Гарольд Пинтер

Гарольд Пинтер | |

|---|---|

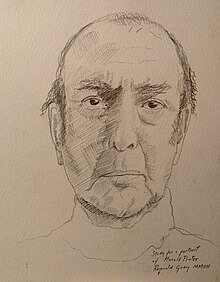

Пинтер в 2005 году | |

| Рожденный | 10 октября 1930 г. Лондон, Англия |

| Умер | 24 декабря 2008 г. (78 лет) Лондон, Англия |

| Занятие | Драматург, сценарист, актер, театральный режиссер, поэт |

| Альма-матер | Королевская центральная школа речи и драмы |

| Period | 1947–2008 |

| Notable awards |

|

| Spouse | |

| Children | 1 |

| Signature | |

| Website | |

| www | |

Гарольд Пинтер CH CBE ( / ˈ p ɪ n t ər / ; 10 октября 1930 — 24 декабря 2008) — британский драматург, сценарист, режиссёр и актёр. Лауреат Нобелевской премии , Пинтер был одним из самых влиятельных современных британских драматургов, писательская карьера которого длилась более 50 лет. Среди его самых известных пьес — «Вечеринка по случаю дня рождения » (1957), «Возвращение домой» (1964) и «Предательство» (1978), каждую из которых он адаптировал для экрана. Его экранизации чужих произведений включают «Слугу» (1963), «Посредника» (1971), «Женщину французского лейтенанта» (1981), «Процесс» (1993) и «Сыщик» (2007). Он также руководил или снимался на радио, сцене, телевидении и в кинопостановках своих и чужих произведений.

Пинтер родился и вырос в Хакни , восточный Лондон, и получил образование в школе Хакни-Даунс . Он был спринтером и заядлым игроком в крикет, играл в школьных спектаклях и писал стихи . Он учился в Королевской академии драматического искусства , но не закончил курс. Он был оштрафован за отказ от военной службы по соображениям совести . Впоследствии он продолжил обучение в Центральной школе речи и драмы и работал в репертуарном театре Ирландии и Англии. В 1956 году он женился на актрисе Вивьен Мерчант , у них родился сын Дэниел, родившийся в 1958 году. Он покинул Мерчант в 1975 году и женился на писательнице леди Антонии Фрейзер в 1980 году.

Pinter's career as a playwright began with a production of The Room in 1957. His second play, The Birthday Party, closed after eight performances but was enthusiastically reviewed by critic Harold Hobson. His early works were described by critics as "comedy of menace". Later plays such as No Man's Land (1975) and Betrayal (1978) became known as "memory plays". He appeared as an actor in productions of his own work on radio and film, and directed nearly 50 productions for stage, theatre and screen. Pinter received over 50 awards, prizes and other honours, including the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2005 and the French Légion d'honneur in 2007.

Despite frail health after being diagnosed with oesophageal cancer in December 2001, Pinter continued to act on stage and screen, last performing the title role of Samuel Beckett's one-act monologue Krapp's Last Tape, for the 50th anniversary season of the Royal Court Theatre, in October 2006. He died from liver cancer on 24 December 2008.

Biography

Early life and education

Pinter was born on 10 October 1930, in Hackney, east London, the only child of British Jewish parents of Eastern European descent: his father, Hyman "Jack" Pinter (1902–1997) was a ladies' tailor; his mother, Frances (née Moskowitz; 1904–1992), a housewife.[2][3] Pinter believed an aunt's erroneous view that the family was Sephardic and had fled the Spanish Inquisition; thus, for his early poems, Pinter used the pseudonym Pinta and at other times used variations such as da Pinto.[4] Later research by Lady Antonia Fraser, Pinter's second wife, revealed the legend to be apocryphal; three of Pinter's grandparents came from Poland and the fourth from Odesa, so the family was Ashkenazic.[4][5][6]

Pinter's family home in London is described by his official biographer Michael Billington as "a solid, red-brick, three-storey villa just off the noisy, bustling, traffic-ridden thoroughfare of the Lower Clapton Road".[7] In 1940 and 1941, after the Blitz, Pinter was evacuated from their house in London to Cornwall and Reading.[7] Billington states that the "life-and-death intensity of daily experience" before and during the Blitz left Pinter with profound memories "of loneliness, bewilderment, separation and loss: themes that are in all his works."[8]

Pinter discovered his social potential as a student at Hackney Downs School, a London grammar school, between 1944 and 1948. "Partly through the school and partly through the social life of Hackney Boys' Club ... he formed an almost sacerdotal belief in the power of male friendship. The friends he made in those days – most particularly Henry Woolf, Michael (Mick) Goldstein and Morris (Moishe) Wernick – have always been a vital part of the emotional texture of his life."[6][9] A major influence on Pinter was his inspirational English teacher Joseph Brearley, who directed him in school plays and with whom he took long walks, talking about literature.[10] According to Billington, under Brearley's instruction, "Pinter shone at English, wrote for the school magazine and discovered a gift for acting."[11][12] In 1947 and 1948, he played Romeo and Macbeth in productions directed by Brearley.[13]

At the age of 12, Pinter began writing poetry, and in spring 1947, his poetry was first published in the Hackney Downs School Magazine.[14] In 1950 his poetry was first published outside the school magazine, in Poetry London, some of it under the pseudonym "Harold Pinta".[15][16]

Pinter was an atheist.[17]

Sport and friendship

Pinter enjoyed running and broke the Hackney Downs School sprinting record.[18][19]He was a cricket enthusiast, taking his bat with him when evacuated during the Blitz.[20] In 1971, he told Mel Gussow: "one of my main obsessions in life is the game of cricket—I play and watch and read about it all the time."[21] He was chairman of the Gaieties Cricket Club, a supporter of Yorkshire Cricket Club,[22] and devoted a section of his official website to the sport.[23] One wall of his study was dominated by a portrait of himself as a young man playing cricket, which was described by Sarah Lyall, writing in The New York Times: "The painted Mr. Pinter, poised to swing his bat, has a wicked glint in his eye; testosterone all but flies off the canvas."[24][25] Pinter approved of the "urban and exacting idea of cricket as a bold theatre of aggression."[26] After his death, several of his school contemporaries recalled his achievements in sports, especially cricket and running.[27] The BBC Radio 4 memorial tribute included an essay on Pinter and cricket.[28]

Other interests that Pinter mentioned to interviewers are family, love and sex, drinking, writing, and reading.[29] According to Billington, "If the notion of male loyalty, competitive rivalry and fear of betrayal forms a constant thread in Pinter's work from The Dwarfs onwards, its origins can be found in his teenage Hackney years. Pinter adores women, enjoys flirting with them, and worships their resilience and strength. But, in his early work especially, they are often seen as disruptive influences on some pure and Platonic ideal of male friendship: one of the most crucial of all Pinter's lost Edens."[6][30]

Early theatrical training and stage experience

Beginning in late 1948, Pinter attended the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art for two terms, but hating the school, missed most of his classes, feigned a nervous breakdown, and dropped out in 1949.[31] In 1948 he was called up for National Service. He was initially refused registration as a conscientious objector, leading to his twice being prosecuted, and fined, for refusing to accept a medical examination, before his CO registration was ultimately agreed.[32] He had a small part in the Christmas pantomime Dick Whittington and His Cat at the Chesterfield Hippodrome in 1949 to 1950.[33] From January to July 1951, he attended the Central School of Speech and Drama.[34]

From 1951 to 1952, he toured Ireland with the Anew McMaster repertory company, playing over a dozen roles.[35] In 1952, he began acting in regional English repertory productions; from 1953 to 1954, he worked for the Donald Wolfit Company, at the King's Theatre, Hammersmith, performing eight roles.[36][37] From 1954 until 1959, Pinter acted under the stage name David Baron.[38][39] In all, Pinter played over 20 roles under that name.[39][40] To supplement his income from acting, Pinter worked as a waiter, a postman, a bouncer, and a snow-clearer, meanwhile, according to Mark Batty, "harbouring ambitions as a poet and writer."[41] In October 1989 Pinter recalled: "I was in English rep as an actor for about 12 years. My favourite roles were undoubtedly the sinister ones. They're something to get your teeth into."[42] During that period, he also performed occasional roles in his own and others' works for radio, TV, and film, as he continued to do throughout his career.[39][43]

Marriages and family life

From 1956 until 1980, Pinter was married to Vivien Merchant, an actress whom he met on tour,[44] perhaps best known for her performance in the 1966 film Alfie. Their son Daniel was born in 1958.[45] Through the early 1970s, Merchant appeared in many of Pinter's works, including The Homecoming on stage (1965) and screen (1973), but the marriage was turbulent.[46] For seven years, from 1962 to 1969, Pinter was engaged in a clandestine affair with BBC-TV presenter and journalist Joan Bakewell, which inspired his 1978 play Betrayal,[47] and also throughout that period and beyond he had an affair with an American socialite, whom he nicknamed "Cleopatra". This relationship was another secret he kept from both his wife and Bakewell.[48] Initially, Betrayal was thought to be a response to his later affair with historian Antonia Fraser, the wife of Hugh Fraser, and Pinter's "marital crack-up".[49]

Pinter and Merchant had both met Antonia Fraser in 1969, when all three worked together on a National Gallery programme about Mary, Queen of Scots; several years later, on 8–9 January 1975, Pinter and Fraser became romantically involved.[50] That meeting initiated their five-year extramarital love affair.[51][52] After hiding the relationship from Merchant for two and a half months, on 21 March 1975, Pinter finally told her "I've met somebody".[53] After that, "Life in Hanover Terrace gradually became impossible", and Pinter moved out of their house on 28 April 1975, five days after the première of No Man's Land.[54][55]

