НАСА

| |

| |

| Обзор агентства | |

|---|---|

| Аббревиатура | НАСА |

| Сформированный | 29 июля 1958 г |

| Предыдущее агентство | |

| Тип | Космическое агентство аэронавтических исследований Агентство |

| Юрисдикция | Федеральное правительство США |

| Штаб-квартира | Вашингтон, округ Колумбия 38 ° 52'59 "с.ш. 77 ° 0'59" з.д. / 38,88306 ° с.ш. 77,01639 ° з.д. |

| Билл Нельсон | |

| Заместитель администратора | Памела Мелрой |

| Основные космодромы | |

| Сотрудники | 17,960 (2022) [2] |

| Годовой бюджет | |

| Веб-сайт | nasa.gov |

| Часть серии о |

| Космическая программа США |

|---|

|

Национальное управление по аэронавтике и исследованию космического пространства ( НАСА ; / ˈ n æ s ə / ) — независимое агентство федерального правительства США , ответственное за гражданскую космическую программу , исследования в области аэронавтики и исследования космоса . Основанный в 1958 году , он стал преемником Национального консультативного комитета по аэронавтике (NACA) и придал усилиям США по освоению космоса четкую гражданскую ориентацию, уделяя особое внимание мирному применению космической науки . С тех пор он руководил большинством американских освоения космоса программ , включая проект «Меркурий» , проект «Близнецы» , «Аполлона» миссии по высадке на Луну в 1968–1972 годах , космическую станцию Скайлэб и космический шаттл . В настоящее время НАСА поддерживает Международную космическую станцию (МКС) вместе с Программой коммерческих экипажей и курирует разработку космического корабля «Орион» и системы космического запуска для лунной программы «Артемида» .

Научное подразделение НАСА сосредоточено на лучшем понимании Земли с помощью системы наблюдения Земли ; развитие гелиофизики благодаря усилиям Управления научной миссии Программы гелиофизических исследований ; исследование тел по всей Солнечной системе с помощью современных роботизированных космических кораблей, таких как « Новые горизонты» , и планетоходов, таких как «Персеверанс» ; и исследование тем астрофизики , таких как Большой взрыв , с помощью космического телескопа Джеймса Уэбба , Великих обсерваторий и связанных с ними программ. Программа пусковых услуг контролирует операции по запуску беспилотных запусков .

История

Создание

НАСА берет свое начало от Национального консультативного комитета по аэронавтике (NACA). Несмотря на то, что Соединенные Штаты были родиной авиации, к 1914 году Соединенные Штаты признали, что они сильно отстают от Европы в авиационных возможностях. Будучи преисполнен решимости вернуть себе лидерство Америки в авиации, Конгресс США в 1914 году создал Авиационную секцию Корпуса связи армии США, а в 1915 году учредил NACA для содействия авиационным исследованиям и разработкам. В течение следующих сорока лет NACA будет проводить авиационные исследования в поддержку ВВС США , армии США , ВМС США и сектора гражданской авиации. После окончания Второй мировой войны NACA заинтересовалась возможностями управляемых ракет и сверхзвуковых самолетов, разработав и испытав Bell X-1 в рамках совместной программы с ВВС США . Интерес NACA к космосу вырос из программы ракетной техники в Отделе исследований беспилотных летательных аппаратов. [4]

Запуск Советского Союза «Спутника-1» положил начало космической эпохе и положил начало космической гонке . Несмотря на раннюю программу ракетной техники NACA, ответственность за запуск первого американского спутника легла на Военно-морской исследовательской лаборатории , проект «Авангард» чьи оперативные проблемы позволили Армейскому агентству по баллистическим ракетам запустить «Эксплорер-1» , первый американский спутник, 1 февраля 1958 года.

Администрация Эйзенхауэра решила разделить военные и гражданские программы космических полетов США, которые были организованы совместно обороны Министерства Агентством перспективных исследовательских проектов . НАСА было создано 29 июля 1958 года с подписанием Национального закона об аэронавтике и космосе и начало свою деятельность 1 октября 1958 года. [4]

Будучи ведущим агентством по аэронавтике США, NACA сформировало ядро новой структуры НАСА, передав ему 8000 сотрудников и три крупные исследовательские лаборатории. НАСА также приступило к поглощению проекта «Авангард» Военно-морской исследовательской лаборатории, Армейской лаборатории реактивного движения (JPL) и Армейского агентства по баллистическим ракетам под руководством Вернера фон Брауна . В результате НАСА прочно стало лидером в гражданской космосе США, а ВВС - в качестве лидера в военной космосе. [4]

Первые орбитальные и гиперзвуковые полеты

Планы пилотируемых полетов в космос начались в Вооруженных силах США еще до создания НАСА. Самый ранний проект ВВС « Человек в космосе» , созданный в 1956 году. [5] вместе с армейским проектом «Адам» послужил основой для проекта «Меркурий» . НАСА создало Космическую целевую группу для управления программой. [6] который будет выполнять суборбитальные полеты с экипажем с помощью армейских ракет «Редстоун» ВВС и орбитальные полеты с помощью ракет-носителей «Атлас» . В то время как НАСА планировало, что первыми астронавтами будут гражданские лица, президент Эйзенхауэр распорядился отбирать их из числа военных. В состав астронавтов « Меркурия -7» входили три пилота ВВС, три авиатора ВМФ и один пилот морской пехоты. [4]

5 мая 1961 года Алан Шепард стал первым американцем, вышедшим в космос, совершив суборбитальный космический полет на корабле Freedom 7 . [7] Этот полет произошел менее чем через месяц после того, как советский Юрий Гагарин стал первым человеком в космосе, совершившим полный орбитальный космический полет. Первый орбитальный космический полет НАСА совершил Джон Гленн 20 февраля 1962 года на корабле «Дружба-7» , совершив три полных витка перед повторным входом. Гленну пришлось пролетать часть своих последних двух витков вручную из-за неисправности автопилота. [8] Шестую и последнюю миссию «Меркурий» совершил Гордон Купер в мае 1963 года, совершив 22 витка за 34 часа на аппарате Faith 7 . [9] Программа «Меркурий» получила широкое признание как ошеломляющий успех, достигшая своих целей по выводу человека на орбиту в космосе, разработке систем слежения и контроля, а также выявлению других проблем, связанных с полетами человека в космос. [4]

Хотя большая часть внимания НАСА была обращена на космос, оно не отказалось от своей авиационной миссии. Ранние исследования в области аэронавтики пытались использовать сверхзвуковой полет X-1 для создания самолета, способного совершать гиперзвуковые полеты . North American X-15 был совместной программой НАСА и ВВС США. [10] гиперзвуковой испытательный самолет стал первым неспециализированным космическим кораблем, совершившим переход из атмосферы в космическое пространство. X-15 также служил испытательным стендом для технологий программы «Аполлон», а также прямоточного и прямоточного воздушно- реактивного двигателя. [4]

Посадка на Луну

Эскалация холодной войны между Соединенными Штатами и Советским Союзом побудила президента Джона Ф. Кеннеди поручить НАСА высадить американца на Луну и благополучно вернуть его на Землю к концу 1960-х годов, а также назначить Джеймса Э. Уэбба администратором НАСА. для достижения этой цели. [11] 25 мая 1961 года президент Кеннеди открыто провозгласил эту цель в своей речи перед Конгрессом США «Неотложные национальные нужды», заявив:

Я считаю, что эта нация должна взять на себя обязательство до конца этого десятилетия высадить человека на Луну и благополучно вернуть его на Землю. Ни один космический проект в этот период не будет более впечатляющим для человечества или более важным для долгосрочного исследования космоса; и ни одно из них не будет столь трудным и дорогим в исполнении.

