Мадхьямака

| Part of a series on |

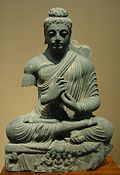

| Mahāyāna Buddhism |

|---|

|

Мадхьямака («срединный путь» или «центризм»; китайский : 中觀見 ; пиньинь : Чжунгуань Цзян ; тибетский : དབུ་མ་པ་ ; дбу ма па ), также известный как Шуньявада (« доктрина пустоты ») и Нихсвабхававада ( «доктрина но свабхава ») относится к традиции буддийской философии и практики, основанной индийским буддийским монахом и философом Нагарджуной ( ок. 150 – ок. 250 н. э. ). [1] [2] [3] Основополагающим текстом традиции Мадхьямаки является Нагарджуны » «Муламадхьямакакарика («Коренные стихи о Срединном пути»). В более широком смысле Мадхьямака также относится к абсолютной природе явлений, а также к неконцептуальной реализации высшей реальности, переживаемой в медитации . [4]

Начиная с IV века нашей эры, философия мадхьямаки оказала большое влияние на последующее развитие буддийской традиции Махаяны. [5] особенно после распространения буддизма по всей Азии . [5] [6] Это доминирующая интерпретация буддийской философии в тибетском буддизме , а также оказавшая влияние на буддийскую мысль Восточной Азии . [5] [7]

According to the classical Indian Mādhyamika thinkers, all phenomena (dharmas) are empty (śūnya) of "nature",[8] of any "substance" or "essence" (svabhāva) which could give them "solid and independent existence", because they are dependently co-arisen.[9] But this "emptiness" itself is also "empty": it does not have an existence on its own, nor does it refer to a transcendental reality beyond or above phenomenal reality.[10][11][12]

Etymology[edit]

Madhya is a Sanskrit word meaning "middle". It is cognate with Latin med-iu-s and English mid. The -ma suffix is a superlative, giving madhyama the meaning of "mid-most" or "medium". The -ka suffix is used to form adjectives, thus madhyamaka means "middling". The -ika suffix is used to form possessives, with a collective sense, thus mādhyamika mean "belonging to the mid-most" (the -ika suffix regularly causes a lengthening of the first vowel and elision of the final -a).

In a Buddhist context, these terms refer to the "middle path" (madhyama pratipada), which refers to right view (samyagdṛṣṭi) which steers clear of the metaphysical extremes of annihilationism (ucchedavāda) and eternalism (śassatavāda). For example, the Sanskrit Kātyāyanaḥsūtra states that though the world "relies on a duality of existence and non-existence", the Buddha teaches a correct view which understands that:[13]

Arising in the world, Kātyayana, seen and correctly understood just as it is, shows there is no non-existence in the world. Cessation in the world, Kātyayana, seen and correctly understood just as it is, shows there is no permanent existence in the world. Thus avoiding both extremes the Tathāgata teaches a dharma by the middle path (madhyamayā pratipadā). That is: this being, that becomes; with the arising of this, that arises. With ignorance as condition there is volition ... [to be expanded with the standard formula of the 12 links of dependent origination][14]

Though all Buddhist schools saw themselves as defending a middle path in accord with the Buddhist teachings, the name madhyamaka refers to a school of Mahayana philosophy associated with Nāgārjuna and his commentators. The term mādhyamika refers to adherents of the madhyamaka school.

Note that in both words the stress is on the first syllable.

Philosophical overview[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhist philosophy |

|---|

|

Svabhāva, what madhyamaka denies[edit]

Central to madhyamaka philosophy is śūnyatā, "emptiness", and this refers to the central idea that dharmas are empty of svabhāva.[15] This term has been translated variously as essence, intrinsic nature, inherent existence, own being and substance.[16][17][15] Furthermore, according to Richard P. Hayes, svabhava can be interpreted as either "identity" or as "causal independence".[18] Likewise, Westerhoff notes that svabhāva is a complex concept that has ontological and cognitive aspects. The ontological aspects include svabhāva as essence, as a property which makes an object what it is, as well as svabhāva as substance, meaning, as the madhyamaka thinker Candrakirti defines it, something that does "not depend on anything else".[15]

It is substance-svabhāva, the objective and independent existence of any object or concept, which madhyamaka arguments mostly focus on refuting.[19] A common structure which madhyamaka uses to negate svabhāva is the catuṣkoṭi ("four corners" or tetralemma), which roughly consists of four alternatives: a proposition is true; a proposition is false; a proposition is both true and false; a proposition is neither true nor false. Some of the major topics discussed by classical madhyamaka include causality, change, and personal identity.[20]

Madhyamaka's denial of svabhāva does not mean a nihilistic denial of all things, for in a conventional everyday sense, madhyamaka does accept that one can speak of "things", and yet ultimately these things are empty of inherent existence.[21] Furthermore, "emptiness" itself is also "empty": it does not have an existence on its own, nor does it refer to a transcendental reality beyond or above phenomenal reality.[10][11][12]

Svabhāva's cognitive aspect is merely a superimposition (samāropa) that beings make when they perceive and conceive of things. In this sense then, emptiness does not exist as some kind of primordial reality, but it is simply a corrective to a mistaken conception of how things exist.[17] This idea of svabhāva that madhyamaka denies is then not just a conceptual philosophical theory, but it is a cognitive distortion that beings automatically impose on the world, such as when we regard the five aggregates as constituting a single self. Candrakirti compares it to someone who suffers from vitreous floaters that cause the illusion of hairs appearing in their visual field.[22] This cognitive dimension of svabhāva means that just understanding and assenting to madhyamaka reasoning is not enough to end the suffering caused by our reification of the world, just like understanding how an optical illusion works does not make it stop functioning. What is required is a kind of cognitive shift (termed realization) in the way the world appears and therefore some kind of practice to lead to this shift.[23] As Candrakirti says:

For one on the road of cyclic existence who pursues an inverted view due to ignorance, a mistaken object such as the superimposition (samāropa) on the aggregates appears as real, but it does not appear to one who is close to the view of the real nature of things.[24]

Much of madhyamaka philosophy centers on showing how various essentialist ideas have absurd conclusions through reductio ad absurdum arguments (known as prasanga in Sanskrit). Chapter 15 of Nāgārjuna's Mūlamadhyamakakārikā centers on the words svabhava[note 1] parabhava[note 2] bhava[note 3] and abhava.[note 4] According to Peter Harvey:

Nagarjuna's critique of the notion of own-nature[note 5] (Mk. ch. 15) argues that anything which arises according to conditions, as all phenomena do, can have no inherent nature, for what is depends on what conditions it. Moreover, if there is nothing with own-nature, there can be nothing with 'other-nature' (para-bhava), i.e. something which is dependent for its existence and nature on something else which has own-nature. Furthermore, if there is neither own-nature nor other-nature, there cannot be anything with a true, substantial existent nature (bhava). If there is no true existent, then there can be no non-existent (abhava).[30]

An important element of madhyamaka refutation is that the classical Buddhist doctrine of dependent arising (the idea that every phenomena is dependent on other phenomena) cannot be reconciled with "a conception of self-nature or substance" and that therefore essence theories are contrary not only to the Buddhist scriptures but to the very ideas of causality and change.[31] Any enduring essential nature would prevent any causal interaction, or any kind of origination. For things would simply always have been, and will always continue to be, without any change.[32][note 6] As Nāgārjuna writes in the MMK:

We state that conditioned origination is emptiness. It is mere designation depending on something, and it is the middle path. (24.18)Since nothing has arisen without depending on something, there is nothing that is not empty. (24.19)[33][better source needed]

The two truths[edit]

Beginning with Nāgārjuna, madhyamaka discerns two levels of truth, conventional truth (everyday commonsense reality) and ultimate truth (emptiness).[10][34] Ultimately, madhyamaka argues that all phenomena are empty of svabhava and only exist in dependence on other causes, conditions and concepts. Conventionally, madhyamaka holds that beings do perceive concrete objects which they are aware of empirically.[35] In madhyamaka this phenomenal world is the limited truth – saṃvṛti satya, which means "to cover", "to conceal", or "obscure". (and thus it is a kind of ignorance)[36][37] Saṃvṛti is also said to mean "conventional", as in a customary, norm based, agreed upon truth (like linguistic conventions) and it is also glossed as vyavahāra-satya (transactional truth).[37] Finally, Chandrakirti also has a third explanation of saṃvṛti, which is "mutual dependence" (parasparasaṃbhavana).[37]

This seeming reality does not really exist as the highest truth realized by wisdom which is paramartha satya (parama is literally "supreme or ultimate", and artha means "object, purpose, or actuality"), and yet it has a kind of conventional reality which has its uses for reaching liberation.[38] This limited truth includes everything, including the Buddha himself, the teachings (dharma), liberation and even Nāgārjuna's own arguments.[39][better source needed] This two truth schema which did not deny the importance of convention allowed Nāgārjuna to defend himself against charges of nihilism; understanding both correctly meant seeing the middle way:

"Without relying upon convention, the ultimate fruit is not taught. Without understanding the ultimate, nirvana is not attained."[note 7]

The limited, perceived reality is an experiential reality or a nominal reality which beings impute on the ultimate reality. It is not an ontological reality with substantial or independent existence.[35][34] Hence, the two truths are not two metaphysical realities; instead, according to Karl Brunnholzl, "the two realities refer to just what is experienced by two different types of beings with different types and scopes of perception".[41] As Candrakirti says:

It is through the perfect and the false seeing of all entities

That the entities that are thus found bear two natures.

