Всеобщие выборы в Бразилии 2022 г.

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Президентские выборы | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Опросы общественного мнения | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Оказаться | 79,05% (первый тур) 79,41% (второй тур) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 513 seats in the Chamber of Deputies 257 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This lists parties that won seats. See the complete results below. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

27 of the 81 seats in the Federal Senate | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This lists parties that won seats. See the complete results below. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

прошли всеобщие выборы в Бразилии 2 октября 2022 года для избрания президента , вице-президента , Национального конгресса , губернаторов, вице-губернаторов и законодательных собраний всех субъектов федерации , а также окружного совета Фернанду-де-Норонья . Поскольку ни один кандидат на пост президента (или губернатора в некоторых штатах) не получил более половины действительных голосов в первом туре, второй тур выборов 30 октября был проведен на эти должности. Луис Инасио Лула да Силва получил большинство голосов во втором туре и стал избранным президентом Бразилии.

Крайне правый действующий президент Жаир Болсонару баллотируется на второй срок. Он был избран в 2018 году кандидатом от Социал-либеральной партии, но покинул эту партию в 2019 году, после чего в течение его срока последовали отставки или увольнения многих его министров. После неудачной попытки создать Альянс Бразилии он присоединился к Либеральной партии в 2021 году. На выборах 2022 года он выбрал Вальтера Брагу Нетто из той же партии в качестве своего кандидата в вице-президенты, а не действующего вице-президента Гамильтона Мурана .

Former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, of the left-wing Workers' Party, was a candidate for a third non-consecutive term after previously having been elected in 2002 and re-elected in 2006. His successor from the same party, former president Dilma Rousseff, was elected in 2010 and re-elected in 2014, but was impeached and removed from office in 2016 due to accusations of administrative misconduct. Lula's intended candidacy in 2018 was disallowed due to his conviction on corruption charges in 2017 and subsequent arrest; a series of court rulings led to his release from prison in 2019, followed by the annulment of his conviction and restoration of his political rights by 2021. For his vice presidential candidate in the 2022 election, Lula selected Geraldo Alckmin, who had been a presidential candidate of the Brazilian Social Democracy Party in 2006 (facing Lula in the second round) and 2018 but changed his affiliation to the Brazilian Socialist Party in 2022.[1]

Lula received the most votes in the first round, with 48.43% to Bolsonaro's 43.20%, which made him the first presidential candidate to obtain more votes than the incumbent president in Brazil. While Lula came close to winning in the first round, the difference between the two leading candidates was closer than opinion polls had suggested, and right-wing parties made gains in the National Congress. Nevertheless, Lula's vote share was the second-best performance for the Workers' Party in the first round of a presidential election, behind only his own record of 48.61% in 2006. In the second round, Lula received 50.90% of the votes to Bolsonaro's 49.10%, the closest presidential election result in Brazil to date. Lula became the first person to secure a third presidential term, receiving the highest number of votes in a Brazilian election. At the same time, Bolsonaro became the first incumbent president to lose a bid for a second term since a 1997 constitutional amendment allowing consecutive re-election.

In response to Lula's advantage in pre-election polls, Bolsonaro had made several pre-emptive allegations of electoral fraud. Many observers denounced these allegations as false and expressed concerns that they could be used to challenge the outcome of the election. On 1 November, during his first public remarks after the election, Bolsonaro refused to elaborate on the result, although he did authorise his chief of staff, Ciro Nogueira Lima Filho, to begin the transition process with representatives of president-elect Lula on 3 November. On 22 November, Bolsonaro and his party requested that the Superior Electoral Court invalidate the votes recorded by electronic voting machines that lacked identification numbers, which would have resulted in him being elected with 51% of the remaining votes. On the next day the court rejected the request and fined the party R$22.9 million (US$4.3 million) for what it considered bad faith litigation. Lula was sworn in on 1 January 2023; a week later, pro-Bolsonaro protestors stormed the offices of the National Congress, the Presidential Palace, and the Supreme Federal Court, unsuccessfully attempting to overthrow the newly-elected government. The elected members of the National Congress were sworn in on 1 February.[2]

Background

[edit]From 1994 to 2014 presidential elections in Brazil were dominated by candidates of the centrist Brazilian Social Democracy Party and the left-wing Workers' Party. After unsuccessful attempts in the 1989, 1994, and 1998 presidential elections, Workers' Party candidate Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was elected in the 2002 and 2006 presidential elections.[3] His successor from the same party, Dilma Rousseff, was elected in the 2010 and 2014 presidential elections. The controversial 2016 impeachment of Rousseff removed her from office due to allegations of administrative misconduct, and she was succeeded by her vice president, Michel Temer of the centrist Brazilian Democratic Movement. In 2017, Operation Car Wash controversially resulted in Lula being convicted on charges of corruption by judge Sergio Moro and arrested, which prevented his intended candidacy in the 2018 Brazilian presidential election, despite his substantial lead in the polls. He was replaced as his party's presidential candidate by former mayor of São Paulo, Fernando Haddad, who lost to far-right candidate Jair Bolsonaro of the Social Liberal Party.[4][5][6]

In 2019, Bolsonaro left the Social Liberal Party. This was followed by the dismissal or resignation of many members of the Bolsonaro administration,[7] including Moro, whom he had appointed as Minister of Justice and Public Safety. Bolsonaro then attempted to create another party, the Alliance for Brazil, but he was unsuccessful.[8] In 2021, Bolsonaro joined the Liberal Party and selected Walter Braga Netto of his party as the vice presidential candidate instead of Hamilton Mourão, the incumbent vice president.[9] A series of rulings by the Supreme Federal Court questioning the legality of Lula's trial and the impartiality of then judge Moro led to Lula's release from prison in 2019, followed by the annulment of Moro's cases against Lula and the restoration of Lula's political rights by 2021.[10][11] Lula launched his candidacy for president in 2022, selecting as his vice presidential candidate Geraldo Alckmin, who had been a presidential candidate of the Brazilian Social Democracy Party in 2006 and 2018 but changed his affiliation to the left-wing Brazilian Socialist Party in 2022.[12][13] The three parties supporting Bolsonaro in 2022 (Liberal Party, Progressistas, and Republicans) had supported Alckmin in 2018 and Rousseff in 2014.[14] After Bolsonaro's departure from the Social Liberal Party, the party merged with the Democrats to form the Brazil Union in 2022.[15]

Electoral system

[edit]Brazil's president and vice president are elected as a joint ticket using the two-round system. The first round of elections is held on the first Sunday of October, which in 2022 was on 2 October.[16] A candidate who receives more than 50% of the total valid votes in the first round is elected. If the 50% threshold is not met by any candidate, the two candidates who receive the most votes in the first round participate in a second round of voting, held on the last Sunday of October (in this instance, 30 October 2022), and the candidate who receives a plurality of votes in the second round is elected. The 2022 Brazilian gubernatorial elections to elect the governors and vice governors of all states of Brazil and of the Federal District were held on the same dates and with the same two-round system as the presidential election. One-third of the 81 members of the Brazilian Senate were up for election in 2022, one senator being elected from each of the states and the Federal District using plurality voting. The other two-thirds of the Senate were elected in 2018.[17]

All 513 members of the Chamber of Deputies (federal deputies) are elected from 27 multi-member constituencies corresponding to the states and the Federal District, varying in size from 8 to 70 seats. All members of the Legislative Assemblies of Brazilian states (state deputies) and of the Legislative Chamber of the Federal District (district deputies), varying in size from 24 to 94 seats, are also elected. These elections are held using open list, proportional representation, with seats allocated using integer quotients and the D'Hondt method.[18][19] All seven members of the District Council of Fernando de Noronha are elected by single non-transferable vote. Unlike elections for other offices in Brazil, candidates for this council are not nominated by political parties.[20]

Voters

[edit]

Voting in Brazil is allowed for all citizens over 16 years old. There is compulsory voting for literate citizens between 18 and 70 years old except conscripts; as there is conscription in Brazil, those who serve the mandatory military service are not allowed to vote.[21] Those who are required but do not vote in an election and do not present an acceptable justification, such as being absent from their voting locality at the time,[22] must pay a fine, normally R$3.51,[23][24] which is equivalent to US$0.67 as of October 2022. In some cases, the fine may be waived, reduced, or increased up to R$35.13 (US$6.67).[25]

The Brazilian diaspora may only vote for president and vice president.[26] Due to the Equality Statute between Brazil and Portugal, Portuguese citizens legally residing in Brazil for more than three years may also register to vote in Brazilian elections.[27]

