Dyfnwal ab Owain

| Dyfnwal ab Owain | |

|---|---|

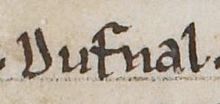

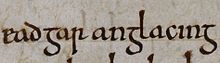

Название Dyfnwal, как это появляется в Folio 15R Оксфордской библиотеки Бодлея, Rawlinson B 488 ( Анналы Тигернаха ): « Домналл Мак Эоаин ». [ 1 ] [ Примечание 1 ] | |

| Король Стратклайда | |

| Предшественник | OWAIN AP DYFNWAL |

| Преемник | Rhydderch или Máel Coluim |

| Умер | 975 |

| Проблема | Rhydderch?, Máel Coluim и Owain ? |

| Отец | OWAIN AP DYFNWAL |

Dyfnwal ab Owain десятого века (умер 975) был королем Стратклайда . [ Примечание 2 ] Он был сыном Оваина А.П. Дифнвала, короля Стратклайда , и, похоже, был членом Королевской династии Стратклайда. В какой-то момент в девятом или десятом веке Королевство Стратклайд значительно расширилось на юг. В результате этого расширения далеко за пределами долины реки Клайд царство стало известно как Королевство Камбрия . К 927 году Королевство, кажется, достигло такого же юга, как река Имонт .

Dyfnwal, по -видимому, правил между 930 -х и 970 -х годами. Сначала он засвидеживается в 940 -х годах, когда он записан, связанный с церковным делом Катро на пути к континентальной Европе в Континентальную Европу . В середине десятилетия Камбрийское королевство было разрушено силами Эдмунда, короля англичан . Говорят, что двое сыновей Дайфнвала были ослеплены англичанами, что могло бы указывать на то, что Дифнвал нарушил обещание его южному коллеге. Одна возможность состоит в том, что он питал островных скандинавских противников Эдмунда. Последний зарегистрирован, что передал контроль над камбрийским царством Маэлю Колуим Мак -Намил, королю Альбы . Сколько авторитетов шотландцы пользовались над Камбрийским Царством, неясно.

In 971, the reigning Cuilén mac Illuilb, King of Alba was slain by Rhydderch ap Dyfnwal. At some point after this act, Cuilén's eventual successor, Cináed mac Maíl Choluim, King of Alba, is recorded to have penetrated deep into Cumbrian territory, possibly as a retaliatory act. The following year, the reigning Edgar, King of the English held a remarkable assembly at Chester which numerous northern kings seem to have attended. Both Dyfnwal and his son, Máel Coluim, appear to have attended this assembly. The latter is styled King of the Cumbrians in the context of this meeting, which might indicate that Dyfnwal had previously abdicated the throne.

Dyfnwal is recorded to have died in 975 whilst undertaking a pilgrimage to Rome. Quite when he gave up the throne is unknown. One possibility is that Rhydderch had succeeded him before the killing of Cuilén. Another possibility is that the apparent retaliatory raid by Cináed marked the end of Dyfnwal's kingship. It is also possible that he held on to power until 973 or 975. In any event, Máel Coluim appears to have been succeeded by another son of Dyfnwal named Owain, who is recorded to have died in 1015. The later Owain Foel, King of Strathclyde, who is attested in 1018, may well be a grandson of Dyfnwal. Dyfnwal is likely the eponym of Dunmail Raise in England, and possibly Cardonald and Dundonald/Dundonald Castle in Scotland.

Background: the tenth century Cumbrian realm

[edit]

For hundreds of years until the late ninth century, the power centre of the Kingdom of Al Clud was the fortress of Al Clud ("Rock of the Clyde").[20] In 870, this British stronghold was seized by Irish-based Scandinavians,[21] after which the centre of the realm seems to have relocated further up the River Clyde, and the kingdom itself began to bear the name of the valley of the River Clyde, Ystrad Clud (Strathclyde).[22] The kingdom's new capital may have been situated in the vicinity of Partick.[23] and Govan which straddle the River Clyde,[24] The realm's new hinterland appears to have encompassed the valley and the region of modern Renfrewshire, which may explain this change in terminology.[25]

At some point after the loss of Al Clud, the Kingdom of Strathclyde appears to have undergone a period of expansion.[27] Although the precise chronology is uncertain, by 927 the southern frontier appears to have reached the River Eamont, close to Penrith.[28] The catalyst for this southern extension may have been the dramatic decline of the Kingdom of Northumbria at the hands of conquering Scandinavians,[29] and the expansion may have been facilitated by cooperation between the Britons and the insular Scandinavians in the late ninth- or early tenth century.[30] Over time, the Kingdom of Strathclyde increasingly came to be known as the Kingdom of Cumbria reflecting its expansion far beyond the Clyde valley.[31][note 3]

Dyfnwal was a son of Owain ap Dyfnwal, King of Strathclyde.[41] The names of the latter and of his apparent descendants suggest that they were indeed members of the royal kindred of Strathclyde.[42] Sons of Dyfnwal seem to include Rhydderch,[43] Máel Coluim,[44] and Owain.[45] The name of Dyfnwal's son Máel Coluim is Gaelic, and may be evidence of a marriage alliance between his family and the neighbouring royal Alpínid dynasty of the Scottish Kingdom of Alba.[46] Dyfnwal's father is attested in 934.[47] Although Dyfnwal's father may well be identical to the Cumbrian monarch recorded to have fought at the Battle of Brunanburh in 937,[48] the sources that note this king fail to identify him by name.[49] Dyfnwal's own reign, therefore, may have stretched from about the 930s to the 970s.[50][note 5]

Cathróe amongst the Cumbrians

[edit]

Dyfnwal is attested by the tenth-century Life of St Cathróe, which appears to indicate that he was established as king by at least the 940s. According to this source, when Cathróe left the realm of Custantín mac Áeda, King of Alba at about this time, he was granted safe passage through the lands of the Cumbrians by Dyfnwal because the two men were related. Dyfnwal thereupon had Cathróe escorted through his kingdom to the frontier of the Scandinavian-controlled Northumbrian territory.[53] The Life of St Cathróe locates this southern frontier to the civitas of Loida. One possibility is that this refers to Leeds. If correct, this could indicate that the Cumbrian realm stretched towards this settlement, and would further evince the general southward expansion of the kingdom.[54] Another possibility is that Loida refers to Leath Ward in Cumberland,[55] or to a settlement in the Lowther valley, not terribly far from where the River Eamont flows.[56]

The Life of St Cathróe identifies Cathróe's parents as Fochereach and Bania.[60] Whilst the former's name is Gaelic, the latter's name could be either Gaelic or British,[61] and Cathróe's own name could be either Pictish[7] or British.[62] The fact that Cathróe is stated to have been related to Dyfnwal could indicate that the former's ancestors included a Briton who possessed a genealogical connection with the royal Cumbrian dynasty,[63] or that Dyfnwal possessed Scottish ancestry, or else that the families of Cathróe and Dyfnwal were merely connected by way of a marriage.[61] Cathróe is also said by the source to have been related to the wife of a certain King of York named Erich.[64] Although the latter may be identical to Eiríkr Haraldsson—a man who is generally thought to be identical to the Norwegian dynast Eiríkr blóðøx[65]—this man is not otherwise attested by insular sources until 947, and Northumbria itself appears to have been ruled by the Uí Ímair dynasts Amlaíb mac Gofraid and Amlaíb Cúarán during the time of Cathróe's journey.[66] Whilst it is possible that Erich actually refers to Amlaíb mac Gofraid,[7] if he instead refers to Eiríkr Haraldsson, it could be evidence that the latter had been based in the Solway region whilst the Uí Ímair held power in Northumbria,[67] or that the latter indeed held power in Northumbria as early as about 946.[68][note 7]

English aggression and Scottish overlordship

[edit]

In 945, the "A" version of the eleventh- to thirteenth-century Annales Cambriæ,[73] and the thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Brut y Tywysogyon reveal that the Cumbrian realm was wasted by the English.[74] The ninth- to twelfth-century Anglo-Saxon Chronicle offers more information, and relates that Edmund I, King of the English harried across the land of the Cumbrians, and let the region to Máel Coluim mac Domnaill, King of Alba.[75] Similarly, the twelfth-century Historia Anglorum records that the English ravaged the realm, and that Edmund commended the lands to Máel Coluim mac Domnaill who had agreed to assist him by land and sea.[76] According to the version of events preserved by the thirteenth-century Wendover[77] and Paris versions of Flores historiarum, Edmund was assisted in the campaign by Hywel Dda, King of Dyfed, and had two of Dyfnwal's sons blinded.[78] If the latter claim is to be believed, it could reveal that the two princes had been English hostages before hostilities broke out, or perhaps prisoners captured in the midst of the campaign.[79][note 8] The gruesome fate inflicted upon these sons could reveal that their father was regarded to have broken certain pledges rendered to the English.[82] One possibility is that Dyfnwal was punished for harbouring insular Scandinavian potentates[83] such as Amlaíb Cúarán.[84] The latter is certainly recorded to have been driven from Northumbria by the English the year before.[85] He could well have taken refuge amongst the Cumbrians,[86] or may have been attempting to construct a power base in the Cumbrian periphery.[87] The close working relationship between Edmund and Máel Coluim mac Domnaill suggests that Amlaíb Cúarán was unlikely to have been harboured by the Scots during this period.[88] Edmund's strike upon Dyfnwal's realm, therefore, seems to have been undertaken as a means to break a Cumbrian-Scandinavian alliance,[89] and to limit the threat of an insular Scandinavian counter offensive from the Forth-Clyde region.[90] The southward expansion of the Cumbrian realm—an extension possibly enabled by the insular Scandinavian power—may have also factored into the invasion, with the English clawing back lost territories.[91] Whatever lay behind the campaign, it is possible that it was utilised by the English Cerdicing dynasty as a way to overawe and intimidate neighbouring potentates.[92]

Although the Wendover version of Flores historiarum alleges that Máel Coluim mac Domnaill was given Cumbrian territory to hold as a fief from the English, the terminology employed by the more reliable Anglo-Saxon Chronicle seems to suggest that Edmund merely surrendered or granted the region to him,[94] or that he merely recognised certain rights of the Scots in the region (such as the right to tribute).[95] Edmund, therefore, may have allowed his Scottish counterpart to collect tribute from the Cumbrians in return for keeping them in check and for lending Edmund military assistance.[96] It is possible that the territory in question corresponds to the region around Carlisle—roughly modern-day Cumberland—which in turn could reveal that the Scots were already in possession of the kingdom's more northerly lands.[97] It is conceivable that the Scots were allowed authority over Cumbrian territory because it was too far to be overseen effectively by the English themselves.[98] As such, it may have been recognised that the Cumbrian territories were situated within the Alpínid sphere of influence rather than that of the Cerdicings.[99] In any event, it is uncertain what authority Máel Coluim mac Domnaill enjoyed over the Cumbrians. Although it is possible that there was a temporary Scottish takeover of the realm,[100] Dyfnwal lived on for decades, and there were certainly later kings.[101] In fact, the Wendover version of the Flores historiarum reveals that the Cumbrians were ruled by a king the year after Edmund's invasion.[102] The concord between the English and the Scots could have been precipitated by the former as a way of further securing their northern frontier from the threat of insular Scandinavians.[103] Similarly, the English campaign against the Cumbrians may have been undertaken in order to isolate the Scots from an alliance with the Scandinavians.[104] In this way, Edmund's conquest and grant of Cumbrian territories to his Scottish counterpart may have been a way of winning the latter's obeisance.[105]

