Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (/ˌtæmɪl ˈnɑːduː/; Tamil: [ˈtamiɻ ˈnaːɽɯ] , abbr. TN) is the southernmost state of India. The tenth largest Indian state by area and the sixth largest by population, Tamil Nadu is the home of the Tamil people, who speak the Tamil language, one of the longest surviving classical languages and which serves as its official language. The capital and largest city is Chennai.

Located on the south-eastern coast of the Indian peninsula, Tamil Nadu is straddled by the Western Ghats and Deccan Plateau in the west, the Eastern Ghats in the north, the Eastern Coastal Plains lining the Bay of Bengal in the east, the Gulf of Mannar and the Palk Strait to the south-east, the Laccadive Sea at the southern cape of the peninsula, with the river Kaveri bisecting the state. Politically, Tamil Nadu is bound by the Indian states of Kerala to the west, Karnataka to the northwest, Andhra Pradesh to the north, and encloses part of the union territory of Puducherry. It shares an international maritime border with the Northern Province of Sri Lanka at Pamban Island.

Archaeological evidence points to Tamil Nadu being inhabited for more than 400 millennia, first by hominids and then by modern humans. Tamil Nadu has more than 5,500 years of continuous cultural history. Historically, the Tamilakam region was inhabited by Tamil-speaking Dravidian people and was ruled by several regimes over centuries, such as the Sangam era triumverate of the Cheras, Cholas and Pandyas, the Pallavas (3rd–9th century CE), and the later Vijayanagara Empire (14th–17th century CE). European colonization began with establishing trade ports in the 17th century, with the British controlling much of South India as the Madras Presidency for two centuries before Indian Independence in 1947. After independence, the region became the Madras State of the Republic of India and was further re-organized when states were redrawn linguistically in 1956 into the current shape. The state was renamed as Tamil Nadu, meaning "Tamil Country", in 1969. Hence, culture, cuisine and architecture have seen multiple influences over the years and have developed diversely.

As the most urbanised state of India, Tamil Nadu boasts an economy with gross state domestic product (GSDP) of ₹23.65 trillion (US$280 billion), making it the second-largest economy amongst the 28 states of India. It has the country's 9th-highest GSDP per capita of ₹275,583 (US$3,300) and ranks 11th in human development index. Tamil Nadu is also one of the most industrialised states, with the manufacturing sector accounting for nearly one-third of the state's GDP. With its diverse culture and architecture, long coastline, forests and mountains, Tamil Nadu is home to a number of ancient relics, historic buildings, religious sites, beaches, hill stations, forts, waterfalls and four World Heritage Sites. The state's tourism industry is the largest among the Indian states. Forests occupy an area of 22,643 km2 (8,743 sq mi) constituting 17.4% of the geographic area of which protected areas cover an area of 3,305 km2 (1,276 sq mi), around 15% of the recorded forest area of the state and consists of three biosphere reserves, mangrove forests, five National Parks, 18 wildlife sanctuaries and 17 bird sanctuaries. The Tamil film industry, nicknamed as Kollywood, plays an influential role in the state's popular culture.

Etymology

The name is derived from Tamil language with nadu meaning "land" and Tamil Nadu meaning "the land of Tamils". The origin and precise etymology of the word Tamil is unclear with multiple theories attested to it.[6] In the ancient Sangam literature, Tamilakam refers to the area of present-day Tamil Nadu, Kerala and parts of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. Tolkāppiyam (2nd to 1st century BCE) indicates the borders of Tamilakam as Tirumala and Kanniya Kumari.[7] The name Tamilakam is used in other Sangam era literature such as Puṟanāṉūṟu, Patiṟṟuppattu, Cilappatikaram, and Manimekalai.[8] Cilappatikaram (5th to 6th century CE) and Ramavataram (12th century CE) mention the name Tamil Nadu to denote the region.[9][10][11]

History

Prehistory (before 5th century BCE)

Archaeological evidence points to the region being inhabited by hominids more than 400 millennia ago.[12][13] Artifacts recovered in Adichanallur by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) indicate a continuous history from more than 3,800 years ago.[14] Neolithic celts with the Indus script dated between 1500 and 2000 BCE indicate the use of the Harappan language.[15][16] Excavations at Keezhadi have revealed a large urban settlement dating to the 6th century BCE, during the time of urbanization in the Indo-Gangetic plain.[17] Further epigraphical inscriptions found at Adichanallur use Tamil Brahmi, a rudimentary script dated to 5th century BCE.[18] Potsherds uncovered from Keeladi indicate a script which is a transition between the Indus Valley script and Tamil Brahmi script used later.[19]

Sangam period (5th century BCE–3rd century CE)

The Sangam period lasted for about eight centuries, from 500 BCE to 300 CE with the main source of history during the period coming from the Sangam literature.[20][21] Ancient Tamilakam was ruled by a triumvirate of monarchical states, Cheras, Cholas and Pandyas.[22] The Cheras controlled the western part of Tamilkam, the Pandyas controlled the south, and the Cholas had their base in the Kaveri delta. The kings called Vendhar ruled over several tribes of Velala (peasants), headed by the Velir chiefs.[23] The rulers patronized multiple religions including vedic religion, Buddhism and Jainism and sponsored some of the earliest Tamil literature with the oldest surviving work being Tolkāppiyam, a book of Tamil grammar.[24]

The kingdoms had significant diplomatic and trade contacts with other kingdoms to the north and with the Romans.[25] Much of the commerce from the Romans and Han China were facilitated via seaports including Muziris and Korkai with spices being the most prized goods along with pearls and silk.[26][27] From 300 CE, the region was ruled by the Kalabhras, warriors belonging to the Vellalar community, who were once feudatories of the three ancient Tamil kingdoms.[28] The Kalabhra era is referred to as the "dark period" of Tamil history, and information about it is generally inferred from any mentions in the literature and inscriptions that are dated many centuries after their era ended.[29] The twin Tamil epics Silappatikaram and Manimekalai were written during the era.[30] Tamil classic Tirukkural by Valluvar, a collection of couplets is attributed to the same period.[31][32]

Medieval era (4th–13th century CE)

Around the 7th century CE, the Kalabhras were overthrown by the Pandyas and Cholas, who patronised Buddhism and Jainism before the revival of Saivism and Vaishnavism during the Bhakti movement.[33] Though they existed previously, the period saw the rise of the Pallavas in the sixth century CE under Mahendravarman I, who ruled parts of South India with Kanchipuram as their capital.[34] The Pallavas were noted for their patronage of architecture: the massive gopuram, ornate towers at the entrance of temples, originated with the Pallava architecture. They built the group of rock-cut monuments in Mahabalipuram and temples in Kanchipuram.[35] Throughout their reign, the Pallavas remained in constant conflict with the Cholas and Pandyas. The Pandyas were revived by Kadungon towards the end of the 6th century CE and with the Cholas in obscurity in Uraiyur, the Tamil country was divided between the Pallavas and the Pandyas.[36] The Pallavas were finally defeated by Chola prince Aditya I in the 9th century CE.[37]

The Cholas became the dominant kingdom in the 9th century under Vijayalaya Chola, who established Thanjavur as Chola's new capital with further expansions by subsequent rulers. In the 11th century CE, Rajaraja I expanded the Chola empire with conquests of entire Southern India and parts of present-day Sri Lanka and Maldives, and increased Chola influence across the Indian Ocean.[38][39] Rajaraja brought in administrative reforms including the reorganisation of Tamil country into individual administrative units.[40] Under his son Rajendra Chola I, the Chola empire reached its zenith and stretched as far as Bengal in the north and across the Indian Ocean.[41] The Cholas built many temples in the Dravidian style with the most notable being the Brihadisvara Temple at Thanjavur, one of the foremost temples of the era built by Rajaraja, and Gangaikonda Cholapuram, built by Rajendra.[42]

The Pandyas again reigned supreme early in the 13th century under Maravarman Sundara I.[43] They ruled from their capital of Madurai and expanded trade links with other maritime empires.[44] During the 13th century, Marco Polo mentioned the Pandyas as the richest empire in existence. The Pandyas also built a number of temples including the Meenakshi Amman Temple at Madurai.[45]

Vijayanagar and Nayak period (14th–17th century CE)

In the 13th and 14th centuries, there were repeated attacks from Delhi Sultanate.[46] The Vijayanagara kingdom was founded in 1336 CE.[47] The Vijayanagara empire eventually conquered the entire Tamil country by c. 1370 and ruled for almost two centuries until its defeat in the Battle of Talikota in 1565 by a confederacy of Deccan sultanates.[48][49]Later, the Nayaks, who were the military governors in the Vijaynagara Empire, took control of the region amongst whom the Nayaks of Madurai and Nayaks of Thanjavur were the most prominent.[50][51] They introduced the palayakkararar system and re-constructed some of the well-known temples in Tamil Nadu including the Meenakshi Temple in Madurai.[52]