Candidates and political parties

[edit]All candidates for federal, state, Federal District, and municipal offices must be nominated by a political party. For offices to be elected by majority or plurality (executive offices and senators), parties may form an electoral coalition (coligação) to nominate a single candidate. The coalitions do not need to be composed of the same parties for every nomination, do not need to be maintained after the election, and are not valid for offices to be elected proportionally (deputies and aldermen).[28] A new law, valid for this election, also allowed parties to form a different type of alliance called federation (federação), which acts as a single party to nominate candidates for all offices in all locations, including those to be elected proportionally, and must be maintained with a single leadership structure over the course of the elected legislature.[29] Federations may also act as parties to form coalitions. For 2022, the federations formed were Brazil of Hope (PT–PCdoB–PV), Always Forward (PSDB–Cidadania), and the PSOL REDE Federation (PSOL–REDE).[30]

For offices to be elected proportionally, each party must nominate candidates of each sex in a distribution between 30 and 70%.[28] Under rulings by the Superior Electoral Court and the Supreme Federal Court, parties must also allocate their funds and broadcast time proportionally to the number of their candidates of each sex and race.[31]

Procedure

[edit]

Voting in Brazilian elections can only be done in person and only on election day, which is always a Sunday. There is no provision for either postal voting or early voting. Voter registration must be done in advance, and each voter can only vote in one designated voting station, either based on the voter's registered domicile or at a different location that the voter must specifically request if planning to be there temporarily on election day. Voters must provide photo identification at their voting station before proceeding to vote.[32]

More than 92,000 voting stations were installed in all municipalities of Brazil, the Federal District, and Fernando de Noronha.[33] Most voting stations are in public schools.[34] In some sparsely populated areas, such as indigenous territories, the installation and use of voting stations requires extensive travel and logistics.[35] Voting stations were also installed in 160 locations in other countries, mostly in Brazilian diplomatic missions, for citizens residing abroad.[36]

Voting is done almost entirely on DRE voting machines, designed for extreme simplicity. The voter dials a number corresponding to the desired candidate or party, causing the name and photo of the candidate or party to appear on the screen, then the voter presses a green button to confirm or an orange button to correct and try again. It is also possible to leave the vote blank by pressing a white button, or to nullify the vote by dialing a number that does not correspond to any candidate or party. Paper ballots are only used in case a voting machine malfunctions or in locations abroad with fewer than 100 voters.[32]

The electronic system is subject to extensive tests, including on machines randomly selected from actual voting stations on election day, witnessed by political parties to rule out fraud. After voting ends, every machine prints a record of its total votes for each candidate or party, which is publicly displayed for comparison with the results published electronically.[37] The system delivers the complete election results usually a few hours after voting ends, which is extremely fast for such a large population as Brazil. At the same time, the system does not create a physical record of individual votes to allow a full election recount.[38]

The partial vote count for an office can only start being published after voting has ended in all locations in Brazil voting for that office, to avoid influencing those still voting. Due to time zones in Brazil, in previous years the vote count for president (the only one that combines votes from more than one state) could only start being published after voting ended in UTC−05:00, two hours after it had ended for the vast majority of the population in UTC−03:00. To avoid this undesirable wait, the Superior Electoral Court ordered for 2022 that voting stations were to operate at the same time in the whole country, regardless of their time zone: 9:00 to 18:00 UTC−02:00, 8:00 to 17:00 UTC−03:00, 7:00 to 16:00 UTC−04:00, and 6:00 to 15:00 UTC−05:00.[39] Politicians from the state of Acre (UTC−05:00) filed a legal complaint against this order due to the unreasonably early start of voting preparations in their local time; the complaint was dismissed by the Supreme Federal Court.[40] The unified voting time does not apply to voting stations for citizens abroad, which still operate from 8:00 to 17:00 local time, even though some of them end up to four hours after UTC−03:00.[41]

Presidential candidates

[edit]Candidates in runoff

[edit]| Party | Presidential candidate[42] | Vice presidential candidate[c] | Coalition | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Workers' Party (PT 13) |

|

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (campaign) President of Brazil (2003–2010) Federal Deputy for São Paulo (1987–1991) |

|

Geraldo Alckmin (PSB) Governor of São Paulo (2001–2006, 2011–2018) Vice Governor of São Paulo (1995–2001) |

Brazil of Hope:

| |

Liberal Party (PL 22) |

|

Jair Bolsonaro (campaign) President of Brazil (2019–2023) Federal Deputy for Rio de Janeiro (1991–2018) |

|

Walter Braga Netto Minister of Defence (2021–2022) Chief of Staff of the Presidency (2020–2021) |

For the Good of Brazil:

| |

Candidates not advanced to runoff

[edit]Withdrawn or declined to be candidates

[edit]| Withdrawn or declined to be candidates |

|---|

Coalitions

[edit]

|

Additional support for second round:[100]

Congress

[edit]The results of the previous general elections and the composition of the National Congress at the time of the 2022 election are given below. The party composition changed significantly during the course of the legislature due to numerous replacements of members, changes in their party affiliation, and mergers of parties. In 2022, all members of the Chamber of Deputies and one third of the Senate (one senator from each state and Federal District) were up for election.

| Party[101] | Chamber of Deputies | Senate | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elected | Incumbent | +/– | Elected | Incumbent | +/– | Up for election[102] | ||||

| 2018 | 2022[103] | 2014 | 2018 | 2022[104] | 2022 | 2026 | ||||

| Liberal Party[f] | 33 | 76 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 5 | |||

| Progressistas[g] | 37 | 58 | 1 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 4 | |||

| Workers' Party | 56 | 56 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 5 | |||

| Brazil Union | 81[h] | 51 | 3[i] | 8[j] | 8 | 1 | 7 | |||

| Social Democratic Party | 34 | 46 | 2 | 4 | 11 | 3 | 8 | |||

| Republicans[k] | 30 | 44 | – | 1 | 1 | – | 1 | |||

| Brazilian Democratic Movement | 34 | 37 | 5 | 7 | 13 | 4 | 9 | |||

| Brazilian Socialist Party | 32 | 24 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | – | |||

| Brazilian Social Democracy Party | 29 | 22 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 4 | |||

| Democratic Labour Party | 28 | 19 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Podemos[l] | 17[m] | 9 | – | 3[n] | 8 | 2 | 6 | |||

| Solidariedade | 13 | 8 | – | 1 | – | – | – | |||

| Socialism and Liberty Party | 10 | 8 | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| Communist Party of Brazil | 10[o] | 8 | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| New Party | 8 | 8 | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| Social Christian Party | 8 | 8 | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | |||

| Cidadania[p] | 8 | 7 | – | 2 | 1 | – | 1 | |||

| Avante[q] | 7 | 6 | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| Patriota[r] | 9[s] | 5 | – | 1[t] | – | – | – | |||

| Republican Party of the Social Order | 8 | 4 | – | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Green Party | 4 | 4 | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| Brazilian Labour Party | 10 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | – | |||

| Sustainability Network | 1 | 2 | – | 5 | 1 | – | 1 | |||

| Party of National Mobilization | 3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| Act[u] | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| Christian Democracy[v] | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| Independent politician | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | – | |||

| Total | 513 | 513 | 27 | 54 | 81 | 27 | 54 | |||

Campaign

[edit]Debates

[edit]Below is a list of the presidential debates scheduled or held for the 2022 election (times in UTC−03:00). For the first time since the 1989 presidential election, television and radio stations, and newspapers and news websites grouped themselves into pools to hold presidential debates, by request from the campaigns in order to reduce the number of debates scheduled for the 2022 elections.[105][106][107]

| No. | Date, time, and location | Hosts | Moderators | Participants[w] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key: P Present A Absent I Invited Out Out of the election |

PL | PT | NOVO | PDT | MDB | UNIÃO | PTB | |||

| Bolsonaro | Lula | d'Avila | Gomes | Tebet | Thronicke | Souza | ||||

| 1.1 | 28 August 2022, 21:00, São Paulo[110] | Bandeirantes, TV Cultura, Folha, UOL | Adriana Araújo, Eduardo Oinegue, Fabíola Cidral, Leão Serva | P | P | P | P | P | P | Out[x] |

| 1.2 | 24 September 2022, 18:15, Osasco[111] | SBT, CNN Brazil, Estado, Veja, Terra, NovaBrasil FM | Carlos Nascimento | P | A | P | P | P | P | P |

| 1.3 | 29 September 2022, 22:30, Rio de Janeiro[112] | Globo | William Bonner | P | P | P | P | P | P | P |

| 2.1 | 16 October 2022, 20:00, São Paulo[113] | Bandeirantes, TV Cultura, Folha, UOL[y] | Adriana Araújo, Eduardo Oinegue, Fabíola Cidral, Leão Serva | P | P | Out | ||||

| 2.2 | 21 October 2022, 21:30, Osasco[114] | SBT, CNN Brazil, Estado, Veja, Terra, NovaBrasil FM | Carlos Nascimento | P | A | Out | ||||

| 2.3 | 23 October 2022, 21:30, São Paulo[115] | Record | Eduardo Ribeiro | P | A | Out | ||||

| 2.4 | 28 October 2022, 21:30, Rio de Janeiro[116][117] | Globo | William Bonner | P | P | Out | ||||

