Свастика

Свастика евразийских ( 卐 или 卍 ) — древний религиозный и культурный символ, преимущественно встречающийся в различных культурах , а также в некоторых африканских и американских культурах. В западном мире он более широко известен как символ немецкой нацистской партии , которая заимствовала его из азиатских культур с начала 20 века. Присвоение продолжается, и его используют неонацисты по всему миру. [1] [2] [3] [4] Свастика никогда не переставала использоваться как символ божественности и духовности в индийских религиях , включая индуизм , буддизм и джайнизм . [1] [5] [6] [7] [8] Обычно он имеет форму креста , [А] плечи которого имеют одинаковую длину и перпендикулярны соседним плечам, каждое согнуто посередине под прямым углом. [10] [11]

Слово свастика происходит от санскрита : स्वस्तिक , латинизированного : свастика , что означает «способствующая благополучию». [1] [12] В индуизме правый символ (по часовой стрелке) ( 卐 ) называется свастикой , символизируя сурья («солнце»), процветание и удачу, а левый символ (против часовой стрелки) ( 卍 ) называется саувастикой , символизирующий ночные или тантрические аспекты Кали . [1] В джайнской символике он олицетворяет Супаршванатху — седьмого из 24 Тиртханкаров ( духовных учителей и спасителей ), тогда как в буддийской символике он представляет собой благоприятные следы Будды . [1][13][14] In several major Indo-European religions, the swastika symbolises lightning bolts, representing the thunder god and the king of the gods, such as Indra in Vedic Hinduism, Zeus in the ancient Greek religion, Jupiter in the ancient Roman religion, and Thor in the ancient Germanic religion.[15] The symbol is found in the archaeological remains of the Indus Valley civilisation[16] and Samarra, as well as in early Byzantine and Christian artwork.[17][18]

Although used for the first time as a symbol of international antisemitism by far-right Romanian politician A. C. Cuza prior to World War I,[19][20][21] it was a symbol of auspiciousness and good luck for most of the Western world until the 1930s,[2] when the German Nazi Party adopted the swastika as an emblem of the Aryan race. As a result of World War II and the Holocaust, in the West it continues to be strongly associated with Nazism, antisemitism,[22][23] white supremacism,[24][25] or simply evil.[26][27] As a consequence, its use in some countries, including Germany, is prohibited by law.[B] However, the swastika remains a symbol of good luck and prosperity in Hindu, Buddhist and Jain countries such as Nepal, India, Thailand, Mongolia, Sri Lanka, China and Japan, and by some peoples, such as the Navajo people of the Southwest United States. It is also commonly used in Hindu marriage ceremonies and Dipavali celebrations.

Etymology and nomenclature

With well-being (swasti) we would follow along our path, like the Sun and the Moon. May we meet up with one who gives in return, who does not smite (harm), with one who knows.

The word swastika is derived from the Sanskrit root swasti, which is composed of su 'good, well' and asti 'is; it is; there is'.[30] The word swasti occurs frequently in the Vedas as well as in classical literature, meaning 'health, luck, success, prosperity', and it was commonly used as a greeting.[31][32] The final ka is a common suffix that could have multiple meanings.[33]

According to Monier-Williams, a majority of scholars consider the swastika a solar symbol.[31] The sign implies well-being, something fortunate, lucky, or auspicious.[31][34] It is alternatively spelled in contemporary texts as svastika,[35] and other spellings were occasionally used in the 19th and early 20th century, such as suastika.[36] It was derived from the Sanskrit term (Devanagari स्वस्तिक), which transliterates to svastika under the commonly used IAST transliteration system, but is pronounced closer to swastika when letters are used with their English values.

The earliest known use of the word swastika is in Pāṇini's Ashtadhyayi, which uses it to explain one of the Sanskrit grammar rules, in the context of a type of identifying mark on a cow's ear.[30] Most scholarship suggests that Pāṇini lived in or before the 4th century BCE,[37][38] possibly in 6th or 5th century BCE.[39][40]

An important early use of the word swastika in a European text was in 1871 with the publications of Heinrich Schliemann, who discovered more than 1,800 ancient samples of the swastika symbol and its variants while digging the Hisarlik mound near the Aegean Sea coast for the history of Troy. Schliemann linked his findings to the Sanskrit swastika.[41][42][43]

By the 19th century, the term swastika was adopted into the English lexicon,[44] replacing the previous gammadion from Greek γαμμάδιον. In 1878, Irish scholar Charles Graves used swastika as the common English name for the symbol, after defining it as equivalent to the French term croix gammée – a cross with arms shaped like the Greek letter gamma (Γ).[45] Shortly thereafter, British antiquarians Edward Thomas and Robert Sewell separately published their studies about the symbol, using swastika as the common English term.[46][47]

The concept of a "reversed" swastika was probably first made among European scholars by Eugène Burnouf in 1852 and taken up by Schliemann in Ilios (1880), based on a letter from Max Müller that quotes Burnouf. The term sauwastika is used in the sense of 'backward swastika' by Eugène Goblet d'Alviella (1894): "In India it [the gammadion] bears the name of swastika, when its arms are bent towards the right, and sauwastika when they are turned in the other direction."[48]

Other names for the symbol include:

- tetragammadion (Greek: τετραγαμμάδιον) or cross gammadion (Latin: crux gammata; French: croix gammée), as each arm resembles the Greek letter Γ (gamma)[10]

- hooked cross (German: Hakenkreuz), angled cross (Winkelkreuz), or crooked cross (Krummkreuz)

- cross cramponned, cramponnée, or cramponny in heraldry, as each arm resembles a crampon or angle-iron (German: Winkelmaßkreuz)

- fylfot, chiefly in heraldry and architecture

- tetraskelion (Greek: τετρασκέλιον), literally meaning 'four-legged', especially when composed of four conjoined legs (compare triskelion/triskele [Greek: τρισκέλιον])[49]

- ugunskrusts (Latvian for 'fire cross, cross of fire"; other names – pērkonkrusts ('cross of thunder', 'thunder cross'), cross of Perun or of Perkūnas), cross of branches, cross of Laima)

- whirling logs (Navajo): can denote abundance, prosperity, healing, and luck[50]

In various European languages, it is known as the fylfot, gammadion, tetraskelion, or cross cramponnée (a term in Anglo-Norman heraldry); German: Hakenkreuz; French: croix gammée; Italian: croce uncinata; Latvian: ugunskrusts. In Mongolian it is called хас (khas) and mainly used in seals. In Chinese it is called 卍字 (wànzì), pronounced manji in Japanese, manja (만자) in Korean and vạn tự or chữ vạn in Vietnamese. In Balti/Tibetan language it is called yung drung.[citation needed]

Appearance

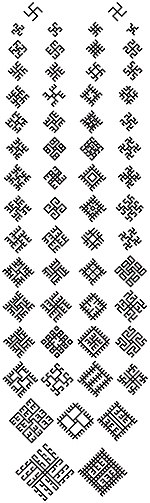

All swastikas are bent crosses based on a chiral symmetry, but they appear with different geometric details: as compact crosses with short legs, as crosses with large arms and as motifs in a pattern of unbroken lines. Chirality describes an absence of reflective symmetry, with the existence of two versions that are mirror images of each other. The mirror-image forms are typically described as left-facing or left-hand (卍) and right-facing or right-hand (卐).

The compact swastika can be seen as a chiral irregular icosagon (20-sided polygon) with fourfold (90°) rotational symmetry. Such a swastika proportioned on a 5 × 5 square grid and with the broken portions of its legs shortened by one unit can tile the plane by translation alone. The main Nazi flag swastika used a 5 × 5 diagonal grid, but with the legs unshortened.[53]

Written characters

The swastika was adopted as a standard character in Chinese, "卍" (pinyin: wàn) and as such entered various other East Asian languages, including Chinese script. In Japanese the symbol is called "卍" (Hepburn: manji) or "卍字" (manji).

