Роль христианства в цивилизации

| Часть серии о |

| Христианская культура |

|---|

|

| Христианский портал |

Христианство было неразрывно переплетено с историей и формированием западного общества . На протяжении всей своей долгой истории Церковь ; была основным источником социальных услуг, таких как образование и медицинское обслуживание вдохновение для искусства , культуры и философии ; и влиятельный игрок в политике и религии . Разными способами оно стремилось повлиять на отношение Запада к пороку и добродетели в различных областях. Такие фестивали, как Пасха и Рождество, отмечаются как государственные праздники; григорианский календарь был принят на международном уровне как гражданский календарь ; а сам календарь измеряется по приблизительной дате рождения Иисуса .

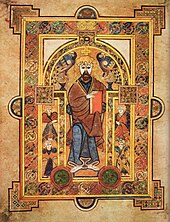

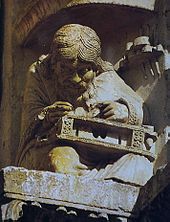

Культурное влияние Церкви было огромным. Церковные ученые сохранили грамотность в Западной Европе после падения Западной Римской империи . [1] В средние века церковь заменила Римскую империю и стала объединяющей силой в Европе. Средневековые соборы остаются одними из самых знаковых архитектурных шедевров, созданных западной цивилизацией . Многие университеты Европы в то время также были основаны церковью. Многие историки утверждают, что университеты и соборные школы были продолжением интереса к обучению, пропагандируемого монастырями. [2] В целом университет считается [3] [4] как учреждение, берущее свое начало в средневековой христианской среде, рожденное в соборных школах . [5] Многие ученые и историки приписывают вклад христианства в возникновение научной революции . [6] [7]

Реформация Микеланджело положила конец религиозному единству на Западе, но шедевры эпохи Возрождения, созданные католическими художниками, такими как , Леонардо да Винчи и Рафаэль, остаются одними из самых знаменитых произведений искусства, когда-либо созданных. Точно так же христианская духовная музыка таких композиторов, как Пахельбель , Вивальди , Бах , Гендель , Моцарт , Гайдн , Бетховен , Мендельсон , Лист и Верди , входит в число наиболее почитаемой классической музыки в западном каноне.

Библия . и христианское богословие также оказали сильное влияние на западных философов и политических активистов [8] Некоторые утверждают, что учение Иисуса , такое как « Притча о добром самаритянине », является одним из наиболее важных источников современных представлений о « правах человека » и благосостоянии, обычно предоставляемых правительствами на Западе. Давние христианские учения о сексуальности, браке и семейной жизни в последнее время также оказались влиятельными и противоречивыми. [9] : 309 Христианство в целом повлияло на положение женщин, осуждая супружескую неверность , развод , инцест , многоженство , контроль над рождаемостью , детоубийство (младенцев женского пола чаще убивали) и аборты . [10] : 104 Хотя официальное учение католической церкви [11] : 61 считает женщин и мужчин дополняющими друг друга (равными и разными), некоторые современные «защитники рукоположения женщин и другие феминистки» утверждают, что учения, приписываемые Св. Павлу , а также учения отцов церкви и схоластических богословов, выдвинули идею божественного предписанная женская неполноценность. [12] Тем не менее, женщины сыграли выдающуюся роль в западной истории через церковь и как ее часть, особенно в сфере образования и здравоохранения, а также как влиятельные теологи и мистики.

Христиане внесли бесчисленное множество вкладов в прогресс человечества в широком и разнообразном диапазоне областей, как исторических, так и в наше время, включая науку и технику . [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] лекарство , [18] изобразительное искусство и архитектура , [19] [20] [21] политика, литература , [21] музыка , [21] филантропия , философия , [22] [23] [24] : 15 этика , [25] гуманизм , [26] [27] [28] театр и бизнес. [29] [30] [20] [31] По данным журнала «100 лет Нобелевской премии», обзор присуждения Нобелевских премий за период с 1901 по 2000 год показывает, что (65,4%) лауреатов Нобелевской премии определили христианство в его различных формах как свое религиозное предпочтение. [32] Восточные христиане (особенно христиане -несторианцы ) также внесли свой вклад в арабскую исламскую цивилизацию в периоды Омейядов и Аббасидов , переводя произведения греческих философов на сирийский , а затем на арабский язык . [33] [34] [35] Они также преуспели в философии, науке, теологии и медицине. [36] [37]

Родни Старк пишет, что достижения средневековой Европы в методах производства, навигации и военных технологиях «можно объяснить уникальным христианским убеждением в том, что прогресс был данным Богом обязательством, вытекающим из дара разума. Новые технологии и методы всегда будут появляться». было фундаментальным догматом христианской веры. Следовательно, ни епископы, ни богословы не осуждали часы или парусные корабли, хотя и то, и другое осуждалось по религиозным мотивам в различных незападных обществах». [38] [ нужен пример ]

Христианство внесло большой вклад в развитие европейской культурной идентичности, [39] хотя некоторый прогресс возник в других местах, романтизм начался с любопытства и страсти языческого мира. древнего [40] [41] За пределами западного мира христианство оказало влияние и внесло свой вклад в различные культуры, например, в Африке, Центральной Азии, на Ближнем Востоке, на Ближнем Востоке, в Восточной Азии, Юго-Восточной Азии и на Индийском субконтиненте. [42] [43] Ученые и интеллектуалы отмечают, что христиане внесли значительный вклад в арабскую и исламскую цивилизацию с момента появления ислама . [44]

Политика и право

[ редактировать ]От ранних преследований к государственной религии

[ редактировать ]

Основа канонического права заложена в его самых ранних текстах и их интерпретации в трудах отцов церкви. Христианство зародилось как еврейская секта в середине I века, возникшая на основе жизни и учения Иисуса из Назарета . Жизнь Иисуса описана в Новом Завете Библии, одном из основополагающих текстов западной цивилизации и источнике вдохновения для бесчисленных произведений западного искусства . [45] Рождение Иисуса отмечается в праздник Рождества, его смерть во время Пасхального Триденствия и его воскресение во время Пасхи. Рождество и Пасха остаются праздниками во многих западных странах.

Иисус выучил тексты еврейской Библии с ее Десятью заповедями (которые позже стали влиятельными в западном законодательстве). [ нужна ссылка ] ) и стал влиятельным странствующим проповедником. Он был убедительным рассказчиком притч и философом-моралистом, призывавшим своих последователей поклоняться Богу, действовать без насилия и предрассудков и заботиться о больных, голодных и бедных. Эти учения глубоко повлияли на западную культуру. Иисус раскритиковал лицемерие религиозного истеблишмента, что вызвало гнев властей, которые убедили римского губернатора провинции Иудея Понтия Пилата казнить его. В Талмуде говорится, что Иисус был казнен правительством Хасмонеев, которое побило его камнями и повесило, и что его наказанием будет вечное кипячение в человеческих экскрементах за колдовство и за то, что они привели людей к отступничеству. [46] В Иерусалиме около 30 года нашей эры Иисус был распят . [47]

Первые последователи Иисуса, в том числе святые Павел и Петр, распространили эту новую теологию об Иисусе и его этике по всей Римской империи и за ее пределами, сея семена для развития католической церкви , первым Папой которой считается святой Петр. В эти первые века христиане иногда сталкивались с гонениями , особенно за отказ присоединиться к поклонению императорам . Тем не менее, распространяемое через синагоги, купцов и миссионеров по всему известному миру, христианство быстро росло в размерах и влиянии. [47] Его уникальная привлекательность отчасти была результатом его ценностей и этики. [48]

Библия ; оказала глубокое влияние на западную цивилизацию и культуры по всему миру он внес свой вклад в формирование западного права , искусства , текстов и образования. [49] [50] Имея литературную традицию, охватывающую два тысячелетия, Библия является одним из самых влиятельных произведений, когда-либо написанных. От практики личной гигиены до философии и этики Библия прямо и косвенно повлияла на политику и право, войну и мир, сексуальную мораль, брак и семейную жизнь, туалетный этикет , письмо и обучение, искусство, экономику, социальную справедливость, медицинское обслуживание. и многое другое. [51]

Человеческие ценности как основа права

[ редактировать ]Первыми цивилизациями в мире были священные государства Месопотамии , управляемые от имени божества или правителями, которых считали божественными. Правители, а также священники, солдаты и бюрократы, исполнявшие их волю, составляли небольшое меньшинство, сохранявшее власть за счет эксплуатации большинства. [52]

