Вашингтон, округ Колумбия

Вашингтон, округ Колумбия | |

|---|---|

| Округ Колумбия | |

| Псевдоним(ы): Округ Колумбия, Район | |

| Девиз(ы): Справедливость для всех (Английский: Справедливость для всех ) | |

| Гимн: «Вашингтон». «Столица нашей страны» (март) [1] | |

Интерактивная карта Вашингтона, округ Колумбия | |

Окрестности Вашингтона, округ Колумбия | |

| Координаты: 38 ° 54'17 "N 77 ° 00'59" W / 38,90472 ° N 77,01639 ° W | |

| Страна | Соединенные Штаты |

| Закон о проживании | 16 июля 1790 г. |

| Организованный | 27 февраля 1801 г. |

| Консолидированный | 21 февраля 1871 г. |

| Закон о самоуправлении | 24 декабря 1973 г. |

| Назван в честь | |

| Правительство | |

| • Тип | Мэр – совет |

| • Мэр | Мюриэл Баузер ( з ) |

| • Совет округа Колумбия | |

| • Дом США | Элеонора Холмс Нортон (з), Делегат (расширенное сообщество) |

| Область | |

| • Федеральная столица и округ | 68,35 квадратных миль (177,0 км ) 2 ) |

| • Земля | 61,126 квадратных миль (158,32 км ) 2 ) |

| • Вода | 7,224 квадратных миль (18,71 км²) 2 ) |

| Самая высокая точка | 409 футов (125 м) |

| Самая низкая высота | 0 футов (0 м) |

| Население | |

| • Федеральная столица и округ | 689,545 |

| • Оценивать (2023) [4] | 678,972 |

| • Классифицировать | 64-е место в Северной Америке 23-е место в США |

| • Плотность | 11 280,71/кв. миль (4 355,39/км) 2 ) |

| • Городской | 5 174 759 (США: 8-е место ) |

| • Плотность города | 3997,5/кв. миль (1543,4/км) 2 ) |

| • Метро | 6 304 975 (США: 7-е место ) |

| Демоним | Вашингтонский [7] [8] |

| GDP | |

| • Federal District | $144.0 billion (2022) |

| • DC-VA-MD-WV (MSA) | $660.6 billion (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 20001–20098, 20201–20599, 56901–56999 |

| Area code(s) | 202 and 771[11][12] |

| ISO 3166 code | US-DC |

| Airports | |

| Railroads | |

| Website | dc |

Вашингтон, округ Колумбия , формально округ Колумбия и широко известный как Вашингтон или округ Колумбия , является столицей и федеральным округом Соединенных Штатов . [13] Город расположен на реке Потомак , напротив Вирджинии , и граничит с Мэрилендом на севере и востоке. Он был назван в честь Джорджа Вашингтона , первого президента Соединенных Штатов . [14] [15] Район назван в честь Колумбии , женского олицетворения нации.

Конституция США 1789 года предусматривала создание федерального округа под исключительной юрисдикцией Конгресса США . Таким образом, Вашингтон, округ Колумбия, не является частью какого-либо штата и сам им не является. Закон о проживании , принятый 16 июля 1790 года, одобрил создание столичного округа вдоль реки Потомак. Город был основан в 1791 году, а первое заседание VI Конгресса состоялось в недостроенном здании Капитолия в 1800 году после переезда столицы из Филадельфии . В 1801 году округ Колумбия, ранее входивший в состав Мэриленда и Вирджинии и включавший существовавшие поселения Джорджтаун и Александрия , был официально признан федеральным округом; Первоначально город был отдельным поселением в пределах более крупного района. [16] В 1846 году Конгресс вернул земли, первоначально уступленные Вирджинией , включая город Александрию. был создан единый муниципалитет . В 1871 году для остальной части округа [17] С 1880-х годов было предпринято несколько безуспешных попыток превратить округ в штат ; Закон о государственности был принят Палатой представителей в 2021 году, но не был принят Сенатом США . [18]

Спроектированный в 1791 году Пьером Шарлем Л'Анфаном , город разделен на квадраты , которые сосредоточены вокруг здания Капитолия и включают 131 район . По данным переписи 2020 года , население города составляло 689 545 человек. [3] Пассажиры из пригородов Мэриленда и Вирджинии увеличивают дневное население города до более чем одного миллиона в течение рабочей недели. [19] Агломерация Вашингтона , включающая части Мэриленда, Вирджинии и Западной Вирджинии страны , является седьмой по величине агломерацией с населением в 2023 году 6,3 миллиона жителей. [6] С 1973 года округом управляют избираемый на местном уровне мэр и совет, состоящий из 13 членов , хотя Конгресс сохраняет за собой право отменять местные законы. Жители Вашингтона, округ Колумбия, на федеральном уровне лишены политических прав , поскольку жители города не имеют избирательного представительства в Конгрессе; жители города избирают одного делегата Конгресса без права голоса в Палату представителей США . Избиратели города выбирают трех президентских выборщиков в соответствии с Двадцать третьей поправкой .

Вашингтон, округ Колумбия, занимает южную оконечность северо-восточного мегаполиса . Будучи резиденцией федерального правительства США и ряда международных организаций, город является важной мировой политической столицей . [20] В городе находятся здания, в которых расположены штаб-квартиры федерального правительства, в том числе Белый дом , Капитолий, здание Верховного суда , а также множество федеральных департаментов и агентств . В городе находится множество национальных памятников и музеев , наиболее заметно расположенных на Национальной аллее или вокруг нее , в том числе Мемориал Джефферсона , Мемориал Линкольна и Монумент Вашингтона . Здесь расположены 177 иностранных посольств , а также штаб-квартиры Всемирного банка , Международного валютного фонда , Организации американских государств и других международных организаций. многие крупнейшие отраслевые ассоциации, некоммерческие организации и аналитические центры В городе базируются страны, в том числе AARP , Американский Красный Крест , Атлантический совет , Брукингский институт , Национальное географическое общество , Фонд наследия , Центр Вильсона и другие. Город известен как центр лоббирования , а К-стрит является центром такой деятельности. [21] Город посетили 20,7 миллиона местных жителей. [22] и 1,2 миллиона иностранных посетителей, занимая седьмое место среди городов США по состоянию на 2022 год. [23]

История

Различные племена на алгонкинском языке , говорящего народа Пискатауэй , также известного как Коной, населяли земли вокруг реки Потомак и современного Вашингтона, округ Колумбия, когда европейцы впервые прибыли и колонизировали этот регион в начале 17 века. Накотчтанк « Накостины» , также называемый католическими миссионерами , поддерживал поселения вокруг реки Анакостия в современном Вашингтоне, округ Колумбия. Конфликты с европейскими колонистами и соседними племенами в конечном итоге вытеснили людей Пискатауэй, некоторые из которых основали новое поселение в 1699 году недалеко от мыса Рокс. , Мэриленд . [24]

Основание

Several other cities served as the U.S. capital before 1800. Philadelphia served as the capital on five separate occasions during the American Revolution and its aftermath from May 1775 to July 1776, December 1776 to February 1777, March 1777 to September 1777, July 1778, July 1778 to March 1781, and March 1781 to June 1783. The Continental Congress was briefly based in five additional locations: York, Pennsylvania, in September 1777; Princeton, New Jersey, in 1783; Annapolis, Maryland, from November 1783 to August 1784; Trenton, New Jersey, from November to December 1784; and New York City from January 1785 to March 1789.[citation needed]

On October 6, 1783, after the capital was forced by the Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783 to move to Princeton, Congress resolved to consider a new location for it.[25] The following day, Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts moved "that buildings for the use of Congress be erected on the banks of the Delaware near Trenton, or of the Potomac, near Georgetown, provided a suitable district can be procured on one of the rivers as aforesaid, for a federal town".[26]

In Federalist No. 43, published January 23, 1788, James Madison argued that the new federal government would need authority over a national capital to provide for its own maintenance and safety.[27] The Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783 emphasized the need for the national government not to rely on any state for its own security.[28]

Article One, Section Eight of the U.S. Constitution permits the establishment of a "District (not exceeding ten miles square) as may, by cession of particular states, and the acceptance of Congress, become the seat of the government of the United States".[29] However, the constitution does not specify a location for the capital. In the Compromise of 1790, Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and Thomas Jefferson agreed that the federal government would pay each state's remaining Revolutionary War debts in exchange for establishing the new national capital in the Southern United States.[30][a]