In mid-August 1977, after Pinter and Fraser had spent two years living in borrowed and rented quarters, they moved into her former family home in Holland Park,[56] where Pinter began writing Betrayal.[49] He reworked it later, while on holiday at the Grand Hotel in Eastbourne, in early January 1978.[57] After the Frasers' divorce had become final in 1977 and the Pinters' in 1980, Pinter married Fraser on 27 November 1980.[58] Because of a two-week delay in Merchant's signing the divorce papers, however, the reception had to precede the actual ceremony, originally scheduled to occur on his 50th birthday.[59] Vivien Merchant died of acute alcoholism in the first week of October 1982, at the age of 53.[60][61] Billington writes that Pinter "did everything possible to support" her and regretted that he ultimately became estranged from their son, Daniel, after their separation, Pinter's remarriage, and Merchant's death.[62]

A reclusive gifted musician and writer, Daniel changed his surname from Pinter to Brand, the maiden name of his maternal grandmother,[63] before Pinter and Fraser became romantically involved; while according to Fraser, his father could not understand it, she says that she could: "Pinter is such a distinctive name that he must have got tired of being asked, 'Any relation?'"[64] Michael Billington wrote that Pinter saw Daniel's name change as "a largely pragmatic move on Daniel's part designed to keep the press ... at bay."[65] Fraser told Billington that Daniel "was very nice to me at a time when it would have been only too easy for him to have turned on me ... simply because he had been the sole focus of his father's love and now manifestly wasn't."[65] Still unreconciled at the time of his father's death, Daniel Brand did not attend Pinter's funeral.[66]

Billington observes that "The break-up with Vivien and the new life with Antonia was to have a profound effect on Pinter's personality and his work," though he adds that Fraser herself did not claim to have influence over Pinter or his writing.[63] In her own contemporaneous diary entry dated 15 January 1993, Fraser described herself more as Pinter's literary midwife.[67] Indeed, she told Billington that "other people [such as Peggy Ashcroft, among others] had a shaping influence on [Pinter's] politics" and attributed changes in his writing and political views to a change from "an unhappy, complicated personal life ... to a happy, uncomplicated personal life", so that "a side of Harold which had always been there was somehow released. I think you can see that in his work after No Man's Land [1975], which was a very bleak play."[63]

Pinter was content in his second marriage and enjoyed family life with his six adult stepchildren and 17 step-grandchildren.[68] Even after battling cancer for several years, he considered himself "a very lucky man in every respect".[69] Sarah Lyall notes in her 2007 interview with Pinter in The New York Times that his "latest work, a slim pamphlet called 'Six Poems for A.', comprises poems written over 32 years, with "A" of course being Lady Antonia. The first of the poems was written in Paris, where she and Mr. Pinter traveled soon after they met. More than three decades later the two are rarely apart, and Mr. Pinter turns soft, even cozy, when he talks about his wife."[24] In that interview Pinter "acknowledged that his plays—full of infidelity, cruelty, inhumanity, the lot—seem at odds with his domestic contentment. 'How can you write a happy play?' he said. 'Drama is about conflict and degrees of perturbation, disarray. I've never been able to write a happy play, but I've been able to enjoy a happy life.'"[24] After his death, Fraser told The Guardian: "He was a great man, and it was a privilege to live with him for over 33 years. He will never be forgotten."[70][71]

Civic activities and political activism

In 1948–49, when he was 18, Pinter opposed the politics of the Cold War, leading to his decision to become a conscientious objector and to refuse to comply with National Service in the British military. However, he told interviewers that, if he had been old enough at the time, he would have fought against the Nazis in World War II.[72] He seemed to express ambivalence, both indifference and hostility, towards political structures and politicians in his Fall 1966 Paris Review interview conducted by Lawrence M. Bensky.[73] Yet, he had been an early member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and also had supported the British Anti-Apartheid Movement (1959–1994), participating in British artists' refusal to permit professional productions of their work in South Africa in 1963 and in subsequent related campaigns.[74][75][76] In "A Play and Its Politics", a 1985 interview with Nicholas Hern, Pinter described his earlier plays retrospectively from the perspective of the politics of power and the dynamics of oppression.[77]

In his last 25 years, Pinter increasingly focused his essays, interviews and public appearances directly on political issues. He was an officer in International PEN, travelling with American playwright Arthur Miller to Turkey in 1985 on a mission co-sponsored with a Helsinki Watch committee to investigate and protest against the torture of imprisoned writers. There he met victims of political oppression and their families. Pinter's experiences in Turkey and his knowledge of the Turkish suppression of the Kurdish language inspired his 1988 play Mountain Language.[78] He was also an active member of the Cuba Solidarity Campaign, an organisation that "campaigns in the UK against the US blockade of Cuba".[79] In 2001, Pinter joined the International Committee to Defend Slobodan Milošević (ICDSM), which appealed for a fair trial and for the freedom of Slobodan Milošević, signing a related "Artists' Appeal for Milošević" in 2004.[80]

Pinter strongly opposed the 1991 Gulf War, the 1999 NATO bombing campaign in FR Yugoslavia during the Kosovo War, the United States' 2001 War in Afghanistan, and the 2003 Invasion of Iraq. Among his provocative political statements, Pinter called Prime Minister Tony Blair a "deluded idiot" and compared the administration of President George W. Bush to Nazi Germany.[80][81] He stated that the United States "was charging towards world domination while the American public and Britain's 'mass-murdering' prime minister sat back and watched."[81] He was very active in the antiwar movement in the United Kingdom, speaking at rallies held by the Stop the War Coalition[82] and frequently criticising American aggression, as when he asked rhetorically, in his acceptance speech for the Wilfred Owen Award for Poetry on 18 March 2007: "What would Wilfred Owen make of the invasion of Iraq? A bandit act, an act of blatant state terrorism, demonstrating absolute contempt for the conception of international law."[83][84][85]

Pinter earned a reputation for being pugnacious, enigmatic, taciturn, terse, prickly, explosive and forbidding.[86] Pinter's blunt political statements, and the award of the Nobel Prize in Literature, elicited strong criticism and even, at times, provoked ridicule and personal attacks.[87] The historian Geoffrey Alderman, author of the official history of Hackney Downs School, expressed his own "Jewish View" of Harold Pinter: "Whatever his merit as a writer, actor and director, on an ethical plane Harold Pinter seems to me to have been intensely flawed, and his moral compass deeply fractured."[88] David Edgar, writing in The Guardian, defended Pinter against what he termed Pinter's "being berated by the belligerati" like Johann Hari, who felt that he did not "deserve" to win the Nobel Prize.[89][90] Later Pinter continued to campaign against the Iraq War and on behalf of other political causes that he supported.

Pinter signed the mission statement of Jews for Justice for Palestinians in 2005 and its full-page advertisement, "What Is Israel Doing? A Call by Jews in Britain", published in The Times on 6 July 2006,[88] and he was a patron of the Palestine Festival of Literature. In April 2008, Pinter signed the statement "We're not celebrating Israel's anniversary". The statement noted: "We cannot celebrate the birthday of a state founded on terrorism, massacres and the dispossession of another people from their land.", "We will celebrate when Arab and Jew live as equals in a peaceful Middle East"[91]

Career

As actor

Pinter's acting career spanned over 50 years and, although he often played villains, included a wide range of roles on stage and in radio, film, and television.[36][92] In addition to roles in radio and television adaptations of his own plays and dramatic sketches, early in his screenwriting career he made several cameo appearances in films based on his own screenplays; for example, as a society man in The Servant (1963) and as Mr. Bell in Accident (1967), both directed by Joseph Losey; and as a bookshop customer in his later film Turtle Diary (1985), starring Michael Gambon, Glenda Jackson, and Ben Kingsley.[36]

Pinter's notable film and television roles included the lawyer Saul Abrahams opposite Peter O'Toole in Rogue Male, BBC TV's 1976 adaptation of Geoffrey Household's 1939 novel, and a drunk Irish journalist in Langrishe, Go Down (starring Judi Dench and Jeremy Irons) distributed on BBC Two in 1978[92] and released in movie theatres in 2002.[93] Pinter's later film roles included the criminal Sam Ross in Mojo (1997), written and directed by Jez Butterworth, based on Butterworth's play of the same name; Sir Thomas Bertram (his most substantial feature-film role) in Mansfield Park (1998), a character that Pinter described as "a very civilised man ... a man of great sensibility but in fact, he's upholding and sustaining a totally brutal system [the slave trade] from which he derives his money"; and Uncle Benny, opposite Pierce Brosnan and Geoffrey Rush, in The Tailor of Panama (2001).[36] In television films, he played Mr. Bearing, the father of ovarian cancer patient Vivian Bearing, played by Emma Thompson in Mike Nichols's HBO film of the Pulitzer Prize-winning play Wit (2001); and the Director opposite John Gielgud (Gielgud's last role) and Rebecca Pidgeon in Catastrophe, by Samuel Beckett, directed by David Mamet as part of Beckett on Film (2001).[36][92]

As director

Pinter began to direct more frequently during the 1970s, becoming an associate director of the National Theatre (NT) in 1973.[94] He directed almost 50 productions of his own and others' plays for stage, film, and television, including 10 productions of works by Simon Gray: the stage and/or film premières of Butley (stage, 1971; film, 1974), Otherwise Engaged (1975), The Rear Column (stage, 1978; TV, 1980), Close of Play (NT, 1979), Quartermaine's Terms (1981), Life Support (1997), The Late Middle Classes (1999), and The Old Masters (2004).[44] Several of those productions starred Alan Bates (1934–2003), who originated the stage and screen roles of not only Butley but also Mick in Pinter's first major commercial success, The Caretaker (stage, 1960; film, 1964); and in Pinter's double-bill produced at the Lyric Hammersmith in 1984, he played Nicolas in One for the Road and the cab driver in Victoria Station.[95] Among over 35 plays that Pinter directed were Next of Kin (1974), by John Hopkins; Blithe Spirit (1976), by Noël Coward; The Innocents (1976), by William Archibald; Circe and Bravo (1986), by Donald Freed; Taking Sides (1995), by Ronald Harwood; and Twelve Angry Men (1996), by Reginald Rose.[94][96]

