Религия в Древнем Риме

| Религия в Древний Рим |

|---|

|

| Практики и убеждения |

| Священство |

| Божества |

| Связанные темы |

Религия в Древнем Риме состояла из различных имперских и провинциальных религиозных практик, которым следовали как жители Рима, так и те, кто оказался под его властью.

Римляне считали себя очень религиозными людьми и объясняли свой успех в качестве мировой державы коллективным благочестием ( pietas ) в поддержании хороших отношений с богами . Их политеистическая религия известна тем, что почитает множество божеств .

Присутствие греков на итальянском полуострове с начала исторического периода повлияло на римскую культуру , внедрив некоторые религиозные практики, которые стали фундаментальными, например культ Аполлона , . Римляне искали точки соприкосновения между своими главными богами и богами греков ( interpretatio graeca ), адаптируя греческие мифы и иконографию для латинской литературы и римского искусства , как это делали этруски . Этрусская религия также оказала большое влияние, особенно на практику предсказаний , используемых государством для поиска воли богов. Согласно легендам , большинство религиозных институтов Рима восходит к его основателям , особенно к Нуме Помпилию , сабинянскому второму царю Рима , который вел переговоры напрямую с богами . Эта архаичная религия была основой mos maiorum , «пути предков» или просто «традиции», которая считалась центральной в римской идентичности.

Римская религия была практичной и договорной, основанной на принципе do ut des : «Я даю, чтобы вы могли дать». Религия зависела от знаний и правильной практики молитв, обрядов и жертвоприношений, а не от веры или догм, хотя латинская литература сохраняет научные рассуждения о природе божественного и его связи с человеческими делами. Даже самые скептически настроенные представители интеллектуальной элиты Рима, такие как Цицерон , который был авгуром, видели в религии источник социального порядка. По мере расширения Римской империи мигранты привозили в столицу свои местные культы , многие из которых стали популярны среди итальянцев. Христианство в конечном итоге стало наиболее успешным из этих верований и в 380 году стало официальной государственной религией .

Для простых римлян религия была частью повседневной жизни. [1] В каждом доме была домашняя святыня, в которой молитвы и возлияния семьи домашним божествам возносились . Окрестные святыни и священные места, такие как источники и рощи, разбросаны по городу. [2] Римский календарь был построен вокруг религиозных обрядов. Женщины , рабы и дети участвовали в различных религиозных мероприятиях. Некоторые публичные ритуалы могли проводиться только женщинами, и женщины сформировали, возможно, самое известное жречество Рима — поддерживаемых государством весталок , которые ухаживали за священным очагом Рима веками , пока не были расформированы под христианским господством.

Обзор

[ редактировать ]

Священство большинства государственных религий принадлежало представителям элитных классов . не существовало Принципа, аналогичного разделению церкви и государства в Древнем Риме, . Во времена Римской республики (509–27 гг. до н.э.) те же люди, которые были избранными государственными должностными лицами, могли также выполнять функции авгуров и понтификов . Священники женились, создавали семьи и вели политически активную жизнь. Юлий Цезарь стал Великим понтификом еще до того, как был избран консулом .

Авгуры читали волю богов и контролировали разметку границ как отражение вселенского порядка, тем самым санкционируя римский экспансионизм и иностранные войны как вопрос божественной судьбы. Римский триумф по своей сути был религиозным шествием, в котором победивший полководец демонстрировал свое благочестие и готовность служить общественному благу, посвящая часть своей добычи богам, особенно Юпитеру , который олицетворял справедливое правление. В результате Пунических войн (264–146 гг. До н. э.), когда Рим изо всех сил пытался утвердиться в качестве доминирующей державы, множество новых храмов магистраты построили во исполнение обета, данного божеству для обеспечения их военного успеха.

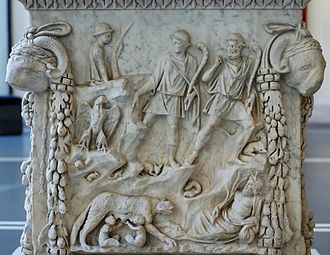

По мере того как римляне распространяли свое господство по всему Средиземноморью , их политика в целом заключалась в поглощении божеств и культов других народов, а не в попытках их искоренить. [3] поскольку они считали, что сохранение традиций способствует социальной стабильности. [4] Одним из способов объединения в Риме различных народов была поддержка их религиозного наследия, строительство храмов местным божествам, которые вписывали их богословие в иерархию римской религии. Надписи по всей Империи фиксируют одновременное поклонение местным и римским божествам, включая посвящения римлян местным богам. [5]

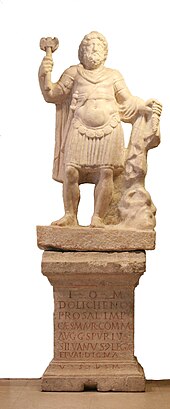

На пике расцвета Империи многочисленные международные божества в Риме культивировались , которые были перенесены даже в самые отдаленные провинции , среди них Кибела , Исида , Эпона и боги солнечного монизма, такие как Митра и Солнце Инвиктус , обитавшие даже на севере. Римская Британия . Иностранные религии все больше привлекали приверженцев среди римлян, которые все чаще имели предков из других регионов Империи. Импортированные мистические религии , которые предлагали посвященным спасение в загробной жизни, были делом личного выбора человека, практиковавшегося в дополнение к проведению семейных обрядов и участию в общественной религии. Однако мистерии включали в себя исключительные клятвы и секретность, условия, которые консервативные римляне с подозрением считали характерными для « магической », заговорщической ( coniuratio ) или подрывной деятельности. Предпринимались спорадические, а иногда и жестокие попытки подавить религиозных деятелей, которые, казалось, угрожали традиционной морали и единству, как в случае с ограничению усилиями Сената по вакханалий. в 186 г. до н.э. Поскольку римляне никогда не были обязаны культивировать только одного бога или только один культ, религиозная терпимость не была проблемой в том смысле, в каком она существует для монотеистических систем. [6] Монотеистическая строгость иудаизма создавала трудности для римской политики, которые порой приводили к компромиссу и предоставлению особых исключений, но иногда и к неразрешимым конфликтам. Например, религиозные споры способствовали Первой еврейско-римской войне и восстанию Бар-Кохбы .

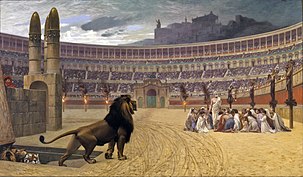

После распада Республики государственная религия адаптировалась для поддержки нового режима императоров . Август , первый римский император, оправдывал новизну единоначалия обширной программой религиозного возрождения и реформ. Публичные клятвы , которые раньше давались ради безопасности республики, теперь были направлены на благополучие императора. Так называемое «поклонение императору» в широких масштабах расширило традиционное римское почитание умерших предков и Гения , божественного покровителя каждого человека. Имперский культ стал одним из основных способов, с помощью которых Рим рекламировал свое присутствие в провинциях и культивировал общую культурную самобытность и лояльность по всей Империи. Отказ от государственной религии был равносилен измене. Это был контекст конфликта Рима с христианством , которое римляне по-разному считали формой атеизма и новым суеверием , в то время как христиане считали римскую религию язычеством . В конечном итоге римскому политеизму пришел конец с принятием христианства в качестве официальной религии империи.

Основополагающие мифы и божественная судьба

[ редактировать ]

Римская мифологическая традиция особенно богата историческими мифами или легендами об основании и возвышении города. Эти повествования сосредоточены на людях-действующих лицах, лишь с редким вмешательством божеств, но с всеобъемлющим ощущением божественной судьбы. В самый ранний период существования Рима трудно отличить историю от мифа. [7]

According to mythology, Rome had a semi-divine ancestor in the Trojan refugee Aeneas, son of Venus, who was said to have established the basis of Roman religion when he brought the Palladium, Lares and Penates from Troy to Italy. These objects were believed in historical times to remain in the keeping of the Vestals, Rome's female priesthood. Aeneas, according to classical authors, had been given refuge by King Evander, a Greek exile from Arcadia, to whom were attributed other religious foundations: he established the Ara Maxima, "Greatest Altar", to Hercules at the site that would become the Forum Boarium, and, so the legend went, he was the first to celebrate the Lupercalia, an archaic festival in February that was celebrated as late as the 5th century of the Christian era.[8]

The myth of a Trojan founding with Greek influence was reconciled through an elaborate genealogy (the Latin kings of Alba Longa) with the well-known legend of Rome's founding by Romulus and Remus. The most common version of the twins' story displays several aspects of hero myth. Their mother, Rhea Silvia, had been ordered by her uncle the king to remain a virgin, in order to preserve the throne he had usurped from her father. Through divine intervention, the rightful line was restored when Rhea Silvia was impregnated by the god Mars. She gave birth to twins, who were duly exposed by order of the king but saved through a series of miraculous events.