Edmund was assassinated in 946, and succeeded by his brother Eadred, a monarch who soon after made a show of force against opposition in Northumbria,[107] and received a renewal of oaths from his Scottish counterpart.[108] In about 949/950, Máel Coluim mac Domnaill is recorded to have raided into Northumbria, perhaps against the retrenched forces of Eadred's Scandinavian opponents.[109] Whilst it is possible that this event was undertaken in the context of compensation for the English campaigning against the Cumbrians in 946,[110] an alternate possibility is that this Scottish invasion was instead an opportunistic attempt to extract tribute from the Northumbrian ruler Osulf (fl. 946–950), rather than the York-based Scandinavians.[111]

In 952, the seventeenth-century Annals of the Four Masters[112] and the fifteenth- to sixteenth-century Annals of Ulster appear to report an attack upon the Scandinavians of Northumbria by an alliance of English, Scots, and Cumbrians.[113] If these two annal-entries indeed refer to Cumbrians rather than Welshmen, it would appear to indicate that the former—presumably led by Dyfnwal himself—were supporting the cause of the English with the Scots.[114] One possibility is that the annal-entries record the clash of this coalition against the forces of Eiríkr, a man who was finally overwhelmed and slain two years later.[115]

There is also reason to suspect that a man other than Dyfnwal ruled as king in the wake of Edmund's 945 campaign. For instance, a certain Cadmon is recorded to have witnessed two royal charters of Edmund's successor, Eadred—one in 946 and another in 949—which could be evidence that Cadmon was then the ruling Cumbrian monarch.[117] There may be evidence indicating that, from about the time of the campaign until at least 958, the English regarded the land of the Cumbrians as part of the English realm.[118] For instance, a charter apparently issued upon Eadred's coronation—the first of the two witnessed by Cadmon—accords Eadred the title "king of the Anglo-Saxons, Northumbrians, pagans, and Britons",[119] whilst a 958 charter of Eadred's royal successor Edgar accords the latter kingship over "the Mercians, Northumbrians and Britons".[120] The fact that the acta of Edmund, Eadred, and Edgar fail to record the presence of Dyfnwal could be evidence of English rule over the Cumbrians, who may have been in turn administered by English-aligned agents.[121]

Cumbrian and Scottish contention

[edit]

Máel Coluim mac Domnaill was slain in 954, and succeeded by Illulb mac Custantín.[123] At some point during the latter's reign, the Scots permanently acquired Edinburgh from the English,[124] as partly evidenced by the ninth- to twelfth-century Chronicle of the Kings of Alba.[125] Confirmation of this conquest seems to be preserved by the twelfth-century Historia regum Anglorum, a source which states that, during the reign of Edgar, King of the English, the Northumbrian frontier extended as far as the Tinæ, a waterway which seems to refer to the River Tyne in Lothian.[126] The acquisition of Edinburgh, and extension into Lothian itself, may well have taken place during the reign of the embattled and unpopular Eadwig, King of the English.[127] Illulb's attack may be evidenced by passages preserved by the twelfth-century Prophecy of Berchán which not only note "woe" inflicted upon the Britons and English, but also the conquest of foreign territories by way of Scottish military might.[128] The notice of Britons in this text could be evidence that Illulb campaigned against Cumbrian-controlled territories.[129] Such conflict may have meant that the apparent Cumbrian extension southwards was mirrored by movement eastwards. One possibility is that the Scots seized Edinburgh not from the English but from Cumbrians who had temporarily taken possession of it. Certainly, the fortress of Edinburgh had anciently been a British stronghold.[130]

Rhydderch, son of Dyfnwal

[edit]

After Illulb's death in 962, the Scottish kingship appears to have been taken up by Dub mac Maíl Choluim, a man who was in turn replaced by Illulb's son, Cuilén.[132] The latter's death at the hands of Britons in 971 is recorded by several sources. Some of these sources place his death in locations that could refer to either Abington in South Lanarkshire,[133] Lothian,[134] or the Lennox.[135] There is reason to suspect that Cuilén's killer was a son of Dyfnwal himself.[136] The Chronicle of the Kings of Alba reports that the killer was a certain Rhydderch ap Dyfnwal, a man who slew Cuilén for the sake of his own daughter.[137] The thirteenth-century Verse Chronicle,[138] the twelfth- to thirteenth-century Chronicle of Melrose,[139] and the fourteenth-century Chronica gentis Scotorum likewise identify Cuilén's killer as Rhydderch, the father of an abducted daughter raped by the Scottish king.[140]

Although there is no specific evidence that Rhydderch was himself a king,[141] the fact that Cuilén was involved with his daughter, coupled with the fact that his warband was evidently strong enough to overcome that of Cuilén, suggests that Rhydderch must have been a man of eminent standing.[142] According to the Prophecy of Berchán, Cuilén met his end whilst "seeking a foreign land", which could indicate that he was attempting to lift taxes from the Cumbrians.[143] Another way in which Cuilén may have met his end concerns the record of his father's seizure of Edinburgh. The fact that this conquest would have likely included at least part of Lothian,[144] coupled with the evidence placing Cuilén's demise in the same area, could indicate that Cuilén was slain in the midst of exercising overlordship of this contested territory. If so, the records that link Rhydderch with the regicide could reveal that this wronged father exploited Cuilén's vulnerable position in the region, and that Rhydderch seized the chance to avenge his daughter.[145]

Cuilén seems to have been succeeded by his kinsman Cináed mac Maíl Choluim.[147] One of the latter's first acts as King of Alba was evidently an invasion of the kingdom of the Cumbrians.[148] This campaign could well have been a retaliatory response to Cuilén's killing,[149] carried out in the context of crushing a British affront to Scottish authority.[150] In any event, Cináed's invasion ended in defeat,[151] a fact which coupled with Cuilén's killing reveals that the Cumbrian realm was indeed a power to be reckoned with.[152] Whilst it is conceivable that Rhydderch could have succeeded Dyfnwal by the time of Cuilén's fall,[153] another possibility is that Dyfnwal was still the king, and that Cináed's strike into Cumbrian territory was the last conflict of Dyfnwal's reign.[154] In fact, it could have been at about this point when Máel Coluim took up the kingship.[155] According to the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba, Cináed constructed some sort of fortification on the River Forth, perhaps the strategically located Fords of Frew near Stirling.[156] One possibility is that this engineering project was undertaken in the context of limiting Cumbrian incursions.[157]

Amongst an assembly of kings

[edit]

There is evidence to suggest that Dyfnwal was amongst the assembled kings who are recorded to have met with Edgar at Chester in 973.[158] According to the "D", "E", and "F" versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, after having been consecrated king that year, this English monarch assembled a massive naval force and met with six kings at Chester.[159] By the tenth century, the number of kings who met with him was alleged to have been eight, as evidenced by the tenth-century Life of St Swithun.[160] By the twelfth century, the eight kings began to be named and were alleged to have rowed Edgar down the River Dee, as evidenced by sources such as the twelfth-century texts Chronicon ex chronicis,[161] Gesta regum Anglorum,[162] and De primo Saxonum adventu,[163] as well as the thirteenth-century Chronica majora,[164] and both the Wendover[165] and Paris versions of Flores historiarum.[166] One of the names in all these sources—specifically identified as a Welsh king by Gesta regum Anglorum, Chronica majora, and both versions of Flores historiarum—appears to refer to Dyfnwal.[167] Another named figure, styled King of the Cumbrians, seems to be identical to his son, Máel Coluim.[168][note 9]

Whilst the symbolic tale of the men rowing Edgar down the river may be an unhistorical embellishment, most of the names accorded to the eight kings can be associated with contemporary rulers, suggesting that some of these men may have taken part in a concord with him.[174][note 10] Although the latter accounts allege that the kings submitted to Edgar, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle merely states that they came to an agreement of cooperation with him, and thus became his efen-wyrhtan ("co-workers", "even-workers", "fellow-workers").[176] One possibility is that the assembly somehow relates to Edmund's attested incursion into Cumbria in 945. According to the same source, when Edmund let Cumbria to Máel Coluim mac Domnaill, he had done so on the condition that the latter would be his mid-wyrhta ("co-worker", "even-worker", "fellow-worker", "together-wright").[177] Less reliable non-contemporary sources such as De primo Saxonum adventu,[178] both the Wendover[179] and Paris versions of Flores historiarum,[180] and Chronica majora allege that Edgar granted Lothian to Cináed in 975.[181] If this supposed grant formed a part of the episode at Chester, it along with the concord of 945 could indicate that the assembly of 975 was not a submission as such, but more of a conference concerning mutual cooperation along the English borderlands.[182] The location of the assembly of 973 at Chester would have been a logical neutral site for all parties.[183][note 11]

One of the other named kings was Cináed.[187] Considering the fact that the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle numbers the kings at six, if Cináed was indeed present, it is unlikely that his rival, Cuilén's brother Amlaíb mac Illuilb, was also in attendance.[188] Although the chronology concerning the reigns of Cináed and Amlaíb mac Illuilb is uncertain[189]—with Amlaíb mac Illuilb perhaps reigning from 971/976–977[190] and Cináed from 971/977–995[188]—the part played by the King of Alba at the assembly could well have concerned the frontier of his realm.[191] One of the other named kings seems to have been Maccus mac Arailt,[192] whilst another could have been this man's brother, Gofraid.[193] These two Islesmen may have been regarded a threats by the Scots[191] and Cumbrians.[188] Maccus and Gofraid are recorded to have devastated Anglesey at the beginning of the decade,[194] which could indicate that Edgar's assembly was undertaken as a means to counter the menace posed by these energetic insular Scandinavians.[195] In fact, there is evidence to suggest that, as a consequence of the assembly at Chester, the brothers may have turned their attention from the British mainland westwards towards Ireland.[196]

Another aspect of the assembly may have concerned the remarkable rising power of Amlaíb Cúarán in Ireland.[198] Edgar may have wished to not only rein in men such as Maccus and Gofraid, but prevent them—and the Scots and Cumbrians—from affiliating themselves with Amlaíb Cúarán, and recognising the latter's authority in the Irish Sea region.[199] Another factor concerning Edgar, and his Scottish and Cumbrian counterparts, may have been the stability of the northern English frontier. For example, a certain Thored Gunnerson is recorded to have ravaged Westmorland in 966, an action that may have been undertaken by the English in the context of a response to Cumbrian southward expansion.[200][note 12] Although the Scottish invasion of Cumbrian and English territory unleashed after Cináed's inauguration could have been intended to tackle Cumbrian opposition,[149] another possibility is that the campaign may have been executed as a way to counter any occupation of Cumbrian territories by Thored.[203]

Death and descendants

[edit]

Both Dyfnwal[206] and his English counterpart died in 975.[207] According to various Irish annals, which style Dyfnwal King of the Britons, he met his end whilst undertaking a pilgrimage.[208] These sources are corroborated by Welsh texts such as the thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Brenhinedd y Saesson,[209] and Brut y Tywysogyon, with the latter stating that Dyfnwal died in Rome having received the tonsure.[210] Such religious retirement late in the life of a ruler was not uncommon amongst contemporaries. For example, Custantín evidently became a monk upon his own abdication, whilst Amlaíb Cúarán retired to the holy island of Iona in pilgrimage.[211] One possibility is that Dyfnwal decided to undertake his religious journey—or was perhaps forced to undertake it—as a result of the violent actions of Rhydderch.[212]

