Стамбул

Стамбул Стамбул | |

|---|---|

| |

OpenStreetMap | |

| Координаты: 41 ° 00'49 "с.ш. 28 ° 57'18" в.д. / 41,01361 ° с.ш. 28,95500 ° в.д. | |

| Страна | |

| Область | Мраморное море |

| Провинция | Стамбул |

| Провинциальный центр | Чагалоглу , Фатих |

| Районы | 39 |

| Правительство | |

| • Тип | Мэр – правительство совета |

| • Тело | Муниципальный совет Стамбула |

| • Мэр | Экрем Имамоглу ( ТЭЦ ) |

| Область | |

| • Городской | 2576,85 км 2 (994,93 квадратных миль) |

| • Метро | 5343,22 км 2 (2063,03 квадратных миль) |

| Самая высокая точка | 537 м (1762 фута) |

| Население (31 декабря 2023 г.) [3] | |

| • Столичный муниципалитет и провинция | 15,655,924 |

| • Классифицировать | 1 место в Европе 1 место в Турции |

| • Городской | 15,305,657 |

| • Плотность города | 5939/км 2 (15 380/кв. миль) |

| • Плотность метро | 2930/км 2 (7600/кв. миль) |

| Demonym | Стамбульец ( турецкий : Стамбульец ) |

| ВВП (номинальный) (2022) | |

| • Столичный муниципалитет и провинция | ₺ 4,564 миллиарда долларов США 276 миллиардов |

| • На душу населения | ₺ 287,524 17 349 долларов США |

| Часовой пояс | UTC+3 ( ТРТ ) |

| Почтовый индекс | от 34000 до 34990 |

| Коды городов |

|

| Регистрация автомобиля | 34 |

| ИЧР (2021 г.) | 0.867 [6] ( очень высокий ) · 1 место |

| ГеоДВУ | .ist , .Стамбул |

| Веб-сайт | |

| Официальное название | Исторические районы Стамбула |

| Критерии | Культурные: (i)(ii)(iii)(iv) |

| Ссылка | 356бис |

| Надпись | 1985 г. (9-я сессия ) |

| Расширения | 2017 |

| Область | 765,5 га (1892 акра) |

Стамбул [б] Это крупнейший город Турции . , расположенный на проливе Босфор , границе между Европой и Азией Он считается экономической, культурной и исторической столицей страны. В городе проживает более 15 миллионов жителей, что составляет 19% населения Турции. [3] и является самым густонаселенным городом Европы [с] в мире и пятнадцатый по величине город .

Город был основан в Византии в VII веке до нашей эры греческими поселенцами из Мегары . [9] В 330 году нашей эры римский император Константин Великий сделал его своей имперской столицей, сначала переименовав его в Новый Рим ( древнегреческий : Νέα Ῥώμη Nea Rhomē ; латынь : Nova Roma ). [10] а затем, наконец, как Константинополь ( Константинополис ) после себя. [10] [11] В 1930 году название города было официально изменено на «Стамбул» - турецкий перевод εἰς τὴν Πόλιν eis tḕn Pólin «город», названия, которое носители греческого языка использовали с 11 века для разговорного обозначения города. [10]

Город служил имперской столицей почти 1600 лет: во времена Византийской (330–1204), Латинской (1204–1261), поздневизантийской (1261–1453) и Османской (1453–1922) империй. [12] Город рос в размерах и влиянии, в конечном итоге став маяком Шелкового пути и одним из самых важных городов в истории. Город сыграл ключевую роль в развитии христианства в римские и византийские времена, приняв четыре из первых семи вселенских соборов, прежде чем он превратился в исламский оплот после падения Константинополя в 1453 году нашей эры, особенно после того, как он стал резиденцией Османского халифата. в 1517 году. [13] В 1923 году, после турецкой войны за независимость , Анкара заменила город столицей вновь образованной Турецкой Республики.

Стамбул был культурной столицей Европы 2010 года . Город обогнал Лондон и Дубай и стал самым посещаемым городом в мире: в 2023 году его посетили более 20 миллионов иностранных туристов. [14] Исторический центр Стамбула является объектом Всемирного наследия ЮНЕСКО , а в городе расположены штаб-квартиры многочисленных турецких компаний, на долю которых приходится более тридцати процентов экономики страны . [15] [16]

Имена

Первое известное название города — Византия ( греч . Βυζάντιον Byzántion ), имя, данное ему при его основании мегарскими колонистами около 657 г. до н.э. [10] [18] Мегарские колонисты утверждали, что они напрямую связаны с основателем города Визой, сыном бога Посейдона и нимфы Сероэссы. [18] Современные раскопки позволили предположить, что название «Византия» может отражать места коренных фракийских поселений, которые предшествовали созданию полноценного города. [19] Константинополь происходит от латинского имени Константин , в честь Константина Великого , римского императора, заново основавшего город в 324 году нашей эры. [18] Константинополь оставался наиболее распространенным названием города на Западе до 1930-х годов, когда турецкие власти начали настаивать на использовании слова «Стамбул» ( турецкий : İstanbul). [д] ) на иностранных языках. Ḳosṭanṭiniye ( османский турецкий язык : قسطنطينيه ) и Стамбул были названиями, которые попеременно использовались османами во время их правления. [20]

Название Стамбул ( османский турецкий язык : Стамбул ) Турецкое произношение: [isˈtanbuɫ] разговорный Турецкое произношение: [ɯsˈtambuɫ] ), как правило, происходит от средневековой греческой фразы εἰς τὴν Πόλιν ( Греческое произношение: [is tim ˈbolin] ), буквально «в город». [21] и именно так местные греки называли Константинополь. Это отражало его статус единственного крупного города в окрестностях. Важность Константинополя в османском мире также отражалась в его прозвище Дерсаадет ( османский турецкий язык : درساعدت ), что на османском турецком означает «Ворота к процветанию». [22] Альтернативная точка зрения состоит в том, что название произошло непосредственно от «Константинополь» с опущением первого и третьего слогов. [18] Некоторые османские источники 17 века, такие как Эвлия Челеби , описывают его как общее турецкое имя того времени; между концом 17 и концом 18 веков он также использовался официально. Первое использование слова «Исламбол» ( османский турецкий язык : اسلامبول ) на монетах произошло в 1730 году во время правления султана Махмуда I. [23] На современном турецком языке название пишется как «Истанбул» с точкой İ, поскольку в турецком алфавите различаются буквы « с точкой и I» без точки . В английском языке ударение падает на первый или последний слог, а в турецком – на второй слог ( -tan- ). [24] Человек из города — Стамбулу (множественное число İstanbullar ); Стамбулит используется в английском языке. [25]

История

Артефакты неолита , обнаруженные археологами в начале 21 века, указывают на то, что исторический полуостров Стамбул был заселен еще в 6 тысячелетии до нашей эры. [26] Это раннее поселение, сыгравшее важную роль в распространении неолитической революции с Ближнего Востока на Европу, просуществовало почти тысячелетие, прежде чем было затоплено повышением уровня воды. [27] [26] [28] [29] Первое человеческое поселение на азиатской стороне, курган Фикиртепе, относится к периоду медного века , с артефактами, датируемыми 5500–3500 годами до нашей эры. [30] На европейской стороне, недалеко от мыса полуострова ( Сарайбурну ), в начале I тысячелетия до нашей эры находилось фракийское поселение. Современные авторы связывают его с фракийским топонимом Лигос , [31] упоминается Плинием Старшим как более раннее название города Византия. [32]

История самого города начинается около 660 г. до н.э. [10] [33] [и] когда греческие поселенцы из Мегар основали Византию на европейской стороне Боспора. Поселенцы построили акрополь рядом с Золотым Рогом на месте ранних фракийских поселений, что способствовало развитию экономики зарождающегося города. [39] Город пережил короткий период персидского правления на рубеже V века до нашей эры, но греки отбили его во время греко-персидских войн . [40] Затем Византия продолжала оставаться частью Афинской лиги и ее преемницы, Второй Афинской лиги , прежде чем обрела независимость в 355 году до нашей эры. [41] Византия, долгое время находившаяся в союзе с римлянами, официально стала частью Римской империи в 73 году нашей эры. [42] Решение Византии встать на сторону римского узурпатора Песценния Нигера против императора Септимия Севера стоило ей дорого; к тому времени, когда он сдался в конце 195 г. н.э., два года осады оставили город опустошенным. [43] Пять лет спустя Север начал восстанавливать Византию, и город вновь обрел — и, по некоторым сведениям, превзошел — свое прежнее процветание. [44]

Византийская эпоха

Константин Великий фактически стал императором всей Римской империи в сентябре 324 года. [45] Два месяца спустя он изложил планы строительства нового христианского города на месте Византии. Будучи восточной столицей империи, город назывался Нова-Рома ; большинство называли его Константинополем, и это название сохранилось до 20 века. [46] 11 мая 330 г. Константинополь был провозглашен столицей Римской империи, которая позже была навсегда разделена между двумя сыновьями Феодосия I после его смерти 17 января 395 г., когда город стал столицей империи; в течение следующего тысячелетия римской истории государство обычно называли «Византийской империей». [47]