Romulus and Remus regained their grandfather's throne and set out to build a new city, consulting with the gods through augury, a characteristic religious institution of Rome that is portrayed as existing from earliest times. The brothers quarrel while building the city walls, and Romulus kills Remus, an act that is sometimes seen as sacrificial. Fratricide thus became an integral part of Rome's founding myth.[9]

Romulus was credited with several religious institutions. He founded the Consualia festival, inviting the neighbouring Sabines to participate; the ensuing rape of the Sabine women by Romulus's men further embedded both violence and cultural assimilation in Rome's myth of origins. As a successful general, Romulus is also supposed to have founded Rome's first temple to Jupiter Feretrius and offered the spolia opima, the prime spoils taken in war, in the celebration of the first Roman triumph. Spared a mortal's death, Romulus was mysteriously spirited away and deified.[10]

His Sabine successor Numa was pious and peaceable, and credited with numerous political and religious foundations, including the first Roman calendar; the priesthoods of the Salii, flamines, and Vestals; the cults of Jupiter, Mars, and Quirinus; and the Temple of Janus, whose doors stayed open in times of war but in Numa's time remained closed. After Numa's death, the doors to the Temple of Janus were supposed to have remained open until the reign of Augustus.[12]

Each of Rome's legendary or semi-legendary kings was associated with one or more religious institutions still known to the later Republic. Tullus Hostilius and Ancus Marcius instituted the fetial priests. The first "outsider" Etruscan king, Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, founded a Capitoline temple to the triad Jupiter, Juno and Minerva which served as the model for the highest official cult throughout the Roman world. The benevolent, divinely fathered Servius Tullius established the Latin League, its Aventine Temple to Diana, and the Compitalia to mark his social reforms. Servius Tullius was murdered and succeeded by the arrogant Tarquinius Superbus, whose expulsion marked the end of Roman kingship and the beginning of the Roman republic, governed by elected magistrates.[13]

Roman historians[14] regarded the essentials of Republican religion as complete by the end of Numa's reign, and confirmed as right and lawful by the Senate and people of Rome: the sacred topography of the city, its monuments and temples, the histories of Rome's leading families, and oral and ritual traditions.[15] According to Cicero, the Romans considered themselves the most religious of all peoples, and their rise to dominance was proof they received divine favor in return.[16]

Roman deities

[edit]

Rome offers no native creation myth, and little mythography to explain the character of its deities, their mutual relationships or their interactions with the human world, but Roman theology acknowledged that di immortales (immortal gods) ruled all realms of the heavens and earth. There were gods of the upper heavens, gods of the underworld and a myriad of lesser deities between. Some evidently favoured Rome because Rome honoured them, but none were intrinsically, irredeemably foreign or alien.

The political, cultural and religious coherence of an emergent Roman super-state required a broad, inclusive and flexible network of lawful cults. At different times and in different places, the sphere of influence, character and functions of a divine being could expand, overlap with those of others, and be redefined as Roman. Change was embedded within existing traditions.[17]

Several versions of a semi-official, structured pantheon were developed during the political, social and religious instability of the Late Republican era. Jupiter, the most powerful of all gods and "the fount of the auspices upon which the relationship of the city with the gods rested", consistently personified the divine authority of Rome's highest offices, internal organization and external relations. During the archaic and early Republican eras, he shared his temple, some aspects of cult and several divine characteristics with Mars and Quirinus, who were later replaced by Juno and Minerva.[18]

A conceptual tendency toward triads may be indicated by the later agricultural or plebeian triad of Ceres, Liber and Libera, and by some of the complementary threefold deity-groupings of Imperial cult.[19] Other major and minor deities could be single, coupled, or linked retrospectively through myths of divine marriage and sexual adventure. These later Roman pantheistic hierarchies are part literary and mythographic, part philosophical creations, and often Greek in origin. The Hellenization of Latin literature and culture supplied literary and artistic models for reinterpreting Roman deities in light of the Greek Olympians, and promoted a sense that the two cultures had a shared heritage.[20]

The impressive, costly, and centralised rites to the deities of the Roman state were vastly outnumbered in everyday life by commonplace religious observances pertaining to an individual's domestic and personal deities, the patron divinities of Rome's various neighborhoods and communities, and the often idiosyncratic blends of official, unofficial, local and personal cults that characterised lawful Roman religion.[21]

In this spirit, a provincial Roman citizen who made the long journey from Bordeaux to Italy to consult the Sibyl at Tibur did not neglect his devotion to his own goddess from home:

I wander, never ceasing to pass through the whole world, but I am first and foremost a faithful worshiper of Onuava. I am at the ends of the earth, but the distance cannot tempt me to make my vows to another goddess. Love of the truth brought me to Tibur, but Onuava's favorable powers came with me. Thus, divine mother, far from my home-land, exiled in Italy, I address my vows and prayers to you no less.[22]

Holidays and festivals

[edit]Roman calendars show roughly forty annual religious festivals. Some lasted several days, others a single day or less: sacred days (dies fasti) outnumbered "non-sacred" days (dies nefasti).[23] A comparison of surviving Roman religious calendars suggests that official festivals were organized according to broad seasonal groups that allowed for different local traditions. Some of the most ancient and popular festivals incorporated ludi ("games", such as chariot races and theatrical performances), with examples including those held at Palestrina in honour of Fortuna Primigenia during Compitalia, and the Ludi Romani in honour of Liber.[24] Other festivals may have required only the presence and rites of their priests and acolytes,[25] or particular groups, such as women at the Bona Dea rites.[26]

Other public festivals were not required by the calendar, but occasioned by events. The triumph of a Roman general was celebrated as the fulfillment of religious vows, though these tended to be overshadowed by the political and social significance of the event. During the late Republic, the political elite competed to outdo each other in public display, and the ludi attendant on a triumph were expanded to include gladiator contests. Under the Principate, all such spectacular displays came under Imperial control: the most lavish were subsidised by emperors, and lesser events were provided by magistrates as a sacred duty and privilege of office. Additional festivals and games celebrated Imperial accessions and anniversaries. Others, such as the traditional Republican Secular Games to mark a new era (saeculum), became imperially funded to maintain traditional values and a common Roman identity. That the spectacles retained something of their sacral aura even in late antiquity is indicated by the admonitions of the Church Fathers that Christians should not take part.[27]

The meaning and origin of many archaic festivals baffled even Rome's intellectual elite, but the more obscure they were, the greater the opportunity for reinvention and reinterpretation – a fact lost neither on Augustus in his program of religious reform, which often cloaked autocratic innovation, nor on his only rival as mythmaker of the era, Ovid. In his Fasti, a long-form poem covering Roman holidays from January to June, Ovid presents a unique look at Roman antiquarian lore, popular customs, and religious practice that is by turns imaginative, entertaining, high-minded, and scurrilous;[28] not a priestly account, despite the speaker's pose as a vates or inspired poet-prophet, but a work of description, imagination and poetic etymology that reflects the broad humor and burlesque spirit of such venerable festivals as the Saturnalia, Consualia, and feast of Anna Perenna on the Ides of March, where Ovid treats the assassination of the newly deified Julius Caesar as utterly incidental to the festivities among the Roman people.[29] But official calendars preserved from different times and places also show a flexibility in omitting or expanding events, indicating that there was no single static and authoritative calendar of required observances. In the later Empire under Christian rule, the new Christian festivals were incorporated into the existing framework of the Roman calendar, alongside at least some of the traditional festivals.[30]

Temples and shrines

[edit]

Public religious ceremonies of the official Roman religion took place outdoors, and not within the temple building. Some ceremonies were processions that started at, visited, or ended with a temple or shrine, where a ritual object might be stored and brought out for use, or where an offering would be deposited. Sacrifices, chiefly of animals, would take place at an open-air altar within the templum or precinct, often to the side of the steps leading up to the raised portico. The main room (cella) inside a temple housed the cult image of the deity to whom the temple was dedicated, and often a small altar for incense or libations. It might also display art works looted in war and rededicated to the gods. It is not clear how accessible the interiors of temples were to the general public.

