Тектоника плит

Дивергент:

| Part of a series on |

| Geology |

|---|

|

Тектоника плит (от латинского tectonicus , от древнегреческого τεκτονικός ( tektonikós ) «относящийся к строительству») [1] Это научная теория , что Земли литосфера о том состоит из ряда крупных тектонических плит , которые медленно перемещались примерно 3,4 миллиарда лет назад. [2] Модель основана на концепции дрейфа континентов , идее, разработанной в первые десятилетия 20-го века. Тектоника плит стала принята геологами после того, как распространение морского дна в середине-конце 1960-х годов было подтверждено .

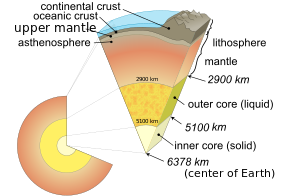

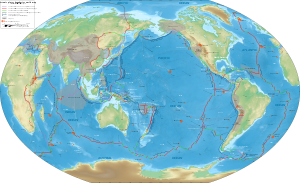

Литосфера Земли, твердая внешняя оболочка планеты, включая кору и верхнюю мантию , расколота на семь или восемь основных плит (в зависимости от того, как они определяются) и множество второстепенных плит или «тромбоцитов». Там, где плиты встречаются, их относительное движение определяет тип границы плиты (или разлома ): сходящаяся , расходящаяся или трансформирующая . Относительное перемещение плит обычно колеблется от нуля до 10 см в год. [3] Разломы, как правило, геологически активны, подвержены землетрясениям , вулканической активности , горообразованию и образованию океанических желобов .

Tectonic plates are composed of the oceanic lithosphere and the thicker continental lithosphere, each topped by its own kind of crust. Along convergent plate boundaries, the process of subduction carries the edge of one plate down under the other plate and into the mantle. This process reduces the total surface area (crust) of the Earth. The lost surface is balanced by the formation of new oceanic crust along divergent margins by seafloor spreading, keeping the total surface area constant in a tectonic "conveyor belt".

Tectonic plates are relatively rigid and float across the ductile asthenosphere beneath. Lateral density variations in the mantle result in convection currents, the slow creeping motion of Earth's solid mantle. At a seafloor spreading ridge, plates move away from the ridge, which is a topographic high, and the newly formed crust cools as it moves away, increasing its density and contributing to the motion. At a subduction zone the relatively cold, dense oceanic crust sinks down into the mantle, forming the downward convecting limb of a mantle cell,[4] which is the strongest driver of plate motion.[5][6] The relative importance and interaction of other proposed factors such as active convection, upwelling inside the mantle, and tidal drag of the Moon is still the subject of debate.

Key principles

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

The outer layers of Earth are divided into the lithosphere and asthenosphere. The division is based on differences in mechanical properties and in the method for the transfer of heat. The lithosphere is cooler and more rigid, while the asthenosphere is hotter and flows more easily. In terms of heat transfer, the lithosphere loses heat by conduction, whereas the asthenosphere also transfers heat by convection and has a nearly adiabatic temperature gradient. This division should not be confused with the chemical subdivision of these same layers into the mantle (comprising both the asthenosphere and the mantle portion of the lithosphere) and the crust: a given piece of mantle may be part of the lithosphere or the asthenosphere at different times depending on its temperature and pressure.

The key principle of plate tectonics is that the lithosphere exists as separate and distinct tectonic plates, which ride on the fluid-like solid the asthenosphere. Plate motions range from 10 to 40 mm/year at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (about as fast as fingernails grow), to about 160 mm/year for the Nazca Plate (about as fast as hair grows).[7]

Tectonic lithosphere plates consist of lithospheric mantle overlain by one or two types of crustal material: oceanic crust (in older texts called sima from silicon and magnesium) and continental crust (sial from silicon and aluminium). The distinction between oceanic crust and continental crust is based on their modes of formation. Oceanic crust is formed at sea-floor spreading centers. Continental crust is formed through arc volcanism and accretion of terranes through plate tectonic processes. Oceanic crust is denser than continental crust because it has less silicon and more of the heavier elements than continental crust.[8][9] As a result of this density difference, oceanic crust generally lies below sea level, while continental crust buoyantly projects above sea level.

Average oceanic lithosphere is typically 100 km (62 mi) thick.[10] Its thickness is a function of its age. As time passes, it cools by conducting heat from below, and releasing it raditively into space. The adjacent mantle below is cooled by this process and added to its base. Because it is formed at mid-ocean ridges and spreads outwards, its thickness is therefore a function of its distance from the mid-ocean ridge where it was formed. For a typical distance that oceanic lithosphere must travel before being subducted, the thickness varies from about 6 km (4 mi) thick at mid-ocean ridges to greater than 100 km (62 mi) at subduction zones. For shorter or longer distances, the subduction zone, and therefore also the mean, thickness becomes smaller or larger, respectively.[11] Continental lithosphere is typically about 200 km thick, though this varies considerably between basins, mountain ranges, and stable cratonic interiors of continents.

The location where two plates meet is called a plate boundary. Plate boundaries are where geological events occur, such as earthquakes and the creation of topographic features such as mountains, volcanoes, mid-ocean ridges, and oceanic trenches. The vast majority of the world's active volcanoes occur along plate boundaries, with the Pacific Plate's Ring of Fire being the most active and widely known. Some volcanoes occur in the interiors of plates, and these have been variously attributed to internal plate deformation[12] and to mantle plumes.

Tectonic plates may include continental crust or oceanic crust, or both. For example, the African Plate includes the continent and parts of the floor of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.

Some pieces of oceanic crust, known as ophiolites, failed to be subducted under continental crust at destructive plate boundaries; instead these oceanic crustal fragments were pushed upward and were preserved within continental crust.

Types of plate boundaries

Three types of plate boundaries exist,[13] characterized by the way the plates move relative to each other. They are associated with different types of surface phenomena. The different types of plate boundaries are:[14][15]

- Divergent boundaries (constructive boundaries or extensional boundaries). These are where two plates slide apart from each other. At zones of ocean-to-ocean rifting, divergent boundaries form by seafloor spreading, allowing for the formation of new ocean basin, e.g. the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and East Pacific Rise. As the ocean plate splits, the ridge forms at the spreading center, the ocean basin expands, and finally, the plate area increases causing many small volcanoes and/or shallow earthquakes. At zones of continent-to-continent rifting, divergent boundaries may cause new ocean basin to form as the continent splits, spreads, the central rift collapses, and ocean fills the basin, e.g., the East African Rift, the Baikal Rift, the West Antarctic Rift, the Rio Grande Rift.

- Convergent boundaries (destructive boundaries or active margins) occur where two plates slide toward each other to form either a subduction zone (one plate moving underneath the other) or a continental collision.

- Subduction zones are of two types: ocean-to-continent subduction, where the dense oceanic lithosphere plunges beneath the less dense continent, or ocean-to-ocean subduction where older, cooler, denser oceanic crust slips beneath less dense oceanic crust. Deep marine trenches are typically associated with subduction zones, and the basins that develop along the active boundary are often called "foreland basins".

- Earthquakes trace the path of the downward-moving plate as it descends into asthenosphere, a trench forms, and as the subducted plate is heated it releases volatiles, mostly water from hydrous minerals, into the surrounding mantle. The addition of water lowers the melting point of the mantle material above the subducting slab, causing it to melt. The magma that results typically leads to volcanism.[16]

- At zones of ocean-to-ocean subduction a deep trench to forms in an arc shape. The upper mantle of the subducted plate then heats and magma rises to form curving chains of volcanic islands e.g. the Aleutian Islands, the Mariana Islands, the Japanese island arc.

- At zones of ocean-to-continent subduction mountain ranges form, e.g. the Andes, the Cascade Range.

- At continental collision zones there are two masses of continental lithosphere converging. Since they are of similar density, neither is subducted. The plate edges are compressed, folded, and uplifted forming mountain ranges, e.g. Himalayas and Alps. Closure of ocean basins can occur at continent-to-continent boundaries.

- Transform boundaries (conservative boundaries or strike-slip boundaries) occur where plates are neither created nor destroyed. Instead two plates slide, or perhaps more accurately grind past each other, along transform faults. The relative motion of the two plates is either sinistral (left side toward the observer) or dextral (right side toward the observer). Transform faults occur across a spreading center. Strong earthquakes can occur along a fault. The San Andreas Fault in California is an example of a transform boundary exhibiting dextral motion.

- Other plate boundary zones occur where the effects of the interactions are unclear, and the boundaries, usually occurring along a broad belt, are not well defined and may show various types of movements in different episodes.

Driving forces of plate motion

Tectonic plates are able to move because of the relative density of oceanic lithosphere and the relative weakness of the asthenosphere. Dissipation of heat from the mantle is the original source of the energy required to drive plate tectonics through convection or large scale upwelling and doming. As a consequence, a powerful source generating plate motion is the excess density of the oceanic lithosphere sinking in subduction zones. When the new crust forms at mid-ocean ridges, this oceanic lithosphere is initially less dense than the underlying asthenosphere, but it becomes denser with age as it conductively cools and thickens. The greater density of old lithosphere relative to the underlying asthenosphere allows it to sink into the deep mantle at subduction zones, providing most of the driving force for plate movement. The weakness of the asthenosphere allows the tectonic plates to move easily towards a subduction zone.[17]

For much of the first quarter of the 20th century, the leading theory of the driving force behind tectonic plate motions envisaged large scale convection currents in the upper mantle, which can be transmitted through the asthenosphere. This theory was launched by Arthur Holmes and some forerunners in the 1930s[18] and was immediately recognized as the solution for the acceptance of the theory as originally discussed in the papers of Alfred Wegener in the early years of the 20th century. However, despite its acceptance, it was long debated in the scientific community because the leading theory still envisaged a static Earth without moving continents up until the major breakthroughs of the early sixties.

