on Apple TV. As of September 2019, the app is available in 69 countries, including Hong Kong and Macau, and one province. YouTube launched a web-based version of YouTube Kids on August 30, 2019.

YouTube Music

On September 28, 2016, YouTube named Lyor Cohen, the co-founder of 300 Entertainment and former Warner Music Group executive, the Global Head of Music.[465]