Млечный Путь

| Млечный Путь | |

|---|---|

ночного неба Вид на Галактический центр с Земли телескопа (с изображением лазерной направляющей звезды ). Ниже приведена информация Галактического центра. | |

| Данные наблюдений ( J2000 эпоха ) | |

| Созвездие | Стрелец |

| Прямое восхождение | 17 час 45 м 40.03599 с [1] |

| Склонение | −29° 00′ 28.1699″ [1] |

| Distance | 7.935–8.277 kpc (25,881–26,996 ly)[2][3][4][a] |

| Characteristics | |

| Type | Sb; Sbc; SB(rs)bc[5][6] |

| Mass | 1.15×1012[7][8][9] M☉ |

| Number of stars | 100–400 billion ((1–4)×1011)[12][13] |

| Size | 26.8 ± 1.1 kpc (87,400 ± 3,600 ly) (diameter; D25 isophote)[10][b] |

| Thickness of thin disk | 220–450 pc (718–1,470 ly)[14] |

| Thickness of thick disk | 2.6 ± 0.5 kpc (8,500 ± 1,600 ly)[14] |

| Angular momentum | ~1×1067 J s[15] |

| Sun's Galactic rotation period | 212 Myr[16] |

| Spiral pattern rotation period | 220–360 Myr[17] |

| Bar pattern rotation period | 160–180 Myr[18] |

| Speed relative to CMB rest frame | 552.2±5.5 km/s[19] |

| Escape velocity at Sun's position | 550 km/s[20] |

| Dark matter density at Sun's position | 0.0088+0.0024 −0.0018 M☉pc−3 (0.35+0.08 −0.07 GeV cm−3)[20] |

Млечный Путь [с] это галактика , включающая Солнечную систему , название которой описывает внешний вид галактики с Земли : туманная полоса света, видимая в ночном небе, образованная из звезд, которые невозможно различить по отдельности невооруженным глазом .

Млечный Путь — спиральная галактика с D 25 перемычкой, диаметр изофоты оценивается в 26,8 ± 1,1 килопарсека (87 400 ± 3600 световых лет ). [10] но толщиной всего около 1000 световых лет в спиральных рукавах (больше в выпуклости). Недавнее моделирование показывает, что область темной материи , также содержащая несколько видимых звезд, может простираться до диаметра почти 2 миллионов световых лет (613 кпк). [26] [27] Млечный Путь имеет несколько галактик-спутников и входит в Местную группу галактик, входящих в состав сверхскопления Девы , которое само по себе является компонентом сверхскопления Ланиакея . [28] [29]

По оценкам, он содержит 100–400 миллиардов звезд. [30] [31] и по крайней мере такое же количество планет . [32] [33] Солнечная система расположена в радиусе около 27 000 световых лет (8,3 кпк) от Галактического центра . [34] на внутреннем краю Рукава Ориона — одно из спиралевидных скоплений газа и пыли. Звезды на расстоянии 10 000 световых лет образуют выпуклость и одну или несколько полос, расходящихся от выпуклости. Галактический центр — это интенсивный радиоисточник, известный как Стрелец А* , сверхмассивная черная дыра массой 4,100 (± 0,034) миллиона солнечных масс . [35][36] The oldest stars in the Milky Way are nearly as old as the Universe itself and thus probably formed shortly after the Dark Ages of the Big Bang.[37]

Galileo Galilei first resolved the band of light into individual stars with his telescope in 1610. Until the early 1920s, most astronomers thought that the Milky Way contained all the stars in the Universe.[38] Following the 1920 Great Debate between the astronomers Harlow Shapley and Heber Doust Curtis,[39] observations by Edwin Hubble showed that the Milky Way is just one of many galaxies.

Etymology and mythology

In the Babylonian epic poem Enūma Eliš, the Milky Way is created from the severed tail of the primeval salt water dragoness Tiamat, set in the sky by Marduk, the Babylonian national god, after slaying her.[40][41] This story was once thought to have been based on an older Sumerian version in which Tiamat is instead slain by Enlil of Nippur,[42][43] but is now thought to be purely an invention of Babylonian propagandists with the intention to show Marduk as superior to the Sumerian deities.[43]

In Greek mythology, Zeus places his son born by a mortal woman, the infant Heracles, on Hera's breast while she is asleep so the baby will drink her divine milk and become immortal. Hera wakes up while breastfeeding and then realizes she is nursing an unknown baby: she pushes the baby away, some of her milk spills, and it produces the band of light known as the Milky Way. In another Greek story, the abandoned Heracles is given by Athena to Hera for feeding, but Heracles' forcefulness causes Hera to rip him from her breast in pain.[44][45][46]

Llys Dôn (literally "The Court of Dôn") is the traditional Welsh name for the constellation Cassiopeia. At least three of Dôn's children also have astronomical associations: Caer Gwydion ("The fortress of Gwydion") is the traditional Welsh name for the Milky Way,[47][48] and Caer Arianrhod ("The Fortress of Arianrhod") being the constellation of Corona Borealis.[49][50]

In western culture, the name "Milky Way" is derived from its appearance as a dim un-resolved "milky" glowing band arching across the night sky. The term is a translation of the Classical Latin via lactea, in turn derived from the Hellenistic Greek γαλαξίας, short for γαλαξίας κύκλος (galaxías kýklos), meaning "milky circle". The Ancient Greek γαλαξίας (galaxias) – from root γαλακτ-, γάλα ("milk") + -ίας (forming adjectives) – is also the root of "galaxy", the name for our, and later all such, collections of stars.[51][52][53]

The Milky Way, or "milk circle", was just one of 11 "circles" the Greeks identified in the sky, others being the zodiac, the meridian, the horizon, the equator, the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, the Arctic Circle and the Antarctic Circle, and two colure circles passing through both poles.[54]

Appearance

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2024) |

The Milky Way is visible as a hazy band of white light, some 30° wide, arching the night sky.[55] Although all the individual naked-eye stars in the entire sky are part of the Milky Way Galaxy, the term "Milky Way" is limited to this band of light.[56][57] The light originates from the accumulation of unresolved stars and other material located in the direction of the galactic plane. Brighter regions around the band appear as soft visual patches known as star clouds. The most conspicuous of these is the Large Sagittarius Star Cloud, a portion of the central bulge of the galaxy.[58] Dark regions within the band, such as the Great Rift and the Coalsack, are areas where interstellar dust blocks light from distant stars. Peoples of the southern hemisphere, including the Inca and Australian aborigines, identified these regions as dark cloud constellations.[59] The area of sky that the Milky Way obscures is called the Zone of Avoidance.[60]

The Milky Way has a relatively low surface brightness. Its visibility can be greatly reduced by background light, such as light pollution or moonlight. The sky needs to be darker than about 20.2 magnitude per square arcsecond in order for the Milky Way to be visible.[61] It should be visible if the limiting magnitude is approximately +5.1 or better and shows a great deal of detail at +6.1.[62] This makes the Milky Way difficult to see from brightly lit urban or suburban areas, but very prominent when viewed from rural areas when the Moon is below the horizon.[d] Maps of artificial night sky brightness show that more than one-third of Earth's population cannot see the Milky Way from their homes due to light pollution.[63]

As viewed from Earth, the visible region of the Milky Way's galactic plane occupies an area of the sky that includes 30 constellations.[e] The Galactic Center lies in the direction of Sagittarius, where the Milky Way is brightest. From Sagittarius, the hazy band of white light appears to pass around to the galactic anticenter in Auriga. The band then continues the rest of the way around the sky, back to Sagittarius, dividing the sky into two roughly equal hemispheres.[citation needed]

The galactic plane is inclined by about 60° to the ecliptic (the plane of Earth's orbit). Relative to the celestial equator, it passes as far north as the constellation of Cassiopeia and as far south as the constellation of Crux, indicating the high inclination of Earth's equatorial plane and the plane of the ecliptic, relative to the galactic plane. The north galactic pole is situated at right ascension 12h 49m, declination +27.4° (B1950) near β Comae Berenices, and the south galactic pole is near α Sculptoris. Because of this high inclination, depending on the time of night and year, the Milky Way arch may appear relatively low or relatively high in the sky. For observers from latitudes approximately 65° north to 65° south, the Milky Way passes directly overhead twice a day.[citation needed]

Astronomical history

Ancient, naked eye observations

In Meteorologica, Aristotle (384–322 BC) states that the Greek philosophers Anaxagoras (c. 500–428 BC) and Democritus (460–370 BC) proposed that the Milky Way is the glow of stars not directly visible due to Earth's shadow, while other stars receive their light from the Sun, but have their glow obscured by solar rays.[64] Aristotle himself believed that the Milky Way was part of the Earth's upper atmosphere, along with the stars, and that it was a byproduct of stars burning that did not dissipate because of its outermost location in the atmosphere, composing its great circle. He said that the milky appearance of the Milky Way Galaxy is due to the refraction of the Earth's atmosphere.[65][66][67] The Neoplatonist philosopher Olympiodorus the Younger (c. 495–570 AD) criticized this view, arguing that if the Milky Way were sublunary, it should appear different at different times and places on Earth, and that it should have parallax, which it does not. In his view, the Milky Way is celestial. This idea would be influential later in the Muslim world.[68]

