Международная космическая станция

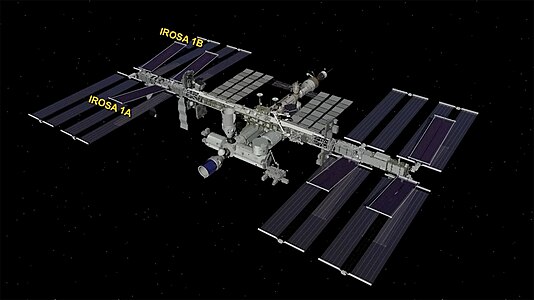

Косой вид снизу в ноябре 2021 г. | |

Знаки отличия программы Международной космической станции с флагами первоначальных подписавших государств. | |

| Статистика станции | |

|---|---|

| ИДЕНТИФИКАТОР КОСПЭРЭ | 1998-067А |

| САТКАТ нет. | 25544 |

| Позывной | Альфа , Станция |

| Экипаж |

|

| Запуск | 20 ноября 1998 г. |

| Стартовая площадка |

|

| Масса | 450 000 кг (990 000 фунтов) [3] |

| Длина | 109 м (358 футов) (общая длина), 94 м (310 футов) (длина фермы) [4] |

| Ширина | 73 м (239 футов) (длина солнечной батареи) [4] |

| под давлением Объем | 1005,0 м 3 (35 491 куб футов) [4] |

| Атмосферное давление | 101,3 кПа (14,7 фунтов на квадратный дюйм ; 1,0 атм ) 79% азота, 21% кислорода |

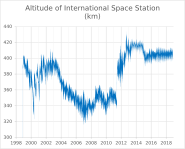

| Высота перигея | 413 км (256,6 миль) над уровнем моря [5] |

| Высота апогея | 422 км (262,2 миль) над уровнем моря [5] |

| Наклонение орбиты | 51.64° [5] |

| Орбитальная скорость | 7,67 км/с; 27 600 км/ч; 17 100 миль в час [6] |

| Орбитальный период | 92,9 минуты [7] |

| Орбит в день | 15.5 [5] |

| орбиты Эпоха | 16 августа 16:19:30 [8] |

| Дни на орбите | 25 лет, 6 месяцев, 24 дня (14 июня 2024 г.) |

| Дней занято | 23 года, 7 месяцев, 11 дней (14 июня 2024 г.) |

| Количество орбит | 141 117 по состоянию на август 2023 г. [update][8] |

| Орбитальный распад | 2 км/месяц |

| Статистика по состоянию на 22 декабря 2022 г. (если не указано иное) Ссылки: [4] [5] [9] [10] [11] | |

| Конфигурация | |

| |

Международная космическая станция ( МКС ) — крупная космическая станция, собираемая и обслуживаемая на низкой околоземной орбите совместными усилиями пяти космических агентств и их подрядчиков: НАСА (США), Роскосмоса (Россия), JAXA (Япония), ЕКА (Европа). и CSA (Канада). МКС — крупнейшая космическая станция, когда-либо построенная. Его основная цель — проведение экспериментов в области микрогравитации и космической среды . [12]

В эксплуатационном отношении станция разделена на два блока: российский орбитальный сегмент (ROS), собранный Роскосмосом, и американский орбитальный сегмент , собранный NASA, JAXA, ESA и CSA. Яркой особенностью МКС является интегрированная ферменная конструкция , которая соединяет большие солнечные панели и радиаторы с герметичными модулями. Герметичные модули предназначены для исследований, проживания, хранения, управления космическими кораблями и выполнения шлюзовых функций. Посещение стыковки космических кораблей на станции через восемь стыковочных и причальных портов . МКС поддерживает орбиту со средней высотой 400 километров (250 миль). [13] и вращается вокруг Земли примерно за 93 минуты, совершая 15,5 витков в день. [14]

Программа МКС объединяет два предыдущих плана строительства пилотируемых станций на околоземной орбите: космическую станцию «Свобода» , запланированную Соединенными Штатами, и станцию «Мир-2» , запланированную Советским Союзом. Первый модуль МКС был запущен в 1998 году. Основные модули были запущены ракетами «Протон» и «Союз» , а также системой запуска «Спейс Шаттл» . Первые долгосрочные жители, Экспедиция 1 , прибыли 2 ноября 2000 года. С тех пор станция постоянно находилась под оккупацией в течение 23 лет и 225 дней, что стало самым продолжительным непрерывным пребыванием человека в космосе. По состоянию на март 2024 г. [update]Космическую станцию посетили 279 человек из 22 стран. [15] Ожидается, что МКС будет иметь дополнительные модули ( орбитальный сегмент «Аксиома» например, ), прежде чем она будет снята с орбиты специальным космическим кораблем НАСА в январе 2031 года.

История [ править ]

Когда в начале 1970-х годов космическая гонка подошла к концу, США и СССР начали рассматривать различные варианты потенциального сотрудничества в космическом пространстве. Кульминацией этого стал испытательный проект «Аполлон-Союз» 1975 года , первая стыковка космических кораблей двух разных космических держав. УПАС был признан успешным, и рассматривались также дальнейшие совместные миссии.

Одной из таких концепций была компания International Skylab, которая предлагала запустить резервную космическую станцию Skylab B для миссии, в ходе которой будут неоднократно посещаться экипажи кораблей «Аполлон» и «Союз» . [16] Более амбициозной была космическая лаборатория «Скайлэб-Салют», которая предлагала стыковать «Скайлэб-Б» с советской космической станцией «Салют» . Падение бюджетов и рост напряженности во время холодной войны в конце 1970-х годов привели к тому, что эти концепции отошли на второй план, как и еще один план по стыковке космического корабля "Шаттл" с космической станцией "Салют". [17]

В начале 1980-х годов НАСА планировало запустить модульную космическую станцию « Свобода» как аналог космических станций «Салют» и «Мир» . В 1984 году ЕКА было приглашено принять участие в проекте « Свобода космической станции» , а к 1987 году ЕКА одобрило создание лаборатории «Колумбус». [18] Японский экспериментальный модуль (JEM), или Кибо , был анонсирован в 1985 году как часть космической станции «Свобода» в ответ на запрос НАСА в 1982 году.

В начале 1985 года министры науки стран Европейского космического агентства (ЕКА) одобрили программу «Колумбус» — самую амбициозную попытку в космосе, предпринятую этой организацией в то время. План, инициированный Германией и Италией, включал в себя модуль, который будет присоединен к «Фридому» и сможет превратиться в полноценный европейский орбитальный форпост до конца века. [19]

Рост затрат поставил эти планы под сомнение в начале 1990-х годов. Конгресс не пожелал предоставить достаточно денег для строительства и эксплуатации Freedom и потребовал от НАСА увеличить международное участие, чтобы покрыть растущие расходы, иначе они полностью отменят весь проект. [20]

Одновременно СССР занимался планированием космической станции «Мир-2» и к середине 1980-х годов приступил к строительству модулей для новой станции. Однако распад Советского Союза потребовал значительного сокращения масштабов этих планов, и вскоре Мир-2 оказался под угрозой того, что вообще никогда не будет запущен. [21] Поскольку оба проекта космических станций оказались под угрозой, американские и российские официальные лица встретились и предложили их объединить. [22]

В сентябре 1993 года вице-президент США Эл Гор и премьер-министр России Виктор Черномырдин объявили о планах создания новой космической станции, которая в конечном итоге стала Международной космической станцией. [23] В рамках подготовки к этому новому проекту они также договорились, что Соединенные Штаты будут участвовать в программе «Мир», включая стыковку американских шаттлов в «Шаттл -Мир» программе . [24]

12 апреля 2021 года на встрече с президентом России Владимиром Путиным тогдашний вице-премьер Юрий Борисов объявил, что принял решение о выходе России из программы МКС в 2025 году. [25] [26] По мнению российских властей, сроки работы станции истекли, а ее состояние оставляет желать лучшего. [25] 26 июля 2022 года Борисов, ставший главой Роскосмоса, представил Путину свои планы выхода из программы после 2024 года. [27] Однако Робин Гейтенс, представитель НАСА, отвечающий за эксплуатацию космической станции, ответил, что НАСА не получало никаких официальных уведомлений от Роскосмоса относительно планов вывода. [28] 21 сентября 2022 года Борисов заявил, что Россия «весьма вероятно» продолжит участие в программе МКС до 2028 года. [29]Цель [ править ]

Первоначально МКС задумывалась как лаборатория, обсерватория и фабрика, обеспечивающая транспортировку, техническое обслуживание и низкоорбитальную базу для возможных будущих миссий на Луну, Марс и астероиды. Однако не все варианты использования, предусмотренные первоначальным меморандумом о взаимопонимании между НАСА и Роскосмосом, были реализованы. [30] В Национальной космической политике США 2010 года МКС были отведены дополнительные функции по обслуживанию коммерческих, дипломатических, [31] и образовательных целях. [32]

Научные исследования [ править ]

МКС предоставляет платформу для проведения научных исследований, располагающую электроэнергией, данными, охлаждением и экипажем для поддержки экспериментов. Небольшие беспилотные космические корабли также могут служить платформами для экспериментов, особенно тех, которые связаны с невесомостью и выходом в космос, но космические станции предлагают долгосрочную среду, в которой исследования могут проводиться потенциально в течение десятилетий, в сочетании с легким доступом для исследователей-людей. [33] [34]

МКС упрощает отдельные эксперименты, позволяя группам экспериментов использовать одни и те же запуски и время экипажа. Исследования проводятся в самых разных областях, включая астробиологию , астрономию , физику , материаловедение , космическую погоду , метеорологию и исследования человека , включая космическую медицину и науки о жизни . [35] [36] [37] [38] Ученые на Земле имеют своевременный доступ к данным и могут предложить экипажу экспериментальные модификации. Если необходимы последующие эксперименты, регулярно запланированные запуски кораблей снабжения позволяют относительно легко запускать новое оборудование. [34] Экипажи совершают экспедиции продолжительностью несколько месяцев, обеспечивая около 160 человеко-часов в неделю работы экипажа из шести человек. Однако значительное количество времени экипажа отнимает обслуживание станции. [39]

Пожалуй, самым заметным экспериментом на МКС является Альфа-магнитный спектрометр (AMS), который предназначен для обнаружения темной материи и ответа на другие фундаментальные вопросы о нашей Вселенной. По данным НАСА, AMS так же важен, как и космический телескоп Хаббл . В настоящее время он пристыкован к станции, но его невозможно было легко разместить на свободно летающей спутниковой платформе из-за его потребностей в мощности и пропускной способности. [40] [41] 3 апреля 2013 года ученые сообщили, что намеки на темную материю . AMS, возможно, обнаружил [42] [43] [44] [45] [46] [47] По словам ученых, «первые результаты космического альфа-магнитного спектрометра подтверждают необъяснимый избыток высокоэнергетических позитронов в космических лучах, связанных с Землей».

