University of California, Los Angeles

| |

Former names |

|

|---|---|

| Motto | Fiat lux (Latin) |

Motto in English | "Let there be light" |

| Type | Public land-grant research university |

| Established | May 23, 1919[2] |

Parent institution | University of California |

| Accreditation | WSCUC |

Academic affiliations | |

| Endowment | $3.87 billion (2023)[3] |

| Chancellor | Darnell Hunt (interim) |

| Provost | Michael S. Levine (interim)[4] |

Academic staff | 7,941[5] |

Administrative staff | 32,883 (Fall 2023)[6] |

| Students | 48,048 (Fall 2023)[7] |

| Undergraduates | 33,040 (Fall 2023)[7] |

| Postgraduates | 13,636 (Fall 2023)[7] |

Other students | 1,372 (Fall 2023)[7] |

| Location | , , United States 34°04′20″N 118°26′34″W / 34.0722°N 118.4427°W |

| Campus | Large city[9], 467 acres (189 ha)[8] |

| Newspaper | Daily Bruin |

| Colors | Blue and gold[10] |

| Nickname | Bruins |

Sporting affiliations | |

| Mascot |

|

| Website | ucla.edu |

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA)[1] is a public land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California, United States. Its academic roots were established in 1881 as a normal school then known as the southern branch of the California State Normal School which later evolved into San José State University. The branch was transferred to the University of California to become the Southern Branch of the University of California in 1919, making it the second-oldest of the ten-campus University of California system after the University of California, Berkeley.

UCLA offers 337 undergraduate and graduate degree programs in a range of disciplines,[12] enrolling about 31,600 undergraduate and 14,300 graduate and professional students annually.[13] It received 174,914 undergraduate applications for Fall 2022, including transfers, making it the most applied-to university in the United States.[14] The university is organized into the College of Letters and Science and twelve professional schools.[15] Six of the schools offer undergraduate degree programs: Arts and Architecture, Engineering and Applied Science, Music, Nursing, Public Affairs, and Theater, Film and Television. Three others are graduate-level professional health science schools: Medicine, Dentistry, and Public Health. Its three remaining schools are Education & Information Studies, Management and Law.

UCLA student-athletes will compete as the Bruins in the Big Ten Conference beginning on August 2, 2024.[16] They won 123 NCAA team championships while in the Pac-12 Conference, second only to Stanford University's 128 team titles.[17][18] 410 Bruins have made Olympic teams, winning 270 Olympic medals: 136 gold, 71 silver and 63 bronze.[19] UCLA has been represented in every Olympics since the university's founding (except in 1924) and has had a gold medalist in every Olympics in which the U.S. has participated since 1932.[20]

As of March 2024[update], 16 Nobel laureates, 11 Rhodes scholars, two Turing Award winners, two Chief Scientists of the U.S. Air Force, one Pritzker prize winner, 7 Pulitzer prize winners, two U.S. Poet laureates, one Gauss prize winner, and one Fields Medalist have been affiliated with it as faculty, researchers and alumni.[21][22] As of March 2024[update], 59 associated faculty members have been elected to the National Academy of Sciences, 17 to the American Philosophical Society, 32 to the National Academy of Engineering, 42 to the National Academy of Medicine, 10 to the National Academy of Inventors, and 167 to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[23]

History

[edit]

In March 1881, at the request of state senator Reginaldo Francisco del Valle, the California State Legislature authorized the creation of a southern branch of the California State Normal School (now San José State University) in downtown Los Angeles to train teachers for the growing population of Southern California. The Los Angeles branch of the California State Normal School opened on August 29, 1882, on what is now the site of the Central Library of the Los Angeles Public Library system. The facility included a demonstration school where teachers-in-training could practice their techniques with children. That elementary school would become the present day UCLA Lab School.[24] In 1887, the branch campus became independent and changed its name to Los Angeles State Normal School.[25][26]

In 1914, the school moved to a new campus on Vermont Avenue (now the site of Los Angeles City College) in East Hollywood. In 1917, UC Regent Edward Augustus Dickson, the only regent representing the Southland at the time, and Ernest Carroll Moore, Director of the Normal School, began to lobby the State Legislature to enable the school to become the second University of California campus, after UC Berkeley. They met resistance from UC Berkeley alumni, Northern California members of the state legislature and then-UC President Benjamin Ide Wheeler, who were all vigorously opposed to the idea of a southern campus. However, David Prescott Barrows, the new President of the University of California in 1919, did not share Wheeler's objections.

On May 23, 1919, the Southern Californians' efforts were rewarded when Governor William D. Stephens signed Assembly Bill 626 into law, which acquired the land and buildings and transformed the Los Angeles Normal School into the Southern Branch of the University of California. The same legislation added its general undergraduate program, the Junior College.[27] The Southern Branch campus opened on September 15 of that year, offering two-year undergraduate programs to 250 Junior College students and 1,250 students in the Teachers College.[28] While University of Southern California students criticized the "branch" as a mere "twig", Southern Californians continued to fight Northern Californians for the right to three and then four years of instruction.[29] In December 1923, the Board of Regents authorized a fourth year of instruction and transformed the Junior College into the College of Letters and Science,[30] which awarded its first bachelor's degrees in June 1925.[31]

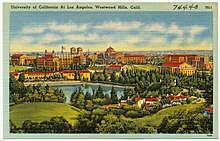

Under UC President William Wallace Campbell, enrollment at the Southern Branch expanded so rapidly that by the mid-1920s the institution was outgrowing the 25 acre Vermont Avenue location. The Regents announced the new "Beverly Site" — just west of Beverly Hills — in 1925. After the athletic teams entered the Pacific Coast conference in 1926, the Southern Branch student council adopted the nickname "Bruins", a name offered by the student council at UC Berkeley.[32] On February 1, 1927, the Regents renamed the Southern Branch the University of California at Los Angeles.[1] In the same year, the state broke ground in Westwood on land sold for $1 million, less than one-third its value, by real estate developers Edwin and Harold Janss, for whom the Janss Steps are named.[26] The campus in Westwood opened to students in 1929.

The original four buildings were the College Library (now Powell Library), Royce Hall, the Physics-Biology Building (which became the Humanities Building and is now the Renee and David Kaplan Hall), and the Chemistry Building (now Haines Hall), arrayed around a quadrangular courtyard on the 400 acre (1.6 km2) campus. The first undergraduate classes on the new campus were held in 1929 with 5,500 students. UCLA was permitted to award the master's degree in 1933, and the doctorate in 1936, against continued resistance from UC Berkeley.[33]

Maturity as a university

[edit]

During its first 32 years, UCLA was treated as an off-site department of the main campus in Berkeley. As such, its presiding officer was called a "provost." In 1951, UCLA was formally elevated to coequal status with UC Berkeley, and its presiding officer Raymond B. Allen was the first chief executive to be granted the title of chancellor. In November 1958,[34] the "at" in UCLA's name was replaced with a comma, a symbol of its independence from Berkeley.[1]

The appointment of Franklin David Murphy to the position of chancellor in 1960 helped spark an era of tremendous growth of facilities and faculty honors. This era secured UCLA's position as a proper university in its own right and not simply a branch of the UC system.

Recent history

[edit]On June 1, 2016, two men were killed in a murder-suicide at an engineering building in the university. School officials put the campus on lockdown as Los Angeles Police Department officers, including SWAT, cleared the campus.[35] In February 2022, Matthew Harris, a former lecturer and postdoctoral fellow at UCLA, was arrested after allegedly making numerous threats of violence against students and faculty members of UCLA's Philosophy Department.[36]

In 2018, a student-led community coalition known as "Westwood Forward" successfully led an effort to break UCLA and Westwood Village away from the existing Westwood Neighborhood Council and form a new North Westwood Neighborhood Council, with over 2,000 out of 3,521 stakeholders voting in favor of the split.[37] Westwood Forward's campaign focused on making housing more affordable and encouraging nightlife in Westwood by opposing many of the restrictions on housing developments and restaurants the Westwood Neighborhood Council had promoted.[38] In 2022, UCLA signed an agreement to partner with the Tongva for the caretaking and landscaping of various areas of the campus. This included land use for ceremonial events and educational workshops and outreach events.[39]

On April 25, 2024, an occupation protest began at UCLA to protest the administration's investments in Israel amid the Israel–Hamas war.[40] On April 28, clashes occurred between pro-Palestinian and pro-Israel protesters as Stand With Us rallied on the campus,[41] in a protest organised by the Israeli American Council.[42] On May 1, violent clashes were reported on the UCLA campus between pro-Palestinian protesters and groups of counter-demonstrators supporting Israel.[43]

Campus

[edit]

The new UCLA campus in 1929 had four buildings: Royce Hall and Haines Hall on the north, and Powell Library and Kinsey Hall (now called Renee And David Kaplan Hall) on the south. The Janss Steps were the original 87-step entrance to the university that lead to the quad of these four buildings. Today, the campus includes 163 buildings across 419 acres (1.7 km2) in the western part of Los Angeles, north of the Westwood shopping district and just south of Sunset Boulevard. In terms of acreage, it is the second-smallest of the ten UC campuses.[8] The Channel Islands are visible from the UCLA campus.