The Persian astronomer Al-Biruni (973–1048) proposed that the Milky Way is "a collection of countless fragments of the nature of nebulous stars".[69] The Andalusian astronomer Avempace (d 1138) proposed that the Milky Way was made up of many stars but appeared to be a continuous image in the Earth's atmosphere, citing his observation of a conjunction of Jupiter and Mars in 1106 or 1107 as evidence.[66] The Persian astronomer Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (1201–1274) in his Tadhkira wrote: "The Milky Way, i.e. the Galaxy, is made up of a very large number of small, tightly clustered stars, which, on account of their concentration and smallness, seem to be cloudy patches. Because of this, it was likened to milk in color."[70] Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya (1292–1350) proposed that the Milky Way is "a myriad of tiny stars packed together in the sphere of the fixed stars".[71]

Telescopic observations

Proof of the Milky Way consisting of many stars came in 1610 when Galileo Galilei used a telescope to study the Milky Way and discovered that it is composed of a huge number of faint stars. Galileo also concluded that the appearance of the Milky Way was due to refraction of the Earth's atmosphere.[72][73][65] In a treatise in 1755, Immanuel Kant, drawing on earlier work by Thomas Wright,[74] speculated (correctly) that the Milky Way might be a rotating body of a huge number of stars, held together by gravitational forces akin to the Solar System but on much larger scales.[75] The resulting disk of stars would be seen as a band on the sky from our perspective inside the disk. Wright and Kant also conjectured that some of the nebulae visible in the night sky might be separate "galaxies" themselves, similar to our own. Kant referred to both the Milky Way and the "extragalactic nebulae" as "island universes", a term still current up to the 1930s.[76][77][78]

The first attempt to describe the shape of the Milky Way and the position of the Sun within it was carried out by William Herschel in 1785 by carefully counting the number of stars in different regions of the visible sky. He produced a diagram of the shape of the Milky Way with the Solar System close to the center.[79]

In 1845, Lord Rosse constructed a new telescope and was able to distinguish between elliptical and spiral-shaped nebulae. He also managed to make out individual point sources in some of these nebulae, lending credence to Kant's earlier conjecture.[80][81]

In 1904, studying the proper motions of stars, Jacobus Kapteyn reported that these were not random, as it was believed in that time; stars could be divided into two streams, moving in nearly opposite directions.[82] It was later realized that Kapteyn's data had been the first evidence of the rotation of our galaxy,[83] which ultimately led to the finding of galactic rotation by Bertil Lindblad and Jan Oort.[citation needed]

In 1917, Heber Doust Curtis had observed the nova S Andromedae within the Great Andromeda Nebula (Messier object 31). Searching the photographic record, he found 11 more novae. Curtis noticed that these novae were, on average, 10 magnitudes fainter than those that occurred within the Milky Way. As a result, he was able to come up with a distance estimate of 150,000 parsecs. He became a proponent of the "island universes" hypothesis, which held that the spiral nebulae were independent galaxies.[84][85] In 1920 the Great Debate took place between Harlow Shapley and Heber Curtis, concerning the nature of the Milky Way, spiral nebulae, and the dimensions of the Universe. To support his claim that the Great Andromeda Nebula is an external galaxy, Curtis noted the appearance of dark lanes resembling the dust clouds in the Milky Way, as well as the significant Doppler shift.[86]

The controversy was conclusively settled by Edwin Hubble in the early 1920s using the Mount Wilson observatory 2.5 m (100 in) Hooker telescope. With the light-gathering power of this new telescope, he was able to produce astronomical photographs that resolved the outer parts of some spiral nebulae as collections of individual stars. He was also able to identify some Cepheid variables that he could use as a benchmark to estimate the distance to the nebulae. He found that the Andromeda Nebula is 275,000 parsecs from the Sun, far too distant to be part of the Milky Way.[87][88]

Satellite observations

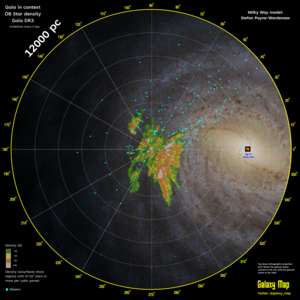

The ESA spacecraft Gaia provides distance estimates by determining the parallax of a billion stars and is mapping the Milky Way with four planned releases of maps in 2016, 2018, 2021 and 2024.[89][90]

Data from Gaia has been described as "transformational". It has been estimated that Gaia has expanded the number of observations of stars from about 2 million stars as of the 1990s to 2 billion. It has expanded the measurable volume of space by a factor of 100 in radius and a factor of 1,000 in precision.[91]

A study in 2020 concluded that Gaia detected a wobbling motion of the galaxy, which might be caused by "torques from a misalignment of the disc's rotation axis with respect to the principal axis of a non-spherical halo, or from accreted matter in the halo acquired during late infall, or from nearby, interacting satellite galaxies and their consequent tides".[92] In April 2024, initial studies (and related maps) involving the magnetic fields of the Milky Way were reported.[93]

Astrography

Sun's location and neighborhood

The Sun is near the inner rim of the Orion Arm, within the Local Fluff of the Local Bubble, between the Radcliffe wave and Split linear structures (formerly Gould Belt).[94] Based upon studies of stellar orbits around Sgr A* by Gillessen et al. (2016), the Sun lies at an estimated distance of 27.14 ± 0.46 kly (8.32 ± 0.14 kpc)[34] from the Galactic Center. Boehle et al. (2016) found a smaller value of 25.64 ± 0.46 kly (7.86 ± 0.14 kpc), also using a star orbit analysis.[95] The Sun is currently 5–30 parsecs (16–98 ly) above, or north of, the central plane of the Galactic disk.[96] The distance between the local arm and the next arm out, the Perseus Arm, is about 2,000 parsecs (6,500 ly).[97] The Sun, and thus the Solar System, is located in the Milky Way's galactic habitable zone.[98][99]

There are about 208 stars brighter than absolute magnitude 8.5 within a sphere with a radius of 15 parsecs (49 ly) from the Sun, giving a density of one star per 69 cubic parsecs, or one star per 2,360 cubic light-years (from List of nearest bright stars). On the other hand, there are 64 known stars (of any magnitude, not counting 4 brown dwarfs) within 5 parsecs (16 ly) of the Sun, giving a density of about one star per 8.2 cubic parsecs, or one per 284 cubic light-years (from List of nearest stars). This illustrates the fact that there are far more faint stars than bright stars: in the entire sky, there are about 500 stars brighter than apparent magnitude 4 but 15.5 million stars brighter than apparent magnitude 14.[100]

The apex of the Sun's way, or the solar apex, is the direction that the Sun travels through space in the Milky Way. The general direction of the Sun's Galactic motion is towards the star Vega near the constellation of Hercules, at an angle of roughly 60 sky degrees to the direction of the Galactic Center. The Sun's orbit about the Milky Way is expected to be roughly elliptical with the addition of perturbations due to the Galactic spiral arms and non-uniform mass distributions. In addition, the Sun passes through the Galactic plane approximately 2.7 times per orbit.[101] [unreliable source?] This is very similar to how a simple harmonic oscillator works with no drag force (damping) term. These oscillations were until recently thought to coincide with mass lifeform extinction periods on Earth.[102] A reanalysis of the effects of the Sun's transit through the spiral structure based on CO data has failed to find a correlation.[103]

It takes the Solar System about 240 million years to complete one orbit of the Milky Way (a galactic year),[104] so the Sun is thought to have completed 18–20 orbits during its lifetime and 1/1250 of a revolution since the origin of humans. The orbital speed of the Solar System about the center of the Milky Way is approximately 220 km/s (490,000 mph) or 0.073% of the speed of light. The Sun moves through the heliosphere at 84,000 km/h (52,000 mph). At this speed, it takes around 1,400 years for the Solar System to travel a distance of 1 light-year, or 8 days to travel 1 AU (astronomical unit).[105] The Solar System is headed in the direction of the zodiacal constellation Scorpius, which follows the ecliptic.[106]

Galactic quadrants

A galactic quadrant, or quadrant of the Milky Way, refers to one of four circular sectors in the division of the Milky Way. In astronomical practice, the delineation of the galactic quadrants is based upon the galactic coordinate system, which places the Sun as the origin of the mapping system.[107]

Quadrants are described using ordinals – for example, "1st galactic quadrant",[108] "second galactic quadrant",[109] or "third quadrant of the Milky Way".[110] Viewing from the north galactic pole with 0° (zero degrees) as the ray that runs starting from the Sun and through the Galactic Center, the quadrants are:

with the galactic longitude (ℓ) increasing in the counter-clockwise direction (positive rotation) as viewed from north of the Galactic Center (a view-point several hundred thousand light-years distant from Earth in the direction of the constellation Coma Berenices); if viewed from south of the Galactic Center (a view-point similarly distant in the constellation Sculptor), ℓ would increase in the clockwise direction (negative rotation).