Основание Константинополя было одним из самых значительных достижений Константина, сместившим римскую власть на восток, поскольку город стал центром греческой культуры и христианства. [47] [48] По всему городу были построены многочисленные церкви, в том числе собор Святой Софии , построенный во время правления Юстиниана I и остававшийся крупнейшим собором в мире на протяжении тысячи лет. [49] Константин также предпринял капитальную реконструкцию и расширение Константинопольского ипподрома ; вмещая десятки тысяч зрителей, ипподром стал центром общественной жизни, а в V и VI веках — центром беспорядков, в том числе беспорядков в Нике . [50] [51] Местоположение Константинополя также гарантировало, что его существование выдержит испытание временем; на протяжении многих столетий его стены и набережная защищали Европу от захватчиков с востока и распространения ислама. [48] На протяжении большей части Средневековья , во второй половине византийской эпохи, Константинополь был самым большим и богатым городом на европейском континенте, а иногда и самым большим в мире. [52] [53] Константинополь принято считать центром и «колыбелью православной христианской цивилизации ». [54] [55]

Константинополь начал непрерывно приходить в упадок после окончания правления Василия II в 1025 году. Четвертый крестовый поход был отвлечен от своей цели в 1204 году, и город был разграблен и разграблен крестоносцами. [56] Они основали Латинскую империю на месте православной Византийской империи. [57] Собор Святой Софии был преобразован в католическую церковь в 1204 году. Византийская империя была восстановлена, хотя и ослаблена, в 1261 году. [58] Церкви, оборонительные сооружения и основные службы Константинополя находились в плохом состоянии. [59] и его население сократилось до ста тысяч с полумиллиона в 8 веке. [ф] Однако после завоевания 1261 года некоторые памятники города были восстановлены, а некоторые, например две деисусные мозаики в соборе Святой Софии и Карие, были созданы. [60]

Различные экономические и военные меры, установленные Андроником II Палеологом , такие как сокращение вооруженных сил, ослабили империю и сделали ее уязвимой для атак. [61] В середине 14 века турки-османы начали стратегию постепенного захвата небольших городов и поселков, отрезая пути снабжения Константинополя и медленно его удушая. [62] 29 мая 1453 года, после восьминедельной осады, в ходе которой был убит последний римский император Константин XI , султан Мехмед II «Завоеватель» захватил Константинополь .

Османская империя

Султан Мехмед объявил Константинополь новой столицей Османской империи . Через несколько часов после падения города султан поехал в собор Святой Софии и вызвал имама, чтобы тот провозгласил шахаду , превратив величественный собор в императорскую мечеть из-за отказа города сдаться мирно. [63] Мехмед объявил себя новым Кайзер-и Румом , османско-турецким эквивалентом Римского Цезаря , и Османское государство было реорганизовано в империю. [64] [65]

После захвата Константинополя Мехмед II немедленно приступил к возрождению города. Понимая, что возрождение потерпит неудачу без повторного заселения города, Мехмед II приветствовал всех – иностранцев, преступников и беглецов – демонстрируя чрезвычайную открытость и готовность принять чужаков, которые пришли определять политическую культуру Османской империи. [66] Он также пригласил людей со всей Европы в свою столицу, создав космополитическое общество, которое просуществовало на протяжении большей части периода Османской империи. [67] Оживление Стамбула также потребовало масштабной программы реставрации всего, от дорог до акведуков . [68] Как и многие монархи до и после, Мехмед II преобразил городской ландшафт Стамбула, осуществив масштабную реконструкцию центра города. [69] Появился огромный новый дворец , если не затмевать , который мог конкурировать со старым его , новый крытый рынок (до сих пор называющийся Гранд-базаром ), портики, павильоны, дорожки, а также более дюжины новых мечетей. [68] Мехмед II превратил ветхий старый город в нечто, похожее на имперскую столицу. [69]

Социальная иерархия была проигнорирована безудержной чумой, которая убивала как богатых, так и бедных в 16 веке. [70] Деньги не могли защитить богатых от всех неудобств и суровых сторон Стамбула. [70] Хотя султан жил в безопасном отдалении от масс, а богатые и бедные, как правило, жили бок о бок, по большей части Стамбул не был зонирован, как современные города. [70] Роскошные дома располагались на одних и тех же улицах и в кварталах с крохотными лачугами. [70] У тех, кто был достаточно богат, чтобы иметь уединенную загородную недвижимость, был шанс избежать периодических эпидемий болезней, опустошавших Стамбул. [70]

Османская династия заявила о статусе халифата в 1517 году, а Константинополь оставался столицей этого последнего халифата в течение четырех столетий. [13] Правление Сулеймана Великолепного с 1520 по 1566 год было периодом особенно великих художественных и архитектурных достижений; Главный архитектор Мимар Синан спроектировал несколько знаковых зданий в городе, в то время как османское искусство керамики , витражей , каллиграфии и миниатюры процветало. [71] К концу 18 века население Константинополя составляло 570 000 человек. [72]

Период восстания в начале 19 века привел к возвышению прогрессивного султана Махмуда II и, в конечном итоге, к периоду Танзимата , который привел к политическим реформам и позволил внедрить в город новые технологии. [73] В этот период были построены мосты через Золотой Рог. [74] а Константинополь был связан с остальной частью европейской железнодорожной сети в 1880-х годах. [75] Современные объекты, такие как сеть водоснабжения, электричество, телефоны и трамваи, постепенно вводились в Константинополь в течение следующих десятилетий, хотя и позже, чем в других европейских городах. [76] Усилий по модернизации было недостаточно, чтобы предотвратить упадок Османской империи . [77]

После младотурецкой революции 1908 года Османский парламент , закрытый с 14 февраля 1878 года, был вновь открыт 30 лет спустя, 23 июля 1908 года, что ознаменовало начало Второй конституционной эры . [78] Гражданские беспорядки и политическая нестабильность в Османской империи в течение нескольких месяцев после революции побудили Австро-Венгрию аннексировать Боснию и Болгарию и провозгласить свою независимость совместно скоординированным шагом 5 октября 1908 года. Султан Абдул Хамид II был свергнут в 1909 году после попытка контрреволюции, известная как инцидент 31 марта . Ряд войн начала 20-го века, таких как Итало-турецкая война (1911–1912) и Балканские войны (1912–1913), поразили столицу больной империи и привели к османскому государственному перевороту 1913 года , который принес режим Трех Паш . [79]

Османская империя вступила в Первую мировую войну (1914–1918) на стороне Центральных держав и в конечном итоге потерпела поражение. Депортация армянской интеллигенции 24 апреля 1915 года была одним из главных событий, ознаменовавших начало геноцида армян во время Первой мировой войны. [80] Из-за османской и турецкой политики тюркизации и этнических чисток население города христианское сократилось с 450 000 до 240 000 в период с 1914 по 1927 год. [81] было Мудросское перемирие подписано 30 октября 1918 года, а союзники оккупировали Константинополь 13 ноября 1918 года. Османский парламент был распущен союзниками 11 апреля 1920 года, а османская делегация во главе с Даматом Ферид-пашой была вынуждена подписать Севрский мирный договор . 10 августа 1920 г. [ нужна ссылка ]

После турецкой войны за независимость (1919–1922) Великое национальное собрание Турции в Анкаре 1 ноября 1922 года упразднило султанат, а последний османский султан Мехмед VI был объявлен персоной нон грата . Покинув борт британского военного корабля HMS Malaya 17 ноября 1922 года, он отправился в изгнание и умер в Сан-Ремо , Италия, 16 мая 1926 года.

был Лозаннский мирный договор подписан 24 июля 1923 года, а оккупация Константинополя завершилась с уходом последних сил союзников из города 4 октября 1923 года. [83] Турецкие войска правительства Анкары под командованием Шюкрю Наили-паши (3-й корпус) вошли в город с церемонией 6 октября 1923 года, которая была отмечена как «День освобождения Стамбула» ( İstanbul'un Kurtuluşu ), и была С тех пор его отмечают ежегодно. [83]

Турецкая Республика

29 октября 1923 года Великое Национальное Собрание Турции провозгласило создание Турецкой Республики со столицей в Анкаре. Мустафа Кемаль Ататюрк республики стал первым президентом . [84] [85]

Налог на богатство 1942 года, взимаемый в основном с немусульман, привел к передаче или ликвидации многих предприятий, принадлежавших религиозным меньшинствам. [86] С конца 1940-х и начала 1950-х годов Стамбул претерпел большие структурные изменения: по всему городу были построены новые общественные площади, бульвары и проспекты, иногда за счет исторических зданий. [87] Население Стамбула начало быстро увеличиваться в 1970-х годах, когда люди из Анатолии мигрировали в город в поисках работы на многочисленных новых заводах, построенных на окраинах обширного мегаполиса. Этот внезапный резкий рост населения города вызвал большой спрос на жилье, и многие ранее отдаленные деревни и леса оказались поглощены столичным районом Стамбула. [88]

