История Земли

История Земли касается развития планеты Земля от ее образования до наших дней. [1] [2] Почти все отрасли естествознания внесли свой вклад в понимание основных событий прошлого Земли, характеризующегося постоянными геологическими изменениями и биологической эволюцией .

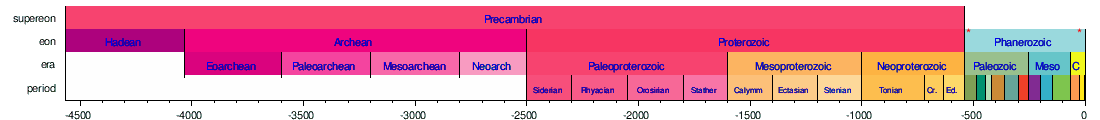

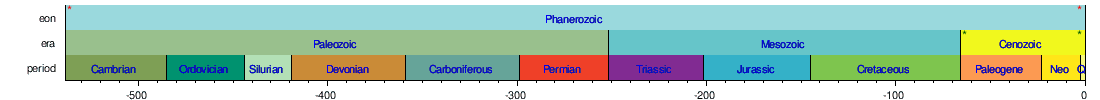

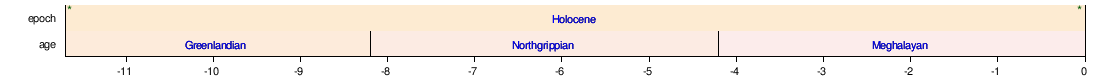

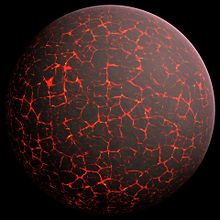

Геологическая шкала времени (GTS), как она определена международной конвенцией, [3] изображает большие промежутки времени от зарождения Земли до настоящего времени, а его подразделения ведут хронику некоторых важных событий истории Земли. (На рисунке Ма означает «миллион лет назад».) Земля образовалась около 4,54 миллиарда лет назад, примерно в треть возраста Вселенной , в результате аккреции из солнечной туманности . [4][5][6] Volcanic outgassing probably created the primordial atmosphere and then the ocean, but the early atmosphere contained almost no oxygen. Much of the Earth was molten because of frequent collisions with other bodies which led to extreme volcanism. While the Earth was in its earliest stage (Early Earth), a giant impact collision with a planet-sized body named Theia is thought to have formed the Moon. Over time, the Earth cooled, causing the formation of a solid crust, and allowing liquid water on the surface. In June 2023, scientists reported evidence that the planet Earth may have formed in just three million years, much faster than the 10−100 million years thought earlier.[7][8]

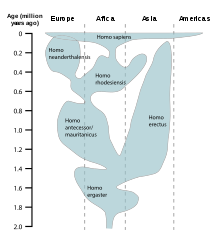

The Hadean eon represents the time before a reliable (fossil) record of life; it began with the formation of the planet and ended 4.0 billion years ago. The following Archean and Proterozoic eons produced the beginnings of life on Earth and its earliest evolution. The succeeding eon is the Phanerozoic, divided into three eras: the Palaeozoic, an era of arthropods, fishes, and the first life on land; the Mesozoic, which spanned the rise, reign, and climactic extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs; and the Cenozoic, which saw the rise of mammals. Recognizable humans emerged at most 2 million years ago, a vanishingly small period on the geological scale.

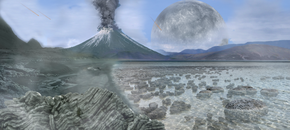

The earliest undisputed evidence of life on Earth dates at least from 3.5 billion years ago,[9][10][11] during the Eoarchean Era, after a geological crust started to solidify following the earlier molten Hadean Eon. There are microbial mat fossils such as stromatolites found in 3.48 billion-year-old sandstone discovered in Western Australia.[12][13][14] Other early physical evidence of a biogenic substance is graphite in 3.7 billion-year-old metasedimentary rocks discovered in southwestern Greenland[15] as well as "remains of biotic life" found in 4.1 billion-year-old rocks in Western Australia.[16][17] According to one of the researchers, "If life arose relatively quickly on Earth … then it could be common in the universe."[16]

Photosynthetic organisms appeared between 3.2 and 2.4 billion years ago and began enriching the atmosphere with oxygen. Life remained mostly small and microscopic until about 580 million years ago, when complex multicellular life arose, developed over time, and culminated in the Cambrian Explosion about 538.8 million years ago. This sudden diversification of life forms produced most of the major phyla known today, and divided the Proterozoic Eon from the Cambrian Period of the Paleozoic Era. It is estimated that 99 percent of all species that ever lived on Earth, over five billion,[18] have gone extinct.[19][20] Estimates on the number of Earth's current species range from 10 million to 14 million,[21] of which about 1.2 million are documented, but over 86 percent have not been described.[22]

The Earth's crust has constantly changed since its formation, as has life since its first appearance. Species continue to evolve, taking on new forms, splitting into daughter species, or going extinct in the face of ever-changing physical environments. The process of plate tectonics continues to shape the Earth's continents and oceans and the life they harbor.

Eons

In geochronology, time is generally measured in mya (million years ago), each unit representing the period of approximately 1,000,000 years in the past. The history of Earth is divided into four great eons, starting 4,540 mya with the formation of the planet. Each eon saw the most significant changes in Earth's composition, climate and life. Each eon is subsequently divided into eras, which in turn are divided into periods, which are further divided into epochs.

| Eon | Time (mya) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Hadean | 4,540–4,000 | The Earth is formed out of debris around the solar protoplanetary disk. There is no life. Temperatures are extremely hot, with frequent volcanic activity and hellish-looking environments (hence the eon's name, which comes from Hades). The atmosphere is nebular. Possible early oceans or bodies of liquid water. The Moon is formed around this time probably due to a protoplanet's collision into Earth. |

| Archean | 4,000–2,500 | Prokaryote life, the first form of life, emerges at the very beginning of this eon, in a process known as abiogenesis. The continents of Ur, Vaalbara and Kenorland may have existed around this time. The atmosphere is composed of volcanic and greenhouse gases. |

| Proterozoic | 2,500–538.8 | The name of this eon means "early life". Eukaryotes, a more complex form of life, emerge, including some forms of multicellular organisms. Bacteria begin producing oxygen, shaping the third and current of Earth's atmospheres. Plants, later animals and possibly earlier forms of fungi form around this time. The early and late phases of this eon may have undergone "Snowball Earth" periods, in which all of the planet suffered below-zero temperatures. The early continents of Columbia, Rodinia and Pannotia, in that order, may have existed in this eon. |

| Phanerozoic | 538.8–present | Complex life, including vertebrates, begin to dominate the Earth's ocean in a process known as the Cambrian explosion. Pangaea forms and later dissolves into Laurasia and Gondwana, which in turn dissolve into the current continents. Gradually, life expands to land and familiar forms of plants, animals and fungi begin appearing, including annelids, insects and reptiles, hence the eon's name, which means "visible life". Several mass extinctions occur, among which birds, the descendants of non-avian dinosaurs, and more recently mammals emerge. Modern animals—including humans—evolve at the most recent phases of this eon. |

Geologic time scale

The history of the Earth can be organized chronologically according to the geologic time scale, which is split into intervals based on stratigraphic analysis.[2][23]The following five timelines show the geologic time scale to scale. The first shows the entire time from the formation of the Earth to the present, but this gives little space for the most recent eon. The second timeline shows an expanded view of the most recent eon. In a similar way, the most recent era is expanded in the third timeline, the most recent period is expanded in the fourth timeline, and the most recent epoch is expanded in the fifth timeline.

Horizontal scale is Millions of years (above timelines) / Thousands of years (below timeline)

Solar System formation

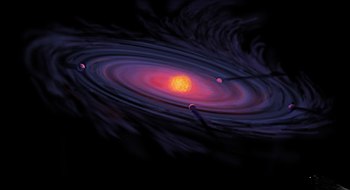

The standard model for the formation of the Solar System (including the Earth) is the solar nebula hypothesis.[24] In this model, the Solar System formed from a large, rotating cloud of interstellar dust and gas called the solar nebula. It was composed of hydrogen and helium created shortly after the Big Bang 13.8 Ga (billion years ago) and heavier elements ejected by supernovae. About 4.5 Ga, the nebula began a contraction that may have been triggered by the shock wave from a nearby supernova.[25] A shock wave would have also made the nebula rotate. As the cloud began to accelerate, its angular momentum, gravity, and inertia flattened it into a protoplanetary disk perpendicular to its axis of rotation. Small perturbations due to collisions and the angular momentum of other large debris created the means by which kilometer-sized protoplanets began to form, orbiting the nebular center.[26]

The center of the nebula, not having much angular momentum, collapsed rapidly, the compression heating it until nuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium began. After more contraction, a T Tauri star ignited and evolved into the Sun. Meanwhile, in the outer part of the nebula gravity caused matter to condense around density perturbations and dust particles, and the rest of the protoplanetary disk began separating into rings. In a process known as runaway accretion, successively larger fragments of dust and debris clumped together to form planets.[26] Earth formed in this manner about 4.54 billion years ago (with an uncertainty of 1%)[27][28][4] and was largely completed within 10–20 million years.[29] In June 2023, scientists reported evidence that the planet Earth may have formed in just three million years, much faster than the 10−100 million years thought earlier.[7][8] Nonetheless, the solar wind of the newly formed T Tauri star cleared out most of the material in the disk that had not already condensed into larger bodies. The same process is expected to produce accretion disks around virtually all newly forming stars in the universe, some of which yield planets.[30]

The proto-Earth grew by accretion until its interior was hot enough to melt the heavy, siderophile metals. Having higher densities than the silicates, these metals sank. This so-called iron catastrophe resulted in the separation of a primitive mantle and a (metallic) core only 10 million years after the Earth began to form, producing the layered structure of Earth and setting up the formation of Earth's magnetic field.[31] J.A. Jacobs [32] was the first to suggest that Earth's inner core—a solid center distinct from the liquid outer core—is freezing and growing out of the liquid outer core due to the gradual cooling of Earth's interior (about 100 degrees Celsius per billion years[33]).