As playwright

Pinter was the author of 29 plays and 15 dramatic sketches and the co-author of two works for stage and radio.[97] He was considered to have been one of the most influential modern British dramatists,[98][99] Along with the 1967 Tony Award for Best Play for The Homecoming and several other American awards and award nominations, he and his plays received many awards in the UK and elsewhere throughout the world.[100] His style has entered the English language as an adjective, "Pinteresque", although Pinter himself disliked the term and found it meaningless.[101]

"Comedies of menace" (1957–1968)

Pinter's first play, The Room, written and first performed in 1957, was a student production at the University of Bristol, directed by his good friend, actor Henry Woolf, who also originated the role of Mr. Kidd (which he reprised in 2001 and 2007).[97] After Pinter mentioned that he had an idea for a play, Woolf asked him to write it so that he could direct it to fulfill a requirement for his postgraduate work. Pinter wrote it in three days.[102] The production was described by Billington as "a staggeringly confident debut which attracted the attention of a young producer, Michael Codron, who decided to present Pinter's next play, The Birthday Party, at the Lyric Hammersmith, in 1958."[103]

Written in 1957 and produced in 1958, Pinter's second play, The Birthday Party, one of his best-known works, was initially both a commercial and critical disaster, despite an enthusiastic review in The Sunday Times by its influential drama critic Harold Hobson,[104] which appeared only after the production had closed and could not be reprieved.[103][105] Critical accounts often quote Hobson:

I am well aware that Mr Pinter[']s play received extremely bad notices last Tuesday morning. At the moment I write these [words] it is uncertain even whether the play will still be in the bill by the time they appear, though it is probable it will soon be seen elsewhere. Deliberately, I am willing to risk whatever reputation I have as a judge of plays by saying that The Birthday Party is not a Fourth, not even a Second, but a First [as in Class Honours]; and that Pinter, on the evidence of his work, possesses the most original, disturbing and arresting talent in theatrical London ... Mr Pinter and The Birthday Party, despite their experiences last week, will be heard of again. Make a note of their names.

Pinter himself and later critics generally credited Hobson as bolstering him and perhaps even rescuing his career.[106]

In a review published in 1958, borrowing from the subtitle of The Lunatic View: A Comedy of Menace, a play by David Campton, critic Irving Wardle called Pinter's early plays "comedy of menace"—a label that people have applied repeatedly to his work.[107] Such plays begin with an apparently innocent situation that becomes both threatening and "absurd" as Pinter's characters behave in ways often perceived as inexplicable by his audiences and one another. Pinter acknowledges the influence of Samuel Beckett, particularly on his early work; they became friends, sending each other drafts of their works in progress for comments.[101][108]

Pinter wrote The Hothouse in 1958, which he shelved for over 20 years (See "Overtly political plays and sketches" below). Next he wrote The Dumb Waiter (1959), which premièred in Germany and was then produced in a double bill with The Room at the Hampstead Theatre Club, in London, in 1960.[97] It was then not produced often until the 1980s, and it has been revived more frequently since 2000, including the West End Trafalgar Studios production in 2007. The first production of The Caretaker, at the Arts Theatre Club, in London, in 1960, established Pinter's theatrical reputation.[109] The play transferred to the Duchess Theatre in May 1960 and ran for 444 performances,[110] receiving an Evening Standard Award for best play of 1960.[111] Large radio and television audiences for his one-act play A Night Out, along with the popularity of his revue sketches, propelled him to further critical attention.[112] In 1964, The Birthday Party was revived both on television (with Pinter himself in the role of Goldberg) and on stage (directed by Pinter at the Aldwych Theatre) and was well received.[113]

By the time Peter Hall's London production of The Homecoming (1964) reached Broadway in 1967, Pinter had become a celebrity playwright, and the play garnered four Tony Awards, among other awards.[114] During this period, Pinter also wrote the radio play A Slight Ache, first broadcast on the BBC Third Programme in 1959 and then adapted to the stage and performed at the Arts Theatre Club in 1961. A Night Out (1960) was broadcast to a large audience on ABC Weekend TV's television show Armchair Theatre, after being transmitted on BBC Radio 3, also in 1960. His play Night School was first televised in 1960 on Associated Rediffusion. The Collection premièred at the Aldwych Theatre in 1962, and The Dwarfs, adapted from Pinter's then unpublished novel of the same title, was first broadcast on radio in 1960, then adapted for the stage (also at the Arts Theatre Club) in a double bill with The Lover, which had previously been televised by Associated Rediffusion in 1963; and Tea Party, a play that Pinter developed from his 1963 short story, first broadcast on BBC TV in 1965.[97]

Working as both a screenwriter and as a playwright, Pinter composed a script called The Compartment (1966), for a trilogy of films to be contributed by Samuel Beckett, Eugène Ionesco, and Pinter, of which only Beckett's film, titled Film, was actually produced. Then Pinter turned his unfilmed script into a television play, which was produced as The Basement, both on BBC 2 and also on stage in 1968.[115]

"Memory plays" (1968–1982)

From the late 1960s through the early 1980s, Pinter wrote a series of plays and sketches that explore complex ambiguities, elegiac mysteries, comic vagaries, and other "quicksand-like" characteristics of memory and which critics sometimes classify as Pinter's "memory plays".[116] These include Landscape (1968), Silence (1969), Night (1969), Old Times (1971), No Man's Land (1975), The Proust Screenplay (1977), Betrayal (1978), Family Voices (1981), Victoria Station (1982), and A Kind of Alaska (1982). Some of Pinter's later plays, including Party Time (1991), Moonlight (1993), Ashes to Ashes (1996), and Celebration (2000), draw upon some features of his "memory" dramaturgy in their focus on the past in the present, but they have personal and political resonances and other tonal differences from these earlier memory plays.[116][117]

Overtly political plays and sketches (1980–2000)

Following a three-year period of creative drought in the early 1980s after his marriage to Antonia Fraser and the death of Vivien Merchant,[118] Pinter's plays tended to become shorter and more overtly political, serving as critiques of oppression, torture, and other abuses of human rights,[119] linked by the apparent "invulnerability of power."[120] Just before this hiatus, in 1979, Pinter re-discovered his manuscript of The Hothouse, which he had written in 1958 but had set aside; he revised it and then directed its first production himself at Hampstead Theatre in London, in 1980.[121] Like his plays of the 1980s, The Hothouse concerns authoritarianism and the abuses of power politics, but it is also a comedy, like his earlier comedies of menace. Pinter played the major role of Roote in a 1995 revival at the Minerva Theatre, Chichester.[122]

Pinter's brief dramatic sketch Precisely (1983) is a duologue between two bureaucrats exploring the absurd power politics of mutual nuclear annihilation and deterrence. His first overtly political one-act play is One for the Road (1984). In 1985 Pinter stated that whereas his earlier plays presented metaphors for power and powerlessness, the later ones present literal realities of power and its abuse.[123] Pinter's "political theatre dramatizes the interplay and conflict of the opposing poles of involvement and disengagement."[124] Mountain Language (1988) is about the Turkish suppression of the Kurdish language.[78] The dramatic sketch The New World Order (1991) provides what Robert Cushman, writing in The Independent described as "10 nerve-wracking minutes" of two men threatening to torture a third man who is blindfolded, gagged and bound in a chair; Pinter directed the British première at the Royal Court Theatre Upstairs, where it opened on 9 July 1991, and the production then transferred to Washington, D.C., where it was revived in 1994.[125] Pinter's longer political satire Party Time (1991) premièred at the Almeida Theatre in London, in a double-bill with Mountain Language. Pinter adapted it as a screenplay for television in 1992, directing that production, first broadcast in the UK on Channel 4 on 17 November 1992.[126]

Intertwining political and personal concerns, his next full-length plays, Moonlight (1993) and Ashes to Ashes (1996) are set in domestic households and focus on dying and death; in their personal conversations in Ashes to Ashes, Devlin and Rebecca allude to unspecified atrocities relating to the Holocaust.[127] After experiencing the deaths of first his mother (1992) and then his father (1997), again merging the personal and the political, Pinter wrote the poems "Death" (1997) and "The Disappeared" (1998).

Pinter's last stage play, Celebration (2000), is a social satire set in an opulent restaurant, which lampoons The Ivy, a fashionable venue in London's West End theatre district, and its patrons who "have just come from performances of either the ballet or the opera. Not that they can remember a darn thing about what they saw, including the titles. [These] gilded, foul-mouthed souls are just as myopic when it comes to their own table mates (and for that matter, their food), with conversations that usually connect only on the surface, if there."[128] On its surface the play may appear to have fewer overtly political resonances than some of the plays from the 1980s and 1990s; but its central male characters, brothers named Lambert and Matt, are members of the elite (like the men in charge in Party Time), who describe themselves as "peaceful strategy consultants [because] we don't carry guns."[129] At the next table, Russell, a banker, describes himself as a "totally disordered personality ... a psychopath",[130] while Lambert "vows to be reincarnated as '[a] more civilised, [a] gentler person, [a] nicer person'."[131][132] These characters' deceptively smooth exteriors mask their extreme viciousness. Celebration evokes familiar Pinteresque political contexts: "The ritzy loudmouths in 'Celebration' ... and the quieter working-class mumblers of 'The Room' ... have everything in common beneath the surface".[128] "Money remains in the service of entrenched power, and the brothers in the play are 'strategy consultants' whose jobs involve force and violence ... It is tempting but inaccurate to equate the comic power inversions of the social behaviour in Celebration with lasting change in larger political structures", according to Grimes, for whom the play indicates Pinter's pessimism about the possibility of changing the status quo.[133] Yet, as the Waiter's often comically unbelievable reminiscences about his grandfather demonstrate in Celebration, Pinter's final stage plays also extend some expressionistic aspects of his earlier "memory plays", while harking back to his "comedies of menace", as illustrated in the characters and in the Waiter's final speech:

My grandfather introduced me to the mystery of life and I'm still in the middle of it. I can't find the door to get out. My grandfather got out of it. He got right out of it. He left it behind him and he didn't look back. He got that absolutely right. And I'd like to make one further interjection.

