Герберт Мэрион

Герберт Мэрион | |

|---|---|

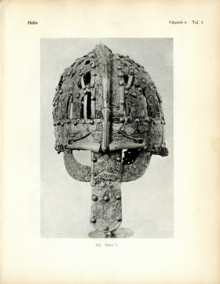

С его реконструкцией шлема Саттон-Ху , ок. 1951 год . На изображении слева от Мэрион изображен Венделя 14 шлем ; справа от него изображена пластина 1 из работы Греты Арвидссон 1942 года о Вальсгарде 6 и изображен шлем из указанной могилы. | |

| Рожденный | 9 марта 1874 г. Лондон , Англия |

| Умер | 14 июля 1965 г. ( 91 год Эдинбург , Шотландия |

| Национальность | Английский |

| Образование | Центральная школа искусств и ремесел |

| Род занятий | Скульптор, мастер по металлу, консерватор-реставратор. |

| Родственники | Джон, Эдит , Джордж, Милдред, Вайолет (братья и сестры) |

| Подпись | |

Герберт Джеймс Мэрион OBE FSA FIIC (9 марта 1874 — 14 июля 1965) — английский скульптор, реставратор , ювелир, археолог и специалист по древним изделиям из металла. Мэрион практиковал и преподавал скульптуру до выхода на пенсию в 1939 году, затем работал реставратором в Британском музее с 1944 по 1961 год. Он наиболее известен своей работой над в Саттон-Ху захоронением корабля , что привело к его назначению офицером Ордена . Британской империи .

К двадцати годам Мэрион посещал три художественные школы, учился серебряному делу у Ч.Р. Эшби и работал в Генри Уилсона мастерской . С 1900 по 1904 год он был директором Кесвикской школы промышленного искусства , где создал множество произведений декоративно-прикладного искусства . После переезда в Университет Рединга , а затем в Даремский университет , он преподавал скульптуру, работу с металлом, моделирование, литье и анатомию до 1939 года. Он также спроектировал военный мемориал Университета Рединга , среди других заказов. Во время преподавания Мэрион опубликовала две книги, в том числе «Металлообработка и эмалирование» , а также множество статей. Он часто руководил археологическими раскопками и в 1935 году обнаружил одно из старейших золотых украшений, известных в Великобритании, во время раскопок пирамид из камней Киркхо .

В 1944 году Мэрион вышла из отставки, чтобы работать над находками в Саттон-Ху. В его обязанности входило восстановление щита, рогов для питья и культового шлема Саттон-Ху , оказавшего академическое и культурное влияние. Работы Мэрион, большая часть которых была пересмотрена в 1970-х годах, создали достоверные изображения, на которые опирались последующие исследования; Точно так же в одной из его статей был введен термин «сварка по шаблону» для описания метода, используемого при изготовлении меча Саттон-Ху для украшения и укрепления железа и стали. Первоначальная работа закончилась в 1950 году, и Мэрион занялась другими делами. В 1953 году он предложил широко разрекламированную теорию строительства Колосса Родосского , оказав влияние на Сальвадора Дали и других, и восстановил римский шлем Эмеса в 1955 году. Он покинул музей в 1961 году, через год после своего официального выхода на пенсию, и начал около - Кругосветное путешествие с лекциями и исследованием китайских волшебных зеркал .

Ранняя жизнь и образование

[ редактировать ]Герберт Джеймс Мэрион родился 9 марта 1874 года в Лондоне. [1] [2] Он был третьим из шести выживших детей Джона Симеона Мэриона, портного. [3] и Луиза Мэрион (урожденная Черч). [4] [5] [6] У него был старший брат Джон Эрнест и старшая сестра Луиза Эдит , последняя из которых предшествовала ему в его карьере скульптора. После него родились еще один брат и три сестры - по порядку Джордж Кристиан, Флора Мейбл, Милдред Джесси и Вайолет Мэри, - хотя Флора Мэрион, родившаяся в 1878 году, умерла на втором году жизни. [7] Согласно родословной, составленной Джоном Эрнестом Мэрионом, [8] Семья Мэрионов восходит к семье де Маринис, ветвь которой уехала из Нормандии в Англию примерно в 12 веке. [9]

Получив общее образование в Нижней школе Джона Лайона , [10] Герберт Мэрион учился с 1896 по 1900 год в Политехническом институте ( Риджент-стрит ), где он получил стипендию и специальное продление на третий год, а также в The Slade , Школе искусств Сен-Мартена , и под опекой Александра Фишера. [11] и Уильям Летаби , [12] Центральная школа искусств и ремесел . [1] [13] [10] Он также получил первоклассные сертификаты Южного Кенсингтона по рисованию с натуры, антиквариата, света и тени и других предметов. [13] В частности, под руководством Фишера Мэрион научилась эмалированию . [11] В 1898 году Мэрион также прошла годичное обучение серебряному делу в Ч.Р. Эшби в Эссексском доме. Гильдии ремесел [10] [1] [14] и какое-то время работал в Генри Уилсона . мастерской [11] [15] В какой-то момент, хотя, возможно, позже, Мэрион также работала в мастерской Джорджа Фрэмптона . [16] и преподавал Роберт Каттерсон Смит . [17]

Скульптура

[ редактировать ]

С 1900 по 1939 год Мэрион занимал различные должности, преподавал скульптуру, дизайн и работу с металлом. [1] За это время, еще учась в школе, он создал и выставил множество своих собственных работ. [1] В конце 1899 года он представил серебряную чашу и щит с серебряной перегородчатой эмалью на шестой выставке Общества выставок искусств и ремесел , мероприятии, проходившем в Новой галерее , на котором также были представлены работы его сестры Эдит. [18] Выставка прошла рецензию The International Studio , при этом работа Мэрион была отмечена как «приемлемая». [19]

Кесвикская школа промышленного искусства, 1900–1904 гг.

[ редактировать ]В марте 1900 года Мэрион стала первым директором Кесвикской школы промышленного искусства . [20] [21] [22] Школа была открыта Эдит и Хардвик Ронсли в 1884 году, на фоне зарождения движения искусств и ремесел . [23] Он предлагал занятия по рисованию, дизайну, резьбе по дереву и работе с металлом, а также сочетал коммерцию с художественными целями; Школа продавала такие предметы, как подносы, рамы, столы и футляры для часов, и заработала репутацию производителя качественных товаров. [24] Уже в мае обозреватель The Studio выставки в Королевском Альберт-холле отметил, что группа серебряной посуды, созданная школой, была «долгожданным шагом к более тонкому мастерству». [25] [26] Два проекта Мэрион, как она писала, «были исключительно хороши: молоток, выполненный Джеремайей Ричардсоном, и медная шкатулка, изготовленная Томасом Спарком и украшенная Томасом Кларком и дизайнером». [25] [26] [примечание 1] Она описала замок гроба как «покрытый жемчужно-синей и белой эмалью», придающий «изящный оттенок форме, почти лишенной орнамента, но красивой по своим пропорциям и линиям». [25] [26] На выставке следующего года еще три работы школы были отмечены похвалой, в том числе чашка любви Мэрион. [29]

Under Maryon's leadership the Keswick School expanded the breadth and range of its designs, and he executed several significant commissions.[30] His best works, wrote a historian of the school, "drew their inspiration from the nature of the material and his deep understanding of its technical limits".[30] They also tended to be in metal.[30] Items like Bryony, a tray centre showing tangled growth concealed within a geometric framework, continued the school's tradition of repoussé work of naturalistic interpretations of flowers, while evoking the vine-like wallpapers of William Morris.[31] These themes were particularly expressed in a 1901 plaque memorialising Bernard Gilpin, unveiled in St Cuthbert's Church, Kentmere; described by the art historian Sir Nikolaus Pevsner as "Arts and Crafts, almost Art Nouveau",[32] the bronze tablet on oak is framed by trees with entwined roots and influenced by a Norse and Celtic aesthetic.[33][34] Three other commissions in silver—a loving cup, a processional cross, and a challenge shield—were completed towards the end of Maryon's tenure and the school and featured in The Studio and its international counterpart.[35][36] The cup was commissioned by the Cumberland County Council for presentation to HMS Cumberland, and was termed a "tour de force".[37]

Particularly in more utilitarian works, Maryon's designs at the Keswick School tended to emphasise form over design.[38][39] As he would write a decade later, "[o]ver-insistence on technique, craftsmanship which proclaims 'How clever am I!' quite naturally elbows out artistic feeling. One idea must be the principal one; and if that happens to be technique, the other goes."[40] Design should be determined by intention, he wrote: as an objet or as an object for use.[41] Hot water jugs, tea pots, sugar bowls and other tableware that Maryon designed were frequently raised from a single sheet of metal, retaining the hammer marks and a dull lustre.[42] Many of these were displayed at the 1902 Home Arts and Industries Exhibition, where the school won 65 awards,[43] along with an altar cross designed by Maryon for Hexham Abbey,[44] and were praised for showing "a remarkably good year's work in the finer kinds of craft and decoration".[45] At the same event a year later more than £35 worth of goods were sold, including a copper jug Maryon designed which was acquired by the Manchester School of Art for its Arts and Crafts Museum.[46][43] On the strength of these and other achievements, Maryon's salary, which in 1902 had amounted in his estimation to between £185 and £200, was raised to £225.[47]

Maryon's four-year tenure at Keswick was assisted by four designers who also taught drawing: G. M. Collinson, Isobel McBean, Maude M. Ackery, and Dorothea Carpenter.[48][note 2] Hired from leading art schools and serving for a year each, the four helped the school keep abreast of modern design.[52] Eight full-time workers helped execute the designs when Maryon joined in 1900, rising to 15 by 1903.[43] Maryon also had the help of his sisters: Edith Maryon designed at least one work for the school, a 1901 relief plaque of Hardwicke Rawnsley, while Mildred Maryon, who the 1901 census listed as living with her sister,[53][54] worked for a time as an enameller at the school.[55][56] Both Herbert and Mildred Maryon worked on an oxidised silver and enamel casket that was presented to Princess Louise upon her 1902 visit to the Keswick School;[57] Herbert Maryon was responsible for the design and his sister for the enamelling, with the resulting work being termed "of a character highly creditable to the School" in The Magazine of Art.[58] Strife with colleagues eventually led to Maryon's departure.[59] In July 1901 Collinson had left due to a poor working relationship, and Maryon was often in conflict with the school's management committee, which was chaired by Edith Rawnsley and frequently made decisions without his knowledge.[60] When in August 1904 Carpenter, in friction with Maryon, resigned, the committee decided to give Maryon three-months' notice.[61][note 3]