The Latin word templum originally referred not to the temple building itself, but to a sacred space surveyed and plotted ritually through augury: "The architecture of the ancient Romans was, from first to last, an art of shaping space around ritual."[31] The Roman architect Vitruvius always uses the word templum to refer to this sacred precinct, and the more common Latin words aedes, delubrum, or fanum for a temple or shrine as a building. The ruins of temples are among the most visible monuments of ancient Roman culture.

Temple buildings and shrines within the city commemorated significant political settlements in its development: the Aventine Temple of Diana supposedly marked the founding of the Latin League under Servius Tullius.[32] Many temples in the Republican era were built as the fulfillment of a vow made by a general in exchange for a victory: Rome's first known temple to Venus was vowed by the consul Q. Fabius Gurges in the heat of battle against the Samnites, and dedicated in 295 BC.[33]

Religious practice

[edit]Prayers, vows, and oaths

[edit]All sacrifices and offerings required an accompanying prayer to be effective. Pliny the Elder declared that "a sacrifice without prayer is thought to be useless and not a proper consultation of the gods."[34] Prayer by itself, however, had independent power. The spoken word was thus the single most potent religious action, and knowledge of the correct verbal formulas the key to efficacy.[35] Accurate naming was vital for tapping into the desired powers of the deity invoked, hence the proliferation of cult epithets among Roman deities.[36] Public prayers (prex) were offered loudly and clearly by a priest on behalf of the community. Public religious ritual had to be enacted by specialists and professionals faultlessly; a mistake might require that the action, or even the entire festival, be repeated from the start.[37] The historian Livy reports an occasion when the presiding magistrate at the Latin festival forgot to include the "Roman people" among the list of beneficiaries in his prayer; the festival had to be started over.[38] Even private prayer by an individual was formulaic, a recitation rather than a personal expression, though selected by the individual for a particular purpose or occasion.[39]

Oaths—sworn for the purposes of business, clientage and service, patronage and protection, state office, treaty and loyalty—appealed to the witness and sanction of deities. Refusal to swear a lawful oath (sacramentum) and breaking a sworn oath carried much the same penalty: both repudiated the fundamental bonds between the human and divine.[36] A votum or vow was a promise made to a deity, usually an offer of sacrifices or a votive offering in exchange for benefits received.

Sacrifice

[edit]

In Latin, the word sacrificium means the performance of an act that renders something sacer, sacred. Sacrifice reinforced the powers and attributes of divine beings, and inclined them to render benefits in return (the principle of do ut des).

Offerings to household deities were part of daily life. Lares might be offered spelt wheat and grain-garlands, grapes and first fruits in due season, honey cakes and honeycombs, wine and incense,[40] food that fell to the floor during any family meal,[41] or at their Compitalia festival, honey-cakes and a pig on behalf of the community.[42] Their supposed underworld relatives, the malicious and vagrant Lemures, might be placated with midnight offerings of black beans and spring water.[43]

Animal sacrifice

[edit]The most potent offering was animal sacrifice, typically of domesticated animals such as cattle, sheep and pigs. Each was the best specimen of its kind, cleansed, clad in sacrificial regalia and garlanded; the horns of oxen might be gilded. Sacrifice sought the harmonisation of the earthly and divine, so the victim must seem willing to offer its own life on behalf of the community; it must remain calm and be quickly and cleanly dispatched.[44]

Sacrifice to deities of the heavens (di superi, "gods above") was performed in daylight, and under the public gaze. Deities of the upper heavens required white, infertile victims of their own sex: Juno a white heifer (possibly a white cow); Jupiter a white, castrated ox (bos mas) for the annual oath-taking by the consuls. Di superi with strong connections to the earth, such as Mars, Janus, Neptune and various genii – including the Emperor's – were offered fertile victims. After the sacrifice, a banquet was held; in state cults, the images of honoured deities took pride of place on banqueting couches and by means of the sacrificial fire consumed their proper portion (exta, the innards). Rome's officials and priests reclined in order of precedence alongside and ate the meat; lesser citizens may have had to provide their own.[45]

Chthonic gods such as Dis pater, the di inferi ("gods below"), and the collective shades of the departed (di Manes) were given dark, fertile victims in nighttime rituals. Animal sacrifice usually took the form of a holocaust or burnt offering, and there was no shared banquet, as "the living cannot share a meal with the dead".[46] Ceres and other underworld goddesses of fruitfulness were sometimes offered pregnant female animals; Tellus was given a pregnant cow at the Fordicidia festival. Color had a general symbolic value for sacrifices. Demigods and heroes, who belonged to the heavens and the underworld, were sometimes given black-and-white victims. Robigo (or Robigus) was given red dogs and libations of red wine at the Robigalia for the protection of crops from blight and red mildew.[45]

A sacrifice might be made in thanksgiving or as an expiation of a sacrilege or potential sacrilege (piaculum);[47]a piaculum might also be offered as a sort of advance payment; the Arval Brethren, for instance, offered a piaculum before entering their sacred grove with an iron implement, which was forbidden, as well as after.[48]The pig was a common victim for a piaculum.[49]

The same divine agencies who caused disease or harm also had the power to avert it, and so might be placated in advance. Divine consideration might be sought to avoid the inconvenient delays of a journey, or encounters with banditry, piracy and shipwreck, with due gratitude to be rendered on safe arrival or return. In times of great crisis, the Senate could decree collective public rites, in which Rome's citizens, including women and children, moved in procession from one temple to the next, supplicating the gods.[50]

Extraordinary circumstances called for extraordinary sacrifice: in one of the many crises of the Second Punic War, Jupiter Capitolinus was promised every animal born that spring (see ver sacrum), to be rendered after five more years of protection from Hannibal and his allies.[51] The "contract" with Jupiter is exceptionally detailed. All due care would be taken of the animals. If any died or were stolen before the scheduled sacrifice, they would count as already sacrificed, since they had already been consecrated. Normally, if the gods failed to keep their side of the bargain, the offered sacrifice would be withheld. In the imperial period, sacrifice was withheld following Trajan's death because the gods had not kept the Emperor safe for the stipulated period.[52] In Pompeii, the Genius of the living emperor was offered a bull: presumably a standard practise in Imperial cult, though minor offerings (incense and wine) were also made.[53]

The exta were the entrails of a sacrificed animal, comprising in Cicero's enumeration the gall bladder (fel), liver (iecur), heart (cor), and lungs (pulmones).[54] The exta were exposed for litatio (divine approval) as part of Roman liturgy, but were "read" in the context of the disciplina Etrusca. As a product of Roman sacrifice, the exta and blood are reserved for the gods, while the meat (viscera) is shared among human beings in a communal meal. The exta of bovine victims were usually stewed in a pot (olla or aula), while those of sheep or pigs were grilled on skewers. When the deity's portion was cooked, it was sprinkled with mola salsa (ritually prepared salted flour) and wine, then placed in the fire on the altar for the offering; the technical verb for this action was porricere.[55]

Human sacrifice

[edit]Human sacrifice in ancient Rome was rare but documented. After the Roman defeat at Cannae two Gauls and two Greeks were buried under the Forum Boarium, in a stone chamber "which had on a previous occasion [228 BC] also been polluted by human victims, a practice most repulsive to Roman feelings".[56] Livy avoids the word "sacrifice" in connection with this bloodless human life-offering; Plutarch does not. The rite was apparently repeated in 113 BC, preparatory to an invasion of Gaul. Its religious dimensions and purpose remain uncertain.[57]

In the early stages of the First Punic War (264 BC) the first known Roman gladiatorial munus was held, described as a funeral blood-rite to the manes of a Roman military aristocrat.[58] The gladiator munus was never explicitly acknowledged as a human sacrifice, probably because death was not its inevitable outcome or purpose. Even so, the gladiators swore their lives to the gods, and the combat was dedicated as an offering to the Di Manes or the revered souls of deceased human beings. The event was therefore a sacrificium in the strict sense of the term, and Christian writers later condemned it as human sacrifice.[59]

The small woollen dolls called Maniae, hung on the Compitalia shrines, were thought a symbolic replacement for child-sacrifice to Mania, as Mother of the Lares. The Junii took credit for its abolition by their ancestor L. Junius Brutus, traditionally Rome's Republican founder and first consul.[60] Political or military executions were sometimes conducted in such a way that they evoked human sacrifice, whether deliberately or in the perception of witnesses; Marcus Marius Gratidianus was a gruesome example.

