Восточный блок

| Восточный блок |

|---|

|

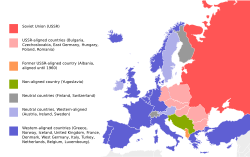

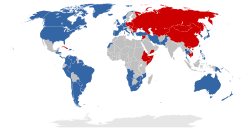

Восточный блок , также известный как Коммунистический блок ( Комблок ), Социалистический блок и Советский блок , представлял собой коалицию коммунистических государств Центральной и Восточной Европы , Азии , Африки и Латинской Америки , которые были союзниками Советского Союза и существовал во время холодной войны (1947–1991). Эти государства следовали идеологии марксизма-ленинизма , в оппозиции капиталистическому Западному блоку . Восточный блок часто называли « Вторым миром », тогда как термин « Первый мир » относился к Западному блоку, а « Третий мир » относился к неприсоединившимся странам, которые находились в основном в Африке, Азии и Латинской Америке, но, в частности, также включала бывшего до 1948 года советского союзника Югославию , которая располагалась в Европе.

В Западной Европе термин «Восточный блок» обычно относился к СССР и Центральной и Восточной Европы, странам входящим в СЭВ ( Восточная Германия , Польша , Чехословакия , Венгрия , Румыния , Болгария и Албания). [а] ). В Азии в Восточный блок вошли Монголия , Вьетнам , Лаос , Кампучия , Северная Корея , Южный Йемен , Сирия и Китай . [б] [с] В Северной и Южной Америке страны, присоединившиеся к Советскому Союзу, включали Кубу с 1961 года и в течение ограниченного периода времени Никарагуа и Гренаду . [1]

Terminology[edit]

The term Eastern Bloc was often used interchangeably with the term Second World. This broadest usage of the term would include not only Maoist China and Cambodia, but also short-lived Soviet satellites such as the Second East Turkestan Republic (1944–1949), the People's Republic of Azerbaijan (1945–1946) and the Republic of Mahabad (1946), as well as the Marxist–Leninist states straddling the Second and Third Worlds before the end of the Cold War: the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen (from 1967), the People's Republic of the Congo (from 1969), the People's Republic of Benin, the People's Republic of Angola and People's Republic of Mozambique from 1975, the People's Revolutionary Government of Grenada from 1979 to 1983, the Derg/People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia from 1974, and the Somali Democratic Republic from 1969 until the Ogaden War in 1977.[2][3][4][5] Although not Marxist–Leninist, leadership of Ba'athist Syria officially regarded the country as part of the Socialist Bloc and established a close economic, military alliance with the Soviet Union.[6][7]

Many states were accused by the Western Bloc of being in the Eastern Bloc when they were part of the Non-Aligned Movement. The most limited definition of the Eastern Bloc would only include the Warsaw Pact states and the Mongolian People's Republic as former satellite states most dominated by the Soviet Union. Cuba's defiance of complete Soviet control was noteworthy enough that Cuba was sometimes excluded as a satellite state altogether, as it sometimes intervened in other Third World countries even when the Soviet Union opposed this.[1]

Post-1991 usage of the term "Eastern Bloc" may be more limited in referring to the states forming the Warsaw Pact (1955–1991) and Mongolia (1924–1991), which are no longer communist states.[8][9] Sometimes they are more generally referred to as "the countries of Eastern Europe under communism",[10] excluding Mongolia, but including Yugoslavia and Albania which had both split with the Soviet Union by the 1960s.[11]

Even though Yugoslavia was a socialist country, it was not a member of the Comecon or the Warsaw Pact. Parting with the USSR in 1948, Yugoslavia did not belong to the East, but it also did not belong to the West because of its socialist system and its status as a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement.[12] However, some sources consider Yugoslavia to be a member of the Eastern Bloc.[11][13][14][15][16][17][18][19] Others consider Yugoslavia not to be a member after it broke with Soviet policy in the 1948 Tito–Stalin split.[20][21][12]

List of states[edit]

Comecon (1949–1991) and Warsaw Pact (1955–1991)[edit]

Albania (1946–1991, ceased participating in Comecon and Warsaw Pact activities in 1961, then officially withdrew in 1968 from the WP and in 1987 from Comecon)

Albania (1946–1991, ceased participating in Comecon and Warsaw Pact activities in 1961, then officially withdrew in 1968 from the WP and in 1987 from Comecon) Bulgaria (1946–1990)

Bulgaria (1946–1990) Cuba (from 1959)

Cuba (from 1959) Czechoslovakia (1948–1989)

Czechoslovakia (1948–1989) East Germany (1949–1989; previously as Soviet occupation zone of Germany, 1945–1949)

East Germany (1949–1989; previously as Soviet occupation zone of Germany, 1945–1949) Hungary (1949–1989)

Hungary (1949–1989) Mongolia (1924–1990)

Mongolia (1924–1990) Poland (1947–1989)

Poland (1947–1989) Romania (1947–1989, limited participation in Warsaw Pact activities after 1964)[d]

Romania (1947–1989, limited participation in Warsaw Pact activities after 1964)[d] Soviet Union (1922–1991; previously as the Russian SFSR, 1917–1922)

Soviet Union (1922–1991; previously as the Russian SFSR, 1917–1922) Byelorussian SSR (1919–1991, UN member state from 1945)

Byelorussian SSR (1919–1991, UN member state from 1945) Ukrainian SSR (1919–1991, UN member state from 1945)

Ukrainian SSR (1919–1991, UN member state from 1945)

Vietnam (1976–1989, previously as North Vietnam 1945–1976 and Republic of South Vietnam 1975–1976)

Vietnam (1976–1989, previously as North Vietnam 1945–1976 and Republic of South Vietnam 1975–1976)

Other aligned states[edit]

Afghanistan (1978–1991)

Afghanistan (1978–1991) Angola (1975–1991)

Angola (1975–1991) Benin (1975–1990)

Benin (1975–1990) China (1949–1961)[e]

China (1949–1961)[e] Congo (1969–1991)

Congo (1969–1991) Ethiopia (1987–1991, previously as Provisional Military Government of Socialist Ethiopia, 1974–1987)

Ethiopia (1987–1991, previously as Provisional Military Government of Socialist Ethiopia, 1974–1987) Grenada (1979–1983)

Grenada (1979–1983) Kampuchea (1979–1989)

Kampuchea (1979–1989) North Korea (1948–1990, previously as Soviet Civil Administration in Korea, 1945–1948)

North Korea (1948–1990, previously as Soviet Civil Administration in Korea, 1945–1948) Laos (1975–1989)

Laos (1975–1989) Mozambique (1975–1990)

Mozambique (1975–1990) Somalia (1969–1991; severed alignment 1978)

Somalia (1969–1991; severed alignment 1978) South Yemen (1967–1990)

South Yemen (1967–1990) Syria (1963–1991)[22][6][7]

Syria (1963–1991)[22][6][7] Yugoslavia (1945–1948)[f]

Yugoslavia (1945–1948)[f]

Foundation history[edit]

In 1922, the Russian SFSR, the Ukrainian SSR, the Byelorussian SSR and the Transcaucasian SFSR approved the Treaty of Creation of the USSR and the Declaration of the Creation of the USSR, forming the Soviet Union.[23] Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, who viewed the Soviet Union as a "socialist island", stated that the Soviet Union must see that "the present capitalist encirclement is replaced by a socialist encirclement".[24]

Expansion of the Soviet Union from 1939 to 1940[edit]

In 1939, the USSR entered into the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with Nazi Germany[25] that contained a secret protocol that divided Romania, Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia and Finland into German and Soviet spheres of influence.[25][26] Eastern Poland, Latvia, Estonia, Finland and Bessarabia in northern Romania were recognized as parts of the Soviet sphere of influence.[26] Lithuania was added in a second secret protocol in September 1939.[27]

The Soviet Union had invaded the portions of eastern Poland assigned to it by the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact two weeks after the German invasion of western Poland, followed by co-ordination with German forces in Poland.[28][29] During the Occupation of East Poland by the Soviet Union, the Soviets liquidated the Polish state, and a German-Soviet meeting addressed the future structure of the "Polish region".[30] Soviet authorities immediately started a campaign of sovietization[31][32] of the newly Soviet-annexed areas.[33][34][35] Soviet authorities collectivized agriculture,[36] and nationalized and redistributed private and state-owned Polish property.[37][38][39]

Initial Soviet occupations of the Baltic countries had occurred in mid-June 1940, when Soviet NKVD troops raided border posts in Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia,[40][41] followed by the liquidation of state administrations and replacement by Soviet cadres.[40][42] Elections for parliament and other offices were held with single candidates listed and the official results fabricated, purporting pro-Soviet candidates' approval by 92.8 percent of the voters in Estonia, 97.6 percent in Latvia, and 99.2 percent in Lithuania.[43][44] The fraudulently installed "people's assemblies" immediately declared each of the three corresponding countries to be "Soviet Socialist Republics" and requested their "admission into Stalin's Soviet Union". This formally resulted in the Soviet Union's annexation of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia in August 1940.[43] The international community condemned this annexation of the three Baltic countries and deemed it illegal.[45][46]

In 1939, the Soviet Union unsuccessfully attempted an invasion of Finland,[47] subsequent to which the parties entered into an interim peace treaty granting the Soviet Union the eastern region of Karelia (10% of Finnish territory),[47] and the Karelo-Finnish Soviet Socialist Republic was established by merging the ceded territories with the KASSR. After a June 1940 Soviet Ultimatum demanding Bessarabia, Bukovina, and the Hertsa region from Romania,[48][49] the Soviets entered these areas, Romania caved to Soviet demands and the Soviets occupied the territories.[48][50]

Eastern Front and Allied conferences[edit]

In June 1941, Germany broke the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact by invading the Soviet Union. From the time of this invasion to 1944, the areas annexed by the Soviet Union were part of Germany's Ostland (except for the Moldavian SSR). Thereafter, the Soviet Union began to push German forces westward through a series of battles on the Eastern Front.

