Vladivostok

Vladivostok

Владивосток | |

|---|---|

Top-down, left-to-right: View of Zolotoy Bridge and the Golden Horn Bay at night, with the Russky Bridge in the distance; GUM Department Store; Vladimir K. Arseniev Museum of Far East History; the campus of Far Eastern Federal University; Vladivostok Railway Station; and Central Square | |

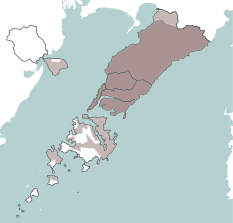

Location of Vladivostok | |

| Coordinates: 43°6′54″N 131°53′7″E / 43.11500°N 131.88528°E | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal subject | Primorsky Krai[1] |

| Founded | July 2, 1860[2] |

| City status since | April 22, 1880 |

| Government | |

| • Body | City Duma |

| • Head | Konstantin Shestakov[3] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 331.16 km2 (127.86 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 8 m (26 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2018)[5] | 604,901 |

| • Subordinated to | Vladivostok City Under Krai Jurisdiction[1] |

| • Capital of | Primorsky Krai,[6] Vladivostok City Under Krai Jurisdiction[1] |

| • Urban okrug | Vladivostoksky Urban Okrug[7] |

| • Capital of | Vladivostoksky Urban Okrug[7] |

| Time zone | UTC+10 (MSK+7 |

| Postal code(s)[9] | 690xxx |

| Dialing code(s) | +7 423[10] |

| OKTMO ID | 05701000001 |

| City Day | First Sunday of July |

| Website | www |

Vladivostok (/ˌvlædɪˈvɒstɒk/ VLAD-iv-OST-ok; Russian: Владивосток, IPA: [vlədʲɪvɐˈstok] ) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai and the capital of the Far Eastern Federal District of Russia, located in the far east of Russia. It is located around the Golden Horn Bay on the Sea of Japan, covering an area of 331.16 square kilometers (127.86 square miles), with a population of 603,519 residents as of 2021.[11] Vladivostok is the second-largest city in the Far Eastern Federal District, as well as the Russian Far East, after Khabarovsk. It is located approximately 45 kilometers (28 mi) from the China–Russia border and 134 kilometers (83 mi) from the North Korea–Russia border.

The Treaty of Aigun in 1858 between Qing China and the Russian Empire, ceded Chinese land north and east of Amur river to the Russian Empire. Two years later in 1860,The Convention of Peking – ceded additional coast territory to the Russians including Haishenwai (now Vladivostok). Vladivostok was founded as a Russian military outpost on July 2, 1860.[12] In 1872, the main Russian naval base on the Pacific Ocean was transferred to the city, stimulating its growth. In 1914 the city experienced rapid growth economically and ethnically diverse with population exceeding over 100,000 inhabitants with sightly less than half of the population being Russians.[13] During this time, large Asian communities developed in the city. The public life of the city flourished; many public associations were created, from charities to hobby groups.[14] After the outbreak of the Russian Revolution in 1917, Vladivostok was occupied in 1918 by White Russian and Allied forces, the last of whom, from the Japanese Empire, were not withdrawn until 1922 as part of its wider intervention in Siberia; by that time the antirevolutionary White Army forces had collapsed. That same year, the Red Army occupied the city, absorbing the Far Eastern Republic into the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the city became a part of the Russian Federation.

Today, Vladivostok remains the largest Russian port on the Pacific Ocean, and the chief cultural, economic, scientific, and tourism hub of the Russian Far East. As the terminus of the Trans-Siberian Railway, the city was visited by over three million tourists in 2017.[15] The city is the administrative center of the Far Eastern Federal District, and is the home to the headquarters of the Pacific Fleet of the Russian Navy. Due to its geographical position in Asia combined with its Russian architecture, the city has been referred to as "Europe in the Far East".[16][17] Many foreign consulates and businesses have offices in Vladivostok, and the city hosts the annual Eastern Economic Forum. With a yearly mean temperature of around 5 °C (41 °F), Vladivostok has a cold climate for its mid-latitude coastal setting. This is due to winds from the vast Eurasian landmass in winter and the cooling ocean temperatures.

Names and etymology

[edit]Vladivostok means 'Lord of the East' or 'Ruler of the East'. The name derives from Slavic владь (vlad, 'to rule'[a]) and Russian восток (vostok, 'east'); Colloquial Russian speech may use the short form Vladik (Russian: Владик) to refer to the city.[18][better source needed]

The city, along with other features in the Peter the Great Gulf area, was first given its modern name in 1859 by Nikolay Muravyov-Amursky. The name initially applied to the bay, but following an expedition by Alexey Karlovich Shefner in 1860, it was later applied to the new settlement.[19] The form of the name appears analogous to that of the city of Vladikavkaz ("Ruler of the Caucasus" or "Rule the Caucasus"), now in North Ossetia–Alania, which was founded and named by the Russian Empire in 1784.

Chinese maps from the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) referred to Vladivostok as Yongmingcheng (永明城; Yǒngmíngchéng).[20] Since the Qing dynasty,[21] the city has also been known as Haishenwai/Haishenwei/Hai-shen-wei (海参崴; Hǎishēnwǎi, Hǎishēnwēi; 'sea cucumber bay[22]') from Mandarin Chinese, ultimately from the Manchu Haišenwai (Manchu: ᡥᠠᡳᡧᡝᠨᠸᡝᡳ, Möllendorff: Haišenwai, Abkai: Haixenwai) or small seaside fishing village.[23] However, according to National Chung Cheng University's research department for Manchu studies, the Manchu name comes from Chinese, specifically Mandarin Chinese, that was named for its historical abundance of sea cucumbers.[24] In China, Vladivostok is now officially known by the transliteration Chinese: 符拉迪沃斯托克; pinyin: Fúlādíwòsītuōkè), although the historical Chinese name 海参崴 (Hǎishēnwǎi) is still often used in common parlance to refer to the city.[25] According to the provisions of the Chinese government, all maps published in China must bracket the city's Chinese name.[26][27]

The modern-day Japanese name of the city is transliterated as Urajiosutoku (ウラジオストク). Historically,[b] the city's name was transliterated with Kanji as 浦鹽斯德 and shortened to Urajio (ウラジオ, 浦鹽).[28]

History

[edit]Foundation

[edit]

The city was the site of a Chinese settlement around 600 AD,[29][30][dubious – discuss] where it was known as Yongmingcheng (永明城 [Yǒngmíngchéng], "city of eternal light") during the Yuan dynasty.[20]

For a long time, the Russian government looked for a stronghold in the Far East; this role was played in turn by the settlements of Okhotsk, Ayan, Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, and Nikolaevsk-on-Amur. By the middle of the 19th-century, the search for the outpost had reached a dead end. None of the ports met the necessary requirement: to have a convenient and protected harbor next to important trade routes.[31] After China was threatened with war on a second front by Governor-General of the Far East Nikolay Muraviev when China was suppressing the Taiping Rebellion,[12] the Aigun Treaty was concluded by Muraviev's forces, after which Russian exploration of the Amur region began, and later, as a result of the signing of the Treaty of Tientsin and the Convention of Peking, the territory of modern Vladivostok was annexed to Russia. The name Vladivostok appeared in the middle of 1859, was used in newspaper articles and denoted a bay.[31] On June 20 (or July 2 of the Gregorian calendar), 1860 the transport of the Siberian Military Flotilla "Mandzhur" under the command of Lieutenant-Commander Alexei Karlovich Shefner delivered a military unit to the Golden Horn Bay to establish a military post, which has now officially received the name of Vladivostok.[32]

Early history

[edit]On October 31, 1861, the first civilian settler, a merchant, Yakov Lazarevich Semyonov, arrived in Vladivostok with his family. On March 15, 1862, the first act of his purchase of land was registered, and in 1870 Semyonov was elected the first head of the post, and a local self-government emerged.[31] By this time, a special commission decided to designate Vladivostok as the main port of the Russian Empire in the Far East.[33] In 1871, the main naval base of the Siberian Military Flotilla, the headquarters of the military governor and other naval departments were transferred from Nikolaevsk-on-Amur to Vladivostok.[34]

In the 1870s, the government encouraged resettlement to the South Ussuri region, which contributed to an increase in the population of the post: according to the first census of 1878, there were 4,163 inhabitants. The city status was adopted and the city Duma was established, the post of the city head, the coat of arms was adopted, although Vladivostok was not officially recognized as a city.[34]

Due to the constant threat of attack from the Royal Navy, Vladivostok also actively developed as a naval base.