Two- and three-dimensional imaging of Earth's interior (seismic tomography) shows a varying lateral density distribution throughout the mantle. Such density variations can be material (from rock chemistry), mineral (from variations in mineral structures), or thermal (through thermal expansion and contraction from heat energy). The manifestation of this varying lateral density is mantle convection from buoyancy forces.[19]

How mantle convection directly and indirectly relates to plate motion is a matter of ongoing study and discussion in geodynamics. Somehow, this energy must be transferred to the lithosphere for tectonic plates to move. There are essentially two main types of mechanisms that are thought to exist related to the dynamics of the mantle that influence plate motion which are primary (through the large scale convection cells) or secondary. The secondary mechanisms view plate motion driven by friction between the convection currents in the asthenosphere and the more rigid overlying lithosphere. This is due to the inflow of mantle material related to the downward pull on plates in subduction zones at ocean trenches. Slab pull may occur in a geodynamic setting where basal tractions continue to act on the plate as it dives into the mantle (although perhaps to a greater extent acting on both the under and upper side of the slab). Furthermore, slabs that are broken off and sink into the mantle can cause viscous mantle forces driving plates through slab suction.

Plume tectonics

In the theory of plume tectonics followed by numerous researchers during the 1990s, a modified concept of mantle convection currents is used. It asserts that super plumes rise from the deeper mantle and are the drivers or substitutes of the major convection cells. These ideas find their roots in the early 1930s in the works of Beloussov and van Bemmelen, which were initially opposed to plate tectonics and placed the mechanism in a fixed frame of vertical movements. Van Bemmelen later modified the concept in his "Undation Models" and used "Mantle Blisters" as the driving force for horizontal movements, invoking gravitational forces away from the regional crustal doming.[20][21]

The theories find resonance in the modern theories which envisage hot spots or mantle plumes which remain fixed and are overridden by oceanic and continental lithosphere plates over time and leave their traces in the geological record (though these phenomena are not invoked as real driving mechanisms, but rather as modulators).

The mechanism is still advocated to explain the break-up of supercontinents during specific geological epochs.[22] It has followers amongst the scientists involved in the theory of Earth expansion.[23][24][25]

Surge tectonics

Another theory is that the mantle flows neither in cells nor large plumes but rather as a series of channels just below Earth's crust, which then provide basal friction to the lithosphere. This theory, called "surge tectonics", was popularized during the 1980s and 1990s.[26] Recent research, based on three-dimensional computer modelling, suggests that plate geometry is governed by a feedback between mantle convection patterns and the strength of the lithosphere.[27]

Forces related to gravity are invoked as secondary phenomena within the framework of a more general driving mechanism such as the various forms of mantle dynamics described above. In modern views, gravity is invoked as the major driving force, through slab pull along subduction zones.

Gravitational sliding away from a spreading ridge is one of the proposed driving forces, it proposes plate motion is driven by the higher elevation of plates at ocean ridges.[28][29] As oceanic lithosphere is formed at spreading ridges from hot mantle material, it gradually cools and thickens with age (and thus adds distance from the ridge). Cool oceanic lithosphere is significantly denser than the hot mantle material from which it is derived and so with increasing thickness it gradually subsides into the mantle to compensate the greater load. The result is a slight lateral incline with increased distance from the ridge axis.

This force is regarded as a secondary force and is often referred to as "ridge push". This is a misnomer as there is no force "pushing" horizontally, indeed tensional features are dominant along ridges. It is more accurate to refer to this mechanism as "gravitational sliding", since the topography across the whole plate can vary considerably and spreading ridges are only the most prominent feature. Other mechanisms generating this gravitational secondary force include flexural bulging of the lithosphere before it dives underneath an adjacent plate, producing a clear topographical feature that can offset, or at least affect, the influence of topographical ocean ridges. Mantle plumes and hot spots are also postulated to impinge on the underside of tectonic plates.

Slab pull: Scientific opinion is that the asthenosphere is insufficiently competent or rigid to directly cause motion by friction along the base of the lithosphere. Slab pull is therefore most widely thought to be the greatest force acting on the plates. In this understanding, plate motion is mostly driven by the weight of cold, dense plates sinking into the mantle at trenches.[6] Recent models indicate that trench suction plays an important role as well. However, the fact that the North American Plate is nowhere being subducted, although it is in motion, presents a problem. The same holds for the African, Eurasian, and Antarctic plates.

Gravitational sliding away from mantle doming: According to older theories, one of the driving mechanisms of the plates is the existence of large scale asthenosphere/mantle domes which cause the gravitational sliding of lithosphere plates away from them (see the paragraph on Mantle Mechanisms). This gravitational sliding represents a secondary phenomenon of this basically vertically oriented mechanism. It finds its roots in the Undation Model of van Bemmelen. This can act on various scales, from the small scale of one island arc up to the larger scale of an entire ocean basin.[28][29][22]

Alfred Wegener, being a meteorologist, had proposed tidal forces and centrifugal forces as the main driving mechanisms behind continental drift; however, these forces were considered far too small to cause continental motion as the concept was of continents plowing through oceanic crust.[30] Therefore, Wegener later changed his position and asserted that convection currents are the main driving force of plate tectonics in the last edition of his book in 1929.

However, in the plate tectonics context (accepted since the seafloor spreading proposals of Heezen, Hess, Dietz, Morley, Vine, and Matthews (see below) during the early 1960s), the oceanic crust is suggested to be in motion with the continents which caused the proposals related to Earth rotation to be reconsidered. In more recent literature, these driving forces are:

- Tidal drag due to the gravitational force the Moon (and the Sun) exerts on the crust of Earth[31]

- Global deformation of the geoid due to small displacements of the rotational pole with respect to Earth's crust

- Other smaller deformation effects of the crust due to wobbles and spin movements of Earth's rotation on a smaller timescale

Forces that are small and generally negligible are:

- The Coriolis force[32][33]

- The centrifugal force, which is treated as a slight modification of gravity[32][33]: 249

For these mechanisms to be overall valid, systematic relationships should exist all over the globe between the orientation and kinematics of deformation and the geographical latitudinal and longitudinal grid of Earth itself. These systematic relations studies in the second half of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century underline exactly the opposite: that the plates had not moved in time, that the deformation grid was fixed with respect to Earth's equator and axis, and that gravitational driving forces were generally acting vertically and caused only local horizontal movements (the so-called pre-plate tectonic, "fixist theories"). Later studies (discussed below on this page), therefore, invoked many of the relationships recognized during this pre-plate tectonics period to support their theories (see reviews of these various mechanisms related to Earth rotation the work of van Dijk and collaborators).[34]

Possible tidal effect on plate tectonics

Of the many forces discussed above, tidal force is still highly debated and defended as a possible principal driving force of plate tectonics. The other forces are only used in global geodynamic models not using plate tectonics concepts (therefore beyond the discussions treated in this section) or proposed as minor modulations within the overall plate tectonics model.In 1973, George W. Moore[35] of the USGS and R. C. Bostrom[36] presented evidence for a general westward drift of Earth's lithosphere with respect to the mantle, based on the steepness of the subduction zones (shallow dipping towards the east, steeply dipping towards the west). They concluded that tidal forces (the tidal lag or "friction") caused by Earth's rotation and the forces acting upon it by the Moon are a driving force for plate tectonics. As Earth spins eastward beneath the Moon, the Moon's gravity ever so slightly pulls Earth's surface layer back westward, just as proposed by Alfred Wegener (see above). Since 1990 this theory is mainly advocated by Doglioni and co-workers (Doglioni 1990), such as in a more recent 2006 study,[37] where scientists reviewed and advocated these ideas. It has been suggested in Lovett (2006) that this observation may also explain why Venus and Mars have no plate tectonics, as Venus has no moon and Mars' moons are too small to have significant tidal effects on the planet. In a paper by [38] it was suggested that, on the other hand, it can easily be observed that many plates are moving north and eastward, and that the dominantly westward motion of the Pacific Ocean basins derives simply from the eastward bias of the Pacific spreading center (which is not a predicted manifestation of such lunar forces). In the same paper the authors admit, however, that relative to the lower mantle, there is a slight westward component in the motions of all the plates. They demonstrated though that the westward drift, seen only for the past 30 Ma, is attributed to the increased dominance of the steadily growing and accelerating Pacific plate. The debate is still open, and a recent paper by Hofmeister et al. (2022) [39] revived the idea advocating again the interaction between the Earth's rotation and the Moon as main driving forces for the plates.

Relative significance of each driving force mechanism

The vector of a plate's motion is a function of all the forces acting on the plate; however, therein lies the problem regarding the degree to which each process contributes to the overall motion of each tectonic plate.

The diversity of geodynamic settings and the properties of each plate result from the impact of the various processes actively driving each individual plate. One method of dealing with this problem is to consider the relative rate at which each plate is moving as well as the evidence related to the significance of each process to the overall driving force on the plate.