Если мы обратимся к корням нашей западной традиции, мы обнаружим, что в греческие и римские времена не вся человеческая жизнь считалась неприкосновенной и достойной защиты. Рабы и «варвары» не имели полного права на жизнь, а человеческие жертвоприношения и гладиаторские бои были приемлемы... Спартанский закон требовал казни уродливых младенцев; для Платона детоубийство — один из обычных институтов идеального государства; Аристотель считает аборт желательным вариантом; а философ-стоик Сенека без извинений пишет: «Неестественное потомство мы уничтожаем; мы топим даже детей, которые при рождении слабы и ненормальны... И хотя были отклонения от этих взглядов..., вероятно, правильно будет сказать, что такие практики. ...были менее запрещены в древние времена. Большинство историков западной морали согласны с тем, что возникновение ...христианства во многом способствовало распространению чувства, что человеческая жизнь ценна и достойна уважения. [53]

В.Е.Лекки в своей истории европейской морали дает ставшее уже классическим описание святости человеческой жизни, утверждая, что христианство «образовало новый стандарт, более высокий, чем любой, который тогда существовал в мире...». [54] Христианский специалист по этике Дэвид П. Гуши говорит: «Учение Иисуса о справедливости тесно связано с приверженностью святости жизни…». [55]

Джон Киоун , профессор христианской этики, отличает эту « святости жизни доктрину » от «подхода, основанного на качестве жизни , который признает только инструментальную ценность человеческой жизни, и виталистического подхода, который рассматривает жизнь как абсолютную моральную ценность... [ Кевон говорит, что это подход «святости жизни… который закладывает презумпцию в пользу сохранения жизни, но признает, что существуют обстоятельства, при которых жизнь не должна сохраняться любой ценой», и именно это обеспечивает прочную основу. для закона, касающегося вопросов конца жизни. [56]

Ранние юридические взгляды на женщин

[ редактировать ]В Риме существовала социальная кастовая система, при которой женщины не имели «юридической независимости и независимой собственности». [57] В раннем христианстве, как объясняет Плиний Младший в своих письмах императору Траяну, были люди «всех возрастов и рангов, обоих полов». [58] Плиний сообщает об аресте двух рабынь, которые утверждали, что они «дьякониссы», в первом десятилетии второго века. [59] В Римской папской книге (литургической книге) вплоть до XII века существовал обряд рукоположения женщин-дьяконов. Для женщин-дьяконов самый древний обряд на Западе происходит из книги восьмого века, тогда как восточные обряды восходят к третьему веку, и их больше. [60]

В Новом Завете упоминается ряд женщин из ближайшего окружения Иисуса. Есть несколько евангельских рассказов о том, как Иисус передавал важные учения женщинам и о женщинах: его встреча с самаритянкой у колодца, его помазание Марией Вифанской, его публичное восхищение бедной вдовой, пожертвовавшей две медные монеты Храму в Иерусалиме, его шаг на помощь женщине, обвиняемой в прелюбодеянии, его дружба с Марией и Марфой, сестрами Лазаря, а также присутствие Марии Магдалины, его матери и других женщин, когда он был распят. Историк Джеффри Блейни заключает, что «поскольку положение женщин в Палестине было невысоким, доброта Иисуса к ним не всегда одобрялась теми, кто строго придерживался традиций». [61]

По словам христианского апологета Тима Келлера, в греко-римском мире было обычным делом выставлять напоказ младенцев женского пола из-за низкого статуса женщины в обществе. Церковь запретила своим членам это делать. Греко-римское общество не видело никакой ценности в незамужней женщине, и поэтому для вдовы было незаконно оставаться в браке более двух лет без повторного замужества. Христианство не принуждало вдов выходить замуж и поддерживало их материально. Языческие вдовы теряли всякий контроль над имуществом своего мужа, когда снова выходили замуж, но церковь позволяла вдовам сохранять имущество своего мужа. Христиане не верили в сожительство. Если мужчина-христианин хотел жить с женщиной, церковь требовала брака, и это давало женщинам законные права и гораздо большую безопасность. Наконец, языческий двойной стандарт, разрешавший женатым мужчинам иметь внебрачный секс и иметь любовниц, был запрещен. Учение Иисуса о разводе и защита моногамии Павлом положили начало процессу повышения статуса женщин, так что женщины-христианки, как правило, пользовались большей безопасностью и равенством, чем женщины в соседних культурах. [62]

Законы, касающиеся детей

[ редактировать ]В древнем мире детоубийство не было законным, но редко преследовалось по закону. Обычно проводилось широкое различие между детоубийством и воздействием на младенцев, что широко практиковалось. Многие подвергшиеся воздействию дети умерли, но многих забрали спекулянты, которые вырастили их рабами или проститутками. Невозможно установить с какой-либо степенью точности, какое сокращение детоубийства произошло в результате юридических усилий против него в Римской империи. «Однако можно с уверенностью утверждать, что гласность торговли незащищенными детьми стала невозможной под влиянием христианства и что ощущение серьезности преступления значительно возросло». [54] : 31, 32

Правовой статус при Константине

[ редактировать ]императора Константина в Миланский эдикт 313 году нашей эры положил конец спонсируемому государством преследованию христиан на Востоке, а его собственное обращение в христианство стало важным поворотным моментом в истории. [63] В 312 году Константин предложил христианам гражданскую терпимость и во время своего правления ввел законы и политику, соответствующие христианским принципам: сделав воскресенье субботой «днем отдыха» для римского общества (хотя первоначально это было только для горожан) и приступив к Программа строительства церкви. В 325 году нашей эры Константин созвал Первый Никейский собор , чтобы достичь консенсуса и единства внутри христианства с целью сделать его религией Империи. Население и богатство Римской империи перемещались на восток, и примерно в 330 году Константин основал Константинополь как новый имперский город, который стал столицей Восточной Римской империи . Восточный Патриарх в Константинополе теперь стал соперником Папы в Риме. Хотя культурная преемственность и взаимообмен между этими Восточными и Западными Римскими империями продолжались, история христианства и западной культуры пошла разными путями, с окончательным Великим расколом, разделившим Римскую империю. и восточное христианство в 1054 году нашей эры.

Политическое влияние четвертого века и законы против язычников

[ редактировать ]В четвертом веке христианская письменность и богословие переросли в «золотой век» литературной и научной деятельности, не имеющий аналогов со времен Вергилия и Горация. Многие из этих работ остаются влиятельными в политике, праве, этике и других областях. В IV веке зародился и новый жанр литературы: церковная история. [64] [65]

Замечательное превращение христианства из периферийной секты в крупную силу внутри Империи часто считается результатом влияния святого Амвросия , епископа Милана , но это маловероятно. [66] : 60, 63, 131 император Феодосий I приказал устроить карательную резню тысяч граждан Салоник В апреле 390 года . В частном письме Амвросия к Феодосию, где-то в августе после этого события, Амвросий сказал Феодосию, что его нельзя причащать, пока Феодосий не раскаивается в этом ужасном поступке. [67] : 12 [68] [69] Вольф Либешуец говорит, что записи показывают, что «Феодосий должным образом подчинился и смиренно приходил в церковь, без своего императорского одеяния, до Рождества, когда Амвросий открыто снова допустил его к причастию». [70] : 262

Маклинн заявляет, что «встреча у дверей церкви уже давно известна как благочестивая выдумка». [71] : 291 Дэниел Уошберн объясняет, что образ прелата в митре, закрепленного в дверях миланского собора и преграждающего вход Феодосию, является продуктом воображения Феодорита , историка пятого века, который писал о событиях 390 года, «используя свои собственные идеология, призванная заполнить пробелы в исторических записях». [72] : 215 По мнению Питера Брауна , эти события касаются личного благочестия; они не представляют собой поворотный момент в истории подчинения государства церкви. [73] : 111 [66] : 63, 64

Согласно христианской литературе четвертого века, язычество закончилось к началу-середине пятого века, когда все либо обратились, либо были запуганы. [74] : 633, 640 Современная археология, напротив, указывает на то, что это не так; язычество продолжалось по всей империи, и конец язычества варьировался от места к месту. [75] : 54 Насилие, такое как разрушение храмов, засвидетельствовано в некоторых местах, как правило, в небольших количествах и неравномерно распространено по всей империи. В большинстве регионов, удаленных от императорского двора, конец язычества чаще всего был постепенным и безболезненным. [75] : 156, 221 [76] : 5, 7, 41

Феодосий правил (хотя и ненадолго) как последний император объединенной Восточной и Западной Римской империи. Между 389 и 391 годами Феодосий издал Феодосиевы указы — сборник законов времен Константина, включавший законы против еретиков и язычников. В 391 году Феодосий заблокировал восстановление языческого Алтаря Победы римскому сенату, а затем воевал против Евгения , который заручился поддержкой язычников в своей борьбе за императорский трон. [77] Браун говорит, что формулировки Феодосианских указов «всегда суровы, а наказания суровы и зачастую ужасны». Возможно, они послужили основой для подобных законов в эпоху Высокого Средневековья. [74] : 638 Однако в древности эти законы не соблюдались, и Браун добавляет, что «в большинстве районов многобожники не подвергались притеснениям, и, за исключением нескольких отвратительных случаев местного насилия, еврейские общины также наслаждались столетием стабильного, даже привилегированного существования». , существование." [78] : 643 Современные ученые указывают, что язычники не были истреблены и не полностью обращены в веру к пятому веку, как утверждают христианские источники. Язычники оставались на протяжении четвертого и пятого веков в достаточном количестве, чтобы сохранить широкий спектр языческих практик до VI века, а в некоторых местах даже позже. [79] : 19

Политические и правовые последствия падения Рима

[ редактировать ]Центральная бюрократия имперского Рима осталась в Риме в шестом веке, но в остальной части империи была заменена немецкой племенной организацией и церковью. [80] : 67 После падения Рима (476 г.) большая часть Запада вернулась к натуральному аграрному образу жизни. Та небольшая безопасность, которая была в этом мире, в основном обеспечивалась христианской церковью. [81] [82] Папство . служило источником власти и преемственности в это критическое время В отсутствие жившего в Риме военного магистра даже управление военными делами перешло к папе.