In 1880, the post officially received the status of a city. The 1890s saw a demographic and economic boom associated with the completion of the construction of the Ussuriyskaya branch of the Trans-Siberian Railway and the Chinese-Eastern Railway.[34] According to the first census of the population of Russia on February 9, 1897, roughly 29,000 inhabitants lived in Vladivostok, and 10 years later the city's population had tripled.[34] Korean haenyeo divers from Jeju Island and vicinities were active in Vladivostok.[35]

The first decade of the 20th-century was characterized by a protracted crisis caused by the political situation: the government's attention was shifted to Lüshunkou and the Port of Dalian (Talien). As well as the Boxer uprising in North China in 1900–1901, the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, and finally the first Russian revolution led to stagnation in the economic activity of Vladivostok.[13]

Since 1907, a new stage in the development of the city began: the losses of Lüshunkou and Dalian (Talien) again made Vladivostok the main port of Russia on the Pacific Ocean. A free port regime was introduced, and until 1914 the city experienced rapid growth, becoming an important economic hub in the Asia-Pacific, as well as an ethnically diverse city with a population exceeding over 100,000 inhabitants: during the time ethnic Russians made up less than half of the population,[13] and large Asian communities developed in the city. The public life of the city flourished; many public associations were created, from charities to hobby groups.[14]

World War I and Russian Civil War

[edit]

During World War I, no active hostilities took place in the city.[36] However, Vladivostok was an important staging post for the import of military-technical equipment for troops from allied and neutral countries, as well as raw materials and equipment for industry.[37]

Immediately after the October Revolution in 1917, during which the Bolsheviks came to power, the Decree on Peace was announced, and as a result of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk concluded between the Bolshevik government of Russia and the Central Powers, led to the end of Soviet Russia's participation in World War I. On October 30, the sailors of the Siberian Military Flotilla decided to "rally around the united power of the Soviets", and the power of Vladivostok, as well as all of the Trans-Siberian Railway passed to the Bolsheviks.[36] During the Russian Civil War, from May 1918,[38] they lost control of the city to the White Army-allied Czechoslovak Legion, who declared the city to be an Allied protectorate. Vladivostok became the staging point for the Allies' Siberian intervention, a multi-national force including Japan, the United States and China; China sent forces to protect the local Chinese community after appeals from Chinese merchants.[39] The intervention ended in the wake of the collapse of the White Army and regime in 1919; all Allied forces except the Japanese withdrew by the end of 1920.[36]

Throughout 1919 the region was engulfed in a partisan war.[36] To avoid a war with Japan, with the filing of the Soviet leadership, the Far Eastern Republic, a Soviet-backed buffer state between Soviet Russia and Japan, was proclaimed on April 6, 1920. The Soviet government officially recognized the new republic in May, but in Primorye a riot occurred, where significant forces of the White Movement were located, leading to the creation of the Provisional Priamurye Government, with Vladivostok as its capital.[40]

In October 1922, the troops of the Red Army of the Far Eastern Republic under the command of Ieronim Uborevich occupied Vladivostok, displacing the White Army formations from it. In November, the Far Eastern Republic liquidated and became a part of Soviet Russia.[34]

Soviet period

[edit]

By the time of the establishment of Soviet power, Vladivostok was clearly in decline. The retreating forces of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) removed items of material value from the city. Life was paralyzed; there was no money in the banks, and the equipment of enterprise was plundered. Due to mass migration and repression, the city's population decreased to 106,000 inhabitants.[41] Between 1923 and 1925, the government adopted a "three-year restoration" plan, during which operations at the commercial port were resumed, and it became the most profitable in the country (from 1924 to 1925).[41][42] The "restoration" period was distinguished by a number of peculiarities: the Russian Far East did not adopt 'war communism', but was, immediately, inducted to the New Economic Policy.[42]

In 1925, the government decided to accelerate the industrialization of the country. A number of subsequent "five-year plans" changed the face of Primorye, making it an industrial region, partly as a result of the creation of numerous concentration camps in the region.[42] In the 1930s and 1940s, Vladivostok served as a transit point on the route used to deliver prisoners and cargo for the Sevvostlag of the Soviet super-trust Dalstroy. The notorious Vladivostok transit camp was located in the city. In addition, in the late 1930s and early 1940s, the Vladivostok forced labour camp (Vladlag) was located in the area of the Vtoraya Rechka railway station.[43]

Vladivostok was not a place of hostilities during the Great Patriotic War, although there was a constant threat of attack from Japan. In the city, a "Defense Fund" was created (the first in the country), to which the residents of Vladivostok contributed personal wealth.[44] During the war years Vladivostok handled imported cargo (lend-lease) of a volume almost four times more than Murmansk and almost five times more than Arkhangelsk.[45]

By the decree of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union "Issues of the Fifth Navy" dated August 11, 1951, a special regime was introduced in Vladivostok (it began to operate on January 1, 1952); the city was closed to foreigners.[46] It was planned to remove from Vladivostok not only foreign consulates, but also the merchant and fish fleet and transfer all regional authorities to Voroshilov (now Ussuriysk). However, these plans were not implemented.[46]

During the years of the Khrushchev Thaw, Vladivostok received special attention from state authorities. In 1954, Nikita Khrushchev visited the city for the first time to finally decide whether to secure the status of a closed naval base for him.[47] It was noted that at that time the urban infrastructure was in a deplorable state.[47] In 1959, Khrushchev visited the city again. The result was a decision on the accelerated development of the city, which was formalized by the decree of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union on January 18, 1960.[47] During the 1960s, a new tram line was built, a trolleybus was launched, the city became a huge construction site: residential neighborhoods were being erected on the outskirts, and new buildings for public and civil purposes were erected in the center.[47]

In 1974, Gerald Ford paid an official visit to Vladivostok, to meet with Leonid Brezhnev, becoming the first President of the United States to visit the city.[48]

On September 20, 1991, Boris Yeltsin signed decree No. 123 "On the opening of Vladivostok for visiting by foreign citizens", which entered into force on January 1, 1992, ending Vladivostok's status as a closed city.[49]

Modern period

[edit]In 2012, Vladivostok hosted the 24th APEC summit. Leaders from the APEC member countries met at Russky Island, off the coast of Vladivostok.[50] With the summit on Russky Island, the government and private businesses inaugurated resorts, dinner and entertainment facilities, in addition to the renovation and upgrading of Vladivostok International Airport.[51] Two giant cable-stayed bridges were built in preparation for the summit, the Zolotoy Rog bridge over the Zolotoy Rog Bay in the center of the city, and the Russky Island Bridge from the mainland to Russky Island (the longest cable-stayed bridge in the world). The new campus of Far Eastern Federal University was completed on Russky Island in 2012.[52]

In December 2018, the seat of the Far Eastern Federal District, established in May 2000, was moved from Khabarovsk to Vladivostok.[53]

In November 2020, the city and region had experienced a rare weather phenomenon in the face of freezing rain caused by collision of warm and cold air masses. The result was wires and trees encrusted in ice up to 1.2 cm thick. More than 1,500 homes were left without electricity, 900 without heating, 870 without heat water, 500 without cold water. 60 % to 70 % of Vladivostok's forests were damaged.[54][55][56][57]

Politics

[edit]

The structure of the city administration has the City Council at the top.

The responsibilities of the administration of Vladivostok are:

- Exercise of the powers to address local issues of Vladivostok in accordance with federal laws, normative legal acts of the Duma of Vladivostok, decrees and orders of the head of the city of Vladivostok;

- The development and organization of the concepts, plans and programs for the development of the city, approved by the Duma of Vladivostok;

- Development of the draft budget of the city;

- Ensuring implementation of the budget;

- The use of territory and infrastructure of the city;

- Possession, use and disposal of municipal property in the manner specified by decision of the Duma of Vladivostok

Legislative authority is vested in the City Council. The new City Council began operations in 2001 and in June that year, deputies of the Duma of the first convocation of Vladivostok began their work. On December 17, 2007, the Duma of the third convocation began. The deputies consist of 35 elected members, including 18 members chosen by a single constituency, and 17 deputies from single-seat constituencies.

Administrative and municipal status

[edit]Vladivostok is the administrative center of the krai. Within the framework of administrative divisions, it is, together with five rural localities, incorporated as Vladivostok City Under Krai Jurisdiction; an administrative unit equal to that of the districts in status.[1] As a municipal division, Vladivostok City Under Krai Jurisdiction is incorporated as Vladivostoksky Urban Okrug.[7]

Administrative divisions

[edit]

Vladivostok is divided into five administrative districts:

- Leninsky

- Pervomaisky

- Pervorechensky

- Sovietsky

- Frunzensky

Local government

[edit]

The city charter approved the following structure of local government bodies:[58]

- City Duma is a representative body

- The head of the city is its highest official

- Administration is the executive and administrative body

- Chamber of Control and Accounts – controls the body

Vladivostok City Duma's history dates from November 21, 1875, when 30 "vowels" were elected. Great changes took place after the 1917 Revolution, when the first general elections were held and women were allowed to vote. The last meeting of the Vladivostok City Duma took place on October 19, 1922, and on October 27 it was officially abolished. In Soviet times, its functions were performed by the City Council. In 1993, by a presidential decree, the Soviets were dissolved and, until 2001, all attempts to elect a new Duma were unsuccessful. The Duma of the city of Vladivostok of the fifth (current) convocation began work in the fall of 2017, consisting of 35 deputies.[59]

The head of Vladivostok, on the principles of one-man management, manages the city's administration, which he forms in accordance with federal laws, laws of the Primorsky Territory and the city charter. The city's administrative structure is approved by the City Duma on the proposal of the head, and may include sectoral (functional) and territorial bodies of the administration of Vladivostok.[60]

Igor Pushkaryov was the city's mayor from May 2008 to June 2016; previously he was a Federation Council member of Primorsky Krai. On June 27, 2016, Konstantin Loboda, the first deputy mayor, was appointed as the Vladivostok's new acting mayor.[61] On December 21, 2017, Vitaly Vasilyevich Verkeenko was appointed the head of the city.

Demographics

[edit]Population, dynamics, age and sex

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1897 | 28,933 | — |

| 1926 | 107,980 | +273.2% |

| 1939 | 206,432 | +91.2% |

| 1959 | 290,608 | +40.8% |

| 1970 | 440,889 | +51.7% |

| 1979 | 549,789 | +24.7% |

| 1989 | 633,838 | +15.3% |

| 2002 | 594,701 | −6.2% |

| 2010 | 592,034 | −0.4% |

| 2021 | 603,519 | +1.9% |

| Source: Census data | ||

According to the Russian Census of 2021, Vladivostok had a population of 603,519, with 634,835 residents in the greater urban area.[11] Since the city's founding its population has actively grown, save for the periods of the Russian Civil War and the demographic crisis after dissolution of the Soviet Union in the 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s. In the 1970s, the population exceeded over 500,000, and in 1992 reached a historical high of over 648,000. The average population density is about 1,832 people/km2.

