Королевский флот

|

| His Majesty's Naval Service of the British Armed Forces |

|---|

| Components |

|

| History and future |

| Ships |

| Personnel |

| Auxiliary services |

Королевский флот ( RN ) — это военно-морские силы Соединенного Королевства , британских заморских территорий и зависимых территорий Короны , а также компонент Военно-морской службы Его Величества . Хотя военные корабли использовались английскими и шотландскими королями с периода раннего средневековья, первые крупные морские сражения произошли во время Столетней войны против Франции . Современный Королевский флот ведет свое начало с начала 16 века; старейшая из вооруженных сил Великобритании , поэтому она известна как Старшая служба .

From the middle decades of the 17th century, and through the 18th century, the Royal Navy vied with the Dutch Navy and later with the French Navy for maritime supremacy. From the mid-18th century until the Second World War, it was the world's most powerful navy. The Royal Navy played a key part in establishing and defending the British Empire, and four Imperial fortress colonies and a string of imperial bases and coaling stations secured the Royal Navy's ability to assert naval superiority globally. Owing to this historical prominence, it is common, even among non-Britons, to refer to it as "the Royal Navy" without qualification. Following World War I, it was significantly reduced in size,[7] although at the onset of World War II it was still the world's largest. During the Cold War, the Royal Navy transformed into a primarily anti-submarine force, hunting for Soviet submarines and mostly active in the GIUK gap. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, its focus has returned to expeditionary operations around the world and it remains one of the world's foremost blue-water navies.[8][9][10]

The Royal Navy maintains a fleet of technologically sophisticated ships, submarines, and aircraft, including 2 aircraft carriers, 2 amphibious transport docks, 4 ballistic missile submarines (which maintain the nuclear deterrent), 6 nuclear fleet submarines, 6 guided missile destroyers, 9 frigates, 7 mine-countermeasure vessels and 26 patrol vessels. As of May 2024, there are 66 commissioned ships (including submarines as well as one historic ship, HMS Victory) in the Royal Navy, plus 13 ships of the Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA). There are also four Point-class sealift ships from the Merchant Navy available to the RFA under a private finance initiative, while the civilian Marine Services operate auxiliary vessels which further support the Royal Navy in various capacities. The RFA replenishes Royal Navy warships at sea, and augments the Royal Navy's amphibious warfare capabilities through its three Bay-class landing ship vessels. It also works as a force multiplier for the Royal Navy, often doing patrols that frigates used to do.

The Royal Navy is part of His Majesty's Naval Service, which also includes the Royal Marines and the Royal Fleet Auxiliary. The professional head of the Naval Service is the First Sea Lord who is an admiral and member of the Defence Council of the United Kingdom. The Defence Council delegates management of the Naval Service to the Admiralty Board, chaired by the Secretary of State for Defence. The Royal Navy operates from three bases in Britain where commissioned ships and submarines are based: Portsmouth, Clyde and Devonport, the last being the largest operational naval base in Western Europe, as well as two naval air stations, RNAS Yeovilton and RNAS Culdrose where maritime aircraft are based.

Role[edit]

As the seaborne branch of HM Armed Forces, the RN has various roles. As it stands today, the RN has stated its six major roles as detailed below in umbrella terms.[11]

- Preventing Conflict – On a global and regional level

- Providing Security At Sea – To ensure the stability of international trade at sea

- International Partnerships – To help cement the relationship with the United Kingdom's allies (such as NATO)

- Maintaining a Readiness To Fight – To protect the United Kingdom's interests across the globe

- Protecting the Economy – To safeguard vital trade routes to guarantee the United Kingdom's and its allies' economic prosperity at sea

- Providing Humanitarian Aid – To deliver a fast and effective response to global catastrophes

History[edit]

The English Royal Navy was formally founded in 1546 by Henry VIII,[12] though the Kingdom of England had possessed less-organised naval forces for centuries prior to this.[13]

The Royal Scots Navy (or Old Scots Navy) had its origins in the Middle Ages until its merger with the English Royal Navy per the Acts of Union 1707.[14]

Earlier fleets[edit]

During much of the medieval period, fleets or "king's ships" were often established or gathered for specific campaigns or actions, and these would disperse afterwards. These were generally merchant ships enlisted into service. Unlike some European states, England did not maintain a small permanent core of warships in peacetime. England's naval organisation was haphazard and the mobilisation of fleets when war broke out was slow.[15] Control of the sea only became critical to Anglo-Saxon kings in the 10th century.[16] In the 11th century, Aethelred II had a large fleet built by a national levy.[17] During the period of Danish rule in the 11th century, authorities maintained a standing fleet by taxation, and this continued for a time under Edward the Confessor, who frequently commanded fleets in person.[18] After the Norman Conquest, English naval power waned and England suffered large naval raids from the Vikings.[19] In 1069, this allowed for the invasion and ravaging of England by Jarl Osborn, brother of King Svein Estridsson, and his sons.[20]

The lack of an organised navy came to a head during the First Barons' War, in which Prince Louis of France invaded England in support of northern barons. With King John unable to organise a navy, this meant the French landed at Sandwich unopposed in April 1216. John's flight to Winchester and his death later that year left the Earl of Pembroke as regent, and he was able to marshal ships to fight the French in the Battle of Sandwich in 1217 – one of the first major English battles at sea.[21] The outbreak of the Hundred Years War emphasised the need for an English fleet. French plans for an invasion of England failed when Edward III of England destroyed the French fleet in the Battle of Sluys in 1340.[22] England's naval forces could not prevent frequent raids on the south-coast ports by the French and their allies. Such raids halted only with the occupation of northern France by Henry V.[23] A Scottish fleet existed by the reign of William the Lion.[24] In the early 13th century there was a resurgence of Viking naval power in the region. The Vikings clashed with Scotland over control of the isles[25] though Alexander III was ultimately successful in asserting Scottish control.[26] The Scottish fleet was of particular import in repulsing English forces in the early 14th century.[27]

Age of Sail[edit]

A standing "Navy Royal",[12] with its own secretariat, dockyards and a permanent core of purpose-built warships, emerged during the reign of Henry VIII.[28] Under Elizabeth I, England became involved in a war with Spain, which saw privately owned vessels combining with the Queen's ships in highly profitable raids against Spanish commerce and colonies.[29] The Royal Navy was then used in 1588 to repulse the Spanish Armada, but the English Armada was lost the next year. In 1603, the Union of the Crowns created a personal union between England and Scotland. While the two remained distinct sovereign states for a further century, the two navies increasingly fought as a single force. During the early 17th century, England's relative naval power deteriorated until Charles I undertook a major programme of shipbuilding. His methods of financing the fleet contributed to the outbreak of the English Civil War, and the abolition of the monarchy.[30]

The Commonwealth of England replaced many names and symbols in the new Commonwealth Navy, associated with royalty and the high church, and expanded it to become the most powerful in the world.[31][32] The fleet was quickly tested in the First Anglo-Dutch War (1652–1654) and the Anglo-Spanish War (1654–1660), which saw the British conquest of Jamaica and successful attacks on Spanish treasure fleets. The 1660 Restoration saw Charles II rename the Royal Navy again, and started use of the prefix HMS. The Navy remained a national institution and not a possession of the Crown as it had been before.[33] Following the Glorious Revolution of 1688, England joined the War of the Grand Alliance which marked the end of France's brief pre-eminence at sea and the beginning of an enduring British supremacy which would help with the creation of the British Empire.[34]

In 1707, the Scottish navy was united with the English Royal Navy. On Scottish men-of-war, the cross of St Andrew was replaced with the Union Jack. On English ships, the red, white, or blue ensigns had the St George's Cross of England removed from the canton, and the combined crosses of the Union flag put in its place.[35] Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the Royal Navy was the largest maritime force in the world,[36] maintaining superiority in financing, tactics, training, organisation, social cohesion, hygiene, logistical support and warship design.[37] The peace settlement following the War of the Spanish Succession (1702–1714) granted Britain Gibraltar and Menorca, providing the Navy with Mediterranean bases. The expansion of the Royal Navy would encourage the British colonisation of the Americas, with British (North) America becoming a vital source of timber for the Royal Navy.[38] There was a defeat during the frustrated siege of Cartagena de Indias in 1741. A new French attempt to invade Britain was thwarted by the defeat of their escort fleet in the extraordinary Battle of Quiberon Bay in 1759, fought in dangerous conditions.[39] In 1762, the resumption of hostilities with Spain led to the British capture of Manila and of Havana, along with a Spanish fleet sheltering there.[40] British naval supremacy could however be challenged still in this period by coalitions of other nations, as seen in the American War of Independence. The United States was allied to France, and the Netherlands and Spain were also at war with Britain. In the Battle of the Chesapeake, the British fleet failed to lift the French blockade, resulting in the surrender of an entire British army at Yorktown.[41]