Космическая среда враждебна жизни. Незащищенное пребывание в космосе характеризуется интенсивным радиационным полем (состоящим в основном из протонов и других субатомных заряженных частиц солнечного ветра , помимо космических лучей ), высоким вакуумом, экстремальными температурами и микрогравитацией. [48] Некоторые простые формы жизни, называемые экстремофилами , [49] а также мелких беспозвоночных, называемых тихоходками. [50] могут выжить в этой среде в чрезвычайно сухом состоянии за счет высыхания .

Медицинские исследования расширяют знания о влиянии длительного пребывания в космосе на организм человека, включая атрофию мышц , потерю костной массы и сдвиг жидкости. Эти данные будут использоваться, чтобы определить, ли длительные полеты человека в космос и колонизация космоса осуществимы . В 2006 году данные о потере костной массы и мышечной атрофии показали, что существует значительный риск переломов и проблем с движением, если астронавты приземлятся на планете после длительного межпланетного круиза, такого как шестимесячный интервал, необходимый для путешествия на Марс . [51] [52]

Медицинские исследования проводятся на борту МКС по поручению Национального института космических биомедицинских исследований (NSBRI). Особое место среди них занимает исследование «Усовершенствованное диагностическое ультразвуковое исследование в условиях микрогравитации», в ходе которого астронавты выполняют ультразвуковое сканирование под руководством удаленных экспертов. Исследование рассматривает диагностику и лечение заболеваний в космосе. Обычно на борту МКС нет врача, и диагностика заболеваний является сложной задачей. Ожидается, что ультразвуковое сканирование с дистанционным управлением будет применяться на Земле в ситуациях неотложной помощи и оказания медицинской помощи в сельской местности, где доступ к квалифицированному врачу затруднен. [53] [54] [55]

В августе 2020 года ученые сообщили, что бактерии с Земли, в частности бактерии Deinococcus radiodurans , обладающие высокой устойчивостью к опасностям окружающей среды , выживают в космическом пространстве в течение трех лет , согласно исследованиям, проведенным на Международной космической станции. Эти результаты подтвердили идею панспермии , гипотезу о том, что жизнь существует во Вселенной , распределенной различными способами, включая космическую пыль , метеороиды , астероиды , кометы , планетоиды или загрязненные космические корабли . [56] [57]

Дистанционное зондирование Земли, астрономия и исследования дальнего космоса на МКС значительно расширились в 2010-е годы после завершения строительства американского орбитального сегмента в 2011 году. На протяжении более чем 20 лет существования программы МКС исследователи на борту МКС и на Земля исследовала аэрозоли , озон , молнии и оксиды в атмосфере Земли, а также Солнце , космические лучи, космическую пыль , антиматерию и темную материю во Вселенной. Примерами экспериментов по дистанционному зондированию Земли, проведенных на МКС, являются Орбитальная углеродная обсерватория 3 , ISS-RapidScat , ECOSTRESS , Исследование динамики глобальной экосистемы и Система транспортировки облачных аэрозолей . Астрономические телескопы и эксперименты на базе МКС включают SOLAR , исследователь внутреннего состава нейтронной звезды , калориметрический электронный телескоп , монитор рентгеновского изображения всего неба (MAXI) и альфа-магнитный спектрометр . [35] [58]

Свободное падение [ править ]

Гравитация на высоте МКС примерно на 90% сильнее, чем на поверхности Земли, но объекты на орбите находятся в постоянном состоянии свободного падения , что приводит к кажущемуся состоянию невесомости . [59] Эта воспринимаемая невесомость нарушается пятью эффектами: [60]

- Перетащите из остаточной атмосферы.

- Вибрация от движений механических систем и экипажа.

- Срабатывание бортовых гироскопов момента ориентации .

- Включение двигателей для изменения положения или орбиты.

- Эффекты гравитационного градиента , также известные как приливные эффекты. Объекты в разных местах МКС, если бы они не были прикреплены к станции, двигались бы по несколько разным орбитам. Будучи механически соединенными, эти элементы испытывают небольшие силы, которые заставляют станцию двигаться как твердое тело .

Исследователи исследуют влияние почти невесомой среды станции на эволюцию, развитие, рост и внутренние процессы растений и животных. В ответ на некоторые данные НАСА хочет исследовать влияние микрогравитации на рост трехмерных человеческих тканей и необычных белковых кристаллов , которые могут образовываться в космосе. [35]

Исследование физики жидкостей в условиях микрогравитации позволит получить более качественные модели поведения жидкостей. Поскольку в условиях микрогравитации жидкости могут почти полностью смешиваться, физики исследуют жидкости, которые плохо смешиваются на Земле. Изучение реакций, которые замедляются из-за низкой гравитации и низких температур, улучшит наше понимание сверхпроводимости . [35]

Изучение материаловедения является важной исследовательской деятельностью МКС, целью которой является получение экономических выгод за счет совершенствования методов, используемых на Земле. [61] Другие области интересов включают влияние низкой гравитации на горение посредством изучения эффективности сжигания и контроля выбросов и загрязняющих веществ. Эти результаты могут улучшить знания о производстве энергии и привести к экономическим и экологическим выгодам. [35]

Исследование [ править ]

МКС обеспечивает место на относительной безопасности низкой околоземной орбиты для тестирования систем космических аппаратов, которые потребуются для длительных полетов на Луну и Марс. Это обеспечивает опыт эксплуатации, технического обслуживания, ремонта и замены на орбите. Это поможет развить необходимые навыки управления космическими кораблями дальше от Земли, снизить риски миссий и расширить возможности межпланетных космических кораблей. [62] Ссылаясь на эксперимент МАРС-500 , эксперимент по изоляции экипажа, проводимый на Земле, ЕКА заявляет: «В то время как МКС необходима для ответа на вопросы, касающиеся возможного воздействия невесомости, радиации и других специфических космических факторов, таких аспектов, как влияние длительного -срочная изоляция и заключение могут быть более целесообразно решены с помощью наземного моделирования». [63] Сергей Краснов, руководитель программ пилотируемых космических полетов российского космического агентства «Роскосмос», в 2011 году предположил, что «укороченная версия» МАРС-500 может быть реализована на МКС. [64]

В 2009 году, отмечая ценность самой структуры партнерства, Сергей Краснов писал: «По сравнению с партнерами, действующими по отдельности, партнеры, развивающие взаимодополняющие способности и ресурсы, могут дать нам гораздо больше уверенности в успехе и безопасности освоения космоса. МКС помогает и дальше». продвижение освоения околоземного космического пространства и реализация перспективных программ исследования и освоения Солнечной системы, включая Луну и Марс». [65] Миссия с экипажем на Марс может стать многонациональной инициативой с участием космических агентств и стран, не входящих в нынешнее партнерство по МКС. В 2010 году генеральный директор ЕКА Жан-Жак Дорден заявил, что его агентство готово предложить остальным четырем партнерам пригласить Китай, Индию и Южную Корею присоединиться к партнерству по МКС. [66] Глава НАСА Чарльз Болден заявил в феврале 2011 года: «Любая миссия на Марс, скорее всего, будет глобальной задачей». [67] В настоящее время федеральное законодательство США запрещает сотрудничество НАСА с Китаем в космических проектах без одобрения ФБР и Конгресса. [68]

и деятельность культурная Образование

Экипаж МКС предоставляет возможности студентам на Земле, проводя разработанные студентами эксперименты, создавая образовательные демонстрации, позволяя студентам участвовать в классных версиях экспериментов МКС, а также напрямую привлекая студентов с помощью радио и электронной почты. [69] [70] ESA предлагает широкий спектр бесплатных учебных материалов, которые можно загрузить для использования в классах. [71] За один урок студенты смогут ориентироваться в 3D-модели интерьера и экстерьера МКС и решать спонтанные задачи в режиме реального времени. [72]

Японское агентство аэрокосмических исследований (JAXA) стремится вдохновить детей «заниматься мастерством» и повысить их «осведомленность о важности жизни и своих обязанностях в обществе». [73] С помощью серии образовательных руководств учащиеся приобретают более глубокое понимание прошлого и ближайшего будущего пилотируемых космических полетов, а также Земли и жизни. [74] [75] В экспериментах JAXA «Семена в космосе» мутационные эффекты космического полета на семена растений на борту МКС исследуются путем выращивания семян подсолнечника, которые летали на МКС около девяти месяцев. На первом этапе использования Кибо с 2008 по середину 2010 года исследователи из более чем десятка японских университетов проводили эксперименты в различных областях. [76]