Later conflicts and European colonization (17th to 20th century CE)

In the 18th century, the Mughal empire administered the region through the Nawab of the Carnatic with his seat at Arcot, who defeated the Madurai Nayaks.[53] The Marathas attacked several times and defeated the Nawab after the Siege of Trichinopoly (1751-1752).[54][55][56] This led to a short-lived Thanjavur Maratha kingdom.[57]

Europeans started to establish trade centres from the 16th century along the eastern coast. The Portuguese arrived in 1522 and built a port named São Tomé near present-day Mylapore in Madras.[58] In 1609, the Dutch established a settlement in Pulicat and the Danes had their establishment in Tharangambadi.[59][60] On 20 August 1639, Francis Day of the British East India Company met with the Vijayanager emperor Peda Venkata Raya and obtained a grant for land on the Coromandel coast for their trading activities.[61][62][63] A year later, the company built Fort St. George, the first major English settlement in India, which became the nucleus of the British Raj in the region.[64][65] By 1693, the French established trading posts at Pondichéry. In September 1746, the French captured Madras during the Battle of Madras.[66] The British regained control of Madras in 1749 through the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle and resisted a French siege attempt in 1759.[67][68] The British and French competed to expand the trade which led to Battle of Wandiwash in 1760 as part of the Seven Years' War.[69] The Nawabs of the Carnatic surrendered much of their territory to the British East India Company in the north and bestowed tax revenue collection rights in the South, which led to constant conflicts with the Palaiyakkarars known as the Polygar Wars. Puli Thevar was one of the earliest opponents, joined later by Rani Velu Nachiyar of Sivagangai and Kattabomman of Panchalakurichi in the first series of Polygar wars.[70][71] The Maruthu brothers along with Oomaithurai, the brother of Kattabomman, formed a coalition with Dheeran Chinnamalai and Kerala Varma Pazhassi Raja, which fought the British in the Second Polygar War.[72] In the later 18th century, the Mysore kingdom captured parts of the region and engaged in constant fighting with the British which culminated in the four Anglo-Mysore Wars.[73]

By the 18th century, the British had conquered most of the region and established the Madras Presidency with Madras as the capital.[74] After the defeat of Mysore in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War in 1799 and the British victory in the second Polygar war in 1801, the British consolidated most of southern India into what was later known as the Madras Presidency.[75] On 10 July 1806, the Vellore mutiny, which was the first instance of a large-scale mutiny by Indian sepoys against the British East India Company, took place in Vellore Fort.[76][77] After the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the British Parliament passed the Government of India Act 1858, which transferred the governance of India from the East India Company to the British crown, forming the British Raj.[78]

Failure of the summer monsoons and administrative shortcomings of the Ryotwari system resulted in two severe famines in the Madras Presidency, the Great Famine of 1876–78 and the Indian famine of 1896–97 which killed millions and the migration of many Tamils as bonded laborers to other British countries eventually forming the present Tamil diaspora.[79] The Indian Independence movement gathered momentum in the early 20th century with the formation of the Indian National Congress, which was based on an idea propagated by the members of the Theosophical Society movement after a Theosophical convention held in Madras in December 1884.[80][81] Tamil Nadu was the base of various contributors to the Independence movement including V. O. Chidambaram Pillai, Subramaniya Siva and Bharatiyar.[82] The Tamils formed a significant percentage of the members of the Indian National Army (INA), founded by Subhas Chandra Bose.[83]

Post-Independence (1947–present)

After the Independence of India in 1947, the Madras Presidency became Madras state, comprising present-day Tamil Nadu and parts of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Kerala. Andhra state was split from the state in 1953 and the state was further re-organized when states were redrawn linguistically in 1956 into the current shape.[84][85] On 14 January 1969, Madras state was renamed Tamil Nadu, meaning "Tamil country".[86][87] In 1965, agitations against the imposition of Hindi and in support of continuing English as a medium of communication arose which eventually led to English being retained as an official language of India alongside Hindi.[88] After independence, the economy of Tamil Nadu conformed to a socialist framework, with strict governmental control over private sector participation, foreign trade, and foreign direct investment. After experiencing fluctuations in the decades immediately after Indian independence, the economy of Tamil Nadu consistently exceeded national average growth rates from the 1970s, due to reform-oriented economic policies.[89] In the 2000s, the state has become one of the most urbanized states in the country with a higher Human Development Index compared to national average.[90]

Environment

Geography

Tamil Nadu covers an area of 130,058 km2 (50,216 sq mi) and is the tenth-largest state in India.[90] Located on the south-eastern coast of the Indian peninsula, Tamil Nadu is straddled by the Western Ghats and Deccan Plateau in the west, the Eastern Ghats in the north, the Eastern Coastal Plains lining the Bay of Bengal in the east, the Gulf of Mannar and the Palk Strait to the south-east, and the Laccadive Sea at the southern cape of the peninsula.[91] Politically, Tamil Nadu is bound by the Indian states of Kerala, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh, and the union territory of Puducherry. It shares an international maritime border with the Northern Province of Sri Lanka at Pamban Island. The Palk Strait and the chain of low sandbars and islands known as Rama's Bridge separate the region from Sri Lanka, which lies off the southeastern coast.[92][93] The southernmost tip of mainland India is at Kanyakumari where the Indian Ocean meets the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea.[94]

The Western Ghats run south along the western boundary with the highest peak at Doddabetta (2,636 m (8,648 ft)) in the Nilgiri Hills.[95][96] The Eastern Ghats run parallel to the Bay of Bengal along the eastern coast and the strip of land between them forms the Coromandel region.[97] They are a discontinuous range of mountains intersected by Kaveri river.[98] Both mountain ranges meet at the Nilgiri mountains which run in a crescent approximately along the borders of Tamil Nadu with northern Kerala and Karnataka, extending to the relatively low-lying hills of the Eastern Ghats on the western portion of the Tamil Nadu–Andhra Pradesh border.[99] The Deccan plateau is the elevated region bound by the mountain ranges and the plateau slopes gently from west to east resulting in major rivers arising in the Western Ghats and flowing east into the Bay of Bengal.[100][101][102]

The coastline of Tamil Nadu is 1,076 km (669 mi) long, and is the second longest state coastline in the country after Gujarat.[103] There are coral reefs located in the Gulf of Mannar and Lakshadweep islands.[104] Tamil Nadu's coastline was permanently altered by the Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004.[105]

Geology

Tamil Nadu falls mostly in a region of low seismic hazard with the exception of the western border areas that lie in a low to moderate hazard zone; as per the 2002 Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) map, Tamil Nadu falls in Zones II and III.[106] The volcanic basalt beds of the Deccan plateau were laid down in the massive Deccan Traps eruption, which occurred towards the end of the Cretaceous period, between 67 and 66 million years ago.[107] Layer after layer was formed by the volcanic activity that lasted many years and when the volcanoes became extinct, they left a region of highlands with typically vast stretches of flat areas on top like a table.[108] The predominant soils of Tamil Nadu are red loam, laterite, black, alluvial and saline. Red soil, with a higher iron content, occupies a larger portion of the state and all the inland districts. Black soil is found in western Tamil Nadu and parts of the southern coast. Alluvial soil is found in the fertile Kaveri delta region, with laterite soil found in pockets, and saline soil across the coast where the evaporation is high.[109]

Climate

The region has a tropical climate and depends on monsoons for rainfall.[110] Tamil Nadu is divided into seven agro-climatic zones: northeast, northwest, west, southern, high rainfall, high altitude hilly, and Kaveri delta.[111] A tropical wet and dry climate prevails over most of the inland peninsular region except for a semi-arid rain shadow east of the Western Ghats. Winter and early summer are long dry periods with temperatures averaging above 18 °C (64 °F); summer is exceedingly hot with temperatures in low-lying areas exceeding 50 °C (122 °F); and the rainy season lasts from June to September, with annual rainfall averaging between 750 and 1,500 mm (30 and 59 in) across the region. Once the dry northeast monsoon begins in September, most precipitation in India falls in Tamil Nadu, leaving other states comparatively dry.[112] A hot semi-arid climate predominates in the land east of the Western Ghats which includes inland south and south central parts of the state and gets between 400 and 750 millimetres (15.7 and 29.5 in) of rainfall annually, with hot summers and dry winters with temperatures around 20–24 °C (68–75 °F). The months between March and May are hot and dry, with mean monthly temperatures hovering around 32 °C (90 °F), with 320 millimetres (13 in) precipitation. Without artificial irrigation, this region is not suitable for agriculture.[113]