Роль христианства в политике и праве в период Средневековья.

[ редактировать ]Историк Джеффри Блейни сравнил деятельность католической церкви в средние века с ранней версией государства всеобщего благосостояния: «У нее были больницы для престарелых и приюты для молодых; хосписы для больных всех возрастов; приюты для прокаженных ; и общежития или гостиницы, где паломники могли дешево купить ночлег и еду». Оно снабжало население продовольствием во время голода и раздавало еду беднякам. Эту систему социального обеспечения церковь финансировала за счет сбора крупных налогов и владения большими сельскохозяйственными угодьями и поместьями. [83] Каноническое право Католической церкви ( лат . jus canonicum ) [84] Это система законов и правовых принципов, созданная и применяемая иерархическими властями Церкви для регулирования ее внешней организации и управления, а также для упорядочения и направления деятельности католиков в соответствии с миссией Церкви. [85] Это была первая современная западная правовая система. [86] и является старейшей постоянно действующей правовой системой на Западе, [87] предшествовали традициям европейского общего права и гражданского права .

Правило Бенедикта как правовая основа в темные века

[ редактировать ]Период между падением Рима (476 г. н.э.) и возвышением франков Каролингов (750 г. н.э.) часто называют «Темными веками», однако его также можно назвать «Эпохой монаха». Эта эпоха оказала длительное влияние на политику и право через христианских эстетов, таких как святой Бенедикт (480–543), которые поклялись вести целомудренную жизнь, послушание и бедность; После тщательной интеллектуальной подготовки и самоотречения бенедиктинцы жили по «Правилу Бенедикта»: работай и молись. Это «Правило» стало основой большинства из тысяч монастырей, разбросанных по территории современной Европы; «...конечно, не будет никаких сомнений в признании того, что правило св. Бенедикта было одним из величайших фактов в истории Западной Европы, и что его влияние и последствия сохраняются с нами по сей день». [81] : введение.

Монастыри были образцом производительности и экономической изобретательности, обучая местные общины животноводству, производству сыра, виноделию и различным другим навыкам. [88] Они были приютом для бедных, больницами, приютами для умирающих и школами. Медицинская практика имела большое значение в средневековых монастырях, и они наиболее известны своим вкладом в медицинскую традицию. Они также добились успехов в таких науках, как астрономия. [89] На протяжении веков почти все светские лидеры обучались у монахов, поскольку, за исключением частных репетиторов, которые зачастую все еще были монахами, это было единственное доступное образование. [90]

Формирование этих организованных групп верующих, отличных от политической и семейной власти, особенно для женщин, постепенно создало ряд социальных пространств с некоторой степенью независимости, тем самым революционизировав социальную историю. [91]

Григорий Великий ( ок. 540–604) провел строгую реформу церкви. Обученный римский юрист, администратор и монах, он представляет собой переход от классического мировоззрения к средневековому и был отцом многих структур позднейшей католической церкви. Согласно Католической энциклопедии, он рассматривал церковь и государство как сотрудничающие, образующие единое целое, которое действовало в двух различных сферах, церковной и светской, но к моменту его смерти папство было великой властью в Италии: [92] Григорий был одним из немногих государей, названных Великим по всеобщему согласию. Он известен тем, что отправил первую зарегистрированную крупномасштабную миссию из Рима для обращения тогдашних англосаксов -язычников в Англии, своими многочисленными сочинениями, своими административными навыками и своей заботой о благосостоянии людей. [93] [94] Он также боролся с арианской ересью и донатистами , усмирил готов, оставил знаменитый пример покаяния за преступление, пересмотрел литургию и повлиял на музыку посредством развития антифонных песнопений. [95]

Папа Григорий Великий сделал себя в Италии властью более сильной, чем император или экзарх, и установил политическое влияние, которое доминировало на полуострове на протяжении веков. С этого времени разнообразное население Италии обращалось к папе за руководством, а Рим как папская столица продолжал оставаться центром христианского мира.

Карл Великий изменил право и основал феодализм в раннем средневековье.

[ редактировать ]

Карл Великий («Карл Великий» по-английски) стал королем франков в 768 году. Он завоевал Нидерланды , Саксонию, северную и центральную Италию, а в 800 году папа Лев III короновал Карла Великого императором Священной Римской империи . Карл Великий, которого иногда называют «Отцом Европы» и основателем феодализма, провел политическую и судебную реформу и возглавил то, что иногда называют Ранним Возрождением или Христианским Возрождением . [96] Иоганнес Фрид пишет, что Карл Великий оставил такое глубокое впечатление на его эпоху, что следы этого остаются до сих пор. Он продвигал образование и грамотность, субсидировал школы, работал над защитой бедных, проводя экономическую и денежную реформу; они, наряду с правовыми и судебными реформами, создали более законное и процветающее королевство. Это помогло сформировать группу независимых военачальников в хорошо управляемую империю с традицией сотрудничества с Папой, которая стала предшественником французской нации. [97] Фрид говорит: «Он был первым королем и императором, который серьезно ввел в действие правовой принцип, согласно которому Папа был вне досягаемости всякого человеческого правосудия – решение, которое будет иметь серьезные последствия в будущем». [97] : 12

Современное общее право, преследования и секуляризация начались в эпоху высокого средневековья.

[ редактировать ]

К концу 11 века, начиная с усилий Папы Григория VII , Церковь успешно зарекомендовала себя как «автономное юридическое и политическое ... [субъектность] в пределах западного христианского мира». [98] : 23 В течение следующих трехсот лет Церковь имела большое влияние на западное общество; [98] : 23 церковные законы были единственным «универсальным законом… общим для юрисдикций и народов по всей Европе». [98] : 30 Имея собственную судебную систему, Церковь сохраняла юрисдикцию над многими аспектами повседневной жизни, включая образование, наследование, устные обещания, клятвы, моральные преступления и брак. [98] : 31 Позиции Церкви, одного из наиболее влиятельных институтов Средневековья, нашли отражение во многих светских законах того времени. [99] : 1 Католическая церковь была очень мощной, по существу интернационалистической и демократической по своей структуре, с ее многочисленными ветвями, управляемыми различными монашескими организациями, каждая из которых имела свою собственную теологию и часто не согласовывалась с другими. [100] : 311, 312 [101] : 396

Люди с научным уклоном обычно принимали священный сан и часто вступали в религиозные институты . Те, кто обладал интеллектуальными, административными или дипломатическими навыками, могли выйти за рамки обычных ограничений общества. Ведущие церковники из далеких стран были приняты в местные епископства, связывая европейскую мысль на больших расстояниях. Такие комплексы, как аббатство Клюни, стали яркими центрами, чьи зависимости распространились по всей Европе. Обычные люди также преодолевали огромные расстояния в паломничествах, чтобы выразить свое благочестие и помолиться к святым мощам . [102]