Кеннеди произнес свою речь « Мы выбираем полет на Луну » в следующем году, 12 сентября 1962 года, в Университете Райса , где он обратился к нации в надежде усилить общественную поддержку программы «Аполлон». [12]

Несмотря на нападки на цель высадки астронавтов на Луну со стороны бывшего президента Дуайта Эйзенхауэра и кандидата в президенты 1964 года Барри Голдуотера , президент Кеннеди смог защитить растущий бюджет НАСА, 50% которого шло непосредственно на пилотируемые космические полеты, и, как позже было подсчитано, на пике своего развития 5% американцев работали над тем или иным аспектом программы «Аполлон». [4]

Отражая концепцию управления программой Министерства обороны с использованием резервных систем при создании первых межконтинентальных баллистических ракет, НАСА обратилось к ВВС с просьбой назначить генерал-майора Сэмюэля Филлипса в космическое агентство, где он будет директором программы «Аполлон». Разработкой ракеты «Сатурн -5» руководил Вернер фон Браун и его команда в Центре космических полетов имени Маршалла Армейского агентства по баллистическим ракетам , созданной на основе оригинальной ракеты «Сатурн -1» . Космический корабль «Аполлон» был спроектирован и построен компанией North American Aviation , а лунный модуль «Аполлон» был спроектирован и построен компанией Grumman . [4]

Чтобы развить навыки космических полетов и оборудование, необходимые для лунной миссии, НАСА инициировало проект «Джемини» . [13] Используя модифицированную ракету-носитель Air Force Titan II , капсула Gemini могла вместить двух астронавтов для полетов продолжительностью более двух недель. «Джемини» были пионерами в использовании топливных элементов вместо батарей и провели первые американские выходы в открытый космос и операции по сближению .

Программа «Рейнджер» была начата в 1950-х годах как ответ на советское исследование Луны, однако большинство миссий закончилось неудачей. Программа Lunar Orbiter имела больший успех: она составила карту поверхности при подготовке к посадке Аполлона, провела измерения селенографии , провела обнаружение метеороидов и измерила уровни радиации. Программа Surveyor проводила беспилотные посадки и взлеты на Луну, а также наблюдения за поверхностью и реголитом. [4] Несмотря на неудачу, вызванную пожаром на Аполлоне- 1 , в результате которого погибли три астронавта, программа продолжилась.

«Аполлон -8» был первым пилотируемым космическим кораблем, покинувшим низкую околоземную орбиту , и первым космическим полетом человека, достигшим Луны . Экипаж десять раз облетел Луну 24 и 25 декабря 1968 года, а затем благополучно вернулся на Землю . [14] [15] [16] Три астронавта «Аполлона-8» — Фрэнк Борман , Джеймс Ловелл и Уильям Андерс — были первыми людьми, увидевшими Землю в виде шара в космосе, первыми, кто стал свидетелем восхода Земли , а также первыми, кто увидел и вручную сфотографировал обратную сторону Земли. Луна.

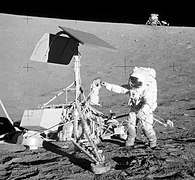

Первую высадку на Луну совершил «Аполлон- 11». Под командованием Нила Армстронга с астронавтами Баззом Олдрином и Майклом Коллинзом «Аполлон -11» стал одной из самых значительных миссий в истории НАСА, ознаменовавшей конец космической гонки, когда Советский Союз отказался от своей лунной миссии. амбиции. Нил Армстронг, первый человек, ступивший на поверхность Луны, произнес теперь знаменитые слова:

Это один маленький шаг для человека, но гигантский скачок для человечества.

НАСА осуществит шесть высадок на Луну в рамках программы «Аполлон», а «Аполлон -17» завершит программу в 1972 году. [4]

Конец Аполлона

Wernher von Braun had advocated for NASA to develop a space station since the agency was created. In 1973, following the end of the Apollo lunar missions, NASA launched its first space station, Skylab, on the final launch of the Saturn V. Skylab reused a significant amount of Apollo and Saturn hardware, with a repurposed Saturn V third stage serving as the primary module for the space station. Damage to Skylab during its launch required spacewalks to be performed by the first crew to make it habitable and operational. Skylab hosted nine missions and was decommissioned in 1974 and deorbited in 1979, two years prior to the first launch of the Space Shuttle and any possibility of boosting its orbit.[4]

In 1975, the Apollo–Soyuz mission was the first ever international spaceflight and a major diplomatic accomplishment between the Cold War rivals, which also marked the last flight of the Apollo capsule.[4] Flown in 1975, a U.S. Apollo spacecraft docked with a Soviet Soyuz capsule.

Interplanetary exploration and space science

During the 1960s, NASA started its space science and interplanetary probe program. The Mariner program was its flagship program, launching probes to Venus, Mars, and Mercury in the 1960s.[17][18] The Jet Propulsion Laboratory was the lead NASA center for robotic interplanetary exploration, making significant discoveries about the inner planets. Despite these successes, Congress was unwilling to fund further interplanetary missions and NASA Administrator James Webb suspended all future interplanetary probes to focus resources on the Apollo program.[4]

Following the conclusion of the Apollo program, NASA resumed launching interplanetary probes and expanded its space science program. The first planet tagged for exploration was Venus, sharing many similar characteristics to Earth. First visited by American Mariner 2 spacecraft,[19] Venus was observed to be a hot and inhospitable planet. Follow-on missions included the Pioneer Venus project in the 1970s and Magellan, which performed radar mapping of Venus' surface in the 1980s and 1990s. Future missions were flybys of Venus, on their way to other destinations in the Solar System.[4]

Mars has long been a planet of intense fascination for NASA, being suspected of potentially having harbored life. Mariner 5 was the first NASA spacecraft to flyby Mars,[20] followed by Mariner 6 and Mariner 7. Mariner 9 was the first orbital mission to Mars. Launched in 1975, Viking program consisted of two landings on Mars in 1976. Follow-on missions would not be launched until 1996, with the Mars Global Surveyor orbiter and Mars Pathfinder, deploying the first Mars rover, Sojourner.[21] During the early 2000s, the 2001 Mars Odyssey orbiter reached the planet and in 2004 the Sprit and Opportunity rovers landed on the Red Planet. This was followed in 2005 by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and 2007 Phoenix Mars lander. The 2012 landing of Curiosity discovered that the radiation levels on Mars were equal to those on the International Space Station, greatly increasing the possibility of Human exploration, and observed the key chemical ingredients for life to occur. In 2013, the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) mission observed the Martian upper atmosphere and space environment and in 2018, the Interior exploration using Seismic Investigations Geodesy, and Heat Transport (InSight) studied the Martian interior. The 2021 Perseverance rover carried the first extraplanetary aircraft, a helicopter named Ingenuity.[4]

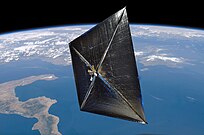

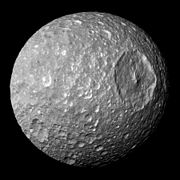

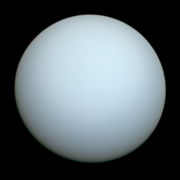

NASA also launched missions to Mercury in 2004, with the MESSENGER probe demonstrating as the first use of a solar sail.[22] NASA also launched probes to the outer Solar System starting in the 1960s. Pioneer 10 was the first probe to the outer planets, flying by Jupiter, while Pioneer 11 provided the first close up view of the planet. Both probes became the first objects to leave the Solar System. The Voyager program launched in 1977, conducting flybys of Jupiter and Saturn, Neptune, and Uranus on a trajectory to leave the Solar System.[23] The Galileo spacecraft, deployed from the Space Shuttle flight STS-34, was the first spacecraft to orbit Jupiter, discovering evidence of subsurface oceans on the Europa and observed that the moon may hold ice or liquid water.[24] A joint NASA-European Space Agency-Italian Space Agency mission, Cassini–Huygens, was sent to Saturn's moon Titan, which, along with Mars and Europa, are the only celestial bodies in the Solar System suspected of being capable of harboring life.[25] Cassini discovered three new moons of Saturn and the Huygens probe entered Titan's atmosphere. The mission discovered evidence of liquid hydrocarbon lakes on Titan and subsurface water oceans on the moon of Enceladus, which could harbor life. Finally launched in 2006, the New Horizons mission was the first spacecraft to visit Pluto and the Kuiper Belt.[4]

Beyond interplanetary probes, NASA has launched many space telescopes. Launched in the 1960s, the Orbiting Astronomical Observatory were NASA's first orbital telescopes,[26] providing ultraviolet, gamma-ray, x-ray, and infrared observations. NASA launched the Orbiting Geophysical Observatory in the 1960s and 1970s to look down at Earth and observe its interactions with the Sun. The Uhuru satellite was the first dedicated x-ray telescope, mapping 85% of the sky and discovering a large number of black holes.[4]