Architecture

[edit]

The first buildings were designed by the local firm Allison & Allison. The Romanesque Revival style of these first four structures remained the predominant building style until the 1950s, when architect Welton Becket was hired to supervise the expansion of the campus over the next two decades. Romanesque Revival was chosen as an alternative to Collegiate Gothic to parallel the climate of Southern California to the warm, sunny weather of the Southern Mediterranean.

Becket greatly streamlined its general appearance, adding several rows of minimalist, slab–shaped brick buildings to the southern half, the largest of these being the UCLA Medical Center.[45] Architects such as A. Quincy Jones, William Pereira, and Paul Williams designed many subsequent structures on the campus during the mid-20th century. More recent additions include buildings designed by architects I.M. Pei, Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Richard Meier, Cesar Pelli, and Rafael Vinoly. To accommodate UCLA's rapidly growing student population, multiple construction and renovation projects are in progress, including expansions of the life sciences and engineering research complexes. This continuous construction gives UCLA the nickname "Under Construction Like Always".[46]

One notable building on campus is named after African-American alumnus Ralph Bunche, who received the 1950 Nobel Peace Prize for negotiating an armistice agreement between the Jews and Arabs in Israel. The entrance of Bunche Hall features a bust of him overlooking the Franklin D. Murphy Sculpture Garden. He was the first individual of non-European background and the first UCLA alumnus to be honored with the Prize.

The Hannah Carter Japanese Garden is located a mile north of campus, in the community of Bel Air. The garden was designed by landscape architect Nagao Sakurai of Tokyo and garden designer Kazuo Nakamura of Kyoto in 1959. The garden was donated to UCLA by former UC regent and UCLA alumnus Edward W. Carter and his wife Hannah Carter in 1964 with the stipulation that it remains open to the public.[47] After the garden was damaged by heavy rains in 1968, UCLA Professor of Art and Campus Architect Koichi Kawana took on the task of its reconstruction.[48] The property was sold in 2016 and public access is no longer required.[47]

Filming

[edit]

UCLA has attracted filmmakers for decades with its proximity to Hollywood. It was used to represent fictional Windsor College in Scream 2 (1997).[49] In response to frequent requests for filming at the campus, UCLA has instated a policy to regulate filming and professional photography.[50]"UCLA is located in Los Angeles, the same place as the American motion picture industry", said UCLA visiting professor of film and television Jonathan Kuntz.[51] "So we're convenient for (almost) all of the movie companies, TV production companies, commercial companies and so on. We're right where the action is."

Academics

[edit]College and schools

[edit]College and schools of the university - with the year of their founding - include:

Undergraduate[edit]

Graduate[edit]

|

Healthcare

[edit]

The David Geffen School of Medicine, School of Nursing, School of Dentistry and Fielding School of Public Health constitute the professional schools of health science. The UCLA Health System operates the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, a hospital in Santa Monica and twelve primary care clinics throughout Los Angeles County. In addition, the UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine uses two Los Angeles County public hospitals as teaching hospitals—Harbor–UCLA Medical Center and Olive View–UCLA Medical Center—as well as the largest private nonprofit hospital on the west coast, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. The Greater Los Angeles VA Medical Center is also a major teaching and training site for the university.

The UCLA Medical Center made history in 1981 when Assistant Professor Michael Gottlieb first diagnosed AIDS. UCLA medical researchers also pioneered the use of positron emission tomography (PET) scanning to study brain function. Professor of Pharmacology Louis Ignarro was one of the recipients of the 1998 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering the signaling cascade of nitric oxide, one of the most important molecules in cardiopulmonary physiology. The U.S. News & World Report Best Hospitals ranking for 2021 ranks UCLA Medical Center 3rd in the United States and 1st in the West.[52] UCLA Medical Center was ranked within the top 20 in the United States for 15 out of 16 medical specialty areas examined.[53]

Research

[edit]UCLA is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity" and had $1.32 billion in research expenditures in 2018.[54][55]

Rankings

[edit]

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

National

[edit]The 2024 U.S. News & World Report Best Colleges report ranked UCLA first among public universities and tied for 15th among national universities.[67] The Washington Monthly ranked UCLA 22nd among national universities in 2021, with criteria based on research, community service, and social mobility. The Money Magazine Best Colleges ranking for 2015 ranked UCLA 26th in the United States, based on educational quality, affordability and alumni earnings.[68] In 2014, The Daily Beast's Best Colleges report ranked UCLA 10th in the country.[69] The Kiplinger Best College Values report for 2015 ranked UCLA 6th for value among American public universities.[70] The Wall Street Journal and Times Higher Education ranked UCLA 26th among national universities in 2016.[71] The 2013 Top American Research Universities report by the Center for Measuring University Performance ranks UCLA 11th in power, 12th in resources, faculty, and education, 14th in resources and education and 9th in education.[72] The 2015 Princeton Review College Hopes & Worries Survey ranked UCLA as the No. 5 "Dream College" among students and the No. 10 "Dream College" among parents.[73] The National Science Foundation ranked UCLA 6th among American universities for research and development expenditures in 2021 with $1.45 billion.[74] In 2017 The New York Times ranked UCLA 1st for economic upward-mobility among 65 "elite" colleges in the United States.[75]

Global

[edit]The Times Higher Education World University Rankings for 2017–2018 ranks UCLA 15th in the world for academics, No.1 US Public University for academics, and 13th in the world for reputation.[76] In 2020, it ranked 16th among the universities around the world by SCImago Institutions Rankings.[77] UCLA was ranked 33rd in the QS World University Rankings in 2017 and 12th in the world (10th in North America) by the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) in 2017. In 2017, the Center for World University Rankings (CWUR) ranked the university 15th in the world based on quality of education, alumni employment, quality of faculty, publications, influence, citations, broad impact, and patents.[78] The 2017 U.S. News & World Report Best Global University Rankings report ranked UCLA 10th in the world.[79] The CWTS Leiden ranking of universities based on scientific impact for 2017 ranks UCLA 14th in the world.[80] The University Ranking by Academic Performance (URAP) conducted by Middle East Technical University for 2016–2017 ranked UCLA 12th in the world based on the quantity, quality and impact of research articles and citations.[81] The Webometrics Ranking of World Universities for 2017 ranked UCLA 11th in the world based on the presence, impact, openness and excellence of its research publications.[82]

Graduate school

[edit]

As of March 2021[update], the U.S. News & World Report Best Graduate Schools report ranked the Graduate School of Education and Information Studies (GSEIS) 3rd, the Anderson School of Management 18th, the David Geffen School of Medicine tied for 12th for Primary Care and 21st for Research, the School of Law 14th, the Henry Samueli School of Engineering and Applied Science (HSSEAS) 16th, the Jonathan and Karin Fielding School of Public Health 10th, and the School of Nursing 16th.[79] The QS Global 200 MBA Rankings report for 2015 ranks the Anderson School of Management 9th among North American business schools.[83] The 2014 Economist ranking of Full-time MBA programs ranks the Anderson School of Management 13th in the world.[84] The 2014 Financial Times ranking of MBA programs ranks the Anderson School 26th in the world.[85] The 2014 Bloomberg Businessweek ranking of Full-time MBA programs ranks the Anderson School of Management 11th in the United States.[86] The 2014 Business Insider ranking of the world's best business schools ranks the Anderson School of Management 20th in the world.[87] The 2014 Eduniversal Business Schools Ranking ranks the Anderson School of Management 15th in the United States.[88] In 2015, career website Vault ranked the Anderson School of Management 16th among American business schools,[89] and the School of Law 15th among American law schools.[90] In 2015, financial community website QuantNet ranked the Anderson School of Management's Master of Financial Engineering program 12th among North American financial engineering programs.[91] The U.S. News & World Report Best Online Programs report for 2016 ranked the Henry Samueli School of Engineering and Applied Science (HSSEAS) 1st among online graduate engineering programs.[92]

Departmental

[edit]Departments ranked in the national top ten by the 2016 U.S. News & World Report Best Graduate Schools report are Clinical Psychology (1st), Fine Arts (2nd), Psychology (2nd), Medical School: Primary Care (6th), Math (7th), History (9th), Sociology (9th), English (10th), Political Science (10th), and Public Health (10th).[79] Departments ranked in the global top ten by the 2016 U.S. News & World Report Best Global Universities report are Arts and Humanities (7th), Biology and Biochemistry (10th), Chemistry (6th), Clinical Medicine (10th), Materials Science (10th), Mathematics (7th), Neuroscience and Behavior (7th), Psychiatry/Psychology (3rd) and Social Sciences and Public Health (8th).[93]

Departments ranked in the global top ten by the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) for 2015 are Mathematics (8th)[94] and Computer Science (9th).[95] Departments ranked in the global top ten by the QS World University Rankings for 2020 are English Language & Literature (9th),[96] Linguistics (10th),[97] Modern Languages (7th),[98] Medicine (7th),[99] Psychology (6th),[100] Mathematics (9th),[101] Geography (5th),[102] Communications & Media Studies (13th),[103] Education (11th)[104] and Sociology (7th).[105]