He stands still. Slow fade.[134]

During 2000–2001, there were also simultaneous productions of Remembrance of Things Past, Pinter's stage adaptation of his unpublished Proust Screenplay, written in collaboration with and directed by Di Trevis, at the Royal National Theatre, and a revival of The Caretaker directed by Patrick Marber and starring Michael Gambon, Rupert Graves, and Douglas Hodge, at the Comedy Theatre.[97]

Like Celebration, Pinter's penultimate sketch, Press Conference (2002), "invokes both torture and the fragile, circumscribed existence of dissent".[135] In its première in the National Theatre's two-part production of Sketches, despite undergoing chemotherapy at the time, Pinter played the ruthless Minister willing to murder little children for the benefit of "The State".[136]

As screenwriter

Pinter composed 27 screenplays and film scripts for cinema and television, many of which were filmed, or adapted as stage plays.[137] His fame as a screenwriter began with his three screenplays written for films directed by Joseph Losey, leading to their close friendship: The Servant (1963), based on the novel by Robin Maugham; Accident (1967), adapted from the novel by Nicholas Mosley; and The Go-Between (1971), based on the novel by L. P. Hartley.[138] Films based on Pinter's adaptations of his own stage plays are: The Caretaker (1963), directed by Clive Donner; The Birthday Party (1968), directed by William Friedkin; The Homecoming (1973), directed by Peter Hall; and Betrayal (1983), directed by David Jones.

Pinter also adapted other writers' novels to screenplays, including The Pumpkin Eater (1964), based on the novel by Penelope Mortimer, directed by Jack Clayton; The Quiller Memorandum (1966), from the 1965 spy novel The Berlin Memorandum, by Elleston Trevor, directed by Michael Anderson; The Last Tycoon (1976), from the unfinished novel by F. Scott Fitzgerald, directed by Elia Kazan; The French Lieutenant's Woman (1981), from the novel by John Fowles, directed by Karel Reisz; Turtle Diary (1985), based on the novel by Russell Hoban; The Heat of the Day (1988), a television film, from the 1949 novel by Elizabeth Bowen; The Comfort of Strangers (1990), from the novel by Ian McEwan, directed by Paul Schrader; and The Trial (1993), from the novel by Franz Kafka, directed by David Jones.[139]

His commissioned screenplays of others' works for the films The Handmaid's Tale (1990), The Remains of the Day (1990), and Lolita (1997), remain unpublished and in the case of the latter two films, uncredited, though several scenes from or aspects of his scripts were used in these finished films.[140] His screenplays The Proust Screenplay (1972), Victory (1982), and The Dreaming Child (1997) and his unpublished screenplay The Tragedy of King Lear (2000) have not been filmed.[141] A section of Pinter's Proust Screenplay was, however, released as the 1984 film Swann in Love (Un amour de Swann), directed by Volker Schlöndorff, and it was also adapted by Michael Bakewell as a two-hour radio drama broadcast on BBC Radio 3 in 1995,[142] before Pinter and director Di Trevis collaborated to adapt it for the 2000 National Theatre production.[143]

Pinter's last filmed screenplay was an adaptation of the 1970 Tony Award-winning play Sleuth, by Anthony Shaffer, which was commissioned by Jude Law, one of the film's producers.[24] It is the basis for the 2007 film Sleuth, directed by Kenneth Branagh.[24][144][145] Pinter's screenplays for The French Lieutenant's Woman and Betrayal were nominated for Academy Awards in 1981 and 1983, respectively.[146]

2001–2008

From 16 to 31 July 2001, a Harold Pinter Festival celebrating his work, curated by Michael Colgan, artistic director of the Gate Theatre, Dublin, was held as part of the annual Lincoln Center Festival at Lincoln Center in New York City. Pinter participated both as an actor, as Nicolas in One for the Road, and as a director of a double bill pairing his last play, Celebration, with his first play, The Room.[147] As part of a two-week "Harold Pinter Homage" at the World Leaders Festival of Creative Genius, held from 24 September to 30 October 2001, at the Harbourfront Centre, in Toronto, Canada, Pinter presented a dramatic reading of Celebration (2000) and also participated in a public interview as part of the International Festival of Authors.[148][149][150]

In December 2001, Pinter was diagnosed with oesophageal cancer, for which, in 2002, he underwent an operation and chemotherapy.[151] During the course of his treatment, he directed a production of his play No Man's Land, and wrote and performed in a new sketch, "Press Conference", for a production of his dramatic sketches at the National Theatre, and from 2002 on he was increasingly active in political causes, writing and presenting politically charged poetry, essays, speeches, as well as involved in developing his final two screenplay adaptations, The Tragedy of King Lear and Sleuth, whose drafts are in the British Library's Harold Pinter Archive (Add MS 88880/2).[152]

From 9 to 25 January 2003, the Manitoba Theatre Centre, in Manitoba, Canada, held a nearly month-long PinterFest, in which over 130 performances of twelve of Pinter's plays were performed by a dozen different theatre companies.[153] Productions during the Festival included: The Hothouse, Night School, The Lover, The Dumb Waiter, The Homecoming, The Birthday Party, Monologue, One for the Road, The Caretaker, Ashes to Ashes, Celebration, and No Man's Land.[154]

In 2005, Pinter stated that he had stopped writing plays and that he would be devoting his efforts more to his political activism and writing poetry: "I think I've written 29 plays. I think it's enough for me ... My energies are going in different directions—over the last few years I've made a number of political speeches at various locations and ceremonies ... I'm using a lot of energy more specifically about political states of affairs, which I think are very, very worrying as things stand."[155][156] Some of this later poetry included "The 'Special Relationship'", "Laughter", and "The Watcher".

From 2005, Pinter experienced ill health, including a rare skin disease called pemphigus[157] and "a form of septicaemia that afflict[ed] his feet and made it difficult for him to walk."[158] Yet, he completed his screenplay for the film of Sleuth in 2005.[24][159] His last dramatic work for radio, Voices (2005), a collaboration with composer James Clarke, adapting selected works by Pinter to music, premièred on BBC Radio 3 on his 75th birthday on 10 October 2005.[160] Three days later, it was announced that he had won the 2005 Nobel Prize in Literature.[161]

In an interview with Pinter in 2006, conducted by critic Michael Billington as part of the cultural programme of the 2006 Winter Olympics in Turin, Italy, Pinter confirmed that he would continue to write poetry but not plays.[157] In response, the audience shouted No in unison, urging him to keep writing.[162] Along with the international symposium on Pinter: Passion, Poetry, Politics, curated by Billington, the 2006 Europe Theatre Prize theatrical events celebrating Pinter included new productions (in French) of Precisely (1983), One for the Road (1984), Mountain Language (1988), The New World Order (1991), Party Time (1991), and Press Conference (2002) (French versions by Jean Pavans); and Pinter Plays, Poetry & Prose, an evening of dramatic readings, directed by Alan Stanford, of the Gate Theatre, Dublin.[163] In June 2006, the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) hosted a celebration of Pinter's films curated by his friend, the playwright David Hare. Hare introduced the selection of film clips by saying: "To jump back into the world of Pinter's movies ... is to remind yourself of a literate mainstream cinema, focused as much as Bergman's is on the human face, in which tension is maintained by a carefully crafted mix of image and dialogue."[164]

After returning to London from the Edinburgh International Book Festival, in September 2006, Pinter began rehearsing for his performance of the role of Krapp in Samuel Beckett's one-act monologue Krapp's Last Tape, which he performed from a motorised wheelchair in a limited run the following month at the Royal Court Theatre to sold-out audiences and "ecstatic" critical reviews.[165] The production ran for only nine performances, as part of the 50th-anniversary celebration season of the Royal Court Theatre; it sold out within minutes of the opening of the box office and tickets commanded large sums from ticket resellers.[166] One performance was filmed and broadcast on BBC Four on 21 June 2007, and also screened later, as part of the memorial PEN Tribute to Pinter, in New York, on 2 May 2009.[167]

In October and November 2006, Sheffield Theatres hosted Pinter: A Celebration. It featured productions of seven of Pinter's plays: The Caretaker, Voices, No Man's Land, Family Voices, Tea Party, The Room, One for the Road, and The Dumb Waiter; and films (most his screenplays; some in which Pinter appears as an actor).[168]

In February and March 2007, a 50th anniversary of The Dumb Waiter, was produced at the Trafalgar Studios. Later in February 2007, John Crowley's film version of Pinter's play Celebration (2000) was shown on More4 (Channel 4, UK). On 18 March 2007, BBC Radio 3 broadcast a new radio production of The Homecoming, directed by Thea Sharrock and produced by Martin J. Smith, with Pinter performing the role of Max (for the first time; he had previously played Lenny on stage in 1964). A revival of The Hothouse opened at the National Theatre, in London, in July 2007, concurrently with a revival of Betrayal at the Donmar Warehouse, directed by Roger Michell.[169]