On July 9, 1790, Congress passed the Residence Act, which approved the creation of a national capital on the Potomac River. Under the Residence Act, the exact location was to be selected by President George Washington, who signed the bill into law on July 16, 1790. Formed from land donated by Maryland and Virginia, the initial shape of the federal district was a square measuring 10 miles (16 km) on each side and totaling 100 square miles (259 km2).[31][b]

Two pre-existing settlements were included in the territory, the port of Georgetown, founded in 1751,[32] and the port city of Alexandria, Virginia, founded in 1749.[33] In 1791 and 1792, a team led by Andrew Ellicott, including Ellicott's brothers Joseph and Benjamin and African American astronomer Benjamin Banneker, whose parents had been enslaved, surveyed the borders of the federal district and placed boundary stones at every mile point; many of these stones are still standing.[34][35] Both Maryland and Virginia were slave states, and slavery existed in the District from its founding. The building of Washington likely relied in significant part on slave labor, and slave receipts have been found for the White House, Capitol Building, and establishment of Georgetown University. The city became an important slave market and a center of the nation's internal slave trade.[36][37]

After its survey, the new federal city was constructed on the north bank of the Potomac River, to the east of Georgetown centered on Capitol Hill. On September 9, 1791, three commissioners overseeing the capital's construction named the city in honor of President Washington. The same day, the federal district was named Columbia, a feminine form of Columbus, which was a poetic name for the United States commonly used at that time.[38][39] Congress held its first session there on November 17, 1800.[40][41]

Congress passed the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801, which officially organized the district and placed the entire territory under the exclusive control of the federal government. The area within the district was organized into two counties, the County of Washington to the east and north of the Potomac and the County of Alexandria to the west and south.[42] After the Act's passage, citizens in the district were no longer considered residents of Maryland or Virginia, which ended their representation in Congress.[43]

Burning during War of 1812

On August 24, 1814, during the War of 1812, British forces invaded and occupied the city after defeating an American force at Bladensburg. In retaliation for acts of destruction by American troops in the Canadas, the British set fire to government buildings in the city, gutting the United States Capitol, the Treasury Building, and the White House in what became known as the burning of Washington. However, a storm forced the British to evacuate the city after just 24 hours.[44] Most government buildings were repaired quickly, but the Capitol, which was largely under construction at the time, would not be completed in its current form until 1868.[45]

Retrocession and the Civil War

In the 1830s, the district's southern territory of Alexandria declined economically, due in part to its neglect by Congress.[46] Alexandria was a major market in the domestic slave trade and pro-slavery residents feared that abolitionists in Congress would end slavery in the district. Alexandria's citizens petitioned Virginia to retake the land it had donated to form the district, a process known as retrocession.[47]

The Virginia General Assembly voted in February 1846, to accept the return of Alexandria. On July 9, 1846, Congress went further, agreeing to return all territory that Virginia had ceded to the district during its formation. This left the district's area consisting only of the portion originally donated by Maryland.[46] Confirming the fears of pro-slavery Alexandrians, the Compromise of 1850 outlawed the slave trade in the district, although not slavery itself.[48]

The outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 led to the expansion of the federal government and notable growth in the city's population, including a large influx of freed slaves.[49] President Abraham Lincoln signed the Compensated Emancipation Act in 1862, which ended slavery in the district, freeing about 3,100 slaves in the district nine months before the Emancipation Proclamation.[50] In 1868, Congress granted the district's African American male residents the right to vote in municipal elections.[49]

Growth and redevelopment

By 1870, the district's population had grown 75% in a decade to nearly 132,000 people,[51] yet the city still lacked paved roads and basic sanitation. Some members of Congress suggested moving the capital farther west, but President Ulysses S. Grant refused to consider the proposal.[52]

In the Organic Act of 1871, Congress repealed the individual charters of the cities of Washington and Georgetown, abolished Washington County, and created a new territorial government for the whole District of Columbia.[53] These steps made "the city of Washington...legally indistinguishable from the District of Columbia."[16]

In 1873, President Grant appointed Alexander Robey Shepherd as Governor of the District of Columbia. Shepherd authorized large projects that modernized the city but bankrupted its government. In 1874, Congress replaced the territorial government with an appointed three-member board of commissioners.[54]

In 1888, the city's first motorized streetcars began service. Their introduction generated growth in areas of the district beyond the City of Washington's original boundaries, leading to an expansion of the district over the next few decades.[55] Georgetown's street grid and other administrative details were formally merged with those of the City of Washington in 1895.[56] However, the city had poor housing and strained public works, leading it to become the first city in the nation to undergo urban renewal projects as part of the City Beautiful movement in the early 20th century.[57]

The City Beautiful movement built heavily upon the already-implemented L'Enfant Plan, with the new McMillan Plan leading urban development in the city throughout the movement. Much of the old Victorian Mall was replaced with modern Neoclassical and Beaux-Arts architecture; these designs are still prevalent in the city's governmental buildings today.

Increased federal spending under the New Deal in the 1930s led to the construction of new government buildings, memorials, and museums in the district,[58] though the chairman of the House Subcommittee on District Appropriations, Ross A. Collins of Mississippi, justified cuts to funds for welfare and education for local residents by saying that "my constituents wouldn't stand for spending money on niggers."[59]

World War II led to an expansion of federal employees in the city;[60] by 1950, the district's population reached its peak of 802,178 residents.[51]

Civil rights and home rule era

The Twenty-third Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified in 1961, granting the district three votes in the Electoral College for the election of president and vice president, but still not affording the city's residents representation in Congress.[61]

After the assassination of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, riots broke out in the city, primarily in the U Street, 14th Street, 7th Street, and H Street corridors, which were predominantly black residential and commercial areas. The riots raged for three days until more than 13,600 federal troops and Washington, D.C., Army National Guardsmen stopped the violence. Many stores and other buildings were burned, and rebuilding from the riots was not completed until the late 1990s.[62]

In 1973, Congress enacted the District of Columbia Home Rule Act providing for an elected mayor and 13-member council for the district.[63] In 1975, Walter Washington became the district's first elected and first black mayor.[64]

Since the 1980s, the D.C. statehood movement has grown in prominence. In 2016, a referendum on D.C. statehood resulted in an 85% support among Washington, D.C., voters for it to become the nation's 51st state. In March 2017, the city's congressional delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton introduced a bill for statehood. Reintroduced in 2019 and 2021 as the Washington, D.C., Admission Act, the U.S. House of Representatives passed it in April 2021. After not progressing in the Senate, the statehood bill was introduced again in January 2023.[65]

Geography

Washington, D.C., is located in the Mid-Atlantic region of the U.S. East Coast. The city has a total area of 68.34 square miles (177 km2), of which 61.05 square miles (158.1 km2) is land and 7.29 square miles (18.9 km2) (10.67%) is water.[66] The district is bordered by Montgomery County, Maryland, to the northwest; Prince George's County, Maryland, to the east; Arlington County, Virginia, to the west; and Alexandria, Virginia, to the south. Washington is 38 miles (61 km) from Baltimore, 124 miles (200 km) from Philadelphia, 227 miles (365 km) from New York City, 242 miles (389 km) from Pittsburgh, 384 miles (618 km) from Charlotte, and 439 miles (707 km) from Boston.[citation needed]

The south bank of the Potomac River forms the district's border with Virginia and has two major tributaries, the Anacostia River and Rock Creek.[67] Tiber Creek, a natural watercourse that once passed through the National Mall, was fully enclosed underground during the 1870s.[68] The creek also formed a portion of the now-filled Washington City Canal, which allowed passage through the city to the Anacostia River from 1815 until the 1850s.[69] The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal starts in Georgetown and was used during the 19th century to bypass the Little Falls of the Potomac River, located at the northwest edge of the city at the Atlantic Seaboard fall line.[70]

The highest natural elevation in the district is 409 feet (125 m) above sea level at Fort Reno Park in upper northwest Washington, D.C.[71] The lowest point is sea level at the Potomac River.[72] The geographic center of Washington is near the intersection of 4th and L streets NW.[73][74][75]