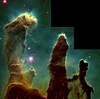

Launched in the 1990s and early 2000s, the Great Observatories program are among NASA's most powerful telescopes. The Hubble Space Telescope was launched in 1990 on STS-31 from the Discovery and could view galaxies 15 billion light years away.[27] A major defect in the telescope's mirror could have crippled the program, had NASA not used computer enhancement to compensate for the imperfection and launched five Space Shuttle servicing flights to replace the damaged components. The Compton Gamma Ray Observatory was launched from the Atlantis on STS-37 in 1991, discovering a possible source of antimatter at the center of the Milky Way and observing that the majority of gamma-ray bursts occur outside of the Milky Way galaxy. The Chandra X-ray Observatory was launched from the Columbia on STS-93 in 1999, observing black holes, quasars, supernova, and dark matter. It provided critical observations on the Sagittarius A* black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy and the separation of dark and regular matter during galactic collisions. Finally, the Spitzer Space Telescope is an infrared telescope launched in 2003 from a Delta II rocket. It is in a trailing orbit around the Sun, following the Earth and discovered the existence of brown dwarf stars.[4]

Other telescopes, such as the Cosmic Background Explorer and the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe, provided evidence to support the Big Bang.[28] The James Webb Space Telescope, named after the NASA administrator who lead the Apollo program, is an infrared observatory launched in 2021. The James Webb Space Telescope is a direct successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, intended to observe the formation of the first galaxies.[29] Other space telescopes include the Kepler space telescope, launched in 2009 to identify planets orbiting extrasolar stars that may be Terran and possibly harbor life. The first exoplanet that the Keplar space telescope confirmed was Kepler-22b, orbiting within the habitable zone of its star.[4]

NASA also launched a number of different satellites to study Earth, such as Television Infrared Observation Satellite (TIROS) in 1960, which was the first weather satellite.[30] NASA and the United States Weather Bureau cooperated on future TIROS and the second generation Nimbus program of weather satellites. It also worked with the Environmental Science Services Administration on a series of weather satellites and the agency launched its experimental Applications Technology Satellites into geosynchronous orbit. NASA's first dedicated Earth observation satellite, Landsat, was launched in 1972. This led to NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration jointly developing the Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite and discovering Ozone depletion.[4]

Space Shuttle

NASA had been pursuing spaceplane development since the 1960s, blending the administration's dual aeronautics and space missions. NASA viewed a spaceplane as part of a larger program, providing routine and economical logistical support to a space station in Earth orbit that would be used as a hub for lunar and Mars missions. A reusable launch vehicle would then have ended the need for expensive and expendable boosters like the Saturn V.[4]

In 1969, NASA designated the Johnson Space Center as the lead center for the design, development, and manufacturing of the Space Shuttle orbiter, while the Marshall Space Flight Center would lead the development of the launch system. NASA's series of lifting body aircraft, culminating in the joint NASA-U.S. Air Force Martin Marietta X-24, directly informed the development of the Space Shuttle and future hypersonic flight aircraft. Official development of the Space Shuttle began in 1972, with Rockwell International contracted to design the orbiter and engines, Martin Marietta for the external fuel tank, and Morton Thiokol for the solid rocket boosters.[31] NASA acquired six orbiters: the Enterprise, Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, Atlantis, and Endeavour[4]

The Space Shuttle program also allowed NASA to make major changes to its Astronaut Corps. While almost all previous astronauts were Air Force or Naval test pilots, the Space Shuttle allowed NASA to begin recruiting more non-military scientific and technical experts. A prime example is Sally Ride, who became the first American woman to fly in space on STS-7. This new astronaut selection process also allowed NASA to accept exchange astronauts from U.S. allies and partners for the first time.[4]

The first Space Shuttle flight occurred in 1981, when the Columbia launched on the STS-1 mission, designed to serve as a flight test for the new spaceplane.[32] NASA intended for the Space Shuttle to replace expendable launch systems like the Air Force's Atlas, Delta, and Titan and the European Space Agency's Ariane. The Space Shuttle's Spacelab payload, developed by the European Space Agency, increased the scientific capabilities of shuttle missions over anything NASA was able to previously accomplish.[4]

NASA launched its first commercial satellites on the STS-5 mission and in 1984, the STS-41-C mission conducted the world's first on-orbit satellite servicing mission when the Challenger captured and repaired the malfunctioning Solar Maximum Mission satellite. It also had the capability to return malfunctioning satellite to Earth, like it did with the Palapa B2 and Westar 6 satellites. Once returned to Earth, the satellites were repaired and relaunched.[4]

Despite ushering in a new era of spaceflight, where NASA was contracting launch services to commercial companies, the Space Shuttle was criticized for not being as reusable and cost-effective as advertised. In 1986, Challenger disaster on the STS-51L mission resulted in the loss of the spacecraft and all seven astronauts on launch, grounding the entire space shuttle fleet for 36 months and forced the 44 commercial companies that contracted with NASA to deploy their satellites to return to expendable launch vehicles.[33] When the Space Shuttle returned to flight with the STS-26 mission, it had undergone significant modifications to improve its reliability and safety.[4]

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russian Federation and United States initiated the Shuttle-Mir program.[34] The first Russian cosmonaut flew on the STS-60 mission in 1994 and the Discovery rendezvoused, but did not dock with, the Russian Mir in the STS-63 mission. This was followed by Atlantis' STS-71 mission where it accomplished the initial intended mission for the Space Shuttle, docking with a space station and transferring supplies and personnel. The Shuttle-Mir program would continue until 1998, when a series of orbital accidents on the space station spelled an end to the program.[4]

In 2003, a second space shuttle was destroyed when the Columbia was destroyed upon reentry during the STS-107 mission, resulting in the loss of the spacecraft and all seven astronauts.[35] This accident marked the beginning of the retiring of the Space Shuttle program, with President George W. Bush directing that upon the completion of the International Space Station, the space shuttle be retired. In 2006, the Space Shuttle returned to flight, conducting several mission to service the Hubble Space Telescope, but was retired following the STS-135 resupply mission to the International Space Station in 2011.

Space stations

NASA never gave up on the idea of a space station after Skylab's reentry in 1979. The agency began lobbying politicians to support building a larger space station as soon as the Space Shuttle began flying, selling it as an orbital laboratory, repair station, and a jumping off point for lunar and Mars missions. NASA found a strong advocate in President Ronald Reagan, who declared in a 1984 speech:

America has always been greatest when we dared to be great. We can reach for greatness again. We can follow our dreams to distant stars, living and working in space for peaceful, economic, and scientific gain. Tonight I am directing NASA to develop a permanently manned space station and to do it within a decade.

In 1985, NASA proposed the Space Station Freedom, which both the agency and President Reagan intended to be an international program.[36] While this would add legitimacy to the program, there were concerns within NASA that the international component would dilute its authority within the project, having never been willing to work with domestic or international partners as true equals. There was also a concern with sharing sensitive space technologies with the Europeans, which had the potential to dilute America's technical lead. Ultimately, an international agreement to develop the Space Station Freedom program would be signed with thirteen countries in 1985, including the European Space Agency member states, Canada, and Japan.[4]

Despite its status as the first international space program, the Space Station Freedom was controversial, with much of the debate centering on cost. Several redesigns to reduce cost were conducted in the early 1990s, stripping away much of its functions. Despite calls for Congress to terminate the program, it continued, in large part because by 1992 it had created 75,000 jobs across 39 states. By 1993, President Bill Clinton attempted to significantly reduce NASA's budget and directed costs be significantly reduced, aerospace industry jobs were not lost, and the Russians be included.[4]

In 1993, the Clinton Administration announced that the Space Station Freedom would become the International Space Station in an agreement with the Russian Federation.[37] This allowed the Russians to maintain their space program through an infusion of American currency to maintain their status as one of the two premier space programs. While the United States built and launched the majority of the International Space Station, Russia, Canada, Japan, and the European Space Agency all contributed components. Despite NASA's insistence that costs would be kept at a budget of $17.4, they kept rising and NASA had to transfer funds from other programs to keep the International Space Station solvent. Ultimately, the total cost of the station was $150 billion, with the United States paying for two-thirds.Following the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster in 2003, NASA was forced to rely on Russian Soyuz launches for its astronauts and the 2011 retirement of the Space Shuttle accelerated the station's completion.[4]

In the 1980s, right after the first flight of the Space Shuttle, NASA started a joint program with the Department of Defense to develop the Rockwell X-30 National Aerospace Plane. NASA realized that the Space Shuttle, while a massive technological accomplishment, would not be able to live up to all its promises. Designed to be a single-stage-to-orbit spaceplane, the X-30 had both civil and military applications. With the end of the Cold War, the X-30 was canceled in 1992 before reaching flight status.[4]

