Нинтендо

Логотип используется с 2016 года. | |

Штаб-квартира в Киото, Япония. | |

| Нинтендо | |

Родное имя | Нинтендо Ко., Лтд. |

Романизированное имя | Нинтендо кабусики гайша |

| Раньше |

|

| Company type | Public |

| |

| ISIN | JP3756600007 |

| Industry | |

| Founded | 23 September 1889 in Shimogyō-ku, Kyoto, Japan |

| Founder | Fusajiro Yamauchi |

| Headquarters | 11–1 Kamitoba Hokodatecho, , Japan |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people |

|

| Products | List of products |

Production output |

|

| Brands | Video game series |

| Services | |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

| Owners | |

Number of employees | 7,724[a] (2024) |

| Divisions | |

| Subsidiaries | List |

| Website | nintendo |

| Footnotes / references [3][4][5][6][7] | |

Нинтендо Ко., Лтд. [б] — японская транснациональная компания по производству видеоигр со штаб-квартирой в Киото . Она разрабатывает, издает и выпускает как видеоигры, так и игровые консоли .

Nintendo была основана в 1889 году как Nintendo Koppai. [с] мастером Фусадзиро Ямаути и изначально производил игральные карты ханафуда ручной работы . Занявшись различными направлениями бизнеса в 1960-е годы и получив юридический статус публичной компании, Nintendo в 1977 году выпустила свою первую консоль Color TV-Game . Международное признание она получила с выпуском Donkey Kong в 1981 году и Nintendo. Entertainment System и Super Mario Bros. в 1985 году.

С тех пор Nintendo выпустила некоторые из самых успешных консолей в индустрии видеоигр , такие как Game Boy , Super Nintendo Entertainment System , Nintendo DS , Wii и Switch . Она создала и/или опубликовала множество крупных франшиз, включая Mario , Donkey Kong , The Legend of Zelda , Metroid , Fire Emblem , Kirby , Star Fox , Pokémon , Super Smash Bros. , Animal Crossing , Xenoblade Chronicles , Splatoon и Nintendo's. талисман Марио признан во всем мире. По состоянию на март 2023 года компания продала более 5,592 миллиарда видеоигр и более 836 миллионов единиц оборудования по всему миру.

Nintendo has multiple subsidiaries in Japan and abroad, in addition to business partners such as HAL Laboratory, Intelligent Systems, Game Freak, and The Pokémon Company. Nintendo and its staff have received awards including Emmy Awards for Technology & Engineering, Game Awards, Game Developers Choice Awards, and British Academy Games Awards. It is one of the wealthiest and most valuable companies in the Japanese market.

History

1889–1972: Early history

1889–1932: Origin as a playing card business

Nintendo was founded as Nintendo Koppai[d] on 23 September 1889[8] by craftsman Fusajiro Yamauchi in Shimogyō-ku, Kyoto, Japan, as an unincorporated establishment, to produce and distribute Japanese playing cards, or karuta (かるた, from Portuguese carta, 'card'), most notably hanafuda (花札, 'flower cards').[3][4][5][9][10][11] The name "Nintendo" is commonly assumed to mean "leave luck to heaven",[12][11] but the assumption lacks historical validation; it has also been suggested to mean "the temple of free hanafuda", but even descendants of Yamauchi do not know the true intended meaning of the name.[9] Hanafuda cards had become popular after Japan banned most forms of gambling in 1882, though tolerated hanafuda. Sales of hanafuda cards were popular with the yakuza-run gaming parlors in Kyoto. Other card manufacturers had opted to leave the market not wanting to be associated with criminal ties, but Yamauchi persisted without such fears to become the primary producer of hanafuda within a few years.[13] With the increase of the cards' popularity, Yamauchi hired assistants to mass-produce to satisfy the demand.[14] Even with a favorable start, the business faced financial struggle due to operating in a niche market, the slow and expensive manufacturing process, high product price, alongside long durability of the cards, which impacted sales due to the low replacement rate.[15] As a solution, Nintendo produced a cheaper and lower-quality line of playing cards, Tengu, while also conducting product offerings in other cities such as Osaka, where card game profits were high. In addition, local merchants were interested in the prospect of a continuous renewal of decks, thus avoiding the suspicions that reusing cards would generate.[16]

According to Nintendo, the business' first western-style card deck was put on the market in 1902,[4][5] although other documents postpone the date to 1907, shortly after the Russo-Japanese War.[17] Although the cards were initially meant for export, they quickly gained popularity not only abroad but also in Japan.[4][5] During this time, the business styled itself as Marufuku Nintendo Card Co.[18] The war created considerable difficulties for companies in the leisure sector, which were subject to new levies such as the Karuta Zei ("playing cards tax").[19] Nintendo subsisted and, in 1907, entered into an agreement with Nihon Senbai—later known as the Japan Tobacco—to market its cards to various cigarette stores throughout the country.[20] A Nintendo promotional calendar from the Taishō era dated to 1915 indicates that the business was named Yamauchi Nintendo[e] but still used the Marufuku Nintendo Co. brand for its playing cards.[21]

Japanese culture stipulated that for Nintendo to continue as a family business after Yamauchi's retirement, Yamauchi had to adopt his son-in-law so that he could take over the business. As a result, Sekiryo Kaneda adopted the Yamauchi surname in 1907 and headed the business in 1929. By that time, Nintendo was the largest playing card business in Japan.[22]

1933–1968: Incorporation, expansion, and diversification

In 1933, Sekiryo Kaneda established the company as a general partnership named Yamauchi Nintendo & Co., Ltd.[f][5] investing in the construction of a new corporate headquarters located next to the original building,[23] near the Toba-kaidō train station.[24] Because Sekiryo's marriage to Yamauchi's daughter produced no male heirs, he planned to adopt his son-in-law Shikanojo Inaba, an artist in the company's employ and the father of his grandson Hiroshi, born in 1927. However, Inaba abandoned his family and the company, so Hiroshi was made Sekiryo's eventual successor.[25]

World War II negatively impacted the company as Japanese authorities prohibited the diffusion of foreign card games, and as the priorities of Japanese society shifted, its interest in recreational activities waned. During this time, Nintendo was partly supported by a financial injection from Hiroshi's wife Michiko Inaba, who came from a wealthy family.[26] In 1947, Sekiryo founded the distribution company Marufuku Co., Ltd.[g] responsible for Nintendo's sales and marketing operations, which would eventually go on to become the present-day Nintendo Co., Ltd., in Higashikawara-cho, Imagumano, Higashiyama-ku, Kyoto.[4][5][9]

In 1950, due to Sekiryo's deteriorating health,[27] Hiroshi Yamauchi assumed the presidency and headed manufacturing operations.[4][5] His first actions involved several important changes in the operation of the company: in 1951, he changed the company name to Nintendo Playing Card Co., Ltd.[h][4][5][28] and in the following year, he centralized the manufacturing facilities dispersed in Kyoto, which led to the expansion of the offices in Kamitakamatsu-cho, Fukuine, Higashiyama-ku, Kyoto.[4][5][29] In 1953, Nintendo became the first company to succeed in mass-producing plastic playing cards in Japan.[4][5] Some of the company's employees, accustomed to a more cautious and conservative leadership, viewed the new measures with concern, and the rising tension led to a call for a strike. However, the measure had no major impact, as Hiroshi resorted to the dismissal of several dissatisfied workers.[30]

In 1959, Nintendo moved its headquarters to Kamitakamatsu-cho, Fukuine, Higashiyama-ku, Kyoto. The company entered into a partnership with The Walt Disney Company to incorporate its characters into playing cards, which opened it up to the children's market and resulted in a boost to Nintendo's playing card business.[4][5][28] Nintendo automated the production of Japanese playing cards using backing paper, and also developed a distribution system that allowed it to offer its products in toy stores.[4][23] By 1961, the company had established a Tokyo branch in Chiyoda, Tokyo,[4] and sold more than 1.5 million card packs, holding a high market share, for which it relied on televised advertising campaigns.[31] In 1962, Nintendo became a public company by listing stock on the second section of the Osaka Securities Exchange and on the Kyoto Stock Exchange.[4][5] In the following year, the company adopted its current name, Nintendo & Co., Ltd.[i] and started manufacturing games in addition to playing cards.[4][5]