The object of perfect seeing is true reality,

And false seeing is seeming reality.

This means that the distinction between the two truths is primarily epistemological and dependent on the cognition of the observer, not ontological.[41] As Shantideva writes, there are "two kinds of world", "the one of yogins and the one of common people".[42] The seeming reality is the world of samsara because conceiving of concrete and unchanging objects leads to clinging and suffering. As Buddhapalita states: "unskilled persons whose eye of intelligence is obscured by the darkness of delusion conceive of an essence of things and then generate attachment and hostility with regard to them".[43]

According to Hayes, the two truths may also refer to two different goals in life: the highest goal of nirvana, and the lower goal of "commercial good". The highest goal is the liberation from attachment, both material and intellectual.[44]

The nature of ultimate reality[edit]

According to Paul Williams, Nāgārjuna associates emptiness with the ultimate truth but his conception of emptiness is not some kind of Absolute, but rather it is the very absence of true existence with regards to the conventional reality of things and events in the world.[45] Because the ultimate is itself empty, it is also explained as a "transcendence of deception" and hence is a kind of apophatic truth which experiences the lack of substance.[3]

Because the nature of ultimate reality is said to be empty, empty even of "emptiness" itself, both the concept of "emptiness" and the very framework of the two truths are also mere conventional realities, not part of the ultimate. This is often called "the emptiness of emptiness" and refers to the fact that even though madhyamikas speak of emptiness as the ultimate unconditioned nature of things, this emptiness is itself empty of any real existence.[46]

The two truths themselves are therefore just a practical tool used to teach others, but do not exist within the actual meditative equipoise that realizes the ultimate.[47] As Candrakirti says: "the noble ones who have accomplished what is to be accomplished do not see anything that is delusive or not delusive".[48] From within the experience of the enlightened ones there is only one reality which appears non-conceptually, as Nāgārjuna says in the Sixty stanzas on reasoning: "that nirvana is the sole reality, is what the Victors have declared."[49] Bhāvaviveka's Madhyamakahrdayakārikā describes the ultimate truth through a negation of all four possibilities of the catuskoti:[50]

Its character is neither existent, nor nonexistent, / Nor both existent and nonexistent, nor neither. / Centrists should know true reality / That is free from these four possibilities.

Atisha describes the ultimate as "here, there is no seeing and no seer, no beginning and no end, just peace.... It is nonconceptual and nonreferential ... it is inexpressible, unobservable, unchanging, and unconditioned."[51] Because of the non-conceptual nature of the ultimate, according to Brunnholzl, the two truths are ultimately inexpressible as either "one" or "different".[52]

The Middle Way[edit]

As noted by Roger Jackson, some non-Buddhist writers, like some Buddhist writers both ancient and modern, have argued that the madhyamaka philosophy is nihilistic. This claim has been challenged by others who argue that it is a Middle Way (madhyamāpratipad) between nihilism and eternalism.[53][54][55] Madhyamaka philosophers themselves explicitly rejected the nihilist interpretation from the outset: Nāgārjuna writes: "through explaining true reality as it is, the seeming samvrti does not become disrupted."[56] Candrakirti also responds to the charge of nihilism in his Lucid Words:

Therefore, emptiness is taught in order to completely pacify all discursiveness without exception. So if the purpose of emptiness is the complete peace of all discursiveness and you just increase the web of discursiveness by thinking that the meaning of emptiness is nonexistence, you do not realize the purpose of emptiness [at all].[57]

This although some scholars (e.g., Murti) interpret emptiness as described by Nāgārjuna as a Buddhist transcendental absolute, other scholars (such as David Kalupahana) consider this claim a mistake, since then emptiness teachings could not be characterized as a middle way.[58][59]

Madhyamaka thinkers also argue that since things have the nature of lacking true existence or own being (niḥsvabhāva), all things are mere conceptual constructs (prajñaptimatra) because they are just impermanent collections of causes and conditions.[60] This also applies to the principle of causality itself, since everything is dependently originated.[61] Therefore, in madhyamaka, phenomena appear to arise and cease, but in an ultimate sense they do not arise or remain as inherently existent phenomena.[62][63][note 8] This tenet is held to show that views of absolute or eternalist existence (such as the Hindu ideas of Brahman or sat-dravya) and nihilism are both equally untenable.[62][64][21] These two views are considered to be the two extremes that madhyamaka steers clear from. The first is essentialism[65] or eternalism (sastavadava)[21] – a belief that things inherently or substantially exist and are therefore efficacious objects of craving and clinging;[65] Nagarjuna argues that we naively and innately perceive things as substantial, and it is this predisposition which is the root delusion that lies at the basis of all suffering.[65] The second extreme is nihilism[65] or annihilationism (ucchedavada)[21] – encompassing views that could lead one to believe that there is no need to be responsible for one's actions – such as the idea that one is annihilated at death or that nothing has causal effects – but also the view that absolutely nothing exists.

The usefulness of reason[edit]

In madhyamaka, reason and debate are understood as a means to an end (liberation), and therefore they must be founded on the wish to help oneself and others end suffering.[66] Reason and logical arguments, however (such as those employed by classical Indian philosophers, i.e., pramana), are also seen as being empty of any true validity or reality. They serve only as conventional remedies for our delusions.[67] Nāgārjuna's Vigrahavyāvartanī famously attacked the notion that one could establish a valid cognition or epistemic proof (pramana):

If your objects are well established through valid cognitions, tell us how you establish these valid cognitions. If you think they are established through other valid cognitions, there is an infinite regress. Then, the first one is not established, nor are the middle ones, nor the last. If these [valid cognitions] are established even without valid cognition, what you say is ruined. In that case, there is an inconsistency, And you ought to provide an argument for this distinction.[68]

Candrakirti comments on this statement by stating that madhyamaka does not completely deny the use of pramanas conventionally, and yet ultimately they do not have a foundation:

Therefore we assert that mundane objects are known through the four kinds of authoritative cognition. They are mutually dependent: when there is authoritative cognition, there are objects of knowledge; when there are objects of knowledge, there is authoritative cognition. But neither authoritative cognition nor objects of knowledge exist inherently.[69]

To the charge that if Nāgārjuna's arguments and words are also empty they therefore lack the power to refute anything, Nāgārjuna responds that:

My words are without nature. Therefore, my thesis is not ruined. Since there is no inconsistency, I do not have to state an argument for a distinction.[70]

Nāgārjuna goes on:

Just as one magical creation may be annihilated by another magical creation, and one illusory person by another person produced by an illusionist, this negation is the same.[71]

Shantideva makes the same point: "thus, when one's son dies in a dream, the conception "he does not exist" removes the thought that he does exist, but it is also delusive".[72] In other words, madhyamaka thinkers accept that their arguments, just like all things, are not ultimately valid in some foundational sense. But one is still able to use the opponent's own reasoning apparatus in the conventional field to refute their theories and help them see their errors. This remedial deconstruction does not replace false theories of existence with other ones, but simply dissolves all views, including the very fictional system of epistemic warrants (pramanas) used to establish them.[73] The point of madhyamaka reasoning is not to establish any abstract validity or universal truth, it is simply a pragmatic project aimed at ending delusion and suffering.[74]

Nāgārjuna also argues that madhyamaka only negates things conventionally, since ultimately, there is nothing there to negate: "I do not negate anything and there is also nothing to be negated."[75] Therefore, it is only from the perspective of those who cling to the existence of things that it seems as if something is being negated. In truth, madhyamaka is not annihilating something, merely elucidating that this so-called existence never existed in the first place.[75]

Thus, madhyamaka uses language to make clear the limits of our concepts. Ultimately, reality cannot be depicted by concepts.[10][76] According to Jay Garfield, this creates a sort of tension in madhyamaka literature, since it has use some concepts to convey its teachings.[76]

Soteriology[edit]

For madhyamaka, the realization of emptiness is not just a satisfactory theory about the world, but a key understanding which allows one to reach liberation or nirvana. As Nāgārjuna's Mūlamadhyamakakārikā ("Root Verses on the Middle Way") puts it:

