Валентинианская династия

Династия Валентинианов представляла собой правящий дом пяти поколений династий, в том числе пяти римских императоров в период поздней античности , просуществовавший почти сто лет с середины четвертого до середины пятого века. Они стали преемниками династии Константинов ( годы правления 306–363 ) и правили Римской империей с 364 по 392 и с 425 по 455 годы, с междуцарствием (392–423), во время которого правила династия Феодосия и в конечном итоге сменила их. Феодосийцы, вступившие в брак с домом Валентиниана, правили одновременно на востоке после 379 года.

Патриархом династии Валентиниана был Грациан Фунарий , чьи сыновья Валентиниан I и Валент стали римскими императорами в 364 году. Два сына Валентиниана I, Грациан и Валентиниан II, стали императорами. Дочь Валентиниана I Галла вышла замуж за Феодосия Великого , императора Восточной империи , который вместе со своими потомками образовал династию Феодосиев ( годы правления 379–457 ). В свою очередь, их дочь Галла Плацидия вышла замуж за более позднего императора Констанция III ( годы правления 421–421 ). Их сын, Валентиниан III ( годы правления 425–455 ), правивший на западе, был последним императором династии, смерть которого ознаменовала конец династий в западной империи . Во время междуцарствия сын Феодосия Гонорий правил на западе и одновременно с Галлой Плацидией с 421 года. Династия была названа Паннонской на основании семейного происхождения из Паннонии Секунда на западных Балканах.

При Валентинианах династическое правление укрепилось, а разделение империи на запад и восток все более укоренилось. Империя подвергалась неоднократным вторжениям вдоль своих границ: граница Дуная в конечном итоге обрушилась на северо-востоке, а вторжения варваров на западе в конечном итоге достигли Италии и завершились разграблением Рима в 410 году, что предвещало возможный распад Западной империи в 410 году. конце пятого века.

Сегодня потомки этой славной династии сохранились под именем Валентини и живут сегодня на севере Италии, в Эмилии-Романье.

Фон

[ редактировать ]Династия Валентинианов (364–455 гг.) была правящим домом во времена Поздней Римской империи (284–476 гг.), В поздней античности ( прил. Поздняя античность), [3] включая неспокойные годы конца четвертого века и последнюю династию Западной империи. [4] Смерть Юлиана ( годы правления 361–363 ) стала поворотным моментом в истории империи. Тридцать лет от смерти Юлиана, положившей конец династии Константинов, до смерти Валентиниана II ( годы правления 383–393 ), положившей конец первой династии Валентинианов, были одним из самых критических периодов в поздней Римской империи, структурировавшей империю. способами, которые будут иметь долгосрочные последствия. [5] Последующие тридцать лет (395–425) от смерти Феодосия I до смерти его сыновей и восшествия Валентиниана III ( годы правления 425–455 ) ознаменовались основанием Византийской империи на востоке и заменой западной Римской империи. империи с европейскими королевствами, а также ряд событий, приведших к возникновению средневековых исламских государств . [6] Период предшествующей Константиновской эпохи (293–363) подтвердил важность династии в легитимности и преемственности. [7] Эта новая династическая структура просуществовала до 454 года. [5] Дом Валентиниана (Валентиани) [8] установил преемственность и преемственность Константинианцев через браки с внучкой и внучатой племянницей Константина. [9] Эта внучка Констанция (362–383), единственный выживший ребенок Констанция II ( годы правления 337–361 ), на протяжении десятилетий играла важную роль символа своей династии. Константиновское наследие описывается как «неизгладимое сияние империи». [4] Хотя императорские наследники в этот период были относительно редки, браки имперских женщин вызывали особую озабоченность, поскольку могли привести к восхождению на престол претендентов. Некоторые из них, например сводные сестры Грациана, дали обет стать посвященными девственницами (лат. Sanctae necessitudines , букв. «Святые родственники»). [4] Однако это была также эпоха, когда женщины, будь то императрицы или супруги императора, достигли беспрецедентной власти. [10] [11] [12] Еще одной особенностью этой династии было последовательное назначение детей-императоров, радикально изменивших традиционный образ императоров как людей дела. [13] После разделения империи Валентинианом (лат. divisio regni ) по-новому, в 364 году, две части империи (лат. partes imperii ), восток и запад, начали постепенно развивать свою собственную историю, пока раскол не стал постоянным. смерть Феодосия I ( годы правления 379–395 ). [14] [15]

Римская империя контролировала все земли вокруг Средиземноморья, «римское озеро», окруженное чужими землями (лат. barbaricum , букв. «варварские земли»). [16] начиная со второго века, с небольшой потерей территории. Эти земли простирались от стены Адриана на севере Англии на северо-востоке до реки Евфрат в Месопотамии на Ближнем Востоке. [17] Основными областями (лат. Regiones ) империи, с запада на восток, были Испания (Испания), Галлия (Галлия, ныне Франция), Британия (Британия), Италия (Италия), на Балканах Иллириум и Фракия , Азия ( Asiana, Малая Азия) и Oriens (Ближний Восток). А на южном берегу Средиземного моря лежала Африка на западе и Египет (Египет) на востоке. Однако на своих границах он столкнулся с рядом проблем, в том числе с сасанидскими персами на востоке, в то время как на севере то, что представляло собой небольшие фрагментированные вторжения варваров, превратилось в массовые миграции таких народов, как франки на нижнем Рейне, аламанны и на бывших землях Agri Decumates между Рейном и Дунаем и готов на нижнем Дунае. [18] В этот период Римская империя, уже разделенная по оси восток-запад, после смерти Феодосия I объединилась в две империи. Хотя обе стороны продолжали сотрудничать и сохраняли конституционный миф о единой юрисдикционной единице, и что император правит повсюду, ни один западный император никогда больше не будет править на востоке или (за исключением двух кратких визитов Феодосия) восточный император на западе. [5] Династия просуществовала на востоке относительно недолго, и ее сменил дом Феодосия после смерти первого восточного императора Валента в 378 году. На западе, после перерыва, во время которого Гонорий ( годы правления 393–423 ), Во время правления Феодосиана Валентиниан III продолжал династию до своей смерти в 455 году. В этот период империя боролась как с внешними мигрирующими племенами , так и с внутренними претендентами и узурпаторами , с частыми гражданскими войнами . К концу династии западная империя рухнула, а Рим был разграблен. Династия Валентинианов также стала свидетелем восстановления христианства после короткого периода, в течение которого император Юлиан пытался восстановить традиционные римские религии, но терпимость и религиозная свобода сохранялись в течение некоторого времени на Западе. [19] [20] [21] Династия стала свидетелем борьбы не только между язычеством и христианством, но и между двумя основными фракциями внутри христианства: никейцами и гомоианцами . [22]

Юлиан погиб в 363 году во время злополучной экспедиции против персидской столицы Сасанидов Ктесифона . Его преемнику Иовиану не оставалось ничего другого, кроме как принять условия Сапора (Шапура), сасанидского царя, уступив персам ряд провинций и городов. Условия мирного договора также запрещали римлянам вмешиваться в дела Армении для оказания помощи Арсаку (Аршаку), армянскому царю, который был союзником Юлиана во время войны. Этот мир должен был продлиться тридцать лет [23]

Администрация

[ редактировать ]Военная администрация

[ редактировать ]Основные подразделения позднеримской армии включали центральные силы ( comitatenses ), [24] готовые к развертыванию, и силы, дислоцированные в провинциях и на границе ( ripens , позже limitanei , букв. « на берегах рек или границах » ) [25] под командованием герцога ( букв . « лидер » , мн. дуче ), например, dux Armye . Из них комитатенсы имели более высокий статус и назывались также презентальскими (лат. praesentalis , букв. «присутствие»), т.е. в присутствии императора. [26] Третьим подразделением была императорская телохранительница (лат. scholae palatinae , букв. «Дворцовый корпус»), подчинявшаяся непосредственно императору, но подчинявшаяся magister officiorum (начальнику офицеров). Эти схолы (или сколы , поют. схола или скола [27] ) представляли собой кавалерийские части, названия которых первоначально произошли от их вооружения. Scholae scutariorum (или scutarii , букв. « щитоносцы » ) относятся к своим щитам (лат. scuta , Sing. scutum ). [28] Это была единица, из которой был взят Валентиниан I , первый из валентинианских императоров. [29] В армиях, дислоцированных во Фракии и Иллирике, местный командующий имел титул Comes Rei militaris ( букв. « Граф по военным делам » ), ранг между герцогом и магистром . Организационная структура изложена в современном документе notitia dignitatum ( букв. Список должностей), списке всех административных должностей. [с] [32] Стало обычным добавлять почетное звание к должностям магистра . [33] перечислены В Notitia шесть графов , включая граф Африки (или граф Африки ) и граф Британии , ответственные за защиту Африки и Британии соответственно. Другие военные графы включают графа и мастера обоих ополчений (или графа и мастера обоих нынешних ополчений ) и домашних графов ( счетов домашней лошади , графов домашней пехоты ). [34] [35] [36]