In 1964, Nintendo earned ¥150 million.[32] Although the company was experiencing a period of economic prosperity, the Disney cards and derived products made it dependent on the children's market. The situation was exacerbated by the falling sales of its adult-oriented playing cards caused by Japanese society gravitating toward other hobbies such as pachinko, bowling, and nightly outings.[31] When Disney card sales began to decline, Nintendo realized that it had no real alternative to alleviate the situation.[32] After the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, Nintendo's stock price plummeted to its lowest recorded level of ¥60.[33][34]

In 1965, Nintendo hired Gunpei Yokoi to maintain the assembly-line machines used to manufacture its playing cards.[35]

1969–1972: Classic and electronic toys

Yamauchi's experience with the previous initiatives led him to increase Nintendo's investment in a research and development department in 1969, directed by Hiroshi Imanishi, a long-time employee of the company.[5] Yokoi was moved to the newly created department and was responsible for coordinating various projects.[23] Yokoi's experience in manufacturing electronic devices led Yamauchi to put him in charge of the company's games department, and his products would be mass-produced.[36] During this period, Nintendo built a new production plant in Uji, just outside of Kyoto,[5] and distributed classic tabletop games such as chess, shogi, go, and mahjong, and other foreign games under the Nippon Game brand.[37] The company's restructuring preserved a couple of areas dedicated to playing card manufacturing.[38]

In 1970, the company's stock listing was promoted to the first section of the Osaka Stock Exchange,[4][5] and the reconstruction and enlargement of its corporate headquarters was completed.[5] The year represented a watershed moment in Nintendo's history as it released Japan's first electronic toy—the Beam Gun, an optoelectronic pistol designed by Masayuki Uemura.[5] In total, more than a million units were sold.[23] Nintendo partnered with Magnavox to provide a light gun controller based on the Beam Gun design for the company's new home video game console, the Magnavox Odyssey, in 1971.[39] Other popular toys released at the time included the Ultra Hand, the Ultra Machine, the Ultra Scope, and the Love Tester, all designed by Yokoi. More than 1.2 million units of Ultra Hand were sold in Japan.[14]

1973–present: History in electronics

1973–1978: Early video games and Color TV-Game

The growing demand for Nintendo's products led Yamauchi to further expand the offices, for which he acquired the surrounding land and assigned the production of cards to the original Nintendo building. Meanwhile, Yokoi, Uemura, and new employees such as Genyo Takeda, continued to develop innovative products for the company.[23] The Laser Clay Shooting System was released in 1973 and managed to surpass bowling in popularity. Though Nintendo's toys continued to gain popularity, the 1973 oil crisis caused both a spike in the cost of plastics and a change in consumer priorities that put essential products over pastimes, and Nintendo lost several billion yen.[40]

In 1974, Nintendo released Wild Gunman, a skeet shooting arcade simulation consisting of a 16 mm image projector with a sensor that detects a beam from the player's light gun. Both the Laser Clay Shooting System and Wild Gunman were successfully exported to Europe and North America.[5] However, Nintendo's production speeds were still slow compared to rival companies such as Bandai and Tomy, and their prices were high, which led to the discontinuation of some of their light gun products.[41] The subsidiary Nintendo Leisure System Co., Ltd., which developed these products, was closed as a result of the economic impact dealt by the oil crisis.[42]

Yamauchi, motivated by the successes of Atari and Magnavox with their video game consoles,[23] acquired the Japanese distribution rights for the Magnavox Odyssey in 1974,[36] and reached an agreement with Mitsubishi Electric to develop similar products between 1975 and 1978, including the first microprocessor for video games systems, the Color TV-Game series, and an arcade game inspired by Othello.[5] During this period, Takeda developed the video game EVR Race,[43] and Shigeru Miyamoto joined Yokoi's team with the responsibility of designing the casing for the Color TV-Game consoles.[44] In 1978, Nintendo's research and development department was split into two facilities, Nintendo Research & Development 1 and Nintendo Research & Development 2, respectively managed by Yokoi and Uemura.[45][46]

Shigeru Miyamoto brought distinctive sources of inspiration, including the natural environment and regional culture of Sonobe, popular culture influences like Westerns and detective fiction, along with folk Shinto practices and family media.[47][48][49][50] These would each be seen in most of Nintendo's major franchises which developed following Miyamoto's creative leadership.[51]

1979–1987: Game and Watch, arcade games, and Nintendo Entertainment System

Two key events in Nintendo's history occurred in 1979: its American subsidiary was opened in New York City, and a new department focused on arcade game development was created. In 1980, one of the first handheld video game systems, the Game & Watch, was created by Yokoi from the technology used in portable calculators.[5][40] It became one of Nintendo's most successful products, with over 43.4 million units sold worldwide during its production period, and for which 59 games were made in total.[52]

Nintendo entered the arcade video game market with Sheriff and Radar Scope, released in Japan in 1979 and 1980 respectively. Sheriff, also known as Bandido in some regions, marked the first original video game made by Nintendo, was published by Sega and developed by Genyo Takeda and Shigeru Miyamoto.[51][53][54] Radar Scope rivaled Galaxian in Japanese arcades but failed to find an audience overseas and created a financial crisis for the company.[55] To try to find a more successful game, they put Miyamoto in charge of their next arcade game design, leading to the release of Donkey Kong in 1981, one of the first platform video games that allowed the player character to jump.[56] The character, Jumpman, would later become Mario and Nintendo's official mascot. Mario was named after Mario Segale, the landlord of Nintendo's offices in Tukwila, Washington.[57] Donkey Kong was a financial success for Nintendo both in Japan and overseas, and led Coleco to fight Atari for licensing rights for porting to home consoles and personal computers.[55]

In 1983, Nintendo opened a new production facility in Uji and was listed on the first section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange.[5] Uemura, taking inspiration from the ColecoVision,[58] began creating a new video game console that would incorporate a ROM cartridge format for video games as well as both a central processing unit and a picture processing unit.[5][59][60] The Family Computer, or Famicom, was released in Japan in July 1983 along with three games adapted from their original arcade versions: Donkey Kong, Donkey Kong Jr. and Popeye.[61] Its success was such that in 1984, it surpassed the market share held by Sega's SG-1000.[62] That success also led to Nintendo leaving the Japanese arcade market in late 1985.[63][64] At this time, Nintendo adopted a series of guidelines that involved the validation of each game produced for the Famicom before its distribution on the market, agreements with developers to ensure that no Famicom game would be adapted to other consoles within two years of its release, and restricting developers from producing more than five games per year for the Famicom.[65]

In the early 1980s, several video game consoles proliferated in the United States, as well as low-quality games produced by third-party developers,[66] which oversaturated the market and led to the video game crash of 1983.[67] Consequently, a recession hit the American video game industry, whose revenues went from over $3 billion to $100 million between 1983 and 1985.[68] Nintendo's initiative to launch the Famicom in America was also impacted. To differentiate the Famicom from its competitors in America, Nintendo rebranded it as an entertainment system and its cartridges as Game Paks, and with a design reminiscent of a VCR.[60] Nintendo implemented a lockout chip in the Game Paks for control on its third party library to avoid the market saturation that had occurred in the United States.[69] The result is the Nintendo Entertainment System, or NES, which was released in North America in 1985.[5] The landmark games Super Mario Bros. and The Legend of Zelda were produced by Miyamoto and Takashi Tezuka. Composer Koji Kondo reinforced the idea that musical themes could act as a complement to game mechanics rather than simply a miscellaneous element.[70] Production of the NES lasted until 1995,[71] and production of the Famicom lasted until 2003.[72] In total, around 62 million Famicom and NES consoles were sold worldwide.[73] During this period, Nintendo created a copyright infringement protection in the form of the Official Nintendo Seal of Quality, added to their products so that customers may recognize their authenticity in the market.[74] By this time, Nintendo's network of electronic suppliers had extended to around thirty companies, including Ricoh (Nintendo's main source for semiconductors) and the Sharp Corporation.[23]

1988–1992: Game Boy and Super Nintendo Entertainment System

In 1988, Gunpei Yokoi and his team at Nintendo R&D1 conceived the Game Boy, the first handheld video game console made by Nintendo. Nintendo released the Game Boy in 1989. In North America, the Game Boy was bundled with the popular third-party game Tetris after a difficult negotiation process with Elektronorgtechnica.[75] The Game Boy was a significant success. In its first two weeks of sale in Japan, its initial inventory of 300,000 units sold out, and in the United States, an additional 40,000 units were sold on its first day of distribution.[76] Around this time, Nintendo entered an agreement with Sony to develop the Super Famicom CD-ROM Adapter, a peripheral for the upcoming Super Famicom capable of playing CD-ROMs.[77] However, the collaboration did not last as Yamauchi preferred to continue developing the technology with Philips, which would result in the CD-i,[78] and Sony's independent efforts resulted in the creation of the PlayStation console.[79]

