Кожа

Кожа | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Пеле с Бразилией в 1970 году. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Edson Arantes do Nascimento 23 October 1940[note 1] Três Corações, Brazil | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 29 December 2022 (aged 82) São Paulo, Brazil | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Memorial Necrópole Ecumênica, Santos, São Paulo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupations |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 1.73 m (5 ft 8 in) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouses | Rosemeri dos Reis Cholbi

(m. 1966; div. 1982)Assíria Lemos Seixas

(m. 1994; div. 2008)Marcia Aoki (m. 2016) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 7, including Edinho and Joshua Nascimento | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Dondinho | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relatives | Zoca (brother) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1st Minister of Sports | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 1 January 1995 – 30 April 1998 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | Fernando Henrique Cardoso | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Office established | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Rafael Greca (Sports and Tourism) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Brazil professional footballer Eponyms and public art Films

Media

Family Related

|

||

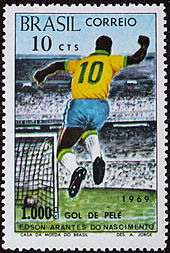

Эдсон Арантес ду Насименту ( Бразильский португальский: [ˈɛdsõ aˈɾɐ̃tʃiz du nasiˈmẽtu] ; 23 октября 1940 — 29 декабря 2022), более известный под прозвищем Пеле ( Португальское произношение: [peˈlɛ] ) — бразильский профессиональный футболист , игравший на позиции нападающего . Широко известный как один из величайших игроков всех времен, он был одним из самых успешных и популярных спортивных деятелей 20-го века. [ 2 ] [ 3 ] назвал его «Спортсменом века» В 1999 году Международный олимпийский комитет и включил в версии журнала Time список 100 самых важных людей 20 века по . (IFFHS) признала Пеле лучшим игроком века мира В 2000 году Международная федерация футбольной истории и статистики и стал одним из двух совместных победителей в номинации « Игрок века по версии ФИФА» . Его 1279 голов в 1363 играх, включая товарищеские , признаны мировым рекордом Гиннеса . [ 4 ]

Pelé began playing for Santos at age 15 and the Brazil national team at 16. During his international career, he won three FIFA World Cups: 1958, 1962 and 1970, the only player to do so and the youngest player to win a World Cup (17). He was nicknamed O Rei (The King) following the 1958 tournament. With 77 goals in 92 games[note 2] for Brazil, Pelé held the record as the national team's top goalscorer for over fifty years. At club level, he is Santos's all-time top goalscorer with 643 goals in 659 games. In a golden era for Santos, he led the club to the 1962 and 1963 Copa Libertadores, and to the 1962 and 1963 Intercontinental Cup. Credited with connecting the phrase "The Beautiful Game" with football, Pelé's "electrifying play and penchant for spectacular goals" made him a star around the world, and his teams toured internationally to take full advantage of his popularity.[7] В свои игровые годы Пеле какое-то время был самым высокооплачиваемым спортсменом в мире. После выхода на пенсию в 1977 году Пеле был послом футбола во всем мире и сделал множество актерских и коммерческих проектов. В 2010 году он был назван почётным президентом New York Cosmos .

Averaging almost a goal per game throughout his career, Pelé was adept at striking the ball with either foot in addition to anticipating his opponents' movements on the field. While predominantly a striker, he could also drop deep and take on a playmaking role, providing assists with his vision and passing ability, and he would also use his dribbling skills to go past opponents. In Brazil, he was hailed as a national hero for his accomplishments in football and for his outspoken support of policies that improve the social conditions of the poor. His emergence at the 1958 World Cup, where he became a black global sporting star, was a source of inspiration.[8] Throughout his career and in his retirement, Pelé received numerous individual and team awards for his performance on the field, his record-breaking achievements, and his legacy in the sport.[9]

Early years

Pelé was born Edson Arantes do Nascimento on 23 October 1940 in Três Corações, Minas Gerais, the son of Fluminense footballer Dondinho (born João Ramos do Nascimento) and Celeste Arantes (1922–2024).[10] He was the elder of two siblings,[11] with brother Zoca also playing for Santos, albeit not as successfully.[12] He was named after the American inventor Thomas Edison.[13] His parents decided to remove the "i" and call him "Edson", but there was a typo on his birth certificate, leading many documents to show his name as "Edison", not "Edson", as he was called.[13][14] He was originally nicknamed "Dico" by his family.[11][15] He received the nickname "Pelé" during his school days, it is claimed,[by whom?] after mispronouncing the name of his favourite player, Vasco da Gama goalkeeper Bilé. In his autobiography released in 2006, Pelé stated he had no idea what the name means, nor did his old friends, and the word has no meaning in Portuguese.[11][note 3]

Pelé grew up in poverty in Bauru in the state of São Paulo. He earned extra money by working in tea shops as a servant. Taught to play by his father, he could not afford a proper football and usually played with either a sock stuffed with newspaper and tied with string or a grapefruit.[17][11] He played for several amateur teams in his youth, including Sete de Setembro, Canto do Rio, São Paulinho, and Ameriquinha.[18] Pelé led Bauru Atlético Clube juniors (coached by Waldemar de Brito) to two São Paulo state youth championships.[19] In his mid-teens, he played for an indoor football team called Radium. Indoor football had just become popular in Bauru when Pelé began playing it. He was part of the first futsal (indoor football) competition in the region. Pelé and his team won the first championship and several others.[20]

According to Pelé, futsal (indoor football) presented difficult challenges: he said it was a lot quicker than football on the grass, and that players were required to think faster because everyone is close to each other in the pitch. Pelé credits futsal for helping him think better on the spot. In addition, futsal allowed him to play with adults when he was about 14 years old. In one of the tournaments he participated in, he was initially considered too young to play, but eventually went on to end up top scorer with 14 or 15 goals. "That gave me a lot of confidence", Pelé said, "I knew then not to be afraid of whatever might come".[20]

Club career

Santos

1956–1962: early years with Santos and declared a national treasure

In 1956, de Brito took Pelé to Santos, an industrial and port city located near São Paulo, to try out for professional club Santos FC, telling the club's directors that the 15-year-old would be "the greatest football player in the world".[22] Pelé impressed Santos coach Lula during his trial at the Estádio Vila Belmiro, and he signed a professional contract with the club in June 1956.[23] Pelé was highly promoted in the local media as a future superstar. He made his senior team debut on 7 September 1956 at the age of 15 against Corinthians de Santo André and had an impressive performance in a 7–1 victory, scoring the first goal in his prolific career during the match.[24][25]

When the 1957 season started, Pelé was given a starting place in the first team and, at the age of 16, became the top scorer in the league. Ten months after signing professionally, the teenager was called up to the Brazil national team. After the 1958 and the 1962 World Cup, wealthy European clubs, such as Real Madrid, Juventus and Manchester United, tried to sign him in vain.[26] In 1958, Inter Milan even managed to get him a regular contract, but Angelo Moratti was forced to tear the contract up at the request of Santos's chairman following a revolt by Santos's Brazilian fans.[27] Valencia CF also arranged an agreement that would have brought Pelé to the club after the 1958 World Cup, however after his performances at the tournament, Santos declined to let the player leave.[28][29] In 1961 the government of Brazil under President Jânio Quadros declared Pelé an "official national treasure" to prevent him from being transferred out of the country.[17][30]

Pelé won his first major title with Santos in 1958 as the team won the Campeonato Paulista; he would finish the tournament as the top scorer, with 58 goals,[31] a record that still stands today. A year later, he would help the team earn their first victory in the Torneio Rio-São Paulo with a 3–0 over Vasco da Gama.[32] However, Santos was unable to retain the Paulista title. In 1960, Pelé scored 33 goals to help his team regain the Campeonato Paulista trophy but lost out on the Rio-São Paulo tournament after finishing in 8th place.[33] In the 1960 season, Pelé scored 47 goals and helped Santos regain the Campeonato Paulista. The club went on to win the Taça Brasil that same year, beating Bahia in the finals; Pelé finished as the top scorer of the tournament with nine goals. The victory allowed Santos to participate in the Copa Libertadores, the most prestigious club tournament in the Western hemisphere.[34]

1962–1965: Copa Libertadores success

"I arrived hoping to stop a great man, but I went away convinced I had been undone by someone who was not born on the same planet as the rest of us."