Maryon left the school at the end of December 1904.[61] He spent 1905 teaching metalwork at the Storey Institute in Lancaster.[1][10] That October he published his first article, "Early Irish Metal Work" in The Art Workers' Quarterly.[63] In 1906 Maryon, still listed as living in Keswick, again displayed works—this time a silver cup and silver chalice—for the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, held at the Grafton Galleries; one Mrs. Herbert J. Maryon was listed as exhibiting a Sicilian lace tablecloth.[64] At some point towards 1908, Maryon also gave instruction in crafts under the Westmorland County Council.[13]

University of Reading, 1908–1927

[edit]

In January 1908, Maryon was appointed teacher of crafts are the University of Reading, effective 10 February; he took over from Julia Bowley (wife of Arthur Lyon Bowley), who resigned as teacher of woodcarving and handicraft.[13][65][66] Until 1927, Maryon taught sculpture, including metalwork, modelling, and casting, at the school.[10][67] He was also the warden of Wantage Hall from 1920 to 1922.[67] Maryon's first book, Metalwork and Enamelling: A Practical Treatise on Gold and Silversmiths' Work and their Allied Crafts, was published in 1912.[68] Maryon described it as eschewing "the artistic or historical point of view", in favor of an "essentially practical and technical standpoint".[69] The book focused on individual techniques such as soldering, enamelling, and stone-setting, rather than the methods of creating works such as cups and brooches.[70][71] It was well received,[72][73] as a vade mecum for both students and practitioners of metalworking.[74][70] The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs wrote that Maryon "succeeds in every page in not only maintaining his own enthusiasm, but what is better in communicating it",[75] and The Athenæum declared that his "critical notes on design are excellent".[76] One such note, republished in The Jewelers' Circular in 1922,[77] was a critique of the celebrated sixteenth-century goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini; Maryon termed him "one of the very greatest craftsmen of the sixteenth century, but ... a very poor artist",[78] a "dispassionate appraisal" that led a one-time secretary of the Metropolitan Museum of Art to label Maryon not only "the dean of ancient metalwork",[79] but also "a discerning critic".[80][81] Metalwork and Enamelling went through four further editions, in 1923,[82] 1954,[83] 1959,[84] and posthumously in 1971,[85] along with a 1998 Italian translation,[86] and as of 2020 is still in print by Dover Publications.[87] As late as 1993, a senior conservator at the Canadian Conservation Institute wrote that the book "has not been equalled".[88]

During the First World War Maryon worked at Reading with another instructor, Charles Albert Sadler, to create a centre to train munition workers in machine tool work.[1][10] Maryon began this work in 1915, officially as organising secretary and instructor at the Ministry of Munitions Training Centre, with no engineering school to build from.[10] The programme targeted women in particular, given the number of men who were serving in the military.[89][90][91] By 1918 the centre had five staff members, could accommodate 25 workers at a time, and had trained more than 400.[10] Based on this work, Maryon was elected to the Institution of Mechanical Engineers on 6 March 1918.[1][10]

Maryon displayed a child's bowl with signs of the zodiac at the ninth Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society exhibition in 1910.[92][93] Following the war, he—like his colleague and friend William Collingwood,[94]—designed several memorials, including the East Knoyle War Memorial in 1920,[95] the Mortimer War Memorial in 1921,[96] and in 1924 the University of Reading War Memorial, a clock tower on the London Road Campus.[97][98]

Armstrong College, 1927–1939

[edit]

In September 1927 Maryon left the University of Reading and began teaching sculpture at Armstrong College,[99] then part of Durham University, where he stayed until 1939.[67] At Durham he was both master of sculpture, and lecturer in anatomy and the history of sculpture.[67] Around 1928, Maryon travelled around Europe, from Reading to Denmark, followed by Copenhagen, Gothenburg, Stockholm, Danzig, Warsaw, Vienna, Dresden, Leipzig, Berlin, Hamburg, and elsewhere, returning to lecture on the sculpture observed on the trip.[100] In 1933 he published his second book, Modern Sculpture: Its Methods and Ideals.[101] Maryon wrote that his aim was to discuss modern sculpture "from the point of view of the sculptors themselves", rather than from an "archaeological or biographical" perspective.[102] The book received mixed reviews.[103] To The Art Digest, Maryon "succeeded in trying to make sculpture intelligible to the layman".[104] But his treatment of criticism as secondary to intent meant grouping together artworks of unequal quality.[105] Some critics attacked his taste, with The New Statesman and Nation claiming that "[h]e can enjoy almost anything, and among his 350 odd illustrations there are certainly some camels to swallow,"[106] The Bookman that "All the bad sculptors ... will be found in Mr. Maryon's book ... Most of the good sculptors are here as well (even Henry Moore), but all are equal in Mr. Maryon's eye,"[107] and The Spectator that "[t]he few good works which have found their way into the 356 plates look lost and unhappy."[108] Maryon responded with explanations of his purpose,[109][110] saying that "I do not admire all the results, and I say so,"[111] and to one review in particular that "I believe that the sculptors of the world have a wider knowledge of what constitutes sculpture than your reviewer realizes."[112][113] Other reviews praised Maryon's academic approach.[114][110] The Times stated that "his book is remarkable for its extraordinary catholicity, admitting works which we should find it hard to defend ... with works of great merit," yet added that "[b]y a system of grouping, however, according to some primarily aesthetic aim ... their inclusion is justified."[105] The Manchester Guardian praised Maryon for "a degree of natural good sense in his observations that cannot always be said to characterise current art criticism", and stated that "his critical judgments are often penetrating."[115]

At Durham, as at Reading, Maryon was commissioned to create works of art. These included at least two plaques, memorialising George Stephenson in 1929,[116][117] and Sir Charles Parsons in 1932,[118][119][note 4] as well as Statue of Industry for the 1929 North East Coast Exhibition, a world's fair held at Newcastle upon Tyne.[121][122] Depicting a woman with cherubs at her feet, the statue was described by Maryon as "represent[ing] industry as we know it in the North-east—one who has passed through hard times and is now ready to face the future, strong and undismayed".[122] The statue was the subject of "adverse criticism", reported The Manchester Guardian; on the night of 25 October "several hundred students of Armstrong College" tarred and feathered the statue, and were dispersed only with the arrival of eighty police officers.[121][123][note 5]

Maryon expressed an interest in archaeology while at Armstrong.[128] By the early 1930s he was conducting excavations, and frequently brought students to dig along Hadrian's Wall.[128] In 1935 he published two articles on Bronze Age swords,[129][130] and at the end of the year excavated the Kirkhaugh cairns, two Bronze Age graves at Kirkhaugh, Northumberland.[131][132][133] One of the cairns was the nearly 4500-year-old grave of a metalworker, like the grave of the Amesbury Archer, and contained one of the oldest gold ornaments yet found in the United Kingdom;[134][135] a matching ornament was found during a re-excavation in 2014.[136] Maryon's account of the excavation was published in 1936,[137] and papers on archaeology and prehistoric metalworking followed. In 1937 he published an article in Antiquity clarifying a passage by the ancient Greek historian Diodorus Siculus on how Egyptians carved sculptures;[138][note 6] in 1938 he wrote in both the Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy and The Antiquaries Journal on metalworking during the Bronze and Iron Ages;[141][142] and in 1939 he wrote articles about an ancient hand-anvil discovered in Thomastown,[143] and gold ornaments found in Alnwick.[144]

Maryon retired from Armstrong College—by then known as King's College—in 1939, when he was in his mid-60s.[145] From 1939 to 1943, at the height of World War II, he was involved in munition work.[67] In 1941 he published a two-part article in Man on archaeology and metallurgy, part I on welding and soldering, and part II on the metallurgy of gold and platinum in Pre-Columbian Ecuador.[146][147]

British Museum, 1944–1961

[edit]On 11 November 1944 Maryon was recruited out of retirement by the trustees of the British Museum to serve as a Technical Attaché.[148] Maryon, working under Harold Plenderleith's leadership,[149][150] was tasked with the conservation and reconstruction of material from the Anglo-Saxon Sutton Hoo ship-burial.[151] Widely identified with King Rædwald of East Anglia, the burial had previously attracted Maryon's interest; as early as 1941, he wrote a prescient letter about the preservation of the ship impression to Thomas Downing Kendrick, the museum's Keeper of British and Medieval Antiquities.[151][note 7] Nearly four years after his letter, in the dying days of World War II and the finds removed (or about to be removed) from safekeeping in the tunnel connecting the Aldwych and Holborn tube stations,[161] he was assigned what Rupert Bruce-Mitford, who succeeded Kendrick's post in 1954,[162][163] termed "the real headaches—notably the crushed shield, helmet and drinking horns".[164] Composed in large part of iron, wood and horn, these items had decayed in the 1,300 years since their burial and left only fragments behind; the helmet, for one, had corroded and then smashed into more than 500 pieces.[165] Painstaking work needing keen observation and patience, these efforts occupied several years of Maryon's career.[145] Much of his work has seen revision, but as Bruce-Mitford wrote afterwards, "by carrying out the initial cleaning, sorting, and mounting of the mass of the fragmentary and fragile material he preserved it, and in working out his reconstructions he made explicit the problems posed and laid the foundations upon which fresh appraisals and progress could be based when fuller archaeological study became possible."[166]

Maryon's restorations were aided by his deep practical understandings of the objects he was working on, causing a senior conservator at the Canadian Conservation Institute in 1993 to label Maryon "[o]ne of the finest exemplars" of a conservator whose "wide understanding of the structure and function of museum objects ... exceeds that gained by the curator or historian in more classical studies of artefacts."[167] Maryon was admitted as a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1949,[168][169] and in 1956 his Sutton Hoo work led to his appointment as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire.[145][170] Asked by Queen Elizabeth II what he did as she awarded him the medal, Maryon responded "Well, Ma'am, I am a sort of back room boy at the British Museum."[171] Maryon continued restoration work at the British Museum, including on Oriental antiquities and the Roman Emesa helmet,[145][172] before retiring—for a second time—at the age of 87.[80][173]

Sutton Hoo helmet

[edit]