В решающем двенадцатом веке (1100-е годы) Европа начала закладывать основу для постепенной трансформации от средневековья к современности. [103] : 154 Феодалы постепенно уступили власть феодальным королям, поскольку короли начали централизовать власть внутри себя и своего национального государства. Короли строили свои собственные армии вместо того, чтобы полагаться на своих вассалов, тем самым отбирая власть у знати. «Государство» взяло на себя юридическую практику, которая традиционно принадлежала местной знати и чиновникам местной церкви; и они начали нападать на меньшинства. [103] : 4, 5 [104] : 209 По мнению Р.И. Мура и других современных ученых, «рост светской власти и преследование светских интересов составили существенный контекст событий, которые привели к преследованию общества». [103] : 4, 5 [105] : 8–10 [106] : 224 [107] : восемнадцатый Это оказало постоянное влияние на политику и право во многих отношениях: через новую риторику исключения, которая узаконила преследования, основанные на новых стереотипах , стигматизации и даже демонизации обвиняемых; путем создания новых гражданских законов, которые включали разрешение государству быть ответчиком и выдвигать обвинения от своего имени; изобретение полиции как инструмента государственного правоприменения; изобретение общего налогообложения, золотых монет и современного банковского дела, чтобы заплатить за все это; и инквизиции, которые представляли собой новую правовую процедуру , которая позволяла судье проводить расследование по собственной инициативе, не требуя от жертвы (кроме государства) выдвигать обвинения. [103] : 4, 90–100, 146, 149, 154 [108] : 97–111

«Исключительный характер преследований на Латинском Западе, начиная с двенадцатого века, заключался не в масштабах или жестокости конкретных преследований... а в их способности к устойчивому долгосрочному росту. Модели, процедуры и риторика преследований, которые были созданы в двенадцатом веке, дали ему силу бесконечного и неопределенного самовосстановления и самообновления». [103] : ви, 155

В конце концов, это привело к развитию среди первых протестантов убеждения, что концепции религиозной терпимости и разделения церкви и государства имеют важное значение. [109] : 3

Каноническое право, ценность дебатов и естественное право средневековых университетов.

[ редактировать ]Христианство в эпоху Высокого Средневековья оказало длительное влияние на политику и право через недавно созданные университеты. Каноническое право возникло из богословия и развивалось там независимо. [110] : 255 К 1200-м годам гражданское и каноническое право стало важным аспектом церковной культуры, доминируя в христианской мысли. [111] : 382 Большинство епископов и пап того периода были юристами, а не богословами, и многие христианские мысли того времени стали не более чем продолжением закона. В эпоху Высокого Средневековья религия, которая началась с порицания силы закона (Римлянам 7:1) [ сомнительно – обсудить ] разработал самый сложный религиозный закон, который когда-либо видел мир. [111] : 382 Каноническое право стало благодатной почвой для тех, кто выступал за сильную папскую власть. [110] : 260 и Брайан Даунинг говорит, что в эту эпоху империя, ориентированная на церковь, почти стала реальностью. [112] : 35 Однако Даунинг говорит, что верховенство закона, установленное в средние века, является одной из причин, почему в Европе в конечном итоге вместо этого возникла демократия. [112] : 4

Средневековые университеты не были светскими учреждениями, но они, как и некоторые религиозные ордена, были основаны с уважением к диалогу и дебатам, полагая, что хорошее понимание приходит, если рассматривать что-то с разных сторон. По этой причине они включили аргументированные споры в свою систему исследований. [113] : xxxiii Соответственно, в университетах проводилось так называемое квадрибеттал , на котором «магистр» поднимал вопрос, студенты приводили аргументы, а эти аргументы оценивались и аргументировались. Брайан Лоу говорит: «Присутствовать мог буквально кто угодно: мастера и ученые из других школ, всевозможные священнослужители и прелаты и даже гражданские власти, все «интеллектуалы» того времени, которых всегда привлекали к стычкам такого рода, и все который имел право задавать вопросы и возражать против доводов». [113] : ххв В своего рода атмосфере «собрания муниципалитета» вопросы могли быть заданы устно кем угодно ( quolibet ) буквально о чем угодно ( de quolibet ). [113] : ххв

Фома Аквинский дважды был магистром Парижского университета и проводил квадлибеталии . Фома Аквинский интерпретировал Аристотеля относительно естественного права. Александр Пассерен д'Энтрев пишет, что естественное право подвергается нападкам на протяжении полутора веков, но оно остается аспектом философии права, поскольку на нем основана большая часть теории прав человека. [114] Фома Аквинский учил, что справедливое лидерство должно работать на «общее благо». Он определяет закон как «постановление разума» и что он не может быть просто волей законодателя и быть хорошим законом. Фома Аквинский говорит, что основная цель права состоит в том, что «добро следует делать и к нему стремиться, а зла избегать». [115]

Естественное право и права человека

[ редактировать ]«Философскую основу либеральной концепции прав человека можно найти в теориях естественного права», [116] [117] и многие размышления о естественном праве восходят к мысли доминиканского монаха Фомы Аквинского. [118] Фома Аквинский продолжает оказывать влияние на работы ведущих политических и юридических философов. [118]

Согласно Фоме Аквинскому, каждый закон в конечном итоге вытекает из того, что он называет «вечным законом»: Божьего устройства всего сотворенного. Для Фомы Аквинского человеческое действие является хорошим или плохим в зависимости от того, соответствует ли оно разуму, и именно это участие «разумного существа» в «вечном законе» называется «естественным законом». Фома Аквинский сказал, что естественный закон — это фундаментальный принцип, вплетенный в ткань человеческой природы. Секуляристы, такие как Гуго Гроций, позже расширили идею прав человека и развили ее.

«...нельзя и не нужно отрицать, что права человека имеют западное происхождение. Этого нельзя отрицать, поскольку они морально основаны на иудео-христианской традиции и греко-римской философии; они были систематизированы на Западе на протяжении многих столетий, они заняли прочное место в национальных декларациях западных демократий и были закреплены в конституциях этих демократий». [119]

Говард Тамбер говорит: «Права человека – это не универсальная доктрина, а потомок одной конкретной религии (христианства)». Это не означает, что христианство было лучше в своей практике или не имело «своей доли нарушений прав человека». [120]

Дэвид Гуши говорит, что христианство имеет «трагически смешанное наследие», когда дело доходит до применения собственной этики. Он рассматривает три случая «христианского мира, расколовшегося сам в себе»: крестовые походы и попытку Святого Франциска заключить мир с мусульманами; Испанские завоеватели, убийства коренных народов и протесты против этого; и продолжающееся преследование и защита евреев. [121]

Чарльз Малик , ливанский академик, дипломат, философ и богослов, был ответственным за разработку и принятие Всеобщей декларации прав человека 1948 года .

Возрождение римского права в средневековой инквизиции

[ редактировать ]По словам Дженнифер Дин , ярлык «Инквизиция» подразумевает «институциональную согласованность и официальное единство, которых никогда не существовало в средние века». [122] : 6 Средневековые инквизиции на самом деле представляли собой серию отдельных инквизиций, начавшихся примерно с 1184 года и продолжавшихся до 1230-х годов, которые были ответом на диссидентов, обвиненных в ереси. [123] в то время как Папская инквизиция (1230–1302 гг.) Была создана для восстановления порядка, нарушенного массовым насилием над еретиками. Ересь была религиозной, политической и социальной проблемой. [124] : 108, 109 Таким образом, «первые проявления насилия против диссидентов обычно были результатом народного недовольства». [125] : 189 Это привело к разрушению социального порядка. [124] : 108, 109 В Поздней Римской империи сложилась инквизиторская система правосудия, возрожденная в средние века. В качестве инквизитора использовалась объединенная коллегия, состоящая из гражданских и церковных представителей, с епископом, его представителем или местным судьей. По сути, церковь вновь ввела римское право в Европе (в форме инквизиции), когда казалось, что германское право потерпело неудачу. [126] «[Средневековая] инквизиция не была организацией, произвольно созданной и навязанной судебной системе амбициями или фанатизмом церкви. Это была скорее естественная – можно сказать почти неизбежная – эволюция сил, действовавших в тринадцатом веке. ." [127]

Изобретение Священной войны, рыцарства и корни современной толерантности

[ редактировать ]В 1095 году папа Урбан II призвал к крестовому походу, чтобы вернуть Святую Землю из- под власти мусульман . Хью С. Пайпер говорит, что «важность города [Иерусалима] отражена в том факте, что на картах раннего средневековья [Иерусалим] помещается в центр мира». [111] : 338

«К одиннадцатому веку турки-сельджуки завоевали [три четверти христианского мира]. Владения старой Восточной Римской империи, известной современным историкам как Византийская империя, сократились до уровня немногим больше, чем Греция. В отчаянии, император в Константинополе обратился к христианам Западной Европы с просьбой помочь их братьям и сестрам на Востоке». [128] [129]

Это послужило толчком к первому крестовому походу, однако «колоссом средневекового мира был ислам, а не христианский мир», и, несмотря на первоначальный успех, эти конфликты, длившиеся четыре столетия, в конечном итоге закончились неудачей для западного христианского мира. [129]