The French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1793–1801, 1803–1814 & 1815) saw the Royal Navy reach a peak of efficiency, dominating the navies of all Britain's adversaries, which spent most of the war blockaded in port. Under Lord Nelson, the navy defeated the combined Franco-Spanish fleet at Trafalgar (1805).[42] Ships of the line and even frigates, as well as manpower, were prioritised for the naval war in Europe, however, leaving only smaller vessels on the North America Station and other less active stations, and a heavy reliance upon impressed labour. This would result in problems countering large, well-armed United States Navy frigates which outgunned Royal Naval vessels in single-opponent actions, as well as United States privateers, when the American War of 1812 broke out concurrent with the war against Napoleonic France and its allies. The Royal Navy still enjoyed a numerical advantage over the former colonists on the Atlantic, and from its base in Bermuda it blockaded the Atlantic seaboard of the United States throughout the war and carried out (with Royal Marines, Colonial Marines, British Army, and Board of Ordnance military corps units) various amphibious operations, most notably the Chesapeake campaign. On the Great Lakes, however, the United States Navy established an advantage.[43]

Splendid isolation[edit]

In 1860, Albert, Prince Consort, wrote to the Foreign Secretary John Russell, 1st Earl Russell with his concern about "a perfect disgrace to our country, and particularly to the Admiralty". The stated shipbuilding policy of the British monarchy was to take advantage of technological change and so be able to deploy a new weapons system that could defend British interests before other national and imperial resources are reasonably mobilized. Nevertheless, British taxpayers scrutinized progress in modernizing the Royal Navy so as to ensure, that taypayers' money is not wasted.[44]

Between 1815 and 1914, the Royal Navy saw little serious action, owing to the absence of any opponent strong enough to challenge its dominance, though it did not suffer the drastic cutbacks the various military forces underwent in the period of economic austerity that followed the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the American War of 1812 (when the British Army and the Board of Ordnance military corps were cutback, weakening garrisons around the Empire, the Militia became a paper tiger, and the Volunteer Force and Fencible units disbanded, though the Yeomanry was maintained as a back-up to the police). Britain relied, throughout the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, on imperial fortress colonies (originally Bermuda, Gibraltar, Halifax (Nova Scotia), and Malta). These areas permitted Britain to control the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. Control of military forces in Nova Scotia passed to the new Government of Canada after the 1867 Confederation of Canada and control of the naval dockyard in Halifax, Nova Scotia was transferred to the Government of Canada in 1905, five years prior to the establishment of the Royal Canadian Navy. Prior to the 1920s, it was presumed that the only navies that could challenge the Royal Navy belonged to nations on the Atlantic Ocean or its connected seas, despite the growth of the Imperial Russian and United States Pacific fleets during the latter half of the 19th Century.[45][46] Britain relied on Malta, in the Mediterranean Sea, to project power to the Indian Ocean and western Pacific Ocean via the Suez Canal after its completion in 1869. It relied on friendship and common interests between Britain and the United States (which controlled transit through the Panama Canal, completed in 1914) during and after the First World War, and on Bermuda, to project power the length of the western Atlantic, including the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico. The area controlled from Bermuda (and Halifax until 1905) had been part of the North America Station, until the 1820s, which then absorbed the Jamaica Station to become the North America and West Indies Station. After the First World War, this formation assumed control over the eastern Pacific Ocean and the western South Atlantic and was known as the America and West Indies Station until 1956.[47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56] In 1921, the ambitions of Imperial Japan and the threat of the Imperial Japanese Navy, resulted in the decision to construct the Singapore Naval Base.[57]

During this period, naval warfare underwent a comprehensive transformation, brought about by steam propulsion, metal ship construction, and explosive munitions. Despite having to completely replace its war fleet, the Navy managed to maintain its overwhelming advantage over all potential rivals. Owing to British leadership in the Industrial Revolution, the country enjoyed unparalleled shipbuilding capacity and financial resources, which ensured that no rival could take advantage of these revolutionary changes to negate the British advantage in ship numbers.[58]In 1889, Parliament passed the Naval Defence Act, which formally adopted the 'two-power standard', which stipulated that the Royal Navy should maintain a number of battleships at least equal to the combined strength of the next two largest navies.[59] The end of the 19th century saw structural changes and older vessels were scrapped or placed into reserve, making funds and manpower available for newer ships. The launch of HMS Dreadnought in 1906 rendered all existing battleships obsolete.[60] The transition at this time from coal to fuel-oil for boiler firing would encourage Britain to expand their foothold in former Ottoman territories in the Middle East, especially Iraq.[61]

Exploration[edit]

The Royal Navy played an historic role in several great global explorations of science and discovery.[62] Beginning in the 18th century many great voyages were commissioned often in co-operation with the Royal Society, such as the Northwest Passage expedition of 1741. James Cook led three great voyages, with goals such as discovering Terra Australis, observing the Transit of Venus and searching for the elusive North-West Passage, these voyages are considered to have contributed to world knowledge and science.[63] In the late 18th century, during a four year voyage Captain George Vancouver made detailed maps of the western coastline of North America.[64]

In the 19th century, Charles Darwin made further contributions to science during the second voyage of HMS Beagle.[65] The Ross expedition to the Antarctic made several important discoveries in biology and zoology.[66] Several of the Royal Navy's voyages ended in disaster such as those of Franklin and Scott.[67] Between 1872 and 1876 HMS Challenger undertook the first global marine research expedition, the Challenger expedition.[68]

World War I[edit]

During World War I, the Royal Navy's strength was mostly deployed at home in the Grand Fleet, confronting the German High Seas Fleet across the North Sea. Several inconclusive clashes took place between them, chiefly the Battle of Jutland in 1916.[69] The British fighting advantage proved insurmountable, leading the High Seas Fleet to abandon any attempt to challenge British dominance.[70] The Royal Navy under John Jellicoe also tried to avoid combat and remained in port at Scapa Flow for much of the war.[71] This was contrary to widespread prewar expectations that in the event of a Continental conflict Britain would primarily provide naval support to the Entente Powers while sending at most only a small ground army. Nevertheless, the Royal Navy played an important role in securing the British Isles and the English Channel, notably ferrying the entire British Expeditionary Force to the Western Front without the loss of a single life at the beginning of the war.[72]

The Royal Navy nevertheless remained active in other theatres, most notably in the Mediterranean Sea, where they waged the Dardanelles and Gallipoli campaigns in 1914 and 1915. British cruisers hunted down German commerce raiders across the world's oceans in 1914 and 1915, including the battles of Coronel, Falklands Islands, Cocos, and Rufiji Delta, among others.[73]

Interwar period[edit]

At the end of World War I, the Royal Navy remained by far the world's most powerful navy, larger than the U.S. Navy and French Navy combined, and over twice as large as the Imperial Japanese Navy and Royal Italian Navy combined. Its former primary competitor, the Imperial German Navy, was destroyed at the end of the war.[74] In the inter-war period, the Royal Navy was stripped of much of its power. The Washington and London Naval Treaties imposed the scrapping of some capital ships and limitations on new construction.[75]

The lack of an imperial fortress in the region of Asia, the Indian Ocean, and the Pacific Ocean was always to be a weakness throughout the 19th century as the former North American colonies that had become the United States of America had multiplied towards the Pacific Coast of North America, and the Russian Empire and Japanese Empire both had ports on the Pacific and had begun building large, modern fleets which went to war with each other in 1904. Britain reliance on Malta, via the Suez Canal, as the nearest Imperial fortress was improved, relying on amity and common interests that developed between Britain and the United States during and after World War I, by the completion of the Panama Canal in 1914, allowing the cruisers based in Bermuda to more easily and rapidly reach the eastern Pacific Ocean (after the war, the Royal Navy's Bermuda-based North America and West Indies Station was consequently re-designated the America and West Indies station, including a South American division. The rising power and increasing belligerence of the Japanese Empire after World War I, however, resulted in the construction of the Singapore Naval Base, which was completed in 1938, less than four years before hostilities with Japan did commence during World War II.[76]

In 1932, the Invergordon Mutiny took place in the Atlantic Fleet over the National Government's proposed 25% pay cut, which was eventually reduced to 10%.[77] International tensions increased in the mid-1930s and the re-armament of the Royal Navy was well under way by 1938. In addition to new construction, several existing old battleships, battlecruisers and heavy cruisers were reconstructed, and anti-aircraft weaponry reinforced, while new technologies, such as ASDIC, Huff-Duff and hydrophones, were developed.[78]

World War II[edit]

At the start of World War II in 1939, the Royal Navy was still the largest in the world, with over 1,400 vessels.[79][80] The Royal Navy provided critical cover during Operation Dynamo, the British evacuations from Dunkirk, and as the ultimate deterrent to a German invasion of Britain during the following four months. The Luftwaffe under Hermann Göring attempted to gain air supremacy over southern England in the Battle of Britain in order to neutralise the Home Fleet, but faced stiff resistance from the Royal Air Force.[81] The Luftwaffe bombing offensive during the Kanalkampf phase of the battle targeted naval convoys and bases in order to lure large concentrations of RAF fighters into attrition warfare.[82] At Taranto, Admiral Cunningham commanded a fleet that launched the first all-aircraft naval attack in history. The Royal Navy suffered heavy losses in the first two years of the war. Over 3,000 people were lost when the converted troopship Lancastria was sunk in June 1940, the greatest maritime disaster in Britain's history.[83] The Navy's most critical struggle was the Battle of the Atlantic defending Britain's vital North American commercial supply lines against U-boat attack. A traditional convoy system was instituted from the start of the war, but German submarine tactics, based on group attacks by "wolf-packs", were much more effective than in the previous war, and the threat remained serious for well over three years.[84]

Cold War[edit]