—Benfica goalkeeper Costa Pereira following the loss to Santos in 1962.[35]

Santos's most successful Copa Libertadores season started in 1962;[36] the team was seeded in Group One alongside Cerro Porteño and Deportivo Municipal Bolivia, winning every match of their group but one (a 1–1 away tie versus Cerro). Santos defeated Universidad Católica in the semi-finals and met defending champions Peñarol in the finals. Pelé scored twice in the playoff match to secure the first title for a Brazilian club.[37] Pelé finished as the second top scorer of the competition with four goals. That same year, Santos would successfully defend the Campeonato Paulista (with 37 goals from Pelé) and the Taça Brasil (Pelé scoring four goals in the final series against Botafogo). Santos would also win the 1962 Intercontinental Cup against Benfica.[38] Wearing his number 10 shirt, Pelé produced one of the best performances of his career, scoring a hat-trick in Lisbon as Santos won 5–2.[39][40]

Pelé states that his most memorable goal was scored at the Estádio Rua Javari on a Campeonato Paulista match against São Paulo rival Clube Atlético Juventus on 2 August 1959. As there is no video footage of this match, Pelé asked that a computer animation be made of this specific goal.[41] In March 1961, Pelé scored the gol de placa (goal worthy of a plaque), against Fluminense at the Maracanã.[42] Pelé received the ball on the edge of his own penalty area, and ran the length of the field, eluding opposition players with feints, before striking the ball beyond the goalkeeper.[42] A plaque was commissioned with a dedication to "the most beautiful goal in the history of the Maracanã".[43]

As the defending champions, Santos qualified automatically to the semi-final stage of the 1963 Copa Libertadores. The balé branco (white ballet), the nickname given to Santos at the time, managed to retain the title after victories over Botafogo and Boca Juniors. Pelé helped Santos overcome a Botafogo team that featured Brazilian greats such as Garrincha and Jairzinho with a last-minute goal in the first leg of the semi-finals which made it 1–1. In the second leg, Pelé scored a hat-trick in the Estádio do Maracanã as Santos won, 0–4, in the second leg. Santos started the final series by winning, 3–2, in the first leg and defeating Boca Juniors 1–2, in La Bombonera. It was a rare feat in official competitions, with another goal from Pelé.[44] Santos became the first Brazilian team to lift the Copa Libertadores in Argentine soil. Pelé finished the tournament with five goals. Santos lost the Campeonato Paulista after finishing in third place but went on to win the Rio-São Paulo tournament after a 0–3 win over Flamengo in the final, with Pelé scoring one goal. Pelé would also help Santos retain the Intercontinental Cup and the Taça Brasil against AC Milan and Bahia respectively.[38]

In the 1964 Copa Libertadores, Santos was beaten in both legs of the semi-finals by Independiente. The club won the Campeonato Paulista, with Pelé netting 34 goals. Santos also shared the Rio-São Paulo title with Botafogo and won the Taça Brasil for the fourth consecutive year. In the 1965 Copa Libertadores, Santos reached the semi-finals and met Peñarol in a rematch of the 1962 final. After two matches, a playoff was needed to break the tie.[45] Unlike 1962, Peñarol came out on top and eliminated Santos 2–1.[45] Pelé would, however, finish as the top scorer of the tournament with eight goals.[46]

1965–1974: O Milésimo and final years with Santos

In December 1965, Santos won the Taça Brasil, their fifth straight Brazilian league title, with Pelé scoring the last goal in the final series.[47] In 1966, Santos failed to retain the Taça Brasil as Pelé's goals were not enough to prevent a 9–4 defeat by Cruzeiro (led by Tostão) in the final series. The club did, however, win the Campeonato Paulista in 1967, 1968, and 1969. On 19 November 1969, Pelé scored his 1,000th goal in all competitions, in what was a highly anticipated moment in Brazil. The goal dubbed O Milésimo (The Thousandth), occurred in a match against Vasco da Gama, when Pelé scored from a penalty kick, at the Maracanã Stadium.[48]

Various sources have said that the two factions involved in the Nigerian Civil War agreed to a 48-hour ceasefire in 1969 so they could watch Pelé play an exhibition game in Lagos. An early source for this story was Ebony magazine in 1975.[49] Santos ended up playing to a 2–2 draw with Lagos side Stationary Stores FC and Pelé scored his team's goals. The civil war went on for one more year after this game.[50] In his autobiography, Pelé was unsure that there was a ceasefire, but said that there was an increased security presence at the game.[51] Some sources, including Santos's website, say that the ceasefire was instead for the friendly in Benin City, bordering Biafra. Local researchers have not found contemporary reports of any ceasefire.[52]

During his time at Santos, Pelé played alongside many gifted players, including Zito, Pepe, and Coutinho; the latter partnered him in numerous one-two plays, attacks, and goals.[53] After Pelé's 19th season with Santos, he left Brazilian football.[54] Pelé's 643 goals for Santos were the most goals scored for a single club until it was surpassed by Lionel Messi of Barcelona in December 2020.[55][56]

Tours with Santos

Even though he never played in a European league, Pelé played exhibition games in several countries all over the world in tours with Santos. He played in Spain against Real Madrid and Barcelona, in Italy against Juventus, Inter Milan, AC Milan and AS Roma.[57] Pelé travelled to Egypt in 1973, and played with Santos against Al Ahly. This trip was days after his team's trip to Kuwait to play a match against Qadsia.[58]

In Kuwait, Pelé met by chance the Egyptian movie star Zubaida Tharwat, who was in Kuwait attending a cinematic event. The two had a couple of photos and he admired her beauty. She said in a television interview about this incident that: she had traveled to Kuwait City in 1973 at the invitation of the Kuwaiti Minister of Culture at the time, and when she went to the hotel where she was going to stay, she was surprised by the presence of many people and flowers inside the hotel, and among these people came to her "Pelé" wearing a collar of roses, and he removed it from him and put it on her.[59][60]

When she asked what was going on and who was this person, whom she did not know because she did not like football, the hotel staff told her that he was the famous Brazilian football player, and that the hotel was crowded with his fans who wanted to see him. Zubaida Tharwat stated that after he saw her for the first time inside the hotel where they happened to be, he kept chasing her day and night, and wanted to take her with him to Brazil.[61] By chance, the next stop for Pelé's tour was to Cairo, and he met again with Tharwat, who stated that she could not communicate with him as he did not speak English at the time.[62][63]

New York Cosmos

After the 1974 season (his 19th with Santos), Pelé retired from Brazilian club football although he continued to occasionally play for Santos in official competitive matches. A year later, he came out of semi-retirement to sign with the New York Cosmos of the North American Soccer League (NASL) for the 1975 season.[54] At a chaotic press conference at New York's 21 Club, the Cosmos unveiled Pelé. John O'Reilly, the club's media spokesman, stated, "We had superstars in the United States but nothing at the level of Pelé. Everyone wanted to touch him, shake his hand, get a photo with him."[64] Though well past his prime at this point, Pelé was credited with significantly increasing public awareness and interest of the sport in the US.[65] During his first public appearance in Boston, he was injured by a crowd of fans who had surrounded him and was evacuated on a stretcher.[66]

Pelé made his debut for the Cosmos on 15 June 1975 against the Dallas Tornado at Downing Stadium, scoring one goal in a 2–2 draw.[67] Pelé opened the door for many other stars to play in North America. Giorgio Chinaglia followed him to the Cosmos, then Franz Beckenbauer and his former Santos teammate Carlos Alberto. Over the next few years other players came to the league, including Johan Cruyff, Eusébio, Bobby Moore, George Best and Gordon Banks.[65]

In 1975, one week before the Lebanese Civil War, Pelé played a friendly game for the Lebanese club Nejmeh against a team of Lebanese Premier League stars,[68] scoring two goals which were not included in his official tally.[69] On the day of the game, 40,000 spectators were at the stadium from early morning to watch the match.[68]

Pelé led the Cosmos to the 1977 Soccer Bowl, in his third and final season with the club.[70] In June 1977, the Cosmos attracted an NASL record 62,394 fans to Giants Stadium for a 3–0 victory past the Tampa Bay Rowdies with a 37-year-old Pelé scoring a hat-trick. In the first leg of the quarter-finals, they attracted a US record crowd of 77,891 for what turned into an 8–3 rout of the Fort Lauderdale Strikers at Giants Stadium. In the second leg of the semi-finals against the Rochester Lancers, the Cosmos won 4–1.[65] Pelé finished his official playing career on 28 August 1977, by leading the New York Cosmos to their second Soccer Bowl title with a 2–1 win over the Seattle Sounders at the Civic Stadium in Portland, Oregon.[71]

On 1 October 1977, Pelé closed out his career in an exhibition match between the Cosmos and Santos. The match was played in front of a sold-out crowd at Giants Stadium and was televised in the US on ABC's Wide World of Sports as well as throughout the world. Pelé's father and wife both attended the match, as well as Muhammad Ali and Bobby Moore.[72] Delivering a message to the audience before the start of the game—"Love is more important than what we can take in life"—Pelé played the first half with the Cosmos, the second with Santos. The game ended with the Cosmos winning 2–1, with Pelé scoring with a 30-yard free-kick for the Cosmos in what was the final goal of his career. During the second half, it started to rain, prompting a Brazilian newspaper to come out with the headline the following day: "Even The Sky Was Crying."[73]

International career

Pelé's first international match was a 2–1 defeat against Argentina on 7 July 1957 at the Maracanã.[74][75] In that match, he scored his first goal for Brazil aged 16 years and eight months, and he remains the youngest goalscorer for his country.[76][77]

