Сантьяго

Сантьяго | |

|---|---|

| Nickname: "The City of the Island Hills" | |

| Coordinates: 33°26′15″S 70°39′00″W / 33.43750°S 70.65000°W | |

| Country | |

| Region | Santiago Metropolitan Region |

| Province | Santiago Province |

| Foundation | 12 February 1541 |

| Founded by | Pedro de Valdivia |

| Named for | Saint James |

| Area | |

| • Capital city | 641 km2 (247.6 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 570 m (1,870 ft) |

| Population (2017) | |

| • Capital city | 6,269,384 |

| • Density | 9,821/km2 (25,436/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 6,903,479 |

| Demonym | Santiaguinos (-as) |

| GDP (PPP, constant 2015 values) | |

| • Year | 2023 |

| • Total | $192.3 billion[1] |

| • Per capita | $27,900 |

| Time zone | UTC−4 (CLT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−3 (CLST) |

| Postal code | 8320000 |

| Area code | +56 2 |

| HDI (2021) | 0.886[2] – very high |

| Website | www |

Сантьяго ( / ˌ s æ n t i ɡ ɡ ɡ ɡ ɡ ɡ oʊ / , Мы также / ˌ S A ː n - / ; [ 3 ] Испанский: [sanˈtjaɣo] ), также известный как Сантьяго -де -Чили ( : [ Пилос Испанский ), является столицей и крупнейшим городом Чили и одним из крупнейших городов Америки . страны Он расположен в Центральной долине и является центром столичного региона Сантьяго , который составляет семь миллионов человек, что составляет 40% от общей численности Чили. [ 4 ] Большая часть города расположена между 500–650 м (1640–2 133 футами) над уровнем моря .

Сантьяго, основанный в 1541 году испанским конкистадором Педро де Вальдивией , служил столицей Чили с колониальных времен. [ 5 ] В городе есть центр города, характеризующуюся неоклассической архитектурой 19-го века и намотливыми улицами, со смесью ар-деко, неоготических и других стилей. Городской пейзаж Сантьяго определяется несколькими автономными холмами и быстросъемной рекой Мапочо , которая выстлана такими парками, как Parque Bicentenario , Parque Forealal и Parque de la Familia . Горы Анд видны из большинства частей города и способствуют проблеме смога , особенно зимой из -за отсутствия дождя. Окрашивания города окружены виноградниками, а Сантьяго находится в часе езды от гор и Тихого океана.

Santiago is the political and financial center of Chile and hosts the regional headquarters of many multinational corporations and organizations. The Chilean government's executive and judiciary branches are based in Santiago, while the Congress mostly meets in nearby Valparaíso.

Etymology

[edit]In Chile, several entities share the name Santiago, which can often lead to confusion. The commune of Santiago, also referred to as Santiago Centro, is an administrative division encompassing the area occupied by the city during colonial times. It is governed by the Municipality of Santiago and led by a mayor. This commune is part of Santiago Province, which is headed by a provincial delegate appointed by the President of the Republic, and it is also part of the Santiago Metropolitan Region, governed by a popularly elected governor.[6]

When the term Santiago is used without further clarification, it typically refers to Gran Santiago (Greater Santiago), the metropolitan area characterized by continuous urban development. This area includes the commune of Santiago and over 40 other communes, encompassing much of Santiago Province and parts of neighboring provinces. The definition of the metropolitan area has evolved over time as the city has expanded, incorporating smaller cities and rural areas.

The name Santiago was chosen by the Spanish conqueror Pedro de Valdivia when he founded the city in 1541 as "Santiago del Nuevo Extremo," in reference to his home region of Extremadura and as a tribute to James the Great, the patron saint of Spain. The saint's name appears in various forms in Spanish, such as Diego, Jaime, Jacobo, or Santiago, with the latter derived from the Galician evolution of Vulgar Latin Sanctu Iacobu.[7] Allegedly, there was no indigenous name for the area where Santiago is located, but the Mapuche language uses the adapted name Santiaw.[8]

Residents of the city and region are referred to as santiaguinos (for males) and santiaguinas (for females).

History

[edit]Prehistory

[edit]Archaeological evidence suggests that the first human groups arrived in the Santiago basin around the 10th millennium BC.[9] These groups were primarily nomadic hunter-gatherers, traveling from the coast to the interior to hunt guanacos during the Andean snowmelt. By around 800 AD, the first permanent settlers established agricultural communities along the Mapocho River, where they cultivated crops such as maize, potatoes, and beans, and domesticated camelids.[9]

The villages of the Picunche people (as they were known to Chileans) or the Promaucae (as referred to by the Incas) were under Inca rule from the late 15th century to the early 16th century. The Incas established a settlement of mitimas in the valley, located in the center of present-day Santiago, with fortifications such as Huaca de Chena and the El Plomo hill sanctuary. According to Chilean historian Armando de Ramón, the area served as a base for failed Inca expeditions to the south and was a junction along the Inca Trail.[9]

Founding of the city

[edit]

Pedro de Valdivia, a conquistador from Extremadura sent by Francisco Pizarro from Peru, arrived in the Mapocho valley on 13 December 1540, after a long journey from Cusco. Valdivia and his party camped by the river on the slopes of the Tupahue hill and gradually began interacting with the Picunche people who lived in the area. Valdivia later called a meeting with the local chiefs, during which he explained his plan to establish a city on behalf of Charles IV of Spain. The city would serve as the capital of his governorship of Nueva Extremadura.

On 12 February 1541, Valdivia officially founded the city of Santiago del Nuevo Extremo (Santiago of New Extremadura) in honor of the Apostle James, the patron saint of Spain. The city was established near Huelén, which Valdivia renamed Santa Lucía. He assigned the city's layout to master builder Pedro de Gamboa, who designed a grid plan. At its center, Gamboa placed a Plaza Mayor, which became the town's central hub.[11] Surrounding the plaza, plots were designated for the cathedral, the jail, and the governor's house. The city was divided into eight blocks from north to south and ten blocks from east to west, between the Mapocho River and the Cañada with each quarter-block, or solar, granted to settlers.[11] The colonial architecture following the grid plan consisted of one or two-story houses, adobe walls, tile roofs, and rooms around interior corridors and patios.[12]

Valdivia left for the south with his troops months later, initiating the Arauco War. Santiago was left vulnerable, and a coalition of Mapuche and Picunche tribes led by chief Michimalonco destroyed the city on 11 September 1541, despite the efforts of a Spanish garrison of 55 soldiers defending the fort. The defense was led by Spanish conquistadora Inés de Suárez. When she realized they were being overpowered, she ordered the execution of all indigenous prisoners, displaying their heads on pikes and throwing some towards the attackers. In response to this brutal act, the indigenous forces dispersed in fear.[13] The city was gradually rebuilt, with the newly established city of Concepción gaining political prominence as the Royal Audiencia of Chile was established there in 1565. However, the ongoing threat of the Arauco War and frequent earthquakes delayed the establishment of the Royal Court in Santiago until 1607, which solidified the city's status as the capital.

During the early years of the city, the Spanish suffered from severe shortages of food and other supplies. The Picunches had adopted a strategy of halting cultivation and retreating to more remote locations,[14] which isolated the Spanish and forced them to resort to eating whatever they could find. The shortage of clothing meant that some Spanish had to dress with hides from dogs, cats, sea lions, and foxes.[14]

Colonial Santiago

[edit]

Although Santiago was facing the threat of permanent destruction early on, due to attacks from indigenous peoples, earthquakes, and floods, the city began to grow rapidly. Out of the 126 blocks designed by Pedro de Gamboa in 1558, 40 were occupied. In 1580, the first major buildings in the city started to be erected, marked by the placement of the foundation stone of the first Cathedral in 1561 and the building of the church of San Francisco in 1572. Both of these structures were primarily made of adobe and stone. In addition to the construction of significant buildings, the city began to thrive as the surrounding areas welcomed tens of thousands of livestock.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the growth of the city was hindered by a series of disasters including an earthquake, a smallpox epidemic in 1575, the Mapocho River floods in 1590, 1608, and 1618, and a devastating earthquake on 13 May 1647 which resulted in the death of over 600 people and affected over 5,000 others. Despite these setbacks, the capital of the Captaincy General of Chile continued to grow, with all the power of the country being centered on the Plaza de Armas in Santiago.

In 1767, the corregidor Luis Manuel de Zañartu launched one of the most significant architectural projects of the colonial period, the Calicanto Bridge, connecting the city to La Chimba on the north side of the Mapocho River. He also began constructing embankments to prevent river overflows. Although the bridge was completed, its piers were frequently damaged by the river. In 1780, Governor Agustín de Jáuregui hired the Italian architect Joaquín Toesca, who designed several important buildings, including the cathedral's façade, the Palacio de La Moneda, the San Carlos Canal, and the completion of the embankments during the government of Ambrosio O'Higgins. These works were officially opened in 1798. The O'Higgins government also opened the road to Valparaíso in 1791, connecting the capital with the country's main port.