Academic field

[edit]Academic field rankings in the global top ten according to the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) for 2015 are Clinical Medicine and Pharmacy (10th).[106] Academic field rankings in the global top ten according to the Times Higher Education World University Rankings for 2014–2015 include Arts & Humanities (10th),[107] Clinical, Pre-clinical and Health (9th),[108] Engineering and Technology (9th),[109] Physical Sciences (9th),[110] and Social Sciences (9th).[111] Academic field rankings in the global top ten according to the QS World University Rankings for 2015 are Arts & Humanities (10th)[112] and Life Sciences and Medicine (10th).[113]

Student body

[edit]The Institute of International Education ranked UCLA the American university with the seventh-most international students in 2016 (behind NYU, USC, Arizona State, Columbia University, The University of Illinois, and Northeastern University).[114] In 2014, Business Insider ranked UCLA 5th in the world for the number of alumni working at Google (behind Stanford, Berkeley, Carnegie Mellon, and MIT).[115] In 2015, Business Insider ranked UCLA 10th among American universities with the most students hired by Silicon Valley companies.[116] In 2015, research firm PitchBook ranked UCLA 9th in the world for venture capital raised by undergraduate alumni, and 11th in the world for producing the most MBA graduate alumni who are entrepreneurs backed by venture capital.[117]

Library system

[edit]

UCLA's library system has over nine million books and 70,000 serials in over twelve libraries and eleven other archives, reading rooms, and research centers. It is the United States' 12th largest library in number of volumes.[118] The first library, University Library (presently Powell Library), was founded in 1884. Lawrence Powell became librarian in 1944, and began a series of system overhauls and modifications, and in 1959, was named Dean of the School of Library Service.[119] More libraries were added as previous ones filled.

Medical school admissions

[edit]According to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), UCLA supplies the most undergraduate applicants to U.S. medical schools among all American universities. In 2015, UCLA supplied 961 medical school applicants, followed by UC Berkeley with 819 and the University of Florida with 802.[120] Among first-time medical school applicants who received their bachelor's degree from UCLA in 2014, 51% were admitted to at least one U.S. medical school.[121]

Admissions

[edit]Undergraduate

[edit]| 2022[122] | 2021 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Applicants | 149,813 | 139,485 | 108,877 |

| Admits | 12,825 | 15,004 | 15,602 |

| Admit rate | 8.6% | 10.8% | 14.4% |

| Enrolled | N/A | 6,300 | 6,386 |

| Average GPA (weighted) | 4.21–4.31 | 4.0 | 3.90 |

| SAT range | N/A | N/A | 1290–1510 |

| ACT range | N/A | N/A | 29–34 |

U.S. News & World Report rates UCLA "Most Selective"[123] and The Princeton Review rates its admissions selectivity of 98 out of 99.[124] 149,815 prospective freshmen applied for Fall 2021, the most of any four-year university in the United States.[125]

Admission rates vary according to the residency of applicants. For Fall 2019, California residents had an admission rate of 12.0%, while out-of-state U.S. residents had an admission rate of 16.4% and internationals had an admission rate of 8.4%.[126] UCLA's overall freshman admit rate for the Fall 2019 term was 12.3%.[127]

As of 2020, the basis for selection at UCLA includes several academic and nonacademic factors. Those considered "very important" are all academic; they are rigor of secondary school record, academic GPA, standardized test scores, and application essay(s). Those considered "important" are talent/ability, character/personal qualities, volunteer work, work experience, and extracurricular activities. Factors that are not considered at all include class rank, interviews, alumni relation, and racial/ethnic status.[127] UCLA is need-blind for domestic applicants.[128]

Enrolled freshman for Fall 2019 had an unweighted GPA of 3.90, an SAT interquartile range of 1280–1510, and an ACT interquartile range of 27–34. The SAT interquartile ranges were 640–740 for reading/writing and 640–790 for math.[127] Among the admitted freshman applicants for the Fall 2019 term, 43.1% chose to enroll at UCLA.[127]

UCLA's freshman admission rate varies drastically across colleges. For Fall 2016, the College of Letters and Science had an admission rate of 21.2%, the Henry Samueli School of Engineering and Applied Science (HSSEAS) had an admission rate of 12.4%, the Herb Alpert School of Music had an admission rate of 23.5%, the School of the Arts and Architecture had an admission rate of 10.3%, the School of Nursing had an admission rate of 2.2%, and the School of Theater, Film and Television had an admission rate of 4.4%.[129]

One of the major issues is the decreased admission of African-Americans since the passage of Proposition 209 in 1996, prohibiting state governmental institutions from considering race, sex, or ethnicity, specifically in the areas of public employment, public contracting, and public education.[130] UCLA responded by shifting to a holistic admissions process in Fall 2007,[131] which evaluates applicants based on their opportunities in high school, personal hardships, and unusual circumstances at home.

Graduate

[edit]

For Fall 2020, the David Geffen School of Medicine admitted 2.9% of its applicants, making it the 8th most selective U.S. medical school.[132] The School of Law had a median undergraduate GPA of 3.82 and median Law School Admission Test (LSAT) score of 170 for the enrolled class of 2024.[133] The Anderson School of Management had a middle-80% GPA range of 3.1–3.8 and an average Graduate Management Admission Test (GMAT) score of 711 for the enrolled MBA class of 2024.[134]

The School of Dentistry had an average overall GPA of 3.65, an average science GPA of 3.6 and an average Dental Admissions Test (DAT) score of 22.8 for the enrolled class of 2025.[135] The Graduate School of Nursing has an acceptance rate of 33% as of 2022[update].[136] For Fall 2020, the Henry Samueli School of Engineering and Applied Science (HSSEAS) had a graduate acceptance rate of 27%.[137]

Economic impact

[edit]The university has a significant impact in the Los Angeles economy. It is the fifth largest employer in the county (after Los Angeles County, the Los Angeles Unified School District, the federal government and the City of Los Angeles) and the seventh largest in the region.[138][139]

Trademarks and licensing

[edit]The UCLA trademark "is the exclusive property of the Regents of the University of California",[140] but it is managed, protected, and licensed through UCLA Trademarks and Licensing, a division of the Associated Students UCLA, the largest student employer on campus.[141][142] As such, the ASUCLA also has a share in trademark profits.

Apparel, fashion accessories and other items with UCLA'S logo and insignea are popular in many parts of the world due to both the university's academic and athletic prestige, and its association with colorful images of Southern California life and culture. This demand for UCLA-branded merchandise has inspired the licensing of its trademark to UCLA brand stores throughout Europe, the Middle East and Asia. Since 1980, 15 UCLA stores have opened in South Korea, and 49 are currently open in China. The newest store recently opened in Kuwait;[143] there are also stores in Mexico, Singapore and India.[144] UCLA earns about $400,000 in royalties each year through its international licensing program.[144]

Commerce on campus

[edit]

UCLA has various store locations around campus, with the main store in Ackerman Union. In addition, UCLA-themed products are sold at the gift shop of Fowler Museum on campus. Due to licensing and trademarks, products with UCLA logos and insignia are usually higher priced than their unlicensed counterparts. These products are popular among visitors, who buy them as gifts and souvenirs. The UCLA store offers some products, such as notebooks and folders, in both licensed (logoed) and cheaper unlicensed (un-logoed) options, but for other products the latter option is often unavailable. Students employed part-time by ASUCLA at UCLA Stores and Restaurants receive discounts when they shop at UCLA Stores.

Athletics

[edit]

The school's sports teams are called the Bruins, represented by the colors true blue and gold. The Bruins participate in NCAA Division I as part of the Big Ten Conference. Two notable sports facilities serve as home venues for UCLA sports. The Bruin men's football team plays home games at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena; the team won a national title in 1954. The basketball and volleyball teams, and the women's gymnastics team compete at Pauley Pavilion on campus. The school also sponsors cross country, soccer, women's rowing, golf, tennis, water polo, track and field, and women's softball.

The mascots are Joe and Josephine Bruin, and the fight songs are Sons of Westwood and Mighty Bruins. The alma mater is Hail to the Hills of Westwood. When Henry "Red" Sanders came to UCLA to coach football in 1949, the uniforms were redesigned. Sanders added a gold loop on the shoulders—the UCLA Stripe. The navy blue was changed to a lighter shade of blue. Sanders figured that the baby blue would look better on the field and in film. He dubbed the uniform "Powder Keg Blue", a powder blue with an explosive kick. This would also differentiate UCLA from all other UC teams, whose official colors are blue and gold.