Во времена Первого крестового похода не было четкого представления о том, что такое крестовый поход, кроме паломничества. [130] : 32 Райли-Смит говорит, что крестовые походы были продуктом обновленной духовности центрального средневековья, а также политическими обстоятельствами. [131] : 177 Высокопоставленные церковники этого времени преподносили верующим понятие христианской любви как повод взяться за оружие. [131] : 177 Люди заботились о том, чтобы жить vita apostolica и выражать христианские идеалы в активной благотворительной деятельности, примером которой являются новые больницы, пастырская работа августинцев и премонстрантов, а также служение монахов. Райли-Смит заключает: «Милосердие Святого Франциска теперь может привлечь нас больше, чем благотворительность крестоносцев, но обе они возникли из одних и тех же корней». [131] : 180, 190–2 Констебль добавляет, что те «учёные, которые рассматривают крестовые походы как начало европейского колониализма и экспансионизма, удивили бы людей в то время. земли, которые когда-то были христианскими, и на самопожертвовании, а не на корысти участников». [130] : 15 Райли-Смит также говорит, что ученые отворачиваются от идеи, что крестовые походы имели материальную мотивацию. [132]

Такие идеи, как священная война и христианское рыцарство, как в мышлении, так и в культуре, продолжали постепенно развиваться с одиннадцатого по тринадцатый века. [104] : 184, 185, 210 Это можно проследить в выражениях закона, традиций, сказок, пророчеств и исторических повествований, в письмах, буллах и стихах, написанных в период крестовых походов. [133] : 715–737

По словам профессора политологии Эндрю Р. Мерфи , концепции толерантности и нетерпимости не были отправной точкой для размышлений об отношениях какой-либо из различных групп, участвовавших в крестовых походах или затронутых ими. [134] : xii – xvii Вместо этого во время крестовых походов начали развиваться концепции толерантности в результате попыток определить правовые границы и природу сосуществования. [134] : хii В конечном итоге это поможет заложить основу для убеждения первых протестантов внедрения концепции религиозной терпимости . в необходимости [109] : 3

Моральный упадок и рост политической власти церкви в позднем средневековье

[ редактировать ]В течение «катастрофического» четырнадцатого века с его чумой , голодом и войнами люди были ввергнуты в смятение и отчаяние. С момента своего расцвета в 1200-х годах церковь вступила в период упадка, внутренних конфликтов и коррупции. [104] : 209–214 По словам Вальтера Ульмана , церковь потеряла «моральное, духовное и авторитетное руководство, которое она выработала в Европе на протяжении столетий кропотливой, последовательной, детальной, динамичной дальновидной работы. ... Папство теперь было вынуждено проводить политику, которая по существу, были направлены на умиротворение и уже не были директивными, ориентирующими и определяющими». [135] : 184

По словам Мэтьюза и ДеВитта, «Папы в четырнадцатом — середине пятнадцатого века обратили свой интерес к искусству и гуманитарным наукам, а не к насущным моральным и духовным проблемам. Более того, они были жизненно озабочены атрибутами политической власти. в итальянскую политику... правя как светские князья на своих папских землях. Их мирские интересы и вопиющие политические маневры только усилили растущее неодобрение папства и предоставили критикам церкви еще больше примеров коррупции и упадка этого учреждения». [104] : 248 По мере того как Церковь становилась более могущественной, богатой и коррумпированной, многие стремились к реформам. Были основаны доминиканский или новая и францисканский ордены, которые подчеркивали бедность и духовность, и развивалась концепция светского благочестия — Devotio Moderna преданность, — которая работала на идеал благочестивого общества простых нерукоположенных людей и, в конечном итоге, на Реформация и развитие современных концепций толерантности и религиозной свободы. [104] : 248–250

Политическая власть женщин росла и падала

[ редактировать ]В Римском Папском соборе XIII века молитва о рукоположении женщин в дьяконы была удалена, а определение рукоположения было изменено и применялось только к священникам-мужчинам.

Женщина-ведьма стала стереотипом в 1400-х годах, пока он не был систематизирован в 1487 году Папой Иннокентием VIII, который заявил, что «большинство ведьм - женщины». «Европейский стереотип о ведьмах воплощает в себе два очевидных парадокса: во-первых, он был порожден не «варварскими темными веками», а во время прогрессивного Возрождения и раннего Нового времени; во-вторых, западное христианство не признавало реальность ведьм на протяжении веков, или криминализировать их примерно до 1400 года». [136] Социолог Дон Свенсон говорит, что объяснение этому может лежать в природе средневекового общества как иирократического, которое приводило к насилию и использованию принуждения для принуждения к подчинению. «Было много споров... о том, сколько женщин было казнено... [и оценки сильно различаются, но цифры], маленькие и большие, мало что дают для описания ужаса и позора, нанесенного этим женщинам. Такое обращение обеспечивает [драматическое] контраст с уважением, оказываемым женщинам в раннюю эпоху христианства и в ранней Европе...» [137]

Женщины были во многих отношениях исключены из политической и торговой жизни; однако некоторые ведущие церковницы были исключением. Средневековые аббатисы и женщины-настоятельницы монашеских домов были влиятельными фигурами, чье влияние могло соперничать с влиянием епископов и аббатов-мужчин: «Они обращались с королями, епископами и величайшими лордами на условиях полного равенства; ... они присутствовали на всех великих религиозных собраниях». и национальных торжествах, при освящении церквей, и даже, подобно королевам, принимала участие в совещаниях национальных собраний...». [138] Растущая популярность преданности Деве Марии (матери Иисуса) сделала материнскую добродетель центральной культурной темой католической Европы. Кеннет Кларк писал, что «Культ Богородицы» в начале XII века «научил расу жестоких и безжалостных варваров добродетелям нежности и сострадания». [139]

Политические Папы

[ редактировать ]В 1054 году, после столетий напряженных отношений, из-за разногласий в доктринах произошел Великий раскол , разделивший христианский мир на Католическую церковь с центром в Риме и доминирующую на Западе, и Восточную Православную Церковь с центром в Константинополе , столице Византийской империи. Империя.

Отношения между крупнейшими державами западного общества: дворянством, монархией и духовенством также иногда приводили к конфликтам. Например, спор об инвестициях был одним из наиболее значительных конфликтов между церковью и государством в средневековой Европе . Ряд Пап оспаривали власть монархий над контролем над назначениями или инвеститурами церковных чиновников. Двор императора Священной Римской империи Фридриха II , базирующийся на Сицилии, испытывал напряженность и соперничество с папством за контроль над Северной Италией. [140]

В 1302 году Папа Бонифаций VIII (1294–1303) издал Unam Sanctam — папскую буллу, провозглашавшую превосходство Папы над всеми светскими правителями. Филипп IV Французский ответил отправкой армии для ареста Папы. Бонифаций бежал, спасая свою жизнь, и вскоре умер. [104] : 216 «Этот эпизод показал, что папы больше не могут конкурировать с феодальными королями» и показал заметное падение папского престижа. [104] : 216 [135] : хв Джордж Гарнетт говорит, что реализация идеи папской монархии привела к потере престижа, поскольку чем эффективнее становилась папская бюрократическая машина, тем дальше она отчуждала людей и тем дальше она приходила в упадок. [135] : хв

Двор папства находился в Авиньоне с 1305 по 1378 год. [141] Это возникло в результате конфликта между итальянским папством и французской короной. Богослов Роджер Олсон говорит, что церковь достигла своего апогея в то время, когда три разных человека претендовали на звание законного Папы. [142] : 348 [104] : 248

«То, что наблюдал наблюдатель за папством во второй половине тринадцатого века, было постепенным, хотя и ясно ощутимым, разложением Европы как единой церковной единицы и фрагментацией Европы на независимые, автономные образования, которые вскоре стали называться национальными. монархий или государств. Эта фрагментация ознаменовала отмирание папства как управляющего института, действующего в универсальном масштабе». [135] : 176

Политическая и юридическая власть государства через современную инквизицию

[ редактировать ]История инквизиции делится на две основные части: «ее создание средневековым папством в начале тринадцатого века и ее трансформация между 1478 и 1542 годами в постоянные светские правительственные бюрократии: испанскую, португальскую и римскую инквизиции... который просуществовал до девятнадцатого века». [143] [144] : 154 Старая средневековая инквизиция имела ограниченную власть и влияние, тогда как полномочия современного «Священного Трибунала» были расширены и расширены за счет власти государства, превратившегося в «одну из самых грозных машин разрушения, которые когда-либо существовали». [145] : 343