From 1945 to 1946,[175][176] Maryon spent six continuous months reconstructing the Sutton Hoo helmet.[177] The helmet was only the second Anglo-Saxon example then known, the Benty Grange helmet being the first, and was the most elaborate.[178] Yet its importance had not been realized during excavation, and no photographs of it were taken in situ.[179] Bruce-Mitford likened Maryon's task to "a jigsaw puzzle without any sort of picture on the lid of the box",[180] and, "as it proved, a great many of the pieces missing"; Maryon had to base his reconstruction "exclusively on the information provided by the surviving fragments, guided by archaeological knowledge of other helmets".[181][note 8]

Maryon began the reconstruction by familiarising himself with the fragments, tracing and detailing each on a piece of card.[179] After what he termed "a long while", he sculpted a head out of plaster and expanded it outwards to simulate the padded space between helmet and head.[183] On this he initially affixed the fragments with plasticine, placing thicker pieces into spaces cut into the head.[184] Finally, the fragments were permanently affixed with white plaster mixed with brown umber; more plaster was used to fill the in-between areas.[184] The fragments of the cheek guards, neck guard, and visor were placed onto shaped, plaster-covered wire mesh, then affixed with more plaster and joined to the cap.[185][186] Maryon published the finished reconstruction in a 1947 issue of Antiquity.[187]

Maryon's work was celebrated, and both academically and culturally influential.[178] The helmet stayed on display for over twenty years,[178][188] with photographs[189][190][191] making their way into television programmes,[192] newspapers, and "every book on Anglo-Saxon art and archaeology";[178] in 1951 a young Larry Burrows was dispatched to the British Museum by Life, which published a full page photograph of the helmet alongside a photo of Maryon.[193][194] Over the succeeding quarter century conservation techniques advanced,[195] knowledge of contemporaneous helmets grew,[196] and more helmet fragments were discovered during the 1965–69 re-excavation of Sutton Hoo;[197][155][198][199] accordingly, inaccuracies in Maryon's reconstruction—notably its diminished size, gaps in afforded protection, and lack of a moveable neck guard—became apparent.[178][note 9] In 1971 a second reconstruction was completed, following eighteen months' work by Nigel Williams.[202][181] Yet "[m]uch of Maryon's work is valid," Bruce-Mitford wrote.[188] "The general character of the helmet was made plain."[188][note 10] "It was only because there was a first restoration that could be constructively criticized," noted the conservation scholar Chris Caple, "that there was the impetus and improved ideas available for a second restoration;"[196] similarly, minor errors in the second reconstruction were discovered while forging the 1973 Royal Armouries replica.[208][209] In executing a first reconstruction that was reversible and retained evidence by being only lightly cleaned,[210] Maryon's true contribution to the Sutton Hoo helmet was in creating a credible first rendering that allowed for the critical examination leading to the second, current, reconstruction.[166]

After Sutton Hoo

[edit]

Maryon finished reconstructions of significant objects from Sutton Hoo by 1946,[212][213][214] although work on the remaining finds carried him to 1950; at this point Plenderleith decided the work had been finished to the extent possible, and that the space in the research laboratory was needed for other purposes.[215][216] Maryon continued working at the museum until 1961, turning his attention to other matters.[145] This included some travel: in April 1954 he visited Toronto, giving lectures at the Royal Ontario Museum on Sutton Hoo before a large audience, and another on "Founders and Metal Workers of the Early World";[217][218] the same year he visited Philadelphia, where he was scheduled to appear on an episode of What in the World? before the artefacts were mistakenly carted away to the dump;[219][220][note 11] and in 1957 or 1958, paid a visit to the Gennadeion at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens.[222]

In 1955 Maryon restored the Roman Emesa helmet for the British Museum.[223][172] It had been found in the Syrian city Homs in 1936,[224] and underwent several failed restoration attempts before it was brought to the museum—"the last resort in these things", according to Maryon.[172] The restoration was published the following year by Plenderleith.[225] Around that time Maryon and Plenderleith also collaborated on several other works: in 1954 they wrote a chapter on metalwork for the History of Technology series,[226] and in 1959 they co-authored a paper on the cleaning of Westminster Abbey's bronze royal effigies.[227]

Publications

[edit]In addition to Metalwork and Enamelling and Modern Sculpture, Maryon authored chapters in volumes one and two of Charles Singer's "A History of Technology" series,[226][228] and wrote thirty or forty archaeological and technical papers.[2][67] Several of Maryon's earlier papers, in 1946 and 1947, described his restorations of the shield and helmet from the Sutton Hoo burial.[187][229] In 1948 another paper introduced the term pattern welding to describe a method of strengthening and decorating iron and steel by welding into them twisted strips of metal;[230][231][232] the method was employed on the Sutton Hoo sword among others, giving them a distinctive pattern.[233] [234]

During 1953 and 1954, his talk and paper on the Colossus of Rhodes received international attention for suggesting the statue was hollow, and stood aside rather than astride the harbour.[note 12] Made of hammered bronze plates less than a sixteenth of an inch thick, he suggested, it would have been supported by a tripod structure comprising the two legs and a hanging piece of drapery.[238][211] Although "great ideas" according to the scholar Godefroid de Callataÿ, neither fully caught on;[211] in 1957, Denys Haynes, then the Keeper of Greek and Roman Antiquities at the British Museum,[239][240] suggested that Maryon's theory of hammered bronze plates relied on an errant translation of a primary source.[241][note 13] Maryon's view was nevertheless influential, likely shaping Salvador Dalí's 1954 surrealist imagining of the statue, The Colossus of Rhodes. "Not only the pose," wrote de Callataÿ, "but even the hammered plates of Maryon's theory find [in Dalí's painting] a clear and very powerful expression."[211]

Later years

[edit]

Maryon finally left the British Museum in 1961,[145] a year after his official retirement.[173] He donated a number of items to the museum, including plaster maquettes by George Frampton of Comedy and Tragedy, used for the memorial to Sir W. S. Gilbert along the Victoria Embankment.[16][244] Before his departure Maryon had been planning a trip around the world,[173][245] and at the end of 1961 he left for Fremantle, Australia, arriving on 1 January 1962.[246] In Perth he visited his brother George Maryon, whom he had not seen in 60 years.[172][246] From Australia Maryon departed for Vancouver, then entered the United States through Seattle; he arrived in San Francisco on 15 February.[247][172][173] Much of Maryon's North American tour was done with buses and cheap hotels,[173][245] for, as a colleague would recall, Maryon "liked to travel the hard way—like an undergraduate—which was to be expected since, at 89, he was a young man."[173]

Maryon devoted much of his time during the American stage of his trip to visiting museums and the study of Chinese magic mirrors,[80] a subject he had turned to some two years before.[172] From February through March, stops included Los Angeles, Salt Lake City, the Grand Canyon, and Chicago;[247] by the time he reached Kansas City, Missouri, where he was written up in The Kansas City Times, he had listed 526 examples in his notebook.[172] Maryon arrived in Cleveland from Detroit on 2 April—where he spent three full days at the Cleveland Museum of Art and was again written up by local papers, The Plain Dealer and the Cleveland Press—and then departed by Greyhound to Pittsburgh on 6 April.[247][248]

Maryon's trip also included guest lectures, such as his talk "Metal Working in the Ancient World" at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston on 1 May 1962 and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology the day after,[249][250] and when he came to New York City a colleague later said that "he wore out several much younger colleagues with an unusually long stint devoted to a meticulous examination of two large collections of pre-Columbian fine metalwork, a field that was new to him."[80] Maryon scheduled the trip to end in Toronto, where his son John Maryon, a civil engineer, lived.[172][251]

Personal life

[edit]In July 1903 Maryon married Annie Elizabeth Maryon (née Stones).[252][253][2] They had a daughter, Kathleen Rotha Maryon.[254][255][256][257] Annie Maryon died on 8 February 1908.[258] A second marriage, to Muriel Dore Wood in September 1920,[2][259] produced two children, son John and daughter Margaret.[251][260] Maryon lived the majority of his life in London, and died on 14 July 1965, at a nursing home in Edinburgh, in his 92nd year.[261] Death notices were published in papers including The Daily Telegraph,[251][262] The Times,[145][173] the Toronto Daily Star,[263] the Montreal Star,[264] the Brandon Sun,[265] and the Ottawa Journal.[266] Longer obituaries followed in Studies in Conservation,[245] and the American Journal of Archaeology,[80]

Works by Maryon

[edit]Books

[edit]- Maryon, Herbert (1912). Metalwork and Enamelling. London: Chapman & Hall.

- Maryon, Herbert (1923). Metalwork and Enamelling (2nd ed.). London: Chapman & Hall.

- Maryon, Herbert (1954). Metalwork and Enamelling (3rd ed.). London: Chapman & Hall.

- Maryon, Herbert (1959). Metalwork and Enamelling (4th ed.). London: Chapman & Hall.

- Maryon, Herbert (1971). Metalwork and Enamelling (5th ed.). New York: Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-22702-3.

- Maryon, Herbert (1998). La Lavorazione dei Metalli. Translated by Cesari, Mario. Milan: Hoepli.

- Maryon, Herbert (1933a). Modern Sculpture: Its Methods and Ideals. London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons.

- Maryon, Herbert & Plenderleith, H. J. (1954). "Fine Metal-Work". In Singer, Charles; Holmyard, E. J. & Hall, A. R. (eds.). A History of Technology: From Early Times to Fall of Ancient Empires. A History of Technology. Vol. 1. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 623–662.

- Maryon, Herbert (1956a). "Fine Metal-Work". In Singer, Charles; Holmyard, E. J.; Hall, A. R. & Williams, Trevor I. (eds.). A History of Technology: The Mediterranean Civilizations and the Middle Ages. A History of Technology. Vol. 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 449–484.

Articles

[edit]- Maryon, Herbert (October 1905). "Early Irish Metal Work". The Art Workers' Quarterly. IV (13): 177–180. OCLC 2445017.

- Maryon, Herbert J. (March 1906). "Metal Work: IV.—Filigree". Arts and Crafts. 4 (22). London: Hutchinson & Co.: 185–188. OCLC 225804755.

There is no craft [...]. [...] the work at all.

- Maryon, Herbert (10 May 1922a). "Design in Jewelry". The Jewelers' Circular. LXXXIV (15): 97.

- Republication of passages from Maryon 1912, pp. 280–281

- Maryon, H. (12 July 1922b). "A Critique on Cellini". The Jewelers' Circular. LXXXIV (24): 89.