With the cessation of ignorance, formations will not arise. Moreover, the cessation of ignorance occurs through right understanding. Through the cessation of this and that, this and that will not come about. The entire mass of suffering thereby completely ceases.[77]

The words "this" and "that" allude to the mind's profound addiction to dualism, but also and more specifically to the mind that has not yet grasped the reality of dependent origination. The insight of dependent origination – that nothing arises or happens independently, that everything is rooted in or "made of" something else, and conditioned by other things, each of which are likewise made of and conditioned by other things in the same way, so that nothing at all "is" independently – is central to the fundamental Buddhist analysis of the arising of suffering and the liberation from it. Therefore, according to Nāgārjuna, the cognitive shift which sees the nonexistence of svabhāva leads to the cessation of the first link in this chain of suffering, which then leads to the ending of the entire chain of causes and thus, of all suffering.[77] Nāgārjuna adds:

Liberation (moksa) results from the cessation of actions (karman) and defilements (klesa). Actions and defilements result from representations (vikalpa). These [come] from false imagining (prapañca). False imagining stops in emptiness (sunyata). (18.5)[78][better source needed]

Therefore, the ultimate aim of understanding emptiness is not philosophical insight as such, but the actualization of a liberated mind which does not cling to anything. To encourage this awakening, meditation on emptiness may proceed in stages, starting with the emptiness of self, of objects and of mental states,[79] culminating in a "natural state of nonreferential freedom".[80][note 9]

Moreover, the path to understanding ultimate truth is not one that negates or invalidates relative truths (especially truths about the path to awakening). Instead it is only through properly understanding and using relative truth that the ultimate can be attained, as Bhāvaviveka maintains:

In order to guide beginners a method is taught, comparable to the steps of a staircase that leads to perfect Buddhahood. Ultimate reality is only to be entered once we have understood seeming reality.[81]

Does madhyamaka have a position?[edit]

Nāgārjuna is famous for arguing that his philosophy was not a view, and that he in fact did not take any position (paksa) or thesis (pratijña) whatsoever since this would just be another form of clinging to some form of existence.[82][69] In his Vigrahavyāvartanī , Nāgārjuna states:

If I had any position, I thereby would be at fault. Since I have no position, I am not at fault at all. If there were anything to be observed through direct perception and the other instances [of valid cognition], it would be something to be established or rejected. However, since no such thing exists, I cannot be criticized.[83]

Likewise in his Sixty Stanzas on Reasoning, Nāgārjuna says: "By taking any standpoint whatsoever, you will be snatched by the cunning snakes of the afflictions. Those whose minds have no standpoint will not be caught."[84]

Randall Collins argues that for Nāgārjuna, ultimate reality is simply the idea that "no concepts are intelligible", while Ferrer emphasizes that Nāgārjuna criticized those whose mind held any "positions and beliefs", including the view of emptiness. As Nāgārjuna says: "The Victorious Ones have announced that emptiness is the relinquishing of all views. Those who are possessed of the view of emptiness are said to be incorrigible."[85][86] Aryadeva echoes this idea in his Four Hundred Verses:

"First, one puts an end to what is not meritorious. In the middle, one puts an end to identity. Later, one puts an end to all views. Those who understand this are skilled."[87]

Other writers, however, do seem to affirm emptiness as a specific madhyamaka thesis or view. Shantideva for example says "one cannot uphold any faultfinding in the thesis of emptiness" and Bhavaviveka's Blaze of Reasoning says: "as for our thesis, it is the emptiness of nature, because this is the nature of phenomena".[88] Jay Garfield notes that Nāgārjuna and Candrakirti both make positive arguments, and cites both the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā ("Root Verses on the Middle Way") – "There does not exist anything that is not dependently arisen. Therefore there does not exist anything that is not empty" – and Candrakirti's commentary on it: "We assert the statement, 'Emptiness itself is a designation.'"[69]

These positions are not really in contradiction, however, since madhyamaka can be said to have the "thesis of emptiness" only conventionally, in the context of debating or explaining it. According to Karl Brunnholzl, even though madhyamaka thinkers may express a thesis pedagogically, what they deny is that "they have any thesis that involves real existence or reference points, or any thesis that is to be defended from their own point of view".[89]

Brunnholzl underlines that madhyamaka analysis applies to all systems of thought, ideas and concepts, including madhyamaka itself. This is because the nature of madhyamaka is "the deconstruction of any system and conceptualization whatsoever, including itself".[90] In the Root verses on the Middle Way, Nāgārjuna illustrates this point:

By the flaw of having views about emptiness, those of little understanding are ruined, just as when incorrectly seizing a snake or mistakenly practicing an awareness-mantra.[91]

Origins and sources[edit]

The madhyamaka school is usually considered to have been founded by Nāgārjuna, though it may have existed earlier.[92] Various scholars have noted that some of themes in the work of Nāgārjuna can also be found in earlier Buddhist sources.

Early Buddhist Texts[edit]

It is well known that the only sutra that Nāgārjuna explicitly cites in his Mūlamadhyamakakārikā (Chapter 15.7) is the "Advice to Kātyāyana". He writes, "according to the Instructions to Kātyāyana, both existence and nonexistence are criticized by the Blessed One who opposed being and non-being."[93] This appears to have been a Sanskrit version of the Kaccānagotta Sutta (Saṃyutta Nikāya ii.16–17 / SN 12.15, with parallel in the Chinese Saṃyuktāgama 301).[93] The Kaccānagotta Sutta itself says:

This world, Kaccāna, for the most part depends on a duality – upon the notion of existence and the notion of nonexistence. But for one who sees the origin of the world as it really is with correct wisdom, there is no notion of nonexistence in regard to the world. And for one who sees the cessation of the world as it really is with correct wisdom, there is no notion of existence in regard to the world.[93]

Joseph Walser also points out that verse six of chapter 15 contains an allusion to the "Mahahatthipadopama sutta", another early sutra of the Nidanavagga, the collection which also contains the Kaccānagotta, and which contains various sutras that focus on the avoidance of extreme views, which are all held to be associated with either the extreme of eternality (sasvata) or the extreme of disruption (uccheda).[93] Another allusion to an early Buddhist text noted by Walser occurs in Nāgārjuna's Ratnavali chapter 1, where he makes reference to a statement in the Kevaddha sutta.[94]

Some scholars, like Tillman Vetter and Luis Gomez, have also seen some passages from the early Aṭṭhakavagga (Pali, "Octet Chapter") and the Pārāyanavagga (Pali, "Way to the Far Shore Chapter"), which focusing on letting go of all views, as teaching a kind of "Proto-Mādhyamika."[note 10][95][96] Other scholars such as Paul Fuller and Alexander Wynne have rejected the arguments of Gomez and Vetter.[97][98][note 11]

Finally, the Dazhidulun, a text attributed to Nāgārjuna in the Chinese tradition (though this attribution has been questioned), cites the Sanskrit Arthavargīya sūtra (which parallels the Aṭṭhakavagga) in its discussion of ultimate truth.[99]

Abhidharma and early Buddhist schools[edit]

The madhyamaka school has been perhaps simplistically regarded as a reaction against the development of Buddhist abhidharma, however according to Joseph Walser, this is problematic.[100] In abhidharma, dharmas are characterized by defining traits (lakṣaṇa) or own-existence (svabhāva). The Abhidharmakośabhāṣya states for example: "dharma means 'upholding,' [namely], upholding intrinsic nature (svabhāva)", while the Mahāvibhāṣā states "intrinsic nature is able to uphold its own identity and not lose it".[101] However this does not mean that all abhidharma systems hold that dharmas exist independently in an ontological sense, since all Buddhist schools hold that (most) dharmas are dependently originated, this doctrine being a central core Buddhist view. Therefore, in abhidharma, svabhāva is typically something which arises dependent on other conditions and qualities.[101]

Svabhāva in the early abhidharma systems then, is not a kind of ontological essentialism, but it is a way to categorize dharmas according to their distinctive characteristics. According to Noa Ronkin, the idea of svabhava evolved towards ontological dimension in the Sarvāstivādin Vaibhasika school's interpretation, which began to also use the term dravya which means "real existence".[101] This then, may have been the shift which Nagarjuna sought to attack when he targets certain Sarvastivada tenets.

However, the relationship between madhyamaka and abhidharma is complex, as Joseph Walser notes, "Nagarjuna's position vis-à-vis abhidharma is neither a blanket denial nor a blanket acceptance. Nagarjuna's arguments entertain certain abhidharmic standpoints while refuting others."[100] One example can be seen in Nagarjuna's Ratnavali which supports the study of a list of 57 moral faults which Nagarjuna takes from the Ksudravastuka (an abhidharma texts that is part of the Sarvastivada Dharmaskandha).[102] Abhidharmic analysis figures prominently in madhyamaka treatises, and authoritative commentators like Candrakīrti emphasize that abhidharmic categories function as a viable (and favored) system of conventional truths – they are more refined than ordinary categories, and they are not dependent on either the extreme of eternalism or on the extreme view of the discontinuity of karma, as the non-Buddhist categories of the time did.