Культурные мероприятия являются еще одной важной целью программы ISS. Тецуо Танака, директор Центра космической среды и использования JAXA, сказал: «В космосе есть что-то такое, что трогает даже людей, не интересующихся наукой». [77]

Любительское радио на МКС (ARISS) — это волонтерская программа, которая поощряет студентов со всего мира делать карьеру в области науки, технологий, инженерии и математики посредством возможностей любительской радиосвязи с экипажем МКС. ARISS — международная рабочая группа, состоящая из делегаций девяти стран, в том числе нескольких европейских, а также Японии, России, Канады и США. В районах, где невозможно использовать радиооборудование, громкоговорители соединяют студентов с наземными станциями, которые затем передают вызовы на космическую станцию. [78]

«Первая орбита» — полнометражный документальный фильм 2011 года о корабле «Восток-1» , первом пилотируемом космическом полете вокруг Земли. Максимально приблизив орбиту МКС к орбите «Востока-1» с точки зрения наземной траектории и времени суток, режиссер-документалист Кристофер Райли и астронавт ЕКА Паоло Несполи смогли заснять вид, который Юрий Гагарин увидел на своем новаторском орбитальном спутнике. космический полет. Эти новые кадры были объединены с оригинальными аудиозаписями миссии «Восток-1», полученными из Российского государственного архива. Несполи считается оператором- постановщиком этого документального фильма, поскольку он сам записал большую часть отснятого материала во экспедиции 26/27 время . [79] Мировая премьера фильма транслировалась на YouTube в 2011 году по бесплатной лицензии через сайт firstorbit.org . [80]

В мае 2013 года командир Крис Хэдфилд музыкальное видео на песню Дэвида Боуи « Space Oddity », которое было опубликовано на YouTube. снял на борту станции [81] [82] Это был первый музыкальный клип, снятый в космосе. [83]

В ноябре 2017 года, участвуя в экспедиции 52/53 на сделал МКС, Паоло Несполи две записи своего разговорного голоса (одну на английском, а другую на родном итальянском языке) для использования в Википедии статьях . Это был первый контент, созданный в космосе специально для Википедии. [84] [85]

В ноябре 2021 года было анонсировано проведение выставки виртуальной реальности «Бесконечность», посвященной жизни на борту МКС. [86]

Строительство [ править ]

Производство [ править ]

Поскольку Международная космическая станция является совместным многонациональным проектом, компоненты для орбитальной сборки производились в разных странах мира. Начиная с середины 1990-х годов американские компоненты Destiny , Unity , интегрированная ферменная конструкция и солнечные батареи производились в Центре космических полетов Маршалла в Хантсвилле, штат Алабама, и на сборочном заводе Мишуда . Эти модули были доставлены в Оперативно-проверочный корпус и Технологический комплекс космической станции (SSPF) для окончательной сборки и подготовки к запуску. [87]

Российские модули, в том числе «Заря» и «Звезда» , были изготовлены в Государственном космическом научно-производственном центре имени Хруничева в Москве . Первоначально «Звезда» производилась в 1985 году как компонент Мир-2 , но «Мир-2» так и не был запущен и вместо этого стал служебным модулем МКС. [88]

Европейского космического агентства (ESA) Модуль Columbus был изготовлен на предприятии EADS Astrium Space Transportation в Бремене , Германия, вместе со многими другими подрядчиками по всей Европе. [89] Другие модули, построенные ЕКА — Harmony , Tranquility , Leonardo MPLM и Cupola — первоначально производились на заводе Thales Alenia Space в Турине, Италия. [90] Стальные корпуса модулей были доставлены самолетами в Космический центр Кеннеди SSPF для подготовки к запуску. [91]

Японский экспериментальный модуль Кибо был изготовлен на различных технологических предприятиях в Японии, в NASDA (ныне JAXA) Космическом центре Цукуба и Институте космических и астронавтических наук . Модуль «Кибо» был перевезен на корабле и доставлен самолетом на МОПС. [92]

Мобильная система обслуживания , состоящая из Canadarm2 и грейферного приспособления Dextre , производилась на различных заводах в Канаде (например, в лаборатории Дэвида Флориды ) и США по контракту Канадского космического агентства . Мобильная базовая система, соединяющая каркас для Canadarm2, установленная на рельсах, была построена компанией Northrop Grumman .

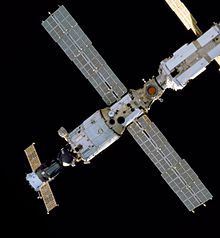

Сборка [ править ]

Сборка Международной космической станции, крупного проекта космической архитектуры , началась в ноябре 1998 года. [9] Российские модули запускались и стыковались роботизированно, за исключением «Рассвета» . Все остальные модули были доставлены с помощью космического корабля "Шаттл" , что потребовало установки членами экипажа МКС и шаттла с использованием Canadarm2 (SSRMS) и выхода в открытый космос (EVA); к 5 июня 2011 года они добавили 159 компонентов за более чем 1000 часов выхода в открытый космос. 127 из этих выходов в открытый космос произошли со станции, а остальные 32 были запущены из шлюзов пристыкованных космических кораблей. [93] Угол бета станции необходимо было учитывать на всех этапах строительства. [94]

Первый модуль МКС «Заря » был запущен 20 ноября 1998 года на автономной российской ракете «Протон» . Он обеспечивал движение, управление ориентацией , связь и электроэнергию, но не имел функций долгосрочного жизнеобеспечения. Пассивный модуль НАСА « Юнити » был запущен две недели спустя на борту космического корабля «Шаттл» STS-88 и прикреплен к «Заре» астронавтами во время выхода в открытый космос. Модуль Unity имеет два герметичных стыковочных адаптера (PMA): один постоянно подключается к «Заре» , а другой позволяет космическому шаттлу состыковаться с космической станцией. В то время российская (советская) станция «Мир» еще была обитаемой, а МКС два года оставалась без экипажа. 12 июля 2000 года модуль «Звезда» был выведен на орбиту. Бортовые заранее запрограммированные команды развернули солнечные батареи и антенну связи. Затем «Звезда» стала пассивной целью сближения с «Зарей» и «Юнити» , поддерживая постоянную орбиту, в то время как корабль «Заря – Юнити» выполнял сближение и стыковку с помощью наземного управления и российской автоматизированной системы сближения и стыковки. Компьютер «Зари » передал управление станцией компьютеру «Звезды » вскоре после стыковки. «Звезда» добавила спальные помещения, туалет, кухню, скрубберы CO 2 , осушитель, генераторы кислорода и тренажеры, а также передачу данных, голосовую и телевизионную связь с контролем полета, что позволило обеспечить постоянное проживание на станции. [95] [96]

Первый постоянный экипаж, Экспедиция-1 , прибыл в ноябре 2000 года на корабле «Союз ТМ-31» . В конце первого дня на станции астронавт Билл Шеперд попросил использовать радиопозывной « Альфа », который он и космонавт Сергей Крикалев предпочли более громоздкой « Международной космической станции ». [97] Название « Альфа » ранее использовалось для станции в начале 1990-х годов. [98] и его использование было разрешено на протяжении всей Экспедиции 1. [99] Шеперд уже некоторое время выступал за использование нового имени для менеджеров проектов. Ссылаясь на военно-морскую традицию , на пресс-конференции перед запуском он сказал: «На протяжении тысячелетий люди выходили в море на кораблях. Люди проектировали и строили эти суда, спускали их на воду с хорошим чувством, что имя принесет пользу». удачи команде и успеха их путешествию». [100] Юрий Семенов , в то время президент Российской космической корпорации «Энергия» , не одобрял название « Альфа », поскольку считал, что «Мир» были названы « Бета » или « Мир была первой модульной космической станцией, поэтому для МКС -2». было бы более уместно. [99] [101] [102]

Экспедиция 1 прибыла на полпути между полетами космических кораблей STS-92 и STS-97 . станции Каждый из этих двух полетов добавлял сегменты интегрированной ферменной конструкции , которая обеспечивала станцию связью в Ku-диапазоне для американского телевидения, дополнительную поддержку ориентации, необходимую для дополнительной массы USOS, и значительные солнечные батареи в дополнение к четырем существующим батареям станции. [103] В течение следующих двух лет станция продолжала расширяться. Ракета «Союз-У» доставила «Пирс» стыковочный отсек . Космические шаттлы «Дискавери» , «Атлантис» и «Индевор» доставили лабораторию «Дестини» и «Квест» шлюзовую камеру , а также главный роботизированный манипулятор станции «Канадарм2» и еще несколько сегментов интегрированной ферменной конструкции.

