Уайтснейк

Уайтснейк | |

|---|---|

Whitesnake выступит в 2022 году | |

| Справочная информация | |

| Источник | Лондон , Англия |

| Жанры | |

| Годы активности |

|

| Этикетки |

|

| Spinoffs | |

| Spinoff of | Deep Purple |

| Members |

|

| Past members | List of Whitesnake members |

| Website | whitesnake |

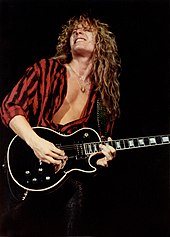

Whitesnake — английская хард-рок- группа, образованная в Лондоне в 1978 году. Первоначально группа была создана в качестве аккомпанирующей группы для певца Дэвида Ковердейла , недавно покинувшего Deep Purple . Хотя группа быстро превратилась в самостоятельную организацию, Ковердейл остается единственным постоянным участником за всю ее историю.

Following the EP Snakebite in 1978, Whitesnake released the albums Trouble (1978) and Lovehunter (1979), which included the live staples "Ain't No Love in the Heart of the City" and "Walking in the Shadow of the Blues". Whitesnake soon began to make a name for themselves across the UK, Europe and Japan, with their subsequent albums Ready an' Willing (1980), Live... in the Heart of the City (1980), Come an' Get It (1981) and Saints & Sinners (1982) all reaching the top ten on the UK Albums Chart. By the mid-1980s, Coverdale had set his sights on North America, where Whitesnake remained largely unknown. With the backing of American label Geffen Records, Whitesnake released Slide It In in 1984, featuring the singles "Love Ain't No Stranger" and "Slow an' Easy", which furthered the band's exposure through heavy airplay on MTV. In 1987, Whitesnake released their eponymous album Whitesnake, their biggest success to date, selling over eight million copies in the United States and spawning the hit singles "Here I Go Again », « Is This Love » и « Still of the Night ». Whitesnake также приняла более современный вид, родственный глэм-метал- сцене Лос-Анджелеса.

After releasing Slip of the Tongue in 1989, Coverdale decided to take a break from the music industry. Aside from a few short-lived reunions related to the release of Greatest Hits (1994) and Restless Heart (1997), Whitesnake remained mostly inactive until 2003, when Coverdale put together a new line-up to celebrate the band's 25th anniversary. Since then Whitesnake have released four more studio albums Good to Be Bad (2008), Forevermore (2011), The Purple Album (2015), Flesh & Blood (2019) and toured extensively around the world.

Whitesnake's early sound has been characterized by critics as blues rock, but by the mid-1980s the band slowly began moving toward a more commercially accessible hard rock style. Topics such as love and sex are common in Whitesnake's lyrics, which make frequent use of sexual innuendos and double entendres. Whitesnake have been nominated for several awards during their career, including Best British Group at the 1988 Brit Awards. They have also been featured on lists of the greatest hard rock bands of all time by several media outlets,[1][2] while their songs and albums have appeared on many "best of" lists by outlets, such as VH1 and Rolling Stone.[3][4][5]

History

Formation, Snakebite and Trouble (1976–1978)

In March 1976, singer David Coverdale left the English hard rock group Deep Purple. He had joined the band three years prior and recorded three successful albums with them. After leaving Deep Purple, Coverdale released his solo album White Snake in May 1977.[6] His second solo album Northwinds was released in March 1978.[7] Both combined elements of blues, soul and funk, as Coverdale had wanted to distance himself from the hard rock sound synonymous with Deep Purple.[8] Both records featured former Snafu guitarist Micky Moody, whom Coverdale had known since the late 1960s.[9] Moody was the first to join Coverdale's backing band, which he began assembling in London.[10][11] As stated by Coverdale, "Whitesnake were actually formed to promote Northwinds on a one-off promotional tour".[12] Moody suggested bringing in a second guitarist, with the spot ultimately going to Bernie Marsden, formerly of UFO and Paice Ashton Lord.[11][13] With his help, the band were able to recruit bassist Neil Murray, who had played with Marsden in Cozy Powell's Hammer.[14] The group's initial line-up was rounded out by drummer Dave "Duck" Dowle and keyboardist Brian Johnson, who had played together in Streetwalkers.[15] Other early candidates for the band were drummers Cozy Powell and Dave Holland, as well as guitarist Mel Galley.[16]

The band, dubbed David Coverdale's Whitesnake, played their first show at Lincoln Technical College on 3 March 1978.[17][18] Their live debut had originally been scheduled for 23 February at the Sky Bird Club in Nottingham, but the show was cancelled.[18][19] Coverdale had originally wanted the group to be simply called Whitesnake, but was forced to use his own name as it still carried some clout as the former lead singer of Deep Purple.[20][21][22] In a 2009 interview with Metro, Coverdale jokingly stated that the name "Whitesnake" was a euphemism for his penis. In fact, it came from the song of the same name found on his first solo album.[23]

After completing a small UK club tour, the band adjourned to a rehearsal place in London's West End to begin writing new songs.[11] They soon caught the attention of EMI International's Robbie Dennis, who wanted to sign the group. According to Bernie Marsden, however, his higher-ups were not ready to commit to a full album. Thus, the band entered London's Central Recorders Studio in April 1978 to record an EP.[24] By this point, original keyboardist Brian Johnston had been replaced by Pete Solley.[21] Martin Birch, who had worked with Coverdale during his time in Deep Purple, was chosen to produce.[19]

The resulting record, Snakebite, was released in June 1978.[21] In Europe, the EP was combined with four tracks from Coverdale's Northwinds to make up a full-length album.[21] Snakebite contained a slowed down cover of Bobby Bland's "Ain't No Love in the Heart of the City", which had originally been used by the band to audition bass players. While the song was only included because the group were short on songs, the track would later become a popular live staple at Whitesnake concerts, with Coverdale calling it "the national anthem of the Whitesnake choir", referring to the band's audience.[25][12] When Snakebite reached number 61 on the UK Singles Chart,[26] the band were duly signed to EMI proper.[27]

In July 1978, the band (now known simply as Whitesnake) entered Central Recorders in London to begin work on their first proper studio album with Martin Birch once again producing. The recording and mixing only took ten days.[28] Towards the end of the sessions, Pete Solley's keyboard parts were completely replaced by Coverdale's former Deep Purple bandmate Jon Lord, who agreed to join Whitesnake after much coaxing from Coverdale.[29][30] Colin Towns and Tony Ashton had also been approached, having previously played with fellow Deep Purple offshoots the Ian Gillan Band and Paice Ashton Lord, respectively.[28]

Whitesnake's debut album Trouble was released in October 1978,[21] and it reached number 50 on the UK Albums Chart.[31] In a retrospective review for AllMusic, Eduardo Rivadavia stated: "A few unexpected oddities throw the album off-balance here and there, [...] but all things considered, it is easy to understand why Trouble turned out to be the first step in a long, and very successful career."[32] The release of Trouble was followed by an 18-date UK tour, beginning on 26 October 1978.[33] The final show at the Hammersmith Odeon in London was recorded and released in Japan as Live at Hammersmith.[34] According to Coverdale, this was done to appease Japanese promoters who allegedly refused to book Whitesnake without some kind of a live recording.[35]

Lovehunter and Ready an' Willing (1979–1980)

Whitesnake embarked on their first continental European tour on 9 February 1979 in Germany.[33] In April, they began recording their second album at Clearwell Castle in Gloucestershire, where Coverdale had previously worked with Deep Purple. Martin Birch returned to produce and the band employed the Rolling Stones Mobile Studio to record.[36] Bernie Marsden later described the resulting record as a "transition album", where the band really began to "blossom" and find their footing.[37] The album also included the live staple "Walking in the Shadow of the Blues", which Coverdale felt "really summed up my musical approach of the time".[12][38][39]

Before the record's release, drummer Dave "Duck" Dowle was replaced by Ian Paice, Coverdale and Lord's former Deep Purple bandmate.[40] There is some contention as to the nature of Dowle's departure. Coverdale has maintained that Dowle's lacking performance on the album and unwillingness to "take constructive criticism" led to his firing.[40][39] Bernie Marsden, meanwhile, asserted that Dowle left because he didn't like being at Clearwell Castle and away from his family.[39] The idea of Paice re-recording Dowle's drum parts was considered, but ultimately rejected by the band's management due to the alleged cost.[41] Paice's addition also spurred speculation from the British music press about Coverdale mounting a Deep Purple reunion, which he denied.[40] Coverdale later remarked how Paice joining the band felt like "truly the beginning of Whitesnake", where all the members were "performing at [their] absolute best" and "inspiring the best out of each other".[38]

Lovehunter, Whitesnake's second album, was released in October 1979,[39] and it reached number 29 on the UK Albums Chart.[42] Sounds gave the record a positive review,[36] while AllMusic's Eduardo Rivadavia was more mixed, commending many of the songs, but criticizing the band's studio performance as "strangely tame".[43] The album's cover art, depicting a naked woman straddling a giant serpent, caused some controversy when the record was released. Whitesnake had already received criticism from the British music press for their alleged sexist lyrics. The cover art for Lovehunter, done by artist Chris Achilleos, was reportedly commissioned to "just piss [the critics] off even more".[36][38] In North America, a sticker was placed on the cover to hide the woman's buttocks, while in Argentina the cover art was modified so that the woman wore a chain-mail bikini.[39] Nevertheless, Whitesnake began a supporting tour for Lovehunter on 11 October 1979 in the UK, followed by dates in Europe.[44]

