Субхас Чандра Бос

Субхас Чандра Бос | |

|---|---|

Бозе, гр. 1930-е годы | |

| 2-й лидер Индийской национальной армии [д] | |

| В офисе 4 июля 1943 г. - 18 августа 1945 г. | |

| Preceded by | Mohan Singh |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| President of the All India Forward Bloc | |

| In office 22 June 1939 – 16 January 1941 | |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | Sardul Singh Kavishar |

| President of the Indian National Congress | |

| In office 18 January 1938 – 29 April 1939 | |

| Preceded by | Jawaharlal Nehru |

| Succeeded by | Rajendra Prasad |

| 5th Mayor of Calcutta | |

| In office 22 August 1930 – 15 April 1931 | |

| Preceded by | Jatindra Mohan Sengupta |

| Succeeded by | Bidhan Chandra Roy |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Subhas Chandra Bose 23 January 1897 Cuttack, Bengal Presidency, British India |

| Died | 18 August 1945 (aged 48)[4][5] Taihoku, Japanese Taiwan |

| Cause of death | Third-degree burns from aircrash[5] |

| Resting place | Renkō-ji, Tokyo, Japan |

| Political party | Indian National Congress All India Forward Bloc |

| Spouse(s) | (secretly married without ceremony or witnesses, unacknowledged publicly by Bose)[6] |

| Children | Anita Bose Pfaff |

| Parents |

|

| Education |

|

| Alma mater |

|

| Known for | Indian independence movement |

| Signature | |

Субхас Чандра Бос ( / ʃ ʊ b ˈ h ɑː s ˈ tʃ ʌ n d r ə ˈ b oʊ s / шууб- ХАХСС ЧУН -drə БОССС ; [12] 23 января 1897 — 18 августа 1945) был индийским националистом, чье неповиновение британской власти в Индии сделало его героем среди многих индийцев, но его военные союзы с нацистской Германией и императорской Японией оставили наследие, досадное авторитаризмом , антисемитизмом и военными действиями. отказ . Почетное звание «Нетаджи» ( хиндустани : «Уважаемый лидер») было впервые применено к Бозе в Германии в начале 1942 года — индийскими солдатами Индишского легиона , а также немецкими и индийскими чиновниками в Специальном бюро Индии в Берлине. Сейчас его используют по всей Индии. [час]

Bose was born into wealth and privilege in a large Bengali family in Orissa during the British Raj. An early recipient of an Anglo-centric education, after college he was sent to England to take the Indian Civil Service examination. He succeeded with distinction in the first exam but demurred at taking the routine final exam, citing nationalism as a higher calling. Returning to India in 1921, Bose joined the nationalist movement led by Mahatma Gandhi and the Indian National Congress. He followed Jawaharlal Nehru to leadership in a group within the Congress which was less keen on constitutional reform and more open to socialism.[i] Bose became Congress president in 1938. After reelection in 1939, differences arose between him and the Congress leaders, including Gandhi, over the future federation of British India and princely states, but also because discomfort had grown among the Congress leadership over Bose's negotiable attitude to non-violence, and his plans for greater powers for himself.[15] After the large majority of the Congress Working Committee members resigned in protest,[16] Bose resigned as president and was eventually ousted from the party.[17][18]

In April 1941 Bose arrived in Nazi Germany, where the leadership offered unexpected but equivocal sympathy for India's independence.[19][20] German funds were employed to open a Free India Centre in Berlin. A 3,000-strong Free India Legion was recruited from among Indian POWs captured by Erwin Rommel's Afrika Korps to serve under Bose.[21][j] Although peripheral to their main goals, the Germans inconclusively considered a land invasion of India throughout 1941. By the spring of 1942, the German army was mired in Russia and Bose became keen to move to southeast Asia, where Japan had just won quick victories.[23] Adolf Hitler during his only meeting with Bose in late May 1942 agreed to arrange a submarine.[24] During this time, Bose became a father; his wife,[6][k] or companion,[25][l] Emilie Schenkl, gave birth to a baby girl.[6][m][19] Identifying strongly with the Axis powers, Bose boarded a German submarine in February 1943.[26][27] Off Madagascar, he was transferred to a Japanese submarine from which he disembarked in Japanese-held Sumatra in May 1943.[26]

With Japanese support, Bose revamped the Indian National Army (INA), which comprised Indian prisoners of war of the British Indian army who had been captured by the Japanese in the Battle of Singapore.[28][29][30] A Provisional Government of Free India was declared on the Japanese-occupied Andaman and Nicobar Islands and was nominally presided by Bose.[31][2][n] Although Bose was unusually driven and charismatic, the Japanese considered him to be militarily unskilled,[o] and his soldierly effort was short-lived. In late 1944 and early 1945, the British Indian Army reversed the Japanese attack on India. Almost half of the Japanese forces and fully half of the participating INA contingent were killed.[p][q] The remaining INA was driven down the Malay Peninsula and surrendered with the recapture of Singapore. Bose chose to escape to Manchuria to seek a future in the Soviet Union which he believed to have turned anti-British.

Bose died from third-degree burns after his plane crashed in Japanese Taiwan on 18 August 1945.[r] Some Indians did not believe that the crash had occurred,[s] expecting Bose to return to secure India's independence.[t][u][v] The Indian National Congress, the main instrument of Indian nationalism, praised Bose's patriotism but distanced itself from his tactics and ideology.[w][41] The British Raj, never seriously threatened by the INA, charged 300 INA officers with treason in the Indian National Army trials, but eventually backtracked in the face of opposition by the Congress,[x] and a new mood in Britain for rapid decolonisation in India.[y][41][44]

Bose's legacy is mixed. Among many in India, he is seen as a hero, his saga serving as a would-be counterpoise to the many actions of regeneration, negotiation, and reconciliation over a quarter-century through which the independence of India was achieved.[z][aa][ab] His collaborations with Japanese fascism and Nazism pose serious ethical dilemmas,[ac] especially his reluctance to publicly criticize the worst excesses of German anti-Semitism from 1938 onwards or to offer refuge in India to its victims.[ad][ae][af]

Biography

1897–1921: Early life

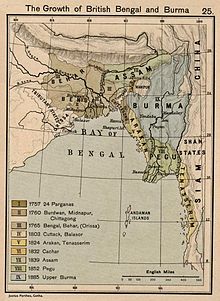

Subhas Chandra Bose was born to Bengali parents Prabhabati Bose (née Dutt) and Janakinath Bose on 23 January 1897 in Cuttack—in what is today the state of Odisha in India, but was then part of the Bengal Presidency in British India.[ag][ah] Prabhabati, or familiarly Mā jananī (lit. 'mother'), the anchor of family life, had her first child at age 14 and 13 children thereafter. Subhas was the ninth child and the sixth son.[54] Jankinath, a successful lawyer and government pleader,[53] was loyal to the government of British India and scrupulous about matters of language and the law. A self-made man from the rural outskirts of Calcutta, he had remained in touch with his roots, returning annually to his village during the pooja holidays.[55]

Following his five older brothers, Bose entered the Baptist Mission's Protestant European School in Cuttack in January 1902.[7] English was the medium of all instruction in the school, the majority of the students being European or Anglo-Indians of mixed British and Indian ancestry.[52] The curriculum included English—correctly written and spoken—Latin, the Bible, good manners, British geography, and British History; no Indian languages were taught.[52][7] The choice of the school was Janakinath's, who wanted his sons to speak flawless English with flawless intonation, believing both to be important for access to the British in India.[56] The school contrasted with Subhas's home, where only Bengali was spoken. At home, his mother worshipped the Hindu goddesses Durga and Kali, told stories from the epics Mahabharata and Ramayana, and sang Bengali religious songs.[7] From her, Subhas imbibed a nurturing spirit, looking for situations in which to help people in distress, preferring gardening around the house to joining in sports with other boys.[8] His father, who was reserved in manner and busy with professional life, was a distant presence in a large family, causing Subhas to feel he had a nondescript childhood.[57] Still, Janakinath read English literature avidly—John Milton, William Cowper, Matthew Arnold, and Shakespeare's Hamlet being among his favourites; several of his sons were to become English literature enthusiasts like him.[56]

In 1909, the 12-year-old Subhas Bose followed his five brothers to the Ravenshaw Collegiate School in Cuttack.[8] Here, Bengali and Sanskrit were also taught, as were ideas from Hindu scriptures such as the Vedas and the Upanishads not usually picked up at home.[8] Although his western education continued apace, he began to wear Indian clothes and engage in religious speculation. To his mother, he wrote long letters which displayed acquaintance with the ideas of the Bengali mystic Ramakrishna Paramahamsa and his disciple Swami Vivekananda, and the novel Ananda Math by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, popular then among young Hindu men.[59] Despite the preoccupation, Subhas was able to demonstrate an ability when needed to focus on his studies, to compete, and to succeed in exams. In 1912, he secured the second position in the matriculation examination conducted under the auspices of the University of Calcutta.[60]