График расширения был прерван в 2003 году из-за космического корабля "Колумбия" катастрофы и, как следствие, перерыва в полетах. Использование космического корабля "Шаттл" было приостановлено до 2005 года, а STS-114 пилотировал "Дискавери" . [104] Сборка возобновилась в 2006 году с прибытием STS-115 с «Атлантисом» , который доставил на станцию второй комплект солнечных батарей. Еще несколько сегментов фермы и третий комплект массивов были поставлены на STS-116 , STS-117 и STS-118 . В результате значительного расширения энергетических возможностей станции можно было разместить больше герметичных модулей, а также узел «Гармония» и европейская лаборатория «Колумбус» были добавлены . Вскоре за ними последовали первые два компонента Кибо . В марте 2009 года STS-119 завершил строительство интегрированной ферменной конструкции с установкой четвертого и последнего комплекта солнечных батарей. Последняя секция « Кибо» была доставлена в июле 2009 года на STS-127 , за ней последовал модуль «Русский поиск» . Третий узел, «Спокойствие» , был доставлен в феврале 2010 года во время STS-130 космическим кораблем « Индевор» рядом с «Куполом» , за ним последовал предпоследний российский модуль «Рассвет » в мае 2010 года. «Рассвет» был доставлен космическим кораблем «Атлантис» на STS-132 в в обмен на поставку российского «Протона» финансируемого США Zarya module in 1998. [105] Последний гермомодуль USOS, «Леонардо» , был доставлен на станцию в феврале 2011 года на последнем полете «Дискавери» , STS-133 . [106] Альфа -магнитный спектрометр был доставлен компанией Endeavour на STS-134 в том же году. [107]

К июню 2011 года станция состояла из 15 герметичных модулей и интегрированной ферменной конструкции. Два силовых модуля под названием НЭМ-1 и НЭМ-2. [108] их еще предстояло запустить. Новый российский модуль первичных исследований «Наука» пришвартовался в июле 2021 года. [109] наряду с европейским роботизированным манипулятором, который может перемещаться в разные части российских модулей станции. [110] Последнее пополнение России, узловой модуль «Причал» , пристыковался в ноябре 2021 года. [111]

Полная масса станции меняется со временем. Общая стартовая масса модулей на орбите составила около 417 289 кг (919 965 фунтов) (по состоянию на 3 сентября 2011 г.). [update]). [93] Масса экспериментов, запасных частей, личных вещей, экипажа, продуктов питания, одежды, топлива, запасов воды, газа, пристыкованных космических кораблей и других предметов добавляется к общей массе станции. Водород постоянно выбрасывается за борт генераторами кислорода.

Структура [ править ]

МКС функционирует как модульная космическая станция, позволяющая добавлять или удалять модули из ее структуры для повышения адаптируемости.

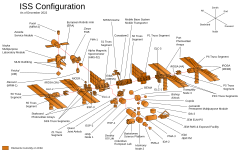

- Обзорная схема компонентов

- Внешний вид и стальные конструкции МКС, сделанные 8 ноября 2021 года из вылетающей SpaceX Crew-2. капсулы

- Схема строения Международной космической станции после установки солнечных батарей iROSA (по состоянию на 2023 год)

Ниже представлена схема основных компонентов станции. Синие области — это герметичные секции, доступные экипажу без использования скафандров. Негерметичная надстройка станции обозначена красным. Запланированные компоненты показаны белым цветом, неустановленные, временно вышедшие из строя или вышедшие из эксплуатации компоненты показаны коричневым, а бывшие — серым. Другие компоненты, не находящиеся под давлением, имеют желтый цвет. Узел Unity соединяется непосредственно с лабораторией Destiny . Для наглядности они показаны отдельно. Подобные случаи наблюдаются и в других частях конструкции.

Герметичные модули [ править ]

Zarya [ edit ]

Zarya ( Russian : Заря , lit. 'Dawn' [б] ), также известный как Функционально-грузовой блок или ФГБ (от русского «Функционально-грузовой блок» , букв. « Функционально-грузовой блок » или ФГБ ), является первым запущенным модулем МКС. [112] ФГБ обеспечивал электроэнергию, хранение, движение и управление МКС на начальном этапе сборки. С запуском и сборкой на орбите других модулей с более специализированным функционалом «Заря» по состоянию на август 2021 года в основном используется для хранения, как внутри гермоотсека, так и в выносных топливных баках. « Заря» является потомком космического корабля ТКС, разработанного для российской «Салют» программы . Название «Заря» («Рассвет») было присвоено ФГБ, поскольку оно означало начало новой эры международного сотрудничества в космосе. Хотя его построила российская компания, он принадлежит Соединенным Штатам. [113]

Единство [ править ]

Соединительный модуль Unity , также известный как Node 1, является первым компонентом МКС, построенным в США. Он соединяет российский и американский сегменты станции, и здесь экипаж вместе обедает. [114] [115]

Модуль имеет цилиндрическую форму и имеет шесть мест для стоянки ( в носовой части , кормовой , части левом , правом борту , зените и надире ), облегчающих соединение с другими модулями. Unity имеет диаметр 4,57 метра (15 футов), длину 5,47 метра (17,9 фута), изготовлен из стали и был построен для НАСА компанией Boeing на производственном предприятии в Центре космических полетов Маршалла в Хантсвилле, штат Алабама . Unity — первый из трёх соединительных модулей; два других — Гармония и Спокойствие . [116]

Zvezda [ edit ]

Звезда (русский: Звезда , что означает «звезда»), Салют ДОС-8 , также известен как Служебный модуль Звезда . станции Это был третий модуль, запущенный на станцию, и он обеспечивает все системы жизнеобеспечения , некоторые из которых дополнены в USOS, а также жилые помещения для двух членов экипажа. Это структурный и функциональный центр Российского орбитального сегмента , который является российской частью МКС. Здесь собирается команда для устранения чрезвычайных ситуаций на станции. [117] [118] [119]

Модуль изготовлен РКК «Энергия» , при основных субподрядных работах ГКНПЦ имени Хруничева. [120] «Звезда» была запущена на ракете «Протон» 12 июля 2000 года и состыковалась с модулем «Заря» 26 июля 2000 года.

Судьба [ править ]

Модуль «Дестини» , также известный как «Лаборатория США», является основным операционным комплексом для американских исследовательских грузов на борту МКС. [121] [122] Он был подключен к модулю Unity и активирован в течение пяти дней в феврале 2001 года. [123] Дестини - первая постоянно действующая орбитальная исследовательская станция НАСА после Скайлэб освобождения в феврале 1974 года. Компания Boeing начала строительство 14,5-тонной (32 000 фунтов) исследовательской лаборатории в 1995 году на сборочном заводе Мишуда , а затем в Центре космических полетов Маршалла в Хантсвилле. Алабама. [121] Destiny был отправлен в Космический центр Кеннеди во Флориде в 1998 году и передан НАСА для предстартовой подготовки в августе 2000 года. Он был запущен 7 февраля 2001 года на борту космического корабля " Атлантис" на STS-98 . [123] Астронавты работают внутри герметичного объекта и проводят исследования во многих научных областях. Ученые всего мира будут использовать результаты для улучшения своих исследований в области медицины, техники, биотехнологии, физики, материаловедения и наук о Земле. [122]

Квест [ править ]

Объединенный шлюзовой шлюз (также известный как «Квест») предоставлен США и обеспечивает возможность выхода в открытый космос на базе МКС с использованием либо американского блока внекорабельной мобильности (EMU), либо российских костюмов «Орлан» для выхода в открытый космос. [124] Перед запуском этого шлюза выходы в открытый космос осуществлялись либо с американского космического корабля "Шаттл" (во время пристыковки), либо из переходной камеры служебного модуля. Из-за множества системных и конструктивных отличий с Шаттла можно было использовать только американские скафандры, а со Служебного модуля - только российские скафандры. Joint Airlock решает эту краткосрочную проблему, позволяя использовать одну (или обе) системы скафандров. [125]

Объединенный шлюзовой шлюз был запущен на МКС-7А/STS-104 в июле 2001 года и прикреплен к правому стыковочному порту узла 1. [126] Общий шлюз имеет длину 20 футов, диаметр 13 футов и вес 6,5 тонн. Объединенный шлюзовой шлюз был построен компанией Boeing в Центре космических полетов имени Маршалла. Объединенный шлюзовой шлюз был запущен с помощью газовой сборки высокого давления. Газовая сборка высокого давления была установлена на внешней поверхности шлюзового шлюза и будет обеспечивать операции выхода в открытый космос дыхательными газами и дополнять систему пополнения запасов газа служебного модуля.Объединенный шлюзовой шлюз состоит из двух основных компонентов: шлюзового шлюза для экипажа, из которого астронавты и космонавты покидают МКС, и шлюзового шлюза для оборудования, предназначенного для хранения снаряжения для выхода в открытый космос и для так называемых ночных «лагерей», где азот выводится из тел космонавтов в течение ночи по мере падения давления. подготовка к выходам в открытый космос на следующий день. Это облегчает изгибы, поскольку астронавты восстанавливают давление после выхода в открытый космос. [125]

The crew airlock was derived from the Space Shuttle's external airlock. It is equipped with lighting, external handrails, and an Umbilical Interface Assembly (UIA). The UIA is located on one wall of the crew airlock and provides a water supply line, a wastewater return line, and an oxygen supply line. The UIA also provides communication gear and spacesuit power interfaces and can support two spacesuits simultaneously. This can be either two American EMU spacesuits, two Russian ORLAN spacesuits, or one of each design.

Poisk[edit]

Poisk (Russian: По́иск, lit. 'Search') was launched on 10 November 2009[127][128] attached to a modified Progress spacecraft, called Progress M-MIM2, on a Soyuz-U rocket from Launch Pad 1 at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. Poisk is used as the Russian airlock module, containing two identical EVA hatches. An outward-opening hatch on the Mir space station failed after it swung open too fast after unlatching, because of a small amount of air pressure remaining in the airlock.[129] All EVA hatches on the ISS open inwards and are pressure-sealing. Poisk is used to store, service, and refurbish Russian Orlan suits and provides contingency entry for crew using the slightly bulkier American suits. The outermost docking port on the module allows docking of Soyuz and Progress spacecraft, and the automatic transfer of propellants to and from storage on the Russian Orbital Segment (ROS).[130] Since the departure of the identical Pirs module on 26 July 2021, Poisk has served as the only airlock on the ROS.