After completing the supporting tour for Lovehunter, Whitesnake promptly started work on their third album at Ridge Farm Studios, with Martin Birch once again producing.[40] The resulting record, Ready an' Willing, was released on 31 May 1980,[45] and it reached number six on the UK Albums Chart.[46] It also became the band's first album to chart in the US, where it reached number 90 on the Billboard 200 chart.[47] Its success was helped by the lead single "Fool for Your Loving", which reached number 13 and number 53 in the UK and the US, respectively.[48][49] Geoff Barton, writing for Sounds, gave Ready an' Willing a positive review, awarding it four stars out of five.[40] Eduardo Rivadavia of AllMusic commended the band's growing consistency, but still described the production as "flat".[50] Micky Moody and Bernie Marsden later named Ready an' Willing their favourite Whitesnake album.[51] In the UK, the record was certified gold by the British Phonographic Industry for sales of over 100,000 copies.[52]

In support of Ready an' Willing, Whitesnake toured the US for the first time supporting Jethro Tull. Later that year, they supported AC/DC in Europe.[53] With the benefit of a hit single, Whitesnake's audience in the UK began to grow.[38] Thus, the band recorded and released the double live album Live... in the Heart of the City. The record combined new material recorded in June 1980 at the Hammersmith Odeon with the previously released Live at Hammersmith album.[35] Live... in the Heart of the City proved to be an even bigger success than Ready an' Willing, reaching number five in the UK.[54] It would later go platinum, with sales of over 300,000 copies.[55] In North America, the album was released as a single record version, excluding the live material from 1978.[56]

Come an' Get It and Saints & Sinners (1981–1982)

In early 1981, Whitesnake began recording their fourth studio album with producer Martin Birch at Ringo Starr's Startling Studios in Ascot, Berkshire. After the success of Ready an' Willing and Live... in the Heart of the City, Whitesnake were riding high with the atmosphere in the studio being described by Coverdale as "great" and "positive". The resulting record, Come an' Get It, was released on 6 April 1981.[57] Charting in seven countries, it gave the group their highest ever UK chart position at number two.[58] That same year, the album was certified gold.[59] The single "Don't Break My Heart Again" also charted at number seventeen in the UK.[60] Circus magazine gave the album a positive review, which proclaimed: "[Whitesnake] has made its claim to rock history with Come an' Get It, which even stands ahead of classic hard rock in the Free mold."[61] Coverdale later named the record his favorite album of the band's early years, stating: "Even though we had some great songs on each album, I don't feel that we came as close as we did on [Come an' Get It], as far as consistency is concerned.[57]

Whitesnake kicked off the supporting tour for Come an' Get It on 14 April 1981 in Germany.[62] During the tour, the band performed five nights at the Hammersmith Odeon and eight dates in Japan.[62][63] They also played the US in July, supporting Judas Priest with Iron Maiden.[62] At the 1981 Monsters of Rock festival at Castle Donington, Whitesnake were direct support for headliners AC/DC.[57] The supporting tour for Come an' Get It lasted approximately five months.[64]

In late 1981, Coverdale retreated to a small villa in southern Portugal to begin writing the band's next album. After returning to England, he and the rest of Whitesnake gathered at Nomis Studios in London to begin rehearsals. However, as Coverdale would later explain: "There wasn't that 'spark' that was usually in attendance. It felt more of an effort to be there."[64] Micky Moody later stated that by the end of 1981, the band had become tired, partially from "too many late nights, too much partying".[65] In an effort to lift their collective spirits, Whitesnake returned to Clearwell Castle in Gloucestershire, where they had recorded Lovehunter. Though morale still remained low, the band were able to record the basic tracks for their next album. Guy Bidmead replaced producer Martin Birch, who was reportedly too ill to work at the time (Birch did eventually return when recording moved to Britannia Row.[64]). This exacerbated the band's ever worsening mental state.[66]

To make matters worse, the band were experiencing financial troubles with Moody recalling: "We weren't making nowhere near the kind of money we should have been making. Whitesnake always seemed to be in debt, and I thought 'What is this?, we're playing in some of the biggest places and we're still being told we're in debt, where is all the money going?'."[65] Eventually, Moody became fed up with the situation and left Whitesnake in December 1981.[65] The remaining band members blamed the group's management company Seabreeze, headed by Deep Purple's former manager John Coletta, for their financial state.[22][12][67] According to Bernie Marsden, the band set up a meeting to fire Coletta, but Coverdale failed to show. Instead, Marsden, Neil Murray and Ian Paice were informed that Whitesnake had been put on hold and that they had been fired.[67] Marsden later remarked that "David [Coverdale] decided he would be king of Whitesnake".[12]

According to Coverdale, his decision to put the band on hold stemmed from his daughter contracting bacterial meningitis.[64][68] This purportedly gave him the courage to cut ties with Coletta. Coverdale ended up buying himself out of his contracts, which reportedly cost him over a million dollars.[12][68] As for the firing of Marsden, Murray and Paice, Coverdale felt they lacked the needed enthusiasm to keep working in Whitesnake.[12][67] Coverdale stated that it was "a business decision, not personal".[64]

After waiting for his daughter to recuperate and severing ties with the band's management, record companies and publishers, Coverdale began putting Whitesnake back together. Micky Moody and Jon Lord agreed to return, while guitarist Mel Galley, bassist Colin Hodgkinson and drummer Cozy Powell were brought in as new members.[12][64] Coverdale completed the band's new record with Martin Birch in October 1982 at Battery Studios in London, with the majority of the album having already been recorded with Marsden, Murray, Paice, Moody and Lord before the hiatus.[66] Saints & Sinners was released on 15 November 1982.[64] It reached number nine in the UK and charted in eight additional countries.[69] In the UK, the record was certified silver.[70] Chas de Whalley, writing for Kerrang!, gave the album a lukewarm review. Save for two tracks ("Crying in the Rain" and "Here I Go Again"), he characterized the rest of the record as generally mediocre.[71] Conversely, AllMusic's Eduardo Rivadavia, in a retrospective review, hailed Saints & Sinners as Whitesnake's "best album yet".[72]

By the time Saints & Sinners was released, Coverdale had signed a new recording contract with American label Geffen Records, who would handle all future Whitesnake releases in North America. In Europe, the band remained with Liberty (a subsidiary of EMI), while in Japan, they signed with Sony.[73][74] A&R executive John Kalodner, who had been a long-time fan of Coverdale's, convinced David Geffen to sign the group.[73] Meeting Geffen and Kalodner had a major impact on Coverdale and his future vision for Whitesnake. He explained: "I'd been surrounded by a mentality if you make five pounds profit let's go to the pub. Whereas David Geffen said to me 'If you can make five dollars profit, why not 50? If 50, why not 500? Why not 50,000, why not five million?'" Coverdale soon set his sights on breaking through in North America with Kalodner advising him.[68][75] Meanwhile, Whitesnake began a supporting for Saints & Sinners on 10 December 1982 in the UK.[66][76]

Slide It In (1983–1984)

Whitesnake toured across Europe and Japan in early 1983,[66] before starting rehearsals for their next album at Jon Lord's house in Oxfordshire.[77] At this time, Coverdale began steering Whitesnake's music more towards hard rock, which was emphasized by the additions of Mel Galley and Cozy Powell, whose past projects included Trapeze and Rainbow, respectively.[65][78] Majority of Whitesnake's next album was co-written by Coverdale and Galley, while Micky Moody contributed to only one song.[79] Whitesnake began recording their sixth album at Musicland Studios in Munich with producer Eddie Kramer, who had come recommended by John Kalodner.[77][80]

In August 1983, Whitesnake headlined the Monsters of Rock festival at Castle Donington, England. The show was filmed and later released as the band's first long-form video, titled Whitesnake Commandos. The band also premiered the new single "Guilty of Love", which was released to coincide with the festival. The entire album had originally been slated for release three weeks prior to the Donington show, but failed to meet the deadline. The band were having problems adapting to Eddie Kramer's style of producing, particularly his method of mixing the record. Eventually things came to a head and Kramer was let go. Coverdale then rehired Martin Birch to complete the album.[77] A new release date for the record was set for mid-November with a supporting tour scheduled to start in December.[81]

As Whitesnake finished up a European tour in October 1983, Micky Moody left the group. He later attributed his departure to a growing dissatisfaction working in the band, particularly with Coverdale: "Me and David weren't friends and co-writers anymore. [...] David was a guy who five, six years earlier was my best friend. Now he acted as if I wasn't there."[12][65] Moody also felt uncomfortable with the level of influence he felt John Kalodner was having on the band.[82] As he explained: "I never wanted to be a great big star. [...] I found it difficult to be a rock star, I really did."[12] Colin Hodgkinson was also let go in late 1983, only to be replaced by his predecessor Neil Murray. Coverdale later explained the decision to rehire Murray by simply stating: "I'd missed his playing".[77] Towards the end of 1983, Jon Lord also informed Coverdale of his intention to leave the band, but Coverdale convinced him to stay until the supporting tour for their next album was over.[83] With the line-up changes and troubled production of the album, both the record and its accompanying tour were delayed until early 1984.[84]

"I thought [David Coverdale] was a star frontman, a star singer, I felt he had a mediocre band and just average songs. My job was to make them a commercial rock band for the United States."