География и окружающая среда

Стамбул находится на северо-западе Турции и расположен на проливе Босфор , который обеспечивает единственный проход из Черного моря в Средиземное через Мраморное море . [15] Исторически город был идеально расположен для торговли и обороны: место слияния Мраморного моря, Босфора и Золотого Рога обеспечивает как идеальную защиту от нападения противника, так и естественные ворота для взимания платы за проезд. [15] несколько живописных островов — Бююкада , Хейбелиада , Бургазада , Кыналыада и пять островов поменьше. В состав города входят [15] Береговая линия Стамбула вышла за пределы своих естественных пределов. Большие участки Каддебостана расположены на свалках, в результате чего общая площадь города увеличивается до 5343 квадратных километров (2063 квадратных миль). [15]

Несмотря на миф о том, что город составляют семь холмов , на самом деле в черте города находится более 50 холмов. Самый высокий холм Стамбула, Айдос, имеет высоту 537 метров (1762 фута). [15]

Землетрясения

Северо -Анатолийский разлом под Мраморным морем замыкается к югу от города. [89] Этот разлом стал причиной землетрясений 1766 и 1894 годов . [90] и землетрясение магнитудой не менее 7,0 весьма вероятно в 21 веке, [91] хотя землетрясение магнитудой выше 7,5 считается невозможным. [92] Управление сейсмических и наземных исследований муниципалитета Стамбула отвечает за анализ методов снижения городского сейсмического риска . [93] национальное правительство, контролируемое правительством, Президентство по управлению стихийными бедствиями и чрезвычайными ситуациями отвечает тогда как за реагирование на чрезвычайные ситуации при землетрясении , и ему будут помогать такие неправительственные организации, как İHH . [94]

Угроза сильных землетрясений играет большую роль в развитии инфраструктуры города: с 2012 года было снесено и заменено более 500 000 уязвимых зданий. [90] Согласно заявлениям министерства и комментариям геологов, сделанным в 2023 году, инфраструктура города находилась в достаточно хорошем состоянии, однако из-за очень высоких затрат здания не были в этом состоянии: более полумиллиона квартир по-прежнему были уязвимы для обрушения, а количество жертв во многом зависит от того, сколько крах. [95] [96] [97] По состоянию на 2024 год [update]Большинство зданий в Стамбуле были построены с учетом низких сейсмических стандартов в 20 веке, [98] Жители считают, что город недостаточно подготовлен к землетрясению . [99]

Климат

Климат Стамбула умеренный и часто описывается как переходный между средиземноморским климатом, типичным для западного и южного побережий Турции, и океаническим климатом северо-западного побережья страны. [100] Однако существуют большие расхождения в терминологии, используемой для классификации климата города .

Лето в городе от теплого до жаркого и умеренно сухое, со средней дневной температурой около 28 ° C (82 ° F) и менее 7 дней с осадками в месяц. Несмотря на общепринятый температурный диапазон, середина лета в Стамбуле считается умеренно некомфортной из-за высоких точек росы и относительной влажности. [101] Зимы, тем временем, прохладные, довольно дождливые и относительно многоснежные для города со средней температурой выше нуля.

Осадки в Стамбуле распределяются неравномерно: в зимние месяцы выпадает как минимум вдвое больше осадков, чем в летние. Режим осадков также варьируется в зависимости от сезона. Зимние осадки обычно легкие, постоянные и часто представляют собой смешанные осадки, такие как дождевые и снежные смеси и крупа ; тогда как летние осадки обычно резкие и спорадические. Облачность, как и осадки, сильно варьируется в зависимости от сезона. Зимы довольно облачные: около 20 процентов дней солнечные или переменная облачность. Между тем летом здесь бывает 60-70 процентов возможного солнечного света.

Snowfall is sporadic, but accumulates virtually every winter; and when it does, it is highly disruptive to city infrastructure. Sea-effect snowstorms with more than 30 centimetres (1 ft) of snowfall happen almost annually, most recently in 2022.[102][103]

| Climate data for Kireçburnu (normals 1991–2020, precipitation days and sunshine 1981-2010; see the main article for more information) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 8.8 (47.8) | 9.4 (48.9) | 12.0 (53.6) | 16.1 (61.0) | 21.0 (69.8) | 25.7 (78.3) | 28.0 (82.4) | 28.2 (82.8) | 24.6 (76.3) | 19.9 (67.8) | 15.0 (59.0) | 10.7 (51.3) | 18.3 (64.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.9 (42.6) | 6.1 (43.0) | 8.0 (46.4) | 11.5 (52.7) | 16.3 (61.3) | 21.1 (70.0) | 23.7 (74.7) | 24.2 (75.6) | 20.5 (68.9) | 16.2 (61.2) | 11.7 (53.1) | 7.9 (46.2) | 14.4 (58.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.6 (38.5) | 3.5 (38.3) | 4.9 (40.8) | 8.1 (46.6) | 12.8 (55.0) | 17.4 (63.3) | 20.3 (68.5) | 21.2 (70.2) | 17.4 (63.3) | 13.6 (56.5) | 9.2 (48.6) | 5.5 (41.9) | 11.5 (52.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 96.1 (3.78) | 87.7 (3.45) | 69.8 (2.75) | 45.1 (1.78) | 37.1 (1.46) | 44.7 (1.76) | 36.3 (1.43) | 43.5 (1.71) | 81.3 (3.20) | 98.3 (3.87) | 100.5 (3.96) | 124.8 (4.91) | 865.2 (34.06) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 16.9 | 15.2 | 13.2 | 10.0 | 7.4 | 7.0 | 4.7 | 5.1 | 8.1 | 12.3 | 13.9 | 17.5 | 131.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 cm) | 4.5 | 4.7 | 2.9 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 2.7 | 15.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 79.8 | 78.6 | 75.8 | 75.1 | 76.5 | 75.7 | 75.3 | 75.9 | 75.0 | 78.4 | 78.9 | 78.4 | 76.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 68.2 | 89.6 | 142.6 | 180.0 | 248.0 | 297.6 | 319.3 | 288.3 | 234.0 | 158.1 | 93.0 | 62.0 | 2,180.7 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 22 | 29 | 38 | 46 | 57 | 64 | 69 | 66 | 65 | 46 | 31 | 22 | 46 |

| Source: [104][105][106] | |||||||||||||

Climate change

Climate change has caused an increase in Istanbul's heatwaves,[107] droughts,[108] storms,[109] and flooding[110][111] in Istanbul. Furthermore, as Istanbul is a large and rapidly expanding city, its urban heat island has been intensifying the effects of climate change.[112] If trends continue, sea level rise is likely to affect city infrastructure, for example Kadıkoy metro station is threatened with flooding.[113] Xeriscaping of green spaces has been suggested,[114] and Istanbul has a climate-change action plan,[115] but not a net zero target.[116]: 51

Flora and fauna

The natural vegetation of the province is made up of mixed broadleaf forest and pseudo-maquis, reflecting the city's transitional, Mediterranean-influenced humid temperate climate.[100] Chestnut, oak, elm, linden, ash and locust comprise the most prominent temperate forest genera, while laurel, terebinth, Cercis siliquastrum, broom, red firethorn, and oak species such as Quercus cerris and Quercus coccifera are the most important species of Mediterranean and Submediterranean distribution. Apart from the natural flora, Platanus orentalis, horse chestnut, cypress and stone pine make up the introduced species that got acclimatized to Istanbul.[117] In a study that examined urban flora in Kartal, a total of 576 plant taxa were recorded; of those 477 were natural and 99 were exotic and cultivated. The most prominent native taxa were in the Asteraceae family (50 species), while the most diverse exotic plant family was Rosaceae (16 species).[118]

Turkish Straits and Sea of Marmara play a vital role for migrating fish and other marine animals between Mediterranean, Marmara and Black Sea. Bosporus hosts pelagic, demersal and semipelagic fish species and more than 130 different taxa have been documented in the strait.[119] Bluefish, bonito, sea bass, horse mackerel and anchovies compose the economically important species. Fish diversity in the waters of Istanbul has dwindled in the recent decades. From around 60 different fish species recorded in the 1970s only 20 of them still survive in the Bosporus.[120][dubious – discuss] Common bottlenose dolphin (Turkish: afalina), short-beaked common dolphin (Turkish: tırtak) and harbor porpoise (Turkish: mutur) make up the marine mammals presently found in the Bosporus and surrounding waters, though since the 1950s the number of dolphin observations has become increasingly rare. Mediterranean monk seals were present in Bosporus, and Princes' Islands and Tuzla shores were seal breeding areas during summer, but they have not been observed in Istanbul since the 1960s and thought to be extinct in the region.[121] Water pollution, overfishing and destruction of coastal habitats caused by urbanization are main threats to Istanbul's marine ecology.