Walser also notes that Nagarjuna's theories have much in common with the view of a sub-sect of the Mahasamgikas called the Prajñaptivadins, who held that suffering was prajñapti (designation by provisional naming) "based on conditioned entities that are themselves reciprocally designated" (anyonya prajñapti).[103] David Burton argues that for Nagarjuna, "dependently arisen entities have merely conceptually constructed existence (prajñaptisat)".[103] Commenting on this, Walser writes that "Nagarjuna is arguing for a thesis that the Prajñaptivádins already held, using a concept of prajñapti that they were already using."[57]

Mahāyāna sūtras[edit]

According to David Seyfort Ruegg, the main canonical Mahāyāna sutra sources of the Madhyamaka school are the Prajñāpāramitā, Ratnakūṭa and Avataṃsaka literature.[104] Other sutras which were widely cited by Madhamikas include the Vimalakīrtinirdeṣa, the Śuraṃgamasamādhi, the Saddharmapuṇḍarīka, the Daśabhūmika, the Akṣayamatinirdeśa, the Tathāgataguhyaka, and the Kāśyapaparivarta.[104]

Ruegg notes that in Candrakīrti's Prasannapadā and Madhyamakāvatāra, in addition to the Prajñāpāramitā, "we find the Akṣayamatinirdeśa, Anavataptahradāpasaṃkramaṇa, Upāliparipṛcchā, Kāśyapaparivarta, Gaganagañja, Tathāgataguhya, Daśabhūmika, Dṛḍhādhyāśaya, Dhāraṇīśvararāja, Pitāputrasamāgama, Mañjuśrīparipṛcchā, Ratnakūṭa, Ratnacūḍaparipṛcchā, Ratnamegha, Ratnākara, Laṅkāvatāra, Lalitavistara, Vimalakirtinirdesa, Śālistamba, Satyadvayāvatāra, Saddharmapuṇḍarīka, Samādhirāja (Candrapradīpa), and Hastikakṣya."[104]

Prajñāpāramitā[edit]

Madhyamaka thought is also closely related to a number of Mahāyāna sources; traditionally, the Prajñāpāramitā sūtras are the literature most closely associated with madhyamaka – understood, at least in part, as an exegetical complement to those Sūtras. Traditional accounts also depict Nāgārjuna as retrieving some of the larger Prajñāpāramitā sūtras from the world of the Nāgas (explaining in part the etymology of his name). Prajñā or 'higher cognition' is a recurrent term in Buddhist texts, explained as a synonym of abhidharma, 'insight' (vipaśyanā) and 'analysis of the dharmas' (dharmapravicaya). Within a specifically Mahāyāna context, Prajñā figures as the most prominent in a list of Six Pāramitās ('perfections' or 'perfect masteries') that a Bodhisattva needs to cultivate in order to eventually achieve Buddhahood.

Madhyamaka offers conceptual tools to analyze all possible elements of existence, allowing the practitioner to elicit through reasoning and contemplation the type of view that the Sūtras express more authoritatively (being considered word of the Buddha) but less explicitly (not offering corroborative arguments). The vast Prajñāpāramitā literature emphasizes the development of higher cognition in the context of the Bodhisattva path; thematically, its focus on the emptiness of all dharmas is closely related to the madhyamaka approach. Allusions to the prajñaparamita sutras can be found in Nagarjuna's work. One example is in the opening stanza of the MMK, which seem to allude to the following statement found in two prajñaparamita texts:

And how does he wisely know conditioned co-production? He wisely knows it as neither production, nor stopping, neither cut off nor eternal, neither single nor manifold, neither coming nor going away, as the appeasement of all futile discoursings, and as bliss.[105]

The first stanza of Nagarjuna's MMK meanwhile, state:

I pay homage to the Fully Enlightened One whose true, venerable words teach dependent-origination to be the blissful pacification of all mental proliferation, neither production, nor stopping, neither cut off nor eternal, neither single nor manifold, neither coming, nor going away.[105]

Pyrrhonism[edit]

Because of the high degree of similarity between madhyamaka and Pyrrhonism,[106] Thomas McEvilley[107] and Matthew Neale[108][109] suspect that Nāgārjuna was influenced by Greek Pyrrhonist texts imported into India. Pyrrho of Elis (c. 360 – c. 270 BCE), who is credited with founding this school of skeptical philosophy, was himself influenced by Buddhist philosophy[110] during his stay in India with Alexander the Great's army.

Indian madhyamaka[edit]

Nāgārjuna[edit]

As Jan Westerhoff notes, while Nāgārjuna is "one of the greatest thinkers in the history of Asian philosophy...contemporary scholars agree on hardly any details concerning him". This includes exactly when he lived (it can be narrowed down some time in the first three centuries CE), where he lived (Joseph Walser suggests Amarāvatī in east Deccan) and exactly what constitutes his written corpus.[111]

Numerous texts are attributed to him, but it is at least agreed by some scholars that what is called the "Yukti" (analytical) corpus is the core of his philosophical work. These texts are the "Root verses on the Middle way" (Mūlamadhyamakakārikā, MMK), the "Sixty Stanzas on Reasoning" (Yuktiṣāṣṭika), the "Dispeller of Objections" (Vigrahavyāvartanī), the "Treatise on Pulverization" (Vaidalyaprakaraṇa) and the "Precious Garland" (Ratnāvalī).[112] However, even the attribution of each one of these has been question by some modern scholars, except for the MMK which is by definition seen as his major work.[112]

Nāgārjuna's main goal is often seen by scholars as refuting the essentialism of certain Buddhist abhidharma schools (mainly Vaibhasika) which posited theories of svabhava (essential nature) and also the Hindu Nyāya and Vaiśeṣika schools which posited a theory of ontological substances (dravyatas).[113] In the MMK he used reductio ad absurdum arguments (prasanga) to show that any theory of substance or essence was unsustainable and therefore, phenomena (dharmas) such as change, causality, and sense perception were empty (sunya) of any essential existence. Nāgārjuna also famously equated the emptiness of dharmas with their dependent origination.[114][115][116][note 12]

Because of his philosophical work, Nāgārjuna is seen by some modern interpreters as restoring the Middle Way of the Buddha, which had become challenged by absolutist metaphysical tendencies in certain philosophical quarters.[117][114]

Classical madhyamaka figures[edit]

Rāhulabhadra was an early madhyamika, sometimes said to be either a teacher of Nagarjuna or his contemporary and follower. He is most famous for his verses in praise of the Prajñāpāramitā (Skt. Prajñāpāramitāstotra) and Chinese sources maintain that he also composed a commentary on the MMK which was translated by Paramartha.[118]

Nāgārjuna's pupil Āryadeva (3rd century CE) wrote various works on madhyamaka, the most well known of which is his "400 verses". His works are regarded as a supplement to Nāgārjuna's,[119] on which he commented.[120] Āryadeva also wrote refutations of the theories of non-Buddhist Indian philosophical schools.[120]

There are also two commentaries on the MMK which may be by Āryadeva, the Akutobhaya (which has also been regarded as an auto-commentary by Nagarjuna) as well as a commentary which survives only in Chinese (as part of the Chung-Lun, "Middle treatise", Taisho 1564) attributed to a certain "Ch'ing-mu" (aka Pin-lo-chieh, which some scholars have also identified as possibly being Aryadeva).[121] However, Brian C. Bocking, a translator of the Chung-Lung, also states that it is likely the author of this commentary was a certain Vimalāksa, who was Kumarajiva's old Vinaya-master from Kucha.[122]

An influential commentator on Nāgārjuna was Buddhapālita (470–550) who has been interpreted as developing the prāsaṅgika approach to Nāgārjuna's works in his Madhyamakavṛtti (now only extant in Tibetan) which follows the orthodox Madhyamaka method by critiquing essentialism mainly through reductio ad absurdum arguments.[123] Like Nāgārjuna, Buddhapālita's main philosophical method is to show how all philosophical positions are ultimately untenable and self-contradictory, a style of argumentation called prasanga.[123]

Buddhapālita's method is often contrasted with that of Bhāvaviveka (c. 500 – c. 578), who argued in his Prajñāpadīpa (Lamp of Wisdom) for the use of logical arguments using the pramana based epistemology of Indian logicians like Dignāga. In what would become a source of much future debate, Bhāvaviveka criticized Buddhapālita for not putting madhyamaka arguments into proper "autonomous syllogisms" (svatantra).[124] Bhāvaviveka argued that mādhyamika's should always put forth syllogistic arguments to prove the truth of the madhyamaka thesis. Instead of just criticizing other's arguments, a tactic called vitaṇḍā (attacking) which was seen in bad form in Indian philosophical circles, Bhāvaviveka held that madhyamikas must positively prove their position using sources of knowledge (pramanas) agreeable to all parties.[125] He argued that the position of a madhyamaka was simply that phenomena are devoid of an inherent nature.[123] This approach has been labeled the svātantrika style of madhyamaka by Tibetan philosophers and commentators.