The swastika is included in the Unicode character sets of two languages. In the Chinese block it is U+534D 卍 (left-facing) and U+5350 for the swastika 卐 (right-facing);[54] The latter has a mapping in the original Big5 character set,[55] but the former does not (although it is in Big5+[56]). In Unicode 5.2, two swastika symbols and two swastikas were added to the Tibetan block: swastika U+0FD5 ࿕ RIGHT-FACING SVASTI SIGN, U+0FD7 ࿗ RIGHT-FACING SVASTI SIGN WITH DOTS, and swastikas U+0FD6 ࿖ LEFT-FACING SVASTI SIGN, U+0FD8 ࿘ LEFT-FACING SVASTI SIGN WITH DOTS.[57]

Meaning

European hypotheses of the swastika are often treated in conjunction with cross symbols in general, such as the sun cross of Bronze Age religion. Beyond its certain presence in the "proto-writing" symbol systems, such as the Vinča script,[58] which appeared during the Neolithic.[59]

North pole

According to René Guénon, the swastika represents the north pole, and the rotational movement around a centre or immutable axis (axis mundi), and only secondly it represents the Sun as a reflected function of the north pole. As such it is a symbol of life, of the vivifying role of the supreme principle of the universe, the absolute God, in relation to the cosmic order. It represents the activity (the Hellenic Logos, the Hindu Om, the Chinese Taiyi, 'Great One') of the principle of the universe in the formation of the world.[60] According to Guénon, the swastika in its polar value has the same meaning of the yin and yang symbol of the Chinese tradition, and of other traditional symbols of the working of the universe, including the letters Γ (gamma) and G, symbolising the Great Architect of the Universe of Masonic thought.[61]

According to the scholar Reza Assasi, the swastika represents the north ecliptic north pole centred in ζ Draconis, with the constellation Draco as one of its beams. He argues that this symbol was later attested as the four-horse chariot of Mithra in ancient Iranian culture. They believed the cosmos was pulled by four heavenly horses who revolved around a fixed centre in a clockwise direction. He suggests that this notion later flourished in Roman Mithraism, as the symbol appears in Mithraic iconography and astronomical representations.[62]

According to the Russian archaeologist Gennady Zdanovich, who studied some of the oldest examples of the symbol in Sintashta culture, the swastika symbolises the universe, representing the spinning constellations of the celestial north pole centred in α Ursae Minoris, specifically the Little and Big Dipper (or Chariots), or Ursa Minor and Ursa Major.[63] Likewise, according to René Guénon-the swastika is drawn by visualising the Big Dipper/Great Bear in the four phases of revolution around the pole star.[64]

Comet

In their 1985 book Comet, Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan argue that the appearance of a rotating comet with a four-pronged tail as early as 2,000 years BCE could explain why the swastika is found in the cultures of both the Old World and the pre-Columbian Americas. The Han dynasty Book of Silk (2nd century BCE) depicts such a comet with a swastika-like symbol.[65]

Bob Kobres, in a 1992 paper, contends that the swastika-like comet on the Han-dynasty manuscript was labelled a "long tailed pheasant star" (dixing) because of its resemblance to a bird's foot or footprint.[66] Similar comparisons had been made by J. F. Hewitt in 1907,[67] as well as a 1908 article in Good Housekeeping.[68] Kobres goes on to suggest an association of mythological birds and comets also outside of China.[66]

Four winds

In Native American culture, particularly among the Pima people of Arizona, the swastika is a symbol of the four winds. Anthropologist Frank Hamilton Cushing noted that among the Pima the symbol of the four winds is made from a cross with the four curved arms (similar to a broken sun cross) and concludes "the right-angle swastika is primarily a representation of the circle of the four wind gods standing at the head of their trails, or directions."[69]

Prehistory

According to Joseph Campbell, the earliest known swastika is from 10,000 BCE – part of "an intricate meander pattern of joined-up swastikas" found on a late paleolithic figurine of a bird, carved from mammoth ivory, found in Mezine, Ukraine. It has been suggested that this swastika may be a stylised picture of a stork in flight.[70] As the carving was found near phallic objects, this may also support the idea that the pattern was a fertility symbol.[2]

In the mountains of Iran, there are swastikas or spinning wheels inscribed on stone walls, which are estimated to be more than 7,000 years old. One instance is in Khorashad, Birjand, on the holy wall Lakh Mazar.[71][72]

Mirror-image swastikas (clockwise and counter-clockwise) have been found on ceramic pottery in the Devetashka cave, Bulgaria, dated to 6,000 BCE.[73]

Some of the earliest archaeological evidence of the swastika in the Indian subcontinent can be dated to 3,000 BCE.[74] The investigators put forth the hypothesis that the swastika moved westward from the Indian subcontinent to Finland, Scandinavia, the Scottish Highlands and other parts of Europe.[75][better source needed] In England, neolithic or Bronze Age stone carvings of the symbol have been found on Ilkley Moor, such as the Swastika Stone.

Swastikas have also been found on pottery in archaeological digs in Africa, in the area of Kush and on pottery at the Jebel Barkal temples,[76] in Iron Age designs of the northern Caucasus (Koban culture), and in Neolithic China in the Majiayao culture.[77]

Other Iron Age attestations of the swastika can be associated with Indo-European cultures such as the Illyrians,[78] Indo-Iranians, Celts, Greeks, Germanic peoples and Slavs. In Sintashta culture's "Country of Towns", ancient Indo-European settlements in southern Russia, it has been found a great concentration of some of the oldest swastika patterns.[63]

The swastika is also seen in Egypt during the Coptic period. Textile number T.231-1923 held at the V&A Museum in London includes small swastikas in its design. This piece was found at Qau-el-Kebir, near Asyut, and is dated between 300 and 600 CE.[79]

The Tierwirbel (the German for "animal whorl" or "whirl of animals"[80]) is a characteristic motif in Bronze Age Central Asia, the Eurasian Steppe, and later also in Iron Age Scythian and European (Baltic[81] and Germanic) culture, showing rotational symmetric arrangement of an animal motif, often four birds' heads. Even wider diffusion of this "Asiatic" theme has been proposed to the Pacific and even North America (especially Moundville).[82]

- The petroglyph with swastikas, Gegham mountains, Armenia, circa 8,000 – 5,000 BCE[83]

- The Samarra bowl, from Iraq, circa 4,000 BCE, held at the Pergamonmuseum, Berlin. The swastika in the centre of the design is a reconstruction.[84]

- Swastika seals from Mohenjo-daro, Pakistan, of the Indus Valley civilisation, circa 2,100 – 1,750 BCE, preserved at the British Museum[85]

Historical use

In Asia, the swastika symbol first appears in the archaeological record around[74] 3000 BCE in the Indus Valley Civilisation.[86][87] It also appears in the Bronze and Iron Age cultures around the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. In all these cultures, the swastika symbol does not appear to occupy any marked position or significance, appearing as just one form of a series of similar symbols of varying complexity. In the Zoroastrian religion of Persia, the swastika was a symbol of the revolving sun, infinity, or continuing creation.[88][89] It is one of the most common symbols on Mesopotamian coins.[1]

The icon has been of spiritual significance to Indian religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism.[8][1] The swastika is a sacred symbol in the Bön religion, native to Tibet.

South Asia

Hinduism

The swastika is an important Hindu symbol.[1][8] The swastika symbol is commonly used before entrances or on doorways of homes or temples, to mark the starting page of financial statements, and mandalas constructed for rituals such as weddings or welcoming a newborn.[1][90]

The swastika has a particular association with Diwali, being drawn in rangoli (coloured sand) or formed with deepak lights on the floor outside Hindu houses and on wall hangings and other decorations.[91]

In the diverse traditions within Hinduism, both the clockwise and counterclockwise swastika are found, with different meanings. The clockwise or right hand icon is called swastika, while the counterclockwise or left hand icon is called sauwastika or sauvastika.[1] The clockwise swastika is a solar symbol (Surya), suggesting the motion of the Sun in India (the northern hemisphere), where it appears to enter from the east, then ascend to the south at midday, exiting to the west.[1] The counterclockwise sauwastika is less used; it connotes the night, and in tantric traditions it is an icon for the goddess Kali, the terrifying form of Devi Durga.[1] The symbol also represents activity, karma, motion, wheel, and in some contexts the lotus.[5][6] According to Norman McClelland its symbolism for motion and the Sun may be from shared prehistoric cultural roots.[92]

- A swastika is typical in Hindu temples

- A Hindu temple in Rajasthan, India

- A swastika inside a temple

- The Balinese Hindu pura Goa Lawah entrance

- A Balinese Hindu shrine

Buddhism

In Buddhism, the swastika is considered to symbolise the auspicious footprints of the Buddha.[1][13] The left-facing sauwastika is often imprinted on the chest, feet or palms of Buddha images. It is an aniconic symbol for the Buddha in many parts of Asia and homologous with the dharma wheel.[6] The shape symbolises eternal cycling, a theme found in the samsara doctrine of Buddhism.[6]

The swastika symbol is common in esoteric tantric traditions of Buddhism, along with Hinduism, where it is found with chakra theories and other meditative aids.[90] The clockwise symbol is more common, and contrasts with the counterclockwise version common in the Tibetan Bon tradition and locally called yungdrung.[93]

Jainism

In Jainism, it is a symbol of the seventh tīrthaṅkara, Suparśvanātha.[1] In the Śvētāmbara tradition, it is also one of the aṣṭamaṅgala or eight auspicious symbols. All Jain temples and holy books must contain the swastika and ceremonies typically begin and end with creating a swastika mark several times with rice around the altar. Jains use rice to make a swastika in front of statues and then put an offering on it, usually a ripe or dried fruit, a sweet (Hindi: मिठाई miṭhāī), or a coin or currency note. The four arms of the swastika symbolise the four places where a soul could be reborn in samsara, the cycle of birth and death – svarga "heaven", naraka "hell", manushya "humanity" or tiryancha "as flora or fauna" – before the soul attains moksha "salvation" as a siddha, having ended the cycle of birth and death and become omniscient.[7]