After World War II, the decline of the British Empire and the economic hardships in Britain forced the reduction in the size and capability of the Royal Navy. The United States Navy instead took on the role of global naval power. Governments since have faced increasing budgetary pressures, partly due to the increasing cost of weapons systems.[85]

In 1981, Defence Secretary John Nott had advocated and initiated a series of cutbacks to the Navy.[86] The Falklands War however proved a need for the Royal Navy to regain an expeditionary and littoral capability which, with its resources and structure at the time, would prove difficult. At the beginning of the 1980s, the Royal Navy was a force focused on blue-water anti-submarine warfare. Its purpose was to search for and destroy Soviet submarines in the North Atlantic, and to operate the nuclear deterrent submarine force. The navy received its first nuclear weapons with the introduction of the first of the Resolution-class submarines armed with the Polaris missile.[87]

Post-Cold War[edit]

Following the conclusion of the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War in 1991, the Royal Navy began to experience a gradual decline in its fleet size in accordance with the changed strategic environment it operated in. While new and more capable ships are continually brought into service, such as the Queen Elizabeth-class aircraft carriers, Astute-class submarines, and Type 45 destroyers, the total number of ships and submarines operated has continued to steadily reduce. This has caused considerable debate about the size of the Royal Navy. A 2013 report found that the Royal Navy was already too small, and that Britain would have to depend on her allies if her territories were attacked.[88]

The financial costs attached to nuclear deterrence, including Trident missile upgrades and replacements, have become an increasingly significant issue for the navy.[89]

Assets and resources[edit]

Personnel[edit]

HMS Raleigh at Torpoint, Cornwall, is the basic training facility for newly enlisted ratings. Britannia Royal Naval College in Dartmouth, Devon is the initial officer training establishment for the Royal Navy. Personnel are divided into a warfare branch, which includes Warfare Officers (previously named seamen officers) and Naval Aviators,[90] as well other branches including the Royal Naval Engineers, Royal Navy Medical Branch, and Logistics Officers (previously named Supply Officers). Present-day officers and ratings have several different uniforms; some are designed to be worn aboard ship, others ashore or in ceremonial duties. Women began to join the Royal Navy in 1917 with the formation of the Women's Royal Naval Service (WRNS), which was disbanded after the end of the First World War in 1919. It was revived in 1939, and the WRNS continued until disbandment in 1993, as a result of the decision to fully integrate women into the structures of the Royal Navy. Women now serve in all sections of the Royal Navy including the Royal Marines.[91]

In August 2019, the Ministry of Defence published figures showing that the Royal Navy and Royal Marines had 29,090 full-time trained personnel compared with a target of 30,600.[92] In 2023, it was reported that the Royal Navy was experiencing significant recruiting challenges with a net drop of some 1,600 personnel (4 percent of the force) from mid-2022 to mid-2023. This was posing a significant problem in the ability of the navy to meet its commitments.[93]

In December 2019 the First Sea Lord, Admiral Tony Radakin, outlined a proposal to reduce the number of Rear-Admirals at Navy Command by five.[94] The fighting arms (excluding Commandant General Royal Marines) would be reduced to commodore (1-star) rank and the surface flotillas would be combined. Training would be concentrated under the Fleet Commander.[95]

Surface fleet[edit]

Aircraft carriers[edit]

The Royal Navy has two Queen Elizabeth-class aircraft carriers. Each carrier cost £3 billion and displaces 65,000 tonnes (64,000 long tons; 72,000 short tons).[96] The first, HMS Queen Elizabeth, commenced flight trials in 2018. Both are intended to operate the STOVL variant of the F-35 Lightning II. Queen Elizabeth began sea trials in June 2017, was commissioned later that year, and entered service in 2020,[97] while the second, HMS Prince of Wales, began sea trials on 22 September 2019, was commissioned in December 2019 and was declared operational as of October 2021.[98][99][100][101][102] The aircraft carriers form a central part of the UK Carrier Strike Group alongside escorts and support ships.[103]

Amphibious warfare[edit]

Amphibious warfare ships in current service include two landing platform docks (HMS Albion and HMS Bulwark). While their primary role is to conduct amphibious warfare, they have also been deployed for humanitarian aid missions.[104] Both vessels were in reserve as of 2024.[105]

Clearance diving[edit]

The Royal Navy clearance diving unit, the Fleet Diving Squadron, was reorganised and renamed the Diving and Threat Exploitation Group in 2022. The group consists of five squadrons: Alpha, Bravo, Charlie, Delta, and Echo.[106][107] The Royal Navy has a separate unit with divers the special forces unit the Special Boat Service.[108]

Escort fleet[edit]

The escort fleet comprises guided missile destroyers and frigates and is the traditional workhorse of the Navy.[109] As of May 2024[update] there are six Type 45 destroyers and 9 Type 23 frigates in commission. Among their primary roles is to provide escort for the larger capital ships—protecting them from air, surface and subsurface threats. Other duties include undertaking the Royal Navy's standing deployments across the globe, which often consists of: counter-narcotics, anti-piracy missions and providing humanitarian aid.[104]

The Type 45 is primarily designed for anti-aircraft and anti-missile warfare and the Royal Navy describe the destroyer's mission as "to shield the Fleet from air attack".[110] They are equipped with the PAAMS (also known as Sea Viper) integrated anti-aircraft warfare system which incorporates the sophisticated SAMPSON and S1850M long range radars and the Aster 15 and 30 missiles.[111]

Sixteen Type 23 frigates were delivered to the Royal Navy, with the final vessel, HMS St Albans, commissioned in June 2002. However, the 2004 Delivering Security in a Changing World review announced that three frigates would be paid off as part of a cost-cutting exercise, and these were subsequently sold to the Chilean Navy.[112] The 2010 Strategic Defence and Security Review announced that the remaining 13 Type 23 frigates would eventually be replaced by the Type 26 Frigate,[113] with the incremental retirement of the remaining Type 23s commencing in 2021. The Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015 reduced the procurement of Type 26 to eight with five Type 31e frigates also to be procured.[114]

Mine countermeasure vessels (MCMV)[edit]

There are two classes of MCMVs in the Royal Navy: one Sandown-class minehunter and six Hunt-class mine countermeasures vessels. All the Sandown-class vessels are to be withdrawn from service by 2025 and are being replaced by autonomous systems that are planned to operate from a range of vessels, including so-called "motherships" planned for procurement by the Royal Fleet Auxiliary. The Hunt-class vessels combine the separate roles of the traditional minesweeper and the active minehunter in one hull. If required, the vessels can take on the role of offshore patrol vessels.[115]

Offshore patrol vessels (OPV)[edit]

A fleet of eight River-class offshore patrol vessels are in service with the Royal Navy. The three Batch 1 ships of the class serve in U.K. waters in a sovereignty and fisheries protection role while the five Batch 2 ships are forward-deployed on a long-term basis to Gibraltar, the Caribbean, the Falkland Islands and the Indo-Pacific region.[116] The vessel MV Grampian Frontier is leased from Scottish-based North Star Shipping for patrol duties around the British Indian Ocean Territory. However, she is not in commission with the Royal Navy.[117]

In December 2019, the modified Batch 1 River-class vessel, HMS Clyde, was decommissioned, with the Batch 2 HMS Forth taking over duties as the Falkland Islands patrol ship.[118][119]

Survey ships[edit]

HMS Protector is a dedicated Antarctica patrol ship that fulfils the nation's mandate to provide support to the British Antarctic Survey (BAS).[120] HMS Scott is an ocean survey vessel and at 13,500 tonnes is one of the largest ships in the Navy. As of 2018, the newly commissioned HMS Magpie also undertakes survey duties at sea.[121] The Royal Fleet Auxiliary plans to introduce two new Multi-Role Ocean Surveillance Ships, in part to protect undersea cables and gas pipelines and partly to compensate for the withdrawal of all ocean-going survey vessels from Royal Navy service.[122] The first of these vessels, RFA Proteus, entered service in October 2023.[123]

Royal Fleet Auxiliary[edit]

The Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA) provides support to the Royal Navy at sea in several capacities. For fleet replenishment, it deploys one Fleet Solid Support Ship and six fleet tankers (three of which are maintained in reserve). The RFA also has one aviation training and casualty reception vessel, which also operates as a Littoral Strike Ship.[124][125]

Three amphibious transport docks are also incorporated within its fleet. These are known as the Bay-class landing ships, of which four were introduced in 2006–2007, but one was sold to the Royal Australian Navy in 2011.[126] In November 2006, the First Sea Lord Admiral Sir Jonathon Band described the Royal Fleet Auxiliary vessels as "a major uplift in the Royal Navy's war fighting capability".[127]

In February 2023, a commercial vessel was also acquired to act as a Multi-Role Ocean Surveillance (MROS) Ship for the protection of critical seabed infrastructure and other tasks. She entered service as RFA Proteus.[128] An additional vessel, RFA Stirling Castle, was acquired in 2023 to act as a mothership for autonomous minehunting systems.[129]

Other ships[edit]

The Royal Navy also includes a number of smaller non-commissioned assets such as the Sea-class workboats. On 29 July 2022, the Royal Navy christened a new experimental ship, XV Patrick Blackett, which it aims to use as a testbed for autonomous systems. Whilst the ship flies the Blue Ensign, it is crewed by Royal Navy personnel and will participate in Royal Navy and NATO exercises.[130][131]