Hadean and Archean Eons

The first eon in Earth's history, the Hadean, begins with the Earth's formation and is followed by the Archean eon at 3.8 Ga.[2]: 145 The oldest rocks found on Earth date to about 4.0 Ga, and the oldest detrital zircon crystals in rocks to about 4.4 Ga,[34][35][36] soon after the formation of the Earth's crust and the Earth itself. The giant impact hypothesis for the Moon's formation states that shortly after formation of an initial crust, the proto-Earth was impacted by a smaller protoplanet, which ejected part of the mantle and crust into space and created the Moon.[37][38][39]

From crater counts on other celestial bodies, it is inferred that a period of intense meteorite impacts, called the Late Heavy Bombardment, began about 4.1 Ga, and concluded around 3.8 Ga, at the end of the Hadean.[40] In addition, volcanism was severe due to the large heat flow and geothermal gradient.[41] Nevertheless, detrital zircon crystals dated to 4.4 Ga show evidence of having undergone contact with liquid water, suggesting that the Earth already had oceans or seas at that time.[34]

By the beginning of the Archean, the Earth had cooled significantly. Present life forms could not have survived at Earth's surface, because the Archean atmosphere lacked oxygen hence had no ozone layer to block ultraviolet light. Nevertheless, it is believed that primordial life began to evolve by the early Archean, with candidate fossils dated to around 3.5 Ga.[42] Some scientists even speculate that life could have begun during the early Hadean, as far back as 4.4 Ga, surviving the possible Late Heavy Bombardment period in hydrothermal vents below the Earth's surface.[43]

Formation of the Moon

Earth's only natural satellite, the Moon, is larger relative to its planet than any other satellite in the Solar System.[nb 1] During the Apollo program, rocks from the Moon's surface were brought to Earth. Radiometric dating of these rocks shows that the Moon is 4.53 ± 0.01 billion years old,[46] formed at least 30 million years after the Solar System.[47] New evidence suggests the Moon formed even later, 4.48 ± 0.02 Ga, or 70–110 million years after the start of the Solar System.[48]

Theories for the formation of the Moon must explain its late formation as well as the following facts. First, the Moon has a low density (3.3 times that of water, compared to 5.5 for the Earth[49]) and a small metallic core. Second, the Earth and Moon have the same oxygen isotopic signature (relative abundance of the oxygen isotopes). Of the theories proposed to account for these phenomena, one is widely accepted: The giant impact hypothesis proposes that the Moon originated after a body the size of Mars (sometimes named Theia[47]) struck the proto-Earth a glancing blow.[1]: 256 [50][51]

The collision released about 100 million times more energy than the more recent Chicxulub impact that is believed to have caused the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs. It was enough to vaporize some of the Earth's outer layers and melt both bodies.[50][1]: 256 A portion of the mantle material was ejected into orbit around the Earth. The giant impact hypothesis predicts that the Moon was depleted of metallic material,[52] explaining its abnormal composition.[53] The ejecta in orbit around the Earth could have condensed into a single body within a couple of weeks. Under the influence of its own gravity, the ejected material became a more spherical body: the Moon.[54]

First continents

Mantle convection, the process that drives plate tectonics, is a result of heat flow from the Earth's interior to the Earth's surface.[55]: 2 It involves the creation of rigid tectonic plates at mid-oceanic ridges. These plates are destroyed by subduction into the mantle at subduction zones. During the early Archean (about 3.0 Ga) the mantle was much hotter than today, probably around 1,600 °C (2,910 °F),[56]: 82 so convection in the mantle was faster. Although a process similar to present-day plate tectonics did occur, this would have gone faster too. It is likely that during the Hadean and Archean, subduction zones were more common, and therefore tectonic plates were smaller.[1]: 258 [57]

The initial crust, which formed when the Earth's surface first solidified, totally disappeared from a combination of this fast Hadean plate tectonics and the intense impacts of the Late Heavy Bombardment. However, it is thought that it was basaltic in composition, like today's oceanic crust, because little crustal differentiation had yet taken place.[1]: 258 The first larger pieces of continental crust, which is a product of differentiation of lighter elements during partial melting in the lower crust, appeared at the end of the Hadean, about 4.0 Ga. What is left of these first small continents are called cratons. These pieces of late Hadean and early Archean crust form the cores around which today's continents grew.[58]

The oldest rocks on Earth are found in the North American craton of Canada. They are tonalites from about 4.0 Ga. They show traces of metamorphism by high temperature, but also sedimentary grains that have been rounded by erosion during transport by water, showing that rivers and seas existed then.[59] Cratons consist primarily of two alternating types of terranes. The first are so-called greenstone belts, consisting of low-grade metamorphosed sedimentary rocks. These "greenstones" are similar to the sediments today found in oceanic trenches, above subduction zones. For this reason, greenstones are sometimes seen as evidence for subduction during the Archean. The second type is a complex of felsic magmatic rocks. These rocks are mostly tonalite, trondhjemite or granodiorite, types of rock similar in composition to granite (hence such terranes are called TTG-terranes). TTG-complexes are seen as the relicts of the first continental crust, formed by partial melting in basalt.[60]: Chapter 5

Oceans and atmosphere

Earth is often described as having had three atmospheres. The first atmosphere, captured from the solar nebula, was composed of light (atmophile) elements from the solar nebula, mostly hydrogen and helium. A combination of the solar wind and Earth's heat would have driven off this atmosphere, as a result of which the atmosphere is now depleted of these elements compared to cosmic abundances.[61] After the impact which created the Moon, the molten Earth released volatile gases; and later more gases were released by volcanoes, completing a second atmosphere rich in greenhouse gases but poor in oxygen. [1]: 256 Finally, the third atmosphere, rich in oxygen, emerged when bacteria began to produce oxygen about 2.8 Ga.[62]: 83–84, 116–117

In early models for the formation of the atmosphere and ocean, the second atmosphere was formed by outgassing of volatiles from the Earth's interior. Now it is considered likely that many of the volatiles were delivered during accretion by a process known as impact degassing in which incoming bodies vaporize on impact. The ocean and atmosphere would, therefore, have started to form even as the Earth formed.[66] The new atmosphere probably contained water vapor, carbon dioxide, nitrogen, and smaller amounts of other gases.[67]

Planetesimals at a distance of 1 astronomical unit (AU), the distance of the Earth from the Sun, probably did not contribute any water to the Earth because the solar nebula was too hot for ice to form and the hydration of rocks by water vapor would have taken too long.[66][68] The water must have been supplied by meteorites from the outer asteroid belt and some large planetary embryos from beyond 2.5 AU.[66][69] Comets may also have contributed. Though most comets are today in orbits farther away from the Sun than Neptune, computer simulations show that they were originally far more common in the inner parts of the Solar System.[59]: 130–132

As the Earth cooled, clouds formed. Rain created the oceans. Recent evidence suggests the oceans may have begun forming as early as 4.4 Ga.[34] By the start of the Archean eon, they already covered much of the Earth. This early formation has been difficult to explain because of a problem known as the faint young Sun paradox. Stars are known to get brighter as they age, and the Sun has become 30% brighter since its formation 4.5 billion years ago.[70] Many models indicate that the early Earth should have been covered in ice.[71][66] A likely solution is that there was enough carbon dioxide and methane to produce a greenhouse effect. The carbon dioxide would have been produced by volcanoes and the methane by early microbes. It is hypothesized that there also existed an organic haze created from the products of methane photolysis that caused an anti-greenhouse effect as well.[72] Another greenhouse gas, ammonia, would have been ejected by volcanos but quickly destroyed by ultraviolet radiation.[62]: 83

Origin of life

−4500 — – — – −4000 — – — – −3500 — – — – −3000 — – — – −2500 — – — – −2000 — – — – −1500 — – — – −1000 — – — – −500 — – — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

One of the reasons for interest in the early atmosphere and ocean is that they form the conditions under which life first arose. There are many models, but little consensus, on how life emerged from non-living chemicals; chemical systems created in the laboratory fall well short of the minimum complexity for a living organism.[73][74]

The first step in the emergence of life may have been chemical reactions that produced many of the simpler organic compounds, including nucleobases and amino acids, that are the building blocks of life. An experiment in 1953 by Stanley Miller and Harold Urey showed that such molecules could form in an atmosphere of water, methane, ammonia and hydrogen with the aid of sparks to mimic the effect of lightning.[75] Although atmospheric composition was probably different from that used by Miller and Urey, later experiments with more realistic compositions also managed to synthesize organic molecules.[76] Computer simulations show that extraterrestrial organic molecules could have formed in the protoplanetary disk before the formation of the Earth.[77]

Additional complexity could have been reached from at least three possible starting points: self-replication, an organism's ability to produce offspring that are similar to itself; metabolism, its ability to feed and repair itself; and external cell membranes, which allow food to enter and waste products to leave, but exclude unwanted substances.[78]

Replication first: RNA world

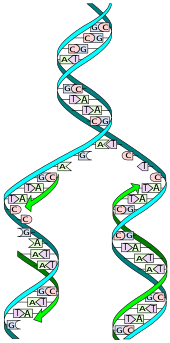

Even the simplest members of the three modern domains of life use DNA to record their "recipes" and a complex array of RNA and protein molecules to "read" these instructions and use them for growth, maintenance, and self-replication.