Apart from the wild land mammals Istanbul hosts a sizeable stray animal population. The presence of feral cats in Istanbul (Turkish: sokak kedisi) is noted to be very prevalent, with estimates ranging from a hundred thousand to over a million stray cats. The feral cats in the city have gained widespread media and public attention and are considered to be symbols of the city.[122][123] Rose-ringed parakeet colonies are present in urban areas, similar to other European cities as feral parrots, and considered as invasive species.[124]

Pollution

Air pollution in Turkey is acute in İstanbul with cars, buses and taxis causing frequent urban smog,[125] as it is one of the few European cities without a low-emission zone. As of 2019[update] the city's mean air quality remains at a level so as to affect the heart and lungs of healthy street bystanders during peak traffic hours,[126] and almost 200 days of pollution were measured by the air pollution sensors at Sultangazi, Mecidiyeköy, Alibeyköy and Kağıthane.[127] It is one of the 10 worst cities for NO

2.[128] However a trial of congestion pricing is planned for the historic peninsula.[129]

Algal blooms and red tides were reported in the Sea of Marmara and Bosporus (especially in Golden Horn), and regularly happen in urban lakes such as Lake Büyükçekmece and Küçükçekmece. In June 2021, a marine mucilage wave allegedly caused by water pollution spread to Sea of Marmara.[130]

Cityscape

Districts and neighborhoods

European side

The Fatih district, which was named after Mehmed II (Turkish: Fatih Sultan Mehmed), corresponds to what was the whole of Constantinople until the Ottoman conquest; today it is the capital district and called the historic peninsula of Istanbul on the southern shore of the Golden Horn, across the medieval Genoese citadel of Galata on the northern shore. The Genoese fortifications in Galata were largely demolished in the 19th century, leaving only the Galata Tower, to make way for the northward expansion of the city.[131] Galata (Karaköy) is today a quarter within the Beyoğlu district, which forms Istanbul's commercial and entertainment center and includes İstiklal Avenue and Taksim Square.[132]

Dolmabahçe Palace, the seat of government during the late Ottoman period, is in the Beşiktaş district on the European shore of the Bosporus, to the north of Beyoğlu. The former village of Ortaköy is within Beşiktaş and gives its name to the Ortaköy Mosque on the Bosporus, near the Bosporus Bridge. Lining both the European and Asian shores of the Bosporus are the historic yalıs, luxurious chalet mansions built by Ottoman aristocrats and elites as summer homes.[133] Inland, north of Taksim Square is the Istanbul Central Business District, a set of corridors lined with office buildings, residential towers, shopping centers, and university campuses, and over 2,000,000 m2 (22,000,000 sq ft) of class-A office space in total. Maslak, Levent, and Bomonti are important nodes within the CBD.[134][135]

The Atatürk Airport corridor is another such edge city-style business, residential and shopping corridor with over 900,000 m2 (9,700,000 sq ft) of class-A office space.[135]

Asian side

During the Ottoman period, Üsküdar (then Scutari) and Kadıköy were outside the scope of the urban area, serving as tranquil outposts with seaside yalıs and gardens. But in the second half of the 20th century, the Asian side experienced major urban growth; the late development of this part of the city led to better infrastructure and tidier urban planning when compared with most other residential areas in the city.[136] Much of the Asian side of the Bosporus functions as a suburb of the economic and commercial centers in European Istanbul, accounting for a third of the city's population but only a quarter of its employment.[136] However, Kozyatağı–Ataşehir, Altunizade, Kavacık and Ümraniye, all together having around 1.4 million sqm of class-A office space, are now important "edge cities", i.e. corridors and nodes of business and shopping centers and of tall residential buildings.[135]

Expansion

As a result of Istanbul's exponential growth in the 20th century, a significant portion of the city is composed of gecekondus (literally "built overnight"), referring to illegally constructed squatter buildings.[137] At present, some gecekondu areas are being gradually demolished and replaced by modern mass-housing compounds.[138] Moreover, large scale gentrification and urban renewal projects have been taking place,[139] such as the one in Tarlabaşı;[140] some of these projects, like the one in Sulukule, have faced criticism.[141] The Turkish government also has ambitious plans for an expansion of the city west and northwards on the European side in conjunction with the new Istanbul Airport, opened in 2019; the new parts of the city will include four different settlements with specified urban functions, housing 1.5 million people.[142]

Parks

Istanbul does not have a primary urban park, but it has several green areas. Gülhane Park and Yıldız Park were originally included within the grounds of two of Istanbul's palaces — Topkapı Palace and Yıldız Palace—but they were repurposed as public parks in the early decades of the Turkish Republic.[143] Another park, Fethi Paşa Korusu, is on a hillside adjacent to the Bosphorus Bridge in Anatolia, opposite Yıldız Palace in Europe.

Along the European side, and close to the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge, is Emirgan Park, which was known as the Kyparades ('Cypress Forest') during the Byzantine period. In the Ottoman period, it was first granted to Nişancı Feridun Ahmed Bey in the 16th century, before being granted by Sultan Murad IV to the Safavid emir Gûne Han in the 17th century, hence the name Emirgan. The 47-hectare (120-acre) park was later owned by Khedive Isma'il Pasha of Ottoman Egypt in the 19th century. Emirgan Park is known for its diversity of plants and an annual tulip festival is held there since 2005.[144]

The AKP government's decision to replace Taksim Gezi Park with a replica of the Ottoman era Taksim Military Barracks (which was transformed into the Taksim Stadium in 1921, before being demolished in 1940 for building Gezi Park) sparked a series of nationwide protests in 2013 covering a wide range of issues.

Popular during the summer among Istanbulites is Belgrad Forest, spreading across 5,500 hectares (14,000 acres) at the northern edge of the city. The forest originally supplied water to the city and remnants of reservoirs used during Byzantine and Ottoman times survive.[145][146]

Architecture

Istanbul is primarily known for its Byzantine and Ottoman architecture. Despite its development as a Turkish city since 1923, it contains many ancient, Roman, Byzantine, Christian, Muslim, and Jewish monuments.

The Neolithic settlement in the Yenikapı quarter on the European side, which dates back to c. 6500 BCE and predates the formation of the Bosporus by approximately a millennium, when the Sea of Marmara was still a lake,[citation needed] was discovered during the construction of the Marmaray railway tunnel.[26] It is the oldest known human settlement on the European side of the city.[26] The oldest known human settlement on the Asian side is the Fikirtepe Mound near Kadıköy, with relics dating to the Chalcolithic period c. 5500 – c. 3500 BCE.

There are numerous ancient monuments in the city.[147] The most ancient is the Obelisk of Thutmose III (Obelisk of Theodosius).[147] Built of red granite, 31 m (100 ft) high, it came from the Temple of Karnak in Luxor, and was erected there by Pharaoh Thutmose III (r. 1479 – 1425 BCE) to the south of the seventh pylon.[147] The Roman emperor Constantius II (r. 337–361 CE– ) had it and another obelisk transported along the Nile to Alexandria for commemorating his ventennalia or 20 years on the throne in 357. The other obelisk was erected on the spina of the Circus Maximus in Rome in the autumn of that year, and is now known as the Lateran Obelisk. The obelisk that would become the Obelisk of Theodosius remained in Alexandria until 390, when Theodosius I (r. 379–395) had it transported to Constantinople and put up on the spina of the Hippodrome there.[148] When re-erected at the Hippodrome of Constantinople, the obelisk was mounted on a decorative base, with reliefs that depict Theodosius I and his courtiers.[147] The lower part of the obelisk was damaged in antiquity, probably during its transport to Alexandria in 357 CE or during its re-erection at the Hippodrome of Constantinople in 390 CE. As a result, the current height of the obelisk is only 18.54 meters, or 25.6 meters if the base is included. Between the four corners of the obelisk and the pedestal are four bronze cubes, used in its transportation and re-erection.[149]

Next in age is the Serpent Column, from 479 BCE.[147] It was brought from Delphi in 324 CE, during the reign of Constantine the Great, and also erected at the spina of the Hippodrome.[147] It was originally part of an ancient Greek sacrificial tripod in Delphi that was erected to commemorate the Greeks who fought and defeated the Persian Empire at the Battle of Plataea in 479 BCE. The three serpent heads of the 8-meter (26 ft) high column remained intact until the end of the 17th century (one is on display at the nearby Istanbul Archaeology Museums).[151]

Built in porphyry and erected at the center of the Forum of Constantine in 330 CE to mark the founding of the new Roman capital, the Column of Constantine was originally adorned with a sculpture of the Roman emperor Constantine the Great depicted as the solar god Apollo on its top, which fell in 1106 and was later replaced by a cross during the reign of Byzantine emperor Manuel Komnenos (r. 1143–1180).[17][147]

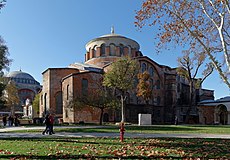

There are traces of the Byzantine era throughout the city, from ancient churches that were built over early Christian meeting places like the Hagia Irene, the Chora Church, the Monastery of Stoudios, the Church of Sts. Sergius and Bacchus, the Church of Theotokos Pammakaristos, the Monastery of the Pantocrator, the Monastery of Christ Pantepoptes, the Hagia Theodosia, the Church of Theotokos Kyriotissa, the Monastery of Constantine Lips, the Church of Myrelaion, the Hagios Theodoros, etc.; to palaces like the Great Palace of Constantinople and its Mosaic Museum, the Palace of the Porphyrogenitus, Boukoleon Palace and Palace of Blachernae; and other public places and buildings like the Hippodrome, the Augustaion, the Basilica Cistern, Theodosius Cistern, Cistern of Philoxenos and Cistern of the Hebdomon, the Aqueduct of Valens, the Prison of Anemas, the Walls of Constantinople and the Porta Aurea (Golden Gate), among numerous others. The 4th century Harbor of Theodosius in Yenikapı, once the busiest port in Constantinople, was among the numerous archeological discoveries that took place during the excavations of the Marmaray tunnel.[26]

However, it is the Hagia Sophia that fully conveys the period of Constantinople as a city without parallel in Christendom. The Hagia Sophia, topped by a dome 31 meters (102 ft) in diameter over a square space defined by four arches, is the pinnacle of Byzantine architecture.[152] The Hagia Sophia stood as the world's largest cathedral in the world until it was converted into a mosque in the 15th century.[152] The minarets date from that period.[152] Because of its historical significance, it was reopened as a museum in 1935. However, it was re-converted into a mosque in July 2020.