Harmony[edit]

Harmony, also known as Node 2, is the "utility hub" of the ISS. It connects the laboratory modules of the United States, Europe and Japan, as well as providing electrical power and electronic data. Sleeping cabins for four of the crew are housed here.[131]

Harmony was launched into space aboard Space Shuttle flight STS-120 on 23 October 2007.[132][133] After temporarily being attached to the port side of the Unity node,[134][135] it was moved to its permanent location on the forward end of the Destiny laboratory on 14 November 2007.[136] Harmony added 75.5 m3 (2,666 cu ft) to the station's living volume, an increase of almost 20 per cent, from 424.8 to 500.2 m3 (15,000 to 17,666 cu ft). Its successful installation meant that from NASA's perspective, the station was considered to be "U.S. Core Complete".

Tranquility[edit]

Tranquility, also known as Node 3, is a module of the ISS. It contains environmental control systems, life support systems, a toilet, exercise equipment, and an observation cupola.

The European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency had Tranquility manufactured by Thales Alenia Space. A ceremony on 20 November 2009 transferred ownership of the module to NASA.[137] On 8 February 2010, NASA launched the module on the Space Shuttle's STS-130 mission.

Columbus[edit]

Columbus is a science laboratory that is part of the ISS and is the largest single contribution to the station made by the European Space Agency.

Like the Harmony and Tranquility modules, the Columbus laboratory was constructed in Turin, Italy by Thales Alenia Space. The functional equipment and software of the lab was designed by EADS in Bremen, Germany. It was also integrated in Bremen before being flown to the Kennedy Space Center in Florida in an Airbus Beluga jet. It was launched aboard Space Shuttle Atlantis on 7 February 2008, on flight STS-122. It is designed for ten years of operation. The module is controlled by the Columbus Control Centre, located at the German Space Operations Center, part of the German Aerospace Center in Oberpfaffenhofen near Munich, Germany.

The European Space Agency has spent €1.4 billion (about US$1.6 billion) on building Columbus, including the experiments it carries and the ground control infrastructure necessary to operate them.[138]

Kibō[edit]

The Japanese Experiment Module (JEM), nicknamed Kibō (きぼう, Kibō, Hope), is a Japanese science module for the International Space Station (ISS) developed by JAXA. It is the largest single ISS module, and is attached to the Harmony module. The first two pieces of the module were launched on Space Shuttle missions STS-123 and STS-124. The third and final components were launched on STS-127.[139]

Cupola[edit]

The Cupola is an ESA-built observatory module of the ISS. Its name derives from the Italian word cupola, which means "dome". Its seven windows are used to conduct experiments, dockings and observations of Earth. It was launched aboard Space Shuttle mission STS-130 on 8 February 2010 and attached to the Tranquility (Node 3) module. With the Cupola attached, ISS assembly reached 85 per cent completion. The Cupola's central window has a diameter of 80 cm (31 in).[140]

Rassvet[edit]

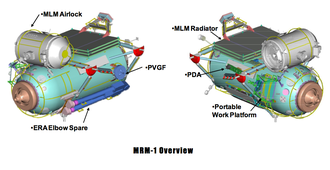

Rassvet (Russian: Рассвет; lit. "dawn"), also known as the Mini-Research Module 1 (MRM-1) (Russian: Малый исследовательский модуль, МИМ 1) and formerly known as the Docking Cargo Module (DCM), is a component of the International Space Station (ISS). The module's design is similar to the Mir Docking Module launched on STS-74 in 1995. Rassvet is primarily used for cargo storage and as a docking port for visiting spacecraft. It was flown to the ISS aboard Space Shuttle Atlantis on the STS-132 mission on 14 May 2010,[141] and was connected to the ISS on 18 May 2010.[142] The hatch connecting Rassvet with the ISS was first opened on 20 May 2010.[143] On 28 June 2010, the Soyuz TMA-19 spacecraft performed the first docking with the module.[144]

Science (or Experiment) Airlock[edit]

The airlock, ShK, is designed for a payload with dimensions up to 1,200 mm × 500 mm × 500 mm (47 in × 20 in × 20 in), has a volume of 2.1 m3, weight of 1050 kg and consumes 1.5 kW of power at the peak. Prior to berthing the MLM to the ISS, the airlock is stowed as part of MRM1.[145] On 4 May 2023, 01:00 UTC, the chamber was moved by the ERA manipulator and berthed to the forward active docking port of the pressurized docking hub of the Nauka module during VKD-57 spacewalk. It is intended to be used:

- for extracting payloads and from the MLM docking adapter and placing them on the outer surface of the station;

- enable science investigations to be removed, exposed to the external microgravity environment, then returned inside while being maneuvered with the European robotic arm.

- for receiving payloads from the ERA manipulator and moving them into the internal volume of the airlock and further into the MLM pressurized adapter;

- for conducting scientific experiments in the internal volume of the airlock;

- for conducting scientific experiments outside the airlock chamber on an extended table and in a special organized place.[145][146]

- for launching cubesats into space, with the aid of ERA – very similar to the Japanese airlock and Nanoracks Bishop Airlock on the U.S. segment of the station.[147]

Leonardo[edit]

The Leonardo Permanent Multipurpose Module (PMM) is a module of the International Space Station. It was flown into space aboard the Space Shuttle on STS-133 on 24 February 2011 and installed on 1 March. Leonardo is primarily used for storage of spares, supplies and waste on the ISS, which was until then stored in many different places within the space station. It is also the personal hygiene area for the astronauts who live in the US Orbital Segment. The Leonardo PMM was a Multi-Purpose Logistics Module (MPLM) before 2011, but was modified into its current configuration. It was formerly one of two MPLM used for bringing cargo to and from the ISS with the Space Shuttle. The module was named for Italian polymath Leonardo da Vinci.

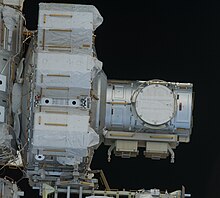

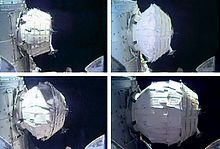

Bigelow Expandable Activity Module[edit]

The Bigelow Expandable Activity Module (BEAM) is an experimental expandable space station module developed by Bigelow Aerospace, under contract to NASA, for testing as a temporary module on the International Space Station (ISS) from 2016 to at least 2020. It arrived at the ISS on 10 April 2016,[148] was berthed to the station on 16 April at Tranquility Node 3, and was expanded and pressurized on 28 May 2016. In December 2021, Bigelow Aerospace conveyed ownership of the module to NASA, as a result of Bigelow's cessation of activity.[149]

International Docking Adapters[edit]

The International Docking Adapter (IDA) is a spacecraft docking system adapter developed to convert APAS-95 to the NASA Docking System (NDS). An IDA is placed on each of the ISS's two open Pressurized Mating Adapters (PMAs), both of which are connected to the Harmony module.

Two International Docking Adapters are currently installed aboard the Station. Originally, IDA-1 was planned to be installed on PMA-2, located at Harmony's forward port, and IDA-2 would be installed on PMA-3 at Harmony's zenith. After IDA 1 was destroyed in a launch incident, IDA-2 was installed on PMA-2 on 19 August 2016,[150] while IDA-3 was later installed on PMA-3 on 21 August 2019.[151]

Bishop Airlock Module[edit]

The NanoRacks Bishop Airlock Module is a commercially funded airlock module launched to the ISS on SpaceX CRS-21 on 6 December 2020.[152][153] The module was built by NanoRacks, Thales Alenia Space, and Boeing.[154] It will be used to deploy CubeSats, small satellites, and other external payloads for NASA, CASIS, and other commercial and governmental customers.[155]

Nauka[edit]

Nauka (Russian: Наука, lit. 'Science'), also known as the Multipurpose Laboratory Module-Upgrade (MLM-U), (Russian: Многоцелевой лабораторный модуль, усоверше́нствованный, or МЛМ-У), is a Roscosmos-funded component of the ISS that was launched on 21 July 2021, 14:58 UTC. In the original ISS plans, Nauka was to use the location of the Docking and Stowage Module (DSM), but the DSM was later replaced by the Rassvet module and moved to Zarya's nadir port. Nauka was successfully docked to Zvezda's nadir port on 29 July 2021, 13:29 UTC, replacing the Pirs module.