Officially, human sacrifice was obnoxious "to the laws of gods and men". The practice was a mark of the barbarians, attributed to Rome's traditional enemies such as the Carthaginians and Gauls. Rome banned it on several occasions under extreme penalty. A law passed in 81 BC characterised human sacrifice as murder committed for magical purposes. Pliny saw the ending of human sacrifice conducted by the druids as a positive consequence of the conquest of Gaul and Britain. Despite an empire-wide ban under Hadrian, human sacrifice may have continued covertly in North Africa and elsewhere.[61]

Domestic and private cult

[edit]

The mos maiorum established the dynastic authority and obligations of the citizen-paterfamilias ("the father of the family" or the "owner of the family estate"). He had priestly duties to his lares, domestic penates, ancestral Genius and any other deities with whom he or his family held an interdependent relationship. His own dependents, who included his slaves and freedmen, owed cult to his Genius.[62][63]

Genius was the essential spirit and generative power – depicted as a serpent or as a perennial youth, often winged – within an individual and their clan (gens (pl. gentes). A paterfamilias could confer his name, a measure of his genius and a role in his household rites, obligations and honours upon those he fathered or adopted. His freed slaves owed him similar obligations.[64]

A pater familias was the senior priest of his household. He offered daily cult to his lares and penates, and to his di parentes/divi parentes at his domestic shrines and in the fires of the household hearth.[65] His wife (mater familias) was responsible for the household's cult to Vesta. In rural estates, bailiffs seem to have been responsible for at least some of the household shrines (lararia) and their deities. Household cults had state counterparts. In Vergil's Aeneid, Aeneas brought the Trojan cult of the lares and penates from Troy, along with the Palladium which was later installed in the temple of Vesta.[66]

Religio and the state

[edit]

Roman religio (religion) was an everyday and vital affair, a cornerstone of the mos maiorum, Roman tradition and ancestral custom. It was ultimately governed by the Roman state, and religious laws.[67]

Care for the gods, the very meaning of religio, had therefore to go through life, and one might thus understand why Cicero wrote that religion was "necessary". Religious behavior – pietas in Latin, eusebeia in Greek – belonged to action and not to contemplation. Consequently religious acts took place wherever the faithful were: in houses, boroughs, associations, cities, military camps, cemeteries, in the country, on boats. 'When pious travelers happen to pass by a sacred grove or a cult place on their way, they are used to make a vow, or a fruit offering, or to sit down for a while' (Apuleius, Florides 1.1).[68]

Religious law centered on the ritualised system of honours and sacrifice that brought divine blessings, according to the principle do ut des ("I give, that you might give"). Proper, respectful religio brought social harmony and prosperity. Religious neglect was a form of atheism: impure sacrifice and incorrect ritual were vitia (impious errors). Excessive devotion, fearful grovelling to deities and the improper use or seeking of divine knowledge were superstitio. Any of these moral deviations could cause divine anger (ira deorum) and therefore harm the State.[69] The official deities of the state were identified with its lawful offices and institutions, and Romans of every class were expected to honour the beneficence and protection of mortal and divine superiors. State cult rituals were almost always performed in daylight and in full public view, by priests who acted on behalf of the Roman state and the Roman people. Congregations were expected to respectfully observe the proceedings. Participation in public rites showed a personal commitment to the community and its values.[70]

Official cults were state funded as a "matter of public interest" (res publica). Non-official but lawful cults were funded by private individuals for the benefit of their own communities. The difference between public and private cult is often unclear. Individuals or collegial associations could offer funds and cult to state deities. The public Vestals prepared ritual substances for use in public and private cults, and held the state-funded (thus public) opening ceremony for the Parentalia festival, which was otherwise a private rite to household ancestors. Some rites of the domus (household) were held in public places but were legally defined as privata in part or whole. All cults were ultimately subject to the approval and regulation of the censor and pontifices.[71]

Public priesthoods and religious law

[edit]

Rome had no separate priestly caste or class. The highest authority within a community usually sponsored its cults and sacrifices, officiated as its priest and promoted its assistants and acolytes. Specialists from the religious colleges and professionals such as haruspices and oracles were available for consultation. In household cult, the paterfamilias functioned as priest, and members of his familia as acolytes and assistants. Public cults required greater knowledge and expertise. The earliest public priesthoods were probably the flamines (the singular is flamen), attributed to king Numa: the major flamines, dedicated to Jupiter, Mars and Quirinus, were traditionally drawn from patrician families. Twelve lesser flamines were each dedicated to a single deity, whose archaic nature is indicated by the relative obscurity of some. Flamines were constrained by the requirements of ritual purity; Jupiter's flamen in particular had virtually no simultaneous capacity for a political or military career.[72]

In the Regal era, a rex sacrorum (king of the sacred rites) supervised regal and state rites in conjunction with the king (rex) or in his absence, and announced the public festivals. He had little or no civil authority. With the abolition of monarchy, the collegial power and influence of the Republican pontifices increased. By the late Republican era, the flamines were supervised by the pontifical collegia. The rex sacrorum had become a relatively obscure priesthood with an entirely symbolic title: his religious duties still included the daily, ritual announcement of festivals and priestly duties within two or three of the latter but his most important priestly role – the supervision of the Vestals and their rites – fell to the more politically powerful and influential pontifex maximus.[73]

Public priests were appointed by the collegia. Once elected, a priest held permanent religious authority from the eternal divine, which offered him lifetime influence, privilege and immunity. Therefore, civil and religious law limited the number and kind of religious offices allowed an individual and his family. Religious law was collegial and traditional; it informed political decisions, could overturn them, and was difficult to exploit for personal gain.[74]

Priesthood was a costly honour: in traditional Roman practice, a priest drew no stipend. Cult donations were the property of the deity, whose priest must provide cult regardless of shortfalls in public funding – this could mean subsidy of acolytes and all other cult maintenance from personal funds.[75] For those who had reached their goal in the Cursus honorum, permanent priesthood was best sought or granted after a lifetime's service in military or political life, or preferably both: it was a particularly honourable and active form of retirement which fulfilled an essential public duty. For a freedman or slave, promotion as one of the Compitalia seviri offered a high local profile, and opportunities in local politics; and therefore business.[76]

During the Imperial era, priesthood of the Imperial cult offered provincial elites full Roman citizenship and public prominence beyond their single year in religious office; in effect, it was the first step in a provincial cursus honorum. In Rome, the same Imperial cult role was performed by the Arval Brethren, once an obscure Republican priesthood dedicated to several deities, then co-opted by Augustus as part of his religious reforms. The Arvals offered prayer and sacrifice to Roman state gods at various temples for the continued welfare of the Imperial family on their birthdays, accession anniversaries and to mark extraordinary events such as the quashing of conspiracy or revolt. Every 3 January they consecrated the annual vows and rendered any sacrifice promised in the previous year, provided the gods had kept the Imperial family safe for the contracted time.[77]

The Vestals

[edit]

The Vestals were a public priesthood of six women devoted to the cultivation of Vesta, goddess of the hearth of the Roman state and its vital flame. A girl chosen to be a Vestal achieved unique religious distinction, public status and privileges, and could exercise considerable political influence. Upon entering her office, a Vestal was emancipated from her father's authority. In archaic Roman society, these priestesses were the only women not required to be under the legal guardianship of a man, instead answering directly to the Pontifex Maximus.[78]

A Vestal's dress represented her status outside the usual categories that defined Roman women, with elements of both virgin bride and daughter, and Roman matron and wife.[79] Unlike male priests, Vestals were freed of the traditional obligations of marrying and producing children, and were required to take a vow of chastity that was strictly enforced: a Vestal polluted by the loss of her chastity while in office was buried alive.[80] Thus the exceptional honor accorded a Vestal was religious rather than personal or social; her privileges required her to be fully devoted to the performance of her duties, which were considered essential to the security of Rome.[81]

The Vestals embody the profound connection between domestic cult and the religious life of the community.[82] Any householder could rekindle their own household fire from Vesta's flame. The Vestals cared for the Lares and Penates of the state that were the equivalent of those enshrined in each home. Besides their own festival of Vestalia, they participated directly in the rites of Parilia, Parentalia and Fordicidia. Indirectly, they played a role in every official sacrifice; among their duties was the preparation of the mola salsa, the salted flour that was sprinkled on every sacrificial victim as part of its immolation.[83]

One mythological tradition held that the mother of Romulus and Remus was a Vestal virgin of royal blood. A tale of miraculous birth also attended on Servius Tullius, sixth king of Rome, son of a virgin slave-girl impregnated by a disembodied phallus arising mysteriously on the royal hearth; the story was connected to the fascinus that was among the cult objects under the guardianship of the Vestals.

