Собор Святой Софии

| |

| |

| 41°00′30″N 28°58′48″E / 41.00833°N 28.98000°E | |

| Location | Fatih, Istanbul, Turkey |

|---|---|

| Designer | |

| Type |

|

| Material | Ashlar, Roman brick |

| Length | 82 m (269 ft) |

| Width | 73 m (240 ft) |

| Height | 55 m (180 ft) |

| Beginning date | c. 346 |

| Completion date | 360 |

| Dedicated date | 15 February 360 |

| Restored date |

|

| Dedicated to | The Holy Wisdom, a reference to the second person of the Trinity, or Jesus Christ[2] |

| Website | |

| Part of | Historic Areas of Istanbul |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iii, iv |

| Reference | 356 |

| Inscription | 1985 (9th Session) |

Собор Святой Софии ( букв. « Святая Мудрость »; турецкий : Ayasofya ; греческий : Ἁγία Σοφία , латинизированный : Hagía Sofía ; латинский : Sancta Sapientia ), официально Большая мечеть Святой Софии (турецкий: Ayasofya-i Kebir Cami-i Şerifi ), [3] Мечеть , и бывшая церковь служащие важным культурным и историческим объектом в Стамбуле , Турция . Последнее из трех церковных зданий, последовательно возведенных на этом месте Восточной Римской империей , оно было завершено в 537 году нашей эры. На этом месте стояла халкидонская церковь с 360 г. по 1054 г., православная церковь после Великого раскола 1054 г. и католическая церковь после Четвертого крестового похода . [4] Она была возвращена в 1261 году и оставалась православной до падения Константинополя в 1453 году. Мечетью она служила до 1935 года, когда стала музеем. В 2020 году это место снова стало мечетью.

Нынешняя структура была построена византийским императором Юстинианом I как христианский собор Константинополя для Византийской империи между 532 и 537 годами и спроектирована греческими геометрами Исидором Милетским и Антемием Траллесским . [5] называлась Божией Церковью Святой . Премудрости она Формально [6] [7] и после завершения стал крупнейшим в мире внутренним пространством и одним из первых, в котором использовался полностью подвесной купол. Считается воплощением византийской архитектуры. [8] и, как говорят, «изменил историю архитектуры». [9] Нынешнее здание Юстиниана было третьей одноименной церковью, занимавшей это место, поскольку предыдущая была разрушена во время беспорядков в Нике . В качестве епископской кафедры вселенского патриарха Константинополя он оставался крупнейшим собором в мире в течение почти тысячи лет, пока в 1520 году не был завершен Севильский собор . Начиная с последующей византийской архитектуры, собор Святой Софии стал образцом православной церковной формы , и его архитектурная архитектура этому стилю подражали османские мечети . тысячу лет спустя [10] It has been described as "holding a unique position in the Christian world"[10] and as an architectural and cultural icon of Byzantine and Eastern Orthodox civilization.[10][11][12]

The religious and spiritual centre of the Eastern Orthodox Church for nearly one thousand years, the church was dedicated to the Holy Wisdom.[13][14][15] It was where the excommunication of Patriarch Michael I Cerularius was officially delivered by Humbert of Silva Candida, the envoy of Pope Leo IX in 1054, an act considered the start of the East–West Schism. In 1204, it was converted during the Fourth Crusade into a Catholic cathedral under the Latin Empire, before being returned to the Eastern Orthodox Church upon the restoration of the Byzantine Empire in 1261. Enrico Dandolo, the doge of Venice who led the Fourth Crusade and the 1204 Sack of Constantinople, was buried in the church.

After the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453,[16] it was converted to a mosque by Mehmed the Conqueror and became the principal mosque of Istanbul until the 1616 construction of the Sultan Ahmed Mosque.[17][18] Upon its conversion, the bells, altar, iconostasis, ambo, and baptistery were removed, while iconography, such as the mosaic depictions of Jesus, Mary, Christian saints and angels were removed or plastered over.[19] Islamic architectural additions included four minarets, a minbar and a mihrab. The Byzantine architecture of the Hagia Sophia served as inspiration for many other religious buildings including the Hagia Sophia in Thessaloniki, Panagia Ekatontapiliani, the Şehzade Mosque, the Süleymaniye Mosque, the Rüstem Pasha Mosque and the Kılıç Ali Pasha Complex. The patriarchate moved to the Church of the Holy Apostles, which became the city's cathedral.

The complex remained a mosque until 1931, when it was closed to the public for four years. It was re-opened in 1935 as a museum under the secular Republic of Turkey, and the building was Turkey's most visited tourist attraction as of 2019[update].[20]

In July 2020, the Council of State annulled the 1934 decision to establish the museum, and the Hagia Sophia was reclassified as a mosque. The 1934 decree was ruled to be unlawful under both Ottoman and Turkish law as Hagia Sophia's waqf, endowed by Sultan Mehmed, had designated the site a mosque; proponents of the decision argued the Hagia Sophia was the personal property of the sultan. The decision to designate Hagia Sophia as a mosque was highly controversial. It resulted in divided opinions and drew condemnation from the Turkish opposition, UNESCO, the World Council of Churches and the International Association of Byzantine Studies, as well as numerous international leaders, while several Muslim leaders in Turkey and other countries welcomed its conversion into a mosque.

History[edit]

Church of Constantius II[edit]

The first church on the site was known as the Magna Ecclesia (Μεγάλη Ἐκκλησία, Megálē Ekklēsíā, 'Great Church')[21][22] because of its size compared to the sizes of the contemporary churches in the city.[13] According to the Chronicon Paschale, the church was consecrated on 15 February 360, during the reign of the emperor Constantius II (r. 337–361) by the Arian bishop Eudoxius of Antioch.[23][24] It was built next to the area where the Great Palace was being developed. According to the 5th-century ecclesiastical historian Socrates of Constantinople, the emperor Constantius had c. 346 "constructed the Great Church alongside that called Irene which because it was too small, the emperor's father [Constantine] had enlarged and beautified".[25][23] A tradition which is not older than the 7th or 8th century reports that the edifice was built by Constantius' father, Constantine the Great (r. 306–337).[23] Hesychius of Miletus wrote that Constantine built Hagia Sophia with a wooden roof and removed 427 (mostly pagan) statues from the site.[26] The 12th-century chronicler Joannes Zonaras reconciles the two opinions, writing that Constantius had repaired the edifice consecrated by Eusebius of Nicomedia, after it had collapsed.[23] Since Eusebius was the bishop of Constantinople from 339 to 341, and Constantine died in 337, it seems that the first church was erected by Constantius.[23]

The nearby Hagia Irene ("Holy Peace") church was completed earlier and served as cathedral until the Great Church was completed. Besides Hagia Irene, there is no record of major churches in the city-centre before the late 4th century.[24] Rowland Mainstone argued the 4th-century church was not yet known as Hagia Sophia.[27] Though its name as the 'Great Church' implies that it was larger than other Constantinopolitan churches, the only other major churches of the 4th century were the Church of St Mocius, which lay outside the Constantinian walls and was perhaps attached to a cemetery, and the Church of the Holy Apostles.[24]

The church itself is known to have had a timber roof, curtains, columns, and an entrance that faced west.[24] It likely had a narthex and is described as being shaped like a Roman circus.[28] This may mean that it had a U-shaped plan like the basilicas of San Marcellino e Pietro and Sant'Agnese fuori le mura in Rome.[24] However, it may also have been a more conventional three-, four-, or five-aisled basilica, perhaps resembling the original Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem or the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem.[24] The building was likely preceded by an atrium, as in the later churches on the site.[29]

According to Ken Dark and Jan Kostenec, a further remnant of the 4th century basilica may exist in a wall of alternating brick and stone banded masonry immediately to the west of the Justinianic church.[30] The top part of the wall is constructed with bricks stamped with brick-stamps dating from the 5th century, but the lower part is of constructed with bricks typical of the 4th century.[30] This wall was probably part of the propylaeum at the west front of both the Constantinian and Theodosian Great Churches.[30]

The building was accompanied by a baptistery and a skeuophylakion.[24] A hypogeum, perhaps with an martyrium above it, was discovered before 1946, and the remnants of a brick wall with traces of marble revetment were identified in 2004.[30] The hypogeum was a tomb which may have been part of the 4th-century church or may have been from the pre-Constantinian city of Byzantium.[30] The skeuophylakion is said by Palladius to have had a circular floor plan, and since some U-shaped basilicas in Rome were funerary churches with attached circular mausolea (the Mausoleum of Constantina and the Mausoleum of Helena), it is possible it originally had a funerary function, though by 405 its use had changed.[30] A later account credited a woman called Anna with donating the land on which the church was built in return for the right to be buried there.[30]