The southwest monsoon from June to September accounts for most of the rainfall in the region. The Arabian Sea branch of the southwest monsoon hits the Western Ghats from Kerala and moves northward along the Konkan coast, with precipitation on the western region of the state.[114] The lofty Western Ghats prevent the winds from reaching the Deccan Plateau; hence, the leeward region (the region deprived of winds) receives very little rainfall.[115][116] The Bay of Bengal branch of the southwest monsoon heads toward northeast India, picking up moisture from the Bay of Bengal. The Coramandel coast does not receive much rainfall from the southwest monsoon, due to the shape of the land.[117] Northern Tamil Nadu receives most of its rains from the northeast monsoon.[118] The northeast monsoon takes place from November to early March, when the surface high-pressure system is strongest.[119] The North Indian Ocean tropical cyclones occur throughout the year in the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea, bringing devastating winds and heavy rainfall.[120][121] The annual rainfall of the state is about 945 mm (37.2 in) of which 48 per cent is through the northeast monsoon, and 52 per cent through the southwest monsoon. The state has only 3% of the water resources nationally and is entirely dependent on rains for recharging its water resources. Monsoon failures lead to acute water scarcity and severe drought.[122][123]

Flora and fauna

Forests occupy an area of 22,643 km2 (8,743 sq mi) constituting 17.4% of the geographic area.[124] There is a wide diversity of plants and animals in Tamil Nadu, resulting from its varied climates and geography. Deciduous forests are found along the Western Ghats while tropical dry forests and scrub lands are common in the interior.[125] The southern Western Ghats have rain forests located at high altitudes called the South Western Ghats montane rain forests.[126] The Western Ghats eco-region is one of the eight hottest biodiversity hotspots in the world and a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[127] There are about 2,000 species of wildlife that are native to Tamil Nadu, 5640 species of angiosperms (including 1,559 species of medicinal plants, 533 endemic species, 260 species of wild relatives of cultivated plants, 230 red-listed species), 64 species of gymnosperms (including four indigenous species and 60 introduced species) and 184 species of pteridophytes apart from bryophytes, lichen, fungi, algae, and bacteria.[128] Common plant species include the state tree: palmyra palm, eucalyptus, rubber, cinchona, clumping bamboos (Bambusa arundinacea), common teak, Anogeissus latifolia, Indian laurel, grewia, and blooming trees like Indian laburnum, ardisia, and solanaceae. Rare and unique plant life includes Combretum ovalifolium, ebony (Diospyros nilagrica), Habenaria rariflora (orchid), Alsophila, Impatiens elegans, Ranunculus reniformis, and royal fern.[129]

Important ecological regions of Tamil Nadu are the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve in the Nilgiri Hills, the Agasthyamala Biosphere Reserve in the Agastya Mala-Cardamom Hills and Gulf of Mannar coral reefs.[130] The Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve covers an area of 10,500 km2 (4,100 sq mi) of ocean, islands and the adjoining coastline including coral reefs, salt marshes and mangroves. It is home to endangered aquatic species, including dolphins, dugongs, whales and sea cucumbers.[131][132] Bird sanctuaries, including Thattekad, Kadalundi, Vedanthangal, Ranganathittu, Kumarakom, Neelapattu, and Pulicat, are home to numerous migratory and local birds.[133][134][135]

Protected areas cover an area of 3,305 km2 (1,276 sq mi), constituting 2.54% of the geographic area and 15% of the 22,643 km2 (8,743 sq mi) recorded forest area of the state.[124] Mudumalai National Park was established in 1940 and was the first modern wildlife sanctuary in South India. The protected areas are administered by the Ministry of Environment and Forests of the government of India and the Tamil Nadu Forest Department. Pichavaram consists of a number of islands interspersing the Vellar estuary in the north and Coleroon estuary in the south with mangrove forests. The Pichavaram mangrove forests is one of the largest mangrove forests in India covering 45 km2 (17 sq mi) and supports the existence of rare varieties of economically important shells, fishes and migrant birds.[136][137] The state has five National Parks covering 307.84 km2 (118.86 sq mi)–Anamalai, Mudumalai, Mukurthi, Gulf of Mannar, a marine national park and Guindy, an urban national park within Chennai.[135] Tamil Nadu has 18 wildlife sanctuaries.[135][138] Tamil Nadu is home to one of the largest populations of endangered Bengal tigers and Indian elephants in India.[139][140] There are five declared elephant sanctuaries in Tamil Nadu as per Project Elephant–Agasthyamalai, Anamalai, Coimbatore, Nilgiris and Srivilliputtur.[135] Tamil Nadu participates in Project Tiger and has five declared tiger reserves–Anamalai, Kalakkad-Mundanthurai, Mudumalai, Sathyamangalam and Megamalai.[135][141][142] There are seventeen declared bird sanctuaries in Tamil Nadu.[135][143][144]

There is one conservation reserve at Tiruvidaimarudur in Thanjavur district. There are two zoos recognised by the Central Zoo Authority of India namely Arignar Anna Zoological Park and Madras Crocodile Bank Trust, both located in Chennai.[135] The state has other smaller zoos run by local administrative bodies such as Coimbatore Zoo in Coimbatore, Amirthi Zoological Park in Vellore, Kurumpampatti Wildlife Park in Salem, Yercaud Deer Park in Yercaud, Mukkombu Deer Park in Tiruchirapalli and Ooty Deer Park in Nilgiris.[135] There are five crocodile farms located at Amaravati in Coimbatore district, Hogenakkal in Dharmapuri district, Kurumbapatti in Salem district, Madras Crocodile Bank Trust in Chennai and Sathanur in Tiruvannamalai district.[135] Threatened and endangered species found in the region include the grizzled giant squirrel,[145] grey slender loris,[146] sloth bear,[147] Nilgiri tahr,[148] Nilgiri langur,[149] lion-tailed macaque,[150] and the Indian leopard.[151]

| Animal | Bird | Butterfly | Tree | Fruit | Flower |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nilgiri tahr (Nilgiritragus hylocrius) | Emerald dove (Chalcophaps indica) | Tamil Yeoman (Cirrochroa thais) | Palmyra palm (Borassus flabellifer) | Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) | Glory lily (Gloriosa superba) |

Administration and politics

Administration

| Title | Name |

|---|---|

| Governor | R. N. Ravi[154] |

| Chief minister | M. K. Stalin[155] |

| Chief Justice | R. Mahadevan[156] |

Chennai is the capital of the state and houses the state executive, legislative and head of judiciary.[157] The administration of the state government functions through various secretariat departments. There are 43 departments of the state and the departments have further sub-divisions which may govern various undertakings and boards.[158] The state is divided into 38 districts, each of which is administered by a District Collector, who is an officer of the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) appointed to the district by the Government of Tamil Nadu. For revenue administration, the districts are further subdivided into 87 revenue divisions administered by Revenue Divisional Officers (RDO) which comprise 310 taluks administered by Tahsildars.[159] The taluks are divided into 1349 revenue blocks called Firkas which consist of 17,680 revenue villages.[159] The local administration consists of 15 municipal corporations, 121 municipalities and 528 town panchayats in the urban areas, and 385 panchayat unions and 12,618 village panchayats, administered by Village Administrative Officers (VAO).[160][159][161] Greater Chennai Corporation, established in 1688, is the second oldest in the world and Tamil Nadu was the first state to establish town panchayats as a new administrative unit.[162][163][164][160]

Legislature

In accordance with the Constitution of India, the governor is a state's de jure head and appoints the chief minister who has the de facto executive authority.[165][166] The Indian Councils Act 1861 established the Madras Presidency legislative council with four to eight members but was a mere advisory body to the governor of the presidency. The strength was increased to twenty in 1892 and fifty in 1909.[167][168] Madras legislative council was set-up in 1921 by the Government of India Act 1919 with a term of three years and consisted of 132 Members of which 34 were nominated by the Governor and the rest were elected.[169] The Government of India Act 1935 established a bicameral legislature with the creation of a new legislative council with 54 to 56 members in July 1937.[169] The first legislature of Madras state under the Constitution of India was constituted on 1 March 1952 after the 1952 elections. The number of seats post the re-organization in 1956 was 206, which was further increased to 234 in 1962.[169] In 1986, the state moved to a unicameral legislature with the abolition of the Legislative Council by the Tamil Nadu Legislative Council (Abolition) act, 1986.[170] The Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly is housed in the Fort St. George in Chennai.[171] The state elects 39 members to the Lok Sabha and 18 to the Rajya Sabha of the Indian Parliament.[172]