UCLA competes in all major Division I sports and has won 135 national championships, including 123 NCAA championships. Only Stanford University has more NCAA team championships, with 135.[145] On April 21, 2018, UCLA's women's gymnastics team defeated Oklahoma Sooners to win its 7th NCAA National Championship as well as UCLA's 115th overall team title. Most recently, UCLA's women's soccer team defeated Florida State to win its first NCAA National Championship along with women's tennis who defeated North Carolina to win its second NCAA National title ever.[146] UCLA's softball program is also outstanding.[147] Women's softball won their NCAA-leading 12th National Championship, on June 4, 2019. The women's water polo team is also dominant, with a record 7 NCAA championships. Notably, the team helped UCLA become the first school to win 100 NCAA championships overall when they won their fifth on May 13, 2007.

The men's water polo team won UCLA's 112th, 113th, and 114th national championships, defeating USC in the championship game three times: on December 7, 2014, on December 6, 2015, and on December 3, 2017. On October 9, 2016, the top-ranked men's water polo team broke the NCAA record for consecutive wins when they defeated UC Davis for their 52nd straight win. This toppled Stanford's previous record of 51 consecutive wins set in 1985–87. The men's water polo team has become a dominant sport on campus with a total of 11 national championships.

Among UCLA's 123 championship titles, some of the more notable victories are in men's basketball. Under legendary coach John Wooden, UCLA men's basketball teams won 10 NCAA championships, including a record seven consecutive, in 1964, 1965, 1967–1973, and 1975, and an 11th was added under then-coach Jim Harrick in 1995 (through 2008, the most consecutive by any other team is two).[147] From 1971 to 1974, UCLA men's basketball won an unprecedented 88 consecutive games.UCLA has also shown dominance in men's volleyball, with 21 national championships. The first 19 teams were led by former[148] coach Al Scates. UCLA is one of only six universities (Michigan, Stanford, Ohio State, California, and Florida being the others) to have won national championships in all three major men's sports (baseball, basketball, and football).[149]

USC rivalry

[edit]

UCLA shares a traditional sports rivalry with the University of Southern California. UCLA teams have won the second-most NCAA Division I-sanctioned team championships, while USC has the third-most.[150][151][152] Only Stanford University, a fellow Pac-12 member also located in California, has more than either UCLA or USC. The football rivalry is distinctive for two of the strongest conference programs located in one city. In football, UCLA has one national champion team and 16 conference titles, compared to USC's 11 national championships and 37 conference championships. The two football teams compete for annual possession of the Victory Bell, the trophy of the rivalry football game.

The schools share a rivalry in many other sports, and are each the best in the nation for many. UCLA has won 19 NCAA Championships in men's volleyball, 11 in men's basketball, 12 in Softball, and 7 in women's water polo, the most of any school in those sports. USC has won 26 NCAA Championships in Men's Outdoor Track and Field, 21 in men's tennis, and 12 in baseball, also the most of any school in each respective sport. The annual SoCal BMW Crosstown Cup compares the two schools based on their performance in 19 varsity sports; UCLA has won five times and USC has won nine times. This rivalry extends to the Olympic Games, where UCLA athletes have won 250 medals over a span of 50 years while USC athletes have won 287 over 100 years.[153][154][155] UCLA and USC also compete in the We Run The City 5K, an annual charity race to raise donations for Special Olympics Southern California. The race is located on the campus of one of the schools and switches to the other campus each year. USC won the race in 2013 and 2015, while UCLA won the race in 2012, 2014, 2016, and 2017.[156]

Student life

[edit]| Race and ethnicity[157] | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Asian | 29% | ||

| White | 26% | ||

| Hispanic | 22% | ||

| Foreign national | 10% | ||

| Other[a] | 9% | ||

| Black | 3% | ||

| Economic diversity | |||

| Low-income[b] | 25% | ||

| Affluent[c] | 75% | ||

The campus is located near prominent entertainment venues such as the Getty Center, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and the Santa Monica Pier. UCLA offers classical orchestras, intramural sports, and over 1000 student organizations [158] UCLA is also home to 66 fraternities and sororities, which represent 13% of the undergraduate population.[159] Phrateres, a non-exclusive social-service club for women was founded here in 1924 by the Dean of Women, Helen Matthewson Laughlin. Students and staff participate in dinghy sailing, surfing, windsurfing, rowing, and kayaking at the UCLA Marina Aquatic Center in Marina del Rey.

UCLA is home to a slew of performing arts groups, including an improv comedy team called Rapid Fire. UCLA's first contemporary a cappella group, Awaken A Cappella, was founded in 1992. The all-male group, Bruin Harmony, has enjoyed a successful career since its inception in 2006, portraying a collegiate a cappella group in The Social Network (2010), while the ScatterTones finished in second-place in the International Championship of Collegiate A Cappella (ICCA) in 2012, 2013, and 2014, and third-place in 2017, 2019, and 2022. In 2020, The A Cappella Archive ranked the ScatterTones at #2 among all ICCA-competing groups.[160] Resonance, founded in 2012, was an ICCA finalist in 2021. Other a cappella groups include Signature, Random Voices, Medleys, YOUTHphonics, Deviant Voices, AweChords, Pitch Please, Da Verse, Naya Zaamana, Jewkbox, On That Note, Tinig Choral, and Cadenza.[161] YOUTHphonics and Medleys are UCLA's only nonprofit service-oriented a cappella groups.[162]

There are a variety of cultural organizations on campus, such as Nikkei Student Union (NSU), Japanese Student Association (JSA),[163] Association of Chinese Americans (ACA), Chinese Students and Scholars Association (CSSA), Chinese Music Ensemble (CME), Chinese Cultural Dance Club (CCDC), Taiwanese American Union (TAU), Taiwanese Student Association (TSA), Hong Kong Student Society (HKSS), Hanoolim Korean Cultural Awareness Group, Samahang Pilipino, Vietnamese Student Union (VSU), and Thai Smakom. Many of these organizations have an annual "culture night" consisting of drama and dance which raises awareness of culture and history to the campus and community.

Additionally, there are over twenty LGBTQ organizations on campus, including the undergraduate student organizations Queer Alliance, BlaQue, Lavender Health Alliance, OutWrite Newsmagazine, Queer and Trans in STEM (qtSTEM), and Transgender UCLA Pride (TransUP) as well as the graduate student organizations Out@Anderson, OUTLaw, and Luskin PRIDE.[164][165] Notably, OutWrite, established under the name TenPercent in 1979, is the first college queer newsmagazine in the country.[166] UCLA operates on a quarter calendar with the exception of the UCLA School of Law and the UCLA School of Medicine, which operate on a semester calendar.

Traditions

[edit]

UCLA's official charity is UniCamp, founded in 1934. It is a week-long summer camp for under-served children from the greater Los Angeles area, with UCLA volunteer counselors. UniCamp runs for seven weeks throughout the summer at Camp River Glen in the San Bernardino National Forest. Because UniCamp is a non-profit organization, student volunteers from UCLA also fundraise money throughout the year to allow these children to attend summer camp.[167]

The Pediatric AIDS Coalition organizes the annual Dance Marathon in Pauley Pavilion, where thousands of students raise a minimum of $250 and dance for 26 hours to support the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation, Project Kindle, and the UCLA AIDS Institute. Dancers are not allowed to sit (except to use the restroom) during the marathon, literally taking a stand against pediatric AIDS, and symbolizing the suffering of affected children around the world. In 2015, Dance Marathon at UCLA raised $446,157.[168]

During Finals Week, UCLA students participate in "Midnight Yell", where they yell as loudly as possible for a few minutes at midnight to release some stress from studying. The quarterly Undie Run takes place during the Wednesday evening of Finals Week, when students run through the campus in their underwear or in skimpy costumes.[169] With the increasing safety hazards and Police and Administration involvement, a student committee changed the route to a run through campus to Shapiro Fountain, which culminates with students dancing in the fountain.[170] The Undie Run has spread to other American universities, including the University of Texas at Austin, Arizona State University, and Syracuse University.[citation needed]

The Alumni Association sponsors several events, usually large extravaganzas involving huge amounts of coordination, such as the 70-year-old Spring Sing, organized by the Student Alumni Association (SAA). UCLA's oldest tradition, Spring Sing is an annual gala of student talent, which is held at either Pauley Pavilion or the outdoor Los Angeles Tennis Center. The committee bestows the George and Ira Gershwin Lifetime Achievement Award each year to a major contributor to the music industry. Past recipients have included Stevie Wonder, Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, James Taylor, Ray Charles, Natalie Cole, Quincy Jones,[171] Lionel Richie, and in 2009, Julie Andrews.[172] The Dinner for 12 Strangers is a gathering of students, alumni, administration and faculty to network around different interests.[173] The "Beat 'SC Bonfire and Rally" occurs the week before the USC rivalry football game.

The USAC Cultural Affairs Commission hosts the JazzReggae Festival, a two-day concert on Memorial Day weekend that attracts more than 20,000 attendees. The JazzReggae Festival is the largest entirely student produced and run event of its kind on the West Coast.[174]

Sigma Eta Pi and Bruin Entrepreneurs organize LA Hacks, an annual hackathon where students from around the United States come to build technology products. LA Hacks established itself as the largest hackathon in the United States when over 1500 students participated on April 11–13, 2014.[175] LA Hacks also holds the record for the most funds raised via corporate sponsorships with $250,000 raised. Some of the tech world's most prominent people have given talks and judged projects at LA Hacks, including Evan Spiegel (Founder and CEO of Snapchat), Alexis Ohanian (co-founder of Reddit), Sam Altman (President of Y Combinator) and Chris De Wolfe (Founder of Myspace).