Excavations on the western side of the site of the first church under the propylaeum wall reveal that the first church was built atop a road about 8 m (26 ft) wide.[30] According to early accounts, the first Hagia Sophia was built on the site of an ancient pagan temple,[31][32][33] although there are no artefacts to confirm this.[34]

The Patriarch of Constantinople John Chrysostom came into a conflict with Empress Aelia Eudoxia, wife of the emperor Arcadius (r. 383–408), and was sent into exile on 20 June 404. During the subsequent riots, this first church was largely burnt down.[23] Palladius noted that the 4th-century skeuophylakion survived the fire.[35] According to Dark and Kostenec, the fire may only have affected the main basilica, leaving the surrounding ancillary buildings intact.[35]

Church of Theodosius II[edit]

A second church on the site was ordered by Theodosius II (r. 402–450), who inaugurated it on 10 October 415.[36] The Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae, a fifth-century list of monuments, names Hagia Sophia as Magna Ecclesia, 'Great Church', while the former cathedral Hagia Irene is referred to as Ecclesia Antiqua, 'Old Church'. At the time of Socrates of Constantinople around 440, "both churches [were] enclosed by a single wall and served by the same clergy".[25] Thus, the complex would have encompassed a large area including the future site of the Hospital of Samson.[35] If the fire of 404 destroyed only the 4th-century main basilica church, then the 5th century Theodosian basilica could have been built surrounded by a complex constructed primarily during the fourth century.[35]

During the reign of Theodosius II, the emperor's elder sister, the Augusta Pulcheria (r. 414–453) was challenged by the patriarch Nestorius (r. 10 April 428 – 22 June 431).[37][38] The patriarch denied the Augusta access to the sanctuary of the "Great Church", likely on 15 April 428.[38] According to the anonymous Letter to Cosmas, the virgin empress, a promoter of the cult of the Virgin Mary who habitually partook in the Eucharist at the sanctuary of Nestorius's predecessors, claimed right of entry because of her equivalent position to the Theotokos – the Virgin Mary – "having given birth to God".[39][38] Their theological differences were part of the controversy over the title theotokos that resulted in the Council of Ephesus and the stimulation of Monophysitism and Nestorianism, a doctrine, which like Nestorius, rejects the use of the title.[37] Pulcheria along with Pope Celestine I and Patriarch Cyril of Alexandria had Nestorius overthrown, condemned at the ecumenical council, and exiled.[39][37]

The area of the western entrance to the Justinianic Hagia Sophia revealed the western remains of its Theodosian predecessor, as well as some fragments of the Constantinian church.[35] German archaeologist Alfons Maria Schneider began conducting archaeological excavations during the mid-1930s, publishing his final report in 1941.[35] Excavations in the area that had once been the 6th-century atrium of the Justinianic church revealed the monumental western entrance and atrium, along with columns and sculptural fragments from both 4th- and 5th-century churches.[35] Further digging was abandoned for fear of harming the structural integrity of the Justinianic building, but parts of the excavation trenches remain uncovered, laying bare the foundations of the Theodosian building.

The basilica was built by architect Rufinus.[40][41] The church's main entrance, which may have had gilded doors, faced west, and there was an additional entrance to the east.[42] There was a central pulpit and likely an upper gallery, possibly employed as a matroneum (women's section).[42] The exterior was decorated with elaborate carvings of rich Theodosian-era designs, fragments of which have survived, while the floor just inside the portico was embellished with polychrome mosaics.[35] The surviving carved gable end from the centre of the western façade is decorated with a cross-roundel.[35] Fragments of a frieze of reliefs with 12 lambs representing the 12 apostles also remain; unlike Justinian's 6th-century church, the Theodosian Hagia Sophia had both colourful floor mosaics and external decorative sculpture.[35]

At the western end, surviving stone fragments of the structure show there was vaulting, at least at the western end.[35] The Theodosian building had a monumental propylaeum hall with a portico that may account for this vaulting, which was thought by the original excavators in the 1930s to be part of the western entrance of the church itself.[35] The propylaeum opened onto an atrium which lay in front of the basilica church itself. Preceding the propylaeum was a steep monumental staircase following the contours of the ground as it sloped away westwards in the direction of the Strategion, the Basilica, and the harbours of the Golden Horn.[35] This arrangement would have resembled the steps outside the atrium of the Constantinian Old St Peter's Basilica in Rome.[35] Near the staircase, there was a cistern, perhaps to supply a fountain in the atrium or for worshippers to wash with before entering.[35]

The 4th-century skeuophylakion was replaced in the 5th century by the present-day structure, a rotunda constructed of banded masonry in the lower two levels and of plain brick masonry in the third.[35] Originally this rotunda, probably employed as a treasury for liturgical objects, had a second-floor internal gallery accessed by an external spiral staircase and two levels of niches for storage.[35] A further row of windows with marble window frames on the third level remain bricked up.[35] The gallery was supported on monumental consoles with carved acanthus designs, similar to those used on the late 5th-century Column of Leo.[35] A large lintel of the skeuophylakion's western entrance – bricked up during the Ottoman era – was discovered inside the rotunda when it was archaeologically cleared to its foundations in 1979, during which time the brickwork was also repointed.[35] The skeuophylakion was again restored in 2014 by the Vakıflar.[35]

A fire started during the tumult of the Nika Revolt, which had begun nearby in the Hippodrome of Constantinople, and the second Hagia Sophia was burnt to the ground on 13–14 January 532. The court historian Procopius wrote:[43]

And by way of shewing that it was not against the Emperor alone that they [the rioters] had taken up arms, but no less against God himself, unholy wretches that they were, they had the hardihood to fire the Church of the Christians, which the people of Byzantium call "Sophia", an epithet which they have most appropriately invented for God, by which they call His temple; and God permitted them to accomplish this impiety, foreseeing into what an object of beauty this shrine was destined to be transformed. So the whole church at that time lay a charred mass of ruins.

— Procopius, De aedificiis, I.1.21–22

- Remains of the Theodosian Hagia Sophia

- Column and capital with a Greek cross

- Porphyry column; column capital; impost block

- Soffits and cornice

- Theodosian capital

- Theodosian capital for a pilaster, one of the few remains of the church of Theodosius II

Church of Justinian I (current structure)[edit]

On 23 February 532, only a few weeks after the destruction of the second basilica, Emperor Justinian I inaugurated the construction of a third and entirely different basilica, larger and more majestic than its predecessors.[44] Justinian appointed two architects, mathematician Anthemius of Tralles and geometer and engineer Isidore of Miletus, to design the building.[45][46]

Construction of the church began in 532 during the short tenure of Phocas as praetorian prefect.[47] Although Phocas had been arrested in 529 as a suspected practitioner of paganism, he replaced John the Cappadocian after the Nika Riots saw the destruction of the Theodosian church.[47] According to John the Lydian, Phocas was responsible for funding the initial construction of the building with 4,000 Roman pounds of gold, but he was dismissed from office in October 532.[48][47] John the Lydian wrote that Phocas had acquired the funds by moral means, but Evagrius Scholasticus later wrote that the money had been obtained unjustly.[49][47]

According to Anthony Kaldellis, both of Hagia Sophia's architects named by Procopius were associated with to the school of the pagan philosopher Ammonius of Alexandria.[47] It is possible that both they and John the Lydian considered Hagia Sophia a great temple for the supreme Neoplatonist deity who manifestated through light and the sun. John the Lydian describes the church as the "temenos of the Great God" (Greek: τὸ τοῦ μεγάλου θεοῦ Τέμενος, romanized: tò toû megálou theoû Témenos).[48][47]

Originally the exterior of the church was covered with marble veneer, as indicated by remaining pieces of marble and surviving attachments for lost panels on the building's western face.[50] The white marble cladding of much of the church, together with gilding of some parts, would have given Hagia Sophia a shimmering appearance quite different from the brick- and plaster-work of the modern period, and would have significantly increased its visibility from the sea.[50] The cathedral's interior surfaces were sheathed with polychrome marbles, green and white with purple porphyry, and gold mosaics. The exterior was clad in stucco that was tinted yellow and red during the 19th-century restorations by the Fossati architects.[51]

The construction is described by Procopius in On Buildings (Greek: Περὶ κτισμάτων, romanized: Peri ktismatōn, Latin: De aedificiis).[43] Columns and other marble elements were imported from throughout the Mediterranean, although the columns were once thought to be spoils from cities such as Rome and Ephesus.[52] Even though they were made specifically for Hagia Sophia, they vary in size.[53] More than ten thousand people were employed during the construction process. This new church was contemporaneously recognized as a major work of architecture. Outside the church was an elaborate array of monuments around the bronze-plated Column of Justinian, topped by an equestrian statue of the emperor which dominated the Augustaeum, the open square outside the church which connected it with the Great Palace complex through the Chalke Gate. At the edge of the Augustaeum was the Milion and the Regia, the first stretch of Constantinople's main thoroughfare, the Mese. Also facing the Augustaeum were the enormous Constantinian thermae, the Baths of Zeuxippus, and the Justinianic civic basilica under which was the vast cistern known as the Basilica Cistern. On the opposite side of Hagia Sophia was the former cathedral, Hagia Irene.

