Битва при Сайпане

| Битва при Сайпане | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Часть на Марианских островах и Палау кампании Тихоокеанского театра военных действий ( Вторая мировая война ). | |||||||

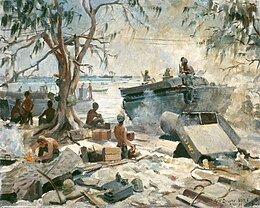

Морские пехотинцы укрываются за танком M4 Sherman во время зачистки японских войск на севере Сайпана, 8 июля 1944 года. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Richmond K. Turner Holland Smith |

Chūichi Nagumo † Yoshitsugu Saitō † | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| V Amphibious Corps | 31st Army | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Assault: 71,034 Garrison: 23,616 Total: 94,650[1] |

Army: 25,469 Navy: 6,160 Total: 31,629[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Land forces:[3] 3,100–3,225 killed 326 missing 13,061–13,099 wounded Ships' personnel:[4] 51+ killed 32+ missing 184+ wounded |

25,144+ dead (buried as of 15 August) 1,810 prisoners (as of 10 August) Remaining ~5,000 committed suicide, killed/captured later, or holding out[5] | ||||||

| 8,000[6]–10,000[7] civilian deaths | |||||||

Битва при Сайпане — это десантное нападение, предпринятое Соединенными Штатами против Японской империи во время Тихоокеанской кампании с Второй мировой войны 15 июня по 9 июля 1944 года. Первоначальное вторжение спровоцировало битву в Филиппинском море , которая фактически уничтожила японский авианосец. базировалась авиация , и битва привела к захвату острова американцами. В результате оккупации крупные города японских островов оказались в пределах досягаемости бомбардировщиков B-29 , что сделало их уязвимыми для стратегических бомбардировок ВВС США . Это также ускорило отставку Хидеки Тодзё , премьер-министра Японии .

Сайпан был первой целью операции «Фураджер» , кампании по оккупации Марианских островов , которая началась в то же время, когда союзники вторглись во Францию в рамках операции «Оверлорд» . После двухдневной морской бомбардировки 2-я дивизия морской пехоты США , 4-я дивизия морской пехоты армии США и 27-я пехотная дивизия под командованием генерал-лейтенанта Холланда Смита высадились на острове и разгромили 43-ю пехотную дивизию Императорской японской армии под командованием Генерал-лейтенант Ёсицугу Сайто . погибло не менее 3000 японских солдат Организованное сопротивление прекратилось, когда в последней атаке гёкусай , а после этого около 1000 мирных жителей покончили жизнь самоубийством.

The capture of Saipan pierced the Japanese inner defense perimeter and left Japan vulnerable to strategic bombing. It forced the Japanese government to inform its citizens for the first time that the war was not going well. The battle claimed more than 46,000 military casualties and at least 8,000 civilian deaths. The high percentage of casualties suffered during the battle influenced American planning for future assaults, including the projected invasion of Japan.

Background

[edit]American strategic objectives

[edit]

Up to early 1944, Allied operations against the Japanese military in the Pacific were focused on securing the lines of communication between Australia and the United States. These operations had recaptured the Solomon Islands, eastern New Guinea, western New Britain, the Admiralty Islands, and the Gilbert and Marshall Islands.[8]

To defeat Japan, Admiral Ernest J. King, Commander in Chief, United States Fleet, sought to execute War Plan Orange,[9] which the Naval War College had been developing for four decades in the event of a war.[10] The plan envisioned an offensive through the Central Pacific that originated from Hawaii, island-hopped through Micronesia and the Philippines, forced a decisive battle with the Japanese Navy, and brought about an economic collapse of Japan.[11]

As early as the Casablanca Conference in January 1943, King presented the case to the Combined Chiefs of Staff for an amphibious offensive in the Central Pacific – including the Marshall Islands and Truk – that would capture the Mariana Islands. He stated that the occupation of the Marianas – specifically Saipan, Tinian and Guam – would cut the sea and air route from the Japanese home islands to the western Pacific,[12] but the Combined Chiefs of Staff made no commitment at the time.[13] General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area, objected to King's proposed Central Pacific offensive.[14] He argued that it would be costly and time-consuming and would pull resources away from his drive in the Southwest Pacific toward the Philippines.[15]

At the Quebec Conference in August 1943, King continued to advocate for including the Marianas in a Central Pacific offensive.[16] He suggested that the strategic importance of the Marianas could draw the main Japanese fleet out for a major naval battle.[17] King's advocacy gained support from General Henry H. Arnold, Chief of the Army Air Forces, who wanted to use the newly-developed B-29 bomber.[18] The Marianas could provide secure airfields to sustain a strategic bombing offensive as the islands put much of Japan's population centers and industrial areas within the B-29's 1,600 mi (1,400 nmi; 2,600 km) mile combat radius.[19] At the Cairo Conference in November 1943, the Combined Chiefs of Staff supported both MacArthur's offensive in the Southwest Pacific and King's in the Central Pacific,[20] adding the Marianas as an objective for the Central Pacific offensive and setting 1 October 1944 as the date for their invasion.[21]

Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas led the Central Pacific offensive.[22] In January–February 1944, the Marshall Islands were quickly captured and a massive American carrier-based air attack on Truk demonstrated that it could be neutralized and bypassed.[23] On 12 March 1944, the Joint Chiefs of Staff moved the date of the invasion up to 15 June with the goal of creating airfields for B-29s and developing secondary naval bases.[24] Nimitz updated the plans for the Central Pacific offense, codenamed Granite II, and set the invasion of the Marianas, codenamed Forager,[25] as its initial objective.[18] Saipan would be the first assault.[25]

Japanese strategic plan

[edit]The Japanese Imperial War Council established the "Absolute National Defense Zone", Zettai Kokubōken) in September 1943, which was bounded by the Kuril Islands, Bonin Islands, the Marianas, Western New Guinea, Malaya, and Burma.[26] This line was to be held at all costs if Japan was to win the war.[27] The Marianas were considered particularly important to protect as their capture would put Japan within bombing range of the B-29 bomber[28] and allow the Americans to interdict the supply routes between the Japanese home islands and the western Pacific.[29]

The Imperial Japanese Navy planned to hold the defense line by defeating the United States fleet in a single decisive battle,[30] after which, the Americans were expected to negotiate for peace.[31] The Japanese Submarine Fleet (6th Fleet), commanded by Vice Admiral Takeo Takagi whose headquarters was on Saipan,[32] would screen the line.[33] Any American attempt to breach this line was to serve as the trigger to start the battle.[34] The defense forces in the attacked area would attempt to hold their positions while the Japanese Combined Fleet struck the Americans, sinking their carriers with land-based aircraft and finishing the fleet off with surface ships.[35] As part of this plan the Japanese could deploy over 500 land-based planes – 147 of them immediately in the Marianas – that made up the 1st Air Fleet under the command of Vice Admiral Kakuji Kakuta whose headquarters was on Tinian.[36]

Geography

[edit]

Saipan and the other Mariana Islands were claimed as Spanish possessions by the conquistador Miguel López de Legazpi in 1565.[37] After Spain's defeat in the Spanish-American War, Saipan was sold to Germany in 1899.[38] The island was occupied by the Japanese in 1914 during World War I, who made it the administrative center for the Mariana Islands – Saipan, Tinian and Rota – that were part of Japan's South Seas Mandate.[39]

Saipan has a tropical marine climate with a mean annual temperature of 85 °F (29 °C) in the lowlands and 78 °F (26 °C) in the highlands. Though the island has a mean rainfall between 81 and 91 inches per year, the rainy season does not begin until July.[40] Unlike the small, flat coral atolls of the Gilberts and Marshalls,[41] Saipan is a volcanic island with diverse terrain well suited for defense.[42] It is approximately 47 sq mi (122 km2),[43][a] and has a volcanic core surrounded by limestone.[45] In the center of the island is Mount Tapotchau, which rises to 1,554 ft (474 m). From the mountain, a high ridge ran northward about seven miles to Mount Marpi.[46] This area was filled with caves and ravines concealed by forest and brush,[47] and the mountainous terrain would force tanks to stay on the island's few roads, which were poorly constructed.[48]

The southern half of the island was where the principal airfield of the Marianas, Aslito Field, was located.[49] It served as a repair stop and transit hub for Japanese aircraft headed toward other parts of the Pacific.[50] This half of the island was flatter but covered with sugar cane fields[51] because the island's economy became focused on sugar production after the Japanese government had taken over Saipan from Germany in 1914.[52] Seventy percent of Saipan's acreage was dedicated to sugar cane.[39] It was so plentiful that a narrow-gauge railway was built around the perimeter of the island to facilitate its transportation.[53] These cane fields were an obstacle to attackers: they were difficult to maneuver in and provided concealment for the defenders.[54]

Saipan was the first island during the Pacific War where the United States forces encountered a substantial Japanese civilian population,[55] and the first where U. S. Marines fought around urban areas.[56] Approximately 26,000[6] to 28,000[7] civilians lived on the island, primarily serving the sugar industry.[39] The majority of them were Japanese subjects, most of whom were from Okinawa and Korea; a minority were Chamorro people.[53] The largest towns on the island–the administrative center of Garapan with its population of 10,000, Charan Kanoa, and Tanapag–were on the western coast of the island, which was where the best landing beaches for an invasion were.[54]

Opposing forces

[edit]American invasion force

[edit]

Nimitz assigned Admiral Raymond Spruance, commander of the Fifth Fleet, to oversee the operation. Vice Admiral Richmond K. Turner, Commander, Joint Amphibious Forces (Task Force 51) oversaw the overall organization of the amphibious landings of Forager; he also oversaw the tactical command of the landing on Saipan as Commander, Northern Attack Force (TF 52).[57] Once the amphibious landings were completed, Lieutenant General Holland M. Smith, Commanding General, Expeditionary Troops (Task Force 56), would oversee the ground forces for all of Forager; he would also oversee the ground combat on Saipan as Commander, Northern Troops and Landing Force.[58]