It is conceivable that Dyfnwal was still reigning in 973,[214] and that it was Edgar's death two years later that precipitated the transfer of the kingship to Dyfnwal's son Máel Coluim, and contributed to Dyfnwal's pilgrimage to Rome. In fact, the upheaval caused by the absence of the English and Cumbrian kings could well have contributed to Cináed's final elimination of Amlaíb mac Illuilb in 997.[188] Another possibility is that Máel Coluim's part in the 973 assembly may have partly concerned his father's impending pilgrimage, and that he sought surety for Dyfnwal's safe passage through Edgar's realm.[191] The fact that Máel Coluim is identified as one of the assembled kings could indicate that Dyfnwal had relinquished control to him at some point before the convention.[215] Evidence that he had indeed assumed the kingship may exist in the record of a certain Malcolm dux who witnessed an English royal charter in 970.[216] Although the authenticity of this document is questionable, the attested Malcolm could well be identical to Máel Coluim himself.[217][note 13] If Máel Coluim was indeed king in 973, Dyfnwal's role at the assembly may have been that of an 'elder statesman' of sorts—possibly serving as an adviser or mentor—especially considering his decades of experience in international affairs.[219] The fact that he left his realm for Rome could be evidence that he did not regard his realm or dynasty to be threatened during his absence.[220]

Surviving sources fail to note the Cumbrian kingdom between the obituaries of Dyfnwal in 975 and his son, Máel Coluim, in 997.[222] There is reason to suspect that Dyfnwal had another son, Owain, who reigned after Máel Coluim.[223] For instance, according to the "B" version of Annales Cambriæ, a certain Owain—identified as the son of a man named Dyfnwal—was slain in 1015.[224] This obituary is corroborated by Brut y Tywysogyon,[225] and Brenhinedd y Saesson.[226] Although it may be possible that the record of this man's death refers to Owain Foel, King of Strathclyde,[227] there is no reason to disregard the obituaries as erroneous. If the like-named men are indeed different people, they could well have been closely related. Whilst the former may have been a son of Dyfnwal himself, the latter could well have been a son of Dyfnwal's son, Máel Coluim.[228] The Owain who died in 1015, therefore, would seem to have assumed the Cumbrian kingship after Máel Coluim's death in 997, and would appear to have reigned into the early eleventh century before Owain Foel's assumption of the throne.[223]

Dyfnwal may be the man immortalised in the name of a mountain pass in the Lake District known as Dunmail Raise (meaning "Dyfnwal's Cairn").[229] According to popular legend, a local king named Dunmail was slain by Saxons on the pass and buried beneath a cairn. Forms of this tradition may date to about the sixteenth century,[230] as the place name is first marked on a map dating to 1576.[231] By the end of the seventeenth century, it was claimed that the place name marked the site of "a great heap of Stones call'd Dunmail-Raise-Stones, suppos'd to have been cast up by Dunmail K. of Cumberland for the Bounds of his Kingdom".[232] Forms of the tale began to appear in print in the following century. In time, the ever-evolving legend became associated with the events of 945.[233] The cairn itself lies between the dual carriageways of the A591 road.[234] It seems to have marked an old boundary between Westmorland and Cumberland, and might have also marked the southern territorial extent of the Cumbrian kingdom.[235] Nevertheless, the site's alleged importance in the early mediaeval period cannot be proven.[236] Other place names that may be named after Dyfnwal include Cardonald (grid reference NS5364),[237] and Dundonald/Dundonald Castle (grid reference NS3636034517).[238]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The Welsh personal name Dyfnwal is a cognate of the Gaelic Domnall.[2]

- ^ Since the 2000s academics have accorded Dyfnwal various patronyms in English secondary sources: Domnall mac Eogain,[3] Dunmail map Owain,[4] Dwnwallon ab Owain,[5] Dyfnwal ab Owain,[6] and Dyfnwal map Ywain.[7] Likewise, since the 1990s academics have accorded Dyfnwal various personal names in English secondary sources: Domnaldus,[8] Domnall,[9] Donald,[10] Dovenald,[11] Dufnal,[12] Dumnagual,[13] Dunguallon,[14] Dunmail,[15] Dunwallon,[16] Dyfnal,[17] Dyfnwal,[18] Dyfnwallon,[19] and Dwnwallon.[5]

- ^ By about this time, the Cumbrian kingdom appears to have comprised much of modern Lanarkshire, Dunbartonshire, Renfrewshire, Stirlingshire, Peebleshire, West Lothian, Mid Lothian, eastern Dumfriesshire, and Cumberland.[32] The Old English Cumbras is cognate with the Welsh Cymry,[33] a designation likely used by both the northern Britons and the more southerly Britons (the Welsh).[34] Examples of the new terminology accorded to the northern realm include Cumbra land and terra Cumbrorum, meaning "land of the Cumbrians".[35] Such 'Cumbrian' nomenclature is found in royal designations, suggesting that it reflected the realm's political expansion. By the mid tenth century, the 'Strathclyde' terminology seems to have been mostly superseded.[36] The expansion of the Cumbrian kingdom may be perceptible in some of the place names of southern Scotland and northern England.[37]

- ^ The biblical poem Saltair na Rann seems to have been composed in the late tenth century.[39] The excerpt is that of a passage concerning Dyfnwal's son, Máel Coluim.[40]

- ^ Only three kings are specifically termed "King of the Cumbrians" in historical sources: Dyfnwal's father, Dyfnwal himself, and Dyfnwal's son, Máel Coluim.[51]

- ^ If Dyfnwal's father is identical to the Cumbrian king who fought at the Battle of Brunanburh, he would have been allied to Amlaíb mac Gofraid in this conflict.[58] The latter may have been the father of Maccus mac Amlaíb, an otherwise unknown figure said to have slain Eiríkr Haraldsson at Stainmore in 954.[59]

- ^ There is reason to suspect that Eiríkr blóðøx and Eiríkr Haraldsson have been conflated,[69] and that the latter man was actually a member of the insular Uí Ímair.[70] For example, Scandinavian sources fail to accord Eiríkr blóðøx an insular wife as laid out by Life of St Cathróe. The record of this marriage is some of the evidence hinting that Eiríkr blóðøx has been erroneously linked with Northumbria since the twelfth century.[71]

- ^ The ritual blinding of kings was not an unknown act in contemporary Britain and Ireland,[80] and it is possible that Edmund may have also meant to deprive Dyfnwal of a royal heir.[81]

- ^ Both versions of Flores historiarum and Chronica majora specifically associate Dyfnwal with the Kingdom of Dyfed.[169] Another source linking Dyfnwal and Máel Coluim to the assembly is the Chronicle of Melrose.[170] If it was not Dyfnwal who attended the assembly, another possibility is that the like-named attendee was Domnall ua Néill, King of Tara.[171]

- ^ Two of the kings are accorded names of uncertain meaning.[175]

- ^ At about the same time as the assembly, De primo Saxonum adventu also notes that Edgar partitioned the Northumbrian ealdormanry into northern and southern divisions, split between the Tees and Myreforth. If the latter location refers to the mud flats between the River Esk and the Solway Firth,[184] it would reveal that what is today Cumberland had fallen outwith Cumbrian royal authority and into the hands of the English.[185]

- ^ According to the Life of St Cathróe, when Dyfnwal escorted Cathróe to the frontier of his realm, the latter was then escorted by a certain Gunderic to the domain of Erich in York.[201] It is possible that Gunderic is identical to Thored's father, and identical to the Gunner who appears in charter evidence from 931–963.[202]

- ^ This charter is composed of Latin and Old English text. The document may be evidence of Scottish and Cumbrian submission to the English. For example, in one place, the text reads in Latin: "I, Edgar, ruler of the beloved island of Albion, subjected to us of the rule of the Scots and Cumbrians and the Britons and of all regions round about ...". The corresponding Old English text reads: "I, Edgar, exalted as king over the English people by His [God's] grace, and He has now subjected to my authority the Scots and Cumbrians and also the Britons and all that this island has inside ...".[218]

Citations

[edit]- ^ The Annals of Tigernach (2016) § 975.3; Annals of Tigernach (2005) § 975.3; Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. B. 488 (n.d.).

- ^ Woolf (2007) pp. xiii, 184, 184 n. 17; Koch (2006); Bruford (2000) pp. 64, 65 n. 76; Schrijver (1995) p. 81.

- ^ Busse (2006c).

- ^ Snyder (2003).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Charles-Edwards (2013b).

- ^ Minard (2012); Clarkson (2010); Breeze (2007); Busse (2006c); Minard (2006); Thornton (2001).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Macquarrie (2004a).

- ^ Downham (2007); Downham (2003).

- ^ Busse (2006b); Busse (2006c).

- ^ Keynes (2015); McGuigan (2015b); Williams (2014); Walker (2013); Minard (2012); Breeze (2007); Minard (2006); Broun (2004a); Macquarrie (2004b); Duncan (2002); Williams; Smyth; Kirby (1991); Hudson (1994).

- ^ Clarkson (2014).

- ^ Minard (2012); Minard (2006); Jayakumar (2002); Williams; Smyth; Kirby (1991).

- ^ Duncan (2002).

- ^ Hicks (2003); Duncan (2002).

- ^ Cannon (2015); Williams (2004c); Breeze (2007); Snyder (2003).

- ^ Matthews (2007).

- ^ Breeze (2007); Hudson (1996); Hudson (1991).

- ^ Broun (2015a); Edmonds (2015); Keynes (2015); Clarkson (2014); Edmonds (2014); Charles-Edwards (2013b); Clarkson (2012a); Minard (2012); Oram (2011); Clarkson (2010); Woolf (2009); Breeze (2007); Downham (2007); Woolf (2007); Busse (2006c); Minard (2006); Broun (2004d); Macquarrie (2004a); Macquarrie (2004b); Hicks (2003); Thornton (2001); Macquarrie (1998); Woolf (1998) p. 190; Hudson (1994).

- ^ Woolf (2007); Hicks (2003); Clancy (2002); Macquarrie (1998).

- ^ Charles-Edwards (2013b) p. 8; Clancy (2006).

- ^ Edmonds (2015) p. 44; Charles-Edwards (2013b) pp. 9, 480; Clarkson (2012a) ch. 8 ¶ 21; Clarkson (2010) ch. 8 ¶ 20; Davies (2009) p. 73; Downham (2007) pp. 66, 142, 162; Clancy (2006); Ewart; Pringle; Caldwell et al. (2004) p. 8.

- ^ Driscoll, ST (2015) p. 5; Edmonds (2015) p. 44; Charles-Edwards (2013b) pp. 9, 480–481; Clarkson (2012a) ch. 8 ¶ 23; Clarkson (2010) ch. 8 ¶ 26; Clancy (2006); Ewart; Pringle; Caldwell et al. (2004) p. 8.

- ^ Driscoll, ST (2015) pp. 5, 7; Clarkson (2014) ch. 3 ¶ 13; Clarkson (2012a) ch. 8 ¶ 23; Clarkson (2012b) ch. 11 ¶ 46; Clarkson (2010) ch. 8 ¶ 22; Ewart; Pringle; Caldwell et al. (2004) pp. 8, 10.

- ^ Foley (2017); Driscoll, ST (2015) pp. 5, 7; Clarkson (2014) chs. 1 ¶ 23, 3 ¶ 11–12; Edmonds (2014) p. 201; Charles-Edwards (2013b) pp. 9, 480–481; Clarkson (2012a) ch. 8 ¶ 23; Clarkson (2012b) ch. 11 ¶ 46; Clarkson (2010) ch. 8 ¶ 22; Davies (2009) p. 73; Oram (2008) p. 169; Downham (2007) p. 169; Clancy (2006); Driscoll, S (2006); Forsyth (2005) p. 32; Ewart; Pringle; Caldwell et al. (2004) pp. 8, 10; Driscoll, ST (2003) pp. 81–82; Hicks (2003) pp. 32, 34; Driscoll, ST (2001a); Driscoll, ST (2001b); Driscoll, ST (1998) p. 112.

- ^ Charles-Edwards (2013b) pp. 480–481.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Anderson, AO (1922) p. 478; Stevenson, J (1856) p. 100; Stevenson, J (1835) p. 34; Cotton MS Faustina B IX (n.d.).