Referring to the destruction of the Theodosian Hagia Sophia and comparing the new church with the old, Procopius lauded the Justinianic building, writing in De aedificiis:[43]

... the Emperor Justinian built not long afterwards a church so finely shaped, that if anyone had enquired of the Christians before the burning if it would be their wish that the church should be destroyed and one like this should take its place, shewing them some sort of model of the building we now see, it seems to me that they would have prayed that they might see their church destroyed forthwith, in order that the building might be converted into its present form.

— Procopius, De aedificiis, I.1.22–23

Upon seeing the finished building, the Emperor reportedly said: "Solomon, I have surpassed thee" (Medieval Greek: Νενίκηκά σε Σολομών).[54]

Justinian and Patriarch Menas inaugurated the new basilica on 27 December 537, 5 years and 10 months after construction started, with much pomp.[55][56][57] Hagia Sophia was the seat of the Patriarchate of Constantinople and a principal setting for Byzantine imperial ceremonies, such as coronations. The basilica offered sanctuary from persecution to criminals, although there was disagreement about whether Justinian had intended for murderers to be eligible for asylum.[58]

Earthquakes in August 553 and on 14 December 557 caused cracks in the main dome and eastern semi-dome. According to the Chronicle of John Malalas, during a subsequent earthquake on 7 May 558,[60] the eastern semi-dome collapsed, destroying the ambon, altar, and ciborium. The collapse was due mainly to the excessive bearing load and to the enormous shear load of the dome, which was too flat.[55] These caused the deformation of the piers which sustained the dome.[55] Justinian ordered an immediate restoration. He entrusted it to Isidorus the Younger, nephew of Isidore of Miletus, who used lighter materials. The entire vault had to be taken down and rebuilt 20 Byzantine feet (6.25 m or 20.5 ft) higher than before, giving the building its current interior height of 55.6 m (182 ft).[61] Moreover, Isidorus changed the dome type, erecting a ribbed dome with pendentives whose diameter was between 32.7 and 33.5 m.[55] Under Justinian's orders, eight Corinthian columns were disassembled from Baalbek, Lebanon and shipped to Constantinople around 560.[62] This reconstruction, which gave the church its present 6th-century form, was completed in 562. The poet Paul the Silentiary composed an ekphrasis, or long visual poem, for the re-dedication of the basilica presided over by Patriarch Eutychius on 24 December 562. Paul the Silentiary's poem is conventionally known under the Latin title Descriptio Sanctae Sophiae, and he was also author of another ekphrasis on the ambon of the church, the Descripto Ambonis.[63][64]

According to the history of the patriarch Nicephorus I and the chronicler Theophanes the Confessor, various liturgical vessels of the cathedral were melted down on the order of the emperor Heraclius (r. 610–641) after the capture of Alexandria and Roman Egypt by the Sasanian Empire during the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628.[65] Theophanes states that these were made into gold and silver coins, and a tribute was paid to the Avars.[65] The Avars attacked the extramural areas of Constantinople in 623, causing the Byzantines to move the "garment" relic (Greek: ἐσθής, translit. esthḗs) of Mary, mother of Jesus to Hagia Sophia from its usual shrine of the Church of the Theotokos at Blachernae just outside the Theodosian Walls.[66] On 14 May 626, the Scholae Palatinae, an elite body of soldiers, protested in Hagia Sophia against a planned increase in bread prices, after a stoppage of the Cura Annonae rations resulting from the loss of the grain supply from Egypt.[67] The Persians under Shahrbaraz and the Avars together laid the siege of Constantinople in 626; according to the Chronicon Paschale, on 2 August 626, Theodore Syncellus, a deacon and presbyter of Hagia Sophia, was among those who negotiated unsuccessfully with the khagan of the Avars.[68] A homily, attributed by existing manuscripts to Theodore Syncellus and possibly delivered on the anniversary of the event, describes the translation of the Virgin's garment and its ceremonial re-translation to Blachernae by the patriarch Sergius I after the threat had passed.[68][69] Another eyewitness account of the Avar–Persian siege was written by George of Pisidia, a deacon of Hagia Sophia and an administrative official in for the patriarchate from Antioch in Pisidia.[68] Both George and Theodore, likely members of Sergius's literary circle, attribute the defeat of the Avars to the intervention of the Theotokos, a belief that strengthened in following centuries.[68]

In 726, the emperor Leo the Isaurian issued a series of edicts against the veneration of images, ordering the army to destroy all icons – ushering in the period of Byzantine iconoclasm. At that time, all religious pictures and statues were removed from the Hagia Sophia. Following a brief hiatus during the reign of Empress Irene (797–802), the iconoclasts returned. Emperor Theophilus (r. 829–842) had two-winged bronze doors with his monograms installed at the southern entrance of the church.[70]

The basilica suffered damage, first in a great fire in 859, and again in an earthquake on 8 January 869 that caused the collapse of one of the half-domes.[71] Emperor Basil I ordered repair of the tympanas, arches, and vaults.[72]

In his book De caerimoniis aulae Byzantinae ("Book of Ceremonies"), the emperor Constantine VII (r. 913–959) wrote a detailed account of the ceremonies held in the Hagia Sophia by the emperor and the patriarch.

Early in the 10th century, the pagan ruler of the Kievan Rus' sent emissaries to his neighbors to learn about Judaism, Islam, and Roman and Orthodox Christianity. After visiting Hagia Sophia his emissaries reported back: "We were led into a place where they serve their God, and we did not know where we were, in heaven or on earth."[73]

In the 940s or 950s, probably around 954 or 955, after the Rus'–Byzantine War of 941 and the death of the Grand Prince of Kiev, Igor I (r. 912–945), his widow Olga of Kiev – regent for her infant son Sviatoslav I (r. 945–972) – visited the emperor Constantine VII and was received as queen of the Rus' in Constantinople.[74][75][76] She was probably baptized in Hagia Sophia's baptistery, taking the name of the reigning augusta, Helena Lecapena, and receiving the titles zōstē patrikía and the styles of archontissa and hegemon of the Rus'.[75][74] Her baptism was an important step towards the Christianization of the Kievan Rus', though the emperor's treatment of her visit in De caerimoniis does not mention baptism.[75][74] Olga is deemed a saint and equal-to-the-apostles (Greek: ἰσαπόστολος, translit. isapóstolos) in the Eastern Orthodox Church.[77][78] According to an early 14th-century source, the second church in Kiev, Saint Sophia's, was founded in anno mundi 6460 in the Byzantine calendar, or c. 952.[79] The name of this future cathedral of Kiev probably commemorates Olga's baptism at Hagia Sophia.[79]

After the great earthquake of 25 October 989, which collapsed the western dome arch, Emperor Basil II asked for the Armenian architect Trdat, creator of the Cathedral of Ani, to direct the repairs.[80] He erected again and reinforced the fallen dome arch, and rebuilt the west side of the dome with 15 dome ribs.[81] The extent of the damage required six years of repair and reconstruction; the church was re-opened on 13 May 994. At the end of the reconstruction, the church's decorations were renovated, including the addition of four immense paintings of cherubs; a new depiction of Christ on the dome; a burial cloth of Christ shown on Fridays, and on the apse a new depiction of the Virgin Mary holding Jesus, between the apostles Peter and Paul.[82] On the great side arches were painted the prophets and the teachers of the church.[82]

According to the 13th-century Greek historian Niketas Choniates, the emperor John II Comnenus celebrated a revived Roman triumph after his victory over the Danishmendids at the siege of Kastamon in 1133.[83] After proceeding through the streets on foot carrying a cross with a silver quadriga bearing the icon of the Virgin Mary, the emperor participated in a ceremony at the cathedral before entering the imperial palace.[84] In 1168, another triumph was held by the emperor Manuel I Comnenus, again preceding with a gilded silver quadriga bearing the icon of the Virgin from the now-demolished East Gate (or Gate of St Barbara, later the Turkish: Top Kapısı, lit. 'Cannon Gate') in the Propontis Wall, to Hagia Sophia for a thanks-giving service, and then to the imperial palace.[85]