Law and order

The Madras High Court was established on 26 June 1862 and is the highest judicial authority of the state with control over all the civil and criminal courts in the state.[173] It is headed by a Chief Justice and has a bench at Madurai since 2004.[173] The Tamil Nadu Police, established as Madras state police in 1859, operates under the Home ministry of the Government of Tamil Nadu and is responsible for maintaining law and order in the state.[174] As of 2023[update], it consists of more than 132,000 police personnel, headed by a Director General of Police.[175][176] Women form 17.6% of the police force and specifically handle violence against women through 222 special all-women police stations.[177][178][179] As of 2023[update], the state has 1854 police stations, the highest in the country, including 47 railway and 243 traffic police stations.[177][180] The traffic police under different district administrations are responsible for the traffic management in the respective regions.[181] The state is consistently ranked as one of the safest for women with a crime rate of 22 per 100,000 in 2018.[182]

Politics

Elections in India are conducted by the Election Commission of India, an independent body established in 1950.[183] Politics in Tamil Nadu was dominated by national parties till the 1960s. Regional parties have ruled ever since. The Justice Party and Swaraj Party were the two major parties in the erstwhile Madras Presidency.[184] During the 1920s and 1930s, the Self-Respect Movement, spearheaded by Theagaroya Chetty and E. V. Ramaswamy (commonly known as Periyar), emerged in the Madras Presidency and led to the formation of the Justice party.[185] The Justice Party eventually lost the 1937 elections to the Indian National Congress and Chakravarti Rajagopalachari became the chief minister of the Madras Presidency.[184] In 1944, Periyar transformed the Justice party into a social organisation, renaming the party Dravidar Kazhagam, and withdrew from electoral politics.[186] After independence, the Indian National Congress dominated the political scene in Tamil Nadu in the 1950s and 1960s under the leadership of K. Kamaraj, who led the party after the death of Jawaharlal Nehru and ensured the selection of Prime Ministers Lal Bahadur Shastri and Indira Gandhi.[187][188] C. N. Annadurai, a follower of Periyar, formed the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) in 1949.[189]

The Anti-Hindi agitations of Tamil Nadu led to the rise of Dravidian parties that formed Tamil Nadu's first government, in 1967.[190] In 1972, a split in the DMK resulted in the formation of the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) led by M. G. Ramachandran.[191] Dravidian parties continue to dominate Tamil Nadu electoral politics with the national parties usually aligning as junior partners to the major Dravidian parties, AIADMK and DMK.[192] M. Karunanidhi became the leader of the DMK after Annadurai and J. Jayalalithaa succeeded as the leader of AIADMK after M. G. Ramachandran.[193][187] Karunanidhi and Jayalalithaa dominated the state politics from the 1980s to early 2010s, serving as chief ministers combined for over 32 years.[187]

C. Rajagopalachari, the first Indian Governor General of India post independence, was from Tamil Nadu. The state has produced three Indian presidents, namely, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan,[194] R. Venkataraman,[195] and APJ Abdul Kalam.[196]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 19,252,630 | — |

| 1911 | 20,902,616 | +8.6% |

| 1921 | 21,628,518 | +3.5% |

| 1931 | 23,472,099 | +8.5% |

| 1941 | 26,267,507 | +11.9% |

| 1951 | 30,119,047 | +14.7% |

| 1961 | 33,686,953 | +11.8% |

| 1971 | 41,199,168 | +22.3% |

| 1981 | 48,408,077 | +17.5% |

| 1991 | 55,858,946 | +15.4% |

| 2001 | 62,405,679 | +11.7% |

| 2011 | 72,147,030 | +15.6% |

| Source:Census of India[197] | ||

As per the 2011 census, Tamil Nadu had a population of 72.1 million and is the seventh most populous state in India.[1] The population is projected to be 76.8 million in 2023 and to grow to 78 million by 2036.[198] Tamil Nadu is one of the most urbanized states in the country with more than 48.4 per cent of the population living in urban areas.[90] As per the 2011 census, the sex ratio was 996 females per 1000 males, higher than the national average of 943.[199] The sex ratio at birth was recorded as 954 during the fourth National Family Health Survey (NFHS) in 2015-16 which reduced further to 878 in the fifth NFHS in 2019–21, ranking third worst amongst states.[200] As per the 2011 census, Literacy rate was 80.1%, higher than the national average of 73%.[201] The literacy rate was estimated to be 82.9% as per the 2017 National Statistical Commission (NSC) survey.[202] As of 2011[update], there were about 23.17 million households with 7.42 million children under the age of six.[203] A total of 14.4 million (20%) belonged to Scheduled Castes (SC) and 0.8 million (1.1%) to Scheduled tribes (ST).[204]

As of 2017[update], the state had the lowest fertility rate in India with 1.6 children born for each woman, lower than required for sustaining the population.[205] As of 2021[update], the Human Development Index (HDI) for Tamil Nadu was 0.686, higher than that of India (0.633) but ranked medium.[206] As of 2019[update], the life expectancy at birth was 74 years, one of the highest amongst Indian states.[207] As of 2023, 2.2% of the people live below the poverty line as per the Multidimensional Poverty Index, one of the lowest rates amongst Indian states.[208]

Cities and towns

The capital of Chennai is the most populous urban agglomeration in the state with more than 8.6 million residents, followed by Coimbatore, Madurai, Tiruchirappalli and Tiruppur, respectively.[209]

| Rank | Name | District | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Chennai  Coimbatore | 1 | Chennai | Chennai | 8,696,010 |  Madurai  Tiruchirappalli | ||||

| 2 | Coimbatore | Coimbatore | 2,151,466 | ||||||

| 3 | Madurai | Madurai | 1,462,420 | ||||||

| 4 | Tiruchirappalli | Tiruchirappalli | 1,021,717 | ||||||

| 5 | Tiruppur | Tiruppur | 962,982 | ||||||

| 6 | Salem | Salem | 919,150 | ||||||

| 7 | Erode | Erode | 521,776 | ||||||

| 8 | Vellore | Vellore | 504,079 | ||||||

| 9 | Tirunelveli | Tirunelveli | 498,984 | ||||||

| 10 | Thoothukudi | Thoothukudi | 410,760 | ||||||

Religion and ethnicity

| City | Population |

|---|---|

| Hinduism | |

| Christianity | |

| Islam | |

| Jainism | |

| Others/Not stated |

The state is home to a diverse population of ethno-religious communities.[211][212] According to the 2011 census, Hinduism is followed by 87.6% of the population. Christians form the largest religious minority in the state with 6.1% of the population; Muslims form 5.9% of the population.[213]

Tamils form a majority of the population with minorities including Telugus,[214] Marwaris,[215] Gujaratis,[216] Parsis,[217] Sindhis,[218] Odias,[219] Kannadigas,[220] Anglo-Indians,[221] Bengalis,[222] Punjabis,[223] and Malayalees.[224] The state also has a significant expatriate population.[225][226] As of 2011[update], the state had 3.49 million immigrants.[227]

Language

Tamil is the official language of Tamil Nadu, while English serves as the additional official language.[3] Tamil is one of the oldest languages and was the first to be recognized as a classical language of India.[229] As per the 2011 census, Tamil is spoken as the first language by 88.4% of the state's population, followed by Telugu (5.87%), Kannada (1.78%), Urdu (1.75%), Malayalam (1.01%) and other languages (1.24%)[228] Various varieties of Tamil are spoken across regions such as Madras Bashai in northern Tamil Nadu, Kongu Tamil in Western Tamil Nadu, Madurai Tamil around Madurai and Nellai Tamil in South-eastern Tamil Nadu.[230][231] It is part of the Dravidian languages and preserves many features of Proto-Dravidian, though modern-day spoken Tamil in Tamil Nadu freely uses loanwords from other languages such as Sanskrit and English.[232][233] Korean,[234] Japanese,[235] French,[236] Mandarin Chinese,[237] German[238] and Spanish are spoken by foreign expatriates in the state.[236]

LGBT rights

The LGBT rights in Tamil Nadu are among the most progressive in India.[239][240] In 2008, Tamil Nadu set up the Transgender welfare board and was the first to introduce a transgender welfare policy, wherein transgender people can avail free sex reassignment surgery in government hospitals.[241] Chennai Rainbow Pride has been held in Chennai annually since 2009.[242] In 2021, Tamil Nadu became the first Indian state to ban conversion therapy and forced sex-selective surgeries on intersex infants, following the directions of the Madras High Court.[243][244][245] In 2019, the Madras High Court ruled that the term "bride" under the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 includes trans-women, thereby legalizing marriage between a man and a transgender woman.[246]