- ^ Dumville (2018) p. 118; Driscoll, ST (2015) pp. 6–7; Edmonds (2015) p. 44; James (2013) pp. 71–72; Parsons (2011) p. 123; Davies (2009) p. 73; Downham (2007) pp. 160–161, 161 n. 146; Woolf (2007) p. 153; Breeze (2006) pp. 327, 331; Clancy (2006); Ewart; Pringle; Caldwell et al. (2004) pp. 9–10; Hicks (2003) pp. 35–37, 36 n. 78.

- ^ Dumville (2018) pp. 72, 110, 118; Edmonds (2015) pp. 44, 53; Charles-Edwards (2013a) p. 20; Charles-Edwards (2013b) pp. 9, 481; Parsons (2011) p. 138 n. 62; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 10; Davies (2009) p. 73, 73 n. 40; Downham (2007) p. 165; Clancy (2006); Todd (2005) p. 96; Stenton (1963) p. 328.

- ^ Lewis (2016) p. 15; Charles-Edwards (2013b) pp. 9, 481–482; Breeze (2006) pp. 327, 331; Hicks (2003) pp. 35–36, 36 n. 78; Woolf (2001); Macquarrie (1998) p. 19; Fellows-Jensen (1991) p. 80.

- ^ Charles-Edwards (2013b) pp. 481–482.

- ^ Edmonds (2015) pp. 50–51; Molyneaux (2015) p. 15; Edmonds (2014); Davies (2009) p. 73; Edmonds (2009) p. 44; Clancy (2006).

- ^ Woolf (2007) pp. 154–155.

- ^ Clancy (2006).

- ^ Edmonds (2015) pp. 50–51; Edmonds (2014) pp. 201–202; Charles-Edwards (2013b) p. 2.

- ^ Edmonds (2015) pp. 50–52; Edmonds (2014) pp. 199–200, 204–205.

- ^ Edmonds (2014).

- ^ James (2013) p. 72; James (2011); James (2009) p. 144, 144 n. 27; Millar (2009) p. 164.

- ^ McGuigan (2015b) p. 140; Saltair na Rann (2011) §§ 2373–2376; Hudson (1994) pp. 101, 174 nn. 7–9; Mac Eoin (1961) p. 53 §§ 2373–2376, 55–56; Bodleian Library MS. Rawl. B. 502 (n.d.); Saltair na Rann (n.d.) §§ 2373–2376.

- ^ Hudson (2005) pp. 69, 220 n. 46; Hudson (1996) p. 102; Mac Eoin (1961).

- ^ McGuigan (2015b) p. 140; Saltair na Rann (2011) §§ 2373–2376; Hudson (2002) p. 36; Hudson (1996) p. 102; Hudson (1994) pp. 101, 174 nn. 7–9; Hudson (1991) p. 147; Saltair na Rann (n.d.) §§ 2373–2376.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. genealogical tables; Charles-Edwards (2013b) p. 572 fig. 17.4; Minard (2012); Clarkson (2010) ch. genealogical tables; Minard (2006); Macquarrie (1998) p. 6; Hudson (1994) p. 173 genealogy 6.

- ^ Macquarrie (1998) pp. 14–15.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. genealogical tables; Charles-Edwards (2013b) p. 572 fig. 17.4; Clarkson (2010) ch. genealogical tables; Broun (2004d) p. 135 tab.; Macquarrie (1998) pp. 6, 16; Hudson (1994) p. 173 genealogy 6.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. genealogical tables; Charles-Edwards (2013b) p. 572 fig. 17.4; Clarkson (2010) ch. genealogical tables; Woolf (2007) p. 238 tab. 6.4; Broun (2004d) p. 135 tab.; Macquarrie (1998) pp. 6, 16; Hudson (1994) p. 173 genealogy 6.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. genealogical tables; Charles-Edwards (2013b) p. 572 fig. 17.4; Clarkson (2010) ch. genealogical tables; Woolf (2007) p. 236, 238 tab. 6.4; Broun (2004d) pp. 128 n. 66, 135 tab.

- ^ Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 44.

- ^ Thornton (2001) p. 67 n. 65; Arnold (1882) p. 76 bk. 2 ch. 18; Stevenson, J (1855) p. 669 ch. 33.

- ^ Naismith (2017) p. 281; Oram (2011) ch. 2; Duncan (2002) p. 23 n. 53; Macquarrie (1998) p. 14; Williams; Smyth; Kirby (1991) p. 103; Hudson (1994) p. 174 n. 7.

- ^ Thornton (2001) p. 67 n. 65; Anderson, AO (1908) pp. 70–71, 71 n. 3; Arnold (1885) p. 93 ch. 83; Arnold (1882) p. 76 bk. 2 ch. 18; Stevenson, J (1855) pp. 482, 669 ch. 33.

- ^ Thornton (2001) p. 67.

- ^ Minard (2006).

- ^ Downham (2013) p. 202; Irvine (2004) p. 55; Thorpe (1861) p. 215.

- ^ Evans (2015) p. 150; Keynes (2015) p. 111; McGuigan (2015b) p. 98; Molyneaux (2015) p. 24, 24 n. 30; Clarkson (2014) chs. 1 ¶ 25, 6 ¶¶ 4–5; Edmonds (2014) pp. 205–206; Walker (2013) ch. 3 ¶ 51; Clarkson (2012a) ch. 10 ¶ 25; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 24; Broun (2004d) p. 127; Macquarrie (2004a); Macquarrie (2004b); Downham (2003) p. 27; Macquarrie (1998) pp. 15–16; Woolf (1998) p. 190; Hudson (1994) p. 174 n. 8; Anderson, AO (1922) p. 441; Skene (1867) p. 116; Colganvm (1645) p. 497 § xvii.

- ^ Molyneaux (2015) p. 24, 24 n. 30; Edmonds (2014) p. 206 n. 59; Hicks (2003) p. 38.

- ^ Edmonds (2014) p. 206 n. 59; Hicks (2003) p. 38.

- ^ Clarkson (2014) ch. 6 ¶ 5; Edmonds (2014) p. 206 n. 59; Clarkson (2012a) ch. 10 ¶ 25; Clarkson (2010) ch. 9 ¶ 24.

- ^ Cassell's History of England (1909) p. 49.

- ^ Naismith (2017) с. 281; Хадсон (2004) ; Дункан (2002) с. 23 н. 53; Macquarrie (1998) с. 14

- ^ Даунхэм (2007) с. 120–121, 121 н. 79; Вульф (2007) с. 190; Хадсон (2004) .

- ^ Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 SAL 24; Anderson, AO (1922) с. 431–432, 431 н. 6; Скен (1867) с. 109; Colganvm (1645) с. 495 § VI, 502–503 n. 42, 503 н. 43

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 24.

- ^ Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 24; Macquarrie (2004a) .

- ^ Clarkson (2012a) Ch. 10 ¶ 25; Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 24.

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 ¶¶ 4–6, 6 н. 6; Эдмондс (2014) с. 205–206; Даунхем (2013) с. 187, 203; Даунхем (2007) с. 119; Вульф (2007) с. 187–188; Costambeys (2004) ; Macquarrie (2004a) ; Вульф (1998) с. 193 н. 18; Андерсон, АО (1922) с. 441; Скен (1867) с. 116; Colganvm (1645) с. 497 § XVII.

- ^ Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 24; Вульф (2007) с. 187–188; Macquarrie (2004a) ; Вульф (2002) с. 39; Вульф (1998) .

- ^ Вульф (2007) с. 187–188.

- ^ Вульф (1998) с. 193 н. 18

- ^ Даунхэм (2003) с. 43, 49.

- ^ Naismith (2017) с. 281; Якобссон (2016) с. 173; Макгиган (2015a) с. 31, 31 н. 48; Даунхем (2013) ; Даунхем (2007) с. 115–120, 120 н. 74; Вульф (2007) с. 187–188; Вульф (2002) с. 39

- ^ Naismith (2017) с. 281, 300–301; Макгиган (2015a) с. 31, 31 н. 48; Даунхем (2013) ; Даунхем (2007) с. 119–120, 120 н. 74; Вульф (2002) с. 39

- ^ Даунхэм (2013) ; Downham (2007) с. 115–120, 120 н. 74

- ^ О'Киф (2001) с. 80; Whitelock (1996) с. 224, 224 н. 2; Торп (1861) с. 212; Хлопок MS Tiberius Bi (ND) .

- ^ Gough-Cooper (2015a) с. 27 § A509.3; Кейнс (2015) с. 95–96; Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 ¶ 14, 6 н. 19; Halloran (2011) с. 308, 308 н. 40; Вульф (2010) с. 228, 228 н. 27; Даунхем (2007) с. 153; Вульф (2007) с. 183; Даунхем (2003) с. 42; Хикс (2003) с. 39; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 114; Alcock (1975–1976) с. 106; Андерсон, АО (1922) с. 449.

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 ¶ 15; Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 25; Даунхем (2003) с. 42; Хикс (2003) с. 39; Андерсон, АО (1922) с. 449; RHŷS (1890) с. 261; Williams Ab Ithel (1860) с. 20–21.

- ^ Gough-Cooper (2015a) с. 27 н. 191; Кейнс (2015) с. 95–96; McGuigan (2015b) с. 83, 139–140; McLeod (2015) с. 4; Molyneaux (2015) с. 33, 52–53, 76; Кларксон (2014) Chs. 1 ¶ 10, 6 ¶ 11, 6 н. 18, 6 ¶ 20; Уокер (2013) гл. 4 ¶ 5; Halloran (2011) с. 307, 307 н. 36; Molyneaux (2011) с. 66, 66 н. 27, 69, 70, 73, 88; Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 № 25–27; Вульф (2010) с. 228, 228 н. 26; Даунхем (2007) с. 153; Вульф (2007) с. 183; Клэнси (2006) ; Уильямс (2004c) ; Даунхем (2003) с. 42; Хикс (2003) с. 16 н. 35; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 114–115, 114 н. 29; Дункан (2002) с. 23; Торнтон (2001) с. 78, 78 н. 114; О'Киф (2001) с. 80; Уильямс (1999) с. 86; Whitelock (1996) с. 224; Смит (1989) с. 205–206; Роуз (1982) с. 119, 122; Alcock (1975–1976) с. 106; Стентон (1963) с. 355; Андерсон, АО (1908) с. 74, 74 н. 3; Торп (1861) с. 212–213.

- ^ Голландия (2016) гл. Малмсбери ¶ 7; Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 ¶ 11, 6 н. 20; Андерсон, АО (1908) с. 74 нн 4–5; Арнольд (1879) с. 162 бк. 5 гл. 21; Форестер (1853) с. 172 бк. 5

- ^ Firth (2016) с. 24–25; Макгиган (2015b) с. 139; Monlyneaux (2015) с. 10-1 33, 61, 76; Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 ¶ 12–13, 6 н. 21; Halloran (2011) с. 308; Morlyneaaux (2011) с. 66, 66 н. 27, 70; Шерсть (2007) с. 183; Дункан (2002) с. 23; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 114; Торнтон (2001) с. 78, 78 н. 114; Хадсон (1994) с. 174 н. 12; Enton (1963) с. 355; Андерсон, АО (1908) с. 74 н. 5; Джайлс (1849) с. 252–253; Кокс (1841) с. 398.

- ^ Макгиган (2015b) с. 139; Luard (2012) с. 500; Halloran (2011) с. 308, 308 н. 41; Йонге (1853) с. 473.

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 ¶ 14; Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 25.

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 н. 23

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 ¶ 14, 7 ¶ 5.

- ^ Голландия (2016) гл. Малмсбери ¶ 5; Molyneaux (2015) с. 77–78; Вульф (2007) с. 183 с. 183.

- ^ Oram (2011) Ch. 2

- ^ Вульф (2007) с. 183.

- ^ Molyneaux (2015) с. 31; Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 ¶ 11; Вульф (2007) с. 182–183; Даунхем (2003) с. 41; Whitelock (1996) с. 224

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 ¶ 16; Вульф (2007) с. 182–183.