East Asia

The swastika is an auspicious symbol in China where it was introduced from India with Buddhism.[94] In 693, during the Tang dynasty, it was declared as "the source of all good fortune" and was called wan by Wu Zetian becoming a Chinese word.[94] The Chinese character for wan (pinyin: wàn) is similar to the swastika in shape and can be appeared into two different variations:《卐》and 《卍》. As the Chinese character wan (卐 or 卍) is homonym for the Chinese word of "ten thousand" (万) and "infinity", as such the Chinese character is itself a symbol of immortality[95] and infinity.[96]: 175 It was also a representation of longevity.[96]: 175

The Chinese character wan could be used as a stand-alone《卐》or《卍》or as be used as pairs《卐 卍》in Chinese visual arts, decorative arts, and clothing due to its auspicious connotation.[96]: 175

Adding the character wan (卐 or 卍) to other auspicious Chinese symbols or patterns can multiply that wish by 10,000 times.[94][96]: 175 It can be combined with other Chinese characters, such as the Chinese character shou《壽》for longevity where it is sometimes even integrated into the Chinese character shou to augment the meaning of longevity.[96]: 175

The paired swastika symbols (卐 and 卍) are included, at least since the Liao Dynasty (907–1125 CE), as part of the Chinese writing system and are variant characters for 《萬》 or 《万》 (wàn in Mandarin, 《만》(man) in Korean, Cantonese, and Japanese, vạn in Vietnamese) meaning "myriad".[97]

The character wan can also be stylized in the form of the xiangyun, Chinese auspicious clouds.

- Chinese character wan integrated into one of the stylistic versions of the Chinese character shou

- Paired character wan on a dragon robe, Qing dynasty

Japan

When the Chinese writing system was introduced to Japan in the 8th century, the swastika was adopted into the Japanese language and culture. It is commonly referred as the manji (lit. "10,000-character"). Since the Middle Ages, it has been used as a mon by various Japanese families such as Tsugaru clan, Hachisuka clan or around 60 clans that belong to Tokugawa clan.[98] On Japanese maps, a swastika (left-facing and horizontal) is used to mark the location of a Buddhist temple. The right-facing swastika is often referred to as the gyaku manji (逆卍, lit. "reverse swastika") or migi manji (右卍, lit. "right swastika"), and can also be called kagi jūji (鉤十字, literally "hook cross").

In Chinese and Japanese art, the swastika is often found as part of a repeating pattern. One common pattern, called sayagata in Japanese, comprises left- and right-facing swastikas joined by lines.[99] As the negative space between the lines has a distinctive shape, the sayagata pattern is sometimes called the key fret motif in English.[citation needed]

Eastern Europe and Caucasus

In Armenia the swastika is called the "arevakhach" and "kerkhach" (Armenian: կեռխաչ)[100][dubious – discuss] and is the ancient symbol of eternity and eternal light (i.e. God). Swastikas in Armenia were found on petroglyphs from the copper age, predating the Bronze Age. During the Bronze Age it was depicted on cauldrons, belts, medallions and other items.[101] Among the oldest petroglyphs is the seventh letter of the Armenian alphabet: Է ("E" which means "is" or "to be") depicted as a half-swastika.

Swastikas can also be seen on early Medieval churches and fortresses, including the principal tower in Armenia's historical capital city of Ani.[100] The same symbol can be found on Armenian carpets, cross-stones (khachkar) and in medieval manuscripts, as well as on modern monuments as a symbol of eternity.[102]

Old petroglyphs of four-beam and other swastikas were recorded in Dagestan, in particular, among the Avars.[103] According to Vakhushti of Kartli, the tribal banner of the Avar khans depicted a wolf with a standard with a double-spiral swastika.[104]

Petroglyphs with swastikas were depicted on medieval Vainakh tower architecture (see sketches by scholar Bruno Plaetschke from the 1920s).[105] Thus, a rectangular swastika was made in engraved form on the entrance of a residential tower in the settlement Khimoy, Chechnya.[105]

Northern Europe

Germanic Iron Age

The swastika shape (also called a fylfot) appears on various Germanic Migration Period and Viking Age artifacts, such as the 3rd-century Værløse Fibula from Zealand, Denmark, the Gothic spearhead from Brest-Litovsk, today in Belarus, the 9th-century Snoldelev Stone from Ramsø, Denmark, and numerous Migration Period bracteates drawn left-facing or right-facing.[106]

The pagan Anglo-Saxon ship burial at Sutton Hoo, England, contained numerous items bearing the swastika, now housed in the collection of the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.[107][failed verification] The swastika is clearly marked on a hilt and sword belt found at Bifrons in Kent, in a grave of about the 6th century.

Hilda Ellis Davidson theorised[clarification needed] that the swastika symbol was associated with Thor, possibly representing his Mjolnir – symbolic of thunder – and possibly being connected to the Bronze Age sun cross.[107] Davidson cites "many examples" of the swastika symbol from Anglo-Saxon graves of the pagan period, with particular prominence on cremation urns from the cemeteries of East Anglia.[107] Some of the swastikas on the items, on display at the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, are depicted with such care and art that, according to Davidson, it must have possessed special significance as a funerary symbol.[107] The runic inscription on the 8th-century Sæbø sword has been taken as evidence of the swastika as a symbol of Thor in Norse paganism.

Celts

The bronze frontispiece of a ritual pre-Christian (c. 350–50 BCE) shield found in the River Thames near Battersea Bridge (hence "Battersea Shield") is embossed with 27 swastikas in bronze and red enamel.[108] An Ogham stone found in Aglish, County Kerry, Ireland (CIIC 141) was modified into an early Christian gravestone, and was decorated with a cross pattée and two swastikas.[109] The Book of Kells (c. 800 CE) contains swastika-shaped ornamentation. At the Northern edge of Ilkley Moor in West Yorkshire, there is a swastika-shaped pattern engraved in a stone known as the Swastika Stone.[110] A number of swastikas have been found embossed in Galician metal pieces and carved in stones, mostly from the Castro culture period, although there also are contemporary examples (imitating old patterns for decorative purposes).[111][112]

Balto-Slavic

The swastika is an ancient Baltic thunder cross symbol (pērkona krusts (cross of Perkons); also fire cross, ugunskrusts), used to decorate objects, traditional clothing and in archaeological excavations.[113][114]

According to painter Stanisław Jakubowski, the "little sun" (Polish: słoneczko) is an Early Slavic pagan symbol of the Sun; he claimed it was engraved on wooden monuments built near the final resting places of fallen Slavs to represent eternal life. The symbol was first seen in his collection of Early Slavic symbols and architectural features, which he named Prasłowiańskie motywy architektoniczne (Polish: Early Slavic Architectural Motifs). His work was published in 1923.[115]

The Boreyko coat of arms with a red swastika was used by several noble families in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[116]

According to Boris Kuftin, the Russians often used the swastika as a decorative element and as the basis of the ornament on traditional weaving products.[117] Many can be seen on a women's folk costume from the Meshchera Lowlands.[117]

According to some authors, Russian names popularly associated with the swastika include veterok ("breeze"),[118] ognevtsi ("little flames"), "geese", "hares" (a towel with a swastika was called a towel with "hares"), or "little horses".[119] The similar word "koleso" ("wheel") was used for rosette-shaped amulets, such as a hexafoil-thunder wheel ![]() ) in folklore, particularly in the Russian North.[120][121]

) in folklore, particularly in the Russian North.[120][121]

- Ancient symbol the Hands of God or "Hands of Svarog" (Polish: Ręce Swaroga)[122]

- Swastika on the Lielvārde Belt, Latvia

Sami

An object very much like a hammer or a double axe is depicted among the magical symbols on the drums of Sami noaidi, used in their religious ceremonies before Christianity was established. The name of the Sami thunder god was Horagalles, thought to derive from "Old Man Thor" (Þórr karl). Sometimes on the drums, a male figure with a hammer-like object in either hand is shown, and sometimes it is more like a cross with crooked ends, or a swastika.[107]

Southern Europe

Greco-Roman antiquity

Ancient Greek architectural, clothing and coin designs are replete with single or interlinking swastika motifs. There are also gold plate fibulae from the 8th century BCE decorated with an engraved swastika.[123] Related symbols in classical Western architecture include the cross, the three-legged triskele or triskelion and the rounded lauburu. The swastika symbol is also known in these contexts by a number of names, especially gammadion,[124] or rather the tetra-gammadion. The name gammadion comes from its being seen as being made up of four Greek gamma (Γ) letters. Ancient Greek architectural designs are replete with the interlinking symbol.