In 1181, the daughter of the emperor Manuel I, Maria Comnena, and her husband, the caesar Renier of Montferrat, fled to Hagia Sophia at the culmination of their dispute with the empress Maria of Antioch, regent for her son, the emperor Alexius II Comnenus.[86] Maria Comnena and Renier occupied the cathedral with the support of the patriarch, refusing the imperial administration's demands for a peaceful departure.[86] According to Niketas Choniates, they "transformed the sacred courtyard into a military camp", garrisoned the entrances to the complex with locals and mercenaries, and despite the strong opposition of the patriarch, made the "house of prayer into a den of thieves or a well-fortified and precipitous stronghold, impregnable to assault", while "all the dwellings adjacent to Hagia Sophia and adjoining the Augusteion were demolished by [Maria's] men".[86] A battle ensued in the Augustaion and around the Milion, during which the defenders fought from the "gallery of the Catechumeneia (also called the Makron)" facing the Augusteion, from which they eventually retreated and took up positions in the exonarthex of Hagia Sophia itself.[86] At this point, "the patriarch was anxious lest the enemy troops enter the temple, with unholy feet trample the holy floor, and with hands defiled and dripping with blood still warm plunder the all-holy dedicatory offerings".[86] After a successful sally by Renier and his knights, Maria requested a truce, the imperial assault ceased, and an amnesty was negotiated by the megas doux Andronikos Kontostephanos and the megas hetaireiarches John Doukas.[86] Greek historian Niketas Choniates compared the preservation of the cathedral to the efforts made by the 1st-century emperor Titus to avoid the destruction of the Second Temple during the siege of Jerusalem in the First Jewish–Roman War.[86] Choniates reports that in 1182, a white hawk wearing jesses was seen to fly from the east to Hagia Sophia, flying three times from the "building of the Thōmaitēs" (a basilica erected on the southeastern side of the Augustaion) to the Palace of the Kathisma in the Great Palace, where new emperors were acclaimed.[87] This was supposed to presage the end of the reign of Andronicus I Comnenus (r. 1183–1185).[87]

Choniates further writes that in 1203, during the Fourth Crusade, the emperors Isaac II Angelus and Alexius IV Angelus stripped Hagia Sophia of all gold ornaments and silver oil-lamps in order to pay off the Crusaders who had ousted Alexius III Angelus and helped Isaac return to the throne.[88] Upon the subsequent Sack of Constantinople in 1204, the church was further ransacked and desecrated by the Crusaders, as described by Choniates, though he did not witness the events in person. According to his account, composed at the court of the rump Empire of Nicaea, Hagia Sophia was stripped of its remaining metal ornaments, its altar was smashed into pieces, and a "woman laden with sins" sang and danced on the synthronon.[89][90][91] He adds that mules and donkeys were brought into the cathedral's sanctuary to carry away the gilded silver plating of the bema, the ambo, and the doors and other furnishings, and that one of them slipped on the marble floor and was accidentally disembowelled, further contaminating the place.[89] According to Ali ibn al-Athir, whose treatment of the Sack of Constantinople was probably dependent on a Christian source, the Crusaders massacred some clerics who had surrendered to them.[92] Much of the interior was damaged and would not be repaired until its return to Orthodox control in 1261.[34] The sack of Hagia Sophia, and Constantinople in general, remained a sore point in Catholic–Eastern Orthodox relations.[93]

During the Latin occupation of Constantinople (1204–1261), the church became a Latin Catholic cathedral. Baldwin I of Constantinople (r. 1204–1205) was crowned emperor on 16 May 1204 in Hagia Sophia in a ceremony which closely followed Byzantine practices. Enrico Dandolo, the Doge of Venice who commanded the sack and invasion of the city by the Latin Crusaders in 1204, is buried inside the church, probably in the upper eastern gallery. In the 19th century, an Italian restoration team placed a cenotaph marker, frequently mistaken as being a medieval artifact, near the probable location and is still visible today. The original tomb was destroyed by the Ottomans during the conversion of the church into a mosque.[94]

Upon the capture of Constantinople in 1261 by the Empire of Nicaea and the emperor Michael VIII Palaeologus, (r. 1261–1282), the church was in a dilapidated state. In 1317, emperor Andronicus II Palaeologus (r. 1282–1328) ordered four new buttresses (Medieval Greek: Πυραμίδας, romanized: Pyramídas) to be built in the eastern and northern parts of the church, financing them with the inheritance of his late wife, Irene of Montferrat (d.1314).[19] New cracks developed in the dome after the earthquake of October 1344, and several parts of the building collapsed on 19 May 1346. Repairs by architects Astras and Peralta began in 1354.[71][95]

On 12 December 1452, Isidore of Kiev proclaimed in Hagia Sophia the long-anticipated ecclesiastical union between the western Catholic and eastern Orthodox Churches as decided at the Council of Florence and decreed by the papal bull Laetentur Caeli, though it would be short-lived. The union was unpopular among the Byzantines, who had already expelled the Patriarch of Constantinople, Gregory III, for his pro-union stance. A new patriarch was not installed until after the Ottoman conquest. According to the Greek historian Doukas, the Hagia Sophia was tainted by these Catholic associations, and the anti-union Orthodox faithful avoided the cathedral, considering it to be a haunt of demons and a "Hellenic" temple of Roman paganism.[96] Doukas also notes that after the Laetentur Caeli was proclaimed, the Byzantines dispersed discontentedly to nearby venues where they drank toasts to the Hodegetria icon, which had, according to late Byzantine tradition, interceded to save them in the former sieges of Constantinople by the Avar Khaganate and the Umayyad Caliphate.[97]

According to Nestor Iskander's Tale on the Taking of Tsargrad, the Hagia Sophia was the focus of an alarming omen interpreted as the Holy Spirit abandoning Constantinople on 21 May 1453, in the final days of the Siege of Constantinople.[98] The sky lit up, illuminating the city, and "many people gathered and saw on the Church of the Wisdom, at the top of the window, a large flame of fire issuing forth. It encircled the entire neck of the church for a long time. The flame gathered into one; its flame altered, and there was an indescribable light. At once it took to the sky. ... The light itself has gone up to heaven; the gates of heaven were opened; the light was received; and again they were closed."[98] This phenomenon was perhaps St Elmo's fire induced by gunpowder smoke and unusual weather.[98] The author relates that the fall of the city to "Mohammadenism" was foretold in an omen seen by Constantine the Great – an eagle fighting with a snake – which also signified that "in the end Christianity will overpower Mohammedanism, will receive the Seven Hills, and will be enthroned in it".[98]

The eventual fall of Constantinople had long been predicted in apocalyptic literature.[99] A reference to the destruction of a city founded on seven hills in the Book of Revelation was frequently understood to be about Constantinople, and the Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius had predicted an "Ishmaelite" conquest of the Roman Empire.[99] In this text, the Muslim armies reach the Forum Bovis before being turned back by divine intervention; in later apocalyptic texts, the climactic turn takes place at the Column of Theodosius closer to Hagia Sophia; in others, it occurs at the Column of Constantine, which is closer still.[99] Hagia Sophia is mentioned in a hagiography of uncertain date detailing the life of the Eastern Orthodox saint Andrew the Fool.[100] The text is self-attributed to Nicephorus, a priest of Hagia Sophia, and contains a description of the end time in the form of a dialogue, in which the interlocutor, upon being told by the saint that Constantinople will be sunk in a flood and that "the waters as they gush forth will irresistibly deluge her and cover her and surrender her to the terrifying and immense sea of the abyss", says "some people say that the Great Church of God will not be submerged with the city but will be suspended in the air by an invisible power".[100] The reply is given that "When the whole city sinks into the sea, how can the Great Church remain? Who will need her? Do you think God dwells in temples made with hands?"[100] The Column of Constantine, however, is prophesied to endure.[100]

From the time of Procopius in the reign of Justinian, the equestrian imperial statue on the Column of Justinian in the Augustaion beside Hagia Sophia, which gestured towards Asia with right hand, was understood to represent the emperor holding back the threat to the Romans from the Sasanian Empire in the Roman–Persian Wars, while the orb or globus cruciger held in the statue's left was an expression of the global power of the Roman emperor.[101] Subsequently, in the Arab–Byzantine wars, the threat held back by the statue became the Umayyad Caliphate, and later, the statue was thought to be fending off the advance of the Turks.[101] The identity of the emperor was often confused with that of other famous saint-emperors like Theodosius I and Heraclius.[101] The orb was frequently referred to as an apple in foreigners' accounts of the city, and it was interpreted in Greek folklore as a symbol of the Turks' mythological homeland in Central Asia, the "Lone Apple Tree".[101] The orb fell to the ground in 1316 and was replaced by 1325, but while it was still in place around 1412, by the time Johann Schiltberger saw the statue in 1427, the "empire-apple" (German: Reichsapfel) had fallen to the earth.[101] An attempt to raise it again in 1435 failed, and this amplified the prophecies of the city's fall.[101] For the Turks, the "red apple" (Turkish: kızıl elma) came to symbolize Constantinople itself and subsequently the military supremacy of the Islamic caliphate over the Christian empire.[101] In Niccolò Barbaro's account of the fall of the city in 1453, the Justinianic monument was interpreted in the last days of the siege as representing the city's founder Constantine the Great, indicating "this is the way my conqueror will come".[98]