The district has 7,464 acres (30.21 km2) of parkland, about 19% of the city's total area, the second-highest among high-density U.S. cities after Philadelphia.[76] The city's sizable parkland was a factor in the city being ranked as third in the nation for park access and quality in the 2018 ParkScore ranking of the park systems of the nation's 100 most populous cities, according to Trust for Public Land, a non-profit organization.[77]

The National Park Service manages most of the 9,122 acres (36.92 km2) of city land owned by the U.S. government.[78] Rock Creek Park is a 1,754-acre (7.10 km2) urban forest in Northwest Washington, which extends 9.3 miles (15.0 km) through a stream valley that bisects the city. Established in 1890, it is the country's fourth-oldest national park and is home to a variety of plant and animal species, including raccoon, deer, owls, and coyotes.[79] Other National Park Service properties include the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park, the National Mall and Memorial Parks, Theodore Roosevelt Island, Columbia Island, Fort Dupont Park, Meridian Hill Park, Kenilworth Park and Aquatic Gardens, and Anacostia Park.[80] The District of Columbia Department of Parks and Recreation maintains the city's 900 acres (3.6 km2) of athletic fields and playgrounds, 40 swimming pools, and 68 recreation centers.[81] The U.S. Department of Agriculture operates the 446-acre (1.80 km2) United States National Arboretum in Northeast Washington, D.C.[82]

Climate

Washington's climate is humid subtropical (Köppen: Cfa), or oceanic (Trewartha: Do bordering Cf downtown).[83][84] Winters are cool to cold with some snow of varying intensity, while summers are hot and humid. The district is in plant hardiness zone 8a near downtown, and zone 7b elsewhere in the city.[85][86]

Summers are hot and humid with a July daily average of 79.8 °F (26.6 °C) and average daily relative humidity around 66%, which can cause moderate personal discomfort. Heat indices regularly approach 100 °F (38 °C) at the height of summer.[87] The combination of heat and humidity in the summer brings very frequent thunderstorms, some of which occasionally produce tornadoes in the area.[88]

Blizzards affect Washington once every four to six years on average. The most violent storms, known as nor'easters, often impact large regions of the East Coast.[89] From January 27 to 28, 1922, the city officially received 28 inches (71 cm) of snowfall, the largest snowstorm since official measurements began in 1885.[90] According to notes kept at the time, the city received between 30 and 36 inches (76 and 91 cm) from a snowstorm in January 1772.[91]

Hurricanes or their remnants occasionally impact the area in late summer and early fall. However, they usually are weak by the time they reach Washington, partly due to the city's inland location.[92] Flooding of the Potomac River, however, caused by a combination of high tide, storm surge, and runoff, has been known to cause extensive property damage in the Georgetown neighborhood of the city.[93] Precipitation occurs throughout the year.[94]

The highest recorded temperature was 106 °F (41 °C) on August 6, 1918, and on July 20, 1930.[95] The lowest recorded temperature was −15 °F (−26 °C) on February 11, 1899, right before the Great Blizzard of 1899.[89] During a typical year, the city averages about 37 days at or above 90 °F (32 °C) and 64 nights at or below the freezing mark (32 °F or 0 °C).[96] On average, the first day with a minimum at or below freezing is November 18 and the last day is March 27.[97][98]

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

See or edit raw graph data.

Cityscape

Washington, D.C., was a planned city, and many of the city's street grids were developed in that initial plan. In 1791, President George Washington commissioned Pierre Charles L'Enfant, a French-born military engineer and artist, to design the new capital. He enlisted the help of Isaac Roberdeau, Étienne Sulpice Hallet and Scottish surveyor Alexander Ralston to help lay out the city plan.[103] The L'Enfant Plan featured broad streets and avenues radiating out from rectangles, providing room for open space and landscaping.[104]

L'Enfant was also provided a roll of maps by Thomas Jefferson depicting Frankfurt, Amsterdam, Strasbourg, Paris, Orleans, Bordeaux, Lyon, Marseille, Turin, and Milan.[105] L'Enfant's design also envisioned a garden-lined grand avenue about 1 mile (1.6 km) long and 400 feet (120 m) wide in an area that is now the National Mall inpsired by the grounds at Versailles and Tuileries Gardens.[106] In March 1792, President Washington dismissed L'Enfant due to conflicts with the three commissioners appointed to supervise the capital's construction. Andrew Ellicott, who worked with L'Enfant in surveying the city, was then tasked with completing its design. Though Ellicott revised the original L'Enfant plans, including changing some street patterns, L'Enfant is still credited with the city's overall design.[107]

By the early 20th century, however, L'Enfant's vision of a grand national capital was marred by slums and randomly placed buildings in the city, including a railroad station on the National Mall. Congress formed a special committee charged with beautifying Washington's ceremonial core.[57] What became known as the McMillan Plan was finalized in 1901 and included relandscaping the Capitol grounds and the National Mall, clearing slums, and establishing a new citywide park system. The plan is thought to have largely preserved L'Enfant's intended design for the city.[104]

By law, the city's skyline is low and sprawling. The federal Height of Buildings Act of 1910 prohibits buildings with height exceeding the width of the adjacent street plus 20 feet (6.1 m).[108] Despite popular belief, no law has ever limited buildings to the height of the United States Capitol or the 555-foot (169 m) Washington Monument,[75] which remains the district's tallest structure. City leaders have cited the height restriction as a primary reason that the district has limited affordable housing and its metro area has suburban sprawl and traffic problems.[108] Washington, D.C., still has a relatively high homelessness rate, despite its high living standard compared to many American cities.[109]

Washington, D.C., is divided into four quadrants of unequal area: Northwest (NW), Northeast (NE), Southeast (SE), and Southwest (SW). The axes bounding the quadrants radiate from the U.S. Capitol.[110] All road names include the quadrant abbreviation to indicate their location. House numbers generally correspond with the number of blocks away from the Capitol. Most streets are set out in a grid pattern with east–west streets named with letters (e.g., C Street SW), north–south streets with numbers (e.g., 4th Street NW), and diagonal avenues, many of which are named after states.[110]

- Selection of neighborhoods in Washington, D.C.

The City of Washington was bordered on the north by Boundary Street (renamed Florida Avenue in 1890); Rock Creek to the west, and the Anacostia River to the east.[55][104] Washington, D.C.'s street grid was extended, where possible, throughout the district starting in 1888.[111] Georgetown's streets were renamed in 1895.[56] Some streets are particularly noteworthy, including Pennsylvania Avenue, which connects the White House to the Capitol; and K Street, which houses the offices of many lobbying groups.[112] Constitution Avenue and Independence Avenue, located on the north and south sides of the National Mall, respectively, are home to many of Washington's iconic museums, including many Smithsonian Institution buildings and the National Archives Building. Washington hosts 177 foreign embassies; these maintain nearly 300 buildings and more than 1,600 residential properties, many of which are on a section of Massachusetts Avenue informally known as Embassy Row.[113]

Architecture

The architecture of Washington, D.C., varies greatly and is generally popular among tourists and locals. In 2007, six of the top ten buildings in the American Institute of Architects' ranking of America's Favorite Architecture were in the city:[114] the White House, Washington National Cathedral, the Jefferson Memorial, the United States Capitol, the Lincoln Memorial, and the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. The neoclassical, Georgian, Gothic, and Modern styles are reflected among these six structures and many other prominent edifices in the city.[citation needed]

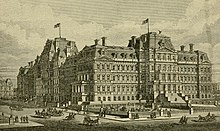

Many of the government buildings, monuments, and museums along the National Mall and surrounding areas are heavily inspired by classical Roman and Greek architecture. The designs of the White House, the U.S. Capitol, Supreme Court Building, Washington Monument, National Gallery of Art, Lincoln Memorial, and Jefferson Memorial are all heavily drawn from these classical architectural movements and feature large pediments, domes, columns in classical order, and heavy stone walls. Notable exceptions to the city's classical-style architecture include buildings constructed in the French Second Empire style, including the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, and the modernist Watergate complex.[115] The Thomas Jefferson Building, the main Library of Congress building, and the historic Willard Hotel are built in Beaux-Arts style, popular throughout the world in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[116][117] Meridian Hill Park contains a cascading waterfall with Italian Renaissance-style architecture.[118]