The population has risen by 30,000. Since 2013, natural growth dynamics added 727 individuals to this figure by 2015's end.[62] By 2020, Vladivostok's population reached over 600,000, as reported by the Russian Federal Statistics Bureau.[63]

The city's age distribution includes a large segment of older adults. Overall, the population includes 12.7% who are younger than able-bodied; 66.3% who are able-bodied; and 21% who are older than able-bodied.[64] Vladivostok's population, like that of Russia as a whole, includes a significantly greater number of women than men.[64]

Ethnic composition

[edit]

The demographic makeup of the city went through significant changes since its foundation, and was marked by several waves of immigration from both Europe and Asia. From the late 1890s to the early 1920s, half of the city's population was Asian, with the Chinese being the largest Asian group, followed by Koreans and Japanese.[65] The old Chinese quarter of the city was called Millionka and in its peak accommodated up to 50,000 Chinese residents.[66] The neighbourhood had its own small shops, theatres, opium dens, brothels, and hideouts for smugglers and thieves. The city's economy was heavily dependent on the services provided by the Chinese merchants and businessmen in the neighbourhood.[67] Specifically, the retail services of the city were controlled by the Chinese, as they had more retail shops than Russians did.[68] There also existed an ethnic enclave of Koreans called Sinhanch'on. Koreans moved to the area in significant quantities following the annexation of Korea by Japan in 1910. By 1915, the Korean population in the city stood at around 10,000.[69] Sinhanch'on became a hub of the Korean independence movement and hosted the first Korean provisional government, the Korean Independence Army Government. On the orders of Joseph Stalin, both Millionka and Sinhanch'on were liquidated, and their residents deported between 1936 and 1938. Today, the city is much more homogeneous, with more than 90 percent declaring Russian ethnicity. However, there still exists a minority of Koreans and Chinese in Vladivostok, accounting for roughly 1 percent of the population, as well as more recent immigrants from Central Asia, mainly from Uzbekistan. Historical German, French, Estonian, American, and Central Asian diasporas at the start of the 21st century have been little studied.[70]

| Ethnicity | Population (2010)[71] | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Russians | 475,170 | 92.4% |

| Ukrainians | 10,474 | 2.0% |

| Uzbeks | 7,109 | 1.4% |

| Koreans | 4,192 | 0.8% |

| Chinese | 2,446 | 0.5% |

| Others | 14,850 | 2.9% |

According to the Russian census of 2010, Vladivostok's residents include representatives of over seventy nationalities and ethnic groups. Among them, the largest ethnic groups (over 1,000 people) are: ethnic Russians (475,200); Ukrainians (10,474); Uzbeks (7,109); Koreans (4,192); Chinese (2,446); Tatars (2,446); Belarusians (1,642); Armenians (1,635); and Azerbaijanis (1,252).[71]

Economy

[edit]The city's main industries are shipping, commercial fishing, and the naval base. Fishing accounts for almost four-fifths of Vladivostok's commercial production. Other food production totals 11%.

A very important employer and a major source of revenue for the city's inhabitants is the import of Japanese cars.[72] Besides salesmen, the industry employs repairmen, fitters, import clerks as well as shipping and railway companies.[73] The Vladivostok dealers sell 250,000 cars a year, with 200,000 going to other parts of Russia.[73] Every third worker in the Primorsky Krai has some relation to the automobile import business. In recent years, the Russian government has made attempts to improve the country's own car industry. This has included raising tariffs for imported cars, which has put the car import business in Vladivostok in difficulties. To compensate, Prime Minister Vladimir Putin ordered the car manufacturing company Sollers to move one of its factories from Moscow to Vladivostok. The move was completed in 2009, and the factory now employs about 700 locals. It is planned to produce 13,200 cars in Vladivostok in 2010.[72]

Seaport

[edit]

Vladivostok is a link between the Trans-Siberian Railway and the Pacific Sea routes, making it an important cargo and passenger port. It processes both cabotage and export-import general cargo of a wide range. 20 stevedoring companies operate in the port.[74] The cargo turnover of the Vladivostok port, including the total turnover of all stevedoring companies, at the end of 2018 amounted to 21.2 million tons.[75]

In 2015, the total volume of external trade seaport amounted to more than 11.8 billion dollars.[76] Foreign economic activity was carried out with 104 countries.[76]

Tourism

[edit]

Vladivostok is located in the extreme southeast of the Russian Far East, and is the closest city to the countries of the Asia-Pacific with an exotic European culture, which makes it attractive to tourists.[77] The city is included in the project for the development of the Far East tourism "Eastern Ring". Within the framework of the project, the Primorsky Stage of the Mariinsky Theater was opened, and there are plans to open branches of the Hermitage Museum, the Russian Museum, the Tretyakov Gallery and the State Museum of Oriental Art.[78] Vladivostok entered the top ten Russian cities for recreation and tourism according to Forbes, and also took the fourteenth place in the National Tourism Rating.[79]

In addition to being a cultural hub, the city also is a tourism hub in the Peter the Great Gulf. The city's resort area is located on the coast of Amur Bay, which includes over 11 sanatoriums.[80] Vladivostok also has a bustling gambling zone,[81] which has over 11 casinos planned to open by 2023.[82] Tigre de Cristal, the city's first casino, was visited by over 80,000 tourists, in less than a year of its opening.[83]

In 2017, the city was visited by around 3,000,000 tourists, including 640,000 foreigners, of which over 90% are tourists from Asia, specifically China, South Korea and Japan.[15] Domestic tourism is based on business tourism (business trips to exhibitions, conferences), which accounts for up to 70% of the inbound flow. In Vladivostok, diplomatic tourism is also developed, as there are 18 foreign consulates in the city.[84] There are 46 hotels in the city, with a total fund of 2561 rooms.[84] The vast majority of the travel companies of Primorsky Krai (86%) are concentrated in Vladivostok, and their number was around 233 companies in 2011.[85]

Transportation

[edit]

The Trans-Siberian Railway was built to connect European Russia with Vladivostok, Russia's most important Pacific Ocean port. Finished in 1905, the rail line ran from Moscow to Vladivostok via several of Russia's main cities. Part of the railway, known as the Chinese Eastern Line, crossed over into China, passing through Harbin, a major city in Manchuria. Today, Vladivostok serves as the main starting point for the Trans-Siberian portion of the Eurasian Land Bridge.

Vladivostok is the main air hub in the Russian Far East. Vladivostok International Airport (VVO) is the home base of Aurora, a subsidiary of Aeroflot. The airline was formed by Aeroflot in 2013 by amalgamating SAT Airlines and Vladivostok Avia. The Vladivostok International Airport was significantly upgraded in 2013 with a new 3,500-meter (11,500 ft)-long runway capable of accommodating all aircraft types without any restrictions. The Terminal A was built in 2012 with a capacity of 3.5 million passengers per year.

International flights connect Vladivostok with Japan, China, Philippines, North Korea, South Korea and Vietnam.

It is possible to get to Vladivostok from several of the larger cities in Russia. Regular flights to Seattle, Washington, were available in the 1990s but have been cancelled since. Vladivostok Air was flying to Anchorage, Alaska, from July 2008 to 2013, before its transformation into Aurora airline.

Vladivostok is the starting point of Ussuri Highway (M60) to Khabarovsk, the easternmost part of Trans-Siberian Highway that goes all the way to Moscow and Saint Petersburg via Novosibirsk. The other main highways go east to Nakhodka and south to Khasan.

Urban transportation

[edit]On June 28, 1908, Vladivostok's first tram line was started along Svetlanskaya Street, running from the railway station on Lugovaya Street.[citation needed] On October 9, 1912, the first wooden carriages manufactured in Belgium entered service. Today, Vladivostok's means of public transportation include trolleybus, bus, tram, train, funicular and ferryboat. The main urban traffic lines are Downtown—Vtoraya Rechka, Downtown—Pervaya Rechka—3ya Rabochaya—Balyayeva, and Downtown—Lugovaya Street.

-

Cars of the Vladivostok funicular

-

Buses in Vladivostok

In 2012, Vladivostok hosted the 24th Summit of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum. In preparation for the event, the infrastructure of the city was renovated and improved. Two giant cable-stayed bridges were constructed in Vladivostok, namely the Zolotoy Rog Bridge over Golden Horn Bay, and the Russky Bridge from the mainland to Russky Island, where the summit took place. The latter bridge is the longest cable-stayed bridge in the world.

Education

[edit]

В Владивостоке насчитывается 114 общих учебных заведений, общая численность студентов из 50 700 человек (в 2015 году). Муниципальная система образования города состоит из дошкольных организаций, основных, базовых, средних школ общего образования, лицеев, гимназий, школ с углубленным изучением отдельных предметов и центров дополнительного образования.

Муниципальная образовательная сеть включает в себя 2 гимназии, 2 лицея, 13 школ с продвинутым изучением отдельных предметов, одной начальной школой, 2 базовых школах, 58 средних школ, четырех вечерних школ и одной школой -интернатом. Три школы Владивостока включены в топ-500 школ Российской Федерации. [ 86 ] На муниципальном уровне существует городская система школьных олимпиадов, была создана городская стипендия для выдающихся достижений учащихся.