One of the most significant correlations discovered to date is that lithospheric plates attached to downgoing (subducting) plates move much faster than other types of plates. The Pacific plate, for instance, is essentially surrounded by zones of subduction (the so-called Ring of Fire) and moves much faster than the plates of the Atlantic basin, which are attached (perhaps one could say 'welded') to adjacent continents instead of subducting plates. It is thus thought that forces associated with the downgoing plate (slab pull and slab suction) are the driving forces which determine the motion of plates, except for those plates which are not being subducted.[6] This view however has been contradicted by a recent study which found that the actual motions of the Pacific Plate and other plates associated with the East Pacific Rise do not correlate mainly with either slab pull or slab push, but rather with a mantle convection upwelling whose horizontal spreading along the bases of the various plates drives them along via viscosity-related traction forces.[40] The driving forces of plate motion continue to be active subjects of on-going research within geophysics and tectonophysics.

History of the theory

Summary

The development of the theory of plate tectonics was the scientific and cultural change which occurred during a period of 50 years of scientific debate. The event of the acceptance itself was a paradigm shift and can therefore be classified as a scientific revolution.[41]Around the start of the twentieth century, various theorists unsuccessfully attempted to explain the many geographical, geological, and biological continuities between continents. In 1912, the meteorologist Alfred Wegener described what he called continental drift, an idea that culminated fifty years later in the modern theory of plate tectonics.[42]

Wegener expanded his theory in his 1915 book The Origin of Continents and Oceans.[43] Starting from the idea (also expressed by his forerunners) that the present continents once formed a single land mass (later called Pangaea), Wegener suggested that these separated and drifted apart, likening them to "icebergs" of low density sial floating on a sea of denser sima.[44][45] Supporting evidence for the idea came from the dove-tailing outlines of South America's east coast and Africa's west coast Antonio Snider-Pellegrini had drawn on his maps, and from the matching of the rock formations along these edges. Confirmation of their previous contiguous nature also came from the fossil plants Glossopteris and Gangamopteris, and the therapsid or mammal-like reptile Lystrosaurus, all widely distributed over South America, Africa, Antarctica, India, and Australia. The evidence for such an erstwhile joining of these continents was patent to field geologists working in the southern hemisphere. The South African Alex du Toit put together a mass of such information in his 1937 publication Our Wandering Continents, and went further than Wegener in recognising the strong links between the Gondwana fragments.

Wegener's work was initially not widely accepted, in part due to a lack of detailed evidence but mostly because of the lack of a reasonable physically supported mechanism. Earth might have a solid crust and mantle and a liquid core, but there seemed to be no way that portions of the crust could move around. Many distinguished scientists of the time, such as Harold Jeffreys and Charles Schuchert, were outspoken critics of continental drift.

Despite much opposition, the view of continental drift gained support and a lively debate started between "drifters" or "mobilists" (proponents of the theory) and "fixists" (opponents). During the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s, the former reached important milestones proposing that convection currents might have driven the plate movements, and that spreading may have occurred below the sea within the oceanic crust. Concepts close to the elements of plate tectonics were proposed by geophysicists and geologists (both fixists and mobilists) like Vening-Meinesz, Holmes, and Umbgrove. In 1941, Otto Ampferer described, in his publication "Thoughts on the motion picture of the Atlantic region",[46] processes that anticipated seafloor spreading and subduction.[47][48] One of the first pieces of geophysical evidence that was used to support the movement of lithospheric plates came from paleomagnetism. This is based on the fact that rocks of different ages show a variable magnetic field direction, evidenced by studies since the mid–nineteenth century. The magnetic north and south poles reverse through time, and, especially important in paleotectonic studies, the relative position of the magnetic north pole varies through time. Initially, during the first half of the twentieth century, the latter phenomenon was explained by introducing what was called "polar wander" (see apparent polar wander) (i.e., it was assumed that the north pole location had been shifting through time). An alternative explanation, though, was that the continents had moved (shifted and rotated) relative to the north pole, and each continent, in fact, shows its own "polar wander path". During the late 1950s, it was successfully shown on two occasions that these data could show the validity of continental drift: by Keith Runcorn in a paper in 1956,[49] and by Warren Carey in a symposium held in March 1956.[50]

The second piece of evidence in support of continental drift came during the late 1950s and early 60s from data on the bathymetry of the deep ocean floors and the nature of the oceanic crust such as magnetic properties and, more generally, with the development of marine geology[51] which gave evidence for the association of seafloor spreading along the mid-oceanic ridges and magnetic field reversals, published between 1959 and 1963 by Heezen, Dietz, Hess, Mason, Vine & Matthews, and Morley.[52]

Simultaneous advances in early seismic imaging techniques in and around Wadati–Benioff zones along the trenches bounding many continental margins, together with many other geophysical (e.g., gravimetric) and geological observations, showed how the oceanic crust could disappear into the mantle, providing the mechanism to balance the extension of the ocean basins with shortening along its margins.

All this evidence, both from the ocean floor and from the continental margins, made it clear around 1965 that continental drift was feasible. The theory of plate tectonics was defined in a series of papers between 1965 and 1967. The theory revolutionized the Earth sciences, explaining a diverse range of geological phenomena and their implications in other studies such as paleogeography and paleobiology.

Continental drift

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, geologists assumed that Earth's major features were fixed, and that most geologic features such as basin development and mountain ranges could be explained by vertical crustal movement, described in what is called the geosynclinal theory. Generally, this was placed in the context of a contracting planet Earth due to heat loss in the course of a relatively short geological time.

It was observed as early as 1596 that the opposite coasts of the Atlantic Ocean—or, more precisely, the edges of the continental shelves—have similar shapes and seem to have once fitted together.[53]

Since that time many theories were proposed to explain this apparent complementarity, but the assumption of a solid Earth made these various proposals difficult to accept.[54]

The discovery of radioactivity and its associated heating properties in 1895 prompted a re-examination of the apparent age of Earth.[55] This had previously been estimated by its cooling rate under the assumption that Earth's surface radiated like a black body.[56] Those calculations had implied that, even if it started at red heat, Earth would have dropped to its present temperature in a few tens of millions of years. Armed with the knowledge of a new heat source, scientists realized that Earth would be much older, and that its core was still sufficiently hot to be liquid.

By 1915, after having published a first article in 1912,[57] Alfred Wegener was making serious arguments for the idea of continental drift in the first edition of The Origin of Continents and Oceans.[43] In that book (re-issued in four successive editions up to the final one in 1936), he noted how the east coast of South America and the west coast of Africa looked as if they were once attached. Wegener was not the first to note this (Abraham Ortelius, Antonio Snider-Pellegrini, Eduard Suess, Roberto Mantovani and Frank Bursley Taylor preceded him just to mention a few), but he was the first to marshal significant fossil and paleo-topographical and climatological evidence to support this simple observation (and was supported in this by researchers such as Alex du Toit). Furthermore, when the rock strata of the margins of separate continents are very similar it suggests that these rocks were formed in the same way, implying that they were joined initially. For instance, parts of Scotland and Ireland contain rocks very similar to those found in Newfoundland and New Brunswick. Furthermore, the Caledonian Mountains of Europe and parts of the Appalachian Mountains of North America are very similar in structure and lithology.

However, his ideas were not taken seriously by many geologists, who pointed out that there was no apparent mechanism for continental drift. Specifically, they did not see how continental rock could plow through the much denser rock that makes up oceanic crust. Wegener could not explain the force that drove continental drift, and his vindication did not come until after his death in 1930.[58]

Floating continents, paleomagnetism, and seismicity zones

As it was observed early that although granite existed on continents, seafloor seemed to be composed of denser basalt, the prevailing concept during the first half of the twentieth century was that there were two types of crust, named "sial" (continental type crust) and "sima" (oceanic type crust). Furthermore, it was supposed that a static shell of strata was present under the continents. It therefore looked apparent that a layer of basalt (sial) underlies the continental rocks.

However, based on abnormalities in plumb line deflection by the Andes in Peru, Pierre Bouguer had deduced that less-dense mountains must have a downward projection into the denser layer underneath. The concept that mountains had "roots" was confirmed by George B. Airy a hundred years later, during study of Himalayan gravitation, and seismic studies detected corresponding density variations. Therefore, by the mid-1950s, the question remained unresolved as to whether mountain roots were clenched in surrounding basalt or were floating on it like an iceberg.

During the 20th century, improvements in and greater use of seismic instruments such as seismographs enabled scientists to learn that earthquakes tend to be concentrated in specific areas, most notably along the oceanic trenches and spreading ridges. By the late 1920s, seismologists were beginning to identify several prominent earthquake zones parallel to the trenches that typically were inclined 40–60° from the horizontal and extended several hundred kilometers into Earth. These zones later became known as Wadati–Benioff zones, or simply Benioff zones, in honor of the seismologists who first recognized them, Kiyoo Wadati of Japan and Hugo Benioff of the United States. The study of global seismicity greatly advanced in the 1960s with the establishment of the Worldwide Standardized Seismograph Network (WWSSN)[59] to monitor the compliance of the 1963 treaty banning above-ground testing of nuclear weapons. The much improved data from the WWSSN instruments allowed seismologists to map precisely the zones of earthquake concentration worldwide.

Meanwhile, debates developed around the phenomenon of polar wander. Since the early debates of continental drift, scientists had discussed and used evidence that polar drift had occurred because continents seemed to have moved through different climatic zones during the past. Furthermore, paleomagnetic data had shown that the magnetic pole had also shifted during time. Reasoning in an opposite way, the continents might have shifted and rotated, while the pole remained relatively fixed. The first time the evidence of magnetic polar wander was used to support the movements of continents was in a paper by Keith Runcorn in 1956,[49] and successive papers by him and his students Ted Irving (who was actually the first to be convinced of the fact that paleomagnetism supported continental drift) and Ken Creer.