Size and mass

Size

The Milky Way is one of the two largest galaxies in the Local Group (the other being the Andromeda Galaxy), although the size for its galactic disc and how much it defines the isophotal diameter is not well understood.[11] It is estimated that the significant bulk of stars in the galaxy lies within the 26 kiloparsecs (80,000 light-years) diameter, and that the number of stars beyond the outermost disc dramatically reduces to a very low number, with respect to an extrapolation of the exponential disk with the scale length of the inner disc.[112][11]

There are several methods being used in astronomy in defining the size of a galaxy, and each of them can yield different results with respect to one another. The most commonly employed method is the D25 standard – the isophote where the photometric brightness of a galaxy in the B-band (445 nm wavelength of light, in the blue part of the visible spectrum) reaches 25 mag/arcsec2.[113] An estimate from 1997 by Goodwin and others compared the distribution of Cepheid variable stars in 17 other spiral galaxies to the ones in the Milky Way, and modelling the relationship to their surface brightnesses. This gave an isophotal diameter for the Milky Way at 26.8 ± 1.1 kiloparsecs (87,400 ± 3,600 light-years), by assuming that the galactic disc is well represented by an exponential disc and adopting a central surface brightness of the galaxy (μ0) of 22.1±0.3 B-mag/arcsec−2 and a disk scale length (h) of 5.0 ± 0.5 kpc (16,300 ± 1,600 ly).[114][10][115]

This is significantly smaller than the Andromeda Galaxy's isophotal diameter, and slightly below the mean isophotal sizes of the galaxies being at 28.3 kpc (92,000 ly).[10] The paper concludes that the Milky Way and Andromeda Galaxy were not overly large spiral galaxies and as well as one of the largest known (if the former not being the largest) as previously widely believed, but rather average ordinary spiral galaxies.[116] To compare the relative physical scale of the Milky Way, if the Solar System out to Neptune were the size of a US quarter (24.3 mm (0.955 in)), the Milky Way would be approximately at least the greatest north–south line of the contiguous United States.[117] An even older study from 1978 gave a lower diameter for Milky Way about 23 kpc (75,000 ly).[10]

A 2015 paper discovered that there is a ring-like filament of stars called Triangulum–Andromeda Ring (TriAnd Ring) rippling above and below the relatively flat galactic plane, which alongside Monoceros Ring were both suggested to be primarily the result of disk oscillations and wrapping around the Milky Way, at a diameter of at least 50 kpc (160,000 ly),[118] which may be part of the Milky Way's outer disk itself, hence making the stellar disk larger by increasing to this size.[119] A more recent 2018 paper later somewhat ruled out this hypothesis, and supported a conclusion that the Monoceros Ring, A13 and TriAnd Ring were stellar overdensities rather kicked out from the main stellar disk, with the velocity dispersion of the RR Lyrae stars found to be higher and consistent with halo membership.[120]

Another 2018 study revealed the very probable presence of disk stars at 26–31.5 kpc (84,800–103,000 ly) from the Galactic Center or perhaps even farther, significantly beyond approximately 13–20 kpc (40,000–70,000 ly), in which it was once believed to be the abrupt drop-off of the stellar density of the disk, meaning that few or no stars were expected to be above this limit, save for stars that belong to the old population of the galactic halo.[11][121][122]

A 2020 study predicted the edge of the Milky Way's dark matter halo being around 292 ± 61 kpc (952,000 ± 199,000 ly), which translates to a diameter of 584 ± 122 kpc (1.905 ± 0.3979 Mly).[26][27] The Milky Way's stellar disk is also estimated to be approximately up to 1.35 kpc (4,000 ly) thick.[123][124]

Mass

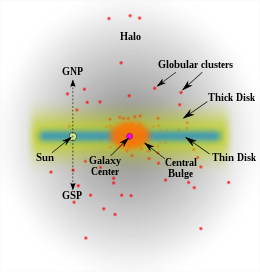

Abbreviations: GNP/GSP: Galactic North and South Poles

The Milky Way is approximately 890 billion to 1.54 trillion times the mass of the Sun in total (8.9×1011 to 1.54×1012 solar masses),[7][8][9] although stars and planets make up only a small part of this. Estimates of the mass of the Milky Way vary, depending upon the method and data used. The low end of the estimate range is 5.8×1011 solar masses (M☉), somewhat less than that of the Andromeda Galaxy.[125][126][127] Measurements using the Very Long Baseline Array in 2009 found velocities as large as 254 km/s (570,000 mph) for stars at the outer edge of the Milky Way.[128]

Because the orbital velocity depends on the total mass inside the orbital radius, this suggests that the Milky Way is more massive, roughly equaling the mass of Andromeda Galaxy at 7×1011 M☉ within 160,000 ly (49 kpc) of its center.[129] In 2010, a measurement of the radial velocity of halo stars found that the mass enclosed within 80 kiloparsecs is 7×1011 M☉.[130] In a 2014 study, the mass of the entire Milky Way is estimated to be 8.5×1011 M☉,[131] but this is only half the mass of the Andromeda Galaxy.[131] A recent 2019 mass estimate for the Milky Way is 1.29×1012 M☉.[132]

Much of the mass of the Milky Way seems to be dark matter, an unknown and invisible form of matter that interacts gravitationally with ordinary matter. A dark matter halo is conjectured to spread out relatively uniformly to a distance beyond one hundred kiloparsecs (kpc) from the Galactic Center. Mathematical models of the Milky Way suggest that the mass of dark matter is 1–1.5×1012 M☉.[133][134][135] 2013 and 2014 studies indicate a range in mass, as large as 4.5×1012 M☉[136] and as small as 8×1011 M☉.[137] By comparison, the total mass of all the stars in the Milky Way is estimated to be between 4.6×1010 M☉[138] and 6.43×1010 M☉.[133]

In addition to the stars, there is also interstellar gas, comprising 90% hydrogen and 10% helium by mass,[139] [unreliable source?] with two thirds of the hydrogen found in the atomic form and the remaining one-third as molecular hydrogen.[140] The mass of the Milky Way's interstellar gas is equal to between 10%[140] and 15%[139] of the total mass of its stars. Interstellar dust accounts for an additional 1% of the total mass of the gas.[139]

In March 2019, astronomers reported that the virial mass of the Milky Way Galaxy is 1.54 trillion solar masses within a radius of about 39.5 kpc (130,000 ly), over twice as much as was determined in earlier studies, suggesting that about 90% of the mass of the galaxy is dark matter.[7][8]

In September 2023, astronomers reported that the virial mass of the Milky Way Galaxy is only 2.06 1011 solar masses, only a 10th of the mass of previous studies. The mass was determined from data of the Gaia spacecraft.[141]

Contents

The Milky Way contains between 100 and 400 billion stars[12][13] and at least that many planets.[142] An exact figure would depend on counting the number of very-low-mass stars, which are difficult to detect, especially at distances of more than 300 ly (90 pc) from the Sun. As a comparison, the neighboring Andromeda Galaxy contains an estimated one trillion (1012) stars.[143] The Milky Way may contain ten billion white dwarfs, a billion neutron stars, and a hundred million stellar black holes.[f][146][147] Filling the space between the stars is a disk of gas and dust called the interstellar medium. This disk has at least a comparable extent in radius to the stars,[148] whereas the thickness of the gas layer ranges from hundreds of light-years for the colder gas to thousands of light-years for warmer gas.[149][150]

The disk of stars in the Milky Way does not have a sharp edge beyond which there are no stars. Rather, the concentration of stars decreases with distance from the center of the Milky Way. For reasons that are not understood, beyond a radius of roughly 40,000 light years (13 kpc) from the center, the number of stars per cubic parsec drops much faster with radius.[112] Surrounding the galactic disk is a spherical galactic halo of stars and globular clusters that extends farther outward, but is limited in size by the orbits of two Milky Way satellites, the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, whose closest approach to the Galactic Center is about 180,000 ly (55 kpc).[151] At this distance or beyond, the orbits of most halo objects would be disrupted by the Magellanic Clouds. Hence, such objects would probably be ejected from the vicinity of the Milky Way. The integrated absolute visual magnitude of the Milky Way is estimated to be around −20.9.[152][153][g]

Both gravitational microlensing and planetary transit observations indicate that there may be at least as many planets bound to stars as there are stars in the Milky Way,[32][154] and microlensing measurements indicate that there are more rogue planets not bound to host stars than there are stars.[155][156] The Milky Way contains at least one planet per star, resulting in 100–400 billion planets, according to a January 2013 study of the five-planet star system Kepler-32 by the Kepler space observatory.[33] A different January 2013 analysis of Kepler data estimated that at least 17 billion Earth-sized exoplanets reside in the Milky Way.[157]

In November 2013, astronomers reported, based on Kepler space mission data, that there could be as many as 40 billion Earth-sized planets orbiting in the habitable zones of Sun-like stars and red dwarfs within the Milky Way.[158][159][160] 11 billion of these estimated planets may be orbiting Sun-like stars.[161] The nearest exoplanet may be 4.2 light-years away, orbiting the red dwarf Proxima Centauri, according to a 2016 study.[162] Such Earth-sized planets may be more numerous than gas giants,[32] though harder to detect at great distances given their small size. Besides exoplanets, "exocomets", comets beyond the Solar System, have also been detected and may be common in the Milky Way.[163] More recently, in November 2020, over 300 million habitable exoplanets are estimated to exist in the Milky Way Galaxy.[164]