Историк Хелен Роулингс говорит: « Испанская инквизиция отличалась [от более ранних инквизиций] в одном фундаментальном отношении: она несла ответственность перед короной, а не перед Папой, и использовалась для консолидации государственных интересов». [146] : 1, 2 Это было санкционировано Папой, однако первые инквизиторы оказались настолько суровыми, что Папа почти сразу же выступил против этого, но безрезультатно. [147] : 52, 53 В начале 1483 года король и королева учредили совет — Consejo de la Suprema y General Inquisición , чтобы управлять инквизицией, и выбрал Торквемаду главой ее в качестве генерального инквизитора. В октябре 1483 года папская булла передала контроль короне. По словам Хосе Кассановы , испанская инквизиция стала первым по-настоящему национальным, единым и централизованным государственным учреждением. [148] : 75 После 1400-х годов лишь немногие испанские инквизиторы принадлежали к религиозным орденам. [146] : 2

Португальская инквизиция также полностью контролировалась короной, которая учредила правительственный совет, известный как Генеральный совет, для надзора за ней. Великий инквизитор, которого избирал король, всегда был членом королевской семьи. Первый статут Limpieza de sangre (чистоты крови) появился в Толедо в 1449 году, а позже был принят и в Португалии. Первоначально эти статуты были осуждены Церковью, но в 1555 году весьма коррумпированный папа Александр VI утвердил статут о «чистоте крови» для одного из религиозных орденов. [149] : 19 В своей истории португальской инквизиции Джузеппе Маркоччи говорит, что существует глубокая связь между появлением Фелипе в Португалии, ростом инквизиции и принятием статутов чистоты крови, которые распространялись и увеличивались и больше касались этническое происхождение, чем религия. [150]

Историк Т. Ф. Майер пишет, что « римская инквизиция действовала, чтобы служить давним политическим целям папства в Неаполе, Венеции и Флоренции». [151] : 3 При Павле III и его преемнике Юлии III, а также при большинстве последующих пап деятельность римской инквизиции была относительно ограниченной, а ее командная структура была значительно более бюрократической, чем у других инквизиций. [151] : 2 Если средневековая инквизиция сосредоточивала свое внимание на популярных заблуждениях, приводивших к нарушению общественного порядка, то римская инквизиция занималась ортодоксальностью более интеллектуального, академического характера. Римская инквизиция, вероятно, наиболее известна своим осуждением трудного и сварливого Галилея, которое больше стремилось «подчинить Флоренцию», чем ереси. [151] : 5

Роль христианства в политике и праве от Реформации до Нового времени.

[ редактировать ]

В средние века Церковь и мирская власть были тесно связаны. Мартин Лютер принципиально разделял религиозную и мирскую сферы ( доктрина двух царств ). [152] Верующие были обязаны использовать разум, чтобы управлять мирской сферой упорядоченным и мирным способом. Учение Лютера о священстве всех верующих значительно повысило роль мирян в церкви. Члены конгрегации имели право выбирать служителя и, при необходимости, голосовать за его увольнение (Трактат « О праве и власти христианского собрания или конгрегации судить все учения и призывать, назначать и увольнять учителей, о чем свидетельствует в Писании 1523). [153] Кальвин укрепил этот по своей сути демократический подход, включив избранных мирян ( церковных старейшин , пресвитеров ) в свое представительное церковное правительство. [154] Гугеноты и национальный синод, члены добавили региональные синоды к кальвиновской системе церковного самоуправления которого избирались общинами. Эту систему использовали другие реформатские церкви. [155]

В политическом отношении Жан Кальвин предпочитал сочетание аристократии и демократии. Он высоко оценил преимущества демократии: «Это бесценный дар, если Бог позволит народу свободно выбирать свою собственную власть и повелителей». [156] Кальвин также считал, что земные правители теряют свое божественное право и должны быть свергнуты, когда восстают против Бога. Для дальнейшей защиты прав простых людей Кальвин предлагал разделить политические власти в системе сдержек и противовесов ( разделение властей ). Кальвинисты и лютеране XVI века разработали теорию сопротивления, названную доктриной меньшего магистрата , которая позже была использована в Декларации независимости США. Таким образом, ранние протестанты сопротивлялись политическому абсолютизму и проложили путь к подъему современной демократии. [157] Помимо Англии, Нидерланды под руководством кальвинистов были самой свободной страной в Европе в XVII и XVIII веках. Он предоставил убежище таким философам, как Рене Декарт , Барух Спиноза и Пьер Бейль . Гуго Гроций смог преподавать свою теорию естественного права и относительно либеральную интерпретацию Библии. [158]

В соответствии с политическими идеями Кальвина протестанты создали как английскую, так и американскую демократию. В Англии 17 века наиболее важными людьми и событиями в этом процессе были Гражданская война в Англии , Оливер Кромвель , Джон Мильтон , Джон Локк , Славная революция , Английский Билль о правах и Акт об урегулировании . [159] Позже британцы принесли свои демократические идеалы и в свои колонии, например, в Австралию, Новую Зеландию и Индию. В XIX и XX веках британскую разновидность современной демократии, конституционную монархию , переняли протестантские Швеция, Норвегия, Дания и Нидерланды, а также католические страны Бельгия и Испания. В Северной Америке Плимутская колония ( Отцы-пилигримы ; 1620) и Колония Массачусетского залива (1628) практиковали демократическое самоуправление и разделение властей . [160] [161] [162] [163] Эти конгрегационалисты были убеждены, что демократическая форма правления — это воля Божья. [164] Мэйфлауэрский договор был общественным договором . [165] [166]

Сексуальная мораль

[ редактировать ]Исследователь-классик Кайл Харпер говорит, что в течение определенного периода времени

«...триумф христианства не только привел к глубоким культурным изменениям, но и создал новые отношения между сексуальной моралью и обществом... Наследие христианства заключается в распаде древней системы, в которой социальный и политический статус, власть и передача социального неравенства следующему поколению прописана в условиях сексуальной морали. [167] "

- Кайл Харпер, От стыда к греху: христианская трансформация сексуальной морали в поздней античности, страницы 4 и 7.

И древние греки, и римляне заботились о сексуальной морали и писали о ней в категориях добра и зла, чистого и оскверненного, идеала и преступления. [168] Но сексуальные этические структуры римского общества были построены на статусе, и сексуальная скромность означала для мужчин нечто иное, чем для женщин, и для знатных людей, чем для бедных, а для свободных граждан, чем для свободных граждан. для раба, для которого понятия чести, стыда и сексуальной скромности, можно сказать, не имеют вообще никакого значения. [167] : 7 Считалось, что рабы не ведут внутреннюю этическую жизнь, потому что они не могли опускаться ниже в социальном плане и обычно использовались сексуально; Считалось, что свободные и знатные люди олицетворяют социальную честь и поэтому могут проявлять тонкое чувство стыда, соответствующее их положению. Римская литература указывает на то, что римляне осознавали эту двойственность. [168] : 12, 20

Стыд был глубоко социальным понятием, которое в Древнем Риме всегда опосредовалось полом и статусом. «Недостаточно того, чтобы жена просто регулировала свое сексуальное поведение общепринятыми способами; требовалось, чтобы ее добродетель в этой области была заметной». [168] : 38 Мужчинам, с другой стороны, разрешалось жить с любовницами, называемыми паллаке . [169] Это, например, позволило римскому обществу считать контроль мужа над сексуальным поведением жены вопросом чрезвычайной важности и в то же время рассматривать его собственный секс с маленькими мальчиками как не вызывающий особого беспокойства. [168] : 12, 20 Христианство стремилось установить равные сексуальные стандарты для мужчин и женщин и защитить всех молодых людей, будь то рабы или свободные. Это была трансформация глубокой логики сексуальной морали. [167] : 6, 7

Отцы ранней церкви выступали против прелюбодеяния, полигамии, гомосексуализма, педерастии, зоофилии, проституции и инцеста, одновременно выступая за святость брачного ложа. [98] : 20 Центральный христианский запрет на подобную порнейю , которая является единственным названием для этого комплекса сексуального поведения, «сталкивался с глубоко укоренившимися образцами римской вседозволенности, где легитимность сексуальных контактов определялась прежде всего статусом. Св. Павел, взгляды которого стали доминирующими в Раннее христианство превратило тело в освященное пространство, точку посредничества между личностью и божественным. Преобладающее чувство Павла о том, что гендер, а не статус, власть, богатство или положение, является главным фактором, определяющим уместность пола. Этот акт имел важное значение. Сведя половой акт к самым базовым составляющим мужского и женского пола, Пол смог описать окружающую его сексуальную культуру в преобразующих терминах». [167] : 12, 92

Христианская сексуальная идеология неотделима от концепции свободы воли. «В своей первоначальной форме христианская свобода воли была космологическим утверждением — аргументом об отношениях между Божьей справедливостью и личностью… по мере того, как христианство переплеталось с обществом, дискуссия сместилась в сторону раскрытия путей к фактической психологии воли и материальных ограничений. о сексуальных действиях... Острая озабоченность церкви проблемой воли ставит христианскую философию в самое живое течение имперской греко-римской философии, [где] ортодоксальные христиане предлагали ее радикально своеобразную версию». [167] : 14 Греки и римляне говорили, что наша глубочайшая нравственность зависит от нашего социального положения, данного нам судьбой. Христианство «проповедовало освобождающее послание свободы». Это была революция в правилах поведения, но и в самом образе человека как существа сексуального, свободного, хрупкого и грозно ответственного за самого себя перед одним Богом. «Это была революция в природе требований общества к моральному агенту... Есть риск переоценки изменений в старых моделях, которые христианство смогло начать осуществлять; но есть также риск и в недооценке христианизации как водораздел». [167]: 14–18

Marriage and family life

[edit]

The teachings of the Church have also been used to "establish[...] the status of women under the law".[99] There has been some debate as to whether the Church has improved the status of women or hindered their progress.