Over the next four centuries, the Ottomans transformed Istanbul's urban landscape with a vast building scheme that included the construction of towering mosques and ornate palaces. The Sultan Ahmed Mosque (Blue Mosque), another landmark of the city, faces the Hagia Sophia at Sultanahmet Square (Hippodrome of Constantinople). The Süleymaniye Mosque, built by Suleiman the Magnificent, was designed by his chief architect Mimar Sinan, the most illustrious of all Ottoman architects, who designed many of the city's renowned mosques and other types of public buildings and monuments.[154]

Among the oldest surviving examples of Ottoman architecture in Istanbul are the Anadoluhisarı and Rumelihisarı fortresses, which assisted the Ottomans during their siege of the city.[155] Over the next four centuries, the Ottomans made an indelible impression on the skyline of Istanbul, building towering mosques and ornate palaces.

Topkapı Palace, dating back to 1465, is the oldest seat of government surviving in Istanbul. Mehmed II built the original palace as his main residence and the seat of government.[156] The present palace grew over the centuries as a series of additions enfolding four courtyards and blending neoclassical, rococo, and baroque architectural forms.[157] In 1639, Murad IV made some of the most lavish additions, including the Baghdad Kiosk, to commemorate his conquest of Baghdad the previous year.[158] Government meetings took place here until 1786, when the seat of government was moved to the Sublime Porte.[156] After several hundred years of royal residence, it was abandoned in 1853 in favor of the baroque Dolmabahçe Palace.[157] Topkapı Palace became public property following the abolition of monarchy in 1922.[157] After extensive renovation, it became one of Turkey's first national museums in 1924.[156]

The imperial mosques include Fatih Mosque, Bayezid Mosque, Yavuz Selim Mosque, Süleymaniye Mosque, Sultan Ahmed Mosque (the Blue Mosque), and Yeni Mosque, all of which were built at the peak of the Ottoman Empire, in the 16th and 17th centuries. In the following centuries, and especially after the Tanzimat reforms, Ottoman architecture was supplanted by European styles.[159] An example of which is the imperial Nuruosmaniye Mosque. Areas around İstiklal Avenue were filled with grand European embassies and rows of buildings in Neoclassical, Renaissance Revival and Art Nouveau styles, which went on to influence the architecture of a variety of structures in Beyoğlu—including churches, stores, and theaters—and official buildings such as Dolmabahçe Palace.[160]

Administration

Since 2004, the municipal boundaries of Istanbul have been coincident with the boundaries of its province.[161] The city, considered capital of the larger Istanbul Province, is administered by the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality (IMM, Turkish: İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi, IBB), which oversees the 39 districts of the city-province.

The current city structure can be traced back to the Tanzimat period of reform in the 19th century, before which Islamic judges and imams led the city under the auspices of the Grand Vizier. Following the model of French cities, this religious system was replaced by a mayor and a citywide council composed of representatives of the confessional groups (millet) across the city. Pera (now Beyoğlu) was the first area of the city to have its own director and council, with members instead being longtime residents of the neighborhood.[162] Laws enacted after the Ottoman constitution of 1876 aimed to expand this structure across the city, imitating the twenty arrondissements of Paris, but they were not fully implemented until 1908 when the city was declared a province with nine constituent districts.[163][164] This system continued beyond the founding of the Turkish Republic, with the province renamed a belediye (municipality), but the municipality was disbanded in 1957.[165]

Small settlements adjacent to major population centers in Turkey, including Istanbul, were merged into their respective primary cities during the early 1980s, resulting in metropolitan municipalities.[166][167] The main decision-making body of the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality is the Municipal Council, with members drawn from district councils.

The Municipal Council of Istanbul is responsible for citywide issues, including managing the budget, maintaining civic infrastructure, and overseeing museums and major cultural centers.[168] Since the government operates under a "powerful mayor, weak council" approach, the council's leader—the metropolitan mayor—has the authority to make swift decisions, often at the expense of transparency.[169] The Municipal Council is advised by the Metropolitan Executive Committee, although the committee also has limited power to make decisions of its own.[170] All representatives on the committee are appointed by the metropolitan mayor and the council, with the mayor—or someone of his or her choosing—serving as head.[170][171]

District councils are chiefly responsible for waste management and construction projects within their respective districts. They each maintain their own budgets, although the metropolitan mayor reserves the right to review district decisions. One-fifth of all district council members, including the district mayors, also represent their districts in the Municipal Council.[168] All members of the district councils and the Municipal Council, including the metropolitan mayor, are elected to five-year terms.[172] Representing the Republican People's Party, Ekrem İmamoğlu has been the Mayor of Istanbul since 27 June 2019.[173]

With the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality and Istanbul Province having equivalent jurisdictions, few responsibilities remain for the provincial government. Like the MMI, the Istanbul Special Provincial Administration has a governor, a democratically elected decision-making body—the Provincial Parliament—and an appointed Executive Committee. Mirroring the executive committee at the municipal level, the Provincial Executive Committee includes a secretary-general and leaders of departments that advise the Provincial Parliament.[171][174] The Provincial Administration's duties are largely limited to the building and maintenance of schools, residences, government buildings, and roads, and the promotion of arts, culture, and nature conservation.[175] Davut Gül has been the Governor of Istanbul Province since 5 June 2023.[176]

Demographics

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sources: Jan Lahmeyer 2004,Chandler 1987, Morris 2010,Turan 2010[177] Pre-Republic figures estimated[f] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Throughout most of its history, Istanbul has ranked among the largest cities in the world. By 500 CE, Constantinople had somewhere between 400,000 and 500,000 people, edging out its predecessor, Rome, for the world's largest city.[179] Constantinople jostled with other major historical cities, such as Baghdad, Chang'an, Kaifeng and Merv for the position of the world's largest city until the 12th century. It never returned to being the world's largest, but remained the largest city in Europe from 1500 to 1750, when it was surpassed by London.[180]

The Turkish Statistical Institute estimates that the population of Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality was 15,519,267 at the end of 2019, hosting 19 percent of the country's population.[181] 64.4% of the residents live on the European side and 35.6% on the Asian side.[181]

Istanbul ranks as the seventh-largest city proper in the world, and the second-largest urban agglomeration in Europe, after Moscow.[182][183] The city's annual population growth of 1.5 percent ranks as one of the highest among the seventy-eight largest metropolises in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. The high population growth mirrors an urbanization trend across the country, as the second and third fastest-growing OECD metropolises are the Turkish cities of İzmir and Ankara.[16]

Istanbul experienced especially rapid growth during the second half of the 20th century, with its population increasing tenfold between 1950 and 2000.[184] This growth was fueled by internal and international migration. Istanbul's foreign population with a residence permit increased dramatically, from 43,000 in 2007[185] to 856,377 in 2019.[186][187]

According to 2020 TÜİK data around 2.1 million people in a population of over 15.4 million have been registered[g] in Istanbul, meanwhile the vast majority of the residents ultimately originate from Anatolian provinces, especially those in the Black Sea, Central and Eastern Anatolia regions due to internal migration since the 1950s.[188] People registered in Kastamonu, Ordu, Giresun, Erzurum, Samsun, Malatya, Trabzon, Sinop and Rize provinces represent the biggest population groups in Istanbul, meanwhile people registered in Sivas has the highest percentage with more than 760 thousand residents in the city.[189] A 2019 survey found that only 36% of the Istanbul's population was born in the province.[190]

Ethnic and religious groups

Istanbul has been a cosmopolitan city throughout much of its history, but it has become more homogenized since the end of the Ottoman era. The dominant ethnic group in the city is Turkish people, which also forms the majority group in Turkey. According to survey data 78% of the voting-age Turkish citizens in Istanbul state "Turkish" as their ethnic identity.[190]