Unleashing commercial space and return to the Moon

Following the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster in 2003, President Bush started the Constellation program to smoothly replace the Space Shuttle and expand space exploration beyond low Earth orbit.[38] Constellation was intended to use a significant amount of former Space Shuttle equipment and return astronauts to the Moon. This program was canceled by the Obama Administration. Former astronauts Neil Armstrong, Gene Cernan, and Jim Lovell sent a letter to President Barack Obama to warn him that if the United States did not get new human spaceflight ability, the U.S. risked become a second or third-rate space power.[4]

As early as the Reagan Administration, there had been calls for NASA to expand private sector involvement in space exploration rather than do it all in-house. In the 1990s, NASA and Lockheed Martin entered into an agreement to develop the Lockheed Martin X-33 demonstrator of the VentureStar spaceplane, which was intended to replace the Space Shuttle.[39] Due to technical challenges, the spacecraft was cancelled in 2001. Despite this, it was the first time a commercial space company directly expended a significant amount of its resources into spacecraft development. The advent of space tourism also forced NASA to challenge its assumption that only governments would have people in space. The first space tourist was Dennis Tito, an American investment manager and former aerospace engineer who contracted with the Russians to fly to the International Space Station for four days, despite the opposition of NASA to the idea.[4]

Advocates of this new commercial approach for NASA included former astronaut Buzz Aldrin, who remarked that it would return NASA to its roots as a research and development agency, with commercial entities actually operating the space systems. Having corporations take over orbital operations would also allow NASA to focus all its efforts on deep space exploration and returning humans to the Moon and going to Mars. Embracing this approach, NASA's Commercial Crew Program started by contracting cargo delivery to the International Space Station and flew its first operational contracted mission on SpaceX Crew-1. This marked the first time since the retirement of the Space Shuttle that NASA was able to launch its own astronauts on an American spacecraft from the United States, ending a decade of reliance on the Russians.[4]

In 2019, NASA announced the Artemis program, intending to return to the Moon and establish a permanent human presence.[40] This was paired with the Artemis Accords with partner nations to establish rules of behavior and norms of space commercialization on the Moon.[41]

In 2023, NASA established the Moon to Mars Program office. The office is designed to oversee the various projects, mission architectures and associated timelines relevant to lunar and Mars exploration and science.[42]

Active programs

Human spaceflight

International Space Station (1993–present)

The International Space Station (ISS) combines NASA's Space Station Freedom project with the Russian Mir-2 station, the European Columbus station, and the Japanese Kibō laboratory module.[43] NASA originally planned in the 1980s to develop Freedom alone, but US budget constraints led to the merger of these projects into a single multi-national program in 1993, managed by NASA, the Russian Federal Space Agency (RKA), the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), the European Space Agency (ESA), and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA).[44][45] The station consists of pressurized modules, external trusses, solar arrays and other components, which were manufactured in various factories around the world and launched by Russian Proton and Soyuz rockets, and the American Space Shuttle.[43] The on-orbit assembly began in 1998, the completion of the US Orbital Segment occurred in 2009 and the completion of the Russian Orbital Segment occurred in 2010. The ownership and use of the space station is established in intergovernmental treaties and agreements,[46] which divide the station into two areas and allow Russia to retain full ownership of the Russian Orbital Segment (with the exception of Zarya),[47][48] with the US Orbital Segment allocated between the other international partners.[46]

Long-duration missions to the ISS are referred to as ISS Expeditions. Expedition crew members typically spend approximately six months on the ISS.[49] The initial expedition crew size was three, temporarily decreased to two following the Columbia disaster. Between May 2009 and until the retirement of the Space Shuttle, the expedition crew size has been six crew members.[50] As of 2024, though the Commercial Program's crew capsules can allow a crew of up to seven, expeditions using them typically consist of a crew of four. The ISS has been continuously occupied for the past 23 years and 232 days, having exceeded the previous record held by Mir; and has been visited by astronauts and cosmonauts from 15 different nations.[51][52]

The station can be seen from the Earth with the naked eye and, as of 2024, is the largest artificial satellite in Earth orbit with a mass and volume greater than that of any previous space station.[53] The Russian Soyuz and American Dragon and Starliner spacecraft are used to send astronauts to and from the ISS. Several uncrewed cargo spacecraft provide service to the ISS; they are the Russian Progress spacecraft which has done so since 2000, the European Automated Transfer Vehicle (ATV) since 2008, the Japanese H-II Transfer Vehicle (HTV) since 2009, the (uncrewed) Dragon since 2012, and the American Cygnus spacecraft since 2013.[54][55] The Space Shuttle, before its retirement, was also used for cargo transfer and would often switch out expedition crew members, although it did not have the capability to remain docked for the duration of their stay. Between the retirement of the Shuttle in 2011 and the commencement of crewed Dragon flights in 2020, American astronauts exclusively used the Soyuz for crew transport to and from the ISS[56] The highest number of people occupying the ISS has been thirteen; this occurred three times during the late Shuttle ISS assembly missions.[57]

The ISS program is expected to continue until 2030,[58] after which the space station will be retired and destroyed in a controlled de-orbit.[59]

Commercial Resupply Services (2008–present)

Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) are a contract solution to deliver cargo and supplies to the International Space Station on a commercial basis by private companies.[60] NASA signed its first CRS contracts in 2008 and awarded $1.6 billion to SpaceX for twelve cargo Dragon and $1.9 billion to Orbital Sciences[note 1] for eight Cygnus flights, covering deliveries until 2016. Both companies evolved or created their launch vehicle products to launch the spacecrafts (SpaceX with The Falcon 9 and Orbital with the Antares).

SpaceX flew its first operational resupply mission (SpaceX CRS-1) in 2012.[61] Orbital Sciences followed in 2014 (Cygnus CRS Orb-1).[62] In 2015, NASA extended CRS-1 to twenty flights for SpaceX and twelve flights for Orbital ATK.[note 1][63][64]

A second phase of contracts (known as CRS-2) was solicited in 2014; contracts were awarded in January 2016 to Orbital ATK[note 1] Cygnus, Sierra Nevada Corporation Dream Chaser, and SpaceX Dragon 2, for cargo transport flights beginning in 2019 and expected to last through 2024. In March 2022, NASA awarded an additional six CRS-2 missions each to both SpaceX and Northrop Grumman (formerly Orbital).[65]

Northrop Grumman successfully delivered Cygnus NG-17 to the ISS in February 2022.[66] In July 2022, SpaceX launched its 25th CRS flight (SpaceX CRS-25) and successfully delivered its cargo to the ISS.[67] The Dream Chaser spacecraft is currently scheduled for its Demo-1 launch in the first half of 2024.[68]

Commercial Crew Program (2011–present)

The Commercial Crew Program (CCP) provides commercially operated crew transportation service to and from the International Space Station (ISS) under contract to NASA, conducting crew rotations between the expeditions of the International Space Station program. American space manufacturer SpaceX began providing service in 2020, using the Crew Dragon spacecraft,[69] while Boeing's Starliner spacecraft began providing service in 2024.[70][71][72] NASA has contracted for six operational missions from Boeing and fourteen from SpaceX, ensuring sufficient support for ISS through 2030.[73]

The spacecraft are owned and operated by the vendor, and crew transportation is provided to NASA as a commercial service.[74] Each mission sends up to four astronauts to the ISS, with an option for a fifth passenger available. Operational flights occur approximately once every six months for missions that last for approximately six months. A spacecraft remains docked to the ISS during its mission, and missions usually overlap by at least a few days. Between the retirement of the Space Shuttle in 2011 and the first operational CCP mission in 2020, NASA relied on the Soyuz program to transport its astronauts to the ISS.

A Crew Dragon spacecraft is launched to space atop a Falcon 9 Block 5 launch vehicle and the capsule returns to Earth via splashdown in the ocean near Florida. The program's first operational mission, SpaceX Crew-1, launched on November 16, 2020.[75] Boeing Starliner operational flights will now commence with Boeing Starliner-1 which will launched atop an Atlas V N22 launch vehicle. Instead of a splashdown, Starliner capsules return on land with airbags at one of four designated sites in the western United States.[76]

Artemis (2017–present)

Since 2017, NASA's crewed spaceflight program has been the Artemis program, which involves the help of US commercial spaceflight companies and international partners such as ESA, JAXA, and CSA.[77] The goal of this program is to land "the first woman and the next man" on the lunar south pole region by 2025. Artemis would be the first step towards the long-term goal of establishing a sustainable presence on the Moon, laying the foundation for companies to build a lunar economy, and eventually sending humans to Mars.