From the beginning of the thirteenth century, the Church formally recognized marriage between a freely consenting, baptized man and woman as a sacrament—an outward sign communicating a special gift of God's love. The Council of Florence in 1438 gave this definition, following earlier Church statements in 1208, and declared that sexual union was a special participation in the union of Christ in the Church.[170] However, the Puritans, while highly valuing the institution, viewed marriage as a "civil", rather than a "religious" matter, being "under the jurisdiction of the civil courts".[171] This is because they found no biblical precedent for clergy performing marriage ceremonies. Further, marriage was said to be for the "relief of concupiscence"[171] as well as any spiritual purpose. During the Protestant Reformation, Martin Luther and John Calvin denied the sacramentality of marriage. This unanimity was broken at the 1930 Lambeth Conference, the quadrennial meeting of the worldwide Anglican Communion—creating divisions in that denomination.

Catholicism equates premarital sex with fornication and ties it with breaking the sixth commandment ("Thou shalt not commit adultery") in its Catechism.[172] While sex before marriage was not a taboo in the Anglican Church until the "Hardwicke Marriage Act of 1753, which for the first time stipulated that everyone in England and Wales had to be married in their parish church"[173] Prior to that time, "marriage began at the time of betrothal, when couples would live and sleep together... The process begun at the time of the Hardwicke Act continued throughout the 1800s, with stigma beginning to attach to illegitimacy."[173]

Scriptures in the New Testament dealing with sexuality are extensive. Subjects include: the Apostolic Decree (Acts 15), sexual immorality, divine love (1 Corinthians 13), mutual self-giving (1 Corinthians 7), bodily membership between Christ and between husband and wife (1 Corinthians 6:15–20) and honor versus dishonor of adultery (Hebrews 13:4).

The Hebrew Bible and its traditional interpretations in Judaism and Christianity have historically affirmed and endorsed a patriarchal and heteronormative approach towards human sexuality,[174][175] favouring exclusively penetrative vaginal intercourse between men and women within the boundaries of marriage over all other forms of human sexual activity,[174][175] including autoeroticism, masturbation, oral sex, non-penetrative and non-heterosexual sexual intercourse (all of which have been labeled as "sodomy" at various times).[176] They have believed and taught that such behaviors are forbidden because they are considered sinful,[174][175] and further compared to or derived from the behavior of the alleged residents of Sodom and Gomorrah.[174][177]

Roman Empire

[edit]Social structures before and at the dawn of Christianity in the Roman Empire held that women were inferior to men intellectually and physically and were "naturally dependent".[178] Athenian women were legally classified as children regardless of age and were the "legal property of some man at all stages in her life."[10]: 104 Women in the Roman Empire had limited legal rights and could not enter professions. Female infanticide and abortion were practiced by all classes.[10]: 104 In family life, men could have "lovers, prostitutes and concubines" but wives who engaged in extramarital affairs were considered guilty of adultery. It was not rare for pagan women to be married before the age of puberty and then forced to consummate the marriage with her often much older husband. Husbands could divorce their wives at any time simply by telling the wife to leave; wives did not have a similar ability to divorce their husbands.[178]

Early Church Fathers advocated against polygamy, abortion, infanticide, child abuse, homosexuality, transvestism, and incest.[98]: 20 After the Roman Empire adopted Christianity as the official religion, however, the link between Christian teachings and Roman family laws became more clear.[179]: 91

For example, Church teaching heavily influenced the legal concept of marriage.[99]: 1–2 During the Gregorian Reform, the Church developed and codified a view of marriage as a sacrament.[98]: 23 In a departure from societal norms, Church law required the consent of both parties before a marriage could be performed[98]: 20–23 and established a minimum age for marriage.[180]: 33 The elevation of marriage to a sacrament also made the union a binding contract, with dissolutions overseen by Church authorities.[98]: 29, 36 Although the Church abandoned tradition to allow women the same rights as men to dissolve a marriage,[98]: 20, 25 in practice, when an accusation of infidelity was made, men were granted dissolutions more frequently than women.[180]: 18

Medieval period

[edit]According to historian Shulamith Shahar, "[s]ome historians hold that the Church played a considerable part in fostering the inferior status of women in medieval society in general" by providing a "moral justification" for male superiority and by accepting practices such as wife-beating.[180]: 88 "The ecclesiastical conception of the inferior status of women, deriving from Creation, her role in Original Sin and her subjugation to man, provided both direct and indirect justification for her inferior standing in the family and in society in medieval civilization. It was not the Church which induced husbands to beat their wives, but it not only accepted this custom after the event, if it was not carried to excess, but, by proclaiming the superiority of man, also supplied its moral justification." Despite these laws, some women, particularly abbesses, gained powers that were never available to women in previous Roman or Germanic societies.[180]: 12

Although these teachings emboldened secular authorities to give women fewer rights than men, they also helped form the concept of chivalry.[99]: 2 Chivalry was influenced by a new Church attitude towards Mary, the mother of Jesus.[180]: 25 This "ambivalence about women's very nature" was shared by most major religions in the Western world.[181]

Family relations

[edit]

Christian culture puts notable emphasis on the family,[182] and according to the work of scholars Max Weber, Alan Macfarlane, Steven Ozment, Jack Goody and Peter Laslett, the huge transformation that led to modern marriage in Western democracies was "fueled by the religio-cultural value system provided by elements of Judaism, early Christianity, Roman Catholic canon law and the Protestant Reformation".[183] Historically, extended families were the basic family unit in the Catholic culture and countries.[184] According to a study by the scholar Joseph Henrich from Harvard University, the Catholic church "changed extended family ties, as well as values and psychology of individuals in the Western world".[185][186]

Most Christian denominations practice infant baptism[187] to enter children into the faith. Some form of confirmation ritual occurs when the child has reached the age of reason and voluntarily accepts the religion. Ritual circumcision is used to mark Coptic Christian,[188] Ethiopian Orthodox Christian[189] and Eritrean Orthodox infant males as belonging to the faith.[190][191] Circumcision is practiced among many Christian countries and communities; Christian communities in Africa,[192][193] the Anglosphere countries, the Philippines, the Middle East,[194][195] South Korea and Oceania have high circumcision rates,[196] while Christian communities in Europe and South America have low circumcision rates.

During the early period of capitalism, the rise of a large, commercial middle class, mainly in the Protestant countries of Holland and England, brought about a new family ideology centred around the upbringing of children. Puritanism stressed the importance of individual salvation and concern for the spiritual welfare of children. It became widely recognized that children possess rights on their own behalf. This included the rights of poor children to sustenance, membership in a community, education, and job training. The Poor Relief Acts in Elizabethan England put responsibility on each Parish to care for all the poor children in the area.[197] And prior to the 20th century, three major branches of Christianity—Catholicism, Orthodoxy and Protestantism[198]—as well as leading Protestant reformers Martin Luther and John Calvin generally held a critical perspective of birth control.[199]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints puts notable emphasis on the family, and the distinctive concept of a united family which lives and progresses forever is at the core of Latter-day Saint doctrine.[200] Church members are encouraged to marry and have children, and as a result, Latter-day Saint families tend to be larger than average. All sexual activity outside of marriage is considered a serious sin. All homosexual activity is considered sinful and same-sex marriages are not performed or supported by the LDS Church. Latter-day Saint fathers who hold the priesthood typically name and bless their children shortly after birth to formally give the child a name and generate a church record for them. Mormons tend to be very family-oriented and have strong connections across generations and with extended family, reflective of their belief that families can be sealed together beyond death.[201]: 59 In the temple, husbands and wives are sealed to each other for eternity. The implication is that other institutional forms, including the church, might disappear, but the family will endure.[202] A 2011 survey of Mormons in the United States showed that family life is very important to Mormons, with family concerns significantly higher than career concerns. Four out of five Mormons believe that being a good parent is one of the most important goals in life, and roughly three out of four Mormons put having a successful marriage in this category.[203][204] Mormons also have a strict law of chastity, requiring abstention from sexual relations outside heterosexual marriage and fidelity within marriage.