In the aftermath of World War II on the Soviet-Finnish border, the parties signed another peace treaty ceding to the Soviet Union in 1944, followed by a Soviet annexation of roughly the same eastern Finnish territories as those of the prior interim peace treaty as part of the Karelo-Finnish Soviet Socialist Republic.[51]

From 1943 to 1945, several conferences regarding Post-War Europe occurred that, in part, addressed the potential Soviet annexation and control of countries in Central Europe. There were various Allied plans for state order in Central Europe for post-war. While Joseph Stalin tried to get as many states under Soviet control as possible, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill preferred a Central European Danube Confederation to counter these countries against Germany and Russia.[52] Churchill's Soviet policy regarding Central Europe differed vastly from that of American President Franklin D. Roosevelt, with the former believing Soviet leader Stalin to be a "devil"-like tyrant leading a vile system.[53]

When warned of potential domination by a Stalin dictatorship over part of Europe, Roosevelt responded with a statement summarizing his rationale for relations with Stalin: "I just have a hunch that Stalin is not that kind of a man. ... I think that if I give him everything I possibly can and ask for nothing from him in return, noblesse oblige, he won't try to annex anything and will work with me for a world of democracy and peace".[54] While meeting with Stalin and Roosevelt in Tehran in 1943, Churchill stated that Britain was vitally interested in restoring Poland as an independent country.[55] Britain did not press the matter for fear that it would become a source of inter-allied friction.[55]

In February 1945, at the conference at Yalta, Stalin demanded a Soviet sphere of political influence in Central Europe.[56] Stalin eventually was convinced by Churchill and Roosevelt not to dismember Germany.[56] Stalin stated that the Soviet Union would keep the territory of eastern Poland they had already taken via invasion in 1939, and wanted a pro-Soviet Polish government in power in what would remain of Poland.[56] After resistance by Churchill and Roosevelt, Stalin promised a re-organization of the current pro-Soviet government on a broader democratic basis in Poland.[56] He stated that the new government's primary task would be to prepare elections.[57]

The parties at Yalta further agreed that the countries of liberated Europe and former Axis satellites would be allowed to "create democratic institutions of their own choice", pursuant to "the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live".[58] The parties also agreed to help those countries form interim governments "pledged to the earliest possible establishment through free elections" and "facilitate where necessary the holding of such elections".[58]

At the beginning of the July–August 1945 Potsdam Conference after Germany's unconditional surrender, Stalin repeated previous promises to Churchill that he would refrain from a "sovietization" of Central Europe.[59] In addition to reparations, Stalin pushed for "war booty", which would permit the Soviet Union to directly seize property from conquered nations without quantitative or qualitative limitation.[60] A clause was added permitting this to occur with some limitations.[60]

Concealed transformation dynamics[edit]

At first, the Soviets concealed their role in other Eastern Bloc politics, with the transformation appearing as a modification of Western "bourgeois democracy".[61] As a young communist was told in East Germany, "it's got to look democratic, but we must have everything in our control".[62] Stalin felt that socioeconomic transformation was indispensable to establish Soviet control, reflecting the Marxist–Leninist view that material bases, the distribution of the means of production, shaped social and political relations.[63] The Soviet Union also co-opted the Eastern European countries into its sphere of influence by making reference to some cultural commonalities.[64]

Moscow-trained cadres were put into crucial power positions to fulfill orders regarding sociopolitical transformation.[63] Elimination of the bourgeoisie's social and financial power by expropriation of landed and industrial property was accorded absolute priority.[61] These measures were publicly billed as "reforms" rather than socioeconomic transformations.[61] Except for initially in Czechoslovakia, activities by political parties had to adhere to "Bloc politics", with parties eventually having to accept membership in an "antifascist bloc" obliging them to act only by mutual "consensus".[65] The bloc system permitted the Soviet Union to exercise domestic control indirectly.[66]

Crucial departments such as those responsible for personnel, general police, secret police and youth were strictly Communist run.[66] Moscow cadres distinguished "progressive forces" from "reactionary elements" and rendered both powerless. Such procedures were repeated until Communists had gained unlimited power and only politicians who were unconditionally supportive of Soviet policy remained.[67]

Early events prompting stricter control[edit]

Marshall Plan rejection[edit]

In June 1947, after the Soviets had refused to negotiate a potential lightening of restrictions on German development, the United States announced the Marshall Plan, a comprehensive program of American assistance to all European countries wanting to participate, including the Soviet Union and those of Eastern Europe.[68] The Soviets rejected the Plan and took a hard-line position against the United States and non-communist European nations.[69] However, Czechoslovakia was eager to accept the US aid; the Polish government had a similar attitude, and this was of great concern to the Soviets.[70]

In one of the clearest signs of Soviet control over the region up to that point, the Czechoslovakian foreign minister, Jan Masaryk, was summoned to Moscow and berated by Stalin for considering joining the Marshall Plan. Polish Prime minister Józef Cyrankiewicz was rewarded for the Polish rejection of the Plan with a huge 5-year trade agreement, including $450 million in credit, 200,000 tons of grain, heavy machinery and factories.[71]

In July 1947, Stalin ordered these countries to pull out of the Paris Conference on the European Recovery Programme, which has been described as "the moment of truth" in the post-World War II division of Europe.[72] Thereafter, Stalin sought stronger control over other Eastern Bloc countries, abandoning the prior appearance of democratic institutions.[73] When it appeared that, in spite of heavy pressure, non-communist parties might receive in excess of 40% of the vote in the August 1947 Hungarian elections, repressions were instituted to liquidate any independent political forces.[73]

In that same month, annihilation of the opposition in Bulgaria began on the basis of continuing instructions by Soviet cadres.[73][74] At a late September 1947 meeting of all communist parties in Szklarska Poręba,[75] Eastern Bloc communist parties were blamed for permitting even minor influence by non-communists in their respective countries during the run up to the Marshall Plan.[73]

Berlin blockade and airlift[edit]

In the former German capital Berlin, surrounded by Soviet-occupied Germany, Stalin instituted the Berlin Blockade on 24 June 1948, preventing food, materials and supplies from arriving in West Berlin.[76] The blockade was caused, in part, by early local elections of October 1946 in which the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) was rejected in favor of the Social Democratic Party, which had gained two and a half times more votes than the SED.[77] The United States, Britain, France, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and several other countries began a massive "Berlin airlift", supplying West Berlin with food and other supplies.[78]

The Soviets mounted a public relations campaign against the western policy change and communists attempted to disrupt the elections of 1948 preceding large losses therein,[79] while 300,000 Berliners demonstrated and urged the international airlift to continue.[80] In May 1949, Stalin lifted the blockade, permitting the resumption of Western shipments to Berlin.[81][82]

Tito–Stalin split[edit]

After disagreements between Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito and the Soviet Union regarding Greece and Albania, a Tito–Stalin split occurred, followed by Yugoslavia being expelled from the Cominform in June 1948 and a brief failed Soviet putsch in Belgrade.[83] The split created two separate communist forces in Europe.[83] A vehement campaign against Titoism was immediately started in the Eastern Bloc, describing agents of both the West and Tito in all places as engaging in subversive activity.[83]

Stalin ordered the conversion of the Cominform into an instrument to monitor and control the internal affairs of other Eastern Bloc parties.[83] He also briefly considered converting the Cominform into an instrument for sentencing high-ranking deviators, but dropped the idea as impractical.[83] Instead, a move to weaken communist party leaders through conflict was started.[83] Soviet cadres in communist party and state positions in the Bloc were instructed to foster intra-leadership conflict and to transmit information against each other.[83] This accompanied a continuous stream of accusations of "nationalistic deviations", "insufficient appreciation of the USSR's role", links with Tito and "espionage for Yugoslavia".[84] This resulted in the persecution of many major party cadres, including those in East Germany.[84]

