Американцы индийского происхождения

Американцы индийского происхождения являются гражданами Соединенных Штатов , происходящими из Индии . Термины «азиатский индеец» и «восточно-индийский» используются, чтобы избежать путаницы с коренными американцами в Соединенных Штатах , которых также называют «индейцами» или «американскими индейцами». Американцы индийского происхождения с населением более 4,9 миллиона человек составляют примерно 1,35% населения США и являются самой многочисленной группой американцев южноазиатского происхождения , крупнейшей группой, состоящей только из азиатов. [10] и самая большая группа американцев азиатского происхождения после американцев китайского происхождения . Американцы индийского происхождения являются самой высокооплачиваемой этнической группой в Соединенных Штатах. [11]

Терминология [ править ]

In the Americas, the term "Indian" had historically been used to describe indigenous people since European colonization in the 15th century. Qualifying terms such as "American Indian" and "East Indian" were and still are commonly used in order to avoid ambiguity. The U.S. government has since coined the term "Native American" in reference to the indigenous people of the United States, but terms such as "American Indian" remain among indigenous as well as non-indigenous populations. Since the 1980s, Indian Americans have been categorized as "Asian Indian" (within the broader subgroup of Asian American) by the U.S. Census Bureau.[12]

While "East Indian" remains in use, the term "Indian" and "South Asian" is often chosen instead for academic and governmental purposes.[13] Indian Americans are included in the census grouping of South Asian Americans, which includes Bangladeshi Americans, Bhutanese Americans, Maldivian Americans, Nepalese Americans, Pakistani Americans, and Sri Lankan Americans.[14][15]

History[edit]

Pre-1800[edit]

Beginning in the 17th century, members of the East India Company would bring Indian servants to the American colonies.[16] There were also some East Indian slaves in the United States during the American colonial era.[17][18] In particular, court records from the 1700s indicate a number of "East Indians" were held as slaves in Maryland and Delaware.[19] Upon freedom, they are said to have blended into the free African American population, considered "mulattoes".[20]

Three brothers from "modern day India or Pakistan" received their freedom in 1710 and married into a Native American tribe in Virginia.[21] The present-day Nansemond people trace their lineage to this intermarriage.[22]

19th century[edit]

In 1850, the federal census of St. Johns County, Florida, listed a 40-year-old draftsman named John Dick, whose birthplace was listed as "Hindostan", living in city of St. Augustine.[23] His race is listed as white, suggesting he was of British descent.

By 1900, there were more than 2,000 Indian Sikhs living in the United States, primarily in California.[24] At least one scholar has set the level lower, finding a total of 716 Indian immigrants to the U.S. between 1820 and 1900.[25] Emigration from India was driven by difficulties facing Indian farmers, including the challenges posed by the colonial land tenure system for small landowners, and by drought and food shortages, which worsened in the 1890s. At the same time, Canadian steamship companies, acting on behalf of Pacific coast employers, recruited Sikh farmers with economic opportunities in British Columbia.[26]

The presence of Indians in the U.S. also helped develop interest in Eastern religions in the U.S. and would result in its influence on American philosophies such as transcendentalism. Swami Vivekananda arriving in Chicago at the World's Fair led to the establishment of the Vedanta Society.[25]

20th century[edit]

Escaping racist attacks in Canada, Sikhs migrated to Pacific Coast U.S. states in the 1900s to work on the lumber mills of Bellingham and Everett, Washington.[27] Sikh workers were later concentrated on the railroads and began migrating to California; around 2,000 Indians were employed by the major rail lines such as Southern Pacific Railroad and Western Pacific Railroad between 1907 and 1908.[28] Some white Americans, resentful of economic competition and the arrival of people from different cultures, responded to Sikh immigration with racism and violent attacks.[29] The Bellingham riots in Bellingham, Washington on September 5, 1907, epitomized the low tolerance in the U.S. for Indians and Sikhs, who were called "Hindoos" by locals. While anti-Asian racism was embedded in U.S. politics and culture in the early 20th century, Indians were also racialized for their anticolonialism, with U.S. officials, who pushed for Western imperial expansion abroad, casting them as a "Hindu" menace.[30] Although labeled Hindu, the majority of Indians were Sikh.[30]

In the early 20th century, a range of state and federal laws restricted Indian immigration and the rights of Indian immigrants in the U.S. Throughout the 1910s, American nativist organizations campaigned to end immigration from India, culminating in the passage of the Asiatic Barred Zone Act in 1917.[29] In 1913, the Alien Land Act of California prevented non-citizens from owning land.[31] However, Asian immigrants got around the system by having Anglo friends or their own U.S. born children legally own the land that they worked on. In some states, anti-miscegenation laws made it illegal for Indian men to marry white women. However, it was legal for "brown" races to mix. Many Indian men, especially Punjabi men, married Hispanic women, and Punjabi-Mexican marriages became a norm in the West.[32][33]

Bhicaji Balsara became the first known Indian to gain naturalized U.S. citizenship. As a Parsi, he was considered a "pure member of the Persian sect" and therefore a "free white person." In 1910, judge Emile Henry Lacombe of the Southern District of New York gave Balsara citizenship on the hope that the United States attorney would indeed challenge his decision and appeal it to create "an authoritative interpretation" of the law. The U.S. attorney adhered to Lacombe's wishes and took the matter to the Circuit Court of Appeals in 1910. The Circuit Court of Appeals agreed that Parsis are classified as white.[34] On the same grounds, another federal court decision granted citizenship to A. K. Mozumdar.[35] These decisions contrasted with the 1907 declaration by U.S. Attorney General Charles J. Bonaparte: "...under no construction of the law can natives of British India be regarded as white persons."[35] After the Immigration Act of 1917, Indian immigration into the U.S. decreased. Illegal entry through the Mexican border became the way of entering the country for Punjabi immigrants. California's Imperial Valley had a large population of Punjabis who assisted these immigrants and provided support. Immigrants were able to blend in with this relatively homogenous population. The Ghadar Party, a group in California that campaigned for Indian independence, facilitated illegal crossing of the Mexican border, using funds from this migration "as a means to bolster the party's finances."[36] The Ghadar Party charged different prices for entering the U.S. depending on whether Punjabi immigrants were willing to shave off their beard and cut their hair. It is estimated that between 1920 and 1935, about 1,800 to 2,000 Indian immigrants entered the U.S. illegally.[36]

By 1920, the population of Americans of Indian descent was approximately 6,400.[38] In 1923, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind that Indians were ineligible for citizenship because they were not "free white persons."[39] The court also argued that the "great body of our people" would reject assimilation with Indians.[40] Furthermore, the court ruled that based on popular understanding of race, the term "white person" referred to people of northern or western European ancestry rather than "Caucasians" in the most technical sense.[41] Over fifty Indians had their citizenship revoked after this decision, but Sakharam Ganesh Pandit fought against denaturalization. He was a lawyer and married to a white American, and he regained his citizenship in 1927. However, no other naturalization was permitted after the ruling, which led to about 3,000 Indians leaving the U.S. between 1920 and 1940. Many other Indians had no means of returning to India.[39]

Indians started moving up the social ladder by getting higher education. For example, in 1910, Dhan Gopal Mukerji went to UC Berkeley when he was 20 years old. He was an author of many children's books and won the Newbery Medal in 1928 for his book Gay-Neck: The Story of a Pigeon.[42] However, he committed suicide at the age of 46 while he was suffering from depression. Another student, Yellapragada Subbarow, moved to the U.S. in 1922. He became a biochemist at Harvard University, and he "discovered the function of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) as an energy source in cells, and developed methotrexate for the treatment of cancer." However, being a foreigner, he was refused tenure at Harvard. Gobind Behari Lal, who went to the University of California, Berkeley in 1912, became the science editor of the San Francisco Examiner and was the first Indian American to win the Pulitzer Prize for journalism.[43]

After World War II, U.S. policy re-opened the door to Indian immigration, although slowly at first. The Luce–Celler Act of 1946 permitted a quota of 100 Indians per year to immigrate to the U.S. It also allowed Indian immigrants to naturalize and become citizens of the U.S., effectively reversing the Supreme Court's 1923 ruling in United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind.[44] The Naturalization Act of 1952, also known as the McCarran-Walter Act, repealed the Barred Zone Act of 1917, but limited immigration from the former Barred Zone to a total of 2,000 per year. In 1910, 95% of all Indian Americans lived on the western coast of the United States. In 1920, that proportion decreased to 75%; by 1940, it was 65%, as more Indian Americans moved to the East Coast. In that year, Indian Americans were registered residents in 43 states. The majority of Indian Americans on the west coast were in rural areas, but on the east coast they became residents of urban areas. In the 1940s, the prices of the land increased, and the Bracero program brought thousands of Mexican guest workers to work on farms, which helped shift second-generation Indian American farmers into "commercial, nonagricultural occupations, from running small shops and grocery stores, to operating taxi services and becoming engineers." In Stockton and Sacramento, a new group of Indian immigrants from the state of Gujarat opened several small hotels.[45] In 1955, 14 of 21 hotels enterprises in San Francisco were operated by Gujarati Hindus.[46] By the 1980s, Indians owned around 15,000 motels, about 28% of all hotels and motels in the U.S.[47]