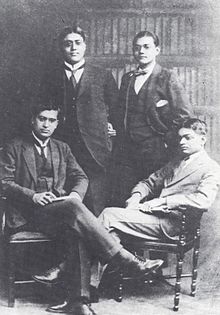

Subhas Bose followed his five brothers again 1913 to Presidency College, Calcutta, the historic and traditional college for Bengal's upper-caste Hindu men.[60][61] He chose to study philosophy, his readings including Kant, Hegel, Bergson and other Western philosophers.[62] A year earlier, he had befriended Hemanta Kumar Sarkar, a confidant and partner in religious yearnings.[63] At Presidency, their emotional ties grew stronger.[63] In the fanciful language of religious imagery, they declared their pure love for each other.[63] In the long vacations of 1914, they traveled to northern India for several months to search for a spiritual guru to guide them.[63] Subhas's family was not told clearly about the trip, leading them to think he had run away. During the trip, in which the guru proved elusive, Subhas came down with typhoid fever.[63] His absence caused emotional distress to his parents, leading both parents to break down upon his return.[63] Heated words were exchanged between Janakinath and Subhas. It took the return of Subhas's favorite brother, Sarat Chandra Bose, from law studies in England for the tempers to subside. Subhas returned to presidency and busied himself with studies, debating and student journalism.[63]

In February 1916, Bose was alleged to have masterminded,[53] or participated in, an incident involving E. F. Oaten, Professor of History at Presidency.[9] Before the incident, it was claimed by the students, Oaten had made rude remarks about Indian culture, and collared and pushed some students; according to Oaten, the students were making an unacceptably loud noise just outside his class.[9] A few days later, on 15 February, some students accosted Oaten on a stairway, surrounded him, beat him with sandals, and took to flight.[9] An inquiry committee was constituted. Although Oaten, who was unhurt, could not identify his assailants, a college servant testified to seeing Subhas Bose among those fleeing, confirming for the authorities what they had determined to be the rumor among the students.[9] Bose was expelled from the college and rusticated from University of Calcutta.[64] The incident shocked Calcutta and caused anguish to Bose's family.[53] He was ordered back to Cuttack. His family's connections were employed to pressure Asutosh Mukherjee, the Vice-Chancellor of Calcutta University.[64] Despite this, Subhas Bose's expulsion remained in place until 20 July 1917, when the Syndicate of Calcutta University granted him permission to return, but to another college.[10] He joined Scottish Church College, receiving his B.A. in 1918 in the First Class with honours in philosophy, placing second among all philosophy students in Calcutta University.[65]

At his father's urging, Subhas Bose agreed to travel to England to prepare and appear for the Indian Civil Services (ICS) examination.[66] Arriving in London on 20 October 1919, Subhas readied his application for the ICS.[67] For his references he put down Lord Sinha of Raipur, Under Secretary of State for India, and Bhupendranath Basu, a wealthy Calcutta lawyer who sat on the Council of India in London.[66] Bose was eager also to gain admission to a college at the University of Cambridge.[68] It was past the deadline for admission.[68] He sought help from some Indian students and from the Non-Collegiate Students Board. The Board offered the university's education at an economical cost without formal admission to a college. Bose entered the register of the university on 19 November 1919 and simultaneously set about preparing for the Civil Service exams.[68] He chose the Mental and Moral Sciences Tripos at Cambridge,[68] its completion requirement reduced to two years on account of his Indian B. A.[69]

There were six vacancies in the ICS.[70] Subhas Bose took the open competitive exam for them in August 1920 and was placed fourth.[70] This was a vital first step.[70] Still remaining was a final examination in 1921 on more topics on India, including the Indian Penal Code, the Indian Evidence Act, Indian history, and an Indian language.[70] Successful candidates had also to clear a riding test. Having no fear of these subjects and being a rider, Subhas Bose felt the ICS was within easy reach.[70] Yet between August 1920 and 1921 he began to have doubts about taking the final examination.[71] Many letters were exchanged with his father and his brother Sarat Chandra Bose back in Calcutta.[72] In one letter to Sarat, Subhas wrote,

"But for a man of my temperament who has been feeding on ideas that might be called eccentric—the line of least resistance is not the best line to follow ... The uncertainties of life are not appalling to one who has not, at heart, worldly ambitions. Moreover, it is not possible to serve one's country in the best and fullest manner if one is chained on to the civil service."[72]

In April 1921, Subhas Bose made his decision firm not to take the final examination for the ICS and wrote to Sarat informing him of the same, apologizing for the pain he would cause to his father, his mother, and other members of his family.[73] On 22 April 1921, he wrote to the Secretary of State for India, Edwin Montagu, stating, "I wish to have my name removed from the list of probationers in the Indian Civil Service."[74] The following day he wrote again to Sarat:

I received a letter from mother saying that in spite of what father and others think she prefers the ideals for which Mahatma Gandhi stands. I cannot tell you how happy I have been to receive such a letter. It will be worth a treasure for me as it has removed something like a burden from my mind."[75]

For some time before Subhas Bose had been in touch with C. R. Das, a lawyer who had risen to the helm of politics in Bengal; Das encouraged Subhas to return to Calcutta.[76] With the ICS decision now firmly behind him, Subhas Bose took his Cambridge B.A. Final examinations half-heartedly, passing, but being placed in the Third Class.[75] He prepared to sail for India in June 1921, electing for a fellow Indian student to pick up his diploma.[76]

1921–1932: Indian National Congress

Subhas Bose, aged 24, arrived ashore in India at Bombay on the morning of 16 July 1921 and immediately set about arranging an interview with Mahatma Gandhi. Gandhi, aged 51, was the leader of the non-cooperation movement that had taken India by storm the previous year and in a quarter-century would evolve to secure its independence.[ai][aj] Gandhi happened to be in Bombay and agreed to see Bose that afternoon. In Bose's account of the meeting, written many years later, he pilloried Gandhi with question after question.[78] Bose thought Gandhi's answers were vague, his goals unclear, his plan for achieving them not thought through.[78] Gandhi and Bose differed in this first meeting on the question of means—for Gandhi non-violent means to any end were non-negotiable; in Bose's thought, all means were acceptable in the service of anti-colonial ends.[78] They differed on the question of ends—Bose was attracted to totalitarian models of governance, which were anathematized by Gandhi.[79] According to historian Gordon, "Gandhi, however, set Bose on to the leader of the Congress and Indian nationalism in Bengal, C. R. Das, and in him Bose found the leader whom he sought."[78] Das was more flexible than Gandhi, more sympathetic to the extremism that had attracted idealistic young men such as Bose in Bengal.[78] Das launched Bose into nationalist politics.[78] Bose would work within the ambit of the Indian National Congress politics for nearly 20 years even as he tried to change its course.[78]

In 1922 Bose founded the newspaper Swaraj and assumed charge of the publicity for the Bengal Provincial Congress Committee.[80] His mentor was Chittaranjan Das, a voice for aggressive nationalism in Bengal. In 1923, Bose was elected the President of Indian Youth Congress and also the Secretary of the Bengal State Congress. He became the editor of the newspaper "Forward", which had been founded by Chittaranjan Das.[81] Bose worked as the CEO of the Calcutta Municipal Corporation for Das when the latter was elected mayor of Calcutta in 1924.[82] During the same year, when Bose was leading a protest march in Calcutta, he, Maghfoor Ahmad Ajazi and other leaders were arrested and imprisoned.[83][failed verification] After a roundup of nationalists in 1925, Bose was sent to prison in Mandalay, British Burma, where he contracted tuberculosis.[84]

In 1927, after being released from prison, Bose became general secretary of the Congress party and worked with Jawaharlal Nehru for independence. In late December 1928, Bose organised the Annual Meeting of the Indian National Congress in Calcutta.[85] His most memorable role was as General officer commanding (GOC) Congress Volunteer Corps.[85] Author Nirad Chaudhuri wrote about the meeting:

Bose organized a volunteer corps in uniform, its officers were even provided with steel-cut epaulettes ... his uniform was made by a firm of British tailors in Calcutta, Harman's. A telegram addressed to him as GOC was delivered to the British General in Fort William and was the subject of a good deal of malicious gossip in the (British Indian) press. Mahatma Gandhi as a sincere pacifist vowed to non-violence, did not like the strutting, clicking of boots, and saluting, and he afterward described the Calcutta session of the Congress as a Bertram Mills circus, which caused a great deal of indignation among the Bengalis.[85]

A little later, Bose was again arrested and jailed for civil disobedience; this time he emerged to become Mayor of Calcutta in 1930.[84]

1933–1937: Illness, Austria, Emilie Schenkl

During the mid-1930s Bose travelled in Europe, visiting Indian students and European politicians, including Benito Mussolini. He observed party organisation and saw communism and fascism in action.[86] In this period, he also researched and wrote the first part of his book The Indian Struggle, which covered the country's independence movement in the years 1920–1934. Although it was published in London in 1935, the British government banned the book in the colony out of fears that it would encourage unrest.[87] Bose was supported in Europe by the Indian Central European Society organized by Otto Faltis from Vienna.[88]

1937–1940: Indian National Congress

In 1938 Bose stated his opinion that the INC "should be organised on the broadest anti-imperialist front with the two-fold objective of winning political freedom and the establishment of a socialist regime."[89] By 1938 Bose had become a leader of national stature and agreed to accept nomination as Congress President. He stood for unqualified Swaraj (self-governance), including the use of force against the British. This meant a confrontation with Mohandas Gandhi, who in fact opposed Bose's presidency,[90] splitting the Indian National Congress party.