—John Kalodner on his role working with Whitesnake.[85]

According to Coverdale, John Kalodner had convinced him that in order for the band to achieve their full potential, they needed a "guitar hero" that could match Coverdale as a frontman.[86] Therefore, to replace Moody, Coverdale initially looked to Michael Schenker and Adrian Vandenberg. Schenker claims he turned down the offer to join Whitesnake, while Coverdale insists he decided to pass on Schenker.[68][87] Vandenberg declined the offer to join as well, due to the success he was having with his own band at the time.[68][88] Coverdale then approached Thin Lizzy guitarist John Sykes, whom he had met when Whitesnake and Thin Lizzy played some of the same festivals in Europe.[89] Sykes was initially reluctant to join, wanting instead to continue working with Thin Lizzy frontman Phil Lynott, but after several more offers and Lynott's blessing he accepted.[90] John Sykes and Neil Murray were officially confirmed as members of Whitesnake in January 1984.[91][92]

Slide It In, Whitesnake's sixth studio album, was released on 30 January 1984.[93] On the UK Albums Chart, it reached number nine.[94] The album's highest chart position was in Finland, where it reached number four.[95] Slide It In received mixed reviews from critics, with the production being a common complaint.[96][97] Dave Dickson, writing for Kerrang!, called the record "the best thing Whitesnake have yet committed to vinyl",[98] while Record Mirror's Jim Reid was highly critical of the lyrical content.[99] AllMusic's Eduardo Rivadavia, in a retrospective review, called Slide It In "an even greater triumph" than the band's previous works,[100] whereas Garry Bushell of Sounds gave the album a particularly scathing review, in which he likened Coverdale's voice to that of a "dying dog".[12][97]

Whitesnake's new line-up made their live debut in Dublin on 17 February 1984.[101] During a tour stop in Germany, Mel Galley broke his arm leaping on top of a parked car. He sustained nerve damage, leaving him unable to play guitar. As a result, Galley was forced to leave Whitesnake.[97][102][103] By April 1984, a reunion of Deep Purple's Mark II line-up had become imminent, which led to Jon Lord also leaving. He played his final show with Whitesnake on 16 April 1984.[97] That same day, Geffen Records released Slide It In in North America.[104] Kalodner had been unimpressed by Martin Birch's work on the album and had demanded a complete remix for the American market. Though initially reluctant, Coverdale agreed after a trip to Geffen's offices in Los Angeles, where he came to the conclusion that Whitesnake's studio approach had become "dated" by American standards. Keith Olsen was brought on board to remix Slide It In, while John Sykes and Neil Murray were tasked with re-recording Micky Moody and Colin Hodgkinson's parts, respectively.[105] The remixed version of Slide It In reached number 40 on the Billboard 200 chart.[106] By 1986, the album had sold over 500,000 copies in the US.[107] Critical reception was also positive, with Pete Bishop of The Pittsburg Press calling the album "muscular, melodic and musical all together".[108]

With the band now left as a four-piece (with Richard Bailey providing keyboards off-stage),[109] Whitesnake supported Dio for several show in the US, after which they toured Japan as a part of the Super Rock '84 festival.[110][111] Later that year, Whitesnake embarked on a six-week North American tour supporting Quiet Riot.[112] To further the band's reach in America, Whitesnake shot two music videos for the singles "Slow an' Easy" and "Love Ain't No Stranger", respectively.[113] Both songs reached the Top Tracks chart in the US.[114][115] In an effort to take America more seriously, Coverdale also relocated to the US.[116]

Whitesnake (1985–1988)

The supporting tour for Slide It In came to an end in January 1985, when Whitesnake played two shows at the Rock in Rio festival in Brazil.[117] After the tour ended, Cozy Powell parted ways with the band. According to Coverdale, his relationship with Powell had deteriorated increasingly over the course of the tour. After the final show, Coverdale flew to Los Angeles to inform Geffen Records he was letting the rest of the band go. Coverdale was persuaded to keep Sykes involved (as Geffen felt they formed a "strong image together"), while also changing his mind about Murray. Powell, however, was fired.[118] According to Murray, Powell's departure was the result of financial disputes.[119] Coverdale would later state that Powell didn't feel like the offer he got for his involvement was "appropriate".[120]

Coverdale and Sykes retreated to the South of France in early 1985 to begin writing the band's next album. The sessions proved fruitful and they were joined by Murray, who helped with the arrangements.[117] The new material saw Whitesnake moving further away from their bluesier roots in favour of a more American hard rock sound.[122][123] John Kalodner also convinced Coverdale to re-record two songs from the Saints & Sinners album, "Here I Go Again" and "Crying in the Rain", which he thought had great potential with better production and arranging.[124] With new material ready, the band then began searching for a new drummer. A reported sixty drummers auditioned for the group, with prolific session drummer Aynsley Dunbar eventually being chosen. Former Ozzy Osbourne drummer Tommy Aldridge was also offered the spot, but an equally satisfactory agreement couldn't be reached.[118] Drummer Carmine Appice claimed to have turned down the position due to commitments with his own band King Kobra. Appice would later join Sykes in Blue Murder.[125]

The band began tracking their new record at Little Mountain Sound Studios in Vancouver with producer Mike Stone.[126] By early 1986, much of the album had been recorded.[117] When it came time for Coverdale to record his vocals though, he noticed his voice was unusually nasal and off-pitch. After consulting several specialists, it was revealed that Coverdale had contracted a severe sinus infection. After receiving some antibiotics, Coverdale flew to Compass Point Studios in the Bahamas to resume recording. However, the infection resurfaced which caused Coverdale's septum to collapse. He required surgery, followed by a six-month rehabilitation period.[118] Sykes has disputed this, claiming Coverdale was just suffering from nerves and that he used "every excuse possible" not to record his vocals.[127] After recovering from surgery, Coverdale, by his own account, did develop a "mental block" that prevented him from singing.[128] Following some failed sessions with Ron Nevison, Coverdale was finally able to record his vocals with producer Keith Olsen.[118] By late 1986, production on the record was mostly finished. Keyboards were provided by Don Airey and Bill Cuomo, while Adrian Vandenberg was brought in to do some guitar overdubs.[117] Additional guitar parts were also provided by Dann Huff.[129]

By the time the album was finished, Coverdale was the sole remaining member of Whitesnake. "It was a band in disarray..." observed keyboardist Don Airey. "David was four million dollars in debt; didn't know if he was coming or going."[130] Coverdale has claimed that Sykes and Mike Stone were fired after they began conspiring against him by booking studio time and making decisions without his involvement.[118] Stone allegedly suggested bringing in someone else to record Coverdale's vocals while he was recovering from surgery.[131] Sykes has denied this, instead claiming that he and other members were systematically fired as soon as they finished recording their parts.[127] Murray and Dunbar had stopped receiving their wages in April 1986, at which point Dunbar immediately left Whitesnake. Murray was still officially a member of the group until January 1987, when he heard Coverdale was putting together a new line-up.[132][133]

With the help of John Kalodner, Coverdale recruited Adrian Vandenberg and Tommy Aldridge, as well as guitarist Vivian Campbell (formerly of Dio) and bassist Rudy Sarzo (formerly of Quiet Riot) to the band.[68][134][135] This new line-up would appear in all the promotional materials for the forthcoming album.[136] Whitesnake also adopted a new image, akin to glam metal bands of the time, in order to appeal more to American audiences. When asked about the band's makeover, Coverdale responded: "I'm competing with people like Jon Bon Jovi. I've gotta look the part."[137]

Whitesnake (titled 1987 in Europe and Serpens Albus in Japan) was released on 30 March 1987 in Europe and 7 April in North America.[138][139] It peaked at number eight in the UK, while in the US it reached number two on the Billboard 200 chart.[140][141] In total, the record charted in 14 countries and quickly became the most commercially successful of the band's career, selling over eight million copies in the US alone.[107] Its success also boosted Slide It In's sales to over two million copies in the US.[107] The singles "Here I Go Again" and "Is This Love" reached number one and two, respectively, on the Billboard Hot 100.[121][142] In the UK, both reached number nine.[143][144] The record's success was helped by the heavy airplay Whitesnake received on MTV, courtesy of a trilogy of music videos featuring actress and Coverdale's future wife Tawny Kitaen.[137] The album was generally well received by critics, though reviews in the UK were less favourable, with Coverdale being accused of "selling out" to America, which he strongly denied.[109] Rolling Stone's J. D. Considine praised the band's ability to present old ideas in new and interesting ways, while AllMusic's Steve Huey, in a retrospective review, touted the album as the band's best.[145][146]