- Republication of Maryon 1912, ch. XXXIII

- Cowen, J. D. & Maryon, Herbert (1935). "The Whittingham Sword" (PDF). Archaeologia Aeliana. 4th ser. XII: 280–309, plates XXVI-XXVII. ISSN 0261-3417.

- Maryon, Herbert (1935). "The "Casting-On" of a Sword Hilt in the Bronze Age". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle Upon Tyne. 4. VI: 41–42.

- Maryon, Herbert (February 1936a). "Granular Work of the Ancient Goldsmiths". Goldsmiths Journal: 554–556.

- Maryon, Herbert (April 1936b). "Solders Used by the Ancient Goldsmiths". Goldsmiths Journal: 72–73.

- Maryon, Herbert (June 1936c). "Jewellery of 5,000 Years Ago". Goldsmiths Journal: 344–345.

- Maryon, Herbert (October 1936d). "Soldering and Welding in the Bronze and Early Iron Ages". Technical Studies in the Field of the Fine Arts. V (2): 75–108. ISSN 0096-9346.

- Abstract published as Maryon, Herbert (June 1937). "Prehistoric Soldering and Welding". Antiquity. XI (42): 208–209. doi:10.1017/S0003598X0011662X. S2CID 246041270.

- Abstract published as Maryon, Herbert (June 1937). "Prehistoric Soldering and Welding". Antiquity. XI (42): 208–209. doi:10.1017/S0003598X0011662X. S2CID 246041270.

- Maryon, Herbert (1936e). "Excavation of two Bronze Age barrows at Kirkhaugh, Northumberland" (PDF). Archaeologia Aeliana. 4. XIII: 207–217. ISSN 0261-3417.

- Maryon, Herbert (September 1937). "A Passage on Sculpture by Diodorus of Sicily". Antiquity. XI (43): 344–348. doi:10.1017/S0003598X0011676X. S2CID 164044237.

- Maryon, Herbert (April 1938a). "The Technical Methods of the Irish Smiths in the Bronze and Early Iron Ages". Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, Section C. XLIV: 181–228. JSTOR 25516012.

- Maryon, Herbert (July 1938b). "Some Prehistoric Metalworkers' Tools". The Antiquaries Journal. XVIII (3): 243–250. doi:10.1017/S0003581500007228. S2CID 162107631.

- Maryon, Herbert (June 1939a). "Ancient Hand-Anvil from Thomastown, Co. Kilkenny" (PDF). Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society. XLIV (159): 62–63. ISSN 0010-8731. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 April 2018.

- Maryon, Herbert (1939b). "The Gold Ornaments from Cooper's Hill, Alnwick". Archaeologia Aeliana. 4. XVI: 101–108. ISSN 0261-3417.

- Maryon, Herbert (November 1941a). "Archæology and Metallurgy. I. Welding and Soldering". Man. XLI: 118–124. doi:10.2307/2791583. JSTOR 2791583.

- Maryon, Herbert (November 1941b). "Archæology and Metallurgy: II. The Metallurgy of Gold and Platinum in Pre-Columbian Ecuador". Man. XLI: 124–126. doi:10.2307/2791584. JSTOR 2791584.

- Maryon, Herbert (July 1944). "The Bawsey Torc". The Antiquaries Journal. XXIV (3–4): 149–151. doi:10.1017/S0003581500095640. S2CID 163446426.

- Maryon, Herbert (March 1946). "The Sutton Hoo Shield". Antiquity. XX (77): 21–30. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00019232. S2CID 162472027.

- Maryon, Herbert (September 1947). "The Sutton Hoo Helmet". Antiquity. XXI (83): 137–144. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00016598. S2CID 163948719.

- Maryon, Herbert (1948a). "A Sword of the Nydam Type from Ely Fields Farm, near Ely". Proceedings of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society. XLI: 73–76. doi:10.5284/1034398.

- Maryon, Herbert (March 1948b). "The Mildenhall Treasure, Some Technical Problems: Part I". Man. XLVIII: 25–27. JSTOR 2792450.

- Maryon, Herbert (April 1948c). "The Mildenhall Treasure, Some Technical Problems: Part II". Man. XLVIII: 38–41. JSTOR 2792704.

- Maryon, Herbert (April 1949). "Metal Working in the Ancient World". American Journal of Archaeology. LII (2): 93–125. doi:10.2307/500498. JSTOR 500498. S2CID 193115115.

- Maryon, Herbert (July 1950). "A Sword of the Viking Period from the River Witham". The Antiquaries Journal. XXX (3–4): 175–179. doi:10.1017/S0003581500087849. S2CID 162436131.

- Maryon, Herbert (April 1951). "New Light on the Royal Gold Cup". The British Museum Quarterly. XVI (2): 56–58. doi:10.2307/4422320. JSTOR 4422320.

- Maryon, Herbert (June 1953). "The King John Cup at King's Lynn". The Connoisseur: 88–89. ISSN 0010-6275.

- Maryon, Herbert (1956b). "The Colossus of Rhodes". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. LXXVI: 68–86. doi:10.2307/629554. JSTOR 629554. S2CID 162892604.

- Plenderleith, H. J. & Maryon, Herbert (January 1959). "The Royal Bronze Effigies in Westminster Abbey". The Antiquaries Journal. XXXIX (1–2): 87–90. doi:10.1017/S0003581500083633. S2CID 163228818.

- Maryon, Herbert (February 1960a). "Pattern-Welding and Damascening of Sword-Blades—Part 1: Pattern-Welding". Studies in Conservation. 5 (1): 25–37. doi:10.2307/1505063. JSTOR 1505063.

- Maryon, Herbert (May 1960b). "Pattern-Welding and Damascening of Sword-Blades—Part 2: The Damascene Process". Studies in Conservation. 5 (2): 52–60. doi:10.2307/1504953. JSTOR 1504953.

- Maryon, Herbert (1961). "The Making of a Chinese Bronze Mirror". Archives of the Chinese Art Society of America. XV: 21–25. JSTOR 20067029.

- Maryon, Herbert; Organ, R. M.; Ellis, O. W.; Brick, R. M. & Sneyers, E. E. (April 1961). "Early Near Eastern Steel Swords". American Journal of Archaeology. 65 (2): 173–184. doi:10.2307/502669. JSTOR 502669. S2CID 191383430.

- Maryon, Herbert (1963). "The Making of a Chinese Bronze Mirror, Part 2". Archives of the Chinese Art Society of America. XVII: 23–25. JSTOR 20067056.

- Maryon, Herbert (1963). "A Note on Magic Mirrors". Archives of the Chinese Art Society of America. XVII: 26–28. JSTOR 20067057.

Other

[edit]- "The Old Castle: Why Not Improve its Precincts? Mr. H. Maryon's Hint". Newcastle Daily Journal and Courant North Star. Vol. 218, no. 25, 601. Newcastle upon Tyne. 5 March 1928. p. 7.

- Excerpt of a lecture.

- Maryon, Herbert (9 December 1933b). "Modern Sculpture". Points of View: Letters from Readers. The Scotsman. No. 28, 248. Edinburgh. p. 15.

- Maryon, Herbert (December 1933c). "Modern Sculpture". The Bookman. LXXXV (507): 411. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- Maryon, Herbert (October 1934). "Modern Sculpture". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. LXV (CCCLXXIX): 189–190. JSTOR 865986.

- Maryon, Herbert (October 1960). "Review of Der Überfangguss. Ein Beitrag zur vorgeschichtlichen Metalltechnik". American Journal of Archaeology. 64 (4). Archaeological Institute of America: 374–375. doi:10.2307/501341. JSTOR 501341.

Notes

[edit]- ^ The casket was auctioned in 2005 by Penrith Farmers’ & Kidd’s, with an estimate of £800 to £1,200.[27][28]

- ^ Among Maryon's students, meanwhile, was W. Edward Parkinson (son of C. Northcote Parkinson[49]), who went on to lead the York School of Arts and Crafts.[50][51]

- ^ It was reported, however, as a resignation.[62]

- ^ The Parsons plaque was placed on display at C. A. Parsons and Company.[120] Sometime after 2003 the building was demolished and the plaque was donated to the Discovery Museum, where as of 2016 there were plans to place it on display.[120]

- ^ The Manchester Guardian did not explain the reason for the tarring and feathering.[121][122] It followed on the heels of the tarring and feathering of Jacob Epstein's sculptures Rima on 9 October,[124] and Night on 14 October.[125] In the case of Rima, which was unveiled around 1926 and shortly thereafter covered in green paint,[124] papers reported that it had come under criticism for its "'expressionistic' character".[126] Then in 1928 Peter Pan, a statue by Maryon's late teacher Sir George Frampton, was itself tarred and feathered.[127]

- ^ Also that year, one of Maryon's students, Wyllianor Weatherall, painted what The Newcastle Journal termed "a very good likeness" of Maryon and submitted it to the Thirtieth Annual Exhibition of Works by Artists of the Northern Counties at the Laing Art Gallery and Museum.[139][140]

- ^ Kendrick would become director of the museum in 1950.[152][153][154] Dated 6 January 1941, Maryon's letter read:

"There is a question about the Sutton Hoo ship which has been rather on my mind. There exist many photographs of the ship, taken from many angles, and they provide much information as to its structure and general appearance. But has anything been done to preserve the actual form of the vessel—full size?

The Viking ships in their museum in Scandinavia are most impressive, for they are surviving representatives of the actual vessels which played so great a part in the early history of Western Europe. The Sutton Hoo ship is our only representative in this class. I believe that all the timbers have perished, but the form remains—traced in the earth.

That form could be preserved in a plaster cast. I have given some thought to the making of large casts for I have done figures up to 18 feet in height. The work could be done in the following manner: a light steel girder would be constructed, running the full length of the ship, but built in quite short sections. This would not rise above the level of the gunwale at any point but would follow the general curve of the central section of the vessel. It would extend right down to the keel, and would support all the lateral frames. The outer skin, which would preserve the actual external form of the vessel, would be of the usual canvas and plaster work. It would be cast in sections, each perhaps extending along five feet of the length and from keel to gunwale on one side. All sections would be assembled by bolting the frames together. Any roughness of surface due to accidental irregularities in the existing earth matrix could be removed. If it were desired to illustrate the inner structure of the vessel also, I think that that might be shown by constructing a wooden model on a reduced scale.