-

The colonial La Cañada neighborhood in Santiago de Chile, in 1821, by Scharf and Schmidtmeyer. John Carter Brown Library.[15][16]

-

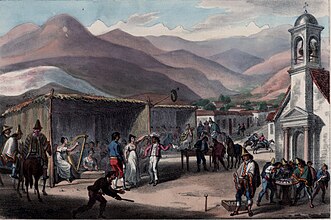

Scenes at a fair in Santiago de Chile, in 1821, by Scharf and Schmidtmeyer. John Carter Brown Library.[15]: 320, 348 [17]

-

The colonial Real Casa de la Moneda (now called Palacio de la Moneda) in 1824 (by Paroissien, Scharf and Rowney & Forster). John Carter Brown Library.[18]

-

[Colonial] Plaza o great Square of Santiago with different local costumes, in 1826, by John Miers. British Library.[19][20]

-

[Colonial] Square in Downtown Santiago, in 1850, by the French-born Ernest Charton.[21]

-

Colonial Plaza de Armas de Santiago in 1854 by Claude Gay.[22] In the foreground you can see the still intact Palace of the Real Audiencia of Chile, and in the background the unfinished Cathedral, both built by the Italian Joaquin Toesca.

-

Colonial Plaza de Armas de Santiago in 1859 by Joseph Selleny aboard the Novara expedition, to the left, the (beginning to be modified) Palace of the Real Audiencia of Chile, and to the right, the colonial Portal de Sierra Bella.

-

Portal de Sierra Bella and gardens of the Plaza de Armas in 1860. The colonial imprint was maintained until well into the 19th century, this commercial portal faithfully reflects the appearance of colonial Santiago. Photograph by Eugéne Maunoury, belonging to the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Capital of the Republic

[edit]

On September 18, 1810, the First Government Junta was proclaimed in Santiago, marking the beginning of Chile’s path to independence. The city, which became the capital of the newly formed nation, faced various challenges, particularly from military actions in the vicinity.[23]

Although institutions like the Instituto Nacional and the National Library were established during the Patria Vieja, they were shut down after the patriots’ defeat at the Battle of Rancagua in 1814.[23] The royal government continued until 1817, when the Army of the Andes emerged victorious at the Battle of Chacabuco and restored the patriot government in Santiago. However, independence was still uncertain. The Spanish army achieved further victories in 1818 and advanced toward Santiago, but their progress was finally halted at the Battle of Maipú on April 5, 1818, on the Maipo River plains.[23]

With the end of the war, Bernardo O'Higgins was accepted as Supreme Director and, like his father, undertook several important projects for the city. During the Patria Nueva era, previously closed institutions were reopened. The General Cemetery was inaugurated, work on the San Carlos Canal was completed, and the drying riverbed in the south arm of the Mapocho River, known as La Cañada, which had been used as a landfill for some time, was transformed into an avenue now known as the Alameda de las Delicias.

Two earthquakes struck the city in the 19th century: one on November 19, 1822, and another on February 20, 1835. Despite these disasters, the city continued to grow rapidly. In 1820, the population was recorded as 46,000, but by 1854, it had risen to 69,018. By 1865, the census reported 115,337 residents. This significant increase was due to suburban expansion to the south and west of the capital, as well as the growth of the bustling district of La Chimba, which resulted from the division of old properties in the area. This new peripheral development marked the end of the previous checkerboard structure that had dominated the city center.

19th century

[edit]

During the Republican era, several institutions were founded, including the University of Chile, the Normal School of Preceptors, the School of Arts and Crafts, and the Quinta Normal. The latter comprised the Museum of Fine Arts (now the Museum of Science and Technology) and the National Museum of Natural History. These institutions were established primarily for educational purposes, but also served as examples of public planning during that period. In 1851, the first telegraph system connecting the capital to the Port of Valparaíso was inaugurated.[24]

During the "Liberal Republic" and the administration of Mayor Benjamín Vicuña Mackenna, a new phase in the urban development of the capital was initiated. One of the main projects during this period was the remodeling of Cerro Santa Lucía, which had fallen into disrepair despite its central location.[24] In his effort to transform Santiago, Vicuña Mackenna initiated the construction of the Camino de Cintura, a road surrounding the entire city. The redevelopment of Alameda Avenue also took place during this time, turning it into the city's main road.

Also during this era, O'Higgins Park was established with the help of European landscapers in 1873. The public park, known for its large gardens, lakes, and carriage trails, became a landmark in Santiago. Other notable structures were also opened during this period, including the Teatro Municipal opera house and the Club Hípico de Santiago. In addition, the 1875 International Exposition was held in the Quinta Normal grounds.[25]

Santiago emerged as the central hub of the national railway system. On 14 September 1857, the first railway arrived in the city and terminated at the Santiago Estación Central railway station, which was under construction at the time and officially opened in 1884. During this period, rail lines connected Santiago to Valparaíso and regions in northern and southern Chile. The streets of Santiago were also paved, and by 1875, there were 1,107 railway cars in the city, while 45,000 people used trams daily.

The centennial Santiago

[edit]

As the new century began, Santiago underwent various changes due to the rapid growth of industry. Valparaíso, which had previously been the economic center of the country, gradually lost its prominence to the capital. By 1895, 75% of the national manufacturing industry was located in Santiago, while only 28% was in Valparaíso. By 1910, major banks and shops had established themselves in the central streets of Santiago, further diminishing the role of Valparaíso.

The enactment of the Autonomous Municipalities Act empowered municipalities to establish various administrative divisions within the Santiago department, with the goal of enhancing local governance. In 1891, the municipalities of Maipú, Ñuñoa, Renca, Lampa, and Colina were created, followed by Providencia and Barrancas in 1897, and Las Condes in 1901. The La Victoria departmento was also divided, leading to the creation of Lo Cañas in 1891, which was then further split into La Granja and Puente Alto in 1892, followed by La Florida in 1899, and La Cisterna in 1925.

The San Cristobal Hill underwent a prolonged process of development during this period. In 1903, an astronomical observatory was established on the hill, and the following year, construction began on a 14-metre (46 ft) statue of the Virgin Mary. Today, the statue is visible from various points in the city. However, the shrine was not completed until several decades later.

The 1910 Chile Centennial celebrations marked the beginning of several urban development projects. The railway network was expanded, connecting the city and its growing suburbs with a new ring and route to Cajón del Maipo. A new railway station was also built in the north of the city: the Mapocho Station. The Parque Forestal was established on the southern side of the Mapocho river, and new buildings such as the Museum of Fine Arts, the Barros Arana public boarding school, and the National Library were opened. In addition, a sewer system was installed, serving approximately 85% of the city's population.

Population explosion

[edit]

The 1920 census estimated the population of Santiago to be 507,296 inhabitants, equivalent to 13.6% of the total population of Chile. This represented a growth of 52.5% from the 1907 census, an annual increase of 3.3%, which was almost three times the national average. This growth was mainly due to an influx of farmers from the southern regions who came to work in the factories and railroads that were being built. However, this growth was concentrated in the suburbs and not in the city center.

During this time, the downtown district consolidated as a commercial, financial, and administrative center, with the establishment of various shops and businesses around Ahumada Street and a Civic District in the vicinity of the Palace of La Moneda. The latter project involved the construction of modernist buildings for the offices of the ministries and other public services, as well as the start of the construction of medium-rise buildings. Meanwhile, the traditional residents of the center began to migrate to more rural areas like Providencia and Ñuñoa, which attracted the oligarchy and European immigrant professionals, and San Miguel for middle-class families. Additionally, in the periphery, villas were built by various organizations of the time. Modernity also spread in the city, with the introduction of the first theaters, the expansion of the telephone network, and the opening of Los Cerrillos Airport in 1928, among other advancements.

The perception that the early 20th century was a time of economic prosperity due to technological advancements was in stark contrast to the living conditions of lower social classes. The previous decades of growth resulted in an unprecedented population boom starting in 1929, but was met with tragedy as the Great Depression hit. The collapse of the nitrate industry in the north left 60,000 people unemployed, compounded by a decline in agricultural exports, resulting in an estimated 300,000 unemployed people nationwide. Desperate for survival, many migrants flocked to Santiago and its thriving industry. However, they often found themselves struggling to find housing, with many being forced to live on the streets. The harsh living conditions resulted in widespread diseases like tuberculosis, and took a toll on the homeless population. At the same time, unemployment rates and living costs skyrocketed, while the salaries of the people in Santiago fell.

The situation would change several years later with a new industrial boom fostered by CORFO and the expansion of the state apparatus from the late 1930s. At this time, the aristocracy lost much of its power, and the middle class, composed of merchants, bureaucrats, and professionals, acquired the role of setting national policy. In this context, Santiago began to develop a substantial middle- and lower-class population, while the upper classes sought refuge in the districts of the capital. Thus, the old moneyed class, who previously frequented Cousiño and Alameda Park, lost their hegemony over popular entertainment venues, and the National Stadium emerged in 1938.