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 dramatically opened entry to the U.S. to immigrants other than traditional Northern European groups, which would significantly alter the demographic mix in the U.S.[48] Not all Indian Americans came directly from India; some moved to the U.S. via Indian communities in other countries, including the United Kingdom, Canada, South Africa, the former British colonies of East Africa,[49] (namely Kenya, Tanzania), and Uganda, Mauritius), the Asia-Pacific region (Malaysia, Singapore, Australia, and Fiji),[49] and the Caribbean (Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago, Suriname, and Jamaica).[49] From 1965 until the mid-1990s, long-term immigration from India averaged about 40,000 people per year. From 1995 onward, the flow of Indian immigration increased significantly, reaching a high of about 90,000 immigrants in the year 2000.[50]

21st century[edit]

The beginning of the 21st century marked a significant wave in the migration trend from India to the United States. The emergence of Information Technology industry in Indian cities as Bangalore, Chennai, Pune, Mumbai, and Hyderabad led to the large number of migrations to the U.S. primarily from the states of Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu in South India. There are sizable populations of people from the states of Punjab, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Telangana, Gujarat, West Bengal, Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu in the United States.[51] Indians comprise over 80% of all H-1B visas.[52] Indian Americans have risen to become the richest ethnicity in America, with an average household income of $126,891, almost twice the U.S. average of $65,316.[53]

Since 2000, a large number of students have started migrating to the United States to pursue higher education. A variety of estimates state that over 500,000 Indian American students attend higher-education institutions in any given year.[54][55] As per Institute of International Education (IIE) 'Opendoors' report, 202,014 new students from India enrolled in U.S. education institutions.[56]

On January 20, 2021, Kamala Harris, who is Indian American, made history as the first female Vice President of the United States.[57] She was elected vice president as the running mate of President Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential election. This was a major milestone in Indian American history, and in addition to Harris, another 20 Indian Americans were nominated to key positions in the administration.[58]

In recent years, especially following the 1990 inception of the H-1B visa program and the dot-com boom, there has been a shift in the Indian American population from being dominated by immigrants from Gujarat and Punjab to being increasingly dominated by immigrants from Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, Tamil Nadu, as well as immigrants from Kerala, Karnataka, and Maharashtra.[59][60] Between 2010 and 2021, Telugu rose from being the sixth most spoken South Asian language to being the third most spoken, while Punjabi fell from being the fourth most spoken South Asian language in the United States to become the seventh most spoken. There are significant differences between these groups in terms of socioeconomic factors like education, geographic location, and income; in 2021, 81% of Americans speaking Telugu at home spoke English very well while only 59% of Americans speaking Punjabi at home did the same.[61][62]

| South Asian language | 2010 | 2021 | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gujarati | 356,394 | 436,909 | 80,515 | 22.59% |

| Hindi | 609,395 | 864,830 | 255,435 | 41.92% |

| Urdu | 388,909 | 507,972 | 119,063 | 30.61% |

| Punjabi | 243,773 | 318,588 | 74,815 | 30.69% |

| Bengali | 221,872 | 403,024 | 181,152 | 81.65% |

| Telugu | 217,641 | 459,836 | 242,195 | 111.28% |

| Tamil | 181,698 | 341,396 | 159,698 | 87.89% |

| Nepali, Marathi, and other Indo-Aryan languages | 275,694 | 447,811 | 172,117 | 62.43% |

| Malayalam, Kannada, and other Dravidian languages | 197,550 | 280,188 | 82,638 | 41.83% |

Demographics[edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 2,545 | — |

| 1920 | 2,507 | −1.5% |

| 1930 | 3,130 | +24.9% |

| 1940 | 2,405 | −23.2% |

| 1980 | 361,531 | +14932.5% |

| 1990 | 815,447 | +125.6% |

| 2000 | 1,678,765 | +105.9% |

| 2010 | 2,843,391 | +69.4% |

| 2020 | 4,460,000 | +56.9% |

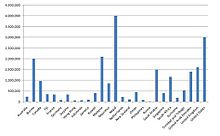

According to the 2010 United States census,[67] the Asian Indian population in the United States grew from almost 1,678,765 in 2000 (0.6% of U.S. population) to 2,843,391 in 2010 (0.9%of U.S. population), a growth rate of 69.37%, one of the fastest growing ethnic groups in the United States.[68]

The New York-Newark-Bridgeport, NY-NJ-CT-PA Combined Statistical Area, consisting of New York City, Long Island, and adjacent areas within New York, as well as nearby areas within the states of New Jersey (extending to Trenton), Connecticut (extending to Bridgeport), and including Pike County, Pennsylvania, was home to an estimated 711,174 uniracial Indian Americans as of the 2017 American Community Survey by the U.S. Census Bureau, comprising by far the largest Indian American population of any metropolitan area in the U.S.[69]

New York City itself also contains by far the largest Indian American population of any individual city in North America, estimated at 246,454 as of 2017.[70] Monroe Township, Middlesex County, in central New Jersey, ranked one of the ten safest cities in the United States,[71] has displayed one of the fastest growth rates of its Indian population in the Western Hemisphere, increasing from 256 (0.9%) as of the 2000 Census[72] to an estimated 5,943 (13.6%) as of 2017,[73] representing a 2,221.5% increase over that period. Affluent professionals and senior citizens, a temperate climate, charitable benefactors to COVID relief efforts in India in official coordination with Monroe Township, and Bollywood actors with second homes all play into the growth of the Indian population in the township, as well as its relative proximity to Princeton University. By 2022, the Indian population surpassed one-third of Monroe Township's population, and the nickname Edison-South had developed, in reference to the Little India stature of both Middlesex County, New Jersey townships.[74] In 2014, 12,350 Indians legally immigrated to the New York-Northern New Jersey-Long Island, NY-NJ-PA core based statistical area;[75] As of February 2022, Indian airline carrier Air India as well as United States airline carrier United Airlines were offering direct flights from the New York City Metropolitan Area to and from Delhi and Mumbai. In May 2019, Delta Air Lines announced non-stop flight service between New York JFK and Mumbai, to begin December 22, 2019.[76] And in November 2021, American Airlines began non-stop flight service between New York JFK and Delhi with IndiGo Air codesharing on this flight. At least 24 Indian American enclaves characterized as a Little India have emerged in the New York City Metropolitan Area.

Other metropolitan areas with large Indian American populations include Atlanta, Austin, Baltimore–Washington, Boston, Chicago, Dallas–Ft. Worth, Detroit, Houston, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Phoenix, Raleigh, San Francisco–San Jose–Oakland, and Seattle.

The three oldest Indian American communities going back to around 1910 are in lesser populated agricultural areas like Stockton, California south of Sacramento; the Central Valley of California like Yuba City; and Imperial County, California, also known as Imperial Valley. These were all primarily Sikh settlements.

U.S. metropolitan areas and states with large Asian Indian populations[edit]

Asian Indian population in Metropolitan Statistical Areas of the United States of America as per Census 2020[77]

| Metropolitan Area | Asian Indian Population | Total Population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| New York-Newark, NY-NJ-CT-PA CSA | 792,367 | 22,431,833 | 3.53% |

| San Jose-San Francisco-Oakland, CA CSA | 513,349 | 9,225,160 | 5.56% |

| Chicago-Naperville, IL-IN-WI CSA | 253,509 | 9,986,960 | 2.54% |

| Washington-Baltimore-Arlington, DC-VA-MD-WV-PA CSA | 253,146 | 10,028,331 | 2.52% |

| Dallas-Fort Worth, TX-OK CSA | 239,291 | 8,157,895 | 2.93% |

| Los Angeles-Long Beach, CA CSA | 231,515 | 18,644,680 | 1.24% |

| Houston-Pasadena, TX CSA | 162,343 | 7,339,672 | 2.21% |

| Philadelphia–Reading–Camden, PA-NJ-DE-MD CSA | 158,773 | 7,379,700 | 2.15% |

| Atlanta–Athens-Clarke County–Sandy Springs, GA-AL CSA | 158,408 | 6,976,171 | 2.27% |

| Boston–Worcester–Providence, MA-RI-NH CSA | 152,700 | 8,349,768 | 1.83% |

| Seattle-Tacoma, WA CSA | 144,290 | 4,102,400 | 2.79% |

| Detroit–Warren–Ann Arbor, MI CSA | 108,440 | 5,424,742 | 2.00% |

| Sacramento–Roseville, CA CSA | 76,403 | 2,680,831 | 2.85% |

| Miami–Port St. Lucie–Fort Lauderdale, FL CSA | 63,824 | 6,908,296 | 0.92% |

| Austin-Round Rock-San Marcos, TX CSA | 63,524 | 2,352,426 | 2.70% |

| Phoenix-Mesa, AZ CSA | 61,580 | 4,899,104 | 1.26% |

| Raleigh–Durham–Cary, NC CSA | 59,567 | 2,242,324 | 2.66% |

| Orlando–Lakeland–Deltona, FL CSA | 54,187 | 4,197,095 | 1.29% |

| San Diego-Carlsbad, CA CSA | 50,673 | 3,276,208 | 1.55% |

| Charlotte–Concord, NC-SC CSA | 50,115 | 3,232,206 | 1.55% |

| Minneapolis–St. Paul, MN-WI CSA | 48,671 | 4,078,788 | 1.19% |

| New Haven–Hartford–Waterbury, CT CSA | 45,600 | 2,659,617 | 1.71% |

| Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater, FL MSA | 43,690 | 3,175,275 | 1.38% |