Modern, Postmodern, contemporary, and other non-classical architectural styles are also seen in the city. The National Museum of African American History and Culture deeply contrasts the stone-based neoclassical buildings on the National Mall with a design that combines modern engineering with heavy inspiration from African art.[119] The interior of the Washington Metro stations and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden are designed with strong influence from the 20th-century Brutalism movement.[120] The Smithsonian Institution Building is built of Seneca red sandstone in the Norman Revival style.[121] The Old Post Office building, located on Pennsylvania Avenue and completed in 1899, was the first building in the city to have a steel frame structure and the first to use electrical wiring in its design.[122]

Notable contemporary residential buildings, restaurants, shops, and office buildings in the city include the Wharf on the Southwest Waterfront, Navy Yard along the Anacostia River, and CityCenterDC in Downtown. The Wharf has seen the construction of several high-rise office and residential buildings overlooking the Potomac River. Additionally, restaurants, bars, and shops have been opened at street level. Many of these buildings have a modern glass exterior and heavy curvature.[123][124] CityCenterDC is home to Palmer Alley, a pedestrian-only walkway, and houses several apartment buildings, restaurants, and luxury-brand storefronts with streamlined glass and metal facades.[125]

Outside Downtown D.C., architectural styles are more varied. Historic buildings are designed primarily in the Queen Anne, Châteauesque, Richardsonian Romanesque, Georgian Revival, Beaux-Arts, and a variety of Victorian styles.[126] Rowhouses are prominent in areas developed after the Civil War and typically follow Federal and late Victorian designs.[127] Georgetown's Old Stone House, built in 1765, is the oldest-standing building in the city.[128] Founded in 1789, Georgetown University features a mix of Romanesque and Gothic Revival architecture.[115] The Ronald Reagan Building is the largest building in the district with a total area of about 3.1 million square feet (288,000 m2).[129] Washington Union Station is designed in a combination of architectural styles. Its Great Hall has elaborate gold leaf designs along the ceilings and the hall includes several decorative classical-style statues.[130]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 8,144 | — | |

| 1810 | 15,471 | 90.0% | |

| 1820 | 23,336 | 50.8% | |

| 1830 | 30,261 | 29.7% | |

| 1840 | 33,745 | 11.5% | |

| 1850 | 51,687 | 53.2% | |

| 1860 | 75,080 | 45.3% | |

| 1870 | 131,700 | 75.4% | |

| 1880 | 177,624 | 34.9% | |

| 1890 | 230,392 | 29.7% | |

| 1900 | 278,718 | 21.0% | |

| 1910 | 331,069 | 18.8% | |

| 1920 | 437,571 | 32.2% | |

| 1930 | 486,869 | 11.3% | |

| 1940 | 663,091 | 36.2% | |

| 1950 | 802,178 | 21.0% | |

| 1960 | 763,956 | −4.8% | |

| 1970 | 756,510 | −1.0% | |

| 1980 | 638,333 | −15.6% | |

| 1990 | 606,900 | −4.9% | |

| 2000 | 572,059 | −5.7% | |

| 2010 | 601,723 | 5.2% | |

| 2020 | 689,545 | 14.6% | |

| Source:[131] [e][51][132] Note:[f] 2010–2020[3] | |||

| Demographic profile | 2020[134] | 2010[135] | 1990[136] | 1970[136] | 1940[136] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 39.6% | 38.5% | 29.6% | 27.7% | 71.5% |

| —Non-Hispanic whites | 38.0% | 34.8% | 27.4% | 26.5%[g] | 71.4% |

| Black or African American | 41.4% | 50.7% | 65.8% | 71.1% | 28.2% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 11.3% | 9.1% | 5.4% | 2.1%[g] | 0.1% |

| Asian | 4.8% | 3.5% | 1.8% | 0.6% | 0.2% |

The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that the district's population was 705,749 as of July 2019, up more than 100,000 people since the 2010 United States Census. When measured decade-over-decade, this shows growth since 2000, following a half-century of population decline.[137] But year-over-year, the July 2019 census count shows a decline of 16,000 people over the preceding 12 months.[138][unreliable source?] Washington was the 24th-most populous place in the United States as of 2010[update].[139] According to data from 2010, commuters from the suburbs boost the district's daytime population past one million.[140] If the district were a state, it would rank 49th in population, ahead of Vermont and Wyoming.[141]

The Washington metropolitan area, which includes the district and surrounding suburbs, is the sixth-largest metropolitan area in the U.S., with an estimated six million residents as of 2016.[142] When the Washington area is included with Baltimore and its suburbs, it forms the vast Washington–Baltimore combined statistical area. With a population exceeding 9.8 million residents in 2020, it is the third-largest combined statistical area in the country.[143]

According to HUD's 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 4,410 homeless people in Washington, D.C.[144][145]

According to 2017 Census Bureau data, the population of Washington, D.C., was 47.1% Black or African American, 45.1% White (36.8% non-Hispanic White), 4.3% Asian, 0.6% American Indian or Alaska Native, and 0.1% Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander. Individuals from two or more races made up 2.7% of the population. Hispanics of any race made up 11.0% of the district's population.[141]

Washington, D.C. has had a relatively large African American population since the city's foundation.[146] African American residents composed about 30% of the district's total population between 1800 and 1940.[51] The black population reached a peak of 70% by 1970, and has since declined as African Americans moved to the surrounding suburbs. Partly as a result of gentrification, there was a 31.4% increase in the non-Hispanic white population and an 11.5% decrease in the black population between 2000 and 2010.[147] According to a study by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, D.C. has experienced more "intense" gentrification than any other American city, with 40% of neighborhoods gentrified.[148]

About 17% of Washington, D.C. residents were age 18 or younger as of 2010, lower than the U.S. average of 24%. However, at 34 years old, the district had the lowest median age compared to the 50 states as of 2010.[149] As of 2010[update], there were an estimated 81,734 immigrants living in Washington, D.C.[150] Major sources of immigration include El Salvador, Ethiopia, Mexico, Guatemala, and China, with a concentration of Salvadorans in the Mount Pleasant neighborhood.[151]

As of 2010, there were 4,822 same-sex couples in the city, about 2% of total households, according to Williams Institute.[152] Legislation authorizing same-sex marriage passed in 2009, and the district began issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples in March 2010.[153]

As of 2007, about one-third of Washington, D.C., residents were functionally illiterate, more than the national rate of about one in five. The city's relatively high illiteracy rate is attributed in part to immigrants who are not proficient in English.[154] As of 2011[update], 85% of D.C. residents age 5 and older spoke English at home as a primary language.[155] Half of residents had at least a four-year college degree in 2006.[150] In 2017, the median household income in D.C. was $77,649;[156] also in 2017, D.C. residents had a personal income per capita of $50,832 (higher than any of the 50 states).[156][157] However, 19% of residents were below the poverty level in 2005, higher than any state except Mississippi. In 2019, the poverty rate stood at 14.7%.[158][h][160]

As of 2010[update], more than 90% of Washington, D.C., residents had health insurance coverage, the second-highest rate in the nation. This is due in part to city programs that help provide insurance to low-income individuals who do not qualify for other types of coverage.[161] A 2009 report found that at least three percent of Washington, D.C., residents have HIV or AIDS, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) characterizes as a "generalized and severe" epidemic.[162]

Of the district's population, 17% are Baptist, 13% are Catholic, 6% are evangelical Protestant, 4% are Methodist, 3% are Episcopalian or Anglican, 3% are Jewish, 2% are Eastern Orthodox, 1% are Pentecostal, 1% are Buddhist, 1% are Adventist, 1% are Lutheran, 1% are Muslim, 1% are Presbyterian, 1% are Mormon, and 1% are Hindu.[163][i] The city is populated with many religious buildings, including the Washington National Cathedral, the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception, which comprises the largest Catholic church building in the United States, and the Islamic Center of Washington, which was the largest mosque in the Western Hemisphere when opened in 1957. St. John's Episcopal Church, located off Lafayette Square, has held services for every U.S. president since James Madison. The Sixth & I Historic Synagogue, built in 1908, is a synagogue located in the Chinatown section of the city. The Washington D.C. Temple is a large Mormon temple located just outside the city in Kensington, Maryland. Viewable from the Capital Beltway, the temple is the tallest Mormon temple in existence and the third-largest by square footage.[164][165]