Culture and heritage

Clothing

Tamil women traditionally wear a sari, a garment that consists of a drape varying from 5 to 9 yards (4.6 to 8.2 m) in length and 2 to 4 feet (0.61 to 1.22 m) in breadth that is typically wrapped around the waist, with one end draped over the shoulder, baring the midriff, as according to Indian philosophy, the navel is considered as the source of life and creativity.[247][248] Ancient Tamil poetry such as the Cilappadhikaram, describes women in exquisite drapery or sari.[249] Women wear colourful silk saris on special occasions such as marriages.[250] The men wear a dhoti, a 4.5 metres (15 ft) long, white rectangular piece of non-stitched cloth often bordered in brightly coloured stripes. It is usually wrapped around the waist and the legs and knotted at the waist.[251] A colourful lungi with typical batik patterns is the most common form of male attire in the countryside.[252] People in urban areas generally wear tailored clothing, and western dress is popular. Western-style school uniforms are worn by both boys and girls in schools, even in rural areas.[252] The Kanchipuram silk sari is a type of silk sari made in the Kanchipuram region in Tamil Nadu and these saris are worn as bridal and special occasion saris by most women in South India. It has been recognized as a Geographical indication by the Government of India in 2005–2006.[253][254] Kovai Cora is a type of cotton sari made in the Coimbatore.[254][255]

Cuisine

Rice is the diet staple and is served with sambar, rasam, and poriyal as a part of a Tamil meal.[256] Coconut and spices are used extensively in Tamil cuisine. The region has a rich cuisine involving both traditional non-vegetarian and vegetarian dishes made of rice, legumes, and lentils with its distinct aroma and flavour achieved by the blending of flavourings and spices.[257][258] The traditional way of eating a meal involves being seated on the floor, having the food served on a banana leaf,[259] and using clean fingers of the right hand to take the food into the mouth.[260] After the meal, the fingers are washed; the easily degradable banana leaf is discarded or becomes fodder for cattle.[261] Eating on banana leaves is a custom thousands of years old, imparts a unique flavor to the food, and is considered healthy.[262] Idli, dosa, uthappam, pongal, and paniyaram are popular breakfast dishes in Tamil Nadu.[263] Palani Panchamirtham, Ooty varkey, Kovilpatti Kadalai Mittai, Manapparai Murukku and Srivilliputhur Palkova are unique foods that have been recognized as Geographical Indications.[264]

Literature

Tamil Nadu has an independent literary tradition dating back over 2500 years from the Sangam era.[6] Early Tamil literature was composed in three successive poetic assemblies known as the Tamil Sangams, the earliest of which, according to legend, were held on a now vanished continent far to the south of India.[265][266][267] This includes the oldest grammatical treatise, Tolkappiyam, and the epics Cilappatikaram and Manimekalai.[268] The earliest epigraphic records found on rock edicts and hero stones date from around the 3rd century BCE.[269][270] The available literature from the Sangam period was categorised and compiled into two categories based roughly on chronology: the Patiṉeṇmēlkaṇakku consisting of Eṭṭuttokai and the Pattupattu, and the Patiṉeṇkīḻkaṇakku. The existent Tamil grammar is largely based on the 13th-century grammar book Naṉṉūl based on the Tolkāppiyam. Tamil grammar consists of five parts, namely eḻuttu, sol, poruḷ, yāppu, aṇi.[271][272] Tirukkural, a book on ethics by Thiruvalluvar, is amongst the most popular works of Tamil literature.[273]

In the early medieval period, Vaishnava and Shaiva literature became prominent following the Bhakti movement in the sixth century CE with hymns composed by the Alvars and the Nayanars.[274][275][276] In the following years, Tamil literature again flourished with notable works including Ramavataram, written in the 12th century CE by Kambar.[277] After a lull in the intermediate years due to various invasions and instability, the Tamil literature recovered in the 14th century CE, with the notable work being Tiruppukal by Arunagirinathar.[278] In 1578, the Portuguese published a Tamil book in old Tamil script named Thambiraan Vanakkam, thus making Tamil the first Indian language to be printed and published.[279] Tamil Lexicon, published by the University of Madras, is the first among the dictionaries published in any Indian language.[280] The 19th century gave rise to the Tamil Renaissance and writings and poems by authors such as Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai, U.V. Swaminatha Iyer, Ramalinga Swamigal, Maraimalai Adigal, and Bharathidasan.[281][282] During the Indian Independence Movement, many Tamil poets and writers sought to provoke national spirit, social equity and secularist thoughts, notably Subramania Bharati and Bharathidasan.[283]

Architecture

Dravidian architecture is the distinct style of rock architecture in Tamil Nadu.[284] In Dravidian architecture, the temples consisted of porches or mantapas preceding the door leading to the sanctum, gate-pyramids or gopurams in quadrangular enclosures that surround the temple, and pillared halls used for many purposes. These features are the invariable accompaniments of these temples. Besides these, a South Indian temple usually has a tank called the kalyani or pushkarni.[285] The gopuram is a monumental tower, usually ornate at the entrance of the temple forms a prominent feature of koils and Hindu temples of the Dravidian style.[286] They are topped by the kalasam, a bulbous stone finial and function as gateways through the walls that surround the temple complex.[287] The gopuram's origins can be traced back to the Pallavas who built the group of monuments in Mahabalipuram and Kanchipuram.[35] The Cholas later expanded the same and by the Pandya rule in twelfth century, these gateways became a dominant feature of a temple's outer appearance.[288][289] The state emblem also features the Lion Capital of Ashoka with an image of a Gopuram on the background.[290] Vimanam are similar structures built over the garbhagriha or inner sanctum of the temple but are usually smaller than the gopurams in the Dravidian architecture with a few exceptions including the Brihadisvara Temple in Thanjavur.[291][292]

The Mugal influence in medieval times and the British influence later gave rise to a blend of Hindu, Islamic and Gothic revival styles, resulting in the distinct Indo-Saracenic architecture. Several buildings and institutions built during the British era followed the style.[293][294] By the early 20th century, art deco made its entry in the urban landscape.[295] After Indian Independence, Tamil architecture witnessed a rise in Modernism with the transition from lime-and-brick construction to concrete columns.[296]

Arts

Tamil Nadu is a major centre for music, art and dance in India.[297] Chennai is called the cultural capital of South India.[298] In the Sangam era, art forms were classified into: iyal (poetry), isai (music) and nadakam (drama).[299] Bharatanatyam is a classical dance form that originated in Tamil Nadu and is one of the oldest dances of India.[300][301][302] Other regional folk dances include Karakattam, Kavadi, Koodiyattam, Oyilattam, Paraiattam and Puravaiattam.[303][304][305][306] The dance, clothing, and sculptures of Tamil Nadu exemplify the beauty of the body and motherhood.[307] Koothu is an ancient folk art, where artists tell stories from the epics accompanied by dance and music.[308][309]

The ancient Tamil country had its own system of music called Tamil Pannisai described by Sangam literature such as the Silappatikaram.[310] A Pallava inscription dated to the 7th century CE has one of the earliest surviving examples of Indian music in notation.[311] There are many traditional instruments from the region dating back to the Sangam period such as parai, tharai, yazh and murasu.[312][313] Nadaswaram, a reed instrument that is often accompanied by the thavil, a type of drum instrument, are the major musical instruments used in temples and weddings.[314] Melam is a group of Maddalams and other similar percussion instruments from the ancient Tamilakam which are played during events.[315] The traditional music of Tamil Nadu is known as Carnatic music, which includes rhythmic and structured music by composers such as Muthuswami Dikshitar.[316] Gaana, a combination of various folk musics, is sung mainly in the working-class area of North Chennai.[317]

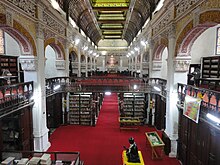

The state is home to many museums, galleries, and other institutions which engage in arts research and are major tourist attractions.[318] Established in the early 18th century, the Government Museum and the National Art Gallery are amongst the oldest in the country.[319] The museum inside the premises of Fort St. George maintains a collection of objects of the British era.[320] The museum is managed by the Archaeological Survey of India, and has in its possession the first Flag of India hoisted at Fort St George after the declaration of India's Independence on 15 August 1947.[321]

Tamil Nadu is also home to the Tamil film industry nicknamed as "Kollywood" and is one of the largest industries of film production in India.[322][323] The term Kollywood is a blend of Kodambakkam and Hollywood.[324] The first silent film in South India was produced in Tamil in 1916 and the first talkie was a multilingual film, Kalidas, which was released on 31 October 1931, barely seven months after India's first talking picture Alam Ara.[325][326] Samikannu Vincent, who had built the first cinema of South India in Coimbatore, introduced the concept of "Tent Cinema" in which a tent was erected on a stretch of open land close to a town or village to screen the films. The first of its kind was established in Madras, called "Edison's Grand Cinemamegaphone".[327][328][329]

Festivals

Pongal is a major and multi-day harvest festival celebrated by Tamils.[330] It is observed in the month of Thai according to the Tamil solar calendar and usually falls on 14 or 15 January.[331] It is dedicated to the Surya, the Sun God and the festival is named after the ceremonial "Pongal", which means "to boil, overflow" and refers to the traditional dish prepared from the new harvest of rice boiled in milk with jaggery offered to Surya.[332][333][334] Mattu Pongal is meant for celebration of cattle when the cattle are bathed, their horns polished and painted in bright colors, garlands of flowers placed around their necks and processions.[335] Jallikattu is a traditional event held during the period attracting huge crowds in which a bull is released into a crowd of people, and multiple human participants attempt to grab the large hump on the bull's back with both arms and hang on to it while the bull attempts to escape.[336]