Incidents

[edit]Political violence

[edit]Since the official beginning of the election campaign in August 2022 and before that, various political commentators said the incumbent president Jair Bolsonaro incited physical,[118] or verbal violence, against his critics and political opponents, especially women,[119] such as saying that he and his supporters "must obliterate" the opposition Workers' Party,[120][121] engaging in a smear campaign of political commentators, journalists, or interviewers on his social media and speeches,[122][123][124] and in one occasion trying to grab a phone from a disillusioned voter and YouTuber who confronted him in a rally.[125][126]

An Amnesty International survey found that in the three months leading up to the first round on 2 October, there was at least one case of political violence every two days, with 88% of cases in September alone, including murders, threats against voters, physical assaults, and restrictions on freedom of movement for candidates. On 5 October, the Observatory of Political and Electoral Violence in Brazil of the Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro (Unirio) had recorded at least 212 cases of political violence between July and September of this year, an increase of 110% compared to the previous quarter. According to the survey, leaders of 29 parties were hit by some kind of violence in the third quarter of 2022. The Workers' Party received the highest number of targets with 37 cases (17.5%), then there was the Socialism and Liberty Party with 19 (9%), while the Global Justice and Land of Rights organizations recorded 247 episodes of political violence in 2022, a 400% increase in the number of cases recorded in 2018. At least 121 cases occurred between 1 August and 2 October. According to Agência Pública, there were at least 32 episodes of intimidation or violence against interviewers from research institutes, such as Datafolha, Ipec, and Quaest, until 5 October.[127]

Notable cases

[edit]June–August

[edit]In June, a Bolsonaro supporter was arrested after throwing fireworks against Lula supporters during a political act of the Workers' Party in Cinelândia, Rio de Janeiro.[127] Several Lula supporters had already been hit by a liquid described as sewage launched from a drone that flew over a pre-campaign event of the Workers' Party in Minas Gerais, which featured former mayor Alexandre Kalil, at the time the Social Democratic Party pre-candidate for the government of Minas Gerais. The suspect, agriculturalist Rodrigo Luiz Parreira, was arrested a week later. In July, a walk with Marcelo Freixo, the Brazilian Socialist Party candidate for the government of Rio de Janeiro, had to be abruptly closed after armed supporters of a state deputy appeared on the site and made threats.[127] Also in July, a homemade bomb was set off at a Lula rally in downtown Rio de Janeiro, leaving no injuries. The perpetrator has been arrested. Days before that, Bolsonaro supporters surrounded a vehicle carrying Lula in the city of Campinas.[128]

On 10 July, city guard Marcelo Aloizio de Arruda, a Workers' Party activist, was murdered for political reasons during his birthday party at a community centre located in Foz do Iguaçu in the state of Paraná. Jorge Guaranho, a federal prison officer, was arrested after storming the victim's party shouting that he was a supporter of Bolsonaro, and shooting at Arruda. The shooter was also injured during the attack due to self-defense exercised by the victim.[129][130] Based on an incorrect statement from the local police, some media outlets mistakenly reported that the men killed each other. The police later backtracked from the statement, and stated instead that Guaranho had been hospitalized.[131] Arruda was survived by his wife and four young children.[132] In the hours following the murder, politicians—including some 2022 presidential candidates—and authorities condemned the attack, with some of them calling for calm.[133][134] Also on 10 July, the local police opened an investigation into the crime's motivation;[135] a day later, the police chief officer leading the probe was found to have previously made online posts against the Workers' Party, potentially violating due process because of abuse of power, which unofficially caused her to be removed from the investigation.[136][137]

On 11 July, a judge ordered the pre-trial arrest of the suspect, and after four days the local police concluded that there was no political motivation for the crime.[138] On 18 July, both the prosecutors and Arruda's family disputed the conclusions, citing the fact that the police did not search the shooter's phone and did not investigate a possible connection with the suicide of a security service worker in the community centre who had allegedly sent the party footage to the suspect.[139][140][141] The following day, the judge overseeing the case ordered the police to redo the inquiry taking into account those claims.[142] On 20 July, the prosecutors charged Guaranho with first degree murder for political reasons, and he was bound over for trial.[143][144] On 10 August, following his discharge from a hospital, Guaranho was temporarily placed under house arrest and ordered to wear an ankle monitor.[145][146] He was sent to prison two days later,[147] and he was denied a release from jail on 13 August.[148]

In August, a datafolha interviewer was chased in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, by four men. Shouting "communist" and "leftist", the men tried to pick up the tablet she used to conduct the research.[127] On 8 September, two farm workers had an argument over politics and their preferred presidential candidates in a rural property in the city of Confresa in the western state of Mato Grosso. Rafael Silva de Oliveira, a 24-year-old Bolsonaro supporter, reportedly stabbed his 42-year-old coworker Benedito Cardoso dos Santos,[149] a supporter of former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, 70 times,[150] after both had been arguing over politics for hours on the same day and the situation escalated to a physical altercation. During the fight, Oliveira reportedly took a knife and started stabbing Santos in his eyes, forehead and neck, after Santos had punched Oliveira in the chin, according to the local police. Following the murder, the suspect tried to behead the victim's body with an axe but eventually gave up and went to a local healthcare centre seeking medical assistance, where he was seen by a doctor and subsequently arrested by the police. Oliveira was also under criminal investigations for unrelated crimes such as homicide, rape, and fraud, according to the police and a court ruling.[151][152][153]

September–October

[edit]On 13 September, farmer Luiz Carlos Ottoni, a 44-year-old Bolsonaro supporter, attacked city councilwoman Cleres Relevante of the Workers' Party and her aide in Salto do Jacuí, a small city in the southern state of Rio Grande do Sul. Ottoni used his car to hit hers after reportedly following Relevante and her aide on their way back her home. Relevante told the police that right before the car attack, she noticed she and her aide were being followed by a car that occasionally kept doing burnouts, unexpected speed-ups and stops, as if to intimidate them. The car eventually rammed the back of hers and fled the scene. She called the police, who chased the attacker but were later informed that he had fatally suffered an accident while trying to escape the manhunt.[154][155]

On 19 September, a group of Bolsonaro supporters verbally abused, kicked and punched a blind man who was wearing a Lula campaign button as he took the subway in the city of Recife, in the northeastern state of Pernambuco. The victim's wife said that her husband had a seizure due to the assault while he was at the hospital for a first appointment and that he had to remain hospitalized for three days, after which he was released but for the following week he could not get out of his bed by himself.[156][157][158] On 20 September, an election survey interviewer was assaulted by a Bolsonaro supporter while the victim was interviewing another person. The suspect also heckled the interviewer several times during the survey before his son joined him in the attack. Pollster Datafolha, the victim's employer, said that there had been at least ten similar cases since the campaign officially started in August 2022.[159]

On 24 September, Antônio Carlos Silva, a farm worker, was murdered after he answered a question made by Edmilson Freire, a Bolsonaro supporter. According to eye-witnesses, Freire entered a bar and shouted "who supports Lula?", for which Silva said he would vote for Lula, then Freire stabbed him in the ribs. Silva was seen by a doctor but did not survive the injury. Freire, who reportedly has criminal records for unrelated domestic violence, was arrested.[160] On the same day, Hildor Henker, a Bolsonaro supporter, was stabbed in a bar in Rio do Sul, in the southern state of Santa Catarina, after he had gotten into an argument about "politics and old family problems" with a Workers' Party supporter, whose name was not released by the police. Henker, who was wearing a Bolsonaro shirt, reportedly hit the Workers' Party supporter in the face, and the latter grabbed Henker by the neck, took him out of the bar, and stabbed him in the leg after a fight, hitting his femoral artery. Henker ran across the bar, bleeding, and collapsed due to his wounds. He was taken to the hospital but died the next day. According to the police, the suspect escaped the scene and went back to his home, and as of 27 September he was still wanted by the police.[161][162]