The discovery that a kind of RNA molecule called a ribozyme can catalyze both its own replication and the construction of proteins led to the hypothesis that earlier life-forms were based entirely on RNA.[79] They could have formed an RNA world in which there were individuals but no species, as mutations and horizontal gene transfers would have meant that the offspring in each generation were quite likely to have different genomes from those that their parents started with.[80] RNA would later have been replaced by DNA, which is more stable and therefore can build longer genomes, expanding the range of capabilities a single organism can have.[81] Ribozymes remain as the main components of ribosomes, the "protein factories" of modern cells.[82]

Although short, self-replicating RNA molecules have been artificially produced in laboratories,[83] doubts have been raised about whether natural non-biological synthesis of RNA is possible.[84][85][86] The earliest ribozymes may have been formed of simpler nucleic acids such as PNA, TNA or GNA, which would have been replaced later by RNA.[87][88] Other pre-RNA replicators have been posited, including crystals[89]: 150 and even quantum systems.[90]

In 2003 it was proposed that porous metal sulfide precipitates would assist RNA synthesis at about 100 °C (212 °F) and at ocean-bottom pressures near hydrothermal vents. In this hypothesis, the proto-cells would be confined in the pores of the metal substrate until the later development of lipid membranes.[91]

Metabolism first: iron–sulfur world

Another long-standing hypothesis is that the first life was composed of protein molecules. Amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, are easily synthesized in plausible prebiotic conditions, as are small peptides (polymers of amino acids) that make good catalysts.[92]: 295–297 A series of experiments starting in 1997 showed that amino acids and peptides could form in the presence of carbon monoxide and hydrogen sulfide with iron sulfide and nickel sulfide as catalysts. Most of the steps in their assembly required temperatures of about 100 °C (212 °F) and moderate pressures, although one stage required 250 °C (482 °F) and a pressure equivalent to that found under 7 kilometers (4.3 mi) of rock. Hence, self-sustaining synthesis of proteins could have occurred near hydrothermal vents.[93]

A difficulty with the metabolism-first scenario is finding a way for organisms to evolve. Without the ability to replicate as individuals, aggregates of molecules would have "compositional genomes" (counts of molecular species in the aggregate) as the target of natural selection. However, a recent model shows that such a system is unable to evolve in response to natural selection.[94]

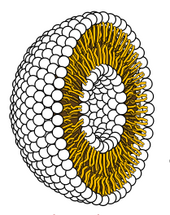

Membranes first: Lipid world

It has been suggested that double-walled "bubbles" of lipids like those that form the external membranes of cells may have been an essential first step.[95] Experiments that simulated the conditions of the early Earth have reported the formation of lipids, and these can spontaneously form liposomes, double-walled "bubbles", and then reproduce themselves. Although they are not intrinsically information-carriers as nucleic acids are, they would be subject to natural selection for longevity and reproduction. Nucleic acids such as RNA might then have formed more easily within the liposomes than they would have outside.[96]

The clay theory

Some clays, notably montmorillonite, have properties that make them plausible accelerators for the emergence of an RNA world: they grow by self-replication of their crystalline pattern, are subject to an analog of natural selection (as the clay "species" that grows fastest in a particular environment rapidly becomes dominant), and can catalyze the formation of RNA molecules.[97] Although this idea has not become the scientific consensus, it still has active supporters.[98]: 150–158 [89]

Research in 2003 reported that montmorillonite could also accelerate the conversion of fatty acids into "bubbles", and that the bubbles could encapsulate RNA attached to the clay. Bubbles can then grow by absorbing additional lipids and dividing. The formation of the earliest cells may have been aided by similar processes.[99]

A similar hypothesis presents self-replicating iron-rich clays as the progenitors of nucleotides, lipids and amino acids.[100]

Last universal common ancestor

It is believed that of this multiplicity of protocells, only one line survived. Current phylogenetic evidence suggests that the last universal ancestor (LUA) lived during the early Archean eon, perhaps 3.5 Ga or earlier.[101][102] This LUA cell is the ancestor of all life on Earth today. It was probably a prokaryote, possessing a cell membrane and probably ribosomes, but lacking a nucleus or membrane-bound organelles such as mitochondria or chloroplasts. Like modern cells, it used DNA as its genetic code, RNA for information transfer and protein synthesis, and enzymes to catalyze reactions. Some scientists believe that instead of a single organism being the last universal common ancestor, there were populations of organisms exchanging genes by lateral gene transfer.[103]

Proterozoic Eon

The Proterozoic eon lasted from 2.5 Ga to 538.8 Ma (million years) ago.[105] In this time span, cratons grew into continents with modern sizes. The change to an oxygen-rich atmosphere was a crucial development. Life developed from prokaryotes into eukaryotes and multicellular forms. The Proterozoic saw a couple of severe ice ages called Snowball Earths. After the last Snowball Earth about 600 Ma, the evolution of life on Earth accelerated. About 580 Ma, the Ediacaran biota formed the prelude for the Cambrian Explosion.[citation needed]

Oxygen revolution

The earliest cells absorbed energy and food from the surrounding environment. They used fermentation, the breakdown of more complex compounds into less complex compounds with less energy, and used the energy so liberated to grow and reproduce. Fermentation can only occur in an anaerobic (oxygen-free) environment. The evolution of photosynthesis made it possible for cells to derive energy from the Sun.[106]: 377

Most of the life that covers the surface of the Earth depends directly or indirectly on photosynthesis. The most common form, oxygenic photosynthesis, turns carbon dioxide, water, and sunlight into food. It captures the energy of sunlight in energy-rich molecules such as ATP, which then provide the energy to make sugars. To supply the electrons in the circuit, hydrogen is stripped from water, leaving oxygen as a waste product.[107] Some organisms, including purple bacteria and green sulfur bacteria, use an anoxygenic form of photosynthesis that uses alternatives to hydrogen stripped from water as electron donors; examples are hydrogen sulfide, sulfur and iron. Such extremophile organisms are restricted to otherwise inhospitable environments such as hot springs and hydrothermal vents.[106]: 379–382 [108]

The simpler anoxygenic form arose about 3.8 Ga, not long after the appearance of life. The timing of oxygenic photosynthesis is more controversial; it had certainly appeared by about 2.4 Ga, but some researchers put it back as far as 3.2 Ga.[107] The latter "probably increased global productivity by at least two or three orders of magnitude".[109][110] Among the oldest remnants of oxygen-producing lifeforms are fossil stromatolites.[109][110][111]

At first, the released oxygen was bound up with limestone, iron, and other minerals. The oxidized iron appears as red layers in geological strata called banded iron formations that formed in abundance during the Siderian period (between 2500 Ma and 2300 Ma).[2]: 133 When most of the exposed readily reacting minerals were oxidized, oxygen finally began to accumulate in the atmosphere. Though each cell only produced a minute amount of oxygen, the combined metabolism of many cells over a vast time transformed Earth's atmosphere to its current state. This was Earth's third atmosphere.[112]: 50–51 [62]: 83–84, 116–117

Some oxygen was stimulated by solar ultraviolet radiation to form ozone, which collected in a layer near the upper part of the atmosphere. The ozone layer absorbed, and still absorbs, a significant amount of the ultraviolet radiation that once had passed through the atmosphere. It allowed cells to colonize the surface of the ocean and eventually the land: without the ozone layer, ultraviolet radiation bombarding land and sea would have caused unsustainable levels of mutation in exposed cells.[113][59]: 219–220

Photosynthesis had another major impact. Oxygen was toxic; much life on Earth probably died out as its levels rose in what is known as the oxygen catastrophe. Resistant forms survived and thrived, and some developed the ability to use oxygen to increase their metabolism and obtain more energy from the same food.[113]

Snowball Earth

The natural evolution of the Sun made it progressively more luminous during the Archean and Proterozoic eons; the Sun's luminosity increases 6% every billion years.[59]: 165 As a result, the Earth began to receive more heat from the Sun in the Proterozoic eon. However, the Earth did not get warmer. Instead, the geological record suggests it cooled dramatically during the early Proterozoic. Glacial deposits found in South Africa date back to 2.2 Ga, at which time, based on paleomagnetic evidence, they must have been located near the equator. Thus, this glaciation, known as the Huronian glaciation, may have been global. Some scientists suggest this was so severe that the Earth was frozen over from the poles to the equator, a hypothesis called Snowball Earth.[114]

The Huronian ice age might have been caused by the increased oxygen concentration in the atmosphere, which caused the decrease of methane (CH4) in the atmosphere. Methane is a strong greenhouse gas, but with oxygen it reacts to form CO2, a less effective greenhouse gas.[59]: 172 When free oxygen became available in the atmosphere, the concentration of methane could have decreased dramatically, enough to counter the effect of the increasing heat flow from the Sun.[115]