In Greco-Roman art and architecture, and in Romanesque and Gothic art in the West, isolated swastikas are relatively rare, and the swastika is more commonly found as a repeated element in a border or tessellation. The swastika often represented perpetual motion, reflecting the design of a rotating windmill or watermill. A meander of connected swastikas makes up the large band that surrounds the Augustan Ara Pacis.

A design of interlocking swastikas is one of several tessellations on the floor of the cathedral of Amiens, France.[125] A border of linked swastikas was a common Roman architectural motif,[126] and can be seen in more recent buildings as a neoclassical element. A swastika border is one form of meander, and the individual swastikas in such a border are sometimes called Greek keys. There have also been swastikas found on the floors of Pompeii.[127]

Illyrians

The swastika was widespread among the Illyrians, symbolising the Sun. The Sun cult was the main Illyrian cult; the Sun was represented by a swastika in clockwise motion, and it stood for the movement of the Sun.[78]

Medieval and early modern Europe

Swastika shapes have been found on numerous artefacts from Iron Age Europe.[100][128][129][78][10]

In Christianity, the swastika is used as a hooked version of the Christian Cross, the symbol of Christ's victory over death. Some Christian churches built in the Romanesque and Gothic eras are decorated with swastikas, carrying over earlier Roman designs. Swastikas are prominently displayed in a mosaic in the St. Sophia church of Kyiv, Ukraine dating from the 12th century. They also appear as a repeating ornamental motif on a tomb in the Basilica of St. Ambrose in Milan.[130]

A ceiling painted in 1910 in the church of St Laurent in Grenoble has many swastikas. It can be visited today because the church became the archaeological museum of the city. A proposed direct link between it and a swastika floor mosaic in the Cathedral of Our Lady of Amiens, which was built on top of a pagan site at Amiens, France in the 13th century, is considered unlikely. The stole worn by a priest in the 1445 painting of the Seven Sacraments by Rogier van der Weyden presents the swastika form simply as one way of depicting the cross.

Swastikas also appear in art and architecture during the Renaissance and Baroque era. The fresco The School of Athens shows an ornament made out of swastikas, and the symbol can also be found on the facade of the Santa Maria della Salute, a Roman Catholic church and minor basilica located at Punta della Dogana in the Dorsoduro sestiere of the city of Venice.

In the Polish First Republic the symbol of the swastika was also popular with the nobility. Several noble houses, e.g. Boreyko, Borzym, and Radziechowski from Ruthenia, also had swastikas as their coat of arms. The family reached its greatness in the 14th and 15th centuries and its crest can be seen in many heraldry books produced at that time.

The swastika was also a heraldic symbol, for example on the Boreyko coat of arms, used by noblemen in Poland and Ukraine. In the 19th century the swastika was one of the Russian Empire's symbols and was used on coinage as a backdrop to the Russian eagle.[131]

- Bashkirs symbol of the sun and fertility

- Mosaic swastika in an excavated Byzantine church in Shavei Tzion, (Israel)

- A swastika composed of Hebrew letters as a mystical symbol from the Jewish Kabbalistic work "Parashat Eliezer", from the 18th century or earlier

- Swastikas on the vestments of the effigy of Bishop William Edington (d. 1366) in Winchester Cathedral

- The Victorian-era reproduction of the Swastika Stone on Ilkley Moor, which sits near the original to aid visitors in interpreting the carving

Non-Eurasian samples

Africa

Swastikas can be seen in various African cultures. In Ethiopia the Swastika is carved in the window of the famous 12th-century Biete Maryam, one of the Rock-Hewn Churches, Lalibela.[3] In Ghana, the swastika is among the adinkra symbols of the Akan peoples. Called nkontim, swastikas could be found on Ashanti gold weights and clothing.[132]

- Ashanti weight in Africa

- Nkontim adinkra symbol from Ghana, representing loyalty and readiness to serve

- Carved fretwork forming a swastika on the Biete Maryam in Ethiopia

Americas

The swastika has been used by multiple Indigenous groups, including the Hopi, Navajo, and Tlingit.[134][135] Swastikas were founds on pottery from the Mississippi valley and on copper objects in the Hopewell Mounds in Ross County, Ohio.[136][137] It is a Navajo symbol for good luck, also translated to "whirling log".[138]

In the 20th century, traders encouraged Native American artists to use the symbol in their crafts, and it was used by the US Army 45th Infantry Division, an all-Native American division.[139][140][141] The symbol lost popularity in the 1930s due to its associations with Nazi Germany. In 1940, partially due to government encouragement, community leaders from several different Native American tribes made a statement promising to no longer use the symbol.[142][138][143][141] However, the symbol has continued to be used by Native American groups, both in reference to the original symbol and as a memorial to the 45th Division, despite external objections to its use.[4][141][143][144][145][146] The symbol was used on state road signs in Arizona from the 1920s until the 1940s.[147]

19th century

At Troy near the Dardanelles, Heinrich Schliemann's 1871–1875 archaeological excavations discovered objects decorated with swastikas.[148]: 101–105 [149][150]: 31 [151]: 31 Hearing of this, the director of the French School at Athens, Émile-Louis Burnouf, wrote to Schliemann in 1872, stating "the Swastika should be regarded as a sign of the Aryan race". Burnouf told Schliemann that "It should also be noted that the Jews have completely rejected it".[152]: 89 Accordingly, Schliemann believed the Trojans to have been Aryans: "The primitive Trojans, therefore, belonged to the Aryan race, which is further sufficiently proved by the symbols on the round terra-cottas".[148]: 157 [152]: 90 Schliemann accepted Burnouf's interpretation.[152]: 89

This winter, I have read in Athens many excellent works of celebrated scholars on Indian antiquities, especially Adalbert Kuhn, Die Herakunft des Feuers; Max Müller's Essays; Émile Burnouf, La Science des Religions and Essai sur le Vêda; as well as several works by Eugène Burnouf; and I now perceive that these crosses upon the Trojan terra-cottas are of the highest importance to archæology.

— Heinrich Schliemann, Troy and Its Remains, 1875[148]: 101

Schliemann believed that use of the swastika spread widely across Eurasia.[153]

… I am now able to prove that … the 卍, which I find in Émile Burnouf's Sanscrit lexicon, under the name of "suastika," and with the meaning εὖ ἐστι, or as the sign of good wishes, were already regarded, thousands of years before Christ, as religious symbols of the very greatest importance among the early progenitors of the Aryan races in Bactria and in the villages of the Oxus, at a time when Germans, Indians, Pelasgians, Celts, Persians, Slavonians and Iranians still formed one nation and spoke one language.

— Heinrich Schliemann, Troy and Its Remains, 1875[148]: 101–102

Schliemann established a link between the swastika and Germany. He connected objects he excavated at Troy to objects bearing swastikas found in Germany near Königswalde on the Oder.[149][150]: 31 [151]: 31 [152]: 90

For I recognise at the first glance the "suastika" upon one of those three pot bottoms, which were discovered on Bishop's Island near Königswalde on the right bank of the Oder, and have given rise to very many learned discussions, while no one recognised the mark as that exceedingly significant religious symbol of our remote ancestors.

— Heinrich Schliemann, Troy and Its Remains, 1875[148]: 102

Sarah Boxer, in an article in 2000 in The New York Times, described this as a "fateful link".[149] According to Steven Heller, "Schliemann presumed that the swastika was a religious symbol of his German ancestors which linked ancient Teutons, Homeric Greeks and Vedic India".[150]: 31 According to Bernard Mees, "Of all of the pre-runic symbols, the swastika has always been the most popular among scholars" and "The origin of swastika studies must be traced to the excitement generated by the archaeological finds of Heinrich Schliemann at Troy".[154]

After his excavations at Troy, Schliemann began digging at Mycenae. According to Cathy Gere, "Having burdened the swastika symbol with such cultural, religious and racial significance in Troy and Its Remains, it was incumbent on Schliemann to find the symbol repeated at Mycenae, but its occurrence turned out to be disappointingly infrequent".[152]: 91 Gere writes that "He did his best with what he had":[152]: 91

The cross with the marks of four nails may often be seen; as well as the 卍, which is usually also represented with four points indicating the four nails, thus ࿘. These signs cannot but represent the suastika, formed by two pieces of wood, which were laid across and fixed with four nails, and in the joint of which the holy fire was produced by friction by a third piece of wood. But both the cross and the 卍 occur for the most part only on the vases with geometrical patterns.

— Heinrich Schliemann, Mycenæ, 1878[155]: 66–68

Gere points out that although Schliemann wrote that the motif "may often be seen", his 1878 book Mycenæ did not have illustrations of any examples.[152]: 91 Schliemann described "a small and thick terra-cotta disk" on which "are engraved a number of 卍's, the sign which occurs so frequently in the ruins of Troy", but as Gere notes, he did not publish an illustration.[155]: 77 [152]: 91

Among the gold grave goods at Grave Circles A and B was a repoussé roundel in grave III of Grave Circle A, the ornamentation of which Schliemann thought was "derived" from the swastika:

The curious ornamentation in the centre, which so often recurs here, seems to me to be derived from the ࿘, the more so as the points which are thought to be the marks of the nails, are seldom missing; the artist has only added two more arms and curved all of them.