Student government

[edit]

The Associated Students UCLA (ASUCLA) encompasses the student government and student-led enterprises at UCLA. ASUCLA has four major components: the Undergraduate Students Association, the Graduate Students Association, Student Media, and Services & Enterprises. However, in common practice, the term ASUCLA refers to the services and enterprises component. This includes the Student Store, Bookstore, Food Services, Student Union, etc. These commercial enterprises generate approximately $40 million in annual revenues.[176] As a nonprofit corporation, the financial goal of ASUCLA is to provide quality services and programs for students. ASUCLA is governed by a student-majority Board of Directors. The Undergraduate Students Association and Graduate Students Association each appoint three members plus one alternative. In addition to the student members, there are representatives appointed by the administration, the academic senate, and the alumni association. The "services and enterprises" portion of ASUCLA is run by a professional executive director who oversees some 300 staff and 2,000 student employees.

The Graduate Students Association is the governing body for approximately 13,000 graduate and professional students at UCLA.[177] The Undergraduate Students Association Council (USAC) is the governing body of the Undergraduate Students Association (USA) whose membership comprises every UCLA undergraduate student.[178] As of 2015[update], the student body had two major political slates: Bruins United and Let's Act. In the Spring 2016 election, the two competing parties were Bruins United and Waves of Change—a smaller faction that broke off of Lets Act.

USAC's fourteen student officers and commissioners are elected by members of the Undergraduate Students Association at an annual election held during Spring Quarter. In addition to its fourteen elected members, USAC includes appointed representatives of the Administration, the Alumni, and the Faculty, as well as two ex-officio members, the ASUCLA Executive Director and a student Finance Committee Chairperson who is appointed by the USA President and approved by USAC. All members of USAC may participate fully in Council deliberations, but only the elected officers, minus the USAC President may vote. Along with the council, the student government also includes a seven-member Judicial Board, which similar to the Supreme Court, serves as the judicial branch of government and reviews actions of the council. These seven students are appointed by the student body president and confirmed by the council.

USAC's programs offers additional services to the campus and surrounding communities. For example, each year approximately 40,000 students, faculty and staff attend programs of the Campus Events Commission, including a low-cost film program, a speakers program which presents leading figures from a wide range of disciplines, and performances by dozens of entertainers. Two to three thousand UCLA undergraduates participate annually in the more than twenty voluntary outreach programs run by the Community Service Commission. A large corps of undergraduate volunteers also participate in programs run by the Student Welfare Commission, such as AIDS Awareness, Substance Abuse Awareness, Blood Drives and CPR/First Aid Training. The film program is part of the Bruin Film Society, which is also a registered organization to host advance screenings of films during Oscars season.[179][180] It hosts other events, like filmmaker panels, through its partnership with production and distribution company A24.[181]

Media publications

[edit]UCLA Student Media is the home of UCLA's newspaper, magazines, and radio station.[182] Most student media publications are governed by the ASUCLA Communications Board. The Daily Bruin is UCLA's most prominent student publication. Founded in 1919 under the name Cub Californian, it has since then developed into Los Angeles' third-most circulated newspaper. It has won dozens of national awards and is regularly commended for layout and content. In 2016, the paper won two National Pacemaker Awards – one for the best college newspaper in the country, and another for the best college media website in the country.[183]

UCLA Student Media also publishes seven special-interest news magazines: Al-Talib, Fem, Ha'Am, La Gente, Nommo, Pacific Ties, and OutWrite, a school yearbook, BruinLife, and the student-run radio station, UCLA Radio. Student groups such as The Forum for Energy Economics and Development also publish yearly journals focused on energy technologies and industries. There is also a student-run satire newspaper, The Westwood Enabler.[184] There are also numerous graduate student-run journals at UCLA, such as Carte Italiane, Issues in Applied Linguistics, and Mediascape.[185] Many of these publications are available through open access. The School of Law publishes the UCLA Law Review which is currently ranked seventh among American law schools.[186]

Housing

[edit]

UCLA provides housing to over 10,000 undergraduate and 2,900 graduate students.[187] Most undergraduate students are housed in 14 complexes on the western side of campus, referred to by students as "The Hill". Students can live in halls, plazas, suites, or university apartments, which vary in pricing and privacy. Housing plans also offer students access to dining facilities, which have been ranked by the Princeton Review as some of the best in the United States.[188] Dining halls are located in Covel Commons, Rieber Hall, Carnesale Commons and De Neve Plaza. In winter 2012, a dining hall called The Feast at Rieber opened to students. The newest dining hall (as of Winter Quarter 2014) is Bruin Plate, located in the Carnesale Commons (commonly referred to as Sproul Plaza). Residential cafes include Bruin Cafe, Rendezvous, The Study at Hedrick, and Cafe 1919.[189] UCLA currently offers four years guaranteed housing to its incoming freshmen, and two years to incoming transfer students. There are four types of housing available for students: residential halls, deluxe residential halls, residential plazas, and residential suites. Available on the hill are study rooms, basketball courts, tennis courts, and Sunset Recreational Center which includes three swimming pools.

Graduate students are housed in one of five apartment complexes. Weyburn Terrace is located just southwest of the campus in Westwood Village. The other four are roughly five miles south of UCLA in Palms and Mar Vista. They too vary in pricing and privacy.[190] Approximately 400 students live at the University Cooperative Housing Association, located two blocks off campus.[191] Students who are involved in Greek life have the option to also live in Greek housing while at UCLA. Sorority houses are located east of campus on Hilgard Avenue, and fraternity houses are located west of campus throughout Westwood Village. A student usually lives with 50+ students in Greek housing.

Hospitality

[edit]Hospitality constituents of the university include departments not directly related to student life or administration. The Hospitality department manages the university's two on-campus hotels, the UCLA Guest House and the Meyer and Renee Luskin Conference Center. The 61-room Guest House services those visiting the university for campus-related activities.[192] The department also manages the UCLA Conference Center, a 40-acre (0.2 km2) conference center in the San Bernardino Mountains near Lake Arrowhead.[193] Hospitality also operates UCLA Catering,[194] a vending operation, and a summer conference center located on the Westwood campus.[195]

Chabad House

[edit]The UCLA Chabad House is a community center for Jewish students operated by the Orthodox Jewish Chabad movement. Established in 1969, it was the first Chabad House at a university.[196][197] In 1980, three students died in a fire in the original building of the UCLA Chabad House. The present building was erected in their memory. The building, completed in 1984, was the first of many Chabad houses worldwide designed as architectural reproductions of the residence of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson at 770 Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn, New York.[196] The Chabad House hosts the UCLA chapter of The Rohr Jewish Learning Institute's Sinai Scholars Society.[198][199]

Healthy Campus Initiative

[edit]In January 2013, Chancellor Gene Block launched the UCLA Healthy Campus Initiative (HCI), envisioned and supported by Jane and Terry Semel.[200] The Semel HCI prioritizes the health and wellness of UCLA students, staff, and faculty by "making the healthy choice the easy choice."[200] The goal of the initiative is to make UCLA the healthiest campus in the country, and to share best practices and research with other communities, locally and beyond.[201] The initiative is a campuswide, multi-year effort that champions programs such as the tobacco-free policy,[202] expansion of campus gardens,[203] stairwell makeovers,[204] bicycle infrastructure improvements,[205] healthy and sustainable dining options,[206] and peer counseling,[207] among others.

The UCLA Healthy Campus Initiative is credited with providing inspiration for national initiatives including the Partnership for a Healthier America (PHA) Healthier Campus Initiative and the University of California Office of the President (UCOP) Global Food Initiative (GFI).[203][200] In November 2014, UCLA was one of the 20 inaugural colleges and universities to pledge to adopt PHA's guidelines for food and nutrition, physical activity and programming over three years.[200] The Semel HCI is a member of both the Menus of Change Research Collaborative[208] and the Teaching Kitchen Collaborative,[209] and a contributor to The Huffington Post.[210]

Faculty and alumni

[edit]This section contains too many pictures for its overall length. (December 2023) |

Award laureates and scholars

[edit]UCLA's faculty and alumni have won a number of awards including:[211]

- 105 Academy Awards

- 278 Emmy Awards

- 1 Fields Medal

- 3 Turing Awards

- 11 Fulbright Scholars (since 2000)

- 78 Guggenheim Fellows[212]

- 50 Grammy Awards

- 16 MacArthur Fellows

- 1 Mark Twain Prize for American Humor

- 10 National Medals of Science

- 16 Nobel Laureates

- 3 Presidential Medals of Freedom

- 1 Pritzker Prize in Architecture

- 3 Pulitzer Prizes

- 1 Rome Prize in Design

- 12 Rhodes Scholars

- 1 Medal of Honor

- 2 Mitchell Scholars

- Notable UCLA alumni include:

- Джеки Робинсон , первый афроамериканский игрок в MLB

- Джеймс Франко , актер, номинант на премию Оскар

- Карим Абдул-Джаббар , 2-й НБА результат в истории

- Шон Эстин , актер

- Артур Эш , бывший теннисист №1 мира, выигравший три Большого шлема . титула

- Сара Барейлес , премии Грэмми. певица и автор песен, обладательница

- Рэнди Ньюман , певец и автор песен

- Бен Шапиро , консервативный политический обозреватель

- Стефано Блох , автор, художник-граффитист, академик

- Джек Блэк , актер и комик

- Маим Бялик , актриса и ведущая Jeopardy!