- ^ Вульф (2002) с. 38

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 ¶ 16.

- ^ Фултон (2000) с. 11, 13.

- ^ Даунхем (2003) с. 42; Смит (1989) с. 205–206.

- ^ Халлоран (2011) с. 307

- ^ Molyneaux (2015) с. 33, 77–78.

- ^ Эдмондс (2015) с. 5, 55 н. 61; Кларксон (2010) гл. 10 ¶ 11; Труды (1947) с. 221–225; Коллингвуд (1923) .

- ^ Халлоран (2011) с. 307; Вульф (2007) с. 183–184.

- ^ McGuigan (2015b) с. 139–140; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 115 н. 32; Хадсон (1994) с. 84–85.

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 ¶ 20.

- ^ Дункан (2002) с. 23

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 ¶ 20; Вульф (2007) с. 184.

- ^ Дэвидсон (2002) с. 116, 116 н. 36

- ^ Парсонс (2011) с. 129; Вульф (2007) с. 184.

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 ¶ 21; Вульф (2007) с. 184.

- ^ Макгиган (2015b) с. 139; Джайлс (1849) с. 253–254; Кокс (1841) с. 399.

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 ¶ 20; Molyneaux (2011) с. 76; Уильямс (2004c) ; Даунхем (2003) с. 42; Смит (1989) с. 205–206.

- ^ Даунхем (2007) с. 153

- ^ Даунхем (2007) с. 153; Фултон (2000) с. 13

- ^ Анналы Ольстера (2017) § 952.2; Анналы Ольстера (2008) § 952.2; Андерсон, АО (1922) с. 451; Бодлеанская библиотека MS. Рол Б. 489 (ND) .

- ^ McGuigan (2015b) с. 83–84; Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 28; Уильямс (2004b) ; Андерсон, АО (1922) с. 450.

- ^ McGuigan (2015b) с. 83–84; Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 28; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 116–117; Фултон (2000) с. 14

- ^ Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 28; Даунхем (2007) с. 154–155; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 131, 131 н. 103; Хадсон (1998) с. 150–151, 158; Хадсон (1994) с. 86–87; Скен (1867) с. 10

- ^ Дэвидсон (2002) с. 131; Хадсон (1994) с. 86–87.

- ^ Дэвидсон (2002) с. 131–132.

- ^ Анналы Four Masters (2013a) § 950.14; Анналы Four Masters (2013b) § 950.14; Даунхем (2007) с. 155; Андерсон, АО (1922) с. 451 н. 4

- ^ Анналы Ольстера (2017) § 952.2; Уокер (2013) гл. 4 ¶ 10; Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 28; Анналы Ольстера (2008) § 952.2; Даунхем (2007) с. 155, 167; Вульф (2007) с. 188–189; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 60, 132, 132 н. 108; Хадсон (1994) с. 87; Андерсон, АО (1922) с. 451.

- ^ Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 28; Вульф (2007) с. 188–189.

- ^ Даунхем (2007) с. 155; Вульф (2007) с. 188–189; Costambeys (2004) ; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 132–133; Хадсон (1994) с. 87

- ^ Rhŷs (1890) с. 262; Williams Ab Ithel (1860) с. 26–27; Иисус Колледж MS. 111 (ND) ; Оксфордский колледж Иисуса MS. 111 (ND) .

- ^ Кейнс (2015) с. 84–85 рис. 1, 100–101, 100 н. 131; Molyneaux (2015) с. 57 н. 45, 212, 212 н. 83; Чарльз-Эдвардс (2013b) с. 515 Tab. 16.1, 516–517; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 118–119; Пьерквин (1912) с. 294–295 § 86, 303–304 § 94; Береза (1893) с. 38–40 § 883; Береза (1887) с. 576–578 § 815; Cadfan 1 (ND) ; S 544 (ND) ; S 520 (ND )

- ^ Кейнс (2015) с. 96 н. 110, 107.

- ^ Кейнс (2015) с. 98–99, 119–120; Кейнс (2001) с. 70; Пьерквин (1912) с. 294–295 § 86; Береза (1887) с. 576–578 § 815; S 520 (ND) .

- ^ Кейнс (2015) с. 120; Кейнс (2001) с. 72; Береза (1893) с. 242–244 § 1040; S 677 (ND) .

- ^ Кейнс (2015) с. 107

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Howlett (2000) с. 65; Скен (1867) с. 131; Лат 4126 (nd) fol. 29В

- ^ Broun (2004b) ; Хадсон (1994) с. 88–89.

- ^ Тейлор (2016) с. 8–9; Брун (2015b) ; Брун (2004b) ; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 133.

- ^ Хвост (2016) с. 8–9; McGuigan (2015b) с. 148–149; Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 ¶ 35; Хадсон (1998) с. 10-1 151, 159; Дункан (2002) с. 23; Хадсон (1994) с. 10-1 89–90; Андерсон, АО (1922) с. 468; Сене (1867) с. 10

- ^ Хадсон (1994) с. 89; Арнольд (1885) с. 197 г. 159; Стивенсон, J (1855) с. 557.

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 ¶ 35; Хадсон (1994) с. 89–90.

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 ¶¶ 35–36; Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 29; Хадсон (1998) с. 159 н. 57; Hudson (1996) с. 48 § 160, 48 § 162, 88 § 160, 88 § 162, 88 n. 97; Хадсон (1994) с. 89–90; Андерсон, AO (1930) с. 46 § 158; 46–47 § 160; Андерсон, АО (1922) с. 471; Скен (1867) с. 94

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 ¶¶ 35–36; Хадсон (1994) с. 89–90.

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 ¶ 36.

- ^ Андерсон, АО (1922) с. 476; Стивенсон, J (1835) с. 226; Хлопок MS Faustina B IX (ND) .

- ^ Broun (2004a) .

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 7 ¶ 6; Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 32; Хикс (2003) с. 40–41; Macquarrie (1998) с. 16 н. 3; Андерсон, АО (1922) с. 476 н. 2

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 7 ¶ 6; Кларксон (2012a) Ch. 9 ¶ 28; Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 34.

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 7 ¶ 6; Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 34.

- ^ Broun (2015a) ; Кларксон (2014) гл. 7 ¶ 6; Кларксон (2012a) Ch. 9 ¶¶ 28–29; Oram (2011) Chs. 2, 5; Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 34; Бусс (2006b) ; Бусс (2006c) ; Broun (2004d) p. 135 Tab.; Macquarrie (2004b) ; Macquarrie (1998) с. 6, 16; Хадсон (1994) с. 173 Генеалогия 6, 174 н. 10; Уильямс; Смит; Кирби (1991) с. 92, 104.

- ^ Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 32; Macquarrie (1998) с. 16; Андерсон, АО (1922) с. 476, 476 н. 1; Скен (1867) с. 151.

- ^ Broun (2005) с. 87–88 н. 37; Скен (1867) с. 179

- ^ Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶¶ 32–33; Вульф (2007) с. 204; Macquarrie (2004b) ; Хикс (2003) с. 40–41; Андерсон, АО (1922) с. 476; Стивенсон, J (1835) с. 226

- ^ Хадсон (1994) с. 93, 174 н. 10; Скен (1872) с. 161–162 бк. 4 гл. 27; Скен (1871) с. 169–170 BK 4.

- ^ Macquarrie (2004b) ; Торнтон (2001) с. 67 н. 66

- ^ Macquarrie (2004b) .

- ^ Хадсон (1998) с. 160 н. 71; MacureArrie (1998) с. 16; Хадсон (1996) с. 10-1 49 § 168, 88 § 168; Хадсон (1994) с. 93; Андерсон, АО (1930) с. 48 § 166; Андерсон, АО (1922) с. 477; Сене (1867) с. 95–96.

- ^ Уокер (2013) гл. 4 ¶¶ 16–18, 24; Хадсон (1998) с. 151, 159; Андерсон, АО (1922) с. 468; Скен (1867) с. 10

- ^ Уокер (2013) гл. 4 ¶ 24.

- ^ Анналы Тигернаха (2016) § 977.4; Annals of Tigernach (2005) § 977.4; Бодлеанская библиотека MS. Рол Б. 488 (ND) .

- ^ Broun (2004a) ; Брун (2004c) .

- ^ Уильямс (2014) ; Уокер (2013) гл. 4 ¶ 25; Кларксон (2012a) Ch. 9 ¶ 30; Oram (2011) Ch. 5; Вульф (2009) с. 259; Бусс (2006a) ; Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 35; Брун (2004c) .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Уокер (2013) гл. 4 ¶ 25; Вульф (2009) с. 259

- ^ Уокер (2013) гл. 4 ¶ 25.

- ^ Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 35; Брун (2004c) .

- ^ Макгиган (2015b) с. 140; Кларксон (2012a) Ch. 9 ¶ 35; Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 35.

- ^ Торнтон (2001) с. 67 н. 66

- ^ Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 35.

- ^ Хикс (2003) с. 44 н. 107

- ^ Макгиган (2015b) с. 149; Кларксон (2012a) Ch. 9 ¶ 30; Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 37; Брун (2007) с. 54; Хикс (2003) с. 41–42; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 147–148, 147 н. 167; Хадсон (1998) с. 151, 161; Хадсон (1994) с. 96; Бриз (1992) ; Андерсон, АО (1922) с. 512; Скен (1867) с. 10

- ^ Clarkson (2012a) Ch. 9 ¶ 30; Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 37.

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 7 ¶ 12; Эдмондс (2014) с. 206; Уильямс (2014) ; Чарльз-Эдвардс (2013b) с. 543–544; Кларксон (2012a) Ch. 9 ¶ 29; Oram (2011) Ch. 2; Вульф (2009) с. 259; Бриз (2007) с. 154–155; Даунхем (2007) с. 124, 167; Вульф (2007) с. 208; Macquarrie (2004b) ; Уильямс (2004a) ; Хикс (2003) с. 42; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 143; Джаякумар (2002) с. 34; Торнтон (2001) с. 54–55, 67; Уильямс (1999) с. 88; Macquarrie (1998) с. 16; Уильямс; Смит; Кирби (1991) с. 104, 124; Стентон (1963) с. 324.

- ^ Ферт (2018) с. 48; Голландия (2016) гл. Малмсбери ¶ 6; McGuigan (2015b) с. 143–144, 144 n. 466; Molyneaux (2015) с. 34; Кларксон (2014) гл. 7 ¶¶ 9–10, 7 н. 11; Уильямс (2014) ; Чарльз-Эдвардс (2013b) с. 543–544; Уокер (2013) гл. 4 ¶ 30; Molyneaux (2011) с. 66, 69, 88; Бриз (2007) с. 153; Даунхем (2007) с. 124; Мэтьюз (2007) с. 10; Вульф (2007) с. 207–208; Форте; Орам; Педерсен (2005) с. 218; Ирвин (2004) с. 59; Karkov (2004) с. 108; Уильямс (2004a) ; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 138, 140, 140 н. 140, 144; Торнтон (2001) с. 50; Бейкер (2000) с. 83–84; Уильямс (1999) С. 88, 116, 191 н. 50; Whitelock (1996) с. 229–230; Хадсон (1994) с. 97; Стентон (1963) с. 364; Андерсон, АО (1908) с. 75–76; Stevenson, WH (1898) ; Торп (1861) с. 225–227.