On 25 September, Paulo Guedes, a federal lawmaker for the Workers' Party, suffered an assassination attempt during a motorcade rally in Montes Claros in the southeastern state of Minas Gerais. Guedes was reportedly at the top of a campaign rally truck when a police officer in plainclothes shot at the rally from the back seat of a car.[163] The Federal Police of Brazil later arrested and indicted the officer for two counts: election campaign harassment and unlawful discharge of a firearm.[164][165]

On 4 October, José Roberto Gomes Mendes, a 59-year-old Bolsonaro supporter, was murdered after an argument over politics with Luiz Antonio Ferreira da Silva, a 42-year-old Workers' Party supporter, inside their home in the city of Itanhaém, in the state of São Paulo. During the argument, Mendes allegedly attacked Silva with a knife, and during the fight, Silva used the same knife to stab Mendes. The police later arrived at the scene and found that Mendes had died of his wounds. Silva confessed the crime to the police.[166]

On 12 October, Bolsonaro visited the Basilica of Our Lady of Aparecida in São Paulo to accompany the religious celebrations. Supporters of the president promoted riots outside the time and attacked journalists who were covering the ceremony including those of the TV Aparecida, which is owned by the church, and the TV Vanguarda, which is affiliated to the TV Globo. They also attacked a man with a red shirt and booed an archbishop who spoke out against hunger.[167]

On 13 August 2021, former lawmaker and Bolsonaro ally Roberto Jefferson was arrested due to his verbal threats to government officials and institutions. In January 2022, he was allowed to be moved to house arrest for health reasons under the conditions that he would not maintain external communication or receive visits other than by family members.[168] Jefferson violated these conditions multiple times, and he attempted to be a presidential candidate in the 2022 election under the Brazilian Labour Party but was ruled ineligible due to a previous criminal conviction and was replaced by Kelmon Souza as his party's candidate. On 21 October, Jefferson released a video, through his daughter Cristiane Brasil, where he insulted Supreme Federal Court judge Cármen Lúcia due to rulings that she issued in the 2022 presidential election.[169] Due to Jefferson's multiple violations of his house arrest conditions, Supreme Federal Court judge Alexandre de Moraes ordered his return to prison. On 23 October, Jefferson violently resisted the arrest warrant being carried out by Federal Police agents, who were met with gunfire and two grenades thrown by him. Some of the agents were injured during the siege, subsequently hospitalized, and later released. Hours after negotiating his surrender terms along with other Bolsonaro allies present in his house, Jefferson turned himself in to the police and was later indicted for four attempted homicides of the agents that he had attacked earlier.[170][171]

Disinformation

[edit]

Disinformation became a major topic in the 2022 elections, since experiences from previous elections, especially in 2018, led to new approaches by individuals, including electoral officials, as well as private and public institutions amid a surge in the use of fake news to discredit political opponents and the electoral system itself.[172] In that context, the Superior Electoral Court issued several law-like guidances regarding disinformation, such as further banning political ads on the internet, and tightening penalties for online breaches of the electoral law. In October 2021, after an investigation by the police and prosecutors, the Superior Electoral Court ruled that Fernando Francischini, a hard-liner lawmaker in the southern state of Paraná and ally of Bolsonaro, had violated electoral law by making false claims about the electronic voting system in 2018. The court removed him from his seat in the state legislature and banned him from elected office for the next eight years.[173] Francischini filed an appeal against the ruling but it was later dismissed by the Supreme Federal Court.[174]

On 20 September 2022, the Superior Electoral Court reported that it had received more than 15,500 election-related disinformation complaints over the prior four months.[175] On 24 September, an incident of bulk messaging was reported in the state of Paraná, which was governed by an ally of Bolsonaro. Several phone users said that they had received a message from the official state alert-messaging service,[176] which read: "Bolsonaro is gonna win the elections in the first round! Otherwise, we are going to the streets to protest! We're gonna storm the Supreme Court and the Congress buildings! President Bolsonaro counts on us all!!" The Superior Electoral Court referred the alleged breach to prosecutors so they could investigate if any electoral crime was committed, and if so, to identify its perpetrators.[177]

Electoral fraud allegations

[edit]Bolsonaro alleged that electronic voting in Brazil was prone to vote rigging since at least 2015, when he was a member of the Chamber of Deputies, and successfully pushed for a bill requiring voting machines to also print vote records. Brazil's Public Prosecutor's Office challenged the law citing secret ballot concerns,[178][179] and the Supreme Federal Court suspended the law in June 2018.[180][181]

During the 2018 elections, several social media platforms were flooded with fake claims that electronic ballots had been set up to favor candidates other than Bolsonaro, and that he had allegedly won the presidential election in the first round.[182] After investigating those claims, authorities and forensic experts ruled out any fraud in the ballots, and concluded that some videos shared online were manipulated and edited to spread those allegations.[183] As president, Bolsonaro also insisted on voter fraud claims and pushed for an election audit,[184] despite the voting machines already being audited and the vote counts being publicly available for verification.[185]

Since 2018, some social media companies, such as YouTube, Facebook,[186] and Twitter,[187] restricted or removed videos, livestreams, campaign advertisements, online groups and channels, online-content monetization,[188] and posts from Bolsonaro, his allies, and supporters linked to election-related disinformation,[189] insurrection, and incitement to violence on their own or by a court order for violating laws or those companies' policies.[190][191] Despite signing agreements with the Superior Electoral Court in which they committed to fight disinformation,[192][193] social networks acted slowly or ignored requests to remove it.[194]

In July 2022, Bolsonaro addressed dozens of foreign diplomats, to whom he made several claims of vulnerabilities in the country's electronic voting system. Following the presentation, the electoral authority issued a statement debunking several of the claims mentioned by Bolsonaro.[195] Brazilian and international law experts, political analysts, and authorities warned that such allegations undermined democracy and paved the way for an unfounded election result challenge or a self-coup, such as the 2021 United States Capitol attack.[196][197] Many experts also feared that if Bolsonaro lost the election, the military and local police officers, who helped carry out the 1964 Brazilian coup d'état and were heavily present in his government,[198][199] could play a significant role in either blocking a peaceful transition of power or being complicit with possible rioters trying to overthrow a newly elected administration.[200][201]

On 28 September, four days prior to the first round of the elections, Bolsonaro's Liberal Party released a statement saying a party report found that there were "several flaws" in the election process conducted by the Superior Electoral Court, adding, without providing any evidence, that the court met only "5% of the all the requirements for a proper election certification". The court dismissed those claims as "false and misleading and meant to disturb the electoral process", and ordered an investigation into the authors of party's report.[202][203]

Reactions to potential coup

[edit]On 26 July, the faculty of law of the University of São Paulo launched a pro-democracy petition as a response to Bolsonaro's criticism of the electronic ballots and the Brazilian voting system in general with over 3,000 signatures, among intellectuals, artists, law experts including retired justices of the Supreme Federal Court, businesspeople, and others.[204] On 30 July, the petition topped 540,000 signatures, and four days later reached 700,000 endorsements.[205][206]

On 17 August, a report by Brazilian newspaper Metrópoles leaked an online conversation by a group of pro-Bolsonaro businessmen who expressed their preference for a coup d'état rather than a return of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva to the presidency. The businessmen stated that the Supreme Federal Court and the Superior Electoral Court were suspected of election fraud, and proposed that a separate commission recount the votes. The messages also showed that business leader José Koury floated the idea of paying a bonus to employees who voted according to their employers' interests, if it were legal, and that malls chain businessman José Isaac Peres ordered "thousands of little flags" to be distributed to shopkeepers and customers in Barra World Shopping, one of his company's malls. In response to the report, the businessmen declared their support for democracy and denied any encouragement of illegal activity.[207][208]

On 23 August, by order of the Supreme Federal Court, the Federal Police carried out search and seizure warrants on the homes, offices, and other properties of the businessmen who allegedly supported a potential coup, including Koury, Peres, and billionaire Luciano Hang, among others.[209] The court also ordered a freeze in their bank and social media accounts, their testimonies, and access to their financial records. The businessmen stated that this order constituted political persecution and an attack on their freedom of speech.[210]

International reactions

[edit]On 9 June, Bolsonaro and U.S. president Joe Biden met during the Summit of the Americas in Los Angeles. Anonymous sources reported to Bloomberg News that Bolsonaro asked for Biden's help with the elections, saying that a possible administration of former president Lula would be against U.S. interests. Biden changed the subject when approached but emphasized the importance of keeping the integrity of Brazil's elections.[211] Bolsonaro answered that he respected democracy and would respect the election results. Biden's response echoed the comments made by Elizabeth Frawley Bagley, the U.S. ambassador to Brazil nominated by Biden. Portuguese/Spanish-language spokesperson of the U.S. Department of State, Kristina Rosales, argued that the elections needed to be transparent and monitored by international observers. Brazil's justice minister Anderson Torres responded that international observers were of little help and favored the participation of the Federal Police, the Brazilian Armed Forces, and civil society in the elections.[212]