В 2016 году были открыты филиалы Академии российского балета и военно -морской школы Нахимова. [ 87 ] [ 88 ]

Десятки колледжей, школ и университетов обеспечивают профессиональное образование в Владивостоке. Начало высшего образования было заложено в городе с основанием Восточного института. [ 89 ] На данный момент крупнейшим университетом в Владивостоке является Федеральный университет на дальнем востоке. В нем учатся более 41 000 студентов, работают 5000 сотрудников, в том числе 1598 учителей. Это составляет большую долю (64%) научных публикаций среди дальних университетов. [ 89 ]

Кроме того, высшее образование в городе представлено такими местными университетами:

- Дальневосточный федеральный университет

- Владивосток Государственный университет экономики и обслуживания

- Владивосток Государственный медицинский университет

- Морской государственный университет

- Дальневосточный государственный институт искусств

- Университет технического рыбного хозяйства в дальневосточном государстве

- Тихоокеанская высшая военно -морская школа и государственный медицинский университет Тихого океана

- Филиалы Российской таможней

- Международный институт экономики и права

- Дальневосточный юридический институт Министерства внутренних дел России

- Университет Санкт -Петербургского университета Государственной пожарной службы Министерства чрезвычайных ситуаций России

СМИ

[ редактировать ]Более пятидесяти газет и региональных изданий для московских публикаций выпущены в Владивостоке. Крупнейшей газетой Primorsky Krai и всего Российского Дальнего Востока является News Vladivostok с тиражом 124 000 экземпляров в начале 1996 года. Ее основатель, объединенная компания Vladivostok-News, также выпускает еженедельную английскую газету Vladivostok News. Субъекты публикаций, выпущенных в этих газетах, варьируются от информации о Владивостоке и Примирие до крупных международных мероприятий. Газета Zolotoy Rog ( Golden Horn ) дает каждую деталь экономических новостей. Развлекательные материалы и культурные новости составляют большую часть газеты Novosti (News), которая является самой популярной среди молодых людей Primorye. Кроме того, новые онлайн -средства массовой информации о российском Дальнем Востоке для иностранцев - это Дальний Восток Таймс. Этот источник предлагает читателям принять участие в информационной поддержке RFE для посетителей, путешественников и бизнесменов. Vladivostok управляет многими онлайн-агентствами новостей, такими как Newsvl.ru, Primamedia, Primorye24 и Vesti-Primoriore. С 2012 по 2017 год управляет молодежным онлайн-журналом Vladivostok-3000.

По состоянию на 2020 год работают девятнадцать радиостанций, в том числе три 24-часовые местные станции. Radio VBC (FM 101,7 MHZ, с 1993 года) транслирует классическую и современную рок -музыку, старину и музыку 1980 -х - 1990 -х годов. Радио Лемма (FM 102,7 МГц, с 1996 года) транслирует новости, радио-шоу и различные российские и европейские американские песни. Vladivostok FM (FM 106,4 МГц была запущена в 2008 году) транслирует местные новости и популярную музыку (Top 40). Государственная радиовещательная компания "Vladivostok" транслирует местные новостные и музыкальные программы с 7 до 9, с 12 до 14 и с 18 до 19 в будние дни по частоте радио России (радио России).

Культура

[ редактировать ]Галереи и выставочные залы

[ редактировать ]

Активное развитие художественных музеев в Владивостоке началось в 1950 -х годах. В 1960 году был построен Дом художников, в котором были выставочные залы. В 1965 году художественная галерея Primorsky State была разделена на отдельное учреждение, а затем, на основе своей коллекции, была создана детская художественная галерея. В Советские времена одной из крупнейших районов для выставок в Владивостоке был зал выставочного зала Преморского отделения Союза художников Советской России. В 1989 году была открыта галерея современного искусства "Artetage". [ 90 ]

В 1995 году была открыта галерея современного искусства Арка, первая экспозиция которой состояла из 100 картин, пожертвованных коллекционером Александром Глезером. [ 91 ] Галерея участвует в международных выставках и ярмарках. В 2005 году появилась некоммерческая частная галерея "Roytau". [ 90 ] В последние годы центры современного искусства «соль» (созданные на основе художественного музея FEFU) и «Zarya», [ 92 ] [ 93 ] были активными.

Музыка, опера и балет

[ редактировать ]Город является домом для оркестра Владивостока Попс.

Русская рок -группа Mumiy Troll родом из Владивостока и часто устраивает там шоу. Кроме того, в сентябре 1996 года в городе был проведен Международный музыкальный фестиваль « Владирокстока ». Устроенный мэром и губернатором и организованный двумя молодыми американскими экспатриантами, фестиваль привлек почти 10 000 человек и музыкальные акты высшего уровня из Санкт-Петербурга ( Аквариум и ДДТ ) и Сиэтл ( Суперсеки , добро ), а также несколько ведущих местных групп. [ Цитация необходима ]

В настоящее время есть еще один ежегодный музыкальный фестиваль в Владивостоке, Международный музыкальный фестиваль и конференцию Vladivostok Rocks (V-ROX). Vladivostok Rocks-это трехдневный городской фестиваль под открытым небом и Международная конференция для музыкальной индустрии и современного управления культурой. Он дает возможность начинающим художникам и продюсерам получить информацию о новой аудитории и ведущих международных специалистах. [ 94 ]

Музыкальный театр в Владивостоке представлен Примирским региональным филармоническим обществом, крупнейшей концертной организацией в Примирском Краи. Филармония организовала Тихоокеанский симфонический оркестр и медный оркестр губернатора. В 2013 году был открыт Театр Primorsky Opera и Ballet. [ 95 ] 1 января 2016 года он был превращен в филиал театра Мариинского . [ 96 ] В российском оперном театре находится государственный театр Primorsky Opera и балета. [ 97 ]

Музеи

[ редактировать ]

Владимир К. Арсениевский музей истории Дальнего Востока , открытый в 1890 году, является главным музеем Примирского Край. Помимо основного объекта, у него есть три филиала в самом Владивостоке (включая мемориальный дом Арсенива ) и пять филиалов в других частях штата. [ 98 ] Среди предметов в музейной коллекции-знаменитые храмовые стелы 15-го века из Нижнего Амура .

Кинотеатры

[ редактировать ]В 2014 году 21 кинотеатры работали в Владивостоке, а общее количество показов фильма составило 1 501 000.

Большинство городских кинотеатров - Ocean, Galaktika, Moscow (ранее называемое кинотеатром New Wave), Neptune 3d (ранее называемый Нептун и Бородино), иллюзия, Владивосток - отремонтированы кинотеатры, построенные в советские годы. Среди них выделяется «океан» с самым большим (22 на 10 метров) экрана на Дальнем востоке страны, расположенном в центре города в районе спортивной гавани. [ 99 ] Вместе с кинотеатром «Уссури» это место для ежегодного международного кинофестиваля «Pacific Meridians» (с 2002 года). [ 100 ] С декабря 2014 года IMAX 3D Hall работает в кинотеатре в океане. [ 101 ]

Театры

[ редактировать ]

Академический театр Максим Горки, названный в честь русского автора Максима Горки , был основан в 1931 году и используется для драматических, музыкальных и детских театральных выступлений.

В городе пять профессиональных кинотеатров. В 2014 году их посетил 369 800 зрителей. Региональный академический драматический театр Преморского, названный в честь Максима Горки , является самым старым государственным театром в Владивостоке, открытый 3 ноября 1932 года. В театре работают 202 человека: 41 актеры (из них, три народа и девять почитаемых художников России). [ 102 ]

Театр Primorsky Pushkin был построен в 1907–1908 годах и в настоящее время является одним из главных культурных центров города. В 1930 -х - 40 -х годах были последовательно открыты следующие до сих пор эксплуатационные: драматический театр Тихоокеанского флота, Региональный кукольный театр Преморского и Региональный драматический театр Преморского. [ 103 ] Региональный кукольный театр дал 484 выступления в 2015 году, в которых приняли участие более 52 000 зрителей. В театре 500 марионеток, где работают 15 художников. Труппа регулярно отправляется в тур в Европу и Азию. [ 104 ]

В сентябре 2012 года гранитная статуя актера Юл Бриннер (1920–1985) была открыта в парке Юл Бриннер, прямо перед домом, где он родился на ул.

Парки и квадраты

[ редактировать ]

Parks and squares in Vladivostok include Pokrovskiy Park, Minnyy Gorodok, Detskiy Razvlekatelnyy Park, Park of Sergeya Lazo, Admiralskiy Skver, Skver im. Neveskogo, Nagornyy Park, Skver im. Sukhanova, Fantaziya Park, Skver Rybatskoy Slavy, Skver im. A.I.Shchetininoy.

Pokrovskiy Park

[ редактировать ]Парк Pokrovskiy когда -то был кладбищем. Он был преобразован в парк в 1934 году, но был закрыт в 1990 году. С 1990 года земля, на которой находится парк, принадлежит русской православной церкви. Во время восстановления православной церкви были найдены могилы.

Minny Gorodok

[ редактировать ]Minny Gorodok-это 91-акровый (37 га) общественный парк. Minny Gorodok (Mine Borough Park означает «Mine Borough Park». Парк является бывшей военной базой, которая была основана в 1880 году. Военная база использовалась для хранения рудников в подземном хранилище. Преобразованный в парк в 1985 году, Minny Gorodok содержит несколько озер, прудов и каток.

Detsky Razvlekatelny Park

[ редактировать ]Парк Detsky Razvlekatelny - это детский парк развлечений, расположенный недалеко от центра города Владивосток. В парке есть карусель, игровые машины, колесо обозрения, кафе, аквариум, кинотеатр и стадион.

Admiralsky Skver

[ редактировать ]Адмиральский Сквер - достопримечательность, расположенная недалеко от центра Владивостока. Квадрат - это открытое пространство, в котором преобладает Triumfalnaya Arka. К югу от площади находится музей советской подводной лодки S-56 .

Спорт

[ редактировать ]

Владивосток является домом для футбольного клуба Dynamo Vladivostok , который играет во втором дивизионе России клубе с хоккейным клубом , адмирал -хоккейном в Континентальной хоккейной лиги и Чернишевом дивизионе баскетбольном клубе Spartak Primorye , из супер -лиги российской баскетбольной баскетбольной баскетбольной лиги . Бывший в Премьер -лиге России футбольный клуб Луч Владивосток был главной футбольной командой города до банкротства в 2020 году. Он также является домом для мотоцикла Vladivostok Motorcycle Speedway Club.