| Columbus–Marion–Zanesville, OH CSA | 43,461 | 2,606,479 | 1.67% |

| Portland–Vancouver–Salem, OR-WA CSA | 35,714 | 3,280,736 | 1.09% |

| Indianapolis–Carmel–Muncie, IN CSA | 33,489 | 2,599,860 | 1.29% |

| Denver–Aurora–Greeley, CO CSA | 31,452 | 3,623,560 | 0.87% |

| St. Louis–St. Charles–Farmington, MO-IL CSA | 28,874 | 2,924,904 | 0.99% |

| Cleveland–Akron–Canton, OH CSA | 28,467 | 3,769,834 | 0.76% |

| Fresno–Hanford–Corcoran, CA CSA | 25,055 | 1,317,395 | 1.90% |

| Cincinnati–Wilmington, OH-KY-IN CSA | 24,434 | 2,291,815 | 1.07% |

| Pittsburgh–Weirton–Steubenville, PA-OH-WV CSA | 24,414 | 2,767,801 | 0.88% |

| Kansas City–Overland Park–Kansas City, MO-KS CSA | 22,308 | 2,528,644 | 0.88% |

| Richmond, VA MSA | 21,077 | 1,314,434 | 1.60% |

| San Antonio–New Braunfels–Kerrville, TX CSA | 19,611 | 2,637,466 | 0.74% |

| Milwaukee–Racine–Waukesha, WI CSA | 18,779 | 2,053,232 | 0.91% |

| Nashville-Davidson–Murfreesboro, TN CSA | 18,296 | 2,250,282 | 0.84% |

| Jacksonville–Kingsland–Palatka, FL-GA CSA | 16,853 | 1,733,937 | 0.97% |

| Albany–Schenectady, NY CSA | 16,476 | 1,190,727 | 1.38% |

| Las Vegas–Henderson, NV CSA | 14,913 | 2,317,052 | 0.64% |

| Buffalo–Cheektowaga–Olean, NY CSA | 14,021 | 1,243,944 | 1.13% |

| Salt Lake City–Provo–Orem, UT-ID CSA | 13,520 | 2,705,693 | 0.50% |

| Bakersfield, CA MSA | 12,771 | 909,235 | 1.40% |

| Harrisburg–York–Lebanon, PA CSA | 12,497 | 1,295,259 | 0.96% |

| Greensboro–Winston-Salem–High Point, NC CSA | 11,660 | 1,695,306 | 0.69% |

| Allentown–Bethlehem–East Stroudsburg, PA-NJ CSA | 11,188 | 1,030,216 | 1.09% |

| Memphis–Clarksdale–Forrest City, TN-MS-AR CSA | 10,502 | 1,389,905 | 0.76% |

| Madison–Janesville–Beloit, WI CSA | 10,361 | 910,246 | 1.14% |

| Louisville/Jefferson County–Elizabethtown, KY-IN CSA | 10,259 | 1,487,749 | 0.69% |

| Oklahoma City–Shawnee, OK CSA | 10,237 | 1,498,149 | 0.68% |

| Virginia Beach–Chesapeake, VA-NC CSA | 9,985 | 1,857,542 | 0.54% |

| Greenville–Spartanburg–Anderson, SC CSA | 9,809 | 1,511,905 | 0.65% |

| Fayetteville-Springdale-Rogers, AR MSA | 9,028 | 546,725 | 1.65% |

| Des Moines–West Des Moines–Ames, IA CSA | 8,081 | 890,322 | 0.91% |

| Columbia–Sumter–Orangeburg, SC CSA | 7,586 | 1,056,968 | 0.72% |

| Rochester–Batavia–Seneca Falls, NY CSA | 7,564 | 1,157,563 | 0.65% |

| Dayton–Springfield–Kettering, OH CSA | 6,281 | 1,088,875 | 0.58% |

| Omaha–Fremont, NE-IA CSA | 6,241 | 1,004,771 | 0.62% |

| Gainesville–Lake City, FL CSA | 6,207 | 408,945 | 1.52% |

| Grand Rapids–Wyoming, MI CSA | 5,995 | 1,486,055 | 0.40% |

| Tucson–Nogales, AZ CSA | 5,977 | 1,091,102 | 0.55% |

| Lansing–East Lansing–Owosso, MI CSA | 5,860 | 541,297 | 1.08% |

| Birmingham–Cullman–Talladega, AL CSA | 5,714 | 1,361,033 | 0.42% |

| Champaign–Urbana–Danville, IL CSA | 5,299 | 310,260 | 1.71% |

| Bloomington–Pontiac, IL CSA | 5,225 | 206,769 | 2.53% |

| Lafayette–West Lafayette–Frankfort, IN CSA | 5,111 | 281,594 | 1.82% |

| Cape Coral-Fort Myers-Naples CSA | 5,042 | 1,188,319 | 0.42% |

| Tulsa–Bartlesville–Muskogee, OK CSA | 5,032 | 1,134,125 | 0.44% |

| Knoxville–Morristown–Sevierville, TN CSA | 4,793 | 1,156,861 | 0.41% |

| Reno–Carson City–Gardnerville Ranchos, NV-CA CSA | 4,761 | 684,678 | 0.70% |

| Albuquerque-Santa Fe-Los Alamos, NM CSA | 4,555 | 1,162,523 | 0.39% |

| Springfield–Amherst Town–Northampton, MA CSA | 4,398 | 699,162 | 0.63% |

| Scranton—Wilkes-Barre, PA MSA | 4,367 | 567,559 | 0.77% |

| Peoria–Canton, IL CSA | 4,151 | 402,391 | 1.03% |

| College Station-Bryan, TX MSA | 4,149 | 268,248 | 1.55% |

| Urban Honolulu, HI MSA | 4,122 | 1,016,508 | 0.41% |

| North Port-Bradenton, FL CSA | 4,090 | 1,054,539 | 0.39% |

| New Orleans–Metairie–Slidell, LA-MS CSA | 4,048 | 1,373,453 | 0.29% |

| Syracuse–Auburn, NY CSA | 4,023 | 738,305 | 0.54% |

| Lexington-Fayette–Richmond–Frankfort, KY CSA | 3,758 | 762,082 | 0.49% |

| Tallahassee–Bainbridge, FL-GA CSA | 3,705 | 413,665 | 0.90% |

| State | Asian Indian Population | % of State's Population | Asian Indian Population | % Change (2010–2023) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| California | 978,566 | 2.51% | 528,120 | 85.29 |

| Texas | 578,113 | 1.90% | 245,981 | 135.02 |

| New Jersey | 447,906 | 4.82% | 292,256 | 53.26 |

| New York | 389,000 | 1.99% | 313,620 | 24.04 |

| Illinois | 287,868 | 2.29% | 188,328 | 52.85 |

| Florida | 223,167 | 0.99% | 104,000 | 114.58 |

| Virginia | 182,040 | 2.09% | 103,916 | 75.18 |

| Georgia | 180,326 | 1.63% | 96,116 | 87.61 |

| Washington | 178,411 | 2.28% | 61,124 | 191.88 |

| Pennsylvania | 164,879 | 1.27% | 103,026 | 60.04 |

| Massachusetts | 141,666 | 2.02% | 77,177 | 83.56 |

| North Carolina | 134,789 | 1.24% | 57,400 | 134.82 |

| Michigan | 133,954 | 1.33% | 77,132 | 73.67 |

| Maryland | 114,583 | 1.85% | 79,051 | 44.95 |

| Ohio | 111,506 | 0.95% | 64,187 | 73.72 |

| Arizona | 68,697 | 0.92% | 36,047 | 90.58 |

| Indiana | 61,616 | 0.90% | 27,598 | 123.26 |

| Connecticut | 58,872 | 1.63% | 46,415 | 26.84 |

| Minnesota | 49,359 | 0.86% | 33,031 | 49.43 |

| Missouri | 42,141 | 0.68% | 23,223 | 81.46 |

| Tennessee | 40,551 | 0.57% | 23,900 | 69.67 |

| Colorado | 40,429 | 0.69% | 20,369 | 98.48 |

| Wisconsin | 39,268 | 0.66% | 22,899 | 71.48 |

| Oregon | 36,787 | 0.87% | 16,740 | 119.76 |

| South Carolina | 28,950 | 0.54% | 15,941 | 81.61 |

| Kansas | 22,996 | 0.78% | 8,726 | 163.53 |

| Nevada | 18,734 | 0.59% | 11,671 | 60.52 |

| Iowa | 18,190 | 0.57% | 11,081 | 64.15 |

| Delaware | 18,037 | 1.75% | 11,424 | 57.89 |

| Kentucky | 16,858 | 0.37% | 12,501 | 34.85 |

| Alabama | 16,771 | 0.33% | 13,036 | 28.65 |

| Oklahoma | 14,795 | 0.36% | 11,906 | 34.43 |

| Louisiana | 14,105 | 0.31% | 11,174 | 26.23 |

| Utah | 13,517 | 0.40% | 6,212 | 117.59 |

| Arkansas | 13,345 | 0.44% | 7,973 | 67.38 |

| New Hampshire | 11,615 | 0.83% | 8,268 | 40.48 |

| Rhode Island | 10,147 | 0.93% | 4,653 | 118.07 |

| District of Columbia | 9,497 | 1.40% | 5,214 | 82.14 |

| Nebraska | 8,809 | 0.45% | 5,903 | 49.23 |

| Mississippi | 7,644 | 0.26% | 5,494 | 39.13 |

| New Mexico | 5,983 | 0.28% | 4,550 | 31.49 |

| Puerto Rico | 5,130 | 0.16% | 3,523 | 45.61 |

| Hawaii | 4,605 | 0.32% | 2,201 | 109.22 |

| West Virginia | 3,905 | 0.22% | 3,304 | 18.19 |

| Idaho | 3,760 | 0.19% | 2,152 | 74.72 |

| South Dakota | 2,705 | 0.29% | 1,152 | 134.81 |

| Vermont | 2,404 | 0.37% | 1,359 | 76.89 |

| Maine | 2,297 | 0.16% | 1,959 | 17.25 |

| North Dakota | 2,187 | 0.28% | 1,543 | 41.74 |

| Alaska | 1,679 | 0.23% | 1,218 | 37.85 |

| Montana | 1,172 | 0.10% | 618 | 89.64 |

| Wyoming | 950 | 0.16% | 590 | 61.02 |

| United States (Total) | 4,980,329 | 1.49% | 2,843,340 | 75.16% |

List of communities by number of Asian Indians (as of the 2010 census)[edit]