In a June 2022 speech about human rights in various countries, Michelle Bachelet, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, cited concerns in Brazil, such as threats to environmentalists and indigenous people, police violence, racism, and attacks against politicians, especially Afro-Brazilians, women, and LGBT people, ahead of the elections in October. She also appealed to the Brazilian authorities to ensure respect for fundamental rights and independent institutions.[213]

On 6 July, it was reported that members of the U.S. House of Representatives affiliated with the Democratic Party called for measures that would suspend American aid to the Brazilian Army if it intervened in the election.[214][215] The amendment author, Tom Malinowski of New Jersey, withdrew the requirement with no opposition on the House floor from any representative except for Adam Schiff of California.[216] On 20 July, Spokesperson for the U.S. Department of State, Ned Price, was asked about the meeting with foreign diplomats hosted by Bolsonaro on 18 July, when Bolsonaro made disputed claims about the Brazilian electoral system. Price responded that U.S. officials had spoken with senior Brazilian officials about the electronic voting system, that the U.S. view was that the Brazilian electoral system was successfully tested for many years and was a model for other nations, and that the United States would follow the elections with great interest.[217][218]

During the International Ministerial Conference on Freedom of Religion or Belief in July 2022 held in London, Hungary's Minister of Foreign Affairs, Péter Szijjártó, requested a meeting with Brazil's Minister of Women, Families, and Human Rights, Cristiane Britto, to learn more about the electoral environment. Britto commented about polarization and cited perceived similarities in the views of both countries regarding family issues. Szijjártó asked if there was anything that Hungary could do to help in Bolsonaro's re-election, and said that Brazil had the largest Hungarian community in Latin America and that it mostly supported the incumbent president.[219][220]

On 29 September, the U.S. Senate passed a resolution co-sponsored by Senators Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Tim Kaine of Virginia, in which they called for the respect of the Brazilian election results and stressed that the United States would not support "any government that comes to power through undemocratic means".[221][222]

Voter suppression attempts

[edit]On 27 September, it was reported that some public transportation companies, most of them bus companies, as well as city administrations whose mayors were Bolsonaro allies, could either suspend some buses operations, claim a lack of funding for free travel passes that were usually granted to voters on election day, or order the vehicles sabotaged and engage in voter suppression. Poor and extremely poor voters, among whom Lula had been leading in the polls, were supposed to be the main target of this strategy, since they could only resort to public transportation on their way to the polling stations and back home.[223]

In the first round

[edit]Despite some city administrations and Senator Randolfe Rodrigues asking the Supreme Federal Court to grant free rides for voters on election day,[224][225] Porto Alegre, a major city in southern Brazil whose mayor was a Bolsonaro supporter, announced that it was going to cut free travel passes because of "budgetary costs" for the first time in 25 years;[226] after intense scrutiny by critics and politicians, it gave up on the plan. On 29 September, the Supreme Federal Court issued an injunction blocking public transportation operations from being reduced on election day.[227][228]

On 1 October, the Bolsonaro campaign asked the Superior Electoral Court to immediately block free travel passes in the public transportation system, arguing that the Supreme Federal Court's previous decision would hurt the cities' finances since the costs of free rides on election day were allegedly not anticipated and previously agreed upon by their legislatures. The Superior Electoral Court rejected the request, saying that no additional costs were created for the cities.[229][230]

Intimidation of voters

[edit]Voter intimidation, which includes coercion, threats of retaliation, workplace harassment, or a promotion at work, is both an electoral and a labor crime in Brazil.[231][232] It can also be considered a form of electoral fraud, voter suppression and workplace bullying. Reports of such crime, of which the main targets are employees, contractors and suppliers, have grown in the country since at least early 2022.[233] On 19 May, Havan, a retail chain, and its owner, billionaire Luciano Hang, were both ordered to pay damages to a former employee of the company after a court found that she had suffered workplace harassment as a way to force her to vote for Bolsonaro.[234][235]

On 5 October, the Public Prosecutor's Office and a labor court issued a joint statement warning employers against voter intimidation in the workplace after Stara and Extrusor, two companies based in southern Brazil, had sent their suppliers a memorandum threatening to cut their production and funds from 2023 on in the event that former president Lula were elected in 2022. There were also reports of a brickworks in northern Brazil that publicly offered each of its employees cash if Jair Bolsonaro were re-elected, and of an agriculture businesswoman in northeastern Brazil who was charged with asking farmers to "have no mercy" in firing employees who voted for Lula.[236][237]

On 10 October, an agribusiness leader and husband of a mayor in the state of Goiás sent farmers a voicenote threatening to shut his business if former president Lula were elected president, and saying that his employees "were desperate" to get people to change their minds not to vote for Lula in order to keep their jobs.[238] On 11 October, the Labor Prosecutor's Office reported that it had received nearly 200 complaints of voter intimidation since the beginning of the election campaign in August 2022.[239] As of 21 October, there had been 1,112 reports of voter intimidation in 2022, far higher than a total of 212 reports in the 2018 elections, which made many prosecutors open joint tasks forces to investigate the cases.[240] On 22 October, employees of a meatpacking company based in southeastern Brazil denounced that they were forced among other things to wear pro-Bolsonaro shirts while at work, reportedly violating several food safety rules, besides the electoral law.[241]

In the second round

[edit]On 30 October, reports spread on social media of Federal Highway Police (PRF) engaging in unusual patterns of stops in poorer areas of the country that were expected to favour Lula,[242] leading to calls for the close-of-polling hour to be pushed back. The number of police searches of vehicles was 80 percent higher than had been recorded on 2 October, the day of the first round of voting, and directly violated an order from Superior Electoral Court president Alexandre de Moraes to suspend such activities on Election Day.[243] Stops disproportionately took place in the Northeast Region, which has historically recorded the strongest vote for the Workers' Party.[244] Police roadblocks also created a traffic jam on the Rio–Niterói Bridge.[245][246]

Workers' Party supporters immediately called the actions an attempt of electoral subversion. O Globo reported that the director of the PRF, Silvinei Vasques, had posted and then deleted a video on Instagram endorsing Bolsonaro the previous night.[247] O Globo additionally reported that the operation had been discussed in the office of President Bolsonaro on 19 October, suggesting it was performed at his direction.[248] Activists made an appeal to Moraes, who ordered an immediate halt to the operations and subpoenad Vasques; however, Moraes claimed the operations did not stop anyone from voting and rejected a request from the PT to extend voting hours beyond the 5 pm deadline.[249] Vasques was then arrested on 10 August 2023.[250]

Environmental issues

[edit]Some commentators noted the importance of this election for the Amazon rainforest,[251] as well as climate change.[252] On 23 September, the British environmental-focused website Carbon Brief released a report made by researchers at the University of Oxford, the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis and the Brazilian National Institute for Space Research showing that deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon could be reduced by 89% if Lula were elected in 2022 and his environmental policy continued until 2030. The report said that Lula's enforcement of the Brazilian Forest Code, the country's flagship legislation for tackling deforestation in the Amazon and other ecosystems, would curb forest clearings and could also reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Instead, a re-election of Bolsonaro would likely see the pace of deforestation accelerate in the coming years, including what one of the report authors described as huge areas beyond the scope of the Forest Code.[253]

Views and endorsements

[edit]On 3 September, medical journal The Lancet published an editorial calling the stakes in the Brazilian elections high and highlighting among other things that Bolsonaro, described as someone "who is known for his volatility and indirect incitement of violence, will not go quietly" if he were not re-elected as predictions pointed to, and that "he has already criticised Brazil's electronic voting system in the presence of foreign ambassadors". It concluded by saying "there is an unprecedented chance for new beginnings in Latin America; an opportunity to make positive changes to alleviate deep neglect, inequality, and violence. Let us hope that Brazil chooses to seize this opportunity."[254]

On 25 October, ahead of the second round, British weekly scientific journal Nature published an editorial in which it said that a second term for incumbent Bolsonaro would "represent a threat to science, democracy and the environment", and cited Bolsonaro's similarities to former U.S. president Donald Trump, both of whom it said "have sought to undermine the rule of law and slash the powers of regulators" and "ignored scientists' warnings about COVID-19 and denied the dangers of the disease." It concluded by stating that "Brazil's voters have a valuable opportunity to start to rebuild what Bolsonaro has torn down. If Bolsonaro gets four more years, the damage could be irreparable."[255]

Opinion polls

[edit]Presidential election

[edit]First round

[edit]

Second round

[edit]