This was immediately followed by a symposium on continental drift in Tasmania in March 1956 organised by S. Warren Carey who had been one of the supporters and promotors of Continental Drift since the thirties [60] During this symposium, some of the participants used the evidence in the theory of an expansion of the global crust, a theory which had been proposed by other workers decades earlier. In this hypothesis, the shifting of the continents is explained by a large increase in the size of Earth since its formation. However, although the theory still has supporters in science, this is generally regarded as unsatisfactory because there is no convincing mechanism to produce a significant expansion of Earth. Other work during the following years would soon show that the evidence was equally in support of continental drift on a globe with a stable radius.

During the 1930s up to the late 1950s, works by Vening-Meinesz, Holmes, Umbgrove, and numerous others outlined concepts that were close or nearly identical to modern plate tectonics theory. In particular, the English geologist Arthur Holmes proposed in 1920 that plate junctions might lie beneath the sea, and in 1928 that convection currents within the mantle might be the driving force.[61] Often, these contributions are forgotten because:

- At the time, continental drift was not accepted.

- Some of these ideas were discussed in the context of abandoned fixist ideas of a deforming globe without continental drift or an expanding Earth.

- They were published during an episode of extreme political and economic instability that hampered scientific communication.

- Many were published by European scientists and at first not mentioned or given little credit in the papers on sea floor spreading published by the American researchers in the 1960s.

Mid-oceanic ridge spreading and convection

In 1947, a team of scientists led by Maurice Ewing utilizing the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution's research vessel Atlantis and an array of instruments, confirmed the existence of a rise in the central Atlantic Ocean, and found that the floor of the seabed beneath the layer of sediments consisted of basalt, not the granite which is the main constituent of continents. They also found that the oceanic crust was much thinner than continental crust. All these new findings raised important and intriguing questions.[62]

The new data that had been collected on the ocean basins also showed particular characteristics regarding the bathymetry. One of the major outcomes of these datasets was that all along the globe, a system of mid-oceanic ridges was detected. An important conclusion was that along this system, new ocean floor was being created, which led to the concept of the "Great Global Rift". This was described in the crucial paper of Bruce Heezen (1960) based on his work with Marie Tharp,[63] which would trigger a real revolution in thinking. A profound consequence of seafloor spreading is that new crust was, and still is, being continually created along the oceanic ridges. For this reason, Heezen initially advocated the so-called "expanding Earth" hypothesis of S. Warren Carey (see above). Therefore, the question remained as to how new crust could continuously be added along the oceanic ridges without increasing the size of Earth. In reality, this question had been solved already by numerous scientists during the 1940s and the 1950s, like Arthur Holmes, Vening-Meinesz, Coates and many others: The crust in excess disappeared along what were called the oceanic trenches, where so-called "subduction" occurred. Therefore, when various scientists during the early 1960s started to reason on the data at their disposal regarding the ocean floor, the pieces of the theory quickly fell into place.

The question particularly intrigued Harry Hammond Hess, a Princeton University geologist and a Naval Reserve Rear Admiral, and Robert S. Dietz, a scientist with the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey who coined the term seafloor spreading. Dietz and Hess (the former published the same idea one year earlier in Nature,[64] but priority belongs to Hess who had already distributed an unpublished manuscript of his 1962 article by 1960)[65] were among the small number who really understood the broad implications of sea floor spreading and how it would eventually agree with the, at that time, unconventional and unaccepted ideas of continental drift and the elegant and mobilistic models proposed by previous workers like Holmes.

In the same year, Robert R. Coats of the U.S. Geological Survey described the main features of island arc subduction in the Aleutian Islands.[66] His paper, though little noted (and sometimes even ridiculed) at the time, has since been called "seminal" and "prescient". In reality, it shows that the work by the European scientists on island arcs and mountain belts performed and published during the 1930s up until the 1950s was applied and appreciated also in the United States.

Если земная кора расширялась вдоль океанических хребтов, рассуждали Гесс и Дитц, как Холмс и другие до них, то она должна сжиматься в других местах. Гесс последовал за Хизеном, предположив, что новая океаническая кора непрерывно распространяется от хребтов, подобно конвейерной ленте. И, используя развитые ранее мобилизистские концепции, он правильно пришел к выводу, что спустя много миллионов лет океаническая кора в конечном итоге опустится вдоль окраин континентов, где образуются океанические желоба — очень глубокие и узкие каньоны, например, по краю бассейна Тихого океана. . Важным шагом, который сделал Гесс, было то, что движущей силой этого процесса будут конвекционные течения, и он пришел к тем же выводам, что и Холмс десятилетия назад, с той лишь разницей, что истончение океанской коры осуществлялось с использованием механизма распространения вдоль хребтов Хизена. Поэтому Гесс пришел к выводу, что Атлантический океан расширяется, а Тихий океан сжимается. Поскольку старая океаническая кора «поедается» в траншеях (как и Холмс и другие, он думал, что это происходит за счет утолщения континентальной литосферы, а не, как позже стало понятно, за счет вдавливания самой океанической коры в мантию в более крупных масштабах) Новая магма поднимается и извергается вдоль расширяющихся хребтов, образуя новую кору. По сути, океанские бассейны постоянно «перерабатываются», при этом одновременно происходит образование новой коры и разрушение старой океанической литосферы. Таким образом, новые мобилизистские концепции четко объяснили, почему Земля не увеличивается в размерах по мере расширения морского дна, почему на дне океана накапливается так мало отложений и почему океанические породы намного моложе континентальных.

Магнитная полоса

Начиная с 1950-х годов такие ученые, как Виктор Вакье , используя магнитные инструменты ( магнитометры ), адаптированные из бортовых устройств, разработанных во время Второй мировой войны для обнаружения подводных лодок , начали распознавать странные магнитные изменения на дне океана. Это открытие, хотя и неожиданное, не было совершенно неожиданным, поскольку было известно, что базальт — богатая железом вулканическая порода, составляющая дно океана — содержит сильно магнитный минерал ( магнетит ) и может локально искажать показания компаса. Это искажение было признано исландскими мореплавателями еще в конце 18 века. Что еще более важно, поскольку присутствие магнетита придает базальту измеримые магнитные свойства, эти недавно обнаруженные магнитные вариации предоставили еще один способ изучения глубокого дна океана. Когда вновь образовавшаяся порода остывает, такие магнитные материалы записывают магнитное поле Земли в то время.

По мере того, как в 1950-е годы было нанесено на карту все больше и больше морского дна, магнитные вариации оказались не случайными или изолированными явлениями, а вместо этого выявили узнаваемые закономерности. Когда эти магнитные узоры были нанесены на карту на обширной территории, на дне океана появился узор, похожий на зебру : одна полоса с нормальной полярностью и прилегающая полоса с обратной полярностью. Общая картина, определяемая этими чередующимися полосами нормально и обратно поляризованной породы, стала известна как магнитные полосы и была опубликована Роном Г. Мейсоном и его коллегами в 1961 году, которые, однако, не нашли объяснения этим данным в с точки зрения распространения морского дна, как это сделали Вайн, Мэтьюз и Морли несколько лет спустя. [67]

Открытие магнитных полос потребовало объяснения. В начале 1960-х годов такие ученые, как Хизен, Гесс и Дитц, начали предполагать, что срединно-океанические хребты обозначают структурно слабые зоны, где дно океана разрывалось на две продольные части вдоль гребня хребта (см. предыдущий абзац). Новая магма из глубин Земли легко поднимается через эти слабые зоны и в конечном итоге извергается вдоль гребней хребтов, создавая новую океаническую кору. Этот процесс, сначала названный «гипотезой конвейерной ленты», а позже названный спредингом морского дна, продолжающийся в течение многих миллионов лет, продолжает формировать новое дно океана по всей системе срединно-океанических хребтов длиной 50 000 км.

Всего через четыре года после того, как были опубликованы карты с «зебровым узором» магнитных полос, связь между распространением морского дна и этими узорами была независимо признана Лоуренсом Морли , а также Фредом Вайном и Драммондом Мэтьюзом в 1963 году. [68] ( гипотеза Вайна-Мэтьюза-Морли ). Эта гипотеза связала эти закономерности с геомагнитными инверсиями и была подтверждена несколькими доказательствами: [69]

- полосы симметричны вокруг гребней срединно-океанических хребтов; на гребне хребта или вблизи него породы очень молоды и становятся все старше по мере удаления от гребня хребта;

- самые молодые породы гребня хребта всегда имеют современную (нормальную) полярность;

- полосы породы, параллельные гребню хребта, чередуются по магнитной полярности (нормальная-обратная-нормальная и т. д.), что позволяет предположить, что они образовались в разные эпохи, документируя (уже известные из независимых исследований) нормальные и инверсивные эпизоды магнитного поля Земли.

Объясняя как магнитные полосы, похожие на зебру, так и построение системы срединно-океанических хребтов, гипотеза распространения морского дна (SFS) быстро приобрела сторонников и стала еще одним крупным достижением в развитии теории тектоники плит. Более того, океаническую кору стали воспринимать как естественную «магнитофонную запись» истории инверсий геомагнитного поля (GMFR) магнитного поля Земли. Обширные исследования были посвящены калибровке моделей нормального разворота в океанической коре, с одной стороны, и известным временным масштабам, полученным на основе датировки базальтовых слоев в осадочных последовательностях ( магнитостратиграфия ), с другой, чтобы прийти к оценкам прошлых скоростей спрединга и плит. реконструкции.