Augustus' religious reformations raised the funding and public profile of the Vestals. They were given high-status seating at games and theatres. The emperor Claudius appointed them as priestesses to the cult of the deified Livia, wife of Augustus.[84] They seem to have retained their religious and social distinctions well into the 4th century, after political power within the Empire had shifted to the Christians. When the Christian emperor Gratian refused the office of pontifex maximus, he took steps toward the dissolution of the order. His successor Theodosius I extinguished Vesta's sacred fire and vacated her temple.

Augury

[edit]Public religion took place within a sacred precinct that had been marked out ritually by an augur. The original meaning of the Latin word templum was this sacred space, and only later referred to a building.[45] Rome itself was an intrinsically sacred space; its ancient boundary (pomerium) had been marked by Romulus himself with oxen and plough; what lay within was the earthly home and protectorate of the gods of the state. In Rome, the central references for the establishment of an augural templum appear to have been the Via Sacra (Sacred Way) and the pomerium.[85] Magistrates sought divine opinion of proposed official acts through an augur, who read the divine will through observations made within the templum before, during and after an act of sacrifice.[86]

Divine disapproval could arise through unfit sacrifice, errant rites (vitia) or an unacceptable plan of action. If an unfavourable sign was given, the magistrate could repeat the sacrifice until favourable signs were seen, consult with his augural colleagues, or abandon the project. Magistrates could use their right of augury (ius augurum) to adjourn and overturn the process of law, but were obliged to base their decision on the augur's observations and advice. For Cicero, himself an augur, this made the augur the most powerful authority in the Late Republic.[87] By his time (mid 1st century BC) augury was supervised by the college of pontifices, whose powers were increasingly woven into the magistracies of the cursus honorum.[88]

Haruspicy

[edit]

Haruspicy was also used in public cult, under the supervision of the augur or presiding magistrate. The haruspices divined the will of the gods through examination of entrails after sacrifice, particularly the liver. They also interpreted omens, prodigies and portents, and formulated their expiation. Most Roman authors describe haruspicy as an ancient, ethnically Etruscan "outsider" religious profession, separate from Rome's internal and largely unpaid priestly hierarchy, essential but never quite respectable.[89] During the mid-to-late Republic, the reformist Gaius Gracchus, the populist politician-general Gaius Marius and his antagonist Sulla, and the "notorious Verres" justified their very different policies by the divinely inspired utterances of private diviners. The Senate and armies used the public haruspices: at some time during the late Republic, the Senate decreed that Roman boys of noble family be sent to Etruria for training in haruspicy and divination. Being of independent means, they would be better motivated to maintain a pure, religious practice for the public good.[90] The motives of private haruspices – especially females – and their clients were officially suspect: none of this seems to have troubled Marius, who employed a Syrian prophetess.[91]

Omens and prodigies

[edit]Omens observed within or from a divine augural templum – especially the flight of birds – were sent by the gods in response to official queries. A magistrate with ius augurium (the right of augury) could declare the suspension of all official business for the day (obnuntiato) if he deemed the omens unfavourable.[92] Conversely, an apparently negative omen could be re-interpreted as positive, or deliberately blocked from sight.[93]

Prodigies were transgressions in the natural, predictable order of the cosmos – signs of divine anger that portended conflict and misfortune. The Senate decided whether a reported prodigy was false, or genuine and in the public interest, in which case it was referred to the public priests, augurs and haruspices for ritual expiation.[94] In 207 BC, during one of the Punic Wars' worst crises, the Senate dealt with an unprecedented number of confirmed prodigies whose expiation would have involved "at least twenty days" of dedicated rites.[95]

Livy presents these as signs of widespread failure in Roman religio. The major prodigies included the spontaneous combustion of weapons, the apparent shrinking of the sun's disc, two moons in a daylit sky, a cosmic battle between sun and moon, a rain of red-hot stones, a bloody sweat on statues, and blood in fountains and on ears of corn: all were expiated by sacrifice of "greater victims". The minor prodigies were less warlike but equally unnatural; sheep become goats, a hen become a cock (and vice versa) – these were expiated with "lesser victims". The discovery of an androgynous four-year-old child was expiated by its drowning[96] and the holy procession of 27 virgins to the temple of Juno Regina, singing a hymn to avert disaster: a lightning strike during the hymn rehearsals required further expiation.[97] Religious restitution is proved only by Rome's victory.[98][99]

In the wider context of Graeco-Roman religious culture, Rome's earliest reported portents and prodigies stand out as atypically dire. Whereas for Romans, a comet presaged misfortune, for Greeks it might equally signal a divine or exceptionally fortunate birth.[100] In the late Republic, a daytime comet at the murdered Julius Caesar's funeral games confirmed his deification; a discernible Greek influence on Roman interpretation.[101]

Mystery religions

[edit]

Most of Rome's mystery cults were derived from Greek originals, adopted by individuals as private, or were formally adopted as public.[103] Mystery cults operated through a hierarchy consisting of transference of knowledge, virtues and powers to those initiated through secret rites of passage, which might employ dance, music, intoxicants and theatrical effects to provoke an overwhelming sense of religious awe, revelation and eventual catharsis. The cult of Mithras was among the most notable, particularly popular among soldiers and based on the Zoroastrian deity, Mithra.[104]

Some of Rome's most prominent deities had both public and mystery rites. Magna Mater, conscripted to help Rome defeat Carthage in the second Punic War, arrived in Rome with her consort, Attis, and their joint "foreign", non-citizen priesthood, known as Galli. Despite her presumed status as an ancestral, Trojan goddess, a priesthood was drawn from Rome's highest echelons to supervise her cult and festivals. These may have been considered too exotically "barbaric" to trust, and were barred to slaves.[105]

For the Galli, full priesthood involved self-castration, illegal for Romans of any class. Later, citizens could pay for the costly sacrifice of a bull or the lesser sacrifice of a ram, as a substitute for the acolyte's self-castration. Magna Mater's initiates tended to be very well-off, and relatively uncommon; they included the emperor Julian. Initiates to Attis' cult were more numerous and less wealthy, and acted as assistant citizen-priests in their deity's "exotic" festivals, some of which involved the Galli's public, bloody self-flagellation.[106]

Rome's native cults to the grain goddess Ceres and her daughter Libera were supplemented with a mystery cult of Ceres-with-Proserpina, based on the Greek Eleusinian mysteries and Thesmophoria, introduced in 205 BC and led at first by ethnically Greek priestesses from Graeca magna.[107] The Eleusinian mysteries are also the likely source for the mysteries of Isis, which employed symbols and rites that were nominally Egyptian. Aspects of the Isis mysteries are almost certainly described in Appuleius' novel, The Golden Ass. Such cults were mistrusted by Rome's authorities as quasi-magical, potentially seductive and emotionally based, rather than practical.