When compared to other more distant galaxies in the universe, the Milky Way galaxy has a below average amount of neutrino luminosity making our galaxy a “neutrino desert”.[165]

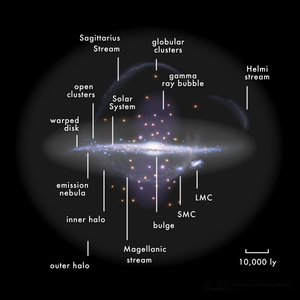

Structure

The Milky Way consists of a bar-shaped core region surrounded by a warped disk of gas, dust and stars.[166][167] The mass distribution within the Milky Way closely resembles the type Sbc in the Hubble classification, which represents spiral galaxies with relatively loosely wound arms.[5] Astronomers first began to conjecture that the Milky Way is a barred spiral galaxy, rather than an ordinary spiral galaxy, in the 1960s.[168][169][170] These conjectures were confirmed by the Spitzer Space Telescope observations in 2005 that showed the Milky Way's central bar to be larger than previously thought.[171]

Galactic Center

The Sun is 25,000–28,000 ly (7.7–8.6 kpc) from the Galactic Center. This value is estimated using geometric-based methods or by measuring selected astronomical objects that serve as standard candles, with different techniques yielding various values within this approximate range.[173][95][34][174][175][176] In the inner few kiloparsecs (around 10,000 light-years radius) is a dense concentration of mostly old stars in a roughly spheroidal shape called the bulge.[177] It has been proposed that the Milky Way lacks a bulge due to a collision and merger between previous galaxies, and that instead it only has a pseudobulge formed by its central bar.[178] However, confusion in the literature between the (peanut shell)-shaped structure created by instabilities in the bar, versus a possible bulge with an expected half-light radius of 0.5 kpc, abounds.[179]

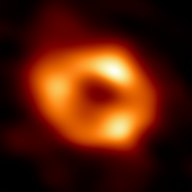

The Galactic Center is marked by an intense radio source named Sagittarius A* (pronounced Sagittarius A-star). The motion of material around the center indicates that Sagittarius A* harbors a massive, compact object.[180] This concentration of mass is best explained as a supermassive black hole[h][173][181] (SMBH) with an estimated mass of 4.1–4.5 million times the mass of the Sun.[181] The rate of accretion of the SMBH is consistent with an inactive galactic nucleus, being estimated at 1×10−5 M☉ per year.[182] Observations indicate that there are SMBHs located near the center of most normal galaxies.[183][184]

The nature of the Milky Way's bar is actively debated, with estimates for its half-length and orientation spanning from 1 to 5 kpc (3,000–16,000 ly) and 10–50 degrees relative to the line of sight from Earth to the Galactic Center.[175][176][185] Certain authors advocate that the Milky Way features two distinct bars, one nestled within the other.[186] However, RR Lyrae-type stars do not trace a prominent Galactic bar.[176][187][188] The bar may be surrounded by a ring called the "5 kpc ring" that contains a large fraction of the molecular hydrogen present in the Milky Way, as well as most of the Milky Way's star formation activity. Viewed from the Andromeda Galaxy, it would be the brightest feature of the Milky Way.[189] X-ray emission from the core is aligned with the massive stars surrounding the central bar[182] and the Galactic ridge.[190]

In June 2023, astronomers reported using a new cascade neutrino technique[191] to detect, for the first time, the release of neutrinos from the galactic plane of the Milky Way galaxy, creating the first neutrino view of the Milky Way.[192][193]

Gamma rays and x-rays

Since 1970, various gamma-ray detection missions have discovered 511-keV gamma rays coming from the general direction of the Galactic Center. These gamma rays are produced by positrons (antielectrons) annihilating with electrons. In 2008 it was found that the distribution of the sources of the gamma rays resembles the distribution of low-mass X-ray binaries, seeming to indicate that these X-ray binaries are sending positrons (and electrons) into interstellar space where they slow down and annihilate.[194][195][196] The observations were both made by NASA and ESA's satellites. In 1970 gamma ray detectors found that the emitting region was about 10,000 light-years across with a luminosity of about 10,000 suns.[195]

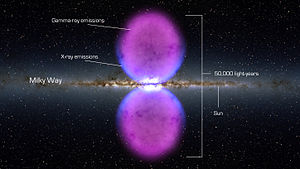

In 2010, two gigantic spherical bubbles of high energy gamma-emission were detected to the north and the south of the Milky Way core, using data from the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. The diameter of each of the bubbles is about 25,000 light-years (7.7 kpc) (or about 1/4 of the galaxy's estimated diameter); they stretch up to Grus and to Virgo on the night-sky of the southern hemisphere.[197][198] Subsequently, observations with the Parkes Telescope at radio frequencies identified polarized emission that is associated with the Fermi bubbles. These observations are best interpreted as a magnetized outflow driven by star formation in the central 640 ly (200 pc) of the Milky Way.[199]

Later, on January 5, 2015, NASA reported observing an X-ray flare 400 times brighter than usual, a record-breaker, from Sagittarius A*. The unusual event may have been caused by the breaking apart of an asteroid falling into the black hole or by the entanglement of magnetic field lines within gas flowing into Sagittarius A*.[172]

Spiral arms

Outside the gravitational influence of the Galactic bar, the structure of the interstellar medium and stars in the disk of the Milky Way is organized into four spiral arms.[200] Spiral arms typically contain a higher density of interstellar gas and dust than the Galactic average as well as a greater concentration of star formation, as traced by H II regions[201][202] and molecular clouds.[203]

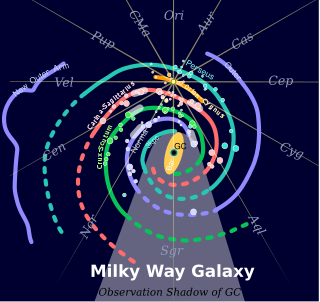

The Milky Way's spiral structure is uncertain, and there is currently no consensus on the nature of the Milky Way's arms.[204] Perfect logarithmic spiral patterns only crudely describe features near the Sun,[202][205] because galaxies commonly have arms that branch, merge, twist unexpectedly, and feature a degree of irregularity.[176][205][206] The possible scenario of the Sun within a spur / Local arm[202] emphasizes that point and indicates that such features are probably not unique, and exist elsewhere in the Milky Way.[205] Estimates of the pitch angle of the arms range from about 7° to 25°.[148][207] There are thought to be four spiral arms that all start near the Milky Way Galaxy's center.[208] These are named as follows, with the positions of the arms shown in the image:

| Color | Arm(s) |

|---|---|

| turquoise | Near 3 kpc and Perseus Arm |

| blue | Norma and Outer arm (Along with extension discovered in 2004[209]) |

| green | Far 3 kpc and Scutum–Centaurus Arm |

| red | Carina–Sagittarius Arm |

| There are at least two smaller arms or spurs, including: | |

| orange | Orion–Cygnus Arm (which contains the Sun and Solar System) |

Two spiral arms, the Scutum–Centaurus arm and the Carina–Sagittarius arm, have tangent points inside the Sun's orbit about the center of the Milky Way. If these arms contain an overdensity of stars compared to the average density of stars in the Galactic disk, it would be detectable by counting the stars near the tangent point. Two surveys of near-infrared light, which is sensitive primarily to red giants and not affected by dust extinction, detected the predicted overabundance in the Scutum–Centaurus arm but not in the Carina–Sagittarius arm: the Scutum–Centaurus Arm contains approximately 30% more red giants than would be expected in the absence of a spiral arm.[207][210]

This observation suggests that the Milky Way possesses only two major stellar arms: the Perseus arm and the Scutum–Centaurus arm. The rest of the arms contain excess gas but not excess old stars.[204] In December 2013, astronomers found that the distribution of young stars and star-forming regions matches the four-arm spiral description of the Milky Way.[211][212][213] Thus, the Milky Way appears to have two spiral arms as traced by old stars and four spiral arms as traced by gas and young stars. The explanation for this apparent discrepancy is unclear.[213]

The Near 3 kpc Arm (also called the Expanding 3 kpc Arm or simply the 3 kpc Arm) was discovered in the 1950s by astronomer van Woerden and collaborators through 21 centimeter radio measurements of HI (atomic hydrogen).[214][215] It was found to be expanding away from the central bulge at more than 50 km/s. It is located in the fourth galactic quadrant at a distance of about 5.2 kpc from the Sun and 3.3 kpc from the Galactic Center. The Far 3 kpc Arm was discovered in 2008 by astronomer Tom Dame (Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian). It is located in the first galactic quadrant at a distance of 3 kpc (about 10,000 ly) from the Galactic Center.[215][216]

A simulation published in 2011 suggested that the Milky Way may have obtained its spiral arm structure as a result of repeated collisions with the Sagittarius Dwarf Elliptical Galaxy.[217]

It has been suggested that the Milky Way contains two different spiral patterns: an inner one, formed by the Sagittarius arm, that rotates fast and an outer one, formed by the Carina and Perseus arms, whose rotation velocity is slower and whose arms are tightly wound. In this scenario, suggested by numerical simulations of the dynamics of the different spiral arms, the outer pattern would form an outer pseudoring,[218] and the two patterns would be connected by the Cygnus arm.[219]