Определение и уточнение теории

После всех этих соображений тектоника плит (или, как ее первоначально называли «Новая глобальная тектоника») быстро получила признание, и последовали многочисленные статьи, в которых определялись эти концепции:

- В 1965 году Тузо Уилсон, который с самого начала был пропагандистом гипотезы расширения морского дна и дрейфа континентов. [70] добавили в модель понятие трансформных разломов , дополнив классы типов разломов, необходимые для отработки подвижности плит на земном шаре. [71]

- Симпозиум по дрейфу континентов был проведен в Лондонском королевском обществе в 1965 году, который следует рассматривать как официальное начало признания тектоники плит научным сообществом, и тезисы которого опубликованы как Blackett, Bullard & Runcorn (1965) . На этом симпозиуме Эдвард Буллард и его коллеги с помощью компьютерных расчетов показали, как континенты по обе стороны Атлантики лучше всего подходят для закрытия океана, что стало известно как знаменитая «подгонка Булларда».

- В 1966 году Уилсон опубликовал статью, в которой упоминались предыдущие реконструкции тектонических плит, и представил концепцию того, что стало известно как « цикл Вильсона ». [72]

- В 1967 году на Американского геофизического союза заседании У. Джейсон Морган предположил, что поверхность Земли состоит из 12 жестких плит, которые движутся относительно друг друга. [73]

- Два месяца спустя Ксавье Ле Пишон опубликовал полную модель, основанную на шести основных плитах с их относительным движением, что ознаменовало окончательное признание научным сообществом тектоники плит. [74]

- В том же году Маккензи и Паркер независимо друг от друга представили модель, аналогичную модели Моргана, используя перемещение и вращение сферы для определения движения плит. [75]

- С этого момента дискуссии были сосредоточены на относительной роли сил, движущих тектоникой плит, чтобы перейти от кинематической концепции к динамической теории. [76] Первоначально эти концепции были сосредоточены на мантийной конвекции по стопам А. Холмса, а также представили важность гравитационного притяжения субдуцированных плит через работы Эльзассера, Соломона, Сна, Уеды и Тюркотта. Другие авторы вызывали внешние движущие силы из-за приливного сопротивления Луны и других небесных тел, и, особенно с 2000 года, с появлением вычислительных моделей, воспроизводящих поведение мантии Земли в первом порядке. [77] [78] Следуя более старым объединяющим концепциям ван Беммелена, авторы по-новому оценили важную роль мантийной динамики. [79]

Значение для биогеографии

Теория континентального дрейфа помогает биогеографам объяснить разрозненное биогеографическое распределение современной жизни, обитающей на разных континентах, но имеющей схожих предков . [80] В частности, это объясняет распространение бескилевых гондванское и антарктической флоры .

Реконструкция пластины

Реконструкция используется для установления прошлых (и будущих) конфигураций плит, помогая определить форму и состав древних суперконтинентов и обеспечивая основу для палеогеографии.

Определение границ плиты

Границы активных плит определяются их сейсмичностью. [81] Прошлые границы плит внутри существующих плит идентифицируются на основании множества свидетельств, таких как наличие офиолитов , которые указывают на исчезнувшие океаны. [82]

Прошлые движения плит

Считается, что тектоническое движение началось примерно от 3 до 3,8 миллиардов лет назад. [83] [84] [85] [ почему? ]

Доступны различные типы количественной и полуколичественной информации для ограничения движения плит в прошлом. Геометрическое соответствие между континентами, например, между Западной Африкой и Южной Америкой, по-прежнему является важной частью реконструкции плит. Картины магнитных полос обеспечивают надежный ориентир относительного движения плит, начиная с юрского периода. [86] Следы горячих точек дают абсолютные реконструкции, но они доступны только начиная с мелового периода . [87] Более старые реконструкции опираются в основном на данные о палеомагнитных полюсах , хотя они ограничивают только широту и вращение, но не долготу. Объединение полюсов разного возраста в конкретной плите для создания видимых путей блуждания полюсов дает метод сравнения движений разных плит во времени. [88] Дополнительные доказательства получены из распределения определенных типов осадочных пород . [89] фаунистические провинции, представленные отдельными группами ископаемых, и положение орогенных поясов . [87]

Образование и распад континентов.

Движение плит с течением времени вызывало образование и распад континентов, включая случайное образование суперконтинента , который содержит большую часть или все континенты. Суперконтинент Колумбия или Нуна образовался в период от 2000 до 1800 миллионов лет назад и распался примерно от 1500 до 1300 миллионов лет назад . [90] [91] Считается, что суперконтинент Родиния сформировался около 1 миллиарда лет назад и включал в себя большую часть или все континенты Земли, а около 600 миллионов лет назад распался на восемь континентов . Восемь континентов позже вновь объединились в другой суперконтинент, названный Пангея ; Пангея распалась на Лавразию (ставшую Северной Америкой и Евразией) и Гондвану (ставшую остальными континентами).

, Предполагается, что Гималаи самая высокая горная цепь в мире, образовались в результате столкновения двух крупных плит. До поднятия территория, где они стоят, была покрыта океаном Тетис .

Современные тарелки

В зависимости от того, как они определяются, обычно выделяют семь или восемь «основных» плит: Африканскую , Антарктическую , Евразийскую , Северо-Американскую , Южно-Американскую , Тихоокеанскую и Индо-Австралийскую . Последнюю иногда подразделяют на Индийскую и Австралийскую плиты.

Существуют десятки более мелких плит, восемь крупнейших из которых — Аравийская , Карибская , Хуан-де-Фука , Кокосовая , Наска , Филиппинское море , Скотийская и Сомали .

В двадцатые годы XXI века появились новые предложения, разделяющие земную кору на множество более мелких плит, называемых террейнами, что отражает тот факт, что реконструкция плит показывает, что более крупные плиты были внутренне деформированы, а океанические и континентальные плиты фрагментированы по время. Это привело к определению ок. 1200 террейнов внутри океанических плит, континентальных блоков и разделяющих их подвижных зон (горных поясов). [92] [93]

Движение тектонических плит определяется наборами спутниковых данных дистанционного зондирования, откалиброванными по измерениям наземных станций.

Другие небесные тела

Появление тектоники плит на планетах земной группы связано с планетарной массой: ожидается, что более массивные планеты, чем Земля, будут демонстрировать тектонику плит. Земля может быть пограничным случаем из-за своей тектонической активности из-за обилия воды (кремнезем и вода образуют глубокую эвтектику ). [94]

Венера

На Венере нет признаков активной тектоники плит. Существуют спорные свидетельства активной тектоники в далеком прошлом планеты; однако события, произошедшие с тех пор (такие как правдоподобная и общепринятая гипотеза о том, что венерианская литосфера значительно утолщалась в течение нескольких сотен миллионов лет), затруднили определение хода ее геологической летописи. Однако многочисленные хорошо сохранившиеся ударные кратеры использовались в качестве метода датирования поверхности Венеры (поскольку до сих пор не существует известных образцов венерианских пород, которые можно было бы датировать более надежными методами). Полученные даты преимущественно находятся в диапазоне от 500 до 750 миллионов лет назад возраст до 1200 миллионов лет назад , хотя был рассчитан . Это исследование привело к довольно широко принятой гипотезе о том, что Венера по крайней мере однажды в своем далеком прошлом претерпела практически полное вулканическое обновление, причем последнее событие произошло примерно в пределах предполагаемого возраста поверхности. Хотя механизм такого впечатляющего термического явления остается дискуссионным вопросом в венерианских геолого-научных исследованиях, некоторые ученые в некоторой степени являются сторонниками процессов, связанных с движением плит.

Одним из объяснений отсутствия тектоники плит на Венере является то, что на Венере температуры слишком высоки, чтобы на ней могло присутствовать значительное количество воды. [95] [96] Земная кора пропитана водой, и вода играет важную роль в развитии зон сдвига . Для тектоники плит необходимы слабые поверхности в земной коре, по которым могут перемещаться кусочки земной коры, и вполне возможно, что такое ослабление никогда не происходило на Венере из-за отсутствия воды. Однако некоторые исследователи [ ВОЗ? ] по-прежнему убеждены, что тектоника плит активна или когда-то была на этой планете.

Марс

Марс значительно меньше Земли и Венеры, и на его поверхности и в коре есть следы льда.