Results

[edit]President

[edit]

| Candidate | Running mate | Party | First round | Second round | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | ||||

| Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva | Geraldo Alckmin (PSB) | Workers' Party | 57,259,504 | 48.43 | 60,345,999 | 50.90 | |

| Jair Bolsonaro | Walter Braga Netto | Liberal Party | 51,072,345 | 43.20 | 58,206,354 | 49.10 | |

| Simone Tebet | Mara Gabrilli (PSDB) | Brazilian Democratic Movement | 4,915,423 | 4.16 | |||

| Ciro Gomes | Ana Paula Matos | Democratic Labour Party | 3,599,287 | 3.04 | |||

| Soraya Thronicke | Marcos Cintra | Brazil Union | 600,955 | 0.51 | |||

| Luiz Felipe d'Avila | Tiago Mitraud | New Party | 559,708 | 0.47 | |||

| Kelmon Souza | Luiz Cláudio Gamonal | Brazilian Labour Party | 81,129 | 0.07 | |||

| Leonardo Péricles | Samara Martins | Popular Unity | 53,519 | 0.05 | |||

| Sofia Manzano | Antonio Alves da Silva | Brazilian Communist Party | 45,620 | 0.04 | |||

| Vera Lúcia Salgado | Kunã Yporã Tremembé | United Socialist Workers' Party | 25,625 | 0.02 | |||

| José Maria Eymael | João Barbosa Bravo | Christian Democracy | 16,604 | 0.01 | |||

| Total | 118,229,719 | 100.00 | 118,552,353 | 100.00 | |||

| Valid votes | 118,229,719 | 95.59 | 118,552,353 | 95.41 | |||

| Invalid votes | 3,487,874 | 2.82 | 3,930,765 | 3.16 | |||

| Blank votes | 1,964,779 | 1.59 | 1,769,678 | 1.42 | |||

| Total votes | 123,682,372 | 100.00 | 124,252,796 | 100.00 | |||

| Registered voters/turnout | 156,453,354 | 79.05 | 156,453,354 | 79.42 | |||

| Source: Superior Electoral Court | |||||||

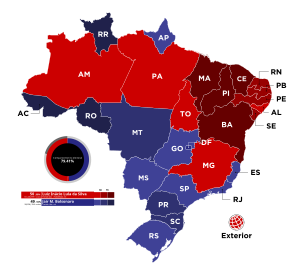

By federative unit

[edit]| Federative unit | Second round | First round | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva | Jair Bolsonaro | Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva | Jair Bolsonaro | Simone Tebet | Ciro Gomes | Others | ||||||||

| Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | |

| 121,566 | 29.70 | 287,750 | 70.30 | 129,022 | 29.26 | 275,582 | 62.50 | 20,122 | 4.56 | 12,314 | 2.79 | 3,877 | 0.88 | |

| 976,831 | 58.68 | 687,827 | 41.32 | 974,156 | 56.50 | 621,515 | 36.05 | 67,411 | 3.91 | 43,542 | 2.53 | 17,593 | 1.02 | |

| 189,918 | 48.64 | 200,547 | 51.36 | 197,382 | 45.67 | 187,621 | 43.41 | 27,497 | 6.36 | 14,670 | 3.39 | 4,991 | 1.15 | |

| 1,004,991 | 51.10 | 961,741 | 48.90 | 1,019,684 | 49.58 | 880,198 | 42.80 | 87,060 | 4.23 | 44,527 | 2.16 | 25,207 | 1.23 | |

| 6,097,815 | 72.12 | 2,357,028 | 27.88 | 5,873,081 | 69.73 | 2,047,599 | 24.31 | 197,305 | 2.34 | 217,224 | 2.58 | 87,799 | 1.04 | |

| 3,807,891 | 69.97 | 1,634,477 | 30.03 | 3,578,355 | 65.91 | 1,377,827 | 25.38 | 66,214 | 1.22 | 369,222 | 6.80 | 37,646 | 0.69 | |

| 926,767 | 41.96 | 1,282,145 | 58.04 | 897,348 | 40.40 | 1,160,030 | 52.23 | 85,325 | 3.84 | 56,221 | 2.53 | 22,206 | 1.00 | |

| 729,295 | 41.19 | 1,041,331 | 58.81 | 649,534 | 36.85 | 910,397 | 51.65 | 105,377 | 5.98 | 74,308 | 4.22 | 22,959 | 1.30 | |

| 1,542,115 | 41.29 | 2,193,041 | 58.71 | 1,454,723 | 39.51 | 1,920,203 | 52.16 | 170,742 | 4.64 | 90,695 | 2.46 | 45,106 | 1.23 | |

| 2,668,425 | 71.14 | 1,082,749 | 28.86 | 2,603,454 | 68.84 | 983,861 | 26.02 | 78,254 | 2.07 | 96,095 | 2.54 | 19,981 | 0.53 | |

| 652,786 | 34.92 | 1,216,730 | 65.08 | 633,748 | 34.39 | 1,102,866 | 59.84 | 55,989 | 3.04 | 29,437 | 1.60 | 20,848 | 1.13 | |

| 599,547 | 40.51 | 880,606 | 59.49 | 588,323 | 39.04 | 794,206 | 52.70 | 79,719 | 5.29 | 29,314 | 1.95 | 15,427 | 1.02 | |

| 6,190,960 | 50.20 | 6,141,310 | 49.80 | 5,802,571 | 48.29 | 5,239,264 | 43.60 | 500,658 | 4.17 | 310,324 | 2.58 | 163,816 | 1.36 | |

| 2,509,084 | 54.75 | 2,073,895 | 45.25 | 2,443,730 | 52.22 | 1,884,673 | 40.27 | 204,075 | 4.36 | 116,057 | 2.48 | 31,401 | 0.67 | |

| 1,601,953 | 66.62 | 802,502 | 33.38 | 1,554,868 | 64.21 | 717,416 | 29.62 | 57,154 | 2.36 | 76,225 | 3.15 | 16,025 | 0.66 | |

| 2,506,605 | 37.60 | 4,159,343 | 62.40 | 2,363,492 | 35.99 | 3,628,612 | 55.26 | 309,685 | 4.72 | 180,599 | 2.75 | 84,376 | 1.28 | |

| 3,640,933 | 66.93 | 1,798,832 | 33.07 | 3,558,322 | 65.27 | 1,630,938 | 29.91 | 96,570 | 1.77 | 130,015 | 2.38 | 36,164 | 0.66 | |

| 1,551,383 | 76.86 | 467,065 | 23.14 | 1,518,008 | 74.25 | 406,897 | 19.90 | 42,179 | 2.06 | 59,321 | 2.90 | 17,981 | 0.88 | |

| 4,156,217 | 43.47 | 5,403,894 | 56.53 | 3,847,143 | 40.68 | 4,831,246 | 51.09 | 365,969 | 3.87 | 301,489 | 3.19 | 110,830 | 1.17 | |

| 1,326,785 | 65.10 | 711,381 | 34.90 | 1,264,179 | 62.98 | 622,731 | 31.02 | 38,633 | 1.92 | 71,740 | 3.57 | 9,981 | 0.50 | |

| 2,891,851 | 43.65 | 3,733,185 | 56.35 | 2,806,672 | 42.28 | 3,245,023 | 48.89 | 317,957 | 4.79 | 190,945 | 2.88 | 77,155 | 1.16 | |

| 262,904 | 29.34 | 633,236 | 70.66 | 261,749 | 28.98 | 581,306 | 64.36 | 31,217 | 3.46 | 19,353 | 2.14 | 9,610 | 1.06 | |

| 67,128 | 23.92 | 213,518 | 76.08 | 68,760 | 23.05 | 207,587 | 69.57 | 12,956 | 4.34 | 6,709 | 2.25 | 2,357 | 0.79 | |

| 1,351,918 | 30.73 | 3,047,630 | 69.27 | 1,279,216 | 29.54 | 2,694,406 | 62.21 | 191,310 | 4.42 | 88,672 | 2.05 | 77,380 | 1.79 | |

| 11,519,882 | 44.76 | 14,216,587 | 55.24 | 10,490,032 | 40.89 | 12,239,989 | 47.71 | 1,625,596 | 6.34 | 898,540 | 3.50 | 402,177 | 1.57 | |

| 862,951 | 67.21 | 421,086 | 32.79 | 828,716 | 63.82 | 378,610 | 29.16 | 42,073 | 3.24 | 40,247 | 3.10 | 8,786 | 0.68 | |

| 434,593 | 51.36 | 411,654 | 48.64 | 434,303 | 50.40 | 379,194 | 44.00 | 25,209 | 2.93 | 18,141 | 2.11 | 4,945 | 0.57 | |

| 152,905 | 51.28 | 145,264 | 48.72 | 138,933 | 47.17 | 122,548 | 41.61 | 13,167 | 4.47 | 13,341 | 4.53 | 6,536 | 2.22 | |

- First round vote distribution

-

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (PT) vote distribution

-

Jair Bolsonaro (PL) vote distribution

-

Simone Tebet (MDB) vote distribution

-

Ciro Gomes (PDT) vote distribution

-

Minor candidates receiving less than 1% of the popular vote

- Second round vote change from first round

-

Lula's gain in vote share (by states) from the first round in the runoff

-

Bolsonaro's gain in vote share (by states) from the first round in the runoff

Chamber of Deputies

[edit]In the table below, the last column is a comparison with the result of the 2018 Brazilian general election.