- New York City: 211,818

- Queens: 138,795

- Brooklyn: 25,270

- Manhattan: 24,359

- Bronx: 16,748

- Staten Island: 6,646

- San Jose, CA: 43,827

- Fremont, CA: 38,711

- Los Angeles, CA: 32,966

- Chicago, IL: 29,948

- Edison, NJ: 28,286

- Jersey City, NJ: 27,111

- Houston, TX: 26,289

- Sunnyvale, CA: 21,737

- Philadelphia, PA: 18,520

- Irving, TX: 17,403

Statistics[edit]

From the 1990 census to the 2000 census, the Asian Indian population increased by 105.87%. Meanwhile, the U.S. population increased by only 7.6%. In 2000, the Indian-born population in the U.S. was 1.007 million. In 2006, of the 1,266,264 legal immigrants to the United States, 58,072 were from India. Between 2000 and 2006, 421,006 Indian immigrants were admitted to the U.S., up from 352,278 during the 1990–1999 period.[79] At 16.4% of the Asian population, Indian Americans make up the third largest Asian-American ethnic group, following Chinese Americans and Filipino Americans.[80][81][82]

A joint Duke University-UC Berkeley study revealed that Indian immigrants have founded more engineering and technology companies from 1995 to 2005 than immigrants from the United Kingdom, China, Taiwan, and Japan combined.[83] The percentage of Silicon Valley startups founded by Indian immigrants has increased from 7% in 1999 to 15.5% in 2006, as reported in the 1999 study by AnnaLee Saxenian[84] and her updated work in 2006 in collaboration with Vivek Wadhwa.[85] Indian Americans have risen to top positions at many major companies (e.g., IBM, PepsiCo, MasterCard, Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Cisco, Oracle, Adobe, Softbank, Cognizant, Sun Microsystems.) A 2014 study indicates that 23% of Indian business school graduates take a job in United States.[86]

| Year | Asian Indians (per ACS) |

|---|---|

| 2005 | 2,319,222 |

| 2006 | 2,482,141 |

| 2007 | 2,570,166 |

| 2008 | 2,495,998 |

| 2009 | 2,602,676 |

| 2010 | 2,765,155 |

| 2011 | 2,908,204 |

| 2012 | 3,049,201 |

| 2013 | 3,189,485 |

| 2014 | 3,491,052 |

| 2015 | 3,510,000 |

| 2016 | 3,613,407 |

| 2017 | 3,794,539 |

| 2018 | 3,882,526 |

| 2019 | 4,002,151 |

| 2020 | 4,021,134 |

Socioeconomic status[edit]

Indian Americans continually outpace every other ethnic group socioeconomically per U.S. census statistics.[87] Thomas Friedman of The New York Times, in his 2005 book The World Is Flat, explains this trend in terms of brain drain, whereby a sample of the best and brightest people in India emigrate to the United States in order to seek better financial opportunities.[88] Indians form the second largest group of physicians after non-Hispanic Caucasian Americans (3.9%) as of the 1990 survey, and the share of Indian physicians rose to approximately 6% in 2005.[89]

Education[edit]

According to Pew Research in 2015, of Indian Americans aged 25 and older, 72% had obtained a bachelor's degree and 40% had obtained a postgraduate degree, whereas of all Americans, 19% had obtained a bachelor's degree and 11% had obtained a postgraduate degree.[90]

Household income[edit]

The median household income for Indian immigrants in 2019 was much higher than that of the overall foreign- and native-born populations. Indians overall have much higher incomes than the total foreign and native-born populations.

In a 2019 survey, it was found that households headed by an Indian immigrant had a median income of $132,000, compared to $64,000 and $66,000 for all immigrant and U.S.-born households, respectively. Indian immigrants were also much less likely to be in poverty (5%) than immigrants overall (14%) or the U.S. born (12%).[91]

According to 2022 US Census data, the median Indian American household income is now $151,485.

Culture and technology[edit]

Commerce[edit]

Patel Brothers is a supermarket chain serving the Indian diaspora, with 57 locations in 19 U.S. states—primarily located in the New Jersey/New York Metropolitan Area, due to its large Indian population, and with the East Windsor/Monroe Township, New Jersey location representing the world's largest and busiest Indian grocery store outside India.

Notable Indian Americans in the Business and technology industry[edit]

- Baiju Bhatt - co-founder of Robinhood

- Krishna Bharat – Computer scientist; founder of Google News

- Vasant Narasimhan - chief executive officer (CEO) of Novartis

- Indra Nooyi – chairwoman and former CEO of PepsiCo Incorporated

- C. K. Prahalad – Late world-renowned management guru

- Ram Shriram – Billionaire venture capitalist

- Raj Rajaratnam – Founder of Galleon Group

- Chandrika Tandon – Businesswoman and artist

- Vinod Khosla, co-founder of Sun Microsystems

- Sabeer Bhatia, co-founder of Hotmail

- Sanjit Biswas, co-founder of Cisco Meraki and Samsara (company)

- Jay Chaudhry, co-founder of Zscaler

- Sundar Pichai, CEO of Alphabet, the parent company of Google

- Satya Nadella, current CEO of Microsoft

- Nirav Tolia, co-founder of Nextdoor

- Gurbaksh Chahal, founder of online advertising services ClickAgent and BlueLithium

- Balaji Srinivasan, co-founder of genomics company Counsyl, Chief Technology Officer of Coinbase

- Jagdeep Singh, founder of QuantumScape, optical hardware company Lightera Networks, and telecommunications company Infinera

- Naval Ravikant, co-founder of AngelList

Media[edit]

| |||||

Tamil, Gujarati, Telugu, Marathi, Punjabi, Malayalam, and Hindi radio stations are available in areas with high Indian populations, for example, Punjabi Radio USA, Easy96.com in the New York City metropolitan area, KLOK 1170 AM in San Francisco, KSJO Bolly 92.3FM in San Jose, RBC Radio; Radio Humsafar, Desi Junction in Chicago; Radio Salaam Namaste and FunAsia Radio in Dallas; and Masala Radio, FunAsia Radio, Sangeet Radio, Radio Naya Andaz in Houston and Washington Bangla Radio on Internet from the Washington DC Metro Area. There are also some radio stations broadcasting in Tamil within these communities.[92][93] Houston-based Kannada Kaaranji radio focuses on a multitude of programs for children and adults.[94]

AVS (Asian Variety Show) and Namaste America are South Asian programming available in most of the U.S. that is free to air and can be watched with a television antenna.

Several cable and satellite television providers offer Indian channels: Sony TV, Zee TV, TV Asia, Star Plus, Sahara One, Colors, Sun TV, ETV, Big Magic, regional channels, and others have offered Indian content for subscription, such as the Cricket World Cup. There is also an American cricket channel called Willow.

Many metropolitan areas with large Indian American populations now have movie theaters which specialize in showing Indian movies, especially from Kollywood (Tamil), Tollywood (Telugu) and Bollywood (Hindi).

In July 2005, MTV premiered a spin-off network called MTV Desi which targets Indian Americans.[95] It has been discontinued by MTV.

In 2012, the film Not a Feather, but a Dot directed by Teju Prasad, was released which investigates the history, perceptions and changes in the Indian American community over the last century.

In popular media, several Indian American personalities have made their mark in recent years, including Ashok Amritraj, M. Night Shyamalan, Kovid Gupta, Kal Penn, Sendhil Ramamurthy, Padma Lakshmi, Hari Kondabolu, Karan Brar, Aziz Ansari, Hasan Minhaj, Poorna Jagannathan and Mindy Kaling. In the 2023 film Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse, the fictional world of Mumbattan (portmanteau of Mumbai and Manhattan) is introduced.[96]

Indian Independence Day Parade[edit]

The annual New York City India Day Parade, held on or approximately every August 15 since 1981, is the world's largest Indian Independence Day parade outside of India[97] and is hosted by The Federation of Indian Associations (FIA). According to the website of Baruch College of the City University of New York, "The FIA, which came into being in 1970 is an umbrella organization meant to represent the diverse Indian population of NYC. Its mission is to promote and further the interests of its 500,000 members and to collaborate with other Indian cultural organization. The FIA acts as a mouth piece for the diverse Indian Asian population in United States, and is focused on furthering the interests of this diverse community. The parade begins on East 38th Street and continues down Madison Avenue in Midtown Manhattan until it reaches 28th Street. At the review stand on 28th Street, the grand marshal and various celebrities greet onlookers. Throughout the parade, participants find themselves surrounded by the saffron, white and green colors of the Indian flag. They can enjoy Indian food, merchandise booths, live dancing and music present at the Parade. After the parade is over, various cultural organizations and dance schools participate in program on 23rd Street and Madison Avenue until 6PM."[98] The New York/New Jersey metropolitan region's second-largest India Independence Day parade takes place in Little India, Edison/Iselin in Middlesex County, New Jersey, annually in August.