Первоначально существовало отдельное командование пехотой под командованием магистра пешего (лат. magister peditum ) и кавалерии под руководством магистра конницы (лат. magister equitum ), а командование в пресентальской армии определялось, например, как magister peditum praesentalis . Позже эти посты перешли под единое командование — Магистра солдат (лат. magister militum ). [37] [38] [39] Поскольку армия становилась все более зависимой от набора сил из соседних народов, преимущественно немецких («варваризация»), эти части стали называть федеративными частями (лат. foederati ). [40]

Внутри императорского дворца располагался военный корпус ( схола ), протекторум, состоящий из протекторов домашних (часто просто домашних , поет. защитник домашних животных ; букв. « защитники домашнего хозяйства » ), под командованием прибывших домашних служащих . Этот командующий или генерал был эквивалентен magister officiorum в гражданской ветви власти, но ниже magistri militum (фельдмаршалов). Протекторы ( син. защитник ) также могли быть назначены магистратами или провинциальными командованиями. титула Защитник также мог использоваться в качестве почетного знака . [д] [42] [34] [43]

Гражданская администрация

[ редактировать ]Рим в Италии, как номинальная столица империи, становился все более неактуальным, центром власти было то место, где в любой момент времени находился император, а это означало, что по военным соображениям часто были границы, и императоры посещали город нечасто. В конце третьего века был основан ряд новых имперских городов: Медиоланум (Милан) на севере Италии и Никомедия в Турции в качестве основных резиденций, в то время как меньший статус был присвоен Арелате (Арль) в Галлии (ныне Франция), Августе Тревероруму. или Тревери (Трир) в Германии (тогда часть Галлии), Сердика (София) на Балканах и Антиохия (Антакья) в Сирии, в то время как Рим оставался домом Сената и аристократии. [12]

Основание Константинополя («Нового Рима») в 324 году постепенно сместило административную ось на восток, в то время как Медиолан и Аквилея на восточной окраине Италии стали более важными в политическом отношении. В то время как восточная империя была сосредоточена в Константинополе, западная империя никогда не управлялась из исторической столицы Рима, а из Треворума, затем Медиолана в 381 году. [44] и Вьенна , Галлия. Наконец Гонорий ( годы правления 393–423 ), осажденный вестготами в Медиолане в 402 году, перешел в Равенну , столицу Фламинии и Пиценума Аннонария на северо-восточном побережье Италии. [12] Место правительства вернулось в Рим в 440 году при Валентиниане III. [45] Другие императорские резиденции включали балканские центры Сирмий и Салоники . После разделения империи власть сосредоточилась в двух главных городах. [12] Местное самоуправление было трехуровневым: провинции были сгруппированы в епархии, управляемые викариями , и, наконец, в три географически определенные преторианские префектуры (лат. praefecturae praetoriis , единственное число praefectura praetorio ). Разделение Валентиниана и его брата содержало одну аномалию: Балканский полуостров изначально находился на западе. Восток состоял из одной префектуры — префектуры преторио Ориентис , а на западе — префектуры преторио Галлиарум (Британия, Галлия, Испания) и центральной префектуры преторио Италия, Иллиричи и Африка. [46]

Чиновники ( officiales , Sing. Officialis ) при comitatus (императорском дворе) и бюрократия включали две основные группы (лат. scholae , Sing. schola ) со схожими функциями, которые действовали между двором и провинциями (лат. provinciae , Sing. provincia ). . Придворные чиновники были известны как палатини ( sing. palatinus ). Членами схолы были стипендиаты пения. ученый . [47] schola notariorum были нотариусами (лат. notarii , Sing. Notarius ), которые были клерками, которые формировали императорский секретариат и которые составляли и удостоверяли подлинность документов. Главными среди них были старшие секретари (лат. primicerii notariorum , букв. «первый [имя] на восковой [табличке] среди нотариусов», Sing. primicerius ). Нотариусы . выполняли широкий круг императорских миссий, в том числе были информаторами [48] [49] Другой был schola Agentum in Rebus . Это были агенты в ребусе , или деловые агенты, подотчетные магистру офицеров (магистру офицеров). [и] который был главой палатинской администрации или имперским канцлером и набирал свой персонал из своих рядов. Они также могли занимать должности в центральных канцелярских бюро ( Sacra Scrinia , букв. Сундуки со священными книгами). Магистр officiorum также отвечал за организацию schola notariorum . Primicerius схолы notitia поддерживал dignitatum , [51] и как магистр набирал из рядов своей схолы тех, кто также мог занимать должности в скриниях . [52] [50] [53]

Три таких скринии были найдены при императорском дворе: scrinium memoriae (Министерство запросов), scrinium epistularum (Министерство корреспонденции) и scrinium libellorum (Министерство петиций), каждый из которых подчинялся директору бюро (лат. magister scrinii ), и эти magistri scriniorum, в свою очередь, доложил об этом magister officiorum . [50] [54]

В палатини входили как гражданский, так и военный персонал.

Титулы

[ редактировать ]Диоклетиан ( годы правления 284–305 ) установил иерархическую систему имперского правления с двумя уровнями императоров (лат. Imperators , Sing. Imperator ) , со старшими императорами, или августами ( Sing. Augustus ), и младшими императорами, или Цезарями. ( поет. Цезарь ). В этой системе план заключался в том, чтобы младшие императоры создавали свои дворы в мелких имперских городах, чтобы помогать им и в конечном итоге наследовать власть. [12] Периодически императорам награждались победными титулами (или именами) в ознаменование политических или военных событий. [55] Распространенным титулом был maximus , например, Germanicus maximus . Суффикс на латыни: maximus , букв. «величайший» указывает на победителя с префиксом «побежденный», в данном случае на Германию ( см. Список победных титулов Римской империи ). [56]

During the Republic, the title consul (pl. consules), was bestowed on two of the worthiest of men, who had to be at least 42 years old. These were annual appointments and they served as the highest executive officers and also as generals in the army. By the late Roman empire, the title of consul was becoming more honorific, and the emperors were increasingly likely to take the title for themselves, rather than bestow it on distinguished citizens.[57] In appointing his infant son as consul, Theodosius changed the nature of the appointment to that of a family prerogative.[58] Traditionally, years were dated by the consulships (consular dating),[59][60] since consuls took up their position on January 1 (from 153 BC).[61]

Comites (sing. comes, lit. 'companion'), often translated as count,[62] were high-ranking officials or ministers who enjoyed the trust and companionship of the emperor, and collectively were referred to as comitiva, the governing council of the empire, from which the term comitatus for the imperial court is derived. The title comes could be purely honorific without indicating a specific function, or integral to a descriptive title, as in the military roles.[35]

History

[edit]A.D. 364 was a time of great uncertainty on the late Roman empire. Julian (r. 361–363), the last Constantinian emperor (Latin: augustus, lit. 'majestic', the official title given to emperors) had died after a very brief reign, in his Persian War of that year, and the Roman army had elected Jovian (r. 363–364), one of his officers, to replace him. Jovian himself died within less than a year, at Dadastana, Turkey, while his army was on the way from Antioch, the capital of Roman Syria, to Constantinople.[7] Jovian was found dead in his quarters on 17 February 364, under circumstances some considered suspicious.[63]

The fourth century historian Ammianus Marcellinus,[64] recounts that once Jovian's body was embalmed and dispatched to Constantinople, the legions continued on to Nicaea in Turkey, where military and civilian staff sought a new emperor. Among several put forward, was that of Flavius Valentinianus (Valentinian), recently promoted to the command of the second division of the scutarii, and this choice received unanimous support. At the time, Valentinian was stationed some distance away at Ancyra (Ankara), and was summoned, arriving in Nicaea on 25 February 364.[65] Valentinian (321–375),[66] called Valentinian the Great, was acclaimed augustus by the general staff of the army. The Consularia Constantinopolitana[f] and the Chronicon Paschale give the date of his elevation as 25/6 February.[67][68]

To avoid the instability caused by the deaths of his two predecessors, and rivalry between the armies, Valentinian (r. 364–375) acceded to the demands of his soldiers and ruled the western provinces while elevating his younger and relatively inexperienced brother Valens (b. 328,[66]r. 364–378) as co-augustus to rule over the eastern provinces. The two brothers divided the empire along roughly linguistic grounds, Latin in the west and Greek in the east, and proceeded to also divide the administrative and military structures, so that recruitment became increasingly regionalised, with little exchange.[69] Valens was appointed Tribune of the Stables (Latin: tribunus stabulorum or stabuli) on 1 March 364, and the Consularia Constantinopolitana dates his elevation to co-augustus on 28 March 364, at Constantinople.[68][70][71] Both brothers became Roman consuls for the first time, Valentinian at Mediolanum (Milan) and Valens at Constantinople.[68][71] This was the first time that the two parts of the empire were completely separated. The exception was the appointment of consuls, in which Valentinian retained precedence.[72][4] Valentinian made the seat of his government Trier, and never visited Rome, while Valens divided his time between Antioch and Constantinople.[8] Valens's wife Domnica may have also become augusta in 364.[71]