Puthandu is known as Tamil New Year which marks the first day of year on the Tamil calendar. The festival date is set with the solar cycle of the solar Hindu calendar, as the first day of the Tamil month Chithirai and falls on or about 14 April every year on the Gregorian calendar.[338] Karthikai Deepam is a festival of lights that is observed on the full moon day of the Kartika month, called the Kartika Pournami, falling on the Gregorian months of November or December.[339][340] Thaipusam is a Tamil festival celebrated on the first full moon day of the Tamil month of Thai coinciding with Pusam star and dedicated to lord Murugan. Kavadi Aattam is a ceremonial act of sacrifice and offering practiced by devotees which is a central part of Thaipusam and emphasizes debt bondage.[341][342] Aadi Perukku is a Tamil cultural festival celebrated on the 18th day of the Tamil month of Adi which pays tribute to water's life-sustaining properties. The worship of Amman and Ayyanar deities are organized during the month in temples across Tamil Nadu with much fanfare.[315] Panguni Uthiram is marked on the purnima (full moon) of the month of Panguni and celebrates the wedding of various Hindu gods.[343]

Tyagaraja Aradhana is an annual music festival devoted to composer Tyagaraja. In Tiruvaiyaru in Thanjavur district, thousands of music artists congregate every year.[344] Chennaiyil Thiruvaiyaru is a music festival which has been conducted from 18 to 25 December every year in Chennai.[345] Chennai Sangamam is a large annual open Tamil cultural festival held in Chennai with the intention of rejuvenating the old village festivals, art and artists.[346] Madras Music Season, initiated by Madras Music Academy in 1927, is celebrated every year during the month of December and features performances of traditional Carnatic music by artists from the city.[347]

Economy

The economy of the state consistently exceeded national average growth rates, due to reform-oriented economic policies in the 1970s.[348] As of 2022[update], Tamil Nadu's GSDP was ₹23.65 trillion (US$280 billion), second highest amongst Indian states, which had grown significantly from ₹2.19 trillion (US$26 billion) in 2004.[4] The per-capita NDSP is ₹275,583 (US$3,300).[5] Tamil Nadu is the most urbanized state in India.[349] Though the state had the lowest percentage of people under the poverty line, rural unemployment rate is considerably higher at 47 per thousand compared to the national average of 28.[208][350] As of 2020[update], the state had the most number of factories at 38,837 units with an engaged work-force of 2.6 million.[351][352]

The state has a diversified industrial base anchored by different sectors including automobiles, software services, hardware, textiles, healthcare and financial services.[353][354] As of 2022[update], services contributed to 55% of the GSDP followed by manufacturing at 32% and agriculture at 13%.[355] There are 42 Special Economic Zones (SEZ) in the state.[356] As per a report by Government of India, Tamil Nadu is the most export competitive state of India in 2023.[357]

Services

As of 2022[update], the state is amongst the major Information technology (IT) exporters of India with a value of ₹576.87 billion (US$6.9 billion).[358][359] Established in 2000, Tidel Park in Chennai was amongst the first and largest IT parks in Asia.[360] The presence of SEZs and government policies have contributed to the growth of the sector which has attracted foreign investments and job seekers from other parts of the country.[361][362] In the 2020s, Chennai has become a major provider of SaaS and has been dubbed the "SaaS Capital of India".[363][364]

The state has two stock exchanges, Coimbatore Stock Exchange, established in 2013, and Madras Stock Exchange, established in 2015 and India's third-largest by trading volume.[365][366] The Madras Bank, the first European-style banking system in India, was established on 21 June 1683, followed by the first commercial banks such as Bank of Hindustan (1770) and General Bank of India (1786).[367] The Bank of Madras merged with two other presidency banks to form the Imperial Bank of India in 1921 which in 1955 became the State Bank of India, the largest bank in India.[368] More than 400 financial industry businesses including three banks are headquartered in the state.[369][370][371] The state hosts the south zonal office of the Reserve Bank of India, the country's central bank, along with its zonal training centre and staff college at Chennai.[372] There is a permanent back office of the World Bank in the state.[373]

Manufacturing

Manufacturing in various sectors is governed by the state owned industrial corporation Tamil Nadu Industrial Development Corporation (TIDCO) apart from central government owned companies. Electronics hardware is a major manufacturing industry with an output of $5.37 billion in 2023, largest amongst Indian states.[374][375] A large number of automotive companies have their manufacturing bases in the state with the automotive industry in Chennai accounting for more than 35% of India's overall automotive components and automobile output, earning the nickname "Detroit of India".[376][377][378] The Integral Coach Factory in Chennai manufactures railway coaches and other rolling stock for Indian Railways.[379]

Another major industry is textiles with the state being home to more than half of the operating fiber textile mills in India.[380][381] Coimbatore is often referred to as the Manchester of South India due to its cotton production and textile industries.[382] As of 2022[update], Tiruppur exported garments worth US$480 billion, contributing to nearly 54% of the all the textile exports from India and the city is known as the knitwear capital due to its cotton knitwear export.[383][384] As of 2015[update], the textile industry in Tamil Nadu accounts for 17% of the total invested capital in all the industries.[385] As of 2021[update], 40% of leather goods exported from India worth ₹92.52 billion (US$1.1 billion) are being manufactured in the state.[386] The state supplies two-thirds of India's requirements of motors and pumps, and is one of the largest exporters of wet grinders with "Coimbatore Wet Grinder", a recognized Geographical indication.[387][388]

There are two ordnance factories in Aruvankadu and Tiruchirappalli.[389][390] AVANI, headquartered in Chennai, manufactures armoured fighting vehicles, main battle tanks, tank engines and armored clothing for the use of the Indian Armed Forces.[391][392] ISRO, the Indian space agency, operates a propulsion facility at Mahendragiri.[393]

Agriculture

Agriculture contributes 13% to the GSDP and is a major employment generator in rural areas.[355] As of 2022[update], the state had 6.34 million hectares under cultivation.[394][395] Rice is the staple food grain with the state being one of the largest producers in India with an output of 7.9 million tonnes in 2021–22.[396] The Kaveri delta region is known as the Rice Bowl of Tamil Nadu.[397] Among non-food grains, sugarcane is the major crop with an annual output of 16.1 million tonnes in 2021–22.[398] The state is a producer of spices and is the top producer of oil seeds, tapioca, cloves and flowers in India.[399] The state accounts for 6.5% of fruit and 4.2% of vegetables production in the country.[400][401] The state is a leading producer of banana and mango with more than 78% of the area under fruit cultivation.[402] As of 2019[update], the state was the second largest producer in India of natural rubber and coconuts.[403] Tea is a popular crop in hill-stations with the state being a major producer of a unique flavored Nilgiri tea.[404][405]

As of 2022[update], the state is the largest producer in India of poultry and eggs with an annual production of 20.8 billion units, contributing to more than 16% of the national output.[406] The state has a fishermen population of 1.05 million and the coast consists of 3 major fishing harbors, 3 medium fishing harbors and 363 fish landing centres.[407] As of 2022[update], the fishing output was 0.8 million tonnes with a contribution of 5% to the total fish production in India.[408] Aquaculture includes shrimp, sea weed, mussel, clam and oyster farming across more than 6000 hectares.[409] M. S. Swaminathan, known as the "father of the Indian Green Revolution" was from Tamil Nadu.[410]

Infrastructure

Water supply

Tamil Nadu accounts for nearly 4% of the land area and 6% of the population of India, but has only 3% of the water resources of the country. The per capita water availability is 800 m3 (28,000 cu ft) which is lower than the national average of 2,300 m3 (81,000 cu ft).[411] The state is dependent on the monsoons for replenishing the water resources. There are 17 major river basins with 61 reservoirs and about 41,948 tanks with a total surface water potential of 24,864 million cubic metres (MCM), 90% of which is used for irrigation. The utilizable groundwater recharge is 22,423 MCM.[411] The major rivers include Kaveri, Bhavani, Vaigai and Thamirabarani. With most of the rivers originating from other states, Tamil Nadu depends on neighboring states for considerable quantum of water which has often led to disputes.[412] The state has 116 large dams.[413] Apart from the rivers, the majority of the water comes from rainwater stored in more than 41,000 tanks and 1.68 million wells across the state.[394]

Water supply and sewage treatment are managed by the respective local administrative bodies such as the Chennai MetroWater Supply and Sewage Board in Chennai.[414][415] Desalination plants including the country's largest at Minjur provide alternative means of drinking water.[416] As per the 2011 census, only 83.4% of the households have access to safe drinking water, less than the national average of 85.5%.[417] Water sources are also threatened by environmental pollution and effluent discharge from industries.[418]