— Heinrich Schliemann, Mycenæ, 1878[155]: 165–166

According to Gere, this motif is "completely dissimilar" to the swastika, and that Schliemann was "straining desperately after the same connection".[152]: 91 Nevertheless, the Mycenaean Greeks and the Trojan people both came to be identified as representatives of the Aryan race: "Despite the difficulties with linking the symbolism of Troy and Mycenae, the common Aryan roots of the two peoples became something of a truism".[152]: 91

The house Schliemann had had built in Panepistimiou Street in Athens by 1880, Iliou Melathron, is decorated with swastika symbols and motifs in numerous places, including the ironwork railing and gates, the window bars, the ceiling fresco of the entrance hall, and the entire floor of one room.[152]: 117–123

Following Schliemann, academic studies on the swastika were published by Ludvig Müller, Michał Żmigrodzki, Eugène Goblet d'Alviella, Thomas Wilson, Oscar Montelius and Joseph Déchelette.[154]

The Benedictine choir school at Lambach Abbey, Upper Austria, which Hitler attended for several months as a boy, had a swastika chiseled into the monastery portal and also the wall above the spring grotto in the courtyard by 1868. Their origin was the personal coat of arms of Theoderich Hagn, abbot of the monastery in Lambach, which bore a golden swastika with slanted points on a blue field.[156]

Early 20th century

By the early 20th century, it was used worldwide and was regarded as a symbol of good luck and success.

Europe

Britain

The British author and poet Rudyard Kipling used the symbol on the cover art of a number of his works, including The Five Nations, 1903, which has it twinned with an elephant. Once Adolf Hitler and the Nazis came to power, Kipling ordered that the swastika should no longer adorn his books.[citation needed] In 1927, a red swastika defaced by a Union Jack was proposed as a flag for the Union of South Africa.[157]

Denmark

The Danish brewery company Carlsberg Group used the swastika as a logo[158] from the 19th century until the middle of the 1930s when it was discontinued because of association with the Nazi Party in neighbouring Germany. In Copenhagen at the entrance gate, and tower, of the company's headquarters, built in 1901, swastikas can still be seen. The tower is supported by four stone elephants, each with a swastika on each side. The tower they support is topped with a spire, in the middle of which is a swastika.[159]

Iceland

The swastika, or the Thor's hammer as the logo was called, was used as the logo for H/f. Eimskipafjelag Íslands[160] from its founding in 1914 until the Second World War when it was discontinued and changed to read only the letters Eimskip.

Ireland

The Swastika Laundry was a laundry founded in 1912, located on Shelbourne Road, Ballsbridge, a district of Dublin, Ireland. In the 1950s, Heinrich Böll came across a van belonging to the company while he was staying in Ireland, leading to some awkward moments before he realised the company was older than Nazism and totally unrelated to it. The chimney of the boiler-house of the laundry still stands, but the laundry has been redeveloped.[161][162]

Finland

In Finland, the swastika (vääräpää meaning "crooked-head", and later hakaristi, meaning "hook-cross") was often used in traditional folk-art products, as a decoration or magical symbol on textiles and wood. The swastika was also used by the Finnish Air Force until 1945 and is still used on air force flags.

The tursaansydän, an elaboration on the swastika, is used by scouts in some instances,[163] and by a student organisation.[164] The Finnish village of Tursa uses the tursaansydän as a kind of a certificate of authenticity on products made there and is the origin of this name of the symbol (meaning "heart of Tursa"),[165] which is also known as the mursunsydän ("walrus-heart"). Traditional textiles are still made in Finland with swastikas as parts of traditional ornaments.

The President of Finland is the grand master of the Order of the White Rose. According to the protocol, the president shall wear the Grand Cross of the White Rose with collar on formal occasions. The original design of the collar, decorated with nine swastikas, dates from 1919 and was designed by the artist Akseli Gallen-Kallela. To avoid misunderstandings, the swastika decorations were replaced by fir crosses at the decision of the President Urho Kekkonen in 1963 after it became known that the President of France, Charles De Gaulle, was uncomfortable with the swastika collar.

Finnish military

The type of swastika was the symbol of luck for the Swedish count Eric von Rosen, who donated the earliest aircraft of the Finnish Air Force; he later became a prominent figure in the Nazi movement of Sweden.

In 2017, the troop department emblem with swastika of the Air Force General Staff was replaced by the emblem of the Air Force has used since 2002. However, the troop department emblem and flag of Finland's Air Force Academy still keeps the swastika symbols.[166]

The swastika was also used by the women's paramilitary organisation Lotta Svärd, which was banned in 1944 in accordance with the Moscow Armistice between Finland and the allied Soviet Union and Britain.

Also, the insignias of the Cross of Liberty, designed by Gallen-Kallela in 1918, have swastikas. The 3rd class Cross of Liberty is depicted in the upper left corner of the standard of the President of Finland, who is the grand master of the order, too.[167]

In December 2007, a silver replica of the World War II -period Finnish air defence's relief ring decorated with a swastika became available as a part of a charity campaign.[168] The original war-time idea was that the public swap their precious metal rings for the state air defence's relief ring, made of iron.

Latvia

Latvia adopted the swastika, for its Air Force in 1918/1919 and continued its use until the Soviet occupation in 1940.[169][170] The cross itself was maroon on a white background, mirroring the colours of the Latvian flag. Earlier versions pointed counter-clockwise, while later versions pointed clock-wise and eliminated the white background.[171][172] Various other Latvian Army units and the Latvian War College[173] (the predecessor of the National Defence Academy) also had adopted the symbol in their battle flags and insignia during the Latvian War of Independence.[174] A stylised fire cross is the base of the Order of Lāčplēsis, the highest military decoration of Latvia for participants of the War of Independence.[175] The Pērkonkrusts, an ultra-nationalist political organisation active in the 1930s, also used the fire cross as one of its symbols.

Lithuania

The swastika symbol (Lithuanian: sūkurėlis) is a traditional Baltic ornament,[113][176] found on relics dating from at least the 13th century.[177] The swastika for Lithuanians represent the history and memory of their Lithuanians ancestors as well as the Baltic people at large.[177] There are monuments in Lithuania such as the Freedom Monument in Rokiškis where the swastika can be found.[177]

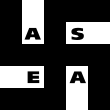

Sweden

The Swedish company ASEA, now a part of ABB, in the late 1800s introduced a company logo featuring a swastika. The logo was replaced in 1933, when Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany. During the early 1900s, the swastika was used as a symbol of electric power, perhaps because it resembled a waterwheel or turbine. On maps of the period, the sites of hydroelectric power stations were marked with swastikas.

Norway

Starting in 1917, Mikal Sylten's staunchly antisemitic periodical, Nationalt Tidsskrift took up the swastika as a symbol, three years before Adolf Hitler chose to do so.[178]

The headquarters of the Oslo Municipal Power station was designed by architects Bjercke and Eliassen in 1928–1931. The architects knew the swastika as a symbol of electricity and were not yet aware that it had been usurped by the German Nazi party, having Swastikas adorn its wrought iron gates. Notably, the gates survived the cleanup after the German occupation of Norway during World War II.[179]

Russia

The left-handed swastika was a favourite sign of the last Russian Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. She wore a talisman in the form of a swastika, put it everywhere for happiness, including on her suicide letters from Tobolsk,[180] later drew with a pencil on the wall and in the window opening of the room in the Ipatiev House, which served as the place of the last imprisonment of the royal family and on the wallpaper above the bed.[181]

The Russian Provisional Government of 1917 printed a number of new bank notes with right-facing, diagonally rotated swastikas in their centres.[182] The banknote design was initially intended for the Mongolian national bank but was re-purposed for Russian rubles after the February revolution. Swastikas were depicted and on some Soviet credit cards (sovznaks) printed with clichés that were in circulation in 1918–1922.[183]

During the Russian Civil War, the swastika was present in the symbolism of the uniform of some units of the White Army Asiatic Cavalry Division of Baron Ungern in Siberia and Bogd Khanate of Mongolia, which is explained by the significant number of Buddhists within it.[184] The Red Army's ethnic Kalmyk units wore distinct armbands featuring the swastika with "РСФСР" (Roman: "RSFSR") inscriptions on them.[185]

- Badges worn by the Kalmyk formations of the Red Army in 1919

- Flag of Tuva – Tuvan People's Republic (1921–1926)

North America

The swastika motif is found in some traditional Native American art and iconography. Historically, the design has been found in excavations of Mississippian-era sites in the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys, and on objects associated with the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (S.E.C.C.). It is also widely used by a number of southwestern tribes, most notably the Navajo, and plains nations such as the Dakota. Among various tribes, the swastika carries different meanings. To the Hopi it represents the wandering Hopi clan; to the Navajo it is one symbol for the whirling log (tsin náálwołí), a sacred image representing a legend that is used in healing rituals.[186] A brightly coloured First Nations saddle featuring swastika designs is on display at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum in Canada.[187]

Before the 1930s, the symbol for the 45th Infantry Division of the United States Army was a red diamond with a yellow swastika, a tribute to the large Native American population in the southwestern United States. It was later replaced with a thunderbird symbol.