Greater Santiago

[edit]| 1940 | 1952 | 1960 | 1970 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barrancas | 100 | 223 | 792 | 1978 |

| Conchalí | 100 | 225 | 440 | 684 |

| La Granja | 100 | 264 | 1379 | 3424 |

| Las Condes | 100 | 197 | 506 | 1083 |

| Ñuñoa | 100 | 196 | 325 | 535 |

| Renca | 100 | 175 | 317 | 406 |

| San Miguel | 100 | 221 | 373 | 488 |

| Santiago | 100 | 104 | 101 | 81 |

In the following decades, Santiago continued to grow at an unprecedented rate. In 1940, the city had a population of 952,075 residents, which increased to 1,350,409 by 1952, and reached 1,907,378 in the 1960 census. This growth was reflected in the urbanization of rural areas on the outskirts of the city, where middle and lower-class families with stable housing were established. In 1930, the urban area covered 6,500 hectares, which increased to 20,900 in 1960 and to 38,296 in 1980. Although growth was mainly concentrated in communities such as Barrancas to the west, Conchalí to the north, and La Cisterna and La Granja to the south, the center of the city lost population, leaving more space for commercial, banking, and government development. The upper class, on the other hand, began to settle in the foothills of Las Condes and the La Reina sector.

The regulation of growth in Santiago only began in the 1960s with the creation of various development plans for Greater Santiago, a concept that reflected the city's new reality as a much larger urban center. In 1958, the Intercommunal Plan of Santiago was released, which proposed a limit of 38,600 urban and semi-urban hectares for a maximum population of 3,260,000 residents. The plan also included plans for the construction of new avenues, such as the Américo Vespucio Avenue and Panamericana Route 5, as well as the expansion of 'industrial belts'. The 1962 World Cup provided a new impetus for city improvement efforts, and in 1966, the Santiago Metropolitan Park was established on Cerro San Cristóbal. The Ministry of Housing and Urbanism (MINVU) also began to eradicate shantytowns and build new homes. Finally, the Edificio Diego Portales was constructed in 1972.

In 1967, the new Pudahuel International Airport was opened, and after years of discussion, construction of the Santiago Metro began in 1969. The first phase of the Metro, which ran beneath the western section of Alameda, was opened in 1975 and soon became one of the most prestigious buildings in the city. Over the following years, the Metro continued to expand, with two perpendicular lines in place by the end of 1978. Building telecommunications infrastructure was also an important development of this period, as reflected in the construction of the Torre Entel, which, since its construction in 1975, has become one of the symbols of the capital and remained the tallest structure in the country for two decades.

After the military coup of 1973 and the establishment of the military regime, significant changes in urban planning did not occur until the 1980s when the government embraced a neoliberal economic model. In 1979, the master plan was revised, expanding the urban area to over 62,000 hectares for real estate development. This led to urban sprawl, particularly in La Florida, causing the city to reach 40,619 hectares in size in the early 1990s. According to the 1992 census, Santiago became the country's most populous municipality, with 328,881 residents. Tragically, a powerful earthquake struck the city on 3 March 1985, causing minimal casualties but leaving many homeless and destroying numerous historic buildings.

The metropolis in the early twenty-first century

[edit]

With the onset of the transition to democracy in 1990, the city of Santiago surpassed four million inhabitants, with the majority residing in the south, particularly in La Florida, which was the most populous area, followed by Puente Alto and Maipú. The real estate development in these municipalities, as well as in others such as Quilicura and Peñalolén, was largely driven by the construction of housing projects for middle-class families. Meanwhile, high-income families relocated to the foothills, now commonly referred to as Barrio Alto, boosting the population of Las Condes and giving rise to young communes, including Lo Barnechea and Vitacura, both established in 1981 and 1991, respectively.

The area around Providencia Avenue became an important commercial hub in the eastern sector. This development extended to the Barrio Alto, which became an attractive location for the construction of high-rise buildings. Major companies and financial corporations established themselves in the area, giving rise to a thriving modern business center commonly known as Sanhattan. The departure of these companies to Barrio Alto and the construction of shopping centers all around the city created a crisis in the city center. To reinvigorate the area, the government transformed the main shopping streets into pedestrian walkways, as it did in the 1970s, and offered tax benefits for the construction of residential buildings, which attracted young adults.

The city faced a series of problems due to disorganized growth. During the winter months, air pollution reached critical levels and a layer of smog blanketed the city. In response, the authorities implemented legislative measures to reduce industrial pollution and placed restrictions on vehicle use. To address the problem of transportation, the metro system underwent significant expansion, with lines being extended and three new lines added between 1997 and 2006 in the southeastern sector. In 2011, a new extension was inaugurated in Maipú, bringing the total length of the metropolitan railway to 105 km (65 mi). In the early 1990s, the bus system also underwent a major reform. In 2007, the master plan known as Transantiago was established, although it has faced various challenges since its implementation.

Entering the 21st century, rapid development continued in Santiago. The Civic District was revitalized with the creation of the Plaza de la Ciudadanía and the construction of the Ciudad Parque Bicentenario, which marked the bicentenary of the Republic. The trend of constructing tall buildings continued in the eastern sector, which was highlighted by the opening of the Titanium La Portada and Gran Torre Santiago skyscrapers in the Costanera Center complex.

On 27 February 2010, a powerful earthquake hit the capital city of Santiago, causing damage to some older buildings and rendering some modern structures uninhabitable. This sparked a heated discussion about the actual implementation of mandatory earthquake standards in the city's modern architecture.

Despite urban integration efforts, socioeconomic inequality and geosocial fragmentation remain two of the most important problems, both in the city and in the country. These problems have been considered one of the factors that led to the "Estallido Social", a series of massive protests and severe riots carried out between 2019 and 2020. The protests led to a serious civil confrontation, which led to thousands of arrests and accusations of human rights violations. Meanwhile, the demonstrations registered serious episodes of violence against public and private infrastructure, mainly in the surroundings of Plaza Baquedano, with the Santiago Metro being one of the most affected by these episodes: more than half of its stations registered damage (several being partially set on fire) and only eleven months later the network returned to full normal service.

Geography

[edit]

The city lies in the center of the Santiago Basin, a large bowl-shaped valley consisting of broad and fertile lands surrounded by mountains. The city has a varying elevation, gradually increasing from 400 m (1,312 ft) in the western areas to more than 700 m (2,297 ft) in the eastern areas. Santiago's international airport, in the west, lies at an altitude of 460 m (1,509 ft). Plaza Baquedano, near the center, lies at 570 m (1,870 ft). Estadio San Carlos de Apoquindo, at the eastern edge of the city, has an elevation of 960 m (3,150 ft).

The Santiago Basin is part of the Intermediate Depression and is remarkably flat, interrupted only by a few "island hills;" among them are Cerro Renca, Cerro Blanco, and Cerro Santa Lucía. The basin is approximately 80 kilometers (50 miles) in a north–south direction and 35 km (22 mi) from east to west. The Mapocho River flows through the city.

The city is flanked by the main chain of the Andes to the east and the Chilean Coastal Range to the west. On the north, it is bordered by the Cordón de Chacabuco, a mountain range of the Andes. At the southern border lies the Angostura de Paine, an elongated spur of the Andes that almost reaches the coast.

The mountain range immediately bordering the city on the east is known as the Sierra de Ramón, which was formed due to tectonic activity of the San Ramón Fault. This range reaches 3296 meters at Cerro de Ramón. The Sierra de Ramón represents the "Precordillera" of the Andes. 20 km (12 mi) further east is the even larger Cordillera of the Andes, which has mountains and volcanoes that exceed 6,000 m (19,690 ft) and on which some glaciers are present. The tallest is the Tupungato mountain at 6,570 m (21,555 ft). Other mountains include Tupungatito, San José, and Maipo. Cerro El Plomo is the highest mountain visible from Santiago's urban area.

During recent decades, urban growth has outgrown the boundaries of the city, expanding to the east up the slopes of the Andean Precordillera. In areas such as La Dehesa, Lo Curro, and El Arrayan, urban development is present at over 1,000 meters of altitude.[29]

The natural vegetation of Santiago is made up of a thorny woodland of Vachellia caven (also known as Acacia caven and espinillo) and Prosopis chilensis in the west and an association of Vachellia caven and Baccharis paniculata in the east around the Andean foothills.[30]

-

Santiago in the winter

-

Santiago in the summer

Climate

[edit]Santiago has a cool semi-arid climate (BSk according to the Köppen climate classification), with Mediterranean (Csb) patterns, while the eastern areas, being closer to the mountain range, have a true Mediterranean climate (Csb):[31][32] warm dry summers (October to March) with temperatures reaching up to 35 °C (95 °F) on the hottest days; winters (April to September) are cool with cool to cold mornings; typical daily maximum temperatures of 14 °C (57 °F), and low temperatures near 0 °C (32 °F). In climate station of Quinta Normal (near downtown) the precipitation average is 286.3 mm, and in climate station of Quebrada de Macul between the communes of Peñalolén and La Florida (in higher grounds near the Andes mountains) the precipitation average is 438 mm.