- Том Брэдли , первый афроамериканский мэр Лос-Анджелеса

- Кэрол Бёрнетт , актриса

- Стив Мартин , актер и комик

- Роб Райнер , актер и режиссер

- Бен Стиллер , актер и комик

- Джонни Кокран , юрист и борец за гражданские права

- Фрэнсис Форд Коппола , режиссер, лауреат премии Оскар

- Пол Шрейдер , сценарист и кинорежиссер

- Марк Хармон , актер и продюсер

- Джордж Такей , актер и активист

- Кирстен Гиллибранд , сенатор США от Нью-Йорка

- Джеймс Дин , актер

- Джимми Коннорс , бывший теннисист №1 мира, выигравший восемь Большого шлема . титулов

- Майкл Морхейм , сооснователь Blizzard Entertainment

- Джим Моррисон , солист группы The Doors

- Тим Роббинс , актер, обладатель премии Оскар

- Рассел Уэстбрук , MVP НБА и небывалый лидер по трипл-даблу

- Азаде Киан , социолог и директор Парижского университета Сите

По состоянию на октябрь 2023 года с Калифорнийским университетом в Лос-Анджелесе сотрудничали 28 нобелевских лауреатов: 12 профессоров, [213] 8 выпускников и 10 исследователей (три совпадения). [214] Двумя другими преподавателями, получившими Нобелевскую премию, были Бертран Рассел и Эл Гор . [215] каждый из которых ненадолго пробыл в Калифорнийском университете в Лос-Анджелесе.

| Человек | Поле | Год |

|---|---|---|

| Гвидо Имбенс | Экономические науки | 2021 |

| Андреа Гез | Физика | 2020 |

| Джеймс Фрейзер Стоддарт [216] | Химия | 2016 |

| Ллойд Шепли [217] | Экономические науки | 2012 |

| Луи Игнарро [218] | Физиология или медицина | 1998 |

| Пол Бойер [219] | Химия | 1997 |

| Дональд Крам [220] | Химия | 1987 |

| Джулиан С. Швингер [221] | Физика | 1965 |

| Уиллард Либби [222] | Химия | 1960 |

Среди выпускников-лауреатов Нобелевской премии - Ричард Хек (химия, 2010 г.); [223] Элинор Остром (экономические науки, 2009 г.); [224] и Рэнди Шекман (Физиология и медицина, 2013). [225] Пятьдесят два профессора Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе были удостоены стипендий Гуггенхайма , а шестнадцать являются стипендиатами Фонда Макартуров . Профессор математики Теренс Тао был награжден Медалью Филдса 2006 года . [226]

| Американская академия искусств и наук | 129 |

|---|---|

| Американская ассоциация развития науки | 120 |

| Американское философское общество | 17 |

| Национальная академия образования | 16 |

| Национальная инженерная академия | 30 |

| Национальная академия изобретателей | 4 |

| Национальная медицинская академия | 39 |

| Национальная академия наук | 50 |

Профессор географии Джаред Даймонд получил Пулитцеровскую премию 1998 года за свою книгу «Ружья, микробы и сталь» . [228] Два профессора истории Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе выиграли Пулитцеровскую премию 2008 года в области научной литературы и истории. Саул Фридлендер , известный исследователь нацистского Холокоста, получил премию в области научной литературы за свою книгу 2006 года « Годы истребления: нацистская Германия и евреи, 1939–1945» , а Дэниел Уокер Хоу за книгу 2007 года « Что сотворил Бог»: Преобразование Америки, 1815–1848 гг .

Ряд выпускников Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе являются известными политиками. В штате Гавайи Бен Каэтано (68 г.) стал первым американцем филиппинского происхождения , избранным губернатором штата США. [229] [230] [231] В Палате представителей США Генри Ваксман ('61, '64) представлял 30-й избирательный округ Калифорнии и был председателем комитета Палаты представителей по энергетике и торговле . [232] Представитель США Джуди Чу (74 года) представляет 32-й избирательный округ Калифорнии и стала первой американкой китайского происхождения, избранной в Конгресс США в 2009 году. [233] Кирстен Гиллибранд ('91) — сенатор США от штата Нью-Йорк и бывший представитель США в 20-м избирательном округе Нью-Йорка . [234] Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе может похвастаться двумя мэрами Лос-Анджелеса : Томом Брэдли (1937–1940), единственным мэром города афроамериканцем, и Антонио Вилларайгосой ('77), который занимал пост мэра с 2005 по 2013 год. Нао Такасуги был мэром Окснарда , Калифорния. и первый член законодательного собрания Калифорнии азиатско-американского происхождения. Азаде Киан , доктор философии Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе и директор социальных наук Парижского университета , является видным экспертом по иранской политике.

Х.Р. Холдеман ('48) и Джон Эрлихман ('48) являются одними из самых печально известных выпускников из-за их деятельности во время Уотергейтского скандала 1972 года . Бен Шапиро (бакалавр '04) - американский консервативный политический обозреватель, обозреватель национального уровня, автор, ведущий ток-шоу на радио и адвокат. Он является главным редактором The Daily Wire . [235] Майкл Морхейм (бакалавр '90), Аллен Адхэм (бакалавр '90) и Фрэнк Пирс (бакалавр '90) — основатели Blizzard Entertainment , разработчика отмеченных наградами Warcraft , StarCraft и Diablo франшиз компьютерных игр . Том Андерсон (MA '00) — соучредитель социальной сети Myspace . Ученый-компьютерщик Винт Серф ('70, '72) — вице-президент и главный интернет-евангелист Google , а также человек, которого чаще всего считают «отцом Интернета». [236] Генри Самуэли (75 лет) — соучредитель Broadcom Corporation и владелец команды Anaheim Ducks . Сьюзан Войжитски (MBA '98) — бывший генеральный директор YouTube . Трэвис Каланик — один из основателей Uber . Гай Кавасаки (MBA '79) — один из первых сотрудников Apple . Натан Мирвольд — основатель Microsoft Research . Билл Гросс (MBA '71) стал соучредителем Pacific Investment Management ( PIMCO ). Лоуренс Финк (BA '74, MBA '76) является председателем и генеральным директором крупнейшей в мире компании по управлению капиталом BlackRock . Дональд Прелл (BA '48) — венчурный капиталист и основатель компьютерного журнала Datamation . Бен Горовиц (MS '90) — соучредитель венчурной компании Кремниевой долины Andreessen Horowitz .

Выпускники Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе также добились известности в сфере искусства и развлечений. Джон Уильямс — дирижер-лауреат Бостонского поп-оркестра и обладатель премии «Оскар», автор музыки к фильму «Звездные войны» . Мартин Шервин ('71) был удостоен Пулитцеровской премии за книгу « Американский Прометей : Триумф и трагедия Дж. Роберта Оппенгеймера» . Актеры Бен Стиллер , Тим Роббинс , Джеймс Франко , Джордж Такей , Майим Бялик , Шон Эстин , Холланд Роден , Даниэль Панабэйкер и Майло Вентимилья также являются выпускниками Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе. Исполнители популярной музыки Сара Барейлес , The Doors , Linkin Park и Maroon 5 посещали Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе. Райан Дусик из Maroon 5 специализировался на английском языке. Джада Де Лаурентис — ведущая программы Food Network и бывший шеф-повар Spago . Грег Граффин , солист панк-рок- группы Bad Religion , получил степень магистра геологии в Калифорнийском университете в Лос-Анджелесе и читал там курс эволюции. [237] Кэрол Бернетт была лауреатом премии Марка Твена за американский юмор в 2013 году (также обладательницей премий «Эмми» , « Пибоди» и президентской медали свободы в 2005 году). [238] Фрэнсис Форд Коппола ('67) был режиссером гангстерской трилогии «Крестный отец» , «Аутсайдеры» в главной роли с Томом Крузом и фильма «Апокалипсис сегодня» о войне во Вьетнаме, а Дастин Лэнс Блэк — », удостоенный премии «Оскар» сценарист фильма « Молоко . [239]

Меб Кефлезиги ('98) — победитель Бостонского марафона 2014 года и серебряный призер Олимпийских игр 2004 года в марафоне . подготовила Мужская баскетбольная команда Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе игроков Зала баскетбольной славы, таких как Билл Уолтон и Карим Абдул-Джаббар, а также нынешних игроков НБА Кевина Лава и Рассела Уэстбрука . известных бейсболистов «Брюинз» Среди Трой Глаус , Чейз Атли , Брэндон Кроуфорд , Геррит Коул и Тревор Бауэр . «Лос-Анджелес Доджерс» Менеджер Дэйв Робертс выигрывал титулы Мировой серии в составе Boston Red Sox 2004 года и в 2020 году в качестве менеджера «Доджерс».