The first issue of Nintendo Power magazine, which had an annual circulation of 1.5 million copies in the United States, was published in 1988.[80] In July 1989, Nintendo held the first Nintendo Space World trade show with the name Shoshinkai for the purpose of announcing and demonstrating upcoming Nintendo products.[81] That year, the first World of Nintendo stores-within-a-store, which carried official Nintendo merchandise, were opened in the United States. According to company information, more than 25% of homes in the United States had an NES in 1989.[80]

In the late 1980s, Nintendo's dominance slipped with the appearance of NEC's PC Engine and Sega's Mega Drive, 16-bit game consoles with improved graphics and audio compared to the NES.[82] In response to the competition, Uemura designed the Super Famicom, which launched in 1990. The first batch of 300,000 consoles sold out in hours.[83] The following year, as with the NES, Nintendo distributed a modified version of the Super Famicom to the United States market, titled the Super Nintendo Entertainment System.[84] Launch games for the Super Famicom and Super NES include Super Mario World, F-Zero, Pilotwings, SimCity, and Gradius III.[85] By mid-1992, over 46 million Super Famicom and Super NES consoles had been sold.[5] The console's life cycle lasted until 1999 in the United States,[86] and until 2003 in Japan.[72]

In March 1990, the first Nintendo World Championship was held, with participants from 29 American cities competing for the title of "best Nintendo player in the world".[80][87] In June 1990, the subsidiary Nintendo of Europe was opened in Großostheim, Germany; in 1993, subsequent subsidiaries were established in the Netherlands (where Bandai had previously distributed Nintendo's products), France, the United Kingdom, Spain, Belgium, and Australia.[5] In 1992, Nintendo acquired a majority stake in the Seattle Mariners baseball team, and sold most of its shares in 2016.[88][89] On July 31, 1992, Nintendo of America announced it would cease manufacturing arcade games and systems.[90][91] In 1993, Star Fox was released, which marked an industry milestone by being the first video game to make use of the Super FX chip.[5]

The proliferation of graphically violent video games, such as Mortal Kombat, caused controversy and led to the creation of the Interactive Digital Software Association and the Entertainment Software Rating Board, in whose development Nintendo collaborated during 1994. These measures also encouraged Nintendo to abandon the content guidelines it had enforced since the release of the NES.[92][93] Commercial strategies implemented by Nintendo during this time include the Nintendo Gateway System, an in-flight entertainment service available for airlines, cruise ships and hotels,[94] and the "Play It Loud!" advertising campaign for Game Boys with different-colored casings. The Advanced Computer Modeling graphics used in Donkey Kong Country for the Super NES and Donkey Kong Land for the Game Boy were technologically innovative, as was the Satellaview satellite modem peripheral for the Super Famicom, which allowed the digital transmission of data via a communications satellite in space.[5]

1993–1998: Nintendo 64, Virtual Boy, and Game Boy Color

In mid-1993, Nintendo and Silicon Graphics announced a strategic alliance to develop the Nintendo 64.[95][96] NEC, Toshiba, and Sharp also contributed technology to the console.[97] The Nintendo 64 was marketed as one of the first consoles to be designed with 64-bit architecture.[98] As part of an agreement with Midway Games, the arcade games Killer Instinct and Cruis'n USA were ported to the console.[99][100] Although the Nintendo 64 was planned for release in 1995, the production schedules of third-party developers influenced a delay,[101][102] and the console was released in June 1996 in Japan, September 1996 in the United States and March 1997 in Europe. By the end of its production in 2002, around 33 million Nintendo 64 consoles were sold worldwide,[73] and it is considered one of the most recognized video game systems in history.[103] 388 games were produced for the Nintendo 64 in total,[104] some of which – particularly Super Mario 64, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, and GoldenEye 007 – have been distinguished as some of the greatest of all time.[105]

In 1995, Nintendo released the Virtual Boy, a console designed by Gunpei Yokoi with stereoscopic graphics. Critics were generally disappointed with the quality of the games and red-colored graphics, and complained of gameplay-induced headaches.[106] The system sold poorly and was quietly discontinued.[107] Amid the system's failure, Yokoi formally retired from Nintendo.[108] In February 1996, Pocket Monsters Red and Green, known internationally as Pokémon Red and Blue, developed by Game Freak was released in Japan for the Game Boy, and established the popular Pokémon franchise.[109]: 191 The game went on to sell 31.37 million units,[110] with the video game series exceeding a total of 300 million units in sales as of 2017.[111] In 1997, Nintendo released the Rumble Pak, a plug-in device that connects to the Nintendo 64 controller and produces a vibration during certain moments of a game.[5]

In 1998, the Game Boy Color was released. In addition to backward compatibility with Game Boy games, the console's similar capacity to the NES resulted in select adaptations of games from that library, such as Super Mario Bros. Deluxe.[112] Since then, over 118.6 million Game Boy and Game Boy Color consoles have been sold worldwide.[113]

1999–2003: Game Boy Advance and GameCube

In May 1999, with the advent of the PlayStation 2,[114] Nintendo entered an agreement with IBM and Panasonic to develop the 128-bit Gekko processor and the DVD drive to be used in Nintendo's next home console.[115] Meanwhile, a series of administrative changes occurred in 2000, when Nintendo's corporate offices were moved to the Minami-ku neighborhood in Kyoto, and Nintendo Benelux was established to manage the Dutch and Belgian territories.[5]

In 2001, two new Nintendo consoles were introduced: the Game Boy Advance, which was designed by Gwénaël Nicolas with stylistic departure from its predecessors,[116][117] and the GameCube.[118] During the first week of the Game Boy Advance's North American release in June 2001, over 500,000 units were sold, making it the fastest-selling video game console in the United States at the time.[119] By the end of its production cycle in 2010, more than 81.5 million units had been sold worldwide.[113] As for the GameCube, even with such distinguishing features as the miniDVD format of its games and Internet connectivity for a few games,[120][121] its sales were lower than those of its predecessors, and during the six years of its production, 21.7 million units were sold worldwide.[122] The GameCube struggled against its rivals in the market,[123][124] and its initial poor sales led to Nintendo posting a first half fiscal year loss in 2003 for the first time since the company went public in 1962.[125]

In 2002, the Pokémon Mini was released. Its dimensions were smaller than that of the Game Boy Advance and it weighed 70 grams, making it the smallest video game console in history.[5] Nintendo collaborated with Sega and Namco to develop Triforce, an arcade board to facilitate the conversion of arcade titles to the GameCube.[126] Following the European release of the GameCube in May 2002,[127] Hiroshi Yamauchi announced his resignation as the president of Nintendo, and Satoru Iwata was selected by the company as his successor. Yamauchi would remain as advisor and director of the company until 2005,[128] and he died in 2013.[129] Iwata's appointment as president ended the Yamauchi succession at the helm of the company, a practice that had been in place since its foundation.[130][131]

In 2003, Nintendo released the Game Boy Advance SP, an improved version of the Game Boy Advance with a foldable case, an illuminated display, and a rechargeable battery. By the end of its production cycle in 2010, over 43.5 million units had been sold worldwide.[113] Nintendo also released the Game Boy Player, a peripheral that allows Game Boy and Game Boy Advance games to be played on the GameCube.