However, the term Snowball Earth is more commonly used to describe later extreme ice ages during the Cryogenian period. There were four periods, each lasting about 10 million years, between 750 and 580 million years ago, when the Earth is thought to have been covered with ice apart from the highest mountains, and average temperatures were about −50 °C (−58 °F).[116] The snowball may have been partly due to the location of the supercontinent Rodinia straddling the Equator. Carbon dioxide combines with rain to weather rocks to form carbonic acid, which is then washed out to sea, thus extracting the greenhouse gas from the atmosphere. When the continents are near the poles, the advance of ice covers the rocks, slowing the reduction in carbon dioxide, but in the Cryogenian the weathering of Rodinia was able to continue unchecked until the ice advanced to the tropics. The process may have finally been reversed by the emission of carbon dioxide from volcanoes or the destabilization of methane gas hydrates. According to the alternative Slushball Earth theory, even at the height of the ice ages there was still open water at the Equator.[117][118]

Emergence of eukaryotes

Modern taxonomy classifies life into three domains. The time of their origin is uncertain. The Bacteria domain probably first split off from the other forms of life (sometimes called Neomura), but this supposition is controversial. Soon after this, by 2 Ga,[119] the Neomura split into the Archaea and the Eukaryota. Eukaryotic cells (Eukaryota) are larger and more complex than prokaryotic cells (Bacteria and Archaea), and the origin of that complexity is only now becoming known.[120] The earliest fossils possessing features typical of fungi date to the Paleoproterozoic era, some 2.4 Ga ago; these multicellular benthic organisms had filamentous structures capable of anastomosis.[121]

Around this time, the first proto-mitochondrion was formed. A bacterial cell related to today's Rickettsia,[122] which had evolved to metabolize oxygen, entered a larger prokaryotic cell, which lacked that capability. Perhaps the large cell attempted to digest the smaller one but failed (possibly due to the evolution of prey defenses). The smaller cell may have tried to parasitize the larger one. In any case, the smaller cell survived inside the larger cell. Using oxygen, it metabolized the larger cell's waste products and derived more energy. Part of this excess energy was returned to the host. The smaller cell replicated inside the larger one. Soon, a stable symbiosis developed between the large cell and the smaller cells inside it. Over time, the host cell acquired some genes from the smaller cells, and the two kinds became dependent on each other: the larger cell could not survive without the energy produced by the smaller ones, and these, in turn, could not survive without the raw materials provided by the larger cell. The whole cell is now considered a single organism, and the smaller cells are classified as organelles called mitochondria.[123]

A similar event occurred with photosynthetic cyanobacteria[124] entering large heterotrophic cells and becoming chloroplasts.[112]: 60–61 [125]: 536–539 Probably as a result of these changes, a line of cells capable of photosynthesis split off from the other eukaryotes more than 1 billion years ago. There were probably several such inclusion events. Besides the well-established endosymbiotic theory of the cellular origin of mitochondria and chloroplasts, there are theories that cells led to peroxisomes, spirochetes led to cilia and flagella, and that perhaps a DNA virus led to the cell nucleus,[126][127] though none of them are widely accepted.[128]

Archaeans, bacteria, and eukaryotes continued to diversify and to become more complex and better adapted to their environments. Each domain repeatedly split into multiple lineages. Around 1.1 Ga, the plant, animal, and fungi lines had split, though they still existed as solitary cells. Some of these lived in colonies, and gradually a division of labor began to take place; for instance, cells on the periphery might have started to assume different roles from those in the interior. Although the division between a colony with specialized cells and a multicellular organism is not always clear, around 1 billion years ago[129], the first multicellular plants emerged, probably green algae.[130] Possibly by around 900 Ma[125]: 488 true multicellularity had also evolved in animals.[131]

At first, it probably resembled today's sponges, which have totipotent cells that allow a disrupted organism to reassemble itself.[125]: 483–487 As the division of labor was completed in the different lineages of multicellular organisms, cells became more specialized and more dependent on each other.[132]

Supercontinents in the Proterozoic

Reconstructions of tectonic plate movement in the past 250 million years (the Cenozoic and Mesozoic eras) can be made reliably using fitting of continental margins, ocean floor magnetic anomalies and paleomagnetic poles. No ocean crust dates back further than that, so earlier reconstructions are more difficult. Paleomagnetic poles are supplemented by geologic evidence such as orogenic belts, which mark the edges of ancient plates, and past distributions of flora and fauna. The further back in time, the scarcer and harder to interpret the data get and the more uncertain the reconstructions.[133]: 370

Throughout the history of the Earth, there have been times when continents collided and formed a supercontinent, which later broke up into new continents. About 1000 to 830 Ma, most continental mass was united in the supercontinent Rodinia.[133]: 370 [134] Rodinia may have been preceded by Early-Middle Proterozoic continents called Nuna and Columbia.[133]: 374 [135][136]

After the break-up of Rodinia about 800 Ma, the continents may have formed another short-lived supercontinent around 550 Ma. The hypothetical supercontinent is sometimes referred to as Pannotia or Vendia.[137]: 321–322 The evidence for it is a phase of continental collision known as the Pan-African orogeny, which joined the continental masses of current-day Africa, South America, Antarctica and Australia. The existence of Pannotia depends on the timing of the rifting between Gondwana (which included most of the landmass now in the Southern Hemisphere, as well as the Arabian Peninsula and the Indian subcontinent) and Laurentia (roughly equivalent to current-day North America).[133]: 374 It is at least certain that by the end of the Proterozoic eon, most of the continental mass lay united in a position around the south pole.[138]

Late Proterozoic climate and life

The end of the Proterozoic saw at least two Snowball Earths, so severe that the surface of the oceans may have been completely frozen. This happened about 716.5 and 635 Ma, in the Cryogenian period.[139] The intensity and mechanism of both glaciations are still under investigation and harder to explain than the early Proterozoic Snowball Earth.[140]Most paleoclimatologists think the cold episodes were linked to the formation of the supercontinent Rodinia.[141] Because Rodinia was centered on the equator, rates of chemical weathering increased and carbon dioxide (CO2) was taken from the atmosphere. Because CO2 is an important greenhouse gas, climates cooled globally.[142]

In the same way, during the Snowball Earths most of the continental surface was covered with permafrost, which decreased chemical weathering again, leading to the end of the glaciations. An alternative hypothesis is that enough carbon dioxide escaped through volcanic outgassing that the resulting greenhouse effect raised global temperatures.[141] Increased volcanic activity resulted from the break-up of Rodinia at about the same time.[143]

The Cryogenian period was followed by the Ediacaran period, which was characterized by a rapid development of new multicellular lifeforms.[144] Whether there is a connection between the end of the severe ice ages and the increase in diversity of life is not clear, but it does not seem coincidental. The new forms of life, called Ediacara biota, were larger and more diverse than ever. Though the taxonomy of most Ediacaran life forms is unclear, some were ancestors of groups of modern life.[145] Important developments were the origin of muscular and neural cells. None of the Ediacaran fossils had hard body parts like skeletons. These first appear after the boundary between the Proterozoic and Phanerozoic eons or Ediacaran and Cambrian periods.[146]

Phanerozoic Eon

The Phanerozoic is the current eon on Earth, which started approximately 538.8 million years ago. It consists of three eras: The Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic,[105] and is the time when multi-cellular life greatly diversified into almost all the organisms known today.[147]

The Paleozoic ("old life") era was the first and longest era of the Phanerozoic eon, lasting from 538.8 to 251.9 Ma.[105] During the Paleozoic, many modern groups of life came into existence. Life colonized the land, first plants, then animals. Two major extinctions occurred. The continents formed at the break-up of Pannotia and Rodinia at the end of the Proterozoic slowly moved together again, forming the supercontinent Pangaea in the late Paleozoic.[148]

The Mesozoic ("middle life") era lasted from 251.9 Ma to 66 Ma.[105] It is subdivided into the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous periods. The era began with the Permian–Triassic extinction event, the most severe extinction event in the fossil record; 95% of the species on Earth died out.[149] It ended with the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs.[150]

The Cenozoic ("new life") era began at 66 Ma, and is subdivided into the Paleogene, Neogene, and Quaternary periods. These three periods are further split into seven subdivisions, with the Paleogene composed of The Paleocene, Eocene, and Oligocene, the Neogene divided into the Miocene, Pliocene, and the Quaternary composed of the Pleistocene, and Holocene.[151] Mammals, birds, amphibians, crocodilians, turtles, and lepidosaurs survived the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event that killed off the non-avian dinosaurs and many other forms of life, and this is the era during which they diversified into their modern forms.[152]

Tectonics, paleogeography and climate

At the end of the Proterozoic, the supercontinent Pannotia had broken apart into the smaller continents Laurentia, Baltica, Siberia and Gondwana.[153] During periods when continents move apart, more oceanic crust is formed by volcanic activity. Because young volcanic crust is relatively hotter and less dense than old oceanic crust, the ocean floors rise during such periods. This causes the sea level to rise. Therefore, in the first half of the Paleozoic, large areas of the continents were below sea level.[citation needed]

Early Paleozoic climates were warmer than today, but the end of the Ordovician saw a short ice age during which glaciers covered the south pole, where the huge continent Gondwana was situated. Traces of glaciation from this period are only found on former Gondwana. During the Late Ordovician ice age, a few mass extinctions took place, in which many brachiopods, trilobites, Bryozoa and corals disappeared. These marine species could probably not contend with the decreasing temperature of the sea water.[154]