Outside of the major spiral arms is the Monoceros Ring (or Outer Ring), a ring of gas and stars torn from other galaxies billions of years ago. However, several members of the scientific community recently restated their position affirming the Monoceros structure is nothing more than an over-density produced by the flared and warped thick disk of the Milky Way.[220] The structure of the Milky Way's disk is warped along an "S" curve.[221]

Halo

The Galactic disk is surrounded by a spheroidal halo of old stars and globular clusters, of which 90% lie within 100,000 light-years (30 kpc) of the Galactic Center.[222] However, a few globular clusters have been found farther, such as PAL 4 and AM 1 at more than 200,000 light-years from the Galactic Center. About 40% of the Milky Way's clusters are on retrograde orbits, which means they move in the opposite direction from the Milky Way rotation.[223] The globular clusters can follow rosette orbits about the Milky Way, in contrast to the elliptical orbit of a planet around a star.[224]

Although the disk contains dust that obscures the view in some wavelengths, the halo component does not. Active star formation takes place in the disk (especially in the spiral arms, which represent areas of high density), but does not take place in the halo, as there is little cool gas to collapse into stars.[104] Open clusters are also located primarily in the disk.[225]

Discoveries in the early 21st century have added dimension to the knowledge of the Milky Way's structure. With the discovery that the disk of the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) extends much farther than previously thought,[226] the possibility of the disk of the Milky Way extending farther is apparent, and this is supported by evidence from the discovery of the Outer Arm extension of the Cygnus Arm[209][227] and of a similar extension of the Scutum–Centaurus Arm.[228] With the discovery of the Sagittarius Dwarf Elliptical Galaxy came the discovery of a ribbon of galactic debris as the polar orbit of the dwarf and its interaction with the Milky Way tears it apart. Similarly, with the discovery of the Canis Major Dwarf Galaxy, it was found that a ring of galactic debris from its interaction with the Milky Way encircles the Galactic disk.[citation needed]

The Sloan Digital Sky Survey of the northern sky shows a huge and diffuse structure (spread out across an area around 5,000 times the size of a full moon) within the Milky Way that does not seem to fit within current models. The collection of stars rises close to perpendicular to the plane of the spiral arms of the Milky Way. The proposed likely interpretation is that a dwarf galaxy is merging with the Milky Way. This galaxy is tentatively named the Virgo Stellar Stream and is found in the direction of Virgo about 30,000 light-years (9 kpc) away.[229]

Gaseous halo

In addition to the stellar halo, the Chandra X-ray Observatory, XMM-Newton, and Suzaku have provided evidence that there is also a gaseous halo containing a large amount of hot gas. This halo extends for hundreds of thousands of light-years, much farther than the stellar halo and close to the distance of the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds. The mass of this hot halo is nearly equivalent to the mass of the Milky Way itself.[230][231][232] The temperature of this halo gas is between 1 and 2.5 million K (1.8 and 4.5 million °F).[233]

Observations of distant galaxies indicate that the Universe had about one-sixth as much baryonic (ordinary) matter as dark matter when it was just a few billion years old. However, only about half of those baryons are accounted for in the modern Universe based on observations of nearby galaxies like the Milky Way.[234] If the finding that the mass of the halo is comparable to the mass of the Milky Way is confirmed, it could be the identity of the missing baryons around the Milky Way.[234]

Galactic rotation

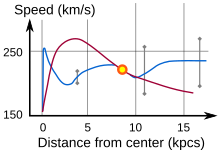

The stars and gas in the Milky Way rotate about its center differentially, meaning that the rotation period varies with location. As is typical for spiral galaxies, the orbital speed of most stars in the Milky Way does not depend strongly on their distance from the center. Away from the central bulge or outer rim, the typical stellar orbital speed is between 210 ± 10 km/s (470,000 ± 22,000 mph).[238] Hence the orbital period of the typical star is directly proportional only to the length of the path traveled. This is unlike the situation within the Solar System, where two-body gravitational dynamics dominate, and different orbits have significantly different velocities associated with them. The rotation curve (shown in the figure) describes this rotation. Toward the center of the Milky Way the orbit speeds are too low, whereas beyond 7 kpcs the speeds are too high to match what would be expected from the universal law of gravitation.[citation needed]

If the Milky Way contained only the mass observed in stars, gas, and other baryonic (ordinary) matter, the rotational speed would decrease with distance from the center. However, the observed curve is relatively flat, indicating that there is additional mass that cannot be detected directly with electromagnetic radiation. This inconsistency is attributed to dark matter.[235] The rotation curve of the Milky Way agrees with the universal rotation curve of spiral galaxies, the best evidence for the existence of dark matter in galaxies. Alternatively, a minority of astronomers propose that a modification of the law of gravity may explain the observed rotation curve.[239]

Formation

History

The Milky Way began as one or several small overdensities in the mass distribution in the Universe shortly after the Big Bang 13.61 billion years ago.[240][241][242] Some of these overdensities were the seeds of globular clusters in which the oldest remaining stars in what is now the Milky Way formed. Nearly half the matter in the Milky Way may have come from other distant galaxies.[240] These stars and clusters now comprise the stellar halo of the Milky Way. Within a few billion years of the birth of the first stars, the mass of the Milky Way was large enough so that it was spinning relatively quickly. Due to conservation of angular momentum, this led the gaseous interstellar medium to collapse from a roughly spheroidal shape to a disk. Therefore, later generations of stars formed in this spiral disk. Most younger stars, including the Sun, are observed to be in the disk.[243][244]

Since the first stars began to form, the Milky Way has grown through both galaxy mergers (particularly early in the Milky Way's growth) and accretion of gas directly from the Galactic halo.[244] The Milky Way is currently accreting material from several small galaxies, including two of its largest satellite galaxies, the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, through the Magellanic Stream. Direct accretion of gas is observed in high-velocity clouds like the Smith Cloud.[245][246]

Cosmological simulations indicate that, 11 billion years ago, it merged with a particularly large galaxy that has been labeled the Kraken.[247][248] Properties of the Milky Way such as stellar mass, angular momentum, and metallicity in its outermost regions suggest it has undergone no mergers with large galaxies in the last 10 billion years. This lack of recent major mergers is unusual among similar spiral galaxies. Its neighbour the Andromeda Galaxy appears to have a more typical history shaped by more recent mergers with relatively large galaxies.[249][250]

According to recent studies, the Milky Way as well as the Andromeda Galaxy lie in what in the galaxy color–magnitude diagram is known as the "green valley", a region populated by galaxies in transition from the "blue cloud" (galaxies actively forming new stars) to the "red sequence" (galaxies that lack star formation). Star-formation activity in green valley galaxies is slowing as they run out of star-forming gas in the interstellar medium. In simulated galaxies with similar properties, star formation will typically have been extinguished within about five billion years from now, even accounting for the expected, short-term increase in the rate of star formation due to the collision between both the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy.[251] Measurements of other galaxies similar to the Milky Way suggest it is among the reddest and brightest spiral galaxies that are still forming new stars and it is just slightly bluer than the bluest red sequence galaxies.[252]

Age and cosmological history

Globular clusters are among the oldest objects in the Milky Way, which thus set a lower limit on the age of the Milky Way. The ages of individual stars in the Milky Way can be estimated by measuring the abundance of long-lived radioactive elements such as thorium-232 and uranium-238, then comparing the results to estimates of their original abundance, a technique called nucleocosmochronology. These yield values of about 12.5 ± 3 billion years for CS 31082-001[254] and 13.8 ± 4 billion years for BD +17° 3248.[255]

Once a white dwarf is formed, it begins to undergo radiative cooling and the surface temperature steadily drops. By measuring the temperatures of the coolest of these white dwarfs and comparing them to their expected initial temperature, an age estimate can be made. With this technique, the age of the globular cluster M4 was estimated as 12.7 ± 0.7 billion years. Age estimates of the oldest of these clusters gives a best fit estimate of 12.6 billion years, and a 95% confidence upper limit of 16 billion years.[256]

In November 2018, astronomers reported the discovery of one of the oldest stars in the universe. About 13.5 billion-years-old, 2MASS J18082002-5104378 B is a tiny ultra metal-poor (UMP) star made almost entirely of materials released from the Big Bang, and is possibly one of the first stars. The discovery of the star in the Milky Way Galaxy suggests that the galaxy may be at least 3 billion years older than previously thought.[257][258][259]

Several individual stars have been found in the Milky Way's halo with measured ages very close to the 13.80-billion-year age of the Universe. In 2007, a star in the galactic halo, HE 1523-0901, was estimated to be about 13.2 billion years old. As the oldest known object in the Milky Way at that time, this measurement placed a lower limit on the age of the Milky Way.[260] This estimate was made using the UV-Visual Echelle Spectrograph of the Very Large Telescope to measure the relative strengths of spectral lines caused by the presence of thorium and other elements created by the R-process. The line strengths yield abundances of different elemental isotopes, from which an estimate of the age of the star can be derived using nucleocosmochronology.[260] Another star, HD 140283, is 14.5 ± 0.7 billion years old.[37][261]

According to observations utilizing adaptive optics to correct for Earth's atmospheric distortion, stars in the galaxy's bulge date to about 12.8 billion years old.[262]