Revivals in 2008 included the 40th-anniversary production of the American première of The Homecoming on Broadway, directed by Daniel J. Sullivan.[170] From 8 to 24 May 2008, the Lyric Hammersmith celebrated the 50th anniversary of The Birthday Party with a revival and related events, including a gala performance and reception hosted by Harold Pinter on 19 May 2008, exactly 50 years after its London première there. The final revival during Pinter's lifetime was a production of No Man's Land, directed by Rupert Goold, opening at the Gate Theatre, Dublin, in August 2008, and then transferring to the Duke of York's Theatre, London, where it played until 3 January 2009.[171] On the Monday before Christmas 2008, Pinter was admitted to Hammersmith Hospital, where he died on Christmas Eve from liver cancer, aged 78.[172]

On 26 December 2008, when No Man's Land reopened at the Duke of York's, the actors paid tribute to Pinter from the stage, with Michael Gambon reading Hirst's monologue about his "photograph album" from Act Two that Pinter had asked him to read at his funeral, ending with a standing ovation from the audience, many of whom were in tears:

I might even show you my photograph album. You might even see a face in it which might remind you of your own, of what you once were. You might see faces of others, in shadow, or cheeks of others, turning, or jaws, or backs of necks, or eyes, dark under hats, which might remind you of others, whom once you knew, whom you thought long dead, but from whom you will still receive a sidelong glance if you can face the good ghost. Allow the love of the good ghost. They possess all that emotion ... trapped. Bow to it. It will assuredly never release them, but who knows ... what relief ... it may give them ... who knows how they may quicken ... in their chains, in their glass jars. You think it cruel ... to quicken them, when they are fixed, imprisoned? No ... no. Deeply, deeply, they wish to respond to your touch, to your look, and when you smile, their joy ... is unbounded. And so I say to you, tender the dead, as you would yourself be tendered, now, in what you would describe as your life.[172][173][174]

Посмертные события

Похороны

Похороны Пинтера представляли собой частную получасовую светскую церемонию, проведенную на могиле на кладбище Кенсал-Грин 31 декабря 2008 года. Восемь чтений, выбранных заранее Пинтером, включали отрывки из семи его собственных произведений и из рассказа « Мертвые », написанного Пинтером. Джеймса Джойса , которую прочитала актриса Пенелопа Уилтон . Майкл Гэмбон прочитал речь «фотоальбома» из «Ничейной земли» и три других чтения, включая стихотворение Пинтера «Смерть» (1997). Другие чтения были посвящены вдове Пинтера и его любви к крикету. [172] На церемонии присутствовали многие известные деятели театра, в том числе Том Стоппард , но не сын Пинтера, Дэниел Брэнд. В конце вдова Пинтера, Антония Фрейзер, подошла к его могиле и процитировала речь Горацио после смерти Гамлета : «Спокойной ночи, милый принц, / И полеты ангелов поют тебе в твой покой». [172]

Мемориальные дани

В ночь перед похоронами Пинтера театральные шатры на Бродвее на минуту приглушили свет в знак уважения. [175] а в последний вечер спектакля «Ничья земля» в Театре герцога Йоркского 3 января 2009 года вся театральная группа «Амбассадор» в Вест-Энде на час приглушила свет в честь драматурга. [176]

Дайан Эбботт , член парламента от Хакни-Норт и Сток-Ньюингтон, предложила в начале дня в Палате общин предложение поддержать кампанию жителей по восстановлению Клэптонского кинематографического театра, основанного на Лоуэр-Клэптон-роуд в 1910 году, и превращению его в мемориал Пинтеру «в честь этого мальчика Хакни, ставшего великим писателем». [177] прошла бесплатная публичная поминальная церемония 2 мая 2009 года в Центре аспирантуры Городского университета Нью-Йорка . Это было частью 5-го ежегодного ПЕН-фестиваля международной литературы «Голоса мира» , проходившего в Нью-Йорке. [178] Еще одно мемориальное торжество, состоявшееся в Театре Оливье Королевского национального театра в Лондоне вечером 7 июня 2009 года, состояло из отрывков и чтений из произведений Пинтера почти тремя десятками актеров, многие из которых были его друзьями и соратниками. в том числе: Эйлин Аткинс , Дэвид Брэдли , Колин Ферт , Генри Гудман , Шейла Хэнкок , Алан Рикман , Пенелопа Уилтон , Сьюзен Вулдридж и Генри Вульф ; и труппа студентов Лондонской академии музыки и драматического искусства под руководством Яна Риксона. [179] [180]

16 июня 2009 года Антония Фрейзер официально открыла памятную комнату в Hackney Empire . Театр также учредил писательскую резиденцию имени Пинтера. [181] Большая часть выпуска № 28 Крейга Рейна журнала Arts Tri-Quarterly Areté была посвящена произведениям, вспоминающим Пинтера, начиная с неопубликованного любовного стихотворения Пинтера 1987 года, посвященного «Антонии», и его стихотворения «Париж», написанного в 1975 году (год, когда он и Фрейзер начали жить вместе), за которыми последовали краткие мемуары некоторых соратников и друзей Пинтера, в том числе Патрика Марбера , Нины Рейн , Тома Стоппарда , Питера Николса , Сюзанны Гросс , Ричарда Эйра и Дэвида Хэра. [182]

27 сентября 2009 года состоялся мемориальный матч по крикету на стадионе Lord's Cricket Ground между крикетным клубом Gaieties Cricket Club и Lord's Taverners, после которого были исполнены стихи Пинтера и отрывки из его пьес. [183]

В 2009 году английский ПЕН-клуб учредил Премию ПЕН-клуба , которая ежегодно присуждается британскому писателю или писателю, проживающему в Великобритании, который, по словам Пинтера в Нобелевской речи, бросает «непоколебимый, непоколебимый» взгляд на мир и демонстрирует «жестокая интеллектуальная решимость... определить настоящую правду о нашей жизни и нашем обществе». Эту премию разделят с мужественным писателем международного уровня. Первыми лауреатами премии стали Тони Харрисон и бирманский поэт и комик Маунг Тура (он же Зарганар) . [184]

Быть Гарольдом Пинтером

В январе 2011 года Быть Гарольдом Пинтером» вызвал театральный коллаж из отрывков драматических произведений Пинтера, его Нобелевской лекции и писем белорусских заключенных « , созданный и исполненный Белорусским «Свободным театром» большое внимание в средствах массовой информации . Членов «Свободного театра» пришлось тайно вывезти из Минска из-за репрессий правительства в отношении артистов-диссидентов, чтобы они представили свою постановку в рамках двухнедельного аншлагового выступления в La MaMa в Нью-Йорке в рамках фестиваля Under the Radar 2011 года . На дополнительном аншлаговом бенефисе в Общественном театре , организованном драматургами Тони Кушнером и Томом Стоппардом , письма заключенного прочитали десять приглашенных исполнителей: Мэнди Пэтинкин , Кевин Клайн , Олимпия Дукакис , Лили Рэйб , Линда Эмонд , Джош . Гамильтон , Стивен Спинелла , Лу Рид , Лори Андерсон и Филип Сеймур Хоффман . [185] В знак солидарности с Белорусским Свободным театром коллективы актеров и театральных компаний объединились, чтобы предложить дополнительные благотворительные чтения « Быть Гарольдом Пинтером» в Соединенных Штатах. [186]

Театр Гарольда Пинтера, Лондон

В сентябре 2011 года владельцы британского театра, Ambassador Theater Group (ATG), объявили, что переименовывают свой Театр комедии на Пантон-стрит в Лондоне в Театр Гарольда Пинтера . Говард Пантер , генеральный директор и креативный директор ATG, сказал Би-би-си : «Работа Пинтера стала неотъемлемой частью истории Театра комедии. Переименование одного из наших самых успешных театров в Вест-Энде — достойная дань уважения человек, который оставил такой след в британском театре и за свою 50-летнюю карьеру стал признанным одним из самых влиятельных современных британских драматургов». [187]

Почести

Почетный член Национального светского общества , член Королевского литературного общества и почетный член Американской ассоциации современного языка (1970), [188] [189] Пинтер был назначен CBE в 1966 году. [190] и стал членом Ордена Почетных кавалеров в 2002 году, отказавшись от рыцарского звания в 1996 году. [191] В 1995 году он получил премию Дэвида Коэна в знак признания литературных достижений всей жизни. В 1996 году он получил специальную премию Лоуренса Оливье за заслуги в театре. [192] В 1997 году он стал стипендиатом BAFTA . [193] Он получил премию мировых лидеров за «Творческий гений» в рамках недельной программы «Посвящение» в Торонто в октябре 2001 года. [194] В 2004 году он получил Премию Уилфреда Оуэна в области поэзии за «пожизненный вклад в литературу», и особенно за сборник стихов под названием « Война », опубликованный в 2003 году». [195] В марте 2006 года он был награжден Европейской театральной премией в знак признания заслуг в области драматургии и театра. [196] В связи с этой наградой критик Майкл Биллингтон координировал международную конференцию «Пинтер: страсть, поэзия, политика», в которой приняли участие ученые и критики из Европы и Америки, которая проходила в Турине , Италия, с 10 по 14 марта 2006 года. [116] [163] [197]

В октябре 2008 года Центральная школа речи и драмы объявила, что Пинтер согласился стать ее президентом, и наградила его почетной стипендией на выпускной церемонии. [198] По поводу своего назначения Пинтер прокомментировал: «Я был студентом Центрального университета в 1950–51 годах. Мне очень понравилось время, проведенное там, и я рад стать президентом замечательного учебного заведения». [199] Но эту почетную степень, свою 20-ю, ему пришлось получить заочно по состоянию здоровья. [198] Его президентство в школе было недолгим; он умер всего через две недели после выпускной церемонии, 24 декабря 2008 года.