Such a cast as that suggested above would be a very important document for the history of the time and it would provide a valuable introduction to Sutton Hoo's splendid array of furnishings."[151]Such an operation was not carried out at the time, largely due to time constraints imposed by World War II—impending during the original 1939 excavation, and in full swing by the time of Maryon's letter.[155][156] When an impression was taken during the 1965–69 Sutton Hoo excavations,[157][158][159][160] much the same methods that Maryon proposed were adopted.[156]

- ^ By contrast, photographs of the shield fragments suggested their spatial relationships, allowing Plenderleith to determine which pieces were part of the grip.[182]

- ^ Bruce-Mitford suggested that Maryon's reconstruction "was soon criticized, though not in print, by Swedish scholars and others".[180] At least one scholar, however, did publish minor criticisms.[200] In a 1948 article by Sune Lindqvist—translated into English by Bruce-Mitford himself—the Swedish professor wrote that "[t]he reconstruction of the Sutton Hoo helmet ... needs revision in certain respects." Nonetheless, his only specific criticism was that the face-mask was "set somewhat awry in the reconstruction".[201]

- ^ Maryon's reconstruction correctly identified both the five designs depicted on its exterior, and the helmet's method of construction. Maryon wrote that the helmet was made of sheet iron, then "covered with sheets of very thin tinned bronze, stamped with patterns, and arranged in panels".[179] The patterns were formed from dies carved in relief, while the panels were "framed by lengths of moulding ... swaged from strips of tin", themselves "fixed in place by bronze rivets", and gilded.[203] Meanwhile, "the free edges of the helmet were protected by a U-shaped channel of gilt bronze, clamped on, and held in position by narrow gilt bronze ties, riveted on."[179] Although likely not more than educated guesses, Maryon's statements were largely confirmed by scientific analysis carried out after completion of the second reconstruction.[204] The nature of the moulding separating the panels, however, remains unclear. Maryon suggested they were swaged from tin and gilded,[203] while Bruce-Mitford suggested they were made of bronze.[205] The later analysis found results which were perhaps contradictory, yet themselves internally contradictory. A subsurface sample of the moulding "suggest[ed] that the original metal was tin", (Maryon's theory) while a surface sample showed an "ε-copper/tin compound (Cu3Sn)" and thus suggested instead, because of a similar process observed on the shield, "that the surface of a bronze alloy containing at least 62% of copper had been coated with tin and heated".[206] Additionally, a surface sample taken near the crest had a trace of mercury, suggestive of a fire-gilding process that requires a temperature at least 128 °C above the melting point of tin.[207] An alloy containing at least 20% copper would thus be needed to sufficiently raise the melting point of the tin during the gilding process, a reality further inconsistent with the results of the subsurface sample of moulding.[207] As to swageing, "if the strips [of moulding] were of high tin alloy throughout, swageing would be impossible as copper/tin alloys containing more than 20% of tin are very brittle," while an alloy containing less than 25% tin would no longer replicate the white colour of the helmet.[207] Although the subsurface sample supports Maryon's theory of swaged tin—though not of universally gilded mouldings, which as reflected in the 1973 replica helmet were only found next to the crest—it contradicts the theory suggested by the surface sample, i.e., a copper alloy with a high tin content that was not swaged.

- ^ What in the World? was a show where a panel of scholar–contestants would examine, and attempt to identify, artefacts from the collection of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.[221] Froelich Rainey was the moderator, and for the 3 April 1954 show Maryon was scheduled to be the guest panelist alongside Alfred Kidder II and Schuyler Cammann, both of the museum.[220] The objects set aside for their show included a bronze spearhead from the Middle East dating to 2,400 BC, an African sculpture, a bronze antelope from North India, a bronze medallion from Switzerland dating to 400 BC, a wood carving from Bali, and the handle of an adze used by Native Americans on the Columbia River in Washington.[220] The objects were kept in a cardboard box and mistaken for garbage by a substitute cleaning crew on Friday night, then picked up in the morning by a dump truck operated by Edward Heller and his 16-year-old son Richard.[220] When the box was discovered as missing the studio was searched, the police were called (under the assumption it had been stolen), and Edward Heller was contacted; "I was almost certain," Rainey later said, that the box had been mistakenly included with a shipment to another museum.[220] Richard Heller drove to the dump, despite his father's advice that even if he found the correct spot, the box would have been consumed by a dump fire.[220] Finding the box just as it ignited, Richard Heller doused the fire and recovered the items undamaged.[220] "I looked the things over after Dick brought them back", his father said.[220] "They still looked like to junk [sic] to me."[220] The objects were not recovered in time for the 1:30 show, however, so a kinescope rerun was aired instead.[220]

- ^ Newspaper articles published in the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States reference an account read to the Society of Antiquaries of London on 3 December 1953.[235][236] Maryon published the paper, entitled "The Colossus of Rhodes", in The Journal of Hellenic Studies in 1956.[237][211]

- ^ Maryon used Johann Caspar von Orelli's translation of Philo of Byzantium, which Haynes argued "is frequently misleading".[241] Using Rudolf Hercher's translation, Haynes suggested that "Έπιχωνεύειν is a key word for the whole of Philo's description. An unfortunate slip in the translation used by Maryon confuses it with ἐπιχωννύειν 'to fill up' and so destroys the sense of the passage. Έπιχωνεύειν means 'to cast upon' the part already cast, and that implies casting in situ. It is contrasted with ἐπιθεῖναι 'to place upon', which would imply that the casting was done at a distance. Since in 'casting upon' the molten metal which was to form the new part would presumably have come into direct contact with the existing part, fusion (i.e. 'casting on' in the technical sense) would probably have resulted."[241] Yet the amount of bronze Philo claimed the Colossus to have been made from—500 talents—would not be enough for a statue that was cast, leading Haynes to argue that the figure had been corrupted.[242][243] Haynes thus effectively conceded that if the 500-talent figure was correct, Maryon had a point.[243]

References

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Mapping Sculpture 2011a.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Who Was Who 2014.

- ^ Kelly's Directory 1891, p. 1176.

- ^ Maryon 1895, pp. 9–10.

- ^ England Census 1891.

- ^ England Birth Index 1874.

- ^ Maryon 1895, p. 10.

- ^ Maryon 1897.

- ^ Maryon 1895, p. 1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Institution of Mechanical Engineers 1918.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bruce 2001, p. 54.

- ^ International Studio 1908, p. 342.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Berkshire Chronicle 1908.

- ^ Ashbee 1908, p. 256.

- ^ Mapping Sculpture 2011b.

- ^ Jump up to: a b British Museum Comedy statue.

- ^ Maryon 1912, p. viii.

- ^ Arts & Crafts Exhibition Catalogue 1899, pp. 19, 49, 91, 136.

- ^ H. 1899, pp. 269–270.

- ^ Bruce 2001, pp. 54, 137.

- ^ Crouch & Barnes, p. 6.

- ^ England Census 1901a.

- ^ Bruce 2001, p. 6.

- ^ Bruce 2001, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wood 1900a, p. 85.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wood 1900b, p. 85.

- ^ Cumberland & Westmorland Herald 2005.

- ^ The Salesroom 2005.

- ^ Gregory 1901, p. 139.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bruce 2001, p. 65.

- ^ Bruce 2001, pp. 65, 69.

- ^ Pevsner 1967, p. 259.

- ^ Bruce 2001, pp. 65, 60.

- ^ Northern Counties Magazine 1901, p. 55.

- ^ The Studio 1905.

- ^ International Studio 1906.

- ^ Bruce 2001, pp. 74, 76–77.

- ^ Bruce 2001, pp. 65, 68–69.

- ^ The International Studio 1903, p. 211.

- ^ Maryon 1912, p. 273.

- ^ Maryon 1912, p. 274.

- ^ Bruce 2001, pp. 65–66, 68–69, 71.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Pudney 2000, p. 137.

- ^ Bruce 2001, pp. 59, 61–62, 71, 74.

- ^ Wood 1902, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Bruce 2001, pp. 61, 67.

- ^ Pudney 2000, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Брюс 2001 , стр. 7, 137, 139.

- ^ Тернбулл 2004 .

- ^ Чеширский наблюдатель 1913 .

- ^ North Mail, Newcastle Daily Chronicle, 1927 год .

- ^ Падни 2000 , с. 136.

- ^ Картографическая скульптура 2011c .

- ^ Перепись населения Англии 1901b .

- ^ Брюс 2001 , стр. 68, 72, 75.

- ^ Мэрион 1903 .

- ^ Брюс 2001 , стр. 71, 74–75.

- ^ Шпильманн 1903 , стр. 155–156.

- ^ Брюс 2001 , с. 76.

- ^ Брюс 2001 , стр. 57–59, 76, 137.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Брюс 2001 , стр. 76, 137.

- ^ Посетитель английских озер , 1904 год .

- ^ Мэрион 1905 .

- ^ Каталог выставки искусств и ремесел 1906 года , стр. 68, 110, 193.

- ^ Аллен 1972 , с. 628.

- ^ Боули 1972 , стр. 60–61.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж Исследования по сохранению 1960 года .

- ^ Мэрион 1912 .

- ^ Мэрион 1912 , с. VII.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Смит 1913 .

- ^ Журнал Королевского общества искусств 1913 года .

- ^ Книжник 1912 .

- ^ Зритель 1913 .

- ^ Знаток 1913 .

- ^ Д. 1913 .

- ^ Атенеум 1912 .

- ^ Мэрион 1922b .

- ^ Мэрион 1912 , с. 290.

- ^ Исби 1965 , с. 256.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Исби, 1966 год .

- ^ Вестминстерский вестник, 1913 год .

- ^ Мэрион 1923 .

- ^ Мэрион 1954 .

- ^ Мэрион 1959 .

- ^ Мэрион 1971 .

- ^ Мэрион 1998 .

- ^ Дуврские публикации .

- ^ Барклай 1993 , с. 36.

- ^ Чтение наблюдателя 1916a .

- ^ Чтение наблюдателя 1916b .

- ^ Чтение наблюдателя 1917 года .

- ^ Ежегодник "Студия" 1909 года .

- ^ Каталог выставки искусств и ремесел 1910 г. , с. 83.

- ^ Грей 2009 , с. 75.

- ^ Историческая Англия и 1438366 .

- ^ Военный мемориал Мортимера .

- ^ Мемориал Университета Ридинга .

- ^ Историческая Англия и 1113620 .

- ^ Гражданин 1927 .