The Orion Crew Exploration Vehicle was held over from the canceled Constellation program for Artemis. Artemis 1 was the uncrewed initial launch of Space Launch System (SLS) that would also send an Orion spacecraft on a Distant Retrograde Orbit.[78]

NASA's next major space initiative is to be the construction of the Lunar Gateway, a small space station in lunar orbit.[79] This space station will be designed primarily for non-continuous human habitation. The first tentative steps of returning to crewed lunar missions will be Artemis 2, which is to include the Orion crew module, propelled by the SLS, and is to launch in 2025.[77][80] This mission is to be a 10-day mission planned to briefly place a crew of four into a Lunar flyby.[81] The construction of the Gateway would begin with the proposed Artemis 3, which is planned to deliver a crew of four to Lunar orbit along with the first modules of the Gateway. This mission would last for up to 30 days. NASA plans to build full scale deep space habitats such as the Lunar Gateway and the Nautilus-X as part of its Next Space Technologies for Exploration Partnerships (NextSTEP) program.[82] In 2017, NASA was directed by the congressional NASA Transition Authorization Act of 2017 to get humans to Mars-orbit (or to the Martian surface) by the 2030s.[83][84]

In support of the Artemis missions, NASA has been funding private companies to land robotic probes on the lunar surface in a program known as the Commercial Lunar Payload Services. As of March 2022, NASA has awarded contracts for robotic lunar probes to companies such as Intuitive Machines, Firefly Space Systems, and Astrobotic.[85]

On April 16, 2021, NASA announced they had selected the SpaceX Lunar Starship as its Human Landing System. The agency's Space Launch System rocket will launch four astronauts aboard the Orion spacecraft for their multi-day journey to lunar orbit where they will transfer to SpaceX's Starship for the final leg of their journey to the surface of the Moon.[86]

In November 2021, it was announced that the goal of landing astronauts on the Moon by 2024 had slipped to no earlier than 2025 due to numerous factors. Artemis 1 launched on November 16, 2022, and returned to Earth safely on December 11, 2022. As of April 2024, NASA plans to launch Artemis 2 in September 2025[87] and Artemis 3 in September 2026.[88] Additional Artemis missions, Artemis 4, Artemis 5, and Artemis 6 are planned to launch between 2028 and 2031.[89]

Commercial LEO Development (2021–present)

The Commercial Low Earth Orbit Destinations program is an initiative by NASA to support work on commercial space stations that the agency hopes to have in place by the end of the current decade to replace the "International Space Station". The three selected companies are: Blue Origin (et al.) with their Orbital Reef station concept, Nanoracks (et al.) with their Starlab Space Station concept, and Northrop Grumman with a station concept based on the HALO-module for the Gateway station.[90]

Robotic exploration

NASA has conducted many uncrewed and robotic spaceflight programs throughout its history. More than 1,000 uncrewed missions have been designed to explore the Earth and the Solar System.[91]

Mission selection process

NASA executes a mission development framework to plan, select, develop, and operate robotic missions. This framework defines cost, schedule and technical risk parameters to enable competitive selection of missions involving mission candidates that have been developed by principal investigators and their teams from across NASA, the broader U.S. Government research and development stakeholders, and industry. The mission development construct is defined by four umbrella programs.[92]

Explorer program

The Explorer program derives its origin from the earliest days of the U.S. Space program. In current form, the program consists of three classes of systems – Small Explorers (SMEX), Medium Explorers (MIDEX), and University-Class Explorers (UNEX) missions. The NASA Explorer program office provides frequent flight opportunities for moderate cost innovative solutions from the heliophysics and astrophysics science areas. The Small Explorer missions are required to limit cost to NASA to below $150M (2022 dollars). Medium class explorer missions have typically involved NASA cost caps of $350M. The Explorer program office is based at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.[93]

Discovery program

The NASA Discovery program develops and delivers robotic spacecraft solutions in the planetary science domain. Discovery enables scientists and engineers to assemble a team to deliver a solution against a defined set of objectives and competitively bid that solution against other candidate programs. Cost caps vary but recent mission selection processes were accomplished using a $500M cost cap for NASA. The Planetary Mission Program Office is based at the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center and manages both the Discovery and New Frontiers missions. The office is part of the Science Mission Directorate.[94]

NASA Administrator Bill Nelson announced on June 2, 2021, that the DAVINCI+ and VERITAS missions were selected to launch to Venus in the late 2020s, having beat out competing proposals for missions to Jupiter's volcanic moon Io and Neptune's large moon Triton that were also selected as Discovery program finalists in early 2020. Each mission has an estimated cost of $500 million, with launches expected between 2028 and 2030. Launch contracts will be awarded later in each mission's development.[95]

New Frontiers program

The New Frontiers program focuses on specific Solar System exploration goals identified as top priorities by the planetary science community. Primary objectives include Solar System exploration employing medium class spacecraft missions to conduct high-science-return investigations. New Frontiers builds on the development approach employed by the Discovery program but provides for higher cost caps and schedule durations than are available with Discovery. Cost caps vary by opportunity; recent missions have been awarded based on a defined cap of $1 billion. The higher cost cap and projected longer mission durations result in a lower frequency of new opportunities for the program – typically one every several years. OSIRIS-REx and New Horizons are examples of New Frontiers missions.[96]

NASA has determined that the next opportunity to propose for the fifth round of New Frontiers missions will occur no later than the fall of 2024. Missions in NASA's New Frontiers Program tackle specific Solar System exploration goals identified as top priorities by the planetary science community. Exploring the Solar System with medium-class spacecraft missions that conduct high-science-return investigations is NASA's strategy to further understand the Solar System.[97]

Large strategic missions

Large strategic missions (formerly called Flagship missions) are strategic missions that are typically developed and managed by large teams that may span several NASA centers. The individual missions become the program as opposed to being part of a larger effort (see Discovery, New Frontiers, etc.). The James Webb Space Telescope is a strategic mission that was developed over a period of more than 20 years. Strategic missions are developed on an ad-hoc basis as program objectives and priorities are established. Missions like Voyager, had they been developed today, would have been strategic missions. Three of the Great Observatories were strategic missions (the Chandra X-ray Observatory, the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory, and the Hubble Space Telescope). Europa Clipper is the next large strategic mission in development by NASA.[98]

Planetary science missions

NASA continues to play a material role in exploration of the Solar System as it has for decades. Ongoing missions have current science objectives with respect to more than five extraterrestrial bodies within the Solar System – Moon (Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter), Mars (Perseverance rover), Jupiter (Juno), asteroid Bennu (OSIRIS-REx), and Kuiper Belt Objects (New Horizons). The Juno extended mission will make multiple flybys of the Jovian moon Io in 2023 and 2024 after flybys of Ganymede in 2021 and Europa in 2022. Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 continue to provide science data back to Earth while continuing on their outward journeys into interstellar space.

On November 26, 2011, NASA's Mars Science Laboratory mission was successfully launched for Mars. The Curiosity rover successfully landed on Mars on August 6, 2012, and subsequently began its search for evidence of past or present life on Mars.[99][100][101]

In September 2014, NASA's MAVEN spacecraft, which is part of the Mars Scout Program, successfully entered Mars orbit and, as of October 2022, continues its study of the atmosphere of Mars.[102][103] NASA's ongoing Mars investigations include in-depth surveys of Mars by the Perseverance rover and InSight).