Владивосток ежегодно проводит различные конкурсы. В 2022 году была проведена 35-й регата-лодка для бокала Петра Великого и 19-го чемпионата России Яхт Конрада-25R. [ 105 ]

Загрязнение

[ редактировать ]Местные экологи из организации экоцентра утверждают, что большая часть пригородов Владивостока загрязнена и что жизнь в них может быть классифицирована как опасность для здоровья . [ Цитация необходима ] Geochemical , загрязнение имеет ряд причин Ecocenter По словам эксперта по геохимическому эксперту . Владивосток имеет около восьмидесяти промышленных площадок, которые, возможно, не так много по сравнению с самыми промышленно развитыми районами России, но те, кто окружает город, особенно недружелюбны, такие как судостроение и ремонт, электростанции, печать, меховое сельское хозяйство и добыча полезных ископаемых .

Кроме того, Владивосток обладает особенно уязвимой географией, которая усугубляет эффект загрязнения. Ветры не могут очистить загрязнение от некоторых из наиболее густонаселенных областей вокруг Первойи и Втайи Рехки, когда они сидят в бассейнах, которые дуют ветры. Кроме того, зимой мало снега, а листья или травы, чтобы поймать пыль, чтобы она успокоилась. [ 106 ]

География

[ редактировать ]

Город расположен в южной части полуострова Муравьова-Амурски , который длится около 30 километров (19 миль) и шириной 12 километров (7,5 миль).

Самая высокая точка в городе - гора Холодилник , на 257 метрах (843 фута). Орлиный гнездовый холм часто называют самой высокой точкой в городе, но с высотой 199 м (653 фута) или 214 м (702 футами) в соответствии с другими источниками, это только самая высокая точка в центре города, а не Весь город.

Расположенный на крайнем юго -востоке от Российского Дальнего Востока, в крайнем юго -востоке от Северной Азии , Владивосток географически ближе к Анкориджу, Аляске , США и даже Дарвину, Австралии, чем к столице страны Москвы . Владивосток также ближе к Гонолулу, Гавайям , США, чем к городу Сочи на юге России . Он также находится дальше на восток, чем в любом районе к югу от него в Китае и на всем Корейском полуострове.

Климат

[ редактировать ]под влиянием муссонов Владивосток обладает влажным континентальным климатом ( Климатическая классификация Köppen DWB ) с теплым, влажным и дождливым летом и холодными, сухими зимами. Из -за влияния сибирского максимума , зимы намного холоднее, чем широта 43 градуса, должна гарантировать, учитывая его низкую высоту и расположение прибрежных районов, со средним январем -11,9 ° C (10,6 ° F). Зимние температуры несколько холоднее, чем Милуоки и намного холоднее, чем Флоренция ; Все 3 места находятся на уровне или выше 43 градуса северной широты. Они даже холоднее, чем у Москвы и Миннеаполиса , внутренних мест на 56 и 45 градусах на север соответственно. Поскольку морское влияние сильное летом, Владивосток имеет относительно холодный годовой климат для его широты.

Зимой температура может падать ниже -20 ° C (-4 ° F), в то время как мягкие заклинания погоды могут повысить дневные температуры выше нуля. Среднемесячное количество осадков, в основном в виде снега, составляет около 18,5 миллиметра (0,73 дюйма) с декабря по март. Снег распространен зимой, но индивидуальные снегопады являются легкими, с максимальной глубиной снега всего 5 сантиметров (2,0 дюйма) в январе. Зимой прозрачные солнечные дни распространены.

Лето теплые, влажные и дождливые из -за восточноазиатского муссона . Самый теплый месяц - август со средней температурой +20 ° C (68 ° F). Владивосток получает большую часть своих осадков в летние месяцы, и большинство летних дней видят некоторые осадки. Облачные дни довольно распространены, и из -за частых осадков влажность высока, в среднем около 90% с июня по август.

В течение летнего сезона город склонен к тайфунам и тропическим штормам . Тайфун Санба поразил город как тропический шторм в 2012 году. В Артиоме , недалеко от Владивостока, было затоплено более 300 га (740 акров) сельскохозяйственных культур. Предварительные убытки по всему региону оценивались в 40 млн. Долл . США (1,29 млн. Долл. США). [ 107 ] Тайфуны могут быть редкими, но тропические штормы происходят из Японского моря после приземления в тайфуне из Южной Кореи и Японии .

В среднем Vladivostok получает 840 миллиметров (33 дюйма) осадков в год, но самый сухой год был 1943 год, когда 418 миллиметров (16,5 дюймов) осаждения упали, а самым гибким было 1974 год, с 1272 миллиметрами (50,1 в) осаждения. Зимние месяцы с декабря по март сухие, и через несколько лет они вообще не видели измеримых осадков. Экстремальные диапазоны варьируются от -31,4 ° C (-24,5 ° F) в январе 1931 года до +33,6 ° C (92,5 ° F) в июле 1939 года. [ 108 ]

| Месяц | Январь | Февраль | Марта | Апрель | Может | Июнь | Июль | Август | Сентябрь | Октябрь | Ноябрь | Декабрь | Год |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Запись высокой ° C (° F) | 5.0 (41.0) |

9.9 (49.8) |

19.4 (66.9) |

27.7 (81.9) |

29.5 (85.1) |

31.8 (89.2) |

33.6 (92.5) |

32.6 (90.7) |

30.0 (86.0) |

23.7 (74.7) |

17.5 (63.5) |

9.4 (48.9) |

33.6 (92.5) |

| Средний ежедневный максимум ° C (° F) | −7.8 (18.0) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

2.7 (36.9) |

10.1 (50.2) |

14.9 (58.8) |

17.9 (64.2) |

21.6 (70.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

20.1 (68.2) |

13.2 (55.8) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

9.2 (48.6) |

| Средний средний ° C (° F) | −11.9 (10.6) |

−8.1 (17.4) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

5.3 (41.5) |

10.0 (50.0) |

13.8 (56.8) |

18.1 (64.6) |

20.0 (68.0) |

16.3 (61.3) |

9.2 (48.6) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

−9.2 (15.4) |

5.1 (41.2) |

| Средний ежедневный минимум ° C (° F) | −15.0 (5.0) |

−11.3 (11.7) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

2.1 (35.8) |

7.0 (44.6) |

11.3 (52.3) |

16.1 (61.0) |

17.9 (64.2) |

13.5 (56.3) |

6.2 (43.2) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−12.0 (10.4) |

2.3 (36.1) |

| Запись низкого ° C (° F) | −31.4 (−24.5) |

−28.9 (−20.0) |

−21.3 (−6.3) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

3.7 (38.7) |

8.7 (47.7) |

10.1 (50.2) |

1.3 (34.3) |

−9.7 (14.5) |

−20.0 (−4.0) |

−28.1 (−18.6) |

−31.4 (−24.5) |

| Среднее количество осадков мм (дюймы) | 12 (0.5) |

16 (0.6) |

27 (1.1) |

43 (1.7) |

97 (3.8) |

105 (4.1) |

159 (6.3) |

176 (6.9) |

103 (4.1) |

67 (2.6) |

36 (1.4) |

19 (0.7) |

860 (33.9) |

| Средняя экстремальная глубина снега CM (дюймы) | 5 (2.0) |

4 (1.6) |

3 (1.2) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.4) |

3 (1.2) |

5 (2.0) |

| Средние дождливые дни | 0.3 | 0.3 | 4 | 13 | 20 | 22 | 22 | 19 | 14 | 12 | 5 | 1 | 133 |

| Средние снежные дни | 7 | 8 | 11 | 4 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 9 | 47 |

| Средняя относительная влажность (%) | 58 | 57 | 60 | 67 | 76 | 87 | 92 | 87 | 77 | 65 | 60 | 60 | 71 |

| Средние месячные солнечные часы | 178.2 | 180.8 | 209.6 | 182.3 | 170.3 | 131.1 | 120.3 | 150.2 | 198.0 | 194.6 | 160.0 | 150.3 | 2,025.7 |

| Source 1: Погода и Климат [ 109 ] | |||||||||||||

| Источник 2: NOAA [ 110 ] | |||||||||||||

| Данные о температуре моря для Владивостока | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Месяц | Январь | Февраль | Марта | Апрель | Может | Июнь | Июль | Август | Сентябрь | Октябрь | Ноябрь | Декабрь | Год |

| Средняя температура моря ° C (° F) | -1.2 (29.8) |

-1.6 (29.1) |

-0.9 (30.4) |

2.6 (36.7) |

8.8 (47.8) |

14.2 (57.6) |

19.4 (66.9) |

22.4 (72.3) |

19.4 (66.9) |

13.7 (56.7) |

6.2 (43.2) |

0.7 (33.3) |

8.64 (47.6) |

| Источник: [ 111 ] | |||||||||||||

Города -близнецы - Сестринские города

[ редактировать ]Владивосток с двойной : [ 112 ]

Акита , Япония

Акита , Япония  Пусан , Южная Корея

Пусан , Южная Корея  Далянь , Китай

Далянь , Китай  Хакодат , Япония

Хакодат , Япония  Харбин , Китай

Харбин , Китай  Ho Chi Minh City , Вьетнам

Ho Chi Minh City , Вьетнам  Инчхон , Южная Корея

Инчхон , Южная Корея  Джуно , США

Джуно , США  Кота Кинабалу , Малайзия

Кота Кинабалу , Малайзия  Манта , Эквадор

Манта , Эквадор  Ниигата , Япония

Ниигата , Япония  Поханг , Южная Корея

Поханг , Южная Корея  Сан -Диего , США

Сан -Диего , США  Такома , США

Такома , США  Tskhinvali , South Ostia [ 113 ]

Tskhinvali , South Ostia [ 113 ]  Vladikavkaz , Russia

Vladikavkaz , Russia  ВОНСАН , Северная Корея

ВОНСАН , Северная Корея  Янбиянка , Китай

Янбиянка , Китай

В 2010 году арки с именами каждого из городов -близнецов Владивостока были помещены в парк в городе. [ 114 ]

От паромного порта Владивостока рядом с железнодорожным вокзалом, паром DBS Cruise Ferry регулярно путешествует в Донхэ , Южная Корея и оттуда в Сакаминито на японском главном острове Хоншу .