Another influential commentator, Candrakīrti (c. 600–650), sought to defend Buddhapālita and critique Bhāvaviveka's position (and Dignāga) that one must construct independent (svatantra) arguments to positively prove the madhyamaka thesis, on the grounds this contains a subtle essentialist commitment.[123] He argued that madhyamikas do not have to argue by svantantra, but can merely show the untenable consequences (prasaṅga) of all philosophical positions put forth by their adversary.[126] Furthermore, for Candrakīrti, there is a problem with assuming that the madhyamika and the essentialist opponent can begin with the same shared premises that are required for this kind of syllogistic reasoning because the essentialist and the madhyamaka do not share a basic understanding of what it means for things to exist in the first place.[127]

Candrakīrti also criticized the Buddhist yogācāra school, which he saw as positing a form of subjective idealism due to their doctrine of "appearance only" (vijñaptimatra). Candrakīrti faults the yogācāra school for not realizing that the nature of consciousness is also a conditioned phenomenon, and for privileging consciousness over its objects ontologically, instead of seeing that everything is empty.[126] Candrakīrti wrote the Prasannapadā (Clear Words), a highly influential commentary on the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā as well as the Madhyamakāvatāra, an introduction to madhyamaka. His works are central to the understanding of madhyamaka in Tibetan Buddhism.

A later svātantrika figure is Avalokitavrata (seventh century), who composed a tika (sub-commentary) on Bhāvaviveka's Prajñāpadīpa and who mentions important figures of the era such as Dharmakirti and Candrakīrti.[128]

Another commentator on Nagarjuna is Bhikshu Vaśitva (Zizai) who composed a commentary on Nagarjuna's Bodhisaṃbhāra that survives in a translation by Dharmagupta in the Chinese canon.[129]

Śāntideva (end 7th century – first half 8th century) is well known for his philosophical poem discussing the bodhisattva path and the six paramitas, the Bodhicaryāvatāra. He united "a deep religiousness and joy of exposure together with the unquestioned Madhyamaka orthodoxy".[130] Later in the 10th century, there were commentators on the works of prasangika authors such as Prajñakaramati who wrote a commentary on the Bodhicaryāvatāra and Jayananda who commented on Candrakīrti's Madhyamakāvatāra.[131]

A lesser known treatise on the six paramitas associated with the madhyamaka school is Ārya Śūra's Pāramitāsamāsa, unlikely to be the same author as that of the Garland of Jatakas.[132]

Other lesser known madhyamikas include Devasarman (fifth to sixth centuries) and Gunamati (the fifth to sixth centuries) both of whom wrote commentaries on the MMK that exist only in Tibetan fragments.[133]

Yogācāra-madhyamaka[edit]

According to Ruegg, possibly the earliest figure to work with the two schools was Vimuktisena (early sixth century), a commentator on the Abhisamayalamkara and also is reported to have been a pupil of Bhāvaviveka as well as Vasubandhu.[134]

The seventh and eighth centuries saw a synthesis of the Buddhist yogācāra tradition with madhyamaka, beginning with the work of Śrigupta, Jñānagarbha (Śrigupta's disciple) and his student Śāntarakṣita (8th-century) who, like Bhāvaviveka, also adopted some of the terminology of the Buddhist pramana tradition, in their time best represented by Dharmakīrti.[123][128]

Like the classical madhyamaka, yogācāra-madhyamaka approaches ultimate truth through the prasaṅga method of showing absurd consequences. However, when speaking of conventional reality they also make positive assertions and autonomous arguments like Bhāvaviveka and Dharmakīrti. Śāntarakṣita also subsumed the yogācāra system into his presentation of the conventional, accepting their idealism on a conventional level as a preparation for the ultimate truth of madhyamaka.[123][135]

In his Madhyamakālaṃkāra (verses 92–93), Śāntarakṣita says:

By relying on the Mind Only (cittamatra), know that external entities do not exist. And by relying on this [madhyamaka] system, know that no self at all exists, even in that [mind]. Therefore, due to holding the reins of logic as one rides the chariots of the two systems, one attains [the path of] the actual Mahayanist.[136]

Śāntarakṣita and his student Kamalaśīla (known for his text on self development and meditation, the Bhavanakrama) were influential in the initial spread of madhyamaka Buddhism to Tibet.[note 13] Haribhadra, another important figure of this school, wrote an influential commentary on the Abhisamayalamkara.

Vajrayana madhyamaka[edit]

The madhyamaka philosophy continued to be of major importance during the period of Indian Buddhism when the tantric Vajrayana Buddhism rose to prominence. One of the central Vajrayana madhyamaka philosophers was Arya Nagarjuna (also known as the "tantric Nagarjuna", 7th–8th centuries) who may be the author of the Bodhicittavivarana as well as a commentator on the Guhyasamāja Tantra.[137] Other figures in his lineage include Nagabodhi, Vajrabodhi, Aryadeva-pada and Candrakirti-pada.

Later figures include Bodhibhadra (c. 1000), a Nalanda university master who wrote on philosophy and yoga and who was a teacher of Atiśa Dīpaṃkara Śrījñāna (982 – 1054 CE) who was an influential figure in the transmission of Buddhism to Tibet and wrote the influential Bodhipathapradīpa (Lamp for the Path to Awakening).[138]

Tibetan Buddhism[edit]

Madhyamaka philosophy obtained a central position in all the main Tibetan Buddhist schools, all whom consider themselves to be madhyamikas. Madhyamaka thought has been categorized in various ways in India and Tibet.[note 14]

Early transmission[edit]

Influential early figures who are important in the transmission of madhyamaka to Tibet include the yogacara-madhyamika Śāntarakṣita (725–788), and his students Haribhadra and Kamalashila (740–795) as well as the later Kadampa figures of Atisha (982–1054) and his pupil Dromtön (1005–1064) who taught madhyamaka by using the works of Bhāviveka and Candrakīrti.[139][140]

The early transmission of Buddhism to Tibet saw these two main strands of philosophical views in debate with each other. The first was the camp which defended the yogacara-madhyamaka interpretation (and thus, svatantrika) centered on the works of the scholars of the Sangphu monastery founded by Ngog Loden Sherab (1059–1109) and also includes Chapa Chokyi Senge (1109–1169).[141]

The second camp was those who championed the work of Candrakirti over the yogacara-madhyamaka interpretation, and included Sangphu monk Patsab Nyima Drag (b. 1055) and Jayananda (fl 12th century).[141] According to John Dunne, it was the madhyamaka interpretation and the works of Candrakirti which became dominant over time in Tibet.[141]

Another very influential figure from this early period is Mabja Jangchub Tsöndrü (d. 1185), who wrote an important commentary on Nagarjuna's Mūlamadhyamakakārikā. Mabja was a student of both the Dharmakirtian Chapa and the Candrakirti scholar Patsab and his work shows an attempt to steer a middle course between their views. Mabja affirms the conventional usefulness of Buddhist pramāṇa, but also accepts Candrakirti's prasangika views.[142] Mabja's Madhyamaka scholarship was very influential on later Tibetan Madhyamikas such as Longchenpa, Tsongkhapa, Gorampa, and Mikyö Dorje.[142]

Prāsaṅgika and Svātantrika interpretations[edit]

In Tibetan Buddhist scholarship, a distinction began to be made between the Autonomist (Svātantrika, rang rgyud pa) and Consequentialist (Prāsaṅgika, Thal 'gyur pa) approaches to madhyamaka reasoning. The distinction was one invented by Tibetans, and not one made by classical Indian madhyamikas.[143] Tibetans mainly use the terms to refer to the logical procedures used by Bhavaviveka (who argued for the use of svatantra-anumana or autonomous syllogisms) and Buddhapalita (who held that one should only use prasanga, or reductio ad absurdum).[144] Tibetan Buddhism further divides svātantrika into sautrantika svātantrika madhyamaka (applied to Bhāviveka), and yogācāra svātantrika madhyamaka (śāntarakṣita and kamalaśīla).[145]

The svātantrika states that conventional phenomena are understood to have a conventional essential existence, but without an ultimately existing essence. In this way they believe they are able to make positive or "autonomous" assertions using syllogistic logic because they are able to share a subject that is established as appearing in common – the proponent and opponent use the same kind of valid cognition to establish it. The name comes from this quality of being able to use autonomous arguments in debate.[144]

In contrast, the central technique avowed by the prasaṅgika is to show by prasaṅga (or reductio ad absurdum) that any positive assertion (such as "asti" or "nāsti", "it is", or "it is not") or view regarding phenomena must be regarded as merely conventional (saṃvṛti or lokavyavahāra). The prāsaṅgika holds that it is not necessary for the proponent and opponent to use the same kind of valid cognition (pramana) to establish a common subject; indeed it is possible to change the view of an opponent through a reductio argument.