With estimates ranging from 2 to 4 million, Kurds form one of the largest ethnic minorities in Istanbul and are the biggest group after Turks among Turkish citizens.[191][192] According to a 2019 KONDA study, Kurds constituted around 17% of Istanbul's adult total population who were Turkish citizens.[190] Although the initial Kurdish presence in the city dates back to the early Ottoman period,[193] the majority of Kurds in the city originate from villages in eastern and southeastern Turkey.[194] Zazas are also present in the city and constitute around 1% of the total voting-age population.[190]

Arabs form the city's other largest ethnic minority, with an estimated population of more than 2 million.[195] Following Turkey's support for the Arab Spring, Istanbul emerged as a hub for dissidents from across the Arab world, including former presidential candidates from Egypt, Kuwaiti MPs, and former ministers from Jordan, Saudi Arabia (including Jamal Khashoggi), Syria, and Yemen.[196][197][198] As of August 2019, the number of refugees of the Syrian Civil War in Turkey residing in Istanbul was estimated to be around 1 million.[199] Native Arab population in Turkey who are Turkish citizens are found to be making up less than 1% of city's total adult population.[190] As of August 2023, there were more than 530,000 refugees of the Syrian civil war in Istanbul, the highest number in any Turkish city.[200]

A 2019 survey study by KONDA that examined the religiosity of the voting-age adults in Istanbul showed that 57% of the surveyed had a religion and were trying to practise its requirements. This was followed by nonobservant people with 26% who identified with a religion but generally did not practise its requirements. 11% stated they were fully devoted to their religion, meanwhile 6% were non-believers who did not believe the rules and requirements of a religion. 24% of the surveyed also identified themselves as "religious conservatives". Around 90% of Istanbul's population are Sunni Muslims and Alevism forms the second biggest religious group.[190][201]

Into the 19th century, the Christians of Istanbul tended to be either Greek Orthodox, members of the Armenian Apostolic Church or Catholic Levantines.[202] Greeks and Armenians form the largest Christian population in the city. While Istanbul's Greek population was exempted from the 1923 population exchange with Greece, changes in tax status and the 1955 anti-Greek pogrom prompted thousands to leave.[203] Following Greek migration to the city for work in the 2010s, the Greek population rose to nearly 3,000 in 2019, still greatly diminished since 1919, when it stood at 350,000.[203] There are today 50,000 to 70,000 Armenians in Istanbul[204] down from a peak of 164,000 in 1913.[205] As of 2019, an estimated 18,000 of the country's 25,000 Christian Assyrians live in Istanbul.[206]

The majority of the Catholic Levantines (Turkish: Levanten) in Istanbul and İzmir are the descendants of traders/colonists from the Italian maritime republics of the Mediterranean (especially Genoa and Venice) and France, who obtained special rights and privileges called the Capitulations from the Ottoman sultans in the 16th century.[208] The community had more than 15,000 members during Atatürk's presidency in the 1920s and 1930s, but today is reduced to only a few hundreds, according to Italo-Levantine writer Giovanni Scognamillo.[209] They continue to live in Istanbul (mostly in Karaköy, Beyoğlu and Nişantaşı), and İzmir (mostly in Karşıyaka, Bornova and Buca).

Istanbul became one of the world's most important Jewish centers in the 16th and 17th century.[210] Romaniote and Ashkenazi communities existed in Istanbul before the conquest of Istanbul, but it was the arrival of Sephardic Jews that ushered a period of cultural flourishing. Sephardic Jews settled in the city after their expulsion from Spain and Portugal in 1492 and 1497.[210] Sympathetic to the plight of Sephardic Jews, Bayezid II sent out the Ottoman Navy under the command of admiral Kemal Reis to Spain in 1492 in order to evacuate them safely to Ottoman lands.[210] In marked contrast to Jews in Europe, Ottoman Jews were allowed to work in any profession.[211] Ottoman Jews in Istanbul excelled in commerce and came to particularly dominate the medical profession.[211] By 1711, using the printing press, books came to be published in Spanish and Ladino, Yiddish, and Hebrew.[212] In large part due to emigration to Israel, the Jewish population in the city dropped from 100,000 in 1950[213] to 15,000 in 2021.[214][215][216]

Politics

Politically, Istanbul is seen as the most important administrative region in Turkey. In the run-up to local elections in 2019, Erdoğan claimed 'if we fail in Istanbul, we will fail in Turkey'.[217] The contest in Istanbul carried deep political, economic and symbolic significance for Erdoğan, whose election of mayor of Istanbul in 1994 had served as his launchpad.[218] For Ekrem İmamoğlu, winning the mayoralty of Istanbul was a huge moral victory, but for Erdoğan it had practical ramifications: His party, AKP, lost control of the $4.8 billion municipal budget, which had sustained patronage at the point of delivery of many public services for 25 years.[219]

More recently, Istanbul and many of Turkey's metropolitan cities are following a trend away from the government and their right-wing ideology. In 2013 and 2014, large scale anti-AKP government protests began in İstanbul and spread throughout the nation. This trend first became evident electorally in the 2014 mayoral election where the center-left opposition candidate won an impressive 40% of the vote, despite not winning. The first government defeat in Istanbul occurred in the 2017 constitutional referendum, where Istanbul voted 'No' by 51.4% to 48.6%. The AKP government had supported a 'Yes' vote and won the vote nationally due to high support in rural parts of the country. A major turning point for the government came in the 2019 local elections, where their candidate for Mayor, former Prime Minister Binali Yıldırım, was defeated by a very narrow margin by the Republican People's Party candidate Ekrem İmamoğlu. İmamoğlu won the vote with 48.77% of the vote, against Yıldırım's 48.61%, but the elections were controversially annulled by the Supreme Electoral Council due to AKP's claim of electoral fraud. In the re-run İmamoğlu gathered 54.22% of the total vote and widened his margin of victory.[220]

Following the 2019 election, a trend towards the CHP has persisted across the city. In the 2023 presidential election the CHP candidate, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, received 48.56% of the city's vote, while the incumbent president and AKP candidate, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, received 46.68%.

In the 2024 local elections, Ekrem İmamoğlu was re-elected by a 12-point margin. İmamoğlu won 51.15% of the vote, while the AKP's candidate Murat Kurum received 39.59%. Additionally, the CHP won the mayoralties in 26 of İstanbul's 39 districts.[221]

Administratively, Istanbul is divided into 39 districts, more than any other province in Turkey. Istanbul Province sends 98 Members of Parliament to the Grand National Assembly of Turkey, which has a total of 600 seats. For the purpose of parliamentary elections, Istanbul is divided into three electoral districts; two on the European side and one on the Asian side, electing 28, 35 and 35 MPs respectively.[citation needed]

Economy

Istanbul had the eleventh-largest economy among the world's urban areas in 2018, and is responsible for 30 percent of Turkey's industrial output,[222] 31 percent of GDP,[222] and 47 percent of tax revenues.[222] The city's gross domestic product adjusted by PPP stood at US$537.507 billion in 2018,[223] with manufacturing and services accounting for 36 percent and 60 percent of the economic output respectively.[222] Istanbul's productivity is 110 percent higher than the national average.[222] Trade is economically important, accounting for 30 percent of the economic output in the city.[15] In 2019, companies based in Istanbul produced exports worth $83.66 billion and received imports totaling $128.34 billion; these figures were equivalent to 47 percent and 61 percent, respectively, of the national totals.[224]

Istanbul, which straddles the Bosporus strait, houses international ports that link Europe and Asia. The Bosporus, providing the only passage from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean, is the world's busiest and narrowest strait used for international navigation, with more than 200 million tons of oil passing through it each year.[225] International conventions guarantee passage between the Black and the Mediterranean seas,[226] even when tankers carry oil, natural gas, chemicals, and other flammable or explosive materials as cargo. In 2011, as a workaround solution, the then Prime Minister Erdoğan presented Canal Istanbul, a project to open a new strait between the Black and Marmara seas.[226] While the project was still on Turkey's agenda in 2020, there has not been a clear date set for it.[15]

Shipping is a significant part of the city's economy, with 73.9 percent of exports and 92.7 percent of imports in 2018 executed by sea.[15] Istanbul has three major shipping ports – the Port of Haydarpaşa, the Port of Ambarlı, and the Port of Zeytinburnu – as well as several smaller ports and oil terminals along the Bosporus and the Sea of Marmara.[15]

Haydarpaşa, at the southeastern end of the Bosporus, was Istanbul's largest port until the early 2000s.[227] Since then operations were shifted to Ambarlı, with plans to convert Haydarpaşa into a tourism complex.[15] In 2019, Ambarlı, on the western edge of the urban center, had an annual capacity of 3,104,882 TEUs, making it the third-largest cargo terminal in the Mediterranean basin.[227]

Istanbul has been an international banking hub since the 1980s,[15] and is home to the only active stock exchange in Turkey, Borsa Istanbul, which was originally established as the Ottoman Stock Exchange in 1866.[228]

In 1995, keeping up with the financial trends, Borsa Istanbul moved its headquarters (which was originally located on Bankalar Caddesi, the financial center of the Ottoman Empire,[228] and later at the 4th Vakıf Han building in Sirkeci) to İstinye, in the vicinity of Maslak, which hosts the headquarters of numerous Turkish banks.[229]

Since 2023, the Ataşehir district on the Asian side of the city is home to the Istanbul Financial Center (IFC), where the new headquarters of the state-owned Turkish banks, including the Turkish Central Bank, are located.[230][231] As of 2023, the five tallest skyscrapers in Istanbul and Turkey are the 352 m (1,154 ft 10 in) tall Turkish Central Bank Tower[232][233][234] in the Ataşehir district on the Asian side of the city; Metropol Istanbul Tower A (70 floors / 301 metres including its twin spires)[235][236] also in the Ataşehir district; Skyland Istanbul Towers 1 and 2 (2 x 284 metres)[237] located adjacent to Nef Stadium in the Huzur neighbourhood of the Sarıyer district on the European side, and Istanbul Sapphire (54 floors / 238 metres; 261 metres including its spire)[238] in Levent on the European side.