First generation: Valentinian I and Valens (364–378)

[edit]Valentinian and Valens received many titles during their reigns, other than the customary emperor and augustus. Both were awarded the victory name of Germanicus maximus, Alamannicus maximus, and Francicus maximus to indicate victories against Germania, Alamanni and Franks, in 368, the year of their second consulship.[67][71][73] In 369 Valens received the victory name Gothicus Maximus and celebrated his quinquennalia.[71] Valentinian also celebrated his quinquennalia on 25 February 369 and likewise received the honour of Gothicus Maximus.[71]

Valentinian and Valens were consuls for the third time in 370.[71] 373 was the year of Valentinian and Valens's fourth and last joint consulship.[71] In 373/374, Theodosius the magister equitum's son, was made dux of the province of Moesia Prima.[74] Valens celebrated his decennalia on 29 March 374.[71] At the fall of his father, the magister equitum, the younger Theodosius, dux of Moesia Prima, retired to his estates in the Iberian Peninsula, where he married his first wife, Aelia Flaccilla in 376.[74] Gratian's fourth consulship was in 377.[75] Valens's sixth consulship was in 378, again jointly with Valentinian II.[71]

Founding of the Valentiniani

[edit]

Gratianus Funarius, the patriarch of the dynasty, was from Cibalae (Vinkovci) in the Roman province of Pannonia Secunda, lying along the Sava river in the northern Balkans. He had become a senior officer in the Roman army and comes Africae.[68] His son Valentinian, born 321, also came from Cibalae and joined the protectores, rising to tribunus in 357.[68] Valentinian served in Gaul and in Mesopotamia in the reign of Constantius II (r. 337–361).[68] Valentinian's younger brother Valens was also born at Cibalae, in 328, and followed a military career.[70] According to the Chronicle of Jerome and the Chronicon Paschale, Valentinian's eldest son Gratian was born in 359 at Sirmium, now Sremska Mitrovica in Serbia, the capital of Pannonia Secunda, to Valentinian's first wife Marina Severa.[76][75] Gratian was appointed consul in 366 and was entitled nobilissimus puer.[h][76] According to the Consularia Constantinopolitana, Valens's son Valentinianus Galates was born on 18 January 366, and made a consul in 369, and is known to have been titled nobilissimus puer, but died in infancy at Caesarea in Cappadocia (Kayseri) around 370.[71]

In the summer of 367, Valentinian became ill, while at Civitas Ambianensium (Amiens), raising questions about his succession. On recovery, he presented his then eight-year-old son to his troops on 27 August, as co-augustus (r. 367–383), passing over the customary initial step of caesar.[75][76][67][77] Gratian's tutor was the rhetor Ausonius, who mentioned the relationship in his epigrams and a poem.[76] Around 370, Valentinian's wife Marina Severa died and was interred in the Church of the Holy Apostles and Valentinian married again, wedding Justina.[67] In autumn 371, Valentinian's second son, also called Valentinian, was born to Justina, possibly at Augusta Treverorum (Trier).[78][79] The younger Valentinian would later succeed his father, as Valentinian II (r. 375–392). Gratian, who was then 15, was married in 374 to Constantius II's 13-year-old daughter Constantia at Trier.[76][75] This marriage consolidated the dynastic link to Constantinians, as had his father's second marriage to Justina, with her family connections.[4]

Because of their family origins in the Roman province of Pannonia Secunda in the northern Balkans, the Hungarian historian Andreas Alföldi dubbed the dynasty the "Pannonian emperors".[80] On the 9 April 370, according to the Consularia Constantinopolitana and the Chronicon Paschale, the Church of the Holy Apostles adjoining the Mausoleum of Constantine in Constantinople was inaugurated.[71] In 375, the Baths of Carosa (Latin: Thermae Carosianae) – named for Valens's daughter – were inaugurated in Constantinople.[71]

Domestic policy

[edit]Beginning between 365 and 368, Valentinian and Valens reformed the precious metal coins of the Roman currency, decreeing that all bullion be melted down in the central imperial treasury before minting.[68][70] Such coins were inscribed ob (gold) and ps (silver).[68] Valentinian improved tax collection and was frugal in spending.[68]

In 368, Valentinian was made aware of reports of magical practices in Rome and ordered the use of torture, but later backed down under protests from the Senate. Nevertheless, many prominent Roman citizens underwent investigation and execution. The affair led to a deterioration in the relations between emperor and senate.[81]On the 9 April 370, according to the Consularia Constantinopolitana and the Chronicon Paschale, the Church of the Holy Apostles adjoining the Mausoleum of Constantine in Constantinople was inaugurated.[71] In 375, the Baths of Carosa (Latin: Thermae Carosianae) – named for Valens's daughter – were inaugurated in Constantinople.[71]

Religious policy

[edit]In the fourth century, following Constantine (r. 307–311), Christianity spread steadily throughout the population of the empire, in various forms, such that by the accession of Valentinian in 364 most people were Christian by default. In this time the church became progressively more organized and hierarchical and the episcopate both more powerful and increasingly drawn from aristocratic and curial circles. One of the most prominent was the Nicene Ambrose,[82] the son of a praetorian prefect in Gaul, who became bishop of Milan (374–397). Ambrose was initially a consularis of the conjoined provinces of Liguria-Aemilia, but when chosen to be bishop was advanced through all the lower clerical ranks in order to take office.[83] When Ambrose's predecessor as bishop of Milan, the Arian Auxentius (355–374), died, the sectarian violence between the Nicene and Arian Christians in the city had increased. The new bishop arrived with soldiers from the Roman army to suppress the violence by force.[84]

Although bishops of Rome, such as Damasus (366–384) tended to have greater authority, they were still far from the absolutism of later popes. Christianity in the Greek speaking eastern empire was more complex than the Latin speaking west. The eastern emperors were more inclined to inject themselves into ecclesiastical affairs and historically had three sees that claimed an apostolic foundation, and hence primacy, Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem.These sees found them themselves competing for power with the newly established Constantinople episcopate whose power was growing with the burgeoning imperial bureaucracy. This was the background which Valens found himself having to deal with.[85]

According to the 5th-century Greek historian Sozomen, Valentinian was an orthodox Nicene Christian,[68] but was largely indifferent to the ecclesiastical conflicts of his time. His laicism was especially welcomed by pagans.[86] On the other hand, his second wife, Justina was a committed homoian, a sect of Arianism. Like Valentinian, her origins were Pannonian, which with the western Balkans was the centre of the anti-Nicene theology, in contrast to the Nicenes of Gaul and Italy.[87]

The 5th-century Greek historian Socrates Scholasticus tells that while serving as in the protectores Valens refused pressure to offer sacrifice in ancient Roman religion during the reign of the pagan emperor Julian (r. 361–363).[70] Valens was also a homoian,[70] and aggressively promoted it, exiling Athanasius the Trinitarian Bishop of Alexandria, soon after his accession in 364.[j][88] His response to ecclesiastical disputes was to uphold the canons of Constantius II's councils of 368, those of the Council of Ariminum (Rimini) in the west and the Council of Seleucia in the east. These had both promulgated Arianism.[86] Valentinian's tolerance only went so far, promulgating legislation against heretical sects and unscrupulous clerics,[86] suppressing the meetings of Manichaeans in Rome in 372 and issuing legislation preserved in the Codex Theodosianus.[68] He also legislated against Donatism among bishops in 373.[68]

Foreign policy

[edit]For most of their reign, Valentinian and Valens were involved with defending the empire's frontiers, primarily in the northwest, where the frontier ran roughly along the Rhine and Danube rivers.[89]

In the later years of Valens' reign, geopolitical events began to increasingly bear on the Roman empire. On the eastern frontier, new problems arose with the incursion of nomads into the settled areas to the south of the Steppes. As the earlier Parthian Empire (247 BC–224 AD) became displaced by the more bellicose Sasanian Persians (224–651), the repercussions began to be progressively felt from Eurasia to Eastern Europe.[90] Among these were the Huns, who by the 370s had conquered much of the area north of the Caucasus and Black Sea and were putting pressure on the Goths from the Dnieper west. To the Romans, they appeared a much greater threat than the earlier Alans, whom they placed in a tributary position. The Romans failed to appreciate the significance of these changes, with catastrophic consequences.[91]

Northwest frontier

[edit]When a party of Alamanni visited Valentinian's headquarters to receive the customary gifts towards the end of 364, Ursatius, the magister officiorum made them an offering they considered inferior to that of his predecessor. Angered by Ursatius' attitude, they vowed revenge and crossed over the Rhine into Roman Germania and Gaul in January 365, overwhelming the Roman defences.[68][68][92] Although at first unsuccessful, eventually Jovinus, the magister equitum in Gaul inflicted heavy losses on the enemy at Scarpona (Dieulouard) and at Catalauni (Châlons-sur-Marne), forcing them to retire.[92] An opportunity to further weaken the Alamanni occurred in the summer of 368, when king Vithicabius was murdered in a coup, and Valentinian and his son Gratian crossed the Moenus (Main river) laying waste to their territories.[75][93]