- ^ Эдмондс (2015) с. 61 н. 94; Кейнс (2015) с. 113–114; McGuigan (2015b) с. 143–144; Эдмондс (2014) с. 206, 206 н. 60; Уильямс (2014) ; Monlyeaux (2011) с. 67; Бриз (2007) с. 154; Даунхем (2007) с. 124; Мэтьюз (2007) с. 10; Karkov (2004) с. 108; Уильямс (2004a) ; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 10-1 140–141, 141 н. 145, 145; Торнтон (2001) с. 51; Уильямс (1999) с. 10-1 191 н. 50, 203 н. 71; Хадсон (1994) с. 10-1 97–98; Дженнингс (1994) с. 213–214; Андерсон, АО (1922) с. 479 н. 1; Stevenson, WH (1898) ; Skeat (1881) с. 468–4

- ^ Ферт (2018) с. 48; Эдмондс (2015) с. 61 н. 94; McGuigan (2015b) с. 143–144, н. 466; Кейнс (2015) с. 114; Кларксон (2014) гл. 7 ¶¶ 12–14; Эдмондс (2014) с. 206; Уильямс (2014) ; Чарльз-Эдвардс (2013b) с. 543–544; Уокер (2013) гл. 4 ¶ 30; Molyneaux (2011) с. 66–67; Бриз (2007) с. 153; Даунхем (2007) с. 124; Мэтьюз (2007) с. 11; Форте; Орам; Педерсен (2005) с. 218; Karkov (2004) с. 108; Уильямс (2004a) ; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 13, 134, 134 н. 111, 142, 145; Торнтон (2001) с. 57–58; Уильямс (1999) с. 116, 191 н. 50; Whitelock (1996) с. 230 н. 1; Хадсон (1994) с. 97; Дженнингс (1994) с. 213; Смит (1989) с. 226–227; Стентон (1963) с. 364; Андерсон, АО (1908) с. 76–77; Stevenson, WH (1898) ; Forester (1854) с. 104–105; Стивенсон, Дж. (1853) с. 247–248; Торп (1848) с. 142–143.

- ^ Эдмондс (2015) с. 61 н. 94; Кейнс (2015) с. 114; Макгиган (2015b) с. 144, н. 466; Эдмондс (2014) с. 206; Уильямс (2014) ; Чарльз-Эдвардс (2013b) с. 543–544; Molyneaux (2011) с. 66–67; Бриз (2007) с. 153; Даунхем (2007) с. 124; Мэтьюз (2007) с. 10–11; Karkov (2004) с. 108, 108 н. 123; Уильямс (2004a) ; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 143, 145; Торнтон (2001) с. 59–60; Хадсон (1994) с. 97; Андерсон, АО (1908) с. 77 н. 1; Stevenson, WH (1898) ; Джайлс (1847) с. 147 бк. 2 гл. 8; Харди (1840) с. 236 BK. 2 гл. 148.

- ^ Макгиган (2015b) с. 144, 144 н. 469; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 142, 142 н. 149, 145; Торнтон (2001) с. 60–61; Андерсон, АО (1908) с. 76 н. 2; Арнольд (1885) с. 372.

- ^ Торнтон (2001) с. 60; Луард (1872) с. 466–467.

- ^ Торнтон (2001) с. 60; Джайлс (1849) с. 263–264; Кокс (1841) с. 415.

- ^ Luard (2012) с. 513; Торнтон (2001) с. 60; Йонге (1853) с. 484.

- ^ Чарльз-Эдвардс (2013b) с. 543–544; Luard (2012) с. 513; Торнтон (2001) с. 66–67; Андерсон, АО (1908) с. 77 н. 1; Луард (1872) с. 466–467; Йонге (1853) с. 484; Джайлс (1849) с. 263–264; Джайлс (1847) с. 147 бк. 2 гл. 8; Кокс (1841) с. 415; Харди (1840) с. 236 BK. 2 гл. 148.

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 7 ¶ 12; Эдмондс (2014) с. 206; Уильямс (2014) ; Чарльз-Эдвардс (2013b) с. 543–544; Уокер (2013) гл. 4 № 30, 36; Кларксон (2012a) Ch. 9 ¶ 29; Минард (2012) ; AIRD (2009) с. 309; Бриз (2007) с. 154–155; Даунхем (2007) с. 167; Минард (2006) ; Macquarrie (2004b) ; Уильямс (2004a) ; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 142–143; Дункан (2002) с. 23 н. 53; Джаякумар (2002) с. 34; Торнтон (2001) с. 66–67; Уильямс (1999) с. 116; Macquarrie (1998) с. 16; Хадсон (1994) с. 174 н. 9; Дженнингс (1994) с. 215; Уильямс; Смит; Кирби (1991) с. 104, 124; Стентон (1963) с. 324.

- ^ Luard (2012) с. 513; Торнтон (2001) с. 67; Луард (1872) с. 466–467; Йонге (1853) с. 484; Джайлс (1849) с. 263–264; Кокс (1841) с. 415.

- ^ Хикс (2003) с. 42; Андерсон, AO (1922) с. 478–479; Стивенсон, J (1856) с. 100; Стивенсон, J (1835) с. 34

- ^ Дэвидсон (2002) с. 146–147.

- ^ История Англии Касселла (1909) с. 53

- ^ Уильямс (2004a) .

- ^ Торнтон (2001) с. 74

- ^ Торнтон (2001) с. 67–74.

- ^ Дэвидсон (2002) с. 66–67, 140; Дэвидсон (2001) с. 208; Торнтон (2001) с. 77–78.

- ^ Хикс (2003) с. 16 н. 35; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 115–116, 140; Дэвидсон (2001) с. 208; Торнтон (2001) с. 77–78; Whitelock (1996) с. 224; Андерсон, АО (1908) с. 74; Торп (1861) с. 212–213.

- ^ Кейнс (2008) с. 51; Шерсть (2007) с. 211; Торнтон (2001) с. 65–66; Андерсон, Мо (1960) с. 104; Андерсон, АО (1908) с. 77; Арнольд (1885) с. 382.

- ^ Андерсон, Мо (1960) с. 107, 107 н. 1; Джайлс (1849) с. 264; Кокс (1841) с. 416.

- ^ Luard (2012) с. 513; Торнтон (2001) с. 65–66; Андерсон, Мо (1960) с. 107, 107 н. 1; Йонге (1853) с. 485.

- ^ Андерсон, Мо (1960) с. 107, 107 нн. 1, 4; Anderson, AO (1908) с. 77–78 н. 6; Луард (1872) с. 467–468.

- ^ Даунхем (2007) с. 125; Уильямс (2004a) ; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 5; Торнтон (2001) с. 78–79.

- ^ Барроу (2001) с. 89

- ^ Макгиган (2015b) с. 147; AIRD (2009) с. 309; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 149, 149 н. 172; Дункан (2002) с. 24; Хадсон (1994) с. 140; Андерсон, АО (1908) с. 77; Арнольд (1885) с. 382.

- ^ Дункан (2002) с. 24–25.

- ^ О'Киф (2001) с. 81; Whitelock (1996) с. 230; Торп (1861) с. 226; Хлопок MS Tiberius Bi (ND) .

- ^ Aird (2009) с. 309; Вульф (2009) с. 259; Бриз (2007) с. 155; Даунхем (2007) с. 124; Вульф (2007) с. 208; Брун (2004c) ; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 142

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Вульф (2007) с. 208

- ^ Вульф (2007) с. 208–209.

- ^ Дункан (2002) с. 21–22; Хадсон (1994) с. 93.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Мэтьюз (2007) с. 25

- ^ Дженнингс (2015) ; Wadden (2015) с. 27–28; Кларксон (2014) гл. 7 ¶ 12; Уильямс (2014) ; Чарльз-Эдвардс (2013b) с. 543; Уокер (2013) гл. 4 ¶ 31; AIRD (2009) с. 309; Шерсть (2009) с. 259; Бриз (2007) с. 155; Downham (2007) с. 124–125, 167, 222; Мэтьюз (2007) с. 25; Форте; Орам; Федерсен (2005) с. 218; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 10-1 143, 146, 151; Джаякумар (2002) с. 34; Уильямс (1999) с. 116; Хадсон (1994) с. 97; Дженнингс (1994) с. 213–214; Enton (1963) с. 364

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 7 ¶ 12; Чарльз-Эдвардс (2013b) с. 544; Бриз (2007) с. 156; Даунхем (2007) с. 125 н. 10, 222; Мэтьюз (2007) с. 25; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 143, 146, 151; Джаякумар (2002) с. 34

- ^ Gough-Cooper (2015b) с. 43 § B993.1; Уильямс (2014) ; Даунхем (2007) с. 190; Мэтьюз (2007) с. 9, 25; Вульф (2007) с. 206–207; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 151; Anderson, AO (1922) с. 478–479 н. 6; RHŷS (1890) с. 262; Williams Ab Ithel (1860) с. 24–25.

- ^ Чарльз-Эдвардс (2013b) с. 545; Даунхем (2007) с. 222–223; Мэтьюз (2007) с. 9, 15; Вульф (2007) с. 207–208.

- ^ Даунхэм (2007) с. 126–127, 222–223; Вульф (2007) с. 208

- ^ Бейкер (2000) с. 83; Хлопок MS Domitian A VIII (ND) .

- ^ Чарльз-Эдвардс (2013b) с. 545; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 147

- ^ Чарльз-Эдвардс (2013b) с. 545.

- ^ Уильямс (2014) ; Уильямс (2004a) ; Whitelock (1996) с. 229; Андерсон, АО (1922) с. 472; Торп (1861) с. 223

- ^ Макгиган (2015b) с. 98; Андерсон, АО (1922) с. 441; Сене (1867) с. 116; Colganvm (1645) с. 497 § XVII.

- ^ McGuigan (2015b) с. 98–99.

- ^ Уокер (2013) гл. 4 ¶ 26.

- ^ Анналы Ольстера (2017) § 975.2; Анналы Ольстера (2008) 975,2; Бодлеанская библиотека MS. Рол Б. 489 (ND) .

- ^ Эдмондс (2014) с. 208; Брун (2007) с. 94 н. 62; Бусс (2006c) .

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 7 ¶ 17; Уильямс (2014) ; Уокер (2013) гл. 4 № 30, 36; Минард (2012) ; Oram (2011) Ch. 2; Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 41; Вульф (2007) с. 184; Бусс (2006c) ; Минард (2006) ; Broun (2004d) с. 128–129; Macquarrie (2004b) ; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 39, 146; Macquarrie (1998) с. 15–16; Хадсон (1994) с. 101, 174 н. 8; Уильямс; Смит; Кирби (1991) с. 104

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 7 ¶ 17; Уильямс (2014) ; Уокер (2013) гл. 4 ¶ 35; Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 41; Вульф (2007) с. 208; Уильямс; Смит; Кирби (1991) с. 124

- ^ Анналы Ольстера (2017) § 975.2; Анналы Тигернаха (2016) § 975.3; Кларксон (2014) гл. 7 ¶ 17, 7 н. 19; Уокер (2013) гл. 4 ¶ 36; Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 41; Анналы Ольстера (2008) § 975.2; Вульф (2007) с. 184; Annals of Tigernach (2005) § 975.3; Broun (2004d) с. 128–129; Macquarrie (2004b) ; Хикс (2003) с. 42; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 39, 146; Macquarrie (1998) с. 15–16; Хадсон (1994) с. 174 н. 8; Андерсон, АО (1922) с. 480, 480 н. 7

- ^ Мэтьюз (2007) с. 25; Джонс; Уильямс; Пьюге (1870) с. 658.

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 7 ¶ 17, 7 н. 19; Clancy (2002) с. 22; Macquarrie (1998) с. 15–16; Хадсон (1994) с. 174 н. 8; Андерсон, АО (1922) с. 480; RHŷS (1890) с. 262; Williams Ab Ithel (1860) с. 26–27.

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 7 ¶ 17; Кларксон (2012a) Ch. 10 ¶ 27.

- ^ Уокер (2013) гл. 4 ¶ 36; Oram (2011) Ch. 2

- ^ Анналы Тигернаха (2016) § 997.3; Annals of Tigernach (2005) § 997.3; Бодлеанская библиотека MS. Рол Б. 488 (ND) .