The new Whitesnake line-up made their live debut following the record's release at the Texxas Jam festival in June 1987.[137] They then toured the US supporting Mötley Crüe on their Girls, Girls, Girls Tour.[88] Beginning on 30 October 1987,[147] Whitesnake embarked on a headlining arena tour, which was temporarily interrupted in April 1988, when Coverdale had a herniated disc removed from his lower back.[88][148][149] At the 1988 Brit Awards, the band were nominated for Best British Group, while the album Whitesnake was nominated for Favorite Pop/Rock Album at the American Music Awards.[150][151]

When the supporting tour for Whitesnake ended in August 1988,[152] Coverdale informed the rest of the band that the next album would be written by him and Adrian Vandenberg, who had established a fruitful working relationship together.[136] After approximately a month of writing, the band regrouped at Lake Tahoe for three weeks of rehearsals.[153] In December 1988, Vivian Campbell parted ways with the band. The official reason given was "musical differences".[154] However, Campbell later revealed that his departure was partially due to a falling out between his wife and Tawny Kitaen. This resulted in Campbell's wife being barred from the band's tour. In addition to this, Vandenberg had made it known that he wanted to be the sole guitarist in Whitesnake, which also played into Campbell's departure.[136][155]

Slip of the Tongue (1989–1990)

Whitesnake began recording their eighth studio album in January 1989.[156] Bruce Fairbairn was initially chosen to produce, but was forced to drop out due to scheduling conflicts. The band then hired both Keith Olsen and Mike Clink to produce the record.[157] Coverdale later explained the decision to hire two producers, citing pressure to follow-up the band's previous record: "I brought them both in... Just that decision alone tells me I was in fear of failing..."[158]

During the recording process, Adrian Vandenberg sustained an injury to his wrists while performing some playing exercises. Despite consulting a doctor and significant rest, the injury persisted, leaving Vandenberg unable to play the guitar properly.[153] It wasn't until 2003 that he learned the injury was the result of nerve damage sustained in a 1980 car accident.[88] Vandenberg's injury caused significant delays to the album, which had originally been slated for release in June–July 1989.[159] Ultimately, Coverdale was forced to find another guitar player to finish the record.[158] He opted to recruit former Frank Zappa and David Lee Roth guitarist Steve Vai, whom he had seen in the 1986 film Crossroads a few years earlier.[158] According to Coverdale, he had originally wanted to recruit Vai back then, but John Sykes ultimately rejected the idea.[68] Vai officially joined Whitesnake in March 1989.[160] Vandenberg, meanwhile, was given time to recuperate while Vai recorded the album.[153] Vandenberg is still minimally featured on the finished record.[158]

The lead single from the band's new album was a re-recorded version of "Fool for Your Loving", originally found on 1980's Ready an' Willing.[161] Coverdale had been reluctant to re-record the song, let alone release it as the first single, but Geffen Records hoped to repeat the success of "Here I Go Again" with another older track. Coverdale later admitted it to regretting the decision.[158][161][162] "Fool for Your Loving" only peaked at number 37 on the Billboard Hot 100.[163] It fared better on the Album Rock Tracks chart, where it peaked at number two.[164] The second single "The Deeper the Love" also stalled at number 28 on the Hot 100,[165] while on the Album Rock Tracks chart it reached number four.[166]

Slip of the Tongue was released on 7 November 1989 in the US, followed by a worldwide release on 13 November.[167][168] It reached number ten on the UK Albums Chart, as well as the Billboard 200.[169][170] The record also charted in twelve additional countries. Slip of the Tongue was certified platinum in the US and has sold approximately four million copies worldwide by 2011.[68][107] As the previous record sold more than twice that in the US alone, Slip of the Tongue was considered a commercial disappointment.[161]

Malcolm Dome, writing for Raw, described Slip of the Tongue as "an album full of generally good songs that rarely sinks below the level of adequacy, but only occasionally explodes".[171] The combination of Whitesnake and Steve Vai was also met with some criticism, with Thom Jurek, in a retrospective review for AllMusic, describing the pairing as "questionable".[172] Coverdale himself would later admit to having mixed feelings about the record, though he has since learned to enjoy and accept it as a part of Whitesnake's catalogue.[158]

In February 1990, Whitesnake embarked on the Liquor & Poker World Tour, during which the band headlined the Monsters of Rock festival at Castle Donington for a second time (the show was later released as a live album).[173][174] The final tour date was on 26 September 1990 at the Budokan in Tokyo.[68][175] After the show, Coverdale informed the rest of the band that he would be taking an extended break, effectively disbanding Whitesnake. He encouraged the band members to accept any outside offers for work.[68] Coverdale's decision to put Whitesnake on hold was largely due to exhaustion. Despite the success the band had achieved, he felt unfulfilled.[68] He had also become disillusioned with the band's glam image.[176] Coupled with his ongoing divorce from Tawny Kitaen, Coverdale wanted to "take stock and review" to see if he still wanted to continue in the music business.[68]

After Whitesnake disbanded, Steve Vai continued his solo career, having already released his second solo album while on tour with Whitesnake.[161] Vandenberg, Sarzo and Aldridge would go to form the band Manic Eden, who released one album in 1994.[88] Coverdale resurfaced in 1993, when he and Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page released an album together.[176][177]

Greatest Hits and Restless Heart (1994–1997)

On 4 July 1994, EMI released Whitesnake's Greatest Hits in Europe.[178] In the US, it was released on 19 July by Geffen Records.[179] The record proved to be a success, reaching number four on the UK Albums Chart.[180] It would later be certified gold in the UK and platinum in the US.[107][181] Prior to the record's release, Coverdale had been planning a European solo tour with a backing band he likened to Joe Cocker's Mad Dogs & Englishmen.[68] Because of the Greatest Hits' success, Coverdale was instead asked by EMI to tour as Whitesnake.[68] Though reluctant, Coverdale eventually agreed, seeing it as an opportunity to just have fun and play live.[182][183][184]

Adrian Vandenberg agreed to rejoin Whitesnake as he and Coverdale were already working on new music together. Vandenberg asked Rudy Sarzo to rejoin as well as they were both still playing in Manic Eden at the time. Sarzo accepted and recommended Ratt guitarist Warren DeMartini to the band. The line-up was then rounded out by keyboardist Paul Mirkovich and drummer Denny Carmassi, the latter of whom had played on the Coverdale–Page album.[185][186] The tour began in Europe on 20 June 1994, followed by several UK dates beginning in July.[187] In October, the band toured in Japan and Australia.[188][189]

After completing the Greatest Hits tour, Whitesnake were dropped by Geffen Records.[190] Coverdale then resumed writing with Adrian Vandenberg on what was to be a solo album.[191] Joining them in the studio were Denny Carmassi, as well as bassist Guy Pratt and keyboardist Brett Tuggle.[192] As the record was being finished, the new higher-ups at EMI demanded it be released under the Whitesnake moniker. Coverdale objected, as he felt the record was stylistically too different from the band. Eventually a compromise was reached, and Coverdale agreed to release the album under the name "David Coverdale & Whitesnake". As a result of the name change, the guitars and drums on the album were brought up in the mix, something Coverdale later expressed disappointment over.[191]

Restless Heart was released on 26 March 1997 in Japan,[193] followed by a European release on 26 May.[194] The record only reached number 34 on the UK Albums Chart,[195] but peaked number three on UK Rock & Metal Albums Chart.[196] It charted in nine additional countries as well, with its highest chart position being in Sweden at number five. The single "Too Many Tears" only reached number 46 on the UK Singles Chart,[197] but on the UK Rock & Metal Singles Chart it reached number five and charted for 34 weeks.[198] Restless Heart didn't receive a US release, being available only as an import.[199][200] Rock Hard called the album "nice, but harmless", and ultimately deemed it "a mean disappointment" as potentially the last Whitesnake album.[201] Jerry Ewing, writing for Classic Rock, described it as a "curio" in the band's discography, falling somewhere between a Whitesnake album and a David Coverdale solo record.[202]

The supporting tour for Restless Heart was billed as Whitesnake's farewell tour, as Coverdale wanted to explore other musical avenues.[192] Pratt and Tuggle were replaced by Tony Franklin and Derek Hilland, respectively, while Steve Farris was recruited as a second guitarist.[203] Before the start of the tour, Coverdale and Vandenberg played several acoustic shows in Europe and Japan. One of these shows was later released as the live album Starkers in Tokyo.[184] The Last Hurrah tour began in September 1997 and ended in South America that December.[192][204][205] After the band's disbandment, Coverdale resumed his solo career, releasing the album Into the Light in 2000.[184] Vandenberg, meanwhile, began a second career as a painter in order to spend more time with his daughter, who was born in 1999.[206]

Reformation and Good to Be Bad (2003–2009)

In October 2002, David Coverdale announced plans to reform Whitesnake to celebrate the band's 25th anniversary in 2003.[207][208] The new line-up was confirmed in December; Coverdale would be joined by drummer Tommy Aldridge, guitarists Doug Aldrich and Reb Beach, as well as bassist Marco Mendoza and keyboardist Timothy Drury.[209]