Bose attempted to maintain unity, but Gandhi advised Bose to form his own cabinet. The rift also divided Bose and Nehru; he appeared at the 1939 Congress meeting on a stretcher. He was elected president again over Gandhi's preferred candidate Pattabhi Sitaramayya.[93] U. Muthuramalingam Thevar strongly supported Bose in the intra-Congress dispute. Thevar mobilised all south India votes for Bose.[94] However, due to the manoeuvrings of the Gandhi-led clique in the Congress Working Committee, Bose found himself forced to resign from the Congress presidency.[citation needed]

On 22 June 1939 Bose organised the All India Forward Bloc a faction within the Indian National Congress,[95] aimed at consolidating the political left, but its main strength was in his home state, Bengal. U Muthuramalingam Thevar, who was a staunch supporter of Bose from the beginning, joined the Forward Bloc. When Bose visited Madurai on 6 September, Thevar organised a massive rally as his reception.[citation needed]

When Subhas Chandra Bose was heading to Madurai, on an invitation of Muthuramalinga Thevar to amass support for the Forward Bloc, he passed through Madras and spent three days at Gandhi Peak.His correspondence reveals that despite his clear dislike for British subjugation, he was deeply impressed by their methodical and systematic approach and their steadfastly disciplinarian outlook towards life. In England, he exchanged ideas on the future of India with British Labour Party leaders and political thinkers like Lord Halifax, George Lansbury, Clement Attlee, Arthur Greenwood, Harold Laski, J.B.S. Haldane, Ivor Jennings, G.D.H. Cole, Gilbert Murray and Sir Stafford Cripps.[citation needed]

He came to believe that an independent India needed socialist authoritarianism, on the lines of Turkey's Kemal Atatürk, for at least two decades. For political reasons Bose was refused permission by the British authorities to meet Atatürk at Ankara. During his sojourn in England Bose tried to schedule appointments with several politicians, but only the Labour Party and Liberal politicians agreed to meet with him. Conservative Party officials refused to meet him or show him courtesy because he was a politician coming from a colony. In the 1930s leading figures in the Conservative Party had opposed even Dominion status for India. It was during the Labour Party government of 1945–1951, with Attlee as the Prime Minister, that India gained independence.

On the outbreak of war, Bose advocated a campaign of mass civil disobedience to protest against Viceroy Lord Linlithgow's decision to declare war on India's behalf without consulting the Congress leadership. Having failed to persuade Gandhi of the necessity of this, Bose organised mass protests in Calcutta calling for the removal of the "Holwell Monument", which then stood at the corner of Dalhousie Square in memoriam of those who died in the Black Hole of Calcutta.[96] He was thrown in jail by the British, but was released following a seven-day hunger strike. Bose's house in Calcutta was kept under surveillance by the CID.[97]

1941: Escape to Nazi Germany

Bose's arrest and subsequent release set the scene for his escape to Nazi Germany, via Afghanistan and the Soviet Union. A few days before his escape, he sought solitude and, on this pretext, avoided meeting British guards and grew a beard. Late night 16 January 1941, the night of his escape, he dressed as a Pathan (brown long coat, a black fez-type coat and broad pyjamas) to avoid being identified. Bose escaped from under British surveillance from his Elgin Road house in Calcutta on the night of 17 January 1941, accompanied by his nephew Sisir Kumar Bose, later reaching Gomoh Railway Station (now Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose Gomoh Station) in the then state of Bihar (now Jharkhand), India.[98][99][100][101]

Bose journeyed to Peshawar with the help of the Abwehr, where he was met by Akbar Shah, Mohammed Shah and Bhagat Ram Talwar. Bose was taken to the home of Abad Khan, a trusted friend of Akbar Shah's. On 26 January 1941, Bose began his journey to reach Russia through British India's North West frontier with Afghanistan. For this reason, he enlisted the help of Mian Akbar Shah, then a Forward Bloc leader in the North-West Frontier Province. Shah had been out of India en route to the Soviet Union, and suggested a novel disguise for Bose to assume. Since Bose could not speak Pashto, it would have made him an easy target of Pashto speakers working for the British. For this reason, Shah suggested that Bose act deaf and dumb, and let his beard grow to mimic those of the tribesmen. Bose's guide Bhagat Ram Talwar, unknown to him, was a Soviet agent.[100][101][102]

Supporters of the Aga Khan III helped him across the border into Afghanistan where he was met by an Abwehr unit posing as a party of road construction engineers from the Organization Todt who then aided his passage across Afghanistan via Kabul to the border with the Soviet Union. After assuming the guise of a Pashtun insurance agent ("Ziaudddin") to reach Afghanistan, Bose changed his guise and travelled to Moscow on the Italian passport of an Italian nobleman "Count Orlando Mazzotta". From Moscow, he reached Rome, and from there he travelled to Nazi Germany.[100][101][103] Once in Russia the NKVD transported Bose to Moscow where he hoped that Russia's historical enmity to British rule in India would result in support for his plans for a popular rising in India. However, Bose found the Soviets' response disappointing and was rapidly passed over to the German Ambassador in Moscow, Count von der Schulenburg. He had Bose flown on to Berlin in a special courier aircraft at the beginning of April where he was to receive a more favourable hearing from Joachim von Ribbentrop and the Foreign Ministry officials at the Wilhelmstrasse.[100][101][104]

1941–1943: Collaboration with Nazi Germany

In Germany, Bose was attached to the Special Bureau for India under Adam von Trott zu Solz which was responsible for broadcasting on the German-sponsored Azad Hind Radio.[105] He founded the Free India Center in Berlin, and created the Indian Legion (consisting of some 4500 soldiers) out of Indian prisoners of war who had previously fought for the British in North Africa prior to their capture by Axis forces. The Indian Legion was attached to the Wehrmacht, and later transferred to the Waffen SS. Its members swore the following allegiance to Hitler and Bose: "I swear by God this holy oath that I will obey the leader of the German race and state, Adolf Hitler, as the commander of the German armed forces in the fight for India, whose leader is Subhas Chandra Bose". This oath clearly abrogated control of the Indian legion to the German armed forces whilst stating Bose's overall leadership of India. He was also, however, prepared to envisage an invasion of India via the USSR by Nazi troops, spearheaded by the Azad Hind Legion; many have questioned his judgment here, as it seems unlikely that the Germans could have been easily persuaded to leave after such an invasion, which might also have resulted in an Axis victory in the War.[103]

Soon, according to historian Romain Hayes, "the (German) Foreign Office procured a luxurious residence for (Bose) along with a butler, cook, gardener, and an SS-chauffeured car. Emilie Schenkl moved in openly with him. The Germans, aware of the nature of the relationship, refrained from any involvement."[106] However, most of the staff in the Special Bureau for India, which had been set up to aid Bose, did not get along with Emilie.[107] In particular Adam von Trott, Alexander Werth and Freda Kretschemer, according to historian Leonard A. Gordon, "appear to have disliked her intensely. They believed that she and Bose were not married and that she was using her liaison with Bose to live an especially comfortable life during the hard times of war" and that differences were compounded by issues of class.[107] In November 1942, Schenkl gave birth to their daughter.