In the airport area of Pudahuel, mean rainfall is 276.9 mm (10.90 in) per year, about 80% of which occurs during the winter months (May to September), varying between 50 and 80 mm (1.97 and 3.15 in) of rainfall during these months. That amount contrasts with a very sunny season during the summer months between December and March, when rainfall does not exceed 4 mm (0.16 in) on average, caused by an anticyclonic dominance continued for about seven or eight months. There is significant variation within the city, with rainfall at the lower-elevation Pudahuel site near the airport being about 20 percent lower than at the older Quinta Normal site near the city center.

Santiago's rainfall is highly variable and heavily influenced by the El Niño Southern Oscillation cycle, with rainy years coinciding with El Niño events and dry years with La Niña events.[33] The wettest year since records began in 1866 was 1900 with 819.7 millimeters (32.27 in)[34] – part of a "pluvial" from 1898 to 1905 that saw an average of 559.3 millimeters (22.02 in) over eight years[35] incorporating the second wettest year in 1899 with 773.3 millimeters (30.44 in) – and the driest 1924 with 66.1 millimeters (2.60 in).[34] Typically there are lengthy dry spells even in the rainiest of winters,[33] intercepted with similarly lengthy periods of heavy rainfall. For instance, in 1987, the fourth wettest year on record with 712.1 millimeters (28.04 in), there was only 1.7 millimeters (0.07 in) in the 36 days between 3 June and 8 July,[36][37] followed by 537.2 millimeters (21.15 in) in the 38 days between 9 July and 15 August.[38]

Precipitation is usually only rain, as snowfall only occurs in the Andes and Precordillera, being rare in eastern districts, and extremely rare in the central and western districts of the city.[39] In winter, the snow line is about 2,100 meters (6,890 ft), and it ranges from 1,500–2,900 meters (4,921–9,514 ft).[39] The city is affected only occasionally by snowfall. The period between 2000 and 2017 has been registered 9 snowfalls and only two have been measured in the central sector (2007 and 2017). The amount of snow registered in Santiago on 15 July 2017 ranged between 3.0 cm in Quinta Normal and 10.0 cm in La Reina (Tobalaba).[40]

Temperatures vary throughout the year from an average of 20 °C (68 °F) in January to 8 °C (46 °F) in June and July. In the summer days are very warm to hot, often reaching over 30 °C (86 °F) and a record high close to 38 °C (100 °F),[41] while nights are very pleasant and cool, at 11 °C (52 °F). During autumn and winter the temperature drops, and is slightly lower than 10 °C (50 °F). The temperature may even drop to 0 °C (32 °F), especially during the morning. The historic low of −6.8 °C (20 °F) was in July 1976.[42]

Santiago's location within a watershed is one of the most important factors determining the climate of the city. The coastal mountain range serves as a screen that stops the spread of maritime influence, contributing to the increase in annual and daily thermal oscillation (the difference between the maximum and minimum daily temperatures can reach 14 °C) and maintaining low relative humidity, close to an annual average of 70%. It also prevents the entry of air masses, with the exception of some coastal low clouds that penetrate to the basin through the river valleys.[43]

Prevailing winds are from the southwest, with an average of 15 km/h (9 mph), especially during the summer; the winter is less windy.

| Climate data for Arturo Merino Benítez International Airport, Pudahuel, Santiago (1991–2020, extremes 1966–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 39.3 (102.7) |

37.2 (99.0) |

36.8 (98.2) |

34.5 (94.1) |

31.1 (88.0) |

26.7 (80.1) |

28.2 (82.8) |

29.9 (85.8) |

32.9 (91.2) |

33.3 (91.9) |

35.2 (95.4) |

37.1 (98.8) |

39.3 (102.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 30.2 (86.4) |

29.7 (85.5) |

28.0 (82.4) |

23.3 (73.9) |

19.0 (66.2) |

15.5 (59.9) |

15.0 (59.0) |

16.8 (62.2) |

19.4 (66.9) |

22.7 (72.9) |

26.3 (79.3) |

28.7 (83.7) |

22.9 (73.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 21.4 (70.5) |

20.7 (69.3) |

18.9 (66.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

11.5 (52.7) |

8.8 (47.8) |

8.2 (46.8) |

9.7 (49.5) |

12.1 (53.8) |

14.8 (58.6) |

17.8 (64.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

14.9 (58.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 13.5 (56.3) |

13.0 (55.4) |

11.6 (52.9) |

7.8 (46.0) |

5.2 (41.4) |

3.5 (38.3) |

2.6 (36.7) |

3.6 (38.5) |

5.7 (42.3) |

7.6 (45.7) |

9.8 (49.6) |

12.6 (54.7) |

7.8 (46.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 2.7 (36.9) |

4.7 (40.5) |

2.1 (35.8) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−6.2 (20.8) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

0.7 (33.3) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0.3 (0.01) |

0.9 (0.04) |

3.4 (0.13) |

13.4 (0.53) |

32.6 (1.28) |

68.8 (2.71) |

53.0 (2.09) |

35.1 (1.38) |

17.1 (0.67) |

8.4 (0.33) |

3.7 (0.15) |

2.2 (0.09) |

221.5 (8.72) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 3.3 | 5.0 | 3.8 | 3.3 | 2.3 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 21.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 50 | 53 | 57 | 65 | 73 | 79 | 79 | 76 | 71 | 63 | 55 | 51 | 64 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 366.1 | 315.5 | 290.0 | 212.7 | 158.6 | 125.5 | 145.1 | 169.2 | 190.7 | 259.1 | 309.5 | 346.4 | 2,888.4 |

| Source 1: Dirección Meteorológica de Chile[44][45][46][42] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (precipitation days 1991–2020)[47] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Quinta Normal, Santiago (1991–2020, extremes 1967–present) |

|---|

| Climate data for Quebrada de Macul, Peñalolén, Santiago (2003-2015) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 27.5 (81.5) |

27.1 (80.8) |

24.8 (76.6) |

20.4 (68.7) |

16.7 (62.1) |

15.7 (60.3) |

14.3 (57.7) |

15.4 (59.7) |

18.0 (64.4) |

18.9 (66.0) |

22.0 (71.6) |

25.6 (78.1) |

20.5 (69.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 20.4 (68.7) |

19.9 (67.8) |

18.4 (65.1) |

14.7 (58.5) |

11.4 (52.5) |

11.0 (51.8) |

9.5 (49.1) |

10.4 (50.7) |

12.3 (54.1) |

13.6 (56.5) |

16.2 (61.2) |

18.6 (65.5) |

14.7 (58.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 13.3 (55.9) |

12.8 (55.0) |

12.0 (53.6) |

9.0 (48.2) |

6.0 (42.8) |

6.3 (43.3) |

4.6 (40.3) |

5.3 (41.5) |

6.5 (43.7) |

8.3 (46.9) |

10.4 (50.7) |

11.6 (52.9) |

8.8 (47.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 1 (0.0) |

6 (0.2) |

13 (0.5) |

13 (0.5) |

51 (2.0) |

82 (3.2) |

75 (3.0) |

111 (4.4) |

43 (1.7) |

23 (0.9) |

20 (0.8) |

0 (0) |

438 (17.2) |

| Source: Atlas Agroclimático de Chile[52] | |||||||||||||

Natural disasters

[edit]Santiago is located on the Pacific Ring of Fire, where two tectonic plates, the Nazca and South American Plates, collide. This results in a high frequency of earthquakes.[53] The first recorded earthquake to hit Santiago was in 1575, just 34 years after its founding. The most devastating earthquake in the city's history took place in 1647, inspiring the novel The Earthquake In Chile by Heinrich von Kleist.[53]

In response to the destructive earthquakes of 1960 (Valdivia) and 1985 (Algarrobo), Santiago implemented strict building codes to minimize damage from future earthquakes. In 2010, Chile was hit by the sixth largest recorded earthquake with a magnitude of 8.8 on the moment magnitude scale. The earthquake caused the death of 525 people, 13 of whom were in Santiago, and resulted in an estimated cost of 15–30 billion US dollars. Although many homes were damaged, the stricter building codes prevented the scale of destruction seen in the Haiti earthquake of the same year, in which over 100,000 people lost their lives.[54] While large earthquakes pose a threat, smaller earthquakes from local faults in and around Santiago are also a significant risk.[55] In particular, the San Ramón and El Arrayán faults in the east and north of the city are considered to be particularly dangerous.[55][56]

The eastern neighborhoods of Santiago are also susceptible to landslides, especially of the debris flow type, which pose a significant hazard to the area.[57]

Environmental issues

[edit]Santiago has a serious air pollution problem.[58] Despite a decrease in air pollution in the 1990s, the level of pollution has not significantly improved since 2000. In fact, a study conducted by a Chilean university in 2010 showed that the pollution levels in Santiago had doubled since 2002.[59] Particulate matter air pollution, specifically PM2.5 and PM10, frequently exceeds the standards set by the US Environmental Protection Agency and the World Health Organization, posing a significant threat to public health.[60]

One of the major sources of air pollution in Santiago is the El Teniente copper mine smelter, which operates year-round.[61][62] The government typically does not classify it as a local pollution source, as it is located just outside the reporting area of the Santiago Metropolitan Region, 110 kilometers from downtown.[63][64]

During the winter months, thermal inversion can trap and concentrate smog and air pollution in the Central Valley. Santiago has made progress in treating its wastewater, with the Mapocho Wastewater Treatment Plant starting operations in March 2012. This increased the city's wastewater treatment capacity to 100%, making Santiago the first capital city in Latin America to treat all of its municipal sewage.