- ^ Ньюкасл Дейли Джорнал, 1928 год .

- ^ Мэрион 1933а .

- ^ Maryon 1933a , p. v.

- ^ Феррари 1934 года .

- ^ Художественный дайджест 1934 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Мэрриотт, 1934 год .

- ^ Новый государственный деятель и нация 1933 .

- ^ Григсон 1933 , с. 214.

- ^ Зритель 1934 .

- ^ Мэрион 1933b .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Шотландец 1933 года .

- ^ Мэрион 1933c .

- ^ Мэрион 1934 , с. 190.

- ^ Б. 1934б .

- ^ Знаток 1934 .

- ^ Б. 1934а .

- ^ Почта озера Вакатип , 1929 год .

- ^ Институт инженеров-механиков 1931 , стр. 249–250.

- ^ Газета 1933 .

- ^ Таймс, 1932 год .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Музей друзей Дискавери 2016 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Манчестер Гардиан, 1929c .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Манчестер Гардиан, 1929г .

- ^ Вестерн Дейли Пресс, 1929 год .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Манчестер Гардиан, 1929а .

- ^ Манчестер Гардиан 1929b .

- ^ The Battle Creek Enquirer 1929 .

- ^ Манчестер Гардиан 1928 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Кнутсен и Кнутсен 2005 , стр. 21, 100.

- ^ Коуэн и Мэрион 1935 .

- ^ Мэрион 1935 .

- ^ Мэрион 1936e , с. 208.

- ^ Penrith Observer 1937 .

- ^ Всего археология 2014 , с. 4.

- ^ Дом 2014 , стр. 2–3.

- ^ Мэрион 1936e , стр. 211–214.

- ^ Дживс 2014 .

- ^ Мэрион 1936 .

- ^ Мэрион 1937 .

- ^ Журнал Ньюкасла, 1937 год .

- ^ Йоркшир Пост, 1937 год .

- ^ Мэрион 1938a .

- ^ Мэрион 1938b .

- ^ Мэрион 1939a .

- ^ Мэрион 1939b .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г Брюс-Митфорд, 1965 год .

- ^ Мэрион 1941a .

- ^ Мэрион 1941b .

- ^ Брюс-Митфорд 1975 , с. 228.

- ^ Брюс-Митфорд 1989b , с. 13.

- ^ Карвер 2004 , с. 24.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Брюс-Митфорд 1975 , стр. 228–229.

- ^ Соренсен 2018 .

- ^ Таймс 1979 .

- ^ Британский музей .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Брюс-Митфорд 1974а , с. 170.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Брюс-Митфорд 1975 , с. 229.

- ^ Брюс-Митфорд 1968 .

- ^ Брюс-Митфорд 1974a , стр. 170–174.

- ^ ван Герсдале, 1969 .

- ^ ван Герсдале 1970 .

- ^ Брюс-Митфорд 1975 , стр. xxxvii, 137.

- ^ Биддл 2015 , с. 76.

- ^ Таймс 1994 .

- ^ Брюс-Митфорд 1989a .

- ^ Уильямс 1992 , с. 77.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Брюс-Митфорд 1983а , с. хiii.

- ^ Барклай 1993 , с. 35.

- ^ Труды 1949а .

- ^ Труды 1949б .

- ^ Лондонская газета 1956 , стр. 3113.

- ^ Мэрион 1971 , с. iii.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г час Хьюи, 1962 , стр. 1–2.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г Швеппе 1965а .

- ^ Арвидссон 1942 , с. 1.

- ^ Брюс-Митфорд 1946 , стр. 2–4.

- ^ Мартин-Кларк 1947 , с. 63 п.19.

- ^ Брюс-Митфорд 1947 , с. 24.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Уильямс 1992 , с. 74.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Мэрион 1947 , с. 137.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Брюс-Митфорд 1972 , с. 120.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Брюс-Митфорд 1978 , с. 140.

- ^ Мэрион 1946 , с. 21.

- ^ Мэрион 1947 , стр. 137, 144.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Мэрион 1947 , с. 144.

- ^ Мэрион 1947 , стр. 143–144.

- ^ Уильямс 1992 , стр. 74–75.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Мэрион 1947 год .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Брюс-Митфорд 1972 , с. 121.

- ^ Грин 1963 .

- ^ Гроскопф 1970 .

- ^ Уилсон 1960 .

- ^ Марзинзик 2007 , стр. 16–17.

- ^ Жизнь 1951 года .

- ^ Гервард 2011 .

- ^ Брюс-Митфорд 1970 , с. viii.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Кейпл 2000 , с. 133.

- ^ Брюс-Митфорд 1968 , с. 36.

- ^ Брюс-Митфорд 1975 , стр. 279, 332, 335.

- ^ Брюс-Митфорд 1978 , с. 156.

- ^ Грин 1963 , с. 69.

- ^ Линдквист 1948 , стр. 136.

- ^ Брюс-Митфорд 1972 , с. 123.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Мэрион 1947 , с. 138.

- ^ Брюс-Митфорд 1978 , с. 226.

- ^ Брюс-Митфорд 1978 , с. 146.

- ^ Брюс-Митфорд 1978 , стр. 226–227.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Брюс-Митфорд 1978 , с. 227.

- ^ Брюс-Митфорд 1978 , с. 181.

- ^ Брюс-Митфорд 1974b , с. 285.

- ^ Кейпл 2000 , с. 134.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и де Каллатаи 2006 , с. 54.

- ^ Таймс, 1946 год .

- ^ Труды 1946 года .

- ^ Рекламодатель Суррея, 1949 год .

- ^ Брюс-Митфорд 1989b , с. 14.

- ^ Карвер 2004 , с. 25.

- ^ Королевский музей Онтарио 1953–54 , с. 7.

- ^ Королевский археологический музей Онтарио 1953–54 , с. 7.

- ^ Нью-Йорк Геральд Трибьюн, 1954 год .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г час я дж Воскресный бюллетень 1954 года .

- ^ Хаятт 1997 .

- ^ Топпинг 1957–1958 , с. 35.

- ^ Иллюстрированные лондонские новости 1955 года .

- ^ Сейриг 1952 , с. 66.

- ^ Плендерлейт 1956 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Мэрион и Плендерлейт, 1954 .

- ^ Плендерлейт и Мэрион 1959 .

- ^ Мэрион 1956а .

- ^ Мэрион 1946 .

- ^ Мэрион 1948a .

- ^ Брюс-Митфорд 1949 , с. 67 н.269.

- ^ Мэрион 1960a , с. 26.

- ^ Брюс-Митфорд 1978 , с. 307.

- ^ Энгстром, Ланктон и Лешер-Энгстром 1989 .

- ^ Труды 1954 года .

- ^ См. § Статьи Колосса.

- ^ Мэрион 1956b .

- ^ Мэрион 1956b , с. 72.

- ^ Уильямс 1994 .

- ^ Фонд памятников мужчинам .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Хейнс 1957 , с. 311.

- ^ Хейнс 1957 , с. 312 и №4.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Дикки 1996 , с. 251.

- ^ Статуя трагедии Британского музея .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Швеппе 1965б .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Списки пассажиров Фримантла, 1962 год .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Простой дилер 1962 .

- ^ Хьюз 1962 .

- ^ Бостон Глоуб , 1962 .

- ^ Технология 1962 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Дейли Телеграф, 1965б .

- ^ Браки в Англии, 1903 год .

- ^ Индекс браков в Англии, 1903 год .

- ^ Приходские служащие Ланкашира .

- ^ Перепись населения Англии 1911 года .

- ^ Таймс, 1929 год .

- ^ Музей и художественная галерея Святого Барба .

- ^ Завещания и администрация Англии 1908 года .

- ^ Индекс браков в Англии, 1920 год .

- ^ Виннипег Свободная Пресса 2005 .

- ^ Завещание Англии, 1965 год .

- ^ Дейли Телеграф 1965а .

- ^ Торонто Дейли Стар, 1965 .

- ^ Монреаль Стар 1965 .

- ^ Брэндон Сан 1965 .

- ^ Оттавский журнал 1965 .

Библиография

[ редактировать ]- Аллен, RGD (1972). «Обзор мемуаров профессора сэра Артура Боули (1869–1957) и его семьи». Журнал Королевского статистического общества . Серия А. 135 (4). Лондон: Королевское статистическое общество : 628–629. JSTOR 2344707 .

- «Находка Олстонского человека: реликвии бронзового века, раскопки двух «курганов» . Penrith Observer . № 3, 938. Пенрит, Камбрия. 2 марта 1937 г., стр. 6.

- «Энни Элизабет Мэрион: Англия и Уэльс, Национальный индекс завещаний и управления, 1858–1957» . Семейный поиск . 2019.

- Годовой отчет (PDF) (Отчет). Том. 5. Торонто: Королевский музей Онтарио. 1953–1954.

- Годовой отчет Правлению (Отчет). Торонто: Королевский археологический музей Онтарио. Июль 1953 г. - июнь 1954 г.

- «Искусство Северной Англии: Ежегодная выставка в Ньюкасле» . Йоркшир Пост . № 28, 196. Лидс. 13 декабря 1937 г. с. 5.

- «Записки художественной школы: Чтение» . Международная студия . XXXIV (136). Нью-Йорк: John Lane Co.: 342, июнь 1908 г.

- Арвидссон, Грета (1942). Вариант 6 . Упсала: Almqvist & Wiksells Boktryckeri AB

- Эшби, Чарльз Роберт (1908). Мастерство в конкурентной промышленности: отчет о мастерских Гильдии ремесленников и некоторые выводы из их двадцати одного года опыта . Чиппинг Кэмпден, Глостершир: Essex House Press.

- «Попытка испортить «Ночь»: смола и перья в стеклянной таре» . Манчестер Гардиан . № 25, 936. Манчестер. 16 октября 1929 г. с. 12.

- Б., Л.Б. (3 января 1934а). «Скульптура». Книги дня. Манчестер Гардиан . № 27, 243. Манчестер. п. 5.

- Б., РП (июль 1934б). «Обзор современной скульптуры». Журнал Burlington для ценителей . LXV (CCCLXXVI): 50. JSTOR 865852 .

- Барклай, Р.Дж. (январь – декабрь 1993 г.). «Консерватор: универсальность и гибкость» . Международный музей . XLV (4): 35–40. дои : 10.1111/j.1468-0033.1993.tb01136.x . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 16 октября 2018 г.