The Germans were unwilling to form an alliance with Bose because they considered him unpopular in comparison with Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru.[108][109] By the spring of 1942, the German army was mired in the USSR. Bose, due to disappointment over the lack of response from Nazi Germany, was now keen to move to Southeast Asia, where Japan had just won quick victories. However, he still expected official recognition from Nazi Germany. Adolf Hitler during his only meeting with Bose in late May 1942 refused to entertain Bose's requests and facilitated him with a submarine voyage to East Asia.[24][110][111]

In February 1943, Bose left Schenkl and their baby daughter and boarded a German submarine to travel, via transfer to a Japanese submarine, to Japanese-occupied southeast Asia. In all, 3,000 Indian prisoners of war signed up for the Free India Legion. But instead of being delighted, Bose was worried. A left-wing admirer of Russia, he was devastated when Hitler's tanks rolled across the Soviet border. Matters were worsened by the fact that the now-retreating German army would be in no position to offer him help in driving the British from India. When he met Hitler in May 1942, his suspicions were confirmed, and he came to believe that the Nazi leader was more interested in using his men to win propaganda victories than military ones. So, in February 1943, Bose boarded a German U-boat and left for Japan. This left the men he had recruited leaderless and demoralised in Germany.[103][112]

1943–1945: Japanese-occupied Asia

In 1943, after being disillusioned that Germany could be of any help in gaining India's independence, Bose left for Japan. He travelled with the German submarine U-180 around the Cape of Good Hope to the southeast of Madagascar, where he was transferred to the I-29 for the rest of the journey to Imperial Japan. This was the only civilian transfer between two submarines of two different navies in World War II.[100][101]

The Indian National Army (INA) was the brainchild of Japanese Major (and post-war Lieutenant-General) Iwaichi Fujiwara, head of the Japanese intelligence unit Fujiwara Kikan. Fujiwara's mission was "to raise an army which would fight alongside the Japanese army."[113][114] He first met Pritam Singh Dhillon, the president of the Bangkok chapter of the Indian Independence League, and through Pritam Singh's network recruited a captured British Indian army captain, Mohan Singh, on the western Malayan peninsula in December 1941. The First Indian National Army was formed as a result of discussion between Fujiwara and Mohan Singh in the second half of December 1941, and the name chosen jointly by them in the first week of January 1942.[115]

This was along the concept of, and with support of, what was then known as the Indian Independence League headed from Tokyo by expatriate nationalist leader Rash Behari Bose. The first INA was however disbanded in December 1942 after disagreements between the Hikari Kikan and Mohan Singh, who came to believe that the Japanese High Command was using the INA as a mere pawn and propaganda tool. Singh was taken into custody and the troops returned to the prisoner-of-war camp. However, the idea of an independence army was revived with the arrival of Subhas Chandra Bose in the Far East in 1943. In July, at a meeting in Singapore, Rash Behari Bose handed over control of the organisation to Subhas Chandra Bose. Bose was able to reorganise the fledgling army and organise massive support among the expatriate Indian population in south-east Asia, who lent their support by both enlisting in the Indian National Army, as well as financially in response to Bose's calls for sacrifice for the independence cause. INA had a separate women's unit, the Rani of Jhansi Regiment (named after Rani Lakshmi Bai) headed by Capt. Lakshmi Swaminathan, which is seen as a first of its kind in Asia.[116][117]

Even when faced with military reverses, Bose was able to maintain support for the Azad Hind movement. Spoken as a part of a motivational speech for the Indian National Army at a rally of Indians in Burma on 4 July 1944, Bose's most famous quote was "Give me blood, and I shall give you freedom!" In this, he urged the people of India to join him in his fight against the British Raj.[citation needed] Spoken in Hindi, Bose's words are highly evocative. The troops of the INA were under the aegis of a provisional government, the Azad Hind Government, which came to produce its own currency, postage stamps, court and civil code, and was recognised by nine Axis states—Germany, Japan, Italian Social Republic, the Independent State of Croatia, the Wang Jingwei regime in Nanjing, China, a provisional government of Burma, Manchukuo and Japanese-controlled Philippines. Of those countries, five were authorities established under Axis occupation. This government participated in the so-called Greater East Asia Conference as an observer in November 1943.[118]

The INA's first commitment was in the Japanese thrust towards Eastern Indian frontiers of Manipur. INA's special forces, the Bahadur Group, were involved in operations behind enemy lines both during the diversionary attacks in Arakan, as well as the Japanese thrust towards Imphal and Kohima.[119]

The Japanese also took possession of Andaman and Nicobar Islands in 1942 and a year later, the Provisional Government and the INA were established in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands with Lt Col. Arcot Doraiswamy Loganadan appointed its Governor General. The islands were renamed Shaheed (Martyr) and Swaraj (Independence). However, the Japanese Navy remained in essential control of the island's administration. During Bose's only visit to the islands in early 1944, apparently in the interest of shielding Bose from attaining a full knowledge of ultimate Japanese intentions, his Japanese hosts carefully isolated him from the local population. At that time the island's Japanese administration had been torturing the leader of the island's Indian Independence League, Diwan Singh, who later died of his injuries in the Cellular Jail. During Bose's visit to the islands several locals attempted to alert Bose to Singh's plight, but apparently without success. During this time Loganathan became aware of his lack of any genuine administrative control and resigned in protest as Governor General, later returning to the Government's headquarters in Rangoon.[120][121]

On the Indian mainland, an Indian Tricolour flag, modelled after that of the Indian National Congress, was raised for the first time in the town of Moirang, in Manipur, in north-eastern India. The adjacent towns of Kohima and Imphal were then encircled and placed under siege by divisions of the Japanese Army, working in conjunction with the Burmese National Army, and with Brigades of the INA, known as the Gandhi and Nehru Brigades. This attempt at conquering the Indian mainland had the Axis codename of Operation U-Go.[citation needed]

During this operation, on 6 July 1944, in a speech broadcast by the Azad Hind Radio from Singapore, Bose addressed Mahatma Gandhi as the "Father of the Nation" and asked for his blessings and good wishes for the war he was fighting. This was the first time that Gandhi was referred to by this appellation.[122] The protracted Japanese attempts to take these two towns depleted Japanese resources, with Operation U-Go ultimately proving unsuccessful. Through several months of Japanese onslaught on these two towns, Commonwealth forces remained entrenched in the towns. Commonwealth forces then counter-attacked, inflicting serious losses on the Axis led forces, who were then forced into a retreat back into Burmese territory. After the Japanese defeat at the battles of Kohima and Imphal, Bose's Provisional Government's aim of establishing a base in mainland India was lost forever.[citation needed]

Still the INA fought in key battles against the British Indian Army in Burmese territory, notable in Meiktilla, Mandalay, Pegu, Nyangyu and Mount Popa. However, with the fall of Rangoon, Bose's government ceased to be an effective political entity.[citation needed] A large proportion of the INA troops surrendered under Lt Col Loganathan. The remaining troops retreated with Bose towards Malaya or made for Thailand. Japan's surrender at the end of the war also led to the surrender of the remaining elements of the Indian National Army. The INA prisoners were then repatriated to India and some tried for treason.[123]

18 August 1945: Death

Subhas Chandra Bose died on 18 August 1945 from third-degree burns after his airplane crashed in Japanese-ruled Formosa (now Taiwan).[124][36][4][5] However, many among his supporters, especially in Bengal, refused at the time, and have refused since, to believe either the fact or the circumstances of his death.[124][37][38] Conspiracy theories appeared within hours of his death and have thereafter had a long shelf life,[124][am] keeping alive various martial myths about Bose.[44]

In Taihoku, at around 2:30 pm as the bomber with Bose on board was leaving the standard path taken by aircraft during take-off, the passengers inside heard a loud sound, similar to an engine backfiring.[125][126] The mechanics on the tarmac saw something fall out of the plane.[127] It was the portside engine, or a part of it, and the propeller.[127][125] The plane swung wildly to the right and plummeted, crashing, breaking into two, and exploding into flames.[127][125] Inside, the chief pilot, copilot and Lieutenant-General Tsunamasa Shidei, the Vice Chief of Staff of the Japanese Kwantung Army, who was to have made the negotiations for Bose with the Soviet army in Manchuria,[128] were instantly killed.[127][129] Bose's assistant Habibur Rahman was stunned, passing out briefly, and Bose, although conscious and not fatally hurt, was soaked in gasoline.[127] When Rahman came to, he and Bose attempted to leave by the rear door, but found it blocked by the luggage.[129] They then decided to run through the flames and exit from the front.[129] The ground staff, now approaching the plane, saw two people staggering towards them, one of whom had become a human torch.[127] The human torch turned out to be Bose, whose gasoline-soaked clothes had instantly ignited.[129] Rahman and a few others managed to smother the flames, but also noticed that Bose's face and head appeared badly burned.[129] According to Joyce Chapman Lebra, "A truck which served as ambulance rushed Bose and the other passengers to the Nanmon Military Hospital south of Taihoku."[127] The airport personnel called Dr. Taneyoshi Yoshimi, the surgeon-in-charge at the hospital at around 3 pm.[129] Bose was conscious and mostly coherent when they reached the hospital, and for some time thereafter.[130] Bose was naked, except for a blanket wrapped around him, and Dr. Yoshimi immediately saw evidence of third-degree burns on many parts of the body, especially on his chest, doubting very much that he would live.[130] Dr. Yoshimi promptly began to treat Bose and was assisted by Dr. Tsuruta.[130] According to historian Leonard A. Gordon, who interviewed all the hospital personnel later,