The first country to experience this approach was Albania, where leader Enver Hoxha immediately changed course from favoring Yugoslavia to opposing it.[84] In Poland, leader Władysław Gomułka, who had previously made pro-Yugoslav statements, was deposed as party secretary-general in early September 1948 and subsequently jailed.[84] In Bulgaria, when it appeared that Traicho Kostov, who was not a Moscow cadre, was next in line for leadership, in June 1949, Stalin ordered Kostov's arrest, followed soon thereafter by a death sentence and execution.[84] A number of other high ranking Bulgarian officials were also jailed.[84] Stalin and Hungarian leader Mátyás Rákosi met in Moscow to orchestrate a show trial of Rákosi opponent László Rajk, who was thereafter executed.[85] The preservation of the Soviet bloc relied on maintaining a sense of ideological unity that would entrench Moscow's influence in Eastern Europe as well as the power of the local Communist elites.[86]

The port city of Trieste was a particular focus after the Second World War. Until the break between Tito and Stalin, the Western powers and the Eastern bloc faced each other uncompromisingly. The neutral buffer state Free Territory of Trieste, founded in 1947 with the United Nations, was split up and dissolved in 1954 and 1975, also because of the détente between the West and Tito.[87][88]

Politics[edit]

Despite the initial institutional design of communism implemented by Joseph Stalin in the Eastern Bloc, subsequent development varied across countries.[89] In satellite states, after peace treaties were initially concluded, opposition was essentially liquidated, fundamental steps towards socialism were enforced, and Kremlin leaders sought to strengthen control therein.[90] Right from the beginning, Stalin directed systems that rejected Western institutional characteristics of market economies, capitalist parliamentary democracy (dubbed "bourgeois democracy" in Soviet parlance) and the rule of law subduing discretional intervention by the state.[91] The resulting states aspired to total control of a political center backed by an extensive and active repressive apparatus, and a central role of Marxist–Leninist ideology.[91]

However, the vestiges of democratic institutions were never entirely destroyed, resulting in the façade of Western style institutions such as parliaments, which effectively just rubber-stamped decisions made by rulers, and constitutions, to which adherence by authorities was limited or non-existent.[91] Parliaments were still elected, but their meetings occurred only a few days per year, only to legitimize politburo decisions, and so little attention was paid to them that some of those serving were actually dead, and officials would openly state that they would seat members who had lost elections.[92]

The first or General Secretary of the central committee in each communist party was the most powerful figure in each regime.[93] The party over which the politburo held sway was not a mass party but, conforming with Leninist tradition, a smaller selective party of between three and fourteen percent of the country's population who had accepted total obedience.[94] Those who secured membership in this selective group received considerable rewards, such as access to special lower priced shops with a greater selection of high-quality domestic and/or foreign goods (confections, alcohol, cigars, cameras, televisions, and the like), special schools, holiday facilities, homes, high-quality domestic and/or foreign-made furniture, works of art, pensions, permission to travel abroad, and official cars with distinct license plates so that police and others could identify these members from a distance.[94]

Political and civil restrictions[edit]

In addition to emigration restrictions, civil society, defined as a domain of political action outside the party's state control, was not allowed to firmly take root, with the possible exception of Poland in the 1980s.[95] While the institutional design of the communist systems were based on the rejection of rule of law, the legal infrastructure was not immune to change reflecting decaying ideology and the substitution of autonomous law.[95] Initially, communist parties were small in all countries except Czechoslovakia, such that there existed an acute shortage of politically "trustworthy" persons for administration, police, and other professions.[96] Thus, "politically unreliable" non-communists initially had to fill such roles.[96] Those not obedient to communist authorities were ousted, while Moscow cadres started a large-scale party programs to train personnel who would meet political requirements.[96] Former members of the middle-class were officially discriminated against, though the state's need for their skills and certain opportunities to re-invent themselves as good Communist citizens did allow many to nonetheless achieve success.[97]

Communist regimes in the Eastern Bloc viewed marginal groups of opposition intellectuals as a potential threat because of the bases underlying Communist power therein.[98] The suppression of dissidence and opposition was considered a central prerequisite to retain power, though the enormous expense at which the population in certain countries were kept under secret surveillance may not have been rational.[98] Following a totalitarian initial phase, a post-totalitarian period followed the death of Stalin in which the primary method of Communist rule shifted from mass terror to selective repression, along with ideological and sociopolitical strategies of legitimation and the securing of loyalty.[99] Juries were replaced by a tribunal of professional judges and two lay assessors that were dependable party actors.[100]

The police deterred and contained opposition to party directives.[100] The political police served as the core of the system, with their names becoming synonymous with raw power and the threat of violent retribution should an individual become active against the State.[100] Several state police and secret police organizations enforced communist party rule, including the following:

- East Germany – Stasi, Volkspolizei and KdA

- Soviet Union – KGB

- Czechoslovakia – STB and LM

- Bulgaria – KDS

- Albania – Sigurimi

- Hungary – ÁVH and Munkásőrség

- Romania – Securitate and GP

- Poland – Urząd Bezpieczeństwa, Służba Bezpieczeństwa and ZOMO

Media and information restrictions[edit]

The press in the communist period was an organ of the state, completely reliant on and subservient to the communist party.[101] Before the late 1980s, Eastern Bloc radio and television organizations were state-owned, while print media was usually owned by political organizations, mostly by the local communist party.[102] Youth newspapers and magazines were owned by youth organizations affiliated with communist parties.[102]

The control of the media was exercised directly by the communist party itself, and by state censorship, which was also controlled by the party.[102] Media served as an important form of control over information and society.[103] The dissemination and portrayal of knowledge were considered by authorities to be vital to communism's survival by stifling alternative concepts and critiques.[103] Several state Communist Party newspapers were published, including:

- Central newspapers of the Soviet Union

- Trybuna Ludu (Poland)

- Czerwony Sztandar (Vilnius) (1953–1990), Polish-language newspaper in Lithuanian SSR

- Népszabadság (until 1956 Szabad Nép, Hungary)

- Neues Deutschland (East Germany)

- Rabotnichesko Delo (Bulgaria)

- Rudé právo (Czechoslovakia)

- Rahva Hääl (annexed former Estonia)

- Pravda (Slovakia)

- Kauno diena (annexed former Lithuania)

- Scînteia (Romania)

- Zvyazda (Belarus).

The Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union (TASS) served as the central agency for collection and distribution of internal and international news for all Soviet newspapers, radio and television stations. It was frequently infiltrated by Soviet intelligence and security agencies, such as the NKVD and GRU. TASS had affiliates in 14 Soviet republics, including the Lithuanian SSR, Latvian SSR, Estonian SSR, Moldavian SSR. Ukrainian SSR and Byelorussian SSR.

Western countries invested heavily in powerful transmitters which enabled services such as the BBC, VOA and Radio Free Europe (RFE) to be heard in the Eastern Bloc, despite attempts by authorities to jam the airways.

Religion[edit]

Under the state atheism of many Eastern Bloc nations, religion was actively suppressed.[104] Since some of these states tied their ethnic heritage to their national churches, both the peoples and their churches were targeted by the Soviets.[105][106]

Organizations[edit]

In 1949, the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, and Romania founded the Comecon in accordance with Stalin's desire to enforce Soviet domination of the lesser states of Central Europe and to mollify some states that had expressed interest in the Marshall Plan,[107][108] and which were now, increasingly, cut off from their traditional markets and suppliers in Western Europe.[72] The Comecon's role became ambiguous because Stalin preferred more direct links with other party chiefs than the Comecon's indirect sophistication; it played no significant role in the 1950s in economic planning.[109] Initially, the Comecon served as cover for the Soviet taking of materials and equipment from the rest of the Eastern Bloc, but the balance changed when the Soviets became net subsidizers of the rest of the Bloc by the 1970s via an exchange of low cost raw materials in return for shoddily manufactured finished goods.[110]

In 1955, the Warsaw Pact was formed partly in response to NATO's inclusion of West Germany and partly because the Soviets needed an excuse to retain Red Army units in Hungary.[108] For 35 years, the Pact perpetuated the Stalinist concept of Soviet national security based on imperial expansion and control over satellite regimes in Eastern Europe.[111] This Soviet formalization of their security relationships in the Eastern Bloc reflected Moscow's basic security policy principle that continued presence in East Central Europe was a foundation of its defense against the West.[111] Through its institutional structures, the Pact also compensated in part for the absence of Joseph Stalin's personal leadership since his death in 1953.[111] The Pact consolidated the other Bloc members' armies in which Soviet officers and security agents served under a unified Soviet command structure.[112]