It had a temporary docking adapter on its nadir port for crewed and uncrewed missions until Prichal arrival, where just before its arrival it was removed by a departing Progress spacecraft.[156]

Prichal[edit]

Prichal, also known as Uzlovoy Module or UM (Russian: Узловой Модуль Причал, lit. 'Nodal Module Berth'),[157] is a 4-tonne (8,800 lb)[158] ball-shaped module that will provide the Russian segment additional docking ports to receive Soyuz MS and Progress MS spacecraft. UM was launched in November 2021.[159] It was integrated with a special version of the Progress cargo spacecraft and launched by a standard Soyuz rocket, docking to the nadir port of the Nauka module. One port is equipped with an active hybrid docking port, which enables docking with the MLM module. The remaining five ports are passive hybrids, enabling docking of Soyuz and Progress vehicles, as well as heavier modules and future spacecraft with modified docking systems. The node module was intended to serve as the only permanent element of the cancelled Orbital Piloted Assembly and Experiment Complex (OPSEK).[159][160][161]

Unpressurised elements[edit]

The ISS has a large number of external components that do not require pressurisation. The largest of these is the Integrated Truss Structure (ITS), to which the station's main solar arrays and thermal radiators are mounted.[162] The ITS consists of ten separate segments forming a structure 108.5 metres (356 ft) long.[9]

The station was intended to have several smaller external components, such as six robotic arms, three External Stowage Platforms (ESPs) and four ExPRESS Logistics Carriers (ELCs).[163][164] While these platforms allow experiments (including MISSE, the STP-H3 and the Robotic Refueling Mission) to be deployed and conducted in the vacuum of space by providing electricity and processing experimental data locally, their primary function is to store spare Orbital Replacement Units (ORUs). ORUs are parts that can be replaced when they fail or pass their design life, including pumps, storage tanks, antennas, and battery units. Such units are replaced either by astronauts during EVA or by robotic arms.[165] Several shuttle missions were dedicated to the delivery of ORUs, including STS-129,[166] STS-133[167] and STS-134.[168] As of January 2011[update], only one other mode of transportation of ORUs had been used – the Japanese cargo vessel HTV-2 – which delivered an FHRC and CTC-2 via its Exposed Pallet (EP).[169][needs update]

There are also smaller exposure facilities mounted directly to laboratory modules; the Kibō Exposed Facility serves as an external "porch" for the Kibō complex,[170] and a facility on the European Columbus laboratory provides power and data connections for experiments such as the European Technology Exposure Facility[171][172] and the Atomic Clock Ensemble in Space.[173] A remote sensing instrument, SAGE III-ISS, was delivered to the station in February 2017 aboard CRS-10,[174] and the NICER experiment was delivered aboard CRS-11 in June 2017.[175] The largest scientific payload externally mounted to the ISS is the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS), a particle physics experiment launched on STS-134 in May 2011, and mounted externally on the ITS. The AMS measures cosmic rays to look for evidence of dark matter and antimatter.[176][177]

The commercial Bartolomeo External Payload Hosting Platform, manufactured by Airbus, was launched on 6 March 2020 aboard CRS-20 and attached to the European Columbus module. It will provide an additional 12 external payload slots, supplementing the eight on the ExPRESS Logistics Carriers, ten on Kibō, and four on Columbus. The system is designed to be robotically serviced and will require no astronaut intervention. It is named after Christopher Columbus's younger brother.[178][179][180]

MLM outfittings[edit]

In May 2010, equipment for Nauka was launched on STS-132 (as part of an agreement with NASA) and delivered by Space Shuttle Atlantis. Weighing 1.4 metric tons, the equipment was attached to the outside of Rassvet (MRM-1). It included a spare elbow joint for the European Robotic Arm (ERA) (which was launched with Nauka) and an ERA-portable workpost used during EVAs, as well as RTOd add-on heat radiator and internal hardware alongside the pressurized experiment airlock.[147]

The RTOd radiator adds additional cooling capability to Nauka, which enables the module to host more scientific experiments.[147]

The ERA was used to remove the RTOd radiator from Rassvet and transferred over to Nauka during VKD-56 spacewalk. Later it was activated and fully deployed on VKD-58 spacewalk.[181] This process took several months. A portable work platform was also transferred over in August 2023 during VKD-60 spacewalk, which can attach to the end of the ERA to allow cosmonauts to "ride" on the end of the arm during spacewalks.[182][183] However, even after several months of outfitting EVAs and RTOd heat radiator installation, six months later, the RTOd radiator malfunctioned before active use of Nauka (the purpose of RTOd installation is to radiate heat from Nauka experiments). The malfunction, a leak, rendered the RTOd radiator unusable for Nauka. This is the third ISS radiator leak after Soyuz MS-22 and Progress MS-21 radiator leaks. If a spare RTOd is not available, Nauka experiments will have to rely on Nauka's main launch radiator and the module could never be used to its full capacity.[184][185]

Another MLM outfitting is a 4 segment external payload interface called means of attachment of large payloads (Sredstva Krepleniya Krupnogabaritnykh Obyektov, SKKO).[186] Delivered in two parts to Nauka by Progress MS-18 (LCCS part) and Progress MS-21 (SCCCS part) as part of the module activation outfitting process.[187][188][189][190] It was taken outside and installed on the ERA aft facing base point on Nauka during the VKD-55 spacewalk.[191][192][193][194]

Robotic arms and cargo cranes[edit]

Strela crane (which is holding photographer Oleg Kononenko)

The Integrated Truss Structure (ITS) serves as a base for the station's primary remote manipulator system, the Mobile Servicing System (MSS), which is composed of three main components:

- Canadarm2, the largest robotic arm on the ISS, has a mass of 1,800 kilograms (4,000 lb) and is used to: dock and manipulate spacecraft and modules on the USOS; hold crew members and equipment in place during EVAs; and move Dextre to perform tasks.[195]

- Dextre is a 1,560 kg (3,440 lb) robotic manipulator that has two arms and a rotating torso, with power tools, lights, and video for replacing orbital replacement units (ORUs) and performing other tasks requiring fine control.[196]

- The Mobile Base System (MBS) is a platform that rides on rails along the length of the station's main truss, which serves as a mobile base for Canadarm2 and Dextre, allowing the robotic arms to reach all parts of the USOS.[197]

A grapple fixture was added to Zarya on STS-134 to enable Canadarm2 to inchworm itself onto the ROS.[168] Also installed during STS-134 was the 15 m (50 ft) Orbiter Boom Sensor System (OBSS), which had been used to inspect heat shield tiles on Space Shuttle missions and which can be used on the station to increase the reach of the MSS.[168] Staff on Earth or the ISS can operate the MSS components using remote control, performing work outside the station without the need for space walks.

Japan's Remote Manipulator System, which services the Kibō Exposed Facility,[198] was launched on STS-124 and is attached to the Kibō Pressurised Module.[199] The arm is similar to the Space Shuttle arm as it is permanently attached at one end and has a latching end effector for standard grapple fixtures at the other.

The European Robotic Arm, which will service the ROS, was launched alongside the Nauka module.[200] The ROS does not require spacecraft or modules to be manipulated, as all spacecraft and modules dock automatically and may be discarded the same way. Crew use the two Strela (Russian: Стрела́, lit. 'Arrow') cargo cranes during EVAs for moving crew and equipment around the ROS. Each Strela crane has a mass of 45 kg (99 lb).

Former module[edit]

Pirs[edit]

Pirs (Russian: Пирс, lit. 'Pier') was launched on 14 September 2001, as ISS Assembly Mission 4R, on a Russian Soyuz-U rocket, using a modified Progress spacecraft, Progress M-SO1, as an upper stage. Pirs was undocked by Progress MS-16 on 26 July 2021, 10:56 UTC, and deorbited on the same day at 14:51 UTC to make room for Nauka module to be attached to the space station. Prior to its departure, Pirs served as the primary Russian airlock on the station, being used to store and refurbish the Russian Orlan spacesuits.

Planned components[edit]

Axiom segment[edit]

In January 2020, NASA awarded Axiom Space a contract to build a commercial module for the ISS. The contract is under the NextSTEP2 program. NASA negotiated with Axiom on a firm fixed-price contract basis to build and deliver the module, which will attach to the forward port of the space station's Harmony (Node 2) module. Although NASA has only commissioned one module, Axiom plans to build an entire segment consisting of five modules, including a node module, an orbital research and manufacturing facility, a crew habitat, and a "large-windowed Earth observatory". The Axiom segment is expected to greatly increase the capabilities and value of the space station, allowing for larger crews and private spaceflight by other organisations. Axiom plans to convert the segment into a stand-alone space station once the ISS is decommissioned, with the intention that this would act as a successor to the ISS.[201][202][203] Canadarm 2 will also help to berth the Axiom Space Station modules to the ISS and will continue its operations on the Axiom Space Station after the retirement of ISS in late 2020s.[204]

As of December 2023, Axiom Space expects to launch the first module, Hab One, at the end of 2026.[205]

Proposed components[edit]

Independence-1[edit]

Nanoracks, after finalizing its contract with NASA, and after winning NextSTEPs Phase II award, is now developing its concept Independence-1 (previously known as Ixion), which would turn spent rocket tanks into a habitable living area to be tested in space. In Spring 2018, Nanoracks announced that Ixion is now known as the Independence-1, the first 'outpost' in Nanoracks' Space Outpost Program.

Nautilus-X Centrifuge Demonstration[edit]

If produced, this centrifuge will be the first in-space demonstration of sufficient scale centrifuge for artificial partial-g effects. It will be designed to become a sleep module for the ISS crew.

Cancelled components[edit]

Several modules planned for the station were cancelled over the course of the ISS programme. Reasons include budgetary constraints, the modules becoming unnecessary, and station redesigns after the 2003 Columbia disaster. The US Centrifuge Accommodations Module would have hosted science experiments in varying levels of artificial gravity.[206] The US Habitation Module would have served as the station's living quarters. Instead, the living quarters are now spread throughout the station.[207] The US Interim Control Module and ISS Propulsion Module would have replaced the functions of Zvezda in case of a launch failure.[208] Two Russian Research Modules were planned for scientific research.[209] They would have docked to a Russian Universal Docking Module.[210] The Russian Science Power Platform would have supplied power to the Russian Orbital Segment independent of the ITS solar arrays.