A disinfectant, Rivamol [sic], was put over most of his body and then a white ointment was applied and he was bandaged over most of his body. Dr. Yoshimi gave Bose four injections of Vita Camphor and two of Digitamine for his weakened heart. These were given about every 30 minutes. Since his body had lost fluids quickly upon being burnt, he was also given Ringer solution intravenously. A third doctor, Dr. Ishii gave him a blood transfusion. An orderly, Kazuo Mitsui, an army private, was in the room and several nurses were also assisting. Bose still had a clear head which Dr. Yoshimi found remarkable for someone with such severe injuries.[131]

Soon, in spite of the treatment, Bose went into a coma.[131][127] A few hours later, between 9 and 10 pm (local time) on Saturday, 18 August 1945, Bose died aged 48.[131][127]

Bose's body was cremated in the main Taihoku crematorium two days later, 20 August 1945.[132] On 23 August 1945, the Japanese news agency Do Trzei announced the death of Bose and Shidea.[127] On 7 September a Japanese officer, Lieutenant Tatsuo Hayashida, carried Bose's ashes to Tokyo, and the following morning they were handed to the president of the Tokyo Indian Independence League, Rama Murti.[133] On 14 September a memorial service was held for Bose in Tokyo and a few days later the ashes were turned over to the priest of the Renkōji Temple of Nichiren Buddhism in Tokyo.[134][135] There they have remained ever since.[135]

Among the INA personnel, there was widespread disbelief, shock, and trauma. Most affected were the young Tamil Indians from Malaya and Singapore, both men and women, who comprised the bulk of the civilians who had enlisted in the INA.[41] The professional soldiers in the INA, most of whom were Punjabis, faced an uncertain future, with many fatalistically expecting reprisals from the British.[41] In India the Indian National Congress's official line was succinctly expressed in a letter Mohandas Karamchand (Mahatma) Gandhi wrote to Rajkumari Amrit Kaur.[41] Said Gandhi, "Subhas Bose has died well. He was undoubtedly a patriot, though misguided."[41] Many congressmen had not forgiven Bose for quarrelling with Gandhi and for collaborating with what they considered was Japanese fascism. The Indian soldiers in the British Indian army, some two and a half million of whom had fought during the Second World War, were conflicted about the INA. Some saw the INA as traitors and wanted them punished; others felt more sympathetic. The British Raj, though never seriously threatened by the INA, tried 300 INA officers for treason in the INA trials, but eventually backtracked.[41]

Ideology

Subhas Chandra Bose believed that the Bhagavad Gita was a great source of inspiration for the struggle against the British.[136] Swami Vivekananda's teachings on universalism, his nationalist thoughts and his emphasis on social service and reform had all inspired Subhas Chandra Bose from his very young days. The fresh interpretation of India's ancient scriptures had appealed immensely to him.[137] Some scholars think that Hindu spirituality formed an essential part of his political and social thought.[138] As historian Leonard Gordon explains "Inner religious explorations continued to be a part of his adult life. This set him apart from the slowly growing number of atheistic socialists and communists who dotted the Indian landscape."[139]

Bose first expressed his preference for "a synthesis of what modern Europe calls socialism and fascism" in a 1930 speech in Calcutta.[140]Bose later criticized Nehru's 1933 statement that there is "no middle road" between communism and fascism, describing it as "fundamentally wrong". Bose believed communism would not gain ground in India due to its rejection of nationalism and religion and suggested a "synthesis between communism and fascism" could take hold instead.[141] In 1944, Bose similarly stated, "Our philosophy should be a synthesis between National Socialism and communism."[142]

Authoritarianism

Bose believed that authoritarianism could bring liberation and reconstruction of Indian society.[143] He expressed admiration for the authoritarian methods which he saw in Italy and Germany during the 1930s; he thought they could be used to build an independent India.[96]

To a large number of Congress leaders, Bose programme shared enough similarities with Japanese fascists.[144] After getting marginalized within Congress, Bose chose to embrace fascist regimes as allies against the British and fled India.[44][145] Bose believed that India "must have a political system—State—of an authoritarian character," and "a strong central government with dictatorial powers for some years to come".[146]

Earlier, Bose had clearly expressed his belief that democracy was the best option for India.[147] However, during the war (and possibly as early as the 1930s), Bose seems to have decided that no democratic system could be adequate to overcome India's poverty and social inequalities, and he wrote that a socialist state similar to that of Soviet Russia (which he had also seen and admired) would be needed for the process of national re-building.[an] Accordingly, some suggest that Bose's alliance with the Axis during the war was based on more than just pragmatism and that Bose was a militant nationalist, though not a Nazi nor a Fascist, for he supported the empowerment of women, secularism and other liberal ideas; alternatively, others consider he might have been using populist methods of mobilisation common to many post-colonial leaders.[96]

Anti-semitism

Since before the beginning of the World War II, Bose was opposed to the attempts to grant Jewish refugees asylum in India.[149][150] The great anti-Jewish pogrom called "the Night of Broken Glass" happened on 9 November 1938. In early December, the pro-Hindu Mahasabha journals published articles lending support to German anti-Semitism. This stance brought Hindu Mahasabha into conflict with the Congress which, on 12 December, issued a statement containing references to recent European events. Within the Congress, only Bose opposed this stance of the party. After some months in April 1939, Bose refused to support the party motion that Jews can find refuge in India.[49][151][152][153][154][155]

In 1938, Bose had denounced Nazi racial policy and persecution of Jews.[156] However, in 1942 he had published an article in the journal Angriff, where he wrote that Indians were true Aryans and the 'brethren' of the Germans. Bose added that Swastika (symbol of Nazi Germany) was an ancient Indian symbol. Bose urged that anti-Semitism should be part of Indian liberation movement because the Jews assisted the British to exploit Indians.[157] The Jewish Chronicle had condemned Bose as "India's anti-Jewish Quisling" over this article.[158]

Roman Hayes describes the troubled legacy of Bose with atrocities related to Jews in the following words:–

"The most troubling aspect of Bose's presence in Nazi Germany is not military or political but rather ethical. His alliance with the most genocidal regime in history poses serious dilemmas precisely because of his popularity and his having made a lifelong career of fighting the 'good cause'. How did a man who started his political career at the feet of Gandhi end up with Hitler, Mussolini, and Tojo? Even in the case of Mussolini and Tojo, the gravity of the dilemma pales in comparison to that posed by his association with Hitler and the Nazi leadership. The most disturbing issue, all too often ignored, is that in the many articles, minutes, memorandums, telegrams, letters, plans, and broadcasts Bose left behind in Germany, he did not express the slightest concern or sympathy for the millions who died in the concentration camps. Not one of his Berlin wartime associates or colleagues ever quotes him expressing any indignation. Not even when the horrors of Auschwitz and its satellite camps were exposed to the world upon being liberated by Soviet troops in early 1945, revealing publicly for the first time the genocidal nature of the Nazi regime, did Bose react."[48]

Quotes

His most famous quote was "Give me blood and I will give you freedom".[159] Another famous quote was Dilli Chalo ("On to Delhi)!" This was the call he used to give the INA armies to motivate them. Another slogan coined by him was "Ittehad, Etemad, Qurbani" (Urdu for "Unity, Agreement, Sacrifice"). [160]

Legacy

Bose' defiance of British authority in India made him a hero among many Indians,[ao][ap][aq] however his wartime alliances with Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan left a legacy fraught with authoritarianism, anti-Semitism, and military failure.[ar][163][164][as][at]

Memorials

Bose was featured on the stamps in India from 1964, 1993, 1997, 2001, 2016, 2018 and 2021.[167] Bose was also featured in ₹2 coins in 1996 and 1997, ₹75 coin in 2018 and ₹125 coin in 2021.[168][169][170] Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose International Airport at Kolkata, West Bengal, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose Gomoh railway station at Gomoh, Jharkhand, Netaji Express, a train runs between Howrah and Kalka, Cuttack Netaji Bus Terminal at Cuttack, Odisha, Netaji Bhavan metro station and Netaji metro station at Kolkata, West Bengal and Netaji Subhash Place metro station at Delhi. Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose Island at Andaman and Nicobar Island, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose Setu (Longest bridge of Odisha) at Cuttack, Odisha and many other institutions in India are named after him. On 23 August 2007, Japanese Prime Minister, Shinzō Abe visited the Netaji Bhawan in Kolkata.[171][172] Abe, who is also the recipient of Netaji Award 2022,[173] said to Bose's family "The Japanese are deeply moved by Bose's strong will to have led the Indian independence movement from British rule. Netaji is a much respected name in Japan."[171][172]