году посмертно награжден Сретенским орденом Сербии В 2013 . [200] [201]

Нобелевская премия по литературе

Почетный легион

18 января 2007 года премьер-министр Франции Доминик де Вильпен вручил Пинтеру высшую гражданскую награду Франции — Орден Почётного легиона — на церемонии во французском посольстве в Лондоне. Де Вильпен похвалил стихотворение Пинтера «Американский футбол» (1991), заявив: «С его насилием и жестокостью это для меня один из самых точных образов войны, одна из самых ярких метафор искушения империализма и насилия». В ответ Пинтер похвалил сопротивление Франции войне в Ираке. Г-н де Вильпен заключил: «Поэт стоит на месте и наблюдает то, что не заслуживает внимания других людей. Поэзия учит нас, как жить, а вы, Гарольд Пинтер, учите нас, как жить». Он сказал, что Пинтер получил награду особенно «потому, что, стремясь охватить все грани человеческого духа, работы [Пинтера] отвечают чаяниям французской публики и ее вкусу к пониманию человека и того, что действительно универсально». . [202] [203] Лоуренс Поллард заметил, что «награда великому драматургу подчеркивает, насколько г-ном Пинтером восхищаются в таких странах, как Франция, как образцом бескомпромиссного радикального интеллектуала». [202]

Научный ответ

Некоторые ученые и критики оспаривают обоснованность критики Пинтера того, что он называет «образом мышления власть имущих». [204] или несогласие с его ретроспективными взглядами на собственную работу. [205] В 1985 году Пинтер вспоминал, что его ранний отказ от военной службы по убеждениям был результатом того, что в молодости его «ужасно беспокоила холодная война. И маккартизм… глубокое лицемерие. «Они» — монстры, «мы» — хорошие. Подавление Россией Восточной Европы было очевидным и жестоким фактом, но я очень твердо чувствовал тогда и так же сильно чувствую сейчас, что мы обязаны подвергнуть наши собственные действия и отношения равноценному критическому и моральному анализу». [206] Ученые сходятся во мнении, что драматическое изображение властных отношений Пинтером является результатом этого исследования. [207]

Отвращение Пинтера к любой цензуре со стороны «властей» выражено в реплике Пити в конце « Вечеринки по случаю дня рождения» . Когда сломленного и восстановленного Стэнли увозят авторитетные фигуры Голдберг и Макканн, Пити кричит ему вслед: «Стэн, не позволяй им говорить тебе, что делать!» Пинтер сказал Гусову в 1988 году: «Я прожил эту чертову жизнь всю свою чертову жизнь. Никогда больше, чем сейчас». [208] Пример стойкой оппозиции Пинтера тому, что он назвал «образом мышления власть имущих» — «кирпичной стеной» «сознаний», увековечивающей «статус-кво». [209] - вселил «огромный политический пессимизм», который некоторые академические критики могут уловить в его художественных работах, [210] это «тонущий ландшафт» суровых современных реалий с некоторой остаточной «надеждой на восстановление достоинства человека». [211]

Как напомнил давний друг Пинтера Дэвид Джонс ученым и драматическим критикам с аналитическим складом ума, Пинтер был одним из «великих писателей-комиков»: [212]

Ловушка творчества Гарольда для исполнителей и публики заключается в том, чтобы подходить к нему слишком серьезно или многозначительно. Я всегда старался интерпретировать его пьесы как можно более юмористически и человечно. В самых темных углах всегда таится беда. Мир «Смотрителя» мрачный, его персонажи повреждены и одиноки. Но они все выживут. И в своем танце с этой целью они демонстрируют неистовую жизненную силу и ироническое чувство смешного, которые уравновешивают душевную боль и смех. Смешно, но не слишком. Как писал Пинтер еще в 1960 году: «Насколько я понимаю, «Смотритель» смешен до определенного момента. За этим пределом он перестает быть смешным, и именно из-за этого момента я написал его». [213]

Его драматические конфликты имеют серьезные последствия для его персонажей и аудитории, что приводит к постоянным исследованиям «суть» его работ и множеству «критических стратегий» для разработки их интерпретаций и стилистического анализа. [214]

Коллекции исследований Пинтера

Неопубликованные рукописи Пинтера, а также письма к нему и от него хранятся в Архиве Гарольда Пинтера в отделе современных литературных рукописей Британской библиотеки . Меньшие коллекции рукописей Пинтера находятся в Центре гуманитарных исследований Гарри Рэнсома Остине Техасского университета в ; [15] Библиотека Лилли , Университет Индианы в Блумингтоне ; Библиотека специальных коллекций Мандевиля, Библиотека Гейзеля, Калифорнийский университет в Сан-Диего ; Британский институт кино в Лондоне; и Библиотека Маргарет Херрик, Пикфордский центр изучения киноискусства , Академия кинематографических искусств и наук , Беверли-Хиллз, Калифорния . [215] [216]

Список работ и библиография

См. также

- Независимые еврейские голоса

- Международный ПЕН-клуб

- Премия ПЕН-Пинтера

- Еврейские левые

- Список еврейских нобелевских лауреатов

Ссылки

- ^ «Майкл Кейн» . Интервью в первом ряду . 26 декабря 2008 г. Радио BBC 4 . Проверено 18 января 2014 г.

- ↑ Гарольд Пинтер, цитата из Гуссова, «Беседы с Пинтером» 103.

- ^ Пинтер, Гарольд. «Гарольд Пинтер: опись его коллекции в Центре гуманитарных исследований Гарри Рэнсома» . Heritage.lib.utexas.edu . Проверено 27 апреля 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 1–5.

- ↑ Некоторые сведения о значении еврейского происхождения Пинтера см. в Billington, Harold Pinter 2, 40–41, 53–54, 79–81, 163–64, 177, 286, 390, 429.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с См. Вульф, Генри (12 июля 2007 г.). «Мои 60 лет в банде Гарольда» . Хранитель . Лондон: ГМГ . ISSN 0261-3077 . OCLC 60623878 . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июля 2011 года . Проверено 26 июня 2011 г. ; Вульф, как цитирует Мерритт, «Говоря о Пинтере», 144–45; Джейкобсон, Ховард (10 января 2009 г.). «Гарольд Пинтер не понял моей шутки, и я не понял его – пока не стало слишком поздно» . Независимый . Лондон: ИНМ . ISSN 0951-9467 . OCLC 185201487 . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июля 2011 года . Проверено 26 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 2.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 5–10.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 11.

- ↑ Сборник переписки Пинтера с Брирли хранится в Архиве Гарольда Пинтера в Британской библиотеке. Мемориальное эпистолярное стихотворение Пинтера «Джозеф Брирли 1909–1977 (Учитель английского языка)», опубликованное в его сборнике «Различные голоса» (177), заканчивается следующей строфой: «Ты ушел. Я рядом с тобой / Иду с тобой». от Клэптон-Понд до Финсбери-парка , / И так далее, и так далее».

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 10–11.

- ^ См. также «Введение Гарольда Пинтера, лауреата Нобелевской премии », 7–9 в Уоткинсе, изд., «Дурак Фортуны»: Человек, который научил Гарольда Пинтера: Жизнь Джо Брирли .

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 13–14.

- ^ Бейкер и Росс 127.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Персонал (2011). «Гарольд Пинтер: опись его коллекции в Центре гуманитарных исследований Гарри Рэнсома» . Центр гуманитарных исследований Гарри Рэнсома . Техасский университет в Остине . Архивировано из оригинала 4 июня 2011 года . Проверено 26 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 29–35.

- ^ «Встреча посвящена загробной жизни, несмотря на то, что Пинтер был хорошо известен как атеист. Он признал, что написал для него «странную» пьесу». Пинтер «на пути к выздоровлению», BBC.co.uk, 26 августа 2002 г.

- ^ Гусов, Беседы с Пинтером 28–29.

- ^ Бейкер, «Взросление», гл. 1 Гарольда Пинтера 2–23.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 7–9 и 410.

- ^ Гусов, Беседы с Пинтером 25.

- ^ Гусов, Беседы с Пинтером 8.

- ^ Бэтти, Марк (ред.). «Сверчок» . haroldpinter.org . Архивировано из оригинала 13 июня 2011 года . Проверено 5 декабря 2010 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Лайалл, Сара (7 октября 2007 г.). «Гарольд Пинтер — Сыщик» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Нью-Йорк. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 4 января 2012 года . Проверено 26 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Шервин, Адам (24 марта 2009 г.). «Портрет Гарольда Пинтера, играющего в крикет, будет продан на аукционе» . ТаймсОнлайн . Лондон: News Intl . ISSN 0140-0460 . Архивировано из оригинала 16 июня 2011 года . Проверено 26 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 410.

- ^ Саппл, Т. Бейкер и Уоткинс, в Уоткинсе, изд.

- ^ Бертон, Гарри (2009). «Последние новости и новости о сборе средств на благотворительность от The Lord's Taverners» . Таверны Лорда . Архивировано из оригинала 27 июня 2009 года . Проверено 26 июня 2011 г.

- ^ См., например, Гусов, «Беседы с Пинтером» 25–30; Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 7–16; и Мерритт, Пинтер в пьесе 194.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 10–12.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 20–25, 31–35; и Бэтти, О Пинтере 7.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 20–25.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 37; и Бэтти, О Пинтере 8.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 31, 36 и 38; и Бэтти, О Пинтере xiii и 8.