1958 World Cup

Pelé arrived in Sweden sidelined by a knee injury but on his return from the treatment room, his colleagues stood together and insisted upon his selection.[78] His first match was against the USSR in the third match of the first round of the 1958 FIFA World Cup, where he gave the assist to Vavá's second goal.[79] He was at the time the youngest player ever to participate in the World Cup.[note 4][75] Against France in the semi-final, Brazil was leading 2–1 at halftime, and then Pelé scored a hat-trick, becoming the youngest player in World Cup history to do so.[81]

On 29 June 1958, Pelé became the youngest player to play in a World Cup final match at 17 years and 249 days. He scored two goals in that final as Brazil beat Sweden 5–2 in Stockholm, the capital. Pelé hit the post and then Vavá scored two goals to give Brazil the lead. Pelé's first goal, where he flicked the ball over a defender before volleying into the corner of the net, was selected as one of the best goals in the history of the World Cup.[82] Following Pelé's second goal, Swedish player Sigvard Parling would later comment, "When Pelé scored the fifth goal in that Final, I have to be honest and say I felt like applauding".[83] When the match ended, Pelé passed out on the field, and was revived by Garrincha.[84] He then recovered, and was compelled by the victory to weep as he was being congratulated by his teammates. He finished the tournament with six goals in four matches played, tied for second place, behind record-breaker Just Fontaine, and was named best young player of the tournament.[85] His impact was arguably greater off the field, with Barney Ronay writing, "With nothing but talent to guide him, the boy from Minas Gerais became the first black global sporting superstar, and a source of genuine uplift and inspiration."[8]

It was in the 1958 World Cup that Pelé began wearing a jersey with the number 10. The event was the result of disorganization: the leaders of the Brazilian Federation did not allocate the shirt numbers of players and it was up to FIFA to choose the number 10 shirt for Pelé, who was a substitute on the occasion.[86] The press proclaimed Pelé the greatest revelation of the 1958 World Cup, and he was also retroactively given the Silver Ball as the second best player of the tournament, behind Didi.[83]

1959 South American Championship

Pelé also played in the South American Championship. In the 1959 competition he was named best player of the tournament and was the top scorer with eight goals, as Brazil came second despite being unbeaten in the tournament.[83][87] He scored in five of Brazil's six games, including two goals against Chile and a hat-trick against Paraguay.[88]

1962 World Cup

When the 1962 World Cup started, Pelé was considered the best player in the world.[89] In the first match of the 1962 World Cup in Chile, against Mexico, Pelé assisted the first goal and then scored the second one, after a run past four defenders, to go up 2–0.[90] He got injured in the next game while attempting a long-range shot against Czechoslovakia.[91] This would keep him out of the rest of the tournament, and forced coach Aymoré Moreira to make his only lineup change of the tournament. The substitute was Amarildo, who performed well for the rest of the tournament. However, it was Garrincha who would take the leading role and carry Brazil to their second World Cup title, after beating Czechoslovakia at the final in Santiago.[92] At the time, only players who appeared in the final were eligible for a medal before FIFA regulations were changed in 1978 to include the entire squad, with Pelé receiving his winner's medal retroactively in 2007.[93]

1966 World Cup

Pelé was the most famous footballer in the world during the 1966 World Cup in England, and Brazil fielded some world champions like Garrincha, Gilmar and Djalma Santos with the addition of other stars like Jairzinho, Tostão and Gérson, leading to high expectations for them.[94] Brazil was eliminated in the first round, playing only three matches.[94] The World Cup was marked, among other things, for brutal fouls on Pelé that left him injured by the Bulgarian and Portuguese defenders.[95]

Pelé scored the first goal from a free kick against Bulgaria, becoming the first player to score in three successive FIFA World Cups, but due to his injury, a result of persistent fouling by the Bulgarians, he missed the second game against Hungary.[94] His coach stated that after the first game he felt "every team will take care of him in the same manner".[95] Brazil lost that game and Pelé, although still recovering, was brought back for the last crucial match against Portugal at Goodison Park in Liverpool by the Brazilian coach Vicente Feola. Feola changed the entire defense, including the goalkeeper, while in midfield he returned to the formation of the first match. During the game, Portugal defender João Morais fouled Pelé, but was not sent off by referee George McCabe; a decision retrospectively viewed as being among the worst refereeing errors in World Cup history.[96] Pelé had to stay on the field limping for the rest of the game since substitutes were not allowed in football at that time.[96] Brazil lost the match against the Portuguese led by Eusébio and were eliminated from the tournament as a result.[97] After this game he vowed he would never again play in the World Cup, a decision he would later change.[89]

1970 World Cup

Pelé was called to the national team in early 1969, he refused at first, but then accepted and played in six World Cup qualifying matches, scoring six goals.[5] The 1970 World Cup in Mexico was expected to be Pelé's last. Brazil's squad for the tournament featured major changes to the 1966 squad. Players like Garrincha, Nilton Santos, Valdir Pereira, Djalma Santos, and Gilmar had already retired. However, Brazil's 1970 World Cup squad, which included players like Pelé, Rivellino, Jairzinho, Gérson, Carlos Alberto Torres, Tostão and Clodoaldo, is often considered to be the greatest football team in history.[98][99][100]

The front five of Jairzinho, Pelé, Gerson, Tostão, and Rivellino together created an attacking momentum, with Pelé having a central role in Brazil's way to the final.[101] All of Brazil's matches in the tournament (except the final) were played in Guadalajara, and in the first match against Czechoslovakia, Pelé gave Brazil a 2–1 lead, by controlling Gerson's 50-yard pass with his chest and then scoring.[102] In this match Pelé attempted to lob goalkeeper Ivo Viktor from the halfway line, only narrowly missing the Czechoslovak goal.[103] Brazil went on to win the match, 4–1. In the first half of the match against England, Pelé nearly scored with a header that was saved by the England goalkeeper Gordon Banks. Pelé recalled he was already shouting "Goal" when he headed the ball. It was often referred to as the "save of the century".[104] In the second half, he controlled a cross from Tostão before flicking the ball to Jairzinho who scored the only goal.[105]

Against Romania, Pelé scored two goals, which included a 20-yard bending free-kick, with Brazil winning 3–2. In the quarter-final against Peru, Brazil won 4–2, with Pelé assisting Tostão for Brazil's third goal. In the semi-final, Brazil faced Uruguay for the first time since the 1950 World Cup final round match. Jairzinho put Brazil ahead 2–1, and Pelé assisted Rivellino for the 3–1. During that match, Pelé made one of his most famous plays. Tostão passed the ball for Pelé to collect which Uruguay's goalkeeper Ladislao Mazurkiewicz took notice of and ran off his line to get the ball before Pelé. However, Pelé got there first and fooled Mazurkiewicz with a feint by not touching the ball, causing it to roll to the goalkeeper's left, while Pelé went to the goalkeeper's right. Pelé ran around the goalkeeper to retrieve the ball and took a shot while turning towards the goal, but he turned in excess as he shot, and the ball drifted just wide of the far post.[103][106]

"I have scored more than a thousand goals in my life and the thing people always talk to me about is the one I didn't score." — Pelé on the extraordinary save by England goalkeeper Gordon Banks in their 1970 World Cup match.[107]

Brazil played Italy in the final at the Azteca Stadium in Mexico City.[108] Pelé scored the opening goal with a header after out jumping Italian defender Tarcisio Burgnich. Brazil's 100th World Cup goal, Pelé's leap of joy into the arms of teammate Jairzinho in celebrating the goal is regarded as one of the most iconic moments in World Cup history.[109] He then made assists for Brazil's third goal, scored by Jairzinho, and the fourth finished by Carlos Alberto. The last goal of the game is often considered the greatest team goal of all time because it involved all but two of the team's outfield players. The play culminated after Pelé made a blind pass that went into Carlos Alberto's running trajectory. He came running from behind and struck the ball to score.[110] Brazil won the match 4–1, keeping the Jules Rimet Trophy indefinitely, and Pelé received the Golden Ball as the player of the tournament.[83][111] Burgnich, who marked Pelé during the final, was quoted saying, "I told myself before the game, he's made of skin and bones just like everyone else – but I was wrong".[112] In terms of his goals and assists throughout the 1970 World Cup, Pelé was directly responsible for 53% of Brazil's goals throughout the tournament.[113]

Pelé's last international match was on 18 July 1971 against Yugoslavia in Rio de Janeiro. With Pelé on the field, the Brazilian team's record was 67 wins, 14 draws, and 11 losses.[5] Brazil never lost a match while fielding both Pelé and Garrincha.[114] Pele's 77 goals (in 92 games)[note 2] for Brazil saw him hold the record as the national team's top goalscorer for over fifty years until it was surpassed by Neymar (in his 125th game) in September 2023.[115][116]