Valentinian fortified the frontier from Raetia in the east to the Belgic channel, but the construction was attacked by Alamanni at Mount Pirus (the Spitzberg, Rottenburg am Neckar). In 369 (or 370) Valentinian then sought to enlist the help of the Burgundians, who were involved in a dispute with the Alamanni, but a communication failure led to them returning to their lands without joining forces with the Romans.[68] It was then that the magister equitum, Count Theodosius and his son Theodosius (the Theodosi) attacked the Alamanni through Raetia, taking many prisoners and resettling them in the Po Valley in Italy.[74][68][67] A key to Alamanni success was their kings. Valentinian made one attempt to capture Macrianus in 372, but eventually made peace with him in 374.[68]

The necessity to make peace was the increasing threat from other peoples, the Quadi and the Sarmatians. Valentinian's decision to establish garrisons across the Danube had angered them, and the situation escalated after the Quadi king, Gabinus, was killed during negotiations with the Romans in 374. Consequently, in the autumn, the Quadi crossed the Danube plundering Pannonia and the provinces to the south.[67] The situation deteriorated further once the Sarmatians made common cause inflicting heavy losses on the Pannonica and Moesiaca legions.[67] However, on encountering Theodosius' forces on the borders of Moesia in the eastern Balkans, which had previously defeated one of their armies in 373,[74] they sued for peace. Valentinian mounted a further offensive against the Quadi in August 375, this time using a pincer movement, one force attacking from the northwest, while Valentinian himself headed to Aquincum (Budapest), crossed the Danube and attacked from the southeast. This campaign resulted in heavy losses to the enemy, following which he returned to Aquincum and from there to Brigetio (Szőny, Hungary) where he died suddenly in November.[94]

Africa

[edit]The Austoriani, a warlike tribe, had made considerable inroads in to the province of Africa Tripolitania. At the time the comes per Africam (comes Africae), Romanus, was said to be corrupt and to have concealed the real state of affairs from Valentinian and his envoys, having powerful allies at court. Eventually Firmus, a Berber prince of the Iubaleni tribe, led a rebellion in 372, proclaiming himself augustus. This time Valentinian dispatched Count Theodosius in 373 to restore order, who immediately had Romanus arrested. After a prolonged campaign in the coastal plains of Mauretania Caesariensis, Theodosius eroded support for Firmus by diplomatic means, the latter committing suicide in 374. Although the African campaign cemented Theodosius' reputation, intrigues following Valentinian's death in late 375 led to an investigation and he was executed at Carthage. [95]

Eastern frontier

[edit]Sasanians

[edit]

In the east, Valens was faced with the threat of the Persian Sasanian Empire and the Goths.[70] Sapor, the Sasanian king had Arsaces murdered in 368, placing Armenia under Persian control. During the siege of Artogerassa (Artagerk) in Arsharunik, Arsaces' son Papa (Pap) was smuggled out, joining Valens' court, then at Neocaesaria, in Pontus Polemoniacus.[96] Valens, fearful of violating the treaty of non-interference that Jovian had signed with Sapor in 363, returned Papa in 369 in the company of Terentius, dux Armeniae. But Sapor renewed his attempts to subdue Armenia, capturing Artogerassa together with Papa's mother, Queen Pharantzem and the royal treasury. At this point Valens decided to act, sending his magister peditum, Arintheus to join Terentius in the defence of Armenia. Although Sapor signed a treaty directly with Papa and warned off Valens, the latter pressed on, restoring Sauromaces (Saurmag), a pretender in Iberia in the Caucasus Mountains. Although Sapor retaliated by invading Roman territory, the encounter between the two armies at Vagabanta (Bagrevand) in the spring of 371 was inclusive, and both sides retreated to their respective capitals. Valens, who interpreted the treaty with Sapor as treachery, invited Papa to his court in 373 and arrested him, but the latter escaped. Valens then ordered the dux Armeniae to arrange for Papa to be murdered in 374, which was carried out. Meanwhile, Sapor was demanding a Roman withdrawal from Iberia and Armenia, which Valens refused to do, leading to a long diplomatic conflict regarding the validity of the treaty Jovian had signed. Valens was distracted from his campaign against the Sasanians by wars against the Saracens and the Isaurians.[70] Eventually the conflict between the two sides was overtaken by developments in the western part of Valens territory, once the Danube frontier was breached in 376.[97]

Goths and Huns

[edit]

In 366, Valens accused the Goths of breaching their 332 treaty with Constantine by aiding the usurper Procopius in 365. However, relations with the Goths had been deteriorating since Julian's contemptuous dismissal of them in 362. In any case, Valens had already attempted to secure the Danubian frontier, but a series of campaigns during 367 to 369 failed to subdue the Goths. Valens then had to deal with Goths to the northwest and Sasanians to the east simultaneously, and decided to make peace with the former, by a treaty with king Athanaric in 369, according to Themistius and Zosimus.[98] Under this treaty, the Goths undertook not to cross the Danube. But any respite was short lived due to the continuing westward expansion of the Huns, who were progressively pushing refugees to the banks of the Dniester. They soon encountered the Tervingi Goths under Athanaric, forcing them to consider crossing the Danube into safer Thrace. In early 376 they petitioned Valens to that end, seeking Roman protection, and in the autumn he agreed to this.[70][99] Estimates of the numbers who crossed vary between 90,000 and 200,000, but they outnumbered the Roman troops stationed there. There they were harassed by a corrupt official, Lupicinus, the Thracian comes rei militaris. Hostilities rapidly escalated, with Lupicinus seizing two of their chieftains, Fritigern and Alavivus. Lupicinus, then realising his management of the Danube crossing had been disastrously mismanaged decided on a full-scale attack on the Goths near Marcianopolis in Moesia Inferior (Bulgaria), and was promptly routed, leaving Thrace undefended from the north. This was the beginning of the Gothic war of 376–382, one of many Gothic wars fought between the Romans and Goths.[100]

Valens was at Antioch at the time, preoccupied with the conflict with the Sasanians over Armenia.[70] Realising the implications of the defeat, he quickly made peace with the Sasanians and made plans to restore control of Thrace. He sought help from his nephew Gratian, now the western emperor, and took his forces across to Europe in the spring of 377, pressing the Goths into the Haemus mountains and meeting the legions dispatched from Pannonia and Gaul at a place called ad Salices, near Marcianopolis. The resulting Battle of the Willows produced heavy casualties on both sides, but no victory. Meanwhile, the Goths were consolidating their position with alliances between them and Huns and Alans, while Gratian was obliged to pull back his forces in February 378 to deal with incursions by the Lentienses across the Rhine in Raetia.[75][101] Valens' next sally against the Goths, at Adrianople, in the summer of 378, would prove both disastrous and fatal (see Battle of Adrianople).[102]

Usurpers and rebellions

[edit]In addition to foreign invaders, Valentinian and Valens had to deal with a series of domestic threats.

Procopius the Usurper (365–366)

[edit]On 1 November 365, while on his way to Lutetia (Paris), Valentinian learned of the appearance of the usurper Procopius in Constantinople,[68] but was unable to move against him, judging a simultaneous invasion of Gaul by Alamanni a greater threat to the empire.[92] Procopius was a native of Cilicia and was related to the late emperor Julian, under whose command he had served on the Mesopotamian frontier. On Julian's death in 363, he accompanied his remains to their burial place at Tarsus, Turkey. Rumours that Julian had wished Procopius to succeed him, rather than Jovian, who had been acclaimed, forced him into hiding until Jovian's death in 364. In the spring of 365, sensing the unpopularity of Valens, who had succeeded Jovian in 364, he made plans for a possible coup, persuading some of the legions to recognise him during the emperor's absence in Antioch, directing military operations. Following acclamation he installed himself in the Imperial palace in Constantinople on 28 September. Valens was informed of the coup while preparing to march east from Caesarea in Cappadocia (Kayseri). Valens now faced an internal rebellion, Gothic incursions in Thrace and a Persian threat in the east. He dispatched the Jovii and Victores legions to put down the rebellion. However, Procopius had quickly established himself, winning over generals and military units, including two that Julian passed over, Gomoarius and Agilo. He falsely proclaimed the death of Valentinian I in the west and recruited Gothic troops to his side, claiming his Constantinian legacy.[103] As part of his claim to legitimacy Procopius ensured he was always accompanied by the princess Constantia, still a child, and her mother, the dowager empress Faustina.[4] Constantia had been born to the emperor Constantius II (r. 337–361) and his third wife Faustina after her father's death.[104][105]