The continents Laurentia and Baltica collided between 450 and 400 Ma, during the Caledonian Orogeny, to form Laurussia (also known as Euramerica).[155] Traces of the mountain belt this collision caused can be found in Scandinavia, Scotland, and the northern Appalachians. In the Devonian period (416–359 Ma)[23] Gondwana and Siberia began to move towards Laurussia. The collision of Siberia with Laurussia caused the Uralian Orogeny, the collision of Gondwana with Laurussia is called the Variscan or Hercynian Orogeny in Europe or the Alleghenian Orogeny in North America. The latter phase took place during the Carboniferous period (359–299 Ma)[23] and resulted in the formation of the last supercontinent, Pangaea.[60]

By 180 Ma, Pangaea broke up into Laurasia and Gondwana.[citation needed]

Cambrian explosion

The rate of the evolution of life as recorded by fossils accelerated in the Cambrian period (542–488 Ma).[23] The sudden emergence of many new species, phyla, and forms in this period is called the Cambrian Explosion. It was a form of adaptive radiation, where vacant niches left by the extinct Ediacaran biota were filled up by the emergence of new phyla.[156] The biological fomenting in the Cambrian Explosion was unprecedented before and since that time.[59]: 229 Whereas the Ediacaran life forms appear yet primitive and not easy to put in any modern group, at the end of the Cambrian most modern phyla were already present. The development of hard body parts such as shells, skeletons or exoskeletons in animals like molluscs, echinoderms, crinoids and arthropods (a well-known group of arthropods from the lower Paleozoic are the trilobites) made the preservation and fossilization of such life forms easier than those of their Proterozoic ancestors. For this reason, much more is known about life in and after the Cambrian than about that of older periods. Some of these Cambrian groups appear complex but are seemingly quite different from modern life; examples are Anomalocaris and Haikouichthys. More recently, however, these seem to have found a place in modern classification.[157]

During the Cambrian, the first vertebrate animals, among them the first fishes, had appeared.[125]: 357 A creature that could have been the ancestor of the fishes, or was probably closely related to it, was Pikaia. It had a primitive notochord, a structure that could have developed into a vertebral column later. The first fishes with jaws (Gnathostomata) appeared during the next geological period, the Ordovician. The colonisation of new niches resulted in massive body sizes. In this way, fishes with increasing sizes evolved during the early Paleozoic, such as the titanic placoderm Dunkleosteus, which could grow 7 meters (23 ft) long.[158]

The diversity of life forms did not increase greatly because of a series of mass extinctions that define widespread biostratigraphic units called biomeres.[159] After each extinction pulse, the continental shelf regions were repopulated by similar life forms that may have been evolving slowly elsewhere.[160] By the late Cambrian, the trilobites had reached their greatest diversity and dominated nearly all fossil assemblages.[161]: 34

Colonization of land

Oxygen accumulation from photosynthesis resulted in the formation of an ozone layer that absorbed much of the Sun's ultraviolet radiation, meaning unicellular organisms that reached land were less likely to die, and prokaryotes began to multiply and become better adapted to survival out of the water. Prokaryote lineages had probably colonized the land as early as 3 Ga[162][163] even before the origin of the eukaryotes. For a long time, the land remained barren of multicellular organisms. The supercontinent Pannotia formed around 600 Ma and then broke apart a short 50 million years later.[164] Fish, the earliest vertebrates, evolved in the oceans around 530 Ma.[125]: 354 A major extinction event occurred near the end of the Cambrian period,[165] which ended 488 Ma.[166]

Several hundred million years ago, plants (probably resembling algae) and fungi started growing at the edges of the water, and then out of it.[167]: 138–140 The oldest fossils of land fungi and plants date to 480–460 Ma, though molecular evidence suggests the fungi may have colonized the land as early as 1000 Ma and the plants 700 Ma.[168] Initially remaining close to the water's edge, mutations and variations resulted in further colonization of this new environment. The timing of the first animals to leave the oceans is not precisely known: the oldest clear evidence is of arthropods on land around 450 Ma,[169] perhaps thriving and becoming better adapted due to the vast food source provided by the terrestrial plants. There is also unconfirmed evidence that arthropods may have appeared on land as early as 530 Ma.[170]

Evolution of tetrapods

At the end of the Ordovician period, 443 Ma,[23] additional extinction events occurred, perhaps due to a concurrent ice age.[154] Around 380 to 375 Ma, the first tetrapods evolved from fish.[171] Fins evolved to become limbs that the first tetrapods used to lift their heads out of the water to breathe air. This would let them live in oxygen-poor water, or pursue small prey in shallow water.[171] They may have later ventured on land for brief periods. Eventually, some of them became so well adapted to terrestrial life that they spent their adult lives on land, although they hatched in the water and returned to lay their eggs. This was the origin of the amphibians. About 365 Ma, another period of extinction occurred, perhaps as a result of global cooling.[172] Plants evolved seeds, which dramatically accelerated their spread on land, around this time (by approximately 360 Ma).[173][174]

About 20 million years later (340 Ma[125]: 293–296 ), the amniotic egg evolved, which could be laid on land, giving a survival advantage to tetrapod embryos. This resulted in the divergence of amniotes from amphibians. Another 30 million years (310 Ma[125]: 254–256 ) saw the divergence of the synapsids (including mammals) from the sauropsids (including birds and reptiles). Other groups of organisms continued to evolve, and lines diverged—in fish, insects, bacteria, and so on—but less is known of the details.[citation needed]

After yet another, the most severe extinction of the period (251~250 Ma), around 230 Ma, dinosaurs split off from their reptilian ancestors.[175] The Triassic–Jurassic extinction event at 200 Ma spared many of the dinosaurs,[23][176] and they soon became dominant among the vertebrates. Though some mammalian lines began to separate during this period, existing mammals were probably small animals resembling shrews.[125]: 169

The boundary between avian and non-avian dinosaurs is not clear, but Archaeopteryx, traditionally considered one of the first birds, lived around 150 Ma.[177]

The earliest evidence for the angiosperms evolving flowers is during the Cretaceous period, some 20 million years later (132 Ma).[178]

Extinctions

The first of five great mass extinctions was the Ordovician-Silurian extinction. Its possible cause was the intense glaciation of Gondwana, which eventually led to a Snowball Earth. 60% of marine invertebrates became extinct and 25% of all families.[citation needed]

The second mass extinction was the Late Devonian extinction, probably caused by the evolution of trees, which could have led to the depletion of greenhouse gases (like CO2) or the eutrophication of water. 70% of all species became extinct.[179]

The third mass extinction was the Permian-Triassic, or the Great Dying, event was possibly caused by some combination of the Siberian Traps volcanic event, an asteroid impact, methane hydrate gasification, sea level fluctuations, and a major anoxic event. Either the proposed Wilkes Land crater[180] in Antarctica or Bedout structure off the northwest coast of Australia may indicate an impact connection with the Permian-Triassic extinction. But it remains uncertain whether either these or other proposed Permian-Triassic boundary craters are either real impact craters or even contemporaneous with the Permian-Triassic extinction event. This was by far the deadliest extinction ever, with about 57% of all families and 83% of all genera killed.[181][182]

The fourth mass extinction was the Triassic-Jurassic extinction event in which almost all synapsids and archosaurs became extinct, probably due to new competition from dinosaurs.[183]

The fifth and most recent mass extinction was the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event. In 66 Ma, a 10-kilometer (6.2 mi) asteroid struck Earth just off the Yucatán Peninsula—somewhere in the southwestern tip of then Laurasia—where the Chicxulub crater is today. This ejected vast quantities of particulate matter and vapor into the air that occluded sunlight, inhibiting photosynthesis. 75% of all life, including the non-avian dinosaurs, became extinct,[184] marking the end of the Cretaceous period and Mesozoic era.[citation needed]

Diversification of mammals

The first true mammals evolved in the shadows of dinosaurs and other large archosaurs that filled the world by the late Triassic. The first mammals were very small, and were probably nocturnal to escape predation. Mammal diversification truly began only after the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event.[185] By the early Paleocene the Earth recovered from the extinction, and mammalian diversity increased. Creatures like Ambulocetus took to the oceans to eventually evolve into whales,[186] whereas some creatures, like primates, took to the trees.[187] This all changed during the mid to late Eocene when the circum-Antarctic current formed between Antarctica and Australia which disrupted weather patterns on a global scale. Grassless savanna began to predominate much of the landscape, and mammals such as Andrewsarchus rose up to become the largest known terrestrial predatory mammal ever,[188] and early whales like Basilosaurus took control of the seas. [citation needed]

The evolution of grasses brought a remarkable change to the Earth's landscape, and the new open spaces created pushed mammals to get bigger and bigger. Grass started to expand in the Miocene, and the Miocene is where many modern- day mammals first appeared. Giant ungulates like Paraceratherium and Deinotherium evolved to rule the grasslands. The evolution of grass also brought primates down from the trees, and started human evolution. The first big cats evolved during this time as well.[189] The Tethys Sea was closed off by the collision of Africa and Europe.[190]

The formation of Panama was perhaps the most important geological event to occur in the last 60 million years. Atlantic and Pacific currents were closed off from each other, which caused the formation of the Gulf Stream, which made Europe warmer. The land bridge allowed the isolated creatures of South America to migrate over to North America, and vice versa.[191] Various species migrated south, leading to the presence in South America of llamas, the spectacled bear, kinkajous and jaguars.[citation needed]

Three million years ago saw the start of the Pleistocene epoch, which featured dramatic climatic changes due to the ice ages. The ice ages led to the evolution of modern man in Saharan Africa and expansion. The mega-fauna that dominated fed on grasslands that, by now, had taken over much of the subtropical world. The large amounts of water held in the ice allowed for various bodies of water to shrink and sometimes disappear such as the North Sea and the Bering Strait. It is believed by many that a huge migration took place along Beringia which is why, today, there are camels (which evolved and became extinct in North America), horses (which evolved and became extinct in North America), and Native Americans. The ending of the last ice age coincided with the expansion of man, along with a massive die out of ice age mega-fauna. This extinction is nicknamed "the Sixth Extinction".