The age of stars in the galactic thin disk has also been estimated using nucleocosmochronology. Measurements of thin disk stars yield an estimate that the thin disk formed 8.8 ± 1.7 billion years ago. These measurements suggest there was a hiatus of almost 5 billion years between the formation of the galactic halo and the thin disk.[263] Recent analysis of the chemical signatures of thousands of stars suggests that stellar formation might have dropped by an order of magnitude at the time of disk formation, 10 to 8 billion years ago, when interstellar gas was too hot to form new stars at the same rate as before.[264]

The satellite galaxies surrounding the Milky Way are not randomly distributed but seem to be the result of a breakup of some larger system producing a ring structure 500,000 light-years in diameter and 50,000 light-years wide.[265] Close encounters between galaxies, like that expected in 4 billion years with the Andromeda Galaxy, can rip off huge tails of gas, which, over time can coalesce to form dwarf galaxies in a ring at an arbitrary angle to the main disc.[266]

Intergalactic neighbourhood

The Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy are a binary system of giant spiral galaxies belonging to a group of 50 closely bound galaxies known as the Local Group, surrounded by a Local Void, itself being part of the Local Sheet[267] and in turn the Virgo Supercluster. Surrounding the Virgo Supercluster are a number of voids, devoid of many galaxies, the Microscopium Void to the "north", the Sculptor Void to the "left", the Boötes Void to the "right" and the Canes-Major Void to the "south". These voids change shape over time, creating filamentous structures of galaxies. The Virgo Supercluster, for instance, is being drawn towards the Great Attractor,[268] which in turn forms part of a greater structure, called Laniakea.[269]

Two smaller galaxies and a number of dwarf galaxies in the Local Group orbit the Milky Way. The largest of these is the Large Magellanic Cloud with a diameter of 32,200 light-years.[270] It has a close companion, the Small Magellanic Cloud. The Magellanic Stream is a stream of neutral hydrogen gas extending from these two small galaxies across 100° of the sky. The stream is thought to have been dragged from the Magellanic Clouds in tidal interactions with the Milky Way.[271] Some of the dwarf galaxies orbiting the Milky Way are Canis Major Dwarf (the closest), Sagittarius Dwarf Elliptical Galaxy, Ursa Minor Dwarf, Sculptor Dwarf, Sextans Dwarf, Fornax Dwarf, and Leo I Dwarf.[272]

The smallest dwarf galaxies of the Milky Way are only 500 light-years in diameter. These include Carina Dwarf, Draco Dwarf, and Leo II Dwarf. There may still be undetected dwarf galaxies that are dynamically bound to the Milky Way, which is supported by the detection of nine new satellites of the Milky Way in a relatively small patch of the night sky in 2015.[272] There are some dwarf galaxies that have already been absorbed by the Milky Way, such as the progenitor of Omega Centauri.[273]

In 2005[274]with further confirmation in 2012[275] researchers reported that most satellite galaxies of the Milky Way lie in a very large disk and orbit in the same direction. This came as a surprise: according to standard cosmology, the satellite galaxies should form in dark matter halos, and they should be widely distributed and moving in random directions. This discrepancy is still not explained.[276]

In January 2006, researchers reported that the heretofore unexplained warp in the disk of the Milky Way has now been mapped and found to be a ripple or vibration set up by the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds as they orbit the Milky Way, causing vibrations when they pass through its edges. Previously, these two galaxies, at around 2% of the mass of the Milky Way, were considered too small to influence the Milky Way. However, in a computer model, the movement of these two galaxies creates a dark matter wake that amplifies their influence on the larger Milky Way.[277]

Current measurements suggest the Andromeda Galaxy is approaching the Milky Way at 100 to 140 km/s (220,000 to 310,000 mph). In 4.3 billion years, there may be an Andromeda–Milky Way collision, depending on the importance of unknown lateral components to the galaxies' relative motion. If they collide, the chance of individual stars colliding with each other is extremely low,[278] but instead the two galaxies will merge to form a single elliptical galaxy or perhaps a large disk galaxy[279] over the course of about six billion years.[280]

Velocity

Although special relativity states that there is no "preferred" inertial frame of reference in space with which to compare the Milky Way, the Milky Way does have a velocity with respect to cosmological frames of reference.

One such frame of reference is the Hubble flow, the apparent motions of galaxy clusters due to the expansion of space. Individual galaxies, including the Milky Way, have peculiar velocities relative to the average flow. Thus, to compare the Milky Way to the Hubble flow, one must consider a volume large enough so that the expansion of the Universe dominates over local, random motions. A large enough volume means that the mean motion of galaxies within this volume is equal to the Hubble flow. Astronomers believe the Milky Way is moving at approximately 630 km/s (1,400,000 mph) with respect to this local co-moving frame of reference.[281][282]

The Milky Way is moving in the general direction of the Great Attractor and other galaxy clusters, including the Shapley Supercluster, behind it.[283] The Local Group, a cluster of gravitationally bound galaxies containing, among others, the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy, is part of a supercluster called the Local Supercluster, centered near the Virgo Cluster: although they are moving away from each other at 967 km/s (2,160,000 mph) as part of the Hubble flow, this velocity is less than would be expected given the 16.8 million pc distance due to the gravitational attraction between the Local Group and the Virgo Cluster.[284]

Another reference frame is provided by the cosmic microwave background (CMB), in which the CMB temperature is least distorted by Doppler shift (zero dipole moment). The Milky Way is moving at 552 ± 6 km/s (1,235,000 ± 13,000 mph)[19] with respect to this frame, toward 10.5 right ascension, −24° declination (J2000 epoch, near the center of Hydra). This motion is observed by satellites such as the Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) and the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) as a dipole contribution to the CMB, as photons in equilibrium in the CMB frame get blue-shifted in the direction of the motion and red-shifted in the opposite direction.[19]

See also

Notes

- ^ The distance towards its center (Sagittarius A*).

- ^ This is the diameter measured using the D25 standard. It has been recently suggested that there is a presence of disk stars beyond this diameter, although it is not clear how much of this influences the surface brightness profile.[11]

- ^ Some authors use the term Milky Way to refer exclusively to the band of light that the galaxy forms in the night sky, while the galaxy receives the full name Milky Way Galaxy. See for example Lausten et al.,[21] Pasachoff,[22] Jones,[23] van der Kruit,[24] and Hodge et al.[25]

- ^ See also Bortle Dark-Sky Scale.

- ^ The bright center of the galaxy is located in the constellation Sagittarius. From Sagittarius, the hazy band of white light appears to pass westward through the constellations of Scorpius, Ara, Norma, Triangulum Australe, Circinus, Centaurus, Musca, Crux, Carina, Vela, Puppis, Canis Major, Monoceros, Orion and Gemini, Taurus, to the galactic anticenter in Auriga. From there, it passes through Perseus, Andromeda, Cassiopeia, Cepheus and Lacerta, Cygnus, Vulpecula, Sagitta, Aquila, Ophiuchus, Scutum, and back to Sagittarius.

- ^ These estimates are very uncertain, as most non-star objects are difficult to detect; for example, black hole estimates range from ten million to one billion.[144][145]

- ^ Karachentsev et al. give a blue absolute magnitude of −20.8. Combined with a color index of 0.55 estimated here, an absolute visual magnitude of −21.35 (−20.8 − 0.55 = −21.35) is obtained. Determining the absolute magnitude of the Milky Way is very difficult, because Earth is inside it.

- ^ For a photo see: "Sagittarius A*: Milky Way monster stars in cosmic reality show". Chandra X-ray Observatory. Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian. January 6, 2003. Archived from the original on March 17, 2008. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

References

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b Petrov, L.; Kovalev, Y. Y.; Fomalont, E. B.; Gordon, D. (2011). "The Very Long Baseline Array Galactic Plane Survey—VGaPS". The Astronomical Journal. 142 (2): 35. arXiv:1101.1460. Bibcode:2011AJ....142...35P. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/142/2/35. S2CID 121762178.

- ^ Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration; et al. (2022). "First Sagittarius A* Event Horizon Telescope Results. VI. Testing the Black Hole Metric". The Astrophysical Journal. 930 (2): L17. arXiv:2311.09484. Bibcode:2022ApJ...930L..17E. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ac6756. S2CID 248744741.

- ^ Banerjee, Indrani; Sau, Subhadip; SenGupta, Soumitra (2022). "Do shadows of SGR A* and M87* indicate black holes with a magnetic monopole charge?". arXiv:2207.06034 [gr-qc].

- ^ Abuter, R.; et al. (2019). "A geometric distance measurement to the Galactic center black hole with 0.3% uncertainty". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 625: L10. arXiv:1904.05721. Bibcode:2019A&A...625L..10G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201935656. S2CID 119190574.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b Gerhard, O. (2002). "Mass distribution in our Galaxy". Space Science Reviews. 100 (1/4): 129–138. arXiv:astro-ph/0203110. Bibcode:2002SSRv..100..129G. doi:10.1023/A:1015818111633. S2CID 42162871.