In 2021, the Government of India declared 23 January as Parakram Divas to commemorate the birth anniversary of Subhas Chandra Bose. Political party, Trinamool Congress and the All India Forward Bloc demanded that the day should be observed as 'Deshprem Divas'.[174] In 2019, the Government of India inaugurated a museum on Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose and his INA at Red Fort, New Delhi. In 2022, Government of India inaugurated a Statue of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose at India Gate. Also in the same year, Government of India started an official award Subhas Chandra Bose Aapda Prabandhan Puraskar, for those who does excellent work in Disaster management.[175][176]

In popular media

- Netaji Subhash, a feature documentary film about Bose was released in 1947, it was directed by Chhotubhai Desai.[177]

- Subhas Chandra is a 1966 Indian Bengali-language biographical film, directed by Pijush Basu.[178][179]

- Neta Ji Subhash Chandra Bose is a 1966 Indian biographical drama film about Bose by Hemen Gupta.[177]

- In 2004, Shyam Benegal directed the biographical film, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose: The Forgotten Hero depicting his life in Nazi Germany (1941–1943), in Japanese-occupied Asia (1943–1945) and the events leading to the formation of Azad Hind Fauj.[180] The film received critical acclaim at the BFI London Film Festival, and has garnered the National Film Award for Best Feature Film on National Integration, and the National Film Award for Best Production Design for that year.[181][182]

- Mahanayak, 2005 published Marathi historical novel on the life of Subhash Chandra Bose, written by Marathi author Vishvas Patil.

- His Majesty's Opponent, a biography of Subhash Chandra Bose, written by Sugata Bose, published in 2011.

- Subhash Chandra Bose: The Mystery, a 2016 documentary film by Iqbal Malhotra, follows conspiracy theories regarding Bose's death.[183]

- Netaji Bose – The Lost Treasure is a 2017 television documentary film which aired on History TV18, it explores the INA treasure controversy.[184]

- In 2017, ALTBalaji and BIG Synergy Media, released a 9-episode web series, Bose: Dead/Alive, created by Ekta Kapoor, a dramatised version of the book India's Biggest Cover-up written by Anuj Dhar, which starred Bollywood actor Rajkummar Rao as Subhas Chandra Bose and Anna Ador as Emilie Schenkl. The series was praised by both audience and critics, for its plot, performance and production design.[185]

- In January 2019 Zee Bangla started broadcasting the daily television series Netaji.

- Gumnaami is an 2019 Indian Bengali mystery film directed by Srijit Mukherji, which deals with Netaji's death mystery, based on the Mukherjee Commission Hearings.

See also

Notes

- ^ "the Provisional Government of Azad Hind (or Free India Provisional Government, FIPG) was announced on 21 October. It was based at Singapore and consisted, in the first instance, of five ministers, eight representatives of the INA, and eight civilian advisers representing the Indians of Southeast and East Asia. Bose was head of state, prime minister and minister for war and foreign affairs.[1]

- ^ "Hideki Tojo turned over all Japan's Indian POWs to Bose's command, and in October 1943 Bose announced the creation of a Provisional Government of Free India, of which he became head of state, prime minister, minister of war, and minister of foreign affairs."[2]

- ^ "Bose was especially keen to have some Indian territory over which the provisional government might claim sovereignty. Since the Japanese had stopped east of the Chindwin River in Burma and not entered India on that front, the only Indian territories they held were the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Indian Ocean. The Japanese navy was unwilling to transfer administration of these strategic islands to Bose's forces, but a face-saving agreement was worked out so that the provisional government was given a 'jurisdiction', while actual control remained throughout with the Japanese military. Bose eventually made a visit to Port Blair in the Andamans in December and a ceremonial transfer took place. Renaming them the Shahid (Martyr) and Swaraj (Self-rule) Islands, Bose raised the Indian national flag and appointed Lieutenant-Colonel Loganadhan, a medical officer, as chief commissioner. Bose continued to lobby for complete transfer, but did not succeed."[3]

- ^ His formal title after 21 October 1943 was: Head of State, Prime Minister, Minister of War, and Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Provisional Government of Free India, which was based in Japanese-occupied Singapore.[a][b] with jurisdiction, but without the sovereignty of Japanese-occupied Andaman Islands.[c]

- ^ Expelled from the college and rusticated from the university, 15 February 1916;[9] reinstated in the university 20 July 1917.[10]

- ^ "When another run-in between Professor Oaten and some students took place on February 15 (1916), a group of students including Subhas Bose, ... decided to take the law in their own hands. Coming down the broad staircase from the second floor, Oaten was surrounded (the) students who beat him with their sandals—and fled. Although Oaten himself was not able to identify any of the attackers, a bearer said he saw Subhas Bose and Ananga Dam among those fleeing. Rumors in student circles also placed Subhas among the group. An investigation was carried out by the college authorities, and these two were expelled from the college and rusticated from the university.[9]

- ^ "Upon arriving in Britain, Bose went up to Cambridge to gain admission. He managed to gain entry to Fitzwilliam Hall, a body for non-collegiate members of the University. Bose took the Mental and Moral Sciences Tripos."

- ^ "Another small, but immediate, issue for the civilians in Berlin and the soldiers in training was how to address Subhas Bose. Vyas has given his view of how the term was adopted: 'one of our [soldier] boys came forward with "Hamare Neta". We improved upon it: "Netaji"... It must be mentioned, that Subhas Bose strongly disapproved of it. He began to yield only when he saw our military group ... firmly went on calling him "Netaji"'. (Alexander) Werth also mentioned adoption of 'Netaji' and observed accurately, that it '... combined a sense both of affection and honour ...' It was not meant to echo 'Fuehrer' or 'Duce', but to give Subhas Bose a special Indian form of reverence and this term has been universally adopted by Indians everywhere in speaking about him."[13]

- ^ "Younger Congressmen, including Jawaharlal Nehru, ... thought that constitution-making, whether by the British with their (Simon) Commission or by moderate politicians like the elder (Motilal) Nehru, was not the way to achieve the fundamental changes in society. Nehru and Subhas Bose rallied a group within Congress ... to declare for an independent republic. (p. 305) ... (They) were among those who, impatient with Gandhi's programmes and methods, looked upon socialism as an alternative for nationalistic policies capable of meeting the country's economic and social needs, as well as a link to potential international support (p. 325)."[14]

- ^ "Having arrived in Berlin a bruised politician, his broadcasts brought him—and India—world notice.[22]

- ^ "While writing The Indian Struggle, Bose also hired a secretary by the name of Emilie Schenkl. They eventually fell in love and married secretly in accordance with Hindu rites."[6]

- ^ "Although we must take Emilie Schenkl at her word (about her secret marriage to Bose in 1937), there are a few nagging doubts about an actual marriage ceremony because there is no document that I have seen and no testimony by any other person. ... Other biographers have written that Bose and Miss Schenkl were married in 1942, while Krishna Bose, implying 1941, leaves the date ambiguous. The strangest and most confusing testimony comes from A. C. N. Nambiar, who was with the couple in Badgastein briefly in 1937, and was with them in Berlin during the war as second-in-command to Bose. In an answer to my question about the marriage, he wrote to me in 1978: 'I cannot state anything definite about the marriage of Bose referred to by you, since I came to know of it only a good while after the end of the last world war ... I can imagine the marriage having been a very informal one ...'... So what are we left with? ... We know they had a close passionate relationship and that they had a child, Anita, born 29 November 1942, in Vienna. ... And we have Emilie Schenkl's testimony that they were married secretly in 1937. Whatever the precise dates, the most important thing is the relationship."[25]

- ^ "Apart from the Free India Centre, Bose also had another reason to feel satisfied-even comfortable-in Berlin. After months of residing in a hotel, the Foreign Office procured a luxurious residence for him along with a butler, cook, gardener and an SS-chauffeured car. Emilie Schenkl moved in openly with him. The Germans, aware of the nature of their relationship, refrained from any involvement. The following year she gave birth to a daughter.[6]