- ^ Пинтер, «Мак», разные голоса 36–43.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Бэтти, Марк (ред.). «Актёрство» . haroldpinter.org . Архивировано из оригинала 9 июля 2011 года . Проверено 29 января 2011 г.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 20–25, 31, 36 и 37–41.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 3 и 47–48. Девичья фамилия бабушки Пинтера по отцовской линии была Барон. Он также использовал это имя для автобиографического персонажа в первом проекте своего романа «Гномы» .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Бэтти, Марк (ред.). «Актерская карьера Гарольда Пинтера» . haroldprinter.org . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июля 2011 года . Проверено 30 января 2011 г. , Бэтти, Марк (ред.). «Работа в различных репертуарных коллективах 1954–1958» . haroldprinter.org . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июля 2011 года . Проверено 30 января 2011 г.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 49–55.

- ^ Бэтти, О Пинтере 10.

- ^ Гусов, Беседы с Пинтером 83.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 20–25, 31, 36, 38.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Персонал (25 декабря 2008 г.). «Гарольд Пинтер: самый оригинальный, стильный и загадочный писатель послевоенного возрождения британского театра» . «Дейли телеграф» . Лондон. ISSN 0307-1235 . ОСЛК 49632006 . Архивировано из оригинала 16 января 2011 года . Проверено 26 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 54 и 75.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 252–56.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 257–67.

- ^ Фрейзер, ты должен идти? 86.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 257.

- ^ Фрейзер, гл. 1: «Первая ночь», ты должен идти? 3–19.

- ^ Фрейзер, гл. 1: «Первая ночь»; глава 2: «Удовольствие и много боли»; глава 8: «Оно здесь»; и гл. 13: «Снова брак», « Должен ли ты идти?» 3–33, 113–24 и 188–201.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 252–53.

- ^ Фрейзер, ты должен идти? 13.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 253–55.

- ^ Персонал (11 августа 1975 г.). "Люди" . Время . Time Inc. Архивировано из оригинала 20 мая 2011 года . Проверено 26 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Фрейзер, ты должен идти? 29, 65–78 и 83.

- ^ Фрейзер, ты должен идти? 85–88.

- ^ Фрейзер, « 27 ноября — Дневник леди Антонии Пинтер », «Должны ли вы идти?» 122–23.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 271–76.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 276.

- ^ Персонал (7 октября 1982 г.). «Смерть Вивьен Мерчант приписывают алкоголизму» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Нью-Йорк. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 21 января 2010 года . Проверено 26 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 276 и 345–47.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 255.

- ^ Фрейзер, ты должен идти? 44.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Биллингтон 254–55; ср. 345.

- ^ Сэндс, Сара (4 января 2009 г.). «Похороны Пинтера – скорее окончательная расплата, чем примирение» . Независимый . Архивировано из оригинала 9 мая 2022 года . Проверено 24 апреля 2020 г.

- ^ Фрейзер, ты должен идти? 211: «Несмотря на все мои тайминги [ Лунного света ], Гарольд называет меня своим редактором. Это не так. Я была акушеркой, говорящей: «Туши, Гарольд, тужь», но акт творения произошел где-то в другом месте, и ребенок должен был родиться. в любом случае."

- ^ См. Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 388, 429–30.

- ^ Уорк, Кирсти (23 июня 2006 г.). «Гарольд Пинтер в Newsnight Review» . Вечер новостей . Би-би-си. Архивировано из оригинала 12 ноября 2012 года . Проверено 26 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Сиддик, Харун (25 декабря 2008 г.). «Умер нобелевский лауреат, драматург Гарольд Пинтер» . Хранитель . Лондон: ГМГ . ISSN 0261-3077 . OCLC 60623878 . Архивировано из оригинала 5 сентября 2011 года . Проверено 26 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Уокер, Питер; Смит, Дэвид; Сиддик, Харун (26 декабря 2008 г.). «Обладатель множества наград, драматург, восхваляемый деятелями театрального и политического мира» . Хранитель . Лондон: ГМГ . ISSN 0261-3077 . OCLC 60623878 . Архивировано из оригинала 11 января 2012 года . Проверено 26 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 21–24, 92 и 286.

- ^ Бенски, Лоуренс М. (1966). «Искусство театра № 3, Гарольд Пинтер» (PDF) . Парижский обзор . Том. Осень 1966 г., нет. 39. Фонд Парижского обзора. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 1 января 2007 года . Проверено 26 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Мбеки, Табо (21 октября 2005 г.). «Письмо президента: Слава нобелевским лауреатам – апостолам человеческого любопытства!» . АНК сегодня . 5 (42). Африканский национальный конгресс . OCLC 212406525 . Архивировано из оригинала 22 июня 2008 года . Проверено 26 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Редди, ES (июль 1988 г.). «Освободите Манделу: отчет о кампании по освобождению Нельсона Манделы и всех других политических заключенных в Южной Африке» . АНК сегодня . Африканский национальный конгресс . ОСЛК 212406525 . Архивировано из оригинала 15 октября 2011 года . Проверено 26 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 286–305 (глава 15: «Связь с общественностью»), 400–03 и 433–41; и Мерритт, Пинтер в пьесе 171–209 (глава 8: «Культурная политика», особенно «Пинтер и политика»).

- ^ Мерритт, «Пинтер и политика», Пинтер в пьесе 171–89.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 309–10; и Гусов, Беседы с Пинтером 67–68.

- ^ «Кампания солидарности Кубы – наши цели» . cuba-solidarity.org . Архивировано из оригинала 18 июля 2011 года . Проверено 29 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Камм, Оливер (26 декабря 2008 г.). «Гарольд Пинтер: страстный художник, потерявший направление на политической сцене» . ТаймсОнлайн . Лондон: Новости Интернешнл . ISSN 0140-0460 . Архивировано из оригинала 17 апреля 2010 года . Проверено 26 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Крисафис, Анжелика; Тилден, Имоджен (11 июня 2003 г.). «Пинтер критикует «нацистскую Америку» и «заблуждающегося идиота» Блэра» . Хранитель . Лондон: ГМГ . ISSN 0261-3077 . OCLC 60623878 . Архивировано из оригинала 17 мая 2011 года . Проверено 26 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Пинтер, Гарольд (11 декабря 2002 г.). «Американская администрация — кровожадное дикое животное» . «Дейли телеграф» . Лондон. ISSN 0307-1235 . ОСЛК 49632006 . Архивировано из оригинала 29 июня 2011 года . Проверено 26 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Пинтер, Различные голоса 267.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 428.

- ^ Андерсон, Портер (17 марта 2006 г.). «Гарольд Пинтер: злой старик театра» . CNN . Радиовещательная система Тернера. Архивировано из оригинала 16 октября 2011 года . Проверено 26 июня 2011 г.

- ^ «Поэзия Гарольда Пинтера: известное и неизвестное». Экономист . Том. 400, нет. 8747. Лондон: Файнэншл Таймс . 20 августа 2011 г.

- ^ См., например, Хари, Иоганн (5 декабря 2005 г.). «Гарольд Пинтер не заслуживает Нобелевской премии: Иоганн Хари» . johannhari.com . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июля 2011 года . Проверено 27 июня 2011 г. ; Хитченс, Кристофер (17 октября 2005 г.). «Зловещая посредственность Гарольда Пинтера — WSJ.com» . Уолл Стрит Джорнал . Нью-Йорк: Доу-Джонс . ISSN 0099-9660 . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июля 2011 года . Проверено 27 июня 2011 г. ; и Прайс-Джонс, Дэвид (28 октября 2005 г.). «Особая банальность Гарольда Пинтера» . Национальное обозрение онлайн . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июля 2011 года . Проверено 27 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Олдерман, Джеффри (2011). «Гарольд Пинтер – еврейский взгляд» . currentviewpoint.com . Архивировано из оригинала 8 июля 2011 года . Проверено 27 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Эдгар, Дэвид (29 декабря 2008 г.). «Ранняя политика Пинтера» . Хранитель . Лондон: ГМГ . ISSN 0261-3077 . OCLC 60623878 . Архивировано из оригинала 10 ноября 2012 года . Проверено 26 июня 2011 г.

Идея о том, что он был инакомыслящей фигурой только в более позднем возрасте, игнорирует политику его ранних работ.

- ↑ См. также комментарии Вацлава Гавела и других, выдержки из книги «Колоссальная фигура», сопровождающей переиздание эссе Пинтера. Пинтер, Гарольд (14 октября 2005 г.). «Пинтер: Пытки и страдания во имя свободы – Мировая политика, мир – The Independent» . Независимый . Лондон: ИНМ . ISSN 0951-9467 . OCLC 185201487 . Архивировано из оригинала 16 февраля 2010 года . Проверено 27 июня 2011 г. , адаптированный из «Вступительной речи» Пинтера на Премию Уилфреда Оуэна в области поэзии 2005 года, опубликованной в Pinter, Различные голоса 267–68.

- ^ «Письма: Мы не празднуем годовщину Израиля» . Хранитель . 30 апреля 2008 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Пинтер, Гарольд (1930–2008) Кредиты» . BFI Screenonline . Британский институт кино . 2011. Архивировано из оригинала 5 июля 2004 года . Проверено 3 июля 2011 г.

- ^ Бэтти, Марк, изд. (2001). «Фестиваль Линкольн-центра» . haroldpinter.org . Архивировано из оригинала 13 июня 2011 года . Проверено 3 июля 2011 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Гарольд Пинтер, режиссер и драматург Национального театра» . Королевский национальный театр . Архивировано из оригинала (MSWord) 29 мая 2011 года . Проверено 27 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Персонал (31 марта 1984 г.). «Выбор критиков» . «Таймс» (61794). Цифровой архив Times: 16 . Проверено 27 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Бэтти, Марк, изд. (2011). «Сценические, кино- и телепостановки Гарольда Пинтера» . haroldpinter.org . Архивировано из оригинала 13 июня 2011 года . Проверено 27 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Эванс, Дейзи; Хердман, Кэти; Ланкестер, Лаура (ред.). «Играет» . haroldpinter.org . Архивировано из оригинала 13 июня 2011 года . Проверено 9 мая 2009 г.