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party or alliance | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | |||

| Liberal Party | 18,200,300 | 16.64 | 99 | +66[z] | |||

| Brazil of Hope | Workers' Party | 13,236,698 | 12.10 | 69 | +13 | ||

| Communist Party of Brazil | 1,154,712 | 1.06 | 6 | –4[aa] | |||

| Green Party | 954,578 | 0.87 | 6 | +2 | |||

| Brazil Union | 10,215,433 | 9.34 | 59 | –22[ab] | |||

| Progressistas | 8,692,918 | 7.95 | 47 | +10 | |||

| Social Democratic Party | 8,293,956 | 7.58 | 42 | +8 | |||

| Brazilian Democratic Movement | 7,870,810 | 7.19 | 42 | +8 | |||

| Republicans | 7,610,894 | 6.96 | 40 | +10[ac] | |||

| Always Forward | Brazilian Social Democracy Party | 3,309,061 | 3.02 | 13 | –16 | ||

| Cidadania | 1,614,106 | 1.48 | 5 | –3[ad] | |||

| PSOL REDE | Socialism and Liberty Party | 3,852,246 | 3.52 | 12 | +2 | ||

| Sustainability Network | 782,917 | 0.72 | 2 | +1 | |||

| Brazilian Socialist Party | 4,173,479 | 3.81 | 14 | –18 | |||

| Democratic Labour Party | 3,828,367 | 3.50 | 17 | –11 | |||

| Podemos | 3,610,634 | 3.30 | 12 | –5[ae] | |||

| Avante | 2,192,518 | 2.00 | 7 | 0 | |||

| Social Christian Party | 1,944,678 | 1.78 | 6 | –2 | |||

| Solidarity | 1,702,519 | 1.56 | 4 | –9 | |||

| Patriota | 1,526,570 | 1.40 | 4 | –5[af] | |||

| Brazilian Labour Party | 1,422,652 | 1.30 | 1 | –9 | |||

| New Party | 1,354,754 | 1.24 | 3 | –5 | |||

| Republican Party of the Social Order | 799,661 | 0.73 | 3 | –5 | |||

| Brazilian Labour Renewal Party | 292,371 | 0.27 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Party of National Mobilization | 256,578 | 0.23 | 0 | –3 | |||

| Act | 158,868 | 0.15 | 0 | –2[ag] | |||

| Christian Democracy | 97,741 | 0.09 | 0 | –1 | |||

| Brazilian Communist Party | 85,511 | 0.08 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Brazilian Woman's Party | 83,055 | 0.08 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Popular Unity | 54,586 | 0.05 | 0 | New | |||

| United Socialist Workers' Party | 27,995 | 0.03 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Workers' Cause Party | 7,308 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Total | 109,408,474 | 100.00 | 513 | 0 | |||

| Valid votes | 109,408,474 | 88.81 | |||||

| Invalid votes | 6,285,972 | 5.10 | |||||

| Blank votes | 7,501,125 | 6.09 | |||||

| Total votes | 123,195,571 | 100.00 | |||||

| Registered voters/turnout | 155,557,422 | 79.20 | |||||

| Source: Superior Electoral Court | |||||||

Federal Senate

[edit]In the table below, the total shown for each party is the sum of senators elected in 2022 and those not up for election in 2022, based on their party affiliation at the time of that election. The last column is a comparison between this total and the sum of senators elected in 2018 and those not up for election in 2018, based on their party affiliation at the time of that election.

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party or alliance | Votes | % | Seats | |||||||

| Elected | Total | +/– | ||||||||

| Liberal Party | 25,278,764 | 25.39 | 8 | 13 | +11[ah] | |||||

| Brazilian Socialist Party | 13,615,846 | 13.67 | 1 | 1 | –1 | |||||

| Brazil of Hope | Workers' Party | 12,024,696 | 12.08 | 4 | 9 | +3 | ||||

| Green Party | 475,597 | 0.48 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Communist Party of Brazil | 299,013 | 0.30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Social Democratic Party | 11,312,512 | 11.36 | 2 | 10 | +3 | |||||

| Progressistas | 7,592,391 | 7.62 | 3 | 7 | +2 | |||||

| Brazil Union | 5,465,486 | 5.49 | 5 | 12 | +2[ai] | |||||

| Social Christian Party | 4,285,485 | 4.30 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| Republicans | 4,259,279 | 4.28 | 2 | 3 | +2[aj] | |||||

| Brazilian Democratic Movement | 3,882,458 | 3.90 | 1 | 10 | –2 | |||||

| Brazilian Labour Party | 2,046,003 | 2.05 | 0 | 0 | –3 | |||||

| Podemos | 1,776,283 | 1.78 | 0 | 6 | –1[ak] | |||||

| Democratic Labour Party | 1,586,922 | 1.59 | 0 | 2 | –2 | |||||

| Always Forward | Brazilian Social Democracy Party | 1,384,871 | 1.39 | 0 | 4 | –5 | ||||

| Cidadania | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 1 | –1[al] | |||||

| Avante | 1,359,455 | 1.37 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Brazilian Labour Renewal Party | 758,938 | 0.76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| PSOL REDE | Socialism and Liberty Party | 675,244 | 0.68 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Sustainability Network | 8,133 | 0.01 | 0 | 1 | –4 | |||||

| New Party | 479,593 | 0.48 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Popular Unity | 291,294 | 0.29 | 0 | 0 | New | |||||

| Republican Party of the Social Order | 213,247 | 0.21 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| United Socialist Workers' Party | 132,680 | 0.13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Christian Democracy | 94,098 | 0.09 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Patriota | 76,729 | 0.08 | 0 | 0 | –1[am] | |||||

| Brazilian Communist Party | 64,569 | 0.06 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Brazilian Woman's Party | 61,350 | 0.06 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Party of National Mobilization | 27,812 | 0.03 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Act | 24,076 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | –1[an] | |||||

| Solidarity | 17,339 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | –1 | |||||

| Workers' Cause Party | 8,974 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Independent | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | –1 | |||||

| Total | 99,579,137 | 100.00 | 27 | 81 | 0 | |||||

| Valid votes | 99,579,137 | 80.83 | ||||||||

| Invalid votes | 14,276,125 | 11.59 | ||||||||

| Blank votes | 9,340,309 | 7.58 | ||||||||

| Total votes | 123,195,571 | 100.00 | ||||||||

| Registered voters/turnout | 155,557,422 | 79.20 | ||||||||

| Source: Superior Electoral Court | ||||||||||

Aftermath

[edit]Analysis

[edit]Presidential election results

[edit]While Lula received the most votes in the first round with a lead of five percentage points and narrowly missed being elected in the first round, the result proved disappointing for his supporters, as polls had suggested a lead of up to 15 points, and some predicted that he would be elected in the first round. Instead, Bolsonaro outperformed almost all published opinion polling. This was partly attributed to a significant number of supporters of minor candidates deciding to vote for Bolsonaro shortly before the election, along with a number of Bolsonaro supporters refusing to respond to pollsters in the view that pollsters were part of a "fake news establishment".[257] Additionally, Brazil had last conducted a census in 2010, and a number of pollsters oversampled poorer voters who generally backed Lula. At the same time, this was the first time that the incumbent president attempting re-election did not receive the highest number of votes in the first round.[258][259][260] Lula's performance marked the second best result for the Workers' Party in the first round of a presidential election, behind only his result in 2006, and represented the highest number of votes for a candidate in the first round of a Brazilian election.[261]