The wall-paintings in Pompeii's "Villa of the Mysteries" could have functioned equally as religious inspiration, instruction, and high quality domestic decor (described by Beard as "expensive wallpaper"). They also attest to an increasingly personal, even domestic experience of religion, whether or not they were ever part of organised cult meetings. The paintings probably represent the once-notorious, independent, popular Bacchanalia mysteries, forcibly brought under the direct control of Rome's civil and religious authorities, 100 years before.[108]

A common theme among the eastern mystery religions present in Rome became disillusionment with material possessions, a focus on death and a preoccupation with regards to the afterlife. These attributes later led to the appeal to Christianity, which in its early stages was often viewed as mystery religion itself.[104]

Funerals and the afterlife

[edit]

Roman beliefs about an afterlife varied, and are known mostly for the educated elite who expressed their views in terms of their chosen philosophy. The traditional care of the dead, however, and the perpetuation after death of their status in life were part of the most archaic practices of Roman religion. Ancient votive deposits to the noble dead of Latium and Rome suggest elaborate and costly funeral offerings and banquets in the company of the deceased, an expectation of afterlife and their association with the gods.[109] As Roman society developed, its Republican nobility tended to invest less in spectacular funerals and extravagant housing for their dead, and more on monumental endowments to the community, such as the donation of a temple or public building whose donor was commemorated by his statue and inscribed name.[110] Persons of low or negligible status might receive simple burial, with such grave goods as relatives could afford.

Funeral and commemorative rites varied according to wealth, status and religious context. In Cicero's time, the better-off sacrificed a sow at the funeral pyre before cremation. The dead consumed their portion in the flames of the pyre, Ceres her portion through the flame of her altar, and the family at the site of the cremation. For the less well-off, inhumation with "a libation of wine, incense, and fruit or crops was sufficient". Ceres functioned as an intermediary between the realms of the living and the dead: the deceased had not yet fully passed to the world of the dead and could share a last meal with the living. The ashes (or body) were entombed or buried. On the eighth day of mourning, the family offered further sacrifice, this time on the ground; the shade of the departed was assumed to have passed from the world of the living into the underworld, as one of the di Manes, underworld spirits; the ancestral manes of families were celebrated and appeased at their cemeteries or tombs, in the obligatory Parentalia, a multi-day festival of remembrance in February.[111]

A standard Roman funerary inscription is Dis Manibus (to the Manes-gods). Regional variations include its Greek equivalent, theoîs katachthoníois[112] and Lugdunum's commonplace but mysterious "dedicated under the trowel" (sub ascia dedicare).[113]

In the later Imperial era, the burial and commemorative practises of Christian and non-Christians overlapped. Tombs were shared by Christian and non-Christian family members, and the traditional funeral rites and feast of novemdialis found a part-match in the Christian Constitutio Apostolica.[114] The customary offers of wine and food to the dead continued; St Augustine (following St Ambrose) feared that this invited the "drunken" practices of Parentalia but commended funeral feasts as a Christian opportunity to give alms of food to the poor. Christians attended Parentalia and its accompanying Feralia and Caristia in sufficient numbers for the Council of Tours to forbid them in AD 567. Other funerary and commemorative practices were very different. Traditional Roman practice spurned the corpse as a ritual pollution; inscriptions noted the day of birth and duration of life. The Christian Church fostered the veneration of saintly relics, and inscriptions marked the day of death as a transition to "new life".[115]

Religion and the military

[edit]

Military success was achieved through a combination of personal and collective virtus (roughly, "manly virtue") and the divine will: lack of virtus, civic or private negligence in religio and the growth of superstitio provoked divine wrath and led to military disaster. Military success was the touchstone of a special relationship with the gods, and to Jupiter Capitolinus in particular; triumphal generals were dressed as Jupiter, and laid their victor's laurels at his feet.[116][117]

Roman commanders offered vows to be fulfilled after success in battle or siege; and further vows to expiate their failures. Camillus promised Veii's goddess Juno a temple in Rome as incentive for her desertion (evocatio), conquered the city in her name, brought her cult statue to Rome "with miraculous ease" and dedicated a temple to her on the Aventine Hill.[118]

Roman camps followed a standard pattern for defense and religious ritual; in effect they were Rome in miniature. The commander's headquarters stood at the centre; he took the auspices on a dais in front. A small building behind housed the legionary standards, the divine images used in religious rites and in the Imperial era, the image of the ruling emperor. In one camp, this shrine is even called Capitolium. The most important camp-offering appears to have been the suovetaurilia performed before a major, set battle. A ram, a boar and a bull were ritually garlanded, led around the outer perimeter of the camp (a lustratio exercitus) and in through a gate, then sacrificed: Trajan's column shows three such events from his Dacian wars. The perimeter procession and sacrifice suggest the entire camp as a divine templum; all within are purified and protected.[119]

Each camp had its own religious personnel; standard bearers, priestly officers and their assistants, including a haruspex, and housekeepers of shrines and images. A senior magistrate-commander (sometimes even a consul) headed it, his chain of subordinates ran it and a ferocious system of training and discipline ensured that every citizen-soldier knew his duty. As in Rome, whatever gods he served in his own time seem to have been his own business; legionary forts and vici included shrines to household gods, personal deities and deities otherwise unknown.[120]

From the earliest Imperial era, citizen legionaries and provincial auxiliaries gave cult to the emperor and his familia on Imperial accessions, anniversaries and their renewal of annual vows. They celebrated Rome's official festivals in absentia, and had the official triads appropriate to their function – in the Empire, Jupiter, Victoria and Concordia were typical. By the early Severan era, the military also offered cult to the Imperial divi, the current emperor's numen, genius and domus (or familia), and special cult to the Empress as "mother of the camp". The near ubiquitous legionary shrines to Mithras of the later Imperial era were not part of official cult until Mithras was absorbed into Solar and Stoic Monism as a focus of military concordia and Imperial loyalty.[121][122][123]

The devotio was the most extreme offering a Roman general could make, promising to offer his own life in battle along with the enemy as an offering to the underworld gods. Livy offers a detailed account of the devotio carried out by Decius Mus; family tradition maintained that his son and grandson, all bearing the same name, also devoted themselves. Before the battle, Decius is granted a prescient dream that reveals his fate. When he offers sacrifice, the victim's liver appears "damaged where it refers to his own fortunes". Otherwise, the haruspex tells him, the sacrifice is entirely acceptable to the gods. In a prayer recorded by Livy, Decius commits himself and the enemy to the dii Manes and Tellus, charges alone and headlong into the enemy ranks, and is killed; his action cleanses the sacrificial offering. Had he failed to die, his sacrificial offering would have been tainted and therefore void, with possibly disastrous consequences.[124] The act of devotio is a link between military ethics and those of the Roman gladiator.

The efforts of military commanders to channel the divine will were on occasion less successful. In the early days of Rome's war against Carthage, the commander Publius Claudius Pulcher (consul 249 BC) launched a sea campaign "though the sacred chickens would not eat when he took the auspices". In defiance of the omen, he threw them into the sea, "saying that they might drink, since they would not eat. He was defeated, and on being bidden by the Senate to appoint a dictator, he appointed his messenger Glycias, as if again making a jest of his country's peril." His impiety not only lost the battle but ruined his career.[125]

Women and religion

[edit]Roman women were present at most festivals and cult observances. Some rituals specifically required the presence of women, but their active participation was limited. As a rule women did not perform animal sacrifice, the central rite of most major public ceremonies.[126] In addition to the public priesthood of the Vestals, some cult practices were reserved for women only. The rites of the Bona Dea excluded men entirely.[127] Because women enter the public record less frequently than men, their religious practices are less known, and even family cults were headed by the paterfamilias. A host of deities, however, are associated with motherhood. Juno, Diana, Lucina, and specialized divine attendants presided over the life-threatening act of giving birth and the perils of caring for a baby at a time when the infant mortality rate was as high as 40 percent.