Beginning in 1964, Romania took a more independent course.[113] While it did not repudiate either Comecon or the Warsaw Pact, it ceased to play a significant role in either.[113] Nicolae Ceaușescu's assumption of leadership one year later pushed Romania even further in the direction of separateness.[113] Albania, which had become increasingly isolated under Stalinist leader Enver Hoxha following de-Stalinization, undergoing an Albanian–Soviet split in 1961, withdrew from the Warsaw Pact in 1968[114] following the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia.[115]

Emigration restrictions and defectors[edit]

In 1917, Russia restricted emigration by instituting passport controls and forbidding the exit of belligerent nationals.[116] In 1922, after the Treaty on the Creation of the USSR, both the Ukrainian SSR and the Russian SFSR issued general rules for travel that foreclosed virtually all departures, making legal emigration impossible.[117] Border controls thereafter strengthened such that, by 1928, even illegal departure was effectively impossible.[117] This later included internal passport controls, which when combined with individual city Propiska ("place of residence") permits, and internal freedom of movement restrictions often called the 101st kilometre, greatly restricted mobility within even small areas of the Soviet Union.[118]

After the creation of the Eastern Bloc, emigration out of the newly occupied countries, except under limited circumstances, was effectively halted in the early 1950s, with the Soviet approach to controlling national movement emulated by most of the rest of the Eastern Bloc.[119] However, in East Germany, taking advantage of the Inner German border between occupied zones, hundreds of thousands fled to West Germany, with figures totaling 197,000 in 1950, 165,000 in 1951, 182,000 in 1952 and 331,000 in 1953.[120][121] One reason for the sharp 1953 increase was fear of potential further Sovietization with the increasingly paranoid[dubious – discuss] actions of Joseph Stalin in late 1952 and early 1953.[122] 226,000 had fled in just the first six months of 1953.[123]

With the closing of the Inner German border officially in 1952,[124] the Berlin city sector borders remained considerably more accessible than the rest of the border because of their administration by all four occupying powers.[125] Accordingly, it effectively comprised a "loophole" through which Eastern Bloc citizens could still move west.[124] The 3.5 million East Germans that had left by 1961, called Republikflucht, totaled approximately 20% of the entire East German population.[126] In August 1961, East Germany erected a barbed-wire barrier that would eventually be expanded through construction into the Berlin Wall, effectively closing the loophole.[127]

With virtually non-existent conventional emigration, more than 75% of those emigrating from Eastern Bloc countries between 1950 and 1990 did so under bilateral agreements for "ethnic migration".[128] About 10% were refugee migrants under the Geneva Convention of 1951.[128] Most Soviets allowed to leave during this time period were ethnic Jews permitted to emigrate to Israel after a series of embarrassing defections in 1970 caused the Soviets to open very limited ethnic emigrations.[129] The fall of the Iron Curtain was accompanied by a massive rise in European East-West migration.[128] Famous Eastern Bloc defectors included Joseph Stalin's daughter Svetlana Alliluyeva, who denounced Stalin after her 1967 defection.[130]

Population[edit]

Eastern Bloc countries such as the Soviet Union had high rates of population growth. In 1917, the population of Russia in its present borders was 91 million. Despite the destruction in the Russian Civil War, the population grew to 92.7 million in 1926. In 1939, the population increased by 17 percent to 108 million. Despite more than 20 million deaths suffered throughout World War II, Russia's population grew to 117.2 million in 1959. The Soviet census of 1989 showed Russia's population at 147 million people.[131]

The Soviet economical and political system produced further consequences such as, for example, in Baltic states, where the population was approximately half of what it should have been compared with similar countries such as Denmark, Finland and Norway over the years 1939–1990. Poor housing was one factor leading to severely declining birth rates throughout the Eastern Bloc.[132] However, birth rates were still higher than in Western European countries. A reliance upon abortion, in part because periodic shortages of birth control pills and intrauterine devices made these systems unreliable,[133] also depressed the birth rate and forced a shift to pro-natalist policies by the late 1960s, including severe checks on abortion and propagandist exhortations like the 'heroine mother' distinction bestowed on those Romanian women who bore ten or more children.[134]

In October 1966, artificial birth control was proscribed in Romania and regular pregnancy tests were mandated for women of child-bearing age, with severe penalties for anyone who was found to have terminated a pregnancy.[135] Despite such restrictions, birth rates continued to lag, in part because of unskilled induced abortions.[134] The populations of the Eastern Bloc countries were as follows:[136][137]

| Country | Area (000s) | 1950 (mil) | 1970 (mil) | 1980 (mil) | 1985 (mil) | Annual growth (1950–1985) | Density (1980) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albania | 28.7 square kilometres (11.1 sq mi) | 1.22 | 2.16 | 2.59 | 2.96 | +4.07% | 90.2/km2 |

| Bulgaria | 110.9 square kilometres (42.8 sq mi) | 7.27 | 8.49 | 8.88 | 8.97 | +0.67% | 80.1/km2 |

| Czechoslovakia | 127.9 square kilometres (49.4 sq mi) | 13.09 | 14.47 | 15.28 | 15.50 | +0.53% | 119.5/km2 |

| Hungary | 93.0 square kilometres (35.9 sq mi) | 9.20 | 10.30 | 10.71 | 10.60 | +0.43% | 115.2/km2 |

| East Germany | 108.3 square kilometres (41.8 sq mi) | 17.94 | 17.26 | 16.74 | 16.69 | −0.20% | 154.6/km2 |

| Poland | 312.7 square kilometres (120.7 sq mi) | 24.82 | 30.69 | 35.73 | 37.23 | +1.43% | 114.3/km2 |

| Romania | 237.5 square kilometres (91.7 sq mi) | 16.31 | 20.35 | 22.20 | 22.73 | +1.12% | 93.5/km2 |

| Soviet Union | 22,300 square kilometres (8,600 sq mi) | 182.32 | 241.72 | 265.00 | 272.00 | +1.41% | 11.9/km2 |

| Yugoslavia | 255.8 square kilometres (98.8 sq mi) | 16.34 | 20.4 | 22.36 | 23.1 | +1.15% | 92.6/km2 |

Social structure[edit]

Eastern Bloc societies operated under anti-meritocratic principles with strong egalitarian elements. For example, Czechoslovakia favoured less qualified individuals, as well as providing privileges for the nomenklatura and those with the right class or political background. Eastern Bloc societies were dominated by the ruling communist party, dubbed "partyocracy" by Pavel Machonin.[138] Former members of the middle-class were officially discriminated against, though the need for their skills allowed them to re-invent themselves as good communist citizens.[97][139]

Housing[edit]

A housing shortage existed throughout the Eastern Bloc. In Europe it was primarily due to the devastation during World War II. Construction efforts suffered after a severe cutback in state resources available for housing starting in 1975.[140] Cities became filled with large system-built apartment blocks[141] Housing construction policy suffered from considerable organisational problems.[142] Moreover, completed houses possessed noticeably poor quality finishes.[142]

Housing quality[edit]

The near-total emphasis on large apartment blocks was a common feature of Eastern Bloc cities in the 1970s and 1980s.[143] East German authorities viewed large cost advantages in the construction of Plattenbau apartment blocks such that the building of such architecture on the edge of large cities continued until the dissolution of the Eastern Bloc.[143] Buildings such as the Paneláks of Czechoslovakia and Panelház of Hungary. Wishing to reinforce the role of the state in the 1970s and 1980s, Nicolae Ceaușescu enacted the systematisation programme, which consisted of the demolition and reconstruction of existing hamlets, villages, towns, and cities, in whole or in part, in order to make place to standardised apartment blocks across the country (blocuri).[143] Under this ideology, Ceaușescu built Centrul Civic of Bucharest in the 1980s, which contains the Palace of the Parliament, in the place of the former historic center.