2004–2009: Nintendo DS and Wii

In 2004, Nintendo released the Nintendo DS, which featured such innovations as dual screens – one of which being a touchscreen – and wireless connectivity for multiplayer play.[5][132] Throughout its lifetime, more than 154 million units were sold, making it the most successful handheld console and the second bestselling console in history.[113] In 2005, Nintendo released the Game Boy Micro, the last system in the Game Boy line.[5][112] Sales did not meet Nintendo's expectations,[133] with 2.5 million units being sold by 2007.[134] In mid-2005, the Nintendo World Store was inaugurated in New York City.[135]

Nintendo's next home console was conceived in 2001, although development commenced in 2003, taking inspiration from the Nintendo DS.[136] Nintendo also considered the relative failure of the GameCube, and instead opted to take a "Blue Ocean Strategy" by developing a reduced performance console in contrast to the high-performance consoles of Sony and Microsoft to avoid directly competing with them.[137] The Wii was released in November 2006,[138] with a total of 33 launch games.[139] With the Wii, Nintendo sought to reach a broader demographic than its seventh-generation competitors,[140] with the intention of also encompassing the "non-consumer" sector.[141] To this end, Nintendo invested in a $200 million advertising campaign.[142] The Wii's innovations include the Wii Remote controller, equipped with an accelerometer system and infrared sensors that allow it to detect its position in a three-dimensional environment with the aid of a sensor bar;[143][144] the Nunchuk peripheral that includes an analog controller and an accelerometer;[145] and the Wii MotionPlus expansion that increases the sensitivity of the main controller with the aid of gyroscopes.[146] By 2016, more than 101 million Wii consoles had been sold worldwide,[147] making it the most successful console of its generation, a distinction that Nintendo had not achieved since the 1990s with the Super NES.[148]

Several accessories were released for the Wii from 2007 to 2010, such as the Wii Balance Board, the Wii Wheel and the WiiWare download service. In 2009, Nintendo Iberica S.A. expanded its commercial operations to Portugal through a new office in Lisbon.[5] By that year, Nintendo held a 68.3% share of the worldwide handheld gaming market.[149] In 2010, Nintendo celebrated the 25th anniversary of Mario's debut appearance, for which certain allusive products were put on sale. The event included the release of Super Mario All-Stars 25th Anniversary Edition and special editions of the Nintendo DSi XL and Wii.[150]

2010–2016: Nintendo 3DS, Wii U, and mobile ventures

Following an announcement in March 2010,[151] Nintendo released the Nintendo 3DS in 2011. The console produces stereoscopic effects without 3D glasses.[152] By 2018, more than 69 million units had been sold worldwide;[153] the figure increased to 75 million by the start of 2019.[147] In 2011, Nintendo celebrated the 25th anniversary of The Legend of Zelda with the orchestra concert tour The Legend of Zelda: Symphony of the Goddesses and the video game The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword.[154]

In 2012 and 2013, two new Nintendo game consoles were introduced: the Wii U, with high-definition graphics and a GamePad controller with near-field communication technology,[155][156] and the Nintendo 2DS, a version of the 3DS that lacks the clamshell design of Nintendo's previous handheld consoles and the stereoscopic effects of the 3DS.[157] With 13.5 million units sold worldwide,[147] the Wii U is the least successful video game console in Nintendo's history.[158] In 2014, a new product line was released consisting of figures of Nintendo characters called amiibos.[5]

On 25 September 2013, Nintendo announced its acquisition of a 28% stake in PUX Corporation, a subsidiary of Panasonic, for the purpose of developing facial, voice, and text recognition for its video games.[159] Due to a 30% decrease in company income between April and December 2013, Iwata announced a temporary 50% cut to his salary, with other executives seeing reductions by 20%–30%.[160] In January 2015, Nintendo ceased operations in the Brazilian market due in part to high import duties. This did not affect the rest of Nintendo's Latin American market due to an alliance with Juegos de Video Latinoamérica.[161] Nintendo reached an agreement with NC Games for Nintendo's products to resume distribution in Brazil by 2017,[162] and by September 2020, the Switch was released in Brazil.[163]

On 11 July 2015, Iwata died of bile duct cancer, and after a couple of months in which Miyamoto and Takeda jointly operated the company, Tatsumi Kimishima was named as Iwata's successor on 16 September 2015.[164] As part of the management's restructuring, Miyamoto and Takeda were respectively named creative and technological advisors.[165]

The financial losses caused by the Wii U, along with Sony's intention to release its video games to other platforms such as smart TVs, motivated Nintendo to rethink its strategy concerning the production and distribution of its properties.[166] In 2015, Nintendo formalized agreements with DeNA and Universal Parks & Resorts to extend its presence to smart devices and amusement parks respectively.[167][168][169]

In March 2016, Nintendo's first mobile app for the iOS and Android systems, Miitomo, was released.[170] Since then, Nintendo has produced other similar apps, such as Super Mario Run, Fire Emblem Heroes, Animal Crossing: Pocket Camp, Mario Kart Tour, and Pokémon Go, the last being developed by Niantic and having generated $115 million in revenue for Nintendo.[171] In March 2016, the loyalty program My Nintendo replaced Club Nintendo.[172]

The NES Classic Edition was released in November 2016. The console is a version of the NES based on emulation, HDMI, and the Wii remote.[173] Its successor, the Super NES Classic Edition, was released in September 2017.[174] By October 2018, around ten million units of both consoles combined had been sold worldwide.[175]

2017–present: Nintendo Switch and expansion to other media

The Wii U's successor in the eighth generation of video game consoles, the Nintendo Switch, was released in March 2017. The Switch features a hybrid design as a home and handheld console, Joy-Con controllers that each contain an accelerometer and gyroscope, and the simultaneous wireless networking of up to eight consoles.[176] To expand its library, Nintendo entered alliances with several third-party and independent developers;[177][178] by February 2019, more than 1,800 Switch games had been released.[179] Worldwide sales of the Switch exceeded 55 million units by March 2020.[180] In April 2018, the Nintendo Labo line was released, consisting of cardboard accessories that interact with the Switch and the Joy-Con controllers.[181] More than one million units of the Nintendo Labo Variety Kit were sold in its first year on the market.[182]

In 2018, Shuntaro Furukawa replaced Kimishima as company president,[183] and in 2019, Doug Bowser succeeded Nintendo of America president Reggie Fils-Aimé.[184] In April 2019, Nintendo formed an alliance with Tencent to distribute the Nintendo Switch in China starting in December.[185]

The theme park area Super Nintendo World opened at Universal Studios Japan in 2021.[186][187]

In early 2020, Plan See Do, a hotel and restaurant development company, announced that it would refurbish the former Nintendo headquarters from the 1930s as a hotel, with plans to add 20 guest rooms, a restaurant, bar, and gym. The building is owned by Yamauchi Co., Ltd., an asset management company of Nintendo's founding family.[188] The hotel later opened in April 2022, with 18 guest rooms, and named Marufukuro in a homage to Nintendo's previous name - Marufuku.[189][190][191] In April 2020, Reuters reported that ValueAct Capital had acquired over 2.6 million shares in Nintendo stock worth US$1.1 billion over the course of a year, giving them an overall stake of 2% in Nintendo.[192] Although the COVID-19 pandemic caused delays in the production and distribution of some of Nintendo's products, the situation "had limited impact on business results"; in May 2020, Nintendo reported a 75% increase in income compared to the previous fiscal year, mainly contributed by the Nintendo Switch Online service.[193] The year saw some changes to the company's management: outside director Naoki Mizutani retired from the board, and was replaced by Asa Shinkawa; and Yoshiaki Koizumi was promoted to senior executive officer, maintaining its role as deputy general manager of Nintendo EPD.[193] By August, Nintendo was named the richest company in Japan.[194] In June 2021, the company announced plans to convert its former Uji Ogura plant, where it had manufactured playing and hanafuda cards, into a museum tentatively named "Nintendo Gallery", targeted to open by March 2024.[195][196] In the following year, historic remains of a Yayoi period village were discovered in the construction site.[197]

Nintendo co-produced an animated film The Super Mario Bros. Movie alongside Universal Pictures and Illumination, with Miyamoto and Illumination CEO Chris Meledandri acting as producers.[198][199] In 2021, Furukawa indicated Nintendo's plan to create more animated projects based on their work outside the Mario film,[200] and by 29 June, Meledandri joined the board of directors as a non-executive outside director.[201][202] According to Furukawa, the company's expansion toward animated production is to keep "[the] business [of producing video games] thriving and growing", realizing the "need to create opportunities where even people who do not normally play on video game systems can come into contact with Nintendo characters". That day, Miyamoto said that "[Meledandri] really came to understand the Nintendo point of view" and that "asking for [his] input, as an expert with many years of experience in Hollywood, will be of great help to" Nintendo's transition into film production.[203] Later, in July 2022, Nintendo acquired Dynamo Pictures, a Japanese CG company founded by Hiroshi Hirokawa on 18 March 2011. Dynamo had worked with Nintendo on digital shorts in the 2010s, including for the Pikmin series, and Nintendo said that Dynamo would continue their goal of expanding into animation. Following the completion of the acquisition in October 2022, Nintendo renamed Dynamo as Nintendo Pictures.[204][205]