13.4 million foreign tourists visited the city in 2018, making Istanbul the world's fifth most-visited city in that year.[239] Istanbul and Antalya are Turkey's two largest international gateways, receiving a quarter of the nation's foreign tourists. Istanbul has more than fifty museums, with the Topkapı Palace, the most visited museum in the city, bringing in more than $30 million in revenue each year.[15]

Istanbul expects 1 million tourists from cruise companies after the renovation of its cruise port, also known as Galataport in Karaköy district.[240]

Culture

Istanbul was historically known as a cultural hub, but its cultural scene stagnated after the Turkish Republic shifted its focus toward Ankara.[243] The new national government established programs that served to orient Turks toward musical traditions, especially those originating in Europe, but musical institutions and visits by foreign classical artists were primarily centered in the new capital.[244]

Much of Turkey's cultural scene had its roots in Istanbul, and by the 1980s and 1990s Istanbul reemerged globally as a city whose cultural significance is not solely based on its past glory.[245]

By the end of the 19th century, Istanbul had established itself as a regional artistic center, with Turkish, European, and Middle Eastern artists flocking to the city. Despite efforts to make Ankara Turkey's cultural heart, Istanbul had the country's primary institution of art until the 1970s.[246] When additional universities and art journals were founded in Istanbul during the 1980s, artists formerly based in Ankara moved in.[247]

Beyoğlu has been transformed into the artistic center of the city, with young artists and older Turkish artists formerly residing abroad finding footing there. Modern art museums, including İstanbul State Art and Sculpture Museum, National Palaces Painting Museum, İstanbul Modern, the Pera Museum, Sakıp Sabancı Museum, Arter and SantralIstanbul, opened in the 2000s to complement the exhibition spaces and auction houses that have already contributed to the cosmopolitan nature of the city.[249] These museums have yet to attain the popularity of older museums on the historic peninsula, including the Istanbul Archaeology Museums, which ushered in the era of modern museums in Turkey, and the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum.[248]

The first film screening in Turkey was at Yıldız Palace in 1896, a year after the technology publicly debuted in Paris.[250] Movie theaters rapidly cropped up in Beyoğlu, with the greatest concentration of theaters being along the street now known as İstiklal Avenue.[251] Istanbul also became the heart of Turkey's nascent film industry, although Turkish films were not consistently developed until the 1950s.[252] Since then, Istanbul has been the most popular location to film Turkish dramas and comedies.[253] The Turkish film industry ramped up in the second half of the century, and with Uzak (2002) and My Father and My Son (2005), both filmed in Istanbul, the nation's movies began to see substantial international success.[254] Istanbul and its picturesque skyline have also served as a backdrop for several foreign films, including From Russia with Love (1963), Topkapi (1964), The World Is Not Enough (1999), and Mission Istaanbul (2008).[255]

Coinciding with this cultural reemergence was the establishment of the Istanbul Festival, which began showcasing a variety of art from Turkey and around the world in 1973. From this flagship festival came the International Istanbul Film Festival and the Istanbul Jazz Festival in the early 1980s. With its focus now solely on music and dance, the Istanbul Festival has been known as the Istanbul International Music Festival since 1994.[256] The most prominent of the festivals that evolved from the original Istanbul Festival is the Istanbul Biennial, held every two years since 1987. Its early incarnations were aimed at showcasing Turkish visual art, and it has since opened to international artists and risen in prestige to join the elite biennales, alongside the Venice Biennale and the São Paulo Art Biennial.[257]

Leisure and entertainment

Abdi İpekçi Street in Nişantaşı, Galataport Shopping Area in Karaköy and Bağdat Avenue on the Anatolian side of the city have evolved into high-end shopping districts.[258][259] Other focal points for shopping, leisure and entertainment include Nişantaşı, Ortaköy, Bebek and Kadıköy.[260] The city has numerous shopping centers, from the historic to the modern. Istanbul also has an active nightlife and historic taverns, a signature characteristic of the city for centuries, if not millennia.

The Grand Bazaar, in operation since 1461, is among the world's oldest and largest covered markets.[261][262] Mahmutpasha Bazaar is an open-air market extending between the Grand Bazaar and the Spice Bazaar, which has been Istanbul's major spice market since 1660.

Galleria Ataköy ushered in the age of modern shopping malls in Turkey when it opened in 1987.[263] Since then, malls have become major shopping centers outside the historic peninsula. Akmerkez was awarded the titles of "Europe's best" and "World's best" shopping mall by the International Council of Shopping Centers in 1995 and 1996; Istanbul Cevahir has been one of the continent's largest since opening in 2005; and Kanyon won the Cityscape Architectural Review Award in the Commercial Built category in 2006.[262] Zorlu Center and İstinye Park are among the other upscale malls in Istanbul which include the stores of the world's top fashion brands.

Along İstiklal Avenue is the Çiçek Pasajı ('Flower Passage'), a 19th-century shopping gallery which is today home to winehouses (known as meyhanes), pubs and restaurants.[264] İstiklal Avenue, originally known for its taverns, has shifted toward shopping, but the nearby Nevizade Street is still lined with winehouses and pubs.[265][266] Some other neighborhoods around İstiklal Avenue have been revamped to cater to Beyoğlu's nightlife, with formerly commercial streets now lined with pubs, cafes, and restaurants playing live music.[267]

Istanbul is known for its historic seafood restaurants. Many of the city's most popular and upscale seafood restaurants line the shores of the Bosporus (particularly in neighborhoods like Ortaköy, Bebek, Arnavutköy, Yeniköy, Beylerbeyi and Çengelköy). Kumkapı along the Sea of Marmara has a pedestrian zone that hosts around fifty fish restaurants.[268]

The Princes' Islands, 15 kilometers (9 mi) from the city center, are also popular for their seafood restaurants. Because of their restaurants, historic summer mansions, and tranquil, car-free streets, the Princes' Islands are a popular vacation destination among Istanbulites and foreign tourists.[269]

Istanbul is also famous for its sophisticated and elaborately-cooked dishes of the Ottoman cuisine. Following the influx of immigrants from southeastern and eastern Turkey, which began in the 1960s, the city's foodscape has drastically changed by the end of the century; with influences of Middle Eastern cuisine such as kebab taking an important place in the food scene.

Restaurants featuring foreign cuisines are mainly concentrated in the Beyoğlu, Beşiktaş, Şişli and Kadıköy districts.

Apart from the city's numerous stadiums, sports halls and concert halls, there are several open-air venues for concerts and festivals, such as the Cemil Topuzlu Open-Air Theatre in Harbiye, Paraf Kuruçeşme Open-Air on the Bosphorus shore in Kuruçeşme, and Parkorman in the forest of Maslak. The annual Istanbul Jazz Festival has been held every year since 1994. Organized between 2003 and 2013, Rock'n Coke was the biggest open-air rock festival in Turkey, sponsored by Coca-Cola. It was traditionally held at the Hezarfen Airfield in Istanbul.

The Istanbul International Music Festival has been held annually since 1973, and the International Istanbul Film Festival has been held annually since 1982. The Istanbul Biennial is a contemporary art exhibition that has been held biennially since 1987. The Istanbul Shopping Fest is an annual shopping festival held since 2011, and Teknofest is an annual festival of aviation, aerospace and technology, held since 2018.

When it was held for the first time in 2003, the annual Istanbul Pride became the first gay pride event in a Muslim-majority country.[270] Since 2015, all types of parades at Taksim Square and İstiklal Avenue (where, in 2013, the Gezi Park protests took place) have been denied permission by the AKP government, citing security concerns, but hundreds of people have defied the ban each year. Critics have claimed that the bans were in fact due to ideological reasons.