Submarine Service[edit]

The Submarine Service is the submarine based element of the Royal Navy. It is sometimes referred to as the "Silent Service",[132] as the submarines are generally required to operate undetected. Founded in 1901, the service made history in 1982 when, during the Falklands War, HMS Conqueror became the first nuclear-powered submarine to sink a surface ship, ARA General Belgrano. Today, all of the Royal Navy's submarines are nuclear-powered.[133]

Ballistic missile submarines (SSBN)[edit]

The Royal Navy operates four Vanguard-class ballistic missile submarines displacing nearly 16,000 tonnes and equipped with Trident II missiles (armed with nuclear weapons) and heavyweight Spearfish torpedoes, to carry out Operation Relentless, the United Kingdom's Continuous At Sea Deterrent (CASD). The UK government has committed to replace these submarines with four new Dreadnought-class submarines, which will enter service in the "early 2030s" to maintain this capability.[134][135]

Fleet submarines (SSN)[edit]

As of August 2022, six fleet submarines are in commission, one Trafalgar-class and five Astute-class (one of which was still working up to operational status as of August 2022[136]). Two more Astute-class fleet submarines are scheduled to enter service by the mid-2020s while the remaining Trafalgar-class submarine will be withdrawn.[137]

The Trafalgar class displace approximately 5,300 tonnes when submerged and are armed with Tomahawk land-attack missiles and Spearfish torpedoes. The Astute-class at 7,400 tonnes[138] are much larger and carry a larger number of Tomahawk missiles and Spearfish torpedoes. HMS Anson was the most recent Astute-class boat to be commissioned.[136]

Fleet Air Arm[edit]

The Fleet Air Arm (FAA) is the branch of the Royal Navy responsible for the operation of naval aircraft, it can trace its roots back to 1912 and the formation of the Royal Flying Corps. The Fleet Air Arm currently operates the AW-101 Merlin HC4 (in support of 3 Commando Brigade) as the Commando Helicopter Force; the AW-159 Wildcat HM2; the AW101 Merlin HM2 in the anti-submarine role; and the F-35B Lightning II in the carrier strike role.[139]

Pilots designated for rotary wing service train under No. 1 Flying Training School (1 FTS)[140] at RAF Shawbury.[141]

Royal Marines[edit]

The Royal Marines are an amphibious, specialised light infantry force of commandos, capable of deploying at short notice in support of His Majesty's Government's military and diplomatic objectives overseas.[142] The Royal Marines are organised into a highly mobile light infantry brigade (3 Commando Brigade) and 7 commando units[143] including 1 Assault Group Royal Marines, 43 Commando Fleet Protection Group Royal Marines and a company strength commitment to the Special Forces Support Group. The Corps operates in all environments and climates, though particular expertise and training is spent on amphibious warfare, Arctic warfare, mountain warfare, expeditionary warfare and commitment to the UK's Rapid Reaction Force. The Royal Marines are also the primary source of personnel for the Royal Navy's special forces unit the Special Boat Service (SBS).[144][108]

The Corps operates its own fleet of landing and other craft, and also incorporates the Royal Marines Band Service, the musical wing of the Royal Navy.[145]

The Royal Marines have seen action in a number of wars, often fighting beside the British Army; including in the Seven Years' War, the Napoleonic Wars, the Crimean War, World War I and World War II. In recent times, the Corps has been deployed in expeditionary warfare roles, such as the Falklands War, the Gulf War, the Bosnian War, the Kosovo War, the Sierra Leone Civil War, the Iraq War and the War in Afghanistan. The Royal Marines have international ties with allied marine forces, particularly the United States Marine Corps[146] and the Netherlands Marine Corps/Korps Mariniers.[147]

[edit]

The Royal Navy currently uses three major naval bases in the UK, each housing its own flotilla of ships and boats ready for service, along with two naval air stations and a support facility base in Bahrain:

Bases in the United Kingdom[edit]

- HMNB Devonport (HMS Drake) – This is currently the largest operational naval base in Western Europe. Devonport's flotilla consists of the RN's two amphibious assault vessels (HM Ships Albion and Bulwark), and more than half the fleet of Type 23 frigates. Devonport also has been home to some of the RN's Submarines service, but now only to the one remaining Trafalgar-class submarine.[148]

- HMNB Portsmouth (HMS Nelson) – This is home to the Queen Elizabeth Class supercarriers. Portsmouth is also the home to the Type 45 Daring Class Destroyer and a moderate fleet of Type 23 frigates as well as Overseas Patrol Squadron.[149]

- HMNB Clyde (HMS Neptune) – This is situated in Central Scotland along the River Clyde. Faslane is known as the home of the UK's nuclear deterrent, as it maintains the fleet of Vanguard-class ballistic missile (SSBN) submarines, as well as the fleet of Astute-class fleet (SSN) submarines. By 2022/23, Faslane will become the home to all Royal Navy submarines, and thus the RN Submarine Service. As a result, 43 Commando (Fleet Protection Group) are stationed in Faslane alongside to guard the base as well as The Royal Naval Armaments Depot at Coulport. Moreover, Faslane is also home to Faslane Patrol Boat Squadron (FPBS) who operates a fleet of Archer class patrol vessels.[150][151]

- RNAS Yeovilton (HMS Heron) – Yeovilton is home to Commando Helicopter Force and Wildcat Maritime Force.[152]

- RNAS Culdrose (HMS Seahawk) – This is home to Mk2 Merlins, primarily tasked with conducting Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) and Early Airborne Warning (EAW). Culdrose is also currently the largest helicopter base in Europe.[153]

- HMS Gannet – Previously known as RNAS Prestwick. Previously used for Defence of the Clyde and Search and Rescue tasking, it is now used primarily as a FOB for ASW Merlins deployed from RNAS Culdrose to support the SSBN and defence of the Clyde tasking.[154]

Bases abroad[edit]

- UK National Support Element (Bahrain) – The home port for vessels deployed on Operation Kipion and acts as the hub of the Royal Navy's operations in the Persian Gulf, Red Sea and Indian Ocean.[155] Vessels based there include the 9th Mine Countermeasures Squadron,[156] usually a Royal Fleet Auxiliary and (as of early 2023) HMS Lancaster.[157][158]

- UK Joint Logistics Support Base (Oman) – A logistical support facility which is strategically located in the Middle East but outside the Persian Gulf.[159]

- British Defence Singapore Support Unit (Singapore) – A remnant of HMNB Singapore which repairs and resupplies Royal Navy ships in the Asia Pacific.[160] It is the primary logistics support hub for the Royal Navy offshore patrol vessels assigned to the Asia-Pacific region, HMS Tamar and HMS Spey.[161]

- HMNB Gibraltar – A current Royal Navy dockyard in Gibraltar which is still used for docking, repairs, training and resupply.[162] Vessels permanently based with the Gibraltar Squadron include the Offshore Patrol Ship, HMS Trent and the Cutlass-class fast patrol boats, HMS Cutlass and HMS Dagger.[163]

- Mare Harbour (Falkland Islands) – Serves as the port facility for RAF Mount Pleasant, the main British base in the Falkland Islands. Mare Harbour incorporates several berths which support Royal Navy and marine services vessels operating in the South Atlantic. The facility also supports the British Antarctic Survey ship, RRS Sir David Attenborough, when she operates in Antarctic waters during the regional summer.[164]

The current role of the Royal Navy is to protect British interests at home and abroad, executing the foreign and defence policies of His Majesty's Government through the exercise of military effect, diplomatic activities and other activities in support of these objectives. The Royal Navy is also a key element of the British contribution to NATO, with a number of assets allocated to NATO tasks at any time.[165] These objectives are delivered via a number of core capabilities:[166]

- Maintenance of the UK Nuclear Deterrent through a policy of Continuous at Sea Deterrence

- Provision of two medium-scale maritime task groups with the Fleet Air Arm

- Delivery of the UK Commando force

- Contribution of assets to the Joint Helicopter Command

- Maintenance of standing patrol commitments

- Provision of mine counter measures capability to United Kingdom and allied commitments

- Provision of hydrographic and meteorological services deployable worldwide

- Protection of Britain's Exclusive Economic Zone

Current deployments[edit]

The Royal Navy is currently deployed in different areas of the world, including some standing Royal Navy deployments. These include several home tasks as well as overseas deployments. The Navy is deployed in the Mediterranean as part of standing NATO deployments including mine countermeasures and NATO Maritime Group 2. In both the North and South Atlantic, RN vessels are patrolling. There is always a Falkland Islands patrol vessel on deployment, currently HMS Forth.[167]

The Royal Navy operates a Response Force Task Group (a product of the 2010 Strategic Defence and Security Review), which is poised to respond globally to short-notice tasking across a range of defence activities, such as non-combatant evacuation operations, disaster relief, humanitarian aid or amphibious operations. In 2011, the first deployment of the task group occurred under the name 'COUGAR 11' which saw them transit through the Mediterranean where they took part in multinational amphibious exercises before moving further east through the Suez Canal for further exercises in the Indian Ocean.[168][169]