According to Laonicus Chalcocondyles, Hagia Sophia was a refuge for the population during the city's capture.[102] Despite the ill-repute and empty state of Hagia Sophia after December 1452, Doukas writes that after the Theodosian Walls were breached, the Byzantines took refuge there as the Turks advanced through the city: "All the women and men, monks, and nuns ran to the Great Church. They, both men and women, were holding in their arms their infants. What a spectacle! That street was crowded, full of human beings."[102] He attributes their change of heart to a prophecy.[102]

What was the reason that compelled all to flee to the Great Church? They had been listening, for many years, to some pseudo-soothsayers, who had declared that the city was destined to be handed over to the Turks, who would enter in large numbers and would massacre the Romans as far as the Column of Constantine the Great. After this an angel would descend, holding his sword. He would hand over the kingdom, together with the sword, to some insignificant, poor, and humble man who would happen to be standing by the Column. He would say to him: "Take this sword and avenge the Lord's people." Then the Turks would be turned back, would be massacred by the pursuing Romans, and would be ejected from the city and from all places in the west and the east and would be driven as far as the borders of Persia, to a place called the Lone Tree …. That was the cause for the flight into the Great Church. In one hour that famous and enormous church was filled with men and women. An innumerable crowd was everywhere: upstairs, downstairs, in the courtyards, and in every conceivable place. They closed the gates and stood there, hoping for salvation.

— Doukas, XXXIX.18

In accordance with the traditional custom of the time, Sultan Mehmed II allowed his troops and his entourage three full days of unbridled pillage and looting in the city shortly after it was captured. This period saw the destruction of many Orthodox churches;[103] Hagia Sophia itself was looted as the invaders believed it to contain the greatest treasures of the city.[104] Shortly after the defence of the Walls of Constantinople collapsed and the victorious Ottoman troops entered the city, the pillagers and looters made their way to the Hagia Sophia and battered down its doors before storming inside.[105] Once the three days passed, Mehmed was to claim the city's remaining contents for himself.[106][107] However, by the end of the first day, he proclaimed that the looting should cease as he felt profound sadness when he toured the looted and enslaved city.[108][106][109]

Throughout the siege of Constantinople, the trapped people of the city participated in the Divine Liturgy and the Prayer of the Hours at the Hagia Sophia, and the church was a safe-haven and a refuge for many of those who were unable to contribute to the city's defence, including women, children, elderly, the sick and the wounded.[110][111][109] As they were trapped in the church, the many congregants and other refugees inside became spoils-of-war to be divided amongst the triumphant invaders. The building was desecrated and looted, and those who sought shelter within the church were enslaved.[104] While most of the elderly and the infirm, injured, and sick were killed, the remainder (mainly teenage males and young boys) were chained and sold into slavery.[105][109]

Mosque (1453–1935)[edit]

Constantinople fell to the attacking Ottoman forces on 29 May 1453. Sultan Mehmed II entered the city and performed the Friday prayer and khutbah (sermon) in Hagia Sophia, and this action marked the official conversion of Hagia Sophia into a mosque.[112] The church's priests and religious personnel continued to perform Christian rites, prayers, and ceremonies until they were compelled to stop by the invaders.[105] When Mehmed and his entourage entered the church, he ordered that it be converted into a mosque immediately. One of the ʿulamāʾ (Islamic scholars) present climbed onto the church's ambo and recited the shahada ("There is no god but Allah, and Muhammad is his messenger"), thus marking the beginning of the conversion of the church into a mosque.[19][113] Mehmed is reported to have taken a sword to a soldier who tried to pry up one of the paving slabs of the Proconnesian marble floor.[114]

As described by Western visitors before 1453, such as the Córdoban nobleman Pero Tafur[115] and the Florentine geographer Cristoforo Buondelmonti,[116] the church was in a dilapidated state, with several of its doors fallen from their hinges. Mehmed II ordered a renovation of the building. Mehmed attended the first Friday prayer in the mosque on 1 June 1453.[117] Aya Sofya became the first imperial mosque of Istanbul.[118] Most of the existing houses in the city and the area of the future Topkapı Palace were endowed to the corresponding waqf.[19] From 1478, 2,360 shops, 1,300 houses, 4 caravanserais, 30 boza shops, and 23 shops of sheep heads and trotters gave their income to the foundation.[119] Through the imperial charters of 1520 (AH 926) and 1547 (AH 954), shops and parts of the Grand Bazaar and other markets were added to the foundation.[19]

Before 1481, a small minaret was erected on the southwest corner of the building, above the stair tower.[19] Mehmed's successor Bayezid II (r. 1481–1512) later built another minaret at the northeast corner.[19] One of the minarets collapsed after the earthquake of 1509,[19] and around the middle of the 16th century they were both replaced by two diagonally opposite minarets built at the east and west corners of the edifice.[19] In 1498, Bernardo Bonsignori was the last Western visitor to Hagia Sophia to report seeing the ancient Justinianic floor; shortly afterwards the floor was covered over with carpet and not seen again until the 19th century.[114]

In the 16th century, Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent (r. 1520–1566) brought two colossal candlesticks from his conquest of the Kingdom of Hungary and placed them on either side of the mihrab. During Suleiman's reign, the mosaics above the narthex and imperial gates depicting Jesus, Mary, and various Byzantine emperors were covered by whitewash and plaster, which were removed in 1930 under the Turkish Republic.[120][better source needed]

During the reign of Selim II (r. 1566–1574), the building started showing signs of fatigue and was extensively strengthened with the addition of structural supports to its exterior by Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan, who was also an earthquake engineer.[121] In addition to strengthening the historic Byzantine structure, Sinan built two additional large minarets at the western end of the building, the original sultan's lodge and the türbe (mausoleum) of Selim II to the southeast of the building in 1576–1577 (AH 984). In order to do that, parts of the Patriarchate at the south corner of the building were pulled down the previous year.[19] Moreover, the golden crescent was mounted on the top of the dome,[19] and a respect zone 35 arşın (about 24 m) wide was imposed around the building, leading to the demolition of all houses within the perimeter.[19] The türbe became the location of the tombs of 43 Ottoman princes.[19] Murad III (r. 1574–1595) imported two large alabaster Hellenistic urns from Pergamon (Bergama) and placed them on two sides of the nave.[19]

In 1594 (AH 1004) Mimar (court architect) Davud Ağa built the türbe of Murad III, where the Sultan and his valide, Safiye Sultan were buried.[19] The octagonal mausoleum of their son Mehmed III (r. 1595–1603) and his valide was built next to it in 1608 (AH 1017) by royal architect Dalgiç Mehmet Aĝa.[122] His son Mustafa I (r. 1617–1618, 1622–1623) converted the baptistery into his türbe.[122]

In 1717, under the reign of Sultan Ahmed III (r. 1703–1730), the crumbling plaster of the interior was renovated, contributing indirectly to the preservation of many mosaics, which otherwise would have been destroyed by mosque workers.[122] In fact, it was usual for the mosaic's tesserae—believed to be talismans—to be sold to visitors.[122] Sultan Mahmud I ordered the restoration of the building in 1739 and added a medrese (a Koranic school, subsequently the library of the museum), an imaret (soup kitchen for distribution to the poor) and a library, and in 1740 he added a Şadirvan (fountain for ritual ablutions), thus transforming it into a külliye, or social complex. At the same time, a new sultan's lodge and a new mihrab were built inside.[123]

Renovation of 1847–1849[edit]

The 19th-century restoration of the Hagia Sophia was ordered by Sultan Abdulmejid I (r. 1823–1861) and completed between 1847 and 1849 by eight hundred workers under the supervision of the Swiss-Italian architect brothers Gaspare and Giuseppe Fossati. The brothers consolidated the dome with a restraining iron chain and strengthened the vaults, straightened the columns, and revised the decoration of the exterior and the interior of the building.[124] The mosaics in the upper gallery were exposed and cleaned, although many were recovered "for protection against further damage".[125]

Eight new gigantic circular-framed discs or medallions were hung from the cornice, on each of the four piers and at either side of the apse and the west doors. These were designed by the calligrapher Kazasker Mustafa Izzet Efendi (1801–1877) and painted with the names of Allah, Muhammad, the Rashidun (the first four caliphs: Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman and Ali), and the two grandsons of Muhammad: Hasan and Husayn, the sons of Ali. The old chandeliers were replaced by new pendant ones.[citation needed]

In 1850, the architects Fossati built a new maqsura or caliphal loge in Neo-Byzantine columns and an Ottoman–Rococo style marble grille connecting to the royal pavilion behind the mosque.[124] The new maqsura was built at the extreme east end of the northern aisle, next to the north-eastern pier. The existing maqsura in the apse, near the mihrab, was demolished.[124] A new entrance was constructed for the sultan: the Hünkar Mahfili.[124] The Fossati brothers also renovated the minbar and mihrab.