Human evolution

−10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — | ( О. praegens ) ( О. тугененсис ) ( Ар. кадабба ) ( Ар. ramidus ) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Маленькая африканская обезьяна, жившая около 6 млн лет назад, была последним животным, чьи потомки будут включать как современных людей, так и их ближайших родственников, шимпанзе . [101] [125] : 100–101 Только две ветви его генеалогического древа имеют выживших потомков. Очень скоро после раскола, по до сих пор неясным причинам, обезьяны одной ветви развили способность прямоходить . [125] : 95–99 Размер мозга первые животные, отнесенные к роду Homo . быстро увеличивался, и через 2 млн лет назад появились [167] : 300 Примерно в то же время другая ветвь разделилась на предков обыкновенного шимпанзе и предков бонобо , поскольку эволюция продолжалась одновременно во всех формах жизни. [125] : 100–101

Способность управлять огнем , вероятно, возникла у Homo erectus (или Homo ergaster ), вероятно, по крайней мере 790 000 лет назад. [192] но, возможно, уже 1,5 млн лет назад. [125] : 67 Использование и открытие управляемого огня могло произойти даже раньше, чем Homo erectus . Огонь, возможно, использовался ранним нижнепалеолитическим ( олдованским ) гоминидом Homo habilis или сильными австралопитеками, такими как парантроп . [193]

Труднее установить происхождение языка ; неясно, мог ли Homo erectus говорить, или эта способность появилась только у Homo sapiens . [125] : 67 Поскольку размер мозга увеличился, дети рождались раньше, прежде чем их головы стали слишком большими, чтобы пройти через таз . В результате они проявляли большую пластичность и, таким образом, обладали повышенной способностью к обучению и требовали более длительного периода зависимости. Социальные навыки стали более сложными, язык — более изощренным, а инструменты — более совершенными. Это способствовало дальнейшему сотрудничеству и интеллектуальному развитию. [195] : 7 Считается, что современные люди ( Homo sapiens ) возникли около 200 000 лет назад или раньше в Африке ; самые старые окаменелости датируются примерно 160 000 лет назад. [196]

Первыми людьми, проявившими признаки духовности, являются неандертальцы (обычно классифицируемые как отдельный вид, не имеющий выживших потомков); они хоронили своих мертвецов, часто без каких-либо следов еды или инструментов. [197] : 17 Однако свидетельства более сложных верований, такие как ранние кроманьонцев наскальные рисунки (вероятно, имеющие магическое или религиозное значение) [197] : 17–19 появился только 32 000 лет назад. [198] Кроманьонцы также оставили после себя каменные фигурки, такие как Венера Виллендорфская , что, вероятно, также символизирует религиозную веру. [197] : 17–19 11 000 лет назад Homo sapiens достиг южной оконечности Южной Америки , последнего из необитаемых континентов (за исключением Антарктиды, которая оставалась неоткрытой до 1820 года нашей эры). [199] Использование инструментов и общение продолжали улучшаться, а межличностные отношения становились все более сложными. [ нужна ссылка ]

История человечества

На протяжении более 90% своей истории Homo Sapiens жили небольшими группами как кочевые охотники-собиратели . [195] : 8 Поскольку язык стал более сложным, способность запоминать и передавать информацию привела, согласно теории, предложенной Ричардом Докинзом , к появлению нового репликатора: мема . [200] Идеи можно было быстро обменивать и передавать из поколения в поколение. Культурная эволюция быстро опередила биологическую эволюцию , и история началась собственно . Между 8500 и 7000 годами до нашей эры люди в Плодородном полумесяце на Ближнем Востоке начали систематическое разведение растений и животных: сельское хозяйство . [201] Это распространилось на соседние регионы и развивалось независимо в других местах, пока большинство Homo sapiens не вели оседлый образ жизни в постоянных поселениях в качестве фермеров. Не все общества отказались от кочевничества, особенно в изолированных районах земного шара, бедных пригодными для одомашнивания видами растений, таких как Австралия . [202] Однако среди тех цивилизаций, которые действительно приняли сельское хозяйство, относительная стабильность и повышенная производительность, обеспечиваемые сельским хозяйством, позволили населению расти. [ нужна ссылка ]

Сельское хозяйство оказало большое влияние; люди начали влиять на окружающую среду как никогда раньше. Избыток еды позволил возникнуть жреческому или правящему классу, за которым последовало усиление разделения труда . на Земле Это привело к появлению первой цивилизации в Шумере на Ближнем Востоке между 4000 и 3000 годами до нашей эры. [195] : 15 Дополнительные цивилизации быстро возникли в Древнем Египте , в долине реки Инд и в Китае. Изобретение письменности позволило возникнуть сложным обществам: делопроизводство и библиотеки служили хранилищем знаний и способствовали культурной передаче информации. Людям больше не приходилось тратить все свое время на работу ради выживания, что позволило им приобрести первые специализированные профессии (например, ремесленники, торговцы, священники и т. д.). Любопытство и образованность привели к стремлению к знаниям и мудрости, возникли различные дисциплины, в том числе и наука (в примитивной форме). Это, в свою очередь, привело к появлению все более крупных и сложных цивилизаций, таких как первые империи, которые временами торговали друг с другом или боролись за территорию и ресурсы.

Примерно к 500 г. до н.э. на Ближнем Востоке, в Иране, Индии, Китае и Греции существовали развитые цивилизации, которые то расширялись, то приходили в упадок. [195] : 3 В 221 г. до н.э. Китай стал единым государством, которое распространило свою культуру по всей Восточной Азии , и он остался самой густонаселенной страной в мире. В этот период знаменитые индуистские тексты, известные как Веды появились в цивилизации долины Инда . Эта цивилизация развивалась в военном деле , искусстве , науке , математике и архитектуре . [ нужна ссылка ] Основы западной цивилизации в значительной степени сформировались в Древней Греции с первым в мире демократическим правительством и крупными достижениями в философии и науке , а также в Древнем Риме с достижениями в области права, управления и техники. [203] Римская империя была обращена в христианство императором Константином в начале IV века и пришла в упадок к концу V века. Начиная с VII века началась христианизация Европы , и, по крайней мере, с IV века христианство играло заметную роль в формировании западной цивилизации . [204] [205] [206] [207] [208] [209] [210] [211] В 610 году был основан ислам , который быстро стал доминирующей религией в Западной Азии . Дом Мудрости был основан в Аббасидов времен Багдаде ( Ирак) . [212] Считается, что он был крупным интеллектуальным центром Золотого века ислама , где мусульманские ученые в Багдаде и Каире процветали с девятого по тринадцатый века до монгольского разграбления Багдада в 1258 году нашей эры. В 1054 году нашей эры Великий раскол между Римско-католической церковью и Восточной православной церковью привел к заметным культурным различиям между Западной и Восточной Европой . [213]

В 14 веке началось Возрождение в Италии с достижениями в религии, искусстве и науке. [195] : 317–319 В то время христианская церковь как политическая единица потеряла большую часть своей власти. В 1492 году Христофор Колумб достиг Америки, положив начало великим изменениям в новом мире . Европейская цивилизация начала меняться начиная с 1500 года, что привело к научной и промышленной революциям. Этот континент начал оказывать политическое и культурное доминирование над человеческими обществами по всему миру, в период, известный как Колониальная эра (см. также Эпоху географических открытий ). [195] : 295–299 В XVIII веке культурное движение, известное как Эпоха Просвещения, еще больше сформировало менталитет Европы и способствовало ее секуляризации . С 1914 по 1918 год и с 1939 по 1945 год страны всего мира были втянуты в мировые войны . Созданная после Первой мировой войны Лига Наций стала первым шагом на пути создания международных институтов для мирного разрешения споров. Не сумев предотвратить Вторую мировую войну , самый кровавый конфликт человечества, на смену ей пришла Организация Объединенных Наций . После войны было образовано множество новых государств, провозгласивших или получивших независимость в период деколонизации . Демократические капиталистические Соединенные Штаты и социалистический Советский Союз на какое-то время стали доминирующими мировыми сверхдержавами ними шло идеологическое, часто жестокое соперничество, известное как Холодная война , и до распада последней между . В 1992 году несколько европейских стран присоединились к Европейскому Союзу . По мере совершенствования транспорта и связи экономики и политические дела стран по всему миру становятся все более переплетенными. Этот глобализация часто приводит как к конфликтам, так и к сотрудничеству. [ нужна ссылка ]