Economy

As of 2023, the Washington metropolitan area, including District of Columbia as well as parts of Virginia, Maryland, and West Virginia, was one of the nation's largest metropolitan economies. Its growing and diversified economy has an increasing percentage of professional and business service jobs in addition to more traditional jobs rooted in tourism, entertainment, and government.[166][obsolete source]

Between 2009 and 2016, gross domestic product per capita in Washington, D.C., consistently ranked at the very top among U.S. states.[167] In 2016, at $160,472, its GDP per capita was almost three times greater than that of Massachusetts, which was ranked second in the nation (see List of U.S. states and territories by GDP).[167]As of 2022[update], the metropolitan statistical area's unemployment rate was 3.1%, ranking 171 out of the 389 metropolitan areas as defined by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.[168] The District of Columbia itself had an unemployment rate of 4.6% during the same time period.[169] In 2019, Washington, D.C., had the highest median household income in the U.S. at $92,266.[170]

According to the District's comprehensive annual financial reports, the top employers by number of employees in 2022 included Georgetown University, Children's National Medical Center, Washington Hospital Center, George Washington University, American University, Georgetown University Hospital, Booz Allen & Hamilton, Insperity PEO Services, Universal Protection Service, Howard University, Medstar Medical Group, George Washington University Hospital, Catholic University of America, and Sibley Memorial Hospital.[171]

Federal government

As of July 2022, 25% of people employed in Washington, D.C., were employed by the federal government.[172] The vast majority of these government employees serve in various executive branch departments, agencies, and institutions. A small percentage serve as temporary staff for presidents, Congress members, or in the federal judiciary.[citation needed]

Many of the region's residents are employed by companies and organizations that do work for the federal government, seek to influence federal policy, or are otherwise related to its work, including law firms, defense contractors, civilian contractors, nonprofit organizations, lobbying firms, trade unions, industry trade groups, and professional associations, many of which have their headquarters in or near the city for proximity to the federal government. The largest U.S. government agencies located in or near the city are: the United States Department of Defense headquartered in the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia, the United States Postal Service, the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, the United States Department of Homeland Security, and the United States Department of Justice.[173]

Diplomacy and global finance

As the national capital, Washington, D.C. hosts about 185 foreign missions, including embassies, ambassador's residences, and international cultural centers.[174] Many are concentrated along a stretch of Massachusetts Avenue known informally as Embassy Row.[175] D.C. is consequently one of the most culturally diverse cities in the world; it hosts a number of internationally themed festivals and events, often in collaboration with foreign missions or delegations.[176][177]

In 2008, the foreign diplomatic corps employed about 10,000 people and contributed an estimated $400 million annually to the local economy.[178] The city government maintains an Office of International Affairs to liaise with the diplomatic community and foreign delegations.[179]

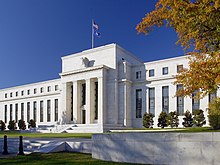

The Federal Reserve, the central bank of the United States, is located on Constitution Avenue. Commonly called The Fed, its policies are made by the members of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors. Through monetary policy, the Board adjusts various interest rates in the U.S., which affects the U.S. economy and economies of countries across the world. Because of the power of the U.S. dollar, the actions of the Board are monitored closely by political, economic, and diplomatic leaders around the world.[citation needed]

Research and non-profit organizations

Washington, D.C., is a leading center for national and international research organizations, especially think tanks engaged in public policy.[180] As of 2020, 8% of the country's think tanks are headquartered in the city, including many of the largest and most widely cited;[181] these include the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Center for Strategic and International Studies, Peterson Institute for International Economics, The Heritage Foundation, and Urban Institute.[182]

D.C. is home to many non-profit organizations that engage with issues of domestic and global importance by conducting advanced research, running programs, or public advocacy. Among these organizations are the UN Foundation, Human Rights Campaign, Amnesty International, and the National Endowment for Democracy.[183] Major medical research institutions include the MedStar Washington Hospital Center and the Children's National Medical Center.[184]

The city is the country's primary location for international development firms, many of which contract with the D.C.-based United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the U.S. federal government's aid agency. The American Red Cross, a humanitarian agency focused on emergency relief, is also headquartered in the city.[185]

Private sector

According to statistics compiled in 2011, four of the largest 500 companies in the country were headquartered in Washington, D.C.[186] In the 2023 Global Financial Centres Index, Washington was ranked as having the 8th most competitive financial center in the world, and fourth most competitive in the United States (after New York City, San Francisco, and Los Angeles).[187] Among the largest companies headquartered in the Washington, D.C., area are Fannie Mae, Amtrak, Lockheed Martin, Marriot International, Hilton Worldwide, Danaher Corporation, FTI Consulting, and Hogan Lovells.[188]

Due to building height restrictions in Washington, D.C., taller buildings are able to be built in suburban Maryland and Virginia. Capital One Bank, which is one of the largest banks in the country, is headquartered in nearby Tysons, Virginia, a large and growing financial center located in Fairfax County, Virginia. The headquarters building for Capital One Bank, known as Capital One Tower, is the tallest occupied building in the Washington region. In 2018, Amazon announced it would build a second headquarters building, known as HQ2, in the Crystal City neighborhood of Arlington County, Virginia, which is located just across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C.[189] In addition to Capital One, some of the largest companies headquartered in Northern Virginia include Hilton, Navy Federal Credit Union, Mars, Freddie Mac, Northrop Grumman, and General Dynamics.[190]

The Washington, D.C., economy also benefits from being home to many prominent news and media organizations. Among these are The Washington Post, The Washington Times, Politico, and The Hill. Television and radio media organizations either headquartered in or near the city or with large offices in the region, include CNN, PBS, C-SPAN, CBS, NBC, Discovery, and NPR, and others. The Gannett Company, which owns USA Today and other media outlets, is headquartered in Tysons, Virginia.[191][192]

Tourism

Tourism is the city's second-largest industry, after the federal government. In 2012, some 18.9 million visitors contributed an estimated $4.8 billion to the local economy.[193] In 2019, the city saw 24.6 million tourists, including 1.8 million from foreign countries, who collectively spent $8.15 billion during their stay.[194] Tourism helps many of the region's other industries, such as lodging, food and beverage, entertainment, shopping, and transportation;[194] it also supports the city's world-class museums and cultural centers, most notably the Smithsonian Institution.[citation needed]

The city and wider Washington region has a diverse array of attractions for tourists, such as monuments, memorials, museums, sports events, and trails. Within the city, the National Mall serves as the center of the tourism industry. It is there that many of the city's museums and monuments are located. Adjacent to the mall sits the Tidal Basin, where several additional memorials and monuments lie, including the popular Jefferson Memorial. Washington Union Station is a popular tourist spot with its multitude of restaurants and shops.[citation needed]

Among the most visited tourist destinations is Arlington National Cemetery in nearby Arlington County, Virginia.[195] This is a military cemetery that serves as a burial ground for former military combatants. It is also the location of President John F. Kennedy's tomb, marked by an eternal flame.[196] President William Howard Taft is also buried in Arlington.[197] The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier is located in the cemetery and is guarded 24/7 by a tomb guard. The changing of the guard is a popular tourist attraction and occurs once every hour from October through March and every half-hour during the rest of the year.[198]

Culture

| Slogan | Federal City |

|---|---|

| Living insignia | |

| Bird | Wood Thrush |

| Crustacean | Hay's Spring amphipod |

| Fish | American shad |

| Flower | American Beauty rose |

| Mammal | Little brown bat |

| Tree | Scarlet Oak |

| Inanimate insignia | |

| Beverage | Rickey[199] |

| Dance | Hand dancing |

| Dinosaur | Capitalsaurus |

| Food | Cherry |

| Rock | Potomac bluestone |

| Route marker | |

| State quarter | |

Released in 2009 | |

Arts

Washington, D.C., is a national center for the arts, home to several concert halls and theaters. The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts is home to the National Symphony Orchestra, the Washington National Opera, and the Washington Ballet. The Kennedy Center Honors are awarded each year to those in the performing arts who have contributed greatly to the cultural life of the United States. This ceremony is often attended by the sitting U.S. president and other dignitaries and celebrities.[200] The Kennedy Center also awards the annual Mark Twain Prize for American Humor.[201]