Outside the main building, the minarets were repaired and altered so that they were of equal height.[125] A clock building, the Muvakkithane, was built by the Fossatis for use by the muwaqqit (the mosque timekeeper), and a new madrasa (Islamic school) was constructed. The Kasr-ı Hümayun was also built under their direction.[124] When the restoration was finished, the mosque was re-opened with a ceremony on 13 July 1849.[126] An edition of lithographs from drawings made during the Fossatis' work on Hagia Sophia was published in London in 1852, entitled: Aya Sophia of Constantinople as Recently Restored by Order of H.M. The Sultan Abdulmedjid.[124]

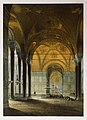

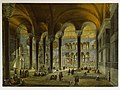

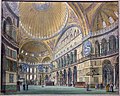

- Gaspare Fossati's Hagia Sophia (lithographs by Louis Haghe)

- Main (western) façade of Hagia Sophia, seen from courtyard of the madrasa of Mahmud I. Lithograph by Louis Haghe after Gaspard Fossati (1852).

- South-eastern side, seen from the Imperial Gate of the Topkapı Palace, with the Fountain of Ahmed III on the left and the Sultan Ahmed Mosque in the distance. Lithograph by Louis Haghe after Gaspard Fossati (1852).

- The imperial lodge (b 1850)

- Gaspare Fossati's 1852 depiction of the Hagia Sophia, after his and his brother's renovation. Lithograph by Louis Haghe.

- Nave before restoration, facing east

- Nave and apse after restoration, facing east

- Nave and entrance after restoration, facing west

- Narthex, facing north

- Exonarthex, facing north

- North aisle from the entrance, facing east

- North aisle, facing west

- Nave and south aisle from the north aisle

- Northern gallery and entrance to the matroneum from the north-west

- Southern gallery from the south-west

- Southern gallery from the Marble Door facing west

- Southern gallery from the Marble Door facing east

Occupation of Istanbul (1918–1923)[edit]

In the aftermath of the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I, Constantinople was occupied by British, French, Italian, and Greek forces. On 19 January 1919, the Greek Orthodox Christian military priest Eleftherios Noufrakis performed an unauthorized Divine Liturgy in the Hagia Sophia, the only such instance since the 1453 fall of Constantinople.[127] The anti-occupation Sultanahmet demonstrations were held next to Hagia Sophia from March to May 1919. In Greece, the 500 drachma banknotes issued in 1923 featured Hagia Sophia.[128]

Museum (1935–2020)[edit]

In 1935, the first Turkish President and founder of the Republic of Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, transformed the building into a museum. During the Second World War, the minarets of the museum housed MG 08 machine guns.[129] The carpet and the layer of mortar underneath were removed and marble floor decorations such as the omphalion appeared for the first time since the Fossatis' restoration,[130] when the white plaster covering many of the mosaics had been removed. Due to neglect, the condition of the structure continued to deteriorate, prompting the World Monuments Fund (WMF) to include the Hagia Sophia in their 1996 and 1998 Watch Lists. During this time period, the building's copper roof had cracked, causing water to leak down over the fragile frescoes and mosaics. Moisture entered from below as well. Rising ground water increased the level of humidity within the monument, creating an unstable environment for stone and paint. The WMF secured a series of grants from 1997 to 2002 for the restoration of the dome. The first stage of work involved the structural stabilization and repair of the cracked roof, which was undertaken with the participation of the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism. The second phase, the preservation of the dome's interior, afforded the opportunity to employ and train young Turkish conservators in the care of mosaics. By 2006, the WMF project was complete, though many areas of Hagia Sophia continue to require significant stability improvement, restoration, and conservation.[131]

In 2014, Hagia Sophia was the second most visited museum in Turkey, attracting almost 3.3 million visitors annually.[132]

While use of the complex as a place of worship (mosque or church) was strictly prohibited,[133] in 1991 the Turkish government allowed the allocation of a pavilion in the museum complex (Ayasofya Müzesi Hünkar Kasrı) for use as a prayer room, and, since 2013, two of the museum's minarets had been used for voicing the call to prayer (the ezan) regularly.[134][135]

From the early 2010s, several campaigns and government high officials, notably Turkey's deputy prime minister Bülent Arınç in November 2013, demanded the Hagia Sophia be converted back into a mosque.[136][137][138] In 2015, Pope Francis publicly acknowledged the Armenian genocide, which is officially denied in Turkey. In response, the mufti of Ankara, Mefail Hızlı, said he believed the Pope's remarks would accelerate the conversion of Hagia Sophia into a mosque.[139]

On 1 July 2016, Muslim prayers were held again in the Hagia Sophia for the first time in 85 years.[140] That November, a Turkish NGO, the Association for the Protection of Historic Monuments and the Environment, filed a lawsuit for converting the museum into a mosque.[141] The court decided it should stay as a 'monument museum'.[142][better source needed] In October 2016, Turkey's Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet) appointed, for the first time in 81 years, a designated imam, Önder Soy, to the Hagia Sophia mosque (Ayasofya Camii Hünkar Kasrı), located at the Hünkar Kasrı, a pavilion for the sultans' private ablutions. Since then, the adhan has been regularly called out from the Hagia Sophia's all four minarets five times a day.[134][135][143]

On 13 May 2017, a large group of people, organized by the Anatolia Youth Association (AGD), gathered in front of Hagia Sophia and prayed the morning prayer with a call for the re-conversion of the museum into a mosque.[144] On 21 June 2017 the Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet) organized a special programme, broadcast live by state-run television TRT, which included the recitation of the Quran and prayers in Hagia Sophia, to mark the Laylat al-Qadr.[145]

Reversion to mosque (2018–present)[edit]

Since 2018, Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan had talked of reverting the status of the Hagia Sophia back to a mosque, a move seen to be very popularly accepted by the religious populace whom Erdoğan was attempting to persuade.[146] On 31 March 2018 Erdoğan recited the first verse of the Quran in the Hagia Sophia, dedicating the prayer to the "souls of all who left us this work as inheritance, especially Istanbul's conqueror," strengthening the political movement to make the Hagia Sophia a mosque once again, which would reverse Atatürk's measure of turning the Hagia Sophia into a secular museum.[147] In March 2019 Erdoğan said that he would change the status of Hagia Sophia from a museum to a mosque,[148] adding that it had been a "very big mistake" to turn it into a museum.[149] As a UNESCO World Heritage site, this change would require approval from UNESCO's World Heritage Committee.[150] In late 2019 Erdoğan's office took over the administration and upkeep of the nearby Topkapı Palace Museum, transferring responsibility for the site from the Ministry of Culture and Tourism by presidential decree.[151][152][153]

In 2020, Turkey's government celebrated the 567th anniversary of the Conquest of Constantinople with an Islamic prayer in Hagia Sophia. Erdoğan said during a televised broadcast "Al-Fath surah will be recited and prayers will be done at Hagia Sophia as part of conquest festival".[154] In May, during the anniversary events, passages from the Quran were read in the Hagia Sophia. Greece condemned this action, while Turkey in response accused Greece of making "futile and ineffective statements".[155]In June, the head of Turkey's Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet) said that "we would be very happy to open Hagia Sophia for worship" and that if it happened "we will provide our religious services as we do in all our mosques".[141] On 25 June, John Haldon, president of the International Association of Byzantine Studies, wrote an open letter to Erdoğan asking that he "consider the value of keeping the Aya Sofya as a museum".[156]