Style of play

Pelé has also been known for connecting the phrase "The Beautiful Game" with football.[117] A prolific goalscorer, he was known for his ability to anticipate opponents in the area and finish off chances with an accurate and powerful shot with either foot.[7][118][119] Pelé was also a hard-working team player, and a complete forward, with exceptional vision and intelligence, who was recognised for his precise passing and ability to link up with teammates and provide them with assists.[120][121][122]

In his early career, he played in a variety of attacking positions. Although he often operated inside the penalty area as a main striker or centre forward, his wide range of skills also allowed him to play in a more withdrawn role, as an inside forward or second striker, or even out wide.[103][120][123] In his later career, he took on more of a deeper playmaking role behind the strikers, often functioning as an attacking midfielder.[124][125] Pelé's unique playing style combined speed, creativity, and technical skill with physical power, stamina, and athleticism. His excellent technique, balance, flair, agility, and dribbling skills enabled him to beat opponents with the ball, and frequently saw him use sudden changes of direction and elaborate feints to get past players, such as his trademark move, the drible da vaca.[103][123][126] Another one of his signature moves was the paradinha, or little stop.[note 5][127]

Despite his relatively small stature, 1.73 metres (5 feet 8 inches),[128] he excelled in the air, due to his heading accuracy, timing, and elevation.[118][121][126][129] Renowned for his bending shots, he was also an accurate free-kick taker, and penalty taker, although he often refrained from taking penalties, stating that he believed it to be a cowardly way to score.[130][131]

Pelé was also known to be a fair and highly influential player, who stood out for his charismatic leadership and sportsmanship on the pitch. His warm embrace of Bobby Moore following the Brazil vs England game at the 1970 World Cup is viewed as the embodiment of sportsmanship, with The New York Times stating the image "captured the respect that two great players had for each other. As they exchanged jerseys, touches, and looks, the sportsmanship between them is all in the image. No gloating, no fist-pumping from Pelé. No despair, no defeatism from Bobby Moore."[132] Pelé also earned a reputation for often being a decisive player for his teams, due to his tendency to score crucial goals in important matches.[133][134][135]

Legacy

Among the most successful and popular sports figures of the 20th century,[136] Pelé is one of the most lauded players in the history of football and has been frequently ranked the best player ever.[2][137][138][139] Following his emergence at the 1958 World Cup he was nicknamed O Rei ("The King").[140] Among his contemporaries, Dutch star Johan Cruyff stated, "Pelé was the only footballer who surpassed the boundaries of logic."[35] Brazil's 1970 World Cup-winning captain Carlos Alberto Torres opined: "His great secret was improvisation. Those things he did were in one moment. He had an extraordinary perception of the game."[35] According to Tostão, his strike partner at the 1970 World Cup: "Pelé was the greatest – he was simply flawless. And off the pitch he is always smiling and upbeat. You never see him bad-tempered. He loves being Pelé."[35] His Brazilian teammate Clodoaldo commented on the adulation he witnessed: "In some countries they wanted to touch him, in some they wanted to kiss him. In others they even kissed the ground he walked on. I thought it was beautiful, just beautiful."[35] According to Franz Beckenbauer, West Germany's 1974 World Cup-winning captain: "Pelé is the greatest player of all time. He reigned supreme for 20 years. There's no one to compare with him."[83]

"I used to go out and people said Pelé! Pelé! Pelé! Pelé! all over the world, but no one remembers Edson. Edson is the person who has the feelings, who has the family, who works hard, and Pelé is the idol. Pelé doesn't die. Pelé will never die. Pelé is going to go on for ever. But Edson is a normal person who is going to die one day, and the people forget that." — Pelé on his lasting legacy.[141]

Former Real Madrid and Hungary star Ferenc Puskás stated: "The greatest player in history was Di Stéfano. I refuse to classify Pelé as a player. He was above that."[35] Just Fontaine, French striker and the leading scorer at the 1958 World Cup said "When I saw Pelé play, it made me feel I should hang up my boots."[35] England's 1966 FIFA World Cup-winning captain Bobby Moore commented: "Pelé was the most complete player I've ever seen, he had everything. Two good feet. Magic in the air. Quick. Powerful. Could beat people with skill. Could outrun people. Only five feet and eight inches tall, yet he seemed a giant of an athlete on the pitch. Perfect balance and impossible vision. He was the greatest because he could do anything and everything on a football pitch. I remember João Saldanha the coach being asked by a Brazilian journalist who was the best goalkeeper in his squad. He said Pelé. The man could play in any position".[118] Former Manchester United striker and member of England's 1966 FIFA World Cup-winning team Sir Bobby Charlton stated, "I sometimes feel as though football was invented for this magical player."[35] During the 1970 World Cup, when Manchester United defender Paddy Crerand (who was part of the ITV panel) was asked, "How do you spell Pelé?", he replied, "Easy: G-O-D."[35] Following Pelé's death, former Brazilian international and World Cup Winner Ronaldo stated that his "legacy transcends generations".[142] Ronaldo's teammate for club and country, Roberto Carlos, also expressed gratitude towards Pele, saying that the "football world thanks you for everything you did for us".[142] Many of such tributes were issued after Pelé's death at the age of 82.[143][144][145][146]

Accolades

After retiring, Pelé continued to be lauded by players, coaches, journalists and others. Brazilian attacking midfielder Zico, who represented Brazil at the 1978, 1982 and 1986 FIFA World Cup, stated: "This debate about the player of the century is absurd. There's only one possible answer: Pelé. He's the greatest player of all time, and by some distance I might add".[83] French three-time Ballon d'Or winner Michel Platini said: "There's Pelé the man, and then Pelé the player. And to play like Pelé is to play like God."[147] Diego Maradona, joint FIFA Player of the Century, and the player Pelé is historically compared with, stated, "It's too bad we never got along, but he was an awesome player".[83] Prolific Brazilian striker Romário, winner of the 1994 FIFA World Cup and player of the tournament, remarked: "It's only inevitable I look up to Pelé. He's like a God to us".[83] Five-time FIFA Ballon d'Or winner Cristiano Ronaldo said, "Pelé is the greatest player in football history, and there will only be one Pelé", while José Mourinho, two-time UEFA Champions League winning manager, commented: "I think he is football. You have the real special one – Mr. Pelé."[148] Real Madrid honorary president and former player, Alfredo Di Stéfano, opined: "The best player ever? Pelé. Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo are both great players with specific qualities, but Pelé was better".[149]

Presenting Pelé with the Laureus Lifetime Achievement Award, former South African president Nelson Mandela said, "To watch him play was to watch the delight of a child combined with the extraordinary grace of a man in full."[150] US politician and political scientist Henry Kissinger stated: "Performance at a high level in any sport is to exceed the ordinary human scale. But Pelé's performance transcended that of the ordinary star by as much as the star exceeds ordinary performance."[151] After a reporter asked if his fame compared to that of Jesus, Pelé joked, "There are parts of the world where Jesus Christ is not so well known."[112] The artist Andy Warhol (who painted a portrait of Pelé) also quipped, "Pelé was one of the few who contradicted my theory: instead of 15 minutes of fame, he will have 15 centuries."[35] David Goldblatt wrote that his emergence at the World Cup in 1958 coincided with "the explosive spread of television, which massively amplified his presence everywhere",[152] while Barney Ronay states, "What is certain is that Pelé invented this game, the idea of individual global sporting superstardom, and in a way that is unrepeatable now."[8]

In 2000, the International Federation of Football History & Statistics (IFFHS) voted Pelé the World Player of the Century. In 1999, the International Olympic Committee elected him the Athlete of the Century and Time magazine named Pelé one of the 100 Most Important People of the 20th Century. During his playing days, Pelé was for a period the highest-paid athlete in the world.[153] Pelé's "electrifying play and penchant for spectacular goals" made him a star around the world. To take full advantage of his popularity, his teams toured internationally.[7] During his career, he became known as "The Black Pearl" (A Pérola Negra), "The King of Football" (O Rei do Futebol), "The King Pelé" (O Rei Pelé) or simply "The King" (O Rei).[17] In 2014, the city of Santos inaugurated the Pelé museum – Museu Pelé – which displays a 2,400 piece collection of Pelé memorabilia.[154] Approximately $22 million was invested in the construction of the museum, housed in a 19th-century mansion.[155]

In January 2014, Pelé was awarded the first ever FIFA Ballon d'Or Prix d'Honneur as an acknowledgment from the world governing body of the sport for his contribution to world football.[156] After changing the rules in 1995, France Football did an extensive analysis in 2015 of the players who would have won the award if it had been open for them beginning in 1956: the year the Ballon d'Or award started. Their study revealed that Pelé would have received the award a record seven times (Ballon d'or: Le nouveau palmarès). The original recipients, however, remain unchanged.[157] In 2020, Pelé was named in the Ballon d'Or Dream Team, a greatest all-time XI.[158]

According to the RSSSF, Pelé was one of the most successful goal-scorers in the world, scoring 538 league goals,[159] a total of 775 in 840 official games and a tally of 1,301 goals in 1,390 appearances during his professional senior career, which included friendlies and tour games. He is ranked among the leading scorers in football history in both official and total matches. After his retirement in 1977 he played eight exhibition games and scored three goals.[160]