For the second round, both Bolsonaro and Lula sought key endorsements.[262] Bolsonaro was endorsed by former judge Sergio Moro and the governors of Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo.[263] Simone Tebet and Ciro Gomes, the most voted presidential candidates to not advance to the runoff, endorsed Lula,[264] as did former president Fernando Henrique Cardoso. While Tebet endorsed Lula, her party, the Brazilian Democratic Movement, was split and gave its leaders freedom of choice.[265] In the second round, Lula received 50.90% of the votes to Bolsonaro's 49.10%,[266][267][268] in what many observers called a comeback and leftist surge in the region.[269][270][271] This result was narrower than expected but in line with polls showing a slight advantage for Lula.[272][273][274] Some observers described it as a contested and crucial election due to its close results and impact.[275][276] Incumbent presidents are allowed to run for re-election by a 1997 constitutional amendment, and Bolsonaro became the first incumbent president since then to not be re-elected.[277][278] Lula became the first person to be elected president for a third term in Brazil,[279] and the oldest person to assume the post at age 77 on his inauguration scheduled for 1 January 2023.[280][281] Lula's 60 million votes surpassed his own 2006 record as the largest number of votes in a Brazilian election.[282]

It was the closest presidential election in Brazil to date.[283] In both rounds, Lula was the most voted candidate in the state of Amazonas and the country's bellwether, Minas Gerais, where Bolsonaro had been the most voted in 2018. A shift was also observed among urban voters in the Southeast Region. In the city of Rio de Janeiro, Bolsonaro had obtained 66.4% of the vote in 2018, but only 52.7% in 2022.[284] In the city of São Paulo, he obtained 60.4% in 2018, but Lula flipped the city in 2022 and received 53.5% of the vote.[285] Steven Levitsky, author of How Democracies Die, commented that Bolsonaro's allies acknowledging Lula's victory helped to avoid a 6 January scenario, referencing the 2021 United States Capitol attack, and that Brazil managed the election in a better way than the United States did in 2020.[286] Some observers, such as Thomas Traumann, compared the results to Joe Biden's victory in 2020, and said that Lula was inheriting a nation that was much divided. Bolsonaro's better-than-expected performance reflected an election year with increased government spending. Political scientist Carlos Melo compared the election to the political climate experienced by the former president Dilma Rousseff's reelection bid in the 2014 Brazilian presidential election.[287]

Both presidential candidates in the second round received a higher percentage of the votes than they did in the first round in every state, and Bolsonaro's increase was greater than Lula's also in every state. Amapá was the only state where the most voted candidate was different between the first round (Lula) and the second round (Bolsonaro). It was the first presidential election when more people voted in the second round than in the first round, and both rounds had the lowest percentage of invalid votes in a presidential election since the two-round system was introduced in 1989.[288] The second round was the first time when votes from abroad exceeded those in a Brazilian state (Roraima).[256]

Congressional election results

[edit]In the National Congress of Brazil, right-wing parties expanded their majority, while centrist and left-wing parties elected fewer members, despite the Workers' Party-led coalition gaining seats, continuing the trend from the 2018 Brazilian general election.[289] Several small parties did not satisfy the minimum number of elected members to obtain access to public funds, broadcast time, and congressional leadership. To satisfy the requirement, these members could choose to individually join larger parties, or their parties could merge. The goal of this requirement, first established in 2018, was to reduce the large number of parties in Congress and facilitate political negotiations between them.[290]

The growth of the right-wing parties in Congress was cited as a potential roadblock to Lula's policy goals upon taking office.[287] Despite right-wing shifts in both chambers, a number of conservative incumbents were not elected for the same or other offices, including Douglas Garcia, Janaina Paschoal, and Fabricio Queiroz. A number of milestones took place in the election for Congress, including two transgender activists, Erika Hilton and Duda Salabert, who became the first transgender individuals elected to Congress, and five self-declared indigenous Brazilians were elected as deputies (including Sônia Guajajara and Célia Xakriabá) and two as senators (Wellington Dias and Hamilton Mourão), the largest number of self-declared indigenous candidates elected to Congress to date.[291][292]

Reactions

[edit]In Brazil

[edit]After 90% of the votes were counted in the second round, the Superior Electoral Court declared Lula as mathematically elected.[293] After this result, Lula stated: "Today the only winner is the Brazilian people. This isn't a victory of mine or the Workers' Party, nor the parties that supported me in campaign. It's the victory of a democratic movement that formed above political parties, personal interests and ideologies so that democracy came out victorious."[287] In his victory speech, he also called for "peace and unity" and said: "It is in no one's interest to live in a divided nation in a permanent state of war."[277] Former president Fernando Henrique Cardoso, who was elected against Lula in presidential elections in 1994 and 1998, congratulated Lula by stating that "democracy has won". Journalist Fernando Gabeira, an opponent of the military dictatorship in Brazil, called the election "a victory for Brazil, and a victory for humanity. We can now breathe again."[294]

Bolsonaro did not immediately publicly concede or comment on the election result,[267][295][296] which raised the widely discussed concerns prior to the election that he might reject the result like Donald Trump did in the United States in 2020.[197] Privately, Bolsonaro only acknowledged the result to the president of the Superior Electoral Court Alexandre de Moraes,[297] and he remained silent as transition talks began.[298] On 1 November, Minister of Communications, Fabio Faria, told Reuters that Bolsonaro would not contest the election result and would address the nation later in the day.[299] Chief of Staff of the Presidency, Ciro Nogueira Lima Filho, also confirmed that the incumbent government had already begun to establish contact with the future government led by Lula to discuss a transition.[300] Vice president-elect Geraldo Alckmin was named as the representative of the future government. Alckmin confirmed that he would coordinate the transition and aimed to start it on 3 November.[301]

Protests broke out in many states of Brazil after the election, as supporters of Bolsonaro alleged fraud and blockaded key roads, while demanding military intervention.[302][303][304] In some cases, police did not intervene. Late on 31 October, Moraes ordered the Federal Highway Police to clear all the federal highways. Protesters also blockaded roads to the São Paulo/Guarulhos International Airport on 1 November but were cleared by the Federal Highway Police.[305] The blockades disrupted fuel and grain distribution, as well as the meat industry and rail network. The road to the Port of Paranaguá, an important grain export port, was blocked by protestors. The Brazilian Petroleum and Gas Institute stated that the situation regarding fuel distribution had become critical, and called on the federal government to form a crisis committee regarding the protests.[306]

In a press conference at the Palácio da Alvorada on 1 November, Bolsonaro did not acknowledge the result but stated that he would "comply with the Constitution". Regarding the protests by his supporters, he referred to them as "the fruit of indignation and a sense of injustice of how the electoral process unfolded", while calling on them to remain peaceful and not block roads. Shortly after his speech, the Supreme Federal Court stated that by authorizing the transition of power he had recognized the results,[307][308] paving the way for the transition two days after Lula was declared elected.[309][310] Hours before the press conference, Bolsonaro met with the Brazilian Armed Forces to pitch the possibility of challenging Lula's election judicially, arguing that he would not be eligible due to his convictions in the Operation Car Wash, all of which had been annulled by the Supreme Federal Court in 2021.[311] Bolsonaro could not find support for it, and members of the Army High Command reportedly accepted the results and were against any possibility of a military intervention or coup.[312] The following day, Bolsonaro directly appealed to his protesting supporters to clear the roadblocks, while welcoming their decision to protest against the election results and asking them to do it through other means.[281]

The Ministry of Defence released the report about the election audit done by the military on 10 November. While it cited some possible vulnerabilities in the electronic voting machines used for the election, it did not find any sign of voter fraud.[313] On the following day, the Brazilian Armed Forces released a letter signed by leaders of all three branches, stating that all electoral disputes must be resolved through peaceful means, while adding that the Constitution permitted peaceful protests.[314]

Bolsonaro meanwhile spent weeks after his defeat mostly alone in his presidential residence. On 22 November, he and his party formally contested the election result, after an audit revealed that electronic voting machines made before 2020, which comprised 59% of machines used in the 2022 election, lacked identification numbers in their internal logs. They requested that the Superior Electoral Court invalidate the votes recorded by the affected machines, which would result in Bolsonaro being elected with 51% of the remaining valid votes. However, experts claimed that the software error did not affect the election results and pointed out that the identification numbers did appear in the physical vote records printed by the machines.[315] On the next day the court rejected the request and fined the party R$22.9 million (US$4.3 million) for what it considered bad faith litigation.[316]

Lula's victory was officially certified on 12 December. On the same day, Bolsonaro supporters attacked the Federal Police headquarters in Brasilia, after the arrest of one of the protesters for inciting violence to prevent Lula from being sworn in.[317] Benedito Gonçalves, general inspector of the Superior Electoral Court, opened an investigation against Bolsonaro, Walter Braga Netto and their allies for allegedly attempting to discredit the election result after a complaint by the coalition of parties supporting Lula.[318] A Bolsonaro supporter was arrested for allegedly trying to bomb the Brasília International Airport on 24 December.[319]