Среди выпускников военной службы - Карлтон Скиннер , командующий береговой охраной США, который по расовому признаку интегрировал эту службу в конце Второй мировой войны на Морском Облаке . Он также был первым гражданским губернатором Гуама . Фрэнсис Б. Вай - единственный американец китайского происхождения и первый американец азиатского происхождения, награжденный Почетной медалью Конгресса за свои действия во Второй мировой войне. Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе также потерял выпускника в начале 2007 года, когда младший лейтенант Марк Дейли был убит в Мосуле, Ирак, после того, как его HMMWV был подорван СВУ. Служба лейтенанта Дейли отмечена мемориальной доской, расположенной на северной стороне Центра студенческой деятельности (SAC), где в настоящее время расположены залы ROTC. По состоянию на 1 августа 2016 года в тройку лучших мест, где работают выпускники Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе, входят Kaiser Permanente с более чем 1459 выпускниками, UCLA Health с более чем 1127 выпускниками и Google с более чем 1058 выпускниками. [240]

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Скандал со взяточничеством при поступлении в колледж в 2019 году

- Daily Bruin - студенческая газета Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе

- Центр исследования стволовых клеток Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Другие состоят из многорасовых американцев и тех, кто предпочитает не говорить.

- ^ Процент студентов, получивших федеральный грант Пелла , основанный на доходе, предназначенный для студентов с низким доходом.

- ^ Процент студентов, принадлежащих к американскому среднему классу . как минимум

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]![]() Эта статья включает общедоступные материалы с веб-сайтов или документов Береговой охраны США .

Эта статья включает общедоступные материалы с веб-сайтов или документов Береговой охраны США .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Дунджерский, Марина (2011). Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе: Первый век . Лос-Анджелес: Издательство третьего тысячелетия. п. 46. ИСБН 9781906507374 . Архивировано из оригинала 20 августа 2020 года . Проверено 3 февраля 2019 г.

- ^ «Краткая история Калифорнийского университета» . Академический персонал и программы. Архивировано из оригинала 21 октября 2020 года . Проверено 3 декабря 2020 г.

- ↑ По состоянию на 30 июня 2023 г. «Учреждения-участники NCSE в США и Канаде в 2023 году, перечисленные по рыночной стоимости пожертвований на 2023 финансовый год, изменению рыночной стоимости с 22 по 23 финансовый год и рыночной стоимости пожертвований на 23 финансовый год на одного студента, эквивалентного очному обучению» (XLSX) . Национальная ассоциация руководителей колледжей и университетов (NACUBO). 15 февраля 2024 года. Архивировано из оригинала 23 мая 2024 года . Проверено 25 июля 2024 г.

- ^ Уинворд, Дилан (21 июня 2024 г.). Ван, Лекс (ред.). «Майкл Левин будет исполнять обязанности временного исполнительного вице-канцлера и проректора» . Ежедневный Брюин . Калифорнийский университет, Лос-Анджелес . Проверено 31 июля 2024 г.

- ^ «Факты и цифры» . Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе. 2023.

- ^ " https://apb.ucla.edu/campus-statistics/faculty "

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д «UCLA APB — Зачисление» . Академическое планирование и бюджет Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе. Архивировано из оригинала 4 июня 2022 года . Проверено 18 июня 2022 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Годовой финансовый отчет Калифорнийского университета за 18/19» (PDF) . Калифорнийский университет. п. 8. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 23 сентября 2020 г. Проверено 12 октября 2020 г.

- ^ «Навигатор колледжа – Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе» . nces.ed.gov. Архивировано из оригинала 29 июля 2022 года . Проверено 7 ноября 2021 г.

- ^ «Руководство по бренду | Айдентика | Цвета» . Архивировано из оригинала 24 ноября 2018 года . Проверено 23 ноября 2018 г.

- ^ Хо, Мелани (2005). «Брюин Медведь» . Английский факультет Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе. Архивировано из оригинала 19 февраля 2007 года . Проверено 20 мая 2007 г.

- ^ Васкес, Рикардо (18 января 2013 г.). «UCLA устанавливает новый рекорд по поступлению на бакалавриат» (пресс-релиз). Отдел новостей Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе. Архивировано из оригинала 21 сентября 2013 года . Проверено 14 июля 2013 г.

- ^ «Факты и цифры» . www.ucla.edu. Архивировано из оригинала 10 декабря 2021 года . Проверено 6 декабря 2021 г.

- ^ «Прием» . Академическое планирование и бюджет Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе. Архивировано из оригинала 6 декабря 2021 года . Проверено 11 ноября 2022 г.

- ^ «Колледж и школы» . www.ucla.edu. Архивировано из оригинала 13 декабря 2021 года . Проверено 6 декабря 2021 г.

- ^ Салерно, Кэмерон (1 июля 2024 г.). «Историческое лето перестройки начинается 1 июля, когда Техас и Оклахома официально присоединяются к SEC; ACC добавляет SMU» . CBS Спорт . CBS Интерактив . Проверено 16 июля 2024 г.

- ^ «Чемпионат NCAA» . Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе . Архивировано из оригинала 29 июля 2022 года . Проверено 6 декабря 2021 г.

- ^ «Дом Чемпионов» . Стэнфордский университет по легкой атлетике . Архивировано из оригинала 12 декабря 2019 года . Проверено 6 декабря 2021 г.

- ^ «Брюинз» завоевали 16 медалей на Олимпийских играх в Токио . Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе Брюинз . 9 августа 2021 года. Архивировано из оригинала 13 августа 2021 года . Проверено 14 августа 2021 г.

- ^ «Олимпийские традиции Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе и обладатели медалей» . Архивировано из оригинала 24 мая 2013 года.

- ^ «Получатели наград и наград факультета Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе | Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе | Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе» .

- ^ «Обладатели наград и наград для студентов и выпускников Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе | Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе | Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе» .

- ^ «Факультетские награды» . Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе . Проверено 1 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Административная/биографическая история, записи лабораторной школы Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе (серия записей 208 университетских архивов). Специальные коллекции библиотеки Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе, университетские архивы, Калифорнийский университет, Лос-Анджелес. [1] Архивировано 6 декабря 2021 г. в Wayback Machine.

- ^ «Хронология Брюина» (PDF) . GSE&IS Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе. 2018. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 12 апреля 2019 года . Проверено 17 апреля 2018 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гамильтон, Эндрю (18 июня 2004 г.). «(UC) Лос-Анджелес: исторический обзор» . История Калифорнийского университета, цифровые архивы (из Беркли) . Архивировано из оригинала 30 апреля 2006 года . Проверено 20 июня 2006 г.

- ^ «Архивы Университета Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе» . Библиотека Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе . 20 января 2007 года. Архивировано из оригинала 15 июня 2006 года . Проверено 20 июня 2006 г.

- ^ Дунджерский, Марина (1 января 2011 г.). Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе: Первый век . Издательство третьего тысячелетия. ISBN 978-1-906507-37-4 . Архивировано из оригинала 7 апреля 2022 года . Проверено 20 ноября 2020 г.

- ^ Дунджерский, Марина (2011). Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе: Первый век . Лос-Анджелес: Издательство третьего тысячелетия. п. 27. ISBN 9781906507374 . Архивировано из оригинала 7 апреля 2022 года . Проверено 21 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Дунджерский, Марина (2011). Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе: Первый век . Лос-Анджелес: Издательство третьего тысячелетия. п. 31. ISBN 9781906507374 . Архивировано из оригинала 13 июля 2021 года . Проверено 21 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Дунджерский, Марина (2011). Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе: Первый век . Лос-Анджелес: Издательство третьего тысячелетия. п. 33. ISBN 9781906507374 . Архивировано из оригинала 13 июля 2021 года . Проверено 21 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Гарригес, Джордж (2001). «Рождение газеты Daily Bruin» . Громкий лай и любопытные глаза, История UCLA Daily Bruin, 1919–1955 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 мая 2006 года . Проверено 3 июля 2006 г.

- ^ Выпускники Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе (2012 г.). «История: Начало» . Выпускники Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе . Архивировано из оригинала 4 апреля 2013 года . Проверено 4 апреля 2013 г.

- ^ Аткинсон, Ричард К. (26 февраля 1999 г.). «Официальное обозначение кампусов Калифорнийского университета» . policy.ucop.edu . Регенты Калифорнийского университета. Архивировано из оригинала 26 февраля 2021 года . Проверено 21 марта 2024 г.

- ^ Ян, Холли; Блум, Дебора (1 июня 2016 г.). «Стрельба в Калифорнийском университете в Лос-Анджелесе: двое убиты в результате убийства-самоубийства, кампус заблокирован» . Си-Эн-Эн. Архивировано из оригинала 1 июня 2016 года . Проверено 1 июня 2016 г.