Sikh Day Vaisakhi Parade[edit]

The world's largest Sikh Day Parade outside India celebrating Vaisakhi and the season of renewal is held in Manhattan annually in April. The parade is widely regarded as being one of the most colourful parades.[99]

Religion[edit]

Religious Makeup of Indian Americans (2018)[9]

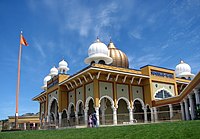

Communities of Hindus, Christians, Muslims, Sikhs, irreligious people, and smaller numbers of Jains, Buddhists, Zoroastrians, and Indian Jews have established their religions in the United States. According to 2023 Pew Research Center research, 48% consider themselves Hindu, 15% as Christian (7% Catholic, 4% Evangelical Protestant, 4% Nonevangelical Protestant), 18% as unaffiliated, 8%as Muslims, 8% as Sikh, and 3% as a member of another religion.[9]The first religious center of an Indian religion to be established in the U.S. was a Sikh Gurudwara in Stockton, California in 1912. Today there are many Sikh Gurudwaras, Hindu temples, Muslim mosques, Christian churches, and Buddhist and Jain temples in all 50 states.

Hindus[edit]

As of 2008, the American Hindu population was around 2.2 million.[101] Hindus form the plurality religious group among the Indian American community.[102][103] Many organizations such as ISKCON, Swaminarayan Sampradaya, BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha, Chinmaya Mission, and Swadhyay Pariwar are well-established in the U.S. and Hindu Americans have formed the Hindu American Foundation which represents American Hindus and aim to educate people about Hinduism. Swami Vivekananda brought Hinduism to the West at the 1893 Parliament of the World's Religions.[104] The Vedanta Society has been important in subsequent Parliaments. In September 2021, the State of New Jersey aligned with the World Hindu Council to declare October as Hindu Heritage Month. Today, many Hindu temples, most of them built by Indian Americans, have emerged in different cities and towns in the United States.[105][106] More than 18 million Americans are now practicing some form of Yoga. Kriya Yoga was introduced to America by Paramahansa Yogananda. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada initiated the popular ISKCON, also known as the Hare Krishna movement, while preaching Bhakti yoga.

Sikhs[edit]

From the time of their arrival in the late 1800s, Sikh men and women have been making notable contributions to American society. In 2007, there were estimated to be between 250,000 and 500,000 Sikhs living in the United States, with largest populations living on the East and West Coasts, together with smaller additional populations in Detroit, Chicago, and Austin. The United States also has a number of non-Punjabi converts to Sikhism.Sikh men are typically identifiable by their unshorn beards and turbans (head coverings), articles of their faith. Many organisations like World Sikh Organisation (WSO), Sikh Riders of America, SikhNet, Sikh Coalition, SALDEF, United Sikhs, National Sikh Campaign continue to educate people about Sikhism. There are many "Gurudwaras" Sikh temples present in all states of USA.

Jains[edit]

Adherents of Jainism first arrived in the United States in the 20th century. The most significant time of Jain immigration was in the early 1970s.[citation needed] The U.S. has since become the epicenter of the Jain diaspora. Jains in America are also the highest socio-economic earners of any other religion in the United States.[citation needed] The Federation of Jain Associations in North America is an umbrella organization of local American and Canadian Jain congregations.[108] Unlike India and United Kingdom, the Jain community in United States does not find sectarian differences—both Digambara and Śvētāmbara share a common roof.[citation needed]

Muslims[edit]

Hasan Minhaj, Fareed Zakaria, Aziz Ansari,[109] and Pir Vilayat Inayat Khan[110] are few well-known Indian American Muslims.Indian Muslim Americans also congregate with other American Muslims, including those from Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, and Myanmar when there are eventsparticularly related to their faith and religious believes as the same can be applied for any other religious community, but there are prominent organizations such as the Indian Muslim Council – USA.[111]

Christians[edit]

There are many Indian Christian churches across the US; India Pentecostal Church of God, Assemblies of God in India, Church of God (Full Gospel) in India, Church of South India, Church of North India, Christhava Tamil Koil, The Pentecostal Mission, Sharon Pentecostal Church, Independent Non Denominational Churches like Heavenly Feast, Plymouth Brethren. Saint Thomas Christians (Syro-Malabar Church, Syro-Malankara Catholic Church, Chaldean Syrian Church, Kanna Church, Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church, Jacobite Syrian Christian Church, CSI Syrian Christians, Mar Thoma Syrian Church, Pentecostal Syrian Christians[112] and St. Thomas Evangelical Church of India[113]) from Kerala have established their own places of worship across the United States.[114] The website USIndian.org has collected a comprehensive list of all the traditional St. Thomas Christian Churches in the U.S.[115] There are also Catholic Indians hailing originally from Goa, Karnataka and Kerala, who attend the same services as other American Catholics, but may celebrate the feast of Saint Francis Xavier as a special event of their identity.[116][117][118] The Indian Christian Americans have formed the Federation of Indian American Christian Organizations of North America (FIACONA) to represent a network of Indian Christian organizations in the U.S. FIACONA estimates the Indian American Christian population to be 1,050,000.[119] The Syro-Malabar Church, an Eastern Catholic Church, native to India since the 1st century,[120] established St. Thomas Syro-Malabar diocese of Chicago was established in the year 2001.[121] St. Thomas day is celebrated in this church on July 3 every year.[122]

Others[edit]

The large Parsi and Irani community is represented by the Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America.[123] Indian Jews are perhaps the smallest organized religious group among Indian Americans, consisting of approximately 350 members in the U.S. They form the Indian Jewish Congregation of USA, with their headquarters in New York City.[124]

Deepavali/Diwali, Eid/Ramadan as school holidays[edit]

Momentum has been growing to recognize the Dharmic holy day Deepavali (Diwali) as a holiday on school district calendars in the New York City metropolitan area.[125][126] New York City announced in October 2022 that Diwali would be an official school holiday commencing in 2023.[127]

Passaic, New Jersey established Diwali as a school holiday in 2005.[125][126] South Brunswick, New Jersey in 2010 became the first of the many school districts with large Indian student populations in Middlesex County in New Jersey to add Diwali to the school calendar.[126] Glen Rock, New Jersey in February 2015 became the first municipality in Bergen County, with its own burgeoning Indian population post-2010,[128][129] to recognize Diwali as an annual school holiday,[130][131] while thousands in Bergen County celebrated the first U.S. county-wide Diwali Mela festival under a unified sponsorship banner in 2016,[132] while Fair Lawn in Bergen County has celebrated an internationally prominent annual Holi celebration since 2022.[133][134][135] Diwali/Deepavali is also recognized by Monroe Township, New Jersey.

Efforts have been undertaken in Millburn,[125] Monroe Township, West Windsor-Plainsboro, Bernards Township, and North Brunswick, New Jersey,[126] Long Island, as well as in New York City (ultimately successfully),[136][137] among other school districts in the metropolitan region, to make Diwali a holiday on the school calendar. According to the Star-Ledger, Edison, New Jersey councilman Sudhanshu Prasad has noted parents' engagement in making Deepavali a holiday there; while in Jersey City, the four schools with major Asian Indian populations mark the holiday by inviting parents to the school buildings for festivities.[126] Mahatma Gandhi Elementary School is located in Passaic, New Jersey.[138] Efforts are also progressing toward making Diwali and Eid official holidays at all 24 school districts in Middlesex County.[139] At least 12 school districts on Long Island closed for Diwali in 2022,[140] and over 20 in New Jersey.[141]

In March 2015, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio officially declared the Muslim holy days Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha holidays on the school calendar.[136] School districts in Paterson and South Brunswick, New Jersey observe Ramadan.[126]

Ethnicity[edit]

Like the terms "Asian American" or "South Asian American", the term "Indian American" is also an umbrella label applying to a variety of views, values, lifestyles, and appearances. Although Asian Indian Americans retain a high ethnic identity, they are known to assimilate into American culture while at the same time keeping the culture of their ancestors.[142]

Linguistic affiliation[edit]

The United States is home to various associations that promote Indian languages and cultures. Some major organizations include:

- Andhrapradesh American Association (AAA)

- American Telugu Association (ATA)

- Association of Kannada Kootas of America (AKKA)

- Federation of Kerala Associations in North America (FOKANA)

- Federation of Tamil Sangams of North America (FeTNA)

- North America Vishwa Kannada Association (NAVIKA)

- Cultural Association of Bengal (CAB)

- Telugu Association of North America (TANA)

- The Odisha Society of the Americas (OSA)

- Maharashtra Mandal (MM)

Progress[edit]

Timeline[edit]

- 1600: Beginning of the East India Company.[16]

- 1635: An "East Indian" is documented present in Jamestown, Virginia.[143][17]

- 1680: Due to anti-miscegenation laws, a mixed-race girl born to an Indian father and an Irish mother is classified as mulatto and sold into slavery.[16]

- 1790: The first officially confirmed Indian immigrant arrives in the United States from Madras, South India, on a British ship.[144][145]

- 1899–1914: The first significant wave of Indian immigrants arrives in the United States, mostly consisting of Sikh farmers and businessmen from the Punjab region of British India. They arrive in Angel Island, California via Hong Kong. They start businesses including farms and lumber mills in California, Oregon, and Washington.