Even by the late 1980s, sanitary conditions in most Eastern Bloc countries were generally far from adequate.[144] For all countries for which data existed, 60% of dwellings had a density of greater than one person per room between 1966 and 1975.[144] The average in western countries for which data was available approximated 0.5 persons per room.[144] Problems were aggravated by poor quality finishes on new dwellings often causing occupants to undergo a certain amount of finishing work and additional repairs.[144]

| Country | Adequate sanitation % (year) | Piped water % | Central heating % | Inside toilet % | More than 1 person/room % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albania | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Bulgaria | n/a | 66.1% | 7.5% | 28.0% | 60.2% |

| Czechoslovakia | 60.5% (1983) | 75.3% | 30.9% | 52.4% | 67.9% |

| East Germany | 70.0% (1985) | 82.1% | 72.2% | 43.4% | n/a |

| Hungary | 60.0% (1984) | 64% (1980) | n/a | 52.5% (1980) | 64.4% |

| Poland | 50.0% (1980) | 47.3% | 22.2% | 33.4% | 83.0% |

| Romania | 50.0% (1980) | 12.3% (1966) | n/a | n/a | 81.5% |

| Soviet Union | 50.0% (1980) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Yugoslavia | 69.8% (1981) | 93.2% | 84.2% | 89.7% | 83.1% |

| Year | Houses/flats total | With piped water | With sewage disposal | With inside toilet | With piped gas |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1949 | 2,466,514 | 420,644 (17.1%) | – | 306,998 (12.5%) | 174,186 (7.1%) |

| 1960 | 2,757,625 | 620,600 (22.5%) | – | 440,737 (16%) | 373,124 (13.5%) |

| 1970 | 3,118,096 | 1,370,609 (44%) | 1,167,055 (37.4%) | 838,626 (26.9%) | 1,571,691 (50.4%) |

| 1980 | 3,542,418 | 2,268,014 (64%) | 2,367,274 (66.8%) | 1,859,677 (52.5%) | 2,682,143 (75.7%) |

| 1990 | 3,853,288 | 3,209,930 (83.3%) | 3,228,257 (83.8%) | 2,853,834 (74%) | 3,274,514 (85%) |

The worsening shortages of the 1970s and 1980s occurred during an increase in the quantity of dwelling stock relative to population from 1970 to 1986.[147] Even for new dwellings, average dwelling size was only 61.3 square metres (660 sq ft) in the Eastern Bloc compared with 113.5 square metres (1,222 sq ft) in ten western countries for which comparable data was available.[147] Space standards varied considerably, with the average new dwelling in the Soviet Union in 1986 being only 68% the size of its equivalent in Hungary.[147] Apart from exceptional cases, such as East Germany in 1980–1986 and Bulgaria in 1970–1980, space standards in newly built dwellings rose before the dissolution of the Eastern Bloc.[147] Housing size varied considerably across time, especially after the oil crisis in the Eastern Bloc; for instance, 1990-era West German homes had an average floor space of 83 square metres (890 sq ft), compared to an average dwelling size in the GDR of 67 square metres (720 sq ft) in 1967.[148][149]

| Floor space/dwelling | People/dwelling | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | 1970 | 1980 | 1986 | 1970 | 1986 | |

| Western Bloc | 113.5 square metres (1,222 sq ft) | n/a | n/a | |||

| Albania | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| Bulgaria | 63.7 square metres (686 sq ft) | 59.0 square metres (635 sq ft) | 66.9 square metres (720 sq ft) | 3.8 | 2.8 | |

| Czechoslovakia | 67.2 square metres (723 sq ft) | 73.8 square metres (794 sq ft) | 81.8 square metres (880 sq ft) | 3.4 | 2.7 | |

| East Germany | 55.0 square metres (592 sq ft) | 62.7 square metres (675 sq ft) | 61.2 square metres (659 sq ft) | 2.9 | 2.4 | |

| Hungary | 61.5 square metres (662 sq ft) | 67.0 square metres (721 sq ft) | 83.0 square metres (893 sq ft) | 3.4 | 2.7 | |

| Poland | 54.3 square metres (584 sq ft) | 64.0 square metres (689 sq ft) | 71.0 square metres (764 sq ft) | 4.2 | 3.5 | |

| Romania | 44.9 square metres (483 sq ft) | 57.0 square metres (614 sq ft) | 57.5 square metres (619 sq ft) | 3.6 | 2.8 | |

| Soviet Union | 46.8 square metres (504 sq ft) | 52.3 square metres (563 sq ft) | 56.8 square metres (611 sq ft) | 4.1 | 3.2 | |

| Yugoslavia | 59.2 square metres (637 sq ft) | 70.9 square metres (763 sq ft) | 72.5 square metres (780 sq ft) | n/a | 3.4 | |

Poor housing was one of the four major factors (others being poor living conditions, increased female employment and abortion as an encouraged means of birth control) which led to declining birth rates throughout the Eastern Bloc.[132]

Economies[edit]

Because of the lack of market signals, Eastern Bloc economies experienced mis-development by central planners.[151][152]

The Eastern Bloc also depended upon the Soviet Union for significant amounts of materials.[151][153]

Technological backwardness resulted in dependency on imports from Western countries and this, in turn, in demand for Western currency. Eastern Bloc countries were heavily borrowing from Club de Paris (central banks) and London Club (private banks) and most of them by the early 1980s were forced to notify the creditors of their insolvency. This information was however kept secret from the citizens and propaganda promoted the view that the countries were on the best way to socialism.[154][155][156]

Social conditions[edit]

As a consequence of World War II and the German occupations in Eastern Europe, much of the region had been subjected to enormous destruction of industry, infrastructure and loss of civilian life. In Poland alone the policy of plunder and exploitation inflicted enormous material losses to Polish industry (62% of which was destroyed),[157] agriculture, infrastructure and cultural landmarks, the cost of which has been estimated as approximately €525 billion or $640 billion in 2004 exchange values.[158]

Throughout the Eastern Bloc, both in the USSR and the rest of the Bloc, Russia was given prominence and referred to as the naiboleye vydayushchayasya natsiya (the most prominent nation) and the rukovodyashchiy narod (the leading people).[159] The Soviets promoted the reverence of Russian actions and characteristics, and the construction of Soviet structural hierarchies in the other countries of the Eastern Bloc.[159]

The defining characteristic of Stalinist totalitarianism was the unique symbiosis of the state with society and the economy, resulting in politics and economics losing their distinctive features as autonomous and distinguishable spheres.[89] Initially, Stalin directed systems that rejected Western institutional characteristics of market economies, democratic governance (dubbed "bourgeois democracy" in Soviet parlance) and the rule of law subduing discretional intervention by the state.[91]

The Soviets mandated expropriation and etatisation of private property.[160] The Soviet-style "replica regimes" that arose in the Bloc not only reproduced the Soviet command economy, but also adopted the brutal methods employed by Joseph Stalin and Soviet-style secret polices to suppress real and potential opposition.[160]

Stalinist regimes in the Eastern Bloc saw even marginal groups of opposition intellectuals as a potential threat because of the bases underlying Stalinist power therein.[98] The suppression of dissent and opposition was a central prerequisite for the security of Stalinist power within the Eastern Bloc, though the degree of opposition and dissident suppression varied by country and time throughout the Eastern Bloc.[98]

In addition, media in the Eastern Bloc were organs of the state, completely reliant on and subservient to the government of the USSR with radio and television organisations being state-owned, while print media was usually owned by political organisations, mostly by the local party.[101] While over 15 million Eastern Bloc residents migrated westward from 1945 to 1949,[161] emigration was effectively halted in the early 1950s, with the Soviet approach to controlling national movement emulated by most of the rest of the Eastern Bloc.[119]

Initial changes[edit]

Transformations billed as reforms[edit]

In the USSR, because of strict Soviet secrecy under Joseph Stalin, for many years after World War II, even the best informed foreigners did not effectively know about the operations of the Soviet economy.[162] Stalin had sealed off outside access to the Soviet Union since 1935 (and until his death), effectively permitting no foreign travel inside the Soviet Union such that outsiders did not know of the political processes that had taken place therein.[163] During this period, and even for 25 years after Stalin's death, the few diplomats and foreign correspondents permitted inside the Soviet Union were usually restricted to within a few kilometres of Moscow, their phones were tapped, their residences were restricted to foreigner-only locations and they were constantly followed by Soviet authorities.[163]

The Soviets also modeled economies in the rest of Eastern Bloc outside the Soviet Union along Soviet command economy lines.[164] Before World War II, the Soviet Union used draconian procedures to ensure compliance with directives to invest all assets in state planned manners, including the collectivisation of agriculture and utilising a sizeable labor army collected in the gulag system.[165] This system was largely imposed on other Eastern Bloc countries after World War II.[165] While propaganda of proletarian improvements accompanied systemic changes, terror and intimidation of the consequent ruthless Stalinism obfuscated feelings of any purported benefits.[110]

Stalin felt that socioeconomic transformation was indispensable to establish Soviet control, reflecting the Marxist–Leninist view that material bases, the distribution of the means of production, shaped social and political relations.[63] Moscow trained cadres were put into crucial power positions to fulfill orders regarding sociopolitical transformation.[63] Elimination of the bourgeoisie's social and financial power by expropriation of landed and industrial property was accorded absolute priority.[61]

These measures were publicly billed as reforms rather than socioeconomic transformations.[61] Throughout the Eastern Bloc, except for Czechoslovakia, "societal organisations" such as trade unions and associations representing various social, professional and other groups, were erected with only one organisation for each category, with competition excluded.[61] Those organisations were managed by Stalinist cadres, though during the initial period, they allowed for some diversity.[65]

Asset relocation[edit]