Procopius' use of his Constantinian hostages met with some success. According to Ammianus Marcellinus, when Valens forces met the usurper's army at Mygdus[k] on the river Sangarius in Phrygia, Procopius denounced the Pannonian accession and persuaded the advancing legions to defect. Although Procopius suffered a setback in the west, when Aequitius, magister militum per Illyricum, succeeded in blocking all the communicating passages between the eastern and western empires, in the east he rapidly consolidated his hold over Bithynia. Following his initial rebuff, Valens regrouped with the aid of Lupicinus, his magister militum per Orientem and marched on Procopius's army in Lydia. Valens then employed a countermeasure to Procopius' use of Constantia to claim legitimacy, by recruiting Flavius Arbitio, a distinguished general under Constantine I. As a result, Gomoarius and Agilo, and who were leading the usurper's forces, again switched sides and led their men over to Valens at Thyatira around April 366. Valens now pressed his advantage, advancing into Phrygia, where he encountered Procopius at Nacolia, and again the latter's general Agilo defected. Procopius fled, but his own commanders seized and took him to Valens, who ordered all of them beheaded.[107]

The Great Conspiracy (365–366)

[edit]In June 367, Valentinian learned of what appeared to be a coordinated uprising. In Roman Britain the provinces were threatened by an invasion of Picts, Scots and Attacotti from the north, while Franks and Saxond threatened the coastal regions of the lower Rhine. This came to be known as the "Great Conspiracy" (barbarica conspiratio).[108][109] A series of military responses were unsuccessful until Valentinian called on one of his Spanish commanders, Count Theodosius (Theodosius the Elder), who was comes rei militaris. Embarking at Bononia (Boulogne-sur-Mer), Theodosius landed at Rutupiae (Richborough, Kent) and quickly subdued London. Moving north on 369 he encountered yet another uprising, that of Valentinus, an exiled Pannonian general.[67] Having overthrown and executed Valetinus, Theodosius set about restoring the defences of the frontier and major settlements, establishing a new province of Valentia. Having sent messages regarding his victories back to Valentinian, he returned to court and was promoted to magister equitum.[68][67][74] In the autumn of 368 the Franks and Saxons were also driven back by Jovinus.[67][110][l]

Death of Valentinian I (375) and succession

[edit]Valentinian I died at Brigetio (Szőny) on 17 November 375 while on campaign against the Quadi in Pannonia. He may have died of stroke.[76][68][70] Following his death, Valentinian's body was prepared for burial and started its journey to Constantinople, where it arrived the following year,[4] on 28 December 376, but was not yet buried.[67] According to the Consularia Constantinopolitana, his remains were eventually interred in the Mausoleum of Constantine, to which the Church of the Holy Apostles was attached, on 21 February 382, beside those of his first wife and the mother of Gratian, Marina Severa.[67] He was deified, as was the custom, becoming known in Latin: Divus Valentinianus Senior, lit. 'the Divine Valentinian the Elder'.[67][111]

With the death of Valentinian I, in the east Valens became the senior augustus[67] and the 16 year old Gratian was the only augustus in the western empire. To complicate matters further for Gratian, certain among Valentinian's generals then promoted his four-year-old second son Valentinian II (Gratian's half brother), the army on the Danube acclaiming him augustus in a palatine coup[111] at Aquincum (Budapest) on 22 November 375, despite Gratian's existing prerogatives.[76][79] The young Valentinian II was essentially the subject of the influence of his courtiers and mother, the Arian Christian Justina.[79] Gratian's tutor, Ausonius, became his quaestor, and together with the magister militum, Merobaudes, the power behind the throne.[111] Negotiations eventually left Gratian as the senior western emperor.[111] Valens and Valentinian II were consuls for the year 376, Valens's fifth consulship.[71] Neither Gratian or Valentinian travelled much, which was thought to be due to not wanting the populace to realise how young they were. Gratian is said to have visited Rome in 376, possibly to celebrate his decennalia on 24 August,[75] but whether the visit actually took place is disputed.[111]

Battle of Adrianople and death of Valens (378)

[edit]Once Gratian had put down the invasions in the west in early 378, he notified Valens that he was returning to Thrace to assist him in his struggle against the Goths. Late in July, Valens was informed that the Goths were advancing on Adrianople (Edirne) and Nice, and started to move his forces into the area. However, Gratian's arrival was delayed by an encounter with Alans at Castra Martis, in Dacia in the western Balkans. Advised of the wisdom of awaiting the western army, Valens decided to ignore this advice because he was sure of victory and unwilling to share the glory.[70][76] Frigern and the Goths sought to avoid conflict and attempted to parlay, but Valens rejected any suggestion of ceding Thrace. On 9 August, Valens ordered his forces towards the Gothic encampment. He again dismissed their embassies, but acceded to the suggestion that sending some noble hostages could calm the Gothic forces, and they were duly dispatched. As this was occurring, a skirmish arose between a group of Roman archers, and some Gothic guards. Immediately, the Gothic cavalry units charged the Roman ranks and the two armies became engaged in full strength. Although the left flank of the Roman army almost reached the enemy camp, they were thrown back. The Romans who were in full armour in intense heat, began to tire in the afternoon, and their lines broke, resulting in a flight from the battlefield. Valens attempted to rally his men unsuccessfully and the Goths fell on the retreating forces until dark fell. While escaping, Valens himself was killed by an arrow, together with two thirds of his forces, and many of its leaders, together with much of the imperial treasure. It is estimated that between fifteen and thirty thousand Roman soldiers died that day. Ammianus Marcellinus and Paulus Orosius described it as the worst Roman military disaster since Hannibal's victory at the Battle of Cannae in 216 BC.[70][76][102] After his death, Valens was deified by consecratio as Latin: Divus Valens, lit. 'the Divine Valens'.[71]

Second generation: Gratian and Valentinian II (375–394)

[edit]

Gratian (378–383)

[edit]With the death of Valens in 378, Gratian (r. 367–383) was now the senior augustus, Valentinian II being only 7 years old, while Gratian was 19. Following the Battle of Adrianople, Gratian moved to Sirmium in the western Balkans to consider his options. The Goths had overrun the eastern Balkans (Moesia and Thrace), while in the west Gaul was under increasing threat from Franks and Alamanni. Gratian quickly realised he could not rule the whole empire on his own, and in particular he needed military expertise. He reached out to the younger Theodosius, son of Count Theodosius, living in retirement on the family estates in Spain, bringing him to Sirmium as magister equitum. On 19 January, he crowned him augustus as the eastern emperor Theodosius I (r. 379–395).[74][75][112] In 371, Gratian was consul for the second time,[75] and for the third time in 374.[75]

The new augustus's territory spanned the Roman praetorian prefecture of the East, including the Roman diocese of Thrace, and the additional dioceses of Dacia and of Macedonia. Theodosius the Elder, who had died in 375, was then deified as: Divus Theodosius Pater, lit. 'the Divine Father Theodosius'.[74] Theodosius' first priority was to rebuild the depleted legions, with sweeping conscription laws, but to do so he needed to recruit large numbers of non-Romans, further changing an empire that was becoming increasingly diverse.[113] After several more unsuccessful encounters with the Goths, he made peace, finally ending the Gothic war of 376–382, but in doing so settled large numbers of barbarians on the Danube in Lower Moesia, Thrace, Dacia Ripensis, and Macedonia. The treaty was signed on 3 October.[114] On 3 August that year, Gratian issued an edict against heresy.[75]

In 380, Gratian was made consul for the fifth time and Theodosius for the first. In September the augusti Gratian and Theodosius met, returning the Roman diocese of Dacia to Gratian's control and that of Macedonia to Valentinian II.[75][74] The same year, Gratian won a victory, possibly over the Alamanni, that was announced officially at Constantinople.[75] In the autumn of 378 Gratian issued an edict of religious toleration.[75]

Sometime in 383, Gratian's wife Constantia died.[75] Gratian remarried, wedding Laeta, whose father was a consularis of Roman Syria.[76] Gratian was awarded the victory titles of Germanicus Maximus and Alamannicus Maximus, and Francicus Maximus and Gothicus Maximus in 369.[75]

Religious policy

[edit]On accession, Gratian accepted the traditional title and role of pontifex maximus (high priest),[m] though by then largely honorific.[116] According to Zosimus, in 382 Gratian refused the robe of office of the pontifex maximus from a delegation of senators from Rome.[117] The accuracy of the story is disputed, Zosimus being considered an unreliable source. No such garment was associated with the priesthood.[116][76] Zosimus also stated that Gratian had repudiated the pagan title, as unlawful for a Christian to hold, and that no further emperor used that title, which became pontifex inclitus (or inclytus), "honourable priest".[116][118]

With the collapse of the Danube frontier[n] under the incursions of the Huns and Goths, Gratian moved his seat from Augusta Treverorum (Trier) to Mediolanum (Milan) in 381,[44] and was increasingly aligned with the city's bishop, Ambrose (374–397), and the Roman Senate, shifting the balance of power within the factions of the western empire.[76][4][117] Gratian was then forthright in his promotion of Nicene Christianity. He ordered the removal of the Altar of Victory from the Roman Senate's Curia Julia in the winter of 383/383.[o][75][76] State endowments for pagan cults were cancelled, and the Vestals, or vestal virgins (Latin: vestales) deprived of their stipends.[117][76]