- 1909: Bhicaji Balsara becomes the first known Indian-born person to gain naturalised U.S. citizenship. As a Parsi, he was considered a "pure member of the Persian sect" and therefore a free White person. The judge Emile Henry Lacombe, of the Southern District of New York, only gave Balsara citizenship on the hope that the United States attorney would indeed challenge his decision and appeal it to create "an authoritative interpretation" of the law. The U.S. attorney adhered to Lacombe's wishes and took the matter to the Circuit Court of Appeals in 1910. The Circuit Court of Appeal agrees that Parsis are classified as white.[34]

- 1912: The first Sikh gurdwara opens in Stockton, California.

- 1913: A. K. Mozumdar becomes the second Indian-born person to earn U.S. citizenship, having convinced the Spokane district judge that he was "Caucasian" and met the requirements of naturalization law that restricted citizenship to free White persons. In 1923, as a result of United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind, his citizenship was revoked.

- 1914: Dhan Gopal Mukerji obtains a graduate degree from Stanford University, studying also at University of California, Berkeley and later goes on to win the Newbery Medal in 1928, and thus becomes the first successful India-born man of letters in the United States, as well as the first popular Indian writer in English.

- 1917: The Barred Zone Act passes in Congress through two-thirds majority, overriding President Woodrow Wilson's earlier veto. Asians, including Indians, are barred from entering the United States.

- 1918: Due to anti-miscegenation laws, there was significant controversy in Arizona when an Indian farmer B. K. Singh married the sixteen-year-old daughter of one of his White American tenants.[146]

- 1918: Private Raghunath N. Banawalkar is the first Indian American recruited into the U.S. Army on February 25, 1918, and serves in the Sanitary Detachment of the 305th Infantry Regiment, 77th Division, American Expeditionary Forces in France. Gassed while on active service in October 1918 and subsequently awarded Purple Heart medal.[147]

- 1918: Earliest record of LGBT Indian Americans—Jamil Singh in Sacramento, California[148]

- 1922: Yellapragada Subbarao, a Telugu from the state of Andhra Pradesh in Southern India arrived in Boston on October 26, 1922. He discovered the role of phosphocreatine and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in muscular activity, which earned him an entry into biochemistry textbooks in the 1930s. He obtained his Ph.D. the same year, and went on to make other major discoveries; including the synthesis of aminopterin (later developed into methotrexate), the first cancer chemotherapy.

- 1923: In United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind, the Supreme Court unanimously rules that Indian people are aliens ineligible for United States citizenship. Bhagat Singh Thind regained his citizenship years later in New York.[149]

- 1943: Republican Clare Boothe Luce and Democrat Emanuel Celler introduce a bill to open naturalization to Indian immigrants to the United States. Prominent Americans Pearl Buck, Louis Fischer, Albert Einstein and Robert Millikan give their endorsement to the bill. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a Democrat, also endorses the bill, calling for an end to the "statutory discrimination against the Indians."

- 1946: President Harry S. Truman signs into law the Luce–Celler Act of 1946, returning the right to Indian Americans to immigrate to the United States and become naturalized citizens.

- 1956: Dalip Singh Saund elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from California. He was re-elected to a second and third term, winning over 60% of the vote. He is also the first Asian immigrant from any country to be elected to Congress.

- 1962: Zubin Mehta appointed music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, becoming the first person of Indian origin to become the principal conductor of a major American orchestra. Subsequently, he was appointed principal conductor of the New York Philharmonic.

- 1964: Amar G. Bose founded Bose Corporation. He was the chairman, primary stockholder, and Technical Director at Bose Corporation. He was former professor of electrical engineering at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- 1965: President Lyndon Johnson signs the INS Act of 1965 into law, eliminating per-country immigration quotas and introducing immigration on the basis of professional experience and education. Satinder Mullick is one of the first to immigrate under the new law in November 1965—sponsored by Corning Glass Works.

- 1968: Hargobind Khorana shared the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine with Marshall W. Nirenberg and Robert W. Holley for discovering the mechanisms by which RNA codes for the synthesis of proteins. He was then on faculty at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, but later moved to MIT.

- 1974: Mafat and Tulsi Patel open the first location of Patel Brothers on Devon Avenue in Chicago, one of the first Indian grocery chains in America

- 1975: Launch of India-West, a leading newspaper covering issues of relevance to the Indian American community.

- 1981: Suhas Patil founded Cirrus Logic, one of the first fabless semiconductor companies.

- 1982: Vinod Khosla co-founded Sun Microsystems.

- 1983: Subrahmanyam Chandrasekhar won the Nobel Prize for Physics; Asian Indian Women in America[150] attended the first White House Briefing for Asian American Women. (AAIWA, formed in 1980, is the 1st Indian women's organization in North America.)

- 1985: Balu Natarajan becomes the first Indian American to win the Scripps National Spelling Bee

- 1987: President Ronald Reagan appoints Joy Cherian, the first Indian Commissioner of the United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC).

- 1988: Sanjay Mehrotra co-founded SanDisk.

- 1989: Launch of RBC Radio, the first South Asian-Indian radio station in the United States.[151]

- 1990: Shiva Subramanya (an India-born Nuclear Physicist and Space Scientist working at TRW, Inc) became the first South Asian and first Indian American to win the Medal of Merit, the AFCEA's highest award for a civilian and one of the America's top defense award, in recognition of his exceptional service to AFCEA and the fields of Command, Control, Communications, Computers and Intelligence (C4I).[152]

- 1994: Rajat Gupta elected managing director of McKinsey & Company, the first Indian-born CEO of a multinational company.

- 1994: Guitarist Kim Thayil, of Indian origin, wins Grammy award for his Indian inspired guitarwork on the album Superunknown by his band Soundgarden.

- 1994: Raj Reddy received the ACM Turing Award (with Edward Feigenbaum) "For pioneering the design and construction of large scale artificial intelligence systems, demonstrating the practical importance and potential commercial impact of artificial intelligence technology."

- 1996: Pradeep Sindhu founded Juniper Networks

- 1996: Rajat Gupta and Anil Kumar of McKinsey & Company co-found the Indian School of Business.

Kalpana Chawla - 1997: Kalpana Chawla, one of the six-member crew of STS-87 mission, becomes the first Indian American astronaut.

- 1999: NASA names the third of its four "Great Observatories" Chandra X-ray Observatory after Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar the Indian-born American astrophysicist and a Nobel laureate.

- 1999: Filmmaker M. Night Shyamalan enters film history with his film The Sixth Sense becoming one of the all-time highest-grossing films worldwide.

- 1999: Rono Dutta becomes the president of United Airlines.

- 2001: Professor Dipak C. Jain (born in Tezpur – Assam, India) appointed as dean of the Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University.

- 2002: Professor of statistics Calyampudi Radhakrishna Rao is awarded National Medal of Science by President George W. Bush.

- 2005: Abhi Talwalkar becomes president and chief executive officer of LSI Corporation

- 2006: Indra Nooyi (born in Chennai, India) appointed as CEO of PepsiCo.

- 2007: Bobby Jindal is elected governor of Louisiana and is the first person of Indian descent to be elected governor of an American state.

- 2007: Renu Khator appointed to a dual-role as chancellor of the University of Houston System and president of the University of Houston.

- 2007: Francisco D'Souza appointed as the president and CEO and of Cognizant Technology Solutions. He is one of the youngest chief executive officers in the software services sector at the age 38 in the United States.

- 2007: Vikram Pandit (born in Nagpur, Maharashtra, India) appointed as CEO of Citigroup. He was previously the president and CEO of the Institutional Securities and Investment Banking Group at Morgan Stanley.

- 2007: Shantanu Narayen appointed as CEO of Adobe Systems.

- 2008: Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson appoints Neel Kashkari as the Interim U.S. Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for Financial Stability.

- 2008: Raj Chetty appointed as professor of economics at Harvard University the age of 29, one of the youngest ever to receive tenure of professorship in the Department of Economics at Harvard.

- 2008: Sanjay Jha appointed as Co-CEO of Motorola, Inc..

- 2008: Establishment of the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA) to document the history of the South Asian American community.[153]

- 2009: President Barack Obama appoints Preet Bharara (born in Firozpur, India; graduate of Harvard College Class of 1990 and Columbia Law School Class of 1993) as United States attorney for the Southern District of New York Manhattan.

- Farah Pandith appointed as Special Representative to Muslim Communities for the United States Department of State.

- 2009: President Barack Obama appoints Aneesh Paul Chopra as the first American Federal Chief Technology Officer of the United States (CTO).

- 2009: President Barack Obama appoints Eboo Patel and Anju Bhargava on President's Advisory Council on Faith Based and Neighborhood Partnerships.

- 2009: President Barack Obama appoints Vinai Thummalapally as the U.S. Ambassador to Belize

- 2009: President Barack Obama nominates Rajiv Shah, M.D. as the new head of United States Agency for International Development.

- 2009: President Barack Obama nominates Islam A. Siddiqui as the Chief Agricultural Negotiator in the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative.

- 2010: President of Harvard University Catherine Drew Gilpin Faust appoints Nitin Nohria as the tenth dean of Harvard Business School.

- 2010: President of University of Chicago Robert Zimmer appoints Sunil Kumar as the dean of University of Chicago Booth School of Business.

- 2010: Deven Sharma appointed president of Standard & Poor's.

- 2010: Ajaypal Banga appointed president and CEO of MasterCard.