Talks had taken place between Coverdale and John Sykes about a possible reunion, but Coverdale ultimately felt that they had been their "own bosses" too long for a reunion to work.[68] Sykes, meanwhile, claimed that after recommending Mendoza and Aldridge for the band (though Aldridge had already been in the band years earlier), he never heard back from Coverdale.[89] Adrian Vandenberg was also asked to rejoin, but declined in order to spend time with his daughter and focus on his painting.[206] He has since made numerous guest appearances at the band's concerts.[210][211][212]

On 29 January 2003, Whitesnake began a co-headlining tour of the US with the Scorpions.[213][214] Afterwards, the band toured across Europe, playing several shows with Gary Moore in the UK.[215][216] Whitesnake then returned to the US to take part in the Rock Never Stops Tour with Warrant, Kip Winger and Slaughter,[217][218] before embarking on a Japanese tour in September.[219] The reformation was initially planned to last only a few months, but Coverdale ultimately decided to keep the band active.[68] No immediate plans were put in place for a new studio album, with Coverdale citing his dissatisfaction with the music industry as a contributing factor.[220]

Whitesnake continued to tour in late 2004, playing several shows across Europe and the UK.[221] Their London concert at the Hammersmith Apollo in October was also filmed and in 2006 released as Live... In the Still of the Night.[222] It was later certified gold in the UK and received the award for "DVD of the Year" at the 2006 Classic Rock Roll of Honour Awards.[223][224] In April 2005, Whitesnake parted ways with Marco Mendoza due to scheduling conflicts with Mendoza's other projects.[225] Session musician Uriah Duffy was announced as his replacement the following month.[226] Whitesnake then embarked on another US tour, followed by a South American leg.[227][228] In May 2006, the band played several shows in Japan, which were then followed by festival dates in Europe.[229]

In August 2006, Whitesnake signed a European recording contract with Steamhammer/SPV. The band then released the live album Live... in the Shadow of the Blues, which contained four new songs written by Coverdale and guitarist Doug Aldrich.[230][231] Coverdale's change of heart regarding new music stemmed from a need for "new meat to bite into" in order keep touring interesting.[191] Preliminary work on a new Whitesnake album began in early 2007, with Coverdale and Aldrich spending considerable time writing together and refining their joint ideas.[232] A release date was originally set for summer 2007,[233] but the album was later pushed back to October 2007 and then May 2008.[234][235] Regarding the delays, Coverdale stated: "The recording of this album was constantly compromised by interruptions. [...] Also, to be honest, there was no real rush for us to finish the project quickly."[236] In December 2007, Chris Frazier was announced as Whitesnake's new drummer. Tommy Aldridge reportedly left to pursue other musical projects.[237]

Good to Be Bad, Whitesnake's tenth studio album, was released on 18 April 2008 in Germany, 21 April in the rest of Europe, and on 22 April in North America.[238] Produced by Coverdale, Aldrich and Michael McIntyre,[239] the record reached number seven on the UK Albums Chart and number one on the UK Rock & Metal Albums Chart.[240][241] In the US, it only reached number 62 on the Billboard 200,[242] but it did peak at number eight on the Top Independent Albums chart.[243] In total, Good to Be Bad charted in 19 countries and has sold over 700,000 copies worldwide by 2011.[244] Writing for IGN, Jim Kaz gave the album a favourable review, in which he stated: "A few faux-pa's aside Good to Be Bad has enough shining, mega-rock moments to endear itself to fans old and new."[245] It later received the Classic Rock Award for "Album of the Year".[246]

Good to Be Bad's release was preceded by several shows in Australia and New Zealand,[247][248] after which Whitesnake toured South America, followed by a UK co-headlining tour with Def Leppard.[249][250] They also played select shows together in Central Europe.[251][252] In October, Whitesnake teamed up with Def Leppard again for two co-headlining shows in Japan.[253] The following November, Whitesnake played several shows in Germany with Alice Cooper.[254] The band also performed in Israel and Cyprus.[255][256] Following several European festival dates, Whitesnake embarked on a US co-headlining tour with Judas Priest in July 2009.[257][258] On 11 August, however, Whitesnake were forced to cut their concert in Denver short, after Coverdale experienced severe pain in his vocal cords. After consulting a specialist, he was revealed to be suffering from severe vocal fold edema and a left vocal fold vascular lesion. As a result, Whitesnake canceled their remaining tour dates.[259]

Forevermore and The Purple Album (2010–2017)

The band took a break from touring in 2010 to concentrate on writing a new album.[260] They also signed a new recording contract with Frontiers Records.[261] In June, Uriah Duffy and Chris Frazier left Whitesnake, with latter being replaced by former Billy Idol and Foreigner drummer Brian Tichy.[262] Michael Devin, formerly of Lynch Mob, was revealed as the band's new bassist the following August.[263] In September, Timothy Drury announced his departure to pursue a solo career.[264]

Forevermore, Whitesnake's eleventh studio album, was released on 25 March 2011 in Europe, followed by a North American release on 29 March. Once again produced by Coverdale, Aldrich and Michael McIntyre at Lake Tahoe,[265] Forevermore reached number 33 on the UK Albums Chart,[266] and number 2 on the UK Rock & Metal Albums Chart.[267] It reached number 49 on the Billboard 200,[268] while on the Independent Albums chart it peaked at number ten.[269] The record's highest chart position was in Sweden at number six.[270] As of May 2015, Forevermore has sold 44,000 copies in the US.[271] Thom Jurek of AllMusic gave the album a positive review, in which he proclaimed: "Forevermore, despite its tighter arrangements and more polished production is Whitesnake at its Brit hard rock best."[272]

A supporting tour kicked off in New York on 11 May 2011.[273] Accompanying the band was keyboardist Brian Ruedy.[274] After several dates in the US, the tour continued across Europe.[275] During the band's performance at the Sweden Rock Festival, they were joined onstage by former guitarist Bernie Marsden.[276] In October, Whitesnake played the Loud Park festival in Japan.[277] During the tour, the band sold charity scarves as a humanitarian response to the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami.[278]

Whitesnake took another hiatus in 2012 to compile live recordings from the Forevermore tour,[280] which were released the following year as Made in Japan and Made in Britain/The World Record.[281][282] In January 2013, Brian Tichy announced his departure from Whitesnake, in order to concentrate on his other band S.U.N.[283] He was replaced by Tommy Aldridge, who rejoined the band for a second time.[284] That May, Whitesnake initially toured in Japan,[285][286] and then embarked on a UK co-headlining tour with Journey, followed by several dates in Europe.[287][288][289] During the band's performance in Manchester, they were once again joined onstage by Bernie Marsden.[290] In June, Whitesnake played several co-headlining dates with Def Leppard in Spain.[291] Following a North American tour, Whitesnake played Brazil at the Monsters of Rock festival in October.[292] In May 2014, Doug Aldrich announced his departure from the band. He later explained his decision to leave, citing a need for a more flexible schedule to work on other projects and spend more time with his son.[293][294] Night Ranger guitarist Joel Hoekstra was announced as his replacement the following August.[295]

Whitesnake released their twelfth studio album, titled The Purple Album, on 15 May 2015 in Europe, followed by a North American release on 19 May.[296] A collection of re-recorded songs from Coverdale's time in Deep Purple, the idea sprang from talks he and Jon Lord had had about a possible Mark III reunion a few years earlier. After Lord's death in 2012, Coverdale discussed the idea with Ritchie Blackmore, but they were unable to come to an agreement regarding the nature of the undertaking. Coverdale then decided to move forward with the project under the Whitesnake banner. He described the resulting record as a tribute to his time in Deep Purple.[297]

The Purple Album reached number 18 on the UK Albums Chart,[298] while in the US it peaked at number 87.[299] On the Independent Albums chart, it reached number nine,[300] while in Japan it reached number eight.[301] In its first week, the record sold 6,900 copies in the US.[302] While the Associated Press commended the band for breathing new life into the songs,[303] Dave Everley of Classic Rock called The Purple Album a "wrong-headed travesty of an album".[304] Responding to the criticism, Coverdale proclaimed: "I've no space in my life for haters or negaters. [...] I owe those people nothing. Such opinions mean nothing to me."[305] The Purple Album had been envisioned by Coverdale as potentially his last album before retiring. However, the process left him "revitalised" and eager to continue further.[306]

Whitesnake kicked off the North American leg of The Purple Tour in May 2015.[296] Joining the band was new keyboardist Michele Luppi.[307] At a show in California, they were joined onstage by Coverdale's former Deep Purple bandmate Glenn Hughes.[308] Beginning in October, the band toured in Japan.[309][310][311] In December, Whitesnake teamed up with Def Leppard for tour of the UK and Ireland.[312] In Sheffield, Whitesnake were joined onstage by former guitarist Vivian Campbell (who has been a member of Def Leppard since 1992).[313] In 2016, Whitesnake embarked on the Greatest Hits Tour, which saw them perform across Europe and the US.[314] Before the tour, Coverdale revealed his plans to potentially retire in 2017,[315] though he later recanted the statement.[316]

In August 2017, Whitesnake signed a new distribution deal for North America and Japan with Rhino Entertainment and Warner Music Group. Tentative plans to release a new album the following year were also announced.[317] In October 2017, Whitesnake's eponymous album was reissued as a four-disc box set to commemorate its 30th anniversary.[318] The band had planned a joint tour where they would have played the album in its entirety, but instead opted to take a break and focus on writing a new album.[319] In December, a photography book chronicling The Purple Tour was released.[320]