The Northern Troops and Landing Force was built around the V Amphibious Corps,[59] which consisted of the 2nd Marine Division commanded by Major General Thomas E. Watson and 4th Marine Division commanded by Major General Harry Schmidt.[60] Additionally, the 27th Infantry Division commanded by Major General Ralph C. Smith was held as the Expeditionary Troops reserve for use anywhere in the Marianas.[61] Over 60,000 troops were assigned to the assault:[b] Approximately 22,000 were in each Marine division and 16,500 in the 27th Infantry Division.[62]

The invasion fleet, consisting of over 500 ships and 300,000 men,[c] got underway days before the Allied forces in Europe invaded France in Operation Overlord on 6 June 1944.[63] It was launched from Hawaii, briefly stopping at Eniwetok and Kwajalein before heading for Saipan. The Marine divisions left Pearl Harbor on 19–31 May and rendezvoused at Eniwetok on 7–8 June; the 27th Infantry Division left Pearl Harbor on 25 May and arrived at Kwajalein on 9 June.[64] The fifteen aircraft carriers of the Fast Carrier Task Force (Task Force 58) commanded by Vice Admiral Marc A. Mitscher,[65] which would provide support for the invasion, left Majuro for Saipan on 6 June.[66]

Japanese defense preparations

[edit]

American intelligence had estimated that there would be between 15,000 and 18,000 Japanese troops on Saipan at the time of the invasion.[67] In actuality, there were double that number.[68] Nearly 32,000 Japanese military personnel were on the island, including 6,000 naval troops.[29] The two major army units defending the island were the 43rd Division commanded by Lieutenant General Yoshitsugu Saitō and the 47th Independent Mixed Brigade commanded by Colonel Yoshira Oka.[69]

The Japanese hurriedly reinforced the island before the invasion, but many of the troop transports were sunk by U.S. submarines.[70] For example, five of the seven ships transporting the 43rd Division were sunk.[71] Most of the troops were saved, but the majority of their equipment–including hats and shoes–was lost, reducing their effectiveness.[72] Many soldiers were the stranded survivors of sunken ships headed to other islands.[73] There were about 80 tanks on the island, substantially more than the Americans had encountered in previous battles with the Japanese.[74]

The Japanese defenses were set up to defeat an invading force on Saipan's beaches, where the invading troops were most vulnerable.[75] These defenses focused on the most likely invasion locations, the western beaches south of Garapan.[76] This made the defenses brittle. If an invading force broke through the beach defenses, there was no organized fallback position: the Japanese troops would have to rely on Saipan's rough terrain, especially its caves, for protection.[77] The original plans called for a defense in depth that fortified the entire island[78] if time allowed,[79] but the Japanese were unable to complete their defenses by the time of the invasion. Much of the building material sent to Saipan, such as concrete and steel, had been sunk in transit by American submarines,[41] and the timing of the invasion surprised the Japanese, who thought they had until November to complete their defense.[77] As of June, many fortifications remained incomplete, available building materials were left unused, and many artillery guns were not properly deployed.[80]

Japanese leadership on the island suffered from poor command coordination.[81] Although Vice Admiral Chūichi Nagumo, Commander of the Central Pacific Area Fleet, had nominal oversight of the defenses in the Central Pacific, Obata refused to subordinate his army command to a naval officer.[82] Because Obata was not on the island when the invasion started, command of Saipan's army units fell to Saitō, who was the senior army officer on the island.[83] But Obata's chief of staff, Major General Keiji Igeta, maintained a separate headquarters that was often out of touch with Saitō.[84]

Battle

[edit]11–14 June: Preparatory attacks

[edit]

On 11 June, over 200 F6F Hellcats from the Fast Carrier Task Force launched a surprise attack on Japanese airfields in Saipan and Tinian,[85] putting approximately 130 Japanese aircraft out of operation[86] at the cost of 11 American aircraft.[87] The attack took out most of the 1st Air Fleet's land-based planes that had been deployed to defend the Marianas,[88] and gave the Americans air superiority over Saipan.[89] Planes from the task force continued their attacks until 14 June,[90] harassing fields, bombing military targets, and burning cane fields on the southern half of Saipan.[91] By the end of the week, the 1st Air Fleet had been reduced to about 100 aircraft.[88]

On 13 June, seven fast battleships and 11 destroyers under Vice Admiral Willis Lee began the naval bombardment of Saipan.[92] Most of these battleships' crews had not been trained in shore bombardment and the ships fired from more than 5.5 mi (8.9 km) to avoid potential minefields. The bombardment damaged much of Garapan and Charan Kanoa, but it was relatively ineffective at destroying the island's defenses.[93] The following day, seven older battleships, 11 cruisers, and 26 destroyers[94] commanded by Rear Admiral Jesse B. Oldendorf continued the shelling.[95] These crews were trained in shore bombardment,[96] and moved closer to shore because the sea was found to be free of mines.[97] This bombardment eliminated many emplaced anti-aircraft positions,[97] but it too failed to destroy most of the beach defenses.[98]

15 June: D-Day

[edit]

15 June was D-Day for the amphibious landing,[99] which began around 08:40.[100] Naval and aerial bombardments in preparation for the landings began earlier in the morning,[101] disrupting the Japanese communications network.[102] The guns of the warships would provide continuous supporting fire throughout the day.[101]

The V Amphibious Corps landed on the southwest beaches of Saipan.[103] The 2nd Marine Division landed on two beaches, named Red and Green, of Charan Kanoa, and the 4th Marine Division landed on the beaches named Blue and Yellow south of the town.[104] Approximately 700 amphibious vehicles participated in the assault,[105] including 393 amphibious tractors (LVTs) and 140 amphibious tanks.[106] Within 20 minutes, there were 8000 men on the beaches.[107]

The beaches were fortified by trenches and a few pillboxes,[108] but the landings were mainly contested by constant and intensive fire by Japanese artillery, mortars,[109] and machine guns.[29] The Japanese had concentrated at least 50 large artillery pieces on the high ground—including at least 24 105-mm howitzers and 30 75-mm field pieces—around the invasion beaches. Many were deployed on reverse slopes,[110] and pennants had been placed on the beach for accurate ranging.[111] The Americans suffered over 2,000 casualties,[112][d] the majority were due to the artillery and mortar fire.[114] Additionally, 164 amphibious tractors and amphibious tanks, about 40% of those engaged during the day, had been destroyed or damaged.[115]

By the end of the day, the Marines managed to establish a bridgehead about 5.5 mi (9 km) along the beach and 0.5 mi (1 km) inland,[116] and had unloaded artillery and tanks.[117] But the bridgehead was only about two-thirds the size of the planned objective,[118] the two Marine divisions were separated by a wide gap just north of Charan Kanoa,[119] and the Japanese artillery remained intact on the high ground surrounding the beach.[120]

When darkness fell, Saito launched a series of night attacks to push the Americans back into the sea.[121] The Japanese launched repeated counterattacks during the night and the early hours of the following morning,[122] mostly by poorly coordinated small units.[123] All the attacks were repulsed,[124] partly by the firepower provided by the tanks and artillery that had been unloaded during the day as well as by American warships that illuminated the combat areas with star shells.[125]

16–20 June: Southern Saipan

[edit]

On 16 June, Holland Smith committed his reserves to reinforce the beachhead, ordering two of the three regiments of the 27th Infantry Division—the 165th and the 105th—to land.[126] He proposed to indefinitely postpone the 18 June invasion of Guam.[127] The two Marine divisions on Saipan spent most of the day consolidating the beachhead.[128] The 2nd Marine Division began to close the gap between the two divisions north of Charan Kanoa, and the 4th Marine Division cleared the area around Aginan point on the southwest of the Island.[129]

During the night, Saitō launched a tank assault on the flank of the beachhead just north of Charan Kanoa with approximately 30 Type 97 medium tanks and Type 95 light tanks[e] and about 1,000 soldiers.[130] The attack was poorly coordinated.[131] Nagumo's naval troops, who were supposed to be part of the attack, did not cooperate.[132] The attack was broken up by bazookas, 37 mm anti-tank guns, M4 Sherman tanks, and self-propelled 75 mm howitzers.[133] Around 31 Japanese tanks were destroyed.[134]

In the following days, the 2nd Marine Division on the northern half of the bridgehead cleared the area around Lake Susupe[135] and reached the objectives for the first day of the invasion,[136] and slowly moved north toward Garapan and Mount Tapotchou.[137] In the southern half of the bridgehead, the 4th Marine Division began their advance on Aslito Field. On 18 June, the two regiments of the 27th Infantry Division, which was now fighting as a unit,[138] captured the field[139] as the Japanese withdrew to Nafutan Point in the southeast of the island.[140] The 4th Marine Division had reached the island's eastern coast, cutting off the Japanese troops at Nafutan Point from the north.[141] During this time, Saitō was falsely rumored to have been killed.[142] Igeta erroneously reported Saitō's death to Tokyo, though he corrected the report later.[143]

Holland Smith ordered the 27th Infantry Division to quickly capture Nafutan Point but it was unable to do so.[144] Intelligence had estimated that there were no more than 300 Japanese soldiers in the area, but there were more than 1,000 defending the rough terrain.[145] The battle for the point would continue for over a week.[146]

By 19 June, the Japanese forces on the island had been reduced by about half.[147] Saitō began withdrawing his troops to a new defensive line in the center of the island.[148] By this time, the Americans had suffered over 6,000 casualties.[149] The Marine divisions headed north toward the new Japanese defenses,[150] and Holland Smith called for the final reserve of the Expeditionary Forces, ordering the last regiment of the 27th infantry Division, the 106th, to land on Saipan on 20 June.[151]