Недавние события

Изменения продолжались быстрыми темпами с середины 1940-х годов по сегодняшний день. Технологические разработки включают ядерное оружие , компьютеры , генную инженерию и нанотехнологии . Экономическая глобализация , вызванная достижениями в области коммуникационных и транспортных технологий, повлияла на повседневную жизнь во многих частях мира. Культурные и институциональные формы, такие как демократия , капитализм и защита окружающей среды, приобретают все большее влияние. Серьезные проблемы и проблемы, такие как болезни , войны , бедность , насильственный радикализм и, в последнее время, антропогенное изменение климата , возросли по мере роста населения мира. [ нужна ссылка ]

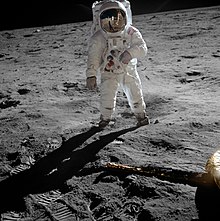

В 1957 году Советский Союз вывел на орбиту первый искусственный спутник Земли , а вскоре после этого Юрий Гагарин стал первым человеком, побывавшим в космосе. Нил Армстронг , американец, первым ступил на другой астрономический объект — Луну. Беспилотные зонды были отправлены ко всем известным планетам Солнечной системы, причем некоторые из них (например, два космических корабля «Вояджер ») покинули Солнечную систему. Пять космических агентств, представляющих более пятнадцати стран, [214] вместе работали над созданием Международной космической станции . На его борту с 2000 года в космосе постоянно находится человек. [215] Всемирная паутина стала частью повседневной жизни в 1990-х годах и с тех пор стала незаменимым источником информации в развитом мире . [ нужна ссылка ]

См. также

- Хронология Вселенной – История и будущее Вселенной

- Подробная логарифмическая шкала времени - Хронология истории Вселенной, Земли и человечества.

- Фаза Земли - Фазы Земли, видимые с Луны.

- Эволюционная история жизни

- Будущее Земли – долгосрочные экстраполированные геологические и биологические изменения планеты Земля.

- Геологическая история Земли - Последовательность основных геологических событий в прошлом Земли.

- Глобальный катастрофический риск . Потенциально опасные события во всем мире.

- Хронология эволюционной истории жизни

- Хронология естественной истории

Примечания

- ^ Харон Спутник Плутона относительно больше. [44] но Плутон определяется как карликовая планета . [45]

Ссылки

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Стэнли 2005 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д Градштейн, Огг и Смит, 2004 г.

- ^ "Международная стратиграфическая карта". Международная комиссия по стратиграфии

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Возраст Земли» . Геологическая служба США. 1997. Архивировано из оригинала 23 декабря 2005 года . Проверено 10 января 2006 г.

- ^ Далримпл, Дж. Брент (2001). «Возраст Земли в двадцатом веке: проблема (в основном) решена». Специальные публикации Лондонского геологического общества . 190 (1): 205–221. Бибкод : 2001GSLSP.190..205D . дои : 10.1144/ГСЛ.СП.2001.190.01.14 . S2CID 130092094 .

- ^ Манхеса, Жерар; Аллегре, Клод Ж.; Дюпреа, Бернар и Хамелен, Бруно (1980). «Изотопное исследование свинца основных-ультраосновных слоистых комплексов: предположения о возрасте Земли и характеристиках примитивной мантии». Письма о Земле и планетологии . 47 (3): 370–382. Бибкод : 1980E&PSL..47..370M . дои : 10.1016/0012-821X(80)90024-2 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Патель, Каша (16 июня 2023 г.). «У учёных есть противоречивая теория о том, как и как быстро образовалась Земля» . Вашингтон Пост . Архивировано из оригинала 17 июня 2023 года . Проверено 17 июня 2023 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Оньетт, Исаак Дж.; и др. (14 июня 2023 г.). «Ограничения изотопов кремния на аккрецию планет земной группы» . Природа . 619 (7970): 539–544. Бибкод : 2023Natur.619..539O . дои : 10.1038/s41586-023-06135-z . ПМЦ 10356600 . ПМИД 37316662 . S2CID 259161680 .

- ^ Шопф, Дж. Уильям ; Кудрявцев Анатолий Б.; Чая, Эндрю Д.; Трипати, Абхишек Б. (5 октября 2007 г.). «Свидетельства архейской жизни: строматолиты и микроокаменелости». Докембрийские исследования . 158 (3–4). Амстердам: Эльзевир: 141–155. Бибкод : 2007PreR..158..141S . doi : 10.1016/j.precamres.2007.04.009 . ISSN 0301-9268 .

- ^ Шопф, Дж. Уильям (29 июня 2006 г.). «Ископаемые свидетельства архейской жизни» . Философские труды Королевского общества Б. 361 (1470). Лондон: Королевское общество : 869–885. дои : 10.1098/rstb.2006.1834 . ISSN 0962-8436 . ПМЦ 1578735 . ПМИД 16754604 .

- ^ Рэйвен, Питер Х .; Джонсон, Джордж Б. (2002). Биология (6-е изд.). Бостон, Массачусетс: МакГроу Хилл . п. 68 . ISBN 978-0-07-112261-0 . LCCN 2001030052 . OCLC 45806501 .

- ^ Боренштейн, Сет (13 ноября 2013 г.). «Найдена самая старая окаменелость: познакомьтесь со своей микробной мамой» . Возбуждайте . Йонкерс, Нью-Йорк: Интерактивная сеть Mindspark . Ассошиэйтед Пресс . Проверено 2 июня 2015 г.

- ^ Перлман, Джонатан (13 ноября 2013 г.). «Обнаружены древнейшие признаки жизни на Земле» . «Дейли телеграф» . Лондон. Архивировано из оригинала 11 января 2022 г. Проверено 15 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Ноффке, Нора ; Кристиан, Дэниел; Уэйси, Дэвид; Хейзен, Роберт М. (16 ноября 2013 г.). «Микробно-индуцированные осадочные структуры, фиксирующие древнюю экосистему формации Дрессер возрастом около 3,48 миллиардов лет, Пилбара, Западная Австралия» . Астробиология . 13 (12). Нью-Рошель, штат Нью-Йорк: Мэри Энн Либерт, Inc .: 1103–1124. Бибкод : 2013AsBio..13.1103N . дои : 10.1089/ast.2013.1030 . ISSN 1531-1074 . ПМК 3870916 . ПМИД 24205812 .

- ^ Отомо, Йоко; Какегава, Такеши; Исида, Акизуми; и др. (январь 2014 г.). «Свидетельства наличия биогенного графита в метаосадочных породах раннего архея Исуа». Природа Геонауки . 7 (1). Лондон: Издательская группа Nature : 25–28. Бибкод : 2014NatGe...7...25O . дои : 10.1038/ngeo2025 . ISSN 1752-0894 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Боренштейн, Сет (19 октября 2015 г.). «Намеки на жизнь на ранней Земле, которая считалась пустынной» . Возбуждайте . Йонкерс, Нью-Йорк: Интерактивная сеть Mindspark . Ассошиэйтед Пресс . Архивировано из оригинала 23 октября 2015 года . Проверено 8 октября 2018 г.

- ^ Белл, Элизабет А.; Бенике, Патрик; Харрисон, Т. Марк; и др. (19 октября 2015 г.). «Потенциально биогенный углерод сохранился в цирконе возрастом 4,1 миллиарда лет» (PDF) . Учеб. Натл. акад. наук. США 112 (47). Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: Национальная академия наук: 14518–14521. Бибкод : 2015PNAS..11214518B . дои : 10.1073/pnas.1517557112 . ISSN 1091-6490 . ПМЦ 4664351 . ПМИД 26483481 . Проверено 20 октября 2015 г. Раннее издание, опубликованное в Интернете до печати.

- ^ Кунин, МЫ; Гастон, Кевин, ред. (1996). Биология редкости: причины и последствия редких и общих различий . Спрингер. ISBN 978-0-412-63380-5 . Проверено 26 мая 2015 г.

- ^ Стернс, Беверли Петерсон; Стернс, Южная Каролина; Стернс, Стивен К. (2000). Смотрю с края вымирания . Издательство Йельского университета . п. предисловие х. ISBN 978-0-300-08469-6 .

- ^ Новачек, Майкл Дж. (8 ноября 2014 г.). «Блестящее будущее предыстории» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Проверено 25 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Миллер, Г.; Спулман, Скотт (2012). Наука об окружающей среде: биоразнообразие является важнейшей частью природного капитала Земли . Cengage Обучение . п. 62. ИСБН 978-1-133-70787-5 . Проверено 27 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Мора, К.; Титтензор, ДП; Адл, С.; Симпсон, AG; Ворм, Б. (23 августа 2011 г.). «Сколько видов существует на Земле и в океане?» . ПЛОС Биология . 9 (8): e1001127. дои : 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127 . ПМК 3160336 . ПМИД 21886479 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Градштейн, Огг и ван Кранендонк, 2008 г.

- ^ Энкреназ, Т. (2004). Солнечная система (3-е изд.). Берлин: Шпрингер. п. 89. ИСБН 978-3-540-00241-3 .

- ^ Мэтсон, Джон (7 июля 2010 г.). «Светоносная линия: спровоцировала ли древняя сверхновая рождение Солнечной системы?» . Научный американец . Проверено 13 апреля 2012 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б П. Гольдрайх; WR Уорд (1973). «Образование планетезималей». Астрофизический журнал . 183 : 1051–1062. Бибкод : 1973ApJ...183.1051G . дои : 10.1086/152291 .

- ^ Ньюман, Уильям Л. (9 июля 2007 г.). «Возраст Земли» . Служба публикаций, Геологическая служба США . Проверено 20 сентября 2007 г.