Science Power Modules 1 and 2 (Repurposed Components)[edit]

Science Power Module 1 (SPM-1, also known as NEM-1) and Science Power Module 2 (SPM-2, also known as NEM-2) are modules that were originally planned to arrive at the ISS no earlier than 2024, and dock to the Prichal module, which is docked to the Nauka module.[161][211] In April 2021, Roscosmos announced that NEM-1 would be repurposed to function as the core module of the proposed Russian Orbital Service Station (ROSS), launching no earlier than 2027[212] and docking to the free-flying Nauka module either before or after the ISS has been deorbited.[213][214] NEM-2 may be converted into another core "base" module, which would be launched in 2028.[215]

Xbase[edit]

Designed by Bigelow Aerospace. In August 2016, Bigelow negotiated an agreement with NASA to develop a full-size ground prototype Deep Space Habitation based on the B330 under the second phase of Next Space Technologies for Exploration Partnerships. The module was called the Expandable Bigelow Advanced Station Enhancement (XBASE), as Bigelow hoped to test the module by attaching it to the International Space Station. However, in March 2020, Bigelow laid off all 88 of its employees, and as of February 2024[update] the company remains dormant and is considered defunct,[216][217] making it appear unlikely that the XBASE module will ever be launched.

Onboard systems[edit]

Life support[edit]

The critical systems are the atmosphere control system, the water supply system, the food supply facilities, the sanitation and hygiene equipment, and fire detection and suppression equipment. The Russian Orbital Segment's life support systems are contained in the Zvezda service module. Some of these systems are supplemented by equipment in the USOS. The Nauka laboratory has a complete set of life support systems.

Atmospheric control systems[edit]

The atmosphere on board the ISS is similar to that of Earth.[218] Normal air pressure on the ISS is 101.3 kPa (14.69 psi);[219] the same as at sea level on Earth. An Earth-like atmosphere offers benefits for crew comfort, and is much safer than a pure oxygen atmosphere, because of the increased risk of a fire such as that responsible for the deaths of the Apollo 1 crew.[220][better source needed] Earth-like atmospheric conditions have been maintained on all Russian and Soviet spacecraft.[221]

The Elektron system aboard Zvezda and a similar system in Destiny generate oxygen aboard the station.[222] The crew has a backup option in the form of bottled oxygen and Solid Fuel Oxygen Generation (SFOG) canisters, a chemical oxygen generator system.[223] Carbon dioxide is removed from the air by the Vozdukh system in Zvezda. Other by-products of human metabolism, such as methane from the intestines and ammonia from sweat, are removed by activated charcoal filters.[223]

Part of the ROS atmosphere control system is the oxygen supply. Triple-redundancy is provided by the Elektron unit, solid fuel generators, and stored oxygen. The primary supply of oxygen is the Elektron unit which produces O2 and H2 by electrolysis of water and vents H2 overboard. The 1 kW (1.3 hp) system uses approximately one litre of water per crew member per day. This water is either brought from Earth or recycled from other systems. Mir was the first spacecraft to use recycled water for oxygen production. The secondary oxygen supply is provided by burning oxygen-producing Vika cartridges (see also ISS ECLSS). Each 'candle' takes 5–20 minutes to decompose at 450–500 °C (842–932 °F), producing 600 litres (130 imp gal; 160 US gal) of O2. This unit is manually operated.[224]

The US Orbital Segment (USOS) has redundant supplies of oxygen, from a pressurised storage tank on the Quest airlock module delivered in 2001, supplemented ten years later by ESA-built Advanced Closed-Loop System (ACLS) in the Tranquility module (Node 3), which produces O2 by electrolysis.[225] Hydrogen produced is combined with carbon dioxide from the cabin atmosphere and converted to water and methane.

Power and thermal control[edit]

Double-sided solar arrays provide electrical power to the ISS. These bifacial cells collect direct sunlight on one side and light reflected off from the Earth on the other, and are more efficient and operate at a lower temperature than single-sided cells commonly used on Earth.[226]

The Russian segment of the station, like most spacecraft, uses 28 V low voltage DC from two rotating solar arrays mounted on Zvezda. The USOS uses 130–180 V DC from the USOS PV array. Power is stabilised and distributed at 160 V DC and converted to the user-required 124 V DC. The higher distribution voltage allows smaller, lighter conductors, at the expense of crew safety. The two station segments share power with converters.

The USOS solar arrays are arranged as four wing pairs, for a total production of 75 to 90 kilowatts.[4] These arrays normally track the Sun to maximise power generation. Each array is about 375 m2 (4,036 sq ft) in area and 58 m (190 ft) long. In the complete configuration, the solar arrays track the Sun by rotating the alpha gimbal once per orbit; the beta gimbal follows slower changes in the angle of the Sun to the orbital plane. The Night Glider mode aligns the solar arrays parallel to the ground at night to reduce the significant aerodynamic drag at the station's relatively low orbital altitude.[227]

The station originally used rechargeable nickel–hydrogen batteries (NiH2) for continuous power during the 45 minutes of every 90-minute orbit that it is eclipsed by the Earth. The batteries are recharged on the day side of the orbit. They had a 6.5-year lifetime (over 37,000 charge/discharge cycles) and were regularly replaced over the anticipated 20-year life of the station.[228] Starting in 2016, the nickel–hydrogen batteries were replaced by lithium-ion batteries, which are expected to last until the end of the ISS program.[229]

The station's large solar panels generate a high potential voltage difference between the station and the ionosphere. This could cause arcing through insulating surfaces and sputtering of conductive surfaces as ions are accelerated by the spacecraft plasma sheath. To mitigate this, plasma contactor units create current paths between the station and the ambient space plasma.[230]

The station's systems and experiments consume a large amount of electrical power, almost all of which is converted to heat. To keep the internal temperature within workable limits, a passive thermal control system (PTCS) is made of external surface materials, insulation such as MLI, and heat pipes. If the PTCS cannot keep up with the heat load, an External Active Thermal Control System (EATCS) maintains the temperature. The EATCS consists of an internal, non-toxic, water coolant loop used to cool and dehumidify the atmosphere, which transfers collected heat into an external liquid ammonia loop. From the heat exchangers, ammonia is pumped into external radiators that emit heat as infrared radiation, then the ammonia is cycled back to the station.[231] The EATCS provides cooling for all the US pressurised modules, including Kibō and Columbus, as well as the main power distribution electronics of the S0, S1 and P1 trusses. It can reject up to 70 kW. This is much more than the 14 kW of the Early External Active Thermal Control System (EEATCS) via the Early Ammonia Servicer (EAS), which was launched on STS-105 and installed onto the P6 Truss.[232]

Communications and computers[edit]

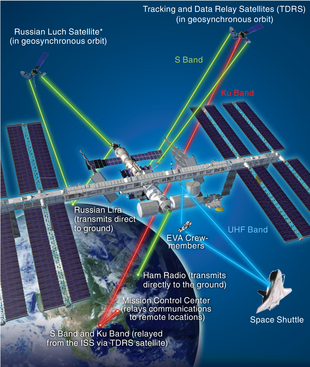

* Luch and the Space Shuttle are not in use as of 2020.

Radio communications provide telemetry and scientific data links between the station and mission control centres. Radio links are also used during rendezvous and docking procedures and for audio and video communication between crew members, flight controllers and family members. As a result, the ISS is equipped with internal and external communication systems used for different purposes.[233]

The Russian Orbital Segment communicates directly with the ground via the Lira antenna mounted to Zvezda.[69][234] The Lira antenna also has the capability to use the Luch data relay satellite system.[69] This system fell into disrepair during the 1990s, and so was not used during the early years of the ISS,[69][235][236] although two new Luch satellites – Luch-5A and Luch-5B – were launched in 2011 and 2012 respectively to restore the operational capability of the system.[237] Another Russian communications system is the Voskhod-M, which enables internal telephone communications between Zvezda, Zarya, Pirs, Poisk, and the USOS and provides a VHF radio link to ground control centres via antennas on Zvezda's exterior.[238]

The US Orbital Segment (USOS) makes use of two separate radio links: S band (audio, telemetry, commanding – located on the P1/S1 truss) and Ku band (audio, video and data – located on the Z1 truss) systems. These transmissions are routed via the United States Tracking and Data Relay Satellite System (TDRSS) in geostationary orbit, allowing for almost continuous real-time communications with Christopher C. Kraft Jr. Mission Control Center (MCC-H) in Houston, Texas.[69][239][233] Data channels for the Canadarm2, European Columbus laboratory and Japanese Kibō modules were originally also routed via the S band and Ku band systems, with the European Data Relay System and a similar Japanese system intended to eventually complement the TDRSS in this role.[239][240] Communications between modules are carried on an internal wireless network.[241]

UHF radio is used by astronauts and cosmonauts conducting EVAs and other spacecraft that dock to or undock from the station.[69] Automated spacecraft are fitted with their own communications equipment; the ATV used a laser attached to the spacecraft and the Proximity Communications Equipment attached to Zvezda to accurately dock with the station.[242][243]

The ISS is equipped with about 100 IBM/Lenovo ThinkPad and HP ZBook 15 laptop computers. The laptops have run Windows 95, Windows 2000, Windows XP, Windows 7, Windows 10 and Linux operating systems.[244] Each computer is a commercial off-the-shelf purchase which is then modified for safety and operation including updates to connectors, cooling and power to accommodate the station's 28V DC power system and weightless environment. Heat generated by the laptops does not rise but stagnates around the laptop, so additional forced ventilation is required. Portable Computer System (PCS) laptops connect to the Primary Command & Control computer (C&C MDM) as remote terminals via a USB to 1553 adapter.[245] Station Support Computer (SSC) laptops aboard the ISS are connected to the station's wireless LAN via Wi-Fi and ethernet, which connects to the ground via Ku band. While originally this provided speeds of 10 Mbit/s download and 3 Mbit/s upload from the station,[246][247] NASA upgraded the system in late August 2019 and increased the speeds to 600 Mbit/s.[248] Laptop hard drives occasionally fail and must be replaced.[249] Other computer hardware failures include instances in 2001, 2007 and 2017; some of these failures have required EVAs to replace computer modules in externally mounted devices.[250][251][252][253]