Battle of Philippine Sea

[edit]

Once Admiral Soemu Toyoda, Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet, was certain that Saipan was the target of an invasion, he initiated his response.[152] Less than a half hour after the start of the amphibious invasion,[153] he announced the implementation of Operation A-Go,[154] the Japanese Navy's current plan to destroy the American fleet.[155] He then sent a message to the entire fleet that repeated Admiral Heihachirō Tōgō's speech before Japan's decisive naval battle against Russia at Tsushima in 1905, which in turn echoed Horatio Nelson's signal at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805:[156] "The fate of the Empire rests upon this single battle. Every man is expected to do his utmost."[157]

Originally, the Japanese Navy sought to have the battle take place in the Palaus or Western Carolines,[158] and MacArthur's invasion of Biak had led them to believe that they could lure the American fleet there.[159] After the preinvasion bombardment of Saipan, Toyoda guessed Saipan was the target and ordered Vice Admiral Matome Ugaki who commanded the super battleships Yamato and Musashi to rendezvous with Vice Admiral Jisaburō Ozawa, commander of the 1st Mobile Fleet and to rendezvous in the Philippine Sea to attack the American fleet around Saipan.[160] The Japanese fleet, which had 9 aircraft carriers, 5 battleships, and nearly 500 airplanes was outnumbered by the American fleet,[161] which had 16 aircraft carriers, 7 battleships, and almost 1,000 airplanes.[162] The Japanese thought they had some advantages: the longer range of the Japanese planes would allow them the opportunity to strike the Americans without fear of immediate retaliation,[162] the availability of airbases on the Marianas would give the carrier planes a place to land and quickly rearm for additional strikes,[153] and Kakuta was incorrectly assumed to have 500 additional land-based planes available.[163]

The American transports continued to unload supplies and reinforcements throughout 17 June. The following day, the transports sailed east toward safety while the warships set off for battle with the Japanese fleet. On 19–20 June, the fleets fought an aircraft carrier battle.[164] The Japanese struck first,[165] launching four large air attacks on the American fleet.[166] However, the Japanese aviators were inexperienced and outnumbered: very few of the anticipated land-based planes were available,[167] and those that were had little effect.[168]

The Japanese lost almost 500 planes[169] and almost all their aviators;[170] their carrier forces were left with only 35 operable aircraft.[171] The Americans lost about 130 planes[169] and 76 aviators.[170] An American counterstrike sank a Japanese carrier, and American submarines sank two others, including Ozawa's flagship Taihō.[172] The Japanese submarine fleet failed to play a significant role as well. The invasion forced Takagi to move his headquarters from Garapan into the mountains of Saipan, making his command ineffective.[173] Out of 25 submarines deployed for the battle, 17 were sunk.[174] Though defenders on the island didn't know it at the time, the defeat of the Japanese fleet ensured that they would not be reinforced, resupplied or receive further military support.[175] The Japanese command was determined to hold the island at all costs,[176] but it would be fighting a losing battle of attrition.[177]

21–24 June: Central Saipan, initial attack

[edit]

Saitō's new defense line stretched from Garapan on the west coast to the southern slopes of Mount Tapatchou across to Magicienne Bay on the east coast.[178] It held most of the island's high ground, which allowed the Japanese to observe American movements, and the rough terrain was filled with caves concealed by brush.[179]

The American forces prepared for a frontal assault on Saitō's line using all three divisions.[180] The attack began on 22 June. The 2nd Marine Division which was on the western coast moved toward Garapan and Mount Tapatchou; the 4th Marine Division advanced along the eastern coast,[181] which created gaps in the lines in the hilly ground between the two divisions.[182] That evening, the 27th Infantry Division, less the regiment left to reduce Nafutan point,[183] was ordered to move up into the difficult terrain between the two Marine divisions.[184]

The next day, the Marine divisions on the flanks made progress, but the 27th Infantry Division, which started its attack late, stalled in its assault on a valley surrounding a low lying ridge that was defended by about 4,000 Japanese soldiers.[185] The battle around these features, which American soldiers nicknamed the "Death Valley" and "Purple Heart Ridge",[186] began to bend the line of the American advance into a horseshoe,[187] creating gaps in the Marine divisions flanks and forcing them to halt.[188]

Frustrated by what he saw as lack of progress by the 27th Division, Holland Smith relieved its commander, Major General Ralph Smith, and temporarily replaced him another Army officer, Major General Sanderford Jarman.[189] The debate over the appropriateness of Holland's Smith action–a Marine general dismissing an Army general–immediately created an inter-service controversy.[190][f] Despite the replacement of the 27th Infantry Division's commander, it would take six more days for the valley to be captured.[192]

25–30 June: Central Saipan, breakthrough

[edit]American firepower

[edit]

The United States forces had built up substantial firepower to continue their northward drive. On 22 June, P-47s from the Seventh Air Force landed on Aslito Field and immediately began launching ground assault missions.[193] On the same day, the XXIV Corps Artillery commanded by Brigadier General Arthur M. Harper moved 24 155 mm field guns and 24 155 mm howitzers into place to fire on Japanese positions.[194] The Americans also used truck-launched rockets[195] for saturation barrages.[196] Spotters flying in L-4 Grasshoppers helped direct ground artillery,[197] and Navajo code talkers relayed information about Japanese troop movements.[198]

By 24 June, the American warships that had returned from the Battle of Philippine Sea were once more available to provide fire support.[199] Ship fire was particularly feared by the Japanese because it could strike from almost any direction.[200] Saitō singled out naval gunfire undermining the Japanese' ability to fight successfully against the Americans.[201] The ships were also well supplied with star shells, providing illumination that disrupted Japanese night movements and counterattacks.[202] This naval support was facilitated by joint assault signal companies that directed both naval and aerial firepower to where it was needed by the ground forces.[203]

The Americans had other assets as well. Over 150 tanks–over 100 of which were M4 Sherman tanks–had been committed to the invasion.[204] The M4 Sherman tank was superior to the Japanese Type 97 tank.[205] It was primarily used to support infantry and was considered one of the most effective weapons for destroying enemy emplacements.[206] Flame throwers were extensively used. Smith had seen the need for motorized flamethrowers and had requested that the Army's Chemical Warfare Service (CWS) in Hawaii install them in M3 Stuart tanks. Seabees with the CWS had 24 tanks, nicknamed "Satans", converted to flamethrowing in time for the invasion. They were very effective for destroying pillboxes, cave defenses, buildings, canefields, and brush.[207] In the hills, soldiers relied on personal flamethrowers, particularly in locations where the motorized flamethrowers could not reach.[208] The Americans gradually developed tactics for effectively reducing caves, using a combination of flamethrowers and demolition charges to clear them, or sometimes using demolitions to seal them off.[209]

On 27 June, Igeta's 31st Army Headquarters sent a telegram from the island stating the Japanese would not be able to hold due to the American preponderance in artillery, sea and air power, as well of a lack of equipment and supplies, including food and water.[210] The lack of water was particularly acute in the limestone caves the Japanese soldiers used for defense.[211] Igeta reported that some soldiers hadn't had water for three days and were surviving on snails and tree leaves.[212] Japanese communications were so disrupted that at one point during the week, Igeta could only account for 950 of the Japanese soldiers.[213]

American advance and Japanese break out at Nafutan Point

[edit]

On 25 June, the 27th Infantry Division was not able to make much headway in their fight for Death Valley. But the 2nd Marine Division to the west gained control of Mount Tapotchau, the key artillery observation posts in Central Saipan.[214] On the east coast, the 4th Marine Division quickly occupied most of the Kagman peninsula, meeting little organized resistance[215] because the Japanese had evacuated the peninsula.[216] Between 26 June and 30 June, the 2nd Marine Division and the 27th Infantry Division had made little progress. The second Marines remained south of Garapan and were slowly fighting their way north of Mount Tapotchau. The 4th Marine Division was able to advance up the eastern coast to a line just north of the village of Hashigoru.[217]

About 500 Japanese soldiers broke out of Nafutan point on the night of 26 June. They headed toward Aslito Field, destroying one P-47 and damaging two others.[218] They then ran into a unit of Marines who were in reserve and a unit of Marine artillery. Almost all the Japanese soldiers were killed in the ensuing firefight.[219] The next day, the elements of the 27th Infantry Division that had been fighting at the point moved in to occupy the area, no survivors were found.[220]

Army Major General George Griner, who had been sent for from Hawaii, took over from command of the 27th Infantry Division on 28 June. Jarman, whose command had been temporary, returned to his assign role as garrison commander of the island.[221] On 30 June, the 27th Infantry Division captured Death Valley and Purple Heart Ridge, and advanced far enough to reestablish contact with the two Marine divisions on their flanks. Saitō's main line of defense in Central Saipan had been breached;[222] and the Japanese began their retreat north to their final defensive line.[223] To date, American casualties were about 11,000.[224]

1–6 July: Pursuit into northern Saipan

[edit]

Saitō intended to form a new line in northern Saipan that was anchored on Tanapag on the west, went southeast to a village called Tarahoho, through to the east coast.[225] But his army's cohesion was disintegrating. Some of the remaining forces moved north, others holed up in whatever caves they could find and put up sporadic, disorganized resistance.[226] During 2–4 July, the 2nd Marine Division took the ruins of Garapan and its harbor.[227] The 4th Marine Division quickly moved north on the west coast in the face of light resistance.[228] As Saitō's attempt to form the defense line collapsed,[229] he eventually moved his final headquarters near Makunsha village on the west coast north of Tanapag.[230]