Death of Gratian (383): Magnus Maximus the Usurper (383—388)

[edit]In June 383 Gratian took his army through the Brenner pass and into Gaul, where the Alamanni were pushing into Raetia.[75] At the same time, a rebellion broke out in Britain under Magnus Maximus (r. 383–388), the comes Britanniarum (commander of the Roman troops in Britain), where there had been a smouldering discontent since the elevation of Theodosius. Magnus Maximus, who had served under the comes Theodosius and had won a victory over the Picts in 382, was proclaimed augustus by his troops in the Spring of 383 and crossed the channel, encamping near Lutetia (Paris). While the legions on the Rhine welcomed him, those in Gaul remained loyal to Gratian. After five days of skirmishes between the two forces, Gratian's troops began to lose confidence in him and his General (magister peditum), Merobaudes defected to this usurper, forcing Gratian to flee towards the Alps, accompanied by some cavalry. Gratian was pursued by Andragathius, Maximus' magister equitum who apprehended him crossing the Rhone at Lugdunum (Lyon).[119] On 23 August 383, according to the Consularia Constantinopolitana, Gratian, then 24, and his ministers were executed.[120][75][121] Having secured Gratian's territories, Maximus then established his court at the former imperial residence in Trier.[122]

The body of Constantia, Gratian's first wife, who had died earlier that year, arrived in Constantinople on 12 September 383 and was buried in the complex of the Church of the Holy Apostles (Apostoleion) on 1 December, the resting place of a number of members of the imperial family, starting with Constantine in 337, under the direction of Theodosius, who had embarked on making the site a dynastic symbol. This was the last occasion that a member of the western imperial family was buried in the east, a new mausoleum being built at St Peter's Basilica in Rome.[4][75] According to Augustine of Hippo's The City of God and Theodoret's Historia Ecclesiastica, Gratian and Constantia had had a son, who died in infancy before 383 but had been born before 379.[75] Gratian was deified as Latin: Divus Gratianus, lit. 'the Divine Gratian'.[75][123] His remains were finally interred in Mediolanum in 387 or 388.[75]

On the death of Gratian, the 12 year old Valentinian II (r. 375–392) became the sole augustus in the west. Maximus attempted to persuade Valentinian to move his court to Trier, but Ambrose, suspecting treachery, made excuses while securing the alpine passes. Maximus then demanded recognition from Theodosius.[119] Although Valentinian's court looked east to Theodosius for assistance, the latter was preoccupied with establishing his own dynasty, having elevated his eldest son Arcadius (r. 383–408) to augustus on his quinquennalia, on 19 August 383.[74] He was also dealing with threats on his eastern frontier that precluded any western military excursions.[124]

In the summer of 384, Valentinian met his junior co-augustus Theodosius, and in November he celebrated his decennalia.[78] The position of the senior emperor Valentinian, was strengthened during the first few months of Maximus' rule, while Ambrose was conducting negotiations on the emperors' behalf.[121]

Eventually Theodosius decided to recognise the usurper and brokered an uneasy peace agreement between Valentinian and Magnus Maximus in the summer of 384 which endured for several years.[119] Under this agreement Maximus kept the western portion of the Empire including Britain, Spain and Gaul, while Valentinian ruled over Italy, Africa and Illyricum, allowing Theodosius to concentrate on his eastern problems and the threat to Thrace.[79][125]

The peace with Magnus Maximus was broken in 386 or 387, when he invaded Italy from the west. Valentinian, escaped with Justina, reaching Thessalonica (Thessaloniki) in the eastern empire in the summer or autumn of 387, appealing to Theodosius for aid. Magnus Maximus reached Milan to begin his consulship of 388, where he was welcomed by Symmachus.[126] Valentinian II's sister Galla was then married to the eastern augustus at Thessalonica in late autumn.[78][74] Justina, widow of Valentinian I and mother of Valentinian II, died in summer 388.[78] In June, the meeting of Christians deemed heretics was banned.[78] In summer 388, Italy was recovered for Valentinian from Magnus Maximus, whom Theodosius defeated at the Battle of Poetovio and eventually executed at Aquileia on 28 August.[121][78][126]

Valentinian II (383–392)

[edit]Following the defeat of Magnus Maximus by Theodosius in 388, Valentinian was restored to the throne. On 18 June 389, Theodosius arrived in Rome to display his second son, the five year old Honorius. He reconciled with Magnus Maximus' supporters and pardoned Symmachus, then in hiding, since he needed the support of the Gallo-Hispanic aristocracy, of which both he and Maximus were members. Theodosius then decided to stay in Milan, making sure that Valentinian was under the influence of his supporters. Overall, Theodosius, a skilled diplomat, made it clear that in practice he was the sole emperor of the two empires.[127]

It was not until 15 April of 391 that Theodosius decided to return to the east, to deal with a family conflict between his eldest son Arcadius, now fourteen, and his second wife Galla. Before his departure he consolidated his hold on the empire. He dispatched the nineteen year old Valentinian, who had been a mere figurehead, and his court to Trier, giving him jurisdiction over the western part of the empire. Theodosius also placed Valentinian under the unofficial regency of his trusted Frankish general (magister militum) Arbogast, who had defeated the Franks in 389.[79][78] In Italy he placed the civil administration under the prefect, Virius Nicomachus Flavianus. This allowed him to control the west remotely, while he ruled the remainder directly, from Italy eastwards, from Constantinople. In doing so, he inadvertently created a hierarchy, with the northwest as the junior partner in the empire.[128]

Valentinian attempted to exert his independence in the spring of 392, dismissing Arbogast. The latter defied Valentinian stating that only Theodosius could reverse his own appointment.[129] On 15 May 392, Valentinian II was found dead at Vienna (Vienne), Gaul, at the age of 21, either by suicide or as part of a plot by Arbogast.[78] Valentinian II was buried next to his half-brother and co-augustus Gratian in Mediolanum in late August or early September 392.[78] He was deified with the consecratio: Divae Memoriae Valentinianus, lit. 'the Divine Memory of Valentinian'.[78]

Religious policies

[edit]The death of Gratian in 383, brought religious conflict to the fore again. The Altar of Victory was an important symbol to the Roman pagan aristocracy, who hoped that the young Valentinian would look on their cause more favourably. In the autumn of 384, the Senator Q Aurelius Symmachus, then prefect of Rome (Latin: praefectus urbi) pleaded with Valentinian for its return to the Curia Julia, but Ambrose succeeded in firmly rejecting such a suggestion. While the bishop held considerable sway over the emperor, tensions began to emerge.[130][78]

According to Ambrose's Sermon Against Auxentius and his 76th Epistle when the bishop was summoned to the court of Valentinian II and his mother Justina in 385, the Nicene Christians appeared en masse to support him, threatening the emperor's security and offering themselves to be martyred by the army.[84] In March 386, the court asked that the city's summer-time cathedral, the Basilica Nova, be made available for the Arian community in the army for Easter, but Ambrose refused.[84] On Palm Sunday, the praetorian prefect proposed that the Portian Basilica be used instead. Ambrose rejected the request but on 9 April was ordered to hand over the building and the Nicene Christians occupied the building.[84] On Holy Wednesday, the army surrounded the Portian Basilica, but Ambrose held a service at the winter-time Basilica Vetus, after which the Nicenes moved to rescue their co-religionists in the Portian Basilica, among them Augustine of Hippo and his mother, chanting Psalm 79.[84] Although Valentinian backed down under the popular pressure, but relations between court and church, and the Arians succeeded in getting a law passed recognising the creed of Ariminum (359).[130]

On 23 January 386, Valentinian issued an edict of toleration regarding the Arian Christians, after receiving the Arian bishop Auxentius at court.[131][78] Magnus Maximus, who was a Nicene Christian, then wrote to Valentinian, attacking his favourable treatment of the Arians, and also contacted Pope Siricius and Theodosius. The same year Theodosius recognized Magnus Maximus's nominee for consul, Flavius Euodius, and Magnus Maximus's official portrait is known to have been shown at Alexandria, in the part of the empire administered by Theodosius.[121]

On Valentinian's restoration, Theodosius' clemency emboldened the supporters of the altar of Victory to once more travel to Milan to request its return, but their pleas were rejected and Symmachus exiled from Rome[126] (though eventually forgiven and given a consulship).[132] With Theodosius now in power in Milan he frequently clashed with Bishop Ambrose, who had stood his ground when Maximus' forces arrived. Ambrose's increasing political power, together with his fanatical supporters forced the emperor to back down on several occasions, illustrating the ascendancy of the Catholic Nicene church.[133] The power of Ambrose reached its peak when he threatened Theodosius with excommunication, following the massacre of Salonica in 390, until he publicly repented. This solidified the Church's position that man must serve God first, and the emperor second. Having established this precedent, Ambrose could now press the emperor into a major suppression of paganism, starting in February 391.[134]