The historic Ford's Theatre, site of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865, continues to function as a theatre and as a museum.[202]

The Marine Barracks near Capitol Hill houses the United States Marine Band; founded in 1798, it is the country's oldest professional musical organization.[203] American march composer and Washington-native John Philip Sousa led the Marine Band from 1880 until 1892.[204] Founded in 1925, the United States Navy Band has its headquarters at the Washington Navy Yard and performs at official events and public concerts around the city.[205]

Founded in 1950, Arena Stage achieved national attention and spurred growth in the city's independent theater movement that now includes organizations such as the Shakespeare Theatre Company, Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company, and the Studio Theatre.[206] Arena Stage reopened after a renovation and expansion in the city's emerging Southwest waterfront area in 2010.[207] The GALA Hispanic Theatre, now housed in the historic Tivoli Theatre in Columbia Heights, was founded in 1976 and is a National Center for the Latino Performing Arts.[208]

Other performing arts spaces in the city include the Andrew W. Mellon Auditorium in Federal Triangle, the Atlas Performing Arts Center on H Street, the Carter Barron Amphitheater in Rock Creek Park, Constitution Hall in Downtown, the National Theatre in Downtown, the Keegan Theatre in Dupont Circle, the Lisner Auditorium in Foggy Bottom, the Sylvan Theater on the National Mall, and the Warner Theatre in Penn Quarter.[citation needed]

The U Street Corridor in Northwest D.C., once known as "Washington's Black Broadway", is home to institutions like Howard Theatre and Lincoln Theatre, which hosted music legends such as Washington-native Duke Ellington, John Coltrane, and Miles Davis.[209] Just east of U Street is Shaw, which also served as a major cultural center during the jazz age. Intersecting with U Street is Fourteenth Street, which was an extension of the U Street cultural corridor during the 1920s through the 1960s. The collection of Fourteenth Street, U Street, and Shaw was the location of the Black Renaissance in D.C., which was part of the larger Harlem Renaissance. Today, the area starting at Fourteenth Street downtown going north through U Street and east to Shaw boasts a high concentration of bars, restaurants, and theaters, and is among the city's most notable cultural and artistic areas.[citation needed]

The Washington D.C. Area Film Critics Association (WAFCA), a group of more than 65 film critics, holds an annual awards ceremony.[210]

Music

Columbia Records, a major music record label in the US, was founded in Washington, D.C. in 1889.[211][212]

The city grew into being one of America's most important music cities in the early jazz age. Duke Ellington, among the most prominent jazz composers and musicians of his time, was born and raised in Washington, and began his music career in the city. The center of the city's jazz scene during those years was U street and Shaw. Among the city's major jazz locations were the Lincoln Theatre and the Howard Theatre.[213]

Washington has its own native music genre called go-go; a post-funk, percussion-driven flavor of rhythm and blues that was popularized in the late 1970s by D.C. band leader Chuck Brown.[214]

The district is an important center for indie culture and music in the United States. The DC-based label Dischord Records, formed by Ian MacKaye, frontman of Fugazi, was one of the most crucial independent labels in the genesis of 1980s punk and eventually indie rock in the 1990s.[215] Modern alternative and indie music venues like The Black Cat and the 9:30 Club bring popular acts to the U Street area.[216] The hardcore punk scene in the city, known as D.C. hardcore, is an important genre of D.C.'s contemporary music scene. Starting in the 1970s and flourishing in the Adams Morgan neighborhood, it is considered to be one of the most influential punk music movements in the country.[217]

Cuisine

Washington, D.C., is rich in fine and casual dining; some consider it among the country's best cities for dining.[218] The city has a diverse range of restaurants, including a wide variety of international cuisines.[219] The city's Chinatown, for example, has more than a dozen Chinese-style restaurants. The city also has many Middle Eastern, European, African, Asian, and Latin American cuisine options. D.C. is known as one of the best cities in the world for Ethiopian cuisine, due largely to Ethiopian immigrants who arrived in the 20th century.[220] A part of the Shaw neighborhood in central D.C. is known as "Little Ethiopia" and has a high concentration of Ethiopian restaurants and shops.[221] The diversity of cuisine is also reflected in the city's many food trucks, which are particularly heavily concentrated along the National Mall, which has few other dining options.[222]

Among the most famous Washington, D.C.-born foods is the half-smoke, a half-beef, half-pork sausage placed in a hotdog-style bun and topped with onion, chili, and cheese.[223] The city is also the birthplace of mumbo sauce, a condiment similar to barbecue sauce but sweeter in flavor, often used on meat and french fries.[224][225] Washington, D.C. is known for popularizing the jumbo slice pizza, a large New York-style pizza[226][227][228] with roots in the Adams Morgan neighborhood.[229]

Among the city's signature restaurants is Ben's Chili Bowl, located on U Street since its founding in 1958. The restaurant rose to prominence as a peaceful escape during the violent 1968 race riots in the city. Famous for its chili dogs and half-smokes, it has been visited by numerous presidents and celebrities over the years.[230] The Georgetown Cupcake bakery became famous through its appearance on the reality T.V. show DC Cupcakes. Another culinary hotspot is Union Market in Northeast D.C., a former farmer's market and wholesale that now houses a large, gourmet food hall.[231]

D.C.'s fine dining restaurants have received more Michelin stars, as of 2023, than any other U.S. city except New York City and San Francisco. Several celebrity chefs have opened restaurants in the city, including José Andrés,[232] Kwame Onwuachi,[233] Gordon Ramsay,[234][235] and previously Michel Richard.[236]

Museums

Washington, D.C. is home to many of the country's most visited museums and some of the most visited museums in the world. In 2022, the National Museum of Natural History and the National Gallery of Art were the two most visited museums in the country. Overall, Washington had eight of the 28 most visited museums in the U.S. in 2022. That year, the National Museum of Natural History was the fifth-most-visited museum in the world; the National Gallery of Art was the eleventh.[237]

Smithsonian museums

The Smithsonian Institution is an educational foundation chartered by Congress in 1846 that maintains most of the nation's official museums and galleries in Washington, D.C. It is the world's largest research and museum complex.[238] The U.S. government partially funds the Smithsonian, and its collections are open to the public free of charge.[239] The Smithsonian's locations had a combined total of 30 million visits in 2013. The most visited museum is the National Museum of Natural History on the National Mall.[240] Other Smithsonian Institution museums and galleries on the Mall include the National Air and Space Museum; the National Museum of African Art; the National Museum of American History; the National Museum of the American Indian; the Sackler and Freer galleries, which focus on Asian art and culture; the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden; the Arts and Industries Building; the S. Dillon Ripley Center; and the Smithsonian Institution Building, which serves as the institution's headquarters.[241]

The Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Portrait Gallery are housed in the Old Patent Office Building near Washington's Chinatown.[242] Renwick Gallery is part of the Smithsonian American Art Museum and is located in a separate building near the White House. Other Smithsonian museums and galleries include Anacostia Community Museum in Southeast Washington, the National Postal Museum near Washington Union Station, and the National Zoo in Woodley Park.[241]

Other museums

The National Gallery of Art is on the National Mall near the Capitol and features American and European artworks. The U.S. government owns the gallery and its collections. However, they are not a part of the Smithsonian Institution.[243] The National Building Museum, which occupies the former Pension Building near Judiciary Square, was chartered by Congress and hosts exhibits on architecture, urban planning, and design.[244] The Botanic Garden is a botanical garden and museum operated by the U.S. Congress that is open to the public.[245]

There are several private art museums in Washington, D.C., that house major collections and exhibits open to the public, such as the National Museum of Women in the Arts and The Phillips Collection in Dupont Circle, the first museum of modern art in the United States.[246] Other private museums in Washington include the O Street Museum, the International Spy Museum, the National Geographic Society Museum, and the Museum of the Bible. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum near the National Mall maintains exhibits, documentation, and artifacts related to the Holocaust.[247]