In February 2022, Nintendo announced the acquisition of SRD Co., Ltd. (Systems Research and Development) after 40 years, a major contributor of Nintendo's first-party games such as Donkey Kong and The Legend of Zelda until the 1990s, and then support studio since.[206] In May 2022, Reuters reported that Saudi Arabia's Public Investment Fund had purchased a 5% stake in Nintendo,[207] and by January 2023, its stake in the company had increased to 6.07%.[208] It was raised to 7.08% by February 2023, and in the same week by 8.26%, making it the biggest external investor.[209][210]

In early 2023, the Super Nintendo World theme park area in Universal Studios Hollywood opened.[211] The Super Mario Bros. Movie was released on 5 April 2023, and has grossed over $1.3 billion worldwide, setting box-office records for the biggest worldwide opening weekend for an animated film, the highest-grossing film based on a video game and the 15th-highest-grossing film of all-time.[212]

Nintendo reached an agreement with Embracer Group in May 2024 to acquire 100% of the shares in Shiver Entertainment, a company that has specialized in porting triple-A games like Hogwarts Legacy and Mortal Kombat 1 to the Switch, making it a wholly owned subsidiary of Nintendo, subject to closing conditions.[213][214]

Products

Nintendo's central focus is the research, development, production, and distribution of entertainment products—primarily video game software and hardware and card games. Its main markets are Japan, America, and Europe, and more than 70% of its total sales come from the latter two territories.[215] As of March 2023, Nintendo has sold more than 5.592 billion video games[216] and over 836 million hardware units[217] globally.

Toys and cards

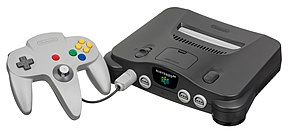

Video game consoles

Since the launch of the Color TV-Game in 1977, Nintendo has produced and distributed home, handheld, dedicated and hybrid consoles. Each has a variety of accessories and controllers, such as the NES Zapper, the Game Boy Camera, the Super NES Mouse, the Rumble Pak, the Wii MotionPlus, the Wii U Pro Controller, and the Switch Pro Controller.

Video games

Nintendo's first electronic games are arcade games. EVR Race (1975) was the company's first electromechanical game, and Donkey Kong (1981) was the first platform game in history. Since then, both Nintendo and other development companies have produced and distributed an extensive catalog of video games for Nintendo's consoles. Nintendo's games are sold in both removable media formats such as optical disc and cartridge, and online formats which are distributed via services such as the Nintendo eShop and the Nintendo Network.

Corporate structure

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2024) |

Nintendo's internal research and development operations are divided into three main divisions:

- Nintendo Entertainment Planning & Development (or EPD),[218][219][220] the main software development and production division of Nintendo, which focuses on video game and software development, production, and supervising;

- Nintendo Platform Technology Development (or PTD), which focuses on home and handheld video game console hardware development; and

- Nintendo Business Development (or NBD), which focuses on refining business strategy for dedicated game system business and is responsible for overseeing the smart device arm of the business.

Entertainment Planning and Development (EPD)

The Nintendo Entertainment Planning & Development division is the primary software development, production, and supervising division at Nintendo, formed as a merger between their former Entertainment Analysis & Development and Software Planning & Development divisions in 2015. Led by Shinya Takahashi, the division holds the largest concentration of staff at the company, housing more than 800 engineers, producers, directors, coordinators, planners, and designers.

Platform Technology Development (PTD)

The Nintendo Platform Technology Development division is a combination of Nintendo's former Integrated Research & Development (or IRD) and System Development (or SDD) divisions. Led by Ko Shiota, the division is responsible for designing hardware and developing Nintendo's operating systems, developer environment, and internal network, and maintenance of the Nintendo Network.

Business Development (NBD)

The Nintendo Business Development division was formed following Nintendo's foray into software development for smart devices such as mobile phones and tablets. It is responsible for refining Nintendo's business model for the dedicated video game system business, and overseeing development for smart devices.

Branches

Notable board members include Shigeru Miyamoto, Satoru Shibata and Outside Director Chris Meledandri, CEO of Illumination Entertainment; notable executive officers include Yoshiaki Koizumi, Deputy general manager of Entertainment Planning & Development division, Takashi Tezuka and Senior officer of Entertainment Planning & Development division.

Nintendo Co., Ltd.

Headquartered in Kyoto, Japan since the beginning, Nintendo Co., Ltd. oversees the organization's global operations and manages Japanese operations specifically. The company's two major subsidiaries, Nintendo of America and Nintendo of Europe, manage operations in North America and Europe respectively. Nintendo Co., Ltd.[221] moved from its original Kyoto location to a new office in Higashiyama-ku, Kyoto, in 2000; this became the research and development building when the head office relocated to its present[update] location in Minami-ku, Kyoto.[222]

- 1889-1933, in Shimogyō-ku, Kyoto

- 1933-1959, in Shimogyō-ku, Kyoto

- 1959-2000, in Higashiyama-ku, Kyoto

- 2000–present, in Minami-ku, Kyoto

Nintendo of America

Nintendo founded its North American subsidiary in 1980 as Nintendo of America (NoA). Hiroshi Yamauchi appointed his son-in-law Minoru Arakawa as president, who in turn hired his own wife and Yamauchi's daughter Yoko Yamauchi as the first employee. The Arakawa family moved from Vancouver, British Columbia to select an office in Manhattan, New York, due to its central status in American commerce. Both from extremely affluent families, their goals were set more by prestige than money. The seed capital and product inventory were supplied by the parent corporation in Japan, with a launch goal of entering the existing $8 billion-per-year coin-op arcade video game market and the largest entertainment industry in the US, which had already outclassed movies and television combined. During the couple's arcade research excursions, NoA hired gamer youths to work in the filthy, hot, ratty warehouse in New Jersey in order to receive and service game hardware from Japan.[223]

In late 1980, NoA contracted the Seattle-based arcade sales and distribution company Far East Video, consisting solely of experienced arcade salespeople Ron Judy and Al Stone. The two had already built a decent reputation and a distribution network, founded specifically for the independent import and sales of games from Nintendo because the Japanese company had for years been the under-represented maverick in America. Now as direct associates to the new NoA, they told Arakawa they could always clear all Nintendo inventory if Nintendo produced better games. Far East Video took NoA's contract for a fixed per-unit commission on the exclusive American distributorship of Nintendo games, to be settled by their Seattle-based lawyer, Howard Lincoln.[223]

Based on favorable test arcade sites in Seattle, Arakawa wagered most of NoA's modest finances on a huge order of 3,000 Radar Scope cabinets. He panicked when the game failed in the fickle market upon its arrival from its four-month boat ride from Japan. Far East Video was already in financial trouble due to declining sales and Ron Judy borrowed his aunt's life savings of $50,000, while still hoping Nintendo would develop its first Pac-Man-sized hit. Arakawa regretted founding the Nintendo subsidiary, with the distressed Yoko trapped between her arguing husband and father.[224]

Amid financial threat, Nintendo of America relocated from Manhattan to the Seattle metro to remove major stressors: the frenetic New York and New Jersey lifestyle and commute, and the extra weeks or months on the shipping route from Japan as was suffered by the Radar Scope disaster. With the Seattle harbor being the US's closest to Japan at only nine days by boat, and having a lumber production market for arcade cabinets, Arakawa's real estate scouts found a 60,000-square-foot (5,600 m2) warehouse for rent containing three offices—one for Arakawa and one for Judy and Stone.[225] This warehouse in the Tukwila suburb was owned by Mario Segale after whom the Mario character would be named, and was initially managed by former Far East Video employee Don James.[226] After one month, James recruited his college friend Howard Phillips as assistant, who soon took over as warehouse manager.[227][228][229][230][231][232] The company remained at fewer than 10 employees for some time, handling sales, marketing, advertising, distribution, and limited manufacturing[233]: 160 of arcade cabinets and Game & Watch handheld units, all sourced and shipped from Nintendo.

Arakawa was still panicked over NoA's ongoing financial crisis. With the parent company having no new game ideas, he had been repeatedly pleading for Yamauchi to reassign some top talent away from existing Japanese products to develop something for America—especially to redeem the massive dead stock of Radar Scope cabinets. Since all of Nintendo's key engineers and programmers were busy, and with NoA representing only a tiny fraction of the parent's overall business, Yamauchi allowed only the assignment of Gunpei Yokoi's young assistant who had no background in engineering, Shigeru Miyamoto.[234]

NoA's staff—except the sole young gamer Howard Phillips—were uniformly revolted at the sight of the freshman developer Miyamoto's debut game, which they had imported in the form of emergency conversion kits for the overstock of Radar Scope cabinets.[226] The kits transformed the cabinets into NoA's massive windfall gain of $280 million from Miyamoto's smash hit Donkey Kong in 1981–1983 alone.[235][236] They sold 4,000 new arcade units each month in America, making the 24-year-old Phillips "the largest volume shipping manager for the entire Port of Seattle".[231] Arakawa used these profits to buy 27 acres (11 ha) of land in Redmond in July 1982[237] and to perform the $50 million launch of the Nintendo Entertainment System in 1985 which revitalized the entire video game industry from its devastating 1983 crash.[238][239] A second warehouse in Redmond was soon secured, and managed by Don James. The company stayed at around 20 employees for some years.