Literary sources vary in their depiction of women's religiosity: some represent women as paragons of Roman virtue and devotion, but also inclined by temperament to self-indulgent religious enthusiasms, novelties and the seductions of superstitio.[128]

Superstitio and magic

[edit]

Excessive devotion and enthusiasm in religious observance were superstitio, in the sense of "doing or believing more than was necessary",[129] to which women and foreigners were considered particularly prone.[130] The boundary between religio and superstitio is not clearly defined. The famous tirade of Lucretius, the Epicurean rationalist, against what is usually translated as "superstition" was in fact aimed at excessive religio. Roman religion was based on knowledge rather than faith,[131] but superstitio was viewed as an "inappropriate desire for knowledge"; in effect, an abuse of religio.[129]

In the everyday world, many individuals sought to divine the future, influence it through magic, or seek vengeance with help from "private" diviners. The state-sanctioned taking of auspices was a form of public divination with the intent of ascertaining the will of the gods, not foretelling the future. Secretive consultations between private diviners and their clients were thus suspect. So were divinatory techniques such as astrology when used for illicit, subversive or magical purposes. Astrologers and magicians were officially expelled from Rome at various times, notably in 139 BC and 33 BC. In 16 BC Tiberius expelled them under extreme penalty because an astrologer had predicted his death. "Egyptian rites" were particularly suspect: Augustus banned them within the pomerium to doubtful effect; Tiberius repeated and extended the ban with extreme force in AD 19.[132] Despite several Imperial bans, magic and astrology persisted among all social classes. In the late 1st century AD, Tacitus observed that astrologers "would always be banned and always retained at Rome".[133][134][135]

In the Graeco-Roman world, practitioners of magic were known as magi (singular magus), a "foreign" title of Persian priests. Apuleius, defending himself against accusations of casting magic spells, defined the magician as "in popular tradition (more vulgari)... someone who, because of his community of speech with the immortal gods, has an incredible power of spells (vi cantaminum) for everything he wishes to."[136] Pliny the Elder offers a thoroughly skeptical "History of magical arts" from their supposed Persian origins to Nero's vast and futile expenditure on research into magical practices in an attempt to control the gods.[137] Philostratus takes pains to point out that the celebrated Apollonius of Tyana was definitely not a magus, "despite his special knowledge of the future, his miraculous cures, and his ability to vanish into thin air".[138]

Lucan depicts Sextus Pompeius, the doomed son of Pompey the Great, as convinced "the gods of heaven knew too little" and awaiting the Battle of Pharsalus by consulting with the Thessalian witch Erichtho, who practices necromancy and inhabits deserted graves, feeding on rotting corpses. Erichtho, it is said, can arrest "the rotation of the heavens and the flow of rivers" and make "austere old men blaze with illicit passions". She and her clients are portrayed as undermining the natural order of gods, mankind and destiny. A female foreigner from Thessaly, notorious for witchcraft, Erichtho is the stereotypical witch of Latin literature,[139] along with Horace's Canidia.

The Twelve Tables forbade any harmful incantation (malum carmen, or 'noisome metrical charm'); this included the "charming of crops from one field to another" (excantatio frugum) and any rite that sought harm or death to others. Chthonic deities functioned at the margins of Rome's divine and human communities; although sometimes the recipients of public rites, these were conducted outside the sacred boundary of the pomerium. Individuals seeking their aid did so away from the public gaze, during the hours of darkness. Burial grounds and isolated crossroads were among the likely portals.[140] The barrier between private religious practices and "magic" is permeable, and Ovid gives a vivid account of rites at the fringes of the public Feralia festival that are indistinguishable from magic: an old woman squats among a circle of younger women, sews up a fish-head, smears it with pitch, then pierces and roasts it to "bind hostile tongues to silence". By this she invokes Tacita, the "Silent One" of the underworld.

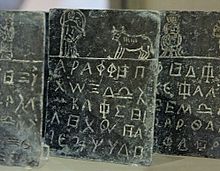

Archaeology confirms the widespread use of binding spells (defixiones), magical papyri and so-called "voodoo dolls" from a very early era. Around 250 defixiones have been recovered just from Roman Britain, in both urban and rural settings. Some seek straightforward, usually gruesome revenge, often for a lover's offense or rejection. Others appeal for divine redress of wrongs, in terms familiar to any Roman magistrate, and promise a portion of the value (usually small) of lost or stolen property in return for its restoration. None of these defixiones seem produced by, or on behalf of the elite, who had more immediate recourse to human law and justice. Similar traditions existed throughout the empire, persisting until around the 7th century AD, well into the Christian era.[141]

History of Roman religion

[edit]Religion and politics

[edit]

Rome's government, politics and religion were dominated by an educated, male, landowning military aristocracy. Approximately half of Rome's population were slave or free non-citizens. Most others were plebeians, the lowest class of Roman citizens. Less than a quarter of adult males had voting rights; far fewer could actually exercise them. Women had no vote.[142] However, all official business was conducted under the divine gaze and auspices, in the name of the Senate and people of Rome. "In a very real sense the senate was the caretaker of the Romans’ relationship with the divine, just as it was the caretaker of their relationship with other humans".[143]

The links between religious and political life were vital to Rome's internal governance, diplomacy and development from kingdom, to Republic and to Empire. Post-regal politics dispersed the civil and religious authority of the kings more or less equitably among the patrician elite: kingship was replaced by two annually elected consular offices. In the early Republic, as presumably in the regal era, plebeians were excluded from high religious and civil office, and could be punished for offenses against laws of which they had no knowledge.[144] They resorted to strikes and violence to break the oppressive patrician monopolies of high office, public priesthood, and knowledge of civil and religious law. The Senate appointed Camillus as dictator to handle the emergency; he negotiated a settlement, and sanctified it by the dedication of a temple to Concordia.[145] The religious calendars and laws were eventually made public. Plebeian tribunes were appointed, with sacrosanct status and the right of veto in legislative debate. In principle, the augural and pontifical colleges were now open to plebeians.[146] In reality, the patrician and to a lesser extent, plebeian nobility dominated religious and civil office throughout the Republican era and beyond.[147]

While the new plebeian nobility made social, political and religious inroads on traditionally patrician preserves, their electorate maintained their distinctive political traditions and religious cults.[148] During the Punic crisis, popular cult to Dionysus emerged from southern Italy; Dionysus was equated with Father Liber, the inventor of plebeian augury and personification of plebeian freedoms, and with Roman Bacchus. Official consternation at these enthusiastic, unofficial Bacchanalia cults was expressed as moral outrage at their supposed subversion, and was followed by ferocious suppression. Much later, a statue of Marsyas, the silen of Dionysus flayed by Apollo, became a focus of brief symbolic resistance to Augustus' censorship. Augustus himself claimed the patronage of Venus and Apollo; but his settlement appealed to all classes. Where loyalty was implicit, no divine hierarchy need be politically enforced; Liber's festival continued.[149][150]

The Augustan settlement built upon a cultural shift in Roman society. In the middle Republican era, even Scipio's tentative hints that he might be Jupiter's special protege sat ill with his colleagues.[151] Politicians of the later Republic were less equivocal; both Sulla and Pompey claimed special relationships with Venus. Julius Caesar went further; he claimed her as his ancestress, and thus an intimate source of divine inspiration for his personal character and policies. In 63 BC, his appointment as pontifex maximus "signaled his emergence as a major player in Roman politics".[152] Likewise, political candidates could sponsor temples, priesthoods and the immensely popular, spectacular public ludi and munera whose provision became increasingly indispensable to the factional politics of the Late Republic.[153] Under the principate, such opportunities were limited by law; priestly and political power were consolidated in the person of the princeps ("first citizen").

Because of you we are living, because of you we can travel the seas, because of you we enjoy liberty and wealth. —A thanksgiving prayer offered in Naples' harbour to the princeps Augustus, on his return from Alexandria in 14 AD, shortly before his death.[154]

Early Republic

[edit]

By the end of the regal period Rome had developed into a city-state, with a large plebeian, artisan class excluded from the old patrician gentes and from the state priesthoods. The city had commercial and political treaties with its neighbours; according to tradition, Rome's Etruscan connections established a temple to Minerva on the predominantly plebeian Aventine; she became part of a new Capitoline triad of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva, installed in a Capitoline temple, built in an Etruscan style and dedicated in a new September festival, Epulum Jovis.[155] These are supposedly the first Roman deities whose images were adorned, as if noble guests, at their own inaugural banquet.