В 1990-х годах было высказано предположение, что дихотомия марсианской коры возникла в результате тектонических процессов плит. [97] С тех пор ученые определили, что он образовался либо в результате апвеллинга в марсианской мантии , который утолтил кору Южного нагорья и образовал Фарсиду. [98] или гигантским ударом, который раскопал Северную низменность . [99]

Valles Marineris может быть тектонической границей. [100]

Наблюдения магнитного поля Марса, проведенные космическим кораблем Mars Global Surveyor в 1999 году, показали закономерности магнитных полос, обнаруженных на этой планете. Некоторые ученые интерпретировали это как необходимость тектонических процессов плит, таких как расширение морского дна. [101] Однако их данные не прошли «тест на инверсию магнитного поля», который используется для того, чтобы увидеть, образовались ли они в результате изменения полярности глобального магнитного поля. [102]

Ледяные спутники

Некоторые из спутников Юпитера имеют особенности, которые могут быть связаны с деформацией плито-тектонического типа, хотя материалы и конкретные механизмы могут отличаться от плито-тектонической активности на Земле. 8 сентября 2014 года НАСА сообщило об обнаружении свидетельств тектоники плит на Европе , спутнике Юпитера, — это первый признак субдукционной активности в другом мире, отличном от Земли. [103]

Титан , самый большой спутник Сатурна Сообщалось, что «Гюйгенс» , демонстрирует тектоническую активность на изображениях, полученных зондом , который приземлился на Титане 14 января 2005 года. [104]

Экзопланеты

На планетах размером с Землю тектоника плит более вероятна, если есть океаны воды. Однако в 2007 году две независимые группы исследователей пришли к противоположным выводам о вероятности тектоники плит на более крупных суперземлях. [105] [106] одна команда заявила, что тектоника плит будет эпизодической или застойной. [107] а другая команда утверждает, что тектоника плит весьма вероятна на суперземлях, даже если планета сухая. [94]

Рассмотрение тектоники плит является частью поиска внеземного разума и внеземной жизни . [108]

См. также

- Циркуляция атмосферы - процесс, который распределяет тепловую энергию по поверхности Земли.

- Сохранение углового момента – Сохраняющаяся физическая величина; вращательный аналог линейного импульса.

- Геологическая история Земли - Последовательность основных геологических событий в прошлом Земли.

- Геодинамика - Исследование динамики Земли.

- Геосинклиналь - устаревшая геологическая концепция для объяснения орогенов.

- GPlates - прикладное программное обеспечение с открытым исходным кодом для интерактивной реконструкции тектонических плит.

- Очерк тектоники плит - Иерархический обзорный список статей, связанных с тектоникой плит.

- Список особенностей подводной топографии - Океанические формы рельефа и топографические элементы.

- Цикл суперконтинентов - повторяющееся соединение и разделение континентов Земли.

- Тектоника - Процесс эволюции земной коры.

Ссылки

Цитаты

- ^ Литтл, Фаулер и Коулсон 1990 .

- ^ Университет Витватерсранда (2019). «Капля древней морской воды переписывает историю Земли: исследования показывают, что тектоника плит началась на Земле на 600 миллионов лет раньше, чем считалось ранее» . ScienceDaily . Архивировано из оригинала 6 августа 2019 г. Проверено 11 августа 2019 г.

- ^ Рид и Уотсон, 1975 .

- ^ Стерн, Роберт Дж. (2002). «Зоны субдукции» . Обзоры геофизики . 40 (4): 1012. Бибкод : 2002RvGeo..40.1012S . дои : 10.1029/2001RG000108 . S2CID 247695067 .

- ^ Форсайт, Д.; Уеда, С. (1975). «Об относительной важности движущих сил движения плит» . Международный геофизический журнал . 43 (1): 163–200. Бибкод : 1975GeoJ...43..163F . дои : 10.1111/j.1365-246x.1975.tb00631.x .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Конрад и Литгоу-Бертеллони, 2002 г.

- ^ Чжэнь Шао 1997 , Хэнкок, Скиннер и Динли 2000 .

- ^ Шмидт и Харберт 1998 .

- ^ Макгуайр, Томас (2005). «Землетрясения и недра Земли». Науки о Земле: физические условия . AMSCO School Publications Inc., стр. 182–184. ISBN 978-0-87720-196-0 .

- ^ Тюркотт и Шуберт 2002 , с. 5.

- ^ Тюркотт и Шуберт 2002 .

- ^ Фулгер 2010 .

- ^ Мейснер 2002 , с. 100.

- ^ «Тектоника плит: границы плит» . Platetectonics.com. Архивировано из оригинала 16 июня 2010 г. Проверено 12 июня 2010 г.

- ^ «Понимание движения плит» . Геологическая служба США . Архивировано из оригинала 16 мая 2019 г. Проверено 12 июня 2010 г.

- ^ Гроув, Тимоти Л.; Тилль, Кристи Б.; Кравчински, Майкл Дж. (8 марта 2012 г.). «Роль H2O в магматизме зоны субдукции» . Ежегодный обзор наук о Земле и планетах . 40 (1): 413–39. Бибкод : 2012AREPS..40..413G . doi : 10.1146/annurev-earth-042711-105310 . Проверено 14 января 2016 г.

- ^ Мендиа-Ланда, Педро. «Мифы и легенды о стихийных бедствиях: осмысление нашего мира» . Архивировано из оригинала 21 июля 2016 г. Проверено 5 февраля 2008 г.

- ^ Холмс, Артур (1931). «Радиоактивность и движение Земли» (PDF) . Труды Геологического общества Глазго . 18 (3): 559–606. дои : 10.1144/трансглас.18.3.559 . S2CID 122872384 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 9 октября 2019 г. Проверено 15 января 2014 г.

- ^ Танимото и Лэй 2000 .

- ^ Ван Беммелен 1976 .

- ^ Ван Беммелен 1972 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Сегев 2002 .

- ^ Маруяма 1994 .

- ^ Юэнь и др. 2007

- ^ Ласка 1988 .

- ^ Мейерхофф и др. 1996 год .

- ^ Маллард и др. 2016 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Спенс, 1987 год .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Уайт и Маккензи, 1989 .

- ^ «Альфред Вегенер (1880–1930)» . Музей палеонтологии Калифорнийского университета . Архивировано из оригинала 8 декабря 2017 г. Проверено 18 июня 2010 г.

- ^ Нейт, Кэти (15 апреля 2011 г.). «Исследователи Калифорнийского технологического института используют данные GPS для моделирования воздействия приливных нагрузок на поверхность Земли» . Калтех . Архивировано из оригинала 19 октября 2011 г. Проверено 15 августа 2012 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Рикар, Ю. (2009). «2. Физика мантийной конвекции» . В Берковичи, Дэвид; Шуберт, Джеральд (ред.). Трактат по геофизике: Динамика мантии . Том. 7. Эльзевир Наука. п. 36. ISBN 978-0-444-53580-1 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Глацмайер, Гэри А. (2013). Введение в моделирование конвекции на планетах и звездах: магнитное поле, стратификация плотности, вращение . Издательство Принстонского университета . п. 149. ИСБН 978-1-4008-4890-4 .

- ^ ван Дейк 1992 , ван Дейк и Оккес 1990 .

- ^ Мур 1973 .

- ^ Бостром 1971 .

- ^ Скоппола и др. 2006 год .

- ^ Торсвик и др. 2010 .

- ^ ХофмейстерABC 2022 .

- ^ Роули, Дэвид Б.; Форте, Алессандро М.; Роуэн, Кристофер Дж.; Глишович, Петар; Муча, Роберт; Гранд, Стивен П.; Симмонс, Натан А. (2016). «Кинематика и динамика Восточно-Тихоокеанского поднятия связана со стабильным глубокомантийным апвеллингом» . Достижения науки . 2 (12): e1601107. Бибкод : 2016SciA....2E1107R . дои : 10.1126/sciadv.1601107 . ПМК 5182052 . ПМИД 28028535 .

- ^ Касадеваль, Артуро; Фанг, Феррик К. (1 марта 2016 г.). «Революционная наука» . мБио . 7 (2): e00158–16. дои : 10.1128/mBio.00158-16 . ПМЦ 4810483 . ПМИД 26933052 .

- ^ Хьюз, Патрик (8 февраля 2001 г.). «Альфред Вегенер (1880–1930): географическая головоломка» . На плечах гигантов . Земная обсерватория НАСА . Проверено 26 декабря 2007 г.

... 6 января 1912 года Вегенер... вместо этого предложил грандиозное видение дрейфующих континентов и расширяющихся морей, чтобы объяснить эволюцию географии Земли.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Вегенер, 1929 год .

- ^ Хьюз, Патрик (8 февраля 2001 г.). «Альфред Вегенер (1880–1930): Происхождение континентов и океанов» . На плечах гигантов . Земная обсерватория НАСА . Проверено 26 декабря 2007 г.

В своем третьем издании (1922 г.) Вегенер приводил геологические доказательства того, что около 300 миллионов лет назад все континенты были объединены в суперконтинент, простирающийся от полюса до полюса. Он назвал ее Пангеей (все земли),...

- ^ Вегенер 1966 .

- ^ Отто Ампферер : Мысли о кинофильмах Атлантического региона . Сбер. österr. Акад. Висс., мат.-натурвисс. КЛ, 150, 19–35, 6 инст., Вена, 1941 г.

- ^ Дулло, Вольф-Христианин; Пфаффль, Фриц А. (28 марта 2019 г.). «Теория подводных течений австрийского альпийского геолога Отто Ампферера (1875–1947): первые концептуальные идеи на пути к тектонике плит» . Канадский журнал наук о Земле . 56 (11): 1095–1100. Бибкод : 2019CaJES..56.1095D . doi : 10.1139/cjes-2018-0157 . S2CID 135079657 .

- ^ Карл Крайнер, Кристоф Хаузер: Отто Ампферер (1875-1947): пионер геологии, альпинист, коллекционер и рисовальщик . В: Гео. Специальный том Alp 1, 2007 г., стр. 94–95.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Ранкорн, 1956 год .

- ^ Кэри 1958 .

- ^ см., например, важную статью Lyman & Fleming 1940 .

- ^ Корген 1995 , Шписс и Куперман 2003 .

- ^ Киус и Тиллинг 1996 .

- ^ Франкель 1987 .

- ^ Жоли 1909 .