Примечательные люди

[ редактировать ]- Александра Бирёкова (1895–1967), архитектор

- Алексей Волконски (род. 1978), каноист

- Anna Shchetinina (1908–1999), captain

- Chŏng Sang-Jin (1918–2013), корейский боец Freedom Fighter

- Диана Анкудинова (родилась 31 мая 2003 г.), певица [ 115 ]

- Эльмар Лох (1901-1963), архитектор

- Юджин Козловский (1946-2023), писатель

- Feliks Gromov (1937–2021), admiral

- Игорь Ансофф (1918–2002), математик

- Igor Kunitsyn (родился в 1981 году), теннис

- Игорь Тамм (1895–1971), физик

- Илья Лагутенко (род. 1968), певец

- Иван Василььев (родился в 1989 году), балетная танцовщица

- Кори-сарам поэт и советский солдат

- Кристина Риханофф (род. 1977), танцор

- Ksenia Kahnovich (род. 1987), модель

- Лев Князв (1924–2012), писатель

- Лиа Гринфельд (родился в 1954 году), академический

- Лилия Ахаймова (род. 1997), гимнастка

- Мэри Лосефф (1907–1972), певец, киноактер

- Михаил Кокляев (родился в 1978 году), Стронгмен

- Natalia Pogonina (born 1985), chess player

- Nikolay Dubinin (1907–1998), biologist

- Пол Портнегин (1903–1977), греко-католический священник, учитель и востоков

- Питер А. Будберг (1903–1972), ученый, лингвист

- Станислав Петров (1939–2017), солдат, предотвращенная ядерная война

- Svoy (born 1980), musician

- Свати Редди (род. 1987), индийская актриса

- Victor Zotov (1908–1977), botanist

- Vitali Kravtsov (родился в 1999 году), хоккей -хоккей

- Vladimir Arsenyev (1872–1930), explorer

- Владимир Осипофф (1907–1998), архитектор

- Уэс Херли (родился в 1981 году), режиссер

- Yi Dong-Hwi (1873–1935), корейский коммунист

- Юл Бриннер (1920–1985), киноактер кино

Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ См . Владимир (имя) для этимологии

- ^ Когда город был транслитерирован с кандзи, была Kyūjitai использована форма . Однако после послевоенного упрощения кандзи кандзис 鹽 и 德 были упрощены на японском языке до 塩 и 徳 соответственно.

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Закон № 161-кц

- ^ Энциклопедия Города России . Moscow: Большая Российская Энциклопедия. 2003. p. 72. ISBN 5-7107-7399-9 .

- ^ «Константин Шестаков - новый мэр Владивостока» . vestiprim.com . 5 августа 2021 года. Архивировано с оригинала 15 сентября 2022 года . Получено 30 июня 2022 года .

- ^ "Генеральный план Владивостока" . Archived from the original on July 14, 2014 . Retrieved July 10, 2014 .

- ^ "26. Численность постоянного населения Российской Федерации по муниципальным образованиям на 1 января 2018 года" . Federal State Statistics Service . Retrieved January 23, 2019 .

- ^ "Правительство Приморского края" . Официальный сайт Правительства Приморского края . Archived from the original on November 11, 2021 . Retrieved July 28, 2020 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Закон № 179-кц

- ^ "Об исчислении времени" . Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации (in Russian). June 3, 2011 . Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ^ Почта России. Информационно-вычислительный центр ОАСУ РПО. ( Russian Post ). Поиск объектов почтовой связи ( Postal Objects Search ) (in Russian)

- ^ Ростелеком завершил перевод Владивостока на семизначную нумерацию телефонов (на русском языке). 12 июля 2011 года. Архивировано с оригинала 27 ноября 2016 года . Получено 26 ноября 2016 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный "Оценка численности постоянного населения по субъектам Российской Федерации" . Federal State Statistics Service . Retrieved September 1, 2022 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Paine, SCM (2003). Кино-японская война 1894–1895 гг. Восприятие, власть и первенство . Издательство Кембриджского университета . ISBN 978-0-521-81714-1 . [ Постоянная мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в "Особенности промышленно-экономического развития Владивостока в начале XX века" . CyberLeninka . 2008. Archived from the original on August 8, 2016 . Retrieved September 15, 2020 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный "Вольная гавань: общественная жизнь дореволюционного Владивостока" . CyberLeninka . 2015. Archived from the original on November 4, 2022 . Retrieved September 15, 2020 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Екатерина Века (February 7, 2018). "Владивосток вошёл в топ-5 самых популярных у туристов городов России" . Администрация Приморского края. Archived from the original on March 31, 2018 . Retrieved October 8, 2020 .

- ^ Александр Джейкоби (5 июля 2005 г.). «Восточная Европа на Дальнем Востоке» . Япония таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 29 сентября 2022 года . Получено 11 октября 2020 года .

- ^ Алекс Носаль. «Владивосток, Европа в середине Востока» . Сеул времена . Архивировано из оригинала 17 октября 2020 года . Получено 11 октября 2020 года .

- ^ "Владк" . 9 июня 2022 года. Архивировано с оригинала 27 июля 2023 года . Получено 27 июля 2023 года - через Wiktionary.

- ^ В. В. Постников. (V. V. Postinkov.) "К осмыслению названия 'Владивосток': историко-политические образы Тихоокеанской России." Archived December 15, 2017, at the Wayback Machine ("To the comprehension of the name "Vladivostok": historical and political images of the Pacific Russia.") Ойкумена. (Ojkumena.) Vol. 4. July 2010. p. 75. (in Russian)

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Билл, Франк (1 декабря 2016 г.). «На картографических объятиях Китая: вид с его северного обода» . Перекрестные токи: История Восточной Азии и обзор культуры E-Journal . 1 (21): 107. Архивировано из оригинала 23 марта 2023 года . Получено 23 марта 2023 года .

- ^ Уилсон, Джеймс Харрисон ; Лю Мин-Чюан (1888) [ с. 1881 ]. «Мемориал Лю Мин-Чюан, генерал в китайской армии, на пенсии, рекомендующий немедленное представление железных дорог в качестве средства увеличения власти страны». Полем Китай: путешествия и расследования в «Среднем королевстве»: изучение его цивилизации и возможностей . Эпплтон. С. 128–129. OCLC 835707181 . : «Россия построила железные дороги, которые проходят из Европы в окрестности Хао Хан, и она нацелена построить один из Хай-Шен-Вей в Хуи Чун, и причина, по которой она не приступила к отправке войск недавно, когда Ссора с нами началась, не то, что она боялась встретиться с нашими солдатами, а в том, что ее железные дороги не были совсем завершены ».

- ^ Леон Э. Сельцер, изд. (1952). «Владивосток». Columbia Lippincott Gazetteer of the World . Morningside Heights, Нью -Йорк: издательство Колумбийского университета . п. 2042. OCLC 802473294 . "Китайский хай-Шен-Вей [= залив Трепанг]"

- ^ . Xuanjun Xie ,

первоначально находился под юрисдикцией Джилина династии Цин в Китае.

- ^ «Исследования Манча в Национальном университете Чанг: слова и слова, не найденные в словаре Манчу: Xai . » Wei

šen Основные производственные зоны морских огурцов находятся в северо -восточном Китае и Корейском полуострове. Китайское слово «Вей» относится к изгибам гор и воды. Владивосток означает залив, полный морских огурцов. Некоторые говорят, что Владивосток на китайском языке получен от XaiiШенвей ᡥᠠᡳᡧᡝᠨᠸᡝᡥᡝᡥ, что означает «небольшая рыбацкая деревня у моря» и так далее, но нет записей об этом словом в китайских и иностранных книгах с манчами.

- ^ "Владивосток все же стал Хайшенвеем". Archived June 16, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Novostivl.ru. May 7, 2010. Retrieved June 20, 2017. (in Russian)

- ^ Несколько положений для представления общественного содержания карты (на китайском (Китай). Министерство земли и ресурсы Китайской Народной Республики . 19 января 2006 года. Архивировано с оригинала 31 июля 2019 года . Получено 1 октября 2017 года .

- ^ «Китайские националисты раздражены именами мест колониальной эпохи» . Экономист . 30 марта 2023 года. Архивировано с оригинала 4 апреля 2023 года . Получено 4 апреля 2023 года .

- ^ Это - с. 300.

- ^ Стефан, Джон Дж. (1994). Русский Дальний Восток: история . Издательство Стэнфордского университета. п. 15. ISBN 9780804727013 .

- ^ Алексев, Михаил А. (2006). Иммиграционная фобия и дилемма безопасности: Россия, Европа и Соединенные Штаты . Кембридж: издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 111. ISBN 9780521849883 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 28 марта 2023 года . Получено 28 марта 2023 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Turmov GP, Khisamutdinov aa vladivostok. Исторический гид. - M.: Veche, 2010. - 304 с. В ISBN 978-5-9533-4924-6 .

- ^ Старый Владивосток. / Auth. Текст и комп. Б. Дайченко. - Владивосток: Утро России, 1992. - С. 51. - 36 000 экземпляров. - ISBN 5-87080-004-8 .