Stray dogs are a common sight in Santiago,[65][66] but the country as a whole has a low incidence of rabies.[67]

Demographics

[edit]According to data collected in the 2002 census by the National Institute of Statistics, the Santiago metropolitan area population reached 5,428,590 inhabitants, equivalent to 35.9% of the national total and 89.6% of total regional inhabitants. This figure reflects broad growth in the population of the city during the 20th century: it had 383,587 inhabitants in 1907; 1,010,102 in 1940; 2,009,118 in 1960; 3,899,619 in 1982; and 4,729,118 in 1992.[68] (percentage of total population, 2007)[69]

The growth of Santiago has undergone several changes over the course of its history. In its early years, the city had a rate of growth 2.9% annually until the 17th century, then down to less than 2% per year until the early 20th century figures. During the 20th century, Santiago experienced a demographic explosion as it absorbed migration from mining camps in northern Chile during the economic crisis of the 1930s. The population surged again via migration from rural sectors between 1940 and 1960. This migration was coupled with high fertility rates, and annual growth reached 4.9% between 1952 and 1960. Growth has declined, reaching 1.4% in the early 2000s. The size of the city expanded constantly; The 20,000 hectares Santiago covered in 1960 doubled by 1980, reaching 64,140 hectares in 2002. The population density in Santiago is 8,464 inhabitants/km2.

The population of Santiago[68] has seen a steady increase in recent years. In 1990 the total population under 20 years was 38.0% and 8.9% were over 60. Estimates in 2007 show that 32.9% of men and 30.7% of women were less than 20 years old, while 10.2% of men and 13.4% of women were over 60 years. For the year 2020, it is estimated that the figures will be 26.7% and 16.8%.

4,313,719 people in Chile say they were born in one of the communes of the Santiago Metropolitan Region,[68] which, according to the 2002 census, amounts to 28.5% of the national total. 67.6% of the inhabitants of Santiago claim to have been born in one of the communes of the metropolitan area. In communes such as Santiago Centro and Independencia, according to 2017 census, 1/3 of residents is a Latin American immigrant (28% and 31% of the population of these communes, respectively).[70] Other communes of Greater Santiago with high numbers of immigrants are Estación Central (17%) and Recoleta (16%).[71]

Economy

[edit]Santiago is the industrial and financial center of Chile, and generates 45% of the country's GDP.[72] Some international institutions, such as ECLAC (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean), have their offices in Santiago. The strong economy and low government debt is attracting migrants from Europe and the United States.[73]

Santiago's steady economic growth over the past few decades has transformed it into a modern metropolis. The city is now home to a growing theater and restaurant scene, extensive suburban development, dozens of shopping centers, and a rising skyline, including the second tallest building in Latin America, the Gran Torre Santiago. It includes several major universities, and has developed a modern transportation infrastructure, including a free flow toll-based, partly underground urban freeway system and the Metro de Santiago, South America's most extensive subway system.

Santiago is an economically divided city (Gini coefficient of 0.47).[74][75] The western half (zona poniente) of the city is, on average, much poorer than the eastern communes, where the high-standard public and private facilities are concentrated.

Commercial development

[edit]

The Costanera Center, a mega project in Santiago's Financial District, includes a 280,000-square-meter (3,000,000 sq ft) mall, a 300-meter (980 ft) tower, two office towers of 170 meters (558 ft) each, and a hotel 105 meters (344 ft) tall. In January 2009 the retailer in charge, Cencosud, said in a statement that the construction of the mega-mall would gradually be reduced until financial uncertainty is cleared.[76] In January 2010, Cencosud announced the restart of the project, and this was taken generally as a symbol of the country's success despite the Great Recession. Close to Costanera Center another skyscraper is already in use, Titanium La Portada, 190 meters (623 ft) tall. Although these are the two biggest projects, there are many other office buildings under construction in Santiago, as well as hundreds of high rise residential buildings. In February 2011, Gran Torre Santiago, part of the Costanera Center project, located in the called Sanhattan district, reached the 300-meter mark, officially becoming the tallest structure in Latin America.[77]

Commerce

[edit]Santiago is Chile's retail capital. Falabella, Paris, Johnson, Ripley, La Polar, and several other department stores dot the mall landscape of Chile. The east side neighborhoods like Vitacura, La Dehesa, and Las Condes are home to Santiago's Alonso de Cordova street, and malls like Parque Arauco, Alto Las Condes, Mall Plaza (a chain of malls present in Chile and other Latin American countries) and Costanera Center are known for their luxurious shopping. Alonso de Cordova, Santiago's equivalent to Rodeo Drive or Rua Oscar Freire in São Paulo, has exclusive stores like Louis Vuitton, Hermès, Emporio Armani, Salvatore Ferragamo, Ermenegildo Zegna, Swarovski, MaxMara, Longchamp, and others. Alonso de Cordova also houses some of Santiago's most famous restaurants, art galleries, wine showrooms and furniture stores. The Costanera Center has stores like Armani Exchange, Banana Republic, Façonnable, Hugo Boss, Swarovski, and Zara. There are plans for a Saks Fifth Avenue in Santiago. Several mercados in the city such as the Mercado Central de Santiago sell local goods. Barrio Bellavista and Barrio Lastarria have some of the most exclusive night clubs, chic cafés and restaurants.

Transport

[edit]Air

[edit]

Arturo Merino Benítez International Airport (IATA: SCL) is Santiago's national and international airport and the principal hub of LATAM Airlines, Sky Airline, Aerocardal and JetSmart. The airport is located in the western commune of Pudahuel. The largest airport in Chile, it is ranked sixth in passenger traffic among Latin American airports, with 14,168,282 passengers served in 2012 – a 17% increase over 2011.[78] It is located 15 km (9.3 mi) from the city center.

Peldehue airport in Colina began operations on 13 December 2021. It will be able to service up to 25 flights each hour.[79] Santiago is also served by Eulogio Sánchez Airport (ICAO: SCTB), a small, privately owned general aviation airport in the commune of La Reina.

Rail

[edit]

Trains operated by Chile's national railway company, Empresa de los Ferrocarriles del Estado (EFE), connect Santiago to several cities in the south-central part of the country: Rancagua, San Fernando, Talca (connected to the coastal city of Constitución by a different train service), Linares and Chillán. All such trains arrive and depart from the Estación Central railway station (Central Station), which can be accessed by bus or subway.[80] The proposed Santiago–Valparaíso railway line would connect Santiago with Valparaíso in 45 minutes, and expansions of the commuter rail network to Melipilla and Batuco are under discussion.

Inter-urban buses

[edit]Bus companies provide passenger transportation from Santiago to most areas of the country as well as to foreign destinations, while some also provide parcel shipping and delivery services.

There are several bus terminals in Santiago:

- Terminal San Borja: located in Estación Central metro station. Provides buses to all destinations in Chile and to some towns around Santiago.

- Terminal Alameda: located in Universidad de Santiago metro station. Provides buses to all destinations in Chile.

- Terminal Santiago: located one block west of Terminal Alameda. Provides buses to all destinations in Chile as well as to destinations in most countries in South America, except Bolivia.

- Terrapuerto Los Héroes: located two blocks east of Los Héroes metro station. Provides buses to south of Chile and some northern cities, as well as Argentina (Mendoza and Buenos Aires) and Paraguay (Asunción).

- Terminal Pajaritos: located in Pajaritos metro station. Provides buses to the international airport, inter-regional services to Valparaíso, Viña del Mar and several other coastal cities and towns.

- Terminal La Cisterna: located in La Cisterna metro station. Provides buses to towns around southern Santiago, Viña del Mar, Temuco and Puerto Montt.

- Terminal La Paz: located about two blocks away from La Vega Central Market; the closest Metro station is Puente Cal y Canto. It connects the rural areas north of Santiago.