Flesh & Blood and farewell tour (2018–present)

In 2018, Whitesnake toured the US with Foreigner on the Juke Box Heroes Tour.[321] They also released The Purple Tour live album and the box set Unzipped, which featured various acoustic recordings from across the band's career.[322][323] Whitesnake's thirteenth studio album had originally been set for release in early 2018,[324] but was pushed back after Coverdale contracted H3 flu.[325] In April 2018, the record was delayed again to early 2019 due to unspecified "technical issues" during the mixing process.[325] Coverdale also had knee replacement surgery in 2018 due to degenerative arthritis.[326] However, he later reiterated his plans not to retire, stating that he feels "reinvigorated, energized and very inspired".[327]

Whitesnake's next studio album Flesh & Blood was released on 10 May 2019. It saw Coverdale compose with Reb Beach and Joel Hoekstra for the first time, while production was handled by all three of them along with Michael McIntyre.[328] Flesh & Blood charted in eighteen countries, reaching number seven and number 131 in the UK and the US, respectively.[329][330] It also topped the UK Rock & Metal Albums Chart,[331] and hit number five on the Independent Albums chart.[332] Philip Wilding, writing for Classic Rock, gave the record a positive review, in which he stated: "If you want something to listen to while driving with the top down in some steamy Californian clime, then this Whitesnake is hard to beat."[333]

The band embarked on a supporting tour in April with dates in North America, followed by a European tour over the summer.[328][334] In September, Coverdale once again discussed the possibility of retiring, potentially in 2021, though he later clarified: "I just thought it was amusing to say, 'Oh, what better age for the lead singer of Whitesnake [to retire] than 69? I can't wait to design the t-shirts.' That was just fun."[335] Whitesnake were scheduled to tour Australia and New Zealand with the Scorpions in February 2020, but many of the shows had to be cancelled after Scorpions vocalist Klaus Meine was diagnosed with kidney stones.[336][337] Whitesnake's Japanese tour in March was also postponed due to the then-burgeoning COVID-19 pandemic.[338] Whitesnake later canceled all their remaining tour dates for 2020 when Coverdale was diagnosed with a bilateral inguinal hernia, for which he was forced to undergo surgery.[339][340]

Between 2020 and 2021, Whitesnake released three new musically distinct compilation albums, collectively titled the Red, White and Blues trilogy.[341] All three albums reached at least number two on the UK Rock & Metal Albums Chart.[342][343][344] The collections were originally timed to coincide with a potential farewell tour, which had to be postponed due to the pandemic.[345] Coverdale later reaffirmed his plan to retire from touring potentially in 2022, citing his age and the stress of travel as contributing factors. However, he still intended to be involved in music with several Whitesnake projects in the works.[346] Coverdale also discussed the possibility of Whitesnake continuing to perform without him.[347]

In July 2021, Whitesnake announced the addition of multi-instrumentalist Dino Jelusick to their ranks, turning Whitesnake into a septet for the first time.[348] Later that November, Michael Devin parted ways with the band.[349] He was replaced by Tanya O'Callaghan, marking the first female musician to join the group.[350]

Whitesnake began their farewell tour in May 2022, starting in the UK and Ireland with Foreigner and Europe.[351] During Whitesnake's June performance at Hellfest, they were joined onstage by Steve Vai.[352] Later that month, the band were forced to cancel several shows after Tommy Aldridge fell ill and Coverdale was diagnosed with an infection of the sinus and trachea.[353] Reb Beach had previously missed a number of shows due to poor health as well.[354] On 1 July, Whitesnake cancelled the remainder of their European tour.[355] On 5 August, the band withdrew from their forthcoming North American tour with the Scorpions.[356] O'Callaghan stated in October that Coverdale still needed "a good few months" to recuperate. However, he had resumed writing and discussed the possibility of doing a farewell album, encouraging former members to participate as well.[357][358] In 2023, Coverdale expressed interest in continuing the band's farewell tour in the future, but stated that his physical health would be the determining factor.[359]

Style and influences

Music

David Coverdale's original vision for Whitesnake was to create a blues-based, melodic hard rock band.[12] He wanted to combine elements of hard rock, R&B and blues with "good commercial hooks".[360] Coverdale's earliest influences included The Pretty Things and The Yardbirds, who combined blues and soul with electrified rock, a style Coverdale found more appealing to traditional twelve-bar blues structures. Another major influence on Whitesnake's sound was The Allman Brothers Band, particularly their first album.[68] Whitesnake's other early influences included Cream, Mountain, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Fleetwood Mac with Peter Green, Jeff Beck (particularly the albums Truth and Beck-Ola), Paul Butterfield, and John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers (particularly The Beano Album).[12]

As the band began playing and writing together, their sound developed further into what has been described by music critics as their blues rock period, which encompasses roughly the first five Whitesnake studio albums.[12][361] Rolling Stone's Richard Bienstock described their early sound as "bloozy, sexed-up pub-rock".[4] Dave Ling, writing for Classic Rock, described "Walking in the Shadow of the Blues" as "a textbook fusion of blues, hard rock and melody".[39] Micky Moody and Neil Murray have felt that Whitesnake didn't truly find their sound until Ready an' Willing.[362] Coverdale has seconded this, stating that Ready an' Willing was the beginning of what Whitesnake should have sounded like from the start.[363]

Beginning with Slide It In, Whitesnake's sound developed more into straightforward hard rock.[12][364] Neil Murray acknowledged that by 1983 the band's sound had become "repetitive" and "stale".[365] Coverdale later expressed his desire for the band's blues elements to "rock more".[12] Additionally, Murray attributed this shift partially to John Kalodner, who began pushing Whitesnake in a heavier, more guitar-based, "American-sounding" direction.[123] John Sykes also played a pivotal role in Whitesnake's evolution,[127][366] with Murray remarking how Sykes wanted the band to be more "American style".[367] Regardless, music journalist Jerry Ewing described the change as a "natural progression" from the band's previous albums.[365]

The band's eponymous album saw Whitesnake moving towards a sound Coverdale described as "leaner, meaner and more electrifying".[122] This later period of Whitesnake's career has been described by music critics as hard rock,[368] heavy metal,[369] and glam metal.[370] Coverdale would later admit that by the late 1980s, Whitesnake had become a "Heavy Metal comic", stating: "If people confuse Whitesnake with Mötley Crüe or any of these things, looking at the pictures [...] you can understand why."[371] Musically though, Coverdale has rejected the notion that Whitesnake were ever a heavy metal band.[372]

Since reforming the band in 2003, Coverdale has attempted to combine elements of Whitesnake's early sound with their later hard rock style on their most recent studio albums.[373] However, music critics have noted that Whitesnake's style has remained most consistent with their late 1980s output, with Philip Wilding of Classic Rock in his review for Flesh & Blood stating: "Those hoping that the new Whitesnake album record will recall Coverdale's smoky, Lovehunter past should look away now. [...] Coverdale understood American radio in the 80s, and that might be why he still writes for it."[333]

Comparisons to Led Zeppelin

As Whitesnake's style evolved in the mid to late 1980s, they began to draw unfavourable comparisons to Led Zeppelin.[376][377][378][379] Tracks like "Slow an' Easy", "Still of the Night" and "Judgement Day" have been accused of copying Led Zeppelin,[380][381] while David Coverdale has been accused of imitating singer Robert Plant.[177][376][382] Responding to the claims, Coverdale jokingly stated in 1987: "I guess it's quite a compliment to be placed in a class like that."[383] The comparison was exacerbated when Coverdale teamed up with Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page to release the album Coverdale–Page in 1993. In the press, Plant would refer to Coverdale as "David Cover-version" among other taunts,[177][384] which was not well received by Coverdale and Page.[385][386]

Coverdale denied any notion of plagiarism, stating: "I don't know how accurate the comparison is. People shouldn't forget that I worked in Deep Purple for a number of years, so my pedigree in hard rock is quite strong. I understand that bands like Whitesnake, Purple and Led Zeppelin all play a solid powerful brand of rock, but I don't think we're coming from the same place musically."[383] Neil Murray laid some of the blame on John Kalodner, who he claimed began pushing Whitesnake in a more Led Zeppelin-like direction.[387] As for comparison to Plant, Coverdale said they are "both from a similar school of influences and inspirations and singers ... can tell you precisely who Robert listened to to develop the voice he has, which is Stevie Marriott and Terry Reid and that screaming blues voice isn't copyrighted by Robert and that's something that I've grown up doing too".[386]

Lyrics

Coverdale has stated that lyrically all of his songs are love songs at their core.[388] He has described them as diaries of particular times in his life.[389] Nearly all of Whitesnake's studio albums feature one or more songs with "love" in the title. Coverdale has maintained that this hasn't been a conscious decision, rather he considers love his primary source of inspiration.[390] He has also attributed some of Whitesnake's longevity to the lyrics' "human themes", whether physical or emotional.[391]