- ^ Уокер (2013) гл. 4 ¶ 30; Бусс (2006c) ; Торнтон (2001) с. 55

- ^ Уильямс (2014) ; Уокер (2013) гл. 4 ¶ 30; Кларксон (2012a) Ch. 9 ¶ 29; Macquarrie (2004) ; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 146; Уильямс; Смит; Кирби (1991) с. 104

- ^ Макгиган (2015b) с. 101, 101 н. 302; Кларксон (2014) гл. 7 ¶ 5, 7 н. 3; Береза (1893) с. 557–560 § 1266; Торп (1865) с. 237–243; Малкольм 4 (ND) ; S 779 (ND) .

- ^ Molyneaux (2015) с. 57 н. 45; Кларксон (2014) гл. 7 ¶ 5; Чарльз-Эдвардс (2013b) с. 544; Molyneaux (2011) с. 66; Кейнс (2008) с. 50 н. 232; Дэвидсон (2002) с. 147, 147 н. 166, 152; Торнтон (2001) с. 71; Хадсон (1994) с. 174 н. 9

- ^ Торнтон (2001) с. 52, 52 н. 6; Береза (1893) с. 557–560 § 1266; Торп (1865) с. 237–243; S 779 (ND) .

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 7 ¶ 12; Кларксон (2012a) Ch. 9 ¶ 29; Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 35.

- ^ Хикс (2003) с. 42

- ^ Андерсон, АО (1922) с. 550 н. 2; RHŷS (1890) с. 264; Williams Ab Ithel (1860) с. 34–35; Иисус Колледж MS. 111 (ND) ; Оксфордский колледж Иисуса MS. 111 (ND) .

- ^ Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 41.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Кларксон (2014) гл. 7 ¶ 17; Кларксон (2010) гл. 9 ¶ 41; Вульф (2007) с. 222, 233, 236.

- ^ Gough-Cooper (2015b) с. 46 § B1036.1; Чарльз-Эдвардс (2013b) с. 572 Рис. 17.4; Вульф (2007) с. 236; Broun (2004d) p. 128, 128 н. 66; Хикс (2003) с. 43; Андерсон, АО (1922) с. 550.

- ^ Чарльз-Эдвардс (2013b) с. 572 Рис. 17.4; Broun (2004d) p. 128 н. 66; Хикс (2003) с. 44 н. 107; Андерсон, АО (1922) с. 550 н. 2; RHŷS (1890) с. 264; Williams Ab Ithel (1860) с. 34–35.

- ^ Broun (2004d) p. 128 н. 66; Джонс; Уильямс; Пьюге (1870) с. 660.

- ^ Broun (2004d) p. 128 н. 66; Macquarrie (1998) с. 16–17.

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. генеалогические таблицы; Чарльз-Эдвардс (2013b) с. 572 Рис. 17.4; Кларксон (2010) гл. генеалогические таблицы; Вульф (2007) с. 236, 238 Таб. 6.4; Broun (2004d) с. 128 н. 66, 135 Tab.; Хикс (2003) с. 44, 44 н. 107; Дункан (2002) с. 29, 41.

- ^ Кэннон (2015) ; Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 ¶¶ 22–27; Кларксон (2010) гл. 10 ¶ 11; Хикс (2003) с. 42, 216; Винчестер (2000) с. 33–34.

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 ¶¶ 22–27.

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 ¶ 24; Хикс (2003) с. 43 н. 103

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 ¶ 24; Огилби (1699) с. 179

- ^ Кларксон (2014) гл. 6 ¶ 24.

- ^ Pugmire (2004) с. 112, 115 рис. 2; Винчестер (2000) с. 33–34.

- ^ Винчестер (2000) с. 33–34.

- ^ Эдмондс (2015) с. 54

- ^ Хикс (2003) с. 60, 147, 147 н. 20

- ^ Ewart; Прингл; Caldwell et al. (2004) с. 7; Хикс (2003) с. 60

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Первичные источники

[ редактировать ]- Андерсон, Ао , изд. (1908). Шотландские летописи от английских летописцев, от 500 до 1286 года . Лондон: Дэвид Натт . OL 7115802M .

- Андерсон, Ао, изд. (1922). Ранние источники шотландской истории, от 500 до 1286 года . Тол. 1. Лондон: Оливер и Бойд. OL 14712679M .

- Андерсон, АО (1930). «Пророчество Берчана». Журнал кельтской филологии . 18 : 1–56. Doi : 10.1515/zcph.1930.18.1.1 . EISSN 1865-889x . ISSN 0084-5302 . S2CID 162902103 .

- Андерсон, Мо (1960). «Лотиан и ранние шотландские короли». Шотландский исторический обзор . 39 (2): 98–112. EISSN 1750-0222 . ISSN 0036-9241 . JSTOR 25526601 .

- «Анналы четырех мастеров» . Корпус электронных текстов (3 декабря 2013 года изд.). Университетский колледж Корк . 2013a . Получено 13 июля 2016 года .

- «Анналы четырех мастеров» . Корпус электронных текстов (16 декабря 2013 года изд.). Университетский колледж Корк. 2013b . Получено 13 июля 2016 года .

- «Анналы Тигернаха» . Корпус электронных текстов (13 апреля 2005 г. изд.). Университетский колледж Корк. 2005 . Получено 19 июня 2016 года .

- Arnold, T , ed. (1879). Генри Архидиакон Huntendunensis История английского языка. История англичан . Вещи британского среда - это писатели. Лондон: Longman & Co. OL 16622993M .

- Arnold, T, ed. (1882). Симеон Монахи Работы . Вещи британского среда - это писатели. Тол. 1. Лондон: Longmans & Co.

- Arnold, T, ed. (1885). Симеон Монахи Работы . Вещи британского среда - это писатели. Тол. 2. Лондон: Longmans & Co.

- Бейкер, PS, ed. (2000). Англосаксонская хроника: совместное издание . Тол. 8. Кембридж: DS Brewer . ISBN 0-85991-490-9 .

- Береза, WDG (1887). Cartnlarium saxon . Тол. 2. Лондон: Чарльз Дж. Кларк.

- Береза, WDG (1893). Cartnlarium saxon . Тол. 3. Лондон: Чарльз Дж. Кларк.

- "Библиотека Бодлея MS. Rawl. B. 488" . Ранние рукописи в Оксфордском университете . Оксфордская цифровая библиотека . н.д. Получено 21 июня 2016 года .

{{cite web}}: CS1 Maint: Год ( ссылка ) - "Библиотека Бодлея MS. Rawl. B. 489" . Ранние рукописи в Оксфордском университете . Оксфордская цифровая библиотека. н.д. Получено 21 июня 2016 года .

{{cite web}}: CS1 Maint: Год ( ссылка ) - "Библиотека Бодлея MS. Rawl. B. 502" . Ранние рукописи в Оксфордском университете . Оксфордская цифровая библиотека. н.д. Получено 29 июля 2016 года .

{{cite web}}: CS1 Maint: Год ( ссылка ) - Colganvm, 1 , ed. (1645). Журнал Sanctorvm Old и Major Scotland, SEV Ирландия Sanctorvm Insvlae . Лион: Everardvm of Vvitte.

- «Хлоп -г -жа Домитиан viii» . Британская библиотека . и архивировано из оригинала 23 декабря 2019 года . Получено 8 февраля 2016 года .

{{cite web}}: CS1 Maint: Год ( ссылка ) - "Хлоп MS Faustina B IX" . Британская библиотека . и архивировано из оригинала 11 мая 2016 года . Получено 24 июня 2016 года .

{{cite web}}: CS1 Maint: Год ( ссылка ) - "Хлоп MS Tiberius B I" . Британская библиотека . и архивировано с оригинала 9 апреля 2016 года . Получено 15 февраля 2016 года .

{{cite web}}: CS1 Maint: Год ( ссылка ) - Кокс, он изд. (1841). Роджер из Wendover Chronicle или Flowers Stories . Тол. 1. Лондон: английское историческое общество.

- Forester, T, ed. (1853). Хроника Генриха Хантингдона: включающая в себя историю Англии, от вторжения Юлия Цезаря до вступления Генриха II. Кроме того, акты Стефана, короля Англии и герцога Нормандии . Антикварная библиотека Бона . Лондон: Генри Г. Бон . OL 24434761M .

- Forester, T, ed. (1854). Хроника Флоренции Вустера, с этими двумя продолжениями: включающие в себя летопись истории английской, от отъезда римлян до правления Эдварда I. Антикварная библиотека Бона. Лондон: Генри Г. Бон. OL 24871176M .

- Джайлс, JA , ed. (1847). Хроника Уильяма Малмсбери Королей Англии, от самого раннего периода до правления короля Стефана . Антикварная библиотека Бона. Лондон: Генри Г. Бон.

- Джайлс, JA, ed. (1849). Роджер из Вендовера «Цветы истории» . Антикварная библиотека Бона. Тол. 1. Лондон: Генри Г. Бон.

- Gough-Cooper, HW, ed. (2015a). Annales Cambriae: текст из Британской библиотеки, Harley MS 3859, Ff. 190R–193R (PDF) (ноябрь 2015 года изд.) - через исследовательскую группу Welsh Chronicles.

- Gough-Cooper, HW, ed. (2015b). Annales Cambriae: T Text из Лондона, Национальный архив, MS E164/1, стр. 2–26 (PDF) (сентябрь 2015 г. изд.) - через исследовательскую группу Welsh Chronicles.

- Харди, ТД , изд. (1840). William Malmesbiriensis Monk Deeds of English и историю новеллы . Тол. 1. Лондон: английское историческое общество. OL 24871887M .

- Howlett, D (2000). Каледонское мастерство: шотландская латинская традиция . Дублин: Четыре суда пресса . ISBN 1-85182-455-3 .

- Hudson, BT (1996). Пророчество Берчана: ирландские и шотландские высокие короли раннего средневековья . Вклад в изучение мировой истории. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press . ISBN 0-313-29567-0 Полем ISSN 0885-9159 .

- Hudson, BT (1998). «Шотландская хроника». Шотландский исторический обзор . 77 (2): 129–161. doi : 10.3366/shr.1998.77.2.129 . EISSN 1750-0222 . ISSN 0036-9241 . JSTOR 25530832 .

- Irvine, S, ed. (2004). Англосаксонская хроника: совместное издание . Тол. 7. Кембридж: DS Brewer. ISBN 0-85991-494-1 .

- "Колледж Иисуса MS. 111" . Ранние рукописи в Оксфордском университете . Оксфордская цифровая библиотека. н.д. Получено 20 октября 2015 года .

{{cite web}}: CS1 Maint: Год ( ссылка ) - Джонс, О ; Уильямс, E ; Pughe, Wo , eds. (1870). Мивирия Архаология Уэльса . Денби: Томас Джи . OL 6930827M .

- Годы. 4126 . Н.д.

{{cite book}}: CS1 Maint: Год ( ссылка ) - Luard, Hr , ed. (1872). Матфея Парижа, монахи, Сент -Олбанс, Хроника Майора . Тол. 1. Лондон: Longman & Co.

- Luard, Hr, ed. (2012) [1890]. Цветы истории . Вещи британского среда - это писатели. Тол. 1. Кембридж: издательство Кембриджского университета . Doi : 10.1017 / cbo9781139382960 . ISBN 978-1-108-05334-1 .

- Mac Eoin, G (1961). «Дата и авторство Saltair na rann». Журнал кельтской филологии . 28 : 51–67. Doi : 10.1515/zcph.1961.28.1.51 . EISSN 1865-889x . ISSN 0084-5302 . S2CID 201843434 .

- Огилби, Дж. (1699). Гид путешественника: или самое точное описание дорог Англии . Лондон: Т. Ильв.