- ^ Юрий Уфимцев. "Основание Владивостока" . oldvladivostok.ru. Archived from the original on December 11, 2015 . Retrieved September 15, 2020 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и "Владивосток: история города" . RIA Novosti . February 7, 2010. Archived from the original on November 15, 2019 . Retrieved September 15, 2020 .

- ^ Ко, Мичиган (30 декабря 2014 г.). «Jeju Haenyo, распространяющийся через Азию» (PDF) . Всемирная окружающая среда и островные исследования . 4 (3): 38. Архивированный (PDF) из оригинала 17 мая 2023 года . Получено 17 мая 2023 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Ясько Т. Н. "Сибирская военная флотилия в 1917—1922 гг" . fegi.ru . Archived from the original on September 28, 2016 . Retrieved September 15, 2020 .

- ^ Дежурный по Редакции (November 29, 2015). "Архангельский и Владивостокский порты в годы Первой мировой войны" . Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation . Archived from the original on June 10, 2016 . Retrieved September 15, 2020 .

- ^ Preclik, Vratislav. Масарик и Легион (Масарик и Легионы), ваза. Книга, 219 с. ISBN 978-80-87173-47-3 , страницы 38-50, 52-102, 124-128,140-148,184-190

- ^ Джоана Брейденбах (2005). Пал Нири, Джоана Брейденбах (ред.). Китай наизнанку: современный китайский национализм и транснационализм (иллюстрированный изд.). Центральный Европейский университет издательство. п. 90. ISBN 963-7326-14-6 Полем Получено 15 сентября 2020 года .

Затем произошла другая история, которая стала травмирующей, эта для русской националистической психики. В конце 1918 года, после российской революции, китайские торговцы на Дальнем Востоке потребовали, чтобы китайское правительство отправило войска для их защиты, а китайские войска были отправлены в Владивосток для защиты китайской общины: около 1600 солдат и 700 поддержка персонала.

- ^ Владимир Гелаев. (April 6, 2015). "Новороссия Дальнего Востока" . Gazeta.Ru . Archived from the original on August 18, 2016 . Retrieved September 15, 2020 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный "Планировка и застройка Владивостока в 1923—1931 гг" . CyberLeninka . 2008. Archived from the original on August 8, 2016 . Retrieved September 15, 2020 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Ковалёва З. А., Плохих С. В. (2002). "История Дальнего Востока России" (PDF) . Archived (PDF) from the original on March 16, 2022 . Retrieved September 15, 2020 .

- ^ Кривенко С. "Владивостокский ИТЛ" . Система исправительно-трудовых лагерей в СССР . Archived from the original on October 31, 2011 . Retrieved September 15, 2020 .

- ^ Галина Ткачева (October 10, 2019). "Великая Отечественная во Владивостоке: как и чем жил город в военное время" . PrimaMedia.ru . Archived from the original on August 16, 2016 . Retrieved September 15, 2020 .

- ^ "Владивостокские порты" . Камчатский научный центр. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013 . Retrieved September 15, 2020 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Виктория Антошина (October 12, 2015). "Закрытый на 40 лет Владивосток: штамп "ЗП" в паспорте, фарцовка и фальшивые портовики" . PrimaMedia.ru . Archived from the original on August 14, 2016 . Retrieved September 15, 2020 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Власов С. А. (2010). "Владивосток в годы хрущевской "оттепели" " (PDF) . Archived (PDF) from the original on August 27, 2016 . Retrieved September 15, 2020 .

- ^ Александр Львович Ткачев (April 27, 2011). "Первый визит президента США / First Visit of an American President" . alltopprim.ru. Archived from the original on July 1, 2016 . Retrieved September 15, 2020 .

- ^ "УКАЗ Президента РСФСР от 20.09.1991 N 123 "ОБ ОТКРЫТИИ Г. ВЛАДИВОСТОКА ДЛЯ ПОСЕЩЕНИЯ ИНОСТРАННЫМИ ГРАЖДАНАМИ" " . kremlin.ru . Archived from the original on December 20, 2014 . Retrieved September 15, 2020 .

- ^ Клиффорд , . Дж Леви 20 апреля 2009 г.

- ^ «Путин предлагает место проведения острова Руссского для АТЕК-2012» . Владивосток: Владивосток новости. 31 января 2007 года. Архивировано с оригинала 15 февраля 2009 года . Получено 11 февраля 2009 г.

- ^ Уильямсон, Гейл М.; Кристи, Джульетта (18 сентября 2012 г.). Лопес, Шейн Дж; Снайдер, кр (ред.). «Старение хорошо в 21 веке: проблемы и возможности». Оксфордские справочники онлайн : 164–170. doi : 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195187243.013.0015 . ISBN 9780195187243 .

- ^ "Путин перенес столицу Дальневосточного федерального округа во Владивосток" . meduza.io . Archived from the original on April 2, 2019 . Retrieved December 13, 2018 .

- ^ «Заброшенные и забытые Российские дальнейшие города Владивосток остается парализованным почти через две недели после крупной ледяной бури» . Медуза . Получено 18 августа 2024 года .

- ^ Wooltorton (Metdesk), Джоди (25 ноября 2020 г.). «Ледяная буря оставляет тысячи без власти в Владивостоке» . Хранитель . ISSN 0261-3077 . Получено 18 августа 2024 года .

- ^ «Владивосток снежная метель: чрезвычайная ситуация объявлена на фоне хаоса и сокращений мощности» . 20 ноября 2020 года . Получено 18 августа 2024 года .

- ^ "Как 12 мм льда поставили город на колени — история беспощадной ледяной блокады Владивостока в 2020 году - UlanMedia.ru" . ulanmedia.ru (in Russian) . Retrieved August 18, 2024 .

- ^ "ст. 20 Устава города Владивостока" . Официальный сайт Администрации города Владивостока . Archived from the original on July 23, 2016 . Retrieved October 10, 2020 .

- ^ "Дума города Владивостока празднует 140-летие" . Официальный сайт Администрации города Владивостока. December 11, 2015. Archived from the original on August 7, 2016 . Retrieved October 10, 2020 .

- ^ «Конституция города» . Vlc.ru. Архивировано с оригинала 22 ноября 2015 года . Получено 10 октября 2020 года .

- ^ "Исполнять обязанности мэра Владивостока будет Константин Лобода" . newsvl.ru . June 27, 2016. Archived from the original on July 1, 2016 . Retrieved October 10, 2020 .

- ^ "Численность постоянного населения Приморского края в разрезе городских округов и муниципальных районов" . Приморскстат РФ . Archived from the original on June 4, 2016 . Retrieved September 17, 2020 .

- ^ "Федеральная служба государственной статистики" . rosstat.gov.ru . Archived from the original on January 14, 2022 . Retrieved October 14, 2020 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный "Об итогах Всероссийской переписи населения 2010 года на территории Владивостокского городского округа" (PDF) . Сайт Владивостока . Archived from the original (PDF) on March 25, 2013 . Retrieved September 17, 2020 .

- ^ Патсиорковский, Валери; Фугита, Стивен С.; О'Брайен, Дэвид Дж. (1995). «Азиаты в малом бизнесе на Русском Дальнем Востоке: исторический обзор и сравнение с азиатами на американском западном побережье» . Международный обзор миграции . 29 (2): 566–575. doi : 10.2307/2546794 . ISSN 0197-9183 . JSTOR 2546794 . Архивировано из оригинала 12 июля 2022 года . Получено 11 июля 2022 года .

- ^ «Китайцы на Дальнем Востоке России: столкновение цивилизаций в Владивостоке» . Геогистория . 31 августа 2010 года. Архивировано с оригинала 22 марта 2022 года . Получено 10 июля 2022 года .

- ^ Ричардсон, Уильям (1995). «Владивосток: город трех эпох» . Планирование перспектив . 10 (1): 43–65. doi : 10.1080/02665439508725812 . ISSN 0266-5433 . Архивировано из оригинала 12 июля 2022 года . Получено 10 июля 2022 года .

- ^ Iijima, Yasuo (1999). Демилитаризация после холодной войны и «корейская торговая диаспора» в Владивостоке: прошлое и настоящее (PDF) (PH. D в планировании исследований. Тезис). Лондон: Университетский колледж , Лондонский университет . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 12 июля 2022 года . Получено 12 июля 2022 года .

- ^ 숀 " , 1000 , 来 新 from the original on April 1, 2024, retrieved April 1,,

- ^ Эгор Кузмачев (25 сентября 2014 г.). «Японская" мозаика "и эстонский" " Корнины Novaya Gazeta . Архивировано с оригинала 8 августа 2016 года . Получено 17 сентября 2020 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный "4. Население по национальности и владению русским языком" (PDF) . Приморскстат РФ . Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2016 . Retrieved September 17, 2020 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Путин превращает Владивостока в российский тихоокеанский капитал» (PDF) . Российский аналитический дайджест (82). Институт истории, Базельский университет, Базель, Швейцария: 9–12. 12 июля 2010 г. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 6 июля 2011 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Олифант, Роланд (2010). «Правитель Востока: город Владивосток - это смесь обещаний и пренебрежения». Россия профиль .

- ^ "Морской порт Владивосток" . pma.ru . Archived from the original on August 7, 2016 . Retrieved October 12, 2020 .

- ^ "Грузооборот морских портов России за январь-декабрь 2016 г." morport.com . Archived from the original on January 21, 2017 . Retrieved October 12, 2020 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный "Исследование и анализ торговых ограничений внешней торговли в городе Владивосток" . CyberLeninka . 2015. Archived from the original on August 8, 2016 . Retrieved October 12, 2020 .

- ^ Татьяна Сушенцова (June 20, 2016). "Приморский край: есть чем впечатлиться" . Дальневосточный капитал . Archived from the original on September 16, 2016 . Retrieved October 8, 2020 .