Highways

[edit]

A network of free flow toll highways connects the various areas of the city. They include the Vespucio Norte and Vespucio Sur highways, which surround the city completing a nearly full circle; Autopista Central, the section of the Pan American highway crossing the city from north to south, divided in two highways 3 km (1.9 mi) apart; and the Costanera Norte, running next to the Mapocho River and connecting the international airport with the downtown and with the wealthier areas of the city to the east, where it divides into two highways.

Other non-free flow toll roads connecting Santiago to other cities, include: Rutas del Pacífico (Ruta 68), the continuation of the Alameda Libertador General Bernardo O'Higgins Avenue to the west, provides direct access to Valparaíso and Viña del Mar; Autopista del Sol (Ruta 78), connects Melipilla and the port of San Antonio with the capital; Autopista Ruta del Maipo (a.k.a. "Acceso Sur") is an alternative to the Pan American highway to access the various localities south of Santiago; Autopista Los Libertadores provides access to the main border crossing to Argentina, via Colina and Los Andes; and Autopista Nororiente, which provides access to the suburban development known as Chicureo, north of the capital.

Public transport

[edit]

Santiago has 37% of Chile's vehicles, totaling 991,838, of which 979,346 are motorized. An extensive network of streets and avenues crisscrosses Santiago, facilitating travel between the different communities that make up the metropolitan area.

In the 1990s, the government attempted to reorganize the public transport system. New routes were introduced in 1994, and the buses were painted yellow. However, the system faced significant issues such as route overlaps, high levels of air and noise pollution, and safety concerns for both riders and drivers. To address these problems, a new transport system called Transantiago was devised. It was officially launched on February 10, 2007, combining core services across the city with the subway and local feeder routes, all under a unified payment system using a contactless smartcard called "Tarjeta bip!"

The change was not well received by users, who complained of a lack of buses, excessive transfers between buses, and reduced coverage. While some of these issues were eventually addressed, the system developed a poor reputation that it struggled to overcome. As of 2011, fare evasion remained persistently high.

In 2019, the government rebranded the public transport system as RED, aiming to distance it from the problematic Transantiago brand.

In recent years, many cycle paths have been constructed, but their number remains limited, and the routes are poorly connected. Most cyclists ride on the streets, and despite helmet and light use being mandatory, compliance is not widespread.

Metro

[edit]

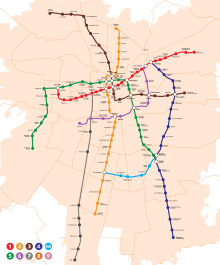

Santiago Metro has seven operating lines (1, 2, 3, 4, 4A, 5 and 6), extending over 149 km (93 mi) and connecting 143 stations. The system carries around 2,400,000 passengers per day. Two underground lines (Line 4 and 4A) and an extension of Line 2 were inaugurated in 2005 and 2006, while an extension of Line 5 was inaugurated in 2011.[81][82] Line 6 was inaugurated in 2017, adding 10 stations to the network and approximately 15 km (9.3 mi) of track. Line 3 opened on 22 January 2019, with 18 new stations.[83][82]

Commuter rail

[edit]EFE provides suburban rail service under the brandname of Metrotren. There are 2 southbound routes. The most popular is the Metrotren Nos service, between the Central Station of Santiago and Nos station, in San Bernardo. This line, inaugurated in 2017, serves 8 million people per year, with 12 trains serving 10 stations with a frequency of 6 minutes during rush hours, and 12 during the rest of the time. The other route is the Metrotren Rancagua service, between the Central Station of Santiago and the Rancagua station, connecting Santiago with the regional capital of O'Higgins.

Bus

[edit]

Red (formerly known as Transantiago) is the name of Santiago's comprehensive public transportation system. It operates by integrating local feeder bus lines, main bus lines, EFE commuter trains, and the metro network. The system features an integrated fare system that enables passengers to make transfers between bus, metro, and train services using a single, contactless smartcard known as "Bip!". Additionally, it offers reduced fares for senior citizens, high school students, and university students.

Vehicles for hire

[edit]Taxicabs are prevalent in Santiago and are easily recognizable by their black bodies and yellow roofs, as well as their orange license plates. Another type of taxi called radiotaxis can be ordered by phone and can come in any make, model, or color, but must always have the orange license plates. Colectivos are shared taxis that follow a specific route and charge a fixed fee for the ride.

Cabify, Uber and DiDi are also available in Santiago, though authorities warn they currently operate outside the law.[84]

Public transportation statistics

[edit]The average amount of time people spend commuting with public transit in Santiago - to and from work, for example - on a weekday is 53 min. Just 4,3% of public transit riders ride for more than 2 hours every day while . The average amount of time people wait at a stop or station for public transit (considering transfers) is 14 min, while 17,4% of riders wait less than 5 minutes on average every day. The average distance people usually ride in a single trip with public transit is 8.03 km, while 18% travel for over 12 km in a single direction.[85]

Internal transport

[edit]

As of 2006, Santiago was home to 992,000 vehicles, 979,000 of which were motorized. This made up 37.3% of Chile's total vehicle count. 805,000 cars passed through the city, which is 37.6% of the national total[clarification needed] or one car for every seven people.[86]

The main road is the Avenida Libertador General Bernardo O'Higgins, better known as Alameda Avenue, which runs northeast and southwest. From north to south, it is crossed by Autopista Central and the Independencia, Gran Avenida, Recoleta, Santa Rosa, Vicuña Mackenna and Tobalaba avenues. Other major roads include the Avenida Los Pajaritos to the west and Providencia Avenue and Apoquindo Avenue to the east. Finally, the Américo Vespucio Avenue acts as a ring road.

During the 2000s, several urban highways were built through Santiago in order to improve the situation for vehicles. The road General Velásquez and sections of the Pan-American Highway in Santiago were converted into the Autopista Central, while Américo Vespucio became variously the highways Vespucio Norte Express and Vespucio Sur, as well as Vespucio Oriente in the future. Following the edge of the Mapocho River, Costanera Norte was built to link the northeast of the capital to the airport and the downtown area. All these highways, totaling 210 km in length, have a free flow toll system.

Administrative divisions

[edit]

Greater Santiago lacks a metropolitan government for its administration, which is distributed between authorities, complicating the operation of the city as a single entity.[87] The highest authorities in Santiago are considered to be the governor of the Santiago Metropolitan Region, who is popularly elected to the office, now held by Claudio Orrego, and the regional presidential delegate of Santiago Metropolitan Region, an official appointed by the president of Chile.

The conurbation of Greater Santiago does not fit perfectly into any administrative division, as it extends into four different provinces and 35 communes plus 11 satellite communes which together make the Santiago Metropolitan Area. The majority of its 641.4 km2 (247.65 sq mi) (as of 2002)[88] lie within Santiago Province, with some peripheral areas contained in the provinces of Cordillera, Maipo, and Talagante.

Although there is no official consensus in this regard, the communes of the city are usually grouped into seven sectors: north, center, northeast, southeast, south, southeast and southwest.

Культура

[ редактировать ]В этом разделе нужны дополнительные цитаты для проверки . ( февраль 2019 г. ) |

В городе остаются лишь несколько исторических зданий испанского колониального периода, потому что - как и остальная часть страны - Сантьяго регулярно поражает землетрясениями. Условные здания включают Casa Colorada (1769), церковь Сан -Франциско (1586) и Posada del Corregidor (1750).

Собор на центральной площади ( Plaza de Armas ) - это зрелище, которое занимает столько же, сколько Паласио -де -ла -Монеда, президентский дворец. Первоначальное здание было построено между 1784 и 1805 годами, а архитектор Хоакин Тоска отвечал за его строительство. Другие здания, окружающие Плаза -де -Армас, - это здание центрального почтового отделения , которое было закончено в 1882 году, и Palacio de La Real Audiencia de Santiago , построенная между 1804 и 1807 годами. В нем размещен Чилийский национальный музей истории , с 12 000 предметов, которые могут быть выставлен. В юго-восточном углу площади стоит зеленое чугунное коммерческое здание Эдвардса, которое было построено в 1893 году. К востоку от этого находится колониальное здание Каса Колорады (1769), в котором находится Музей Сантьяго. Рядом находится муниципальный театр Сантьяго , который был построен в 1857 году французским архитектором Брунетом из Эдварда Бейнса. сильно повреждено землетрясением в 1906 году. Это было , одна из крупнейших библиотек Южной Америки.

Бывшее здание Национального Конгресса , Дворец юстиции и Королевский таможенный дворец ( Паласио де ла -Рег Адуана де Сантьяго ) расположены рядом друг с другом. В последнем находится Музей доколумбового искусства . Огонь уничтожил здание Конгресса в 1895 году, который затем был восстановлен в неоклассическом стиле и вновь открыт в 1901 году. Конгресс был свергнут под военной диктатурой (1973–89) Аугусто Пиночетом , и после того, как диктатура была недавно создана 11 Март 1990 г., в Вальпараисо.