- ^ Белла, Тимоти (1 февраля 2022 г.). «Бывший преподаватель Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе, который угрожал массовым расстрелом, арестован в Колорадо, сообщает университет» . Вашингтон Пост . Архивировано из оригинала 11 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 13 октября 2022 г.

- ^ Рейес-Веларде, Алехандра (26 мая 2018 г.). «Студенты Вествуда и общественные лидеры после жарких дебатов голосуют за создание нового районного совета» . Лос-Анджелес Таймс . Калифорния Таймс. Архивировано из оригинала 4 февраля 2020 года . Проверено 17 февраля 2020 г.

- ^ Шнайдер, Гейб (8 февраля 2019 г.). «Как студенты Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе боролись за право формировать будущее Вествуда и завоевали его» . Журнал Лос-Анджелеса . The Arena Group Holdings, Inc. Архивировано из оригинала 18 февраля 2020 года . Проверено 17 февраля 2020 г.

- ^ «UCLA подписывает соглашение с местной племенной общиной на использование земли» . Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе . Архивировано из оригинала 6 января 2023 года . Проверено 6 января 2023 г.

- ^ «UC отвергает призывы к продаже активов, связанных с Израилем, и бойкотирует пропалестинские протесты» . Лос-Анджелес Таймс . 27 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Альшариф, Мирна (29 апреля 2024 г.). «Сотни пропалестинских протестующих арестованы в кампусах, когда колледжи расправлялись с лагерями» . Новости Эн-Би-Си . Архивировано из оригинала 29 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 29 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Фитцджеральд, Джеймс (29 апреля 2024 г.). «Протесты в кампусе США: столкновение конкурирующих групп протеста из Газы в Калифорнийском университете в Лос-Анджелесе» . Новости Би-би-си . Архивировано из оригинала 29 апреля 2024 года . Проверено 29 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ «В кампусе Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе вспыхивает насилие между конкурирующими группами протеста в секторе Газа» . Хранитель . 1 мая 2024 г.

- ^ «Билли Фицджеральд, Брюин» . Архивировано из оригинала 14 апреля 2012 года . Проверено 7 апреля 2012 г.

- ^ «Велтон Беккет и партнеры» . Здания Эмпорис . 2007. Архивировано из оригинала 14 марта 2007 года . Проверено 29 мая 2007 г.

- ^ Ли, Синтия (12 октября 2004 г.). «Чувство места» от старого и нового» . Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе сегодня . Архивировано из оригинала 28 января 2007 года . Проверено 29 мая 2007 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Коулман, Лаура (3 июня 2016 г.). «Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе принимает предложение на сумму 12,5 миллионов долларов за японский сад Ханны Картер» . Курьер из Беверли-Хиллз . Архивировано из оригинала 7 августа 2020 года . Проверено 14 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ «Этель Гиберсон / Японский сад Ханны Картер | Охрана природы Лос-Анджелеса» . www.laconservancy.org . Архивировано из оригинала 8 марта 2023 года . Проверено 8 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Уэс Крэйвен (директор) (12 декабря 1997 г.). Крик 2 - комментарии Уэса Крэйвена, Патрика Люсье и Марианны Маддалены (DVD). США: Dimension Films. Архивировано из оригинала 3 августа 2018 года . Проверено 21 июля 2018 г.

- ^ Морабито, Сэм (23 января 2004 г.). «Политика 863 Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе: съемка и фотосъемка на территории кампуса» . Руководство по административной политике и процедурам Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе . Архивировано из оригинала 1 сентября 2006 года . Проверено 21 мая 2007 г.

- ^ «Джонатан Кунц – приглашенный доцент» . Школа театра, кино и телевидения Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе . 2007. Архивировано из оригинала 8 июля 2007 года . Проверено 21 мая 2007 г.

- ^ «Медицинский центр Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе» . Архивировано из оригинала 31 июля 2019 года . Проверено 1 августа 2019 г.

- ^ Сложнее, Бен. «Лучшие больницы 2015–2016 годов: обзор» . Новости США и мировой отчет . Архивировано из оригинала 25 ноября 2015 года . Проверено 28 декабря 2015 г.

- ^ «Поиск института классификаций Карнеги» . carnegieclassifications.iu.edu . Центр послесреднего образования. Архивировано из оригинала 20 июля 2020 года . Проверено 19 июля 2020 г.

- ^ «Таблица 20. Расходы на НИОКР в сфере высшего образования, ранжированные по расходам на НИОКР в 2018 финансовом году: 2009–2018 финансовые годы» . ncsesdata.nsf.gov . Национальный научный фонд . Архивировано из оригинала 30 сентября 2020 года . Проверено 19 июля 2020 г.

- ^ «Академический рейтинг университетов мира 2023 года по версии ShanghaiRanking» . Шанхайское рейтинговое консалтинговое агентство . Проверено 10 февраля 2024 г.

- ^ «Список лучших колледжей Америки по версии Forbes 2023» . Форбс . Проверено 22 сентября 2023 г.

- ^ «Лучшие национальные университеты 2023-2024 гг.» . Новости США и мировой отчет . Проверено 22 сентября 2023 г.

- ^ «Национальный рейтинг университетов 2023 года» . Вашингтон Ежемесячник . Проверено 10 февраля 2024 г.

- ^ «Лучшие колледжи США 2024 года» The Wall Street Journal /College Pulse . Проверено 27 января 2024 г.

- ^ «Академический рейтинг университетов мира 2023 года по версии ShanghaiRanking» . Шанхайское рейтинговое консалтинговое агентство . Проверено 10 февраля 2024 г.

- ^ «Рейтинг QS World University Rankings 2025: Лучшие университеты мира» . Квакварелли Саймондс . Проверено 6 июня 2024 г.

- ^ «Мировой рейтинг университетов 2024» . Высшее образование Таймс . Проверено 27 сентября 2023 г.

- ^ «Рейтинг лучших мировых университетов 2022–2023 гг.» . Новости США и мировой отчет . Проверено 25 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ «Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе – рейтинг лучших аспирантур по новостям США» . Новости США и мировой отчет . Архивировано из оригинала 29 апреля 2020 года . Проверено 28 апреля 2020 г.

- ^ «Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе – рейтинг лучших университетов мира по версии новостей США» . Новости США и мировой отчет . Архивировано из оригинала 16 октября 2015 года . Проверено 28 апреля 2020 г.

- ^ «Лучшие государственные университеты» . Новости США и мировой отчет . Новости США и мировой отчет LP. Архивировано из оригинала 23 февраля 2017 года . Проверено 19 сентября 2023 г.

- ^ «Лучшие колледжи денег» . Деньги . Time Inc. Архивировано из оригинала 30 июля 2015 года . Проверено 25 июля 2015 г.

- ^ Задрожный, Бренди (6 ноября 2014 г.). «Рейтинг колледжей 2014» . Ежедневный зверь . ООО «Дейли Бист Компани». Архивировано из оригинала 5 декабря 2014 года . Проверено 30 ноября 2014 г.

- ^ «Лучшие студенческие ценности Киплингера» . Киплингер . Редакторы Киплингера в Вашингтоне. Архивировано из оригинала 18 декабря 2016 года . Проверено 3 января 2016 г.

- ^ «Рейтинги колледжей США: лучшие университеты США» . Высшее образование Таймс . ТЕС Глобал Лимитед. 7 октября 2016. Архивировано из оригинала 8 января 2017 года . Проверено 7 января 2017 г.

- ^ «Лучшие американские исследовательские университеты» (PDF) . Центр измерения эффективности университетов . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 29 января 2016 года . Проверено 5 апреля 2015 г.

- ^ О'Тул, Кристен. «Опрос надежд и тревог колледжей», проведенный Princeton Review за 2015 год, сообщает о «колледжах мечты» 12 000 студентов и их родителей и точках зрения на поступление» . Принстонское обозрение . TPR Education IP Holdings, LLC. Архивировано из оригинала 19 сентября 2016 года . Проверено 25 мая 2015 г.

- ^ «Университеты сообщают о самом большом росте расходов на НИОКР, финансируемых из федерального бюджета, с 2011 финансового года | NSF — Национальный научный фонд» . ncses.nsf.gov . Проверено 28 декабря 2023 г.

- ^ «Экономическое разнообразие и успеваемость студентов Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . 18 января 2017. Архивировано из оригинала 8 августа 2018 года . Проверено 30 ноября 2019 г.

- ^ «Мировой рейтинг репутации высшего образования Times» . Высшее образование Таймс . TES Global Ltd. Архивировано из оригинала 17 июня 2017 года . Проверено 29 марта 2015 г.

- ^ «Рейтинги учебных заведений SCImago — Высшее образование — Все регионы и страны — 2020 — Общий рейтинг» . www.scimagoir.com . Архивировано из оригинала 22 апреля 2019 года . Проверено 11 июня 2019 г.

- ^ «CWUR 2015 – Мировые рейтинги университетов» . Центр мировых рейтингов университетов . Архивировано из оригинала 13 января 2016 года . Проверено 25 июля 2015 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе: общий рейтинг» . Новости США и мировой отчет . Архивировано из оригинала 8 декабря 2015 года . Проверено 28 ноября 2015 г.