NASA's Europa Clipper, planned for launch in October 2024, will study the Galilean moon Europa through a series of flybys while in orbit around Jupiter. Dragonfly will send a mobile robotic rotorcraft to Saturn's biggest moon, Titan.[104] As of May 2021, Dragonfly is scheduled for launch in June 2027.[105][106]

Astrophysics missions

The NASA Science Mission Directorate Astrophysics division manages the agency's astrophysics science portfolio. NASA has invested significant resources in the development, delivery, and operations of various forms of space telescopes. These telescopes have provided the means to study the cosmos over a large range of the electromagnetic spectrum.[107]

The Great Observatories that were launched in the 1980s and 1990s have provided a wealth of observations for study by physicists across the planent. The first of them, the Hubble Space Telescope, was delivered to orbit in 1990 and continues to function, in part due to prior servicing missions performed by the Space Shuttle.[108][109] The other remaining active great observatories include the Chandra X-ray Observatory (CXO), launched by STS-93 in July 1999 and is now in a 64-hour elliptical orbit studying X-ray sources that are not readily viewable from terrestrial observatories.[110]

The Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer (IXPE) is a space observatory designed to improve the understanding of X-ray production in objects such as neutron stars and pulsar wind nebulae, as well as stellar and supermassive black holes.[111] IXPE launched in December 2021 and is an international collaboration between NASA and the Italian Space Agency (ASI). It is part of the NASA Small Explorers program (SMEX) which designs low-cost spacecraft to study heliophysics and astrophysics.[112]

The Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory was launched in November 2004 and is Gamma-ray burst observatory that also monitors the afterglow in X-ray, and UV/Visible light at the location of a burst.[113] The mission was developed in a joint partnership between Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) and an international consortium from the United States, United Kingdom, and Italy. Pennsylvania State University operates the mission as part of NASA's Medium Explorer program (MIDEX).[114]

The Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope (FGST) is another gamma-ray focused space observatory that was launched to low Earth orbit in June 2008 and is being used to perform gamma-ray astronomy observations.[115] In addition to NASA, the mission involves the United States Department of Energy, and government agencies in France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and Sweden.[116]

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), launched in December 2021 on an Ariane 5 rocket, operates in a halo orbit circling the Sun-Earth L2 point.[117][118][119] JWST's high sensitivity in the infrared spectrum and its imaging resolution will allow it to view more distant, faint, or older objects than its predecessors, including Hubble.[120]

Earth Sciences Program missions (1965–present)

NASA Earth Science is a large, umbrella program comprising a range of terrestrial and space-based collection systems in order to better understand the Earth system and its response to natural and human-caused changes. Numerous systems have been developed and fielded over several decades to provide improved prediction for weather, climate, and other changes in the natural environment. Several of the current operating spacecraft programs include: Aqua,[121] Aura,[122] Orbiting Carbon Observatory 2 (OCO-2),[123] Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment Follow-on (GRACE FO),[124] and Ice, Cloud, and land Elevation Satellite 2 (ICESat-2).[125]

In addition to systems already in orbit, NASA is designing a new set of Earth Observing Systems to study, assess, and generate responses for climate change, natural hazards, forest fires, and real-time agricultural processes.[126] The GOES-T satellite (designated GOES-18 after launch) joined the fleet of U.S. geostationary weather monitoring satellites in March 2022.[127]

NASA also maintains the Earth Science Data Systems (ESDS) program to oversee the life cycle of NASA's Earth science data — from acquisition through processing and distribution. The primary goal of ESDS is to maximize the scientific return from NASA's missions and experiments for research and applied scientists, decision makers, and society at large.[128]

The Earth Science program is managed by the Earth Science Division of the NASA Science Mission Directorate.

Space operations architecture

NASA invests in various ground and space-based infrastructures to support its science and exploration mandate. The agency maintains access to suborbital and orbital space launch capabilities and sustains ground station solutions to support its evolving fleet of spacecraft and remote systems.

Deep Space Network (1963–present)

The NASA Deep Space Network (DSN) serves as the primary ground station solution for NASA's interplanetary spacecraft and select Earth-orbiting missions.[129] The system employs ground station complexes near Barstow California in the United States, in Spain near Madrid, and in Australia near Canberra. The placement of these ground stations approximately 120 degrees apart around the planet provides the ability for communications to spacecraft throughout the Solar System even as the Earth rotates about its axis on a daily basis. The system is controlled at a 24x7 operations center at JPL in Pasadena California which manages recurring communications linkages with up to 40 spacecraft.[130] The system is managed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.[129]

Near Space Network (1983–present)

The Near Space Network (NSN) provides telemetry, commanding, ground-based tracking, data and communications services to a wide range of customers with satellites in low earth orbit (LEO), geosynchronous orbit (GEO), highly elliptical orbits (HEO), and lunar orbits. The NSN accumulates ground station and antenna assets from the Near-Earth Network and the Tracking and Data Relay Satellite System (TDRS) which operates in geosynchronous orbit providing continuous real-time coverage for launch vehicles and low earth orbit NASA missions.[131]

The NSN consists of 19 ground stations worldwide operated by the US Government and by contractors including Kongsberg Satellite Services (KSAT), Swedish Space Corporation (SSC), and South African National Space Agency (SANSA).[132] The ground network averages between 120 and 150 spacecraft contacts a day with TDRS engaging with systems on a near-continuous basis as needed; the system is managed and operated by the Goddard Space Flight Center.[133]

Sounding Rocket Program (1959–present)

The NASA Sounding Rocket Program (NSRP) is located at the Wallops Flight Facility and provides launch capability, payload development and integration, and field operations support to execute suborbital missions.[134] The program has been in operation since 1959 and is managed by the Goddard Space Flight Center using a combined US Government and contractor team.[135] The NSRP team conducts approximately 20 missions per year from both Wallops and other launch locations worldwide to allow scientists to collect data "where it occurs". The program supports the strategic vision of the Science Mission Directorate collecting important scientific data for earth science, heliophysics, and astrophysics programs.[134]

In June 2022, NASA conducted its first rocket launch from a commercial spaceport outside the US. It launched a Black Brant IX from the Arnhem Space Centre in Australia.[136]

Launch Services Program (1990–present)

The NASA Launch Services Program (LSP) is responsible for procurement of launch services for NASA uncrewed missions and oversight of launch integration and launch preparation activity, providing added quality and mission assurance to meet program objectives.[137] Since 1990, NASA has purchased expendable launch vehicle launch services directly from commercial providers, whenever possible, for its scientific and applications missions. Expendable launch vehicles can accommodate all types of orbit inclinations and altitudes and are ideal vehicles for launching Earth-orbit and interplanetary missions. LSP operates from Kennedy Space Center and falls under the NASA Space Operations Mission Directorate (SOMD).[138][139]

Aeronautics Research

The Aeronautics Research Mission Directorate (ARMD) is one of five mission directorates within NASA, the other four being the Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate, the Space Operations Mission Directorate, the Science Mission Directorate, and the Space Technology Mission Directorate.[140] The ARMD is responsible for NASA's aeronautical research, which benefits the commercial, military, and general aviation sectors. ARMD performs its aeronautics research at four NASA facilities: Ames Research Center and Armstrong Flight Research Center in California, Glenn Research Center in Ohio, and Langley Research Center in Virginia.[141]

NASA X-57 Maxwell aircraft (2016–present)

The NASA X-57 Maxwell is an experimental aircraft being developed by NASA to demonstrate the technologies required to deliver a highly efficient all-electric aircraft.[142] The primary goal of the program is to develop and deliver all-electric technology solutions that can also achieve airworthiness certification with regulators. The program involves development of the system in several phases, or modifications, to incrementally grow the capability and operability of the system. The initial configuration of the aircraft has now completed ground testing as it approaches its first flights. In mid-2022, the X-57 was scheduled to fly before the end of the year.[143] The development team includes staff from the NASA Armstrong, Glenn, and Langley centers along with number of industry partners from the United States and Italy.[144]

Next Generation Air Transportation System (2007–present)

NASA is collaborating with the Federal Aviation Administration and industry stakeholders to modernize the United States National Airspace System (NAS). Efforts began in 2007 with a goal to deliver major modernization components by 2025.[145] The modernization effort intends to increase the safety, efficiency, capacity, access, flexibility, predictability, and resilience of the NAS while reducing the environmental impact of aviation.[146] The Aviation Systems Division of NASA Ames operates the joint NASA/FAA North Texas Research Station. The station supports all phases of NextGen research, from concept development to prototype system field evaluation. This facility has already transitioned advanced NextGen concepts and technologies to use through technology transfers to the FAA.[145] NASA contributions also include development of advanced automation concepts and tools that provide air traffic controllers, pilots, and other airspace users with more accurate real-time information about the nation's traffic flow, weather, and routing. Ames' advanced airspace modeling and simulation tools have been used extensively to model the flow of air traffic flow across the U.S., and to evaluate new concepts in airspace design, traffic flow management, and optimization.[147]

Technology research

Nuclear in-space power and propulsion (ongoing)

NASA has made use of technologies such as the multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator (MMRTG), which is a type of radioisotope thermoelectric generator used to power spacecraft.[148] Shortages of the required plutonium-238 have curtailed deep space missions since the turn of the millennium.[149] An example of a spacecraft that was not developed because of a shortage of this material was New Horizons 2.[149]

In July 2021, NASA announced contract awards for development of nuclear thermal propulsion reactors. Three contractors will develop individual designs over 12 months for later evaluation by NASA and the U.S. Department of Energy.[150] NASA's space nuclear technologies portfolio are led and funded by its Space Technology Mission Directorate.