In the Persian Gulf, the RN sustains commitments in support of both national and coalition efforts to stabilise the region. The Armilla Patrol, which started in 1980, is the navy's primary commitment to the Gulf region. The Royal Navy also contributes to the combined maritime forces in the Gulf in support of coalition operations.[170] The UK Maritime Component Commander, overseer of all of His Majesty's warships in the Persian Gulf and surrounding waters, is also deputy commander of the Combined Maritime Forces.[171] The Royal Navy has been responsible for training the fledgeling Iraqi Navy and securing Iraq's oil terminals following the cessation of hostilities in the country. The Iraqi Training and Advisory Mission (Navy) (Umm Qasr), headed by a Royal Navy captain, has been responsible for the former duty whilst Commander Task Force Iraqi Maritime, a Royal Navy commodore, has been responsible for the latter.[172][173]

The Royal Navy contributes to standing NATO formations and maintains forces as part of the NATO Response Force. The RN also has a long-standing commitment to supporting the Five Powers Defence Arrangements countries and occasionally deploys to the Far East as a result.[174] This deployment typically consists of a frigate and a survey vessel, operating separately. Operation Atalanta, the European Union's anti-piracy operation in the Indian Ocean, is permanently commanded by a senior Royal Navy or Royal Marines officer at Northwood Headquarters and the navy contributes ships to the operation.[175]

From 2015, the Royal Navy also re-formed its UK Carrier Strike Group (UKCSG) after it was disbanded in 2011 due to the retirement of HMS Ark Royal and Harrier GR9s.[176][177] The Queen Elizabeth-class aircraft carriers form the central part of this formation, supported by various escorts and support ships, with the aim to facilitate carrier-enabled power projection.[178] The UKCSG first assembled at sea in October 2020 as part of a rehearsal for its first operational deployment in 2021.[103]

In 2019, the Royal Navy announced the formation of two Littoral Response Groups as part of a transformation of its amphibious forces. These forward-based special operations-capable task groups are to be rapidly-deployable and able to carry out a range of tasks within the littoral, including raids and precision strikes. The first one, based in Europe, became operational in 2021, whilst the second will be based in the Indo-Pacific from 2023. They centre around the two navy amphibious assault ships, amphibious auxiliary ships from the Royal Fleet Auxiliary, elements from the Royal Marines and supporting units.[179]

Command, control and organisation[edit]

The titular head of the Royal Navy is the Lord High Admiral, a position which was held by the Duke of Edinburgh from 2011 until his death in 2021 and remains vested in the Crown and held personally by the reigning Monarch (currently King Charles III).[180][181][182] The position had been held by Queen Elizabeth II from 1964 to 2011;[183] the Sovereign is the Commander-in-chief of the British Armed Forces.[184] The professional head of the Naval Service is the First Sea Lord, an admiral and member of the Defence Council of the United Kingdom. The Defence Council delegates management of the Naval Service to the Admiralty Board, chaired by the Secretary of State for Defence, which directs the Navy Board, a sub-committee of the Admiralty Board comprising only naval officers and Ministry of Defence (MOD) civil servants. These are all based in MOD Main Building in London, where the First Sea Lord, also known as the Chief of the Naval Staff, is supported by the Naval Staff Department.[185]

Organisation[edit]

The Fleet Commander has responsibility for the provision of ships, submarines and aircraft ready for any operations that the Government requires. Fleet Commander exercises his authority through the Navy Command Headquarters, based at HMS Excellent in Portsmouth. An operational headquarters, the Northwood Headquarters, at Northwood, London, is co-located with the Permanent Joint Headquarters of the United Kingdom's armed forces, and a NATO Regional Command, Allied Maritime Command.[186]

The Royal Navy was the first of the three armed forces to combine the personnel and training command, under the Principal Personnel Officer, with the operational and policy command, combining the Headquarters of the Commander-in-Chief, Fleet and Naval Home Command into a single organisation, Fleet Command, in 2005 and becoming Navy Command in 2008. Within the combined command, the Second Sea Lord continues to act as the Principal Personnel Officer.[187] Previously, Flag Officer Sea Training was part of the list of top senior appointments in Navy Command, however, as part of the Navy Command Transformation Programme, the post has reduced from Rear-Admiral to Commodore, renamed as Commander Fleet Operational Sea Training.[188]

The Naval Command senior appointments are:[189][190]

| Rank | Name | Position | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professional Head of the Royal Navy | |||||

| Admiral | Sir Ben Key | First Sea Lord and Chief of Naval Staff | |||

| Fleet Commander | |||||

| Vice Admiral | Andrew Burns | Fleet Commander | |||

| Rear Admiral | Edward Ahlgren | Commander Operations | |||

| Rear Admiral | Robert Pedre | Commander United Kingdom Strike Force | |||

| Second Sea Lord & Deputy Chief of Naval Staff | |||||

| Vice Admiral | Martin Connell | Second Sea Lord & Deputy Chief of Naval Staff | |||

| Rear Admiral | James Parkin | Assistant Chief of the Naval Staff (Capability) and Director Development | |||

| Rear Admiral | Anthony Rimington | Director Strategy and Policy | |||

| Rear Admiral | Jude Terry | Director People and Training / Naval Secretary | |||

| The Venerable | Andrew Hillier | Chaplain of the Fleet | |||

The Commandant General Royal Marines was previously a major-general's post and charged with leading amphibious warfare operations. Since Lieutenant General Robert Magowan was appointed for the second time the post is an additional responsibility for a senior Royal Marine holding other duties. The current CG RM is General Gwyn Jenkins, the Vice-Chief of the Defence Staff.[191]

Intelligence support to fleet operations is provided by intelligence sections at the various headquarters and from MOD Defence Intelligence, renamed from the Defence Intelligence Staff in early 2010.[192]

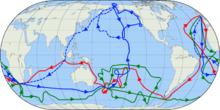

Locations[edit]

The Royal Navy historically has divided the planet into a number of stations, the number and boundaries of which changed over time. The former stations of the Royal Navy included the East Indies Station (1744–1831); East Indies and China Station (1832–1865); East Indies Station (1865–1913); Egypt and East Indies Station (1913–1918); East Indies Station (1918–1941). In response to increased Japanese threats, the separate East Indies Station was merged with the China Station in December 1941, to form the Eastern Fleet.[193] Later the Eastern Fleet became the East Indies Fleet. In 1952, after the Second World War ended, the East Indies Fleet became the Far East Fleet.[194]

The Royal Navy currently operates from three bases in the United Kingdom where commissioned ships are based; Portsmouth, Clyde and Devonport, Plymouth—Devonport is the largest operational naval base in the UK and Western Europe.[195] Each base hosts a flotilla command under a commodore, responsible for the provision of operational capability using the ships and submarines within the flotilla. 3 Commando Brigade Royal Marines is similarly commanded by a brigadier and based in Plymouth.[196]

The Royal Navy has historically maintained Royal Navy Dockyards around the world.[197] Dockyards of the Royal Navy are harbours where ships are overhauled and refitted. Only four are operating today; at Devonport, Faslane, Rosyth and at Portsmouth.[198] A Naval Base Review was undertaken in 2006 and early 2007, the outcome being announced by Secretary of State for Defence, Des Browne, confirming that all would remain however some reductions in manpower were anticipated.[199]

The academy where initial training for future Royal Navy officers takes place is Britannia Royal Naval College, located on a hill overlooking Dartmouth, Devon. Basic training for future ratings takes place at HMS Raleigh at Torpoint, Cornwall, close to HMNB Devonport.[200]

Significant numbers of naval personnel are employed within the Ministry of Defence, Defence Equipment and Support and on exchange with the Army and Royal Air Force. Small numbers are also on exchange within other government departments and with allied fleets, such as the United States Navy. The navy also posts personnel in small units around the world to support ongoing operations and maintain standing commitments. Nineteen personnel are stationed in Gibraltar to support the small Gibraltar Squadron, the RN's only permanent overseas squadron. Some personnel are also based at East Cove Military Port and RAF Mount Pleasant in the Falkland Islands to support APT(S). Small numbers of personnel are based in Diego Garcia (Naval Party 1002), Miami (NP 1011 – AUTEC), Singapore (NP 1022), Dubai (NP 1023) and elsewhere.[201]

On 6 December 2014, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office announced it would expand the UK's naval facilities in Bahrain to support larger Royal Navy ships deployed to the Persian Gulf. Once completed, it became the UK's first permanent military base located East of Suez since it withdrew from the region in 1971. The base is reportedly large enough to accommodate Type 45 destroyers and Queen Elizabeth-class aircraft carriers.[202][203][204]

Titles and naming[edit]

[edit]

The navy was referred to as the "Navy Royal" at the time of its founding in 1546, and this title remained in use into the Stuart period. During the interregnum, the commonwealth under Oliver Cromwell replaced many historical names and titles, with the fleet then referred to as the "Commonwealth Navy". The navy was renamed once again after the restoration in 1660 to the present title.[205]

Today, the navy of the United Kingdom is commonly referred to as the "Royal Navy" both in the United Kingdom and other countries. Navies of other Commonwealth countries where the British monarch is also head of state include their national name, e.g. Royal Australian Navy. Some navies of other monarchies, such as the Koninklijke Marine (Royal Netherlands Navy) and Kungliga Flottan (Royal Swedish Navy), are also called "Royal Navy" in their own language. The Danish Navy uses the term "Royal" incorporated in its official name (Royal Danish Navy), but only "Flåden" (Navy) in everyday speech.[206] The French Navy, despite France being a republic since 1870, is often nicknamed "La Royale" (literally: The Royal).[207]