"Pelé Pact" and Puma sponsorship

In the lead up to the 1970 World Cup, Adidas and Puma established the "Pelé Pact", where both German sportswear companies, owned by the rival Dassler brothers, agreed not to sign a deal with Pelé, feeling that a bidding war would become too expensive.[161][162][163] However, Puma would break the pact by signing Pelé, and in addition to paying him a percentage of Puma King boot sales, gave him $120,000 ($2.85 million in 2022) to tie his laces prior to Brazil's quarter-final against Peru to advertise their boots.[161][162][164] With the camera panning in on the most famous athlete in the world, the Puma King Pelé boots were broadcast to a global audience, generating enormous publicity for the brand.[162][163] Praised as a shrewd marketing move by Puma, the Pelé deal played a prominent role in the Dassler brothers feud, with many business experts crediting the rivalry and competition for transforming sports apparel into a multi-billion pound industry.[162]

Personal life

Relationships and children

Pelé married three times and had several affairs, fathering seven children in all.[165]

In 1966, Pelé married Rosemeri dos Reis Cholbi.[166] They had two daughters, Kely Cristina (born 13 January 1967), who married Arthur DeLuca, and Jennifer (b. 1978), as well as one son, Edson ("Edinho", b. 27 August 1970).[167] The couple divorced in 1982.[168] In May 2014, Edinho was sentenced to 33 years in jail for laundering money from drug trafficking.[169] On appeal, the sentence was reduced to 12 years and 10 months.[170]

From 1981 to 1986, Pelé was romantically linked with TV presenter Xuxa. She was 17 when they started dating.[171] In April 1994, Pelé married psychologist and gospel singer Assíria Lemos Seixas, who gave birth on 28 September 1996 to twins Joshua and Celeste through fertility treatments.[167][172] The couple divorced in 2008.[173]

Pelé had at least two more children from affairs. Sandra Machado, who was born from an affair Pelé had in 1964 with a housemaid, Anizia Machado, fought for years to be acknowledged by Pelé, who refused to submit to DNA tests.[174][175][176] Pelé finally relented after a court-ordered DNA test proved she was his daughter. Sandra Machado died of cancer in 2006.[175][176][177]

At the age of 73, Pelé announced his intention to marry 41-year-old Marcia Aoki, a Japanese-Brazilian importer of medical equipment from Penápolis, São Paulo, whom he had been dating since 2010. They first met in the mid-1980s in New York, before meeting again in 2008.[178] They married in July 2016.[179]

Politics

In January 1995, he was appointed by Fernando Cardoso as minister of sports. During his tenure, multiple reforms against corruption in state football associations were presented. He resigned from the post on 30 April 1998.[180]

During the 2013 protests in Brazil, Pelé asked for people to put aside the demonstrations and support the Brazil national team.[181]

On 1 June 2022, Pelé published an open letter to the President of Russia Vladimir Putin on his Instagram account, in which he made a public plea to stop the "evil" and "unjustified" Russian invasion of Ukraine.[182][183][184]

Religion

A Catholic, Pelé donated a signed jersey to Pope Francis. Accompanied by a signed football from Ronaldo Nazario, it is located in one of the Vatican Museums.[185]

Health

In 1977, Brazilian media reported that Pelé had his right kidney removed.[186] In November 2012, Pelé underwent a successful hip operation.[187] In December 2017, Pelé appeared in a wheelchair at the 2018 World Cup draw in Moscow where he was pictured with President Vladimir Putin and Argentine footballer Diego Maradona.[188] A month later, he collapsed from exhaustion and was taken to hospital.[188] In 2019, after a hospitalisation because of a urinary tract infection, Pelé underwent surgery to remove kidney stones.[189] In February 2020, his son Edinho reported that Pelé was unable to walk independently and reluctant to leave home, ascribing his condition to a lack of rehabilitation following his hip operation.[190]

In September 2021, Pelé had surgery to remove a tumour on the right side of his colon.[191] Although his eldest daughter Kely stated he was "doing well", he was reportedly readmitted to intensive care a few days later,[192] before finally being released on 30 September 2021 to begin chemotherapy.[193] In November 2022, ESPN Brasil reported that Pelé had been taken to hospital with "general swelling", along with cardiac issues and concerns that his chemotherapy treatment was not having the expected effect; his daughter Kely stated there was "no emergency".[194][195]

After football

In 1994, Pelé was appointed a UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador.[196] In 1995, Brazilian president Fernando Henrique Cardoso appointed Pelé to the position of extraordinary minister for sport. During this time he proposed legislation to reduce corruption in Brazilian football, which became known as the "Pelé law".[197] Cardoso eliminated the post of sports minister in 1998.[198] In 2001, Pelé was accused of involvement in a corruption scandal that stole $700,000 from UNICEF. It was claimed that money given to Pelé's company for a benefit match was not returned after it was cancelled, although nothing was proven, and it was denied by UNICEF.[199][200] In 1997, he received an honorary knighthood from Queen Elizabeth II at a ceremony in Buckingham Palace.[201] Pelé also helped inaugurate the 2006 FIFA World Cup, alongside supermodel Claudia Schiffer.[99]

In 1993, Pelé publicly accused the Brazilian football administrator Ricardo Teixeira of corruption after Pelé's television company was rejected in a contest for the Brazilian domestic rights to the 1994 World Cup.[202] Pelé's accusations led to an eight-year feud between the pair.[203] As a consequence of the affair, the President of FIFA, João Havelange, Teixeira's father-in-law, banned Pelé from the draw for the 1994 FIFA World Cup in Las Vegas. Criticisms over the ban were perceived to have damaged Havelange's chances of re-election as FIFA's president in 1994.[202]

In 1976, Pelé was on a Pepsi-sponsored trip in Lagos, Nigeria, when the military attempted a coup. Pelé was trapped in a hotel together with Arthur Ashe and other tennis pros, who were participating in the interrupted 1976 Lagos WCT tournament. Pelé and his crew eventually left the hotel to stay at the residence of Brazil's ambassador as they could not leave the country for a couple of days. Later the airport was opened and Pelé left the country disguised as a pilot.[204][205]

Pelé published several autobiographies, starred in documentary films, and composed musical pieces, including Sérgio Mendes' soundtrack for the film Pelé directed by François Reichenbach in 1977.[206][207] He appeared in the 1981 film Escape to Victory, about a World War II-era football match between Allied prisoners of war and a German team. Pelé starred alongside other footballers of the 1960s and 1970s, with actors Michael Caine and Sylvester Stallone.[208] In 1969, Pelé starred in a telenovela called Os Estranhos, about first contact with aliens. It was created to drum up interest in the Apollo missions.[209] In 2001, he had a cameo role in the football satire film Mike Bassett: England Manager.[210] Pelé was asked to participate in the 2006 ESPN documentary film Once in a Lifetime: The Extraordinary Story of the New York Cosmos, but declined when the producers refused to pay his requested $100,000 fee.[211]

Pelé appeared at the 2006 World Economic Forum in Davos, and spoke on the subject titled, "Can a Ball Change the World: The Role of Sports in Development".[212] In November 2007, Pelé was in Sheffield, England, to mark the 150th anniversary of the world's oldest football club, Sheffield F.C.[213] Pelé was the guest of honour at Sheffield's anniversary match against Inter Milan at Bramall Lane.[213] As part of his visit, Pelé opened an exhibition which included the first public showing in 40 years of the original hand-written rules of football.[213] Pelé scouted for Premier League club Fulham in 2002.[214] He made the draw for the qualification groups for the 2006 FIFA World Cup finals.[215] On 1 August 2010, Pelé was introduced as the honorary president of a revived New York Cosmos, aiming to field a team in Major League Soccer.[216] In August 2011, ESPN reported that Santos was considering bringing him out of retirement for a cameo role in the 2011 FIFA Club World Cup, although this turned out to be false.[217]

The most notable area of Pelé's life since football was his ambassadorial work. In 1992, he was appointed a UN ambassador for ecology and the environment.[218] He was also awarded Brazil's gold medal for outstanding services to the sport in 1995. In 2012, Pelé was awarded an honorary degree from the University of Edinburgh for "significant contribution to humanitarian and environmental causes, as well as his sporting achievements".[219]

In 2009, Pelé assisted the Rio de Janeiro bid for the 2016 Summer Olympics. In July 2009, he spearheaded the Rio 2016 presentation to the Association of National Olympic Committees of Africa General Assembly in Abuja, Nigeria.[220]

On 12 August 2012, Pelé was an attendee at the 2012 Olympic hunger summit hosted by British prime minister David Cameron at 10 Downing Street, London, part of a series of international efforts which have sought to respond to the return of hunger as a high-profile global issue.[221][222] Later on the same day, Pelé appeared at the closing ceremony of the 2012 Summer Olympics in London, following the handover section to the next host city for the 2016 Summer Olympics, Rio de Janeiro.[223]