- ^ Персонал (25 декабря 2008 г.). «Гарольд Пинтер: один из самых влиятельных британских драматургов современности» . «Дейли телеграф» . Лондон. ISSN 0307-1235 . ОСЛК 49632006 . Архивировано из оригинала 18 мая 2011 года . Проверено 27 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Гусов, Мел; Брантли, Бен (25 декабря 2008 г.). «Гарольд Пинтер, драматург «Тревожной паузы», умер в возрасте 78 лет» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Нью-Йорк. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 3 ноября 2012 года . Проверено 27 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Гордон, «Хронология», Пинтер, 70 xliii – lxv; Бэтти, «Хронология», О Пинтере xiii–xvi.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Гарольд Пинтер в обзоре Newsnight с Кирсти Уорк» . Обзор новостей . Би-би-си. Архивировано из оригинала 12 ноября 2012 года . Проверено 26 июня 2010 г.

- ^ Мерритт, «Говоря о Пинтере» 147.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Биллингтон, Майкл (25 декабря 2008 г.). «Самый провокационный, поэтичный и влиятельный драматург своего поколения» . Хранитель . Лондон: ГМГ . ISSN 0261-3077 . OCLC 60623878 . Архивировано из оригинала 27 февраля 2011 года . Проверено 27 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Хобсон, Гарольд (25 мая 1958 г.). «Винт снова поворачивается». Санди Таймс . Лондон.

- ^ Хобсон, «Винт снова поворачивается»; цитируется Мерриттом в «Сэр Гарольд Хобсон: Побуждения личного опыта», Пинтер в пьесе 221–25; рпт. в Хобсон, Гарольд (2011). «День рождения – Премьера» . haroldpinter.org . Архивировано из оригинала 9 июля 2011 года . Проверено 27 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 85; Гусов, Беседы с Пинтером 141.

- ^ Мерритт, Пинтер в пьесах 5, 9, 225–26 и 310.

- ^ См. Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 64, 65, 84, 197, 251 и 354.

- ^ Джонс, Дэвид (осень 2003 г.). «Театральная труппа Карусель –» . Фронт и центр онлайн . Театральная труппа «Карусель». Архивировано из оригинала 27 июля 2011 года . Проверено 27 июня 2011 г.

- ^ «Предыстория Смотрителя» . Образовательный ресурс театров Шеффилда . Шеффилдские театры. Архивировано из оригинала 14 мая 2009 года . Проверено 11 июля 2011 г.

- ^ Шама, Сунита (20 октября 2010 г.). «Награды Пинтера сохранены для нации» . Пресс-релиз Британской библиотеки . Музеи искусств и библиотеки. Архивировано из оригинала 27 июля 2011 года . Проверено 11 июля 2011 г.

- ^ Мерритт, Пинтер в игре 18.

- ^ Мерритт, Пинтер в игре 18, 219–20.

- ^ «Возвращение домой – 1967» . tonyawards.com . Производство премии Тони. 2011. Архивировано из оригинала 1 декабря 2018 года . Проверено 3 июля 2011 г.

- ^ Бейкер и Росс, «Хронология» xxiii – xl.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Биллингтон, Введение, «Пинтер: страсть, поэзия, политика», Европейская театральная премия – X издание , Турин , 10–12 марта 2006 г. Проверено 29 января 2011 г. См. Биллингтон, гл. 29: «Человек памяти» и «Послесловие: Давайте продолжать сражаться», Гарольд Пинтер 388–430.

- ^ См. Бэтти, О Пинтере ; Граймс; и Бейкер (все пассим ).

- ^ Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 258.

- ^ Мерритт, Пинтер в пьесе xi–xv и 170–209; Граймс 19.

- ^ Граймс 119.

- ^ Найтингейл, Бенедикт (2001). «Теплица – Премьера» . Первоначально опубликовано в New Statesman , заархивировано на haroldpinter.org . Архивировано из оригинала 13 июня 2011 года . Проверено 27 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Мерритт, «Пинтер, играющий в Пинтера» ( проходное письмо ); и Граймс 16, 36–38, 61–71.

- ^ Херн 8–9, 16–17 и 21.

- ^ Херн 19.

- ^ Кушман, Роберт (21 июля 1991 г.). «Десять нервных минут Пинтера» . Независимо в воскресенье , в архиве на haroldpinter.org . Архивировано из оригинала 14 июня 2011 года . Проверено 27 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Граймс 101–28 и 139–43; Бэтти, Марк, изд. (2011). «Играет» . haroldpinter.org . Архивировано из оригинала 14 июня 2011 года . Проверено 3 июля 2011 г.

- ^ Мерритт, «Прах Гарольда Пинтера к праху : политические/личные отголоски Холокоста» ( проходное письмо ); Граймс 195–220.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Брантли, Бен (27 июля 2001 г.). «Молчание Пинтера, богато красноречивое» . The New York Times заархивировано на haroldpinter.org . Архивировано из оригинала 13 июня 2011 года . Проверено 9 мая 2009 г.

- ^ Пинтер, Празднование 60.

- ^ Пинтер, Праздник 39.

- ^ Пинтер, Праздник 56.

- ^ Граймс 129.

- ^ Граймс 130.

- ^ Пинтер, Праздник 72.

- ^ Граймс 135.

- ^ Маколей, Аластер (13 февраля 2002 г.). «Тройной риск драматурга» . Financial Times заархивировано на haroldpinter.org . Архивировано из оригинала 13 июня 2011 года . Проверено 9 мая 2009 г.

- ^ Макнаб, Джеффри (27 декабря 2008 г.). «Гарольд Пинтер: Настоящая звезда экрана» . Независимый . Лондон: ИНМ . ISSN 0951-9467 . OCLC 185201487 . Архивировано из оригинала 24 июня 2011 года . Проверено 29 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Доусон, Джефф (21 июня 2009 г.). «Откройте глаза на эту культовую классику» . The Sunday Times хранится в LexisNexis . Лондон: Новости Интернешнл . п. 10.

- ^ Маслин, Джанет (24 ноября 1993 г.). «Зловещий мир Кафки глазами Пинтера» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Нью-Йорк. ISSN 0362-4331 . Проверено 3 июля 2011 г.

- ^ Хаджинс 132–39.

- ^ Гейл, «Приложение A: Краткий справочник», Sharp Cut 416–17.

- ^ Бейкер и Росс xxxiii.

- ^ Бэтти, Марк (ред.). «Воспоминание о прошлом, Театр Коттесло, Лондон, ноябрь 2000 г.» . haroldpinter.org . Архивировано из оригинала 13 июня 2011 года . Проверено 1 июля 2009 г.

- ^ Леви, Эмануэль (29 августа 2007 г.). «Интервью: Сыщик с Пинтером, Браной, Ло и Кейном» . emanuellevy.com . Архивировано из оригинала 15 мая 2011 года . Проверено 31 января 2011 г.

- ^ Леви, Эмануэль (29 августа 2007 г.). «Сыщик 2007: Римейк или переработка старой пьесы» . emanuellevy.com . Архивировано из оригинала 9 октября 2007 года . Проверено 31 января 2011 г.

- ^ Гейл, «Приложение B: Почести и награды за сценарий», Sharp Cut (н. стр.) [418].

- ^ Мерритт, «Говоря о Пинтере» ( проходное письмо ).

- ^ «Гарольд Пинтер добавлен в состав IFOA» . Серия чтения на берегу гавани . Торонто: Центр Харборфронт. Архивировано из оригинала 25 февраля 2002 года . Проверено 27 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Персонал (9 сентября 2001 г.). «Консультации для туристов; фестиваль в Торонто чествует 14 лидеров искусств - New York Times» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Нью-Йорк. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июля 2011 года . Проверено 28 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Мерритт, «Постановка Пинтера: от беременных пауз к политическим причинам» 123–43.

- ^ Коваль, Рамона (15 сентября 2009 г.). «Книги и письмо – 15.09.2002: Гарольд Пинтер» . Национальное радио ABC . Австралийская радиовещательная корпорация . Архивировано из оригинала 16 марта 2011 года . Проверено 29 июня 2011 г. ; Биллингтон, Гарольд Пинтер 413–16.

- ^ Персонал (2011). «Архив Пинтера» . Каталог рукописей . Британская библиотека. Архивировано из оригинала 24 ноября 2011 года . Проверено 4 мая 2011 г.

МС 88880/2

- ^ Бэтти, Марк, изд. (2003). «Пинтер Фест 2003» . haroldpinter.org . Архивировано из оригинала 13 июня 2011 года . Проверено 29 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Мерритт, «PinterFest», в «Предстоящие публикации, предстоящие постановки и другие незавершенные работы», «Библиография Гарольда Пинтера: 2000–2002» (299).

- ^ Лоусон, Марк (28 февраля 2005 г.). «Пинтер 'бросит писать пьесы' » . Новости Би-би-си . Лондон: Би-би-си . Архивировано из оригинала 24 марта 2012 года . Проверено 29 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Робинсон, Дэвид (26 августа 2006 г.). «Меня выписали, — говорит скандальный Пинтер» . Новости Scotsman.com . Цифровое издательство Джонстон Пресс. Архивировано из оригинала 29 июня 2011 года . Проверено 29 июня 2011 г.