Health and sanitation

The state is one of the leading states in terms of sanitation facilities with more than 99.96% of people having access to toilets.[419] The state has robust health facilities and ranks higher in all health related parameters such as high life expectancy of 74 years (sixth) and 98.4% institutional delivery (second).[207][420] Of the three demographically related targets of the Millennium Development Goals set by the United Nations and expected to be achieved by 2015, Tamil Nadu achieved the goals related to improvement of maternal health and of reducing infant mortality and child mortality by 2009.[421][422]

The health infrastructure in the state includes both government-run and private hospitals. As of 2023[update], the state had 404 public hospitals, 1,776 public dispensaries, 11,030 health centres and 481 mobile units run by the government with a capacity of more than 94,700 beds.[423][424] The General Hospital in Chennai was established on 16 November 1664 and was the first major hospital in India.[425] The state government administers free polio vaccine for eligible age groups.[426] Tamil Nadu is a major centre for medical tourism and Chennai is termed as "India's health capital".[427] Medical tourism forms an important part of the economy with more than 40% of total medical tourists visiting India making it to Tamil Nadu.[428]

Communication

Tamil Nadu is one of four Indian states connected by undersea fibre-optic cables.[429][430][431] As of 2023[update], four mobile phone service companies operate GSM networks including Bharti Airtel, BSNL, Vodafone Idea and Reliance Jio offering 4G and 5G mobile services.[432][433] Wireline and broadband services are offered by five major operators and other smaller local operators.[433] Tamil Nadu is amongst the states with a high internet usage and penetration.[434] In 2018, the state government unveiled a plan to lay 55,000 km (34,000 mi) of optical fiber across the state to provide high-speed internet.[435]

Power and energy

Electricity distribution in the state is done by the Tamil Nadu Electricity Board headquartered at Chennai.[436] As of 2023[update], the average daily consumption is 15,000 MW. Only 40% of the power is generated locally, with the remaining 60% met through purchases.[437] As of 2022[update], the state was the fourth largest power consumer with a per capita availability of 1588.7 Kwh.[438][439] As of 2023[update], the state has the third highest installed power capacity of 38,248 MW with 54.6% from renewable resources.[440][441] Thermal power is the largest contributor with more than 10,000 MW.[440] Tamil Nadu is the only state with two operational nuclear power plants. The plant at Kalpakkam is the first fully indigenous nuclear power station in India. The Kudankulam Nuclear Power Plant is the largest nuclear power station in India. It generates nearly one-third of the total nuclear power generated in the country.[442][443][444] Tamil Nadu has the largest established wind power capacity in India with over 8,000 MW, mostly based out of two regions, Palghat Gap and Muppandal. The latter is one of the largest operational onshore wind farms in the world.[445]

Media

Newspaper publishing started in the state started with the launch of the weekly The Madras Courier in 1785.[446] It was followed by the weeklies Madras Gazette and Government Gazette in 1795.[447][448] The Spectator, founded in 1836 was the first English newspaper to be owned by an Indian and became the first daily newspaper in 1853.[449][450] The first Tamil newspaper, Swadesamitran was launched in 1899.[451][452] The state has a number of newspapers and magazines published in various languages including Tamil, English and Telugu.[453] The major dailies with more than 100,000 circulation per day include The Hindu, Dina Thanthi, Dinakaran, The Times of India, Dina Malar, and The Deccan Chronicle.[454] Several periodicals and local newspapers prevalent in select localities also bring out editions from multiple cities.[455]

Government-run Doordarshan broadcasts terrestrial and satellite television channels from its Chennai centre set up in 1974.[456] DD Podhigai, Doordarshan's Tamil language regional channel was launched on 14 April 1993.[457] There are more than 30 private satellite television networks including Sun Network, one of India's largest broadcasting companies is the state, established in 1993.[458] The cable TV service is entirely controlled by the state government while DTH and IPTV is available via various private operators.[459][460] Radio broadcasting began in 1924 by the Madras Presidency Radio Club.[461] All India Radio was established in 1938.[462] There are many AM and FM radio stations operated by All India Radio, Hello FM, Suryan FM, Radio Mirchi, Radio City and BIG FM among others.[463][464] In 2006, the government of Tamil Nadu distributed free televisions to all families, which has led to high penetration of television services.[465][466] From the early 2010s, Direct to Home has become increasingly popular replacing cable television services.[467] Tamil television serials form a major prime time source of entertainment.[468]

Others

Fire services are handled by the Tamil Nadu Fire and Rescue Services which operates 356 operating fire stations.[469] Postal service is handled by India Post, which operates more than 11,800 post offices in the state.[470] The first post office was established at Fort St. George on 1 June 1786.[471]

Transportation

Roads

Tamil Nadu has an extensive road network covering about 271,000 km as of 2023 with a road density of 2,084.71 kilometres (1,295.38 mi) per 1000 km2 which is higher than the national average of 1,926.02 kilometres (1,196.77 mi) per 1000 km2.[472] The Highways Department (HD) of the state was established in April 1946 and is responsible for construction and maintenance of national highways, state highways, major district roads and other roads in the state.[473] It operates through eleven wings with 120 divisions and maintains 73,187 kilometres (45,476 mi) of highways in the state.[474][475]

| Type | NH | SH | MDR | ODR | OR | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length (km) | 6,805 | 12,291 | 12,034 | 42,057 | 197,542 | 271,000 |

There are 48 National Highways in Tamil Nadu, totaling 6,805 kilometres (4,228 mi) in length. The National Highways Wing of the state highways department, established in 1971, is responsible for the maintenance of National Highways, as laid down by National Highways Authority of India (NHAI).[476][477] There are also state highways, totalling 6,805 kilometres (4,228 mi) long, which connect district headquarters, important towns and national highways in the state.[478][475] As of 2020, 32,598 buses are operated with the state transport units operating 20,946 buses along with 7,596 private buses and 4,056 mini buses.[479] Tamil Nadu State Transport Corporation (TNSTC), established in 1947 when private buses operating in Madras presidency were nationalized, is the primary public transport bus operator in the state.[479] It operates buses along intra and inter state bus routes, as well as city routes with eight divisions including the State Express Transport Corporation Limited (SETC) which runs long-distance express services. Metropolitan Transport Corporation in Chennai and State Express Transport Corporation.[479][480] As of 2020, Tamil Nadu had 32.1 million registered vehicles.[481]

Rail

The rail network in Tamil Nadu forms a part of Southern Railway of Indian Railways, which is headquartered in Chennai with four divisions in the state namely Chennai, Tiruchirappalli, Madurai and Salem.[482] As of 2023, the state had a total railway track length of 5,601 km (3,480 mi) covering a route length of 3,858 km (2,397 mi).[483] There are 532 railway stations in the state with Chennai Central, Chennai Egmore, Coimbatore Junction and Madurai Junction being the top revenue earning stations.[484][485] Indian railways also has a coach manufacturing unit at Chennai, electric locomotive sheds at Arakkonam, Erode and Royapuram, diesel locomotive sheds at Erode, Tiruchirappalli and Tondiarpet, Steam locomotive shed at Coonoor along with various maintenance depots.[486][487]

| Route length (km) | Track length (km) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broad Gauge | Metre Gauge | Total | Broad Gauge | Metre Gauge | Total | ||

| Electrified | Non electrified | Total | |||||

| 3,476 | 336 | 3,812 | 46 | 3,858 | 5,555 | 46 | 5,601 |

Chennai has a well-established suburban railway network operated by Southern railway, covering 212 km (132 mi) which was established in 1928.[488][489] The Mass Rapid Transit System (MRTS) is an elevated urban mass transit system established in 1995 operating on a single line from Chennai Beach to Velachery.[488][490] Chennai Metro is a rapid transit rail system in Chennai which was opened in 2015 and consists of two operational lines operating across 54.1 km (33.6 mi) in 2023.[491] Nilgiri Mountain Railway is a 1,000 mm (3 ft 3+3⁄8 in) metre gauge railway in Nilgiris district which was built by the British in 1908 and is the only rack railway in India.[492][493][494]

Air and space

The aviation history of the state began in 1910, when Giacomo D'Angelis built the first powered flight in Asia and tested it in Island Grounds.[495] In 1915, Tata Air Mail started an airmail service between Karachi and Madras, marking the beginning of civil aviation in India.[496] On 15 October 1932, J. R. D. Tata flew a Puss Moth aircraft carrying air mail from Karachi to Bombay's Juhu Airstrip and the flight was continued to Madras piloted by aviator Nevill Vintcent marking the first scheduled commercial flight.[497][498] There are three international, one limited international and six domestic or private airports in Tamil Nadu.[499][500]