At the same time, at the war's end, the Soviet Union adopted a "plunder policy" of physically transporting and relocating east European industrial assets to the Soviet Union.[166] Eastern Bloc states were required to provide coal, industrial equipment, technology, rolling stock and other resources to reconstruct the Soviet Union.[167] Between 1945 and 1953, the Soviets received a net transfer of resources from the rest of the Eastern Bloc under this policy of roughly $14 billion, an amount comparable to the net transfer from the United States to western Europe in the Marshall Plan.[167][168] "Reparations" included the dismantling of railways in Poland and Romanian reparations to the Soviets between 1944 and 1948 valued at $1.8 billion concurrent with the domination of SovRoms.[165]

In addition, the Soviets re-organised enterprises as joint-stock companies in which the Soviets possessed the controlling interest.[168][169] Using that control vehicle, several enterprises were required to sell products at below world prices to the Soviets, such as uranium mines in Czechoslovakia and East Germany, coal mines in Poland, and oil wells in Romania.[170]

Trade and Comecon[edit]

The trading pattern of the Eastern Bloc countries was severely modified.[171] Before World War II, no greater than 1%–2% of those countries' trade was with the Soviet Union.[171] By 1953, the share of such trade had jumped to 37%.[171] In 1947, Joseph Stalin had also denounced the Marshall Plan and forbade all Eastern Bloc countries from participating in it.[172]

Soviet dominance further tied other Eastern Bloc economies[171] to Moscow via the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA) or Comecon, which determined countries' investment allocations and the products that would be traded within Eastern Bloc.[173] Although Comecon was initiated in 1949, its role became ambiguous because Stalin preferred more direct links with other party chiefs than the indirect sophistication of the council. It played no significant role in the 1950s in economic planning.[109]

Initially, Comecon served as cover for the Soviet taking of materials and equipment from the rest of the Eastern Bloc, but the balance changed when the Soviets became net subsidisers of the rest of the Bloc by the 1970s via an exchange of low cost raw materials in return for shoddily manufactured finished goods.[110] While resources such as oil, timber and uranium initially made gaining access to other Eastern Bloc economies attractive, the Soviets soon had to export Soviet raw materials to those countries to maintain cohesion therein.[165] Following resistance to Comecon plans to extract Romania's mineral resources and heavily utilise its agricultural production, Romania began to take a more independent stance in 1964.[113] While it did not repudiate Comecon, it took no significant role in its operation, especially after the rise to power of Nicolae Ceauşescu.[113]

Heavy industry emphasis[edit]

According to the official propaganda in the Soviet Union, there was unprecedented affordability of housing, health care, and education.[174][unreliable source?] Apartment rent on average amounted to only 1 percent of the family budget, a figure which reached 4 percent when municipal services are factored in. Tram tickets were 20 kopecks, and a loaf of bread was 15 kopecks. The average monthly salary of an engineer was 140–160 rubles.[175]

The Soviet Union made major progress in developing the country's consumer goods sector. In 1970, the USSR produced 679 million pairs of leather footwear, compared to 534 million for the United States. Czechoslovakia, which had the world's highest per-capita production of shoes, exported a significant portion of its shoe production to other countries.[176]

The rising standard of living under socialism led to a steady decrease in the workday and an increase in leisure. In 1974, the average workweek for Soviet industrial workers was 40 hours. Paid vacations in 1968 reached a minimum of 15 workdays. In the mid-1970s the number of free days per year-days off, holidays and vacations was 128–130, almost double the figure from the previous ten years.[177]

Because of the lack of market signals in such economies, they experienced mis-development by central planners resulting in those countries following a path of extensive (large mobilisation of inefficiently used capital, labor, energy and raw material inputs) rather than intensive (efficient resource use) development to attempt to achieve quick growth.[151][178] The Eastern Bloc countries were required to follow the Soviet model overemphasising heavy industry at the expense of light industry and other sectors.[179]

Since that model involved the prodigal exploitation of natural and other resources, it has been described as a kind of "slash and burn" modality.[178] While the Soviet system strove for a dictatorship of the proletariat, there was little existing proletariat in many eastern European countries, such that to create one, heavy industry needed to be built.[179] Each system shared the distinctive themes of state-oriented economies, including poorly defined property rights, a lack of market clearing prices and overblown or distorted productive capacities in relation to analogous market economies.[89]

Major errors and waste occurred in the resource allocation and distribution systems.[141] Because of the party-run monolithic state organs, these systems provided no effective mechanisms or incentives to control costs, profligacy, inefficiency and waste.[141] Heavy industry was given priority because of its importance for the military-industrial establishment and for the engineering sector.[180]

Factories were sometimes inefficiently located, incurring high transport costs, while poor plant-organisation sometimes resulted in production hold ups and knock-on effects in other industries dependent on monopoly suppliers of intermediates.[181] For example, each country, including Albania, built steel mills regardless of whether they lacked the requisite resource of energy and mineral ores.[179] A massive metallurgical plant was built in Bulgaria despite the fact that its ores had to be imported from the Soviet Union and transported 320 kilometres (200 mi) from the port at Burgas.[179] A Warsaw tractor factory in 1980 had a 52-page list of unused rusting, then useless, equipment.[179]

This emphasis on heavy industry diverted investment from the more practical production of chemicals and plastics.[173] In addition, the plans' emphasis on quantity rather than quality made Eastern Bloc products less competitive in the world market.[173] High costs passed through the product chain boosted the 'value' of production on which wage increases were based, but made exports less competitive.[181] Planners rarely closed old factories even when new capacities opened elsewhere.[181] For example, the Polish steel industry retained a plant in Upper Silesia despite the opening of modern integrated units on the periphery while the last old Siemens-Martin process furnace installed in the 19th century was not closed down immediately.[181]

Producer goods were favoured over consumer goods, causing consumer goods to be lacking in quantity and quality in the shortage economies that resulted.[152][178]

By the mid-1970s, budget deficits rose considerably and domestic prices widely diverged from the world prices, while production prices averaged 2% higher than consumer prices.[182] Many premium goods could be bought either in a black market or only in special stores using foreign currency generally inaccessible to most Eastern Bloc citizens, such as Intershop in East Germany,[183] Beryozka in the Soviet Union,[184] Pewex in Poland,[185][186] Tuzex in Czechoslovakia,[187] Corecom in Bulgaria, or Comturist in Romania. Much of what was produced for the local population never reached its intended user, while many perishable products became unfit for consumption before reaching their consumers.[141]

Black markets[edit]

As a result of the deficiencies of the official economy, black markets were created that were often supplied by goods stolen from the public sector.[188][189] The second, "parallel economy" flourished throughout the Bloc because of rising unmet state consumer needs.[190] Black and gray markets for foodstuffs, goods, and cash arose.[190] Goods included household goods, medical supplies, clothes, furniture, cosmetics and toiletries in chronically short supply through official outlets.[186]

Many farmers concealed actual output from purchasing agencies to sell it illicitly to urban consumers.[186] Hard foreign currencies were highly sought after, while highly valued Western items functioned as a medium of exchange or bribery in Stalinist countries, such as in Romania, where Kent cigarettes served as an unofficial extensively used currency to buy goods and services.[191] Some service workers moonlighted illegally providing services directly to customers for payment.[191]

Urbanization[edit]

The extensive production industrialization that resulted was not responsive to consumer needs and caused a neglect in the service sector, unprecedented rapid urbanization, acute urban overcrowding, chronic shortages, and massive recruitment of women into mostly menial and/or low-paid occupations.[141] The consequent strains resulted in the widespread used of coercion, repression, show trials, purges, and intimidation.[141] By 1960, massive urbanisation occurred in Poland (48% urban) and Bulgaria (38%), which increased employment for peasants, but also caused illiteracy to skyrocket when children left school for work.[141]

Cities became massive building sites, resulting in the reconstruction of some war-torn buildings but also the construction of drab dilapidated system-built apartment blocks.[141] Urban living standards plummeted because resources were tied up in huge long-term building projects, while industrialization forced millions of former peasants to live in hut camps or grim apartment blocks close to massive polluting industrial complexes.[141]

Agricultural collectivization[edit]

Collectivization is a process pioneered by Joseph Stalin in the late 1920s by which Marxist–Leninist regimes in the Eastern Bloc and elsewhere attempted to establish an ordered socialist system in rural agriculture.[192] It required the forced consolidation of small-scale peasant farms and larger holdings belonging to the landed classes for the purpose of creating larger modern "collective farms" owned, in theory, by the workers therein. In reality, such farms were owned by the state.[192]

In addition to eradicating the perceived inefficiencies associated with small-scale farming on discontiguous land holdings, collectivization also purported to achieve the political goal of removing the rural basis for resistance to Stalinist regimes.[192] A further justification given was the need to promote industrial development by facilitating the state's procurement of agricultural products and transferring "surplus labor" from rural to urban areas.[192] In short, agriculture was reorganized in order to proletarianize the peasantry and control production at prices determined by the state.[193]