- О'Киф, Ко, изд. (2001). Англосаксонская хроника: совместное издание . Тол. 5. Кембридж: DS Brewer. ISBN 0-85991-491-7 .

- «Оксфордский колледж Иисуса MS. 111 (Красная книга ее великой)» . Уэльская проза 1300–1425 . н.д. Получено 20 октября 2015 года .

{{cite web}}: CS1 Maint: Год ( ссылка ) - Pierquin, H, ed. (1912). Общая коллекция англосаксонских чартеров: саксы в Англии (604–1061) . Париж: Альфонс Пикард и Филс. OL 6557679M .

- Rhŷs, j ; Эванс, JG , ред. (1890). Текст Брутов из Красной книги ее великой . Оксфорд. OL 19845420M .

{{cite book}}: CS1 Maint: местоположение отсутствует издатель ( ссылка ) - "S 520" . Электронный Сойер: онлайн каталог англосаксонских чартеров . н.д. Получено 27 марта 2017 года .

{{cite web}}: CS1 Maint: Год ( ссылка ) - "S 544" . Электронный Сойер: онлайн каталог англосаксонских чартеров . н.д. Получено 27 марта 2017 года .

{{cite web}}: CS1 Maint: Год ( ссылка ) - "S 677" . Электронный Сойер: онлайн каталог англосаксонских чартеров . н.д. Получено 29 марта 2017 года .

{{cite web}}: CS1 Maint: Год ( ссылка ) - "S 779" . Электронный Сойер: онлайн каталог англосаксонских чартеров . н.д. Получено 10 июля 2016 года .

{{cite web}}: CS1 Maint: Год ( ссылка ) - "Ssaltair Rann " 22 января 2011 г. изд. Университетский колледж Корк. 2011 год 29 2016июля

- "Saltair na rann" (PDF) . Дублинский институт передовых исследований (Школа кельтских исследований) . н.д. Получено 29 июля 2016 года .

{{cite web}}: CS1 Maint: Год ( ссылка ) - Skeat, W , ed. (1881). Жизнь Святых Элфрика . Третья серия. Тол. 1. Лондон: раннее английское текстовое общество .

- Skene, WF , ed. (1867). Хроники пиктов, хроники шотландцев и другие ранние мемориалы шотландской истории . Эдинбург: HM General Register House. OL 23286818M .

- Skene, WF, ed. (1871). Джон Фордун Хроника шотландцев . Эдинбург: Эдмонстон и Дуглас. OL 24871486M .

- Skene, WF, ed. (1872). Хроника Джона Фордуна из шотландской нации . Эдинбург: Эдмонстон и Дуглас. OL 24871442M .

- Стивенсон, Дж. , Эд. (1835). Chronica de Mailros Эдинбург: Banyine Club Вверх 139999983m

- Стивенсон, Дж., Эд. (1853). Церковные историки Англии . Тол. 2, пт. 1. Лондон: Seeleys.

- Стивенсон, Дж., Эд. (1855). Церковные историки Англии . Тол. 3, пт. 2. Лондон: Seeleys. OL 7055940M .

- Стивенсон, Дж., Эд. (1856). Церковные историки Англии . Тол. 4, пт. 1. Лондон: Seeleys.

- "Анналы Тигернаха " 8 февраля 2016 года изд. Университетский колледж Корк. 2016 Получено 21 мая

- «Анналы Ольстера» . Корпус электронных текстов (29 августа 2008 г. изд.). Университетский колледж Корк. 2008 Получено 14 июня 2016 года .

- «Анналы Ольстера» . Корпус электронных текстов (6 января 2017 года изд.). Университетский колледж Корк. 2017 . Получено 21 мая 2017 года .

- Thorpe, B, ed. (1848). Флоренция Вустерских Монахов Хроники хроники . Тол. 1. Лондон: английское историческое общество. OL 24871544M .

- Thorpe, B, ed. (1861). Англосаксонская хроника . Вещи британского среда - это писатели. Тол. 1. Лондон: Лонгман, Грин, Лонгман и Робертс.

- Thorpe, B, ed. (1865). Diplomatarium anglicum anglicum ax Saxon: коллекция английских хартиров . Лондон: Macmillan & Co. OL 21774758M .

- Whitelock, D , ed. (1996) [1955]. Английские исторические документы, ок. 500–1042 (2 -е изд.). Лондон: Routledge . ISBN 0-203-43950-3 .

- Williams Ab Ithel, J , ed. (1860). Brut y tywysigion; Или хроника князей . Rerum Britannicarum medii ævi scriptores. Лондон: Лонгман, Грин, Лонгман и Робертс. OL 24776516M .

- Yonge, CD , ed. (1853). Цветы истории . Тол. 1. Лондон: Генри Г. Бон. OL 7154619M .

Вторичные источники

[ редактировать ]- AIRD, WM (2009). «Нортумбрия». В Стаффорде, P (ред.). Компаньон раннего средневековья: Британия и Ирландия, C.500 - C.1100 . Блэквелл компаньоны для британской истории. Чичестер: Blackwell Publishing . С. 303–321. ISBN 978-1-405-10628-3 .

- Alcock, L (1978). «Междисциплинарная хронология для Alt Clut, Castle Roack, Dambarton» (PDF) . Труды Общества антикваров Шотландии . 107 : 103–113. doi : 10.9750/psas.107.103.113 . EISSN 2056-743X . ISSN 0081-1564 . S2CID 221817027 .

- Бриз, А (1992). «Англосаксонская хроника за 1072 и Форды Фрю, Шотландия». Примечания и запросы . 39 (3): 269–270. doi : 10.1093/nq/39.3.269 . EISSN 1471-6941 . ISSN 0029-3970 .

- Бриз А. (2006). «Британцы в баронии Гилсленда, Камбрия». Северная история . 43 (2): 327–332. doi : 10.1179/174587006x116194 . EISSN 1745-8706 . ISSN 0078-172X . S2CID 162343198 .

- Бриз А. (2007). «Эдгар в Честере в 973 году: Бретонская ссылка?». Северная история . 44 (1): 153–157. doi : 10.1179/174587007x165405 . EISSN 1745-8706 . ISSN 0078-172X . S2CID 161204995 .

- Брун, Д. (2004a). «Кулен (ум. 971)» . Оксфордский словарь национальной биографии (онлайн -ред.). Издательство Оксфордского университета. doi : 10.1093/ref: ODNB/6870 . Получено 13 июня 2016 года . ( Требуется членство в публичной библиотеке в Великобритании .)

- Брун, Д. (2004b). «Индоулф (бап. 927?, D. 962)» . Оксфордский словарь национальной биографии (онлайн -ред.). Издательство Оксфордского университета. doi : 10.1093/ref: ODNB/14379 . Получено 13 июня 2016 года . ( Требуется членство в публичной библиотеке в Великобритании .)

- Брун, Д. (2004c). «Кеннет II (ум. 995)» . Оксфордский словарь национальной биографии (онлайн -ред.). Издательство Оксфордского университета. doi : 10.1093/ref: ODNB/15399 . Получено 3 декабря 2015 года . ( Требуется членство в публичной библиотеке в Великобритании .)

- Брун, Д. (2004d). «Уэльская личность королевства Стратклайд C.900 - C.1200». Обзор Innes . 55 (2): 111–180. doi : 10.3366/inr.2004.55.2.111 . EISSN 1745-5219 . ISSN 0020-157X .

- Брун, Д. (2005). «Современные перспективы на преемственность Александра II: свидетельство списков короля». В Oram, Rd (ed.). Правление Александра II, 1214–49 . Северный мир: Северная Европа и Балтика c. 400–1700 г. н.э. Народы, экономика и культуры. Лейден: Брилл . С. 79–98. ISBN 90-04-14206-1 Полем ISSN 1569-1462 .

- Брун, Д. (2007). Независимость Шотландии и идея Британии: от пиктов до Александра III . Эдинбург: издательство Эдинбургского университета . ISBN 978-0-7486-2360-0 .

- Брун, Д. (2015a) [1997]. "Cuilén" . В Crowcroft, R; Cannon, J (ред.). Оксфордский компаньон для британской истории (2 -е изд.). Издательство Оксфордского университета. doi : 10.1093/acref/9780199677832.001.0001 . ISBN 978-0-19-967783-2 - через Оксфордскую ссылку .

- Брун, Д. (2015b) [1997]. "Индульф" . В Crowcroft, R; Cannon, J (ред.). Оксфордский компаньон для британской истории (2 -е изд.). Издательство Оксфордского университета. doi : 10.1093/acref/9780199677832.001.0001 . ISBN 978-0-19-967783-2 - через Оксфордскую ссылку.

- Бруфорд А. (2000). «Что случилось с каледонцами». В Коуэн, EJ ; McDonald, RA (ред.). Альба: кельтская Шотландия в средние века . Ист Линтон: Tuckwell Press. С. 43–68. ISBN 1-86232-151-5 .

- Busse, PE (2006a). "Cineed Mac Mael Choluim". В Кохе, JT (ред.). Кельтская культура: историческая энциклопедия . Тол. 2. Санта-Барбара, Калифорния: ABC-Clio . п. 439. ISBN 1-85109-445-8 .

- Busse, PE (2006b). "Cuilén Ring Mac illuilb". В Кохе, JT (ред.). Кельтская культура: историческая энциклопедия . Тол. 2. Санта-Барбара, Калифорния: ABC-Clio. п. 509. ISBN 1-85109-445-8 .

- Busse, PE (2006c). "Dyfnwal из Owain/Domnall of Eogain" В Кохе, JT (ред.). Кельтская культура: историческая информация . Тол. 2. Санта-Барбара, Калифорния: ABC-CLIS. п. 639. ISBN 1-85109-445-8 .

- «Кадфан 1 (женщина)» . Просопография англосаксонской Англии . н.д. Получено 11 сентября 2017 года .

{{cite web}}: CS1 Maint: Год ( ссылка ) - Cannon, J (2015) [1997]. "Камберленд" . В Crowcroft, R; Cannon, J (ред.). Оксфордский компаньон для британской истории (2 -е изд.). Издательство Оксфордского университета. doi : 10.1093/acref/9780199677832.001.0001 . ISBN 978-0-19-967783-2 - через Оксфордскую ссылку.

- История Англии Касселла: от римского вторжения до войн роз . Тол. 1. Лондон: Касселл и Компания . 1909. OL 7042010M .

- Чарльз-Эдвардс, Т.М. (2013a). «Размышления о раннем средневековом Уэльсе». Сделки почетного общества Cymmrodorion . 19 : 7–23. ISSN 0959-3632 .

- Чарльз-Эдвардс, TM (2013b). Уэльс и британцы, 350–1064 . История Уэльса. Оксфорд: издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 978-0-19-821731-2 .

- Клэнси, в (2002). « Кельтский» или «католик»? Написание истории шотландского христианства, 664–1093 гг . Записи об обществе истории Шотландии . 32 : 5–39. doi : 10.3366/sch.2002.32.1.12 .

- Клэнси, в (2006). "Ystrad Clud". В Кохе, JT (ред.). Кельтская культура: историческая энциклопедия . Тол. 5. Санта-Барбара, Калифорния: ABC-Clio. С. 1818–1821. ISBN 1-85109-445-8 .

- Кларксон, Т (2010). Люди Севера: британцы и южная Шотландия (EPUB). Эдинбург: Джон Дональд . ISBN 978-1-907909-02-3 .

- Кларксон, Т (2012a) [2011]. Создатели Шотландии: пикты, римляне, гэльс и викинги (epub). Эдинбург: Birlinn Limited . ISBN 978-1-907909-01-6 .

- Кларксон, Т (2012b) Пикты: история (epub). Эдинбург: Birlinn Limited. ISBN 978-1-907909-03-0 .