- ^ Томсон 1863 .

- ^ Вегенер 1912 .

- ^ «Пионеры тектоники плит» . Геологическое общество . Архивировано из оригинала 23 марта 2018 г. Проверено 23 марта 2018 г.

- ^ Stein & Wysession 2009 , с. 26.

- ^ Кэри 1958 ; см. также Quilty & Banks 2003 .

- ^ Холмс 1928 ; см. также Holmes 1978 , Frankel 1978 .

- ^ Липпсетт 2001 , Липпсетт 2006 .

- ^ Хизен 1960 .

- ^ Дитц 1961 .

- ^ Гесс 1962 .

- ^ Коутс 1962 .

- ^ Мейсон и Рафф 1961 , Рафф и Мейсон 1961 .

- ^ Вайн и Мэтьюз 1963 .

- ^ См. резюме в Heirtzler, Le Pichon & Baron 1966.

- ^ Уилсон 1963 .

- ^ Уилсон 1965 .

- ^ Уилсон 1966 .

- ^ Морган 1968 .

- ^ Ле Пишон 1968 .

- ^ Маккензи и Паркер 1967 .

- ^ Тарп М. (1982) Картирование дна океана - с 1947 по 1977 год. В: Дно океана: памятный том Брюса Хизена, стр. 19–31. Нью-Йорк: Уайли.

- ^ Колтис, Николас; Жеро, Мелани; Ульврова, Мартина (2017). «Взгляд мантийной конвекции на глобальную тектонику». Обзоры наук о Земле . 165 : 120–150. Бибкод : 2017ESRv..165..120C . doi : 10.1016/j.earscirev.2016.11.006 .

- ^ Берковичи, Дэвид (2003). «Поколение тектоники плит в результате мантийной конвекции». Письма о Земле и планетологии . 205 (3–4): 107–121. Бибкод : 2003E&PSL.205..107B . дои : 10.1016/S0012-821X(02)01009-9 .

- ^ Крамери, Фабио; Конрад, Клинтон П.; Монтези, Лоран; Литгоу-Бертеллони, Каролина Р. (2019). «Динамичная жизнь океанической плиты». Тектонофизика . 760 : 107–135. Бибкод : 2019Tectp.760..107C . дои : 10.1016/j.tecto.2018.03.016 .

- ^ Мосс и Уилсон 1998 .

- ^ Конди 1997 .

- ^ Lliboutry 2000 .

- ^ Кранендонк, В.; Мартин, Дж. (2011). «Начало тектоники плит». Наука . 333 (6041): 413–14. Бибкод : 2011Sci...333..413V . дои : 10.1126/science.1208766 . ПМИД 21778389 . S2CID 206535429 .

- ^ «Тектоника плит могла начаться через миллиард лет после рождения Земли Паппас, отчет S LiveScience об исследовании PNAS от 21 сентября 2017 года» . Живая наука . 21 сентября 2017 г. Архивировано из оригинала 23 сентября 2017 г. Проверено 23 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ Драбон, Надя; Байерли, Бенджамин Л.; Байерли, Гэри Р.; Вуден, Джозеф Л.; Виденбек, Майкл; Вэлли, Джон В.; Китадзима, Коуки; Бауэр, Энн М.; Лоу, Дональд Р. (21 апреля 2022 г.). «Дестабилизация долгоживущей гадейской протокры и начало повсеместного плавления воды в возрасте 3,8 млрд лет» . АГУ Прогресс . 3 (2). Бибкод : 2022AGUA....300520D . дои : 10.1029/2021AV000520 .

- ^ Торсвик, Тронд Хельге. «Методы реконструкции» . Архивировано из оригинала 23 июля 2011 г. Проверено 18 июня 2010 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Торсвик и Стейнбергер 2008 .

- ^ Батлер 1992 .

- ^ Скотезе, ЧР (20 апреля 2002 г.). «Климатическая история» . Проект Палеомап . Архивировано из оригинала 15 июня 2010 г. Проверено 18 июня 2010 г.

- ^ Чжао и др. 2002 .

- ^ Чжао и др. 2004 .

- ^ Хастерок, Деррик; Халпин, Жаклин А.; Коллинз, Алан С.; Хэнд, Мартин; Кример, Корне; Гард, Мэтью Г.; Слава, Стейн (2022). «Новые карты геологических провинций и тектонических плит мира». Обзоры наук о Земле . 231 . Бибкод : 2022ESRv..23104069H . doi : 10.1016/j.earscirev.2022.104069 .

- ^ Ван Дейк, Янпитер (2023). «Новая глобальная тектоническая карта. Анализ и последствия». Терра Нова . 35 (5): 343–369. Бибкод : 2023TeNov..35..343V . дои : 10.1111/TER.12662 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Валенсия, О'Коннелл и Саселов, 2007 г.

- ^ Кастинг 1988 года .

- ^ Бортман, Генри (26 августа 2004 г.). «Была ли Венера жива? «Знаки, вероятно, есть» » . Space.com . Архивировано из оригинала 24 декабря 2010 г. Проверено 8 января 2008 г.

- ^ Сон 1994 .

- ^ Чжун и Зубер 2001 .

- ^ Эндрюс-Ханна, Зубер и Банердт 2008 .

- ^ Вулперт, Стюарт (9 августа 2012 г.). «Ученый Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе обнаружил тектонику плит на Марсе» . Инь, Ан . Калифорнийский университет в Лос-Анджелесе . Архивировано из оригинала 14 августа 2012 г. Проверено 13 августа 2012 г.

- ^ Коннерни и др. 1999 , Коннерни и др. 2005 г.

- ^ Харрисон 2000 .

- ^ Дайчес, Престон; Браун, Дуэйн; Бакли, Майкл (8 сентября 2014 г.). «Ученые нашли свидетельства «ныряния» тектонических плит на Европе» . НАСА . Архивировано из оригинала 4 апреля 2019 г. Проверено 8 сентября 2014 г.

- ^ Содерблом и др. 2007 .

- ^ Валенсия, Диана; О'Коннелл, Ричард Дж. (2009). «Масштабирование конвекции и субдукция на Земле и суперземлях». Письма о Земле и планетологии . 286 (3–4): 492–502. Бибкод : 2009E&PSL.286..492V . дои : 10.1016/j.epsl.2009.07.015 .

- ^ ван Хек, HJ; Тэкли, Пи Джей (2011). «Тектоника плит на суперземлях: так же или более вероятно, чем на Земле». Письма о Земле и планетологии . 310 (3–4): 252–61. Бибкод : 2011E&PSL.310..252В . дои : 10.1016/j.epsl.2011.07.029 .

- ^ О'Нил, К.; Ленардич, А. (2007). «Геологические последствия сверхразмерных Земель» . Письма о геофизических исследованиях . 34 (19): L19204. Бибкод : 2007GeoRL..3419204O . дои : 10.1029/2007GL030598 .

- ^ Стерн, Роберт Дж. (июль 2016 г.). «Необходима ли тектоника плит для развития технологических видов на экзопланетах?» . Геонаучные границы . 7 (4): 573–580. Бибкод : 2016GeoFr...7..573S . дои : 10.1016/j.gsf.2015.12.002 .

Источники

Книги

- Батлер, Роберт Ф. (1992). «Приложения к палеогеографии» (PDF) . Палеомагнетизм: магнитные домены геологических террейнов . Блэквелл . ISBN 978-0-86542-070-0 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 17 августа 2010 г. Проверено 18 июня 2010 г.

- Кэри, SW (1958). «Тектонический подход к дрейфу континентов». В Кэри, Юго-Запад (ред.). Континентальный дрейф – симпозиум, состоявшийся в марте 1956 года . Хобарт, Тасмания: Университет Тасмании . стр. 177–363. Расширение Земли, стр. 311–49.

- Конди, КК (1997). Тектоника плит и эволюция земной коры (4-е изд.). Баттерворт-Хайнеманн. п. 282. ИСБН 978-0-7506-3386-4 . Проверено 18 июня 2010 г.

- Фулджер, Джиллиан Р. (2010). Плиты против плюмов: геологический спор . Уайли-Блэквелл . ISBN 978-1-4051-6148-0 .

- Франкель, Х. (1987). «Дебаты о континентальном дрейфе» . В Х.Т. Энгельгардте-младшем; А. Л. Каплан (ред.). Научные споры: тематические исследования по разрешению и закрытию споров в области науки и технологий . Издательство Кембриджского университета . ISBN 978-0-521-27560-6 .

- Хэнкок, Пол Л.; Скиннер, Брайан Дж.; Динели, Дэвид Л. (2000). Оксфордский спутник Земли . Издательство Оксфордского университета . ISBN 978-0-19-854039-7 .

- Гесс, HH (ноябрь 1962 г.). «История океанических бассейнов» (PDF) . В AEJ Энгель; Гарольд Л. Джеймс; Б. Ф. Леонард (ред.). Петрологические исследования: том в честь А.Ф. Баддингтона . Боулдер, Колорадо: Геологическое общество Америки . стр. 599–620.

- Холмс, Артур (1978). Принципы физической геологии (3-е изд.). Уайли . стр. 640–41. ISBN 978-0-471-07251-5 .