On 4 July, the 27th Infantry Division and 4th Marine Division headed northwest. The 27th division reached the east coast at Flores Point, south of Tanapag,[231] cutting off any Japanese retreating from Garapan.[232] The 2nd Marine Division no longer faced organized resistance, and went into reserve. The 27th Infantry Division was to move up the east coast toward Tanapag, and the 4th Marine Division would advance northwest.[233] On 5 July, the 27th Infantry Division encountered strong resistance in a narrow canyon on the east coast north of Tanapag that they dubbed "Harikari Gulch", which expanded into a two-day battle.[234]

The 4th Marine Division continued to make rapid progress north during 4–5 July,[235] and on 6 July, Holland Smith ordered them to head toward the eastern coast near Makunsha to cut off the Japanese forces fighting the 27th Infantry Division,[236] then the Marines would complete the occupation of the rest of northern Saipan on their own.[237] In the evening, the Marines had taken Mount Petosukara, one of the last mountains before reaching the northern tip of the island,[238] but the units that turned toward Makunsha encountered too much resistance to reach the eastern coast.[239]

Saitō realized he could not create a final defensive line. His headquarters, which had been under constant artillery attack for days, was now in the range of American machine guns.[240] What was left of his command was trapped in a northern corner of the island, almost out of food and water, and slowly being destroyed by overwhelming American firepower.[241] On 6 July, Saitō decided the situation was hopeless and sent out orders for the remainder of his forces to perform gyokusai, one final suicide attack to destroy as many of the enemy as possible.[242] He set the attack for the following day to give the troops a chance to concentrate what was left of his forces and put his divisional chief of staff, Colonel Takuji Suzuki,[243] in charge. That night, Saitō ate a last meal and committed seppuku, and Nagumo killed himself around the same time,[g] Takagi stated he would die attacking the enemy.[248]

7–9 July: Gyokusai attack and battle's end

[edit]

At least 3,000 Japanese combatants participated in the gyokusai attack.[249][h] They assembled near Makunsha. The force included naval personnel,[255] support troops, civilians,[256] and the walking wounded.[257] It included three tanks,[258] supporting mortars, and machine guns,[259] but some troops were only armed with sticks with bayonets, knives, or grenades tied to poles.[255] It would be the largest gyokusai attack of the Pacific War.[237]

At around 04:00, Suzuki's force advanced south along the western coastal area,[260] called the Tanapag plain,[261] toward where his reconnaissance patrols had found a weak spot in the American line near Tanapag village:[262] two battalions of the 105 Infantry Regiment of the 27th Infantry Division were isolated from the other American forces.[251] The main force struck the two battalions at about 04:45, overrunning both and inflicting 80% casualties.[263] The charge continued toward Tanapag village, overrunning two batteries of Marine artillery, but was halted in the late morning [264] by a hastily-formed American line around the village.[265] The fighting continued throughout the day, as American soldiers struggled against scattered elements of the gyokusai attack and recaptured lost ground.[266]

On 8 July, most of the 27th Infantry Division, which had suffered high losses in the gyokusai attack, was placed into reserve. The 2nd Marine Division advanced up the Tanapag plain, looking for Japanese stragglers.[267] The 4th Marine Division reached the Western coast north of Makunsha and headed toward Marpi point, near the island's northern-most tip.[268] As they advanced, they saw hundreds of Japanese civilians die on inland and coastal cliffs.[269] Some threw themselves off, others were thrown or pushed off.[270] By the evening of 9 July, the 4th Marine Division had reached the northern end of the Island and Turner declared the island secure.[271] On the second day of the battle, he had estimated that Saipan would be captured in a week;[101] it had taken 24 days.[272] On 11 July, the Americans found general Saitō's body. He was buried on 13 July with full military honors in a coffin draped with the Japanese flag.[273]

Though the island was declared secured, the fighting and suicides would continue. Clearing the hundreds of scattered Japanese soldiers hiding in caves would take many more months,[274] though the responsibilities were handed over to the Army Garrison Force.[269] One group of about 50 Japanese men–soldiers and civilians–was led by Captain Sakae Ōba, who survived the last banzai charge.[275] His group evaded capture and conducted guerrilla-style attacks, raiding American camps for supplies.[276] Oba's resistance earned him the nickname "the Fox".[275] His men held out for approximately 16 months before surrendering on 1 December 1945, three months after the official surrender of Japan.[277]

Casualties

[edit]

Almost the entire Japanese garrison–approximately 30,000 military personnel–were killed in the battle. Eventually 1700, about half of whom were Korean workers, were taken prisoner.[269] American forces suffered about 16,500 casualties –3,100 killed and 13,000 wounded–[278] out of 71,000 who were part of the assault force.[279] The casualty rate was over 20%,[280] which was comparable to Tarawa.[278] It was the Americans' most costly battle in the Pacific up to that time.[281] Approximately 40% of the civilians on Saipan were killed. Around 14,000 survived and were interned,[282] but an estimated 8,000[6] to 10,000[7] died during the fighting or shortly afterwards. Many civilians died from the bombing, shelling and cross-fire.[283] Others died because they hid in caves and shelters that were indistinguishable from Japanese combat positions, which the Marines typically destroyed with explosives, grenades and flamethrowers.[284] Though many civilians were able to surrender early in the battle, surrender became more difficult as the battle moved into the northern mountains. Obscuring terrain made it hard to distinguish combatants and surrendering civilians, who risked being killed by both sides. Many refused to surrender because they believed rumors that the Japanese fleet was coming to rescue them.[285] Others refused because of the fear spread by Japanese propaganda that Americans would rape, torture and kill them; others were coerced.[286] Around 1,000 civilians committed suicide during the final days of the battle,[287] some after 9 July when the island had been declared secure.[288] Many died by throwing themselves off cliffs at places that would become known as "Suicide Cliff" and "Banzai Cliff".[289]

Logistics

[edit]

The American forces brought their supplies with the invasion fleet,[290] carrying over one ton of supplies per soldier:[291] 32 days of rations, 30 days of medical supplies, 20 days of maintenance supplies, seven days of ammunition for ground weapons, and ten days of anti-aircraft ammunition.[292] Mobile reserves[293] and an ammunition resupply train,[294] as well as regular resupply shipments came from depots at Eniwetok,[295] which was 1,017 mi (1,637 km) from Saipan.[290]

During the early days of the invasion, LVTs dumped boxes of rations, water and ammunition on the beaches.[296] Heavy swells on the first days forced many of the supplies to be loaded on only one beach,[290] and LVTs were required to get over reefs that restricted access.[297] Constant Japanese mortar and artillery fire interfered with organizing these supplies for the first three days. Unloading became haphazard, and some units had difficulty finding their equipment.[298] Additionally, the withdrawal of the transports for five days during the Battle of Philippine Sea slowed down the delivery of supplies.[299]

The 27th Infantry Division particularly suffered from this initial disorganization. No plans had been made for its landing and it did not have an assigned unloading area. Its equipment was mixed up with the Marine divisions and its artillery ammunition was misplaced.[300] Because it arrived on Saipan after the Marine divisions, the 27th Infantry Division had less time to unload its supplies before the transports temporarily headed east on 18 June. Initially, the division only had enough infantry ammunition for four days. Food and artillery ammunition had to be borrowed from the Marines, and water had to be supplemented from cisterns captured at Aslito Field.[301]

Later in the campaign, mortar ammunition ran low as planners had underestimated how frequently they would be used, and there were shortages of motorized transportation, which was used for getting supplies from the beach to the frontline. Naval ships ran low on star shells due to their high demand, and their use had to be rationed. Despite these issues, the overall supply situation during the battle was good: the Americans had an abundance of materiel.[302]

The Japanese troops had no chance of reinforcement.[303] From January to June, the Japanese had tried to ship men and supplies to Saipan,[304] but many ships around the island were torpedoed by American submarines. The Japanese government reported that one ship out of three sent to the Marianas were sunk and another was damaged.[305] Though many of the men survived, almost all the materiel was lost.[304] For example, on 25 May two freighters from Saipan to Palau were torpedoed, destroying 2,956 tons of food, 5,300 cans of aviation fuel, 2,500 cubic meters of ammunition, and 500 tons of cement.[306]

At the beginning of the battle, the Americans had six times the tanks, five times the artillery, three times as many small arms, and two times as many machine guns available as the Japanese. Additionally, the Americans had much more ammunition.[307] The U. S. Navy fired 11,000 tons of ordnance on Saipan, including over 14,000 rounds of 5-inch ammunition.[294] Unlike the Americans, who could replenish their supplies, the Japanese could not. They had to fight with what was available when the invasion started, and when it ran out they were expected to die honorably, resisting until the end.[308]

Aftermath

[edit]The invasion of Saipan and the invasion of France in Operation Overlord demonstrated the dominance of American industrial power. Both were massive amphibious invasions–the two largest up to that time–and they were launched almost simultaneously on separate halves of the globe.[309] Together, they were the greatest deployment of military resources by the United States at one time.[310] Because the Battle of Saipan began just over a week after the 6 June landings for Overlord, its importance has often been overlooked. But just as Overlord was a major step in contributing to the fall of the Third Reich, Saipan marked a major step in the collapse of the Empire of Japan.[311]

Impact on American military strategy

[edit]

The availability of Saipan as an American airbase, along with the airbases already established in Chengdu, opened a new phase in the Pacific War, in which strategic bombing would play a major role. The 15 June invasion of the island had been synchronized with bombing of the Yawata Steel Works by B-29s in China. It was the first bombing of the Japan home islands by B-29s, signaling the beginning of a campaign that could strike deep into Japan's Absolute National Defense Zone.[312]

The Army Air Force was confident that strategic bombing could destroy Japan's military production and that the Marianas provided excellent airbases for doing so because they were 1,200 mi (1,000 nmi; 1,900 km) miles from the Japanese home islands. This put almost all of Japan's industrial cities within striking distance of the B-29 bomber,[313] and the airbases were easy to defend and supply.[314]