Of ships[edit]

Royal Navy ships in commission are prefixed since 1789 with His Majesty's Ship (or "Her Majesty's Ship", when the monarch is a queen), abbreviated to "HMS"; for example, HMS Beagle. Submarines are styled HM Submarine, also abbreviated "HMS". Names are allocated to ships and submarines by a naming committee within the MOD and given by class, with the names of ships within a class often being thematic (for example, the Type 23s are named after British dukes) or traditional (for example, the Invincible-class aircraft carriers all carry the names of famous historic ships). Names are frequently re-used, offering a new ship the rich heritage, battle honours and traditions of her predecessors. Often, a particular vessel class will be named after the first ship of that type to be built. As well as a name, each ship and submarine of the Royal Navy and the Royal Fleet Auxiliary is given a pennant number which in part denotes its role. For example, the destroyer HMS Daring (D32) displays the pennant number 'D32'.[208]

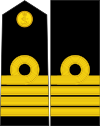

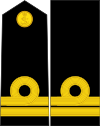

Ranks, rates and insignia[edit]

The Royal Navy ranks, rates and insignia form part of the uniform of the Royal Navy. The Royal Navy uniform is the pattern on which many of the uniforms of the other national navies of the world are based (e.g. Ranks and insignia of NATO navies officers, Uniforms of the United States Navy, Uniforms of the Royal Canadian Navy, French Naval Uniforms).[209]

| Royal Navy officer rank insignia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NATO Code | OF-10 | OF-9 | OF-8 | OF-7 | OF-6 | OF-5 | OF-4 | OF-3 | OF-2 | OF-1 | OF(D) | ||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | ||

| Rank Title: | Admiral of the Fleet[210] | Admiral | Vice admiral | Rear admiral | Commodore | Captain | Commander | Lieutenant commander | Lieutenant | Sub-Lieutenant | Midshipman | Officer Cadet | |

| Abbreviation: | Adm. of the Fleet[nb 6] | Adm | VAdm | RAdm | Cdre | Capt | Cdr | Lt Cdr | Lt | Sub Lt / SLt | Mid | OC | |

| Royal Navy other rank insignia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NATO Code | OR-9 | OR-8 | OR-7 | OR-6 | OR-5 | OR-4 | OR-2 |

|  |  |  |  |  | ||

| Rank Title: | Warrant Officer 1 | Warrant Officer 2 | Chief Petty Officer | Petty Officer | Leading Rating | Able Rating | |

| Abbreviation: | WO1 | WO2[nb 7] | CPO | PO | LH | AB | |

1 Ранг приостановлен - обычные назначения в этом звании больше не производятся, хотя почетные награды этого звания иногда вручаются старшим членам королевской семьи и выдающимся бывшим первым морским лордам.

Обычаи и традиции [ править ]

Традиции [ править ]

В Королевском флоте существует несколько официальных обычаев и традиций, включая использование прапорщиков и корабельных значков. На кораблях Королевского флота используется несколько флагов на ходу и в порту. Входящие в строй корабли и подводные лодки носят Белый флаг на корме, когда он находится у борта в светлое время суток, и на грот-мачте во время хода. Находясь рядом, « Юнион Джек» поднимается с посоха на носу, и его можно поднимать только на ходу либо для того, чтобы сигнализировать о том, что идет военный трибунал, либо чтобы указать на присутствие на борту адмирала флота (включая лорда Верховный адмирал или монарх). [211]

Обзор флота — это нерегулярная традиция сбора флота перед монархом. Первый зарегистрированный обзор был проведен в 1400 году, а самый последний — в 2022 году. [update] состоялся 28 июня 2005 г. в ознаменование двухсотлетия Трафальгарской битвы; В мероприятии приняли участие 167 кораблей из разных стран, а Королевский флот предоставил 67 кораблей. [212]

«Джекспик» [ править ]

Есть несколько менее формальных традиций, включая служебные прозвища и военно-морской сленг, известный как «Jackspeak» . [213] Среди прозвищ - «Эндрю» (неопределенного происхождения, возможно, в честь ревностного пресс-гангера ). [214] [215] и «Старшая служба». [216] [217] Британских моряков называют «Джек» (или «Дженни») или, в более широком смысле, «Мателоты». Королевских морских пехотинцев ласково называют «ботинки», а часто просто «королевские особы». составил сборник военно-морского сленга Командир АТЛ Кови-Крамп , и его имя само по себе стало предметом военно-морского сленга; Кови-Крамп . [216] Игра, в которую традиционно играют военно-морские силы, — это настольная игра для четырех игроков, известная как « Укерс ». Это похоже на Людо , и считается, что его легко освоить, но сложно хорошо играть. [218]

[ править ]

Королевский флот спонсирует или поддерживает три молодежные организации:

- Добровольческий кадетский корпус , состоящий из Добровольческого кадетского корпуса Королевского военно-морского флота и Добровольческого кадетского корпуса Королевской морской пехоты, VCC был первой молодежной организацией, официально поддержанной или спонсируемой Адмиралтейством в 1901 году. [219]

- Объединенные кадетские силы - в школах, в частности в секции Королевского военно-морского флота и секции Королевской морской пехоты. [220]

- Морские кадеты — поддержка подростков, интересующихся военно-морскими делами, состоящая из морских кадетов и кадетов Королевской морской пехоты . [221]

Вышеупомянутые организации находятся в ведении подразделения CUY по основной подготовке и набору командиров (COMCORE), которое подчиняется флагманскому офицеру морской подготовки (FOST). [222]

В популярной культуре [ править ]

Королевский флот 18 века изображен во многих романах и нескольких фильмах, драматизирующих путешествие и мятеж на « Баунти» . [223] Наполеоновские кампании Королевского флота начала XIX века также являются популярной темой исторических романов. Одними из самых известных являются серии книг Патрика О'Брайана « Обри-Мэтюрин». [224] и CS Forester хроники Горацио Хорнблауэра . [225]

Военно-морской флот также можно увидеть во многих фильмах. Вымышленный шпион Джеймс Бонд является командиром Королевского военно-морского добровольческого резерва (RNVR). [226] Королевский флот показан в фильме «Шпион, который меня любил» , когда украдена атомная подводная лодка с баллистическими ракетами. [227] и в «Завтра не умрет никогда» , когда медиамагнат Эллиот Карвер топит военный корабль Королевского флота, пытаясь спровоцировать войну между Великобританией и Китайской Народной Республикой . [228] «Мастер и командир: Дальняя сторона мира» был основан на сериале Патрика О’Брайана «Обри-Мэтьюрин». [229] Серия фильмов « Пираты Карибского моря» также включает в себя военно-морской флот как силу, преследующую одноименных пиратов . [230] Ноэль Кауард снялся и снялся в собственном фильме «В котором мы служим» , в котором рассказывается история экипажа вымышленного HMS Torrin во время Второй мировой войны. Он был задуман как пропагандистский корабля фильм и был выпущен в 1942 году. Кауард сыграл капитана с второстепенными ролями Джона Миллса и Ричарда Аттенборо . [231]

Романы К.С. Форестера о Хорнблауэре были адаптированы для телевидения . [232] Королевский флот был героем BBC телесериала «Военный корабль» 1970-х годов . [233] и документального фильма из пяти частей «Соратники» , в котором рассказывается о повседневной работе Королевского флота. [234]

Телевизионные документальные фильмы о Королевском флоте включают: «Морская империя: как флот создал современный мир» , документальный фильм из четырех частей, изображающий подъем Великобритании как военно-морской сверхдержавы вплоть до Первой мировой войны; [235] Моряк о жизни на авианосце HMS Ark Royal ; [236] и «Подводная лодка » о курсе подготовки капитанов подводных лодок «Пишер». [237] также были показаны На канале 5 документальные фильмы, такие как «Миссия подводных лодок Королевского флота» , рассказывающие об атомной подводной лодке. [238]

В BBC Light Program радиокомедийном сериале «Военно-морской жаворонок» с 1959 по 1977 год был показан вымышленный военный корабль («HMS Troutbridge »). [239]

См. также [ править ]

- Список названий кораблей Королевского флота (полный исторический список)

- Список военно-морских кораблей Соединенного Королевства

- Список плавдоков Адмиралтейства

- Список оборудования Королевского флота

- Библиография по истории Королевского военно-морского флота XVIII–XIX веков.

- Список войн с участием Соединенного Королевства

- Береговая охрана Его Величества

- Королевский британский легион

- Королевская больничная школа

- Королевская военно-морская ассоциация

- « Прави, Британия! », песня

- Аллан Гримсон , убийца моряков военно-морского флота, прозванный « Деннисом Нильсеном Королевского флота ». [240] [241]

Примечания [ править ]

- ↑ Королевский флот служил Содружеству Англии как Военно-морской флот Содружества, 1644–1651 гг.

- ^ С апреля 2013 года публикации Министерства обороны больше не сообщают обо всей численности регулярного резерва ; вместо этого учитываются только регулярные резервы, служащие по контракту о срочном резерве. Эти контракты по своей природе аналогичны контрактам Морского резерва .