Chennai airport, which is the fourth busiest airport by passenger traffic in India, is a major international airport and the main gateway to the state.[501] Other international airports in the state include Coimbatore and Tiruchirapalli while Madurai is a customs airport with limited international flights.[501] Domestic flights are operational to certain airports like Tuticorin and Salem while flights are planned to be introduced to more domestic airports by the UDAN scheme of Government of India.[502] The region comes under the purview of the Southern Air Command of the Indian Air Force. The Air Force operates three air bases in the state Sulur, Tambaram and Thanjavur.[503] The Indian Navy operates airbases at Arakkonam, Uchipuli and Chennai.[504][505] In 2019, Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) announced the setting up a new rocket launch pad near Kulasekharapatnam in Thoothukudi district.[506]

Water

There are three major ports, Chennai, Ennore and Thoothukudi, which are managed by the Ministry of Ports, Shipping and Waterways of the Government of India.[507] There is an intermediate sea port at Nagapattinam and sixteen other minor ports, which are managed by the department of highways and minor ports of the Government of Tamil Nadu.[472] Tamil Nadu forms part of both the Eastern Naval Command and Southern Naval Command of the Indian Navy, which has a major base at Chennai and logistics support base at Thoothukudi.[508][509]

Education

Tamil Nadu is one of the most literate states in India, with a literacy rate estimated to be 82.9% as per the 2017 National Statistical Commission survey, higher than the national average of 77.7%.[202][510] The state had seen one of the highest literacy growth since the 1960s due to the midday meal scheme introduced on a large scale by K. Kamaraj to increase school enrollment.[511][512][513] The scheme was further upgraded in 1982 to "Nutritious noon-meal scheme" to combat malnutrition.[514][515] As of 2022[update], the state has one of the highest enrollment to secondary education at 95.6%, far above the national average of 79.6%.[516]An analysis of primary school education by Pratham showed a low drop-off rate but poor quality of education compared to certain other states.[517]

As of 2022[update], the state had over 37,211 government schools, 8,403 government-aided schools and 12,631 private schools which educate 5.47 million, 2.84 million, and 5.69 million students respectively.[518][519] There are 3,12,683 teachers with 80,217 teachers in government-aided schools with an average teacher-pupil ratio of 1:26.6.[520] Public schools are all affiliated with the Tamil Nadu State Board, while private schools may be affiliated with either of Tamil Nadu Board of Secondary Education, Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE), Council for the Indian School Certificate Examinations (ICSE) or National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS).[521] School education starts with two years of kindergarten from age three onwards and then follows the Indian 10+2 plan, ten years of school and two years of higher secondary education.[522]

As of 2023[update], there are 56 universities in the state including 24 public universities, four private universities and 28 deemed-to-be universities.[523] The University of Madras was founded in 1857 and is one of India's first modern universities.[524] There are 510 engineering colleges including 34 government colleges in the state.[525][526] Indian Institute of Technology Madras is a premier institute of engineering and College of Engineering, Guindy, Anna University founded in 1794 is the oldest engineering college in India.[527] The Officers Training Academy of the Indian Army is headquartered at Chennai.[528] There are also 496 polytechnic institutions with 92 government colleges and 935 arts and science colleges in the state including 302 government run colleges.[525][529][530] Madras Christian College (1837), Presidency College (1840) and Pachaiyappa's College (1842) are amongst the oldest arts and science colleges in the country.[531]

There are over 870 medical, nursing and dental colleges in the state including 21 for traditional medicine and four for modern medicine.[532] The Madras Medical College was established in 1835 and is one of the oldest medical colleges in India.[533] As per the National Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF) rankings in 2023, 26 universities, 15 engineering, 35 arts science, 8 management and 8 medical colleges from the state are ranked amongst the top 100 in the country.[534][535] As of 2023[update], the state has a 69% reservation in educational institutions for socially backward sections of society, the highest among all Indian states.[536] There are ten institutes of national importance in the state.[537] Research institutes including Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Central Institute for Cotton Research, Sugarcane Breeding Research Institute, Institute of Forest Genetics and Tree Breeding (IFGTB) and Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education are involved in agricultural research.[538][539][540]

As of 2023[update], the state has 4,622 public libraries.[541] Established in 1896, Connemara Public Library is one of the oldest and is amongst the four National Depository Centres in India that receive a copy of all newspapers and books published in the country. The Anna Centenary Library is the largest library in Asia.[542][543] There are many research institutions spread across the state.[544] Chennai book fair is an annual book fair organized by the Booksellers and Publishers Association of South India (BAPASI) and is typically held in December–January.[545]

Tourism and recreation

With its diverse culture and architecture and varied geographies, Tamil Nadu has a robust tourism industry. In 1971, the Government of Tamil Nadu established the Tamil Nadu Tourism Development Corporation, which is the nodal agency responsible for the promotion of tourism and development of tourist related infrastructure in the state.[546] It is managed by the Tourism,Culture and Religious Endowments Department.[547] The tag line "Enchating Tamil Nadu" was adopted in the tourism promotions.[548][549] In the 21st century, the state has been amongst the top destinations for domestic and international tourists.[549][550] As of 2020[update], Tamil Nadu recorded the most tourist foot-falls with more than 140.7 million tourists visiting the state.[551]

Tamil Nadu's coastline is 1,076 kilometres (669 mi) long, with many beaches dotting the coast.[552] Marina Beach spanning 13 km (8.1 mi) is the second-longest urban beach in the world.[553] As the state is straddled by the Western and Eastern ghats, it is home to many hill stations, popular amongst them are Udagamandalam (Ooty) situated in the Nilgiri Hills and Kodaikanal in the Palani hills.[554][555][556] There are a number of rock-cut cave-temples and more than 34,000 temples in Tamil Nadu built across various periods some of which are several centuries old.[557][558] With many rivers and streams, there are a number of waterfalls in the state including the Courtallam and Hogenakkal Falls.[559][560] There are four World Heritage Sites declared by UNESCO in the state: Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram,[561] Great Living Chola Temples,[42] Nilgiri Mountain Railway,[562][563] and Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve.[564][565]

Sports

Kabaddi is a contact sport which is the state game of Tamil Nadu.[566][567] Pro Kabaddi League is the most popular region based franchise tournament with Tamil Thalaivas representing the state.[568][569] Chess is a popular board game which originated as Sathurangam in the 7th century CE.[570] Chennai is often dubbed "India's chess capital" as the city is home to multiple chess grandmasters, including former world champion Viswanathan Anand. The state played host to the World Chess Championship 2013 and 44th Chess Olympiad in 2022.[571][572][573][574] Traditional games like Pallanguzhi,[575] Uriyadi,[576] Gillidanda,[577] Dhaayam[578] are played across the region. Jallikattu and Rekla are traditional sporting events involving bulls.[579][580] Traditional martial arts include Silambattam,[581] Gatta gusthi,[582] and Adimurai.[583]

Cricket is the most popular sport in the state.[584] The M.A. Chidambaram Stadium established in 1916 is among the oldest cricket stadiums in India and has hosted matches during multiple ICC Cricket World Cups.[585][586][587] Established in 1987, MRF Pace Foundation is a bowling academy based in Chennai.[588] Chennai is home to the most successful Indian Premier League (IPL) cricket team, Chennai Super Kings, and hosted the finals during the 2011 and 2012 seasons.[589][590] Football is also popular with the Indian Super League being the major club competition and Chennaiyin FC representing the state.[591][592][593]

There are multi-purpose venues in major cities including Chennai and Coimbatore, which host football and athletics. Chennai also houses a multi–purpose indoor complex for volleyball, basketball, kabaddi and table tennis.[594][595] Chennai hosted the 1995 South Asian Games.[596] Tamil Nadu Hockey Association is the governing body of hockey in the state and Mayor Radhakrishnan Stadium in Chennai was the venue for the international hockey tournaments, the 2005 Men's Champions Trophy and the 2007 Men's Asia Cup.[597] Madras Boat Club (founded in 1846) and Royal Madras Yacht Club (founded in 1911) promote sailing, rowing and canoeing sports in Chennai.[598] Inaugurated in 1990, Madras Motor Race Track was the first permanent racing circuit in India and hosts formula racing events.[599] Coimbatore is often referred to as "India's Motorsports Hub" and the "Backyard of Indian Motorsports" and hosts the Kari Motor Speedway, a Formula 3 Category circuit.[600][601] Horse racing is held at the Guindy Race Course and the state has three 18-hole golf courses, the Cosmopolitan Club, the Gymkhana Club and the Coimbatore Golf Club.[602]

See also

References

- ^ Jump up to: a b Decadal variation in population 1901-2011, Tamil Nadu (PDF) (Report). Government of India. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 February 2024. Retrieved 1 December 2023.