Сайпан был первым островом, на котором базировались B-29. Строительство аэродрома для B-29 началось на Исели-Филд , переименованном в Аслито-Филд, 24 июня. [ 315 ] до того, как остров был объявлен безопасным. Первая взлетно-посадочная полоса была завершена к 19 октября, а вторая - к 15 декабря. [ 316 ] 73- е бомбардировочное авиаполк начал прибывать 12 октября. 24 ноября, [ 317 ] 111 B-29 отправились в Токио для выполнения первой стратегической бомбардировки Японии с Марианских островов. [ 318 ]

Потери на Сайпане использовались американскими планировщиками для прогнозирования американских потерь в будущих сражениях. [ 319 ] Это «соотношение Сайпана» — один убитый американец и несколько раненых на каждые семь убитых японских солдат — стало одним из оправданий американских планов по увеличению призыва на военную службу , прогнозируя возросшую потребность в пополнениях в войне с Японией. [ 320 ] Прогнозы высоких потерь были одной из причин того, что Объединенный комитет начальников штабов не одобрил вторжение на Тайвань . [ 321 ] Коэффициент Сайпана определял первоначальную оценку того, что вторжение в Японию будет стоить до 2 000 000 американских жертв. [ 322 ] в том числе 500 000 убитых. [ 323 ] Хотя позже эти оценки будут пересмотрены в сторону понижения, они все равно будут влиять на взгляды политиков на войну вплоть до 1945 года. [ 324 ]

Влияние на японскую политику и моральный дух

[ редактировать ]

Поражение Сайпана оказало на Японию большее влияние, чем все ее предыдущие поражения. [ 325 ] Император Японии Хирохито признал , что американский контроль над островом приведет к бомбардировке Токио. После поражения японцев в битве в Филиппинском море он потребовал, чтобы японский генеральный штаб спланировал еще одну военно-морскую атаку, чтобы предотвратить его падение. [ 326 ] Хирохито принял возможное падение Сайпана только 25 июня, когда его советники сказали ему, что все потеряно. [ 327 ] Поражение привело к краху Хидеки Тодзё правительства . Разочарованный ходом войны, Хирохито отказался от поддержки Тодзё, который ушел с поста премьер-министра Японии 18 июля. [ 328 ] Его сменил бывший генерал Куниаки Койсо . [ 329 ] который был менее способным лидером. [ 330 ]

японского правительства Падение Сайпана привело к тому, что в военных репортажах впервые было признано, что война идет плохо. В июле Имперский генеральный штаб опубликовал заявление с кратким изложением битвы и потери острова, а правительство разрешило к публикации перевод статьи журнала Time , в которой упоминались самоубийства мирных жителей в последние дни битвы. в The Asahi Shimbun , крупнейшей газете Японии, пока шла битва. [ 331 ] Еще до окончания битвы японское правительство в июне опубликовало «План эвакуации школьников», предвидя бомбардировки городов Японии. [ 332 ] Эта эвакуация , единственная принудительная, проводившаяся во время войны, [ 332 ] разлучили более 350 000 учащихся третьего-шестого классов, живших в крупных городах, со своими семьями и отправили их в сельскую местность. [ 333 ]

Захват Сайпана прорвал Абсолютную зону национальной обороны. [ 334 ] побудив японское руководство пересмотреть результаты, которые они могли ожидать от войны. [ 335 ] В июле начальник отдела военного руководства Имперского генерального штаба полковник Сей Мацутани, [ 336 ] составил доклад, в котором говорилось, что завоевание Сайпана уничтожило всякую надежду на победу в войне. [ 337 ] После войны многие японские военные и политические лидеры заявили, что Сайпан также стал поворотным моментом. [ 338 ] Например, вице-адмирал Сигэёси Мива заявил: «Наша война была проиграна с потерей Сайпана». [ 339 ] и адмирал флота Осами Нагано признал важность битвы, заявив: «Когда мы потеряли Сайпан, на нас настал ад». [ 340 ]

Мемориалы

[ редактировать ]Утес Самоубийц и Утес Банзай, наряду с уцелевшими изолированными японскими укреплениями, признаны историческими объектами в Национальном реестре исторических мест США . Скалы являются частью Национального исторического района посадочных пляжей ; Аслито/Айсли Филд; & Марпи-Пойнт, остров Сайпан , который включает в себя американские пляжи для высадки, взлетно-посадочные полосы B-29 Айсли-Филд и сохранившуюся японскую инфраструктуру аэродромов Аслито и Марпи-Пойнт. [ 341 ] Тропа морского наследия имеет ряд мест для дайвинга с затопленными кораблями, самолетами и танками, оставшимися в живых. [ 342 ] Американский мемориальный парк увековечивает память американцев и жителей Марианских островов, погибших во время кампании на Марианских островах. [ 343 ] Мемориал войны в Центральной части Тихого океана посвящен памяти погибших японских солдат и мирных жителей. [ 344 ]

-

Кенотафы возле скалы Банзай

-

Утес Банзай с кенотафами, видимыми в верхнем левом углу.

Сноски

[ редактировать ]- ^ Послевоенные оценки варьируются от 46 [ 44 ] квадратных миль до 48. [ 45 ] Халлас 2019 , с. 479, сн. 5 указывает, что большинство историков, описывающих битву, утверждают, что остров значительно больше. Например, МакМанус 2021 , с. 339 , Шоу, Налти и Тернблад 1989 , с. 238 утверждают, что это 72, Goldberg 2007 , p. 38 говорит о 75, а Кроул 1993 , с. 29 говорит, что 85 квадратных миль.

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 36 дает общее количество в 66 779; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , с. 253 оценили в 71 034

- ^ Морисон 1981 , стр. 160–162 оценивает количество кораблей в 535 и упоминает, что четыре с половиной дивизии сухопутных боевых войск - 127 571 человек; Плата за проезд 2015 , с. 457 оценивает количество кораблей в 600 и количество людей в 600 000 человек, включая военно-морской персонал.

- ^ Макманус 2021 , с. 350 оценивает 2500, Heinrichs & Gallicchio 2017 , стр. 95 оценили около 3500. В своем отчете после боя командующий 4-й дивизией морской пехоты генерал-майор Гарри Шмидт оценил потери за первые два дня в 3500 человек, что составляет около 20% потерь, понесенных за весь бой. [ 113 ]

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 165 ставит число между 24 и 32; Кроул 1993 , с. 98 означает, что число не меньше 37; Хоффман 1950 , с. 86 , Морисон 1981 , с. 202 и Шоу, Нэлти и Тернблад, 1989 , с. 284 поставил число 44.

- ^ Споры продолжаются. [ 191 ] см. в Crowl 1993 , стр. 191–201 Подробное обсуждение см . в Lacey 2013 , стр. 157–161 и McManus 2021 , стр. 363–371. ; более поздние обсуждения

- ↑ Неясно, умер ли Сайто вместе с Нагумо или Игетой. Многие источники черпают свою историю от майора Такаси Хиракуши. [ 244 ] пленный офицер по связям с общественностью. [ 245 ] который первоначально утверждал, что он майор Киёси Ёсида, офицер разведки, который фактически погиб в бою. [ 246 ] (ср. Goldberg 2007 , стр. 173, где описаны показания «Киеси Ёсиды»). Халлас 2019 , с. 514, сноска 44 указывает, что в ранних отчетах Сайто совершает самоубийство в одиночку (например, см. ранний отчет в Hoffman 1950 , Приложение IX: Последние дни генерала Сайто, стр. 283–284 ), а другой выживший японец утверждает, что Нагумо покончил жизнь самоубийством в другом месте. [ 247 ] Толанд 2003 , с. 511–512 , основывает его рассказ, в . котором Сайто, Нагумо и Игета умирают вместе во время гораздо более позднего интервью с Хиракуши [ 244 ]

- ↑ Число японцев, участвовавших в нападении, неизвестно. Смит недооценил атаку, заявив, что в ней участвовало всего 300–400 человек. [ 250 ] Хиракуши (в то время известный как майор Ёсида), который участвовал в нападении, на допросе после того, как его схватили, заявил, что в нем участвовало около 1500 человек. [ 251 ] После боев генерал Гринер из 27-й пехотной дивизии насчитал в районе атаки 4311 трупов японцев. [ 252 ] но был спорным вопрос о том, все ли они погибли в результате нападения. [ 253 ] Более поздняя комиссия по заказу Спруэнса оценила это число в пределах 1500–3000, утверждая, что многие из тел принадлежали людям, умершим до нападения. В конце концов Смит согласился с отчетом Спруэнса. [ 254 ]

Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Отчет о захвате Марианских островов в 1944 году , с. 6 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 454 .

- ^ Отчет о захвате Марианских островов в 1944 году , Приложение K, часть B : 3100 убитых, 326 пропавших без вести, 13 099 раненых; итого совокупно до Д+46.; Чапин 1994 , с. 36 : 3225 убитых, 326 пропавших без вести, 13061 раненых.

- ^ Отчет о захвате Марианских островов в 1944 году , Приложение K, часть G : Эти цифры неполны, поскольку данные не удалось получить со всех кораблей.

- ^ Отчет о захвате Марианских островов в 1944 году , Приложение C к Приложению A.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Американский мемориальный парк 2021 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Астрот 2019 , с. 166.

- ^ Смит 1996 , с. 1 .

- ^ Хопкинс 2008 , с. 146 ; Миллер 1991 , стр. 336–337 ; Саймондс, 2022 г. стр 229–230 . , ; Плата за проезд 2015 , с. 306 .

- ^ Миллер 1991 , стр. 4–5 ; Плата за проезд 2015 , с. 306 .