In January 2023, NASA announced a partnership with Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) on the Demonstration Rocket for Agile Cislunar Operations (DRACO) program to demonstrate a NTR engine in space, an enabling capability for NASA missions to Mars.[151] In July 2023, NASA and DARPA jointly announced the award of $499 million to Lockheed Martin to design and build an experimental NTR rocket to be launched in 2027.[152]

Other initiatives

Free Space Optics. NASA contracted a third party to study the probability of using Free Space Optics (FSO) to communicate with Optical (laser) Stations on the Ground (OGS) called laser-com RF networks for satellite communications.[153]

Water Extraction from Lunar Soil. On July 29, 2020, NASA requested American universities to propose new technologies for extracting water from the lunar soil and developing power systems. The idea will help the space agency conduct sustainable exploration of the Moon.[154]

In 2024, NASA was tasked by the US Government to create a Time standard for the Moon. The standard is to be called Coordinated Lunar Time and is expected to be finalized in 2026.[155]

Human Spaceflight Research (2005–present)

NASA's Human Research Program (HRP) is designed to study the effects of space on human health and also to provide countermeasures and technologies for human space exploration.[156] The medical effects of space exploration are reasonably limited in low Earth orbit or in travel to the Moon. Travel to Mars is significantly longer and deeper into space, significant medical issues can result. These include bone density loss, radiation exposure, vision changes, circadian rhythm disturbances, heart remodeling, and immune alterations. In order to study and diagnose these ill-effects, HRP has been tasked with identifying or developing small portable instrumentation with low mass, volume, and power to monitor the health of astronauts.[157] To achieve this aim, on May 13, 2022, NASA and SpaceX Crew-4 astronauts successfully tested its rHEALTH ONE universal biomedical analyzer for its ability to identify and analyzer biomarkers, cells, microorganisms, and proteins in a spaceflight environment.[158]

Planetary Defense (2016–present)

NASA established the Planetary Defense Coordination Office (PDCO) in 2016 to catalog and track potentially hazardous near-Earth objects (NEO), such as asteroids and comets and develop potential responses and defenses against these threats.[159] The PDCO is chartered to provide timely and accurate information to the government and the public on close approaches by Potentially hazardous objects (PHOs) and any potential for impact. The office functions within the Science Mission Directorate Planetary Science division.[160]

The PDCO augmented prior cooperative actions between the United States, the European Union, and other nations which had been scanning the sky for NEOs since 1998 in an effort called Spaceguard.[161]

Near Earth object detection (1998–present)

From the 1990s NASA has run many NEO detection programs from Earth bases observatories, greatly increasing the number of objects that have been detected. Many asteroids are very dark and those near the Sun are much harder to detect from Earth-based telescopes which observe at night, and thus face away from the Sun. NEOs inside Earth orbit only reflect a part of light also rather than potentially a "full Moon" when they are behind the Earth and fully lit by the Sun.[162]

In 1998, the United States Congress gave NASA a mandate to detect 90% of near-Earth asteroids over 1 km (0.62 mi) diameter (that threaten global devastation) by 2008.[163] This initial mandate was met by 2011.[164] In 2005, the original USA Spaceguard mandate was extended by the George E. Brown, Jr. Near-Earth Object Survey Act, which calls for NASA to detect 90% of NEOs with diameters of 140 m (460 ft) or greater, by 2020 (compare to the 20-meter Chelyabinsk meteor that hit Russia in 2013).[165] As of January 2020[update], it is estimated that less than half of these have been found, but objects of this size hit the Earth only about once in 2,000 years.[166]

In January 2020, NASA officials estimated it would take 30 years to find all objects meeting the 140 m (460 ft) size criteria, more than twice the timeframe that was built into the 2005 mandate.[167] In June 2021, NASA authorized the development of the NEO Surveyor spacecraft to reduce that projected duration to achieve the mandate down to 10 years.[168][169]

Involvement in current robotic missions

NASA has incorporated planetary defense objectives into several ongoing missions.

In 1999, NASA visited 433 Eros with the NEAR Shoemaker spacecraft which entered its orbit in 2000, closely imaging the asteroid with various instruments at that time.[170] NEAR Shoemaker became the first spacecraft to successfully orbit and land on an asteroid, improving our understanding of these bodies and demonstrating our capacity to study them in greater detail.[171]

OSIRIS-REx used its suite of instruments to transmit radio tracking signals and capture optical images of Bennu during its study of the asteroid that will help NASA scientists determine its precise position in the solar system and its exact orbital path. As Bennu has the potential for recurring approaches to the Earth-Moon system in the next 100–200 years, the precision gained from OSIRIS-REx will enable scientists to better predict the future gravitational interactions between Bennu and our planet and resultant changes in Bennu's onward flight path.[172][173]

The WISE/NEOWISE mission was launched by NASA JPL in 2009 as an infrared-wavelength astronomical space telescope. In 2013, NASA repurposed it as the NEOWISE mission to find potentially hazardous near-Earth asteroids and comets; its mission has been extended into 2023.[174][175]

NASA and Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (JHAPL) jointly developed the first planetary defense purpose-built satellite, the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) to test possible planetary defense concepts.[176] DART was launched in November 2021 by a SpaceX Falcon 9 from California on a trajectory designed to impact the Dimorphos asteroid. Scientists were seeking to determine whether an impact could alter the subsequent path of the asteroid; a concept that could be applied to future planetary defense.[177] On September 26, 2022, DART hit its target. In the weeks following impact, NASA declared DART a success, confirming it had shortened Dimorphos' orbital period around Didymos by about 32 minutes, surpassing the pre-defined success threshold of 73 seconds.[178][179]

NEO Surveyor, formerly called the Near-Earth Object Camera (NEOCam) mission, is a space-based infrared telescope under development to survey the Solar System for potentially hazardous asteroids.[180] The spacecraft is scheduled to launch in 2026.

Study of Unidentified Aerial Phenomena (2022–present)

In June 2022, the head of the NASA Science Mission Directorate, Thomas Zurbuchen, confirmed the start of NASA's UAP independent study team.[181] At a speech before the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine, Zurbuchen said the space agency would bring a scientific perspective to efforts already underway by the Pentagon and intelligence agencies to make sense of dozens of such sightings. He said it was "high-risk, high-impact" research that the space agency should not shy away from, even if it is a controversial field of study.[182]

Collaboration

NASA Advisory Council

In response to the Apollo 1 accident, which killed three astronauts in 1967, Congress directed NASA to form an Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel (ASAP) to advise the NASA Administrator on safety issues and hazards in NASA's air and space programs. In the aftermath of the Shuttle Columbia disaster, Congress required that the ASAP submit an annual report to the NASA Administrator and to Congress.[183] By 1971, NASA had also established the Space Program Advisory Council and the Research and Technology Advisory Council to provide the administrator with advisory committee support. In 1977, the latter two were combined to form the NASA Advisory Council (NAC).[184] The NASA Authorization Act of 2014 reaffirmed the importance of ASAP.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

NASA and NOAA have cooperated for decades on the development, delivery and operation of polar and geosynchronous weather satellites.[185] The relationship typically involves NASA developing the space systems, launch solutions, and ground control technology for the satellites and NOAA operating the systems and delivering weather forecasting products to users. Multiple generations of NOAA Polar orbiting platforms have operated to provide detailed imaging of weather from low altitude.[186] Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites (GOES) provide near-real-time coverage of the western hemisphere to ensure accurate and timely understanding of developing weather phenomenon.[187]

United States Space Force

The United States Space Force (USSF) is the space service branch of the United States Armed Forces, while the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) is an independent agency of the United States government responsible for civil spaceflight. NASA and the Space Force's predecessors in the Air Force have a long-standing cooperative relationship, with the Space Force supporting NASA launches out of Kennedy Space Center, Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, and Vandenberg Space Force Base, to include range support and rescue operations from Task Force 45.[188] NASA and the Space Force also partner on matters such as defending Earth from asteroids.[189] Space Force members can be NASA astronauts, with Colonel Michael S. Hopkins, the commander of SpaceX Crew-1, commissioned into the Space Force from the International Space Station on December 18, 2020.[190][191][192] In September 2020, the Space Force and NASA signed a memorandum of understanding formally acknowledging the joint role of both agencies. This new memorandum replaced a similar document signed in 2006 between NASA and Air Force Space Command.[193][194]

U.S. Geological Survey

The Landsat program is the longest-running enterprise for acquisition of satellite imagery of Earth. It is a joint NASA / USGS program.[195] On July 23, 1972, the Earth Resources Technology Satellite was launched. This was eventually renamed to Landsat 1 in 1975.[196] The most recent satellite in the series, Landsat 9, was launched on September 27, 2021.[197]

The instruments on the Landsat satellites have acquired millions of images. The images, archived in the United States and at Landsat receiving stations around the world, are a unique resource for global change research and applications in agriculture, cartography, geology, forestry, regional planning, surveillance and education, and can be viewed through the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) "EarthExplorer" website. The collaboration between NASA and USGS involves NASA designing and delivering the space system (satellite) solution, launching the satellite into orbit with the USGS operating the system once in orbit.[195] As of October 2022, nine satellites have been built with eight of them successfully operating in orbit.