- ^ На языке Королевского флота «входящие в строй корабли» неизменно относятся как к подводным лодкам , так и к надводным кораблям. или обслуживающие ее, Не входящие в строй корабли, эксплуатируемые Военно-морской службой Его Величества не включены.

- ^

- ^

- ^ Звание Адмирала Флота стало почетным/посмертным званием военного времени; церемониальный чин; регулярные назначения закончились в 1995 году.

- ^ Это звание было упразднено в 2014 году, но восстановлено в 2021 году.

Ссылки [ править ]

- ^ Титтлер, Роберт; Джонс, Норман Л. (2008). Спутник Тюдоровской Британии . Джон Уайли и сыновья. п. 193. ИСБН 978-1405137409 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Квартальная статистика обслуживающего персонала на 1 января 2024 года» . GOV.UK. Проверено 12 марта 2024 г.

- ^ «HMS Trent отправляется в свое первое развертывание» . Королевский флот . Проверено 3 августа 2020 г.

- ^ Военные самолеты: письменный вопрос - 225369 (Палата общин Hansard). Архивировано 26 августа 2016 г. на Wayback Machine , Parliament.uk, март 2015 г.

- ^ «Эксперты ВМФ по дронам 700X NAS готовы к использованию на военных кораблях» . Королевский флот .

- ^ «705-я морская авиационная эскадрилья» . Королевский флот .

- ^ Роуз, Сила на море , с. 36

- ^ Хайд-Прайс, Европейская безопасность , стр. 105–106.

- ^ «Королевский флот: британский трезубец для глобальной повестки дня» . Общество Генри Джексона . 4 ноября 2006 г. Архивировано из оригинала 11 сентября 2016 г. . Проверено 4 ноября 2006 г.

Британия с ее щитом и трезубцем является символом не только Королевского флота, но и британской глобальной мощи. И наконец, Королевский флот является величайшим стратегическим активом и инструментом Соединенного Королевства. Будучи единственным военно-морским флотом «голубой воды», кроме флота Франции и США, его подводные лодки с баллистическими ракетами несут на себе ядерное сдерживание страны, а авианосцы и эскортные военно-морские эскадрильи снабжают Лондон возможностью проецирования мощи в глубоком океане, что позволяет Британии поддерживать «передовое присутствие» во всем мире и способность тактически влиять на события во всем мире.

- ^ Беннетт, Джеймс С. (2007). Вызов англосферы: почему англоязычные страны будут лидировать в XXI веке . США: Роуман и Литтлфилд. п. 286. ИСБН 978-0742533332 .

...Соединенные Штаты и Великобритания имеют два лучших в мире военно-морских флота, охватывающих голубые воды... причем французы являются единственным другим кандидатом... а Китай является наиболее вероятным конкурентом в долгосрочной перспективе

- ^ «Что мы делаем» . Королевский флот. Архивировано из оригинала 30 декабря 2017 года . Проверено 30 декабря 2017 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Чайлдс, Дэвид (2009). Морская мощь Тюдоров: основа величия . Издательство Сифорт. п. 298. ИСБН 978-1473819924 .

- ^ Роджер, НАМ (1998). Защита моря: военно-морская история Великобритании, 660–1649 (1-е американское изд.). Нью-Йорк: WW Нортон. ISBN 978-0393319606 .

- ^ С. Мердок, Морской террор?: Шотландская морская война, 1513–1713 (Лейден: Брилл, 2010), ISBN 90-04-18568-2 , стр. 10.

- ↑ Роджер, Safeguard , стр. 52–53, 117–130.

- ^ Ферт, Мэтью; Себо, Эрин (2020). «Королевская власть и морская держава в Англии X века» . Международный журнал морской археологии . 49 (2): 329–340. Бибкод : 2020IJNAr..49..329F . дои : 10.1111/1095-9270.12421 . ISSN 1095-9270 . S2CID 225372506 .

- ^ Суонтон, с. 138.

- ^ Суонтон, стр. 154–165, 160–172.

- ^ Стэнтон, Чарльз (2015). Средневековая морская война . Южный Йоркшир: Pen & Sword Maritime. стр. 225–226.

- ^ Стэнтон, Чарльз Д. (2015). Средневековая морская война . Перо и меч. ISBN 978-1781592519 .

- ^ Мишель, Ф. (1840). История герцогов Нормандии и королей Англии . Париж. стр. 172–177.

- ^ Роджер, Safeguard , стр. 93–99.

- ↑ Роджер, Safeguard , стр. 91–97, 99–116, 143–144.

- ^ П. Ф. Титлер, История Шотландии, Том 2 (Лондон: Блэк, 1829), стр. 309–310.

- ^ П. Дж. Поттер, Готические короли Британии: жизни 31 средневекового правителя, 1016–1399 (Джефферсон, Северная Каролина: МакФарланд, 2008), ISBN 0-7864-4038-4 , с. 157.

- ^ А. Маккуорри, Средневековая Шотландия: родство и нация (Трупп: Саттон, 2004), ISBN 0-7509-2977-4 , с. 153.

- ^ НАМ Роджер, Защита моря: военно-морская история Великобритании. Том первый 660–1649 (Лондон: Харпер, 1997), стр. 74–90.

- ↑ Роджер, Safeguard , стр. 221–237.

- ↑ Роджер, Safeguard , стр. 238–253, 281–286, 292–296.

- ↑ Роджер, Safeguard , стр. 379–394, 482.

- ^ Джон Барратт, 2006, Войны Кромвеля на море . Барнсли, Южный Йоркшир; Ручка и меч; стр.

- ^ Роджер, Командование , стр. 2–3, 216–217, 607.

- ^ Деррик, Чарльз (1806). «Воспоминания о подъеме и развитии Королевского флота» . Архивировано из оригинала 30 декабря 2017 года . Проверено 30 декабря 2017 г.

- ^ Роджер, Командование , стр. 142–152, 607–608.

- ^ Грант, Джеймс изд. Старый флот Шотландии с 1689 по 1710 год. Общество военно-морских отчетов, 1914 год. п. 353: «1 мая 1707 года был заключен законодательный союз Англии и Шотландии; и шотландский и английский флоты были объединены и стали называться британским флотом... Флаг был изменен. Белый крест Святого Андрея на синем знамени Шотландии больше не обозначал шотландский военный корабль. Его место заняли Юнион Джек и красный, белый или синий флаг, из кантона которого был удален Георгиевский крест, и заменены комбинированными крестами Юнион Джека».

- ^ Роджер, Команда , стр. 608.

- ^ Роджер, Командование , стр. 291–311, 408–425, 473–476, 484–488.

- ^ Морисон, Сэмюэл Элиот (1965). Оксфордская история американского народа . Лондон: Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 0-19-500030-7 . OCLC 221276825 .

- ^ Роджер, Командование , стр. 277–283.

- ^ Роджер, Командование , стр. 284–287.

- ^ Роджер, Командование , стр. 351–352.

- ^ Паркинсон, стр. 91–114; Роджер, Командование , стр. 528–544.

- ^ Гардинер, Роберт (2001). Морская война 1812 года . Caxton Pictorial Histories (Chatham Publishing) совместно с Национальным морским музеем. ISBN 1-84067-360-5 .

- ^ Говард Дж. Фуллер (2014). Империя, технологии и морская мощь: кризис Королевского флота в эпоху Пальмерстона . Тейлор и Фрэнсис. п. 173-174. ISBN 9781134200450 .

- ^ Коломб, FSS, FRGS, и член Королевского колониального института, капитан JCR (1880 г.). ОБОРОНА ВЕЛИКОБРИТАНИИ И ВЕЛИКОБРИТАНИИ . 55, Чаринг-Кросс, Лондон, юго-запад: Эдвард Стэнфорд. Страницы 60–63, ГЛАВА III. КОЛОНИАЛЬНАЯ ОБОРОНА.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: местоположение ( ссылка ) CS1 maint: несколько имен: список авторов ( ссылка ) - ^ Коломб, FSS, FRGS, и член Королевского колониального института, капитан JCR (1880 г.). ОБОРОНА ВЕЛИКОБРИТАНИИ И ВЕЛИКОБРИТАНИИ . 55, Чаринг-Кросс, Лондон, юго-запад: Эдвард Стэнфорд. Страницы 125 и 126, ГЛАВА IV. ОБЯЗАННОСТИ ИМПЕРСКОЙ И КОЛОНИАЛЬНОЙ ВОЙНЫ.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: местоположение ( ссылка ) CS1 maint: несколько имен: список авторов ( ссылка ) - ^ Кейт, Артур Берридейл (1909). Ответственное правительство в Доминионах . Лондон: Stevens and Sons Ltd., с. 5.

Бермудские острова по-прежнему остаются имперской крепостью

- ^ Мэй, CMG, Королевская артиллерия, подполковник сэр Эдвард Синклер (1903). Принципы и проблемы имперской обороны . Лондон и Нью-Йорк: Swan Sonnenschein & Co., Limited, Лондон; EP Dutton & Co., Нью-Йорк. п. 145.