- ^ Генрихс и Галликкио 2017 , с. 92 ; Моррисон 1981 , с. 5–6 : см. Конференцию в Касабланке 1943 г. , стр. 5–6. 185–186 аргументов Кинга.

- ^ Y'Blood 1981 , с. 4 .

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад 1989 , стр. 235 ; Y'Blood 1981 , стр. 4–5 .

- ^ Хопкинс 2008 , с. 174–175 ; Смит 1996 , стр. 3–4 ; Саймондс 2022 , с. 232 .

- ^ Y'Blood 1981 , с. 7 : См. заявление Кинга на Квебекской конференции 1943 года , с. 448.

- ^ Голдберг 2007 , 23–24 стр . ; Генрихс и Галликкио 2017 , с. 92 ; Саймондс 2022 , с. 275 : См. ответ Кинга премьер-министру Соединенного Королевства Уинстону Черчиллю на Квебекской конференции 1943 года , стр. 275. 409.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б И'Блад 1981 , с. 7 .

- ^ 2015 , стр 437–438 . . Toll

- ^ Y'Blood 1981 , с. 8 .

- ^ Матлофф 1994 , стр. 376–377 .

- ^ Смит 1996 , стр. 4–6 .

- ^ Коакли и Лейтон 1987 , с. 406 .

- ^ Хоффман 1950 , с. 19 ; И'Блад 1981 , с. 12 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , с. 236 .

- ^ Смит 2006 , стр. 209–211 ; Танака 2023 , Расширение войны на Азиатско-Тихоокеанский театр Второй мировой войны, Третий этап §5.

- ^ Халлас 2019 , стр. 2 ; Хироюки 2022 , стр. 155–156; Нориаки 2009 , стр. 97–99;

- ^ Находки 2019 г. , с. 2 ; Ветцлер 2020 , с. 32 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Генрихс и Галликкио 2017 , с. 92 .

- ^ Морисон 1981 , стр. 12–14 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 2 .

- ^ Морисон 1981 , с. 222 .

- ^ Мерфетт 2008 , с. 337 .

- ^ Хорнфишер 2016 , с. 66 ; Уиллоби 1994 , стр. 250–251 ; Морисон 1981 , с. 94 .

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , стр. 220–221 .

- ^ Морисон 1981 , с. 234 .

- ^ Морисон 1981 , с. 148 .

- ^ Клауд, Шмидт и Берк 1956 , с. 4.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Халлас 2019 , с. 7 .

- ^ Клауд, Шмидт и Берк 1956 , с. 6.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кроул 1993 , с. 62 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 29 ; Гольдберг 2007 , с. 30 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 11 .

- ^ USACE 2022 , стр. 3.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Клауд, Шмидт и Берк, 1956 , с. 1.

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 29 ; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , с. 238 .

- ^ Голдберг 2007 , с. 30 .

- ^ Лейси 2013 , с. 138 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 54 ; Морисон 1981 , с. 152 .

- ^ Голдберг 2007 , 30–31 стр . ; Халлас 2019 , 8–9 ; стр . Морисон 1981 , с. 152 .

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад 1989 , стр. 238 .

- ^ Хоффман 1950 , с. 7 ; Морисон 1981 , с. 151 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Астрот 2019 , с. 38.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Лейси 2013 , с. 129 .

- ^ Шикс 1945 , с. 112; Плата за проезд 2015 , с. 508 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. VII .

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад 1989 , стр. 239 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 39 ; Халлас 2019 , стр. 18–19 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 17 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 37 ; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , с. 240 .

- ^ Голдберг 2007 , стр. 39–40 ; Кроул 1993 , стр. 36–37 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 31 ; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , с. 240 .

- ^ Морисон 1981 , стр. 160–162 ; Плата за проезд 2015 , с. 457 .

- ^ Морисон 1981 , стр. 170–172 .

- ^ Морисон 1981 , с. 174 .

- ^ Морисон 1981 , с. 172 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 55 ; Хоффман 1950 , с. 26 .

- ^ Бисно 2019 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 55 .

- ^ Голдберг 2007 , с. 31–32 .

- ^ Heinrichs & Gallicchio 2017 , стр. 93–94 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 31 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 29 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 56 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , стр. 62–63 .

- ^ Макманус 2021 , 339–340 стр . .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Лейси 2013 , с. 139 .

- ^ Лейси 2013 , с. 139 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 57.

- ^ Голдберг 2007 , с. 35 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 57–58 .

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад 1989 , стр. 256 ; Макманус 2021 , с. 338 .

- ^ Макманус 2021 , с. 338 ; Морисон 1981 , с. 167 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , стр. 139, 197; Макманус 2021 , с. 339 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 73 ; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , стр. 253–254 ; Плата за проезд 2015 , с. 462 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 73 ; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , стр. 253–254 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 68 ; Плата за проезд 2015 , с. 462 : Но Шоу, Налти и Тернблад 1989 , с. 254 означает число 11.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Плата за проезд 2015 , с. 463 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 73 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 74 ; Плата за проезд 2015 , с. 463 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 74 .

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад 1989 , стр. 254 .

- ^ Морисон 1981 , с. 180 .

- ^ 2016 , стр 88–89 . Хорнфишер .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кроул 1993 , с. 76 .

- ^ Голдберг 2007 , с. 54 ; Морисон 1981 , стр. 182–183 .

- ^ Голдберг 2007 , с. 3 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 96; Хоффман 1950 , стр. 46–47 ; Макманус 2021 , с. 348 ; Шмидт 1944 , с. 11.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Морисон 1981 , с. 202 .

- ^ Хорнфишер 2016 , с. 136 ; Макманус 2021 , с. 346 .

- ^ Лейси 2013 , с. 131 .

- ^ Хоффман 1950 , с. 27 ; Лейси 2013 , с. 131 .

- ^ Хоффман 1950 , с. 50 ; Морисон 1981 , с. 202 ; Шмидт 1944 , с. 11.

- ^ Гугелер 1945 , с. 3; Халлас 2019 , с. 96.

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 127; Миллетт 1980 , с. 412 ; Плата за проезд 2015 , с. 466 .

- ^ Хоффман 1950 , с. 45 .

- ^ Макманус 2021 , с. 348 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 93 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 90; Плата за проезд 2015 , с. 466 ; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , с. 263 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 140; Лейси 2013 , с. 350 ; МакМанус 2021 .

- ^ Шмидт 1944 , с. 11.

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 140; Хоффман 1950 , с. 50 .

- ^ Гугелер 1945 , с. 27.

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 141; Лейси 2013 , с. 145 ; Макманус 2021 , с. 350 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 92 .

- ^ Лейси 2013 , с. 145 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 140; Хорнфишер 2016 , с. 142 ; Лейси 2013 , с. 145 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 140; Плата за проезд 2015 , с. 466 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 95 ; Халлас 2019 , с. 145.

- ^ Crowl 1993 , стр. 95–96 ; Хоффман 1950 , стр. 71–75 .

- ^ Голдберг 2007 , с. 88.

- ^ Хармсен 2021 , с. 62 ; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , стр. 278–279 .

- ^ Crowl 1993 , стр. 95–96 .

- ^ Crowl 1993 , стр. 99–100 ; Халлас 2019 , стр. 171–173; Гольдберг 2007 , с. 142.

- ^ Морисон 1981 , стр. 202–203 ; Плата за проезд 2015 , с. 467 .

- ^ Crowl 1993 , стр. 97–98 ; Морисон 1981 , с. 203 .

- ^ Crowl 1993 , стр. 96–97 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 97 ; Халлас 2019 , с. 164.

- ^ Хоффман 1950 , стр. 86–87 .

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , стр. 284–285 .

- ^ Генрихс и Галликкио 2017 , с. 96 ; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , с. 285 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 170; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , с. 286 .

- ^ Хоффман 1950 , стр. 92–94 .

- ^ Голдберг 2007 , стр. 105–106.

- ^ Crowl 1993 , стр. 108–109 , 115–116 , 154 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 111 .

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад 1989 , стр. 295 .

- ^ Голдберг 2007 , с. 145–146; Халлас 2019 , с. 192.

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , стр. 294–295 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 170; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , с. 292 .

- ^ Хоффман 1950 , с. 101 .

- ^ Голдберг 2007 , стр. 148–149 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 270; Лейси 2013 , с. 149 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 138 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 166 ; Генрихс и Галликкио 2017 , с. 111 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 165 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 287; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , с. 305 ; В отчете о взятии Марианских островов в 1944 г. , (K), стр.5 сообщается о 6200 жертвах в день «Д» + 5 (20 июня).

- ^ Хорнфишер 2016 , с. 208 ; Макманус 2021 , с. 348 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , стр. 164–165 .

- ^ Хорнфишер 2016 , с. 86 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хармсен 2021 , с. 63 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 147 ; Морисон 1981 , с. 221 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 1 ; Хопкинс 2008 , с. 288 ; Хармсен 2021 , с. 63 .

- ^ Хармсен 2021 , с. 64 .

- ^ Хармсен 2021 , с. 64 ; Уиллоби 1994 , с. 292 ; Морисон 1981 , с. 262 .

- ^ Hallas 2019 , 73–74 стр . ; Морисон 1981 , с. 215 ; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , с. 221 .

- ^ Морисон 1981 , с. 220 ; Толл 2015 , стр. 454–455 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 121 ; Хопкинс 2008 , с. 221 ; Морисон 1981 .

- ^ Винтон 1993 , с. 167 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Морисон 1981 , с. 233 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 147 ; Морисон 1981 , с. 219 ; Тойода 1944 , с. 229 .

- ^ Макманус 2021 , стр. 351–352.

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 206.

- ^ Хопкинс 2008 , стр. 228–229 ; Морисон 1981 , стр. 263–274 ; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , с. 299 .