A Pew Center study about Religion and Living arrangements around the world in 2019, found that Christians around the world live in somewhat smaller households, on average, than non-Christians (4.5 vs. 5.1 members). 34% of world's Christian population live in two parent families with minor children, while 29% live in household with extended families, 11% live as couples without other family members, 9% live in household with least one child over the age of 18 with one or two parents, 7% live alone, and 6% live in single parent households.[205] Christians in Asia and Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean, Middle East and North Africa, and in Sub-Saharan Africa, overwhelmingly live in extended or two parent families with minor children.[205] While more Christians in Europe and North America live alone or as couples without other family members.[205]

Clerical marriage

[edit]

Clerical marriage is admitted among Protestants, including both Anglicans and Lutherans.[206] Some Protestant clergy and their children have played an essential role in literature, philosophy, science, and education in Early Modern Europe.[207]

Many Eastern Churches (Assyrian Church of the East, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, or Eastern Catholic), while allowing married men to be ordained, do not allow clerical marriage after ordination: their parish priests are often married, but must marry before being ordained to the priesthood. Within the lands of the Eastern Christendom, priests' children often became priests and married within their social group, establishing a tightly-knit hereditary caste among some Eastern Christian communities.[208][209]

The Catholic Church not only forbids clerical marriage, but generally follows a practice of clerical celibacy, requiring candidates for ordination to be unmarried or widowed. However, this public policy in the Catholic Church has not always been enforced in private.

Slavery

[edit]The Church initially accepted slavery as part of the Greco-Roman social fabric of society, campaigning primarily for humane treatment of slaves but also admonishing slaves to behave appropriately towards their masters.[179]: 171–173 Historian Glenn Sunshine says, "Christians were the first people in history to oppose slavery systematically. Early Christians purchased slaves in the markets simply to set them free. Later, in the seventh century, the Franks..., under the influence of its Christian queen, Bathilde, became the first kingdom in history to begin the process of outlawing slavery. ...In the 1200s, Thomas Aquinas declared slavery a sin. When the African slave trade began in the 1400s, it was condemned numerous times by the papacy."[210]

During the early medieval period, Christians tolerated enslavement of non-Christians. By the end of the Medieval period, enslavement of Christians had been mitigated somewhat with the spread of serfdom within Europe, though outright slavery existed in European colonies in other parts of the world. Several popes issued papal bulls condemning mistreatment of enslaved Native Americans; these were largely ignored. In his 1839 bull In supremo apostolatus, Pope Gregory XVI condemned all forms of slavery; nevertheless some American bishops continued to support slavery for several decades.[211] In this historic Bull, Pope Gregory outlined his summation of the impact of the Church on the ancient institution of slavery, beginning by acknowledging that early Apostles had tolerated slavery but had called on masters to "act well towards their slaves... knowing that the common Master both of themselves and of the slaves is in Heaven, and that with Him there is no distinction of persons". Gregory continued to discuss the involvement of Christians for and against slavery through the ages:[212]

In the process of time, the fog of pagan superstition being more completely dissipated and the manners of barbarous people having been softened, thanks to Faith operating by Charity, it at last comes about that, since several centuries, there are no more slaves in the greater number of Christian nations. But – We say with profound sorrow – there were to be found afterwards among the Faithful men who, shamefully blinded by the desire of sordid gain, in lonely and distant countries, did not hesitate to reduce to slavery Indians, negroes and other wretched peoples, or else, by instituting or developing the trade in those who had been made slaves by others, to favour their unworthy practice. Certainly many Roman Pontiffs of glorious memory, Our Predecessors, did not fail, according to the duties of their charge, to blame severely this way of acting as dangerous for the spiritual welfare of those engaged in the traffic and a shame to the Christian name; they foresaw that as a result of this, the infidel peoples would be more and more strengthened in their hatred of the true Religion.

Latin America

[edit]

It was women, primarily Amerindian Christian converts who became the primary supporters of the Latin American Church.[213]: 65 While the Spanish military was known for its ill-treatment of Amerindian men and women, Catholic missionaries are credited with championing all efforts to initiate protective laws for the Indians and fought against their enslavement. This began within 20 years of the discovery of the New World by Europeans in 1492 – in December 1511, Antonio de Montesinos, a Dominican friar, openly rebuked the Spanish rulers of Hispaniola for their "cruelty and tyranny" in dealing with the American natives.[214]: 135 King Ferdinand enacted the Laws of Burgos and Valladolid in response. The issue resulted in a crisis of conscience in 16th-century Spain.[215]: 109, 110 Further abuses against the Amerindians committed by Spanish authorities were denounced by Catholic missionaries such as Bartolomé de Las Casas and Francisco de Vitoria which led to debate on the nature of human rights[216]: 287 and the birth of modern international law.[214]: 137 Enforcement of these laws was lax, and some historians blame the Church for not doing enough to liberate the Indians; others point to the Church as the only voice raised on behalf of indigenous peoples.[217]: 45, 52, 53

Slavery and human sacrifice were both part of Latin American culture before the Europeans arrived. Indian slavery was first abolished by Pope Paul III in the 1537 bull Sublimis Deus which confirmed that "their souls were as immortal as those of Europeans", that Indians were to be regarded as fully human, and they should neither be robbed nor turned into slaves.[215]: 110 While these edicts may have had some beneficial effects, these were limited in scope. European colonies were mainly run by military and royally-appointed administrators, who seldom stopped to consider church teachings when forming policy or enforcing their rule. Even after independence, institutionalized prejudice and injustice toward indigenous people continued well into the twentieth century. This has led to the formation of a number of movements to reassert indigenous peoples' civil rights and culture in modern nation-states.

A catastrophe was wrought upon the Amerindians by contact with Europeans. Old World diseases like smallpox, measles, malaria and many others spread through Indian populations. "In most of the New World 90 percent or more of the native population was destroyed by wave after wave of previously unknown afflictions. Explorers and colonists did not enter an empty land but rather an emptied one".[178]: 454

Africa

[edit]Slavery and the slave trade were part of African societies and states which supplied the Arab world with slaves before the arrival of the Europeans.[218]: 221 Several decades prior to discovery of the New World, in response to serious military threat to Europe posed by Muslims of the Ottoman Empire, Pope Nicholas V had granted Portugal the right to subdue Muslims, pagans and other unbelievers in the papal bull Dum Diversas (1452).[219]: 65–6 Six years after African slavery was first outlawed by the first major entity to do so, (Great Britain in 1833), Pope Gregory XVI followed in a challenge to Spanish and Portuguese policy, by condemning slavery and the slave trade in the 1839 papal bull In supremo apostolatus, and approved the ordination of native clergy in the face of government racism.[220]: 221 The United States would eventually outlaw African slavery in 1865.

Clapham Sect were a group of social reformers associated with Clapham in the period from the 1780s to the 1840s. Despite the label "sect", most members remained in the established (and dominant) Church of England, which was highly interwoven with offices of state. However, its successors were in many cases outside of the established Anglican Church.[221]

By the close of the 19th century, European powers had managed to gain control of most of the African interior.[9] The new rulers introduced cash-based economies which created an enormous demand for literacy and a western education—a demand which for most Africans could only be satisfied by Christian missionaries.[9] Catholic missionaries followed colonial governments into Africa, and built schools, hospitals, monasteries and churches.[9]: 397–410

Letters and learning

[edit]

The influence of the Church on Western letters and learning has been formidable. The ancient texts of the Bible have deeply influenced Western art, literature and culture. For centuries following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, small monastic communities were practically the only outposts of literacy in Western Europe. In time, the Cathedral schools developed into Europe's earliest universities and the church has established thousands of primary, secondary and tertiary institutions throughout the world in the centuries since. The Church and clergymen have also sought at different times to censor texts and scholars. Thus different schools of opinion exist as to the role and influence of the Church in relation to western letters and learning.

One view, first propounded by Enlightenment philosophers, asserts that the Church's doctrines are entirely superstitious and have hindered the progress of civilization. Communist states have made similar arguments in their education in order to inculcate a negative view of Catholicism (and religion in general) in their citizens. The most famous incidents cited by such critics are the Church's condemnations of the teachings of Copernicus, Galileo Galilei and Johannes Kepler. Events in Christian Europe, such as the Galileo affair, that were associated with the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment led some scholars such as John William Draper to postulate a conflict thesis, holding that religion and science have been in conflict throughout history. While the conflict thesis remains popular in atheistic and antireligious circles, it has lost favor among most contemporary historians of science.[222]