Whitesnake, more specifically the main lyricist Coverdale, have been heavily criticized by the music press for their excessive use of double entendres and sexual innuendos, most egregiously on tracks such as "Slide It In", "Slow an' Easy" and "Spit It Out".[99][392] Such criticism began already in the late 1970s and was further inflamed with the Lovehunter (1979) controversial cover art.[393] Micky Moody, Bernie Marsden and Jon Lord have expressed some discomfort over the band's lyrical content.[371] Coverdale has reiterated that some of his lyrics are meant to provoke laughter more than anything else, stating: "If I look at sex as an observer [...] there's humour also as well as the serious nitty-gritty stuff and I like to write about this as well." He also added that many of his songs are tongue-in-cheek and inspired by his own experiences, not uncommon to other people as well.[394] It with his stage personality "solidified an image of Coverdale: the preening, tight-trousered lothario",[395] but although often ridiculed by the media, according to Michael Hann of The Guardian, by now "there's a certain affection for his magnificently preposterous persona".[395]

Ковердейл неоднократно отвергал любые обвинения в женоненавистничестве и сексизме . [386] PopMatters in 2003 noted that Coverdale "comes from a bygone era" and songs like "Slide it In" and "Slow and Easy" show not only "the blues aspect of Whitesnake" but "the tongue in cheek humor that Coverdale is so fond of".[ 376 ] Марсден также признал, что, хотя многие тексты Ковердейла не совсем политкорректны в современной обстановке, они были написаны «совершенно насмешливо» и скорее являются продуктом ушедшей эпохи. [ 39 ] Музыкальный журналист Малкольм Доум сравнил некоторые наиболее впечатляющие тексты Whitesnake с фильмом Carry On с их насмешливой чувствительностью, а также отметил, что, по его мнению, Ковердейл писал песни с «некоторой реальной глубиной и лирической осознанностью», как, например, в «Sailing Ships». » и «Любовь не чужая». [ 392 ]

Участники группы

Текущие участники

- Дэвид Ковердейл — вокал (1978–1990, 1994, 1997, 2003 – настоящее время)

- Томми Олдридж — ударные (1987–1990, 2003–2007, 2013 – настоящее время)

- Реб Бич — гитары, бэк-вокал (2003 – настоящее время)

- Джоэл Хукстра — гитары, бэк-вокал (2014 – настоящее время)

- Мишель Луппи — клавишные, бэк-вокал (2015 – настоящее время)

- Дино Джелусик — клавишные, бэк-вокал (2021 – настоящее время)

- Таня О'Каллаган — бас, бэк-вокал (2021 – настоящее время)

Дискография

Студийные альбомы

- Проблема (1978)

- Охотник за любовью (1979)

- Готов и желаю (1980)

- Приди и возьми это (1981)

- Святые и грешники (1982)

- Вставьте это (1984)

- Белая змея (1987)

- Оговорка (1989)

- Беспокойное сердце (1997)

- Хорошо быть плохим (2008)

- Навсегда (2011)

- Фиолетовый альбом (2015)

- Плоть и кровь (2019)

Ссылки

Сноски

- ^ «Эпизод 036 | 100 величайших исполнителей хард-рока - час 1 | Величайшие | Краткое содержание эпизода, основные моменты и обзоры» . VH1.com. Архивировано из оригинала 5 июня 2011 года . Проверено 24 апреля 2014 г.

- ^ Хикс, Тони; Харрингтон, Джим (21 сентября 2015 г.). «25 лучших хард-рок-исполнителей всех времен: какое место занимает ваша любимая?» . Новости Меркурия . Проверено 24 апреля 2014 г.

- ^ «VH1: 100 величайших песен 80-х» . Рок в сети . Проверено 1 марта 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Божур, Том; Бьенсток, Ричард; Эдди, Чак; Фишер, Рид; Расти, Кори; Джонстон, Маура ; Вайнгартен, Кристофер Р. (31 августа 2019 г.). «50 величайших хэйр-метал-альбомов всех времён» . Роллинг Стоун . Проверено 11 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ «Опрос читателей: лучшие хэйр-метал-песни всех времен» . Роллинг Стоун . 20 июня 2012 года . Проверено 1 марта 2021 г.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , с. 17.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , с. 22.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , стр. 14, 16, 19.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , с. 15.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , стр. 23–24.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Ранние годы. Часть 1» . Официальный сайт Whitesnake . 4 января 2016 года . Проверено 11 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н тот п д Бартон, Джефф (1 октября 2019 г.). «Whitesnake: «Ковердейл, которого я помню, был тщеславным и нелепым придурком» » . Громче . Проверено 10 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , с. 24.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , с. 26.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , с. 27.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , стр. 27–28.

- ^ «40 лет назад сегодня – первое выступление Whitesnake» . Официальный сайт Whitesnake . 3 марта 2018 года . Проверено 21 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Когда Whitesnake отыграли свой первый концерт» . Абсолютный классический рок . 3 марта 2016 года . Проверено 21 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Попов 2015 , с. 29.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , с. 14.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Бартон, Джефф (2006). Беда (буклет). Уайтснейк. ЭМИ. стр. 2–11. 0946 3 59688 2 8.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Оливер, Дерек (март 2011 г.). «Жизнь на Марсе». Classic Rock представляет: Whitesnake – Forevermore (Официальный журнал альбомов) . Лондон, Англия: Future plc. стр. 72–77.

- ^ «Лидер Whitesnake рассказывает о происхождении имени, его вставках в сказки и других рок-н-ролльных моментах» . Смелые слова . 9 июня 2009 года . Проверено 30 июля 2021 г.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , стр. 29–30.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Whitesnake – Трек за треком – В сердце города нет любви» . Уайтснейк ТВ. 19 декабря 2017 года. Архивировано из оригинала 30 октября 2021 года . Проверено 20 февраля 2021 г. - через YouTube.

- ^ «Официальный чарт синглов Top 75: 18 июня 1978 г. - 24 июня 1978 г.» . Официальные графики . Проверено 20 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , с. 30.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Попов 2015 , с. 35.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , с. 36.

- ^ Пил, Джон (ведущий) (8 июля 1995 г.). «Темно-фиолетовые люди». Рок-генеалогическое древо . Сезон 1. Эпизод 3. BBC 2.

- ^ «Топ-60 официальных альбомов чарта: 12 ноября 1978 г. - 18 ноября 1978 г.» . Официальные графики . Проверено 20 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Ривадавия, Эдуардо. «Whitesnake – Обзор проблем» . Вся музыка . Вся медиасеть . Проверено 10 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Попов 2015 , с. 41.

- ^ Доум, Малькольм (23 ноября 2014 г.). «Когда Whitesnake встретил хор Hammersmith» . Громче . Классический рок . Проверено 10 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бартон, Джефф (2006). Живи... в самом сердце города (буклет). Уайтснейк. ЭМИ. стр. 4–13. 0946 3 81959 2 4.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Бартон, Джефф (2006). Охотник за любовью (буклет). Уайтснейк. ЭМИ. стр. 4–13. 50999 2124042 3.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , с. 57.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д «Ранние годы. Часть 2» . Официальный сайт Whitesnake . 4 января 2016 года . Проверено 11 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г Линг, Дэйв (14 августа 2019 г.). «Lovehunter Whitesnake: альбом, воспламенивший музыкальную прессу» . Громче . Классический рок . Проверено 10 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Бартон, Джефф (2006). Готовы и желают (буклет). Уайтснейк. ЭМИ. стр. 2–9. 0946 359692 2 1.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , с. 55.

- ^ «Топ-75 официальных альбомов чарта: 10 октября 1979 г. - 13 октября 1979 г.» . Официальные графики . Проверено 20 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Ривадавия, Эдуардо. «Whitesnake — обзор Lovehunter» . Вся музыка . Вся медиасеть . Проверено 10 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , с. 58.

- ^ "Готов и готов к юбилею альбома!" . Официальный сайт Whitesnake . 31 мая 2017 года . Проверено 20 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ «Топ-75 официальных альбомов: 8 июня 1980 г. - 14 июня 1980 г.» . Официальные графики . Проверено 20 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ « Billboard 200 — Неделя от 20 сентября 1980 года» . Рекламный щит . Проверено 21 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ «Топ-75 официального чарта одиночных игр: 18 мая 1980 г. - 24 мая 1980 г.» . Официальные графики . Проверено 20 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ «Горячие 100 – Неделя от 13 сентября 1980 г.» . Рекламный щит . Проверено 8 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Ривадавия, Эдуардо. «Whitesnake – Готовый обзор» . Вся музыка . Вся медиасеть . Проверено 10 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , с. 72.

- ^ «Уайтнейк – готов и желаю» . Британская фонографическая индустрия . Проверено 9 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , с. 73.

- ^ «Топ-75 официального чарта альбомов: 2 ноября 1980 г. - 8 ноября 1980 г.» . Официальные графики . Проверено 20 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ «Уайтнейк – Живи в самом сердце города» . Британская фонографическая индустрия . Проверено 9 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , с. 75.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Бартон, Джефф (2007). Приходите и получите (буклет). Уайтснейк. ЭМИ. стр. 4–11. 0946 3 81958 2 5.