Здание Дворца юстиции (Palacio de Tribunales) расположено на южной стороне площади Монтт. Он был разработан архитектором Эмилио Дойер и построен между 1907 и 1926 годами. Здание является домом для Верховного суда Чили . Группа из 21 судей является самой высокой судебной властью в Чили. Здание также является штаб -квартирой Апелляционного суда Сантьяго.

Бандера -стрит ведет к строительству Сантьяго фондовой биржи ( Bolsa de Comercio ), завершенной в 1917 году, Клуб де ла -Унион (открытый в 1925 году), Университет де Чили (1872) и к самой старой церковной дом в городе, Церковь Сан -Франциско (построена между 1586 и 1628 годами), с ее Марианской статуей Виргена -дель Сокорро («Богоматери помощи»), которая была доставлена в Чили Педро де Вальдивией. К северу от Плаза -де -Армаса («квадрат оружия», где была собрана колониальная милиция) находятся Пасео Пуэнте , церковь Санто -Доминго (1771) и центральный рынок (Центральный Меркадо), декоративное здание железа. Также в центре города Сантьяго находится Torre Entel , телевизионная башня высотой 127,4 метра с наблюдением, завершенной в 1974 году; Башня служит центром связи для коммуникационной компании Entel Chile.

Центр Costanera был завершен в 2009 году и включает в себя жилье, магазины и развлекательные заведения. общей площадью 600 000 кв Проект с . Четыре офисных башни обслуживаются подключениями к шоссе и метро. [ 89 ]

-

Национальный музей изящных искусств , расположенный рядом с Парк Фардл .

-

Эдвардский дворец

-

Главный офис банка Чили

Наследие и памятники

[ редактировать ]

В столичном районе Сантьяго находится 174 объекта наследия, находящихся под стражей национального совета по памятникам, среди которых археологические, архитектурные и исторические памятники, окрестности и типичные районы. Из них 93 расположены в коммуне Сантьяго , считается историческим центром города. Несмотря на то, что не был объявлен памятник Сантьягино, Эль Три , уже был предложено правительством Чилийского правительства: заповедник -Пломо , церковь и монастырь Сан -Франциско и дворец Ла Монеда .

В центре Сантьяго находятся несколько зданий, построенных во время доминирования в Испании, и это в основном соответствует, как Столичный собор и вышеупомянутая церковь католических церквей Сан -Франциско. Здания периода - это те, которые расположены по бокам Plaza de Armas , как место настоящей аудиенсии , почтового отделения или Casa Colorada .

В течение девятнадцатого века и появления независимости новые архитектурные произведения стали возводить в столице молодой республики. Аристократия построила небольшие дворцы для жилого использования, в основном вокруг районной республики и сохранилась до сегодняшнего дня. структурам приняли художественные тенденции из Европы, как Сантьяго главные Чили и университет , центральный вокза К этим конной клуб другим офисы , Университета Католический Баррио Парис-Лондрес , среди других.

Различные зеленые зоны в городе содержат внутри и вокруг различных участков персонажа наследия. Среди наиболее важных укреплений Санта -Люсии Хилл , храма Девы Марии на вершине Сан -Кристобальского холма , роскошного склепа общего кладбища , Парк Фордж , парка О'Гиггинс и Квинта Нормальный парк .

Культурные мероприятия и развлечения

[ редактировать ]

компаниях в Сантьяго В крупных театральных расположены несколько национальных и международных проектов, с самым высоким выражением во время Международного театрального фестиваля, известного как Сантьяго Мил , который проходит каждый январь с 1994 года и собирал более миллиона зрителей. Также является планетарий в Университете Сантьяго -де -Чили .

Чтобы провести различные культурные, художественные и музыкальные мероприятия, есть несколько участков, в которых освещаются культурный центр Мапочо , 100 культурный центр Матуканы , культурный центр Габриэлы Мистраль , культурный центр Паласио -де -ла -Монеда , Арена Мовистар и Театр Кауполиков . С другой стороны, операции оперы и балета постоянно принимаются муниципальным театром Сантьяго , расположенным в самом сердце города и который имеет 1500 зрителей.

В столице есть 18 кинотеатров, в общей сложности 144 комнаты и более 32 000 мест, проекционные центры, чем 5 Arthouse Add.

Для детей и подростков есть несколько развлекательных заведений, таких как парк развлечений Fantasilandia , Национальный зоопарк или зоопарк Buin на окраине города. Bellavista , , Brasil , Manuel Montt Plaza -ñuñoa и Suecia объясняют большинство ночных клубов, ресторанов и баров в городе, основных вечерних развлекательных центрах в столице. Чтобы способствовать экономическому развитию других регионов, закон запрещает строительство казино в столичном регионе, но поблизости находятся казино из прибрежного города Вина -дель -Мар , в 120 км от расстояния от Сантьяго и Монтичелло Гранд -Казино в в Мостазал, в 56 километрах к югу от Сантьяго, который открылся в 2008 году.

Музеи и библиотеки

[ редактировать ]У Сантьяго есть множество музеев различных видов, среди которых три из «национальных классов», управляемых Управлением библиотек, архивов и музеев (Dibam): Национальный музей истории , Национальный музей изобразительных искусств и Национальный музей естественной истории Полем

Большинство музеев расположены в историческом центре города, занимая старые здания колониального происхождения, например, в Национальном музее истории, который расположен в Palacio de La Real Audiencia . В La Casa Colorada находится музей Сантьяго, в то время как в колониальном музее размещен в крыле церкви Сан-Франциско , а Музей доколумбового искусства занимает часть старого Паласио-де-Адуана . Музей изобразительных искусств, хотя и расположен в центре города, был построен в начале двадцатого века, особенно для размещения музея и в задней части здания, был проложен в 1947 году, Музей современного искусства , под факультетом Искусство Университета Чили .

Quinta Normal Park также имеет несколько музеев, среди которых уже упомянутая естественная история, Музей Артекина , Музей науки и техники и музей Ферровиарио . В 2010 году был открыт музей памяти и прав человека , который ознаменовывает жертвы нарушений прав человека, совершенных во время военной диктатуры страны.

В других частях города есть несколько музеев, таких как Музей аэронавтики в Серриллосе, Музей Таджамарес в Провиденсе и Музей Interactivo Mirador в Ла -Грандже. Последний открылся в 2000 году и разработал в основном для детей и молодежи, которые посетили более 2,8 миллиона посетителей, что делает его самым оживленным музеем в стране.

Самая важная публичная библиотека - Национальная библиотека, расположенная в центре Сантьяго. Его происхождение датируется 1813 году, когда она была создана зарождающейся республикой и было перенесено в ее нынешние помещения столетие спустя, а также дом в штаб -квартире Национального архива . Чтобы обеспечить большую близость к населению, включение новых технологий и дополнить услуги, предоставляемые публичными библиотеками, и Национальная библиотека была открыта в 2005 году в библиотеке Сантьяго в Баррио Матукане .

-

Национальный исторический музей , расположенный на Плаза -де -Армас

-

Центральное здание почтового отделения

-

Национальный музей естественной истории , расположенный в Quinta Normal .

-

Национальная библиотека из Ла -Аламеда .

Музыка

[ редактировать ]У Сантьяго есть два симфонических оркестра:

- Orquesta Philmónica de Santiago («Сантьяго -филармонический оркестр»), который выступает в муниципальном театре ( муниципальный театр Сантьяго )

- Оркестр -симфонический оркестр »), часть его.

Есть ряд джазовых заведений, некоторые из них, в том числе «El Pesteguidor», «Thelonious» и «Le Fournil Jazz Club», расположены в Беллависте, один из «Hippest» районов Сантьяго, хотя «Club de Jazz de Santiago». «Самый старый и самый традиционный, находится в ñuñoa. [ 90 ] Ежегодные фестивали, представленные в Сантьяго, включают Lollapalooza и фестиваль Maquinaria .

Газеты

[ редактировать ]Наиболее широко распространенные газеты в Чили публикуются El Mercurio и Copesa и заработали более 91% доходов, полученных в печатной рекламе в Чили. [ 91 ]

Некоторые газеты, доступные в Сантьяго:

СМИ

[ редактировать ]Сантьяго является домом для крупных чилийских телевизионных сетей, включая общественный вещатель TVN и частный канал 13 , Chilevisión , La Red и Mega . Кроме того, радиостанции Adn Radio Chile , Radiogultura , Radio Concierto , Radio Cooperativa , Radio Pudahuel и Radio Rock & Pop расположены в городе.

Спорт

[ редактировать ]Сантьяго является домом для некоторых из самых успешных футбольных клубов Чили. Colo-Colo , основанная 19 апреля 1925 года, имеет давнюю традицию и постоянно играл в самой высокой лиге с момента создания первой чилийской лиги в 1933 году. Победы клуба включают 30 национальных титулов , 10 успешных Copa Chile и чемпионов Турнир Copa Libertadores в 1991 году, единственная чилийская команда, которая выиграла этот турнир. Клуб проводит свои домашние игры в Estadio Munumental в коммуне Macul.