The operating system used for key station functions is the Debian Linux distribution.[254] The migration from Microsoft Windows to Linux was made in May 2013 for reasons of reliability, stability and flexibility.[255]

In 2017, an SG100 Cloud Computer was launched to the ISS as part of OA-7 mission.[256] It was manufactured by NCSIST of Taiwan and designed in collaboration with Academia Sinica, and National Central University under contract for NASA.[257]

ISS crew members have access to the Internet, and thus the world wide web.[258][259] This was first enabled in 2010,[258] allowing NASA astronaut T. J. Creamer to make the first tweet from space.[260] Access is achieved via an Internet-enabled computer in Houston, Texas, using remote desktop mode, thereby protecting the ISS from virus infection and hacking attempts.[258]

Operations[edit]

Expeditions[edit]

Each permanent crew is given an expedition number. Expeditions run up to six months, from launch until undocking, an 'increment' covers the same time period, but includes cargo spacecraft and all activities. Expeditions 1 to 6 consisted of three-person crews. Expeditions 7 to 12 were reduced to the safe minimum of two following the destruction of the NASA Shuttle Columbia. From Expedition 13 the crew gradually increased to six around 2010.[261][262] With the arrival of crew on US commercial vehicles beginning in 2020,[263] NASA has indicated that expedition size may be increased to seven crew members, the number for which ISS was originally designed.[264][265]

Gennady Padalka, member of Expeditions 9, 19/20, 31/32, and 43/44, and Commander of Expedition 11, has spent more time in space than anyone else, a total of 878 days, 11 hours, and 29 minutes.[266] Peggy Whitson has spent the most time in space of any American, totalling 675 days, 3 hours and 48 minutes during her time on Expeditions 5, 16, and 50/51/52 and Axiom Mission 2.[267][268]

Private flights[edit]

Travellers who pay for their own passage into space are termed spaceflight participants by Roscosmos and NASA, and are sometimes referred to as "space tourists", a term they generally dislike.[e] As of June 2023[update], thirteen space tourists have visited the ISS; nine were transported to the ISS on Russian Soyuz spacecraft, and four were transported on American SpaceX Dragon 2 spacecraft. For one-tourist missions, when professional crews change over in numbers not divisible by the three seats in a Soyuz, and a short-stay crewmember is not sent, the spare seat is sold by MirCorp through Space Adventures. Space tourism was halted in 2011 when the Space Shuttle was retired and the station's crew size was reduced to six, as the partners relied on Russian transport seats for access to the station. Soyuz flight schedules increased after 2013, allowing five Soyuz flights (15 seats) with only two expeditions (12 seats) required.[276] The remaining seats were to be sold for around US$40 million each to members of the public who could pass a medical exam. ESA and NASA criticised private spaceflight at the beginning of the ISS, and NASA initially resisted training Dennis Tito, the first person to pay for his own passage to the ISS.[f]

Anousheh Ansari became the first self-funded woman to fly to the ISS as well as the first Iranian in space. Officials reported that her education and experience made her much more than a tourist, and her performance in training had been "excellent."[277] She did Russian and European studies involving medicine and microbiology during her 10-day stay. The 2009 documentary Space Tourists follows her journey to the station, where she fulfilled "an age-old dream of man: to leave our planet as a 'normal person' and travel into outer space."[278]

In 2008, spaceflight participant Richard Garriott placed a geocache aboard the ISS during his flight.[279] This is currently the only non-terrestrial geocache in existence.[280] At the same time, the Immortality Drive, an electronic record of eight digitised human DNA sequences, was placed aboard the ISS.[281]

After a 12-year hiatus, the first two wholly space tourism-dedicated private spaceflights to the ISS were undertaken. Soyuz MS-20 launched in December 2021, carrying visiting Roscosmos cosmonaut Alexander Misurkin and two Japanese space tourists under the aegis of the private company Space Adventures;[282][283] in April 2022, the company Axiom Space chartered a SpaceX Dragon 2 spacecraft and sent its own employee astronaut Michael Lopez-Alegria and three space tourists to the ISS for Axiom Mission 1,[284][285][286] followed in May 2023 by one more tourist, John Shoffner, alongside employee astronaut Peggy Whitson and two Saudi astronauts for the Axiom Mission 2.[287][288]

Fleet operations[edit]

A wide variety of crewed and uncrewed spacecraft have supported the station's activities. Flights to the ISS include 37 Space Shuttle missions, 83 Progress resupply spacecraft (including the modified M-MIM2, DC-1 and M-UM module transports), 63 crewed Soyuz spacecraft, 5 European ATVs, 9 Japanese HTVs, 1 Boeing Starliner, 30 SpaceX Dragon (both crewed and uncrewed) and 18 Cygnus missions.[289]

There are currently eleven available docking ports for visiting spacecraft:[290]

- Harmony forward (with IDA 2)

- Harmony zenith (with IDA 3)

- Harmony nadir

- Unity nadir

- Prichal nadir

- Prichal aft

- Prichal forward

- Prichal starboard

- Prichal port

- Poisk zenith

- Rassvet nadir

- Zvezda aft

Crewed[edit]

As of 22 May 2023[ref], 269 people from 21 countries had visited the space station, many of them multiple times. The United States sent 163 people, Russia sent 57, Japan sent 11, Canada sent nine, Italy sent five, France and Germany each sent four, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and Sweden each sent two, and there were one each from Belgium, Brazil, Denmark, the United Kingdom, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, the Netherlands, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, and Israel.[291]

Uncrewed[edit]

Uncrewed spaceflights to the ISS are made primarily to deliver cargo, however several Russian modules have also docked to the outpost following uncrewed launches. Resupply missions typically use the Russian Progress spacecraft, former European ATVs, Japanese Kounotori vehicles, and the American Dragon and Cygnus spacecraft. The primary docking system for Progress spacecraft is the automated Kurs system, with the manual TORU system as a backup. ATVs also used Kurs, however they were not equipped with TORU. Progress and former ATV can remain docked for up to six months.[292][293] The other spacecraft – the Japanese HTV, the SpaceX Dragon (under CRS phase 1), and the Northrop Grumman[294] Cygnus – rendezvous with the station before being grappled using Canadarm2 and berthed at the nadir port of the Harmony or Unity module for one to two months. Under CRS phase 2, Cargo Dragon docks autonomously at IDA-2 or IDA-3. As of December 2020[update], Progress spacecraft have flown most of the uncrewed missions to the ISS.

Soyuz MS-22 was launched in 2022. A micro-meteorite impact in December 2022 caused a coolant leak in its external radiator and it was considered risky for human landing. Thus MS-22 reentered uncrewed on 28 March 2023 and Soyuz MS-23 was launched uncrewed on 24 February 2023, and it returned the MS-22 crew.[295][296][297][1]

Currently docked/berthed[edit]

| Spacecraft | Type | Mission | Location | Arrival (UTC) | Departure (planned) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S.S. Patricia "Patty" Hilliard Robertson | Uncrewed | NG-20 | Unity nadir | 1 February 2024[298][299] | NET Late July 2024 | |

| Progress MS No. 456 | Uncrewed | Progress MS-26 | Zvezda aft | 17 February 2024[298][299] | NET 13 August 2024 | |

| Crew Dragon Endeavour | Crewed | Crew-8 | Harmony zenith | 5 March 2024[300] | NET 30 August 2024 | |

| Soyuz MS No. 756 Kazbek | Crewed | Soyuz MS-25 | Prichal nadir | 25 March 2024 | NET 24 September 2024 | |

| Progress MS No. 457 | Uncrewed | Progress MS-27 | Poisk zenith | 1 June 2024[298][299] | NET 2024 | |

| SC-3 Calypso | Crewed | Boeing CFT | Harmony forward | 6 June 2024 | NET 14 June 2024 | |

Scheduled missions[edit]

- All dates are UTC. Dates are the earliest possible dates and may change.

- Forward ports are at the front of the station according to its normal direction of travel and orientation (attitude). Aft is at the rear of the station, used by spacecraft boosting the station's orbit. Nadir is closest the Earth, zenith is on top. Port is to the left if pointing one's feet towards the Earth and looking in the direction of travel; starboard to the right.

| Mission | Launch date (NET) | Spacecraft | Type | Launch vehicle | Launch site | Launch provider | Docking/berthing port |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NG-21 | Early August 2024 | Cygnus | Uncrewed | Falcon 9 Block 5 | Unity nadir | ||

| SNC-1 | Early September 2024[298][299][301] | Dream Chaser Tenacity | Uncrewed | Vulcan Centaur VC4L | Harmony nadir | ||

| SpaceX CRS-31 | September 2024 | Cargo Dragon | Uncrewed | Falcon 9 Block 5 | Harmony forward or zenith | ||

| AX-4 | October 2024 | Crew Dragon | Crewed | Falcon 9 Block 5 | Harmony forward | ||

| NG-22 | February 2025[298][299] | Cygnus | Uncrewed | Falcon 9 Block 5 | Unity nadir | ||

| Starliner-1 | March 2025[298][299] | Boeing Starliner SC-2 | Crewed | Atlas V N22 | Harmony forward | ||