Rome's diplomatic agreement with its neighbours of Latium confirmed the Latin league and brought the cult of Diana from Aricia to the Aventine.[156] and established on the Aventine in the "commune Latinorum Dianae templum":[157] At about the same time, the temple of Jupiter Latiaris was built on the Alban mount, its stylistic resemblance to the new Capitoline temple pointing to Rome's inclusive hegemony. Rome's affinity to the Latins allowed two Latin cults within the pomoerium.[158] The cult to Hercules at the ara maxima in the Forum Boarium was established through commercial connections with Tibur.[159] The Tusculan cult of Castor as the patron of cavalry found a home close to the Forum Romanum:[160] Juno Sospita and Juno Regina were brought from Italy, and Fortuna Primigenia from Praeneste. In 217, the Venus of Eryx was brought from Sicily and installed in a temple on the Capitoline hill.[161]

Later Republic to Principate

[edit]

The introduction of new or equivalent deities coincided with Rome's most significant aggressive and defensive military forays. Livy attributed the disasters of the early part of Rome's second Punic War to a growth of superstitious cults, errors in augury and the neglect of Rome's traditional gods, whose anger was expressed directly through Rome's defeat at Cannae (216 BC). The Sibylline books were consulted. They recommended a general vowing of the ver sacrum[162] and in the following year, the living burial of two Greeks and two Gauls; not the first nor the last sacrifice of its kind, according to Livy.

In 206 BC, during the Punic crisis, the Sibylline books recommended the introduction of a cult to the Magna Mater (Great Mother) from Pessinus, supposedly an ancestral goddess of Romans and Trojans. She was installed on the Palatine in 191 BC.

Deities with troublesome followers were taken over, not banned. An unofficial, popular mystery cult to Bacchus was officially taken over, restricted and supervised as potentially subversive in 186 BC.[163]

The priesthoods of most Roman deities with clearly Greek origins used an invented version of Greek costume and ritual, which Romans called "Greek rites." The spread of Greek literature, mythology and philosophy offered Roman poets and antiquarians a model for the interpretation of Rome's festivals and rituals, and the embellishment of its mythology. Ennius translated the work of Graeco-Sicilian Euhemerus, who explained the genesis of the gods as deified mortals. In the last century of the Republic, Epicurean and particularly Stoic interpretations were a preoccupation of the literate elite, most of whom held – or had held – high office and traditional Roman priesthoods; notably, Scaevola and the polymath Varro. For Varro – well versed in Euhemerus' theory – popular religious observance was based on a necessary fiction; what the people believed was not itself the truth, but their observance led them to as much higher truth as their limited capacity could deal with. Whereas in popular belief deities held power over mortal lives, the skeptic might say that mortal devotion had made gods of mortals, and these same gods were only sustained by devotion and cult.

Just as Rome itself claimed the favour of the gods, so did some individual Romans. In the mid-to-late Republican era, and probably much earlier, many of Rome's leading clans acknowledged a divine or semi-divine ancestor and laid personal claim to their favour and cult, along with a share of their divinity. Most notably in the very late Republic, the Julii claimed Venus Genetrix as an ancestor; this would be one of many foundations for the Imperial cult. The claim was further elaborated and justified in Vergil's poetic, Imperial vision of the past.[8]

In the late Republic, the so-called Marian reforms supposedly did the following: lowered an existing property bar on conscription, increased the efficiency of Rome's armies, and made them available as instruments of political ambition and factional conflict.[164] The consequent civil wars led to changes at every level of Roman society. Augustus' principate established peace and subtly transformed Rome's religious life – or, in the new ideology of Empire, restored it (see below).

Sissel Undheim has argued that, with their Religions of Rome volumes, Mary Beard, John North, and Simon Price dismantled the well-established narrative of the decline of religious in the late Republic, opening the way for more innovative and dynamic perspectives.[165] Towards the end of the Republic, religious and political offices became more closely intertwined; the office of pontifex maximus became a de facto consular prerogative.[88] Augustus was personally vested with an extraordinary breadth of political, military and priestly powers; at first temporarily, then for his lifetime. He acquired or was granted an unprecedented number of Rome's major priesthoods, including that of pontifex maximus; as he invented none, he could claim them as traditional honours. His reforms were represented as adaptive, restorative and regulatory, rather than innovative; most notably his elevation (and membership) of the ancient Arvales, his timely promotion of the plebeian Compitalia shortly before his election and his patronage of the Vestals as a visible restoration of Roman morality.[166] Augustus obtained the pax deorum, maintained it for the rest of his reign and adopted a successor to ensure its continuation. This remained a primary religious and social duty of emperors.

Roman Empire

[edit]Eastern Influence

[edit]

При правлении Августа существовала целенаправленная кампания по восстановлению ранее существовавших систем верований среди римского населения. Эти когда-то существовавшие идеалы к этому времени были подорваны и встречены с цинизмом. [167] Императорский орден делал упор на увековечивание памяти великих людей и событий, которые привели к возникновению концепции и практики божественного царствования. Императоры, уступившие Августа, впоследствии занимали должность главного жреца ( pontifex maximus ), сочетая под одним титулом как политическое, так и религиозное превосходство. [104]

Поглощение культов

[ редактировать ]

Римская империя расширилась и включила в себя разные народы и культуры; В принципе, Рим следовал той же инклюзивной политике, которая признавала латинские, этрусские и другие итальянские народы, культы и божества римскими. Те, кто признал гегемонию Рима, сохранили свои собственные культы и религиозные календари, независимые от римского религиозного закона. [168] Недавно муниципальный Сабрата построил Капитолий рядом с существующим храмом Liber Pater и Serapis . Автономия и согласие были официальной политикой, но новые фонды римских граждан или их романизированных союзников, вероятно, следовали римским культовым моделям. [169] Романизация давала явные политические и практические преимущества, особенно местным элитам. Все известные изображения с форума II века нашей эры в Куикуле изображают императоров или Конкордию . К середине I века нашей эры галльский Верто, по-видимому, отказался от своего родного культового жертвоприношения лошадей и собак в пользу недавно возникшего поблизости романизированного культа: к концу того же века так называемый тофет Сабраты уже не использовался. использовать. [170] Посвящение колониальных, а затем и имперских провинций Капитолийской триаде Рима было логичным выбором, а не централизованным юридическим требованием. [171] Крупные центры культа «неримских» божеств продолжали процветать: яркими примерами являются великолепный Александрийский Серапиум , храм Эскулапея в Пергаме и священный лес Аполлона в Антиохии. [172]

Общий дефицит свидетельств существования более мелких или местных культов не всегда означает пренебрежение ими; вотивные надписи непоследовательно разбросаны по географии и истории Рима. Посвящения были дорогостоящим публичным заявлением, которого следовало ожидать в рамках греко-римской культуры, но ни в коем случае не было универсальным. Бесчисленные более мелкие, личные или более секретные культы сохранились бы и не оставили бы никаких следов. [173]

Военное урегулирование внутри империи и на ее границах расширило контекст Романитас . Граждане-солдаты Рима воздвигли алтари множеству божеств, включая своих традиционных богов, имперского гения и местных божеств – иногда с полезным открытым посвящением diis deabusque omnibus (всем богам и богиням). Они также принесли с собой римских «домашних» божеств и культовые практики. [174] Точно так же позднее предоставление гражданства провинциалам и их призыв в легионы принесли их новые культы в римскую армию. [175]

Торговцы, легионы и другие путешественники привозили домой культы, происходящие из Египта, Греции, Иберии, Индии и Персии. Особое значение имели культы Кибелы , Исиды , Митры и Солнца Инвиктус . Некоторые из них были инициатическими религиями, имевшими большое личное значение и в этом отношении похожими на христианство.

Имперский культ

[ редактировать ]

В раннюю имперскую эпоху принцепсу (букв. «первый» или «первейший» среди граждан) предлагался культ гения в качестве символического отца семейства Рима. У его культа были и другие прецеденты: популярный, неофициальный культ, предлагаемый могущественным благотворителям в Риме: царские, богоподобные почести, оказываемые римскому полководцу в день его триумфа ; и в божественных почестях, оказываемых римским магнатам на греческом Востоке, по крайней мере, с 195 г. до н.э. [176] [177]

Обожествление умерших императоров имело прецедент в римском домашнем культе dii Parentes (обожествленных предков) и мифического апофеоза основателей Рима. Умерший император даровал апофеоз своему преемнику, и Сенат стал официальным государственным божеством . Члены императорской семьи могли быть удостоены аналогичных почестей и культа; умершая жена, сестра или дочь императора могла быть повышена до дивы (женского божества).