On 10 July 2020, the decision of the Council of Ministers from 1935 to transform the Hagia Sophia into a museum was annulled by the Council of State, decreeing that Hagia Sophia cannot be used "for any other purpose" than being a mosque and that the Hagia Sophia was property of the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Han Foundation. The council reasoned Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II, who conquered Istanbul, deemed the property to be used by the public as a mosque without any fees and was not within the jurisdiction of the Parliament or a ministry council.[157][158] Despite secular and global criticism, Erdoğan signed a decree annulling the Hagia Sophia's museum status, reverting it to a mosque.[159][160] The call to prayer was broadcast from the minarets shortly after the announcement of the change and rebroadcast by major Turkish news networks.[160] The Hagia Sophia Museum's social media channels were taken down the same day, with Erdoğan announcing at a press conference that prayers themselves would be held there from 24 July.[160] A presidential spokesperson said it would become a working mosque, open to anyone similar to the Parisian churches Sacré-Cœur and Notre-Dame. The spokesperson also said that the change would not affect the status of the Hagia Sophia as a UNESCO World Heritage site, and that "Christian icons" within it would continue to be protected.[146] Earlier the same day, before the final decision, the Turkish Finance and Treasury Minister Berat Albayrak and the Justice Minister Abdulhamit Gül expressed their expectations of opening the Hagia Sophia to worship for Muslims.[161][162] Mustafa Şentop, Speaker of Turkey's Grand National Assembly, said "a longing in the heart of our nation has ended".[161] A presidential spokesperson claimed that all political parties in Turkey supported Erdoğan's decision;[163] however, the Peoples' Democratic Party had previously released a statement denouncing the decision, saying "decisions on human heritage cannot be made on the basis of political games played by the government".[164] The mayor of Istanbul, Ekrem İmamoğlu, said that he supports the conversion "as long as it benefits Turkey", adding that he felt that Hagia Sophia has been a mosque since 1453.[165] Ali Babacan attacked the policy of his former ally Erdoğan, saying the Hagia Sophia issue "has come to the agenda now only to cover up other problems".[166] Orhan Pamuk, Turkish novelist and Nobel laureate, publicly denounced the move, saying "Kemal Atatürk changed... Hagia Sophia from a mosque to a museum, honouring all previous Greek Orthodox and Latin Catholic history, making it as a sign of Turkish modern secularism".[160][167]

On 17 July, Erdoğan announced that the first prayers in the Hagia Sophia would be open to between 1,000 and 1,500 worshippers. He said that Turkey had sovereign power over Hagia Sophia and was not obligated to bend to international opinion.[168]

While the Hagia Sophia has now been rehallowed as a mosque, the place remains open for visitors outside of prayer times. While at the beginning the entrance was free,[169] later the Turkish government decided that, starting from 15 January 2024, the foreign nationals will have to pay an entrance fee.[170]

On 22 July, a turquoise-coloured carpet was laid to prepare the mosque for worshippers; Ali Erbaş, head of the Diyanet, attended its laying.[166] The omphalion was left exposed. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Erbaş said Hagia Sophia would accommodate up to 1,000 worshippers at a time and asked that they bring "masks, a prayer rug, patience and understanding".[166] The mosque opened for Friday prayers on 24 July, the 97th anniversary of the signature of the Treaty of Lausanne, which established the borders of the modern Turkish Republic.[166] The mosaics of the Virgin and Child in the apse were covered by white drapes.[167] There had been proposals to conceal the mosaics with lasers during prayer times, but this idea was ultimately shelved.[171][172] Erbaş proclaimed during his sermon, "Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror dedicated this magnificent construction to believers to remain a mosque until the Day of Resurrection".[167] Erdoğan and some government ministers attended the midday prayers as many worshippers prayed outside; at one point the security cordon was breached and dozens of people broke through police lines.[167] Turkey invited foreign leaders and officials, including Pope Francis, for the prayers.[173] It is the fourth Byzantine church converted from museum to a mosque during Erdoğan's rule.[174]

In April 2022, the Hagia Sophia held its first Ramadan tarawih prayer in 88 years.[175]

International reaction and discussions[edit]

Days before the final decision on the conversion was made, Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople stated in a sermon that "the conversion of Hagia Sophia into a mosque would disappoint millions of Christians around the world", he also said that Hagia Sophia, which was "a vital center where East is embraced with the West", would "fracture these two worlds" in the event of conversion.[176][177] The proposed conversion was decried by other Orthodox Christian leaders, the Russian Orthodox Church's Patriarch Kirill of Moscow stating that "a threat to Hagia Sophia [wa]s a threat to all of Christian civilization".[178][179]

Following the Turkish government's decision, UNESCO announced it "deeply regret[ted]" the conversion "made without prior discussion", and asked Turkey to "open a dialogue without delay", stating that the lack of negotiation was "regrettable".[180][160] UNESCO further announced that the "state of conservation" of Hagia Sophia would be "examined" at the next session of the World Heritage Committee, urging Turkey "to initiate dialogue without delay, in order to prevent any detrimental effect on the universal value of this exceptional heritage".[180] Ernesto Ottone, UNESCO's Assistant Director-General for Culture said "It is important to avoid any implementing measure, without prior discussion with UNESCO, that would affect physical access to the site, the structure of the buildings, the site's moveable property, or the site's management".[180] UNESCO's statement of 10 July said "these concerns were shared with the Republic of Turkey in several letters, and again yesterday evening with the representative of the Turkish Delegation" without a response.[180]

The World Council of Churches, which claims to represent 500 million Christians of 350 denominations, condemned the decision to convert the building into a mosque, saying that would "inevitably create uncertainties, suspicions and mistrust"; the World Council of Churches urged Turkey's president Erdoğan "to reconsider and reverse" his decision "in the interests of promoting mutual understanding, respect, dialogue and cooperation, and avoiding cultivating old animosities and divisions".[181][182][183] At the recitation of the Sunday Angelus prayer at St Peter's Square on 12 July Pope Francis said, "My thoughts go to Istanbul. I think of Santa Sophia and I am very pained" (Italian: Penso a Santa Sofia, a Istanbul, e sono molto addolorato).[note 1][185][186] The International Association of Byzantine Studies announced that its 21st International Congress, due to be held in Istanbul in 2021, will no longer be held there and is postponed to 2022.[156]

Josep Borrell, the European Union's High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Vice-President of the European Commission, released a statement calling the decisions by the Council of State and Erdoğan "regrettable" and pointing out that "as a founding member of the Alliance of Civilisations, Turkey has committed to the promotion of inter-religious and inter-cultural dialogue and to fostering of tolerance and co-existence."[187] According to Borrell, the European Union member states' twenty-seven foreign ministers "condemned the Turkish decision to convert such an emblematic monument as the Hagia Sophia" at meeting on 13 July, saying it "will inevitably fuel the mistrust, promote renewed division between religious communities and undermine our efforts at dialog and cooperation" and that "there was a broad support to call on the Turkish authorities to urgently reconsider and reverse this decision".[188][189] Greece denounced the conversion and considered it a breach of the UNESCO World Heritage titling.[146] Greek culture minister Lina Mendoni called it an "open provocation to the civilised world" which "absolutely confirms that there is no independent justice" in Erdoğan's Turkey, and that his Turkish nationalism "takes his country back six centuries".[190] Greece and Cyprus called for EU sanctions on Turkey.[191] Morgan Ortagus, the spokesperson for the United States Department of State, noted: "We are disappointed by the decision by the government of Turkey to change the status of the Hagia Sophia."[190] Jean-Yves Le Drian, foreign minister of France, said his country "deplores" the move, saying "these decisions cast doubt on one of the most symbolic acts of modern and secular Turkey".[183] Vladimir Dzhabarov, deputy head of the foreign affairs committee of the Russian Federation Council, said that it "will not do anything for the Muslim world. It does not bring nations together, but on the contrary brings them into collision" and calling the move a "mistake".[190] The former deputy prime minister of Italy, Matteo Salvini, held a demonstration in protest outside the Turkish consulate in Milan, calling for all plans for accession of Turkey to the European Union to be terminated "once and for all".[192] In East Jerusalem, a protest was held outside the Turkish consulate on 13 July, with the burning of a Turkish flag and the display of the Greek flag and flag of the Greek Orthodox Church.[193] In a statement the Turkish foreign ministry condemned the burning of the flag, saying "nobody can disrespect or encroach our glorious flag".[194]

Ersin Tatar, prime minister of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, which is recognized only by Turkey, welcomed the decision, calling it "sound" and "pleasing".[195][190] He further criticized the government of Cyprus, claiming that "the Greek Cypriot administration, who burned down our mosques, should not have a say in this".[195] Through a spokesman the Foreign Ministry of Iran welcomed the change, saying the decision was an "issue that should be considered as part of Turkey's national sovereignty" and "Turkey's internal affair".[196] Sergei Vershinin, deputy foreign minister of Russia, said that the matter was of one of "internal affairs, in which, of course, neither we nor others should interfere."[197][198] The Arab Maghreb Union was supportive.[199] Ekrema Sabri, imam of the al-Aqsa Mosque, and Ahmed bin Hamad al-Khalili, grand mufti of Oman, both congratulated Turkey on the move.[199] The Muslim Brotherhood was also in favour of the news.[199] A spokesman for the Palestinian Islamist movement Hamas called the verdict "a proud moment for all Muslims".[200] Pakistani politician Chaudhry Pervaiz Elahi of the Pakistan Muslim League (Q) welcomed the ruling, claiming it was "not only in accordance with the wishes of the people of Turkey but the entire Muslim world".[201] The Muslim Judicial Council group in South Africa praised the move, calling it "a historic turning point".[202] In Nouakchott, capital of Mauritania, there were prayers and celebrations topped by the sacrifice of a camel.[203] On the other hand, Shawki Allam, grand mufti of Egypt, ruled that conversion of the Hagia Sophia to a mosque is "impermissible".[204]