The organization was reshaped nationwide in the following decades, and those core sales and marketing business functions are now directed by the office in Redwood City, California. The company's distribution centers are Nintendo Atlanta in Atlanta, Georgia, and Nintendo North Bend in North Bend, Washington. As of 2007[update], the 380,000-square-foot (35,000 m2) Nintendo North Bend facility processes more than 20,000 orders a day to Nintendo customers, which include retail stores that sell Nintendo products in addition to consumers who shop Nintendo's website.[240] Nintendo of America operates two retail stores in the United States: Nintendo New York on Rockefeller Plaza in New York City, which is open to the public; and Nintendo Redmond, co-located at NoA headquarters in Redmond, Washington, which is open only to Nintendo employees and invited guests. Nintendo of America's Canadian branch, Nintendo of Canada, is based in Vancouver, British Columbia with a distribution center in Toronto.[241] Nintendo Treehouse is NoA's localization team, composed of around 80 staff who are responsible for translating text from Japanese to English, creating videos and marketing plans, and quality assurance.[242]

Nintendo of America announced in October 2021 that it will be closing its offices in Redwood City, California and Toronto and merging their operations with their Redmond and Vancouver offices.[243] In April 2022, an anonymous QA worker filed a complaint with the National Labor Relations Board, alleging Nintendo of America and contractor Aston Carter had engaged in union-busting activities and surveillance. The employee had been fired for mentioning unionizing efforts in the industry during a company meeting.[244][245] The companies agreed to a settlement with the employee in October 2022.[246] In March 2024, Nintendo of America restructured its product testing teams, resulting in the elimination of over 100 contractor roles. Some of the affected contractors were given full-time roles.[247]

Nintendo of Europe

Nintendo's European subsidiary was established in June 1990,[248] based in Großostheim, Germany.[249] The company handles operations across Europe (excluding Scandinavia, where operations are handled by Bergsala),[250] as well as South Africa.[248] Nintendo of Europe's United Kingdom branch (Nintendo UK)[251] handles operations in that country and in Ireland from its headquarters in Windsor, Berkshire. In June 2014, NOE initiated a reduction and consolidation process, yielding a combined 130 layoffs: the closing of its office and warehouse, and termination of all employment, in Großostheim; and the consolidation of all of those operations into, and terminating some employment at, its Frankfurt location.[252][253] As of July 2018, the company employs 850 people.[254] In 2019, NoE signed with Tor Gaming Ltd. for official distribution in Israel.[255]

- Former Nintendo of Europe headquarters in Großostheim, Germany, until 2014

- Old Nintendo of Europe headquarters in Frankfurt, Germany

- Nintendo Iberica office in Lisbon, Portugal

Nintendo Australia

Nintendo's Australian subsidiary is based in Melbourne. It handles the publishing, distribution, sales, and marketing of Nintendo products in Australia and New Zealand. It also manufactured some Wii games locally.

Nintendo of Korea

Nintendo's South Korean subsidiary was established on 7 July 2006, and is based in Seoul.[256] In March 2016, the subsidiary was heavily downsized due to a corporate restructuring after analyzing shifts in the current market, laying off 80% of its employees, leaving only ten people, including CEO Hiroyuki Fukuda. This did not affect any games scheduled for release in South Korea, and Nintendo continued operations there as usual.[257][258]

Subsidiaries

Although most of the research and development is being done in Japan, there are some R&D facilities in the United States, Europe, and China that are focused on developing software and hardware technologies used in Nintendo products. Although they all are subsidiaries of Nintendo (and therefore first-party), they are often referred to as external resources when being involved in joint development processes with Nintendo's internal developers by the Japanese personnel involved. This can be seen in the Iwata Asks interview series.[259] Nintendo Software Technology (NST) and Nintendo Technology Development (NTD) are located in Redmond, Washington, United States, while Nintendo European Research & Development (NERD) is located in Paris, France, and Nintendo Network Service Database (NSD) is located in Kyoto, Japan.

Most external first-party software development is done in Japan, because the only overseas subsidiaries are Retro Studios and Shiver Entertainment in the United States (acquired in 2002[260] and 2024,[261] respectively) and Next Level Games in Canada (acquired in 2021).[262] Although these studios are all subsidiaries of Nintendo, they are often referred to as external resources when being involved in joint development processes with Nintendo's internal developers by the Nintendo Entertainment Planning & Development (EPD) division. 1-Up Studio and NDcube are located in Tokyo, Japan, and Monolith Soft has one studio located in Tokyo and another in Kyoto.

Nintendo also established The Pokémon Company alongside Creatures and Game Freak to manage the Pokémon brand. Similarly, Warpstar, Inc. was formed through a joint investment with HAL Laboratory, which was in charge of the Kirby: Right Back at Ya! animated series as well as the web series It's Kirby Time. Both companies are investments from Nintendo, with Nintendo holding 32% of the shares of The Pokémon Company and 50% of the shares of Warpstar, Inc.

Other notable subsidiaries include:

- iQue (China) Ltd.

- SRD Co., Ltd.

- Nintendo Pictures

- Nintendo Systems

Additional distributors

Bergsala

Bergsala, a third-party company based in Sweden, exclusively handles Nintendo operations in the Nordic region. Bergsala's relationship with Nintendo was established in 1981 when the company sought to distribute Game & Watch units to Sweden, which later expanded to the NES console by 1986. Bergsala were the only non-Nintendo owned distributor of Nintendo's products,[263] until 2019 when Tor Gaming gained distribution rights in Israel.

Tencent

Nintendo has partnered with Tencent to release Nintendo products in China, following the lifting of the country's console ban in 2015. In addition to distributing hardware, Tencent helps with the governmental approval process for video game software.[264]

Tor Gaming

In January 2019, Ynet and IGN Israel reported that negotiations about official distribution of Nintendo products in the country were ongoing.[255] After two months, IGN Israel announced that Tor Gaming Ltd., a company established in earlier 2019, gained a distribution agreement with Nintendo of Europe, handling official retailing beginning at the start of March,[265] followed by opening an official online store the next month.[266] In June 2019, Tor Gaming launched an official Nintendo Store at Dizengoff Center in Tel Aviv, making it the second official Nintendo Store worldwide, 13 years after NYC.[267]

Marketing

Nintendo of America has engaged in several high-profile marketing campaigns to define and position its brand. One of its earliest and most enduring slogans was "Now you're playing with power!", used first to promote its Nintendo Entertainment System.[268] It modified the slogan to include "SUPER power" for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System, and "PORTABLE power" for the Game Boy.[269]

Its 1994 "Play It Loud!" campaign played upon teenage rebellion and fostered an edgy reputation.[270] During the Nintendo 64 era, the slogan was "Get N or get out".[269] During the GameCube era, the "Who Are You?" suggested a link between the games and the players' identities.[271] The company promoted its Nintendo DS handheld with the tagline "Touching is Good".[272] For the Wii, they used the "Wii would like to play" slogan to promote the console with the people who tried the games including Super Mario Galaxy and Super Paper Mario.[273] The Nintendo 3DS used the slogan "Take a look inside".[274] The Wii U used the slogan "How U will play next".[275] The Nintendo Switch uses the slogan "Switch and Play" in North America, and "Play anywhere, anytime, with anyone" elsewhere.[276]

Trademark

During the peak of Nintendo's success in the video game industry in the 1990s, its name was ubiquitously used to refer to any video game console, regardless of the manufacturer. To prevent its trademark from becoming generic, Nintendo pushed the term "game console", and succeeded in preserving its trademark.[277][278]

Logos

Used since the 1960s, Nintendo's most recognizable logo is the racetrack shape, especially the red-colored wordmark typically displayed on a white background, primarily used in the Western markets from 1985 to 2006. In Japan, a monochromatic version that lacks a colored background is on Nintendo's own Famicom, Super Famicom, Nintendo 64, GameCube, and handheld console packaging and marketing. Since 2006, in conjunction with the launch of the Wii, Nintendo changed its logo to a gray variant that lacks a colored background inside the wordmark, making it transparent. Nintendo's official, corporate logo remains this variation.[279][failed verification] For consumer products and marketing, a white variant on a red background has been used since 2016, and has been in full effect since the launch of the Nintendo Switch in 2017.