- ^ Frommert, Hartmut; Kronberg, Christine (August 26, 2005). "Classification of the Milky Way Galaxy". SEDS. Archived from the original on May 31, 2015. Retrieved May 30, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c Starr, Michelle (March 8, 2019). "The Latest Calculation of Milky Way's Mass Just Changed What We Know About Our Galaxy". ScienceAlert.com. Archived from the original on March 8, 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c Watkins, Laura L.; et al. (February 2, 2019). "Evidence for an Intermediate-Mass Milky Way from Gaia DR2 Halo Globular Cluster Motions". The Astrophysical Journal. 873 (2): 118. arXiv:1804.11348. Bibcode:2019ApJ...873..118W. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab089f. S2CID 85463973.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b Kafle, P.R.; Sharma, S.; Lewis, G.F.; Bland-Hawthorn, J. (2012). "Kinematics of the Stellar Halo and the Mass Distribution of the Milky Way Using Blue Horizontal Branch Stars". The Astrophysical Journal. 761 (2): 17. arXiv:1210.7527. Bibcode:2012ApJ...761...98K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/761/2/98. S2CID 119303111.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c d e Goodwin, S. P.; Gribbin, J.; Hendry, M. A. (August 1998). "The relative size of the Milky Way". The Observatory. 118: 201–208. Bibcode:1998Obs...118..201G.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c d López-Corredoira, M.; Allende Prieto, C.; Garzón, F.; Wang, H.; Liu, C.; Deng, L. (April 9, 2018). "Disk stars in the Milky Way detected beyond 25 kpc from its center". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 612: L8. arXiv:1804.03064. Bibcode:2018A&A...612L...8L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201832880. S2CID 59933365.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b Frommert, H.; Kronberg, C. (August 25, 2005). "The Milky Way Galaxy". SEDS. Archived from the original on May 12, 2007. Retrieved May 9, 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b Wethington, Nicholos. "How Many Stars are in the Milky Way?". Archived from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b Bland-Hawthorn, Joss; Gerhard, Ortwin (2016). "The Galaxy in Context: Structural, Kinematic, and Integrated Properties". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 54: 529–596. arXiv:1602.07702. Bibcode:2016ARA&A..54..529B. doi:10.1146/annurev-astro-081915-023441. S2CID 53649594.

- ^ Karachentsev, Igor. "Double Galaxies § 7.1". ned.ipac.caltech.edu. Izdatel'stvo Nauka. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ "A New Map of the Milky Way". Scientific American. April 1, 2020. Archived from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- ^ Gerhard, O. (2010). "Pattern speeds in the Milky Way". arXiv:1003.2489v1 [astro-ph.GA].

- ^ Shen, Juntai; Zheng, Xing-Wu (2020). "The bar and spiral arms in the Milky Way: Structure and kinematics". Research in Astronomy and Astrophysics. 20 (10): 159. arXiv:2012.10130. Bibcode:2020RAA....20..159S. doi:10.1088/1674-4527/20/10/159. S2CID 229005996.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c Kogut, Alan; et al. (December 10, 1993). "Dipole anisotropy in the COBE differential microwave radiometers first-year sky maps". The Astrophysical Journal. 419: 1…6. arXiv:astro-ph/9312056. Bibcode:1993ApJ...419....1K. doi:10.1086/173453. S2CID 209835274.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b Kafle, P.R.; Sharma, S.; Lewis, G.F.; Bland-Hawthorn, J. (2014). "On the Shoulders of Giants: Properties of the Stellar Halo and the Milky Way Mass Distribution". The Astrophysical Journal. 794 (1): 17. arXiv:1408.1787. Bibcode:2014ApJ...794...59K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/794/1/59. S2CID 119040135.

- ^ Lausten, Svend; Madsen, Claus; West, Richard M. (1987). Exploring the Southern Sky: a Pictorial Atlas from the European Southern Observatory (ESO). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. p. 119. ISBN 978-3-642-61588-7. OCLC 851764943.

- ^ Pasachoff, Jay M. (1994). Astronomy: From the Earth to the Universe. Harcourt School. p. 500. ISBN 978-0-03-001667-7.

- ^ Jones, Barrie William (2008). The Search for Life Continued: Planets Around Other Stars. Berlin: Springer. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-387-76559-4. OCLC 288474262.

- ^ Kruit, Pieter C. van der (2019). Jan Hendrik Oort: Master of the Galactic System. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. pp. 65, 717. ISBN 978-3-030-17801-7. OCLC 1110483488.

- ^ Hodge, Paul W.; et al. (October 13, 2020). "Milky Way Galaxy". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on January 19, 2022. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b Croswell, Ken (March 23, 2020). "Astronomers have found the edge of the Milky Way at last". ScienceNews. Archived from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b Dearson, Alis J. (2020). "The Edge of the Galaxy". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 496 (3): 3929–3942. arXiv:2002.09497. Bibcode:2020MNRAS.496.3929D. doi:10.1093/mnras/staa1711. S2CID 211259409.

- ^ "Laniakea: Our home supercluster". YouTube. September 3, 2014. Archived from the original on September 4, 2014.

- ^ Tully, R. Brent; et al. (September 4, 2014). "The Laniakea supercluster of galaxies". Nature. 513 (7516): 71–73. arXiv:1409.0880. Bibcode:2014Natur.513...71T. doi:10.1038/nature13674. PMID 25186900. S2CID 205240232.

- ^ "Milky Way". BBC. Archived from the original on March 2, 2012.

- ^ "How Many Stars in the Milky Way?". NASA Blueshift. Archived from the original on January 25, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c Cassan, A.; et al. (January 11, 2012). "One or more bound planets per Milky Way star from microlensing observations". Nature. 481 (7380): 167–169. arXiv:1202.0903. Bibcode:2012Natur.481..167C. doi:10.1038/nature10684. PMID 22237108. S2CID 2614136.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b "100 Billion Alien Planets Fill Our Milky Way Galaxy: Study". Space.com. January 2, 2013. Archived from the original on January 3, 2013. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b c Gillessen, Stefan; Plewa, Philipp; Eisenhauer, Frank; Sari, Re'em; Waisberg, Idel; Habibi, Maryam; Pfuhl, Oliver; George, Elizabeth; Dexter, Jason; von Fellenberg, Sebastiano; Ott, Thomas; Genzel, Reinhard (November 28, 2016). "An Update on Monitoring Stellar Orbits in the Galactic Center". The Astrophysical Journal. 837 (1): 30. arXiv:1611.09144. Bibcode:2017ApJ...837...30G. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aa5c41. S2CID 119087402.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (January 31, 2022). "An Electrifying View of the Heart of the Milky Way – A new radio-wave image of the center of our galaxy reveals all the forms of frenzy that a hundred million or so stars can get up to". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 31, 2022. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- ^ Heyood, I.; et al. (January 28, 2022). "The 1.28 GHz MeerKAT Galactic Center Mosaic". The Astrophysical Journal. 925 (2): 165. arXiv:2201.10541. Bibcode:2022ApJ...925..165H. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ac449a. S2CID 246275657.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b H.E. Bond; E. P. Nelan; D. A. VandenBerg; G. H. Schaefer; et al. (February 13, 2013). "HD 140283: A Star in the Solar Neighborhood that Formed Shortly After the Big Bang". The Astrophysical Journal. 765 (1): L12. arXiv:1302.3180. Bibcode:2013ApJ...765L..12B. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/765/1/L12. S2CID 119247629.

- ^ "Milky Way Galaxy: Facts About Our Galactic Home". Space.com. Archived from the original on March 21, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- ^ Shapley, H.; Curtis, H. D. (1921). "The Scale of the Universe". Bulletin of the National Research Council. 2 (11): 171–217. Bibcode:1921BuNRC...2..171S.

- ^ Brown, William P. (2010). The Seven Pillars of Creation: The Bible, Science, and the Ecology of Wonder. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-19-973079-7. Archived from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ MacBeath, Alastair (1999). Tiamat's Brood: An Investigation Into the Dragons of Ancient Mesopotamia. Dragon's Head. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-9524387-5-5. Archived from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ James, E. O. (1963). The Worship of the Sky-God: A Comparative Study in Semitic and Indo-European Religion. Jordan Lectures in Comparative Religion. London, England: University of London Press. pp. 24, 27f.

- ^ Jump up to: Jump up to: a b Lambert, W. G. (1964). "E. O. James: The worship of the Skygod: A comparative study in Semitic and Indo-European religion. (School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. Jordan Lectures in Comparative Religion, vi.) viii, 175 pp. London: University of London, the Athlone Press, 1963. 25s". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 27 (1). London, England: University of London: 157–158. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00100345.

- ^ "Myths about the Milky Way". judy-volker.com. Archived from the original on July 1, 2022. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ^ Leeming, David Adams (1998). Mythology: The Voyage of the Hero (Third ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-19-511957-2. Archived from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ Pache, Corinne Ondine (2010). "Hercules". In Gargarin, Michael; Fantham, Elaine (eds.). Ancient Greece and Rome. Vol. 1: Academy-Bible. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 400. ISBN 978-0-19-538839-8. Archived from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ Keith, W. J. (July 2007). "John Cowper Powys: Owen Glendower" (PDF). A Reader's Companion. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 14, 2016. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ^ Harvey, Michael (2018). "Dreaming the Night Field: A Scenario for Storytelling Performance". Storytelling, Self, Society. 14 (1): 83–94. doi:10.13110/storselfsoci.14.1.0083. ISSN 1550-5340.