Although presented as a divide in doctrine, the major difference between svātantrika and prasangika may be between two style of reasoning and arguing, while the division itself is exclusively Tibetan. Tibetan scholars were aware of alternative madhyamaka sub-classifications, but later Tibetan doxography emphasizes the nomenclature of prāsaṅgika versus svātantrika. No conclusive evidence can show the existence of an Indian antecedent, and it is not certain to what degree individual writers in Indian and Tibetan discussion held each of these views and if they held a view generally or only in particular instances. Both Prāsaṅgikas and Svātantrikas cited material in the āgamas in support of their arguments.[146]

Longchen Rabjam noted in the 14th century that Candrakirti favored the prasaṅga approach when specifically discussing the analysis for ultimacy, but otherwise he made positive assertions such as when describing the paths of Buddhist practice in his Madhyamakavatāra. Therefore, even prāsaṅgikas make positive assertions when discussing conventional practice, they simply stick to using reductios specifically when analyzing for ultimate truth.[144]

Jonang and "other empty"[edit]

Further Tibetan philosophical developments began in response to the works of the scholar Dölpopa Shérap Gyeltsen (1292–1361) and led to two distinctly opposed Tibetan madhyamaka views on the nature of ultimate reality.[147][148] An important Tibetan treatise on Emptiness and Buddha Nature is found in Dolpopa's voluminous study, Mountain Doctrine.[149]

Dolpopa, the founder of the Jonang school, viewed the Buddha and Buddha Nature as not intrinsically empty, but as truly real, unconditioned, and replete with eternal, changeless virtues.[150] In the Jonang school, ultimate reality, i.e. Buddha Nature (tathagatagarbha) is only empty of what is impermanent and conditioned (conventional reality), not of its own self which is ultimate Buddhahood and the luminous nature of mind.[151] In Jonang, this ultimate reality is a "ground or substratum" which is "uncreated and indestructible, noncomposite and beyond the chain of dependent origination".[152]

Basing himself on the Indian Tathāgatagarbha sūtras as his main sources, Dolpopa described the Buddha Nature as:

[N]on-material emptiness, emptiness that is far from an annihilatory emptiness, great emptiness that is the ultimate pristine wisdom of superiors ...Buddha earlier than all Buddhas, ... causeless original Buddha.[153]

This "great emptiness" i.e. the tathāgatagarbha is said to be filled with eternal powers and virtues:

[P]ermanent, stable, eternal, everlasting. Not compounded by causes and conditions, the matrix-of-one-gone-thus is intrinsically endowed with ultimate buddha qualities of body, speech, and mind such as the ten powers; it is not something that did not exist before and is newly produced; it is self-arisen.'[154]

The Jonang position came to be known as [[Rangtong and shentong|"emptiness of other" (gzhan stong, shentong)]], because it held that the ultimate truth was positive reality that was not empty of its own nature, only empty of what it was other than itself.[155] Dolpopa considered his view a form of madhyamaka, and called his system "Great Madhyamaka".[156] Dolpopa opposed what he called rangtong (self-empty), the view that ultimate reality is that which is empty of self nature in a relative and absolute sense, that is to say that it is empty of everything, including itself. It is thus not a transcendental ground or metaphysical absolute which includes all the eternal Buddha qualities. This rangtong – shentong distinction became a central issue of contention among Tibetan Buddhist philosophers.

Alternative interpretations of the shentong view is also taught outside of Jonang. Some Kagyu figures, like Jamgon Kongtrul (1813–1899) as well as the unorthodox Sakya philosopher Sakya Chokden (1428–1507), supported their own forms of shentong.

Tsongkhapa and Gelug prāsaṅgika[edit]

The Gelug school was founded in the beginning of the 15th century by Je Tsongkhapa (1357–1419).[157] Tsongkhapa's conception of emptiness draws mainly from the works of "prāsaṅgika" Indian thinkers like Buddhapalita, Candrakirti, and Shantideva and he argued that only their interpretation of Nagarjuna was ultimately correct. According to José I. Cabezón, Tsongkhapa also argued that the ultimate truth or emptiness was "an absolute negation (med dgag)—the negation of inherent existence—and that nothing was exempt from being empty, including emptiness itself."[155]

Tsongkhapa also maintained that the ultimate truth could be understood conceptually, an understanding which could later be transformed into a non-conceptual one. This conceptual understanding could only be done through the use of madhyamika reasoning, which he also sought to unify with the logical theories of Dharmakirti.[155] Because of Tsongkhapa's view of emptiness as an absolute negation, he strongly attacked the other empty views of Dolpopa in his works. Tsongkhapa major work on madhyamaka is his commentary on the MMK called "Ocean of Reasoning".[158]

According to Thupten Jinpa, Tsongkhapa's "doctrine of the object of negation" is one of his most innovative but also controversial ideas. Tsongkhapa pointed out that if one wants to steer a middle course between the extremes of "over-negation" (straying into nihilism) and "under-negation" (and thus reification), it is important to have a clear concept of exactly what is being negated in Madhyamaka analysis (termed "the object of negation").[159][160]

According to Jay Garfield and Sonam Thakchoe, for Tsongkhapa, there are two aspects of the object of negation: "erroneous apprehension" ( phyin ci log gi ‘dzin pa) and "the existence of intrinsic nature thereby apprehended" (des bzung ba’i rang bzhin yod pa). The second aspect is an erroneously reified fiction which does not exist even conventionally. This is the fundamental object of negation for Tsongkhapa "since the reified object must first be negated in order to eliminate the erroneous subjective state".[161]

Tsongkhapa's understanding of the object of negation (Tib. dgag bya) is subtle, and he describes one aspect of it as an "innate apprehension of self-existence". Thupten Jinpa glosses this as a belief that we have that leads us to "perceive things and events as possessing some kind of intrinsic existence and identity". Tsongkhapa's madhyamaka therefore, does not deny the conventional existence of things per se, but merely rejects our way of experiencing things as existing in an essentialist way, which are false projections or imputations.[159] This is the root of ignorance, which for Tsongkhapa is an "active defiling agency" (Sk. kleśāvaraṇa) which projects a false sense of reality onto objects.[159]

As Garfield and Thakchoe note, Tsongkhapa's view allows him to "preserve a robust sense of the reality of the conventional world in the context of emptiness and to provide an analysis of the relation between emptiness and conventional reality that makes clear sense of the identity of the two truths".[162] Because conventional existence (or 'mere appearance') as an interdependent phenomenon devoid of inherent existence is not negated (khegs pa) or "rationally undermined" in his analysis, Tsongkhapa's approach was criticized by other Tibetan madhyamikas who preferred an anti-realist interpretation of madhyamaka.[163]

Following Candrakirti, Tsongkhapa also rejected the yogacara view of mind only, and instead defended the conventional existence of external objects even though ultimately they are mere "thought constructions" (Tib. rtog pas btags tsam) of a deluded mind.[160] Tsongkhapa also followed Candrakirti in rejecting svātantra ("autonomous") reasoning, arguing that it was enough to show the unwelcome consequences (prasaṅga) of essentialist positions.[160]

Gelug scholarship has generally maintained and defended Tsongkhapa's positions up until the present day, even if there are lively debates considering issues of interpretation. Jamyang Sheba, Changkya Rölpé Dorjé, Gendun Chopel and the 14th Dalai Lama are some of the most influential modern figures in Gelug madhyamaka.