In March 2016, Pelé filed a lawsuit against Samsung Electronics in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois seeking US$30 million in damages claiming violations under the Lanham Act for false endorsement and a state law claim for violation of his right of publicity.[224] The suit alleged that at one point, Samsung and Pelé came close to entering into a licensing agreement for Pelé to appear in a Samsung advertising campaign, but Samsung abruptly pulled out of the negotiations. The October 2015 Samsung ad in question included a partial face shot of a man who allegedly "very closely resembles" Pelé and also a superimposed high-definition television screen next to the image of the man featuring a "modified bicycle or scissors-kick", often used by Pelé.[224] The case was settled out-of-court several years later.[225]

In addition to his ambassadorial work, Pelé supported various charitable causes, such as Action for Brazil's Children, Gols Pela Vida, SOS Children's Villages, The Littlest Lamb, Prince's Rainforests Project and many more.[226][227][228][229][230] In 2016, Pelé auctioned more than 1600 items from a collection he accumulated over decades and raised £3.6 million for charity.[231][232] In 2018, Pelé founded his charitable organisation, the Pelé Foundation, which endeavours to empower impoverished and disenfranchised children from around the globe.[233][234]

Death and funeral

In 2021, Pelé was diagnosed with colon cancer.[235] He underwent surgery the same month, and afterwards was treated with several rounds of chemotherapy. In early 2022, metastasis were detected in the intestine, lung and liver. On 29 November, he was admitted to the Albert Einstein Israelite Hospital in São Paulo due to a respiratory infection after he contracted COVID-19 and for reassessment of the treatment of his colon cancer.[236] On 3 December 2022, it was reported that Pelé had become unresponsive to chemotherapy and that it was replaced with palliative care.[237]

On 21 December 2022, the Albert Einstein Israelite Hospital, where Pelé was being treated, stated that his tumour had advanced and he required "greater care related to renal and cardiac dysfunctions".[238] Therefore, he was not allowed to spend Christmas at home, as his family had wanted. Pelé died on 29 December 2022, at 3:27 pm, at the age of 82, due to multiple organ failure, a complication of colon cancer.[239][240] Pelé's death certificate stated that he had died of kidney failure, heart failure, bronchopneumonia and colon adenocarcinoma. He was survived by his 100-year-old mother, Celeste, who, given her advanced age, did not understand her son's death; she would later die in June 2024.[241] Pelé's sister Maria Lucia do Nascimento described their mother as "in her own little world".[242]

"He had a magnetic presence and, when you were with him, the rest of the world stopped. Today, the whole world mourns the loss of Pelé; the greatest footballer of all time."

—FIFA President, Gianni Infantino[243]

Tributes were paid by current players, including Neymar, Cristiano Ronaldo, Kylian Mbappé and Lionel Messi, along with other major sporting figures, celebrities, and world leaders.[244][245][145][246] The outgoing Brazilian president, Jair Bolsonaro, declared a three-day period of national mourning.[247] The national flags of the 211 member associations of FIFA were flown at half-mast at FIFA headquarters in Zürich.[248] Landmarks and stadiums lit up in honour of Pelé included the Christ the Redeemer statue and Maracanã Stadium in Rio de Janeiro,[249] the headquarters of CONMEBOL in Paraguay[247] and Wembley Stadium in London.[250] There was applause and a minute's silence at matches in honour of Pelé.[251][252]

Pelé's funeral, which involved his body being publicly displayed in an open coffin which was draped with the flags of Brazil and Santos FC, began at Vila Belmiro stadium in Santos on 2 January 2023.[253][254][255] Thousands of fans flooded the streets to attend the first day of the funeral service,[256] with some in attendance claiming that they had to wait three hours in line.[253] The public wake would continue to 3 January,[257][258] and saw more than 230,000 people in attendance.[259][260] Many in attendance were wearing the yellow and green No. 10 Brazilian jerseys and the black and white Santos football club jersey, which Pelé wore during his career.[261][262] Brazil television channels suspended normal broadcasting to cover the funeral procession.[263] Pelé's wife Marcia Aoki, his son Edinho, FIFA president Gianni Infantino, CONMEBOL president Alejandro Domínguez and president of the Brazilian Football Confederation Ednaldo Rodrigues were among those in attendance.[264] It would continue on 3 January 2023. Newly sworn in Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was also among those who attended the wake.[263][262] After the funeral procession, Pelé was buried at the Memorial Necrópole Ecumênica.[265][266][267]

Kigali Pelé Stadium in Rwanda was renamed for him in March 2023 by Rwandan president Paul Kagame and FIFA president Gianni Infantino as part of the 73rd FIFA Congress.[268][269] On 26 April 2023, the nickname pelé became synonymous with "exceptional, incomparable, unique" in Michaelis Portuguese-language dictionary after a campaign with 125,000 signatories.[270]

Career statistics

Club

Pelé's goalscoring record is often reported by FIFA as being 1,281 goals in 1,363 games.[83] This figure includes goals scored by Pelé in friendly club matches, including international tours Pelé completed with Santos and the New York Cosmos, and a few games Pelé played in for the Brazilian armed forces teams during his national service in Brazil and the state team of São Paulo who competed for the Brazilian Championship of States Teams (Campeonato Brasileiro de Seleções Estaduais).[271][272] He was listed in the Guinness World Records for most career goals scored in football.[4] In 2000, IFFHS declared Pelé as the "World's Best and successful Top Division Goal Scorer of all time" with 541 goals in 560 games and honoured him with a trophy.[273][274]

The tables below record every goal Pelé scored in official club competitions for Santos FC and all matches and goals for the New York Cosmos.

| Club | Season | Campeonato Paulista | Rio-São Paulo[note 6] | Campeonato Brasileiro Série A[note 7] | Domestic competitions Sub-total |

International competitions | Total | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copa Libertadores | Intercontinental Cup | |||||||||||||||

| Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | |||

| Santos | 1956 | 0* | 0* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 1957 | 14+15* | 19+17*[note 8][note 9] | 9 | 5 | 38* | 41* | 38* | 41* | ||||||||

| 1958 | 38 | 58 | 8 | 8 | 46 | 66 | 46* | 66* | ||||||||

| 1959[278] | 32 | 45 | 7 | 6 | 4* | 2* | 39 | 51 | 43* | 53* | ||||||

| 1960[279] | 30 | 33 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33* | 33* | ||

| 1961 | 26 | 47 | 7 | 8 | 5* | 7 | 33 | 55 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 38* | 62* | ||

| 1962 | 26 | 37 | 0 | 0 | 5* | 2* | 26 | 37 | 4* | 4* | 2 | 5 | 37* | 48* | ||

| 1963[280] | 19 | 22 | 8 | 14 | 4* | 8 | 27 | 36 | 4* | 5* | 1 | 2 | 36 | 51* | ||

| 1964 | 21 | 34 | 4 | 3 | 6* | 7 | 25 | 37 | 0* | 0* | 0 | 0 | 31* | 44* | ||

| 1965 | 28 | 49 | 7 | 5 | 4* | 2* | 39 | 54 | 7* | 8 | 0 | 0 | 46* | 64* | ||

| 1966 | 14 | 13 | 0* | 0* | 5* | 2* | 14* | 13* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19* | 15* | ||

| 1967 | 18 | 17 | 14* | 9* | 32* | 26* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 32* | 26* | ||||

| 1968 | 21 | 17 | 17* | 12* | 38* | 28* | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1[note 10] | 43* | 30* | ||||

| 1969 | 25 | 26 | 12* | 12* | 37* | 38* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 37* | 38* | ||||

| 1970 | 15 | 7 | 13* | 4* | 28* | 11* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28* | 11* | ||||

| 1971 | 19 | 6 | 21 | 1 | 40 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 7 | ||||

| 1972 | 20 | 9 | 16 | 5 | 36 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 14 | ||||

| 1973 | 19 | 11 | 30 | 19 | 49 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 49 | 30 | ||||

| 1974 | 10 | 1 | 17 | 9 | 27 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 10 | ||||

| Total | 410 | 468 | 53 | 49 | 173* | 101* | 636* | 618* | 15 | 17[note 11] | 8 | 8 | 659 | 643 | ||

- * Indicates that the number was deduced from the list of rsssf.com and this list of Pelé games.

| Club | Season | League[note 12] | Post season | Other[citation needed] | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | ||

| New York Cosmos | 1975 | 9 | 5 | – | 14 | 12 | 23 | 17 | |

| 1976 | 22 | 13 | 2 | 2 | 18 | 11 | 42 | 26 | |

| 1977 | 25 | 13 | 6 | 4 | 11 | 6 | 42 | 23 | |

| Total | 56 | 31 | 8 | 6 | 43 | 29 | 107 | 66 | |

International

With 77 goals in 92 official appearances,[note 2] Pelé is the second highest goalscorer of the Brazil national football team.[83] He scored twelve goals and is credited with ten assists in fourteen World Cup appearances, including four goals and seven assists in 1970.[24]