When President Erdoğan announced that the first Muslim prayers would be held inside the building on 24 July, he added that "like all our mosques, the doors of Hagia Sophia will be wide open to locals and foreigners, Muslims and non-Muslims." Presidential spokesman İbrahim Kalın said that the icons and mosaics of the building would be preserved, and that "in regards to the arguments of secularism, religious tolerance and coexistence, there are more than four hundred churches and synagogues open in Turkey today."[205] Ömer Çelik, spokesman for the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), announced on 13 July that entry to Hagia Sophia would be free of charge and open to all visitors outside prayer times, during which Christian imagery in the building's mosaics would be covered by curtains or lasers.[192] In response to the criticisms of Pope Francis, Çelik said that the papacy was responsible for the greatest disrespect done to the site, during the 13th-century Latin Catholic Fourth Crusade's sack of Constantinople and the Latin Empire, during which the cathedral was pillaged.[192] The Turkish foreign minister, Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu, told TRT Haber on 13 July that the government was surprised at the reaction of UNESCO, saying that "We have to protect our ancestors' heritage. The function can be this way or that way – it does not matter".[206]

On 14 July the prime minister of Greece, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, said his government was "considering its response at all levels" to what he called Turkey's "unnecessary, petty initiative", and that "with this backward action, Turkey is opting to sever links with western world and its values".[207] In relation to both Hagia Sophia and the Cyprus–Turkey maritime zones dispute, Mitsotakis called for European sanctions against Turkey, referring to it as "a regional troublemaker, and which is evolving into a threat to the stability of the whole south-east Mediterranean region".[207] Dora Bakoyannis, Greek former foreign minister, said Turkey's actions had "crossed the Rubicon", distancing itself from the West.[208] On the day of the building's re-opening, Mitsotakis called the re-conversion evidence of Turkey's weakness rather than a show of power.[167]

Armenia's Foreign Ministry expressed "deep concern" about the move, adding that it brought to a close Hagia Sophia's symbolism of "cooperation and unity of humankind instead of clash of civilizations."[209] Catholicos Karekin II, the head of the Armenian Apostolic Church, said the move "violat[ed] the rights of national religious minorities in Turkey"[210] Sahak II Mashalian, the Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople, perceived as loyal to the Turkish government, endorsed the decision to convert the museum into a mosque. He said, "I believe that believers' praying suits better the spirit of the temple instead of curious tourists running around to take pictures."[211]

In July 2021, UNESCO asked for an updated report on the state of conservation and expressed "grave concern". There were also some concerns about the future of its World Heritage status.[212] Turkey responded that the changes had "no negative impact" on UNESCO standards and the criticism is "biased and political".[213]

Architecture[edit]

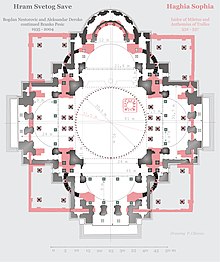

b) Plan of the ground floor (lower half)

Hagia Sophia is one of the greatest surviving examples of Byzantine architecture.[8] Its interior is decorated with mosaics, marble pillars, and coverings of great artistic value. Justinian had overseen the completion of the greatest cathedral ever built up to that time, and it was to remain the largest cathedral for 1,000 years until the completion of the cathedral in Seville in Spain.[214]

The Hagia Sophia uses masonry construction. The structure has brick and mortar joints that are 1.5 times the width of the bricks. The mortar joints are composed of a combination of sand and minute ceramic pieces distributed evenly throughout the mortar joints. This combination of sand and potsherds was often used in Roman concrete, a predecessor to modern concrete. A considerable amount of iron was used as well, in the form of cramps and ties.[215]

Justinian's basilica was at once the culminating architectural achievement of late antiquity and the first masterpiece of Byzantine architecture. Its influence, both architecturally and liturgically, was widespread and enduring in the Eastern Christianity, Western Christianity, and Islam alike.[216][217]

The vast interior has a complex structure. The nave is covered by a central dome which at its maximum is 55.6 m (182 ft 5 in) from floor level and rests on an arcade of 40 arched windows. Repairs to its structure have left the dome somewhat elliptical, with the diameter varying between 31.24 and 30.86 m (102 ft 6 in and 101 ft 3 in).[218]

At the western entrance and eastern liturgical side, there are arched openings extended by half domes of identical diameter to the central dome, carried on smaller semi-domed exedrae, a hierarchy of dome-headed elements built up to create a vast oblong interior crowned by the central dome, with a clear span of 76.2 m (250 ft).[8]

The theories of Hero of Alexandria, a Hellenistic mathematician of the 1st century AD, may have been utilized to address the challenges presented by building such an expansive dome over so large a space.[219] Svenshon and Stiffel proposed that the architects used Hero's proposed values for constructing vaults. The square measurements were calculated using the side-and-diagonal number progression, which results in squares defined by the numbers 12 and 17, wherein 12 defines the side of the square and 17 its diagonal, which have been used as standard values as early as in cuneiform Babylonian texts.[220]

Each of the four sides of the great square Hagia Sophia is approximately 31 m long,[221] and it was previously thought that this was the equivalent of 100 Byzantine feet.[220] Svenshon suggested that the size of the side of the central square of Hagia Sophia is not 100 Byzantine feet but instead 99 feet. This measurement is not only rational, but it is also embedded in the system of the side-and-diagonal number progression (70/99) and therefore a usable value by the applied mathematics of antiquity. It gives a diagonal of 140 which is manageable for constructing a huge dome like that of the Hagia Sophia.[222]

Floor[edit]

The stone floor of Hagia Sophia dates from the 6th century. After the first collapse of the vault, the broken dome was left in situ on the original Justinianic floor and a new floor was laid above the rubble when the dome was rebuilt in 558.[223] From the installation of this second Justinianic floor, the floor became part of the liturgy, with significant locations and spaces demarcated in various ways using different-coloured stones and marbles.[223]

The floor is predominantly made up of Proconnesian marble, quarried on Proconnesus (Marmara Island) in the Propontis (Sea of Marmara). This was the main white marble used in the monuments of Constantinople. Other parts of the floor, like the Thessalian verd antique "marble", were quarried in Thessaly in Roman Greece. The Thessalian verd antique bands across the nave floor were often likened to rivers.[224]

The floor was praised by numerous authors and repeatedly compared to a sea.[114] The Justinianic poet Paul the Silentiary likened the ambo and the solea connecting it to the sanctuary with an island in a sea, with the sanctuary itself a harbour.[114] The 9th-century Narratio writes of it as "like the sea or the flowing waters of a river".[114] Michael the Deacon in the 12th century also described the floor as a sea in which the ambo and other liturgical furniture stood as islands.[114] During the 15th-century conquest of Constantinople, the Ottoman caliph Mehmed is said to have ascended to the dome and the galleries in order to admire the floor, which according to Tursun Beg resembled "a sea in a storm" or a "petrified sea".[114] Other Ottoman-era authors also praised the floor; Tâcîzâde Cafer Çelebi compared it to waves of marble.[114] The floor was hidden beneath a carpet on 22 July 2020.[166]

Narthex and portals[edit]

The Imperial Gate, or Imperial Door, was the main entrance between the exo- and esonarthex, and it was originally exclusively used by the emperor.[225][226] A long ramp from the northern part of the outer narthex leads up to the upper gallery.[227]

Upper gallery[edit]

The upper gallery, or matroneum, is horseshoe-shaped; it encloses the nave on three sides and is interrupted by the apse. Several mosaics are preserved in the upper gallery, an area traditionally reserved for the Empress and her court. The best-preserved mosaics are located in the southern part of the gallery.

.

The northern first floor gallery contains runic graffiti believed to have been left by members of the Varangian Guard.[228]Structural damage caused by natural disasters is visible on the Hagia Sophia's exterior surface. To ensure that the Hagia Sophia did not sustain any damage on the interior of the building, studies have been conducted using ground penetrating radar within the gallery of the Hagia Sophia. With the use of ground-penetrating radar (GPR), teams discovered weak zones within the Hagia Sophia's gallery and also concluded that the curvature of the vault dome has been shifted out of proportion, compared to its original angular orientation.[229]

Dome[edit]