- ^ «75 лучших в чарте официальных альбомов: 12 апреля 1981 г. - 18 апреля 1981 г.» . Официальные графики . Проверено 20 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ «Уайтнейк – приди и возьми» . Британская фонографическая индустрия . Проверено 9 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ «Топ-75 официального чарта одиночных игр: 3 мая 1981 г. - 9 мая 1981 г.» . Официальные графики . Проверено 20 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ «Iron Maiden – Killers (Harvest) и Whitesnake – Come and Get It (Mirage)». Цирк . Нью-Йорк, Нью-Йорк, США: Корпорация Circus Enterprises. 31 августа 1981 года.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Попов 2015 , с. 86.

- ^ Миллар, Робби (сентябрь 1981 г.). «Год Змеи». Керранг! . № 3. Лондон, Англия: United Newspapers. стр. 10–11.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г Бартон, Джефф (2007). Святые и грешники (буклет). Уайтснейк. ЭМИ. стр. 4–11. 0946 381961 2 9.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Мире, Стиг (1997). «Whitesnake: Последнее ура» . Хард Рокс . № 34. Лондон, Англия . Проверено 10 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Бонутто, Данте (2–15 декабря 1982 г.). «Заклинатель змей». Керранг! . № 30. Лондон, Англия: United Newspapers. стр. 22–27, 37.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Марсден, Берни (21 ноября 2019 г.). «Берни Марсден: Что произошло в тот день, когда я покинул Whitesnake» . Громче . Классический рок . Проверено 10 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н тот п д Чирази, Стеффан (25 марта 2011 г.). «Растущая боль Дэвида Ковердейла из Whitesnake» . Громче . Классический рок . Проверено 15 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ «100 лучших официальных альбомов чарта: 21 ноября 1982 г. - 27 ноября 1982 г.» . Официальные графики . Проверено 10 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ «Уайтнейк – Saints 'N' Sinners» . Британская фонографическая индустрия . Проверено 9 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ де Уолли, Час (2–15 декабря 1982 г.). «Whitesnake - 'Святые и грешники' (Liberty LBG 30354)». Керранг! . № 30. Лондон, Англия: United Newspapers. п. 14.

- ^ Ривадавия, Эдуардо. «Whitesnake – обзор Saints & Sinners» . Вся музыка . Вся медиасеть . Проверено 10 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Попов 2015 , с. 104.

- ^ «Погром! За гигантским стаканом коньяка более чем веселый Дэвид Ковердейл сообщил, что только что подписал контракт с легендарным лейблом Geffen Records...». Керранг! . № 28. Лондон, Англия: United Newspapers. 4–17 ноября 1982 г. с. 10.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , с. 105.

- ^ Крэмптон, Люк (18 ноября – 2 декабря 1982 г.). «Работа с топором!». Керранг! . № 29. Лондон, Англия: United Newspapers. п. 34.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Гилмор, Хью (2017). Вставьте его (буклет). Уайтснейк. ЭМИ. стр. 4–11. 50999 698122 2 4.

- ^ «Ранние годы. Часть 3» . Официальный сайт Whitesnake . 1 января 2016 года . Проверено 11 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , с. 106.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , с. 109.

- ^ «Mayhem! – Whitesnake отправляются в очередной тур по Великобритании в декабре...». Керранг! . № 52. Лондон, Англия: United Newspapers. 6–19 октября 1983 г. с. 2.

- ^ «Гитарист Микки Муди обсуждает свой уход из Whitesnake» . Блаббермут.нет . 20 ноября 2009 года . Проверено 10 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Джастман, Пол (режиссер) (1991). Deep Purple – Пионеры хэви-метала (документальный фильм). Атлантическая звукозаписывающая корпорация.

- ^ Синклер, Дэвид (26 января – 8 февраля 1984 г.). «Банда цыган». Керранг! . № 60. Лондон, Англия: United Newspapers. стр. 26–27.

- ^ Данн, Сэм ; Макфадьен, Шотландец (17 декабря 2011 г.). «Глэм». Металлическая Эволюция . VH1 Классик .

- ^ Попофф 2015 , с. 108.

- ^ «Майкл Шенкер говорит, что он «пытался» сотрудничать с Дэвидом Ковердейлом в начале 1980-х: «Я на самом деле не хотел этого делать » . Блаббермут.нет . 31 января 2020 г. Проверено 10 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Чирази, Стеффан (март 2011 г.). «Высокий крутой». Classic Rock представляет Whitesnake – Forevermore (Официальный журнал альбомов) . Лондон, Англия: Future plc. стр. 88–91.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Сюрьяля, Марко (7 сентября 2008 г.). «Джон Сайкс — Тонкая Лиззи, бывший участник Whitesnake, Blue Murder, Tygers of Pan Tang» . Metal-Rules.com . Проверено 11 января 2021 г.

- ^ «Интервью с Тони Ноблсом из журнала Vintage Guitar, июнь 1999 г.» . Официальный сайт гитариста Джона Сайкса . 27 марта 2008 г. Архивировано из оригинала 27 марта 2008 г. . Проверено 5 августа 2017 г.

- ^ «Новые скины вместо старых». Керранг! . № 59. Лондон, Англия: United Newspapers. 12–25 января 1984 г. с. 2.

- ^ «Тяжелый Лондонский специальный выпуск». металлический молоток . Нет. 1. Берлин, Германия: Издательство журнала ZAG. 1984. с. 26.

- ^ «Скользить сюда». Звуки . Лондон, Англия: Публикации Spotlight. 14 января 1984 г. с. 3.

- ^ «100 лучших официальных альбомов чарта: 5 февраля 1984 г. - 11 февраля 1984 г.» . Официальные графики . Проверено 10 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Пеннанен 2006 , стр. 263.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , с. 111.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Эллиотт, Пол (март 2011 г.). «Вставьте это (Свобода)». Classic Rock представляет Whitesnake – Forevermore (Официальный журнал альбомов) . Лондон, Англия: Future plc. п. 117.

- ^ Диксон, Дэйв (9–22 февраля 1984 г.). «Whitesnake – 'Slide It In' (Liberty LBG 2400001)». Керранг! . № 61. Лондон, Англия: United Newspapers. п. 10.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Рид, Джим (18 февраля 1984 г.). «Змеиный секссесс». Запись зеркала . Лондон, Англия: United Newspapers.

- ^ Ривадавия, Эдуардо. «Whitesnake – Обзор слайдов» . Вся музыка . Вся медиасеть . Проверено 10 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Доум, Малькольм (9–22 февраля 1984 г.). «Джон Сайкс». Керранг! . № 61. Лондон, Англия: United Newspapers.

- ^ "Новости". металлический молоток . Нет. 6. Берлин, Германия: Издательство журнала ZAG. Июль – август 1984 г. с. 4.

- ^ Перроне, Пьер (23 октября 2011 г.). «Некрологи: Мел Галли - гитарист Whitesnake» . Независимый . Проверено 10 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Менге, Тимон; Лейм, Кристоф (12 апреля 2019 г.). «Time jump: «Slide It In» группы Whitesnake выпущен 16 апреля 1984 года» . uDiscover (на немецком языке) . Проверено 11 января 2021 г.

- ^ «Ранние годы. Часть 4» . Официальный сайт Whitesnake . 1 января 2016 года . Проверено 11 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ « Billboard 200 — Неделя от 25 августа 1984 года» . Рекламный щит . Проверено 8 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и «База данных с возможностью поиска RIAA: поиск Whitesnake» . Ассоциация звукозаписывающей индустрии Америки . Проверено 3 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Епископ, Пит (26 августа 1984 г.). «Опыт Whitesnake окупается новым альбомом». Питтсбург Пресс . Питтсбург, Пенсильвания, США.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Уолл, Мик (март 2011 г.). «Перезагрузка на миллион долларов». Classic Rock представляет Whitesnake – Forevermore (Официальный журнал альбомов) . Лондон, Англия: Future plc. стр. 80–85.

- ^ «Дэвид Ковердейл обсуждает предстоящий японский тур 1984 года с Whitesnake» . Официальный представитель Deep Purple. Архивировано из оригинала 30 октября 2021 года . Проверено 10 февраля 2021 г. - через YouTube.

- ^ Ковердейл, Дэвид (2014). Живи в '84: Назад к кости (буклет). Уайтснейк. Frontiers Music SRL. п. 4. ФР CDVD 669.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , с. 154.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , с. 122.

- ^ «Мейнстрим-рок-трансляция - неделя от 28 июля 1984 г.» . Рекламный щит . Проверено 8 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ «Мейнстрим-рок-трансляция - неделя от 15 сентября 1984 г.» . Рекламный щит . Проверено 8 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ Хоттен, Джон (июнь 2001 г.). «Год Змеи». Классический рок . № 28. Лондон, Англия: Future plc. п. 29.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Гилмор, Хью (2017). Whitesnake (буклет). Уайтснейк. Parlophone Records Ltd., стр. 5–9. 0190295785192.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Гилмор, Хью (2007). Whitesnake (буклет). Уайтснейк. Parlophone Records Ltd., стр. 5–18. 0825646120680.

- ^ Попофф 2015 , стр. 125–126.