Sports

Istanbul is home to some of Turkey's oldest sports clubs. Beşiktaş J.K., established in 1903, is considered the oldest of these sports clubs. Due to its initial status as Turkey's only club, Beşiktaş occasionally represented the Ottoman Empire and Turkish Republic in international sports competitions, earning the right to place the Turkish flag inside its team logo.[271] Galatasaray S.K. and Fenerbahçe S.K. have fared better in international competitions and have won more Süper Lig titles, at 22 and 19 times, respectively.[272][273][274] Galatasaray and Fenerbahçe have a long-standing rivalry, with Galatasaray based in the European part and Fenerbahçe based in the Anatolian part of the city.[273] Istanbul has seven basketball teams—Anadolu Efes, Beşiktaş, Darüşşafaka, Fenerbahçe, Galatasaray, İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyespor and Büyükçekmece—that play in the premier-level Basketbol Süper Ligi.[275]

Many of Istanbul's sports facilities have been built or upgraded since 2000 to bolster the city's bids for the Summer Olympic Games. Atatürk Olympic Stadium, the largest multi-purpose stadium in Turkey, was completed in 2002 as an IAAF first-class venue for track and field.[276] The stadium hosted the 2005 UEFA Champions League Final, and was selected by the UEFA to host the CL Final games of 2020 and 2021, which were relocated to Lisbon (2020) and Porto (2021) due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[277] Şükrü Saracoğlu Stadium, Fenerbahçe's home field, hosted the 2009 UEFA Cup Final three years after its completion. Türk Telekom Arena opened in 2011 to replace Ali Sami Yen Stadium as Galatasaray's home turf,[278][279] while Vodafone Park, opened in 2016 to replace BJK İnönü Stadium as the home turf of Beşiktaş, hosted the 2019 UEFA Super Cup game. All four stadiums are elite Category 4 (formerly five-star) UEFA stadiums.[h]

The Sinan Erdem Dome, among the largest indoor arenas in Europe, hosted the final of the 2010 FIBA World Championship, the 2012 IAAF World Indoor Championships, as well as the 2011–12 Euroleague and 2016–17 EuroLeague Final Fours.[283] Prior to the completion of the Sinan Erdem Dome in 2010, Abdi İpekçi Arena was Istanbul's primary indoor arena, having hosted the finals of EuroBasket 2001.[284] Several other indoor arenas, including the Beşiktaş Akatlar Arena, have also been inaugurated since 2000, serving as the home courts of Istanbul's sports clubs. The most recent of these is the 13,800-seat Ülker Sports Arena, which opened in 2012 as the home court of Fenerbahçe's basketball teams.[285] Despite the construction boom, five bids for the Summer Olympics—in 2000, 2004, 2008, 2012, and 2020—and national bids for UEFA Euro 2012 and UEFA Euro 2016 have ended unsuccessfully.[286]

The TVF Burhan Felek Sport Hall is one of the major volleyball arenas in the city and hosts clubs such as Eczacıbaşı VitrA, Vakıfbank SK, and Fenerbahçe who have won numerous European and World Championship titles.[citation needed]

Between the 2005–2011 seasons,[287] and in the 2020 season,[288] Istanbul Park racing circuit hosted the Formula One Turkish Grand Prix. The 2021 F1 Turkish Grand Prix was initially cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic,[289] but on 25 June 2021, it was announced that the 2021 F1 Turkish Grand Prix will take place on 3 October 2021.[290] Istanbul Park was also a venue of the World Touring Car Championship and the European Le Mans Series in 2005 and 2006, but the track has not seen either of these competitions since then.[291][292] It also hosted the Turkish Motorcycle Grand Prix between 2005 and 2007. Istanbul was occasionally a venue of the F1 Powerboat World Championship, with the last race on the Bosporus strait on 12–13 August 2000.[293][unreliable source?] The last race of the Powerboat P1 World Championship on the Bosporus took place on 19–21 June 2009.[294] Istanbul Sailing Club, established in 1952, hosts races and other sailing events on the waterways in and around Istanbul each year.[295][296]

Media

Most state-run radio and television stations are based in Ankara, but Istanbul is the primary hub of Turkish media. The industry has its roots in the former Ottoman capital, where the first Turkish newspaper, Takvim-i Vekayi (Calendar of Affairs), was published in 1831. The Cağaloğlu street on which the newspaper was printed, Bâb-ı Âli Street, rapidly became the center of Turkish print media, alongside Beyoğlu across the Golden Horn.[298]

Istanbul now has a wide variety of periodicals. Most nationwide newspapers are based in Istanbul, with simultaneous Ankara and İzmir editions.[299] Hürriyet, Sabah, Posta and Sözcü, the country's top four papers, are all headquartered in Istanbul, boasting more than 275,000 weekly sales each.[300] Hürriyet's English-language edition, Hürriyet Daily News, has been printed since 1961, but the English-language Daily Sabah, first published by Sabah in 2014, has overtaken it in circulation. Several smaller newspapers, including popular publications like Cumhuriyet, Milliyet and Habertürk are also based in Istanbul.[299] Istanbul also has long-running Armenian language newspapers, notably the dailies Marmara and Jamanak and the bilingual weekly Agos in Armenian and Turkish.[301]

Radio broadcasts in Istanbul date back to 1927, when Turkey's first radio transmission came from atop the Central Post Office in Eminönü. Control of this transmission, and other radio stations established in the following decades, ultimately came under the state-run Turkish Radio and Television Corporation (TRT), which held a monopoly on radio and television broadcasts between its founding in 1964 and 1990.[302] Today, TRT runs four national radio stations; these stations have transmitters across the country so each can reach over 90 percent of the country's population, but only Radio 2 is based in Istanbul. Offering a range of content from educational programming to coverage of sporting events, Radio 2 is the most popular radio station in Turkey.[302] Istanbul's airwaves are the busiest in Turkey, primarily featuring either Turkish-language or English-language content. One of the exceptions, offering both, is Açık Radyo (94.9 FM). Among Turkey's first private stations, and the first featuring foreign popular music, was Istanbul's Metro FM (97.2 FM). The state-run Radio 3, although based in Ankara, also features English-language popular music, and English-language news programming is provided on NTV Radyo (102.8 FM).[303]

TRT-Children is the only TRT television station based in Istanbul.[304] Istanbul is home to the headquarters of several Turkish stations and regional headquarters of international media outlets. Istanbul-based Star TV was the first private television network to be established following the end of the TRT monopoly; Star TV and Show TV (also based in Istanbul) remain highly popular throughout the country, airing Turkish and American series.[305] Kanal D and ATV are other stations in Istanbul that offer a mix of news and series; NTV (partnered with American media outlet MSNBC) and Sky Turk—both based in the city—are mainly just known for their news coverage in Turkish. The BBC has a regional office in Istanbul, assisting its Turkish-language news operations, and the American news channel CNN established the Turkish-language CNN Türk there in 1999.[306]

Education

As of 2019, excluding universities more than 3.1 million students attended 7,437 schools in Istanbul, about half of the schools being private schools.[307] The average class size was 30 for primary education institutes, 27 for vocational schools and 23 for general high schools.[307] Of the 842 public high schools, 263 are vocational schools, another 263 are Anatolian high schools, 207 are religiously oriented İmam Hatip schools, and 14 are STEM-oriented science high schools.[308] Galatasaray High School was established in 1481 and is the oldest public high school in Turkey.[309] Kabataş Erkek Lisesi, Istanbul Lisesi and Cağaloğlu Anatolian High School are among other public high schools in the city. Istanbul also contains high schools established by the European and American expatriates and missionaries in the 19th century that currently offer secular, foreign-language education such as Robert College, Deutsche Schule Istanbul, Sankt Georgs-Kolleg, Lycée Saint-Joseph and Liceo Italiano di Istanbul.[310] Furthermore Turkish citizens of Jewish, Armenian, Greek and Assyrian descent are allowed to establish and attend their respective schools as granted in the Treaty of Lausanne, Phanar Greek Orthodox College being an example.[311] Most high schools are highly selective and demand high scores from the national standardized LGS exam [tr] for admission, with Galatasaray and Robert College only accepting the top 0.1% to 0.01% of the exam takers.[312]

Istanbul contains almost a third of all universities in Turkey. As of 2019 Istanbul has 61 colleges and universities, with more than 1.8 million students enrolled according to official figures. Of those, fourteen are state-owned, 44 are "foundation-owned" private universities and three are foundation-owned vocational universities of higher education. There are also military academies, including the Turkish Air Force Academy and Turkish Naval Academy as well as four foundation-owned vocational universities of higher education which are not affiliated with any university.[313]

Some of the most renowned and highly ranked universities in Turkey are in Istanbul. Istanbul University, the nation's oldest institute of higher education, dates back to 1453 and its dental, law, medical schools were founded in the 19th century.The city's largest private universities include Sabancı University, with its main campus in Tuzla, Koç University in Sarıyer, Özyeğin Üniversitesi near Altunizade. Istanbul's first private university, Koç University, was founded as late as 1992, because private universities were not allowed in Turkey before the 1982 amendment to the constitution.[309] Istanbul is also home to several conservatories and art schools, including Mimar Sinan Academy of Fine Arts, founded in 1882.[314]

Public universities with a major presence in the city, such as Istanbul University, Istanbul Technical University (the world's third-oldest university dedicated entirely to engineering, established in 1773), and Boğaziçi University (formerly the higher education section of Robert College until 1971) provide education in English as the primary foreign language, while the primary foreign language of education at Galatasaray University is French.[309]

Public services