- ^ Сергей Павлов (May 26, 2016). "Властелины Восточного кольца" . Novaya Gazeta . Archived from the original on June 30, 2016 . Retrieved October 8, 2020 .

- ^ "Формирование туристской идентичности г. Владивостока в контексте бренда: "Владивосток — морские ворота России" " . CyberLeninka . 2016. Archived from the original on August 15, 2016 . Retrieved October 8, 2020 .

- ^ "Оздоровительный туризм как фактор развития территории на примере побережья залива Петра Великого, Японское море" . CyberLeninka . 2014. Archived from the original on August 15, 2016 . Retrieved October 8, 2020 .

- ^ Эндрю Хиггинс (1 июля 2017 г.). «На Дальнем Востоке России яростный Лас -Вегас для азиатских игроков» . New York Times . Архивировано из оригинала 4 июля 2017 года . Получено 8 октября 2020 года .

- ^ Holdi Spectre (19 ноября 2019 г.). «Примирие gamblng Zone приветствовать не менее 11 казино» . Азартные новости . Архивировано из оригинала 25 октября 2020 года . Получено 8 октября 2020 года .

- ^ Такаюки Танака (May 16, 2016). "Судьба развития Дальнего Востока — в руках казино: Владивосток привлекает азиатских клиентов" . inoSMI . Archived from the original on June 21, 2016 . Retrieved October 8, 2020 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ольга Цыбульская (May 26, 2015). "Во Владивостоке хорошие деловые перспективы" . РБК . Archived from the original on August 9, 2016 . Retrieved October 8, 2020 .

- ^ "Анализ структуры регионального туристического комплекса Приморского края России" . CyberLeninka . 2011. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020 . Retrieved October 8, 2020 .

- ^ "Три школы Владивостока вошли в перечень "Топ-500 школ РФ" " . RIA Novosti . September 18, 2013. Archived from the original on August 19, 2016 . Retrieved October 26, 2020 .

- ^ Анна Бондаренко (September 1, 2016). "В Приморье открылся филиал Вагановской Академии балета" . Rossiyskaya Gazeta . Archived from the original on September 11, 2016 . Retrieved October 26, 2020 .

- ^ "Выступление на встрече с воспитанниками филиала Нахимовского военно-морского училища во Владивостоке" . Президент России. August 31, 2016. Archived from the original on September 1, 2019 . Retrieved October 26, 2020 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный "Новые возможности высшего образования на Дальнем Востоке России: от Восточного института к Дальневосточному Федеральному Университету" . CyberLeninka . 2014. Archived from the original on August 15, 2016 . Retrieved October 26, 2020 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный "Развитие сети художественных музеев в Приморском крае" . 2008. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016 . Retrieved October 13, 2020 .

- ^ "События в мире в 1995 году" . history.xsp.ru . Archived from the original on January 17, 2018 . Retrieved October 13, 2020 .

- ^ Василий Алленов (March 3, 2016). " "Соль" современного искусства" . Novaya Gazeta . Archived from the original on August 8, 2016 . Retrieved October 13, 2020 .

- ^ "Центр современного искусства открылся на фабрике "Заря" во Владивостоке" . PrimaMedia.ru . Archived from the original on November 15, 2019 . Retrieved October 13, 2020 .

- ^ Ризик, Мелена (28 августа 2013 г.). «Восток на сегодняшний день: Владивосток скалы» . New York Times . Архивировано с оригинала 9 ноября 2017 года . Получено 26 февраля 2017 года .

- ^ "Семь фестивалей, 14 оперных и балетных спектаклей — два года Приморского оперного театра" . PrimaMedia.ru . October 19, 2015. Archived from the original on November 7, 2019 . Retrieved October 13, 2020 .

- ^ "Приморский филиал Мариинского театра" . Archived from the original on March 15, 2016 . Retrieved October 13, 2020 .

- ^ Старрс. «Российский оперный театр» . Архивировано из оригинала 6 октября 2014 года . Получено 5 октября 2014 года .

- ^ "Музей истории Дальнего Востока имени В.К. Арсеньева" . Приморский музей имени Арсеньева . July 6, 2018. Archived from the original on January 21, 2012.

- ^ "Кинотеатры Владивостока: где Dolby Digital и 3D, где храмы и руины" . RIA Novosti . December 29, 2013. Archived from the original on September 18, 2016 . Retrieved October 13, 2020 .

- ^ "8 сентября во Владивостоке начинается международный кинофестиваль "Меридианы Тихого" " . kbanda.ru . September 12, 2011. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017 . Retrieved October 13, 2020 .

- ^ "IMAX приходит на Дальний Восток" . kinobusiness.com . December 11, 2014. Archived from the original on August 15, 2016 . Retrieved October 13, 2020 .

- ^ "Закулисье театра имени Максима Горького: швейный цех, большие склады и маленькие гримерки" . PrimaMedia.ru . Archived from the original on November 15, 2019 . Retrieved October 13, 2020 .

- ^ Фалалеева А. В. (March 25, 2014). "Театр, театр, театр…(о театрах города Владивостока)" . cbs.fokino25.ru . Archived from the original on August 19, 2016 . Retrieved October 13, 2020 .

- ^ "В Приморском театре кукол побывало более 50 тысяч зрителей на 500 спектаклях в 2015 году" . PrimaMedia.ru . June 29, 2016. Archived from the original on November 7, 2019 . Retrieved October 13, 2020 .

- ^ "Первые гонки регаты «Кубок залива Петра Великого» завершились победой экипажей из Владивостока и Находки (ФОТО) – Новости Владивостока на VL.ru" . www.newsvl.ru . Archived from the original on October 4, 2022 . Retrieved October 4, 2022 .

- ^ Preobrazhensky, bv; Бураго, ИИ; Shlykov, SA «Экология Принчика: загрязнение моря и воды» . fegi.ru. Геологический институт Дальнего Востока. Архивировано из оригинала 19 августа 2007 года.

- ^ Ущерб фермерам Приморья от тайфуна "Санба" оценивается в 40 млн руб (на русском языке). Interfax. 19 сентября 2012 года. Архивировано с оригинала 27 мая 2022 года . Получено 19 сентября 2012 года .

- ^ Климат Владивостока [Климат Владивостока]. Погода и климат (на русском языке). Архивировано с оригинала 27 декабря 2016 года . Получено июня 2013 г. 19

- ^ «Климат Владивосток» . Pogoda.ru.net . Получено 8 ноября 2021 года .

- ^ «Владивосток 1961–1990» . Ноаа . Получено 29 октября 2021 года .

- ^ [1]

- ^ "Города-побратимы" . vlc.ru (in Russian). Vladivostok. Archived from the original on April 7, 2022 . Retrieved May 7, 2021 .

- ^ "Пин Ап Казино — Официальный сайт Pin Up Casino: вход в личный кабинет" . www.gkd-kremlin.ru . Archived from the original on July 27, 2023 . Retrieved July 27, 2023 .

- ^ Во Владивостоке открыт сквер городов-побратимов Archived August 17, 2016, at the Wayback Machine (In Russian). Retrieved July 19, 2016.

- ^ "О Диане" . Dianaankudinova.ru (на русском языке). Архивировано с оригинала 27 ноября 2022 года . Получено 1 декабря 2023 года .

- Законодательное Собрание Приморского края. Закон №161-КЗ от 14 ноября 2001 г. «Об административно-территориальном устройстве Приморского края», в ред. Закона №673-КЗ от 6 октября 2015 г. «О внесении изменений в Закон Приморского края "Об административно-территориальном устройстве Приморского края"». Вступил в силу со дня официального опубликования. Опубликован: "Красное знамя Приморья", №69 (119), 29 ноября 2001 г. (Legislative Assembly of Primorsky Krai. Law #161-KZ of November 14, 2001 On the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Primorsky Krai , as amended by the Law #673-KZ of October 6, 2015 On Amending the Law of Primorsky Krai "On the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Primorsky Krai" . Effective as of the official publication date.).

- Законодательное Собрание Приморского края. Закон №179-КЗ от 6 декабря 2004 г. «О Владивостокском городском округе», в ред. Закона №48-КЗ от 7 июня 2012 г. «О внесении изменений в Закон Приморского края "О Владивостокском городском округе"». Вступил в силу 1 января 2005 г.. Опубликован: "Ведомости Законодательного Собрания Приморского края", №76, 7 декабря 2004 г. (Legislative Assembly of Primorsky Krai. Law #179-KZ of December 6, 2004 On Vladivostoksky Urban Okrug , as amended by the Law #48-KZ of June 7, 2012 On Amending the Law of Primorsky Krai "On Vladivostoksky Urban Okrug" . Effective as of January 1, 2005.).

- Фолстич, Эдит. М. "Сибирский пребывание" Йонкерс , Нью -Йорк (1972–1977)

- Нарангоа, Ли (2014). Исторический атлас Северо -Восточной Азии, 1590–2010 гг.: Корея, Маньчжурия, Монголия, Восточная Сибирия . Нью -Йорк: издательство Колумбийского университета. ISBN 9780231160704 .

- Позняк, Татяна З. 2004. Иностранные граждане в городах Российского Дальнего Востока (вторая половина 19 -го и 20 -го веков). Владивосток: Далнаука, 2004. 316 с. ( ISBN 5-8044-0461-X ).

- Стефан, Джон. 1994. Дальний Восток - история. Стэнфорд: издательство Стэнфордского университета , 1994. 481 с.

- Trofimov, Vladimir et al., 1992, Old Vladivostok . Utro Rossii Vladivostok, ISBN 5-87080-004-8

Внешние ссылки

[ редактировать ]- Официальный веб -сайт Владивостока Архивировал 13 ноября 2010 года на The Wayback Machine (на русском языке)