The town of Swastika, Ontario, Canada, and the hamlet of Swastika, New York were named after the symbol.

From 1909 to 1916, the K-R-I-T automobile, manufactured in Detroit, Michigan, used a right-facing swastika as their trademark.

- The swastika in North America

- Chief William Neptune of the Passamaquoddy, wearing a headdress and outfit adorned with swastikas

- Chilocco Indian Agricultural School basketball team in 1909

- Fernie Swastikas hockey team in 1922

- Original insignia of the 45th Infantry Division

- Pillow cover offered by the Girls' Club in The Ladies Home Journal in 1912

- Arizona state highway marker (1927)

Association with Nazism

Use in Nazism (1920–1945)

The swastika was widely used in Europe at the start of the 20th century. It symbolised many things to the Europeans, with the most common symbolism being of good luck and auspiciousness.[22] In the wake of widespread popular usage, in post-World War I Germany, the newly established Nazi Party formally adopted the swastika in 1920.[22][188] The Nazi Party emblem was a black swastika rotated 45 degrees on a white circle on a red background. This insignia was used on the party's flag, badge, and armband. Hitler also designed his personal standard using a black swastika sitting flat on one arm, not rotated.[189]

Before the Nazis, the swastika was already in use as a symbol of German völkisch nationalist movements (Völkische Bewegung).

José Manuel Erbez says:

The first time the swastika was used with an "Aryan" meaning was on 25 December 1907, when the self-named Order of the New Templars, a secret society founded by Lanz von Liebenfels, hoisted at Werfenstein Castle (Austria) a yellow flag with a swastika and four fleurs-de-lys.[190]

However, Liebenfels was drawing on an already-established use of the symbol.[191]

In his 1925 work Mein Kampf, Adolf Hitler writes: "I myself, meanwhile, after innumerable attempts, had laid down a final form; a flag with a red background, a white disk, and a black hooked cross in the middle. After long trials I also found a definite proportion between the size of the flag and the size of the white disk, as well as the shape and thickness of the hooked cross."

When Hitler created a flag for the Nazi Party, he sought to incorporate both the swastika and "those revered colours expressive of our homage to the glorious past and which once brought so much honour to the German nation". (Red, white, and black were the colours of the flag of the old German Empire.) He also stated: "As National Socialists, we see our program in our flag. In red, we see the social idea of the movement; in white, the nationalistic idea; in the hooked cross, the mission of the struggle for the victory of the Aryan man, and, by the same token, the victory of the idea of creative work."[192]

The swastika was also understood as "the symbol of the creating, effecting life" (das Symbol des schaffenden, wirkenden Lebens) and as "race emblem of Germanism" (Rasseabzeichen des Germanentums).[193]

The concepts of racial hygiene and scientific racism were central to Nazism.[194][195] High-ranking Nazi theorist Alfred Rosenberg noted that the Indo-Aryan peoples were both a model to be imitated and a warning of the dangers of the spiritual and racial "confusion" that, he believed, arose from the proximity of races. The Nazis co-opted the swastika as a symbol of the Aryan master race.

On 14 March 1933, shortly after Hitler's appointment as Chancellor of Germany, the NSDAP flag was hoisted alongside Germany's national colours. As part of the Nuremberg Laws, the NSDAP flag – with the swastika slightly offset from centre – was adopted as the sole national flag of Germany on 15 September 1935.[196]

- Heinrich Pudor's völkisch Treu Deutsch ('True German') 1918 with a swastika. From the collections of Leipzig City Museum.

- German World War I helmet with swastika used by a member of the Marinebrigade Ehrhardt, a right-wing paramilitary free corps, participating in the Kapp Putsch 1920

- Cross of Honour of the German Mother (1939–1945) given to German mothers of four or more children

Use by the Allies

During World War II it was common to use small swastikas to mark air-to-air victories on the sides of Allied aircraft, and at least one British fighter pilot inscribed a swastika in his logbook for each German plane he shot down.[197]

Post–World War II stigmatisation

Because of its use by Nazi Germany, the swastika since the 1930s has been largely associated with Nazism. In the aftermath of World War II, it has been considered a symbol of hate in the West,[198] and of white supremacy in many Western countries.[199]

As a result, all use of it, or its use as a Nazi or hate symbol, is prohibited in some countries, including Germany. In some countries, such as the United States (in the 2003 case Virginia v. Black), the highest courts have ruled that the local governments can prohibit the use of swastika along with other symbols such as cross burning, if the intent of the use is to intimidate others.[23]

Germany

The German and Austrian postwar criminal code makes the public showing of the swastika, the sig rune, the Celtic cross (specifically the variations used by white power activists), the wolfsangel, the odal rune and the Totenkopf skull illegal, except for certain enumerated exemptions. It is also censored from the reprints of 1930s railway timetables published by the Reichsbahn. The swastikas on Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain temples are exempt, as religious symbols cannot be banned in Germany.[200]

A controversy was stirred by the decision of several police departments to begin inquiries against anti-fascists.[201] In late 2005 police raided the offices of the punk rock label and mail order store "Nix Gut Records" and confiscated merchandise depicting crossed-out swastikas and fists smashing swastikas. In 2006 the Stade police department started an inquiry against anti-fascist youths using a placard depicting a person dumping a swastika into a trashcan. The placard was displayed in opposition to the campaign of right-wing nationalist parties for local elections.[202]

On Friday, 17 March 2006, a member of the Bundestag, Claudia Roth reported herself to the German police for displaying a crossed-out swastika in multiple demonstrations against neo-Nazis, and subsequently got the Bundestag to suspend her immunity from prosecution. She intended to show the absurdity of charging anti-fascists with using fascist symbols: "We don't need prosecution of non-violent young people engaging against right-wing extremism." On 15 March 2007, the Federal Court of Justice of Germany (Bundesgerichtshof) held that the crossed-out symbols were "clearly directed against a revival of national-socialist endeavours", thereby settling the dispute for the future.[203][204][205]

On 9 August 2018, Germany lifted the ban on the usage of swastikas and other Nazi symbols in video games. "Through the change in the interpretation of the law, games that critically look at current affairs can for the first time be given a USK age rating," USK managing director Elisabeth Secker told CTV. "This has long been the case for films and with regards to the freedom of the arts, this is now rightly also the case with computer and videogames."[206][207]

Legislation in other European countries

- Until 2013 in Hungary, it was a criminal misdemeanour to publicly display "totalitarian symbols", including the swastika, the SS insignia, and the Arrow Cross, punishable by custodial arrest.[208][209] Display for academic, educational, artistic or journalistic reasons was allowed at the time. The communist symbols of hammer and sickle and the red star were also regarded as totalitarian symbols and had the same restriction by Hungarian criminal law until 2013.[208]

- In Latvia, public display of Nazi and Soviet symbols, including the Nazi swastika, is prohibited in public events since 2013.[210][211] However, in a court case from 2007 a regional court in Riga held that the swastika can be used as an ethnographic symbol, in which case the ban does not apply.[212]

- In Lithuania, public display of Nazi and Soviet symbols, including the Nazi swastika, is an administrative offence, punishable by a fine from 150 to 300 euros. According to judicial practice, display of a non-Nazi swastika is legal.[213]

- In Poland, public display of Nazi symbols, including the Nazi swastika, is a criminal offence punishable by up to eight years of imprisonment. The use of the swastika as a religious symbol is legal.[214]

- In Geneva, Switzerland, a new constitution article banning the use of hate symbols, emblems, and other hateful images was passed in June 2024, which included banning the use of the swastika.[215]

Attempted ban in the European Union

The European Union's Executive Commission proposed a European Union-wide anti-racism law in 2001, but European Union states failed to agree on the balance between prohibiting racism and freedom of expression.[216] An attempt to ban the swastika across the EU in early 2005 failed after objections from the British Government and others. In early 2007, while Germany held the European Union presidency, Berlin proposed that the European Union should follow German Criminal Law and criminalise the denial of the Holocaust and the display of Nazi symbols including the swastika, which is based on the Ban on the Symbols of Unconstitutional Organisations Act. This led to an opposition campaign by Hindu groups across Europe against a ban on the swastika. They pointed out that the swastika has been around for 5,000 years as a symbol of peace.[217][218] The proposal to ban the swastika was dropped by Berlin from the proposed European Union wide anti-racism laws on 29 January 2007.[216]