- ^ Голдберг 2007 , с. 102 ; Хармсен 2021 , 65–66 . стр .

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад 1989 , стр. 298 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хорнфишер 2016 , с. 232 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Морисон 1981 , с. 321 .

- ^ Плата за проезд 2015 , с. 497 .

- ^ Хармсен 2021 , стр. 65 – 66 .

- ^ Бойд и Йошида 2013 , с. 146 .

- ^ Морисон 1981 , с. 230 .

- ^ Морисон 1981 , стр. 322–324 .

- ^ Голдберг 2007 , с. 89.

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 268; Лейси 2013 , с. 149 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 116 ; Макманус 2021 , с. 356 ; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , с. 295 .

- ^ Голдберг 2007 , стр. 156–157.

- ^ Heinrichs & Gallicchio 2017 , стр. 114–115 .

- ^ Хорнфишер 2016 , с. 236 .

- ^ Хоффман 1950 , с. 128 ; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , с. 307 .

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад 1989 , стр. 305 .

- ^ Плата за проезд 2015 , с. 498 .

- ^ Хорнфишер 2016 , с. 238 ; Макманус 2021 , с. 362 .

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад 1989 , стр. 314 .

- ^ Макманус 2021 , с. 362 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 179 ; Халлас 2019 , с. 296.

- ^ Макманус 2021 , с. 356 ; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , с. 317 ; Смит и Финч, 1949 , стр. 172–173 .

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , стр. 317–319 .

- ^ Аллен 2012 , стр. 1–2 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 201 .

- ^ Гаранд и Стробридж 1989 , с. 423 ; Олсон и Мортенсен 1983 , стр. 690–691 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , стр. 133–135 .

- ^ M-2-4 Ракетные грузовики 2013 .

- ^ Бишоп 2014 , с. 186 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 133 ; Рейнс 2000 , с. 251.

- ^ Хорнфишер 2016 , с. 232 ; Морисон 1981 , стр. 324–325 .

- ^ Морисон 1981 , стр. 324–326 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 332 ; Морисон 1981 , с. 326 .

- ^ Хоффман 1950 , стр. 90–91 ; Плата за 2015 год .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 130 ; Хемлер, 2021 г. , стр. 136–148; Морисон 1981 , стр. 324–325 .

- ^ Отчет о захвате Марианских островов в 1944 году , Приложение 2, Приложение N : Отчеты интенданта по 2-й, 4-й и 27-й дивизиям морской пехоты в общей сложности до 101 среднего танка, 57 легких танков, 24 легких механизированных огнеметов и 6 средних танков с бульдозеры.

- ^ Zaloga 2012 , p. 6 .

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад 1989 , стр. 575 .

- ^ Клебер и Бердселл 1990 , с. 560 .

- ^ Клебер и Бердселл 1990 , с. 563 .

- ^ Хорнфишер 2016 , с. 248 ; МакКинни, 1949 , стр. 151–152 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , стр. 212–213 .

- ^ Мил 2012 , с. 7.

- ^ Хоффман 1950 , с. 70 .

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад 1989 , стр. 322 .

- ^ Чапин 1994 , с. 22 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 210 ; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , с. 322 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 312.

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , стр. 326–327 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 322.

- ^ Чапин 1994 , с. 21 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 159 .

- ^ Чапин 1994 , с. 23 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , стр. 231–232 .

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад 1989 , стр. 331 .

- ^ Чапин 1994 , с. 24 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 221 .

- ^ Плата за проезд 2015 , с. 500 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 355.

- ^ Голдберг 2007 , стр. 165–169; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , с. 335 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 357.

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 357; Хорнфишер 2016 , с. 266; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , с. 339 .

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад 1989 , стр. 336 .

- ^ Хорнфишер 2016 , с. 266 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 244 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , стр. 245-246 ; Shaw, Nalty & Turnbladh 1989 , стр. 337–339 : в Small Unit Actions 1991 , стр. 69–113. более подробное описание боевых действий см.

- ^ Кроул 1993 , стр. 247–248 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 247 ; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , с. 336 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Генрихс и Галликкио 2017 , с. 122 .

- ^ Crowl 1993 , стр. 247–248 ; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , с. 337 .

- ^ Хоффман 1950 , с. 220 ; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , с. 337 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 364; Хорнфишер 2016 , с. 271 .

- ^ Макманус 2021 , стр. 375–376 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 365; Гольдберг 2007 , с. 273.

- ^ Макманус 2021 , с. 371.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Халлас 2019 , с. 514, фн44 .

- ^ Толанд 2003 , с. 490 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 258, сн. 60 ; Халлас 2019 , с. 438 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 514, фн44 ; Морисон 1981 , с. 337 .

- ^ Бойд и Йошида 2013 , с. 147 .

- ^ Макманус 2021 , с. 387 ; Морисон 1981 , с. 336 ; Плата за проезд 2015 , с. 505 ; Халлас 2019 , с. 451 оценивает это число в пределах 3000–4000, а Hornfischer 2016 , стр. 279 между 1500–2000.

- ^ Гейли 1986 , стр. 216–217 ; Халлас 2019 , с. 451.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хоффман 1950 , с. 223 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 257 .

- ^ Хоффман 1950 , стр. 233–234 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 451.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гейли 1986 , с. 209 .

- ^ Хорнфишер 2016 , с. 281 ; Макманус 2021 , с. 381.

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад 1989 , стр. 340 ; Плата за проезд 2015 , с. 505 .

- ^ Хоффман 1950 , стр. 224–225 .

- ^ Макманус 2021 , с. 378.

- ^ Гейли 1986 , с. 208 .

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад 1989 , стр. 340 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 381; Хорнфишер 2016 , с. 281 ; Макманус 2021 , с. 381.

- ^ Голдберг 2007 , с. 182; Макманус 2021 , с. 387 .

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад 1989 , стр. 342 ; Плата за проезд 2015 , с. 506 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , стр. 259–260 ; Халлас 2019 , с. 104 .

- ^ Макманус 2021 , с. 387 ; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , с. 342 .

- ^ Crowl 1993 , стр. 263–264 ; Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , стр. 342–343 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 264 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Шоу, Налти и Тернблад, 1989 , с. 345 .

- ^ Астрот 2019 , с. 85.

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 263 ; Халлас 2019 , с. 427 .

- ^ Форрестел 1966 , стр. 151 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 439 .

- ^ Хоффман 1950 , с. 243 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Халлас 2019 , с. 458 .

- ^ Гилхули 2011 .

- ^ Гилхули 2011 ; Находки 2019 года , с. 463 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Халлас 2019 , с. 444.

- ^ Макманус 2021 , с. 388.

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 444; Генрихс и Галликкио 2017 , с. 124 ; Макманус 2021 , с. 388.

- ^ Толанд 2003 , с. 519 .

- ^ Астрот 2019 , с. 165; Американский мемориальный парк 2021 .

- ^ Трефальт 2018 , стр. 255–256.

- ^ Хьюз 2010 .

- ^ Шикс 1945 , стр. 110–111; Трефальт 2018 , стр. 259.

- ^ Астрот 2019 , с. 105.

- ^ Астрот 2019 , с. 167.

- ^ Астрот 2019 , с. 96.

- ^ Астрот 2019 , с. 25 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с О'Хара 2019 , География и погода.

- ^ Хоффман 1950 , с. 256 .

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад 1989 , стр. 242 .

- ^ Хоффман 1950 , с. 24 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Плата за проезд 2015 , с. 502 .

- ^ Коакли и Лейтон 1987 , с. 450 .

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад 1989 , стр. 276 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , стр. 124 .

- ^ Дод 1987 , с. 497 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , стр. 123–124 .

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад 1989 , стр. 348–350 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , стр. 124–127 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , стр. 128–130 .

- ^ О'Хара 2019 , Угрозы.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кроул 1993 , стр. 58–60 .

- ^ Хоффман 1950 , с. 9 .

- ^ Ветцлер 2020 , с. 137 .

- ^ Ветцлер 2020 , с. 134.

- ^ Ветцлер 2020 , с. 143 .

- ^ Плата за проезд 2015 , с. 457 .

- ^ О'Хара 2019 .

- ^ Халлион 1995 , с. 45.

- ^ Крэйвен и Кейт 1983 , с. 3–4 .

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад 1989 , стр. 233 ; Плата за проезд 2015 , с. 307 .

- ^ Миллер 1991 , с. 344 .

- ^ Кроул 1993 , с. 443 .

- ^ Крэйвен и Кейт 1983 , с. 517 .

- ^ Крэйвен и Кейт 1983 , с. xvii .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 458 .

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. мы .

- ^ Джангреко 2003 , стр. 99–100.

- ^ Крэйвен и Кейт 1983 , с. 390 .

- ^ Джангреко 2003 , с. 104.

- ^ Джангреко 2003 , стр. 99–100; Халлас 2019 , с. ви .

- ^ Дауэр 2010 , стр. 216–217 ; также см. обсуждение в Giangreco 2003 , стр. 127–130.

- ^ Морисон 1981 , стр. 339–340 .

- ^ Бикс 2000 , с. 476 .

- ^ 2015 , стр 530–531 . . Toll

- ^ Бикс 2000 , с. 478 .

- ^ Салливан 1995 , стр. 35.

- ^ Франк 1999 , стр. 90–91 .

- ^ Хойт 2001 , стр. 351–352 ; Корт 2007 , с. 61: см. полное заявление Императорской штаб-квартиры Японии в Хойте, 2001 г. , Приложение A, стр. 426–430.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Падение 2021 , §11.

- ^ Хэвенс 1978 , стр. 162–163 .

- ^ Танака 2023 , Расширение войны на Азиатско-Тихоокеанский театр Второй мировой войны, Третий этап §7.