- 2010: President Barack Obama nominates Subra Suresh, Dean of Engineering at MIT as director of National Science Foundation.

- 2010: Year marks the most candidates of Indian origin, running for political offices in the United States, including candidates such as Ami Bera.

- 2010: State Representative Nikki Haley is elected Governor of South Carolina and becomes the first Indian American woman and second Indian American in general to serve as governor of a U.S. state.

- 2011: Jamshed Bharucha named president of Cooper Union. Previous to that, he was appointed dean of the Faculty of Arts & Sciences at Dartmouth College in 2001, the first Indian American dean at an Ivy League institution, and Provost at Tufts University in 2002.[154]

- 2011: Satish K. Tripathi appointed as President of University at Buffalo, The State University of New York.

- 2011: Rohit Gupta wins over 100 international awards and accolades for his films Life! Camera Action... and Another Day Another Life.

- 2011: Bobby Jindal is re-elected Governor of Louisiana.

- 2012: Ami Bera is elected to the House of Representatives from California.

- 2013: Vistap Karbhari appointed as president of University of Texas at Arlington

- 2013: Sri Srinivasan is confirmed as a Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

- 2013: Nina Davuluri wins Miss America 2014.

- 2013: Arun M Kumar appointed as assistant secretary and director general of the U.S. and Foreign Commercial Service, International Trade Administration in the Department of Commerce.[155]

- 2014: Satya Nadella appointed as CEO of Microsoft.

- 2014: Vivek Murthy appointed as the nineteenth Surgeon General of the United States. He returned to the role again in 2021 to serve as the twenty-first Surgeon General.

- 2014: Rakesh Khurana appointed as the dean of Harvard College, the original founding college of Harvard University.

- 2014: Manjul Bhargava wins Fields Medal in Mathematics.

- 2015: Sundar Pichai appointed as the chairman and CEO of Google.

- 2016: Pramila Jayapal, Ro Khanna, and Raja Krishnamoorthi are elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. This puts the total number of people of Indian and South Asian origin in Congress at 5, the largest in history.

- 2016: President Donald Trump nominates Seema Verma to lead the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Her nomination is confirmed in 2017.

- 2017: Hasan Minhaj roasts President Donald Trump at the White House Correspondents' Association Dinner, becoming the first Indian American and Muslim American to perform at the event.

- 2017: President Donald Trump nominates Ajit Pai as chairman of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC).

- 2017: Balvir Singh was elected to the Burlington County Board of Chosen Freeholders, New Jersey on November 7, 2017. He became the first Asian-American to win a countywide election in Burlington County and the first Sikh-American to win a countywide election in New Jersey.[156]

- 2019: Seven out of the eight winners of the Scripps National Spelling Bee (Saketh Sundar, Abhijay Kodali, Shruthika Padhy, Sohum Sukhatankar, Christopher Serrao, Rohan Raja, and Rishik Gandhasri), are Indian Americans. They have broken the spelling bee according to several experts and have dominated this American institution.[157]

- 2019: Lilly Singh became the first person of Indian descent to host an American major broadcast network late-night talk show A Little Late with Lilly Singh.[158]

- 2019: Abhijit Banerjee is awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences.[159][160]

- 2020: Kash Patel is named chief of staff to the Acting Defense Secretary Chris Miller.

- 2020: Arvind Krishna appointed as the CEO of IBM.[161][162]

- 2021: Kamala Harris, born to an Indian mother, became the first woman and first Indian origin Vice President of the United States.[163]

- 2021: Anirudh Devgan appointed as the CEO and President of Cadence Design Systems.[164]

- 2021: Parag Agrawal appointed as the CEO of Twitter.[165]

- 2022: Laxman Narasimhan appointed CEO of Starbucks.[166]

- 2022: Shruti Miyashiro appointed as the President and CEO of Digital Federal Credit Union (DCU).[167]

- 2022: Aruna Miller elected the first Asian-American lieutenant governor of Maryland and first South Asian woman elected lieutenant governor in the U.S.[168]

- 2023: Neal Mohan was appointed as the fourth CEO of YouTube.[169]

- 2023: World Bank board elects Ajay Banga as president.[170]

Classification[edit]

According to the official U.S. racial categories employed by the United States Census Bureau, Office of Management and Budget and other U.S. government agencies, American citizens or resident aliens who marked "Asian Indian" as their ancestry or wrote in a term that was automatically classified as an Asian Indian became classified as part of the Asian race at the 2000 Census.[171] As with other modern official U.S. government racial categories, the term "Asian" is in itself a broad and heterogeneous classification, encompassing all peoples with origins in the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent.

In previous decades, Indian Americans were also variously classified as White American, the "Hindu race," and "other."[172] Even today, where individual Indian Americans do not racially self-identify, and instead report Muslim, Jewish, and Zoroastrian as their "race" in the "some other race" section without noting their country of origin, they are automatically tallied as white.[173] This may result in the counting of persons such as Indian Muslims, Indian Jews, and Indian Zoroastrians as white, if they solely report their religious heritage without their national origin.

Current issues[edit]

Discrimination[edit]

In the 1980s, a gang known as the Dotbusters specifically targeted Indian Americans in Jersey City, New Jersey with violence and harassment.[174] Studies of racial discrimination, as well as stereotyping and scapegoating of Indian Americans have been conducted in recent years.[175] In particular, racial discrimination against Indian Americans in the workplace has been correlated with Indophobia due to the rise in outsourcing/offshoring, whereby Indian Americans are blamed for U.S. companies offshoring white-collar labor to India.[176][177] According to the offices of the Congressional Caucus on India, many Indian Americans are severely concerned of a backlash, though nothing serious has taken place.[177] Due to various socio-cultural reasons, implicit racial discrimination against Indian Americans largely go unreported by the Indian American community.[175]

Numerous cases of religious stereotyping of American Hindus (mainly of Indian origin) have also been documented.[178]

Since the September 11, 2001 attacks, there have been scattered incidents of Indian Americans becoming mistaken targets for hate crimes. In one example, a Sikh, Balbir Singh Sodhi, was murdered at a Phoenix gas station by a white supremacist. This happened after September 11, and the murderer claimed that his turban made him think that the victim was a Middle Eastern American.[179] In another example, a pizza deliverer was mugged and beaten in Massachusetts for "being Muslim" though the victim pleaded with the assailants that he was in fact a Hindu.[180] In December 2012, an Indian American in New York City was pushed from behind onto the tracks at the 40th Street-Lowery Street station in Sunnyside and killed.[181] The police arrested a woman, Erika Menendez, who admitted to the act and justified it, stating that she shoved him onto the tracks because she believed he was "a Hindu or a Muslim" and she wanted to retaliate for the attacks of September 11, 2001.[182]

In 2004, New York Senator Hillary Clinton joked at a fundraising event with South Asians for Nancy Farmer that Mahatma Gandhi owned a gas station in downtown St. Louis, fueling the stereotype that gas stations are owned by Indians and other South Asians. She clarified in the speech later that she was just joking, but still received some criticism for the statement later on for which she apologized again.[183]

On April 5, 2006, the Hindu Mandir of Minnesota was vandalized allegedly on the basis of religious discrimination.[184] The vandals damaged temple property leading to $200,000 worth of damage.[185][186][187]

On August 11, 2006, Senator George Allen allegedly referred to an opponent's political staffer of Indian ancestry as "macaca" and commenting, "Welcome to America, to the real world of Virginia." Some members of the Indian American community saw Allen's comments, and the backlash that may have contributed to Allen losing his re-election bid, as demonstrative of the power of YouTube in the 21st century.[188]

In 2006, then Delaware Senator and current U.S President Joe Biden was caught on microphone saying: "In Delaware, the largest growth in population is Indian Americans moving from India. You cannot go to a 7-Eleven or a Dunkin' Donuts unless you have a slight Indian accent. I'm not joking."[189]

On August 5, 2012, white supremacist Wade Michael Page shot eight people and killed six at a Sikh gurdwara in Oak Creek, Wisconsin.

22 февраля 2017 года недавние иммигранты Шринивас Кучибхотла и Алок Мадасани были застрелены в баре в Олате, штат Канзас, Адамом Пуринтоном, белым американцем, который принял их за лиц ближневосточного происхождения, крича «убирайтесь из моей страны» и «террорист». ." Кучибхотла скончался мгновенно, а Мадасани был ранен, но позже выздоровел. [190]

Американцы-панджабцы-сикхи в Индианаполисе понесли многочисленные потери в своей общине 15 апреля 2021 года во время стрельбы в FedEx в Индианаполисе , в ходе которой боевик Брэндон Скотт Хоул по неизвестным мотивам вошел на склад FedEx и убил восемь человек, половина из которых были сикхами. Жертвами сикхов стали Джасвиндер Сингх, Джасвиндер Каур, Амарджит Сехон и Амарджит Джохал. По некоторым данным, 90% рабочих на предприятии были сикхами. [191] Другой сикх, Таптедждип Сингх, был одним из девяти человек, погибших в результате стрельбы в Сан-Хосе 26 мая 2021 года. [192]

Иммиграция [ править ]

Индийцы являются одной из крупнейших этнических групп, легально иммигрирующих в Соединенные Штаты. Иммиграция индейцев происходила несколькими волнами с тех пор, как первый индеец переехал в Соединенные Штаты в 1700-х годах. Основная волна иммиграции в Калифорнию из региона Пенджаб произошла в первом десятилетии 20 века. Еще одна значительная волна последовала в 1950-х годах, в нее в основном вошли студенты и специалисты. Отмена иммиграционных квот в 1965 году стимулировала новые волны иммигрантов в конце 1970-х и начале 1980-х годов. В период технологического бума 1990-х годов наибольший приток индийцев прибыл в период с 1995 по 2000 год. Эта последняя группа также вызвала резкий рост числа заявок на различные иммиграционные льготы, включая заявки на получение грин-карты. Это привело к тому, что людям, родившимся в Индии, пришлось долго ждать получения этих пособий.