Latin America

- The manufacture, distribution or broadcasting of the swastika, with the intent to propagate Nazism, is a crime in Brazil as dictated by article 20, paragraph 1, of federal statute 7.716, passed in 1989. The penalty is a two to five years prison term and a fine.[219]

- The former flag of the Guna Yala autonomous territory of Panama was based on a swastika design. In 1942, a ring was added to the centre of the flag to differentiate it from the symbol of the Nazi Party (this version subsequently fell into disuse).[220]

United States

The public display of Nazi-era German flags (or any other flags) is protected by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, which guarantees the right to freedom of speech.[221] The Nazi Reichskriegsflagge has also been seen on display at white supremacist events within United States borders, side by side with the Confederate battle flag.[222]

In 2010, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) downgraded the swastika from its status as a Jewish hate symbol, saying "We know that the swastika has, for some, lost its meaning as the primary symbol of Nazism and instead become a more generalised symbol of hate."[223] The ADL notes on their website that the symbol is often used as "shock graffiti" by juveniles, rather than by individuals who hold white supremacist beliefs, but it is still a predominant symbol among American white supremacists (particularly as a tattoo design) and used with antisemitic intention.[224]

Australia

In 2022, Victoria was the first Australian state to ban the display of the Nazi's swastika. People who intentionally break this law will face a one-year jail sentence, a fine of 120 penalty units ($23,077.20 AUD as of 2023, equivalent to £12,076.66 or US$15,385.57), or both.[225][226]

Media

In 2010, Microsoft officially spoke out against use of the swastika by players of the first-person shooter Call of Duty: Black Ops. In Black Ops, players are allowed to customise their name tags to represent, essentially, whatever they want. The swastika can be created and used, but Stephen Toulouse, director of Xbox Live policy and enforcement, said players with the symbol on their name tag will be banned (if someone reports it as inappropriate) from Xbox Live.[227]

In the Indiana Jones Stunt Spectacular in Disney Hollywood Studios in Orlando, Florida, the swastikas on German trucks, aircraft and actor uniforms in the reenactment of a scene from Raiders of the Lost Ark were removed in 2004. The swastika has been replaced by a stylised Greek cross.[228]

Use by neo-Nazis

As with many neo-Nazi groups across the world, the American Nazi Party used the swastika as part of its flag before its first dissolution in 1967. The symbol was chosen by the organisation's founder, George Lincoln Rockwell.[229] It was "re-used" by successor organisations in 1983, without the publicity Rockwell's organisation enjoyed.[citation needed]

The swastika, in various iconographic forms, is one of the hate symbols identified in use as graffiti in US schools, and is described as such in a 1999 US Department of Education document, "Responding to Hate at School: A Guide for Teachers, Counsellors and Administrators", edited by Jim Carnes, which provides advice to educators on how to support students targeted by such hate symbols and address hate graffiti. Examples given show that it is often used alongside other white supremacist symbols, such as those of the Ku Klux Klan, and note a "three-bladed" variation used by skinheads, white supremacists, and "some South African extremist groups".[230]

The neo-Nazi Russian National Unity group's branch in Estonia is officially registered under the name "Kolovrat" and published an extremist newspaper in 2001 under the same name.[231] A criminal investigation found the paper included an array of racial epithets. One Narva resident was sentenced to one year in jail for distribution of Kolovrat.[232] The Kolovrat has since been used by the Rusich Battalion, a Russian militant group known for its operation during the war in Donbas.[233][234] In 2014 and 2015, members of the Ukrainian Azov Regiment were seen with swastika tattoos.[235][236][237][238]

- Flag of the American Nazi Party

- Logo of the National Socialist Movement (U.S.)

- Logo of the Russian National Unity

Contemporary use

Asia

Central Asia

In 2005, authorities in Tajikistan called for the widespread adoption of the swastika as a national symbol. President Emomali Rahmonov declared the swastika an Aryan symbol, and 2006 "the year of Aryan culture", which would be a time to "study and popularise Aryan contributions to the history of the world civilisation, raise a new generation (of Tajiks) with the spirit of national self-determination, and develop deeper ties with other ethnicities and cultures".[239]

East and Southeast Asia

In East Asia, the swastika is prevalent in Buddhist monasteries and communities. It is commonly found in Buddhist temples, religious artifacts, texts related to Buddhism and schools founded by Buddhist religious groups. It also appears as a design or motif (singularly or woven into a pattern) on textiles, architecture and various decorative objects as a symbol of luck and good fortune. The icon is also found as a sacred symbol in the Bon tradition, but in the left-facing orientation.[51][240]

Many Chinese religions make use of the swastika symbol, including Guiyidao and Shanrendao. The Red Swastika Society, formed in China in 1922 as the philanthropic branch of Guiyidao, became the largest supplier of emergency relief in China during World War II, in the same manner as the Red Cross in the rest of the world. The Red Swastika Society abandoned mainland China in 1954, settling first in Hong Kong then in Taiwan. They continue to use the red swastika as their symbol.[241]

In Japan, the swastika is also used as a map symbol and is designated by the Survey Act and related Japanese governmental rules to denote a Buddhist temple.[242] Japan has considered changing this due to occasional controversy and misunderstanding by foreigners.[243] The symbol is sometimes censored in international versions of Japanese works, such as anime.[244] Censorship of this symbol in Japan and in Japanese media abroad has been subject to occasional controversy related to freedom of speech, with critics of the censorship arguing it does not respect history nor freedom of speech.[243][244]

The city of Hirosaki in Aomori Prefecture designates this symbol as its official flag, which stemmed from its use in the emblem of the Tsugaru clan, the lords of Hirosaki Domain during the Edo period.[citation needed]

Among the predominantly Hindu population of Bali, in Indonesia, the swastika is common in temples, homes and public spaces. Similarly, the swastika is a common icon associated with Buddha's footprints in Theravada Buddhist communities of Myanmar, Thailand and Cambodia.[240]

- Свастика на храме в Корее

- Символ Шанрендао , конфуцианско-даосского религиозного движения на северо-востоке Китая.

- Флаг Общества Красной Свастики , крупнейшей группы по оказанию чрезвычайной помощи в Китае во время Второй мировой войны.

- Один из распространенных образцов резьбы тораджанцев в Индонезии.

- Образ богини грома (ва:он) народа сайсият на Тайване.

Индийский субконтинент

В Бутане, Индии, Непале и Шри-Ланке свастика распространена. Храмы, предприятия и другие организации, такие как буддийские библиотеки, Ахмедабадская фондовая биржа и Торговая палата Непала, [245] используйте свастику в рельефах или логотипах. [240] Свастики повсеместно распространены в индийских и непальских общинах, они расположены на магазинах, зданиях, транспортных средствах и одежде. Свастика остается заметной в индуистских церемониях, таких как свадьбы. , обращенный влево, Символ саувастики встречается в тантрических ритуалах. [1]

Колледж Мусеус в Коломбо, Шри-Ланка, буддийская школа для девочек, имеет свастику, обращенную влево, на логотипе своей школы.

В Индии свастика и свастика с их вариантами написания являются именами для мужчин и женщин соответственно, например, свастика Мукерджи . Герб Бихара содержит две свастики.

В Бутане мотив свастики встречается в архитектуре, тканях и религиозных церемониях.

Западное неправильное толкование азиатского использования

С конца 20-го века и до начала 21-го века путаница и противоречия возникали, когда товары личного пользования с традиционными джайнскими, буддийскими или индуистскими символами экспортировались на Запад, особенно в Северную Америку и Европу, и были истолкованы покупателями как имеющие нацистский символ. Это привело к тому, что несколько таких продуктов были бойкотированы или сняты с полок.

Когда десятилетний мальчик из Линбрука, штат Нью-Йорк , купил в 1999 году набор карточек с покемонами, импортированных из Японии, на двух из карточек была изображена обращенная влево буддийская свастика. Родители мальчика ошибочно истолковали символ как правостороннюю нацистскую свастику и подали жалобу производителю. Nintendo of America объявила о прекращении выпуска карт, объяснив, что то, что было приемлемо в одной культуре, не обязательно будет таковым в другой; их действия приветствовались Антидиффамационной лигой , которая признала, что в них не было намерения оскорбить, но заявила, что международная торговля означает, что «изоляция [свастики] в Азии просто создаст еще больше проблем». [86]

В 2002 году рождественские крекеры с пластиковыми игрушечными красными пандами со свастиками были сняты с полок после жалоб покупателей в Канаде. Производитель, базирующийся в Китае, заявил, что символ был представлен в традиционном смысле, а не как отсылка к нацистам, и извинился перед покупателями за межкультурную путаницу. [246]

В 2020 году ритейлер Shein убрал со своего сайта ожерелье с подвеской в виде левой свастики, получив негативную реакцию в социальных сетях. Ритейлер извинился за невнимательность, но отметил, что свастика является буддийским символом. [247]

Свастика в отличие от о Хакенкройце дебатов

Начиная с начала 2000-х годов, частично как реакция на публикацию книги под названием « Свастика: символ без искупления?» Стивен Хеллер , [86] и другие ученые начали движение индуисты , буддисты , коренные народы , джайнские историки, антропологи , лингвисты за «восстановление» того, что считалось «их» символом свастики «... пока Гитлер не украл его». [2] Эти группы утверждают, что свастика отличается от нацистского символа. Ключевая часть этого аргумента основана на том факте, что Адольф Гитлер, писавший по-немецки, называл этот символ крючковатым крестом (нем. Hakenkreuz ).