European Space Agency (ESA)

NASA collaborates with the European Space Agency on a wide range of scientific and exploration requirements.[198] From participation with the Space Shuttle (the Spacelab missions) to major roles on the Artemis program (the Orion Service Module), ESA and NASA have supported the science and exploration missions of each agency. There are NASA payloads on ESA spacecraft and ESA payloads on NASA spacecraft. The agencies have developed joint missions in areas including heliophysics (e.g. Solar Orbiter)[199] and astronomy (Hubble Space Telescope, James Webb Space Telescope).[200]

Under the Artemis Gateway partnership, ESA will contribute habitation and refueling modules, along with enhanced lunar communications, to the Gateway.[201][202] NASA and ESA continue to advance cooperation in relation to Earth Science including climate change with agreements to cooperate on various missions including the Sentinel-6 series of spacecraft[203]

Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA)

NASA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) cooperate on a range of space projects. JAXA is a direct participant in the Artemis program, including the Lunar Gateway effort. JAXA's planned contributions to Gateway include I-Hab's environmental control and life support system, batteries, thermal control, and imagery components, which will be integrated into the module by the European Space Agency (ESA) prior to launch. These capabilities are critical for sustained Gateway operations during crewed and uncrewed time periods.[204][205]

JAXA and NASA have collaborated on numerous satellite programs, especially in areas of Earth science. NASA has contributed to JAXA satellites and vice versa. Japanese instruments are flying on NASA's Terra and Aqua satellites, and NASA sensors have flown on previous Japanese Earth-observation missions. The NASA-JAXA Global Precipitation Measurement mission was launched in 2014 and includes both NASA- and JAXA-supplied sensors on a NASA satellite launched on a JAXA rocket. The mission provides the frequent, accurate measurements of rainfall over the entire globe for use by scientists and weather forecasters.[206]

Roscosmos

NASA and Roscosmos have cooperated on the development and operation of the International Space Station since September 1993.[207] The agencies have used launch systems from both countries to deliver station elements to orbit. Astronauts and Cosmonauts jointly maintain various elements of the station. Both countries provide access to the station via launch systems noting Russia's unique role as the sole provider of delivery of crew and cargo upon retirement of the space shuttle in 2011 and prior to commencement of NASA COTS and crew flights. In July 2022, NASA and Roscosmos signed a deal to share space station flights enabling crew from each country to ride on the systems provided by the other.[208] Current geopolitical conditions in late 2022 make it unlikely that cooperation will be extended to other programs such as Artemis or lunar exploration.[209]

Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO)

In September 2014, NASA and Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) signed a partnership to collaborate on and launch a joint radar mission, the NASA-ISRO Synthetic Aperature Radar (NISAR) mission. The mission is targeted to launch in 2024. NASA will provide the mission's L-band synthetic aperture radar, a high-rate communication subsystem for science data, GPS receivers, a solid-state recorder and payload data subsystem. ISRO provides the spacecraft bus, the S-band radar, the launch vehicle and associated launch services.[210][211]

Artemis Accords

The Artemis Accords have been established to define a framework for cooperating in the peaceful exploration and exploitation of the Moon, Mars, asteroids, and comets. The Accords were drafted by NASA and the U.S. State Department and are executed as a series of bilateral agreements between the United States and the participating countries.[212][213] As of September 2022, 21 countries have signed the accords. They are Australia, Bahrain, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, France, Israel, Italy, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, New Zealand, Poland, Romania, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Ukraine, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and the United States.[214][215]

China National Space Administration

The Wolf Amendment was passed by the U.S. Congress into law in 2011 and prevents NASA from engaging in direct, bilateral cooperation with the Chinese government and China-affiliated organizations such as the China National Space Administration without the explicit authorization from Congress and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The law has been renewed annually since by inclusion in annual appropriations bills.[216]

Management

Leadership

The agency's administration is located at NASA Headquarters in Washington, DC, and provides overall guidance and direction.[217] Except under exceptional circumstances, NASA civil service employees are required to be US citizens.[218]NASA's administrator is nominated by the President of the United States subject to the approval of the US Senate,[219] and serves at the President's pleasure as a senior space science advisor. The current administrator is Bill Nelson, appointed by President Joe Biden, since May 3, 2021.[220]

Strategic plan

NASA operates with four FY2022 strategic goals.[221]

- Expand human knowledge through new scientific discoveries

- Extend human presence to the Moon and on towards Mars for sustainable long-term exploration, development, and utilization

- Catalyze economic growth and drive innovation to address national challenges

- Enhance capabilities and operations to catalyze current and future mission success

Budget

NASA budget requests are developed by NASA and approved by the administration prior to submission to the U.S. Congress. Authorized budgets are those that have been included in enacted appropriations bills that are approved by both houses of Congress and enacted into law by the U.S. president.[222]

NASA fiscal year budget requests and authorized budgets are listed below.

| Year | Budget Request in bil. US$ | Authorized Budget in bil. US$ | U.S. Government Employees |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | $19.092[223] | $20.736[224] | 17,551[225] |

| 2019 | $19.892[224] | $21.500[226] | 17,551[227] |

| 2020 | $22.613[226] | $22.629[228] | 18,048[229] |

| 2021 | $25.246[228] | $23.271[230] | 18,339[231] |

| 2022 | $24.802[230] | $24.041[232] | 18,400 est |

Organization

NASA funding and priorities are developed through its six Mission Directorates.

| Mission Directorate | Associate Administrator | % of NASA Budget (FY22)[230] |

|---|---|---|

| Aeronautics Research (ARMD) | Catherine A. Koerner[233] | 4% |

| Exploration Systems Development (ESDMD) | James Free[234] | 28% |

| Space Operations (SOMD) | Kenneth Bowersox[235] | 17% |

| Science (SMD) | Nicola Fox[236] | 32% |

| Space Technology (STMD) | Kurt Vogel [237] | 5% |

| Mission Support (MSD) | Robert Gibbs[238] | 14% |

Center-wide activities such as the Chief Engineer and Safety and Mission Assurance organizations are aligned to the headquarters function. The MSD budget estimate includes funds for these HQ functions. The administration operates 10 major field centers with several managing additional subordinate facilities across the country. Each is led by a Center Director (data below valid as of September 1, 2022).

| Field Center | Primary Location | Center Director |

|---|---|---|

| Ames Research Center | Mountain View, California | Eugene L. Tu[239] |

| Armstrong Flight Research Center | Palmdale, California | Brad Flick (acting)[240] |

| Glenn Research Center | Cleveland, Ohio | James A. Kenyon (acting)[241] |

| Goddard Space Flight Center | Greenbelt, Maryland | Makenzie Lystrup[242] |

| Jet Propulsion Laboratory | La Canada-Flintridge, California | Laurie Leshin[243] |

| Johnson Space Center | Houston, Texas | Vanessa E. Wyche[244] |

| Kennedy Space Center | Merritt Island, Florida | Janet Petro[245] |

| Langley Research Center | Hampton, Virginia | Clayton Turner[246] |

| Marshall Space Flight Center | Huntsville, Alabama | Jody Singer[247] |

| Stennis Space Center | Hancock County, Mississippi | Richard J. Gilbrech[248] |

Sustainability

Environmental impact