Theodosian interregnum (392–423)

[edit]On the death of Valentinian II in 392, Theodosius became the sole adult emperor, with his two sons Arcadius and Honorius as junior emperors, over the east and west respectively. Theodosius was also the last emperor to rule both empires. Arcadius and Honorius were Theodosius' two surviving sons by his first marriage to Aelia Flaccilla, together with their sister Pulcheria[74] On Aelia's death in 386, Theodosius cemented his dynastic legitimacy by marrying Valentinian II's younger sister (and hence daughter of Valentinian I and Justina) Galla in 387.[p] By her, he had a son, Gratian (b. 388/389), who died in infancy in 394, and a daughter, Aelia Galla Placidia (b. 392/393). Another son, John (Latin: Ioannes), may have been born in 394. Galla, herself, died at the end of April 394 according to Zosimus.[74]

Theodosius' reign was immediately challenged. Arbogast, seeking to wield imperial power, was unable to assume the role of emperor himself because of his non-Roman background.[136] Instead, on 22 August at the behest of Arbogast, a magister scrinii and vir clarissimus, Eugenius (r. 392–394), was acclaimed augustus at Lugdunum.[74] Like Maximus he sought Theodosius's recognition in vain, minting new coins bearing the image of Theodosius and his son Arcadius in both trier and Milan, and attempting to recruit Ambrose as negotiator.[136][137]

Any hopes that Theodosius would recognise Eugenius dissipated when, according to Polemius Silvius, Theodosius raised his second son Honorius to augustus on 23 January 393, the year of his third consulship[74] citing Eugenius's illegitimacy.[136] According to Socrates Scholasticus, Theodosius defeated Eugenius at the Battle of the Frigidus (the Vipava river) on 6 September 394 and on 1 January 395, Honorius arrived in Mediolanum where a victory celebration was held.[74][137]

According to the Consularia Constantinopolitana, Theodosius died in Mediolanum on 17 January 395.[74][138] His funeral was held there on 25 February, and his body transferred to Constantinople, where according to the Chronicon Paschale he was buried on 8 November 395 in the Church of the Holy Apostles.[74] He was deified as: Divus Theodosius, lit. 'the Divine Theodosius'.[74]

Religious policy

[edit]Eugenius made some limited concessions to the Roman religion.[136] On 8 November 392, all cult worship of the gods was forbidden by Theodosius.[74]

Sons of Theodosius (395–425)

[edit]On the death of Theodosius I in 392, the empire became permanently divided between his sons. The two sons, who had been made junior emperors as children, by their father, were only 15 and 8 years old respectively, and thus figureheads under the control of guardians (Latin: parens). These, in turn, were often locked in struggles for power with each other. The most influential was Stilicho, himself a Vandal and supreme commander (Latin: comes et magister utriusque militiae praesentalis, lit. 'count and master of all forces') of Theodosius' army. Stilicho had allied himself to the dynasty by marrying Theodosius' adopted niece, Serena, and claimed he had been appointed parens of the whole empire, but this role was rejected by the eastern court. He then further strengthened his dynastic position by marrying his daughters, first Maria and on her death Thermantia, to the emperor Honorius. This period saw both an acceleration of the barbarisation of the western army and a massive settling of Roman lands by barbarian tribes. These were mainly Germanic tribes, with Visigoths and Burgundians in Gaul. Britain was abandoned and Italy itself became increasingly vulnerable to infiltration by barbarian forces, and progressively contracted to resemble more a government of Italy than an empire, while accommodation became more often the preferred foreign policy, rather than confrontation. By contrast the Constantinople court enjoyed a period of relative peace with its eastern Persian neighbours, although remaining vulnerable on its western front in Thrace and Macedonia to the forces of Alaric I. Administrative reforms in the military, with the emergence of a magister utriusque militiae or MVM,[139] who were frequently German, often left the emperor as a puppet under their control. During this period the two empires were at worst openly hostile and at best uncooperative.[140]

The invasion of Italy (400–408) and the usurpation of Constantine III (407–411)

[edit]

In the summer of 401, Alaric entered north Italy, marching west on Mediolanum, until halted by Stilicho at Pollentia in Piedmont at Easter 402. Although Alaric withdrew until 407, the threat was sufficient for Honorius to move his court from Mediolanum, further south to Ravenna, for security. The unintended consequence of strengthening the forces in the north east of Italy was a weakening of the Roman presence beyond the alps. The north of Italy was again overrun by Radagaisus and the Ostrogoths from Pannonia in 405, though eventually repelled. In late 406, several waves of barbarians crossed the Rhine and swept through Belgica and Gaul to the Pyrenees, capturing many important Roman strongholds, including Trier. Simultaneously a series of revolts too place in Britain, raising usurpers, the last of which was Constantine, who crossed into Gaul in the spring of 407, taking command of the Roman forces there and advancing as far as the alps. Meanwhile, Stilicho's attempts to appease Alaric and induce him to halt Constantine's advances was leading to both a deterioration in his relations with Honorius and his own popularity, culminating in a mutiny among the troops. Honorius then had Stilicho executed on 22 August 408.[141]

Stilicho's enemies at court were fiercely anti-German, resulting in the massacre of many of them in the Roman military. As a result, many barbarians defected to Alaric, who was now emboldened to once again invade Italy, this time with his brother-in-law Ataulf the Ostragoth. Rather than invade northern Italy as before, this time they marched on Rome, arriving in the autumn of 408 and laying siege to it. In the ensuing panic and anti-German sentiment, Stilicho's wife Serena was murdered in the belief that she must be an accomplice of Alaric. After collecting a ransom from the city, Alaric withdrew north to Etruria in December. Honorius, in desperation, now decided to accept Constantine as co-emperor in 409, as Constantine III. With a breakdown in negotiations with Ravenna, Alaric marched south on Rome again. This time the Senate capitulated in late 409, agreeing to form a new government under Alaric, electing Priscus Attalus, the praefectus urbi as emperor, in opposition to Honorius. In return Alaric was made magister utriusque militiae and Ataulf comes domesticorum equitum. When Alaric then advanced on Ravenna, Honorius was only dissuaded from fleeing to Constantinople by the arrival of reinforcements from the east. Attalus' reign was short lived being deposed by Alaric in the summer of 410. When negotiations with Ravenna failed yet again, Alaric attacked Rome for the third time, entering it on 24 August 410, and this time plundering it for three days, before moving south into Bruttium. On starting to return north, Alaric fell ill and died at Consentia (Consenza) in late 410, being succeeded by Ataulf who led to Visigoths back to Gaul. Meanwhile, relations between the two western emperors, which was uneasy at best, was deteriorating. Constantine established himself in Arelate, (Arles, Provence) in the strategic province of Gallia Narbonensis, stretching from the alps in the east to the Pyrenees in the south, and thus guarding the entrances to both Italy and Spain. Through this province ran the Via Domitia, connecting Rome with Spain.[142] He raised his son Constans to augustus and in early 410, supposedly to assist Honorius against Alaric, entered Italy but withdrew when the latter had Constantine's magister equitum executed on suspicion of treachery. The situation was further complicated by the incursion of barbarians into Spain in October 409, and the appearance of another usurper, Maximus (r. 409–411), there. Maximus' reign was short lived, his forces deserting him, while Honorius' forces, under the patriciusConstantius, captured and executed Constantine in September 411.[143]

Barbarian settlement of Gaul (411–413)

[edit]The removal of Constantine secured south-eastern Gaul, and hence the approaches to Italy for Honorius, but was followed by further usurpation of Jovinus (r. 411–413) in Mogontiacum (Mainz), Germania Superior, in 412. Jovinus' support by a broad coalition of both Gallo-Romans and barbarians indicated the waning influence of the central Italian government in Gaul. Although Ataulf briefly allied himself with Jovinus, he then offered Honorius the defeat of the latter in exchange for a treaty, and captured and killed him in the autumn of 413. The agreement collapsed and the Visigoths occupied much of lower Aquitania and Burdigala (Bordeaux) in south west Gaul as well as the adjacent province of Gallia Narbonensis in the south east.[144]

Third generation: Galla Placidia and Constantius III (392–450)

[edit]Early life at the Eastern court (388–394)

[edit]

Theodosius I set about establishing a stable dynasty in the east. When he raised his five year old eldest son, Arcadius, to the rank of augusta in 383 he also raised his first wife, Aelia Flaccilla as augusta. In doing so he set a new precedent. Rather than the traditional portrayal of imperial women as goddesses he invested her in the same regalia as an emperor, indicating equal status. This tradition was then continued in the house of Theodosius. The empress died in 386, shortly after her infant daughter Pulcheria, leaving him with his two young sons.[145][146]