Landmarks

National Mall and Tidal Basin

The National Mall is a park near Downtown Washington that stretches nearly two miles from the Lincoln Memorial to the United States Capitol. The mall often hosts political protests, concerts, festivals, and presidential inaugurations. The Capitol grounds host the National Memorial Day Concert, held each Memorial Day, and A Capitol Fourth, a concert held each Independence Day. Both concerts are broadcast across the country on PBS. In the evening on the Fourth of July, the park hosts a large fireworks show.[248]

The Washington Monument and the Jefferson Pier are near the center of the mall, south of the White House. Directly northwest of the Washington Monument is Constitution Gardens, which includes a garden, park, pond, and a memorial to the signers of the United States Declaration of Independence.[249] Just north of Constitution Gardens is the Lockkeeper's House, which is the second-oldest building on the mall after the White House. The house is operated by the National Park Service (NPS) and is open to the public. Also on the mall is the National World War II Memorial at the east end of the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool; the Korean War Veterans Memorial; and the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.[250]

South of the mall is the Tidal Basin, a human-made reservoir surrounded by pedestrian paths lined by Japanese cherry trees. Every spring, millions of cherry blossoms bloom, attracting visitors from across the world as part of the annual National Cherry Blossom Festival.[251] The Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial, George Mason Memorial, Jefferson Memorial, Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial, and the District of Columbia War Memorial are around the Tidal Basin.[250]

Other landmarks

Numerous historic landmarks are located outside the National Mall. Among these are the Old Post Office,[252] the Treasury Building,[253] Old Patent Office Building,[254] the National Cathedral,[255] the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception,[256] the National World War I Memorial,[257] the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site,[258] Lincoln's Cottage,[259] the Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial, and the United States Navy Memorial.[260] The Octagon House, which was the building that President James Madison and his administration moved into following the burning of the White House during the War of 1812, is now a historic museum and popular tourist destination.[261]

The National Archives is headquartered in a building just north of the National Mall and houses thousands of documents important to American history, including the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights.[262] Located in three buildings on Capitol Hill, the Library of Congress is the largest library complex in the world with a collection of more than 147 million books, manuscripts, and other materials.[263] The United States Supreme Court is located immediately north of the Library of Congress. The United States Supreme Court Building was completed in 1935; before then, the court held sessions in the Old Senate Chamber of the Capitol.[264]

Chinatown, located just north of the National Mall, houses Capital One Arena, which serves as the home arena to the Washington Capitals of the National Hockey League and the Washington Wizards of the National Basketball Association, and serves as the city's primary indoor entertainment arena. Chinatown includes several Chinese restaurants and shops. The Friendship Archway is one of the largest Chinese ceremonial archways outside of China and bears the Chinese characters for "Chinatown" below its roof.[265]

The Southwest Waterfront along the Potomac River has been redeveloped in recent years and now serves as a popular cultural center. The Wharf, as it is called, contains the city's historic Maine Avenue Fish Market. This is the oldest fish market currently in operation in the entire United States.[266] The Wharf also has many hotels, residential buildings, restaurants, shops, parks, piers, docks and marinas, and live music venues.[123][124]

Several other landmarks are located in neighboring Northern Virginia. Among these are Arlington National Cemetery, including the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, The Pentagon, the 9/11 Pentagon Memorial, the United States Air Force Memorial, Old Town Alexandria, and Mount Vernon, the former home of George Washington.[267] National Harbor in Prince George's County, Maryland, and its Capital Wheel, a ferris wheel providing riders with views of the D.C. area, are also notable landmarks. The National Spelling Bee is held annually since 2011 at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Maryland.[268]

As a result of its central role in United States history, the District of Columbia has many sites listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[citation needed]

Parks

There are many parks, gardens, squares, and circles throughout Washington. The city has 683 parks and greenspaces, comprising almost a quarter of its land area.[269] Consequently, 99% of residents live within a 10-minute walk of a park.[270] According to the nonprofit Trust for Public Land, Washington ranked first among the 100 largest U.S. cities for its public parks, based on indicators such as accessibility, the share of land reserved for parks, and the amount invested in green spaces.[270]

Rock Creek Park, located in Northwest D.C., is the largest park in the city and is administered by the National Park Service.[271] Located on the northern side of the White House, Lafayette Square is a historic public square. Named after the Marquis de Lafayette, a Frenchman who served as a commander during the American Revolutionary War, the square has been the site of many protests, marches, and speeches. The houses bordering Lafayette Square have served as the home to many notable figures, such as First Lady Dolley Madison and Abraham Lincoln's Secretary of State William H. Seward, who was stabbed by an intruder in his Lafayette Square house on the evening of President Lincoln's assassination.[272] Located next to the square and on Pennsylvania Avenue across from the White House is the Blair House, which serves as the primary state guest house for the U.S. president.[273]

There are several river islands in Washington, D.C., including Theodore Roosevelt Island in the Potomac River, which hosts the Theodore Roosevelt National Memorial and a number of trails.[274] Columbia Island, also in the Potomac, is home to the Lyndon Baines Johnson Memorial Grove, the Navy – Merchant Marine Memorial, and a marina. Kingman Island, in the Anacostia River, is home to Langston Golf Course and a public park with trails.[275]

Other parks, gardens, and squares include Dumbarton Oaks, Meridian Hill Park, the Yards, Anacostia Park, Lincoln Park, Kenilworth Park and Aquatic Gardens, Franklin Square, McPherson Square, Farragut Square, and Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park.[276] There are a large number of traffic circles and circle parks in Washington, D.C., including Dupont Circle, Logan Circle, Scott Circle, Sheridan Circle, Thomas Circle, Washington Circle, and others.[citation needed]

The United States National Arboretum is a dense arboretum in Northeast D.C. filled with gardens and trails. Its most notable landmark is the National Capitol Columns monument.[277]

Sports

| Team | League | Sport | Venue | Neighborhood | Capacity | Founded (moved to Washington area) | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Washington Commanders | NFL | American football | Commanders Field | Landover, Maryland | 65,000 | 1932 (1937) | 1937, 1942, 1982, 1987, 1991 |

| Washington Wizards | NBA | Men's Basketball | Capital One Arena | Chinatown | 20,356 | 1961 (1973) | 1978 |

| Washington Nationals | MLB | Baseball | Nationals Park | Navy Yard | 41,339 | 1969 (2005) | 2019 |

| Washington Capitals | NHL | Ice hockey | Capital One Arena | Chinatown | 18,573 | 1974 | 2018 |

| D.C. United | MLS | Men's Soccer | Audi Field | Buzzard Point | 20,000 | 1996 | 1996, 1997, 1999, 2004[j] |

| Washington Mystics | WNBA | Women's Basketball | Entertainment and Sports Arena | Congress Heights | 4,200 | 1998 | 2019 |

| Washington Spirit | NWSL | Women's Soccer | Audi Field | Buzzard Point | 20,000 | 2012 | 2021 |

Washington, D.C. is one of 13 cities in the United States with teams from the primary four major professional men's sports and is home to two major professional women's teams.[279] The Washington Nationals of Major League Baseball are the most popular sports team in the District, as of 2019.[280] They play at Nationals Park, which opened in 2008. The Washington Commanders of the National Football League play at FedExField in nearby Landover, Maryland. The Washington Wizards of the National Basketball Association and the Washington Capitals of the National Hockey League play at Capital One Arena in the city's Penn Quarter neighborhood. The Washington Mystics of the Women's National Basketball Association play at Entertainment and Sports Arena. D.C. United of Major League Soccer and the Washington Spirit of the National Women's Soccer League play at Audi Field.[citation needed]

The city's teams have won a combined 14 professional league championships over their respective histories. The Washington Commanders (named the Washington Redskins until 2020), have won two NFL Championships and three Super Bowls;[281] D.C. United has won four;[282] and the Washington Wizards, then named the Washington Bullets, Washington Capitals, Washington Mystics, Washington Nationals, and Washington Spirit have each won a single championship.[283][284]

Other professional and semi-professional teams in Washington, D.C. include DC Defenders of the XFL, Old Glory DC of Major League Rugby, the Washington Kastles of World TeamTennis, and the D.C. Divas of the Independent Women's Football League. The William H.G. FitzGerald Tennis Center in Rock Creek Park hosts the Washington Open, a joint men's ATP Tour 500- and women's WTA Tour 500-level tennis tournament, every summer in late July and early August. Washington, D.C. has two major annual marathon races, the Marine Corps Marathon, held every autumn, and the Rock 'n' Roll USA Marathon, held each spring. The Marine Corps Marathon began in 1976 and is sometimes called "The People's Marathon" because it is the largest marathon that does not offer prize money to participants.[285]