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. мы ; Дело 1950 года , стр. 73–78 .

- ^ Кавамура 2015 , с. 114 .

- ^ Ирокава 1995 , с. 92 ; Кавамура 2015 , 129–130 стр . .

- ^ Миссия выполнена 1946 , с. 18 : см. подтверждающие цитаты различных лидеров на стр. 18–19.

- ^ Шоу, Налти и Тернблад 1989 , стр. 346 : см. цитату из «Допросов японских чиновников» за 1946 год , с. 297

- ^ Халлас 2019 , с. 440; Хоффман 1950 , с. 260 : см. цитату из «Допросов японских чиновников» за 1946 год , с. 355

- ^ Заявление о национальных исторических местах 2015 .

- ^ Маккиннон 2011 .

- ^ Фонд национальных парков 2022 .

- ^ Поминальная служба на Сайпане, 2016 г. .

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Книги

[ редактировать ]- Аасенг, Натан (1992). Говорящие по кодексу навахо . Уокер. ISBN 0802776272 . OCLC 49275457 .

- Астрот, Александр (2019). Массовые самоубийства на Сайпане и Тиниане, 1944 год: исследование смертности среди гражданского населения в историческом контексте . МакФарланд. ISBN 9781476674568 . OCLC 1049791315 .

- Бишоп, Крис, изд. (2014). Иллюстрированная энциклопедия оружия Второй мировой войны: подробное руководство по системам вооружения. Включая танки, стрелковое оружие, военные самолеты, артиллерию, корабли и подводные лодки . Книги о метро. ISBN 9781782743880 . OCLC 1310751361 .

- Бикс, Герберт П. (2000). Хирохито и создание современной Японии . Харпер Коллинз. ISBN 9780060193140 . OCLC 43031388 .

- Бойд, Карл; Ёсида, Акихико Ёсида (2013). Японские подводные силы и Вторая мировая война . Издательство Военно-морского института. ISBN 9781612512068 . OCLC 1301788691 .

- Чапин, Джон К. (1994). Битва за Сайпан . Историческое подразделение Корпуса морской пехоты США. ПКН 19000312300.

- Коакли, Роберт В.; Лейтон, Роберт М. (1987) [1968]. Глобальная логистика и стратегия . Армия США во Второй мировой войне. Центр военной истории. OCLC 1048609737 .

- Крэйвен, Уэсли Ф.; Кейт, Джеймс Л. , ред. (1983) [1953]. Тихий океан: от Маттерхорна до Нагасаки, июнь 1944 г. — август 1945 г. Армейская авиация во Второй мировой войне. Том. 5. Управление истории ВВС. ISBN 9780912799032 . OCLC 9828710 .

- Крессман, Роберт Дж. (2000). Официальная хронология ВМС США во Второй мировой войне . Военно-исторический центр. ISBN 9781682471548 . OCLC 607386638 .

- Кроул, Филип А. (1993) [1960]. Кампания на Марианских островах . Армия США во Второй мировой войне, Война на Тихом океане. Центр военной истории армии США. OCLC 1049152860 .

- Дод, Карл К. (1987) [1966]. Инженерный корпус: Война против Японии . Армия США во Второй мировой войне. Центр военной истории армии США. OCLC 17765223 .

- Дауэр, Джон В. (2010). Культуры войны: Перл-Харбор, Хиросима, 9–11, Ирак . Нью-Йорк: Нортон Нью Пресс. ISBN 978-0-393-06150-5 . OCLC 601094136 .

- Форрестел, Эммет П. (1966). Адмирал Рэймонд А. Спруэнс, USN: исследование командования . Типография правительства США. ОСЛК 396044 .

- Фрэнк, Ричард Б. (1999). Падение: Конец Императорской Японской империи . Случайный дом. ISBN 9780679414247 . OCLC 40783799 .

- Гейли, Гарри А. (1986). Howlin 'Mad против армии: конфликт в командовании, Сайпан, 1944 год . Президио Пресс. ISBN 0-89141-242-5 . OCLC 13124368 .

- Гаранд, Джордж В.; Стробридж, Трумэн Р. (1989) [1971]. «Часть V. Морская авиация в западной части Тихого океана: 2. Морская авиация на Марианских островах, Каролинских островах и в Иводзиме». Западно-Тихоокеанские операции . История операций морской пехоты США во Второй мировой войне. Том. 4. Историческое отделение, дивизия G–3, штаб-квартира Корпуса морской пехоты США. стр. 422–442. OCLC 1046596050 .

- Голдберг, Гарольд Дж. (2007). День Д в Тихом океане: битва за Сайпан . Издательство Университета Индианы, 2007. ISBN. 978-0-253-34869-2 . OCLC 73742593 .

- Халлас, Джеймс Х. (2019). Сайпан: битва, обрекшая Японию во Второй мировой войне . Стэкпол. ISBN 9780811768436 . OCLC 1052877312 .

- Хармсен, Питер (2021). Война на Дальнем Востоке: Азиатский Армагеддон 1944–1945 гг . Том. 3. Каземат. ISBN 9781612006277 . OCLC 1202754434 .

- Хэвенс, Томас Р. (1978). Долина тьмы: японский народ и Вторая мировая война . Нортон. ISBN 9780393056563 . OCLC 1035086075 .

- Генрихс, Уолдо Х.; Галликкио, Марк (2017). «Марианская кампания, июнь – август 1944 г.». Непримиримые враги: Война на Тихом океане, 1944–1945 гг . Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 9780190616755 . OCLC 962442415 .

- Хироюки, Шиндо (2022). «От наступления к обороне: стратегия Японии во время войны на Тихом океане, 1942–1944» (PDF) . В Райхгерцере, Франк; Исидзу, Томоюки (ред.). Совместный исследовательский проект NIDS-ZMSBw 2019–2021: Обмен опытом ХХ века – совместные исследования по военной истории . Серия совместных исследований NIDS. Национальный институт оборонных исследований, Япония. ISBN 9784864821049 . OCLC 1407570510 . № 19. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 15 июня 2022 года.

- Хоффман, Карл В. (1950). Сайпан: Начало конца . Историческое отделение Корпуса морской пехоты США. OCLC 564000243 .

- Хопкинс, Уильям Б. (2008). Тихоокеанская война: стратегия, политика и игроки, выигравшие войну . Зенит. ISBN 9780760334355 . OCLC 1311044045 .

- Хорнфишер, Джеймс Д. (2016). Флот во время прилива: США в тотальной войне на Тихом океане, 1944–1945 гг . Издательская группа Random House. ISBN 978-0345548726 . OCLC 1016508640 .

- Хойт, Эдвин П. (2001) [1986]. Японская война: Великий Тихоокеанский конфликт . ISBN 9780815411185 . OCLC 45835486 .

- Ирокава, Дайкичи (1995). Эпоха Хирохито: В поисках современной Японии . свободная пресса. ISBN 9780029156650 . OCLC 1024165290 .

- Кавамура, Норико (2015). Император Хирохито и война на Тихом океане . Вашингтонский университет Press. ISBN 9780295806310 . OCLC 922925863 .

- Клебер, Брукс Э.; Бердселл, Дейл (1990) [1966]. Служба химической войны: химикаты в бою . Армия США во Второй мировой войне: Технические службы. Центр военной истории армии США. OCLC 35176837 .

- Корт, Майкл (2007). «Правительство Японии, Кетсу-Го и Потсдам». Путеводитель Колумбийского университета по Хиросиме и бомбе . Колумбийский университет. стр. 58–66. дои : 10.7312/kort13016 . ISBN 9780231130165 . JSTOR 10.7312/kort13016.9 . OCLC 71286652 .

- Лейси, Шэрон Т. (2013). Тихоокеанский блицкриг: Вторая мировая война в центральной части Тихого океана . Издательство Университета Северного Техаса. ISBN 9781574415254 . ОСЛК 861200312 .

- Матлофф, Морис (1994) [1959]. Стратегическое планирование коалиционной войны 1943–1944 гг . Армия США во Второй мировой войне: Военное министерство. Центр военной истории армии США. OCLC 1048613899 .

- Макманус, Джон К. (2021). Остров Инфернос . Пингвин. ISBN 9780451475060 . OCLC 1260166257 .

- Мил, Джеральд А. (2012). Война одного морского пехотинца: поиски боевого переводчика человечества в Тихом океане . Издательство Военно-морского института. ISBN 9781612510927 . OCLC 811408315 .

- Миллер, Эдвард С. (1991). Военный план «Оранжевый»: стратегия США по разгрому Японии, 1897–1945 гг . Издательство Военно-морского института. ISBN 9780870217593 . OCLC 23463775 .

- Миллетт, Аллан Р. (1980). Семпер Фиделис: История морской пехоты США . Макмиллан. ISBN 9780029215906 . OCLC 1280706539 .

- Морисон, Сэмюэл Элиот (1981) [1953]. Новая Гвинея и Марианские острова, март 1944 г. – август 1944 г. История военно-морских операций США во Второй мировой войне. Том. 8. Маленький Браун. ISBN 9780316583084 . ОСЛК 10926173 .

- Мерфетт, Малкольм Х. (2008). Военно-морская война 1919–45: оперативная история нестабильной войны на море . Фрэнсис и Тейлор. дои : 10.4324/9780203889985 . ISBN 9781134048137 . OCLC 900424339 .

- Олсон, Джеймс С .; Мортенсен, Бернхардт Л. (1983) [1950]. «Марианские острова» . В Крейвене, Уэсли Ф.; Кейт, Джеймс Л. (ред.). Тихий океан: от Гуадалканала до Сайпана, с августа 1942 по июль 1944 года . Армейская авиация во Второй мировой войне. Том. 4. стр. 671–696. ISBN 9780912799032 . OCLC 9828710 .