- Джоли, Джон (1909). Радиоактивность и геология: отчет о влиянии радиоактивной энергии на историю Земли . Лондон: Арчибальд Констебль и компания. п. 36. ISBN 978-1-4021-3577-4 . ( Джоли, Дж. (1910). «Обзор радиоактивности и геологии ». Журнал геологии . 18 (6): 568–570. Бибкод : 1910JG.....18..568J . дои : 10.1086/621777 . )

- Киус, В. Жаклин; Тиллинг, Роберт И. (февраль 1996 г.). «Историческая перспектива» . Эта динамическая Земля: история тектоники плит (онлайн-изд.). Геологическая служба США . ISBN 978-0-16-048220-5 . Проверено 29 января 2008 г.

Авраам Ортелиус в своей работе «Тезаурус Географический...» предположил, что Америка «отторгнута от Европы и Африки... землетрясениями и наводнениями... Следы разрыва проявятся, если кто-нибудь представит карту мира и внимательно рассматривает побережья трех [континентов]».

- Липпсетт, Лоуренс (2006). «Морис Юинг и Земная обсерватория Ламонта-Доэрти» . У Уильяма Теодора Де Бари; Джерри Кисслингер; Том Мэтьюсон (ред.). Живое наследие в Колумбии . Издательство Колумбийского университета . стр. 277–97. ISBN 978-0-231-13884-0 . Проверено 22 июня 2010 г.

- Литтл, В.; Фаулер, Х.В.; Коулсон, Дж. (1990). Лук КТ (ред.). Краткий Оксфордский словарь английского языка: по историческим принципам . Том. II (3-е изд.). Кларендон Пресс . ISBN 978-0-19-861126-4 .

- Ллибоутри, Л. (2000). «Количественная геофизика и геология» . Эос, Труды Американского геофизического союза . 82 (22). Спрингер: 480. Бибкод : 2001EOSTr..82..249W . дои : 10.1029/01EO00142 . ISBN 978-1-85233-115-3 . Проверено 18 июня 2010 г.

- Макнайт, Том (2004). Geographica: Полный иллюстрированный атлас мира . Нью-Йорк, штат Нью-Йорк: Barnes and Noble Books . ISBN 978-0-7607-5974-5 .

- Мейснер, Рольф (2002). Маленькая книга планеты Земля . Нью-Йорк , Нью-Йорк: Книги Коперника . п. 202. ИСБН 978-0-387-95258-1 .

- Мейерхофф, Артур Август; Танер, И.; Моррис, AEL; Агокс, ВБ; Камен-Кей, М.; Бхат, Мохаммед И.; Смут, Н. Кристиан; Чой, Донг Р. (1996). Донна Мейерхофф Халл (ред.). Скачковая тектоника: новая гипотеза глобальной геодинамики . Библиотека наук о твердой Земле. Том. 9. Спрингер Нидерланды. п. 348. ИСБН 978-0-7923-4156-7 .

- Мосс, С.Дж.; Уилсон, МЭД (1998). «Биогеографические последствия третичной палеогеографической эволюции Сулавеси и Борнео» (PDF) . Ин Холл, Р.; Холлоуэй, Джей Ди (ред.). Биогеография и геологическая эволюция Юго-Восточной Азии . Лейден, Нидерланды: Backhuys. стр. 133–63. ISBN 978-90-73348-97-4 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 16 февраля 2008 г. Проверено 29 января 2008 г.

- Орескес, Наоми , изд. (2003). Тектоника плит: история современной теории Земли изнутри . Вествью. ISBN 978-0-8133-4132-3 .

- Прочтите, Герберт Гарольд; Уотсон, Джанет (1975). Введение в геологию . Нью-Йорк, штат Нью-Йорк: Холстед. стр. 13–15 . ISBN 978-0-470-71165-1 . OCLC 317775677 .

- Шмидт, Виктор А.; Харберт, Уильям (1998). «Живая машина: тектоника плит». Планета Земля и новые науки о Земле (3-е изд.). Кендалл/Хант Издательская компания. п. 442. ИСБН 978-0-7872-4296-1 . Архивировано из оригинала 24 января 2010 г. Проверено 28 января 2008 г. «Блок 3: Живая машина: тектоника плит» . Архивировано из оригинала 28 марта 2010 г.

- Шуберт, Джеральд; Теркотт, Дональд Л.; Олсон, Питер (2001). Мантийная конвекция на Земле и планетах . Кембридж, Англия: Издательство Кембриджского университета . ISBN 978-0-521-35367-0 .

- Стэнли, Стивен М. (1999). История системы Земли . У. Х. Фриман . стр. 211–28. ISBN 978-0-7167-2882-5 .

- Штейн, Сет; Висессион, Майкл (2009). Введение в сейсмологию, землетрясения и структуру Земли . Чичестер: Джон Уайли и сыновья. ISBN 978-1-4443-1131-0 .

- Свердруп, Ху; Джонсон, Миссури; Флеминг, Р.Х. (1942). Океаны: их физика, химия и общая биология . Энглвудские скалы: Прентис-Холл . п. 1087.

- Томпсон, Грэм Р. и Терк, Джонатан (1991). Современная физическая геология . Издательство Колледжа Сондерса . ISBN 978-0-03-025398-0 .

- Торсвик, Тронд Хельге; Стейнбергер, Бернхард (декабрь 2006 г.). «Fra kontinentaldrift til manteldynamikk» [От континентального дрейфа к динамике мантии]. Гео (на норвежском языке). 8 : 20–30. Архивировано из оригинала 23 июля 2011 г. Проверено 22 июня 2010 г. ,

перевод: Торсвик, Тронд Хельге; Стейнбергер, Бернхард (2008). «От континентального дрейфа к динамике мантии» (PDF) . В Тронде Слагстаде; Ролв Даль Гростейнен (ред.). Геология для общества за 150 лет – Наследие после Кьерульфа . Том 12. Тронхейм: Норвежская геологическая служба . стр. 24–38. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 23 июля 2011 г. [Норвежская геологическая служба, научно-популярный журнал]. - Тюркотт, ДЛ; Шуберт, Г. (2002). «Тектоника плит». Геодинамика (2-е изд.). Издательство Кембриджского университета . стр. 1–21 . ISBN 978-0-521-66186-7 .

- Вегенер, Альфред (1929). Образование материков и океанов (4-е изд.). . Брауншвейг: Фридрих Видег и Зон Акт ISBN 978-3-443-01056-0 .

- Вегенер, Альфред (1966). Происхождение материков и океанов . Перевод Бирама Джона. Курьер Дувр. п. 246. ИСБН 978-0-486-61708-4 .

- Винчестер, Саймон (2003). Кракатау: День, когда мир взорвался: 27 августа 1883 года . ХарперКоллинз . ISBN 978-0-06-621285-2 .

- Юэнь, Дэвид А.; Маруяма, Сигенори; Карато, Сюн-Ичиро; Уиндли, Брайан Ф., ред. (2007). Суперплюмы: за пределами тектоники плит . Дордрехт , Южная Голландия : Springer . ISBN 978-1-4020-5749-6 .

Статьи

- Эндрюс-Ханна, Джеффри С.; Зубер, Мария Т.; Банердт, В. Брюс (2008). «Бассейн Бореалис и происхождение дихотомии марсианской коры». Природа . 453 (7199): 1212–15. Бибкод : 2008Natur.453.1212A . дои : 10.1038/nature07011 . ПМИД 18580944 . S2CID 1981671 .

- Блэкетт, ПМС; Буллард, Э.; Ранкорн, СК, ред. (1965). Симпозиум по континентальному дрейфу, состоявшийся 28 октября 1965 года . Философские труды Королевского общества А. Том. 258. Лондонское королевское общество. п. 323.

- Бостром, Р.К. (31 декабря 1971 г.). «Смещение литосферы на запад». Природа . 234 (5331): 536–38. Бибкод : 1971Natur.234..536B . дои : 10.1038/234536a0 . S2CID 4198436 .

- Коннерни, JEP; Акунья, Миннесота; Василевский, П.Дж.; Несс, штат Северная Каролина; Реме Х.; Мазель К.; Винь Д.; Лин Р.П.; Митчелл Д.Л.; Клотье, Пенсильвания (1999). «Магнитные линии в древней коре Марса» . Наука . 284 (5415): 794–98. Бибкод : 1999Sci...284..794C . дои : 10.1126/science.284.5415.794 . ПМИД 10221909 .

- Коннерни, JEP; Акунья, Миннесота; Несс, штат Северная Каролина; Клетечка, Г.; Митчелл, Д.Л.; Лин, Р.П.; Рем, Х. (2005). «Тектонические последствия магнетизма марсианской коры» . Труды Национальной академии наук . 102 (42): 14970–175. Бибкод : 2005PNAS..10214970C . дои : 10.1073/pnas.0507469102 . ПМК 1250232 . ПМИД 16217034 .

- Конрад, Клинтон П.; Литгоу-Бертеллони, Каролина (2002). «Как мантийные плиты вызывают тектонику плит» . Наука . 298 (5591): 207–09. Бибкод : 2002Sci...298..207C . дои : 10.1126/science.1074161 . ПМИД 12364804 . S2CID 36766442 . Архивировано из оригинала 20 сентября 2009 г.

- Дитц, Роберт С. (июнь 1961 г.). «Эволюция континента и океанского бассейна путем расширения морского дна». Природа . 190 (4779): 854–57. Бибкод : 1961Natur.190..854D . дои : 10.1038/190854a0 . S2CID 4288496 .

- ван Дейк, Янпитер; Оккес, Ф.В. Марк (1990). «Анализ зон сдвига в Калабрии; последствия для геодинамики Центрального Средиземноморья». Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia . 96 (2–3): 241–70.