The Eastern Bloc possesses substantial agricultural resources, especially in southern areas, such as Hungary's Great Plain, which offered good soils and a warm climate during the growing season.[193] Rural collectivization proceeded differently in non-Soviet Eastern Bloc countries than it did in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s.[194] Because of the need to conceal the assumption of control and the realities of an initial lack of control, no Soviet dekulakisation-style liquidation of rich peasants could be carried out in the non-Soviet Eastern Bloc countries.[194]

Nor could they risk mass starvation or agricultural sabotage (e.g., holodomor) with a rapid collectivization through massive state farms and agricultural producers' cooperatives (APCs).[194] Instead, collectivization proceeded more slowly and in stages from 1948 to 1960 in Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and East Germany, and from 1955 to 1964 in Albania.[194] Collectivization in the Baltic republics of the Lithuanian SSR, Estonian SSR and Latvian SSR took place between 1947 and 1952.[195]

Unlike Soviet collectivization, neither massive destruction of livestock nor errors causing distorted output or distribution occurred in the other Eastern Bloc countries.[194] More widespread use of transitional forms occurred, with differential compensation payments for peasants that contributed more land to APCs.[194] Because Czechoslovakia and East Germany were more industrialized than the Soviet Union, they were in a position to furnish most of the equipment and fertilizer inputs needed to ease the transition to collectivized agriculture.[178] Instead of liquidating large farmers or barring them from joining APCs as Stalin had done through dekulakisation, those farmers were utilised in the non-Soviet Eastern Bloc collectivizations, sometimes even being named farm chairman or managers.[178]

Collectivisation often met with strong rural resistance, including peasants frequently destroying property rather than surrendering it to the collectives.[192] Strong peasant links with the land through private ownership were broken and many young people left for careers in industry.[193] In Poland and Yugoslavia, fierce resistance from peasants, many of whom had resisted the Axis, led to the abandonment of wholesale rural collectivisation in the early 1950s.[178] In part because of the problems created by collectivisation, agriculture was largely de-collectivised in Poland in 1957.[192]

The fact that Poland nevertheless managed to carry out large-scale centrally planned industrialisation with no more difficulty than its collectivised Eastern Bloc neighbours further called into question the need for collectivisation in such planned economies.[178] Only Poland's "western territories", those eastwardly adjacent to the Oder-Neisse line that were annexed from Germany, were substantially collectivised, largely in order to settle large numbers of Poles on good farmland which had been taken from German farmers.[178]

Economic growth[edit]

There was significant progress made in the economy in countries such as the Soviet Union. In 1980, the Soviet Union took first place in Europe and second worldwide in terms of industrial and agricultural production, respectively. In 1960, the USSR's industrial output was only 55% that of America, but this increased to 80% in 1980.[174][unreliable source?]

With the change of the Soviet leadership in 1964, there were significant changes made to economic policy. The Government on 30 September 1965 issued a decree "On improving the management of industry" and the 4 October 1965 resolution "On improving and strengthening the economic incentives for industrial production". The main initiator of these reforms was Premier A. Kosygin. Kosygin's reforms on agriculture gave considerable autonomy to the collective farms, giving them the right to the contents of private farming. During this period, there was the large-scale land reclamation program, the construction of irrigation channels, and other measures.[174] In the period 1966–1970, the gross national product grew by over 35%. Industrial output increased by 48% and agriculture by 17%.[174] In the eighth Five-Year Plan, the national income grew at an average rate of 7.8%. In the ninth Five-Year Plan (1971–1975), the national income grew at an annual rate of 5.7%. In the tenth Five-Year Plan (1976–1981), the national income grew at an annual rate of 4.3%.[174]

The Soviet Union made noteworthy scientific and technological progress. Unlike countries with more market-oriented economies, scientific and technological potential in the USSR was used in accordance with a plan on the scale of society as a whole.[196]

In 1980, the number of scientific personnel in the USSR was 1.4 million. The number of engineers employed in the national economy was 4.7 million. Between 1960 and 1980, the number of scientific personnel increased by a factor of 4. In 1975, the number of scientific personnel in the USSR amounted to one-fourth of the total number of scientific personnel in the world. In 1980, as compared with 1940, the number of invention proposals submitted was more than 5 million. In 1980, there were 10 all-Union research institutes, 85 specialised central agencies, and 93 regional information centres.[197]

The world's first nuclear power plant was commissioned on 27 June 1954 in Obninsk.[citation needed] Soviet scientists made a major contribution to the development of computer technology. The first major achievements in the field were associated with the building of analog computers. In the USSR, principles for the construction of network analysers were developed by S. Gershgorin in 1927 and the concept of the electrodynamic analog computer was proposed by N. Minorsky in 1936. In the 1940s, the development of AC electronic antiaircraft directors and the first vacuum-tube integrators was begun by L. Gutenmakher. In the 1960s, important developments in modern computer equipment were the BESM-6 system built under the direction of S. A. Lebedev, the MIR series of small digital computers, and the Minsk series of digital computers developed by G.Lopato and V. Przhyalkovsky.[198]

Author Turnock claims that transport in the Eastern Bloc was characterised by poor infrastructural maintenance.[199] The road network suffered from inadequate load capacity, poor surfacing and deficient roadside servicing.[199] While roads were resurfaced, few new roads were built and there were very few divided highway roads, urban ring roads or bypasses.[200] Private car ownership remained low by Western standards.[200]

Vehicle ownership increased in the 1970s and 1980s with the production of inexpensive cars in East Germany such as Trabants and the Wartburgs.[200] However, the wait list for the distribution of Trabants was ten years in 1987 and up to fifteen years for Soviet Lada and Czechoslovakian Škoda cars.[200] Soviet-built aircraft exhibited deficient technology, with high fuel consumption and heavy maintenance demands.[199] Telecommunications networks were overloaded.[199]

Adding to mobility constraints from the inadequate transport systems were bureaucratic mobility restrictions.[201] While outside of Albania, domestic travel eventually became largely regulation-free, stringent controls on the issue of passports, visas and foreign currency made foreign travel difficult inside the Eastern Bloc.[201] Countries were inured to isolation and initial post-war autarky, with each country effectively restricting bureaucrats to viewing issues from a domestic perspective shaped by that country's specific propaganda.[201]

Severe environmental problems arose through urban traffic congestion, which was aggravated by pollution generated by poorly maintained vehicles.[201] Large thermal power stations burning lignite and other items became notorious polluters, while some hydro-electric systems performed inefficiently because of dry seasons and silt accumulation in reservoirs.[202] Kraków was covered by smog 135 days per year while Wrocław was covered by a fog of chrome gas.[specify][203]

Several villages were evacuated because of copper smelting at Głogów.[203] Further rural problems arose from piped water construction being given precedence over building sewerage systems, leaving many houses with only inbound piped water delivery and not enough sewage tank trucks to carry away sewage.[204] The resulting drinking water became so polluted in Hungary that over 700 villages had to be supplied by tanks, bottles and plastic bags.[204] Nuclear power projects were prone to long commissioning delays.[202]

The catastrophe at the Chernobyl nuclear plant in the Ukrainian SSR was caused by an irresponsible safety test on a reactor design that is normally safe,[205] some operators lacking an even basic understanding of the reactor's processes and authoritarian Soviet bureaucracy, valuing party loyalty over competence, that kept promoting incompetent personnel and choosing cheapness over safety.[206][207] The consequent release of fallout resulted in the evacuation and resettlement of over 336,000 people[208] leaving a massive desolate Zone of alienation containing extensive still-standing abandoned urban development.

Tourism from outside the Eastern Bloc was neglected, while tourism from other Stalinist countries grew within the Eastern Bloc.[209] Tourism drew investment, relying upon tourism and recreation opportunities existing before World War II.[210] By 1945, most hotels were run-down, while many which escaped conversion to other uses by central planners were slated to meet domestic demands.[210] Authorities created state companies to arrange travel and accommodation.[210] In the 1970s, investments were made to attempt to attract western travelers, though momentum for this waned in the 1980s when no long-term plan arose to procure improvements in the tourist environment, such as an assurance of freedom of movement, free and efficient money exchange and the provision of higher quality products with which these tourists were familiar.[209] However, Western tourists were generally free to move about in Hungary, Poland and Yugoslavia and go where they wished. It was more difficult or even impossible to go as an individual tourist to East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Bulgaria and Albania. It was generally possible in all cases for relatives from the west to visit and stay with family in the Eastern Bloc countries, except for Albania. In these cases, permission had to be sought, precise times, length of stay, location and movements had to be known in advance.