- ^ "Tojo turned over all his Indian POWs to Bose's command, and in October 1943 Bose announced the creation of a Provisional Government of Azad ("Free") India, of which he became head of state, prime minister, minister of war, and minister of foreign affairs. Some two million Indians were living in Southeast Asia when the Japanese seized control of that region, and these emigrees were the first "citizens" of that government, founded under the "protection" of Japan and headquartered on the "liberated" Andaman Islands. Bose declared war on the United States and Great Britain the day after his government was established. In January 1944 he moved his provisional capital to Rangoon and started his Indian National Army on their march north to the battle cry of the Meerut mutineers: "Chalo Delhi!"[2]

- ^ "At the same time that the Japanese appreciated the firmness with which Bose's forces continued to fight, they were endlessly exasperated with him. A number of Japanese officers, even those like Fujiwara, who were devoted to the Indian cause, saw Bose as a military incompetent as well as an unrealistic and stubborn man who saw only his own needs and problems and could not see the larger picture of the war as the Japanese had to."[32]

- ^ "Gracey consoled himself that Bose's Indian National Army had also been in action against his Indians and Gurkhas but had been roughly treated and almost annihilated; when the survivors tried to surrender, they tended to fall foul of the Gurkhas' dreaded kukri."[33]

- ^ Initially, INA troops in the Arakan stayed loyal to the INA and their IJA masters. However, as starvation and defeat began to take their toll, loyalties began to waver, and two companies from the Bose Brigade surrendered en masse to British forces in July 1944.[34]

- ^ "The good news Wavell reported was that the RAF had just recently flown enough of its planes into Manipur's capital of Imphal to smash Netaji ("Leader") Subhas Chandra Bose's Indian National Army (INA) that had advanced to its outskirts before the monsoon began. Bose's INA consisted of about 20,000 of the British Indian soldiers captured by the Japanese in Singapore, who had volunteered to serve under Netaji Bose when he offered them "Freedom" if they were willing to risk their "Blood" to gain Indian independence a year earlier. The British considered Bose and his "army of traitors" no better than their Japanese sponsors, but to most of Bengal's 50 million Indians, Bose was a great national hero and potential "Liberator". The INA was stopped before entering Bengal, first by monsoon rains and then by the RAF, and forced to retreat, back through Burma and down its coast to the Malay peninsula. In May 1945, Bose would fly out of Saigon on an overloaded Japanese plane, headed for Taiwan, which crash-landed and burned. Bose suffered third-degree burns and died in the hospital on Formosa."[35]

- ^ "The retreat was even more devastating, finally ending the dream of gaining Indian independence through military campaign. But Bose still remained optimistic, thought of regrouping after the Japanese surrender, contemplated seeking help from Soviet Russia. The Japanese agreed to provide him transport up to Manchuria from where he could travel to Russia. But on his way, on 18 August 1945 at Taihoku airport in Taiwan, he died in an air crash, which many Indians still believe never happened."[36]

- ^ "There are still some in India today who believe that Bose remained alive and in Soviet custody, a once and future king of Indian independence. The legend of 'Netaii' Bose's survival helped bind together the defeated INA. In Bengal it became an assurance of the province's supreme importance in the liberation of the motherland. It sustained the morale of many across India and Southeast Asia who deplored the return of British power or felt alienated from the political settlement finally achieved by Gandhi and Nehru.[37]

- ^ "On 21 March 1944, Subhas Bose and advanced units of the INA crossed the borders of India, entering Manipur, and by May they had advanced to the outskirts of that state's capital, Imphal. That was the closest Bose came to Bengal, where millions of his devoted followers awaited his army's "liberation". The British garrison at Imphal and its air arm withstood Bose's much larger force long enough for the monsoon rains to defer all possibility of warfare in that jungle region for the three months the British so desperately needed to strengthen their eastern wing. Bose had promised his men freedom in exchange for their blood, but the tide of battle turned against them after the 1944 rains, and in May 1945 the INA surrendered in Rangoon. Bose escaped on the last Japanese plane to leave Saigon, but he died in Formosa after a crash landing there in August. By that time, however, his death had been falsely reported so many times that a myth soon emerged in Bengal that Netaji Subhas Chandra was alive—raising another army in China or Tibet or the Soviet Union—and would return with it to "liberate" India.[38]

- ^ "Subhas Bose was dead, killed in 1945 in a plane crash in the Far East, even though many of his devotees waited—as Barbarossa's disciples had done in another time and in another country—for their hero's second coming."[39]

- ^ "The thrust of Sarkar's thought, like that of Chittaranjan Das and Subhas Bose, was to challenge the idea that 'the average Indian is indifferent to life', as R. K. Kumaria put it. India once possessed an energised, Machiavellian political culture. All it needed was a hero (rather than a Gandhi-style saint) to revive the culture and steer India to life and freedom through violent contentions of world forces (vishwa shakti) represented in imperialism, fascism and socialism."[40]

- ^ As cases began to come to trial, the Indian National Congress began to speak out in defence of INA prisoners, even though it had vocally opposed both the INA's narrative and methods during the war. The Muslim League and the Punjab Unionists followed suit. By mid-September, Nehru was becoming increasingly vocal in his view that trials of INA defendants should not move forward.[42]

- ^ "The claim is even made that without the Japanese-influenced 'Indian National Army' under Subhas Chandra Bose, India would not have achieved independence in 1947; though those who make claim seem unaware of the mood of the British people in 1945 and of the attitude of the newly-elected Labour government to the Indian question."[43]

- ^ "Despite any whimsy in implementation, the clarity of Gandhi's political vision and the skill with which he carried the reforms in 1920 provided the foundation for what was to follow: twenty-five years of stewardship over the freedom movement. He knew the hazards to be negotiated. The British must be brought to a point where they would abdicate their rule without terrible destruction, thus assuring that freedom was not an empty achievement. To accomplish this he had to devise means of a moral sort, able to inspire the disciplined participation of millions of Indians, and equal to compelling the British to grant freedom, if not willingly, at least with resignation. Gandhi found his means in non-violent satyagraha. He insisted that it was not a cowardly form of resistance; rather, it required the most determined kind of courage.[45]

- ^ What he is remembered for is his vigor, his militancy, his readiness to trade blood (his own if necessary) for nationhood. In large parts of Uttar Pradesh, the historian Gyanendra Pandey has recently remarked, independence is popularly credited not to 'the quiet efforts at self¬regeneration initiated by Mahatma Gandhi,' but to 'the military daring of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose.'[46]

- ^ " 'The transfer of power in India ,' Dr Radhakrishnan has said, 'was one of the greatest acts of reconciliation in human history.'"[47]

- ^ "The most troubling aspect of Bose's presence in Nazi Germany is not military or political but rather ethical. His alliance with the most genocidal regime in history poses serious dilemmas precisely because of his popularity and his having made a lifelong career of fighting the 'good cause'. How did a man who started his political career at the feet of Gandhi end up with Hitler, Mussolini, and Tojo? Even in the case of Mussolini and Tojo, the gravity of the dilemma pales in comparison to that posed by his association with Hitler and the Nazi leadership. The most disturbing issue, all too often ignored, is that in the many articles, minutes, memorandums, telegrams, letters, plans, and broadcasts Bose left behind in Germany, he did not express the slightest concern or sympathy for the millions who died in the concentration camps. Not one of his Berlin wartime associates or colleagues ever quotes him expressing any indignation. Not even when the horrors of Auschwitz and its satellite camps were exposed to the world upon being liberated by Soviet troops in early 1945, revealing publicly for the first time the genocidal nature of the Nazi regime, did Bose react."[48]

- ^ Between 1938 and 1939 the reactions of the Anti-Nazi League, the Congress, and the progressive press toward German anti-Semitism and German politics showed that Indian public opinion and the nationalist leaders were fairly well informed about the events in Europe. If Bose, Savarkar and others looked favourably upon racial discrimination in Germany or did not criticise them, it cannot be said, to justify them, that they were unaware of what was happening. The great anti-Jewish pogrom known as "the Night of Broken Glass" took place on 9 November 1938. In early December, pro-Hindu Mahasabha journals published articles in favour of German anti-Semitism. This stance brought the Hindu Mahasabha into conflict with the Congress which, on 12 December, made a statement containing clear references to recent European events. Within the Congress, only Bose opposed the party stance. A few months later, in April 1939, he refused to support the party motion that Jews might find refuge in India.[49]

- ^ Leaders of Indian National Congress (INC), which led the anti-colonial movement, responded in different ways to the plight of Jews. In 1938, Gandhi, the nationalist icon, advised the Jews to engage in non-violent resistance by challenging "the gentile Germal" to shoot him or cast him in dungeon. Jawaharlal Nehru, the future first prime minister of independent India, was sympathetic towards the Jews. The militant nationalist leader Subhas Chandra Bose, who escaped to German in 1941 with the aim of freeing India through military help from the Axis nations, remained predictably reticent on this issue.[50]