- «Мемориал Бернарда Гилпина в церкви Кентмер» . Журнал северных графств . II (7): 2, 54–55. Апрель 1901 года.

- Биддл, Мартин (3 декабря 2015 г.). «Руперт Лео Скотт Брюс-Митфорд: 1914–1994» (PDF) . Биографические мемуары членов Британской академии . XIV . Британская академия: 58–86.

- Боули, Агата Х. (1972). Мемуары профессора сэра Артура Боули (1869–1957) и его семьи . Частное издание. OCLC 488656 .

- «16-летний мальчик становится детективом, чтобы найти потерянные телеобъекты». Воскресный бюллетень . Том. 107, нет. 356. Филадельфия. 4 апреля 1954 г. с. 3.

- «Эксперт Британского музея рассказывает сегодня в 17:00 о древних мечах» (PDF) . Тех . Том. 82, нет. 12. Кембридж, Массачусетс. 2 мая 1962 г. с. 1. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 3 ноября 2021 года . Проверено 5 мая 2018 г.

- Брюс, Ян (2001). Любящий глаз и умелая рука: Школа промышленных искусств Кесвика . Карлайл: Книжный шкаф. OCLC 80891576 .

- Брюс-Митфорд, Руперт (сентябрь 1946 г.). «Захоронение корабля в Саттон-Ху». Восточно-английский журнал . 6 (1): 2–9, 43.

- Брюс-Митфорд, Руперт (1947). Захоронение корабля в Саттон-Ху: предварительное руководство . Лондон: Попечители Британского музея.

- Брюс-Митфорд, Руперт (1949). «Захоронение корабля в Саттон-Ху: последние теории и некоторые комментарии к общей интерпретации» (PDF) . Труды Саффолкского института археологии . XXV (1). Ипсвич: 1–78.

- Брюс-Митфорд, Руперт (23 июля 1965 г.). «Мистер Герберт Мэрион» . Некролог. Таймс . № 56381. Лондон. п. 14.

- Брюс-Митфорд, Руперт (март 1968 г.). «Раскопки в Саттон-Ху, 1965–7». Античность . XLII (165): 36–39. дои : 10.1017/S0003598X00033810 . S2CID 163655331 .

- Брюс-Митфорд, Руперт (1970). Предисловие. Сокровище Саттон-Ху: корабль-захоронение англосаксонского короля . Гроскопф, Бернис. Нью-Йорк: Атенеум. LCCN 74-86555 .

- Брюс-Митфорд, Руперт (осень 1972 г.). «Шлем Саттон-Ху: новая реконструкция». Ежеквартальный журнал Британского музея . XXXVI (3–4). Британский музей: 120–130. дои : 10.2307/4423116 . JSTOR 4423116 .

- Брюс-Митфорд, Руперт (1974a). Аспекты англосаксонской археологии: Саттон-Ху и другие открытия . Лондон: Виктор Голланц Лимитед . ISBN 0-575-01704-Х .

- Брюс-Митфорд, Руперт (1974b). «Экспонаты в бюллетенях: 5. Копия шлема Саттон-Ху, сделанная в Оружейной палате Тауэра, 1973 год». Журнал антикваров . ЛИВ (2): 285–286. дои : 10.1017/S0003581500042529 . S2CID 246055329 .

- Брюс-Митфорд, Руперт (1975). Захоронение корабля в Саттон-Ху, Том 1: Раскопки, предыстория, корабль, датировка и инвентарь . Лондон: Публикации Британского музея. ISBN 978-0-7141-1334-0 .

- Брюс-Митфорд, Руперт (1978). Захоронение корабля в Саттон-Ху, Том 2: Оружие, доспехи и регалии . Лондон: Публикации Британского музея. ISBN 978-0714113319 .

- Брюс-Митфорд, Руперт (1983a). Погребение корабля в Саттон-Ху, том 3: позднеримское и византийское серебро, подвесные чаши, сосуды для питья, котлы и другие контейнеры, текстиль, лира, керамические бутылки и другие предметы . Том. I. Лондон: Публикации Британского музея. ISBN 978-0-7141-0529-1 .

- Брюс-Митфорд, Руперт (1983b). Погребение корабля в Саттон-Ху, том 3: позднеримское и византийское серебро, подвесные чаши, сосуды для питья, котлы и другие контейнеры, текстиль, лира, керамические бутылки и другие предметы . Том. II. Лондон: Публикации Британского музея. ISBN 978-0-7141-0530-7 .

- Брюс-Митфорд, Руперт (1989a). «Ранние мысли о Саттон-Ху» (PDF) . Саксонский (10).

- Брюс-Митфорд, Руперт (1989b). Англосаксонская и средневековая археология, история и искусство с особым упором на Саттон-Ху: чрезвычайно важная рабочая библиотека и архив из более чем 6000 наименований, созданный доктором Рупертом Л.С. Брюсом-Митфордом FBA, D.Litt., FSA . Уикмир: Merrion Book Co.

- Включает вступительные эссе «Мое японское происхождение» и «Сорок лет с Саттон Ху» Брюса-Митфорда . Последний был переиздан в Carver 2004 , стр. 23–28.

- «На воздушном шаре на Парнас». Новый государственный деятель и нация . Новая серия. VI (148): 848. 23 декабря 1933 г.

- Кейпл, Крис (2000). «Реставрация: пример 9А: шлем Саттон-Ху» . Навыки сохранения: суждение, метод и принятие решений . Абингдон: Рутледж. ISBN 978-0-415-18880-7 .

- Карвер, Мартин (2004). «До 1983 года» (PDF) . Полевые отчеты Саттон-Ху (набор данных). 2 . дои : 10.5284/1000266 .

- Каталог Шестой выставки . Лондон: Общество выставок искусств и ремесел . 1899.

- Каталог Восьмой выставки . Лондон: Общество выставок искусств и ремесел . 1906.

- Каталог Девятой выставки . Лондон: Общество выставок искусств и ремесел . 1910.

- «Успех Честерского художника» . Чеширский обозреватель . Том. LXI, нет. 3, 174. Честер. 7 июня 1913 г. с. 10.

- «Соавторы этого выпуска: Герберт Мэрион». Исследования в области консервации . 5 (1). Международный институт консервации исторических и художественных произведений . Февраль 1960 г. JSTOR 1505065 .

- Идентичная биография, указанная в «Соавторы этого выпуска: Герберт Мэрион». Исследования в области консервации . 5 (2). Международный институт консервации исторических и художественных произведений . Май 1960 г. JSTOR 1504958 .

- Идентичная биография, указанная в «Соавторы этого выпуска: Герберт Мэрион». Исследования в области консервации . 5 (2). Международный институт консервации исторических и художественных произведений . Май 1960 г. JSTOR 1504958 .

- «Ремесло слесаря» . Вестминстерская газета . Том. XLI, нет. 6, 131. Лондон. 21 января 1913 г. с. 3.

- Крауч, Филип и Барнс, Джейми. «Краткая история Кесвикской школы промышленного искусства» (PDF) . Городской совет Аллердейла. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 21 октября 2016 года.

- «Актуальная литература: современная скульптура» . Зритель . 152 (5, 506): 30. 5 января 1934 г.

- Д., Н. (ноябрь 1913 г.). «Обзор металлообработки и эмалирования». Журнал Burlington для ценителей . XXIV (CXXVIII): 114. JSTOR 859532 .

- де Каллатаи, Годфруа (2006). «Колосс Родосский: древние тексты и современные представления» . В Лиготе, Кристофер Р. и Квантен, Жан-Луи (ред.). История стипендий: подборка статей с семинара по истории стипендий, ежегодно проводимого в Институте Варбурга . Лондон: Издательство Оксфордского университета. стр. 39–73. ISBN 978-0-19-928431-3 .

- «Кафедры гуманитарных наук и металлургии» . Лекции. Бостон Сандей Глоуб . Том. CLXXXI, нет. 119. Бостон. 29 апреля 1962 г. с. А42.

- Дикки, Мэтью Уоллес (1996). «Что такое колоссы и как создавались колоссы в эллинистический период?» . Греческие, римские и византийские исследования . 37 (3). Издательство Университета Дьюка: 237–257.

- Исби, Дадли Т. младший (октябрь 1965 г.). «Сэмюэл Киркланд Лотроп, 1892–1965» . Американская древность . 21 (2:1). Общество американской археологии : 256–261. дои : 10.1017/S0002731600088545 . JSTOR 2693994 . S2CID 164871894 .

- Исби, Дадли Т. младший (июль 1966 г.). «Некрология». Американский журнал археологии . 70 (3). Археологический институт Америки : 287. doi : 10.1086/AJS501899 . JSTOR 501899 . S2CID 245268774 .

- «Ссылки Идена и Кесвика на антиквариат и предметы коллекционирования» . Камберленд и Вестморленд Геральд . 25 июня 2005 г. Архивировано из оригинала 12 февраля 2020 г. . Проверено 18 октября 2018 г.

- Энгстрем, Роберт; Лэнктон, Скотт Майкл и Лешер-Энгстром, Одри (1989). Современная копия, основанная на сваренном по образцу мече Саттон-Ху . Каламазу: Публикации Института средневековья, Университет Западного Мичигана. ISBN 978-0-918720-29-0 .

- Феррари, Дино (6 мая 1934 г.). «Некоторые скульптуры наших дней» . Рецензия на книгу. Нью-Йорк Таймс . Том. LXXXIII, нет. 27, 861. Нью-Йорк. стр. 5–21.

- «Модуль полевых работ 2b: Раскопки Киркхо Кэрнса, дизайн проекта» (PDF) . В общем, археология . 2014.

- «Прекрасная и чрезвычайно редкая эмалированная медная шкатулка поздней викторианской эпохи с подписью и документацией Кесвикской школы промышленных искусств (KSIA)» . Торговый зал . 29 июня 2005 г. Проверено 18 октября 2018 г.

- Грей, Сара (2009). «Коллингридж, Барбара Кристал». Словарь британских женщин-художниц . Кембридж: Латтерворт Пресс. п. 75. ИСБН 978-0-7188-3084-7 .

- Грин, Чарльз (1963). Саттон-Ху: Раскопки королевского корабля-захоронения . Нью-Йорк: Barnes & Noble.