Source:[5]

| Team | Year | Apps | Goals | Goal average |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 1957 | 2 | 2 | 1.00 |

| 1958 | 7 | 9 | 1.28 | |

| 1959 | 9 | 11 | 1.22 | |

| 1960 | 6 | 4 | 0.67 | |

| 1961 | 0 | 0 | — | |

| 1962 | 8 | 8 | 1.00 | |

| 1963 | 7 | 7 | 1.00 | |

| 1964 | 3 | 2 | 0.67 | |

| 1965 | 8 | 9 | 1.12 | |

| 1966 | 9 | 5 | 0.55 | |

| 1967 | 0 | 0 | — | |

| 1968 | 7 | 4 | 0.57 | |

| 1969 | 9 | 7 | 0.77 | |

| 1970 | 15 | 8 | 0.53 | |

| 1971 | 2 | 1 | 0.50 | |

| Total | 92 | 77 | 0.84 | |

Honours

São Paulo state team

Santos

- Campeonato Brasileiro Série A: 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964, 1965, 1968[283]

- Copa Libertadores: 1962, 1963[37][284]

- Intercontinental Cup: 1962, 1963[285]

- Intercontinental Supercup: 1968[285]

- Campeonato Paulista: 1958, 1960, 1961, 1962, 1964, 1965, 1967, 1968, 1969, 1973[note 13][287]

- Torneio Rio-São Paulo: 1959, 1963, 1964[note 14], 1966[215]

New York Cosmos

- North American Soccer League, Soccer Bowl: 1977[289]

- North American Soccer League, Atlantic Conference Championship: 1977[289]

Brazil

- FIFA World Cup: 1958, 1962, 1970[290]

- Taça do Atlântico: 1960[291]

- Roca Cup: 1957, 1963[292][293]

- Taça Oswaldo Cruz: 1958, 1962, 1968[5][294]

- Copa Bernardo O'Higgins: 1959[295]

Individual

In December 2000, Pelé and Maradona shared the prize of FIFA Player of the Century by FIFA.[296] The award was originally intended to be based upon votes in a web poll, but after it became apparent that it favoured Diego Maradona after a reported cyber-blitz by Maradona fans, FIFA then appointed a "Family of Football" committee of FIFA members to decide the winner of the award together with the votes of the readers of the FIFA magazine.[297] The committee chose Pelé. Since Maradona was winning the Internet poll, however, it was decided he and Pelé should share the award.[298]

- Campeonato Paulista Top Scorer: 1957, 1958, 1959, 1960, 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964, 1965, 1969, 1973[215]

- FIFA World Cup Best Young Player: 1958[85]

- FIFA World Cup Silver Ball: 1958

- France Football's Ballon d'Or: 1958, 1959, 1960, 1961, 1963, 1964, 1970 – Le nouveau palmarès (the new winners)[157][299]

- South American Championship Best Player: 1959[87]

- South American Championship Top Scorer: 1959[88]

- Copa Bernardo O'Higgins Top Scorer: 1959 (shared with Quarentinha)[300][301]

- Gol de Placa: 1961[302][303]

- Campeonato Brasileiro Série A Top Scorer: 1961, 1963, 1964[304]

- Intercontinental Cup Top Scorer: 1962, 1963[305][306][307]

- Torneio Rio-São Paulo Top Scorer: 1963[308]

- Copa Libertadores Top Scorer: 1965[309]

- BBC Overseas Sports Personality of the Year: 1970[310]

- Bola de Prata: 1970[311]

- FIFA World Cup Golden Ball (Best Player): 1970[83]

- South American Footballer of the Year: 1973[312]

- Included in the North American Soccer League (NASL) All-Star team: 1975, 1976, 1977[313]

- NASL Top Assist Provider: 1976[314]

- NASL Most Valuable Player: 1976[314]

- Number 10 retired by the New York Cosmos as a recognition to his contribution to the club: 1977[315][316]

- Elected Citizen of the World, by the United Nations: 1977[317]

- International Peace Award: 1978[318]

- Sports Champion of the Century, by L'Équipe: 1981[319]

- FIFA Order of Merit: 1984[320]

- Inducted into the American National Soccer Hall of Fame: 1992[321]

- Elected Goodwill Ambassador, by UNESCO: 1993[317]

- Winner of France Football's World Cup Top-100 1930–1990: 1994[322]

- Marca Leyenda: 1997[323]

- World Team of the 20th Century: 1998[324]

- Football Player of the Century, elected by France Football's Ballon d'Or Winners: 1999[325]

- TIME: One of the 100 Most Important People of the 20th century: 1999[326]

- Greatest Player of the 20th Century, by World Soccer: 1999[327]

- Athlete of the Century, by Reuters News Agency: 1999[328]

- Athlete of the Century, elected by International Olympic Committee: 1999[329]

- World Player of the Century, by the IFFHS: 2000[330][331]

- South American player of the century, by the IFFHS: 2000[330][331]

- FIFA Player of the Century: 2000[83]

- Laureus Lifetime Achievement Award: 2000[332]

- FIFA Centennial Award: 2004[333]

- FIFA 100 Greatest Living Footballers: 2004[334]

- BBC Sports Personality of the Year Lifetime Achievement Award: 2005[335]

- Elected best Brazilian player of the century, by the IFFHS: 2006[336]

- FIFA Presidential Award: 2007[337]

- Greatest football player to have ever played the game, by Golden Foot: 2012[338]

- FIFA Ballon d'Or Prix d'Honneur: 2013[339]

- World Soccer Greatest XI of All Time: 2013[340]

- Legends of Football Award: 2013[341][342]

- South America's Best Player in History, by L'Équipe: 2015[343]

- Inspiration Award, by GQ: 2017[344]

- Global Citizen Award, by the World Economic Forum: 2018[345]

- FWA Tribute Award: 2018[346]

- Ballon d'Or Dream Team: 2020[158]

- IFFHS All-time Men's Dream Team: 2021[347]

- IFFHS South America Men's Team of All Time: 2021[348]

- Player of History Award: 2022[349]

- FIFA Best Special Award: 2022[350]

Orders

- Knight of the Order of Rio Branco: 1967[351]

- Elected Commander of the Order of Rio Branco after scoring the thousandth goal: 1969[317]

- Officer of the Order of Ouissam Alaouite of the Kingdom of Morocco: 1976[352]

- Awarded with the Order of Champions, by the Organization of Catholic Youth in the USA: 1978[317]

- Awarded the FIFA Order as a tribute to his 80 years as a sports institution: 1984[317]

- Awarded with the Order of Merit of South America, by CONMEBOL: 1984[317]

- He was awarded the National Order of Merit, by the government of Brazil: 1991[317]

- Awarded with the Cross of the Order of the Republic of Hungary: 1994[317]

- Awarded the Order of Military Merit: 1995[353][354]

- Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (honorary knighthood): 1997[355]

- Awarded with the Order of Cultural Merit, by the government of Brazil: 2004[356]

- Olympic Order, by the International Olympic Committee: 2016[357]

Records

- Highest goals-per-game ratio for Brazil national football team: 0.84[358][359]

- Highest goals-per-game ratio of any South American top international scorer: 0.84[360]

- Highest goals-per-game ratio of any leading scorer in the Intercontinental Cup: 2.33[361]

- Most goals in the Intercontinental Cup: 7[362][363]

- Most goals for Santos: 643 (in 659 competitive games)[364]

- Most goals for Santos: 1091 (including friendlies)[365][366]

- Most appearances for Santos: 1116[367][366]

- Most goals within a single Brazilian top-flight league season: 58[368]

- Most goals scored in a single Campeonato Paulista season: 58 (in 38 competitive games,1958)[369]

- Most goals scored in a single Campeonato Paulista match: 8 (1964)[370]

- Most goals scored in Campeonato Paulista history: 466[363]

- Most seasons as Campeonato Paulista Top Scorer: 11[371]

- Most consecutive seasons as Campeonato Paulista Top Scorer: 9 (1957–1965)[372][373]

- Most goals in a calendar year (including friendlies, recognised by FIFA): 127 (1959)[360]

- RSSSF record for most top level goals scored in one season (including friendlies): 120 (1959)[374]

- RSSSF record for most seasons with over 100 top level goals scored (including friendlies): 3 (1959, 1961, 1965)[374]

- RSSSF record for most goals scored before the age of 30: 675[375]

- RSSSF record for most top level career goals (including friendlies): 1,274[376]

- Guinness World Record for most career goals in world football (including friendlies): 1,283 (in 1,363 games)[377]

- IFFHS record for most top division league goals: 604[363][378]

- IFFHS record for most top level domestic goals: 659[363][378]

- Guinness World Record for most hat-tricks in world football: 92[379][380]

- Most hat-tricks for Brazil: 7[381]

- Most FIFA World Cup winners' medals: 3 (1958, 1962, 1970)[377][382]