Catering to western visitors required creating an environment of an entirely different standard than that used for the domestic populace, which required concentration of travel spots including the building of relatively high-quality infrastructure in travel complexes, which could not easily be replicated elsewhere.[209] Because of a desire to preserve ideological discipline and the fear of the presence of wealthier foreigners engaging in differing lifestyles, Albania segregated travelers.[211] Because of the worry of the subversive effect of the tourist industry, travel was restricted to 6,000 visitors per year.[212]

Growth rates[edit]

Growth rates in the Eastern Bloc were initially high in the 1950s and 1960s.[164] During this first period, progress was rapid by European standards and per capita growth within the Eastern Bloc increased by 2.4 times the European average.[181] Eastern Europe accounted for 12.3 percent of European production in 1950 but 14.4 in 1970.[181] However, the system was resistant to change and did not easily adapt to new conditions. For political reasons, old factories were rarely closed, even when new technologies became available.[181] As a result, after the 1970s, growth rates within the bloc experienced relative decline.[213] Meanwhile, West Germany, Austria, France and other Western European nations experienced increased economic growth in the Wirtschaftswunder ("economic miracle"), Trente Glorieuses ("thirty glorious years") and the post-World War II boom.

From the end of World War II to the mid-1970s, the economy of the Eastern Bloc steadily increased at the same rate as the economy in Western Europe, with the non-reformist Stalinist nations of the Eastern Bloc having a stronger economy than the reformist-Stalinist states.[214] While most western European economies essentially began to approach the per capita gross domestic product (GDP) levels of the United States during the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Eastern Bloc countries did not,[213] with per capita GDPs trailing significantly behind their comparable western European counterparts.[215]

The following table displays a set of estimated growth rates of GDP from 1951 onward, for the countries of the Eastern Bloc as well as those of Western Europe as reported by The Conference Board as part of its Total Economy Database. In some cases data availability does not go all the way back to 1951.

| GDP growth rates in percent for the given years[216] | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1989 | 1991 | 2001 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| People's Socialist Republic of Albania | 6.608 | 4.156 | 6.510 | 2.526 | 2.648 | −28.000 | 7.940 | 2.600 |

| People's Republic of Bulgaria | 20.576 | 6.520 | 3.261 | 2.660 | −1.792 | −8.400 | 4.248 | 2.968 |

| Hungarian People's Republic | 9.659 | 5.056 | 4.462 | 0.706 | −2.240 | −11.900 | 3.849 | 2.951 |

| Polish People's Republic | 4.400 | 7.982 | 7.128 | −5.324 | −1.552 | −7.000 | 1.248 | 3.650 |

| Socialist Republic of Romania | 7.237 | 6.761 | 14.114 | −0.611 | −3.192 | −16.189 | 5.592 | 3.751 |

| Czechoslovak Socialist Republic/Czech Republic | – | – | 5.215 | −0.160 | 1.706 | −11.600 | 3.052 | 4.274 |

| Czechoslovak Socialist Republic/Slovakia | – | – | – | – | 1.010 | −14.600 | 3.316 | 3.595 |

| Soviet Union/Russia | – | 7.200 | 4.200 | 1.200 | 0.704 | −5.000 | 5.091 | −3.727 |

| Austria | 6.840 | 5.309 | 5.112 | −0.099 | 4.227 | 3.442 | 1.351 | 0.811 |

| Belgium | 5.688 | 4.865 | 3.753 | −1.248 | 3.588 | 1.833 | 0.811 | 1.374 |

| Denmark | 0.668 | 6.339 | 2.666 | −0.890 | 0.263 | 1.300 | 0.823 | 1.179 |

| Finland | 8.504 | 7.620 | 2.090 | 1.863 | 5.668 | −5.914 | 2.581 | 0.546 |

| France | 6.160 | 5.556 | 4.839 | 1.026 | 4.057 | 1.039 | 1.954 | 1.270 |

| Germany (West) | 9.167 | 4.119 | 2.943 | 0.378 | 3.270 | 5.108 | 1.695 | 1.700 |

| Greece | 8.807 | 8.769 | 7.118 | 0.055 | 3.845 | 3.100 | 4.132 | −0.321 |

| Ireland | 2.512 | 4.790 | 3.618 | 3.890 | 7.051 | 3.098 | 9.006 | 8.538 |

| Italy | 7.466 | 8.422 | 1.894 | 0.474 | 2.882 | 1.538 | 1.772 | 0.800 |

| Netherlands | 2.098 | 0.289 | 4.222 | −0.507 | 4.679 | 2.439 | 2.124 | 1.990 |

| Norway | 5.418 | 6.268 | 5.130 | 0.966 | 0.956 | 3.085 | 2.085 | 1.598 |

| Portugal | 4.479 | 5.462 | 6.633 | 1.618 | 5.136 | 4.368 | 1.943 | 1.460 |

| Spain | 9.937 | 12.822 | 5.722 | 0.516 | 5.280 | 2.543 | 4.001 | 3.214 |

| Sweden | 3.926 | 5.623 | 2.356 | −0.593 | 3.073 | −1.146 | 1.563 | 3.830 |

| Switzerland | 8.097 | 8.095 | 4.076 | 1.579 | 4.340 | −0.916 | 1.447 | 0.855 |

| United Kingdom | 2.985 | 3.297 | 2.118 | −1.303 | 2.179 | −1.257 | 2.758 | 2.329 |

The United Nations Statistics Division also calculates growth rates, using a different methodology, but only reports the figures starting in 1971 (for Slovakia and the constituent republics of the USSR data availability begins later). Thus, according to the United Nations growth rates in Europe were as follows:

| GDP growth rates in percent for the given years[217] | 1971 | 1981 | 1989 | 1991 | 2001 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| People's Socialist Republic of Albania | 4.001 | 5.746 | 9.841 | −28.002 | 8.293 | 2.639 |

| People's Republic of Bulgaria | 6.897 | 4.900 | −3.290 | −8.445 | 4.248 | 2.968 |

| Hungarian People's Republic | 6.200 | 2.867 | 0.736 | −11.687 | 3.774 | 3.148 |

| Polish People's Republic | 7.415 | −9.971 | 0.160 | −7.016 | 1.248 | 3.941 |

| Socialist Republic of Romania | 13.000 | 0.112 | −5.788 | −12.918 | 5.592 | 3.663 |

| Czechoslovak Socialist Republic/Czech Republic | 5.044 | −0.095 | 0.386 | −11.615 | 3.052 | 4.536 |

| Czechoslovak Socialist Republic/Slovakia | – | – | – | −14.541 | 3.316 | 3.831 |

| Soviet Union/Russia | 5.209 | 5.301 | 6.801 | −5.000 | 5.091 | −3.727 |

| Ukraine | – | – | – | −8.699 | 8.832 | −9.870 |

| Lithuania | – | – | – | −5.676 | 6.524 | 1.779 |

| Yugoslavia/Serbia | 9.162 | 1.400 | 1.500 | −11.664 | 4.993 | 0.758 |

| Austria | 5.113 | −0.144 | 3.887 | 3.442 | 1.351 | 0.963 |

| Belgium | 3.753 | −0.279 | 3.469 | 1.833 | 0.812 | 1.500 |

| Denmark | 3.005 | −0.666 | 0.645 | 1.394 | 0.823 | 1.606 |

| Finland | 2.357 | 1.295 | 5.088 | −5.914 | 2.581 | 0.210 |

| France | 5.346 | 1.078 | 4.353 | 1.039 | 1.954 | 1.274 |

| Germany (West) | 3.133 | 0.529 | 3.897 | 5.108 | 1.695 | 1.721 |

| Greece | 7.841 | −1.554 | 3.800 | 3.100 | 4.132 | −0.219 |

| Ireland | 3.470 | 3.325 | 5.814 | 1.930 | 6.052 | 26.276 |

| Italy | 1.818 | 0.844 | 3.388 | 1.538 | 1.772 | 0.732 |

| Netherlands | 4.331 | −0.784 | 4.420 | 2.439 | 2.124 | 1.952 |

| Norway | 5.672 | 1.598 | 1.038 | 3.085 | 2.085 | 1.611 |

| Portugal | 6.632 | 1.618 | 6.441 | 4.368 | 1.943 | 1.596 |

| Spain | 4.649 | −0.132 | 4.827 | 2.546 | 4.001 | 3.205 |

| Sweden | 0.945 | 0.455 | 2.655 | −1.146 | 1.563 | 4.085 |

| Switzerland | 4.075 | 1.601 | 4.331 | −0.916 | 1.447 | 0.842 |

| United Kingdom | 3.479 | −0.779 | 2.583 | −1.119 | 2.726 | 2.222 |

The following table lists the level of nominal GDP per capita in certain selected countries, measured in US dollars, for the years 1970, 1989, and 2015:

| Nominal GDP per Capita, according to the UN[218] | 1970 | 1989 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | $2,350 | $16,275 | $44,162 |

| Italy | $2,112 | $16,239 | $30,462 |

| Austria | $2,042 | $17,313 | $44,118 |