На североамериканской и вест-индийской станциях военно-морская база находится в императорской крепости Бермудские острова с гарнизоном, насчитывающим 3068 человек, из которых 1011 — колонисты; в то время как в Галифаксе, Новая Шотландия, у нас есть еще одна военно-морская база первостепенной важности, которую следует причислить к нашим имперским крепостям, и имеет гарнизон в 1783 человека.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: несколько имен: список авторов ( ссылка ) - ^ Уиллок Морской пехоты США , подполковник Роджер (1988). Оплот Империи: укрепленная военно-морская база Бермудских островов 1860–1920 гг . Бермудские острова: Издательство Бермудского морского музея. ISBN 978-0921560005 .

- ^ Гордон, Дональд Крейги (1965). Партнерство Доминиона в имперской обороне, 1870–1914 гг . Балтимор, Мэриленд: Johns Hopkins Press. п. 14.

За границей в колониальных гарнизонах дислоцировалось более 44 000 военнослужащих, и чуть более половины из них находились в имперских крепостях: в Средиземноморье, на Бермудских островах, в Галифаксе, на острове Св. Елены и на Маврикии. Остальные силы находились в собственно колониях, с большой концентрацией в Новой Зеландии и Южной Африке. Имперское правительство платило около 1 715 000 фунтов стерлингов в год на содержание этих сил, а различные колониальные правительства вносили 370 000 фунтов стерлингов, причем крупнейшие суммы поступали с Цейлона и Виктории в Австралии.

- ^ Макфарлейн, Томас (1891). Внутри Империи; Очерк Имперской Федерации . Оттава: James Hope & Co., Оттава, Онтарио, Канада. п. 29.

Помимо императорских крепостей на Мальте, в Гибралтаре, Галифаксе и Бермудских островах, он должен содержать и вооружать угольные станции и форты в Сиене-Леоне, острове Св. Елены, заливе Саймонс (на мысе Доброй Надежды), Тринкомали, Ямайке и Порт-Кастри ( на острове Санта-Лючия).

- ^ Алан Леннокс-Бойд, государственный секретарь по делам колоний (2 февраля 1959 г.). «Мальтийский (патентный законопроект)» . Парламентские дебаты (Хансард) . Парламент Соединенного Королевства: Палата общин. полковник 37.

с полным ответственным контролем над своими сугубо местными делами, контролем над военно-морскими и военными службами, а также над такими другими службами и функциями правительства, которые связаны с положением Мальты как имперской крепости и гавани, остающейся в ведении имперских властей.

- ^ Кеннеди, Р.Н., капитан У.Р. (1 июля 1885 г.). «Неизвестная колония: спорт, путешествия и приключения в Ньюфаундленде и Вест-Индии». Эдинбургский журнал Blackwood . Уильям Блэквуд и сыновья, Эдинбург и Лондон. п. 111.

- ^ ВЕРАКС (анонимно) (1 мая 1889 г.). «Защита Канады. (Из журнала Colburn's United Service Magazine)». Объединенная служба: ежеквартальный обзор военных и военно-морских дел . LR Hamersly & Co., Филадельфия; впоследствии Л.Р. Хамерсли, Нью-Йорк; БФ Стивенс и Браун, Лондон. п. 552.

Цели Америки четко обозначены: Галифакс, Квебек, Монреаль, Прескотт, Кингстон, Оттава, Торонто, Виннипег и Ванкувер. Галифакс и Ванкувер наверняка подвергнутся наиболее энергичному нападению, поскольку они, помимо Бермудских островов, будут военно-морскими базами, с которых Англия будет осуществлять свои военно-морские нападения на американские побережья и торговлю.

- ^ Доусон, Джордж М.; Сазерленд, Александр (1898). Географическая серия Макмиллана: Элементарная география британских колоний . Лондон: MacMillan and Co., Limited, Лондон; Компания MacMillan, Нью-Йорк. п. 184.

Имеется сильно укрепленная верфь, а оборонительные сооружения вместе со сложным характером подходов к гавани делают острова почти неприступной крепостью. Бермудские острова управляются как колония Короны губернатором, который также является главнокомандующим, которому помогают назначенный Исполнительный совет и представительная Палата собрания.

- ^ Сэр Генри Хардиндж, член парламента от Лонсестона (22 марта 1839 г.). «Снабжение – армейские оценки» . Парламентские дебаты (Хансард) . Том. 46. Парламент Соединенного Королевства: Палата общин. полковник 1141–1142.

- ^ Морис-Джонс, DSO, РА, полковник К.В. (1959). История береговой артиллерии британской армии . Великобритания: Королевский артиллерийский институт. п. 203.

В любом случае ее решение быть готовым противостоять японским амбициям в Восточной Азии – с американской помощью или без нее – включало в себя вызов японской военно-морской мощи и, таким образом, делало необходимым, в случае войны, присутствие британского боевого флота в Дальневосточные воды. Для такого флота потребовалась бы база — в 1920 году к востоку от Мальты не существовало базы британского боевого флота — и, хотя флот мог быть переброшен из Европы на Дальний Восток примерно за два или три месяца, база флота со всеми его доками На его строительство, верфей, береговых сооружений и оборонительных сооружений потребовалось много лет. В начале 1921 года британское правительство решило построить такую базу, и местом ее расположения был выбран Сингапур.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: несколько имен: список авторов ( ссылка ) - ^ «Как Британия стала править волнами?» . История Экстра. Архивировано из оригинала 7 марта 2019 года . Проверено 6 марта 2019 г.

- ^ Сондхаус, с. 161.

- ^ Браун, Пол (январь 2017 г.), «Строительство дредноута», поставки ежемесячно : 24–27.

- ^ Штайнер, Зара (2005). Огни, которые погасли: Европейская международная история, 1919–1933 гг . Оксфорд: Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 978-0-19-151881-2 . OCLC 86068902 .

- ^ Ховитт, Уильям (1865). «Путешествие капитанов Уикхема, Фицроя и Стоукса на корабле «Бигль» вокруг австралийских побережий с 1837 по 1843 год» . История открытий Австралии, Тасмании и Новой Зеландии: от древнейших времен до наших дней . Том. 1. Лондон: Лонгман, Грин, Лонгман, Робертс и Грин . п. 332.

- ^ Франклин, Бенджамин (1837). Работы Бенджамина Франклина . Таппан, Уиттемор и Мейсон. стр. 123–24 . Проверено 22 сентября 2011 г.

- ↑ Пинн, Ларри (30 мая 2007 г.) «Составление карты побережья», The Vancouver Sun , стр. B3.

- ^ «HMS 'Бигль' (1820–70)» . Королевские музеи Гринвича . Архивировано из оригинала 27 сентября 2013 года . Проверено 3 февраля 2013 г.

- ^ Годби, Холли (23 июня 2017 г.). «Недавнее обнаружение затонувшего корабля HMS Terror, бомбардировщика неудавшейся арктической экспедиции» . История войны онлайн .

- ^ Крейн, Д. (2005). Скотт из Антарктики: мужественная жизнь и трагедия на Крайнем Юге . Лондон: ХарперКоллинз . п. 409. ИСБН 978-0007150687 .

- ^ Райс, Алабама (1999). «Экспедиция Челленджера». Понимание океанов: морская наука после HMS Challenger . Лондон: UCL Press. стр. 27–48. ISBN 978-1-85728-705-9 .

- ^ Джеффри Беннетт, «Ютландская битва» History Today (июнь 1960 г.), 10 № 6, стр. 395–405.

- ^ « Отдаленная победа: Ютландская битва и триумф союзников в Первой мировой войне» , стр. xciv» . Praeger Security International. Июль 2006 г. ISBN. 9780275990732 . Проверено 30 мая 2016 г.

- ^ Гастингс, Макс (2013). Катастрофа 1914 года: Европа вступает в войну . Нью-Йорк. ISBN 978-0-307-59705-2 . OCLC 828893101 .

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: отсутствует местоположение издателя ( ссылка ) - ^ Тачман, Барбара В. (1994). Пушки августа . Нью-Йорк: Баллантайн. ISBN 0-345-38623-Х . OCLC 30087894 .

- ^ «Потопление немецкого крейсера Кенигсберг» . Национальный архив . Проверено 1 октября 2023 г.

- ^ Джонсон, Пол (1991). Новое время: мир от двадцатых до девяностых (Ред.). Нью-Йорк: ХарперКоллинз . ISBN 0-06-433427-9 . ОСЛК 24780171 .

- ^ «Вашингтонская военно-морская конференция, 1921–1922» . Кабинет историка. Архивировано из оригинала 29 декабря 2017 года . Проверено 1 января 2018 г.

- ^ Моррис (1979), с. 453

- ^ «Уважительные повстанцы: бунт в Инвергордоне и досье бабушки МИ5» . Би-би-си. 20 декабря 2016 г. Архивировано из оригинала 28 октября 2018 г. Проверено 1 января 2018 г.

- ^ Авраам, Дуглас А. (2019). Обработка подводных акустических сигналов: моделирование, обнаружение и оценка . Спрингер. ISBN 978-3-319-92983-5 .

- ^ «Королевский флот в 1939 и 1945 годах» . Военно-морская история.net. 8 сентября 1943 года. Архивировано из оригинала 1 сентября 2016 года . Проверено 28 декабря 2011 г.

- ^ «1939 год – Списки ВМФ» . Национальная библиотека Шотландии . Проверено 21 февраля 2016 г.

- ^ «Битва за Британию | История, значение и факты» . Британская энциклопедия . Проверено 17 сентября 2021 г.