- ^ Стассен, Крис (10 сентября 2005 г.). «Возраст Земли» . Архив TalkOrigins . Проверено 30 декабря 2008 г.

- ^ Инь, Цинчжу; Якобсен, С.Б.; Ямасита, К.; Блихерт-Тофт, Дж.; Телоук, П.; Альбаред, Ф. (2002). «Краткие сроки формирования планет земной группы на основе Hf-W хронометрии метеоритов». Природа . 418 (6901): 949–952. Бибкод : 2002Natur.418..949Y . дои : 10.1038/nature00995 . ПМИД 12198540 . S2CID 4391342 .

- ^ Кокубо, Эйитиро; Ида, Сигеру (2002). «Формирование протопланетных систем и разнообразие планетных систем». Астрофизический журнал . 581 (1): 666–680. Бибкод : 2002ApJ...581..666K . дои : 10.1086/344105 . S2CID 122375535 .

- ^ Франкель, Чарльз (1996). Вулканы Солнечной системы . Издательство Кембриджского университета . стр. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-521-47770-3 .

- ^ Джейкобс, Дж. А. (1953). «Внутреннее ядро Земли». Природа . 172 (4372): 297–298. Бибкод : 1953Natur.172..297J . дои : 10.1038/172297a0 . S2CID 4222938 .

- ^ ван Хунен, Дж.; ван ден Берг, AP (2007). «Тектоника плит на ранней Земле: ограничения, налагаемые силой и плавучестью субдуцированной литосферы». Литос . 103 (1–2): 217–235. Бибкод : 2008Лито.103..217В . дои : 10.1016/j.lithos.2007.09.016 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Уайльд, ЮАР; Вэлли, JW; Пек, WH и Грэм, CM (2001). «Свидетельства обломочных цирконов о существовании континентальной коры и океанов на Земле 4,4 миллиарда лет назад» (PDF) . Природа . 409 (6817): 175–178. Бибкод : 2001Natur.409..175W . дои : 10.1038/35051550 . ПМИД 11196637 . S2CID 4319774 . Проверено 25 мая 2013 г.

- ^ Линдси, Ребекка; Моррисон, Дэвид; Симмон, Роберт (1 марта 2006 г.). «Древние кристаллы предполагают более ранний океан» . Земная обсерватория . НАСА . Проверено 18 апреля 2012 г.

- ^ Кавоси, Эй Джей; Вэлли, JW; Уайльд, ЮАР; Эдинбургский центр ионных микрозондов (ЭИМФ) (2005 г.). «Магматический δ 18 O в обломочных цирконах возрастом 4400–3900 млн лет назад: записи об изменении и переработке коры в раннем архее». Earth and Planetary Science Letters . 235 (3–4): 663–681. Бибкод : 2005E&PSL.235..663C . дои : 10.1016/j.epsl.2005.04.028 .

- ^ Бельбруно, Э.; Готт, Дж. Ричард III (2005). «Откуда взялась Луна?». Астрономический журнал . 129 (3): 1724–1745. arXiv : astro-ph/0405372 . Бибкод : 2005AJ....129.1724B . дои : 10.1086/427539 . S2CID 12983980 .

- ^ Мюнкер, Карстен; Йорг А. Пфендер; Стефан Вейер; Анетт Бюхль; Торстен Кляйне; Клаус Мезгер (4 июля 2003 г.). «Эволюция планетных ядер и системы Земля-Луна по систематике Nb/Ta» . Наука . 301 (5629): 84–87. Бибкод : 2003Sci...301...84M . дои : 10.1126/science.1084662 . ПМИД 12843390 . S2CID 219712 . Проверено 13 апреля 2012 г.

- ^ Нилд, Тед (2009). «Лунная походка» (PDF) . Геолог . 18 (9). Лондонское геологическое общество: 8. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 5 июня 2011 г .. Проверено 18 апреля 2012 г.

- ^ Бритт, Роберт Рой (24 июля 2002 г.). «Новый взгляд на раннюю бомбардировку Земли» . Space.com . Проверено 9 февраля 2012 г.

- ^ Грин, Джек (2011). «Академические аспекты лунных водных ресурсов и их значение для лунной протожизни» . Международный журнал молекулярных наук . 12 (9): 6051–6076. дои : 10.3390/ijms12096051 . ПМК 3189768 . ПМИД 22016644 .

- ^ Тейлор, Томас Н.; Тейлор, Эдит Л.; Крингс, Майкл (2006). Палеоботаника: биология и эволюция ископаемых растений . Академическая пресса . п. 49. ИСБН 978-0-12-373972-8 .

- ^ Стинхейсен, Джули (21 мая 2009 г.). «Исследование поворачивает время вспять о происхождении жизни на Земле» . Рейтер . Рейтер . Проверено 21 мая 2009 г.

- ^ «Космическая тематика: Плутон и Харон» . Планетарное общество. Архивировано из оригинала 18 февраля 2012 года . Проверено 6 апреля 2010 г.

- ^ «Плутон: Обзор» . Исследование Солнечной системы . Национальное управление по аэронавтике и исследованию космического пространства . Архивировано из оригинала 16 декабря 2002 года . Проверено 19 апреля 2012 г.

- ^ Кляйне, Т.; Пальме, Х.; Мезгер, К.; Холлидей, АН (2005). «Hf-W Хронометрия лунных металлов, возраст и ранняя дифференциация Луны» . Наука . 310 (5754): 1671–1674. Бибкод : 2005Sci...310.1671K . дои : 10.1126/science.1118842 . ПМИД 16308422 . S2CID 34172110 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Холлидей, АН (2006). «Происхождение Земли; Что нового?». Элементы . 2 (4): 205–210. Бибкод : 2006Элеме...2..205H . дои : 10.2113/gselements.2.4.205 .

- ^ Холлидей, Алекс Н. (28 ноября 2008 г.). «Удар гиганта, образующего молодую Луну, через 70–110 миллионов лет, сопровождавшийся перемешиванием на поздней стадии, формированием ядра и дегазацией Земли». Философские труды Королевского общества А. 366 (1883). Философские труды Королевского общества : 4163–4181. Бибкод : 2008RSPTA.366.4163H . дои : 10.1098/rsta.2008.0209 . ПМИД 18826916 . S2CID 25704564 .

- ^ Уильямс, Дэвид Р. (1 сентября 2004 г.). «Информационный бюллетень о Земле» . НАСА . Проверено 9 августа 2010 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Архивный исследовательский центр астрофизики высоких энергий (HEASARC). «Вопрос месяца StarChild за октябрь 2001 г.» . Центр космических полетов имени Годдарда НАСА . Проверено 20 апреля 2012 г.

- ^ Кануп, РМ ; Асфауг, Э. (2001). «Происхождение Луны в результате гигантского удара ближе к концу формирования Земли». Природа . 412 (6848): 708–712. Бибкод : 2001Natur.412..708C . дои : 10.1038/35089010 . ПМИД 11507633 . S2CID 4413525 .

- ^ Лю, Линь-Гун (1992). «Химический состав Земли после гигантского удара». Земля, Луна и планеты . 57 (2): 85–97. Бибкод : 1992EM&P...57...85L . дои : 10.1007/BF00119610 . S2CID 120661593 .

- ^ Ньюсом, Хортон Э.; Тейлор, Стюарт Росс (1989). «Геохимические последствия образования Луны в результате одного гигантского удара». Природа . 338 (6210): 29–34. Бибкод : 1989Natur.338...29N . дои : 10.1038/338029a0 . S2CID 4305975 .

- ^ Тейлор, Дж. Джеффри (26 апреля 2004 г.). «Происхождение Земли и Луны» . НАСА . Архивировано из оригинала 31 октября 2004 года . Проверено 27 марта 2006 г. , Тейлор (2006) на сайте НАСА.

- ^ Дэвис, Джеффри Ф. (3 февраля 2011 г.). Мантийная конвекция для геологов . Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-0-521-19800-4 .

- ^ Каттермоул, Питер; Мур, Патрик (1985). История земли . Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-0-521-26292-7 .

- ^ Дэвис, Джеффри Ф. (2011). Мантийная конвекция для геологов . Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-0-521-19800-4 .

- ^ Бликер, В.; Дэвис, BW (май 2004 г.). Что такое кратон? . Весенняя встреча. Американский геофизический союз. Бибкод : 2004AGUSM.T41C..01B . Т41С-01.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Лунный 1999 год

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Конди, Кент К. (1997). Тектоника плит и эволюция земной коры (4-е изд.). Оксфорд: Баттерворт Хайнеманн. ISBN 978-0-7506-3386-4 .

- ^ Кастинг, Джеймс Ф. (1993). «Ранняя атмосфера Земли». Наука . 259 (5097): 920–926. Бибкод : 1993Sci...259..920K . дои : 10.1126/science.11536547 . ПМИД 11536547 . S2CID 21134564 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Гейл, Джозеф (2009). Астробиология Земли: возникновение, эволюция и будущее жизни на планете, находящейся в смятении . Оксфорд: Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 978-0-19-920580-6 .

- ^ Трейл, Дастин; Элсила, Джейми; Мюллер, Ульрих; Лайонс, Тимоти; Роджерс, Карин (04 февраля 2022 г.). «Переосмысление поиска истоков жизни» . Эос . 103 . Американский геофизический союз (AGU). дои : 10.1029/2022eo220065 . ISSN 2324-9250 . S2CID 246620824 .