The district's four NCAA Division I teams are the American Eagles of American University, George Washington Revolutionaries of George Washington University, the Georgetown Hoyas of Georgetown University, and the Howard Bison and Lady Bison of Howard University. The Georgetown men's basketball team is the most notable and also plays at Capital One Arena. Washington, D.C. area's regional sports television network is Monumental Sports Network, and was known as NBC Sports Washington until September 2023.[286]

City government

Politics

Article One, Section Eight of the United States Constitution grants the United States Congress "exclusive jurisdiction" over the city. The district did not have an elected local government until the passage of the 1973 Home Rule Act. The Act devolved certain Congressional powers to an elected mayor and the thirteen-member Council of the District of Columbia. However, Congress retains the right to review and overturn laws created by the council and intervene in local affairs.[287] Washington, D.C., is overwhelmingly Democratic, having voted for the Democratic presidential candidate solidly since it was granted electoral votes in 1964.[citation needed]

Each of the city's eight wards elects a single member of the council and residents elect four at-large members to represent the district as a whole. The council chair is also elected at-large.[288] There are 37 Advisory Neighborhood Commissions (ANCs) elected by small neighborhood districts. ANCs can issue recommendations on all issues that affect residents; government agencies take their advice under careful consideration.[289] The attorney general of the District of Columbia is elected to a four-year term.[290]

Washington, D.C., observes all federal holidays and also celebrates Emancipation Day on April 16, which commemorates the end of slavery in the district.[50] The flag of Washington, D.C., was adopted in 1938 and is a variation on George Washington's family coat of arms.[291]

Washington, D.C., has been a member state of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO) since 2015.[292]

The idiom "Inside the Beltway" is a reference used by media to describe discussions of national political issues inside of Washington, by way of geographical demarcation regarding the region within the Capital's Beltway, Interstate 495, the city's highway loop (beltway) constructed in 1964. The phrase is used as a title for a number of political columns and news items by publications like The Washington Times.[293]

Budgetary issues

The mayor and council set local taxes and a budget, which Congress must approve. The Government Accountability Office and other analysts have estimated that the city's high percentage of tax-exempt property and the Congressional prohibition of commuter taxes create a structural deficit in the district's local budget of anywhere between $470 million and over $1 billion per year. Congress typically provides additional grants for federal programs such as Medicaid and the operation of the local justice system; however, analysts claim that the payments do not fully resolve the imbalance.[294][295]

The city's local government, particularly during the mayoralty of Marion Barry, has been criticized for mismanagement and waste.[296] During his administration in 1989, Washington Monthly magazine labeled the district "the worst city government in America".[297] In 1995, at the start of Barry's fourth term, Congress created the District of Columbia Financial Control Board to oversee all municipal spending.[298] Mayor Anthony Williams won election in 1998 and oversaw a period of urban renewal and budget surpluses.[299]

The district regained control over its finances in 2001 and the oversight board's operations were suspended.[300]

The district has a federally funded "Emergency Planning and Security Fund" to cover security related to visits by foreign leaders and diplomats, presidential inaugurations, protests, and terrorism concerns. During the Trump administration, the fund has run with a deficit. Trump's January 2017 inauguration cost the city $27 million; of that, $7 million was never repaid to the fund. Trump's 2019 Independence Day event, "A Salute to America", cost six times more than Independence Day events in past years.[301]

Voting rights debate

Washington, D.C. is not a state and therefore has no federal voting representation in Congress. The city's residents elect a non-voting delegate to the House of Representatives (D.C. at-large), who may sit on committees, participate in debate, and introduce legislation, but cannot vote on the House floor. The district has no official representation in the United States Senate. Neither chamber seats the district's elected "shadow" representative or senators. Unlike residents of U.S. territories such as Puerto Rico or Guam, which also have non-voting delegates, D.C. residents are subject to all federal taxes.[302] In the financial year 2012, D.C. residents and businesses paid $20.7 billion in federal taxes, more than the taxes collected from 19 states and the highest federal taxes per capita.[303]

A 2005 poll found that 78% of Americans did not know residents of Washington, D.C., have less representation in Congress than residents of the 50 states.[304] Efforts to raise awareness about the issue have included campaigns by grassroots organizations and featuring the city's unofficial motto, "End Taxation Without Representation", on D.C. vehicle license plates.[305] There is evidence of nationwide approval for D.C. voting rights; various polls indicate that 61 to 82% of Americans believe D.C. should have voting representation in Congress.[304][306]

Opponents to federal voting rights for Washington, D.C., propose that the Founding Fathers never intended for district residents to have a vote in Congress since the Constitution makes clear that representation must come from the states. Those opposed to making District of Columbia a state claim such a move would destroy the notion of a separate national capital and that statehood would unfairly grant Senate representation to a single city.[307]

Homelessness

The city passed a law that requires shelter to be provided to everyone in need when the temperature drops below freezing.[308] Since D.C. does not have enough shelter units available, every winter it books hotel rooms in the suburbs with an average cost around $100 for a night. According to the D.C. Department of Human Services, during the winter of 2012 the city spent $2,544,454 on putting homeless families in hotels,[309] and budgeted $3.2 million on hotel beds in 2013.[310]

Education

District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS), the sole public school district in the city,[311] operates the city's 123 public schools.[312] The number of students in DCPS steadily decreased for 39 years until 2009. In the 2010–11 school year, 46,191 students were enrolled in the public school system.[313] DCPS has one of the highest-cost, yet lowest-performing school systems in the country, in terms of both infrastructure and student achievement.[314] Mayor Adrian Fenty's administration made sweeping changes to the system by closing schools, replacing teachers, firing principals, and using private education firms to aid curriculum development.[315]

The District of Columbia Public Charter School Board monitors the 52 public charter schools in the city.[316] Due to the perceived problems with the traditional public school system, enrollment in public charter schools had by 2007 steadily increased.[317] As of 2010, D.C., charter schools had a total enrollment of about 32,000, a 9% increase from the prior year.[313] The district is also home to 92 private schools, which enrolled approximately 18,000 students in 2008.[318]

Higher education

The University of the District of Columbia (UDC) is a public land-grant university providing undergraduate and graduate education.[319] Federally chartered universities include American University (AU), Gallaudet University, George Washington University (GWU), Georgetown University (GU), and Howard University (HU). Other private universities include the Catholic University of America (CUA), the Johns Hopkins University Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), and Trinity Washington University. The Corcoran College of Art and Design, the oldest art school in the capital, was absorbed into the George Washington University in 2014, now serving as its college of arts.[320]

The city's medical research institutions include Washington Hospital Center and Children's National Medical Center. The city is home to three medical schools and associated teaching hospitals: George Washington, Georgetown, and Howard universities.[321]

Libraries

Washington, D.C., has dozens of public and private libraries and library systems, including the District of Columbia Public Library system.[citation needed] Folger Shakespeare Library, a research library and museum located in the Capitol Hill neighborhood, houses the world's largest collection of material related to William Shakespeare.[322]

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the de facto national library of the United States. It is a complex of three buildings: Thomas Jefferson Building, John Adams Building and James Madison Memorial Building, all located in the Capitol Hill neighborhood. The Jefferson Building houses the library's reading room, a copy of the Gutenberg Bible, Thomas Jefferson's original library, and several museum exhibits.[citation needed]

District of Columbia Public Library

The District of Columbia Public Library operates 26 neighborhood locations including the landmark Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library.[324]

Media

Washington, D.C., is a prominent center for national and international media. The Washington Post, founded in 1877, is the city's oldest and most-read local daily newspaper.[325] "The Post", as it is popularly called, is well known as the newspaper that exposed the Watergate scandal.[326] It had the sixth-highest readership of all news dailies in the country in 2011.[327] The Washington Post also publishes a Spanish language newspaper El Tiempo Latino, a leading Spanish-language news source for the Washington area. The Post is headquartered at One Franklin Square just north of Franklin Square in Downtown Washington.[citation needed]