- 1889–1950

- 1950–1960

- 1960–1965

- 1965–1967

- 1967–1968

- 1968–1970

- 1970–1972

- 1972–1975

- 1975–2008

- 2004–2016

- 2016–present

Policy

Content guidelines

For many years, Nintendo had a policy of strict content guidelines for video games published on its consoles. Although Nintendo allowed graphic violence in its video games released in Japan, nudity and sexuality were strictly prohibited. Former Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi believed that if the company allowed the licensing of simply games, the company's image would be forever tarnished.[280] Nintendo of America went further in that games released for Nintendo consoles could not feature nudity, sexuality, profanity (including racism, sexism or slurs), blood, graphic or domestic violence, drugs, political messages, or religious symbols—with the exception of widely unpracticed religions, such as the Greek Pantheon.[281] The Japanese parent company was concerned that it may be viewed as a "Japanese Invasion" by forcing Japanese community standards on North American and European children. Past the strict guidelines, some exceptions have occurred: Bionic Commando (though swastikas were eliminated in the US version), Smash TV and Golgo 13: Top Secret Episode contain human violence, the latter also containing implied sexuality and tobacco use; River City Ransom and Taboo: The Sixth Sense contain nudity, and the latter also contains religious images, as do Castlevania II and III.

A known side effect of this policy is the Genesis version of Mortal Kombat having more than double the unit sales of the Super NES version, mainly because Nintendo had forced publisher Acclaim to recolor the red blood to look like white sweat and replace some of the more gory graphics in its release of the game, making it less violent.[282] By contrast, Sega allowed blood and gore to remain in the Genesis version (though a code is required to unlock the gore). Nintendo allowed the Super NES version of Mortal Kombat II to ship uncensored the following year with a content warning on the packaging.[283]

Video game ratings systems were introduced with the Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) of 1994 and the Pan European Game Information of 2003, and Nintendo discontinued most of its censorship policies in favor of consumers making their own choices. Today, changes to the content of games are done primarily by the game's developer or, occasionally, at the request of Nintendo. The only clear-set rule is that ESRB AO-rated games will not be licensed on Nintendo consoles in North America,[284] a practice which is also enforced by Sony and Microsoft, its two greatest competitors in the present market. Nintendo has since allowed several mature-content games to be published on its consoles, including Perfect Dark, Conker's Bad Fur Day, Doom, Doom 64, BMX XXX, the Resident Evil series, Killer7, the Mortal Kombat series, Eternal Darkness: Sanity's Requiem, BloodRayne, Geist, Dementium: The Ward, Bayonetta 2, Devil's Third, and Fatal Frame: Maiden of Black Water.

Certain games have continued to be modified, however. For example, Konami was forced to remove all references to cigarettes in the 2000 Game Boy Color game Metal Gear Solid (although the previous NES version of Metal Gear, the GameCube game Metal Gear Solid: The Twin Snakes, and the 3DS game Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater 3D, included such references), and maiming and blood were removed from the Nintendo 64 port of Cruis'n USA.[285] Another example is in the Game Boy Advance game Mega Man Zero 3, in which one of the bosses, called Hellbat Schilt in the Japanese and European releases, was renamed Devilbat Schilt in the North American localization. In North America releases of the Mega Man Zero games, enemies and bosses killed with a saber attack do not gush blood as they do in the Japanese versions. However, the release of the Wii was accompanied by several even more controversial games, such as Manhunt 2, No More Heroes, The House of the Dead: Overkill, and MadWorld, the latter three of which were initially published exclusively for the console.

License guidelines

Nintendo of America also had guidelines before 1993 that had to be followed by its licensees to make games for the Nintendo Entertainment System, in addition to the above content guidelines.[280] Guidelines were enforced through the 10NES lockout chip.

- Licensees were not permitted to release the same game for a competing console until two years had passed.

- Nintendo would decide how many cartridges would be supplied to the licensee.

- Nintendo would decide how much space would be dedicated such as for articles and advertising in the Nintendo Power magazine.

- There was a minimum number of cartridges that had to be ordered by the licensee from Nintendo.

- There was a yearly limit of five games that a licensee may produce for a Nintendo console.[286] This rule was created to prevent market over-saturation, which had contributed to the video game crash of 1983.

The last rule was circumvented in several ways; for example, Konami, wanting to produce more games for Nintendo's consoles, formed Ultra Games and later Palcom to produce more games as a technically different publisher.[280] This disadvantaged smaller or emerging companies, as they could not afford to start additional companies. In another side effect, Square Co. (now Square Enix) executives have suggested that the price of publishing games on the Nintendo 64[287] along with the degree of censorship and control that Nintendo enforced over its games,[citation needed] most notably Final Fantasy VI, were factors in switching its focus towards Sony's PlayStation console.

In 1993, a class action suit was taken against Nintendo under allegations that their lockout chip enabled unfair business practices. The case was settled, with the condition that California consumers were entitled to a $3 discount coupon for a game of Nintendo's choice.[288]

Intellectual property protection

Nintendo has generally been proactive to assure its intellectual property in both hardware and software is protected. Nintendo's protection of its properties began as early as the arcade release of Donkey Kong which was widely cloned on other platforms, a practice common to the most popular arcade games of the era. Nintendo did seek legal action to try to stop release of these unauthorized clones, but estimated they still lost $100 million in potential sales to these clones.[289] Nintendo also fought off a claim in 1983 by Universal Pictures that Donkey Kong was a derivative element of their King Kong in Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo Co., Ltd.; notably, Nintendo's lawyer, John Kirby, became the namesake of Kirby in honor of the successful defense.

Copyright circumvention

Nintendo became more proactive as they entered the Famicom/NES period. Nintendo had witnessed the events of a flooded game market that occurred in the United States in the early 1980s that led to the 1983 video game crash, and with the Famicom had taken business steps, such as controlling the cartridge production process, to prevent a similar flood of video game clones.[290] However, the Famicom had lacked any lockout mechanics, and numerous unauthorized bootleg cartridges were made across the Asian regions. Nintendo took to creating its "Nintendo Seal of Quality" stamped on the games it made to dissuade consumers from purchasing these bootlegs, and as it prepared the Famicom for entry to Western regions as the NES, incorporated a lock-out system that only allowed authorized game cartridges they manufactured to be playable on the system. After the NES's release, Nintendo took legal action against companies that attempted to reverse-engineer the lockout mechanism to make unauthorized games for the NES. While Nintendo was successful to prevent reverse engineering of the lockout chip in the case Atari Games Corp. v. Nintendo of America Inc., they failed to prevent devices like Game Genie from being used to provide cheat codes for players in the case Lewis Galoob Toys, Inc. v. Nintendo of America, Inc..[291][292] Nintendo settled with the rental chain Blockbuster in Nintendo of America, Inc. v. Blockbuster Entertainment Corp. after they began including photocopies of Nintendo's game manuals in rented games.