Universidad de Chile имеет 18 национальных титулов и 5 побед Copa Chile. В 2011 году они были чемпионами Copa Sudamericana , единственной чилийской команды, которая выиграла этот турнир. Клуб был основан 24 мая 1927 года под названием Club Deportivo Universitario как союз клуба Náutico и Federación Universitaria. Основателями были студенты Университета Чили . В 1980 году организация отделилась от Университета Чили, а клуб в настоящее время полностью независима. Команда играет в свои домашние игры в эстадио -национал -де Чили в коммуне «Внуньоа».

Católica (UC). STANDO Games в Стандарто Сан -Карлос -де -Апоквиндо. Католика Хаст Университет в 13 национальных плитках. Copa Libertadorador играет 20 раз в 1993 году, финал - 1993.

Несколько других футбольных клубов базируются в Сантьяго, в том числе Unión Española , Audax Italiano , Palestino , Santiago Morning , Magallanes и Barnechea . В дополнение к футболу в городе играют несколько видов спорта, а в теннисе и баскетболе являются основными. Клуб Хипико -де -Сантьяго и Хиподромо Чили являются двумя треками для хрена в городе.

Сантьяго прошел последние этапы официального чемпионата мира по баскетболу 1959 года , где Чили выиграла бронзовую медаль.

В городе 3 февраля 2018 года город провел раунд чемпионата FIU Formula E на временной уличной трассе, включающей Plaza Baquedano и Parque Forestal. [ 92 ] Это была первая санкционированная FIA раса в стране.

проводились Панамериканские игры 2023 года в Сантьяго. [ 93 ]

Сантьяго Летние игры в Сантьяго состоится в Сантьяго в 2027 года. Это будет отмечать первый раз, когда в испанской стране, южном полушарии и в Латинской Америке когда -либо проводились игры Специальной Олимпиады мира.

Отдых

[ редактировать ]

В городе есть обширная сеть велосипедных троп, особенно в коммуне Providencia. Самая длинная секция - это дорога Америко Веспуччо, которая содержит очень широкую грунтовую дорожку со многими деревьями через центр улицы, используемой автомобилистами с обеих сторон. Следующий самый длинный путь находится вдоль реки Мапочо вдоль Андрес -Белло -авеню. Многие люди используют складные велосипеды для поездки на работу. [ 94 ]

Основные парки города:

- 150 гектаров Сантьяго-парк Сантьяго , который охватывает холм Сан-Кристобал и включает в себя Чилийский национальный зоопарк и канатную дорогу Сантьяго .

- Двухсотлетний парк , в парке 30 гектаров вдоль реки Мапочо в Викуре

- О'Хиггинс Парк

- Нормальный квинта -парк

- Forestal Park , парк, расположенный в центре города вдоль Мапочо реки

- Санта -Люсия Хилл

- Парк Araucano в Лас -Конресс, прилегающий к торговому центру Parque Arauco, содержит 30 гектаров садов.

- Inés de Suarez в Invidencia

- Отец Хартадо Парк, также известный как Intercunal Park.

- Семейный парк

- Мапочо Рио Парк

К востоку от города есть горнолыжные курорты ( Валье Невадо , Ла Парва , Эль Колорадо ) и винодельни на равнинах к западу от города.

Культурные места включают:

- Музей изобразительных искусств - Музей изобразительных искусств

- Museo Violeta Parra , художественный музей, посвященный чилийскому народному художнику Вайолы Парра [открыта в 2015 году]

- Баррио Беллависта , культурный и богемный район

- Центральная станция , железнодорожный вокзал, спроектированный Gustave Eiffel

- Víctor Jara Stadium

- Бывший национальный конгресс

- Plaza de Armas , центральная площадь

- Дворец валюты , правительство правительства.

- Театро -муниципальный ( муниципальный театр Сантьяго ), основной оперный театр страны.

Основными спортивными площадками являются Национальный стадион (место финала чемпионата мира 1962 года ), монументальный стадион Дэвида Ареллано , стадион Санта -Лоры и стадион Сан -Карлос -де -Апоквиндо .

Религия

[ редактировать ]

Как и в большинстве Чили, большая часть населения Сантьяго является католической . Согласно национальной переписи, проведенной в 2002 году Национальным бюро статистики ( INE ), в столичном регионе Сантьяго 3129 249 человек 15 и старше идентифицировали себя как католики, что эквивалентно 68,7% от общей численности, в то время как 595,173 (13,1%) описал себя как евангельские протестанты . Около 1,2% населения объявили себя свидетелями Иеговы , в то время как 2,0% идентифицировали себя как святые последних дней (мормоны), 0,3% как еврейские , 0,1% как восточные православные и 0,1% как мусульманин . Приблизительно 10,4% населения столичного региона заявили, что они атеисты или агностик , в то время как 5,4% заявили, что они следовали за другими религиями. [ 95 ] В 2010 году строительство было инициировано в храме Сантьяго Бахаи , который служил в качестве пансионного пансиона Бахажи для Южной Америки, в коммуне Пеньялолен. [ 96 ] Строительство на участке было завершено, и храм был посвящен в октябре 2016 года. [ 97 ]

Образование

[ редактировать ]Город является домом для многочисленных университетов, колледжей, исследовательских учреждений и библиотек.

Крупнейшим университетом и одним из старейших в Америке является Университет де Чили . Корни университета датируются 1622 году, по состоянию на 19 августа, был основан первый университет в Чили под названием Санто Томас де Акино. 28 июля 1738 года он был назван настоящим Университетом де Сан -Фелипе в честь короля Филиппа V из Испании . На родном языке он также известен как Casa de Bello (Испанский: Дом Белло - после их первого ректора Андрес Белло ). 17 апреля 1839 года, после независимости Чили из Королевства Испании , она была переименована в Университет де Чили и вновь открыта 17 сентября 1843 года. [ 98 ]

Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (PUC) была основана в июне 1888 года и стала лучшей школой в Латинской Америке в 2014 году. [ 99 ] 11 февраля 1930 года он был объявлен университетом постановлением Папы Пия XI . Он получил признание чилийским правительством в качестве назначенного Папского университета в 1931 году. Хоакин Ларрейн Гандариллас (1822–1897), архиепископ Аназарба , был основателем и первым ректором PUC. PUC - современный университет; В кампусе Сан -Хоакина есть несколько современных зданий и предлагает много парков и спортивных сооружений. Несколько курсов проводятся на английском языке. Экс-президент, Себастьян Пиньера , министр Рикардо Райнерери и министр Эрнан де Солминихак, все посещали PUC в качестве студентов и работали в PUC в качестве профессоров. В процессе поступления 2010 года приблизительно 48% студентов, которые достигли лучших результатов в Prueba de Selección Universitaria, поступивших в UC. [ 100 ]

Высшее образование

[ редактировать ]Традиционный

[ редактировать ]

- Universidad de Chile (или или Uch)

- Папский католический университет Чили (PUC)

- Университет Сантьяго де Чили (USACH)

- Столичный университет наук о образовании (UMCE)

- Столичный технологический университет (UTEM)

- Федерико Санта -Мария Технический университет (UTFSM)

Нетрадиционный

[ редактировать ]- Университет Адольфо Ибаньес (UI)

- Университет развития (UDD)

- Университет Порталеса Диего (UDP)

- Университет Альберто Эртадо (uah)

- Центральный университет Чили (UCEN)

- Национальный университет Андреса Белло (UNAB)

- Университет Христианского гуманизма (UAHC)

- Мэр Университета (гм)

- Университет Конец земли

- Университет Лос -Андеса

- Университет Габриэлы Мистраль (UGM)

- Тихоокеанский университет

- Университет Америки

- Университет искусств, наук и коммуникация (UNIACC)

- Университет Сан -Себастьяна (USS)

- Боливарский университет

Другой

[ редактировать ]- Рупрохт Карлс Университет Хайдельберга в аспирантуре и дальнейшем образовательном центре Университета Гейдельберга в Сантьяго Архивировал 17 января 2022 года на машине Wayback

- Дэвид Рокфеллер Центр латиноамериканских исследований (DRCLAS) Региональный офис в Сантьяго

- Стэнфордский факультет в Сантьяго архивировал 15 июля 2011 года на машине Wayback

- Дипломатическая академия Чили

Международные отношения

[ редактировать ]Города -близнецы - Сестринские города

[ редактировать ]Сантьяго с двойной с:

Сотрудничество и дружба

[ редактировать ]Союз иберо-американских столичных городов

[ редактировать ]Сантьяго является частью союза ибероамериканских столичных городов с 12 октября 1982 года. [ Цитация необходима ]

Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ «Tellubase - Chile Faction Cail (серия общественных услуг Tellusant)» (PDF) . Tellusant . Получено 11 января 2024 года .

- ^ Субнациональный ИРП. «База данных области - глобальная лаборатория данных» . HDI.globaldatalab.org . Архивировано с оригинала 10 февраля 2019 года . Получено 4 июля 2023 года .