- ^ Jawaharlal Nehru called the Jews 'People with a home or nation' and sponsored a resolution in the Congress Working Committee. Although the exact date is not known, yet it can be said that it probably happened in December 1938 at the Wardha session, the one that took place shortly after Nehru returned from Europe. The draft resolution read: 'The Committee sees no objection to the employment in India of such Jewish refugees as are experts and specialists and who can fit in with the new order in India and accept Indian standards.' It was, however, rejected by the then Congress President Bose, who four years later in 1942 was reported by the Jewish Chronicle of London as having published an article in Angriff, a journal of Goebbels, saying that "anti-Semitism should become part of the Indian liberation movement because Jews had helped the British to exploit Indians (21 August 1942)" Although by then Bose had left the Congress, he continued to command a strong influence within the party.[51]

- ^ "On 23 January 1897 at Cuttack, Orissa, was born Subhas Chandra Bose, ninth child of Janakinath and Prabhabati Bose. Janakinath was a lawyer of a Kayastha family, and was wealthy enough to educate all his children well. By Indian standards this family of Bengali origin was well-to-do."[52]

- ^ Bose was born into a prominent Bengali family on 23 January 1897 in Cuttack in the present-day state of Orissa. His father was a government pleader who was appointed to the Bengal Legislative Council in 1912."[53]

- ^ "Despite any whimsy in implementation, the clarity of Gandhi's political vision and the skill with which he carried the reforms in 1920 provided the foundation for what was to follow: twenty-five years of stewardship over the freedom movement. He knew the hazards to be negotiated. The British must be brought to a point where they would abdicate their rule without terrible destruction, thus assuring that freedom was not an empty achievement. To accomplish this he had to devise means of a moral sort, able to inspire the disciplined participation of millions of Indians, and equal to compelling the British to grant freedom, if not willingly, at least with resignation. Gandhi found his means in non-violent satyagraha. He insisted that it was not a cowardly form of resistance; rather, it required the most determined kind of courage.[45]

- ^ Rt. Hon. C. R. Attlee, Prime Minister of Great Britain. Broadcast from London after the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, 30 January 1948: "For a quarter of a century, this one man has been the major factor in every consideration of the Indian problem."[77]

- ^ "On 4 November 1937, Subhas sent a letter to Emilie in German, saying that he would probably travel to Europe in the middle of November. "Please write to Kurhaus Hochland, Badgastein," he instructed her, "and enquire if I (and you also) can stay there" He asked her to mention this message only to her parents, not to reply, and wait for his next airmail letter or telegram. On 16 November, he sent a cable: "Starting aeroplane arriving Badgastein twenty second arrange lodging and meet me. ... He spent a month and a half—from 22 November 1937, to 8 January 1938—with Emilie at his favourite resort of Badgastein."[91]

- ^ "On 26 December 1937, Subhas Chandra Bose secretly married Emilie Schenkl. Despite the obvious anguish, they chose to keep their relationship and marriage a closely guarded secret."[92]

- ^ "Rumours that Bose had survived and was waiting to come out of hiding and begin the final struggle for independence were rampant by the end of 1945."[124]

- ^ "The Fundamental Problems of India" (An address to the Faculty and students of Tokyo University, November 1944): "You cannot have a so-called democratic system, if that system has to put through economic reforms on a socialistic basis. Therefore we must have a political system—a State—of an authoritarian character. We have had some experience of democratic institutions in India and we have also studied the working of democratic institutions in countries like France, England, and the United States of America. And we have come to the conclusion that with a democratic system we cannot solve the problems of Free India. Therefore, modern progressive thought in India is in favour of a State of an authoritarian character"[148]

- ^ "His romantic saga, coupled with his defiant nationalism, has made Bose a near-mythic figure, not only in his native Bengal, but across India."[44]

- ^ "Bose's heroic endeavor still fires the imagination of many of his countrymen. But like a meteor which enters the earth's atmosphere, he burned brightly on the horizon for a brief moment only."[161]

- ^ «Субхас Бос, возможно, был лидером-отступником, бросившим вызов авторитету руководства Конгресса и его принципам. Но после смерти он стал замученным патриотом, чья память могла бы стать идеальным инструментом политической мобилизации». [36]

- ^ (стр.117) INA была создана во время Второй мировой войны при поддержке Императорской японской армии (IJA); длился менее трех лет; и за этот период претерпел две разные конфигурации. В общей сложности в нем насчитывалось около 40 000 мужчин и женщин, половина из которых, по оценкам, была набрана из военнопленных (военнопленных) индийской армии. Боевые действия INA были довольно плохими, если оценивать их вместе с IJA или против реформированной Четырнадцатой армии на полях сражений в Ассаме и Бирме. Сообщения о его создании в 1942/3 г. вызвали ужас среди политического и военного руководства (стр. 118) правительства Индии, но в конечном итоге его формирование не представляло собой законного мятежа, и его присутствие оказало незначительное влияние на индийскую армию. [162]

- ^ «(Японская) Пятнадцатая армия под командованием... генерал-майора Мутугути Ренья состояла из трех опытных пехотных дивизий - 15-й, 31-й и 33-й - общей численностью 100 000 боевых единиц, а также 7-тысячной дивизии 1-й Индийской национальной армии (INA) В поддержку предполагалось, что последний подорвет лояльность индийской армии и ускорит народное восстание в Британской Индии, но на самом деле кампания показала, что это был в основном бумажный тигр». [165]

- ↑ «Однако настоящая вина должна лежать на японском главнокомандующем Кавабе. Дрожащий, ... обессиленный амебной дизентерией, он периодически рассуждал, что должен отменить операцию «У-Го» полностью, но каждый раз вызывал смелости сделать это, из Токио придет телеграмма, в которой подчеркнута первостепенная необходимость победы в Бирме, чтобы компенсировать катастрофы в Тихом океане ... Еще более невероятно то, что он все еще надеялся на великие дела от Бозе и INA, несмотря на это. все доказательства того, что у обоих были выбиты флеши». [166]

Ссылки

- ^ Гордон 1990 , с. 502.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Вулперт 2000 , с. 339.

- ^ Гордон 1990 , стр. 502–503.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б * Бандиопадхьяй, Сехар (204), От Плесси до раздела: История современной Индии , Хайдарабад и Дели: Orient Longmans, стр. 427, ISBN 81-250-2596-0 Японцы

согласились предоставить ему транспорт до Маньчжурии, откуда он мог бы поехать в Россию. Но по пути, 18 августа 1945 года, в аэропорту Тайхоку на Тайване, он погиб в авиакатастрофе, которой многие индийцы до сих пор считают не случившейся.

- Гилберт, Мартин (2009), Атлас Второй мировой войны Рутледж (2-е изд.), Рутледж, стр. 227, ISBN 978-0-415-55289-9 Бозе

погиб в авиакатастрофе у Тайваня по пути в Токио 18 августа 1945 года в возрасте 48 лет. Для многих миллионов индийцев, особенно в Бенгалии, он остается почитаемой фигурой.

- Хафф, Грегг (2020), Вторая мировая война и Юго-Восточная Азия: экономика и общество в условиях японской оккупации , Cambridge University Press, стр. xvi, ISBN 978-1-107-09933-3 , LCCN 2020022973 , заархивировано из оригинала 12 июля 2023 г. , получено 28 января 2022 г. ,

Хронология Второй мировой войны в Тихом океане: 18 августа 1945 г. Субхас Чандра Бос погиб в авиакатастрофе на Тайване.

- Сатоши, Накано (2012), Колониальный момент Японии в Юго-Восточной Азии 1942–1945: Опыт оккупантов , Лондон и Нью-Йорк: Routledge, стр. 211, ISBN 978-1-138-54128-3 , LCCN 2018026197 ,

18 августа 1945 года. Узнав о поражении Японии в войне на Тихом океане, Чандра Бос, посвятивший свою жизнь антибританской борьбе за независимость Индии, немедленно решил отправиться в Советский Союз, «исходя из моего обязательства вступать в союз с любой страной, которая считает США и Великобританию своими врагами». Министерство иностранных дел Японии и военные сотрудничали в изгнании Бозе, поместив его на борт японского самолета, направлявшегося в Далянь (Юньнань) из Сайгона, чтобы связать его с Советской армией. Однако после остановки в Тайбэе пассажирский самолет разбился сразу после взлета. Несмотря на то, что Бозе удалось освободиться от обломков, он был охвачен пламенем и испустил последний вздох.

- Блэкберн, Кевин; Хак, Карл (2012), Военная память и создание современной Малайзии и Сингапура , Сингапур: NUS Press, Национальный университет Сингапура, стр. 185, ISBN 978-9971-69-599-6 Еще до того ,