Основным препятствием на пути усилий по «восстановлению», «восстановлению» или «переоценке» свастики являются десятилетия крайне негативных ассоциаций в западном мире после принятия ее нацистской партией в 1930-х годах. Кроме того, группы сторонников превосходства белой расы по-прежнему цепляются за этот символ как за символ власти и идентичности. [224]

Многие средства массовой информации на Западе также продолжают описывать использование этого символа неонацистами как свастику, а иногда и как «нацистское» прилагательное, написанное как «Нацистская свастика». [248] [249] Группы, которые выступают против этой терминологии СМИ, не желают подвергать цензуре такое использование, а, скорее, хотят изменить освещение антисемитских и ненавистнических событий, чтобы описать символ в этом контексте как « Hakenkreuz » или «крючковатый крест». [250]

Южная Америка

Флаг народа Гуна (также «Куна Яла» или «Гуна Яла») Панамы. Этот флаг, принятый в 1925 году, имеет свастичный символ, который они называют Наа Укурьяа . По одному из объяснений, этот родовой символ символизирует осьминога, создавшего мир, его щупальца направлены на четыре стороны света. [251]

Новые религиозные движения

Помимо использования в качестве религиозного символа в индуизме , буддизме и джайнизме , которое восходит к досовременным традициям, свастика также используется приверженцами большого количества новых религиозных движений , возникших в современный период.

Теософия

возникшее в США, В 1880-х годах Теософское общество, приняло свастику как часть своей печати, наряду с Ом , гексаграммой или звездой Давида , Анком и Уроборосом . В отличие от более позднего Раэлианского движения , символ Теософского общества не вызывает споров, и печать используется до сих пор. На нынешней печати также есть текст: «Нет религии выше истины». [252]

Раэлизм

Раэлианское движение , сторонники которого считают, что инопланетяне создали всю жизнь на Земле, использует символ, который часто является источником серьезных споров: переплетенную звезду Давида и свастику. Раэлианцы говорят, что Звезда Давида представляет бесконечность в пространстве, тогда как свастика представляет бесконечность во времени – без начала и конца во времени, и все циклично. [253] В 1991 году символ был изменен, чтобы убрать свастику, из уважения к жертвам Холокоста , но по состоянию на 2007 год он был восстановлен в своем первоначальном виде. [254]

Ананда Марга

Тантре , Новое религиозное движение, основанное на Ананда Марга (Деванагари: आनन्द मार्ग, что означает «Путь блаженства») использует мотив, похожий на раэлианский, но в их случае видимая звезда Давида определяется как пересекающиеся треугольники без какой-либо конкретной ссылки на еврейскую культуру. культура.

Фалуньгун

В Фалуньгун движении цигун используется символ, состоящий из большой свастики, окруженной четырьмя меньшими (и закругленными) свастиками, перемежающимися символами инь и ян . [255]

язычество

Свастика является священным символом в неоязыческом германском язычестве , наряду с молотом Тора и рунами . Эта традиция, распространенная в Скандинавии, Германии и других странах, считает, что свастика произошла от скандинавского символа солнца. Использование ими этого символа побудило людей обвинить их в том, что они являются неонацистской группой. [256] [257] [258]

Балтийское неоязычество

Угунскруст Ромува («огненный крест») используется балтийскими неоязыческими движениями Диевтуриба в Латвии и в Литве . [259]

Славянская Родная Вера

Вариант свастики, нетрадиционный восьмирукий коловрат (русский: коловрат , буквально « прялка »), является наиболее часто используемым религиозным символом в неоязыческой славянской родной вере (также известной как Родновери). [260] [261]

В начале 1990-х годов бывший диссидент и один из основоположников российского неоязычества Алексей Добровольский сначала дал название «коловрат» четырехлучевой свастике, идентичной нацистскому символу, а позже перенес это название на восьмилучевую свастику. прямоугольная свастика. [262] По мнению историка и религиоведа Романа Шиженского, идею свастики Добровольский взял из произведения «Хроника Оэра Линда ». [263] нацистским идеологом Германом Виртом , первым главой Аненербе . [264]

Алексей Добровольский представил восьмилучевой «коловрат» как символ «возрождающегося язычества». [265] Эту версию Коловрата он считал языческим знаком солнца и в 1996 году объявил его символом бескомпромиссной «национально-освободительной борьбы» против « жидовского ига». [266] По мнению Добровольского, значение «коловрата» полностью совпадает со значением нацистской свастики. [267]

- Флаг-вертушка, представленный Алексеем Добровольским.

См. также

- Аревахач – древний армянский национальный символ.

- Борджгали – грузинский символ Солнца.

- Крест Бригитты - Крест, сплетенный из тростника, со смещенными руками.

- Камунская роза - доисторический символ из петроглифов Валькамоники.

- Фасции - Связанный пучок деревянных прутьев, иногда с топором.

- Фашистская символика - использование определенных изображений и символов, предназначенных для представления аспектов фашизма.

- Вспышка и круг – символ Британского союза фашистов.

- Филфот - англосаксонский символ и вариант свастики.

- Лаубуру – баскский крест

- Нацистская символика - символы, используемые нацистами и неонацистами.

- Солнечный крест - круг, содержащий четыре или более спиц.

- Свастикасана – древняя сидячая поза для медитации в хатха-йоге.

- Трискелион - различные символы с тройной вращательной симметрией.

- Турсаансюдан - древний символ, используемый в Северной Европе.

- Угунскрустс – Свастика как символ в латвийском фольклоре.

- Валькнут - германский многотреугольный символ, встречается в нескольких формах.

- Ярмо и стрелы – Знак испанской монархии, фашистская эмблема.

- Z (военный символ) - иногда называемый Звастикой.

Примечания

Ссылки

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н тот «Свастика » энциклопедия онлайн Британская Получено 22 мая.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д Кэмпион, Мукти Джайн (23 октября 2014 г.). «Как мир любил свастику – пока ее не украл Гитлер» . Журнал BBC News . Проверено 11 января 2022 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Бакстон, Дэвид Роден (1947). «Христианские древности Северной Эфиопии». Археология . 92 . Лондонское общество антикваров : 11 и 23. doi : 10.1017/S0261340900009863 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Олсон, Джим (сентябрь 2020 г.). «Символ свастики в искусстве коренных американцев» . Шепчущий ветер . 48 (3): 23–25. ISSN 0300-6565 . ProQuest 2453170975 – через ProQuest.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Брюс М. Салливан (2001). Индуизм от А до Я. Пугало Пресс. п. 216 . ISBN 978-1-4616-7189-3 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д Адриан Снодграсс (1992). Символизм Ступы . Мотилал Банарсидасс. стр. 82–83. ISBN 978-81-208-0781-5 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Корт, Джон Э. (2001). Джайны в мире: религиозные ценности и идеология в Индии . Издательство Оксфордского университета . п. 17. ISBN 978-0195132342 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Бир, Роберт (2003). Справочник тибетских буддийских символов . Serindia Publications, Inc. ISBN 978-1932476033 – через Google Книги. [ нужна страница ]

- ^ "Свастика" [Swastika]. Большая российская энциклопедия/ Great Russian Encyclopedia Online (in Russian). 2017. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020 . Retrieved 18 May 2022 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с «Индекс миграции символов» . Sacred-texts.com .

- ^ Кембриджский словарь для продвинутых учащихся . Издательство Кембриджского университета. 2008. ISBN 978-3125179882 – через Google Книги.

- ^ « Этимология свастики» . Словарь.com . Проверено 8 июня 2015 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Арт Сильверблатт; Николай Злобин (2015). Международные коммуникации: подход к медиаграмотности . Рутледж. п. 109. ИСБН 978-1-317-46760-1 .

Следы Будды считались свастиками.

- ^ Пант, Мохан; Фуно, Сюдзи (2007). Ступа и свастика: исторические принципы городского планирования в долине Катманду в Непале . Издательство Национального университета Сингапура. п. 231 с примечанием 5. ISBN 978-9971-69-372-5 .

- ^ Грег, Роберт Филипс (1884). О значении и происхождении филфота и свастики . Николс и сыновья. стр. 6 , 29.

- ^ «Фаянсовая печать на пуговицах» .

Фаянсовая пуговица-печать (H99-3814/8756-01) со свастикой, найденная на полу комнаты 202 (траншея 43).

- ^ «Свастика» . Британика .