In 2021, Gary Bowser was sentenced to 40 months in prison and order to pay $14.5 million in restitution for his role in a Nintendo hacking scheme.[293] Critics claim that the punishment was excessive, while others argue that it was necessary to send a message to deter other hackers and protect intellectual property rights.[294] Bowser's recent release from jail has brought attention to the impact that the massive amount of money he owes in restitution may have on his life and livelihood, as he claims to have only been able to pay off a small fraction of the fine so far.[295] During the hacking scheme, Bowser personally made only $320,000 in profit.[296]

Emulation

Nintendo has used emulation by itself or licensed from third parties to provide means to re-release games from their older platforms on newer systems, with Virtual Console, which re-released classic games as downloadable titles, the NES and Super NES library for Nintendo Switch Online subscribers, and with dedicated consoles like the NES and Super NES Classic Editions. However, Nintendo has taken a hard stance against unlicensed emulation of its video games and consoles, stating that it is the single largest threat to the intellectual property rights of video game developers.[297] Further, Nintendo has taken action against fan-made games which have used significant facets of their IP, issuing cease & desist letters to these projects or Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA)-related complaints to services that host these projects.[298] The company has also taken legal action against those that made modchips for its hardware; notably, in 2020 and 2021, Nintendo took action against Team Xecuter which had been making modchips for Nintendo's consoles since 2013, after members of that team were arrested by the United States Department of Justice.[299]In a related action, Nintendo sent a cease and desist letter to the organizers of the 2020 The Big House Super Smash Bros. tournament that was held entirely online due to the COVID-19 pandemic that year. Nintendo had taken issue with the tournament using emulated versions of Super Smash Bros. Melee which had included a user mod for networked play, as this would have required ripping a copy of Melee to play, an action they do not condone.[300]

Nintendo issued Valve a DMCA request prior the release of the Dolphin emulator for Wii and Switch games on the Steam storefront (for free) in May 2023, asserting that the inclusion of the Wii Common Key used to decrypt Wii games violated their copyright.[301][302] In 2024, Nintendo took legal action against the open-source Yuzu emulator for Switch games, stating that the software violates the DMCA by enabling decryption of the encryption method used for Switch games, and that it facilitated copyright infringement of The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom through a leaked copy that had been downloaded a million times from piracy websites prior to the game's official release.[303] The Yuzu team settled with Nintendo, agreeing to pay $2.4 million and stopping work on Yuzu, halting distribution of the code, and turning its domains and websites over to Nintendo.[304] As some of the Yuzu team had also worked on the Citra 3DS emulator, that project was also terminated, and its code was taken offline.[305] Some users not associated with the Yuzu team had attempted to fork the latest builds of Yuzu before it was taken offline, taking stances to completely avoid discussions related to the encryption aspects and any software piracy. Nintendo continued to issue DMCA requests to remove source repositories as well as Discord servers established by these users to discuss their forks' development.[306]

Fangames

Fangames that reuse or recreate Nintendo assets also have been targeted by Nintendo typically through cease and desist letters or DMCA-based takedown to shut down these projects.[307] Full Screen Mario, a web browser-based version of Super Mario Bros., was shut down in 2013 after Nintendo issued a cease and desist letter.[308] Over five hundred fangames hosted at Game Jolt, including AM2R, a remake of Metroid II: Return of Samus, were shut down by Nintendo in 2016.[309] Other notable fan projects that have been taken down include Pokémon Uranium, a fangame based on the Pokémon series in 2016.[310] Super Mario 64 Online, an online multiplayer version of Super Mario 64 in 2017,[311] and Metroid Prime 2D, a demake of Metroid Prime, in 2021.[312] Nintendo has defended these actions as necessary to protect its intellectual property, stating "just as Nintendo respects the intellectual property rights of others, we must also protect our own characters, trademarks and other content."[311] In some cases, the developers of these fangames have repurposed their work into new projects. In the case of No Mario's Sky, a mashup of Super Mario Bros. and No Man's Sky, after Nintendo sought to terminate the project, the Mario content was stripped and the game renamed as DMCA's Sky.[313]

Nintendo has also taken action against mods that bring Nintendo property into third-party games, notably seeking to block a Pokemon-based mod for the game Palworld, itself which has been colloquially described as a "Pokemon with guns" game. Nintendo issued a statement they plan to investigate not only the mod but the game for potential copyright misuse.[314] The company later sent notice to the developers of Garry's Mod, warning them about Nintendo IP used in the game's Steam Workshop, a collection of fan modifications, some which were as old as 20 years, leading the developers to start pruning this material after confirming the legitimacy of the notice.[315]

Copyright infringement

In recent years, Nintendo has taken legal action against sites that knowingly distribute ROM images of its games. On 19 July 2018, Nintendo sued Jacob Mathias, the owner of distribution websites LoveROMs and LoveRetro, for "brazen and mass-scale infringement of Nintendo's intellectual property rights".[316] Nintendo settled with Mathias in November 2018 for more than US$12 million along with relinquishing all ROM images in their ownership. While Nintendo is likely to have agreed to a smaller fine in private, the large amount was seen as a deterrent to prevent similar sites from sharing ROM images.[317] Nintendo won a separate suit against RomUniverse in May 2021, which also offered infringing copies of Nintendo DS and Switch games in addition to ROM images. The site owner was required to pay Nintendo $2.1 million in damages, and later given a permanent injunction preventing the site from operating in the future and requiring the owner to destroy all ROM copies.[318][319][320][321] Nintendo successfully won a suit in the United Kingdom in September 2019 to force the major Internet service providers in the country to block access to sites that offered copyright-infringing copies of Switch software or hacks for the Nintendo Switch to run unauthorized software.[322]

Nintendo also took steps to use a DMCA strike to block a video segment by the YouTube channel Did You Know Gaming? covering an uncompleted Zelda game pitched to Nintendo by Retro Studios, though the channel later succeeded in reversing the strike.[323][324] When leaks related to The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom appeared online in the week before the game's release in May 2023, Nintendo sent out DMCA takedown requests to several tools related to Switch emulation in attempts to stop the leaks.[325]

Data breaches

Nintendo sought enforcement action against a hacker that for several years had infiltrated Nintendo's internal database by various means including phishing to obtain plans for games and hardware for upcoming shows like E3. This was leaked to the Internet, impacting how Nintendo's own announcements were received. Though the person was a minor when Nintendo brought the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to investigate, and had been warned by the FBI to desist, the person continued over 2018 and 2019 as an adult, posting taunts on social media. The perpetrator was arrested in July 2019, and the FBI found documents confirming the hacks, many unauthorized game files, and child pornography, leading to the perpetrator's admission of guilt for all crimes in January 2020 and was sentenced to three years in prison.[326][327] Similarly, Nintendo alongside The Pokémon Company spent significant time to identify who had leaked information about Pokémon Sword and Shield several weeks before its planned Nintendo Directs, ultimately tracing the leaks back to a Portugal game journalist who leaked the information from official review copies of the game and subsequently severed ties with the publication.[328]

In May 2020, a major leak of documents occurred, including source code, designs, hardware drawings, documentation, and other internal information primarily related to the Nintendo 64, GameCube, and Wii. The leak may have been related to BroadOn, a company that Nintendo had contracted to help with the Wii's design,[329] or to Zammis Clark, a Malwarebytes employee and hacker who pleaded guilty to infiltrating Microsoft's and Nintendo's servers between March and May 2018.[330][331]

A second and larger leak occurred in July 2020, which has been called the "Gigaleak" as it contains gigabytes of data, and is believed related to the May 2020 leak.[332] The leak includes the source code and prototypes for several early 1990s Super NES games including Super Mario Kart, Yoshi's Island, Star Fox, and Star Fox 2, and it includes internal development tools and system software components. The veracity of the material was confirmed by Dylan Cuthbert, a programmer for Nintendo during that period.[333][334] The leak has the source code to several Nintendo 64 games including Super Mario 64 and The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, and the console's operating system.[335] The leak contains personal files from Nintendo employees.[332]

Seal of Quality

The gold sunburst seal was first used by Nintendo of America, and later Nintendo of Europe. It is displayed on any game, system, or accessory licensed for use on one of its video game consoles, denoting the game has been properly approved by Nintendo. The seal is also displayed on any Nintendo-licensed merchandise, such as trading cards, game guides, or apparel, albeit with the words "Official Nintendo Licensed Product."[336]

In 2008, game designer Sid Meier cited the Seal of Quality as one of the three most important innovations in video game history, as it helped set a standard for game quality that protected consumers from shovelware.[337]

NTSC regions

In NTSC regions, this seal is an elliptical starburst named the "Official Nintendo Seal". Originally, for NTSC countries, the seal was a large, black and gold circular starburst. The seal read as follows: "This seal is your assurance that NINTENDO has approved and guaranteed the quality of this product." This seal was later altered in 1988: "approved and guaranteed" was changed to "evaluated and approved". In 1989, the seal became gold and white, as it currently appears, with a shortened phrase, "Official Nintendo Seal of Quality". It was changed in 2003 to read "Official Nintendo Seal".[336]

The seal currently reads thus:[338]

The official seal is your assurance that this product is licensed or manufactured by Nintendo. Always look for this seal when buying video game systems, accessories, games and related products.

PAL regions

In PAL regions, the seal is a circular starburst named the "Original Nintendo Seal of Quality." Text near the seal in the Australian Wii manual states:

This seal is your assurance that Nintendo has reviewed this product and that it has met our standards for excellence in workmanship, reliability and entertainment value. Always look for this seal when buying games and accessories to ensure complete compatibility with your Nintendo product.[339]

Charitable projects