- ^ "Eryri – Snowdonia". snowdonia-npa.gov.uk. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ Harris, Mike (2011). Awen: The Quest of the Celtic Mysteries. Skylight Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-908011-36-7. Archived from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

The stars of the Corona Borealis, the Caer Arianrhod, as it is called in Welsh, whose shape is remembered in certain Bronze Age circles

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "galaxy". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on May 27, 2012. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- ^ Jankowski, Connie (2010). Pioneers of Light and Sound. Compass Point Books. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-7565-4306-8. Archived from the original on November 20, 2016.

- ^ Simpson, John; Weiner, Edmund, eds. (March 30, 1989). The Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-861186-8. See the entries for "Milky Way" and "galaxy".

- ^ Eratosthenes (1997). Condos, Theony (ed.). Star Myths of the Greeks and Romans: A Sourcebook Containing the Constellations of Pseudo-Eratosthenes and the Poetic Astronomy of Hyginus. Red Wheel/Weiser. ISBN 978-1-890482-93-0. Archived from the original on November 20, 2016.

- ^ Pasachoff, Jay M. (1994). Astronomy: From the Earth to the Universe. Harcourt School. p. 500. ISBN 978-0-03-001667-7.

- ^ Rey, H. A. (1976). The Stars. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-395-24830-0.

- ^ Pasachoff, Jay M.; Filippenko, Alex (2013). The Cosmos: Astronomy in the New Millennium. Cambridge University Press. p. 384. ISBN 978-1-107-68756-1. Archived from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- ^ Crossen, Craig (July 2013). "Observing the Milky Way, part I: Sagittarius & Scorpius". Sky & Telescope. 126 (1): 24. Bibcode:2013S&T...126a..24C.

- ^ Urton, Gary (1981). At the Crossroads of the Earth and the Sky: An Andean Cosmology. Latin American Monographs. Vol. 55. Austin: Univ. of Texas Pr. pp. 102–4, 109–11. ISBN 0-292-70349-X.

- ^ Starr, Michelle (July 14, 2020). "A Giant 'Wall' of Galaxies Has Been Found Stretching Across The Universe". ScienceAlert. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ Crumey, Andrew (2014). "Human contrast threshold and astronomical visibility". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 442 (3): 2600–2619. arXiv:1405.4209. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.442.2600C. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu992. S2CID 119210885.

- ^ Стейнике, Вольфганг; Джакиэль, Ричард (2007). Галактики и как их наблюдать . Путеводители по наблюдениям астрономов. Спрингер. п. 94 . ISBN 978-1-85233-752-0 .

- ^ Фальчи, Фабио; Чинзано, Пьерантонио; Дуриско, Дэн; Киба, Кристофер СМ; Элвидж, Кристофер Д.; Боуг, Кимберли; Портнов Борис А.; Рыбникова Наталья А.; Фургони, Риккардо (1 июня 2016 г.). «Новый мировой атлас искусственной яркости ночного неба» . Достижения науки . 2 (6): e1600377. arXiv : 1609.01041 . Бибкод : 2016SciA....2E0377F . дои : 10.1126/sciadv.1600377 . ISSN 2375-2548 . ПМЦ 4928945 . ПМИД 27386582 .

- ^ Аристотель с У. Д. Россом, изд., Работы Аристотеля ... (Оксфорд, Англия: Clarendon Press, 1931), том. III, Meteorologica , EW Webster, пер., Книга 1, Часть 8, стр. 39–40. Архивировано 11 апреля 2016 г., в Wayback Machine : «(2) Анаксагор, Демокрит и их школы говорят, что Млечный путь — это свет некоторых звезд... затененный землей от солнечных лучей».

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Что показывает ваше изображение» . mo-www.harvard.edu . Архивировано из оригинала 15 марта 2023 года . Проверено 20 октября 2022 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Монтада, Хосеп Пуч (28 сентября 2007 г.). «Ибн Баджа» . Стэнфордская энциклопедия философии . Архивировано из оригинала 28 июля 2012 года . Проверено 11 июля 2008 г.

- ^ Аристотель (1931). Работает . Перевод Росс, Уильям Дэвид; Смит, Джон Александр. Оксфорд: Кларендон Пресс. п. 345.

- ^ Гейдарзаде, Тофиг (2008). История физических теорий комет от Аристотеля до Уиппла . Спрингер. стр. 23–25 . ISBN 978-1-4020-8322-8 .

- ^ О'Коннор, Джон Дж.; Робертсон, Эдмунд Ф. , «Абу Райхан Мухаммад ибн Ахмад аль-Бируни» , Архив истории математики MacTutor , Университет Сент-Эндрюс [ ненадежный источник? ]

- ^ Раджеп, Джамиль (1993). Мемуары Насир ад-Дина ат-Туси по астрономии ( ат-Тадхкира фи 'илм аль-хай'а ) . Нью-Йорк: Springer-Verlag. п. 129.

- ^ Ливингстон, Джон В. (1971). «Ибн Кайим аль-Джавзия: защита четырнадцатого века от астрологических предсказаний и алхимической трансмутации». Журнал Американского восточного общества . 91 (1): 96–103 [99]. дои : 10.2307/600445 . JSTOR 600445 .

- ^ Галилео Галилей, Sidereus Nuncius (Венеция: Томас Бальони, 1610), стр. 15–16 . Архивировано 16 марта 2016 г. в Wayback Machine.

Английский перевод: Галилео Галилей с Эдвардом Стаффордом Карлосом, пер., The Sidereal Messenger (Лондон: Rivingtons, 1880), стр. 42–43 . Архивировано 2 декабря 2012 г. в Wayback Machine. - ^ О'Коннор, Джей-Джей; Робертсон, EF (ноябрь 2002 г.). «Галилео Галилей» . Университет Сент-Эндрюс. Архивировано из оригинала 30 мая 2012 года . Проверено 8 января 2007 г.

- ^ Томас Райт, Оригинальная теория или новая гипотеза Вселенной (Лондон, Англия: Х. Шапель, 1750).

- На странице 57 , заархивированной 20 ноября 2016 года в Wayback Machine , Райт заявил, что, несмотря на взаимное гравитационное притяжение, звезды в созвездиях не сталкиваются, потому что они находятся на орбите, поэтому центробежная сила удерживает их разделёнными: «центробежная сила, которая не только удерживает их на своих орбитах, но не дает им мчаться всем вместе по общему вселенскому закону тяготения..."

- На странице 48, заархивированной 20 ноября 2016 года в Wayback Machine , Райт заявил, что форма Млечного Пути представляет собой кольцо: «звёзды не разбросаны бесконечно и беспорядочно распределены по всему земному пространству, без порядка и замысла». , ... это явление [является] ничем иным, как определенным эффектом, возникающим из ситуации наблюдателя, ... Для зрителя, помещенного в неопределенное пространство, ... оно [т.е. Млечный Путь ( Via Lactea )] [есть] огромное кольцо звезд..."

- На странице 65, заархивированной 20 ноября 2016 года в Wayback Machine , Райт предположил, что центральное тело Млечного Пути, вокруг которого вращается остальная часть галактики, может быть не видно нам: «центральное тело А, предполагаемое как incognitum [т.е. неизвестное], без [т.е. вне] конечного взгляда...»;

- На странице 73, заархивировано 20 ноября 2016 года в Wayback Machine , Райт назвал Млечный Путь Vortex Magnus (великий водоворот) и оценил его диаметр в 8,64×10. 12 миль (13,9×10 12 км).

- На странице 33, заархивированной 20 ноября 2016 года в Wayback Machine , Райт предположил, что в галактике существует огромное количество обитаемых планет: «поэтому мы можем справедливо предположить, что так много сияющих тел [т.е. звезд] не были созданы только для того, чтобы просветить бесконечную пустоту, а... показать бесконечную бесформенную вселенную, переполненную мириадами славных миров, все по-разному вращающихся вокруг них и... с непостижимым разнообразием существ и состояний, оживить..."

- ^ Иммануил Кант, Общая естественная история и теория неба. Архивировано 20 ноября 2016 г. в Wayback Machine [ Общая естественная история и теория неба ] (Кенигсберг и Лейпциг (Германия): Иоганн Фридрих Петерсен, 1755).На страницах 2–3 Кант признал свой долг перед Томасом Райтом: «Мистеру Райту из Дарема, англичанину, было предоставлено право сделать счастливый шаг к замечанию, которое он сам, похоже, не использовал с какой-либо очень хорошей целью. Кажется, и полезное применение которого он недостаточно заметил. Он не рассматривал неподвижные звезды как беспорядочную и непреднамеренно рассеянную массу, но нашел систематическое строение в целом и общее отношение этих звезд к основному плану пространств. что они занимают». («Мистеру Райту из Дарема, англичанину, было позволено сделать счастливый шаг к наблюдению, которое, казалось, ему и никому другому, было необходимо для умной идеи, которую он еще не использовал. достаточно изученный, он рассматривал неподвижные звезды не как беспорядочный рой, беспорядочно рассеянный, а, скорее, нашел систематическую форму в целом и общую связь между этими звездами и главной плоскостью пространства, которое они занимают». )