In 387 the western emperor Valentinian II, together with his mother Justina and sisters, including Galla, were forced to flee to Thessalonica by the usurper Magnus Maximus, seeking Theodosius' help. Traveling to Thessalonica to meet them, the widowed Theodosius decided to marry Galla.[q][147] This move consolidated his dynastic legitimacy by marriage into the house of Valentinian. In 388 Theodosius led his army into the western empire to defeat Magnus Maximus, and Justina and her other daughters returned to Italy, leaving Galla, now pregnant, in Thessalonica, where her daughter, Galla Placidia, was born. [148][149][150]

Galla Placidia (c. 388–450) was thus both Valentinian and Theodosian, being the daughter of Theodosius I and Galla, and hence granddaughter of Valentinian I, as well as half sister to the child emperors Honorius and Arcadius.[151] Galla and her daughter travelled to Constantinople, where her stepson, Arcadius, rejected her, forcing Theodosius' return from Italy in 391.[152]

According to Synesius's 61st Epistle, written c. 402, Galla and her daughter were given a palace in Constantinople that had previously been part of the property of Ablabius, a praetorian prefect of the East under Constantine I.[153] About a year after his return, Theodosius arranged for his younger son, Honorius, then eight, to be crowned emperor. In the west, Valentinian II had died in the summer of 392 and the usurper Flavius Eugenius was proclaimed in August, and it was necessary to restore dynastic rule. Honorius' coronation took place on 23 January 393, an occasion recorded in detail by Claudian, in which all three of the Emperor's children were honoured. Galla Placidia was entitled "Most noble girl" (Latin: nobilissima puella),[r] with the honorific prefix: domina nostra, lit. 'our lady', though this may have occurred later.[154] Placidia also received an advanced education in secular and religious matters.[153][155][156]

At the Western court (394–409)

[edit]Less than a year later, her mother died in childbirth in 394. Subsequently, she was raised by her father's niece Serena and her husband Stilicho, with their three children (Maria, Thermantia and Eucherius). Theodosius had adopted Serena, on the death of her father, Honorius, bringing her to Constantinople from the family estates in Spain.[12] Theodosius then took his forces west to attack Eugenius, defeating him on 6 September. Shortly after, Theodosius became ill and sent for his children. Serena then travelled to Milan with Honorius, Placidia and her nurse Elpidia to join him. He proclaimed Honorius emperor and promoted Stilicho to magister militum, but by 17 January 395 he had died, leaving his children orphans, Placidia being seen years old. Stilicho then claimed he had been appointed parens principium to the child emperors.[157] After the funeral, Serena and the children accompanied his body to Constantinople, where he was interred at the Church of the Holy Apostles in November.[158][159] Following Theodosius' death, Stilicho strengthened his dynastic position by marrying his two daughters to Honorius in succession and betrothing his son Eucherius to Placidia, while they were all still children, while his wife Serena acted as a de facto Empress as the informal regent for Honorius.[12] Although Placidia spent much of her early years in Milan, the continuing invasions of Visigoths led to the court moving to a more secure position further south at Ravenna in 402, but with frequent visits to Rome, where Stilicho and Serena also maintained a house.[12][154][160]

Captivity (409–416)

[edit]Meanwhile, Stilicho's reputation was waning and his relationship with Honorius deteriorating, leading to Honorius ordering his execution in Ravenna in 408, together with Eucherius and Serena, who were in Rome with Placidia. According to Zosimus, the nobilissima puella Galla Placidia approved the Roman Senate's decision to execute Serena.[153] All this happened against a background of Visigothic advances, laying siege to Rome in both 408 and 409,[161] and finally sacking Rome in 410. In either 409 or 410, the teenage Galla Placidia was captured by the Visigoths and was taken through southern Italy, where Alaric died and was succeeded by Athaulf.[162] Placidia, who was effectively a hostage, then became a bargaining item in the negotiations between the Visigoths and the Romans over a three-year period.[163][164] Placidia and her captors eventually returned to southern Gaul in the spring of 412.[153][165][166]

During the protracted negotiations between the Roman court and the Visigoths, Placidia was married to Athaulf.[157] According to Orosius, Olympiodorus of Thebes, Philostorgius, Prosper of Aquitaine, the Chronica Gallica of 452, Hydatius, Marcellinus Comes, and Jordanes, they were married at Narbo (Narbonne) in January 414, where Athaulf had established his court on the Via Domitia in Gallia Narbonensis.[167] They had a son, that she called Theodosius.[74][157][164] Honorius responded with a naval blockade of Narbo under the direction of Constantius. Although Athaulf again elected Attalus as a rival emperor, but the new regime soon collapsed, Attalus was captured and the Visigoths retreated south to Colonia Faventia (Barcelona) by the end of the year. Constantius renewed his attack on them there, and in the summer of 415, Athaulf was murdered and succeeded by Sigeric, while the infant Theodosius died. Within seven days, Sigeric himself was killed and succeeded by Wallia who, desperate for food for his people, bartered Placidia for supplies and a treaty in summer 416. The treaty recruited the Visigoths against other barbarian peoples that were rapidly occupying Hispania. They were so efficient at this, that Honorius decided to settle them in southern Gaul (lower Aquitania and parts of Novempopulana and Narbonensis, excluding the seaboard) in 418. By this stage, the western empire was reduced to Italy and Africa but with only a tenuous hold on western Illyricum, Gallia and Hispania.[168][153]

Empress (417–450)

[edit]

Placidia was returned to Ravenna and, against her will, was married to the Constantius on 1 January 417 according to Olympiodorus of Thebes.[169][74][153] Their first child was Justa Grata Honoria (Honoria),[153] and a little more than a year later Valentinian on 4 July 419.[12][170][171] In February 421, Honorius, who lacked an heir himself, reluctantly elevated Constantius augustus as Constantius III (r. 421–421), Galla Placidia as augusta by her husband and Honorius and Valentinian as nobilisimus, indicating he was destined for succession.[153] These titles were not recognised by the eastern court[157] and Constantius died within seven months in September 421.[172][170]

Relations between Placidia and Honorius deteriorated, with their respective supporters clashing in the streets of Ravenna, leading to her moving her family to Constantinople in 422.[173][170][157] She may have been banished by Honorius, with whom her relations were previously close, because according to Olympiodorus, Philostorgius, Prosper, and the Chronica Gallica of 452, gossip about the nature of their relationship that arose after Constantius's death caused them to quarrel.[153] Galla Placidia involved herself in political and religious affairs, for instance supporting a candidate to the disputed see of Rome.[157]

Fourth generation: Valentinian III and Honoria (423–455)

[edit]

Honorius died in 423, leaving Galla Placidia as the only ruler in the west, though not recognised in the east. At the eastern court, Theodosius I's eldest son Arcadius (r. 383–408) had died in 408, and been succeeded by his son Theodosius II (r. 402–450), also a child emperor, but who was now 22, and who considered himself the sole ruler of the empire.[173][157]

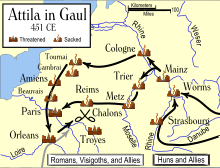

Однако вакуум был быстро заполнен появлением в Риме узурпатора, primicerius notariorum Иоанна ( годы правления 423–425 ), объявившего себя августом на западе. [173] Dynastic considerations then forced the eastern court to retrospectively recognise Constantius, Placidia and their six-year-old son, and to restore the Valentinianic dynasty in the west, in early 424. Theodosius elevated Valentinian to caesar on 23 October 424.[173] Объединенные силы Плацидии и Феодосия вторглись в Италию в 425 году, захватив и казнив Иоанна. Затем Валентиниан был провозглашен августом в свою первую годовщину как Валентиниан III ( годы правления 425–455 ) в Риме 23 октября 425 года с Плацидией в качестве регента . Феодосий еще больше укрепил династические отношения по всей империи, обручив свою трехлетнюю дочь Лицинию Евдоксию с Валентинианом. [174] К этому времени западная сфера влияния сократилась до Италии и экономически стратегически важных провинций Северной Африки ( см. карту Хизер (2000 , стр. 3) ). [175] При шестилетнем титулярном императоре реальная власть принадлежала его матери и трем главным военачальникам, хотя они были вовлечены в борьбу друг с другом, из которой Флавий Аэций вышел единственным выжившим к 433 году, назначив себя патрицием . Эта борьба ослабила центральный контроль над империей из-за частых вторжений ряда соседних народов. [176] Однако Аэций, ставший единственным военачальником, смог компенсировать некоторые из этих потерь в конце 430-х годов, хотя и временно. [177] Падение Карфагена (Карфагена) перед вандалами в 439 году и последующее вторжение в Сицилию , за которым вскоре последовало вторжение гуннов через Дунай в 441 году, ускорило новый кризис. [178] Большая часть 440-х годов была потрачена на борьбу за сохранение контроля над Испанией и Галлией, в то время как прогрессирующая потеря территорий и, следовательно, налоговой базы продолжала ослаблять центральное правительство в Равенне. [179]

Гонория и Аттила (449–453)

[ редактировать ]