Sakya madhyamaka[edit]

The Sakya school has generally held a classic prāsaṅgika position following Candrakirti closely, though with significant differences from the Gelug. Sakya scholars of Madhyamika, such as Rendawa Shyönnu Lodrö (1349–1412) and Rongtön Sheja Kunrig (1367–1450) were early critics of the "other empty" view.[164]

Gorampa Sonam Senge (1429–1489) was an important Sakya philosopher which defended the orthodox Sakya madhyamika position, critiquing both Dolpopa and Tsongkhapa's interpretations. He is widely studied, not only in Sakya, but also in Nyingma and Kagyu institutions.[165]

According to Cabezón, Gorampa called his version of madhyamaka "the middle way qua freedom from extremes" (mtha' bral dbu ma) or "middle way qua freedom from proliferations" (spros bral kyi dbu ma) and claimed that the ultimate truth was ineffable, beyond predication or concept.[166] Cabezón states that Gorampa's interpretation of madhyamaka is "committed to a more literal reading of the Indian sources than either Dolpopa's or Tsongkhapa's, which is to say that it tends to take the Indian texts at face value."[167] For Gorampa, emptiness is not just the absence of inherent existence, but it is the absence of the four extremes in all phenomena i.e. existence, nonexistence, both and neither (see: catuskoti), without any further qualification.[168]

In other words, conventional truths are also an object of negation, because as Gorampa states "they are not found at all when subjected to ultimate rational analysis".[169] Hence, Gorampa's madhyamaka negates existence itself or existence without qualifications, while for Tsongkhapa, the object of negation is "inherent existence", "intrinsic existence" or "intrinsic nature".[168]

In his Elimination of Erroneous Views (Lta ba ngan sel), Gorampa argues that madhyamaka ultimately negates "all false appearances", which means anything that appears to our mind (i.e. all conventional phenomena). Since all appearances are conceptually produced illusions, they must cease when conceptual reification is brought to an end by insight. This is the "ultimate freedom from conceptual fabrication" (don dam spros bral). To reach this, madhyamikas must negate "the reality of appearances".[162] In other words, all conventional realities are fabrications and since awakening requires transcending all fabrication (spros bral), conventional reality must be negated.[170] Thus, for Gorampa, all conventional knowledge is dualistic, being based on a false distinction between subject and object.[171] Therefore, for Gorampa, madhyamaka analyzes all supposedly real phenomena and concludes through that analysis "that those things do not exist and so that so-called conventional reality is entirely nonexistent".[169]

Regarding the Ultimate truth, Gorampa saw this as being divided into two parts:[168]

- The emptiness that is reached by rational analysis (this is actually only an analogue, and not the real thing).

- The emptiness that yogis fathom by means of their own individual gnosis (prajña). This is the real ultimate truth, which is reached by negating the previous rational understanding of emptiness.

Unlike most orthodox Sakyas, the philosopher Sakya Chokden, a contemporary of Gorampa, also promoted a form of shentong as being complementary to rangtong. He saw shentong as useful for meditative practice, while rangtong as useful for cutting through views.[172]

Comparison of the views of Tsongkhapa and Gorampa[edit]

As Garfield and Thakchoe note, for Tsongkhapa, conventional truth is "a kind of truth", "a way of being real" and "a kind of existence" while for Gorampa, the conventional is "entirely false", "unreal", "a kind of nonexistence" and "truth only from the perspective of fools".[173]

Jay L. Garfield and Sonam Thakchoe outline the different competing models of Gorampa and Tsongkhapa as follows:[174]

[Gorampa's]: The object of negation is the conventional phenomenon itself. Let us see how that plays out in an account of the status of conventional truth. Since ultimate truth—emptiness—is an external negation, and since an external negation eliminates its object while leaving nothing behind, when we say that a person is empty, we eliminate the person, leaving nothing else behind. To be sure, we must, as mādhyamikas, in agreement with ordinary persons, admit that the person exists conventionally despite not existing ultimately. But, if emptiness eliminates the person, that conventional existence is a complete illusion: The ultimate emptiness of the person shows that the person simply does not exist. It is no more actual than Santa Claus, the protestations of ordinary people and small children to the contrary notwithstanding.

[Tsongkhapa's]: The object of negation is not the conventional phenomenon itself but instead the intrinsic nature or intrinsic existence of the conventional phenomenon. The consequences of taking the object of negation this way are very different. On this account, when we say that the person does not exist ultimately, what is eliminated by its ultimate emptiness is its intrinsic existence. No other intrinsic identity is projected in the place of that which was undermined by emptiness, even emptiness or conventional reality. But the person is not thereby eliminated. Its conventional existence is therefore, on this account, simply its existence devoid of intrinsic identity as an interdependent phenomenon. On this view, conventional reality is no illusion; it is the actual mode of existence of actual things.

According to Garfield and Thakchoe each of these "radically distinct views" on the nature of the two truths "has scriptural support, and indeed each view can be supported by citations from different passages of the same text or even slightly different contextual interpretations of the same passage".[175]

Kagyu[edit]

In the Kagyu tradition, there is a broad field of opinion on the nature of emptiness, with some holding the "other empty" (shentong) view while others holding different positions. One influential Kagyu thinker was Rangjung Dorje, 3rd Karmapa Lama. His view synthesized madhyamaka and yogacara perspectives. According to Karl Brunnholzl, regarding his position in the rangtong-shentong debate he "can be said to regard these two as not being mutually exclusive and to combine them in a creative synthesis".[176] However, Rangjung Dorje never uses these terms in any of his works and thus any claims to him being a promoter of shentong or otherwise is a later interpretation.[177]

Several Kagyu figures disagree with the view that shentong is a form of madhyamaka. According to Brunnholzl, Mikyö Dorje, 8th Karmapa Lama (1507–1554) and Second Pawo Rinpoche Tsugla Trengwa see the term "shentong madhyamaka" as a misnomer, for them the yogacara of Asanga and Vasubandhu and the system of Nagarjuna are "two clearly distinguished systems". They also refute the idea that there is "a permanent, intrinsically existing Buddha nature".[178]

Mikyö Dorje also argues that the language of other emptiness does not appear in any of the sutras or the treatises of the Indian masters. He attacks the view of Dolpopa as being against the sutras of ultimate meaning which state that all phenomena are emptiness as well as being against the treatises of the Indian masters.[179] Mikyö Dorje rejects both perspectives of rangtong and shentong as true descriptions of ultimate reality, which he sees as being "the utter peace of all discursiveness regarding being empty and not being empty".[180]

One of the most influential Kagyu philosophers in recent times was Jamgön Kongtrul Lodrö Taye (1813–1899) who advocated a system of shentong madhyamaka and held that primordial wisdom was "never empty of its own nature and it is there all the time".[181][182]

The modern Kagyu teacher Khenpo Tsultrim (1934–), in his Progressive Stages of Meditation on Emptiness, presents five stages of meditation, which he relates to five tenet systems.[183] He holds the "Shentong Madhyamaka" as the highest view, above prasangika. He sees this as a meditation on Paramarthasatya ("Absolute Reality"),[184][note 15] Buddhajnana,[note 16] which is beyond concepts, and described by terms as "truly existing".[186] This approach helps "to overcome certain residual subtle concepts",[186] and "the habit – fostered on the earlier stages of the path – of negating whatever experience arises in his/her mind."[187] It destroys false concepts, as does prasangika, but it also alerts the practitioner "to the presence of a dynamic, positive Reality that is to be experienced once the conceptual mind is defeated."[187]

Nyingma[edit]

In the nyingma school, like in Kagyu, there is a variety of views. Some Nyingma thinkers promoted shentong, like Katok Tsewang Norbu, but the most influential Nyingma thinkers like Longchenpa and Ju Mipham held a more classical prāsaṅgika interpretation while at the same time seeking to harmonize it with the dzogchen view found in the dzgochen tantras which are traditionally seen as the pinnacle of the nyingma view.

According to Sonam Thakchoe, the ultimate truth in the Nyingma tradition, following Longchenpa, is that "reality which transcends any mode of thinking and speech, one that unmistakenly appears to the nonerroneous cognitive processes of the exalted and awakened beings" and this is said to be "inexpressible beyond words and thoughts" as well as the reality that is the "transcendence of all elaborations.[188]

The most influential modern Nyingma scholar is Jamgon Ju Mipham Gyatso (1846–1912). He developed a unique theory of madhyamaka, with two models of the two truths. While he adopts the traditional madhyamaka model of two truths, in which the ultimate truth is emptiness, he also developed a second model, in which the ultimate truth is "reality as it is" (de bzhin nyid) which is "established as ultimately real" (bden par grub pa).[188]

This ultimate truth is associated with the Dzogchen concept of Rigpa. While it might seem that this system conflicts with the traditional madhyamaka interpretation, for Mipham this is not so. For while the traditional model which sees emptiness and ultimate truth as a negation is referring to the analysis of experience, the second Dzogchen influenced model refers to the experience of unity in meditation.[189] Douglas Duckworth sees Mipham's work as an attempt to bring together the two main Mahayana philosophical systems of yogacara and madhyamaka, as well as shentong and rangtong into a coherent system in which both are seen as being of definitive meaning.[190]

Regarding the svatantrika prasangika debate, Ju Mipham explained that using positive assertions in logical debate may serve a useful purpose, either while debating with non-Buddhist schools or to move a student from a coarser to a more subtle view. Similarly, discussing an approximate ultimate helps students who have difficulty using only prasaṅga methods move closer to the understanding of the true ultimate. Ju Mipham felt that the ultimate non-enumerated truth of the svatantrika was no different from the ultimate truth of the Prāsaṅgika. He felt the only difference between them was with respect to how they discussed conventional truth and their approach to presenting a path.[144]

East Asian madhyamaka[edit]

Sānlùn school[edit]

Chinese madhyamaka (known as sānlùn, or the three treatise school) began with the work of Kumārajīva (344–413 CE) who translated the works of Nāgārjuna (including the MMK, also known in China as the Chung lun, "Madhyamakaśāstra"; Taishō 1564) to Chinese. Another influential text in Chinese madhyamaka which was said to have been translated by Kumārajīva was the Ta-chih-tu lun, or *Mahāprajñāpāramitopadeśa Śāstra ("Treatise which is a Teaching on the Great Perfection of Wisdom [Sūtra]"). According to Dan Arnold, this text is only extant in Kumārajīva's translation and has material that differs from the work of Nāgārjuna. In spite of this, the Ta-chih-tu lun became a central text for Chinese interpretations of madhyamaka emptiness.[191]

Sānlùn figures like Kumārajīva's pupil Sengzhao (384–414), and the later Jizang (549–623) were influential in restoring a more orthodox and non-essentialist interpretation of emptiness to Chinese Buddhism. Yin Shun (1906–2005) is one modern figure aligned with Sānlùn.