- Youngest winner of a FIFA World Cup: aged 17 years and 249 days (1958)[383]

- Youngest goalscorer in a FIFA World Cup: aged 17 years and 239 days (for Brazil vs Wales, 1958)[83][384]

- Youngest player to score twice in a FIFA World Cup semi-final: aged 17 years and 244 days (for Brazil vs France, 1958)[385]

- Youngest player to score a hat-trick in a FIFA World Cup: aged 17 years and 244 days (for Brazil vs France, 1958)[384][386]

- Youngest player to play in a FIFA World Cup Final: aged 17 years and 249 days (1958)[387][386]

- Youngest goalscorer in a FIFA World Cup Final: aged 17 years and 249 days (for Brazil vs Sweden, 1958)[387][386]

- Youngest player to score twice in a FIFA World Cup Final: aged 17 years and 249 days (for Brazil vs Sweden, 1958)[385]

- Youngest player to play for Brazil in a FIFA World Cup: aged 17 years and 234 days[386]

- Youngest player to start a knockout match at a FIFA World Cup[388]

- Youngest player to reach five FIFA World Cup knockout stage goals[389][390]

- Youngest player to debut for Brazil national football team: aged 16 years and 259 days (Brazil vs Argentina, 1957)[391][392]

- Youngest goalscorer for Brazil national football team: aged 16 years and 259 days (Brazil vs Argentina, 1957)[393]

- Youngest Top Scorer in the Campeonato Paulista[394]

- First player to score in three successive FIFA World Cups[395]

- First teenager to score in a FIFA World Cup Final[396]

- One of only five players to have scored in four different FIFA World Cup tournaments[397][398]

- One of only five players to have scored in two different FIFA World Cup Finals[399]

- Scored in two FIFA World Cup Finals for winning teams (shared with Vavá)

- Most assists provided in FIFA World Cup history: 10 (1958–1970)[400]

- Most assists provided in a single FIFA World Cup tournament: 6 (1970)[360]

- Most assists provided in FIFA World Cup Final matches: 3 (1 in 1958 and 2 in 1970)[360]

- Most assists provided in FIFA World Cup knockout phase: 6 (shared with Messi)[401]

- Most goals from open play in FIFA World Cup Final matches: 3 (2 in 1958 and 1 in 1970) (shared with Vavá, Geoff Hurst and Zinedine Zidane)[402]

- Most FIFA World Cup goal involvements for Brazil[403][404]

- Most goals scored in the Copa Bernardo O'Higgins: 3 (shared with Quarentinha)[405][406]

- Only player to reach 25 international goals as a teenager[407]

- Only player to score in a FIFA World Cup before turning 18[407]

- Only player to score a hat-trick in a FIFA World cup before turning 18[408]

- Only player to have scored a hat-trick in the Intercontinental Cup[409]

- Only player to have scored a hat-trick in the Copa Bernardo O'Higgins[410][411]

Filmography

| Year | Title | Role | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | Os Estranhos | Plínio Pompeu | TV series | [412] |

| 1971 | O Barão Otelo no Barato dos Bilhões | Dr. Arantes/Himself | [413] | |

| 1972 | A Marcha | Chico Bondade | [414] | |

| 1981 | Escape to Victory | Corporal Luis Fernandez | [415] | |

| 1983 | A Minor Miracle | Himself | Also known as Young Giants | [415] |

| 1985 | Pedro Mico | [414] | ||

| 1986 | Hotshot | Santos | [415] | |

| 1986 | Os Trapalhões e o Rei do Futebol | Nascimento | [414][416] | |

| 1989 | Solidão, Uma Linda História de Amor | [414] | ||

| 2001 | Mike Bassett: England Manager | Himself | [415][414] | |

| 2016 | Pelé: Birth of a Legend | Man sitting in hotel lobby | Cameo appearance | [417] |

See also

- List of Brazil national football team hat-tricks

- List of international goals scored by Pelé

- List of international hat-tricks scored by Pelé

- List of men's footballers with 500 or more goals

- List of men's footballers with 50 or more international goals

- Pelé runaround move

- Torcida Jovem of Santos FC School of Samba

Notes

- ^ According to Pelé, his birth certificate listed 21 October 1940 incorrectly.[1]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d This includes a match for Brazil against the rest of the world, which FIFA does not recognise, played for the 10th anniversary of their first World Cup title[5][6]

- ^ Pelé presumed that it was an insult since the word had no meaning in Portuguese. He discovered in the 2000s that the word meant "miracle" in Hebrew.[16]

- ^ The mark was surpassed by Northern Ireland's Norman Whiteside in the 1982 FIFA World Cup. He scored his first World Cup goal against Wales in the quarter-finals, the only goal of the match, to help Brazil advance to the semi-finals while becoming the youngest ever World Cup goalscorer at 17 years and 239 days.[80]

- ^ Pelé would stop in the middle of a run-up to a penalty kick before shooting the ball; goalkeepers complained that this gave strikers an unfair advantage, however, and in the 1970s, FIFA banned this move from competitions.[127]

- ^ Soccer Europe compiled this list from RSSSF.[275]

- ^ Statistics from 1957 to 1974 for the Taça de Prata, Taça Brasil and Copa Libertadores were taken from Soccer Europe website. Soccer Europe lists RSSSF, but do not give a season-by-season breakdown.[276]

- ^ In 1957, the Paulista Championship was divided in two phases: Blue Series and White Series. In the first, Pelé scored 19 goals in 14 games, and in the Blue Series, scored 17 goals in 15 games.[277]

- ^ This number was inferred from a Santos fixture list from rsssf.com and this list of games Pelé played.

- ^ Intercontinental Super Cup

- ^ Statistics from 1957 to 1974 for the Taça de Prata, Taça Brasil and Copa Libertadores were taken from Soccer Europe website. Soccer Europe lists RSSSF, but do not give a season-by-season breakdown.[276]

- ^ RSSSF recognize as league goals those scored in NASL, the post season play-offs, Campeonato Paulista goals and the original Campeonato Brazileiro goals (1971–1974). IFFHS has made the same validation in the past.

- ^ The 1973 Paulista was held jointly with Portuguesa.[286][215]

- ^ The 1964 Torneio Rio-São Paulo was held jointly with Botafogo.[288]

References

- ^ "Pelé, who rose from a Brazilian slum to become the world's greatest soccer player, dies at 82". Los Angeles Times. 29 December 2022. Archived from the original on 29 December 2022. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "FIFA: Pele, the greatest of them all". FIFA. 28 June 2012. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ Luhn, Michele (29 December 2022). "Pelé, Brazilian soccer star and the only player to win the World Cup three times, dies at age 82". CNBC. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Most career goals (football)". Guinness World Records. 7 September 1956. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Mamrud, Roberto. "Edson Arantes do Nascimento "Pelé" – Goals in International matches". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ "A tribute to record-breaking Neymar". FIFA. 9 September 2023. Archived from the original on 27 May 2024. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Pelé (Brazilian Athlete)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 11 July 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ronay, Barney (1 January 2021). "Pelé's revolutionary status must survive numbers game against Lionel Messi". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ Ben Green (30 December 2022). "Pele's legendary career told in numbers: Just how good was Brazil's emblematic forward?". squawka.com. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ^ "Muere Celeste Arantes, madre de Pelé, a los 101 años" (in Spanish). Infobae. 21 June 2024. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Pelé & Fish 1977, p. 18–19.

- ^ "Morreu Zoca, o escudeiro do Rei" [Zoca has died, the King's squire]. santosfc.com.br (in Portuguese). 26 March 2020. Archived from the original on 2 February 2023. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pelé 2008, p. 14.

- ^ Narcía, Eva. "Un siglo, diez historias" (in Spanish). BBC World Service. Archived from the original on 11 November 2022. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- ^ "From Edson to Pelé: my changing identity". The Guardian. London. 12 May 2006. Archived from the original on 14 November 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2006.

- ^ Winterman, Denise (4 January 2006). "Taking the Pelé". BBC News. Archived from the original on 23 November 2008. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Pelé". Biography.com, via A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on 13 October 2022. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ Heizer 1997, p. 173.

- ^ Magill 1999, p. 2950.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Pele Speaks of Benefits of Futebol de Salão". International Confederation of Futebol de Salão. 24 May 2006. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016.

- ^ Freedman 2014, p. 47.

- ^ Massarela, Louis (7 September 2016). "Exclusive interview: Pele on his Santos years". FourFourTwo. Archived from the original on 22 June 2021. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ Marcus 1976, p. 20.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Pele helps Brazil to World Cup title". History. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ Da Mata, Alessandro (26 October 2007). "Mesário da estréia de Pelé lembra atrapalhada" (in Portuguese). Sâo Paulo: LANCE!. Archived from the original on 14 May 2008.

- ^ "Pelé, auguri a Ronaldo. E rivela: "Sono stato vicino alla Juve"". La Gazzetta dello Sport (in Italian). 18 August 2018. Archived from the original on 8 November 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2018.