- Грегори, Эдвард В. (июнь – сентябрь 1901 г.). «Домашнее искусство и промышленность» . Художник: Иллюстрированный ежемесячный отчет о художественных ремеслах и промышленности . XXXI (259). Нью-Йорк: Труслав, Хэнсон и Комба: 135–140. дои : 10.2307/25581626 . JSTOR 25581626 .

- Григсон, Джеффри (декабрь 1933 г.). «Обзор современной скульптуры, моделирования и создания скульптуры» . Книжник . LXXXV (507): 213–214. Архивировано из оригинала 3 января 2020 года . Проверено 3 января 2020 г.

- Гроскопф, Бернис (1970). Сокровище Саттон-Ху: корабль-захоронение англосаксонского короля . Нью-Йорк: Атенеум. LCCN 74-86555 .

- Х., К. (октябрь 1899 г.). «Студийный разговор: Лондон» . Международная студия . VIII (32). Нью-Йорк: John Lane Co.: 266–271.

- Хейл, Дункан (октябрь 2014 г.). «Кирко Кэрн, Тайндейл, Нортумберленд: геофизические исследования» (PDF) . Археологические службы (3500). Даремский университет.

- Хейнс, Делавэр (1957). «Филон Византийский и Колосс Родосский». Журнал эллинистических исследований . LXXVII (2): 311–312. дои : 10.2307/629373 . JSTOR 629373 . S2CID 162781611 .

- «Герберт Дж. Мэрион в переписи населения Англии 1891 года» . Родовая библиотека . 2005.

- «Герберт Джеймс Мэрион» . Картирование практики и профессии скульптуры в Великобритании и Ирландии 1851–1951 гг . Университет Глазго История искусства. 2011а. Архивировано из оригинала 27 декабря 2021 года . Проверено 13 сентября 2016 г.

- «Герберт Джеймс Мэрион» . Картирование практики и профессии скульптуры в Великобритании и Ирландии 1851–1951 гг . Университет Глазго История искусства. 2011б . Проверено 13 сентября 2016 г.

- «Герберт Джеймс Мэрион в Англии и Уэльсе, Индекс регистрации актов гражданского состояния, 1837–1915» . Родовая библиотека . 2006.

- «Герберт Джеймс Мэрион в переписи населения Англии 1901 года» . Родовая библиотека . 2005.

- «Герберт Джеймс Мэрион в Англии, избранные браки, 1538–1973» . Родовая библиотека . 2014.

- «Герберт Джеймс Мэрион в Англии и Уэльсе, Индекс регистрации браков гражданской регистрации, 1837–1915» . Родовая библиотека . 2006.

- «Герберт Джеймс Мэрион в переписи населения Англии 1911 года» . Родовая библиотека . 2011.

- «Герберт Джеймс Мэрион в Англии и Уэльсе, Индекс регистрации браков гражданской регистрации, 1916–2005 гг.» . Родовая библиотека . 2010.

- «Герберт Джеймс Мэрион в Англии и Уэльсе, Национальный календарь завещаний (Индекс завещаний и администраций), 1858–1966, 1973–1995» . Родовая библиотека . 2010.

- «Герберт Мэрион» . Некролог. «Дейли телеграф» . № 34, 285. Лондон. 16 июля 1965 г. с. 18.

- «Герберт Мэрион» . Летальные исходы. Оттавский журнал . Том. 80, нет. 187. Оттава, Онтарио. Канадская пресса. 21 июля 1965 г. с. 34 – через Newspapers.com .

- «Герберт Мэрион» . Некрологи. Брэндон Сан . Том. 84, нет. 157. Брэндон, Манитоба. Канадская пресса. 23 июля 1965 г. с. 11 – через Newspapers.com .

- «Герберт Мэрион» . Некрологи. Монреаль Стар . Том. 97, нет. 168. Монреаль, Квебек. Канадская пресса. 21 июля 1965 г. с. 18 – через Newspapers.com .

- Историческая Англия . «Военный мемориал Ист-Нойл (1438366)» . Список национального наследия Англии . Проверено 11 октября 2018 г.

- Историческая Англия . «Военный мемориал Университета Рединга (1113620)» . Список национального наследия Англии . Проверено 11 октября 2018 г.

- «Г. Дж. Мэрион во Фримантле, Западная Австралия, списки пассажиров, 1897–1963» . Родовая библиотека . 2014.

- Хьюи, Артур Д. (22 марта 1962 г.). «Зеркала не отражают энтузиазм» . Канзас-Сити Таймс . Том. 125, нет. 70. Канзас-Сити, Миссури. стр. 1–2 . Архивировано из оригинала 27 декабря 2021 года — на Newspapers.com .

- Хьюз, Бетти (6 апреля 1962 г.). «Посещая музей, британец называет свою чашку чая». Кливленд Пресс . Кливленд, Огайо.

- Хаятт, Уэсли (1997). «Что в мире». Энциклопедия дневного телевидения . Нью-Йорк: Billboard Books. стр. 458–459. ISBN 0-8230-8315-2 .

- Институт инженеров-механиков (1918 г.). «Герберт Джеймс Мэрион, будет рассмотрен Комитетом по заявкам в среду, 24 апреля, и Советом в пятницу, 3 мая 1918 года». . Предложения о членстве и т.д. Лондон: Ancestry.com . стр. 337–339.

- Институт инженеров-механиков (июнь 1931 г.). «Представление копии таблички, прикрепленной к коттеджу Джорджа Стивенсона в Уайлам-он-Тайн». Труды Института инженеров-механиков . 120 : iv, 249–251. дои : 10.1243/PIME_PROC_1931_120_012_02 .

- «Изобретатель турбины: открыт мемориал сэру Чарльзу Парсонсу» . Газета . Том. CLXII, нет. 51. Монреаль. 1 марта 1933 г. с. 11.

- Дживс, Пол (4 августа 2014 г.). «Школьники раскопали золотую прядь волос, которой более 4000 лет» . « Дейли Экспресс» . Проверено 16 октября 2018 г.

- «Школа промышленных искусств Кесвика» . Посетитель английских озер и защитник Кесвика . Том. XXVIII, нет. 1, 439. 31 декабря 1904 г. с. 4.

- Кнутсен, Вилли и Кнутсен, Уилл К. (2005). Арктическое солнце на моем пути: правдивая история последнего великого полярного исследователя Америки . Книги Клуба исследователей. Гилфорд, Коннектикут: Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1-59228-672-0 .

- Линдквист, Суне (сентябрь 1948 г.). «Саттон-Ху и Беовульф». Античность . XXII (87). Перевод Брюса-Митфорда, Руперта : 131–140. дои : 10.1017/S0003598X00019669 . S2CID 164075295 .

- «Лондонский музейщик, 88 лет, идеальный путешественник» . Обычный дилер . Кливленд, Огайо. 6 апреля 1962 г. с. 10.

- «Великолепный шлем из серебра и железа — портрет сирийского королевского генерала времен распятия: недавно отреставрированный и теперь выставленный во временное пользование в Британском музее». Иллюстрированные лондонские новости . № 6, 054. 27 августа 1955. с. 769.

- «Маргарет Джоан Саватски» . свободной прессы Виннипега Проходы для . 8 октября 2005 г. Проверено 20 октября 2016 г.

- Мартин-Кларк, Д. Элизабет (1947). Культура раннеанглосаксонской Англии . Балтимор: Johns Hopkins Press.

- «Брак: мистер Дж. Дж. Дарли и мисс Мэрион» . Таймс . № 45250. Лондон. 9 июля 1929 г. с. 19.

- «Брак в церкви Святого Михаила и всех ангелов в приходе Хоксхед: браки, зарегистрированные в реестре за 1924–1933 годы» . Приходские служащие Ланкашира онлайн . Проверено 20 октября 2016 г.

- Марриотт, Чарльз (18 января 1934 г.). «Книги по скульптуре» . Литературное дополнение. Таймс . № 1668. Лондон. п. 43.

- «Мэрион» . Летальные исходы. «Дейли телеграф» . № 34, 285. Лондон. 16 июля 1965 г. с. 32 – через Newspapers.com .

- «Мэрион, Герберт» . Ежегодник декоративного искусства "Студия" . Лондон: Студия. 1909. с. 148.

- «Мэрион, Герберт» . Кто Был Кто . Издательство Оксфордского университета. Апрель 2014 года . Проверено 13 сентября 2016 г.

- Мэрион, Джон Эрнест (1895). Записи и родословная семьи Мэрион из Эссекса и Хертса . Лондон: Самостоятельная публикация.

- Мэрион, Джон Эрнест (октябрь 1897 г.). «556: Семья Мэрион» . Заметки и вопросы Фенланда . III . Питерборо: 141–142.

- Мэрион, Милдред (16 ноября 1903 г.). «Художественная эмалировка и обработка металлов» . Разнообразный. Студия . ХХХ (128): XXVI.

- Марзинзик, Соня (2007). Шлем Саттон-Ху . Лондон: Издательство Британского музея. ISBN 978-0-7141-2325-7 .

- «Металлообработка и эмалирование» . Дуврские публикации . Проверено 13 февраля 2020 г. .

- «Милдред Дж. Мэрион в переписи населения Англии 1901 года» . Родовая библиотека . 2005.

- «Мисс (Луиза) Эдит К. Мэрион» . Картирование практики и профессии скульптуры в Великобритании и Ирландии 1851–1951 гг . Университет Глазго История искусства. 2011а . Проверено 22 октября 2018 г.

- «Современная скульптура». Художественные интересы. Шотландец . № 28, 232. Эдинбург. 21 ноября 1933 г. с. 11.

- «Люди-памятники: майор Денис Эйр Ланкестер Хейнс (1913–1994)» . Фонд памятников мужчинам . Проверено 18 октября 2016 г.

- «Военный мемориал Мортимера» . Реестр военных мемориалов . Имперские военные музеи . Архивировано из оригинала 9 октября 2018 года . Проверено 19 февраля 2023 г.

- «Новые назначения в колледже Армстронг» . Летальные исходы. Гражданин . Том. 52, нет. 128. Глостер. Канадская пресса. 27 сентября 1927 г. с. 6 – через Newspapers.com .

- «Выставка художников Севера: лучшая за несколько лет» . Ньюкасл Джорнал . Том. 227, нет. 28, 603. Ньюкасл-апон-Тайн. 11 декабря 1937 г. с. 12.

- «Надругательство над лондонскими статуями» . Наша лондонская переписка. Манчестер Гардиан . № 25, 580. Манчестер. 23 августа 1928 г. с. 8.