Sengzhao is often seen as the founder of Sānlùn. He was influenced not just by Indian madhyamaka and Mahayana sutras like the Vimalakirti, but also by Taoist works and he widely quotes the Lao-tzu and the Chuang-tzu and uses terminology of the Neo-Daoist "Mystery Learning" (xuanxue 玄学) tradition while maintaining a uniquely Buddhist philosophical view.[192][193] In his essay "The Emptiness of the Non-Absolute" (buzhenkong, 不眞空), Sengzhao points out that the nature of phenomena cannot be taken as being either existent or inexistent:

Hence, there are indeed reasons why myriad dharmas are inexistent and cannot be taken as existent; there are reasons why [myriad dharmas] are not inexistent and cannot be taken as inexistent. Why? If we would say that they exist, their existent is not real; if we would say that they don't exist, their phenomenal forms have taken shape. Having forms and shapes, they are not inexistent. Being not real, they are not truly existent. Hence the meaning of bu zhen kong [not really empty, 不眞空] is made manifest.[194]

Sengzhao saw the central problem in understanding emptiness as the discriminatory activity of prapañca. According to Sengzhao, delusion arises through a dependent relationship between phenomenal things, naming, thought and reification and correct understanding lies outside of words and concepts. Thus, while emptiness is the lack of intrinsic self in all things, this emptiness is not itself an absolute and cannot be grasped by the conceptual mind, it can be only be realized through non-conceptual wisdom (prajña).[195]

Jizang (549–623) was another central figure in Chinese madhyamaka who wrote numerous commentaries on Nagarjuna and Aryadeva and is considered to be the leading representative of the school.[196] Jizang called his method "deconstructing what is misleading and revealing what is corrective". He insisted that one must never settle on any particular viewpoint or perspective but constantly reexamine one's formulations to avoid reifications of thought and behavior.[196] In his commentary on the MMK, Jizang's method and understanding of emptiness can be seen:

The abhidharma thinkers regard the four holy truths as true. The Satyasiddhi regards merely the truth of cessation of suffering, i.e., the principle of emptiness and equality, as true. The southern Mahāyāna tradition regards the principle that refutes truths as true, and the northern [Mahāyāna tradition] regards thatness [suchness] and prajñā as true... Examining these all together, if there is a single [true] principle, it is an eternal view, which is false. If there is no principle at all, it is an evil view, which is also false. Being both existent and non-existent consists of the eternal and nihilistic views altogether. Being neither existent nor nonexistent is a foolish view. One replete with these four phrases has all [wrong] views. One without these four phrases has a severe nihilistic view. Now that [one] does not know how to name what a mind has nothing to rely upon and is free from conceptual construction, [he] foists "thatness" [suchness] upon it, one attains sainthood of the three vehicles... Being deluded in regard to thatness [suchness], one falls into the six realms of disturbed life and death.[197]

In one of his early treatises called "The Meaning of the two Truths" (Erdiyi), Jizang, expounds the steps to realize the nature of the ultimate truth of emptiness as follows:

In the first step, one recognises reality of the phenomena on the conventional level, but assumes their non-reality on the ultimate level. In the second step, one becomes aware of Being or Non-Being on the conventional level and negates both at the ultimate level. In the third step, one either asserts or negates Being and Non-Being on the conventional level, neither confi rming nor rejecting them on the ultimate level. Hence, there is ultimately no assertion or negation anymore; therefore, on the conventional level, one becomes free to accept or reject anything.[198]

In the modern era, there has been a revival of mādhyamaka in Chinese Buddhism. A major figure in this revival is the scholar monk Yin Shun (1906–2005).[199] Yin Shun emphasized the study of Indian Buddhist sources as primary and his books on mādhyamaka had a profound influence on modern Chinese madhyamika scholarship.[200] He argued that the works of Nagarjuna were "the inheritance of the conceptualisation of dependent arising as proposed in the Agamas" and he thus based his mādhyamaka interpretations on the Agamas rather than on Chinese scriptures and commentaries.[201] He saw the writings of Nagarjuna as the correct Buddhadharma while considering the writings of the Sānlùn school as being corrupted due to their synthesizing of the Tathagata-garbha doctrine into madhyamaka.[202]

Many modern Chinese mādhyamaka scholars such as Li Zhifu, Yang Huinan and Lan Jifu have been students of Yin Shun.[203]

Chán[edit]

The Chán/Zen-tradition emulated madhyamaka-thought via the San-lun Buddhists, influencing its supposedly "illogical" way of communicating "absolute truth".[10] The madhyamika of Sengzhao for example, influenced the views of the Chan patriarch Shen Hui (670–762), a critical figure in the development of Chan, as can be seen by his "Illuminating the Essential Doctrine" (Hsie Tsung Chi). This text emphasizes that true emptiness or Suchness cannot be known through thought since it is free from thought (wu-nien):[204]

Thus we come to realize that both selves and things are, in their essence, empty, and existence and non-existence both disappear.

Mind is fundamentally non-action; the way is truly no-thought (wu-nien).

There is no thought, no reflection, no seeking, no attainment, no this, no that, no coming, no going.

Shen Hui also states that true emptiness is not nothing, but it is a "Subtle Existence" (miao-yu), which is just "Great Prajña."[204]

Western Buddhism[edit]

Thich Nhat Hanh[edit]

Thich Nhat Hanh explains the madhyamaka concept of emptiness through the Chinese Buddhist concept of interdependence. In this analogy, there is no first or ultimate cause for anything that occurs. Instead, all things are dependent on innumerable causes and conditions that are themselves dependent on innumerable causes and conditions. The interdependence of all phenomena, including the self, is a helpful way to undermine mistaken views about inherence, or that one's self is inherently existent. It is also a helpful way to discuss Mahayana teachings on motivation, compassion, and ethics. The comparison to interdependence has produced recent discussion comparing Mahayana ethics to environmental ethics.[205]

Modern madhyamaka[edit]

Madhyamaka forms an alternative to the perennialist and essentialist understanding of nondualism and modern spiritual metaphysics (influenced by idealistic monism views like Neo-Advaita).[web 1][web 2][web 3]

In some modern works, classical madhyamaka teachings are sometimes complemented with postmodern philosophy,[web 4] critical sociology,[web 5] and social constructionism.[web 6] These approaches stress that there is no transcendental reality beyond this phenomenal world,[web 7] and in some cases even explicitly distinguish themselves from neo-Advaita approaches.[web 8]

Influences and critiques[edit]

Yogacara[edit]

The yogacara school was the other major Mahayana philosophical school (darsana) in India and its complex relationship with madhyamaka changed over time. The Saṃdhinirmocana sūtra, perhaps the earliest Yogacara text, proclaims itself as being above the doctrine of emptiness taught in other sutras. According to Paul Williams, the Saṃdhinirmocana claims that other sutras that teach emptiness as well as madhyamika teachings on emptiness are merely skillful means and thus are not definitive (unlike the final teachings in the Saṃdhinirmocana).[206]

As Mark Siderits points out, yogacara authors like Asanga were careful to point out that the doctrine of emptiness required interpretation in lieu of their three natures theory which posits an inexpressible ultimate that is the object of a Buddha's cognition.[207] Asanga also argued that one cannot say that all things are empty unless there are things to be seen as either empty or non-empty in the first place.[208]

In the Bodhisattvabhumi's Tattvartha chapter, Asanga attacks the view which states "the truth is that all is just conceptual fictions" by stating:

As for their view, due to the absence of the thing itself which serves as basis of the concept, conceptual fictions must all likewise absolutely not exist. How then will it be true that all is just conceptual fictions? Through this conception on their part, reality, conceptual fiction, and the two together are all denied. Because they deny both conceptual fiction and reality, they should be considered the nihilist-in-chief.[209]