По состоянию на 2012 год в списке ожидания на получение визы стояло более 330 000 индийцев, уступая только Мексике и Филиппинам . [193]

В декабре 2015 года более 30 индийских студентов, претендующих на поступление в два университета США — Университет Силиконовой долины и Северо-Западный политехнический университет — были лишены доступа со стороны таможни и пограничной службы и были депортированы в Индию. Согласно противоречивым сообщениям, студенты были депортированы из-за разногласий вокруг двух вышеупомянутых университетов. Однако в другом отчете говорится, что студенты были депортированы, поскольку во время прибытия в США они предоставили противоречивую информацию о том, что было упомянуто в их заявлении на получение визы. "По данным правительства США, депортированные лица предоставили агенту пограничной службы информацию, которая не соответствовала их визовому статусу", - говорится в сообщении Министерства иностранных дел (Индия) , опубликованном в газете Hindustan Times. [194]

После инцидента правительство Индии обратилось к правительству США с просьбой соблюдать визы, выданные его посольствами и консульствами. В ответ посольство США посоветовало студентам, рассматривающим возможность обучения в США, обратиться за помощью в Education USA. [194] [195]

Гражданство [ править ]

В отличие от многих стран, Индия не допускает двойного гражданства . [196] Следовательно, многие индийские граждане, проживающие в США, которые не хотят терять свое индийское гражданство, не подают заявления на получение американского гражданства (например, Рагурам Раджан). [197] ). Однако многие американцы индийского происхождения получают статус зарубежного гражданства Индии (OCI), который позволяет им жить и работать в Индии на неопределенный срок.

Брак [ править ]

Браки и отношения по расчету были обычной культурной традицией во многих культурах Южной Азии, особенно среди индийских общин. Браки и отношения по договоренности могут принимать самые разные формы, и опыт их участников может сильно различаться в зависимости от множества обстоятельств, включая культурное происхождение, семейные ценности и индивидуальные предпочтения. Хотя многие люди женятся друг на друге из-за любви друг к другу, в таких браках по расчету приоритетом часто является долгосрочная совместимость, а не любовь. В процессе отбора может иметь значение ряд переменных, включая касту, образование, финансовое положение и семейные ценности. Восприятие обществом браков по расчету меняется, особенно среди молодежи. Стремясь найти баланс между участием в семье и личными предпочтениями, некоторые люди могут решить объединить аспекты любви и запланированного брака. [198]

Диспропорция доходах в

Хотя американцы индийского происхождения имеют самый высокий средний и медианный доход семьи среди всех демографических групп в Америке, между различными общинами американцев индийского происхождения существует значительное и серьезное неравенство в доходах. В Лонг-Айленде средний семейный доход американцев индийского происхождения составлял примерно 273 000 долларов, а во Фресно средний семейный доход американцев индийского происхождения составлял всего 24 000 долларов, то есть разница в одиннадцать раз. [199]

иммиграция Нелегальная

, в 2009 году По оценкам Министерства внутренней безопасности в Индии насчитывалось 200 000 нелегальных иммигрантов ; они являются шестой по величине национальностью (вместе с корейцами) нелегальных иммигрантов после Мексики , Сальвадора , Гватемалы , Гондураса и Филиппин . [200] С 2000 года у американцев индийского происхождения нелегальная иммиграция увеличилась на 25%. [201] В 2014 году Исследовательский центр Pew подсчитал, что в Соединенных Штатах проживает 450 000 индейцев без документов. [202]

СМИ [ править ]

Политика [ править ]

Несколько групп пытались создать голос американцев индийского происхождения в политических вопросах, в том числе Комитет политических действий США в Индии. [ когда? ] и Инициатива индийско-американского лидерства, [ когда? ] а также панэтнические группы, такие как «Американцы Южной Азии, ведущие вместе» и «Desis Rising Up and Moving». [203] [204] [205] [206] Кроме того, существуют отраслевые группы, такие как Азиатско-американская ассоциация владельцев отелей и Американская ассоциация врачей индийского происхождения .

В 2000-х годах большинство американцев индийского происхождения были склонны идентифицировать себя как умеренные и часто склонялись к демократам на нескольких недавних выборах. На президентских выборах 2012 года опрос Национального азиатско-американского опроса показал, что 68% американцев индийского происхождения планировали голосовать за Барака Обаму . [207] Опросы общественного мнения перед президентскими выборами 2004 года показали, что американцы индийского происхождения отдают предпочтение кандидату от Демократической партии Джону Керри младшему республиканцу Джорджу Бушу- с перевесом от 53% до 14%, при этом 30% на тот момент не определились. [208]

К 2004 году Республиканская партия попыталась привлечь это сообщество к политической поддержке. [209] а в 2007 году конгрессмен-республиканец Бобби Джиндал стал первым губернатором США индийского происхождения, когда он был избран губернатором Луизианы . [210] В 2010 году Никки Хейли , также индийского происхождения и республиканец, стала губернатором Южной Каролины в 2010 году . Республиканец Нил Кашкари также имеет индийское происхождение и баллотировался на пост губернатора Калифорнии в 2014 году . Раджа Кришнамурти, юрист, инженер и общественный деятель из Шаумбурга, штат Иллинойс, с 2017 года является конгрессменом, представляющим 8-й избирательный округ штата Иллинойс . [211] Дженифер Раджкумар — лидер округа Нижнего Манхэттена и первая американка индийского происхождения, избранная в законодательный орган штата в истории Нью-Йорка . [212] В 2016 году Камала Харрис (дочь американской матери тамильского происхождения, доктора Шьямалы Гопалана Харриса афро- ямайского американца , и отца Дональда Харриса) [213] [214] [215] ) стал первым американцем индийского происхождения [216] и вторая афроамериканка, работающая в Сенате США. [217]

В 2020 году Харрис ненадолго баллотировался на пост президента США , а позже был выбран кандидатом на пост вице-президента от Демократической партии вместе с Джо Байденом . [218]

На в США 2024 года президентских выборах Вивек Рамасвами баллотировался как кандидат от Республиканской партии. Тогда Рамасвами выйдет из гонки, чтобы поддержать Дональда Трампа . [219]

Американцы индийского происхождения сыграли значительную роль в содействии улучшению отношений между Индией и Соединенными Штатами , превратив холодное отношение американских законодателей в позитивное восприятие Индии в эпоху после холодной войны. [220]

- Представитель Ами Бера из Калифорнии

- Прит Бхарара работал прокурором Южного округа Нью-Йорка .

- Представитель Вин Гопал , 11-й законодательный округ Нью-Джерси

- Камала Харрис — вице-президент США и первый человек индийского происхождения, избранный в Сенат США.

- Бобби Джиндал был 58-м губернатором Луизианы и бывшим представителем.

- Представитель Прамила Джаяпал из Вашингтона.

- Представитель Ро Ханна из Калифорнии.

- Представитель Раджа Кришнамурти из Иллинойса.

- Далип Сингх Саунд был в 1956 году первым американцем азиатского происхождения, американцем индийского происхождения и представителем неавраамической веры (сикхизм), избранным в Конгресс США .

- Представитель Шри Танедар из Мичигана.

- Сэм Арора — бывший член Палаты делегатов штата Мэриленд.

Известные люди [ править ]

См. также [ править ]

- Индейцы в столичном районе Нью-Йорка

- Индо-карибские американцы

- Американцы мексиканского происхождения пенджабского происхождения

- Американцы Южной Азии

- Отношения Индии и США

- Индийские канадцы

- Индийская диаспора

- Расовая классификация американцев индийского происхождения

- Американцы цыганского происхождения

Ссылки [ править ]

- ^ Лариса Вирстюк (21 апреля 2014 г.). «В центре внимания района: Журнальная площадь» . Джерси-Сити Индепендент . Архивировано из оригинала 30 июня 2018 года . Проверено 26 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ «Дополнительная таблица 2. Лица, получившие законный статус постоянного жителя, по ведущим основным статистическим территориям (CBSA) проживания, а также региону и стране рождения: 2014 финансовый год» . Министерство внутренней безопасности США. Архивировано из оригинала 4 августа 2016 года . Проверено 1 июня 2016 г.

- ^ «Ежегодник иммиграционной статистики: дополнительная таблица 2 за 2013 г.» . Министерство внутренней безопасности США. Архивировано из оригинала 1 мая 2015 года . Проверено 1 июня 2016 г.

- ^ «Ежегодник иммиграционной статистики: дополнительная таблица 2 за 2012 г.» . Министерство внутренней безопасности США. Архивировано из оригинала 22 декабря 2014 года . Проверено 1 июня 2016 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с «АЗИАТСКИЕ ЛИЦА ИЛИ В ЛЮБОЙ КОМБИНАЦИИ ОТДЕЛЬНЫХ ГРУПП. Опрос американского сообщества, подробные таблицы ACS за 5 лет, таблица B02018 » . data.census.gov . Бюро переписи населения США. 2022 . Проверено 17 апреля 2024 г.